Foundations of Green Sample Preparation: Principles, Methods, and Applications for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Green Sample Preparation (GSP) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Foundations of Green Sample Preparation: Principles, Methods, and Applications for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Green Sample Preparation (GSP) for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of green analytical chemistry, details cutting-edge methodologies like pressurized liquid extraction and solvent-free techniques, and offers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. By integrating modern green assessment tools such as AGREE and ComplexGAPI, the article establishes a framework for validating and comparing methods, empowering scientists to implement sustainable practices without compromising analytical performance in biomedical and clinical research.

The Core Principles of Green Sample Preparation: Building a Sustainable Analytical Foundation

Defining Green Sample Preparation (GSP) in Modern Analytical Chemistry

Green Sample Preparation (GSP) represents a fundamental paradigm shift in analytical chemistry, moving away from traditional, resource-intensive sample processing toward more sustainable and environmentally benign practices. As a cornerstone of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), GSP focuses on minimizing the environmental impact of chemical analysis at its very first stage—sample preparation—which has traditionally been the most waste-generating step in analytical workflows [1]. This transition aligns with the broader principles of Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC), which seeks to transform the linear "take-make-dispose" model into a waste-free, resource-efficient framework [1]. The growing adoption of GSP reflects an increasing awareness within the scientific community that ecological considerations must be integrated alongside analytical performance metrics when developing new methodologies. Within the foundation of green sample preparation research, GSP establishes critical criteria for evaluating and improving the sustainability of analytical processes through measurable, objective metrics that account for environmental impact, operator safety, and economic viability.

Core Principles and Definitional Framework

Green Sample Preparation is defined by its adherence to a set of core principles designed to minimize the environmental footprint of sample processing while maintaining analytical integrity. The foundational strategy involves reducing or eliminating hazardous reagents, minimizing energy consumption, and decreasing waste generation throughout the preparation process [1]. These principles align with the twelve SIGNIFICANCE principles of Green Analytical Chemistry, which provide a comprehensive framework for assessing the greenness of analytical methods [2].

A critical distinction exists between GSP and the broader concept of sustainability. While sustainability encompasses a "triple bottom line" balancing economic, social, and environmental pillars, GSP primarily focuses on the environmental dimension through technical implementations [1]. The practice emphasizes source reduction rather than end-of-pipe solutions, seeking to prevent waste generation at the source rather than managing it after creation. This preventative approach represents the most environmentally sound and economically viable strategy for pollution control within analytical laboratories.

The theoretical framework of GSP rests on four primary implementation strategies that guide method development:

- Acceleration of sample preparation steps through assisted techniques (e.g., ultrasound, microwaves)

- Parallel processing of multiple samples to increase throughput

- Automation of preparation procedures to enhance precision and reduce reagent consumption

- Integration of multiple preparation steps into streamlined workflows [1]

These strategies collectively enable analytical chemists to maintain methodological performance while significantly reducing resource consumption and environmental impact.

Current Research Initiatives and Methodological Advances

Green Sample Preparation in Separation Sciences

Current research in separation sciences demonstrates the practical implementation of GSP principles through various technological innovations. Modern approaches focus on miniaturized extraction techniques that dramatically reduce solvent consumption while maintaining or improving analytical performance [1]. These include methods such as vortex-assisted extraction and fields assisted by ultrasound and microwaves, which enhance extraction efficiency and accelerate mass transfer while consuming significantly less energy compared to traditional heating methods like Soxhlet extraction [1].

The application of automated systems represents another significant advancement, offering dual benefits of improved reproducibility and reduced resource consumption. Automation aligns perfectly with GSP principles by saving time, lowering reagent and solvent consumption, and consequently reducing waste generation [1]. Additionally, automated systems minimize human intervention, thereby significantly reducing operator exposure to hazardous chemicals and associated risks.

Assessment Metrics and Method Evaluation

The evaluation of GSP methodologies relies on standardized metric systems that quantify environmental performance. Several assessment tools have been developed, including:

- Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) metric: A comprehensive calculator that evaluates methods based on all 12 principles of GAC, providing a pictogram score between 0-1 [2]

- Analytical Eco-Scale: Assigns penalty points for non-green parameters, with results indicating whether a procedure is "acceptable" or "ideally green" [2]

- Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI): Utilizes a pictogram with a three-grade, traffic light color scheme to represent environmental performance [2]

These assessment tools enable researchers to objectively compare the greenness of different sample preparation methods and identify areas for improvement. However, recent research emphasizes the importance of using quantitative indicators based on empirical data rather than relying solely on theoretical models, which often require estimations and assumptions that may introduce inaccuracies [3].

Table 1: Key Metric Systems for Assessing Green Sample Preparation Methods

| Metric System | Assessment Approach | Output Format | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE [2] | Evaluates all 12 GAC principles with user-defined weights | 0-1 score with clock-like pictogram | Comprehensive, flexible weighting system |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [2] | Penalty points subtracted from base 100 | Numerical score (100 = ideal) | Simple calculation, clear interpretation |

| GAPI [2] | Multi-criteria evaluation with traffic light scheme | Colored pictogram | Visual, intuitive representation |

| NEMI [2] | Binary assessment of four criteria | Pictogram with filled/unfilled quadrants | Simple, quick assessment |

Implementing GSP: Practical Methodologies and Protocols

Strategic Approaches for GSP Implementation

The practical implementation of GSP involves strategic modifications to traditional sample preparation techniques. Research indicates four primary ways to maximize sample throughput while aligning with GSP principles:

- Accelerating the sample preparation step through improved kinetics

- Treating several samples in parallel to increase efficiency

- Automating sample preparation to enhance precision and reduce consumption

- Integrating multiple steps into simplified workflows [1]

Miniaturization represents a particularly effective strategy, as it simultaneously reduces sample size, solvent consumption, and reagent use while frequently improving analytical performance through preconcentration effects. The application of assisted extraction methods such as ultrasound and microwave energy significantly accelerates mass transfer compared to conventional techniques, reducing both processing time and energy requirements [1].

Quantitative Evaluation Framework

Proper evaluation of GSP methodologies requires empirical, quantitative data rather than subjective assessments. A Good Evaluation Practice (GEP) framework recommends using directly measurable indicators to ensure objectivity and reproducibility [3]. Key quantitative metrics for GSP assessment include:

- Electricity consumption measured for specific numbers of analyses (e.g., kWh per 100 samples)

- Carbon footprint calculations based on energy consumption and local energy emissivity

- Total mass/volume of waste generated during analytical procedures

- Mass/volume of particularly hazardous reagents used

- Total volume of water consumption (tap, distilled, ultrapure)

- Total time required for method implementation and application [3]

These empirical measurements provide objective data for comparing the environmental performance of different sample preparation methods and identifying opportunities for improvement.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Green Sample Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function in GSP | Green Characteristics | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-based solvents [2] | Replacement for petroleum-derived solvents | Renewable feedstocks, lower toxicity | Must maintain analytical performance |

| Water-based solutions [2] | Extraction and separation media | Non-toxic, readily available | May require modifiers for hydrophobic analytes |

| Ionic liquids | Green solvent alternatives | Low volatility, tunable properties | Requires assessment of environmental impact |

| Solid-phase microextraction fibers [1] | Solvent-free extraction | Minimal waste, reusability | Suitable for miniaturized systems |

| Molecularly imprinted polymers | Selective extraction materials | Reusability, reduced consumption | High selectivity reduces cleanup needs |

GSP Experimental Protocol: An Integrated Workflow

The following experimental protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for developing and validating green sample preparation methods:

Method Scoping and Objective Definition

- Define analytical objectives and performance requirements

- Identify potential green alternatives to conventional preparation methods

- Establish sustainability targets alongside analytical performance criteria

Green Method Development

- Select appropriate miniaturization strategies based on sample matrix and analytes

- Identify less hazardous solvent alternatives using solvent selection guides

- Design integrated workflows to combine multiple preparation steps

- Implement automation where feasible to improve reproducibility and reduce consumption

Analytical Validation

- Establish method performance characteristics (precision, accuracy, detection limits)

- Verify that green methods meet analytical validation criteria

- Compare performance with conventional methods to ensure comparable quality

Greenness Assessment

- Apply multiple metric systems (AGREE, GAPI, Eco-Scale) for comprehensive evaluation

- Collect empirical data on energy consumption, waste generation, and reagent use

- Compare greenness scores with previously published methods for benchmarking

- Identify potential areas for further improvement through iterative optimization

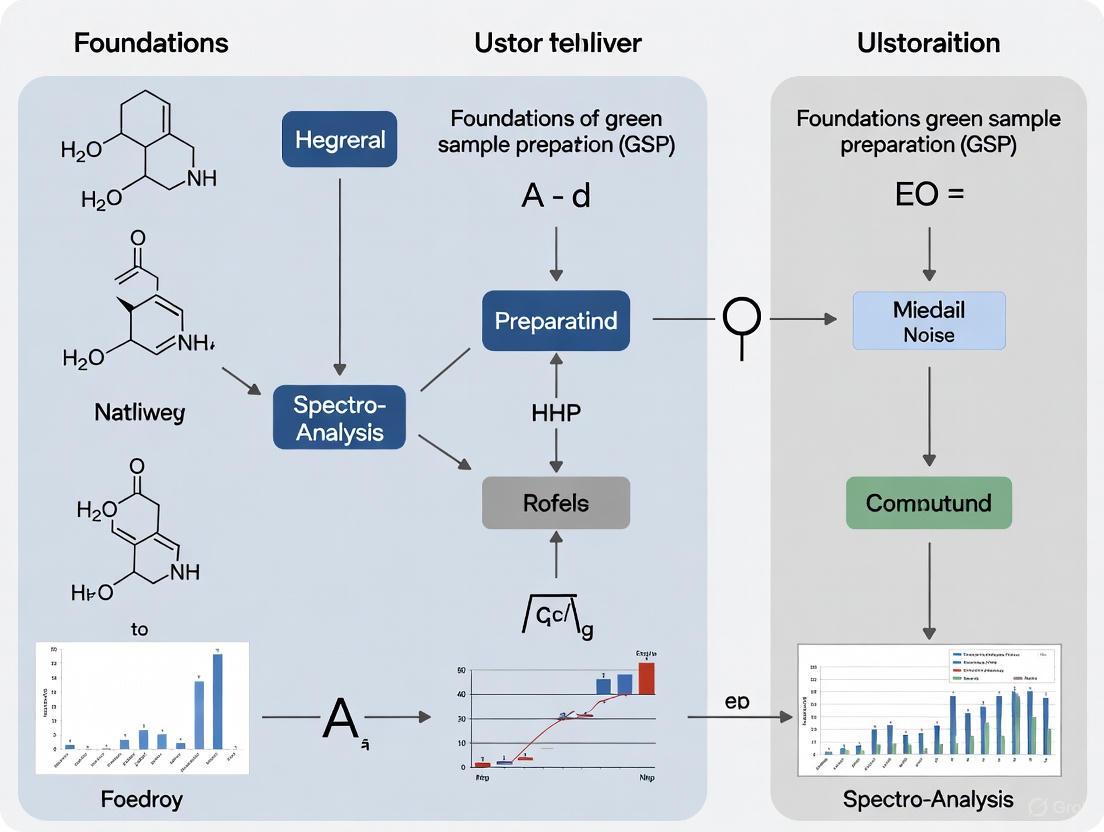

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical relationships and decision points in developing GSP methods:

Challenges and Future Directions in GSP Research

Current Barriers to Implementation

Despite significant advances, several challenges impede the widespread adoption of GSP practices. Analytical chemistry remains a traditional and conservative field, with limited cooperation between key stakeholders including industry, academia, and regulatory bodies [1]. This coordination failure presents a significant barrier to transitioning from linear "take-make-dispose" models to circular approaches that demand far more collaboration than conventional methods [1].

Regulatory frameworks present another significant challenge. Recent assessments of standard methods from CEN, ISO, and Pharmacopoeias revealed that 67% of methods scored below 0.2 on the AGREEprep metric (where 1 represents the highest possible score) [1]. This demonstrates that many official methods still rely on resource-intensive and outdated techniques, creating institutional barriers to implementing greener alternatives.

The Rebound Effect and Mitigation Strategies

An important consideration in GSP implementation is the rebound effect, where efficiency gains lead to unintended consequences that offset environmental benefits [1]. For example, a novel, low-cost microextraction method might lead laboratories to perform significantly more extractions than before, increasing the total volume of chemicals used and waste generated [1]. Similarly, automation may lead to over-testing simply because the technology makes it possible.

Mitigation strategies include:

- Optimizing testing protocols to avoid redundant analyses

- Using predictive analytics to identify when tests are truly necessary

- Implementing smart data management systems

- Establishing sustainability checkpoints in standard operating procedures

- Training laboratory personnel on rebound effect implications [1]

Future Research Priorities

Future GSP research should focus on:

- Developing standardized, empirical metrics for greenness assessment

- Creating disruptive technologies that prioritize strong sustainability over incremental improvements

- Establishing stronger university-industry partnerships to commercialize green innovations

- Updating regulatory frameworks to incorporate greenness criteria in method validation

- Exploring nature-inspired solutions that align analytical chemistry with ecological principles

The transition from weak sustainability (where natural resource consumption is compensated by technological progress) to strong sustainability (which acknowledges ecological limits and planetary boundaries) represents the ultimate future direction for GSP research [1]. This paradigm shift requires fundamental changes in how analytical chemists approach method development, with environmental considerations becoming central rather than ancillary to the process.

The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry as a Guide for GSP

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged as a transformative framework that aligns analytical practices with the goals of environmental sustainability. Born from the broader principles of green chemistry, GAC specifically addresses the unique challenges and opportunities within analytical science, with a particular focus on the sample preparation stage, which is often the most resource-intensive and polluting part of the analytical workflow [4] [5]. The foundational 12 principles of GAC provide a comprehensive roadmap for developing methodologies that minimize environmental impact while maintaining, and often enhancing, analytical performance [5]. Within this framework, Green Sample Preparation (GSP) has crystallized as a dedicated subfield, establishing ten specific principles that guide the reduction of solvent consumption, energy usage, and waste generation during sample processing [6] [7]. This technical guide explores how the 12 principles of GAC serve as a foundational guide for GSP, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the theoretical underpinnings, practical protocols, and assessment tools needed to advance sustainable practices in their laboratories.

The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

The 12 principles of GAC were formulated to adapt the original green chemistry principles to the specific context and challenges of analytical methods [5]. They serve as the definitive framework for greening all stages of analysis, with direct implications for sample preparation. The principles can be remembered using the mnemonic SIGNIFICANCE [5] [7].

Table 1: The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

| Principle Number | Core Concept | Mnemonic Letter | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Select Direct Techniques | S | Choose direct analytical methods to avoid sample treatment altogether [5]. |

| 2 | Integrate Processes | I | Combine analytical operations and processes to save energy and reagents [5]. |

| 3 | Narrow Sample Size | N | Minimize sample sizes and the number of samples collected [5]. |

| 4 | In-situ Measurements | I | Perform measurements in the field or at the point of need when possible [5]. |

| 5 | Function Automatically | F | Implement automated and miniaturized methods to improve efficiency and safety [5]. |

| 6 | Avoid Derivatization | I | Eliminate derivatization steps, which require additional reagents and generate waste [5]. |

| 7 | Generate Minimal Waste | G | Prevent waste generation and have a proper waste management plan [5]. |

| 8 | Consume Less Energy | C | Reduce the overall energy demands of the analytical process [5]. |

| 9 | Choose Safer Reagents | A | Select reagents and solvents with lower toxicity and environmental impact [5]. |

| 10 | Employ Multi-Analyte | N | Develop methods that can determine multiple analytes in a single run [5]. |

| 11 | Use Renewable Sources | C | Utilize reagents and materials derived from renewable feedstocks [5]. |

| 12 | Ensure Operator Safety | E | Minimize risks of accidents, exposure, and other hazards to the analyst [5]. |

The relationship between these principles and their collective impact on greening the sample preparation workflow is visualized below.

Implementing GAC Principles in Green Sample Preparation

Strategic Approaches for GSP

Translating the 12 GAC principles into practical GSP requires a multi-faceted strategy. The following approaches are critical for developing effective and sustainable sample preparation methods.

Miniaturization and Automation: Miniaturization directly addresses principles 2 (minimal sample size) and 7 (minimal waste) by scaling down extraction volumes and apparatus, leading to drastic reductions in solvent consumption [1]. For instance, moving from a traditional liquid-liquid extraction using hundreds of milliliters of solvent to a microscale extraction using only a few milliliters exemplifies this strategy. Automation, aligned with principle 5, not only improves throughput and reproducibility but also enhances operator safety (principle 12) by reducing direct handling of hazardous samples and reagents [1]. Automated systems can precisely control solvent volumes and disposal, further minimizing waste.

Alternative Energy Sources and Solvent Selection: Replacing conventional heating with alternative energy sources like ultrasound or microwaves is a key tactic for principle 8 (energy efficiency). Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) uses cavitation to disrupt cell walls, enhancing extraction efficiency while operating at lower temperatures and shorter times compared to Soxhlet extraction [4] [8]. Solvent selection is paramount for principles 5 (safer solvents) and 9 (safer reagents). The shift from hazardous organic solvents like chlorinated hydrocarbons or petroleum ether to safer alternatives such as ethanol, water, or supercritical COâ‚‚ is a central tenet of GSP [4] [9]. For example, a method using acidified ethanol-water for anthocyanin extraction is significantly greener than one using acidified methanol or acetone [4].

Method Integration and Direct Analysis: Integration of analytical steps (principle 2) simplifies workflows and reduces resource use. Techniques like QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) integrate extraction and clean-up into a streamlined process, minimizing the number of separate operations and the associated solvent and material consumption [10]. The ideal, though not always achievable, GSP method is direct analysis (principle 1), which eliminates the sample preparation stage entirely. When possible, techniques that allow for the direct injection of samples, potentially after simple filtration or dilution, represent the ultimate in green sample preparation [10] [5].

Experimental Protocol: A Comparative Study of PLE and UAE

The following detailed protocol from a study on anthocyanin extraction from purple corn demonstrates the practical application of GAC principles using two green techniques: Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) [4].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GSP

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Protocol | Green Justification / Property |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol (EtOH) | Primary extraction solvent | Safer, biodegradable, and derived from renewable feedstocks compared to traditional MeOH or ACN [4] [11]. |

| o-Phosphoric Acid (o-PA) | Acidifying agent for solvent | Used in low concentration (2%) to stabilize pH-sensitive anthocyanins [4]. |

| Water | Co-solvent in extraction | Non-toxic, safe, and readily available. A prime example of a green solvent [4] [9]. |

| Diatomaceous Earth | Dispersing agent for sample in PLE | Inert, reusable material that aids in creating a uniform extraction bed [4]. |

| Purple Corn Powder | Sample matrix (Anthocyanin source) | Model complex food matrix for evaluating the extraction methods [4]. |

Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) Protocol

- Instrumentation and Setup: A Dionex ASE 200 system or equivalent is used. A 5 mL stainless-steel extraction cell is prepared by placing two cellulose filters at the bottom [4].

- Sample Preparation: 0.5 g of homogenized purple corn powder is thoroughly dispersed with 1.5 g of diatomaceous earth using a mortar and pestle. This mixture is loaded into the pre-assembled extraction cell. The remaining cell volume is filled with more diatomaceous earth, and a final cellulose filter is placed on top [4].

- Extraction Parameters: The extraction is performed using a solvent mixture of 2% o-phosphoric acid in ethanol and water (1:1, v/v). The optimal conditions are:

- Temperature: 95 °C

- Pressure: 1500 psi

- Static Time: 3 minutes (1 cycle)

- Flush Volume: 70% of cell volume (3.5 mL)

- Purge Time: 90 seconds with inert gas (e.g., Nâ‚‚)

- Post-Extraction Processing: The resulting extract (approx. 5 mL) is collected. For analysis, an aliquot is diluted 1:9 with an appropriate mobile phase (e.g., water/ACN with acid modifier) and filtered before injection into an HPLC system [4].

Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) Protocol

- Instrumentation and Setup: An ultrasonic bath or probe system with controlled temperature is required. A typical setup uses a sealed extraction vessel placed in the ultrasonic bath or directly sonicated with a probe [4].

- Sample Preparation: 0.5 g of homogenized purple corn powder is accurately weighed directly into the extraction vessel.

- Extraction Parameters: The sample is mixed with a solvent mixture of 2% o-phosphoric acid in ethanol and water (1:1, v/v). The optimal conditions are:

- Solvent Volume: 10 mL

- Temperature: Maintained at 40 °C

- Ultrasound Frequency/ Power: Specific to the equipment (e.g., 40 kHz for a bath)

- Extraction Time: 10 minutes

- Post-Extraction Processing: After sonication, the extract is allowed to cool. It is then centrifuged (e.g., 5000 rpm for 5 min) to separate solid particulates. The supernatant is collected, and an aliquot is diluted and filtered before HPLC analysis, similar to the PLE extract [4].

Assessment of Greenness and Practical Applicability

Evaluating the environmental and practical performance of GSP methods is crucial for their adoption. Standardized metrics allow for the quantitative comparison of different techniques.

Table 3: Greenness and Applicability Assessment of PLE and UAE

| Assessment Metric | Pressurized Liquid Extraction (PLE) | Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) | Interpretation of Scores |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREEprep Score [4] [7] | 0.73 | 0.76 | Scores range 0-1 (1=ideal greenness). Both are high, with UAE having a slight edge. |

| BAGI Score [4] | 77.5 | 72.5 | Scores method practicality. PLE scored higher on throughput and sensitivity. |

| Key Green Advantages | Higher throughput, lower limits of detection [4]. | Lower energy use, less waste generation [4]. | PLE favors performance; UAE favors waste/energy reduction. |

| Method Validation | Precision (RSD ≤ 5.4%), Accuracy (97.1-101.9% recovery) [4]. | Precision (RSD ≤ 5.4%), Accuracy (97.1-101.9% recovery) [4]. | Both methods were rigorously validated per FDA guidelines, proving reliability [4]. |

The field of GSP continues to evolve beyond the foundational principles of GAC. Emerging frameworks like White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) and Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) are pushing the boundaries of sustainability. WAC seeks a balance between the three pillars of greenness (environmental impact), redness (analytical performance), and blueness (practicality and cost), ensuring that methods are not only eco-friendly but also economically viable and analytically sound [6]. Meanwhile, CAC advocates for a systemic shift from a linear "take-make-dispose" model to a circular one that eliminates waste, keeps materials in use, and minimizes resource consumption [1]. This involves designing methods for reagent recovery, recycling of sorbents, and using waste as a resource.

A critical consideration for the future is avoiding the "rebound effect," where the efficiency gains of a greener method are offset by its widespread or excessive use. For example, a cheap, low-solvent microextraction technique might lead to a dramatic increase in the total number of analyses performed, ultimately increasing the overall environmental burden [1]. Mitigating this requires a mindful laboratory culture and optimized testing protocols.

In conclusion, the 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry provide an indispensable and robust guide for the research and development of Green Sample Preparation methods. As demonstrated by the validated protocols for PLE and UAE, a principled approach to method development leads to sustainable workflows that minimize environmental impact without compromising analytical rigor. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting these principles, supported by modern assessment tools and a forward-looking perspective on circularity and balance, is no longer optional but essential for pioneering a sustainable future in analytical science.

In modern analytical science, the processes of sample preparation and analysis are fundamental to research and drug development. However, traditional methodologies have often relied on hazardous chemicals, energy-intensive equipment, and wasteful practices, creating significant environmental footprints and potential safety risks for personnel. The concept of Green Sample Preparation (GSP) has therefore emerged as a critical foundation for sustainable science, aiming to redesign analytical workflows at their core. This paradigm shift is not merely an ethical choice but a practical necessity, driven by stringent environmental regulations, occupational safety requirements, and the economic need for greater efficiency. This technical guide explores the key drivers—the core principles, methodologies, and metrics—that enable researchers to minimize environmental impact while simultaneously enhancing laboratory safety. By integrating these drivers into daily practice, scientists can align their work with the broader goals of sustainable development, creating analytical methods that are not only scientifically robust but also environmentally benign and safe to perform.

Theoretical Foundations: From GAC and GSP to White Analytical Chemistry

The movement toward sustainable laboratories is built upon a structured theoretical framework that has evolved from broad principles to specific, actionable guidelines.

The Evolution of Green Chemistry in Analytical Science

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) emerged in 2000 as an extension of the original Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry [12]. GAC focuses specifically on applying these ideals to analytical techniques, with the goal of decreasing or eliminating dangerous solvents, reagents, and other materials, while also providing rapid and energy-saving methodologies that maintain critical validation parameters [12]. This represents a fundamental shift in how analytical challenges are approached, prioritizing environmental benignity alongside traditional metrics of success.

The Ten Principles of Green Sample Preparation (GSP)

As sample preparation is often the most resource-intensive and hazardous stage of analysis, the Ten Principles of Green Sample Preparation (GSP) were established to provide a more targeted roadmap [13]. These principles offer direct guidance for minimizing impact during this crucial phase and include key directives such as:

- Minimizing sample and reagent amounts.

- Using safer solvents and reagents.

- Minimizing energy consumption and additional preparation steps.

- Reducing health hazards and operational safety risks.

- Maximizing sample throughput and extraction efficiency [13].

The Holistic Framework of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC)

The most recent evolution in this field is White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), a holistic paradigm that extends beyond the eco-centric focus of GAC [14]. WAC proposes an RGB model that evaluates analytical methods across three balanced dimensions:

- Green (Environmental Impact): Encompasses GAC and GSP principles, focusing on waste prevention, energy efficiency, and operator safety.

- Red (Analytical Performance): Assesses method sensitivity, selectivity, accuracy, and precision.

- Blue (Practical & Economic Factors): Considers cost, time, simplicity, and feasibility [14].

This integrated framework ensures that methods are not only environmentally friendly but also analytically sound and practically viable, promoting truly sustainable and efficient analytical practices.

Key Drivers for Reducing Environmental Impact

Implementing sustainable laboratory practices requires a focus on specific, actionable drivers. The most significant levers for reducing environmental impact are reagent selection, waste management, and energy consumption.

Driver 1: Adoption of Green Solvents

The transition from traditional solvents to green solvents is a pivotal shift toward sustainable science [15]. Conventional solvents like benzene and chloroform are often volatile, toxic, and persistent in the environment. Green solvents, conversely, are characterized by their low toxicity, renewable origins, and reduced environmental impact [15].

Table 1: Comparison of Conventional and Green Solvents

| Solvent Type | Examples | Key Characteristics | Environmental & Safety Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Solvents | Benzene, Chloroform, Acetone | Petroleum-based, high volatility, often toxic | Occupational hazards, environmental pollution, volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions [15] |

| Bio-based Solvents | Bio-ethanol, Ethyl Lactate, D-limonene | Derived from renewable resources (e.g., sugarcane, orange peels) [15] | Biodegradable, lower toxicity, reduced carbon footprint from renewable feedstocks |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Mixtures of hydrogen bond donors/acceptors (e.g., Choline Chloride + Urea) | Low volatility, non-flammable, tunable, simple synthesis [15] | Generally low toxicity, biodegradable components, reduced waste generation |

| Supercritical Fluids | Supercritical COâ‚‚ | Non-toxic, non-flammable, gas at ambient conditions [15] | Avoids petroleum derivatives, but requires energy for pressurization |

Driver 2: Miniaturization and Waste Reduction

Miniaturization of analytical methods is a powerful strategy for waste prevention. Techniques such as liquid-phase microextraction and the use of micro-sized stationary phases dramatically reduce solvent consumption from hundreds of milliliters to just a few milliliters or less per sample [12] [14]. This directly reduces the volume of hazardous waste generated, simplifying disposal and lowering environmental burden. The foundational metric here is the E-Factor, which quantifies the mass of waste generated per unit of product or, in analytical terms, per sample processed. A lower E-Factor indicates a greener process.

Driver 3: Energy-Efficient Technologies

Energy consumption is a major contributor to the carbon footprint of analytical laboratories. Key strategies for improvement include:

- Adopting Low-Energy Techniques: Methods like dilute-and-shoot eliminate energy-intensive extraction and concentration steps [14].

- Utilizing Ambient Temperature Processes: Several microextraction techniques operate at room temperature, avoiding the energy demand of heating or cooling [12].

- Exploring Alternative Energy Sources: The Carbon Footprint Reduction Index (CaFRI) is a modern metric that encourages the use of clean or renewable energy to power analytical equipment [12].

The following workflow diagram illustrates how these key drivers are integrated into a holistic green sample preparation process.

Key Drivers for Enhancing Laboratory Safety

Reducing environmental impact frequently goes hand-in-hand with enhancing laboratory safety. Safer chemicals and processes inherently protect the well-being of researchers.

Driver 1: Substitution and Reagent Hazard Reduction

The most effective strategy for improving safety is hazard elimination through substitution. This involves:

- Replacing Toxic Reagents: Switching to safer alternatives. For example, using citrus-based terpenes like D-limonene instead of chlorinated solvents for extraction [15].

- Utilizing Safer Solvent Classes: Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) are often non-flammable and have low volatility, reducing risks of fire and inhalation exposure compared to traditional organic solvents [15].

- Implementing Administrative Controls: The University of Washington's Laboratory Safety Manual emphasizes that staff must have access to and be trained on Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) that specifically address chemical hazards [16].

Driver 2: Process Intensification and Automation

Simplifying and automating workflows reduces direct human interaction with hazardous materials.

- Miniaturization: Using smaller volumes of reagents not only reduces waste but also minimizes the potential consequences of spills or exposures [12].

- Automation and On-site Analysis: Employing automated systems or developing methods for on-site analysis reduces manual handling of samples and reagents, thereby lowering operator risk [12] [14].

- Closed-System Designs: Techniques that operate in sealed vessels prevent the release of harmful vapors into the laboratory atmosphere.

Driver 3: Waste Management and Risk Assessment

Proactive waste management is crucial for both environmental and safety outcomes.

- Waste Minimization: By generating less waste through miniaturization, laboratories reduce the volume of material that must be stored, handled, and disposed of as hazardous waste [16].

- Hazard Awareness: Tools like the Green Extraction Tree (GET) include explicit criteria for "Process Risk Assessment," evaluating health hazards and operational safety risks to ensure they are considered during method development [13].

Table 2: Green Assessment Tools for Evaluating Method Safety and Sustainability

| Assessment Tool | Type | Key Safety and Environmental Criteria | Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE [12] | Comprehensive Metric | Scores based on the 12 Principles of GAC, including energy consumption, waste, and toxicity. | Pictogram and a score from 0 (not green) to 1 (ideal). |

| AGREEprep [12] | Sample Prep Metric | Focuses on solvents, reagents, waste, and energy used specifically in sample preparation. | Weighted score and visual pictogram. |

| Green Extraction Tree (GET) [13] | Natural Products Focus | Evaluates renewable materials, solvent safety, waste, health hazards, and operational risks. | "Tree" pictogram with color-coded leaves and a final score. |

| NEMI [12] | Basic Pictogram | Simple check for PBT (Persistent, Bioaccumulative, Toxic) chemicals, hazardous waste, and corrosivity. | Quadrant pictogram with checkmarks. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Equipping the laboratory with the right tools is essential for implementing green and safe sample preparation methods. The following table details key research reagent solutions.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Sample Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function in GSP | Green & Safety Attributes |

|---|---|---|

| Bio-based Ethanol [15] | Extraction solvent for a wide range of analytes. | Derived from renewable resources (e.g., sugarcane), readily biodegradable, lower toxicity than synthetic alternatives. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) [15] | Tunable extraction media for selective isolation of target compounds. | Low volatility and non-flammability enhance lab safety; can be made from natural, non-toxic components. |

| Supercritical COâ‚‚ [15] | Extraction fluid, particularly for non-polar compounds. | Non-toxic and non-flammable; leaves no solvent residue in the extract, eliminating downstream exposure. |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) [15] | Designer solvents for specific separations and extractions. | Negligible vapor pressure prevents inhalation hazards; however, requires assessment of aquatic toxicity and biodegradability. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles [14] | Sorbents for magnetic solid-phase extraction. | Enable rapid separation without centrifugation, saving time and energy; can be functionalized for specificity. |

| Dimethyl Phthalate | Dimethyl Phthalate, CAS:131-11-3, MF:C10H10O4, MW:194.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dipivefrin | Dipivefrin (Dipivalyl Epinephrine) | Dipivefrin hydrochloride is a prodrug of epinephrine for research applications. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO), not for human consumption. |

A Practical Workflow: Integrating Drivers into an Experimental Protocol

This section provides a detailed methodology for a sugaring-out-induced homogeneous liquid–liquid microextraction (SULLME) method, evaluated using modern greenness metrics [12]. This case study demonstrates the practical application of the key drivers.

1. Experimental Objective: To isolate and concentrate antiviral compounds from a liquid sample using a miniaturized, greener approach.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Sample: Aqueous solution containing target analytes.

- Green Solvents (Driver 1): A water-miscible organic solvent (e.g., acetone or acetonitrile) and a sugar (e.g., glucose or fructose).

- Apparatus: Centrifuge tubes (15 mL), micropipettes, and a centrifuge.

3. Detailed Methodology: 1. Sample Introduction: Transfer 10 mL of the aqueous sample into a 15 mL centrifuge tube. 2. Induction of Homogeneity: Add 1-2 mL of a water-miscible organic solvent to the tube and mix thoroughly. This creates a homogeneous solution. 3. Phase Separation via "Sugaring-out": Add a large excess of sugar (e.g., 4 g of glucose) to the homogeneous solution. Vigorously vortex or shake the mixture until the sugar dissolves. The high concentration of sugar will decrease the solubility of the organic solvent in water, causing it to separate as a distinct phase on top of the aqueous solution. 4. Phase Collection: Centrifuge the tube at 3500 rpm for 5 minutes to accelerate and complete phase separation. Using a micropipette, carefully collect the smaller, organic phase which now contains the concentrated analytes. 5. Analysis: The extracted concentrate is now ready for instrumental analysis (e.g., HPLC or GC).

4. Greenness and Safety Assessment: A multi-metric evaluation of this SULLME protocol reveals its strengths and weaknesses [12]:

- MoGAPI Score: 60/100, indicating moderate greenness. Strengths include miniaturization (Driver 2) and use of some green solvents (Driver 1). Weaknesses include moderate reagent toxicity and waste generation >10 mL per sample [12].

- AGREE Score: 0.56/1.0. The method benefits from miniaturization and semi-automation potential (Driver 2), but is marked down for the use of toxic/flammable solvents and moderate waste generation [12].

- CaFRI Score: 60/100. The method has low analytical energy consumption (0.1–1.5 kWh/sample, Driver 3), but loses points for non-renewable energy sources and lack of CO₂ tracking [12].

The following diagram maps the experimental workflow and its alignment with the key drivers, providing a visual guide to the integrated process.

The journey toward sustainable and safe laboratories is guided by a clear set of technical and philosophical principles. The key drivers—adopting green solvents, embracing miniaturization, improving energy efficiency, substituting hazardous reagents, and automating processes—are not isolated concepts but are deeply interconnected. As demonstrated by the RGB model of White Analytical Chemistry, true progress is achieved only when environmental impact (green), analytical performance (red), and practical feasibility (blue) are balanced and optimized together [14]. The foundational thesis of GSP research is that this balance is attainable. By leveraging the frameworks, metrics, and experimental protocols detailed in this guide, researchers and drug development professionals can systematically design and implement methodologies that uphold the highest standards of scientific rigor while fulfilling their responsibility to protect both the well-being of laboratory personnel and the health of our planet.

Green Sample Preparation (GSP) represents a critical paradigm shift in analytical chemistry, focusing on the fundamental goals of minimizing solvent consumption, reducing energy usage, and curtailing waste generation. As the most resource-intensive stage of analytical workflows, sample preparation has become a primary target for sustainability improvements within the framework of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) [12] [15]. This transformation is driven by both environmental concerns and practical economic benefits, aligning analytical practices with the principles of sustainable science [1].

The transition from conventional linear "take-make-dispose" models to circular approaches requires rethinking traditional methodologies [1]. Modern GSP strategies embrace miniaturization, automation, and integration to achieve these fundamental goals while maintaining analytical performance [1]. This whitepaper examines the current state of GSP implementation, assessment methodologies, and future directions for researchers and drug development professionals working within the foundational framework of GSP research.

Minimizing Solvent Consumption: Strategies and Solutions

Green Solvent Alternatives

The shift from traditional organic solvents to greener alternatives represents a cornerstone of solvent minimization strategies. Conventional solvents like benzene, chloroform, and acetone are increasingly being replaced by safer, renewable options with reduced environmental impact [15].

Table 1: Classification and Properties of Green Solvents

| Solvent Category | Representative Examples | Key Advantages | Limitations/Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-based Solvents | Ethanol, ethyl lactate, D-limonene | Renewable feedstocks, biodegradable, low toxicity [15] | Some may have purity variability |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) | Various cation-anion combinations | Negligible vapor pressure, tunable properties [15] | Complex synthesis, potential toxicity [15] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Choline chloride-urea mixtures | Simple synthesis, biodegradable, low cost [15] | Viscosity may challenge handling |

| Supercritical Fluids | COâ‚‚ | Non-toxic, easily separated, tunable solvation [15] | High pressure equipment required [15] |

The principles of ideal green solvents extend beyond their application performance to include characteristics such as biodegradability, low toxicity, sustainable manufacturing processes, low volatility, and compatibility with analytical techniques [15]. For instance, bio-based solvents derived from cereal/sugar sources (e.g., bio-ethanol), oleoproteinaceous materials (e.g., fatty acid esters), or wood (e.g., terpenes like D-limonene) offer renewable alternatives to petroleum-derived solvents [15].

Microextraction Techniques and Solvent Volume Reduction

Miniaturization represents one of the most effective strategies for solvent reduction. Liquid-phase microextraction (LPME) techniques have demonstrated remarkable efficiency in minimizing solvent consumption while maintaining analytical performance.

A notable example is the biosolvent-based liquid-liquid microextraction method for quantifying β-blockers in human urine, which utilized only 65 μL of molten menthol as the extraction medium [17]. This approach eliminated traditional toxic solvents and demonstrated excellent analytical performance with detection limits of 11-17 ng mLâ»Â¹, underscoring how miniaturization achieves dual benefits of solvent reduction and maintained efficacy [17].

The Green Extraction Tree (GET) metric tool specifically emphasizes solvent minimization as a key criterion, assigning higher scores to methods that minimize solvent and reagent amounts while prioritizing safer alternatives [13]. This reflects the growing recognition that solvent selection and volume reduction are interdependent considerations in green method development.

Reducing Energy Consumption: Efficient System Design

Energy-Efficient Extraction Technologies

Energy consumption during sample preparation presents another significant environmental impact factor. Traditional techniques like Soxhlet extraction are particularly energy-intensive, creating substantial opportunities for improvement through alternative technologies.

The application of assisted fields such as ultrasound and microwaves represents a strategic approach to reducing energy demands. These technologies enhance extraction efficiency and accelerate mass transfer while consuming significantly less energy compared to traditional heating methods [1]. Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE), for instance, utilizes high-frequency sound waves to disrupt sample matrices through cavitation effects, enabling efficient extraction at lower temperatures and reduced processing times [18].

Pressurized liquid extraction (PLE) employs elevated temperatures and pressures to enhance extraction efficiency while potentially reducing overall energy consumption through shorter extraction cycles [18]. A comparative study of anthocyanin extraction from purple corn demonstrated that both PLE and UAE could achieve excellent extraction efficiency using sustainable solvent systems, with the energy consumption profile varying between techniques [18].

System Optimization and Integration

Beyond equipment selection, strategic system design significantly influences energy consumption in sample preparation. The principles of Green Sample Preparation explicitly recommend maximizing sample throughput through parallel processing, which effectively reduces energy consumption per sample [1]. Automation represents another key strategy, as automated systems not only save time but also optimize energy usage through programmed protocols and reduced manual intervention [1].

Process integration, where multiple preparation steps are consolidated into a single, continuous workflow, offers additional energy savings by eliminating intermediate processing stages and associated energy requirements [1]. This approach simplifies operations while cutting down on both resource use and energy consumption.

Waste Generation Minimization: Circular Approaches

Source Reduction Strategies

Waste minimization begins with source reduction, fundamentally addressing waste generation at its origin. Microextraction techniques naturally align with this principle by dramatically reducing the volumes of solvents and reagents consumed, thereby diminishing waste streams at the source [17].

The GET metric tool explicitly incorporates waste minimization as a key criterion, evaluating methods based on their ability to minimize byproduct and waste generation throughout the extraction process [13]. Similarly, the Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) assesses the environmental impact of analytical methods, including waste production and potential for recycling [19].

Waste Management and Circular Economy Integration

Beyond source reduction, comprehensive waste management strategies complete the sustainability picture. The principles of Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) emphasize keeping materials in use for as long as possible, fundamentally challenging the linear "take-make-dispose" model [1]. This approach requires coordination across all stakeholders, including manufacturers, researchers, routine labs, and policymakers [1].

Practical waste management considerations include solvent recycling programs, proper treatment of hazardous waste streams, and design for degradability where applicable. The transition from weak sustainability models (where natural resource consumption is acceptable if compensated by technological progress) to strong sustainability (which acknowledges ecological limits and planetary boundaries) represents the ultimate goal for waste management in analytical chemistry [1].

Assessment Metrics: Quantifying Greenness

Greenness Assessment Tools

The development of comprehensive assessment metrics has been instrumental in advancing GSP implementation. Multiple tools now exist to evaluate the environmental performance of sample preparation methods, each with distinct strengths and applications.

Table 2: Greenness Assessment Metrics for Sample Preparation

| Metric Tool | Focus Area | Output Format | Key Strengths | Recent Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGREEprep [12] | Sample preparation | Pictogram + score (0-1) | Specific to sample preparation, weighted criteria [12] | SULLME method evaluation (score: 0.56) [12] |

| GET [13] | Natural product extraction | Tree diagram + score (0-2 per criterion) | Integrates GSP & green extraction principles [13] | Ginseng extraction evaluation [13] |

| AMGS [19] | Chromatographic methods | Numerical score | Incorporates solvent energy, EHS, instrument energy [19] | Pharmaceutical method assessment [19] |

| ComplexMoGAPI [17] | Entire analytical method | Modified GAPI pictogram | Includes sample preparation and preliminary steps [17] | Menthol-based microextraction evaluation [17] |

These tools enable researchers to quantitatively compare methods, identify areas for improvement, and make informed decisions regarding sustainability. For instance, the application of multiple metrics (MoGAPI, AGREE, AGSA, CaFRI) to evaluate a sugaring-out liquid-liquid microextraction (SULLME) method provided a multidimensional view of its environmental profile, highlighting strengths in miniaturization while revealing weaknesses in waste management [12].

Complementary Assessment Frameworks

Beyond dedicated greenness metrics, complementary frameworks like White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) integrate environmental sustainability with methodological practicality and analytical performance [17]. This holistic approach ensures that green methods maintain the robustness and reliability required for pharmaceutical analysis and other demanding applications.

The Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) focuses on practical applicability aspects, complementing greenness assessments by evaluating factors such as cost, time, and operational simplicity [18]. In the comparison of PLE and UAE for anthocyanin extraction, BAGI scores of 77.5 and 72.5 respectively confirmed both techniques as viable for routine analysis while AGREEprep scores of 0.73 and 0.76 highlighted their environmental sustainability [18].

Experimental Protocols: Implementing GSP Principles

Biosolvent-Based Microextraction Protocol

The following protocol demonstrates the implementation of GSP principles for pharmaceutical analysis, adapted from the determination of β-blockers in human urine [17]:

Reagents and Materials:

- Pharmaceuticals: Propranolol and carvedilol standards

- Extraction solvent: Menthol (65 μL per sample)

- Internal standard: Ethyl paraben solution

- Salt solution: Sodium chloride (30% w/w)

- Reconstitution solvent: Methanol (HPLC grade)

Equipment:

- HPLC-UV system with C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm)

- Microcentrifuge capable of 10,000 rpm

- Ultrasonic bath

- Vortex mixer

- Ice bath apparatus

Procedure:

- Place 250 μL of undiluted human urine in a microcentrifuge tube

- Add 150 μL of NaCl solution (30% w/w), 50 μL of ISTD solution, and 50 μL of analyte mixture

- Add 65 μL of molten menthol (preheated to 40°C) as extraction solvent

- Vortex mix for 10 seconds

- Sonicate for 30 seconds to disperse menthol microdroplets

- Centrifuge at 10,000 rpm for 2 minutes

- Immediately transfer to ice bath to solidify menthol phase

- Remove and discard aqueous layer using a syringe

- Dissolve solidified menthol in 500 μL methanol

- Transfer to HPLC vial for analysis

HPLC Conditions:

- Mobile phase: 0.1% formic acid in water and methanol (50:50, v/v)

- Flow rate: 1.0 mL minâ»Â¹

- Column temperature: 25°C

- Detection: UV at 230 nm

- Injection volume: 10 μL

This protocol exemplifies multiple GSP principles: solvent minimization (65 μL menthol), use of safer solvents (menthol instead of traditional organic solvents), energy optimization (room temperature operation except for mild preheating), and waste reduction (miniaturized scale) [17].

Sustainable Extraction of Bioactive Compounds

For natural product extraction, the following protocol compares PLE and UAE for anthocyanin extraction from purple corn [18]:

Pressurized Liquid Extraction Protocol:

- Sample: 0.5 g purple corn powder mixed with 1.5 g diatomaceous earth

- Extraction solvent: 2% o-phosphoric acid in ethanol:water (1:1, v/v)

- Conditions: 95°C, 1500 psi, one static extraction cycle of 3 minutes

- Equipment: Dionex ASE 200 with 5 mL stainless-steel cells

- Flush volume: 70% cell capacity, purge time 90 seconds

Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Protocol:

- Sample: 0.5 g purple corn powder

- Extraction solvent: 2% o-phosphoric acid in ethanol:water (1:1, v/v)

- Solvent volume: 10 mL

- Conditions: 40°C, 30 minutes, 40 kHz frequency

- Equipment: Ultrasonic bath with temperature control

Both methods demonstrated excellent analytical performance with coefficient of determination ≥ 0.9992, detection limits of 0.30–1.70 mg/kg, and precision with RSD ≤ 5.4% [18]. The environmental assessment revealed PLE offered higher throughput while UAE minimized waste and energy consumption, providing options for different laboratory priorities [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Green Sample Preparation

| Material/Reagent | Function in GSP | Green Advantages | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menthol [17] | Biosolvent for microextraction | Natural origin, low toxicity, biodegradable | LPME of β-blockers from urine [17] |

| Ethanol-Water Mixtures [18] | Extraction solvents | Renewable, low toxicity, food-grade | Anthocyanin extraction from purple corn [18] |

| Ionic Liquids [15] | Tunable extraction media | Low volatility, customizable properties | Extraction of various analytes |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents [15] | Green extraction media | Biodegradable, low cost, simple preparation | Natural product extraction |

| Supercritical COâ‚‚ [15] | Non-polar extraction solvent | Non-toxic, easily separated, tunable | Lipid extraction, essential oils |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers [20] | Selective sorbents | Reusability, reduced solvent consumption | Selective extraction from complex matrices |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks [20] | Advanced sorbent materials | High capacity, potential reusability | Microextraction techniques |

| Disparlure | Disparlure: Gypsy Moth Sex Pheromone for Research | High-purity Disparlure, the sex pheromone of the spongy moth (Lymantria dispar). For research into mating disruption and pest control. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Djenkolic acid | Djenkolic acid, CAS:498-59-9, MF:C7H14N2O4S2, MW:254.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The fundamental goals of minimizing solvent use, reducing energy consumption, and curtailing waste generation represent more than technical challenges—they embody a necessary evolution in analytical practice. The strategies and methodologies outlined in this whitepaper demonstrate that substantial progress is achievable through green solvent adoption, miniaturization, energy-efficient technologies, and systematic waste reduction.

The ongoing development of comprehensive assessment metrics provides researchers with critical tools to quantify and compare environmental performance, driving continuous improvement in GSP methodologies. As the field advances, the integration of circular economy principles and strong sustainability models will further transform analytical chemistry, aligning it with broader environmental objectives [1].

For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing these fundamental goals offers a pathway to maintaining analytical excellence while reducing environmental impact. The experimental protocols and assessment frameworks presented herein provide practical starting points for implementation, supporting the transition toward truly sustainable analytical science.

Diagram: Green Sample Preparation Implementation Workflow

GSP Implementation Workflow: This diagram illustrates the systematic approach to implementing Green Sample Preparation principles, from fundamental goals through specific strategies to final assessment and sustainable outcomes.

The growing emphasis on sustainability has propelled the development of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), a dedicated branch of chemistry focused on minimizing the environmental impact of analytical procedures [21]. While the foundational 12 principles of Green Chemistry provided an initial framework, they proved insufficient for addressing the specific challenges of chemical analysis [21]. This led to the establishment of the 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry, offering a more tailored framework for developing eco-friendly analytical methods [21]. Within this framework, sample preparation has been identified as a critical step due to its typical consumption of solvents, sorbents, reagents, and energy [21]. To navigate this complex landscape and objectively evaluate the environmental footprint of analytical methods, several metric tools have been developed. This guide provides an in-depth examination of three significant tools: AGREEprep, ComplexGAPI, and the AGREE II instrument, detailing their applications, methodologies, and roles in advancing sustainable research practices, particularly within the context of green sample preparation (GSP) research.

The AGREEprep Metric

AGREEprep is the first dedicated metric tool designed specifically for evaluating the environmental impact of analytical sample preparation methods [22] [21]. It shifts the assessment focus from the broad principles of GAC to the ten specialized principles of Green Sample Preparation (GSP) [21]. The tool utilizes user-friendly, open-source software to calculate and visualize results, producing an intuitive pictogram that offers both a quantitative score and a qualitative overview of the method's performance across all ten criteria [22] [21].

The ten principles of GSP that form the basis for AGREEprep are [21]:

- Favor in situ sample preparation

- Use safer solvents and reagents

- Target sustainable, reusable, and renewable materials

- Minimize waste

- Minimize sample, chemical and material amounts

- Maximize sample throughput

- Integrate steps and promote automation

- Minimize energy consumption

- Choose the greenest possible post-sample preparation configuration for analysis

- Ensure safe procedures for the operator

Detailed Methodology and Assessment Protocol

The AGREEprep assessment involves a systematic evaluation of a sample preparation method against the ten GSP principles. The following workflow outlines the key steps in conducting this assessment, from data collection to the final interpretation.

Data Collection and Inputs: To perform an assessment, essential data must be gathered from the analytical procedure [22]. This includes:

- Solvents and Reagents: Types, volumes, and their associated hazard profiles.

- Energy Consumption: Amount of energy required for heating, cooling, or agitation.

- Generated Waste: Total volume and toxicity of waste produced.

- Sample Throughput: Number of samples processed per unit of time.

- Operator Safety: Data on exposure to hazardous materials and overall procedural safety.

Scoring and Weighting System: Each of the ten criteria is assigned a score between 0 and 1 [21]. AGREEprep incorporates a weighting system to acknowledge that not all criteria are equally important. The tool provides default weights but allows assessors to customize them based on specific analytical goals. An example of default weighting is shown in the table below [21].

Output and Interpretation: The final output is a circular pictogram divided into ten sections, each corresponding to one GSP principle [21]. The color of each section (green, yellow, or red) indicates its performance. The overall greenness score, displayed in the center, ranges from 0 (worst) to 1 (best). This visual representation allows for immediate identification of a method's strengths and weaknesses [21].

Key Experiment: Assessing Phthalate Esters in Water

AGREEprep was used to evaluate six different sample preparation procedures for determining phthalate esters in water [21]. One assessed procedure was the EPA standard 8061A employing liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) with 180 mL of dichloromethane [21]. Another was a modern microextraction technique that consumed only 1.5 mL of an ionic liquid [21].

Findings: The LLE method received a low overall score, with red and yellow sections highlighting significant environmental concerns, particularly related to hazardous solvent use and waste generation [21]. In contrast, the microextraction method achieved a high score, with most sectors colored green, demonstrating its superior greenness profile [21]. This experiment showcases AGREEprep's effectiveness in differentiating between traditional and modern approaches and identifying specific aspects for improvement.

Research Reagent Solutions for Green Sample Preparation

The following table details key materials and their functions in developing greener sample preparation methods, as informed by the principles of GSP.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Sample Preparation

| Material/Reagent | Function in Sample Preparation | Green Alternative & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Dichloromethane | Traditional solvent for liquid-liquid extraction (LLE). | Ionic Liquids or Cyclodextrins; safer profiles and reduced volumes [21]. |

| Sulfuric Acid / Sodium Hydroxide | pH adjustment for extraction. | Use of weaker acids/bases or buffers; reduced hazard and easier waste disposal. |

| Commercial Sorbents (e.g., C18) | Solid-phase extraction (SPE) packing material. | Biosorbents or renewable materials; target sustainability and reusability [21]. |

| Disposable Extraction Cartridges | Single-use devices for SPE. | Reusable devices or automated systems; minimize material waste and integrate steps [21]. |

The Complementary Green Analytical Procedure Index (ComplexGAPI)

The Complementary Green Analytical Procedure Index (ComplexGAPI) is an advanced assessment tool that builds upon the widely adopted Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) [23] [24]. While GAPI evaluates the analytical procedure itself—from sample collection to final analysis—ComplexGAPI addresses a critical gap by extending the assessment to include processes performed prior to the analytical step [24]. This includes the synthesis and manufacturing of specialized solvents, sorbents, reagents, or other materials used in the analytical procedure, providing a more comprehensive "cradle-to-grave" evaluation [24].

Methodology and Diagram Specification

The core feature of ComplexGAPI is the addition of a hexagonal field to the original GAPI pictogram. This new section is subdivided to evaluate different aspects of the pre-analysis phase, such as the greenness of the synthesis pathways for reagents and sorbents [24]. Each sub-field is colored based on whether it meets specific requirements, maintaining the green-yellow-red color scheme to indicate performance [24].

Assessment Protocol:

- Define Scope: Identify all reagents, solvents, and materials used in the analytical method and trace their origin.

- Evaluate Pre-Analytical Processes: Assess the synthesis and manufacturing processes of these inputs against green chemistry principles (e.g., atom economy, use of safer solvents, energy efficiency).

- Conduct Standard GAPI Assessment: Evaluate the main analytical procedure (sample collection, transport, storage, preparation, and final analysis) using the standard GAPI protocol [24].

- Generate Pictogram: Use the available freeware software to input the data and generate the final ComplexGAPI pictogram, which incorporates both the pre-analysis hexagon and the standard GAPI diagram [23] [24].

Key Application: Evaluation of Pesticide Determination Methods

The utility of ComplexGAPI was demonstrated by evaluating different analytical protocols for determining pesticides in urine samples [24]. This application highlighted how methods that might appear green when considering only the analytical step can reveal a different profile upon a more comprehensive assessment. For instance, a method utilizing a specially synthesized sorbent could score lower if the synthesis of that sorbent involved hazardous reagents or generated significant waste, a drawback that would be captured in the pre-analysis hexagon of ComplexGAPI but missed by standard GAPI [24].

The AGREE II Instrument

It is crucial to distinguish the AGREE II instrument from the AGREEprep and AGREE metrics. AGREE II is a generic tool designed to assess the quality and methodological rigor of clinical practice guidelines [25] [26]. It does not evaluate the greenness of analytical methods. However, for drug development professionals and researchers operating in a regulated environment, AGREE II provides a critical framework for ensuring that clinical guidelines—which may recommend specific analytical or diagnostic procedures—are developed with transparency, rigor, and editorial independence [25].

Methodology and Domain Structure

The AGREE II instrument consists of 23 key items organized into six domains, followed by two global assessment items [25] [26]. Each item is rated on a 7-point scale (from 1, "strongly disagree," to 7, "strongly agree"). The six domains are:

- Scope and Purpose: Concerns the overall aim of the guideline and the specific health questions it addresses [25].

- Stakeholder Involvement: Evaluates the extent to which the guideline was developed by the appropriate stakeholders and represents the views of its intended users [25].

- Rigor of Development: Assesses the process of gathering and synthesizing evidence, the methods for formulating recommendations, and the procedure for updating them [25]. This is the most comprehensive domain.

- Clarity of Presentation: Pertains to the language, structure, and format of the guideline [25].

- Applicability: Examines the barriers and facilitators to implementing the guideline, and whether it provides advice or tools for application [25].

- Editorial Independence: Evaluates whether the recommendations are unbiased by funding bodies and competing interests of the development group members [25].

Domain scores are calculated by summing the scores of all items in a domain and scaling the total as a percentage of the maximum possible score for that domain [25].

Comparative Analysis of Green Assessment Tools

The following table provides a structured comparison of the core green assessment tools discussed, highlighting their specific focuses, methodologies, and outputs.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Green Assessment Tools

| Feature | AGREEprep | ComplexGAPI | AGREE II Instrument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Sample preparation step only [21]. | Entire analytical procedure + pre-analysis processes [24]. | Quality of clinical practice guidelines [25]. |

| Foundation | 10 Principles of Green Sample Preparation [21]. | GAC attributes, expanding on GAPI [24]. | 6 domains of guideline quality [25]. |

| Assessment Output | Pictogram (circle with 10 sections) & overall score (0-1) [21]. | Pictogram (includes pre-analysis hexagon) [24]. | Individual domain scores & overall guideline assessment [25]. |

| Quantification | Yes, weighted overall score [21]. | Primarily qualitative (color-coded). | Yes, scored domains and items [25]. |

| Key Application | Comparing & improving sample preparation methods [22] [21]. | Comprehensive life-cycle-like assessment of analytical methods [24]. | Appraising the development process of clinical guidelines [25]. |

The adoption of robust green assessment tools is fundamental to advancing the principles of sustainable science. AGREEprep, ComplexGAPI, and AGREE II, though designed for different purposes, each play a vital role in this ecosystem. For researchers focused on the foundations of green sample preparation, AGREEprep offers the most specific and targeted framework for evaluating and improving this critical step. Meanwhile, ComplexGAPI provides a broader, more holistic view of the entire analytical lifecycle, ensuring that upstream processes are not overlooked. By systematically applying these tools, scientists and drug development professionals can make informed decisions, validate their green claims with tangible evidence, and collectively drive innovation toward a more sustainable future in analytical chemistry.

Implementing Green Sample Preparation: Advanced Techniques and Practical Applications

Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction (HS-SPME) has emerged as a premier green sample preparation technique that aligns perfectly with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC). This solvent-free approach integrates sampling, extraction, concentration, and sample introduction into a single step, dramatically reducing the use of hazardous solvents and minimizing waste generation [27] [28]. The technique operates by exposing a coated fiber to the headspace above a sample, allowing volatile and semi-volatile analytes to partition into the fiber coating through absorption or adsorption mechanisms [29]. Since its invention in 1989 by Pawliszyn and colleagues, SPME has been widely adopted across various fields, including environmental science, food analysis, pharmaceuticals, and metabolomics, establishing itself as a key enabling technology for sustainable analytical practices [27] [28].

The fundamental principle of HS-SPME is based on establishing equilibrium between the sample matrix, the headspace, and the fiber coating [29]. In the context of green sample preparation (GSP) research, HS-SPME represents a significant advancement over traditional techniques such as liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) and solid-phase extraction (SPE), which typically consume substantial amounts of organic solvents [30] [31]. The environmental benefits of HS-SPME are substantial, with recent assessments using tools like AGREE, AGREEprep, and ComplexGAPI confirming its superior sustainability profile compared to solvent-based methods [32]. Furthermore, the technique's compatibility with miniaturized sampling approaches and its ability to be automated make it particularly valuable for developing eco-friendly analytical workflows that maintain high analytical performance while reducing environmental impact [27] [32].

Theoretical Foundations and Principles

The Three-Phase Equilibrium System

The theoretical foundation of HS-SPME rests on a three-phase equilibrium system comprising the sample matrix, the headspace (gas phase), and the fiber coating [29]. The extraction process is governed by the partitioning of analytes between these three phases, which is influenced by the physicochemical properties of both the analytes and the sample matrix. When a sample is placed in a sealed vial and brought to a controlled temperature, volatile compounds distribute themselves between the sample matrix and the headspace according to their partition coefficients. The SPME fiber, when introduced into the headspace, provides a third phase into which analytes can partition, thus establishing a three-phase system [29].

The kinetics and efficiency of this process are controlled by several factors, including the mass transfer of analytes from the sample to the headspace, and subsequently from the headspace to the fiber coating. For effective HS-SPME operation, the system must approach equilibrium, though quantitative analysis can be performed before equilibrium is reached if extraction conditions are carefully controlled and consistent [30]. The amount of analyte extracted by the fiber at equilibrium is directly proportional to its initial concentration in the sample, which forms the basis for quantitative analysis. This relationship can be expressed as n = Kfs × Vf × C0, where n is the amount of analyte extracted, Kfs is the fiber-sample distribution coefficient, Vf is the fiber coating volume, and C0 is the initial analyte concentration in the sample [30].

Key Parameters Governing HS-SPME Efficiency

Several critical parameters influence the efficiency and reproducibility of HS-SPME extractions, each affecting the equilibrium dynamics of the three-phase system. Fiber chemistry represents perhaps the most important parameter, as the selectivity and affinity of the fiber coating for target analytes directly determines extraction efficiency [33] [29]. Common commercial fibers include polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), divinylbenzene/PDMS (DVB/PDMS), carboxen/PDMS (CAR/PDMS), and the triphasic DVB/CAR/PDMS, each offering different selectivity for various compound classes [33] [29] [34].

Extraction temperature significantly impacts HS-SPME performance by influencing the partition coefficients of analytes between the sample, headspace, and fiber. Elevated temperatures generally increase the Henry's constant of volatile compounds, favoring their transfer from the liquid phase to the headspace [30] [29]. However, excessively high temperatures can decrease the fiber-coating/gas distribution coefficient, potentially reducing the amount of analyte extracted onto the fiber [29]. Extraction time must be optimized for each application, as it determines how close the system comes to equilibrium [29]. While reaching full equilibrium provides maximum sensitivity, sufficiently reproducible extractions can often be achieved with shorter, non-equilibrium times to improve throughput [30].

The sample matrix composition profoundly affects analyte partitioning through factors such as ionic strength, pH, and the presence of interfering compounds. The addition of salts like sodium chloride can decrease the solubility of polar analytes in the aqueous phase, driving them into the headspace through the "salting-out" effect [33] [29]. The headspace-to-sample volume ratio also critically influences sensitivity, as a larger headspace volume relative to the sample can enhance the mass transfer of analytes to the fiber [29]. Finally, agitation of the sample accelerates extraction kinetics by improving mass transfer from the sample to the headspace, reducing the time required to reach equilibrium [33] [29].

Critical Method Development Parameters

Fiber Selection and Chemistry

The selection of an appropriate fiber coating is arguably the most critical decision in HS-SPME method development, as it directly determines the selectivity and sensitivity of the extraction. Different fiber coatings exhibit varying affinities for compound classes based on their chemical properties, including polarity, molecular weight, and volatility [33] [29]. The polydimethylsiloxane/divinylbenzene (PDMS/DVB) fiber is particularly effective for extracting volatile polar compounds such as alcohols, esters, and ketones, making it well-suited for food and flavor analysis [31]. The carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane (CAR/PDMS) fiber excels at trapping very volatile and low-molecular-weight compounds, including gases and light solvents, which makes it ideal for environmental applications targeting volatile halogenated compounds [33]. The divinylbenzene/carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane (DVB/CAR/PDMS) triphasic fiber offers the broadest range of extraction capabilities, combining the benefits of both DVB and CAR particles with a PDMS matrix, making it suitable for untargeted analyses where a wide volatility range of compounds needs to be captured [29] [34].