Advanced Spectroscopy in Environmental Monitoring: Techniques, Applications, and Best Practices for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive review of the latest spectroscopic techniques and their pivotal role in environmental monitoring.

Advanced Spectroscopy in Environmental Monitoring: Techniques, Applications, and Best Practices for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of the latest spectroscopic techniques and their pivotal role in environmental monitoring. It covers foundational principles of atomic and molecular spectroscopy, explores advanced methodological applications for detecting diverse contaminants like heavy metals, microplastics, and PFAS, and offers practical guidance for troubleshooting and optimizing analytical procedures. A dedicated section on method validation and comparative analysis empowers researchers and drug development professionals to select appropriate techniques, ensure data reliability, and adhere to regulatory standards, highlighting the critical intersection of environmental analysis and biomedical research.

Core Principles and the Expanding Arsenal of Environmental Spectroscopy

In environmental monitoring research, accurate trace elemental analysis is paramount for assessing pollution levels, ensuring regulatory compliance, and understanding biogeochemical cycles. Atomic spectroscopy techniques form the cornerstone of modern elemental analysis, providing the sensitivity, specificity, and throughput required for contemporary environmental challenges. Among these techniques, Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS), Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES), and Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) represent the most widely adopted methodologies in analytical laboratories. Each technique offers distinct advantages and limitations concerning detection limits, sample throughput, operational complexity, and cost structure. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these core atomic spectroscopy techniques, focusing on their fundamental principles, operational parameters, and specific applications within environmental research. The selection of an appropriate analytical technique is guided by multiple factors, including required detection limits, sample matrix complexity, regulatory guidelines, and operational constraints. By synthesizing current technical specifications and methodological approaches, this guide aims to equip researchers and scientists with the knowledge necessary to optimize their analytical strategies for trace elemental analysis in diverse environmental matrices.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Comparison

Core Principles of Operation

Atomic spectroscopy techniques determine elemental composition by measuring the interaction of light with atoms. The fundamental processes, however, differ significantly between techniques. Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) operates on the principle of ground-state atoms absorbing light at characteristic wavelengths. When a sample is atomized in a flame or graphite furnace, it absorbs light from a hollow cathode lamp tuned to a specific element, with the absorption magnitude proportional to the element's concentration [1]. Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) utilizes a high-temperature argon plasma (6,000-10,000 K) to excite atoms and ions from the sample. As these excited species return to lower energy states, they emit light at element-specific wavelengths, which is measured by optical spectrometry [2] [3]. Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) also employs a high-temperature plasma but as an efficient ionization source. The resulting ions are then separated and quantified based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) using a mass spectrometer, typically a quadrupole, magnetic sector, or time-of-flight analyzer [4].

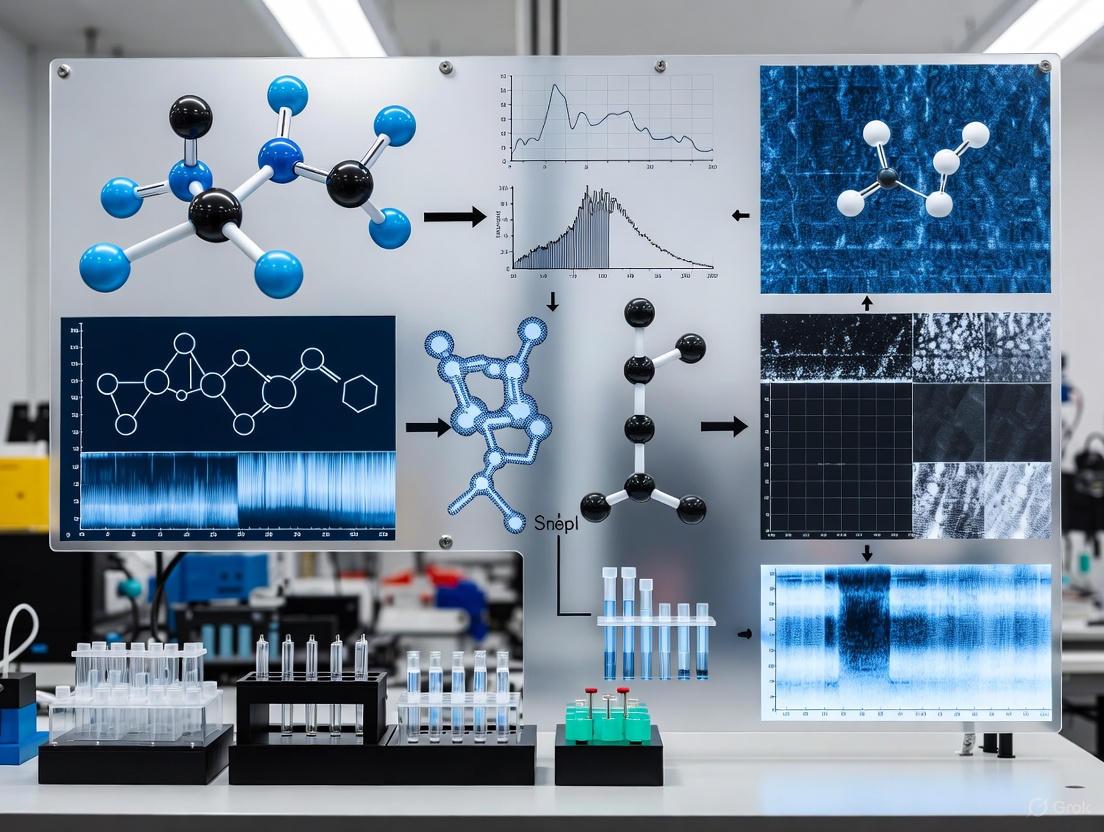

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflows and logical relationships between these three core analytical techniques:

Comprehensive Technical Comparison

The selection of an appropriate atomic spectroscopy technique requires careful consideration of performance specifications and operational parameters. The following table provides a detailed comparison of key technical characteristics for AAS, ICP-OES, and ICP-MS:

| Performance Characteristic | AAS | ICP-OES | ICP-MS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Detection Limits | Parts per million (ppm) range [1] | Parts per billion (ppb) range [5] | Parts per trillion (ppt) range [5] [4] |

| Linear Dynamic Range | Up to 10² [1] | Up to 10ⶠ[3] | Up to 10⸠[3] |

| Sample Throughput | Low (single-element analysis) [1] | High (simultaneous multi-element) [5] | High (simultaneous multi-element) [5] |

| Multi-Element Capability | Limited (typically single element) [1] | Excellent (up to 70 elements simultaneously) [2] | Excellent (most elements simultaneously) [5] |

| Sample Matrix Tolerance | Good for simple matrices [1] | High (up to 30% TDS) [5] [6] | Low (~0.2% TDS); requires dilution [5] |

| Isotopic Analysis | Not available | Not available | Yes [5] [4] |

| Operational Cost | Low [1] [7] | Moderate | High [1] |

| Capital Cost | $25,000 - $80,000 (new) [1] | Higher than AAS | $100,000 - $300,000+ [1] |

| Skill Requirements | Simple operation [1] | Moderate technical expertise [5] | Highly skilled operator [1] |

| Key Regulatory Methods | EPA 200.5, EPA 200.9 [5] | EPA 200.7, EPA 6010 [5] | EPA 200.8, EPA 6020 [5] |

ICP-MS achieves its exceptional sensitivity, with detection limits extending into the parts-per-quadrillion range for some elements, through a process that is remarkably only about 0.00002% efficient. This inefficiency stems from losses at various stages: sample transport to plasma (~1%), ionization in plasma (~90% for most metals), ion extraction through interface cones (~2% each for sampler and skimmer cones), ion transmission through optics (~60%), mass separation in quadrupole (~80%), and finally ion detection in electron multiplier (~90%) [4].

Technique Selection Guidelines

Choosing the optimal technique depends on specific analytical requirements. AAS is ideal for laboratories with lower sample volumes, simpler matrices (drinking water, basic food products), and budget constraints where routine analysis of specific metals at ppm levels is required [1] [7]. ICP-OES provides a balanced solution for laboratories needing simultaneous multi-element analysis with robust tolerance for complex matrices like wastewater, soil digests, and solid waste [5] [6]. Its ability to handle high total dissolved solids (up to 30%) makes it particularly valuable for environmental samples with complex matrices [5]. ICP-MS is the premier technique for applications demanding ultra-trace detection limits (ppt), isotopic information, or speciation analysis (when coupled with chromatography) [5] [4]. It is essential for monitoring toxic elements with very low regulatory limits, such as arsenic and mercury in drinking water, where ICP-OES lacks sufficient sensitivity [5].

Advanced Methodologies and Environmental Applications

Experimental Protocols for Environmental Analysis

Analysis of Toxic Elements in Cannabis and Botanical Materials

The analysis of arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury in cannabis exemplifies a challenging application requiring low detection limits in a complex organic matrix [6].

Sample Digestion Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh 1.00 g of homogenized plant material into a microwave digestion vessel.

- Acid Addition: Add 10 mL of concentrated trace metal grade nitric acid (HNO₃) and 0.3 mL of concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl). HCl enhances mercury stability.

- Microwave Digestion: Digest using a ramped temperature program to safely reach 230°C and maintain for 15 minutes (e.g., MARS 6 System, CEM Corporation).

- Post-Digestion Processing: Gravimetrically bring digestates to a final weight of 15 g. Filtration is typically unnecessary when using nebulizers with large sample channel internal diameters (~0.75 mm) [6].

Critical ICP-OES Analysis Parameters:

- Nebulizer: High-efficiency nebulizer (e.g., OptiMist Vortex) with external impact surface to improve sensitivity by approximately a factor of two [6].

- Matrix-Matched Calibration: Prepare standards in 33% HNO₃/2% HCl containing 1150 ppm carbon (as potassium hydrogen phthalate) and 600 ppm calcium to compensate for carbon-based spectral interferences and calcium-induced stray light [6].

- Analytical Lines: Monitor As 189.042 nm, Cd 214.438 nm, Pb 220.353 nm, and Hg 194.227 nm, with appropriate background correction.

Trace Impurity Analysis in High-Purity Copper

The semiconductor industry requires detection of sub-ppm impurities in high-purity metals [6].

Sample Preparation and ICP-OES Analysis:

- Digestion: Digest 0.500 g of copper sample with 5.0 mL of 50% (v/v) trace metal grade nitric acid.

- Dilution: Bring solution to a final volume of 10 mL with high-purity water, resulting in a 5% (w/v) copper solution and a dilution factor of 20.

- Calibration: Prepare matrix-matched calibration standards using high-purity copper digested identically to samples and spiked with impurity elements (e.g., 20, 200, and 2000 ppb).

- Instrumentation: Use axially-viewed ICP-OES with additional gas flow between spray chamber and torch to reduce sample deposition. This methodology achieves detection limits of 0.06-0.100 ppm for challenging elements like bismuth, tellurium, selenium, and antimony in the solid copper matrix [6].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and consumables essential for atomic spectroscopy analysis in environmental research:

| Reagent/Consumable | Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Trace Metal Grade Acids | Sample digestion and preservation; calibration standard preparation | High purity (e.g., HNO₃, HCl) with verified low blank levels for target elements [6]. |

| Certified Elemental Standards | Instrument calibration and quality control | Single-element and multi-element solutions with NIST-traceable concentrations [6]. |

| High-Purity Argon Gas | Plasma generation (ICP-OES, ICP-MS) and nebulization | ≥99.996% purity to ensure plasma stability and minimize spectral interferences [4]. |

| Matrix-Matching Reagents | Compensation for spectral and non-spectral interferences | High-purity salts (e.g., KHP for carbon, CaCO₃ for calcium) to mimic sample matrix in calibration standards [6]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Method validation and accuracy verification | Environmental matrices (e.g., water, soil, plant) with certified element concentrations. |

| Nebulizers and Spray Chambers | Sample introduction system generation of fine aerosol | Concentric, V-groove (e.g., Babington), or high-efficiency types (e.g., OptiMist Vortex) matched to sample matrix [6]. |

| Sampler and Skimmer Cones | Interface components (ICP-MS) | Nickel or platinum cones with precisely sized orifices for ion extraction from plasma [4]. |

Addressing Analytical Challenges in Environmental Monitoring

Environmental samples present unique challenges including complex matrices, low analyte concentrations, and stringent regulatory requirements. ICP-OES has emerged as a viable alternative to ICP-MS for many trace analysis applications when coupled with high-efficiency sample introduction systems. This approach can meet demanding detection limits while maintaining the technique's inherent robustness against high dissolved solids [6]. For ICP-MS, polyatomic interferences (e.g., ArCl⺠on Asâºâ·âµ) remain a significant challenge in environmental analysis. Collision-reaction cell technology efficiently removes many interferences, though current EPA Method 200.8 (version 5.4) cannot use collision cell technology for drinking water analysis, reducing its effectiveness for regulatory compliance [5]. For elemental speciation studies, such as differentiating between toxic arsenite (As³âº) and less toxic arsenate (Asâµâº), HPLC-ICP-MS coupling is the preferred methodology, combining the separation power of liquid chromatography with the sensitive detection of ICP-MS [3].

Atomic spectroscopy techniques provide a powerful toolkit for addressing the complex challenges of trace elemental analysis in environmental monitoring and pharmaceutical development. AAS remains a cost-effective solution for targeted single-element analysis at ppm concentrations. ICP-OES offers a robust, multi-element platform for laboratories analyzing diverse sample matrices with moderate detection limit requirements. ICP-MS stands as the most sensitive technique, delivering unparalleled detection limits and isotopic information for the most demanding applications. Recent advancements in sample introduction technology, interference management, and automated sample preparation continue to expand the capabilities of these techniques. The optimal selection depends on a critical evaluation of analytical requirements, sample characteristics, regulatory frameworks, and operational constraints. As environmental monitoring faces evolving challenges from emerging contaminants and stricter regulations, these atomic spectroscopy techniques will continue to be indispensable tools for researchers and scientists committed to ensuring environmental safety and public health.

The accurate identification and monitoring of environmental pollutants are critical to safeguarding ecosystems and public health. Within this context, molecular spectroscopy techniques have emerged as powerful, non-destructive tools for the detection and analysis of a wide spectrum of contaminants. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three core spectroscopic methods—Raman, Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR), and Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy—focusing on their operational principles, specific applications in pollutant identification, and detailed experimental protocols. The content is framed within a broader thesis on the role of analytical spectroscopy in advancing environmental monitoring research, offering scientists and drug development professionals a comparative resource for selecting and implementing these techniques.

The global spectroscopy equipment market, valued at an estimated $23.5 billion in 2024, is experiencing significant growth, driven in part by stringent environmental monitoring mandates and the rising need for robust analytical tools in pharmaceuticals and environmental science [8]. Technological advancements, particularly the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) for data interpretation and the development of portable and handheld field-deployable systems, are reshaping the capabilities and applications of these instruments [9] [8].

Core Techniques and Instrumentation

Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy analyzes the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser, to probe molecular vibrational modes. The resulting spectrum serves as a unique molecular "fingerprint," enabling the identification of chemical substances. A significant advancement is Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS), which uses nanostructured metallic substrates to amplify the inherently weak Raman signal by factors as large as 10^10 to 10^14, allowing for the detection of trace-level contaminants [10].

- Recent Instrumental Developments: The market has seen a trend toward portable and handheld Raman systems, which now constitute

27%of the market and are growing at twice the rate of benchtop systems [9]. For instance, Metrohm offers the TaticID-1064ST, a handheld Raman spectrometer designed for hazardous materials response teams, featuring an on-board camera and note-taking capabilities for field documentation [11]. Horiba's PoliSpectra represents another trend: fully automated systems for high-throughput screening, such as rapid analysis of 96-well plates in pharmaceutical applications [11].

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

FT-IR spectroscopy measures the absorption of infrared light by a sample, corresponding to the excitation of molecular vibrations. It is renowned for its high specificity in identifying unknown materials and confirming chemical composition. A key strength is its comprehensive application scope, from quality verification to gas analysis.

- Recent Instrumental Developments: The Bruker Vertex NEO platform exemplifies innovation in FT-IR, pioneering vacuum technology that removes atmospheric interferences (e.g., water vapor and COâ‚‚), which is particularly beneficial for studying proteins and working in the far-IR region [11]. Furthermore, FT-IR is a cornerstone technique for microplastics analysis. Thermo Fisher Scientific provides integrated solutions, such as the Nicolet RaptIR FT-IR Microscope, which enables high-speed imaging and extensive reporting for analyzing large sample areas, alongside specialized libraries for particle identification [12] [13].

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy

UV-Vis spectroscopy measures the absorption of light in the ultraviolet and visible regions by molecules, resulting from electronic transitions. While historically used for concentration quantification, its role in environmental screening is expanding due to its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and portability.

- Recent Instrumental Developments: New developments have focused on enhancing portability and application range. For example, the NaturaSpec Plus from Spectral Evolution is a field-deployable UV-Vis-NIR instrument that includes real-time video and GPS, simplifying documentation during field studies [11]. Shimadzu has also introduced new laboratory UV-Vis instruments with advanced software functions to ensure data integrity [11]. A prominent application is in water analysis, where UV-Vis provides an immediate, chemical-free method for quantifying residual chlorine and fluoride levels in drinking water [14].

Comparative Technical Analysis

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of Raman, FT-IR, and UV-Vis spectroscopy for direct comparison.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopy Techniques for Pollutant Identification

| Feature | Raman Spectroscopy | FT-IR Spectroscopy | UV-Vis Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Underlying Principle | Inelastic light scattering (vibrational) | Infrared light absorption (vibrational) | UV/Vis light absorption (electronic) |

| Spectral Range | Typically 500-2000 cmâ»Â¹ (fingerprint region) | Typically 4000-400 cmâ»Â¹ | ~190-800 nm |

| Primary Pollutant Applications | Microplastics, dyes, inorganic pigments, pharmaceuticals (often via SERS) [10] | Polymer identification (e.g., microplastics), organic functional groups, gas analysis [12] [13] | Water quality (bacterial load, chlorine, fluoride), nitrates, aromatic organics [14] |

| Detection Limits | Trace to single-molecule with SERS [10] | Varies; parts per billion (ppb) to percent for gases [12] | Varies; generally higher than vibrational techniques [15] |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal for solids; SERS requires substrate | Minimal for ATR; may require pressing for transmission | Minimal; often just dilution for liquids |

| Key Strength | Excellent for aqueous samples, minimal sample prep, high specificity with SERS | Strong library matching, excellent for organic compound ID, robust gas analysis | Portability, cost-effectiveness, rapid screening |

| Key Limitation | Fluorescence interference, weak native signal without SERS | Strong water absorption can interfere, sample heating possible | Less specific, often requires calibration for mixtures |

Experimental Protocols for Environmental Analysis

SERS Protocol for Pesticide Detection on Surfaces

This protocol is adapted from methods used for detecting phosmet and thiabendazole on fruit skins [10].

- Objective: To detect and identify pesticide residues on environmental surfaces (e.g., plant leaves, soil) using SERS.

- Materials:

- Portable or benchtop Raman spectrometer.

- SERS-active substrates (e.g., colloidal gold or silver nanoparticles, or immobilized nanoparticle membranes).

- Methanol or ethanol (HPLC grade).

- Calibration standards of target pesticides.

- Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: If using colloidal nanoparticles, ensure they are well-dispersed. For immobilized substrates, confirm integrity.

- Sample Collection: Swab the surface of interest with a solvent-moistened swab.

- Sample Deposition: Transfer the swab extract onto the SERS substrate and allow to dry.

- Data Acquisition: Place the substrate in the spectrometer. Acquire spectra with a

785 nmor1064 nmlaser to minimize fluorescence. Typical settings:5-30 secondsintegration time,2-5 accumulations. - Data Analysis: Pre-process spectra (cosmic ray removal, baseline correction). Use machine learning models (e.g., PCA or PLS-DA) or spectral library matching for pesticide identification and quantification.

- Critical Notes: Reproducibility depends on substrate homogeneity. Matrix effects from the sample can influence enhancement; internal standards are recommended for quantification.

FT-IR Protocol for Microplastic Polymer Identification and Ageing Assessment

This protocol is based on methodologies for analyzing microplastics from freshwater environments [13].

- Objective: To identify the polymer type and assess the weathering degree of microplastic particles.

- Materials:

- FT-IR spectrometer with an ATR (Attenuated Total Reflectance) accessory (e.g., diamond crystal).

- Forceps, fine tweezers.

- Vacuum desiccator.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Collect environmental particles (e.g., via filtration from water). Rinse with purified water to remove salts and biofilms. Air-dry in a clean desiccator.

- Particle Mounting: Place a single microplastic particle directly onto the ATR crystal. Use the pressure clamp to ensure good optical contact.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire a background spectrum. Collect the sample spectrum over the range

4000-500 cmâ»Â¹with32 scansand a4 cmâ»Â¹resolution. - Polymer Identification: Compare the obtained spectrum against commercial polymer libraries (e.g., Thermo Scientific OMNIC libraries). A match score >

85%is typically considered a positive ID. - Ageing Assessment: Calculate degradation indexes from the spectrum:

- Carbonyl Index (CI):

CI = Absorbance at ~1715 cmâ»Â¹ / Absorbance of Reference Peak (e.g., ~1465 cmâ»Â¹ for PE/PP) - Hydroxyl Index (HI):

HI = Absorbance at ~3400 cmâ»Â¹ / Absorbance of Reference Peak

- Carbonyl Index (CI):

- Critical Notes: Ensure the particle is clean and firmly pressed onto the ATR crystal. The reference peak is polymer-specific; use the methylene deformation band at

~1465 cmâ»Â¹for polyolefins.

UV-Vis Protocol for Rapid Water Quality Screening

- Objective: To rapidly screen water samples for key quality parameters like bacterial contamination indicators and disinfectant levels.

- Materials:

- Portable or benchtop UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

- Quartz or UV-transparent plastic cuvettes.

- Filtration assembly (if needed for turbid samples).

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Filter the water sample if it is turbid to reduce light scattering.

- Blank Measurement: Fill a cuvette with purified water and use it to take a blank measurement.

- Data Acquisition: Place the prepared sample in the spectrometer and acquire an absorption spectrum from

200 nmto700 nm. - Data Interpretation:

- Bacterial Contamination Indicator: A strong absorption peak at

~260 nmsuggests the presence of nucleic acids, indicating microbial contamination [14]. - Free Chlorine: Use specific methods that employ colorimetric reagents (e.g., DPD method), measuring absorption at

515 nm.

- Bacterial Contamination Indicator: A strong absorption peak at

- Critical Notes: This is a screening method. Positive results for bacterial indicators should be confirmed with standard microbiological tests. Calibration curves are necessary for quantitative analysis of specific compounds.

Workflow and Data Interpretation

The following diagram illustrates a generalized decision-making workflow for applying these spectroscopic techniques in environmental analysis.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting the experimental protocols described in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis of Pollutants

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SERS Substrates (e.g., Gold/Silver Nanoparticles) | Signal enhancement for trace pollutant detection in Raman spectroscopy. | Colloidal solutions are common; reproducible fabrication is critical. Stability and shelf-life vary [10]. |

| ATR Crystals (e.g., Diamond) | Enables direct solid/sample contact for FT-IR measurement with minimal prep. | Diamond is durable and chemically inert, ideal for hard particles and corrosive samples [13]. |

| Specialized FT-IR Gas Cell | Contains gas samples for analysis of emissions or ambient air. | Long-pathlength cells (e.g., 2-10 m) are used to enhance sensitivity for low-concentration gases [12]. |

| Ultrapure Water System (e.g., Milli-Q) | Provides reagent water for sample preparation, dilution, and blank measurements. | Essential for avoiding contamination in sensitive environmental analyses, especially in UV-Vis and FT-IR [11]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Calibration and validation of spectroscopic methods for specific pollutants. | Includes polymer standards for microplastics, pesticide standards for SERS, and gas mixtures for FT-IR [13]. |

Raman, FT-IR, and UV-Vis spectroscopy offer a complementary and powerful toolkit for addressing the complex challenge of pollutant identification. Raman spectroscopy, particularly with SERS, provides unparalleled sensitivity for trace analysis. FT-IR remains the gold standard for polymer identification and detailed molecular fingerprinting. UV-Vis spectroscopy offers a rapid, cost-effective solution for screening and quantification. The ongoing trends of miniaturization for field deployment and the integration of AI for advanced data processing are significantly enhancing the real-time monitoring capabilities of these techniques [9] [8]. For researchers and scientists, the strategic selection and application of these methods, guided by the specific analytical question and sample matrix, are paramount to advancing environmental monitoring and protection efforts.

X-ray based spectroscopic and diffractive techniques represent a cornerstone of modern analytical science, providing non-destructive means to interrogate the elemental and structural composition of materials. Within the critical field of environmental monitoring, X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) and X-ray Diffraction (XRD) have emerged as indispensable tools for assessing contamination, understanding geochemical processes, and ensuring regulatory compliance. These techniques offer complementary insights: XRF delivers quantitative elemental analysis of environmental samples, while XRD reveals the crystalline phases and molecular structures that determine a contaminant's mobility, stability, and bioavailability [16] [17]. The application of these methods has transformed environmental monitoring from simple concentration measurements to sophisticated molecular-level understanding of pollutant behavior in complex systems.

The fundamental advantage of X-ray techniques lies in their ability to provide rapid, non-destructive analysis with minimal sample preparation, enabling both laboratory and field-based characterization of environmental samples [18] [19]. As regulatory frameworks become increasingly stringent and the need for understanding contaminant speciation grows, XRF and XRD offer the scientific community powerful tools to address pressing environmental challenges from heavy metal contamination in soils to particulate matter in air. This technical guide examines the principles, methodologies, and applications of these techniques within the context of environmental monitoring research.

X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) Fundamentals

Physical Principles and Instrumentation

X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) operates on the principle of exciting atoms within a sample and measuring the characteristic secondary X-rays emitted as the atoms return to their ground state. When high-energy X-rays strike a material, they can eject electrons from the inner shells of constituent atoms, creating unstable, excited atoms. As electrons from outer shells fill these vacancies, they emit fluorescent X-rays with energy specific to the element and electronic transition involved [16]. These characteristic X-ray energies, typically measured in kiloelectron volts (keV), serve as unique fingerprints for elemental identification, while the intensity of the emissions correlates with elemental concentration [16].

The fundamental equation governing the relationship in XRF is: $$E = k(Z - σ)^2$$ where E is the energy of the characteristic X-ray, Z is the atomic number of the element, and k and σ are constants. This relationship demonstrates why XRF is particularly sensitive to heavier elements, as the energy difference between electron shells increases with atomic number. For environmental applications, XRF can identify and quantify elements ranging from light elements like magnesium (Mg) to heavy metals like lead (Pb) and uranium (U) [19].

XRF Technique Variants

Two primary XRF configurations exist, each with distinct advantages for environmental analysis:

Energy-Dispersive XRF (EDXRF): This approach excites and detects all elements simultaneously, providing a complete spectrum of energies with characteristic peaks that identify the elements present [16]. EDXRF instruments are generally more compact, cost-effective, and suitable for rapid screening of multiple elements. They are particularly valuable for air particulate monitoring, where the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Compendium Method IO-3.3 specifies their use for analyzing up to 40 elements from filters collecting ambient particulate matter within just 20 minutes [16].

Wavelength-Dispersive XRF (WDXRF): This method employs diffracting crystals to physically separate characteristic X-rays by wavelength before detection [16]. WDXRF provides superior spectral resolution and lower detection limits, enabling precise measurement of elements with overlapping spectral lines (such as arsenic and lead, whose energy levels differ by only 0.017 keV) [16]. This makes it indispensable for accurate quantification of trace metals in complex matrices like mineral-rich soils and sediments.

Table 1: Comparison of EDXRF and WDXRF for Environmental Applications

| Parameter | EDXRF | WDXRF |

|---|---|---|

| Resolution | Moderate (~150 eV) | High (~10 eV) |

| Detection Limits | ppm range | ppb to ppm range |

| Analysis Speed | Fast (seconds to minutes) | Slower (minutes to tens of minutes) |

| Spectral Overlaps | Can be problematic for adjacent elements | Effectively resolves overlaps |

| Typical Applications | Field screening, rapid multi-element analysis | High-precision laboratory analysis |

| Throughput | Moderate | High (can process 60+ samples/hour) |

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Fundamentals

Physical Principles and Instrumentation

X-ray Diffraction (XRD) exploits the wave nature of X-rays and the periodic arrangement of atoms in crystalline materials to determine structural properties. When a monochromatic X-ray beam strikes a crystalline sample, the regularly spaced atoms act as scattering centers, causing the X-rays to interfere constructively only in specific directions determined by the atomic arrangement [17]. This phenomenon is described by Bragg's Law: $$nλ = 2d sinθ$$ where n is an integer representing the order of reflection, λ is the X-ray wavelength, d is the spacing between crystal lattice planes, and θ is the angle between the incident ray and the crystal plane [17] [20]. The resulting diffraction pattern serves as a unique fingerprint for each crystalline phase, enabling identification and structural characterization.

The key requirements for XRD analysis include a monochromatic X-ray source (typically copper with characteristic Kα radiation at λ = 1.5418 Å), a crystalline or partially crystalline sample, and precise geometric arrangement of source, sample, and detector [17]. Modern diffractometers employ sophisticated goniometers to maintain exact angular relationships during measurement, with detection systems ranging from simple point detectors to advanced position-sensitive detectors that significantly reduce data collection times [17].

XRD Technique Variants

XRD encompasses several specialized approaches tailored to different sample types and information requirements:

Powder XRD: The most common environmental application, used for analyzing fine-grained soils, sediments, and particulate matter where single crystals are unavailable [17] [21]. The random orientation of crystallites produces continuous diffraction cones recorded as concentric rings, which are then converted to intensity versus 2θ plots for analysis.

Single-Crystal XRD: Provides the most comprehensive structural information but requires high-quality single crystals, making it less common for heterogeneous environmental samples [22] [21]. It remains invaluable for determining molecular structures of purified environmental contaminants or mineral standards.

Thin-Film XRD and Grazing Incidence XRD: Specialized approaches for analyzing surface layers, coatings, or thin films on environmental particles [21].

Table 2: XRD Techniques for Environmental Analysis

| Technique | Sample Requirements | Information Obtained | Environmental Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Powder XRD | Fine-grained powder (~1-10 μm particles) | Phase identification, quantitative phase analysis, crystallite size, strain | Soil mineralogy, sediment composition, particulate matter characterization |

| Single-Crystal XRD | Single crystal >0.1 mm | Complete crystal structure, atomic positions, bond lengths/angles | Molecular structure of pure mineral phases or synthetic environmental compounds |

| Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS) | Nanoparticles in suspension or solid matrix | Particle size distribution, shape, nanostructure (1-100 nm) | Nanoparticle characterization, pore size distribution in soils |

| X-ray Reflectivity | Flat, smooth surfaces | Layer thickness, density, roughness | Surface coatings on environmental particles |

Environmental Applications of XRF and XRD

Soil and Sediment Analysis

Soil represents a critical environmental compartment where XRF and XRD provide complementary information for comprehensive contamination assessment. XRF excels at rapid elemental profiling of toxic metals including the eight Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) metals (Ag, As, Ba, Cd, Cr, Hg, Pb, Se) and other priority pollutants [18] [19]. Field-portable XRF (FPXRF) instruments enable real-time mapping of contamination plumes with GPS integration, allowing for immediate on-site decisions during environmental assessment and remediation projects [19].

XRD complements elemental data by identifying specific mineral phases that control metal mobility and bioavailability. For instance, XRD can distinguish between crystalline iron oxides (e.g., goethite, hematite) that strongly adsorb heavy metals versus more soluble sulfate or carbonate minerals that may release metals under changing environmental conditions [17]. This phase-specific information is crucial for accurate risk assessment and selection of appropriate remediation strategies. The combination of these techniques allows researchers to understand not just what elements are present, but how they are incorporated into the soil matrix—information that determines long-term stability and potential for groundwater contamination.

Air Quality Monitoring

XRF has become the preferred technique for analyzing airborne particulate matter collected on filters due to its non-destructive nature, minimal sample preparation, and sensitivity to a broad range of elements [16] [18]. Using EDXRF, up to 40 elements can be identified from ambient air filters in approximately 20 minutes, providing essential data for source apportionment and compliance monitoring [16]. The non-destructive aspect is particularly valuable as filters remain available for subsequent analyses by other techniques.

XRD finds application in air quality monitoring through characterization of crystalline components in particulate matter, such as quartz, cristobalite, and metal oxides, which have specific health implications [17]. This is especially important in occupational settings and industrial areas where specific mineral dusts represent significant health hazards. The ability to quantify crystalline silica phases, known carcinogens, makes XRD an essential tool for comprehensive air quality assessment beyond simple mass-based measurements.

Water Quality Assessment

While XRF is predominantly used for solid samples, it can analyze the suspended fraction in aqueous samples and concentrated residues from water samples [19]. XRF sensitivity for heavy elements like mercury, lead, and cadmium makes it valuable for screening water contamination, though techniques like atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) and inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES) typically provide lower detection limits for dissolved components [19].

For sediment analysis associated with water quality, both XRF and XRD provide essential information. XRF quantifies elemental contaminants, while XRD identifies mineral carriers and precipitation products that control element cycling between sediment and water columns. This combined approach is particularly powerful for understanding the fate of contaminants in aquatic systems and assessing the potential for sediment remobilization of historical pollution.

Experimental Protocols for Environmental Analysis

XRF Analysis of Soil Samples

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Field Sampling: Collect representative soil samples using appropriate protocols (e.g., composite sampling from multiple points within a defined area). For FPXRF, samples can be analyzed in-situ or from minimally processed bulk material [19].

- Laboratory Preparation: Oven-dry samples at 105°C until constant weight is achieved. Gently grind to break aggregates without destroying mineral structures, then sieve through a 150-μm mesh to ensure particle size homogeneity [19].

- Pellet Preparation: Mix 4-5 grams of dried powder with a binding agent (e.g., cellulose wax) in a 40:1 sample-to-binder ratio. Compress in a hydraulic press at 15-25 tons for 1-2 minutes to form stable pellets for analysis [19].

Instrumental Analysis:

- Calibration: Use certified reference materials (CRMs) with matrices similar to the environmental samples to establish calibration curves for target elements.

- Measurement Conditions: For EDXRF analysis of heavy metals, typical conditions include 40-50 kV voltage, automatic current selection, and 60-100 second measurement time per sample to achieve detection limits compliant with EPA Method 6200 [18] [19].

- Quality Control: Include blanks, duplicates, and CRMs in each analytical batch (minimum frequency of 5%) to ensure data quality and identify potential contamination or drift.

Data Interpretation: Convert net peak intensities to elemental concentrations using fundamental parameters, empirical coefficients, or Compton normalization methods. Compare results against regulatory guidelines such as EPA Regional Screening Levels for initial risk assessment.

XRD Analysis of Soil Mineralogy

Sample Preparation:

- Size Fractionation: Sieve samples to obtain the <2-μm fraction (clay minerals) and 2-50-μm fraction (silt) for separate analysis, as different mineral types dominate various size fractions.

- Specimen Mounting: For random powder orientation, back-load samples into cavity mounts to minimize preferred orientation. For clay mineral identification, prepare oriented mounts by depositing clay suspensions on glass slides.

- Special Treatments: For complex mineral assemblages, apply glycolation (ethylene glycol vapor saturation for 24 hours) and heating (550°C for 2 hours) to distinguish between expanding clay minerals.

Data Collection:

- Instrument Parameters: Use Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) with voltage of 40-45 kV and current of 40 mA. Employ a step size of 0.02° 2θ and counting time of 1-2 seconds per step across a range of 2-70° 2θ for comprehensive mineral identification [17] [23].

- Special Scans: For clay mineral analysis, collect slow scans (0.25° 2θ/min) in the 2-32° 2θ range on oriented mounts before and after treatments.

Data Analysis:

- Phase Identification: Compare diffraction patterns with reference patterns from the International Centre for Diffraction Data (ICDD) database using search-match software.

- Quantitative Analysis: Employ Rietveld refinement methods for accurate quantification of multi-phase assemblages, using internal standards (e.g., corundum) to determine amorphous content [17].

- Crystallinity Assessment: Determine crystallinity indices (e.g., quartz crystallinity index) based on peak width at half height, which provides information about crystal size and perfection.

Research Reagent Solutions for Environmental X-ray Analysis

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Environmental XRF/XRD Analysis

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Quality control, method validation, calibration | Select matrix-matched CRMs (e.g., NIST soil standards) for accurate quantification |

| Hydraulic Pellet Press | Sample preparation for XRF | Produces uniform pellets for reproducible analysis; 15-25 ton capacity recommended |

| XRF Sample Cups and Mylar Films | Liquid sample containment | Enable analysis of water samples and suspensions |

| Microcrystalline Cellulose | Binder for powder pellets | Provides structural integrity to pressed pellets without interfering with elemental analysis |

| Silicon Powder Standard | XRD instrument alignment | Verifies instrument performance and angular calibration |

| Oriented Sample Holders | Clay mineral analysis | Specialized holders for textured mount preparation essential for clay mineral identification |

Comparative Analysis and Future Directions

Technique Comparison and Complementary Nature

XRF and XRD provide fundamentally different but complementary information about environmental samples. XRF delivers quantitative elemental composition but cannot distinguish between different chemical forms of an element. XRD identifies crystalline phases but may miss amorphous components or trace phases below its detection limit (typically 1-2%). The synergy between these techniques is particularly powerful for environmental forensics and understanding contaminant behavior.

For example, elevated arsenic concentrations detected by XRF could originate from various sources: anthropogenic pesticides, natural sulfides, or iron oxide sorption. XRD can identify the specific arsenic-bearing phases, critically informing risk assessment and remediation approaches. Similarly, XRD might identify lead-bearing minerals like anglesite or cerussite, while XRF quantifies the total lead content to evaluate contamination levels against regulatory thresholds [16] [17].

Emerging Trends and Advanced Applications

The field of X-ray analysis for environmental monitoring continues to evolve with several promising developments:

Field-Portable and Handheld Instruments: Technological advances have made FPXRF and even portable XRD instruments increasingly sophisticated, enabling real-time decision-making during field investigations and reducing the time between sample collection and data interpretation [19].

Micro-focused X-ray Techniques: Micro-XRF and micro-XRD mapping provide spatial resolution down to micrometers, allowing researchers to investigate heterogeneity within environmental samples and establish associations between specific elements and mineral hosts [24].

Synchrotron-Based Methods: While requiring large-scale facilities, synchrotron XRF and XRD offer orders of magnitude better sensitivity and resolution, enabling speciation of trace metals and characterization of nanoscale environmental particles [22] [21].

Integrated Spectroscopic Approaches: Combining XRF and XRD with complementary techniques like Raman spectroscopy and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) provides a more comprehensive understanding of environmental samples, particularly for mixed organic-inorganic contaminants [24].

Data Integration and Machine Learning: Advanced computational approaches are being developed to handle the complex datasets generated by combined XRF-XRD analyses, with machine learning algorithms increasingly used for pattern recognition, phase identification, and predictive modeling of contaminant behavior [25] [24].

As environmental challenges grow more complex, the integration of XRF and XRD within a multidisciplinary analytical framework will continue to provide essential insights for monitoring, assessment, and remediation of contaminated systems. These techniques form the foundation of modern environmental geochemistry and will remain indispensable tools for protecting ecosystem and human health in an increasingly contaminated world.

The field of environmental monitoring is undergoing a fundamental transformation, driven by the critical need for immediate, on-site data collection to address pressing challenges from industrial pollution to climate change. Traditional laboratory-based analysis, while highly accurate, often faces significant limitations including delays in results, high costs, and difficulties in handling complex environmental matrices [26]. The emerging paradigm leverages modular spectroscopy and advanced sensing technologies that are becoming faster, smaller, and more powerful, enabling researchers and regulators to deploy analytical instruments directly in the field for real-time, in situ monitoring [27]. This transition represents a monumental shift from the era of extracting samples for laboratory analysis to an age of continuous, autonomous environmental observation, providing a more dynamic and comprehensive picture of natural processes and anthropogenic impacts.

The technological advances in spectroscopic instrumentation now allow sensor suppliers to create systems rugged and reliable enough for long-term operation in harsh field conditions [27]. As noted by Tommaso Julitta of JB Hyperspectral, the flexibility of modern spectrometers enables customization with specific mirrors, gratings, or spectral ranges to meet diverse environmental monitoring needs [27]. This adaptability, combined with portability, has opened new frontiers in environmental monitoring, from tracking arsenic pollution in aquatic environments to measuring snow reflectance properties that affect water availability [27] [26]. The integration of these technologies into compact, automated workflows sets new benchmarks for environmental monitoring technology, providing critical tools for environmental agencies and policymakers to enable earlier interventions to protect ecosystems and human health [27] [26].

Technological Enablers of Portable Spectroscopy

Core Spectroscopic Techniques for Field Deployment

Several spectroscopic techniques have been adapted and optimized for field deployment, each offering unique capabilities for environmental analysis. These methods leverage different principles of light-matter interaction to identify and quantify various environmental components, whether gaseous, liquid, or solid [28].

Table 1: Core Spectroscopic Techniques for Environmental Field Deployment

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Primary Environmental Applications | Key Advantages for Field Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Fluorescence Spectroscopy (AFS) | Measures light emitted by excited atoms returning to ground state | Detection of heavy metals like arsenic in water [26] | Ultra-low detection limits (0.005 μg/L for arsenic); high specificity for trace metal analysis |

| Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) | Analyzes atomic emission from laser-generated plasma | Quantitative analysis of metals in steels, soils, and heavy metals [29] | Minimal sample preparation; simultaneous multi-element analysis; real-time detection capabilities |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Probes inelastic scattering of light by molecules | Identification of minerals, pollutants, and biological samples; deep-sea geochemical analysis [27] [28] | Complementary to IR spectroscopy; sensitive to molecular vibrations; suitable for aqueous samples |

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy | Measures light emitted after photon absorption | Detection of organic pollutants (PAHs), oils spills; dissolved organic matter tracking [27] [28] | High sensitivity and selectivity for specific compound classes; trace-level detection capabilities |

| Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy | Analyzes infrared absorption spectra using interferometry | Identification of greenhouse gases, organic pollutants, and particulate matter [28] | High spectral resolution; rapid scanning capability; simultaneous identification of multiple compounds |

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | Measures dielectric properties of a medium as a function of frequency | Detection of waterborne pollutants using nanomembrane sensors [30] | Low-cost; portable; compatible with microcontroller platforms; simplified acquisition architecture |

Enabling Hardware and Design Innovations

The transition from laboratory to field deployment has been made possible by significant advancements in spectrometer design and supporting technologies. Modern field-deployable systems incorporate ruggedized components that can withstand harsh environmental conditions, including temperature fluctuations, moisture, vibration, and corrosive atmospheres [27]. The miniaturization of optical components, light sources, and detectors has been crucial to developing portable systems without sacrificing analytical performance. Furthermore, the integration of low-power electronics and battery operation enables extended deployment in remote locations where grid power is unavailable [27] [26].

These hardware innovations are complemented by sophisticated system integration. For instance, the Flow Injection–Hydride Generation–Atomic Fluorescence Spectroscopy (FI-HG-AFS) system for arsenic monitoring integrates multiple technological modules—flow injection technology, hydrogen generation through water electrolysis, and an on-line pre-reduction heating module—into a unified, automated platform that is both environmentally adaptable and precise [26]. Similarly, portable measurement systems based on nanomembranes for pollutant detection employ simplified, scalable EIS acquisition architecture compatible with microcontroller-based platforms, ensuring simplicity in signal conditioning while maintaining analytical capability [30].

Performance Metrics and Comparative Analysis

The effectiveness of portable spectroscopic systems must be evaluated against rigorous performance metrics to establish their reliability for environmental monitoring applications. Quantitative comparison of these technologies reveals their capabilities and limitations in field deployment scenarios.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Portable Spectroscopic Systems

| Analytical System | Target Analyte | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Precision (RSD) | Analysis Time/Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FI-HG-AFS System [26] | Total Dissolved Inorganic Arsenic | 0.005 μg/L | 0.0–5.0 μg/L | 0.6% – 7.3% | Up to 50 automated analyses per day |

| VSC-mIPW-PLS with LIBS [29] | Chromium in Steel | Not specified | RMSEP: ≤5.1817 | Not specified | Rapid; minimal sample preparation |

| VSC-mIPW-PLS with LIBS [29] | Nickel in Steel | Not specified | RMSEP: ≤1.9759 | Not specified | Rapid; minimal sample preparation |

| VSC-mIPW-PLS with LIBS [29] | Manganese in Steel | Not specified | RMSEP: ≤2.5848 | Not specified | Rapid; minimal sample preparation |

| Portable EIS with Nanomembranes [30] | Benzoquinone | 0.1 mM | Monotonic response to increasing concentrations | Reliable discrimination across concentrations | Real-time sensing capabilities |

The performance data demonstrates that modern portable systems achieve sensitivity and precision comparable to traditional laboratory instruments. The FI-HG-AFS system for arsenic detection exemplifies this capability with exceptional detection limits (0.005 μg/L) that enable monitoring at environmentally relevant concentrations, while maintaining high precision (0.6-7.3% RSD) and substantial throughput (up to 50 analyses daily) [26]. Similarly, the LIBS system with advanced variable selection methods shows credible prediction ability for multiple elements in steel samples, with root mean square errors of prediction (RMSEP) indicating high accuracy for quantitative analysis [29]. These performance characteristics make portable spectroscopic systems viable alternatives to traditional laboratory methods for many environmental monitoring applications.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: On-Site Determination of Total Dissolved Inorganic Arsenic Using Portable AFS

The Flow Injection–Hydride Generation–Atomic Fluorescence Spectroscopy (FI-HG-AFS) system represents a comprehensive methodology for automated, continuous monitoring of arsenic in natural waters [26].

Principle: The method integrates flow injection technology with hydride generation and atomic fluorescence detection to convert dissolved inorganic arsenic species into volatile arsine gas (AsH₃), which is then quantified by atomic fluorescence spectrometry.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Introduction: Automated continuous collection of water samples directly from the water body (river, lake, or seawater) using a peristaltic pump system.

- On-line Pre-reduction: Reduction of all dissolved inorganic arsenic species to arsenite (As(III)) using an on-line pre-reduction heating module with optimized potassium permanganate and potassium persulfate reagents.

- Hydride Generation: Mixing of the reduced sample with sodium tetrahydroborate (NaBH₄) in an acid medium (HCl) to generate volatile arsine gas (AsH₃).

- Gas-Liquid Separation: Separation of the generated arsine gas from the liquid phase in a gas-liquid separator.

- Detection: Introduction of the arsine gas into a hydrogen-argon flame atomizer for atomization, followed by excitation with an appropriate light source and measurement of atomic fluorescence at characteristic wavelengths.

- Data Processing: Automated data acquisition, processing, and reporting of total dissolved inorganic arsenic concentrations.

Quality Control Measures:

- System calibration using standard solutions across the linear range (0.0-5.0 μg/L)

- Validation of recovery rates (97.8-107.8%) using spiked environmental samples (tap water, lake water, seawater)

- Continuous monitoring of key parameters including chemical vapor generation conditions and kinetic processes of arsenic pre-reduction

This methodology successfully addresses the common issue of arsenic species oxidation during measurement, a significant challenge that compromises data reliability in conventional techniques [26].

Protocol 2: Quantitative Analysis of Environmental Samples Using LIBS with Advanced Variable Selection

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) combined with stable variable selection methods provides a robust approach for quantitative analysis of elements in solid environmental samples [29].

Principle: LIBS uses a high-energy laser pulse to generate a microplasma on the sample surface, and the characteristic atomic emissions from the cooling plasma are analyzed to determine elemental composition.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- For steel samples: Clean the surface with a laser to avoid contamination, then acquire spectra from multiple locations (typically 5 spots) to account for heterogeneity.

- For soil/sediment samples: Homogenize and potentially pelletize without chemical treatment.

- Spectral Acquisition:

- Use a Q-switched Nd:YAG laser (1064 nm wavelength, 20 Hz repetition rate, 300 mJ pulse energy).

- Focus the laser beam 1 mm below the sample surface using a focusing lens (f = 75 mm).

- Accumulate 20 laser pulses from each point to ensure spectral stability.

- Collect spectra using a mid-step spectrometer with ICCD camera synchronized to the laser pulse.

- Spectral Preprocessing:

- Normalize spectra to correct for pulse-to-pulse energy variations.

- Apply wavelet denoising to improve signal-to-noise ratio.

- Variable Selection using VSC-mIPW-PLS:

- Calculate stability factors for all spectral variables.

- Perform PLS regression and compute variable importance.

- Apply iterative predictor weighting with hard threshold determination.

- Eliminate variables with importance below the threshold.

- Repeat until optimal variable set is identified based on RMSECV.

- Model Building and Validation:

- Develop quantitative calibration models using selected variables.

- Validate models using test sets with different partitioning scenarios (e.g., 9 different partitions).

- Evaluate model performance using RMSEP for unknown samples.

Critical Parameters:

- Laser parameters: wavelength, pulse energy, repetition rate, focus position

- Spectral acquisition: delay time, gate width, spectral resolution

- Variable selection: stability factor calculation, threshold determination

This protocol emphasizes the importance of stable variable selection to overcome the limitations of traditional algorithms that show poor adaptability to different data set partitions, ensuring robust quantitative analysis across varying environmental conditions [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of portable spectroscopic monitoring requires careful selection of reagents and materials optimized for field deployment. The following table details key research reagent solutions and their specific functions in environmental analysis protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Portable Environmental Monitoring

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Specifications | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-reduction Reagents | Potassium permanganate, potassium persulfate of analytical purity | Reduction of arsenic species to As(III) prior to hydride generation | FI-HG-AFS system for total dissolved inorganic arsenic [26] |

| Hydride Generation Reagents | Sodium tetrahydroborate (NaBH₄) in stabilized formulations, hydrochloric acid | Generation of volatile arsine gas (AsH₃) from inorganic arsenic | Atomic fluorescence detection of arsenic in water samples [26] |

| Nanomembrane Sensors | PPF+Ni nanomembranes | Selective detection of target analytes through impedance changes | Portable EIS system for waterborne pollutants [30] |

| Calibration Standards | Certified reference materials, matrix-matched standards | Instrument calibration and method validation | Quantitative analysis using LIBS and AFS [26] [29] |

| Ultrapure Water | Produced by Millipore purification systems or equivalent | Preparation of reagents and dilution of samples to ensure accuracy | All wet chemical procedures to prevent contamination [26] |

| Stabilization Buffers | pH-specific buffer solutions | Maintenance of optimal pH for chemical reactions and species stability | Hydride generation, fluorescence assays [26] |

| PCSK9-IN-29 | PCSK9-IN-29, MF:C26H26FNO6S, MW:499.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Pepluanin A | Pepluanin A, MF:C43H51NO15, MW:821.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The selection and quality of these reagents directly impact the accuracy, precision, and detection limits of portable monitoring systems. For instance, the use of analytical purity reagents and ultrapure water in the FI-HG-AFS system was essential to achieve the remarkable detection limit of 0.005 μg/L for arsenic while maintaining recovery rates between 97.8% and 107.8% across different water matrices [26]. Similarly, specialized nanomembranes enabled the development of portable EIS systems with sensitivity sufficient to detect benzoquinone at 0.1 mM concentrations [30]. These materials represent critical enabling components that make field-deployable spectroscopic systems viable alternatives to traditional laboratory methods.

Future Perspectives and Emerging Trends

The field of portable and real-time environmental monitoring continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends likely to shape future developments. Multi-analyte detection capabilities are becoming increasingly important, with research focusing on systems that can simultaneously monitor multiple contaminants without sacrificing sensitivity or portability [26] [30]. The integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence for data processing and pattern recognition represents another significant frontier, enabling more sophisticated interpretation of complex spectral data from environmental matrices [28]. Furthermore, the development of wireless sensor networks incorporating multiple spectroscopic nodes will facilitate comprehensive spatial and temporal monitoring across large geographical areas, providing unprecedented insights into environmental processes and pollution dynamics [30].

Advances in nanomaterial-based sensors promise to enhance both the selectivity and sensitivity of portable monitoring systems while reducing power requirements and costs [30]. Similarly, the miniaturization of spectroscopic components, including quantum cascade lasers, micro-plasma sources, and compact detectors, will continue to drive reductions in size, weight, and power consumption of field-deployable instruments [27] [28]. As these technologies mature, portable spectroscopic monitoring will become increasingly accessible and widely deployed, transforming our ability to understand and protect environmental systems through continuous, real-time observation rather than periodic sampling. This technological evolution supports a proactive approach to environmental management, enabling earlier detection of contamination events and more effective protection of ecosystem and human health [27] [26] [28].

Targeted Analysis: Spectroscopic Methods for Specific Environmental Contaminants

Trace Metal and Potentially Toxic Element (PTE) Analysis in Water, Soil, and Food using ICP-MS/OES

Elemental analysis of environmental matrices is a cornerstone of modern environmental monitoring research. The accurate quantification of trace metals and Potentially Toxic Elements (PTEs) like lead, cadmium, mercury, and arsenic in water, soil, and food is critical for assessing ecosystem health and human safety [31]. These contaminants are persistent in the environment and cause severe health impacts even at low exposure levels [31]. Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) have emerged as two principal analytical techniques that leverage the inductively coupled plasma source to address these challenges. This technical guide, framed within the context of spectroscopic research, provides an in-depth comparison of these techniques, detailed methodologies, and their application in environmental analysis.

Fundamental Techniques: ICP-MS and ICP-OES

Principles of Operation

ICP-OES operates on the principle of atomic emission. Samples are introduced into a high-temperature argon plasma (6000–10,000 K), where the constituent elements are atomized and excited. As these excited atoms return to lower energy states, they emit photons at characteristic wavelengths, which are separated and measured by an optical spectrometer [32].

ICP-MS also uses a high-temperature plasma (approximately 5500 °C) but as an ion source. The plasma not only atomizes the sample but also efficiently ionizes the elements. These ions are then extracted into a mass spectrometer (typically a quadrupole or time-of-flight analyzer), where they are separated and quantified based on their mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios [31] [32]. A key difference is that in the plasma, all molecular bonds are broken, and the data correspond to the total elemental content, independent of the original chemical species [31].

Comparative Technical Performance

The choice between ICP-OES and ICP-MS is governed by the specific analytical requirements, including required detection limits, sample matrix, and regulatory standards.

Table 1: Comparison of ICP-OES and ICP-MS for Trace Element Analysis

| Parameter | ICP-OES | ICP-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Optical Emission | Mass Spectrometry |

| Typical Detection Limits | Parts per billion (ppb) | Parts per trillion (ppt) |

| Dynamic Range | 4–5 orders of magnitude | 6–9 orders of magnitude |

| Multi-element Capability | High | Very High |

| Isotopic Analysis | Not applicable | Available |

| Tolerance for Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) | High (up to ~30%) [5] | Lower (~0.2%), though can be improved with dilution [5] |

| Primary Interferences | Spectral line overlap | Polyatomic and isobaric ions |

| Operational and Maintenance Costs | Lower | Higher [32] |

| Common Regulatory Methods | EPA 200.5, EPA 200.7 [5] | EPA 200.8, EPA 6020 [5] |

Technique Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines the decision-making process for selecting the appropriate analytical technique based on project requirements.

Analytical Methodologies and Protocols

Sample Preparation: A Critical First Step

Proper sample preparation is crucial for converting diverse matrices into a homogenous, dissolved state suitable for plasma introduction while minimizing contamination and preserving analyte integrity [31].

Microwave-Assisted Acid Digestion: This closed-vessel method is a best practice for solid samples (soil, food, plant matter). It allows for precise control over temperature and pressure, enabling complete decomposition of organic matrices and dissolution of target elements at elevated temperatures (e.g., 230°C) while minimizing the loss of volatile elements like Hg and As [6]. A typical digestion protocol for 1.00 g of plant material (e.g., cannabis, crops) uses 10 mL of concentrated HNO₃ with 0.3 mL of concentrated HCl to stabilize mercury [6].

Dilution and Filtration: Aqueous samples with simple matrices (e.g., drinking water) may require only acidification and filtration. However, high-TDS samples for ICP-MS often need significant dilution to prevent matrix effects and instrumental drift [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ICP-MS/OES Sample Preparation

Reagent/Material Function Example Use Case Nitric Acid (HNO₃), Trace Metal Grade Primary digesting agent for organic matrices; oxidizes organic matter. Digestion of food, plant, and soil samples [6]. Hydrochloric Acid (HCl), Trace Metal Grade Supplementary acid; helps dissolve oxides and stabilizes certain elements. Added to nitric acid to stabilize mercury during digestion [6]. Internal Standard Solution Compensates for instrument drift and matrix-induced signal suppression/enhancement. Online addition of Sc, Y, In, or Bi to all samples and standards [33]. Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) Validates method accuracy and precision by comparing measured values to certified values. Analysis of NIST soil or ERM food CRMs with each batch of samples. Collision/Reaction Cell Gases Mitigates polyatomic spectral interferences in ICP-MS. Using helium (He) gas in a collision cell to remove interferences on arsenic [34].

Instrumental Analysis and Optimization

ICP-MS Optimization: Modern ICP-MS systems often feature collision/reaction cells (e.g., triple-quadrupole systems) to remove polyatomic interferences. For instance, the interference of ArCl⺠on arsenic at m/z 75 can be mitigated by using a reaction gas that reacts with As⺠but not ArCl⺠[34]. Robustness for high-matrix samples can be improved using a nebulizer with a large sample channel internal diameter (e.g., ~0.75 mm) to resist clogging and aerosol dilution techniques [34] [6].

ICP-OES Sensitivity Enhancement: For applications requiring lower detection limits with ICP-OES, sensitivity can be boosted by a factor of two using high-efficiency sample introduction systems. This includes nebulizers that use an external impact surface to create a finer aerosol, combined with baffled cyclonic spray chambers [6]. Matching the calibration standards to the sample matrix (e.g., by adding residual carbon and calcium to standards for plant analysis) is critical for accuracy when spectral interferences are present [6].

Experimental Workflow for Environmental Analysis

The generalized workflow for a multi-matrix environmental study, from sample collection to data reporting, is depicted below.

Applications in Environmental Matrices

Food Safety Analysis

ICP-MS has become an indispensable key technology in food safety due to its ability to accurately determine toxic elements at ppb/ppt levels [31]. Applications include the analysis of lead and cadmium in cereals, mercury and arsenic in aquatic products, and multiple PTEs in dairy products and vegetables [31]. The technique supports risk assessment and regulation, with the number of applications in the literature growing at an average annual rate of 12–15% over the last decade [31]. Laser Ablation ICP-MS (LA-ICP-MS) is further used for the spatial distribution analysis of elements within food products [31].

Water Quality Monitoring

Both ICP-OES and ICP-MS are used for compliance with the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) and the Clean Water Act (CWA) [5]. ICP-OES is more robust for analyzing groundwater, wastewater, and samples with high total dissolved solids [5]. In contrast, ICP-MS is the preferred method for achieving the very low detection limits required for toxic elements like arsenic and lead in drinking water [5]. It is important to note that for drinking water compliance, a single technique is often insufficient; a combination of ICP-OES (for minerals) and ICP-MS (for toxic metals) or Graphite Furnace AA is typically required [5].

Soil and Sediment Analysis

Soil contamination with PTEs like lead, cadmium, and arsenic represents a significant environmental concern due to persistence and harmful effects on ecosystems and human health [25]. While traditional analysis involves acid digestion followed by ICP-OES or ICP-MS, spectroscopic advances are offering new paths. Visible–Near Infrared (Vis-NIR) spectroscopy, combined with machine learning models, is emerging as a greener, faster, and more scalable alternative for predicting PTE content in soils, though it faces challenges in standardization and model accuracy [25].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The application landscape for ICP-MS continues to evolve beyond total elemental quantification. Single-particle ICP-MS is used for nanoparticle characterization, and speciation analysis, achieved by coupling ICP-MS with chromatography (e.g., HPLC-ICP-MS), allows for the determination of different chemical forms of elements, which is crucial for accurate toxicological assessment (e.g., As(III) vs. As(V)) [34] [33].

Future directions focus on increasing accessibility through lower-cost instrumentation, further automation, and the development of portable systems for on-site analysis [31] [34]. The integration of machine learning with spectroscopic data, as seen in other fields like Raman spectroscopy for plastic identification [24], is poised to enhance data analysis and interpretation in elemental monitoring as well.

Detection and Quantification of Microplastics and Nanoplastics with Raman and FT-IR Spectroscopy

The pervasive distribution of microplastics (MPs, <5 mm) and nanoplastics (NPs, <1 μm) in global ecosystems has established them as a critical environmental pollutant of concern [35] [36]. Their potential for bioaccumulation and adverse ecological and health impacts necessitates the development of robust, reliable analytical methods for their identification and quantification [37] [36]. Within the broader context of spectroscopy in environmental monitoring, vibrational spectroscopy techniques, specifically Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) and Raman spectroscopy, have emerged as the foundational tools for this task [35]. These techniques are prized for their molecular specificity, enabling definitive polymer identification, and are often considered gold-standard methods in the field [35] [38]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the principles, methodologies, and advanced applications of FT-IR and Raman spectroscopy for the analysis of micro- and nanoplastics, serving the needs of researchers and scientists engaged in environmental monitoring and analytical chemistry.

Fundamental Principles and a Comparative Analysis

Core Principles of FT-IR and Raman Spectroscopy

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy probes the interaction between matter and infrared radiation. It measures the absorption of IR light by chemical bonds in a sample, which occurs at specific frequencies corresponding to the vibrational modes of those bonds. The result is a spectrum that serves as a molecular "fingerprint" [39] [40]. Modern micro-FTIR (μ-FTIR) systems, especially those equipped with Focal Plane Array (FPA) detectors, allow for the rapid chemical imaging of samples, simultaneously collecting thousands of spatially resolved spectra [40]. FT-IR can be operated in several modes, including transmission, transflectance, and Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR), the latter being common for analyzing thick or strong-absorbing samples with minimal preparation, albeit with a risk of cross-contamination [40].

Raman spectroscopy is a complementary technique that analyzes the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser. When light interacts with a molecule, the energy shift (Raman shift) of the scattered photons provides information about the vibrational modes in the system [41]. A key advantage of Raman spectroscopy is its superior spatial resolution (down to ~0.5 μm) compared to conventional micro-FTIR, owing to the shorter wavelength of the laser light used. This makes it particularly suitable for identifying smaller particles, including many nanoplastics [42] [38]. Furthermore, Raman spectroscopy is less affected by water interference, simplifying the analysis of aqueous samples [42].

Technique Comparison: Capabilities and Limitations

The selection between FT-IR and Raman spectroscopy involves a careful trade-off based on analytical needs. The following table summarizes their key characteristics for micro- and nanoplastic analysis.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of FT-IR and Raman spectroscopy for micro- and nanoplastic detection.

| Parameter | FT-IR Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Principle | Measures absorption of infrared light | Measures inelastic scattering of monochromatic light |

| Spatial Resolution | Diffraction-limited, typically ≥10-20 μm [37] [38] | Higher, can reach ~0.5 μm, suitable for nanoplastics [42] [38] |

| Key Strength | High chemical specificity; minimal fluorescence interference from pigments/weathered samples [40] [42] | Higher spatial resolution; minimal interference from water [42] [38] |

| Primary Limitation | Limited spatial resolution for nanoplastics; strong water absorption can interfere [37] [40] | Susceptible to fluorescence interference, which can swamp the signal [40] [42] |

| Common Modes | Transmission, Transflectance, ATR [40] | Confocal Raman, Raman Imaging [42] |

| Sample Presentation | Often requires IR-transparent or reflective filters; ATR allows direct contact [40] | Can often be analyzed on glass slides or in solution with minimal preparation [42] |

Experimental Workflows and Standardization

A generalized, streamlined workflow for the detection and quantification of MNPs using spectroscopic techniques involves several critical stages from sample collection to data analysis. The process is visualized below.

Figure 1: A generalized experimental workflow for the detection and quantification of microplastics and nanoplastics using FT-IR and Raman spectroscopy.

Sample Preparation Protocols

Proper sample preparation is critical for accurate analysis. Environmental samples (water, sediment, biological tissue) require processing to isolate plastic particles.

- Filtration and Substrate Selection: Water samples are typically vacuum-filtered. The choice of filter substrate is instrument-dependent. Aluminum oxide filters are ideal for μ-FTIR in transflectance mode due to their high reflectivity, while silicon or gold-coated filters are preferred for Raman analysis as they minimize background interference [40]. For FT-IR transmission mode, IR-transparent filters such as polycarbonate or cellulose nitrate are used, though these may require subsequent dissolution to avoid spectral overlap [40].

- Density Separation: For soil or sediment samples, density separation using solutions such as sodium chloride (NaCl) or sodium iodide (NaI) is employed to float less dense plastic particles away from mineral material [42].