Hot-Start PCR: Revolutionizing Specificity for Low-Concentration Sample Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging Hot-Start PCR to achieve superior amplification specificity and sensitivity with low-concentration nucleic acid samples.

Hot-Start PCR: Revolutionizing Specificity for Low-Concentration Sample Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging Hot-Start PCR to achieve superior amplification specificity and sensitivity with low-concentration nucleic acid samples. It explores the foundational principles behind Hot-Start activation, detailing various methodological approaches from antibody-based inhibition to novel primer modification technologies. The content delivers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing reactions, and presents rigorous validation data comparing the performance of Hot-Start methods against conventional PCR, with a particular focus on challenging applications such as rare allele detection, multiplex assays, and clinical diagnostics where sample material is limited.

The Specificity Challenge: Why Low-Concentration Samples Demand Hot-Start PCR

In the realm of molecular biology, particularly in applications involving low concentration samples, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a cornerstone technique. However, its sensitivity and reproducibility are often compromised by off-target amplification, primarily in the form of primer dimers and mis-priming [1]. These artefacts arise during reaction setup and initial thermal cycling phases when temperatures are sub-optimal, allowing primers to bind non-specifically to each other or to non-target regions on the DNA template [2] [3]. This nonspecific amplification competes with the desired reaction for essential substrates like primers, DNA polymerase, and dNTPs, significantly reducing the efficiency and yield of the target amplicon [1]. The challenge is especially acute in diagnostic applications, forensics, and low-copy-number target detection, where maximizing specificity and sensitivity is paramount [2] [3]. This application note details the underlying causes of off-target amplification and provides validated protocols employing Hot Start PCR strategies to mitigate these issues, framed within broader research on improving specificity in low-concentration samples.

Understanding the Mechanisms of Amplification Artefacts

Off-target amplifications are fundamental challenges that plague PCR efficiency, especially when working with limited template. The two most common artefacts are primer dimers and mis-priming, which occur under low-stringency conditions.

Primer Dimers

Primer dimers form when the 3' ends of primers anneal complementarily to each other instead of the target template. DNA polymerase then extends these primers, generating short, unwanted duplex products [3]. This self-annealing is facilitated at the lower temperatures encountered during reaction setup and the initial PCR cycles. The resulting primer dimers are themselves efficient amplification templates, leading to their exponential accumulation and sequestering of reaction resources [2] [1].

Mis-Priming

Mis-priming occurs when primers bind to regions of the template DNA with partial complementarity, rather than to the intended target sequence [2] [4]. Under the less stringent conditions at lower temperatures, these partial matches are stable enough for the DNA polymerase to initiate DNA synthesis. This leads to a complex mixture of nonspecific amplification products, which appear as smears or multiple bands upon gel electrophoresis [5]. The impact is particularly severe in samples with a high ratio of host-to-target DNA, such as human biopsy samples, where primers can bind to the abundant human genomic DNA [4].

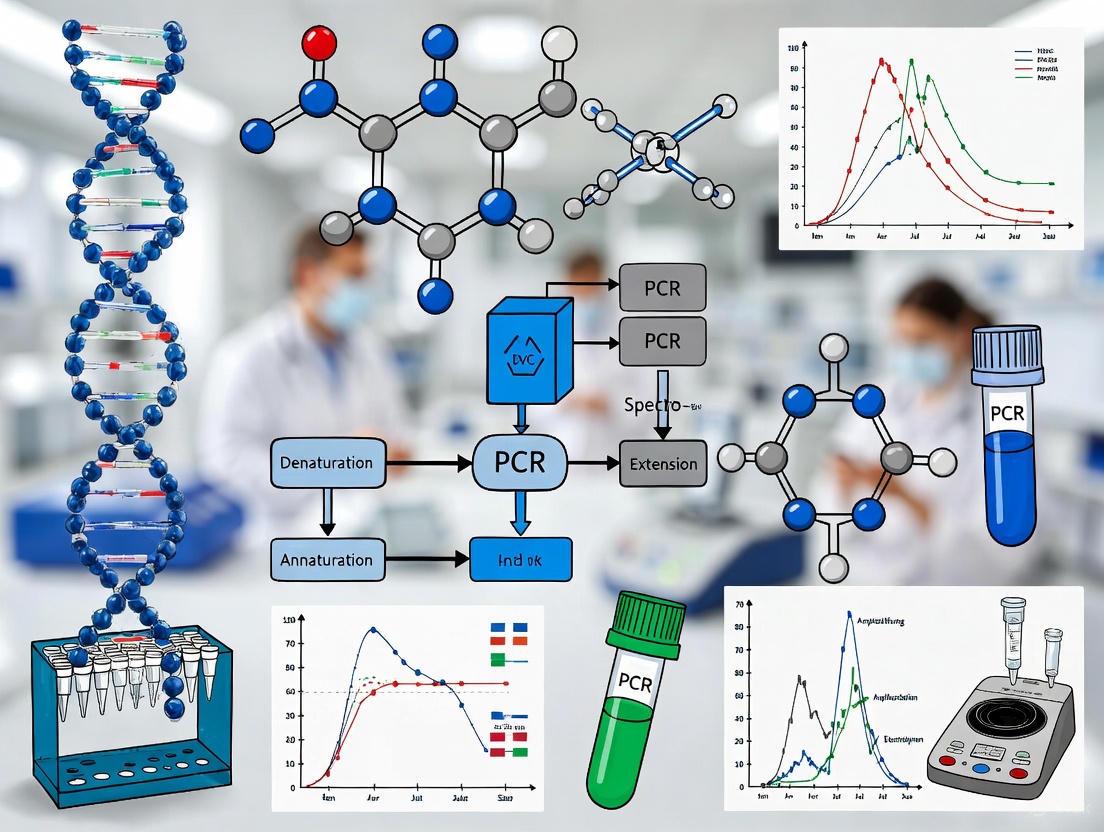

The following diagram illustrates the sequence of events leading to these artefacts and the core principle of the Hot Start solution.

Quantitative Impact of Off-Target Amplification

The detrimental effects of off-target amplification are not merely theoretical; they have quantifiable impacts on PCR sensitivity, specificity, and efficiency. The following tables summarize key experimental data that highlight these impacts and the demonstrated efficacy of Hot Start solutions.

Table 1: Impact of Off-Target Amplification on Assay Sensitivity [1]

| Template Copy Number | Unmodified Primers (Detectable?) | CleanAmp Turbo Primers (Detectable?) | CleanAmp Precision Primers (Detectable?) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5,000 | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 500 | No | Yes | Yes |

| 50 | No | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | No | No | Yes |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Hot Start Methods in a Model HIV-1 tat Gene Amplification [1]

| PCR Method | Primer Dimer Formation | Target Amplicon Yield | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unmodified Primers | High (Robust) | Moderate | Significant competition from artefacts |

| Antibody-Based Hot Start Taq | Low | Moderate | - |

| Chemically Modified Hot Start Taq | Low | Moderate | - |

| CleanAmp Turbo Primers | Very Low (Slight after 40 cycles) | High | - |

| CleanAmp Precision Primers | None Detected | High (delayed at 30 cycles) | Purest amplicon profile |

The data in Table 1 underscores a critical challenge: with unmodified primers, detection fails at 500 template copies or fewer because off-target amplification dominates the reaction, making it impossible to distinguish genuine signal from noise. Implementing Hot Start primers, particularly the precision type, lowers the detection limit by at least two orders of magnitude, enabling robust single-copy detection. Table 2 demonstrates that primer-based Hot Start methods can outperform enzyme-based methods in suppressing primer dimers while maintaining or even increasing the target amplicon yield.

Established Protocols for Mitigating Off-Target Effects

The following protocols provide detailed methodologies for employing Hot Start techniques to achieve specific amplification, particularly from challenging, low-concentration samples.

Protocol: Hot Start PCR Using Thermolabile Modified Primers

This protocol utilizes primers incorporating a 4-oxo-1-pentyl (OXP) phosphotriester modification, such as CleanAmp primers, to prevent extension until a high-temperature activation step [2] [1].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Primers: Forward and reverse primers synthesized with a thermolabile CleanAmp modification (e.g., Turbo or Precision) on the 3'-terminal internucleotide linkage. Resuspend in sterile TE buffer or nuclease-free water to a stock concentration of 100 µM.

- DNA Polymerase: Standard, unmodified Taq DNA Polymerase.

- Template DNA: 1 pg–10 ng of plasmid/viral DNA or 1 ng–1 µg of genomic DNA in a volume of 0.5-8 µL [6] [5].

- 10X PCR Buffer: Typically supplied with the DNA polymerase.

- MgClâ‚‚: 25 mM stock. Concentration must be optimized if not included in the buffer.

- dNTP Mix: 10 mM stock of each dNTP.

- Nuclease-free Water.

II. Experimental Procedure

- Reaction Setup on Ice: Assemble the following 50 µL reaction mixture on ice:

- Nuclease-free Water: Q.S. to 50 µL

- 10X PCR Buffer: 5 µL

- MgCl₂ (25 mM): 1.5-4 µL (Final conc. 1.5-2.0 mM) [6]

- dNTP Mix (10 mM): 1 µL (Final conc. 200 µM each)

- CleanAmp Forward Primer (100 µM): 0.1-0.5 µL (Final conc. 0.2-1.0 µM)

- CleanAmp Reverse Primer (100 µM): 0.1-0.5 µL (Final conc. 0.2-1.0 µM)

- Template DNA: Variable (e.g., 0.5-8 µL)

- Taq DNA Polymerase: 0.5-2.5 units (e.g., 0.5 µL of a 1 U/µL stock)

- Thermal Cycling: Transfer the PCR tube to a preheated thermal cycler and run the following program:

- Initial Activation/Denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes.

- This critical step both activates the primers by cleaving the thermolabile group and denatures the template DNA.

- Amplification (25-40 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 15-30 seconds.

- Anneal: 50-60°C for 15-30 seconds.

- Extend: 68°C for 45-60 seconds per 1 kb.

- Final Extension: 68°C for 5 minutes.

- Hold: 4-10°C.

- Initial Activation/Denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes.

III. Data Analysis

- Analyze 5-10 µL of the PCR product by agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Compare with a control reaction using unmodified primers. Successful implementation will show a single, strong band of the expected size and a marked reduction or elimination of primer dimer and smearing.

Protocol: One-Step Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR) with Hot Start for RNA Targets

This protocol is adapted for sensitive amplification from RNA templates, combining reverse transcription and PCR in a single tube, thus minimizing handling and potential contamination [2] [1].

I. Materials and Reagents

- Primers: Sequence-specific primers with CleanAmp modifications or a Hot Start DNA polymerase.

- RNA Template: 1 pg–1 µg of total RNA.

- Reverse Transcriptase: e.g., M-MLV RT.

- Hot Start DNA Polymerase or unmodified Taq with CleanAmp Primers.

- dNTP Mix: 10 mM stock.

- RNase Inhibitor.

- 5X RT-PCR Buffer.

II. Experimental Procedure

- Reaction Assembly: Combine components on ice. A typical 50 µL reaction includes:

- Nuclease-free Water: Q.S. to 50 µL

- 5X RT-PCR Buffer: 10 µL

- MgCl₂ (25 mM): 3-6 µL (Final conc. 1.5-3.0 mM)

- dNTP Mix (10 mM): 1 µL (Final conc. 200 µM each)

- Forward & Reverse Primers: 0.1-0.5 µL each (Final conc. 0.2-1.0 µM)

- RNase Inhibitor: 10-20 units

- M-MLV RT: 100-200 units

- Hot Start Taq DNA Polymerase: 1.25 units

- RNA Template: Variable

- Thermal Cycling:

- Reverse Transcription: 42-50°C for 15-60 minutes.

- Initial Denaturation / Hot Start Activation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes.

- Amplification (25-40 cycles): 95°C for 15-30 sec, 50-60°C for 30-60 sec, 68°C for 1 min/kb.

- Final Extension: 68°C for 5-10 minutes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate reagents is crucial for successfully implementing Hot Start PCR. The table below catalogs key solutions for preventing off-target amplification.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Hot Start PCR

| Reagent Category | Specific Example(s) | Mechanism of Action | Key Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heat-Activatable Primers | CleanAmp (OXP-modified) Primers [2] [1] | Thermolabile group (e.g., 4-oxo-1-pentyl) blocks the 3' end; removed at high temp to restore native primer. | Offers flexibility; use with standard polymerase. "Turbo" for speed, "Precision" for maximum purity [1]. |

| Antibody-Inhibited Polymerase | Platinum Taq, AmpliTaq Gold [2] [3] | Antibody binds polymerase active site, denaturing at high temp to release active enzyme. | Widely used; simple setup. Activation requires a prolonged initial denaturation. |

| Aptamer-Inhibited Polymerase | Highly specific oligonucleotides [3] | Oligonucleotide aptamer binds and inhibits polymerase; dissociates at high temperature. | Fast activation kinetics; effective for shorter protocols [3]. |

| Hot Start dNTPs | dNTPs with heat-labile protecting groups [3] | Protecting group on the 3'-OH prevents incorporation; cleaved at high temperature. | Can be used with any polymerase; replacing one or two natural dNTPs may be sufficient [3]. |

| Physical Separation | Wax Beads [3] | A physical barrier (e.g., wax) separates polymerase from other components; melts during first denaturation. | A low-cost, manual method. Less convenient for high-throughput workflows. |

| PF-46396 | PF-46396, MF:C27H29F3N2O, MW:454.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| PF-00956980 | PF-00956980, CAS:1262832-74-5, MF:C18H26N6O, MW:342.44 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Workflow for Selecting a Hot Start Method

The following diagram provides a logical decision pathway for selecting the most appropriate Hot Start strategy based on experimental requirements.

Off-target amplification represents a significant impediment to the reliability of PCR, especially in the context of low-concentration sample research. As demonstrated, primer dimers and mis-priming severely deplete reaction resources, lower sensitivity, and complicate data interpretation. The integration of Hot Start PCR methodologies, whether through modified primers, inhibited polymerases, or other chemical strategies, provides a robust and effective solution by imposing a stringent thermal activation barrier. The quantitative data and detailed protocols provided herein offer researchers a clear pathway to significantly enhance the specificity, sensitivity, and overall success of their amplification assays, thereby strengthening the validity of downstream analyses and conclusions in critical research and diagnostic endeavors.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, yet its sensitivity and reproducibility are often compromised by off-target amplification, especially when working with low-concentration samples. A common source of this problem is the premature activity of DNA polymerases at non-stringent temperatures. Hot-Start PCR is a powerful modification designed to suppress this pre-mature enzyme activity, thereby significantly enhancing the specificity and yield of target amplifications. This technique is particularly crucial for applications demanding high sensitivity, such as the detection of single-copy DNA molecules, blood-borne infectious agents, defective or cancerous genes, and forensic sample analysis [2]. By inhibiting polymerase activity until an elevated temperature is reached, Hot-Start mechanisms prevent the extension of nonspecifically bound primers and the formation of primer-dimers during reaction setup and the initial thermal cycler ramp-up [2] [7]. This application note details the fundamental principles of Hot-Start PCR, its mechanisms, and provides validated protocols for its use in sensitive research applications.

Mechanisms of Hot-Start Activation

The core principle of Hot-Start PCR is the reversible inhibition of the DNA polymerase enzyme until the reaction mixture reaches a high temperature, typically during the initial denaturation step. This prevents any enzymatic activity during the reaction setup at lower, permissive temperatures. Several sophisticated biochemical strategies have been developed to achieve this, each with distinct advantages.

Common Hot-Start Technologies

The table below summarizes the primary Hot-Start technologies employed in modern PCR.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Hot-Start PCR Technologies

| Hot-Start Technology | Mechanism of Action | Key Benefits | Potential Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-Based [7] [8] | A neutralizing antibody binds the polymerase's active site, blocking activity until the initial denaturation step inactivates the antibody. | Short activation time; full enzyme activity is restored; features are similar to the non-hot-start version [7]. | Presence of higher levels of exogenous proteins (antibodies) in the reaction [7]. |

| Chemical Modification [7] | Polymerase is covalently modified with chemical groups that block activity. Activity is restored by prolonged heating during initial denaturation. | Stringent inhibition; method is free of animal-origin components [7]. | Longer activation time is required; full enzyme activity may not always be restored [7]. |

| Aptamer-Based [9] | Oligonucleotide aptamers bind to the polymerase, inhibiting activity until high temperatures denature the aptamer. | Short activation time; free of animal-origin components [7]. | May be less stringent; reversible activation may not work well with low-melting-temperature primers [7]. |

| Primer-Based [2] [1] | Thermolabile groups (e.g., 4-oxo-1-pentyl or CleanAmp) are added to the 3'-end of primers, blocking extension until heat-mediated removal. | Does not require a modified enzyme; offers great flexibility and control; can be used with any DNA polymerase [2] [1]. | Requires specialized primer synthesis; the thermolabile group must be introduced during oligonucleotide manufacture. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of how these different mechanisms function to suppress premature activity and then become activated.

Consequences of Pre-Mature Activity

Without Hot-Start activation, DNA polymerases can exhibit significant activity at room temperature. This leads to two major types of off-target amplification:

- Mis-priming: Primers bind to regions of the template with partial complementarity and are extended, generating nonspecific products that compete with the desired amplicon for reagents [2].

- Primer-dimer formation: Primers hybridize to each other and are extended, creating short, unwanted amplification artifacts. This issue is exacerbated at low template concentrations, as the primers are in large molar excess over the target [2] [1].

Hot-Start technology mitigates these issues by ensuring that the polymerase only becomes active at high stringency temperatures, where primer binding is highly specific.

Quantitative Performance Data

The implementation of Hot-Start PCR provides tangible, quantitative improvements in assay performance. The following table summarizes key metrics that are enhanced, particularly critical for low-concentration sample research.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Enhancements with Hot-Start PCR

| Performance Metric | Improvement with Hot-Start PCR | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Sensitivity | Up to 100-fold increase; detection of as low as 3-5 target copies per μL [9] [1]. | Using CleanAmp Precision Primers vs. unmodified primers in a Lambda DNA template system [1]. |

| Amplification Specificity | Significant reduction or elimination of primer-dimer and mis-priming products [8] [1]. | Endpoint PCR analysis showing clean target bands with Hot-Start vs. multiple nonspecific bands with standard polymerase. |

| Target Yield | Increased yield of the desired amplicon due to reduced competition for reagents (primers, dNTPs, polymerase) [1]. | Comparison of amplicon band intensity in gel electrophoresis. |

| Reaction Setup Flexibility | Assembled reactions remain stable at room temperature for up to 24 hours without loss of specificity [8]. | Reactions were assembled and left on the bench for 24 hours before thermal cycling, with no increase in off-target products. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Hot-Start Specificity Using a Standard Master Mix

This protocol uses a commercial antibody-based Hot-Start master mix to amplify a challenging target, demonstrating the reduction of nonspecific amplification [8].

Research Reagent Solutions

- GoTaq Hot Start Green Master Mix (2X): Contains GoTaq Hot Start Polymerase, 2X Reaction Buffer (pH 8.5), 400µM dNTPs, and 4mM MgCl₂. The green dye allows for direct gel loading [8].

- Template DNA: Human genomic DNA (e.g., 100 ng/µL).

- Primers: Specific for a human genomic target (e.g., β-globin).

- Nuclease-Free Water.

Methodology

- Reaction Assembly: Prepare a 50 µL reaction on the lab bench at room temperature.

- 25 µL of 2X GoTaq Hot Start Green Master Mix

- 1 µL of Forward Primer (10 µM)

- 1 µL of Reverse Primer (10 µM)

- 1 µL of Template DNA (100 ng)

- 22 µL of Nuclease-Free Water

- Thermal Cycling: Place the tubes in a thermal cycler and run the following protocol.

- Initial Denaturation: 2 minutes at 94°C (This step inactivates the antibody and activates the polymerase)

- 35 Cycles:

- Denature: 30 seconds at 94°C

- Anneal: 30 seconds at 55-60°C (optimize for your primers)

- Extend: 1 minute per 1 kb at 72°C

- Final Extension: 5 minutes at 72°C

- Hold: 4°C

- Analysis: Analyze 10 µL of the PCR product by agarose gel electrophoresis. Compare against a control reaction set up with a non-hot-start master mix. The Hot-Start reaction should show a single, strong band of the expected size with minimal primer-dimer.

Protocol 2: High-Sensitivity Detection with CleanAmp Primers

This protocol employs a primer-based Hot-Start approach for extreme sensitivity, ideal for low-copy-number targets [2] [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

- DNA Polymerase: Standard, unmodified Taq DNA Polymerase.

- CleanAmp Primers: Primers synthesized with thermolabile 4-oxo-1-pentyl (OXP) groups on the 3'-terminal internucleotide linkages [2] [1].

- Template: Serially diluted Lambda genomic DNA (e.g., from 50,000 to 5 copies).

- dNTP Mix: 10 mM each.

- 10X PCR Buffer: (e.g., containing 100 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM KCl, pH 8.3).

- MgClâ‚‚: 25 mM.

Methodology

- Reaction Assembly: Prepare a 25 µL reaction on the bench.

- 2.5 µL of 10X PCR Buffer

- 1.5 µL of MgCl₂ (25 mM)

- 0.5 µL of dNTP Mix (10 mM each)

- 0.5 µL of CleanAmp Forward Primer (10 µM)

- 0.5 µL of CleanAmp Reverse Primer (10 µM)

- 1 Unit of unmodified Taq DNA Polymerase

- Variable amount of Template DNA

- Nuclease-Free Water to 25 µL

- Thermal Cycling:

- Initial Denaturation/Activation: 5 minutes at 95°C (This step cleaves the OXP groups, generating unmodified, extendable primers).

- 40-45 Cycles:

- Denature: 30 seconds at 95°C

- Anneal: 30 seconds at 60°C

- Extend: 1 minute at 72°C

- Final Extension: 5 minutes at 72°C

- Hold: 4°C

- Analysis: Use agarose gel electrophoresis or SYBR Green real-time PCR for detection. With CleanAmp Precision Primers, specific amplification should be detectable with as few as 5 copies of input template, a significant improvement over unmodified primers [1].

The experimental workflow for this high-sensitivity protocol is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of Hot-Start PCR for sensitive detection requires a set of key reagents and an understanding of their function.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Hot-Start PCR

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Hot-Start PCR |

|---|---|

| Antibody-Based Hot-Start Master Mix (e.g., GoTaq Hot Start) [8] | A ready-to-use mixture providing convenience, room-temperature setup stability, and a short activation time. Ideal for routine sensitive PCR. |

| Chemically Modified Hot-Start Polymerase (e.g., AmpliTaq Gold) [7] | Offers stringent inhibition for challenging assays, though it requires a longer initial activation time. |

| CleanAmp or OXP-Modified Primers [2] [1] | Provides a primer-based Hot-Start method that is compatible with any standard DNA polymerase, offering maximum flexibility and high sensitivity for low-copy-number applications. |

| dNTP Mix | The building blocks for DNA synthesis. Using a high-quality, nuclease-free dNTP mix is critical for efficient amplification. |

| Optimized PCR Buffer | Provides the optimal ionic environment and pH for polymerase activity and primer hybridization. The specific buffer is often supplied with the polymerase. |

| PGMI-004A | PGAM1 Inhibitor: 3,4-Dihydroxy-9,10-dioxo-N-(4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-9,10-dihydroanthracene-2-sulfonamide |

| PLX5622 | PLX5622, CAS:1303420-67-8, MF:C21H19F2N5O, MW:395.4 g/mol |

Hot-Start PCR is an indispensable technique for modern molecular biology, providing a critical solution to the problem of nonspecific amplification. By understanding and applying the fundamental principles of how different Hot-Start mechanisms suppress pre-mature enzyme activity, researchers can dramatically improve the specificity, sensitivity, and reliability of their PCR assays. This is particularly vital for applications involving low-concentration samples, such as in clinical diagnostics, biodefense, and single-cell analysis. The protocols and data provided here offer a framework for integrating Hot-Start methods into a research pipeline, ensuring robust and reproducible results in the most demanding experimental contexts.

In the pursuit of detecting minute quantities of nucleic acids, researchers often encounter a paradoxical challenge: as template concentration decreases, the prevalence of off-target amplification increases. This inverse relationship poses significant obstacles in critical applications such as early disease diagnosis, single-cell genomics, and forensic analysis, where target DNA is inherently limited. The core mechanism driving this phenomenon stems from reaction kinetics—at low concentrations, primers outnumber genuine target sites by orders of magnitude, creating a competitive environment where nonspecific binding and primer-dimer formation are statistically favored [2]. Understanding and mitigating this effect is paramount for obtaining reliable results from trace samples.

Hot-start PCR methodologies provide a powerful countermeasure to this challenge by imposing a thermal activation barrier that prevents DNA polymerase activity during reaction setup and initial heating phases [2]. By withholding polymerase function until higher temperatures are achieved, these methods significantly raise the stringency of primer annealing, thereby suppressing the nonspecific amplification pathways that disproportionately affect low-template reactions. This application note explores the mechanistic basis of this concentration-dependent specificity loss and provides optimized protocols to maintain amplification fidelity even at the limits of detection.

Mechanistic Analysis: How Low Template Concentration Drives Off-Target Effects

The Kinetic Imbalance in Low-Template Reactions

The fundamental challenge in low-template PCR arises from basic biochemical principles. When template DNA becomes limiting, the molar ratio of primers to target sequence increases dramatically. This imbalance creates a kinetic scenario where primers are more likely to encounter and bind to partially complementary off-target sites or other primer molecules than to their intended target [2]. These nonspecific interactions, though thermodynamically less stable, become statistically significant due to the vast excess of primer molecules competing for limited specific binding sites.

At the molecular level, this manifests as two primary artifacts: mis-priming and primer-dimer formation. Mis-priming occurs when primers bind to regions of the template with partial complementarity, leading to amplification of unintended sequences that compete with the desired product for reaction resources [2]. Primer-dimer formation involves cross-hybridization between primer molecules themselves, creating short artifacts that amplify efficiently due to their small size and high concentration [10]. Both phenomena consume critical reaction components—primers, dNTPs, and polymerase activity—thereby reducing the efficiency of target amplification and potentially generating false-positive signals.

The Hot-Start Solution: Imposing Thermal Stringency

Hot-start activation strategies directly address this kinetic challenge by introducing a temporal control mechanism. Through various chemical, physical, or enzymatic approaches, hot-start methods maintain DNA polymerase in an inactive state during reaction setup and the initial heating phase [2]. This prevention of enzymatic activity at lower temperatures is crucial because it is during these stages that nonspecific primer binding is most likely to occur.

The thermodynamic basis for this solution lies in the temperature dependence of nucleic acid hybridization. At lower temperatures (below 45°C), the energy barrier for primer binding is reduced, allowing stable hybridization even with mismatched sequences. As temperature increases, the stringency of hybridization increases, requiring greater complementarity for stable binding. Hot-start methods leverage this principle by ensuring that polymerase extension cannot occur until the reaction reaches more stringent temperatures where only perfectly matched primer-template complexes remain stable [2]. This simple yet powerful concept effectively eliminates the amplification of off-target products that form during low-stringency conditions.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Template Concentration on PCR Specificity

| Template Copy Number | Expected Specific Product Yield | Typical Off-Target Artifacts | Recommended Countermeasure |

|---|---|---|---|

| >10,000 copies | High yield, minimal artifacts | Rare primer-dimer formation | Standard PCR protocols sufficient |

| 1,000–10,000 copies | Good yield, some competition | Visible primer-dimer, minor mis-priming | Moderate hot-start activation |

| 100–1,000 copies | Reduced yield, significant competition | Pronounced primer-dimer, multiple bands | Strong hot-start method required |

| <100 copies | Very low yield, potential failure | Dominant off-target amplification | Multiplexed hot-start strategies |

Experimental Evidence: Documenting the Concentration-Specificity Relationship

Systematic Evaluation of OXP-Modified Primers

Recent research has provided compelling experimental evidence for the critical relationship between template concentration and amplification specificity. In a comprehensive study evaluating thermolabile 4-oxo-1-pentyl (OXP) phosphotriester-modified primers, investigators demonstrated significant improvements in specificity and efficiency when amplifying low-copy targets [2]. The modified primers contained one or two OXP modifications at the 3′-terminal internucleotide linkages, which impaired DNA polymerase extension at lower temperatures but restored full primer functionality after thermal activation.

The experimental design compared conventional primers against OXP-modified equivalents across a range of template concentrations (from 10^6 copies down to single-copy targets). In endpoint PCR analysis, reactions employing standard primers showed a dramatic increase in nonspecific amplification and primer-dimer formation as template concentration decreased below 1,000 copies. In contrast, reactions using OXP-modified primers maintained high specificity even at the lowest concentrations tested, with minimal off-target product formation [2]. Real-time PCR monitoring further revealed that the cycle threshold (Ct) values for specific products remained consistent with OXP-modified primers across concentration gradients, while control reactions showed increasing Ct values and irregular amplification curves as template became limiting.

Protocol: Specificity Rescue for Low-Template Amplification

Principle: This protocol utilizes hot-start activation with OXP-modified primers to maintain amplification specificity when working with limited template. The method is particularly effective for applications such as circulating tumor DNA detection, single-cell analysis, and ancient DNA characterization [2].

Reagents and Equipment:

- OXP-modified forward and reverse primers (0.4–0.5 μM each)

- Hot-start DNA polymerase (e.g., OneTaq Hot Start DNA Polymerase)

- Appropriate reaction buffer with Mg²⺠(1.5–2.0 mM final concentration)

- dNTP mix (200 μM each)

- Limited template DNA (1–100 copies)

- Thermal cycler with heated lid capability

Procedure:

- Prepare master mix on ice containing:

- 1× Hot-start reaction buffer

- 0.4–0.5 μM each OXP-modified primer

- 200 μM each dNTP

- 1.25 units hot-start DNA polymerase

- Nuclease-free water to adjust volume

Add template DNA last, using appropriate precautions to prevent contamination with higher-concentration DNA sources.

Cap tubes and immediately transfer to thermal cycler preheated to 94°C.

Execute the following thermal profile:

- Initial denaturation: 94°C for 2 minutes

- 35–40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 94°C for 15–30 seconds

- Annealing: Temperature optimized 5°C below primer Tm for 30 seconds

- Extension: 68°C for 45–60 seconds per kb

- Final extension: 68°C for 5 minutes

- Hold at 4°C

Analyze products by agarose gel electrophoresis or appropriate detection method.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If specificity remains suboptimal, increase annealing temperature in 2°C increments.

- For extremely low templates (<10 copies), consider increasing cycle number to 40–45 cycles.

- Faint specific bands with high background may indicate insufficient hot-start activation; verify polymerase activation temperature matches protocol.

Table 2: Optimization Parameters for Low-Template Hot-Start PCR

| Parameter | Standard Range | Low-Template Optimization | Effect on Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer concentration | 0.05–1 μM | 0.4–0.5 μM | Higher concentrations increase mis-priming; lower concentrations reduce sensitivity [11] |

| Mg²⺠concentration | 1.5–2.0 mM | 1.5 mM (minimize) | Higher Mg²⺠reduces stringency and promotes off-target amplification [12] |

| Annealing temperature | Varies by primer | 5°C below Tm | Increased temperature improves stringency but may reduce yield [12] |

| Cycle number | 25–35 | 35–40 | Increased cycles amplify specific product but also increase background [13] |

| Polymerase units | 0.25–5 units/50 μL | 1.25 units/50 μL | Excess enzyme increases nonspecific amplification [11] |

Integrated Workflow for Maximum Specificity

Diagram 1: Specificity Optimization Workflow for Low-Template PCR. This integrated approach combines modified primers, careful reaction setup, and thermal stringency to suppress off-target amplification.

Research Reagent Solutions for Low-Template Applications

Table 3: Essential Reagents for High-Specificity Low-Template PCR

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function in Low-Template PCR | Optimization Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hot-start DNA polymerase | OneTaq Hot Start DNA Polymerase | Aptamer-based inhibition prevents primer-dimer formation during setup [11] | Use 1.25 units/50 μL reaction; activate at 94°C for 30 seconds |

| Modified primers | OXP phosphotriester-modified primers | Thermolabile modifications block extension until high-temperature activation [2] | Incorporate 1-2 modifications at 3'-terminal linkages; use 0.4-0.5 μM final concentration |

| Reaction buffer | OneTaq GC Reaction Buffer | Enhanced formulation maintains polymerase activity with GC-rich targets [11] | Supplement with 10-20% GC enhancer for difficult templates |

| Buffer additives | DMSO (2-10%) | Disrupts secondary structure in GC-rich regions that impede amplification [12] | Titrate concentration (start with 5%) to balance specificity and yield |

| Magnesium solution | MgClâ‚‚ (25 mM stock) | Essential polymerase cofactor whose concentration directly affects fidelity [12] | Titrate from 1.5-2.0 mM in 0.2 mM increments for optimal specificity |

The established inverse relationship between template concentration and amplification specificity presents both a challenge and an opportunity for molecular diagnostics and research. Through strategic implementation of hot-start methodologies, particularly when combined with advanced primer engineering approaches such as OXP modifications, researchers can effectively decouple sensitivity from specificity in low-template applications. The protocols and reagents detailed in this application note provide a validated framework for maintaining amplification fidelity even when working with single-copy targets.

As molecular applications continue to push detection limits downward—whether in liquid biopsy applications, environmental DNA monitoring, or single-cell transcriptomics—the principles outlined here will become increasingly central to experimental success. Future innovations will likely focus on integrating multiple specificity-enhancement strategies while maintaining the practical accessibility necessary for widespread adoption across diverse research and clinical settings.

Core Components and Mechanisms of Hot-Start Activation

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, but conventional amplification can be plagued by nonspecific amplification, a critical issue when working with low-concentration samples. This nonspecific amplification occurs because DNA polymerases retain partial enzymatic activity at the temperatures used for reaction setup (typically room temperature), allowing for the extension of primers bound to template sequences with low homology (mispriming) and the formation of primer-dimers [14] [15]. These side reactions compete with the amplification of the desired target, drastically reducing yield, sensitivity, and assay reliability—a significant problem when the starting template copy number is limited [16] [2].

Hot-Start PCR was developed to overcome these limitations by suppressing enzymatic activity until the first high-temperature denaturation step is achieved [14]. The core principle involves strategically inhibiting a key reaction component—typically the DNA polymerase—during reaction assembly and the initial thermal cycler ramp-up. This inhibition is released at elevated temperatures (>90°C), ensuring that the polymerase becomes active only under the stringent conditions of the first denaturation step, thereby preventing the amplification of non-target sequences [15] [17]. For research involving scarce samples, such as single-cell analysis or circulating tumor DNA detection, the enhanced specificity and sensitivity afforded by Hot-Start activation are not merely beneficial but essential for obtaining meaningful and reproducible results [2].

Core Mechanisms of Hot-Start Activation

The efficacy of Hot-Start PCR hinges on the precise temporal control of DNA polymerase activity. This is achieved through various biochemical strategies that block the enzyme's active site or essential co-factors until a specific activation temperature is reached. The most common methods involve modifications to the DNA polymerase itself, though innovative primer-based approaches have also been developed.

Polymerase-Targeted Inhibition Strategies

| Hot-Start Technology | Mechanism of Action | Activation Temperature & Time | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-Based [7] [16] | An antibody binds the polymerase's active site, sterically blocking its function. | ~95°C for 2 minutes [16]; Short activation time. | Full restoration of native enzyme activity; features similar to non-hot-start versions [7]. | Presence of exogenous animal-derived proteins [17] [7]. |

| Chemical Modification [7] [17] | Polymerase is covalently linked with chemical groups that block activity. | >90°C for 5-15 minutes; Longer activation time [16] [7]. | High inhibition stringency; free of animal-derived components [7]. | Full enzyme activation not always possible; can affect long target amplification [7]. |

| Affibody Molecule-Based [7] | Engineered alpha-helical peptide proteins bind and inhibit the polymerase. | Short activation time [7]. | Low protein content in reaction; animal-origin free [7]. | Potentially less stringent than antibody method; poorer room-temperature stability [7]. |

| Aptamer-Based [14] [7] | Oligonucleotides bind to the polymerase, inhibiting activity. | Short activation time [7]. | Free of animal-origin components [7]. | May be less stringent, leading to nonspecific amplification; poor room-temperature stability [7]. |

Primer-Targeted and Physical Barrier Strategies

Beyond polymerase modification, other methods exist to implement the Hot-Start principle. Physical barrier methods involve using materials like wax beads to physically separate key reaction components (e.g., Mg²⺠or polymerase) from the rest of the mixture during setup. During the first denaturation step, the wax melts, allowing the components to mix and the reaction to commence [17] [18]. A more recent innovation is the use of modified primers with thermolabile groups. For instance, primers can be synthesized with 4-oxo-1-pentyl (OXP) phosphotriester modifications at their 3'-terminal ends. These modifications render the primers unextendable by DNA polymerase at low temperatures. During the initial high-temperature step, the OXP groups are rapidly cleaved, converting the primers into their natural, extendable phosphodiester form [2]. This method directly prevents primer-dimer formation and mispriming at the source.

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow and mechanism of Hot-Start PCR, from reaction setup to specific amplicon generation:

Quantitative Performance Data

The theoretical advantages of Hot-Start PCR are borne out in empirical data, which demonstrate clear improvements in sensitivity, specificity, and robustness compared to standard PCR. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from commercial Hot-Start systems, which are critical for researchers selecting a system for low-concentration sample work.

Table 1. Performance benchmarking of selected Hot-Start DNA polymerases.

| Polymerase / Master Mix | Hot-Start Method | Sensitivity (Limit of Detection) | Specificity (Non-specific Amplification) | Inhibitor Tolerance | Bench Stability After Setup |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platinum II Taq Hot-Start DNA Polymerase [19] | Antibody | ~5 copies of human genomic DNA [19] | High; enables co-cycling of multiple targets [19] | High (e.g., to humic acid, hemin) [19] | 24 hours at room temperature [19] |

| GoTaq Hot Start Master Mixes [16] | Antibody | Successful amplification of a 1.3 kb fragment from low nanogram amounts of human gDNA [16] | Marked reduction in primer-dimer and nonspecific products compared to standard Taq [16] | Not explicitly stated | 24 hours at room temperature [16] |

| IsoFast Hot Start Bst Polymerase [9] | Aptamer (AptaLock) | As low as 3 target copies/μL in colorimetric LAMP [9] | Designed for minimal background amplification [9] | Not explicitly stated | Stable for cold and room temperature setup [9] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This protocol is designed for the amplification of low-copy-number targets (e.g., <10â´ copies) using a Hot-Start DNA polymerase, such as an antibody-based formulation [17] [16]. The procedure emphasizes steps critical for maximizing specificity and yield.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2. Essential materials and reagents for Hot-Start PCR.

| Item | Function / Description | Example Products / Components |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Core enzyme whose activity is inhibited at low temperatures to prevent nonspecific amplification. | Platinum II Taq [19], GoTaq Hot Start Polymerase [16], DreamTaq Hot Start [7] |

| PCR Buffer | Provides optimal ionic environment and pH for polymerase activity and primer hybridization. | Often supplied as 10X concentrate with MgClâ‚‚ [17] [16]. |

| dNTP Mix | Building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for DNA synthesis. | Typically used at 200 µM of each dNTP in the final reaction [17]. |

| Primers | Forward and reverse oligonucleotides that define the target sequence. | Should be designed for high specificity and used at 0.1-1 µM each [17]. |

| Template DNA | The sample containing the target sequence to be amplified. | For low-copy work, use 10-100 ng of genomic DNA or equivalent [17]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent to bring the reaction to volume; must be free of nucleases. | - |

Reaction Setup and Thermal Cycling

Preparation:

- Assemble all reagents on ice. Though Hot-Start polymerases are inactive at room temperature, starting from cold reagents is an extra precaution.

- Calculate the required volumes of each component based on the final reaction volume. A typical volume is 25-50 µL [17].

- Use barrier pipette tips to prevent contamination [16].

Master Mix Preparation: In a nuclease-free tube, combine the following components in the order listed to create a master mix for multiple reactions, reducing pipetting error and ensuring consistency:

- Nuclease-Free Water (to final volume)

- 10X Reaction Buffer (1X final concentration)

- dNTP Mix (200 µM final concentration for each dNTP)

- Forward Primer (0.1-1 µM final concentration)

- Reverse Primer (0.1-1 µM final concentration)

- Hot-Start DNA Polymerase (e.g., 1.25 units per reaction) Mix the master mix thoroughly by gentle vortexing and brief centrifugation.

Aliquoting and Template Addition:

- Aliquot the appropriate volume of master mix into individual PCR tubes or a multi-well plate.

- Add the template DNA to each reaction. Include a negative control (no template) that receives nuclease-free water instead of template.

- Seal the tubes or plate.

Thermal Cycling: Place the samples in a thermal cycler and run the following program [17] [16] [19]:

- Initial Denaturation / Hot-Start Activation: 95°C for 2-10 minutes.

- Critical Step: This extended hold is crucial for fully activating the Hot-Start polymerase and denaturing the template.

- Amplification Cycles (25-35 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15-30 seconds.

- Annealing: 45-65°C for 15-30 seconds. Note: The optimal temperature must be determined based on the primer Tm. Some advanced polymerases allow for a universal 60°C annealing temperature [19].

- Extension: 72°C for 30-60 seconds per kilobase of target amplicon. Faster polymerases may require less time (e.g., 15 sec/kb) [19].

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes to ensure all amplicons are fully extended.

- Hold: 4-10°C ∞.

- Initial Denaturation / Hot-Start Activation: 95°C for 2-10 minutes.

The procedural workflow for the entire experiment, from preparation to analysis, is summarized below:

Application Notes for Low-Concentration Samples

In the context of low-concentration sample research, the choice of Hot-Start protocol and polymerase can significantly impact experimental outcomes. For targets present in very low copy numbers (e.g., single-copy genes in complex genomic DNA), the high specificity of antibody-based Hot-Start systems is recommended to prevent background amplification from overwhelming the signal [19] [2]. When processing many samples on automated liquid-handling platforms, the room-temperature stability (often up to 24 hours) of modern Hot-Start master mixes is indispensable for ensuring consistency across plates [16] [19].

For particularly challenging amplifications, such as those from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue or in the presence of inhibitors, selecting a Hot-Start polymerase with demonstrated inhibitor tolerance is crucial. Engineering polymerases like Platinum II Taq have been shown to successfully amplify DNA from FFPE samples and in the presence of humic acid or hemin, where other polymerases fail [19]. Furthermore, combining Hot-Start PCR with other specificity-enhancing strategies, such as touchdown PCR—where the annealing temperature starts high and gradually decreases over cycles—can further refine amplification specificity for rare targets [15].

Hot-Start activation is a powerful strategy that addresses the fundamental challenge of nonspecific amplification in PCR. By controlling polymerase activity through biochemical or physical means, it ensures that DNA synthesis initiates only under stringent conditions. The core components—the inhibited polymerase or modified primers—work in concert with a tailored thermal cycling protocol to dramatically improve assay specificity, sensitivity, and yield. For researchers in drug development and clinical diagnostics working with low-concentration samples, incorporating a well-validated Hot-Start method is a critical step towards obtaining robust, reliable, and interpretable genetic data. The available suite of Hot-Start technologies, from antibody-based to novel primer-mediated approaches, provides flexible solutions to meet the demanding requirements of modern molecular research.

A Practical Guide to Hot-Start Technologies and Their Applications

In the realm of molecular biology, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is an indispensable technique for amplifying specific DNA sequences. However, its efficacy, particularly with low-concentration samples, is often compromised by nonspecific amplification and primer-dimer formation. These artifacts predominantly arise when the DNA polymerase exhibits residual activity at the lower temperatures present during reaction setup. Hot-start PCR was developed to circumvent this limitation, and among the various strategies, antibody-mediated inhibition represents a classic and widely adopted approach. This method employs a neutralizing monoclonal antibody to bind and inhibit Taq DNA polymerase at ambient temperatures, with enzymatic activity being restored during the initial denaturation step of the thermal cycling process. The TaqStart Antibody facilitates a "hot start" without the need for physical barrier separation, thereby enhancing the specificity and yield of PCR amplifications, a critical factor for research and diagnostics involving scarce template DNA [20].

Core Mechanism and Advantages

The fundamental principle of the anti-Taq approach involves the reversible inhibition of Taq DNA polymerase by a specific monoclonal antibody. At room temperature, the antibody binds to the enzyme's active site, sterically blocking its activity and preventing the extension of misprimed sequences or primer-dimers. During the initial high-temperature denaturation step (typically 95°C for 2-5 minutes), the antibody is denatured and dissociates from the polymerase, rendering the enzyme fully active for the subsequent amplification cycles [7].

This mechanism offers several significant advantages for sensitive applications:

- Prevention of Nonspecific Amplification: By blocking polymerase activity during reaction setup, it minimizes the amplification of off-target sequences and primer-dimers [7] [21].

- Increased Sensitivity and Yield: Reactions are more sensitive and produce a higher yield of the desired amplicon, which is particularly beneficial for low-copy-number targets [20].

- Benchtop Stability and Throughput Compatibility: Assembled reactions remain stable at room temperature, making this method suitable for high-throughput and automated liquid-handling platforms [7].

- Rapid Activation: Unlike some chemically modified hot-start enzymes, antibody-mediated inhibition requires only a standard initial denaturation step to activate the polymerase, with full activity restored post-activation [7].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Hot-Start Technologies

| Hot-Start Technology | Key Feature | Activation Requirement | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-Mediated | Antibody blocks the active site. | Short initial denaturation (e.g., 95°C for 2 min). | Presence of exogenous antibody protein. |

| Chemical Modification | Polymerase is covalently modified. | Longer activation time (e.g., 95°C for 10+ min). | Can affect amplification of long targets (>3 kb). |

| Aptamer-Mediated | An oligonucleotide aptamer binds the enzyme. | Dissociates at lower temperatures. | May be less stringent; activation can be reversible. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Antibody-Mediated Hot-Start PCR

The following protocol is designed for a standard 50 µL reaction to amplify a target from a low-concentration DNA sample, such as genomic DNA or cDNA.

Reagent Preparation and Setup

- Assemble all reaction components on ice or a cooling block to further minimize non-specific activity.

- Prepare a master mix for multiple reactions to ensure consistency.

Reaction Assembly

- Combine the following components in a sterile PCR tube:

- 1X PCR Buffer (supplied with the enzyme)

- 200 µM of each dNTP

- 1.5-2.5 mM MgClâ‚‚ (concentration may require optimization)

- 0.2-1.0 µM of each forward and reverse primer

- 1-100 ng of template DNA (for genomic DNA; less for high-copy targets)

- 1.25 U of Taq DNA Polymerase

- A 1:1 Molar Ratio of TaqStart Antibody (relative to the polymerase)

- Nuclease-free water to a final volume of 50 µL

Thermal Cycling

- Transfer the tubes to a pre-heated thermal cycler and run the following program:

- Initial Denaturation / Antibody Inactivation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes.

- Amplification (25-40 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 20-30 seconds.

- Anneal: 50-65°C for 20-30 seconds (temperature must be determined empirically).

- Extend: 72°C for 15-60 seconds per kilobase of amplicon.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C.

Post-Amplification Analysis

- Analyze the PCR products using agarose gel electrophoresis.

- Compared to a non-hot-start control, successful implementation should result in a single, intense band of the expected size and a reduction or elimination of smearing and primer-dimer artifacts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Antibody-Mediated Hot-Start PCR

| Reagent | Function / Role in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Taq DNA Polymerase | The core thermostable enzyme that catalyzes DNA synthesis. |

| Anti-Taq Monoclonal Antibody | The inhibitory agent that enables the hot start by binding to and neutralizing the polymerase at low temperatures. |

| dNTPs | The building blocks (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP) for new DNA strands. |

| Target-Specific Primers | Short, single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides that define the start and end of the DNA region to be amplified. |

| MgClâ‚‚ | A critical cofactor for DNA polymerase activity; its concentration often requires optimization. |

| PCR Buffer | Provides the optimal ionic environment and pH for the PCR. |

| PRN1371 | PRN1371, CAS:1802929-43-6, MF:C26H30Cl2N6O4, MW:561.5 g/mol |

| PRN694 | PRN694, CAS:1575818-46-0, MF:C28H35F2N5O2S, MW:543.7 g/mol |

Mechanism of Antibody-Mediated Hot-Start PCR

The diagram below illustrates the sequential mechanism of how antibody-mediated hot-start PCR prevents non-specific amplification.

Antibody-mediated inhibition remains a cornerstone of robust PCR setup, providing a reliable and effective means to enhance amplification specificity and sensitivity. The classic anti-Taq approach is particularly powerful for challenging applications such as the detection of low-abundance targets, multiplex PCR, and clinical diagnostics, where the fidelity of the amplification is paramount. By integrating this method into standard protocols, researchers can achieve more reproducible and interpretable results, thereby advancing the reliability of downstream analyses in genomic research and drug development.

Heat-activatable DNA polymerases represent a cornerstone of modern Hot Start PCR technology, engineered to remain inactive during reaction setup at ambient temperatures and activate only upon exposure to high initial denaturation temperatures. This controlled activation mechanism is crucial for applications requiring high specificity and sensitivity, particularly when amplifying low-copy-number targets in complex backgrounds or when prolonged room-temperature setup is unavoidable. The fundamental principle involves chemical, physical, or antibody-based modifications that reversibly inhibit polymerase activity at lower temperatures, thereby preventing the extension of non-specifically annealed primers and the formation of primer-dimers during reaction preparation [3] [22]. Upon heating, the inhibitory constraint is released, rendering the enzyme fully active for the subsequent amplification cycles.

The necessity for such precision stems from a well-understood limitation of conventional PCR: DNA polymerase possesses residual activity even at lower temperatures. When reaction components are mixed at room temperature, this activity can facilitate non-specific primer binding and extension, leading to the synthesis of undesired by-products such as mis-primed sequences and primer-dimers [2] [3]. These by-products compete with the desired target for reaction resources, significantly reducing amplification efficiency and yield, especially when the target nucleic acid is present in low concentrations. Heat-activatable polymerases address this problem by imposing a thermal barrier on enzyme activity, ensuring that the first synchronous extension occurs only after the reaction mixture has reached a high, stringent temperature, thereby dramatically improving amplification specificity and sensitivity [23] [19].

Mechanisms of Heat Activation

The innovation behind heat-activatable DNA polymerases lies in the diverse biochemical strategies employed to temporarily inhibit enzymatic activity. These methods can be broadly categorized, each with distinct mechanisms and operational characteristics crucial for experimental planning.

Table 1: Comparison of Heat Activation Mechanisms

| Mechanism Type | Inhibitory Agent | Activation Trigger | Key Characteristics | Typical Activation Time/Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-Mediated [23] [19] | Monoclonal antibody bound to the polymerase | Heat denaturation of the antibody | Rapid activation, high specificity, common in commercial kits | ~2 minutes at 92°C [22] |

| Chemical Modification [2] | Thermolabile 4-oxo-1-pentyl (OXP) groups on primers | Thermal cleavage of modifications to yield natural primers | Prevents primer extension; applicable to any primer sequence | Elevated temperatures during initial denaturation |

| Physical Separation [3] | Wax barrier or frozen layer | Melting of the physical barrier | Simple principle; requires manual preparation | Melting point of wax or ice |

| Oligonucleotide Aptamers [3] | Highly specific inhibitory oligonucleotides | Temperature-dependent dissociation | High specificity of inhibition | Higher annealing temperatures |

Among these, antibody-mediated inhibition and chemically modified primers represent the most widely adopted and robust approaches. Antibody-mediated Hot Start PCR, utilized in enzymes like Platinum II Taq and JumpStart Taq, involves a neutralizing monoclonal antibody that binds directly to the DNA polymerase, sterically blocking its active site [23] [19]. This antibody-polymerase complex is stable at room temperature. During the initial denaturation step of the PCR cycle (typically 94-95°C), the antibody is irreversibly denatured and dissociates, releasing the fully active polymerase into the reaction [22]. This method is favored for its speed and reliability, requiring only a brief initial denaturation to activate the enzyme.

An alternative and innovative strategy involves the chemical modification of the PCR primers themselves, rather than the enzyme. This approach utilizes primers synthesized with one or two thermolabile 4-oxo-1-pentyl (OXP) phosphotriester (PTE) groups at the 3'-terminal internucleotide linkages [2]. The presence of these OXP modifications impairs the DNA polymerase's ability to extend the primer at lower temperatures. When the reaction is heated, these protecting groups are cleaved, converting the modified primer into a natural phosphodiester (PDE) oligonucleotide that is a fully functional substrate for the DNA polymerase. This method offers a unique "primer-based" Hot Start activation that is independent of the enzyme's modification [2].

Diagram 1: Mechanism of heat-activatable DNA polymerases. The process begins with an inactive polymerase at room temperature, preventing non-specific amplification. Activation occurs during initial denaturation, enabling specific target amplification.

Quantitative Performance Data

The superiority of heat-activatable DNA polymerases is demonstrated through rigorous benchmarking against conventional enzymes across multiple performance metrics. The quantitative data reveals significant enhancements in sensitivity, speed, and robustness, which are critical for research and diagnostic applications.

Sensitivity and Specificity: The primary advantage of Hot Start polymerases is their ability to detect low-copy-number targets with high fidelity. Studies show that the use of OXP-modified primers as substitutes for unmodified primers in PCR resulted in significant improvement in the specificity and efficiency of nucleic acid target amplification, which is particularly vital for applications like genetic testing, clinical diagnostics, and forensics [2]. Commercial systems like Platinum II Taq Hot-Start DNA Polymerase demonstrate reliable amplification from as little as 0.016 ng of human genomic DNA, equating to approximately 5 copies, with minimal non-specific background in no-template controls [19].

Amplification Speed and Efficiency: Engineered hot-start enzymes offer substantial improvements in processivity. For instance, Platinum II Taq exhibits a DNA synthesis rate that is four times faster than traditional Taq polymerases (15 sec/kb versus 1 min/kb), enabling the completion of PCR runs in as little as 30 minutes [19]. Furthermore, features like a universal primer annealing protocol at 60°C eliminate the need for extensive primer annealing temperature optimization and allow for the co-cycling of multiple PCR assays with different amplicon lengths in a single run, streamlining high-throughput workflows [19].

Inhibitor Tolerance: The performance of heat-activatable polymerases in suboptimal conditions is another key differentiator. Certain engineered versions display high tolerance to common PCR inhibitors such as humic acid, hemin, and xylan, facilitating successful amplification from challenging samples like formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues without the need for extensive nucleic acid purification [19].

Table 2: Quantitative Benchmarking of a Commercial Heat-Activatable DNA Polymerase

| Performance Metric | Platinum II Taq Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Conventional Taq / Other Hot-Start Enzymes |

|---|---|---|

| Synthesis Rate [19] | 15 seconds/kb (4x faster than conventional Taq) | 60 seconds/kb (conventional Taq) |

| Detection Sensitivity [19] | ~5 copies (0.016 ng human genomic DNA) | Varies; often higher copy number required |

| Inhibitor Tolerance [19] | High (to humic acid, hemin, xylan) | Low to moderate |

| Universal Annealing [19] | Yes (60°C for any primer pair) | No (requires specific Tm calculation) |

| Benchtop Stability [19] | 24 hours for assembled reactions | Often less stable |

| Max Target Length [19] | Up to 5 kb | Up to 5 kb (for standard Taq) |

Application Notes for Low Concentration Samples

Amplifying low concentration samples presents unique challenges, including increased susceptibility to non-specific amplification and stochastic effects. Heat-activatable DNA polymerases are specifically designed to overcome these hurdles. For low-copy-number targets in complex backgrounds, the stringent activation condition is critical. It ensures that the enzyme is only active when the primer-binding specificity is highest, thereby minimizing off-target amplification that could otherwise overwhelm or obscure the signal from the genuine target [22]. This is paramount in applications such as liquid biopsy, pathogen detection in early infection, and single-cell genomics, where the target of interest is scarce.

When working with such samples, the choice of buffer system and reaction composition is also crucial. For instance, the use of specialized buffers like qPCR Buffer (e.g., #PCR-279 from Jena Bioscience) that contain a well-balanced ratio of potassium-, ammonium-, and magnesium-ions can further enhance specificity and minimize by-product formation [22]. Furthermore, optimization of the MgClâ‚‚ concentration within a range of 1.5-2.0 mM is recommended, as lower concentrations can favor higher specificity, which is often the priority when template is limiting [22].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Endpoint PCR with Antibody-Mediated Hot Start Polymerase

This protocol is adapted from commercial systems and is designed for robust amplification of specific targets from standard DNA templates, ideal for cloning, genotyping, or general amplification [23] [22].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Hot Start DNA Polymerase: e.g., JumpStart Taq DNA Polymerase or similar antibody-inactivated enzyme [23].

- 10x Reaction Buffer: Supplied with the enzyme, often containing MgClâ‚‚.

- dNTP Mix: 10 mM of each dATP, dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP.

- Primers: Forward and reverse primers, resuspended to a working concentration of 10 μM.

- Template DNA: 10 ng to 100 ng of genomic DNA or 1-5 μL of cDNA.

- PCR-grade Water: Nuclease-free to prevent degradation of reagents.

- Equipment: Pipettes, sterile microcentrifuge tubes, thin-walled PCR tubes, and a thermal cycler.

Procedure:

- Master Mix Preparation: Thaw all reaction components (except the DNA polymerase) on ice. Vortex and centrifuge briefly. Prepare a master mix in a sterile 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube on ice according to the table below. Include a 10% volume excess to account for pipetting error.

Table 3: Master Mix Setup for a 25 μL Reaction

| Component | Final Concentration/Amount | Volume per 25 μL Reaction |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Reaction Buffer | 1x | 2.5 μL |

| dNTP Mix (10 mM each) | 200 μM | 0.5 μL |

| Forward Primer (10 μM) | 200-400 nM | 0.5 - 1.0 μL |

| Reverse Primer (10 μM) | 200-400 nM | 0.5 - 1.0 μL |

| Hot Start Polymerase | 0.025-0.05 units/μL | 0.125-0.25 μL (e.g., for 5 U/μL) |

| PCR-grade Water | To volume | Variable |

| Total Master Mix Volume | 20 μL |

- Aliquot and Add Template: Aliquot 20 μL of the master mix into each PCR tube. Add 5 μL of DNA template to each tube for a final reaction volume of 25 μL. Mix by gently pipetting and centrifuge briefly to collect the contents at the bottom of the tube.

- Thermal Cycling: Place the tubes in a thermal cycler and run the following program:

- Initial Denaturation/Activation: 95°C for 2 minutes (activates the polymerase) [22].

- Amplification (25-35 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 10-20 seconds.

- Annealing: 50-68°C for 10-20 seconds (optimize based on primer Tm).

- Extension: 72°C for 20 seconds per kb of amplicon.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C ∞.

- Analysis: Analyze 5-10 μL of the PCR product by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Protocol 2: PCR Using Heat-Activatable Modified Primers

This protocol utilizes a primer-based Hot Start strategy with OXP-modified primers, offering an alternative when enzyme-based hot start is not available or for specialized applications [2].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials:

- Standard DNA Polymerase: e.g., recombinant Taq DNA polymerase.

- Corresponding 10x PCR Buffer (with MgClâ‚‚ or without).

- dNTP Mix: 10 mM of each dNTP.

- OXP-Modified Primers: Primers containing thermolabile 4-oxo-1-pentyl groups at the 3'-terminal internucleotide linkages, resuspended to 10 μM [2].

- Template DNA.

- PCR-grade Water.

Procedure:

- Reaction Assembly: Prepare the reaction mix on ice. For a 50 μL reaction, combine:

- 5 μL of 10x PCR Buffer

- 1 μL of 10 mM dNTP Mix

- 1-2 μL of each OXP-modified primer (10 μM)

- 10-100 ng of template DNA

- 0.5-1.0 units of standard Taq DNA Polymerase

- PCR-grade water to 50 μL.

- Thermal Cycling: Immediately transfer the tubes to a pre-heated thermal cycler and run a standard PCR protocol. The critical step is the prolonged initial denaturation to ensure complete cleavage of the OXP groups. A typical program is:

- Initial Denaturation/Activation: 95°C for 3-5 minutes.

- Amplification (30-40 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds.

- Annealing: Tm-specific temperature for 30 seconds.

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 7-10 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C ∞.

- Kinetics of Primer Conversion: As studied in the literature, the conversion of OXP-modified oligonucleotides to their natural PDE form is rapid at 95°C in PCR buffer, ensuring primers are available for extension within the first cycle [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Heat-Activatable PCR

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description | Example Product / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody-Mediated Hot Start Polymerase | Inactivated by antibody; activated by heat. Provides ease of use and rapid activation. | Platinum II Taq, JumpStart Taq [23] [19] |

| Primers with OXP Modifications | Chemically modified primers block extension until heat-cleavage occurs. | Synthesized with 4-oxo-1-pentyl groups on 3'-end [2] |

| Optimized Reaction Buffer | Provides optimal ionic conditions (K+, NH4+, Mg2+) for specificity and yield. | qPCR Buffer, Crystal Buffer [22] |

| MgClâ‚‚ Solution (25 mM) | Separate component for fine-tuning Mg2+ concentration, critical for specificity. | For optimization between 1.5-2.0 mM final concentration [22] |

| PCR-grade Water | Nuclease-free water to prevent degradation of reaction components. | Essential for reproducibility and sensitivity |

| dNTP Mix | Building blocks for DNA synthesis. | 200 μM each dNTP is a standard final concentration [22] |

| Pyr10 | Pyr10, CAS:1315323-00-2, MF:C18H13F6N3O2S, MW:449.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pyrazinib | Pyrazinib (P3)|(E)-2-(2-(Pyrazin-2-yl)vinyl)phenol | (E)-2-(2-(Pyrazin-2-yl)vinyl)phenol (Pyrazinib, P3) is a novel small molecule radiosensitiser for oesophageal adenocarcinoma research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, yet its utility, particularly in multiplex assays and low-copy-number target detection, is often compromised by off-target amplification artifacts such as primer-dimer formation and mis-priming [24] [1]. These non-specific products consume crucial reaction substrates, thereby lowering the efficiency and sensitivity of the desired amplification [1]. Hot Start activation strategies are designed to mitigate these issues by inhibiting DNA polymerase activity during reaction setup at lower, less stringent temperatures [2].

This application note focuses on a primer-based Hot Start strategy employing primers containing thermolabile 4-oxo-1-pentyl (OXP) phosphotriester modifications, commercially available as CleanAmp Primers [2] [1]. We detail the mechanism, provide quantitative performance data, and outline standardized protocols for implementing these primers to achieve superior specificity and sensitivity in challenging PCR applications.

Mechanism of Action

CleanAmp Primers are oligonucleotides incorporating one or two thermolabile OXP modifications at the 3'-terminal internucleotide linkages [2]. These modifications serve as steric and ionic blockers, preventing DNA polymerase from initiating primer extension at non-stringent temperatures (e.g., during reaction setup) [2] [1]. During the initial denaturation step of the PCR thermal cycle, the OXP groups are rapidly hydrolyzed, converting the modified primers into their native, extendable phosphodiester form [2]. This controlled activation ensures that primers are only available for extension when the reaction temperature is sufficiently high to promote specific hybridization, thereby drastically reducing off-target amplification [1].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and key benefits of using OXP-modified primers in a Hot Start PCR protocol.

Performance Data & Comparative Analysis

Specificity and Sensitivity in Endpoint PCR

Studies comparing unmodified primers to CleanAmp Turbo and Precision primers demonstrate a significant reduction in off-target amplification. In a model system amplifying a region of HIV-1 genomic DNA, unmodified primers produced robust primer-dimer artifacts that competed with the 365 bp target amplicon [1]. Turbo Primers significantly reduced primer-dimer formation and increased target yield, while Precision Primers eliminated detectable primer-dimer, yielding a pure amplicon product [1].

The limit of detection (LOD) is markedly improved using OXP-modified primers. In real-time PCR assays using SYBR Green detection, unmodified primers failed to reliably detect a target below 500 copies [1]. In contrast, CleanAmp Turbo Primers lowered the LOD by ten-fold (50 copies), and CleanAmp Precision Primers achieved a hundred-fold improvement, detecting as low as 5 target copies [1].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of CleanAmp Primers in Endpoint and Real-Time PCR

| Primer Type | Off-Target Amplification | Limit of Detection | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unmodified Primers | High levels of primer-dimer and mis-priming [1] | ~500 copies [1] | Standard performance, prone to artifacts |

| CleanAmp Turbo Primers | Significantly reduced primer-dimer [1] | ~50 copies (10-fold improvement) [1] | Fast activation, ideal for standard and fast-cycling PCR |

| CleanAmp Precision Primers | Primer-dimer eliminated [1] | ~5 copies (100-fold improvement) [1] | Slower activation, optimal for high-sensitivity applications |

Performance in Multiplex PCR

Multiplex PCR, which amplifies multiple targets in a single reaction, is highly susceptible to primer-dimer formation and preferential amplification of certain targets due to the increased number of primer pairs [24] [1]. Evaluation of a triplex PCR assay showed that unmodified primers failed to amplify the longest amplicon (962 bp) at template concentrations below 50,000 copies, indicating severe preferential amplification [1]. Conversely, CleanAmp Turbo Primers enabled balanced co-amplification of all three targets across a broad concentration range (50 to 500,000 copies) with uniform efficiency [1]. Real-time duplex PCR data further confirmed that Turbo Primers provided earlier quantification cycle (Cq) values than unmodified primers, especially at low template concentrations where unmodified primers sometimes failed to detect the target altogether [1].

Table 2: CleanAmp Primer Performance in Multiplex PCR Applications

| Application Challenge | Performance with Unmodified Primers | Performance with CleanAmp Turbo Primers |

|---|---|---|

| Balanced Amplification | Preferential amplification of shorter targets; longer amplicons (962 bp) not detected at low copy numbers [1] | Uniform amplification of all targets (139 bp, 533 bp, 962 bp) across a 10,000-fold template range [1] |

| Sensitivity | Detection limit of ~5,000 copies in a triplex format [1] | Detection limit of 50 copies, a 100-fold improvement in sensitivity [1] |

| Real-Time Quantitative PCR | Delayed Cq values; some targets undetected at low concentrations (e.g., 50 copies) [1] | Earlier, reproducible Cq values for all targets, enabling reliable quantification [1] |

Comparison with Other Hot Start Methods

CleanAmp Primers used with standard, unmodified Taq DNA polymerase were compared against various specialized Hot Start DNA polymerases [1]. Endpoint PCR analysis revealed that the amplicon yield from reactions using Turbo Primers exceeded that of all tested Hot Start polymerases [1]. Furthermore, Precision Primers with unmodified Taq produced amplicon yield equal to or greater than the other Hot Start systems while offering superior specificity [1]. CleanAmp Primers are also compatible with a wide range of thermostable DNA polymerases beyond Taq, including Tth, Tfl, and Deep Vent, making them a versatile and cost-effective Hot Start solution [1].

Protocols

Protocol: Endpoint Triplex PCR with CleanAmp Primers

This protocol is adapted from studies demonstrating improved multiplex PCR performance using OXP-modified primers [24].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| CleanAmp Primers (Turbo or Precision) | Thermolabile modified primers for Hot Start activation. Used at 200 nM each [24]. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Standard, unmodified thermostable DNA polymerase. 1.25 U per 50 µL reaction [24]. |

| 10X PCR Buffer | Typically supplied with DNA polymerase. Final composition: 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mM KCl [24]. |

| MgClâ‚‚ Solution | Magnesium chloride, a co-factor for DNA polymerase. Final concentration: 2.5 mM [24]. |

| dNTP Mix | Deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP). Final concentration: 0.2 mM each [24]. |

| Template DNA | e.g., Bacteriophage Lambda genomic DNA. Serial dilutions from 50 to 500,000 copies per reaction [24]. |

Procedure

- Prepare Master Mix: On ice, combine the following components in a sterile, nuclease-free tube for a single 50 µL reaction:

- Nuclease-free water: to 50 µL final volume

- 10X PCR Buffer: 5 µL

- 50 mM MgCl₂: 2.5 µL (for 2.5 mM final)

- 10 mM dNTP Mix: 1 µL (for 0.2 mM final)

- CleanAmp Forward and Reverse Primers (for three targets, six primers total, 10 µM stock each): 1 µL each (for 200 nM final each)

- Taq DNA Polymerase (5 U/µL): 0.25 µL (for 1.25 U)

- Template DNA: Variable volume (e.g., 5 µL)

- Thermal Cycling: Place the tubes in a thermal cycler and run the following profile:

- Initial Activation/Denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes. This step is critical for hydrolyzing the OXP modifications and activating the primers.

- Amplification (35 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 40 seconds

- Anneal: 56°C for 30 seconds

- Extend: 72°C for 2 minutes

- Final Extension: 72°C for 7 minutes.

- Hold: 4°C.

- Analysis: Analyze 20 µL of the PCR product by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel stained with an appropriate DNA intercalating dye.

Protocol: Real-Time Duplex PCR with TaqMan Probes

This protocol is suitable for sensitive, quantitative multiplex detection [24] [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| CleanAmp Turbo Primers | Recommended for real-time applications due to their faster activation kinetics. Used at 200 nM each [24]. |

| TaqMan Probes | Hydrolysis probes (e.g., FAM, HEX, Cy5-labeled) for specific target detection. Used at 100 nM [24]. |