Advanced Strategies for Optimizing Calibration Curves in Quantitative Spectroscopic Analysis

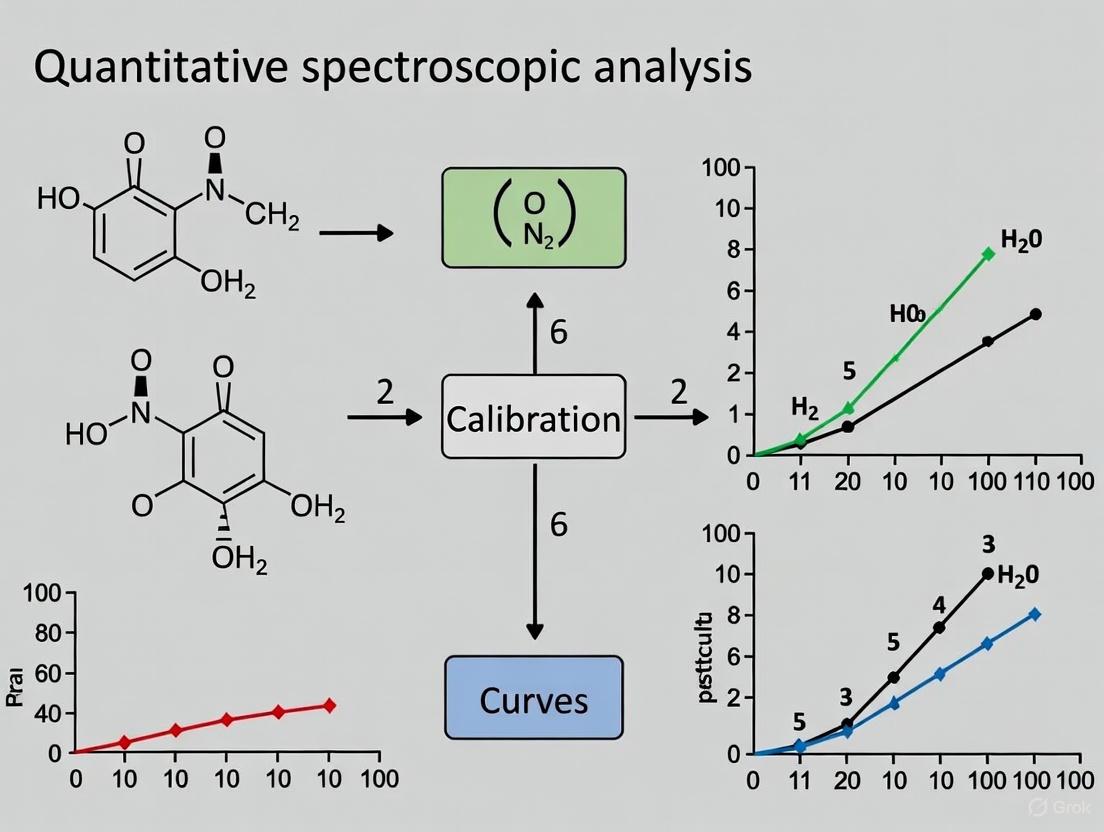

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing calibration curves to enhance the accuracy, precision, and reliability of quantitative spectroscopic analysis.

Advanced Strategies for Optimizing Calibration Curves in Quantitative Spectroscopic Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing calibration curves to enhance the accuracy, precision, and reliability of quantitative spectroscopic analysis. It covers foundational principles of method validation—including limits of detection (LOD) and quantitation (LOQ)—explores traditional and advanced calibration methodologies, offers practical troubleshooting strategies for common instrumental issues, and details rigorous validation protocols per ICH guidelines. By integrating foundational knowledge with modern techniques like AI-assisted chemometrics and continuous calibration, this resource aims to support the development of robust analytical methods essential for pharmaceutical quality control and clinical research.

Core Principles: Understanding Calibration Curves and Key Validation Parameters

The Critical Role of Calibration in Quantitative Spectroscopic Accuracy

Troubleshooting Guides

Spectrometer Fails to Calibrate or Shows Noisy Data

Problem: Your spectrometer won't calibrate, produces error messages, or gives very noisy, unstable readings (often with absorbance values stuck at 3.0 or above) [1].

Solution:

- Check sample concentration: Absorbance values should ideally be between 0.1 and 1.0. For highly concentrated samples, dilute and retest [1].

- Verify the light source: Switch to uncalibrated mode to observe the full spectrum. A flat graph in certain regions may indicate a faulty or degraded light source [1].

- Ensure a clear light path: Confirm the cuvette is inserted correctly, filled with enough sample, and made of material compatible with your measurement type (e.g., quartz for UV) [1].

- Inspect the solvent: Some solvents absorb strongly in the UV region. Try a blank with water, then measure your solvent directly. If absorbance is high, dilute or switch solvents [1].

- Perform a power reset (LabQuest users): Power-related issues can cause calibration failures with interfaces like LabQuest 2 or 3 [1].

Poor Accuracy Despite Apparent Successful Calibration

Problem: The calibration process completes, but sample analysis yields inaccurate or inconsistent results, or the calibration curve has a poor fit.

Solution:

- Verify wavelength accuracy: Use certified reference materials (CRMs) like holmium oxide solution or filters. Inaccurate wavelength selection is a primary source of error [2] [3].

- Check for stray light: This is a common cause of negative deviation from the Beer-Lambert law, especially at high absorbance values. It can be tested with specialized cutoff filters [2] [3].

- Assess photometric linearity: Test using a series of neutral density filters with known transmittance values. Non-linearity indicates issues with the detector or electronics [3].

- Confirm proper baseline correction: Always use a pure solvent or appropriate blank to zero the instrument before measuring standards and unknowns [4].

- Validate with independent standards: Run a control standard not used in the calibration curve to verify the model's predictive accuracy [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Calibration Concepts

Q1: What is a calibration curve and why is it critical in spectroscopy? A calibration curve (or standard curve) is a graphical tool that relates the instrumental response (e.g., absorbance) to the concentration of an analyte. It is the foundation of quantitative analysis because it allows researchers to determine the concentration of an unknown sample by interpolating its measured signal onto the curve. Its accuracy directly determines the validity of all subsequent quantitative results [6] [4].

Q2: What is the Beer-Lambert Law and how does it relate to calibration? The Beer-Lambert Law (A = εlc) states that the absorbance (A) of a sample is directly proportional to its concentration (c). This linear relationship is the fundamental principle that makes quantitative spectroscopy possible. Here, ε is the molar absorptivity and l is the path length. A calibration curve is the practical application of this law [6] [7].

Q3: How often should I calibrate my spectrophotometer? The frequency depends on usage, required accuracy, and regulatory environment. Best practice is to perform a full calibration check at the beginning of each analysis session or series of experiments. For regulated laboratories (e.g., following GLP or GMP), specific schedules are mandated. Instruments should also be recalibrated after any maintenance, lamp changes, or if operational issues are suspected [3].

Technical and Procedural FAQs

Q4: My calibration curve is not linear. What could be wrong? Non-linearity can arise from several issues [3]:

- Excessive stray light: A primary cause, especially noticeable at higher absorbances.

- Instrumental deviations: Problems with the monochromator (poor resolution, incorrect bandwidth) or detector.

- Chemical factors: Sample degradation, molecular associations, or changes in refractive index at high concentrations.

- Stray light is often the root cause of linearity failure, as it violates the core assumption of monochromatic light in the Beer-Lambert Law [3].

Q5: What are the key parameters to check during spectrophotometer calibration? A comprehensive calibration should verify these core parameters [3]:

- Wavelength accuracy: Confirms the instrument is measuring at the correct wavelength.

- Photometric accuracy: Ensures the instrument reports the correct absorbance/transmittance value.

- Stray light: Quantifies unwanted light outside the target bandwidth.

- Spectral resolution: Assesses the instrument's ability to distinguish closely spaced spectral features.

Q6: Can I use the same calibration curve for different instruments or cuvettes? No. Calibration is specific to the instrument, optical configuration, and even the cuvette used. A curve generated on one device is not directly transferable to another due to differences in light sources, grating characteristics, and detector responses. Similarly, switching between glass, plastic, and quartz cuvettes, which have different light transmission properties, requires a new calibration [8] [1].

Data Presentation

Critical Spectrophotometer Calibration Parameters and Tests

This table summarizes the key parameters that must be checked to ensure instrument accuracy, the common methods for testing them, and the typical acceptance criteria [2] [3].

| Parameter | Description & Importance | Common Test Methods | Acceptance Criteria Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength Accuracy | Verifies the instrument selects the correct wavelength. Critical for qualitative ID and quantitative accuracy. | Holmium oxide filters/solutions, emission line sources (e.g., Hg, Deuteriun), didymium glass. | Deviation ≤ ±1.0 nm in UV/VIS region [2] [3]. |

| Photometric Accuracy | Ensures the detector correctly measures absorbance/transmittance. Directly impacts concentration accuracy. | Neutral density filters (NIST-traceable), potassium dichromate solutions. | Absorbance error ≤ ±0.01 AU or as per pharmacopeia [3]. |

| Stray Light | Measures "false" light outside the target band. Causes negative deviation from Beer-Lambert law at high absorbance. | Liquid or solid cutoff filters (e.g., potassium chloride, sodium iodide). | Stray light ratio < 0.1% at specified wavelength [2] [3]. |

| Spectral Resolution | Ability to distinguish adjacent spectral features. Affects peak shape and height accuracy. | Measurement of the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of a sharp emission line. | Resolve closely spaced peaks (e.g., Hg 365.0/365.5 nm) or meet manufacturer's SBW spec [2]. |

Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Reliable Calibration

This table lists the key reagents, standards, and equipment necessary for preparing calibration curves and validating instrument performance [6] [3] [4].

| Item | Function and Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Standard | A high-purity material used to prepare a stock solution with a known, exact analyte concentration. | Should be of highest available purity (>99.9%), stable, and conform to pharmacopeial standards if applicable. |

| Volumetric Glassware | For precise dilution and preparation of standard solutions. | Use Class A volumetric flasks and pipettes to minimize preparation errors. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Physical standards used to test instrument parameters like wavelength and photometric accuracy. | Must be NIST-traceable. Examples: holmium oxide for wavelength, neutral density filters for photometry [3]. |

| UV-Vis Cuvettes | Sample holders. The material must be transparent in the spectral range of interest. | Quartz: For UV range. Glass/Plastic: For VIS range only. Matched cuvettes are critical for difference measurements. |

| Appropriate Solvent | The liquid used to dissolve the analyte and prepare the blank. | Must be transparent at the measurement wavelength and not react with the analyte. The blank and standards must use the same solvent. |

| TP-10 | TP-10, MF:C26H19F3N4O, MW:460.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| EN219 | EN219, MF:C17H13Br2ClN2O, MW:456.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Creating a UV-Vis Calibration Curve

Principle: A calibration curve is generated by measuring the absorbance of a series of standard solutions with known concentrations. The relationship between absorbance and concentration is described by the Beer-Lambert Law (A = εlc), which is typically linear for ideal conditions [6] [4].

Materials and Equipment [4]:

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Gloves, lab coat, safety glasses.

- Standard solution of the analyte.

- High-purity solvent (e.g., deionized water, HPLC-grade methanol).

- Precision pipettes and tips.

- Volumetric flasks or microtubes.

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

- Compatible cuvettes (e.g., quartz for UV).

- Computer with data analysis software.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Prepare a concentrated stock solution: Accurately weigh the primary standard and dissolve it in a volumetric flask to create a solution of known concentration [4].

- Perform serial dilution:

- Label a series of volumetric flasks or microtubes (a minimum of five standards is recommended).

- Pipette a specific volume of the stock solution into the first flask and dilute with solvent to the mark. Mix thoroughly.

- From this first dilution, pipette a volume into the next flask and dilute again. Repeat this process to create a series of standards that cover the expected concentration range of your unknown samples [4].

- Prepare samples and blanks: Transfer each standard solution to a clean cuvette. Prepare an unknown sample cuvette and a "blank" cuvette containing only the solvent [4].

- Measure absorbance:

- Place the blank in the spectrophotometer and zero the instrument.

- Measure each standard solution in triplicate and record the average absorbance values. This improves statistical reliability [4].

- Measure the absorbance of your unknown sample(s).

- Plot the data and analyze:

- Create a scatter plot with concentration on the x-axis and absorbance on the y-axis.

- Perform a linear regression analysis (y = mx + b) to obtain the equation of the line and the coefficient of determination (R²). An R² value ≥ 0.995 is typically considered excellent for quantitative work [4].

- Validate the curve: Analyze a control standard of known concentration that was not used to create the curve. The predicted concentration should fall within an acceptable margin of error (e.g., ±5%) of the true value.

Core Calibration Parameters and Their Interactions

The accuracy of a calibration curve depends on the proper functioning of several interrelated instrument parameters. Understanding these relationships is key to effective troubleshooting [3].

Key Terminology

- Absorbance (A): A logarithmic measure of the amount of light absorbed by a sample at a specific wavelength. It is the primary signal used in quantitative UV-Vis spectroscopy [6] [7].

- Beer-Lambert Law: The fundamental principle stating a linear relationship between absorbance and the concentration of an absorbing species: A = εlc [7].

- Certified Reference Material (CRM): A reference material characterized by a metrologically valid procedure, with one or more specified properties accompanied by a certificate that provides the value of the specified property and its associated uncertainty and statement of traceability. Essential for instrument validation [3].

- Photometric Linearity: The ability of an instrument to produce a photometric response that is directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte over a defined range [3].

- Stray Light: Any detected light that is outside the nominal wavelength band selected by the monochromator. It is a primary source of error, particularly at high absorbance values [2] [3].

- Wavelength Accuracy: The agreement between the wavelength scale indicated by the instrument and the true wavelength [2] [3].

What are the LOB, LOD, and LOQ, and how do they differ?

The Limit of Blank (LOB), Limit of Detection (LOD), and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) are fundamental performance characteristics that describe the lowest concentrations of an analyte that an analytical procedure can reliably distinguish [9] [10].

- Limit of Blank (LOB): The highest apparent analyte concentration expected to be found when replicates of a blank sample (containing no analyte) are tested. It is the threshold above which a signal is unlikely to be due to background noise alone [9] [11].

- Limit of Detection (LOD): The lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably distinguished from the LOB and at which detection is feasible. It is the level at which the measurement has a high probability (e.g., 95%) of being greater than zero [9] [12]. The analyte may be detected at this level, but not necessarily quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy.

- Limit of Quantitation (LOQ): The lowest concentration at which the analyte can not only be reliably detected but also quantified with stated acceptable criteria for precision (impression) and accuracy (bias) [9] [13]. It is the limit for precise quantitative measurements.

The relationship between these parameters is sequential: LOB < LOD ≤ LOQ [9]. The following diagram illustrates their statistical relationship, showing how LOD is distinguished from the blank and how LOQ requires greater signal confidence for reliable quantification.

How are LOB, LOD, and LOQ calculated?

Different analytical guidelines, such as those from CLSI and ICH, provide protocols for determining these limits. The appropriate method depends on your analytical technique [14]. The table below summarizes the common calculation approaches.

| Parameter | Sample Type | Recommended Replicates | Key Characteristics | Common Calculation Formulas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Limit of Blank (LOB) [9] | Sample containing no analyte | Establishment: 60Verification: 20 | Highest concentration expected from a blank sample | Non-Parametric: Based on ordered blank results [11]. Parametric: LOB = meanblank + 1.645(SDblank) [9] |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) [9] [15] | Sample with low analyte concentration | Establishment: 60Verification: 20 | Lowest concentration distinguished from LoB | Via LoB: LOD = LoB + 1.645(SDlow concentration sample) [9]. Via Calibration: LOD = 3.3 × σ / S [15] |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) [9] [13] [15] | Sample with low analyte concentration at or above LOD | Establishment: 60Verification: 20 | Lowest concentration quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy | Via Calibration: LOQ = 10 × σ / S [15]. Functional Sensitivity: Concentration at which CV = 20% [9]. LOQ ≥ LOD [9] |

Explanation of Terms:

- σ (Sigma): The standard deviation of the response. This can be the standard deviation of the blank, the residual standard deviation of a regression line, or the standard deviation of the y-intercepts of regression lines [15].

- S: The slope of the analytical calibration curve [15].

- SDlow concentration sample: The standard deviation of measurements from a sample with a low concentration of analyte [9].

What experimental protocol should I follow to determine LOB and LOD?

The following workflow, based on the CLSI EP17-A2 standard, provides a robust method for characterizing LOB and LOD in analytical assays, including digital PCR [11]. This protocol emphasizes the importance of using a representative sample matrix to accurately assess background noise.

Detailed Steps:

- Define Blank Sample: A blank sample should not contain the target analyte but should be in the same matrix as your test samples (e.g., drug-free plasma, wild-type DNA) [11].

- Analyze Blank Replicates: Perform your analytical procedure on at least 30 (N≥30) independently prepared blank samples to achieve a 95% confidence level [11].

- Calculate LoB (Non-Parametric Approach):

- Export and order the concentration results from the blank samples in ascending order (Rank 1 to Rank N).

- Calculate the rank position: X = 0.5 + (N × PLoB), where PLoB is the desired probability (e.g., 0.95 for 95%).

- The LoB is determined by interpolating between the concentrations at the ranks flanking X [11].

- Prepare Low-Level (LL) Samples: Create samples with a known, low concentration of the analyte, typically between one and five times the calculated LoB. These should be prepared independently [11].

- Analyze LL Replicates: Analyze a minimum of five different LL samples (J≥5), with at least six replicates (n≥6) each [11].

- Calculate LoD:

- Check that the variability (standard deviation) between the different LL samples is not significantly different using a statistical test like Cochran's test.

- Calculate the pooled (global) standard deviation (SDL) from all LL sample replicates.

- Calculate the coefficient Cp, which is a multiplier based on the t-statistic for the 95th percentile and your total number of replicates. A simplified value of 1.645 is often used for a large number of replicates [11].

- Compute the LoD using the formula: LoD = LoB + Cp × SDL [11].

How do I apply LOB and LOD results to interpret my sample data?

Once the LoB and LoD are established for an assay, they form objective criteria for decision-making on experimental data, especially for samples with low analyte concentrations [11].

| Condition | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Measured Concentration ≤ LoB | The analyte was not detected in the sample. |

| LoB < Measured Concentration < LoD | The analyte is detected but cannot be reliably quantified. The value should be reported as an estimate or as "< LoD". |

| Measured Concentration ≥ LoD | The analyte is detected and quantifiable. The reported concentration should meet the predefined precision and accuracy goals for the method [9] [11]. |

What are the common issues when determining LOB and LOD, and how can I troubleshoot them?

- Problem: High number of false positives in blank samples.

- Troubleshooting: This suggests potential contamination or high assay background noise [11].

- Check all reagents and samples for contamination. Prepare fresh blanks and reagents.

- For molecular assays (like dPCR), inspect positive signals to rule out artifacts [11].

- If contamination is ruled out, the false positives represent the biological/analytical noise of the assay. The assay may need re-optimization to improve specificity and lower the LoB [11].

- Troubleshooting: This suggests potential contamination or high assay background noise [11].

- Problem: Inconsistent or unreproducible LOD.

- Troubleshooting: This often stems from high imprecision in low-concentration sample measurements.

- Ensure your Low-Level (LL) samples are stable and homogenous.

- Verify that the concentration range of your LL samples is appropriate (1-5x LoB). A range that is too wide can cause high variability [11].

- Use a sufficient number of LL samples and replicates to robustly estimate standard deviation.

- Troubleshooting: This often stems from high imprecision in low-concentration sample measurements.

- Problem: The calculated LOD is not clinically or analytically relevant.

- Troubleshooting: The method's sensitivity may be insufficient for its intended purpose.

- The LOD must be "fit for purpose." If the required sensitivity is not achieved, fundamental re-development of the analytical method (e.g., sample preparation, detection chemistry) may be necessary [9].

- Troubleshooting: The method's sensitivity may be insufficient for its intended purpose.

Research Reagent Solutions for LoB/LoD Studies

| Material / Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Analyte-Free Matrix | Serves as the blank sample for LoB determination. It mimics the test sample composition without the analyte, crucial for assessing background noise (e.g., charcoal-stripped serum, wild-type DNA) [11]. |

| Certified Reference Material (CRM) | Used to prepare calibration standards and low-level (LL) samples with known, traceable analyte concentrations, ensuring accuracy in LOD/LOQ calculations. |

| Internal Standard | A compound added at a known concentration to all samples and calibrators to correct for sample preparation losses and instrumental variability, improving the precision of quantitative results, especially near the LOQ [16]. |

| High-Purity Solvents & Water | Used for preparing blanks, standards, and sample dilutions. Their purity is critical to minimize background signal and contamination that can adversely affect the LoB. |

In the validation of analytical and bioanalytical methods, the Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ) are two crucial performance parameters [17]. The LOD represents the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably detected by the method, but not necessarily quantified with exact precision. The LOQ is the lowest concentration that can be quantitatively measured with acceptable levels of precision and accuracy [17]. Accurately determining these values is essential for researchers to understand the limitations and applicability of their analytical methods, particularly in sensitive fields like pharmaceutical analysis and clinical diagnostics [17] [18].

Despite their importance, the absence of a universal protocol for establishing LOD and LOQ has led to varied approaches, and the values obtained can differ significantly depending on the chosen method [17] [18]. This guide compares common determination strategies to help you select the most appropriate one for your research.

FAQs on LOD and LOQ Determination

1. What are the most common methods for determining LOD and LOQ?

The most frequently used methods can be categorized as follows [17] [18]:

- Classical/Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N): This practical approach estimates LOD at a concentration where the signal is 3 times the baseline noise, and LOQ where it is 10 times the noise [18].

- Standard Deviation of the Response and Slope (SDR): This statistical method uses the standard deviation of the response (σ) and the slope of the calibration curve (s) with the formulas LOD = 3.3 × σ/s and LOQ = 10 × σ/s [19].

- Graphical Methods:

- Accuracy Profile: A graphical tool that uses tolerance intervals to determine the concentration range where a method provides results with acceptable accuracy [17].

- Uncertainty Profile: An advanced graphical strategy similar to the accuracy profile but incorporates measurement uncertainty, providing a precise estimate of the LOQ as the intersection of uncertainty intervals with acceptability limits [17].

2. How do the results from different methods compare?

Studies show that different methods can yield significantly different LOD and LOQ values for the same analysis [18]. The signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) method often provides the lowest, most optimistic values, while the standard deviation of the response and slope (SDR) method typically results in the highest, most conservative values [18]. In contrast, graphical methods like the uncertainty and accuracy profiles offer a more realistic and relevant assessment of the method's capabilities [17].

3. When should I use graphical methods like the uncertainty profile?

Graphical methods are particularly valuable when you need a realistic and reliable assessment of your method's quantitative capabilities at low concentrations [17]. They are highly recommended for methods where precise knowledge of the lowest measurable concentration is critical, such as in pharmaceutical bioanalysis or clinical assay development [17]. These methods simultaneously validate the bioanalytical procedure and estimate measurement uncertainty.

4. My calibration curve is linear. Can I simply use the SDR method?

While the standard deviation of the response and slope method is a valid and commonly used statistical technique, it is important to be aware that it can sometimes provide overestimated LOD and LOQ values compared to other approaches [18]. It is a good practice to compare its results with another method, such as the signal-to-noise ratio, to ensure consistency and understand the sensitivity of your method fully [18].

Comparison of LOD/LOQ Determination Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the different approaches to help you make an informed selection.

| Method | Basis of Calculation | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise (S/N) [18] | Ratio of analyte signal to baseline noise | Simple, intuitive, and quick to implement | Can provide underestimated values; relies on a stable baseline [18] | Initial, rapid assessment during method development |

| Standard Deviation & Slope (SDR) [19] | Statistical parameters from the calibration curve | Uses common regression outputs; objective calculation | Can provide overestimated values; highly dependent on calibration quality [18] | Common in regulated environments (e.g., following FDA criteria) [18] |

| Accuracy Profile [17] | Graphical analysis based on tolerance intervals for accuracy | Provides a realistic validity domain; visual and reliable | More complex to implement than classical methods [17] | Validation of methods where the quantitative range must be clearly defined |

| Uncertainty Profile [17] | Graphical analysis based on tolerance intervals and measurement uncertainty | Provides the most precise estimate of measurement uncertainty; defines LOQ rigorously [17] | Most complex to calculate and implement [17] | High-stakes applications like pharmaceutical bioanalysis where precision is critical [17] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining LOD/LOQ via Standard Deviation of Response and Slope

This method is widely used in various analytical techniques, including HPLC and ELISA [19].

- Prepare Calibration Standards: Create a series of standard solutions at known concentrations across the expected range, including low concentrations near the predicted limits.

- Run Analysis: Analyze each standard solution multiple times (e.g., n=3 or more) to generate a response (e.g., peak area, absorbance) for each concentration.

- Generate Calibration Curve: Plot the average response against the concentration for each standard. Perform linear regression to obtain the equation of the line (y = mx + c) and the slope (s).

- Calculate Standard Deviation: Calculate the standard deviation (σ) of the response. This can be the standard deviation of the y-intercepts of the regression lines or the standard deviation of the responses from low-concentration standards.

- Compute LOD and LOQ: Use the standard formulas to calculate the limits.

- LOD = 3.3 × σ / s

- LOQ = 10 × σ / s [19]

Protocol 2: Determining LOQ via the Uncertainty Profile

This robust graphical method is implemented through the following workflow [17]:

Key Steps Explained:

- Define Acceptance Limits (λ): Establish the desired accuracy limits (e.g., ±15%) based on the method's intended use and regulatory guidelines [17].

- Collect Data and Build Models: Analyze validation standards across multiple series/days. Generate all possible calibration models from the data [17].

- Calculate Tolerance Intervals: For each concentration level, compute a two-sided β-content γ-confidence tolerance interval. This interval is calculated as the mean result (±) a tolerance factor (ktol) multiplied by the reproducibility standard deviation (σm) [17].

- Determine Measurement Uncertainty: For each concentration level, derive the standard measurement uncertainty, u(Y), from the tolerance interval using the formula: u(Y) = (U - L) / [2 * t(ν)], where U and L are the upper and lower tolerance limits, and t(ν) is the Student t quantile [17].

- Construct the Uncertainty Profile: Create a graph plotting the mean result (±) the expanded uncertainty (k * u(Y), where k is a coverage factor, usually 2 for 95% confidence) against the concentration. Overlay the predefined acceptance limits (-λ, λ) on the same graph [17].

- Make a Decision and Find LOQ: If the entire uncertainty interval falls within the acceptance limits across a concentration range, the method is valid for that range. The LOQ is accurately found at the lowest concentration where the uncertainty interval intersects the acceptability limit. This is calculated using linear algebra to find the intersection point's coordinates [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials used in developing and validating quantitative analytical methods, as referenced in the studies.

| Item | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) [20] | Provides a known, traceable standard to validate the accuracy and calibration of an analytical method. |

| High-Purity Solvents & Reagents | Ensures that impurities do not interfere with the analyte signal, which is critical for achieving low LOD/LOQ. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [19] | Used as a carrier protein to create conjugates for hapten-based immunoassays (e.g., for vancomycin LFA). |

| Biotin-Avidin/Streptavidin System [19] | Used to enhance signal detection in immunoassays and biosensors, improving assay sensitivity. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNP) [19] | Commonly used as a visual or spectroscopic label in lateral flow assays and other biosensors. |

| Nitrocellulose Membrane [19] | The porous matrix used in lateral flow immunoassays for capillary flow and immobilization of capture molecules. |

| 2PACz | 2PACz|20999-38-6|Hole Transport Material |

| Acid red 131 | Acid red 131, CAS:652145-29-4, MF:C35H28N2O2, MW:508.6 g/mol |

Workflow for Calibration Curve Optimization

Optimizing your calibration is a foundational step for reliable LOD/LOQ determination. The following workflow integrates modern calibration techniques to enhance overall data quality.

Key Steps Explained:

- Traditional vs. Continuous Calibration: While traditional methods use discrete standard solutions, continuous calibration techniques, which involve infusing a concentrated calibrant into a matrix, can generate extensive data points. This reduces time and labor while significantly improving calibration precision and accuracy [21].

- Advanced Data Processing: Utilize available open-source code and web applications to process calibration data, perform smoothing, and fit appropriate equations, which provides better quality-of-fit and dynamic range estimates [21].

- Quality Assessment: Before proceeding to LOD/LOQ calculations, rigorously assess the calibration curve's linearity, the pattern of residuals, and the usable dynamic range. A high-quality curve is a prerequisite for accurate limit determination.

Establishing the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) for Your Method

This technical support resource provides practical guidance on implementing the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) to enhance the robustness of your quantitative spectroscopic methods.

FAQs: Understanding the Analytical Target Profile (ATP)

1. What is an Analytical Target Profile (ATP)?

An Analytical Target Profile (ATP) is a prospective summary of the performance characteristics that describe the intended purpose and anticipated performance criteria of an analytical measurement [22]. It defines the required quality of the reportable value produced by an analytical procedure and serves as the foundation for method development, validation, and ongoing performance verification throughout its lifecycle [22] [23].

2. How does the ATP differ from a method validation protocol?

While a method validation protocol confirms that a specific, established procedure meets acceptance criteria, the ATP is a forward-looking, performance-based definition that is independent of a specific technique. It defines what the method must achieve (e.g., maximum acceptable uncertainty), not how to achieve it. Multiple analytical techniques can be designed to meet the same ATP [22].

3. What are the key components of an ATP?

According to regulatory guidelines, an ATP should include [22]:

- A description of the intended purpose of the analytical procedure

- Details on the product attributes to be measured

- Relevant performance characteristics with associated performance criteria

- Measurement requirements for one or more quality attributes

- Upper limits on the precision and accuracy of the reportable value

4. When should I develop an ATP for my method?

The ATP should be defined early in the method development process, as it drives the selection of analytical technology and provides the design goals for the new analytical procedure [22] [23]. It then serves as a foundation for procedure qualification and monitoring throughout the method's lifecycle.

5. How specific should my ATP be regarding calibration approaches?

The ATP should define the required quality of the reportable value but typically remains independent of the specific measurement technology [22]. This allows flexibility in selecting the most appropriate calibration strategy (e.g., external calibration, standard addition, internal standard) that meets the predefined performance criteria for your specific application [24] [21].

Troubleshooting Guides: ATP Implementation Challenges

Issue 1: Defining Appropriate Performance Criteria

Challenge: Establishing scientifically sound performance criteria that balance rigor with practical achievability.

Solutions:

- Base criteria on intended use: For critical quality attributes, set tighter limits on precision and accuracy [23].

- Consider existing guidance: Leverage ICH Q2(R1) validation parameters as a starting point, but tailor them to your specific needs through the ATP [23].

- Focus on combined uncertainty: Adopt a more holistic approach by combining accuracy and precision into a combined uncertainty characteristic rather than treating them separately [23].

- Reference authoritative sources: Consult IUPAC guidelines and ISO standards for established calibration quality criteria [25].

Issue 2: Managing Calibration Curve Uncertainty

Challenge: High uncertainty in regression models affects the reliability of quantitative results.

Solutions:

- Evaluate weighting procedures: When concentration ranges span several orders of magnitude, implement weighted regression to account for non-constant variance across the calibration range [25].

- Assess curve fitting alternatives: For non-linear responses, consider quadratic regression or median-based robust regressions that are less sensitive to outliers [25].

- Expand data points: Use methods like continuous calibration to generate extensive calibration data, improving precision and accuracy while reducing time and labor demands [21].

- Verify linearity assumptions: Test whether quadratic regression provides statistically significant improvement over linear models for your specific analytical system [25].

Issue 3: Addressing Matrix Effects in Complex Samples

Challenge: Sample matrix components interfere with analyte signal, compromising result accuracy.

Solutions:

- Select appropriate calibration strategy: For virgin olive oil analysis, external matrix-matched calibration (EC) demonstrated superior reliability over standard addition (AC) or internal standard (IS) methods [24].

- Validate matrix effect mitigation: Systematically evaluate and confirm the absence or presence of matrix effects when selecting your calibration strategy [24].

- Use matrix-matched standards: Prepare calibration standards in a matrix as similar as possible to the real samples, using refined material confirmed to be free of target analytes [24].

- Consider standard addition: When a strong matrix effect interferes with analyte signal, implement standard addition calibration despite its more time-consuming nature [24].

Issue 4: Ensuring Method Performance Throughout Lifecycle

Challenge: Maintaining ATP compliance as methods transition from development to routine use.

Solutions:

- Establish ongoing monitoring: Use the ATP as a guide for monitoring procedure performance during its entire lifecycle [22].

- Implement system suitability tests: Define tests based on ATP requirements to verify method performance before each use.

- Document deviations: Record any performance variations and investigate root causes relative to ATP criteria.

- Plan for method updates: Use the ATP as a stable reference point when method modifications become necessary, ensuring changes still meet original performance requirements [23].

Experimental Protocol: ATP-Driven Calibration Strategy Development

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for developing and validating a calibration strategy aligned with ATP requirements for quantitative spectroscopic analysis.

Materials and Equipment

| Category | Item | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumentation | Sonico Luminescence Spectrometer | RRS intensity measurements [26] |

| Gas Chromatograph with FID | Separation and detection of volatile compounds [24] | |

| Dynamic Head Space System | Preconcentration of volatile compounds [24] | |

| Software | Star Chromatography Workstation | Chromatographic data processing [24] |

| Excel with statistical functions | Regression analysis and uncertainty calculations [25] | |

| Consumables | Tenax TA adsorbent traps | Volatile compound adsorption/desorption [24] |

| TRB-WAX capillary column | Compound separation [24] | |

| Quartz sample cells | Spectroscopic measurements [26] |

Procedure

Step 1: Define ATP Performance Criteria

- Document the analyte(s), required reportable range, and maximum acceptable uncertainty

- Establish specificity requirements based on intended method use

- Define accuracy (bias) and precision limits aligned with decision risks [23]

Step 2: Select and Optimize Calibration Model

- Prepare calibration standards across the required range (e.g., 14 points for volatile compounds) [24]

- Evaluate homoscedasticity by analyzing variance across concentration levels [25]

- Select regression model:

Step 3: Validate Calibration Strategy

- Assess linearity through statistical significance of quadratic term [25]

- Determine LOD and LOQ using signal-to-noise or uncertainty approaches [26] [25]

- Evaluate accuracy through spike recovery or reference materials [24]

- Verify precision across multiple replicates and days [24]

Step 4: Compare Calibration Approaches (where applicable)

- Prepare external matrix-matched standards in refined oil matrix [24]

- Implement standard addition for matrix effect assessment [24]

- Test internal standardization for response correction [24]

- Select optimal approach based on ATP criteria compliance [24]

Step 5: Document and Transfer

- Record final calibration parameters, including weighting factors and regression equations

- Establish system suitability tests based on ATP requirements

- Define ongoing monitoring procedures for lifecycle management [22]

Workflow Visualization: ATP Development Process

Pro Tips for Success

- Leverage regulatory guidance: ICH Q14 and USP <1220> provide established frameworks for ATP implementation [22].

- Challenge correlation coefficient reliance: The correlation coefficient (r) alone is insufficient for evaluating calibration quality; focus instead on uncertainty associated with the regression [25].

- Consider continuous calibration: Modern continuous calibration approaches can reduce time and labor while improving precision through extensive data generation [21].

- Document rationale: Clearly document the scientific justification for selected performance criteria and calibration approaches to facilitate regulatory communication [22].

Fundamentals of Linear Regression and the Beer-Lambert Law in Spectroscopy

Understanding the Core Principle: The Beer-Lambert Law

The Beer-Lambert Law (also known as Beer's Law) is a fundamental principle that forms the basis for quantitative analysis in absorption spectroscopy. It states a linear relationship between the absorbance of light by a substance and its concentration in a solution [27] [28].

The law is expressed by the equation: A = εlc Where:

- A is the measured Absorbance (a dimensionless quantity) [27] [29].

- ε is the Molar Absorptivity (or molar extinction coefficient), a substance-specific constant with units of L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹ [29] [30].

- l is the Path Length, the distance light travels through the sample, typically in centimeters (cm) [29] [30].

- c is the Concentration of the absorbing species, usually in moles per liter (mol/L) [29] [30].

In practice, for a given instrument and analyte, the path length (l) and molar absorptivity (ε) are constant, making absorbance (A) directly proportional to concentration (c). This relationship allows researchers to determine the concentration of an unknown sample by measuring its absorbance [27] [30].

Relationship Between Absorbance and Transmittance Absorbance is derived from transmittance. Transmittance (T) is the fraction of incident light (Iâ‚€) that passes through a sample (I): T = I / Iâ‚€ [27] [28]. Percent transmittance is %T = 100% × T [27]. Absorbance is calculated as the negative logarithm of the transmittance: A = -logâ‚â‚€(T) = logâ‚â‚€(Iâ‚€/I) [27] [28] [29].

This logarithmic relationship converts the exponential decay of light intensity into a linear scale suitable for calibration and quantification [28]. The table below shows how absorbance and transmittance values relate.

| Absorbance | Transmittance |

|---|---|

| 0 | 100% |

| 1 | 10% |

| 2 | 1% |

| 3 | 0.1% |

| 4 | 0.01% |

| 5 | 0.001% |

Table: Correspondence between Absorbance and Transmittance values [27].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is my calibration curve not linear, especially at high concentrations? The Beer-Lambert Law assumes ideal conditions, which can break down at high concentrations (typically above 10 mM) [29]. Deviations from linearity, known as "chemical deviations," occur due to:

- Molecular Interactions: At high concentrations, absorbing molecules can aggregate or interact with each other, altering their absorption properties [31] [29].

- Changes in Refractive Index: The proportionality constant ε can become dependent on concentration at high levels, violating a key assumption of the law [31].

- Solution Non-Ideality: The law is most accurate for dilute solutions. In concentrated solutions, electrostatic interactions between ions can affect absorption [31].

2. My model performs well on calibration data but poorly on new samples. What is happening? This is a classic sign of overfitting or model degradation over time [32] [33].

- Overfitting: Your model may be too complex, having learned the noise in your specific calibration dataset rather than the general relationship. This reduces its predictive power for new data [34].

- Instrumental Drift: Small changes in the instrument's performance over time, such as wavelength shift (x-axis) or photometric shift (y-axis), can render an initially perfect model inaccurate, requiring frequent bias adjustments [33].

3. What is the correct way to use a calibration curve to find an unknown concentration? This is a common point of confusion. The correct statistical method is inverse regression [35].

- The Mistake: The classical calibration method involves regressing absorbance (Y) on known concentrations (X) to create the curve, then simply solving the regression equation for X given a new Y (absorbance) value.

- The Fix: The proper inverse regression approach uses the calibration curve to create a prediction interval for a new observation. The concentration of the unknown is estimated from the calibration data, accounting for the uncertainty in both the regression line and the new measurement. Using standard linear regression software incorrectly can lead to biased results, though the difference may be small in some cases [35].

4. Why is it discouraged to use the term "Optical Density" (OD)? While the terms "Absorbance" and "Optical Density" (OD) are often used interchangeably, the use of Optical Density is discouraged by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) [27]. "Absorbance" is the preferred and more precise term in quantitative spectroscopic analysis.

Troubleshooting Guide

This guide helps you diagnose and fix common problems in spectroscopic calibration.

Problem 1: Non-Linear Calibration Curve

- Symptoms: The scatter plot of absorbance vs. concentration curves upward or downward, or the residual plot shows a clear pattern (e.g., a U-shape) instead of random scatter [32].

- Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The relationship is inherently non-linear, often at high concentrations [32] [31].

- Solution: Dilute your samples to a concentration range where the Beer-Lambert Law holds (typically lower concentrations). If non-linearity is due to the nature of the analyte, you can try a mathematical transformation of the variables or use non-linear regression methods [32].

- Cause: Stray light or instrumental limitations [31].

- Solution: Ensure your spectrophotometer is well-maintained and calibrated. Use a cuvette with an appropriate path length to keep absorbance within the instrument's optimal range (often 0.1 - 1.0 AU).

Problem 2: High Prediction Error or Poor Model Performance

- Symptoms: The model has a low R² value, or predictions for new samples are inaccurate and imprecise.

- Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Outliers or high-leverage points in your calibration data that disproportionately influence the regression line [32].

- Solution: Examine the calibration data and residual plots to identify outliers. Investigate whether these are due to experimental error and consider removing them if justified [32].

- Cause: Insufficient or poor-quality calibration data [34].

- Solution: Prepare a sufficient number of calibration standards (a common rule of thumb is at least 5-6 standards for a linear model). Ensure they are prepared accurately across the concentration range of interest and that their absorbance values are measured precisely [34].

- Cause: Collinearity in multivariate calibration (when using multiple wavelengths). Wavelengths that are highly correlated provide redundant information [36] [32].

- Solution: Use variable selection techniques like Genetic Algorithms (GAs) or Bayesian variable selection to identify the most informative wavelengths and build a more robust model [36].

Problem 3: Correlated Error Terms (Autocorrelation)

- Symptoms: Most common in time-series data. The residual plot versus time (or the order of measurement) shows a sequential pattern, such as runs of positive or negative residuals [32] [34].

- Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The instrument's response may drift during the measurement sequence [32] [33] [34].

- Solution: Randomize the order in which you measure your standards and samples. If drift is known, incorporate it into the model or use instrument-specific correction methods. For time-series data, consider using models that account for autocorrelation [32] [34].

Problem 4: Non-Constant Variance (Heteroscedasticity)

- Symptoms: The residual plot shows a "funnel" shape, where the spread of the residuals increases or decreases with the fitted values (concentration) [32] [34].

- Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: The variance of the measurement error is often proportional to the concentration level [34].

- Solution: Apply a variance-stabilizing transformation to the response variable (absorbance), such as a logarithm or square root. Alternatively, use weighted least squares regression instead of ordinary least squares, where each data point is weighted inversely to its variance [34].

The following workflow provides a visual summary of the diagnostic and corrective process for calibration issues.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials & Reagents

The following table lists key items and their functions for a successful spectroscopic experiment based on the Beer-Lambert Law.

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Spectrophotometer | The core instrument that emits light at a specific wavelength and measures the intensity of light before (Iâ‚€) and after (I) it passes through the sample to calculate absorbance [28]. |

| Cuvette | A container, typically with a standard path length of 1 cm, that holds the sample solution. It must be made of a material transparent to the wavelength of light used (e.g., quartz for UV, glass/plastic for visible light) [27] [29]. |

| Standard Solutions | A series of solutions with precisely known concentrations of the analyte. These are used to construct the calibration curve, which is the reference for determining unknown concentrations [30]. |

| Blank Solution | The solvent or matrix without the analyte. It is used to zero the spectrophotometer (set to 100% transmittance or 0 absorbance), accounting for any light absorption by the solvent or cuvette [31]. |

| Buffer Solutions | Used to maintain a constant pH, which is critical as the molar absorptivity (ε) of many compounds can be sensitive to changes in pH [29]. |

| CP-10 | CP-10, CAS:2366268-80-4, MF:C44H49N13O7, MW:871.9 g/mol |

| VUAA1 | VUAA1, CAS:525582-84-7, MF:C19H21N5OS, MW:367.47 |

Experimental Protocol: Building a Robust Calibration Curve

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating a reliable calibration model for quantitative analysis.

Step 1: Preparation of Standard Solutions

- Prepare a stock solution of the analyte with a known, high concentration.

- Perform a series of precise dilutions to create at least 5-6 standard solutions that span the expected concentration range of your unknown samples [30].

- Ensure all solutions, including the blank, are prepared in the same solvent and matrix to minimize interference.

Step 2: Absorbance Measurement

- Turn on the spectrophotometer and allow it to warm up. Set the wavelength to the maximum absorbance (λmax) of your analyte [29].

- Using a matched cuvette, measure your blank solution and use it to zero the instrument.

- Measure the absorbance of each standard solution in a randomized order to prevent systematic drift from affecting the results [32]. Replicate measurements are recommended.

Step 3: Construction of the Calibration Curve

- Plot the data with concentration on the x-axis and the mean absorbance on the y-axis [35] [30].

- Perform a linear regression to find the line of best fit. The equation will be of the form A = slope × c + intercept [35] [30].

- Statistically, for predicting an unknown concentration from an absorbance reading, the method of inverse regression should be applied to this calibration data to obtain an unbiased estimate [35].

Step 4: Validation

- Use the calibration curve to predict the concentration of a validation standard (a standard not used in building the curve).

- Assess the accuracy and precision of the prediction. This helps verify that the model is robust and not overfitted.

The following diagram illustrates this workflow.

Practical Implementation: Designing and Executing Robust Calibration Methods

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the primary cause of matrix effects in quantitative analysis? Matrix effects occur when compounds co-eluting with your analyte interfere with the ionization process in detectors like those in mass spectrometers, causing ion suppression or enhancement [37]. These effects are primarily caused by differences in the sample matrix (e.g., salts, organic compounds, acids) between your calibration standards and unknown samples, which can alter nebulization efficiency, plasma temperature, or ionization yield [5] [37].

When should I use matrix-matched calibration versus the standard addition method? Use matrix-matched calibration when a blank matrix is available and the sample matrix is relatively consistent [5] [38]. This is common in regulated bioanalysis or pesticide testing in specific food types [39]. Use the standard addition method for samples with unique, complex, or unknown matrices where obtaining a true blank is difficult, such as with endogenous analytes or highly variable sample types [5] [37]. Standard addition is more robust but also more labor-intensive and time-consuming [37].

How many calibration points are sufficient, and how should they be spaced? Regulatory guidelines often recommend a minimum of six non-zero calibrators [38]. For best practices, use 6-8 calibration points [40]. These points should not be prepared from one continuous serial dilution to avoid propagating pipetting errors; instead, prepare several independent stock solutions and perform dilutions from these [40]. Spacing should ideally be logarithmic across the expected concentration range [40] [41].

Can a high correlation coefficient (R²) guarantee an accurate calibration curve? No. A high R² value does not guarantee accuracy, especially at the lower end of the calibration range [41]. The error of high-concentration standards can dominate the regression fit, making the curve appear linear while providing poor accuracy for low-concentration samples [41]. Always verify curve performance with quality control samples at low, medium, and high concentrations [38].

What is the role of an internal standard, and how do I select the right one? Internal standards correct for variations in sample introduction, ionization efficiency, and sample preparation [38] [42]. Stable isotope-labeled (SIL) internal standards are the gold standard for mass spectrometry because they mimic the analyte almost perfectly in chemical behavior and retention time [38] [37]. For techniques like ICP-OES, choose an internal standard element not present in your samples, with similar ionization potential and behavior to your analyte [42].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inaccurate Low-End Quantification

Symptoms: Poor recovery for quality control samples at low concentrations, even with an acceptable R² value for the calibration curve [41].

Solutions:

- Re-calibrate with a Low-Level Curve: Construct a new calibration curve using standards only at low concentrations (e.g., blank, 0.5, 2.0, and 10.0 ppb) instead of a wide-range curve. This prevents high-concentration standards from dominating the regression fit [41].

- Investigate Blank Contamination: Ensure your calibration blank is clean. Contamination in the blank is subtracted from all measurements and can disproportionately affect low-concentration accuracy [41].

- Apply Weighted Regression: Use a weighted regression model (e.g., 1/x or 1/x²) to minimize the influence of heteroscedasticity (non-constant variance across the concentration range) and improve accuracy at the low end [38] [39].

Problem: Significant Matrix Effects Causing Ion Suppression/Enhancement

Symptoms: Inconsistent analyte recovery; signal intensity changes when the sample matrix changes; poor reproducibility [37].

Solutions:

- Improve Sample Cleanup: Optimize your sample preparation (e.g., using selective extraction or d-SPE clean-up in QuEChERS methods) to remove interfering matrix components [37] [39].

- Optimize Chromatography: Adjust chromatographic parameters to separate the analyte from co-eluting matrix interferences. This shifts the analyte's retention time away from regions of ion suppression/enhancement [37].

- Use a Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard (SIL-IS): This is the most effective correction method. The SIL-IS experiences the same matrix effects as the analyte, allowing the response ratio (analyte/SIL-IS) to remain accurate [38] [37].

- Employ Matrix-Matched Calibration: Prepare your calibration standards in a matrix that is free of the analyte but otherwise matches the sample composition as closely as possible [38] [39].

Problem: Poor Internal Standard Performance

Symptoms: High variability in internal standard recovery between samples; internal standard recovery outside the acceptable range (e.g., ±20-30%) [42].

Solutions:

- Verify Selection Criteria: Confirm the internal standard is not naturally present in any sample. Ensure it does not have spectral interferences with target analytes and that it behaves similarly (e.g., same ionization type) in the plasma or ion source [42].

- Check Addition Technique: Ensure the internal standard is added consistently to all samples and standards. Use precise, automated pipetting or an internal standard pump to minimize pipetting error [42].

- Investigate Matrix Composition: For ICP-OES, samples with high concentrations of easily ionized elements (e.g., Na, K) can affect internal standard performance. In such cases, use an internal standard with an ionization behavior (atomic or ionic line) that matches your analyte [42].

- Consider Multiple Internal Standards: For multi-analyte panels, a single internal standard may not be suitable for all analytes. It may be necessary to use multiple internal standards to cover all analytes accurately [5] [42].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Matrix-Matched Calibration Curve for Endogenous Analytes

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in quantitative proteomics and clinical mass spectrometry [40] [38].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope-Labeled (SIL) Analytes | Serves as the calibrator; allows quantification of the endogenous, unlabeled analyte in the sample. |

| Biological Matrix (e.g., plasma, serum) | The "matrix-matched" component. It should be as identical as possible to the sample matrix. |

| Charcoal-Stripped or Synthetic Matrix | Used if a natural matrix devoid of the endogenous analyte is required but not fully achievable. |

| Isotope-Enriched Water (H₂¹â¸O) | Can be used in enzymatic digestion to label peptides, creating a labeled matrix for calibration [40]. |

Methodology:

- Prepare the Calibration Matrix: Obtain a matrix that matches your sample type (e.g., human plasma). To create a "blank," remove the endogenous analyte via methods like charcoal stripping or dialysis. Verify the removal efficiency [38].

- Create Calibration Points: Spike known, varying concentrations of the stable isotope-labeled version of your analyte into the prepared matrix. This creates a reverse calibration curve [40] [38].

- Design the Dilution Scheme: Prepare at least six non-zero calibration points. Use a logarithmic spacing across the expected concentration range. To avoid error propagation, create several independent stock solutions and perform serial dilutions from these, rather than from a single stock [40].

- Sample Processing and Analysis: Process the calibration standards and unknown samples identically (same digestion, extraction, and cleanup procedures).

- Data Regression: Plot the instrument response (ratio of unlabeled analyte peak area to SIL-IS peak area) against the known concentration of the SIL standard. Apply appropriate weighting (e.g., 1/x) if heteroscedasticity is present [38].

Protocol 2: Standard Addition Method for Complex Matrices

This protocol is applicable when a blank matrix is unavailable or samples have highly variable matrices [37].

Methodology:

- Divide the Sample: Split the sample into four or five equal aliquots.

- Spike the Aliquots: Leave one aliquot unspiked. To the remaining aliquots, add known and increasing concentrations of your target analyte.

- Dilute to Volume: Ensure all aliquots, including the unspiked one, are brought to the same final volume with a suitable solvent. This keeps the matrix constant across all samples.

- Analysis and Plotting: Analyze all aliquots and plot the measured instrument signal on the y-axis against the concentration of the analyte added on the x-axis.

- Calculate Original Concentration: Extend the best-fit line of the data backwards until it intersects the x-axis. The absolute value of this x-intercept represents the original concentration of the analyte in the sample [37].

Workflow and Strategy Visualization

FAQs: Core Concepts and Application

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between the standard addition and internal standardization techniques?

A1: The core difference lies in their approach to handling matrix effects. The standard addition method involves adding known quantities of the analyte directly to the sample itself. This technique is particularly powerful for analyzing samples with complex or unknown matrices, as it compensates for interference by ensuring that the calibrant and analyte experience an identical chemical environment [43]. Internal standardization, conversely, involves adding a known amount of a foreign element (the internal standard) to all samples, blanks, and calibration standards. The calibration is then built using the signal ratio of the analyte to the internal standard, which corrects for instrumental fluctuations and some physical matrix effects [44] [45].

Q2: When should I choose the standard addition method over a conventional calibration curve?

A2: Standard addition is the recommended technique when you are working with samples that have a complex, variable, or unknown matrix, and you suspect that matrix effects could significantly alter the analytical signal. Common applications include the analysis of biological fluids (e.g., blood, urine), environmental samples (e.g., soil extracts, river water), and pharmaceutical formulations where excipients may interfere [44] [43]. It is especially crucial when an internal standard that corrects for plasma-related effects cannot be found [44].

Q3: What are the critical assumptions and requirements for internal standardization to be effective?

A3: For internal standardization to work correctly, several assumptions must hold true [44] [45]:

- The internal standard element must not be present in the original sample.

- It must have no spectral interferences from the analyte or the sample matrix.

- The internal standard must respond similarly to the analyte concerning changes in instrumental conditions (e.g., plasma temperature in ICP, nebulizer uptake).

- The method of adding the internal standard must be highly precise, with the same amount added to all standards and samples.

Q4: My internal standard is not correcting for matrix effects adequately. What could be wrong?

A4: This is a common issue. The likely cause is that the internal standard's behavior in the plasma does not perfectly match that of your analyte. The matrix effect can be element-specific, influenced by factors like excitation potential. An internal standard that effectively corrects for nebulizer-related effects may fail to correct for plasma-related effects if its excitation characteristics are different from the analyte's [44]. In such cases, using multiple internal standards (Multi-Internal Standard Calibration, MISC) or advanced techniques like multi-wavelength internal standardization (MWIS) can provide a broader and more effective correction [45].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Problems

| Problem Symptom | Possible Cause | Troubleshooting Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Linearity in Standard Addition Curve | • Incorrect spike concentrations (too high/low) [44]. • Significant instrument drift during measurement [44]. • Non-linear response outside the method's dynamic range. | • Re-estimate the unknown concentration and spike to achieve 1x, 2x, and 3x the original level [44]. • Use a measurement sequence that intersperses blanks and samples to monitor and correct for drift [44]. • Verify the linear range of your instrument and ensure all measurements fall within it. |

| Inaccurate Results with Internal Standard | • The internal standard is present in the sample [44]. • Spectral interference on the internal standard's line [44]. • The internal standard does not mimic the analyte's response to the matrix. | • Analyze a sample blank to check for the presence of the internal standard. • Carefully scan the spectral region around the internal standard's wavelength for interferences [44]. • Validate your method using standard addition or switch to a more chemically similar internal standard. |

| High Variability in Replicate Analyses | • Inconsistent addition of the internal standard solution [44]. • Inconsistent sample preparation (e.g., grinding, dilution). • Contaminated argon gas or samples [46]. | • Use a high-precision pipette and ensure the same lot of internal standard solution is used throughout [44]. • Follow a strict and consistent sample preparation protocol. Avoid touching samples with bare hands [46]. • Check argon quality; regrind samples to remove surface contamination [46]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Advanced Calibration Techniques

| Technique | Key Principle | Best For | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Wavelength Internal Standardization (MWIS) [45] | Uses multiple analyte wavelengths and multiple internal standard wavelengths from just two solutions to create a robust, matrix-matched calibration. | ICP-OES and other techniques where multiple wavelengths are available. Corrects for both instrumental drift and sample matrix effects. | High number of data points for calibration from minimal solutions; eliminates need for a single "perfect" internal standard. | Requires multiple emission lines; newer technique requiring specific data processing. |

| Standard Dilution Analysis (SDA) [45] | An automated on-line dilution of an analyte standard creates the calibration curve within the sample matrix. | FAAS, ICP-OES, ICP-MS, MIP-OES. | Automates standard addition, increasing throughput; corrects for matrix effects. | Requires instrumental setup for automated dilution; can be slower than conventional calibration. |

| Multi-Energy Calibration (MEC) [45] | Uses multiple analyte wavelengths (or isotopes in MS) to build a calibration curve without the need for an external internal standard. | Techniques with multiple strong characteristic lines (e.g., LIBS, MIP-OES, HR-CS-GFMAS). | Matrix-matched; does not require adding a foreign internal standard. | Not suitable for analytes with few emission lines (e.g., As, Pb). |

| Isotope Dilution Mass Spectrometry (IDMS) [44] | Uses an enriched stable isotope of the analyte as the perfect internal standard. A definitive method based on isotope ratio measurements. | ICP-MS for certification of reference materials and high-precision analysis. | Considered a primary method; highly accurate and immune to matrix effects and drift. | Not applicable to monoisotopic elements; requires expensive isotopically enriched standards. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Addition Procedure for UV-Vis Spectrophotometry

This protocol details the steps for determining an unknown analyte concentration in a complex matrix using the standard addition method [43].

Workflow Overview

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the standard addition procedure:

Step-by-Step Instructions:

Preparation of Test Solutions:

- Accurately pipette equal volumes of the sample solution (with unknown concentration, C~x~) into a series of volumetric flasks (e.g., five 10-mL flasks) [43].

- To each flask, add increasing, but known, volumes (V~s~) of a standard solution of the analyte with a known concentration (C~s~). For example, add 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 mL.

- Dilute all solutions to the mark with an appropriate solvent. Ensure a uniform matrix by adding the same volume of solvent to the "0" spike (the control).

Measurement of Instrument Response:

- Using your spectrometer (e.g., UV-Vis), measure the analytical signal (S) for each prepared solution. This could be absorbance, fluorescence intensity, or emission intensity.

- Record the signal for each solution against a solvent blank.

Data Analysis and Calculation:

- Plot the measured signals (y-axis) against the concentration of the added analyte standard in the final solution (x-axis). Alternatively, you can plot against the volume of standard added, but concentration is more universal.

- Perform a linear regression analysis on the data points to obtain the equation of the line: ( S = m \times C_{added} + b ), where ( m ) is the slope and ( b ) is the y-intercept.

- The unknown original concentration in the sample is calculated from the absolute value of the x-intercept (where S=0). The formula is: ( Cx = \frac{b \times Cs}{m \times V_x} ) where V~x~ is the volume of the sample aliquot used [43].

Protocol 2: Implementing Multi-Wavelength Internal Standardization (MWIS) for ICP-OES

This protocol is based on a novel methodology that efficiently corrects for both instrumental drift and matrix effects [45].

Workflow Overview

The following diagram illustrates the solution preparation and core logic of the MWIS technique:

Step-by-Step Instructions:

Solution Preparation:

- Solution 1: Combine 50% by volume of your sample solution with 50% of a mixture containing your suite of internal standards and blank solvent. This ensures the sample matrix is diluted consistently [45].

- Solution 2: Combine 50% by volume of the same sample solution with 50% of a mixture containing the same amount of internal standards as in Solution 1, plus a known concentration of all analytes of interest, and blank solvent to maintain constant volume and matrix [45].

Data Acquisition:

- Using your ICP-OES, measure the emission signals for all relevant wavelengths of your analytes and all selected internal standards in both Solution 1 and Solution 2.

Data Processing and Calibration:

- For each analyte and each internal standard, calculate the signal ratio (Analyte Signal / Internal Standard Signal) in both solutions. Using multiple internal standards generates a large number of data points [45].

- The change in these ratio values between Solution 1 and Solution 2, caused by the known addition of the analyte standard, is used to construct a calibration curve. The slope of this curve, derived from the two data points per ratio, allows for the back-calculation of the original analyte concentration in the sample [45]. This process is typically handled by specialized software or scripts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Advanced Calibration

| Item | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Internal Standards | Added to samples and standards to correct for instrumental drift and physical matrix effects [44]. | Select elements not present in samples and with excitation behavior similar to analytes. Common choices for ICP include Sc, Y, In, Tb, Bi [44]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Used for method validation and verification of accuracy against a known standard [45]. | Ensure CRMs have a matrix similar to your samples. |

| Enriched Isotope Spikes | Used in Isotope Dilution Mass Spectrometry (IDMS) as the ideal internal standard [44]. | Requires ICP-MS. Not available for monoisotopic elements. |

| Ultrapure Water / Solvent | Used for preparing blanks, standards, and dilutions to prevent contamination [47]. | Systems like the Milli-Q series are standard. Essential for preparing mobile phases and sample dilution [47]. |

| Matrix-Matching Additives | Chemicals used to make the calibration standard's background matrix similar to the sample matrix. | Reduces matrix effects in external calibration. Can be salts, acids, or other major sample components. |

| LTV-1 | LTV-1, CAS:347379-29-7, MF:C26H20N2O5S, MW:472.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| IR415 | IR415, MF:C13H14F2N4S, MW:296.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support resource addresses common challenges and questions researchers may encounter when implementing continuous calibration methods in quantitative spectroscopic and analytical research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the main advantage of continuous calibration over traditional methods? Continuous calibration significantly reduces the time and labor required for creating calibration curves. Instead of manually preparing and measuring discrete standard solutions, it involves the continuous infusion of a calibrant into a matrix while monitoring the instrument response in real-time. This generates extensive data points, leading to improved calibration precision and accuracy [21].

Q2: My computational model has high accuracy, but its predictive probabilities are unreliable. What is happening? This is a classic sign of a poorly calibrated model. A model can have high accuracy while being overconfident or underconfident, meaning its predicted probabilities do not reflect the true likelihood of correctness. This is often linked to model overfitting, large model size, lack of regularization, or distribution shifts between training and test data. Techniques like post-hoc calibration (e.g., Platt scaling) or train-time uncertainty quantification methods (e.g., Bayesian Neural Networks) can address this [48].

Q3: Can calibration models developed for bulk macroscopic analysis be used for microscopic hyperspectral images? Yes, but it requires a specialized calibration transfer approach. Direct use is not feasible due to differences in instrumentation, optical configurations, and the pervasive issue of Mie-type scattering in microscopy. A deep learning-based transfer method can adapt regression models from macroscopic spectra to apply to microscopic pixel spectra, enabling spatially resolved quantitative chemical analysis [49].

Q4: How can I perform quantitative analysis in high-throughput experimentation without isolating every product for calibration? A workflow combining GC-MS for product identification with a GC system equipped with a Polyarc (PA) microreactor for quantification is effective. The Polyarc reactor converts organic compounds to methane, ensuring a uniform detector response in the FID that depends only on the number of carbon atoms. This allows for accurate, calibration-free yield quantification of diverse reaction products [50].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Issue 1: Overconfident Predictions from Neural Network Models

- Problem: Model probabilities are skewed towards extremes and do not match empirical accuracy.

- Solution: Apply post-hoc calibration methods such as Platt scaling, which fits a logistic regression model to the classifier's logits. For more robust uncertainty estimation, implement train-time methods like Monte Carlo Dropout or Bayesian Last Layer approaches, which treat model parameters as probability distributions [48].

Issue 2: Failure in Calibration Transfer from Macro to Micro Spectrometry

- Problem: Models built on bulk IR spectra perform poorly when applied to hyperspectral images.

- Solution: Implement a two-model microcalibration pipeline. First, a transfer model accounts for variability between macroscopic spectra and microscopic pixel spectra, effectively handling differences in optics and light-scattering effects. Second, a pre-established regression model is applied to the transferred data for quantitative analysis [49].

Issue 3: Implementation and Data Processing Bottlenecks

- Problem: Automating the analysis of large, multi-substrate reaction arrays is hindered by proprietary data formats and manual processing.

- Solution: Utilize open-source data processing tools like the pyGecko Python library. It parses raw GC data, automates peak detection and integration, calculates retention indices, and correlates analytical data with experimental metadata, drastically reducing analysis time [50].

Experimental Protocols for Continuous Calibration

Protocol 1: Generating Continuous Calibration Curves for Spectroscopy

This protocol outlines the procedure for creating high-precision calibration curves using continuous infusion, applicable to UV-Vis and IR spectroscopy [21].

Solution Preparation: