Advanced Spectroscopy in Food Quality Control: Current Techniques, AI Integration, and Future Directions for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements and applications of spectroscopic techniques in food quality control, tailored for researchers and scientists.

Advanced Spectroscopy in Food Quality Control: Current Techniques, AI Integration, and Future Directions for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements and applications of spectroscopic techniques in food quality control, tailored for researchers and scientists. It explores the foundational principles of key methods such as IR, Raman, NMR, and MS, and details their specific applications in authenticity verification, contaminant detection, and compositional analysis. The review critically examines the integration of machine learning and chemometrics for data interpretation, addresses persistent technical and economic challenges hindering widespread adoption, and offers a comparative analysis of method performance and validation protocols. By synthesizing cutting-edge research and future trends, this work serves as a vital resource for professionals developing robust, non-destructive analytical frameworks for food safety and quality assurance.

Core Principles and the Analytical Shift to Non-Destructive Spectroscopy

In the field of food quality control, the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter serves as the foundational principle for many advanced analytical techniques. This interaction provides a non-destructive window into the chemical and physical composition of food products, enabling researchers to ensure safety, authenticate authenticity, and monitor quality without destroying samples [1] [2]. Spectroscopic methods leverage the way molecules absorb, reflect, or emit electromagnetic radiation to generate characteristic signals that serve as molecular fingerprints [3] [4]. The growing consumer demand for safe, high-quality food products has accelerated the adoption of these technologies throughout the food production chain [5]. This technical guide explores the core principles of this fundamental interaction and its practical application through various spectroscopic techniques that are revolutionizing food quality assessment.

Core Principles of Radiation-Matter Interaction

When electromagnetic radiation interacts with matter, several phenomena can occur, including absorption, reflection, transmission, and emission. The specific outcome depends on the energy of the photons and the molecular structure of the material. These interactions cause changes in the radiation's intensity, direction, wavelength, phase, or polarization, which can be measured and correlated with chemical properties [3].

The electromagnetic spectrum encompasses a wide range of wavelengths and energies, each interacting with matter in distinct ways. The energy of electromagnetic radiation is inversely proportional to its wavelength, following the equation E = hc/λ, where E is energy, h is Planck's constant, c is the speed of light, and λ is wavelength. This relationship is crucial because it determines which molecular transitions can be excited by specific regions of the spectrum [1].

Table 1: Electromagnetic Spectrum Regions Used in Food Spectroscopy

| Spectral Region | Wavelength Range | Energy Transitions Probed | Example Applications in Food Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Terahertz (THz) | 0.1-10 THz (3 mm - 30 μm) | Intermolecular vibrations, crystalline phonon modes | Detection of pesticides, mycotoxins, adulteration identification [3] |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) | 780-2500 nm | Overtones and combinations of CH, OH, NH vibrations | Quantification of protein, fat, moisture, soluble solids in fruits and dairy [1] [5] |

| Mid-Infrared (MIR) | 2.5-25 μm | Fundamental molecular vibrations | Identification of functional groups, chemical bonding analysis [4] |

| Raman | Varies with laser source | Inelastic scattering providing molecular fingerprints | Detection of foodborne pathogens, ethanol quantification in beverages [4] |

| Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) | 200-800 nm | Electronic transitions | Concentration measurement of analytes, classification of food additives [4] |

Hydrogen-containing groups (such as -OH, -CH, -NH, and -SH) are particularly important in food analysis because they exhibit strong, characteristic responses to electromagnetic radiation, especially in the near-infrared region. These groups undergo vibrational transitions when exposed to specific wavelengths, creating unique spectral signatures that can be quantified and correlated with chemical composition [5]. The absorption bands observed in spectroscopy correspond to transitions between discrete molecular energy states, with the absorption frequency related to the energy difference between these states according to ΔE = hν.

Spectroscopic Techniques in Food Analysis

Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy

NIR spectroscopy (780-2500 nm) captures overtones and combination bands of molecular vibrations involving CH, OH, and NH bonds [1]. Although these absorptions are weaker and broader than those in the mid-infrared region, they enable deeper penetration into samples, making NIR particularly suitable for non-destructive analysis of food products [1]. The technique has been widely applied to quantify key food quality attributes such as protein and fat in meat and dairy products, moisture content for shelf-life evaluation, and soluble solids content (SSC) and acidity in fruits [1]. Modern applications combine NIR with hyperspectral imaging (HSI) to simultaneously obtain spatial and spectral information, creating comprehensive food quality assessment systems [1].

Terahertz (THz) Spectroscopy

Terahertz spectroscopy operates in the 0.1-10 THz range, between microwave and infrared regions, combining the penetration capability of microwaves with the resolving power of infrared light [3]. THz photons possess low energy (on the order of millielectron volts) and are weakly absorbed by most non-metallic and non-polar materials, enabling non-destructive identification and quantitative analysis of food components [3]. The technology exists in two complementary modalities: time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS), which uses femtosecond laser pulses to capture broadband temporal responses for rapid monitoring of compositional changes, and frequency-domain spectroscopy (THz-FDS), which offers high-resolution detection at specific frequencies for precise identification of trace contaminants [3].

Advanced Spectroscopy Techniques

Several other spectroscopic techniques play important roles in food quality assessment. Raman spectroscopy, including surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), provides molecular fingerprinting capabilities for detecting low concentrations of analytes [4]. Fluorescence spectroscopy detects light emission by substances and is used for tracking molecular interactions and identifying adulteration [4]. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy offers detailed information about molecular structure and conformational subtleties through the interaction of nuclear spin properties with an external magnetic field [4]. Each technique provides complementary information, and their combined use offers a comprehensive approach to food analysis.

Table 2: Comparison of Spectroscopic Techniques for Food Analysis

| Technique | Key Strengths | Limitations | Data Analysis Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIR Spectroscopy | Non-destructive, rapid, suitable for online monitoring, deep penetration | Weak and overlapping absorption bands, limited sensitivity | PLSR, PCA, SVM, CNN, preprocessing with SNV and MSC [1] [5] |

| Terahertz Spectroscopy | Penetrates packaging, sensitive to intermolecular vibrations, low photon energy | Strong water absorption, scattering effects in complex matrices, limited databases | Signal preprocessing, feature wavelength selection, machine learning optimization [3] |

| Raman/SERS | High sensitivity, molecular specificity, minimal sample preparation | Fluorescence interference, matrix effects in complex foods | Microfluidic integration, molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) [4] |

| ICP-MS/OES | Exceptional sensitivity for trace elements, multi-element capability | Destructive, requires sample preparation, expensive instrumentation | OPLS-DA, heatmaps, canonical discriminant analysis [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

General Workflow for Spectroscopic Analysis

The following workflow represents a standardized approach for spectroscopic analysis in food quality control:

Sample Preparation: For liquid foods (milk, juice, oils), ensure homogeneity through shaking or stirring. Solid foods may require grinding or slicing to create consistent surface properties. Minimal preparation is a key advantage of spectroscopic techniques [5].

Instrument Calibration: Perform wavelength calibration using certified reference materials. For quantitative analysis, develop calibration models using samples with known reference values obtained through traditional analytical methods (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS) [1].

Spectral Acquisition: Position samples appropriately in the instrument. For transmission measurements, use consistent pathlength cells. For reflectance measurements, maintain consistent distance and angle relative to the detector. Acquire multiple scans and average to improve signal-to-noise ratio [1] [5].

Data Preprocessing: Apply techniques such as Standard Normal Variate (SNV), Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC), Savitzky-Golay filtering, or derivative spectra to reduce noise, correct baselines, and minimize light scattering effects [2] [5].

Chemometric Analysis: Employ multivariate analysis including Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for exploratory analysis, Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) for quantitative models, and classification algorithms like Support Vector Machines (SVM) for qualitative discrimination [2] [5].

Model Validation: Use cross-validation or independent test sets to evaluate model performance. Report key metrics including Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP), coefficient of determination (R²), and classification accuracy [1].

Specific Protocol: NIR for Liquid Food Adulteration Detection

This protocol details the detection of adulterants in liquid foods such as oils or milk using NIR spectroscopy:

Materials: Portable or benchtop NIR spectrometer, liquid transmission cell with fixed pathlength (typically 1-10 mm), pure and adulterated samples, chemometrics software [5].

Procedure:

- Collect spectral data from pure liquid food samples (e.g., pure peanut oil) to establish a baseline [5].

- Prepare adulterated samples by mixing the pure food with known concentrations of adulterants (e.g., cheaper oils in premium olive oil) [5].

- Acquire NIR spectra of all samples across the 780-2500 nm range. For each sample, collect at least 32 scans at multiple locations if possible [5].

- Apply preprocessing: Use S-G convolutional smoothing and SNV techniques to eliminate noise interference [5].

- Perform data dimensionality reduction using PCA methods [5].

- Develop a PLS regression model to correlate spectral data with adulteration concentration. Alternatively, use classification algorithms (KNN, SVM) to distinguish pure from adulterated samples [5].

- Validate the model using a separate set of samples not included in the calibration [5].

Expected Outcomes: Studies have reported high predictive power with R² values >0.93 for quantification of adulterants in oils [5].

Specific Protocol: Terahertz Spectroscopy for Contaminant Detection

This protocol applies terahertz time-domain spectroscopy (THz-TDS) to detect chemical contaminants in food products:

Materials: THz-TDS system with femtosecond laser, transmission or reflection cell, samples with and without target contaminants [3].

Procedure:

- Place the sample in the THz beam path. For transmission mode, position the sample between the emitter and detector. For reflection mode, angle the sample appropriately [3].

- Acquire time-domain waveforms with and without the sample present [3].

- Transform the time-domain data to frequency domain using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) [3].

- Extract optical parameters including absorption coefficient and refractive index from the transformed data [3].

- Apply chemometric methods for feature extraction and model development. Use machine learning algorithms such as support vector machines or convolutional neural networks to classify contaminated versus uncontaminated samples [3].

- Validate classification accuracy using independent sample sets [3].

Technical Considerations: The strong absorption of THz radiation by water molecules complicates analysis of high-moisture foods. Scattering effects from complex sample matrices may require specialized correction algorithms [3].

Data Analysis and Computational Approaches

Modern spectroscopy generates complex, high-dimensional data that requires sophisticated computational approaches for meaningful interpretation. Chemometrics combines mathematics, statistics, and computer science to extract chemical information from spectral data [2]. Key steps in the analysis pipeline include:

Data Preprocessing: Techniques such as Standard Normal Variate (SNV) and Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) address light scattering variations, while derivatives enhance spectral resolution by removing baseline offsets [2].

Exploratory Analysis: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) reduces data dimensionality and identifies patterns, trends, and outliers in multivariate spectral data [2].

Multivariate Calibration: Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) establishes relationships between spectral data (X-matrix) and reference measurements (Y-matrix), effectively handling collinearity in spectral variables [1] [2].

Classification Methods: Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) categorize samples based on their spectral patterns [5].

Machine learning and deep learning approaches have shown remarkable success in analyzing NIR and HSI data for food inspection [1]. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can automatically extract relevant features from spectral data and have demonstrated superior capability in modeling complex nonlinear relationships compared to conventional methods [1]. To address the challenge of limited labeled datasets, advanced approaches such as Active Learning (AL) and Semi-Supervised Learning (SSL) can significantly improve data efficiency - in some cases reducing the number of labeled samples needed by more than 50% [6].

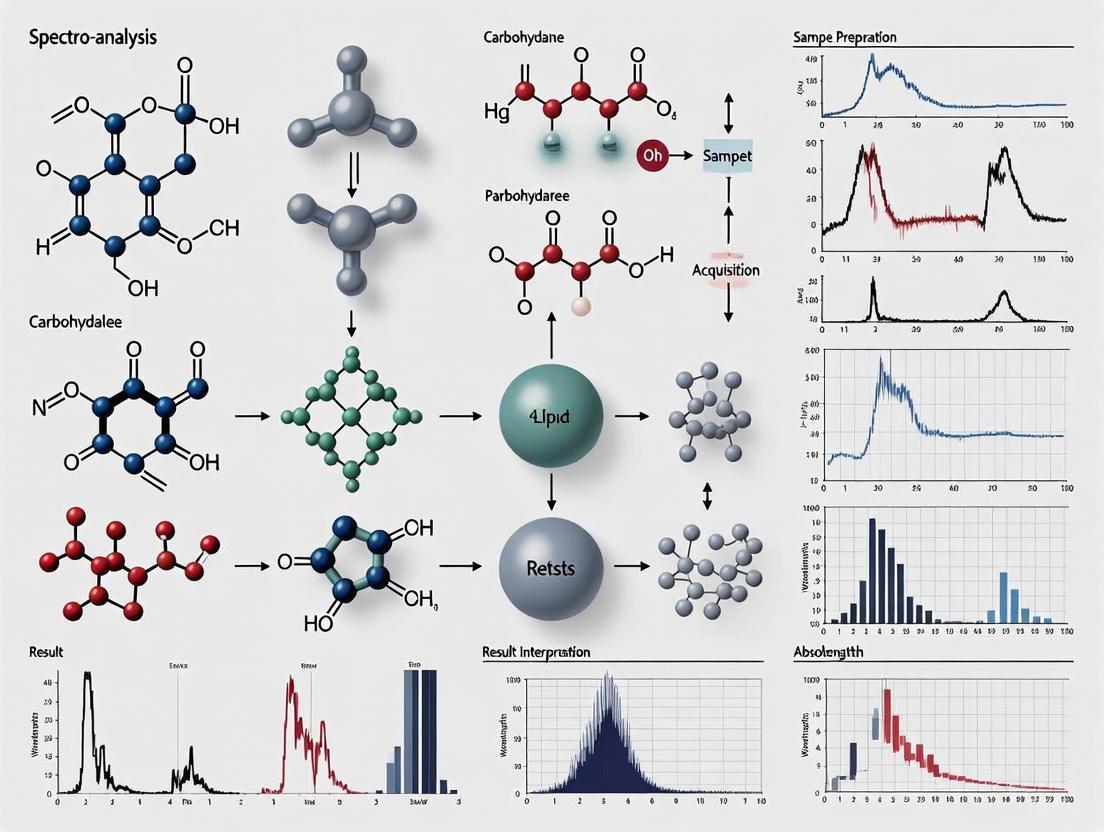

The following diagram illustrates a comparative data analysis workflow incorporating both traditional chemometrics and modern machine learning approaches:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Spectroscopy in Food Research

| Item | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Instrument calibration and method validation | NIST traceable standards for wavelength verification, chemical standards for quantitative calibration [4] |

| Standard Normal Variate (SNV) | Spectral preprocessing to reduce scattering effects | Correcting for particle size effects in powdered foods, pathlength variations in liquids [2] [5] |

| Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) | Spectral preprocessing to remove scattering effects | Addressing light scattering differences in heterogeneous solid foods [2] |

| Savitzky-Golay Filter | Smoothing and derivative calculation for spectral preprocessing | Noise reduction while preserving spectral features, enhancing resolution through derivatives [5] |

| Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) | Multivariate calibration method | Building quantitative models for predicting composition (protein, fat, moisture) from spectral data [1] [5] |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | Deep learning for automated feature extraction | Complex nonlinear modeling of spectral data, achieving superior performance for quality attribute prediction [1] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Selective capture of target analytes in SERS | Enhancing detection specificity for trace contaminants in complex food matrices [4] |

| Portable Spectrometers | Field-based and point-of-care analysis | In-situ testing for geographic origin traceability, rapid screening for adulteration at processing facilities [5] |

| Vin-C01 | Vin-C01, MF:C20H24N2O, MW:308.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AT-9010 tetrasodium | AT-9010 tetrasodium, MF:C11H13FN5Na4O13P3, MW:627.13 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The fundamental interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter provides the scientific foundation for a powerful suite of analytical tools that are transforming food quality control research. As spectroscopic technologies continue to evolve, their integration with advanced chemometric methods and machine learning algorithms is creating unprecedented capabilities for non-destructive, rapid, and accurate food analysis. Future developments will likely focus on improving detection sensitivity, expanding spectral databases, enhancing portability for field applications, and establishing standardized protocols for broader adoption across the food industry. The ongoing innovation in this field promises to further strengthen food safety systems and meet the growing global demand for high-quality, authentic food products.

In the realm of food quality control research, the demand for precise, rapid, and non-destructive analytical methods has never been greater. Spectroscopic techniques form the backbone of modern food analysis, enabling researchers to ensure safety, authenticate authenticity, and monitor quality from production to consumption. These techniques exploit the interactions between light and matter to reveal detailed information about the chemical composition, structure, and physical properties of food products. The integration of spectroscopy with advanced data analysis represents a paradigm shift in food science, offering unprecedented capabilities for addressing complex challenges in food safety and quality assurance. This review provides a comprehensive technical overview of the fundamental spectroscopic techniques—Near-Infrared (NIR), Raman, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis), and Mass Spectrometry (MS)—that constitute the essential toolkit for researchers and scientists in food quality control.

Core Spectroscopic Techniques: Principles and Food Science Applications

The application of spectroscopic techniques in food science has revolutionized quality control processes, enabling non-destructive analysis, real-time monitoring, and sophisticated pattern recognition for authenticity verification. Table 1 summarizes the fundamental principles, key applications, and technical considerations of each major technique in food analysis.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Spectroscopic Techniques in Food Quality Control

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Key Applications in Food Analysis | Typical Detection Limits | Sample Preparation Needs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy | Absorption of NIR light (780-2500 nm) by hydrogen-containing groups (-OH, -NH, -CH) [7] [5] | Quantitative analysis of proteins, polysaccharides, polyphenols; Adulteration detection; Geographic origin tracing [7] [5] | Varies by component; Suitable for major constituents | Minimal; Often requires no preparation; Direct analysis of solids/liquids |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Inelastic scattering of light revealing molecular vibrational fingerprints [8] | Pesticide detection; Foodborne pathogen identification; Microbial contamination; Adulteration [8] [4] | Trace-level with SERS (e.g., pesticides, toxins) [8] | Minimal for conventional Raman; SERS may require nanostructured substrates |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy | Absorption of radiofrequency radiation by atomic nuclei in magnetic field [9] | Metabolite profiling; Authenticity verification (e.g., milk, spices); Adulteration detection; Molecular structure elucidation [9] [4] | High-resolution molecular information | Varies; High-field may need deuterated solvents; Low-field often non-destructive |

| Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy | Electronic transitions in molecules at UV-Vis wavelengths [10] [4] | Detection of adulterants (Sudan Red, melamine); Beverage component analysis; Wine sensory attributes [10] [4] | Varies; Suitable for colored compounds and chromophores | Often requires dissolution or extraction |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Ionization and mass-to-charge ratio separation of molecules [11] | Trace contaminant detection; Aroma and bioactive compound profiling; Pesticide residue analysis [11] | Very low (e.g., µg·kg−1 for antimicrobials) [11] | Typically extensive; Often coupled with chromatography |

The complementary nature of these techniques provides a powerful multidimensional analytical platform. While NIR spectroscopy excels in rapid, non-destructive quantitative analysis of major food components, Raman spectroscopy offers superior molecular fingerprinting capabilities with minimal sample preparation. NMR spectroscopy provides unparalleled structural elucidation power, and UV-Vis serves as a workhorse for routine analysis of chromophores. Mass spectrometry, particularly when coupled with separation techniques like chromatography, delivers exceptional sensitivity and specificity for trace-level contaminants and complex mixtures.

Advanced Technical Methodologies and Protocols

NIR Spectroscopy with Chemometrics for Liquid Food Adulteration

The detection of adulteration in liquid foods such as oils and milk represents a significant challenge in food quality control. NIR spectroscopy coupled with chemometrics has emerged as a powerful solution for rapid, non-destructive screening.

Experimental Protocol:

- Instrumentation: Utilize a portable NIR spectrometer (780-2500 nm wavelength range) with a reflectance probe for liquid analysis [5].

- Sample Preparation: For edible oil adulteration studies, prepare calibration samples by mixing pure peanut oil with adulterants (e.g., cheaper vegetable oils) in known concentrations (0-100%) [5].

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect spectra in triplicate for each sample using a direct contact probe. Employ a background reference scan before each sample set.

- Spectral Preprocessing: Apply Savitzky-Golay (S-G) convolutional smoothing and Standard Normal Variate (SNV) transformation to reduce scattering effects and instrumental noise [5].

- Variable Selection: Implement Competitive Adaptive Reweighted Sampling (CARS) to identify key wavelengths most correlated with adulteration levels [5].

- Model Development: Develop Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression models correlating spectral data with adulteration concentrations. Validate using cross-validation and independent test sets [5].

Performance Metrics: This methodology has demonstrated high predictive power with R² values exceeding 0.93 and Root Mean Square Error of Cross-Validation (RMSECV) below 4.43% for peanut oil adulteration quantification [5].

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) for Trace Contaminant Detection

SERS dramatically enhances the sensitivity of conventional Raman spectroscopy, enabling detection of trace-level contaminants such as pesticides, mycotoxins, and veterinary drug residues.

Experimental Protocol:

- Substrate Preparation: Fabricate or commercially source SERS-active substrates. Common configurations include:

- Sample Extraction: For pesticide analysis in tea, employ solid-phase extraction to isolate target analytes from the complex matrix [8].

- SERS Measurement: Apply sample extract to SERS substrate. Acquire spectra using a portable Raman spectrometer with 785 nm excitation laser, typically with 1-10 second integration time.

- Data Analysis: Preprocess spectra with baseline correction and vector normalization. Employ machine learning algorithms (e.g., convolutional neural networks) for quantitative prediction of contaminant concentrations [8].

Performance Metrics: SERS has achieved detection limits as low as 0.8 μg·kg−1 for certain pesticides in complex food matrices, surpassing regulatory requirements [8].

NMR-Based Metabolomics for Food Authentication

NMR spectroscopy provides a comprehensive approach to food authentication through metabolite profiling and geographical origin verification.

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation:

- Data Acquisition: Acquire ¹H NMR spectra using a benchtop NMR spectrometer (e.g., 60 MHz) or high-field instrument. Standard parameters include: 32-64 scans, 4s relaxation delay, and water suppression pulse sequence [9] [12].

- Multivariate Analysis: Process spectra (phase correction, baseline correction, binning). Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA) to identify discriminatory metabolites [9].

- Marker Identification: Statistically validate potential markers based on variable importance in projection (VIP) scores and correlation coefficients.

Performance Metrics: NMR-based metabolomics has successfully differentiated geographical origins of various food products with classification accuracies exceeding 95% in controlled studies [9].

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Integrated spectroscopic analysis workflow for food quality control

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of spectroscopic techniques in food analysis requires specific reagents and materials tailored to each methodology. Table 2 catalogues the essential research reagent solutions for the featured techniques.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Spectroscopic Food Analysis

| Technique | Key Reagents/Materials | Technical Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIR Spectroscopy | Solid Standard Reference Materials (for calibration); Liquid Cell Accessories; Reflective Background Plates | Instrument calibration; Sample presentation; Signal optimization | Quantification of protein, moisture, fat in powders; Adulteration screening in oils [5] |

| Raman/SERS | SERS-active substrates (Au/Ag nanoparticles); Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs); Microfluidic chips | Signal enhancement; Selective recognition; Automated fluid handling | Pesticide detection in tea; Mycotoxin screening; Pathogen identification [8] [4] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Deuterated Solvents (D₂O, CDCl₃, DMSO-d6); NMR Reference Standards (TMS, DSS); Solvent Suppression Kits | Signal locking; Chemical shift referencing; Water signal suppression | Metabolite profiling in milk; Authenticity verification of spices; Adulteration detection [9] [12] |

| Chromatography-MS | QuEChERS Extraction Kits; Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges; Derivatization Reagents; Isotope-labeled Internal Standards | Sample cleanup; Analyte enrichment; Signal normalization; Quantification accuracy | Pesticide multiresidue analysis; Antimicrobial detection in lettuce; Fatty acid profiling [11] |

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Chromogenic Derivatization Reagents; Certified Reference Materials; Cuvettes (quartz, glass, plastic) | Analyte visualization; Method validation; Sample containment | Detection of illegal dyes; Beverage component analysis; Additive quantification [10] [4] |

The integration of spectroscopic techniques represents the future of food quality control research, offering powerful, complementary capabilities for comprehensive food analysis. NIR spectroscopy provides rapid screening for major components, Raman spectroscopy enables specific molecular fingerprinting, NMR delivers detailed structural information, UV-Vis serves as a workhorse for routine analysis, and MS provides exceptional sensitivity for trace contaminants. The convergence of these technologies with artificial intelligence, chemometrics, and miniaturized instrumentation is driving a transformation in food analysis toward real-time, non-destructive, and highly accurate quality assessment. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will play an increasingly critical role in ensuring global food safety, authenticity, and quality in an increasingly complex food supply chain.

The global food industry faces mounting challenges in ensuring product safety, quality, and authenticity amidst increasing regulatory scrutiny and consumer demand. Traditional analytical methods, while effective, are often destructive, labor-intensive, time-consuming, and environmentally harmful due to their reliance on chemicals and extensive sample preparation [2]. This has catalyzed a paradigm shift toward non-destructive, green analytical technologies that preserve sample integrity and facilitate rapid, in-situ analysis. Advanced spectroscopic techniques, particularly those based on vibrational spectroscopy, have emerged as transformative tools for addressing these challenges [13] [14]. This whitepaper explores the operational principles, validation milestones, and practical applications of these technologies within food quality control research, highlighting their integration with advanced chemometrics, miniaturized instrumentation, and artificial intelligence to build scalable, sustainable food safety solutions.

Conventional analytical techniques for food quality assessment, including liquid chromatography (HPLC) and gas chromatography (GC), have long been the gold standard in laboratories. These methods are powerful for separation, identification, and quantification of individual food components and contaminants. However, they present significant limitations: they are inherently destructive, requiring homogenization and extensive preparation of samples; they are laborious and time-consuming, delaying results from hours to days; they often require skilled personnel and expensive reagents; and they generate chemical waste, posing environmental concerns [2]. Such drawbacks render them unsuitable for rapid, high-throughput screening, real-time process monitoring, or in-field applications, creating a critical gap in the modern food supply chain.

Incidents of food adulteration, such as the melamine in milk scandal in China and the addition of lead oxide to paprika, have underscored the vulnerability of global food systems and the urgent need for robust, rapid analytical tools [2]. In response, non-destructive analytical technologies have emerged, leveraging the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter to obtain chemical and physical information without compromising the sample's integrity [15]. This shift aligns with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry, minimizing the use of hazardous substances and energy while enabling faster, more efficient quality control from farm to fork.

Fundamental Principles of Key Non-Destructive Techniques

Non-destructive spectroscopic techniques are primarily based on the absorption or scattering of light, providing a molecular fingerprint of the sample. The following sections detail the most prominent technologies in food research.

Vibrational Spectroscopy: NIR and MIR

Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy operates in the wavelength range of 700–2500 nm [15]. It measures overtones and combination bands of fundamental molecular vibrations, primarily those involving C-H, O-H, and N-H bonds [16]. While NIR spectra are complex and consist of broad, overlapping bands, this technique is highly versatile for quantitative analysis of constituents like moisture, protein, fat, and carbohydrates in various food matrices [17].

Mid-Infrared (MIR) Spectroscopy covers the 2500–25000 nm range and probes the fundamental vibrational modes of molecules [15]. It provides intense, isolated, and reliable absorption bands, making it highly specific for identifying functional groups and chemical structures. Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, a dominant MIR technique, uses an interferometer and Fourier transformation to simultaneously collect high-resolution spectral data over a wide spectral range [18]. It is particularly useful for identifying organic materials and specific molecular structures.

Raman Spectroscopy and Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS)

Raman Spectroscopy is based on the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, providing information about molecular vibrations through changes in polarizability [14]. It is complementary to IR spectroscopy and is particularly advantageous for analyzing aqueous samples because water is a weak scatterer. Raman spectroscopy excels in measuring specific molecular vibrations, such as -C≡C- stretching, C=C stretching, and -S-S- stretching [16].

Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) is an advanced variant that enhances the inherently weak Raman signal by several orders of magnitude. This is achieved by adsorbing the target analyte onto specially prepared roughened metal surfaces or colloidal nanoparticles (e.g., gold or silver) [13] [4]. SERS enables the detection of trace-level contaminants, including pesticides, veterinary drug residues, and foodborne pathogens, with high sensitivity [4] [14].

Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) and Other Electronic Spectroscopies

Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) combines spectroscopy with digital imaging. It captures a full spectrum for each pixel in an image, thereby simultaneously providing spatial and chemical information about a sample [13]. This makes it exceptionally powerful for visualizing the distribution of quality attributes and contaminants within a food product.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy measures the absorption of light in the 190–780 nm range, which causes electronic transitions in molecules [16]. It is widely used for quantifying analytes like pigments, food additives, and certain contaminants in solutions.

Fluorescence Spectroscopy detects the emission of light from molecules that have been excited by photons of a higher energy. It is highly sensitive and is often used to study molecular interactions, kinetics, and to detect adulteration in products like oils [4].

Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques

The table below summarizes the operational characteristics, strengths, and limitations of the primary non-destructive techniques discussed.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of non-destructive spectroscopic techniques for food quality control.

| Technique | Spectral Range | Measured Interaction | Key Applications in Food Analysis | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIR Spectroscopy | 700–2500 nm [15] | Overtone/combination vibrations (C-H, O-H, N-H) | Quantification of moisture, protein, fat, sugars [17] | Deep penetration, rapid, excellent for quantitative analysis | Complex spectra requiring chemometrics, sensitive to water, lower specificity |

| MIR/FTIR Spectroscopy | 2500–25000 nm [15] | Fundamental vibrations | Identification of functional groups, authentication, contaminant detection [4] | High specificity, rich structural information | Limited penetration depth, can be incompatible with fiber optics |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Varies (laser-dependent) | Inelastic light scattering (polarizability) | Molecular fingerprinting, detection of non-polar groups [16] | Minimal water interference, requires little to no sample prep | Inherently weak signal, can be hindered by fluorescence |

| SERS | Varies (laser-dependent) | Enhanced inelastic scattering | Detection of trace analytes (pesticides, toxins, pathogens) [4] | Extreme sensitivity (single-molecule possible), high specificity | Complex substrate fabrication, potential signal instability |

| Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) | UV-Vis-NIR-MIR | Spatially resolved absorption/reflectance | Mapping of component distribution, defect and contaminant visualization [13] | Combines spatial and spectral data | Large data sets, computationally intensive |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Implementing non-destructive techniques requires a structured workflow from sample preparation to data analysis. Below is a generalized protocol adaptable for various techniques and food matrices.

General Workflow for Non-Destructive Food Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for applying non-destructive analytical techniques in food research.

Diagram 1: Core analytical workflow.

Sample Preparation and Presentation

Unlike traditional methods, non-destructive techniques typically require minimal sample preparation. The key is consistent presentation to the spectrometer. For solid foods (e.g., fruits, grains, meat), ensure a uniform and representative surface for analysis. For liquids (e.g., milk, oil), use a consistent pathlength cuvette or a dip probe. The sample temperature should be controlled and recorded, as it can influence spectral features [2] [17].

Instrument Calibration and Validation

Regular calibration of the spectrometer using manufacturer-provided standards (e.g., for wavelength and intensity) is crucial. For quantitative analysis, the development of a robust calibration model is essential. This involves:

- Calibration Set: Using a large set of samples (n > 50) with known reference values for the property of interest (e.g., Brix, fat content) determined by standard methods.

- Validation Set: Using a separate, independent set of samples to test the model's predictive performance [15] [17].

Spectral Data Acquisition

Acquire spectra according to the instrument's specifications. For NIR, this typically involves reflectance or interactance mode for solids and transmittance for liquids. For Raman, focus the laser beam on a representative spot. Multiple scans per sample are recommended and averaged to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

Data Pre-processing and Chemometric Modeling

Raw spectral data contains unwanted variation (noise, light scattering, baseline drift). Pre-processing is critical to remove these artifacts.

- Common Pre-processing Techniques: Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC), Standard Normal Variate (SNV), Savitzky-Golay derivatives, and detrending [2].

- Chemometric Modeling: Use multivariate statistical methods to extract meaningful information.

- Unsupervised Learning (e.g., Principal Component Analysis - PCA): For exploratory data analysis to identify natural groupings or outliers.

- Supervised Learning (e.g., Partial Least Squares - PLS): For building quantitative regression models to predict analyte concentrations.

- Classification (e.g., Linear Discriminant Analysis - LDA, PLS-Discriminant Analysis): For authenticating origin or detecting adulteration [2] [14].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Soluble Solids in Fruit via NIR

Aim: To non-destructively predict the soluble solids content (SSC, °Brix) in intact apples using a portable NIR spectrometer.

Materials and Reagents: Table 2: Key research reagents and solutions for NIR protocol.

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Portable NIR Spectrometer (e.g., Viavi MicroNIR, Thermo Fisher Phazir) [14] | The core instrument for spectral acquisition in the field or lab. |

| Reference Materials (e.g., ceramic tile) | For instrument calibration and background (dark current) correction. |

| Destructive Refractometer | To obtain the reference °Brix values for model calibration and validation. |

| Software (e.g., Unscrambler, CAMO) | For chemometric analysis, including pre-processing and PLS regression. |

Methodology:

- Sample Selection: Select a large number of apples (e.g., >100) covering the expected range of maturity and SSC.

- Reference Analysis: For each apple, after NIR scanning, homogenize a portion of the pulp and measure the SSC using a calibrated digital refractometer to obtain the reference "ground truth" value [17].

- Spectral Acquisition: Wipe the apple surface clean. Hold the NIR spectrometer probe firmly against a marked, representative spot on the fruit (e.g., the equator). Acquire spectra in reflectance mode. Take multiple scans per fruit and average them.

- Chemometric Model Development:

- Pre-processing: Apply SNV and a first derivative to the raw spectra to reduce scattering effects and enhance spectral features.

- Calibration: Use PLS regression to correlate the pre-processed spectral data (X-matrix) with the reference SSC values (Y-matrix). Use a calibration set comprising ~70% of the samples.

- Validation: Test the model's performance by predicting the SSC in the remaining ~30% of samples (validation set). Key performance metrics include the Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP) and the coefficient of determination (R²) [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Chemometric Approaches

Successful implementation relies on a combination of hardware, software, and analytical frameworks.

Table 3: Essential toolkit for non-destructive food analysis research.

| Category | Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumentation | Portable NIR/Raman Spectrometer | For in-situ, field-based data collection [14]. |

| Data Analysis | Chemometrics Software (e.g., with PCA, PLS, SVM algorithms) | For extracting meaningful information from complex spectral data [2]. |

| Advanced Sensing | SERS Substrates (e.g., gold nanoparticles, nanostructured surfaces) | To dramatically enhance Raman signals for trace-level detection [4]. |

| Sample Handling | Microfluidic Chips ("Lab-on-a-Chip") | To automate and miniaturize sample handling, often integrated with SERS for pathogen detection [4]. |

| Data Integration | Cloud Computing & IoT Platforms | For storing, sharing, and processing large spectral datasets, enabling real-time decision-making [14]. |

| 1,4-DPCA | DpC|Di-2-pyridylketone 4-cyclohexyl-4-methyl-3-thiosemicarbazone | Di-2-pyridylketone 4-cyclohexyl-4-methyl-3-thiosemicarbazone (DpC) is a potent, second-generation iron chelator for cancer research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human or veterinary diagnostics or therapeutic use. |

| MAY0132 | MAY0132, MF:C16H15ClF3N, MW:313.74 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Chemometric Workflow

Modern analysis often involves sophisticated data fusion and machine learning strategies, as shown in the workflow below.

Diagram 2: Advanced data analysis workflow.

- Data Fusion: Combines data from multiple sources (e.g., NIR and Raman) to improve model accuracy and robustness. This can occur at different levels:

- Low-level: Merging raw data matrices.

- Mid-level: Combining features extracted from each data source (e.g., principal components).

- High-level: Combining the predictions from individual models [14].

- Machine Learning: Algorithms like support vector machines (SVM) and deep learning networks can model complex, non-linear relationships in spectral data, further enhancing predictive ability and enabling the identification of subtle patterns indicative of fraud or contamination [2] [14].

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite their transformative potential, several challenges hinder the widespread adoption of non-destructive technologies.

- Economic and Technical Barriers: The initial cost of high-end spectroscopic instruments can be prohibitive for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) [15]. Additionally, technical challenges such as signal instability in heterogeneous food matrices, model transferability between instruments, and the need for large, robust calibration datasets remain significant hurdles [13] [15].

- Expertise Gap: The effective use of these technologies requires expertise in both instrumental operation and chemometric data analysis, a skillset not always present in industrial quality control labs [15].

Future development is focused on bridging these gaps through several key innovations:

- Instrument Miniaturization and Portability: The continued development of compact, low-cost, and handheld spectrometers (e.g., smartphone-integrated NIR) is making the technology more accessible and suitable for field use [14].

- AI and Automation: The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning automates data analysis, improves model calibration and transferability, and facilitates real-time decision-making [13] [14].

- Hybrid Platforms: The development of hybrid systems (e.g., HSI-SERS, electrochemical-fluorescence) offers synergistic advantages, such as enhanced specificity and multiplexing capabilities for detecting multiple contaminants simultaneously [13].

Non-destructive, green analytical tools represent the future of food quality control research and application. Techniques like NIR, Raman, and HSI, empowered by advanced chemometrics and AI, offer a powerful alternative to traditional destructive methods. They enable rapid, in-situ, and environmentally friendly assessment of food safety, quality, and authenticity. While challenges related to cost, model robustness, and expertise persist, ongoing trends in miniaturization, data fusion, and automation are steadily overcoming these barriers. The adoption of these technologies is pivotal for building a more transparent, efficient, and sustainable global food supply chain, ultimately ensuring the delivery of safe and high-quality products to consumers.

Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) represent two cornerstone analytical techniques for trace element analysis in food quality control. These methods provide the sensitivity, accuracy, and multi-element capabilities essential for ensuring food safety, nutritional quality, and authenticity. Within a broader spectroscopy research framework, these techniques address critical analytical challenges in complex food matrices, from detecting toxic heavy metal contaminants to verifying nutritional mineral content and geographical origin. The fundamental difference between these techniques lies in their detection mechanisms: ICP-OES measures the light emitted by excited atoms or ions, while ICP-MS separates and detects ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio [19]. This technical guide examines the operational principles, methodological considerations, and practical applications of both techniques, providing researchers with a comprehensive resource for their analytical workflows.

Fundamental Techniques: ICP-OES and ICP-MS

ICP-OES: Principles and Applications

ICP-OES utilizes an argon plasma, sustained by a radio frequency (RF) generator, to atomize and ionize sample constituents. The extreme plasma temperatures (6000-10000 K) excite electrons to higher energy states. As these electrons return to ground state, they emit photons at characteristic wavelengths specific to each element [20]. The intensity of this emitted light is directly proportional to the concentration of the element in the sample [20]. A spectrometer disperses this light, allowing for simultaneous measurement of multiple elements.

Key applications in food analysis include multi-element screening for nutritional and toxic elements [21] [22], with recent studies demonstrating its use for profiling ten trace elements (As, Pb, Cr, Zn, Fe, Co, Cd, Ni, Mn, Al) in coffee [4] and metals in pet food [21]. The technique offers a linear dynamic range of up to six orders of magnitude (10â¶), making it suitable for analyzing elements across wide concentration ranges [19].

ICP-MS: Principles and Applications

ICP-MS similarly uses an argon plasma for sample atomization and ionization. However, instead of measuring emitted light, it extracts ions from the plasma into a mass spectrometer, which separates them according to their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) [19]. This process provides exceptional sensitivity with detection limits often extending to parts per trillion (ppt) levels [19], and the capability to analyze over 80 elements [19].

Its primary applications in food control encompass ultra-trace analysis of toxic elements like Pb, Hg, and Cd [22], speciation studies to determine different forms of elements (e.g., via hyphenation with HPLC) [23], and authenticity studies through isotopic fingerprinting [24] [4]. The linear dynamic range for ICP-MS can reach eight orders of magnitude (10â¸) in modern instruments [19].

Technical Comparison and Selection Criteria

The choice between ICP-OES and ICP-MS depends on specific analytical requirements. Table 1 provides a direct comparison of their key technical characteristics.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of ICP-OES and ICP-MS for Elemental Analysis

| Parameter | ICP-OES | ICP-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Method | Measurement of emitted light intensity [19] | Measurement of mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of ions [19] |

| Typical Detection Limits | Parts per billion (ppb) to parts per million (ppm) level [22] [19] | Parts per trillion (ppt) to ppb level [22] [19] |

| Linear Dynamic Range | Up to 6 orders of magnitude (10â¶) [19] | Up to 8 orders of magnitude (10â¸) [19] |

| Elemental Coverage | ~73 elements; broad multi-element capability [19] | ~82 elements; includes isotopic information [19] |

| Primary Interferences | Spectral (overlapping emission lines) [19] | Isobaric (ions of same m/z), polyatomic [22] [19] |

| Sample Throughput | High; relatively short run times [19] | High; most analyses under 1 minute [19] |

| Operational Complexity & Cost | Lower initial and operational costs; simpler method development [19] | Higher initial cost (2-3x ICP-OES); requires high-purity reagents; more complex method development [19] |

Beyond the specifications in Table 1, practical selection depends on the analytical problem. ICP-OES is ideal for routine analysis of elements at higher concentrations (e.g., nutritional minerals like Mg, P, Fe), for high-throughput screening of samples with complex matrices, and when budget constraints are a primary concern [22] [19]. ICP-MS is the preferred technique when ultra-trace level detection is required (e.g., for regulated heavy metals like arsenic and cadmium), when isotopic information is needed, or for analyzing challenging elements that are difficult to determine with ICP-OES [22] [19].

The following decision pathway provides a visual guide for selecting the appropriate technique:

Experimental Protocols in Food Analysis

Sample Preparation Workflow

Robust sample preparation is critical for accurate results. The general workflow for solid food samples is summarized below, incorporating key quality control measures:

A typical microwave-assisted digestion protocol for a food sample (e.g., 0.5 g) uses 6 mL of trace metal grade nitric acid (HNO₃) and 1 mL of hydrochloric acid (HCl) [22]. HNO₃ is preferred for its oxidizing properties and the high solubility of nitrate salts [20]. For plant-based materials containing silicates, hydrofluoric acid (HF) may be required, with boric acid used for neutralization [20]. Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) can be added to aid oxidation of organic components [20].

ICP-OES Method for Metal Quantification in Pet Food

A recent study on metal content in pet food exemplifies a rigorous ICP-OES method [21]:

- Sample Analysis: Prepared samples were analyzed for ten metals (Al, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, Pb, Zn) via ICP-OES, run in triplicate.

- Quality Control: Blanks were run with each sample batch to monitor reagent contamination. A calibration standard was re-run every 10 samples as a check. Relative standard deviations (RSD) among replicates were maintained below 15%.

- Calibration & Validation: Calibration curves were established using a blank and five standards with a regression coefficient (R²) of at least 0.999. Limits of detection (LOD) were estimated from blank analyses.

ICP-MS Method for Toxic Elements in Food

For determining toxic elements at lower concentrations, a comparable ICP-MS method can be employed [22]:

- Interference Management: Cell-based ICP-MS (e.g., Dynamic Reaction Cell) is used to remove polyatomic interferences. For example, arsenic (mass 75) is measured using a DRC to compensate for the interference from ³âµClâ´â°Ar [22].

- Validation: Method accuracy is confirmed through analysis of certified reference materials (CRMs) such as NIST 1548a (Typical Diet) [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Proper selection of reagents and materials is fundamental to preventing contamination and ensuring analytical accuracy. Table 2 lists key items for sample preparation and analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ICP Analysis

| Item | Function / Purpose | Technical Specification / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Primary digesting agent for organic matrices [20]. | Trace metal grade; high purity to minimize blank values [22]. |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) | Auxiliary digesting acid [22]. | Trace metal grade; can introduce spectral interferences in ICP-OES [20]. |

| Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) | Dissolution of silicates in plant materials [20]. | Requires specialized PTFE labware and extreme caution; excess neutralized with boric acid [20]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) | Oxidizing agent for enhanced digestion of organic components [20]. | Trace metal grade. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Method validation and quality assurance [22]. | Matrix-matched (e.g., NIST 1548a Typical Diet) [22]. |

| ICP Multielement Standard | Calibration and quality control during analysis [21]. | Certified plasma emission ICP standard. |

| Ultrapure Water | Sample dilution and all reagent preparation [21]. | ICP-OES grade or equivalent (e.g., 18 MΩ·cm resistivity). |

| Polypropylene Filters | Removal of undissolved solids post-digestion [20]. | 0.45 μm or 0.22 μm; preferred over glass fiber to avoid metal adsorption/introduction [20]. |

| Remdesivir-d4 | Remdesivir-d4, MF:C27H35N6O8P, MW:606.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| TEAD-IN-12 | TEAD-IN-12, MF:C22H20F3N3O3, MW:431.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application in Food Quality Control: A Regulatory Perspective

In food quality control, ICP-OES and ICP-MS address distinct but complementary challenges. Current regulatory frameworks, such as those from the U.S. FDA and the European Pet Food Industry Federation (FEDIAF), provide foundational safety standards but often fail to fully account for chronic, low-level exposure to heavy metals in food products [21]. This regulatory gap underscores the need for sensitive monitoring.

Research using ICP-OES in pet food has revealed significant variability in metal content across different brands and types (wet vs. dry), highlighting the necessity for batch-level testing of high-risk ingredients like organ meats and fish [21]. For human foods, ICP-MS is indispensable for enforcing low regulatory limits, as demonstrated in its ability to detect lead in fruit drinks at levels that would be missed by ICP-OES [22]. Furthermore, the multi-element profiling capability of both techniques is increasingly used with chemometric analysis to verify the geographical origin and authenticity of foodstuffs like chicken meat and olive oil [25] [4].

ICP-OES and ICP-MS are powerful and complementary analytical techniques that form the backbone of modern trace element analysis in food quality control. ICP-OES offers robust, high-throughput analysis for major and minor elements, while ICP-MS provides unparalleled sensitivity for ultra-trace contaminants and isotopic analysis. The choice between them should be guided by specific analytical needs, including required detection limits, sample matrix, regulatory demands, and available resources. As the field advances, the integration of these techniques with chemometrics and sample preparation automation will further enhance their role in ensuring food safety, authenticity, and nutritional quality, solidifying their status as indispensable tools in spectroscopic research.

Vibrational spectroscopy encompasses a suite of analytical techniques that probe molecular structures by measuring their interaction with infrared light. These techniques are grounded in the principle that molecules vibrate at specific frequencies when exposed to electromagnetic radiation. The resulting absorption and scattering patterns create a unique "molecular fingerprint" for any given sample, enabling precise identification and quantification of its chemical constituents [26] [27]. In the context of modern food quality control research, the application of these non-destructive, rapid tools is revolutionizing how the industry ensures the safety, authenticity, and nutritional value of food products, from raw ingredients to finished goods [28] [14].

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) and Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy are two of the most prominent vibrational techniques. They are particularly powerful for analyzing organic compounds and are increasingly integrated with advanced chemometric methods and artificial intelligence to extract meaningful information from complex spectral data [26] [10]. This technical guide delves into the core principles, methodologies, and applications of these techniques, providing a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists engaged in chemical analysis and product development.

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations

Fundamental Molecular Vibrations

At the heart of vibrational spectroscopy is the excitation of molecular bonds. When a molecule is irradiated with infrared light, it absorbs energy at frequencies that match the natural vibrational frequencies of its chemical bonds, such as C-H, O-H, and N-H. These vibrations include stretching (symmetrical and asymmetrical) and bending (scissoring, rocking, wagging, twisting) modes. The specific frequencies at which energy is absorbed are dictated by the bond strength and the masses of the atoms involved, making the infrared spectrum a direct reflection of the sample's molecular composition [26] [29].

The following diagram illustrates the foundational principle of how light interacts with a molecule to produce a spectrum, which serves as its molecular fingerprint.

FTIR vs. NIR Spectroscopy: A Comparative Analysis

While both FTIR and NIR spectroscopy measure molecular vibrations, they operate in different regions of the electromagnetic spectrum and provide complementary information.

FTIR Spectroscopy typically operates in the mid-infrared (MIR) region (approximately 4000–400 cmâ»Â¹). This region corresponds to the fundamental vibrations of molecular bonds. As a result, FTIR spectra feature sharp, well-defined peaks that are highly specific for identifying functional groups and elucidating molecular structure [26] [27]. It is often the preferred method for in-depth structural analysis, such as determining the secondary structure of proteins [26].

NIR Spectroscopy utilizes the near-infrared region (approximately 780–2500 nm or 12,820–4000 cmâ»Â¹). This region captures overtones and combination bands of fundamental vibrations, primarily from hydrogen-containing groups (O-H, N-H, C-H) [26] [5]. NIR absorption bands are typically broader and overlap more than in the MIR, making direct interpretation challenging. However, this complexity is readily decoded with chemometrics, making NIR ideal for rapid quantitative analysis of bulk components like protein, moisture, and fat in complex matrices [7] [30].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of FTIR and NIR Spectroscopy

| Feature | FTIR (Mid-IR) | NIR |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Region | 4000 – 400 cmâ»Â¹ | 12,820 – 4000 cmâ»Â¹ (780 – 2500 nm) |

| Type of Bands | Fundamental vibrations | Overtones and combination bands |

| Spectral Appearance | Sharp, well-resolved peaks | Broad, overlapping bands |

| Primary Analytical Use | Qualitative structural analysis | Quantitative bulk analysis |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal to moderate (e.g., ATR) | Minimal to none |

| Penetration Depth | Lower (micrometers) | Higher (millimeters) |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The successful application of FTIR and NIR spectroscopy relies on robust experimental workflows, which can be broken down into three critical stages, as shown below.

Sample Preparation and Handling

A significant advantage of vibrational spectroscopy is its minimal sample preparation requirement, which facilitates high-throughput analysis.

- Solid Samples (Powders, Grains): Samples often require homogenization via grinding to a consistent particle size to reduce light scattering and ensure spectral reproducibility. For FTIR, the Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) accessory is widely used, where the sample is pressed directly onto a crystal for measurement with little to no preparation [27]. For NIR, samples can be analyzed as-is in a cup or vial using a diffuse reflectance module [26] [31].

- Liquid Samples (Milk, Oils): Liquids can be analyzed directly in transmission or reflectance cells. Care must be taken to ensure consistent path length and to avoid air bubbles, which can scatter light and introduce noise [5] [30].

- Intact Samples (Seeds, Fruits): NIR spectroscopy is uniquely suited for non-destructive analysis of whole, intact samples. For instance, single buckwheat seeds can be analyzed directly in a reflectance module, preserving the sample for future use [31].

Spectral Acquisition Parameters

Precise instrument configuration is vital for acquiring high-quality, reproducible data.

- FTIR Acquisition: A typical protocol involves collecting 16-64 scans per spectrum at a resolution of 4-8 cmâ»Â¹ to ensure a high signal-to-noise ratio. The background spectrum (e.g., from the empty ATR crystal) must be collected under identical conditions and subtracted from the sample spectrum [26].

- NIR Acquisition: For quantitative analysis of agricultural products, a protocol might specify 32 scans per sample across the 900-1700 nm range with a resolution of 7-10 nm, as demonstrated in a study on buckwheat [31]. The use of a portable NIR spectrometer enables these measurements to be taken in the field or at-line in a processing facility [14].

Data Processing and Chemometric Analysis

Raw spectral data is rich in information but requires processing to extract meaningful insights. This is where chemometrics—the application of mathematical and statistical methods to chemical data—becomes indispensable [26] [5].

Spectral Preprocessing: Raw spectra are affected by physical light scattering and instrumental noise. Preprocessing techniques are applied to remove these non-chemical artifacts.

Model Development: After preprocessing, calibration models are built to correlate spectral data with reference chemical data.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is an unsupervised method used for exploratory data analysis and identifying natural clustering or outliers in the data.

- Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) is the most common method for developing quantitative models to predict the concentration of an analyte (e.g., protein content).

- Support Vector Machine (SVM) and other machine learning algorithms are increasingly used to handle complex, non-linear relationships in spectral data, often outperforming traditional methods [31] [10].

Table 2: Key Chemometric Techniques in Vibrational Spectroscopy

| Technique | Type | Primary Function | Typical Application in Food Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNV / MSC | Preprocessing | Correct for light scattering effects | Analysis of powdered ingredients, grains |

| Savitzky–Golay Derivative | Preprocessing | Enhance spectral resolution, remove baseline offset | Resolving overlapping protein and water bands |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Unsupervised | Dimensionality reduction, outlier detection | Identifying geographical origin, detecting abnormal samples |

| Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) | Supervised | Build quantitative predictive models | Predicting protein, moisture, fat content |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Supervised | Classification and regression for complex data | Discriminating between authentic and adulterated oils |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Vibrational Spectroscopy Experiments

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ATR Crystal (Diamond, ZnSe) | Enables internal reflectance for FTIR measurement of solids and liquids without preparation. | Pressing a powder sample onto the crystal for direct measurement of protein structure [27]. |

| High-Purity Solvents (e.g., Hexane, Methanol) | Extraction of specific compounds for reference analysis or sample cleaning. | Defatting oilseed meals prior to protein analysis to reduce spectral interference [26]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Calibration and validation of spectroscopic models against gold-standard methods. | Using flour with known protein content (via Kjeldahl) to build a PLSR model for NIR [26]. |

| SERS Substrates (Gold/Silver Nanoparticles) | Enhances weak Raman signals by several orders of magnitude for trace-level detection. | Detecting pesticide residues or mycotoxins in fruit juices at parts-per-billion levels [14] [10]. |

| Spectralon or White Reference Tile | Provides a calibrated, highly reflective surface for instrument calibration in NIR. | Performing a white reference scan before sample measurement to define 100% reflectance [14]. |

| CYP11B2-IN-2 | CYP11B2-IN-2, MF:C16H13FN2O2, MW:284.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| WD6305 | WD6305, MF:C61H75F2N11O5S, MW:1112.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Applications in Food Quality Control: Quantitative Data

The utility of FTIR and NIR spectroscopy is best demonstrated through concrete quantitative applications in food research and quality control.

Table 4: Quantitative Applications of Vibrational Spectroscopy in Food Analysis

| Analytical Target | Food Matrix | Technique | Model Performance | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Content | Tartary Buckwheat | NIR + SVR | R²p = 0.9247, RMSEP = 0.3906 | [31] |

| Total Flavonoids | Tartary Buckwheat | NIR + SVR | R²p = 0.9811, RMSEP = 0.1071 | [31] |

| Protein Content | Lentils | NIR + PLSR | High accuracy vs. reference methods | [26] |

| Geographical Origin | Tea Oil | NIR + CNN | Prediction accuracy of 97.92% | [5] |

| Adulteration | Peanut Oil | NIR + PLS | R² > 0.9311 | [5] |

| Protein Secondary Structure | Soy Protein Isolate | FTIR | Quantification of α-helix, β-sheet ratios | [26] |

The field of vibrational spectroscopy is being propelled forward by several key technological trends. The miniaturization of spectrometers into handheld and portable devices allows for real-time, on-site analysis at any point in the supply chain, from the farm to the processing plant [14]. Furthermore, the integration of data fusion strategies, which combine data from multiple spectroscopic techniques (e.g., NIR, FTIR, Raman) or from spectroscopy and other sensors, provides a more holistic and accurate characterization of food samples [14] [10]. Finally, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and deep learning are revolutionizing spectral data interpretation. These algorithms can automatically extract subtle patterns from complex spectra, improving the accuracy of predictive models and enabling automation in quality control systems as part of the Industry 4.0 framework [26] [28] [10].

In conclusion, FTIR and NIR spectroscopy are powerful, versatile tools for molecular fingerprinting. FTIR excels in providing detailed molecular-level structural information, while NIR offers unparalleled speed and efficiency for quantitative analysis of bulk components. Their non-destructive nature, minimal sample preparation requirements, and synergy with advanced chemometrics make them indispensable in modern food quality control research. As technology continues to evolve toward miniaturization, data fusion, and AI-driven analytics, these spectroscopic techniques are poised to become even more central to ensuring food safety, authenticity, and quality.

Technique Selection and Real-World Applications in Food Analysis

Food adulteration represents a significant global challenge, impacting consumer health, eroding market trust, and causing substantial economic losses. This whitepaper examines the application of advanced spectroscopic techniques for authenticating three high-risk commodities: honey, olive oil, and spices. Framed within the broader context of spectroscopy in food quality control research, this technical guide details how these non-destructive methods, combined with modern chemometrics, provide robust solutions for detecting economically motivated adulteration. The transition from traditional, destructive analytical methods to rapid, spectroscopic techniques aligns with the Food 4.0 framework, emphasizing digitalization and real-time monitoring throughout the food supply chain [27]. This review synthesizes recent advancements (2023-2025) to provide researchers and drug development professionals with detailed methodologies, performance data, and practical tools for implementation.

Core Spectroscopic Techniques and Principles

The authentication of food products relies on detecting unique chemical fingerprints that are altered by adulteration. Vibrational spectroscopy techniques are particularly powerful for this purpose.

- Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy: Probes overtones and combinations of fundamental molecular vibrations, particularly from C-H, O-H, and N-H bonds. It is highly versatile for analyzing diverse sample types, from powders to liquids, with minimal preparation [32] [27].

- Mid-Infrared (MIR) and Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: Focuses on the fundamental vibrational transitions of chemical bonds. The integration of Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) modules has significantly enhanced its utility for direct analysis of complex food matrices [4] [27].

- Raman Spectroscopy: Compliments IR spectroscopy by detecting changes in molecular polarizability. It is especially sensitive to symmetric covalent bonds (e.g., C-C, C=C) and is less affected by water, making it suitable for high-moisture foods [4] [27].

- Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS): A rapid, elemental analysis technique where a high-energy laser pulse ablates a minute amount of material to create a plasma. The emitted light provides a unique elemental fingerprint of the sample [33].

- Fluorescence Spectroscopy: Measures the emission of light from molecules after they have absorbed photons. Side-front face fluorescence spectroscopy is highly sensitive to minor chemical changes caused by adulteration [34].

The effective interpretation of the complex data generated by these techniques requires chemometrics—the application of mathematical and statistical methods to extract meaningful information [2]. The standard workflow is outlined below.

Case Studies in Food Authentication

Honey Adulteration

Honey is frequently adulterated with inexpensive sweeteners like corn syrup or by mixing high-value single-flower honey with lower-cost multi-flower varieties [35].

Table 1: Advanced Methods for Honey Authentication

| Technique | Adulterant/Target | Detection Limit/Resolution | Chemometric Model(s) | Reported Accuracy/Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas Sensor (BME688) [35] | Multi-flower honey in chestnut honey | 5% - 25% mixture resolution | BCLF, MLP, VCLF, KNN | Up to 100% classification for 25% blends; High precision for 5% resolution |

| Hyperspectral Imaging [36] | Sugar syrups (e.g., HFCS, sucrose) | - | ANN, SVM, KNN, Random Forest | >98% classification accuracy |

| FTIR Spectroscopy [37] | Corn syrup, rice syrup | - | Chemometric models | Effective for sweetener detection |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Gas Sensor with Machine Learning

This protocol is adapted from the study using the BME688 gas sensor for rapid detection of honey adulteration [35].

- Sample Preparation: Pure, high-value single-flower honey (e.g., chestnut honey) is mixed with a lower-value multi-flower honey at specific ratios (e.g., 0%, 5%, 10%, ..., 100% adulteration). A minimum of three replicates per ratio is recommended.

- Data Acquisition: Using the BME688 gas sensor, which detects a broad spectrum of gases including VOCs and VSCs in the parts per billion (ppb) range. A fixed mass of each honey mixture is placed in a sealed vial and allowed to equilibrate. The sensor headspace is then analyzed, capturing a "digital fingerprint" of the volatile composition. Multiple scans per sample are performed to ensure data robustness.

- Data Preprocessing: The raw sensor data is preprocessed to minimize noise and correct for baseline drift. Techniques such as Standard Normal Variate (SNV) or Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) may be applied.

- Machine Learning & Modeling: The preprocessed sensor data (features) are linked to the known adulteration levels (labels). Various machine learning algorithms are trained and validated:

- Algorithms: Broad Learning Classifier (BCLF), Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), Voting Classifier (VCLF), and k-Nearest Neighbors (KNN).

- Validation: Models are evaluated using hold-out validation or k-fold cross-validation. Performance is assessed based on classification accuracy for identifying mixture ratios and detection limits.

Olive Oil Adulteration

Extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) is a high-value product commonly adulterated with lower-quality oils such as pomace, soybean, sunflower, and corn oils [33] [34].

Table 2: Advanced Methods for Olive Oil Authentication

| Technique | Adulterant/Target | Detection Limit/Resolution | Chemometric Model(s) | Reported Accuracy/Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIBS [33] | Pomace, soybean, sunflower, corn oils | 10% - 90% mixtures | PCA, LDA, SVM, Logistic Regression, Gradient Boosting | High classification accuracies (up to 95-100%) |

| Side-Front Face Fluorescence [34] | Virgin, refined, pomace oils in EVOO | As low as 5% | Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) | Up to 100% classification accuracy |

| FTIR & Raman Spectroscopy [33] | Hazelnut oil in EVOO | From 1% to 90% | k-NN, Continuous Locality Preserving Projections | High discrimination accuracies |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS)

This protocol is based on work detecting olive oil adulteration using LIBS and machine learning [33].

- Sample Preparation: Pure EVOO samples are adulterated with lower-quality oils (e.g., pomace, corn, soybean, sunflower oil) at concentrations ranging from 10% to 90% (e.g., in 10% increments). Each mixture should be homogenized thoroughly.

- LIBS Spectral Acquisition: A pulsed laser (e.g., Nd:YAG) is focused onto a small volume of the oil sample, generating a microplasma. The light emitted from this plasma is collected and dispersed by a spectrometer, yielding a full spectrum that serves as an elemental fingerprint. Multiple laser shots per sample are averaged to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Data Preprocessing: Raw LIBS spectra undergo preprocessing. This includes background subtraction, normalization to a reference line or total intensity, and wavelength calibration. Techniques like Savitzky-Golay smoothing can be applied to reduce noise.

- Chemometric Analysis:

- Exploratory Analysis: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is used to visualize natural clustering and identify outliers.

- Classification Modeling: Supervised algorithms such as Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Gradient Boosting (GB) are trained to distinguish pure from adulterated oils and to identify the specific adulterant.

- Validation: Model performance is rigorously tested via internal cross-validation and external validation using a separate test set not used in model training.

Spice Adulteration

Spices are vulnerable to adulteration with foreign materials, including other plant parts, synthetic dyes, and hazardous substances [32] [38].

Table 3: Advanced Methods for Spice Authentication

| Technique | Adulterant/Target | Example Adulterants | Chemometric Model(s) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) [32] [38] | Bulking agents, foreign seeds | Olive leaves in oregano, walnut shells in cinnamon | PCA, PLS-DA, Machine Learning | Rapid, non-invasive, suitable for handheld devices |

| X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) [38] | Heavy metals/inorganic pigments | Lead chromate in turmeric | - | Direct detection of toxic elemental adulterants |

| Chromatography [38] | Synthetic dyes | Metanil Yellow in turmeric | - | High specificity for separating colorants |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) for Spices

This protocol outlines the use of NIRS, a cornerstone of modern, non-invasive spice analysis [32] [38].

- Sample Preparation & Presentation: Spice samples (both authentic and suspected adulterated) are ground to a consistent particle size to reduce light scattering effects. The powder is presented in a standardized sample cup. For quantitative analysis, calibration samples with known adulterant concentrations are prepared.

- Spectral Collection: NIR spectra are collected in diffuse reflectance mode across the wavelength range of 780-2500 nm. Each sample is scanned multiple times, and the spectra are averaged. The environment (e.g., temperature, humidity) should be controlled if possible.

- Spectral Preprocessing: Due to scattering from powder particles, preprocessing is critical. Standard Normal Variate (SNV) and Detrending are commonly applied to remove multiplicative interferences and baseline shifts. First or second derivatives (e.g., Savitzky-Golay derivatives) are used to enhance subtle spectral features and resolve overlapping peaks.

- Model Development and Deployment: