Antibody Titration for Optimal Assay Performance: A Complete Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing antibody concentration through titration, a critical step for ensuring assay reproducibility and data quality.

Antibody Titration for Optimal Assay Performance: A Complete Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing antibody concentration through titration, a critical step for ensuring assay reproducibility and data quality. It covers the foundational principles of why titration is essential to overcome the reproducibility crisis, details step-by-step methodological protocols for flow cytometry and other applications, offers extensive troubleshooting for common issues like high background and weak signal, and discusses advanced validation techniques and comparative analyses of different normalization methods. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging computational tools, this guide serves as a vital resource for achieving precise and reliable experimental results in biomedical research.

Why Antibody Titration is Foundational to Reproducible Science

The Reproducibility Crisis and the Role of Antibody Validation

Understanding the Reproducibility Crisis

What is the antibody reproducibility crisis, and why does it matter?

The reproducibility crisis in biomedical science is significantly driven by inconsistent antibody performance. Antibodies are essential tools, but many are not consistent or do not work as described, leading to wasted resources and low-quality science [1]. A core problem is that antibodies are "incredibly finicky research reagents, with considerable lot-to-lot variability," making their authenticity difficult to track and validate [1]. This has resulted in widespread reports of researchers failing to replicate findings or having to retract publications [1].

What are the main causes?

The crisis stems from several key factors:

- Poor Antibody Characterization: Many antibodies are not adequately validated for their intended applications [1].

- Lot-to-Lot Variability: Performance can shift significantly between different production batches of the same antibody, forcing researchers to re-optimize assays repeatedly [1].

- Inadequate Reporting: A lack of proper identification of antibodies in scientific literature, occurring in an estimated 20% to 50% of the time, exacerbates the problem [1].

- Misleading Validation Data: For example, an antibody validated using recombinant protein might show an intense band, creating unrealistic expectations for its performance on low-abundance endogenous targets if the datasheet is not read carefully [2].

Core Principles of Antibody Validation

What does proper antibody validation entail?

Validation confirms that an antibody is specific, sensitive, and reproducible for a specific application. The International Working Group for Antibody Validation (IWGAV) has recommended key pillars for validation [1]. The following table outlines the core strategies:

| Validation Strategy | Core Principle | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Strategies | Confirming loss of signal in KO cells or tissues. | Considered a gold standard for confirming specificity. |

| Orthogonal Methods | Comparing protein detection results with a different, non-antibody-based method (e.g., RNA in situ hybridization). | Validates the antibody's expected staining pattern. |

| Independent Antibody Validation | Using two or more independent antibodies that recognize different epitopes on the same target. | Corroboration of results increases confidence. |

| Biochemical Verification | Ensuring the antibody detects the correct protein based on its biochemical properties (e.g., size). | Can be misleading if relying solely on overexpressed recombinant protein [2]. |

| Biophysical Characterization | Using methods like mass spectrometry to confirm the antibody's identity, purity, and aggregation state. | Creates an "antibody fingerprint" for batch-to-batch consistency [1]. |

How can I use RNA in situ hybridization for validation?

RNAscope in situ hybridization (ISH) serves as a powerful orthogonal method to validate immunohistochemistry (IHC) results. It can:

- Provide High Data Quality: One researcher reported testing 13 different antibodies without trustworthy results before turning to RNAscope ISH, which saved the project [3].

- Offer a Clear Path for Difficult Targets: For proteins with no available or poorly performing antibodies, designing a probe for the mRNA can accelerate research [3].

Optimizing Antibody Concentration Through Titration

Why is titration research critical for optimization?

Titration is fundamental to finding the optimal antibody concentration that provides a strong specific signal with minimal background. Using an antibody at an inappropriate concentration is a direct path to non-reproducible results. As one expert notes, assay conditions often require re-titration with new antibody batches, a process that halts research and consumes time [1].

What is the best method for titration?

The checkerboard titration is a highly efficient approach for immunoassays like ELISA, as it allows you to optimize two variables—such as antibody concentration and sample concentration—simultaneously [4] [5]. The workflow for this method is outlined below.

A step-by-step protocol for checkerboard titration

- Plate Setup: Prepare a 96-well microplate. Titrate your coating antibody or antigen across the columns in a series of doubling dilutions. Simultaneously, titrate your detection antibody down the rows in another series of doubling dilutions [4].

- Incubation and Washes: Follow your standard ELISA protocol for incubation, blocking, and washing steps [4].

- Signal Development: Add substrate to develop the colorimetric or chemiluminescent signal.

- Data Analysis: Measure the signal and calculate the signal-to-noise ratio for each well (the signal from a positive well divided by the signal from a negative control well). The optimal concentrations are those that yield the highest signal-to-noise ratio [5].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

What are some common problems and their solutions?

Here is a guide to frequent issues across key applications, framed within the context of improper antibody concentration or validation.

Western Blot Troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Cause Related to Antibody/Antigen | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Signal | Antibody concentration too low; target not present. | Increase antibody concentration; run a positive control [6]. |

| High Background | Antibody concentration too high. | Titrate antibody to find optimal dilution; increase washing [6]. |

| Multiple Bands | Antibody is not specific; binds to unrelated proteins. | Use KO control to confirm specificity; check antibody datasheet for known isoforms [6] [2]. |

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) / Immunocytochemistry (ICC) Troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Cause Related to Antibody/Antigen | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Staining | Epitope masked by fixation; insufficient antibody concentration. | Optimize antigen retrieval method; increase antibody concentration or incubation time [7]. |

| High Background | Non-specific antibody binding; concentration too high. | Improve blocking; titrate down primary antibody; use a secondary antibody pre-adsorbed against the sample species [7]. |

| Nonspecific Staining | Antibody cross-reactivity; inadequate blocking. | Validate antibody specificity with KO control; increase blocking time [7]. |

Flow Cytometry Troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Cause Related to Antibody/Antigen | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No Signal / Weak Intensity | Insufficient antibody; intracellular target not accessible. | Increase antibody concentration; ensure proper permeabilization for intracellular targets [6]. |

| High Fluorescence Intensity | Antibody concentration too high. | Reduce the amount of antibody added to each sample [6]. |

| High Background / High % Positive Cells | Gain set too high; excess antibody. | Adjust flow cytometer settings; decrease antibody concentration [6]. |

Advanced Validation and Best Practices

How can I implement long-term solutions in my lab?

- Demand Rigorous Validation: Before purchase, carefully analyze the antibody datasheet for application-specific validation data, especially genetic or orthogonal validation [2] [8].

- Use Recombinant Antibodies: When possible, choose recombinant antibodies. They are produced from a specific genetic sequence, eliminating the cell-line drift and lot-to-lot variability inherent in traditional hybridoma-produced antibodies [1].

- Employ Robust Controls: Always include the following controls to ensure your assay is performing correctly [4]:

- Positive Control: A sample with a known amount of the target to confirm the assay works.

- Negative Control: A sample lacking the target (e.g., KO cell line) to assess non-specific binding.

- Secondary Antibody Control: A sample with no primary antibody to check for secondary antibody specificity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| KO Cell Lines or Tissues | Gold-standard control for confirming antibody specificity via genetic strategies. |

| Recombinant Antibodies | Provide superior batch-to-batch consistency due to production from a defined DNA sequence [1]. |

| RNAscope ISH Assays | A powerful orthogonal method using in situ hybridization to validate IHC antibody results [3]. |

| Phosphatase-treated Lysates | Essential for validating phosphospecific antibodies by confirming loss of signal upon treatment [8]. |

| Pre-adsorbed Secondary Antibodies | Secondary antibodies that have been adsorbed against immunoglobulins of multiple species to reduce cross-reactivity and lower background [7]. |

By understanding the root causes of the reproducibility crisis and implementing rigorous antibody validation and titration protocols, researchers can generate more reliable, trustworthy, and reproducible data.

Core Concepts: The Critical Role of Antibody Titration

What is antibody titration and why is it a cornerstone of reliable research?

Antibody titration is the systematic process of determining the optimal concentration of an antibody to use in a specific assay. It is a critical optimization step to ensure that your experimental results are both sensitive and specific. The core principle is to find the antibody dilution that provides the best possible signal-to-noise ratio, which means a strong, specific signal from your target with minimal background interference [9] [10].

How do under-titration and over-titration lead to dramatically different experimental failures?

The consequences of incorrect antibody concentration are not merely a matter of weak signals; they represent two distinct pathways to experimental failure that can severely compromise data interpretation:

- Under-Titration (Too Little Antibody): When the antibody concentration is too low, there are insufficient antibody molecules to bind to all the target antigens present. This can cause a genuinely positive cell population to appear negative or dim, leading to false-negative results and a significant underestimation of your target population [9].

- Over-Titration (Too Much Antibody): At excessively high concentrations, antibodies begin to bind to low-affinity, off-target sites they would normally ignore. This non-specific binding creates a high background signal, which can make negative populations appear positive, resulting in false-positive results [9] [10]. This phenomenon is a major driver of the well-documented "reproducibility crisis" in biomedical research [9].

The table below summarizes the key pitfalls and their impacts on data quality.

| Pitfall | Impact on Signal | Impact on Background | Final Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under-Titration | Signal is too weak or lost [9] | Background may be low | False Negatives: Positive populations are masked or missed [9] |

| Over-Titration | Signal may saturate | High background due to non-specific binding [9] [10] | False Positives: Negative populations appear positive [9] |

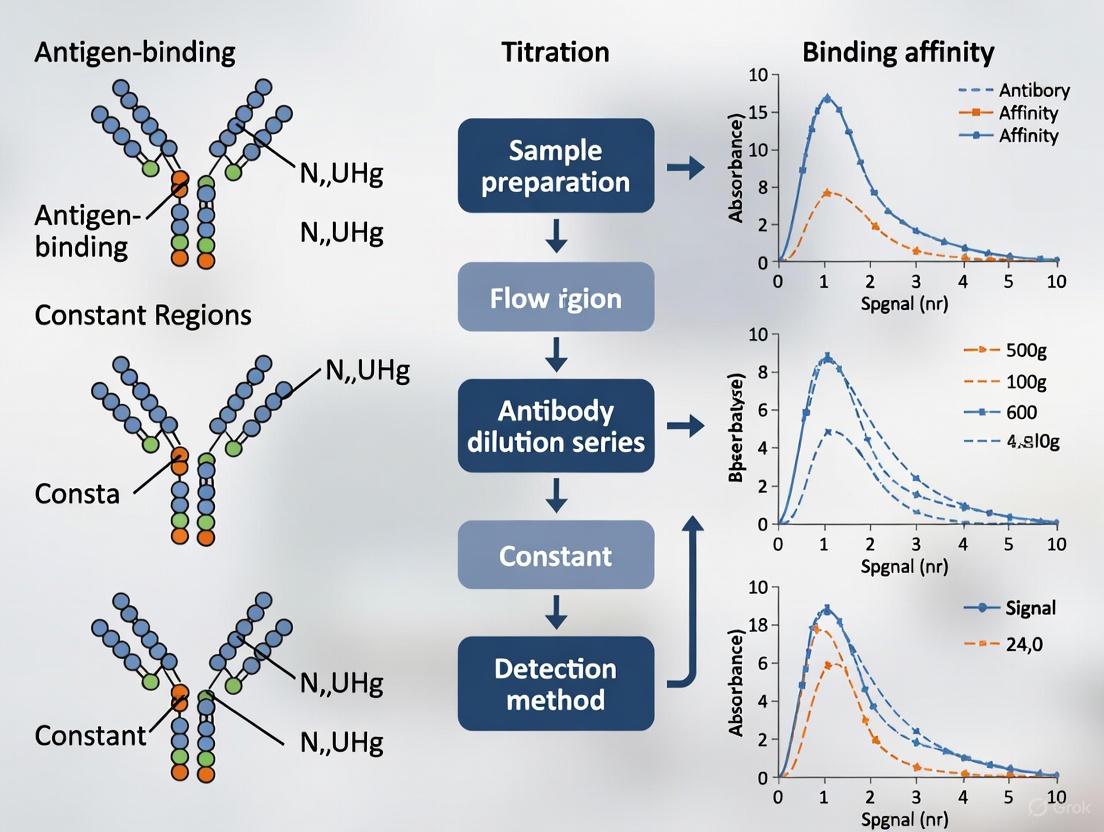

The Pathway to False Results: This diagram illustrates how incorrect antibody concentrations lead to distinct false data pathways.

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: My flow cytometry data shows high background. Is over-titration the cause?

Yes, over-titration is a primary cause of high background in flow cytometry. When too much antibody is used, it binds non-specifically to low-affinity targets and Fc receptors on cells, increasing the signal in your negative population [10] [11]. To confirm and resolve this:

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Perform an Antibody Titration: Re-titrate the problematic antibody to find the concentration that maximizes the Stain Index (which accounts for both signal and background), not just the brightest signal [9] [10].

- Implement Blocking: Use Fc receptor blocking reagents and protein blockers (e.g., BSA or serum) to reduce non-specific binding [11].

- Review Controls: Ensure your fluorescence-minus-one (FMO) and isotype controls are properly set up to distinguish specific signal from background [11].

- Preventative Measure: Always titrate antibodies under the same conditions (cell type, staining buffer, incubation time) as your final experiment [9].

FAQ: I can't detect my target protein by immunohistochemistry (IHC). Could under-titration be the problem?

Absolutely. Under-titration is a common reason for weak or absent staining in IHC [12]. If the primary antibody concentration is too low or the incubation time is too short, the signal will be undetectable.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Increase Antibody Concentration: Perform a titration experiment to determine the optimal antibody dilution for your specific tissue and fixation conditions [12].

- Optimize Antigen Retrieval: The epitope recognized by your antibody might be masked due to fixation. Optimize antigen retrieval conditions to expose the target [12].

- Validate Antibody Specificity: Confirm that your antibody is compatible with IHC and recognizes the target in its native, fixed state [12].

- Additional Check: Verify that the protein of interest is expressed in your tissue sample using alternative methods or databases [12].

FAQ: My ELISA results are inconsistent with high background. How can I address this?

High background in ELISA is frequently caused by non-specific binding, cross-reactivity, or suboptimal reagent concentrations, all of which are related to a lack of proper optimization [13].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- * Titrate All Antibodies:* Titrate both your capture and detection antibodies to find concentrations that minimize background while maintaining a strong specific signal [13].

- Improve Blocking: Use effective blocking buffers (e.g., those containing BSA, serum, or specialized commercial blockers) to cover non-specific binding sites on the plate and sample proteins [13].

- Check for Cross-Reactivity: Ensure your antibodies are highly specific for the target analyte to prevent binding to similar molecules [13].

- Optimize Washing: Inadequate washing is a common culprit. Ensure thorough and consistent washing between all steps to remove unbound reagents [13].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Standard Protocol: Antibody Titration for Flow Cytometry

This protocol provides a robust method for establishing the optimal antibody concentration for flow cytometry applications [9].

Materials:

- Antibody of interest, labeled with a fluorochrome

- Staining buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline with 1% bovine serum albumin)

- Cell suspension (1–5 × 10^6 cells/mL) containing a mix of positive and negative cells

- Centrifuge, flow cytometer, and round-bottom tubes

Method:

- Prepare Serial Dilutions: Label 7 tubes. Add 50 µL of staining buffer to each. Add 50 µL of your stock antibody (e.g., at 4x the manufacturer's recommendation) to the first tube, mix well, and serially transfer 50 µL to the next tube, repeating until tube 7. Discard 50 µL from tube 7 [9].

- Stain Cells: Add 100 µL of the cell suspension to all tubes. Mix well and incubate for 30 minutes in the dark (or as per your standard protocol) [9].

- Wash and Resuspend: Wash the cells three times by adding 2 mL of staining buffer and centrifuging at 300 x g for 5 minutes. After the final wash, remove the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in 200 µL of staining buffer [9].

- Acquire and Analyze Data: Run the samples on a flow cytometer. For each dilution, identify the positive and negative populations and record the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of both.

Data Analysis and Interpretation:

- Calculate the Stain Index (SI): For each antibody dilution, calculate the Stain Index using the formula:

SI = (Medpos - Medneg) / (2 * SDneg), whereMedposis the MFI of the positive population, andMednegandSDnegare the median and standard deviation of the negative population, respectively [10]. - Plot the Titration Curve: Create a graph plotting the Stain Index against the antibody concentration (or dilution).

- Determine Optimal Concentration: The optimal antibody concentration is the one that yields the maximum Stain Index [9] [10]. On the curve, this is the "peak" before the SI starts to decrease at higher concentrations due to increasing background.

Titration Workflow: The four key steps for performing an antibody titration experiment.

Comparative Data Across Techniques

The optimal antibody concentration is highly dependent on the sensitivity of the detection method used. The following table, adapted from a study comparing immunocytochemistry methods, illustrates how the required antibody concentration changes dramatically with different techniques [14].

| Immunocytochemistry Method | Relative Primary Antibody Concentration for Optimal Staining | Relative Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Tagged Secondary Antibody | 20- to 100-fold higher | Least sensitive |

| ABC–Streptavidin Fluorescence | 10- to 30-fold higher | ~3x more sensitive than direct method |

| TSA-Amplified Fluorescence | 2-fold higher | Most sensitive fluorescence method |

| ABC–NiDAB (Immunoperoxidase) | 1 (baseline) | Most sensitive; 100-200x more sensitive than direct fluorescence |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Solutions

The following table lists key materials and reagents critical for successful antibody titration and troubleshooting common pitfalls.

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Staining Buffer (PBS + 1% BSA) | Provides an isotonic solution for staining while using protein (BSA) to block non-specific binding [9]. | A universal base for flow cytometry and other immunoassays. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent | Blocks Fc receptors on immune cells to prevent antibody binding that is not antigen-specific [11]. | Critical for staining immune cells to reduce background (false positives). |

| Viability Dye | Distinguishes live from dead cells; dead cells bind antibodies non-specifically [10]. | Use before antibody staining to exclude a common source of false positives. |

| Specialized Blocking Buffers | Complex mixtures designed to block non-specific binding sites on assay plates and sample proteins in ELISA [13]. | Essential for reducing high background in solid-phase assays like ELISA. |

| Reference Control Antibodies | Well-characterized antibodies (positive and negative controls) used to validate assay performance [15]. | Crucial for verifying that your experimental setup is working. |

| BX-320 | BX-320, CAS:702676-93-5, MF:C23H31BrN8O3, MW:547.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Picfeltarraenin IB | Picfeltarraenin IB, MF:C42H64O14, MW:792.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Stain Index, Signal-to-Noise Ratio, and Optimal Dilution

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Stain Index and why is it important?

The Stain Index (SI) is a metric used primarily in flow cytometry to determine the relative brightness of a fluorochrome and its ability to distinguish a positive signal from background. It is calculated by taking the difference between the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the positive and negative cell populations, divided by the spread of the negative population [16].

Stain Index = (Median Positive - Median Negative) / (Standard Deviation Negative * 2) [16]

This formula makes the Stain Index a superior statistic for comparing fluorophores because it accounts for both the separation between the positive and negative peaks and the spread of the negative population. A higher Stain Index indicates better resolution between positive and negative signals, which is crucial for accurately identifying cell populations, especially those expressing low levels of a marker [16] [17].

How does Signal-to-Noise Ratio differ from Stain Index?

While both metrics assess assay sensitivity, the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N) is a simpler calculation: the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the positive cells divided by the MFI of the negative cells [17].

The key difference is that the Stain Index incorporates the variance (standard deviation) of the negative population, while the S/N does not. The diagram below illustrates two scenarios with the same S/N but different Stain Indices due to the width of the negative peak. The Stain Index provides a better measure of population resolution because a wider negative peak can make it harder to distinguish a dim positive signal [17].

Why is determining the optimal antibody dilution critical?

Using the correct antibody concentration is fundamental for generating reliable, reproducible data in assays like flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry (IHC) [18] [19].

- Too little antibody can lead to a weak signal, making a positive population appear negative and resulting in suboptimal data resolution and high variability [18] [19].

- Too much antibody can cause non-specific binding, high background staining, detector overloading, and increased spillover in flow cytometry, potentially making a negative population appear positive [18] [19].

The optimal antibody concentration is defined by the point of maximum Stain Index, which ensures the best possible separation between the positive signal and background noise [18]. This concentration must be determined empirically through titration for each specific antibody, sample type, and staining protocol [19].

Experimental Protocol: Antibody Titration for Flow Cytometry

The following is a detailed methodology for titrating a fluorochrome-conjugated antibody for flow cytometry analysis to find its optimal dilution [18] [19].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Antibody of Interest | The fluorochrome-conjugated antibody to be titrated. |

| Staining Buffer (PBS with 1% BSA) | Provides an isotonic solution for washing and staining cells; BSA reduces non-specific binding. |

| Cell Suspension | A sample containing a mix of cells that are positive and negative for the target antigen (e.g., PBMCs). |

| V-bottom 96-well Plates | Ideal for efficient staining and washing of cells with minimal loss. |

| Centrifuge with Plate Adapters | For pelleting cells during wash steps. |

| Multichannel Pipette | Enables rapid and consistent processing of multiple titration points. |

| Flow Cytometer | Instrument for acquiring and analyzing the stained samples. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Prepare Antibody Serial Dilutions:

- Label a series of 8-12 tubes or wells in a 96-well plate [19].

- Add an appropriate volume of staining buffer to all wells.

- Prepare the first dilution of the antibody. It is recommended to start at double the manufacturer's recommended volume/test or at a concentration of 1000 ng/test [19].

- Perform a 2-fold serial dilution across the plate. Using a multichannel pipette, mix the solution well before transferring half of the volume to the next well. Continue this process, discarding the excess volume from the final well [18] [19].

Add Cells:

- Prepare a single-cell suspension at a concentration of 1–5 × 10ⶠcells/mL. The cells should be prepared (e.g., fixed, permeabilized) as they will be for the final experiment [18].

- Add a consistent volume of cell suspension (e.g., 100 µL containing 1–5 × 10ⵠcells) to each antibody dilution well. Ensure the final staining volume is consistent across all wells [18] [19].

Stain and Wash Cells:

- Incubate the cells with the antibody for the recommended time and temperature (e.g., 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark) [18].

- Wash the cells by adding 2 mL of staining buffer, centrifuging for 5 minutes at 300-400 × g, and carefully decanting the supernatant. Repeat this wash step three times [18].

- After the final wash, resuspend the cell pellets in a fixed volume of staining buffer for acquisition on the flow cytometer [18].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Acquire data on a flow cytometer for all titration points.

- For each dilution, record the Median Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) of both the positive and negative cell populations, and the Standard Deviation (SD) of the negative population [16].

- Calculate the Stain Index for each antibody dilution using the formula [16].

- Plot the Stain Index values against the antibody concentration (or dilution factor). The optimal antibody concentration is the one that yields the maximum Stain Index [18]. The workflow and decision process for this analysis is summarized below.

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Poor or No Staining in IHC/Flow Cytometry

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient antibody concentration | Perform antibody titration; use a higher antibody concentration or incubate for a longer time (e.g., overnight at 4°C) [20] [21]. |

| Inadequate antigen retrieval (IHC) | Optimize the antigen unmasking method. Using a microwave oven or pressure cooker for heat-induced epitope retrieval (HIER) is often preferred over a water bath [20]. |

| Antibody incompatibility | Ensure the primary antibody is validated for your specific application (e.g., IHC, flow cytometry) and that the secondary antibody is raised against the species of the primary antibody [21]. |

| Sample or reagent degradation | Use freshly prepared tissue sections for IHC [20] [21]. Store all antibodies according to the manufacturer's instructions and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [21]. |

Problem: High Background Staining

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Primary antibody concentration is too high | Titrate the antibody to find the optimal concentration. A lower concentration often reduces non-specific binding [20] [21]. |

| Insufficient blocking | Increase the blocking incubation period or change the blocking reagent (e.g., use normal serum or BSA) [20] [21]. |

| Endogenous enzyme activity (IHC) | Quench endogenous peroxidase activity with a 3% Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ solution or phosphatase activity with levamisole prior to primary antibody incubation [20] [21]. |

| Inadequate washing | Wash slides or cells thoroughly 3 times for 5 minutes after primary and secondary antibody incubations [20]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Antibody Performance and Titration

Why is antibody titration necessary even when using vendor-recommended concentrations? Vendor recommendations are based on standard assay conditions that often differ from your specific experimental setup. Titration determines the optimal antibody concentration that provides the brightest specific signal with the lowest background for your unique combination of cell type, fixation method, and staining protocol. Using a predetermined concentration can lead to false-positive or false-negative results; proper titration saves reagents and improves data quality [10] [18].

How do fixation and permeabilization specifically affect antibody binding? Fixation and permeabilization can significantly alter the cellular environment and antigen availability. Fixation, particularly with cross-linking aldehydes like formaldehyde, can mask or destroy epitopes, potentially reducing antibody binding. Permeabilization exposes a wider range of intracellular epitopes, which can increase non-specific antibody binding and background noise if not properly blocked [22] [23] [12].

Does the type of cell sample affect how I should titrate my antibodies? Yes, significantly. Different cell types express varying levels of Fc receptors, which can cause non-specific binding. Their autofluorescence profiles and intrinsic antigen density also differ. An antibody titrated on one cell type (e.g., PBMCs) may not be optimal for another (e.g., a cultured cell line). Always titrate antibodies using the same cell type and preparation method as your final experiment [23] [18].

Fixation and Permeabilization

What is the impact of fixation on transcriptomic data in multi-omics experiments? In single-cell multi-omics, fixation and permeabilization are necessary for intracellular protein detection but can negatively impact RNA data. One study found that these steps negatively impacted the detection of the whole transcriptome, allowing only about 60% of the transcriptomic signature of immune stimulation to be detected. However, a modified fixation/permeabilization method was recommended for combined measurements, as it resulted in lower transcriptomic loss [22].

Can fixation itself be optimized to better preserve cellular structures? Yes. Research shows that a fast formaldehyde-based fixation method, especially when combined with membrane permeabilization, can effectively preserve cellular ultrastructure. This pre-stabilization uncouples cellular dynamics from the staining process, allowing for better control and reduced distortion of the spatial proteome during subsequent steps [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Weak or No Signal

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Low Antigen Availability | Perform antigen retrieval (e.g., heat-induced epitope retrieval for IHC) [12]. |

| Antibody Concentration Too Low | Increase antibody concentration and/or perform a titration experiment to find the optimal dilution [12]. |

| Over-fixation / Epitope Masking | Optimize fixation conditions; reduce fixation time; try alternative fixatives [12]. |

| Ineffective Permeabilization | Validate permeabilization reagent concentration and incubation time; ensure it is appropriate for your target [23]. |

Problem: High Background Signal

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient Blocking | Use a more concentrated blocking solution; increase blocking time; use normal serum from the secondary antibody host species [23] [12]. |

| Antibody Concentration Too High | Decrease antibody concentration; perform titration to find the concentration with the best stain index [18] [12]. |

| Non-specific Fc Receptor Binding | Include an Fc receptor blocking step using normal serum or a commercial blocking reagent [23]. |

| Inadequate Washing | Increase the number and/or volume of washes; add a mild detergent like Tween-20 to wash buffers [25] [12]. |

Problem: Poor Reproducibility Between Experiments

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Inconsistent Antibody Staining | Titrate all antibodies under the exact same conditions (buffer, time, temperature) as your final experiment [10] [18]. |

| Variability in Fixation | Standardize fixation protocol (concentration, time, temperature) across all samples; fix tissues as soon as possible after collection [12]. |

| Degraded Reagents | Prepare fresh buffers for each assay; aliquot antibodies to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles [25]. |

| Uneven Coating or Staining | Ensure all solutions are thoroughly mixed; use calibrated pipettes; seal plates to prevent evaporation [25]. |

Impact of Fixation and Stimulation on Cell Capture

The following table summarizes quantitative data from a single-cell multi-omics study, showing how experimental conditions like stimulation and fixation affect the number of cells captured and qualified for sequencing. The data highlights the cell loss that can occur due to these processing steps [22].

| Experimental Condition | Captured Cells (HiSeq) | Qualified Cells (HiSeq) | Cell Loss (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unstimulated | 128 | 113 | 11.7% |

| Stimulated | 193 | 183 | 5.2% |

| Unstimulated + Fixation | 59 | 54 | 8.5% |

| Stimulated + Fixation | 82 | 78 | 4.9% |

| Unstimulated + Fix/Perm Method 1 | 91 | 87 | 4.4% |

| Stimulated + Fix/Perm Method 1 | 39 | Information Missing | Information Missing |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Antibody Titration for Flow Cytometry

This protocol establishes the optimal concentration of an antibody for flow cytometry by calculating the stain index, which balances signal and noise [18].

Materials:

- Antibody of interest, fluorochrome-conjugated

- Cell suspension (1–5 × 10ⶠcells/mL) containing positive and negative populations

- Staining buffer (PBS with 1% BSA)

- Round-bottom tubes

- Flow cytometer

Method:

- Prepare serial dilutions: Label 7 tubes. Add 50 µL of staining buffer to each. Add 50 µL of the antibody (at 4x the manufacturer's recommended concentration) to tube 1. Mix and transfer 50 µL to tube 2. Continue this serial dilution to tube 7, discarding 50 µL from the last tube.

- Stain cells: Add 100 µL of cell suspension to all tubes. Mix well.

- Incubate: incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark.

- Wash: Add 2 mL of staining buffer to each tube. Centrifuge for 5 minutes at 300 × g, 4 °C. Remove supernatant. Repeat wash twice.

- Resuspend and acquire: Resuspend cells in 200 µL of staining buffer. Acquire data on a flow cytometer.

- Analyze: For each dilution, identify the positive and negative cell populations. Calculate the Stain Index (SI) using the formula: SI = (Median MFI of Positive Population - Median MFI of Negative Population) / (2 × Standard Deviation of Negative Population).

- Plot and determine optimum: Plot the SI against the antibody dilution. The optimal concentration is at the peak of the titration curve.

Protocol 2: Blocking for High-Parameter Intracellular Staining

This protocol reduces non-specific background for intracellular staining by implementing a blocking step after permeabilization [23].

Materials:

- Normal serum (e.g., rat, mouse - matched to the host species of your antibodies)

- Tandem stabilizer

- FACS buffer

- Permeabilization buffer (e.g., BD Perm/Wash)

Method:

- Fix and permeabilize cells according to your standard protocol.

- Prepare blocking solution: Create a solution containing normal serum and tandem stabilizer diluted in FACS buffer.

- Block: Resuspend the fixed and permeabilized cell pellet in the blocking solution.

- Incubate: incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature in the dark.

- Stain: Without washing, add the intracellular antibody master mix directly to the cells and proceed with the staining incubation.

Workflow and Signaling Diagrams

Antibody Titration and Validation Workflow

Experimental Variables Impacting Antibody Performance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Normal Serum | Used in blocking to reduce non-specific binding via Fc receptors. Should be from the same species as the staining antibodies [23]. |

| Tandem Stabilizer | A commercial additive that prevents the degradation of tandem fluorophores, which can cause erroneous signal spillover [23]. |

| Brilliant Stain Buffer | Contains polyethylene glycol (PEG) that mitigates dye-dye interactions between polymer-based "Brilliant" fluorophores, reducing non-specific binding [23]. |

| Formaldehyde / PFA | A fast-acting crosslinking fixative that preserves cellular ultrastructure by stabilizing protein interactions. Commonly used at 2-4% [22] [24]. |

| Triton X-100 / Saponin | Detergents used for permeabilization. They create pores in lipid bilayers, allowing antibodies to access intracellular targets [24]. |

| Staining Buffer (with BSA) | A protein-based buffer used to wash and resuspend cells. BSA helps minimize non-specific antibody binding to cell surfaces [18]. |

| Lactose octaacetate | Lactose octaacetate, MF:C28H38O19, MW:678.6 g/mol |

| Methyl(2-methylsilylethyl)silane | Methyl(2-methylsilylethyl)silane|High-Purity |

A Step-by-Step Protocol for Antibody Titration in Flow Cytometry

FAQs: Core Concepts and Controls

Q1: Why is it essential to have both positive and negative cell populations in a titration experiment? A positive control confirms your antibody can detect the target antigen, while a negative control (such as unstained cells or an isotype control) establishes the background fluorescence level. The optimal antibody concentration is the one that provides the highest signal-to-noise ratio or staining index, effectively distinguishing the positive population from the negative. Without both, you cannot accurately determine this ratio and may use an antibody concentration that is too high (increasing background) or too low (diminishing signal) [26].

Q2: What types of negative controls should I use? Several types of negative controls are critical for accurate data interpretation:

- Unstained Cells: Cells processed identically but without the addition of any antibody. This establishes the level of cellular autofluorescence [27] [28].

- Isotype Control: Cells stained with an antibody that has the same immunoglobulin isotype and fluorochrome as your test antibody but with no specificity for the target antigen. This helps identify non-specific antibody binding [27] [29].

- Fluorescence Minus One (FMO) Control: In multicolor panels, this is a tube stained with all antibodies except one. It is used to set the boundary for positive staining in that specific channel, accounting for spillover fluorescence from the other colors [28].

Q3: My target antigen has very low expression. How can I ensure a good positive signal for titration? For weakly expressed targets, always pair them with the brightest fluorochrome available (e.g., PE) to maximize detection. Using a dim fluorochrome (e.g., FITC) on a low-density target can result in a poor or absent signal. Furthermore, consider using compensation beads as a positive control instead of cells, especially if the positive cell population is small or has low antigen density. The beads can be stained with your antibody to provide a uniformly bright positive population for accurate compensation and titration [28].

Q4: What are the consequences of using an incorrect antibody concentration? Using an antibody concentration that is too high leads to high non-specific binding, increased background fluorescence, and wasted reagents. Using a concentration that is too low results in a weak or absent specific signal, failing to saturate all antigen binding sites. Both scenarios reduce the resolution and reliability of your experiment [26] [30].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal | Low antigen expression; Inadequate fixation/permeabilization (intracellular targets); Old/degraded antibodies; Incorrect laser/PMT settings [29] [30]. | Use brighter fluorochrome for low-density targets [29]; Titrate antibody to find optimal concentration [26] [30]; Include a positive control with known antigen expression [30]; Verify instrument settings and laser alignment [30]. |

| High Background / Non-Specific Staining | Antibody concentration too high; Non-specific Fc receptor binding; Presence of dead cells; Incomplete washing [29] [30]. | Titrate antibody to lower concentration [30]; Block cells with BSA, Fc receptor block, or normal serum [29]; Use a viability dye to exclude dead cells [28] [29]; Increase number of wash steps [29]. |

| No Distinct Positive Population | Insufficient positive cells; Antibody does not recognize the target antigen; Over-compensation in multicolor panels [30]. | Add unstained cells to sample to better visualize background if positive cells are rare [26]; Confirm antibody-host species compatibility [30]; Use FMO controls to correctly set positive gates [28]. |

| Unexpected Double Population | Presence of cell doublets/clumps; Two distinct cell populations express the target [30]. | Gently pipette or filter sample to create a single-cell suspension before staining and running [30]; Check expected expression patterns for your cell sample [30]. |

Experimental Protocol: Antibody Titration for Optimal Concentration

This protocol outlines the serial dilution of a directly labeled antibody to determine the concentration that provides the best separation between positive and negative cell populations [27].

Key Reagents:

- Antibody of interest (centrifuged at 15,000 x g to remove aggregates)

- Cell suspension with a known mix of positive and negative cells

- Staining buffer (e.g., PBS with 2% BSA)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

- Normal IgG for blocking

- Flow cytometry tubes

Methodology:

- Prepare Antibody Dilutions: Create a series of six 2-fold serial dilutions of your antibody stock in PBS. For example, start with 10 µl of stock antibody + 20 µl PBS. For the next tube, add 10 µl of the previous dilution to 20 µl of PBS, and so on [27].

- Prepare Cells: Resuspend your cell sample at a concentration of 5-10 x 10ⶠcells/ml in staining buffer containing 200 µg/ml normal IgG for Fc receptor blocking. Aliquot 50 µl of cells into each flow cytometry tube [27].

- Stain Cells: Add 10 µl of each antibody dilution to its own tube of cells. Also prepare unstained cells (autofluorescence control) and an isotype control tube [27].

- Incubate and Wash: Mix the tubes gently and incubate on ice for 15-45 minutes in the dark. Add 2 ml of cold wash buffer, centrifuge, and aspirate the supernatant. Repeat the wash step [27].

- Resuspend and Analyze: Resuspend the cell pellets in a protein-free buffer and analyze on the flow cytometer [27].

Data Analysis: For each antibody dilution, record the Mean Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) of both the positive and negative cell populations. Calculate either the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) or the Staining Index (SI) [26].

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): = MFI (Positive Population) / MFI (Negative Population)

- Staining Index (SI): = [MFI (Positive) - MFI (Negative)] / (2 x Standard Deviation of Negative)

The optimal antibody titer is the one that yields the highest SNR or SI value [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Cell Preparation & Titration |

|---|---|

| Positive Control Cells/Beads | Provides a brightly stained population to set PMT voltages, calculate compensation, and determine the specific signal during titration. Essential for low-abundance targets [28]. |

| Compensation Beads | Uniform particles that bind antibodies, providing consistent negative and bright positive populations for every fluorochrome. Critical for accurate spillover compensation in multicolor panels [28]. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Solution | Reduces non-specific antibody binding by blocking Fc receptors on cells, thereby lowering background staining in both positive and negative populations [29]. |

| Viability Dye | Distinguishes live from dead cells. Dead cells are highly autofluorescent and bind antibodies non-specifically; excluding them from analysis is crucial for clean data [28] [29]. |

| Brilliant Stain Buffer | Prevents non-specific interactions and fluorescence quenching between polymer-based dyes (e.g., Brilliant Violet, Super Bright) when used in the same staining panel [28]. |

| Isotype Control | An antibody with irrelevant specificity but the same isotype and fluorochrome as the primary antibody. Serves as a critical negative control for gating and identifying non-specific binding [27] [29]. |

| Axillaridine A | Axillaridine A, MF:C30H42N2O2, MW:462.7 g/mol |

| Corydamine | Corydamine, MF:C20H18N2O4, MW:350.4 g/mol |

Serial dilution is a foundational technique in laboratories, crucial for optimizing antibody concentration through titration research. This guide provides detailed workflows and troubleshooting advice to help researchers achieve precise and reproducible results in drug development.

The Serial Dilution Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete serial dilution process, from initial preparation to final incubation.

Step-by-Step Protocol for Serial Dilution

Preparation Phase

- Work Area Preparation: Clean and disinfect your work area with 70% ethanol. Ensure all equipment is sterile [31].

- Tube Labeling: Label each dilution tube with the corresponding dilution factor (e.g., 10â»Â¹, 10â»Â², 10â»Â³, etc.) and date [32] [31].

- Diluent Preparation: Use an appropriate diluent such as sterile saline, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), or culture medium [33] [31].

Dilution Phase

- Initial Sample Preparation: Vortex the bacterial sample or mix the antibody solution thoroughly to ensure even distribution [31].

- First Dilution (10â»Â¹): Transfer 1 mL of the sample into 9 mL of diluent. Mix thoroughly by vortexing or pipetting [32] [31].

- Subsequent Dilutions:

Antibody Titration Specific Steps

For antibody titration, the process follows the same principle but with smaller volumes:

- Prepare a series of tubes with appropriate diluent [34].

- Begin with the stock antibody solution.

- Perform serial dilutions by transferring consistent volumes from one tube to the next [34].

- Mix each dilution thoroughly before moving to the next [35].

Incubation and Analysis

- Plating: For microbial work, transfer 0.1 mL of selected dilutions onto agar plates and spread evenly [31].

- Incubation: Secure plates and incubate at the optimal temperature for the organism [31].

- Analysis: After incubation, count colonies or analyze antibody binding to determine optimal concentrations [35] [31].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Equipment | Function in Serial Dilution |

|---|---|

| Sterile Dilution Tubes | Contain diluent and successive dilutions [31] |

| Sterile Pipettes/Micropipettes | Accurate measurement and transfer of liquids [33] [31] |

| Sterile Saline or Buffer | Serves as diluent to maintain cell/antibody viability [31] |

| Vortex Mixer | Ensures homogeneous mixing at each dilution step [33] [31] |

| Agar Plates | Solid medium for plating microbial dilutions [31] |

| FC Block | Reduces non-specific antibody binding in flow cytometry [34] |

| Brilliant Stain Buffer | Prevents dye-dye interactions in flow cytometry panels [23] [36] |

Troubleshooting Common Serial Dilution Issues

Inconsistent Results Between Replicates

Problem: Significant variation between technical replicates suggests pipetting inconsistency [33]. Solution:

- Calibrate pipettes regularly and use proper pipetting technique [33].

- Use the same pipette and operator for all dilutions when possible.

- Avoid pipetting very small volumes (<1 μL) which can lead to inaccuracies [33].

Contamination in Higher Dilutions

Problem: Unexpected colony growth in negative controls or higher dilutions [31]. Solution:

- Maintain strict aseptic technique throughout the process.

- Work in a laminar flow hood or near a Bunsen burner [31].

- Use fresh, sterile pipette tips for each transfer [33].

Non-Linear Dilution Series

Problem: Results don't follow expected dilution patterns. Solution:

- Ensure thorough mixing at each dilution step before transfer [35] [33].

- Verify that diluent and sample volumes are precise [31].

- Check that the stock solution is properly homogenized before starting [31].

Poor Antibody Staining Results

Problem: Suboptimal signal-to-noise ratio in antibody titration. Solution:

- Include FC receptor blocking steps to reduce non-specific binding [23] [34].

- Use appropriate buffer additives like Brilliant Stain Buffer for polymer dyes [23] [36].

- Ensure antibody concentrations are within the optimal detection range [36].

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between 2-fold and 10-fold serial dilutions?

- 10-fold dilutions (1 mL sample + 9 mL diluent) are used when you need to cover a wide concentration range quickly, such as for microbial enumeration [35].

- 2-fold dilutions (equal volumes of sample and diluent) provide higher precision for determining exact concentrations, such as minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) testing [35].

How do I calculate the final dilution factor? The final dilution factor is calculated by multiplying the dilution factors of each step. For example, a 7-step 10-fold serial dilution would have a final dilution factor of 10â· (10,000,000) [35].

What dilution range should I use for antibody titration? For antibody titration, start with the manufacturer's recommended concentration and create a series of 2-fold dilutions to determine the optimal staining concentration with the best signal-to-noise ratio [36] [34].

Why are my higher dilutions showing inconsistent results? Higher dilutions are most affected by pipetting errors as these accumulate through the series [35]. Ensure proper technique and consider using larger volumes for higher dilutions to minimize error impact.

How can I improve reproducibility in my serial dilutions?

- Document all dilution steps, volumes transferred, and dilution factors accurately [33].

- Standardize cell numbers to reduce batch effects [23].

- Use multichannel pipettes for high-throughput work to improve consistency [23].

Best Practices for Serial Dilution in Antibody Titration Research

- Plan Your Dilution Series: Before starting, decide on dilution factors and the number of dilutions needed based on your experimental goals [33].

- Maintain Aseptic Technique: For microbial work, always use sterile equipment and proper technique to prevent contamination [31].

- Thorough Mixing: After each dilution step, mix contents thoroughly to ensure uniform distribution [35] [33].

- Accurate Documentation: Record all dilution steps, volumes, and dilution factors for reproducibility [33].

- Include Controls: Always include appropriate positive and negative controls in your experimental design [34].

By following these detailed protocols and troubleshooting guidelines, researchers can optimize their serial dilution techniques for more reliable and reproducible results in antibody titration and broader drug development applications.

Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most critical steps to ensure reproducibility in multiplex immunofluorescence (mIF) staining? A robust mIF workflow requires rigorous tissue quality controls, a balanced multiplex assay staining format, standardized staining and imaging protocols, and validation for both internal and external reproducibility [37]. Key steps include proper antibody selection and optimization, use of appropriate controls, and minimizing variables in pre-analytic, analytic, and post-analytic stages [37].

Q2: My flow cytometry data shows high background fluorescence. What could be the cause? High background often stems from non-specific antibody binding, insufficient washing, or the presence of dead cells [38] [39]. Fc receptor-mediated binding is a common cause, which can be blocked using Fc receptor blocking reagents or normal serum [38] [40]. Other causes include excessive antibody concentration, cell autofluorescence, or poor compensation [39].

Q3: In my ELISA, I'm getting a weak or no signal even though I know the analyte is present. How can I troubleshoot this? Begin by verifying that all reagents are within expiration dates and were prepared correctly [41]. Check that the standard was handled properly and that buffers are not contaminated [42]. Ensure the plate was not allowed to dry out during incubations and that the substrate solution was fresh and prepared immediately before use [42] [43]. Increasing primary or secondary antibody concentration or extending incubation times may also help [43].

Troubleshooting Common Assay Problems

Flow Cytometry Troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal | Inadequate fixation/permeabilization [38].Target not induced or expressed [38].Dim fluorochrome on low-density target [39].Incorrect laser/PMT settings [38]. | Titrate antibodies and optimize fixation/permeabilization protocol [39].Use brightest fluorochrome for lowest density targets [38].Verify instrument configuration matches fluorochrome [39]. |

| High Background | Non-specific Fc receptor binding [38] [39].Too much antibody [38].Presence of dead cells [38].Insufficient washing [39]. | Use Fc receptor block (e.g., serum, anti-CD16/32) [40].Titrate antibody to optimal concentration [38].Use a viability dye (e.g., PI, 7-AAD) to gate out dead cells [38] [39].Increase wash number, duration, or volume [39]. |

| Poor Resolution of Cell Cycle Phases | High flow rate on cytometer [38].Insufficient staining with DNA dye [38]. | Use the lowest flow rate setting to reduce CVs [38].Resuspend pellet directly in PI/RNase solution and incubate >10 min [38]. |

ELISA Troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Background | Insufficient washing [41].Plate over-developed [42].Concentration of detection antibody too high [42].Non-specific antibody binding [43]. | Increase number and/or duration of washes [41].Stop reaction promptly with stop solution [43].Titrate detection antibody to optimal dilution [42].Ensure adequate blocking step with protein (e.g., BSA, serum) [43]. |

| Weak or No Signal | Reagents added in wrong order or prepared incorrectly [41].Standard degraded [42].Capture antibody did not bind plate [41].Buffer contains sodium azide (inhibits HRP) [42]. | Repeat assay, check calculations and preparation [41].Use fresh standard vial [42].Use validated ELISA plates (not tissue culture plates) [41].Use azide-free buffers or wash thoroughly [42]. |

| Poor Precision (High Well-to-Well Variation) | Inconsistent pipetting [42].Insufficient or uneven washing [41].Plate allowed to dry out [42].Reagents not mixed well before addition [42]. | Calibrate pipettes and use proper technique [43].Check automated plate washer for clogged ports [41].Keep plate covered during incubations [42].Mix all reagents and samples thoroughly before use [42]. |

Multiplex Immunofluorescence (mIF) Troubleshooting

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Reproducibility | Pre-analytic variables (fixation, storage) [37].Lot-to-lot antibody variability [37].Inadequate antibody validation [37]. | Standardize and automate staining protocols where possible [37].Use monoclonal or recombinant antibodies for higher consistency [37].Use rigorous tissue controls for antibody validation [37]. |

| High Background or Non-specific Staining | Suboptimal antibody concentration [37].Incompatible panel design [37].Inadequate epitope retrieval [44]. | Optimize antibody dilution for each specific clone [37].Select antibodies from different host species for multiplex panels [37].Consider glycerol-enhanced HIER (G-HIER) for improved antigen retrieval on membrane slides [44]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Dot Blot for Rapid Antibody Concentration Optimization

This quicker alternative to full Western blots helps determine the optimal primary and secondary antibody concentrations [45].

Materials:

- Nitrocellulose Membrane

- Blocking Buffer (e.g., PBS with 5% non-fat dry milk)

- Primary Antibody (various dilutions)

- Secondary Antibody (various dilutions, HRP-conjugated)

- Wash Buffer (e.g., PBS with 0.1% Tween-20)

- Substrate Working Solution (e.g., Chromogenic or Chemiluminescent)

Methodology:

- Prepare Samples: Create a range of dilutions for your protein sample and your primary antibody.

- Prepare Membrane: Cut a nitrocellulose membrane into 1 cm strips. Each strip will be used to test one or two primary antibody dilutions.

- Dot Protein: Dot the protein samples onto the membrane strips in minimal volume. For volumes over 5 µL, dot multiple times on the same spot, allowing it to dry completely between applications. Let the membrane dry for 10-15 minutes.

- Block: Soak the membrane in blocking buffer for 1-2 hours at room temperature on an orbital shaker.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Apply the different primary antibody dilutions to the respective membrane strips. Incubate for 1 hour on an orbital shaker.

- Wash: Wash the membrane strips thoroughly with wash buffer.

- Secondary Antibody Incubation: Apply the different secondary antibody dilutions to the strips. Incubate for 1 hour on a shaker.

- Wash: Wash the membrane strips again thoroughly.

- Detect: Prepare the substrate working solution and incubate with the nitrocellulose strips for ~5 minutes, or until color develops (for chromogenic substrates). Image the membrane.

- Analysis: The optimal protein and antibody concentrations will yield dark, clear dots with minimal background [45].

Protocol 2: "Dish Soap Protocol" for Simultaneous Transcription Factor and Fluorescent Protein Detection in Flow Cytometry

This protocol uses a custom, low-cost fixation and permeabilization buffer to overcome the classic trade-off between efficient nuclear staining and fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP) retention [46].

Materials:

- FACS Buffer (PBS with 2.5% FBS and 2 mM EDTA) [46]

- Fixative: 2% Formaldehyde with 0.05% Fairy dish soap and 0.5% Tween-20 [46]

- Permeabilization Buffer: PBS with 0.05% Fairy dish soap [46]

- Fc Receptor Block

- Primary and Secondary Antibodies

Methodology:

- Surface Staining: Perform surface staining as you normally would. Count cells, block Fc receptors, stain with surface marker antibodies, and wash.

- Fixation: Centrifuge the cells (400-600 x g, 5 min), discard the supernatant, and resuspend the cell pellet in 200 µl of the fixative. Incubate for 30 minutes at room temperature in the dark (perform in a fume hood).

- Wash: Centrifuge (600 x g, 5 min) and remove the supernatant. Dispose of formaldehyde waste appropriately.

- Permeabilization and Block: Resuspend the cell pellet in 100 µl of permeabilization buffer. Incubate for 15-30 minutes at room temperature. Fc receptor blocking can be repeated at this stage by adding the block to the perm buffer.

- Wash: Wash the cells twice in FACS buffer.

- Intracellular Staining: Stain with antibodies against intracellular targets (e.g., transcription factors) overnight in FACS buffer at 4°C. The protocol notes that additional permeabilization is not necessary [46].

- Final Wash and Acquisition: Wash the cells twice in FACS buffer and acquire data on a flow cytometer [46].

Standardized Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Fc Receptor Block | Blocks Fc receptors on immune cells (e.g., monocytes) to prevent non-specific antibody binding, a major cause of high background in flow cytometry and other assays [38] [40]. |

| Fixable Viability Dyes | Distinguish live from dead cells in fixed samples. Dead cells bind antibodies non-specifically; gating them out is critical for clean data [38] [39]. |

| Methanol-Free Formaldehyde | A crosslinking fixative preferred for intracellular staining, as it prevents loss of intracellular proteins due to premature permeabilization before crosslinking is complete [38]. |

| Mild Detergents (Saponin) | Creates pores in membranes without dissolving them, ideal for staining cytoplasmic antigens and preserving fluorescent proteins [46] [40]. |

| Harsh Detergents (Triton X-100) | Dissolves nuclear and cellular membranes, providing access to nuclear and cytoskeletal antigens for antibody staining [40]. |

| BSA or Serum-Based Blocking Buffers | Used in ELISA and other immunoassays to coat unused protein-binding sites on plates or membranes, preventing non-specific attachment of detection antibodies [42] [43]. |

| Tween-20 in Wash Buffers | A mild detergent added to wash buffers (e.g., PBS-T) to help dislodge non-specifically bound antibodies and reduce background across all immunoassays [42] [43]. |

| Naringenin trimethyl ether | Naringenin trimethyl ether, MF:C18H18O5, MW:314.3 g/mol |

| Methyl Rosmarinate | Methyl Rosmarinate, CAS:99353-00-1, MF:C19H18O8, MW:374.3 g/mol |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is antibody titration necessary, and why can't I just use the vendor-recommended concentration? Vendor-recommended concentrations are a good starting point but are determined under the vendor's specific conditions, which are likely different from your actual assay. Titrating the antibody yourself ensures optimization for your specific cell types, staining protocol, and instrument, maximizing the signal-to-noise ratio for your experiment [10] [18]. Using a non-optimal concentration can lead to false-negative or false-positive results, wasting precious samples and time [18].

2. What is the Stain Index (SI), and why is it used to find the optimal concentration? The Stain Index is a calculated metric that quantifies the separation between a positive signal and background noise. A higher SI indicates better resolution [10] [47]. The optimal antibody concentration is identified as the point on the titration curve that gives the highest SI, ensuring the brightest specific signal with the lowest possible background [10] [19].

3. My titration curve has no clear plateau. What does this mean? A titration curve without a clear saturation plateau often indicates that the antibody has low affinity for its target [18]. In this case, the optimal antibody concentration can be difficult to determine, and the experiment may be prone to both false-negative and false-positive results. You may need to select a different antibody clone or reagent.

4. Do I need to re-titrate an antibody if I change a part of my protocol? Yes. Any change to critical assay conditions—such as the cell type, staining volume, incubation time or temperature, fixation method, or the flow cytometer itself—can alter the optimal antibody concentration. To ensure consistent, high-quality results, you should re-titrate antibodies whenever your staining protocol changes [10] [19].

5. How many dilution points are needed for a reliable titration? While there is no universal standard, an informal survey suggests that many researchers use at least 5 dilution points [47]. The key is to use enough serial dilutions to confidently identify the peak of the Stain Index curve and the plateau of the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) [47]. A typical titration may use 8-12 points [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Separation Between Positive and Negative Populations

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Antibody concentration is too high, leading to increased non-specific binding and background noise.

- Solution: Perform a titration experiment. The calculated optimal concentration is often lower than the vendor's recommendation, which reduces background and saves reagent [10].

- Cause: Inadequate Fc receptor blocking, leading to non-specific antibody binding.

- Solution: Include an Fc receptor blocking step prior to antibody staining, especially when working with innate immune cells like monocytes [19].

- Cause: The staining index was not calculated or used to determine the optimal concentration.

Problem: High Signal Variability Between Experimental Repeats

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Antibody is not used at a saturating concentration, making the signal sensitive to small variations in staining conditions.

- Solution: For experiments comparing biomarker expression between samples using MFI, ensure the antibody is used at a saturating concentration. If a fluorophore-conjugated antibody does not saturate on its own, a novel "spike-in" method with unlabelled antibody of the same clone can be used to achieve saturation [48].

- Cause: Incorrect scaling up from the titration reaction.

- Solution: Remember that antibody titration is most influenced by concentration and volume, not cell number. If you stain the same number of cells in a larger volume, you will need more antibody. However, staining more cells in the same volume typically does not require a proportional increase in antibody [10].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Standard Protocol for Antibody Titration

This protocol is adapted for a 96-well plate format and can be scaled to the number of antibodies being tested [19].

1. Prepare Antibody Serial Dilutions:

- Label a V-bottom 96-well plate for each antibody.

- Add 150 µL of staining buffer to all wells except the first.

- Prepare the first (highest) concentration of antibody in the first well. For antibodies with a known concentration (e.g., µg/mL), a starting point of 1000 ng/test is recommended. For those described by µL/test, start at double the recommended volume [19].

- Perform 2-fold serial dilutions across the plate. Using a multichannel pipette, mix the solution in the first column and transfer 150 µL to the next column. Repeat this process for all columns, discarding 150 µL from the final well [19].

2. Stain Cells:

- Prepare a single cell suspension (e.g., PBMCs) at a concentration of 2 × 10^6 cells/mL in staining buffer [19].

- Add 100 µL of the cell suspension (containing 2 × 10^5 cells) to each well of the titration plate. The final staining volume will be 250 µL.

- Pipette to mix and incubate for 20 minutes at room temperature in the dark (or according to your specific staining protocol).

- Centrifuge the plate at 400 × g for 5 minutes, decant the supernatant, and blot on a paper towel.

- Resuspend the cells in 200 µL of staining buffer and repeat the wash step twice.

- Resuspend the final pellet in an appropriate volume of buffer for acquisition on your flow cytometer [19].

Data Analysis: Calculating the Stain Index and Plotting the Curve

After acquiring the data on your flow cytometer, follow these steps to construct the titration curve.

1. Gating and Data Export:

- Gate on your population of interest (e.g., single, live cells) and then identify the positive and negative populations for your marker.

- For each dilution, record the Median Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) of both the positive population (Medpos) and the negative population (Medneg).

- Also record the 84th percentile of the negative population (84%neg). This value represents the right-side spread of the negative curve, which is a measure of background noise [10].

2. Calculate the Stain Index (SI):

Use the following formula for each antibody dilution [10]:

SI = (Medpos - Medneg) / (2 × 84%neg)

Some sources use a slightly different denominator. The key is to be consistent within your own analysis.

3. Construct the Titration Curve:

- Create a plot with the antibody concentration (or dilution factor) on the x-axis and the calculated Stain Index on the y-axis.

- The optimal antibody concentration is identified as the point that yields the maximum Stain Index [10] [47].

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for titration data analysis.

The following table summarizes the key metrics you will collect and calculate during the titration analysis.

Table 1: Key Metrics for Titration Curve Construction

| Antibody Concentration | MFI (Positive) | MFI (Negative) | 84th %ile (Negative) | Calculated Stain Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| e.g., 1:50 | Recorded Value | Recorded Value | Recorded Value | Calculated Value |

| e.g., 1:100 | Recorded Value | Recorded Value | Recorded Value | Calculated Value |

| e.g., 1:200 | Recorded Value | Recorded Value | Recorded Value | Calculated Value |

| e.g., 1:400 | Recorded Value | Recorded Value | Recorded Value | Calculated Value |

| e.g., 1:800 | Recorded Value | Recorded Value | Recorded Value | Calculated Value |

| e.g., 1:1600 | Recorded Value | Recorded Value | Recorded Value | Calculated Value |

The diagram below summarizes the interpretation of the titration curve once it is plotted.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Antibody Titration

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Flow Staining Buffer (e.g., PBS with 1% BSA) | Provides an isotonic environment for cells and antibodies. The protein (BSA) helps block non-specific binding sites to reduce background [19] [18]. |

| V-bottom 96-well Plates | Ideal format for efficient staining and washing of multiple samples simultaneously via centrifugation [19]. |

| Multichannel Pipette | Critical for accurately and efficiently performing serial dilutions and handling reagents across multiple wells [19]. |

| Cell Preparation | A suspension of cells known to contain both positive and negative populations for the marker of interest. PBMCs are a common choice [19] [18]. |

| Viability Dye | Recommended for inclusion in the titration to exclude dead cells, which can increase background noise and data variability [10] [47]. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent | Used prior to staining to prevent antibodies from binding non-specifically to Fc receptors on certain immune cells, thereby reducing background [19]. |

| 1,3,5-Tricaffeoylquinic acid | 1,3,5-Tricaffeoylquinic Acid|High-Purity Reference Standard |

| Camaric acid | Camaric acid, MF:C35H52O6, MW:568.8 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Common Titration Problems: From Weak Signal to High Background

FAQs on Antibody-Related Signal Failure

How do antibody age and improper storage lead to weak signal?

Antibody degradation is a primary cause of diminished fluorescence. Over time, and with improper handling, antibodies can lose their ability to bind their target effectively.

- Repeated Freeze-Thaw Cycles: Multiple freeze-thaw cycles can cause antibody aggregation and degradation. Antibodies should be aliquoted in small, single-use volumes (e.g., 10 µL) and stored at –20°C or –80°C to avoid this issue [49].

- Time and Temperature Stress: Experimental data has shown that prolonged storage, especially over years, can have a pronounced impact on fluorescence intensity, as observed in studies with CD25-PE and CD8-APC antibodies [50].

- Light Exposure: Fluorophores are light-sensitive. Antibodies conjugated to fluorescent dyes must be stored in the dark, with vials wrapped in foil, to prevent photobleaching [51] [52]. Incubations and sample storage should also be done in the dark.

What are the signs that my target is inaccessible?

Target inaccessibility, often called "epitope masking," prevents the antibody from binding even if the target protein is present.

- Over-fixation: Excessive incubation with aldehyde-based fixatives like formaldehyde can cross-link proteins and obscure the epitope [49].

- Insufficient Permeabilization: If the cell membrane is not adequately made permeable, large antibody molecules cannot enter the cell to reach intracellular targets [53] [49].

- Epitope Conformation: The process of fixing and preparing samples can sometimes alter the three-dimensional structure of the protein, hiding the epitope recognized by the antibody [54].

My antibody is new and stored correctly, but I still get no signal. What now?

If antibody integrity is confirmed, the issue likely lies elsewhere in the experimental workflow.

- Antibody Incompatibility: Ensure the secondary antibody is raised against the host species of the primary antibody (e.g., an anti-mouse secondary for a mouse primary antibody) [53] [49].

- Insufficient Antibody Concentration: The primary antibody concentration may be too dilute to detect the target, especially if it is low-abundance. A titration experiment is crucial to find the optimal dilution [53] [51].

- Protein Not Present or Not Induced: Verify that your target protein is expressed in your experimental cell line and that it has been properly induced [51] [49].

Troubleshooting Guide: Weak or No Signal

The following table summarizes the primary causes and solutions for weak or absent fluorescence signals, with a focus on antibody and target-related factors.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Weak or No Fluorescence Signal

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Experimental Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody Degradation (Age/Storage) | Aliquot antibodies to minimize freeze-thaw cycles; store at recommended temperature in the dark [49] [50]. | Use a positive control antibody known to be functional to rule out general protocol failure. |

| Incorrect Antibody Concentration | Perform an antibody titration experiment to determine the optimal signal-to-noise ratio [53] [49]. | For Cell Signaling Technology antibodies, incubate primary antibody at 4°C overnight for optimal results [51]. |

| Target Inaccessibility | Optimize fixation and permeabilization conditions. For aldehyde-fixed samples, consider an antigen retrieval step (e.g., incubation in a pre-heated urea buffer at 95°C for 10 min) [49]. | If possible, test different fixatives or avoid over-fixation. |

| Incompatible Antibody Pair | Confirm secondary antibody is specific for the host species of the primary antibody [53] [55]. | Use validated "matched pairs" or check product datasheets for confirmed compatibility. |

| Low Abundance Target | Increase signal amplification by using polyclonal antibodies (bind multiple epitopes) or specialized amplification systems like biotin-streptavidin or tyramide signal amplification (TSA) [53] [55]. | Indirect immunofluorescence (using a secondary antibody) provides inherent signal amplification over direct methods [55]. |

Experimental Protocols for Verification

Protocol 1: Antibody Titration for Optimal Concentration

A key thesis of this resource is that optimizing antibody concentration through titration is fundamental. This protocol helps diagnose issues related to both weak signal and high background.

- Prepare a Dilution Series: Dilute your primary antibody in a suitable buffer (e.g., PBS with 1% BSA) to create a series of concentrations. A typical starting range is 2-3 dilutions above and below the manufacturer's recommended concentration.

- Apply to Test Samples: Apply each dilution to identical, control samples that are known to express your target protein.

- Process in Parallel: Complete the entire immunofluorescence protocol (blocking, primary, washing, secondary, mounting) on all samples simultaneously to ensure consistent conditions.

- Image and Analyze: Image all samples using identical microscope settings (exposure time, gain, laser power). The optimal dilution provides the strongest specific signal with the lowest background [53] [49].

Protocol 2: Verifying Target Accessibility with Antigen Retrieval

This protocol is used when you suspect the epitope has been masked during fixation.

- After fixation and permeabilization, incubate the samples in an antigen retrieval buffer (e.g., 100 mM Tris, 5% (w/v) urea, pH 9.5).

- Pre-heat the buffer to 95°C before adding the samples.

- Incubate at 95°C for 10 minutes.

- Cool and Wash: Remove the samples and allow them to cool to room temperature, then wash three times in PBS before proceeding with the blocking and antibody incubation steps [49].

Diagnostic Workflow and Reagent Solutions

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for diagnosing the root cause of a weak or absent fluorescence signal, focusing on the key areas of antibody integrity and target accessibility.

Diagnosing Weak Fluorescence Signal

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Signal Optimization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Aliquoted Antibodies | Prevents loss of activity from repeated freeze-thaw cycles; ensures consistent reagent quality [49] [50]. | Store small (e.g., 10 µL) single-use aliquots at -20°C or -80°C. |

| Anti-Fade Mounting Medium | Presves fluorescence signal during microscopy by reducing photobleaching [51]. | Use for all samples, especially when imaging requires long exposure times. |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffer | Unmasks epitopes that have been obscured by aldehyde-based fixation, restoring antibody binding [49]. | Typically requires a heat-induced step (95°C) for effectiveness. |

| Signal Amplification Kits | Increases detection sensitivity for low-abundance targets by attaching multiple fluorophores per antibody [55]. | Examples: Tyramide Signal Amplification (TSA) or biotin-streptavidin systems. |

| Validated Matched Pair | Pre-compatible primary and secondary antibodies guaranteed to work together, eliminating incompatibility issues [54] [55]. | Essential for setting up new assays or multiplexing. |