Electronic Transitions in UV-Vis Spectroscopy: A Foundational Guide for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the basic theory of electronic transitions in Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Electronic Transitions in UV-Vis Spectroscopy: A Foundational Guide for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the basic theory of electronic transitions in Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of how molecules absorb light, from the types of electronic transitions (σ→σ*, n→σ*, π→π*, n→π*) to the governing selection rules. The scope extends to practical methodologies for interpreting spectra, quantitative analysis using the Beer-Lambert law, and troubleshooting common experimental errors. It further addresses the critical validation of UV-Vis data through comparisons with advanced techniques like HPLC and NMR, highlighting its specific applications and limitations in a biomedical research context for tasks like compound quantification and purity assessment.

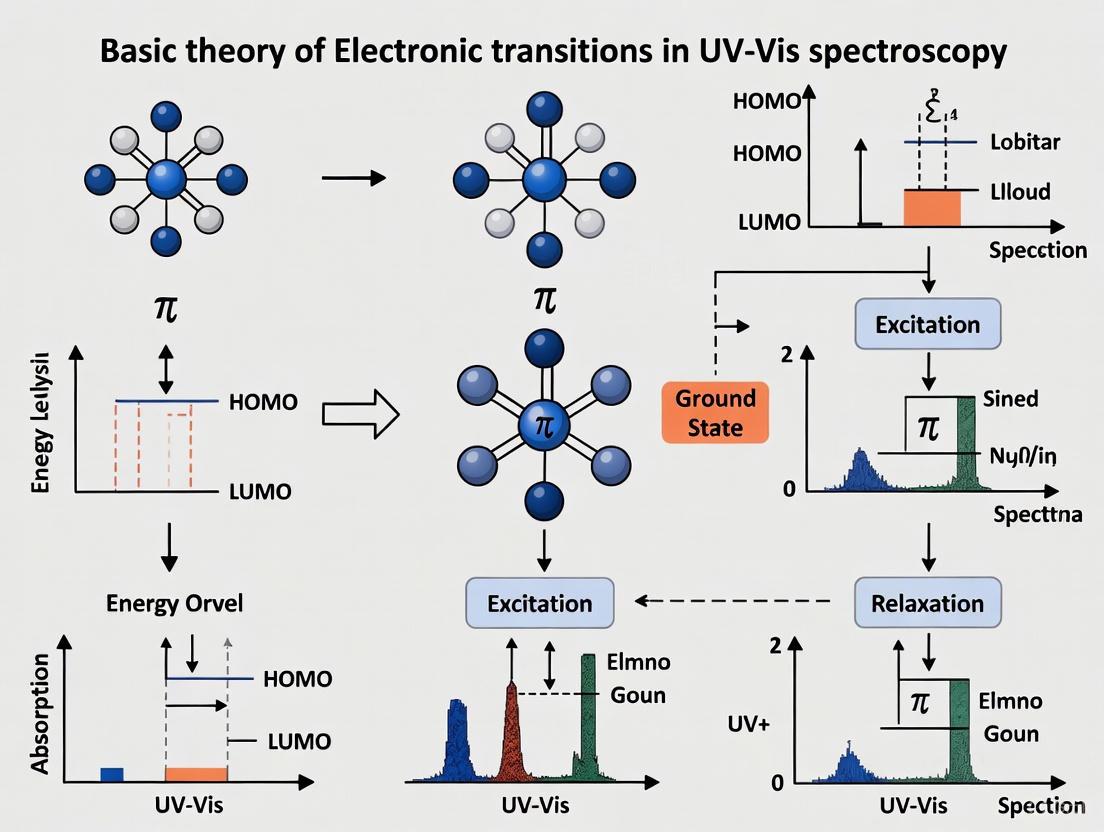

The Physics of Light Absorption: Core Principles of Electronic Transitions

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy investigates the interaction between light and matter, specifically focusing on how molecules absorb photons to undergo electronic transitions [1]. When a molecule absorbs light in the UV or visible region of the electromagnetic spectrum, electrons are promoted from their ground state to a higher energy excited state [2]. This process forms the foundation for one of the most widely used techniques in analytical chemistry, biochemistry, and pharmaceutical research for identifying compounds, determining concentrations, and understanding electronic structures [3].

The fundamental principle governing this interaction is the precise relationship between the energy of the photon absorbed and the energy gap between molecular orbitals [4]. The energy of a photon must exactly match the difference in energy between the initial and final states for absorption to occur, as described by the equation E = hν, where E is energy, h is Planck's constant, and ν is frequency [4]. This relationship connects the measurable quantity of absorbed light wavelength to the intrinsic electronic properties of molecules, providing researchers with a powerful tool for structural analysis and quantification [5].

Fundamental Physics of the Energy-Wavelength Relationship

The Quantum Mechanical Basis of Light Absorption

The interaction of light with matter occurs in discrete energy packets called photons. Each photon carries an energy quantitively described by the equation:

[

E = h\nu = \frac{hc}{\lambda}

]

where E is the energy of the photon, h is Planck's constant (6.626 × 10â»Â³â´ J·s), ν is the frequency of the light, c is the speed of light (3.00 × 10⸠m/s), and λ is the wavelength [4]. This relationship reveals the inverse proportionality between photon energy and wavelength: longer wavelengths correspond to lower energy photons, while shorter wavelengths correspond to higher energy photons [5].

When a molecule intercepts a photon whose energy precisely matches the energy difference between its ground state and an excited state (ΔE), the photon can be absorbed, promoting an electron to a higher energy orbital [1]. The frequency at which this occurs is given by:

[

\nu = \frac{ΔE}{h}

]

This fundamental quantum mechanical principle directly links the absorption wavelength observed in a UV-Vis spectrum to the electronic structure of the molecule under investigation [4].

Molecular Orbitals and Electronic Transitions

In molecular systems, electrons occupy specific molecular orbitals with defined energy levels [6]. The most critical orbitals for UV-Vis spectroscopy are:

- HOMO (Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital): The highest-energy orbital containing electrons

- LUMO (Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital): The lowest-energy vacant orbital

The energy separation between the HOMO and LUMO, known as the HOMO-LUMO gap, determines the wavelength of light a molecule will absorb [6] [1]. Molecules with small HOMO-LUMO gaps absorb longer wavelengths (potentially in the visible region), while those with large gaps absorb shorter wavelengths (in the UV region) [4].

Table 1: Common Electronic Transitions in UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Transition Type | Energy Requirement | Typical λmax Range | Molar Absorptivity (ε) | Chromophores Involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ → σ* | Very High | < 150 nm | High | C-C, C-H single bonds |

| n → σ* | High | 150-250 nm | Medium | Saturated compounds with lone pairs |

| Ï€ → Ï€* | Moderate | 200-400 nm (up to 700 nm with conjugation) | High (1,000-10,000 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) | Alkenes, alkynes, carbonyls, conjugated systems |

| n → Ï€* | Low | 250-500 nm | Low (10-100 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) | Compounds with both Ï€ bonds and lone pairs (e.g., carbonyls) |

For organic molecules, the most relevant transitions observed in conventional UV-Vis spectroscopy (200-800 nm) are π → π and n → π transitions [2]. These involve electrons in pi orbitals (found in double and triple bonds) and non-bonding orbitals (lone pairs on heteroatoms such as oxygen or nitrogen) [5].

Quantitative Relationship in Experimental Spectroscopy

The Beer-Lambert Law

The Beer-Lambert law forms the cornerstone of quantitative analysis using UV-Vis spectroscopy [3]. This law establishes a linear relationship between the absorbance of a solution and the concentration of the absorbing species: [ A = \varepsilon \cdot c \cdot l ] where:

Ais the measured absorbance (unitless)εis the molar absorptivity or extinction coefficient (L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹)cis the concentration of the absorbing species (mol/L)lis the path length of the sample cell (cm) [1]

The molar absorptivity (ε) is a characteristic property of a compound at a specific wavelength, representing how strongly it absorbs light at that wavelength [5]. Its magnitude reflects both the size of the chromophore and the probability of the electronic transition, with strongly absorbing chromophores having values >10,000 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹ [5].

Energy Calculations in Practical Applications

The direct relationship between photon energy and wavelength allows researchers to calculate the energy associated with electronic transitions from experimental UV-Vis spectra. The energy difference between molecular orbitals can be determined using the absorption maximum (λmax):

[

ΔE = \frac{hc}{\lambda_{max}}

]

where λmax is the wavelength of maximum absorption [4].

Table 2: Energy-Wavelength Conversion for Common Electronic Transitions

| Compound | Transition Type | λmax (nm) | Energy (kJ/mol) | Energy (kcal/mol) | Orbitals Involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethene | π → π* | 170 | 704 | 164 | HOMO(π) → LUMO(π*) |

| Butadiene | π → π* | 217 | 551 | 132 | HOMO(π) → LUMO(π*) |

| Hexatriene | π → π* | 258 | 464 | 111 | HOMO(π) → LUMO(π*) |

| Carbonyl n→π* | n → π* | 290 | 412 | 98 | HOMO(n) → LUMO(π*) |

| Carbonyl π→π* | π → π* | 180 | 664 | 159 | HOMO(π) → LUMO(π*) |

| β-Carotene | π → π* | 470 | 254 | 61 | HOMO(π) → LUMO(π*) |

This quantitative relationship enables researchers to predict the color of compounds, understand bond strengths, and design molecules with specific light-absorption properties for applications ranging from photovoltaics to pharmaceuticals [4].

Experimental Protocols for Validating the Energy-Wavelength Relationship

Protocol 1: Determining λmax and Molar Absorptivity

Objective: To determine the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) and molar absorptivity (ε) for a conjugated organic compound.

Materials and Reagents:

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer with scanning capability

- Matched quartz cuvettes (path length typically 1.0 cm)

- Analytical balance

- Volumetric flasks

- HPLC-grade solvent (e.g., hexane, methanol, water)

- Pure analyte of known molecular weight

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh 5-10 mg of analyte and dissolve in solvent to make a stock solution of known concentration (typically 10â»Â³ to 10â»âµ M).

- Dilution Series: Prepare a series of dilutions covering an appropriate concentration range (e.g., 10â»â´ to 10â»â¶ M).

- Blank Measurement: Fill a cuvette with pure solvent and place in the reference beam.

- Spectral Scan: Place the most concentrated sample in the sample beam and scan from 200-800 nm (or appropriate range) to identify λmax.

- Absorbance Measurement: At the identified λmax, measure the absorbance of all standard solutions.

- Data Analysis: Plot absorbance versus concentration. The slope of this plot equals

ε·l, from which ε can be calculated using the known path length.

Validation: The linearity of the Beer-Lambert plot (R² > 0.995) confirms the validity of the relationship within the concentration range studied [3].

Protocol 2: Investigating Conjugation Effects on λmax

Objective: To demonstrate how extended conjugation reduces the HOMO-LUMO gap, shifting λmax to longer wavelengths.

Materials and Reagents:

- Series of polyenes with increasing conjugation length (e.g., ethene, butadiene, hexatriene, octatetraene)

- UV-grade hexane as solvent

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Quartz cuvettes

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare solutions of each polyene at approximately 10â»âµ M concentration in hexane.

- Spectral Acquisition: Obtain full UV-Vis spectra for each compound.

- λmax Determination: Identify the wavelength of maximum absorption for each polyene.

- Energy Calculation: Calculate the energy difference (ΔE) for each transition using the equation

ΔE = hc/λmax. - Data Correlation: Plot λmax versus number of double bonds and ΔE versus number of double bonds.

Expected Results: As conjugation increases, λmax shifts to longer wavelengths (bathochromic shift), and ΔE decreases, demonstrating the relationship between molecular structure, orbital energies, and absorption wavelength [4].

Factors Influencing the Energy-Wavelength Relationship

Chromophore Structure and Conjugation

Conjugation represents the most significant structural factor affecting the energy-wavelength relationship in organic molecules [5]. Extended conjugation across multiple double bonds leads to a bathochromic shift (red shift), where absorption moves to longer wavelengths [4]. This occurs because conjugation lowers the energy of the π* orbital while raising the energy of the π orbital, thereby reducing the HOMO-LUMO gap [6].

For example, while isolated ethene absorbs at 170 nm, butadiene with two conjugated double bonds absorbs at 217 nm, and hexatriene with three conjugated double bonds absorbs at 258 nm [4]. With sufficient conjugation, absorption moves into the visible region, producing colored compounds such as β-carotene (λmax = 470 nm), which appears orange [1].

Solvent Effects

The solvent environment significantly influences absorption spectra through various interactions [2]. The same compound may exhibit different λmax values in different solvents due to:

- Polarity Effects: Polar solvents tend to cause bathochromic (red) shifts for π→π* transitions due to better stabilization of the more polar excited state [2].

- Hydrogen Bonding: For n→π* transitions, hydrogen-bonding solvents (e.g., water, alcohols) stabilize the non-bonding electrons, increasing the transition energy and causing a hypsochromic shift (blue shift) to shorter wavelengths [2].

- Polarizability: Solvents with high electron polarizability can differentially stabilize ground and excited states through dispersion forces.

These solvent effects must be carefully controlled and reported for reproducible results, with solvent choice specified in all experimental protocols [3].

Auxochromic Substituents

Auxochromes are functional groups that, while not chromophores themselves, modify the absorption characteristics of chromophores when attached to them [6]. Common auxochromes include -OH, -NH₂, -OR, and -Cl groups, which typically contain lone pairs of electrons that can interact with the π system of the chromophore [6].

The effect of auxochromes depends on their electronic character:

- Electron-donating groups (e.g., -OH, -NHâ‚‚) typically cause bathochromic shifts by raising the HOMO energy level

- Electron-withdrawing groups (e.g., -NOâ‚‚, -COOH) may cause hypsochromic or bathochromic shifts depending on their position and interaction with the chromophore

These substituent effects follow predictable patterns that have been codified in empirical rules such as the Woodward-Fieser rules for dienes and carbonyl compounds [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Specifications | Importance in Energy-Wavelength Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample holder for UV-Vis measurements | Path lengths: 1.0 cm (standard); Transmission range: 200-2500 nm | Essential for accurate absorbance measurements; Glass absorbs UV light, so quartz is necessary below 350 nm |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Instrument for measuring light absorption | Wavelength range: 190-1100 nm; Bandwidth: <2 nm for research-grade | Must provide precise wavelength control to accurately determine λmax and energy calculations |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Dissolving samples for analysis | Low UV absorbance; High purity | Minimize solvent background absorption; Common choices: water, acetonitrile, hexane, methanol |

| Deuterium Lamp | UV light source for spectrophotometer | Covers 190-400 nm range | Provides continuous spectrum in UV region for electronic transition studies |

| Tungsten-Halogen Lamp | Visible light source for spectrophotometer | Covers 350-1100 nm range | Essential for studying transitions in visible region (colored compounds) |

| NIST-Traceable Standards | Wavelength and absorbance calibration | Holmium oxide filters (wavelength); Neutral density filters (absorbance) | Ensure instrument accuracy for valid energy-wavelength relationship studies |

| Microvolume UV-Vis Systems | Sample-limited applications | Requires 0.5-2 µL sample volume; Path length: 0.2-1.0 mm | Enables analysis of precious samples while maintaining accurate energy-wavelength measurements |

| Nispomeben | Nispomeben, CAS:1443133-41-2, MF:C21H27NO4, MW:357.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Janex-1-m | Janex-1-m, CAS:406484-24-0, MF:C15H13N3O3, MW:283.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Considerations and Research Applications

Instrumental Factors Affecting Measurements

Several instrumental parameters must be controlled to obtain accurate data for energy-wavelength relationship studies [3]:

- Spectral Bandwidth: The range of wavelengths transmitted simultaneously affects resolution. For sharp absorption peaks, narrower bandwidths (1-2 nm) are essential to accurately determine λmax [3].

- Stray Light: Light reaching the detector at wavelengths other than the target wavelength causes deviation from the Beer-Lambert law, particularly at high absorbances (>2 AU) [3].

- Wavelength Accuracy: Small errors in wavelength calibration become significant when calculating transition energies, especially for sharp peaks [3].

Pharmaceutical and Biopharmaceutical Applications

In pharmaceutical research, understanding the energy-wavelength relationship enables critical quality control and characterization applications [7]:

- Drug Purity Assessment: UV-Vis spectroscopy quantifies API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient) concentration and detects impurities based on their characteristic absorption spectra [7].

- Protein Characterization: Proteins containing aromatic amino acids (tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine) exhibit UV absorption at 280 nm, allowing quantification without separation [3].

- Real-Time Release Testing (RTRT): UV-Vis spectroscopy serves as a process analytical technology (PAT) tool for real-time quality assessment during manufacturing, with studies confirming sufficient penetration depth (up to 1.38 mm) for representative sampling in tablet analysis [7].

- Binding Studies: Changes in absorption spectra upon ligand binding provide information about protein-ligand interactions and binding constants.

The precise relationship between absorption characteristics and molecular structure makes UV-Vis spectroscopy an indispensable tool throughout drug development, from initial discovery to final quality control [7].

The fundamental relationship between photon energy and wavelength provides the physical basis for interpreting electronic transitions in UV-Vis spectroscopy. Through the direct correlation E = hc/λ, researchers can connect measurable absorption wavelengths to molecular orbital energy gaps, enabling both qualitative identification and quantitative analysis of chemical compounds. Factors including chromophore conjugation, solvent effects, and auxochromic substituents systematically influence this relationship, providing valuable structural information. In pharmaceutical applications, these principles support critical quality assessments and real-time monitoring, demonstrating the enduring utility of the energy-wavelength relationship in advancing scientific research and drug development.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is a fundamental analytical technique that probes the electronic structure of molecules by measuring their absorption of light in the ultraviolet and visible regions of the electromagnetic spectrum (typically 190-800 nm) [8] [9]. The core principle underlying this technique is that molecules contain electrons in specific molecular orbitals, and these electrons can be promoted to higher energy orbitals when they absorb photons with energy matching the difference between orbital energy levels [4]. This absorption of light results in electronic transitions, which provide crucial information about molecular structure, conjugation, and functional groups [10] [11].

The energy required for electronic transitions follows Planck's relation (E = hν), where the energy gap (ΔE) between molecular orbitals determines the wavelength of light absorbed [4] [12]. In molecular orbital theory, electrons normally occupy the lowest energy orbitals in the ground state configuration. When light of appropriate energy interacts with a molecule, electrons may be excited from the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), or to other higher energy unoccupied orbitals [13] [5]. This promotion of electrons from ground state to excited state orbitals forms the basis for understanding the four primary types of electronic transitions in organic molecules: σ→σ, n→σ, π→π, and n→π transitions [12] [11].

Fundamental Theory of Molecular Orbitals and Transitions

Molecular Orbital Framework

In molecular orbital theory, atomic orbitals combine to form molecular orbitals that are delocalized over the entire molecule [14]. When atoms bond together, their atomic orbitals interact to create bonding orbitals (lower energy) and antibonding orbitals (higher energy). The bonding orbitals are characterized by constructive interference between atomic wavefunctions, with electron density concentrated between nuclei, while antibonding orbitals result from destructive interference, with electron density excluded from the internuclear region [14] [4]. The sigma (σ) orbitals are formed by head-on overlap of atomic orbitals, creating electron density along the bond axis. Pi (π) orbitals result from side-by-side overlap of p orbitals, creating electron density above and below the bond axis. Non-bonding (n) orbitals are typically lone pair orbitals on heteroatoms that do not participate in bonding [15].

The energy ordering of these orbitals generally follows: σ < π < n < π* < σ* [15]. This energy hierarchy is crucial for understanding the relative energies required for different electronic transitions. When molecules absorb ultraviolet or visible light, electrons are promoted from filled to empty orbitals, with the energy requirement determined by the difference between these orbital energy levels [13].

Selection Rules and Transition Probabilities

Not all possible electronic transitions occur with equal probability. Selection rules govern the likelihood of transitions between electronic states [11]. The spin selection rule states that transitions between states of different spin multiplicity are forbidden—singlet-to-singlet transitions are allowed, while singlet-to-triplet transitions are forbidden. The Laporte selection rule (or parity selection rule) states that for centrosymmetric molecules, transitions between orbitals of the same parity (gg or uu) are forbidden, while transitions between orbitals of different parity (gu) are allowed [11].

The intensity of absorption is proportional to the square of the transition dipole moment, which depends on the overlap between the orbitals involved in the transition [5]. Forbidden transitions may still occur with weak intensity due to vibronic coupling, which relaxes the strict selection rules by mixing vibrational and electronic states [11].

The Four Primary Electronic Transitions

σ→σ* Transitions

Sigma to sigma-star transitions represent the promotion of an electron from a bonding σ orbital to an antibonding σ* orbital [13] [12]. These transitions require substantial energy since σ bonds are strong, typically resulting in absorption at short wavelengths in the vacuum UV region below 150 nm [4]. For example, molecular hydrogen (H₂) undergoes a σ→σ* transition at approximately 111-135 nm, corresponding to an energy gap of about 258 kcal/mol [13] [14]. Similarly, ethane exhibits a σ→σ* transition around 135 nm [12]. These high-energy transitions are generally not observable with standard UV-Vis spectrophotometers, which typically operate down to about 190-220 nm [13] [4]. The study of σ→σ* transitions requires specialized instrumentation, including vacuum chambers to eliminate oxygen absorption and high-energy light sources [4].

Table 1: Characteristics of σ→σ* Transitions

| Compound | λmax (nm) | Energy (kcal/mol) | ε (L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) | Observation Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚ (Hydrogen) | 111-135 | ~258 | - | Vacuum UV conditions |

| CH₃-CH₃ (Ethane) | 135 | ~212 | - | Vacuum UV conditions |

| C-H bond | <120 | >238 | - | Vacuum UV conditions |

| C-C bond | <120 | >238 | - | Vacuum UV conditions |

n→σ* Transitions

Non-bonding to sigma-star transitions occur when electrons in non-bonding orbitals (lone pairs) on heteroatoms such as oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, or halogens are promoted to σ* orbitals [12] [11]. These transitions generally require less energy than σ→σ* transitions, typically appearing in the range of 150-250 nm [11]. For instance, water exhibits an n→σ* transition at 167 nm with a molar absorptivity of 7,000 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹ [12]. Similarly, methanol and other alcohols show n→σ* transitions below 200 nm [5]. The exact energy of n→σ* transitions depends on the heteroatom involved and the electron-withdrawing or donating characteristics of substituents. These transitions are typically weaker than π→π* transitions but stronger than n→π* transitions [11].

Table 2: Characteristics of n→σ* Transitions

| Compound | λmax (nm) | ε (L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) | Heteroatom | Solvent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚O (Water) | 167 | 7,000 | Oxygen | - |

| CH₃OH (Methanol) | 183 | - | Oxygen | - |

| CH₃Cl | 173 | - | Chlorine | - |

| (CH₃)₂O (Dimethyl ether) | 184 | - | Oxygen | - |

π→π* Transitions

Pi to pi-star transitions involve the promotion of an electron from a bonding Ï€ orbital to an antibonding Ï€* orbital in systems with double bonds or aromatic rings [13] [12]. Isolated Ï€ bonds, such as in ethylene (ethene), absorb at around 165-174 nm [13] [4]. However, conjugation dramatically affects the energy of π→π* transitions—as conjugation increases, the energy gap between Ï€ and Ï€* orbitals decreases, resulting in absorption at longer wavelengths [13] [10]. For example, 1,3-butadiene absorbs at 217 nm, and 1,3,5-hexatriene at 258 nm [13]. With extensive conjugation, π→π* transitions can shift into the visible region, as evidenced by β-carotene (11 conjugated double bonds) which absorbs at 470 nm, appearing orange [13] [4]. These transitions are typically strong, with high molar absorptivities (ε > 10,000 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) due to good orbital overlap between the Ï€ and Ï€* orbitals [5] [15].

Table 3: Characteristics of π→π* Transitions in Selected Alkenes

| Compound | λmax (nm) | ε (L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) | Conjugation Length | Color |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethene | 165-174 | - | Isolated π bond | Colorless |

| 1,3-Butadiene | 217 | 21,000 | 2 conjugated π bonds | Colorless |

| 1,3,5-Hexatriene | 258 | 35,000 | 3 conjugated π bonds | Colorless |

| β-Carotene | 470 | 15,000 | 11 conjugated π bonds | Orange |

n→π* Transitions

Non-bonding to pi-star transitions occur in molecules containing both Ï€ bonds and heteroatoms with non-bonding electrons, such as carbonyl compounds (aldehydes, ketones, carboxylic acids) and azo compounds [13] [15]. In these transitions, an electron from a non-bonding orbital on a heteroatom (typically oxygen or nitrogen) is promoted to a Ï€* orbital [15]. These are the lowest energy electronic transitions, typically occurring in the range of 270-300 nm for simple carbonyls [15] [10]. For example, acetone exhibits an n→π* transition at 275 nm [15]. These transitions are characteristically weak (ε = 10-100 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) due to poor orbital overlap between the non-bonding orbital (which is perpendicular to the Ï€ system) and the Ï€* orbital [5] [15]. The n→π* transitions are highly sensitive to solvent effects, typically shifting to shorter wavelengths (hypsochromic or blue shift) with increasing solvent polarity [12] [15].

Table 4: Characteristics of n→π* Transitions

| Compound | λmax (nm) | ε (L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) | Functional Group | Transition Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetone | 275 | ~15 | Ketone | n→π* |

| Acetaldehyde | 290 | ~17 | Aldehyde | n→π* |

| 4-methyl-3-penten-2-one | 314 | - | Enone | n→π* (conjugated) |

Experimental Protocols in UV-Vis Spectroscopy

Instrumentation and Measurement Methodology

UV-Vis spectroscopy relies on sophisticated instrumentation to accurately measure light absorption across the ultraviolet and visible spectrum [8]. A typical UV-Vis spectrophotometer consists of four main components: a light source, wavelength selector, sample container, and detector [8] [9]. For measurements across both UV and visible regions, instruments often employ multiple light sources—deuterium lamps for UV light (190-400 nm) and tungsten or halogen lamps for visible light (400-800 nm) [8]. The wavelength selector, typically a monochromator containing a diffraction grating, isolates specific wavelengths from the broad spectrum emitted by the light source [8]. Modern monochromators generally feature diffraction gratings with 1200-2000 grooves per mm, providing optimal resolution for spectroscopic measurements [8].

Sample containers (cuvettes) must be carefully selected based on the wavelength range of interest. Quartz or fused silica cuvettes are essential for UV measurements below 350 nm, as glass and plastic cuvettes absorb strongly in the UV region [8]. For measurements in the visible range only, glass or plastic cuvettes may be suitable. The path length of cuvettes is typically 1 cm, though shorter path lengths (e.g., 1 mm) may be used for highly absorbing samples [8]. The detector, often a photomultiplier tube (PMT) or photodiode, converts the transmitted light intensity into an electrical signal for measurement [8].

The fundamental measurement in UV-Vis spectroscopy follows the Beer-Lambert Law: A = εlc, where A is absorbance, ε is the molar absorptivity coefficient (L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹), l is the path length (cm), and c is the concentration (mol·Lâ»Â¹) [8] [10]. Absorbance values between 0.1 and 1.0 are generally considered optimal for accurate quantification, corresponding to 10-80% light absorption [8].

Sample Preparation and Solvent Selection

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining reliable UV-Vis spectra. Samples are typically prepared as solutions, with concentrations carefully chosen to ensure absorbance values remain within the instrument's linear dynamic range (generally A < 1) [8]. For quantitative work, a series of standard solutions with known concentrations is prepared to establish a calibration curve [8].

Solvent selection requires careful consideration as solvents can significantly influence absorption spectra. Common solvents for UV-Vis spectroscopy include [5]:

- Water: Transparent above 190 nm, suitable for aqueous samples

- Hexane/cyclohexane: Non-polar, transparent above 200 nm

- Acetonitrile: Polar aprotic, transparent above 190 nm

- Methanol/ethanol: Polar protic, transparent above 205 nm

- Chloroform: Transparent above 245 nm

Solvent effects are particularly important for n→π* transitions, which typically exhibit blue shifts (hypsochromic shifts) in polar solvents due to hydrogen bonding with lone pair electrons [12] [15]. Conversely, π→π* transitions often show red shifts (bathochromic shifts) in polar solvents due to stabilization of the excited state [11].

Table 5: UV Cutoff Wavelengths of Common Solvents

| Solvent | UV Cutoff (nm) | Polarity | Suitability for Different Transitions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water | 190 | High | Good for most transitions |

| Acetonitrile | 190 | Medium-High | Excellent for most transitions |

| Hexane | 200 | Low | Good for most transitions |

| Methanol | 205 | High | Good for most transitions |

| Ethanol | 205 | High | Good for most transitions |

| Chloroform | 245 | Low | Limited for n→π* transitions |

| Carbon tetrachloride | 265 | Low | Limited for n→π* transitions |

Data Collection and Analysis Protocol

Standard protocol for collecting and interpreting UV-Vis spectral data [8] [10]:

- Instrument Calibration: Warm up the spectrophotometer for 15-30 minutes to stabilize the light source. Perform a baseline correction with the blank solvent to account for solvent absorption.

- Spectral Scanning: Scan samples over the appropriate wavelength range (typically 190-800 nm) with a scanning speed appropriate for the sample (typically medium speed for routine analyses).

- Peak Identification: Identify λmax values (wavelengths of maximum absorption) for all significant peaks in the spectrum.

- Absorbance Measurement: Record absorbance values at each λmax, ensuring they fall within the optimal range of 0.1-1.0. For concentrated samples, apply appropriate dilution factors.

- Spectral Interpretation: Correlate observed transitions with molecular structure:

- Absorbance at 200-220 nm suggests isolated π bonds or n→σ* transitions

- Absorbance at 210-250 nm indicates conjugated dienes or π→π* transitions

- Absorbance at 250-300 nm suggests extended conjugation or aromatic systems

- Weak absorbance at 270-300 nm indicates n→π* transitions in carbonyls

- Quantitative Analysis: For concentration determination, measure absorbance at the specific λmax and apply the Beer-Lambert law using previously determined molar absorptivity values.

Advanced Considerations and Research Applications

Chromophores and Conjugation Effects

Chromophores are functional groups or structural elements that absorb specific wavelengths of UV or visible light due to the presence of π electrons or heteroatoms with non-bonding electrons [13] [5]. Common chromophores include carbonyl groups, carbon-carbon double and triple bonds, aromatic rings, azo groups (-N=N-), and nitro groups (-NO₂) [5] [15]. The absorption characteristics of chromophores are dramatically influenced by conjugation—the presence of alternating single and multiple bonds that creates a system of delocalized π electrons [13] [10].

Conjugation reduces the energy gap between π and π* orbitals, resulting in bathochromic shifts (red shifts) to longer wavelengths and hyperchromic effects (increased absorption intensity) [13] [4]. This effect is clearly demonstrated in polyene series: ethene (λmax = 170 nm), 1,3-butadiene (λmax = 217 nm), 1,3,5-hexatriene (λmax = 258 nm), and β-carotene with 11 conjugated double bonds (λmax = 470 nm) [13] [4]. In drug development, understanding conjugation effects is crucial for designing molecules with specific light absorption properties, which can influence photostability, color, and biological activity [8] [9].

Solvent Effects and Spectral Shifts

Solvent choice significantly impacts UV-Vis spectra through several mechanisms [12] [11]. Polar solvents can cause bathochromic (red) shifts in π→π* transitions by stabilizing the more polar excited state through dipole-dipole interactions [11]. Conversely, n→π* transitions typically exhibit hypsochromic (blue) shifts in polar protic solvents due to hydrogen bonding with the non-bonding electrons in the ground state, which increases the energy required for transition [15] [11]. These solvent effects must be carefully considered when comparing literature values, as λmax can shift by 10-30 nm depending on solvent polarity [12].

Quantitative Analysis and the Beer-Lambert Law

The Beer-Lambert law forms the foundation for quantitative applications of UV-Vis spectroscopy [8] [10]. According to this relationship, absorbance (A) is directly proportional to concentration (c), path length (l), and the molar absorptivity coefficient (ε): A = εlc [8]. For accurate quantification, measurements should be made at the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax), and absorbance values should fall within the linear range of the instrument (typically A < 1) [8]. The molar absorptivity (ε) provides information about transition probability, with values ranging from <100 for forbidden transitions (n→π) to >10,000 for allowed transitions (π→π in conjugated systems) [5] [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 6: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Item | Specification/Type | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvents | HPLC-grade hexane, acetonitrile, methanol, water | Sample dissolution and reference measurements | UV transparency, purity, compatibility with sample |

| Cuvettes | Quartz (UV), glass (vis), plastic (vis) | Sample containment during measurement | Path length (typically 1 cm), wavelength compatibility |

| Light Sources | Deuterium lamp (UV), tungsten/halogen lamp (vis) | Provide broad-spectrum illumination | Stability, lifespan, switching at 300-350 nm |

| Wavelength Selector | Monochromator with diffraction grating | Isolate specific wavelengths | Groove density (1200-2000 grooves/mm), resolution |

| Detectors | Photomultiplier tube (PMT), photodiode | Convert light intensity to electrical signal | Sensitivity, dynamic range, signal-to-noise ratio |

| Standard Compounds | Potassium dichromate, holmium oxide | Instrument calibration and validation | Wavelength accuracy verification, absorbance standards |

| Buffer Systems | Phosphate, acetate, borate buffers | Maintain pH for biological samples | UV transparency at working concentrations |

| Reference Materials | Solvent-matched blanks | Baseline correction | Matrix matching with sample solution |

| UMPK ligand 1 | UMPK ligand 1, MF:C15H22N4O5S, MW:370.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 8-Nitro-2'3'cAMP | 8-Nitro-2'3'cAMP, MF:C10H11N6O8P, MW:374.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The comprehensive understanding of σ→σ, n→σ, π→π, and n→π transitions provides a fundamental framework for interpreting UV-Vis spectra and extracting meaningful structural information about molecules. These electronic transitions, governed by well-defined selection rules and influenced by molecular structure, conjugation, and solvent environment, serve as powerful diagnostic tools in molecular characterization [13] [12] [10]. The experimental protocols outlined in this work, combined with proper instrumentation and reagent selection, enable researchers to obtain reliable, reproducible spectral data for both qualitative identification and quantitative analysis [8] [9].

In pharmaceutical research and drug development, UV-Vis spectroscopy offers invaluable applications ranging from compound identification and purity assessment to concentration determination and kinetic studies [8] [9]. The ability to correlate spectral features with specific electronic transitions allows medicinal chemists to make informed decisions about molecular design, particularly regarding chromophore incorporation and conjugation extension to modulate light absorption properties. As UV-Vis instrumentation continues to advance with improved sensitivity, miniaturization, and automation, the technique remains an indispensable tool in the scientist's analytical arsenal, providing immediate insights into electronic structure through the well-established principles of orbital interactions.

Understanding Charge-Transfer Transitions in Metal Complexes and Drug Molecules

Charge-transfer (CT) transitions represent a crucial class of electronic transitions in molecular spectroscopy, playing a fundamental role in ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) research. These transitions occur when electronic charge is redistributed between different parts of a molecular system, typically between an electron donor and an electron acceptor. In contrast to localized d-d transitions in metal complexes, CT transitions involve significant spatial redistribution of electron density and are characterized by high intensity and broad spectral bands [16] [17]. The fundamental theory underlying these transitions was first comprehensively described by Mulliken in the 1950s, establishing the quantum mechanical basis for donor-acceptor interactions [18].

In the context of metal complexes, CT transitions can be classified into two primary categories: Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT), where electron density moves from ligand-based orbitals to metal-centered orbitals, and Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT), involving electron transfer from metal-based orbitals to ligand-based orbitals [19] [16]. The directionality of these transitions depends critically on the relative energies of the molecular orbitals involved and the redox properties of both the metal center and ligands [16]. Understanding these electronic transitions provides fundamental insights into photophysical processes, redox chemistry, and biological recognition events relevant to pharmaceutical development.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Theoretical Framework

Electronic Structure Basis

Charge-transfer transitions originate from the quantum mechanical interaction between electron donors and acceptors, forming new molecular aggregates in the ground state known as charge-transfer complexes (CTCs) [18]. These complexes exhibit unique electronic structures characterized by:

- Orbital Interactions: CT transitions typically involve the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of the donor and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the acceptor [18]. The energy gap between these orbitals determines the wavelength of the CT absorption band.

- Transition Intensity: CT bands are notably intense (high molar absorptivity) because they involve orbitals that are spatially separated, resulting in large transition dipole moments [17]. This contrasts with forbidden d-d transitions that yield weak absorption bands.

- Solvent Effects: The position and intensity of CT bands are highly sensitive to solvent polarity due to stabilization of the charge-separated state in polar media [18].

The theoretical framework for understanding CT transitions has evolved from Marcus theory, which classically describes electron transfer rates, to modern computational approaches including density functional theory (DFT) and time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) [20]. These methods allow precise prediction of CT transition energies and intensities by calculating electronic structures and simulating UV-Vis spectra [21] [22].

Molecular Orbital Interactions in Charge-Transfer Transitions

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental orbital interactions in charge-transfer transitions:

This diagram illustrates the two primary CT mechanisms in metal complexes. In LMCT transitions, electrons move from ligand-centered molecular orbitals to metal-centered orbitals, typically occurring when ligands possess high-energy filled orbitals and metals have low-energy vacant orbitals. Conversely, MLCT transitions involve electron transfer from metal-centered orbitals to ligand-centered orbitals, commonly observed in metals with relatively high-energy d-electrons and ligands with low-energy π* orbitals [19] [16] [17].

Experimental Characterization Methods

Spectroscopic Techniques

Multiple spectroscopic methods are employed to characterize charge-transfer complexes and their transitions:

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: The primary technique for identifying CT transitions through the appearance of new absorption bands that don't exist in the individual spectra of donor and acceptor components [18]. CT bands are typically broad and appear at wavelengths longer than 400 nm [18].

Benesi-Hildebrand Analysis: Used to determine the formation constant (KCTC) and molar extinction coefficient (εCTC) of 1:1 CT complexes by measuring absorbance at varying donor/acceptor concentrations [18]. The modified equation applied is:

(\frac{Ca Cd}{A} = \frac{1}{K{CTC}\varepsilon{CTC}} + \frac{Ca + Cd}{\varepsilon_{CTC}})

where (Ca) and (Cd) represent acceptor and donor concentrations, and A is the measured absorbance [18].

- Stoichiometry Determination: Multiple methods including Job's continuous variation, photometric titration, and conductometric titration establish the donor:acceptor ratio in CT complexes, typically confirming 1:1 stoichiometry [18].

Comprehensive Workflow for Charge-Transfer Complex Analysis

The experimental characterization of charge-transfer complexes follows a systematic workflow encompassing preparation, analysis, and application phases:

This comprehensive workflow illustrates the integrated experimental and computational approach required for thorough characterization of charge-transfer complexes. The process begins with sample preparation where donors and acceptors are combined in appropriate solvents, typically resulting in immediate color formation indicating CT complexation [18]. Solution analysis employs UV-Vis spectroscopy to identify characteristic CT bands, followed by stoichiometric determination using Job's method and stability constant calculation via Benesi-Hildebrand analysis [18]. Advanced characterization includes solid-state analysis through FTIR, NMR, and X-ray diffraction, complemented by computational studies using DFT and TD-DFT to predict electronic structures and validate experimental findings [21] [22]. Bioactivity assessment forms the final stage, evaluating potential pharmaceutical applications through DNA binding studies and antimicrobial assays [18].

Quantitative Data in Charge-Transfer Transitions

Spectroscopic Parameters of Characterized Charge-Transfer Complexes

Table 1: Experimental spectroscopic parameters of documented charge-transfer complexes

| Complex System | CT Band (nm) | Formation Constant (KCTC) L·molâ»Â¹ | Molar Extinction Coefficient (εCTC) L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹ | Stoichiometry (D:A) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPD-DDQ (in AN) [18] | 434, 542, 588 | 125.09 × 10² | 9.84 × 10² | 1:1 |

| OPD-DDQ (in MeOH) [18] | 463 | 56.50 × 10² | 8.12 × 10² | 1:1 |

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-TMP [21] | 247.3, 212.5 | - | 139, 97* | - |

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-NOR [21] | 280.2, 239.2 | - | 142, 358* | - |

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-CIP [21] | 254.5, 239.5 | - | 887, 365* | - |

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-OFL [21] | 285.2, 268.2, 254.5 | - | 177, 832, 226* | - |

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-SMR [21] | 241.3, 205.5, 193.6 | - | 289, 318, 169* | - |

*Oscillator strengths (f) × 10³ from TD-DFT calculations [21]

Frontier Molecular Orbital Energies in Charge-Transfer Complexes

Table 2: HOMO-LUMO energy gaps calculated for charge-transfer complexes

| Complex System | HOMO Energy (eV) | LUMO Energy (eV) | HOMO-LUMO Gap (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-TMP [21] | -5.85 | -0.49 | 5.36 |

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-NOR [21] | -5.82 | -1.39 | 4.43 |

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-CIP [21] | -5.81 | -1.39 | 4.42 |

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-OFL [21] | -5.56 | -1.36 | 4.20 |

| Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-SMR [21] | -5.98 | -1.27 | 4.71 |

The HOMO-LUMO energy gap provides critical insights into the chemical reactivity and kinetic stability of charge-transfer complexes. Systems with smaller energy gaps, such as Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-OFL (4.20 eV), typically exhibit higher chemical reactivity compared to those with larger gaps like Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚-TMP (5.36 eV) [21]. These quantum chemical parameters enable prediction of charge transfer propensity and complex stability.

Charge-Transfer in Metal Complexes

Transition Metal Complexes

In transition metal chemistry, CT transitions produce intense colors in coordination compounds. The key transitions include:

- d-d Transitions: These involve electronic excitation between metal-centered d-orbitals. They are Laporte-forbidden, resulting in weak absorption bands with low molar absorptivity (ε typically 10-100 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) [17].

- Charge-Transfer Transitions: In contrast to d-d transitions, CT transitions are fully allowed and produce intense absorption bands with high molar absorptivity (ε typically >1,000 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) [17]. The energy required for MLCT transitions is generally higher than for d-d transitions, but they occur more efficiently [17].

The electronic factors controlling CT transitions in metal complexes can be tuned through strategic ligand design. For ruthenium polypyridyl complexes, incorporating electron-donating "push" ligands and electron-withdrawing "pull" ligands can systematically alter MLCT transition energies [16]. Substitution at specific positions on bipyridine ligands (4,4' vs 5,5' vs 6,6') significantly impacts the π* orbital energy, enabling precise tuning of absorption maxima from 500 nm to 580 nm [16].

Lanthanide Complexes

For lanthanide ions, LMCT transitions are predominantly observed for easily reducible ions like Eu³⺠and Yb³⺠with easily oxidized ligands [16]. These transitions occur when ligands possess sufficiently high-energy occupied orbitals that can donate electrons to vacant f-orbitals on the metal center. The CT behavior in lanthanide complexes differs fundamentally from transition metals due to the core-like nature of 4f orbitals, resulting in distinctive photophysical properties.

Charge-Transfer in Drug Molecules and Pharmaceutical Applications

Antibiotic Charge-Transfer Complexes

Charge-transfer interactions play significant roles in pharmaceutical sciences, particularly in understanding drug-receptor interactions and antibiotic mechanisms. Studies on fluoroquinolone antibiotics (norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin) with hydrogen peroxide demonstrate characteristic CT transitions between 239-285 nm, with oscillator strengths quantified through TD-DFT calculations [21]. These computational studies provide insights into the electronic structures responsible for antibiotic activity and potential degradation pathways.

The biological relevance of CT complexes extends to DNA binding interactions. Studies on the OPD-DDQ charge-transfer complex revealed intercalative binding with calf thymus DNA, exhibiting a substantial binding constant of 6.0 × 10âµ L·molâ»Â¹ [18]. This suggests potential biological implications for CT complexes in pharmaceutical contexts, possibly interfering with DNA replication processes in microorganisms.

Analytical and Bioactivity Applications

Pharmaceutical applications of charge-transfer complexes include:

- Bioactivity: CT complexes often exhibit enhanced antimicrobial properties compared to their individual components. The OPD-DDQ complex demonstrated notable antibacterial activity exceeding the standard drug tetracycline in some assessments [18].

- Drug-Receptor Studies: CT interactions serve as models for understanding drug-receptor binding mechanisms, as these complexes mimic the electron donor-acceptor interactions that frequently occur in biological systems [18].

- Analytical Detection: CT-based methods enable detection of non-chromophoric compounds that are otherwise difficult to analyze by conventional UV-Vis spectroscopy [23]. Metal complex-based CT interactions facilitate "switch on/off" sensing strategies for various analytes.

Computational Approaches and Theoretical Modeling

Density Functional Theory Applications

Modern computational methods, particularly density functional theory (DFT), have become indispensable tools for studying charge-transfer transitions:

- Geometry Optimization: DFT calculations at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level provide optimized ground-state structures of CT complexes, identifying the most stable binding configurations between donors and acceptors [21] [22].

- TD-DFT Calculations: Time-dependent DFT predicts electronic excitation energies and oscillator strengths, allowing direct comparison with experimental UV-Vis spectra [21] [22]. These calculations successfully reproduce CT band positions and intensities.

- Molecular Orbital Analysis: HOMO-LUMO energy calculations quantify charge transfer propensity and chemical reactivity [21]. Electron density distributions reveal preferred sites for donor-acceptor interactions.

Marcus Theory and Electron Transfer Kinetics

The Marcus-Hush theory provides the fundamental framework for understanding electron transfer kinetics in charge-transfer processes [19] [20]. This classical theory relates the rate constant for electron transfer to the reorganization energy (λ) and the thermodynamic driving force (ΔG°):

[ k{ET} = \frac{2\pi}{\hbar} |H{AB}|^2 \frac{1}{\sqrt{4\pi\lambda kB T}} \exp\left[-\frac{(\lambda + \Delta G^\circ)^2}{4\lambda kB T}\right] ]

Where (H_{AB}) is the electronic coupling matrix element between donor and acceptor states. For outer-sphere electron transfer reactions, the Franck-Condon principle restricts electron transfer to nuclear configurations where the donor and acceptor states are degenerate, requiring vibrational excitation to achieve suitable geometry [19].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for charge-transfer studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in CT Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Acceptors | Component that receives electron density in CT complex | DDQ, chloranil, TCNQ [18] |

| Electron Donors | Component that donates electron density in CT complex | O-phenylenediamine, pharmaceuticals [18] |

| Polar Solvents | Medium for studying CT interactions in solution | Acetonitrile, methanol [18] |

| Deuterated Solvents | NMR characterization of CT complexes | DMSO-d6, CDCl3 [22] |

| Metal Salts | Synthesis of metal complexes for MLCT/LMCT studies | Cobalt(II) acetate, copper(II) acetate [22] |

| Schiff Base Ligands | Chelating ligands for stable metal complexes | Tetradentate Nâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ donors [22] |

| FT-IR Spectrophotometer | Structural characterization of CT complexes | KBr pellet method [22] |

| Computational Software | DFT/TD-DFT calculations of electronic structure | Gaussian 09, VASP [21] [22] |

Charge-transfer transitions represent a fundamental electronic process with significant implications across inorganic chemistry, pharmaceutical sciences, and materials research. The intense, solvent-sensitive nature of CT bands makes them readily identifiable in UV-Vis spectroscopy and provides valuable information about donor-acceptor interactions in molecular systems. For metal complexes, the distinction between LMCT and MLCT transitions depends critically on the relative orbital energies of metal centers and ligands, which can be systematically tuned through strategic ligand design. In pharmaceutical contexts, CT complexes model drug-receptor interactions and often exhibit enhanced bioactivity. Contemporary research continues to advance our understanding of these transitions through integrated experimental and computational approaches, particularly using TD-DFT to predict and rationalize CT band positions and intensities. The ongoing development of CT-based materials and pharmaceutical applications ensures continued relevance of these fundamental electronic transitions in spectroscopic research and drug development.

Electronic spectroscopy serves as a fundamental tool for probing the electronic structure of atoms and molecules, particularly in the development and characterization of pharmaceutical compounds. The intensity of spectral bands is governed by quantum mechanical selection rules that dictate the probability of electronic transitions. This whitepaper provides an in-depth examination of the two primary selection rules—the Spin Selection Rule and the Laporte Selection Rule—which define the allowedness or forbiddenness of transitions in UV-Vis spectroscopy. Framed within the context of electronic transition theory, this guide explores the theoretical foundations, practical implications, and exceptions to these rules, with specific application to transition metal complexes relevant to coordination chemistry and drug development research. The comprehensive analysis includes quantitative spectral data, experimental methodologies for observing these transitions, and visual tools to aid researchers in interpreting complex spectroscopic data.

In UV-Vis spectroscopy, the absorption of electromagnetic radiation promotes electrons from ground states to excited states, producing characteristic spectra that reveal critical information about molecular structure and energy levels. However, not all conceivable transitions between electronic states are equally probable; some transitions yield intense absorption bands, while others are faint or unobservable under standard conditions. Selection rules are quantum mechanical guidelines that predict which electronic transitions are "allowed" (high probability) and which are "forbidden" (low probability) based on symmetry and spin considerations [24]. These rules are paramount for researchers and drug development professionals who utilize spectroscopy to characterize metal complexes, organic chromophores, and pharmaceutical compounds.

The intensity of an absorption band is directly proportional to the transition probability, quantified by the molar absorptivity (ε). Forbidden transitions, while possible under certain conditions, exhibit significantly lower intensities than their allowed counterparts [24]. Two principal selection rules govern electronic transitions in centrosymmetric molecules and transition metal complexes: the Spin Selection Rule and the Laporte Selection Rule. Understanding their individual and combined effects is essential for accurate spectral interpretation and for designing compounds with desired photophysical properties in pharmaceutical applications.

The Laporte Selection Rule

Theoretical Foundation

The Laporte Selection Rule is a symmetry-based selection rule that applies rigorously to atoms and molecules possessing a center of inversion (centrosymmetric molecules) [25]. It states that electronic transitions that conserve parity (symmetry with respect to inversion) are forbidden. In practical terms, this means:

- Allowed transitions: Those involving a change in parity (

g → uoru → g) - Forbidden transitions: Those between states of the same parity (

g → goru → u) [24] [25]

The rule derives from the transition moment integral ∫ ψₑₗ μ̂ ψₑₗᵉˣ dτ, where ψₑₗ and ψₑₗᵉˣ are the wavefunctions of the initial and final electronic states, and μ̂ is the electric dipole moment operator [26]. This operator is odd under inversion. For the integral to be non-zero (indicating an allowed transition), the integrand must be even under inversion, which only occurs when the initial and final states have different parity [26].

In atomic orbitals, s and d orbitals are gerade (symmetric with respect to inversion), while p and f orbitals are ungerade (antisymmetric) [25]. Consequently, the Laporte Rule forbids pure s→s, p→p, d→d, and f→f transitions in centrosymmetric environments, but allows s→p, p→d, and d→f transitions, as these involve a change in parity [27].

Application to Transition Metal Complexes

The Laporte Rule is particularly significant in the electronic spectroscopy of transition metal complexes, where it explains the relative weakness of d-d transitions in octahedral complexes (which possess a center of inversion) [24] [25]. For example, in an octahedral complex, d orbitals have g symmetry, so transitions between them (g → g) are Laporte-forbidden [24]. Despite this forbiddenness, such transitions are observed in spectra but with low intensities (molar absorptivities generally below 100 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹), indicating that the selection rule can be relaxed under certain conditions [24] [25].

Table 1: Laporte Selection Rule Applications in Different Molecular Symmetries

| Molecular Geometry | Center of Inversion? | d-d Transition Status |

Typical Molar Absorptivity (ε, L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Octahedral (e.g., [Co(Hâ‚‚O)₆]²âº) | Yes | Laporte-forbidden | ~10 [25] |

| Tetrahedral (e.g., [CoClâ‚„]²â») | No | Laporte-allowed | ~600 [25] |

| Linear | Yes | Laporte-forbidden | Low (≤100) [24] |

| Square Planar | No | Laporte-allowed | Moderate to High |

Mechanisms of Rule Relaxation

Despite the theoretical forbiddenness, d-d transitions are observed in octahedral complexes due to two primary mechanisms that relax the Laporte Rule:

Vibronic Coupling: Molecular vibrations cause temporary distortions that disrupt the center of inversion. During these asymmetric vibrations, the

gandusymmetry labels become undefined, momentarily allowing the forbidden transition [24] [25]. Transitions occurring through this mechanism are called vibronic transitions. This is the dominant reason whyd-dbands are observable, albeit weak, in octahedral complexes [24].Orbital Mixing: In complexes with π-donor or π-acceptor ligands, metal

dorbitals can mix with ligand orbitals of different parity (e.g.,porbitals). This mixing introduces someucharacter into the predominantlygcharacterdorbitals, making the transitions partially allowed [24]. Additionally, in non-centrosymmetric geometries like tetrahedral complexes, the Laporte Rule does not apply at all, andd-dtransitions are allowed, resulting in more intense absorption bands [24] [25]. For instance, the tetrahedral [CoCl₄]²⻠complex (ε ≈ 600) has significantly more intense coloration than the octahedral [Co(H₂O)₆]²⺠complex (ε ≈ 10) [25].

Figure 1: The Laporte Rule and its relaxation mechanisms in centrosymmetric molecules. Although d-d transitions are formally forbidden, they become weakly observable through vibronic coupling and orbital mixing.

The Spin Selection Rule

Theoretical Foundation

The Spin Selection Rule dictates that electronic transitions must not involve a change in the total spin angular momentum of the system. Formally, this requires that ΔS = 0, meaning the spin multiplicity of the system remains unchanged [24] [28]. This rule arises because the electric dipole operator, which governs the interaction with radiation, does not act on electron spin. Therefore, a transition cannot directly flip the spin of an electron.

In the term symbols used to represent electronic states, the spin multiplicity is indicated by the left-hand superscript. The Spin Selection Rule thus allows transitions between states with the same superscript, such as ¹S → ¹P or ³T → ³A, but forbids transitions between states with different spin multiplicities, such as ³T → ¹D (a singlet-triplet transition) [24].

Practical Implications and Exceptions

Spin-forbidden transitions exhibit extremely low probabilities and consequently yield very faint spectral bands, with molar absorptivities (ε) often in the range of 10â»Â³ to 1 L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹ [27]. A classic example is the octahedral complex [Mn(Hâ‚‚O)₆]²âº; its manganese(II) ion has a dâµ high-spin configuration. The ground state is â¶Aâ‚g, and the lowest-energy excited states are quartet states (â´Tâ‚g, â´Tâ‚‚g). Transitions to these states are both Laporte-forbidden (being g→g) and spin-forbidden (ΔS = 1). The combined effect of these prohibitions results in such weak absorption that dilute solutions of this complex appear nearly colorless [27] [28].

The primary mechanism for relaxation of the Spin Selection Rule is spin-orbit coupling. This is an electromagnetic interaction between the electron's spin and its orbital motion around the nucleus. It effectively mixes pure spin states, creating new wavefunctions that are admixtures of different spin multiplicities (e.g., mixing some singlet character into a triplet state) [28]. This mixing provides a pathway for otherwise forbidden transitions to gain a small but non-zero probability. The strength of spin-orbit coupling increases with the atomic number of the element, making spin-forbidden transitions more pronounced for heavier metal ions like those in the second and third transition series, as well as lanthanides and actinides [25].

Combined Effect of Selection Rules and Experimental Manifestations

Quantitative Spectral Intensities

In transition metal complexes, the Spin and Laporte selection rules often operate simultaneously. The observed intensity of an absorption band depends on the degree to which each rule is obeyed or violated. The table below categorizes transition types based on their adherence to these rules and their resulting spectral intensities.

Table 2: Classification of Electronic Transitions by Selection Rules and Resulting Intensities

| Transition Type | Spin Rule | Laporte Rule | Typical εmax (L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) | Example Complex |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spin & Laporte Forbidden | Violated | Violated | 10â»Â³ - 1 | [Mn(Hâ‚‚O)₆]²⺠[27] |

| Spin Allowed, Laporte Forbidden | Obeyed (ΔS=0) | Violated | 1 - 100 | [Cr(H₂O)₆]³⺠[24] [27] |

| Spin Allowed, Laporte Allowed | Obeyed (ΔS=0) | Obeyed (e.g., g→u) | 100 - 1000 | Tetrahedral [CoCl₄]²⻠[25] [27] |

| Charge-Transfer | Often Obeyed | Often Obeyed | 1,000 - 10ⶠ| [MnOâ‚„]â», [Fe(CN)₆]³⻠[27] |

Experimental Protocols for Electronic Spectroscopy

The following section outlines a generalized experimental methodology for acquiring and interpreting UV-Vis-NIR spectra of transition metal complexes to assess the operation of selection rules.

Sample Preparation

- Reagent Solutions: Prepare a solution of the complex under study at a concentration typically between 1×10â»âµ M and 1×10â»Â² M, depending on the expected absorption intensity. For weakly absorbing (highly forbidden) transitions, higher concentrations are required.

- Solvent Selection: Choose a solvent that is transparent in the spectral region of interest and does not coordinate with the metal ion in a way that alters the complex's geometry. Common choices include water, acetonitrile, and dichloromethane.

- Cuvette Selection: Use spectrophotometric cuvettes with appropriate path lengths (usually 1 cm) and material (e.g., quartz for UV-Vis, silica or glass for visible region only).

Data Acquisition

- Baseline Correction: Collect a baseline spectrum using a cuvette filled only with the pure solvent.

- Sample Measurement: Obtain the absorption spectrum of the complex solution across the relevant wavelength range (e.g., 200-800 nm for UV-Vis, or extending to ~2500 nm for NIR if needed for certain

d-dorf-ftransitions). - Parameter Settings: Use a moderate spectral bandwidth (e.g., 1-2 nm) to resolve individual bands without excessive loss of light intensity. Perform multiple scans and average them to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, which is crucial for detecting weak forbidden bands.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Band Assignment: Identify the number, position (energy, λmax in nm or cmâ»Â¹), and intensity (εmax) of absorption bands.

- Intensity as a Diagnostic Tool:

- Weak bands (ε < 100): Suggest either spin-forbiddenness, Laporte-forbiddenness, or both. This is characteristic of

d-dtransitions in centrosymmetric complexes. - Moderate bands (ε ~ 10²-10³): Often indicate Laporte-allowed transitions, such as

d-dtransitions in tetrahedral complexes or those involving significant orbital mixing. - Intense bands (ε > 10³): Typically signify fully allowed transitions, most commonly Charge-Transfer (CT) transitions (e.g., Ligand-to-Metal or Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer) [27].

- Weak bands (ε < 100): Suggest either spin-forbiddenness, Laporte-forbiddenness, or both. This is characteristic of

- Comparison with Theoretical Predictions: Compare the observed spectrum with energy level diagrams (e.g., Tanabe-Sugano diagrams) and selection rule predictions to assign specific electronic transitions (e.g.,

â´Aâ‚‚g → â´Tâ‚‚gfor[Cr(Hâ‚‚O)₆]³âº).

Figure 2: A workflow for diagnosing the nature of an electronic transition based on its molar absorptivity (ε_max), using the selection rules as a guide.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Studying Electronic Transitions

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

Transition Metal Salts (e.g., CoCl₂, KMnO₄, Cr(NO₃)₃) |

Source of metal centers for synthesizing coordination complexes with varied d-electron configurations. |

Spectroscopic Grade Solvents (e.g., H₂O, CH₃CN, CH₂Cl₂) |

Dissolve complexes without introducing significant background absorption in the UV-Vis region. |

Ligand Library (e.g., Hâ‚‚O, NH₃, CNâ», Clâ», phenanthroline, porphyrins) |

Create complexes with different geometries (octahedral, tetrahedral), ligand field strengths, and electronic properties to probe selection rules. |

| Quartz Cuvettes (path lengths 1 cm, 0.1 cm, etc.) | Hold liquid samples for measurement; quartz is transparent from UV to IR. |

| UV-Vis-NIR Spectrophotometer | Instrument for measuring absorption spectra across the ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared regions. |

| Tanabe-Sugano Diagrams | Theoretical charts for correlating observed transition energies with ligand field parameters (Δ_o, B) in d⿠metal complexes. |

| RGT-018 | RGT-018, MF:C27H24F3N7O2, MW:535.5 g/mol |

| APY29 | APY29, MF:C17H16N8, MW:332.4 g/mol |

The Spin and Laporte selection rules provide the fundamental theoretical framework for understanding the intensities of bands in electronic spectra. While the Spin Selection Rule (ΔS = 0) forbids transitions that change the total spin, the Laporte Rule forbids transitions that conserve parity in centrosymmetric molecules. Forbidden transitions, a hallmark of d-d spectra in octahedral complexes, are observed with low intensity due to relaxation mechanisms like vibronic coupling, orbital mixing, and spin-orbit coupling.

For researchers in drug development and materials science, these rules are not mere theoretical constructs but essential tools. They enable the decoding of complex spectra to extract information on oxidation states, coordination geometry, and ligand environment of metal centers in biologically relevant complexes and catalysts. The ability to distinguish between Laporte-forbidden d-d transitions, fully allowed charge-transfer bands, and the transitions of organic chromophores is critical for assigning spectral features and designing molecules with tailored photophysical and photocatalytic properties. Mastery of these governing rules empowers scientists to fully leverage UV-Vis spectroscopy as a powerful probe of electronic structure.

Within the foundational theory of electronic transitions underpinning UV-Vis spectroscopy, the Franck-Condon Principle stands as a cornerstone for interpreting spectral profiles. This principle asserts that electronic transitions occur on a time scale vastly shorter than nuclear motion, resulting in vertical transitions that simultaneously populate vibrational states in the excited electronic manifold. The probability of these vibronic transitions is governed by the overlap of vibrational wavefunctions, quantitatively expressed by the Franck-Condon factor. This whitepaper provides an in-depth examination of the principle's quantum mechanical foundation, its manifestation in absorption and emission spectra, and detailed methodologies for its application in quantitative spectroscopic analysis, with particular relevance for researchers in molecular spectroscopy and drug development.

The interaction of light with matter, particularly the absorption of ultraviolet or visible light by molecules, excites electrons from their ground state to higher energy levels. However, a comprehensive understanding of UV-Vis spectra extends beyond purely electronic transitions. Within any electronic state, a molecule exists in a set of quantized vibrational energy levels. The total energy of a molecule is thus the sum of its electronic, vibrational, and rotational energies. While rotational fine structure is often unresolved in solution-phase spectra of complex molecules, the vibrational progression remains a critical feature shaping the absorption band profile.

The Franck-Condon Principle provides the theoretical framework for understanding the intensities of these vibronic transitions—the coupled electronic and vibrational transitions. Formulated by James Franck and Edward Condon in 1926, the principle posits that "an electronic transition takes place so rapidly that a vibrating molecule does not change its internuclear distance appreciably during the transition" [29]. This is a direct consequence of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, which allows for the separation of electronic and nuclear wavefunctions due to the significant mass disparity between electrons and nuclei [30] [31]. During the femtosecond-scale electronic transition, the nuclei are effectively frozen in place, leading to a vertical transition on a potential energy diagram [32].

Theoretical Foundation of the Franck-Condon Principle

Quantum Mechanical Formulation

The quantum mechanical treatment of the Franck-Condon principle derives from the transition probability, ( P ), between an initial state ( |\psi{initial}\rangle ) and a final state ( |\psi{final}\rangle ), which is proportional to the square of the transition dipole moment matrix element [31]:

[ P{i \rightarrow f} = \left| \langle \psi^{*}{final} | \boldsymbol{\mu} | \psi_{initial} \rangle \right|^2 ]

The total wavefunction can be separated into electronic (( \psi{el} )), vibrational (( \psi{v} )), and spin (( \psi{s} )) components: ( \psi{total} = \psi{el} \psi{v} \psi_{s} ) [30]. Within the Condon approximation, which assumes the electronic transition moment is independent of nuclear coordinates, the transition probability simplifies to a product of factors:

[ P \propto \underbrace{ \left| \int \psi{v}'^{*} \psi{v} d\tau{n} \right|^2 }{\text{Franck-Condon Factor}} \times \underbrace{ \left| \int \psi{e}'^{*} \mu{e} \psi{e} d\tau{e} \right|^2 }{\text{Orbital Selection Rule}} \times \underbrace{ \left| \int \psi{s}'^{*} \psi{s} d\tau{s} \right|^2 }_{\text{Spin Selection Rule}} ]

The first term, the square of the overlap integral of the initial and final vibrational wavefunctions, is the Franck-Condon Factor. It is this factor that dictates the relative intensity of vibrational transitions within an electronic absorption or emission band [30] [31]. The subsequent terms enforce the orbital and spin selection rules for the electronic transition itself.

The Semiclassical Picture: Vertical Transitions

The semiclassical interpretation provides an intuitive picture: because the electronic transition is instantaneous relative to nuclear vibration, it is represented by a vertical arrow on a potential energy curve (or surface) diagram, where the x-axis represents nuclear coordinates (e.g., internuclear distance in a diatomic molecule) and the y-axis represents the potential energy [30] [32]. The most probable transition originates from the most probable nuclear configuration of the initial state. For a molecule in the vibrational ground state (v=0), this is typically at the classical turning points of the oscillation. The vertical arrow projects this configuration upward to the potential energy curve of the excited electronic state. The vibrational level in the excited state that is intersected by this vertical line has the greatest spatial overlap with the initial vibrational wavefunction and thus the highest transition probability [30] [29].

Manifestations in Absorption Spectroscopy

The shape of an electronic absorption band is a direct fingerprint of the vibrational level structure in the excited state and the shift in equilibrium geometry between the two electronic states.

Case Studies in Band Profile Analysis

The interplay between the potential energy surfaces of the ground and excited states leads to distinct spectral profiles, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Franck-Condon Principle Case Studies and Resulting Spectral Profiles

| Case | Equilibrium Geometry Shift | Most Probable Transition | Spectral Profile | Example Molecule |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Minimal or No Shift | v"=0 → v'=0 | Strong 0-0 band; rapidly diminishing intensity for higher v' [29] | O₂ [29] |

| Case 2 | Small Shift | v"=0 → v'=2 (example) | Intensity maximum at a non-zero v' band; structured progression [29] | CO [29] |

| Case 3 | Large Shift | v"=0 → high v' (near dissociation) | Continuum spectrum with no vibrational structure [29] | I₂ [29] |

The Franck-Condon Factor and Absorption Intensity

The intensity of an absorption peak corresponding to a transition from the ground vibrational level of the electronic ground state (v") to a specific vibrational level of the electronic excited state (v') is proportional to the Franck-Condon factor, ( \left| \langle \psi{v'} | \psi{v"} \rangle \right|^2 ) [30] [31]. This factor quantifies the degree of spatial overlap between the two vibrational wavefunctions. When the potential energy curves are aligned, the 0-0 transition has the largest overlap. A shift in the equilibrium geometry reduces the overlap for the 0-0 transition and increases it for transitions to higher vibrational levels (v' > 0), as illustrated in the diagram below.

Experimental Protocols and Data Interpretation

Protocol for Measuring and Assigning Vibronic Structure

Objective: To record the UV-Vis absorption spectrum of a molecule with vibrational resolution and assign the vibronic progression using Franck-Condon analysis.

Materials and Reagents:

- High-purity analyte molecule (e.g., organic dye, polyatomic aromatic hydrocarbon).

- Spectrophotometric-grade solvent (e.g., n-hexane, cyclohexane).

- Quartz cuvettes (path length 1 cm).

- High-resolution UV-Vis/NIR spectrophotometer.

- Thermostatted cell holder.

- Data analysis software (e.g., Python with NumPy/SciPy, MATLAB, Origin).

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a dilute solution of the analyte (typical absorbance < 1.0 at the peak maximum) to minimize aggregation and inner-filter effects. Degas the solution if necessary to eliminate oxygen quenching.

- Instrumental Configuration: Use a spectrophotometer capable of a spectral bandwidth less than 0.5 nm. Maintain a constant, low temperature (e.g., 77 K using a cryostat or 100-150 K in a glass-forming solvent) to reduce thermal broadening of vibrational lines [30]. Scan at a slow speed with high data density.

- Data Collection: Record the baseline-corrected absorption spectrum across the relevant electronic transition.

- Peak Assignment: Identify the peak with the shortest wavelength/largest energy, which is assigned as the 0-0 transition [30]. Subsequent peaks at lower energies are assigned as 0-1, 0-2, etc., corresponding to transitions to successively higher vibrational levels (v'=1, v'=2, ...) in the excited electronic state.

- Franck-Condon Analysis:

- Measure the relative areas under each vibronic peak to obtain experimental intensities.

- Construct a harmonic (or anharmonic) oscillator model for the ground and excited states.

- Calculate the Franck-Condon factors for the various v"=0 to v' transitions.

- Iteratively adjust the model parameters (e.g., the shift in equilibrium position, vibrational frequencies) until the calculated Franck-Condon factors match the experimentally observed intensity pattern.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Franck-Condon Studies

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Spectrophotometric-Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents with low UV-Vis cutoff are essential to avoid spurious absorption bands that obscure the vibrational structure of the analyte. |

| Quzrtz Cuvettes | Required for UV-Vis transmission measurements. Matched cuvettes for sample and reference ensure accurate baseline correction. |

| Cryostat or Cooling Cell Holder | Cooling the sample reduces thermal energy, which narrows the individual vibrational linewidths, revealing resolved vibronic structure [30]. |

| High-Resolution Spectrophotometer | Instrumentation with fine spectral bandwidth and high signal-to-noise ratio is critical for resolving closely spaced vibrational peaks. |