Advanced Strategies for Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Sensitivity Improvement: From Novel Materials to AI-Driven Optimization

This article provides a comprehensive overview of cutting-edge techniques for enhancing Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) biosensor sensitivity, a critical factor for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Advanced Strategies for Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Sensitivity Improvement: From Novel Materials to AI-Driven Optimization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of cutting-edge techniques for enhancing Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) biosensor sensitivity, a critical factor for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of SPR and key sensitivity metrics, delves into advanced methodologies including novel 2D materials, photonic crystal fiber (PCF) designs, and AI-driven optimization. The content offers practical troubleshooting guidance for common experimental challenges and presents a comparative analysis of recent, high-performance sensor configurations validated for applications like cancer detection and pathogen identification. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with the latest research breakthroughs, this resource serves as a vital guide for developing next-generation, high-sensitivity SPR biosensors.

Understanding SPR Fundamentals and Key Metrics for Sensitivity Enhancement

Core Principles of Surface Plasmon Resonance and Evanescent Field Interaction

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free optical technique used for the real-time analysis of biomolecular interactions [1]. When plane-polarized light hits a metal film under conditions of total internal reflection, it can generate an evanescent field that propagates at the interface between the metal and a dielectric medium, such as a buffer solution [1] [2]. The core principle of SPR sensing relies on the fact that this phenomenon is exquisitely sensitive to changes in the refractive index at the metal surface. When molecules bind to a ligand immobilized on this surface, the local refractive index changes, leading to a measurable shift in the SPR signal [1] [3].

The evanescent field is a non-propagating electromagnetic field that arises during total internal reflection [4] [5]. Its electric field amplitude decays exponentially with distance from the interface, typically extending only a few hundred nanometers into the lower-index medium [6]. This confinement of the evanescent field is crucial for SPR, as it ensures that the sensing mechanism is highly surface-specific, primarily interacting with molecules bound to the sensor surface rather than those free in solution [1]. A key hallmark of a pure evanescent field is that there is no net flow of electromagnetic energy into the medium where it decays, a fact confirmed by a time-averaged Poynting vector of zero in that direction [4].

Core Physical Principles

Total Internal Reflection and the Evanescent Wave

The foundation of SPR is total internal reflection (TIR). TIR occurs when light traveling through an optically dense medium (e.g., glass) meets an interface with a less dense medium (e.g., water or air) at an angle greater than the so-called critical angle [1]. While the incident wave is entirely reflected, an electromagnetic field, known as the evanescent wave, penetrates a short distance into the rarer medium [6] [5].

The properties of this evanescent wave are defined by two key equations. The electric field amplitude ( E ) at a distance ( x ) from the interface is given by: [ E = E0 \exp(-x/dp) ] where ( E0 ) is the field at the interface, and ( dp ) is the penetration depth [6]. This depth, typically on the order of the wavelength of light, dictates how far the field extends and is calculated as: [ dp = \frac{\lambda}{2\pi n1 \sqrt{\sin^2\theta - (n2/n1)^2}} ] where ( \lambda ) is the wavelength of light in a vacuum, ( \theta ) is the angle of incidence, and ( n1 ) and ( n2 ) are the refractive indices of the denser and rarer media, respectively (( n1 > n2 )) [6].

Surface Plasmons and Resonance

Surface plasmons are collective oscillations of free electrons at the surface of a conductor, such as a thin gold film [3]. For SPR to occur, these plasmons must be excited by the evanescent field. This requires energy and momentum matching, which is achieved by using p-polarized light and a coupling mechanism like a prism [3]. The momentum of the incident light is increased by passing it through the high-index prism, allowing it to couple to the surface plasmons [3] [5].

At a specific combination of angle and wavelength—the resonance condition—energy is transferred from the incident light to the surface plasmons, causing a sharp dip in the intensity of the reflected light [1]. The exact resonance condition is extremely sensitive to the refractive index within the evanescent field, making it a powerful probe for detecting molecular adsorption and binding events on the metal surface [3].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of the Evanescent Field and Surface Plasmons

| Characteristic | Evanescent Field | Surface Plasmons |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Non-propagating electromagnetic field | Collective oscillations of electrons at a metal surface |

| Generation | Total internal reflection at a dielectric interface | Coupling of light energy to a metal-dielectric interface |

| Field Profile | Exponentially decaying with distance from interface | Confined to the metal surface |

| Energy Transport | No net energy flow in the decay direction | Energy is dissipated as heat in the metal |

| Primary Role in SPR | Probe the local refractive index | Transduce refractive index change into a measurable optical signal |

Standard Experimental Configurations

Two primary prism configurations are used to excite surface plasmons:

- Kretschmann Configuration: This is the most commonly used setup in practical applications [3]. A thin metal film (e.g., 50 nm gold) is directly deposited onto the prism base. The evanescent wave generated by TIR in the prism penetrates through the metal film and excites surface plasmons at the outer interface between the metal and the sample solution [3].

- Otto Configuration: In this setup, the metal film is separated from the prism by a small gap [3]. The evanescent wave from the prism traverses this gap to excite the surface plasmons on the metal film. This configuration is less common for biosensing.

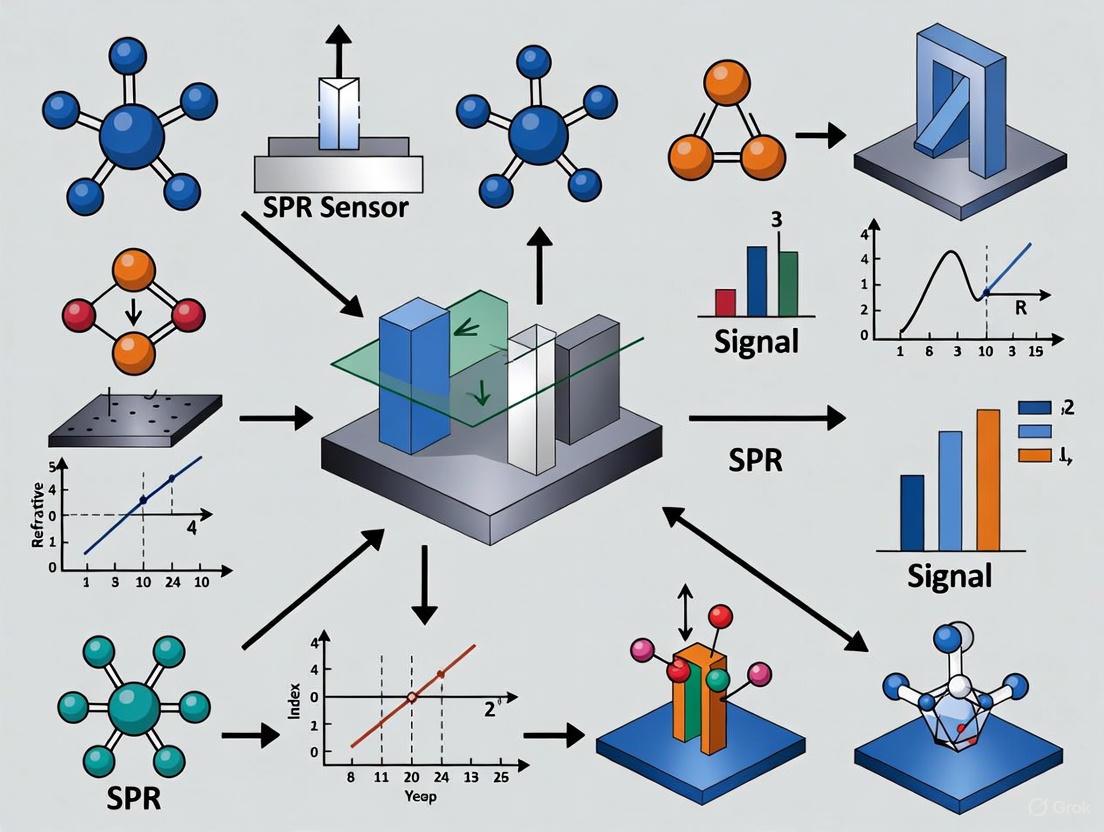

The following diagram illustrates the core components and the process of SPR in the Kretschmann configuration.

Figure 1: SPR excitation in the Kretschmann configuration shows the key components and energy transfer.

Techniques for Improving SPR Sensitivity

Enhancing the sensitivity of SPR sensors is a major focus of research, enabling the detection of smaller molecules and lower analyte concentrations. Recent advancements include material science and innovative fiber optic designs.

Functional Overlayers and Material Enhancements

A prominent method involves depositing a thin, high-index overlayer on the metal film. A 2025 experimental study demonstrated that coating a gold film with Indium Tin Oxide (ITO) significantly boosts sensitivity [7]. The research showed that sensitivity increases with ITO thickness up to an optimal point, beyond which the resonance dip broadens, reducing detection accuracy.

Table 2: Performance of ITO-Enhanced POF SPR Sensors (Refractive Index Range: 1.33-1.37 RIU)

| Sensor Configuration | Sensitivity (nm/RIU) | Figure of Merit (RIUâ»Â¹) | Resolution (RIU) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold (40 nm) only | 1,328 | Not Specified | Not Specified | [7] |

| Gold (40 nm) + ITO (25 nm) | 2,258 | 10.13 | 2.74 × 10â»â´ | [7] |

| Sensitivity Enhancement | ~70% Increase | - | - | [7] |

This approach simplifies fabrication as it can be applied to a simple cladding-etched fiber without complex side-polishing, enhancing robustness while providing a large interaction area [7].

Fiber Optic Geometries and Grating Structures

Optical fibers can replace prisms to create miniaturized, portable SPR systems [6] [7]. Sensitivity is enhanced by modifying the fiber to increase the interaction between the guided light and the analyte.

Key fiber-based sensitivity enhancement techniques include:

- Fiber Tapering: Stretching a fiber to create a narrow waist, which increases the fractional power of the light in the evanescent field.

- Cladding Removal: Chemically etching or mechanically polishing the fiber cladding to access the evanescent field.

- Specialized Grating Structures: Fabricating periodic structures within the fiber core, such as:

- Fiber Bragg Gratings (FBG): Reflect a specific wavelength.

- Tilted Fiber Bragg Gratings (TFBG): Efficiently couple light from the core to cladding modes, providing highly sensitive measurements [6].

The workflow for developing and characterizing a high-sensitivity fiber SPR sensor is summarized below.

Figure 2: Key fabrication steps for creating a high-sensitivity POF SPR sensor.

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Ligand Immobilization and Experimental Workflow

A typical SPR experiment involves immobilizing one interactant (the ligand) on the sensor chip and flowing the other (analyte) over the surface in solution [1] [2]. The binding response is monitored in real-time as a sensorgram, a plot of response (in Resonance Units, RU) versus time [1].

Protocol: General Steps for an SPR Binding Kinetics Experiment

- Sensor Chip Selection: Choose an appropriate sensor chip. Common types include dextran (CM5), planar, streptavidin, and NTA chips [8].

- System Preparation: Prime the microfluidic system with running buffer to establish a stable baseline [1].

- Ligand Immobilization: Immobilize the ligand onto the sensor surface. This can be achieved via:

- Covalent Coupling: Using amine, thiol, or aldehyde chemistry.

- Capture Coupling: Utilizing high-affinity capture systems like streptavidin-biotin or antibody-Fc tags [1].

- Analyte Binding (Association): Inject a concentration series of the analyte over the ligand surface and a reference surface. The binding causes an increase in the SPR signal [1].

- Dissociation: Replace the analyte solution with buffer. The decrease in signal as the analyte dissociates is monitored [1].

- Surface Regeneration (Optional): Inject a regeneration solution (e.g., low pH or high salt) to remove bound analyte without damaging the immobilized ligand, preparing the surface for a new cycle [8] [1].

Data Interpretation and Kinetic Analysis

The sensorgram provides rich information on the interaction:

- Association Phase: The rate of signal increase is used to determine the association rate constant (( k_a )).

- Dissociation Phase: The rate of signal decrease is used to determine the dissociation rate constant (( k_d )).

- Equilibrium Analysis: The response at steady-state for each analyte concentration can be used to calculate the equilibrium dissociation constant (( KD )), a measure of affinity, where ( KD = kd / ka ) [1] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful SPR experimentation relies on a suite of specialized consumables and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Materials for SPR Experiments

| Item | Function and Description | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sensor Chips | Solid supports with a gold film and specialized coatings for ligand attachment. | Dextran (CM5), Planar, Streptavidin, NTA chips [8] [2]. |

| Running Buffer | The solution used to hydrate the system and dissolve analytes; must contain a detergent to minimize non-specific binding. | HBS-EP (0.01 M HEPES, 0.15 M NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% v/v Surfactant P20) is common; detergent (e.g., 0.05% Tween 20) is critical [2]. |

| Immobilization Reagents | Chemicals for activating the sensor surface and covalently coupling the ligand. | N-ethyl-N'-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) for amine coupling [2]. |

| Regeneration Solutions | Solutions that disrupt the ligand-analyte interaction, restoring the baseline without denaturing the ligand. | Acidic (e.g., 10 mM Glycine-HCl, pH 1.5-2.5), Basic (e.g., 10-50 mM NaOH), or High Salt solutions [8] [1]. |

| Analysis Software | Specialized software for quantifying kinetic rate constants and affinity from sensorgram data. | Integrated with instruments like Biacore T200; used for global fitting of data [2]. |

| ML336 | ML336, MF:C19H21N5O3, MW:367.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PF-4800567 | PF-4800567, CAS:1188296-52-7, MF:C17H18ClN5O2, MW:359.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The interaction between the evanescent field and surface plasmons forms the foundational principle of SPR technology. Ongoing research continues to push the boundaries of sensitivity through innovative materials like ITO overlayers and advanced fiber optic geometries. The availability of robust protocols and a wide array of specialized reagents makes SPR an indispensable tool in modern bioscience. Its label-free, real-time capability to quantify biomolecular interactions ensures its continued critical role in drug discovery, diagnostics, and life sciences research.

The quantitative evaluation of surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensors relies on four fundamental performance metrics that collectively determine their effectiveness in detecting molecular interactions: sensitivity, figure of merit (FOM), resolution, and full width at half maximum (FWHM). These parameters are intrinsically linked and provide critical insights into a sensor's ability to detect minute refractive index changes with precision and accuracy.

Sensitivity quantifies the sensor's response to changes in the refractive index at the sensing interface, while FWHM represents the spectral width of the resonance curve at half its maximum depth. The FOM is a composite parameter calculated as the ratio of sensitivity to FWHM, providing a comprehensive measure of overall sensor performance. Resolution defines the smallest detectable refractive index change, representing the sensor's detection limit. For researchers and drug development professionals, optimizing these parameters is essential for developing biosensors capable of detecting low-abundance biomarkers, monitoring drug-target interactions with high precision, and performing therapeutic drug monitoring.

Recent advances in SPR technology, including novel nanostructures, two-dimensional materials, and algorithmic optimization approaches, have significantly enhanced these performance metrics, pushing detection limits toward single-molecule levels. This document provides a structured analysis of these metrics, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to guide the development and implementation of high-performance SPR systems in biomedical research.

Quantitative Comparison of SPR Sensor Performance

The table below summarizes representative performance metrics achieved by various SPR sensor configurations reported in recent literature, demonstrating the significant enhancements possible through material and design innovations.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Advanced SPR Sensor Configurations

| Sensor Configuration | Sensitivity | FOM (RIUâ»Â¹) | Resolution (RIU) | FWHM | Detection Range/Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowtie-shaped PCF SPR [9] | 143,000 nm/RIU | 2,600 | 6.99×10â»â· | N/R | Refractive index: 1.32-1.44 |

| PVP/Au Optical Fiber SPR [10] | 11,580 nm/RIU | 628.74 | N/R | 96.5 nm/RIU | Refractive index: 1.39-1.45 |

| ZnO/Ag/Si₃N₄/WS₂ Architecture [11] | 342.14 deg/RIU | 124.86 | N/R | N/R | Blood cancer cell detection |

| Algorithm-Optimized SPR [12] | 230.22% improvement | 110.94% improvement | 54 ag/mL (0.36 aM) | N/R | Mouse IgG detection |

Abbreviations: N/R: Not explicitly reported; PCF: Photonic crystal fiber; PVP: Polyvinylpyrrolidone

The data reveals how specific design strategies enhance particular performance aspects. The bowtie-shaped photonic crystal fiber (PCF) SPR sensor achieves exceptional wavelength sensitivity through its unique geometry that strengthens light-matter interaction [9]. Conversely, the PVP/Au-coated optical fiber sensor demonstrates that incorporating high-refractive-index polymers can significantly improve both sensitivity and FOM by deepening the resonance dip and narrowing the FWHM [10]. The algorithmic optimization approach highlights that simultaneous multi-parameter optimization can deliver comprehensive performance enhancements across all key metrics [12].

Experimental Protocols for Performance Validation

Refractive Index Sensitivity Measurement Protocol

Purpose: To quantitatively characterize the sensitivity of an SPR biosensor to changes in the refractive index of the analyte medium.

Materials Required:

- SPR sensor system with optical interrogation capability

- Series of calibrated refractive index solutions (e.g., glycerol-water mixtures, sodium chloride solutions)

- Flow cell or immersion chamber compatible with the sensor

- Temperature control system (±0.1°C stability)

- Data acquisition software

Procedure:

- Initialize the SPR instrument and allow sufficient warm-up time for light source and electronics stabilization.

- Establish a stable baseline using deionized water or the lowest refractive index solution.

- For wavelength-interrogation systems:

- Record the resonance wavelength shift for each standard solution

- Plot resonance wavelength versus refractive index

- Calculate sensitivity as the slope of the linear regression fit (nm/RIU)

- For angular-interrogation systems:

- Record the resonance angle shift for each standard solution

- Plot resonance angle versus refractive index

- Calculate sensitivity as the slope of the linear regression fit (deg/RIU)

- Perform triplicate measurements for each refractive index standard to establish statistical significance.

Data Analysis: The sensitivity (S) is calculated using the formula: [ S = \frac{\Delta \lambda}{\Delta n} \quad \text{or} \quad S = \frac{\Delta \theta}{\Delta n} ] where Δλ is the resonance wavelength shift, Δθ is the resonance angle shift, and Δn is the refractive index change.

FWHM and FOM Characterization Protocol

Purpose: To determine the full width at half maximum of the SPR resonance dip and calculate the figure of merit.

Materials Required:

- SPR sensor with spectral or angular scanning capability

- Analytic solution with known refractive index

- Data processing software capable of curve fitting

Procedure:

- Acquire a high-resolution SPR spectrum or angular scan using a stable reference solution.

- Identify the minimum reflectivity point (resonance depth).

- Locate the two points on either side of the resonance where the reflectivity equals half of the maximum depth.

- Calculate FWHM as the spectral or angular separation between these two points.

- For wavelength-interrogation systems, FWHM is expressed in nanometers; for angular-interrogation, in degrees.

- Calculate FOM using the previously determined sensitivity and FWHM: [ \text{FOM} = \frac{S}{\text{FWHM}} ]

Validation: Repeat measurements should yield FWHM variations of less than 5%, confirming system stability and measurement reliability.

Performance Enhancement Strategies and Mechanisms

Material-Based Enhancement Approaches

The strategic incorporation of specialized materials has proven highly effective for improving SPR sensor performance. The use of high-refractive-index polymers like polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) creates a heterogeneous-core structure that enhances the evanescent field interaction, leading to simultaneous improvement in both sensitivity (11,580 nm/RIU) and FOM (628.74 RIUâ»Â¹) [10]. Similarly, two-dimensional materials such as tungsten disulfide (WSâ‚‚) when incorporated into multilayer architectures (e.g., BK7/ZnO/Ag/Si₃Nâ‚„/WSâ‚‚) significantly boost field confinement, achieving sensitivity of 342.14 deg/RIU for cancer cell detection [11].

The bowtie-shaped photonic crystal fiber design employs a 30-nm gold layer and strategically arranged air holes of different diameters to achieve exceptional wavelength sensitivity (143,000 nm/RIU) and FOM (2,600) [9]. This design enhances light propagation toward the plasmonic material while maintaining practical fabricability through optimized pitch parameters.

Algorithm-Assisted Optimization Approaches

Recent advances incorporate computational optimization to simultaneously enhance multiple performance parameters. The multi-objective particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm synchronously optimizes critical design parameters including incident angle, chromium adhesion layer thickness, and gold film thickness [12]. This approach has demonstrated remarkable improvements of 230.22% in sensitivity, 110.94% in FOM, and 90.85% in depth-quality factor (DFOM), enabling ultrasensitive detection of mouse IgG down to 54 ag/mL (0.36 aM) [12].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for SPR Performance Enhancement

| Material/Category | Specific Examples | Function in SPR Enhancement |

|---|---|---|

| 2D Materials | WSâ‚‚, MoSâ‚‚, WSeâ‚‚ | Enhance evanescent field strength through high surface-to-volume ratio and strong light-matter interactions [11] |

| High-RI Polymers | Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Increase resonance strength and deepen resonance dip, improving both sensitivity and FOM [10] |

| Plasmonic Metals | Gold, Silver | Generate surface plasmons; thickness optimization critical for performance [9] [12] |

| Adhesion Layers | Chromium | Improve metal film adhesion to substrate; thickness affects overall sensitivity [12] |

| Dielectric Spacers | ZnO, Si₃N₄ | Optimize distance between metal layer and sensing medium for field enhancement [11] |

Schematic Representations of Optimization Strategies

Material-Enhanced SPR Mechanism

Diagram 1: Material-enhanced SPR sensor architecture for performance improvement.

Algorithmic Optimization Workflow

Diagram 2: Algorithmic optimization workflow for SPR performance enhancement.

The systematic optimization of essential performance metrics—sensitivity, FOM, resolution, and FWHM—is fundamental to advancing SPR biosensor technology for pharmaceutical and clinical applications. As demonstrated by the documented cases, both material innovations and computational approaches can dramatically enhance these parameters, enabling detection capabilities approaching single-molecule levels. The integration of two-dimensional materials, high-refractive-index polymers, and sophisticated optimization algorithms represents a powerful strategy for developing next-generation biosensors. These advancements will continue to push the boundaries of molecular detection, providing researchers and drug development professionals with increasingly powerful tools for biomarker discovery, drug-target interaction analysis, and therapeutic monitoring.

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) technologies have revolutionized label-free detection methods in biomedical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and pharmaceutical development. These optical phenomena occur when incident light excites collective oscillations of free electrons at the interface between a metal and dielectric medium, generating evanescent fields that are exquisitely sensitive to minute changes in the local environment [13]. The performance of SPR-based sensors is fundamentally governed by the selection of plasmonic materials, whose electronic structure determines key operational parameters including resonance frequency, field enhancement capabilities, and charge transfer efficiency [14]. Among the various materials investigated, gold, silver, and copper have emerged as the most significant noble metals for practical SPR applications due to their favorable optical properties and material characteristics.

The development of plasmonic sensing traces back to 1957 when Ritchie first predicted the existence of surface plasmon waves, with experimental demonstrations following in the late 1960s on silver films and diffraction gratings [14]. The field expanded significantly after the first observation of Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) in 1974 on roughened silver electrodes, which marked the beginning of a comprehensive family of surface enhancement techniques [14]. Today, SPR biosensors have evolved into sophisticated platforms capable of detecting analytes at single-molecule levels under specific conditions, forming the basis of modern diagnostic techniques including SHERLOCK, DETECTR, and SERS-CRISPR [14]. The critical importance of material selection has intensified with the expanding applications of SPR technology, driving rigorous comparative studies of gold, silver, and copper to optimize sensor performance across diverse operating conditions.

Fundamental Properties of Plasmonic Materials

The performance of plasmonic materials in SPR sensing is governed by their intrinsic electronic structure and resulting dielectric function. Surface plasmons are collective oscillations of free electrons at metal-dielectric interfaces, which can propagate along the surface as surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) or remain confined as localized surface plasmons (LSPs) in nanoparticles [13]. The resonance condition depends critically on the complex permittivity of the metal, which exhibits large negative values in the real part and minimal dielectric losses in the imaginary part at optical frequencies [14].

The plasmonic behavior of metals stems from their ability to support coherent electron oscillations when excited by electromagnetic radiation. Noble metals like gold, silver, and copper possess high electron densities and distinct interband transition thresholds that define their spectral operating windows [14]. The dielectric function of these metals follows a frequency-dependent behavior described by Drude-Lorentz models, incorporating both free-electron contributions and interband transitions [15] [16]. This complex dielectric response directly influences the localization and propagation of surface plasmons, determining critical sensor parameters including sensitivity, resonance sharpness, and operating wavelength range.

Material selection for SPR applications requires balancing multiple optical and material properties. The ideal plasmonic material should exhibit strong negative real permittivity, low optical losses, chemical stability, and compatibility with functionalization chemistry. Additionally, practical considerations including fabrication ease, cost, and integration with photonic structures further influence material selection for specific sensing applications [17] [7]. Understanding these fundamental properties provides the foundation for rational design of SPR sensors with optimized performance characteristics.

Comparative Analysis of Gold, Silver, and Copper

Material Properties and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Primary Plasmonic Materials

| Property | Gold (Au) | Silver (Ag) | Copper (Cu) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmonic Frequency Range | Visible to Near-IR | Visible | Visible |

| Sensitivity Performance | High (Up to 143,000 nm/RIU in optimized structures) [16] | Higher theoretical sensitivity than Au [17] | Moderate |

| Chemical Stability | Excellent (resistant to oxidation) [17] | Poor (requires protective layers) [17] | Poor (prone to oxidation) [16] |

| Fabrication Considerations | Reliable thin-film deposition [17]; Excellent bioconjugation chemistry [17] | Uniform deposition challenging [16]; Tarnishing issues [17] | Requires graphene coating to prevent oxidation [16] |

| Biocompatibility | High | Moderate | Low |

| Cost | High | Moderate | Low |

| Typical Applications | High-precision biosensors [17] [16]; Medical diagnostics [13] | High-sensitivity applications where stability is addressed [17] | Cost-sensitive applications with protective coatings [16] |

Detailed Performance Analysis

Gold stands as the most widely utilized plasmonic material, particularly for biological sensing applications, due to its exceptional chemical stability and reliable performance. Gold's surface chemistry allows for straightforward functionalization with thiol-based ligands, enabling robust bioconjugation for specific target detection [17]. This combination of optical properties and chemical robustness makes gold the preferred choice for applications requiring long-term stability and reproducible results. Recent demonstrations include bowtie-shaped PCF sensors achieving remarkable sensitivity of 143,000 nm/RIU and photonic crystal fiber biosensors optimized with machine learning approaches reaching 125,000 nm/RIU [16] [18] [19].

Silver exhibits superior plasmonic characteristics in theory, with stronger field enhancement and lower ohmic losses compared to gold [17]. These properties translate to potentially higher sensitivity and sharper resonance peaks, making silver attractive for applications demanding ultimate performance. Sensors utilizing silver substrates demonstrate higher theoretical sensitivity compared to gold-based counterparts [17]. However, silver's significant limitation lies in its poor chemical stability – it readily tarnishes in air and aqueous environments, requiring protective passivation layers that complicate fabrication and can degrade performance [17]. This susceptibility to oxidation has limited silver's practical implementation despite its attractive optical properties.

Copper offers a cost-effective alternative to precious metals like gold and silver, with plasmonic properties that theoretically approach those of silver. However, copper's high susceptibility to oxidation presents a fundamental challenge for practical implementation [16]. When exposed to ambient conditions, copper surfaces rapidly form oxide layers that severely degrade plasmonic performance. To address this limitation, researchers have investigated protective strategies including graphene coatings that shield copper from oxidation while maintaining optical accessibility [16]. Such approaches enable copper utilization in cost-sensitive applications where extreme sensitivity is not required.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics in SPR Biosensing Applications

| Material | Sensor Configuration | Maximum Wavelength Sensitivity (nm/RIU) | Amplitude Sensitivity (RIUâ»Â¹) | Figure of Merit (RIUâ»Â¹) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold | Bowtie-shaped PCF SPR | 143,000 | 6,242 | 2,600 | [16] |

| Gold | D-shaped PCF with TiOâ‚‚ | 42,000 | -1,862.72 | 1,393.13 | [17] |

| Gold | Machine learning-optimized PCF | 125,000 | -1,422.34 | 2,112.15 | [18] [19] |

| Silver | D-shaped PCF with TiOâ‚‚ | 30,000 | N/R | N/R | [17] |

| Copper | Graphene-protected | 2,000 | N/R | N/R | [16] |

Experimental Protocols for Plasmonic Material Characterization

Protocol: Fabry-Pérot Resonance Method for Dispersion Characterization

Objective: To accurately characterize the plasmonic dispersion relation and efficiency of metal films using Fabry-Pérot resonances in extraordinary optical transmission (EOT) structures.

Principle: This method reconstructs the plasmon dispersion relation from transmission spectra peaks obtained from plasmonic gratings with systematically varied unit cell sizes. Each grating serves as a discrete probe in momentum space, with Fabry-Pérot resonances localized within subwavelength apertures providing the fundamental data for dispersion mapping [15].

Materials and Equipment:

- Plasmonic grating samples with varying periodicities

- Tunable laser source (visible to NIR range)

- Transmission spectroscopy setup

- FEM and FDTD simulation software

- Perfectly Matched Layer (PML) boundary conditions

Procedure:

- Sample Fabrication: Prepare free-standing metallic slabs perforated with periodic air apertures forming subwavelength FP resonators. Maintain identical superstrate and substrate media (air) to eliminate impedance mismatch.

- Optical Measurements: Perform normal incidence transmission measurements using TM-polarized illumination to excite transverse magnetic modes while suppressing TE modes.

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect transmission spectra for each grating variant, identifying resonance peaks corresponding to Fabry-Pérot modes.

- Modal Analysis: Implement non-Hermitian modal decomposition using Finite Element Method (FEM) to elucidate eigenstates of the plasmonic system and quantify modal hybridization.

- FDTD Validation: Corroborate FEM results with Finite-Difference Time-Domain (FDTD) simulations using broadband pulse excitation from multiple randomly distributed point sources.

- Dispersion Reconstruction: Track FP resonance shifts across discrete in-plane momenta to map the plasmon dispersion relation using a composite rectifying factor that accounts for material properties and geometry [15].

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the energy localization ratio (Θ) to quantify spatial distribution of electromagnetic energy

- Extract resonant frequencies and associated field distributions from power spectral density via Fast Fourier Transform

- Reconstruct dispersion curves from resonance frequencies of Fabry-Pérot modes, scaled by geometry-dependent correction factors

Protocol: Sensitivity Measurement for SPR Biosensors

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the wavelength and amplitude sensitivity of SPR biosensors utilizing different plasmonic materials.

Principle: SPR sensors detect minute refractive index changes through resonance condition shifts. When the propagation constant of surface plasmon polaritons matches the wavevector of incident polarized light, resonance occurs, resulting in characteristic absorption or loss peaks. As analyte RI changes, the phase-matching condition shifts, enabling detection [13] [16].

Materials and Equipment:

- SPR sensor platform (prism, optical fiber, or PCF-based)

- Polarized light source

- Spectrometer or angular interrogation system

- Reference analytes with known refractive indices

- Flow cell or analyte delivery system

- Metal deposition equipment (sputter coater, evaporator)

Procedure:

- Sensor Fabrication: a. For optical fiber sensors: Etch cladding or create D-shaped structure to access evanescent field b. Deposit plasmonic metal film (40-50 nm thickness optimal for gold) using sputter coating with thickness monitoring c. For enhanced stability: Apply protective layers (TiOâ‚‚, ITO, graphene) as needed d. Functionalize surface with appropriate biorecognition elements

Experimental Setup: a. Connect light source and spectrometer to sensor platform b. Implement flow system for analyte delivery c. Establish temperature control if required for precise measurements

Measurement Sequence: a. Record reference spectrum in air or reference buffer b. Measure background spectrum with light source off c. Introduce analytes with varying refractive indices d. Collect transmission spectra for each analyte e. Calculate normalized SPR transmission spectrum by dividing the difference between sample and background spectra by the difference between reference and background spectra [7]

Data Collection: a. Record resonance wavelength shifts (for wavelength interrogation) b. Measure reflectance/intensity changes (for amplitude interrogation) c. Repeat measurements for statistical significance

Data Analysis:

- Plot resonance wavelength versus refractive index for wavelength sensitivity (Sλ = Δλ/Δn)

- Calculate amplitude sensitivity using SA = (1/T(λ)) × (ΔT(λ)/Δn) where T(λ) is transmission

- Determine sensor resolution (minimum detectable RI change)

- Compute figure of merit (FOM = S/FWHM) where FWHM is full width at half maximum [16]

Advanced Material Configurations and Hybrid Approaches

Enhanced Structures for Performance Improvement

Recent advances in plasmonic sensing have focused on hybrid material systems that combine the advantages of multiple materials while mitigating their individual limitations. These approaches include:

Gold-Based Hybrid Structures: The combination of gold with high-index dielectric materials has demonstrated significant sensitivity enhancements. For instance, D-shaped photonic crystal fiber sensors with gold-TiOâ‚‚ layers achieve improved performance through enhanced evanescent field interaction and optimized coupling between core modes and surface plasmon polaritons [17]. Similarly, the addition of indium tin oxide (ITO) overlayers to gold films in polymer optical fiber sensors has shown 70% sensitivity enhancement compared to gold-only configurations, reaching 2258 nm/RIU with optimal ITO thickness of 25 nm [7].

Silver Stabilization Strategies: To address silver's oxidation issues, researchers have developed protective coating strategies using dielectric materials like TiOâ‚‚ [17]. These approaches maintain silver's superior plasmonic properties while providing necessary environmental protection. Additionally, bimetallic structures combining silver with more stable metals offer compromised solutions with tunable optical properties.

Copper Protection Methods: Graphene layers have been successfully implemented to prevent copper oxidation while maintaining optical accessibility for plasmonic excitation [16]. Two-dimensional materials like transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) and MXenes have also shown promise as protective layers and sensitivity enhancers for copper-based plasmonic sensors [13] [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Plasmonic Sensor Development

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gold (Au) Target | Primary plasmonic layer | High purity (99.99%) for sputtering; enables reliable thin-film deposition with excellent bioconjugation chemistry [17] |

| Silver (Ag) Target | High-sensitivity plasmonic layer | Requires protective coatings (TiOâ‚‚) due to tarnishing; offers higher theoretical sensitivity than gold [17] |

| ITO Powder/Target | High-index overlayer | Enhances sensitivity when deposited over gold; optimal thickness ~25 nm [7] |

| TiOâ‚‚ Nanoparticles | Protective layer and sensitivity enhancer | Applied over silver or gold layers; increases refractive index sensitivity [17] |

| Graphene Oxide | Protective monolayer and charge transfer mediator | Prevents oxidation of copper and silver surfaces; enhances SERS signals [16] |

| Thiol-PEG Compounds | Surface functionalization | Enable biomolecule conjugation to gold surfaces; create anti-fouling layers |

| Silane Coupling Agents | Surface modification | Functionalize oxide surfaces (ITO, TiOâ‚‚) for biomolecule immobilization |

| PF-5006739 | PF-5006739, CAS:1293395-67-1, MF:C22H22FN7O, MW:419.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (3S,4R)-PF-6683324 | (3S,4R)-PF-6683324, MF:C24H23F4N5O4, MW:521.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing Plasmonic Sensor Configurations and Experimental Workflows

Diagram Title: Plasmonic Sensor Development Workflow

Diagram Title: SPR Sensing Fundamental Principle

The critical role of plasmonic materials in SPR sensitivity improvement is unequivocal, with gold, silver, and copper each offering distinct advantages and limitations for specific sensing applications. Gold remains the preferred choice for most biological sensing scenarios due to its exceptional chemical stability, well-established surface chemistry, and reliable performance across diverse operating conditions. Silver offers superior theoretical sensitivity and field enhancement capabilities but requires careful environmental protection to mitigate oxidation issues. Copper presents a cost-effective alternative for appropriate applications when implemented with suitable protective strategies.

Future developments in plasmonic sensing will likely focus on advanced hybrid materials that combine the advantages of multiple material systems while addressing their individual limitations. The integration of two-dimensional materials like graphene, TMDCs, and MXenes with traditional plasmonic metals shows particular promise for next-generation sensors with enhanced sensitivity and environmental stability [13] [17]. Additionally, machine learning-driven design optimization is emerging as a powerful approach for rapidly developing high-performance sensor geometries tailored to specific application requirements [18] [19].

As SPR technologies continue evolving toward point-of-care diagnostics and miniaturized platforms, the rational selection and engineering of plasmonic materials will remain fundamental to achieving the sensitivity, specificity, and reliability demanded by modern sensing applications across biomedical, environmental, and security domains.

Photonic crystal fiber-based surface plasmon resonance (PCF-SPR) sensors represent a advanced sensing technology that combines the unique light-guiding properties of photonic crystal fibers with the high sensitivity of surface plasmon resonance. Unlike conventional optical fibers, PCFs contain a periodic arrangement of air holes running along their length, which allows for precise control over optical properties such as dispersion, birefringence, and confinement loss [18]. When integrated with SPR technology, these sensors enable highly sensitive, label-free, and real-time detection of biological and chemical analytes by monitoring changes in the local refractive index [20].

The fundamental operating principle of PCF-SPR sensors relies on the coupling between the core-guided mode in the PCF and surface plasmon polariton (SPP) modes excited at a metal-dielectric interface. When phase-matching conditions are met between these modes, resonance occurs, resulting in a sharp loss peak in the transmission spectrum. Any alteration in the refractive index of the analyte surrounding the sensor shifts this resonance condition, enabling precise detection of molecular binding events [20] [21]. This mechanism has positioned PCF-SPR sensors as powerful tools across diverse fields including medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, food safety, and pharmaceutical inspection [20] [17].

Key PCF-SPR Configurations and Performance Analysis

Recent advances in PCF-SPR technology have led to the development of numerous sensor configurations, each offering distinct advantages for specific applications. The structural design profoundly influences key performance metrics including sensitivity, detection range, and fabrication feasibility.

Common Configurations and Characteristics

Table 1: Comparison of Key PCF-SPR Sensor Configurations

| Configuration Type | Key Features | Sensitivity Range | RI Detection Range | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-Shaped [17] | Polished flat surface for easy plasmonic layer deposition; often uses Au/TiOâ‚‚ layers | Up to 42,000 nm/RIU [17] | 1.30 - 1.40 [17] | Multi-cancer cell detection, biomedical diagnostics |

| Dual-Channel/Dual-Core [22] [23] | Multiple sensing channels; simultaneous multi-analyte detection | 10,000 - 14,500 nm/RIU [22] [23] | 1.36 - 1.41 [22] | Biomedical analysis, environmental monitoring |

| Bowtie-Shaped [16] | Combines internal and external sensing; enhanced light confinement | Up to 143,000 nm/RIU [16] | 1.32 - 1.44 [16] | Biological and chemical sensing |

| Open Channel [20] | Analyte-filled air holes; increased interaction with guided modes | Varies by specific design | Varies by specific design | Chemical and biological detection |

| Concave/Microgroove [21] | Polished upper section with microgroove; reduces core-analyte distance | 3,700 - 5,100 nm/RIU [21] | 1.19 - 1.40 [21] | Medical testing, environmental monitoring |

Performance Metrics Analysis

Table 2: Detailed Performance Metrics of Recent PCF-SPR Sensors

| Sensor Description | Max. Wavelength Sensitivity (nm/RIU) | Amplitude Sensitivity (RIUâ»Â¹) | Figure of Merit (RIUâ»Â¹) | Resolution (RIU) | Plasmonic Materials |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bowtie-Shaped PCF [16] | 143,000 | 6,242 | 2,600 | 6.99×10â»â· | Gold |

| ML-Optimized Design [18] | 125,000 | -1,422.34 | 2,112.15 | 8.00×10â»â· | Gold |

| D-Shaped with Au/TiOâ‚‚ [17] | 42,000 | -1,862.72 | 1,393.13 | - | Gold, TiOâ‚‚ |

| Dual-Polarization [22] | 14,500 (Upper), 13,600 (Right) | - | - | ~7.00×10â»â¶ | Gold, Silver, TiOâ‚‚ |

| Concave with MoSâ‚‚/Au [21] | 5,100 | - | 29.14 | 1.96×10â»âµ | MoSâ‚‚, Gold |

| Taguchi-Optimized Dual-Core [23] | 10,000 | 235,882 | - | - | Silver, TiOâ‚‚ |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Numerical Analysis of PCF-SPR Sensors Using Finite Element Method

Purpose: To simulate and analyze the performance of a PCF-SPR sensor using computational methods. Background: The finite element method (FEM) is widely employed for modeling light propagation, plasmonic resonance behavior, and sensor response in PCF-SPR structures [20] [22].

Materials and Software:

- COMSOL Multiphysics (v5.4 or newer) with RF Module

- High-performance computing workstation

- Perfectly matched layer (PML) boundary conditions

Procedure:

- Geometry Construction: Create the PCF cross-section geometry using the software's drawing tools. Define air holes in a periodic arrangement (typically hexagonal) with specified pitch (Λ) and hole diameters (d1, d2, d3) [16].

- Material Definition: Assign material properties:

- Mesh Generation: Apply triangular mesh elements with finer discretization at metal-dielectric interfaces where field gradients are steepest. Ensure element quality exceeds 0.7 [16].

- Boundary Conditions: Implement PML as the outermost layer to absorb scattered radiation [22] [21].

- Mode Analysis: Solve for eigenmodes in the wavelength range of interest (typically 0.5-2.0 μm). Identify fundamental core mode and surface plasmon polariton (SPP) modes.

- Loss Calculation: Compute confinement loss using the formula: αloss = (8.686 × 2π/λ) × Im(neff) × 10ⴠ(dB/cm) [21].

- Parameter Extraction: Determine resonance wavelength, sensitivity, and figure of merit from loss spectra.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For convergence issues, refine mesh density at critical interfaces

- Verify material models are appropriate for the wavelength range

- Ensure PML thickness is sufficient to prevent back-reflections

Protocol 2: Fabrication of D-Shaped PCF-SPR Sensors

Purpose: To fabricate a D-shaped PCF-SPR sensor with Au/TiOâ‚‚ layers for cancer cell detection. Background: D-shaped configurations simplify metal deposition by providing a flat, polished surface that positions the metal layer closer to the fiber core, enhancing coupling efficiency [17].

Materials:

- Photonic crystal fiber (silica-based)

- Polishing papers (various grit sizes)

- Gold and titanium dioxide sputtering targets

- Optical adhesive

- Precision polishing jig

- Surface plasmon resonance setup (light source, polarizer, spectrometer)

Procedure:

- Fiber Preparation: Cut PCF to desired length (typically 1-2 cm). Carefully strip protective coating if present.

- Side-Polishing: Mount PCF securely in polishing jig. Progressively polish using decreasing abrasive sizes (15 μm to 0.3 μm) until the core is nearly exposed. Monitor polishing depth using microscopic inspection [17].

- Surface Cleaning: Use oxygen plasma treatment to remove organic contaminants and activate the silica surface.

- Metal Deposition:

- Employ magnetron sputtering to deposit a thin gold film (typically 30-50 nm)

- Maintain deposition rate at 0.1-0.3 Ã…/s for uniform coverage

- For TiOâ‚‚ coating, use reactive sputtering in argon-oxygen atmosphere [17]

- Quality Assessment: Characterize film thickness and uniformity using atomic force microscopy or surface profilometry.

- Sensor Integration: Mount fabricated sensor in flow cell system with precision alignment for optical characterization.

Safety Considerations:

- Follow standard laboratory safety protocols for sputtering systems

- Use appropriate personal protective equipment when handling chemicals

- Implement proper ventilation during deposition processes

Protocol 3: Multi-Analyte Detection Using Dual-Channel PCF-SPR Sensors

Purpose: To simultaneously detect two different analytes using a dual-channel PCF-SPR sensor. Background: Dual-channel sensors utilize different plasmonic materials (e.g., gold and silver) and polarization directions to enable simultaneous detection of multiple parameters [22].

Materials:

- Dual-channel PCF-SPR sensor [22]

- Tunable laser source (visible to near-infrared)

- Programmable syringe pumps for analyte delivery

- Optical spectrum analyzer

- Polarization controller

Procedure:

- Sensor Characterization: Initially characterize sensor response using reference analytes with known refractive indices.

- Experimental Setup:

- Connect tunable laser source to sensor input via single-mode fiber

- Implement polarization controller to select appropriate polarization states for each channel

- Connect sensor output to optical spectrum analyzer

- Integrate microfluidic delivery systems for both analytes [22]

- Baseline Measurement: Record loss spectra with reference solutions in both channels.

- Analyte Introduction: Simultaneously introduce test analytes into their respective channels using programmable pumps.

- Data Acquisition: Monitor resonance wavelength shifts in real-time for both channels simultaneously.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate wavelength sensitivity for each channel: Sλ = Δλ/Δn (nm/RIU)

- Determine sensor resolution: R = Δn × (Δλmin/Δλshift)

- Assess cross-talk between channels by analyzing interference effects

Validation Method:

- Compare results with standard analytical methods for target analytes

- Perform reproducibility tests with multiple sensor samples

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualization

PCF-SPR Sensor Working Principle and Signal Transduction

Diagram 1: PCF-SPR Signal Transduction Pathway. This workflow illustrates the sequential process from light introduction to detection signal generation in PCF-SPR sensors.

Multi-Channel PCF-SPR Sensing Workflow

Diagram 2: Dual-Channel PCF-SPR Sensing Workflow. This diagram shows the parallel processing of two analytes using different sensing channels and polarization states in multi-analyte detection systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for PCF-SPR Sensor Development

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Notes | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold (Au) | Primary plasmonic material; provides strong SPR response and chemical stability | Optimal thickness: 30-50 nm; deposited via sputtering or thermal evaporation | [17] [23] |

| Silver (Ag) | Alternative plasmonic material; higher sensitivity but requires protection from oxidation | Often used with protective layers (TiOâ‚‚); enhances sensitivity in specific wavelength ranges | [22] [23] |

| Titanium Dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) | Protective layer; enhances sensitivity by generating surface electrons | Prevents oxidation of silver; improves coupling between core mode and SPP mode | [22] [17] [23] |

| Molybdenum Disulfide (MoSâ‚‚) | 2D transition metal dichalcogenide; enhances SPR excitation | Higher optical absorption than graphene; improves wavelength sensitivity | [21] |

| Silica (SiOâ‚‚) | Background material for PCF; provides mechanical support and optical guidance | Refractive index follows Sellmeier equation; compatible with fiber drawing processes | [22] [21] |

| Specific Recognition Elements | Enable selective analyte binding | Antibodies, aptamers, molecularly imprinted polymers for targeted detection | [20] |

| PIK-293 | PIK-293, CAS:900185-01-5, MF:C22H19N7O, MW:397.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| PLX51107 | PLX51107, CAS:1627929-55-8, MF:C26H22N4O3, MW:438.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of PCF-SPR sensing continues to evolve with several promising directions. The integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence represents a paradigm shift in sensor optimization and data analysis. ML algorithms can predict optical properties, optimize design parameters, and enhance detection accuracy, significantly reducing computational costs and development time [20] [18]. Explainable AI methods, particularly Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), provide insights into how different design parameters influence sensor performance, enabling more targeted optimization strategies [18].

Material innovation remains a crucial frontier, with continued exploration of two-dimensional materials beyond graphene, including MXenes and transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDCs) [20] [21]. These materials offer enhanced sensitivity and stability compared to conventional plasmonic materials. Additionally, the development of multi-functional sensors capable of simultaneous detection of multiple parameters addresses the growing need for comprehensive analytical platforms in complex biological and environmental samples [22].

Despite significant progress, challenges remain in standardization, fabrication scalability, and implementation in real-world settings. Future research will likely focus on addressing these limitations while further enhancing sensitivity and specificity through synergistic combinations of novel materials, advanced computational methods, and innovative structural designs [20].

Novel Materials, Structural Designs, and AI for Next-Generation SPR Sensors

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) biosensing technology has fundamentally transformed analytical biochemistry and diagnostic applications by enabling label-free, real-time detection of biomolecular interactions. The sensing principle relies on exciting collective electron oscillations (surface plasmons) at a metal-dielectric interface, typically using the Kretschmann configuration where a thin metallic film is deposited on a prism. When the energy and momentum of incident light match those required to excite surface plasmons, a sharp dip in reflectance occurs at a specific resonance angle. This resonance condition is exquisitely sensitive to refractive index changes at the sensor surface, allowing detection of binding events without fluorescent or radioactive labeling [24] [25].

Despite their success, conventional SPR biosensors using single metal layers face limitations in sensitivity, especially for detecting low-molecular-weight analytes and low-abundance biomarkers. Two-dimensional (2D) nanomaterials have emerged as powerful enhancers for SPR platforms due to their extraordinary properties, including atomically thin structures, exceptionally high surface-to-volume ratios, and unique optical characteristics that strengthen light-matter interactions. These materials enhance sensor performance through several mechanisms: increased adsorption of target biomolecules, enhanced electromagnetic field confinement at the sensing interface, and protection of reactive metallic layers from oxidation [25] [26].

This Application Note provides a comprehensive technical overview of three prominent 2D materials—graphene, MXene, and black phosphorus (BP)—for boosting SPR biosensor performance. We present structured quantitative comparisons, detailed experimental protocols for fabricating and characterizing 2D material-enhanced SPR sensors, and practical guidance for researchers and drug development professionals implementing these advanced sensing platforms.

Material Properties and Enhancement Mechanisms

Graphene

Graphene, a single layer of sp²-hybridized carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice, enhances SPR biosensors through its exceptionally high surface area (~2630 m²/g) that provides extensive probe immobilization capacity. When deposited on noble metal surfaces, graphene functions as a dielectric spacer that amplifies local field intensities while protecting the metal from oxidation. Its biocompatibility and versatile functionalization chemistry through both covalent and non-covalent mechanisms further enhance its utility in biosensing applications. The material's enhanced adsorption characteristics for various biomolecules significantly improve sensitivity for targets that produce minimal refractive index perturbations [24] [27].

MXenes

MXenes, a rapidly growing family of two-dimensional transition metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides, exhibit metallic Drude behavior with high carrier density and abundant surface terminations (-O, -OH, -F) that allow fine tuning of permittivity. These surface functional groups provide abundant sites for biomolecule immobilization without complex pre-functionalization steps. Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene, the most widely studied variant, demonstrates exceptionally high electrical conductivity and hydrophilic surfaces that promote biomolecular interactions. When incorporated into SPR platforms, MXene sheets intensify near-field confinement without severe damping, increasing both sensitivity and detection precision [28] [26].

Black Phosphorus (BP)

Black phosphorus possesses a puckered honeycomb structure with strong in-plane anisotropy and a layer-dependent direct bandgap that differentiates it from other 2D materials. BP exhibits remarkable optical properties including a high refractive index (n ≈ 3.5) that significantly enhances phase matching conditions for surface plasmon excitation. The material's saturable absorption properties and high carrier mobility make it particularly suitable for biophotonics sensing applications. Unlike other 2D materials, BP maintains stability when exposed to air, making it highly suitable for SPR biosensor applications requiring consistent performance. Its anisotropic optical response enables pronounced electromagnetic field confinement at sensor interfaces [24] [29] [30].

Table 1: Comparative Properties of 2D Materials for SPR Enhancement

| Material | Key Properties | Enhancement Mechanism | Functionalization Chemistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene | High surface area (2630 m²/g), excellent electrical conductivity, biocompatibility | Field amplification, molecular enrichment | π-π stacking, covalent bonding with oxygen-containing groups |

| MXene | Metallic conductivity, hydrophilic surface, tunable surface terminations | Strong field confinement, high biomolecule loading | Direct coordination to -OH, -O, -F groups |

| Black Phosphorus | Anisotropic optical response, layer-dependent bandgap, high refractive index (~3.5) | Strong light-matter interaction, enhanced phase matching | Covalent functionalization via phosphorus atoms |

Performance Analysis and Quantitative Comparisons

Sensitivity Enhancements with Individual 2D Materials

The integration of 2D materials consistently demonstrates substantial improvements in SPR sensor sensitivity, defined as the resonance angle shift per refractive index unit (RIU). Graphene-modified SPR sensors show a 25% sensitivity enhancement with 10 graphene layers compared to conventional gold-only sensors, achieving sensitivities of approximately 159-200°/RIU depending on the underlying metal and excitation wavelength [27]. Monolayer graphene on silver substrates achieves particularly high performance due to graphene's protective effect against silver oxidation while enhancing electromagnetic field confinement.

MXene-based SPR configurations exhibit exceptional performance, with Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene layers on copper films demonstrating sensitivity up to 312°/RIU for breast cancer biomarker detection, more than doubling the response of dielectric-only stacks. This enhancement stems from MXene's high electrical conductivity and fully functionalized surface that promotes biomolecular interactions while intensifying surface charge oscillations [28].

Black phosphorus consistently delivers the highest sensitivity enhancements among 2D materials due to its exceptionally high refractive index. BP-based SPR sensors achieve sensitivities of 181°/RIU for 5nm BP layers on silver films, with optimized hybrid structures reaching 464.4°/RIU for early-stage malaria detection and up to 466°/RIU in specialized waveguide configurations. The anisotropic properties of BP enable tunable sensor responses based on crystal orientation, offering an additional dimension for performance optimization [29] [30] [31].

Hybrid Structures and Synergistic Effects

Heterostructures combining multiple 2D materials leverage complementary properties to achieve performance beyond individual materials. Graphene-BP heterostructures exploit graphene's high surface area and BP's anisotropic optical response, enabling pronounced electromagnetic field confinement at the sensor interface. Optimized five-layer configurations (BK7/Ag/graphene/BP/analyte) achieve sensitivity of 300°/RIU at n = 1.35 RIU with a figure of merit of 45.455 RIUâ»Â¹ and detection limit of 0.018 RIU, surpassing single-material architectures [24].

MXene-TMDC hybrid structures represent another high-performance configuration, with Au/WS₂/Au/monolayer Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene structures achieving 198°/RIU sensitivity in aqueous solutions—a 41.43% enhancement over conventional Au-based SPR sensors. The TMDC layer enhances light absorption while MXene provides superior biomolecular loading capacity, creating a synergistic effect that boosts overall sensor response [26].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of 2D Material-Enhanced SPR Biosensors

| Sensor Configuration | Sensitivity (°/RIU) | Figure of Merit (RIUâ»Â¹) | Detection Limit (RIU) | Application Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Au | 137-159 | - | - | Baseline [27] [26] |

| Ag/10-layer Graphene | 200 | - | - | General biosensing [27] |

| Cu/MXene (Sysâ‚„) | 312 | 48-58 | 2.0×10â»âµ | Cancer detection [28] |

| Ag/BP (5nm) | 181 | - | - | Biochemical sensing [29] |

| Ag/SN/BP/ssDNA | 464.4 | - | - | Malaria diagnosis [31] |

| Ag/Graphene/BP | 300 | 45.46 | 0.018 | Low-RI detection [24] |

| Au/WSâ‚‚/Au/MXene | 198 | - | - | Aqueous sensing [26] |

| Cu/BP | 348.07 | - | - | CEA detection [32] |

| Cu/Graphene | 314.32 | - | - | CEA detection [32] |

Key Performance Metrics and Analysis

Beyond sensitivity, 2D materials significantly improve other critical sensor parameters. The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the resonance dip determines detection accuracy (DA = Δθ/FWHM), with sharper resonance curves enabling more precise angle tracking. BP- and MXene-based sensors consistently demonstrate superior quality factors (QF = SRI/FWHM) ranging from 30-58 RIUâ»Â¹, compared to approximately 25 RIUâ»Â¹ for conventional gold sensors. The figure of merit (FoM = SRI×(1-Rmin)/FWHM) provides a comprehensive performance indicator that balances sensitivity against signal sharpness and depth, with hybrid 2D material structures achieving FoM values exceeding 45 RIUâ»Â¹ [28] [30].

The limit of detection (LoD = Δn/Δθ × 0.005°) represents the smallest measurable refractive index change, with MXene and BP-enhanced sensors achieving LoDs as low as 2.0×10â»âµ RIU, sufficient to resolve minute refractive index increments (Δn = 0.014-0.024 RIU) associated with early-stage cancer biomarkers in biofluids. This exceptional resolution enables detection of low-abundance biomarkers at clinically relevant concentrations [28].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sensor Fabrication and 2D Material Integration

BK7 Prism Functionalization Protocol

- Begin with rigorous cleaning of BK7 glass prisms using piranha solution (30% Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚:Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„, 3:7 v/v) for 10 minutes with periodic shaking to remove surface contaminants and air bubbles

- Rinse thoroughly with ultrapure water and dry under nitrogen flow

- For graphene transfer: Deposit 40-65nm silver films using electron-beam evaporation or sputtering under ultra-high vacuum conditions, optionally with chromium or titanium adhesion layers

- Transfer monolayer graphene (CVD-grown or commercial) onto silver surface using wet transfer or stamping techniques

- Remove residual polymers from transfer process through appropriate solvent treatment and thermal annealing

MXene Integration Method

- Synthesize Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene via selective etching of Al from Ti₃AlC₂ MAX phase using HF or LiF/HCl solutions

- Centrifuge and collect multilayer MXene suspension, followed by intercalation and delamination to produce single-layer flakes

- Deposit copper film (40-45nm) on prism surface as plasmonic layer

- Apply silicon nitride spacer layer (5-7nm) using chemical vapor deposition or sputtering

- Deposit MXene sheets via spin-coating (2000-3000 rpm for 30-60s) or immersion methods to achieve uniform monolayer coverage

Black Phosphorus Transfer Protocol

- Mechanically exfoliate BP crystals onto PDMS stamps or purchase commercial BP films

- Optimize BP thickness (typically 1-8nm) through optical contrast identification

- Precisely align and transfer BP layers onto sensor surface using dry transfer systems at controlled temperature (80-100°C) and pressure conditions

- Immediately encapsulate BP with protective dielectric layer (e.g., Al₂O₃) to prevent ambient degradation while maintaining optical accessibility

Surface Functionalization for Specific Applications

DNA and RNA Detection Functionalization

- Activate graphene or MXene surface carboxyl groups using EDC/NHS chemistry (0.4M EDC/0.1M NHS in MES buffer, pH 6.0) for 30 minutes

- Immerse sensor in ssDNA probe solution (1-10μM in PBS, pH 7.4) for 2-4 hours to form amide bonds

- Quench unreacted sites with 1M ethanolamine-HCl (pH 8.5) for 15 minutes

- Validate functionalization by measuring resonance angle shift (>0.2° indicates successful probe immobilization)

Protein and Antibody Immobilization Protocol

- Treat BP or graphene surface with oxygen plasma (50W, 30s) to enhance surface hydrophilicity

- Incubate with protein A/G solution (50μg/mL in acetate buffer, pH 5.0) for 1 hour to facilitate oriented antibody immobilization

- Block non-specific binding sites with 1% BSA or casein in PBS for 30 minutes

- Apply specific antibodies (10-100μg/mL in PBS) for target capture, optimizing concentration for maximal binding response

Virus Detection Setup (PRRSV Model)

- Functionalize GO-modified sensor with CY polypeptide (NHâ‚‚-CCYHWWSWPSYTQSS-COOH) via EDC/NHS chemistry

- Establish baseline resonance in phosphate-buffered saline for 15 minutes

- Inject virus samples (multiplicity of infection 0.2-1.7) in culture medium containing 10% serum

- Monitor resonance angle shift in real-time, with linear response indicating specific virus capture [33]

Diagram 1: SPR Sensor Fabrication Workflow

Measurement, Data Analysis, and Machine Learning Integration

SPR Measurement and Performance Characterization

Angular Interrogation Protocol

- Employ TM-polarized monochromatic light source (λ = 633nm standard)

- Mount functionalized sensor in Kretschmann configuration with index-matching fluid

- Scan incident angle range of 50-80° with 0.001° resolution using precision rotation stage

- Record reflectance spectra at 1Hz acquisition rate to track dynamic binding events

- Determine resonance angle (θSPR) by locating reflectance minimum through Lorentzian fitting

- Calculate sensitivity (S = ΔθSPR/Δn) using analyte solutions with known refractive indices (typically 1.33-1.38 RIU range)

Performance Metric Calculation

- Extract full width at half maximum (FWHM) from reflectance curves

- Compute detection accuracy: DA = Δθ/FWHM

- Determine quality factor: QF = SRI/FWHM

- Calculate figure of merit: FoM = SRI×(1-Rmin)/FWHM

- Establish limit of detection: LoD = (Δn/Δθ) × 0.005°

- For comprehensive assessment: CSF = SRI×(Rmax-Rmin)/FWHM [28] [31]

Machine Learning for Sensor Optimization and Prediction

Advanced machine learning techniques significantly enhance SPR sensor design and data analysis. K-nearest neighbors (KNN) regression demonstrates excellent reliability for predicting sensor behavior, yielding R² values between 92-100% and mean absolute errors of 0.005-0.012 RIU when trained on electromagnetic simulation data. Genetic algorithms (GA) efficiently optimize complex multilayer structures by simultaneously tuning metal thickness and 2D material layer numbers to maximize sensitivity at specific wavelengths. Explainable AI (XAI) approaches, including SHAP analysis, identify analyte refractive index and wavelength as the most influential factors governing sensor performance, providing physical insights for rational design [24] [27].

Diagram 2: Machine Learning Integration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for 2D Material-Enhanced SPR

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate Materials | BK7 glass prisms | Optical coupling element | n = 1.5151 @ 633nm [24] |

| CaFâ‚‚ prisms | High-index coupling | Alternative to BK7 [30] | |

| Plasmonic Metals | Silver (Ag) target | High-sensitivity plasmonic layer | 40-65nm thickness, 99.99% purity [24] |

| Copper (Cu) target | Cost-effective alternative | 40-47nm thickness with protective layers [28] | |

| 2D Materials | CVD graphene films | Enhanced field confinement | Monolayer, 0.34nm thickness [27] |

| Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene flakes | High biomolecule loading | Monolayer, 0.993nm thickness [26] | |

| Black phosphorus crystals | Anisotropic response | 1-8nm thickness, encapsulated [29] | |

| Functionalization | Cysteamine hydrochloride | Surface linker molecule | 100mM in ethanol, 12h incubation [33] |

| EDC/NHS kit | Carboxyl group activation | 0.4M EDC/0.1M NHS in MES buffer [33] | |

| ssDNA probes | Specific target capture | 1-10μM in PBS, sequence-dependent [31] | |

| Blocking Agents | Bovine serum albumin | Non-specific binding reduction | 1% in PBS, 30min incubation [33] |

| Ethanolamine-HCl | Quenching unreacted sites | 1M, pH 8.5, 15min treatment [33] | |

| QCA570 | QCA570, MF:C39H33N7O4S, MW:695.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| ILK-IN-3 | ILK-IN-3, CAS:866409-68-9, MF:C10H12N6O, MW:232.25 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The integration of two-dimensional materials represents a paradigm shift in surface plasmon resonance biosensing, enabling unprecedented sensitivity and detection capabilities for clinical diagnostics and drug development applications. Graphene, MXene, and black phosphorus each offer unique advantages, with graphene providing exceptional surface area and protection, MXene delivering high conductivity and facile functionalization, and black phosphorus contributing anisotropic properties and strong light-matter interactions.

Hybrid heterostructures that combine multiple 2D materials demonstrate synergistic effects that surpass individual material performance, with graphene-BP configurations achieving 300°/RIU sensitivity and MXene-TMDC structures showing 41.43% enhancement over conventional sensors. The incorporation of machine learning for sensor optimization and data analysis further enhances the capability to design application-specific sensors with maximized performance.

As SPR biosensing advances toward point-of-care applications, 2D materials will play an increasingly critical role in balancing high sensitivity with practical requirements for stability, reproducibility, and multiplexed detection. Future developments will likely focus on optimizing fabrication protocols for large-scale production, enhancing material stability under physiological conditions, and creating standardized functionalization approaches for specific clinical targets.

This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for two advanced surface plasmon resonance (SPR) sensor configurations: the bowtie photonic crystal fiber (PCF) and thin-film bimetallic layers. These structures represent significant advancements in the pursuit of higher sensitivity, specificity, and practicality for refractive index (RI) sensing in medical diagnostics, drug development, and environmental monitoring. The notes include performance benchmarks, step-by-step fabrication and simulation procedures, and essential reagent solutions to facilitate implementation by researchers and scientists.

Application Note 1: Bowtie Photonic Crystal Fiber (PCF)-SPR Sensor

The optimized bowtie PCF-SPR sensor demonstrates exceptional performance across a broad refractive index range, making it suitable for detecting diverse biological and chemical analytes [16] [34]. Its key quantitative performance metrics are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the Bowtie PCF-SPR Sensor

| Performance Parameter | Value | Conditions / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Wavelength Sensitivity (WS) | 143,000 nm/RIU | Maximum achieved sensitivity [16] [34]. |

| Amplitude Sensitivity (AS) | 6,242 RIUâ»Â¹ | Maximum achieved sensitivity [16]. |

| Figure of Merit (FOM) | 2,600 RIUâ»Â¹ | Indicates superior overall performance [16]. |

| Sensor Resolution | 6.99 × 10â»â· RIU | Minimum detectable refractive index change [16]. |

| Refractive Index Range | 1.32 - 1.44 | Effective sensing range for analytes [16]. |

| Pitch (Λ) | 9.0 µm | Larger pitch simplifies fabrication [16]. |

| Gold Layer Thickness | 30 nm | Optimized plasmonic layer [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: Design and Simulation

Objective: To model, simulate, and analyze the performance of a bowtie PCF-SPR sensor using COMSOL Multiphysics software.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Procedures:

Step 1: Define Geometry and Materials

- Create a 2D cross-section of the PCF with a hexagonal array of three layers of air holes [16].

- Implement the bowtie configuration by removing the central air hole and strategically placing air holes of different diameters (d₠= 0.65Λ, d₂ = 0.34Λ, d₃ = 0.85Λ) to enhance light propagation to the plasmonic material [16].

- Introduce a central open channel and coat it with a 30 nm gold layer as the plasmonic material [16].

Step 2: Mesh Generation

Step 3: Specify Material Properties

- Silica (SiOâ‚‚): Use as the base fiber material. Its refractive index can be defined using a built-in model in COMSOL (e.g., the Sellmeier equation) [16] [20].

- Gold: Model the complex permittivity of the 30 nm gold layer using the Drude-Lorentz model to accurately represent its plasmonic behavior in simulations [16].

- Analyte: Assign a user-defined refractive index within the range of 1.32 to 1.44 to the sensing channel [16].

Step 4: Run Mode Analysis and Post-Processing

- Perform a mode analysis study to find the effective index of the core-guided mode and the surface plasmon polariton (SPP) mode [16] [18].

- Calculate the confinement loss (α) using the formula: α = (40Ï€ / (ln(10)λ)) × Im(neff) × 10â¶, where Im(neff) is the imaginary part of the effective mode index and λ is the wavelength [16] [18].

- Identify the resonance wavelength (λ_res) from the peak of the confinement loss spectrum [16].

- Compute performance metrics as follows:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Bowtie PCF-SPR Sensor

| Material / Solution | Function / Role | Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Silica (SiOâ‚‚) | Base substrate for the photonic crystal fiber. | Standard material for PCF fabrication; optical properties defined by Sellmeier equation [16] [20]. |

| Gold (Au) Target | Plasmonic material layer. | High chemical stability and strong plasmonic resonance; thermal evaporation for a 30 nm layer [16] [18]. |

| Analyte Solutions | Samples for detection and characterization. | Refractive index range of 1.32 to 1.44 (e.g., aqueous solutions, biomolecules) [16]. |

| COMSOL Multiphysics | Finite Element Method (FEM) simulation software. | Platform for modeling light propagation, plasmonic resonance, and sensor performance [16] [20]. |

Application Note 2: Bimetallic Layer SPR Sensor

Bimetallic configurations combine the advantages of different metals, such as the high sensitivity of silver and the chemical stability of gold, to enhance SPR sensor performance. Integration with 2D materials like Metal Halide Perovskites (MHPs) or Black Phosphorus (BP) further boosts sensitivity and selectivity [35] [36].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Bimetallic SPR Sensors with Enhancers

| Sensor Configuration | Sensitivity (°/RIU) | Quality Factor (RIUâ»Â¹) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cu/Ag + CsSnI₃ (MHP) | 460 | 109.48 | Highest sensitivity; MHP thickness optimized to 8 nm [35]. |

| Ag/Au + BP | 240 | 34.7 | Includes TiOâ‚‚/SiOâ‚‚ bi-layer for light screening [36]. |

| Ag/Au (Baseline) | 147 | Not Specified | 130.8% improvement over Ag/Cu configuration [35]. |

| Au/MXene/Graphene | 163.63 | 17.52 | Used for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) detection [37]. |

Experimental Protocol: Kretschmann Configuration Setup

Objective: To construct and characterize a bimetallic SPR biosensor in the Kretschmann configuration, enhanced with 2D materials.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Procedures:

Step 1: Substrate and Layer Preparation

- Clean a BK7 prism (or other coupling prism) thoroughly using standard solvents and plasma treatment to ensure a clean, hydroxylated surface [36] [37].

- Step 2: Thin-Film Deposition