Lambda Max (λmax) in UV-Vis Spectroscopy: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of lambda max (λmax) in UV-Vis spectroscopy, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

Lambda Max (λmax) in UV-Vis Spectroscopy: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of lambda max (λmax) in UV-Vis spectroscopy, addressing the critical needs of researchers and drug development professionals. It covers fundamental principles linking molecular structure to absorption characteristics, practical methodologies for quantification and analysis in pharmaceutical applications, essential troubleshooting for measurement accuracy, and validation frameworks for regulatory compliance. By integrating foundational theory with advanced applications, this guide serves as an essential resource for ensuring data integrity in biomedical research, quality control, and material characterization.

Understanding Lambda Max: The Fundamental Principles of UV-Vis Absorption

In the realm of UV-Vis spectroscopy, lambda max (λmax) is defined as the wavelength at which a chemical substance exhibits its strongest absorption of light [1] [2]. This parameter is not merely a descriptive characteristic; it is a fundamental quantitative property that provides deep insights into the electronic structure of molecules and serves as a critical tool for identification and quantification in analytical chemistry [1] [3]. For researchers and drug development professionals, precise knowledge of a compound's λmax is indispensable. It ensures the highest sensitivity and accuracy in quantitative measurements, minimizes deviations from the Beer-Lambert law, and forms the basis for method development in analytical protocols [4]. The value of λmax is influenced by the molecular environment, including the solvent, pH, and temperature, making its determination under controlled conditions a vital step in spectroscopic analysis [2].

This technical guide explores the definition of lambda max within the broader context of UV-Vis spectroscopy research. It delves into the theoretical principles underlying electronic transitions, provides detailed experimental methodologies for its determination, and discusses its critical applications in scientific and industrial settings, particularly emphasizing its utility in the pharmaceutical sciences.

Theoretical Foundations: Electronic Transitions and Chromophores

The Origin of Absorption Spectra

Ultraviolet-Visible spectroscopy probes the excitation of electrons from a ground state to an excited state through the absorption of light energy [5] [3]. The energy of the absorbed photon ((E)) must exactly match the energy difference ((\Delta E)) between the two electronic states involved, a relationship governed by the equation (E = h\nu), where (h) is Planck's constant and (\nu) is the frequency of the light [5]. This relationship is commonly expressed in terms of wavelength ((\lambda)), making λmax a direct reporter on the energy gap within a molecule [3].

The probability and energy of these electronic transitions depend heavily on the molecular orbitals involved. The most common transitions in organic molecules include [3] [2]:

- (\pi \rightarrow \pi^*)

- (n \rightarrow \pi^*)

- (\sigma \rightarrow \sigma^*)

- (n \rightarrow \sigma^*)

For a transition to be observed in the UV-Vis region (typically 200-800 nm), the energy gap must correspond to photons within this range. Molecules with only single bonds ((\sigma)-bonds) have large (\Delta E) values, absorbing at short wavelengths (<200 nm) in the deep UV and thus appearing colorless to the human eye [5]. In contrast, the presence of chromophores—functional groups that absorb light, typically involving (\pi)-electrons or heteroatoms with non-bonding electrons—shifts the absorption to longer, more accessible wavelengths [3].

The Impact of Conjugation on Lambda Max

A paramount factor affecting λmax is conjugation—the presence of alternating single and multiple bonds in a molecule. As conjugation increases, the energy gap ((\Delta E)) between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) decreases [5] [3]. This reduction in (\Delta E) corresponds to the absorption of lower-energy photons, meaning the λmax shifts to a longer wavelength (bathochromic shift).

This effect is powerfully illustrated by a simple series of conjugated hydrocarbons [5]:

- Ethene (1 double bond): λmax ≈ 174 nm

- Buta-1,3-diene (2 conjugated double bonds): λmax ≈ 217 nm

- Hexa-1,3,5-triene (3 conjugated double bonds): λmax ≈ 253 nm

This systematic bathochromic shift with increasing conjugation is a cornerstone of structure-property relationships in organic chemistry and is extensively leveraged in the design of dyes, pigments, and pharmaceutical compounds [3].

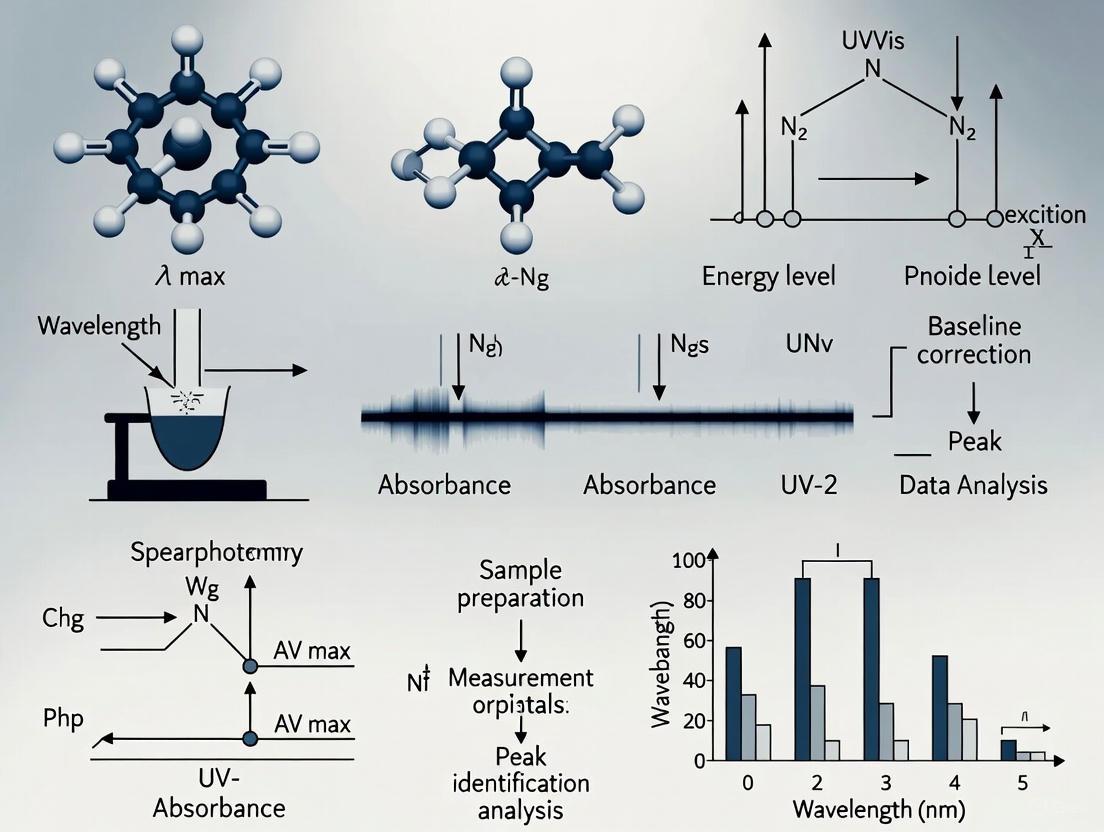

The following diagram illustrates the core concepts of electronic transitions and the effect of conjugation on the HOMO-LUMO energy gap, which directly determines Lambda Max.

Experimental Determination of Lambda Max

Standardized Protocol for Measurement

Accurately determining the λmax of a compound is a foundational experimental procedure. The following protocol, adaptable for compounds like paracetamol or potassium permanganate, outlines the critical steps [6] [4].

Step 1: Sample Preparation A stock solution of the analyte is prepared by dissolving a precisely weighed mass of the pure compound in a suitable solvent. The solvent must be transparent in the spectral region of interest; common choices include water, ethanol, and hexane [2]. For example, a paracetamol stock solution can be prepared by dissolving 5 mg in 50 mL of distilled water, resulting in a 100 µg/mL solution [4]. A working dilution is then prepared from this stock to ensure the absorbance readings fall within the ideal range of the instrument (typically 0.2 to 1.0 AU).

Step 2: Spectroscopic Scanning

- The UV-Vis spectrophotometer is initialized and allowed to warm up. A cuvette filled with the pure solvent (the "blank") is used to calibrate the instrument's baseline (100% transmittance or 0 absorbance) [4].

- The blank is replaced with the cuvette containing the sample solution.

- The absorbance of the sample is measured across a broad wavelength range (e.g., 200-400 nm for a UV-absorbing compound, or 400-600 nm for a colored compound like KMnOâ‚„), taking readings at regular intervals (e.g., 5 or 10 nm increments). Finer increments can be used near a suspected peak for greater accuracy [4].

Step 3: Data Plotting and Analysis The absorbance values are plotted against their corresponding wavelengths. The resulting spectrum will show one or more absorption peaks. The wavelength corresponding to the highest point of the most intense peak is identified as the λmax [1] [4]. For instance, potassium permanganate exhibits a λmax of approximately 530 nm, which is responsible for its intense purple color [6].

Workflow Visualization

The experimental journey from sample preparation to the identification of Lambda Max follows a structured workflow, as visualized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The reliable determination of λmax requires specific laboratory materials and instruments. The following table details the essential components of the research toolkit.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for Lambda Max Determination

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | The core analytical instrument that passes light of varying wavelengths through the sample and measures the intensity of absorption [5] [2]. |

| Quartz or Glass Cuvettes | Containers that hold the sample solution. Quartz is required for UV wavelengths (<350 nm), while glass or plastic can be used for the visible range only [1]. |

| High-Purity Solvent | A solvent that does not absorb significantly in the region of interest (e.g., water, ethanol, hexane) to avoid interfering with the sample's absorption spectrum [2]. |

| Analytical Balance | Used for precise weighing of the analyte to prepare solutions of accurate and known concentration [4]. |

| Volumetric Flasks | Used for precise preparation and dilution of standard and sample solutions to specified volumes, ensuring concentration accuracy [4]. |

| Standard Compound (e.g., Paracetamol, KMnOâ‚„) | A high-purity reference material with a known absorption profile, used for method validation and calibration [6] [4]. |

| Fmoc-Thr(Trt)-OH | Fmoc-Thr(Trt)-OH|CAS 133180-01-5|Peptide Synthesis |

| BOC-D-alanine | BOC-D-alanine, CAS:7764-95-6, MF:C8H15NO4, MW:189.21 g/mol |

Quantitative Applications and Prediction of Lambda Max

The Role of Lambda Max in Quantitative Analysis

Lambda max is intrinsically linked to quantitative analysis via the Beer-Lambert Law [1] [2]: [ A = \epsilon \, l \, c ] where:

- (A) is the measured absorbance at λmax,

- (\epsilon) is the molar absorptivity (a constant specific to the compound at λmax),

- (l) is the path length of the cuvette (usually 1 cm),

- (c) is the concentration of the solution.

The law states that absorbance is directly proportional to concentration. Measuring absorbance at λmax is crucial because it provides the highest sensitivity (largest signal per unit concentration) and minimizes potential errors from slight instrumental wavelength drifts, as the slope of the absorbance curve is flattest at the peak [2]. Concentration can be determined either by using a known molar absorptivity value ((\epsilon)) or, more reliably, by constructing a calibration curve of absorbance versus concentration for a series of standard solutions [1].

Empirical Prediction Using Woodward-Fieser Rules

For conjugated organic molecules, λmax can be predicted empirically using Woodward-Fieser rules [7]. These rules assign a base value for λmax depending on the core chromophore (e.g., conjugated diene or carbonyl) and then add incremental contributions for various structural features such as alkyl substituents, exocyclic double bonds, and extended conjugation [7].

Table 2: Sample Woodward-Fieser Rule Calculations for Conjugated Dienes and Carbonyls

| Structural Feature | Contribution to λmax |

|---|---|

| Base Value: Homoannular (s-cis) Diene | 253 nm |

| Base Value: Heteroannular (s-trans) Diene | 217 nm |

| Base Value: α,β-Unsaturated Ketone | 215 nm |

| Each Alkyl Substituent on Diene | +5 nm |

| Each Exocyclic Double Bond | +5 nm |

| Extended Conjugation (Double Bond) | +30 nm |

| Polar Group (e.g., -OCOCH₃) at α position | +0 nm |

| Polar Group (e.g., -OCOCH₃) at β position | +10 nm |

Example Calculation: For a heteroannular diene with three alkyl substituents and one exocyclic double bond: Base value = 217 nm Alkyl substituents (3 × 5 nm) = +15 nm Exocyclic double bond = +5 nm Predicted λmax = 217 + 15 + 5 = 237 nm [7]

These rules enable researchers to make informed predictions about the electronic structure and spectroscopic behavior of novel synthetic compounds.

Lambda Max in Modern Research and Data Science

The determination and application of λmax have entered a new era with the integration of high-throughput computation and data mining. Large-scale, auto-generated databases are now being constructed by text-mining tools like ChemDataExtractor, which can parse thousands of scientific articles to compile records of λmax and molar absorptivity (ε) [8]. One such database contains over 18,000 records of experimentally determined UV/vis absorption maxima [8].

These experimental datasets are used to benchmark and validate high-throughput computational methods, such as Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory (TD-DFT), which can predict λmax from first principles [8]. The strong correlation between computed and experimental values lays the foundation for reliable in silico prediction of optical properties, accelerating the discovery of new materials for optoelectronics, organic photovoltaics, and pharmaceutical development [8]. This synergy between experimental data and computational modeling represents the cutting edge of research in spectroscopic characterization.

Lambda max (λmax), the wavelength at which a substance exhibits its maximum absorbance, is a fundamental parameter in UV-Vis spectroscopy that provides a direct window into the electronic structure of molecules. This in-depth technical guide explores the quantum chemical principles underlying λmax, focusing on the role of electronic transitions between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). Framed within broader UV-Vis spectroscopy research, this article examines how λmax serves as an experimental probe of molecular energy levels, how it correlates with molecular structure, and its critical applications in material science and drug development. The precise measurement of λmax enables researchers to quantify electronic transitions, characterize chromophores, and determine concentration, forming the basis for analytical protocols across scientific disciplines.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy investigates the interaction between light and matter, specifically focusing on how molecules absorb electromagnetic radiation in the ultraviolet (typically 190-400 nm) and visible (400-700 nm) regions. This absorption occurs because the energy of the incoming photons matches the energy required to promote electrons from ground states to excited states. The fundamental equation governing this interaction is E = hν, where E represents the energy of the photon, h is Planck's constant, and ν is the frequency of the light [5]. This relationship forms the quantum mechanical basis for all electronic spectroscopy.

When a molecule absorbs light of appropriate energy, an electron undergoes a transition from a lower-energy orbital to a higher-energy orbital. The most common and electronically significant transition occurs between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). The energy difference between these frontier orbitals (ΔE) directly determines the wavelength of light absorbed according to the relationship ν = ΔE/h [5]. The wavelength at which this absorption is strongest is designated as λmax (pronounced "lambda max"), which serves as a characteristic fingerprint for a molecule's electronic structure and a quantitative parameter for analysis [5] [1].

Table 1: Fundamental Equations in UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Equation | Variables | Relationship | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| E = hν | E = energy, h = Planck's constant, ν = frequency | Direct proportionality | Relates photon energy to its frequency |

| ν = ΔE/h | ΔE = HOMO-LUMO energy gap | Direct proportionality | Determines frequency needed for electronic transition |

| c = νλ | c = speed of light, λ = wavelength | Inverse proportionality | Connects frequency and wavelength of light |

| A = εlc | A = absorbance, ε = molar absorptivity, l = pathlength, c = concentration | Direct proportionality (Beer-Lambert Law) | Relates absorption to concentration for quantification |

Theoretical Framework: Molecular Orbitals and HOMO-LUMO Transitions

Molecular Orbital Theory Foundations

The molecular orbital (MO) theory provides the theoretical framework for understanding electronic transitions. When atomic orbitals combine, they form molecular orbitals that are delocalized over the entire molecule. For a simple diatomic molecule like hydrogen (H₂), two atomic orbitals combine to form two molecular orbitals: a bonding σ orbital (lower energy) and an antibonding σ* orbital (higher energy) [5]. The energy difference between these orbitals (ΔE) corresponds to the energy required for an electronic transition from σ to σ*. For H₂, this transition occurs at 112 nm, deep in the UV region [5]. In organic molecules, the most relevant transitions for UV-Vis spectroscopy involve π and n (non-bonding) electrons.

Frontier Molecular Orbital Theory

The Frontier Molecular Orbital theory emphasizes the importance of the HOMO and LUMO in determining chemical reactivity and spectroscopic properties. The HOMO represents the highest-energy orbital containing electrons, while the LUMO is the lowest-energy vacant orbital. The energy gap between these frontier orbitals dictates the wavelength of absorption; a smaller HOMO-LUMO gap results in absorption at longer wavelengths [5]. This principle explains why molecules with extended π-systems, which have small HOMO-LUMO gaps, absorb in the visible region and appear colored.

Selection Rules and Transition Probability

Not all electronic transitions are equally probable. Selection rules govern the likelihood of transitions between electronic states:

- Spin selection rule: Transitions that conserve spin multiplicity are allowed (e.g., singlet→singlet).

- Orbital selection rule: Transitions between orbitals of the same symmetry are allowed.

- Laporte rule: In centrosymmetric molecules, transitions between orbitals of the same parity (gg or uu) are forbidden.

The intensity of an absorption band depends on how well these selection rules are followed, with molar absorptivity (ε) values ranging from <100 for forbidden transitions to >100,000 for fully allowed transitions [9]. Vibronic coupling and spin-orbit coupling can relax these rules, making some formally forbidden transitions observable.

Factors Influencing Lambda Max

Conjugation and Electronic Delocalization

Conjugation, the alternation of single and multiple bonds in a molecule, has a profound effect on λmax by lowering the HOMO-LUMO energy gap. As conjugation length increases, the energy required for π→π* transitions decreases, resulting in a bathochromic shift (red shift) of λmax to longer wavelengths [5]. This relationship is systematic and predictable:

Table 2: Effect of Conjugation on Lambda Max

| Compound | Conjugated System | λmax (nm) | HOMO-LUMO Gap | Color |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethene | C=C | 171 [5] | 164 kcal/mol [5] | Colorless |

| Buta-1,3-diene | Conjugated diene | 217 [1] | Reduced | Colorless |

| Hexatriene | Conjugated triene | 258 [5] | Further reduced | Colorless |

| β-carotene | Extended polyene | 450-500 [5] | Minimal | Orange |

The quantum mechanical explanation for this effect lies in the formation of molecular orbitals that are delocalized across the entire conjugated system. In extended π-systems, the HOMO is raised in energy while the LUMO is lowered, reducing the energy gap and shifting absorption to longer wavelengths.

Substituent Effects and Electron Deficiency

The electron-withdrawing or electron-donating character of substituents significantly influences λmax by modifying the HOMO and LUMO energy levels. Research on acceptor-acceptor'-acceptor (A-A'-A) triads demonstrates how increasing the electron-deficiency of pendant groups systematically reduces the LUMO energy level, leading to bathochromic shifts [10]. In a study comparing triads with different electron-accepting pendants, λmax values progressively red-shifted with increasing electron-withdrawing power: benzothiadiazole (BTD-P) at 445 nm, naphthalene diimide (NDI-P) at 514 nm, and perylene diimide (PTCDI-EH-P) at 587 nm [10]. Computational analysis confirmed that the LUMOs were primarily localized on the most electron-deficient pendants, demonstrating how strategic molecular design can tune electronic properties.

Solvent and Environmental Effects

The solvent environment can significantly influence λmax through various solute-solvent interactions. Polar solvents can stabilize excited states more effectively than ground states, leading to solvatochromic shifts. Specific solvent effects include:

- Polarity effects: Polar solvents cause bathochromic shifts for π→π* transitions due to better stabilization of the more polar excited state.

- Hydrogen bonding: Protic solvents can cause shifts in n→π* transitions through hydrogen bonding with lone pair electrons.

- Refractive index effects: The general solvent effect related to the refractive index can cause small shifts.

Temperature also affects spectral appearance; lowering temperature reduces vibrational broadening, allowing resolution of vibrational fine structure within electronic transitions [9].

Experimental Determination and Protocols

UV-Vis Spectrometer Operation

The UV-Vis spectrometer operates on the principle of measuring light absorption as a function of wavelength. Key components include:

- Light source: Typically deuterium lamp (UV) and tungsten lamp (visible)

- Monochromator: Selects specific wavelengths

- Sample compartment: Holds sample and reference cells

- Detector: Measures transmitted light intensity

The instrument shines light of varying wavelengths through the sample and measures absorbance at each wavelength, generating a spectrum of absorbance versus wavelength [5]. Only wavelengths corresponding to ΔE for electronic transitions will be strongly absorbed, producing characteristic peaks.

Sample Preparation and Measurement Protocols

Materials and Reagents:

- Spectrophotometric grade solvents (e.g., dichloromethane, acetonitrile, hexane)

- Quartz cuvettes (for UV region, 190-400 nm)

- Glass or plastic cuvettes (for visible region, 400-800 nm)

- Analytical balance for precise weighing

- Volumetric flasks for solution preparation

Procedure:

- Prepare sample solution at appropriate concentration (typically 1-5 μM for qualitative analysis, depending on ε) [10]

- Use same solvent for sample and reference (blank) to cancel solvent absorption

- Fill cuvette, ensuring no air bubbles or fingerprints in light path

- Place in spectrometer and scan appropriate wavelength range (e.g., 200-800 nm)

- Identify λmax as the wavelength of maximum absorbance in each peak

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Technical Specifications | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample container | 1 cm pathlength, transparent down to 190 nm | Essential for UV measurements below 350 nm |

| Spectrophotometric Solvents | Dissolution medium | Low UV cutoff, high purity | Dichloromethane (DCM): λcutoff ~235 nm |

| Concentration Standards | Calibration | Accurately prepared stock solutions | Serial dilution from primary stock |

| Reference Solution | Blank measurement | Pure solvent matching sample solution | Corrects for solvent and cuvette absorption |

Quantitative Analysis Using Lambda Max

The Beer-Lambert Law forms the basis for quantitative analysis: A = εlc, where A is absorbance, ε is molar absorptivity (in Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹), l is pathlength (in cm), and c is concentration (in M) [1]. Two primary methods are employed:

Direct Calculation: If ε is known at λmax, concentration can be directly calculated from absorbance: [ c = \frac{A}{εl} ] For example, with A = 1.92, ε = 19,400 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹, and l = 1 cm: [ c = \frac{1.92}{19400} = 9.90 \times 10^{-5} \, \text{mol/L} ] [1]

Calibration Curve Method:

- Prepare standard solutions of known concentrations bracketing the unknown

- Measure absorbance at λmax for each standard

- Plot absorbance versus concentration

- Determine unknown concentration from the linear regression curve

This method is preferred as it doesn't rely on literature ε values and accounts for any deviations from the Beer-Lambert Law at higher concentrations [1].

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Chromophore Identification and Compound Characterization

Lambda max serves as a critical parameter for identifying chromophores and characterizing molecular structure. By comparing experimental λmax values with known chromophore data, researchers can identify functional groups and conjugation patterns [1]. For example:

- Simple alkenes (C=C): 170-200 nm

- Carbonyl compounds (C=O): π→π* ~180 nm, n→π* ~280-300 nm

- Conjugated dienes: 217-280 nm

- Aromatic compounds: 250-300 nm (with fine structure)

The combination of λmax position and molar absorptivity (ε) provides a powerful tool for structural elucidation. For instance, ethanal shows two peaks at 180 nm (ε=10,000) and 290 nm (ε=15), characteristic of π→π* and n→π* transitions, respectively [1].

Pharmaceutical Analysis and Quality Control

In drug development, λmax is utilized in multiple critical applications:

- Purity assessment: Contaminants often produce additional absorption peaks or shift λmax

- Concentration determination: API quantification in formulations using established ε values

- Polymorph identification: Different crystal forms can exhibit λmax shifts

- Dissolution testing: Monitoring drug release through absorbance at λmax

The reproducibility of λmax measurements makes it invaluable for quality control and method validation in pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Material Science and Electronic Materials Design

In organic electronics, strategic molecular design manipulates HOMO-LUMO gaps to achieve desired λmax values for specific applications:

- Organic photovoltaics: Materials designed with λmax matching solar spectrum

- OLEDs: Emitters tuned for specific colors through HOMO-LUMO gap engineering

- Sensors: Chromophores engineered for λmax shifts upon analyte binding

The study of A-A'-A triads demonstrates how systematic molecular design can tune electronic properties [10]. Computational methods complement experimental λmax measurements, enabling prediction of HOMO-LUMO gaps and optical properties before synthesis.

Lambda max represents far more than just a peak position on a spectrum; it is a fundamental manifestation of quantum chemical principles that provides direct insight into molecular electronic structure. The relationship between λmax and the HOMO-LUMO energy gap forms the basis for understanding how molecular structure influences light absorption, enabling researchers to design molecules with tailored optical properties. As research advances in areas from pharmaceutical development to organic electronics, the precise measurement and interpretation of λmax continues to be an essential tool for connecting molecular structure with electronic behavior. The ability to predict and manipulate λmax through rational molecular design represents a powerful approach for developing new materials with optimized optical and electronic characteristics for targeted applications.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy operates on a fundamental principle of molecular orbital theory: the absorption of light occurs when the energy of incoming photons precisely matches the energy gap (ΔE) between molecular orbitals, promoting electrons from ground state to excited state orbitals [11]. This technique measures how molecules absorb light in the ultraviolet (typically 190-400 nm) and visible (400-800 nm) regions of the electromagnetic spectrum, providing critical insights into electronic structure [12]. The parameter λmax, defined as the wavelength of maximum absorbance, serves as a direct experimental probe of these energy gaps, making it a cornerstone parameter in spectroscopic analysis [13]. For researchers in drug development and materials science, understanding the relationship between ΔE and λmax is essential for interpreting spectral data, identifying chromophores, and elucidating molecular structure.

Fundamental Orbital Interactions

At the heart of UV-Vis spectroscopy lies the promotion of electrons from occupied to unoccupied molecular orbitals. When light energy matches the energy difference (ΔE) between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), absorption occurs [5]. This relationship is governed by the equation ΔE = hc/λ, where h is Planck's constant, c is the speed of light, and λ is the wavelength of absorbed light [11]. A smaller HOMO-LUMO energy gap corresponds to longer wavelength absorption, while a larger gap requires higher energy (shorter wavelength) light for electronic excitation.

Types of Electronic Transitions

Different molecular orbitals give rise to characteristic electronic transitions with distinct energy requirements and probabilities:

- π→π* Transitions: Occur in molecules with unsaturated centers, requiring less energy than σ→σ* transitions. For isolated double bonds (e.g., ethene), these transitions typically occur around 170-190 nm [5].

- n→π* Transitions: Involve promotion of electrons from non-bonding orbitals (lone pairs) to π* anti-bonding orbitals. These transitions are of lower energy (longer wavelength) but also lower probability, resulting in weaker absorption bands [14].

- n→σ* Transitions: Require more energy than n→π* transitions, typically appearing in the 150-250 nm range [15].

- σ→σ* Transitions: Represent the highest energy transitions, occurring below 150 nm, beyond the range of conventional UV-Vis spectrometers [5].

The spatial overlap between orbitals significantly affects transition probabilities. π→π* transitions typically show high molar absorptivities (ε > 10,000) due to good orbital overlap, while n→π* transitions display much lower intensities (ε = 10-100) due to poor spatial overlap between non-bonding and π* orbitals [3].

The Critical Relationship Between ΔE and λmax

Theoretical Foundations

The inverse relationship between the energy gap (ΔE) and the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) forms the theoretical basis for interpreting UV-Vis spectra. As conjugation increases, the HOMO-LUMO gap narrows due to orbital mixing, resulting in a bathochromic shift (red shift) of λmax to longer wavelengths [14]. This systematic relationship allows researchers to make structural predictions based on spectral data.

The following conceptual diagram illustrates this fundamental relationship and the experimental process for measuring it:

Quantitative Data: Conjugation Effects on λmax

The effect of conjugation on λmax demonstrates the direct relationship between orbital energy gaps and absorption characteristics. As conjugation length increases, the HOMO-LUMO gap systematically decreases, resulting in predictable bathochromic shifts:

Table 1: Effect of Conjugation on Absorption Characteristics

| Compound | Conjugation Length | λmax (nm) | ΔE (kcal/mol) | Color |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethene | Isolated C=C | 171 [14] | 164 [5] | Colorless |

| Buta-1,3-diene | Conjugated Diene | 217 [14] | 132* | Colorless |

| Hexa-1,3,5-triene | Conjugated Triene | 258 [14] | 111* | Colorless |

| β-carotene | Extended Conjugation | 450-500 [11] | 60-65* | Orange |

*Calculated values based on ΔE = hc/λ

This systematic bathochromic shift with increasing conjugation provides researchers with a powerful tool for structural characterization. The introduction of auxochromes (electron-donating or withdrawing groups) further modifies these energy gaps through resonance and inductive effects, enabling fine-tuning of absorption properties in pharmaceutical compounds and functional materials [15].

Experimental Determination of λmax

Instrumentation and Methodology

Modern UV-Vis spectrophotometers employ sophisticated optical systems to precisely measure absorption spectra. The core components include:

- Light Sources: Deuterium lamps for UV region (190-400 nm) and tungsten/halogen lamps for visible region (400-800 nm) [12]

- Monochromator: Typically a diffraction grating (1200-2000 grooves/mm) for wavelength selection with 1-2 nm bandwidth [12]

- Sample Compartment: Quartz cuvettes for UV measurements (path length typically 1.0 cm) [12]

- Detection System: Photomultiplier tubes or photodiode arrays for light detection [12]

The following workflow diagram outlines the standardized protocol for λmax determination:

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful UV-Vis spectroscopy requires carefully selected reagents and materials to ensure accurate and reproducible results:

Table 2: Essential Materials for UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample containment | 1 cm path length, UV-transparent (190-2500 nm) [12] |

| Spectroscopic Solvents | Sample matrix | HPLC-grade, low UV absorption (e.g., acetonitrile, hexane) [15] |

| Deuterium Lamp | UV light source | 190-400 nm continuous spectrum [12] |

| Tungsten-Halogen Lamp | Visible light source | 400-800 nm continuous spectrum [12] |

| Holmium Oxide Filter | Wavelength calibration | NIST-traceable standards (241, 279, 287, 333, 345, 361, 418, 536 nm) [12] |

| Neutral Density Filters | Photometric calibration | Absorbance standards (0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0 A) [12] |

Quantitative Analysis Using Beer-Lambert Law

The Beer-Lambert law provides the foundation for quantitative analysis in UV-Vis spectroscopy, expressed as A = εcl, where A is absorbance, ε is molar absorptivity (Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹), c is concentration (M), and l is path length (cm) [12]. For accurate quantification:

- Absorbance measurements should fall within the linear range (typically 0.1-1.0 AU) [15]

- λmax provides the optimal wavelength for quantification due to maximum sensitivity and minimized concentration errors [13]

- Molar absorptivity (ε) at λmax serves as a compound-specific constant for concentration determination [3]

Spectral Interpretation and Advanced Considerations

Systematic Interpretation Framework

Interpreting UV-Vis spectra requires a structured approach to extract meaningful structural information:

- Identify λmax Values: Locate all local absorption maxima, noting both position and intensity [15]

- Assign Electronic Transitions: Correlate λmax with possible transitions (π→π, n→π, charge-transfer) [14]

- Identify Chromophores: Recognize characteristic absorption patterns of functional groups [3]

- Assess Conjugation Effects: Evaluate bathochromic shifts indicating extended π-systems [14]

- Quantitative Analysis: Apply Beer-Lambert law for concentration determination [12]

Characteristic Chromophore Absorptions

Different functional groups exhibit distinctive absorption patterns based on their electronic structure:

Table 3: Characteristic λmax Values for Common Chromophores

| Chromophore | Transition Type | λmax Range (nm) | Molar Absorptivity (ε) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isolated C=C | π→π* | 170-190 [5] | 10,000-16,000 [3] |

| Carbonyl | n→π* | 270-300 [15] | 10-100 [3] |

| Conjugated Diene | π→π* | 220-250 [15] | 20,000-30,000 [14] |

| Aromatic | π→π* | 250-280 [15] | 200-5,000 [3] |

| Polyene | π→π* | Varies with conjugation | 30,000-100,000 [14] |

Advanced Structural Applications

Beyond simple identification, UV-Vis spectroscopy provides sophisticated structural insights:

- Secondary Structure Analysis: Protein α-helix content shows characteristic ~208 nm and ~222 nm π→π* transitions [16]

- Nanoparticle Characterization: Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance (LSPR) of gold nanoparticles appears as strong visible absorption (500-600 nm) sensitive to size, shape, and environment [17]

- Aggregation Studies: Hypochromic effects and broadening indicate molecular aggregation or stacking interactions [15]

- Solvent Effects: Polar solvents cause red shifts in π→π* transitions but blue shifts in n→π* transitions due to differential solvation of ground and excited states [3]

The fundamental relationship between molecular orbital energy gaps (ΔE) and absorption wavelength (λmax) provides the theoretical foundation for UV-Vis spectroscopy. Through systematic examination of electronic transitions, researchers can extract detailed structural information about chromophores, conjugation, and substituent effects. The precise determination of λmax enables both qualitative identification and quantitative analysis of compounds across pharmaceutical, materials, and biological research. As instrumentation advances, the principles of molecular orbital theory continue to guide interpretation of increasingly complex spectral data, making UV-Vis spectroscopy an indispensable tool for understanding electronic structure and guiding molecular design in research and development.

In Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy, the wavelength of maximum absorption, denoted as lambda max (λmax), is a fundamental parameter that provides critical insights into the electronic structure of molecules [1] [3]. This characteristic value represents the specific wavelength at which a molecule most efficiently absorbs light, corresponding to the energy required to promote an electron from its ground state to an excited state [5] [18]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the factors that govern λmax is not merely an academic exercise; it is essential for applications ranging from compound identification and quantification to the rational design of chromophores for pharmaceutical and material science applications. The value of λmax is primarily dictated by two key structural features within a molecule: the chromophore, the core light-absorbing unit, and the auxochrome, a substituent that modifies the absorption properties of the chromophore [19] [20]. This guide delves into the intricate relationship between these structural features and the resulting spectral properties, providing a technical foundation for advanced research and development.

Theoretical Foundations of Electronic Transitions

The Origin of Absorption Spectra

UV-Vis spectroscopy measures the absorption of light by a sample as a function of wavelength. The absorption occurs when the energy of an incoming photon matches the energy required for an electronic transition within the molecule [5]. This energy relationship is described by the equation: [ E = h\nu = \frac{hc}{\lambda} ] where ( E ) is the energy of the transition, ( h ) is Planck's constant, ( c ) is the speed of light, ( \nu ) is the frequency, and ( \lambda ) is the wavelength [3]. Consequently, a molecule with a smaller energy gap (( \Delta E )) between its ground and excited states will absorb light of longer wavelength (lower energy) [5].

Types of Electronic Transitions

The energy required for electronic transitions, and thus the observed λmax, depends on the nature of the molecular orbitals involved. The primary transitions observed in the UV-Vis region are:

- ( \pi \rightarrow \pi^* ) Transition: This occurs in molecules with unsaturated centers, such as alkenes and alkynes. It involves the promotion of an electron from a bonding ( \pi )-orbital to an antibonding ( \pi^* )-orbital [18]. For example, ethene has a ( \pi \rightarrow \pi^* ) λmax at 171 nm [1].

- ( n \rightarrow \pi^* ) Transition: This transition requires the least energy and is characteristic of molecules containing heteroatoms (like O, N, S) with non-bonding electrons adjacent to a π-system, such as in carbonyl compounds. An example is the transition in ethanal observed at 290 nm [1] [18].

- ( n \rightarrow \sigma^* ) and ( \sigma \rightarrow \sigma^* ) Transitions: These generally require high energy and typically appear in the far-UV region (<200 nm) [18].

The general order of increasing transition energy is: [ n \rightarrow \pi^* < \pi \rightarrow \pi^* < n \rightarrow \sigma^* < \sigma \rightarrow \sigma^* ] [18]

Table: Characteristic Electronic Transitions and Associated Energies

| Transition Type | Example Compound | Approximate λmax (nm) | Molar Absorptivity (ε, L molâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ( \sigma \rightarrow \sigma^* ) | Hydrogen (Hâ‚‚) | 112 [5] | - |

| ( \pi \rightarrow \pi^* ) | Ethene | 171 [1] | ~10,000 |

| ( n \rightarrow \pi^* ) | Ethanal | 290 [1] | ~15 |

| ( n \rightarrow \sigma^* ) | Alkyl Halides | ~180 [18] | Low |

Structural Features Governing Lambda Max

Chromophores: The Core Light-Absorbing Units

A chromophore is a covalently unsaturated group within a molecule that is responsible for its absorption of UV or visible radiation [19] [20]. Chromophores contain π-electrons or non-bonding (n) electrons that can be excited to higher energy states [18]. The most common chromophores are conjugated systems where alternating single and double bonds allow for the delocalization of π-electrons across a larger molecular framework [20].

Diagram Title: Structural Impact on Lambda Max

The Profound Impact of Conjugation

Conjugation is the single most important factor affecting the λmax of a chromophore. As the extent of conjugation increases, the energy difference (ΔE) between the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) and the Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO) decreases [5] [18]. This results in a bathochromic shift—a shift of λmax to a longer wavelength [3].

Table: Effect of Conjugation on the λmax of Polyenes

| Compound | Structure | Number of Conjugated Double Bonds | λmax (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethene | Hâ‚‚C=CHâ‚‚ | 1 | 171 [1] |

| Buta-1,3-diene | Hâ‚‚C=CH-CH=CHâ‚‚ | 2 | 217 [1] |

| Hexa-1,3,5-triene | Hâ‚‚C=CH-CH=CH-CH=CHâ‚‚ | 3 | 258 [5] |

| β-Carotene | Extended Polyene | 11 | 452 [20] |

Auxochromes: Functional Modifiers of Absorption

An auxochrome is a saturated or unsaturated group containing one or more pairs of non-bonded electrons that, when attached to a chromophore, alters both the wavelength and the intensity of absorption [19] [18]. Common auxochromes include -OH, -NHâ‚‚, -OR, and -Cl [19] [20]. They exert their influence primarily through mesomeric (resonance) effects, which extend the conjugation by donating or accepting electrons, and to a lesser extent, inductive effects.

- Mechanism of Action: The non-bonded electrons on the auxochrome interact with the π-system of the chromophore, effectively increasing the conjugation length and stabilizing the excited state. This reduces the HOMO-LUMO energy gap, leading to a bathochromic (red) shift and often a hyperchromic effect (increase in absorption intensity, ε) [19] [18].

- Example: Benzene itself has a λmax of 255 nm. Attaching a hydroxyl group (-OH) to form phenol results in a bathochromic shift to 270 nm. Attaching an amino group (-NH₂) to form aniline causes an even larger shift to 280 nm, demonstrating the powerful electron-donating ability of different auxochromes [18].

Table: Effect of Auxochromes on the λmax of Benzene

| Compound | Auxochrome | λmax (nm) | Observed Shift |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzene | - | 255 [18] | Baseline |

| Phenol | -OH | 270 [18] | Bathochromic (15 nm) |

| Aniline | -NHâ‚‚ | 280 [18] | Bathochromic (25 nm) |

Classification of Spectral Shifts

The alterations in the absorption spectrum caused by chromophores and auxochromes are systematically categorized as follows:

- Bathochromic Shift (Red Shift): A shift of λmax to a longer wavelength. This is caused by the introduction of auxochromes, an increase in conjugation, or a change to a more polar solvent (for π→π* transitions) [19] [18].

- Hypsochromic Shift (Blue Shift): A shift of λmax to a shorter wavelength. This can occur due to the removal of conjugation or a change in solvent polarity (for n→π* transitions) [19] [18].

- Hyperchromic Effect: An increase in the intensity (absorptivity, ε) of the absorption peak [19] [18].

- Hypochromic Effect: A decrease in the intensity of the absorption peak, often due to structural deformations that disrupt optimal orbital overlap [19].

Experimental Protocol for Determining Lambda Max

The following detailed methodology, adapted from a validated study on terbinafine hydrochloride, outlines the procedure for determining λmax and constructing a calibration curve for quantitative analysis [21].

Materials and Reagents

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

| Item | Specification/Function |

|---|---|

| Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) | High-purity standard (e.g., Terbinafine HCl) [21]. |

| Solvent | Distilled water or other suitable solvent (e.g., buffered solution, methanol) that does not absorb in the region of interest [21]. |

| Volumetric Flasks | For accurate preparation and dilution of standard and sample solutions (e.g., 10 ml, 100 ml) [21]. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Instrument with scanning capability across the UV-Vis range (e.g., 200-400 nm) [12]. |

| Cuvettes | Quartz cuvettes are required for UV analysis below ~350 nm; glass or plastic may be used for visible light measurements [12]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Preparation of Standard Stock Solution

- Accurately weigh 10 mg of the pure analyte (e.g., Terbinafine HCl).

- Transfer it to a 100 ml volumetric flask.

- Add approximately 20 ml of solvent (e.g., distilled water) and shake manually for 10 minutes to dissolve.

- Dilute to the mark with the same solvent to obtain a stock solution with a concentration of 100 μg/ml [21].

Selection of Wavelength of Maximum Absorption (λmax)

- Pipette 0.5 ml of the standard stock solution into a 10 ml volumetric flask and dilute to the mark with solvent to achieve a concentration of 5 μg/ml.

- Fill a quartz cuvette with this diluted solution and place it in the spectrophotometer.

- Scan the solution within the wavelength range of 200-400 nm against a blank (solvent only).

- Identify the wavelength at which maximum absorption occurs. This is the λmax. In the referenced study, terbinafine hydrochloride showed a λmax at 283 nm [21].

Linearity and Calibration Curve Study

- Prepare a series of standard solutions of known concentrations to bracket the expected concentration of the unknown sample. For example:

- Pipette 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, and 3.0 ml of the stock solution into a series of 10 ml volumetric flasks.

- Dilute each to the mark with solvent to obtain concentrations of 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 μg/ml, respectively [21].

- Measure the absorbance of each standard solution at the predetermined λmax.

- Plot a graph of absorbance (y-axis) versus concentration (x-axis). The method is considered linear if the correlation coefficient (r²) is ≥ 0.999 [21]. The slope of this line relates to the molar absorptivity (ε).

- Prepare a series of standard solutions of known concentrations to bracket the expected concentration of the unknown sample. For example:

Validation: Accuracy and Precision

- Accuracy (Recovery Test): To a pre-analyzed sample, add a known amount of standard at three different levels (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120%). Reanalyze the solution and calculate the percentage recovery, which should ideally be between 98-102% [21].

- Precision: Analyze three different concentrations of the drug (e.g., 10, 15, and 20 μg/ml) multiple times on the same day (intra-day) and on different days over a week (inter-day). The method is precise if the % Relative Standard Deviation (%RSD) is less than 2% [21].

Diagram Title: UV-Vis Analysis Workflow

Advanced Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

The principles of chromophores and auxochromes are leveraged in sophisticated ways in modern drug development.

- UV Dissolution Imaging: This emerging technology combines UV spectroscopy with spatial resolution to visualize and quantify drug dissolution and release in real-time. It relies on the drug substance's inherent UV absorbance (its chromophore) to create concentration maps near the solid-liquid interface, providing insights into release mechanisms from dosage forms that are not possible with traditional bulk solution analysis [22].

- Form Selection and Drug-Excipient Compatibility: In pre-formulation studies, UV-Vis spectroscopy is used to select the optimal solid form (e.g., polymorph, salt) of an API by detecting subtle shifts in λmax or changes in absorption profile that may indicate interactions between the drug's chromophore and excipients [22].

- Routine Quality Control: The validated method described in Section 5 is a rapid, precise, and cost-effective tool for the quantitative analysis of APIs in bulk and finished pharmaceutical formulations, ensuring compliance with quality standards [21].

The interplay between chromophores and auxochromes is a cornerstone of molecular spectroscopy, dictating the critical parameter of lambda max. A deep understanding of how conjugation and substituent effects manipulate the electronic energy levels of a molecule allows researchers to predict and interpret UV-Vis spectra with precision. This knowledge transcends basic compound identification, forming the basis for advanced analytical techniques in pharmaceutical research, including formulation development, dissolution testing, and quality control. As imaging and real-time monitoring technologies continue to evolve, the fundamental principles governing lambda max will remain essential for innovation in drug development and material science.

In ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy, the wavelength at which a molecule exhibits maximum absorption, known as lambda max (λmax), is a fundamental parameter that provides deep insight into its electronic structure [12]. For researchers and drug development professionals, interpreting changes in λmax is a critical technique for probing molecular interactions, confirming chemical structures, and understanding the behavior of chromophores in various environments [23]. These changes are systematically categorized as bathochromic shifts (a shift to a longer wavelength, also called a red shift) and hypsochromic shifts (a shift to a shorter wavelength, or blue shift), alongside changes in absorption intensity termed hyperchromic (increase) and hypochromic (decrease) effects [24] [25]. This guide explores the molecular underpinnings of these shifts, focusing on the roles of conjugation and substituents, which are central to manipulating and interpreting UV-Vis spectra in research.

Foundational Concepts: Electronic Transitions and Spectral Shifts

UV-Vis spectroscopy measures the absorption of light by a molecule, which promotes electrons from the ground state to an excited state [5]. The energy required for this promotion is determined by the difference between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) [26]. According to the equation ( E = hc / \lambda ), the energy (( E )) of the absorbed photon is inversely proportional to its wavelength (( \lambda )) [3]. Therefore, a smaller HOMO-LUMO energy gap results in absorption at longer wavelengths (bathochromic shift), while a larger gap results in absorption at shorter wavelengths (hypsochromic shift) [25] [27].

These shifts are quantified by measuring the change in the absorption maximum under different conditions, using the formula: [ \Delta \lambda = \lambda{\text{state 2}} - \lambda{\text{state 1}} ] where a positive ( \Delta \lambda ) indicates a bathochromic shift and a negative value indicates a hypsochromic shift [28]. The accompanying changes in absorption intensity (molar absorptivity, ε) are just as diagnostically important; a bathochromic shift is often accompanied by a hyperchromic effect due to a more probable electronic transition [25].

Table 1: Glossary of Key Terms in Spectral Shifts

| Term | Definition | Common Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Bathochromic Shift | Shift of λmax to a longer wavelength (lower energy) [28] | Extension of conjugation; solvent change (positive solvatochromism) [24] [25] |

| Hypsochromic Shift | Shift of λmax to a shorter wavelength (higher energy) [29] | Reduction of conjugation; solvent change (negative solvatochromism) [27] |

| Hyperchromic Effect | Increase in the intensity of absorption (higher ε) [24] | Increased probability of the electronic transition [25] |

| Hypochromic Effect | Decrease in the intensity of absorption (lower ε) [24] | Steric hindrance or molecular aggregation [27] |

| Chromophore | The part of a molecule responsible for its color or UV absorption [3] | A system containing π-electrons, such as a C=C bond or a carbonyl group [26] |

| Auxochrome | A substituent that modifies the λmax and intensity of a chromophore [25] | Groups with lone pairs like -OH or -NH₂ that can extend conjugation [25] |

The Pivotal Role of Conjugation in Lambda Max

Conjugation, the alternation of single and multiple bonds in a molecule, is the most significant structural feature leading to a bathochromic shift. It works by stabilizing the LUMO more than the HOMO, thereby reducing the energy gap between them [26] [25]. This effect is cumulative; each additional conjugated double bond in a polyene system lowers the HOMO-LUMO gap further, shifting the absorption spectrum out of the UV and into the visible region, which imparts color to the molecule [5] [24].

Table 2: The Effect of Conjugation Length on Lambda Max in Polyenes

| Compound | Number of Conjugated Double Bonds | Approximate λmax (nm) | Observed Color |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethene | 1 | 165 [26] / 170 [5] | Colorless |

| 1,3-Butadiene | 2 | 217 [26] | Colorless |

| 1,3,5-Hexatriene | 3 | 258 [26] | Colorless |

| β-Carotene | 11 | 470 [26] | Orange [26] |

The underlying molecular orbital theory explains this phenomenon clearly. In a conjugated system, the π molecular orbitals are delocalized over the entire chain. As the chain lengthens, the number of interacting orbitals increases, causing the energy levels to cluster more closely together. This leads to a systematic decrease in the HOMO-LUMO gap [26]. The diagram below illustrates this conceptual relationship.

Figure 1: The Causal Link Between Conjugation and Spectral Shifts

The Influence of Substituents and Environmental Factors

Substituents attached to a chromophore can significantly alter its λmax by either donating or withdrawing electrons, thereby modifying the electron density and energy levels of the π-system.

- Auxochromes: Electron-donating groups (EDGs) such as

-OH,-NH₂, and-ORtypically induce a bathochromic shift [25]. These groups possess lone pairs of electrons that can conjugate with the chromophore's π-system, extending the conjugation and lowering the HOMO-LUMO gap. For instance, while benzoic acid absorbs at ~230 nm, para-aminobenzoic acid absorbs at 288 nm—a bathochromic shift of 58 nm [25]. - Electron-Withdrawing Groups (EWGs): The effect of EWGs is more complex and depends on their interaction with the chromophore. In some cases, they can also cause a bathochromic shift when conjugated, but their primary effect is often to alter the electron density distribution.

Conversely, structural modifications that reduce conjugation cause hypsochromic shifts. A classic example is ortho-substitution in biphenyls. Unsubstituted biphenyl has a λmax of 250 nm, but introducing a methyl group at the ortho position (2-methylbiphenyl) twists the rings out of planarity due to steric hindrance. This reduces effective conjugation, increases the HOMO-LUMO gap, and causes a hypsochromic shift to 237 nm [27].

Environmental factors are equally critical in applied research:

- Solvent Polarity (Solvatochromism): The polarity of the solvent can stabilize the ground state and excited state of a chromophore to different extents, leading to shifts in λmax [28]. For π→π* transitions, the excited state is often more polar than the ground state. A more polar solvent stabilizes the excited state more effectively, leading to a bathochromic shift (positive solvatochromism) [25]. Conversely, for n→π* transitions, the ground state (with a lone pair) is typically more polar. A polar solvent stabilizes the ground state more, resulting in a hypsochromic shift (negative solvatochromism) [27].

- pH Changes: Protonation or deprotonation of pH-sensitive groups like carboxylic acids or amines can alter the electron-donating or withdrawing nature of a substituent. For example, protonation of an auxochrome like

-NHâ‚‚to form-NH₃âºremoves its ability to donate electrons, which can cause a hypsochromic shift [27].

Table 3: Summary of Substituent and Environmental Effects on Lambda Max

| Factor | Type of Change | Effect on λmax | Molecular Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extended Conjugation | Structural | Bathochromic [24] | Reduced HOMO-LUMO gap from orbital delocalization [26] |

| Auxochrome (e.g., -OH, -NHâ‚‚) | Substituent | Bathochromic [25] | Lone pairs extend conjugation, stabilizing LUMO [25] |

| Steric Hindrance | Structural | Hypsochromic [27] | Reduces planarity, decreasing effective conjugation [27] |

| Solvent Polarity (π→π*) | Environmental | Bathochromic [25] | Polar solvent stabilizes polar excited state more [25] |

| Solvent Polarity (n→π*) | Environmental | Hypsochromic [27] | Polar solvent stabilizes polar ground state more [27] |

| Protonation of Auxochrome | Environmental | Hypsochromic [27] | Converts electron-donating group into electron-withdrawing group [27] |

Experimental Protocols for UV-Vis Analysis

Accurately measuring λmax and observing these shifts requires meticulous experimental technique. The following protocol outlines the standard methodology for obtaining a UV-Vis absorption spectrum.

Core Instrumentation and Workflow

A UV-Vis spectrophotometer consists of several key components: a light source (e.g., deuterium lamp for UV, tungsten/halogen lamp for visible), a monochromator to select specific wavelengths, a sample holder, and a detector (e.g., photomultiplier tube or photodiode array) [12]. The fundamental workflow involves measuring the intensity of light passing through a sample ((I)) and comparing it to the intensity through a reference blank ((I0)) to calculate absorbance ((A = \log(I0/I))) across a range of wavelengths [12]. The relationship between absorbance and concentration is governed by the Beer-Lambert Law ((A = \epsilon c l)), where (\epsilon) is the molar absorptivity, (c) is the concentration, and (l) is the path length [12].

Figure 2: Simplified Workflow of a UV-Vis Spectrophotometer

Step-by-Step Measurement Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the analyte in a suitable solvent that is transparent in the spectral region of interest. Common choices are water, hexane, or methanol. For UV work below ~300 nm, high-purity "UV-cutoff" solvents are essential [12].

- Reference (Blank) Measurement: Fill a high-quality cuvette (e.g., quartz for UV, silica or plastic for visible) with the pure solvent and place it in the sample beam. Run a baseline correction or "zero" measurement to account for solvent and cuvette absorption [12].

- Sample Measurement: Replace the blank with the cuvette containing the analyte solution. Ensure the absorbance is within the instrument's linear range (preferably below 1.5, and ideally below 1.0 for accurate quantitation) [12]. If the absorbance is too high, dilute the sample.

- Data Acquisition: Scan across the desired wavelength range (e.g., 200-800 nm). The instrument will output a plot of absorbance versus wavelength. The peak(s) in this spectrum correspond to λmax values [3].

- Analysis of Shifts: To study the effect of a variable (e.g., solvent, pH), repeat the measurement under the new condition while keeping the analyte concentration constant. Any movement of the λmax is reported as a bathochromic or hypsochromic shift [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Item | Function / Purpose | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Holds liquid sample in the light path. | Required for UV measurements below ~300 nm as quartz is transparent to UV light; glass and plastic cuvettes absorb strongly in the UV [12]. |

| Spectroscopic Grade Solvents | Dissolves the analyte for analysis. | Must have low absorbance in the spectral region of interest. Common choices: water, hexane, acetonitrile, methanol. Check the solvent's UV cutoff wavelength [12]. |

| Deuterium & Tungsten Lamps | Provides broad-spectrum UV and visible light, respectively. | Many instruments use both lamps and switch between them during a scan. Lamp life is finite and intensity decreases with age, requiring periodic replacement [12]. |

| Monochromator (Diffraction Grating) | Selects a specific, narrow band of wavelengths from the broad source to pass through the sample. | Holographic gratings with a groove frequency of ≥1200 grooves per mm provide a good balance of resolution and usable wavelength range [12]. |

| Photomultiplier Tube (PMT) Detector | Converts transmitted light intensity into an electrical signal for measurement. | Highly sensitive for detecting very low light levels, making it suitable for low-absorbance samples or high-resolution applications [12]. |

| Buffer Solutions | Maintains a constant pH for studying pH-sensitive chromophores or biomolecules. | Necessary for experiments investigating hypsochromic/bathochromic shifts induced by protonation/deprotonation [27]. |

| N-BOC-3-Fluoro-D-phenylalanine | N-BOC-3-Fluoro-D-phenylalanine, CAS:114873-11-9, MF:C14H18FNO4, MW:283.29 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| DNP-X acid | DNP-X acid, CAS:10466-72-5, MF:C12H15N3O6, MW:297.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Applications in Research and Development

The principles of spectral shifts are leveraged in advanced research across multiple fields, providing critical data on molecular properties and interactions.

- Nanoparticle Synthesis and Monitoring: UV-Vis spectroscopy is indispensable in nanotechnology. During the synthesis of colloidal silver nanoparticles via silver salt reduction, the formation and growth of nanoparticles are tracked by the appearance and shift of a surface plasmon resonance (SPR) absorption band around 400 nm. As nanoparticles grow, this peak undergoes a bathochromic shift, and stabilization of the peak indicates the reaction's completion [23].

- Sensor Development: Hypsochromic and bathochromic shifts form the basis of many chemical sensors. For instance, a nano-hydrogel colloidal array designed for humidity detection swells with water, changing the particle spacing and size. This change causes a bathochromic shift in its absorption spectrum, which is visible as a color change and can be correlated directly to humidity levels [23].

- Drug Discovery and Biochemistry: In drug development, the interaction of a small molecule with a biological target (like a protein or DNA) can alter the molecule's electronic environment. This interaction often results in a measurable bathochromic or hypsochromic shift, which can be used to determine binding constants and probe the binding mode [23]. Furthermore, monitoring these shifts in real-time using stopped-flow techniques coupled with UV-Vis can elucidate reaction kinetics and mechanisms in complex biological systems [23].

By mastering the interpretation of bathochromic and hypsochromic shifts, scientists can extract a wealth of information from UV-Vis spectroscopy, making it a powerful and versatile tool in modern chemical and pharmaceutical research.

Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is an analytical technique that measures the amount of discrete wavelengths of UV or visible light absorbed by or transmitted through a sample in comparison to a reference or blank sample [12]. This property is influenced by the sample composition, providing information on what is in the sample and at what concentration. The technique relies on the principle that electrons in different bonding environments require different specific amounts of energy to promote to higher energy states, which is why light absorption occurs at different wavelengths for different substances [12].

Within this framework, lambda max (λmax) represents a fundamental parameter in UV-Vis spectroscopy, defined as the wavelength at which a compound exhibits its highest absorbance [15]. This characteristic peak reflects the energy required for specific electronic transitions within molecules and serves as a distinguishing feature for identifying functional groups based on their characteristic absorption behavior [15]. The precise determination of λmax and comprehensive understanding of band shapes provide critical insights for researchers and drug development professionals, enabling compound identification, quantification, and structural analysis essential for pharmaceutical applications [30] [31].

Theoretical Foundations of Electronic Transitions

Molecular Orbitals and Energy Transitions

UV-Vis spectroscopy probes electronic transitions within molecules. When sample molecules are exposed to light with energy matching a possible electronic transition, some light energy is absorbed as electrons are promoted to higher energy orbitals [3]. According to the equation E = hν, the energy of light is inversely proportional to its wavelength, meaning shorter wavelengths carry more energy [5]. Generally, energetically favored electron promotion occurs from the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), producing an excited state species [3].

The energy gap between HOMO and LUMO varies with molecular structure, which explains why different substances absorb light at different wavelengths. For example, in molecular hydrogen (H₂), the energy difference (ΔE) corresponds to an absorption wavelength of 112 nm, deep in the UV region [5]. This principle extends to more complex molecules, where specific structural features dramatically influence absorption characteristics.

Chromophores and Characteristic Absorptions

Chromophores are light-absorbing groups within molecules that contain π-electrons or heteroatoms with non-bonding valence-shell electron pairs [3]. Isolated chromophores typically absorb in the UV region, but conjugation generally moves absorption maxima to longer wavelengths, making conjugation a major structural feature identifiable by this technique [3].

Table 1: Common Chromophores and Their Characteristic Absorption Ranges

| Chromophore/Functional Group | Transition Type | Typical λmax Range (nm) | Molar Absorptivity (ε) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonyl (isolated) | n→π* | 270-300 | 10-100 |

| Carbonyl (conjugated) | n→π* | 300-350 | 100-1000 |

| Double bond (isolated) | π→π* | 160-190 | 1,000-10,000 |

| Double bond (conjugated) | π→π* | 220-280 | 10,000-25,000 |

| Aromatic system | π→π* | 250-280 | 200-5,000 |

| Nitro group | n→π* | 350-400 | 10-50 |

| Nitro group | π→π* | 200-250 | 5,000-10,000 |

The spatial distribution of orbitals significantly affects transition probabilities. For example, the n→π* transition in carbonyl groups has much lower molar absorptivity (ε ≈ 10-100) compared to π→π* transitions (ε ≈ 1,000-10,000) because the n-orbitals do not overlap well with the π* orbital [3]. This difference in transition probability provides valuable structural information when interpreting spectra.

Instrumentation and Measurement Principles

UV-Vis Spectrophotometer Components

A UV-Vis spectrophotometer consists of several key components that work together to measure light absorption across wavelengths [12]:

- Light Source: Provides steady emission across a wide wavelength range. Instruments may use a single xenon lamp for both UV and visible ranges, or separate lamps (deuterium for UV, tungsten or halogen for visible) with a switchover typically occurring between 300-350 nm [12].

- Wavelength Selection: Monochromators containing diffraction gratings (typically 1200 grooves/mm or higher) separate light into narrow bands. Blazed holographic diffraction gratings tend to provide significantly better quality measurements than ruled diffraction gratings [12].

- Sample Analysis: Samples are typically placed in quartz cuvettes for UV examination, as glass and plastic absorb UV light. Proper reference measurements (blank samples) are crucial for obtaining accurate absorbance values [12].

- Detection: Photomultiplier tubes (PMT) or semiconductor-based detectors (photodiodes, CCDs) convert light into electronic signals. PMT detectors are especially useful for detecting very low light levels [12].

Figure 1: UV-Vis instrument workflow showing key components and light path.

Fundamental Quantitative Relationships

The relationship between light absorption and sample properties is governed by the Beer-Lambert Law, expressed as A = ε × c × l, where A is absorbance, ε is molar absorptivity, c is concentration, and l is path length [12] [31]. Absorbance is calculated as A = log(I₀/I), where I₀ is the intensity of incident light and I is the intensity of transmitted light [32].

For accurate quantification, absorbance values should generally be maintained between 0.1 and 1.0, as values outside this range may lead to decreased accuracy due to instrumental limitations [12] [15]. When absorbance exceeds 1.0, samples should be diluted or path length reduced to maintain measurement reliability [12].

Systematic Approach to Spectral Interpretation

Identifying Lambda Max and Absorption Features

The first step in interpreting a UV-Vis spectrum involves locating λmax, the wavelength of maximum absorption, which corresponds to the highest point on absorption peaks [32] [15]. For example, NAD+ exhibits λmax at 260 nm, while the food coloring Red #3 shows λmax at 524 nm in the visible region [32].

Beyond identifying λmax, analysts should characterize several key spectral features:

- Peak Intensity: The height of absorption peaks provides information about transition probability and concentration. Higher intensities typically associate with allowed transitions like π→π, while lower intensities characterize forbidden transitions like n→π [15].

- Band Shape: Sharp, distinct peaks suggest pure samples with discrete transitions, while broad or overlapping peaks may indicate multiple chromophores, molecular aggregation, or solvent interactions [15].

- Number of Peaks: Multiple absorption bands suggest either several distinct chromophores or a single chromophore capable of multiple electronic transitions [15].

Table 2: Diagnostic Interpretation of Spectral Features

| Spectral Feature | Structural Implication | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Single sharp peak | Single dominant chromophore | Purity assessment of pharmaceuticals [31] |

| Broad absorption band | Multiple overlapping transitions or aggregated species | Detection of protein aggregation [30] |

| Multiple distinct peaks | Different chromophores or transition types | Analysis of combination drugs [31] |

| Bathochromic shift (red shift) | Increased conjugation or solvent polarity effects | Confirmation of extended conjugation in dyes [15] |

| Hypsochromic shift (blue shift) | Reduced conjugation or conformational changes | Monitoring molecular encapsulation [30] |

| Hyperchromic effect | Increased transition probability | Assessing DNA denaturation [15] |

| Hypochromic effect | Restricted electronic transitions | Studying drug-DNA interactions [15] |

Analyzing the Impact of Conjugation

Conjugation dramatically affects λmax values by lowering the energy gap between HOMO and LUMO orbitals. As conjugation length increases, λmax shifts to longer wavelengths [5]:

- Ethene: λmax = 174 nm (single π-bond)

- Butadiene: λmax = 217 nm (conjugated diene)

- Hexatriene: λmax = 258 nm (conjugated triene)

This systematic bathochromic shift with increasing conjugation provides valuable structural insights. For example, β-carotene, with its extensive conjugated system, absorbs at 455 nm and appears orange [3]. Similarly, the difference between colorless, short-conjugation compounds and colored, highly conjugated compounds becomes readily apparent through their λmax values [5].

Figure 2: Relationship between conjugation length and spectral properties.

Experimental Protocols for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Single Component Pharmaceutical Assay

The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) describes standardized methods for pharmaceutical assays using UV-Vis spectroscopy [31]. For paracetamol analysis:

Standard Solution Preparation: Prepare a stock solution of reference standard paracetamol (100 mg/L) by dissolving 10 mg in 1 mL methanol and diluting to 100 mL with deionized water. Create a working standard by diluting stock solution 10:100 with deionized water [31].

Test Sample Preparation: Prepare the test sample using the same method as the working standard, ensuring representative sampling of the pharmaceutical formulation [31].

Spectral Measurement: Using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer, scan both standard and test samples between 200-400 nm using deionized water as blank. Measure absorbance at λmax = 243 nm with instrument parameters set to 1 nm spectral bandwidth and normal scanning speed [31].

Calculation: Determine quantity using the formula: Paracetamol in test sample (mg) = Standard weight (mg) × [A(test)/A(standard)] Calculate percent assay as: % Assay = [Paracetamol in test sample (mg)/Test sample weight (mg)] × 100 USP specifications typically require 98.0-101.0% for compliance [31].

Multicomponent Analysis Methodology

For combination drugs containing multiple active ingredients, simultaneous equation methods enable quantification of individual components:

Individual Stock Solutions: Prepare separate stock solutions (100 mg/L) for each component (e.g., paracetamol and aspirin) using 0.1 M HCl as diluent, sonicating for 20 minutes to ensure complete dissolution [31].

Working Standards: Dilute stock solutions to 10 mg/L working standards using 0.1 M HCl [31].

Standard Spectra Collection: Using multicomponent analysis software mode, measure absorbance spectra (200-400 nm) of pure component solutions in 10 mm quartz cuvettes, using 0.1 M HCl as blank [31].

Sample Measurement: Prepare mixture samples with varying component ratios and measure their absorbance spectra under identical conditions [31].

Concentration Calculation: Apply simultaneous equations based on absorbance contributions at characteristic wavelengths: A'(x+y) = ε'xcxl + ε'ycyl A(x+y) = εxcxl + εycyl where A' and A represent absorbances at two different wavelengths, ε represents molar absorptivity, c represents concentration, and l represents path length [31].

Hemoglobin Quantification Methods

In developing hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers (HBOCs), accurate Hb quantification is essential [30]:

Hb Extraction: Wash bovine blood three times with 0.9% NaCl solution (2000×g, 20 min, 4°C). Mix resulting RBC pellet with distilled water and toluene (1:1:0.4 ratio), separate in funnel overnight at 4°C. Collect stroma-free Hb solution from lowest layer, centrifuge (8000×g, 20 min, 4°C), and filter [30].

Quantification Methods: Compare non-specific methods (BCA, Coomassie Blue, A280) with Hb-specific methods (cyanmetHb, SLS-Hb) using serial dilutions of Hb stocks [30].

Method Validation: The SLS-Hb method demonstrates superior specificity, ease of use, cost efficiency, and safety compared to cyanmetHb-based methods, making it preferable for HBOC characterization [30].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for UV-Vis Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz cuvettes | 10 mm path length | Sample holder transparent to UV light [12] |

| Methanol | HPLC grade | Solvent for stock solution preparation [31] |

| Hydrochloric acid | 0.1 M solution | Acidic diluent for aspirin stability [31] |

| Sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) | Reagent grade | Hb-specific chromogen for quantification [30] |

| BCA working reagent | Commercial kit | Protein quantification via copper reduction [30] |

| Coomassie Plus reagent | Commercial kit | Protein binding dye for Bradford assay [30] |

| Potassium cyanide | Reagent grade | Conversion to cyanmetHb for specific detection [30] |

Advanced Interpretation and Troubleshooting

Spectral Shifts and Their Interpretation

Spectral shifts provide valuable information about molecular environment and structural changes:

- Bathochromic Shift (Red Shift): Movement to longer wavelengths caused by increased conjugation, solvent polarity effects, or auxochrome presence. For example, extending conjugation in polyenes progressively shifts λmax to longer wavelengths [5] [15].

- Hypsochromic Shift (Blue Shift): Movement to shorter wavelengths typically indicating reduced conjugation, changes in molecular conformation, or solvent effects [15].

- Hyperchromic Effect: Increased absorption intensity often resulting from conformational changes that enhance transition probabilities [15].

- Hypochromic Effect: Decreased absorption intensity suggesting aggregation or interactions that restrict electronic transitions [15].

Common Experimental Artifacts and Solutions

Several factors can compromise spectral quality and interpretation accuracy:

- Solvent Selection Errors: Solvents that absorb in the same wavelength range as the sample (e.g., acetone below 330 nm) can obscure sample absorption. Solvent polarity can induce solvatochromic shifts, while hydrogen-bonding solvents may interact with chromophores [15].

- Sample Preparation Issues: Improper dilution, weighing errors, or incomplete dissolution can cause inaccurate absorbance readings. Particulate matter or bubbles can scatter light, particularly at shorter wavelengths [15].

- Instrumental Factors: Stray light from imperfect monochromators may reduce absorbance accuracy at high concentrations. Bandwidth effects can cause peak broadening and reduced resolution [15].

- Cuvette Problems: Scratched or dirty cuvettes scatter light, increasing apparent absorbance. Mismatched cuvettes between sample and reference introduce systematic errors [15].