Green Chromatographic Methods: Principles, Applications, and Metrics for Sustainable Analytical Chemistry

This article provides a comprehensive overview of green chromatographic methods, addressing the critical need for sustainable practices in analytical laboratories.

Green Chromatographic Methods: Principles, Applications, and Metrics for Sustainable Analytical Chemistry

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of green chromatographic methods, addressing the critical need for sustainable practices in analytical laboratories. It explores the foundational principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and the paradigm shift from a linear 'take-make-dispose' model to a Circular Analytical Chemistry framework. The content details practical methodological advances, including solvent reduction strategies, miniaturization, and alternative techniques like UHPLC and SFC. It further tackles troubleshooting and optimization challenges, such as the rebound effect and barriers to commercialization. Finally, it offers a comparative analysis of modern greenness assessment tools—AGREE, GAPI, AES, and BAGI—enabling researchers and pharmaceutical professionals to validate, select, and implement eco-friendly methods without compromising analytical performance.

The Principles of Green Chromatography: From GAC to Circularity

Defining Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and its 12 Core Principles

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) represents a transformative paradigm in chemical analysis, dedicated to minimizing the environmental footprint and health risks associated with traditional laboratory practices [1]. Evolving from the broader principles of green chemistry, GAC has matured into a specialized discipline with measurable practices and well-defined objectives [1]. This approach seeks to align analytical processes with global sustainability goals by reducing the use of toxic reagents, decreasing energy consumption, and preventing the generation of hazardous waste [2].

The historical development of GAC gained significant momentum in 2013 when Gałuszka and coworkers proposed a dedicated set of green analytical chemistry principles, catalyzing focused thinking in the field after analytical chemists had been slower than their synthetic chemistry counterparts to adopt green principles [3]. The drive toward GAC responds to increasing scrutiny of analytical chemistry's environmental footprint, traditionally reliant on resource-intensive methods and harmful solvents [2]. For researchers in drug development and other industrial settings, adopting GAC principles not only addresses environmental concerns but also enhances laboratory safety, reduces operational costs, and improves efficiency [4].

The 12 Core Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

The 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry provide a comprehensive framework for designing and implementing environmentally benign analytical techniques [2] [5]. These principles serve as practical guidelines for making analytical workflows safer and more sustainable while maintaining scientific robustness and data quality.

Table 1: The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

| Principle Number | Principle Name | Technical Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Direct Techniques | Use direct analytical techniques to minimize or eliminate sample preparation [5]. |

| 2 | Reduced Sample Size | Minimize sample size and number of samples to limit material consumption and waste generation [5]. |

| 3 | In Situ Measurements | Favor in-situ measurements to avoid sample transport and potential contamination [5]. |

| 4 | Waste Minimization | Minimize waste generation at every stage of the analytical process [5]. |

| 5 | Safer Solvents/Reagents | Select safer, less toxic solvents and reagents [5]. |

| 6 | Avoid Derivatization | Avoid derivatization steps that require additional chemicals and generate waste [5]. |

| 7 | Energy Efficiency | Minimize energy consumption through efficient instrumentation and methodologies [5]. |

| 8 | Miniaturization/Reagent-Free | Develop and use reagent-free or miniaturized methods [5]. |

| 9 | Automation/Integration | Implement automation and integration to enhance efficiency and reduce errors [5]. |

| 10 | Multi-Analyte Approach | Adopt multi-analyte or multi-parameter methods to maximize information per analysis [5]. |

| 11 | Real-Time Analysis | Pursue real-time analysis for immediate decision-making and waste prevention [5]. |

| 12 | Greenness Assessment | Apply greenness metrics to quantify and improve environmental performance [5]. |

These principles collectively address the entire analytical lifecycle, from initial sample collection to final determination and waste disposal. Unlike traditional analytical approaches that prioritize precision and selectivity often at environmental expense, GAC integrates sustainability considerations from the earliest stages of method development [5].

Greenness Assessment Tools and Metrics

The implementation of GAC's twelfth principle – concerning greenness assessment – has led to the development of standardized metrics that enable quantitative evaluation of analytical methods' environmental performance. These tools provide researchers with objective criteria for comparing and improving their analytical procedures.

Table 2: Key Greenness Assessment Tools in Analytical Chemistry

| Assessment Tool | Graphical Output | Main Focus | Output Type | Notable Features | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | Pictogram with 4 quadrants | Basic hazard screening | Qualitative (pass/fail) | Simple, quick visual assessment | [6] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Numerical score (0-100) | Reagent toxicity and energy use | Semi-quantitative | Penalty point system; higher score = greener | [5] [6] |

| GAPI | Color-coded pictogram | Entire analytical workflow | Semi-quantitative | Visualizes 5 stages of method | [5] [6] |

| AGREE | Radial chart (0-1) | All 12 GAC principles | Quantitative | Comprehensive single-score metric | [5] [6] |

| AGREEprep | Pictogram with score | Sample preparation | Quantitative | First dedicated sample prep metric | [5] [6] |

| BAGI | "Asteroid" pictogram + % score | Method applicability | Quantitative | Assesses practical viability | [5] |

The Analytical Eco-Scale assigns a total score of 100 points for an ideal green analysis, with penalty points subtracted based on amounts of solvents/reagents, energy consumption, hazards, and waste produced [6]. The Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) offers a more detailed visual evaluation through a pictogram representing different stages of an analytical procedure, color-coded based on environmental impact (green for low, yellow for moderate, red for high impact) [3].

The AGREE metric, introduced in 2020, represents a significant advancement by integrating all 12 GAC principles into a holistic algorithm that provides both a single-score evaluation and an intuitive graphic output [5] [6]. This tool evaluates parameters including solvent toxicity, energy consumption, sample preparation complexity, and analytical throughput – the method's capacity to process high sample volumes efficiently, which directly impacts both sustainability and operational feasibility [5].

More recently, the Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) has emerged as a complementary tool that addresses practical and operational aspects of analytical methods, evaluating ten key attributes related to applicability including analysis type, throughput, reagent availability, automation, and sample preparation [5]. This aligns with the emerging concept of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which seeks to balance analytical performance (red), environmental sustainability (green), and practical applicability (blue) [5].

GAC Implementation in Chromatographic Methods

Green Approaches in HPLC and UHPLC

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is widely used in pharmaceutical analysis and quality control but traditionally relies on hazardous organic solvents like acetonitrile and methanol, generates large volumes of chemical waste, and consumes considerable energy [5]. Implementing GAC principles in HPLC involves several key strategies:

- Alternative solvent systems: Replacement of traditional solvents with greener alternatives such as ethanol, water, ethyl acetate, or bio-based solvents [7] [5]. For example, a green RP-HPLC method for analyzing olmesartan medoxomil utilized a combination of ethyl acetate and ethanol (50:50% v/v) as the mobile phase instead of more hazardous solvents [7].

- Miniaturization and micro-HPLC: Scaling down analytical separations to reduce solvent consumption and waste generation [5].

- Method optimization: Developing streamlined methods that reduce run times while maintaining resolution and sensitivity [8].

The environmental impact of analytical methods becomes particularly significant when scaled across global manufacturing networks. A case study of rosuvastatin calcium illustrates this point: with approximately 25 LC analyses per batch and an estimated 1000 batches produced globally each year, a single API can consume approximately 18,000 liters of mobile phase annually just for chromatographic analysis [3].

Green Sample Preparation Techniques

Sample preparation is often the most polluting stage of analytical processes [8]. Green sample preparation techniques include:

- Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME): A solvent-free technique that combines extraction and enrichment using a coated silica fiber [8]. SPME minimizes solvent use, reduces sample preparation time, and enhances sensitivity for various analytes.

- QuEChERS: A methodology recognized as being "quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe" [8]. Originally developed for pesticide residue analysis, it uses minimal solvents compared to traditional extraction methods and employs dispersive solid-phase extraction for sample clean-up.

- Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE): While a traditional technique, modern SPE approaches focus on minimizing solvent volumes and using safer solvents [8].

These green sample preparation methods align with multiple GAC principles, including waste minimization, safer solvents, and reduced energy consumption.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed Protocol: Green HPLC Method for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Objective: To develop and validate a green RP-HPLC method for the analysis of olmesartan medoxomil (OLM) in bulk drugs, self-microemulsifying drug delivery systems (SMEDDS), and marketed tablets [7].

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: Lichrosphere 250 × 4.0 mm RP C8 column with 5 μm packing

- Mobile Phase: Ethyl acetate:ethanol (50:50% v/v) – selected as green alternatives to traditional solvents

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Detection: UV detection at 250 nm

- Injection Volume: 20 μL

Sample Preparation:

- For bulk drug: Direct dissolution in mobile phase

- For SMEDDS: Appropriate dilution with mobile phase

- For tablets: Powder extraction and filtration

Method Validation Parameters:

- Linearity: evaluated over concentration range 5-30 μg/mL

- Selectivity: resolution of OLM peak from degradation products

- Accuracy: percentage recovery (98.67%-101.25%)

- Precision: intra-day and inter-day RSD < 2%

- Robustness: deliberate variations in flow rate and mobile phase composition

Greenness Assessment: The method was assessed using Analytical Eco-Scale and GAPI metrics, showing significant improvements over conventional methods due to the use of ethyl acetate and ethanol instead of more hazardous solvents like acetonitrile or methanol [7].

Detailed Protocol: QuEChERS Extraction for Complex Matrices

Objective: To extract multiple analytes from complex matrices with minimal solvent use and waste generation [8].

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize sample and weigh 10-15 g into a centrifuge tube

- Extraction: Add acetonitrile (10 mL) and shake vigorously for 1 minute

- Salting Out: Add magnesium sulfate (4 g) and sodium chloride (1 g), then shake immediately and vigorously for 1 minute

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at >4000 rpm for 5 minutes

- Clean-up: Transfer supernatant to a d-SPE tube containing PSA sorbent and magnesium sulfate

- Analysis: Shake and centrifuge, then inject supernatant into chromatographic system

Green Features:

- Minimal solvent consumption compared to traditional extraction methods

- Reduced waste generation

- Elimination of chlorinated solvents

- High throughput capability

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Tool/Reagent | Function in GAC | Green Advantages | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Green solvent for extraction and chromatography | Biodegradable, low toxicity, renewable source | Mobile phase component in HPLC [7] |

| Ethyl Acetate | Green organic solvent | Lower toxicity compared to acetonitrile or methanol | RP-HPLC mobile phase [7] |

| Water | Ultimate green solvent | Non-toxic, non-flammable, readily available | Reverse-phase chromatography with special columns [4] |

| Supercritical COâ‚‚ | Extraction and chromatography solvent | Non-toxic, non-flammable, easily removed | Supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) [2] |

| Ionic Liquids | Alternative solvents and electrolytes | Non-volatile, tunable properties, recyclable | Extraction media, GC stationary phases [2] |

| Primary Secondary Amine (PSA) | Sorbent for clean-up | Effective removal of polar interferences | QuEChERS method for sample preparation [8] |

| SPME Fibers | Solvent-free extraction | Eliminates solvent use, simple operation | Direct extraction from various matrices [8] |

| Presenilin 1 (349-361) | Presenilin 1 (349-361), MF:C56H93N21O19, MW:1364.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Nmda-IN-2 | NMDA-IN-2|NMDA Receptor Antagonist|RUO | NMDA-IN-2 is a potent NMDA receptor antagonist for neurological research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

Visualization of GAC Principles and Implementation

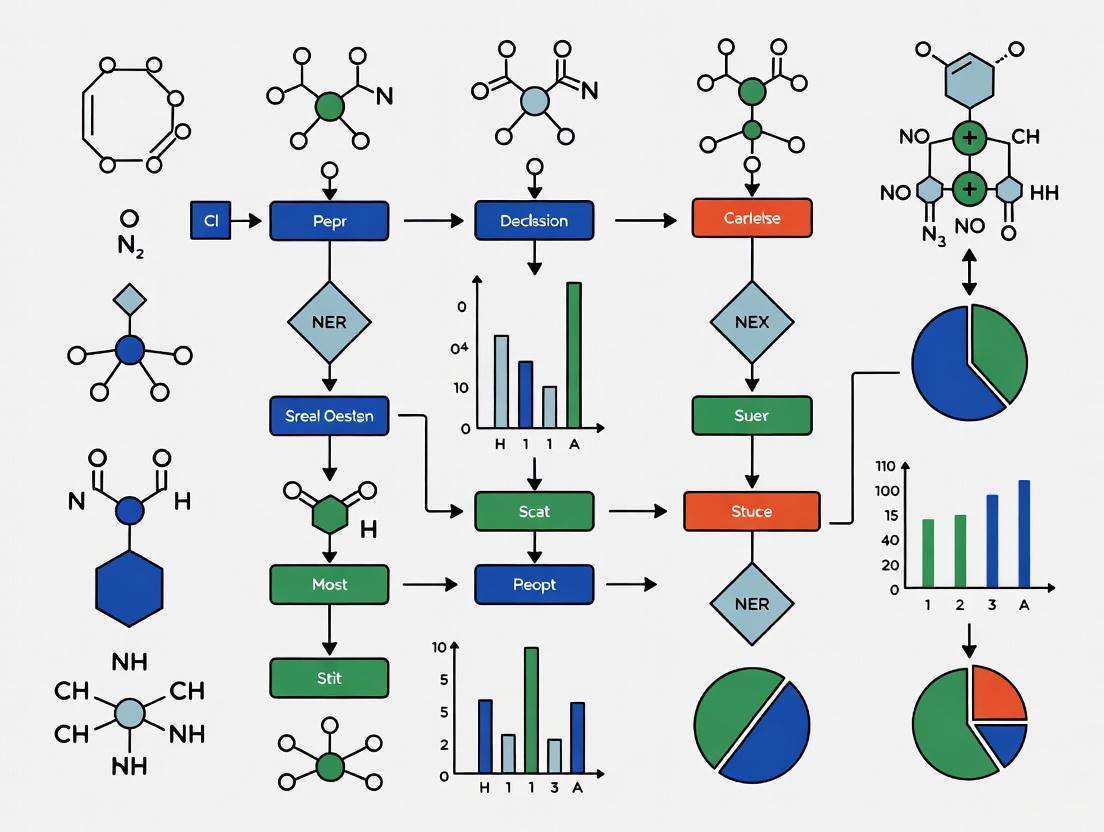

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between the 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry and their practical implementation in analytical workflows:

GAC Principles and Implementation Pathway - This diagram illustrates how GAC principles translate into practical implementation through specific methods, with continuous assessment ensuring effectiveness.

Green Analytical Chemistry represents a fundamental shift in how chemical analysis is conceived and conducted, emphasizing environmental stewardship, sustainability, and efficiency alongside analytical performance [2]. By integrating the 12 principles of GAC, analytical chemists can significantly mitigate the adverse impacts of traditional analytical practices while positioning themselves as drivers of innovation in sustainable science [2].

The ongoing evolution of GAC includes emerging trends such as circular analytical chemistry, which focuses on minimizing waste and keeping materials in use [9], and the application of artificial intelligence to optimize workflows and minimize resource consumption [2]. For researchers and drug development professionals, adopting GAC principles offers the dual benefit of reducing environmental impact while simultaneously improving operational efficiency, enhancing safety, and reducing costs [4].

As regulatory frameworks increasingly mandate greener technologies, GAC is poised to become a cornerstone of compliance and innovation in both industrial and academic settings [2]. The continued development and refinement of greenness assessment metrics will provide researchers with robust tools to quantify and improve their environmental performance, driving the field toward a more sustainable future.

In the pursuit of environmentally responsible science, the terms sustainability and circularity are frequently used interchangeably within analytical chemistry, creating conceptual confusion that impedes meaningful progress. For analytical laboratories, particularly those employing chromatographic methods, understanding this distinction is not merely semantic but fundamental to implementing effective environmental strategies. Sustainability is a broader, normative concept tied to what people value and should be done, balancing three interconnected pillars: economic, social, and environmental needs—often called the "triple bottom line" [9]. It is designed to reduce harm and extraction, ensuring that present needs are met without compromising future generations [10]. In contrast, circularity is a more specific approach focused on resource management within this broader framework. It aims to eliminate waste and pollution, keep products and materials in use, and regenerate natural systems [10]. Circularity is a subset of sustainability, representing a tangible pathway toward achieving sustainable goals through a redesigned, waste-free economic model [11] [10].

The analytical chemistry sector, including drug development and pharmaceutical quality control, has traditionally operated under a linear "take-make-dispose" model, relying on energy-intensive processes, non-renewable resources, and generating significant waste [9] [12]. This linear pattern creates unsustainable environmental pressures, feeding the triple planetary crisis of climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution [12]. A paradigm shift is now occurring to align analytical practices with sustainability science and circular economy principles, moving toward a system that is not just less harmful but actively restorative and regenerative [9]. For chromatography labs, this transition involves rethinking every aspect of operation—from solvent selection and instrument energy consumption to end-of-life management of columns and reagents—making the clarity between sustainability and circularity a critical operational concern.

The Conceptual Framework: Goals and Interrelationships

The Twelve Goals of Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC)

The framework for Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) has been formulated into twelve distinct goals, providing a concrete pathway for laboratories [12]. CAC is defined as an analytical chemistry system that aims at eliminating waste, circulating products and materials, minimizing hazards, and saving resources and the environment. It promotes resource efficiency and emphasizes keeping products and materials in circulation for as long as possible in a sustainable manner.

Table 1: The Twelve Goals of Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC)

| Goal Category | Specific Goal | Description & Application in Analytical Labs |

|---|---|---|

| Resource Management | 1. Save Resources | Minimize consumption of materials, energy, and water in all processes [12]. |

| 2. Use Renewable Resources | Prefer solvents and materials derived from renewable feedstocks [12]. | |

| 3. Reduce Waste Generation | Implement strategies to minimize waste at the source [12]. | |

| Material Circulation | 4. Reuse & Recycle | Reuse analytical equipment, containers, and reagents; recycle materials like solvents [12]. |

| 5. Recover & Repurpose | Recover valuable components from waste streams for new applications [12]. | |

| 6. Incorporate Recycled Content | Use products made from recycled materials in laboratory operations [12]. | |

| Hazard & Risk Reduction | 7. Eliminate & Minimize Hazards | Substitute hazardous solvents/reagents with safer alternatives [12]. |

| 8. Design for Degradation | Use materials that safely degrade after their useful life [12]. | |

| 9. Avoid Unnecessary Production | Rationalize analytical testing to prevent over-consumption [12]. | |

| Systemic Integration | 10. Integrate Processes & Techniques | Combine analytical steps to improve efficiency and reduce resource use [12]. |

| 11. Collaborate Across the Value Chain | Work with manufacturers, suppliers, and waste managers to close material loops [12]. | |

| 12. Promote a Circular Mindset | Train and encourage staff to adopt circular economy principles in their work [12]. |

Visualizing the Transition from Linear to Circular Systems

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental structural differences between the traditional linear model, open-loop recycling, and the ideal closed-loop circular system for analytical chemistry.

Practical Implementation in Chromatographic Methods

Green Chromatography: A Sustainable Foundation

Green Chromatography focuses primarily on minimizing the immediate environmental impact of analytical methods. This aligns with the "weak sustainability" model, which assumes that natural resources can be consumed as long as technological progress compensates for the damage [9]. The core strategies involve:

- Solvent Replacement and Reduction: A primary lever for greening chromatographic methods is addressing the mobile phase. This includes replacing hazardous solvents like acetonitrile with greener alternatives such as ethanol or methanol, using aqueous mobile phases where possible, and employing additives like ionic liquids to improve efficiency [13]. A case study on rosuvastatin calcium analysis reveals that a single liquid chromatography method, when scaled to ~1000 batches annually, can consume approximately 18,000 liters of mobile phase, underscoring the massive cumulative impact [3].

- Instrument and Column Innovation: Technological advances are key drivers. Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) using columns packed with smaller particles (e.g., 1.7 µm) can reduce solvent consumption by up to 80% compared to conventional HPLC while maintaining or improving separation efficiency [3] [13]. Similarly, employing narrow-bore columns (internal diameter ≤ 2.1 mm) can slash mobile phase use by up to 90% [13].

- Methodology Optimization: Techniques like Elevated Temperature Liquid Chromatography reduce mobile phase viscosity, enabling faster flow rates or the use of longer columns, thereby accelerating analysis times and reducing solvent use [13]. Furthermore, experimental design (e.g., Fractional Factorial, Box-Behnken) helps develop robust methods with fewer experiments, conserving resources [14].

Circular Chromatography: Closing the Loops

Circularity in the chromatography lab pushes beyond reduction to fundamentally redesign systems, aiming for "strong sustainability" that acknowledges ecological limits and seeks to restore natural capital [9]. This involves:

- Solvent Recycling and Recovery: Implementing onsite solvent recovery systems to purify and reuse waste solvents from the mobile phase preparation and eluent waste streams. This keeps materials in use and directly addresses the "dispose" phase of the linear model.

- Equipment and Column Lifecycle Management: Collaborating with manufacturers to take back used columns for refurbishment or material recovery. This includes refilling column hardware with new stationary phase or recovering precious metals from hardware components. Promoting the use of equipment designed for disassembly and repair also extends product lifespans.

- Waste Valorization: Investigating opportunities to repurpose analytical waste. For instance, certain solvent wastes from one analytical method could potentially be used as a starting material for another, less critical process, or even in a different application outside the lab.

Quantitative Greenness Assessment Tools

To measure progress, labs are adopting standardized metrics. These tools provide a quantitative basis for comparing methods and guiding development.

Table 2: Key Metrics for Assessing Greenness and Circularity in Analytical Methods

| Metric Tool | Approach | Key Circularity & Sustainability Considerations | Example Application in Chromatography |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) | Evaluates solvent energy of production/disposal, EHS (Environment, Health, Safety), and instrument energy consumption [3]. | Integrates lifecycle thinking (energy of production) and hazard minimization, bridging green and circular goals. | Used at AstraZeneca to trend and improve the sustainability profile of chromatographic methods across a drug portfolio [3]. |

| AGREEprep | A comprehensive metric providing a score from 0-1 (1=best) based on multiple green analytical chemistry principles [9]. | Assesses aspects like waste generation, resource consumption, and reagent toxicity. | A study of 174 standard methods (CEN, ISO) found 67% scored below 0.2, highlighting the urgent need for updating official methods [9]. |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | A semi-quantitative tool assigning penalty points for hazardous reagents, energy consumption, and waste; a higher score (out of 100) is greener [3]. | Focuses on the negative impacts of the method, encouraging waste and hazard reduction. | Useful for quick comparisons between methods to identify major areas for improvement [3]. |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | A cradle-to-grave analysis of the environmental burdens associated with all stages of a product or process [3]. | The most holistic approach for circularity, evaluating all inputs and outputs across the entire lifecycle. | Applied to analytical methods and sample preparation to understand the full environmental footprint, though data-intensive [3]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Reagents and Solutions for Green and Circular Chromatography

Transitioning to more sustainable and circular practices requires a shift in the materials and methods used in daily laboratory work.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Sustainable and Circular Chromatography

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Green/Circular Advantage & Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol (from renewable sources) | Mobile phase organic modifier | Replaces more toxic and energy-intensive acetonitrile; biodegradable and can be produced from biomass [13]. |

| Supercritical COâ‚‚ | Primary mobile phase in Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC) | Non-toxic, non-flammable, and largely recyclable; significantly reduces organic solvent use by up to 90% [13]. |

| Water | Mobile phase component | The greenest solvent; used in aqueous mobile phases to eliminate or reduce organic solvent content [13]. |

| Ionic Liquids / Deep Eutectic Solvents | Mobile phase additives or extraction solvents | Can replace volatile organic compounds; tunable properties and low volatility enhance safety and can be designed for recyclability [13]. |

| Modern Silica-Based Phases (e.g., Type B, Hybrid) | Stationary phase for columns | Reduced metal content and improved end-capping minimize the need for hazardous mobile phase additives (e.g., triethylamine) [15]. |

| Usp28-IN-4 | Usp28-IN-4, MF:C22H18Cl2N2O3S, MW:461.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PROTAC EGFR degrader 4 | PROTAC EGFR degrader 4, MF:C55H70N12O4S, MW:995.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Overcoming Challenges and Seizing Opportunities

The transition from a linear to a circular model in analytical labs faces significant barriers. A major challenge is coordination failure—the lack of collaboration among manufacturers, researchers, routine labs, and policymakers [9]. Circular Analytical Chemistry relies on all stakeholders embracing circular principles and working together, which is often difficult in a traditional and conservative field [9]. Furthermore, a linear mindset persists, with a strong focus on analytical performance (speed, sensitivity) while often neglecting sustainability factors like resource efficiency and end-of-life material management [9].

Another critical consideration is the rebound effect, where efficiency gains are offset by increased consumption. For example, a novel, low-cost microextraction method might lead laboratories to perform significantly more analyses, ultimately increasing the total volume of chemicals used and waste generated [9]. Mitigating this requires optimizing testing protocols and fostering a mindful laboratory culture.

To drive change, regulatory agencies must play a more active role by assessing the environmental impact of standard methods and establishing clear timelines for phasing out those that score low on green metrics [9]. Financial incentives for early adopters and integrating green metrics into method validation processes can powerfully accelerate this transition [9]. Finally, strengthening university-industry partnerships is crucial to bridge the gap between academic innovations in green methods and their commercialization and widespread adoption in real-world practice [9].

The Linear 'Take-Make-Dispose' Model vs. the Circular Analytical Chemistry Framework

Analytical chemistry, particularly in pharmaceutical research and drug development, plays a crucial role in ensuring product quality and safety. However, its traditional operational model—characterized by significant consumption of reagents, organic solvents, and energy—imposes a considerable environmental burden. This article contrasts the prevailing linear 'take-make-dispose' model with the emerging framework of Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC), providing a technical guide for scientists seeking to align their chromatographic methods with the principles of sustainability. The transition is not merely an environmental consideration but a holistic approach that enhances method robustness, economic efficiency, and regulatory compliance while minimizing ecological impact [9] [16].

The global scale of the linear economy's impact is stark. The world extracts over 100 billion tonnes of raw materials annually, with more than 90% wasted after a single use [17]. In the laboratory, conventional High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) methods are significant contributors to this problem, consuming large amounts of hazardous organic solvents and generating substantial toxic waste [16]. The circular economy presents a viable alternative, a model that could boost the EU's GDP by €1.8 trillion by 2030 and create 700,000 new jobs [17]. Within analytical chemistry, this translates to the CAC framework, a systemic rethinking designed to eliminate waste, keep resources in use, and regenerate natural systems [9].

Contrasting the Linear and Circular Frameworks

The Linear 'Take-Make-Dispose' Model in the Laboratory

The linear economy, a "take-make-waste" production model, dominates many industrial and scientific sectors [17]. In an analytical chemistry context, this model manifests as a one-way flow of materials:

- Take: Extract and process raw materials to produce high-purity solvents, reagents, and single-use consumables.

- Make: Manufacture and use analytical instruments, columns, and plasticware.

- Dispose: Discard solvents as toxic waste, and dispose of columns and consumables in landfills or via incineration after their short, single-use lifecycles [17] [18].

This model is inherently resource-depleting and relies on the assumption that resources and the planet's waste absorption capacity are infinite [18]. Its consequences include rising waste management costs, lost economic value from discarded materials, and significant environmental damage from resource extraction and waste processing [17].

The Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) Framework

Circular Analytical Chemistry is a regenerative system that aims to eliminate waste and keep resources in use for as long as possible [9]. It shifts the focus from a one-way pipeline to a closed-loop system. The framework is built on three core principles:

- Design out waste and pollution from the outset, eliminating toxic materials and reducing resource consumption through thoughtful design choices [19].

- Keep products and materials in use by extending the lifecycle of instruments, reagents, and materials through repair, refurbishment, and recycling [19].

- Regenerate natural systems by favoring biodegradable solvents and supporting practices that restore rather than deplete ecosystems [19].

Unlike the narrow focus on environmental footprint, CAC integrates strong economic considerations and aims for a systemic transformation that requires collaboration across manufacturers, researchers, routine labs, and policymakers [9].

Table 1: Core Differences Between Linear and Circular Models in Analytical Chemistry

| Factor | Linear Analytical Model | Circular Analytical Chemistry Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Resource Use | Extracts and discards finite virgin materials. | Reuses, recycles, and regenerates materials in closed loops. |

| Waste Management | Relies on landfill and incineration of solvents and consumables. | Designs out waste; treats "waste" as a resource for new cycles. |

| Business/Model Focus | Sells instruments and consumables for single-use/disposal. | Promotes Product-as-a-Service (e.g., instrument leasing), refill, and resale. |

| Design Philosophy | Prioritizes performance/cost, often with planned obsolescence. | Designs for durability, modularity, repairability, and upgradability. |

| Economic Driver | Value from high-volume, single-use consumable sales. | Value from long-term utility, service models, and material recovery. |

Diagram 1: Linear vs. Circular Material Flows. The circular model emphasizes feedback loops to eliminate waste.

Implementing Circularity in Chromatographic Methods

Transitioning from a linear to a circular model requires practical strategies across the lifecycle of an analytical method. The following sections provide a detailed, actionable guide for separation scientists.

Green Sample Preparation (GSP)

Sample preparation is often a resource-intensive initial step. Adopting Green Sample Preparation (GSP) principles can drastically reduce its environmental footprint [9].

- Maximize Sample Throughput: This can be achieved by:

- Accelerating the Single Step: Applying assisted fields like ultrasound or microwaves can enhance extraction efficiency and speed, consuming significantly less energy than traditional heating methods like Soxhlet extraction [9].

- Parallel Processing: Using miniaturized systems that handle multiple samples simultaneously increases overall throughput and reduces energy consumed per sample [9].

- Automation: Automated systems save time, lower reagent consumption, reduce waste generation, and minimize operator exposure to hazardous chemicals [9].

- Integration of Steps: Streamlining multi-step preparations into a single, continuous workflow cuts down on resource use and material loss [9].

Solvent Selection and Management

The choice of mobile phase solvent is one of the most significant levers for greening liquid chromatography. Classical solvents like acetonitrile and methanol have considerable environmental, health, and safety (EHS) concerns.

- Green Solvent Selection Guides: Utilize established guides from Pfizer, GSK, Sanofi, or the CHEM21 project to rank solvents based on EHS criteria [16]. A key strategy is substituting toxic classical solvents with greener alternatives. For example, dihydrolevoglucosenone (Cyrene), a bio-based solvent derived from renewable feedstock, shows promising potential for chromatographic applications [16].

- Solvent Recycling: Implement in-lab distillation and purification systems to recover and reuse organic solvents from the mobile phase waste stream, closing the material loop.

- Biodegradable Solvents: Favor solvents that can safely break down in the environment, particularly for biological cycles, ensuring they are free of toxic additives [18].

Table 2: Greenness Ranking and Properties of Common HPLC Solvents (Adapted from CHEM21 and ACS Guides)

| Solvent | Environmental (E) Profile | Health (H) Profile | Safety (S) Profile | Recommended Greenness for LC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | Preferred | Preferred | Preferred | Ideal |

| Ethanol | Preferred | Recommended | Recommended | Preferred |

| Acetone | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| 2-Propanol | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended | Recommended |

| Methanol | Problematic | Problematic | Recommended | Use with Care |

| Acetonitrile | Problematic | Problematic | Recommended | Use with Care |

| n-Hexane | Hazardous | Hazardous | Hazardous | Avoid |

Instrumentation and Energy Efficiency

Analytical instruments are significant energy consumers. A typical HPLC/UHPLC instrument is energy-intensive, and laboratories can emit about 22% of the COâ‚‚ emissions associated with petrol cars per day [16].

- Miniaturization of Instruments: Modern miniature gas chromatographs and compact LC systems offer a smaller laboratory footprint, less heat generation, and lower power consumption while performing routine analytical tasks [20].

- Reducing Analysis Time: Using monolithic or core–shell columns with improved performance allows for shorter column lengths and faster analysis times. This directly reduces solvent consumption and instrument energy use per run [16]. Sub-2 µm particle columns in UHPLC systems also enable rapid separations, further saving solvent and energy [16].

- Carrier Gas Choice in GC: From a sustainability perspective, helium is a poor choice due to ongoing shortages and its non-renewable nature. Nitrogen is often a suitable and greener alternative for temperature-programmed analyses, while hydrogen (despite requiring generators) offers faster separations [20].

Method Validation and Assessment Tools

Evaluating the environmental impact of analytical methods is crucial for a meaningful transition to CAC. Several metrics have been developed to score the greenness of analytical methods.

- Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS): This metric, suited for chromatographic methods, focuses on the mass of solvents used, health and environmental measures of the solvents, and energy utilization for both solvents and instrumentation [20].

- AGREEprep Metric: A widely adopted tool for assessing the greenness of sample preparation methods. A recent evaluation of 174 standard methods from CEN, ISO, and Pharmacopoeias revealed that 67% scored below 0.2 on the AGREEprep scale (where 1 is the highest), highlighting the urgent need to update official methods [9].

- White Analytical Chemistry (WAC): This approach extends beyond environmental impact. It provides a balanced assessment by weighing three components equally: Method Greenness (green), Method Analytical Efficiency (red), and Method Practicality (blue). The overall "white" strength represents the method's sustainability percentage, ensuring that greenness does not come at the cost of performance or practicality [16] [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials for Green Chromatography

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Circular Analytical Chemistry

| Item | Function in Circular Practice | Traditional Linear Alternative |

|---|---|---|

| Bio-based Solvents (e.g., Cyrene) | Function as a green organic modifier in the mobile phase, derived from renewable biomass instead of petrochemicals. | Acetonitrile, Tetrahydrofuran |

| Core-Shell Particle Columns | Enable faster separations with lower backpressure, reducing analysis time, solvent consumption, and energy use. | Fully porous, longer columns |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers | Allow for solvent-free or minimal-solvent sample preparation and concentration. | Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) |

| Automated Sample Preparation Systems | Reduce solvent volumes, improve reproducibility, and minimize human exposure to hazardous chemicals. | Manual sample preparation |

| Hydrogen or Nitrogen Generator | Provides a sustainable and continuous supply of carrier gas for GC, reducing reliance on helium cylinders. | Helium gas cylinders |

| Hdac-IN-43 | HDAC-IN-43|Potent HDAC Inhibitor|For Research Use | HDAC-IN-43 is a potent histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor for cancer research. It modulates epigenetic regulation. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Erasin | Erasin, MF:C20H19N3O3, MW:349.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Overcoming Barriers to Implementation

The transition to CAC faces two primary challenges: a lack of clear direction and coordination failure among stakeholders [9].

- The Rebound Effect: A critical barrier is the rebound effect, where efficiency gains are offset by increased consumption. For example, a cheap, green microextraction method might lead laboratories to perform significantly more analyses, negating the environmental benefit. Mitigation requires optimizing testing protocols and fostering a mindful laboratory culture [9].

- Modernizing Regulatory Methods: Regulatory agencies play a critical role. They must assess the environmental impact of standard methods and establish clear timelines for phasing out those that score low on green metrics. Integrating greenness metrics into method validation and providing financial incentives for early adopters are powerful motivators for change [9].

- Fostering Collaboration: Progress hinges on collaboration between academia, industry, and regulatory bodies. University-industry partnerships are essential to bridge the gap between groundbreaking research and commercialized products [9]. A systems-thinking approach, which holistically evaluates all steps of an analytical method and their external impacts, is crucial for avoiding unintended consequences and achieving true sustainability [20].

Diagram 2: Multi-stakeholder Collaboration for CAC. All actors must align their goals to accelerate the transition.

The transition from the linear 'take-make-dispose' model to a Circular Analytical Chemistry framework is a necessary evolution for the field of separation science. This shift is not merely an ecological ideal but a comprehensive strategy that enhances economic resilience, method efficiency, and regulatory future-proofing. By adopting Green Sample Preparation, selecting sustainable solvents, optimizing instrumentation for energy efficiency, and utilizing modern assessment tools, researchers and drug development professionals can lead this transformation. The journey toward circularity demands a collaborative effort, a willingness to innovate, and the application of systems thinking. By embracing these principles, the analytical community can significantly reduce its environmental footprint while continuing to advance scientific discovery and ensure public health.

The pharmaceutical industry is undergoing a significant transformation, driven by an urgent need to align analytical practices with broader sustainability goals. Green chromatography emerges as a strategic response to this need, systematically addressing the environmental, safety, and economic shortcomings of traditional chromatographic methods. This approach is not merely an ethical consideration but a comprehensive framework that redefines efficiency in the analytical laboratory. Framed within a broader thesis on green chromatographic methods, this whitepaper examines the core drivers propelling this shift, demonstrating how integrating green principles from the initial stages of method development leads to robust, sustainable, and economically viable analytical procedures. The transition is supported by the adoption of standardized metrics, technological innovations in instrumentation, and a growing body of evidence illustrating the tangible benefits of sustainable practices for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Environmental Impact Driver

The environmental footprint of analytical methods, once considered negligible, is now recognized as substantial, especially when scaled across global pharmaceutical development and quality control operations. A compelling case study on the manufacturing of rosuvastatin calcium illustrates this scale: with approximately 25 liquid chromatography (LC) analyses performed per batch, each consuming about 18 L of mobile phase, the global production of an estimated 1000 batches annually results in the consumption and disposal of approximately 18,000 liters of mobile phase for a single active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) [3]. This example shatters the perception of insignificant environmental impact and underscores the urgent need for sustainable practices.

Quantifying Environmental Impact with the Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS)

A significant advancement in measuring environmental impact is the Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS), a comprehensive metric developed by the American Chemical Society's Green Chemistry Institute in collaboration with industry partners [3]. The AMGS provides a holistic evaluation of chromatographic methods across multiple dimensions, including:

- The energy consumed in the production and disposal of solvents.

- Solvent safety and toxicity profiles.

- Instrumental energy consumption [3].

By integrating AMGS into routine procedures, organizations like AstraZeneca have systematically improved their sustainability profiles, reduced hazardous waste, and promoted the development of greener alternatives, thereby turning environmental strategy into measurable action [3].

Key Strategies for Reducing Environmental Impact

Table 1: Strategies for Minimizing Chromatography's Environmental Footprint

| Strategy | Description | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Reduction | Adoption of Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) which uses smaller particle-size columns and lower flow rates. | Reduces solvent consumption while maintaining or improving separation quality [22]. |

| Green Solvents | Replacing traditional solvents like acetonitrile and methanol with safer alternatives such as ethanol, or switching to techniques like Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC) that use supercritical COâ‚‚. | Lowers toxicity and environmental hazard of waste streams [22]. |

| Energy Efficiency | Utilizing instruments with energy-saving features (e.g., standby modes) and optimizing workflows to reduce run times. | Directly lowers the carbon footprint of analytical operations [22]. |

| Waste Management | Implementing solvent recycling programs and efficient waste disposal systems. | Minimizes the generation and environmental impact of hazardous waste [22]. |

The Operator Safety Driver

Operator safety is an integral component of green chromatography, directly linked to the reduction of hazardous exposures in the laboratory environment. The traditional reliance on large volumes of toxic solvents like acetonitrile and methanol in conventional High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) poses significant occupational health risks [23]. Green chromatography addresses this by promoting the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), which focus on minimizing or eliminating dangerous solvents and reagents, thereby creating a safer workspace for analysts [23].

Assessment Tools for Safety and Hazard Evaluation

Safety is quantitatively integrated into method design through modern greenness assessment tools. The Analytical Eco-Scale, for example, employs a penalty-point system where methods are assessed against ideal green conditions. Hazardous reagents, unsafe instrument configurations, and the generation of large amounts of toxic waste incur penalty points, subtracting from a base score of 100. A higher final score indicates a greener and safer method [24] [25]. Furthermore, the AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) metric incorporates all 12 principles of GAC, which include directives for minimizing sample preparation, using safer solvents, and ensuring operator safety, providing a comprehensive visual and numerical score of a method's safety and environmental profile [24] [23].

Practical Methodologies for Enhancing Safety

Green Sample Preparation: Techniques such as Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) and stir-bar sorptive extraction (SBSE) are being widely adopted. These methods significantly reduce solvent consumption and operator exposure to hazardous chemicals while maintaining high analytical efficiency [23]. Automation and Integration: Automation of sample preparation is a key strategy aligned with Green Sample Preparation (GSP) principles. Automated systems minimize human intervention, which directly lowers the risks of handling errors and operator exposure to hazardous chemicals [9]. Solvent Replacement: A key methodology is the replacement of high-toxicity solvents with safer alternatives. A documented green stability-indicating method for the analysis of fluorescein sodium and benoxinate hydrochloride successfully replaced toxic acetonitrile with a less hazardous mixture of isopropanol and buffer, creating a safer operational environment without compromising analytical performance [25].

The Economic Benefits Driver

The adoption of green chromatography is not only an environmental and safety imperative but also a source of significant economic advantage. The economic benefits are realized through reduced operational costs, increased efficiency, and alignment with global sustainability standards that can influence market access and corporate reputation.

Direct and Indirect Economic Advantages

Table 2: Economic Benefits of Adopting Green Chromatography Practices

| Benefit Category | Economic Impact | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced Solvent Costs | Direct cost savings from purchasing lower volumes of solvents, coupled with decreased expenses for waste disposal. | UHPLC methods consume significantly less solvent per analysis, leading to proportional savings [22]. |

| Increased Laboratory Efficiency | Faster analysis times and higher throughput free up instrument time and personnel resources. | Shorter run times achieved with UHPLC or optimized methods allow a single instrument to perform more analyses per day [22] [25]. |

| Waste Management Cost Reduction | Lower volumes of hazardous waste lead to lower costs for storage, transportation, and treatment. | Solvent recycling programs and miniaturized methods directly reduce waste-related expenditures [22]. |

| Error Mitigation | Software that detects issues (e.g., sample contamination) can halt runs early, preventing costly solvent waste and instrument time onæ— æ•ˆ analyses. | Reduces unnecessary retesting and reanalysis, conserving resources [22]. |

The Broader Business Case

The economic argument extends beyond direct cost savings. The pharmaceutical industry's commitment to sustainability, exemplified by goals like AstraZeneca's ambition for carbon-zero analytical laboratories by 2030, is increasingly linked to long-term economic stability and social responsibility [3]. Furthermore, the concept of a circular economy is gaining traction, where the focus on minimizing waste and keeping materials in use offers not just environmental benefits but also strong economic advantages by creating a more resource-efficient operational model [9]. Adopting green practices also future-proofs laboratories against increasingly stringent environmental regulations and potential financial penalties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Frameworks and Experimental Protocols

The successful implementation of green chromatography relies on a suite of standardized assessment tools and a systematic approach to method development. These frameworks allow scientists to quantitatively evaluate and optimize their methods against sustainability criteria.

Key Greenness Assessment Tools

Table 3: Key Metrics for Assessing the Greenness of Analytical Methods

| Tool Name | Output Format | Key Features & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) | Comprehensive metric | Evaluates solvent energy, toxicity, and instrument energy consumption. Used for strategic portfolio assessment [3]. |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Numerical score (0-100) | A penalty-point system based on reagent hazards, energy use, and waste. Simple and suitable for routine analysis [24] [25]. |

| Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) | Color-coded pictogram | Provides a visual assessment of the entire analytical workflow, from sample collection to detection, helping to identify high-impact steps [24] [23]. |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) | Numerical score (0-1) & circular pictogram | Incorporates all 12 principles of GAC into a user-friendly, comprehensive output, facilitating easy comparison between methods [24] [23]. |

| AGREEprep | Numerical score & pictogram | The first dedicated tool for evaluating the environmental impact of the sample preparation step [24]. |

| Mt KARI-IN-4 | Mt KARI-IN-4, MF:C13H8FN5O3S2, MW:365.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fluorescent Substrate for Subtillsin | Fluorescent Substrate for Subtillsin, MF:C66H80N14O18, MW:1357.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Protocol: A Green Stability-Indicating Method

The following detailed protocol, adapted from a published study, exemplifies the practical application of green principles in developing a chromatographic method for pharmaceutical analysis [25].

1. Analytical Target Profile (ATP): To develop a green, robust, and fast stability-indicating method for the concomitant analysis of fluorescein sodium and benoxinate hydrochloride in the presence of their degradation products within four minutes [25].

2. Critical Method Parameters (CMPs):

- Organic modifier type and concentration

- Buffer pH

- Flow rate

- Column temperature [25]

3. Screening and Optimization via Quality by Design (QbD):

- Screening Design: A Fractional Factorial Design (FFD) was used to screen the large number of CMPs with a minimal number of experiments, identifying the most influential factors.

- Optimization Design: A Box-Behnken Design (BBD), a response surface methodology, was then employed to model the interactions between the critical factors and locate the optimum chromatographic conditions. Notably, greenness metrics (Ecoscale and EAT scores) were included as responses to be optimized during this process [25].

4. Optimum Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: Eclipse Plus C18 (100 mm × 4.6 mm, 3.5 µm)

- Mobile Phase: Isopropanol / 20 mM Potassium dihydrogen phosphate buffer (pH 3.0) in the ratio 27:73 (v/v)

- Flow Rate: 1.5 mL/min

- Column Temperature: 40 °C

- Detection: DAD at 220 nm

- Analytical Runtime: < 4 minutes [25]

5. Greenness Assessment of the Protocol: This method was designed with greenness as a core objective. It replaced the conventionally used acetonitrile with the less toxic isopropanol and minimized the analysis time, thereby reducing solvent consumption and waste generation. The method's greenness was quantitatively assessed using the Analytical Eco-Scale and HPLC-EAT tools, confirming its superior environmental profile compared to previously reported methods [25].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Green Chromatography

| Item | Function in Green Context | Example from Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Eclipse Plus C18 Column | High-efficiency column enabling faster separations and lower solvent consumption. | The core separation medium [25]. |

| Isopropanol | A less hazardous and greener alternative to more toxic solvents like acetonitrile. | Used as the organic modifier in the mobile phase [25]. |

| Potassium Dihydrogen Phosphate | Used for preparing aqueous buffer component of the mobile phase. | The buffer salt for the aqueous mobile phase component [25]. |

| Ethanol | A renewable, less toxic solvent considered a green alternative for chromatography. | Cited as a green solvent option in broader practices [23] [22]. |

| Supercritical COâ‚‚ | The primary mobile phase in Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC), replacing organic solvents. | Used in SFC to drastically reduce organic solvent use [22]. |

Visualizing the Green Chromatography Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for developing a green chromatographic method, from goal definition to validation, highlighting the continuous assessment of environmental impact.

Green Method Development Workflow

The conceptual framework of the Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) can be visualized as a multi-faceted assessment system that evaluates the overall environmental impact of a chromatographic method.

AMGS Assessment Framework

The transition to green chromatography is a strategic imperative, powerfully driven by the interconnected goals of reducing environmental impact, enhancing operator safety, and realizing economic benefits. The adoption of frameworks like the Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) and practical tools such as AGREE and Analytical Eco-Scale provides researchers and drug development professionals with the means to quantify and optimize their methods. As demonstrated by the experimental protocol, integrating Green Analytical Chemistry principles and Quality by Design from the outset results in methods that are not only environmentally responsible and safer for analysts but also more efficient and cost-effective. The future of chromatography is unequivocally green, and its widespread adoption is essential for the pharmaceutical industry to meet its scientific and sustainability obligations.

Regulatory and Industry Trends Pushing Green Adoption

The global chemical and pharmaceutical industries are undergoing a significant transformation driven by the urgent need for sustainable practices. Green chemistry has evolved from a voluntary initiative to a strategic business imperative, with regulatory pressures, corporate responsibility goals, and economic advantages converging to accelerate adoption [26]. Within this broader context, analytical laboratories are facing mounting pressure to minimize their environmental footprint, particularly in techniques as resource-intensive as chromatography. Traditional chromatographic methods consume substantial amounts of hazardous solvents, generate considerable waste, and pose safety risks to operators [13] [27]. The transition to green chromatographic techniques represents a critical component of the industry's response to these challenges, enabling researchers and drug development professionals to maintain analytical performance while aligning with sustainability principles and compliance requirements. This whitepaper examines the key regulatory and industry trends propelling this shift and provides a technical guide for implementation.

Key Regulatory Drivers

The regulatory landscape for chemical management is rapidly evolving worldwide, creating a complex framework that directly impacts analytical laboratory operations.

Global Chemical Safety and Sustainability Regulations

Governments and international bodies are strengthening chemical regulations with a pronounced emphasis on sustainability and hazard reduction [28].

- European Union Green Deal & Chemicals Strategy for Sustainability (CSS): The EU is implementing stricter authorization requirements and new restrictions on substances of concern under REACH, potentially including an "essential use" concept that could limit certain solvents and reagents in non-essential applications [28].

- US TSCA Updates: The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) continues to prioritize risk evaluations of existing chemicals and refine reporting obligations, increasing scrutiny on persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic (PBT) substances often used in analytical chemistry [28].

- Asia-Pacific Regulations: China (MEE Order No. 12) and South Korea (K-REACH) are introducing more stringent chemical registration and assessment requirements, creating a complex global compliance landscape for multinational pharmaceutical and chemical companies [28].

PFAS and Persistent Chemical Restrictions

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are facing heightened regulatory scrutiny worldwide due to their environmental persistence and potential health risks [29] [28]. This has direct implications for analytical practices, as PFAS are sometimes used in chromatographic workflows and equipment. The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) is advancing broad PFAS restrictions under REACH, while the U.S. EPA is expanding PFAS reporting rules and implementing new drinking water standards [28]. These regulations simultaneously drive demand for PFAS testing using chromatography while necessitating the elimination of PFAS from the analytical methods themselves [30].

Green Chemistry Principles in Analytical Guidance

While not always legislated, green chemistry principles are increasingly being incorporated into regulatory guidance documents and industry best practices. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines, particularly Q3A-Q3D on impurities, emphasize the importance of robust analytical methods, creating opportunities for implementing greener approaches that maintain or enhance data quality [13]. Regulatory agencies are showing growing acceptance of green alternative methods, especially when accompanied by validation data demonstrating equivalence or superiority to conventional methods [13] [27].

Industry Adoption Trends

Market forces and technological advancements are complementing regulatory pressures to drive green adoption across the analytical chemistry landscape.

Market Growth and Economic Incentives

The analytical instrument sector is experiencing strong growth, with the chromatography market projected to reach $19.8 billion by 2030, growing at a CAGR of 8.4% from 2025 [31]. This expansion is partly driven by sustainability demands, with pharmaceutical, environmental, and chemical research laboratories increasingly prioritizing green technologies [30]. Major instrument vendors reported increased revenues in Q2 2025, with recurring revenues from consumables growing 11%, indicating sustained laboratory activity and a shift toward more sustainable workflow solutions [30].

Table 1: Chromatography Market Growth Projections

| Market Segment | 2024/2025 Value | 2030 Projection | CAGR | Primary Green Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Chromatography Market | $13.3 billion (2025) [31] | $19.8 billion [31] | 8.4% [31] | Biopharmaceutical demand, Green manufacturing practices |

| Liquid Chromatography Segment | Leading with 36.4% share (2024) [32] | Sustained dominance | - | Solvent reduction capabilities, Automation compatibility |

| North American Market | 40.3% global share (2024) [32] | Maintained leadership | - | Strict regulatory standards, Pharmaceutical sector demand |

Pharmaceutical Industry Leadership

The pharmaceutical and biotechnology sector represents the largest end-user of chromatography, accounting for 41.2% of the market in 2024 [32]. This sector is increasingly adopting green analytical chemistry principles in response to both regulatory pressures and corporate sustainability commitments. Key drivers include the need to reduce solvent consumption in quality control laboratories, minimize waste generation from analytical processes, and improve operator safety [13]. The growth of biopharmaceuticals, including monoclonal antibodies, cell and gene therapies, and biosimilars, is further accelerating this trend, as these complex molecules often require sophisticated chromatographic purification and analysis that benefits from green chemistry innovations [31] [32].

Digitalization and Green Chemistry Convergence

The integration of digital tools is emerging as a powerful enabler of green chromatography practices. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are being applied to optimize method development, predict optimal solvent systems, and reduce experimental waste [29]. Digital twins—virtual replicas of physical assets—allow operators to simulate and optimize chromatographic methods before implementation in the real world, significantly reducing solvent consumption during method development [26]. Additionally, automated regulatory databases and compliance tracking systems are helping laboratories navigate the complex global regulatory landscape more efficiently while maintaining sustainable operations [28].

Green Chromatography Techniques and Methodologies

Several technical approaches have emerged that enable significant reductions in the environmental impact of chromatographic analysis while maintaining or enhancing analytical performance.

Green Liquid Chromatography (GLC)

Green Liquid Chromatography encompasses multiple strategies for reducing the environmental impact of traditional HPLC methods, primarily focused on solvent reduction and substitution [13].

Solvent Replacement Strategies

Replacing traditional solvents with greener alternatives is a fundamental approach in GLC. Acetonitrile, commonly used in reversed-phase HPLC, is increasingly being substituted with ethanol-water or methanol-water mixtures [13] [33]. Ethanol is particularly promising as it can be produced from renewable biomass, offers lower toxicity, and provides comparable separation efficiency with only minor modifications to existing methods [33]. Research indicates that approximately 30% of ethanol-based methods employ columns with reduced particle diameters without requiring column heating, maintaining performance while reducing energy consumption [33].

Table 2: Green Solvent Alternatives for Liquid Chromatography

| Solvent | Green Attributes | Performance Considerations | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Renewable feedstocks, lower toxicity | High viscosity, UV absorbance below 220 nm | Reversed-phase separations, Pharmaceutical analysis [33] |

| Acetone | Low toxicity, biodegradable | High UV absorbance, volatility | Mid-UV range applications, Preparative chromatography |

| Propylene Carbonate | Biodegradable, low volatility | High viscosity, limited water miscibility | Normal phase separations |

| Dimethyl Carbonate | Low toxicity, biodegradable | Limited polarity range | Binary mobile phase systems |

| Cyrene (Dihydrolevoglucosenone) | Renewable bio-based solvent | High viscosity, UV absorption | Specialty separations, Research applications [33] |

Instrumental and Column Advancements

Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) has revolutionized pharmaceutical analysis by enabling significant reductions in analysis times and solvent consumption. Studies demonstrate that UHPLC can achieve up to 80% reduction in solvent usage while maintaining or improving separation efficiency compared to conventional HPLC [13]. The implementation of narrow-bore columns (internal diameter ≤2.1 mm) can reduce mobile phase consumption by up to 90% compared to standard 4.6 mm columns without compromising chromatographic performance [13]. Elevated temperature liquid chromatography (ETLC) represents another green approach, as increased column temperatures reduce mobile phase viscosity, enabling faster flow rates or the use of longer columns with higher efficiency, ultimately reducing solvent consumption [13].

Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC)

Supercritical Fluid Chromatography utilizes supercritical COâ‚‚ as the primary mobile phase component, significantly reducing or eliminating organic solvent consumption [13] [27]. SFC is particularly valuable for chiral separations, natural product analysis, and purification in pharmaceutical development. The technique offers several green advantages:

- Supercritical COâ‚‚ is non-toxic, non-flammable, and readily available from renewable sources

- Reduces organic solvent consumption by 70-90% compared to normal-phase chromatography

- Faster separations due to lower viscosity and higher diffusion rates of supercritical fluids

- Easier product recovery after preparative separations [27]

Current research focuses on expanding SFC applications beyond traditional normal-phase domains and improving compatibility with highly polar compounds through modifier optimization and column development [27].

Alternative Carrier Gases in Gas Chromatography

Traditional gas chromatography relies heavily on helium, a non-renewable resource with supply chain vulnerabilities. Green approaches in GC include:

- Replacement of helium with hydrogen as carrier gas, produced from water electrolysis

- Implementation of low thermal mass (LTM) technology for significant energy savings through rapid heating and cooling cycles

- Development of nitrogen generators for on-site production, reducing transportation impacts [27]

While these alternatives sometimes present challenges such as reduced sensitivity with hydrogen carrier gas, careful optimization of analytical parameters can balance sustainability with analytical rigor [27].

Experimental Protocols for Green Chromatography

Implementing green chromatography requires methodical approaches to method development and validation. Below are detailed protocols for key green chromatographic techniques.

UHPLC Method Translation with Solvent Reduction

Objective: Translate a conventional HPLC method to UHPLC while reducing solvent consumption by at least 60% without compromising resolution.

Materials and Equipment:

- UHPLC system with pressure capability ≥1000 bar

- UHPLC column (sub-2μm particles, 50-100mm length, 2.1mm internal diameter)

- Conventional HPLC method parameters (column dimensions, particle size, flow rate)

Procedure:

- Calculate scaling factors: Using column length (L), particle size (dp), and internal diameter (ID) from original method to new column.

- Flow rate scaling: Fâ‚‚ = F₠× (ID₂²/ID₲) × (Lâ‚‚/Lâ‚) × (dpâ‚/dpâ‚‚)

- Gradient time scaling: tâ‚‚ = t₠× (Fâ‚/Fâ‚‚) × (Lâ‚‚/Lâ‚) × (ID₂²/ID₲)

System suitability test: Prepare reference standard and evaluate key parameters (resolution, peak asymmetry, efficiency) using scaled method.

Optimize gradient profile: If resolution is inadequate, adjust gradient slope while maintaining the same reduced gradient time (tₚ = t₆ × F/Vₘ).

Validate the method according to ICH Q2(R1) guidelines for specificity, linearity, accuracy, precision, and robustness.

Expected Outcomes: A validated UHPLC method with significantly reduced solvent consumption (typically 60-80% reduction), shorter analysis time, and maintained or improved resolution compared to the original HPLC method [13].

Ethanol-Water Mobile Phase Development for Reversed-Phase HPLC

Objective: Develop a stability-indicating method using ethanol-water mobile phases as an alternative to acetonitrile-based methods.

Materials and Equipment:

- HPLC system with low-dwell-volume mixing capability

- Columns: C18, phenyl-hexyl, or polar-embedded stationary phases

- Solvents: HPLC-grade ethanol and water

- Reference standards and forced degradation samples

Procedure:

- Initial scouting: Perform isocratic screening with 20-50% ethanol in water on different stationary phases to identify optimal column chemistry.

Gradient optimization: Develop a linear gradient method based on initial scouting results, adjusting gradient slope and duration to achieve resolution of all critical peaks.

Column temperature optimization: Evaluate temperatures between 30-60°C to reduce backpressure and improve efficiency (ethanol-water mixtures have higher viscosity than acetonitrile-water).

Forced degradation studies: Apply optimized method to acid, base, oxidative, thermal, and photolytic degradation samples to demonstrate stability-indicating capability.

Method validation: Perform validation according to regulatory requirements, paying particular attention to UV detection performance at potentially higher wavelengths necessitated by ethanol's UV cutoff [33].

Expected Outcomes: A validated reversed-phase HPLC method using ethanol-water mobile phases that provides comparable or superior separation to acetonitrile-based methods while reducing environmental impact and toxicity [13] [33].

Visualization of Green Method Implementation Strategy

The following workflow diagram illustrates a systematic approach for implementing green chromatography methods in pharmaceutical analysis, integrating regulatory, technical, and validation considerations.

Green Method Implementation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of green chromatography requires specific reagents, columns, and instruments designed to optimize environmental performance while maintaining analytical quality.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Green Chromatography

| Item | Function | Green Attributes | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol (HPLC-grade) | Green mobile phase component | Renewable feedstock, lower toxicity than acetonitrile | Higher viscosity requires temperature optimization; check UV cutoff [33] |

| Supercritical COâ‚‚ | Primary mobile phase for SFC | Non-toxic, non-flammable, from renewable sources | Requires specialized equipment; excellent for non-polar to moderately polar compounds [27] |

| UHPLC Columns (sub-2μm particles, 2.1mm ID) | High-efficiency separations | Enable significant solvent reduction through smaller dimensions | Compatible with high-pressure systems (>1000 bar); provides faster analysis [13] |

| Fused-Core/Superficially Porous Particles | Stationary phase technology | Reduce solvent consumption through higher efficiency | Enable high efficiency at lower backpressure than fully porous sub-2μm particles |

| Water (HPLC-grade) | Green mobile phase component | Non-toxic, non-flammable | Foundation of aqueous mobile phases; replacement for organic solvents where possible [13] |

| Hydrogen Generators | Carrier gas for GC | Produce hydrogen on-demand, eliminating helium use | Requires safety precautions; provides excellent chromatographic efficiency [27] |

| Ionic Liquids | GC stationary phases, LC modifiers | Low volatility reduces exposure risks | Customizable selectivity; thermal stability for high-temperature GC [13] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Extraction, mobile phase additives | Biodegradable, low toxicity, renewable sources | Emerging application in chromatography; requires method development [29] [33] |

| Axl-IN-9 | Axl-IN-9|Potent AXL Kinase Inhibitor for Research | Axl-IN-9 is a potent AXL kinase inhibitor for cancer research. It targets AXL to block oncogenic signaling. This product is For Research Use Only. | Bench Chemicals |

| Antileishmanial agent-8 | Antileishmanial agent-8, MF:C18H16O4, MW:296.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The adoption of green chromatography is no longer an optional consideration but a necessity driven by converging regulatory, economic, and environmental factors. Regulatory trends worldwide are increasingly restricting hazardous solvents and promoting sustainable practices, while industry demands for efficiency and corporate responsibility further accelerate this transition. Techniques such as UHPLC, SFC, and solvent replacement strategies now offer viable pathways to significantly reduce the environmental impact of pharmaceutical analysis without compromising data quality. For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing these green chromatographic methods represents an opportunity to align with global sustainability initiatives while maintaining regulatory compliance and operational excellence. The continued evolution of green chromatography will undoubtedly play a critical role in building a more sustainable future for the pharmaceutical and chemical industries.

Implementing Green Strategies: Techniques and Applications in Pharmaceutical Analysis

The pursuit of sustainability in analytical laboratories has made solvent reduction a primary goal in modern chromatography. Traditional high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) methods are increasingly being reevaluated due to their significant environmental footprint. A conventional chromatographic separation using a standard column (15–25 cm in length, 4.6 mm internal diameter) running continuously generates approximately 1500 mL of waste daily; if the mobile phase contains 50% organic solvent, this equates to around 750 mL of solvent that must be produced and subsequently disposed of, typically through energy-intensive incineration [34]. Within this context, three strategic approaches have emerged as particularly effective for reducing solvent consumption without compromising analytical performance: Ultrahigh-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC), Microflow Liquid Chromatography (Microflow LC), and optimization of column dimensions. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these approaches, offering researchers and drug development professionals detailed methodologies for implementing sustainable chromatographic practices aligned with the principles of green analytical chemistry.

Ultrahigh-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC)

Principles and Solvent Reduction Mechanisms

UHPLC technology utilizes very small particles (often sub-2 µm) in the stationary phase and operates at significantly higher pressures (exceeding 1000 bar) compared to conventional HPLC. This configuration fundamentally improves chromatographic efficiency through its effect on the van Deemter equation, which describes the relationship between linear velocity and plate height. With UHPLC, the use of well-packed small particles creates more uniform flow paths, thereby lowering the "A" term (eddy diffusion), while shortened diffusion distances reduce the "C" term (mass transfer) [35]. The practical consequence is a dramatic lowering and flattening of the van Deemter curve, enabling high-efficiency separations with shorter columns and faster run times, which directly translates to reduced solvent consumption per analysis [35].