Interference Correction Methods: A Critical Comparison of Detection Limit Improvements in Bioanalysis

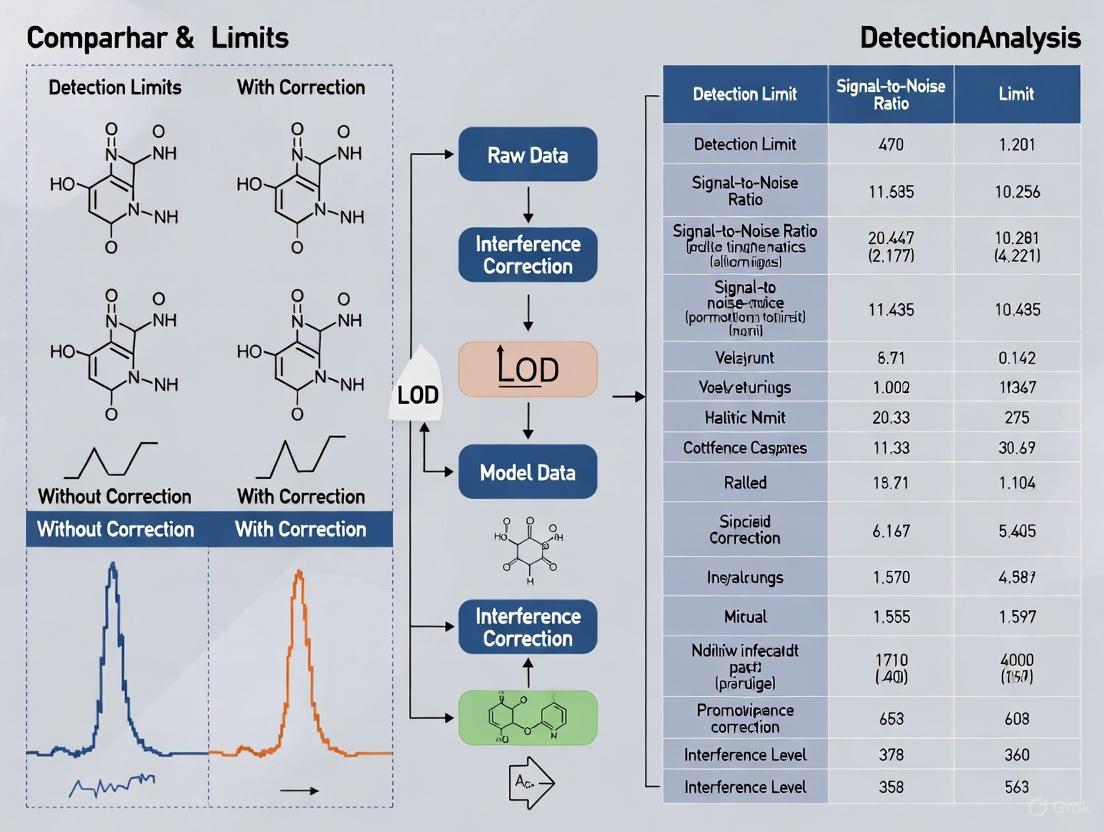

This article provides a comprehensive examination of how interference correction methods impact detection limits in analytical techniques crucial for drug development, including immunoassays, LC-MS/MS, and ICP-based platforms.

Interference Correction Methods: A Critical Comparison of Detection Limit Improvements in Bioanalysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of how interference correction methods impact detection limits in analytical techniques crucial for drug development, including immunoassays, LC-MS/MS, and ICP-based platforms. Aimed at researchers and bioanalytical scientists, it explores the foundational concepts of interference and detection limits, details practical correction methodologies, offers troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls, and establishes a framework for the rigorous validation of correction approaches. By synthesizing current research and practical guidelines, this resource aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to enhance assay accuracy, sensitivity, and reliability in the presence of complex sample matrices and interfering substances.

Understanding Interference and Its Impact on Detection Limits

In analytical chemistry and bioanalysis, the Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ) are fundamental performance characteristics that define the capabilities of an analytical method at low analyte concentrations. The LOD represents the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from the analytical background noise, while the LOQ is the lowest concentration that can be quantitatively measured with acceptable precision and accuracy [1] [2]. These parameters are particularly crucial in pharmaceutical development, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics, where detecting and quantifying trace levels of substances directly impacts research validity and decision-making processes.

Understanding the distinction between these metrics is essential for method validation. The LOD answers the question "Is the analyte present?" whereas the LOQ addresses "How much of the analyte is present?" with defined reliability [2]. The relationship between these limits and their determination becomes increasingly complex when accounting for matrix effects and interference, a critical consideration in the comparison of detection limits with and without interference correction methods.

Theoretical Definitions and Distinctions

Limit of Detection (LOD)

The Limit of Detection (LOD), also referred to as the detection limit, is defined as the lowest possible concentration at which a method can detect—but not necessarily quantify—the analyte within a matrix with a specified degree of confidence [1]. It represents the concentration where the analyte signal can be reliably distinguished from the background noise. The LOD is typically applied in qualitative determinations of impurities and limit tests, though it may sometimes be required for quantitative procedures [1]. At concentrations near the LOD, an analyte's presence can be confirmed, but the exact concentration cannot be precisely determined.

Limit of Quantification (LOQ)

The Limit of Quantification (LOQ), or quantification limit, is the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably quantified by the method with acceptable precision and trueness [1]. Unlike the LOD, which merely confirms presence, the LOQ ensures that measured concentrations fall within an acceptable uncertainty range, allowing for accurate quantification [2]. This parameter is essential for quantitative determinations of impurities and degradation products in pharmaceutical analysis and other fields requiring precise low-level measurements.

Conceptual Relationship

The conceptual relationship between LOD and LOQ establishes that the LOQ is always greater than or equal to the LOD [3]. This hierarchy exists because quantification demands greater certainty, precision, and reliability than mere detection. The ratio between these limits typically ranges from approximately 3:1 to 5:1 depending on the calculation method and analytical technique [1] [4]. This relationship underscores a fundamental analytical principle: it is possible to detect an analyte without being able to quantify it accurately, but reliable quantification inherently requires definitive detection.

Methodologies for Determining LOD and LOQ

Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N)

The signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) approach is commonly applied to instrumental methods that exhibit baseline noise, such as HPLC and other chromatographic techniques [1]. This method compares signals from samples containing low analyte concentrations against blank signals to determine the minimum concentration where the analyte signal can be reliably detected or quantified. For LOD determination, a generally acceptable S/N ratio is 3:1, while LOQ typically requires a ratio of 10:1 [1] [4]. This approach is particularly valuable for its simplicity and direct instrument-based application, though it may not adequately account for all sources of methodological variation.

Standard Deviation and Slope Method

The standard deviation and slope method utilizes statistical parameters derived from calibration data or blank measurements. For this approach, the LOD is calculated as 3.3 × σ / S, where σ represents the standard deviation of the response and S is the slope of the calibration curve [1]. Similarly, the LOQ is calculated as 10 × σ / S [1]. The standard deviation (σ) can be determined through two primary approaches:

- Standard deviation of the blank: Measuring multiple blank samples and calculating the standard deviation from the obtained responses [1]

- Standard deviation from the calibration curve: Using the standard deviation of y-intercepts of regression lines or the residual standard deviation of the regression line [1]

This method provides a more statistically rigorous foundation but requires careful experimental design to ensure accurate parameter estimation.

Visual Examination

Visual examination offers a non-instrumental approach for determining LOD and LOQ, particularly applicable to methods without sophisticated instrumentation. For LOD, this might involve identifying the minimum concentration of an antibiotic that inhibits bacterial growth by calculating the zone of inhibition [1]. For LOQ, visual determination could include titration experiments where known analyte concentrations are added until a visible change (e.g., color transition) occurs [1]. While less statistically rigorous, this approach remains valuable for certain analytical systems where instrumental detection is impractical.

Advanced Graphical and Statistical Approaches

Recent methodological advances include sophisticated graphical and statistical approaches for determining LOD and LOQ:

- Uncertainty Profile: An innovative validation approach based on tolerance intervals and measurement uncertainty that provides a decision-making graphical tool [5]

- Accuracy Profile: A graphical method that uses tolerance intervals for result interpretation and defines the quantitation limit as the lowest concentration level where the tolerance interval remains within acceptance limits [5]

Comparative studies indicate that these graphical tools offer more realistic assessments of LOD and LOQ compared to classical statistical concepts, which may provide underestimated values [5].

Table 1: Comparison of LOD and LOQ Determination Methods

| Method | Basis | LOD Calculation | LOQ Calculation | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Instrument baseline noise | S/N = 3:1 [1] | S/N = 10:1 [1] | HPLC, chromatographic methods [1] |

| Standard Deviation & Slope | Statistical parameters from calibration | 3.3 × σ / S [1] | 10 × σ / S [1] | Photometric determinations, ELISAs [1] |

| Visual Examination | Observable response | Lowest detectable level [1] | Lowest quantifiable level with acceptable precision [1] | Microbial inhibition, titrations [1] |

| Uncertainty Profile | Tolerance intervals & measurement uncertainty | Intersection of uncertainty intervals with acceptability limits [5] | Lowest value of validity domain [5] | Bioanalytical methods, HPLC in plasma [5] |

Experimental Protocols and Data Presentation

Standard Protocol for LOD/LOQ Determination via Signal-to-Noise

Objective: To determine the LOD and LOQ of an analytical method using the signal-to-noise ratio approach.

Materials and Equipment:

- Calibrated analytical instrument (e.g., HPLC, GC)

- Blank samples (matrix without analyte)

- Standard solutions with known low concentrations of analyte

- Appropriate solvents and reagents

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Ensure the analytical instrument is properly calibrated and stabilized [4]

- Blank Analysis: Perform multiple measurements (n ≥ 6) of blank samples to establish the baseline noise [4]

- Low Concentration Standard Analysis: Analyze standards with known low concentrations of analyte in the expected LOD/LOQ range

- Signal and Noise Measurement: For each standard, measure the average signal height (or area) of the analyte peak and the baseline noise in a representative region

- Calculation: Calculate the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) for each standard by dividing the analyte signal by the baseline noise

- LOD Determination: Identify the concentration where S/N ≈ 3:1 through interpolation if necessary [1]

- LOQ Determination: Identify the concentration where S/N ≈ 10:1 through interpolation if necessary [1]

- Verification: Analyze replicates (n ≥ 6) at the estimated LOD and LOQ to verify acceptable detection and quantification performance

Standard Protocol for LOD/LOQ Determination via Calibration Curve

Objective: To determine the LOD and LOQ using the standard deviation and slope method from calibration data.

Procedure:

- Calibration Standards Preparation: Prepare a minimum of 6 calibration standards with concentrations in the expected low range of the method [6]

- Sample Analysis: Analyze each calibration standard in replicate (n ≥ 3)

- Calibration Curve Construction: Plot the instrument response against concentration and perform linear regression to obtain the slope (S) and y-intercept [6]

- Standard Deviation Determination: Calculate the standard deviation (σ) of the response. This can be derived from:

- Calculation: Compute LOD as 3.3 × σ / S and LOQ as 10 × σ / S [1]

- Experimental Verification: Prepare and analyze samples at the calculated LOD and LOQ concentrations to verify performance

Experimental Data from Literature

Table 2: Experimental LOD and LOQ Values for Organochlorine Pesticides in Different Matrices [7]

| Matrix | Analytical Technique | LOD Range (μg/L or μg/g) | LOQ Range (μg/L or μg/g) | Extraction Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | GC-ECD | 0.001 - 0.005 | 0.002 - 0.016 | Solid Phase Extraction |

| Sediment | GC-ECD | 0.001 - 0.005 | 0.003 - 0.017 | Soxhlet Extraction |

Table 3: Comparison of LOD and LOQ Values for Sotalol in Plasma Using Different Assessment Approaches [5]

| Assessment Approach | LOD Value | LOQ Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Statistical Concepts | Underestimated values | Underestimated values | Provides conservative estimates [5] |

| Accuracy Profile | Relevant and realistic assessment | Relevant and realistic assessment | Graphical tool using tolerance intervals [5] |

| Uncertainty Profile | Relevant and realistic assessment | Relevant and realistic assessment | Provides precise measurement uncertainty [5] |

Impact of Interference and Matrix Effects

Matrix effects represent a significant challenge in accurately determining LOD and LOQ, particularly in complex samples such as biological fluids, environmental samples, and pharmaceutical formulations. These effects arise from:

- Co-eluting substances in chromatographic methods that contribute to baseline noise or directly interfere with analyte detection [7]

- Ion suppression or enhancement in mass spectrometric detection caused by matrix components affecting ionization efficiency

- Nonspecific binding in immunoassay methods leading to elevated background signals

- Physical matrix effects such as viscosity differences that alter analyte introduction or detection characteristics

The presence of interference typically elevates both LOD and LOQ values by increasing the baseline noise (σ) in the calculation, thereby reducing the overall sensitivity and reliability of the method at low concentrations [7].

Interference Correction Methods

Several approaches can mitigate interference and matrix effects:

- Sample Preparation Techniques: Methods such as solid-phase extraction, liquid-liquid extraction, and protein precipitation can remove interfering substances before analysis [7] [4]

- Matrix-Matched Calibration: Using calibration standards prepared in the same matrix as samples to compensate for matrix effects [4]

- Internal Standardization: Employing structurally similar internal standards that experience similar matrix effects as the analyte [5]

- Chromatographic Resolution: Optimizing separation conditions to resolve analytes from potential interferents [7]

- Background Correction: Mathematical or instrumental techniques to subtract background signals [4]

Comparative Data: With vs. Without Interference Correction

Table 4: Impact of Interference Correction Methods on LOD and LOQ Values

| Analytical Scenario | LOD | LOQ | Precision at LOQ (%CV) | Accuracy at LOQ (%Bias) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncorrected Matrix Effects | Elevated | Elevated | >20% [8] | >15% |

| With Matrix-Matched Calibration | Improved | Improved | 15-20% [8] | 10-15% |

| With Efficient Sample Cleanup | Optimal | Optimal | <15% | <10% |

| With Internal Standardization | Optimal | Optimal | <15% [5] | <10% |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LOD/LOQ Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Matrix-Matched Blank | Provides baseline for noise determination and specificity assessment | Blank plasma for bioanalysis; purified water for environmental analysis [8] |

| Internal Standards | Corrects for variability in sample preparation and analysis | Stable isotope-labeled analogs for LC-MS/MS; structural analogs for HPLC [5] |

| High-Purity Reference Standards | Ensures accurate calibration and quantification | Certified reference materials for instrument calibration [7] |

| Solid-Phase Extraction Cartridges | Removes matrix interferents and concentrates analytes | C18 cartridges for pesticide extraction from water [7] |

| Derivatization Reagents | Enhances detectability of low-concentration analytes | Reagents for improving GC-ECD sensitivity [7] |

| Quality Control Materials | Verifies method performance at low concentrations | Prepared samples at LOD and LOQ levels for validation [8] |

| FR 113680 | FR 113680, CAS:126088-92-4, MF:C35H39N5O6, MW:625.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| LAB 149202F | LAB 149202F, CAS:94343-58-5, MF:C16H18N2O4, MW:302.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The accurate determination of Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ) is fundamental to evaluating analytical method performance, particularly for applications requiring trace-level analysis. While multiple approaches exist for establishing these parameters—including signal-to-noise ratio, standard deviation and slope method, and visual examination—each offers distinct advantages and limitations. Recent advances in graphical approaches such as uncertainty profiles and accuracy profiles provide more realistic assessments compared to classical statistical concepts [5].

The critical influence of matrix effects and interference on LOD and LOQ values necessitates careful method design and appropriate correction strategies. Techniques such as matrix-matched calibration, internal standardization, and efficient sample preparation significantly improve method sensitivity and reliability at low concentrations. When reporting analytical results, values between the LOD and LOQ should be interpreted with caution, as they indicate the analyte's presence but lack the precision required for accurate quantification [2] [4]. As analytical technologies advance and regulatory expectations evolve, the appropriate determination and application of these fundamental metrics remain essential for generating reliable data in research and quality control environments.

In analytical science and clinical diagnostics, the accuracy of a measurement is paramount. However, this accuracy is frequently challenged by interferences—substances or effects that alter the correct value of a result. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding and mitigating these interferences is critical for developing robust assays and ensuring reliable data. This guide provides a structured comparison of three principal interference categories—Spectral, Matrix, and Immunological—framed within the context of research on detection limits and correction methods. We will objectively compare the performance of analytical systems with and without the application of interference correction protocols, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Spectral Interference

Spectral interference occurs when a signal from a non-target substance is mistakenly detected as or overlaps with the signal of the analyte. This is a predominant challenge in spectroscopic techniques like Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) and optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) [9] [10].

- Mechanisms and Types: In ICP-MS, spectral overlaps are primarily caused by polyatomic ions formed from combinations of plasma gases, solvent-derived ions, and sample matrix components [9] [10]. For instance, the determination of sulfur (³²S), manganese (âµâµMn), and iron (âµâ¶Fe) is severely hampered by interferences from ¹â¶Oâ‚‚âº, (¹â¶OH)â‚‚âº, â´â°Ar¹â´NHâº, and â´â°Ar¹â¶O⺠ions [9]. In ICP-OES, interferences can be a direct spectral overlap or a wing overlap from a nearby high-intensity line, elevating the background signal [10].

- Impact on Detection Limits: The presence of spectral interferences can dramatically degrade detection limits (LOD). In one study, the detection limit for Cadmium (Cd) at 228.802 nm degraded from 0.004 ppm (spectrally clean) to approximately 0.5 ppm in the presence of 100 ppm Arsenic (As) due to direct spectral overlap—a more than 100-fold loss [10].

Correction Methods and Performance

Several strategies exist to overcome spectral interferences, each with varying effects on analytical performance.

Table 1: Comparison of Spectral Interference Correction Methods in ICP-MS

| Correction Method | Principle | Key Improvement | Limitation/Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interference Standard Method (IFS) [9] | Uses an argon species (e.g., ³â¶Arâº) as an internal standard to correct for fluctuations in the interfering signal. | Significantly improved accuracy for S, Mn, and Fe determination in food samples. | Relies on similar behavior of IFS and interfering ions in the plasma. |

| Collision/Reaction Cells (DRC, CRI) [9] | Introduces gases (e.g., NH₃, Hâ‚‚) to cause charge transfer or chemical reactions that remove interfering ions. | Effectively eliminates interferences like â´â°Ar³âµCl⺠on â·âµAs⺠[9]. | Requires instrument modification; gas chemistry must be optimized. |

| High-Resolution ICP-MS [10] | Physically separates analyte and interferent signals using a high-resolution mass spectrometer. | Directly resolves many polyatomic interferences. | Higher instrument cost and complexity. |

The Interference Standard Method (IFS) is a notable mathematical correction that does not require instrument modification. Application of IFS for sulfur, manganese, and iron determination in food samples by ICP-QMS significantly improved accuracy by minimizing the interfering ion's contribution to the total signal [9].

The following workflow outlines the steps for identifying and correcting spectral interferences using the IFS method and other common techniques.

Matrix Interference

Matrix interference arises from the bulk properties of the sample itself (e.g., viscosity, pH, organic content) or the presence of non-analyte components that alter the analytical measurement's efficiency, often through non-specific binding or physical effects [11] [12].

- Sources and Examples: Common sources include lipemia (high lipid content), hemolysis, and the use of specific anticoagulants like EDTA or heparin [11]. Lipemia can interfere in nephelometric and turbidimetric assays [11]. High concentrations of proteins or salts can also change the ionic strength or viscosity of the sample, affecting antigen-antibody binding in immunoassays or nebulization efficiency in ICP-MS [12].

- Impact on Detection Limits: Matrix effects can lead to both false positives and false negatives. In immunoassays, they can physically mask the antibody binding site or cause steric hindrance [11] [12]. The measurable concentration of hormones like free thyroxine (FT4) can be altered by free fatty acids displacing the hormone from its binding globulins [11]. These effects can raise the effective LOD by increasing background noise or suppressing the analyte signal.

Correction Methods and Performance

Mitigating matrix interference often involves sample pre-treatment or sophisticated calibration strategies.

Table 2: Comparison of Matrix Interference Mitigation Strategies

| Mitigation Strategy | Principle | Key Improvement | Limitation/Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Dilution | Reduces concentration of interfering matrix components. | Simple and often effective; can restore linearity. | May dilute analyte below LOD; not suitable for all matrices. |

| Sample Pre-treatment (e.g., extraction, digestion) | Removes or destroys interfering matrix. | Can effectively eliminate specific interferences like lipids or proteins. | Adds complexity, time, and risk of analyte loss. |

| Matrix-Matched Calibration | Uses calibration standards with a matrix similar to the sample. | Theoretically compensates for matrix effects. | Difficult and costly to obtain/make a perfect match; not universal. |

| Standard Addition Method | Spike known analyte amounts into the sample. | Directly accounts for matrix-induced signal modulation. | Labor-intensive; requires more sample and analysis time. |

The effectiveness of these strategies is context-dependent. For example, in a study on lateral flow immunoassays (LFIAs) for T-2 toxin, using time-resolved fluorescent microspheres (TRFMs) as labels helped reduce matrix effects due to their long fluorescence lifetime, which minimized background autofluorescence from the sample matrix [13].

Immunological Interference

Immunological interference is specific to assays that rely on antigen-antibody binding, such as ELISA and other immunoassays. These interferences can cause falsely elevated or falsely low results, potentially leading to misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment [11] [12].

- Mechanisms and Types:

- Heterophile Antibodies and Human Anti-Animal Antibodies (HAAAs): These are endogenous human antibodies that can bind to assay antibodies. In sandwich immunoassays, they can form a "bridge" between the capture and detection antibodies even in the absence of the analyte, causing a false positive [11] [12].

- Cross-reactivity: Occurs when structurally similar molecules (e.g., drug metabolites, or hormones from the same family) compete for binding to the assay antibody [11] [12]. For instance, digoxin immunoassays can show cross-reactivity with digoxin-like immunoreactive factors or metabolites of spironolactone [11].

- Hook Effect: A high-dose hook effect is seen in immunometric assays where extremely high analyte concentrations saturate both capture and detection antibodies, preventing the formation of the "sandwich" complex and leading to a falsely low signal [11] [12].

- Impact on Clinical Decisions: The consequences can be severe. There are documented cases of patients undergoing unnecessary chemotherapy, hysterectomy, or lung resection due to persistent false-positive human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) results caused by heterophile antibody interference [12].

Correction Methods and Performance

Detecting and correcting for immunological interference requires specific techniques.

Table 3: Comparison of Immunological Interference Detection and Resolution Methods

| Method | Principle | Key Improvement | Limitation/Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serial Sample Dilution | A non-linear dilution profile suggests interference. | Simple first step for detection. | Does not identify the type of interference. |

| Use of Blocking Reagents | Adds non-specific animal serum or commercial blockers to neutralize heterophile antibodies. | Can resolve a majority of heterophile interferences [11]. | Not always effective; some antibodies have high affinity [12]. |

| Sample Pre-treatment with Acid Dissociation | Disrupts immune complexes by altering pH, useful for overcoming target interference in anti-drug antibody (ADA) assays. | Effectively reduced dimeric target interference in a bridging immunoassay for BI X [14]. | Requires optimization of acid type/concentration and a neutralization step [14]. |

| Analyzing with an Alternate Assay | Using a different manufacturer's kit or method format. | Can reveal method-dependent interference. | Costly and time-consuming. |

A robust experimental protocol for addressing target interference in drug bridging immunoassays, as detailed by [14], involves acid dissociation:

- Sample Treatment: Mix the sample (e.g., plasma or serum) with a panel of different acids (e.g., HCl, citric acid) at varying concentrations.

- Incubation: Allow the acidification to proceed for a set time to dissociate drug-target complexes.

- Neutralization: Add a neutralization buffer to restore the sample to an assay-compatible pH.

- Analysis: Run the treated sample in the standard immunoassay protocol (e.g., electrochemiluminescence assay). This method was shown to overcome interference from soluble dimeric targets without the need for complex immunodepletion strategies [14].

The diagram below illustrates the primary mechanisms of immunological interference in a sandwich immunoassay and the corresponding points of action for correction methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the right reagents is fundamental to developing robust assays and implementing effective interference correction protocols.

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Interference Management in Immunoassays and Spectroscopy

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Role in Interference Management |

|---|---|---|

| Blocking Reagents (e.g., animal serums, inert proteins) | Reduce non-specific binding in immunoassays. | Neutralize heterophile antibodies and minimize matrix effects by occupying non-specific sites [11] [12]. |

| Acid Panel (e.g., HCl, Citric Acid, Acetic Acid) | Used for sample pre-treatment and elution. | Disrupts immune complexes in acid dissociation protocols to resolve target interference in immunogenicity testing [14]. |

| Specific Antibodies (Monoclonal vs. Polyclonal) | Serve as primary capture/detection agents. | High-affinity, monoclonal antibodies reduce cross-reactivity, while polyclonal antibodies can offer higher signal in some formats. |

| Labeling Kits (e.g., Biotin, SULFO-TAG) | Enable signal detection in various assay platforms. | Quality of conjugation (Degree of Labeling, monomeric purity) is critical to avoid reagent-induced interference and false signals [14]. |

| Interference Standards (e.g., ³â¶Ar⺠in ICP-MS) | Serve as internal references for signal correction. | Used in the Interference Standard Method (IFS) to correct for polyatomic spectral interferences by monitoring argon species [9]. |

| IC87201 | IC87201, CAS:866927-10-8, MF:C13H10Cl2N4O, MW:309.15 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Furanone C-30 | Furanone C-30, MF:C5H2Br2O2, MW:253.88 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Spectral, matrix, and immunological interferences present distinct but significant challenges across analytical platforms, consistently leading to a degradation of detection limits and potential reporting of erroneous data. The experimental data and protocols summarized in this guide demonstrate that while these interferences are pervasive, effective correction strategies exist.

The key to managing interferences lies in a systematic approach: first, understanding the underlying mechanisms; second, implementing appropriate detection protocols such as serial dilution or analysis by an alternate method; and third, applying targeted correction strategies. These include mathematical corrections like the IFS method for spectral interference, sample pre-treatment and matrix-matching for matrix effects, and the use of blocking reagents or acid dissociation for immunological interference. For researchers, the choice of reagents—from high-specificity antibodies to optimized blocking agents—is a critical factor in building assay resilience. By integrating these correction methodologies into the assay development and validation workflow, scientists and drug developers can significantly improve the accuracy, reliability, and clinical utility of their analytical data.

In analytical science, interference refers to the effect of substances or factors that alter the accurate measurement of an analyte, compromising data integrity and leading to erroneous conclusions. The failure to identify and correct for these interferents has profound consequences across diagnostic, pharmaceutical, and environmental fields, resulting in false positives, false negatives, and inaccurate quantitation. Within the context of comparing detection limits with and without interference correction methods, understanding these consequences is paramount for developing robust analytical protocols. This guide objectively compares the performance of various correction methodologies, demonstrating how uncorrected interference inflates detection limits and skews experimental outcomes, while validated correction strategies restore analytical accuracy and reliability.

Types of Interference and Their Mechanisms

Interferences in analytical techniques are broadly categorized based on their origin and mechanism. The table below summarizes the primary types and their impacts.

Table 1: Common Types of Analytical Interferences and Their Effects

| Interference Type | Main Cause | Common Analytical Techniques Affected | Potential Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Interference | Overlap of emission wavelengths or mass-to-charge ratios [10] [15] | ICP-OES, ICP-MS | False positives, inaccurate quantitation |

| Matrix Effects | Sample components affecting ionization efficiency [16] | LC-MS/MS, GC-MS/MS | Signal suppression/enhancement, inaccurate quantitation |

| Cross-Reactivity | Structural similarities causing non-specific antibody binding [11] | Immunoassays | False positives/false negatives |

| Physical Interferences | Matrix differences affecting nebulization or viscosity [15] | ICP-OES, ICP-MS | Drift, signal variability, inaccurate quantitation |

| Chemical Interferences | Matrix differences affecting atomization/ionization in the plasma [15] | ICP-OES | Falsely high or low results |

Consequences of Uncorrected Interference

False Negatives and Failed Detection

Uncorrected interference is a primary driver of false negatives, where an analyte present at a significant concentration goes undetected. This often occurs when interference causes signal suppression or when the analyte's response is inherently low.

In immunoassays, heterophile antibodies or human anti-animal antibodies can block the binding of the analyte to the reagent antibodies, leading to falsely low reported concentrations [11]. This can have severe clinical repercussions; for example, a false-negative result for cardiac troponin could delay diagnosis and treatment for a myocardial infarction [11].

Similarly, in chromatographic techniques, the phenomenon of detection bias is a critical concern. In extractables and leachables (E&L) studies for pharmaceuticals, an Analytical Evaluation Threshold (AET) is established to determine which compounds require toxicological assessment. This threshold often assumes similar Response Factors (RF) for all compounds. However, a compound with a low RF may not generate a signal strong enough to surpass the AET, even if its concentration is toxicologically relevant, leading to a false negative and potential patient risk [17].

False Positives and Misidentification

False positives occur when an interfering substance is mistakenly identified and quantified as the target analyte. This can lead to unnecessary further testing, incorrect diagnoses, and wasted resources.

Spectral overlap in ICP-OES is a classic example, where an emission line from a matrix element directly overlaps with the analyte's wavelength, causing a falsely elevated result [10] [15]. In mass spectrometry, an interferent sharing the same transition as a target pesticide can lead to misidentification and a false positive report, especially if it is present at both required transitions [16].

Cross-reactivity in immunoassays is another common cause. For instance, some digoxin immunoassays show cross-reactivity with digoxin-like immunoreactive factors found in patients with renal failure or with metabolites of drugs like spironolactone, potentially leading to a false-positive diagnosis of digoxin toxicity [11].

Inaccurate Quantitation and the Impact on Data Integrity

Even when detection occurs, interference can severely compromise the accuracy of quantification. This inaccurate quantitation can manifest as either over- or under-estimation of the true analyte concentration.

Matrix effects in LC-MS/MS are a predominant source of quantitative error. Co-eluting matrix components can suppress or enhance the ionization of the analyte in the ion source, severely compromising accuracy, reproducibility, and sensitivity [16]. A study evaluating pesticide residues found that matrix effects can lead to both identification and quantification errors, affecting the determination of a wide range of pesticides [16].

In pharmaceutical analysis, quantification bias in E&L studies arises from the variability in relative response factors (RRF). When semi-quantitation is performed against a limited number of reference standards that have different RFs than the compounds of interest, the resulting concentration data is approximate and can lead to both unwarranted concerns and, more dangerously, false negatives [17].

Comparative Experimental Data: The Cost of Uncorrection vs. The Benefit of Solutions

The following tables summarize quantitative data from research that illustrates the consequences of uncorrected interference and the performance of different correction methods.

Table 2: Impact of Spectral Interference (As on Cd) in ICP-OES [10]

| Concentration of Cd (ppm) | Relative Conc. As/Cd | Uncorrected Relative Error (%) | Best-Case Corrected Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 1000 | 5100 | 51.0 |

| 1 | 100 | 541 | 5.5 |

| 10 | 10 | 54 | 1.1 |

| 100 | 1 | 6 | 1.0 |

Note: This data demonstrates that the quantitative error from spectral overlap is most severe at low analyte concentrations and high interferent-to-analyte ratios. While mathematical correction reduces the error, it does not fully restore performance at very low concentrations, as seen by the 51% error at 0.1 ppm Cd.

Table 3: Performance of Different Quantitation Methods in E&L Studies [17]

| Quantitation Approach | Key Principle | Impact on False Negatives | Impact on Quantitative Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncorrected AET | Assumes uniform response factors for all compounds. | High incidence; low-responding compounds are missed. | High quantitative bias due to ignored RRF variability. |

| Uncertainty Factor (UF) | Applies a blanket correction factor to the AET based on RRF variability. | Reduces false negatives but does not eliminate them. | Does not correct for quantitative bias. |

| RRFlow Model | Applies a specific average corrective factor (RRFi) for each compound after identity confirmation. | Significantly reduces false negatives. | Mitigates quantitative error by rescaling concentrations based on experimental RRF. |

Note: Numerical simulations benchmarking these methods showed that a combined UF and RRFlow approach resulted in a lower incidence of both type I (false positive) and type II (false negative) errors compared to UF-only approaches [17].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Interference

To objectively compare the performance of analytical methods with and without interference correction, standardized evaluation protocols are essential.

This protocol is designed to systematically identify and quantify matrix-induced interference.

- Sample Preparation: Extract a series of relevant blank matrices (e.g., different fruits and vegetables) using the multiresidue extraction methods under evaluation (e.g., QuEChERS, ethyl acetate, Dutch mini-Luke).

- Analysis of Blank Extracts: Inject the blank matrix extracts into the LC-MS/MS or GC-MS/MS system.

- Identification of Common Transitions: For each target analyte (e.g., pesticide), check the blank matrix chromatograms for any signal within a specific retention time window (e.g., ± 0.2 min) of the analyte that matches one of its diagnostic mass transitions. This identifies "potential" false positives.

- Quantification of Signal Suppression/Enhancement (SSE):

- Prepare a pure standard solution in a solvent.

- Prepare a standard at the same concentration in the blank matrix extract.

- Inject both and compare the peak areas.

- Calculate SSE (%) = (Peak Area in Matrix Extract / Peak Area in Solvent) × 100%.

- An SSE < 100% indicates signal suppression; >100% indicates enhancement.

- Error Evaluation: Spike the target analytes into the blank matrices at known concentrations and analyze. Compare the identified and quantified results against the known values to determine false negative and inaccurate quantitation rates.

This protocol validates that an HPLC method can accurately measure the analyte amidst potential interferents.

- Forced Degradation Studies: Stress the drug substance and product under various conditions (e.g., acid, base, oxidation, heat, light) to generate degradation products.

- Analysis of Stressed Samples: Run the stressed samples using the candidate HPLC method.

- Peak Purity Assessment: Use a photodiode array (PDA) detector to check that the main analyte peak is pure and does not co-elute with any degradation product. This is confirmed by comparing spectra across the peak.

- Resolution Check: Ensure that the analyte peak is baseline-resolved from all other peaks (impurities, degradation products, excipients). A resolution (Rs) of greater than 2.0 between the analyte and the closest eluting potential interferent is typically desired.

- Blank and Placebo Interference Check: Run procedural blanks and placebo formulations to confirm the absence of interfering peaks at the retention time of the analyte.

Workflow Diagram: A Strategic Path for Interference Management

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for identifying, evaluating, and correcting analytical interference, integrating the protocols and concepts discussed.

Interference Management Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful management of analytical interference relies on a suite of essential reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions for robust method development and validation.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Interference Management

| Item / Reagent | Function in Interference Management | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Matrix-Matched Standards | Calibration standards prepared in a blank matrix extract to compensate for matrix-induced signal suppression or enhancement [16]. | GC-MS/MS, LC-MS/MS analysis of complex samples (e.g., food, biological fluids). |

| Blocking Reagents | Substances (e.g., non-specific IgG) added to sample to neutralize heterophile antibody or human anti-animal antibody interference [11]. | Diagnostic immunoassays. |

| High-Purity Reference Standards | Authentic, pure substances of the target analyte and known interferents used to study cross-reactivity, establish RRFs, and validate method specificity [17] [18]. | All quantitative techniques, especially HPLC/UPLC and GC for pharmaceutical analysis. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (SIL-IS) | Internal standards with nearly identical chemical properties to the analyte that co-elute and experience the same matrix effects, allowing for correction during quantification [16]. | LC-MS/MS and GC-MS quantitative assays. |

| Forced Degradation Samples | Stressed drug samples containing degradation products, used to demonstrate the stability-indicating property and specificity of a method by proving separation of analyte from impurities [18]. | HPLC/UPLC method validation for pharmaceuticals. |

| Orthogonal Separation Columns | Columns with different stationary phases (e.g., C18 vs. phenyl) or separation mechanisms used to confirm analyte identity and purity when interference is suspected [18]. | Peak purity investigation in chromatography. |

| (S)-Alprenolol | (S)-Alprenolol, CAS:23846-71-1, MF:C15H23NO2, MW:249.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| iCRT 14 | iCRT 14, CAS:677331-12-3, MF:C21H17N3O2S, MW:375.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The consequences of uncorrected interference—false positives, false negatives, and inaccurate quantitation—pose a significant threat to analytical integrity across research, clinical, and regulatory domains. Data clearly demonstrates that uncorrected methods suffer from dramatically higher error rates and compromised detection limits. A methodical approach, incorporating rigorous evaluation protocols like matrix effect studies and forced degradation, followed by the application of targeted correction strategies such as the RRFlow model, matrix-matched calibration, and isotopic internal standards, is not merely a best practice but a necessity. By objectively comparing these approaches, this guide underscores that investing in robust interference correction is fundamental to generating reliable, defensible, and meaningful scientific data.

The development and accurate bioanalysis of biotherapeutic drugs are fundamentally linked to the assessment of immunogenicity. A critical manifestation of immunogenicity is the development of anti-drug antibodies (ADA), which are immune responses generated by patients against the therapeutic protein [19]. The presence of ADA can significantly alter the pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of a drug, leading to data that does not reflect the true behavior of the therapeutic agent in the body [20] [19].

ADA affects drug exposure by influencing its clearance, tissue distribution, and overall bioavailability. These interactions can lead to either an overestimation or underestimation of true drug concentrations, thereby skewing PK assay results and complicating the interpretation of a drug's efficacy and safety profile [20]. This case study examines the mechanisms by which ADA interferes with PK assays and objectively compares the performance of standard detection methods against advanced protocols designed to correct for this interference, within the broader thesis of comparing detection limits with and without interference correction methods.

Mechanisms: How ADA Interferes with PK Assays

The interference of ADA in pharmacokinetic assays is primarily driven by its ability to form complexes with the drug, which masks the true concentration of the free, pharmacologically active molecule. The following diagram illustrates the core mechanisms and consequences of this interference.

The interference mechanisms can be broken down into two main pathways:

Direct Assay Interference: ADA can bind to the therapeutic drug in the sample matrix (e.g., serum or plasma), forming immune complexes [21] [20]. This binding can sterically hinder the epitopes recognized by the capture and detection reagents (e.g., anti-idiotypic antibodies) used in ligand-binding PK assays [22]. The result is a failure to detect the drug, leading to a false reporting of low drug concentration [21].

Biological Clearance Alteration: The formation of drug-ADA complexes in vivo can alter the normal clearance pathway of the drug [20] [19]. These complexes are often cleared more rapidly by the reticuloendothelial system, leading to unexpectedly low drug exposure. Conversely, in some cases, ADA can act as a carrier, prolonging the drug's presence in circulation, which results in an erratic and unpredictable PK profile that obscures the true relationship between dose and exposure [19].

Comparative Experimental Data: Standard vs. Correction-Enabled Methods

A critical component of this research involves comparing the performance of standard PK/ADA assays against methods that incorporate interference correction protocols, such as acid dissociation. The following tables summarize quantitative data from experimental studies, highlighting the limitations of standard methods and the enhanced performance of corrected assays.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ADA Assays With and Without Acid Dissociation Pre-treatment

| Assay Condition | Detection Limit | Drug Tolerance Level | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Bridging ELISA/ECL [23] [21] | 100-500 ng/mL | Low (1-10 μg/mL) | High false-negative rate due to drug competition |

| Acid Dissociation-Enabled Assay [21] [24] | 50-100 ng/mL | High (100-500 μg/mL) | Requires optimization of acid type, pH, and neutralization |

Table 2: Impact of ADA Interference on PK Assay Parameters for a Model Monoclonal Antibody

| PK Assay Parameter | Without ADA Interference | With Significant ADA Interference |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy (% Bias) | -8.5% to 12.1% [20] | -45% to 60% (Estimated from observed impacts [21]) |

| Measured Cmax | Represents true peak exposure | Can be falsely elevated or suppressed [19] |

| Measured Half-life (tâ‚/â‚‚) | Consistent with molecular properties | Often significantly shortened [20] [19] |

The data demonstrate that standard assays suffer from poor drug tolerance, meaning that the presence of even moderate levels of circulating drug can out-compete the assay reagents for ADA binding, leading to false-negative results [21]. Similarly, for PK assays, the presence of ADA introduces significant bias, severely impacting the accuracy of reported drug concentrations.

Methodologies: Detailed Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol for Acid Dissociation to Overcome Drug Interference in ADA/PK Assays

The acid dissociation method is a cornerstone technique for breaking drug-ADA complexes, thereby freeing ADA for detection and providing a more accurate PK measurement [21] [24].

- Sample Preparation: Mix 50 μL of serum or plasma sample with 100 μL of a low-pH dissociation buffer (e.g., 375 mM acetic acid, pH ~2.5, or 0.1 M Glycine-HCl, pH 2.0) [24].

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture at room temperature for 60-120 minutes with gentle shaking to ensure complete dissociation of drug-ADA complexes [24].

- Neutralization: After dissociation, neutralize the sample pH back to a physiological range (pH 7-8) using a pre-determined volume of neutralization buffer (e.g., 1 M Tris-base). The use of a specialized, alkaline ADA sample dilution buffer (e.g., NGB I, pH=8) at this stage can aid in neutralization and prepare the sample for the subsequent immunoassay [25].

- Analysis: The processed sample can now be analyzed using the standard bridging ELISA or ECL assay. The dissociation step ensures that ADA, previously masked in complexes, is available for detection [21].

Experimental Workflow for Assessing ADA Impact on PK

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive experimental workflow designed to evaluate and correct for the impact of ADA on pharmacokinetic data.

This workflow allows researchers to directly quantify the discrepancy introduced by ADA. A significant difference in measured drug concentration between the standard assay (Path A) and the acid-dissociation-enabled assay (Path B) is a direct indicator of ADA interference. This data can then be correlated with ADA titer to understand the relationship between immune response and PK data distortion.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Interference Correction

Successfully mitigating ADA interference requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for robust ADA and PK analysis.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ADA and PK Assays

| Reagent / Solution | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Acid Dissociation Buffer (e.g., Glycine-HCl, Acetic Acid) [21] [24] | Breaks drug-ADA complexes to unmask hidden analytes. | Critical for improving drug tolerance; requires careful optimization of concentration and incubation time. |

| Specialized Sample Dilution Buffer (e.g., NGB I) [25] | Neutralizes acid-treated samples and provides an optimal matrix for the immunoassay. | Its alkaline nature (pH=8) is specifically designed to counteract the low pH of the acid dissociation step. |

| High-Performance Closeding Buffer (e.g., StrongBlock III) [25] | Blocks unused binding sites on assay plates to minimize non-specific binding and background noise. | Contains modified proteins and heterophilic blocking agents to improve signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Positive Control Antibody [23] | Serves as a quality control to validate assay sensitivity and performance during method development. | Ideally a high-affinity, drug-specific antibody; often anti-idiotypic antibody from immunized animals. |

| Drug-Tolerant ECL/ELISA Reagents | The core components of the immunoassay platform. | Bridging format is most common; reagents are often optimized for use with dissociation protocols [23] [20]. |

| Atelopidtoxin | Atelopidtoxin, CAS:18138-19-7, MF:C8H5NS2, MW:179.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| IEM-1754 | IEM-1754, MF:C16H32Br2N2, MW:412.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The skewing of pharmacokinetic assay results by anti-drug antibodies presents a formidable challenge in biotherapeutic development. This case study demonstrates that standard PK and ADA assays are often inadequate, yielding significantly biased data due to drug interference. The experimental data and detailed protocols provided establish that correction methods, notably acid dissociation, are not merely optional but essential for obtaining accurate analytical results. By adopting these advanced methodologies and leveraging specialized reagents, scientists can de-risk immunogenicity issues, generate more reliable PK/PD correlations, and make better-informed decisions throughout the drug development lifecycle.

A Toolkit of Interference Correction Strategies for Modern Platforms

Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has established itself as a cornerstone analytical technique in pharmaceutical, clinical, and environmental research due to its exceptional sensitivity and specificity [26]. This technology combines the superior separation power of liquid chromatography with the selective detection capabilities of tandem mass spectrometry, making it indispensable for analyzing complex mixtures in biological and environmental matrices [26]. However, the analytical reliability of LC-MS/MS methods can be compromised by several factors, including isobaric interferences and ion suppression effects, which may lead to inaccurate quantification [27] [28] [29]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of LC-MS/MS performance against alternative techniques, with a specific focus on evaluating detection limits with and without advanced interference correction methods. The objective data presented herein will empower researchers and drug development professionals to make informed decisions about analytical platform selection based on their specific sensitivity, selectivity, and throughput requirements.

Performance Comparison of Mass Spectrometry Platforms

The choice of mass spectrometry platform significantly impacts analytical performance, particularly when measuring trace-level compounds in complex sample matrices. Different MS technologies offer distinct trade-offs between sensitivity, selectivity, and cost, making platform selection critical for method development.

Comparison of LC-MS Platforms for Zeranol Analysis

A comprehensive evaluation of four liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry platforms for analyzing zeranols in urine demonstrated distinct performance characteristics across low-resolution and high-resolution systems [30]. The study compared two low-resolution linear ion trap instruments (LTQ and LTQXL) and two high-resolution platforms (Orbitrap and Time-of-Flight/G1).

Table 1: Performance Comparison of MS Platforms for Zeranol Analysis [30]

| MS Platform | Resolution Category | Sensitivity Ranking | Selectivity | Measured Variation (%CV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orbitrap | High-resolution | 1 (Highest) | Excellent | Smallest (Lowest) |

| LTQ | Low-resolution | 2 | Moderate | Moderate |

| LTQXL | Low-resolution | 3 | Moderate | Moderate |

| G1 (V mode) | High-resolution | 4 | Good | Higher |

| G1 (W mode) | High-resolution | 5 (Lowest) | Good | Highest |

| (-)-Gallopamil | (-)-Gallopamil, CAS:36622-40-9, MF:C28H40N2O5, MW:484.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| iGP-1 | 4-{[4-(1H-Benzimidazol-2-yl)phenyl]amino}-4-oxobutanoic acid | Explore 4-{[4-(1H-Benzimidazol-2-yl)phenyl]amino}-4-oxobutanoic acid (CAS 27031-00-1), a high-purity benzimidazole derivative for Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapy. | Bench Chemicals |

The Orbitrap platform demonstrated superior overall performance with the highest sensitivity and smallest measurement variation [30]. High-resolution platforms exhibited significantly better selectivity, successfully differentiating between concomitant peaks (e.g., a concomitant peak at 319.1915 from the analyte at 319.1551) that low-resolution systems could not resolve within a unit mass window [30].

LC-MS versus GC-MS for Environmental Contaminant Analysis

A comparative study of LC-MS and GC-MS for analyzing pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in surface water and treated wastewaters revealed technique-specific advantages [31]. HPLC-TOF-MS (Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometer) demonstrated lower detection limits than GC-MS for many compounds, while liquid-liquid extraction provided superior overall recoveries compared to solid-phase extraction [31]. Both instrumental and extraction techniques showed considerable variability in efficiency depending on the physicochemical properties of the target analytes.

Interference Correction Methods in LC-MS/MS

Detuning Ratio for Interference Detection

The detuning ratio (DR) has been developed as a novel approach to detect potential isomeric or isobaric interferences in LC-MS/MS analysis [27] [28]. This method leverages the differential influences of MS instrument settings on the ion yield of target analytes. When isomeric or isobaric interferences are present, they can cause a measurable shift in the DR for an affected sample [28].

In experimental evaluations using two independent test systems (Cortisone/Prednisolone and O-Desmethylvenlafaxine/cis-Tramadol HCl), the DR effectively indicated the presence of isomeric interferences [28]. This technique can supplement the established method of ion ratio (IR) monitoring to increase the analytical reliability of clinical MS analyses [27]. The DR approach is particularly valuable for identifying interferences that might otherwise go undetected using conventional confirmation methods.

IROA Workflow for Ion Suppression Correction

Ion suppression remains a significant challenge in mass spectrometry-based analyses, particularly in non-targeted metabolomics. The IROA TruQuant Workflow utilizes a stable isotope-labeled internal standard (IROA-IS) library with companion algorithms to measure and correct for ion suppression while performing Dual MSTUS normalization of MS metabolomic data [29].

This innovative approach has been validated across multiple chromatographic systems, including ion chromatography (IC), hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC), and reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC)-MS in both positive and negative ionization modes [29]. Across these diverse conditions, detected metabolites exhibited ion suppression ranging from 1% to >90%, with coefficients of variation ranging from 1% to 20% [29]. The IROA workflow effectively nullified this suppression and associated error, enabling accurate concentration measurements even for severely affected compounds like pyroglutamylglycine which exhibited up to 97% suppression in ICMS negative mode [29].

Figure 1: IROA Workflow for Ion Suppression Correction. This diagram illustrates the sequential process from sample preparation to normalized data output, highlighting the key steps in detecting and correcting ion suppression effects.

Detection Limit Advancements in Mass Spectrometry

The progressive improvement in mass spectrometry detection limits has followed a trajectory resembling Moore's Law in computing, though the rate of advancement varies between ideal and practical analytical conditions [32].

Historical Trends in Detection Limits

Industry data from SCIEX spanning 1982 to 2012 demonstrates an impressive million-fold improvement in sensitivity, with detection limits advancing from nanogram per milliliter concentrations in the early 1980s to sub-femtogram per milliliter levels in contemporary instruments [32]. This represents an acceleration beyond the Moore's Law trajectory, highlighting the rapid pace of technological innovation in mass spectrometry.

However, academic literature presents a more modest improvement rate. Analysis of reported detection limits for glycine over a 45-year period shows exponential improvement but at a gradient of 0.1, below what would satisfy Moore's Law [32]. This discrepancy between industry specifications and practical laboratory performance underscores the significant influence of matrix effects and real-world analytical conditions on achievable detection limits.

Table 2: Detection Limit Trends in Mass Spectrometry [32]

| Data Source | Time Period | Improvement Factor | Rate Compared to Moore's Law | Key Factors Influencing Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry (SCIEX) | 1982-2012 | ~1,000,000x | Greater than Moore's Law | Pure standards, clean matrix, new instruments |

| Academic (Glycine) | 45 years | Exponential but slower | Below Moore's Law | Complex matrices, method variability, older instruments |

| Practical Applications | Varies | Matrix-dependent | Highly variable | Sample cleanup, ion suppression, instrument maintenance |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

HPLC-MS/MS Method for Broad-Spectrum Contaminant Detection

An efficient HPLC-MS/MS method has been developed for detecting a broad spectrum of hydrophilic and lipophilic contaminants in marine waters, employing a design of experiments (DoE) approach for multivariate optimization [33]. The method simultaneously analyzes 40 organic micro-contaminants with wide polarity ranges, including pharmaceuticals, pesticides, and UV filters.

Chromatographic Conditions: Separation was performed on a pentafluorophenyl column (PFP) using mobile phase A (water with 0.1% formic acid) and mobile phase B (acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid). A face-centered design was applied with mobile phase flow and temperature as study factors, and retention time and peak width as responses [33].

Mass Spectrometry Parameters: Analysis was conducted using an Agilent 6430 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization. Source parameters included drying gas temperature (300°C), flow (11 L/min), and nebulizer pressure (15 psi) [33]. The optimized method enabled analysis of all 40 analytes in 29 minutes with detection limits at ng/L levels.

LC-MS³ Method for Toxic Natural Product Screening

Liquid chromatography-high-resolution MS³ has been evaluated for screening toxic natural products, demonstrating improved identification performance compared to conventional LC-HR-MS (MS²) for a small group of toxic natural products in serum and urine specimens [34].

Experimental Protocol: A spectral library of 85 natural products (79 alkaloids) containing both MS² and MS³ mass spectra was constructed. Grouped analytes were spiked into drug-free serum and urine to produce contrived clinical samples [34]. The method provided more in-depth structural information, enabling better identification of several analytes at lower concentrations, with MS²-MS³ tree data analysis outperforming MS²-only analysis for a subset of compounds (4% in serum, 8% in urine) [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LC-MS/MS Analysis

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pentafluorophenyl (PFP) Column | Provides multiple interaction mechanisms for separating diverse compounds | Separation of 40 emerging contaminants with broad polarity ranges [33] |

| IROA Internal Standard (IROA-IS) | Enables ion suppression correction and normalization | Non-targeted metabolomics across different biological matrices [29] |

| Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balanced (HLB) Sorbent | Extracts compounds with medium hydrophilicity in passive sampling | Polar Organic Chemical Integrative Samplers (POCIS) for environmental water monitoring [33] |

| β-glucuronidase from Helix pomatia | Deconjugates glucuronidated metabolites prior to analysis | Urine sample preparation for zeranol biomonitoring studies [30] |

| Chem Elut Cartridges | Support liquid-liquid extraction during solid-phase extraction | Sample cleanup for zeranol analysis in urine [30] |

| II-B08 | II-B08, MF:C33H27N5O4, MW:557.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lankacyclinol A | Lankacyclinol A | Lankacyclinol A is a decarboxylated lankacidin antibiotic for antimicrobial research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

LC-MS/MS remains the premier analytical technique for sensitive and specific detection across diverse application domains, though its performance is significantly influenced by instrument platform selection and effective interference management. High-resolution mass spectrometry platforms, particularly Orbitrap technology, provide superior selectivity and sensitivity for complex analytical challenges [30]. The implementation of advanced interference correction methods, including the detuning ratio for isobaric interference detection [28] and IROA workflows for ion suppression correction [29], substantially enhances data reliability. These technical advancements, coupled with continuous improvements in detection limits [32], ensure that LC-MS/MS will maintain its critical role in drug development, clinical research, and environmental monitoring. Researchers should carefully consider the trade-offs between low-resolution and high-resolution platforms while implementing appropriate interference correction strategies to optimize analytical outcomes for their specific applications.

The development of biopharmaceuticals, or new biological entities (NBEs), is often complicated by their inherent potential to elicit an immune response in patients, leading to the production of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) [14]. The detection and characterization of these ADAs are critical for evaluating clinical safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetics [14] [35]. The bridging immunoassay, which can detect all isotypes of ADA by forming a bridge between capture and detection drug reagents, has emerged as the industry standard for immunogenicity testing [14] [35]. However, a significant challenge in this format is its susceptibility to interference, particularly from soluble multimeric drug targets, which can cause false-positive signals and compromise assay specificity [14] [35]. Similarly, the presence of excess drug can lead to false-negative results by competing for ADA binding sites [36] [35].

Acid dissociation has been established as a key technique to mitigate these interferences. This method involves treating samples with acid to dissociate ADA-drug or target-drug complexes, followed by a neutralization step to allow ADA detection in the bridging assay [14] [37]. This guide objectively compares the performance of acid dissociation with other emerging techniques, providing experimental data and protocols to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Mechanisms of Interference in Immunogenicity Assays

Understanding the sources of interference is fundamental to selecting the appropriate mitigation strategy. The following diagram illustrates how both drug and drug target interference manifest in a standard bridging immunoassay.

The primary mechanisms of interference are:

- Drug Interference (False Negatives): High levels of circulating free drug can saturate the binding sites of ADAs. This prevents the ADAs from forming a bridge between the capture and detection reagents in the assay, leading to a false-negative result [36] [35].

- Target Interference (False Positives): Soluble, multimeric drug targets can act as bridging molecules by simultaneously binding to the capture and detection drug reagents. This creates a signal indistinguishable from a true ADA bridge, resulting in a false-positive result [14] [35]. Acid dissociation used to improve drug tolerance can sometimes exacerbate this problem by disrupting drug-target complexes and releasing multimeric targets [35].

Comparative Analysis of Interference Mitigation Techniques

Several strategies have been developed to overcome interference in ADA assays. The table below provides a structured comparison of acid dissociation with other prominent techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Techniques for Mitigating Interference in ADA Assays

| Technique | Mechanism of Action | Advantages | Limitations | Reported Impact on Sensitivity & Drug Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acid Dissociation | Uses low pH to dissociate ADA-drug complexes, followed by neutralization [14] [37]. | Simple, time-efficient, and cost-effective [14]. Broadly applicable. | May cause protein denaturation/aggregation [14]. Can exacerbate target interference by releasing multimeric targets [36] [35]. | Significant improvement in drug tolerance; however, may cause ~25% signal loss in some assays [14]. |

| PandA (Precipitation and Acid Dissociation) | Combines PEG precipitation of immune complexes with acid dissociation and capture on a high-binding plate under acidic conditions [36]. | Effectively eliminates both drug and target interference. Prevents re-association of interference factors. | More complex workflow than simple acid dissociation. Requires optimization of PEG concentration. | Demonstrated significant improvement in ADA detection in the presence of excess drug (up to 100 μg/mL) for three different mAb therapeutics [36]. |

| Anti-Target Antibodies | Uses a competing anti-target antibody to "scavenge" the soluble drug target in the sample [35]. | Can be highly specific. Does not require sample pretreatment steps. | Risk of inadvertently removing non-neutralizing ADAs if the scavenger antibody is too similar to the drug [35]. High-quality, specific anti-target antibodies may not be available [14]. | Successfully mitigated target interference in a bridging assay for a fully human mAb therapeutic [35]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction with Acid Dissociation (SPEAD) | Uses a solid-phase capture step under acidic conditions to isolate ADAs [36]. | Efficiently separates ADAs from interfering substances. | Labor-intensive and low-throughput [14]. | Improved drug tolerance, though sensitivity may not be maintained [36]. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Optimized Acid Dissociation Protocol

A detailed protocol for implementing acid dissociation, based on recent research, is provided below.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Acid Dissociation Experiment

| Research Reagent Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Panel of Acids (e.g., HCl, Acetic Acid) | Disrupts non-covalent interactions in ADA-drug and target-drug complexes [14]. |

| Neutralization Buffer (e.g., Tris, NaOH) | Restores sample to a pH suitable for the immunoassay reaction [14] [37]. |

| Biotin- and SULFO-TAG-Labeled Drug | Serve as capture and detection reagents, respectively, in the bridging ELISA or ECL assay [14]. |

| Positive Control (PC) Antibody | A purified anti-drug antibody used to monitor assay performance and sensitivity [14]. |

| Acid-Treatment Plate | A high-binding carbon plate used in some protocols to capture complexes after acid dissociation [36]. |

Sample Pretreatment:

- Mix the sample (e.g., serum or plasma) with an acid solution. Researchers have optimized this step using a panel of different acids and concentrations (e.g., HCl) to effectively disrupt dimeric target interactions [14].

- Incubate the acidified sample for a defined period (e.g., 60-90 minutes) at a controlled temperature (e.g., 37°C) [37].

Neutralization:

Immunoassay Execution:

- The neutralized sample is then used in the standard bridging immunoassay protocol. The dissociated ADAs are now free to bridge the biotinylated and SULFO-TAG-labeled drug reagents [14].

- The signal is measured via electrochemiluminescence (ECL) on an MSD platform or colorimetrically in an ELISA [14].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps of this protocol and its comparison to an alternative method.

Key Experimental Findings and Data

The performance of acid dissociation is best understood in the context of direct experimental comparisons.

Table 3: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Mitigation Strategies

| Assay Condition | Analyte | Key Performance Metric | Result | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Bridging Assay | Drug B | Target Interference | High (False positives in 100% normal serum) | Target dimerizes at low pH [36]. |

| Bridging Assay with Acid Dissociation | BI X (scFv) | Target Interference | Significantly Reduced | Optimized acid panel treatment in human/cyno matrices [14]. |

| Bridging Assay with Acid Dissociation | BI X (scFv) | Signal Loss | ~25% | Observed when using salt-based buffers; highlights need for optimization [14]. |

| PandA Method | Drug A, B, C | Drug Tolerance | Effective at 1, 10, and 100 μg/mL | Overcame limitations of acid dissociation alone [36]. |

| PandA Method | Insulin Analogue | Relative Error Improvement | >99% to ≤20% | Acid dissociation in a Gyrolab platform [38]. |

The data demonstrates that while acid dissociation is a powerful and simple tool for mitigating drug interference, its application must be optimized and its limitations carefully considered. The choice of acid, concentration, and incubation time must be tailored to the specific drug-target-ADA interaction to maximize interference removal while minimizing impacts on assay sensitivity and reagent integrity [14].

For assays where acid dissociation alone is insufficient—particularly when soluble multimeric targets cause significant false-positive results—alternative or complementary strategies like the PandA method offer a robust solution [36]. The PandA method's key advantage is its ability to prevent the re-association of interfering molecules after dissociation, a challenge inherent in simple acid dissociation with neutralization [36].

In conclusion, the selection of an interference mitigation strategy should be guided by a thorough understanding of the interfering substances and the mechanism of the therapeutic drug. Acid dissociation remains a cornerstone technique due to its simplicity and efficacy, but researchers must be prepared to employ more sophisticated methods like PandA or target scavenging when confronted with complex interference profiles to ensure the accuracy and reliability of immunogenicity assessments.

Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) are powerful analytical techniques for multi-element determination. However, both are susceptible to spectral interferences that can compromise data accuracy, particularly in complex matrices encountered in pharmaceutical and environmental research. Spectral interferences occur when an interfering species overlaps with the signal of the analyte of interest, leading to signal suppression or enhancement and ultimately, false negative or positive results [39]. In ICP-OES, these interferences manifest as direct or partial spectral overlaps at characteristic wavelengths [39] [40]. In ICP-MS, interferences primarily arise from isobaric overlaps (elements with identical mass-to-charge ratios) and polyatomic ions formed from plasma gases and sample matrix components [41] [42].

The impact of uncorrected spectral interferences is profound, degrading the accuracy and precision of methods and potentially invalidating regulatory compliance data [39]. Within regulated environments, such as those governed by US EPA methods 200.7 (for ICP-OES) or 200.8 (for ICP-MS), demonstrating freedom from spectral interferences is mandatory [39] [43]. This article objectively compares the principles and applications of Inter-Element Correction (IEC) and other methods for resolving spectral interferences in ICP-OES and ICP-MS, providing researchers with the experimental protocols and data needed for informed methodological choices.

Fundamental Principles and Comparison of ICP-OES and ICP-MS

Core Operating Principles

The fundamental difference between the two techniques lies in their detection mechanisms. ICP-OES is based on atomic emission spectroscopy. Samples are introduced into a high-temperature argon plasma (~6000-10000 K), where constituents are vaporized, atomized, and excited. As excited electrons return to lower energy states, they emit light at element-specific wavelengths. A spectrometer measures the intensity of this emitted light to identify and quantify elements [43] [40] [41]. ICP-MS, conversely, functions as an elemental mass spectrometer. The plasma serves to generate ions from the sample. These ions are then accelerated into a mass analyzer (e.g., a quadrupole), which separates and quantifies them based on their mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) [43] [41].

This divergence in detection principle directly leads to their different interference profiles and performance characteristics, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Fundamental comparison of ICP-OES and ICP-MS techniques.

| Parameter | ICP-OES | ICP-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Optical emission at characteristic wavelengths [41] | Mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio of ions [41] |

| Typical Detection Limits | Parts per billion (ppb, µg/L) for most elements [43] [40] | Parts per trillion (ppt, ng/L) for most elements [43] [41] |

| Linear Dynamic Range | 4-6 orders of magnitude [40] [41] | 6-9 orders of magnitude [41] [44] |

| Primary Interference Type | Spectral overlaps (direct or partial) [39] [40] | Isobaric overlaps, polyatomic ions [41] [42] |

| Isotopic Analysis | Not applicable [41] [44] | Available and routine [41] [44] |

| Matrix Tolerance (TDS) | High (up to ~2-30% total dissolved solids) [43] [45] | Low (typically <0.1-0.5% TDS) [43] [44] |

Visualizing ICP Techniques and Interferences

The following diagrams illustrate the core components and primary interference pathways for both ICP-OES and ICP-MS.

Interference Correction Methodologies

Inter-Element Correction (IEC) in ICP-OES

Inter-Element Correction is a well-established mathematical approach to correct for unresolvable direct spectral overlaps in ICP-OES [39]. It is accepted as a gold standard in many regulated methods [39]. The IEC method relies on characterizing the contribution of an interfering element to the signal at the analyte's wavelength. A correction factor is empirically determined and applied to subsequent sample analyses.

Experimental Protocol for IEC:

- Preparation of Interference Check Solution: Prepare a single-element standard solution containing a high concentration of the suspected interfering element, but with the analyte element absent.

- Analysis and Factor Calculation: Analyze this interference check solution. The apparent concentration of the analyte measured at its specific wavelength is entirely due to the interference. The IEC factor (k) is calculated as: k = (Apparent Analyte Concentration) / (Concentration of Interfering Element) [39].

- Integration into Software: Modern ICP-OES software (e.g., Thermo Scientific Qtegra ISDS) allows direct input of IEC equations. The general form for the corrected analyte concentration is: Corrected [Analyte] = Measured [Analyte] - (k × [Interferent]) [39].

- Validation: The effectiveness of the IEC must be demonstrated routinely, typically by analyzing the interference check solution as part of the daily workflow. The result for the analyte should be close to zero, confirming the correction is functioning correctly [39].

Alternative and Complementary Correction Techniques