Greenness Evaluation in Analytical Science: A Comparative Analysis of Chemometrics vs. Traditional Chromatography

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of greenness evaluation for chemometric techniques and traditional chromatographic methods in pharmaceutical analysis and drug development.

Greenness Evaluation in Analytical Science: A Comparative Analysis of Chemometrics vs. Traditional Chromatography

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of greenness evaluation for chemometric techniques and traditional chromatographic methods in pharmaceutical analysis and drug development. It explores the foundational principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), examines methodological applications of both approaches, discusses optimization strategies using modern assessment tools, and presents validation frameworks for comparative analysis. By integrating insights from current literature and emerging metrics, this review serves as a strategic guide for researchers and scientists seeking to implement sustainable analytical practices while maintaining analytical performance and regulatory compliance.

Principles and Evolution of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC)

The 12 SIGNIFICANCE Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) represents a fundamental shift in how chemical analysis is conducted, emphasizing environmental stewardship, sustainability, and efficiency alongside analytical performance [1]. As environmental regulations tighten and industries increasingly prioritize sustainable practices, GAC has evolved from a niche concern to a central tenet of scientific responsibility [2] [3]. This transformation is guided by a framework of principles specifically adapted for analytical chemistry. Among these, the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic offers a concise and actionable summary of key green analytical practices [4].

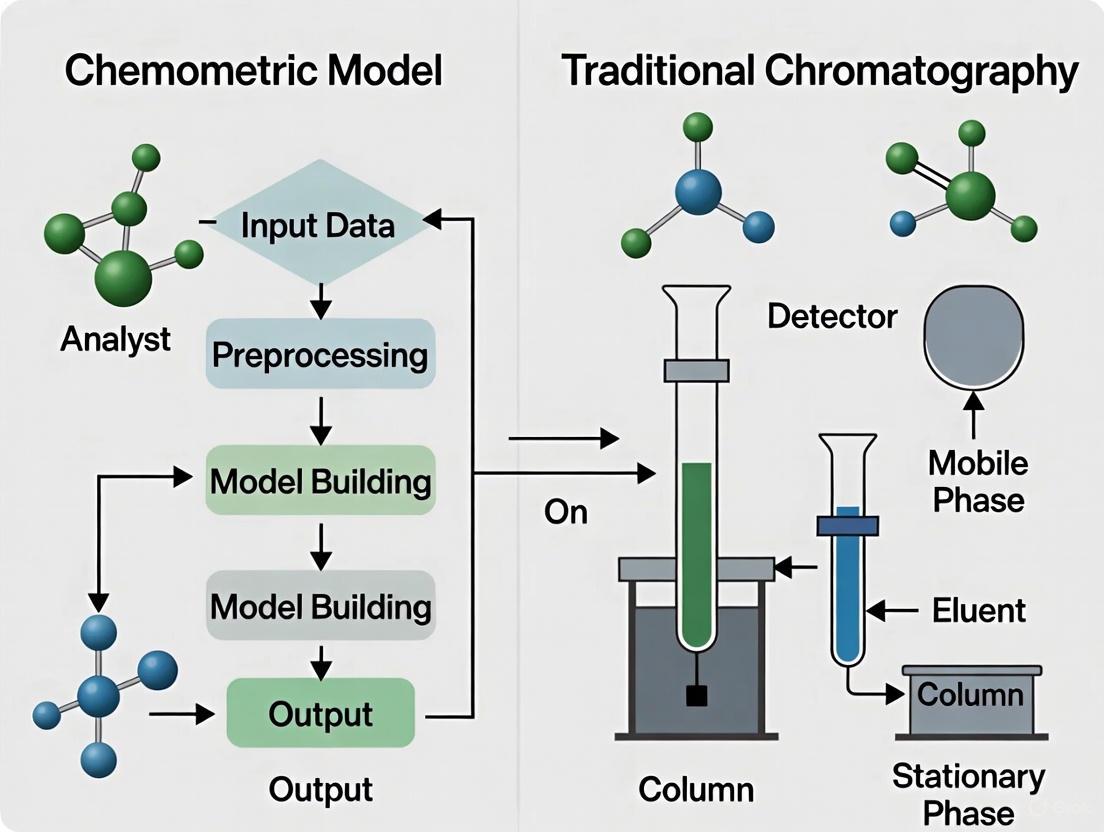

This guide objectively compares the greenness of two analytical approaches: modern chemometrics and traditional chromatography. Chemometrics uses mathematical and statistical methods to extract maximum information from chemical data, often enabling reduced reagent consumption and waste generation. Traditional chromatography, while highly effective, frequently involves larger volumes of solvents and energy-intensive processes. The evaluation is framed within the broader thesis of greenness evaluation, providing researchers and drug development professionals with clear metrics and methodologies for assessing the environmental footprint of their analytical techniques.

The SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic of Green Analytical Practices

The SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic encapsulates the core objectives of Green Analytical Chemistry, providing a practical framework for greening laboratory practices [4]. Each letter represents a strategic goal as shown in the diagram below:

Greenness Assessment Tools and Metrics

Objective evaluation of analytical methods requires standardized metrics and tools. The following table summarizes the primary greenness assessment tools and key performance indicators used in GAC.

Table 1: Greenness Assessment Tools for Analytical Methods

| Tool/Metric | Primary Function | Output Format | Key Parameters Assessed |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) [2] | Initial environmental screening | Pictogram (four quadrants) | Persistence, bioaccumulation, toxicity, corrosiveness |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [2] | Comprehensive lifecycle assessment | Color-coded pictogram (5 pentagrams) | Reagent toxicity, energy consumption, waste generation, safety hazards |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) [2] | Holistic evaluation based on 12 GAC principles | Circular pictogram with score (0-1) | All 12 GAC principles with weighted scoring |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) [5] [6] | Measures material efficiency | Numerical ratio (kg materials/kg product) | All materials used in the process (reactants, solvents, process aids) |

| E-Factor [5] [6] | Quantifies waste generation | Numerical ratio (kg waste/kg product) | Mass of waste produced relative to product |

| Atom Economy [5] [7] [6] | Evaluates synthetic efficiency | Percentage (%) | Formula weight of atoms utilized in final product |

These tools enable researchers to quantitatively compare the environmental performance of different analytical methods. For instance, the AGREE tool provides a comprehensive evaluation based on the 12 principles of GAC, generating a visual output and a numerical score that allows for straightforward comparison between methods [2].

Experimental Protocols for Greenness Evaluation

Methodology for Comparative Analysis

To objectively evaluate the greenness of chemometrics versus traditional chromatography, the following experimental protocol can be employed:

1. Method Selection and Design

- Select a representative analytical problem (e.g., active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) quantification in a drug formulation)

- Develop two methodological approaches:

- Traditional Method: Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RP-HPLC) with sample preparation, organic solvents, and external calibration

- Chemometrics Method: UV-Vis spectroscopy with multivariate calibration

2. Data Collection Parameters

- Traditional Chromatography: Mobile phase: acetonitrile/water (60:40 v/v); Flow rate: 1.0 mL/min; Column: C18 (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm); Injection volume: 20 μL; Detection: UV at 254 nm

- Chemometrics Approach: Spectral range: 200-400 nm; Pathlength: 1 cm; Sample volume: 2 mL; Multivariate calibration: Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression

3. Greenness Assessment

- Apply AGREE, GAPI, and NEMI tools to both methods using standardized input parameters

- Calculate Process Mass Intensity (PMI) and E-Factor for both methods

- Record energy consumption using calibrated power meters

4. Validation of Analytical Performance

- Evaluate both methods for accuracy, precision, sensitivity, and robustness using validation standards

- Ensure both methods meet acceptable analytical figures of merit before greenness comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for GAC Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in GAC | Traditional Alternative | Green Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water as solvent [1] [3] | Replacement for organic solvents in extraction and chromatography | Acetonitrile, methanol | Non-toxic, non-flammable, biodegradable |

| Bio-based solvents (e.g., ethanol, ethyl lactate) [1] [3] | Solvent for extraction and analysis | Halogenated solvents (e.g., chloroform, dichloromethane) | Derived from renewable feedstocks, lower toxicity |

| Ionic liquids [1] | Stationary phases in chromatography, extraction solvents | Volatile organic compounds | Non-volatile, reusable, tunable properties |

| Supercritical COâ‚‚ [1] [3] | Extraction and chromatography fluid | Organic solvents in SFE and SFC | Non-toxic, non-flammable, easily removed |

| Solid-phase microextraction (SPME) fibers [1] [3] | Solventless sample preparation | Liquid-liquid extraction | Eliminates solvent use, minimal waste |

| Microfluidic chips [3] | Miniaturized analytical platforms | Conventional bench-scale apparatus | Dramatically reduced reagent and sample consumption |

| L-(+)-Ampicillin-d5 | L-(+)-Ampicillin-d5, MF:C16H19N3O4S, MW:354.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Sulfo-QSY21-NHS | Sulfo-QSY21-NHS, MF:C45H39ClN4O13S3, MW:975.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Quantitative Comparison: Chemometrics vs. Traditional Chromatography

The following table presents a comparative analysis of the greenness performance between chemometrics-assisted spectroscopy and traditional chromatography methods, based on experimental data and literature findings.

Table 3: Greenness Performance Comparison: Chemometrics vs. Traditional Chromatography

| Evaluation Parameter | Traditional HPLC Method | Chemometrics-Assisted Method | Experimental Measurement Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Volume | 1-5 mL | 50-200 μL | Measured using calibrated micropipettes and volumetric flasks |

| Solvent Consumption | 500-1000 mL per run | 2-5 mL per analysis | Quantified by solvent purchase records and waste collection |

| Energy Consumption | 0.8-1.2 kWh per analysis | 0.1-0.3 kWh per analysis | Measured with power meters connected to instruments |

| Analysis Time | 15-30 minutes | 1-5 minutes | Timed from sample introduction to result acquisition |

| Waste Generation | 500-1000 mL organic waste | 2-5 mL primarily aqueous waste | Collected and measured in designated waste containers |

| PMI (Process Mass Intensity) | 50-100 [5] | 5-15 | Calculated as total mass inputs/mass of product [6] |

| E-Factor | 25-100 [6] | 5-20 | Calculated as mass of waste/mass of product [6] |

| AGREE Score | 0.4-0.6 [2] | 0.7-0.9 [2] | Calculated using AGREE software with 12 principle inputs |

| Hazard Profile | Moderate-High (flammable, toxic solvents) | Low (aqueous systems) | Assessed using GAPI pictogram and reagent safety data sheets |

The experimental workflow for this comparative assessment involves multiple stages, from sample introduction to final greenness scoring as shown in the diagram below:

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The experimental data demonstrates that chemometrics approaches generally offer superior greenness profiles compared to traditional chromatography methods. The significant reductions in solvent consumption, waste generation, and analysis time position chemometrics as a valuable strategy for advancing Green Analytical Chemistry principles [2] [1].

However, the adoption of greener methodologies faces challenges, including the need for method validation and initial investment in new equipment and training [3]. The validation process ensures that new eco-friendly analysis methods provide results as accurate and reproducible as established techniques, which is particularly important in regulated industries like pharmaceutical development [3].

Future innovations in GAC will likely focus on further integration of automation, miniaturization, and alternative energy sources [1] [3]. The application of artificial intelligence and machine learning for method optimization and the development of more sustainable materials will continue to push the boundaries of what constitutes green analysis [1]. Furthermore, the incorporation of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) provides a comprehensive perspective on the environmental impact of analytical methods, considering every stage from raw material sourcing to disposal [1]. This systemic view helps identify areas for improvement and ensures that green alternatives deliver genuine environmental benefits without compromising analytical performance.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the transition to greener analytical methods represents both an ethical responsibility and a practical pathway to greater efficiency, safety, and cost-effectiveness [3]. By applying the SIGNIFICANCE principles and utilizing the assessment tools and protocols outlined in this guide, laboratories can systematically reduce their environmental footprint while maintaining high standards of analytical excellence.

The growing awareness of environmental issues and the detrimental impact of laboratory practices has fundamentally transformed analytical chemistry, leading to the establishment of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC). GAC represents an environmentally conscious methodology aimed at mitigating the negative effects of analytical techniques on ecosystems and human health [8]. This paradigm shift created an urgent need for standardized ways to evaluate the environmental impact of analytical methods, driving the development of greenness assessment tools [9]. This evolution has progressed from simple, binary evaluations to sophisticated, multi-factorial metrics that provide comprehensive environmental profiling of entire analytical workflows [10] [9].

The initial driver for this development was the recognition that traditional green chemistry metrics like E-Factor or Atom Economy were inadequate for assessing analytical procedures [9]. Analytical methods involve unique considerations including sample preparation, instrument energy consumption, and waste generation per analysis, necessitating specialized evaluation tools. This historical progression from the first simple pictograms to today's advanced digital calculators reflects the analytical community's deepening commitment to integrating environmental responsibility into methodological development and selection [10] [9].

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Major Greenness Assessment Metrics

| Year | Metric Tool | Key Innovation | Assessment Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | NEMI [11] | First standardized pictogram; four criteria | Basic environmental criteria |

| 2012 | Analytical Eco-Scale [9] | Semi-quantitative scoring via penalty points | Reagents, energy, waste |

| 2018 | GAPI [9] | Comprehensive visual workflow assessment | Entire analytical process |

| 2020 | AGREE [12] [9] | 12 GAC principles with weighted score | Holistic evaluation with pictogram and numerical output |

| 2022 | AGREEprep [12] | Specialized sample preparation focus | 10 Green Sample Preparation principles |

| 2023+ | RGB, BAGI, AGSA [13] | Multi-dimensional assessment beyond greenness | Integration with analytical performance and practicality |

The Foundational First Generation: Simple Pictograms and Scoring

The earliest greenness assessment tools emerged as straightforward, visually intuitive systems that provided at-a-glance environmental evaluations. These first-generation metrics established the crucial foundation for all subsequent developments in the field.

National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI)

Introduced in 2002, the National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI) was the pioneering tool for greenness assessment [11]. Its pictogram features a circle divided into four quadrants, each representing a different environmental criterion. A quadrant is colored green only if the method meets that specific requirement [11] [9]. The four criteria are:

- PBT: No chemicals used are persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic.

- Hazardous Waste: No reagents are listed as hazardous (D, F, P, or U lists).

- Corrosivity: The pH remains between 2 and 12 during analysis.

- Waste Generation: Total waste produced is ≤50 g per sample [11].

While NEMI was widely appreciated for its simplicity and accessibility, its binary structure (green/blank) and limited scope offered insufficient granularity to distinguish between methods of varying environmental performance or assess complete analytical workflows [9].

Analytical Eco-Scale Assessment (AES)

The Analytical Eco-Scale Assessment (AES) introduced a semi-quantitative approach to address NEMI's limitations [9]. It operates on a penalty points system, starting from an ideal baseline score of 100 for a perfectly green analysis. Points are subtracted for hazardous reagents, high energy consumption (>0.1 kWh per sample), and waste generation [11]. The final score provides a more differentiated evaluation:

- >75: Excellent green analysis

- 50-75: Acceptable green analysis

- <50: Insufficiently green analysis [13]

Although AES enabled better method comparison than NEMI, it still relied heavily on expert judgment for penalty assignment and lacked a visual component, limiting its accessibility for non-specialists [9].

The Second Generation: Comprehensive Visual Assessment

As GAC principles gained wider adoption, the need for more detailed evaluation tools led to the development of second-generation metrics that provided comprehensive visualization of environmental impacts across entire analytical workflows.

Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI)

The Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) represented a significant advancement by addressing the complete analytical process through a five-part, color-coded pictogram [9]. GAPI evaluates each stage of analysis—from sample collection and preservation through preparation and instrumental determination—using a traffic-light color system (green, yellow, red) to indicate environmental impact levels [14] [9]. This approach allowed researchers to visually identify specific high-impact stages within a method that could be targeted for improvement. Despite its more comprehensive scope, GAPI does not generate an overall greenness score, limiting direct comparability between methods, and its color assignments can involve subjective interpretation [9].

Analytical Greenness (AGREE) Metric

The AGREE metric, developed in 2020, marked a substantial evolution in greenness assessment by incorporating all 12 principles of GAC into a unified evaluation framework [8] [12] [9]. AGREE calculates a weighted score from 0 to 1 for each principle, with the final result displayed in a clock-like pictogram where the central number and color (red to green) provide an immediate overall assessment [12]. The tool is open-source and accessible, enhancing its adoption across the analytical community [12]. AGREE's key strength lies in its comprehensive coverage of GAC principles and user-friendly output format. However, it does not fully account for pre-analytical processes and involves some subjectivity in weighting its evaluation criteria [9].

AGREE Metric Calculation Workflow: The AGREE tool transforms input parameters based on the 12 GAC principles into a comprehensive output featuring a clock-like pictogram, numerical score, and color coding [12] [9].

The Specialized Third Generation: Targeted and Holistic Metrics

Recent developments in greenness assessment have focused on creating specialized tools for specific analytical stages while also expanding beyond purely environmental considerations to embrace more holistic sustainability frameworks.

AGREEprep: Sample Preparation Focus

Recognizing that sample preparation often represents the most environmentally impactful stage of analysis, AGREEprep was introduced in 2022 as the first dedicated metric for evaluating sample preparation techniques [12]. This tool applies the 10 principles of Green Sample Preparation (GSP) and provides both visual and quantitative outputs, with a cumulative score greater than 0.5 indicating an acceptably green method [12]. Studies comparing methodologies have demonstrated that microextraction-based sample preparation techniques consistently achieve higher AGREEprep scores, validating the tool's effectiveness in identifying environmentally superior approaches [12]. However, as a specialized tool, AGREEprep must be used alongside broader metrics like AGREE for complete method evaluation [9].

White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) and the RGB Model

The most recent evolution in assessment frameworks is White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which expands beyond purely environmental concerns to balance three equally important dimensions [13]:

- Red (Analytical Performance): Sensitivity, selectivity, accuracy, precision

- Green (Environmental Impact): Solvent toxicity, waste generation, energy consumption

- Blue (Practicality & Economics): Cost, time, simplicity, operational factors [13]

The resulting "whiteness" represents the ideal balance where a method demonstrates excellent analytical capabilities, minimal environmental impact, and strong practical utility [13]. This integrated approach addresses the criticism that earlier green metrics sometimes overlooked analytical performance and practical implementation in pursuit of environmental benefits [8] [13].

WAC RGB Model Structure: White Analytical Chemistry integrates three complementary dimensions—red (analytical performance), green (environmental impact), and blue (practicality)—to achieve balanced method assessment [13].

Comparative Analysis of Metric Tools: Experimental Data

The evolution of greenness metrics can be clearly observed through comparative studies that apply multiple assessment tools to the same analytical methods. One such investigation evaluated 10 different chromatographic methods for determining UV filters in cosmetic samples using both AGREE and AGREEprep [12]. The results demonstrated that microextraction methods consistently achieved higher greenness scores in both metrics, with AGREEprep proving particularly effective at highlighting the environmental advantages of miniaturized sample preparation techniques [12].

Table 2: Greenness Score Comparison of UV Filter Analytical Methods [12]

| Method Number | Analytical Technique | Sample Preparation Method | AGREE Score | AGREEprep Score | Overall Greenness Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LC-UV | Solvent dissolution | 0.42 | 0.38 | Low |

| 2 | LC-DAD | Solvent extraction | 0.45 | 0.41 | Low |

| 3 | GC-MS | Solvent extraction with derivatization | 0.38 | 0.35 | Lowest |

| 4 | LC-MS/MS | Solid-phase extraction (SPE) | 0.52 | 0.48 | Medium |

| 5 | LC-MS/MS | Pressurized liquid extraction (PLE) | 0.49 | 0.45 | Medium |

| 6 | LC-MS/MS | Microextraction by packed sorbent (MEPS) | 0.65 | 0.62 | High |

| 7 | GC-MS | Micro-MSPD | 0.68 | 0.66 | High |

| 8 | LC-MS/MS | Dispersive solid-phase microextraction | 0.71 | 0.69 | Highest |

| 9 | LC-UV | Ultrasound-assisted DLLME | 0.67 | 0.65 | High |

| 10 | LC-UV | Dynamic HF-LPME | 0.69 | 0.67 | Highest |

A separate comparative study evaluating Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) for milk analysis demonstrated how multi-metric assessment provides comprehensive environmental profiling [14]. The research applied NEMI, Analytical Eco-Scale, AGREE, and ComplexGAPI to both techniques, consistently showing FTIR's superior greenness credentials due to its minimal solvent requirements, direct analysis capability, and lower energy consumption [14]. This type of multi-tool evaluation helps validate findings across different metric systems and provides complementary insights into various environmental aspects.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Greenness Assessment

Protocol for AGREE Assessment of Chromatographic Methods

The following detailed methodology outlines the standardized approach for evaluating the greenness of chromatographic methods using the AGREE metric tool, based on established protocols from comparative studies [12]:

Software Installation: Download the open-source AGREE calculator from the official website: https://mostwiedzy.pl/AGREE [12]

Data Collection for Each Analytical Method:

- Reagent Information: Document all solvents, chemicals, and reagents used in the procedure, including volumes and concentrations. Cross-reference with safety data sheets to determine toxicity classifications.

- Energy Consumption: Calculate total energy usage in kWh per sample, including sample preparation, extraction, and chromatographic separation steps.

- Waste Generation: Quantify total waste produced per analysis (g or mL), considering both organic and inorganic waste streams.

- Instrumentation Parameters: Document instrument type, analysis time, throughput (samples per hour), and any special requirements like derivatization.

- Operator Safety: Identify any requirements for special personal protective equipment or handling procedures for hazardous materials.

Input Parameter Assignment:

- Enter collected data into the 12 input fields corresponding to the GAC principles.

- Apply default weighting factors for initial assessment, with optional adjustment based on method-specific priorities.

- Generate the output pictogram and numerical score.

Result Interpretation:

Protocol for Comparative Multi-Metric Assessment

For comprehensive evaluation, researchers increasingly employ multiple metrics to gain different perspectives on method greenness [14] [9]:

Tool Selection: Choose complementary metrics that assess different aspects (e.g., AGREE for overall greenness, AGREEprep for sample preparation, and RGB model for whiteness assessment).

Standardized Data Collection: Gather consistent data across all methods being compared, including:

- Sample size and preparation time

- Solvent types and volumes

- Energy consumption per analysis

- Waste generation and treatment

- Throughput and analytical performance parameters

Parallel Application:

- Apply each metric tool using the same dataset.

- Document all scoring decisions and weighting factors for reproducibility.

- Generate all relevant pictograms and numerical scores.

Triangulation of Results:

- Compare outcomes across different metrics to identify consistent patterns.

- Resolve discrepancies through careful re-examination of assessment criteria.

- Generate a comprehensive greenness profile that highlights both strengths and weaknesses of each method.

Critical Analysis:

- Identify specific steps in the analytical procedure that contribute most significantly to environmental impact.

- Propose targeted improvements for problematic steps.

- Select the optimal method based on balanced consideration of all assessment results.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Green Analytical Chemistry

The implementation of green analytical methods requires specific reagents and materials that minimize environmental impact while maintaining analytical performance. The following table details key solutions used in the development and application of environmentally sustainable analytical methods.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function in Green Analysis | Environmental Advantage | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-based Solvents (e.g., ethanol, ethyl acetate) | Extraction and separation media | Renewable sources, lower toxicity, biodegradable | Solvent replacement in sample preparation [9] |

| Ionic Liquids | Green extraction solvents | Negligible vapor pressure, recyclable | Miniaturized extraction techniques [12] |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Solid-phase extraction sorbents | Enable miniaturization, reduce solvent volume | MSPE, quick analyte separation [13] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers | Selective recognition elements | Reusable, reduce reagent consumption | Solid-phase microextraction [10] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents | Green solvent systems | Biodegradable, low toxicity, renewable precursors | Liquid-phase microextraction [12] |

| Portable Field Sampling Kits | On-site sample collection and preservation | Eliminate transport, enable direct analysis | In-situ monitoring, reduced storage [9] |

The historical development from NEMI to comprehensive modern metrics represents a remarkable evolution in how the analytical chemistry community evaluates and prioritizes environmental sustainability. The field has progressed from basic binary pictograms to sophisticated multi-dimensional assessment frameworks that balance environmental impact with analytical performance and practical implementation [10] [9] [13]. Current challenges in metric development include minimizing subjectivity in assessments, establishing standardized weighting factors, and incorporating lifecycle considerations beyond immediate laboratory operations [10]. Future directions point toward increased integration of artificial intelligence for automated assessment, development of real-time greenness monitoring systems, and creation of unified platforms that combine multiple metric tools for comprehensive sustainability profiling [10] [9]. As greenness metrics continue to evolve, they will play an increasingly crucial role in guiding analytical chemists toward methodologies that are not only scientifically robust but also environmentally responsible and economically viable, ultimately supporting the broader transition toward sustainable science practices.

Key Drivers for Sustainable Practices in Pharmaceutical Analysis

The pharmaceutical industry faces increasing pressure to align drug development and quality control with environmental sustainability goals. Traditional analytical methods, particularly in chromatography, often involve hazardous solvents, generate significant waste, and consume substantial energy, creating a substantial environmental footprint [9] [15]. In response, Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged as a critical discipline focused on minimizing the environmental impact of analytical methods while maintaining scientific robustness [9] [16]. This transformation is driven by regulatory pressures, corporate sustainability initiatives, and a growing recognition that ecological responsibility and analytical excellence are not mutually exclusive [15] [17]. The industry is now evolving beyond GAC toward White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), a holistic framework that balances environmental sustainability (green) with analytical performance (red) and practical applicability (blue) [8] [18]. This comparison guide examines the key drivers propelling this sustainable transformation, objectively evaluating how greenness assessment metrics and emerging technologies are reshaping pharmaceutical analysis.

Greenness Assessment Metrics: Evaluating Environmental Performance

The adoption of sustainable practices requires robust tools to quantify and compare the environmental performance of analytical methods. Numerous greenness assessment metrics have been developed, each with distinct approaches and evaluation criteria.

Evolution of Greenness Assessment Tools

The progression of greenness metrics reflects a shift from basic qualitative evaluations to comprehensive quantitative assessments incorporating multiple environmental factors:

First-Generation Tools: The National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI) introduced a simple pictogram evaluating four basic criteria: persistent/bioaccumulative/toxic substances, hazardous chemicals, corrosiveness, and waste generation [9] [18]. While accessible, its binary (pass/fail) approach lacked granularity for distinguishing between degrees of greenness [9].

Semi-Quantitative Advances: The Analytical Eco-Scale (AES) provided a more nuanced evaluation by assigning penalty points for non-green attributes subtracted from a base score of 100 [9] [18]. Methods scoring ≥75 are classified as "excellent green," 50-74 as "acceptable green," and below 50 as "insufficient greenness" [18].

Comprehensive Metrics: The Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) expanded assessment scope with a color-coded pictogram covering the entire analytical process from sample collection to detection [9] [16]. This enabled identification of high-impact stages within methods.

Modern Quantitative Tools: Analytical Greenness (AGREE) incorporates all 12 GAC principles into a unified evaluation, providing both a visual pictogram and a numerical score from 0-1 [9] [12] [16]. AGREEprep specifically targets sample preparation—often the most waste-intensive step—based on 10 green sample preparation principles [9] [12].

Specialized Innovations: The Carbon Footprint Reduction Index (CaFRI) addresses climate impact by estimating carbon emissions associated with analytical procedures [9]. ChlorTox calculates chemical risk by comparing substance hazards to chloroform as a reference standard [18].

Comparative Analysis of Greenness Assessment Tools

Table 1: Comparison of Major Greenness Assessment Metrics in Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Tool | Assessment Scope | Output Format | Scoring System | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI [9] [18] | Basic environmental criteria | 4-quadrant pictogram | Binary (green/white) | Simple, intuitive | Lacks granularity, limited criteria |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [9] [18] | Reagents, energy, waste | Numerical score | 0-100 (higher=greener) | Semi-quantitative, enables comparison | Subjective penalty assignments |

| GAPI [9] [16] | Entire analytical workflow | 5-section color pictogram | Color-coded (green-yellow-red) | Comprehensive scope, visual | No overall score, somewhat subjective |

| AGREE [9] [12] [16] | 12 GAC principles | Circular pictogram + number | 0-1 (higher=greener) | Holistic, quantitative, user-friendly | Does not fully address pre-analytical steps |

| AGREEprep [9] [12] | Sample preparation | Circular pictogram + number | 0-1 (higher=greener) | Focuses on critical step, quantitative | Must be used with broader tools |

| BAGI [16] [18] | Method applicability | Numerical score + pictogram | 0-100 (higher=better) | Assesses practical feasibility | Does not directly address environmental impact |

Experimental Protocol: Applying Multiple Metrics for Comprehensive Assessment

A case study evaluating a sugaring-out liquid-liquid microextraction (SULLME) method for determining antiviral compounds demonstrates how complementary assessment tools provide a multidimensional sustainability profile [9]:

Method Evaluation: The SULLME method was analyzed across its entire workflow, noting consumption of solvents/reagents, energy requirements, waste generation, safety considerations, and operational parameters.

Multi-Tool Assessment:

- Modified GAPI (MoGAPI): Score of 60/100 indicated moderate greenness, with positive contributions from green solvents and microextraction, but drawbacks in specific storage requirements, moderately toxic substances, and vapor emissions [9].

- AGREE: Score of 56/100 reflected a balanced profile, with strengths in miniaturization and semi-automation but weaknesses in toxic solvent use and moderate waste generation [9].

- Analytical Green Star Analysis (AGSA): Score of 58.33/100 highlighted strengths in semi-miniaturization but limitations in manual handling and absence of waste management [9].

- CaFRI: Score of 60/100 indicated moderate climate impact, with low energy consumption (0.1-1.5 kWh/sample) but no renewable energy or COâ‚‚ tracking [9].

Interpretation: The multi-metric approach revealed the method's strengths in miniaturization but consistent weaknesses in waste management and reagent safety, providing clear direction for sustainability improvements [9].

Key Drivers for Adoption of Sustainable Analytical Practices

Regulatory and Stakeholder Pressure

Pharmaceutical companies face increasingly stringent environmental regulations and stakeholder expectations regarding sustainable operations [15] [17]. Regulatory bodies worldwide are implementing stricter requirements for chemical processes and waste management, compelling the industry to adopt greener analytical approaches [15]. Additionally, the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Initiative has established principles guiding industry expectations for environmental responsibility throughout the supply chain [17]. Leading pharmaceutical companies now publish detailed sustainability reports tracking ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) metrics, reflecting growing transparency demands from investors, consumers, and regulatory agencies [17].

Operational Efficiency and Economic Benefits

Sustainable practices in pharmaceutical analysis frequently yield significant economic advantages through reduced resource consumption and waste disposal costs [15]. Atom economy—designing synthetic methods to maximize incorporation of materials into the final product—reduces waste generation while improving process efficiency [15]. For instance, Pfizer achieved a 50% reduction in waste through implementation of green chemistry principles, demonstrating the substantial cost savings possible [15]. Similarly, Merck redesigned the synthesis of sitagliptin (a diabetes drug), reducing waste while simultaneously cutting water and energy usage [15]. These improvements align environmental benefits with enhanced operational efficiency and reduced production costs.

Technological Innovations Enabling Green Transitions

Table 2: Technological Innovations Driving Sustainable Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Innovation Category | Specific Technologies | Sustainable Benefits | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Solvent Systems [15] [16] | Water, ethanol, supercritical COâ‚‚, bio-based solvents | Reduce toxicity, waste, and environmental impact | Replacing dichloromethane and acetonitrile with safer alternatives |

| Miniaturized Techniques [9] [16] | Micro-extraction, micro-HPLC, lab-on-a-chip | Reduce solvent consumption (often to <10 mL) and waste generation | Liquid-phase microextraction techniques for sample preparation |

| Alternative Energy Sources [19] | Microwave-assisted extraction, ultrasound extraction | Reduce energy consumption and processing time | Accelerated extraction techniques for sample preparation |

| Process Intensification [19] | Continuous flow synthesis, inline monitoring | Enhance atom economy, reduce waste and energy use | Continuous manufacturing of pharmaceutical intermediates |

| Biocatalysis [15] [19] | Enzymatic processes, whole-cell catalysis | Enable milder conditions, reduce hazardous reagents | Enzyme-based synthesis of sitagliptin at Merck |

| Artificial Intelligence [19] | Generative AI, machine learning for reaction optimization | Predict optimal conditions, reduce experimental waste | AI-assisted discovery of green solvents and catalysts |

Experimental Protocol: Greenness Comparison of Chromatographic Methods for UV Filter Analysis

A comparative study of 10 chromatographic methods for determining UV filters in cosmetic samples demonstrates the application of greenness assessment to guide method selection [12]:

Method Selection: Researchers selected 10 literature methods employing various sample preparation techniques: conventional solvent dissolution (Methods 1-2), solvent extraction with derivatization (Method 3), solid-phase extraction (SPE, Method 4), pressurized liquid extraction (PLE, Method 5), and microextraction techniques including MEPS, µ-MSPD, DSPME, US-VA-DLLME, and dynamic HF-LPME (Methods 6-10) [12].

Assessment Protocol: Each method was evaluated using AGREE for the overall procedure and AGREEprep specifically for sample preparation steps. Input parameters included reagent types/volumes, energy consumption, waste generation, throughput, and operational hazards [12].

Results: Microextraction-based methods (particularly Methods 6-10) achieved significantly higher greenness scores in AGREEprep assessment due to minimal solvent consumption, reduced waste generation, and improved safety profiles [12]. Methods employing derivatization (Method 3) and large solvent volumes scored poorest.

Conclusion: The study recommended microextraction techniques coupled with modern chromatographic systems as the most environmentally sustainable approach for routine analysis, demonstrating how greenness metrics can guide laboratory practice toward reduced ecological impact [12].

The Emergence of White Analytical Chemistry: Balancing Sustainability with Performance

The evolution beyond GAC has led to White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which integrates three complementary dimensions: environmental sustainability (green), analytical performance (red), and practical applicability (blue) [8] [18]. This holistic framework recognizes that unconditional increases in greenness at the expense of functionality are counterproductive for sustainable development [8].

The Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) has emerged as a key metric to assess the practical viability of analytical methods, complementing environmental-focused tools like AGREE [16] [18]. BAGI evaluates ten applicability attributes including analysis type, throughput, reagent availability, automation, and sample preparation complexity, providing both a numerical score and visual output [16]. In pharmaceutical analysis case studies, methods achieving high BAGI scores (e.g., 72.5 for a paclitaxel quantification method) demonstrate strong practical feasibility alongside environmental and performance attributes [18].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Sustainable Analysis

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Reagent/Solution Category | Specific Examples | Function in Analysis | Sustainable Attributes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Green Solvents [15] [16] | Water, ethanol, supercritical COâ‚‚, ethyl acetate | Replacement for hazardous organic solvents | Less toxic, biodegradable, often renewable sources |

| Bio-Based Reagents [15] | Plant-derived precursors, enzymes, biocatalysts | Synthesis, extraction, and analysis | Renewable feedstocks, reduced toxicity, biodegradable |

| Solid Supported Reagents [15] | Polymer-supported catalysts, immobilized enzymes | Enable catalysis and specific reactions | Recyclable, reduce waste, improve separation |

| Renewable Derivatization Agents [15] | Bio-based labeling reagents | Sample preparation for detection | Reduced toxicity from renewable sources |

| Safer Sorbents [12] | Molecularly imprinted polymers, green silica | Sample preparation and extraction | Reduced environmental impact, improved selectivity |

The pharmaceutical industry's transition toward sustainable analytical practices is driven by a powerful convergence of regulatory requirements, economic incentives, technological innovations, and evolving assessment methodologies. Greenness evaluation metrics have progressed from basic checklists to sophisticated tools that provide comprehensive, quantitative environmental assessments of analytical methods. The emergence of White Analytical Chemistry represents a paradigm shift, recognizing that truly sustainable methods must balance environmental responsibility with analytical performance and practical applicability.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolution offers a clear framework for selecting, optimizing, and implementing analytical methods that advance both scientific and sustainability goals. The ongoing development of green assessment tools, coupled with technological innovations in solvent systems, miniaturization, and alternative energy sources, provides a robust toolkit for reducing the environmental footprint of pharmaceutical analysis while maintaining the high-quality standards essential for drug development and quality control.

The pursuit of scientific discovery, particularly in fields like pharmaceutical development, relies heavily on two broad categories of methodologies: instrument-intensive (e.g., traditional chromatography) and computational (e.g., chemometrics, AI modeling). These methodologies diverge fundamentally in their environmental impact pathways, resource consumption patterns, and associated carbon footprints. Instrument-intensive techniques, such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), consume physical resources—solvents, reagents, and materials—leading to direct waste generation and high energy consumption from laboratory equipment [12] [9]. In contrast, computational methods primarily consume electricity for data processing in servers and data centers, creating a significant, but often less visible, carbon footprint influenced by the energy source of the computing infrastructure [20] [21]. Understanding these divergent pathways is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to align their work with sustainability goals without compromising scientific integrity. This guide provides an objective comparison of these environmental impacts, supported by experimental data and standardized assessment protocols.

Quantitative Comparison of Environmental Footprints

Direct comparisons of environmental impact require a focus on specific, equivalent tasks. The following tables summarize quantitative data from studies comparing computational and traditional physical methods for similar research and development outcomes.

Table 1: Carbon Emission Reductions from Virtualization in Semiconductor R&D A study by Lam Research compared the carbon footprint of traditional physical experiments in semiconductor research to equivalent virtual simulations [22].

| Research and Development Activity | Carbon Emission Reduction with Virtualization |

|---|---|

| General Hardware Prototyping and Process Optimization | ~20% |

| Plasma Ion Simulations | ~80% |

Contextual Note: The study further contextualized that producing one full-loop wafer has a lifetime footprint of approximately 1,500 kg of COâ‚‚. A high-end computer running virtualization tools would need to operate for over three years (27,000 hours) to emit an equivalent amount [22].

Table 2: Carbon Emissions of Creative Tasks: AI vs. Humans A study in Scientific Reports compared the carbon emissions of AI systems and humans performing equivalent writing and illustrating tasks [23].

| Task Performer | COâ‚‚e per Page of Text (Relative to Humans) | COâ‚‚e per Image (Relative to Humans) |

|---|---|---|

| AI Systems | 130 - 1,500 times less | 310 - 2,900 times less |

| Human Counterparts | Baseline | Baseline |

Illustrative Example: The training of the GPT-3 AI model produces an estimated 552 metric tons of COâ‚‚e. When amortized over its many queries, the operational impact of a single ChatGPT query is approximately 2.2 grams of COâ‚‚e [23]. In perspective, this is significantly less than the emissions from streaming one hour of video content, estimated at 34g COâ‚‚e [20].

Methodologies for Environmental Impact Assessment

To ensure objectivity, standardized metrics and protocols are essential for evaluating the environmental impact of analytical and computational methods.

Experimental Protocols for Greenness Assessment in Analytical Chemistry

The evaluation of instrument-intensive methods relies on Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles. The following protocols detail how key greenness assessment tools are applied to analytical methods, such as chromatography [9].

- Tool Application: Researchers select an analytical procedure for evaluation (e.g., an HPLC method for determining cannabinoids in oils [24]). The method is broken down into its constituent steps: sample collection, preparation, transportation, storage, and final analysis by the instrument.

- Data Collection: For each step, data is collected on the type and volume of solvents and reagents used, energy consumption of equipment, amount and hazardousness of waste generated, and the number of procedural steps.

- Scoring with Multiple Metrics: The method is evaluated using several standardized metrics, which may include:

- AGREE (Analytical Greenness Metric): Uses the 12 principles of GAC to generate a score from 0 to 1 and a circular pictogram. A score above 0.5 is generally considered green [12] [9].

- Analytical Eco-Scale: Assigns penalty points to non-green aspects of the method (e.g., hazardous reagents, high energy use). These are subtracted from a base score of 100; a score above 75 represents an excellent green analysis [24].

- GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index): Employs a color-coded pictogram to assess the environmental impact of each stage of the analytical process [24].

- Interpretation: The scores and pictograms from the different metrics are compared to identify environmental hotspots within the method and to choose the greenest available option.

Experimental Protocols for Carbon Footprinting in Computational Science

Assessing the environmental impact of computational work involves calculating the carbon dioxide equivalent (COâ‚‚e) emissions associated with a specific calculation or model run [21].

- Goal and Scope Definition: The researcher defines the computational task to be assessed, such as training a machine learning model or running a genome-wide association study (GWAS).

- Resource Inventory Analysis: The primary data collected is the total computational runtime and the specific hardware used (e.g., type and number of Central Processing Units (CPUs) or Graphics Processing Units (GPUs)).

- Carbon Footprint Calculation: The calculation incorporates two key factors [21]:

- Energy Consumption: The runtime and hardware specifications are used to calculate the total electricity consumed, measured in kilowatt-hours (kWh).

- Carbon Intensity of Electricity: The location of the data center determines the mix of energy sources (e.g., coal, natural gas, renewables) used to generate the electricity. This is expressed as grams of COâ‚‚e per kWh.

- Impact Assessment: The total carbon footprint is calculated by multiplying energy consumption by the carbon intensity. Tools like the Green Algorithms Initiative calculator or CodeCarbon can automate this process [21].

- Interpretation and Optimization: The result is a single carbon footprint value (e.g., kgCOâ‚‚e) for the computational task. This allows researchers to compare software tools or optimize code to reduce emissions.

Visualization of Greenness Evaluation Frameworks

The following diagrams illustrate the logical structures of two prominent greenness assessment tools, providing a visual guide to their evaluation criteria.

AGREE Metric Evaluation Framework

AGREE Metric Evaluation Workflow

The AGREE framework provides a comprehensive evaluation of an entire analytical method against the 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), resulting in a unified score and pictogram [9].

AGREEprep Metric Evaluation Framework

AGREEprep Sample Prep Workflow

The AGREEprep framework is a specialized tool focused exclusively on the sample preparation stage of an analytical method, evaluating it against 10 principles of Green Sample Preparation [12] [9].

Table 3: Core Components for Instrument-Intensive and Computational Methods

| Item | Function/Description | Relevance to Environmental Impact |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC-grade Organic Solvents (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile) | Mobile phase for separating analytes in a chromatographic column [12]. | High volumes contribute to hazardous waste and resource depletion [9]. |

| Derivatization Reagents | Chemicals used to alter analytes for better detection, often in Gas Chromatography (GC) [12]. | Typically hazardous, posing risks to operator health and the environment [9]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Devices used to concentrate and purify analytes from a sample matrix [12]. | Consumable plastic waste that requires disposal after use. |

| Energy Grid Mix Data | The composition of energy sources (coal, gas, nuclear, renewables) powering a data center. | Determines the carbon intensity (g COâ‚‚e/kWh) of computational work [21]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Hardware (CPUs/GPUs) | Processors that perform the complex calculations for simulations and data analysis. | Primary driver of energy consumption in computational science; efficiency varies [21]. |

| Software & Algorithms | Code that defines the computational model or analysis (e.g., BOLT-LMM for genomics). | Algorithmic efficiency dramatically impacts energy use; newer versions can be far greener [21]. |

Greenness Assessment in Practice: Tools and Applications for Chromatography and Chemometrics

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged as a critical discipline focused on minimizing the negative environmental impact of analytical procedures while maintaining their efficacy and reliability. The concept of GAC, introduced in 2000, aims to reduce or eliminate the dangerous effects of analytical activities on human safety, health, and the environment [25] [9]. This represents a significant shift in how analytical challenges are approached, with an increased emphasis on environmental benignity. GAC motivates analytical chemists to address health, safety, and environmental issues during analysis by implementing measures such as using solventless extraction techniques, employing less toxic solvents, and miniaturizing devices for sample preparation and detection [25] [9].

The foundation of GAC is built upon frameworks such as the 12 principles of GAC (signified by the mnemonic "SIGNIFICANCE") and the 10 principles of Green Sample Preparation (GSP) [25] [26]. However, due to the varying characteristics and requirements of different analytical procedures, these principles alone are insufficient for comprehensively assessing the greenness of analytical methods. This challenge led to the development of dedicated metric tools designed to evaluate, quantify, and compare the environmental impact of analytical methodologies [25] [27]. The evolution of these metrics has progressed from basic tools to increasingly sophisticated and holistic assessment systems that enable chemists to design, select, and implement methods that are both scientifically robust and ecologically sustainable [9].

This guide provides a comprehensive overview and comparison of six major GAC metrics: the National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI), Analytical Eco-Scale (AES), Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI), Analytical Greenness Metric (AGREE), AGREE for sample preparation (AGREEprep), and the recently introduced Greenness Evaluation Metric for Analytical Methods (GEMAM). The objective comparison presented here focuses on their underlying principles, assessment methodologies, applications, and limitations within the context of greenness evaluation for chemometrics and traditional chromatography research, serving the needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Historical Development and Evolution of GAC Metrics

The development of GAC metrics has progressed significantly from simple binary assessments to comprehensive, multi-faceted evaluation tools. This evolution reflects the growing sophistication in understanding and quantifying the environmental impact of analytical methods. The timeline below illustrates key milestones in the development of these assessment tools.

Timeline of Major GAC Metric Development

The National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI), introduced in 2002, was one of the first systematic attempts to assess method greenness [11]. Its simple pictogram-based approach provided a basic yes/no evaluation against four environmental criteria. In 2012, the Analytical Eco-Scale brought a more quantitative approach by assigning penalty points to non-green attributes [11]. The field advanced significantly with the introduction of the Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) in 2018, which offered a more comprehensive visual assessment of the entire analytical process [9] [28].

The development of the Analytical Greenness Metric (AGREE) in 2020 marked a substantial step forward by incorporating all 12 principles of GAC and providing both a numerical score and visual output [29]. This was followed by AGREEprep in 2022, the first tool specifically designed for evaluating sample preparation steps [26]. Most recently, 2024 saw the introduction of GEMAM, which integrates both GAC principles and GSP factors into a unified assessment framework [25]. This progression demonstrates a clear trend toward more specialized, comprehensive, and user-friendly assessment tools that provide both qualitative and quantitative insights into method greenness.

Comprehensive Comparison of Major GAC Metrics

Fundamental Characteristics and Assessment Methodologies

The six major GAC metrics employ distinct approaches, criteria, and output formats for evaluating the environmental impact of analytical methods. The following table provides a systematic comparison of their key characteristics, with a focus on their underlying principles and output formats.

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Characteristics of Major GAC Metrics

| Metric | Year Introduced | Assessment Basis | Output Format | Scoring System | Key Focus Areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | 2002 [11] | 4 basic criteria [11] | Quadrant pictogram [11] | Binary (green/uncolored) [11] | PBT chemicals, hazardous solvents, pH, waste amount [11] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | 2012 [11] | Penalty point system [28] | Numerical score [28] | 0-100 scale (100 = ideal) [11] [28] | Reagents, waste, energy, hazards [11] |

| GAPI | 2018 [9] [28] | 5 stages of analytical process [28] | 5 pentagrams with colored sections [28] | Qualitative (green/yellow/red) [28] | Sample collection to detection [28] |

| AGREE | 2020 [29] | 12 principles of GAC [29] | Circular pictogram with score [29] | 0-1 scale (1 = ideal) [29] | Comprehensive GAC principles [29] |

| AGREEprep | 2022 [26] | 10 principles of GSP [26] | Circular pictogram with score [26] | 0-1 scale (1 = ideal) [26] | Sample preparation specifically [26] |

| GEMAM | 2024 [25] | 12 GAC principles + 10 GSP factors [25] | Hexagonal pictogram with score [25] | 0-10 scale (10 = ideal) [25] | Six aspects: sample, reagent, instrument, method, waste, operator [25] |

Evaluation Criteria and Scope

Each metric varies significantly in its comprehensiveness and the specific aspects of analytical methods it evaluates. The following diagram illustrates the relationships between the different metrics and their primary assessment focus areas.

GAC Metrics and Their Primary Assessment Focus

NEMI employs the simplest approach, evaluating only four basic criteria: whether chemicals used are not on the persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic (PBT) list; whether solvents are not hazardous; whether pH is between 2-12; and whether waste generated is less than 50 g [11]. The Analytical Eco-Scale expands assessment to include reagent toxicity, energy consumption, and waste generation, assigning penalty points that are subtracted from an ideal score of 100 [11] [28].

GAPI provides a more comprehensive evaluation across five stages of the analytical process, using a color-coded system (green, yellow, red) for each stage but lacks an overall numerical score [28]. AGREE represents a significant advancement by incorporating all 12 principles of GAC into a unified assessment that generates both a visual output and a numerical score between 0 and 1 [29]. AGREEprep specializes exclusively in sample preparation, applying the 10 principles of Green Sample Preparation (GSP) with customizable weighting of criteria [26]. The newest metric, GEMAM, integrates both GAC principles and GSP factors, evaluating six key aspects (sample, reagent, instrument, method, waste, and operator) across 21 criteria and presenting results on a 0-10 scale [25].

Comparative Analysis of Strengths and Limitations

Each GAC metric presents distinct advantages and limitations that determine their suitability for different applications and contexts.

Table 2: Strengths and Limitations of Major GAC Metrics

| Metric | Key Strengths | Major Limitations | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | Simple, intuitive pictogram; Quick visual assessment [11] | Qualitative only; Limited criteria; Cannot differentiate degree of greenness [9] [11] | Preliminary screening; Educational purposes |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Quantitative score; Enables direct comparison; Considers reagent amounts [11] [28] | Subjective penalty assignment; No visual component; Does not consider hazard severity [9] [28] | Quick numerical comparison; Complementing visual tools |

| GAPI | Visualizes entire analytical process; Identifies problematic stages [9] [28] | No overall score; Subjective color assignment; Limited comparability [28] | Process optimization; Identifying improvement areas |

| AGREE | Comprehensive (12 principles); Combined visual and numerical output; User-friendly software [29] | Does not fully address pre-analytical processes; Subjective weighting [9] | Holistic method evaluation; Research publications |

| AGREEprep | Specialized for sample preparation; Customizable weights; High specificity [26] | Only covers sample preparation; Must be used with other tools for full assessment [26] | Sample preparation optimization; Microextraction evaluation |

| GEMAM | Integrates GAC + GSP; Flexible weighting; Both qualitative and quantitative output [25] | Newer tool with less established track record; More complex assessment [25] | Comprehensive method development; Latest research studies |

Experimental Protocols and Application Case Studies

Standardized Assessment Methodology for GAC Metrics

To ensure consistent and comparable evaluation of analytical methods using different GAC metrics, researchers should follow a standardized protocol. The workflow below outlines a systematic approach for applying these tools in method assessment and comparison.

Standardized Workflow for GAC Metric Application

Step 1: Method Documentation - Completely detail all aspects of the analytical procedure, including sample collection, storage, preparation, reagents, instrumentation, method parameters, waste generation, and operator safety considerations [25] [12].

Step 2: Data Collection - Quantify all relevant parameters including sample size, solvent types and volumes, reagent amounts and hazards, energy consumption, waste volumes and treatment, analysis time, throughput, and safety measures [12] [11].

Step 3: Metric Selection - Choose appropriate metrics based on assessment goals. AGREE provides comprehensive evaluation, AGREEprep specializes in sample preparation, GAPI offers process-stage visualization, Analytical Eco-Scale enables numerical comparison, and GEMAM provides integrated GAC+GSP assessment [25] [26] [29].

Step 4: Assessment Execution - Utilize available software tools for each metric: AGREE and AGREEprep software (https://mostwiedzy.pl/AGREE), MoGAPI software (bit.ly/MoGAPI), and GEMAM software (https://gitee.com/xtDLUT/Gemam/releases/tag/Gemam-v1) [25] [12] [28].

Step 5: Result Interpretation - Interpret scores according to established thresholds: Analytical Eco-Scale (>75 excellent, 50-75 acceptable); AGREE and AGREEprep (closer to 1 = greener); GEMAM (0-10 scale, higher = greener) [25] [11] [29].

Step 6: Comparative Analysis - Compare multiple methods using the same metric, identify weaknesses for improvement, and select the greenest option that maintains analytical performance [12].

Case Study: Evaluation of Chromatographic Methods for UV Filter Analysis

A recent study compared the greenness of 10 chromatographic methods for determining UV filters in cosmetic samples using AGREE and AGREEprep tools, providing valuable insights into practical application of GAC metrics [12]. The methods evaluated included techniques based on liquid chromatography and gas chromatography with various sample preparation approaches.

Experimental Methods: The assessment included a European standard method (Method 1) and nine literature methods with different sample preparation techniques: solvent dissolution (Methods 1-2), solvent extraction with derivatization (Method 3), solid-phase extraction (SPE, Method 4), pressurized liquid extraction (PLE, Method 5), and five microextraction methods (MEPS, µ-MSPD, DSPME, US-VA-DLLME, and dynamic HF-LPME-HPLC-UV for Methods 6-10) [12].

Assessment Protocol: Each method was evaluated using both AGREE and AGREEprep metrics following the standardized software protocols. The AGREE assessment considered all 12 GAC principles, while AGREEprep focused specifically on the 10 GSP principles for sample preparation steps [12].

Key Findings: The results demonstrated that microextraction methods (Methods 6-10) consistently achieved higher greenness scores in AGREEprep assessment due to their minimal solvent consumption, reduced waste generation, and improved safety profiles [12]. The study also revealed that methods incorporating derivatization steps (Method 3) showed significantly lower greenness scores due to the use of additional hazardous reagents and increased waste generation. The comprehensive assessment enabled clear identification of environmental hotspots in each method and provided guidance for improving their greenness profiles [12].

Case Study: Evaluation of SULLME Method Using Multiple Metrics

A comparative evaluation of a sugaring-out liquid-liquid microextraction (SULLME) method for determining antiviral compounds using multiple GAC metrics (MoGAPI, AGREE, AGREEprep, and AGSA) demonstrated the value of complementary assessment approaches [9].

Method Details: The SULLME method employed microextraction techniques with reduced solvent consumption (<10 mL per sample), semi-automation, and avoided derivatization steps, but used moderately toxic substances and generated >10 mL of waste per sample without specific treatment [9].

Multi-Metric Assessment Results: The method obtained a MoGAPI score of 60/100, AGREE score of 0.56, AGSA score of 58.33, and Carbon Footprint Reduction Index (CaFRI) score of 60 [9]. The convergent results across different metrics confirmed the method's moderate greenness level, with strengths in miniaturization and automation but weaknesses in waste management and reagent safety.

Interpretation: The case study highlighted how different metrics provide complementary insights while generally converging on similar conclusions about overall method greenness. The consistent identification of waste management as a weakness across multiple metrics provided clear direction for method improvement [9].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for GAC Implementation

Successful implementation of GAC principles and accurate application of greenness metrics requires specific reagents, materials, and tools that enable more sustainable analytical practices.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function in GAC | Application Examples | Green Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) | Alternative green extraction solvents [27] | Microextraction techniques; Liquid-liquid extraction [27] | Biodegradable; Low toxicity; Renewable sourcing [27] |

| Ionic liquids | Designer solvents for selective extraction [27] | Sample preparation; Chromatography | Low volatility; Tunable properties; Reusable [27] |

| Solid-phase microextraction (SPME) fibers | Solventless extraction [12] | Sample preparation for chromatographic analysis [12] | Minimal solvent use; Reusable; Small sample sizes [12] |

| Molecularly imprinted polymers | Selective sorbents for sample preparation [12] | Solid-phase extraction; Microextraction [12] | High selectivity; Reusable; Reduced reagent consumption [12] |

| Bio-based sorbents | Sustainable materials for extraction [25] | Sample clean-up; Pre-concentration | Renewable materials; Reduced environmental impact [25] |

| Water-based mobile phases | Green chromatographic separations [11] | HPLC; UHPLC methods | Reduced organic solvent use; Lower toxicity [11] |

| Energy-efficient instruments | Reduced power consumption [25] | All instrumental analysis | Lower energy requirements; Reduced carbon footprint [25] |

| Automated systems | Improved efficiency and safety [25] | Sample preparation; Analysis | Reduced reagent consumption; Higher throughput; Enhanced operator safety [25] |

The evolution of GAC metrics from simple binary tools like NEMI to comprehensive, multi-faceted assessment systems like AGREE and GEMAM reflects the growing sophistication in evaluating the environmental impact of analytical methods. Currently, no single metric is universally superior; each offers unique strengths for different assessment contexts. NEMI provides quick screening, Analytical Eco-Scale enables numerical comparison, GAPI visualizes process stages, AGREE offers comprehensive GAC principle evaluation, AGREEprep specializes in sample preparation, and GEMAM integrates both GAC and GSP frameworks.

The future development of GAC metrics will likely focus on increased standardization, integration of life-cycle assessment principles, incorporation of carbon footprint calculations, and development of unified platforms that combine multiple evaluation perspectives [9] [30]. Tools like the Carbon Footprint Reduction Index (CaFRI) represent emerging directions that align analytical chemistry with broader climate goals [9]. Additionally, the integration of artificial intelligence for automated assessment and the development of interactive digital dashboards may further simplify and standardize greenness evaluation [30].

For researchers and method developers, selecting the appropriate GAC metric depends on specific assessment needs: AGREE and GEMAM for comprehensive evaluation, AGREEprep for focused sample preparation assessment, and Analytical Eco-Scale for straightforward numerical comparison. Applying multiple complementary metrics provides the most robust evaluation of method greenness, enabling informed decisions that balance analytical performance with environmental sustainability. As GAC continues to evolve, these metrics will play an increasingly vital role in guiding the analytical community toward more sustainable practices without compromising analytical quality.

The field of analytical chemistry is undergoing a fundamental paradigm shift to align with sustainability science, moving away from traditional, resource-intensive practices toward more environmentally responsible methodologies [31]. This transition is particularly relevant for chromatography, a cornerstone technique in pharmaceutical and environmental analysis where high consumption of solvents and energy raises significant environmental concerns [31] [32]. The conventional "take-make-dispose" model of analytical chemistry is increasingly being challenged by frameworks like Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) and the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) [31].

This comparison guide examines how High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography (HPTLC) are adapting to these sustainability demands within pharmaceutical applications. We objectively evaluate both techniques through recent case studies, employing standardized greenness assessment tools to provide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with evidence-based comparisons for method selection.

Greenness Evaluation Frameworks: Tools for Objective Assessment

The move toward sustainable analytical chemistry relies on standardized metrics to quantitatively evaluate environmental impact. Several well-established tools now enable objective comparison of method greenness:

AGREE (Analytical GREEnness Metric): This comprehensive tool evaluates methods against all 12 principles of GAC, providing a score from 0 to 1 along with an intuitive circular pictogram [9] [32]. Its holistic approach has made it increasingly popular for overall method assessment.

AGREEprep: A specialized tool focusing specifically on sample preparation, often the most environmentally impactful step in analytical workflows [9]. It evaluates parameters through ten specific criteria.

GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index): This semi-quantitative tool uses a color-coded pictogram to represent environmental impact across the entire analytical procedure, from sample collection to final determination [32] [33].

BAGI (Blue Applicability Grade Index): Recently introduced to complement greenness metrics, BAGI assesses practical methodology aspects including throughput, cost, and operational simplicity [32] [33]. This tool is particularly valuable for evaluating real-world laboratory implementation.

NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index): An early and simple tool using a binary pictogram to indicate whether a method meets basic environmental criteria [9].

These tools form the basis for the objective comparisons presented in the following case studies, enabling standardized evaluation across different methodological approaches.

Case Study 1: Simultaneous Quantification of Cardiovascular Drugs and Mutagenic Impurity

Experimental Protocol and Methodologies

A 2025 study directly compared HPTLC-densitometry and a chemometric approach (Firefly Algorithm-optimized partial least squares, FA-PLS) for simultaneously quantifying bisoprolol fumarate (BIP), amlodipine besylate (AML), and 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde (HBZ), a Class 3 mutagenic impurity [34].

HPTLC Method Details:

- Stationary Phase: Silica gel 60 F₂₅₄ plates (10 × 10 cm)

- Mobile Phase: Ethyl acetate–ethanol (7:3, v/v)

- Development: Automated chamber (25 ± 0.5°C, 40 ± 2% RH) with 25-minute saturation

- Detection: Densitometry at 230 nm with 8 × 0.1 mm slit dimension

- Sample Application: 8 mm bands at 10 mm intervals via automated applicator

FA-PLS Spectrophotometry Details:

- Instrumentation: Double-beam UV-Vis spectrophotometer with 1 cm path length quartz cuvettes

- Chemometrics: Firefly Algorithm for variable selection with Hammersley Sequence Sampling validation

- Design: 52-mixture experimental design (25 calibration mixtures)

Performance Comparison and Greenness Assessment

The table below summarizes the analytical performance and sustainability metrics for both methods:

Table 1: Performance and sustainability comparison of HPTLC and chemometric methods for cardiovascular drug analysis

| Parameter | HPTLC-Densitometry | FA-PLS Spectrophotometry |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Range | 50-600 ng/band (BIS), 100-600 ng/band (AML), 10-200 ng/band (HBZ) | 0.5-25.0 μg/mL (BIS), 1.0-30.0 μg/mL (AML), 0.1-10.0 μg/mL (HBZ) |

| Detection Limit | 3.56-20.52 ng/band | 0.011-0.120 μg/mL |

| Precision (RSD) | ≤ 2% | ≤ 2% |

| Correlation Coefficient (r) | ≥ 0.9995 | ≥ 0.9995 |

| AGREE Score | 0.82 | 0.83 |

| GEMAM Index | 7.015 | 7.487 |

| Carbon Footprint | 0.037 kg COâ‚‚/sample | 0.021 kg COâ‚‚/sample |

| NEMI Profile | Perfect | Perfect |

| BAGI Score | 87.50 | 90.00 |

Both methods demonstrated excellent analytical performance with correlation coefficients ≥0.9995 and precision RSD ≤2% [34]. The FA-PLS method showed slightly better sensitivity with detection limits of 0.011-0.120 μg/mL compared to 3.56-20.52 ng/band for HPTLC [34]. Sustainability assessment revealed exceptional environmental profiles for both approaches, with perfect NEMI scores and high AGREE ratings of 0.82 (HPTLC) and 0.83 (FA-PLS) [34].

The carbon footprint analysis favored the FA-PLS method (0.021 kg COâ‚‚/sample) over HPTLC (0.037 kg COâ‚‚/sample), while both methods aligned with multiple UN Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being), SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), and SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) [34].

Case Study 2: Analysis of Veterinary Drugs in Bovine Tissue

Experimental Protocol and Methodologies

A 2025 study developed and validated an HPTLC-densitometric method for simultaneous quantification of florfenicol (FLR) and meloxicam (MEL) in bovine muscle tissue, addressing public health concerns regarding veterinary drug residues [35].

HPTLC Method Details:

- Stationary Phase: Aluminum HPTLC plates (20×20 cm) with 5 μm silica gel 60 F₂₅₄

- Mobile Phase: Glacial acetic acid:methanol:triethylamine:ethyl acetate (0.05:1.00:0.10:9.00, by volume)

- Detection: Densitometry at 230 nm with esomeprazole as internal standard

- Sample Preparation: Tissue homogenization, spiking with standards, addition of EDTA and internal standard, extraction with methanol

- Linearity Range: 0.03-3.00 μg/band (MEL), 0.50-9.00 μg/band (FLR)

Performance Metrics and Greenness Profile

The method demonstrated excellent linearity with correlation coefficients >0.999 for both analytes [35]. Validation according to ICH guidelines confirmed the method's reliability, reproducibility, and selectivity for monitoring regulatory compliance with maximum residue limits (MRLs) set by the European Commission (200 μg/kg for FLR and 20 μg/kg for MEL in bovine muscle) [35].

The environmental impact was evaluated using five greenness assessment tools, confirming its eco-friendly credentials [35]. The method's sustainability derived from several factors: minimal solvent consumption compared to conventional HPLC, reduced sample preparation steps, and the capability to analyze multiple samples simultaneously on a single plate, significantly improving throughput while reducing waste generation.

Case Study 3: Stability-Indicating Assay of Antihistamine/Decongestant Combination

Experimental Protocol and Methodologies

A direct comparison of RP-HPLC and HPTLC methods for estimating phenylephrine hydrochloride (PHE) and doxylamine succinate (DOX) in presence of doxylamine oxidative degradation product (DOX DEG) was conducted in a 2025 study [33].

HPLC Method Details:

- Column: Xterra C18 (100 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm)

- Mobile Phase: Ethanol:0.01 M phosphate buffer pH=5.0 (30:70, v/v)

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Detection: DAD at 260 nm

- Injection Volume: 20 μL

- Run Time: 10 minutes

HPTLC Method Details:

- Stationary Phase: TLC aluminum sheets with silica gel 60 Fâ‚‚â‚…â‚„

- Mobile Phase: Ethanol:methylene chloride:ammonia 30% (7:2.5:0.5, v/v/v)

- Detection: UV at 260 nm

- Band Width: 6 mm

Performance Comparison and Greenness Assessment

Table 2: Performance comparison of HPLC and HPTLC methods for antihistamine/decongestant combination

| Parameter | HPLC Method | HPTLC Method |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Range | 5-100 μg/mL (DOX, PHE), 5-30 μg/mL (DOX DEG) | 4-26 μg/band (DOX, PHE), 0.5-10 μg/band (DOX DEG) |

| LOD | 1.44 μg/mL (DOX), 1.59 μg/mL (PHE), 0.84 μg/mL (DOX DEG) | 0.76 μg/band (DOX), 0.65 μg/band (PHE), 0.16 μg/band (DOX DEG) |

| LOQ | 4.32 μg/mL (DOX), 4.77 μg/mL (PHE), 2.52 μg/mL (DOX DEG) | 2.28 μg/band (DOX), 1.95 μg/band (PHE), 0.48 μg/band (DOX DEG) |

| Precision | Complies with ICH guidelines | Complies with ICH guidelines |

| Analysis Time | 10 minutes per sample | Multiple samples simultaneously |

Both methods were validated according to ICH guidelines and proven to be reliable, reproducible, and selective for stability-indicating assays [33]. The HPTLC method demonstrated superior sensitivity with lower LOD and LOQ values, particularly for the degradation product (0.16 μg/band LOD for DOX DEG) compared to HPLC (0.84 μg/mL) [33].