Advanced Strategies for Improving Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Spectroscopic Data: From Foundational Concepts to AI Applications

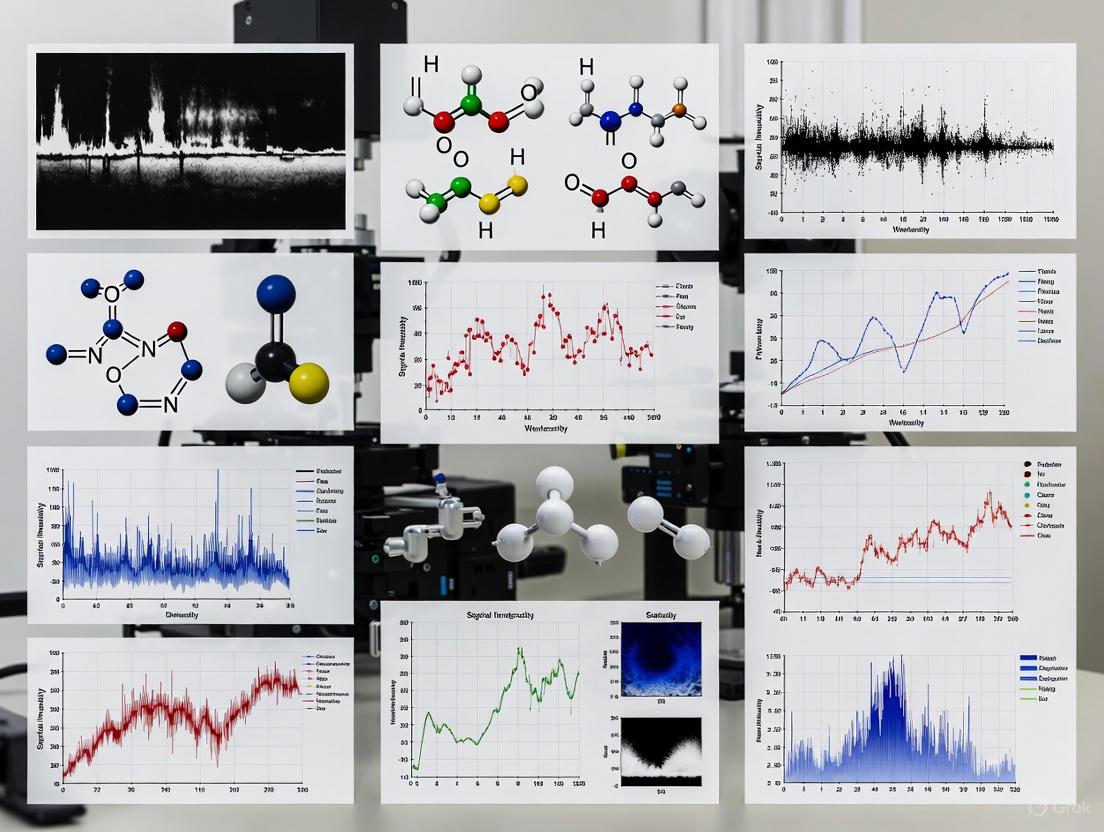

This comprehensive article explores advanced methodologies for enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in spectroscopic data analysis, specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Advanced Strategies for Improving Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Spectroscopic Data: From Foundational Concepts to AI Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive article explores advanced methodologies for enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in spectroscopic data analysis, specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. Covering both theoretical foundations and practical applications, the content examines traditional computational approaches like multi-pixel calculations and signal averaging alongside emerging artificial intelligence techniques. The article provides systematic troubleshooting guidance for common SNR challenges, discusses validation protocols according to international standards, and presents comparative analyses of different SNR enhancement strategies. By synthesizing current research and real-world case studies—including applications in planetary exploration and pharmaceutical analysis—this resource serves as an essential reference for professionals seeking to optimize spectroscopic detection limits, improve analytical precision, and implement robust SNR improvement protocols in biomedical and clinical research settings.

Understanding Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Fundamental Concepts and Measurement Principles in Spectroscopy

In spectroscopic analysis, the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a fundamental metric that compares the level of a desired analytical signal to the level of background noise. It quantifies how clearly a target analyte can be detected and measured amidst the inherent variability and interference present in any analytical system. A high SNR indicates a strong, clear signal, whereas a low SNR means the signal is obscured by noise, compromising detection reliability [1] [2].

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and the American Chemical Society (ACS) have established standardized methodologies for calculating SNR and defining the Limit of Detection (LOD). These standards provide a consistent statistical framework for determining the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably detected by an analytical method. The LOD is universally defined as the concentration that yields an SNR of 3, meaning the signal is three times greater than the background noise. This provides 99.9% confidence that the measured feature is a real signal and not a random noise fluctuation [3] [4] [5].

For researchers in drug development and other fields requiring precise trace analysis, understanding and correctly applying these standards is not merely a technical formality; it is essential for ensuring the accuracy, reproducibility, and regulatory compliance of their spectroscopic methods.

Standard SNR Calculation Methodologies

The IUPAC and ACS standards define SNR as the ratio of the measured signal (S) to the standard deviation of that signal (σS), which represents the noise [3]. The fundamental equation is:

SNR = S / σS

However, the practical application of this definition in spectroscopy, particularly Raman spectroscopy, varies, leading to different calculation methods and, consequently, different reported LODs for the same data [3].

Comparison of Single-Pixel vs. Multi-Pixel SNR Calculations

Research demonstrates that the choice of SNR calculation method significantly impacts the reported detection limits. These methods can be broadly categorized into two approaches [3]:

- Single-Pixel Method: This traditional method calculates the signal intensity based on only the center pixel of a Raman band. The noise is typically derived from the standard deviation of the baseline in a signal-free region of the spectrum.

- Multi-Pixel Methods: These methods use information from multiple pixels across the entire Raman band. This category includes:

- Multi-Pixel Area Method: The signal is calculated as the integrated area under the band.

- Multi-Pixel Fitting Method: A function (e.g., a Gaussian curve) is fitted to the band, and the signal is derived from the parameters of this fit.

A comparative study on data from the SHERLOC instrument aboard the Perseverance rover quantified the differences between these methods. The findings are summarized in the table below [3]:

Table 1: Impact of SNR Calculation Method on Detection Capability

| SNR Calculation Method | Reported SNR for Si-O Band | Relative Improvement in LOD | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Pixel | Baseline for comparison | -- | Simplicity |

| Multi-Pixel Area | ~1.2x higher | Significant decrease | Uses full band signal |

| Multi-Pixel Fitting | ~2x or more higher | Significant decrease | Uses full band signal; models band shape |

The critical implication is that multi-pixel methods provide a better (lower) Limit of Detection because they utilize the signal across the full bandwidth, making them more robust for detecting weak spectral features. For instance, a potential organic carbon feature observed by SHERLOC was calculated to have an SNR of 2.93 (below the LOD) using a single-pixel method, but an SNR of 4.00–4.50 (well above the LOD) using multi-pixel methods [3].

Experimental Protocol: Measuring SNR for a Spectrometer

The following protocol, based on standard practices, details how to characterize the SNR of a spectrometer system [6] [7].

- Setup: Illuminate the spectrometer with a stable, broadband light source (e.g., a calibrated lamp) using an optical fiber. The light should be configured so that the spectral peak is nearly saturated at a low integration time.

- Dark Measurement: Collect a set of 25-50 spectra with the light source shut off or the entrance closed to measure the dark signal and its associated electronic noise.

- Signal Measurement: Collect a set of 25-50 spectra with the light source on.

- Calculation:

- For each pixel (or wavelength) in the spectrum, calculate the mean signal of the light measurements (( S )) and the mean dark signal (( D )).

- For the same pixel, calculate the standard deviation (( σ )) of the light measurements.

- The SNR for that pixel is given by: SNR = (( S - D ) ) / ( σ ).

- Analysis: Plot the calculated SNR values against the signal intensity (( S - D )) for all pixels to generate an SNR response curve for the entire spectrometer. The maximum SNR is typically reported at or near detector saturation [7].

Diagram: Workflow for Experimental SNR Measurement

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions and Materials for SNR Optimization

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | To minimize background signal (noise) caused by fluorescent or absorbing impurities in the mobile phase or sample matrix. | Essential for UV-Vis and fluorescence spectroscopy. Critical for liquid chromatography-coupled systems (LC-MS, HPLC-UV) [8]. |

| Stable Broadband Light Source | To provide a consistent and uniform illumination for system characterization and SNR measurement. | Used for initial spectrometer SNR validation and periodic performance checks [7]. |

| Standard Reference Material | To provide a known and stable signal for method development, calibration, and comparing SNR across different instruments or days. | e.g., A stable fluorescent dye or a Raman scatterer with a well-characterized peak [3]. |

| Optical Bandpass Filter | To isolate specific wavelengths, reducing stray light and background noise for more sensitive measurements. | Placed between the light source and the detector to improve SNR in specific spectral regions [2]. |

| Temperature-Controlled Sample Holder | To minimize thermally-induced signal drift and noise caused by fluctuations in the sample or instrument environment. | Improves baseline stability in sensitive measurements [8]. |

| Cowaxanthone B | Cowaxanthone B, MF:C25H28O6, MW:424.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ac-DMQD-CHO | Ac-DMQD-CHO|Caspase-3 Inhibitor|Research Compound | Ac-DMQD-CHO is a potent, selective caspase-3 inhibitor for apoptosis research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Improving SNR in Spectroscopic Experiments

FAQ: My signal is too weak and close to the noise floor. What can I do to improve my SNR?

Low SNR is a common challenge in trace analysis. The following troubleshooting guide outlines practical steps to increase signal, reduce noise, or both.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio

| Problem Area | Troubleshooting Action | Technical Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Strength | Increase illumination power or laser intensity (if sample permits). | Directly increases the photon flux from the analyte, boosting the signal [2]. |

| Increase detector integration time. | Collects photons over a longer period, linearly increasing the signal [7]. | |

| Use a detector with higher quantum efficiency or one matched to your spectral range. | Improves the probability of converting incident photons into a measurable electrons [7]. | |

| For UV-Vis: Operate at the analyte's absorbance maximum. | Maximizes the signal strength for a given concentration [8]. | |

| Noise Sources | Use frame averaging or spectral scanning. | Averaging N spectra reduces random noise by a factor of √N [9] [7]. |

| Control temperature for the sample, detector, and key optical components. | Reduces thermal drift and associated low-frequency (1/f) noise [2] [8]. | |

| Ensure reagent and solvent purity to reduce chemical background. | Minimizes baseline noise from fluorescent or scattering impurities [8]. | |

| Employ sample cleanup (e.g., filtration, solid-phase extraction). | Removes interferents that contribute to background noise and signal suppression [8]. | |

| Data Processing | Apply post-processing smoothing (e.g., Savitsky-Golay, Gaussian convolution). | Reduces high-frequency noise in the acquired spectrum [4]. |

| Use multi-pixel SNR calculation methods for Raman bands. | More accurately quantifies weak signals by utilizing information across the entire spectral feature, improving effective LOD [3]. |

FAQ: How do I determine if my peak is a real signal or just noise?

According to IUPAC standards, a peak is generally considered statistically significant and real if its Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is 3 or greater [3] [4] [5]. This threshold provides 99.9% confidence that the observed feature is not a random fluctuation of the baseline noise. For quantitative work, a higher SNR of 10 is typically required for the Limit of Quantification (LOQ) [4].

FAQ: Can I use software to improve a low SNR after I've collected my data?

Yes, but with caution. Software smoothing (e.g., Savitsky-Golay, Fourier transform, wavelet transform) can reduce apparent noise and is an integral part of many analytical workflows [4]. However, it is critical to understand that these algorithms process the raw data and cannot recover information that is completely lost in the noise. Over-smoothing can also distort peak shapes, suppress weak but real signals, and broaden peaks, potentially leading to inaccurate integration and interpretation. The most reliable approach is always to optimize SNR during data acquisition wherever possible [4] [9].

Diagram: Decision Tree for SNR Improvement Strategies

The Critical Relationship Between SNR, Limit of Detection (LOD), and Analytical Sensitivity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental relationship between Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), Limit of Detection (LOD), and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ)?

A1: The Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a primary determinant of an method's detection capabilities. The LOD is the lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably distinguished from the background noise, while the LOQ is the lowest concentration that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy [4] [10]. According to international guidelines, an SNR of 3:1 is generally considered acceptable for estimating the LOD, while an SNR of 10:1 is required for the LOQ [4]. In practice, for real-life samples with challenging conditions, a more conservative SNR of 3:1 to 10:1 for LOD and 10:1 to 20:1 for LOQ is often applied to ensure robustness [4].

Q2: Why might my method fail to detect impurities known to be present in my sample, and how is this related to SNR?

A2: If the signal from a substance is not sufficiently distinguishable from the unavoidable baseline noise of the analytical method—meaning the signal is similar to or smaller than the noise—the substance will not be detected [4]. This is a direct consequence of a low SNR. Furthermore, the use of data smoothing filters (e.g., time constants in UV detectors) to reduce baseline noise can, if over-applied, flatten smaller substance peaks until they are no longer distinguishable from the detector baseline, effectively raising the practical LOD [4].

Q3: What are the best practices for improving SNR without losing critical data from low-concentration analytes?

A3: The best approach is to optimize the analytical method to either increase the signal of the sample substance or reduce the baseline noise of the analytical procedure [4]. If mathematical smoothing is necessary, use post-acquisition processing methods (e.g., Gaussian convolution, Savitsky-Golay smoothing, Fourier, or wavelet transforms) on the preserved raw data. This allows you to undo smoothing steps or apply different filters without permanent data loss, unlike electronic filters applied during data acquisition [4]. Always check if the SNR is sufficient with less or even without data filtering first.

Key Quantitative Standards for SNR, LOD, and LOQ

The following table summarizes the standard and practical SNR values associated with detection and quantification limits, as per international guidelines and real-world application.

Table 1: SNR Standards for LOD and LOQ

| Parameter | Formal Guideline (e.g., ICH Q2) | Practical "Real-Life" SNR (Example) | Key Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | SNR of 3:1 [4] | SNR between 3:1 and 10:1 [4] | The lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably detected, but not necessarily quantified, from the background noise [10]. |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | SNR of 10:1 [4] | SNR from 10:1 to 20:1 [4] | The lowest analyte concentration that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy [10]. |

Understanding the Limits: LoB, LoD, and LoQ

A comprehensive understanding of low-concentration analysis requires distinguishing between three key limits. The Limit of Blank (LoB) describes the noise of the method, while the Limit of Detection (LoD) and Limit of Quantitation (LoQ) define the capabilities for reliably detecting and quantifying the analyte, respectively [10].

Table 2: Statistical Definitions of LoB, LoD, and LoQ

| Parameter | Sample Type | Calculation (Parametric) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit of Blank (LoB) | Sample containing no analyte [10] | mean_blank + 1.645(SD_blank) [10] |

The highest apparent analyte concentration expected from a blank sample. It represents the 95th percentile of the blank signal distribution [10]. |

| Limit of Detection (LoD) | Sample with low concentration of analyte [10] | LoB + 1.645(SD_low concentration sample) [10] |

The lowest concentration likely to be reliably distinguished from the LoB. Ensures a 95% probability that a true low-level sample will be detected [10]. |

| Limit of Quantitation (LoQ) | Sample at or above the LoD [10] | LoQ ≥ LoD (Determined by meeting predefined bias/imprecision goals) [10] |

The lowest concentration at which the analyte can be quantified with defined levels of bias and imprecision [10]. |

Workflow for Determining Analytical Limits

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for SNR and Sensitivity Optimization

| Item / Solution | Critical Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Blank Matrix | A sample containing all matrix constituents except the analyte, essential for accurate LoB determination and assessing background interference [11]. |

| Ultra-Low Concentration Calibrators | Samples with known, low concentrations of analyte used to empirically determine the LoD and LoQ and verify method performance at the detection limits [10]. |

| Chromatography Data System (CDS) with Advanced Algorithms | Software (e.g., Chromeleon CDS) using algorithms like Cobra and SmartPeaks for intelligent integration and adaptive smoothing to reduce noise without losing valuable peak information [4]. |

| Low-Noise Instrumental Components | Using detectors and electronics designed for low noise (e.g., Thermo Scientific Vanquish Diode Array Detector HL) is fundamental to achieving a high baseline SNR [4]. |

| Reference Standard Materials | High-purity analyte standards for preparing accurate calibration curves and fortified samples to validate sensitivity and detection limit claims [11]. |

| 9,10-Dimethoxycanthin-6-one | 9,10-Dimethoxycanthin-6-one, CAS:155861-51-1, MF:C16H12N2O3, MW:280.28 g/mol |

| Melilotigenin C | Melilotigenin C, MF:C30H48O3, MW:456.7 g/mol |

FAQs: Identifying and Troubleshooting Noise in Spectroscopy

FAQ 1: My spectroscopic signal is weak and buried in noise. What is the first thing I should check?

Start with your sample preparation and instrument alignment. Contaminated samples, unclean cuvettes, or fingerprints can introduce unexpected spectral peaks and scatter light, severely degrading your signal [12]. Ensure your sample is properly positioned in the beam path and that all optical components (e.g., lenses, fibers) are correctly aligned to maximize signal collection [12]. Also, verify that your light source has been allowed to warm up for the recommended time (e.g., 20 minutes for tungsten halogen lamps) to achieve stable output [12].

FAQ 2: I am using a chemometric model for quantitative analysis. How can I ensure the results are reliable and not skewed by noise?

Avoid the common error of using complex algorithms like neural networks without first validating them against simpler methods. Always compare the performance of your advanced model (e.g., a neural network) against classical approaches like univariate calibration or partial least squares (PLS) analysis [13]. Ensure your dataset is large enough to be statistically significant and that results are validated on external data not used during training. Crucially, design your experiments to avoid systematic biases, such as by analyzing samples in a random order [13].

FAQ 3: What is a practical method to distinguish a genuine, weak spectral signal from random background noise?

Employ a multi-pixel signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) calculation instead of relying on a single-pixel measurement. Single-pixel methods only use signal from the center of a spectral band, ignoring valuable signal information distributed across the full bandwidth. Multi-pixel methods can detect spectral features earlier and more reliably because they incorporate this additional signal, improving the assessment of spectral features and lowering the limit of detection [14].

The table below categorizes common noise sources in spectroscopic systems and provides targeted solutions for improving signal quality.

| Noise Category | Specific Source | Impact on Signal | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instrumental | Detector Noise (e.g., dark current, readout electronics) [15] | Introduces uncorrelated additive noise, a key limitation for machine learning analysis [15]. | Ensure spectrometer is cooled; use appropriate gate/detection times to minimize dark current. |

| Light Source Instability (e.g., fluctuations in pump power or beam alignment) [15] | Introduces intensity-dependent or correlated additive noise [15]. | Allow light source to fully warm up; check alignment of modular components or optical fibers [12]. | |

| Optical Fiber Damage | Causes low signal transmission and light leakage [12]. | Inspect fibers for bending/twisting damage; replace with cables of the same length and specifications [12]. | |

| Environmental | Thermal Fluctuations | Affects reaction rates, solute solubility, and sample concentration [12]. | Use temperature-controlled sample holders; maintain consistent temperature between measurements [12]. |

| Stray Light | Increases background, reducing overall SNR. | Ensure a sealed, uninterrupted light path; use appropriate beam dumps and light baffles. | |

| Sample-Induced | Contamination | Introduces unexpected spectral peaks and light scattering [12]. | Use high-purity solvents; handle samples and cuvettes with gloved hands; clean substrates thoroughly [12]. |

| Inappropriate Concentration | High concentration causes excessive light scattering; low concentration yields weak signal [12]. | Dilute concentrated samples; use a cuvette with a shorter path length for highly absorbing samples [12]. | |

| Chemical Interference (e.g., in LIBS Plasma) | Causes self-absorption of emitted light, distorting spectral lines [13]. | Use established methods to evaluate and compensate for self-absorption; do not confuse it with self-reversal [13]. |

Advanced Methodologies for Noise Reduction

Multi-Pixel Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) Calculation

- Principle: This method improves detection limits by utilizing the signal across the entire bandwidth of a spectral band (e.g., a Raman peak), rather than just its center pixel. This approach leverages more of the available signal information [14].

- Protocol:

- Acquire your spectral data as usual.

- For a target spectral feature, define a region of interest (ROI) that covers its full width.

- Calculate the signal by integrating the intensity across all pixels within this ROI.

- Calculate the noise from a nearby, signal-free region of the background.

- Compute the SNR as the ratio of the integrated signal to the standard deviation of the background.

- Application: This method has been successfully applied to data from the SHERLOC instrument on the Mars Perseverance rover, confirming weak signals such as the first Raman detection of organic carbon on Mars [14].

Data-Driven Noise Reduction Using Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD)

- Principle: EEMD is a data-adaptive technique that decomposes a noisy signal into oscillatory components called Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs). Noise is typically associated with higher-frequency oscillations, which can be identified and removed [16].

- Protocol:

- Use the EEMD algorithm to decompose the observed noisy signal, ( x(k) ), into a collection of IMFs, ( ci(k) ), and a residue, ( r(k) ), such that ( x(k) = \sum{i=1}^{n} c_i(k) + r(k) ) [16].

- Analyze the Instantaneous Half Period (IHP), the time interval between two adjacent zero-crossings within each IMF. Noise-dominated oscillations typically have a shorter IHP than signal-dominated ones [16].

- Set a threshold and set to zero any waveform (between zero-crossings) with an IHP shorter than this threshold.

- Reconstruct the denoised signal using the processed IMFs.

- Application: This fully data-driven method has been validated for denoising stress wave signals in non-destructive testing and is suitable for preprocessing various types of spectroscopic data [16].

Machine Learning for Noise Characterization and Mitigation

- Principle: Neural networks (NNs) can be trained on large libraries of simulated spectra to map noisy experimental data onto underlying physical properties, even in the presence of specific noise types [15].

- Protocol:

- Generate a Training Set: Simulate a large database of pristine spectra (e.g., 2D electronic spectra) based on your system's physical model, covering the range of parameters of interest [15].

- Introduce Realistic Noise: Systematically add multisourced noise (additive, correlated, intensity-dependent) to the simulated spectra to create a realistic training dataset [15].

- Train the Network: Train a neural network to predict the target property (e.g., electronic coupling) from the noisy spectral data [15].

- Validate and Apply: Test the NN's accuracy on held-out data. Studies show NNs can maintain high accuracy if the SNR exceeds threshold values (e.g., ~12.4 for uncorrelated additive noise) [15].

- Application: This approach has been used to extract molecular electronic couplings from noisy two-dimensional electronic spectroscopy (2DES) and to rapidly characterize and mitigate noise in transmon qubits for quantum computing [15] [17].

Workflow: A Systematic Approach to Noise Diagnosis

The following diagram outlines a logical pathway for diagnosing and addressing common noise issues in spectroscopic experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and their functions for optimizing spectroscopic experiments and mitigating noise.

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes/Substrates | Essential for UV-Vis measurements due to high transmission in UV and visible light regions. Ensures the light path is not absorbed by the container itself [12]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Minimizes sample contamination, which can introduce unexpected spectral peaks and scatter light, degrading the signal-to-noise ratio [12]. |

| Optical Fibers with SMA Connectors | Guide light between modular components. A tight seal prevents light leakage, and using the correct length ensures optimal signal transmission [12]. |

| Calibration Standards | A sufficient number of well-characterized standards (typically ≥10) is crucial for creating accurate calibration curves and correctly determining Limits of Detection (LOD) and Quantification (LOQ) [13]. |

| Neural Network Training Library | A large database of simulated spectra, incorporating realistic noise models, is essential for training machine learning models to interpret noisy experimental data [15]. |

| Dynamical Decoupling Sequences | Used in quantum spectroscopy to probe and mitigate specific environmental noise sources, helping to preserve quantum coherence for more accurate measurements [17]. |

| Broussoflavonol F | Broussoflavonol F, MF:C25H26O6, MW:422.5 g/mol |

| ganoderic acid TR | ganoderic acid TR, CAS:862893-75-2, MF:C30H44O4, MW:468.7 g/mol |

For researchers in spectroscopy and drug development, determining the faintest trace of an analyte that your instrument can reliably detect is a fundamental task. The concept of the Minimum Detection Threshold is central to this, and it is quantitatively defined by a Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) of 3. This FAQ guide explains the statistical significance of this threshold and provides practical protocols for its application in your spectroscopic research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What does a "Detection Threshold" mean in spectroscopy? The detection threshold, or Limit of Detection (LOD), is the lowest quantity of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from the absence of that analyte (a blank sample) with a stated confidence level. It is the level at which a measurement becomes statistically significant [18].

2. Why is an SNR of 3 specifically used as the minimum detection threshold? An SNR of 3 is a widely accepted convention that corresponds to a 99.7% confidence level for detecting a signal above the background noise, assuming the noise follows a normal (Gaussian) distribution.

- Statistical Basis: In a normal distribution, approximately 99.7% of all random, noisy data points will fall within ±3 standard deviations (σ) of the mean noise level. A signal that is 3σ above the mean noise level has a very low probability (less than 0.3%) of being caused by a random fluctuation of the noise itself [18]. This means you can be over 99% confident that the signal is real and not just background variation.

- Balancing Errors: This threshold directly controls the probability of a false positive (Type I error), where you mistakenly identify noise as a signal. Setting the threshold at SNR=3 keeps this risk acceptably low for most analytical purposes [18].

3. Is an SNR of 3 sufficient for all types of detection? No, an SNR of 3 is specifically for the detection of a signal's presence. More demanding tasks require higher SNRs [19]:

- Discrimination: Telling two different signals apart requires an SNR about 3 dB greater than the detection level.

- Recognition: Identifying a specific signal requires an SNR about 3 dB greater than the discrimination level.

- Comfortable Communication/Comprehension: For clear and unambiguous interpretation (e.g., in speech or data transmission), an SNR of 15-25 dB or higher is often desired [20] [19].

4. How does improving the SNR affect the Limit of Detection (LOD)? Improving the SNR directly lowers (improves) your LOD. A higher SNR means your instrument can detect fainter signals buried in the noise. Research has shown that using multi-pixel SNR calculation methods, which utilize information across the entire spectral band, can report a 1.2 to 2-fold (or more) increase in SNR for the same Raman feature compared to single-pixel methods. This results in a significantly lower and better LOD [3].

5. What are common factors that degrade SNR in spectroscopic experiments? Several factors can introduce noise and reduce your SNR:

- Electronic Noise: Inherent noise from the detector and electronics [21].

- Source Instability: Fluctuations in the power of your light source (e.g., laser, lamp).

- Background Interference: Stray light, fluorescence from the sample or substrate, or ambient light.

- Sample Preparation: Inconsistencies in how samples are prepared or presented to the instrument.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Low SNR in Spectroscopic Data

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| High baseline noise across entire spectrum | Electronic detector noise or unstable source [21]. | Increase source power (if possible), cool the detector, increase integration time, or check instrument connections. |

| Noise concentrated at specific wavelengths | Background interference or source emission lines. | Take a background spectrum and subtract it, use spectral filters, or ensure a dark measurement environment. |

| Inconsistent SNR between similar samples | Inconsistent sample preparation or presentation. | Standardize sample preparation protocol (e.g., concentration, homogeneity, path length). |

| SNR decreases over time | Source lamp aging or detector degradation. | Perform routine instrument maintenance and calibration. |

Guide 2: Improving Your Detection Limit: A Step-by-Step Protocol

Objective: To verify the Limit of Detection (LOD) for a specific analyte and improve it by optimizing data processing.

Background: The LOD can be estimated from the calibration curve using the formula: LOD = 3.3 * (Std Error of Regression) / Slope [18]. This protocol uses this relationship to quantify improvements.

Materials & Reagents:

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Standard analyte samples | To create a calibration curve. |

| Blank matrix (solvent) | To measure background signal. |

| Spectrophotometer / Raman system | The core analytical instrument. |

| Data processing software (e.g., Python, R, Origin) | For calculating SNR and performing regression analysis. |

Experimental Protocol:

Step 1: Establish a Calibration Curve

- Prepare a dilution series of your analyte in the relevant matrix, covering a range from well above to near the expected LOD.

- Measure each standard (including multiple blank measurements) using your standard spectroscopic method.

- Plot the measured signal (e.g., peak height or area) against the analyte concentration.

- Perform a linear regression to obtain the slope and standard error of the regression (Sy).

Step 2: Calculate the Initial LOD

- Calculate the initial LOD using the formula: Initial LOD = 3.3 * (Sy / Slope) [18].

Step 3: Apply a Multi-Pixel Signal Calculation

- Do not use only the intensity of the center pixel of your spectral band of interest [3].

- Instead, integrate the signal across the full bandwidth of the peak. This can be the total area under the peak or the result of a fitting function applied to the entire band [3].

- For the noise component (σs), use the standard deviation of the signal measurement value you have chosen [3].

Step 4: Recalculate SNR and LOD

- Recalculate the SNR for your low-concentration samples using the multi-pixel method: SNR = S / σs.

- Construct a new calibration curve using the multi-pixel signal values.

- Calculate the new LOD using the new Sy and Slope values from the improved calibration curve. You should observe a lower LOD value, confirming enhanced sensitivity.

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Statistical Decision Workflow for Detection

SNR vs. Detection Capability Relationship

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the effective date of the updated USP <621> chapter, and what specifically changes for signal-to-noise ratio?

A: The revised USP <621> chapter becomes effective on May 1, 2025 [22]. The update refines the methodology for determining the signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio. The baseline must be extrapolated, and the noise must be determined over a distance of at least five times the peak width at half-height [22] [23]. It is crucial to perform this measurement after the injection of a blank, positioned around the location where the analyte peak is expected [23].

Q: Our laboratory operates globally. How do we reconcile differences in S/N calculations between USP and European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.) guidelines?

A: This is a common challenge. The Ph. Eur. had initially moved to a 20-times peak width requirement but reverted to the fivefold requirement, aligning more closely with the current USP definition [24]. The key is to use the compendial method specified for the market you are serving. Deviating from the prescribed method for a pharmacopoeia can lead to underestimating limits of detection (LOD) and quantitation (LOQ), potentially causing validation failures and regulatory scrutiny [24]. For internal methods, ensure your standard operating procedure clearly defines and validates the calculation method.

Q: Does a USP <621> S/N measurement replace the need for instrument qualification for SNR?

A: No. The S/N measurement defined in USP <621> is a System Suitability Test (SST) parameter, not a test for Analytical Instrument Qualification (AIQ) [22]. The S/N ratio is dependent on the specific analytical procedure, including the column, mobile phase, and detector conditions. AIQ ensures the instrument is fundamentally sound, while the SST confirms the entire method is performing adequately for the specific analysis on the day it is run [22].

Q: We are submitting a Type IA variation to the EMA. What is the deadline to ensure it is processed before the agency's 2025 year-end closure?

A: The European Medicines Agency (EMA) advises that to ensure validation within the 30-day timeframe before its closure, Type IA and IAIN variations should be submitted no later than November 21, 2025 [25] [26]. For Type IB variations, the submission deadline for a procedure start in 2025 is November 30, 2025 [25].

Troubleshooting Common SNR Validation Issues

Problem: Inconsistent S/N values between instruments or software platforms.

- Cause & Solution: Different instrumentation and software may calculate noise differently (e.g., using root mean square (RMS) versus peak-to-peak measurements) [24]. To resolve this, standardize the noise measurement interval across all instruments in your laboratory according to the pharmacopoeial definition. Calibrate and qualify all instruments and data systems regularly to ensure consistent performance and calculation algorithms [24].

Problem: Low S/N ratio impairing data accuracy, particularly in research applications like Brillouin spectroscopy.

- Cause & Solution: Low S/N is a common challenge in sensitive spectroscopic techniques, which can render data analysis protocols unreliable [27]. Beyond optimizing your experiment optically (e.g., increasing light source intensity or integration time), you can employ software-based denoising algorithms. Techniques like Maximum Entropy Reconstruction (MER) and Wavelet Analysis (WA) have been shown to significantly improve the accuracy and precision of extracted spectral parameters, even at very low SNRs (≥1) [27]. For spectrometer systems, leveraging hardware-accelerated High-Speed Averaging Mode can provide a superior SNR per unit time by performing significantly more spectral averages [28].

Problem: Uncertainty on when the S/N ratio must be measured as a system suitability parameter.

- Cause & Solution: The S/N SST is not required for every analysis. The new USP <621> definition makes it explicit that system sensitivity is measured when determining impurities at or near their limits of quantification [22]. Always consult the specific monograph first. If it specifies a reporting threshold, you must measure the S/N. For impurity procedures, this test is a strongly recommended part of the control strategy to ensure the chromatography is fit-for-purpose on the day of analysis [22].

Table 1: Key Regulatory Updates and Deadlines (2025-2026)

| Agency/Guideline | Key Update / Requirement | Effective / Deadline Date |

|---|---|---|

| USP <621> Chromatography | Revision to Signal-to-Noise ratio definition and system suitability requirements [22]. | May 1, 2025 [22] |

| EMA Type IA/IAIN Variations | Recommended submission deadline for validation before year-end closure [25] [26]. | November 21, 2025 [25] |

| EMA Type IB Variations | Recommended submission deadline for procedure start in 2025 [25]. | November 30, 2025 [25] |

| EPA TSCA SNURs (Final Rule) | Requires 90-day notification for significant new uses of certain chemical substances [29] [30]. | Effective January 5, 2026 [29] |

Table 2: SNR Improvement through Signal Averaging

| Averaging Method | Key Principle | Theoretical SNR Improvement | Example / Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Based Averaging | Averaging multiple sequential spectral scans [28]. | Increases by √(number of scans) [28] | 100 scans → 10x SNR improvement (e.g., 300:1 to 3000:1) [28] |

| Spatial (Boxcar) Averaging | Averaging signal from adjacent detector pixels [28]. | Increases by √(number of pixels averaged) [28] | - |

| Hardware-Accelerated (HSAM) | High-speed averaging in spectrometer hardware [28]. | ~3x per second improvement in one documented case [28] | Ocean SR2 spectrometer; crucial for time-critical applications [28] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials and Solutions for SNR-Optimized Experiments

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Pharmacopoeial Reference Standard | Essential for performing system suitability testing, including S/N measurement, as required by USP <621>. Using a sample instead is not acceptable [22]. |

| OceanDirect Software Developers Kit | A device driver platform with an API that allows control of Ocean Optics spectrometers and enables access to High-Speed Averaging Mode for improved SNR [28]. |

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) System | The core instrument for analyses governed by USP <621>. Must be properly qualified, and methods must be validated for compliance [22]. |

| Denoising Software Algorithms | Implementation of algorithms like Maximum Entropy Reconstruction (MER) and Wavelet Analysis (WA) can be applied post-acquisition to improve parameter extraction from noisy spectra [27]. |

| Lucyoside B | Lucyoside B, MF:C42H68O15, MW:813.0 g/mol |

| Leptomerine | Leptomerine, MF:C13H15NO, MW:201.26 g/mol |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Signal-to-Noise Ratio per USP <621>

This protocol outlines the steps to correctly measure the S/N ratio for a system suitability test under the updated USP <621> guidelines, effective May 1, 2025 [22].

- Preparation: Equilibrate the HPLC (or other chromatographic) system with the mobile phase as prescribed in the analytical method.

- Blank Injection: Inject the prescribed blank solution (e.g., solvent) and record the chromatogram.

- Reference Solution Injection: Inject the prescribed reference solution (a standard at or near the limit of quantification for the impurity peak of interest).

- Identify the Peak: In the chromatogram from the reference solution, identify the peak for which the S/N is being determined.

- Measure Peak Width: Determine the peak width at half-height (Wh).

- Locate Noise Region: In the blank chromatogram, locate a region that is free from other interfering peaks and is, if possible, situated equally around the place where the analyte peak would be found.

- Define Measurement Window: The distance over which the noise is measured must be at least 5 times the Wh measured in Step 5 [22] [23].

- Measure Noise and Signal:

- Measure the peak-to-peak noise (N) in the defined window of the blank chromatogram.

- Measure the height of the peak (H) from the extrapolated baseline in the reference solution chromatogram.

- Calculate S/N Ratio: Calculate the Signal-to-Noise ratio using the formula: S/N = 2H / N [24]. Note that USP defines S/N with a multiplicative factor of 2, which differs from a simple H/N ratio [24].

- Verify Acceptance: Compare the calculated S/N value against the monograph or method specification. A typical requirement for the limit of quantification (LOQ) is an S/N of 10 [22].

Workflow Diagram: SNR Validation and Regulatory Compliance Pathway

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for establishing and troubleshooting SNR validation in a regulated environment.

Computational and Experimental Methods for SNR Enhancement in Spectral Analysis

Core Concepts: The "Why" Behind Signal Averaging

What is signal averaging and what problem does it solve?

Signal averaging is a signal processing technique applied in the time domain intended to increase the strength of a signal relative to noise that is obscuring it [31]. It is a fundamental method for enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in spectroscopic and other analytical data, allowing researchers to detect and quantify weak signals that would otherwise be buried in random noise [32] [33]. This is particularly crucial in techniques like 13C NMR spectroscopy, where the natural abundance of the 13C isotope is only about 1.1%, resulting in inherently weak signals [34].

How does averaging improve the signal-to-noise ratio?

The improvement stems from the different behavior of deterministic signals and random noise when multiple measurements are combined. A consistent signal adds directly, while random noise, being uncorrelated, adds more slowly.

- Signal Enhancement: The underlying signal (S) is determinate and sums directly: ( S_n = nS ), where ( n ) is the number of scans or measurements [33].

- Noise Reduction: The noise (N), being random and uncorrelated, sums as the square root of the sum of its variances: ( N_n = \sqrt{n} \sigma ), where ( \sigma ) is the standard deviation of the noise in a single scan [33] [31].

- Net SNR Improvement: The overall signal-to-noise ratio improves proportionally to the square root of the number of scans, ( n ) [33] [31] [35]: [ (S/N)n = \frac{Sn}{sn} = \frac{nS}{\sqrt{n}s} = \sqrt{n} \cdot (S/N){n=1} ]

Table: Signal-to-Noise Ratio Improvement with Averaging

| Number of Scans (n) | Theoretical SNR Improvement Factor |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1x |

| 4 | 2x |

| 16 | 4x |

| 64 | 8x |

| 256 | 16x |

Practical Implementation: The "How-To" Guide

What are the primary signal averaging methods?

Two primary methodological approaches are commonly employed, each with specific use cases.

Ensemble Averaging This method involves collecting multiple independent scans or trials and averaging them point-by-point [35]. It is the classic application of signal averaging and requires that the signals are perfectly aligned in time or space. This approach is ideal for repeated, time-locked experiments, such as in evoked potential tests in biomedical engineering or repeated spectroscopic measurements of a stable sample [32] [35].

Moving Average (Boxcar Averaging) This technique operates on a single run of data by averaging a sliding window of consecutive data points [36] [33]. It is a smoothing filter that reduces high-frequency noise within a single trace. The width of the averaging window (e.g., 3, 5, 7 points) determines the degree of smoothing and the extent of high-frequency signal loss [33].

What are the essential assumptions for effective signal averaging?

The technique's robustness relies on several key assumptions [32]:

- Uncorrelated Signal and Noise: The signal and noise are statistically independent.

- Known Signal Timing: The timing (or period) of the signal of interest is known, which is crucial for proper alignment in ensemble averaging.

- Consistent Signal: A consistent signal component exists across all repeated measurements.

- Zero-Mean Random Noise: The noise is random, has a mean of zero, and a constant variance.

Violations of these assumptions, such as the presence of correlated noise or signal drift, will degrade the performance of the averaging process [31].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

My SNR is not improving with averaging. What could be wrong?

- Check for Signal Drift: Ensure your sample and instrument are stable over the measurement period. A time-dependent change in the signal ( S ) or the noise ( s ) will undermine the averaging process [33].

- Verify Signal Alignment (for Ensemble Averaging): In ensemble averaging, imperfect alignment of the signals before averaging will cause the desired signal to be attenuated. Always use a reliable trigger or synchronizing signal to align replicates [32].

- Investigate for Correlated Noise: Signal averaging is most effective against random noise. If the noise contains correlated components (e.g., 60 Hz power line interference, drift), the improvement will be less than the theoretical (\sqrt{n}) [31]. Consider using band-stop filters or other pre-processing to remove specific noise sources.

- Confirm Measurement Consistency: Ensure that the experimental conditions are identical for each scan. Variations in sample position, concentration, or instrument response will manifest as noise.

How do I choose between ensemble and moving average methods?

The choice depends on your experimental setup and data characteristics.

- Use Ensemble Averaging when: You can acquire multiple, independent replicates of the measurement, and the signal of interest is time-locked or can be perfectly aligned. This is the preferred method for maximizing SNR when possible, as it directly leverages the (\sqrt{n}) law [35].

- Use Moving Average when: You only have a single run of data, and the high-frequency content of your signal is not critical. Be aware that it acts as a low-pass filter and can distort the signal by attenuating high-frequency components and broadening sharp features [33].

Table: Comparison of Signal Averaging Methods

| Feature | Ensemble Averaging | Moving Average (Boxcar) |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirement | Multiple, aligned scans or trials | A single run of data |

| Impact on Signal | Preserves the underlying signal shape | Can distort sharp features and peaks |

| Noise Reduction | Reduces random noise across scans | Smoothes high-frequency noise within a scan |

| Best For | Stable samples, time-locked responses (e.g., NMR, VEP tests) | Quick smoothing of a single trace, real-time processing |

| SNR Improvement | (\propto \sqrt{n}) (number of scans) | Limited by window width and signal frequency content |

Is there a point of diminishing returns for signal averaging?

Yes. The SNR improves with the square root of the number of scans, ( n ) [33]. This means the relative benefit decreases as ( n ) increases. For instance, going from 1 to 4 scans doubles the SNR, but to double it again, you need 12 more scans (for a total of 16). This non-linear relationship means that practical considerations like total experiment time and sample stability often limit the number of useful averages. Furthermore, all instruments have a practical signal averaging limit set by residual non-random artifacts like electronic noise floors or mechanical vibrations [32].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Standard Protocol for Ensemble Averaging in Spectroscopy

This protocol is adapted for a general spectroscopic context, such as NMR or optical spectroscopy.

Aim: To acquire a spectrum with an improved signal-to-noise ratio through the averaging of multiple scans.

Materials & Reagents:

- Stable standard sample or analyte of interest

- Spectrometer (NMR, FTIR, etc.)

- Data acquisition software capable of storing individual scans

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a stable sample with a known spectral signature.

- Instrument Calibration: Ensure the spectrometer is properly calibrated and aligned.

- Define Acquisition Parameters: Set the spectral range, resolution, and single-scan acquisition time.

- Initiate Multi-Scan Acquisition: Start a data acquisition run to collect ( n ) successive scans (e.g., ( n ) = 1, 4, 16, 64, 256). Save each scan individually.

- Data Alignment: If necessary, computationally align all scans to a common reference point (e.g., a solvent peak in NMR).

- Averaging: Sum all ( n ) scans and divide the result by ( n ) to create the final averaged spectrum.

- SNR Calculation: Calculate the SNR for the averaged spectrum and compare it to a single scan to verify the (\sqrt{n}) improvement.

Protocol for Validating Signal Averaging Performance

This test verifies that your instrument's signal averaging is performing as expected.

Aim: To test and validate the signal averaging capability of a spectrometer by measuring photometric noise reduction versus the number of scans.

Materials & Reagents:

- A stable reference standard suitable for your spectrometer.

- Spectrometer with signal averaging functionality.

Procedure [32]:

- Obtain a series of replicate scan-to-scan spectra.

- Process and average subsets of these scans for the following number of scans: 1, 4, 16, 64, 256, 1024, etc., up to the maximum measurement time of interest.

- Calculate the noise level (e.g., standard deviation) at specific, well-defined wavenumbers or wavelengths for each averaged spectrum.

- Compare the measured noise to the expected noise reduction factor. The noise level should be reduced by a factor of 2 for every quadrupling of the scan number (e.g., from 1 to 4, from 4 to 16). Report a failure if the measured noise level is at least twice the expected value [32].

Table: Signal Averaging Validation Table

| Number of Scans | Expected Noise Reduction Factor | Measured Photometric Noise | Measured Noise Reduction Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1x | ||

| 4 | 1/2x | ||

| 16 | 1/4x | ||

| 64 | 1/8x | ||

| 256 | 1/16x |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Signal Averaging Experiments

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Stable Reference Standard | A chemically stable compound with a known, sharp spectral signature. Used for instrument calibration and validation of signal averaging performance. |

| Deuterated Solvent (for NMR) | Provides the signal for the deuterium lock in NMR spectrometers, ensuring field-frequency stability during long averaging experiments. Essential for achieving consistent signal alignment across scans. |

| Quantum Efficiency Test Chart | Used in fluorescence microscopy and other optical techniques to verify camera specifications and calibrate the relationship between photon flux and signal output, which is critical for noise analysis [37]. |

| Background/Blank Sample | A sample containing all components except the analyte. Its averaged signal is used for background subtraction, helping to isolate the signal of interest from systematic noise. |

| Loureirin C | Loureirin C |

| Rhodiolin | Rhodiolin, MF:C25H20O10, MW:480.4 g/mol |

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Spectroscopic Detection. This resource provides practical troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions (FAQs) to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals implement multi-pixel signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) calculations in their spectroscopic work. This content supports the broader thesis that leveraging full spectral bandwidth through multi-pixel methodologies significantly improves detection limits in spectroscopic data research, enabling more reliable identification of weak spectral features in applications ranging from pharmaceutical analysis to astrobiological exploration [3] [14].

FAQs: Understanding Multi-Pixel SNR Fundamentals

What are multi-pixel SNR calculations and how do they differ from traditional methods?

Multi-pixel SNR calculations utilize information from multiple pixels across the entire spectral bandwidth of a signal, unlike single-pixel methods that only consider the intensity at the center pixel of a spectral band [3] [14].

Key Differences:

- Single-Pixel Methods: Use only the center pixel intensity in a Raman band, ignoring valuable signal information distributed across adjacent pixels [14]

- Multi-Pixel Methods: Incorporate signal from all pixels within the spectral feature's bandwidth, providing a more comprehensive measurement of the actual signal [3]

This approach is particularly valuable for detecting weak spectral features where signal is distributed across multiple detector elements [3].

Why do different SNR calculation methods produce significantly different detection limits?

Different SNR calculation methods produce varying detection limits because they employ distinct mathematical approaches to quantify both signal and noise components [3]. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines SNR as the ratio of signal magnitude (S) to the standard deviation of that signal (σs) [3]:

SNR = S/σs

However, implementations vary significantly in how S and σs are derived [3]:

Table: Comparison of SNR Calculation Methodologies

| Method Category | Signal Measurement Approach | Reported SNR Improvement | Limit of Detection Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Pixel | Center pixel intensity only | Reference value | Higher detection limit |

| Multi-Pixel Area | Integration across bandwidth | ~1.2-2+ fold increase | Lower detection limit |

| Multi-Pixel Fitting | Fitted function across band | ~1.2-2+ fold increase | Lower detection limit |

These methodological differences make direct comparison of SNR values across studies challenging and emphasize the need for standardized reporting [3].

How much improvement can I expect by implementing multi-pixel SNR methods?

Research demonstrates that multi-pixel methods report approximately 1.2 to over 2-fold larger SNR for the same Raman feature compared to single-pixel methods [3]. This translates to significantly improved detection limits, enabling identification of spectral features that would otherwise remain undetectable.

Case Study Example: In analysis of a potential organic carbon feature observed by the SHERLOC instrument on Mars (Montpezat target, sol 0349) [3]:

- Single-pixel methods: SNR = 2.93 (below detection threshold)

- Multi-pixel methods: SNR = 4.00-4.50 (above detection threshold)

This critical difference determined whether the spectral feature could be statistically validated as a genuine signal rather than noise [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Detection Limits Across Research Teams

Symptoms: Different research groups reporting significantly different detection limits for the same analytes; difficulty reproducing published detection thresholds.

Solution: Implement standardized multi-pixel SNR protocols

Experimental Protocol for Standardized Multi-Pixel SNR Calculation:

Data Acquisition: Collect spectral data with sufficient resolution to characterize the full bandwidth of interest [3]

Spectral Feature Identification:

- Identify potential spectral features of interest

- Define the relevant bandwidth containing the feature

Multi-Pixel Area Method:

- Calculate total signal (S) by integrating intensity across all pixels within the defined bandwidth

- Compute standard deviation (σs) of background regions adjacent to the feature

- Apply formula: SNR = S/σs [3]

Multi-Pixel Fitting Method:

- Fit an appropriate function (Gaussian, Lorentzian, etc.) to the spectral feature across all relevant pixels

- Use the fitted peak intensity or area as the signal measurement (S)

- Calculate noise from residual standard deviation or background regions [3]

Validation: Compare both multi-pixel methods against single-pixel approach to quantify improvement

Diagram Title: Multi-Pixel SNR Calculation Workflow

Problem: Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Weak Spectral Features

Symptoms: Marginal detection statistics; uncertainty in distinguishing genuine spectral features from instrumental or environmental noise; inconsistent detection of low-concentration analytes.

Solution: Optimize experimental parameters to maximize multi-pixel SNR

Table: Noise Source Identification and Mitigation Strategies

| Noise Source | Impact on SNR | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Shot Noise | Increases with signal strength; dominant noise source at high signals [38] | Increase integration time; operate near detector saturation without blooming [38] |

| Dark Current Noise | Contributes variance even without signal [38] | Cool detector; reduce integration time if dark current dominated [38] |

| Read Noise | Fixed per read operation [38] | Frame averaging; binning multiple spectral channels [38] |

| Digitization Noise | Quantization error in analog-to-digital conversion [38] | Use detectors with higher bit depth; match signal range to ADC range [38] |

Experimental Protocol for SNR Optimization:

Parameter Assessment:

Integration Time Optimization:

- Systematically increase integration time (Δt) while monitoring for detector saturation

- Maximum SNR achieved just below saturation point [38]

Spectral Binning Implementation:

Illumination Optimization:

- Increase source brightness where possible

- Ensure optimal focus and alignment to maximize signal collection

Diagram Title: SNR Optimization Decision Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Pixel SNR Experiments

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Reference Materials | Validation of detection limits | Use certified materials with known spectral features for method validation |

| Spectral Calibration Sources | Wavelength accuracy verification | Essential for proper bandwidth definition in multi-pixel methods |

| Signal Enhancement Reagents | Boost weak spectral features | Surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) substrates; fluorescence quenchers |

| Noise Characterization Tools | Quantify system noise sources | Dark current reference samples; uniform illumination sources |

| Data Processing Software | Implement multi-pixel algorithms | Custom scripts for bandwidth integration; spectral fitting routines |

| Astressin | Astressin, MF:C161H269N49O42, MW:3563.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5-Nitro-1H-indazole-3-carbonitrile | 5-Nitro-1H-indazole-3-carbonitrile, CAS:90348-29-1, MF:C8H4N4O2, MW:188.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Technical Notes

Statistical Validation of Detection Claims

When implementing multi-pixel SNR methods, maintain rigorous statistical standards:

- False Positive Control: Use the IUPAC standard of SNR ≥ 3 for statistical significance of detection [3]

- Validation Testing: Apply both multi-pixel and single-pixel methods to confirm detection claims

- Uncertainty Quantification: Report both the SNR value and the calculation methodology to enable proper interpretation

Computational Considerations

Implementation of multi-pixel methods requires:

- Bandwidth Definition: Consistent algorithmic approach to defining spectral feature boundaries

- Background Subtraction: Robust methods for distinguishing signal from background

- Error Propagation: Proper accounting of uncertainty through computational steps

Multi-pixel SNR calculations represent a significant advancement in spectroscopic detection capabilities, particularly for weak spectral features in pharmaceutical research and analytical science. By implementing the troubleshooting guides and methodologies outlined in this technical support center, researchers can achieve lower detection limits and more reliable statistical validation of spectral features. The consistent application of these multi-pixel approaches will enhance comparability across studies and advance the field of spectroscopic analysis.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support resource addresses common challenges researchers face when applying digital filters to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in spectroscopic data.

Moving Average Filter Troubleshooting

Q1: My processed signal is noticeably smoother, but important sharp peaks have been broadened. What is the cause and how can I fix this?

This is a classic trade-off between noise reduction and signal preservation. The moving average filter applies equal weight to all data points in its window, which smears sharp features.

- Cause: The window size is too large for the rate of change of your signal. A large window averages over a wider time range, blurring rapid transitions and sharp peaks.

- Solutions:

- Reduce the window size. Start with a small window (e.g., 3-5 points) and increase gradually until you achieve a good balance between smoothness and feature preservation.

- Consider a weighted filter. Switch to a Gaussian filter or a Savitzky-Golay filter, which are designed to better preserve signal shape by giving more weight to central points in the window [39] [40].

- Verification: Process a synthetic dataset with known peak shapes and widths. Optimize the filter window to minimize peak broadening while achieving your target SNR.

Q2: The filtered signal shows a time lag compared to the original raw data. Is this expected?

Yes, this is an expected characteristic of causal moving average filters.

- Cause: The filter output at time

tis calculated based on a window of points that includestand previous points. This intrinsic dependency on past data introduces a phase shift [41]. - Solutions:

- Use a

'same'convolution mode. In software (e.g., Python'snumpy.convolve), usingmode='same'centers the filter output relative to the input, which can minimize the apparent lag, though some edge effects will remain [39]. - Post-process for zero-phase shift. For offline analysis, use forward-and-backward filtering (

filtfiltfunction in tools like SciPy). This processes the data in both directions to cancel out the phase delay, though it increases computational load.

- Use a

Gaussian Filter Troubleshooting

Q3: How do I choose the correct sigma (σ) value for my Gaussian filter?

The sigma parameter controls the width of the Gaussian kernel and thus the degree of smoothing.

- Guideline: The sigma value should be chosen based on the characteristic scale of the features you wish to preserve. A good starting point is to relate it to the width of your spectral peaks [40].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Estimate the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of a representative, noise-free peak in your spectrum.

- Set the filter span (the window length) approximately equal to this FWHM.

- The sigma (σ) is related to the filter span. In many implementations, you can directly specify the span, and the sigma is derived automatically to cover the window effectively (e.g., the Gaussian function is nearly zero for values beyond ±3.5σ) [40].

- Systematically vary sigma and evaluate the output using both SNR metrics and visual inspection for feature preservation.

Q4: The Gaussian filter is effective on most of my signal, but the edges of the spectral range are distorted. How can I prevent this?

Edge distortion is a common issue with all convolution-based filters because the filter window extends beyond the available data at the edges.

- Cause: At the start and end of the dataset, the filter lacks sufficient data points to compute a true weighted average, leading to artifacts.

- Solutions:

- Use padding. Extend the signal at both ends before filtering. Common padding methods include:

- Symmetric Padding: Mirror the signal at the boundaries.

- Wrap-around: Assume the signal is periodic (use with caution for non-periodic data).

- Constant Value: Pad with a constant value (e.g., zero or the mean of the signal).

- Truncate the output. After applying the filter to the padded signal, discard the padded sections to retain a clean, filtered signal of the original length.

- Use padding. Extend the signal at both ends before filtering. Common padding methods include:

Fourier Transform (Spectral) Filter Troubleshooting

Q5: After applying a low-pass FFT filter, my signal has "ringing" artifacts (ripples) near sharp edges. What causes this and how is it mitigated?

This phenomenon is known as the Gibbs phenomenon.

- Cause: It results from the abrupt truncation of high-frequency components in the frequency domain, which corresponds to multiplying by a "brick-wall" filter. This sharp cutoff in the frequency domain creates ripples in the time domain [42].

- Solutions:

- Use a gentle filter roll-off. Instead of an ideal brick-wall filter, use a filter with a gradual transition between passband and stopband. A Gaussian filter in the frequency domain is an excellent choice as it is smooth and minimizes ringing [42].

- Apply a windowing function. Before filtering, multiply your time-domain signal by a window function (e.g., Hamming, Hann) that gently tapers the signal to zero at the edges. This reduces the sharp discontinuities that cause severe ringing.

Q6: How can I objectively determine the correct cutoff frequency for my FFT filter?

Choosing the right cutoff frequency is critical for separating signal from noise.

- Protocol for Determining Cutoff Frequency:

- Compute the Power Spectral Density (PSD): Take the FFT of your signal and plot the squared magnitude of the frequencies (the PSD) [43].

- Identify the Noise Floor: In the PSD plot, locate the frequency region where the signal power drops to a relatively constant, low level. This is the noise floor.

- Set the Cutoff: Set the cutoff frequency just above the point where the signal power begins to merge into the noise floor. This preserves most of the true signal components while attenuating the dominant noise frequencies.

- Validation: Filter the signal using this cutoff and inspect the result. The filtered signal should retain its key morphological features while appearing significantly smoother.

Filter Performance and Selection Guide

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each filter type to guide your selection.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Digital Filtering Techniques for Spectroscopic Data

| Filter Type | Key Characteristics | Best Use Cases | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moving Average | Finite Impulse Response (FIR); equal weights [39] | Rapid prototyping; reducing white noise in time-domain signals; simple hardware implementation [41] | Simple to understand and implement; retains sharp step response; computationally efficient [39] [41] | Poor stopband performance; smears sharp features; trade-off between noise reduction and resolution [39] |

| Gaussian | Weighted average; weights defined by Gaussian kernel [40] | Smoothing while preserving peak shape; pre-processing for peak detection [40] | Excellent smoothing without sharp cutoffs; optimal for preserving signal shape relative to moving average; no negative weights [40] | Edge distortion effects; can still broaden peaks if sigma is too large [40] |

| Fourier Transform (FFT) | Converts signal to frequency domain for manipulation [42] | Removing specific periodic noise (e.g., 50/60 Hz line noise); separating signal and noise with distinct frequency bands [43] [42] | Highly effective at removing stationary periodic noise; direct control over frequency components | Potential for ringing artifacts (Gibbs phenomenon); non-local effects (editing a frequency affects the entire signal) [42] |

Experimental Protocol: Systematic SNR Improvement Workflow

This protocol outlines a standardized method for applying and validating digital filters on a spectroscopic dataset.

1. Define a Performance Metric

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): Calculate as

SNR = 10 * log10(Psignal / Pnoise), wherePdenotes the power (mean square value) [44]. - For validation, use a clean reference signal or a region known to contain only noise.

2. Initial Data Inspection

- Plot the raw signal in both the time and frequency domains (using FFT) to identify the nature of the noise (white, periodic, etc.) [43].

3. Filter Application and Optimization

- Moving Average: Systematically increase the window size and plot the resulting SNR and feature broadening against window size to find the optimum.

- Gaussian: Vary the

sigmaparameter (or filter span) and observe its effect on both SNR and the FWHM of known peaks. - FFT-Based: Inspect the FFT spectrum to identify noise frequencies. Apply a band-stop or low-pass filter and adjust the cutoff frequencies iteratively.

4. Validation and Artifact Check

- Visually compare the filtered and raw signals for any introduced distortions, such as peak broadening, ringing, or edge effects.

- Quantitatively compare the SNR improvement using the metric from Step 1.

The following workflow diagram visualizes the key decision points in this protocol:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Data for Filtering Experiments

| Item Name | Function / Role | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Dataset | A clean signal with analytically defined peaks, used for validating filter performance and quantifying artifacts. | A sum of Gaussian or Lorentzian peaks on a known baseline, with programmable additive noise. |

| Reference Material | A physical or data standard with a well-characterized spectrum, used for instrument calibration and filter validation. | NIST Standard Reference Material (e.g., for Raman or fluorescence spectroscopy). |

| Numerical Computing Environment | Software platform for implementing algorithms, performing numerical analysis, and visualizing data. | Python (with NumPy, SciPy), MATLAB, or Julia. |

| Signal Processing Toolbox | A library of pre-written functions for digital filter design, implementation, and analysis. | scipy.signal in Python or the Signal Processing Toolbox in MATLAB. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Resources | GPU-accelerated computing can drastically speed up processing, especially for large datasets or complex filters like implicit formulations [45]. | NVIDIA CUDA, cloud computing instances. |

| Methyl ganoderate H | Methyl Ganoderate H|CAS 98665-11-3|For Research | Methyl Ganoderate H is a natural triterpenoid fromGanoderma lucidumwith a moderate inhibitory effect on NO production. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Mulberrofuran H | Mulberrofuran H, CAS:89199-99-5, MF:C27H22O6, MW:442.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common DCNN Spectral Denoising Issues

1. Problem: The denoised spectrum shows loss of weak but critical signals.

- Cause: The neural network may be over-regularized or trained on data that does not adequately represent low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) conditions. It might be treating weak genuine signals as noise.

- Solution:

- Review Training Data: Ensure your training set includes examples with weak target signals. If using experimental data, incorporate pairs of low-noise and high-noise measurements of the same sample to teach the network what signal to preserve [46].

- Architecture Adjustment: Consider using a residual learning architecture, where the network learns the noise profile and subtracts it from the input, helping to preserve the underlying signal [47] [46].

- Validation: Always validate your model's performance on a test set that contains known weak signals and quantify the signal-to-residual background ratio to ensure improvement [46].

2. Problem: The model performs well on one instrument's data but poorly on another's.

- Cause: This is often due to different noise characteristics between instruments. A model trained on data from one source may not generalize well to another.

- Solution:

- Domain Adaptation: Incorporate data from multiple instruments or experimental setups into your training dataset to create a more robust model [48].

- Input Normalization: Apply robust normalization techniques to minimize systematic differences between datasets. For example, normalizing frames by their total intensity can help [46].

- Hybrid Training: Train the network on a combination of experimental data and data with artificially added noise that simulates the target instrument's noise profile [46].

3. Problem: Training is unstable or the model fails to converge.

- Cause: This can be caused by an inappropriate learning rate, poorly scaled input data, or a complex network architecture that is difficult to train.

- Solution:

- Data Preprocessing: Ensure your input data is properly scaled. A common practice is to normalize pixel or spectral intensities, for instance, to a [0, 1] range [49].

- Optimizer Selection: Use optimizers known for stability, such as the Adam optimizer with its AMSGrad variant, which can improve convergence [46].

- Residual Learning: Implement a residual learning framework. Instead of predicting the clean spectrum directly, the network can be tasked with predicting the noise pattern, which is often easier to learn [47] [46].

4. Problem: The model introduces "hallucinated" features not present in the original data.

- Cause: This can occur due to overfitting on the training data or when using generative aspects of deep learning that are not strictly faithful to the ground truth.

- Solution:

- Scientific Denoising Principle: For scientific data, use training strategies that prioritize faithfulness to the ground truth. Supervised training with accurately paired low- and high-fidelity experimental data is crucial [46].

- Regularization: Increase regularization techniques (e.g., L2 regularization, dropout) during training to reduce overfitting.

- Architecture Choice: Simpler networks or those with proven scientific application, like a modified U-Net or DnCNN, may be more reliable than highly complex generative models for this task [49].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the main advantage of using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks (DCNNs) over traditional smoothing methods for spectral denoising?

A1: Traditional smoothing methods, like Savitzky-Golay or moving averages, apply a fixed mathematical operation that often trades off noise reduction for spectral resolution, which can blur sharp features and suppress weak signals [50]. DCNNs, by contrast, learn complex, non-linear relationships from data. They can distinguish between noise and signal more intelligently, leading to superior noise suppression while better preserving the integrity of weak and sharp spectral features [47] [46]. This is particularly valuable for revealing subtle signals in scientific data, such as weak charge density waves in X-ray diffraction [46].

Q2: I have a limited set of noisy data. How can I train a DCNN if I don't have clean "ground truth" data?

A2: There are several strategies to address this common challenge:

- Noise2Noise Training: Train the network using pairs of two independent noisy measurements of the same sample. The network learns to predict the clean signal from the noisy inputs without ever seeing a perfect ground truth [46].

- Leverage Chemical Prior Knowledge: In techniques like Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI), isotopic ions (noisier) can be paired with their corresponding monoisotopic ions (cleaner) to create a training set, as demonstrated by the De-MSI method [49].

- Data Augmentation: Artificially expand your training set by applying transformations like rotation, mirroring, and random adjustments to global brightness to your existing data [46].

Q3: What are the key differences between DCNNs and Transformer-based models for spectral denoising?

A3: