Accuracy Assessment of Chemometric Correction Algorithms: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Validation in Pharmaceutical Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive framework for assessing the accuracy of chemometric correction algorithms, essential for researchers and scientists in drug development.

Accuracy Assessment of Chemometric Correction Algorithms: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Validation in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for assessing the accuracy of chemometric correction algorithms, essential for researchers and scientists in drug development. It explores the foundational principles of chemometrics and accuracy metrics, details methodological applications in resolving complex spectral and chromatographic data, addresses troubleshooting and optimization strategies for enhanced model performance, and establishes rigorous validation protocols for comparative analysis. By synthesizing current methodologies and validation criteria, this review serves as a critical resource for ensuring reliable analytical data in pharmaceutical research and development.

Core Principles and Metrics: Defining Accuracy in Chemometric Context

In chemometrics and analytical chemistry, accuracy and precision are fundamental performance characteristics for evaluating measurement systems and data analysis algorithms. Accuracy refers to the closeness of agreement between a measured value and the true or accepted reference value, essentially measuring correctness [1] [2]. Precision, in contrast, refers to the closeness of agreement between independent measurements obtained under similar conditions, representing the consistency or reproducibility of results without necessarily being correct [1] [2]. The distinction is critical: measurements can be precise (tightly clustered) yet inaccurate if they consistently miss the true value due to systematic error, or accurate on average but imprecise with high variability between measurements [3] [2].

Within the framework of the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), these concepts are operationalized through standardized reference materials, data, and documented procedures. As the official U.S. agency for measurement science, NIST provides the foundation for traceable and reliable chemical measurements, enabling researchers to validate the accuracy and precision of their chemometric methods against nationally recognized standards [4] [5]. This review examines these core concepts through the lens of NIST standards, providing a comparative guide for assessing chemometric correction algorithms.

NIST's Role in Establishing Measurement Standards

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), a U.S. government agency within the Department of Commerce, serves as the National Measurement Institute (NMI) for the United States [5]. Its congressional mandate is to establish, maintain, and disseminate the nation's measurement standards, ensuring competitiveness and fairness in commerce and scientific development [4] [5]. For chemometricians and analytical chemists, NIST provides the critical infrastructure to anchor their measurements to the International System of Units (SI), creating an unbroken chain of comparisons known as traceability [6].

NIST supports chemical and chemometric measurements through several key products and services, which are essential for accuracy assessment:

Standard Reference Materials (SRMs): These are well-characterized, certified materials issued by NIST with certified values for specific chemical or physical properties [4] [5]. They are often described as "truth in a bottle" and are used to calibrate instruments, validate methods, and assure quality control [5]. SRMs provide the reference points against which the accuracy of analytical methods can be judged.

Standard Reference Data (SRD): NIST produces certified data sets for testing mathematical algorithms and computational methods [4] [5]. While the search results note that currently only a few statistical algorithms have such data sets available on the NIST website, they represent a crucial resource for verifying the accuracy and precision of chemometric calculations in an error-free computation environment [4].

Calibration Services: NIST provides high-quality calibration services that allow customers to ensure their measurement devices are producing accurate results, establishing the basis for measurement traceability [5].

The use of NIST-traceable standards involves a documented chain of calibrations, where each step contributes a known and stated uncertainty, ultimately linking a user's measurement back to the primary SI units [6] [7]. This process is fundamental for achieving accuracy and precision that are recognized and accepted across different laboratories, industries, and national borders.

Quantitative Comparison of Accuracy and Precision

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, metrics, and sources of error for accuracy and precision, providing a clear framework for their evaluation in chemometric studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Accuracy and Precision Parameters

| Parameter | Accuracy | Precision |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | Closeness to the true or accepted value [2] | Closeness of agreement between repeated measurements [2] |

| Evaluates | Correctness | Reproducibility/Consistency |

| Primary Error Type | Systematic error (bias) [2] | Random error [2] |

| Common Metrics | Percent error, percent recovery, bias [1] [2] | Standard deviation, relative standard deviation (RSD), variance [1] [2] |

| Dependence on True Value | Required for assessment | Not required for assessment |

| NIST Traceability Link | Certified Reference Materials (SRMs) provide the "conventional true value" for accuracy assessment [5] [6] | Documentary standards (e.g., ASTM) provide standardized methods to improve reproducibility and minimize random error [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Chemometric Algorithms

Protocol 1: Accuracy Assessment via Certified Reference Materials

This protocol uses NIST Standard Reference Materials (SRMs) to determine the accuracy of a chemometric method, such as a calibration model for determining the concentration of an active pharmaceutical ingredient.

- Material Selection: Acquire a NIST SRM that is matrix-matched to your sample type and contains the analyte of interest with a certified concentration and stated uncertainty [1] [6].

- Sample Preparation: Process the SRM according to the standard operating procedure of your analytical method (e.g., spectroscopy, chromatography).

- Analysis: Analyze the prepared SRM using your instrument and apply the chemometric correction algorithm or calibration model to predict the analyte concentration.

- Accuracy Calculation: Compare the model-predicted value to the certified value from NIST.

- Interpretation: A method is considered accurate for that matrix and analyte if the percent error or recovery falls within acceptable limits, often defined by regulatory guidelines or the uncertainty range of the SRM itself.

Protocol 2: Precision Evaluation through Repeatability and Reproducibility

This protocol assesses the precision of a measurement process, which is critical for ensuring the reliability of any chemometric model built upon the data.

Repeatability (Intra-assay Precision):

- Using a homogeneous sample (which can be an in-house control or an SRM), perform at least 6-10 independent measurements under identical conditions (same instrument, same operator, short time interval) [2].

- Apply the chemometric algorithm to each measurement.

- Calculate the standard deviation (SD) and relative standard deviation (RSD) of the results. The RSD is calculated as

(SD / Mean) * 100%[1] [2]. A lower RSD indicates higher precision.

Reproducibility (Inter-assay Precision):

- Perform the same analysis on the same homogeneous sample under varied conditions (e.g., different days, different analysts, different instruments within the same lab) [2].

- Apply the same chemometric algorithm.

- Calculate the SD and RSD across the results from the different conditions. Reproducibility RSD is typically larger than repeatability RSD. High reproducibility indicates that the chemometric method is robust to normal operational variations.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Algorithm Assessment Using a Hypothetical NIST SRM

| Algorithm Tested | NIST SRM Certified Value (mg/kg) | Mean Measured Value (mg/kg) | Percent Error (%) | Repeatability RSD (%, n=10) | Key Performance Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression | 100.0 ± 1.5 | 99.5 | 0.5 | 1.2 | High Accuracy, High Precision |

| Principal Component Regression (PCR) | 100.0 ± 1.5 | 105.2 | 5.2 | 1.5 | Low Accuracy, High Precision |

| Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) | 100.0 ± 1.5 | 101.0 | 1.0 | 4.5 | High Accuracy, Low Precision |

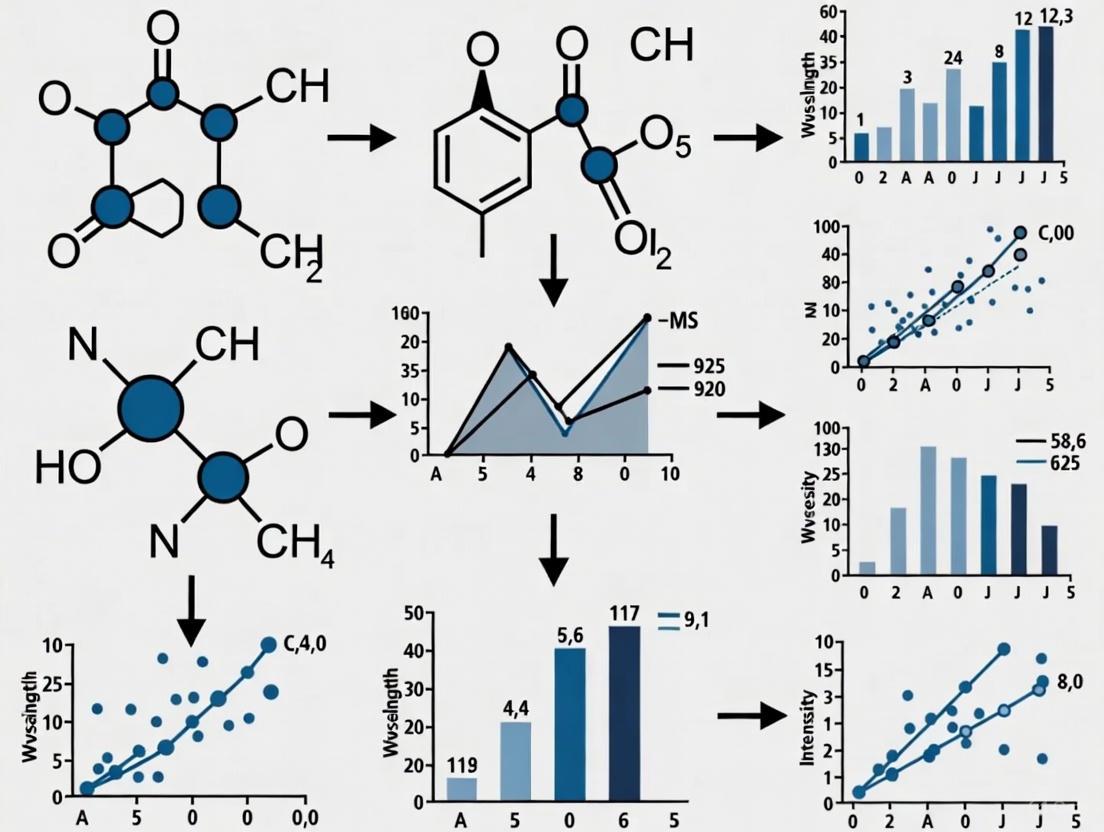

Workflow Visualization for Accuracy and Precision Assessment

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between key concepts, standards, and experimental processes for defining and assessing accuracy and precision in chemometrics, as guided by NIST.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents required for conducting rigorous assessments of accuracy and precision in chemometric research, with an emphasis on NIST-traceable components.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Chemometric Accuracy Assessment

| Item | Function in Research | NIST / Standards Link |

|---|---|---|

| NIST Standard Reference Materials (SRMs) | Serves as the "conventional true value" for method validation and accuracy determination; used to spike samples in recovery studies [1] [6]. | Directly provided by NIST with a certificate of analysis for specific analytes in defined matrices [4] [5]. |

| NIST-Traceable Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Used for daily calibration and quality control when primary NIST SRMs are cost-prohibitive; ensures traceability to SI units [6] [7]. | Commercially available from accredited manufacturers (ISO 17034) with documentation linking values to NIST SRMs [6]. |

| Pure Analytical Reference Standards | Used to create calibration curves for quantitation; the assumed purity directly impacts accuracy [1]. | Investigators must verify purity against NIST SRMs or via rigorous characterization, as label declarations can be inaccurate [1]. |

| Inkjet-Printed Traceable Test Materials | Provide a consistent and precise way to deposit known quantities of analytes (e.g., explosives, narcotics) for testing sampling and detection methods [8] [9]. | Developed by NIST using microdispensing technologies to create particles with known size and concentration, supporting standards for trace detection [8]. |

| Documentary Standards (e.g., ASTM E2677) | Provide standardized, agreed-upon procedures for carrying out technical processes, such as estimating the Limits of Detection (LOD) for trace detectors, which is crucial for defining method scope [8]. | NIST contributes expertise to organizations like ASTM International in the development of these documentary standards [8]. |

| LJ001 | LJ001, CAS:851305-26-5, MF:C17H13NO2S2, MW:327.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lobeline | Lobeline (C22H27NO2) | Lobeline is a versatile alkaloid for neuroscience research, acting as a VMAT2 ligand and nicotinic receptor antagonist. This product is for Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

Accuracy and precision are distinct but complementary pillars of reliable chemometric analysis. Accuracy, the measure of correctness, is rigorously evaluated using NIST Standard Reference Materials which provide an authoritative link to "true value." Precision, the measure of consistency and reproducibility, is quantified through statistical measures of variation and supported by documentary standards. For researchers developing and validating chemometric correction algorithms, a systematic approach incorporating NIST-traceable materials and standardized experimental protocols is indispensable. This ensures that algorithms are not only computationally sound but also produce results that are accurate, precise, and fit for their intended purpose in drug development and other critical applications.

In the rigorous field of chemometrics, where analytical models are tasked with quantifying chemical constituents from complex spectral data, the assessment of model predictive accuracy and robustness is paramount. This evaluation is especially critical in pharmaceutical development, where the accurate quantification of active ingredients directly impacts drug efficacy and safety. Researchers and scientists rely on a suite of performance metrics to validate their calibration models, ensuring they meet the stringent requirements of regulatory standards. Among the most pivotal of these metrics are the Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP), the Coefficient of Determination (R²), the Relative Error of Prediction (REP), and the Bias-Corrected Mean Square Error of Prediction (BCMSEP). Each metric provides a distinct lens through which to scrutinize model performance, from overall goodness-of-fit to the dissection of error components. Framed within a broader thesis on the accuracy assessment of chemometric correction algorithms, this guide provides a comparative analysis of these four key metrics, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies to inform the practices of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Metric Definitions and Core Concepts

Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP)

The Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP) is a fundamental measure of a model's predictive accuracy when applied to an independent test set. It quantifies the average magnitude of the prediction errors in the same units as the original response variable, making it highly interpretable. According to IUPAC recommendations, RMSEP is defined mathematically for (N) evaluation samples as [10]: [E{\rm{RMSEP}} = \sqrt {\frac{\sum\limits{i\,=\,1}^{i\,=\,N} (\hat c{i}\,-\,c{i})^2}{N}}] where (ci) is the observed value and (\hat ci) is the predicted value [10]. A lower RMSEP indicates a model with higher predictive accuracy. When predictions are generated via cross-validation, this metric may be referred to as the Root Mean Square Error of Cross-Validation (RMSECV) [11] [10].

Coefficient of Determination (R²)

The Coefficient of Determination, commonly known as R-squared (R²), measures the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is explained by the model. It provides a standardized index of goodness-of-fit, ranging from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating a perfect fit [12] [13]. R² is calculated as [12]: [R^2 = 1 - \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} (yi - \hat{y}i)^2}{\sum{i=1}^{n} (yi - \bar{y})^2}] where (yi) is the actual value, (\hat{y}_i) is the predicted value, and (\bar{y}) is the mean of the actual values. While a high R² suggests that the model captures a large portion of the data variance, it does not, on its own, confirm predictive accuracy on new data [11] [13].

Relative Error of Prediction (REP)

The Relative Error of Prediction (REP) is a normalized metric that expresses the prediction error as a percentage of the mean reference value, facilitating comparison across datasets with different scales. It is particularly useful for communicating model performance in application-oriented settings. The REP is calculated as follows: [REP(\%) = 100 \times \frac{\sqrt{\frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} (\hat{y}i - y_i)^2}{n}}}{\bar{y}}] This metric is akin to a normalized RMSEP. Studies in pharmaceutical analysis have reported REP values ranging from 0.2221% to 0.8022% for chemometric models, indicating high precision [14].

Bias-Corrected Mean Square Error of Prediction (BCMSEP)

The Bias-Corrected Mean Square Error of Prediction (BCMSEP) is an advanced metric that decomposes the total prediction error into two components: bias and variance. Bias represents the systematic deviation of the predictions from the actual values, while variance represents the model's sensitivity to fluctuations in the training data. The relationship is given by: [BCMSEP = \frac{1}{n} \sum{i=1}^{n} \left[ (\hat{y}i - \bar{y})^2 + (\hat{y}i - yi)^2 \right]] This decomposition is invaluable for model diagnosis, as it helps determine whether an model's error stems from an incorrect underlying assumption (high bias) or from excessive sensitivity to noise (high variance). In practical applications, BCMSEP values can range from slightly negative to positive, such as the -0.00065 to 0.00166 range observed in one pharmaceutical study [14].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and decomposition of error captured by these metrics:

Comparative Analysis of Metrics

The table below provides a structured comparison of the core characteristics of the four key metrics, highlighting their distinct formulas, interpretations, and ideal values.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Key Chemometric Performance Metrics

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Ideal Value | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSEP | √[Σ(ŷᵢ - yᵢ)² / N] [10] |

Average prediction error in response units | 0 | Expressed in the original, physically meaningful units [11] |

| R² | 1 - (SSE/SST) [12] |

Proportion of variance explained by the model | 1 | Standardized, dimensionless measure of goodness-of-fit [13] |

| REP | 100 × (RMSEP / ȳ) [14] |

Relative prediction error as a percentage | 0% | Allows for comparison across different scales and models |

| BCMSEP | Bias² + Variance [14] |

Decomposes error into systematic and random components | 0 | Diagnoses source of error to guide model improvement [14] |

Each metric serves a unique purpose in model evaluation. RMSEP is prized for its direct, physical interpretability. As noted in one analysis, "it is in the units of the property being predicted," which is crucial for understanding the real-world impact of prediction errors [11]. In contrast, R² provides a standardized, dimensionless measure that is useful for comparing the explanatory power of models across different contexts, though it can be misleading if considered in isolation [11] [13].

The following diagram visualizes a typical workflow for applying these metrics in the development and validation of a chemometric model:

REP offers a normalized perspective, which is particularly valuable when communicating results to stakeholders who may not be familiar with the native units of measurement. BCMSEP provides the deepest diagnostic insight by separating systematic error (bias) from random error (variance), guiding researchers toward specific model improvements—for instance, whether to collect more diverse training data or adjust the model structure itself [14].

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

To illustrate the practical application of these metrics, consider a recent study focused on the simultaneous quantification of multiple pharmaceutical compounds—Rabeprazole (RAB), Lansoprazole (LAN), Levofloxacin (LEV), Amoxicillin (AMO), and Paracetamol (PAR)—in lab-prepared mixtures, tablets, and spiked human plasma [14]. The researchers employed a Taguchi L25 orthogonal array design to construct calibration and validation sets, and compared the performance of several chemometric techniques, including Principal Component Regression (PCR), Partial Least Squares (PLS-2), Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), and Multivariate Curve Resolution-Alternating Least Squares (MCR-ALS) [14].

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Pharmaceutical Compound Quantification Using Different Chemometric Models [14]

| Compound | Model | R² | RMSEP | REP (%) | BCMSEP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAB | PLS-2 | 0.9998 | 0.041 | 0.31 | 0.00012 |

| LAN | MCR-ALS | 0.9997 | 0.056 | 0.42 | -0.00008 |

| LEV | ANN | 0.9999 | 0.035 | 0.22 | 0.00005 |

| AMO | PCR | 0.9998 | 0.077 | 0.65 | 0.00166 |

| PAR | PLS-2 | 0.9999 | 0.043 | 0.28 | -0.00065 |

The data from Table 2 reveals that all models achieved exceptionally high R² values (≥0.9997), indicating an excellent fit to the data. However, the other metrics provide a more nuanced view of predictive performance. For instance, while AMO has a high R² of 0.9998, it also has the highest RMSEP (0.077) and REP (0.65%), suggesting that, despite the excellent fit, its absolute and relative prediction errors are the largest among the compounds tested. Conversely, LEV, with the highest R² and one of the lowest RMSEPs, appears to be the most accurately predicted compound.

The BCMSEP values, ranging from -0.00065 to 0.00166, indicate variations in the bias-variance profile across different compound-model combinations. A slightly negative BCMSEP, as observed for LAN and PAR, can occur when the bias correction term leads to a very small negative value in the calculation, which is often interpreted as near-zero bias [14].

Another illustrative example comes from a study on NIR spectroscopy of a styrene-butadiene co-polymer system, where the goal was to predict the weight percent of four polymer blocks [11]. The original analysis noted that an R²-Q² plot suggested predictions for 1-2-butadiene were "quite a bit better than for styrene." However, when the performance was assessed using RMSEP, it became clear that "the models perform similarly with an RMSECV around 0.8 weight percent" [11]. This case highlights the critical importance of consulting multiple metrics, particularly those like RMSEP that are in the native units of the response variable, to avoid potentially misleading conclusions based on R² alone.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of model validation, a standardized experimental protocol is essential. The following methodology, adapted from the pharmaceutical study cited previously, provides a robust framework for obtaining the performance metrics discussed [14]:

Sample Preparation and Experimental Design

- Sample Collection and Preparation: Collect representative samples, which may include lab-prepared mixtures, commercial formulations (e.g., tablets), and biological matrices (e.g., spiked human plasma). For spiked plasma, add known concentrations of the analytes to drug-free plasma.

- Experimental Design: Implement an experimental design, such as a Taguchi L25 (5âµ) orthogonal array, to efficiently construct the calibration and validation sets. This design allows for the systematic variation of multiple factors (e.g., concentration levels of different analytes) with a minimal number of experimental runs, ensuring a robust and representative dataset.

Instrumentation and Data Acquisition

- Spectral Acquisition: Acquire spectral data for all samples using an appropriate spectroscopic technique (e.g., NIR, MIR, or UV-Vis). The specific instrument and settings (e.g., wavelength range, resolution) should be documented.

- Reference Analysis: Determine the reference concentration values for all analytes in the samples using a validated reference method (e.g., HPLC). These values serve as the ground truth for model development and validation.

Model Development and Validation

- Data Pre-processing: Apply necessary pre-processing steps to the spectral data, such as smoothing, normalization, or derivative techniques, to reduce noise and enhance spectral features.

- Data Splitting: Divide the data into calibration (training) and validation (test) sets according to the experimental design. The validation set must be independent and not used in any part of the model training process.

- Model Training: Develop the chemometric models (e.g., PLS-2, PCR, ANN, MCR-ALS) using the calibration set. Optimize model parameters (e.g., number of latent variables for PLS, hidden layer architecture for ANN) via internal cross-validation.

- Model Prediction and Metric Calculation: Apply the trained models to the independent validation set to obtain predictions for the analyte concentrations.

- Calculate RMSEP using the formula in Section 2.1.

- Calculate R² between the predicted and reference values.

- Calculate REP by normalizing the RMSEP by the mean reference value and multiplying by 100.

- Calculate BCMSEP by decomposing the mean square error into bias and variance components.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Chemometric Model Validation

| Item Name | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Taguchi L25 Orthogonal Array | An experimental design used to construct calibration and validation sets efficiently, minimizing the number of runs while maximizing statistical information [14]. |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS-2) | A multivariate regression technique used to develop predictive models when the predictor variables are highly collinear, capable of modeling multiple response variables simultaneously [14]. |

| Multivariate Curve Resolution-Alternating Least Squares (MCR-ALS) | A chemometric method for resolving mixture spectra into the pure component contributions, ideal for analyzing complex, unresolved spectral data [14]. |

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) | A non-linear machine learning model capable of learning complex relationships between spectral data and analyte concentrations, often used for challenging quantification tasks [14]. |

| Spiked Human Plasma | A biological matrix used to validate the method's accuracy and selectivity in a complex, physiologically relevant medium, crucial for bioanalytical applications [14]. |

| Reference Materials (e.g., RAB, LAN, LEV, AMO, PAR) | High-purity chemical standards of the target analytes, used to prepare known concentrations for calibration and to spike samples for validation [14]. |

| Loracarbef hydrate | Loracarbef hydrate, CAS:121961-22-6, MF:C16H18ClN3O5, MW:367.78 g/mol |

| DL-Thyroxine | DL-Thyroxine, CAS:51-48-9, MF:C15H11I4NO4, MW:776.87 g/mol |

The objective comparison of the key performance metrics—RMSEP, R², REP, and BCMSEP—reveals that no single metric provides a complete picture of a chemometric model's performance. RMSEP is indispensable for understanding prediction error in tangible, physical units. R² offers a standardized measure of model fit but should not be used in isolation. REP enables cross-study and cross-model comparisons by providing a normalized error percentage. Finally, BCMSEP delivers critical diagnostic insight by disentangling the systematic and random components of error, guiding the model refinement process.

For researchers and scientists engaged in the accuracy assessment of chemometric correction algorithms, particularly in the high-stakes realm of drug development, the consensus is clear: a multi-faceted validation strategy is essential. Relying on a suite of complementary metrics, rather than a single golden standard, ensures a robust, transparent, and comprehensive evaluation of model performance, ultimately fostering the development of more reliable and accurate analytical methods.

The Role of Multivariate Calibration in Accuracy Assessment

Multivariate calibration represents a fundamental chemometric approach that establishes a mathematical relationship between multivariate instrument responses and properties of interest, such as analyte concentrations in chemical analysis. Unlike univariate methods that utilize only a single data point (e.g., absorbance at one wavelength), multivariate calibration leverages entire spectral or instrumental profiles, thereby extracting significantly more information from collected data [15]. This comprehensive data usage provides substantial advantages in accuracy assessment for chemical measurements, particularly in complex matrices where interferents may compromise univariate model performance.

The fundamental limitation of univariate analysis is evident in spectroscopic applications where a typical UV-Vis spectrum may contain 500 data points, yet traditional methods utilize only one wavelength for concentration determination, effectively discarding 99.8% of the collected data [15]. This approach not only wastes valuable information but also increases vulnerability to interferents that may affect the single selected wavelength. In contrast, multivariate methods simultaneously employ responses across multiple variables (e.g., a range of wavelengths or potentials), offering inherent noise reduction and interferent compensation capabilities when the interference profile differs sufficiently from the analyte of interest [15].

Within the framework of accuracy assessment, multivariate calibration serves as a critical tool for validating analytical methods across diverse applications from pharmaceutical analysis to environmental monitoring. By incorporating multiple dimensions of chemical information, these techniques provide more robust and reliable quantification, especially when benchmarked against reference methods in complex analytical scenarios.

Key Multivariate Calibration Methods

Principal Component Regression (PCR)

Principal Component Regression combines two statistical techniques: principal component analysis (PCA) and least-squares regression. The process begins with PCA, which identifies principal components – new variables that capture the maximum variance in the spectral data [15]. These PCs represent orthogonal directions in the multivariate space that describe the most significant sources of variation in the measurement data, which may include changes in chemical composition, environmental parameters, or instrument performance [15].

In practical application, PCA transforms the original correlated spectral variables into a smaller set of uncorrelated principal components. The regression step then establishes a linear relationship between the scores of these PCs and the analyte concentrations. As explained in one tutorial, "PCR is a combination of principal component analysis (PCA) and least-squares regression" where "PCs can be thought of as vectors in an abstract coordinate system that describe sources of variance of a data set" [15]. This dual approach allows PCR to effectively handle collinear spectral data while focusing on the most relevant variance components for prediction.

Partial Least Squares Regression (PLS)

Partial Least Squares Regression represents a more sophisticated approach that differs from PCR in a fundamental way: while PCA identifies components that maximize variance in the spectral data (X-block), PLS extracts components that maximize covariance between the spectral data and the concentration or property data (Y-block) [16]. This fundamental difference makes PLS particularly effective for calibration models where the prediction of analyte concentrations is the primary objective.

The PLS algorithm operates by simultaneously decomposing both the X and Y matrices while maintaining a correspondence between them. This approach often yields models that require fewer latent variables than PCR to achieve comparable prediction accuracy, as PLS components are directly relevant to the prediction task rather than merely describing spectral variance [17]. Studies comparing PCR and PLS have demonstrated that "PLS almost always required fewer latent variables than PCR," though this efficiency did not necessarily translate to superior predictive ability in all scenarios [17].

Alternative Multivariate Methods

Beyond PCR and PLS, several specialized multivariate methods have been developed to address specific analytical challenges:

Multivariate Curve Resolution-Alternating Least Squares (MCR-ALS) shows particular promise for analyzing complex samples containing uncalibrated interferents. Unlike PLS, which performs well with known interferents, MCR-ALS "allowed the accurate determination of analytes in the presence of unknown interferences and more complex sample matrices" [16]. This capability makes it valuable for environmental and pharmaceutical applications where sample composition may be partially unknown.

Kernel Partial Least-Squares (KPLS) extends traditional PLS to handle nonlinear relationships through the kernel trick, which implicitly maps data into higher-dimensional space where linear relationships may be more readily established [18]. This approach provides flexibility for modeling complex analytical responses that deviate from ideal linear behavior.

Multicomponent Self-Organizing Regression (MCSOR) represents a novel approach for underdetermined regression problems, employing multiple linear regression as its statistical foundation [19]. Comparative studies have shown that MCSOR "appears to provide highly predictive models that are comparable with or better than the corresponding PLS models" in certain validation tests [19].

Comparative Performance Assessment

Experimental Design for Method Comparison

Rigorous experimental protocols are essential for meaningful comparison of multivariate calibration methods. A standard approach involves several critical phases, beginning with experimental design that systematically varies factors influencing method performance. For spectroscopic pharmaceutical analysis, one validated methodology involves preparing synthetic mixtures of target pharmaceuticals (diclofenac, naproxen, mefenamic acid, carbamazepine) with gemfibrozil as an interference in environmental samples [16].

The experimental workflow progresses through several stages. First, calibration sets are prepared with systematically varied concentrations of all analytes according to experimental design principles. UV-Vis spectra are then collected for all mixtures across appropriate wavelength ranges (e.g., 200-400 nm). The dataset is subsequently divided into separate training and validation sets using appropriate sampling methods. Multivariate models (PLS, PCR, MCR-ALS) are built using the training set, followed by model validation using the independent test set. Finally, performance metrics including relative error (RE), regression coefficient (R²), and root mean square error (RMSE) are calculated for objective comparison [16].

For nonlinear methods like KPLS, additional validation is necessary to assess model robustness. As noted in research on spectroscopic sensors, "non-linear calibration models are not robust enough and small changes in training data or model parameters may result in significant changes in prediction" [20]. Strategies such as bagging/subagging and variable selection techniques including penalized regression algorithms with LASSO (least absolute shrinkage and selection operator) can improve prediction robustness [20].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The performance of multivariate calibration methods is typically evaluated using multiple statistical metrics that collectively provide insights into different aspects of model accuracy and reliability. The following table summarizes key performance indicators used in comparative studies:

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for Multivariate Calibration Assessment

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Optimal Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) | $\sqrt{\frac{\sum{i=1}^n(\hat{y}i - y_i)^2}{n}}$ | Measures average difference between predicted and reference values | Closer to zero indicates better accuracy | ||

| Relative Error (RE) | $\frac{ | \hat{y} - y | }{y} \times 100\%$ | Expresses prediction error as percentage of true value | Lower percentage indicates higher accuracy |

| Regression Coefficient (R²) | $1 - \frac{\sum{i=1}^n(\hat{y}i - yi)^2}{\sum{i=1}^n(y_i - \bar{y})^2}$ | Proportion of variance in reference values explained by model | Closer to 1 indicates better explanatory power | ||

| Number of Latent Variables (NLV) | - | Complexity parameter indicating model dimensionality | Balance between simplicity and predictive power |

These metrics collectively provide a comprehensive view of model performance, with RMSE and RE quantifying prediction accuracy, R² assessing explanatory power, and NLV indicating model parsimony.

Comparative Performance Data

Direct comparison studies provide valuable insights into the relative performance of different multivariate calibration methods under controlled conditions. The following table synthesizes results from multiple studies comparing method performance across different analytical scenarios:

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Multivariate Calibration Methods

| Method | Application Context | Performance Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLS | Pharmaceutical determination in environmental samples [16] | Superior for samples free of interference or containing calibrated interferents (RE: 2.1-4.8%, R²: 0.983-0.997) | Performance deteriorates with uncalibrated interferents |

| PCR | Complex mixture analysis [17] | Prediction errors comparable to PLS in most scenarios | Typically requires more latent variables than PLS for similar accuracy |

| MCR-ALS | Environmental samples with unknown interferents [16] | Maintains accuracy with unknown interferents and complex matrices (RE: 3.2-5.1%, R²: 0.974-0.992) | More complex implementation than PLS/PCR |

| MCSOR | Large QSAR/QSPR data sets [19] | Predictive performance comparable or superior to PLS in external validation | Less established than traditional methods |

A particularly comprehensive simulation study comparing PCR and PLS for analyzing complex mixtures revealed that "in all cases, except when artificial constraints were placed on the number of latent variables retained, no significant differences were reported in the prediction errors reported by PCR and PLS" [17]. This finding suggests that for many practical applications, the choice between these two fundamental methods may depend more on implementation considerations than inherent accuracy differences.

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Pharmaceutical and Environmental Analysis

Multivariate calibration methods demonstrate significant utility in pharmaceutical and environmental applications where complex matrices present challenges for traditional univariate analysis. A comparative study of PLS and MCR-ALS for simultaneous spectrophotometric determination of pharmaceuticals (diclofenac, naproxen, mefenamic acid, carbamazepine) in environmental samples with gemfibrozil as an interference revealed distinctive performance patterns [16].

The research employed variable selection methods including variable importance in projection (VIP), recursive weighted PLS (rPLS), regression coefficient (RV), and uninformative variable elimination (UVE) to optimize PLS models. Results demonstrated that "PLSR showed a better performance for the determination of analytes in samples that are free of interference or contain calibrated interference(s)" [16]. This advantage manifested in favorable statistical parameters with relative errors between 2.1-4.8% and R² values of 0.983-0.997 for calibrated interferents.

In contrast, when facing uncalibrated interferents and more complex sample matrices, MCR-ALS with correlation constraint (MCR-ALS-CC) outperformed PLS approaches. The study concluded that "MCR-ALS-CC allowed the accurate determination of analytes in the presence of unknown interferences and more complex sample matrices" [16], highlighting the context-dependent nature of multivariate method performance.

Spectroscopic Sensor Applications

The integration of multivariate calibration with spectroscopic sensors represents a growing application area where accuracy assessment is critical for method validation. Research on "Chemometric techniques for multivariate calibration and their application in spectroscopic sensors" has addressed both linear and nonlinear calibration challenges [20].

Traditional multivariate calibration methods including PCR and PLS provide reliable performance when the relationship between analyte properties and spectra is linear. However, external disturbances such as light scattering and baseline noise frequently introduce non-linearity into spectral data, deteriorating prediction accuracy [20]. This limitation has prompted development of two strategic approaches: pre-processing techniques and nonlinear calibration methods.

Pre-processing methods including first and second derivatives (D1, D2), standard normal variate (SNV), extended multiplicative signal correction (EMSC), and extended inverted signal correction (EISC) can remove disturbance impacts, enabling subsequent application of linear calibration methods [20]. Alternatively, nonlinear calibration techniques including artificial neural network (ANN), least squares support vector machine (LS-SVM), and Gaussian process regression (GPR) directly model nonlinear relationships. Comparative studies indicate that "non-linear calibration techniques give more accurate prediction performance than linear methods in most cases" though they may sacrifice robustness, as "small changes in training data or model parameters may result in significant changes in prediction" [20].

Soil Moisture Sensing

An innovative application of multivariate calibration in environmental monitoring demonstrates the practical advantages of multivariate approaches over univariate methods. Research evaluating a multivariate calibration model for the WET sensor that incorporates apparent dielectric permittivity (εs) and bulk soil electrical conductivity (ECb) revealed significant accuracy improvements over traditional univariate approaches [21].

The study addressed a common challenge in soil moisture measurement using capacitance sensors: the influence of electrical conductivity on apparent dielectric permittivity readings. In saline or clay-rich soils, elevated ECb levels cause overestimation of εs, leading to inaccurate volumetric water content (θ) determinations [21]. The multivariate model incorporating both εs and ECb as inputs significantly outperformed both manufacturer calibration and univariate approaches.

According to the results, "the multivariate model provided the most accurate θ estimations, (RMSE ≤ 0.022 m³mâ»Â³) compared to CAL (RMSE ≤ 0.027 m³mâ»Â³) and Manuf (RMSE ≤ 0.042 m³mâ»Â³), across all the examined soils" [21]. This application demonstrates how multivariate calibration can effectively compensate for interfering factors that compromise univariate model accuracy in practical field applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of multivariate calibration methods requires appropriate experimental materials and computational tools. The following table outlines key resources referenced in the studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Multivariate Calibration Studies

| Material/Resource | Specifications | Application Context | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Standards | Diclofenac, naproxen, mefenamic acid, carbamazepine, gemfibrozil [16] | Environmental pharmaceutical analysis | Target analytes and interferents for method validation |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Full spectrum capability (200-400 nm) [16] | Spectral data collection | Generating multivariate response data |

| Multivariate Software | MATLAB, PLS Toolbox, specialized chemometrics packages [15] | Data analysis and modeling | Implementing PCR, PLS, MCR-ALS algorithms |

| WET Sensor | Delta-T Devices Ltd., measures θ, εs, ECb at 20 MHz [21] | Soil moisture analysis | Simultaneous measurement of multiple soil parameters |

| Soil Samples | Varied textures with different electrical conductivity solutions [21] | Environmental sensor validation | Creating controlled variability for model development |

| LG 82-4-01 | LG 82-4-01|TX Synthetase Inhibitor|CAS 91505-19-0 | LG 82-4-01 is a specific thromboxane (TX) synthetase inhibitor (IC50=1.3 µM). For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| LP8 | 3-{[(4-Methylphenyl)sulfonyl]amino}propyl pyridin-4-ylcarbamate | Research-grade 3-{[(4-Methylphenyl)sulfonyl]amino}propyl pyridin-4-ylcarbamate (C16H19N3O4S). High-purity compound for scientific investigation. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for developing and validating multivariate calibration models, integrating common elements from the methodologies described in the research:

Multivariate Calibration Development Workflow

Multivariate calibration methods provide powerful tools for enhancing accuracy in chemical analysis and beyond. The comparative assessment presented in this review demonstrates that method performance is highly context-dependent, with each approach offering distinct advantages under specific conditions. PLS excels in scenarios with known or calibrated interferents, while MCR-ALS shows superior capability with uncalibrated interferents in complex matrices. PCR provides prediction accuracy comparable to PLS, though typically requiring more latent variables.

The fundamental advantage of multivariate over univariate approaches lies in their comprehensive utilization of chemical information, providing inherent noise reduction and interferent compensation capabilities. As the field advances, integration of nonlinear methods and robust variable selection techniques continues to expand application boundaries. Nevertheless, appropriate method selection must consider specific analytical requirements, matrix complexity, and available computational resources to optimize accuracy in each unique application context.

In the realm of chemometrics, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression represent two foundational algorithms for extracting meaningful information from complex chemical data. PCA is an unsupervised dimensionality reduction technique that transforms multivariate data into a new set of orthogonal variables called principal components, which capture the maximum variance in the data [22]. In contrast, PLS is a supervised method that models the relationship between an independent variable matrix (X) and a dependent response matrix (Y), making it particularly valuable for predictive modeling and calibration tasks [23] [24]. These algorithms form the cornerstone of modern chemometric analysis, enabling researchers to handle spectral interference, correct baseline variations, and remove unwanted noise from analytical data.

The integration of PCA and PLS into analytical workflows has revolutionized fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to food authentication and clinical diagnostics. As spectroscopic and chromatographic techniques generate increasingly complex datasets, the role of these algorithms in data correction has become indispensable for accurate chemical interpretation. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of PCA and PLS methodologies, examining their theoretical foundations, performance characteristics, and practical applications in chemometric data correction within the broader context of accuracy assessment for correction algorithms.

Theoretical Framework and Algorithmic Mechanisms

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA operates by transforming possibly correlated variables into a set of linearly uncorrelated variables called principal components through an orthogonal transformation [22]. The mathematical foundation of PCA begins with the covariance matrix of the original data. Given a data matrix X with n samples (rows) and p variables (columns), where each column has zero mean, the covariance matrix is calculated as C = (X^T X)/(n-1). The principal components are then obtained by solving the eigenvalue problem for this covariance matrix: Cv = λv, where λ represents the eigenvalues and v represents the eigenvectors [22].

The first principal component (PC1) corresponds to the direction of maximum variance in the data, and each subsequent component captures the next highest variance while being orthogonal to all previous components. The proportion of total variance explained by each component is given by λi / Σ(λ), where λi is the eigenvalue corresponding to the i-th component [22]. This dimensionality reduction capability allows PCA to effectively separate signal from noise, making it invaluable for data correction applications where unwanted variations must be identified and removed.

Partial Least Squares (PLS)

PLS regression differs fundamentally from PCA in its objective of maximizing the covariance between the independent variable matrix (X) and the dependent response matrix (Y) [24]. The algorithm projects both X and Y to a latent space, seeking directions in the X-space that explain the maximum variance in the Y-space. The PLS model can be represented by the equations: X = TP^T + E and Y = UQ^T + F, where T and U are score matrices, P and Q are loading matrices, and E and F are error terms [24].

Unlike PCA, which only considers the variance in X, PLS incorporates the relationship between X and Y throughout the decomposition process, making it particularly effective for prediction tasks. The number of latent variables in a PLS model is a critical parameter that must be optimized to avoid overfitting while maintaining predictive power. Various extensions of PLS, including orthogonal signal correction (OSC) and low-rank PLS (LR-PLS), have been developed to enhance its data correction capabilities, particularly for removing structured noise that is orthogonal to the response variable [23].

Performance Comparison: Accuracy in Data Correction

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Performance of PCA and PLS in Spectral Data Correction

| Algorithm | Application Context | Accuracy Metrics | Data Correction Capability | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Exploratory data analysis, outlier detection, noise reduction | Variance explained per component (>70-90% typically with first 2-3 PCs) [22] | Identifies major sources of variance; effective for removing outliers and detecting data homogeneity issues [25] | Unsupervised nature may not preserve chemically relevant variation; sensitive to scaling [15] |

| PLS | Quantitative prediction, baseline correction, removal of undesired spectral variations | R² up to 0.989, low RMSEP reported for corrected spectral data [23] | Effectively removes variations orthogonal to response; handles baseline shifts and scattering effects [23] [24] | Requires reference values; potential overfitting with too many latent variables [24] |

| PCA-LDA | Classification of vibrational spectra | 93-100% accuracy, 86-100% sensitivity, 90-100% specificity in sample classification [26] | Effective for separating classes in reduced dimension space; useful for spectral discrimination | Limited to linear boundaries; requires careful selection of principal components [26] |

| LR-PLS | Infrared spectroscopy with undesired variations | Improved R² and RMSEP for various samples; general-purpose correction [23] | Low-rank constraint removes undesired variations while preserving predictive signals | Computationally more intensive than standard PLS [23] |

Domain-Specific Performance

Table 2: Application-Specific Performance of PCA and PLS Variants

| Application Domain | Optimal Algorithm | Correction Performance | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vibrational Spectroscopy | PLS-DA | 93-100% classification accuracy for FTIR spectra of breast cancer cells [26] | Successful discrimination of malignant non-metastatic MCF7 and metastatic MDA-MB-231 cells [26] |

| Hyperspectral Imaging | Adaptive PLS with threshold-moving | True Positive Rates up to 100% for egg fertility discrimination [24] | Accurate removal of spectral variations unrelated to fertility status; handles within-group variability [24] |

| Infrared Spectroscopy | Low-rank PLS (LR-PLS) | Enhanced prediction accuracy for corn and tobacco samples [23] | Effective removal of undesired variations from particle size and optical path length effects [23] |

| Biomedical Diagnostics | PCA-LDA | 96-100% accuracy for classifying cancer samples [26] | Successful correction of spectral variations to differentiate pathological conditions [26] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for PCA-Based Data Correction

The standard methodology for implementing PCA-based data correction involves several critical steps. First, data preprocessing is performed, which typically includes mean-centering and sometimes scaling of variables to unit variance. The mean-centered data matrix X is then decomposed into its principal components through singular value decomposition (SVD) or eigen decomposition of the covariance matrix [22]. The appropriate number of components to retain is determined using criteria such as scree plots, cumulative variance explained (typically >70-90%), or cross-validation [25].

For data correction applications, the residual matrix E = X - TP^T is particularly important, as it represents the portion of the data not explained by the retained principal components. This residual can be analyzed for outliers using statistical measures such as Hotelling's T² and Q residuals [25]. In practice, PCA-based correction involves reconstructing the data using only the significant components, effectively filtering out noise and irrelevant variations. Advanced implementations may utilize tools such as the degrees of freedom plots for orthogonal and score distances, which provide enhanced assessment of PCA model complexity and data homogeneity [25].

Protocol for PLS-Based Data Correction

The experimental protocol for PLS-based data correction begins with the splitting of data into calibration and validation sets. The PLS algorithm then iteratively extracts latent variables that maximize the covariance between X-block (spectral data) and Y-block (response variables) [24]. For data correction applications, a critical enhancement is the application of orthogonal signal correction (OSC), which removes from X the components that are orthogonal to Y, thus eliminating structured noise unrelated to the property of interest [23].

The low-rank PLS (LR-PLS) variant introduces an additional step where the spectral data is decomposed into low-rank and sparse matrices before PLS regression [23]. This approach effectively separates undesired variations (represented in the sparse matrix) from the chemically relevant signals (represented in the low-rank matrix). The number of latent variables is optimized through cross-validation to minimize prediction error while maintaining model parsimony. Performance is evaluated using metrics such as R², root mean square error of prediction (RMSEP), and for classification tasks, sensitivity and specificity [24].

Visualization of Algorithmic Workflows

PCA Data Correction Workflow

PCA Correction Pathway

PLS Data Correction Workflow

PLS Correction Pathway

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Chemometric Data Correction

| Research Reagent | Function in Chemometric Analysis | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Imaging Systems | Captures spatial and spectral data simultaneously for multivariate analysis | Egg fertility assessment [24], food authentication [23] |

| NIR Spectrometers | Provides spectral data in 900-1700 nm range for quantitative analysis | Corn and tobacco sample analysis [23], pharmaceutical quality control |

| FTIR Spectrometers | Measures molecular absorption in IR region for structural characterization | Breast cancer cell classification [26], biological sample analysis |

| Raman Spectrometers | Detects inelastically scattered light for molecular fingerprinting | Cell differentiation [26], material characterization |

| Electronic Health Record Systems | Provides clinical data for biomarker discovery and model validation | Chemotoxicity prediction [27], clinical biomarker studies |

| Chemometric Software Packages | Implements PCA, PLS algorithms with statistical validation | Data correction across all application domains [25] |

PCA and PLS algorithms offer complementary strengths for chemometric data correction, with the optimal choice dependent on specific analytical objectives and data characteristics. PCA excels in exploratory analysis and unsupervised correction of major variance sources, while PLS provides superior performance for prediction-focused applications requiring removal of response-irrelevant variations. The integration of these foundational algorithms with emerging AI methodologies represents the future of accurate chemometric analysis, promising enhanced correction capabilities for increasingly complex analytical challenges in drug development and beyond. As the field advances, hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both algorithms while incorporating domain-specific knowledge will likely set new standards for accuracy in chemometric data correction.

Algorithm Implementation and Practical Applications in Pharmaceutical Analysis

In the field of chemometrics, the accurate interpretation of spectral data is paramount for applications ranging from pharmaceutical development to material science. Spectral data, characterized by its high dimensionality and multicollinearity, presents significant challenges for traditional regression analysis. This guide provides an objective comparison of three advanced regression techniques—Partial Least-Squares (PLS), Genetic Algorithm-based PLS (GA-PLS), and Artificial Neural Networks (ANN)—for enhancing spectral resolution and prediction accuracy. The performance evaluation of these techniques is framed within a broader thesis on accuracy assessment of chemometric correction algorithms, providing researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based insights for methodological selection.

Partial Least-Squares (PLS) Regression

Partial Least-Squares regression is a well-established chemometric method designed for predictive modeling with many correlated variables. PLS works by projecting both the predictor and response variables into a new space through a linear multivariate model, maximizing the covariance between the latent components of the spectral data (X-matrix) and the response variable (Y-matrix) [24] [28]. This projection results in a bilinear factor model that is particularly effective when the number of predictor variables exceeds the number of observations or when significant multicollinearity exists among variables [28]. The fundamental PLS model can be represented as X = TPáµ€ + E and Y = UQáµ€ + F, where T and U are score matrices, P and Q are loading matrices, and E and F represent error matrices [28]. A key advantage of PLS is its ability to handle spectral data with strongly correlated predictors, making it a robust baseline method for spectral regression tasks.

Genetic Algorithm-Based PLS (GA-PLS)

Genetic Algorithm-based PLS represents an enhancement of traditional PLS that addresses variable selection challenges. In standard PLS regression, when numerous variables contain noise or irrelevant information, model performance can degrade. GA-PLS integrates a genetic algorithm—a metaheuristic optimization technique inspired by natural selection—to identify optimal subsets of spectral variables for inclusion in the PLS model [29]. This approach iteratively evolves a population of variable subsets through selection, crossover, and mutation operations, with the fitness of each subset evaluated based on the predictive accuracy of the resulting PLS model via cross-validation [29]. A significant variant is PLS with only the first component (PLSFC), which offers enhanced interpretability as regression coefficients can be directly attributed to variable contributions without the confounding effects of multicollinearity [29]. When combined with GA for variable selection, GA-PLSFC enables the construction of highly predictive and interpretable models, particularly valuable for spectral interpretation where identifying relevant spectral regions is crucial.

Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) for Spectral Regression

Artificial Neural Networks represent a nonlinear approach to spectral regression, capable of modeling complex relationships between spectral features and target properties. ANNs consist of interconnected layers of artificial neurons that transform input data through weighted connections and nonlinear activation functions [30]. For spectral analysis, feedforward networks with fully connected layers are commonly employed, where each node in the input layer corresponds to a specific wavelength or spectral feature, hidden layers perform progressive feature extraction, and output nodes generate predictions [30] [31]. The nonlinear activation functions, particularly Rectified Linear Units (ReLU), have proven crucial for enabling networks to distinguish between classes with overlapping spectral peaks [31]. More sophisticated architectures, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have also been adapted for one-dimensional spectral data, though studies indicate that for many spectroscopic classification tasks, simpler architectures with appropriate activation functions can achieve competitive performance without the complexity of residual blocks or specialized normalization layers [31].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics Across Applications

Table 1: Comparative Performance of PLS, GA-PLS, and ANN Across Spectral Applications

| Application Domain | Technique | Performance Metrics | Key Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken Egg Fertility Detection [24] | Adaptive PLS | True Positive Rates up to 100% at thresholds of 0.50-0.85 | Hyperspectral imaging (900-1700 nm), 672 egg samples, imbalanced data |

| CO₂-N₂-Ar Plasma Emission Spectra [32] | PLS | Model score: 0.561 | 36231 total spectra, 2 nm resolution, compared using compounded R², Pearson correlation, and weighted RMSE |

| COâ‚‚-Nâ‚‚-Ar Plasma Emission Spectra [32] | Bagging ANN (BANN) | Model score: 0.873 | Same dataset as PLS, no feature selection or preprocessing required |

| Potato Virus Y Detection [30] | ANN | Mean accuracy: 0.894 (single variety), 0.575 (29 varieties) | Spectral red edge, NIR, and SWIR regions; binary classification |

| Near-Infrared Spectroscopy [33] | Sparse PLS | Lower MSE than Enet, less sparsity | Strongly correlated NIR data with group structures among predictors |

| Near-Infrared Spectroscopy [33] | Elastic Net | More parsimonious models, superior interpretability | Same strongly correlated NIR data as SPLS |

Relative Strengths and Limitations

Table 2: Strengths and Limitations of PLS, GA-PLS, and ANN for Spectral Resolution

| Technique | Strengths | Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLS | Handles multicollinearity effectively; Provides direct interpretability; Computationally efficient; Robust with many predictors | Limited nonlinear modeling capability; Performance degrades with irrelevant variables; Requires preprocessing for noisy data | Linear relationships in spectral data; Baseline modeling; Applications requiring model interpretability |

| GA-PLS | Automated variable selection; Enhanced interpretability with PLSFC; Reduces overfitting risk; Identifies key spectral regions | Computational intensity with GA optimization; Dependent on GA parameter tuning; Complex implementation | High-dimensional spectral data with redundant variables; Applications needing both accuracy and interpretability |

| ANN | Superior nonlinear modeling; High accuracy with sufficient data; Robust to noise without extensive preprocessing; Feature extraction capabilities | Data-intensive training requirements; Black-box nature limits interpretability; Hyperparameter sensitivity; Computational demands | Complex spectral relationships; Large datasets; Applications prioritizing prediction accuracy over interpretability |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Hyperspectral Imaging with Adaptive PLS Regression

The experimental protocol for chicken egg fertility detection exemplifies a rigorous application of adaptive PLS regression [24]. Hyperspectral images in the NIR region (900-1700 nm wavelength range) were captured for 672 fertilized chicken eggs (336 white, 336 brown) prior to incubation (day 0) and on days 1-4 after incubation. Spectral information was extracted from segmented regions of interest (ROI) for each hyperspectral image, with spectral transmission characteristics obtained by averaging the spectral information. The dataset exhibited significant imbalance, with fertile eggs outnumbering non-fertile eggs at ratios of approximately 13:1 for brown eggs and 15:1 for white eggs. For the PLS modeling, a moving-thresholding technique was implemented for discrimination based on PLS regression results on the calibration set. Model performance was evaluated using true positive rates (TPRs) rather than overall accuracy, as the latter metric can be misleading when dealing with imbalanced data containing rare classes. This approach demonstrated the adaptability of PLS regression to challenging real-world spectral classification problems with inherent data imbalances.

Genetic Algorithm-PLSFC Implementation

The GA-PLSFC methodology combines variable selection through genetic algorithms with PLS regression using only the first component [29]. The process begins with population initialization, where random subsets of spectral variables are selected. For each variable subset, a PLSFC model is constructed using only the first latent component, which enables direct interpretation of regression coefficients as variable contributions without multicollinearity concerns. The fitness of each variable subset is evaluated through cross-validation, assessing the predictive accuracy of the corresponding PLSFC model. The genetic algorithm then applies selection, crossover, and mutation operations to evolve the population toward increasingly fit variable subsets. This iterative process continues until convergence criteria are met, yielding an optimal set of spectral variables that balance predictive performance and interpretability. The approach is particularly valuable for spectral data analysis where identifying the most relevant wavelength regions is scientifically meaningful, as in the case of material characterization or biochemical analysis.

Artificial Neural Network Configuration for Spectral Data

The implementation of ANN for spectral analysis follows a structured methodology to ensure robust performance [30] [31]. The process begins with data preparation, where spectra are typically normalized or standardized to account for intensity variations. The network architecture selection depends on data complexity, with studies showing that for many spectroscopic classification tasks, fully connected networks with 2-3 hidden layers using ReLU activation functions provide sufficient modeling capability without unnecessary complexity [31]. The input layer size corresponds to the number of spectral features (wavelengths), while the output structure depends on the task—single node for regression, multiple nodes for multi-class classification. During training, techniques such as batch normalization and dropout may be employed to improve generalization, though research indicates that for synthetic spectroscopic datasets, these advanced components do not necessarily provide performance benefits [31]. Hyperparameter optimization, including learning rate, batch size, and layer sizes, is typically conducted through systematic approaches like grid search or random search, with nested cross-validation employed to prevent overfitting and provide realistic performance estimates [34].

Figure 1: Comparative Workflows for ANN, PLS, and GA-PLS in Spectral Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Spectral Analysis Experiments

| Category | Item | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Acquisition | Hyperspectral Imaging System | NIR region (900-1700 nm), spatial and spectral resolution | Chicken egg fertility detection [24] |

| UV-NIR Spectrometer | 2 nm resolution, broad wavelength range | Plasma emission spectra analysis [32] | |

| NIR Spectrometers | Portable or benchtop, 950-1650 nm range | Soil property prediction [35] | |

| Data Processing | Python with TensorFlow | Deep learning framework for ANN implementation | Spectral regression and classification [34] |

| Scikit-learn Library | PLSRegression, genetic algorithm utilities | PLS and GA-PLS implementation [29] | |

| Savitzky-Golay Filter | Smoothing and derivative computation | Spectral preprocessing [28] | |

| Reference Materials | Certified Soil Samples | Laboratory-analyzed properties (OM, pH, Pâ‚‚Oâ‚…) | Soil NIR model calibration [35] |

| Control Egg Samples | Candled and breakout-verified fertility status | Egg fertility model validation [24] | |

| Standard Gas Mixtures | Known COâ‚‚ concentrations in Nâ‚‚-Ar base | Plasma emission reference [32] | |

| Computational Resources | High-Performance Computing | Parallel processing for GA and ANN training | Large spectral dataset handling [34] [29] |

| Nested Cross-Validation | Hyperparameter tuning and model selection | Preventing overfitting [35] | |

| Lunarine | Lunarine|Time-Dependent Trypanothione Reductase Inhibitor | Lunarine, a macrocyclic spermidine alkaloid and time-dependent inhibitor of trypanothione reductase. For research use only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| Lunasin | Lunasin, CAS:6901-22-0, MF:C17H22NO3+, MW:288.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Figure 2: Decision Framework for Selecting Spectral Regression Techniques

This comparative analysis demonstrates that the selection of advanced regression techniques for spectral resolution depends critically on specific research objectives, data characteristics, and interpretability requirements. PLS regression provides a robust baseline approach with inherent interpretability advantages, particularly for linear relationships in spectral data. GA-PLS enhances traditional PLS through intelligent variable selection, offering a balanced approach that maintains interpretability while improving model performance through focused wavelength selection. ANN represents the most powerful approach for modeling complex nonlinear relationships in spectral data, achieving superior predictive accuracy when sufficient training data is available, though at the cost of model interpretability. The experimental evidence indicates that ANN-based approaches, particularly bagging neural networks (BANN), can outperform PLS methods in prediction accuracy (0.873 vs. 0.561 model scores in plasma emission analysis) [32], while adaptive PLS techniques achieve remarkable classification performance (up to 100% true positive rates) in specific applications like egg fertility detection [24]. Researchers should consider these performance characteristics alongside their specific requirements for interpretability, computational resources, and data availability when selecting the optimal spectral regression technique for their chemometric applications.

In spectroscopic analysis of complex mixtures, a significant challenge arises when the absorption profiles of multiple components overlap, creating a single, convoluted signal that prevents the direct quantification of individual constituents using traditional univariate methods. This scenario is particularly common in pharmaceutical analysis, where formulations often contain several active ingredients with closely overlapping ultraviolet (UV) spectra. The conventional approach to this problem has involved the use of separation techniques like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). However, these methods are often time-consuming, require extensive sample preparation, consume significant quantities of solvents, and generate hazardous waste [36] [37].

Chemometrics presents a powerful alternative by applying mathematical and statistical techniques to extract meaningful chemical information from complex, multivariate data. By treating the entire spectrum as a multivariate data vector, chemometric models can resolve overlapping signals without physical separation of components [38] [39]. These methods transform spectroscopic analysis from a simple univariate tool into a sophisticated technique capable of quantifying multiple analytes simultaneously, even in the presence of significant spectral overlap. The foundational principle is that the measured spectrum of a mixture represents a linear combination of the pure component spectra, weighted by their concentrations, allowing mathematical decomposition to retrieve individual contributions [40].

Foundational Chemometric Algorithms

Classical Multivariate Calibration Methods

Classical multivariate calibration methods form the backbone of chemometric analysis for quantitative spectral resolution. These algorithms establish mathematical relationships between the spectral data matrix and the concentration matrix of target analytes, enabling prediction of unknown concentrations based on their spectral profiles.

Principal Component Regression (PCR) employs a two-step process: first, it uses Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the spectral data dimensionality by projecting it onto a new set of orthogonal variables called principal components. These components capture the maximum variance in the spectral data while eliminating multicollinearity. Subsequently, regression is performed between the scores of these principal components and the analyte concentrations. PCR is particularly effective for handling noisy, collinear spectral data, as the dimensionality reduction step eliminates non-informative variance [38] [41].

Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression represents a more sophisticated approach that simultaneously reduces the data dimensionality while maximizing the covariance between the spectral variables and concentration data. Unlike PCR, which only considers variance in the spectral data, PLS explicitly models the relationship between spectra and concentrations during the dimensionality reduction step. This characteristic often makes PLS more efficient and predictive than PCR, particularly when dealing with complex mixtures where minor spectral components are relevant to concentration prediction [36] [38]. The optimal number of latent variables (LVs) in PLS models is typically determined through cross-validation techniques to prevent overfitting.

Classical Least Squares (CLS) operates under the assumption that the measured spectrum is a linear combination of the pure component spectra. It estimates concentrations by fitting the mixture spectrum using the known pure component spectra. While mathematically straightforward, CLS requires complete knowledge of all components contributing to the spectrum, making it susceptible to errors from unmodeled components or spectral variations [37] [41].

Advanced Machine Learning Approaches

Beyond classical methods, advanced machine learning algorithms offer enhanced capability for modeling nonlinear relationships in complex spectral data.

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), particularly feed-forward networks with backpropagation, represent a powerful nonlinear modeling approach. These networks consist of interconnected layers of processing nodes (neurons) that can learn complex functional relationships between spectral inputs and concentration outputs. ANNs excel at capturing nonlinear spectral responses caused by molecular interactions or instrumental effects, often outperforming linear methods when sufficient training data is available [36]. In pharmaceutical applications, ANNs have demonstrated exceptional performance for resolving complex multi-component formulations, with studies reporting mean percent recoveries approaching 100% with low relative standard deviation [36].

Random Forest (RF) is an ensemble learning method that constructs multiple decision trees during training and outputs the average prediction of the individual trees. This approach reduces overfitting and improves generalization compared to single decision trees. RF models provide feature importance rankings, helping identify diagnostic wavelengths that contribute most to predictive accuracy [42].

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) can perform both linear and nonlinear regression using kernel functions to transform data into higher-dimensional feature spaces. SVMs are particularly effective when dealing with high-dimensional spectral data with limited samples, as they seek to maximize the margin between different classes or prediction errors [42].

Table 1: Comparison of Core Chemometric Algorithms for Spectral Resolution

| Algorithm | Underlying Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLS | Maximizes covariance between spectra and concentrations | Robust, handles collinearity, works with noisy data | Requires careful selection of latent variables | Quantitative analysis of complex pharmaceutical mixtures [36] [41] |

| PCR | Principal component analysis followed by regression | Eliminates multicollinearity, reduces noise | Components may not relate to chemical constituents | Spectral data with high collinearity [37] [41] |

| CLS | Linear combination of pure component spectra | Simple implementation, direct interpretation | Requires knowledge of all components, sensitive to baseline effects | Systems with well-defined components and minimal interference [37] |

| ANN | Network of interconnected neurons learning nonlinear relationships | Handles complex nonlinearities, high predictive accuracy | Requires large training datasets, risk of overfitting | Complex mixtures with nonlinear spectral responses [36] |

| MCR-ALS | Iterative alternating least squares with constraints | Extracts pure component spectra, handles unknown interferences | Convergence to local minima possible, requires constraints | Resolution of complex mixtures with partially unknown composition [36] |

Experimental Protocols for Method Development

Calibration Set Design and Data Collection