Advancements and Evaluation of SERS Substrates for Sensitive Detection of Environmental Pollutants

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) has emerged as a powerful analytical technique for the trace-level detection of environmental pollutants, offering unparalleled sensitivity, molecular fingerprinting capability, and potential for on-site analysis.

Advancements and Evaluation of SERS Substrates for Sensitive Detection of Environmental Pollutants

Abstract

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) has emerged as a powerful analytical technique for the trace-level detection of environmental pollutants, offering unparalleled sensitivity, molecular fingerprinting capability, and potential for on-site analysis. This article provides a comprehensive evaluation of SERS substrates, from fundamental enhancement mechanisms and innovative nanomaterial designs to their practical application in detecting pesticides, heavy metals, biotoxins, and organic contaminants. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the review systematically compares substrate performance, addresses key challenges in reproducibility and quantitative analysis, and explores the integration of computational design and artificial intelligence. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with cutting-edge methodological advances and validation frameworks, this work serves as a critical resource for navigating the development and application of SERS technologies in environmental monitoring and public health protection.

Principles and Design of SERS Substrates: From Plasmonics to Nanomaterial Innovation

Electromagnetic and Chemical Enhancement Mechanisms in SERS

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) has emerged as a powerful analytical technique that transcends the sensitivity limitations of conventional Raman spectroscopy. By leveraging nanostructured materials, primarily noble metals, SERS can amplify inherently weak Raman signals by factors ranging from 10ⴠto as high as 10¹¹, enabling single-molecule detection in ideal configurations [1] [2]. This extraordinary enhancement capability makes SERS particularly valuable for detecting trace environmental pollutants, where sensitivity and specificity are paramount. The signal amplification in SERS originates from two distinct but potentially synergistic mechanisms: the electromagnetic enhancement mechanism (EM) and the chemical enhancement mechanism (CM) [2]. Understanding the interplay between these mechanisms is crucial for researchers evaluating SERS substrates for environmental applications, as it directly influences substrate selection, experimental design, and analytical performance.

The evaluation of SERS substrates for environmental pollutant detection presents unique challenges, including complex sample matrices, low analyte concentrations, and the need for reliable field deployment. This comparison guide objectively examines the fundamental enhancement mechanisms, their relative contributions to SERS performance, and practical implications for environmental research. By synthesizing current research trends and experimental data, this guide provides a framework for selecting and optimizing SERS substrates based on their enhancement characteristics and application requirements.

Fundamental Principles of SERS Enhancement

Electromagnetic Enhancement Mechanism

The electromagnetic enhancement mechanism (EM) is widely recognized as the dominant contributor to SERS intensity, typically accounting for 10â´ to 10â¸-fold signal amplification [1] [2]. This mechanism originates from the excitation of localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) in plasmonic nanostructures, primarily composed of noble metals such as gold (Au) and silver (Ag) [2]. When incident light interacts with these metallic nanostructures at frequencies matching their collective electron oscillation frequency, it induces resonant oscillations known as surface plasmons. This resonance creates dramatically enhanced electromagnetic fields at specific locations on the nanostructure surface, particularly at sharp tips or within narrow gaps between particles—regions famously termed "hot spots" [1] [3].

The electromagnetic enhancement process involves two complementary effects: first, the enhanced local field amplifies the excitation of Raman scattering when light interacts with molecules located within these hot spots; second, the same enhancement mechanism amplifies the Raman-shifted emission from the molecules [2]. Since both the incoming and outgoing processes are enhanced, the overall Raman intensity scales approximately with the fourth power of the local field enhancement (E/Eâ‚€), explaining the extraordinary amplification factors achievable through EM [3]. The EM mechanism is largely non-specific, depending primarily on the molecular proximity to enhanced fields rather than specific chemical interactions, making it broadly applicable across various analyte types.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Electromagnetic Enhancement

| Characteristic | Description | Implication for SERS Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Enhancement Factor | 10ⴠ- 10⸠| Provides major contribution to overall SERS signal |

| Distance Dependence | Sharp decay (~dâ»Â¹Â²) | Requires analyte proximity to substrate surface |

| Material Dependence | Noble metals (Ag, Au, Cu) | Limited to plasmonic materials |

| Specificity | Non-specific | Broadly applicable to various analytes |

| Spatial Distribution | Localized at "hot spots" | Signal heterogeneity requires careful sampling |

Chemical Enhancement Mechanism

The chemical enhancement mechanism (CM) provides a secondary but significant contribution to SERS signals, typically offering 10¹ to 10³-fold enhancement [2]. Unlike the physically-based EM mechanism, CM involves direct chemical interactions between the analyte molecules and the substrate surface at the quantum mechanical level. This mechanism primarily arises from charge transfer between the energy levels of the metal substrate and the adsorbed molecules, which creates new electronic states and resonances that increase the Raman scattering cross-section [2] [3].

The chemical enhancement process requires direct chemical adsorption of target molecules onto the substrate surface, often through specific functional groups that facilitate charge transfer. The enhancement depends critically on the molecular orbitals of both the adsorbate and substrate, making it highly specific to particular molecule-substrate combinations [3]. While CM provides substantially lower overall enhancement compared to EM, its importance lies in its ability to selectively enhance specific analytes based on their chemical properties, potentially improving detection specificity in complex environmental samples. Additionally, CM exhibits a much weaker distance dependence than EM, maintaining effectiveness for directly adsorbed molecules even outside the strongest electromagnetic hot spots.

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Chemical Enhancement

| Characteristic | Description | Implication for SERS Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Enhancement Factor | 10¹ - 10³ | Secondary contribution to SERS signal |

| Distance Dependence | Weak decay | Effective for directly adsorbed molecules |

| Material Dependence | Various semiconductors/metals | Broader material options including MXenes |

| Specificity | Highly specific | Selective enhancement based on chemistry |

| Adsorption Requirement | Direct chemical bonding | Requires specific molecular functionalities |

Synergistic Effects and Combined Enhancement

In practical SERS applications, electromagnetic and chemical enhancement mechanisms do not operate independently but rather exhibit complex synergistic interactions [2]. The combined enhancement factor is not merely the product of individual EM and CM factors, as both mechanisms can influence each other through various interfacial interactions. For instance, chemical bonding can alter the local electronic environment of plasmonic nanostructures, potentially modifying their plasmonic properties and thus the electromagnetic enhancement. Conversely, strong electromagnetic fields can influence charge transfer processes, affecting the chemical enhancement component.

This synergy is particularly evident in hybrid SERS substrates that combine plasmonic metals with functional materials such as semiconductors, graphene, or metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [2]. In these systems, the plasmonic components provide strong electromagnetic enhancement, while the functional materials contribute additional chemical enhancement and improved molecular adsorption. The development of such multifunctional substrates represents a frontier in SERS research, with demonstrated improvements in both sensitivity and specificity for environmental pollutant detection [4] [2].

Comparative Analysis of Enhancement Mechanisms

The relative contributions and characteristics of electromagnetic and chemical enhancement mechanisms have profound implications for SERS substrate design and application. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental processes and synergistic relationship between these two primary enhancement mechanisms in SERS:

The comparative performance of these enhancement mechanisms can be quantitatively evaluated across multiple parameters critical for environmental sensing applications:

Table 3: Direct Comparison of EM and CM Mechanisms

| Parameter | Electromagnetic Enhancement | Chemical Enhancement |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Enhancement Factor | 10ⴠ- 10⸠[1] [2] | 10¹ - 10³ [2] |

| Primary Physical Basis | Plasmon resonance in noble metals | Charge transfer complexes |

| Distance Dependence | Strong (∼dâ»Â¹Â²) [5] | Weak |

| Material Requirements | Au, Ag, Cu nanostructures [2] | Various metals/semiconductors |

| Molecular Specificity | Low | High [3] |

| Optimal Substrate Types | Nanoparticles, nanogaps, 3D architectures [1] | Functionalized surfaces, MXenes [3] |

| Contribution to Total SERS | Major (∼10â¶-10â¸) | Minor (∼10¹-10³) |

| Environmental Application | Broad pollutant detection | Selective target identification |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Coffee-Ring Effect for Quantitative Dry Analyte Detection

A recent innovative methodology leverages the "coffee ring effect" to improve reproducibility in SERS measurements of transparent dry analytes, particularly relevant for environmental contaminants like glyphosate [6]. This protocol involves adding non-interfering silicon microparticles to the analyte solution, which is then drop-cast onto a silicon-based SERS substrate. During evaporation, the silicon particles aggregate at the drop periphery, concentrating the dry analyte in these defined areas and enabling reproducible laser targeting.

Detailed Methodology:

- Substrate Preparation: Utilize silicon-based SERS substrates with immobilized plasmonic nanoparticles.

- Sample Preparation: Add 1-5 μm silicon microparticles to the analyte solution at optimized concentration.

- Deposition: Apply 10-20 μL of the prepared sample solution onto the substrate surface.

- Drying: Allow controlled evaporation under ambient conditions (23°C, 45% RH recommended).

- Measurement: Focus laser beam at the coffee-ring periphery where analyte concentration is highest.

Performance Data: This approach demonstrated exceptional sensitivity for glyphosate detection with a limit of detection (LOD) of 9.30 × 10â»Â¹â° M and limit of quantification (LOQ) of 9.41 × 10â»Â¹â° M, competitive with established methodologies but without requiring derivatization or extensive sample pretreatment [6]. The method primarily leverages electromagnetic enhancement through the plasmonic substrate while addressing key reproducibility challenges in dry sample analysis.

Protocol 2: Signal-Differentiated SERS Nose Array for Explosive Compound Detection

For detecting environmental contaminants with structural similarities, such as nitro-explosives, a signal-differentiated SERS (SD-SERS) array approach has been developed to enhance discrimination capability [3]. This protocol employs multiple SERS substrates with varied chemical and physical properties to generate differentiated response patterns, enabling more reliable identification through machine learning analysis.

Detailed Methodology:

- Substrate Fabrication: Create six distinct SERS substrates combining:

- Two MXene materials (Mo₂C and Ti₃C₂) for chemical enhancement variation

- Three self-assembled monolayers with different adsorption affinities

- Gold nanobipyramids (AuNBPs) for electromagnetic hot spots

- SD-SERS Array Assembly: Integrate the six substrates into a unified detection platform.

- Sample Exposure: Introduce analyte gas (e.g., TNT) to the array under controlled conditions.

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect Raman spectra from all six substrate elements.

- Pattern Analysis: Process multi-dimensional spectral data with machine learning algorithms (e.g., PCA, LDA) for classification.

Performance Data: Finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations established that AuNBPs provide superior electromagnetic enhancement compared to alternative nanostructures like gold nanostars (AuNSs) or gold nanorods (AuNRs) [3]. The SD-SERS array successfully discriminated TNT from structurally similar compounds (2,4-DNPA) with high accuracy, demonstrating the value of combining multiple enhancement mechanisms for complex environmental detection scenarios.

Protocol 3: Three-Dimensional SERS Substrates for Enhanced Biosensing

Three-dimensional SERS substrates represent a significant advancement over traditional 2D platforms, particularly for analyzing complex biological and environmental samples [1]. These substrates provide volumetric enhancement through increased hot spot density and improved analyte accessibility, achieving enhancement factors exceeding 10⸠with higher reproducibility (RSD typically <10%).

Detailed Methodology:

- Substrate Selection: Choose appropriate 3D architecture based on application:

- Vertically aligned nanowire arrays

- Porous metal frameworks and aerogels

- Dendritic and fractal nanostructures

- Core-shell and hollow nanospheres

- Fabrication Technique: Employ suitable method such as:

- Template-assisted electrochemical deposition

- Galvanic replacement and dealloying

- Freeze-drying and self-assembly processes

- Hybrid integration approaches

- Functionalization: Modify with recognition elements (antibodies, aptamers) for specific targeting.

- Sample Application: Apply liquid samples directly to 3D substrate, leveraging capillary action.

- Signal Acquisition: Utilize standard Raman instrumentation with optimized laser focusing.

Performance Data: 3D SERS substrates consistently outperform 2D equivalents across multiple parameters, offering >10⸠enhancement factors compared to 10âµ-10â· for 2D substrates, with significantly improved reproducibility (RSD <10% vs. moderate reproducibility for 2D) [1]. The 3D architecture facilitates analyte transport and retention in complex matrices like environmental water samples, addressing key limitations of planar substrates.

Research Reagent Solutions for SERS Substrates

The selection of appropriate materials and reagents is fundamental to successful SERS substrate development and application. The following toolkit summarizes essential components and their functions in constructing high-performance SERS platforms for environmental detection:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SERS Applications

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in SERS Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmonic Materials | Au, Ag nanoparticles and nanostructures [1] [2] | Provide electromagnetic enhancement via LSPR |

| 2D Materials | Mo₂C MXene, Ti₃C₂ MXene [3] | Enable chemical enhancement through charge transfer |

| Functionalization Agents | Self-assembled monolayers (SAMs), aptamers, antibodies [1] [3] | Enhance selectivity and molecular adsorption |

| Support Structures | Silicon wafers, graphene, porous frameworks [6] [1] | Provide mechanical stability and additional enhancement |

| Shape-Directing Agents | CTAC, CTAB, silver nitrate [3] | Control nanostructure morphology during synthesis |

| Reducing Agents | Sodium borohydride, ascorbic acid, citrate [3] | Facilitate controlled metal nanoparticle growth |

| Additives for Assembly | Silicon microparticles (1-5 μm) [6] | Enable coffee-ring effect for reproducible deposition |

Advanced Substrate Architectures and Performance Trends

The evolution of SERS substrates has progressed from simple metal nanoparticles to sophisticated engineered architectures that optimize both electromagnetic and chemical enhancement mechanisms. Three-dimensional substrates represent a particularly significant advancement, addressing key limitations of traditional 2D platforms through structural innovations that enhance sensitivity, reproducibility, and applicability to complex environmental samples [1].

Table 5: Comparison of 2D vs. 3D SERS Substrates

| Feature | 2D SERS Substrates | 3D SERS Substrates |

|---|---|---|

| Hot Spot Distribution | Confined to planar surface [1] | Volumetric in all dimensions [1] |

| Typical Enhancement Factor | 10âµâ€“10â· [1] | >10⸠[1] |

| Reproducibility | Moderate | High (RSD typically <10%) [1] |

| Analyte Accessibility | Limited surface diffusion [1] | Enhanced via pores and 3D networks [1] |

| Fabrication Methods | Lithography, self-assembly [1] | Template growth, dealloying, freeze-drying [1] |

| Application Flexibility | Limited to flat surfaces | Compatible with irregular surfaces [1] |

The development of multifunctional substrates represents another frontier in SERS technology, particularly for environmental applications [4] [2]. These advanced platforms integrate plasmonic components with additional functional materials such as semiconductors, graphene, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and stimuli-responsive polymers. This integration creates synergistic enhancement effects while incorporating capabilities like molecular recognition, preconcentration, and signal modulation [2]. For instance, hydrogel-based SERS substrates with embedded nanoparticles have demonstrated responsive sensing of pH and glucose concentrations in physiological conditions, suggesting potential for adaptive environmental monitoring [1].

The following diagram illustrates the progressive development and classification of SERS substrates, highlighting the evolution from simple metallic structures to advanced multifunctional systems:

Emerging research continues to push the boundaries of SERS performance through innovative substrate designs. Stimuli-responsive architectures that modulate their enhancement properties in response to environmental changes offer promising avenues for smart sensing platforms [1]. Similarly, the integration of digital SERS approaches with artificial intelligence-assisted data processing is addressing traditional challenges in spectral interpretation and quantification, particularly for complex environmental mixtures [5] [4]. These advancements collectively contribute to the growing adoption of SERS beyond specialized research laboratories into practical environmental monitoring applications.

The comparative analysis of electromagnetic and chemical enhancement mechanisms in SERS reveals a complex landscape where substrate design decisions directly impact analytical performance for environmental detection applications. Electromagnetic enhancement provides the dominant contribution to signal amplification, with carefully engineered nanostructures achieving extraordinary enhancement factors exceeding 10⸠through optimized plasmonic properties and hot spot density [1]. Chemical enhancement, while offering more modest amplification, provides valuable molecular specificity and complementary enhancement through charge transfer mechanisms [2] [3].

The evolution toward advanced substrate architectures, particularly three-dimensional and multifunctional platforms, demonstrates the increasing sophistication in harnessing both enhancement mechanisms synergistically [4] [1] [2]. These developments address key challenges in environmental pollutant detection, including sensitivity requirements for trace analytes, reproducibility across complex sample matrices, and selectivity for target compounds in the presence of interferents. The integration of innovative methodological approaches—such as coffee-ring effect utilization, signal-differentiated arrays, and machine learning-assisted analysis—further enhances the practical utility of SERS for environmental monitoring [6] [3].

As SERS technology continues to mature, the deliberate optimization of both electromagnetic and chemical enhancement pathways will remain central to developing next-generation environmental sensors. The ongoing convergence of nanotechnology, materials science, and data analytics promises to overcome current limitations while expanding the application scope of SERS in addressing pressing environmental challenges.

Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) and the Creation of 'Hot Spots'

Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) has emerged as a powerful analytical technique for the ultrasensitive detection of environmental pollutants, leveraging the remarkable signal amplification provided by localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) and strategically engineered 'hot spots'. This guide provides a comparative evaluation of SERS substrate technologies, focusing on their LSPR properties and hot spot generation capabilities for pollutant detection. We systematically analyze experimental data and fabrication methodologies for various substrate architectures, highlighting their performance metrics, limitations, and suitability for different environmental monitoring applications. The data presented herein aims to equip researchers with the necessary information to select optimal SERS substrates for specific pollutant detection scenarios.

Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) is a collective oscillation of conduction electrons in metallic nanostructures when excited by incident light at resonant frequencies [2]. This phenomenon generates enhanced localized electromagnetic fields at the nanoparticle surfaces, which dramatically amplify the Raman signals of molecules located near these surfaces—the fundamental basis of Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) [7].

The electromagnetic enhancement mechanism, predominantly responsible for SERS signal amplification (by factors of 10^4-10^8), primarily arises from this LSPR effect when plasmon excitations in metallic nanosystems match the excitation wavelength used for Raman experiments [8]. A secondary chemical enhancement mechanism (typically contributing factors of 10-10^3) involves charge transfer between the plasmonic nanostructures and analyte molecules [7] [2].

'Hot spots' refer to nanoscale gaps (typically <10 nm) between metallic nanostructures where the localized electromagnetic field is significantly enhanced due to plasmon coupling [9]. These regions can provide extraordinary Raman enhancement factors reaching 10^8-10^12, making them crucial for detecting trace-level pollutants in environmental samples [1].

Comparative Performance of SERS Substrates

The design and fabrication of SERS substrates directly influence their LSPR properties, hot spot density, and ultimately, their analytical performance for pollutant detection. The following table compares the key characteristics of major SERS substrate types.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of SERS Substrates for Environmental Pollutant Detection

| Substrate Type | Enhancement Factor (EF) | Hot Spot Characteristics | Reproducibility (RSD) | Representative Pollutants Detected | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Planar Substrates [1] | 10^5-10^7 | Confined to planar surface; sparse distribution | Moderate (>15%) | Organic dyes, pesticides | ~10^-8 M [8] | Simple fabrication; good for surface characterization | Limited surface area; uneven hot spot distribution |

| 3D Nanostructured Substrates [1] | >10^8 | Volumetric distribution; high density | High (<10%) | Heavy metals, pharmaceuticals [1] | ~10^-12 M [1] | Increased surface area; improved analyte accessibility | Complex fabrication; potential mechanical instability |

| Metal Nanoparticle Colloids [7] | 10^6-10^10 | Dynamic, solution-dependent | Low (~20-30%) | Pesticides, herbicides [8] | 10^-9-10^-15 M [8] | Easy preparation; high enhancement potential | Poor reproducibility; aggregation-dependent |

| Template-Assisted Nanostructures [1] | 10^7-10^9 | Controlled spacing and distribution | Moderate-High (10-15%) | Mycotoxins, organic pollutants [2] | ~10^-10 M | Tunable geometry; relatively scalable | Template removal steps; potential defects |

| Flexible SERS Substrates [10] | 10^6-10^8 | Strain-dependent distribution | Moderate (~15%) | Pesticides on surfaces [2] | ~10^-9 M | Conformal contact; field-deployable | Signal variation with bending; lower enhancement |

The progression from traditional 2D to advanced 3D SERS substrates represents a significant technological evolution. Three-dimensional substrates extend the enhancement volume into the Z-dimension, creating a more isotropic and dense distribution of hot spots compared to their 2D counterparts [1]. Structures such as vertically aligned nanowires, dendritic frameworks, and porous scaffolds generate hot spots throughout their vertical and internal volumes, leading to higher overall enhancement factors exceeding 10^8 and improved signal reproducibility with relative standard deviations typically below 10% [1].

Experimental Protocols for SERS Substrate Evaluation

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Au@Ag Nanocuboids for Dye Detection

Objective: To fabricate a densely packed monolayer of plasmonic Au@Ag nanocuboids for ultrasensitive detection of organic dyes in water samples [8].

Materials:

- Chloroauric acid (HAuClâ‚„) solution

- Silver nitrate (AgNO₃)

- Ascorbic acid (reducing agent)

- Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, surfactant)

- Seed solution (small gold nanoparticles)

Methodology:

- Seed Preparation: Prepare gold nanoparticle seeds by reducing HAuClâ‚„ with sodium borohydride in the presence of CTAB.

- Growth Solution: Prepare a growth solution containing HAuCl₄, AgNO₃, ascorbic acid, and CTAB.

- Nanocuboid Formation: Add seed solution to the growth solution and allow nanocuboids to form over 30 minutes.

- Substrate Assembly: Centrifuge and redisperse nanocuboids in deionized water, then deposit onto a silicon wafer to form a densely packed monolayer.

- Characterization: Use SEM to verify monolayer formation and uniformity.

- SERS Measurement: Apply malachite green (MG) solution (8.7×10^-10 M) in fishpond water to the substrate and acquire SERS spectra with 785 nm excitation.

Results: This substrate achieved a detection limit of 8.7×10^-10 M for MG in fishpond water, with enhancement primarily arising from the edges and corners of nanocuboids that generate numerous electromagnetic hot spots [8].

Protocol 2: Fabrication of TiOâ‚‚/Ag Flower-Like Nanomaterial for Lake Water Monitoring

Objective: To develop a semiconductor-metal hybrid SERS substrate for trace-level pollutant detection in lake waters [8].

Materials:

- Titanium isopropoxide (Ti precursor)

- Silver nitrate (AgNO₃)

- Ethanol and deionized water

- Hydrofluoric acid (HF, morphology control agent)

Methodology:

- TiO₂ Nanostructure Synthesis: Hydrothermally treat titanium isopropoxide with HF at 180°C for 24 hours to form flower-like TiO₂ nanostructures.

- Silver Decoration: Immerse TiO₂ nanostructures in AgNO₃ solution and expose to UV light to photoreduce silver ions to nanoparticles.

- Substrate Characterization: Use SEM/TEM to confirm the uniform distribution of Ag nanoparticles on TiOâ‚‚ surfaces.

- Performance Evaluation: Test the substrate with malachite green solutions in water from Fuxian and Dian lakes with concentrations as low as 10^-12 M.

Results: The TiOâ‚‚/Ag flower-like nanomaterial achieved exceptional detection limits of 10^-12 M for MG in lake waters. The enhancement mechanism combines electromagnetic enhancement from Ag nanoparticle hot spots with chemical enhancement through charge transfer in the molecule-semiconductor-metal system [8].

Fundamental Mechanisms and Theoretical Framework

LSPR and Hot Spot Formation

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanism of LSPR and hot spot formation in metallic nanostructures:

Diagram 1: LSPR and hot spot formation mechanism.

The electromagnetic enhancement in SERS originates from the amplified electromagnetic fields generated when incident light excites LSPR in metallic nanostructures. When plasmonic nanoparticles are closely spaced (typically <10 nm apart), theinteracting electromagnetic fields create localized regions of intense field enhancement known as "hot spots" [9]. In these regions, the Raman signal of molecules can be enhanced by factors up to 10^10-10^12, enabling single-molecule detection in optimal conditions [1].

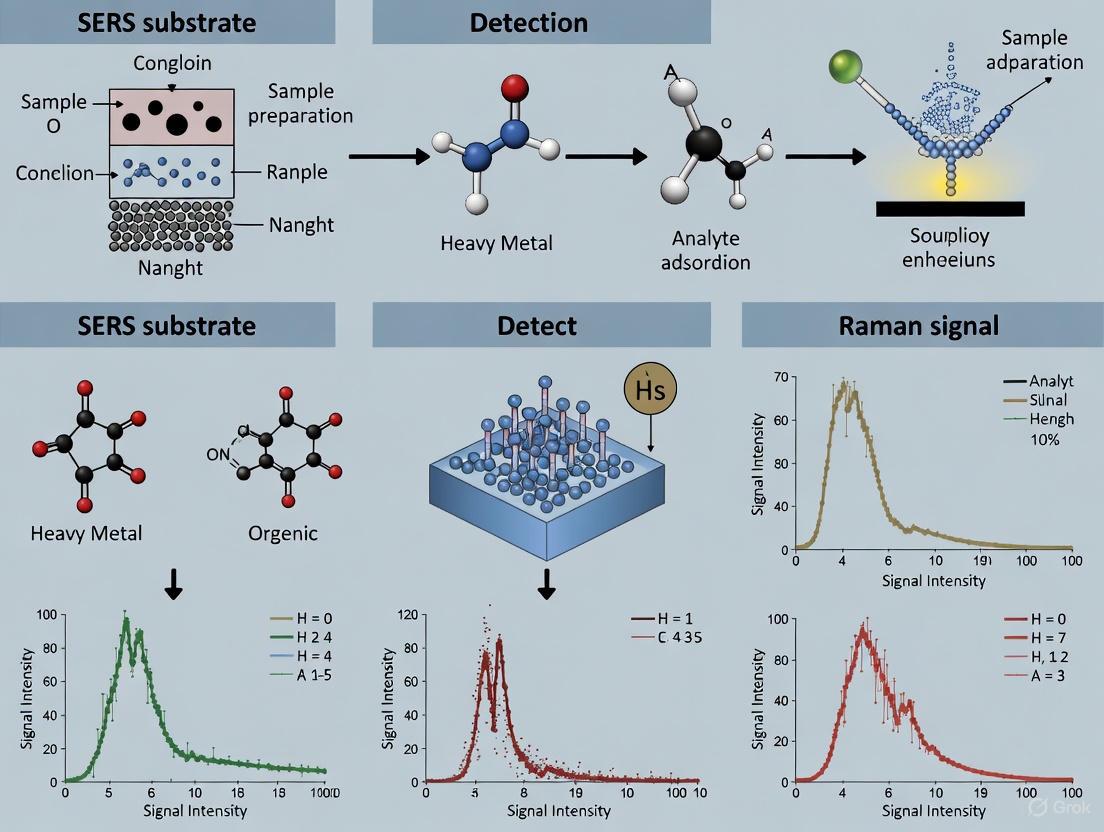

SERS Workflow for Environmental Pollutant Detection

The following diagram outlines a typical SERS-based workflow for detecting pollutants in environmental samples:

Diagram 2: SERS workflow for pollutant detection.

Research Reagent Solutions for SERS Substrate Development

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for SERS Substrate Fabrication and Application

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in SERS Technology | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmonic Metals | Gold (Au), Silver (Ag), Copper (Cu) nanoparticles | Generate LSPR effect and electromagnetic enhancement | Ag provides highest enhancement but oxidizes; Au offers better stability [2] |

| Shape-Directing Agents | CTAB, citrate, PVP | Control nanostructure morphology and hot spot formation | Critical for creating sharp edges and nanogaps [8] |

| Semiconductor Materials | TiOâ‚‚, ZnO, graphene | Provide chemical enhancement and charge transfer | Used in hybrid substrates for synergistic enhancement [2] |

| Functionalization Agents | Thiols, silanes, antibodies, aptamers | Enable selective capture of target pollutants | Improve specificity in complex environmental matrices [10] |

| Raman Reporters | Rhodamine 6G, crystal violet, thiolated dyes | Serve as signal probes in indirect detection | Must have strong affinity for metal surface and high Raman cross-section [11] |

Advanced Substrate Architectures and Performance Optimization

Recent innovations in SERS substrate design have focused on precisely controlling nanogeometry to maximize hot spot density and LSPR tuning. Three-dimensional SERS substrates represent a significant advancement over traditional 2D platforms, offering volumetric enhancement through architectures such as vertically aligned nanowires, dendritic frameworks, porous scaffolds, and core-shell nanospheres [1].

The electromagnetic enhancement in these advanced structures benefits from multiple factors including light trapping and multiple scattering effects within the 3D matrix, which increase the interaction path length between light and analytes [1]. Furthermore, chemical enhancement can be optimized in hybrid materials that combine plasmonic metals with semiconductors or graphene, creating charge-transfer pathways that additionally amplify Raman signals [2].

For environmental applications, functionalized SERS substrates incorporating molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) or specific capture agents like antibodies have demonstrated remarkable selectivity and sensitivity. For instance, a defect-graphene/Ag-MIP substrate achieved an extraordinary detection limit of 2.5×10^-15 M for p-nitroaniline in river water, highlighting the potential of targeted SERS platforms for trace pollutant monitoring [8].

The strategic engineering of LSPR properties and hot spot distribution in SERS substrates has dramatically advanced the capabilities for environmental pollutant detection. As evidenced by the comparative data, 3D substrates and hybrid nanomaterials consistently outperform conventional 2D platforms in terms of enhancement factors, reproducibility, and detection limits for various classes of pollutants.

Future development directions include the creation of stimuli-responsive SERS substrates that modulate their enhancement properties based on environmental conditions, multifunctional hybrid platforms that combine detection with catalytic degradation of pollutants, and data-driven optimization strategies employing machine learning to design optimal nanostructures [1]. The integration of SERS substrates with microfluidic systems for automated sample processing and the development of portable, field-deployable sensors will further expand the practical applications of this powerful technology in environmental monitoring scenarios.

Addressing current challenges related to substrate reproducibility, mechanical stability, and standardization will be crucial for the transition of laboratory-developed SERS substrates to commercially viable environmental sensors. With continued interdisciplinary innovation focusing on both fundamental mechanisms and practical applications, SERS technology is poised to play an increasingly significant role in environmental protection and public health safety.

Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) has emerged as a powerful analytical technique for the sensitive detection of environmental pollutants, leveraging the unique properties of noble metal nanostructures to amplify the weak Raman signals of target molecules. The enhancement primarily arises from two mechanisms: electromagnetic enhancement, driven by localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) in noble metals, and chemical enhancement involving charge transfer between the analyte and substrate [12] [1]. Gold (Au), silver (Ag), and their bimetallic nanostructures have become the cornerstone of high-performance SERS substrates due to their exceptional plasmonic properties, tunability, and ability to generate intense electromagnetic "hot spots" [13] [14]. Within environmental monitoring, these substrates demonstrate unparalleled capability in detecting trace-level contaminants such as pesticides, antibiotics, and heavy metals, offering a rapid, non-destructive, and highly specific alternative to conventional analytical methods [15] [16]. This guide provides a comparative evaluation of these noble metal substrates, focusing on their experimental performance in detecting environmental pollutants, to inform researchers and scientists in the field.

Performance Comparison of SERS Substrates

The performance of SERS substrates is quantified by key metrics such as Enhancement Factor (EF), Limit of Detection (LOD), reproducibility, and stability. The table below summarizes the experimental performance of various gold, silver, and bimetallic nanostructures as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Noble Metal-Based SERS Substrates

| Substrate Type | Specific Morphology/Composition | Target Analyte (Application) | Enhancement Factor (EF) | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold (Au) | Au nanoparticles on Si micro/nano-hybrid structure [13] | Rhodamine 6G (Model compound) | ~10⸠(calculated) | 10â»Â¹Â² M | High sensitivity, excellent stability & reusability |

| Silver (Ag) | Flower-like Ag nanoparticles on flexible sponge [17] | Thiram (Pesticide) | 6.63 × 10ⵠ| 0.1 mg/L | Flexibility, cost-effectiveness |

| Silver (Ag) | Ag nanoparticles self-assembly [18] | Model analyte | Not specified | Near single-molecule | Ultra-high sensitivity |

| Bimetallic (Au-Ag) | MXene-Ni/Ag composite [16] | Thiram (Pesticide) | SPF* of 8.2 × 10ⶠ| 10â»â¹ M | High sensitivity, good reproducibility & stability |

| Bimetallic (Au-Ag) | Au-Ag core-shell nanoparticles [14] | Various food contaminants | 10ⶠto 10¹² (from gaps) | Varies by analyte | Tunable plasmonics, synergistic enhancement |

| Gold (Au) | Laser & plasma-treated AuNPs on glass [19] | Amoxicillin (Antibiotic) | ~3 × 10⸠| 9 × 10â»Â¹â° M | High EF, good consistency, reusability |

*SPF: SERS Performance Factor

Comparative Analysis

- Gold Nanostructures: Substrates like the Au nanoparticle-decorated Si hierarchical structure demonstrate exceptionally high EFs and low LODs for model compounds, alongside remarkable stability and reusability—key for practical applications [13]. The combination of a high-surface-area 3D structure with Au nanoparticles creates abundant hot spots.

- Silver Nanostructures: Silver substrates, such as flower-like Ag particles on sponge, often achieve very high EFs and low LODs, sometimes rivaling or exceeding gold for specific applications [17]. Ag generally provides stronger electromagnetic enhancement than Au but can suffer from oxidation, potentially limiting its long-term stability.

- Bimetallic Nanostructures: Au-Ag bimetallic substrates harness the advantages of both metals. For instance, the MXene-Ni/Ag composite shows high sensitivity for pesticide detection [16]. Au-Ag core-shell and alloy structures exhibit tunable plasmonic properties and synergistic effects that can lead to superior stability and enhancement compared to their monometallic counterparts [14].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reproducibility of SERS-based detection, standardized protocols for substrate fabrication and measurement are crucial. The following sections detail methodologies cited in the performance table.

This protocol describes a method to create a wafer-scale SERS substrate with high sensitivity and stability.

- Step 1: Fabrication of Silicon Micropillars. A P-type <100> silicon wafer is used as the base. Micropillar arrays are fabricated on the silicon surface using photolithography and Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) etching.

- Step 2: Catalytic Metal Film Deposition. A thin, continuous film of gold (Au) is deposited onto the micro-structured silicon surface using magnetron sputtering.

- Step 3: Formation of Nanopatterned Au via Thermal Dewetting. The sample is subjected to a thermal annealing process (first dewetting). This causes the thin, metastable Au film to agglomerate into nano-islands and clusters due to surface energy minimization, effectively creating a nanopatterned catalytic mask.

- Step 4: Metal-Assisted Chemical Etching (MACE). The sample undergoes MACE, where the catalytic Au nanopatterns etch the underlying silicon in a solution of HF and Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚. This forms silicon nanowires on the sidewalls of the micropillars, creating a hierarchical micro/nano-structure.

- Step 5: Decoration with Au Nanoparticles. A second Au film is sputtered onto the hierarchical structure, followed by a second thermal dewetting process. This final step decorates the entire 3D silicon structure with dense, well-adhered Au nanoparticles, which are the primary sources of SERS hot spots.

This protocol outlines the synthesis of a sensitive and reproducible bimetallic composite substrate for trace pesticide detection.

- Step 1: Preparation of MXene Nanosheets. Monolayer Ti₃C₂Tx MXene nanosheets are prepared, typically by selective etching of the Al layer from the MAX phase (Ti₃AlC₂) and subsequent delamination.

- Step 2: Synthesis of Ni/Ag Nanoparticles. Nickel-Silver (Ni/Ag) bimetallic nanoparticles with different atomic ratios are synthesized separately through a chemical reduction method.

- Step 3: Composite Formation via Transmetallation. The pre-synthesized Ni/Ag nanoparticles are modified onto the surface of the monolayer MXene nanosheets. This is achieved through a transmetallation reaction, which facilitates a strong interaction between the nanoparticles and the MXene sheets, forming the final MXene-Ni/Ag composite substrate.

A generalized workflow for acquiring and analyzing SERS spectra from environmental samples is detailed below.

- Step 1: Substrate Preparation. Commercial or lab-fabricated SERS substrates are prepared. They may be used as-is or subjected to pre-cleaning/activation steps (e.g., oxygen plasma treatment) to ensure consistency.

- Step 2: Analyte Adsorption. The target analyte (e.g., pesticide, antibiotic) is adsorbed onto the substrate surface. This is commonly done by depositing a small volume (e.g., 1-10 µL) of the analyte solution onto the substrate and allowing it to dry at room temperature. For some experiments, immersion for a set time (e.g., 1 hour) is used [12].

- Step 3: Raman Spectra Acquisition.

- The substrate is placed under a Raman microscope equipped with a laser source (common wavelengths are 532 nm, 633 nm, or 785 nm).

- The laser power at the sample is set to a non-destructive level (typically a few mW).

- Multiple spectra (e.g., 15-20) are collected from different random spots on the substrate to account for spatial heterogeneity and obtain a statistically representative dataset [12] [20].

- Integration time and number of accumulations are optimized for each substrate-analyte system.

- Step 4: Spectral Preprocessing. Collected spectra are processed to remove cosmic rays, fluorescence background (e.g., using penalized least-squares algorithm), and noise (smoothing). Spectra are often normalized to account for minor fluctuations in laser power or alignment [20].

- Step 5: Data Analysis.

- Quantification: The intensity of a characteristic Raman peak of the analyte is measured and correlated with its concentration using a calibration curve.

- Classification/Screening: Machine learning algorithms (e.g., XGBoost, PCA) can be employed to automatically identify high-quality spectra or classify unknown samples based on their spectral fingerprints [20].

Signaling Pathways and Enhancement Mechanisms

The exceptional performance of SERS substrates is rooted in the fundamental physical and chemical processes that lead to signal amplification. The following diagram and explanation detail these mechanisms.

The overall SERS enhancement is a product of the electromagnetic and chemical mechanisms.

Electromagnetic Enhancement (EM): This is the dominant contributor, accounting for enhancement factors of 10ⶠto 10¹² [1]. When incident laser light strikes a noble metal nanostructure (e.g., a gold nanoparticle), it excites the collective oscillation of conduction electrons, known as Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) [13] [12]. This resonance creates a greatly enhanced electromagnetic field around the nanoparticle. The effect is dramatically amplified in interstitial spaces between particles (nanogaps) or at sharp tips—regions known as "hot spots" [13] [14]. When a target molecule is located within such a hot spot, both the incoming laser light and the outgoing Raman scattered signal are amplified, leading to an enormous boost in the detected Raman intensity.

Chemical Enhancement (CM): This mechanism typically provides a more modest enhancement (10-10³) [1]. It involves a charge transfer process between the energy levels of the metal substrate and the adsorbed analyte molecule. This interaction effectively changes the polarizability of the molecule, leading to an increase in its Raman scattering cross-section. While weaker than the EM effect, chemical enhancement is molecule-specific and contributes to the overall SERS signal.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and application of high-performance SERS substrates require a suite of specialized materials and reagents. The following table lists key items used in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for SERS Substrate Development

| Material/Reagent | Function in SERS Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Silicon Wafers | A common, versatile base/support for fabricating structured SERS substrates. | Used as a base for creating micro-pillars and nanowires in hierarchical structures [13]. |

| Gold (III) Chloride Trihydrate (HAuClâ‚„) | A precursor salt for the synthesis of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) via chemical reduction. | Synthesis of stabilizer-free AuNPs for deposition onto substrates [19]. |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | A precursor salt for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). | Formation of flower-like Ag nanoparticles for flexible sponge substrates [17]. |

| Rhodamine 6G (R6G) / Rhodamine B | Standard dye molecules used as model analytes to evaluate, benchmark, and compare the performance (EF, LOD) of SERS substrates. | Used as a probe molecule to test sensitivity and calculate enhancement factors [13] [12] [19]. |

| Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) | A highly corrosive etchant used in the fabrication of silicon-based nanostructures. | Key component in Metal-Assisted Chemical Etching (MACE) to create silicon nanowires [13]. |

| MXene (Ti₃C₂Tx) | An emerging 2D material used as a support; it concentrates target molecules via strong adsorption, improving sensitivity. | Serves as a platform in the MXene-Ni/Ag composite substrate for pesticide detection [16]. |

| Thiram / Amoxicillin | Representative environmental pollutants (pesticide and antibiotic) used as target analytes to demonstrate real-world application. | Detection of thiram at trace levels to validate substrate performance for food/environmental safety [16] [17]. |

| 9-(Tetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-9H-purine-6-thiol | 9-(Tetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-9H-purine-6-thiol, CAS:42204-09-1, MF:C9H10N4OS, MW:222.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5-Azidoindole | 5-Azidoindole|CAS 81524-74-5|Research Chemical |

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) has established itself as a powerful analytical technique for the ultrasensitive detection of environmental pollutants, traditionally relying on noble metal substrates like gold and silver nanoparticles for signal amplification. However, the evolution of application requirements—driven by needs for operational durability, cost-effectiveness, and sustainability—has catalyzed the exploration of alternative materials. Emerging non-noble materials, particularly MXenes, graphene oxide, and semiconductor composites, are now challenging the dominance of conventional substrates by offering unique advantages including enhanced stability, tunable surface chemistry, and multifunctionality [21]. These materials leverage sophisticated charge-transfer mechanisms and, when engineered into hybrid structures, can generate synergistic enhancement effects that rival their noble metal counterparts [21] [22]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the SERS performance of these emerging material classes, focusing on their application in detecting environmental pollutants, with supporting experimental data and detailed protocols to inform research and development in this rapidly advancing field.

Performance Comparison of Non-Noble Material Classes

The following tables summarize key performance metrics for the three primary classes of non-noble SERS substrates, based on recent experimental findings.

Table 1: Overall SERS Performance Comparison for Pollutant Detection

| Material Class | Representative Substrate | Target Pollutant | Reported Limit of Detection (LOD) | Enhancement Factor (EF) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MXenes | Au NP-engineered Ti3C2Tx | Methylene Blue | 10-11 M [23] | 1010 [23] | Exceptional conductivity, high stability (83% signal after 5 months) [23] |

| Ti3C2Tx (VAF on paper) | Rhodamine B | 20 nM [22] | N/R | Cost-effective, high spot-to-spot reproducibility [22] | |

| Graphene Oxide | N-doped Graphene | Rhodamine B | N/R | 1011 [22] | Strong chemical enhancement (CM) via π-π interactions [24] [22] |

| Semiconductor Composites | Semiconductor/Metal Hybrids | Model Dyes | N/R | 108 - 1011 [21] | Synergistic EM/CM enhancement, photocatalytic self-cleaning [21] |

Table 2: Comparison of Enhancement Mechanisms and Functional Properties

| Material Class | Dominant Enhancement Mechanism(s) | Stability & Recyclability | Remarks / Specific Functionality |

|---|---|---|---|

| MXenes | Chemical (Charge Transfer) [22], can be coupled with EM in hybrids [23] | High; retains 83% signal after 5 months; magnetic composites enable easy recovery [23] [25] | High conductivity promotes efficient charge transfer [22]. Functional groups aid analyte adsorption [26]. |

| Graphene Oxide | Chemical (CM) via charge transfer and π-π interactions [24] [27] | Good; but performance depends on integration with other materials | Excellent for adsorbing aromatic molecules; often used to improve performance of other substrates [24]. |

| Semiconductor Composites | Combined CM and EM (in hybrids) [21] | Excellent; inherent self-cleaning via photodegradation enables substrate reuse [21] | Enables real-time monitoring of photocatalytic reactions and degradation of pollutants [21]. |

Abbreviations: NP (Nanoparticle), VAF (Vacuum-Assisted Filtration), N/R (Not Reported in the reviewed studies), EM (Electromagnetic Enhancement), CM (Chemical Enhancement).

Detailed Experimental Protocols from Key Studies

Protocol: High-Performance SERS Platform Based on Au NP-MXene

- Substrate Synthesis: The substrate was prepared by engineering gold nanoparticles (Au NPs) in situ on Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets. This creates a hybrid platform where the MXene provides a robust, conductive foundation and facilitates charge transfer, while the Au NPs contribute electromagnetic enhancement through localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) [23].

- SERS Measurement: A Raman spectrometer equipped with a suitable laser source is used. The analyte solution (e.g., Methylene Blue or BDE-47) is drop-cast onto the substrate and allowed to dry. Spectra are then collected from multiple spots to assess signal intensity and reproducibility [23].

- Performance Validation: The platform achieved an exceptional LOD of 10-11 M for Methylene Blue, with an EF of 1010. It also successfully detected the persistent organic pollutant BDE-47 at concentrations below the regulatory threshold of 10-6 M. The relative standard deviation (RSD) was calculated to validate signal repeatability. Stability was confirmed by testing a substrate after 5 months of storage, which retained 83% of its original SERS signal intensity [23].

Protocol: Fabrication of Robust MXene Substrates via Vacuum-Assisted Filtration

- Substrate Fabrication: Few-layer Ti3C2Tx MXene dispersions are prepared. The substrate is created by depositing the MXene dispersion onto filter paper using vacuum-assisted filtration (VAF). This method produces a dense and uniform MXene layer, which is critical for performance [22].

- Comparative Analysis: The study compared VAF against spray coating. VAF resulted in a denser MXene layer with higher uniformity, leading to superior spot-to-spot and substrate-to-substrate reproducibility [22].

- SERS Performance and Analysis: Using Rhodamine B as a probe molecule, the VAF-fabricated substrate demonstrated a low LOD of 20 nM. A key finding was that the surface morphology and the presence of MXene aggregates significantly influence analyte distribution and the resultant SERS enhancement. The dense layer from VAF minimizes unfavorable aggregation, contributing to its superior and reproducible performance [22].

Protocol: Dual-Functional Magnetic Substrate for Detection and Degradation

- Substrate Synthesis: A ternary nanocomposite, MXene@Fe3O4@Ag NPs, was synthesized using co-precipitation and electrostatic self-assembly techniques. Fe3O4 provides magnetism for easy recovery, Ag NPs offer plasmonic enhancement, and MXene serves as the conductive platform [25].

- SERS Detection: The substrate was used for the ultrasensitive detection of Crystal Violet (CV), achieving an extraordinarily low LOD of 1.08 × 10-12 M. Finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) simulations confirmed that the gaps between the Ag NPs on the composite structure create strong electromagnetic "hot spots" responsible for the significant signal enhancement [25].

- Self-Cleaning and Recyclability: Following detection, the same substrate was used for pollutant degradation. Under light irradiation, the composite catalyzes the photo-Fenton reaction, generating hydroxyl radicals that degrade the adsorbed CV molecules. The magnetic property allows the substrate to be easily collected with a magnet after the degradation cycle, enabling its reuse for multiple rounds of detection and degradation [25].

Mechanisms and Workflows: A Visual Guide

The performance of these non-noble materials is governed by distinct enhancement mechanisms. The following diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms and a typical workflow for a dual-functional SERS substrate.

Diagram: SERS enhancement mechanisms and a typical workflow for a detection-degradation-recovery-reuse cycle enabled by advanced composite substrates [21] [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Developing Non-Noble SERS Substrates

| Item | Function / Role | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MXene Precursors | Source for synthesizing MXene layers. | MAX phases (e.g., Ti3AlC2); selectively etched to produce Ti3C2Tx [26] [25]. |

| Semiconductor Photocatalysts | Provide chemical enhancement and self-cleaning functionality. | TiO2, ZnO, Fe23; used for charge transfer and photocatalytic degradation of analytes [21]. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | Enhances adsorption and chemical enhancement. | GO sheets; improve performance via π-π stacking with aromatic pollutant molecules [24] [21]. |

| Noble Metal Salts | For constructing hybrid substrates with EM enhancement. | Precursors for Ag, Au nanoparticles (e.g., AgNO3); incorporated to create "hot spots" [23] [25]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Enable substrate recovery and recyclability. | Fe3O4 nanoparticles; allow collection with an external magnet [25]. |

| Cellulose/Paper Substrates | Low-cost, flexible, and sustainable support. | Filter paper or nanocellulose films; serve as a platform for depositing active SERS materials [27] [22]. |

| Model Pollutant Dyes | Standard analytes for evaluating SERS performance. | Rhodamine B (RhB), Methylene Blue (MB), Crystal Violet (CV); used for calibration and LOD determination [23] [22] [25]. |

| Etching Agents | For synthesizing MXenes from MAX phases. | Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) or in-situ HF-forming mixtures; used to selectively remove the 'A' layer from MAX [26]. |

| N,N'-Bis(3-triethoxysilylpropyl)thiourea | N,N'-Bis(3-triethoxysilylpropyl)thiourea Coupling Agent | N,N'-Bis(3-triethoxysilylpropyl)thiourea, a sulfur-functional silane. Used as a coupling agent and for mercury detection. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2-Hydroxy-3-methoxy-6beta-naltrexol | 2-Hydroxy-3-methoxy-6beta-naltrexol|CAS 57355-35-8 | High-purity 2-Hydroxy-3-methoxy-6beta-naltrexol for analytical research and ANDA development. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The systematic comparison presented in this guide demonstrates that MXenes, graphene oxide, and semiconductor composites are viable and powerful alternatives to traditional noble-metal SERS substrates. MXenes, particularly in hybrid architectures, stand out for their exceptional sensitivity and stability. Semiconductor composites offer the unique advantage of multifunctionality, integrating sensing with self-cleaning via photocatalysis. Graphene oxide plays a crucial role in enhancing analyte adsorption through its rich chemistry.

Future research will likely focus on optimizing the cost-effectiveness and scalability of these materials, especially MXenes, whose long-term stability against oxidation requires further engineering [26]. The integration of biorecognition elements (e.g., aptamers, antibodies) with these substrates is a promising avenue to improve selectivity in complex environmental matrices [24]. As these challenges are addressed, non-noble SERS substrates are poised to become the foundation for the next generation of robust, multifunctional, and field-deployable sensors for environmental monitoring.

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) has emerged as a powerful analytical technique that dramatically amplifies the inherently weak Raman scattering signal, enabling single-molecule detection sensitivity [27]. The enhancement mechanism primarily arises from two interconnected phenomena: electromagnetic enhancement (EM) and chemical enhancement (CM). The electromagnetic effect, contributing the majority of signal enhancement (up to 10^8-fold), occurs when localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) is excited on nanostructured metal surfaces, generating intensely localized electromagnetic fields known as "hot spots" [28] [8]. The chemical mechanism, while providing more modest enhancement (typically 10-1000-fold), involves charge transfer between the analyte molecules and the substrate surface, which can alter the polarizability of the molecules [29] [28]. The efficiency of both mechanisms is profoundly influenced by the nanoscale morphology of the SERS substrate—specifically the size, shape, and interparticle distance of the nanostructures—which dictates the plasmonic coupling and field confinement effects [30].

For environmental pollutant detection, these morphological parameters determine critical performance metrics including enhancement factor (EF), limit of detection (LOD), and signal reproducibility [8]. This guide systematically compares how different nanostructural characteristics influence SERS performance for detecting trace organic pollutants, heavy metals, and pathogenic microorganisms in environmental samples.

Comparative Analysis of Nanostructural Parameters

The following sections analyze the individual contributions of size, shape, and interparticle distance to SERS enhancement, with quantitative performance data summarized in Table 1.

Nanostructure Size Effects

Nanoparticle size directly governs the spectral position and intensity of the localized surface plasmon resonance. Optimal sizes typically range between 40-160 nm for noble metals, balancing scattering efficiency and field penetration depth [31] [19]. Experimental studies with gold nanodiscs demonstrate that 160nm diameter structures exhibit strong plasmonic resonances in the near-infrared window, which is advantageous for biological and environmental sensing due to reduced background interference [31]. Smaller nanoparticles (10-30 nm) produce weaker electromagnetic fields but higher density coverage, while excessively large structures (>200 nm) support multiple plasmon modes that can broaden the resonance spectrum and reduce enhancement efficiency [30].

Size uniformity critically affects signal reproducibility. Controlled studies using physically synthesized nanodiscs with identical dimensions (160nm diameter, 20nm thickness) revealed that uniform structures provide consistent enhancement factors, whereas polydisperse systems yield unpredictable signal variations [31]. For lead-free halide double perovskite Cs₂AgBiBr₆ nanoflakes, post-growth annealing controlled self-trapped exciton defects, with defect density directly correlating with SERS signal intensity [29].

Nanostructure Shape Effects

Shape determines the curvature and sharpness features where electromagnetic fields concentrate most intensely. Structures with sharp edges, tips, and high aspect ratios—such as nanotriangles, nanocuboids, and nanostars—generate significantly stronger field enhancement compared to spherical nanoparticles due to the lightning rod effect [28] [8].

Comparative studies demonstrate that triangular gold nanoplates assembled with gold nanospheres create double-sided superstructures with abundant hot spots, enabling sensitive detection of pathogenic bacteria like Listeria monocytogenes and S. xylosus [28]. Similarly, Au@Ag nanocuboids arranged in densely packed monolayers leverage their edges and corners to generate intense electromagnetic hot spots, achieving detection of malachite green (MG) at concentrations as low as 10â»Â¹Â² M in lake water [8]. The anisotropic nature of non-spherical structures also enables polarization-dependent SERS responses, which can be exploited for advanced sensing schemes.

Interparticle Distance Effects

Interparticle distance, or "nanogap," is perhaps the most critical parameter for SERS enhancement, with the strongest electromagnetic fields occurring in gaps of 1-10 nm [30]. When nanoparticles are brought within this proximity, their plasmon fields interact synergistically, creating enhancement factors that scale exponentially with decreasing distance [32]. One study established a generalized exponential relationship between SERS efficiency and the non-dimensional interparticle distance/particle diameter ratio for gold and silver nanoisland arrangements [32].

Gradient SERS substrates with systematically varying gap sizes demonstrate this effect clearly, showing that average gap sizes of ~11 nm produce significantly higher enhancement compared to regions with ~50 nm gaps [30]. The formation of connected metal island films with controlled percolation paths represents an effective strategy for creating optimal interparticle separation, as evidenced by annealed gold films that develop interconnected islands with tunable nanogaps [30]. For composite substrates, precise control of nanogaps has been achieved through block copolymer templates that position silver nanoparticles at optimal distances, enabling reproducible hot spot engineering [8].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of SERS Substrates by Morphological Characteristics

| Morphology Characteristic | Substrate Type | Optimal Parameters | Enhancement Factor (EF) | Detection Limit (Pollutant) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | Gold nanodiscs | 160 nm diameter, 20 nm thickness | N/A | N/A | [31] |

| Silver nanoparticles | ~45-50 nm diameter | N/A | ~10â»Â¹Â² M (R6G) | [19] | |

| Gold nanoparticles in island film | 10-20 nm radius | N/A | ~10â»â¸ M (BPE/MB) | [30] | |

| Shape | Au@Ag nanocuboids | Sharp edges/corners | N/A | 8.7×10â»Â¹â° M (MG) | [8] |

| Triangular Au nanoplates with Au nanospheres | Double-sided assembly | N/A | Pathogenic bacteria | [28] | |

| Porous gold supraparticles | Interstitial gaps between nanoparticles | N/A | 10â»â¸ M (MGITC) | [8] | |

| Interparticle Distance | Gradient Au island film | ~11 nm gap size | N/A | ~10â»â¸ M (BPE/MB) | [30] |

| Block copolymer with AgNPs | Controlled nanogaps | N/A | 10â»â¶ M (Rhodamine B) | [8] | |

| Lead-free perovskite nanoflakes | Defect-controlled | 5.04×10â· | ~10â»Â¹â° M (MB/R6G) | [29] | |

| Composite Structures | Cold plasma/laser AuNPs | Uniform deposition | ~3×10⸠| 10â»Â¹Â² M (R6G), 9×10â»Â¹â° M (amoxicillin) | [19] |

| Cellulose with metal NPs | Flexible substrate | Up to 10¹¹ | Various pollutants | [27] |

Experimental Protocols for SERS Substrate Fabrication and Evaluation

Fabrication of Gradient SERS Substrates with Multiple Resonances

This protocol describes creating substrates with spatially varying morphology to rapidly screen optimal enhancement parameters [30]:

- Substrate Preparation: Begin with clean glass or silicon substrates. Thermal evaporation deposits a thin gold film (typically 10-30 nm thickness) using a geometry where the evaporation source is positioned at a specific distance from the substrate center to create a thickness gradient.

- Thermal Annealing: Anneal the deposited film under controlled atmosphere (argon or vacuum) at 300-500°C for 30-60 minutes. This process transforms the continuous film into disconnected islands with size and spacing gradients across the substrate.

- Morphological Characterization: Use scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to verify the formation of nanoparticle-like features at substrate edges progressing to connected island structures near the center. Image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ, Gwydion) quantifies particle sizes and gap distributions across different regions.

- Optical Validation: Collect extinction spectra across multiple positions to confirm varying plasmon resonances. The spectral maximum should red-shift and broaden when moving from nanoparticle-rich regions to connected island regions.

Synthesis of Lead-Free Halide Double Perovskite Nanoflakes

This method produces environmentally friendly SERS substrates with enhanced stability [29]:

- Precursor Preparation: Dissolve stoichiometric ratios of cesium (Cs), silver (Ag), and bismuth (Bi) precursors in suitable solvents (typically dimethylformamide or dimethyl sulfoxide).

- Crystallization: Introduce the precursor solution into a poor solvent (typically toluene) under vigorous stirring to induce rapid crystallization of Cs₂AgBiBr₆ nanoflakes.

- Post-Growth Annealing: Anneal the collected nanoflakes under argon atmosphere at 200-300°C for 1-2 hours. This critical step controls self-trapped exciton defects by minimizing AgBi and BiAg anti-site disorders, which directly enhances SERS performance through improved charge transfer.

- Quality Assessment: Characterize crystal structure using X-ray diffraction and analyze photoluminescence spectra to confirm defect density modulation. Higher defect densities correlate with increased SERS signals.

Combined Cold Plasma and Laser Treatment for AuNP Substrates

This rapid fabrication method produces high-performance substrates with excellent reproducibility [19]:

- Substrate Pretreatment: Clean glass slides sequentially with distilled water, ethanol, and acetone. Dry under nitrogen gas. Treat with cold atmospheric pressure plasma (0.9 W power) for 30 seconds to dramatically reduce surface roughness and enhance surface energy (water contact angle decreases from 59° to 0°).

- Nanoparticle Deposition: Apply 3 µL of stabilizer-free gold nanoparticle solution (~45 nm diameter, 1.2 OD concentration) to the confined treatment area.

- Laser-Assisted Assembly: Expose the area to a 532 nm green laser (480 mW power) for 15 minutes. This facilitates uniform deposition of AuNPs across the entire treated area, creating abundant hot spots.

- Performance Validation: Test substrates with rhodamine 6G (R6G) solutions, achieving enhancement factors of ~3×10⸠and detection limits of 10â»Â¹Â² M. The substrates should maintain performance after 10 reuse cycles.

Visualization of SERS Enhancement Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental relationships between nanostructure morphology and SERS enhancement efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for SERS Substrate Development

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Example | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Chloride (HAuCl₄·3Hâ‚‚O) | Gold nanoparticle precursor | Synthesis of AuNPs for SERS substrates [19] | Provides Au³⺠ions for reduction to Auâ°; basis for most gold nanostructures |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | Silver nanoparticle precursor | Fabrication of Ag NPs and Ag-based composites [28] | Source of Ag⺠ions; forms high-enhancement silver nanostructures |

| Trisodium Citrate | Reducing and stabilizing agent | Synthesis of spherical Au and Ag nanoparticles [33] | Controls nucleation and growth; prevents aggregation in colloids |

| Lead-Free Perovskite Precursors | Environmentally friendly substrate material | Cs₂AgBiBr₆ nanoflakes for sustainable SERS [29] | Cesium, silver, bismuth salts; avoids lead toxicity while maintaining performance |

| Rhodamine 6G (R6G) | Model analyte for SERS calibration | Evaluation of enhancement factors [29] [19] | Standard dye for performance comparison; well-established Raman fingerprints |

| Methylene Blue (MB) | Model pollutant for detection studies | Trace organic pollutant detection [29] [30] | Cationic dye representing environmental contaminants; used for LOD determination |

| Functionalized Cellulose | Sustainable substrate platform | Flexible, biodegradable SERS substrates [27] | Various forms (nanofibers, crystals); low intrinsic Raman background |

| Block Copolymers (e.g., PS-b-PAA) | Nanostructure template | Controlled assembly of nanoparticles [8] | Creates periodic patterns for precise nanoparticle positioning |

| MgSOâ‚„ | Aggregation agent for colloidal NPs | Salt-induced aggregation for hot spot formation [33] | Induces controlled nanoparticle clustering without competing for surface sites |

| 3-Oxo-2-tetradecyloctadecanoic acid | 3-Oxo-2-tetradecyloctadecanoic Acid | Research-grade 3-Oxo-2-tetradecyloctadecanoic acid for laboratory use. This branched fatty acid is for research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| 3,4',5-Trihydroxy-3',6,7-trimethoxyflavone | 3,4',5-Trihydroxy-3',6,7-trimethoxyflavone|CAS 578-71-2 | Bench Chemicals |

The systematic comparison presented in this guide demonstrates that precise control over nanostructure morphology—specifically size, shape, and interparticle distance—is fundamental to optimizing SERS substrates for environmental pollutant detection. The quantitative data reveals that enhancement factors spanning from 10â· to 10¹¹ can be achieved through rational morphological design, enabling detection limits as low as 10â»Â¹âµ M for certain pollutants [29] [27] [8].

Future developments in SERS substrate technology will likely focus on multifunctional morphologies that combine optimal geometrical parameters with advanced material properties. Lead-free perovskite nanoflakes represent a promising direction, addressing toxicity concerns while maintaining high enhancement factors through defect engineering [29]. Similarly, sustainable substrates based on functionalized cellulose offer an environmentally responsible alternative without compromising performance [27]. The integration of machine learning approaches with high-throughput fabrication methods, such as gradient substrates, will accelerate the discovery of optimal morphological parameters for specific environmental applications [30]. As standardization in enhancement factor calculation methodologies improves, more reliable comparisons between different morphological strategies will emerge, further advancing the field of SERS-based environmental monitoring [27].

SERS in Action: Deploying Advanced Substrates for Real-World Pollutant Detection

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) has emerged as a powerful analytical technique for the detection of trace-level environmental pollutants, combining the molecular fingerprinting capability of Raman spectroscopy with significant signal amplification. This guide focuses on the evaluation of SERS substrates for detecting organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides at sub-μg L−1 levels, a critical requirement for environmental and food safety monitoring. The core principle of SERS relies on the dramatic enhancement of Raman signals when target molecules are adsorbed onto or near specially designed nanostructured surfaces, primarily through electromagnetic and chemical enhancement mechanisms [7]. The development of reliable SERS substrates has become a central research theme in environmental pollutant detection, with ongoing efforts to improve sensitivity, reproducibility, and applicability to real-world samples [34].

Performance Comparison of SERS Substrates

The analytical performance of SERS substrates varies significantly based on their material composition, nanostructure design, and functionalization strategies. The tables below summarize key performance metrics for various substrate types reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance comparison of SERS substrates for pesticide detection

| Substrate Type | Target Pesticides | Detection Limit | Enhancement Factor | Reproducibility (RSD) | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noble metal nanoparticles (Ag/Au) [35] [7] | Organophosphorus pesticides | sub-μg L−1 to low μg L−1 | Up to 10^10 [7] | 5-15% [35] | High enhancement, tunable plasmonics |

| Bimetallic hybrids [35] | Organophosphorus compounds | Sub-μg L−1 range | Not specified | 5-15% | Improved stability and sensitivity |

| MOF-derived systems [35] | Various pesticides | Low μg L−1 | Not specified | Not specified | High surface area, selective adsorption |

| Hydrogel-loaded Ag nanoparticle aggregates [36] | Model pollutants (Malachite Green) | 10^-12 M for Nile Blue [36] | 1.4 × 10^7 for MG [36] | 6.74% (200 μm × 200 μm area) [36] | Salt-resistant, 3D hot spots |

| Semiconductor-photocatalyst hybrids [37] | Organic molecules | Varies by target | Not specified | Not specified | Self-cleaning, reusable |

Table 2: SERS detection of specific pesticide classes

| Pesticide Class | Characteristic Functional Groups & Vibrational Bands | Representative Substrates | Typical Detection Limits | Matrix Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organophosphorus [35] [38] | P=O, P=S groups ~650-850 cmâ»Â¹ [35] | Au/Ag nanostructures, aptamer-functionalized substrates [35] [39] | sub-μg L−1 to low μg L−1 [35] | Fruit/vegetable surfaces, juices, grains, water [35] |

| Carbamates [38] | C-N stretching ~1000-1100 cmâ»Â¹ [38] | Functionalized noble metal nanoparticles | Not specified | Tomato peels, agricultural products [38] |

| Pyrethroids [38] | Benzene ring breathing modes, C=C stretching [38] | Portable Raman systems with 1064 nm laser | Not specified | Tomato peels, crop surfaces [38] |

Experimental Protocols for SERS Substrate Evaluation

Substrate Fabrication and Characterization

Hydrogel-Loaded Silver Nanoparticle Aggregates (3D-SERS) This innovative substrate combines physically induced colloidal silver nanoparticle aggregates (AgNAs) with an agarose hydrogel matrix to create a three-dimensional SERS-active material [36]. The fabrication begins with synthesis of monodisperse silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) by heating deionized water (250 mL) containing glycerol (1 mL) to 95°C, followed by addition of silver nitrate (45 mg) and sodium citrate (5 mL, 1%) under vigorous stirring [36]. After continuous heating for 30 minutes until the solution turns greenish brown, the AgNPs are cooled, concentrated tenfold, and subjected to a freeze-thaw process (-20°C for 12 hours, then thawed at room temperature) [36]. The thawed dispersion is sonicated for 10 minutes to form AgNAs. For hydrogel incorporation, 1 mL of 2% agarose solution is mixed with 100 μL of 10-fold-concentrated AgNAs solution, heated to 90°C until homogenized, then rapidly cooled in a Petri dish to form the final 3D substrate [36].

Commercial Gold Nanostructured Substrates Comparative studies often include commercially available SERS substrates. For instance, Type A substrates feature glass covered with gold nanostructures, Type B consists of silicon plates with gold nanostructures, and Type C contains gold and silver nanostructures on silicon [12]. These substrates are characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to analyze surface morphology, particle size distribution, and interstructural distances, which critically influence SERS enhancement [12].

Analyte Preparation and Measurement Procedures

Standard Solution Preparation For quantitative evaluation, Rhodamine B solutions are typically prepared across concentrations ranging from 10^-2 M down to 10^-12 M [12]. The base 10^-2 M solution is prepared by mixing 0.144 g of Rhodamine B with 30 mL of deionized water, followed by serial tenfold dilutions [12]. For pesticide detection, stock solutions are prepared in appropriate solvents (e.g., methanol or deionized water) at concentrations of 50% v/v, then applied to real-world samples like tomato peels for validation studies [38].

SERS Measurement Protocol Substrates are immersed in analyte solutions for predetermined times (e.g., 1 hour for Rhodamine B), then removed and dried for 15 minutes before measurement to increase analyte proximity to active surfaces and quench fluorescence [12]. Measurements are typically performed using Raman spectrometers with 532 nm excitation lasers, though 1064 nm lasers are increasingly used to reduce fluorescence in biological samples [38]. The system is calibrated using a crystalline silicon plate (520 cm^-1 peak) before measurements [12]. Multiple measurements (15-20 points) are averaged to minimize signal fluctuations, with fluorescence backgrounds removed using spline approximations [12].

Enhancement Factor Calculation The analytical enhancement factor (AEF) is calculated using the formula: AEF = (ISERS / IRaman) × (CRaman / CSERS) where ISERS and IRaman are the measured intensities of a specific Raman peak in SERS and normal Raman measurements, respectively, and CRaman and CSERS are the corresponding analyte concentrations [12].

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The SERS detection process involves multiple interconnected steps from substrate design to analyte detection. The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for SERS-based pesticide detection.

SERS Detection Workflow for Pesticide Analysis

The SERS enhancement mechanism involves two primary pathways that operate synergistically to amplify Raman signals, as illustrated in the following diagram.

SERS Enhancement Mechanisms

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful SERS-based pesticide detection requires carefully selected materials and reagents optimized for specific detection scenarios.

Table 3: Essential research reagents for SERS-based pesticide detection

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) [12] [36] | Primary SERS substrate, electromagnetic enhancement | Environmental pollutant detection, pesticide monitoring [34] [36] | Size (20-100 nm), shape, aggregation control |

| Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) [12] | SERS substrate, better chemical stability than Ag | Commercial substrates, bio-sensing [12] | Size, surface chemistry, functionalization |