Green HPLC for Pharmaceuticals: A 2025 Guide to Sustainable, Compliant, and Robust Methods

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and pharmaceutical development professionals on implementing Green HPLC principles.

Green HPLC for Pharmaceuticals: A 2025 Guide to Sustainable, Compliant, and Robust Methods

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and pharmaceutical development professionals on implementing Green HPLC principles. It covers the foundational concepts of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), practical strategies for developing eco-friendly methods using modern columns and instrumentation, troubleshooting for enhanced sensitivity and robustness, and a complete framework for validation according to ICH guidelines. By integrating sustainability with regulatory compliance, this guide aims to empower scientists to build efficient, reliable, and environmentally responsible analytical procedures for drug development and quality control.

The Principles of Green HPLC: Building Sustainable and Compliant Foundations

Understanding the 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and the SIGNIFICANCE Framework

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged as a fundamental discipline within analytical science, focusing on minimizing the environmental impact of analytical activities while maintaining the high-quality standards required for reliable results [1]. The concept originated in 2000 as an extension of green chemistry, recognizing that analytical laboratories, despite working on a smaller scale than industrial processes, collectively generate significant waste and consume considerable resources [1] [2]. The core challenge of GAC lies in reaching an optimal compromise between the analytical quality of results and improving the environmental friendliness of analytical methods [1].

The framework for GAC has evolved significantly from the original 12 principles of green chemistry proposed by Anastas and Warner, which were primarily designed for synthetic chemistry and only partially applicable to analytical practice [1] [3]. This evolution led to the development of specialized principles and assessment tools specifically tailored to the unique requirements and workflows of analytical chemistry, with particular relevance to pharmaceutical analysis where routine testing generates substantial solvent waste and energy consumption [4] [5].

The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

Gałuszka et al. (2013) proposed a adapted set of 12 principles specifically designed for analytical chemistry, selecting four from the original green chemistry principles and supplementing them with eight new principles to address the specific needs and challenges of analytical practice [1] [6]. These principles provide a comprehensive framework for greening analytical methods across their entire lifecycle, from sample collection to waste management.

Table 1: The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

| Principle Number | Principle Description | Key Application in Pharmaceutical Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Direct analytical techniques should be applied to avoid sample treatment | Use of non-invasive techniques or minimal sample preparation |

| 2 | Minimal sample size and minimal number of samples are goals | Microsampling approaches and statistical sampling plans |

| 3 | In situ measurements should be performed | Process Analytical Technology (PAT) for real-time monitoring |

| 4 | Integration of analytical processes and operations saves energy and reduces reagents | Combined extraction-cleanup-detection systems |

| 5 | Automated and miniaturized methods should be selected | Automated HPLC systems with microfluidic capabilities |

| 6 | Derivatization should be avoided | Development of direct detection methods |

| 7 | Generation of large volume of analytical waste should be avoided and proper management of waste should be ensured | Solvent reduction and waste recycling programs |

| 8 | Multi-analyte or multi-parameter methods are preferred versus methods using one analyte at a time | Multi-component HPLC assays for drug formulations |

| 9 | The use of energy should be minimized | Energy-efficient instrumentation and standby modes |

| 10 | Natural, reusable, and biodegradable reagents should be preferred | Bio-based solvents for extraction and separation |

| 11 | Toxic reagents should be eliminated or replaced | Substitution of acetonitrile with greener alternatives |

| 12 | The safety of the operator should be increased | Automated handling of hazardous materials |

The four principles retained from the original green chemistry principles include prevention of waste, safer solvents and auxiliaries, design for energy efficiency, and reduction of derivatization [1]. The eight additional principles address analytical-specific concerns such as direct measurement techniques, miniaturization, automation, multi-analyte methods, and operator safety [1].

The SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic Framework

To facilitate practical implementation and recall of the GAC principles, the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic was developed as an easily remembered guide for laboratory practices [1]. This framework encapsulates the core objectives of green analytical chemistry in a structured format that can be readily applied during method development and optimization.

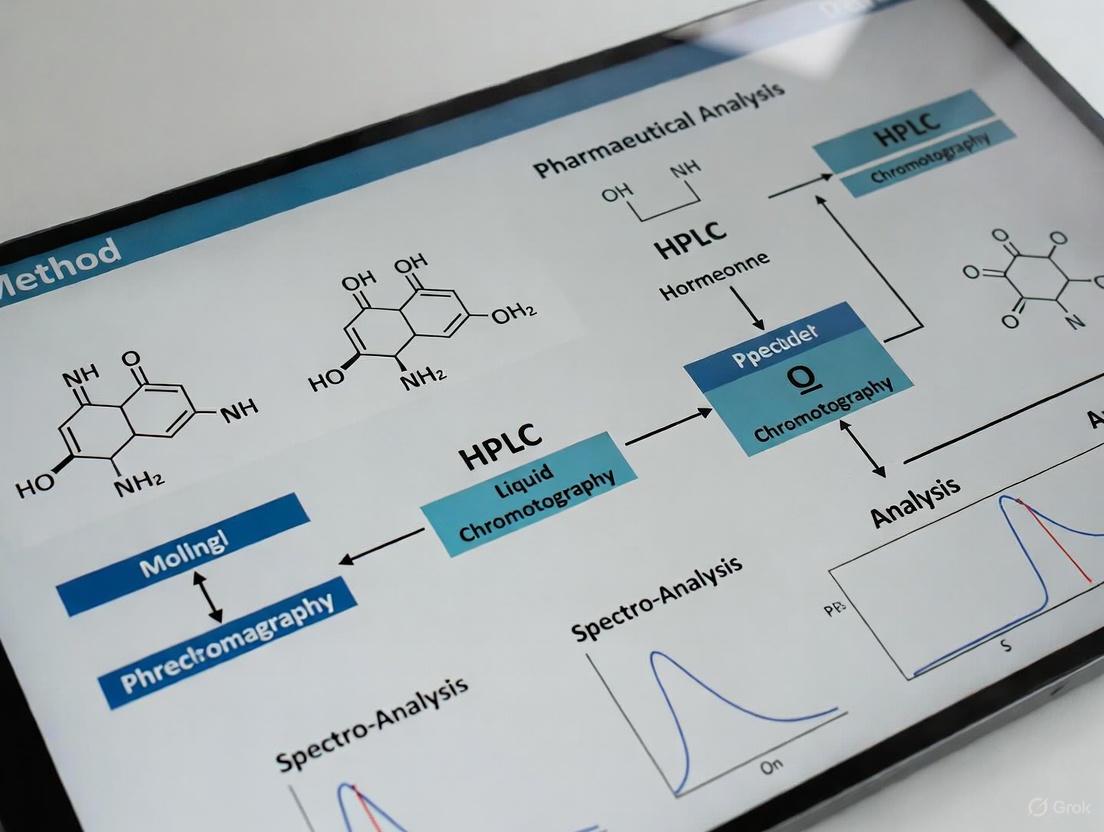

Diagram 1: SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential application of the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic components in developing green analytical methods for pharmaceutical analysis.

The SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic breaks down as follows [1]:

- S - Select direct analytical methods to avoid sample treatment

- I - Integrate analytical processes and operations

- G - Generate no large volume of waste

- N - Never waste energy; minimize requirements

- I - Implement automated and miniaturized methods

- F - Favor natural, reusable, and biodegradable reagents

- I - Increase safety for the operator

- C - Carry out multi-analyte or multi-parameter methods

- A - Avoid derivatization

- N - Note minimal sample size and number of samples

- C - Choose in situ measurements

- E - Enable proper waste management and treatment

This framework serves as a practical checklist for analytical chemists developing new methods, particularly in pharmaceutical quality control where regulatory requirements must be balanced with environmental considerations.

Greenness Assessment Tools and Metrics

The implementation of GAC principles requires robust assessment methodologies to evaluate and compare the environmental performance of analytical methods. Numerous greenness assessment tools have been developed, each with distinct approaches, advantages, and limitations [4] [2].

Table 2: Comparison of Major Greenness Assessment Metrics

| Assessment Tool | Assessment Approach | Output Format | Key Parameters Evaluated | Pharmaceutical Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI [4] [2] | Binary assessment against 4 criteria | Pictogram (4 quadrants) | PBT chemicals, hazardous waste, corrosivity, waste amount | Screening of compendial methods |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [4] | Penalty point system based on hazards | Numerical score (0-100) | Reagent toxicity, amount, energy consumption, waste | Method optimization comparisons |

| GAPI [2] | Color-coded assessment of entire process | Pictogram (5 sections) | Sample collection, preservation, preparation, transportation, detection | Comprehensive method evaluation |

| AGREE [4] [7] | Assessment based on 12 GAC principles | Pictogram + numerical score (0-1) | All 12 GAC principles | HPLC method validation [7] |

| AGREEprep [2] | Focused on sample preparation | Pictogram + numerical score (0-1) | Sample preparation-specific parameters | Sample preparation optimization |

| AMGS [5] | Industry-developed metric | Numerical score | Solvent energy, safety/toxicity, instrument energy | Pharmaceutical quality control |

The progression of these metrics demonstrates a shift from simple binary assessments to comprehensive, quantitative tools that provide detailed insights into the environmental impact of analytical methods [2]. The Analytical Greenness (AGREE) metric, for example, has gained significant traction in pharmaceutical analysis due to its comprehensive coverage of the 12 GAC principles and user-friendly output combining both pictorial and numerical scores [4] [7].

Application in Pharmaceutical Analysis: Case Studies

Green RP-HPLC Method for Flavokawain A Analysis

A recent development of a green reverse-phase HPLC method for quantification of Flavokawain A in bulk and tablet dosage forms demonstrates practical application of GAC principles [7]. The method employed methanol:water (85:15 v/v) as mobile phase, eliminating more hazardous solvents like acetonitrile. The isocratic elution at 1.0 mL/min flow rate contributed to reduced solvent consumption compared to gradient methods.

The method was systematically validated according to ICH guidelines and achieved an AGREE metric score of 0.79, indicating good environmental performance [7]. Key green features included:

- Use of less toxic ethanol-based sample preparation

- Isocratic elution reducing solvent waste

- Absence of derivatization agents

- Reduced energy consumption through optimized chromatographic conditions

Green HPLC-Fluorescence Method for Sacubitril/Valsartan

A green HPLC-fluorescence method for simultaneous analysis of sacubitril and valsartan in pharmaceutical forms and human plasma further illustrates GAC implementation [8]. The method utilized ethanol-based mobile phase instead of traditional acetonitrile, significantly reducing environmental impact and operator hazard.

The method was comprehensively assessed using multiple greenness metrics (Analytical Eco-Scale, AGREE, complex GAPI, AGSA, CaFRI, RGBfast, Click Analytical Chemistry Index), demonstrating the trend toward multi-metric assessment for comprehensive environmental profiling [8]. The method achieved high sensitivity with low LOD and LOQ values (0.035 µg/mL for both analytes), proving that green methods can maintain excellent analytical performance.

Experimental Protocols for Green HPLC Method Development

Protocol 1: Green Solvent Screening and Optimization

Objective: Identify and optimize greener solvent systems for pharmaceutical HPLC analysis.

Materials and Equipment:

- HPLC system with UV/Vis or PDA detector

- C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm or smaller particle size)

- Candidate green solvents (ethanol, methanol, acetone, ethyl acetate)

- Reference standards of target pharmaceuticals

- pH adjustment reagents (phosphoric acid, ammonium hydroxide)

Procedure:

- Prepare stock solutions of target analytes in appropriate solvents

- Screen ethanol-water and methanol-water mobile phases in isocratic mode

- Evaluate ethanol-based mobile phases with pH modification (2.5-7.0)

- Assess methanol-ethanol mixtures with water as ternary systems

- Optimize flow rate (0.8-1.2 mL/min) for separation efficiency and solvent reduction

- Validate method performance (linearity, precision, accuracy, sensitivity)

- Calculate greenness scores using AGREE and other metrics

Evaluation Criteria: Chromatographic performance (resolution, efficiency, peak symmetry), method validation parameters, and greenness metric scores.

Protocol 2: Miniaturization and Method Scaling

Objective: Develop miniaturized HPLC methods to reduce solvent consumption and waste generation.

Materials and Equipment:

- UHPLC system compatible with reduced flow rates

- Sub-2µm particle columns (50-100 mm length)

- Micro-flow solvent delivery system

- Low-volume detection cells

- Automated sample injector with minimal carryover

Procedure:

- Scale existing methods from conventional to narrow-bore columns

- Optimize flow rates for kinetic performance (0.2-0.6 mL/min)

- Adjust injection volumes for maintained sensitivity

- Modify gradient programs for scaled column volumes

- Validate scaled method against original performance criteria

- Quantify solvent savings and waste reduction

- Assess economic impact of reduced solvent consumption

Evaluation Criteria: Solvent consumption per analysis, analysis time, maintenance of chromatographic performance, cost savings.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | Green Characteristics | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Mobile phase component | Biobased, biodegradable, low toxicity | Alternative to acetonitrile in RP-HPLC [8] |

| Methanol | Mobile phase, extraction solvent | Less toxic than acetonitrile, widely available | Primary organic modifier in mobile phases [7] |

| Water | Mobile phase component | Non-toxic, renewable | Universal green solvent for HPLC |

| Ethyl acetate | Extraction solvent | Low toxicity, biobased origin | Liquid-liquid extraction of pharmaceuticals |

| Liquid COâ‚‚ | Extraction solvent | Non-flammable, recyclable | SFE of natural products |

| Aqueous surfactants | Extraction media | Low volatility, biodegradable | Cloud point extraction techniques |

| Natural deep eutectic solvents | Extraction media | Biodegradable, low toxicity | Green sample preparation |

| Isotretinoin | Isotretinoin | High-purity Isotretinoin for research applications. Explore its role in sebocyte apoptosis, dermatology, and oncology studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Janthitrem F | Janthitrem F, CAS:90986-52-0, MF:C39H51NO7, MW:645.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implementation Strategy and Future Perspectives

Implementing GAC principles in pharmaceutical analysis requires a systematic approach that balances environmental goals with analytical performance and regulatory compliance. A phased implementation strategy is recommended:

- Assessment Phase: Evaluate current methods using multiple greenness metrics to establish baseline environmental performance [4] [2].

- Optimization Phase: Apply SIGNIFICANCE framework to identify improvement opportunities in existing methods [1].

- Replacement Phase: Develop new methods incorporating green principles from initial design stages.

- Validation Phase: Ensure new methods meet analytical performance requirements while demonstrating improved greenness scores.

- Continuous Improvement: Monitor advancements in green assessment tools and methodologies for ongoing optimization.

The field continues to evolve with emerging trends including:

- Circular Analytical Chemistry: Transition from linear "take-make-dispose" models to circular frameworks focusing on resource recovery and reuse [9].

- Carbon Footprint Assessment: Development of tools like CaFRI (Carbon Footprint Reduction Index) to specifically address climate impacts [2].

- Strong Sustainability Models: Shifting beyond efficiency improvements toward methods that actively contribute to ecological restoration [9].

- Standard Method Updates: Increasing pressure on regulatory agencies to update compendial methods with poor greenness scores [9].

The integration of GAC principles with emerging analytical technologies and the adoption of comprehensive assessment metrics will continue to drive the pharmaceutical industry toward more sustainable analytical practices without compromising the quality and reliability essential for patient safety and product efficacy.

The pharmaceutical industry is increasingly adopting the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) to align with global sustainability goals. Within this framework, Green High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) has emerged as a critical methodology for reducing the environmental impact of analytical processes while maintaining the high-quality standards required for drug development and quality control. Green HPLC is defined as the application of GAC principles to liquid chromatography, specifically aiming to minimize or eliminate the use of hazardous solvents, reduce waste generation, and lower energy consumption without compromising analytical performance [10].

The transition to Green HPLC represents a paradigm shift from traditional "take-make-dispose" linear models toward more sustainable and circular approaches in analytical chemistry [9]. This shift is particularly relevant in pharmaceutical analysis, where hundreds of chromatographic systems operate daily for quality control, resulting in significant consumption of organic solvents and generation of hazardous waste [10]. The fundamental objectives of Green HPLC align with the twelve principles of GAC, which emphasize waste prevention, safer solvents and auxiliaries, design for energy efficiency, and reduction of derivatives throughout the analytical lifecycle [11].

Core Objectives of Green HPLC

Solvent Reduction and Substitution

Primary Objective: Minimize or replace hazardous organic solvents with greener alternatives while maintaining chromatographic performance.

The most significant environmental impact of conventional HPLC methods comes from mobile phase composition. Acetonitrile and methanol, commonly used in reversed-phase HPLC, pose environmental and safety concerns due to their toxicity and waste generation [10]. Green HPLC addresses this through several strategies:

Ethanol-based mobile phases: Ethanol serves as a greener alternative to acetonitrile and methanol due to its lower toxicity and higher sustainability profile. A recently developed green HPLC-fluorescence method for simultaneous analysis of sacubitril and valsartan utilizes a mobile phase comprising 30 mM phosphate buffer (pH 2.5) and ethanol in a ratio of 40:60 v/v, demonstrating effective separation without hazardous solvents [8].

Miniaturization: Reducing column dimensions from conventional 4.6 mm ID to narrow-bore (2-3 mm ID) or micro-bore (1-2 mm ID) columns significantly decreases mobile phase consumption. This reduction directly translates to lower solvent purchase costs, reduced waste disposal expenses, and diminished environmental impact [10].

Pure aqueous mobile phases: When feasible, developing methods that use water as the primary mobile phase component eliminates organic solvent consumption entirely, though this approach may require specialized stationary phases or elevated temperatures to maintain adequate separation efficiency [10].

Waste Minimization

Primary Objective: Implement strategies that prevent waste generation and promote recycling within the analytical workflow.

The concept of Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) provides a framework for transitioning HPLC methods from a linear "take-make-dispose" model to a circular approach that eliminates waste and keeps materials in use [9]. Key waste minimization strategies include:

Solvent recovery systems: Implementing distillation apparatus for collecting and purifying waste mobile phases enables solvent reuse, significantly reducing both purchasing costs and waste disposal volumes.

Waste stream segregation: Separating aqueous and organic waste streams facilitates more efficient recycling and treatment processes, minimizing cross-contamination that complicates waste management.

Method optimization for speed: Reducing run times through optimized gradients or using advanced stationary phases directly decreases solvent consumption per analysis. Techniques such as ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) operating at higher pressures with smaller particle columns (sub-2μm) can reduce analysis times by up to 80% compared to conventional HPLC [10].

Energy Consumption Reduction

Primary Objective: Develop chromatographic methods that minimize energy requirements without compromising analytical performance.

Energy efficiency in HPLC systems primarily relates to operational parameters that affect power consumption:

Ambient temperature operation: Developing methods that perform separations at room temperature eliminates the energy requirements for column heating, which typically consumes 30-50% of the total instrument power [12].

Reduced flow rates: Miniaturized systems operating at lower flow rates (e.g., 0.2-0.5 mL/min for narrow-bore columns versus 1-2 mL/min for conventional columns) decrease pump energy requirements and reduce solvent consumption simultaneously [10].

System automation and integration: Automated systems with sleep modes or automatic shut-off protocols during idle periods significantly reduce energy consumption in laboratories running multiple instruments [9].

Quantitative Metrics for Green HPLC Assessment

Greenness Assessment Tools

Several metric-based tools have been developed to quantitatively evaluate the environmental friendliness of analytical methods, including HPLC procedures:

Table 1: Greenness Assessment Metrics for HPLC Methods

| Assessment Tool | Evaluated Parameters | Output Format | Green HPLC Focus Areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREEprep [11] | Sample preparation, energy consumption, waste generation, operator safety | Score 0-1 (1=greenest) | Sample throughput, solvent consumption, energy per sample |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [11] | Reagent toxicity, energy consumption, waste amount | Penalty points (lower=greener) | Solvent hazard, waste volume, energy use |

| GAPI [11] | Entire method lifecycle from sample collection to final determination | Pictogram with color coding | Solvent choice, waste treatment, energy requirements |

| NEMI [11] | Persistence, bioaccumulation, toxicity, corrosivity | Pictogram (green=pass) | Solvent environmental impact, waste hazard |

| Complex GAPI [8] | Comprehensive method assessment including additional green criteria | Enhanced pictogram | Multi-dimensional environmental impact |

Solvent and Waste Reduction Metrics

The effectiveness of Green HPLC implementations can be quantified through specific metrics that track environmental and economic benefits:

Table 2: Quantitative Environmental Benefits of Green HPLC Strategies

| Strategy | Traditional Approach | Green HPLC Approach | Reduction Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Consumption | 1-2 mL/min (4.6 mm column) | 0.2-0.5 mL/min (2.1 mm column) | 60-80% reduction [10] |

| Analysis Time | 10-30 minutes | 3-10 minutes (UHPLC, optimized methods) | 50-80% reduction [10] |

| Solvent Toxicity | Acetonitrile, Methanol | Ethanol, Water-based | Significant hazard reduction [8] |

| Energy Consumption | Heated columns (30-50°C) | Ambient temperature operation | ~30% reduction in instrument energy use [12] |

| Waste Generation | 10-50 mL per run | 1-10 mL per run | 60-90% reduction [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Green HPLC Method Development

Protocol 1: Green HPLC-Fluorescence Method for Pharmaceutical Analysis

This protocol outlines a green HPLC-fluorescence method for the simultaneous analysis of tamsulosin hydrochloride (TAM) and tolterodine tartrate (TTD), demonstrating key principles of solvent reduction and waste minimization [12].

Materials and Equipment:

- HPLC system with quaternary pump, degasser, and fluorescence detector

- ODS column (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm particle size)

- Acetonitrile (HPLC grade), water (HPLC grade), phosphate buffer reagents

- Standard compounds: TAM and TTD reference standards

Mobile Phase Composition:

- Solvent A: Acetonitrile

- Solvent B: Water

- Solvent C: Phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 3.0)

Gradient Program:

- 0-1 min: 40% A, 60% B, 0% C

- 1-5.5 min: Linear gradient to 50% A, 0% B, 50% C

- 5.5-9 min: Linear gradient to 80% A, 0% B, 20% C

- 9-10 min: Return to initial conditions (40% A, 60% B, 0% C)

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Flow rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Column temperature: Ambient

- Detection: Fluorescence with excitation at 280 nm, emission at 350 nm

- Injection volume: 20 μL

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare stock solutions of TAM and TTD in methanol at 200 μg/mL concentration

- For tablet analysis, weigh and powder tablets, then extract with methanol

- For biological samples (plasma, urine), use protein precipitation with methanol followed by centrifugation

Method Performance:

- Linear range: 0.1-1.5 μg/mL for TAM, 1-15 μg/mL for TTD

- Retention times: 5.66 min for TAM, 7.26 min for TTD

- Greenness assessment: AGREE and GAPI tools confirmed significant adherence to green principles

Protocol 2: Sustainable HPLC Method for Sacubitril and Valsartan

This protocol describes an eco-friendly HPLC method with fluorescence detection for simultaneous determination of sacubitril and valsartan using green solvents [8].

Materials and Equipment:

- HPLC system with isocratic pump and fluorescence detector

- C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm)

- Ethanol (HPLC grade), phosphate buffer reagents

- Ibuprofen as internal standard

Mobile Phase:

- 30 mM phosphate buffer (pH 2.5):Ethanol (40:60 v/v)

- Isocratic elution mode

- Flow rate: 1.0 mL/min

Detection Parameters:

- 0-3.2 min: λex = 250 nm, λem = 380 nm

- 3.2-5.2 min: λex = 250 nm, λem = 320 nm

- After 5.2 min: λex = 220 nm, λem = 289 nm

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare stock solutions in ethanol (1 mg/mL)

- For tablet analysis, extract powdered tablets with ethanol followed by sonication and filtration

- For plasma samples, use protein precipitation with methanol followed by centrifugation

Method Validation:

- Linearity: 0.035-2.205 μg/mL for sacubitril, 0.035-4.430 μg/mL for valsartan

- Greenness assessment: Evaluated using Analytical Eco-Scale, AGREE, complex GAPI, and other metrics confirming eco-friendly characteristics

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Green HPLC

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Green HPLC Implementation

| Item | Function in Green HPLC | Green Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Primary organic modifier in mobile phase | Lower toxicity, biodegradable, renewable source [8] |

| Water | Aqueous component of mobile phase | Non-toxic, zero cost, environmentally benign |

| Phosphate Buffers | pH control in mobile phase | Replace ion-pairing reagents that hinder solvent recycling |

| Narrow-bore Columns (2.1 mm ID) | Analytical separation | Reduce mobile phase consumption by ~80% [10] |

| Core-Shell Particles | Stationary phase for efficient separation | Enable faster separations with lower backpressure |

| In-line Degassers | Mobile phase preparation | Eliminate need for helium sparging (resource-intensive) |

| Automated Solvent Recycling Systems | Waste management | Enable recovery and reuse of mobile phase components |

| Janthitrem G | Janthitrem G, CAS:90986-51-9, MF:C39H51NO6, MW:629.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Jasmine lactone | Jasmine lactone, CAS:25524-95-2, MF:C10H16O2, MW:168.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implementation Workflow and Strategic Framework

The transition to Green HPLC requires a systematic approach that encompasses method development, optimization, and validation phases while incorporating sustainability metrics at each stage.

Green HPLC Implementation Workflow

The implementation of Green HPLC principles in pharmaceutical analysis represents a significant step toward sustainable laboratory practices. By focusing on the core objectives of solvent reduction and substitution, waste minimization, and energy consumption reduction, researchers can maintain analytical performance while substantially decreasing environmental impact. The protocols and frameworks presented provide practical pathways for integrating these principles into routine pharmaceutical analysis.

Future developments in Green HPLC will likely focus on increased automation, further miniaturization, and the adoption of circular economy principles throughout the analytical workflow [9]. The concept of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which balances greenness with analytical and practical criteria, offers a comprehensive framework for evaluating method sustainability [11]. As regulatory agencies increasingly emphasize environmental considerations, the adoption of Green HPLC methodologies will become essential for pharmaceutical laboratories committed to sustainable development goals.

The integration of International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R2) guidelines with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical analysis. This application note provides a detailed framework for developing and validating high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) methods that simultaneously meet rigorous regulatory standards and sustainability objectives. By combining Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) principles with modern greenness assessment tools, we demonstrate how method robustness, reproducibility, and environmental responsibility can be achieved in alignment with United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The protocols outlined herein enable pharmaceutical scientists to maintain regulatory compliance with ICH Q2(R2) and USP requirements while significantly reducing the environmental footprint of analytical methods.

Traditional HPLC methods in pharmaceutical analysis often consume substantial amounts of hazardous solvents, generate significant waste, and require high energy consumption, creating tension between regulatory requirements and environmental responsibility [13]. The recent adoption of ICH Q2(R2) "Validation of Analytical Procedures" in March 2024 provides an updated framework for analytical procedure validation, while the parallel ICH Q14 guideline offers scientific approaches for analytical procedure development, together enabling more flexible, science- and risk-based approaches to method lifecycle management [14] [15].

Simultaneously, the field of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged with 12 principles specifically adapted to analytical practices, focusing on minimizing hazardous solvent use, reducing waste generation, and improving energy efficiency [13] [16]. The concept of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) further expands this paradigm by balancing environmental sustainability (green) with analytical performance (red) and practical/economic feasibility (blue) [13]. This integrated approach ensures that methods are not only environmentally friendly but also scientifically valid and practically implementable in regulated environments.

Regulatory Framework Integration

ICH Q2(R2) and Modern Validation Approaches

The ICH Q2(R2) guideline provides a comprehensive framework for validation of analytical procedures, emphasizing scientific rigor throughout the method lifecycle. Key validation parameters include accuracy, precision, specificity, detection limit, quantitation limit, linearity, and range [17]. The 2024 update reinforces these principles while allowing for enhanced flexibility through:

- Design of Experiments (DoE) approaches for robustness testing [18]

- Stability-indicating methods with enhanced specificity requirements [18]

- Ongoing Performance Verification (OPV) for continuous method monitoring [18]

- Analytical Procedure Lifecycle Management (APLCM) concepts [19]

Synergy with Green Analytical Chemistry Principles

The systematic approach advocated by ICH Q2(R2) and ICH Q14 aligns powerfully with GAC principles when properly implemented. The AQbD framework provides a structured methodology for incorporating environmental considerations throughout method development:

Table 1: Alignment of ICH Q2(R2) Validation Parameters with Green Analytical Chemistry Principles

| ICH Q2(R2) Parameter | GAC Principle Alignment | Sustainable Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Minimize sample preparation & derivatization | Use high-efficiency columns to reduce solvent consumption |

| Precision | In-line measurements & automation | Automated systems with reduced manual operations |

| Accuracy | Direct analysis of samples | Reduced sample preparation steps & reagents |

| Linearity & Range | Multi-analyte procedures | Single method for multiple analytes to reduce total runs |

| Robustness | Method transferability & miniaturization | DoE to establish operable ranges for green parameters |

Sustainable HPLC Method Development Protocol

Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) Workflow

The AQbD approach provides a systematic framework for developing methods that are both regulatory-compliant and environmentally sustainable:

Experimental Protocol: Green HPLC Method Development

Phase 1: ATP Definition and Green Objective Setting

- Define the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) specifying required performance criteria including accuracy, precision, and sustainability targets [20] [19]

- Establish green objectives: solvent toxicity reduction, waste minimization, energy efficiency

- Document both analytical and environmental requirements in the ATP template

Phase 2: Green Solvent Selection and Chromatographic Optimization

- Replace traditional solvents with green alternatives:

- Column selection: Choose high-efficiency columns (core-shell, monolithic, or sub-2µm particles) to reduce analysis time and solvent consumption [13]

- DoE optimization: Implement a Central Composite Design or Box-Behnken Design to optimize:

- Mobile phase composition (organic:aqueous ratio)

- Flow rate (minimized while maintaining efficiency)

- Column temperature (optimized for reduced backpressure)

- Gradient profile (shortened where possible) [20]

Phase 3: Method Scaling and Greenness Assessment

- Scale down where possible:

- Reduce column dimensions (e.g., 150mm to 50-100mm)

- Adjust flow rates proportionally

- Maintain linear velocity for equivalent separation efficiency [13]

- Assess method greenness using multiple metrics:

Method Validation According to ICH Q2(R2)

The validation of sustainable HPLC methods must demonstrate equivalent analytical performance to conventional methods while documenting environmental benefits:

Table 2: ICH Q2(R2) Validation of Sustainable HPLC Methods

| Validation Parameter | Experimental Procedure | Sustainability Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Forced degradation studies; peak purity assessment | Use of green mobile phases; reduced hazardous waste |

| Linearity | Minimum 5 concentrations, triplicate injections | Reduced standard consumption; ethanol-water calibration |

| Accuracy | Spike recovery at 80%, 100%, 120% | Green solvent sample preparation; minimized volumes |

| Precision | Repeatability (n=6), intermediate precision (different days) | Automated injection to reduce solvent consumption |

| LOD/LOQ | Signal-to-noise ratio (3:1 & 10:1) | High-sensitivity detection to reduce sample loading |

| Robustness | DoE for deliberate variations in green parameters | Establish MODR for flow rate, temperature, %ethanol |

Ongoing Performance Verification (OPV) Protocol

- System suitability testing with green reference standards

- Control charts for key method parameters (retention time, peak area, resolution)

- Periodic greenness assessment using AGREE or GAPI to ensure maintained sustainability

- Documentation of environmental metrics (solvent consumption, waste generation)

Greenness Assessment Tools and Metrics

A comprehensive sustainability assessment requires multiple complementary tools:

Table 3: Greenness Assessment Metrics for HPLC Methods

| Assessment Tool | Output Type | Key Metrics Evaluated | Scoring System |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE | Pictogram + Numerical (0-1) | All 12 GAC principles | 0 (not green) to 1 (ideal green) |

| GAPI/MoGAPI | Color-coded pictogram | 5-stage analytical process | Green/Yellow/Red for each stage |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Numerical score (0-100) | Reagents, waste, energy, toxicity | 100 (ideal) minus penalty points |

| NEMI | Binary pictogram | Persistence, toxicity, corrosivity, waste | Pass/Fail for 4 criteria |

| White Analytical Chemistry | RGB balance score | Red: performance, Green: eco-friendliness, Blue: practicality | Balance across all three aspects |

Research Reagent Solutions for Sustainable HPLC

Table 4: Essential Materials for Green HPLC Method Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Green Alternative | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol (bio-based) | Mobile phase organic modifier | Replacement for acetonitrile | Compatible with RP-HPLC; UV cutoff ~210nm [20] |

| Water | Mobile phase aqueous component | Solvent for hydrophilic analytes | Use high-purity (HPLC grade) with green modifiers |

| Cyrene (dihydrolevoglucosenone) | Bio-based solvent | Alternative to DMA, DMF, NMP | High boiling point advantageous for recycling [13] |

| High-Efficiency Columns | Stationary phase | Core-shell, monolithic, sub-2µm | Reduced analysis time & solvent consumption [13] |

| Ethyl Acetate (green) | Normal phase solvent | Replacement for hexane, chloroform | Preferred in several solvent selection guides [13] |

Case Study: AQbD-Driven Green HPLC for Pharmaceutical Compounds

Application: Simultaneous determination of metronidazole and nicotinamide using green RP-HPLC [20]

Experimental Protocol:

- ATP Definition: Simultaneous quantification of both compounds with resolution >2.0, accuracy 98-102%, and green score >0.70 by AGREE

- Mobile Phase: Ethanol-sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.5) in gradient elution

- Column: C18 core-shell column (100mm × 4.6mm, 2.7µm)

- DoE Optimization: Central Composite Design for ethanol concentration, flow rate, and temperature

- Validation: Full validation per ICH Q2(R2) with greenness assessment

Results:

- AGREE score: 0.75 (high greenness) [20]

- NQS: ~63% (good environmental performance)

- Resolution: 2.8 (exceeds requirements)

- Solvent reduction: 45% compared to conventional method

- Analysis time: Reduced by 30% through optimized gradient

Implementation Strategy and Regulatory Considerations

Successful implementation of sustainable HPLC methods requires careful planning and documentation:

Technology Transfer Protocol

Documentation requirements:

- Comparative validation data (green vs. conventional method)

- Greenness assessment results (AGREE, GAPI scores)

- Environmental impact statement (solvent reduction, waste minimization)

- Control strategy for maintaining both analytical and green performance

Change management under ICH Q14:

White Analytical Chemistry Balance Assessment

The harmonization of ICH Q2(R2) compliance with sustainability objectives represents not just a regulatory requirement but a strategic imperative for modern pharmaceutical analysis. The protocols outlined in this application note demonstrate that rigorous method validation and environmental responsibility are mutually achievable goals. By adopting AQbD principles with integrated green chemistry considerations, pharmaceutical scientists can develop robust, transferable methods that significantly reduce environmental impact while maintaining full regulatory compliance.

The framework of White Analytical Chemistry provides a balanced approach for evaluating methods across three critical dimensions: analytical performance (red), environmental impact (green), and practical feasibility (blue). This holistic assessment ensures that sustainable methods are not only environmentally friendly but also scientifically valid and practically implementable in regulated pharmaceutical environments.

The paradigm of analytical chemistry is shifting towards sustainability without compromising analytical performance. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and its advanced iterations present significant environmental and efficiency advantages over traditional analytical methods. Within pharmaceutical analysis, where precision, reliability, and throughput are paramount, the adoption of greener chromatographic practices aligns with global sustainability goals while enhancing operational efficacy. This application note provides a comparative analysis focused on the environmental footprint and efficiency gains of modern HPLC, supported by structured data, detailed protocols, and green chemistry principles tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Quantitative Comparative Analysis

Modern HPLC and Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) systems demonstrate marked improvements over traditional methods across key environmental and performance metrics. The following tables summarize quantitative comparisons based on current literature and empirical data.

Table 1: Environmental Impact Comparison of Chromatographic Methods [9] [10] [16]

| Parameter | Traditional Methods (e.g., GC, open-column) | Conventional HPLC | Modern UHPLC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Solvent Consumption per Analysis | 100-1000 mL | 10-100 mL | 1-5 mL |

| Analysis Time | 30-120 minutes | 10-30 minutes | 1-5 minutes |

| Energy Consumption | High (long run times) | Moderate | Low (short run times) |

| Hazardous Waste Generation | High | Moderate | Low |

| AGREEprep Greenness Score (0-1) | Often <0.2 [9] | 0.3-0.5 | 0.6-0.8 |

Table 2: Efficiency and Performance Metrics [21] [22] [23]

| Performance Metric | Conventional HPLC (5µm particles) | UHPLC (<2µm particles) | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Plates per Column | ~10,000 - 15,000 | ~20,000 - 40,000 | ~200-300% Increase |

| Optimal Flow Rate | 1.0 - 2.0 mL/min | 0.2 - 0.6 mL/min | ~70% Reduction |

| Operating Pressure | Up to 400 bar (6000 psi) | Up to 1000-1500 bar (15,000-22,000 psi) | ~250% Increase |

| Sample Throughput (per day) | 10-20 analyses | 50-100+ analyses | ~400% Increase |

Green HPLC Experimental Protocol

This section details a standardized protocol for developing and validating a green HPLC method for the simultaneous analysis of a model active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and its related impurities, incorporating Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) principles.

Protocol: AQbD-Driven Green RP-HPLC Method for Pharmaceutical Analysis

I. Analytical Target Profile (ATP) Definition

The ATP is to develop a precise, robust, and stability-indicating RP-HPLC method for the simultaneous quantification of [API Name] and its [Number] key related impurities. The method must achieve a resolution (Rs) of >2.0 between all critical peak pairs, possess a run time of <10 minutes, and align with Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles by minimizing acetonitrile use and waste generation [20].

II. Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) and Risk Assessment

- CQAs: Resolution, tailing factor, retention time of the last peak, and peak capacity.

- Risk Assessment Tool: An Ishikawa (fishbone) diagram is constructed to identify potential sources of variability. Critical Method Parameters (CMPs) are prioritized via a Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA). Key CMPs typically include mobile phase pH, organic modifier gradient, column temperature, and flow rate [20] [24].

III. Design of Experiments (DoE) and Optimization

- Software: Use commercial method development software (e.g., Fusion QbD, DryLab) for in silico modeling.

- DoE Approach: A Central Composite Design (CCD) is employed to model the relationship between CMPs and CQAs. The design space is explored for three factors:

- Mobile Phase pH: Range 2.5 - 6.5

- Gradient Time (%B): Range 5 - 15 minutes

- Temperature: Range 25 - 45 °C

- Green Objective: The organic modifier (

[Methanol or Ethanol]) concentration is capped at 60% to reduce hazardous solvent use [20].

IV. Final Method Conditions

- Column: C18-PFP (100 x 2.1 mm, 1.7 µm) [25]

- Mobile Phase A:

[Aqueous Buffer, e.g., 10 mM Ammonium Acetate, pH 4.0] - Mobile Phase B:

[Green Organic Solvent, e.g., Ethanol or Methanol] - Gradient Program:

[Specify detailed gradient based on DoE results] - Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Column Temperature:

[Optimized Temperature, e.g., 35°C] - Injection Volume: 2 µL

- Detection: UV-PDA at

[Specify Wavelength]

V. Method Validation Validate the method per ICH Q2(R1) guidelines for specificity, accuracy, precision, linearity, range, and robustness within the established Method Operable Design Region (MODR) [20].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the AQbD-driven green HPLC method development process.

Environmental Impact Assessment Protocol

A critical component of green method development is the systematic evaluation of environmental impact using standardized metrics.

Protocol: Assessing Method Greenness

I. Selection of Assessment Tools

- Primary Tool: AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) metric software is recommended as it provides a comprehensive, holistic score (0-1) based on all 12 principles of GAC, with an intuitive graphical output [16] [20].

- Supplementary Tools: The Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) pictogram offers a visual summary of environmental impact across the entire analytical workflow [16].

II. Data Input and Calculation

- Inputs for AGREE: The tool requires inputs on energy consumption, sample preparation steps, waste amount and hazard, reagent toxicity, operator safety, and throughput [16].

- Procedure: Input data derived from the finalized method conditions (Section 3.1) into the AGREE calculator. The output is a circular pictogram with a final score; a score >0.75 is considered excellent for a green method [20].

III. Interpretation and Reporting

- The overall AGREE score and the colored sections of the pictogram quickly highlight strengths and weaknesses in the method's environmental profile.

- Compare the score against legacy methods or literature benchmarks to demonstrate improvement. For instance, a recent study on an irbesartan method achieved an AGREE score of 0.75, signifying high sustainability [20].

Assessment Visualization

The diagram below outlines the decision-making pathway for selecting and applying greenness assessment tools.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Green HPLC [10] [22] [25]

| Item | Function/Description | Green & Efficiency Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol (as Mobile Phase Modifier) | Replaces acetonitrile or methanol as the organic solvent in reversed-phase chromatography. | Biodegradable, less toxic, and derived from renewable resources. A key green alternative [20]. |

| Core-Shell Particle Columns | Stationary phase with a solid core and porous shell (e.g., 2.6-2.7 µm). | Provides efficiency near sub-2 µm particles but at lower backpressure, enabling faster separations on standard HPLC hardware and reducing solvent consumption [22] [25]. |

| Sub-2 µm Fully Porous Particle Columns | The standard for UHPLC, enabling high-resolution separations. | Drastically reduces analysis time and solvent use by >80% compared to 5 µm particles, but requires UHPLC instrumentation [25] [23]. |

| Narrow-Bore Columns (e.g., 2.1 mm i.d.) | The column format for analytical-scale UHPLC. | Reduces solvent flow rates and consumption by ~80% compared to standard 4.6 mm i.d. columns without sacrificing detection sensitivity [25]. |

| AQbD Software (e.g., Fusion, DryLab) | Software for computer-assisted method development and optimization. | Reduces the number of physical experiments (trial-and-error), saving significant solvent, time, and labor during method development [25] [20]. |

| Greenness Assessment Software (AGREE, GAPI) | Tools for quantitatively evaluating the environmental impact of an analytical method. | Provides a standardized metric to justify and communicate the sustainability of a method, guiding continuous improvement [16] [20]. |

| Javanicin C | Javanicin C, CAS:126149-71-1, MF:C22H34O7, MW:410.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hancolupenone | Hancolupenone, CAS:132746-04-4, MF:C30H48O, MW:424.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The transition from traditional methods to advanced, green-focused HPLC represents a convergence of analytical excellence and environmental responsibility. The quantitative data, detailed protocols, and toolkit provided herein demonstrate that significant reductions in solvent consumption, analysis time, and hazardous waste are achievable without compromising data quality. By adopting AQbD principles, modern column technologies, and standardized greenness metrics, pharmaceutical researchers and scientists can effectively enhance laboratory efficiency while contributing to the broader objectives of sustainable science.

The development of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) methods in pharmaceutical analysis is increasingly guided by the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), which aims to minimize environmental impact and enhance operator safety without compromising analytical performance [11] [10]. Within the broader context of a thesis on green HPLC for pharmaceuticals, the evaluation of a method's environmental footprint is paramount. This has spurred the creation of specialized assessment tools that move beyond traditional metrics focused solely on analytical performance [2].

The Analytical Eco-Scale and the Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) metric are two pivotal tools that enable researchers to quantify and benchmark the greenness of their analytical procedures [26] [16]. The Analytical Eco-Scale offers a straightforward, penalty-based scoring system, while AGREE provides a more comprehensive, multi-factorial evaluation based on the 12 principles of GAC [26]. Their adoption is critical for transitioning from the traditional "take-make-dispose" linear model towards a more sustainable and circular analytical chemistry framework, which is essential for the future of the pharmaceutical industry [9]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for implementing these two core metrics.

The Analytical Eco-Scale Tool

Principle and Definition

The Analytical Eco-Scale is a semi-quantitative assessment tool that provides an easily interpretable score for the greenness of an analytical method. It operates on a penalty-point system where an ideal, perfectly green method has a base score of 100 [26] [16]. Points are subtracted from this perfect score for every aspect of the procedure that does not conform to ideal green principles [27]. The resulting score provides a direct comparison between methods, encouraging transparent evaluation [2].

Calculation Protocol

Protocol Title: Calculating the Analytical Eco-Scale Score for an HPLC Method. Principle: The greenness of an analytical procedure is evaluated by assigning penalty points for hazardous reagents, energy consumption, waste generation, and occupational hazards. The final score is calculated by subtracting the total penalty points from a base score of 100 [26]. Experimental Procedure:

- Identify Components: List all reagents, solvents, and instruments used in the entire analytical process, from sample preparation to final detection.

- Assign Penalty Points: Refer to the penalty points table (Table 1) and assign points for each non-green element.

- Calculate Total Penalty: Sum all penalty points.

- Determine Eco-Scale Score: Subtract the total penalty from 100.

Final Score Interpretation:

- >75: Excellent green analysis.

- >50: Acceptable green analysis.

- <50: Insufficient greenness [26].

Table 1: Typical penalty points for the Analytical Eco-Scale assessment.

| Parameter | Condition | Penalty Points |

|---|---|---|

| Reagents | >10 mL of hazardous solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) | 1-5 |

| Toxic reagent (e.g., heavy metals) | 3 | |

| Corrosive reagent | 2 | |

| Irritant | 1 | |

| Energy (per sample) | >1.5 kWh | 2 |

| 0.1-1.5 kWh | 1 | |

| <0.1 kWh | 0 | |

| Occupational Hazard | Lack of safety measures for toxic substances | 2-3 |

| Required personal protective equipment | 1 | |

| Waste | >10 mL per sample | 3-5 |

| 1-10 mL per sample | 1 | |

| No waste treatment procedure | 3 |

Application Example

In a case study quantifying Posaconazole via RP-HPLC using methanol:water (95:05), the method's greenness was evaluated. The high volume of methanol likely incurred a penalty, but the absence of derivatization and a relatively simple isocratic flow contributed positively. The method was validated as environmentally benign based on its Eco-Scale score alongside other metrics [27].

The AGREE Metric Tool

Principle and Definition

The AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) metric is a modern, comprehensive tool that evaluates the greenness of an analytical method against all 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry [2] [26]. It uses a unified algorithm to generate a score between 0 and 1, where 1 represents ideal greenness [26] [16]. A key feature of AGREE is its intuitive circular pictogram, which provides an at-a-glance visual summary of the method's performance across all 12 principles, making it easy to identify strengths and weaknesses [2].

Calculation Protocol

Protocol Title: Determining the AGREE Score and Pictogram for an Analytical Method. Principle: The assessment is based on the 12 principles of GAC, each scored and weighted within an algorithm. The output is a score from 0 to 1 and a radial diagram where each section corresponds to one principle [26]. Experimental Procedure:

- Gather Method Data: Compile detailed information on the entire analytical procedure.

- Use Dedicated Software: Utilize the open-source AGREE software, inputting data as prompted [26].

- Input for Each Principle: The software will guide the assessment of each of the 12 GAC principles (see Table 2 for examples).

- Generate Output: The software automatically calculates the final score and produces the colored pictogram.

Table 2: Mapping of the 12 GAC principles for AGREE assessment with example HPLC considerations.

| Principle Number | Description | HPLC Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Direct analysis | Use of LC-MS to avoid sample derivatization. |

| 2 | Reduced sample size | Miniaturized extraction or small injection volumes. |

| 3 | In-situ measurement | Not typically applicable to standard HPLC. |

| 4 | Minimize waste | Solvent reduction via narrow-bore columns [25]. |

| 5 | Safer solvents | Substitute acetonitrile with ethanol where possible [25]. |

| 6 | Avoid derivatization | Develop methods that do not require derivatization. |

| 7 | Energy conservation | Use ambient column temperature instead of heated. |

| 8 | Reagent-free/miniaturization | Employ micro-extraction techniques for sample prep. |

| 9 | Automation & integration | Use autosamplers and online sample preparation. |

| 10 | Multi-analyte methods | Develop methods for multiple active ingredients. |

| 11 | Real-time analysis | Not typically applicable to standard HPLC. |

| 12 | Operator safety | Use of less toxic solvents to reduce exposure risk. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the steps involved in performing an AGREE assessment.

Application Example

A study developing a green RP-HPLC method for the simultaneous quantification of EGCG and RA used AGREE, among other tools, to validate its environmental sustainability. The method employed a methanol and 0.1% formic acid mobile phase, and the AGREE score helped confirm its alignment with GAC principles, supporting its claim as a green alternative [28].

Comparative Analysis: Eco-Scale vs. AGREE

While both tools assess greenness, their approaches and outputs are complementary. The table below provides a direct comparison to guide tool selection.

Table 3: Comparative analysis of the Analytical Eco-Scale and AGREE metric.

| Feature | Analytical Eco-Scale | AGREE Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Basis of Assessment | Penalty points for hazardous elements [26] | 12 Principles of GAC [26] |

| Output Type | Numerical score (from 100) [26] | Numerical score (0-1) and pictogram [2] |

| Key Strength | Simple, fast, and easy to interpret [26] | Comprehensive, holistic, and visually intuitive [2] |

| Primary Limitation | Lacks a visual component; can be subjective in assigning penalties [2] | Does not fully account for pre-analytical processes (e.g., reagent synthesis) [2] |

| Ideal Use Case | Initial, rapid screening of methods; educational purposes | Detailed justification of greenness in research publications; comprehensive method optimization |

Essential Reagents and Materials for Green HPLC

Transitioning to greener HPLC practices involves careful selection of solvents, columns, and instrumentation. The following toolkit lists key components for developing sustainable methods in a pharmaceutical context.

Table 4: Research reagent solutions and materials for green HPLC method development.

| Item | Function in Green HPLC | Example & Green Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Eco-Friendly Solvents | Replace hazardous traditional solvents. | Ethanol, Water: Bio-derived, less toxic, and biodegradable alternatives to acetonitrile and methanol [20] [25]. |

| Narrow-Bore Columns | Reduce mobile phase consumption. | 2.1 mm i.d. columns: Can reduce solvent usage by up to 80% compared to standard 4.6 mm i.d. columns [25]. |

| Advanced Particle Columns | Shorten run times, reducing solvent and energy use. | Sub-2-µm FPP or SPP columns: Provide high efficiency, enabling faster separations and significant solvent savings [25]. |

| Alternative Stationary Phases | Improve selectivity to enhance efficiency. | C18-PFP phases: Can provide superior selectivity for certain separations, allowing for shorter columns and greener methods [25]. |

| Method Modeling Software | Minimize laboratory experimentation and solvent waste. | In-silico modeling tools: Predict optimal conditions (e.g., solvent substitutions, column chemistries) without physical trials [25]. |

The Analytical Eco-Scale and AGREE metrics are indispensable for modern pharmaceutical analysis, providing robust, standardized frameworks to evaluate and improve the environmental footprint of HPLC methods. The Eco-Scale serves as an excellent tool for rapid initial assessment, while AGREE offers a thorough, principle-based evaluation suitable for regulatory justification and high-impact research. As the field moves towards stronger sustainability models and circular economy principles, the integration of these tools from the initial stages of method development, particularly when combined with frameworks like Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD), is no longer optional but a fundamental aspect of responsible and forward-thinking analytical science [9] [20].

Implementing Green HPLC Methods: Modern Columns, Solvent Reduction, and Real-World Applications

The pursuit of green analytical chemistry (GAC) principles in pharmaceutical analysis is driving significant innovation in high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Among the most impactful advancements are the adoption of superficially porous particles (SPPs) and inert hardware in HPLC columns, which collectively address the core objectives of sustainability—reducing solvent consumption and analysis time—while improving data quality for metal-sensitive analytes [29] [25]. These technologies enable laboratories to maintain high analytical performance while aligning with environmental and safety goals. SPPs provide efficiency comparable to sub-2µm fully porous particles (FPPs) but at significantly lower operating pressures, facilitating faster separations and reduced solvent use on conventional HPLC instrumentation [30] [31]. Concurrently, the trend toward inert or biocompatible hardware mitigates detrimental analyte-surface interactions, thereby improving peak shape and analytical recovery for challenging pharmaceutical compounds such as phosphorylated molecules and metal-chelaters [29]. This application note details practical protocols and data for implementing these column technologies to develop greener, more robust HPLC methods for pharmaceutical analysis.

Technical Background and Key Concepts

Particle Architecture: FPP vs. SPP

The fundamental difference between particle types lies in their structure. Fully Porous Particles (FPPs) are traditional spherical silica particles with an interconnected network of pores extending from the surface to the center, offering high surface area but longer diffusion paths for analytes [30] [31]. Superficially Porous Particles (SPPs), also known as core-shell particles, feature a solid, non-porous silica core surrounded by a thin, porous outer shell [30]. This engineered structure confers key kinetic advantages: the solid core reduces the path length for analyte diffusion (the C-term in the van Deemter equation), while the highly uniform, monodisperse nature of SPPs promotes more homogeneous column packing, minimizing flow path variability (the A-term) [31]. The result is enhanced efficiency, often matching that of sub-2µm FPPs but with backpressures similar to larger FPPs, making them suitable for both HPLC and UHPLC systems [30] [31].

The Role of Inert Hardware

Inert HPLC column hardware is internally treated or manufactured from alternative materials to minimize exposed metal surfaces, typically stainless steel, that can interact with analytes [29]. These interactions are particularly problematic in pharmaceutical analysis for compounds containing phosphate groups, chelators, or certain heterocycles, leading to peak tailing, adsorption, and poor recovery [29]. Inert columns ensure more reliable and reproducible quantification of such metal-sensitive molecules, a critical requirement in drug impurity profiling and bioanalysis [29].

Alignment with Green Chemistry

The combination of SPPs and inert hardware directly supports Green Analytical Chemistry principles. SPPs enable faster separations and the use of narrower-bore columns, drastically cutting solvent consumption and waste generation [25]. Inert hardware enhances method robustness and longevity, reducing the frequency of column replacement and associated resource use [29]. Together, they facilitate the development of fit-for-purpose, sustainable methods without compromising the stringent performance demands of the pharmaceutical industry [9] [25].

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Materials for HPLC Method Development with SPP and Inert Columns

| Item | Function/Description | Example Vendors/Catalog Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SPP Reversed-Phase Columns | High-efficiency separation of small molecules and peptides; available in various chemistries (C18, phenyl-hexyl, etc.) | Advanced Materials Technology (Halo), Thermo Scientific (Accucore), Agilent (Poroshell) [29] [30] |

| Inert Hardware Columns | Minimize metal-sensitive analyte interaction; improve peak shape and recovery for chelating compounds | Restek (Raptor Inert, Force Inert), Advanced Materials Technology (Halo Inert) [29] |

| Inert Guard Cartridges | Protect the analytical column from contaminants and particulates while maintaining inert flow path | Restek (Raptor Inert Guard, Force Inert Guard), YMC (Accura BioPro IEX, Triart Guard) [29] |

| HPLC-Grade Green Solvents | Mobile phase modifiers; ethanol is a less toxic, biodegradable alternative to acetonitrile [32] [25] | Various; specify high-purity, low-UV absorbance grades |

| MS-Compatible Additives | Volatile buffers for mass spectrometric detection (e.g., formic acid, ammonium formate) | Various; use high-purity grades suitable for intended detection mode |

| Pharmaceutical Analyte Standards | System suitability and method development test mixtures | USP, commercial standards, or in-house synthesized compounds |

Comparative Performance Data

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The following tables summarize key performance characteristics of SPP and inert columns, providing a basis for informed column selection.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Particle Technologies for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Parameter | 5µm FPP (Traditional) | Sub-2µm FPP (UHPLC) | 2.7µm SPP (Modern) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Particle Size | 5.0 µm | 1.7 - 1.9 µm | 2.6 - 2.7 µm |

| Typical Efficiency (Plates/Column) | Lower | Very High | High (Comparable to sub-2µm FPP) [30] [31] |

| Optimal Linear Velocity | Narrower range | Broader range | Broader range [30] |

| Operating Pressure | Low | Very High (may require UHPLC) | Moderate (compatible with many HPLC systems) [30] [31] |

| Solvent Consumption (vs. 5µm FPP) | Baseline | Up to 85% reduction [25] | >50% reduction [25] |

| Analysis Time (vs. 5µm FPP) | Baseline | Significant reduction | Significant reduction [30] |

| Recommended Application | General, older methods | High-throughput, complex separations | Fast, efficient analysis on standard or UHPLC systems [29] [31] |

Table 3: Application-Based Selection Guide for Inert and SPP Columns

| Analytical Challenge | Recommended Column Type | Key Benefit | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorylated Compounds | Inert SPP or FPP | Improved peak shape and recovery | Analysis of nucleotides, phosphorylated drugs [29] |

| Metal-Chelating Compounds | Inert SPP or FPP | Prevents analyte adsorption and loss | PFAS, certain pesticides, chelating APIs [29] |

| Basic Compounds/Peptides | SPP with charged surface | Enhanced peak symmetry | Peptide mapping, basic drug substances [29] |

| High-Throughput Analysis | SPP (any hardware) | Fast separations with high efficiency | QC release testing, bioanalytical sampling [30] [25] |

| Method Transfer to Greener Solvents | Inert SPP or FPP | Robust performance with alternative solvents like ethanol [32] [25] | General method greening |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Method Translation from FPP to SPP for Solvent Reduction

This protocol outlines the systematic transfer of an existing method from a traditional FPP column to an SPP column to achieve faster analysis and reduced solvent consumption [30] [25].

Workflow Overview

Materials:

- HPLC or UHPLC system compatible with the expected pressure

- Original FPP column (e.g., 150 mm x 4.6 mm, 5µm C18)

- Selected SPP column (e.g., 100 mm x 3.0 mm, 2.7µm C18)

- Mobile phase components and analyte standards

Procedure:

- Document Original Parameters: Record all parameters from the FPP method: column dimensions (L x id), particle size (dp), flow rate (F), gradient time (tG), and mobile phase composition.

- Select SPP Column: Choose an SPP column with equivalent stationary phase chemistry. A common strategy is to select a column with similar length and a smaller internal diameter (e.g., from 4.6 mm to 2.1-3.0 mm) to maximize solvent savings [25].

- Calculate Scaled Parameters:

- Flow Rate: Adjust to maintain equivalent linear velocity. Formula: Fâ‚‚ = Fâ‚ * (id₂² / id₲) [25].

- Example: Translating from 4.6 mm to 2.1 mm id: F₂ = 1.0 mL/min * (2.1² / 4.6²) ≈ 0.21 mL/min.

- Gradient Time: Adjust to maintain the same number of column volumes. Formula: tGâ‚‚ = tGâ‚ * (Fâ‚ / Fâ‚‚) * (Lâ‚‚ / Lâ‚) * (id₂² / id₲).

- Injection Volume: Adjust proportional to column volume. Formula: Vinjâ‚‚ = Vinjâ‚ * (Lâ‚‚ / Lâ‚) * (id₂² / id₲).

- Flow Rate: Adjust to maintain equivalent linear velocity. Formula: Fâ‚‚ = Fâ‚ * (id₂² / id₲) [25].

- Initial Scouting Run: Execute the method with the scaled parameters. Monitor backpressure and peak shape.

- Fine-Tuning: The superior kinetics of SPPs may allow for further optimization.

- Slightly increase the flow rate to leverage the flatter C-term of the van Deemter curve, reducing run time without significant efficiency loss [31].

- Shorten the gradient or column length if the initial run shows excess separation.

- Validation: Once optimized, perform a system suitability test against method requirements to ensure the translated method is fit-for-purpose.

Protocol 2: Method Development for Metal-Sensitive Analytes Using Inert Hardware

This protocol describes developing a robust method for analytes prone to metal interaction, such as pharmaceuticals with chelating functional groups [29].

Workflow Overview

Materials:

- Inert HPLC column (e.g., Restek Raptor Biphenyl, Halo Inert C18)

- Standard (non-inert) column of similar chemistry for comparison

- High-purity solvents (HPLC grade) and additives

- Mobile phase prepared with ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm)

- Standard solution of the metal-sensitive analyte

Procedure:

- Column Selection: Choose an inert column with a stationary phase appropriate for the analyte. Biphenyl phases can offer alternative selectivity via π-π interactions, which is beneficial for aromatic metal-chelaters [29].

- Mobile Phase Preparation: Use high-purity water and solvents to minimize exogenous metal contamination. Consider additives like chelating agents (e.g., EDTA) with caution, only if compatible with detection (especially MS).

- Initial Scouting Gradient: Use a wide gradient (e.g., 5-100% organic over 10-20 minutes) on the inert column to determine the approximate retention window of the analyte.

- Comparative Analysis: Run the optimized initial method on both the inert column and a standard column of similar chemistry. Compare key outcomes:

- Peak Area (Recovery): Significantly higher recovery on the inert column indicates analyte adsorption on the standard column.

- Peak Shape (Symmetry): Asymmetry factors closer to 1.0 on the inert column indicate reduced metal interaction.

- Method Optimization: Fine-tune the pH, buffer concentration, and gradient profile on the inert column to achieve baseline resolution of all critical pairs. The improved peak shape often simplifies optimization.

- Method Validation: Assess the method for recovery, linearity, precision, and accuracy to confirm that the use of inert hardware has resulted in a reliable and reproducible assay.

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

- Pressure Spike After Column Connection: Ensure the SPP column is being used within its pressure rating. Check for mismatched fittings or blockage from the previous system. Always use a guard cartridge [29].

- Poor Peak Shape on Inert Column: Verify that the issue is metal-related by comparing with a standard column. If problem persists, consider secondary interactions (e.g., silanol activity) and evaluate different inert stationary phases [29].

- Insufficient Retention on SPP Column: The slightly lower surface area of SPPs can lead to slightly less retention. Counter this by starting with a weaker mobile phase (e.g., 5% less organic) or selecting an SPP phase with greater ligand density [31].

- Maximizing Green Benefits: To further enhance sustainability, pair SPP/inert columns with green solvent alternatives like ethanol, especially when using UV detection [32] [25]. Utilize method modeling software to predict optimal conditions and minimize laboratory waste during development [25].

Within pharmaceutical analysis, the adoption of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles is crucial for reducing the environmental impact of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) methods. A significant portion of this impact stems from the consumption of hazardous organic solvents. This application note details a two-pronged, practical strategy to achieve substantial solvent reduction: first, by transferring methods from Totally Porous Particle (TPP) columns to Superficially Porous Particle (SPP) columns, and second, by scaling methods down to microbore column formats. This approach aligns with global green chemistry initiatives and directly addresses the high costs and environmental burdens associated with solvent use and waste disposal in pharmaceutical quality control and research laboratories [33] [32].

Background and Principles

The Green Imperative in HPLC

Traditional reversed-phase HPLC methods, particularly those based on standard 4.6 mm i.d. columns, consume large volumes of solvents like acetonitrile and methanol. A single instrument operating with a 1 mL/min flow rate can generate approximately 1.5 liters of waste per day, amounting to hundreds of liters annually [32]. Beyond the environmental footprint, this consumption poses occupational health risks and significant costs for solvent procurement and waste disposal. The 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry provide a framework for addressing these issues, emphasizing waste minimization, the use of safer solvents, and energy efficiency [26].

Column Technologies: TPP vs. SPP

- Totally Porous Particles (TPP): Traditional packings where the entire particle is a porous network. While highly retentive, analytes must diffuse in and out of the deep pores, which can limit efficiency, especially at higher flow rates.

- Superficially Porous Particles (SPP): Also known as fused-core or core-shell particles, SPP consist of a solid, non-porous core surrounded by a thin, porous outer layer. This architecture reduces diffusion paths, leading to lower backpressure and higher efficiency compared to TPP of the same particle size. This allows the use of longer columns or higher flow rates for faster analysis without sacrificing resolution [29].

The Role of Column Geometry

The internal diameter (i.d.) of a column is a primary determinant of mobile phase consumption. Solvent usage is proportional to the square of the column radius. Migrating a method from a conventional 4.6 mm i.d. column to a 2.1 mm i.d. microbore column reduces the cross-sectional area by approximately 80%, leading to a corresponding 80% reduction in solvent consumption at the same linear velocity [34]. This scaling principle, when combined with the efficiency of SPP technology, enables dramatic improvements in the greenness of analytical methods.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Method Transfer from TPP to SPP Columns

This protocol guides the direct replacement of a TPP column with an SPP column of similar dimensions and chemistry to reduce run time and solvent use.

Materials:

- HPLC/UHPLC System: Capable of operating at pressures up to 1000 bar.

- Original TPP Column: e.g., 150 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 µm C18.

- Replacement SPP Column: e.g., Halo or similar, 150 mm x 4.6 mm, 2.7 µm C18.

- Mobile Phase: As specified in the original method.

Procedure:

- Column Selection: Choose an SPP column with a bonded phase (e.g., C18, C8, phenyl-hexyl) equivalent to your original TPP column. Consult column selectivity databases like the Hydrophobic Subtraction Model to ensure compatibility [35] [36].

- System Setup: Install the new SPP column. Note that the operating pressure will likely be higher due to the smaller particle size.

- Initial Method Transfer: Use the original method's mobile phase composition, flow rate, and gradient time unchanged. Perform an initial injection of a standard mixture.

- Method Optimization:

- Flow Rate Increase: If the initial separation is successful, systematically increase the flow rate (e.g., in 0.1-0.2 mL/min increments). The enhanced efficiency of SPP columns often allows for a 50-100% increase in flow rate without significant loss of resolution or exceeding pressure limits.

- Gradient Adjustment: If the flow rate is increased, proportionally shorten the gradient time to maintain the same gradient steepness. The formula is:

t_G2 = t_G1 * (F1 / F2), wheret_Gis gradient time andFis flow rate.

- System Suitability: After optimization, run system suitability tests to confirm the method meets all required parameters (resolution, tailing factor, plate count).

Protocol 2: Scaling to Microbore Format

This protocol describes how to linearly scale a method from a conventional 4.6 mm i.d. column to a 2.1 mm i.d. microbore column for maximum solvent savings.

Materials:

- HPLC/UHPLC System: Optimized for low dwell volume and extra-column dispersion. This is critical for maintaining efficiency with microbore columns [34].

- SPP Microbore Column: e.g., 2.1 mm i.d., with the same stationary phase as the original method.

- Mobile Phase: Identical to the original method.

Procedure:

- Calculate Scaling Factor: The key parameter is the volumetric flow rate factor.

Adjust Gradient Time: To maintain the identical gradient elution profile, the gradient time must be scaled by the same factor.

t_G2 = t_G1 * (F1 / F2)In this case,F1 / F2 ≈ 4.8, meaning the gradient time on the microbore system should be approximately one-fifth of the original time.System Configuration: Ensure the system is configured for microbore work:

- Use a low-dispersion, low-volume flow cell in the detector.

- Employ the shortest possible connection tubing with small internal diameter (e.g., 0.0025").

- Be aware that the instrument's dwell volume will become more significant; adjustments to the gradient start time may be necessary [36].

Validation: Execute the scaled method and verify that retention times, resolution, and peak symmetry are consistent with the original separation.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision-making process for implementing these solvent-saving strategies:

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Solvent Savings