Life Cycle Assessment for Analytical Methods: A Strategic Framework for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to applying Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to analytical methods used in pharmaceutical research and drug development.

Life Cycle Assessment for Analytical Methods: A Strategic Framework for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to applying Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to analytical methods used in pharmaceutical research and drug development. Tailored for scientists, researchers, and development professionals, it bridges the gap between traditional LCA practices and the specific needs of analytical laboratories. The content covers foundational LCA principles, detailed methodological steps for application, strategies to overcome common implementation challenges, and approaches for validating and comparing environmental footprints. By adopting this framework, professionals can make informed decisions to reduce the environmental impact of their research while maintaining scientific rigor and compliance with emerging industry standards.

LCA Foundations: Integrating Environmental Impact Assessment into Analytical Science

Defining Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for Analytical Methods

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a systematic, scientific method for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product's life cycle, from raw material extraction to disposal, use, or recycling [1]. Recognized worldwide by the ISO 14040 and 14044 series of the International Organization for Standardization, this methodology provides a comprehensive framework for quantifying environmental footprints, enabling researchers and drug development professionals to make informed, data-driven sustainability decisions [1] [2]. By considering every phase of a product's existence, LCA moves beyond single-metric analyses to offer a multi-criteria perspective on environmental performance, helping to identify improvement opportunities, optimize processes, and avoid problem-shifting between different life cycle stages or environmental impact categories [1] [3].

Within the context of analytical methods and pharmaceutical development, LCA serves as a crucial tool for assessing the sustainability of research reagents, laboratory protocols, and manufacturing processes. The pharmaceutical industry faces increasing pressure to reduce its environmental footprint while maintaining high standards of product quality and efficacy. LCA provides the rigorous methodological foundation needed to evaluate analytical methods objectively, comparing alternatives based on their full life cycle impacts rather than narrow functional characteristics [4]. This holistic approach is particularly valuable for identifying sustainability hotspots in complex supply chains and for guiding the development of greener analytical techniques that minimize resource consumption and environmental emissions without compromising analytical performance [1].

Methodological Framework of LCA

The conduct of a Life Cycle Assessment follows a standardized framework established by international ISO standards 14040 and 14044, which ensures consistency, credibility, and transparency across studies [1] [2]. This framework structures the assessment into four distinct but interdependent phases that guide practitioners from initial goal-setting through final interpretation. Understanding this methodological structure is essential for researchers applying LCA to analytical methods, as it provides the rigor necessary for generating comparable and reliable results.

The Four Phases of LCA

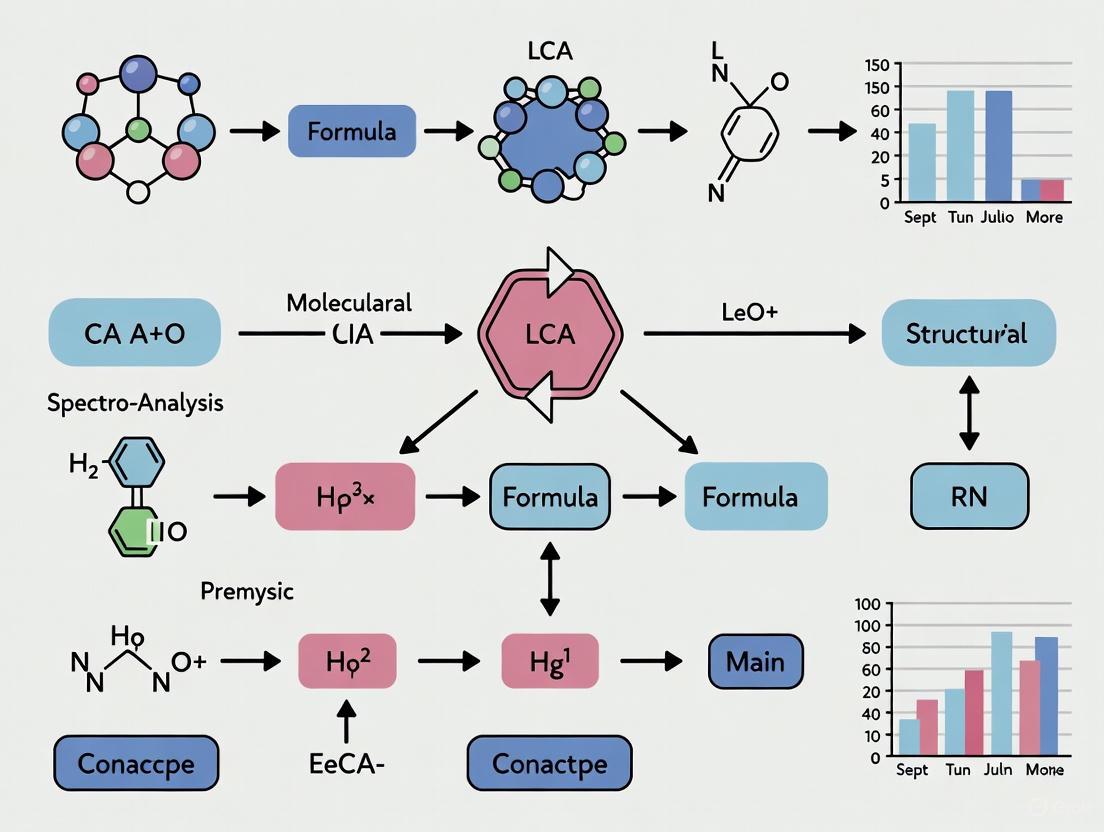

The LCA methodology is built around four standardized stages as defined by ISO 14040 and 14044: (1) Goal and Scope Definition; (2) Inventory Analysis; (3) Impact Assessment; and (4) Interpretation [1] [2] [3]. Each stage serves a specific purpose in the comprehensive assessment process, contributing to a complete understanding of the environmental aspects of the product or process under investigation. The relationship between these phases is iterative rather than purely sequential, with insights from later stages often informing refinements to earlier assumptions and boundaries [3]. The following diagram illustrates the interconnected nature of these four phases:

Goal and Scope Definition

The first phase establishes the fundamental purpose, boundaries, and depth of the LCA study [2]. Researchers must clearly define the objectives of the assessment, specifying the product or analytical method under investigation, the intended application of the results, and the target audience [3]. A critical element of this phase is defining the functional unit, which provides a standardized quantitative reference to which all inputs and outputs are normalized, enabling fair comparisons between alternative products or systems [4] [5]. The scope definition establishes the system boundaries, determining which life cycle stages and processes will be included in the assessment, which impact categories will be considered, and any specific assumptions or limitations that apply to the study [2] [3]. For analytical methods, this might involve deciding whether to include the production of laboratory equipment, the generation of ultra-pure water, or the disposal of hazardous waste streams within the system boundaries.

Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Analysis

The Life Cycle Inventory phase involves the systematic compilation and quantification of all relevant inputs and outputs throughout the product's life cycle [2] [4]. Inputs may include resources, energy, and materials, while outputs encompass products, co-products, and emissions to air, water, and soil [1]. This data-intensive stage requires careful collection of information from various sources, including direct measurement, industry reports, scientific literature, and specialized LCA databases [2]. For pharmaceutical analytical methods, this might involve tracking the quantities of solvents, reagents, and consumables used; energy consumption of analytical instruments; transportation of materials; and waste generation from laboratory activities. The quality of the LCI data directly influences the reliability of the overall assessment, making transparency in data sources, collection methods, and calculation procedures essential for credible results [2].

Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

The Life Cycle Impact Assessment phase translates the inventory data into potential environmental impacts using scientifically established models [2] [3]. During this stage, researchers select appropriate impact categories (such as climate change, resource depletion, human toxicity, or ecotoxicity) and apply characterization factors to convert inventory flows into representative impact indicators [2] [6]. For example, greenhouse gas emissions might be aggregated into global warming potential expressed as COâ‚‚-equivalents [2]. The LCIA phase provides the essential link between the extensive inventory data and the environmentally relevant interpretation of that data, helping to identify which processes contribute most significantly to different types of environmental impacts [3]. This phase is particularly important for analytical methods, where trade-offs between different impact categories (e.g., reducing organic solvent use might increase energy consumption) must be objectively evaluated.

Interpretation

The interpretation phase involves analyzing the results from both the inventory and impact assessment to draw meaningful conclusions, identify limitations, and make recommendations [2] [4]. Researchers evaluate the significance of the findings through techniques such as contribution analysis (identifying hotspots), uncertainty analysis (assessing data reliability), and sensitivity analysis (testing how results change with different assumptions) [2]. This phase should deliver actionable insights that address the goals defined at the outset of the study, whether for improving the environmental performance of an analytical method, comparing alternative techniques, or informing strategic decisions in pharmaceutical development [3]. The interpretation must be transparent about the study's limitations and the influence of methodological choices on the results to provide a balanced understanding of the conclusions [2].

Comparative Analysis of LCA Approaches

The application of LCA to analytical methods requires selecting an appropriate modeling approach that aligns with the study's goals and context. Different LCA approaches offer distinct frameworks for defining system boundaries, handling multi-functionality, and modeling market interactions. The choice between these approaches significantly influences the study outcomes and interpretations, making it essential for researchers to understand their comparative strengths and applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Major LCA Approaches for Analytical Methods

| Approach | Definition | Best Use Cases | Key Advantages | Important Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attributional LCA | Models the direct environmental flows attributed to a product's life cycle [5] | Environmental product declarations, carbon footprint accounting, hotspot analysis | Provides a static snapshot of a system; intuitive inventory compilation; well-established methods | May not capture market-mediated consequences; limited suitability for strategic planning |

| Consequential LCA | Models how environmental flows change in response to decisions, including market mechanisms [5] | Evaluating system expansion, policy changes, large-scale technology adoption | Addresses actual consequences of decisions; models market interactions; suitable for future-oriented assessments | Higher complexity; increased data requirements; greater uncertainty in market modeling |

| Prospective LCA | Assesses emerging technologies or systems with future-oriented modeling and scenarios [7] | Evaluating developing analytical methods, clean energy technologies, novel pharmaceutical processes | Informs early-stage R&D; incorporates technological learning; models future background systems | High uncertainty; requires scenario development; complex integration of temporal considerations |

| Dynamic LCA | Incorporates temporal aspects of emissions and background systems into inventory and impact assessment [8] | Technologies with long life cycles, time-sensitive impacts (e.g., climate change), evolving electricity grids | More realistic temporal representation; improved accuracy for timing-sensitive impact categories | Methodological complexity; limited database support; computationally intensive |

For pharmaceutical analytical methods, the choice between these approaches depends largely on the decision context. Attributional LCA is typically sufficient for comparing the footprint of established analytical techniques or generating environmental product declarations for laboratory materials [5]. Conversely, consequential or prospective approaches may be more appropriate when evaluating the introduction of novel analytical technologies that might displace existing methods or when assessing how the environmental profile of a method might evolve with changes in the energy grid or reagent supply chains [7]. Dynamic LCA offers the potential for more realistic assessments of analytical methods with significant temporal variations in their impacts, such as those using refrigerants with time-dependent global warming effects or methods employed in regions with rapidly decarbonizing electricity grids [8].

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Case Study: LCA of Sustainable Cementitious Composites

While direct LCAs of pharmaceutical analytical methods are not extensively represented in the retrieved search results, a relevant case study from materials science illustrates the experimental protocol for conducting a comprehensive LCA. This study on sustainable ultra-high strength engineered cementitious composites (UHS-ECC) demonstrates the rigorous methodology required for comparative life cycle assessment of alternative material formulations [6].

Experimental Methodology

The research employed a two-phase methodology, beginning with experimental development of sustainable UHS-ECC incorporating recycled concrete powder (RCP) as partial cement replacement and waste tire steel fiber (WTSF) as reinforcement [6]. Various mix proportions were systematically tested, with RCP replacement levels ranging from 5% to 20% of cement content and hybrid fiber systems combining WTSF and polyethylene fibers at different volume fractions (0.5% to 2%) [6]. The mixing protocol involved: (a) dry mixing of cement, fly ash, silica fume, and sand for 2-3 minutes; (b) addition of water and superplasticizer with mixing for 10-12 minutes; and (c) gradual incorporation of fibers with additional mixing for 5-6 minutes to ensure uniform dispersion [6]. Workability was evaluated using mini-slump spread tests according to ASTM C1437, followed by curing at 85°C for 9 days to stimulate pozzolanic activity and early hydration reactions [6].

In the second phase, a comprehensive LCA was performed using OpenLCA software and the Ecoinvent database to analyze the environmental impacts of UHS-ECC production [6]. The assessment employed a cradle-to-gate system boundary encompassing raw material extraction, transportation, and manufacturing. Eighteen major components were evaluated, with focus on key impact categories including climate change potential (GWPâ‚‚â‚€), fossil resource depletion, human toxicity, and particulate matter formation [6]. The functional unit was defined as one cubic meter of composite material, enabling direct comparison between conventional and alternative formulations.

Comparative LCA Data and Results

The experimental results demonstrated that UHS-ECC achieved a maximum compressive strength of 129 MPa at 5% RCP replacement, with gradual decline at higher substitution rates [6]. The LCA results revealed significant environmental advantages for the sustainable formulations, as summarized in the following table:

Table 2: Comparative LCA Results for Sustainable vs. Conventional Cementitious Composites [6]

| Impact Category | Conventional ECC | RCP-Modified ECC (5% replacement) | Reduction | RCP-Modified ECC (20% replacement) | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate Change Potential (GWPâ‚‚â‚€) | Baseline | 16% lower | 16% | 12% lower | 12% |

| Fossil Resource Depletion | Baseline | 19% lower | 19% | 15% lower | 15% |

| Human Toxicity | Baseline | 14% lower | 14% | 10% lower | 10% |

| Particulate Matter Formation | Baseline | 13% lower | 13% | 9% lower | 9% |

The findings demonstrated that incorporating waste materials (RCP and WTSF) significantly reduced environmental impacts across multiple categories, with optimal performance observed at moderate replacement levels [6]. This case study provides a methodological template for pharmaceutical researchers conducting similar comparative assessments of analytical methods, where alternative reagents, solvents, or protocols might be evaluated for their environmental performance alongside traditional approaches.

Application to Pharmaceutical Analytical Methods

The experimental protocol from the cementitious composites case study can be adapted for pharmaceutical analytical methods by modifying the system boundaries and impact categories to reflect laboratory-specific concerns. For HPLC method comparison, for instance, the assessment would quantify the environmental footprint of mobile phase preparation (including solvent production, purification, and transportation), instrument manufacturing and operation energy consumption, column packing materials, waste disposal processes, and any specialized detection reagents. The functional unit would be defined according to the analytical service provided, such as "per sample analyzed" or "per unit of analytical information generated," enabling fair comparison between methods with different throughput, sensitivity, or operational requirements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The implementation of LCA for analytical methods requires both conceptual understanding and practical tools for data collection and analysis. The following table outlines key resources and software solutions that support the conduct of rigorous life cycle assessments in pharmaceutical and analytical research contexts.

Table 3: Essential LCA Research Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OpenLCA | Software | Comprehensive LCA modeling [6] | Academic research, sustainable product development | Open-source; extensive database integration; scenario comparison [2] |

| Ecoinvent Database | Database | Background life cycle inventory data [6] | Inventory development for common materials and energy | Comprehensive coverage; standardized datasets; regular updates [6] |

| SimaPro | Software | Robust analytics and impact assessment [2] | Environmental product declarations, detailed impact studies | Extensive database; standardized reporting templates; ISO compliance [2] |

| GaBi Software | Software | Complex supply chain evaluation [2] | Corporate sustainability reporting, supply chain optimization | Precise carbon footprint analysis; automated reporting; scenario modeling [2] |

| ISO 14040/14044 | Standard | Methodological framework for LCA [1] [2] | Ensuring credibility and compliance in all LCA studies | Defines principles and framework; specifies reporting requirements [2] |

| Levoglucosan-d7 | Levoglucosan-d7, MF:C6H10O5, MW:169.18 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | |

| 7'-Hydroxy ABA-d7 | 7'-Hydroxy ABA-d7, MF:C15H20O5, MW:287.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

For researchers implementing LCA of analytical methods, OpenLCA offers an accessible entry point due to its open-source nature and capability to integrate with specialized databases [2] [6]. The Ecoinvent database provides critical background data for common laboratory inputs such as solvents, chemicals, and energy sources [6]. Commercial solutions like SimaPro and GaBi may be preferable in industrial settings requiring standardized reporting and compliance with specific regulatory frameworks [2]. Regardless of the software selection, adherence to ISO 14040/14044 standards remains essential for maintaining methodological rigor and ensuring the credibility of assessment results [1] [2].

Life Cycle Assessment provides an essential methodological framework for quantitatively evaluating the environmental dimensions of analytical methods in pharmaceutical research and development. The standardized four-phase structure of LCA—encompassing goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, impact assessment, and interpretation—offers a systematic approach to identifying environmental hotspots, comparing alternative methodologies, and guiding the development of more sustainable analytical practices [1] [2] [3]. As the field evolves, emerging approaches including prospective, consequential, and dynamic LCA are expanding the methodological toolbox available to researchers addressing increasingly complex sustainability challenges [7] [8].

For the pharmaceutical and analytical science communities, the adoption of LCA represents an opportunity to extend traditional metrics of analytical performance (sensitivity, selectivity, throughput) to include environmental considerations. This holistic perspective aligns with growing regulatory and societal expectations for sustainable research practices while offering the potential for identifying efficiency improvements and cost savings through reduced resource consumption and waste generation [1] [3]. As databases and assessment methods continue to develop, LCA is poised to become an increasingly integral component of analytical methods development, validation, and comparison—providing the evidentiary basis for truly sustainable pharmaceutical research and manufacturing.

Core Principles and the ISO 14040/14044 Framework

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a systematic, scientific method for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with a product, process, or service throughout its entire life cycle [1] [3]. Recognized as the gold standard for environmental impact assessment, LCA provides a comprehensive framework that moves beyond singular metrics to offer a holistic view of environmental footprints [1]. The core principles of LCA are established in the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards 14040 and 14044, which provide the foundational framework and detailed requirements for conducting credible and consistent LCA studies [9] [10].

The fundamental principle of LCA is its cradle-to-grave perspective, which mandates the consideration of all life cycle stages: raw material extraction, manufacturing and processing, transportation, usage, and end-of-life treatment [3] [10]. This comprehensive scope prevents problem-shifting, where reducing an impact in one area inadvertently increases it in another or transfers it to a different environmental medium [3]. LCA is also characterized by its quantitative and data-driven nature, relying on rigorous inventory data and scientifically validated impact assessment methods to convert resource flows and emissions into potential environmental effects [1] [11].

Furthermore, LCA is a relative approach, meaning environmental impacts are calculated in relation to a defined functional unit. This functional unit quantifies the performance of the product system being studied, ensuring comparisons are made on a common basis [10]. For instance, an LCA comparing packaging materials would define the functional unit as "the packaging required to contain 1 liter of a beverage," rather than simply comparing one kilogram of each material [12]. This principle of functionality is crucial for delivering fair and meaningful results.

The ISO 14040/14044 Framework: A Detailed Breakdown

The ISO 14040 and 14044 standards form the internationally accepted backbone of LCA methodology. ISO 14040:2006 provides the overarching principles and framework for LCA, while ISO 14044:2006 specifies the detailed requirements and guidelines [9] [12]. These standards organize the LCA process into four interdependent phases, ensuring studies are comprehensive, consistent, and transparent. The framework is iterative, with insights from later phases often informing and refining earlier steps [12] [3].

Phase 1: Goal and Scope Definition

The initial and arguably most critical phase involves defining the goal and scope of the LCA study. This stage sets the foundation for all subsequent work and determines the study's overall direction and credibility [12] [10].

The goal must unambiguously state the intended application, the reasons for carrying out the study, the intended audience, and whether the results are intended for comparative assertion and disclosure to the public [3]. The scope defines the breadth and depth of the study by specifying:

- Functional Unit: A quantified description of the system's function, as previously discussed, which serves as the reference basis for all calculations [10].

- System Boundaries: A clear specification of which unit processes are included in the assessment. Common boundaries include:

- Cradle-to-Gate: Includes activities from raw material extraction (cradle) up to the factory gate.

- Cradle-to-Grave: Encompasses the entire life cycle from raw material extraction through production, use, and final disposal (grave) [3] [13].

- Cradle-to-Cradle: A circular approach where the end-of-life phase is a recycling process, and materials are reused in new products [3].

- Impact Categories: The environmental issues selected for investigation, such as global warming potential, water use, eutrophication, or acidification [14] [10].

- Data Quality Requirements: Specifications for the data needed regarding time, geography, and technology [9].

Failure to precisely define these elements can lead to studies that are inconsistent, incomparable, and unreliable, as highlighted by harmonization issues in building LCA datasets [15].

Phase 2: Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Analysis

The Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) analysis is the data collection and calculation phase aimed at quantifying the relevant inputs (e.g., energy, raw materials) and outputs (e.g., emissions, waste) associated with the product system throughout its life cycle [12] [3]. This phase is often the most complex and resource-intensive, requiring the compilation of a detailed inventory of all flows within the system boundaries [1].

Data collection can involve:

- Measured data: Directly from processes, such as from utility meters or production records.

- Secondary data: From commercial life cycle inventory databases (e.g., ecoinvent, GaBi) or from Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) [11] [10].

- Modeled or estimated data: Used when specific data is unavailable, though with associated uncertainty [11].

A key challenge in this phase is ensuring data quality, as the reliability of the entire LCA hinges on the accuracy and representativeness of the inventory data. Data gaps, insufficient data from supply chains, and high costs of data collection are common hurdles [11] [16]. The final output of the LCI is a comprehensive list of all inputs from the environment and outputs to the environment, normalized per the defined functional unit.

Phase 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

The Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) phase translates the inventory data into potential environmental impacts. It provides a more accessible and evaluative understanding of the LCI results [12] [10]. The ISO standards define mandatory and optional elements of the LCIA.

The mandatory elements include:

- Selection of Impact Categories: Such as global warming potential, ozone depletion, and human toxicity [15].

- Classification: Assigning LCI results to the chosen impact categories (e.g., assigning carbon dioxide and methane emissions to the global warming category).

- Characterization: Modeling the LCI flows within each category and converting them into a common unit (e.g., converting all greenhouse gases into COâ‚‚-equivalents) using characterization factors [3].

Optional elements, which add depth to the interpretation, include:

- Normalization: Expressing results relative to a reference value, such as total emissions for a region, to understand the relative magnitude of each impact.

- Grouping: Sorting or ranking impact categories.

- Weighting: Emphasizing the most critical impact categories based on value choices (this is a sensitive step as it introduces subjectivity) [12].

The LCIA results provide a profile of the product system's potential contributions to different environmental problems, which is crucial for identifying environmental "hotspots" [3].

Phase 4: Interpretation

Interpretation is the phase where findings from the inventory analysis and the impact assessment are combined to reach conclusions and provide recommendations in accordance with the defined goal and scope [10]. This phase involves three key activities:

- Identification of Significant Issues: Determining which life cycle stages, processes, or impact categories contribute most to the overall results [3].

- Evaluation: Assessing the study for completeness, sensitivity, and consistency. This includes checking that all relevant data has been included, testing how sensitive the results are to key assumptions, and ensuring that methods are applied consistently [9] [12].

- Conclusions, Limitations, and Recommendations: Formulating reasoned conclusions, explaining the limitations of the study, and providing actionable recommendations for decision-makers [10].

The interpretation phase is not merely a final step; it is an iterative activity that should occur throughout the LCA process to ensure the study remains on track and robust [12].

Figure 1: The iterative four-phase structure of an LCA study according to ISO 14040 and 14044. The interpretation phase provides critical feedback to all other phases.

Comparative Analysis of LCA Guidelines and Frameworks

While ISO 14040 and 14044 are the primary international standards, numerous other guidelines and frameworks have emerged to address specific methodological gaps or sectoral needs. A comparative analysis reveals both alignment and divergence, which can significantly impact the reliability and comparability of LCA studies [14].

Key Methodological Differences Across Frameworks

A comparative analysis of six LCA guidelines and frameworks applicable to the plastic packaging industry highlighted significant methodological variations. These differences span critical aspects of the LCA process, as detailed in Table 1 [14].

Table 1: Comparison of Methodological Aspects Across LCA Guidelines

| Methodological Aspect | ISO 14040/14044 (Baseline) | Other Guidelines (e.g., PEF, Packaging-specific PCRs) | Potential Impact on Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Boundaries | Defines principles for setting boundaries but allows flexibility. | May prescribe specific, fixed boundaries (e.g., mandatory inclusion of packaging or capital equipment). | Affects which processes are included, directly altering the total calculated impact [14]. |

| Allocation Methods | Prefers avoiding allocation by process subdivision; where unavoidable, provides general guidance. | May mandate specific allocation procedures (e.g., for recycling and reused materials). | Different allocation rules for multi-output or EOL processes can drastically change the results assigned to a product [14]. |

| Cut-off Criteria | Does not specify a universal cut-off rule. | Often define specific material or energy cut-off criteria (e.g., mass, energy, environmental significance). | Can lead to the exclusion of non-obvious but environmentally significant flows, affecting completeness [14]. |

| Impact Categories | Does not prescribe a mandatory set of categories. | Often require a specific, pre-defined set of impact categories and characterization models (e.g., in PEF). | Makes studies more comparable but may overlook impact categories relevant to specific products [14]. |

| Data Quality & Requirements | Specifies general requirements for data quality (e.g., time, geography, technology). | May impose stricter, standardized data quality requirements and specific background database usage. | Influences the representativeness and uncertainty of the study; stricter rules enhance consistency [14]. |

Implications for Research and Industry

The misalignments between different LCA guidelines create significant challenges for multinational companies and researchers. Companies operating in different markets may need to conduct multiple LCAs for the same product to conform to varying regional or client-specific requirements, leading to increased costs and potential confusion [14]. For the research community, these inconsistencies hinder the comparability of LCA results and the creation of harmonized datasets, as seen in efforts to compile building LCA data where non-harmonized methods limit data usability [15].

Essential Research Toolkit for LCA Practitioners

Conducting a robust LCA requires a combination of standardized methodologies, reliable data sources, and specialized software tools. The following toolkit outlines the essential resources for researchers and professionals in the field.

Core Methodological Standards and Supporting Documents

Table 2: Foundational and Supporting Standards for LCA

| Standard / Document | Function and Purpose |

|---|---|

| ISO 14040:2006 | Provides the overarching principles and framework for LCA studies [9] [10]. |

| ISO 14044:2006 | Specifies detailed requirements and guidelines for all LCA phases, including critical review [9] [12]. |

| ISO 14025 | Defines the principles and procedures for developing Type III environmental declarations (EPDs), which are based on LCA [12] [10]. |

| ISO/TR 14047 | Provides examples illustrating the application of ISO 14044 for life cycle impact assessment [12]. |

| ISO/TS 14048 | Specifies the format for documenting LCA data, ensuring clear and consistent data reporting [12]. |

| Ethambutol-d4 | Ethambutol-d4, MF:C10H24N2O2, MW:208.33 g/mol |

| Milbemycin A3 Oxime | Milbemycin A3 Oxime, MF:C31H43NO7, MW:541.7 g/mol |

Specialized LCA software is indispensable for managing the complexity of data and calculations. These platforms guide users through the LCA workflow, provide access to life cycle inventory databases, and automate impact calculations [11].

Table 3: Key Resources for LCA Modeling and Data

| Tool Category | Function and Purpose |

|---|---|

| LCA Software (e.g., EandoX) | Comprehensive platforms that support the entire LCA workflow, from data collection and modeling to impact assessment and reporting. They help ensure consistency, save time, and support standards compliance (ISO 14040, ISO 14044) [11]. |

| Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Databases (e.g., ecoinvent, GaBi) | Repositories of background data on materials, energy, and processes. They provide the foundational data for building product system models and are often integrated into LCA software [11]. |

| Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) | Standardized reports of a product's environmental performance based on LCA. EPDs are a valuable source of verified, third-party data for specific products, especially in business-to-business contexts [3] [10]. |

The ISO 14040 and 14044 framework provides an indispensable, rigorous foundation for conducting credible and consistent Life Cycle Assessments. Its structured, four-phase approach ensures a comprehensive and scientifically sound evaluation of environmental impacts from a cradle-to-grave perspective. For researchers and professionals, mastery of this framework is not merely an academic exercise but a prerequisite for generating reliable data that can inform sustainable design, strategic policy, and transparent environmental claims.

However, the existence of multiple, sometimes conflicting, sector-specific guidelines presents a significant challenge to the comparability and harmonization of LCA results. This landscape underscores the critical importance of transparently reporting the goal, scope, and all methodological choices within any LCA study. As the field evolves, the core principles enshrined in ISO 14040 and 14044 will continue to serve as the essential anchor, ensuring that despite methodological diversity, all LCAs are built upon a common foundation of scientific integrity and robustness.

The Critical Role of LCA in Sustainable Pharmaceutical Development

In the pharmaceutical industry, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has emerged as a critical methodology for quantifying the environmental footprint of drug development and manufacturing. As regulators, payers, and patients increasingly demand environmental transparency, LCA provides a standardized, science-based approach to assess impacts from raw material extraction to manufacturing, distribution, use, and end-of-life [17]. The pharmaceutical industry faces unique challenges in implementing LCA, including complex global supply chains, confidentiality issues, and the lack of sector-specific standards until recently [18] [19]. This guide explores the current state of pharmaceutical LCA, comparing methodological approaches, experimental data, and emerging standards that are shaping sustainable drug development.

Current Landscape and Research Gaps in Pharmaceutical LCA

The Standardization Challenge

A significant challenge in pharmaceutical LCA has been the lack of industry-specific standards. The ISO 14040-44 standards provide comprehensive, industry-neutral guidance but allow considerable discretion in methodological choices, leading to potentially varying environmental footprints for the same product [17] [18]. This inconsistency is particularly problematic when nearly 80% of a pharmaceutical product's carbon footprint often comes from purchased raw materials rather than direct manufacturing activities [18].

To address this gap, a consortium of eleven major pharmaceutical companies joined forces with the British Standards Institution (BSI) and the UK National Health Service (NHS) to develop PAS 2090:2025, the first publicly available specification for pharmaceutical LCAs [20] [17]. This standard aims to establish consistent Product Category Rules (PCR) to enable robust, comparable product LCAs across the sector.

Research Gaps Across Therapeutic Areas

Current LCA research in pharmaceuticals reveals significant disparities in coverage across therapeutic areas. A 2025 review of 51 LCA studies identified 59 different drugs, with clear concentrations in specific categories [19]:

Table: Distribution of LCA Studies Across Pharmaceutical Categories

| Therapeutic Category | Number of Drugs Studied | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Central Nervous System | 31 | Anesthetics (sevoflurane, desflurane, propofol) |

| Infectious Diseases | 12 | Various antibiotics |

| Respiratory | 8 | Inhalers (pMDIs, DPIs) |

| Endocrine & Metabolic | 4 | Not specified |

| Cardiovascular | 2 | Not specified |

| Oncology | 1 | Not specified |

| Genitourinary | 0 | CKD medications missing |

This distribution contrasts sharply with actual market patterns. For instance, oncology drugs accounted for ¥2,279 billion in 2024 sales in Japan (a 43.1% increase over 5 years), yet have minimal LCA coverage [19]. Similarly, cardiovascular (¥1,242 billion) and endocrine/metabolic (¥1,340 billion) drugs represent substantial markets with limited LCA research. Most notably, no LCA studies exist for drugs used in chronic kidney disease (CKD), despite global warming being a known risk factor for CKD progression and approximately one-third to one-half of the carbon footprint in dialysis therapy deriving from pharmaceuticals [19].

LCA Software and Tools: A Comparative Analysis

Specialized vs. General LCA Software

Pharmaceutical LCA requires specialized tools that can handle complex supply chains and specific manufacturing processes. While general LCA software exists, the industry is developing tailored solutions:

Table: Comparison of LCA Software Capabilities Relevant to Pharma

| Software Tool | Expertise Required | Key Pharma-Relevant Features | Limitations for Pharma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Tools (SimaPro, Sphera GaBi) | High (LCA specialists) | Robust modeling, custom scenarios, regulatory compliance | Steep learning curve, high cost |

| OpenLCA | High (technical users) | Open-source, extensible, multiple database support | Setup intensive, requires expertise |

| Sector-Specific Platforms | Medium to Low | Automated data collection, supplier engagement, scenario modeling | Early development stage for pharma |

| Pharma LCA Consortium Tool | Low (non-experts) | Purpose-built for pharma, standardized PCR implementation | Not yet fully available |

Emerging Pharma-Specific Solutions

The Pharma LCA Consortium is developing a tool to support the implementation of Product Category Rules across the sector for use by non-LCA experts [20]. This initiative aims to make LCA methodology freely accessible to all pharmaceutical companies and stakeholders, addressing the critical barrier of technical expertise that has limited widespread LCA adoption in pharma.

Experimental Data and Case Studies in Pharmaceutical LCA

LCA Protocol for Pharmaceutical Assessment

Conducting a robust LCA in the pharmaceutical sector requires strict adherence to standardized protocols while accounting for industry-specific complexities:

Table: Key Components of Pharmaceutical LCA Methodology

| LCA Phase | Pharma-Specific Considerations | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Goal and Scope Definition | Defining functional units (e.g., per dose, per treatment course), system boundaries (cradle-to-gate vs. cradle-to-grave) | PAS 2090 guidance, stakeholder requirements |

| Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) | Solvent use, energy-intensive processes, cleaning validation, waste management, supply chain complexity | Supplier data, manufacturing records, Ecoinvent database |

| Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) | Multiple impact categories (global warming, human toxicity, water use), normalization, weighting | ReCiPe, EF 3.1, TRACI methods |

| Interpretation | Hotspot identification, scenario analysis, improvement strategies | Comparative analysis, sensitivity testing |

Representative Experimental Findings

Case studies from industry leaders demonstrate consistent patterns in pharmaceutical LCA results:

GSK's Cradle-to-Gate LCA of Small Molecule API

- Solvent use accounted for up to 75% of energy use and 50% of greenhouse gas emissions [17]

- Key finding: Solvent recovery offered substantially better environmental performance than incineration

- Methodology: Development of modular LCA approach and chemical tree database covering 125 materials

Janssen's LCA of Biologic API (Infliximab)

- Culture media, especially animal-derived materials (ADMs), were the largest environmental impact drivers [17]

- Process insight: Switching to animal-free media (as with ustekinumab) reduced resource consumption by up to 7.5 times

- Facility impact: HVAC systems accounted for 75-80% of electricity use in the manufacturing plant

Inhalers: pMDIs vs. DPIs

- Substantially larger carbon footprint for pressurized metered-dose inhalers (pMDIs) compared to dry powder inhalers (DPIs) [19]

- Impact reduction strategy: Switching from pMDIs to alternative inhaler types

Anesthetics: Intravenous vs. Gaseous

- Environmental impact of intravenous anesthetics like propofol is four orders of magnitude lower than nitrous oxide [19]

- Clinical implication: Consideration of CFP can inform clinical choice where medically equivalent options exist

Diagram Title: Pharmaceutical LCA Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmaceutical LCA

Implementing effective LCA in pharmaceutical research requires specific methodological tools and data resources:

Table: Essential Research Toolkit for Pharmaceutical LCA

| Tool/Resource | Function in Pharma LCA | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| PAS 2090:2025 Standard | Provides product category rules specific to pharmaceuticals | Ensuring consistent methodology for comparing drug products |

| Chemical Tree Databases | Maps environmental impacts of chemical precursors | GSK's database covering 125 materials for API footprint calculation |

| Supplier Engagement Tools | Collect primary environmental data from supply chain | Carbon Maps' platform for supplier sustainability assessments |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) Metrics | Measures resource efficiency of manufacturing processes | Identifying high-impact synthesis steps for optimization |

| Life Cycle Inventory Databases | Provides background data for common materials and processes | Ecoinvent, Agri-footprint for upstream impact calculations |

| Scenario Modeling Tools | Tests environmental impact of process changes | Evaluating solvent substitution or energy efficiency improvements |

The pharmaceutical industry stands at a critical juncture in its sustainability journey. With the upcoming PAS 2090 standard and growing stakeholder pressure for environmental transparency, LCA is poised to become an integral part of drug development and manufacturing decisions. The current research gaps, particularly in high-volume therapeutic areas like oncology, cardiovascular, and kidney disease, represent both a challenge and opportunity for researchers and drug development professionals [19]. As standardized methodologies become established and tools become more accessible, LCA will increasingly inform supplier selection, process optimization, and even clinical choices where environmentally preferable alternatives exist with equivalent efficacy. The critical role of LCA lies in its ability to make visible the hidden environmental costs of pharmaceuticals, enabling evidence-based progress toward more sustainable healthcare systems.

Diagram Title: Pharmaceutical LCA Implementation Pathway

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has evolved from a niche environmental tool into a critical framework for strategic decision-making, particularly in research-intensive fields like pharmaceuticals and medical device development. For professionals driving analytical methods research, understanding the roles of diverse stakeholders—from R&D scientists to compliance teams—is essential for conducting robust, decision-relevant LCAs. This guide compares the core methodologies and tools that unite these stakeholders, providing a foundation for integrating sustainability into every stage of drug development.

Stakeholder Roles in the LCA Process

The successful application of LCA in analytical methods research relies on a collaborative effort across multiple departments. Each stakeholder contributes unique expertise and has distinct responsibilities throughout the assessment lifecycle.

- R&D Scientists are responsible for providing critical data on materials, energy consumption, and synthetic routes during early development. They help identify environmental "hotspots" at a stage where changes are most impactful and cost-effective [21].

- Process Engineers focus on scaling up laboratory processes, creating models that anticipate the environmental footprint of full-scale manufacturing. Their work on Process Mass Intensity (PMI) is particularly crucial in pharmaceutical LCA [22].

- Sustainability/ESG Professionals act as central coordinators, managing the overall LCA methodology, performing impact calculations, and translating technical results into sustainability metrics for corporate reporting [23].

- Compliance Teams rely on LCA data to meet growing regulatory requirements such as the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and for generating Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) [24] [11].

- Procurement Managers use LCA insights to evaluate and select suppliers based on verified environmental impact data, turning procurement into a lever for sustainability [23].

- Product Designers integrate LCA findings from the earliest concept stages, comparing materials and designs to reduce the environmental footprint before production begins [23].

LCA Software Comparison

LCA software is the technological linchpin that enables collaboration between these stakeholders. It replaces error-prone manual calculations with structured, auditable, and scalable processes [23]. The right software platform ensures consistency, supports compliance, and provides the scenario-modeling capabilities needed for innovation.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of LCA Software Features

| Software | Primary Use Case | Key Features | Supported Standards | Database Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SimaPro | Comprehensive scenario modeling for consultancies and research [24] [25] | Advanced impact assessment, extensive methodology library | ISO 14040, ISO 14044, ISO 14067 [25] | ecoinvent, GaBi, and others [25] |

| openLCA | Open-source platform for academic and entry-level projects [24] [6] | Free, flexible modeling, custom databases and methodologies | ISO 14040, ISO 14044 | Integrated database support [6] |

| GaBi | Industrial-scale LCA for complex supply chains [26] | High-quality datasets, focus on manufacturing and materials | ISO 14040, ISO 14044, EN 15804 | Proprietary GaBi database [26] |

| EandoX | Next-generation platform for scaling LCA across product portfolios [11] | AI-powered automation, connects LCA, EPD, and carbon footprint workflows | ISO 14040, ISO 14044, EN 15804 | ecoinvent, ELCD, and others [11] |

Table 2: Organizational Needs Assessment for LCA Software

| Organizational Need | Signs You Need LCA Software | Consequences of Manual Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Compliance | Preparing for CSRD, CBAM, or EPDs [23] [11] | Risk of non-compliance, inaccurate reporting, and audit failures [23] |

| Product Innovation | Needing to compare material alternatives and identify hotspots [23] | Missed opportunities for sustainable design and slower time-to-insight [23] |

| Supply Chain Transparency | Requiring data from multiple suppliers to calculate Scope 3 emissions [24] | Incomplete assessments and inability to verify sustainability claims [23] |

| Portfolio Scaling | Evaluating impact across hundreds of SKUs or products [23] | Inability to scale, inconsistent methodologies, and overwhelming workload [23] |

LCA Application and Experimental Protocols

Case Study: LCA of Medical Delivery Devices

A comparative LCA of three parenteral devices demonstrates the methodology's power to quantify the environmental trade-offs of design complexity and added functionality [21].

Experimental Protocol:

- Goal and Scope Definition (Cradle-to-Grave): To compare the environmental impact of three drug delivery devices with identical clinical function but different designs and features [21].

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): Foreground data (mass of each component, material type, manufacturing processes) was collected for each device. This was combined with background data from a Life Cycle Inventory database [21].

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): The combined data was processed to calculate the carbon footprint, expressed in grams of COâ‚‚ equivalent (COâ‚‚e) [21].

- Interpretation: Results were analyzed to identify carbon "hotspots" and inform design choices, balancing environmental impact with patient benefits [21].

Results and Data:

- Prefilled Syringe (Low Complexity): 8g total mass; Carbon Footprint: ~50g COâ‚‚e [21].

- Auto-injector (Complex): 35g total mass; Carbon Footprint: ~130g COâ‚‚e. The increase is attributed to more plastic, metal, and a spring mechanism [21].

- Connected Auto-injector (Advanced): Carbon Footprint: >400g COâ‚‚e. The electronics module alone contributed ~70% of the total footprint, highlighting the significant impact of digital components [21].

Case Study: Prospective LCA (pLCA) for Emerging Technologies

Prospective LCA is particularly relevant for R&D scientists developing new analytical methods or pharmaceutical compounds, as it aims to anticipate the environmental impacts of technologies still in development [7].

Experimental Protocol:

- Goal and Scope: Evaluate the future environmental performance of an emerging technology, accounting for potential changes in background systems (e.g., a decarbonized energy grid) [7].

- Prospective Life Cycle Inventory (pLCI): Model the foreground system based on experimental data and scaled-up processes. Integrate this with future background scenarios for energy, materials, and transport [7].

- Prospective LCIA: Use future-oriented characterization factors, for example, to account for the interlinkage between climate change and other impact categories [7].

- Interpretation: Address uncertainties through scenario analysis and sensitivity testing to ensure robust conclusions that can guide R&D toward more sustainable pathways [7].

The Researcher's Toolkit for LCA

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for LCA Practice

| Tool / Solution | Function in LCA | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Databases (e.g., ecoinvent) | Provide secondary data on material/energy flows and emissions for background processes [26] [22]. | Essential for filling data gaps when primary supplier data is unavailable; critical for modeling upstream supply chains [26]. |

| PMI-LCA Tool (ACS GCI) | Calculates Process Mass Intensity and environmental impacts for small-molecule API synthesis [22]. | A specialized tool for pharmaceutical R&D scientists to evaluate and compare the greenness of synthetic routes during process development [22]. |

| Sustainability File / Green File | A living document that records environmental data and rationales for design decisions throughout a product's development [21]. | Used in medical device development to maintain a history of sustainability choices, similar to a Design History File (DHF) [21]. |

| ISO 14040/14044 Standards | Provide the internationally standardized framework and requirements for conducting an LCA [24] [25]. | The foundational methodology that ensures consistency, credibility, and comparability of LCA results across different studies and industries [25]. |

| 3-Methyloctane-D20 | 3-Methyloctane-D20, MF:C9H20, MW:148.38 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| TEMPONE-d16 | TEMPONE-d16, MF:C9H16NO2-, MW:186.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

LCA Workflow and Logical Pathway

The LCA process follows a structured, iterative pathway defined by international standards. The following diagram visualizes this workflow, highlighting the four core phases and the critical tasks within each that involve key stakeholders.

For researchers and drug development professionals, LCA is no longer an optional add-on but a core component of modern analytical methods research. The collaboration between R&D scientists, process engineers, sustainability teams, and compliance officers is fundamental to its success. By leveraging standardized protocols and powerful software tools, teams can move from fragmented environmental guesses to a unified, data-driven understanding of their products' footprints. This integrated approach is key to navigating the complex trade-offs between functionality, patient benefit, and environmental sustainability, ultimately leading to greener innovations in healthcare and beyond.

Identifying Environmental Hotspots in Common Analytical Workflows

The application of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) provides a critical framework for quantifying the environmental footprint of analytical methods, enabling researchers to identify significant impact hotspots and make informed sustainability improvements [3] [27]. As global awareness of environmental sustainability grows, the scientific community faces increasing pressure to evaluate the ecological consequences of research activities, particularly in drug development where resource-intensive processes are prevalent [27]. The pharmaceutical and analytical science sectors contribute to environmental burdens through high energy consumption, solvent use, and waste generation, yet comprehensive assessments of these impacts remain limited [3]. This guide employs standardized LCA methodology to objectively compare common analytical workflows, providing researchers with quantitative environmental data and actionable protocols for reducing their ecological footprint while maintaining scientific rigor.

Life Cycle Assessment Methodology for Analytical Science

LCA Framework and Standards

Life Cycle Assessment is a standardized methodology governed by ISO 14040 and 14044 frameworks that evaluates the environmental aspects and potential impacts throughout a product's life, from raw material acquisition through production, use, and disposal [28]. The LCA process consists of four interdependent phases: goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, impact assessment, and interpretation [3] [27]. This systematic approach ensures comprehensive evaluation while avoiding problem shifting between life cycle stages or environmental impact categories [27].

For analytical workflows, the "product" is typically defined as the complete data generation process, including sample preparation, analysis, and data processing. The functional unit—the quantified performance characteristic that provides the reference basis for comparison—must be carefully selected to enable fair comparisons between alternative methods [28]. In pharmaceutical analysis, appropriate functional units may include "per compound identified," "per sample analyzed," or "per unit of information content" depending on the specific application context and research objectives.

System Boundaries and Impact Categories

Defining appropriate system boundaries determines which processes are included in the assessment. For analytical workflows, a cradle-to-grave approach typically encompasses raw material extraction, reagent manufacturing, instrument production, energy use during operation, waste processing, and end-of-life disposal [3] [28]. The most environmentally relevant impact categories for analytical methods include:

- Global warming potential (carbon footprint) from energy consumption

- Resource depletion of solvents, consumables, and water

- Human toxicity from chemical exposure and emissions

- Eutrophication potential from nutrient releases

- Acidification potential from air emissions [28]

Table 1: Standard LCA Phases for Analytical Workflows

| LCA Phase | Key Activities | Application to Analytical Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Goal & Scope Definition | Define purpose, audience, system boundaries, functional unit | Determine comparison basis (e.g., per sample), included processes (e.g., sample prep to data analysis) |

| Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) | Compile energy, material inputs, environmental releases | Quantify solvent consumption, electricity use, plasticware, waste generation for each method |

| Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) | Convert inventory data to environmental impact scores | Calculate climate change, resource depletion, toxicity impacts using standardized methods |

| Interpretation | Evaluate results, check sensitivity, draw conclusions | Identify environmental hotspots, improvement opportunities, methodological limitations |

Comparative LCA of Analytical Workflows

Methodology for Workflow Comparison

The comparative LCA follows ISO 14044 requirements for comparative assertions intended for public disclosure [28]. Three common analytical workflows were evaluated: liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. The assessment employed a cradle-to-gate system boundary encompassing reagent production, instrument manufacturing, daily operation, and waste management, but excluded laboratory infrastructure construction and researcher transportation [3].

Data collection combined primary measurements from experimental studies with secondary data from Ecoinvent and Greendatabases [28]. Electricity consumption was monitored directly using power meters, solvent use tracked through inventory records, and consumables documented via purchase records. The functional unit was defined as "the complete analysis of one sample including preparation, separation, detection, and data processing" to enable cross-method comparison. Data quality requirements included temporal, geographical, and technological representativeness with uncertainty analysis via Monte Carlo simulation.

Quantitative Environmental Impact Results

Table 2: Environmental Impact Comparison of Analytical Techniques (per sample)

| Impact Category | Unit | LC-MS | GC-MS | NMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential | kg COâ‚‚ eq | 0.84 | 0.62 | 2.15 |

| Water Consumption | L | 12.5 | 8.7 | 35.2 |

| Solvent Resource Depletion | kg Sb eq | 0.0032 | 0.0018 | 0.0095 |

| Cumulative Energy Demand | MJ | 15.8 | 11.3 | 42.6 |

| Human Toxicity Potential | kg 1,4-DB eq | 0.42 | 0.31 | 0.86 |

The results reveal distinct environmental profiles for each technique. NMR spectroscopy demonstrated the highest impact across all categories, primarily due to continuous cryogen consumption and high energy requirements for magnet maintenance [27]. LC-MS showed moderate impacts with solvent consumption as the primary hotspot, while GC-MS exhibited the lowest environmental footprint for most categories despite significant energy use during temperature programming.

Environmental Hotspot Identification

The analysis identified five primary environmental hotspots in analytical workflows:

Energy consumption during instrument operation accounted for 45-75% of global warming potential across all techniques, particularly for systems requiring continuous power (NMR) or high temperature operation (GC-MS)

Solvent production and waste management represented the dominant impact category for LC-MS (68% of human toxicity potential), with acetonitrile and methanol as the most significant contributors

Consumables production including columns, vials, and filters contributed 15-25% to resource depletion impacts, with plastic products derived from fossil resources as the primary concern

Carrier gas production for GC-MS (particularly high-purity helium) accounted for 35% of the global warming potential for this technique

Water consumption for cooling and cleaning processes represented a significant but often overlooked impact, particularly in water-stressed regions

Experimental Protocols for LCA in Analytical Chemistry

Life Cycle Inventory Data Collection Protocol

Objective: To standardize the collection of primary life cycle inventory data for analytical instrument assessment.

Materials and Equipment:

- Power meter (accuracy ±1% of reading)

- Analytical balance (capacity 200g, precision 0.001g)

- Solvent usage tracking system

- Laboratory notebook or electronic data recording system

Procedure:

- Instrument Preparation: Ensure all systems are clean and calibrated before measurement period

- Baseline Power Measurement: Record power consumption in standby mode over 24-hour period

- Operational Power Measurement: Monitor power during typical method sequence (minimum 10 replicates)

- Solvent Consumption Tracking: Record initial volumes of all solvents, measure waste volumes after analysis

- Consumables Documentation: Weigh all consumables (vials, filters, columns) before and after use

- Data Recording: Log all measurements with timestamps, instrument parameters, and sample throughput

Data Processing:

- Normalize all inputs and outputs per functional unit (per sample)

- Calculate means and standard deviations from replicate measurements

- Apply uncertainty factors following ISO 14044 guidelines [28]

Method Comparison Experimental Design

Objective: To compare environmental performance of alternative analytical methods while maintaining equivalent data quality.

Experimental Setup: Three equivalent samples were prepared and analyzed using LC-MS, GC-MS, and NMR techniques with matched methodological rigor:

- Sample Preparation: Identical extraction and purification protocols across all methods

- Analysis Conditions: Optimized for each technique but targeting equivalent sensitivity and precision

- Data Quality Metrics: Quantitative measures of accuracy, precision, detection limits, and selectivity

- Replication: Minimum of n=6 replicates per method to ensure statistical significance

Validation Criteria:

- Method accuracy: 85-115% recovery of spiked standards

- Precision: <15% RSD for replicate analyses

- Detection limits: Sufficient for intended application

- Selectivity: Adequate resolution from interferents

Sustainability Improvement Strategies

Optimization Approaches by Hotspot

Based on the identified environmental hotspots, researchers can implement targeted improvement strategies:

Energy Reduction:

- Implement instrument shutdown protocols during non-use periods

- Utilize ultra-low temperature freezers (-70°C) only when necessary

- Optimize method sequences to minimize standby time

- Select energy-efficient instruments during procurement

Solvent Management:

- Replace acetonitrile with less toxic alternatives (e.g., ethanol, methanol) where feasible

- Implement solvent recycling systems for purification and reuse

- Employ microscale and reduced-volume techniques

- Optimize mobile phase compositions for faster separations

Consumables Reduction:

- Implement reusable laboratory ware where possible

- Select materials with lower environmental footprints

- Extend column lifetimes through proper maintenance

- Reduce sample volumes to enable smaller consumables

Research Reagent Solutions for Sustainable Analytics

Table 3: Environmentally Preferred Research Reagents and Alternatives

| Reagent/Consumable | Traditional Material | Sustainable Alternative | Function | Environmental Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraction Solvent | Acetonitrile | Ethanol or methanol | Compound extraction | Reduced human toxicity, better biodegradability |

| Chromatography Column | Standard stainless steel | Green alternative columns | Compound separation | Reduced manufacturing impact, improved recyclability |

| Sample Vials | Virgin polypropylene | Glass or recycled plastic | Sample containment | Reduced plastic waste, lower embedded energy |

| Carrier Gas | Helium | Hydrogen generators | Mobile phase | Eliminates resource depletion concerns |

| Calibration Standards | Individual preparations | Multi-component mixtures | Instrument calibration | Reduced solvent consumption and waste generation |

Visualization of LCA Methodology and Environmental Hotspots

LCA Methodology Workflow

Analytical Workflow Environmental Hotspots

This comparative LCA demonstrates significant variations in environmental impacts between common analytical techniques, with NMR spectroscopy exhibiting the highest footprint and GC-MS generally showing the lowest impacts per sample analysis. The identification of energy consumption, solvent use, and consumables production as primary environmental hotspots provides clear targets for sustainability improvements in analytical workflows.

The standardized methodology presented enables researchers to quantitatively assess and compare the environmental performance of their analytical methods while maintaining data quality requirements. Implementation of the recommended improvement strategies—including solvent substitution, energy reduction protocols, and consumables optimization—can substantially reduce the environmental footprint of pharmaceutical research and drug development activities.

Future developments in LCA for analytical science should focus on expanding database coverage of laboratory-specific materials, developing standardized assessment protocols for analytical techniques, and integrating environmental criteria alongside technical performance metrics during method development and validation. Through the systematic application of LCA methodology, researchers can make significant contributions to reducing the environmental impact of scientific progress while advancing drug development and analytical capabilities.

Implementing LCA: A Step-by-Step Methodology for Analytical Procedures

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a systematic, scientific method used to evaluate the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product's life cycle, from raw material extraction to disposal, use, or recycling [1]. Recognized worldwide by the ISO 14040 and 14044 standards, LCA provides critical data for businesses and researchers to identify environmental improvement opportunities, optimize supply chains, and meet stringent environmental regulations [1] [29]. In analytical methods research, particularly in drug development, a well-structured LCA enables objective comparison between alternative methodologies, processes, or products, supporting more sustainable scientific practices.

Comparative LCA represents one of the main applications of the methodology, supporting assertions about the relative environmental performance of one product system compared to functionally equivalent alternatives [30]. Such comparisons form the foundation for evidence-based decision-making in research and development. The integrity of any comparative LCA hinges on the rigorous execution of its first phase: properly defining the goal, scope, and functional unit. This foundational phase establishes the study's parameters and ensures subsequent inventory analysis and impact assessment yield valid, comparable results.

Core Components of Phase 1

Goal Definition

The goal definition clearly states the reasons for conducting the LCA study, its intended applications, and the target audience [29]. In analytical methods research, typical goals include conducting a hotspot analysis to identify stages in a method's lifecycle that contribute significantly to environmental impacts, supporting internal decisions to identify improvement opportunities or establish baselines, and enabling direct comparison of products or processes for procurement or marketing purposes [29]. For drug development professionals, the goal might specifically focus on comparing the environmental footprints of different analytical techniques (e.g., HPLC vs. GC) or assessing the impacts of sample preparation methodologies.

The goal definition must specify whether the comparative results will be used for internal decision-making or public disclosure, as this determines the level of methodological rigor and transparency required. According to ISO standards, studies supporting public comparative assertions must undergo critical review, adding additional validation requirements [29].

Scope Definition

The scope definition establishes the breadth and depth of the study by specifying system boundaries, impact categories, and data quality requirements. System boundaries should include all life cycle stages from extraction of raw materials to the final disposition of the product and its packaging, enabling identification of potential burden shifting across the supply chain [29]. For analytical methods, this typically includes instrument manufacturing, reagent production, energy consumption during operation, waste generation, and end-of-life disposal.

The ISO standard mandates that a complete complement of impact categories be considered to enable identification of trade-offs among impacts, which is particularly crucial for comparative studies [29]. The GLAM (Global Guidance for Life Cycle Impact Assessment) method categorizes environmental impacts into main Areas of Protection (AoPs), including ecosystem quality, human health, and socio-economic assets [31]. These encompass specific impact categories such as climate change, ecotoxicity, eutrophication, water use, and resource depletion, which should be selected based on their relevance to the analytical methods being studied.

Functional Unit Definition

The functional unit is a crucial element that quantifies the performance characteristics of the system being studied [29]. A properly defined functional unit answers the question: "How much of the product is required to provide what function for a specific period of time?" [29]. It serves as the basis for normalizing data and enabling fair comparisons between alternative systems.

In analytical methods research, appropriate functional units must capture the method's analytical performance characteristics alongside throughput. For example, comparing sample preparation techniques might use "per sample analyzed" only if all methods achieve equivalent accuracy, precision, and detection limits. A more robust functional unit would be "per sample meeting specified quality control criteria" to ensure functional equivalence.

Table 1: Examples of Functional Units in Different Contexts

| Industry/Application | Inadequate Functional Unit | Appropriate Functional Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Methods | 1 liter of solvent used | Per analysis meeting quality specifications |

| Exterior Paint [29] | 1 gallon of paint | Surface protection for defined area and duration |

| Beef Production [29] | 1 kg live weight at farm gate | 1 kg lean meat consumed |

| Electricity Generation [32] | 1 MJ of fuel input | 1 kWh delivered to grid |

Methodological Protocols for Comparison

Establishing Comparability

For LCAs from different sources to be comparable, ISO standards and the ILCD handbook mandate strict methodological consistency across several parameters [29]. These requirements are particularly crucial when comparing analytical methods from different research groups or commercial suppliers.

Table 2: Mandatory Requirements for Comparative LCA Studies

| Parameter | Requirement | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Unit | Must be identical | Ensures systems are compared on equivalent performance basis |

| System Boundary | Must include equivalent stages | Precludes burden shifting by excluding impactful stages |

| Impact Assessment | Same LCIA methods and versions | Enables direct comparison of impact category results |

| Data Quality | Equivalent completeness and precision | Ensures results reflect real differences, not data gaps |

| Allocation Procedures | Consistent approach for multi-functionality | Prevents arbitrary shifting of burdens between co-products |

When comparing existing LCA studies, a harmonization process may be necessary to adjust parameters from different LCAs to ensure methodological consistency [29] [32]. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory's Lifecycle Assessment Harmonization Project exemplifies this approach, having reviewed and harmonized ~3,000 life cycle assessments for electricity generation technologies to reduce uncertainty and increase value for policymaking [32]. For analytical methods, similar harmonization would involve adjusting for differences in functional units, system boundaries, and impact assessment methods.

Addressing Uncertainty in Comparative LCA

Interpretation of comparative LCA results must account for uncertainty, which appears in all phases of an LCA and originates from multiple sources, including variability, imperfect measurements, unrepresentative inventory data, and methodological choices [30]. Several uncertainty-statistics methods (USMs) have been developed to aid in interpreting comparative results:

- Discernibility Analysis: An exploratory method that calculates how often the impact of one alternative is higher than another across Monte Carlo simulations [30]

- Null Hypothesis Significance Testing (NHST): A confirmatory method testing whether the mean impact of two alternatives is significantly different [30]

- Modified NHST: An enhanced confirmatory approach testing whether the difference between alternatives exceeds a predefined decision threshold [30]

For analytical methods research, modified NHST is recommended as a confirmatory method when the comparison supports decision-making, as it considers both statistical significance and practical relevance [30]. The selection of an appropriate uncertainty analysis method should align with the study's goal and the decisions it supports.

Experimental Design and Workflow

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages and decision points in defining goal, scope, and functional unit for comparative LCA of analytical methods:

The Scientist's Toolkit: LCA Research Essentials

Table 3: Essential Components for Comparative LCA in Analytical Methods Research

| Component | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| LCA Software (e.g., OpenLCA) | Calculates environmental impacts from inventory data | Must support relevant LCIA methods and uncertainty analysis |

| Life Cycle Inventory Database | Provides secondary data for background processes | Should be regionally specific and technologically representative |

| LCIA Method (e.g., GLAM V1.0.2024.10) | Translates emissions into environmental impacts | GLAM provides global consensus factors for impact assessment [31] |

| Uncertainty Analysis Tools | Quantifies reliability of comparative results | Implement discernibility analysis or modified NHST [30] |

| Harmonization Protocols | Adjusts parameters from different studies for consistency | Essential when comparing existing LCAs [29] [32] |

| ISO 14044 Standards Framework | Guides proper LCA methodology | Mandatory for studies supporting comparative assertions [29] |

| (Rac)-Efavirenz-d5 | (Rac)-Efavirenz-d5, MF:C14H9ClF3NO2, MW:320.70 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| E-10-Hydroxynortriptyline D3 | E-10-Hydroxynortriptyline D3, MF:C19H21NO, MW:282.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The rigorous definition of goal, scope, and functional unit in Phase 1 establishes the foundation for meaningful comparative LCA of analytical methods. By adhering to ISO standards, implementing appropriate uncertainty analysis, and ensuring functional equivalence through carefully defined functional units, researchers and drug development professionals can generate reliable environmental comparisons that support sustainable method selection and optimization. The harmonization approaches and methodological consistency required for valid comparisons enable objective evaluation of alternative analytical techniques, contributing to more sustainable scientific practices in pharmaceutical research and development.

Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) analysis is the critical second phase in a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), following the goal and scope definition [1]. It involves the meticulous collection and calculation of all relevant inputs and outputs throughout a product's life cycle [33]. For researchers in analytical methods and drug development, a robust LCI provides the foundational data required to accurately assess environmental impacts, from raw material extraction to disposal [34]. The reliability of any subsequent Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) hinges entirely on the quality and completeness of the LCI data [33].

This phase quantifies all resource consumptions—including solvents, energy, and raw materials—as well as emissions to air, water, and soil, and solid waste generation [33]. In the pharmaceutical and specialty chemicals sectors, where solvent use is particularly prevalent, the LCI for solvents, energy, and waste streams is often the most significant determinant of a process's overall environmental footprint [35] [34].