Greenness Comparison in Analytical Chemistry: Spectroscopic vs. Chromatographic Methods for Pharmaceutical Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the greenness of spectroscopic and chromatographic methods, crucial for researchers and professionals in drug development seeking to implement sustainable laboratory practices.

Greenness Comparison in Analytical Chemistry: Spectroscopic vs. Chromatographic Methods for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the greenness of spectroscopic and chromatographic methods, crucial for researchers and professionals in drug development seeking to implement sustainable laboratory practices. It covers the foundational principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and its evolution into White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which balances ecological, practical, and analytical performance. The content details specific green methodologies for both technique types, including solvent replacement and miniaturization strategies. A significant focus is placed on modern greenness assessment tools like AGREE, GAPI, and AGREEprep, providing a framework for troubleshooting, optimization, and objective validation. The article concludes with a forward-looking perspective on integrating sustainability into analytical method selection and development.

Principles and Evolution of Green Analytical Chemistry

Defining Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and its 12 Core Principles

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) is a specialized branch of analytical chemistry focused on developing and applying environmentally friendly methods and practices in chemical analysis [1]. It aims to minimize the environmental impact of analytical activities by reducing waste and energy consumption, using safer solvents and reagents, and ensuring the safety of operators, all while maintaining the high accuracy and reliability of analytical results [2] [3]. The core of GAC is a set of 12 principles that provide a framework for making analytical practices more sustainable [2] [4].

The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

The 12 principles of GAC were adapted from the original 12 principles of green chemistry to better fit the specific needs and processes of analytical laboratories [2] [4]. They serve as practical guidelines for chemists.

The table below outlines these 12 core principles.

| Principle Number | Principle Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Direct analytical techniques should be applied to avoid sample treatment. [2] |

| 2 | Minimal sample size and minimal number of samples are goals. [2] |

| 3 | In situ measurements should be performed. [2] |

| 4 | Integration of analytical processes and operations saves energy and reduces the use of reagents. [2] |

| 5 | Automated and miniaturized methods should be selected. [2] |

| 6 | Derivatization should be avoided. [2] |

| 7 | Generation of a large volume of analytical waste should be avoided and proper management of analytical waste should be provided. [2] |

| 8 | Multi-analyte or multi-parameter methods are preferred versus methods using one analyte at a time. [2] |

| 9 | The use of energy should be minimized. [2] |

| 10 | Reagents obtained from renewable sources should be preferred. [2] |

| 11 | Toxic reagents should be eliminated or replaced. [2] |

| 12 | The safety of the operator should be increased. [2] |

These principles emphasize a holistic approach to greening the entire analytical process, from sample collection to waste management [2] [5].

The Framework of White Analytical Chemistry

A modern extension of GAC is the concept of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which proposes that a perfect analytical method should balance three key aspects: Red (analytical performance), Green (environmental impact), and Blue (practical and economic feasibility) [4] [5]. The ideal "white" method achieves a harmonious balance among all three dimensions.

Greenness Assessment: Tools for Evaluating Methods

To objectively evaluate how well an analytical method aligns with GAC principles, several metric tools have been developed. These tools help researchers quantify and compare the environmental footprint of their methods [3] [5].

The following table summarizes the most prominent greenness assessment tools.

| Tool Name | Type of Output | Key Features | Best Used For |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) [5] | Pictogram (binary) | Simple yes/no evaluation of 4 criteria: PBT (persistent, bioaccumulative, toxic), hazardous, corrosive, and waste volume. [5] | Quick, basic initial screening. [5] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [3] | Numerical score (0-100) | Penalty points are subtracted from an ideal score of 100 for hazardous reagents, energy consumption, and waste. [5] | Semi-quantitative comparison between methods. [5] |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [3] [5] | Color-coded pictogram | Evaluates the entire analytical process in 5 steps, from sampling to waste treatment, using a traffic-light color system. [5] | Detailed, visual identification of environmental hotspots in a method. [5] |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) [3] [5] | Numerical score (0-1) & circular pictogram | Assesses the method against all 12 principles of GAC, providing an at-a-glance visual and a quantitative score for easy comparison. [3] [5] | Comprehensive and user-friendly overall greenness assessment. [5] |

| AGREEprep [5] | Numerical score (0-1) & pictogram | A dedicated tool for evaluating the environmental impact of the sample preparation step only. [5] | In-depth analysis of sample preparation, which is often the least green step. [5] |

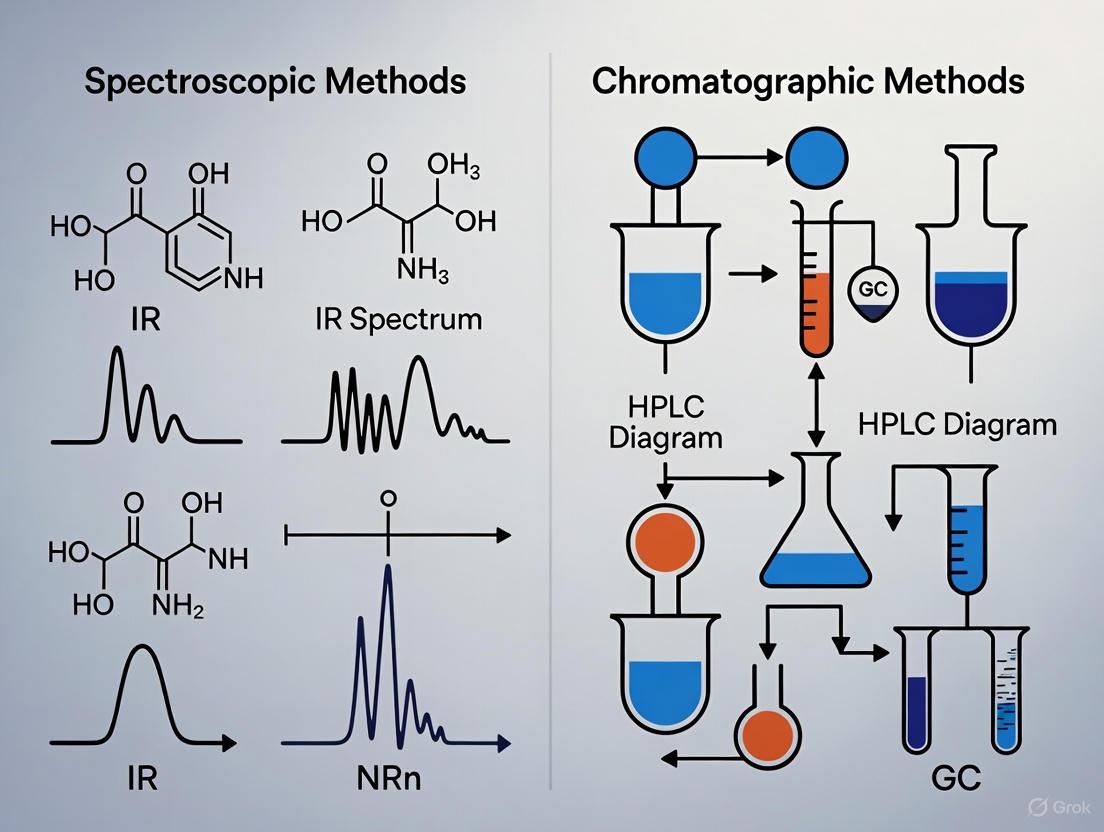

Comparative Analysis: Spectroscopy vs. Chromatography

From the perspective of GAC, spectroscopic and chromatographic techniques have distinct advantages and disadvantages. The choice between them often involves a trade-off between analytical performance, speed, cost, and environmental impact—the core of the "Golden Triangle of Chemical Analysis" [6].

Spectroscopy as a Green Alternative

Spectroscopic techniques often align well with GAC principles, particularly for direct analysis and waste reduction.

- Direct Analysis and Minimal Sample Preparation: Techniques like Infrared (IR) spectroscopy often require little to no sample preparation. For cannabis plant material, for instance, the only preparation may be grinding, with no solvents required [6]. This directly supports GAC Principles 1 (direct techniques) and 2 (minimal sample size) [2].

- Speed and Efficiency: Analysis by IR spectroscopy is very fast, taking about two minutes per sample, which minimizes energy use (Principle 9) [6]. It allows for high-throughput analysis without generating significant waste (Principle 7) [4].

- Non-Destructive Nature: Many spectroscopic methods are non-destructive, allowing the sample to be recovered and reused, which prevents waste (Principle 7) and is crucial in fields like forensic science and archaeology [7].

Chromatography and its Greening Potential

Chromatography, particularly High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), is a powerful workhorse in labs but is traditionally less green due to its high solvent consumption.

- High Solvent Consumption and Waste Generation: A major environmental drawback of HPLC is the large volume of organic solvents, like acetonitrile, used in the mobile phase, leading to significant hazardous waste (contrary to Principles 7 and 11) [8] [9].

- Sample Preparation: Sample prep for chromatographic analysis of solids can be intensive, involving weighing, grinding, solvent extraction, agitation, and filtration, which consumes reagents and time [6].

- Paths to Greener Chromatography:

- Alternative Solvents: Replacing toxic acetonitrile with greener alternatives like methanol or ethanol is a primary strategy [8] [9].

- Method Miniaturization: Techniques like UHPLC (Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography) use smaller columns and significantly lower solvent volumes, supporting Principles 5 (miniaturization) and 7 (waste reduction) [2].

- In silico Modeling: Computer-assisted method development is an emerging green approach. It drastically reduces the need for laborious and solvent-intensive experimental trial-and-error, allowing scientists to design greener methods virtually before any lab work begins [9].

Experimental Comparison: Potency Analysis of Cannabinoids

A practical comparison of spectroscopy and chromatography for cannabinoid potency analysis highlights the real-world trade-offs between these techniques [6].

Experimental Protocol 1: HPLC Analysis

This protocol is based on established methods for determining cannabinoid profiles in cannabis plant material and is considered a primary method due to its high accuracy [6].

- Objective: To separate, identify, and quantify individual cannabinoids (e.g., THC, CBD) in dried cannabis plant material with high accuracy.

- Sample Preparation:

- Weigh a precise amount of dried and ground plant material.

- Add a known volume of an appropriate organic solvent (e.g., methanol).

- Agitate the mixture (e.g., via vortexing or sonication) to extract cannabinoids.

- Filter the solution to remove solid particulates.

- Dilute the filtrate to a concentration within the instrument's linear range.

- Instrumentation & Data Analysis: HPLC system with a UV-Vis detector. Quantification is achieved by comparing the peak areas of samples to those of pure reference standards [6].

Experimental Protocol 2: IR Spectroscopic Analysis

This protocol is a secondary method, typically calibrated using reference data from chromatographic analysis, but offers significant advantages in speed and greenness [6].

- Objective: To rapidly determine the total potency of key cannabinoids in dried cannabis plant material with minimal sample preparation.

- Sample Preparation:

- Grind the dried plant material to a consistent particle size.

- Instrumentation & Data Analysis: FT-IR Spectrometer with an ATR (Attenuated Total Reflection) accessory. A calibration model is developed using chemometrics to correlate spectral data (peak heights/areas) to reference potency values [6].

Comparison of Results and Greenness

The table below summarizes the key differences in performance and environmental impact between the two experimental approaches.

| Aspect | HPLC (Chromatography) | IR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Performance (Red) | High Accuracy. Considered a primary method. Excellent for complex mixtures and distinguishing between similar compounds. [6] [10] | Good Accuracy. A secondary method. May struggle with very complex mixtures but is sufficient for many routine applications. [6] |

| Practicality & Cost (Blue) | Slower, Higher Cost. Analysis can take 10-20 minutes per sample. Requires skilled operators, costly reagents, and waste disposal. [6] | Fast, Lower Cost. Analysis takes ~2 minutes per sample. Easier to operate and has lower ongoing costs. [6] |

| Key GAC Principles (Green) | High solvent waste generation. Often uses toxic solvents. Higher energy consumption per sample. [6] [9] | Minimal to no solvent waste. Non-destructive. Fast, low energy per sample. [6] |

| Best Application | Regulatory testing, method development, and analysis of complex unknown mixtures where maximum accuracy is required. [6] | High-throughput quality control, raw material screening, and process monitoring where speed and eco-friendliness are priorities. [6] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Selecting the right reagents and materials is critical for implementing Green Analytical Chemistry. The following table lists key solutions and their functions, with a focus on greener alternatives.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | Green Considerations & Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Solvents (Mobile Phase) | To dissolve the sample and carry it through a chromatographic system. | Replace toxic acetonitrile with methanol or ethanol [9]. Use supercritical COâ‚‚ (in SFC) or water where possible [8]. |

| Extraction Solvents | To isolate analytes from a solid or complex sample matrix. | Use bio-based solvents derived from renewable resources (e.g., limonene) [2]. Implement miniaturized techniques like liquid-liquid microextraction (LLME) to reduce volume [5]. |

| Derivatization Agents | To chemically modify an analyte to make it detectable or to improve separation. | Avoid derivatization altogether (GAC Principle 6) by choosing direct analytical techniques [2]. |

| Calibration Standards | To create a reference for identifying and quantifying analytes. | Use pure, certified reference materials for chromatography. For spectroscopy, use pre-characterized samples to build robust calibration models [6]. |

| Stationary Phases | The packed material in a chromatography column that separates mixture components. | Choose long-lasting and efficient columns (e.g., UHPLC) to reduce solvent consumption and waste over time [2]. |

| PCSK9-IN-29 | PCSK9-IN-29, MF:C26H26FNO6S, MW:499.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pepluanin A | Pepluanin A, MF:C43H51NO15, MW:821.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The journey toward greener laboratories is guided by the 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry. The choice between techniques like spectroscopy and chromatography is not about finding a single "winner," but about selecting the most appropriate tool for the analytical problem while minimizing environmental impact.

- For maximum accuracy and resolution in complex mixtures, chromatography remains the gold standard, but its greenness can be significantly improved through miniaturization, solvent replacement, and in-silico modeling [9].

- For rapid, high-throughput, and low-cost analysis with minimal waste, spectroscopy presents a compelling and inherently greener alternative [4] [6].

The future of GAC lies in the broader adoption of the White Analytical Chemistry model, which encourages a balanced consideration of analytical quality, practical feasibility, and ecological footprint [4] [5]. By leveraging modern assessment tools like AGREE and GAPI, researchers can make informed decisions, driving innovation and enabling a more sustainable practice of analytical science.

The field of analytical chemistry has undergone a significant paradigm shift, moving from a singular focus on analytical performance to a more holistic approach that balances environmental responsibility, practical feasibility, and analytical quality. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) emerged as a transformative philosophy aimed at minimizing the environmental impact of analytical processes by reducing hazardous solvent use, energy consumption, and waste generation [11] [12]. While GAC successfully raised awareness about the ecological footprint of analytical methods, its primary emphasis on environmental aspects sometimes came at the expense of analytical performance and practical implementation in routine laboratories [13] [12].

White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) has recently emerged as an integrated framework that addresses the limitations of GAC. Founded in 2021, WAC represents a holistic approach that reconciles environmental sustainability with analytical functionality and practical applicability [11] [14]. The term "white" symbolizes purity and completeness, reflecting the balanced integration of three essential dimensions: analytical performance (red), environmental impact (green), and practical/economic factors (blue) [11] [13]. This comprehensive model ensures that modern analytical methods are not only environmentally responsible but also analytically sound and practically feasible for routine implementation in research and quality control settings [12].

The RGB Model: Deconstructing the Pillars of WAC

The foundational framework of White Analytical Chemistry is the RGB model, which evaluates analytical methods across three independent but complementary dimensions [11] [13]. This color-coded system provides a structured approach to method assessment and development.

The Green Dimension: Environmental Sustainability

The green component incorporates the established principles of GAC, focusing on minimizing the environmental impact of analytical processes [11] [12]. Key considerations include:

- Reducing or eliminating hazardous chemicals and solvents without compromising process quality [11]

- Minimizing waste generation and implementing waste prevention strategies [11]

- Optimizing energy efficiency throughout the analytical process [15]

- Enhancing operator safety through reduced exposure to toxic substances [11]

- Promoting miniaturization and automation to reduce resource consumption [11] [15]

This dimension aligns with the original 12 principles of GAC, which serve as a comprehensive framework for implementing sustainable analytical practices [12].

The Red Dimension: Analytical Performance

The red component addresses the critical analytical parameters that ensure method reliability and suitability for its intended purpose [11] [13]. Key performance metrics include:

- Sensitivity and selectivity for accurate detection and quantification [11]

- Accuracy and precision to ensure reproducible and valid results [13] [12]

- Robustness and reliability across different operational conditions [12]

- Appropriate limits of detection and quantification for the analytical context [11]

- Linear range and recovery for method validation [13]

This dimension acknowledges that environmental sustainability cannot compromise the fundamental analytical requirements necessary for generating scientifically valid data [12].

The Blue Dimension: Practical and Economic Feasibility

The blue component introduces practical considerations that determine whether a method can be successfully implemented in routine laboratory practice [11] [13]. Key factors include:

- Cost-effectiveness and economic viability [11] [12]

- Analysis time and throughput requirements [11]

- Simplicity of operation and user-friendliness [11] [13]

- Equipment requirements and availability [12]

- Ease of method transfer between laboratories [13]

This practical dimension recognizes that even environmentally perfect methods with excellent analytical performance will not be widely adopted if they are too complex, time-consuming, or expensive for routine implementation [12].

Comparative Experimental Data: Spectroscopic vs. Chromatographic Methods

A comprehensive study evaluating five spectrophotometric methods for analyzing chloramphenicol (CHL) and dexamethasone sodium phosphate (DSP) in ophthalmic formulations provides compelling experimental data for comparing spectroscopic and chromatographic approaches within the WAC framework [16].

Analytical Performance Comparison (Red Dimension)

Table 1: Analytical Performance of Spectrophotometric Methods for DSP Analysis (Red Dimension)

| Method | Linear Range (μg/mL) | LOD (μg/mL) | LOQ (μg/mL) | Wavelength (nm) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDW | 4.00-40.00 | 0.93 | 2.79 | 239.0/254.0 | Handles spectral overlap |

| FSD | 2.00-32.00 | 0.65 | 1.95 | 242.0 | Superior sensitivity |

| RD | 4.00-32.00 | 0.70 | 2.10 | 225.0-240.0 | Effective for mixtures |

| DD1 | 4.00-32.00 | 0.80 | 2.40 | 249.0 | Good resolution |

The spectrophotometric methods demonstrated excellent analytical performance with linearity maintained across clinically relevant concentration ranges. The Fourier Self-Deconvolution (FSD) method showed particularly strong sensitivity with the lowest LOD (0.65 μg/mL) and LOQ (1.95 μg/mL) values [16]. For CHL analysis, the zero-order spectra method at 292.0 nm provided a linear range of 2.00-32.00 μg/mL with LOD and LOQ values of 0.96 and 2.88 μg/mL, respectively [16]. All methods were validated according to ICH guidelines and successfully addressed challenges of spectral overlap and collinearity in the binary mixture [16].

Greenness and Practicality Assessment

Table 2: Greenness and Practicality Assessment Scores for Analytical Methods

| Assessment Tool | Spectrophotometric Methods [16] | Typical HPLC Methods [16] | Ideal Score | Assessment Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Eco-Scale | 75-85 (Excellent to Acceptable) | <75 (Requires Improvement) | 100 | Penalty point system |

| AGREE | 0.75-0.85 (Light Green) | 0.50-0.70 (Yellow-Green) | 1.0 | 12 GAC principles |

| GAPI | 2-3 Red Sections | 4-6 Red Sections | All Green | Qualitative pentagrams |

| BAGI | 70-85/100 | 60-75/100 | 100 | Practical applicability |

The greenness assessment reveals distinct advantages for spectroscopic methods. The Analytical Eco-Scale evaluation awarded the spectrophotometric methods scores above 75, categorizing them as "excellent green analysis," while typical HPLC methods often score below this threshold [16]. The AGREE metric, which evaluates compliance with all 12 GAC principles, produced pictograms with light green colors (scores 0.75-0.85) for the spectroscopic approaches, indicating strong environmental performance [16].

Assessment Tools and Metrics for WAC Implementation

The implementation of White Analytical Chemistry requires robust assessment tools that can quantitatively evaluate each dimension of the RGB model. Recent advances have produced several specialized metrics.

Greenness Assessment Tools

Multiple tools have been developed to evaluate the environmental dimension of analytical methods:

Analytical Eco-Scale: Uses a penalty point system where scores above 75 indicate excellent green analysis, between 50-75 represent acceptable green analysis, and below 50 are considered insufficient [16].

AGREE (Analytical GREEness): Utilizes a clock-like pictogram that assesses all 12 principles of GAC, producing a score from 0-1 with corresponding color coding from red to green [15] [16].

GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index): Employs a qualitative pictogram with five pentagrams representing different analytical steps, color-coded green, yellow, or red based on environmental impact [16].

Comprehensive WAC Assessment Metrics

Emerging tools specifically designed for WAC implementation include:

BAGI (Blue Applicability Grade Index): Focuses on the practical/economic (blue) dimension by evaluating method practicality, cost, time, and operational simplicity [11] [16]. It generates a score with different shades of blue indicating practicality levels [11].

RGB 12 Model: Specifically designed for WAC assessment, this tool simultaneously evaluates red (analytical), green (environmental), and blue (practical) aspects, calculating an overall "whiteness" score that reflects method balance [17].

Modified Assessment Approaches: Recent innovations include MoGAPI (Modified GAPI) which adds criteria for storage, transport, and waste quantification, and VIGI (Violet Innovation Grade Index) which assesses method innovation [11].

Advanced Methodologies and Implementation Strategies

Systematic Optimization Approaches

The successful implementation of WAC principles benefits significantly from systematic methodologies:

Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD): A systematic approach to method development that focuses on understanding critical quality attributes and their relationship with critical method parameters [13] [12]. AQbD aligns perfectly with WAC's red dimension by ensuring robust, accurate, and reproducible analytical methods [12].

Design of Experiments (DoE): Employed to optimize multiple method parameters simultaneously, DoE helps identify ideal operational conditions that balance all three WAC dimensions [13] [12]. This statistical approach efficiently explores the relationship between variables and method responses [12].

Case studies demonstrate the successful application of these approaches. In one example, a WAC-assisted AQbD strategy led to the development of a validated, sustainable, and cost-effective RP-HPLC method for analyzing azilsartan, medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and cilnidipine in human plasma, achieving an excellent white WAC score [13].

Miniaturization and Microextraction Techniques

Modern analytical technologies that support WAC implementation include:

Microextraction Techniques: Approaches such as Fabric Phase Sorptive Extraction (FPSE), magnetic SPE, capsule phase microextraction (CPME), and ultrasound-assisted microextraction significantly reduce solvent consumption while maintaining analytical performance [11].

Miniaturized Systems: These systems reduce reagent consumption, waste generation, and energy requirements while often improving analytical performance through enhanced sensitivity and selectivity [15].

Alternative Sample Preparation: Techniques like "dilute-and-shoot" methods eliminate extensive sample preparation steps, reducing both environmental impact and analysis time [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for WAC-Compliant Method Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | WAC Dimension | Sustainability Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Green solvent for extraction and dilution | Green/Blue | Renewable, biodegradable alternative to acetonitrile |

| Water | Primary solvent for mobile phases | Green | Minimal environmental impact, non-toxic |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Sorbents for microextraction | Green/Red | Enable miniaturization, reduce solvent use |

| Polymer-Based Sorbents | FPSE and CPME materials | Green/Red/Blue | Reusable, reduce solvent consumption |

| Ethyl Acetate | Greener solvent alternative | Green | Less toxic than chlorinated solvents |

| Ganodermanondiol | Ganodermanondiol, MF:C30H48O3, MW:456.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (-)-Isodocarpin | (-)-Isodocarpin, MF:C20H26O5, MW:346.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The selection of appropriate reagents and materials plays a crucial role in achieving WAC compliance. The movement toward greener solvents represents a significant trend in sustainable method development [11] [15]. Ethanol has emerged as a particularly valuable solvent due to its renewable origin, biodegradability, and reduced toxicity compared to traditional alternatives like acetonitrile [16]. In the assessment of spectrophotometric methods for CHL and DSP analysis, ethanol was successfully employed as the primary solvent, contributing to excellent greenness scores while maintaining strong analytical performance [16].

Advanced materials such as magnetic nanoparticles and fabric-phase sorptive extraction media enable miniaturization of sample preparation, dramatically reducing solvent consumption from milliliters to microliters while maintaining or even enhancing analytical sensitivity [11]. These materials support the green dimension by reducing waste generation, the red dimension by improving analytical performance, and the blue dimension by simplifying operational procedures and reducing costs [11].

White Analytical Chemistry represents the future of sustainable analytical practices by successfully integrating environmental responsibility with analytical excellence and practical feasibility. The WAC framework moves beyond the limitations of Green Analytical Chemistry by acknowledging that sustainability without functionality is impractical, while performance without environmental consideration is irresponsible [12].

The comparative analysis of spectroscopic and chromatographic methods reveals that spectroscopic techniques generally offer advantages in the green and blue dimensions, with simpler operation, faster analysis times, reduced solvent consumption, and lower equipment costs [16]. Chromatographic methods, while sometimes more demanding in terms of resources, can provide superior separation capabilities for complex mixtures, with their overall WAC score significantly improvable through miniaturization, automation, and solvent substitution [11] [15].

The implementation of WAC principles is further supported by emerging initiatives such as Green Financing for Analytical Chemistry (GFAC), a dedicated funding model designed to promote innovations aligned with GAC and WAC goals [13]. This financial framework recognizes that the initial development of sustainable methods may require additional resources but ultimately leads to more economically viable and environmentally responsible analytical practices [13] [12].

As the analytical community continues to adopt and refine the WAC approach, the framework promises to guide the development of analytical methods that are not only scientifically valid but also environmentally responsible and practically implementable – truly representing the optimal balance for modern analytical chemistry [11] [13] [12].

Fundamental Green Characteristics of Spectroscopic Techniques

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged as a critical discipline focused on minimizing the environmental footprint of chemical measurements, evolving from the broader green chemistry movement initiated in the 1990s [4]. The fundamental inspiration for "green chemistry" stems from the need for sustainable development, providing a framework for chemists to address health, safety, and environmental issues during analysis [4] [5]. This represents a significant shift in how analytical challenges are approached while striving for environmental benignity. The core principles of GAC emphasize reducing or eliminating dangerous solvents, reagents, and materials while maintaining rapid and energy-saving methodologies that preserve essential validation parameters [5]. Within this context, spectroscopic techniques have gained prominence as inherently greener alternatives to traditional separation-based methods, particularly in pharmaceutical analysis and other industrial applications where frequent testing generates substantial waste streams [4].

The assessment of a method's greenness has become crucial to ensure adherence to sustainability goals and environmental precautions [5]. Traditional green chemistry metrics like E-Factor or Atom Economy proved inadequate for assessing analytical chemistry methods, leading to the development of specialized greenness assessment tools [5]. This comprehensive analysis examines the fundamental green characteristics of spectroscopic techniques, comparing them with chromatographic methods within the framework of established greenness assessment metrics, to provide researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based guidance for sustainable method selection.

Established Greenness Assessment Frameworks for Analytical Methods

The evolution of greenness assessment tools has progressed from basic checklists to comprehensive, quantitative frameworks that enable systematic evaluation of analytical methods [5]. These metrics provide standardized approaches for comparing the environmental impact of different analytical techniques, considering factors such as reagent toxicity, energy consumption, waste generation, and operator safety.

Table 1: Key Greenness Assessment Metrics for Analytical Methods

| Metric | Type | Assessment Basis | Output Format | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) | Qualitative | Four environmental criteria | Binary pictogram | Simple, accessible | Lacks granularity; doesn't assess full workflow [5] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Semi-quantitative | Penalty points for non-green attributes | Numerical score (0-100) | Facilitates method comparison; encourages transparency | Relies on expert judgment; lacks visual component [5] [15] |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | Semi-quantitative | Entire analytical process | Five-part color-coded pictogram | Comprehensive; visual identification of high-impact stages | No overall score; somewhat subjective color assignments [5] |

| AGREE (Analytical Greenness Metric) | Quantitative | 12 principles of GAC | Circular pictogram with score (0-1) | Comprehensive coverage; user-friendly; facilitates comparison | Doesn't sufficiently account for pre-analytical processes [5] [15] |

| AGREEprep | Quantitative | 10 green sample preparation principles | Circular pictogram with score (0-1) | Focuses on sample preparation (often highest impact) | Must be used with broader tools for full method evaluation [5] [15] |

| AGSA (Analytical Green Star Analysis) | Quantitative | Multiple green criteria | Star-shaped diagram with integrated score | Visual comparison; combines intuitive visualization with scoring | Newer method with less established track record [5] |

These assessment tools have enabled a more systematic approach to evaluating the environmental impact of analytical techniques, moving beyond simple performance characteristics to incorporate sustainability as a key metric in method development and selection [5]. The progression of metrics highlights the growing importance of integrating environmental responsibility into analytical science, enabling chemists to design, select, and implement methods that are both scientifically robust and ecologically sustainable [5].

Figure 1: Evolution of greenness assessment frameworks for analytical techniques, showing the progression from fundamental principles to specific evaluation tools and their application to different methodological approaches.

Fundamental Green Characteristics of Spectroscopic Techniques

Spectroscopic techniques offer several inherent green advantages that align with the core principles of Green Analytical Chemistry, particularly when compared to chromatographic methods that often involve substantial solvent consumption and waste generation [4] [18].

Minimal Sample Preparation Requirements

A significant green advantage of spectroscopic methods lies in their reduced sample preparation requirements. Many spectroscopic analyses can be performed with minimal or no sample pretreatment, directly analyzing samples without extensive extraction, purification, or derivatization steps [4]. This characteristic substantially reduces the consumption of organic solvents and reagents, which represent major environmental concerns in analytical chemistry [18]. Furthermore, the non-destructive nature of many spectroscopic techniques enables sample reuse or recycling, further minimizing waste generation [4]. The compatibility of spectroscopy with minimal sample preparation was highlighted in a comprehensive review of pharmaceutical analysis, which noted that "non-destructive spectroscopic techniques" are increasingly adopted specifically for their green advantages [4].

Reduced Solvent Consumption and Waste Generation

Solvent consumption represents one of the most significant environmental impacts in analytical chemistry, particularly for liquid chromatography methods that may utilize hundreds of milliliters of organic solvents daily [18]. Spectroscopy dramatically reduces this impact, as many spectroscopic methods require little to no solvent for operation [4]. This reduction in solvent use simultaneously decreases waste generation, eliminating the need for costly and environmentally problematic waste disposal procedures [18]. The green credentials of spectroscopy are further enhanced when these techniques are combined with chemometric modeling, which can extract meaningful information from complex spectral data without requiring extensive sample preparation or separation steps [19].

Rapid Analysis and High Throughput Capabilities

Spectroscopic methods typically offer significantly faster analysis times compared to chromatographic separations, enabling higher sample throughput with reduced energy consumption per analysis [7]. This efficiency translates to lower operational costs and diminished environmental impact through reduced resource utilization. Atomic emission spectroscopy, for example, can provide analysis results for more than twenty elements simultaneously within 1 to 2 minutes, dramatically improving analytical efficiency [7]. The high-throughput capabilities of spectroscopic plate readers have been demonstrated in solubility studies, where UV-Vis and nephelometric plate readers served as environmentally preferable substitutes for HPLC in high-throughput determination of solubility, with correlation values reaching 0.95 compared to chromatographic methods [20].

Non-Destructive Analysis and Sample Conservation

The non-destructive character of many spectroscopic techniques represents another significant green advantage, particularly valuable for analyzing precious, limited, or irreplaceable samples [7]. This capability enables subsequent analyses using complementary techniques or archival preservation of samples, supporting more comprehensive analytical approaches without additional resource consumption. This characteristic makes spectroscopy particularly valuable for applications such as antique analysis, criminal forensics, and pharmaceutical development where sample conservation is paramount [7]. Additionally, the flexible sampling modes of spectroscopic analyzers allow for detection and analysis of rare and precious metals with minimal sample loss, further enhancing their green credentials [7].

Comparative Greenness Assessment: Spectroscopy vs. Chromatography

Direct comparisons using standardized greenness metrics demonstrate the environmental advantages of spectroscopic techniques over chromatographic methods across multiple application domains.

Table 2: Quantitative Greenness Comparison of Analytical Techniques for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Analytical Technique | Application | Assessment Tool | Score | Key Green Advantages | Environmental Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FT-IR Spectroscopy | Multi-component pharmaceutical analysis | GAPI | Moderate greenness | Minimal sample preparation; no solvents required; non-destructive | Energy consumption for operation [4] |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometry | Solubility determination | NEMI | High greenness | Rapid analysis; minimal waste; high throughput | May require solvents for some applications [20] |

| UHPLC | Pharmaceutical compounds | AGREE | 56/100 | Reduced solvent consumption vs. conventional HPLC | Still requires organic solvents; hazardous waste generation [18] [5] |

| SFC | Chiral separations | AGREE | >70/100 | Uses supercritical COâ‚‚ instead of organic solvents | Energy requirements for maintaining pressure [18] |

| HPLC with traditional sample preparation | UV filters in cosmetics | AGREEprep | 20-40/100 | Established regulatory methods | High solvent consumption; hazardous waste [15] |

| HPLC with microextraction | UV filters in cosmetics | AGREEprep | >50/100 | Reduced solvent volumes; miniaturization | Still generates some hazardous waste [15] |

The integration of chemometric modeling with spectroscopic techniques has further enhanced their greenness credentials. A recent study demonstrated that implementing chemometric-based methodologies can increase the Eco-Scale score by approximately 40 points in specific analytical scenarios [19]. This enhancement stems from substituting intricate, environmentally taxing sample preparation procedures with simpler yet information-rich analytical instruments such as optical spectrometers, with multivariate processing enabling analysts to obtain required information without resource-intensive protocols [19].

Greenness Assessment in Practice: Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Green Spectroscopic Analysis of Pharmaceutical Compounds

A validated experimental protocol for green spectroscopic analysis of active pharmaceutical ingredients involves minimal sample preparation and rapid analysis [4]. The methodology begins with representative sampling of the pharmaceutical formulation, typically requiring only 2-3 mg of material for analysis [7]. For solid dosage forms, the sample is gently homogenized without solvent extraction. The analysis proceeds with direct measurement using appropriate spectroscopic techniques: FT-IR for structural identification, UV-Vis for quantification, or NIR for rapid quality screening [4]. For UV-Vis analysis, where solvent use is necessary, ethanol or water are preferred over more hazardous organic solvents [4]. Data acquisition employs chemometric processing using multivariate calibration models, which enables analysis of complex mixtures without separation [19]. This protocol typically achieves analysis times under 5 minutes per sample with minimal waste generation, compared to 20-30 minutes for equivalent chromatographic methods [4].

Assessment Protocol for Chromatographic Methods with Green Improvements

Chromatographic methods can incorporate green improvements to enhance their environmental profile, though they generally remain less green than spectroscopic alternatives [18] [15]. Method development begins with solvent selection, preferring ethanol or water-methanol mixtures over acetonitrile when possible [18]. For liquid chromatography, UHPLC is selected over conventional HPLC to reduce solvent consumption by 50-80% through smaller particle-size columns and lower flow rates [18]. Sample preparation employs microextraction techniques such as ultrasound-assisted dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction (UA-DLLME) or salting-out assisted liquid-liquid extraction (SALLME) to minimize solvent volumes to less than 1 mL per sample [21] [15]. Method optimization focuses on reducing run times through gradient elution while maintaining resolution [18]. Waste management includes solvent recycling programs and proper segregation of hazardous waste [18]. This approach was validated in a study analyzing pyrethrins and pyrethroids in baby food, where UA-DLLME provided appropriate linearity, recoveries of 75-120%, and precision with RSD values ≤16% while reducing environmental impact [21].

Figure 2: Comparative workflow analysis showing the streamlined nature of spectroscopic techniques versus the more complex, resource-intensive process of chromatographic methods, highlighting key differentiators in environmental impact.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Green Analytical Chemistry

The implementation of green analytical techniques requires specific reagents and materials that align with sustainability principles while maintaining analytical performance.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Green Analytical Techniques

| Reagent/Material | Function | Green Alternative | Environmental Benefit | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Solvent for extraction and analysis | Replaces acetonitrile or methanol | Biobased, less toxic, biodegradable | UV-Vis spectroscopy, sample preparation [4] [18] |

| Supercritical COâ‚‚ | Mobile phase for chromatography | Replaces organic solvent mixtures | Non-toxic, recyclable, reduced waste | Supercritical Fluid Chromatography [18] |

| Water | Solvent for extraction and analysis | Replaces organic solvents | Non-toxic, non-flammable, safe | HPLC mobile phases, sample preparation [4] |

| Chemometric Software | Multivariate data analysis | Replaces extensive sample preparation | Reduces reagent consumption; enables direct analysis | NIR, IR, Raman spectroscopy [19] |

| Microextraction Devices | Sample preparation | Replaces liquid-liquid extraction | Reduces solvent volumes from mL to μL | UA-DLLME, SALLE [21] [15] |

| Biobased Reagents | Derivatization or reaction | Replace synthetic hazardous reagents | Renewable sourcing, reduced toxicity | Spectrophotometric reactions [4] |

The comprehensive assessment of fundamental green characteristics demonstrates that spectroscopic techniques offer significant environmental advantages over chromatographic methods across multiple metrics, including reduced solvent consumption, minimal waste generation, faster analysis times, and non-destructive operation. These advantages align strongly with the twelve principles of Green Analytical Chemistry and are quantifiable through established assessment tools such as AGREE, AGREEprep, and Analytical Eco-Scale. The integration of chemometric modeling further enhances the greenness of spectroscopic methods by enabling the analysis of complex samples without extensive preparation or separation steps.

While chromatographic techniques have made substantial progress through approaches such as UHPLC, SFC, and microextraction, they generally remain less green than spectroscopic alternatives due to their inherent reliance on solvents and more energy-intensive operation. The concept of White Analytical Chemistry provides a balanced framework for method selection, considering not only environmental impact but also practical and economic factors. For researchers and drug development professionals seeking to implement more sustainable analytical practices, spectroscopic techniques represent the greenest option for many application scenarios, particularly when combined with chemometric data processing and minimal sample preparation protocols.

Fundamental Green Characteristics of Chromatographic Techniques

Green chromatography encompasses a suite of strategies aimed at minimizing the environmental impact of chromatographic analyses while maintaining analytical performance. Rooted in the 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), this approach promotes the reduction of hazardous solvent use, energy consumption, and waste generation throughout the analytical workflow [22]. The drive towards sustainability in laboratories is not merely an ethical choice but a practical response to the significant environmental footprint of traditional methods; a single liquid chromatograph can generate over 1.5 liters of liquid waste daily [23]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the green characteristics of various chromatographic techniques, offering a foundation for researchers and drug development professionals to make informed, environmentally conscious decisions without compromising data quality.

The assessment of a method's greenness has evolved from simple solvent considerations to holistic evaluations using multiple metrics. Modern green chromatography seeks to balance the three pillars of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC): analytical performance (red), environmental impact (green), and practical applicability (blue) [22] [24]. The following sections detail the tools for quantifying greenness, compare mainstream techniques, and provide experimental protocols for implementing sustainable practices in analytical laboratories.

Greenness Assessment Metrics and Tools

Evaluating the environmental footprint of chromatographic methods requires robust, standardized metrics. Several tools have been developed to provide quantitative and visual assessments of method greenness, each with distinct focuses and output formats.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Greenness Assessment Tools

| Tool Name | Main Focus | Output Type | Scoring Range | Key Principles Assessed | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE (Analytical GREEness) [22] [15] | Entire analytical procedure | Clock-like pictogram | 0 to 1 | All 12 GAC principles | Holistic single-score metric; intuitive graphic output |

| AGREEprep [22] [15] | Sample preparation | Round pictogram + score | 0 to 1 | 10 Green Sample Preparation principles | First dedicated sample prep metric; open-source software |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [17] [22] | Entire analytical workflow | Color-coded pictogram | N/A (qualitative) | 5 stages of method lifecycle | Easy visualization of impact across workflow steps |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [22] | Reagents, energy, waste | Penalty points | Ideal = 100 | Solvent toxicity, energy, waste | Semi-quantitative; simple penalty-point system |

| BAGI (Blue Applicability Grade Index) [22] | Practical applicability | Pictogram + % score | 0% to 100% | Throughput, cost, automation | Evaluates practical viability alongside greenness |

These tools enable objective comparison between methods. For instance, a study evaluating 10 chromatographic methods for UV filter analysis in cosmetics used AGREE and AGREEprep to demonstrate that microextraction sample preparation techniques consistently achieved higher greenness scores than conventional approaches [15]. The choice of tool often depends on the analysis focus; AGREE offers a comprehensive view, while AGREEprep is invaluable for optimizing the often problematic sample preparation stage. The trend is toward integration of these assessments early in method development to guide analysts toward more sustainable practices without the need for later remediation.

Comparative Greenness of Chromatographic Techniques

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and UHPLC

HPLC is a workhorse in pharmaceutical and environmental analysis but traditionally relies heavily on hazardous solvents like acetonitrile and methanol, generating significant waste [22]. Greening strategies primarily focus on solvent reduction and substitution. Key advances include:

- Column Geometry: Transitioning from standard 4.6 mm i.d. columns to narrow-bore 2.1 mm i.d. columns can reduce solvent consumption by over 80% for the same separation [25].

- Particle Technology: Utilizing sub-2-µm particles in UHPLC and superficially porous particles (SPP) provides greater efficiency, allowing for shorter column lengths and faster run times, leading to solvent savings of up to 85% compared to conventional HPLC [25].

- Solvent Replacement: Ethanol and dimethyl carbonate (DMC) are promising green alternatives. A 2025 study confirmed that ethanol and DMC can effectively replace acetonitrile and methanol in reversed-phase separations of both polar and non-polar substances without compromising performance [26].

The main challenge for green HPLC lies in modes like HILIC (Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography), which is highly dependent on acetonitrile. Current solutions involve exploring alternative stationary phases or using ion-exchange chromatography where applicable [25].

Gas Chromatography (GC)

GC is inherently greener than HPLC in one key aspect: it uses gases instead of liquid solvents as the mobile phase, eliminating solvent waste entirely [27] [23]. Its green profile is shaped by other factors:

- Carrier Gas Selection: Helium is common but is a non-renewable resource. Hydrogen, produced sustainably by generators, offers faster separations and is the greenest choice despite safety perceptions. Nitrogen is a chromatographically viable and safe alternative, though slower than helium or hydrogen [27] [24].

- Energy Consumption: Conventional GC ovens are energy-intensive. Low Thermal Mass (LTM) technology uses resistive heating to drastically reduce power usage and enable rapid heating and cooling, cutting analysis and cycle times [27].

- Derivatization: A significant obstacle to green GC is the frequent need for derivatization to make analytes volatile. This adds steps, reagents, and waste, contravening GAC principles [24]. Where possible, direct analysis should be prioritized.

Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC)

SFC primarily uses supercritical COâ‚‚ as the mobile phase, which is non-toxic, non-flammable, and obtained from renewable sources [27]. This makes SFC a fundamentally green technique, particularly for preparative-scale separations. COâ‚‚'s low viscosity allows for high flow rates without the high backpressures of liquid chromatography, facilitating faster separations and higher throughput. While often modified with organic solvents like methanol, the typical proportion is low (5-40%), leading to a substantial reduction in organic solvent consumption compared to HPLC [27].

Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC)

TLC is a simple, low-cost technique that consumes minimal solvent per analysis. However, its greenness is highly dependent on the solvent system chosen. The use of solvent mixtures containing hexane, acetone, and trichloromethane, while effective for separations like plant pigments, raises toxicity and waste concerns [28]. Greener approaches include using ethanol alone or in combination with water as the mobile phase, though this may compromise separation efficiency [28]. The small scale of TLC means waste volumes are low, but proper disposal of developed plates is still necessary.

Table 2: Quantitative Greenness Comparison of Chromatographic Techniques

| Technique | Relative Solvent Consumption | Typical Solvent Hazard | Energy Demand | Inherent Green Advantages | Inherent Green Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC/UHPLC | High | High (ACN, MeOH) | Medium-High | Versatility; easy miniaturization | High hazardous waste generation |

| GC | None (Gas Mobile Phase) | Low (Carrier Gases) | Medium-High (Oven) | No solvent waste; high efficiency | Often requires derivatization |

| SFC | Low (Mainly COâ‚‚) | Very Low | Medium | Uses non-toxic, renewable COâ‚‚ | Limited to non-polar/medium polar analytes |

| TLC | Very Low | Variable (Often High) | Very Low | Minimal equipment/energy | Less quantitative; solvent use can be hazardous |

Experimental Protocols for Green Chromatographic Analysis

Protocol 1: Green UHPLC Method Development with Ethanol

This protocol outlines the replacement of acetonitrile with ethanol in reversed-phase UHPLC, based on a 2025 study [26].

- Objective: To develop a UHPLC method using ethanol as a green alternative to acetonitrile while maintaining resolution for a mixture of non-polar and polar compounds.

- Materials and Reagents:

- Analytes: A test mixture of non-polar (e.g., alkylbenzenes) and polar (e.g., pharmaceuticals) substances.

- Solvents: Ethanol (HPLC grade), Acetonitrile (HPLC grade, for comparison), and purified water.

- Stationary Phases: Three columns with different selectivities (e.g., C18, diphenyl, perfluorinated phenyl).

- Instrumentation: UHPLC system capable of handling high backpressures.

- Methodology:

- Initial Scouting: Perform initial gradient separations with acetonitrile-water and ethanol-water on the C18 column. Note differences in retention and selectivity.

- Column Screening: Compare the separation performance of the three different stationary phases with the ethanol-water mobile phase. Selectivity is more powerful than efficiency for achieving resolution with green solvents.

- Optimization: Use predictive modeling software (e.g., DryLab) to model the effect of gradient time, temperature, and pH on the separation with ethanol. This reduces the number of physical experiments, saving solvents and time [25].

- Validation: Compare the final ethanol-based method against the acetonitrile-based method for key parameters: resolution, analysis time, peak symmetry, and sensitivity.

- Greenness Assessment: Calculate the AGREE score for both the acetonitrile and ethanol methods. The use of ethanol, coupled with a narrow-bore column and software-assisted optimization, is expected to yield a significantly higher score due to reduced toxicity and waste [26].

Protocol 2: Fast GC with Hydrogen Carrier Gas

This protocol details the translation of a conventional GC method to a faster, greener method using hydrogen as the carrier gas [27].

- Objective: To reduce the analysis time and environmental impact of a GC method for complex mixtures (e.g., PCBs, pesticides) by using hydrogen carrier gas and optimized temperature programming.

- Materials and Reagents:

- Standard Mixture: A standard containing the target analytes.

- Carrier Gases: Hydrogen (from generator or cylinder) and Helium (for baseline comparison).

- Columns: Conventional column (e.g., 30 m x 0.25 mm i.d.) and a narrow-bore column (e.g., 10 m x 0.10 mm i.d.).

- Instrumentation: GC or GC-MS system with electronic pressure control.

- Methodology:

- Baseline Method: Establish separation on the conventional column with helium carrier gas at 1.5 mL/min constant flow and a standard temperature program.

- Carrier Gas Substitution: Directly switch the carrier gas to hydrogen, maintaining the same flow rate. Observe the reduction in analysis time (approximately 30% faster for the same resolution) [27].

- Method Translation: Use Method Translation Software (MTS) to recalculate the method parameters for the narrow-bore column. The software will output new, faster flow rates and steeper temperature ramps while preserving the original separation [27].

- Verification: Run the standard mixture with the new translated method on the narrow-bore column with hydrogen. Confirm that critical peak pairs are still resolved.

- Greenness Assessment: The method eliminates reliance on non-renewable helium, reduces analysis time (lowering energy consumption), and increases sample throughput. This can be visualized with the GAPI tool, showing improvements in energy consumption and waste categories [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chromatography

| Item | Function in Green Chromatography | Example & Green Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Green Solvents | Replacing hazardous mobile phase components | Ethanol, Dimethyl Carbonate: Less toxic, biodegradable alternatives to acetonitrile [26]. |

| Hydrogen Generator | On-demand production of GC carrier gas | Eliminates gas cylinder waste and transportation footprint; provides a renewable, high-performance alternative to helium [27] [24]. |

| Narrow-Bore Columns (e.g., 2.1 mm i.d.) | Reducing solvent consumption in HPLC/UHPLC | Decrease mobile phase flow rates from ~1.0 mL/min to ~0.2-0.4 mL/min, cutting solvent use and waste by >80% [25]. |

| Sub-2-µm & SPP Particles | Increasing chromatographic efficiency | Enable faster separations or shorter columns, leading to significant reductions in solvent consumption and analysis time [25]. |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) | Solventless sample preparation | Eliminates or drastically reduces the use of organic solvents for extraction, aligning with GAC principles [23] [24]. |

| Predictive Method Development Software | In-silico optimization of methods | Reduces the number of physical experiments required for method development, saving significant amounts of solvents, energy, and time [25]. |

| Ilexsaponin B2 | Ilexsaponin B2, MF:C47H76O17, MW:913.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SPR7 | (2S)-2-[(4-chloro-2-methylphenyl)carbamoylamino]-N-[(E,3S)-6-oxo-1-phenylhept-4-en-3-yl]-3-phenylpropanamide | Explore (2S)-2-[(4-chloro-2-methylphenyl)carbamoylamino]-N-[(E,3S)-6-oxo-1-phenylhept-4-en-3-yl]-3-phenylpropanamide for your research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Workflow and Decision Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting and optimizing chromatographic methods based on green principles.

Green Method Selection and Optimization Pathway - This workflow guides the selection between GC and LC based on analyte properties and outlines key optimization steps for each to enhance environmental friendliness.

The diagram below details the core concepts of White Analytical Chemistry, which provides the framework for modern green method assessment.

Three Pillars of White Analytical Chemistry - The WAC model defines an ideal method as one that harmoniously balances analytical performance (Red), environmental impact (Green), and practical utility (Blue) [22].

In the modern analytical laboratory, the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) have become essential for reducing the environmental impact of chemical analysis while maintaining analytical performance [5]. The drive toward sustainability has prompted the development of dedicated metrics to evaluate and quantify the "greenness" of analytical methods, providing scientists with standardized tools for environmental assessment [29] [30]. Among the numerous metrics available, four have emerged as foundational tools: the National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI), Analytical Eco-Scale Assessment (AES), Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI), and Analytical GREEnness Metric (AGREE) [31] [30]. These tools help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals make informed decisions when developing new methods, particularly when comparing different analytical approaches such as spectroscopic versus chromatographic techniques [32] [33].

The evolution of these metrics reflects a growing sophistication in assessing environmental impact. Early tools like NEMI offered simple, binary evaluations, while later developments like GAPI and AGREE provide more nuanced, comprehensive assessments that cover multiple stages of the analytical process [30] [5]. Understanding the strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of each tool is crucial for accurately evaluating and improving the environmental profile of analytical methods in pharmaceutical development and other research fields.

National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI)

NEMI, first launched in 2002, represents one of the earliest efforts to create a standardized greenness assessment tool [34] [30]. Developed by the multi-agency Methods and Data Comparability Board, it was designed as a searchable database to help scientists compare environmental methods based on standardized criteria [34]. The NEMI pictogram employs a simple quartered circle design where each quadrant represents a different environmental criterion, colored green if the method meets that criterion [30].

The four criteria assessed are: (1) whether chemicals used are not on the Persistent, Bioaccumulative, and Toxic (PBT) list; (2) whether no solvents used are on the D, F, P, or U hazardous wastes lists; (3) whether the method pH is between 2 and 12 to avoid corrosiveness; and (4) whether waste generated is ≤50 g [30]. This tool's primary advantage is its simplicity and immediate visual communication of basic environmental compliance [31] [30]. However, its binary assessment system (either meeting or not meeting criteria) provides limited differentiation between methods, as noted in a comparative study where 14 out of 16 methods for assaying hyoscine N-butyl bromide had identical NEMI pictograms [31]. This lack of granularity has led to the development of more sophisticated assessment tools.

Analytical Eco-Scale Assessment (AES)

The Analytical Eco-Scale offers a semi-quantitative approach to greenness assessment [30]. Proposed in 2012, it operates on the principle of assigning penalty points to various non-green aspects of an analytical method, which are subtracted from a base score of 100 representing an "ideal green analysis" [30] [5]. Penalty points are assigned for hazardous reagents, energy consumption exceeding 0.1 kWh per sample, and waste generation [30].

The resulting score provides a straightforward numerical evaluation: scores >75 represent excellent green analysis, scores >50 represent acceptable green analysis, and scores <50 indicate inadequate greenness [30]. This metric offers greater differentiation between methods compared to NEMI and has been widely applied in method evaluations [33] [30]. However, it still relies on expert judgment in assigning penalty points and lacks a visual component beyond the numerical score [5].

Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI)

GAPI was developed to address the need for a more comprehensive visual assessment tool [29] [30]. It employs a five-segment pictogram that evaluates the entire analytical process across multiple stages: from sample collection and preservation through sample preparation and transportation to instrumental analysis [30]. Each segment is divided into several sub-areas that are color-coded based on their environmental impact: green for low impact, yellow for moderate impact, and red for high impact [29] [5].

This tool provides a more detailed breakdown of environmental impact at each stage of the analytical procedure, helping identify specific areas for improvement [31]. GAPI has been widely adopted in the scientific community due to its holistic approach and visual intuitiveness [30]. The main limitations include its complexity compared to simpler tools like NEMI and AES, and the lack of an overall numerical score, which can make direct comparison between methods somewhat subjective [31] [5].

Analytical GREEnness Metric (AGREE)

AGREE represents one of the most advanced and user-friendly assessment tools [30] [5]. Developed based on the 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry, it provides both a comprehensive visual output and a numerical score between 0 and 1 [30]. The tool generates a circular pictogram divided into 12 sections, each corresponding to one GAC principle, with colors ranging from green (ideal) to red (unacceptable) [30] [5].

A key advantage of AGREE is its balance between comprehensiveness and usability [31]. The tool is available as an open-access calculator, making it accessible to researchers [30]. It effectively highlights the weakest points in analytical techniques needing greenness improvements [31]. A comparative study found that AGREE provided reliable numerical assessments and had merits of simplicity and automation over GAPI [31]. Recent extensions like AGREEprep have been developed specifically for evaluating sample preparation steps [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Characteristics of Greenness Assessment Tools

| Metric | Year Introduced | Assessment Type | Output Format | Scope of Assessment | Scoring System |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | 2002 | Qualitative | Binary pictogram | 4 basic criteria | Pass/Fail for each criterion |

| AES | 2012 | Semi-quantitative | Numerical score (0-100) | Reagents, energy, waste | Penalty point system |

| GAPI | 2018 | Semi-quantitative | Multi-colored pictogram | 10+ aspects across analytical process | Color-coded (green/yellow/red) |

| AGREE | 2020 | Quantitative | Numerical score (0-1) + colored pictogram | 12 principles of GAC | Weighted criteria with visual output |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Application in Method Selection and Development

Comparative studies demonstrate how these metrics perform in real-world scenarios, particularly in pharmaceutical analysis. A 2021 study evaluating 16 chromatographic methods for assaying hyoscine N-butyl bromide revealed significant differences in the effectiveness and discriminative power of each tool [31]. NEMI was least effective in method differentiation, with 14 of the 16 methods having identical pictograms, while AES, GAPI, and AGREE provided more nuanced evaluations that enabled better method selection [31].

A 2024 study comparing HPLC methods with different detectors (PDA, FLD, ELSD) for melatonin determination applied all four assessment tools and found that AGREE and AES provided the most reliable numerical assessments for objective comparison [33]. The study emphasized the importance of applying multiple assessment tools to gain complementary insights into method greenness, as each tool highlights different aspects of environmental impact [33].

Strengths and Limitations in Practice

Each metric exhibits distinct advantages and limitations in practical applications. NEMI's simplicity makes it accessible but limits its utility for comprehensive assessments [31] [5]. AES provides quantitative results but lacks visual representation of specific problem areas [30]. GAPI offers detailed visual assessment across the entire analytical procedure but can be complex to implement and doesn't provide an overall numerical score [31]. AGREE balances comprehensive coverage with user-friendly output but involves some subjectivity in weighting criteria [5].

Recent research indicates a trend toward using multiple complementary metrics rather than relying on a single tool [33] [5]. This approach provides a more balanced and complete assessment of method greenness, offsetting the limitations of individual tools while leveraging their respective strengths.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Greenness Metrics in Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Metric | Discriminatory Power | Ease of Use | Comprehensiveness | Visual Clarity | Recommendation for Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | Low | High | Low | Medium | Preliminary screening |

| AES | Medium | Medium | Medium | Low | Quick numerical comparison |

| GAPI | High | Medium | High | High | Detailed process analysis |

| AGREE | High | Medium-High | High | High | Comprehensive evaluation |

Experimental Protocols for Greenness Assessment

Standardized Evaluation Methodology

Implementing a systematic approach to greenness assessment ensures consistent and comparable results across different methods and laboratories. The following protocol outlines a comprehensive evaluation procedure suitable for comparing spectroscopic and chromatographic methods:

Step 1: Method Documentation - Compile complete details of the analytical procedure including sample preparation, reagents and solvents (with amounts and hazards), instrumentation, energy requirements, analysis time, and waste generation [30] [35].

Step 2: NEMI Assessment - Check method compliance with the four NEMI criteria using official PBT and hazardous waste lists. Create the NEMI pictogram, coloring each quadrant where criteria are met [30].

Step 3: AES Calculation - Start with a base score of 100. Subtract penalty points for hazardous reagents (based on type and quantity), energy consumption >0.1 kWh/sample, and waste generation. Calculate the final score and assign the appropriate greenness category [30].

Step 4: GAPI Evaluation - Complete the GAPI template for each stage of the analytical process. Assign color codes (green/yellow/red) to each sub-area based on established criteria. Combine all segments into the final pictogram [29] [30].

Step 5: AGREE Analysis - Input method parameters into the AGREE calculator or spreadsheet. Evaluate each of the 12 GAC principles based on the specified criteria. Generate the final score and colored pictogram [30] [5].

Step 6: Comparative Analysis - Compile results from all metrics, identifying consistencies and discrepancies. Determine overall greenness profile and identify specific areas for improvement [31] [33].

Case Study Implementation

A recent study on melatonin analysis provides a practical example of this protocol in action [33]. Researchers developed and validated three HPLC methods (PDA, FLD, ELSD) and evaluated their environmental performance using all four assessment tools. The methods utilized green solvent alternatives (ethanol-water instead of acetonitrile-water or methanol-water mixtures) to improve environmental profiles [33].

The assessment revealed how each metric provided different insights: NEMI gave basic compliance information, AES offered numerical scores for ranking, GAPI identified specific high-impact steps in each method, and AGREE provided a balanced overall evaluation with visual representation of strengths and weaknesses across all GAC principles [33]. This multi-metric approach enabled the researchers to objectively compare their methods and demonstrate their greenness credentials comprehensively.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function in Green Analysis | Environmental Advantage | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Alternative mobile phase solvent | Lower toxicity compared to acetonitrile or methanol | HPLC analysis of melatonin [33] |

| Water | Green solvent for extraction and separation | Non-toxic, readily available | Mobile phase component with ethanol [33] |

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) | Extraction medium | Biodegradable, low toxicity | Sample preparation in microextraction techniques [32] |

| Miniaturized Extraction Devices | Sample preparation | Reduced solvent consumption (often <1 mL) | Liquid-phase microextraction techniques [30] [35] |

The evolution of greenness assessment tools from simple binary indicators like NEMI to comprehensive metrics like AGREE reflects the growing sophistication of Green Analytical Chemistry [5]. Each tool offers unique strengths: NEMI for quick compliance checks, AES for straightforward numerical scoring, GAPI for detailed process analysis, and AGREE for balanced comprehensive evaluation [31] [30] [5].

For researchers comparing spectroscopic and chromatographic methods, employing multiple complementary metrics provides the most robust assessment of environmental impact [33] [5]. This multi-tool approach enables identification of specific areas for improvement while providing both qualitative and quantitative data to support method selection and development decisions [31] [36]. As green chemistry principles become increasingly integrated into analytical science, these assessment tools will play a vital role in guiding the development of sustainable analytical methods that maintain scientific rigor while minimizing environmental impact [29] [5].

Implementing Green Spectroscopic and Chromatographic Methods

Green Solvent Substitution in HPLC and UHPLC Mobile Phases

The application of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles in liquid chromatography is driving a significant shift toward sustainability in analytical laboratories worldwide. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) remain indispensable tools for pharmaceutical analysis, quality control, and research, yet their environmental footprint is substantial due to the large volumes of hazardous organic solvents consumed as mobile phases [37]. Conventional solvents like acetonitrile and methanol present significant environmental, health, and safety concerns, with acetonitrile classified as "problematic" according to the CHEM21 classification system, which evaluates solvents based on safety, health, and environmental criteria [37]. The quest for sustainable chromatographic practices has accelerated research into green solvent alternatives that can reduce toxicity and environmental impact without compromising analytical performance. This guide objectively compares the performance of conventional and green solvents, providing experimental data and methodologies to support scientists in making informed, sustainable choices for their chromatographic applications.

The Problem with Conventional Solvents

Traditional reversed-phase HPLC and UHPLC methods predominantly rely on acetonitrile and methanol as organic modifiers in mobile phases. A standard chromatographic system operating with a 4.6 mm internal diameter column at 1 mL/min flow rate generates approximately 1.5 liters of waste daily, half of which is organic solvent requiring disposal, typically through high-temperature incineration [37]. Acetonitrile, accounting for 20% of global production for analytical use, poses particular concerns: it is toxic through ingestion, inhalation, or skin contact and can cause symptoms ranging from dizziness to severe respiratory distress. Environmentally, it is highly soluble, can persist in aquatic systems, and contributes to air pollution [37]. These factors have driven the pharmaceutical and chemical industries to develop solvent selection guides that balance efficacy with safety and environmental sustainability [37].

Promising Green Solvent Alternatives

Several green solvents have emerged as viable replacements for traditional mobile phase components, each with distinct properties, advantages, and limitations. The most promising alternatives include:

Ethanol (EtOH): A bio-based solvent derived from renewable resources like sugarcane or corn [26] [38]. It offers low toxicity, biodegradability, and reduced environmental impact compared to acetonitrile. Its use in HPLC has grown significantly, with 135 documented applications in RP-HPLC, demonstrating its versatility and effectiveness [37].

Dimethyl Carbonate (DMC): An environmentally friendly solvent with favorable green credentials. It is biodegradable, has low toxicity, and is produced through cleaner processes compared to traditional solvents [26] [39].

Propylene Carbonate (PC): A polar carbonate ester with high dipole moment (approximately 4.9 Debye) that influences its miscibility and elution strength in chromatographic applications [39].

Water: As the most environmentally benign solvent, water is ideal in terms of toxicity, waste impact, and cost. However, its high polarity can lead to stationary phase collapse in reversed-phase systems, requiring specially designed columns with high hydrophobic carbon content and relatively hydrophilic surfaces [37].

Supercritical COâ‚‚: Used primarily in supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC), COâ‚‚ is non-flammable, non-toxic, and easily recycled. While not a direct replacement for HPLC mobile phases, it represents a complementary green approach worth considering for suitable applications [37].

Table 1: Properties of Conventional and Green Solvents

| Solvent | CHEM21 Classification | Toxicity | Environmental Impact | Biodegradability | UV Cut-off (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | Problematic | High | Persistent, bioaccumulative | Slow | 190 |

| Methanol | Problematic | Moderate | Moderate | Fast | 205 |

| Ethanol | Preferred | Low | Low | Fast | 210 |

| Dimethyl Carbonate | Preferred | Low | Low | Fast | 240 |

| Propylene Carbonate | Preferred | Low | Low | Fast | 240 |

| Water | Recommended | None | None | N/A | <190 |

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data

Chromatographic Performance Metrics