Beyond Linearity: A Practical Guide to Addressing Beer-Lambert Law Deviations in Biomedical Assays

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on understanding, identifying, and correcting deviations from the Beer-Lambert law in concentration assays.

Beyond Linearity: A Practical Guide to Addressing Beer-Lambert Law Deviations in Biomedical Assays

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on understanding, identifying, and correcting deviations from the Beer-Lambert law in concentration assays. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it explores the chemical and instrumental factors causing non-linearity, presents traditional and machine learning-based methodological corrections, offers troubleshooting protocols for assay optimization, and delivers a framework for the rigorous validation of analytical methods. The content synthesizes current research to equip scientists with strategies to ensure data accuracy and reliability in quantitative biomedical analysis, from early research to clinical applications.

Revisiting the Basics: Understanding the Causes and Types of Beer-Lambert Law Deviations

Core Principles of the Beer-Lambert Law and Its Fundamental Assumptions

Table of Contents

- Core Principles and Mathematical Formulation

- Fundamental Assumptions of the Law

- Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Deviations

- FAQs: Resolving Experimental Issues

- Essential Experimental Protocols

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Core Principles and Mathematical Formulation

The Beer-Lambert Law (also known as Beer's Law) is a fundamental principle in optical spectroscopy that provides a quantitative relationship between the absorption of light and the properties of the material through which the light is traveling [1] [2]. It is indispensable for determining the concentration of an analyte in a solution.

The law is mathematically expressed as:

A = εlc

- A is the Absorbance (also known as optical density), a dimensionless quantity.

- ε is the Molar Absorbivity or molar extinction coefficient (in L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹), a constant that indicates how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at a specific wavelength.

- l is the Path Length (in cm), the distance the light travels through the solution, typically the width of the cuvette.

- c is the Concentration of the absorbing species in the solution (in mol/L or M).

Absorbance is defined through the relationship with the intensity of incident light (Iâ‚€) and transmitted light (I) [3]:

A = logâ‚â‚€ (Iâ‚€ / I)

The following diagram illustrates the core components and logical relationships of the Beer-Lambert Law.

The logarithmic relationship between transmittance (T = I/Iâ‚€) and absorbance means that absorbance increases linearly with concentration. This relationship is critical for creating calibration curves [1]. The table below shows how absorbance correlates with percent transmittance.

Table 1: Absorbance and Transmittance Relationship

| Absorbance (A) | Percent Transmittance (%T) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 100% |

| 1 | 10% |

| 2 | 1% |

| 3 | 0.1% |

| 4 | 0.01% |

| 5 | 0.001% |

Source: Adapted from [1]

Fundamental Assumptions of the Law

The linear relationship A = εlc holds true only under specific conditions. Deviations occur when the following fundamental assumptions are violated [5] [6] [7]:

- Monochromatic Light: The incident light should consist of a single wavelength. The use of polychromatic light, especially with a wide bandwidth, can lead to deviations because the molar absorptivity (ε) varies with wavelength [5].

- Low Concentrations: The absorbing molecules must act independently of each other. At high concentrations (typically above 10 mM), interactions between molecules (e.g., dimerization or aggregation) can alter the absorptivity, leading to a non-linear calibration curve [5] [8].

- Homogeneous Solution: The sample must be a uniform solution without particulates that could scatter light. Scattering from colloids or suspended particles causes apparent absorption, violating the law's assumptions [7].

- No Chemical Changes: The absorbance should be due to a single, stable chemical species. Factors like changes in pH, solvent, or complexation equilibria can shift the absorption spectrum or change the absorptivity [5].

- No Fluorescence or Photoreaction: The law assumes that the loss of beam intensity is solely due to absorption. If the sample fluoresces or undergoes a photoreaction, the measured transmitted intensity will be affected, leading to inaccurate absorbance readings [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Deviations

This guide helps diagnose and correct issues that cause deviations from the Beer-Lambert Law.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Deviations

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-linear calibration curve | High analyte concentration leading to molecular interactions [5]. | Dilute the sample to a concentration within the linear range (often A < 1.5) [8]. |

| Chemical equilibrium shift with concentration (e.g., dimerization) [5]. | Use buffered solutions to maintain constant pH and chemical environment. | |

| Irreproducible absorbance readings | Inconsistent path length due to use of mismatched cuvettes [5]. | Use a matched pair of cuvettes for sample and blank. |

| Presence of air bubbles or particulates in the sample that scatter light. | Filter or centrifuge the sample to ensure clarity. Degas if necessary. | |

| Negative deviation (lower than expected absorbance) | Stray light within the instrument, a significant issue at high absorbance values [5]. | Ensure the instrument is well-maintained and calibrated. Avoid measuring absorbance at the extremes of the instrument's wavelength range. |

| Inaccurate concentration determination | Use of an inappropriate wavelength (e.g., not at λ_max or on a steep slope of the peak) [8]. | Always perform measurements at or near the absorption maximum (λ_max) where the signal is less affected by small wavelength errors. |

| Incorrect blank solution that does not account for solvent or matrix absorption. | Prepare a blank that matches the sample matrix as closely as possible, including all reagents except the analyte [5]. |

The following workflow provides a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving deviations from expected results.

FAQs: Resolving Experimental Issues

Q1: Why does the Beer-Lambert law fail at high concentrations? At high concentrations (generally above 10 mM), the absorbing molecules are in close proximity. This can lead to electrostatic interactions, dimerization, or aggregation, which alter the molar absorptivity (ε) of the molecule [5] [7]. Additionally, changes in the refractive index at high concentrations can contribute to non-linearity [7].

Q2: My sample is colored, but the absorbance does not change linearly with concentration. What could be wrong? This is a classic sign of a chemical deviation. The colored compound may be participating in an equilibrium that is concentration-dependent, such as association or complexation [5]. For example, cobalt(II) chloride solutions can change from pink to blue due to association at higher concentrations. Check the chemical stability of your analyte and ensure the pH and solvent conditions are controlled.

Q3: How important is the use of a blank, and how should I prepare it? The blank is critical for accurate results. It is used to set the 0% absorbance (100% transmittance) baseline, accounting for absorption from the solvent, the cuvette, and any other reagents in your sample matrix [5]. The blank should be a solution identical to your sample but without the analyte. For instance, if your sample is a protein in a buffer, the blank should be the buffer alone.

Q4: What is the ideal absorbance range for accurate measurements? For most instruments, absorbance readings between 0.1 and 1.0 are considered highly reliable. Readings below 0.1 have a high relative noise level, while readings above 1-2 mean very little light is reaching the detector, making measurements sensitive to instrumental noise and stray light [1] [8]. Always dilute your samples to fall within this optimal range.

Q5: Can I use the Beer-Lambert law for a mixture of absorbing species? Yes, but only if the species do not interact with each other. The total absorbance for a multi-component mixture at a given wavelength is the sum of the individual absorbances [9] [2]: Atotal = εâ‚lcâ‚ + ε₂lcâ‚‚ + ... + εnlc_n To determine the concentration of each species, you need to measure the absorbance at multiple wavelengths (at least as many wavelengths as there are components) and solve the resulting system of equations.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Creating a Linear Calibration Curve

This is the standard method for quantifying an unknown sample's concentration.

- Stock Solution Preparation: Prepare a stock solution of the analyte with a accurately known concentration.

- Standard Dilutions: Using serial dilution, prepare a series of standard solutions with concentrations spanning the expected range of your unknown. A minimum of five standards is recommended.

- Spectrum Acquisition: Using an appropriate path length cuvette (e.g., 1 cm) and a matched blank (the solvent), record the absorption spectrum of each standard solution.

- Identify λmax: Determine the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) from the spectra.

- Measure Absorbance: Record the absorbance of each standard at λ_max.

- Plot Calibration Curve: Create a scatter plot of Absorbance (y-axis) versus Concentration (x-axis). Perform linear regression to obtain the equation of the best-fit line (A = slope * c + intercept). The slope of this line is equal to εl [1] [9].

- Validate Linearity: Ensure the R² value of the linear fit is >0.99. Significant curvature indicates a deviation from the Beer-Lambert law, requiring sample dilution or investigation into chemical factors.

Protocol 2: Determining an Unknown Concentration

- Measure Unknown: Using the same instrumental settings and cuvette, measure the absorbance of the unknown sample at the same λ_max used for the calibration curve.

- Calculate Concentration: Use the equation from your calibration curve to calculate the concentration: cunknown = (Aunknown - intercept) / slope

Table 3: Example Data for a Rhodamine B Calibration Curve

| Concentration (M) | Absorbance at λ_max |

|---|---|

| 1.00 × 10â»âµ | 0.105 |

| 2.00 × 10â»âµ | 0.215 |

| 4.00 × 10â»âµ | 0.428 |

| 6.00 × 10â»âµ | 0.642 |

| 8.00 × 10â»âµ | 0.851 |

| Unknown | 0.520 |

Source: Inspired by [1]. For an unknown with an absorbance of 0.520, the calculated concentration would be approximately 6.11 × 10â»âµ M.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials and Reagents for Beer-Lambert Experiments

| Item | Function and Critical Notes |

|---|---|

| Spectrophotometer / Plate Reader | Instrument used to measure the intensity of light transmitted through a sample. Must be calibrated for wavelength accuracy and photometric linearity. |

| Matched Cuvettes (e.g., 1 cm path length) | High-quality quartz (for UV-Vis) or glass/plastic (for Vis) cells that hold the sample. A "matched" pair ensures identical path lengths, which is critical for accurate blank subtraction [5]. |

| Analytical Balance | Used for precise weighing of solutes to prepare stock solutions of accurate molarity. |

| Volumetric Flasks and Pipettes | Essential for preparing precise dilutions and ensuring accurate concentration data. |

| Buffer Solutions (e.g., Phosphate Buffered Saline) | Used to maintain a constant pH, which is crucial for analytes whose absorption spectrum is pH-sensitive (e.g., phenol red, nucleic acids) [5]. |

| Sample Filtration Syringe & Filters (0.22 µm or 0.45 µm) | Used to remove particulates or turbidity from samples that could cause light scattering and falsely high absorbance readings. |

| Reference Standards (e.g., K₂Cr₂O₇, KMnO₄) | Well-characterized compounds with known molar absorptivity, used for instrument validation and method verification [10]. |

| 11-Deoxy-13-deoxodaunorubicin | 11-Deoxy-13-deoxodaunorubicin, MF:C27H31NO8, MW:497.5 g/mol |

| DNA Gyrase-IN-16 | DNA Gyrase-IN-16, MF:C17H15N3O3, MW:309.32 g/mol |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Addressing Positive and Negative Deviations from Linearity

Problem: A calibration curve of absorbance versus concentration shows significant deviation from a straight line, either curving upwards (positive deviation) or downwards (negative deviation) at higher concentrations.

Solution: Follow this logical troubleshooting pathway to identify and correct the most common chemical causes.

Detailed Corrective Actions

For Positive Deviations (Upward Curve):

- Analyte Dilution: For most molecules, non-linear behaviour is observed at concentrations above 10 mM [5]. Prepare fresh dilutions of the stock solution to ensure the working concentration is within the ideal linear range, typically below 10 mM [5].

- Wavelength Selection: If dilution is not feasible, consider using a wavelength where the molar absorptivity (ε) is lower. This can bring the measured absorbance values into a linear range without altering the sample concentration.

For Negative Deviations (Downward Curve):

- pH Control: For analytes like phenol red or chromates/dichromates, prepare both the sample and reference blank using a buffered solution that maintains a pH where the analyte's absorbing form is stable [5].

- Chemical Verification: Confirm the chemical state of your analyte. If complexation or dissociation is suspected, use techniques like mass spectrometry or NMR to verify the molecular species present in solution at the working concentration.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: At what analyte concentration should I expect the Beer-Lambert law to start deviating from linearity? The critical concentration varies by molecule. For most absorbing species, non-linear behaviour is observed at concentrations above 10 mM [5]. However, some molecules like methylene blue can show deviations at concentrations as low as 10 µM [5]. Empirical investigation on lactate in scattering media like serum and whole blood suggests nonlinearities may become significant, justifying the use of more complex, non-linear models in such matrices, even at physiologically relevant concentrations [11].

Q2: Why does the pH of the solvent cause deviation, and how can I prevent it? A change in pH can alter the electronic structure of a chromophore, leading to a different absorption spectrum [5]. For example, phenol red changes from yellow (absorbing in acidic media) to red (absorbing in basic media) due to an internal proton migration [5]. To prevent this, always use an appropriate pH buffer for both your sample and reference blank solutions to ensure the analyte exists in a single, stable absorbing form [5].

Q3: What is an example of complexation causing a deviation, and how is it identified?

Cobalt chloride is a classic example. In solution, it can exist in a pink form but associates at higher concentrations into a blue complex [5]. This association changes the molar absorptivity. The reaction is an equilibrium:

2 CoCl₂ ⇌ Co(CoCl₄)

(Pink) (Blue)

The degree of association increases with concentration, leading to a deviation from the Beer-Lambert law [5]. This is often identified by a visible color change in the solution at different concentrations.

Q4: Are deviations from the Beer-Lambert law always a problem? Not necessarily. While deviations complicate quantitative analysis, they can also provide valuable insights into the physicochemical behavior of the analyte, such as molecular interactions, equilibrium constants, and aggregation states [11] [5]. Understanding the cause of the deviation can be as important as obtaining the concentration value itself.

Table 1: Threshold Concentrations for Observed Deviations in Common Analytes

| Analyte | Linear Range (Approx.) | Concentration at Deviation | Type of Deviation | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Molecules [5] | < 10 mM | > 10 mM | Positive/Negative | Solute-solvent interactions, hydrogen bonding |

| Methylene Blue [5] | < 10 µM | ~10 µM | Positive | Molecular association/aggregation |

| Lactate (in PBS) [11] | 0-600 mM (see study) | No substantial nonlinearity found | Minimal | High concentration alone was not a primary cause |

| Cobalt Chloride [5] | Low Concentration | Increasing Concentration | Positive | Association (2CoCl₂ ⇌ Co(CoCl₄)) |

Table 2: Summary of Chemical Factors and Mitigation Strategies

| Chemical Factor | Impact on Absorbance | Example | Corrective Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Analyte Concentration [5] | Alters molecular environment & interactions; causes non-proportional A vs. c | Most molecules above 10 mM | Serial dilution into linear range (< 10 mM) |

| pH Change [5] | Shifts acid/base equilibrium; changes chromophore structure | Phenol red, Chromate/Dichromate | Use pH buffer; match blank and sample pH |

| Complexation / Association [5] | Creates new chemical species with different ε | CoCl₂ (Pink to Blue) | Characterize equilibrium; work at dilute concentrations |

Experimental Protocol: Investigating pH-Induced Deviations

Aim: To empirically demonstrate and correct for Beer-Lambert law deviations caused by a pH-sensitive analyte.

Materials:

- Spectrophotometer with visible light source

- Matched pair of cuvettes (e.g., 1 cm path length)

- pH buffer solutions (e.g., pH 4.0, 6.0, and 8.0)

- Analyte stock solution (e.g., phenol red)

- Dilution tubes and pipettes

Method:

- Solution Preparation:

- Prepare three sets of standard solutions of phenol red (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 20 µM) each in a different pH buffer (pH 4.0, 6.0, 8.0).

- Prepare corresponding blank solutions for each pH containing only the buffer.

Absorbance Measurement:

- Using the spectrophotometer, zero the instrument with the pH 4.0 blank.

- Measure the absorbance of each pH 4.0 standard at the wavelength of maximum absorbance (λmax).

- Repeat the zeroing and measurement process for the sets at pH 6.0 and pH 8.0 using their respective blanks.

Data Analysis:

- Plot absorbance versus concentration for each pH set on the same graph.

- Perform linear regression and compare the slopes (which reflect the apparent molar absorptivity, ε) and the linearity (R²) of the three plots.

Expected Outcome: The calibration curves will have different slopes and may show varying degrees of linearity, visually demonstrating that pH alters the absorbing species and can cause deviations if not controlled. This validates the requirement for a buffered system.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Mitigating Chemical Deviations

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| pH Buffer Solutions | Maintains constant proton concentration in sample and blank. | Prevents shifts in acid-base equilibria of the analyte, ensuring a single, stable absorbing form [5]. |

| Optically Matched Cuvettes | Holds sample and reference blank in the light path. | Eliminates artifacts and inaccuracies in absorbance readings due to differences in the cell windows [5]. |

| High-Purity Solvent | Dissolves analyte to prepare stock and standard solutions. | Minimizes interference from impurities that could absorb light or chemically interact with the analyte. |

| Dilution Series Standards | Creates a calibration curve across a range of concentrations. | Empirically defines the linear working range of the assay and helps identify the onset of deviations [5]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my absorbance vs. concentration curve become non-linear at high concentrations? Chemical deviations occur at high concentrations (typically above 10 mM) due to molecular interactions, such as solute-solvent interactions and hydrogen bonding, which alter the absorption characteristics. For some dyes like methylene blue, this can happen at concentrations as low as 10 µM [5].

Q2: My sample is turbid. How does this affect absorbance measurements? Scattering media, such as microalgae suspensions or whole blood, cause significant deviations from the Beer-Lambert law due to light scattering effects. In such cases, the use of complex, nonlinear models like Support Vector Regression (SVR) or Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) may be justified for accurate concentration estimation [12] [13].

Q3: Can my instrument's light source cause measurement errors? Yes, the use of polychromatic light (light with a nonzero spectral width) is a well-known source of systematic error, as the Beer-Lambert law holds strictly for monochromatic light. The deviation magnitude depends on the spectral width and the slope of the molecular extinction coefficient [14].

Q4: What are some design strategies to reduce stray light? Key strategies include: using high-quality, blazed diffraction gratings; making optical system interiors highly absorbing with glossy black paint; employing order-sorting filters; and hiding all mounting brackets and screws that might scatter light. Using apertures and underfilling optical components also helps [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Non-Linear Absorbance

Problem: Positive or negative curvature in the absorbance vs. concentration plot. Solutions:

- Dilute the Sample: Ensure the analyte concentration is within the known linear range for the specific molecule, typically below 10 mM [5].

- Control Chemical Environment: Maintain a constant, specified pH for both blank and sample solutions, as some absorbers (e.g., phenol red) change color with pH [5].

- Use Advanced Modeling: For inherent non-linearity, employ an extended model like ( A = \epsilon' \cdot c^\alpha \cdot l^\beta ), where ( \alpha ) and ( \beta ) are correction coefficients, which has shown superior performance in describing non-linear absorbance [13].

Guide 2: Mitigating Scattering Effects in Suspensions

Problem: Significant deviations in absorbance when measuring scattering samples like cell cultures. Solutions:

- Empirical Model Validation: Compare the performance of linear models (PLS, PCR) against non-linear models (SVR, Random Forests). If non-linear models perform significantly better, it indicates scattering-induced non-linearity is present [12].

- Apply a Scattering-Corrected Model: Use the extended Bouguer-Lambert-Beer model (( A = \epsilon' \cdot c^\alpha \cdot l^\beta )) which can accurately describe absorbance in microalgae suspensions where the classic law fails [13].

Guide 3: Minimizing Instrumental Errors from Polychromatic Light and Stray Light

Problem: Systematic errors due to non-ideal instrument properties. Solutions:

- Validate with Standard: In HPLC/UV, systematic error from polychromatic light depends on ( |c{SAMPLE} - c{STANDARD}| ). Using a standard close to the sample concentration can minimize this error [14].

- Optimize Slit Width: Use the smallest possible entrance and exit slits to reduce the range of wavelengths and stray light [15].

- Ensure Matched Cells: Always use an optically matched pair of measuring cells and match the composition of blank and sample solutions as closely as possible [5].

The following table summarizes key experimental findings on deviations from the Beer-Lambert law.

Table 1: Documented Deviations from the Beer-Lambert Law

| Cause of Deviation | Experimental System | Impact on Absorbance Model | Performance (R²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Concentration [5] | Methylene Blue solutions (>10 µM) | Positive or negative curvature in calibration plot | Non-linear |

| Light Scattering [13] | Phaeodactylum tricornutum & Chlorella vulgaris suspensions | Classic BLB law fails | BLB Law: as low as 0.94 |

| Light Scattering [12] | Lactate in serum and whole blood | Justifies use of non-linear machine learning models | Extended Model: >0.995 [13] |

| Polychromatic Light [14] | HPLC/UV spectrophotometric assay | Systematic errors up to ~4% | Model-dependent |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Verification of Linearity and Scattering Effects

This protocol is adapted from investigations into lactate and microalgae suspensions [12] [13].

Objective: To test the validity of the Beer-Lambert law and its extended model for a given sample type by simultaneously varying concentration and path length.

Materials:

- Potassium dichromate solution or microalgae suspension (Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Chlorella vulgaris)

- Series of calibrated cuvettes with path lengths (e.g., 1 cm, 0.5 cm, 0.2 cm, 0.1 cm)

- UV-Vis Spectrophotometer

- Calibrated balances and volumetric flasks

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare samples with a range of concentrations. For instance, dilute a stock solution to create a series where the product of concentration and path length ((c \cdot l)) is constant across different path lengths.

- Absorbance Measurement: Measure the absorbance of each sample at each available path length.

- Data Fitting: Fit the collected data (absorbance, concentration, path length) to both the classical Beer-Lambert law ((A = \epsilon \cdot c \cdot l)) and the extended model ((A = \epsilon' \cdot c^\alpha \cdot l^\beta)).

- Model Comparison: Compare the correlation coefficient (R²) and root mean square error of the two models to determine which more accurately describes the system.

Protocol 2: Isolating the Effect of High Concentrations

This protocol is based on an empirical investigation of lactate in buffer solutions [12].

Objective: To determine if high analyte concentration alone introduces significant non-linearity.

Materials:

- Phosphate Buffer Solution (PBS)

- Analyte (e.g., lactate)

- UV-Vis or NIR Spectrophotometer

Method:

- Dataset Creation: Generate a dataset by varying the analyte concentration in PBS over a very wide range (e.g., 0–600 mmol/L).

- Model Training and Validation: Fit both linear (e.g., PLS, PCR) and non-linear (e.g., SVR with non-linear kernels) models to the spectral data.

- Performance Comparison: Use cross-validation to compare model performance metrics (e.g., RMSECV, R²). If non-linear models do not perform substantially better, it suggests high concentration alone may not be the primary source of non-linearity.

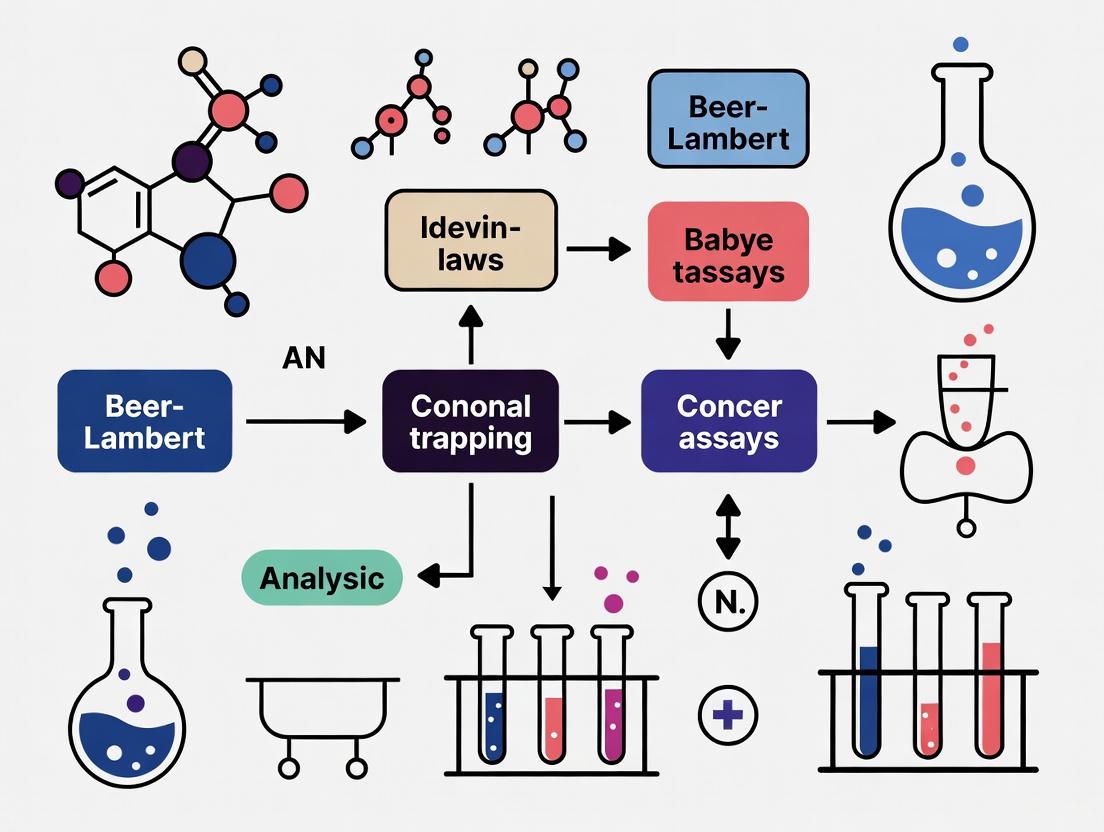

Experimental Workflow and Factor Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the key instrumental and physical factors discussed and their impact on absorbance measurements.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials used in the experiments cited in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Research Materials and Their Functions

| Material/Reagent | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Potassium Dichromate Solution [13] [5] | A standard reference material used to validate spectrophotometric linearity and study chemical deviations (e.g., chromate-dichromate equilibrium). |

| Microalgae Suspensions (Phaeodactylum tricornutum, Chlorella vulgaris) [13] | Used as a model scattering medium to investigate significant deviations from the Beer-Lambert law caused by light scattering. |

| Phosphate Buffer Solution (PBS) [12] | Provides a non-scattering matrix to isolate and study the effects of high analyte concentration without interference from scattering particles. |

| Human Serum & Whole Blood [12] | Representative complex, scattering biological matrices used to test the performance of analytical models in real-world applications. |

Identifying Positive and Negative Deviations from Calibration Curves

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Negative Deviations from Beer-Lambert Law

Problem: A calibration curve shows a negative intercept, where the best-fit line crosses the y-axis below zero.

Explanation: A negative intercept suggests your instrument signal (e.g., absorbance) is lower than expected at low concentrations. This is a negative deviation from the ideal Beer-Lambert behavior, which expects a line passing through the origin (0,0) [16].

Primary Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: High concentration range or non-linear detector response.

- Symptoms: Negative intercept occurs when calibrating over a very wide range (e.g., three orders of magnitude). The detector may not respond linearly across the entire range [16].

- Solution: Restrict the calibration range to where the detector response is known to be linear. Avoid extrapolating concentrations below your lowest calibration point.

Cause 2: Error in preparation of standard solutions.

- Symptoms: Negative intercept for one specific analyte when multiple analytes are run from the same mixture; other analytes may show normal curves [16].

- Solution: Re-prepare the stock and standard solutions, checking for calculation or dilution errors. Use a fresh stock solution if possible.

Cause 3: Constant background noise or bias.

- Symptoms: The intercept is a significant value compared to the signals of your lower calibration points [16].

- Solution: Investigate instrumental background signals. Run and subtract a proper reagent blank. Check for impurities in solvents or cuvettes.

Note: Do not automatically force the regression line through the origin, as this can mask a real problem with your analysis [16].

Guide 2: Diagnosing Positive Deviations (Curvature) from Beer-Lambert Law

Problem: The calibration plot of absorbance versus concentration is not a straight line but curves upward or downward, deviating from linearity.

Explanation: The Beer-Lambert Law assumes a perfectly linear relationship. Real-world factors can cause positive deviations, where the absorbance is higher than predicted, or a loss of linearity [17] [14].

Primary Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Use of polychromatic light.

- Symptoms: Systematic error that is independent of absorption magnitude; can occur even at absorbances <1 [14].

- Solution: Use a spectrophotometer with a narrower spectral bandwidth or a more monochromatic light source (e.g., a laser). Ensure the wavelength is set to the maximum absorbance (λmax) of the analyte.

Cause 2: Chemical interactions of the analyte.

- Symptoms: Curvature is more pronounced at high concentrations.

- Solution:

Cause 3: Stray light or instrumental limitations.

The flowchart below outlines the systematic diagnostic process for both negative and positive deviations:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My calibration curve has a correlation coefficient (r) of 0.999. Does this guarantee it is linear and accurate?

No. A high correlation coefficient alone is not sufficient to prove linearity [18]. A curve with a subtle but consistent bend can still have an r value very close to 1. You must also perform a visual inspection of the residuals (the differences between the measured data points and the fitted line). A random pattern of residuals suggests a good fit, while a curved pattern indicates a lack-of-fit, meaning a non-linear model might be more appropriate [18].

FAQ 2: When should I use a weighted linear regression for my calibration curve?

You should consider a weighted regression when your calibration spans a wide concentration range and the variance (or standard deviation) of your instrument response is not constant across that range [18]. This is common in techniques like LC-MS/MS. If the scatter of your data points is greater at high concentrations than at low concentrations (a phenomenon called heteroscedasticity), an unweighted regression will be unduly influenced by the high-concentration points, leading to inaccurate concentration predictions for low-level samples. Weighting (e.g., 1/x or 1/x²) counteracts this [18].

FAQ 3: Is it ever acceptable to force my calibration curve through the origin (0,0)?

Generally, no. Forcing the curve through the origin is not recommended without a strong statistical and chemical justification [18] [16]. A non-zero intercept often reveals a real, underlying issue in your method, such as a constant background signal from impurities or the solvent, which should be investigated and corrected. Artificially setting the intercept to zero can bias all your subsequent concentration calculations [16].

The following table summarizes common types of deviations, their quantitative impact, and acceptable limits based on analytical guidelines.

Table 1: Summary of Calibration Curve Deviations and Criteria

| Deviation Type | Typical Quantitative Impact | Acceptance Criteria & Validation Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Intercept | Significant when intercept is large relative to low-standard signals [16]. | The intercept should not be statistically different from zero. Back-calculated standard concentrations should be within ±15% of nominal (±20% at LLOQ) [18]. |

| Non-Linearity (Curvature) | Systematic errors up to ~4% due to polychromatic light, independent of absorption magnitude [14]. | Assessed by lack-of-fit test and residual plots. A linear model is preferred if it adequately describes the concentration-response [18]. |

| Correlation Coefficient (r) | N/A | Should be submitted, but a value close to 1 is not sufficient evidence of linearity. Must be supported by residual analysis [18]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Verification of Beer-Lambert Law Linearity and Detection of Deviations

This protocol allows you to experimentally verify the linear range of your assay and identify deviations.

Methodology:

- Preparation of Standards: Prepare a series of at least 5-8 standard solutions of the analyte in the same matrix as your samples. The concentrations should span the entire expected range, from below the quantitation limit to the upper limit [18].

- Instrumental Analysis: Measure the instrument response (e.g., absorbance) for each standard solution. Perform each measurement in replicate (at least three times) to assess precision [18].

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the average response (y-axis) against the concentration (x-axis).

- Perform a linear regression to obtain the best-fit line, slope, intercept, and correlation coefficient.

- Create a residual plot: Plot the residuals (observed Y - calculated Y) against the concentration [18].

- Interpretation:

- Ideal/Linear: The data points lie on a straight line, and the residual plot shows a random scatter of points around zero.

- Deviation Detected: The response curve shows curvature, and/or the residual plot shows a clear, non-random (e.g., U-shaped) pattern [18].

Protocol 2: Troubleshooting a Negative Intercept in GC-ECD Analysis

This specific protocol is based on a case study for troubleshooting a negative intercept in Gas Chromatography with an Electron Capture Detector (GC-ECD) [16].

Methodology:

- Verify Individual Analyte Behavior: Check if the negative intercept occurs for only one specific analyte or for all analytes in the mixture. If it is isolated to one, the problem is likely specific to that compound's standards [16].

- Re-prepare Stock Solution: The most common cause for a single-analyte issue is an error in preparing the stock solution. Accurately prepare a fresh stock solution of the problematic analyte [16].

- Re-run Calibration: Serially dilute the new stock solution to create fresh calibration standards and re-run the calibration series.

- Check Instrument Background: If the problem persists, inject a pure solvent blank to check for any system peaks or contaminants that might be causing a constant negative bias in the signal [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Reliable Calibration Curves

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Analytical Standards | Certified reference materials ensure accurate known concentrations for calibration, minimizing one of the largest potential sources of error. |

| Appropriate Solvent/Matrix Blank | A blank prepared in the same matrix (e.g., plasma, solvent) as the standards and samples is essential for correcting background signal and verifying the absence of interference [18]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Independently prepared samples at low, medium, and high concentrations within the calibration range. They are used to verify the accuracy and precision of the method during validation and routine analysis [18]. |

| Certified Volumetric Glassware | Using Class A pipettes and flasks ensures that volumes are delivered and contained with the highest possible accuracy, which is critical for precise serial dilutions. |

| Standard Cuvettes | Using cuvettes with a consistent and known path length (typically 1.00 cm) is critical because absorbance is directly proportional to path length (A = εbc) [9] [3]. |

| Covidcil-19 | Covidcil-19, MF:C16H14N4O2, MW:294.31 g/mol |

| SP-471 | SP-471, MF:C33H26BrN5, MW:572.5 g/mol |

Quantitative Data on Linear Range Thresholds

The following table summarizes key findings from empirical investigations into concentration thresholds where deviations from the Beer-Lambert law begin to manifest.

Table 1: Documented Concentration Thresholds for Beer-Lambert Law Linearity

| Analyte | Matrix/Solvent | Concentration Range Studied | Observed Threshold for Deviation | Key Experimental Condition | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Absorbing Molecules | Various Solvents | - | ~10 mM (Typical) | Varies with molecular polarizability | [19] [5] |

| Methylene Blue | Aqueous Solution | - | ~10 µM (Early Deviation) | Specific solute-solvent interactions | [5] |

| Lactate | Phosphate Buffer Solution (PBS) | 0 - 600 mmol/L | No substantial nonlinearities up to 600 mmol/L | NIR Spectroscopy | [11] |

| SOâ‚‚ | Gas Cell (UV Region) | Varying total column density | Deviation increases with total column density | Spectral resolution: 0.1 nm, 0.3 nm, 0.5 nm | [20] |

| Phthalocyanine Ligand | Solvents of varying polarity | 1×10â»â¶ – 5×10â»â´ mol/L | Deviation via specific association | Non-polar solvents lead to H-aggregates | [21] |

| NO | Gas (230 nm wavelength) | - | ~6 mg/m² | - | [20] |

| NH₃ | Gas (230 nm wavelength) | - | ~36 mg/m² | - | [20] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Establishing a Linear Concentration Range

This protocol allows researchers to empirically determine the concentration threshold for Beer-Lambert law adherence for their specific analyte-instrument system [22] [20].

Key Materials:

- Stock solution of the analyte of known, high concentration.

- Appropriate solvent for serial dilution.

- Spectrophotometer or microplate reader.

- Matched cuvettes or appropriate microplates (e.g., transparent for absorbance).

Methodology:

- Wavelength Selection: Identify the wavelength of maximum absorbance (λmax) for your analyte by running an absorbance spectrum scan. If the species is well-known, consult literature for its established λmax and molar absorptivity (ε) [22].

- Standard Curve Generation:

- Prepare a blank using the pure solvent or buffer.

- Serially dilute the stock solution to create a series of standards (typically 5-8) that span a wide concentration range, from very low to the maximum solubility or expected experimental range.

- Zero the instrument with the blank.

- Measure the absorbance of each standard at the selected λmax.

- Data Analysis and Threshold Determination:

- Plot the measured absorbance (y-axis) against the corresponding concentration (x-axis).

- Perform a linear regression analysis. The Beer-Lambert law dictates that this plot should be a straight line passing through the origin (A = εbc) [22].

- Visually and statistically inspect the plot. The concentration at which the data points begin to consistently deviate from the linear regression line represents the practical threshold concentration for your system.

- For high-precision work, use statistical tests (e.g., residual analysis) to objectively identify the point of nonlinearity.

Protocol for Investigating Scattering Media

This protocol is adapted from empirical investigations into nonlinearities caused by scattering matrices, such as biological fluids [11].

Key Materials:

- Analyte of interest (e.g., lactate).

- Series of increasingly scattering matrices: e.g., Phosphate Buffer Solution (PBS) -> Human Serum -> Whole Blood.

- Spectrophotometer equipped with appropriate light source (NIR, mid-IR).

- Equipment for in vivo transcutaneous measurement (if applicable).

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Spike a constant, physiologically relevant concentration of your analyte into each matrix type (PBS, serum, whole blood). Ensure the concentration is within the linear range previously established in a clear solution.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire optical spectra (e.g., NIR, mid-IR) for all samples.

- Predictive Modeling:

- Fit both linear (e.g., Partial Least Squares - PLS, Principal Component Regression - PCR) and nonlinear (e.g., Support Vector Regression with nonlinear kernels, Random Forests) models to the spectral data from each matrix.

- Use cross-validation to evaluate and compare the performance (e.g., using RMSECV - Root Mean Square Error of Cross-Validation) of linear versus nonlinear models for each dataset [11].

- Interpretation: A significant and consistent improvement in the predictive performance of nonlinear models over linear models for a specific matrix (e.g., whole blood) is strong empirical evidence that scattering-induced nonlinearities are present and meaningful for that medium [11].

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

FAQ: Why does my absorbance vs. concentration curve bend at high concentrations?

This positive or negative deviation from linearity can be caused by several factors:

- Chemical Interactions: At high concentrations, solute molecules interact with each other, which can alter their absorptivity. This includes phenomena like dimerization or aggregation [21] [5]. The solvent environment around each molecule changes, affecting its ability to absorb light [19].

- Instrumental Limitations: The Beer-Lambert law assumes perfectly monochromatic light. Real instruments use a band of wavelengths. At very high absorbances, where the analyte absorbs strongly across a range of wavelengths, this polychromaticity can cause deviations [20] [5]. Stray light is another common contributor [5].

- Scattering and Reflection: In non-ideal, turbid media like blood or cell lysates, light is not only absorbed but also scattered. This scattering effectively increases the path length the light travels, leading to higher-than-expected absorbance readings [11] [23]. Reflection and interference effects at cuvette surfaces can also play a role [19].

FAQ: My sample is highly scattering (e.g., whole blood). How can I accurately determine concentration?

For highly scattering media, the classical Beer-Lambert law is often insufficient. You should employ:

- Modified Beer-Lambert Law (MBLL): This version incorporates a Differential Pathlength Factor (DPF) to account for the increased path length due to scattering. The form is

OD = -log(I/I₀) = DPF ⋅ μa ⋅ dio + G, whereDPFis the factor,μais the absorption coefficient,diois the inter-optode distance, andGis a geometry-dependent factor [23]. - Nonlinear Machine Learning Models: As explored in the experimental protocol, models like Support Vector Regression (SVR) with nonlinear kernels or Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) can model the complex relationship between spectra and concentration in scattering media more effectively than linear models like PLS [11].

- Chemical Separation or Dilution: If feasible, precipitating or removing scattering components (like cells from blood), or diluting the sample into a linear range in a clear buffer can restore linearity, provided the analyte concentration remains detectable [24].

FAQ: I am working with a new compound. How can I quickly check if my assay is in the linear range?

- Perform a Serial Dilution: This is the most direct method. Prepare your sample at the expected concentration, then serially dilute it 2-fold for 3-4 steps. Measure the absorbance of all dilutions. If the relationship is linear, the absorbance should halve with each dilution. Any significant deviation indicates you are outside the linear range [22].

FAQ: What are the best practices to minimize deviations in my absorbance measurements?

- Use Matched Cuvettes: Always use an optically matched pair of cuvettes for the sample and blank to avoid artifacts from differences in glass [5].

- Maintain Consistent pH and Solvent: Ensure the pH and solvent composition of your blank and standards are identical, as these can affect the analyte's absorptivity and chemical form [5].

- Avoid High Concentrations: Whenever possible, dilute your samples to fall within the empirically determined linear range for your analyte-instrument system [5].

- Verify Wavelength Purity: Use the narrowest bandwidth setting on your monochromator that provides a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio to best approximate monochromatic light [20].

Visual Guides

Diagram 1: Conceptual Breakdown of Beer-Lambert Linearity

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Threshold Determination

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Reliable Absorbance Assays

| Item | Function / Rationale | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Optically Matched Cuvettes | Hold sample and blank for measurement. | Ensure pathlength is identical and known. Mismatched cuvettes cause significant baseline errors [5]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Dissolve analyte and prepare blank. | Must be transparent at the measurement wavelength and free of fluorescent contaminants or absorbing impurities. |

| pH Buffers | Maintain constant chemical environment. | Critical for analytes whose absorption changes with pH (e.g., phenol red) [5]. |

| Cyclic Olefin Copolymer (COC) Plates | For UV absorbance below 320 nm. | Standard polystyrene plates absorb strongly in deep UV; COC is transparent, essential for DNA/RNA quantification (A260) [25]. |

| Hydrophobic Microplates | Minimize meniscus formation in microplate assays. | A meniscus alters the effective path length, distorting absorbance readings and concentration calculations [25]. |

Modern Correction Strategies: From Traditional Dilution to Machine Learning

Establishing a Robust Linear Range with Serial Dilution Protocols

The linear range of an analytical procedure is the concentration interval over which the method can obtain test results directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in the sample [26]. Establishing this range is fundamental in pharmaceutical analysis, clinical diagnostics, and biomedical research, as it ensures the reliability of quantitative measurements.

The theoretical foundation for this linear relationship is often based on the Beer-Lambert Law (also called the Beer-Bouguer-Lambert Law) [2]. This law states that the absorbance (A) of a solution is directly proportional to the concentration (c) of the absorbing species and the path length (l) of the light through the solution, expressed as (A = \varepsilon l c), where (\varepsilon) is the molar absorptivity coefficient [22] [2].

However, this relationship is an idealization, and deviations from the Beer-Lambert Law are common in practice. These deviations can arise from factors such as the use of polychromatic light sources, very high analyte concentrations, and measurements in highly scattering media like serum or whole blood [11] [19] [14]. Therefore, establishing a robust linear range through systematic serial dilution is not merely a regulatory formality but a critical scientific procedure to ensure data integrity.

Serial Dilution Protocols for Linear Range Establishment

Serial dilution is a step-wise series of dilutions where the dilution factor remains constant for each step [27]. It is a cornerstone technique for preparing a range of analyte concentrations from a stock solution.

Core Protocol: 2-Fold and 10-Fold Serial Dilutions

The two most common serial dilution methods are 2-fold and 10-fold dilutions. The choice depends on the application's required precision and the expected concentration range.

- 10-Fold Serial Dilution: This method involves diluting one part of the sample with nine parts of diluent. It is ideal for rapidly reducing a high concentration to a more manageable level over a broad range [27].

- 2-Fold Serial Dilution: This method involves mixing equal volumes of the sample and the diluent. It provides a higher resolution of concentrations within a specific range and is preferred for experiments requiring greater precision, such as determining the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of an antimicrobial drug [27].

The workflow for a generic serial dilution is as follows:

Calculations for Serial Dilution

Accurate calculations are essential for a successful serial dilution. The following equations are used [27]:

- Transfer Volume: ( \text{Transfer Volume} = \frac{\text{Final Volume}}{\text{Dilution Factor}} )

- Diluent Volume: ( \text{Diluent Volume} = \text{Final Volume} - \text{Transfer Volume} )

- Final Dilution Factor: ( \text{Final Dilution Factor} = (\text{Dilution Factor})^{\text{Number of Steps}} )

For example, to set up a 5-step 2-fold serial dilution in a final volume of 1 mL:

- Transfer Volume = 1 mL / 2 = 0.5 mL

- Diluent Volume = 1 mL - 0.5 mL = 0.5 mL

- Final Dilution Factor of the fifth tube = ( 2^5 = 32 )

Troubleshooting Beer-Lambert Law Deviations

Deviations from linearity can compromise analytical results. The following table summarizes common causes and their solutions.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Beer-Lambert Law Deviations

| Issue | Underlying Cause | Symptoms | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polychromatic Light Source [19] [14] | Assay beam has nonzero spectral width (( \Gamma )) and interacts with a region where the molar absorptivity (( \varepsilon )) is changing. | Absorbance reads lower than expected; non-linearity even at moderate absorbances. | Use a instrument with a narrower bandwidth; select an analyte's absorbance peak where ( \frac{d\varepsilon}{d\omega} ) is minimal. |

| High Analyte Concentration [11] [19] [28] | At high concentrations, solute molecules interact, changing their absorptivity. Refractive index changes can also cause deviations. | Curve flattens and plateaus at high concentrations; negative deviation from linearity. | Dilute samples to fall within the validated linear range; focus on weaker absorption bands for analysis [19]. |

| Scattering Media [11] | Media like whole blood or turbid solutions scatter light, leading to path length uncertainty and additional signal loss. | Non-linear response, particularly in biological matrices like serum and blood. | Use nonlinear machine learning models (e.g., SVR with RBF kernel) for calibration; apply scattering correction algorithms. |

| Chemical & Instrumental Factors [28] | Stray light, improper calibration, chemical reactions (association, dissociation), or fluorescence. | Curvature in the calibration plot, poor fit, y-intercept significantly non-zero. | Use high-quality cuvettes; ensure instrument is calibrated; use chemically stable analytes in a suitable solvent. |

Workflow for Investigating Linearity Issues

The following diagram provides a logical pathway for diagnosing and addressing linearity problems.

Data Analysis and Validation of the Linear Range

Key Parameters for Validation

Once serial dilutions are prepared and measured, the data must be rigorously analyzed. According to ICH guidelines, the linearity of an analytical procedure is its ability to yield results directly proportional to analyte concentration [26] [29].

- Correlation Coefficient (R²): While widely used, R² alone is insufficient as it only measures the fitting correlation and suffers from heteroscedasticity. A value of R² ≥ 0.997 is often considered acceptable [26] [29].

- Y-Intercept: The absolute value of the y-intercept from the linear regression should be as small as possible. A line passing through the origin indicates a perfect proportional relationship [29].

- Visual Inspection: The calibration plot should be visually linear across the claimed range without systematic curvature.

Advanced Method: Double Logarithm Linear Fitting

A more robust method for validating the linearity of results (sample dilution linearity) involves a double logarithm function linear fitting [29]. This method directly tests the proportionality between the theoretical (or dilution factor) and measured concentrations.

- Principle: For a perfectly proportional relationship (y = kx), taking the logarithm of both sides gives ( \log(y) = \log(k) + \log(x) ), which is a straight line with a slope of 1.

- Procedure:

- Take the logarithms (same base) of both the theoretical concentrations (or dilution factors) and the back-calculated measured concentrations.

- Perform a least-squares linear regression on the log-transformed data.

- The slope of this log-log plot indicates the proportionality. A slope of 1 indicates a directly proportional relationship, a slope of -1 indicates an inversely proportional relationship, and a slope of 0 indicates no relationship [29].

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Linear Range Studies

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Stock Solution (Analyte) | The concentrated solution of the target analyte used as the starting material for all serial dilutions. |

| Appropriate Diluent | The solvent used to dilute the stock solution. It must not react with the analyte and should be compatible with the sample matrix (e.g., culture medium for cells) [27]. |

| Blank Solution | A solution containing all components except the analyte, used to zero the spectrophotometer and establish a baseline absorbance [22]. |

| Calibration Standards | A series of solutions with known concentrations of the analyte, prepared via serial dilution, used to construct the standard curve. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between linearity and range? A: Linearity is the ability of a method to produce results proportional to analyte concentration, demonstrating the quality of the relationship. The Range is the interval between the upper and lower concentration levels for which suitable precision, accuracy, and linearity have been demonstrated, defining the span of usable concentrations [26].

Q2: Why does my calibration curve have a good R² value but the y-intercept is far from zero? A: A high R² only indicates a strong correlation, not necessarily a proportional relationship. A large y-intercept suggests a constant systematic error, such as a background signal from the matrix or an instrumentation offset. The linear regression has compensated for this by shifting the line away from the origin [29]. You should investigate your blank and sample preparation procedure.

Q3: How many concentration levels should I use for a linearity study? A: A minimum of five to six concentration levels is recommended to adequately define the linear range [26]. For example, a study might include levels at 50%, 70%, 100%, 130%, and 150% of the target specification.

Q4: My samples are in a scattering medium like blood. Can I still use a linear model? A: Empirical evidence suggests that nonlinearities are often present in scattering media [11]. In such cases, a linear model like PLS may be insufficient. Justify the use of more complex, nonlinear machine learning models like Support Vector Regression (SVR) with nonlinear kernels, which can model these complex relationships more effectively [11].

Q5: What are the main limitations of serial dilutions? A: The primary limitations are reproducibility and error accumulation. Slight pipetting errors or inaccuracies accumulate over each dilution step, making the highest dilutions the least accurate and precise [27]. Using calibrated, well-maintained pipettes and proper technique is critical.

Sample and Solvent Matrix Matching to Minimize Chemical Interferences

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is a sample matrix, and what are matrix effects?

The matrix includes all components of a sample other than the analyte you are trying to measure. According to IUPAC, the matrix effect is the "combined effect of all components of the sample other than the analyte on the measurement of the quantity" [30]. In practice, this means that substances in the sample (such as proteins, fats, salts, or other chemicals) can interfere with the assay, leading to inaccurate concentration readings [31] [32]. This interference can either suppress or enhance the analytical signal [32].

Why is matrix matching crucial for assays based on the Beer-Lambert Law?

The Beer-Lambert Law (A = εcl) establishes a direct relationship between absorbance (A) and analyte concentration (c) [22]. This law assumes a perfect, interference-free system. However, in real-world samples, matrix components can alter the absorbance, causing significant deviations from the law's linear relationship [33] [19]. Matrix matching minimizes these chemical interferences by ensuring that the standards used for calibration experience the same matrix effects as the unknown samples, leading to more accurate and reliable concentration measurements [30].

How can I detect and quantify matrix effects in my experiment?

A common and effective method is the post-extraction spike experiment [32]. This involves comparing the signal of your analyte in a pure solvent to its signal when added to a pre-processed sample matrix.

Protocol for Assessing Matrix Effects:

- Prepare a calibration curve of your analyte in a pure solvent.

- Take several aliquots of your sample matrix (e.g., milk, serum) and process them through your entire extraction and cleanup procedure.

- After processing, "spike" these blank matrix samples with known concentrations of your analyte.

- Analyze these spiked matrix samples and plot a second calibration curve based on their signals.

- Compare the slopes of the two calibration curves using the following formula [32]:

Interpretation of Results:

| ME% Value | Interpretation | Effect on Assay |

|---|---|---|

| ≈ 0% | No significant matrix effect | Accurate quantification is likely. |

| < -20% | Signal Suppression | Reported concentrations may be falsely low. |

| > +20% | Signal Enhancement | Reported concentrations may be falsely high [32]. |

What are the main strategies for minimizing matrix interference?

Several practical strategies can be employed to manage matrix effects:

- Sample Dilution: Diluting the sample with an appropriate buffer can reduce the concentration of interfering components below a critical level. The optimal dilution factor must be determined experimentally [34] [35].

- Matrix-Matched Calibration: This is considered a gold-standard approach. Instead of using solvent-based standards, you prepare your calibration standards in the same blank matrix as your unknown samples (e.g., drug-free plasma, extracted food samples) [31] [30] [35]. This ensures that the calibration curve and the samples experience identical matrix effects.

- Standard Addition Method (SAM): This involves spiking the sample itself with increasing known amounts of the analyte and plotting the signal response. While highly effective, it can be more sample- and time-consuming, especially for complex mixtures [30].

- Improved Sample Preparation: Techniques such as protein precipitation, solid-phase extraction (SPE), or filtration can remove interfering matrix components before analysis [31].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Matrix-Matched Calibration for HPLC Analysis

This protocol outlines the steps to create and use matrix-matched standards for the accurate quantification of an analyte, such as an antibiotic in milk, using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) [31].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Blank Matrix: A sample identical to your test samples but known to be free of the analyte (e.g., drug-free milk or serum) [31].

- Analyte Standard: A pure reference standard of the compound you are quantifying.

- Extraction Solvents: Such as acetonitrile for protein precipitation [31].

- Centrifuge and Filtration Units: For sample cleanup (e.g., 0.22 µm PVDF syringe filters) [31].

- HPLC System: Equipped with a suitable column (e.g., C18) and detector [31].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Preparation of Matrix-Matched Calibration Standards:

- Take a volume of your blank matrix (e.g., 2 mL of milk) and add known concentrations of your analyte standard to create a series of calibration levels (e.g., low, medium, high) [31].

- Process these spiked standards through the entire sample preparation workflow alongside your unknown samples.

Sample Preparation:

- Protein Precipitation: Add a precipitating solvent like acetonitrile to the sample (e.g., 4 mL to 2 mL of milk). Mix thoroughly [31].

- Incubation: Stir and/or sonicate the mixture for a defined period (e.g., 20 minutes) to ensure complete interaction [31].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the samples at high speed (e.g., 5180 rpm for 15 minutes) to pellet the precipitated proteins and other solids [31].

- Filtration: Carefully collect the supernatant and pass it through a fine filter (e.g., 0.22 µm PVDF syringe filter) to ensure it is particle-free before injection into the HPLC system [31].

Instrumental Analysis and Quantification:

- Inject the processed matrix-matched standards and unknown samples into the HPLC system.

- Plot the peak area (or height) of the analyte from the standards against their known concentrations to create your matrix-matched calibration curve.

- Use the equation of this curve to calculate the concentration of the analyte in your unknown samples.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Blank Matrix | Serves as the foundation for matrix-matched calibration standards. | Drug-free milk, serum, or plasma [31]. |

| Analyte Standard | The pure reference material used to prepare calibration standards and spike samples for recovery experiments. | Ceftiofur crystalline-free acid for antibiotic analysis [31]. |

| Protein Precipitant | Removes proteins from biological matrices, clarifying the sample and reducing interference. | Acetonitrile is commonly used [31]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Selectively purifies and concentrates the analyte, removing a wide range of matrix interferents. | C18-bonded silica cartridges for reversed-phase extraction. |

| Internal Standard (IS) | A compound added in a constant amount to all samples and standards to correct for variability in sample preparation and instrument response. | Stable-isotope-labeled analogs of the analyte are ideal for mass spectrometry [31]. |

| Acid/Base for pH Adjustment | Used to disrupt analyte-matrix interactions or to optimize the chemical environment for extraction or analysis. | Hydrochloric acid (HCl) for acid dissociation of target complexes in immunoassays [36]. |

| 6"'-Deamino-6"'-hydroxyparomomycin I | 6"'-Deamino-6"'-hydroxyparomomycin I, MF:C23H44N4O15, MW:616.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Anticancer agent 220 | Anticancer agent 220, MF:C22H19Cl3N2O6, MW:513.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualizing the Impact of Matrix Matching

The following diagram illustrates how matrix-matched calibration corrects for signal suppression or enhancement, ensuring the calibration curve accurately reflects the relationship between concentration and signal in the sample matrix.

The Beer-Lambert Law is a fundamental principle in analytical chemistry that establishes a linear relationship between the absorbance of light and the concentration of an absorbing species in a solution [9]. This relationship is mathematically expressed as ( A = \epsilon l c ), where ( A ) is the absorbance, ( \epsilon ) is the molar absorptivity, ( l ) is the path length, and ( c ) is the concentration [9]. However, this law exhibits significant deviations from linearity under real-world experimental conditions, including at high analyte concentrations, in highly scattering media, or when using non-monochromatic light sources [10] [20] [5]. These limitations pose substantial challenges for researchers and professionals in drug development who require precise concentration measurements.

Advanced computational methods, particularly machine learning (ML) models like ridge regression, now offer powerful alternatives to traditional calibration curves. By learning complex relationships between spectral data and concentration that exist beyond the linear regime of the Beer-Lambert law, these models enable accurate quantification even in the presence of classical deviations [10] [11]. This technical support center provides a comprehensive guide to implementing these computational solutions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary causes of deviation from the Beer-Lambert law that ML models can address? ML models are particularly effective at addressing deviations caused by:

- High Analyte Concentrations: At high concentrations, solute-solute interactions alter the sample's absorption characteristics and refractive index, leading to fundamental deviations [33].

- Scattering Media: Biological matrices like serum and whole blood scatter light, violating the law's assumption of a non-scattering, homogeneous medium [11].

- Chemical Equilibria: Changes in pH or concentration can shift chemical equilibria (e.g., chromate-dichromate), changing the absorption spectrum [5].

- Polychromatic Light: The law assumes perfectly monochromatic light. Real-world instruments use a band of wavelengths, and the additivity of polychromatic light intensity can cause instrumental deviations [20].

Q2: Why choose ridge regression over other machine learning models for concentration estimation? Ridge regression is a linear model enhanced with L2 regularization [10]. It is especially well-suited for spectroscopic data because it efficiently handles multicollinearity, where absorbance values at different wavelengths are highly correlated. The regularization component prevents overfitting—a critical concern with datasets that have a high number of wavelengths (variables) relative to a small number of samples [10]. It often provides a robust baseline model that is simpler to implement and interpret than more complex nonlinear models.

Q3: When should I consider using nonlinear machine learning models? Nonlinear models such as Support Vector Regression (SVR) with non-linear kernels or Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) become advantageous when the relationship between spectral data and concentration is inherently nonlinear. Empirical evidence suggests this is often the case in highly scattering media, such as whole blood or in transcutaneous measurements [11]. If a well-tuned linear model like ridge regression delivers unsatisfactory performance, it indicates that nonlinearities in your data may be significant enough to justify the additional complexity of these models [11].

Q4: How do I prepare image-based data for a ridge regression model? The process involves converting visual information into a numerical format:

- Image Capture: Standardize the setup—use a fixed background, consistent distance from the sample, and controlled lighting [10].

- Pre-processing: Convert the high-resolution image to a grayscale array (e.g., downsampling to 20x20 pixels) [10].

- Data Vectorization: Flatten the 2-dimensional grayscale image array into a single row of data, where each pixel's intensity becomes a feature [10].

- Dataset Creation: Combine the vectorized data from all images into a single data matrix, which is used to train the ridge regression model [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Model Performance Issues

| Problem Description | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor prediction accuracy on both training and test data. | Insufficient model complexity for nonlinear data. | Transition to a nonlinear model like SVR with an RBF kernel or a Neural Network [11]. |

| Model performs well on training data but poorly on unseen test data (Overfitting). | High model complexity; too many features (wavelengths) without enough samples. | Increase the regularization strength (alpha) in ridge regression. Simplify the model or use feature selection to reduce the number of input wavelengths [10]. |

| High error even with a nonlinear model. | Suboptimal hyperparameters (e.g., kernel scale, error tolerance). | Implement a nested cross-validation routine with a Bayesian optimizer to automatically tune hyperparameters [11]. |

Data Quality and Pre-processing Issues

| Problem Description | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High correlation between features (Multicollinearity). | Absorbance values at adjacent wavelengths are naturally highly correlated. | This is a strength of ridge regression, as it is designed to handle multicollinearity. Ensure regularization is applied [10]. |

| Inconsistent results from image-based data. | Variations in lighting, camera angle, or sample container. | Create a standardized imaging setup: fixed background, controlled distance from the sample, and consistent camera settings (magnification, focus) [10]. |

| Low signal-to-noise ratio in spectral data. | Instrument noise or a low concentration of the target analyte. | Use a spectrometer with better sensitivity. Increase the number of scans to average out noise, or ensure samples are within the optimal concentration range for the instrument. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Developing a Ridge Regression Model for Concentration Assays

This protocol outlines the steps to create a machine learning model for predicting chemical concentration, using potassium dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) as an example [10].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) / Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄) | Ideal colored compounds for testing the model; their concentrated solutions deviate from the Beer-Lambert law [10]. |

| Distilled Water | Provides a chemically inert solvent to prevent unwanted reactions during solution preparation [33]. |

| Smartphone or Digital Camera | Acts as a low-cost detector for image-based data collection in a point-and-shoot strategy [10]. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | The gold-standard instrument for validating model predictions and generating traditional absorbance data [33]. |

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a stock solution of Kâ‚‚Crâ‚‚O₇ (e.g., 1.0 x 10â»Â² M) by dissolving 0.74 g in 250 mL of distilled water [10].

- Using the molarity equation, perform a serial dilution to create a wide range of standard concentrations (e.g., from 5.0 x 10â»âµ M to 7.0 x 10â»Â³ M). This range should cover both the linear and nonlinear regimes of the Beer-Lambert law [10].

- Data Acquisition (Image-Based):

- Place 3 mL of each standard solution in identical test tubes (e.g., 1.2 cm diameter).

- Use a standardized imaging setup: a white background, a fixed distance (e.g., 30 cm), and consistent camera settings (e.g., 5x magnification) [10].

- Capture an image for each concentration. A robust model may require 100+ images for training [10].

- Data Pre-processing:

- Use a bulk image cropping tool to convert all images to a lower, uniform resolution (e.g., 20 x 20 pixels) [10].

- In a Python environment (e.g., Google Colab), convert each image file into a numerical array.

- Convert the RGB image arrays to grayscale to simplify the data.

- Flatten each 2D grayscale array into a single row (tuple), creating a single feature vector per image [10].

- Model Training and Validation:

- Combine all feature vectors into a data matrix and assign the known concentrations as the target variable.

- Split the dataset into a training set (e.g., 80% of images) and a test set (e.g., 20%) using the

train_test_splitfunction in Python [10]. - Train a ridge regression model on the training set. Use cross-validation on the training set to fine-tune the hyperparameter

alpha(regularization strength) [10]. - Evaluate the final model's performance on the held-out test set using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Squared Error (MSE), and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) [10].

Workflow Visualization: ML vs. Traditional Analysis

The diagram below contrasts the traditional Beer-Lambert approach with the machine learning workflow for concentration estimation.

Performance Metrics of Ridge Regression Models

The following table summarizes the predictive accuracy achievable with ridge regression models on different types of data, as demonstrated in recent studies.

| Analyte | Sample Matrix | Data Type | Key Performance Metrics (MAE, MSE, RMSE) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kâ‚‚Crâ‚‚O₇ | Aqueous Solution | 210 Smartphone Images | MAE: 1.4 × 10â»âµMSE: 3.4 × 10â»Â¹â°RMSE: 1.0 × 10â»âµ | [10] |

| Kâ‚‚Crâ‚‚O₇ | Aqueous Solution | 100 iOS Phone Images | MAE: 6.3 × 10â»â¶MSE: 5.7 × 10â»Â¹Â¹RMSE: 7.6 × 10â»â¶ | [10] |

| KMnOâ‚„ | Aqueous Solution | Smartphone Images | High correlation with actual values (Precise metrics not listed in excerpt) | [10] |

| Lactate | Phosphate Buffer (0-20 mmol/L) | NIR Spectra | Linear models (PLS, Ridge) performed as well as nonlinear models, suggesting negligible nonlinearity in this range. | [11] |

| Lactate | Whole Blood | NIR Spectra | Nonlinear models (e.g., SVR) outperformed linear models, indicating significant nonlinearity from scattering. | [11] |

Abbreviations: MAE: Mean Absolute Error; MSE: Mean Squared Error; RMSE: Root Mean Squared Error.

Comparison of Linear and Nonlinear Model Performance on Lactate Estimation

This table compares the performance of different models across various sample matrices, highlighting the effect of scattering media on model choice. Data adapted from [11].

| Sample Matrix | Linear Model (PLS) Performance | Nonlinear Model (SVR) Performance | Justification for Model Choice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphate Buffer Solution (PBS) | Comparable to nonlinear models | Comparable to linear models | In a non-scattering medium, the relationship remains largely linear, so complex models offer no significant advantage [11]. |

| Human Serum | Slightly worse than nonlinear models | Better than linear models | The increased scattering in serum introduces mild nonlinearities that nonlinear models can capture [11]. |

| Sheep Blood | Worse than nonlinear models | Best performance | The highly scattering nature of whole blood creates significant nonlinear effects, making nonlinear models necessary for accurate predictions [11]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Image Capture | Inconsistent image colors/lighting | Variable ambient lighting; inconsistent camera settings [10] | Use fixed-distance setup (e.g., 30 cm); uniform white background; fixed camera magnification [10] |

| Low signal-to-noise ratio | Autofluorescence from media components [25] | Use media without phenol red or FBS; employ black microplates to reduce background noise [25] | |

| Sample Preparation | Meniscus formation in wells | Use of reagents like TRIS, acetate, or detergents; hydrophilic plate surfaces [25] | Use hydrophobic microplates; avoid meniscus-forming reagents; fill wells to maximum capacity [25] |

| Deviation from Beer-Lambert law at high concentrations | Analyte-analyte molecular interactions; changes in refractive index [19] [33] | Employ image-based ML analysis which relies on color intensity beyond Beer-Lambert limits [10] | |

| Data & Analysis | Poor model prediction accuracy | Insufficient training data; incorrect model hyperparameters [10] [37] | Increase training image dataset (e.g., 100-210 images); fine-tune ridge regression hyperparameters [10] |

| High variability in fluorescence readings | Heterogeneous sample distribution in wells [25] | Use well-scanning feature with orbital or spiral pattern to average signal across well [25] |

Frequently Asked Questions

General Methodology

Q: How can image analysis overcome Beer-Lambert law limitations? A: The Beer-Lambert law deviates at high concentrations due to molecular interactions and refractive index changes [19] [33]. Image-based machine learning models circumvent these limitations by directly correlating solution color intensity to concentration without relying on the linear absorbance-concentration relationship [10]. This approach depends solely on visual properties captured in images.

Q: What are the key advantages of this method over traditional spectrophotometry? A: This method requires minimal sample preparation, uses inexpensive equipment (smartphone camera), minimizes need for expert training, and works effectively at high concentrations where Beer-Lambert law fails [10].