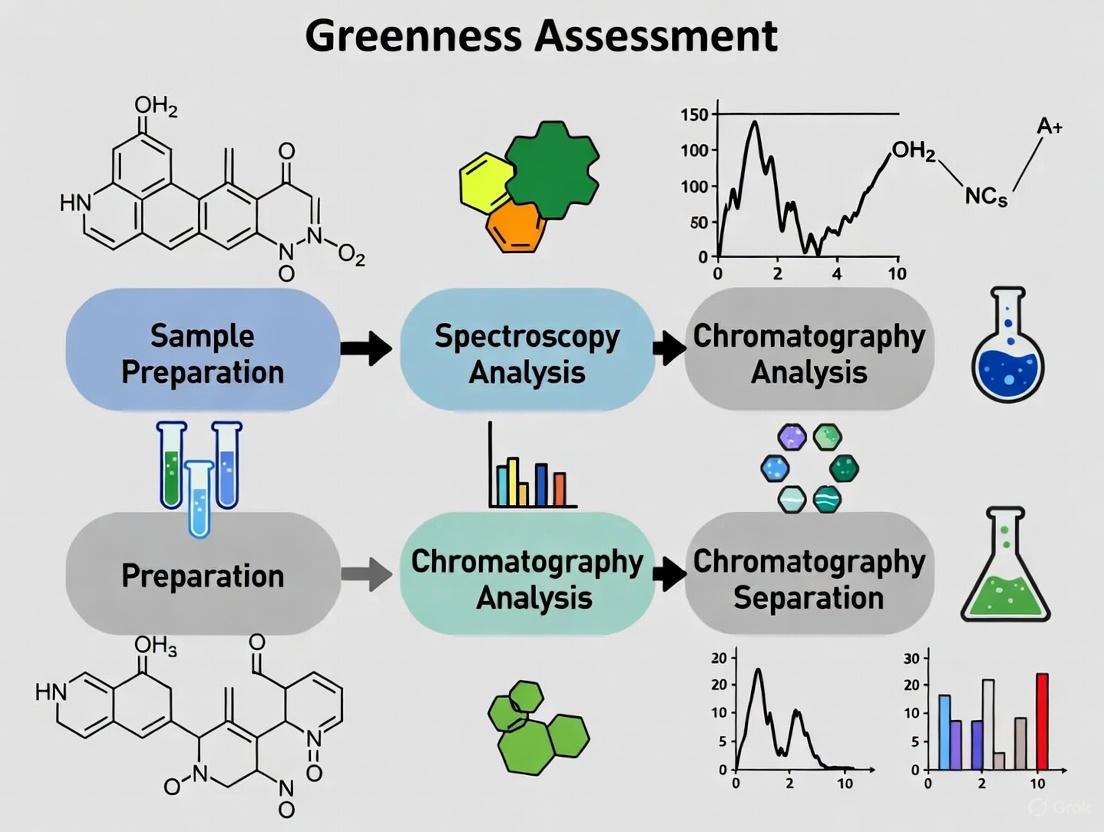

Greenness Assessment of Spectroscopy vs. Chromatography for Pharmaceuticals: A Sustainable Analytical Strategy Guide

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the greenness profiles of spectroscopic and chromatographic methods in pharmaceutical analysis.

Greenness Assessment of Spectroscopy vs. Chromatography for Pharmaceuticals: A Sustainable Analytical Strategy Guide

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the greenness profiles of spectroscopic and chromatographic methods in pharmaceutical analysis. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), detailing established assessment tools like AGREE, NEMI, GAPI, and Eco-Scale. It covers methodological applications of green techniques such as Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy, and green liquid chromatography, including UHPLC and SFC. The content also addresses troubleshooting common sustainability challenges and offers optimization strategies, such as solvent substitution and miniaturization. Finally, it presents a framework for the comparative validation of methods, balancing ecological impact with analytical performance to guide the selection of environmentally benign and efficient analytical procedures.

Principles and Metrics of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC)

In the modern pharmaceutical laboratory, the drive for innovation is increasingly balanced by the responsibility for environmental stewardship. Green Chemistry—defined as the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use or generation of hazardous substances—provides a framework for this balance [1]. Its application has expanded into the analytical sphere through Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), which aims to mitigate the adverse effects of analytical activities on human health and the environment [2]. This guide objectively evaluates two foundational analytical techniques, chromatography and spectroscopy, through the lens of GAC principles. The comparison utilizes established greenness assessment tools and experimental data to provide drug development professionals with a clear, evidence-based framework for selecting methodologies that align with both scientific rigor and sustainability goals.

Analytical Techniques and Green Chemistry Principles

Core Principles of Green Chemistry

The 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, established by Anastas and Warner, provide a comprehensive framework for sustainable chemical practice [3]. For analytical scientists, several principles are particularly relevant:

- Prevention: It is better to prevent waste than to treat or clean it up after it has been created.

- Safer Solvents and Auxiliaries: The use of auxiliary substances should be made unnecessary wherever possible and innocuous when used.

- Design for Energy Efficiency: Energy requirements should be recognized and minimized.

- Real-time Analysis for Pollution Prevention: Analytical methodologies need to be further developed to allow for real-time, in-process monitoring and control prior to the formation of hazardous substances [3] [4].

These principles have been adapted into the 12 principles of GAC, which serve as crucial guidelines for implementing greener practices in analytical procedures [2].

Fundamental Differences Between Chromatography and Spectroscopy

Chromatography and spectroscopy represent fundamentally different approaches to chemical analysis:

- Chromatography is primarily a separation technique that separates components of a mixture based on their differential partitioning between a mobile and a stationary phase [5]. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is a common example in pharmaceutical analysis.

- Spectroscopy is primarily a detection and identification technique that identifies and quantifies substances based on their interaction with light or other forms of electromagnetic radiation [5]. UV-Vis spectroscopy is a typical example.

In practice, these techniques are often combined—chromatography separates complex mixtures, and spectroscopy provides identification and quantification of the separated components [5].

Greenness Assessment Metrics for Analytical Methods

The greenness of an analytical method must be quantitatively assessed to make objective comparisons. Several standardized metrics have been developed for this purpose:

Table 1: Greenness Assessment Metrics for Analytical Methods

| Metric Tool | Type of Output | Key Parameters Assessed | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) | Pictogram (pass/fail for 4 criteria) | PBT chemicals, hazardous solvents, corrosivity, waste amount [2] | Simple, visual, immediate general information [2] | Qualitative only, limited scope, time-consuming search process [6] [2] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Numerical score (100 = ideal) | Reagent hazards, energy consumption, waste generation [2] | Quantitative, facilitates direct comparison between methods [6] [2] | Relies on expert judgment for penalty points, lacks visual component [6] |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | Color-coded pictogram (5 parts) | Entire analytical process from sampling to detection [6] [2] | Comprehensive, visual identification of high-impact stages [6] | No overall score, some subjectivity in color assignment [6] |

| AGREE (Analytical Greenness) | Pictogram + numerical score (0-1) | Based on all 12 GAC principles [6] [2] | Comprehensive, user-friendly, facilitates comparison [6] | Does not fully account for pre-analytical processes, some subjective weighting [6] |

| AGREEprep | Pictogram + numerical score (0-1) | Sample preparation-specific parameters [6] [2] | Focuses on often-overlooked sample preparation stage [6] | Must be used with broader tools for full method evaluation [6] |

Experimental Comparison: Chromatography vs. Spectroscopy

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A direct performance comparison between Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) and Paper Spray-Mass Spectrometry (PS-MS) for quantifying kinase inhibitors in plasma provides insightful experimental data [7].

Protocol for LC-MS Method [7]:

- Sample Preparation: 100 μL of patient plasma aliquot mixed with 300 μL of methanolic internal standard solution. Vortexed at 2000 rpm for 5 minutes and centrifuged at 10,000g for 5 minutes at 5°C.

- Chromatography: 10 μL of supernatant injected into Thermo Scientific Vanquish Flex UHPLC system with Hypersil GOLD aQ column.

- Separation: 9-minute LC separation using gradient elution with mobile phases A (0.1% formic acid in water) and B (0.1% formic acid in methanol).

- Detection: Triple quadrupole mass spectrometer with heated electrospray ionization mode.

Protocol for PS-MS Method [7]:

- Sample Preparation: 100 μL of plasma mixed with 200 μL of methanolic internal standard solution. Vortexed and centrifuged as above.

- Spotting: 10 μL of supernatant transferred onto VeriSpray sample plate and dried at room temperature for 30 minutes.

- Analysis: Paper spray ionization coupled directly to triple quadrupole mass spectrometer.

- Detection: Analysis time of approximately 2 minutes with no chromatographic separation.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Kinase Inhibitor Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | Application in LC-MS | Application in PS-MS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dabrafenib (DAB) | BRAF kinase inhibitor analyte | Quantified in patient plasma [7] | Quantified in patient plasma [7] |

| Trametinib (TRAM) | MEK kinase inhibitor analyte | Quantified in patient plasma [7] | Quantified in patient plasma [7] |

| OH-Dabrafenib | Active metabolite of dabrafenib | Monitored for metabolism patterns [7] | Monitored for metabolism patterns [7] |

| Formic Acid | Mobile phase modifier | 0.1% in water and methanol [7] | 0.1% in spray solvent [7] |

| Methanol | Extraction solvent/Sample preparation | Used in sample preparation [7] | Used in sample preparation [7] |

| Human K2EDTA Plasma | Biological matrix | Sample matrix for analysis [7] | Sample matrix for analysis [7] |

Quantitative Performance and Greenness Comparison

Experimental data from the kinase inhibitor monitoring study provides a direct comparison of analytical performance:

Table 3: Quantitative Performance Comparison of LC-MS vs. PS-MS [7]

| Parameter | LC-MS Method | PS-MS Method | Green Chemistry Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Time | 9 minutes | 2 minutes | PS-MS reduces energy consumption (Principle #6: Design for Energy Efficiency) [3] |

| Imprecision (%) | 1.3-9.7% across analytes | 3.2-9.9% across analytes | LC-MS offers slightly better precision but both are clinically acceptable |

| Analytical Measurement Range - Trametinib | 0.5-50 ng/mL | 5.0-50 ng/mL | LC-MS offers broader dynamic range, potentially reducing need for sample re-analysis |

| Correlation with Patient Samples | Reference method | r = 0.9807-0.9977 | Both methods provide clinically comparable results |

| Solvent Consumption | Higher (continuous flow during separation) | Minimal (spray solvent only) | PS-MS significantly reduces solvent use (Principle #5: Safer Solvents) [3] |

| Waste Generation | Higher | Minimal | PS-MS prevents waste (Principle #1: Prevention) [3] |

Analytical Workflow Comparison: LC-MS vs. PS-MS

Significance and Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Greenness Profile in Pharmaceutical Analysis

The application of greenness assessment metrics reveals significant differences between analytical approaches:

Solvent Consumption and Waste Generation: Traditional LC-MS methods typically generate more than 10 mL of waste per sample, while microextraction techniques like those used in PS-MS can limit solvent consumption to less than 10 mL [6]. This directly addresses Principle #1 (Prevention) and Principle #5 (Safer Solvents) [3].

Energy Efficiency: Methods with shorter run times (e.g., PS-MS at 2 minutes vs. LC-MS at 9 minutes) significantly reduce energy consumption, aligning with Principle #6 (Design for Energy Efficiency) [7] [3].

Throughput and Resource Utilization: The AGREE metric assesses sample throughput as an important greenness parameter. Methods processing only 1-2 samples per hour (like some traditional approaches) score lower than high-throughput methods [6].

Strategic Implementation for Sustainable Science

The choice between chromatographic and spectroscopic methods involves balancing multiple factors:

For Targeted Analysis of Simple Mixtures: Direct spectroscopic methods often provide superior greenness profiles with minimal sample preparation, reduced solvent consumption, and faster analysis times [5] [8].

For Complex Biological Matrices: Chromatographic separation remains essential for reliable results despite higher environmental impact [7] [9]. The key is to optimize these methods using green chemistry principles—for example, by replacing hazardous solvents with safer alternatives [1] [4].

Emerging Hybrid Techniques: Approaches like PS-MS represent a middle ground, maintaining the specificity of mass spectrometric detection while eliminating the solvent-intensive chromatographic separation step [7].

The integration of Green Chemistry principles into pharmaceutical analysis represents both an ethical imperative and a practical opportunity for innovation. This comparison demonstrates that while chromatography and spectroscopy serve different analytical needs, both can be evaluated and optimized using standardized greenness assessment metrics like AGREE, GAPI, and Analytical Eco-Scale. For pharmaceutical researchers, the strategic selection and development of analytical methods must balance analytical performance with environmental impact. Techniques like PS-MS that reduce solvent consumption, analysis time, and waste generation without compromising data quality represent the future of sustainable pharmaceutical analysis. As green metrics continue to evolve, they will provide even more sophisticated tools for quantifying and improving the environmental profile of the analytical methods that drive drug discovery and development.

In the modern pharmaceutical laboratory, ensuring the safety and efficacy of a drug is no longer the sole priority. The environmental impact of the analytical methods used in research and quality control has become a critical concern, driving the emergence of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC). GAC aims to minimize the environmental footprint of analytical procedures by reducing hazardous waste, conserving energy, and promoting the use of safer chemicals [6] [10]. This paradigm shift has necessitated the development of reliable ways to measure and quantify environmental performance, leading to the creation of greenness assessment tools.

This guide traces the evolution of these tools, from simple, early concepts to today's sophisticated, multi-faceted metrics. It provides an objective comparison of their designs, outputs, and applications, with a special focus on their use in evaluating spectroscopic and chromatographic methods for pharmaceutical analysis. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this toolkit is essential for designing sustainable, ecologically responsible, and compliant analytical workflows.

The Evolution of Greenness Assessment Metrics

The development of greenness assessment tools has progressed from basic checklists to comprehensive, quantitative software-based metrics. The diagram below illustrates this evolutionary pathway and the logical relationship between the different tools.

This evolution shows a clear trend: each new tool was developed to address the limitations of its predecessors. The journey began with the National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI), which used a simple pictogram with four criteria, offering a binary (yes/no) greenness evaluation [6]. Its key limitation was the inability to distinguish between different degrees of environmental impact [6].

The Analytical Eco-Scale introduced a semi-quantitative approach by assigning penalty points for non-green aspects like hazardous reagents or high energy consumption. A score is calculated by subtracting these points from 100, with a higher score indicating a greener method [11]. This allowed for easier comparison between methods.

A significant leap came with the Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI), which expanded the assessment to the entire analytical workflow via a color-coded pictogram [6]. This visual tool covers 15 criteria across sampling, preparation, instrumentation, and more, using a traffic-light system (green, yellow, red) to quickly identify problematic stages [12]. Later enhancements, ComplexGAPI and Modified GAPI (MoGAPI), incorporated pre-analytical processes and cumulative scoring to improve comprehensiveness and comparability [6].

The Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) metric represented a major advancement by integrating all 12 principles of GAC into a unified evaluation [12]. It outputs a clock-like pictogram with a central score from 0 to 1, providing an at-a-glance holistic assessment [11]. Its dedicated counterpart, AGREEprep, is the first tool specifically designed to evaluate the sample preparation step, which is often a significant source of environmental impact [10].

The most recent evolution is the concept of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which seeks a balance between analytical performance (Red), environmental impact (Green), and practical and economic feasibility (Blue) [11]. To quantify the practical "blue" dimension, the Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) was developed, assessing factors like analysis time, cost, and operational simplicity [10].

Comparative Analysis of Major Assessment Tools

A clear understanding of the different features and outputs of these tools is crucial for selecting the right one for a specific application. The table below provides a structured, quantitative comparison of the major metrics.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Greenness Assessment Tools

| Tool Name | Graphical Output | Output Type | Scope of Assessment | Scoring System | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI [6] | Simple pictogram | Qualitative | Entire method | Binary (Pass/Fail 4 criteria) | Pioneering but limited in detail. |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [11] | Numerical score | Semi-quantitative | Entire method | Score out of 100 (100 = ideal) | Penalty point system; easy comparison. |

| GAPI [12] [6] | Multi-section pictogram | Semi-quantitative | Entire analytical workflow | Color-based (Green/Yellow/Red) | Visualizes impact of each analytical step. |

| AGREE [12] [11] | Clock-like radial chart | Quantitative | Entire method, based on 12 GAC principles | 0 to 1 (1 = ideal) | Most comprehensive; open-source software available. |

| AGREEprep [12] | Clock-like radial chart | Quantitative | Sample preparation only, based on 10 GSP principles | 0 to 1 (1 = ideal) | First dedicated sample prep metric; open-source software. |

| BAGI [10] | Asteroid-shaped pictogram | Quantitative | Practicality and applicability of the method | Score based on 10 criteria | Complements green metrics within the WAC concept. |

Application in Pharmaceutical Research: Spectroscopy vs. Chromatography

The choice between spectroscopic and chromatographic methods is common in pharmaceuticals. Greenness assessment tools provide a data-driven way to evaluate their environmental profiles, moving beyond traditional metrics of speed and accuracy.

Case Study: UV-Spectroscopy vs. HPLC for Drug Analysis

A 2025 study developed five green UV-spectrophotometric methods for analyzing chloramphenicol and dexamethasone in ophthalmic drops and compared them against a published High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) method [11]. The results from multiple assessment tools are summarized below.

Table 2: Greenness Scores for UV-Spectroscopy vs. HPLC from a Case Study [11]

| Analytical Method | Analytical Eco-Scale Score | AGREE Score | Inferred GAPI Profile |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Spectrophotometry (D0) | > 75 (Excellent Green) | > 0.80 (High) | Likely mostly green (minor yellow) |

| Reported HPLC Method | Not explicitly stated (lower) | Significantly lower | Likely significant yellow/red sections |

The study concluded that the proposed spectrophotometric methods were excellent green alternatives, outperforming the reference HPLC method in all greenness metrics [11]. The spectrophotometric techniques typically use simpler instrumentation with lower energy demands and often require smaller volumes of less toxic solvents (e.g., ethanol), leading to a superior environmental profile [11].

Broader Context: The Environmental Burden of Chromatography

While HPLC is a workhorse in pharmaceutical labs, its environmental impact is significant. A life-cycle analysis of a single LC method for a widely used generic drug, rosuvastatin calcium, revealed that approximately 18,000 liters of mobile phase are consumed and disposed of annually for this one drug alone [13]. This underscores why the perception that analytical methods have an insignificant environmental impact is "pervasive and damaging" [13]. This heavy solvent consumption is a primary reason HPLC methods often score lower on metrics like AGREE and GAPI, which penalize high waste generation and the use of hazardous chemicals.

The Push for Greener Chromatography

In response, the chromatography industry is actively developing more sustainable solutions. Trends for 2025 highlight a shift toward miniaturized instrumentation, reduced power and solvent consumption, and the use of alternative, greener solvents [14] [10]. Furthermore, the Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS), a comprehensive metric developed by the ACS Green Chemistry Institute, is being used by companies like AstraZeneca to evaluate and improve the sustainability of their chromatographic methods [13]. The overall goal is to reduce the cumulative environmental cost without compromising the critical data that chromatography provides for drug development.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and tools referenced in the studies and experiments cited in this guide, which are essential for conducting greenness assessments.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Greenness Assessment

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| AGREE & AGREEprep Software | Free, open-source software for calculating AGREE and AGREEprep scores. | Used to generate the quantitative greenness score and pictogram for an analytical method [12]. |

| Ethanol | A common solvent classified as a greener alternative to acetonitrile or methanol. | Used as the primary solvent in the green UV-spectrophotometric analysis of chloramphenicol and dexamethasone [11]. |

| Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) | A metric evaluating solvent energy, safety/toxicity, and instrument energy consumption. | Used by AstraZeneca to perform a strategic departmental-level assessment of the greenness of their chromatographic portfolio [13]. |

| Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) | A tool to quantitatively assess the practicality and operational feasibility of an analytical method. | Used alongside green metrics to provide a "white" assessment balancing greenness, practicality, and analytical performance [10] [11]. |

Experimental Protocols for Greenness Assessment

Implementing a greenness assessment is a systematic process. The workflow below outlines the general protocol for evaluating an analytical method, drawing from the methodologies used in the cited case studies [12] [11].

Detailed Procedural Steps:

- Method Deconstruction: Break down the analytical procedure into discrete steps, as done in the UV-filter cosmetics study [12]. Key stages include sample collection, preparation, instrumental analysis, and data processing.

- Data Collection: Meticulously record all parameters required by the chosen metrics. This includes:

- Reagents: Type, quantity, and safety data (e.g., GHS hazard statements).

- Energy: Instrument power requirements and run time.

- Waste: Total volume and toxicity of waste generated.

- Throughput: Number of samples processed per hour [10].

- Tool Selection: Choose metrics based on the assessment's goal. For a quick visual overview, GAPI is suitable. For a comprehensive score based on all 12 GAC principles, AGREE is ideal. To focus on the sample prep, use AGREEprep. For a balanced White assessment, combine AGREE with BAGI.

- Software Input: Utilize the freely available software for tools like AGREE and AGREEprep. For other tools, apply the defined criteria and scoring algorithms manually.

- Interpretation and Improvement: Analyze the output to identify the least green aspects of the method. This could be a specific reagent, a high-energy step, or a waste-intensive process. Use this insight to explore greener alternatives, such as solvent substitution or method miniaturization.

The evolution of greenness assessment tools has equipped pharmaceutical scientists with a robust and sophisticated toolkit to quantify and minimize the environmental impact of their work. From the early days of NEMI to the comprehensive, software-driven AGREE and the balanced perspective of White Analytical Chemistry, these metrics provide the critical data needed to make informed, sustainable choices.

As the case studies demonstrate, these tools enable objective comparisons, revealing that techniques like spectroscopy can offer excellent green credentials for certain applications, while chromatography is undergoing a necessary green transformation. For the modern drug development professional, integrating these assessments into routine method development and selection is no longer optional but a fundamental responsibility. By doing so, the industry can advance human health while steadfastly protecting the health of the planet.

In the pharmaceutical industry, the choice between spectroscopic and chromatographic techniques is not solely based on performance; the environmental impact of these methods is an increasingly critical factor. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) aims to minimize the adverse effects of analytical activities on human health and the environment by reducing hazardous solvent use, energy consumption, and waste generation [15] [6]. The evaluation of this environmental impact relies on specialized assessment tools that provide standardized metrics for comparing method sustainability. Within the context of pharmaceutical research, this assessment framework allows scientists to make informed decisions when developing new analytical methods for drug analysis, quality control, and stability testing.

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of four established greenness assessment metrics—NEMI, Analytical Eco-Scale, GAPI, and AGREE—that are routinely applied to evaluate both spectroscopic and chromatographic methods in pharmaceutical analysis. Understanding the principles, applications, and limitations of these tools enables researchers to select not only the most analytically sound technique but also the most environmentally sustainable approach for their specific application, thereby aligning laboratory practices with global sustainability goals and regulatory expectations [16].

Metric Profiles and Comparative Analysis

National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI)

Principles and Characteristics: The National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI) is one of the earliest and simplest tools developed for greenness assessment. Its pictogram consists of four quadrants, each representing a different environmental criterion: (1) PBT (persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic chemicals), (2) hazardous chemicals, (3) corrosive pH, and (4) waste quantity [6] [17]. A quadrant is colored green if the method meets the criteria for that category, providing a quick, at-a-glance assessment.

Strengths and Limitations: NEMI's primary advantage is its simplicity and user-friendliness, requiring minimal time or expertise to interpret [17]. However, this simplicity is also its greatest weakness. The binary (green/blank) scoring system lacks granularity, making it difficult to distinguish between methods with moderate versus significant environmental impacts [6]. Furthermore, NEMI does not cover the entire analytical workflow, focusing only on specific chemical hazards and waste, while ignoring critical factors like energy consumption, operator safety, and sample preparation [15] [18]. Its limited scope often results in low sensitivity for comparative assessments, as evidenced by a study of 16 chromatographic methods for hyoscine N-butyl bromide, where 14 methods had identical NEMI pictograms, failing to reveal meaningful differences in their environmental impact [17].

Analytical Eco-Scale

Principles and Characteristics: The Analytical Eco-Scale offers a semi-quantitative approach to greenness assessment. It begins with a base score of 100 and subtracts penalty points for each non-green aspect of the analytical method, such as the use of hazardous reagents, high energy consumption, or large waste generation [6] [19]. The final score provides a direct numerical comparison between methods, with a higher score indicating a greener method. Scores above 75 are classified as "excellent green analysis," while scores below 50 represent "inadequate green analysis" [17] [19].

Strengths and Limitations: The Analytical Eco-Scale's key strength is its quantitative output, which facilitates straightforward ranking and comparison of different methods [17]. The penalty system encourages transparency in reporting all non-ideal procedures. However, a significant limitation is its reliance on expert judgment for assigning penalty points, which can introduce subjectivity [6]. Additionally, the tool lacks a visual pictogram, which may reduce its immediate accessibility and impact, particularly for non-specialists or in educational contexts [6].

Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI)

Principles and Characteristics: The Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) was developed to provide a more comprehensive and visually intuitive assessment than its predecessors. GAPI employs a five-part, color-coded pictogram (green, yellow, red) that covers the entire analytical process, from sample collection and preservation through sample preparation to instrumental analysis and final determination [6] [20]. Each segment is divided into several sub-areas, allowing for a detailed evaluation of each step's environmental impact.

Strengths and Limitations: GAPI's primary advantage is its comprehensive scope and ability to visually pinpoint the specific stages within an analytical method that have the highest environmental impact [6]. This detailed visualization helps analysts identify areas for improvement. A notable limitation is that GAPI does not generate a single, overall numerical score, making direct, at-a-glance comparisons between methods slightly more challenging [17]. Furthermore, the assignment of colors can still involve a degree of subjectivity [6]. To address some of these limitations, modified versions such as MoGAPI (Modified GAPI) and ComplexGAPI have been developed to incorporate cumulative scoring and pre-analytical processes, respectively [6].

Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) Metric

Principles and Characteristics: The Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) metric represents a significant advancement in greenness assessment tools. It evaluates methods based on all 12 principles of GAC, resulting in a unified result that combines a circular pictogram divided into 12 sections with a numerical score between 0 and 1 [15] [6]. Each section of the pictogram corresponds to one GAC principle and is colored on a gradient from red to green, while the central score provides a quantitative measure. The calculation is often automated via software, enhancing objectivity and ease of use [17].

Strengths and Limitations: AGREE's main strengths are its comprehensiveness, alignment with the foundational principles of GAC, and user-friendly output that combines visualization with a quantitative score [17]. The software-driven calculation reduces subjectivity. A limitation is that it may not fully account for pre-analytical processes, such as the synthesis of reagents [6]. Its dedicated counterpart, AGREEprep, was specifically designed to evaluate the sample preparation step, which is often the most resource-intensive part of an analysis [15] [21]. A large-scale evaluation of 174 standard methods using AGREEprep revealed generally poor performance, with 67% of methods scoring below 0.2, highlighting a significant gap in the sustainability of common analytical practices [21].

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Key Greenness Assessment Metrics

| Metric | Assessment Scope | Scoring System | Output Format | Primary Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | Limited (4 criteria) | Binary (Pass/Fail) | Four-quadrant pictogram | Simple, fast, user-friendly [17] | Lacks granularity; low discrimination power [6] [17] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Broad | Semi-quantitative (100 - Penalties) | Numerical score (0-100) [19] | Facilitates direct method ranking; transparent [17] | Subjective penalty assignment; lacks visual component [6] |

| GAPI | Comprehensive (Full lifecycle) | Qualitative (Green, Yellow, Red) | Multi-section pictogram | Identifies high-impact stages visually [6] | No overall numerical score; some subjectivity [6] [17] |

| AGREE | Comprehensive (12 GAC Principles) | Quantitative (0-1) | 12-section pictogram + central score | Comprehensive, software-assisted, easy comparison [6] [17] | May not fully cover pre-analytical steps [6] |

Greenness Assessment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a recommended decision pathway for selecting and applying greenness assessment tools to analytical methods, particularly in the context of pharmaceutical research involving spectroscopy and chromatography.

Diagram 1: Greenness assessment tool selection workflow.

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Case Study: Comparative Assessment of Cannabinoid Analysis Methods

A recent study provides a robust protocol for the comparative application of multiple greenness metrics. The research aimed to evaluate eight different HPLC and UHPLC methods for determining cannabinoids in oils using NEMI, Analytical Eco-Scale, AGREE, and GAPI [19].

Experimental Protocol:

- Method Identification: A systematic literature review was conducted to identify relevant chromatographic methods for cannabinoid analysis in oil matrices.

- Data Extraction: Key method parameters were extracted, including sample preparation techniques, solvent types and volumes, energy consumption, waste generation, and instrument type.

- Metric Application: Each of the eight shortlisted methods was systematically evaluated using the four assessment tools according to their standard protocols.

- Comparative Analysis: The outputs from the different metrics were compared to draw conclusions about the relative greenness of the methods.

Results and Findings:

- The Analytical Eco-Scale proved highly effective in this context. It categorized seven methods as "acceptable" (scoring between 50-73) and one method as "excellent" (scoring 80) [19].

- The study concluded that the application of GAC metrics during method development is crucial for reducing the environmental footprint of analytical activities [19].

Case Study: AQbD-Driven Green HPLC Method Development

The integration of Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) with GAC principles represents a transformative approach for developing robust and sustainable methods. A case study developed an AQbD-driven RP-HPLC method for quantifying irbesartan in chitosan nanoparticles [16].

Experimental Protocol:

- Define Analytical Target Profile (ATP): The method's purpose and required performance criteria (accuracy, precision, greenness) were established.

- Risk Assessment: Tools like Ishikawa diagrams and Failure Mode & Effects Analysis (FMEA) were used to identify Critical Method Parameters (CMPs) such as mobile phase composition and flow rate.

- Design of Experiments (DoE): A Central Composite Design was employed to systematically optimize the CMPs while minimizing experimental runs, aligning with green goals.

- Method Validation & Greenness Assessment: The optimized method, which used an ethanol-sodium acetate mobile phase, was validated and its greenness was confirmed using AGREE and other metrics [16].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Green Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Item | Function in Analysis | Green Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Less toxic alternative mobile phase component in HPLC/UHPLC [16] [20]. | Biobased, renewable, less hazardous than acetonitrile or methanol [16]. |

| Water | Solvent for mobile phases and sample preparation [20]. | Non-toxic, safe, and readily available. |

| Phosphate Buffers | Used to adjust pH of mobile phases to control separation [20]. | Should be prepared in minimal concentrations to reduce waste toxicity. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Sorbents | For sample clean-up and pre-concentration of analytes [22]. | Method should be optimized to minimize sorbent and solvent use. |

| Core-Shell or Sub-2µm Columns | Stationary phases for HPLC/UHPLC to enhance separation efficiency [16]. | Enable faster run times and reduced solvent consumption per analysis. |

The comparative analysis of NEMI, Analytical Eco-Scale, GAPI, and AGREE reveals a clear evolution in greenness assessment: from simple, binary tools to comprehensive, quantitative, and software-assisted metrics. For modern pharmaceutical researchers comparing spectroscopy and chromatography, AGREE and GAPI currently offer the most balanced approach, providing the detail needed for a meaningful environmental impact assessment.

The future of greenness assessment lies in holistic frameworks that balance environmental sustainability with analytical performance and practical applicability. The White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) concept integrates the "green" dimension with "red" (analytical performance) and "blue" (practicality) criteria [23]. New tools like the Red Analytical Performance Index (RAPI) for "redness" and the Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) for "blueness" are emerging to complement established green metrics [20] [23]. Furthermore, the integration of AQbD with GAC provides a systematic framework for building sustainability into methods from their inception, ensuring they are not only environmentally sound but also robust, reliable, and ready to meet the demands of modern pharmaceutical analysis [16].

In the pursuit of environmentally responsible science, the terms "sustainability" and "circularity" are often used interchangeably within analytical chemistry, creating conceptual ambiguity that hinders meaningful progress. While both frameworks aim to reduce environmental impact, they operate on fundamentally different economic models and principles. Sustainability represents a holistic concept balancing three interconnected pillars: economic stability, social well-being, and environmental conservation [24]. In contrast, circularity operates primarily within the environmental and economic dimensions, focusing specifically on minimizing waste and keeping products and materials in circulation for as long as possible [25] [24].

This distinction carries profound implications for analytical chemistry, where traditional practices have largely followed a linear "take-make-consume and dispose" model [25]. The analytical chemistry sector's reliance on energy-intensive processes, non-renewable resources, and waste generation creates unsustainable pressures on the environment [24]. While Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has made significant strides in reducing the environmental footprint of analytical methods through minimized solvent use, energy efficiency, and waste reduction [26] [6], it predominantly aligns with linear economy approaches rather than circular ones [25].

The emerging framework of Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) represents a more transformative approach, aiming to eliminate waste, circulate products and materials, minimize hazards, and save resources throughout the entire analytical system [25]. This evolution from green to circular thinking necessitates new assessment metrics and methodological approaches, particularly when comparing established techniques like chromatography with emerging spectroscopic methods in pharmaceutical research.

Theoretical Foundations and Assessment Metrics

The Principles of Green and Circular Analytical Chemistry

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) established twelve guiding principles to reduce the environmental impact of analytical methods [6] [10]. These principles emphasize direct analytical techniques, reduced sample size, in situ measurements, waste minimization, safer solvents, and energy efficiency, providing a foundation for more sustainable practices [10]. The principles are operationalized through practical strategies including solvent replacement, sample preparation minimization, and alternative extraction methods [26].

Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) expands beyond GAC's focus on laboratory practices by introducing twelve complementary goals that target the radical transformation of the entire analytical chemistry system [25]. These goals address the full lifecycle of analytical products, advocating for resource recovery, recycling, and extended producer responsibility, thus connecting post-use and production while preserving natural resources [25].

Greenness Assessment Tools for Analytical Methods

The development of standardized metrics has been crucial for evaluating the environmental performance of analytical methods. The table below summarizes key assessment tools and their applications to spectroscopy and chromatography.

Table 1: Greenness Assessment Metrics for Analytical Methods

| Metric Tool | Full Name | Primary Focus | Output Type | Applicability to Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | National Environmental Methods Index | Basic environmental criteria | Binary pictogram | Foundational tool for both techniques [6] |

| AES | Analytical Eco-Scale | Penalty points for non-green attributes | Numerical score (0-100) | Applied to MS methods; useful for both [27] [6] |

| GAPI | Green Analytical Procedure Index | Entire analytical workflow | Color-coded pictogram | Comprehensive workflow assessment [6] [10] |

| AGREE | Analytical Greenness Metric | All 12 GAC principles | Radial chart (0-1) + score | Holistic evaluation for both techniques [27] [6] [10] |

| AGREEprep | AGREE for Sample Preparation | Sample preparation stage | Pictogram + score | Critical for sample-intensive methods [6] [10] |

| BAGI | Blue Applicability Grade Index | Practical applicability | "Asteroid" pictogram + score | Complementary RGB model assessment [10] |

These metrics enable researchers to quantify and compare the environmental performance of analytical methods, though they primarily address the "green" (environmental) component rather than full circularity or the complete sustainability triad [6] [10]. The emerging concept of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) addresses this limitation by integrating the Red-Green-Blue (RGB) model, where red represents methodological performance, green addresses environmental sustainability, and blue evaluates practical applicability [6] [10].

Analytical Techniques in Pharmaceutical Research

Chromatographic Methods: Capabilities and Environmental Profile

Chromatographic techniques, particularly High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Gas Chromatography (GC), remain foundational in pharmaceutical analysis due to their separation power, sensitivity, and quantitative capabilities [26] [28]. These techniques separate mixture components through differential partitioning between mobile and stationary phases, enabling precise quantification of individual analytes in complex matrices [28].

The primary environmental concerns for chromatographic methods include substantial organic solvent consumption, high energy requirements, and significant waste generation—conventional HPLC can produce 1-1.5 liters of waste per day [26]. Sample preparation for chromatographic analysis, particularly for solid samples like plant materials, often involves multiple steps including weighing, grinding, solvent extraction, agitation, filtration, and dilution [28].

Recent advancements focus on greening chromatographic approaches through:

- Solvent reduction and replacement with greener alternatives like ethanol or water [26]

- Method miniaturization using techniques like UHPLC and micro-HPLC [26] [14] [10]

- Alternative sample preparation methods such as Solid Phase Extraction (SPE), QuEChERS, and Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) [26]

- Direct chromatographic methods that eliminate sample preparation entirely where feasible [26]

- Instrumental innovations including reduced power consumption, solvent usage, and operational costs [14]

Spectroscopic Methods: Capabilities and Environmental Profile

Spectroscopic techniques, particularly infrared (IR) and ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) spectroscopy, study the interaction of light with matter to provide quantitative and qualitative information based on Beer's Law [28]. These techniques enable rapid analysis of cannabinoids in various matrices including plant material, extracts, and distillates with minimal sample preparation—often requiring only grinding for solids or simple placement on a window for liquids using attenuated total reflection (ATR) [28].

The environmental advantages of spectroscopic methods include:

- Minimal solvent requirements and reduced chemical consumption [28]

- Rapid analysis times (approximately 2 minutes per sample for IR spectroscopy) [28]

- Lower energy consumption compared to chromatographic systems [28]

- Minimal waste generation due to reduced reagent use [28]

However, spectroscopic methods face limitations in complex mixture analysis due to overlapping spectral signatures and generally serve as secondary techniques requiring calibration against primary methods [28] [29].

Comparative Analysis: Sustainability Dimensions

Table 2: Sustainability Comparison of Spectroscopy and Chromatography for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Parameter | Chromatography | Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Scope | Separation and quantification of individual mixture components [28] [29] | Determination of main functional groups; compound class identification [28] [29] |

| Multi-analyte Capability | Requires separation; limited by chromatographic resolution [28] | Simultaneous multi-element/compound determination without separation [29] |

| Sample Preparation | Often extensive; particularly for solid samples [28] | Minimal; sometimes direct analysis without treatment [28] [29] |

| Solvent Consumption | High (traditional methods); reduced with green approaches [26] | Minimal to none [28] |

| Energy Demand | High (pumps, ovens, detectors) [26] | Moderate to low [28] |

| Waste Generation | Significant (1-1.5 L/day for traditional HPLC) [26] | Minimal [28] |

| Analysis Speed | Minutes to hours per sample [28] | Seconds to minutes [28] [29] |

| Applicability | Primary method for quantification; regulatory compliance [28] | Secondary analysis; requires reference methods [28] |

Circularity Assessment: Beyond Environmental Metrics

The Twelve Goals of Circular Analytical Chemistry

Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) introduces a goal-setting framework that transcends the environmental focus of GAC by addressing the entire analytical lifecycle [25]. The twelve goals of CAC include:

- Reducing resource consumption by minimizing materials and energy inputs

- Using renewable resources where possible

- Preventing waste generation through smarter design

- Managing waste responsibly when generation is unavoidable

- Encouraging recycling and recovery of materials

- Promoting reuse of products and materials

- Implementing resource recovery from waste streams

- Eliminating hazards to human health and the environment

- Improving energy efficiency across operations

- Enabling the use of renewable energy

- Designing sustainable products with circularity in mind

- Implementing sustainable manufacturing processes [25]

This framework requires evaluating analytical techniques not merely by their immediate environmental impact but by their position within circular systems that maintain material value through multiple use cycles.

Circularity Challenges in Analytical Practice

The transition from linear to circular analytical chemistry faces significant implementation barriers. Analytical chemistry remains a traditional and conservative field with limited cooperation between key stakeholders including manufacturers, researchers, routine laboratories, and policymakers [24]. This coordination failure hinders the development of circular processes such as solvent recycling, column reconditioning, or instrument remanufacturing, which demand far more collaboration than conventional linear methods [24].

Additionally, the rebound effect presents a paradoxical challenge where efficiency gains in analytical methods lead to increased overall resource consumption through more frequent testing [24]. For example, a novel low-cost microextraction method that uses minimal solvents might lead laboratories to perform significantly more extractions, ultimately increasing total chemical usage and waste generation [24].

Experimental Protocols for Greenness Assessment

Methodology for Comparative Technique Evaluation

To objectively assess the greenness and circularity of analytical techniques, researchers should implement standardized evaluation protocols:

AGREE Assessment Protocol:

- Define assessment scope - clearly bound the analytical system to be evaluated

- Gather input data - collect information on solvents, reagents, energy consumption, waste generation, and instrumentation

- Apply AGREE calculator - input data into open-access AGREE software

- Interpret results - analyze the radial diagram and numerical score (0-1) across all 12 GAC principles

- Compare alternatives - use scores to benchmark against other methodological approaches [6] [10]

Sample Preparation Evaluation with AGREEprep:

- Document the sample preparation workflow in detail

- Quantify material flows - measure solvents, reagents, and consumables

- Evaluate the ten AGREEprep criteria - including sample mass, collection time, and operator safety

- Generate comparative scores - use dedicated software for standardized assessment [6]

Experimental Design for Circularity Assessment

Evaluating circularity requires expanded experimental boundaries that consider the complete lifecycle of analytical components:

Solvent Recovery Efficiency Protocol:

- Establish baseline consumption - measure solvent volumes used in standard methods

- Implement recovery systems - install distillation or purification apparatus

- Quantify recovery rates - measure the percentage of solvent successfully reclaimed

- Test analytical performance - verify that recovered solvents maintain method validity

- Calculate circularity metrics - determine the reduction in virgin solvent demand

Instrument End-of-Life Management Assessment:

- Document manufacturer take-back programs - identify existing circular infrastructure

- Quantify remanufacturing potential - assess the percentage of components suitable for reuse

- Measure recycling rates - determine the proportion of materials successfully cycled

- Evaluate upgradeability - assess design features that extend functional lifespan

The following workflow diagram illustrates the strategic decision process for implementing circular principles in analytical method development:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Sustainable Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function | Green/Circular Attributes | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol & Water | Green solvent replacement | Renewable, biodegradable, low toxicity | Mobile phase modifier in HPLC [26] [10] |

| Primary Secondary Amine (PSA) | Dispersive SPE sorbent | Efficient cleanup with reduced solvent consumption | QuEChERS extraction for pharmaceuticals [26] |

| Solid Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers | Solvent-free sample preparation | Reusable, minimal waste generation | Direct extraction of analytes from solutions [26] |

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADESs) | Biobased extraction media | Renewable feedstock, biodegradable | Alternative to conventional organic solvents [27] |

| Micropillar Array Columns | Lithographically engineered separation | Enhanced efficiency, reduced solvent consumption | UHPLC for pharmaceutical analysis [14] |

| ML307 | ML307, MF:C28H36ClN7O, MW:522.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| SRC-1 (686-700) | SRC-1 (686-700), MF:C77H131N27O21, MW:1771.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The differentiation between sustainability and circularity in analytical chemistry represents more than semantic precision—it acknowledges distinct frameworks with complementary strengths. Green Analytical Chemistry focuses primarily on minimizing the environmental impact of analytical processes through reduced solvent toxicity, waste generation, and energy consumption [26] [6]. Circular Analytical Chemistry expands this vision by transforming the entire analytical system to eliminate waste and circulate materials, integrating strong economic considerations while addressing social aspects less prominently [25] [24].

For pharmaceutical researchers selecting between spectroscopic and chromatographic techniques, this distinction enables more informed decisions that align with broader organizational sustainability goals. Chromatography offers unparalleled separation power and regulatory acceptance but requires significant greening interventions to reduce its environmental footprint [26] [28]. Spectroscopy provides rapid, solvent-free analysis with inherent green advantages but faces limitations in complex mixture analysis [28] [29].

The future of sustainable pharmaceutical analysis lies not in universally favoring one technique over another, but in developing integrated approaches that leverage the strengths of both methods while applying the complementary frameworks of sustainability and circularity. This requires ongoing innovation in green chemistry principles, adoption of circular economy models, and honest assessment of trade-offs between analytical performance, environmental impact, and practical feasibility [24] [14]. Through this multidimensional approach, analytical chemistry can transform from a source of environmental concern to a leader in sustainable scientific practice.

The Role of Regulatory Guidelines (ICH, USP) in Promoting Green Practices

The pharmaceutical industry faces the dual challenge of ensuring stringent product quality while minimizing its environmental footprint. Regulatory guidelines established by the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) and the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) provide the fundamental framework for pharmaceutical quality control and assurance [30] [31]. Traditionally focused on safety, efficacy, and quality, these guidelines are increasingly intersecting with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), which aims to reduce the environmental impact of analytical methods [10] [6]. This article explores how ICH and USP guidelines implicitly and explicitly promote greener practices in pharmaceutical analysis, particularly within the context of choosing between spectroscopic and chromatographic techniques for drug development.

The evolution of green chemistry from a specialized interest to a core consideration in analytical science reflects a broader shift toward sustainable practices. Green analytical chemistry has emerged as a critical discipline focused on minimizing the environmental footprint of analytical methods by reducing or eliminating dangerous solvents, reagents, and other materials while maintaining rigorous validation parameters [6]. This alignment between regulatory compliance and environmental responsibility creates a powerful impetus for adopting greener approaches in pharmaceutical analysis.

Fundamental Regulatory Guidelines: ICH and USP

ICH Guidelines Framework

The International Council for Harmonisation represents a collaborative effort between regulatory authorities and the pharmaceutical industry to develop globally harmonized guidelines. Formed in 1990, ICH seeks to streamline and standardize technical requirements for the development, registration, and post-approval phases of pharmaceutical products [31]. Several key ICH guidelines provide the foundation for pharmaceutical quality control:

- ICH Q7: Good Manufacturing Practice for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) establishes requirements for maintaining cleanroom integrity and controlling potential contaminants during manufacturing [31].

- ICH Q8 to Q12: These guidelines emphasize a systematic approach to pharmaceutical development encompassing quality-by-design (QbD) principles, risk management, and continuous improvement throughout the product lifecycle [31].

- ICH Q9: Quality Risk Management outlines a systematic approach to risk management throughout the pharmaceutical lifecycle, enhancing decision-making processes related to manufacturing and ensuring product quality and patient safety [31].

For impurity profiling specifically, ICH guidelines Q3A (new drug substances), Q3B (new drug products), Q3C (residual solvents), and Q3D (elemental impurities) provide critical frameworks for identification, qualification, and control specifications [30]. These guidelines classify impurities into categories such as organic impurities (process-related and degradation products), inorganic impurities, and residual solvents, establishing thresholds for reporting, identification, and qualification.

USP Standards and Requirements

The United States Pharmacopeia establishes enforceable standards that define the identity, strength, quality, purity, and consistency of drugs, excipients, and dietary supplements. While rooted in the United States, USP standards have global influence, with many countries adopting or aligning their standards with USP to foster international harmonization [31].

USP General Chapter 797 provides specific requirements for the design and maintenance of cleanrooms used in compounding sterile preparations, encompassing parameters such as air quality, cleanliness, temperature, and humidity control [31]. This chapter mandates routine environmental monitoring of cleanrooms to ensure compliance with specified standards, including monitoring airborne particulates and microbial contamination. These requirements, while focused on product quality, inherently encourage efficient resource use and waste reduction—core principles of green chemistry.

Greenness Assessment Tools and Methodologies

Established Greenness Assessment Metrics

The evaluation of analytical methods' environmental impact has evolved significantly, with several robust tools now available to quantify greenness:

Table 1: Key Greenness Assessment Tools for Analytical Methods

| Tool | Graphical Representation | Main Focus | Output Type | Notable Features | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAPI | Color-coded pictogram | Entire analytical workflow | Pictogram | Easy visualization, no total score | [10] |

| AGREE | Radial chart | 12 principles of GAC | Score 0-1 + pictogram | Holistic single-score metric | [10] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Numerical score | Hazardous chemicals, energy, waste | Penalty-point system | Simple scoring (ideal=100) | [6] |

| BAGI | Pictogram + % score | Method applicability | Score + visual | Assesses practical viability | [10] |

| NEMI | Simple pictogram | Basic environmental criteria | Binary (pass/fail) | Limited differentiation | [6] |

The Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) tool exemplifies the advancement in greenness assessment. It integrates all 12 GAC principles into a holistic algorithm, providing a single-score evaluation supported by an intuitive graphic output [10]. The AGREE chart assigns scores on a scale from 0 to 1, delivering a normalized assessment of key parameters including solvent toxicity, energy consumption, sample preparation complexity, and analytical throughput.

The Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) complements these greenness tools by addressing practical and operational aspects of analytical methods [10]. BAGI evaluates ten key attributes related to applicability—including analysis type, throughput, reagent availability, automation, and sample preparation—and provides both a numeric score and a visual "asteroid" pictogram. This tool is particularly relevant for routine food and pharmaceutical laboratories where practical viability is as important as environmental sustainability.

The White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) Framework

The concept of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) has emerged to balance analytical performance (red), environmental sustainability (green), and practical applicability (blue) [10] [6]. A "white" method harmonizes all three dimensions, creating an optimal balance for real-world implementation. This framework encourages method development that satisfies regulatory requirements while advancing sustainability goals.

Diagram 1: White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) Framework. This diagram illustrates how the WAC model balances three critical dimensions, all converging toward regulatory compliance.

Greenness in Practice: Spectroscopy vs. Chromatography

Green Spectroscopic Methods

Spectroscopic techniques often demonstrate inherent green advantages due to their minimal solvent consumption and reduced waste generation. A recent study developed a green spectrofluorimetric method for quantifying sodium oxybate in pharmaceutical and plasma samples using carbon quantum dots (CQDs) as a sustainable fluorescent probe [32]. The method functionalized CQDs with a sodium oxybate-tetraphenylborate complex to enhance selectivity, detecting the drug via fluorescence quenching at 450 nm after excitation at 365 nm.

Experimental Protocol: Green Spectrofluorimetric Analysis

- Sample Preparation: Pharmaceutical samples were prepared by transferring 1 mL of Xyrem oral solution to a 100-mL volumetric flask and diluting with distilled water [32].

- Plasma Sample Preparation: 1 mL of pooled plasma was mixed with sodium oxybate aliquots, followed by protein precipitation with 3 mL of acetonitrile and centrifugation for 30 minutes [32].

- Measurement: The supernatant was evaporated, reconstituted with distilled water, and mixed with 0.70 mL of functionalized CQDs and 1.25 mL of acetate buffer (pH 5) [32].

- Analysis: Fluorescence quenching was measured after 5 minutes incubation at room temperature [32].

- Greenness Assessment: The method achieved a notably elevated greenness score using the AGREE metric, attributed to minimal solvent consumption and avoidance of hazardous chemicals [32].

Green Chromatographic Methods

Chromatographic techniques have traditionally posed environmental challenges due to substantial solvent consumption, but recent advances have significantly improved their greenness profile. A comparative assessment of twelve chromatographic methods for cilnidipine utilized six greenness metrics: GAPI, AGREE, Analytical Eco-Scale, ChlorTox scale, BAGI, and RGB 12 [33]. The study highlighted strategies for improving chromatographic greenness, including solvent substitution, method miniaturization, and waste reduction.

Experimental Protocol: Green GC-MS Analysis

- Instrumentation: Agilent 7890A GC with 5975C mass spectrophotometer and 5% Phenyl Methyl Silox column (30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm) [34].

- Carrier Gas: Helium at constant flow rate of 2 mL/minute [34].

- Temperature Settings: Transfer line 280°C, source quadrupole 230°C, ion source 150°C [34].

- Sample Preparation: PAR/MET stock solution (500/100 mg/mL) in ethanol, with working solutions prepared by 10-fold dilution [34].

- Separation: Achieved within 5 minutes with detection at m/z 109 (PAR) and 86 (MET) [34].

- Validation: Linear ranges of 0.2-80 μg/mL for PAR and 0.3-90 μg/mL for MET with precision (RSD) <4% [34].

- Greenness Assessment: BAGI score of 82.5 confirmed environmental superiority over conventional LC methods [34].

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

Table 2: Greenness Comparison of Spectroscopic vs. Chromatographic Methods

| Parameter | Green Spectrofluorimetry [32] | Green GC-MS [34] | Conventional HPLC [34] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Consumption | Minimal (mL range) | Moderate (uses ethanol) | High (hundreds of mL organic solvents) |

| Energy Consumption | Low | Moderate-High | Moderate |

| Analysis Time | ~5 minutes incubation | 5 minutes runtime | 15-30 minutes typical |

| Waste Generation | Very low | Low | High |

| Toxicity | Low (water, acetate buffer) | Moderate (ethanol) | High (acetonitrile, methanol) |

| Sample Throughput | High | High | Moderate |

| Regulatory Compliance | Full validation per ICH | Full validation per ICH | Full validation per ICH |

Greenness Assessment in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Regulatory Alignment with Green Principles

While ICH and USP guidelines do not explicitly mandate green methods, their emphasis on risk management, resource efficiency, and quality control inherently supports greener approaches. ICH Q9's focus on risk management aligns with the GAC principle of using safer solvents and reagents [31]. Similarly, USP's standards for sterile compounding environments encourage efficient resource use and contamination prevention, indirectly reducing waste [31].

The pharmaceutical quality system outlined in ICH Q10 promotes continuous improvement and optimization of processes, providing a framework for implementing greener analytical methods without compromising quality [31]. This alignment creates opportunities for method developers to incorporate greenness assessment tools alongside traditional validation parameters.

Case Study: Green Method Validation

A comparative greenness assessment of chromatographic methods for cilnidipine demonstrates how regulatory requirements and environmental considerations can be integrated [33]. The study evaluated twelve methods using six assessment tools, revealing that methods with superior greenness profiles maintained full compliance with ICH validation requirements while reducing environmental impact through:

- Solvent substitution: Replacing acetonitrile with ethanol or methanol in mobile phases [30]

- Miniaturization: Using narrow-bore columns (≤2.1 mm diameter) to reduce mobile phase consumption by up to 90% [30]

- Method optimization: Reducing run times and streamlining sample preparation [33]

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Green Analytical Methods

| Reagent/Material | Function | Green Alternative | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | HPLC mobile phase | Ethanol, methanol | Chromatography [30] |

| Carbon Quantum Dots | Fluorescent probe | Sustainable nanomaterials | Spectrofluorimetry [32] |

| Tetraphenylborate | Ion-pairing agent | Selective complexation | Method selectivity [32] |

| Supercritical COâ‚‚ | Mobile phase | Non-toxic alternative to organic solvents | SFC [30] |

| Ionic Liquids | Mobile phase additive | Improve chromatography | HPLC, CE [30] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents | Extraction media | Biobased, low toxicity | Sample preparation [30] |

Regulatory guidelines from ICH and USP provide a critical foundation for integrating green practices into pharmaceutical analysis. While primarily focused on product quality and patient safety, these guidelines establish frameworks that align with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry. The comparative analysis of spectroscopic and chromatographic methods reveals significant opportunities for reducing the environmental impact of pharmaceutical analysis while maintaining regulatory compliance.

The emergence of comprehensive greenness assessment tools like AGREE, GAPI, and BAGI enables quantitative evaluation of method environmental performance, facilitating the development of "white" methods that balance analytical performance, practical applicability, and environmental sustainability. As the pharmaceutical industry continues to embrace sustainability goals, the integration of greenness assessment with regulatory compliance will play an increasingly important role in advancing pharmaceutical analysis practices that protect both patient health and the environment.

Future developments will likely see greater harmonization between explicit green chemistry principles and regulatory requirements, driven by advances in green metric tools, sustainable technologies, and growing industry commitment to environmental responsibility.

Implementing Green Spectroscopy and Chromatography in the Lab

In the pharmaceutical industry, the drive towards sustainability has intensified the focus on Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), which aims to minimize the environmental impact of analytical methods [6]. This represents a significant shift from traditional techniques, such as chromatography, which often involve substantial consumption of hazardous solvents, generate considerable waste, and require high energy input [13]. The cumulative environmental burden of these methods, when scaled across global pharmaceutical manufacturing and thousands of analyses, is substantial [13]. Vibrational spectroscopic techniques, particularly Near-Infrared (NIR) and Raman spectroscopy, have emerged as powerful, reagent-free alternatives, offering a pathway to reduce this environmental footprint significantly [35]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two techniques, underpinned by experimental data, to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their pursuit of greener analytical practices.

Fundamental Principles

NIR Spectroscopy operates within the 780 to 2500 nanometers segment of the electromagnetic spectrum. It probes the overtone and combination bands of fundamental molecular vibrations, such as C-H, O-H, and N-H stretches [36]. Its working mechanism is based on the absorption of near-infrared radiation by these chemical bonds, providing insights into the functional groups present and their concentrations [36].

Raman Spectroscopy, named after Sir C. V. Raman, is based on the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser. When light interacts with a sample, a tiny fraction of the scattered photons undergo a shift in energy (frequency) corresponding to the vibrational energies of the molecules, creating a unique spectral fingerprint [36].

Key Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Development

- Raw Material Identification: Both techniques are used for the rapid, non-destructive verification of incoming raw materials and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [37] [36].

- Process Monitoring and PAT: As Process Analytical Technology (PAT) tools, they enable real-time, in-line monitoring of critical process steps such as reactions, crystallization, and solvent exchanges, facilitating Quality by Design (QbD) [37].

- Polymer Dissolution Monitoring: Raman has been successfully applied to monitor dissolved polymer concentrations during dissolution-based recycling processes, with models developed to predict concentration across different solvent systems [38].

- Content Uniformity and Dissolution Prediction: Both NIR and Raman chemical imaging have been used to predict the dissolution profiles of sustained-release tablets by quantifying the concentration and particle size of release-controlling excipients like Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) [39].

- Water Quantification in Deep Eutectic Solvents: These techniques have been evaluated as cost-effective, label-free tools for monitoring water content in Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES), which are promising green solvent alternatives [35].

Experimental Comparison: Performance Data and Protocols

Quantitative Comparison of Analytical Performance

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for NIR and Raman spectroscopy from direct comparison studies.

Table 1: Direct Performance Comparison of NIR and Raman Spectroscopy

| Application / Metric | NIR Performance | Raman Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Quantification in NADES (RMSEP) [35] | Benchtop: 0.56% added waterHandheld: 0.68% added water | 0.67% added water | Levulinic Acid/L-Proline NADES; PLSR models. |

| Dissolution Profile Prediction (Average fâ‚‚ similarity) [39] | 57.8 | 62.7 | Sustained-release tablets; based on HPMC concentration & particle size from chemical imaging. |

| Analysis Speed [36] | 2 – 5 seconds | ~1 Minute | Typical time for substance identification. |

| Polymer Concentration Monitoring [38] | Effective with EPO-PLSR for multi-solvent systems. | Effective with EPO-PLSR for multi-solvent systems; sometimes superior to ATR-IR. | Monitoring dissolved polypropylene in various solvents. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure the reproducibility of the comparative data, the following summarizes the key methodologies from the cited studies.

Protocol 1: Water Quantification in Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) [35]

- Objective: To monitor water content in Levulinic Acid/L-Proline (LALP) NADES.

- Sample Preparation: LALP NADES was prepared in a 2:1 molar ratio via heating and stirring. Samples with systematically varied added water concentrations (0% to ~16.7% w/w) were created.

- Data Acquisition: ATR-IR, NIR (benchtop and handheld), and Raman (in quartz cuvettes) spectra were collected for all samples.

- Data Analysis: Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) models were built to correlate spectral data to the known added water concentration. Model performance was evaluated using Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP) and mean relative error.

Protocol 2: Predicting Tablet Dissolution Profiles [39]

- Objective: To predict the drug release rate from sustained-release tablets based on chemical images.

- Sample Preparation: Tablets with varying concentrations and particle sizes of HPMC were manufactured.

- Data Acquisition: Both Raman and NIR chemical images (hyperspectral data cubes) were collected for the tablets.

- Data Analysis: Classical Least Squares (CLS) was used to create concentration maps of HPMC. A Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) was then applied to extract HPMC particle size information. Finally, an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) used the average HPMC concentration and predicted particle size to forecast the complete dissolution profile.

Protocol 3: Monitoring Polymer Content in Multi-Solvent Systems [38]

- Objective: To monitor dissolved polypropylene (PP) concentration in various solvents and their mixtures.

- Sample Preparation: Solutions of PP in different solvents (e.g., xylene, decalin) at varying concentrations were prepared.

- Data Acquisition: Raman and NIR spectra were collected for these solutions.

- Data Analysis: Two modeling approaches were used: 1) Single-solvent PLSR models, and 2) A multi-solvent model using External Parameter Orthogonalisation (EPO) to remove the spectral contribution of the solvent, allowing for a generalized calibration.

Greenness Assessment: A Framework for Evaluation

The "greenness" of an analytical method is systematically evaluated using dedicated assessment tools that consider multiple environmental and safety criteria. The evolution of these metrics has progressed from basic pictograms to comprehensive, quantitative scores [6].

Diagram 1: Greenness assessment workflow. The process involves defining the method, selecting tools like AGREE or GAPI, and implementing improvements.

Key Greenness Assessment Tools

- AGREE (Analytical GREEnness):

- GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index):

- Uses a five-part, color-coded pictogram to assess the environmental impact of each stage in an analytical procedure [6].

- AGREEprep:

- The first tool dedicated specifically to evaluating the environmental impact of sample preparation, which is often the most resource-intensive step [6].

- NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index):

- An early, simple pictogram indicating whether a method meets four basic environmental criteria related to toxicity, waste, and safety [6].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions in experiments comparing NIR and Raman spectroscopy.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Item | Function & Application | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) | Green solvent model system for testing water quantification methods [35]. | Levulinic Acid/L-Proline (2:1 molar ratio) [35]. |

| Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose (HPMC) | A common sustained-release agent in tablets; its concentration and particle size determine drug release rates [39]. | Used as a critical quality attribute in dissolution profile prediction models [39]. |

| Chemometric Software | Essential for building quantitative models (e.g., PLSR, ANN) and processing spectral data [35] [39]. | Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) for water quantification; Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) for particle size analysis [35] [39]. |

| Calibration Standards | Samples with known concentrations of the target analyte, used to build a predictive model [37]. | Precisely prepared solvent mixtures or spiked reaction masses with concentrations validated by a reference method like GC [37]. |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) Probes | Robust, in-line probes that can be immersed in reaction vessels for real-time monitoring [37]. | Fiber-optic immersion probes compliant with safety standards (e.g., ATEX) for use in manufacturing environments [37]. |

The direct comparison of NIR and Raman spectroscopy reveals that neither technique is universally superior; instead, they offer complementary strengths. Raman spectroscopy often provides greater chemical specificity and clearer spectral features in complex matrices, which can translate to slightly better predictive performance in some quantitative applications, such as dissolution profiling [39]. NIR spectroscopy, however, frequently excels in speed, operational safety, and suitability for in-line PAT applications due to its non-destructive nature and rapid analysis times [39] [36].

The most significant shared advantage of both techniques over traditional chromatographic methods is their inherently greener profile. As reagent-free, non-destructive methods that minimize or eliminate solvent consumption and waste generation, NIR and Raman spectroscopy align perfectly with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry [35] [6]. The choice between them should be guided by the specific analytical problem, the nature of the sample, and the required balance between specificity, speed, and ease of implementation. Their adoption represents a critical step toward more sustainable and efficient pharmaceutical research and development.