Green Chemistry in Spectroscopic Sample Preconcentration: Sustainable Strategies for Modern Analytics

This article explores the integration of Green Chemistry principles into spectroscopic sample preconcentration, a critical and often resource-intensive step in analytical workflows.

Green Chemistry in Spectroscopic Sample Preconcentration: Sustainable Strategies for Modern Analytics

Abstract

This article explores the integration of Green Chemistry principles into spectroscopic sample preconcentration, a critical and often resource-intensive step in analytical workflows. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive examination of the foundational drivers, innovative methodologies, and practical optimization strategies shaping sustainable analysis. The content covers the transition from traditional solvents to greener alternatives like ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents, the application of miniaturized techniques such as solid-phase and liquid-phase microextraction, and the critical role of greenness assessment tools (AGREE, AGREEprep, NEMI) in validating and comparing method sustainability. By synthesizing current trends and future directions, this review serves as a strategic guide for implementing eco-friendly preconcentration techniques that maintain analytical rigor while reducing environmental impact.

The Principles and Drivers of Green Sample Preconcentration

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) represents a transformative paradigm in chemical analysis, dedicated to minimizing the environmental footprint and health risks associated with traditional laboratory practices [1]. By integrating the principles of green chemistry into analytical methodologies, GAC seeks to align analytical processes with the overarching goals of sustainability, reducing the use of toxic reagents, energy consumption, and generation of hazardous waste [2]. This shift is particularly crucial in fields like spectroscopic sample preconcentration research, where traditional methods often consume large volumes of solvents and generate significant waste [3]. GAC transforms analytical workflows into tools that not only achieve high performance but also actively contribute to global sustainability objectives [1] [2].

The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

The 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry provide a comprehensive framework for designing and implementing environmentally benign analytical techniques. These principles, derived from the foundational work of Paul Anastas and John C. Warner, serve as a practical roadmap for developing safer, more efficient, and sustainable analytical methods [2] [4].

Table: The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

| Principle Number | Principle Name | Core Objective | Application in Sample Preconcentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Waste Prevention | Design processes to avoid generating waste | Miniaturized methods to reduce/eliminate waste solvents |

| 2 | Atom Economy | Maximize incorporation of materials into the product | Design efficient chemical reactions for analyte binding |

| 3 | Less Hazardous Chemical Syntheses | Use and generate substances with low toxicity | Employ non-toxic chelating agents and surfactants |

| 4 | Designing Safer Chemicals | Design effective, low-toxicity chemical products | Develop safer solvents and sorbents |

| 5 | Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries | Minimize use of auxiliary substances/select safer ones | Replace organic solvents with water, ILs, DES, or SUPRAS |

| 6 | Design for Energy Efficiency | Minimize energy requirements of processes | Use ambient temperature processes or alternative energy sources |

| 7 | Use of Renewable Feedstocks | Use renewable rather than depleting raw materials | Employ bio-based solvents or sorbents from natural sources |

| 8 | Reduce Derivatives | Avoid unnecessary derivatization steps | Minimize or eliminate sample pre-processing steps |

| 9 | Catalysis | Prefer catalytic rather than stoichiometric reagents | Use catalytic processes to enhance extraction efficiency |

| 10 | Design for Degradation | Design products to break down into harmless substances | Use biodegradable surfactants (e.g., Triton X-114) |

| 11 | Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention | Develop in-process monitoring and control to prevent pollution | Implement real-time sensors to minimize repetitive analysis |

| 12 | Inherently Safer Chemistry for Accident Prevention | Choose substances and forms to minimize accident risks | Select solvents with high flash points and low vapor pressure |

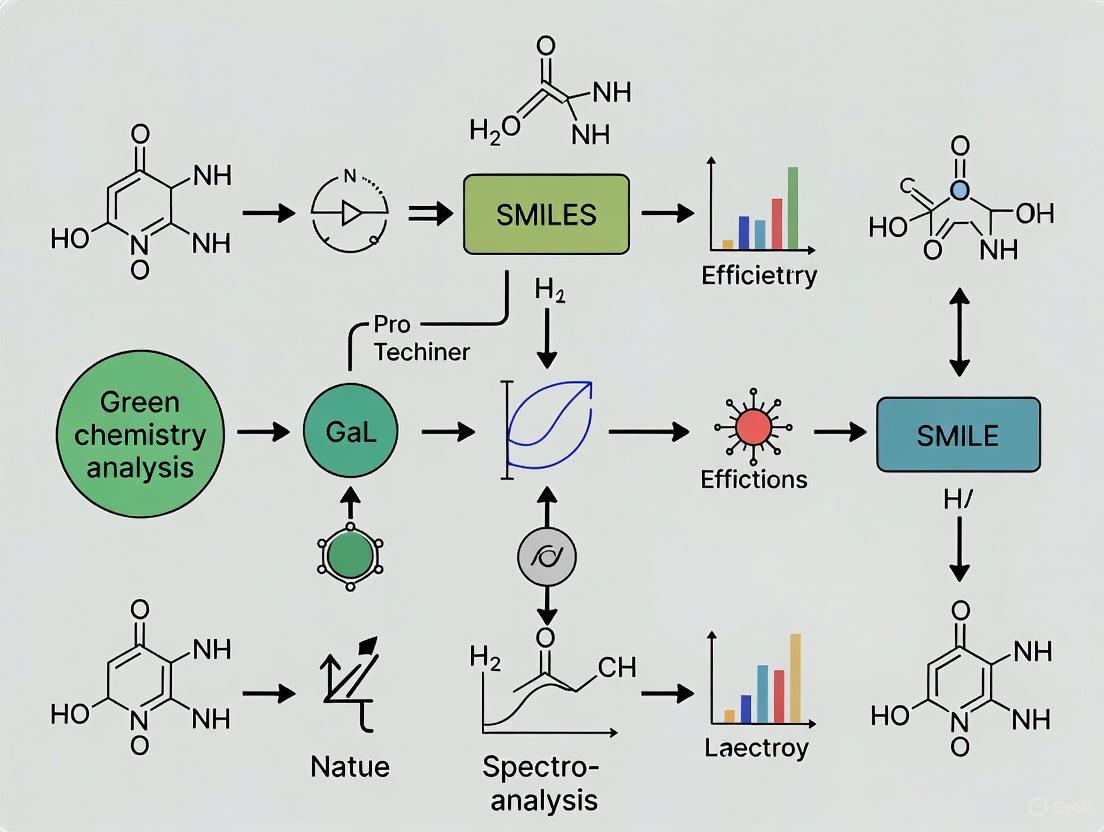

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and workflow integration of these principles within an analytical method development process.

GAC Principles Workflow

Green Preconcentration Methods: A Troubleshooting Guide

Adopting green preconcentration techniques can present challenges. This section addresses common issues through FAQs and detailed protocols.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My green microextraction method gives low recovery compared to traditional Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE). What could be wrong? Low recovery in microextraction often stems from inefficient mass transfer. Traditional LLE uses large solvent volumes and vigorous shaking, whereas microextraction relies on subtle equilibrium. Ensure you have optimized key parameters:

- pH adjustment: The sample pH must be suitable for the formation of a neutral, hydrophobic complex between the metal ion and the chelating agent [5].

- Surfactant/Solvent Volume: In Cloud Point Extraction (CPE), precise surfactant concentration (e.g., Triton X-114) is critical for forming a distinct surfactant-rich phase [3] [5].

- Time and Temperature: Adhere strictly to incubation and centrifugation times. In CPE, heating to the cloud-point temperature is essential for phase separation [5].

Q2: The surfactant-rich phase in my Cloud Point Extraction is too viscous to handle. How can I fix this? High viscosity is a common issue. The solution is to dissolve the surfactant-rich phase in a small volume of a compatible solvent after phase separation and cooling. A standard protocol is to treat the surfactant-rich phase with 200 μL of 0.1 mol Lâ»Â¹ HNO₃ in ethanol (1:1, v/v) to drastically reduce viscosity and facilitate analysis [5].

Q3: Are ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents (DES) truly "green" alternatives? This is a nuanced area. While ionic liquids were initially hailed as green due to their negligible vapor pressure, their synthesis can involve toxic reagents, and their environmental toxicity is sometimes a concern [6]. DESs are often a greener alternative, prepared by mixing low-toxicity, sometimes natural, precursors (e.g., choline chloride and urea). However, their high viscosity can be a practical challenge, potentially requiring a dilution step before instrumental analysis [6]. Always evaluate the entire life cycle of the solvent.

Q4: What is the "rebound effect" in Green Analytical Chemistry? The rebound effect occurs when a greener method leads to unintended consequences that offset its environmental benefits. For example, a novel, low-cost microextraction method might be so efficient that laboratories perform significantly more analyses than before, increasing the total volume of chemicals used and waste generated [7]. Mitigation strategies include optimizing testing protocols to avoid redundant analyses and fostering a mindful laboratory culture where resource consumption is actively monitored [7].

Q5: How can I objectively evaluate the "greenness" of my analytical method? The analytical community is increasingly using metric-based tools to quantify greenness. The AGREEprep metric is one such tool designed specifically for sample preparation methods [7]. It provides a score based on multiple criteria aligned with GAC principles. Studies using AGREEprep have revealed that many official standard methods score poorly, highlighting the urgent need to update them with greener alternatives [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Cloud Point Extraction (CPE) for Trace Metal Preconcentration

This protocol is adapted from a method for determining Cobalt (Co) and Lead (Pb) in water samples [5].

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for CPE

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Description | Notes on Green Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Triton X-114 (0.5% v/v) | Non-ionic surfactant | Biodegradable surfactant; forms the extracting phase. |

| 8-Hydroxyquinoline (Oxine) | Chelating agent | Forms neutral, hydrophobic complexes with metal ions. |

| Acetate Buffer (pH 7.0) | pH Control | Ensures optimal pH for metal-chelate formation. |

| HNO₃ in Ethanol (0.1 M) | Dilution Solvent | Reduces viscosity of the surfactant-rich phase for analysis. |

Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: To a 25 mL aliquot of standard or filtered water sample, add 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-114 and 5 × 10â»Â³ mol Lâ»Â¹ oxine.

- pH Adjustment: Adjust the pH to 7.0 using a 0.1 M acetate buffer.

- Incubation: Place the mixture in an ultrasonic bath at 50°C for 10 minutes to reach the cloud point, then let it stand for 30 minutes.

- Phase Separation: Centrifuge for 10 minutes at 3500 rpm to compact the surfactant-rich phase.

- Cooling: Cool the tubes in an ice bath for 10 minutes to solidify the surfactant-rich phase.

- Analysis: Decant the aqueous phase. Dissolve the surfactant-rich phase in 200 μL of 0.1 mol Lâ»Â¹ HNO₃ in ethanol and analyze by Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (FAAS).

The following diagram visualizes this CPE workflow.

Cloud Point Extraction Workflow

Protocol 2: Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (DLLME) with Green Solvents

DLLME miniaturizes traditional LLE, using microliters of solvent instead of milliliters [3].

Workflow:

- Solvent Selection: Prepare a mixture of a green extraction solvent (e.g., a low-toxicity Deep Eutectic Solvent - DES) and a disperser solvent (e.g., ethanol).

- Rapid Injection: Rapidly inject this mixture into an aqueous sample using a syringe. This produces a cloudy solution full of fine droplets of the extraction solvent, providing a large surface area for rapid analyte extraction.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the mixture to sediment the dense extraction solvent droplets at the bottom of the tube.

- Analysis: Use a micro-syringe to withdraw the sedimented phase for instrumental analysis. The key green advantage is the dramatically reduced solvent volume [3] [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Green Materials & Solvents

Table: Essential Green Reagents and Materials for Sample Preconcentration

| Category | Example | Key Function | Green Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surfactants | Triton X-114 | Forms micelles for extracting analytes in CPE [5] | Biodegradable, non-ionic, low cloud point. |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) | e.g., [C₄MIM][PF₆] | Extraction solvent in microextraction [3] | Negligible vapor pressure, tunable properties. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | e.g., Choline Chloride:Urea | Biodegradable extraction solvent [6] | Low toxicity, biodegradable, often from renewable sources. |

| Supramolecular Solvents (SUPRAS) | e.g., Hexanoic acid-based vesicles | Nanostructured solvents for efficient extraction [6] | Can be synthesized in situ, biodegradable. |

| Biosorbents | Chitosan, Cellulose, Cork | Natural sorbents in solid-phase microextraction [6] | Renewable, biodegradable, derived from waste. |

| Magnetic Nanomaterials | Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles | Sorbent retrievable with an external magnet [6] | Simplifies separation, reduces time/energy, reusable. |

| MS645 | MS645, MF:C48H54Cl2N10O2S2, MW:938.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| F5446 | F5446, MF:C26H17ClN2O8S, MW:552.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Green Analytical Chemistry is more than a scientific discipline; it is an essential pathway for reducing the ecological impact of analytical processes while driving innovation [2]. By adopting its 12 principles and implementing the green preconcentration methods and troubleshooting guides detailed in this article, researchers and drug development professionals can significantly advance the sustainability of their spectroscopic work. The future of GAC is promising, with emerging technologies like artificial intelligence offering new ways to optimize workflows and minimize waste, ultimately contributing to a more sustainable future for analytical science and industry [2] [7].

Welcome to the Green Preconcentration Technical Support Center

This resource is designed for researchers and scientists integrating green chemistry principles into spectroscopic sample preconcentration. Below, you will find targeted troubleshooting guides, detailed experimental protocols, and answers to frequently asked questions to help you optimize your methods for both environmental and analytical performance.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What makes a preconcentration method "green"? A green preconcentration method minimizes its environmental footprint across several dimensions. This includes reducing or eliminating hazardous solvent use, lowering energy consumption, integrating safer & biodegradable reagents, minimizing waste generation, and applying metrics for formal greenness assessment [9] [10].

FAQ 2: Why is there a specific focus on the sample preparation step? Sample preparation is often the most resource-intensive part of the analytical workflow. It can involve large volumes of solvents, significant energy input, and hazardous reagents, making it a primary target for greening efforts. Focusing here offers the greatest potential for reducing the overall environmental impact of an analysis [9] [10].

FAQ 3: Besides environmental benefits, what are other advantages of greener preconcentration? Greener methods often lead to substantial economic benefits. They can reduce costs associated with solvent purchase, waste disposal, and energy consumption [11]. Furthermore, they frequently enhance operator safety by reducing exposure to toxic chemicals and can improve analytical performance through miniaturization and automation [9].

FAQ 4: What are the most common greenness assessment tools for analytical methods? Several tools have been developed, each with its strengths. The table below summarizes the key metrics [9] [12]:

| Tool Name | Type of Output | Key Features | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) | Pictogram (Binary) | Simple, yes/no evaluation against four basic criteria [9]. | A quick, initial check [9]. |

| AGREE (Analytical GREENness) | Pictogram & Numerical Score (0-1) | Comprehensive assessment based on all 12 principles of GAC [9]. | A balanced, single-score comparison of entire methods [9]. |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | Pictogram (Color-coded) | Visual assessment of the entire analytical process from sampling to detection [9]. | Identifying environmental hotspots within a method's workflow [9]. |

| Analytic Eco-Scale | Numerical Score | Assigns penalty points to non-green parameters; score of 100 is ideal [9]. | Semi-quantitative comparison and benchmarking [9]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Environmental Footprint in Solvent-Based Preconcentration

Problem: Your liquid-liquid extraction method uses large volumes of hazardous organic solvents.

Solution: Transition to miniaturized or solvent-free techniques.

- Recommended Action: Implement a Sugaring-Out Induced Homogeneous Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (SULLME). This method uses sugars to induce phase separation, drastically reducing solvent volumes to less than 10 mL per sample [9].

- Protocol: SULLME for Aqueous Samples

- Prepare Sample: Measure 1 mL of liquid sample (e.g., water) into a microcentrifuge tube.

- Add Sugaring-Out Agent: Introduce a mass of a sugar (e.g., glucose or fructose) sufficient to create a saturated solution.

- Add Extraction Solvent: Add a small volume (< 100 µL) of a water-miscible organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile).

- Mix: Vortex the mixture vigorously until a homogeneous solution is formed.

- Induce Separation: Add a small amount of water to the homogenous solution. This will decrease the solubility of the organic solvent, leading to the formation of a separate microextract phase.

- Separate: Centrifuge the mixture to complete phase separation and sediment the microextract at the bottom of the tube.

- Analyze: The microextract can be directly injected or reconstituted for spectroscopic analysis [9].

Issue 2: Excessive Energy Consumption

Problem: Your preconcentration process (e.g., evaporation, pumping) is energy-intensive.

Solution: Optimize process design and integrate energy-efficient technologies.

- Recommended Action: For water treatment or process stream analysis, integrate membrane preconcentration prior to the main treatment or analysis step. This reduces the volume that needs to be processed by energy-intensive equipment [13].

- Protocol: Nanofiltration Preconcentration for Aqueous Samples

- Setup: Use a commercial spiral-wound nanofiltration (NF) membrane module (e.g., NF270 or NF90).

- Filtration: Pump the aqueous sample (e.g., industrial process water) through the NF module.

- Concentrate: The membrane retains the target analytes (e.g., persistent organic pollutants like PFHxA) in the retentate stream, reducing the volume for the next step by 5-10 times.

- Process Concentrate: The small-volume retentate, now with a higher analyte concentration and often higher ionic strength, can be processed with a subsequent method (e.g., electrochemical degradation or direct spectroscopic analysis) with dramatically lower overall energy consumption [13].

Issue 3: Poor Greenness Assessment Scores

Problem: Your method receives a low score on AGREE or other greenness metrics.

Solution: Systematically address the low-scoring criteria identified by the assessment tool.

- Diagnosis: Calculate your method's AGREE score. The output pictogram will visually highlight poorly performing principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (e.g., principle #5 on waste generation, or principle #12 on operator safety) [9].

- Corrective Actions:

- If waste generation is high (#5): Switch to micro-extraction techniques or automate the process to reduce solvent and sample volumes [9].

- If operator safety is low (#12): Replace toxic/flammable solvents with safer alternatives (e.g., bio-based solvents, deep eutectic solvents) and ensure the process is contained or automated [9].

- If energy consumption is high (#6): Use ambient temperature processes where possible and avoid energy-intensive equipment like large vacuum evaporators [9].

Experimental Protocols for Greener Preconcentration

Protocol 1: Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe (QuEChERS) Extraction

QuEChERS is a well-established green sample preparation method for solid and complex matrices.

Workflow Overview:

Steps:

- Weigh: Place 10-15 g of homogenized sample (e.g., fruit, vegetable tissue) into a 50 mL centrifuge tube.

- Extract: Add 10-15 mL of an extraction solvent (typically acetonitrile) and shake for 1 minute.

- Salt Out: Add a pre-mixed salt packet containing anhydrous magnesium sulfate (MgSOâ‚„) to remove water and sodium chloride (NaCl) to induce phase separation. Shake vigorously for 1-3 minutes.

- Centrifuge: Centrifuge the mixture at >3000 RCF for 5 minutes to achieve complete phase separation.

- Clean-up: Transfer an aliquot (e.g., 1 mL) of the upper extract layer to a dispersive-SPE tube containing clean-up sorbents (e.g., PSA for organic acids, C18 for fats).

- Clarify: Shake the d-SPE tube and centrifuge to sediment the sorbents.

- Analyze: The clarified supernatant is ready for direct spectroscopic analysis or further preconcentration [10].

Protocol 2: Integrated Membrane Preconcentration and Analysis

This protocol is ideal for reducing the energy footprint when treating or analyzing large volumes of dilute aqueous samples.

Workflow Overview:

Steps:

- Feed: Pump the dilute aqueous sample (e.g., process water, environmental surface water) through a nanofiltration (NF) or tight ultrafiltration (UF) membrane system.

- Preconcentrate: Continue filtration, collecting the purified permeate stream separately. The target analytes are retained and concentrated in a significantly smaller retentate volume (e.g., 10-50x concentration factor).

- Analyze: The small-volume retentate can now be analyzed directly with techniques like UV-Vis or fluorescence spectroscopy, or with a secondary micro-extraction method. The preconcentration step reduces the energy required for subsequent analysis by over 70% compared to processing the entire original volume [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key reagents and materials for implementing greener preconcentration methods, along with their functions and green alternatives.

| Reagent/Material | Traditional Function | Greener Alternative & Its Function |

|---|---|---|

| Organic Solvents (e.g., Chloroform, Dichloromethane) | Extraction solvent in Liquid-Liquid Extraction. | Bio-based solvents (e.g., Ethyl Lactate, Cyrene): Safer, biodegradable extraction solvents. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES): Tunable, low-toxicity solvents for extraction [9] [10]. |

| Solid Sorbents (e.g., Silica-based C18) | Retain analytes in Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE). | Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs): Provide high selectivity, reducing interference and need for cleanup. Biopolymer Sorbents (e.g., chitosan): Renewable, biodegradable sorbents for SPE [10]. |

| Salts (e.g., NaCl, MgSOâ‚„) | Salting-out agent in QuEChERS and SULLME to separate organic phase. | Potassium salts or other naturally abundant salts can be used. The key green aspect is enabling miniaturization [10]. |

| Sugars (e.g., Glucose, Fructose) | Not traditionally used. | Sugaring-Out Agents: Induce phase separation in SULLME, replacing energy-intensive evaporation steps [9]. |

| Nanofiltration Membranes (e.g., NF270) | Preconcentration of aqueous streams, rejecting contaminants while allowing water and some salts to pass. | Membranes with high permeability: Reduce pumping energy. The green function is waste rejection and volume reduction [13]. |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Core Principles and Definitions

Q1: What defines a "green" sample preparation method? A green sample preparation method is designed to minimize its environmental and safety impact by adhering to the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry [14]. Key objectives include reducing or eliminating the use of hazardous solvents, minimizing energy consumption, cutting down on waste generation, and improving overall safety for the operator [3] [14]. The ideal green method uses smaller sample volumes, less toxic reagents, and generates less waste compared to traditional techniques [3].

Q2: Why is it important to move away from traditional liquid-liquid extraction (LLE)? Traditional LLE often requires large volumes of potentially toxic organic solvents, which are harmful to human health and the environment [3]. The procedure is also considered tedious, involves multiple stages, and generates waste that is costly and time-consuming to treat and dispose of [3].

Q3: What are the key metrics for evaluating the greenness of a method? While not exhaustive, two key quantitative metrics are:

- Enhancement Factor: This indicates the preconcentration power of a method. A higher factor means a greater ability to concentrate the analyte, allowing for the use of a smaller initial sample volume [5].

- Process Mass Intensity (PMI): This is the total sum of input materials (solvents, reagents, etc.) required to produce a single unit (e.g., kg) of the desired product or analyte [14]. Minimizing PMI directly reduces waste.

FAQ: Method Selection and Implementation

Q4: My analysis requires high sensitivity. Which green preconcentration techniques are suitable for trace metal analysis? For trace metal determination in samples like seawater, several miniaturized and greener techniques are highly effective:

- Cloud Point Extraction (CPE): Uses small amounts of non-ionic surfactants instead of toxic organic solvents [3] [5].

- Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (DLLME): Uses microliter volumes of extraction solvent, drastically reducing solvent consumption [3].

- Ionic Liquid-Based Microextraction: Employs room-temperature ionic liquids (RTILs) as environmentally friendlier solvents due to their negligible vapor pressure and high stability [3].

Q5: How can I reduce plastic and solid waste in my lab? Research facilities can produce up to 12 times more waste per square foot than office spaces [15]. Key strategies include:

- Optimize Experiments: Design experiments to use fewer materials [15].

- Reuse and Recycle: Implement programs to recycle nitrile gloves and lab plastics. Many consumables can be safely reused after proper washing and sterilization [15].

- Leverage Take-Back Programs: Many manufacturers offer programs to collect and recycle their product packaging and containers [15].

Q6: What are some direct, safer substitutes for common hazardous reagents? Adopting safer alternatives is a core part of green chemistry [16]. The table below lists several common substitutions.

| Hazardous Reagent | Safer Alternative | Key Advantage of Alternative |

|---|---|---|

| Ethidium Bromide | Commercial substitutes (e.g., GelRed, GelGreen) | Less mutagenic and toxic [16] |

| Sodium Azide (powder) | Dilute sodium azide solution or 1-2% 2-chloroacetamide | Reduces risk of exposure from toxic powder [16] |

| PMSF or DFP (protease inhibitors) | Pefabloc SC | Safer to handle, more stable in water [16] |

| Isopropyl alcohol (in freezing) | Alcohol-free freezing containers (e.g., CoolCell) | Eliminates flammable solvent [16] |

| SDS & Acrylamide (powders) | Pre-cast gels | Avoids handling of toxic powders [16] |

| Glass Pasteur Pipets | Polystyrene aspirating pipets | Prevents breakage and sharps injuries [16] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Green Methods

Q7: Issue: In Cloud Point Extraction, phase separation is incomplete or slow.

- Cause 1: Incorrect temperature. The solution must be heated above the cloud point temperature of the surfactant.

- Solution: Ensure the water bath is accurately controlled. For Triton X-114, a temperature of 50°C is typically effective [5].

- Cause 2: Insufficient centrifugation.

- Solution: Centrifuge for at least 10 minutes at 3500 rpm to ensure complete separation of the surfactant-rich phase [5].

Q8: Issue: Recovery of analytes is low in microextraction techniques.

- Cause 1: The pH of the sample is not optimal for complex formation.

- Solution: Systematically investigate the effect of pH. For example, the Co and Pb complex with 8-hydroxyquinoline is optimal at pH 7.0 [5].

- Cause 2: The concentration of the complexing agent or surfactant is insufficient.

- Solution: Re-optimize the amount of chelating agent (e.g., oxine) and surfactant (e.g., Triton X-114) to ensure complete complexation and extraction [5].

Q9: Issue: My method is generating too much solvent waste.

- Cause: Reliance on traditional LLE or large-volume SPE protocols.

- Solution: Transition to microextraction techniques like DLLME or SPME [3] [17]. Alternatively, implement solvent recovery and reuse systems, such as rotary evaporators or nitrogen evaporators, to distill and collect used solvents for future use [18] [14].

Experimental Protocols for Green Sample Preparation

Protocol 1: Cloud Point Extraction for Trace Metals

This protocol details the determination of cobalt (Co) and lead (Pb) in water samples using Cloud Point Extraction (CPE) with Triton X-114, as described in the research [5].

Workflow Overview

1. Reagents and Materials

- Non-ionic Surfactant: Triton X-114 [5].

- Chelating Agent: 8-hydroxyquinoline (oxine) solution: Dissolve in ethanol and dilute with 0.01 M acetic acid [5].

- Standard Solutions: 1000 μg Lâ»Â¹ stock solutions of Co and Pb [5].

- Buffer: 0.1 M acetate and phosphate buffer for pH adjustment [5].

- Dilution Solvent: 0.1 mol Lâ»Â¹ HNO₃ in ethanol (1:1, v/v) [5].

- Labware: Centrifuge tubes, pipettes, a centrifuge, a heated water bath or ultrasonic bath, and an ice bath [5].

2. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Aliquoting: Transfer a 25 mL aliquot of the standard or filtered water sample into a suitable centrifuge tube [5].

- Reagent Addition: Add reagents to the sample:

- 5 × 10â»Â³ mol Lâ»Â¹ of 8-hydroxyquinoline (oxine).

- 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-114 surfactant [5].

- pH Adjustment: Adjust the pH of the solution to 7.0 using 0.1 mol Lâ»Â¹ HNO₃/NaOH and the appropriate buffer [5].

- Cloud Point Incubation: Place the tube in an ultrasonic bath at 50°C for 10 minutes to reach the cloud point, then let it stand for 30 minutes to allow for phase separation [5].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the tube at 3500 rpm for 10 minutes to complete the phase separation [5].

- Cooling: Cool the tube in an ice bath for 10 minutes to solidify the surfactant-rich phase [5].

- Phase Decanting: Carefully decant the supernatant aqueous phase by inverting the tube [5].

- Dilution: Add 200 μL of 0.1 mol Lâ»Â¹ HNO₃ in ethanol to the surfactant-rich phase to reduce its viscosity [5].

- Analysis: Introduce the final solution for analysis by Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (FAAS) [5].

3. Method Performance Data The following table summarizes the quantitative performance of this CPE method for the determination of Co and Pb [5].

| Metal | Enhancement Factor | Detection Limit (μg Lâ»Â¹) | Optimal pH | Linear Range (μg Lâ»Â¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cobalt (Co) | 70 | 0.26 | 7.0 | 20 - 100 |

| Lead (Pb) | 50 | 0.44 | 7.0 | 20 - 100 |

Protocol 2: Solid-Phase Microextraction for GC-MS

This protocol outlines a general SPME procedure for solvent-free extraction of volatile and semi-volatile compounds prior to Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis.

Workflow Overview

1. Reagents and Materials

- SPME Fiber Assembly: A fused silica fiber coated with an appropriate stationary phase (e.g., PDMS, CAR/PDMS) for the target analytes [19].

- SPME Vial: A glass vial with a septum cap.

- Sample: Liquid or solid sample.

2. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Equilibration: Place the sample in the SPME vial and allow it to equilibrate, potentially with heating and stirring, to facilitate the partitioning of analytes into the headspace [19].

- Exposure: Expose the SPME fiber to the sample's headspace (headspace-SPME) or directly immerse it into a liquid sample (DI-SPME) for a predetermined time. Analytes diffuse and are adsorbed onto the fiber's coating [19].

- Retraction: Retract the fiber back into the needle assembly.

- Injection: Insert the SPME needle into the hot injection port of the GC system.

- Desorption: Expose the fiber in the injector, where the trapped analytes are thermally desorbed and transferred directly onto the GC column with the carrier gas flow [19].

- Analysis: Initiate the GC-MS run.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials used in the green sample preparation methods discussed.

| Item | Function/Application | Green & Safety Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Triton X-114 | Non-ionic surfactant used in Cloud Point Extraction [3] [5]. | Replaces toxic organic solvents; low cloud point temperature [3]. |

| Room Temp Ionic Liquids | Solvents for metal determinations in microextraction [3]. | Negligible vapor pressure, high stability, low viscosity [3]. |

| Pefabloc SC | Protease inhibitor for protein isolation [16]. | Safer alternative to highly toxic PMSF and DFP; water-soluble [16]. |

| SPME Fiber | Solvent-free extraction for GC-MS [19] [17]. | Eliminates solvent use; fast and simple [19]. |

| CoolCell | Alcohol-free container for controlled rate cell freezing [16]. | Eliminates flammable isopropyl alcohol and associated risks [16]. |

| Disposable Plastic Aspirating Pipets | For cell culture media aspiration [16]. | Prevents breakage and sharps injuries from glass Pasteur pipets [16]. |

| Digestion Indicator | Internal control protein for MS sample prep standardization [20]. | Improves reproducibility, reducing wasted runs and resources [20]. |

| 7-BIA | 7-BIA, MF:C15H18O6, MW:294.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| G0507 | G0507|LolCDE Inhibitor | G0507 is a potent LolCDE ABC transporter inhibitor for Gram-negative bacteria research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary environmental and practical concerns associated with traditional preconcentration methods? Traditional preconcentration methods, particularly those based on linear "take-make-dispose" models, raise significant environmental concerns due to their high consumption of energy and reagents, and substantial waste generation [7]. From a practical standpoint, these methods are often time-consuming and tedious, requiring large sample volumes and multi-step procedures that can lead to material loss, contamination, and compromised analytical precision [21] [22] [7]. The reliance on volatile, toxic, and persistent organic solvents (e.g., benzene, chloroform) also creates occupational hazards and regulatory challenges [23].

FAQ 2: How does the "rebound effect" undermine green initiatives in analytical chemistry? The rebound effect occurs when improvements in efficiency lead to unintended consequences that offset the intended environmental benefits [7]. For example, a novel, low-cost microextraction method might use minimal solvents per analysis. However, because it is cheap and accessible, laboratories might perform significantly more analyses than before, increasing the total volume of chemicals used and waste generated. Similarly, automation might lead to over-testing simply because the technology allows it, ultimately diminishing or negating the initial green advantages [7].

FAQ 3: What green solvents are available to replace traditional toxic options in sample preparation? Several classes of green solvents have been developed as safer, more sustainable alternatives [23].

- Bio-based solvents: Derived from renewable resources like plants, cereals, or agricultural waste. Examples include bio-ethanol, ethyl lactate, and terpenes like D-limonene from orange peels [23].

- Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs): A combination of a hydrogen bond donor and acceptor. They are low-cost, biodegradable, non-flammable, and have low toxicity [23].

- Supercritical fluids: Such as supercritical COâ‚‚, which is non-toxic and can be tuned with temperature and pressure. It avoids petroleum derivatives but can be energy-intensive to maintain at critical pressure and temperature [23].

- Ionic liquids (ILs): Salts in a liquid state with negligible vapor pressure. Their properties can be finely tuned, but their green credentials depend on a full lifecycle assessment, as their synthesis can be energy-intensive and some can be toxic or persistent [23].

FAQ 4: What strategies exist for reducing energy consumption during the preconcentration step? Adapting traditional techniques to the principles of green sample preparation (GSP) involves optimizing for energy efficiency [7]. Key strategies include:

- Applying assisting fields: Using vortex mixing, ultrasound, or microwaves to enhance extraction efficiency and speed up mass transfer, consuming significantly less energy than traditional heating methods like Soxhlet extraction [7].

- Automation and parallel processing: Automated systems save time and lower reagent consumption. Treating several samples in parallel increases overall throughput and reduces the energy consumed per sample [7].

- Process integration: Streamlining multi-step procedures into a single, continuous workflow cuts down on resource use and energy [7].

- Method acceleration: Using high-flow-rate, low-back-pressure materials like monolithic sorbents reduces processing time and associated energy use [24].

FAQ 5: How can functionalized monoliths improve selectivity and reduce solvent use? Functionalized monoliths are porous sorbents that can be synthesized in various formats and their surface chemistry tailored for specific applications [24]. Their large macropores allow samples to be percolated at high flow rates with very low back pressure, facilitating rapid processing [24]. They can be functionalized with biomolecules (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) or made into molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) to selectively capture target analytes, effectively eliminating matrix components that often interfere with analysis [24]. When miniaturized in capillaries for coupling with nanoLC, they enable drastic reductions in solvent consumption and sample volume, sometimes down to a few microliters per sample [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Analytical Throughput and Long Sample Preparation Times

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Sequential and manual sample processing.

- Solution: Implement parallel processing and automation. Using systems that handle multiple samples simultaneously or automated SPE (Solid-Phase Extraction) dramatically increases throughput and reduces hands-on time [7].

- Cause: Slow mass transfer during extraction.

- Solution: Integrate assisting fields like ultrasound (sonication) or microwave energy into the extraction process. These technologies accelerate mass transfer, significantly reducing the time required for extraction compared to passive methods [7].

- Cause: Inefficient sorbent format causing high back pressure and slow flow rates.

- Solution: Employ monolithic sorbents. Their large flow-through channels permit high sample flow rates without generating high back pressure, drastically cutting down preconcentration time [24].

Problem 2: Excessive Solvent Consumption and Waste Generation

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Use of traditional, large-scale extraction techniques (e.g., conventional Liquid-Liquid Extraction).

- Solution: Transition to miniaturized techniques. Methods that use functionalized monoliths in capillary formats or other micro-extraction techniques can reduce solvent consumption to the microliter range [24].

- Cause: Multi-step procedures leading to cumulative solvent use.

- Solution: Integrate and automate sample preparation steps. Online coupling of SPE with LC, for instance, automates the entire process and minimizes solvent and sample consumption by eliminating transfer steps [24].

- Cause: Reliance on toxic conventional solvents.

- Solution: Substitute with green solvents. Replace solvents like chloroform and benzene with safer alternatives such as bio-based ethanol, deep eutectic solvents, or supercritical COâ‚‚ where technically feasible [23].

Problem 3: Poor Selectivity Leading to Matrix Effects and Signal Suppression/Enhancement in LC-MS

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Non-selective sorbents co-extracting interfering matrix components.

- Solution: Use highly selective sorbents. Functionalized monoliths with immobilized antibodies, aptamers, or Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) are designed to retain only the target analytes, effectively purifying the extract and eliminating matrix effects [24].

- Cause: Inadequate clean-up following extraction.

- Solution: Implement selective clean-up protocols such as Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) with sorbents tailored to your analyte. Techniques like gel permeation chromatography can also separate desired analytes from complex organic matrices [22].

Quantitative Data on Preconcentration Challenges

The table below summarizes key quantitative challenges and metrics associated with traditional preconcentration methods.

Table 1: Quantitative Challenges of Traditional Preconcentration Methods

| Challenge Area | Specific Issue | Quantitative Impact / Metric | Green Chemistry Concern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Errors | Inadequate sample preparation | Contributes to ~60% of all spectroscopic analytical errors [21] | Data validity, resource waste from repeated analyses |

| Standard Method Greenness | Performance of official standard methods (CEN, ISO) | 67% of methods scored below 0.2 on the AGREEprep scale (where 1 is highest greenness) [7] | High resource intensity, outdated techniques |

| Solvent Toxicity | Use of conventional organic solvents | Traditional solvents (e.g., benzene, chloroform) are volatile, toxic, and persistent [23] | Environmental pollution, occupational hazards |

| Energy Consumption | Use of techniques like Soxhlet extraction | High energy demand due to prolonged heating and cooling cycles [7] | Reliance on non-renewable energy, high carbon footprint |

Experimental Protocols for Improved Preconcentration

Protocol 1: On-Line Preconcentration using Functionalized Monoliths coupled with LC-MS

This protocol uses a monolithic sorbent functionalized for selective extraction, enabling high-throughput analysis with minimal solvent [24].

1. Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Monolith-based Preconcentration

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Functionalized Monolith | Porous polymer sorbent synthesized in a capillary or column format. Can be functionalized with antibodies, aptamers, or as a MIP for selective extraction [24]. |

| Cross-linking Agent | Chemical reagent used during monolith synthesis to create a stable, porous polymer structure [24]. |

| Functional Monomers | Molecules that provide the chemical functionality for interacting with the target analyte or for subsequent biomolecule grafting [24]. |

| Template Molecule (for MIPs) | The target analyte or a close analog, used to create specific recognition cavities within the Molecularly Imprinted Polymer [24]. |

| Washing Solvents | A series of solvents (e.g., water, buffer, mild organic solvent) to remove non-specifically bound matrix components after sample loading [24]. |

| Elution Solvent | A small volume of a strong solvent (e.g., organic solvent with pH shift) to desorb the purified target analytes from the monolith for transfer to the LC-MS [24]. |

2. Methodology

- Monolith Preparation/Synthesis: Synthesize the monolith directly within a capillary or column. For MIPs, this involves polymerizing functional monomers and cross-linker in the presence of the template molecule. After polymerization, thoroughly wash the monolith to remove the template, leaving behind specific recognition cavities [24].

- System Setup: Couple the monolithic extraction column online with the analytical LC column and mass spectrometer using a column-switching valve.

- Sample Loading/Pre-concentration: Percolate the sample (after possible dilution and pH adjustment) through the monolith at a high flow rate (e.g., 0.2 ml/min). The target analytes are selectively retained while the matrix components pass through.

- Washing: Wash the monolith with an appropriate buffer or solvent for a set time (e.g., 5 minutes) to remove any residual, weakly bound matrix components.

- Elution and Transfer: Switch the valve to place the monolith in line with the analytical LC column and mass spectrometer. Desorb the retained analytes using a strong elution solvent or by leveraging a pH shift, transferring them onto the analytical column.

- Analysis: Initiate the LC gradient program to separate the analytes, which are then detected by the MS.

The workflow below illustrates the on-line preconcentration process using a functionalized monolith.

Protocol 2: Green Preconcentration using Solid-Phase Extraction with Reduced Solvent Volumes

This protocol outlines a general approach for greener SPE, focusing on solvent reduction and substitution.

1. Methodology

- Sorbent Selection: Choose a sorbent suitable for your analytes (e.g., C18 for reversed-phase, ion-exchange for charged compounds). Consider newer green sorbents.

- Conditioning: Condition the SPE cartridge with a minimal volume of a green solvent (e.g., bioethanol) followed by water or buffer.

- Sample Loading: Load the sample, which may be pre-acidified or pH-adjusted to enhance analyte retention.

- Washing: Wash the sorbent with a small volume of a mild washing solution (e.g., water or a low-percentage green solvent in water) to remove impurities.

- Elution: Elute the analytes with the smallest possible volume of an effective green elution solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate or a DES). Collect the eluent for direct analysis or gently evaporate and reconstitute in a mobile phase-compatible solvent.

The decision process for implementing a greener SPE protocol is shown below.

The Role of Preconcentration as a Bottleneck and Target for Sustainable Innovation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is the sample preconcentration step considered a bottleneck in analytical methods? Sample preparation is often the most time-consuming part of an analysis, accounting for about 60% of the total time spent on tasks in the analytical laboratory [25]. It is also a significant source of error, responsible for approximately 30% of all experimental errors [25]. Traditional techniques like liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) or solid-phase extraction (SPE) can be slow, labor-intensive, and require large volumes of hazardous organic solvents, making them a primary target for innovation toward greater sustainability [25].

2. What are the key principles for "greening" my sample preconcentration methods? Greening your methods focuses on minimizing environmental impact and enhancing operator safety. Key principles include [25]:

- Miniaturization: Scaling down procedures to use smaller sample and solvent volumes.

- Reducing Hazardous Waste: Eliminating or drastically cutting the use of toxic organic solvents.

- Energy Efficiency: Employing methods that consume less energy.

- Operator Safety: Improving the safety and simplicity of the procedures. These principles are evaluated using dedicated metric tools like AGREEprep and ComplexGAPI [26].

3. My analytical results show poor reproducibility. Could my preconcentration method be the cause? Yes. Poor reproducibility often stems from the sample preparation step. Common issues include [21]:

- Inhomogeneous Samples: Incomplete homogenization before extraction leads to non-representative sampling.

- Matrix Effects: Components in the sample matrix can interfere with the extraction or detection of your analyte.

- Contamination: Introduction of contaminants during the multi-step process can cause spurious results. Ensuring sample homogeneity through proper grinding or mixing and using clean, dedicated equipment can mitigate these issues [21].

4. What are some green alternatives to traditional liquid-liquid extraction? Several efficient and greener microextraction techniques have been developed:

- Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME): A solvent-free technique that uses a coated fiber to extract and concentrate analytes [25].

- Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (DLLME): Uses microliter volumes of extraction solvent, drastically reducing waste [25].

- Fabric-Phase Sorptive Extraction (FPSE): Uses a fabric substrate coated with a sol-gel sorbent, minimizing solvent use and sample pretreatment [25].

- Gel-based Electromembrane Extraction (G-EME): Uses a gel membrane and an electric field to selectively extract charged analytes, reducing organic solvent consumption [27].

5. How do I quantitatively assess and compare the "greenness" of different preconcentration methods? You can use validated green metric tools to generate a score for your method. For example:

- Analytical Greenness Metric Approach (AGREE): Provides a score from 0 to 1, where a higher score is greener. For instance, a modern method like Rapid Synergistic-Deep Eutectic Solvent Cloud Point Extraction (RS-DES-CPE) scored 0.81, while a traditional Cloud Point Extraction (CPE) scored 0.67 [28].

- Complementary Green Analytical Procedure Index (ComplexGAPI): Offers a detailed pictogram to visualize the environmental impact of the entire analytical procedure [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Extraction Efficiency and Poor Recovery

This occurs when the amount of analyte extracted from the sample is lower than expected, leading to poor sensitivity and inaccurate quantification.

Possible Causes and Solutions

- Cause: Inefficient transfer of analytes in passive diffusion-based methods.

- Solution: Switch to an active extraction technique. Electromembrane Extraction (EME) applies an electric potential to drive charged analytes across a membrane, significantly accelerating the extraction kinetics compared to passive methods like hollow-fiber liquid-phase microextraction [27].

- Cause: Poor selection of extraction solvent or sorbent.

- Solution: Utilize innovative materials. Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) are a new class of green solvents that can be synthesized to have high selectivity and extraction efficiency for target analytes, as demonstrated in methods for determining metals in beverages [28]. Other advanced materials include Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) [29].

- Cause: The method is not optimized for the sample's pH or ionic strength.

- Solution: Systematically optimize chemical parameters. For G-EME, key factors to control include the pH of the donor and acceptor solutions to ensure analytes are in their charged state, and the ionic strength to manage current density and electroendosmosis effects [27].

- Cause: Inefficient transfer of analytes in passive diffusion-based methods.

Experimental Protocol: Rapid Synergistic-Deep Eutectic Solvent Cloud Point Extraction (RS-DES-CPE) This protocol is an example of a green and efficient method for preconcentrating trace metals [28].

- Synthesize the DES: Combine a hydrogen bond donor (e.g., a carboxylic acid) and a hydrogen bond acceptor (e.g., a quaternary ammonium salt) at a specific molar ratio with gentle heating until a clear, homogeneous liquid forms.

- Prepare Sample: Adjust the pH of your aqueous sample (e.g., bottled beverage) to the optimum value for chelation.

- Chelate and Extract: Add a chelating agent (e.g., 2-hydroxy-5-p-tolylazobenzaldehyde) and a non-ionic surfactant (e.g., TritonX-114) to the sample. Then, introduce the synthesized DES as a green synergistic reagent.

- Induce Phase Separation: Heat the solution above its cloud point to separate the surfactant-rich phase containing the preconcentrated analytes from the aqueous phase.

- Analysis: The surfactant-rich phase can then be injected into an electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometer (ETAAS) for quantification.

Problem 2: High Organic Solvent Consumption and Waste Generation

Traditional methods that use large volumes of harmful solvents pose environmental and safety risks.

Possible Causes and Solutions

- Cause: Use of conventional LLE or SPE.

- Solution: Implement a miniaturized technique. Fabric-Phase Sorptive Extraction (FPSE) uses a fabric substrate with a sol-gel sorbent coating, which allows for direct extraction from the sample with minimal or no solvent use during the extraction itself [25].

- Cause: Using large volumes of solvents for elution in SPE.

- Solution: Adopt microextraction techniques. DLLME and Single-Drop Microextraction (SDME) use volumes in the microliter range, reducing solvent consumption and waste generation by orders of magnitude [25].

- Cause: Use of conventional LLE or SPE.

Experimental Protocol: Gel-based Electromembrane Extraction (G-EME) This protocol highlights a method that virtually eliminates organic solvent use during the extraction phase [27].

- Prepare Gel Membrane: Create a hydrogel using a biocompatible material like agarose, agar, or chitosan. Cast it into a support to form a thin membrane between donor and acceptor compartments.

- Set Up Extraction: Fill the donor compartment with the sample solution. Fill the acceptor compartment with an appropriate aqueous buffer.

- Apply Electric Field: Insert electrodes into the donor and acceptor solutions and apply a controlled electric potential (typically 10-100 V). Charged analytes will migrate across the gel membrane from the donor to the acceptor phase.

- Collect and Analyze: After a set extraction time, collect the acceptor solution, which now contains your preconcentrated and cleaned-up analytes, for instrumental analysis.

Problem 3: Long Sample Processing Time

Slow extraction kinetics can drastically reduce laboratory throughput.

- Possible Causes and Solutions

- Cause: Reliance on slow, passive diffusion.

- Solution: Apply energy. Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE) and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE) use microwave energy or ultrasonic waves to greatly accelerate the extraction process [25].

- Cause: Manual and multi-step procedures.

- Solution: Integrate automation. Techniques like Lab-in-Syringe (LIS) or automated on-flow systems can combine several steps (e.g., extraction, separation, injection) into a single, automated process, saving time and improving reproducibility [29].

- Cause: Reliance on slow, passive diffusion.

The following workflow contrasts conventional approaches with modern, sustainable solutions for tackling preconcentration challenges:

The table below quantifies and compares the performance of various methods, highlighting the advantages of greener approaches.

| Method | Greenness Score (AGREE) | Key Advantage | Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid Synergistic-DES-CPE [28] | 0.81 | High extraction efficiency, reduced time & energy | Requires synthesis of DES |

| Traditional Cloud Point Extraction | 0.67 | Simpler setup | Longer extraction time, lower greenness score [28] |

| Gel-based EME | N/A (Reported as greener) | Minimal solvent use, high selectivity | Can be complex to set up initially [27] |

| Fabric-Phase Sorptive Extraction | N/A (Reported as greener) | Minimal sample pretreatment, reusable | Can have low sample capacity [25] |

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key reagents and materials that are central to developing modern, sustainable preconcentration methods.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Green/Sustainable Attribute |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) [28] | Green extraction solvent; improves efficiency and reduces time. | Low toxicity, biodegradable, often made from natural compounds. |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) [25] | Replacement for volatile organic solvents; tunable properties. | Low vapor pressure, non-flammable, highly stable. |

| Agarose/Agar Gel [27] | Matrix for gel-based electromembrane extraction (G-EME). | Biocompatible, biodegradable, eliminates need for organic membrane solvent. |

| Sol-Gel Sorbents [25] | Coating for FPSE and SPME; high chemical and thermal stability. | Allows for creation of tailored, high-efficiency sorbents with strong bonding to substrate. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [29] | Advanced sorbent material with extremely high surface area. | Enhances extraction capacity and speed, leading to reduced solvent and sample use. |

Innovative Green Preconcentration Techniques and Solvents for Spectroscopy

In the realm of analytical chemistry, particularly in spectroscopic sample preconcentration research for drug development, the sample preparation stage is crucial. Traditional liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) and solid-phase extraction (SPE) methods often involve large volumes of hazardous organic solvents, generating significant waste and posing health risks to researchers. The principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) advocate for minimizing this environmental impact by reducing or eliminating hazardous substances throughout the analytical process [10]. Miniaturization of extraction techniques stands as a core strategy to achieve these goals. Microextraction methodologies have emerged as sustainable, efficient, and effective alternatives to conventional macroextraction, offering superior green credentials while maintaining, and often enhancing, analytical performance [30] [10]. This technical support guide explores the troubleshooting and practical implementation of these advanced techniques.

Microextraction vs. Macroextraction: A Quantitative Comparison

The transition from macro to micro scale extraction brings tangible benefits. The following table summarizes the key differences:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Extraction Techniques

| Characteristic | Macroextraction | Microextraction |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Solvent Volume | 10s - 1000s mL | < 1 mL [30] |

| Sample Size | Large | Small [30] |

| Automation Potential | Low to Moderate | High (via autosamplers, fluid techniques, 96-well plates) [30] |

| Environmental Impact | High (significant hazardous waste) | Low (minimal solvent consumption, reduced waste) [10] |

| Key Principles | Exhaustive extraction | Equilibrium-based or non-exhaustive extraction [30] |

| Cost per Analysis | Higher (solvent & disposal) | Lower |

| Common Techniques | Traditional LLE, Soxhlet, SPE | SPME, DLLME, HF-LPME, SDME, EME [30] |

Troubleshooting Common Microextraction Challenges

FAQ 1: Why is my analyte recovery low or inconsistent in Liquid-Phase Microextraction (LPME)?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Instability of the Extraction Solvent. In techniques like Single-Drop Microextraction (SDME), the droplet can be dislodged easily. In Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (DLLME), the dispersion may be incomplete.

- Solution: For SDME, ensure the syringe needle is in good condition and avoid agitation that is too vigorous. For DLLME, optimize the type and volume of the disperser solvent to achieve a stable cloudy solution without forming an overly stable emulsion that is difficult to collapse [30].

- Cause: Suboptimal Solvent Selection. The green solvent may not have sufficient affinity for the target analytes.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the choice of sustainable green solvent. Ionic Liquids (ILs) or Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) can be tailored for specific analyte interactions due to their adjustable physicochemical properties [31] [8]. Ensure the solvent is compatible with your spectroscopic detection method.

- Cause: Inefficient Mass Transfer. The extraction may not have reached equilibrium.

- Solution: Increase extraction time and/or agitation speed (e.g., vortex mixing, shaking). For hollow-fiber LPME (HF-LPME), ensure the pore structure of the fiber is properly filled and wetted [30].

FAQ 2: What causes poor sensitivity or high background noise in Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME)?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Active Sites on the Fiber or Sample Matrix. Secondary interactions, such as with residual silanol groups on SPME fibers, can cause analyte adsorption and tailing, leading to poor peak shape and sensitivity in subsequent chromatography.

- Solution: Use a SPME fiber with a different coating chemistry (e.g., mixed-mode coatings like PDMS-DVB) to minimize unwanted interactions. For complex matrices, a sample cleanup step or a different sample dilution can reduce fouling of the fiber [8].

- Cause: Fiber Saturation or Damage. The fiber coating may be overloaded, physically scratched, or degraded by high injection port temperatures (in GC).

- Solution: Reduce the sample concentration or extraction time to avoid overloading. Visually inspect the fiber for damage and follow manufacturer-recommended temperature and pH limits. Consistently use a guard column if injecting into an LC system to protect the analytical column from any potential fiber bleed or carryover [32].

- Cause: Carryover or Contamination. Analytes from a previous run may remain on the fiber, or the fiber may be contaminated.

- Solution: Implement a thorough and validated fiber conditioning/cleaning step between injections. Run blank injections to check for ghost peaks originating from the fiber or other system components [32].

FAQ 3: How can I manage matrix effects when analyzing complex plant or biological samples?

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Co-extraction of Interfering Compounds. Complex samples like plant materials contain proteins, fats, pigments, and other compounds that can be co-extracted, leading to signal suppression or enhancement in mass spectrometry.

- Solution: Incorporate a cleanup step into your microextraction protocol. The QuEChERS method is highly effective, using dispersive SPE (d-SPE) sorbents to remove fatty acids, sugars, and other interferences [10] [8]. Magnetic SPE (MSPE) is another rapid cleanup option where magnetic sorbent particles can be easily separated from the sample [8].

- Cause: Strong Sample Matrix. The sample itself may inhibit efficient analyte transfer to the extractant.

- Solution: Use the method of standard additions for quantification to correct for matrix effects. For solid samples, ensure proper particle size reduction (grinding) and consider slurry formation to improve extraction efficiency [8].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (DLLME) with Green Solvents

Principle: A water-immiscible extraction solvent is dispersed into the aqueous sample via a water-miscible disperser solvent, creating a large surface area for rapid analyte partitioning [30].

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a homogeneous aqueous sample (e.g., 5 mL of river water or diluted plasma) in a conical-bottom glass tube.

- Extraction Mixture: Rapidly inject a mixture containing a few tens of microliters (µL) of extraction solvent (e.g., a DES or a bio-based solvent) and a few hundred µL of disperser solvent (e.g., methanol or acetone) into the sample using a syringe.

- Dispersion and Extraction: A cloudy solution forms immediately. Vortex the mixture for a predetermined time (e.g., 30-60 seconds) to facilitate extraction.

- Phase Separation: Centrifuge the tube for 5 minutes at 4000 rpm to sediment the fine droplets of the extraction solvent at the bottom.

- Analysis: Carefully withdraw the sedimented phase with a micro-syringe and transfer it to an autosampler vial for spectroscopic analysis (e.g., LC-MS or GC-MS) [30] [31].

Protocol 2: In-Vivo Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) for Plant Studies

Principle: A SPME probe is directly inserted into the living plant tissue to sample the interstitial fluid, providing a unique "fingerprint" with minimal damage to the plant [8].

Detailed Methodology:

- SPME Fiber Selection: Choose a fiber coating appropriate for your target analytes (e.g., polar compounds might require a CAR/PDMS or HLB coating).

- Fiber Conditioning: Condition the fiber according to the manufacturer's instructions in a GC or LC injector prior to first use.

- In-Vivo Sampling: Gently insert the SPME fiber into the stem, leaf, or root of the plant for a specified sampling time (minutes to hours) to allow analytes to adsorb onto the coating.

- Post-Extraction: Retract the fiber and immediately introduce it into the analytical instrument for desorption and analysis (e.g., a GC-MS injector). No further cleanup is typically required [8].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between the core principles of Green Analytical Chemistry and the benefits delivered by microextraction techniques.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

This table outlines essential materials used in modern, green microextraction protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Green Microextraction

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) | Salts in liquid state below 100°C; used as tunable, non-volatile extraction solvents in LPME to replace hazardous organic solvents [31]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) | Mixtures of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors that form liquids; biodegradable, low-cost, and designable green extractants [31] [8]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Used in Magnetic Solid-Phase Extraction (MSPE) as dispersible sorbents; easily separated using an external magnet, simplifying the cleanup process [8]. |

| QuEChERS Kits | Pre-packaged kits containing salts (MgSOâ‚„, NaCl) and d-SPE sorbents (PSA, C18) for quick, effective, rugged, and safe sample cleanup in complex matrices [10]. |

| HLB Sorbent | Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balanced polymer; a versatile sorbent used in SPE and SPME for extracting a broad range of polar and non-polar analytes [10]. |

| PDMS/DVB Fibers | Polydimethylsiloxane/Divinylbenzene coated fibers for SPME; effective for a wide range of volatile and semi-volatile compounds from headspace or direct immersion [8]. |

| abc99 | abc99, MF:C22H21ClN4O5, MW:456.9 g/mol |

| ML206 | ML206, MF:C19H16F2N4O, MW:354.4 g/mol |

Workflow Visualization: Implementing a Green Microextraction Method

The following workflow diagram provides a logical, step-by-step guide for developing and troubleshooting a microextraction method.

Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) and Novel Sorbents from Tunable Materials and Waste Valorization

SPME Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems & Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Green Chemistry-Aligned Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Recovery [33] [34] | - Incorrect fiber coating polarity [35] [36].- Insufficient extraction time (pre-equilibrium) [35] [36].- Inefficient desorption (incorrect time/temperature) [35].- Competition from sample headspace [35]. | - Select fiber coating based on "like-dissolves-like" [36].- Precisely control extraction time; use a stopwatch for pre-equilibrium extractions [36].- Optimize thermal desorption parameters for the GC inlet [35].- Keep sample and headspace volumes consistent; consider headspace sampling for dirty matrices [35] [36]. |

| Poor Reproducibility [33] [34] | - Variable extraction time, especially pre-equilibrium [36].- Inconsistent sample volume or headspace volume [35].- Variable flow rates or agitation during extraction [35].- Fiber degradation or contamination from previous runs [36]. | - Standardize all timing parameters [36].- Use consistent vial sizes and sample volumes [35].- Employ controlled agitation (e.g., magnetic stirring) for faster, more consistent extraction [35] [36].- Implement a rigorous and consistent fiber cleaning/conditioning protocol between uses [36]. |

| Fiber Degradation [36] | - Exposure to extreme pH [37].- Physical damage from vial septa or sample particulates.- Thermal degradation during desorption. | - Use headspace mode for complex, dirty, or highly acidic/basic samples to prolong fiber life [36].- Filter or centrifuge samples before direct immersion SPME.- Ensure desorption temperature is within the fiber's specified operating range [36]. |

| Insufficient Cleanup / Matrix Effects [34] | - Lack of selectivity in fiber coating, leading to co-extraction of interferences. | - Utilize highly selective novel sorbents (e.g., MIPs, MOFs) tailored to your analyte [38].- Switch to headspace-SPME to avoid non-volatile matrix components [36].- Adjust sample ionic strength (salting-out) to improve volatility and extraction of analytes [35]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on SPME and Green Sorbents

Q1: What makes SPME a "green" sample preparation technique? SPME aligns with the principles of green chemistry by significantly reducing or eliminating the use of organic solvents throughout the analytical process [38] [35] [36]. It is a solvent-less technique that integrates sampling, extraction, concentration, and desorption into a single step, thereby minimizing waste generation, reducing analyst exposure to hazardous chemicals, and lowering disposal costs [38].

Q2: How do I choose the right SPME fiber coating for my application? Fiber selection is based on the chemical properties (polarity, volatility) of your target analytes and the sample matrix, following the "like-dissolves-like" principle [35] [36].

- For non-polar analytes (e.g., hydrocarbons, PCBs): Use non-polar coatings like Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) [36].

- For polar analytes (e.g., alcohols, acids): Use polar coatings like Polyacrylate (PA) or Carbowax/Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) [36].

- For a broad range of volatiles: Use mixed-mode coatings like Carboxen/PDMS (CAR/PDMS) or Divinylbenzene/Carboxen/PDMS (DVB/CAR/PDMS) [38] [36].

The coating thickness also matters: thicker films (e.g., 100 µm) offer higher capacity for volatile compounds, while thinner films (e.g., 7 µm) are better for semi-volatiles and larger molecules, with the added benefit of faster equilibration [36].

Q3: What are the key advantages of novel tunable sorbents over traditional materials? Novel sorbents, such as Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs), and Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs), offer superior and tunable selectivity [38]. Their structures and surface chemistry can be deliberately designed to create specific interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding, π-π interactions, size exclusion) with target molecules, leading to enhanced enrichment capabilities and cleaner extracts by reducing co-extraction of interferences [38].

Q4: How can waste valorization contribute to the development of new SPME sorbents? Waste valorization involves using waste products as raw materials, supporting a circular economy. In SPME, this can include the development of bio-based graphene materials or carbon sorbents derived from agricultural or industrial waste [38] [39]. This approach not only reduces the cost and environmental impact of sorbent synthesis but also leads to the creation of biodegradable or more environmentally friendly materials, further greening the analytical workflow [38] [39].

Q5: What is the difference between direct immersion and headspace SPME, and when should I use each?

- Direct Immersion (DI-SPME): The fiber is immersed directly into the liquid sample. It is suitable for analytes with a strong affinity for the sample matrix and is often used for semi-volatile compounds [36].

- Headspace (HS-SPME): The fiber is exposed to the gas phase above the sample. It is ideal for volatile organic compounds (VOCs), complex or dirty samples (e.g., oils, blood, soil slurries), as it protects the fiber from irreversible damage by non-volatile matrix components, thereby extending its lifetime [38] [36].

SPME Experimental Protocol: A Detailed Workflow

Protocol for Headspace-SPME-GC-MS Analysis of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs)

1. Materials and Reagents

- SPME fiber assembly (e.g., Carboxen/PDMS or DVB/CAR/PDMS for VOCs) [36].

- GC-MS system equipped with a dedicated SPME inlet liner.

- Sample vials with PTFE/silicone septa and crimp caps.

- Magnetic stirrer and stir bars (if agitation is used).

- Internal standards (as required for quantification).

2. Sample Preparation

- Transfer a consistent volume of sample (liquid or solid suspension) to the vial. For quantitative consistency, it is critical to maintain identical sample and headspace volumes across all vials [35].

- (Optional) Add a salt (e.g., NaCl, Naâ‚‚SOâ‚„) to increase ionic strength. This can enhance the extraction of less volatile analytes by reducing their solubility in the aqueous phase (salting-out effect) [35].

- (Optional) Add internal standard(s).

- Seal the vial immediately.

3. SPME Extraction

- Condition the fiber: According to the manufacturer's instructions, thermally condition the fiber in the GC inlet prior to its first use and as needed between runs to prevent carryover [36].

- Incubate: Place the sealed vial in a heated agitator block to reach a stable temperature. Incubation time and temperature should be optimized and kept constant.

- Expose and Extract: Pierce the vial septum with the SPME needle, then extend the fiber into the headspace. Begin timing the extraction. If applicable, activate agitation to reduce equilibration time [35] [36].

- Retract and Withdraw: After a pre-determined extraction time (which must be rigorously controlled, especially if working in the pre-equilibrium region [36]), retract the fiber into the needle and withdraw the assembly from the vial.

4. GC-MS Analysis

- Inject: Immediately introduce the SPME needle into the hot GC inlet.

- Desorb: Extend the fiber and leave it in the inlet for the optimized desorption time (typically 1-5 minutes) to transfer the analytes onto the head of the GC column [35].

- Run: Start the GC-MS program. The fiber remains in the inlet for the entire desorption time to ensure complete transfer of analytes and to clean the fiber for the next injection [36].

Novel Sorbent Materials for Green Microextraction

The development of advanced sorbent materials is crucial for enhancing the efficiency and selectivity of SPME within a green chemistry framework [38]. The table below summarizes key classes of these novel materials.

Table: Advanced Sorbent Materials for Green Microextraction

| Sorbent Class | Key Characteristics & Green Merits | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [38] | - High surface area, tunable porosity.- Functionalizable for specific interactions (e.g., H-bonding, π-π).- Superior selectivity via steric fit and complementarity. | Environmental monitoring of pollutants [38]. |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) [38] | - Crystalline structures with high stability.- Tunable design for precise molecular recognition. | Coating for SPME fibers and related techniques [38]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [38] | - "Smart adsorbents" with pre-determined selectivity.- High chemical and mechanical stability.- Reduces need for extensive cleanup, saving solvents. | Selective sample preparation in bioanalysis; In-tube SPME [38]. |

| Graphene-Based Materials (GBMs) [38] [39] | - Large surface area; functionalizable with green materials (e.g., ILs, bio-based).- Supports development of biodegradable materials. | Hybrid adsorbents for offline techniques (SBSE, d-µ-SPE) [38] [39]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [38] | - High thermal stability, enabling fiber reuse.- Can be functionalized with Ionic Liquids (ILs) for enhanced performance. | Reusable SPME coatings for VOC analysis [38]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Materials for SPME and Novel Sorbent Research

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| SPME Fiber Assemblies | The core consumable. Available in various coatings (PDMS, PA, CAR/PDMS, etc.) and film thicknesses to target different analyte classes [35] [36]. |

| Tunable Coating Materials (MOFs, COFs) | Supramolecular materials used to create selective SPME coatings with high enrichment factors and tailored selectivity for target analytes [38]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Custom-synthesized polymers containing cavities complementary to a target molecule, offering high selectivity and reducing matrix effects [38]. |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) | Used as green modifiers or components in hybrid sorbents (e.g., with CNTs) to enhance extraction efficiency and thermal stability [38]. |

| Hybrid Graphene-Based Materials | Versatile adsorbents that combine graphene's large surface area with other functional materials (ILs, polymers) for improved extraction in miniaturized techniques [38] [39]. |

SPME Process and Sorbent Selection Visualizations

SPME Workflow

Sorbent Selection Logic

Troubleshooting Guides

Common SFODME Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable or sinking organic drop | Incorrect solvent density; excessive stirring speed; solvent properties [40]. | Use low-density solvents (e.g., 1-undecanol, 1-dodecanol); reduce stirring speed; ensure solvent has low water solubility [41] [40]. |

| Poor extraction efficiency/recovery | Incorrect pH; insufficient chelating agent; short extraction time; low temperature [42] [40]. | Optimize pH for complex formation (e.g., pH 2.7 for Pb with ILs); ensure adequate chelating agent concentration; increase extraction time; adjust sample temperature [42] [40]. |

| Difficulty solidifying the solvent | Unsuitable solvent melting point; insufficient cooling time [41]. | Select solvent with melting point near room temperature (10-30°C); ensure adequate time in ice bath (at least 5 minutes) [41] [42]. |

| Emulsion formation | Surfactant-like compounds in sample matrix; excessive mixing force [43]. | Gently swirl sample instead of vigorous shaking; add salt (e.g., NaCl) to increase ionic strength and "salt out" the emulsion; filter through glass wool or a phase separation filter paper [43]. |

| Low preconcentration factor | Volume of extraction solvent too large; sample volume too small [42]. | Minimize volume of extraction solvent (e.g., 20 μL); increase volume of aqueous sample where practical [42]. |

General Liquid-Liquid Microextraction Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Cloudy solution does not form (DLLME) | Incorrect ratio of disperser-to-extraction solvent; unsuitable solvents [3]. | Adjust solvent ratio; ensure extraction solvent is immiscible with water and disperser solvent is miscible with both [3]. |