Advanced DNA Concentration Methods for Low Yield Samples: A 2025 Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals grappling with DNA concentration from low-yield and challenging samples.

Advanced DNA Concentration Methods for Low Yield Samples: A 2025 Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals grappling with DNA concentration from low-yield and challenging samples. It covers the foundational causes of low DNA yield, evaluates modern methodological approaches from commercial kits to innovative in-house protocols, and delivers robust troubleshooting and optimization strategies. A critical comparison of validation techniques, including spectrophotometry and fluorometry, is presented to ensure accurate DNA quantification and integrity assessment for downstream applications like sequencing and PCR. The insights herein are designed to enhance recovery success rates in genomics research, clinical diagnostics, and biopharmaceutical development.

Understanding the Challenge: Why DNA Yield is Low and Why It Matters

The increasing reliance on genetic analysis across biomedical research, drug development, and clinical diagnostics has intensified the challenge of obtaining sufficient high-quality DNA from limited or degraded source materials. Efficient DNA recovery from challenging samples is a critical determinant of success in downstream applications such as next-generation sequencing (NGS), single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping, and quantitative PCR (qPCR). This application note details the characteristics and processing methodologies for three common sources of low-yield DNA: dried blood spots (DBS), historical archives, and processed biological materials. We provide a structured comparison of DNA yield across sample types, detailed experimental protocols for optimal recovery, and visual workflows to guide researchers in navigating the complexities of low-input genetic studies.

Sample Source Characteristics and DNA Yield Comparison

Dried Blood Spots (DBS)

Dried blood spots represent a minimally invasive microsampling technique widely used in neonatal screening, pharmacokinetic studies, and biobanking. The primary challenge with DBS is the extremely low starting blood volume (approximately 8.7 µL per standard 6 mm disk), which directly limits total DNA yield [1]. Despite this limitation, DNA from DBS remains stable for extended periods; studies confirm that HBV DNA levels in DBS showed no significant difference after 14 days of storage at both 4°C and room temperature, supporting their use in real-world settings where cold chain logistics are impractical [2].

Historical Archives

Historical DNA samples encompass a broad range of materials, including formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, archived stained slides, and forensic samples stored for extended periods. These samples are particularly prone to DNA degradation through multiple pathways: oxidative damage from exposure to environmental stressors, hydrolytic cleavage of DNA backbone bonds, and enzymatic breakdown by nucleases if not properly inactivated during initial processing [3]. The degradation manifests as DNA fragmentation, which compromises integrity and reduces the average fragment length recoverable, thereby limiting applicability in assays requiring long amplification products.

Processed Biological Materials

This category includes tissues preserved in various solutions (e.g., ethanol, RNAlater), forensic samples like bone and hair, and biologically processed materials such as fecal samples. DNA yield from these sources is highly variable and depends on the specific preservation method and tissue type. A 2024 study evaluating DNA yield from various white-tailed deer tissues found that storage method and preservative choice significantly influence final DNA concentration [4]. For instance, ear tissue stored in a proprietary preservative at room temperature provided adequate DNA for SNP panels, whereas refrigerated retropharyngeal lymph nodes without preservative showed compromised yield.

Table 1: DNA Yield and Characteristics Across Low-Yield Sample Sources

| Sample Source | Typical DNA Yield Range | Primary Limitations | Optimal Storage Conditions | Recommended Downstream Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dried Blood Spots (DBS) | Variable; ~10-100 ng/µL from 6mm punch [1] | Very low starting volume, inhibition from card matrix | Room temperature (stable ≥14 days), -20°C long-term [2] | qPCR (e.g., TREC), SNP genotyping, targeted sequencing [1] |

| Historical Archives | Highly variable; dependent on age and preservation | Fragmentation, cross-linking (FFPE), oxidative damage | -80°C (ideal), controlled environment to minimize further degradation | Targeted sequencing, FFPE-optimized NGS, methylation analysis [3] |

| Processed Materials | Wide range based on tissue and preservative | PCR inhibitors (e.g., EDTA, pigments), co-extracted contaminants | Method-dependent: ethanol (room temp), most tissues (-20°C to -80°C) | ddRADseq, medium-high density SNP panels, metagenomics (fecal) [4] |

Table 2: Impact of Sample Handling on DNA Yield and Quality

| Handling Factor | Impact on DNA Yield/Quality | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Time to preservation | Inverse correlation with yield; increased enzymatic degradation | Process immediately or use stabilizing preservatives |

| Storage temperature | Higher temperatures accelerate hydrolytic/oxidative damage | Flash freeze in LN₂, store at -80°C; room temp stable with specific preservatives [3] |

| Preservative type | Significant impact on recovery; ethanol superior to dry storage for many tissues [4] | Match preservative to tissue type and intended analysis |

| Extraction method | Dramatically affects yield; Chelex outperforms column methods for DBS [1] | Optimize protocol for specific sample type; prioritize yield vs. purity based on application |

Experimental Protocols for DNA Recovery

Optimized DNA Extraction from Dried Blood Spots

Principle: Efficient release of DNA from filter paper matrix while minimizing inhibitory substance co-extraction through a combination of chemical and thermal treatment.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Chelex-100 resin (50-100 mesh-size, dry)

- PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline)

- Tween20 solution (0.5% in PBS)

- Thermal cycler or dry bath (95°C capability)

- Microcentrifuge

- 6 mm DBS punch

Protocol Steps:

- Punch Preparation: Using a sterile 6 mm punch, transfer one DBS disk to a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Initial Hydration: Add 1 mL of Tween20 solution (0.5% in PBS) to the punch. Incubate overnight at 4°C.

- Washing: Carefully remove Tween20 solution and add 1 mL of PBS. Incubate for 30 minutes at 4°C.

- Chelation: Remove PBS and add 50 µL of pre-heated 5% (m/v) Chelex-100 solution (56°C).

- Thermal Lysis: Pulse-vortex for 30 seconds, then incubate at 95°C for 15 minutes, with brief pulse-vortexing every 5 minutes during incubation.

- Clarification: Centrifuge for 3 minutes at 11,000 rcf to pellet Chelex beads and paper debris.

- Recovery: Transfer supernatant to a new tube using a P200 pipette. Re-centrifuge and perform a final transfer using a P20 pipette for precision.

- Storage: Store extracted DNA at -20°C until use [1].

Optimization Notes:

- Elution Volume: Reduction from 150 µL to 50 µL significantly increases final DNA concentration without compromising yield [1].

- Starting Material: Increasing from one to two 6 mm spots did not significantly improve DNA concentration, suggesting optimal recovery from a single punch.

DNA Extraction from Challenging Processed Materials (e.g., Bone, Ethanol-Preserved Tissues)

Principle: Combination of mechanical disruption and chemical demineralization (for mineralized tissues) to access intracellular DNA while protecting it from degradation.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Bead Ruptor Elite homogenizer or equivalent

- specialized bead tubes (ceramic or stainless steel)

- EDTA-containing buffer (for demineralization)

- Proteinase K

- QIAGEN DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit

- Thermal incubator (56°C)

Protocol Steps:

- Sample Preparation: For bone, cut ~25 mg cortical bone using sterile scalpel. For ethanol-preserved tissues, use ~4 mm² section.

- Demineralization (Bone Only): Incubate bone fragments in 500 µL EDTA-containing buffer for 24-72 hours at 4°C with agitation.

- Mechanical Disruption: Transfer tissue to bead tube containing appropriate beads. Process in Bead Ruptor Elite with optimized settings (speed: 4-5 m/s, time: 30-60 seconds, temperature control: 4°C).

- Enzymatic Lysis: Add ATL buffer and Proteinase K (from kit). Incubate at 56°C for 3-24 hours until complete lysis.

- DNA Purification: Follow manufacturer's protocol for QIAGEN DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit.

- Elution: Elute in 50-150 µL AE buffer for concentration optimization [3] [4].

Technical Considerations:

- EDTA Balance: While essential for demineralization, EDTA is a PCR inhibitor; remove completely during wash steps.

- Temperature Control: Excessive heat during homogenization accelerates DNA oxidation and hydrolysis; use cryo-cooling for sensitive samples.

- Bead Selection: Ceramic beads for tough tissues, stainless steel for bacterial cells, glass for standard tissues.

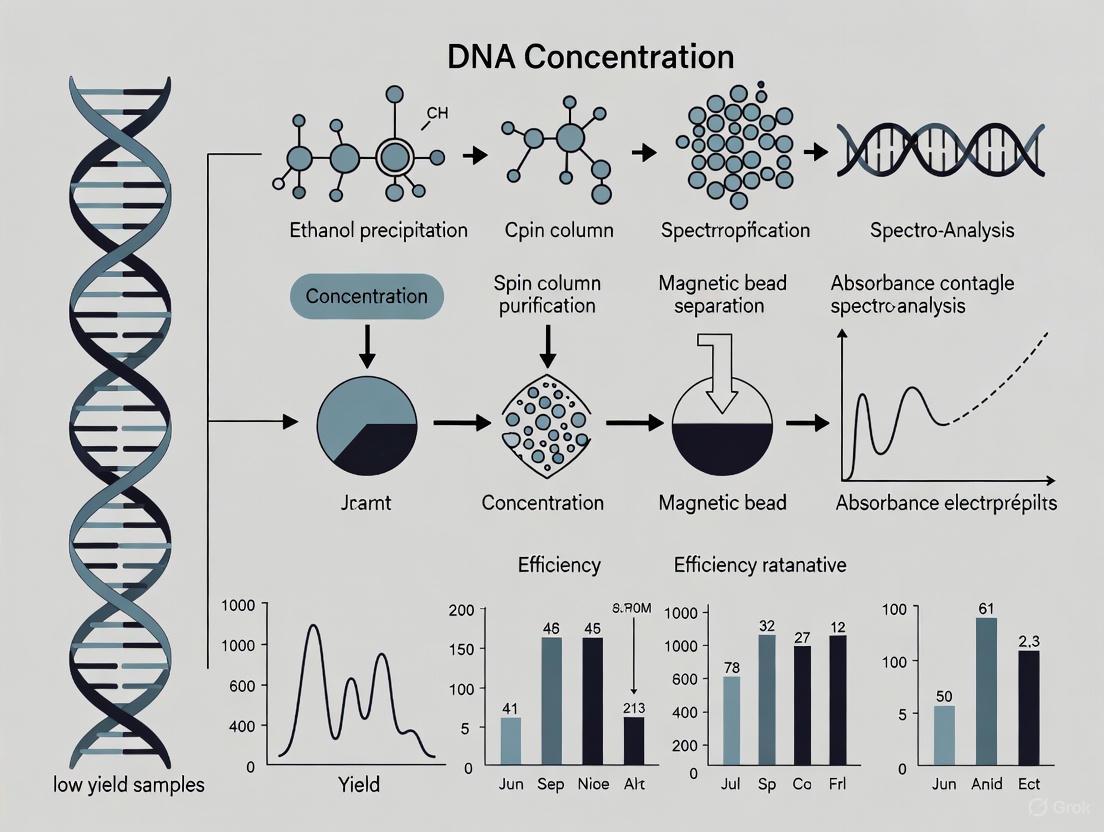

Workflow Visualization

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Low-Yield DNA Extraction

| Reagent/Kit | Primary Function | Optimal Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Chelex-100 Resin | Chelates divalent cations, preventing DNA degradation during boiling; facilitates DNA release | DBS extraction; rapid preparation for PCR-based assays [1] |

| QIAGEN DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | Silica-membrane based purification; removes inhibitors, yields high-purity DNA | Processed tissues, ethanol-preserved samples, historical archives [4] |

| Bead Ruptor Elite Homogenizer | Mechanical disruption of tough matrices (bone, plant) with controlled parameters | Mineralized tissues, fibrous materials, bacterial cells [3] |

| Ultra-mild Bisulfite (UMBS) Chemistry | Gentler bisulfite conversion preserving DNA integrity for methylation studies | Historical samples, low-input epigenetic analysis [5] |

| High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit | Rapid purification with reduced inhibitor carryover; includes internal QC | Samples with PCR inhibitors; rapid turnaround needed [1] |

The integrity of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is paramount for successful genetic analysis, a concern that becomes critically acute when working with low-yield, challenging samples commonly encountered in forensic science, ancient DNA research, cancer studies, and metagenomics [3]. The mechanisms of DNA degradation—primarily hydrolysis, oxidation, and enzymatic breakdown—pose significant obstacles to DNA concentration and purification methods, particularly when sample material is irreplaceable or available in minute quantities [3]. Understanding these degradation pathways is not merely an academic exercise; it is a practical necessity for developing robust protocols that maximize DNA recovery and quality. Compromised DNA samples lead to substantial research losses annually, affecting everything from PCR amplification to next-generation sequencing outcomes [3]. This document details the core degradation mechanisms and provides optimized, actionable protocols to mitigate their effects within the broader context of DNA concentration methods for low-yield sample research.

Core Mechanisms of DNA Degradation

DNA degradation is a natural process that severely impacts genetic material quality, making it difficult to analyze or amplify. The primary mechanisms work through distinct chemical pathways to compromise DNA integrity.

Hydrolytic Damage

Hydrolysis occurs when water molecules break the chemical bonds in the DNA backbone. This process can lead to depurination, where purine bases (adenine and guanine) are removed, leaving behind abasic sites that can stall polymerases during amplification [3]. If hydrolytic damage is extensive, it can fragment DNA into unusable pieces. Hydrolysis is significantly accelerated in acidic or basic conditions and at elevated temperatures. Using buffered solutions that maintain a stable pH and storing samples in dry or frozen conditions can significantly reduce hydrolysis-related degradation [3].

Oxidative Damage

Oxidation represents one of the most common causes of DNA damage, especially in samples exposed to environmental stressors like heat, UV radiation, or reactive oxygen species (ROS) [3]. These oxidative agents modify nucleotide bases, leading to strand breaks and structural changes that interfere with replication and sequencing. The presence of metal ions can catalyze these oxidative reactions. Incorporating antioxidants into storage buffers and employing proper storage conditions, such as freezing samples at -80°C or maintaining them in oxygen-free environments, can help slow this destructive process [3].

Enzymatic Breakdown

Enzymatic degradation, primarily caused by nucleases, presents a major challenge in biological samples like blood, tissue, or saliva [3]. These enzymes are specifically designed to degrade nucleic acids and can rapidly break down DNA if not properly inactivated immediately upon sample collection. Effective countermeasures include heat treatment during extraction, using chelating agents like EDTA to sequester metal co-factors required by many nucleases, and incorporating nuclease inhibitors into extraction and storage buffers to protect DNA from enzymatic degradation throughout processing and preservation [3].

Table 1: DNA Degradation Mechanisms and Protective Strategies

| Mechanism | Primary Causes | Impact on DNA | Protective Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrolysis | Water molecules, extreme pH, heat | Depurination, strand breakage, fragmentation | Stable pH buffers, dry/frozen storage, chelating agents |

| Oxidation | Heat, UV radiation, reactive oxygen species | Base modifications, strand breaks, cross-links | Antioxidants, -80°C storage, oxygen-free environments |

| Enzymatic Breakdown | Endogenous and exogenous nucleases | Strand cleavage, complete digestion | Heat inactivation, EDTA, nuclease inhibitors, rapid processing |

Quantitative Assessment of DNA Degradation

Evaluating DNA degradation is crucial for determining sample viability and selecting appropriate downstream analytical methods. The Degradation Index (DI) has emerged as a valuable quantitative metric, particularly in forensic contexts [6]. The DI is calculated by comparing the quantitative PCR (qPCR) results of longer versus shorter DNA targets, effectively measuring the extent of fragmentation [6] [7].

Research demonstrates that degraded DNA yields significantly less polymorphic information than non-degraded DNA due to a reduction in the effective copy number of target loci available for amplification [6]. Importantly, the relationship between degradation and analytical success is not always straightforward; studies show that STR and Y-STR profiles and allele detection rates vary depending on the degradation pattern, such as fragmentation or UV irradiation, even when the DI remains the same [6]. This underscores the importance of understanding not just the degree but also the nature of degradation when processing challenging samples.

Table 2: Impact of DNA Degradation on Genetic Analysis Techniques

| Analysis Method | Typical Fragment Size | Impact of Degradation | Suitable for Degraded DNA? |

|---|---|---|---|

| STR Analysis | 100-450 bp [7] | Incomplete profiles, allele dropout, reduced heterozygosity | Limited - fails as fragment size decreases |

| mtDNA Sequencing | <50 bp [7] | Minimal impact due to small target size | Excellent - preferred for highly degraded samples |

| SNP/InDel Analysis | 60-120 bp | Reduced efficiency for larger amplicons | Good - especially with optimized short amplicons |

| Next-Generation Sequencing | Varies by platform | Reduced library complexity, coverage gaps | Moderate - requires specialized library prep methods [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Studying DNA Degradation

Protocol: Artificial DNA Degradation via UV-C Irradiation

Background: Naturally degraded samples represent a valid resource for method validation; however, their degradation state cannot be well defined [7] [9]. This protocol enables rapid, reproducible generation of artificially degraded DNA to mimic natural degradation states for evaluating and optimizing genotyping applications.

Materials:

- DNA samples extracted from blood or tissues

- UV-C irradiation unit (254 nm wavelength) with germicidal lamps [7] [9]

- Low TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 8)

- Microtubes (Axygen, 0.6 mL)

- Quantitative PCR system with degradation-sensitive assays

- Capillary electrophoresis system for STR analysis

Method:

- Extract DNA using your preferred method (e.g., QIAamp DNA Blood Maxi Kit) and quantify using sensitive qPCR methods [7].

- Dilute DNA with low TE buffer to prepare stock solutions of desired concentrations (1 ng/μL, 7 ng/μL, and 14 ng/μL have been validated) [7].

- Prepare 10-20 μL aliquots in 0.6 mL microtubes.

- Position aliquots in microtubes on their side under the UV-C light source at a distance of approximately 11 cm from the lamps [7].

- Expose samples to UV-C light at a photometric power of 12 W for timed intervals (30 seconds to 5 minutes) [7].

- Remove replicates at each time point (e.g., every 30 seconds) to create a degradation series.

- Quantify degradation using qPCR assays targeting different fragment lengths and calculate the Degradation Index (DI) as: DI = [DNA amount of long target (e.g., 143 bp)] / [DNA amount of short target (e.g., 69 bp)] [7].

- Analyze degradation progression using STR typing or other appropriate genotyping methods.

Notes: This protocol produces a gradual decrease in DNA fragment size that mimics natural degradation. The process is largely independent of starting DNA amount, though concentration may slightly shift the degradation pattern [7]. Always include appropriate safety measures when working with UV-C light, including protective shielding.

Protocol: DNA Extraction from Challenging Dried Blood Spot Samples

Background: Dried Blood Spot (DBS) samples represent a common low-yield, challenging sample type in neonatal screening and clinical research. Optimal DNA extraction is crucial for downstream genetic analyses.

Materials:

- Dried Blood Spot samples on collection cards

- Chelex-100 resin (Sigma-Aldrich, 50-100 mesh-size, dry) [1]

- Tween20 solution (0.5% Tween20 in PBS)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Microtube punches (3 mm and 6 mm)

- Heating block or water bath

- Centrifuge

- QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen) - for comparison [1]

Method (Chelex Boiling Protocol):

- Punch one 6 mm DBS spot into a microfuge tube [1].

- Incubate overnight at 4°C in 1 mL of Tween20 solution (0.5% Tween20 prepared in PBS) [1].

- Remove Tween20 solution and add 1 mL of PBS to the DBS punch.

- Incubate for 30 minutes at 4°C, then remove PBS wash.

- Add 50 μL of pre-heated 5% (m/v) Chelex-100 solution (56°C) to the punch [1].

- Pulse-vortex for 30 seconds, then incubate at 95°C for 15 minutes, with brief pulse-vortexing every 5 minutes during incubation.

- Centrifuge for 3 minutes at 11,000 rcf to pellet Chelex beads and residual paper.

- Transfer supernatant to a new Eppendorf tube using a P200 pipette.

- Repeat centrifugation and transfer using a P20 pipette for precision.

- Store extracted DNA at -20°C.

Optimization Notes: Research indicates that decreasing elution volumes (150 μL vs. 100 μL vs. 50 μL) significantly increases DNA concentration without increasing starting material [1]. The Chelex boiling method has demonstrated significantly higher DNA recovery compared to column-based methods, making it particularly advantageous for research in low-resource settings and large population studies [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successfully working with degraded, low-yield DNA samples requires specialized reagents and equipment designed to maximize recovery and minimize further degradation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for DNA Degradation Research

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Chelex-100 Resin | Chelating agent that binds metal ions, inhibiting nucleases and protecting DNA during extraction [1]. | Particularly effective for DNA extraction from Dried Blood Spots; cost-effective for high-throughput studies [1]. |

| EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) | Powerful chelating agent that demineralizes tough samples like bone while inhibiting metal-dependent nucleases [3]. | Balance is crucial as excess EDTA can inhibit downstream PCR; often used in combination with mechanical homogenization [3]. |

| UV-C Irradiation Unit | Artificial degradation source for generating standardized degraded DNA samples for method validation [7] [9]. | Operates at 254 nm wavelength; enables reproducible degradation patterns in as little as 5 minutes [7]. |

| Bead Ruptor Elite | Mechanical homogenizer that uses bead beating to lyse tough samples while minimizing DNA shearing through precise parameter control [3]. | Optimal for difficult samples (bone, tissue, bacteria); specialized bead types (ceramic, stainless steel) improve efficacy [3]. |

| CTAB Buffer | Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide-based extraction buffer particularly effective for tissues rich in phenolic compounds, like fungal samples [10]. | Often enhanced with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) for improved DNA purity and yield from challenging biological samples [10]. |

| Binding Buffer D | Silica bead binding buffer optimized for ancient and degraded DNA extraction, facilitating adsorption of fragmented DNA [8]. | Enables efficient recovery of short DNA fragments typical of degraded specimens; compatible with high-throughput applications [8]. |

| PF-05175157 | PF-05175157, CAS:1301214-47-0, MF:C23H27N5O2, MW:405.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PF-06273340 | PF-06273340, CAS:1402438-74-7, MF:C23H22ClN7O3, MW:479.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Mitigation Strategies for Degraded DNA Analysis

Library Preparation Methods for Degraded DNA

When DNA is significantly degraded, standard library preparation methods often fail. Specialized approaches have been developed specifically for highly fragmented DNA:

- Santa Cruz Reaction (SCR): A cost-effective, DIY library build method that demonstrates superior effectiveness at retrieving degraded DNA from challenging specimens like museum samples. SCR is easily implemented at high throughput for low cost, making it ideal for large-scale degraded DNA studies [8].

- Commercial Kits for Low-Input DNA: Commercially available kits such as the xGen ssDNA & Low-Input DNA Library Preparation Kit are specifically designed for challenging samples, though they typically come at higher cost compared to DIY methods [8].

- NEB Next Ultra II: A widely used library preparation kit that can be optimized for degraded DNA by modifying SPRI bead ratios (e.g., 1.2x) to better retain small fragments and using uracil-tolerant polymerases to accommodate damaged bases [8].

Alternative Genetic Markers for Highly Degraded DNA

When nuclear DNA is too degraded for standard STR analysis, alternative markers can rescue genetically informative data:

- Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) Sequencing: Due to its high copy number per cell and circular structure that resists degradation, mtDNA can often be successfully retrieved from samples where nuclear DNA is unusable [7]. MtDNA variation is based on SNPs, which can be successfully retrieved from degraded DNA down to less than 50 bp [7].

- Short Insertion/Deletion (InDel) Polymorphisms: These markers typically have shorter amplicon sizes than STRs and can be successfully amplified from more degraded templates [7].

- Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs): SNP panels can be designed with very short amplicon sizes (<100 bp), making them ideal for analysis of highly degraded DNA that fails STR analysis [7].

The successful analysis of low-yield DNA samples requires a comprehensive understanding of degradation mechanisms and their practical implications for laboratory workflows. Hydrolytic, oxidative, and enzymatic degradation pathways each present distinct challenges that can be mitigated through appropriate sample handling, preservation, and extraction strategies. The protocols and methodologies presented here provide a foundation for optimizing DNA recovery from challenging samples, emphasizing the importance of matching analytical approaches to degradation states—whether through artificial degradation validation, specialized extraction methods, or alternative genetic markers. As research continues to push the boundaries of what's possible with minimal and compromised DNA samples, these core principles will remain essential for generating reliable, reproducible results across diverse fields from forensic science to clinical diagnostics and ancient DNA research.

Impact of Sample Collection, Storage Conditions, and Freeze-Thaw Cycles on DNA Integrity

Within the context of advanced research on DNA concentration methods for low-yield samples, preserving the initial integrity of DNA is a foundational prerequisite for success. This application note systematically details how pre-analytical variables—sample collection, storage conditions, and freeze-thaw cycles—critically impact DNA quality and quantity. The subsequent quantitative data, detailed protocols, and optimized workflows are designed to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the evidence-based strategies needed to maximize DNA recovery from precious, limited samples, thereby ensuring the reliability of downstream genetic analyses.

The Impact of Storage Conditions on DNA Integrity

Long-term storage stability is a major concern for biobanks and long-term research studies. The temperature and physical state of storage are primary determinants of DNA integrity.

Quantitative Analysis of Long-Term Storage

Table 1: Impact of Long-Term Storage on DNA Quality from Blood Samples

| Storage Duration | Storage Temperature | Sample Conditions | % Samples Meeting Quality Standards (≥20 ng/µL, A260/280 1.7-1.9) | DNA Integrity Number (DIN) >7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7-21 years [11] | -20°C | Suboptimal, multiple freeze-thaw cycles | 75.7% | 57.8% |

| Up to 12 years [11] | -20°C | Suboptimal, multiple freeze-thaw cycles | 83.5% (highest proportion) | Not Specified |

| Theoretical [12] | -18°C | Encapsulated in silica | Potentially >2 million years | Not Specified |

| Theoretical [12] | 9.4°C | Encapsulated in silica | ~2000 years | Not Specified |

| Theoretical [12] | Room Temperature | Encapsulated in silica | 20-90 years | Not Specified |

Key Mechanisms of DNA Degradation During Storage

DNA degradation during storage occurs through several chemical pathways [3]:

- Hydrolysis: The cleavage of the phosphodiester backbone in the presence of water, leading to strand breaks.

- Oxidation: Reactive oxygen species (ROS) modify nucleotide bases, causing mutations and strand breaks.

- Enzymatic Breakdown: Endogenous nucleases (DNases) can remain active if not properly inactivated during storage.

Dehydrated or encapsulated storage formats can dramatically slow these processes. Encapsulation in an inorganic silica matrix, for instance, has been shown to substantially enhance DNA stability, allowing for theoretical shelf-lives of millennia at freezing temperatures [12].

The Effect of Freeze-Thaw Cycles on DNA Yield and Integrity

Repeated freezing and thawing of samples is a common but often overlooked source of DNA degradation and yield loss, primarily due to the mechanical stress of ice crystal formation and recrystallization.

Quantitative Impact of Freeze-Thaw Cycles

Table 2: Documented Impact of Freeze-Thaw Cycles on DNA

| Sample Type | Number of Freeze-Thaw Cycles | Impact on DNA | Experimental Method of Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood [13] | A single freeze cycle | Yield reduced by >25% | DNA quantification; Southern blot |

| Whole Blood [13] | Repeated cycles | No detectable degradation via Southern blot | DNA fingerprinting after digestion |

| Capillary Blood [11] | Unknown number (due to freezer malfunctions) | 75.7% of samples still provided usable DNA | Spectrophotometry; Automated electrophoresis (TapeStation) |

| General Sample [14] | Multiple | DNA degradation and reduced quality | PCR, NGS performance metrics |

Optimized Protocols for Sample Collection and Storage

The following protocols are designed to minimize DNA damage during the initial handling and long-term preservation of samples, with a focus on challenging sample types.

Protocol: Collection and Storage of Whole Blood for DNA Analysis

This protocol is optimized for obtaining high-quality DNA from whole blood, a common source material [15] [14].

Principle: To collect blood in a manner that prevents clotting and inhibits nucleases, followed by rapid processing and storage at a temperature that minimizes degradation.

Reagents and Equipment:

- EDTA blood collection tubes

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Access to -80°C or -20°C freezer

Procedure:

- Collection: Draw blood directly into EDTA tubes. Do not use heparin, as it inhibits downstream PCR reactions [14].

- Short-Term Storage: If processing within 48 hours, store samples at 4°C [15].

- Long-Term Storage:

- Avoidance of Freeze-Thaw: Aliquot the blood or DNA extract into single-use portions to avoid repeated freezing and thawing [15] [14].

Protocol: Extraction of DNA from Dried Blood Spots (DBS) using Chelex Resin

This cost-effective and efficient protocol is ideal for neonatal screening or field studies where resources are limited [1].

Principle: Chelex-100 resin chelates polyvalent metal ions, inhibiting nucleases that degrade DNA. Boiling disrupts cells and denatures proteins, releasing DNA into solution.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Chelex-100 resin (50-100 mesh, sodium form)

- Tween20

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

- Heat block or water bath (95°C)

- Centrifuge

- 6 mm DBS punch

Procedure:

- Punch: Excise one 6 mm disk from the DBS sample.

- Soak and Wash:

- Incubate the punch in 1 mL of 0.5% Tween20 solution overnight at 4°C.

- Remove Tween20, add 1 mL of PBS, and incubate for 30 minutes at 4°C. Remove PBS.

- Chelation and Lysis:

- Add 50 µL of pre-heated 5% (m/v) Chelex solution to the punch.

- Pulse-vortex for 30 seconds.

- Incubate at 95°C for 15 minutes, with brief pulse-vortexing every 5 minutes.

- Pellet and Recover:

- Centrifuge at 11,000 rcf for 3 minutes to pellet resin and debris.

- Carefully transfer the supernatant to a new tube. The supernatant contains the extracted DNA and is stable at -20°C [1].

Optimization Notes:

- Using a smaller elution volume (50 µL) significantly increases the final DNA concentration compared to larger volumes (100 or 150 µL) [1].

- Increasing the starting material (e.g., two 6 mm punches) did not significantly boost DNA yield in qPCR assays [1].

Protocol: Enhanced DNA Extraction from Tough Samples using Mechanical Lysis

This protocol is designed for difficult-to-lyse samples such as bone, plant material, or microlepidopterans, where standard chemical lysis is insufficient [3] [16].

Principle: Mechanical homogenization using beads physically disrupts tough cell walls and tissues, followed by a standard chemical extraction to purify the released DNA.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Lysis buffer (e.g., CTL buffer) and Proteinase K

- Bead Ruptor homogenizer or similar bead-beating instrument

- Bead tubes (ceramic, zirconia/silica, or stainless steel)

- Wide-bore pipette tips (to prevent shearing of high-molecular-weight DNA)

Procedure:

- Preparation: Place sample (e.g., a pool of insect pupae) in a bead tube containing lysis buffer and beads [16].

- Homogenization:

- Use a Bead Ruptor Elite or similar homogenizer.

- Optimize parameters (speed, time, and cycle duration) to balance efficient lysis with minimizing DNA shearing. For example, use short, controlled bursts [3].

- Digestion: Following homogenization, add Proteinase K and incubate with agitation for an extended period (e.g., 60 minutes) to ensure complete digestion of proteins [16].

- Purification: Proceed with standard phenol-chloroform extraction or commercial column-based purification.

- Elution: Elute DNA in a suitable buffer (e.g., TE) at room temperature to maximize yield [16].

Experimental Workflow for Assessing DNA Integrity

The following workflow provides a logical sequence for researchers to collect, process, and validate their samples for DNA integrity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for DNA Integrity Research

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| EDTA Blood Collection Tubes [15] [14] | Anticoagulant that preserves DNA integrity; preferred over heparin. | Heparin can inhibit downstream PCR and should be avoided. |

| QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit [11] | Silica-column-based DNA extraction from blood. | Used successfully on blood stored for over 21 years at -20°C. |

| Chelex-100 Resin [1] | Rapid, cost-effective DNA extraction for DBS; chelates metal ions to inhibit nucleases. | Ideal for large-scale screening; yields may be lower but sufficient for qPCR. |

| Proteinase K [15] [14] | Enzyme that digests proteins and inactivates nucleases during lysis. | Use fresh aliquots; extended incubation time (30-60 mins) improves yield. |

| Ceramic Beads [17] [3] | Mechanical disruption of tough samples (e.g., bone, insects). | Bead type and homogenization parameters must be optimized to prevent excessive DNA shearing. |

| DNA Stable & Silica Matrices [12] | Commercial products for room-temperature DNA storage by anhydrous stabilization. | Encapsulation in silica can theoretically preserve DNA for millennia at low temperatures. |

| Agilent 2200 TapeStation [11] | Automated electrophoresis system for assessing DNA Integrity Number (DIN). | A DIN >7 is generally considered high molecular weight, intact DNA. |

| PF470 | PF470, CAS:1539296-45-1, MF:C18H16N6O, MW:332.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PF-06446846 | PF-06446846, MF:C22H20ClN7O, MW:433.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

In molecular biology research, the success of downstream applications—from routine PCR to advanced next-generation sequencing—is fundamentally dependent on the initial quality of the isolated DNA. For researchers working with low-yield samples, such as historical archives, dried blood spots, or challenging microbiological specimens, defining and achieving these quality benchmarks is particularly critical. The DNA Integrity Number (DIN), a quantitative measure of DNA fragmentation, has emerged as a crucial metric alongside traditional spectrophotometric ratios (A260/280) for predicting sample performance in modern genomic workflows. This application note synthesizes current research to establish clear, evidence-based benchmarks for DNA quantity, purity, and quality, providing validated protocols to help researchers achieve these standards even with the most challenging sample types.

Establishing DNA Quality Benchmarks

Spectrophotometric Purity Ratios

The A260/280 ratio is a primary indicator of nucleic acid purity, specifically detecting contamination by proteins or phenol. The A260/230 ratio serves as a secondary check for contaminants like salts, carbohydrates, or organic compounds [18].

Table 1: Accepted Spectrophotometric Purity Ratios for DNA and RNA

| Sample Type | Target A260/280 | Acceptable Range | Target A260/230 |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | ~1.8 | 1.7-1.9 [19] | 2.0-2.2 [18] |

| RNA | ~2.0 | 1.9-2.1 | 2.0-2.2 [18] |

Deviations from these ranges indicate potential contamination: elevated A260/280 ratios may suggest RNA contamination in DNA samples, while low ratios typically indicate protein contamination. Low A260/230 ratios often reflect carryover of organic compounds from extraction reagents [18].

DNA Integrity Number (DIN) and Quantification

The DNA Integrity Number (DIN) provides a quantitative measure of DNA fragmentation on a scale of 1-10, with higher numbers indicating less fragmentation [19]. This metric is particularly valuable for predicting performance in long-read sequencing and other applications requiring high-molecular-weight DNA.

Table 2: DNA Quality and Quantity Benchmarks Across Sample Types

| Sample Type | Storage Conditions | DNA Yield | A260/280 | DIN | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historical Blood Samples | -20°C, 7-21 years, suboptimal | ≥20 ng/μL (75.7% of samples) | 1.7-1.9 (75.7% of samples) | ≥7 (57.8% of samples) | [19] |

| Cryopreserved Tumors | Liquid nitrogen | 4.2x higher yield vs. FFPE | Comparable to FFPE | Significantly higher vs. FFPE (9x more DNA >40,000 bp) | [20] |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | N/A | 17.9 μg (CB method) vs. 1.9 μg (conventional) | 1.86 (CB method) vs. 1.22 (conventional) | N/A | [21] |

| Turtle Blood | Fresh, with PBS dilution | 36.2-74.7 ng/μL | 1.76-1.87 | N/A | [22] |

Experimental Protocols for Quality DNA Extraction

Chloroform-Bead Method for Challenging Microorganisms

Background: Efficient extraction of high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from mycobacteria remains challenging due to their thick mycolic acid-rich cell walls. The chloroform-bead (CB) method combines chemical and mechanical disruptions to overcome these challenges, eliminating the need for enzymatic treatment and reducing processing time from 2-3 days to 2 hours while ensuring complete sample sterilization [21].

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Transfer one loopful of mycobacterial cells (approximately 10 mg) from solid media to a 2.0 mL screw-cap tube containing 600 mg of 0.2 mm diameter glass beads [21].

- Initial Disruption: Add 700 μL of 0.1 M NaCl/TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and 500 μL of chloroform to the tube. Vortex at 2,700 rpm for 7 minutes using a vortex with Turbomix attachment [21].

- RNase Treatment: Treat the resulting mixture with RNase A for 20 minutes [21].

- Purification: Perform phenol-chloroform and chloroform extractions in a phase-lock tube [21].

- DNA Precipitation: Precipitate DNA using isopropanol and dissolve in 100 μL elution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5) [21].

Validation: Multi-laboratory evaluation demonstrated the CB method's superiority over conventional methods for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (DNA yield: 17.9 vs 1.9 μg, purity A260/A230: 1.86 vs 1.22, both P < 0.001). The method has been successfully applied to >32 nontuberculous mycobacterial species (n = 1,058) with performance comparable to M. tuberculosis [21].

Optimized DNA Extraction from Suboptimal Blood Samples

Background: Historical blood samples stored under suboptimal conditions present unique challenges for DNA extraction. This protocol demonstrates that satisfactory DNA quality can be achieved from samples stored at -20°C for up to 21 years with unknown freeze-thaw cycles [19].

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Thaw blood samples and use the entire blood volume (varies from <10 μL to 500 μL). For samples <250 μL, dilute to 250 μL with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) [19].

- Lysis: Add Qiagen protease and lysis buffer directly to the 0.5 mL EDTA tube to minimize risk of leaving residual dried blood. Pulse vortex for 15 seconds to dissolve any dried blood and remaining small clots [19].

- Incubation: Incubate sample mixture according to manufacturer's instructions for QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit [19].

- Column Purification: Transfer the mixture to a QIAamp spin column, centrifuge, and wash according to manufacturer's protocol [19].

- Elution: Elute DNA in the recommended buffer and store at -20°C [19].

Validation: Analysis of 1,012 capillary blood samples showed 75.7% met quality standards for DNA quantity (≥20 ng/μL) and purity (A260/280 ratio 1.7-1.9). Of 270 randomly selected samples, 57.8% had a DIN of 7 or higher, indicating high molecular weight DNA [19].

Chelex Extraction from Dried Blood Spots

Background: DNA extraction from dried blood spots (DBS) is essential for neonatal screening programs and large population studies. This protocol describes a cost-effective Chelex method that outperforms column-based approaches for qPCR applications [1].

Protocol:

- Punch Preparation: Punch one 6 mm DBS disk into a microfuge tube [1].

- Pre-incubation: Incubate overnight at 4°C in 1 mL of Tween20 solution (0.5% Tween20 in PBS) [1].

- Washing: Remove Tween20 solution, add 1 mL PBS, and incubate for 30 minutes at 4°C [1].

- Chelex Extraction: Remove PBS wash, add 50 μL of pre-heated 5% (m/v) Chelex-100 solution (56°C). Pulse vortex for 30 seconds [1].

- Incubation: Incubate at 95°C for 15 minutes, with brief pulse-vortexing every 5 minutes [1].

- Clarification: Centrifuge for 3 minutes at 11,000 rcf to pellet Chelex beads and residual paper. Transfer supernatant to a new tube [1].

Optimization: Decreasing elution volumes from 150 μL to 50 μL significantly increased DNA concentrations without requiring additional starting material. The Chelex method yielded significantly (p < 0.0001) higher DNA concentrations compared to column-based methods [1].

Quality Control Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated quality control workflow for DNA extraction and qualification:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Equipment for Quality DNA Extraction

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit | Silica-membrane based purification | Effective for historical blood samples; modify protocol for small volumes [19] |

| Chloroform-Bead Setup | Mechanical and chemical cell disruption | Essential for tough cell walls (e.g., mycobacteria); combines 0.2mm glass beads with chloroform [21] |

| Chelex-100 Resin | Ionic chelating resin | Cost-effective for DBS DNA extraction; ideal for PCR-based applications [1] |

| Phase-Lock Tubes | Interface separation | Facilitates phenol-chloroform extraction; simplifies aqueous-organic separation [21] |

| Agilent 2200 TapeStation | Fragment analysis | Provides DIN scoring; essential for quality assessment pre-sequencing [19] |

| DeNovix DS-11 Spectrophotometer | Nucleic acid quantification | Measures concentration, A260/280, and A260/230 ratios with wavelength accuracy of 0.5nm [18] |

| Bead Ruptor Elite | Mechanical homogenization | Provides precise control over homogenization parameters; minimizes DNA shearing [3] |

| PF-06471553 | N-(2-cyclobutyltriazol-4-yl)-2-[2-(3-methoxyphenyl)acetyl]-1,3-dihydroisoindole-5-sulfonamide | High-purity N-(2-cyclobutyltriazol-4-yl)-2-[2-(3-methoxyphenyl)acetyl]-1,3-dihydroisoindole-5-sulfonamide for research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Bosutinib isomer | Bosutinib isomer, CAS:1391063-17-4, MF:C26H29Cl2N5O3, MW:530.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Establishing clear benchmarks for DNA quantity, purity, and quality is fundamental to successful molecular research, particularly when working with challenging, low-yield samples. The protocols and benchmarks presented here provide researchers with evidence-based criteria for evaluating DNA suitability for downstream applications. By implementing these standardized assessment methods and optimized extraction protocols, laboratories can significantly improve the reliability and reproducibility of their genomic analyses, even when working with suboptimal sample materials.

Proven DNA Concentration and Extraction Techniques for Demanding Samples

The integrity of downstream molecular analyses in life science research and diagnostic applications is fundamentally contingent on the quality and quantity of the isolated nucleic acids. This is particularly critical when dealing with low-yield samples, a common challenge in fields ranging from forensic science to liquid biopsy-based oncology testing. The efficacy of DNA concentration methods is largely determined by the upstream extraction methodology employed. Among the plethora of available techniques, silica-column-based, magnetic bead-based, and in-house boiling protocols represent three core methodologies, each with distinct advantages and limitations concerning yield, purity, scalability, and cost-effectiveness. This application note provides a structured evaluation of these three core DNA extraction methodologies—silica columns, magnetic beads, and in-house boiling protocols—framed within the context of research requiring high recovery from low-yield samples. It synthesizes recent comparative data, delineates detailed experimental protocols, and offers guidance for method selection to optimize outcomes in demanding research and diagnostic pipelines.

Comparative Performance Analysis

A summary of key performance metrics for the three DNA extraction methodologies, derived from recent comparative studies, is presented in the table below. This data is essential for selecting the appropriate method based on the specific requirements of the research, particularly when working with limited sample material.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of DNA Extraction Methodologies for Low-Yield Samples

| Performance Metric | Silica Spin Columns | Magnetic Beads | In-House Boiling (Chelex) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical DNA Yield | Moderate [1] | High [23] | Very High (for DBS samples) [1] |

| Purity (A260/A280) | High [24] | High [24] | Lower (carries inhibitors) [1] [25] |

| Hands-on Time | Moderate | Low (especially when automated) [26] | Low [1] |

| Throughput & Automation | Medium (manual or vacuum manifolds) [27] | High (easily automated) [27] [26] | Low (manual) |

| Cost per Sample | Moderate | Low to High (depends on automation) [27] | Very Low [1] |

| Sensitivity (LOD) | High [24] | Very High [23] | Variable; susceptible to inhibitors [25] |

| Downstream Compatibility | Broad (PCR, NGS, etc.) [24] | Broad (PCR, NGS, etc.) [23] | Best for PCR; inhibitors may affect other assays [1] |

| Reproducibility | High | Very High [26] | Moderate |

Key Insights from Comparative Data

- Yield vs. Purity Trade-off: While the Chelex boiling method demonstrated significantly higher DNA concentrations from dried blood spots (DBS) compared to several column-based methods (QIAamp, DNeasy) and a TE buffer boiling method [1], this high yield can come at the cost of purity. The lack of purification steps means the extract may contain PCR inhibitors [1] [25].

- Inhibitor Resistance: A study on HPV detection highlighted a critical weakness of the boiling method: its susceptibility to interference from hemoglobin. The HPV signal was lost at hemoglobin concentrations of 30 g/L, whereas the magnetic bead method showed robust resistance, detecting HPV even at 60 g/L [25]. This is a vital consideration for bloody samples.

- Efficiency and Speed: Novel optimizations of magnetic bead protocols, such as the SHIFT-SP method, have dramatically reduced extraction times to 6-7 minutes while achieving nearly complete nucleic acid recovery from the sample, outperforming a commercial column-based method which took 25 minutes and yielded only half the DNA [23].

- Application-Specific Performance: For loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assays targeting Clostridium perfringens, spin columns and magnetic beads yielded DNA of higher purity and quality, with spin columns showing superior sensitivity. However, the simple Hotshot (HS) boiling method was deemed the most practical for resource-limited settings, despite lower sensitivity [24].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Silica Spin Column-Based Extraction (Optimized for Tissues)

This protocol is adapted from the QIAamp DNA Mini kit procedure for tissues, incorporating an extended incubation step as used in DBS protocols for better yield [1].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Lysis Buffer (ATL): Contains chaotropic salts to denature proteins and facilitate DNA binding to silica.

- Proteinase K: A broad-spectrum protease for enzymatic digestion of cellular proteins.

- Wash Buffers (AW1, AW2): Ethanol-based solutions containing chaotropic salts to remove contaminants while keeping DNA bound to the membrane.

- Elution Buffer (AE): Low-salt buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 9.0) or nuclease-free water to disrupt DNA-silica binding and elute pure DNA.

Procedure:

- Lysis: Place up to 25 mg of tissue in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. Add 180 µL of Buffer ATL and 20 µL of Proteinase K. Vortex thoroughly and incubate at 56°C for 1-3 hours (or until the tissue is completely lysed). Vortex occasionally.

- Optional Incubation: Briefly spin the tube to remove drops from the lid. For enhanced yield from complex samples, an additional 10-minute incubation at 85°C may be performed [1].

- Binding: Add 200 µL of Buffer AL to the lysate. Mix immediately by pulse-vortexing for 15 seconds. Incubate at 70°C for 10 minutes.

- Precipitation: Add 200 µL of ethanol (96-100%) to the mixture and vortex again.

- Column Loading: Carefully apply the entire mixture (including any precipitate) to the QIAamp Mini spin column. Centrifuge at 6,000 × g for 1 minute. Place the column in a clean 2 mL collection tube and discard the flow-through.

- Washing I: Add 500 µL of Buffer AW1 to the column. Centrifuge at 6,000 × g for 1 minute. Discard the flow-through.

- Washing II: Add 500 µL of Buffer AW2 to the column. Centrifuge at full speed (20,000 × g) for 3 minutes. Discard the flow-through.

- Final Spin: Place the column in a new 2 mL collection tube and centrifuge at full speed for 1 minute to eliminate any residual ethanol.

- Elution: Transfer the column to a clean 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. Apply 50-150 µL of Buffer AE or nuclease-free water to the center of the membrane. Allow it to stand for 5 minutes at room temperature, then centrifuge at 6,000 × g for 1 minute. For higher concentrations, elution in a smaller volume (e.g., 50 µL) is recommended [1].

Protocol 2: Magnetic Bead-Based Extraction (Rapid High-Yield Method)

This protocol is based on the optimized SHIFT-SP method, which uses a low-pH binding buffer and active mixing for high-speed, high-efficiency recovery [23].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Lysis Binding Buffer (LBB): A guanidinium-based chaotropic buffer, adjusted to pH ~4.1, to promote nucleic acid binding to silica.

- Magnetic Silica Beads: Paramagnetic particles coated with a silica surface.

- Wash Buffer: Typically an ethanol-based solution to remove salts and other impurities.

- Elution Buffer: Low-salt Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer or nuclease-free water.

Procedure:

- Lysis and Binding: Combine 100 µL of sample with 500 µL of Lysis Binding Buffer (pH ~4.1) and 30-50 µL of magnetic silica bead suspension in a 1.5 mL tube.

- Active Binding: Perform "tip-based" mixing by repeatedly aspirating and dispensing the entire mixture for 1-2 minutes using a pipette. This ensures rapid and uniform exposure of the beads to the lysate. For 1000 ng input DNA, a 2-minute binding with 50 µL beads achieved ~96% binding efficiency [23].

- Magnetic Separation: Place the tube on a magnetic stand for 1 minute or until the solution clears. Carefully aspirate and discard the supernatant without disturbing the bead pellet.

- Washing I: With the tube still on the magnet, add 500 µL of Wash Buffer. Gently flick the tube to resuspend the beads. Let it stand for 30 seconds, then aspirate and discard the supernatant.

- Washing II: Repeat the wash step a second time to ensure complete removal of inhibitors.

- Drying: Briefly air-dry the bead pellet for 1-2 minutes to evaporate residual ethanol. Do not over-dry.

- Elution: Remove the tube from the magnetic stand. Add 20-50 µL of Elution Buffer and resuspend the beads thoroughly by pipetting. For rapid and complete elution, incubate at 70°C for 1 minute [23].

- Final Separation: Return the tube to the magnetic stand. After the solution clears (approximately 1 minute), transfer the eluate containing the purified DNA to a new tube.

Protocol 3: In-House Boiling Protocol (Chelex-100 Resin)

This is a cost-effective and rapid method, optimized for DNA extraction from Dried Blood Spots (DBS), yielding high concentrations of DNA suitable for PCR [1].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Chelex-100 Resin: A chelating resin in sodium form (50-100 mesh-size, dry), which binds metal ions that act as cofactors for nucleases.

- Tween20 Solution (0.5%): A non-ionic detergent in PBS to aid in cell lysis and protein solubilization.

- Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS): A balanced salt solution for washing cellular material.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Punch one 6 mm disk from a DBS card and place it in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Soaking and Washing:

- Add 1 mL of 0.5% Tween20 solution to the punch. Incubate overnight at 4°C.

- Remove the Tween20 solution. Add 1 mL of PBS and incubate for 30 minutes at 4°C. Remove and discard the PBS.

- Boiling Extraction:

- Add 50 µL of a pre-heated 5% (w/v) Chelex-100 solution (in water) to the punch.

- Pulse-vortex for 30 seconds.

- Incubate at 95°C for 15 minutes, with brief pulse-vortexing every 5 minutes during the incubation.

- Clarification:

- Centrifuge the tube at 11,000 × g for 3 minutes to pellet the Chelex beads and paper debris.

- Transfer the supernatant to a new tube using a pipette.

- Repeat the centrifugation and transfer the supernatant again to ensure the complete removal of all beads and particles [1].

- Storage: The extracted DNA can be stored at -20°C. For optimal results in qPCR, a final elution volume of 50 µL is recommended [1].

Methodology Selection Workflow

The following decision diagram outlines the logical process for selecting the most appropriate DNA extraction methodology based on key research parameters.

Diagram 1: DNA Extraction Method Selection

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of the described protocols relies on a set of core reagents. The table below details these essential materials and their functions within the DNA extraction workflows.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Extraction

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Chaotropic Salts (e.g., Guanidine HCl, NaI) | Denature proteins, inactivate nucleases, and enable DNA binding to silica surfaces in both column and bead methods. | Guanidinium thiocyanate-based lysis offers excellent nuclease inactivation and inhibitor removal [23]. |

| Silica Matrix | The solid phase that selectively binds DNA in the presence of chaotropic salts and high ionic strength. | Available as a membrane in spin columns or as a coating on magnetic beads. Binding capacity varies. |

| Proteinase K | A broad-spectrum serine protease that digests proteins and nucleases, facilitating cell lysis and freeing DNA. | Essential for efficient lysis of animal tissues and other protein-rich samples. |

| Chelex-100 Resin | A chelating resin that binds divalent cations (e.g., Mg²âº), inactivating nucleases and protecting DNA during boiling. | The basis of simple, low-cost boiling protocols; results in a crude but PCR-compatible extract [1]. |

| Ethanol-based Wash Buffers | Remove salts, metabolites, and other contaminants from the silica-bound DNA while retaining the DNA on the matrix. | Residual ethanol must be completely evaporated as it can inhibit downstream enzymatic reactions. |

| Low-Salt Elution Buffer (e.g., TE, AE Buffer) | Disrupts the interaction between DNA and the silica matrix by creating a low-ionic-strength environment, releasing pure DNA. | Heated elution (70°C) can increase DNA yield, especially from magnetic beads [23]. |

The selection of an optimal DNA extraction methodology is a critical, sample-dependent decision that profoundly impacts the success of subsequent concentration and analysis steps in low-yield research. Silica spin columns offer a robust balance of purity and convenience for routine applications. Magnetic bead-based systems excel in throughput, automation potential, and recovery efficiency, making them superior for high-value, low-concentration samples, albeit often at a higher initial equipment cost. The in-house Chelex boiling protocol stands out as an unparalleled cost-effective and rapid method for specific applications like genotyping from DBS, despite its limitations in purity and compatibility with advanced downstream assays. Researchers are advised to align their choice with a comprehensive assessment of their specific sample type, required throughput, budget, and the purity demands of their ultimate analytical platform.

The analysis of dried blood spots (DBS) represents a critical methodology in biomedical research, particularly for studies involving low-yield samples where conventional DNA extraction methods often prove inefficient or cost-prohibitive. Within this context, the Chelex-100 resin extraction method emerges as a superior alternative, offering significant advantages in recovery efficiency, operational simplicity, and economic feasibility [1]. This protocol deep dive examines the optimized Chelex-100 methodology for DNA concentration from DBS, framing it within the broader thesis research on efficient nucleic acid isolation from limited biological specimens.

Recent comparative studies have demonstrated that the Chelex-100 boiling method yields significantly higher DNA concentrations compared to commercial column-based kits, making it particularly advantageous for research settings with resource constraints or large-scale sampling requirements [1] [28]. The method's effectiveness stems from the resin's ability to chelate divalent metal ions that serve as cofactors for DNases, thereby protecting nucleic acids from degradation during the extraction process [29]. This technical overview provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementing this optimized protocol, complete with quantitative performance data, workflow visualizations, and practical reagent specifications.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Method Comparison

Recent research provides compelling quantitative evidence supporting the Chelex-100 method for DNA extraction from DBS. A comprehensive 2025 study comparing five extraction methods found that the Chelex boiling method yielded significantly higher (p < 0.0001) ACTB DNA concentrations compared to column-based methods including QIAamp DNA Mini Kit, High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit, and DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit [1].

Table 1: DNA Yield Comparison Across Extraction Methods

| Extraction Method | Type | Relative DNA Yield | 260/280 Ratio | Cost per Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chelex-100 (Optimized) | Boiling method | Highest [1] | ~1.7-1.9 [19] | Lowest [28] |

| High Pure PCR Template Kit | Column-based | Moderate [1] | ~1.8-2.0 | High |

| QIAamp DNA Mini Kit | Column-based | Low [1] | ~1.8-2.0 | High |

| DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit | Column-based | Low [1] | ~1.8-2.0 | High |

| TE Buffer Boiling | Boiling method | Low [1] | Variable | Very Low |

Another study demonstrated that a control Chelex protocol yielded 590% more DNA than the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, with absolute efficiency of 54% compared to just 9% for the column-based method [28]. Further optimization increased this efficiency to 68%, highlighting the method's superior recovery capacity from limited samples [28].

Impact of Protocol Modifications

Table 2: Optimization Parameters and Their Effects on DNA Yield

| Parameter | Standard Protocol | Optimized Approach | Effect on DNA Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elution Volume | 150 µL | 50 µL | Significant increase in concentration [1] |

| Starting Material | 1 × 6 mm punch | 2 × 6 mm punches | No significant improvement [1] |

| Extraction Steps | Single heat precipitation | Second heat precipitation | 29% increase (p < 0.001) [28] |

| Detergent Type | Tween 20 | Saponin or Triton X-100 | Moderate improvement [28] |

| Resin Mesh Size | 50-100 | 200-400 | Easier handling with wide-bore tips [28] |

Optimization studies reveal that reducing elution volumes from 150 µL to 50 µL significantly increases DNA concentration without compromising yield [1]. Interestingly, increasing starting material from one to two 6 mm punches did not significantly improve DNA recovery, suggesting optimal utilization of available material occurs with single-punch processing [1]. Incorporating a second heat precipitation step from the same DBS increased gDNA yield by 29% (p < 0.001), further enhancing method efficiency [28].

Experimental Protocols

Optimized Chelex-100 Protocol for DBS

Reagents and Materials

- Chelex-100 resin (50-100 or 200-400 mesh), sodium form [1] [28]

- Molecular grade Tween 20, Triton X-100, or saponin [28]

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer or molecular grade water for elution [28]

- Dried blood spots on appropriate filter paper (Whatman 903, Grade 3, or EUROIMMUN) [1] [28]

- 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes (preferably LoBind) [28]

- Wide-bore pipette tips (critical for handling resin) [28]

Step-by-Step Procedure

Punch Preparation: Excise one 6 mm punch from each DBS using a sterile paper punch and transfer to a labeled 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube [1].

Initial Hydration: Add 1 mL of freshly prepared 0.5% Tween 20 in PBS to each tube. Invert several times to ensure complete immersion of the punch. Incubate at 4°C overnight [1] [28].

Wash Step: Carefully remove the detergent solution without disturbing the punch. Add 1 mL of fresh PBS, invert several times, and incubate at 4°C for 30 minutes. Remove PBS completely after incubation [1].

Chelex Addition: Prepare a 5% (w/v) Chelex-100 suspension in molecular grade water or TE buffer and pre-heat to 56°C. Add 50 µL of the pre-heated Chelex solution to each tube [1].

Heat Incubation: Pulse-vortex tubes for 30 seconds. Incubate at 95°C for 15 minutes, with brief pulse-vortexing every 5 minutes during the incubation [1].

Pellet Formation: Centrifuge tubes at 20,000 × g for 3 minutes to pellet Chelex beads and residual paper debris [1] [28].

Supernatant Transfer: Carefully transfer the supernatant to a new 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube using a P200 pipette. Avoid transferring any resin or particulate matter [1].

Secondary Clarification: Centrifuge the transferred supernatant again at 20,000 × g for 3 minutes. Transfer 40-45 µL of the clarified supernatant to a clean tube using a P20 pipette, taking care to avoid any pellet [1].

Storage: Store extracted DNA at -20°C for immediate use or -80°C for long-term preservation [28].

For enhanced yield, consider implementing a second heat precipitation: add fresh Chelex solution to the original tube with the punch and repeat steps 5-8, then combine with the first extraction [28].

Modified Protocol with Precipitation for Enhanced Purity

For applications requiring higher purity DNA, implement these additional steps after the standard Chelex protocol:

Protein Precipitation: Add 7.5M ammonium acetate to the Chelex-extracted supernatant to achieve a final concentration of 2.5M. Incubate on ice for 5 minutes until protein precipitate forms. Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes and transfer clear supernatant to a new tube [29].

DNA Precipitation: Add 3M sodium acetate to achieve 0.3M final concentration, followed by 200 µL ice-cold isopropanol. Mix gently and incubate at -30°C for 4 hours. Centrifuge at 15,000 × g for 1 hour at 4°C to pellet DNA [29].

Wash Steps: Discard supernatant and wash pellet twice with 75% ice-cold ethanol, centrifuging at 15,000 × g for 10 minutes between washes. Perform a final wash with 100% ice-cold isopropanol [29].

Resuspension: Air-dry pellet for 7-10 minutes and resuspend in 10-50 µL deionized water or TE buffer. Incubate at 55°C for 10 minutes to facilitate dissolution [29].

This modification yields a 20-fold increase in DNA concentration and significantly improved 260/230 ratios from approximately 0.4 to 2.35, making it suitable for more sensitive downstream applications [29].

Workflow Visualization

Figure 1. Chelex-100 DNA Extraction Workflow from Dried Blood Spots

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Chelex-100 DBS DNA Extraction

| Reagent/Equipment | Specification | Function | Alternative/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chelex-100 Resin | 50-100 mesh or 200-400 mesh, sodium form | Chelates divalent cations, protects DNA from nucleases | Bio-Rad suppliers; 200-400 mesh easier to handle [28] |

| Detergent | 0.5% Tween 20, Triton X-100, or saponin in PBS | Cell membrane lysis and protein solubilization | Saponin may show batch variability [28] |

| Wash Buffer | 1X PBS, pH 7.4 | Removes hemoglobin and other PCR inhibitors | Must be molecular grade [1] |

| Elution Solution | Molecular grade water, 10 mM Tris-Cl, or TE buffer | DNA resuspension and storage | TE buffer provides DNase protection [28] |

| Filter Paper | Whatman 903, Grade 3, or EUROIMMUN | Blood sample collection and storage | Passive absorption papers preferred over FTA for this protocol [1] [28] |

| Microcentrifuge Tubes | 1.5 mL, preferably LoBind | Sample processing | Reduces DNA adhesion to tube walls [28] |

| Pipette Tips | Wide-bore (for resin handling) | Liquid transfer without clogging | Essential when using larger resin mesh sizes [28] |

Applications and Validation

Downstream Applications

The DNA extracted via this optimized Chelex-100 protocol is suitable for numerous downstream applications including:

- Quantitative PCR: Successfully used for amplification of single-copy genes (ACTB) and T-cell receptor excision circles (TREC) for severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) screening [1]

- Rare allele detection: Capable of identifying rare donor alleles at frequencies of 10 in 100,000 genomic equivalents, enabling microchimerism studies [28]

- Pathogen detection: Effective for simultaneous detection of host and pathogen DNA in field-collected specimens [30]

- Molecular identification: Suitable for species identification and genotyping in various research contexts [30]

Quality Assessment and Validation

Rigorous quality assessment should include:

- Spectrophotometric analysis: DNA concentration and purity (A260/280 ratio target: 1.7-1.9) [19]

- Amplification efficiency: PCR amplification of housekeeping genes (e.g., ACTB, beta-globin) to confirm usability [1] [28]

- Inhibition testing: Inclusion of internal amplification controls when applying to new sample batches

Comparative validation studies demonstrate that the Chelex method shows 93% sensitivity and 82% specificity relative to established salting-out protocols, with no significant differences in sample positivity rates across various PCR applications [30].

The optimized Chelex-100 resin method represents a paradigm shift in DNA extraction from dried blood spots, particularly within the context of low-yield sample research. Its superior cost-effectiveness, minimal hands-on time, and robust DNA recovery address critical limitations of conventional silica-based methods while maintaining compatibility with sophisticated downstream applications including qPCR and rare allele detection. The protocol detailed in this application note provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for implementing this methodology, complete with optimization parameters and quality assessment metrics. As research continues to prioritize resource-efficient laboratory practices, the Chelex-100 extraction method stands as an indispensable tool in the molecular researcher's arsenal, particularly for large-scale screening programs and studies conducted in resource-limited settings.

The purification, concentration, and recovery of DNA from agarose gels is a foundational procedure in molecular biology, essential for downstream applications such as cloning, sequencing, and PCR. However, these steps present a significant challenge when working with small DNA fragments (<100 bp) and low-yield samples, where efficiency and cost become critical factors. While numerous commercial kits are available, they often exhibit limitations in recovering small fragments and require minimum elution volumes that preclude effective sample concentration [31].

This application note details a modified freeze-squeeze method, an optimized classical technique that provides a highly efficient, inexpensive, and simple alternative for purifying and concentrating small DNA fragments. This protocol is particularly valuable within a research context focused on maximizing data yield from precious, low-concentration samples, such as those encountered in microbiome studies, forensic analysis, and ancient DNA research [32] [31] [33].

Method Comparison & Advantages

Traditional commercial kits, often reliant on silica-based columns, can be inefficient for small DNA fragments and typically specify a minimum elution volume (often 20 µL), which limits how much a sample can be concentrated [31]. The modified freeze-squeeze method addresses these shortcomings.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Modified Freeze-Squeeze vs. Commercial Kit

| Parameter | Commercial Kit | Modified Freeze-Squeeze Method |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum Fragment Size Recovered | >100 bp | ~60 bp [32] |

| Minimum Practical Elution Volume | ~20 µL | 2.5 µL [31] |

| Recovery at Low Concentration | Fragment recovered at 15-20 µg | Fragment recovered at ~5 µg [31] |

| Relative Recovery Yield | Baseline | Approx. 50% higher yield at comparable concentrations [31] |

| Estimated Cost per Purification | $1.30 - $2.90 [34] | ~$0.04 [35] |

The data demonstrate that the modified protocol enables a higher degree of concentration by allowing elution in very small volumes and provides superior recovery efficiency for low-concentration samples, all at a fraction of the cost of commercial solutions.

Detailed Protocol: Modified Freeze-Squeeze Method

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function/Specification |

|---|---|

| TE Buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 1 mM EDTA) | Elution and storage of DNA [31]. |

| Sodium Acetate (3 M, pH 5.2) | Salt for alcohol-based DNA precipitation [31]. |

| Ethanol (100% and 70%) | DNA precipitation and washing of pellet [31]. |

| 1X TBE Buffer | Gel electrophoresis [31]. |

| Agarose | Standard agarose is sufficient; low-melting point is not required [31]. |

| GelRed | Nucleic acid gel stain for visualization [31]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Gel Electrophoresis and Excision

Mechanical Disruption

- Transfer the gel slice to a sterile 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Grind the gel slice into a fine paste using a metal rod or similar tool [31].

Elution

Freeze-Thaw and Separation

DNA Precipitation

- Transfer the supernatant (the solubilized gel solution) to a new 1.5 mL tube.

- Add 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and 2.5 volumes of ice-cold 100% ethanol [31].

- Incubate overnight at -20°C to precipitate the DNA. Note: Incubation time can be adjusted based on initial DNA concentration [31].

Pellet Washing and Resuspension

- Centrifuge the tube at 16,000 x g for 20 minutes at room temperature to pellet the DNA.

- Carefully discard the supernatant.

- Wash the pellet with 600 µL of 70% ethanol (v/v) to remove salts [31].

- Air-dry the pellet and resuspend it in TE buffer or nuclease-free water to the desired volume (as low as 2.5 µL for high concentration) [31].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps of this protocol.

Method Validation and Applications

The functionality of DNA purified via this modified freeze-squeeze method has been rigorously validated for downstream molecular applications.

- PCR and Re-amplification: Purified fragments can be successfully re-amplified by PCR, demonstrating the removal of inhibitors and the integrity of the DNA [32] [31].

- Cloning and Sequencing: The purified DNA is of sufficient quality and purity for use in cloning experiments and subsequent sequencing, confirming its compatibility with standard enzymatic reactions [31] [34].

- MicroRNA Analysis: This specific protocol has been successfully applied to isolate and identify microRNAs from Giardia lamblia, underscoring its efficacy for recovering very small nucleic acids [32] [33].

The modified freeze-squeeze method is a robust, cost-effective, and highly efficient technique for the purification and concentration of small DNA fragments from agarose gels. Its ability to recover fragments as small as 60 bp and resuspend them in volumes as low as 2.5 µL provides a significant advantage for researchers working with low-yield samples. This protocol offers a practical and accessible solution that enhances the feasibility of projects where sample concentration and cost are limiting factors.

Sample pre-homogenization is a critical first step in the workflow for analyzing low-yield and challenging biological samples, directly impacting the quantity and quality of nucleic acids recovered. Mechanical disruption via bead beating has emerged as a superior method for lysing tough tissue structures and resilient cell walls, facilitating the release of intracellular content while preserving the integrity of high molecular weight (HMW) DNA. This process is particularly vital for downstream applications such as long-read sequencing, Hi-C, and RNA-seq, where the integrity of the starting material is paramount. The core principle involves agitating samples at high speed in the presence of small, dense beads, generating shear forces that physically disrupt tissues and cells. When optimized, this method outperforms traditional enzymatic or chemical lysis for a wide range of recalcitrant sample types, from plant and fungal tissues to skeletal muscle and corals [36].

The strategy of "pellet protection" is integral to this process, referring to a set of practices designed to safeguard the often-invisible nucleic acid pellet during and after homogenization. This involves maintaining consistent cryogenic conditions to prevent freeze-thaw cycles that degrade DNA, ensuring complete homogenization into a fine powder to maximize yield, and carefully handling the homogenate during subsequent processing steps to avoid loss. For research on low-yield samples, where every nanogram of DNA is precious, a robust and optimized bead-beating protocol is not just beneficial—it is essential [36].

Core Principles and Optimization

The efficacy of bead beating homogenization hinges on several adjustable physical parameters. Optimizing these factors is required to balance complete tissue disruption against the risk of shearing and degrading the target nucleic acids.

- Bead Material and Diameter: The choice of bead material (e.g., stainless steel, zirconium oxide, tungsten carbide) and size directly influences the grinding efficiency and the degree of shear stress. Larger beads (e.g., 3mm) deliver greater impact force suitable for tough, fibrous tissues, while smaller beads (e.g., 0.1mm) are more effective for breaking down bacterial and fungal cell walls. The optimal diameter is tissue-specific; for instance, 2.3 mm zirconium/silica beads were found to be ideal for homogenizing mouse lung tissue to isolate microorganisms without compromising viability [37].

- Homogenization Speed and Time: The duration and intensity of the bead-beating process must be carefully calibrated. Insufficient time or speed results in incomplete lysis and low yield, whereas excessive homogenization can generate heat and shear forces that fragment HMW DNA. Studies have demonstrated that even for the same equipment, settings must be tailored to the sample type, with recommendations varying from a single 15-second cycle for delicate bryophytes to three 30-second cycles for robust plant and arthropod tissues [36].

- Cryogenic Preservation: Processing samples in a deep-frozen state, typically over dry ice or liquid nitrogen, is a cornerstone of pellet protection. Cryogenic conditions maintain nucleic acid integrity by inhibiting nuclease activity and preventing thawing. The Sanger Tree of Life protocol explicitly mandates that all tissue handling should be performed "on sterilised surfaces over dry ice to avoid contamination and freeze/thaw cycles" [36].

- Sample Input and Tube Selection: Using the appropriate tissue mass and reinforced sample tubes is crucial for preventing tube failure and cross-contamination. Recommended input masses are precisely defined based on the tissue type and downstream application (e.g., 20–40 mg for chordate DNA extraction, 15–25 mg for RNA) [36]. Using tubes that can withstand the impact of beads, such as 2 mL reinforced tubes or 4 mL polycarbonate vials for particularly tough samples like hard corals, is essential for experimental success [36].

Experimental Protocols