Managing Sample Turbidity and Light Scattering in Drug Solutions: From Fundamental Principles to Regulatory Compliance

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing turbidity and light scattering in pharmaceutical solutions.

Managing Sample Turbidity and Light Scattering in Drug Solutions: From Fundamental Principles to Regulatory Compliance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing turbidity and light scattering in pharmaceutical solutions. It covers the fundamental causes and implications of turbidity, explores advanced analytical techniques like Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and nephelometry, and offers practical troubleshooting strategies. The content also addresses critical validation requirements and regulatory considerations to ensure data integrity and compliance throughout the drug development lifecycle, from early discovery to final product release.

Understanding Turbidity and Light Scattering: Fundamental Principles and Impact on Drug Development

Turbidity is the cloudiness or haziness of a fluid caused by the presence of suspended particles that are invisible to the naked eye. These particles scatter and absorb light, preventing it from transmitting straight through the liquid. In pharmaceutical research, particularly in drug solution development, managing turbidity is critical as it directly impacts drug solubility, bioavailability, and safety [1] [2].

The underlying mechanism is light scattering. When a beam of light passes through a liquid sample, it interacts with suspended particles. The light is scattered in different directions, and the intensity and pattern of this scattered light provide information about the concentration, size, and sometimes the shape of the particles [3]. This phenomenon is described by several key techniques:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS): Measures fluctuations in scattered light intensity to determine the size of nanoparticles (typically 5-500 nm) undergoing Brownian motion [3].

- Static Light Scattering (SLS): Measures the time-averaged intensity of scattered light at various angles to determine molecular weight and particle size over a broader range (0.1 µm to 100 µm) [3].

- Nephelometry: Specifically measures the intensity of light scattered at a specific angle (often 90 degrees) to determine particle concentration [2].

- Turbidimetry: Measures the intensity of light transmitted directly through a sample; higher particle concentration scatters more light, resulting in less transmitted light [4].

For drug development professionals, controlling turbidity is essential for ensuring drug product quality and efficacy, particularly for injectable and ophthalmic solutions where particulate matter can pose significant patient risks [5] [6].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Troubleshooting Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Erratic/Unstable Readings [4] [7] | Sample precipitation/settling during measurement; Air bubbles in sample. | Use fresh samples; Control reaction times; Ensure gentle mixing (no vigorous shaking); Allow decantation time for bubbles to settle; Inspect sample for bubbles before measurement [4] [7]. |

| Abnormally High or Low Values [4] [7] | Dirty or scratched sample cuvettes; Incorrect calibration; Contaminated or expired standards. | Clean cuvettes with lint-free cloth; Replace damaged cuvettes; Recalibrate instrument before use; Check expiration dates of standards; Store standards properly to avoid contamination [4] [7]. |

| Negative Results [4] | Sample turbidity is below instrument's detection limit; Incorrect calibration range. | Verify instrument's lower detection limit; Re-calibrate using standards with concentrations appropriate for the expected sample range [4]. |

| Overloaded Samples [7] | Particle concentration exceeds instrument's measurement range; Incorrect sample dilution. | Dilute sample to fall within instrument's linear range; Follow manufacturer's dilution instructions precisely; Ensure thorough sample mixing for uniform particle dispersion [7]. |

| Calibration Problems [7] [8] | Contamination on optical surfaces; Insufficient instrument warm-up time. | Regularly clean lenses/cuvettes with manufacturer-recommended solution; Allow turbidity meter to warm up for the recommended time (e.g., 5 minutes) before use [7] [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between nephelometry and turbidimetry? Nephelometry measures the amount of light scattered by particles in a sample, typically at a 90-degree angle. It is often more sensitive for low particle concentrations. Turbidimetry, in contrast, measures the reduction in intensity of transmitted light (i.e., light that passes straight through the sample) due to scattering and absorption by particles [4] [2]. The choice depends on the sample's characteristics and the required sensitivity.

Why is kinetic solubility important in early drug discovery? Kinetic solubility refers to the concentration at which a compound precipitates out of solution in a short time frame. Testing this early in drug discovery helps identify compounds with poor solubility, which are high-risk candidates likely to fail in later development stages due to low bioavailability. High-throughput kinetic solubility screens using nephelometry can rapidly rank compounds, saving significant time and resources [2].

How do USP standards relate to turbidity and particulate matter? The United States Pharmacopeia (USP) sets strict limits on subvisible particulate matter in injectable and ophthalmic drug products to ensure patient safety. For example:

- USP <788> (Injections) limits particles to ≤6000 per container ≥10 µm and ≤600 per container ≥25 µm [5].

- USP <789> (Ophthalmic Solutions) has stricter, per-volume limits [5]. While not a compendial method, turbidity and light scattering techniques are vital orthogonal tools for monitoring and controlling these particulates during formulation and quality control [5].

What environmental factors can affect turbidity measurements? Ambient conditions can significantly impact results. Strong ambient light can interfere with the sensor's accuracy, and extreme temperature variations can affect instrument reliability and sample stability. Measurements should be performed away from direct sunlight and intense artificial lights, and instruments should be used within their specified temperature ranges [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Turbidimetric Measurement for Antigen Quantification

This protocol outlines a method for quantifying antigen concentration in a solution based on the formation of antigen-antibody complexes, which increase turbidity [4].

Sample Preparation

- Prepare a series of test tubes containing:

- Blank: Distilled water.

- Standard Curve: Serial dilutions of known antigen standards.

- Samples: Unknown samples to be tested.

- Add an equal volume of specific, particle-bound antibody reagent to each tube.

- Mix the contents of each tube thoroughly and incubate as required for complex formation [4].

Turbidimetry Measurement

- After incubation, analyze each mixture with a turbidimeter or a plate reader capable of measuring transmitted light.

- The level of transmitted light is inversely proportional to the amount of antigen in the solution. Higher antigen concentration leads to more complex formation, increasing turbidity and decreasing transmitted light [4].

Data Analysis

- Read the absorbance (optical density) of the standard samples.

- Plot a standard curve with antigen concentration on the x-axis and absorbance on the y-axis.

- Read the absorbance of the unknown sample tubes and use the standard curve to calculate their antigen concentrations [4].

Protocol 2: Two-Point Calibration of a Turbidity Sensor

Regular calibration is essential for accurate measurements. This is a generalized protocol based on industry practices [8].

Preparation

- Connect the turbidity sensor to the interface and allow it to warm up for at least five minutes.

- Enter the calibration mode in the data-collection software.

First Calibration Point (High Value)

- Gently invert the bottle containing the turbidity standard solution (e.g., 100 NTU) four times. Note: Do not shake, as this can introduce bubbles.

- Wipe the outside of the bottle with a clean, lint-free cloth.

- Place the bottle into the sensor, aligning any markings on the bottle with those inside the sensor chamber.

- Close the lid. Once the reading stabilizes, enter the known value of the standard (e.g., "100") and confirm/keep the value [8].

Second Calibration Point (Blank/Zero Value)

- Prepare a blank by rinsing and filling an empty sample bottle with distilled water to the fill line.

- Seal the bottle with the lid and wipe the outside clean.

- Place the blank bottle into the sensor, ensuring proper alignment.

- Close the lid. Once the reading stabilizes, enter "0" as the value and confirm/keep the value [8].

- The calibration is now complete. Subsequent sample measurements will be based on this calibration curve.

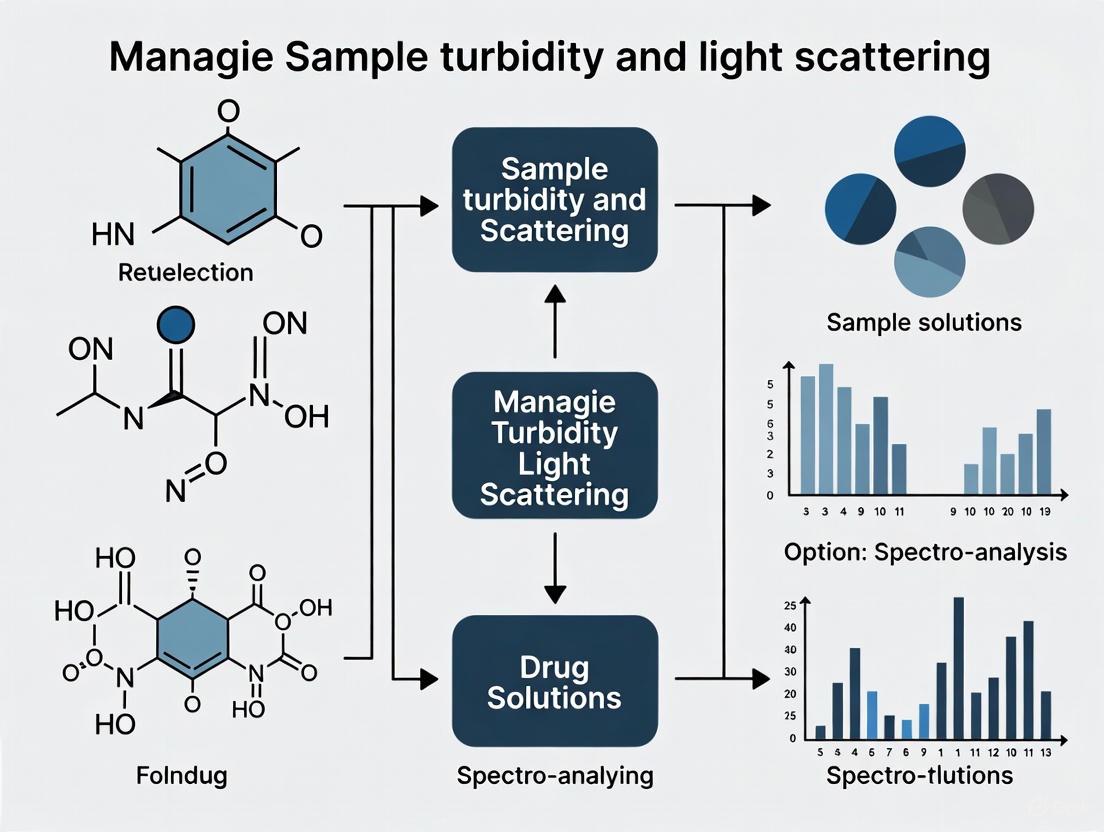

Visualizations and Workflows

Light Scattering Mechanisms

Light Scattering Measurement Principles

Turbidity Experiment Workflow

Experimental and Troubleshooting Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Turbidity Standards (e.g., Formazin) | Used to calibrate the turbidity meter, ensuring accurate and traceable measurements across different instruments and laboratories [8]. |

| Particle-Bound Antibodies | Essential for immunoturbidimetric assays. They bind to the target antigen in a sample, forming larger complexes that increase measurable turbidity [4]. |

| High-Purity Solvents & Buffers (e.g., McIlvaine buffer) | Provide a consistent and controlled chemical environment (pH, ionic strength) for solubility and particle analysis, minimizing interference from uncontrolled variables [1]. |

| Precipitation Inhibitors (e.g., specific polymers, cyclodextrins) | Excipients screened using turbidity methods to identify formulations that prevent drug precipitation, thereby maintaining supersaturation and enhancing bioavailability [1] [2]. |

| Lint-Free Wipes & Clean Cuvettes | Critical for preventing contamination from dust, fibers, or fingerprints, which are significant sources of error, especially in low-level turbidity measurements [4] [7]. |

| 1-Methyl-3-amino-4-cyanopyrazole | 1-Methyl-3-amino-4-cyanopyrazole, CAS:21230-50-2, MF:C5H6N4, MW:122.13 g/mol |

| 3,5-Dibromo-4-methoxybenzoic acid | 3,5-Dibromo-4-methoxybenzoic acid, CAS:4073-35-2, MF:C8H6Br2O3, MW:309.94 g/mol |

Turbidity, the cloudiness or haziness of a fluid caused by suspended particles, is a critical quality attribute in pharmaceutical solutions. It serves as a key indicator of product quality, safety, and stability. In drug development and manufacturing, unexpected turbidity can signal serious problems ranging from particulate contamination to chemical instability. This technical support guide addresses the common causes of turbidity—including algae, silt, clay, precipitated iron, and bacteria—within the broader context of managing sample turbidity and light scattering in pharmaceutical research.

Turbidity is quantified using Nephelometric Turbidity Units (NTU), which measure a solution's ability to scatter light [9] [10]. This light scattering occurs when suspended particles act as tiny mirrors that redirect incoming light in different directions [10]. For pharmaceutical applications, controlling turbidity is essential not only for product aesthetics but more importantly for ensuring efficacy, safety, and compliance with regulatory standards.

Fundamental Causes and Impact of Turbidity

Pharmaceutical solutions can become turbid due to various particulate contaminants, each with distinct origins and characteristics:

Bacteria and Microorganisms: Microbial growth introduces cells and cellular debris into solutions. Recent research demonstrates that bacterial activity can be detected through laser speckle imaging due to the light scattering properties of bacterial colonies [11] [12]. Certain bacteria can also cause precipitation of other dissolved components.

Inorganic Particles: Silt and clay particles may be introduced through water sources or as contaminants in raw materials. These particles typically range from 10 to 100 microns in diameter and can be identified by their mineral composition [10].

Precipitated Iron: Iron can precipitate out of solution, particularly when using iron-containing compounds like Fe(III)-EDTA or Fe(III)-citrate in formulations. Studies show that iron release rates differ between complexes, with Fe(III)-citrate releasing iron more readily than Fe(III)-EDTA, leading to potential precipitation and turbidity [13].

Algae and Organic Matter: While less common in controlled manufacturing, algal contamination can occur in water systems or from botanically-derived ingredients, introducing chlorophyll-containing cells and organic debris that scatter light [10].

Impact on Pharmaceutical Processes

Turbidity affects multiple aspects of pharmaceutical development and manufacturing:

Product Quality: Suspended particles may alter drug delivery characteristics, especially in injectable formulations where clarity is mandatory [9] [14].

Process Efficiency: High turbidity can clog filters, scale equipment, and reduce the efficiency of processing systems [9].

Analytical Interference: Turbidity interferes with light-based analytical methods, including spectrophotometry and dynamic light scattering, potentially leading to inaccurate particle size measurements [15] [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnostic Flowchart

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach to diagnosing turbidity issues in pharmaceutical solutions:

Troubleshooting Common Scenarios

Scenario 1: Sudden Turbidity Increase Across Multiple Batches

- Problem: Multiple production batches show unexpected turbidity increases.

- Investigation Steps:

- Check water purification system performance and conductivity readings.

- Verify integrity of filters in manufacturing equipment.

- Review recent changes in raw material suppliers or specifications.

- Inspect cleaning and sterilization procedures for equipment.

- Potential Solutions:

- Replace water purification system filters and validate water quality.

- Implement additional filtration step (0.22 μm) before final packaging.

- Revise raw material acceptance criteria to include turbidity limits.

Scenario 2: Turbidity Development During Storage

- Problem: Solutions become turbid during stability studies.

- Investigation Steps:

- Conduct accelerated stability testing at different temperatures.

- Perform pH monitoring over time to detect shifts.

- Analyze particulate composition using microscopic and spectroscopic methods.

- Check container closure integrity for potential leaching.

- Potential Solutions:

- Adjust formulation pH to enhance stability.

- Add appropriate stabilizers to prevent precipitation.

- Modify packaging to prevent interaction with container.

Scenario 3: Interference with Analytical Measurements

- Problem: Turbidity interferes with Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) measurements for nanoparticle characterization.

- Investigation Steps:

- Potential Solutions:

- Implement sample pre-filtration (0.22 μm) when appropriate.

- Use degassing procedures to remove air bubbles.

- Optimize DLS measurement parameters (duration, temperature, angle) [14].

Research Reagent Solutions for Turbidity Management

The following table summarizes key reagents and materials used in turbidity research and control:

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Turbidity Management

| Reagent/Material | Function in Turbidity Management | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 0.22 μm Filters | Removal of particulate contaminants | Sample preparation for DLS; solution clarification [14] |

| Citric Acid | Prevents iron precipitation through chelation | Stabilization of iron-containing formulations [16] [13] |

| EDTA | Metal chelation to prevent precipitation | Preservation of solution clarity in metal-sensitive formulations [13] |

| NaCl Solutions | Controls ionic strength in stability studies | Testing formulation robustness under different conditions [16] |

| Turbidity Standards | Instrument calibration | Ensuring measurement accuracy in quality control [7] [10] |

| Particle-bound Antibodies | Turbidimetric immunoassays | Quantification of specific analytes in solution [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Turbidity Analysis

Dynamic Light Scattering for Nanoparticle Characterization

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) is a laser-based method used to measure the size and distribution of particles in liquid samples by analyzing light scattered due to the Brownian motion of particles [15] [14].

Materials and Equipment:

- DLS instrument (e.g., Malvern Zetasizer)

- High-quality chemicals (ensure purity to avoid interference)

- 0.22 μm filters for sample preparation

- Clean, particle-free cuvettes

- Temperature-controlled sample chamber

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

Instrument Setup:

Measurement Parameters:

Data Analysis:

- Calculate Polydispersity Index (PDI): Values below 0.1 indicate monodisperse samples, while above 0.5 suggests aggregation [14].

- Report hydrodynamic diameter (Z-average) for monomodal distributions.

- For multimodal distributions, use appropriate algorithms (e.g., non-negative least squares analysis) [15].

Troubleshooting DLS Measurements:

- Unstable readings: Check for sample precipitation, settling, or air bubbles [4].

- High polydispersity: Consider additional filtration or sample purification.

- Irregular correlation functions: Verify sample concentration isn't too high, causing multiple scattering.

Turbidimetric Measurement of Particle Concentrations

Turbidimetry measures the intensity of transmitted light to determine the concentration of suspended substances [4].

Materials and Equipment:

- Turbidimeter or spectrophotometer

- Matched cuvettes

- Particle standards for calibration

- Lint-free cloth for cleaning cuvettes

Procedure:

- Instrument Calibration:

Sample Measurement:

Data Collection:

- Take multiple readings to ensure stability.

- Record values in NTU (Nephelometric Turbidity Units).

- Compare against calibration curve for quantitative analysis.

Advanced Technical FAQs

Q1: How does turbidity affect drug quality and efficacy? Turbidity directly impacts product quality and patient safety. Suspended particles can:

- Alter drug delivery characteristics and bioavailability [14]

- Cause physical instability in formulations

- Potentially harbor pathogens that are protected from disinfectants [9]

- Clog filters and delivery systems in administration devices [9]

Q2: What are the key differences between static and dynamic light scattering methods?

- Static Light Scattering analyzes time-averaged intensity of scattered light to determine molecular weight and radius of gyration [15].

- Dynamic Light Scattering analyzes intensity fluctuations caused by Brownian motion to determine hydrodynamic size and size distribution [15].

- DLS is generally faster and more sensitive to aggregation, while SLS provides more structural information [14].

Q3: How can we distinguish between biological and non-biological causes of turbidity?

- Microscopic Analysis: Direct visualization can identify cellular structures.

- Culture Methods: Biological particles will grow under appropriate conditions.

- Staining Techniques: Specific dyes can differentiate organic vs. inorganic particles.

- Spectroscopic Methods: FTIR and Raman spectroscopy identify chemical composition [12].

Q4: What preventive measures are most effective for controlling turbidity in pharmaceutical water systems?

- Regular monitoring and maintenance of water purification systems

- Proper design of distribution systems to prevent stagnation

- Effective sanitization procedures to control microbial growth

- Filtration using appropriate pore sizes (0.22 μm for bacterial removal)

- Validation of cleaning procedures for equipment and containers

Q5: How does particle composition affect light scattering measurements? Different particles scatter light differently based on:

- Refractive Index: Particles with higher refractive index differences from the medium scatter more light [15].

- Particle Size: Larger particles scatter more light at small angles, while smaller particles scatter more uniformly [10].

- Particle Shape: Non-spherical particles create asymmetric scattering patterns [15].

- Color/Pigmentation: Colored particles absorb specific wavelengths, affecting scattering measurements [10].

The following table summarizes key quantitative relationships in turbidity management:

Table: Turbidity Measurement Standards and Parameters

| Parameter | Acceptable Range | Critical Value | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Turbidity (NTU) | <1 NTU for purified water | >100 NTU impacts fish communities [10] | Pharmaceutical water quality [9] |

| Polydispersity Index (PDI) | 0.1-0.3 acceptable for pharmaceuticals [14] | >0.5 indicates significant aggregation [14] | DLS measurements of nanoparticle formulations [14] |

| Hydrodynamic Size | 10-100 nm ideal for bloodstream circulation [14] | >200 nm risk immune clearance [14] | Drug delivery system optimization [14] |

| Zeta Potential | ±30 mV for good electrostatic stability [16] | Near 0 mV indicates instability [16] | Colloidal stability assessment [16] |

| Iron Release Rate | 55 Mâ»Â¹dayâ»Â¹ (Fe(III)-EDTA, dark, 20°C) [13] | 11,330 Mâ»Â¹dayâ»Â¹ (Fe(III)-Cit, dark, 30°C) [13] | Tetracycline degradation studies [13] |

Light Scattering Principles Diagram

This technical support resource provides pharmaceutical researchers with comprehensive guidance for understanding, troubleshooting, and preventing turbidity issues in drug solutions. Proper management of turbidity and light scattering phenomena is essential for developing stable, effective, and safe pharmaceutical products.

The Critical Link Between Drug Solubility, Bioavailability, and Solution Clarity

Core Concepts: Understanding Turbidity, Solubility, and Bioavailability

What is the fundamental link between drug solubility, solution clarity, and bioavailability?

A drug's solubility is its ability to dissolve in a solvent, forming a clear solution. Solution clarity, often quantitatively measured as turbidity, indicates the presence of undissolved, suspended drug particles that scatter light [17]. Bioavailability is the proportion of the drug that enters circulation to exert its therapeutic effect. For a drug to be absorbed, it must first be in a dissolved state. Therefore, a cloudy, turbid solution signifies poor drug solubility, which is a primary rate-limiting step for absorption and directly leads to low bioavailability [18] [19].

Why is managing turbidity and light scattering critical in pre-formulation studies?

Managing turbidity is essential because it is a direct, measurable indicator of a drug's supersaturation and precipitation behavior [18]. During dissolution, a drug may temporarily achieve a supersaturated state (concentration higher than its equilibrium solubility) before precipitating. This precipitation, which causes a solution to become turbid, can be monitored in real-time using turbidimetry and light scattering techniques [20] [3]. Since maintaining supersaturation is key to enhancing absorption for poorly soluble drugs, these techniques are vital for screening polymers and formulations that inhibit precipitation and stabilize the drug in its dissolved state [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Addressing Poor Solubility and High Turbidity in Formulation

| Problem | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Performance Indicator (KPI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Dissolution Rate & High Turbidity | High crystallinity of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API). | Implement a top-down approach like nanomilling to reduce particle size and increase surface area [19]. | Increase in dissolution rate; decrease in turbidity (NTU). |

| Poor Solubility in Biorelevant Media | Drug precipitation at different pH levels (e.g., in intestinal fluid). | Develop an amorphous solid dispersion (SD) using polymers like Soluplus or HPMCP to inhibit recrystallization [18]. | AUC (Area Under the Curve) in pharmacokinetic studies [18]. |

| Rapid Drug Precipitation | Inability to maintain supersaturation. | Use lipid-based systems (e.g., SEDDS/SMEDDS) to keep the drug solubilized in lipid droplets upon dilution [19]. | Duration of supersaturation (>2 hours) in pH-shift dissolution tests [18]. |

| Unstable Nanosuspension | Particle agglomeration over time. | Incorporate stabilizers (e.g., PVA, Parteck MXP) and consider a lipid coat for nanocrystals [18] [19]. | Particle size stability (DLS measurements) over shelf-life [3]. |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Managing Turbidity Interference in Analytical Measurements

| Problem | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Performance Indicator (KPI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate Photometric Analysis | Light scattering by suspended particles mimics absorbance [17]. | Filter the sample using a 0.45 µm or 0.22 µm membrane, ensuring the analyte is not bound to particles [17]. | Recovery of >95% of the known analyte concentration. |

| High Background Signal | Sample turbidity interferes with the target analyte's signal. | Dilute the sample with a compatible solvent (e.g., deionized water) to reduce particle concentration [17]. | Linear response in calibration curve after dilution factor adjustment. |

| Variable Results | Particle size and distribution change over time. | Use instruments with automatic turbidity detection and correction (e.g., NANOCOLOR spectrophotometers) [17]. | Coefficient of variation (CV) of <5% in replicate measurements. |

| Difficulty in Endpoint Determination | Gradual precipitation causes continuous signal drift. | Apply dynamic light scattering (DLS) to monitor particle size changes in real-time, identifying the onset of aggregation [3]. | Clear identification of aggregation onset time. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the difference between turbidimetry and nephelometry, and when should I use each?

- Turbidimetry measures the intensity of light transmitted through a sample at an angle of 0° to the incident beam. It is best for samples with moderate to high turbidity, where significant light is scattered [21] [20].

- Nephelometry measures the intensity of light scattered by the sample, typically at a 90° angle. It is more sensitive and is preferred for samples with low turbidity and small particle sizes [21] [17].

The choice depends on your sample's particle concentration and size. Nephelometry is more sensitive for dilute suspensions, while turbidimetry is more robust for concentrated ones [20].

FAQ 2: How can I quantitatively link solution turbidity to a drug's bioavailability?

Turbidity itself is an in-vitro measurement, but it correlates with bioavailability through the concept of supersaturation maintenance. You can establish a link as follows:

- Use a pH-shift dissolution test to simulate the gastrointestinal transition [18].

- Monitor turbidity (in NTU) and drug concentration simultaneously.

- Correlate the time-point of precipitation onset (sharp increase in turbidity) with the drop in dissolved drug concentration.

- In in-vivo studies, formulations that maintain a clear solution (low turbidity) for longer periods consistently show higher AUC (Area Under the Curve), indicating better bioavailability [18].

FAQ 3: Which polymers are most effective at reducing turbidity by preventing drug precipitation?

The effectiveness of a polymer depends on the drug's properties and the target absorption site. The table below summarizes high-performance polymers based on recent studies:

| Polymer | Primary Function | Key Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Soluplus | Excellent solubilizer and crystallization inhibitor for amorphous solid dispersions [18] [19]. | Maintaining supersaturation of weakly basic drugs in intestinal fluids [19]. |

| HPMCP (HP-55) | pH-dependent polymer that dissolves in intestinal fluid and inhibits recrystallization [18]. | Targeted drug release in the intestine; protecting drugs from precipitation in gastric pH [18]. |

| PVA (Parteck MXP) | Provides good processability in Hot-Melt Extrusion (HME) and inhibits recrystallization in gastric environments [18]. | Enhancing solubility and stability of drugs in stomach fluid [18]. |

| EUDRAGIT FS 100 | Designed for colon-targeted delivery, also enhances drug solubility [19]. | Treating localized diseases of the colon while improving solubility [19]. |

FAQ 4: My formulation is a clear solution in the vial but becomes turbid upon dilution. What is happening and how can I prevent it?

This is a classic sign of solvent-mediated precipitation. The formulation is likely a co-solvent system or a lipid-based concentrate that is stable in its concentrated form. Upon dilution in aqueous media (like simulated gastric fluid), the solvent capacity drops, leading to rapid supersaturation and precipitation of the drug.

Solutions to prevent this:

- Reformulate using self-emulsifying systems (SEDDS/SMEDDS) that form a fine emulsion upon dilution, entrapping the drug in oil droplets [19].

- Incorporate precipitation inhibitors like polymers (e.g., HPMC, PVP) that interfere with the crystal nucleation and growth process [18].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Formazin Turbidity Standard Preparation for Sensor Calibration

Principle: Formazin is a synthetic polymer suspension used as a primary standard for calibrating turbidimeters due to its reproducibility [21].

Materials:

- Hydrazine Sulfate (99% purity)

- Hexamethylenetetramine (99% purity)

- Distilled Water

- Volumetric Flasks (50 mL)

- Magnetic Stirrer

Methodology:

- Prepare a 4000 NTU Stock:

- Dissolve 1% w/v of hydrazine sulfate in 50 mL of distilled water.

- Dissolve 10% w/v of hexamethylenetetramine in 50 mL of distilled water.

- Mix both solutions in a single container and allow to stand for 48 hours at room temperature for complete polymerization and stabilization [21].

- Prepare Dilution Series:

- Perform serial dilutions of the 4000 NTU stock with distilled water to create a standard curve covering your expected turbidity range (e.g., 0.5 to 4000 NTU) [21].

- Calibration:

- Measure the transmitted or scattered light intensity for each standard.

- Plot the instrument response against the known NTU values to create a calibration curve.

Protocol 2: Assessing Drug Precipitation via pH-Shift Dissolution with Turbidity Measurement

Principle: This test simulates the transit of a drug from the stomach (acidic) to the intestine (neutral) and monitors the resulting precipitation via turbidity [18].

Materials:

- USP Apparatus II (Paddle)

- Dissolution tester with integrated turbidimeter or offline sampling capability

- Simulated Gastric Fluid (pH 1.2) without enzymes

- Simulated Intestinal Fluid (pH 6.8) without enzymes

- 0.45 µm Syringe Filters

Methodology:

- Gastric Phase: Place the formulation in 500 mL of Simulated Gastric Fluid at 37°C. Agitate at 50 rpm.

- Monitoring: At predetermined time points (e.g., 15, 30, 45, 60 min), withdraw samples.

- Filter a portion immediately and analyze for drug concentration via HPLC.

- Measure the turbidity (in NTU) of an unfiltered portion.

- pH-Shift Phase: After 2 hours, add a pre-warmed concentrated buffer solution to raise the medium pH to 6.8, simulating entry into the intestine.

- Intestinal Phase: Continue sampling and measuring both drug concentration and turbidity for the duration of the test (e.g., up to 6 hours).

- Data Analysis: Plot drug concentration and turbidity versus time. The point where turbidity spikes indicates precipitation, which should correspond with a drop in dissolved drug concentration.

Quantitative Data: Bioavailability Enhancement of Itraconazole Formulations

The following table summarizes pharmacokinetic data from a study on Itraconazole (ITZ), a poorly soluble drug, demonstrating how formulations that manage solubility and precipitation directly enhance bioavailability [18].

| Formulation | Description | AUC0–48h in Rats (mean ± SD) | Relative Bioavailability vs. Sporanox |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sporanox (Reference) | Marketed spray-dried formulation | 1073.9 ± 314.7 ng·h·mLâ»Â¹ | 1.0x |

| SD-1 Pellet | PVA-based, rapid release in gastric fluid [18] | 2969.7 ± 720.6 ng·h·mLâ»Â¹ | ~2.8x |

| SD-2 Pellet | HPMCP/Soluplus-based, release in intestinal fluid [18] | 7.50 ± 4.50 μg·h·mLâ»Â¹ (in dogs) | ~2.2x (vs. SD-1 in dogs) [18] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Soluplus | A polymer used in hot-melt extrusion to create amorphous solid dispersions, enhancing solubility and inhibiting crystallization [18] [19]. |

| HPMCP (HP-55) | A pH-dependent polymer that dissolves in the intestine, used to target drug release and inhibit precipitation in higher pH environments [18]. |

| Formazin Standard | The primary standard suspension for calibrating turbidimeters and nephelometers, ensuring accurate and reproducible turbidity measurements [21]. |

| Lipid Excipients (for SEDDS/SMEDDS) | A mixture of glycerides and surfactants that form fine oil-in-water emulsions upon gentle agitation, maintaining drug solubilization in the gut [19]. |

| Parteck MXP (PVA) | A polyvinyl alcohol polymer with excellent hot-melt extrusion processability, used to inhibit drug recrystallization in solid dispersions [18]. |

| EUDRAGIT Polymers | A family of polymers (e.g., FS 100) allowing for site-specific drug release in the GI tract, enhancing absorption where permeability is highest [19]. |

| 1-Bromopentadecane-D31 | 1-Bromopentadecane-D31, MF:C15H31Br, MW:322.50 g/mol |

| tert-Butyl (4-iodobutyl)carbamate | Tert-butyl 4-iodobutylcarbamate|CAS 262278-40-0 |

Visual Workflows and Diagrams

Diagram 1: Drug Solubility & Bioavailability Workflow

Diagram 2: Light Scattering & Turbidity Measurement

How Turbidity Shelters Pathogens and Affects Drug Safety Profiles

Turbidity, the cloudiness or haziness of a fluid caused by suspended particles, is a critical parameter in both water quality and pharmaceutical manufacturing. While often viewed as a simple aesthetic issue, elevated turbidity provides a protective shield for pathogenic microorganisms, compromising water disinfection and creating significant risks for drug safety and efficacy. In pharmaceutical research and development, unexpected turbidity in drug solutions can indicate physicochemical instability, microbial contamination, or particle aggregation that may alter drug performance. This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers and drug development professionals facing challenges related to sample turbidity and light scattering in their experimental workflows.

FAQs: Turbidity in Pharmaceutical Research

Q1: How does turbidity actually protect pathogens from disinfection methods? Turbidity protects pathogens through physical shielding. Suspended solid particles act as barriers that shield viruses and bacteria from disinfectants like chlorine [22]. Similarly, these suspended solids can protect microorganisms from ultraviolet (UV) sterilization by preventing the light from reaching and damaging the pathogens [22]. The higher the turbidity level, the greater the risk that pathogens may survive disinfection processes, potentially leading to gastrointestinal diseases, especially in immunocompromised individuals [22].

Q2: What level of turbidity in water is considered acceptable for pharmaceutical use? Regulatory standards for turbidity in water vary by region and application. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency requires that public water systems using conventional or direct filtration methods must not have turbidity higher than 1.0 NTU at the plant outlet, with 95% of monthly samples not exceeding 0.3 NTU [22] [23]. The European turbidity standard is higher at 4 NTU [22]. For critical pharmaceutical applications, many utilities strive to achieve levels as low as 0.1 NTU to ensure water purity [22].

Q3: Can turbidity in drug solutions indicate product quality issues? Yes, turbidity in drug solutions can signal significant quality concerns. Microbial contamination of pharmaceuticals can lead to changes in their physicochemical characteristics, potentially altering active ingredient content or converting them to toxic products [24]. A study of nonsterile pharmaceuticals found that 50% of tested products were heavily contaminated with microorganisms including Klebsiella, Bacillus, and Candida species [24]. Such contamination not only poses infection risks but may also cause physicochemical deterioration that renders products unsafe.

Q4: What is the relationship between dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements and turbidity? Dynamic light scattering and turbidity measurements both utilize light interaction with particles but provide different information. DLS analyzes intensity fluctuations from Brownian motion to determine hydrodynamic size of nanoparticles [25] [26], while turbidity measures light scattering and absorption to assess sample cloudiness [22]. For protein formulations and nanomedicines, an increase in turbidity often indicates aggregation that can be further characterized by DLS to determine the size distribution of the aggregates [25].

Q5: How does sample turbidity affect light scattering experiments in drug development? High turbidity can significantly complicate light scattering experiments used in drug development. In DLS, excessively turbid samples can cause multiple scattering effects where scattered light is re-scattered before detection, compromising size measurements [26]. This is particularly problematic when characterizing nanoparticle drug delivery systems where accurate size measurement (typically 10-1000 nm) is essential for predicting biodistribution and targeting efficiency [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Turbidity in Water for Pharmaceutical Use

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consistently high turbidity in source water | Surface water runoff, algal blooms, sediment disturbance | Implement pre-filtration (e.g., sand filters), adjust flocculation/coagulation processes | Regular monitoring of source water quality, watershed management |

| Turbidity spikes after filtration | Filter breakthrough, improper backwashing, membrane damage | Check filter integrity, optimize backwash cycles, replace damaged membranes | Continuous turbidity monitoring of individual filter effluents [23] |

| Variable turbidity affecting processes | Seasonal changes, storm events, upstream contamination | Use ratio turbidimeters for wide measurement range (0.1-10,000 NTU) [23] | Install multiple monitoring points (intake, pre-filtration, post-filtration) [23] |

Guide 2: Managing Turbidity in Drug Formulations and Analysis

| Problem | Impact on Research | Solution Approach | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unexpected turbidity in protein solutions | Indicates aggregation, may affect efficacy and safety | Characterize with DLS/SEC-MALS; optimize buffer conditions | For antibodies/ADCs, monitor aggregation via DLS and intrinsic fluorescence [27] |

| Turbidity interfering with analytical measurements | Compromised UV-Vis spectra, inaccurate concentration readings | Centrifugation or filtration; use alternative detection methods | For DLS, ensure sample turbidity doesn't cause multiple scattering [26] |

| Microbial contamination causing turbidity | Product spoilage, potential toxicity | Implement strict aseptic techniques; add preservatives | Study showed 50% contamination in nonsterile drugs; proper handling critical [24] |

Experimental Protocols and Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Turbidity Measurement and Pathogen Protection Assessment

Objective: Evaluate the relationship between turbidity levels and pathogen protection in pharmaceutical water systems.

Materials:

- Nephelometer or turbidimeter (calibrated with formazin standards)

- Sterile sample cuvettes

- Microfiber cloth for cleaning cuvettes

- Microbial cultures (e.g., Bacillus species)

- Chlorine-based disinfectant

- Culture media (nutrient agar, Sabouraud's dextrose agar)

Methodology:

- Calibrate turbidimeter using standard solutions per manufacturer instructions [28] [23]

- Prepare samples with varying turbidity levels (0.1, 1, 10, 100 NTU) using appropriate particles

- Inoculate samples with standardized microbial inoculum

- Apply disinfectant at specified concentrations and contact times

- Quantify surviving microorganisms using spread-plating on appropriate media [24]

- Correlate survival rates with initial turbidity levels

Table: Typical Turbidity Levels and Implications

| Turbidity Range (NTU) | Classification | Pathogen Protection Potential | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| <0.1 | Excellent | Minimal | Suitable for critical pharmaceutical applications |

| 0.1-1.0 | Good | Low | Meets drinking water standards; acceptable for most uses |

| 1.0-10 | Moderate | Moderate | Requires filtration; investigate source |

| 10-100 | High | Significant | Unsuitable; implement treatment |

| >100 | Very High | Extensive | Reject source water; extensive treatment needed |

Protocol 2: Monitoring Drug Solution Stability via Light Scattering

Objective: Characterize nanoparticle aggregation and stability in drug formulations using dynamic light scattering.

Materials:

- Dynamic light scattering instrument (e.g., DynaPro series)

- Disposable or quartz cuvettes

- Buffer solutions for sample preparation

- Protein/nanoparticle drug formulation

- Centrifugal filters for sample clarification

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Clarify samples by centrifugation if necessary; adjust concentration to instrument specifications [26]

- Instrument Setup: Set temperature to 25°C (or desired condition); select appropriate measurement angle (90° or backscatter) [25]

- Data Acquisition: Perform measurements in triplicate; acquisition time typically 10-30 seconds per run [29]

- Size Analysis: Use autocorrelation function and Stokes-Einstein relationship to calculate hydrodynamic radius [26]

- Stability Assessment: Monitor changes in size distribution and polydispersity index over time or under stress conditions

Table: DLS Size Interpretation for Drug Nanoparticles

| Hydrodynamic Size Range | Polydispersity Index (PDI) | Interpretation | Formulation Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| <10 nm | <0.1 | Monodisperse, likely monomers | Optimal for tissue penetration |

| 10-100 nm | 0.1-0.2 | Near-monodisperse | Ideal for drug delivery; avoids RES clearance [26] |

| 100-500 nm | 0.2-0.3 | Moderately polydisperse | May include some aggregates |

| >500 nm | >0.3 | Highly polydisperse, aggregated | Significant stability issues; requires reformulation |

Visualization: Turbidity and Pathogen Protection Mechanisms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Materials for Turbidity and Light Scattering Research

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Formazin Standard | Primary turbidity calibration reference [23] | Provides consistent polymer size distribution; available at various NTU values |

| Nephelometer | Measures scattered light at 90° for low turbidity samples [22] [23] | Ideal for compliance monitoring; range typically 0-1000 NTU |

| Ratio Turbidimeter | Measures multiple angles for high turbidity samples [23] | Handles extreme ranges (0.1-10,000 NTU); uses transmitted and reflected light |

| Dynamic Light Scattering Instrument | Measures hydrodynamic size of nanoparticles [25] [26] | Essential for characterizing protein aggregates, liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles |

| Sterile Sample Cuvettes | Holds samples for turbidity and DLS measurements | Must be clean, scratch-free; fingerprints affect readings [28] |

| Microfiber Cloth | Cleans cuvette surfaces without scratching [28] | Critical for removing smudges that cause false high readings |

| Membrane Filters | Removes particles for sample clarification | Various pore sizes (0.22 μm for sterilization, 0.02 μm for nanoparticles) |

| Buffer Components (PBS, etc.) | Provides controlled ionic environment | Affects particle stability and aggregation; must be particle-free |

| 1,3-Dimethoxybenzene-D10 | 1,3-Dimethoxybenzene-D10, MF:C8H16O2, MW:154.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 4E-Deacetylchromolaenide 4'-O-acetate | 4E-Deacetylchromolaenide 4'-O-acetate, MF:C22H28O7, MW:404.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Turbidity serves as both an indicator of water quality and a direct factor in compromising drug safety profiles by sheltering pathogens from disinfection methods. Through proper monitoring techniques, including nephelometry for turbidity assessment and dynamic light scattering for nanoparticle characterization, researchers can identify and mitigate risks associated with particulate contamination. The protocols and troubleshooting guides presented here provide practical approaches for maintaining sample integrity throughout pharmaceutical development processes, ultimately contributing to safer and more effective drug products.

In Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), the path a photon takes before reaching the detector fundamentally determines the reliability of your size measurements. Single scattering occurs when a photon scatters off a single particle before being detected, providing direct information about that particle's Brownian motion. In contrast, multiple scattering happens when photons are scattered multiple times by different particles before reaching the detector, which randomizes the signal and compromises data accuracy [30] [31].

For researchers in drug development, managing this distinction is crucial when working with turbid samples like drug solutions and formulations. Multiple scattering becomes significant when sample turbidity increases, typically at high particle concentrations, leading to underestimated particle sizes and misleading conclusions about product stability and efficacy [30] [32].

Theoretical Foundations: Single vs. Multiple Scattering

The Ideal Case: Single Scattering

In a single scattering event, laser light interacts with a particle undergoing Brownian motion, scattering once, and then travels directly to the detector. The random motion of the particle causes Doppler broadening of the laser frequency, creating detectable intensity fluctuations over time [15].

These intensity fluctuations are analyzed via the autocorrelation function, which decays at a rate proportional to the particle's diffusion speed. The correlation function for a monodisperse sample in single scattering conditions follows a predictable exponential decay pattern [33] [34]:

g¹(q;τ) = exp(-Γτ)

where Γ is the decay rate, τ is the delay time, and q is the scattering vector. This relationship enables precise calculation of the hydrodynamic radius via the Stokes-Einstein equation [33] [34].

The Problem: Multiple Scattering

Multiple scattering occurs predominantly in turbid or concentrated samples where the mean free path of photons between particles is short. In this scenario, photons undergo a series of scattering events before detection, creating a composite signal that no longer accurately represents the motion of any single particle [30] [31].

Table 1: Key Differences Between Single and Multiple Scattering

| Characteristic | Single Scattering | Multiple Scattering |

|---|---|---|

| Photon Path | One scattering event before detection | Multiple scattering events before detection |

| Information Content | Direct relationship to particle diffusion | Randomized, indirect relationship to diffusion |

| Apparent Size | Accurate hydrodynamic radius | Artificially smaller sizes |

| Sample Concentration | Dilute, transparent samples | Concentrated, turbid samples |

| Correlation Function | High intercept, clear decay | Reduced intercept, faster decay |

| Polydispersity | Accurate representation | Artificially broadened |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in photon paths between single and multiple scattering scenarios:

Multiple scattering increases the randomness of the scattering signal, decreasing the correlation and making particles appear to move faster than they actually are. The net result is that DLS size measurements in the presence of multiple scattering are biased toward smaller sizes [30].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying Multiple Scattering

Key Symptoms of Multiple Scattering

Researchers should be alert to these telltale signs of multiple scattering in their DLS data:

Concentration-Dependent Sizing: Apparent particle size decreases systematically with increasing sample concentration [30] [32].

Reduced Correlation Function Intercept: The measured intercept (amplitude) of the correlation function decreases at higher concentrations [30].

Increased Apparent Polydispersity: The size distribution appears broader than expected, with the width increasing with concentration [30].

Unphysical Results: Size measurements that contradict other characterization methods or known sample properties [32].

Table 2: Quantitative Symptoms of Multiple Scattering in a 200 nm Polystyrene Standard

| Concentration | Apparent Size (nm) | Correlation Intercept | Polydispersity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dilute | 200 | 0.95 | 0.02 |

| Moderate | 185 | 0.85 | 0.08 |

| High | 160 | 0.70 | 0.15 |

| Very High | 135 | 0.55 | 0.25 |

Data adapted from Malvern Panalytical technical documentation [30].

Experimental Protocols for Detection

Protocol 1: Concentration Series Test

- Prepare a series of dilutions from your stock sample

- Measure each concentration using the same DLS settings

- Plot apparent size and correlation function intercept against concentration

- Interpretation: A significant decrease in either parameter indicates multiple scattering becoming dominant [30]

Protocol 2: Path Length Dependence

- Use an instrument with variable measurement position capability

- Measure the same sample at different path lengths from the cuvette wall

- Compare the apparent sizes obtained

- Interpretation: Significant differences indicate multiple scattering effects [30]

Solutions and Mitigation Strategies

Sample Preparation Approaches

Optimal Dilution: The most straightforward approach is diluting the sample until the measured size becomes concentration-independent. This establishes the optimal concentration range for accurate DLS analysis [30] [32].

Sample Clarification: Remove dust and aggregates through centrifugation or filtration. For proteins, consider centrifugation at 10,000-15,000 × g for 10-30 minutes before measurement [33] [15].

Solvent Matching: For nanoparticle dispersions, ensure the dispersant has similar refractive index to the particles where possible, though this must be balanced with maintaining colloidal stability [35].

Instrumental Solutions

Backscatter Detection (NIBS): Non-Invasive Back Scatter technology measures at an angle of 173° and automatically positions the measurement point within the sample. This minimizes the path length that scattered light travels through the sample, reducing the probability of multiple scattering [30].

Cross-Correlation Techniques: 3D-dynamic light scattering methods use two beams and detectors to isolate singly scattered light by cross-correlation, effectively suppressing contributions from multiple scattering [33].

Low-Angle Measurements: For some samples, particularly those containing large aggregates, measurements at lower angles (as low as 15°) can provide better characterization, though these require specialized instrumentation [33] [32].

Table 3: Instrument Configuration Guide for Turbid Samples

| Sample Type | Recommended Angle | Optical Configuration | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transparent, small particles | 90° | Side scattering | Maximizes signal for weakly scattering samples |

| Moderately concentrated | 173° | Backscatter (NIBS) | Reduces path length, minimizes multiple scattering |

| Highly concentrated, opaque | 173° with adjusted position | Backscatter with reduced path length | Further minimizes multiple scattering effects |

| Samples with large aggregates | 13-15° | Forward scattering | Enhances sensitivity to large particles |

Alternative Techniques for Highly Turbid Samples

When multiple scattering cannot be sufficiently suppressed in DLS, consider these alternative approaches:

Diffusing-Wave Spectroscopy (DWS): A specialized technique for strongly scattering media that explicitly accounts for multiple scattering, though it requires different theoretical analysis [33].

Nephelometry: Measures scattered light intensity at specific angles, useful for aggregation studies and solubility screening in drug development [36].

Asymmetrical Flow Field-Flow Fractionation (AF4): Separates particles by size before detection, allowing analysis of complex mixtures and overcoming some limitations of batch DLS [35].

FAQs: Addressing Common Researcher Concerns

Q1: My drug formulation is turbid due to high concentration. How can I obtain accurate DLS data? A: Implement a backscatter (NIBS) detection system if available, as it can measure much higher concentrations than conventional 90° systems. Alternatively, use the concentration series approach to identify the maximum concentration where sizing remains consistent, then report this diluted size with appropriate caveats [30].

Q2: How does multiple scattering lead to artificially small sizes? A: Multiple scattering increases the randomness of photon arrival times at the detector, making the intensity fluctuations appear faster. Since faster fluctuations are interpreted as faster diffusion (and thus smaller size), the apparent hydrodynamic radius is underestimated [30] [31].

Q3: Are single-angle DLS instruments suitable for characterizing nanoparticles for drug delivery? A: Single-angle instruments at large angles (90° or 173°) have limitations for precise size determination, particularly for non-spherical particles or complex mixtures. Their results should be interpreted with caution, and multiangle DLS is recommended for rigorous characterization, especially when correlating size with biological behavior [32].

Q4: What concentration range typically avoids multiple scattering issues? A: The optimal concentration depends on particle size and optical properties. As a general guideline, the sample should be sufficiently transparent that you can clearly read text through a standard cuvette filled with the sample. Empirically, perform a dilution series to identify where measured size becomes concentration-independent [30] [32].

Q5: How does serum protein binding affect DLS measurements of nanomedicines? A: Serum proteins form a "corona" around nanoparticles, increasing their apparent size and potentially causing aggregation. This represents a real physicochemical change rather than an artifact, but requires careful interpretation since the measured size now includes both the nanoparticle and its protein corona [32].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Materials for Reliable DLS Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Size Standards | Verification of instrument performance and methodology | Use NIST-traceable nanosphere standards (e.g., 100 nm polystyrene) |

| Syringe Filters | Sample clarification | 0.02-0.45 μm pore size, compatible with sample solvent |

| Ultrapure Salts | Control ionic strength | For buffer preparation to maintain colloidal stability |

| Refractometer | Measure solvent refractive index | Critical for accurate size calculation via Stokes-Einstein equation |

| Quality Cuvettes | Sample containment | Optically clear, chemically clean, appropriate path length |

Understanding and managing multiple scattering effects is fundamental to obtaining accurate DLS data, particularly in pharmaceutical research where samples often include turbid drug formulations and complex biological media. By recognizing the symptoms of multiple scattering and implementing appropriate mitigation strategies—whether through sample preparation, instrumental configuration, or alternative techniques—researchers can ensure their size measurements reliably reflect true particle characteristics rather than optical artifacts.

The key principles are to validate your methodology with concentration series, utilize appropriate detection geometry for your sample type, and interpret DLS data with awareness of its limitations in complex, concentrated systems. With these approaches, DLS remains an invaluable tool for characterizing drug delivery systems and biopharmaceuticals across the development pipeline.

In drug development and research, managing sample turbidity is a critical parameter for ensuring product quality, safety, and efficacy. Turbidity, the cloudiness or haziness of a fluid caused by suspended particles, serves as a key indicator in various biopharmaceutical processes. It can signal the presence of unwanted particulates, inform on cell density in bioreactors, or affect the analysis of drug solutions themselves. This technical support guide focuses on the precise measurement of turbidity, specifically explaining the two predominant units—NTU and FNU—their appropriate applications, and troubleshooting common issues encountered by researchers and scientists. Understanding these concepts is fundamental for maintaining rigorous standards in pharmaceutical manufacturing and research, where the accurate quantification of suspended matter can directly impact product stability, sterility, and final release.

Understanding Turbidity Units: NTU vs. FNU

Turbidity is quantified using standardized units, with Nephelometric Turbidity Units (NTU) and Formazin Nephelometric Units (FNU) being the most prevalent in scientific and industrial applications. Both units are calibrated using the same primary standard, Formazin, and both measure the intensity of light scattered at a 90-degree angle from the incident beam, a method known as nephelometry [37] [38]. Despite these similarities, the crucial difference lies in the instrumentation and the underlying regulatory standards they comply with.

The table below provides a clear comparison of these two units:

Table: Key Differences Between NTU and FNU

| Feature | NTU (Nephelometric Turbidity Unit) | FNU (Formazin Nephelometric Unit) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Measures scattered light at a 90-degree angle | Measures scattered light at a 90-degree angle |

| Light Source | White light (visible spectrum, 400-600 nm) [37] | Infrared light (860 nm) [37] |

| Governing Standard | US EPA Method 180.1 [37] [38] | ISO 7027 (European standard) [37] [38] |

| Primary Application | Common in drinking water and wastewater treatment under US regulations; used in various industrial and research settings [38]. | Preferred in European markets and for applications requiring compliance with ISO standards; ideal for colored samples [37] [38]. |

| Key Advantage | Well-established protocol in the US. | Infrared light minimizes color interference, providing more reliable readings for colored samples [38]. |

For most practical purposes, 1 NTU is considered equivalent to 1 FNU on a Formazin standard scale [39]. However, it is critical to understand that measurements taken on the same sample with different light sources (white vs. infrared) may yield different values due to the varied interaction of light with particle size and color [37]. This distinction is vital for data comparison and regulatory reporting.

Other units you may encounter include:

- FTU (Formazin Turbidity Unit): A generic unit that does not specify the measurement method [38] [39].

- FAU (Formazin Attenuation Unit): Measures the reduction (attenuation) of transmitted light at 180 degrees and is not recognized by most regulatory agencies for compliance turbidity measurement [37] [38].

- JTU (Jackson Turbidity Units): An outdated, visual method that is no longer in common use [38].

Visualizing Turbidity Measurement Principles

The following diagram illustrates the core principles of nephelometric turbidity measurement and the key difference between NTU and FNU.

Troubleshooting Common Turbidity Meter Issues

Accurate turbidity measurement is sensitive to technique and instrument status. The following guide addresses common problems, their causes, and solutions relevant to a research environment.

Table: Turbidity Meter Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate/ High or Low Values | 1. Contaminated optics: Dust, fingerprints, or dried residue on vial or lens [7] [4].2. Improper calibration: Out-of-date standards, incorrect procedure, or contaminated standards [7].3. Scratched or faulty cuvette: Scratches can scatter light [7] [4]. | • Clean optical surfaces and vials with lint-free cloth and recommended solution [7].• Follow manufacturer's calibration procedure precisely using fresh, certified standards [7] [40].• Inspect and replace damaged cuvettes [7]. |

| Unstable/ Erratic Readings | 1. Settling or sedimentation: Particles settling during measurement [41].2. Air bubbles (microscopic): Tiny bubbles scatter light [7] [41] [4].3. Insufficient warm-up time: Electronics or lamp not stable [7]. | • Ensure homogeneous sample mixing before measurement [7].• Allow sample to decant after mixing to let bubbles rise; handle gently to avoid introducing bubbles [7].• Use the meter's signal-averaging function (e.g., 5-10 measurements) [41].• Allow instrument to warm up for the recommended time [7]. |

| Negative Results | 1. Sample clearer than blank: Sample turbidity is at or below the instrument's blank reference [41].2. Incorrect blanking: Meter was accidentally blanked on a turbid standard [41]. | • Verify sample is expected to be more turbid than the blank.• Restore factory calibration settings and re-perform blanking with a true 0 NTU standard [41]. |

| Calibration Errors | 1. Standard out of tolerance: Reading deviates too far from expected value (e.g., >50%) [41].2. Using a zero sample to calibrate: Attempting to use the blank for calibration instead of only for setting the blank reference [41]. | • Use fresh, in-date calibration standards. Ensure standards match the instrument's requirements [7] [41].• Blank the meter with a 0 NTU standard, then calibrate with an appropriate non-zero standard (e.g., 1.0, 10 NTU) [41]. |

| Power/ Electronic Issues | 1. Low or faulty battery: Inconsistent power leads to unreliable operation [7] [41].2. Loose connections: Cables or battery not secure [7]. | • Use high-quality, brand-name alkaline batteries or operate with an AC adapter [41].• Check and secure all electrical connections [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the correlation between turbidity (NTU/FNU) and suspended solids (mg/L)? While the relationship is empirical and sample-specific, a rough correlation exists: 1 mg/L of suspended solids is approximately equal to 3 NTU [38]. However, this factor can vary significantly depending on the size, shape, and refractive index of the particles, so site-specific calibration is recommended for precise work.

Q2: My turbidimeter displays an "Err 2" message. What does this mean? An "Err 2" typically indicates a calibration error where the reading of the standard solution deviates by more than the allowable range (often more than 50%) from its stated value [41]. This is usually caused by using expired or inappropriate standard solutions, or a problem with the initial blanking step. Check the standard's shelf life, reset the meter to factory calibration, and ensure proper blanking [41].

Q3: Why should I use an infrared (FNU) meter for my drug solution samples? Infrared light (as used in FNU meters per ISO 7027) is less susceptible to interference from the color of a sample [37] [38]. If your drug solutions have any intrinsic color, using an FNU-compliant instrument can provide more accurate turbidity readings by minimizing this color-induced error.

Q4: How often should I calibrate my turbidity meter? For research-grade accuracy, calibrate your meter before each use or at least at the beginning of each analytical session [4]. Always recalibrate if you change the measurement range, when using a new batch of standards, or if you suspect the results are inaccurate [7] [40].

Q5: Are there any safety concerns with turbidity calibration standards? Yes, the primary standard, Formazin, is traditionally made from hydrazine sulfate, a carcinogenic substance [42]. For safety, many commercial suppliers offer ready-made, stable Formazin solutions or safer, polymer-based surrogate standards that are certified to be equivalent. Always check the Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) and handle all standards with appropriate laboratory safety practices.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key materials and reagents essential for performing accurate turbidity measurements in a research and development context.

Table: Essential Reagents and Materials for Turbidity Analysis

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Formazin Standards | Primary reference material for calibrating turbidity meters across all scales (NTU, FNU, etc.) [38] [42]. Available in various concentrations (e.g., 0.1, 1, 10, 100, 1000 NTU). |

| Deionized/Distilled Water | Used for preparing blank (0.00 NTU) standards, diluting samples, and rinsing cuvettes to prevent contamination [4]. |

| Particle-Bound Antibodies | Critical reagent in immunoturbidimetric assays, where antigen-antibody complex formation increases turbidity for quantitative analysis of specific proteins or biomarkers [4]. |

| Reaction Buffer | Provides the optimal pH and ionic strength environment for consistent and reproducible reaction conditions, particularly in kinetic or biochemical turbidimetry [4]. |

| Antigen Standards | Used in immunoturbidimetry to create a standard curve for determining the concentration of an unknown antigen in a sample [4]. |

| Lint-Free Wipes | Essential for properly cleaning the external surfaces of sample cuvettes without introducing scratches or fibers that can scatter light and cause errors [7] [41]. |

| Certified Cuvettes | Specially designed vials that ensure consistent optical path length and clarity. Using scratched or non-certified cuvettes can lead to significant measurement inaccuracies [7]. |

| Disialyloctasaccharide | Disialyloctasaccharide, CAS:58902-60-6, MF:C76H125N5O57, MW:2020.8 g/mol |

| 6-Bromo-2-chloroquinolin-4-amine | 6-Bromo-2-chloroquinolin-4-amine, CAS:1256834-38-4, MF:C9H6BrClN2, MW:257.51 g/mol |

Analytical Techniques and Practical Applications: DLS, Nephelometry, and Sample Preparation

Why Turbidity Challenges DLS Measurements

In DLS, the fundamental theory assumes a single scattering event: a photon hits a particle, scatters once, and is detected [43]. Turbid samples, with their high concentration of particles or strongly scattering particles, violate this assumption. Here, photons are likely to be scattered multiple times before being detected—a phenomenon known as multiple scattering [43] [44].

Multiple scattering corrupts the core measurement because the detected fluctuation signal no longer corresponds to the true, fast Brownian motion of a single particle. Instead, it reflects a slower, composite motion, leading to the calculation of an apparently smaller particle size and unreliable data [44].

Methodologies for Reliable DLS in Turbid Samples

Several advanced methodologies have been developed to overcome the challenge of multiple scattering.

Technical Instrument Solutions

Modern DLS instruments incorporate hardware and optical configurations to physically minimize multiple scattering.

| Solution | Principle | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Backscattering Detection (173°-175°) [45] [43] | Detects scattered light at a near-180° angle, placing the scattering volume close to the cuvette wall. | Drastically reduces the photon path length in the sample, minimizing chances for multiple scattering. Ideal for concentrated/turbid samples [45]. |

| Adjustable Laser Focus Position [45] [43] | The instrument shifts the laser's focus point closer to the inner wall of the cuvette. | Further shortens the light path within the sample, enhancing the effectiveness of backscattering measurements [43]. |

| Automatic Angle & Position Selection [45] [43] | The instrument measures transmittance and other parameters to automatically select the optimal detection angle and focus position. | Removes user guesswork, ensuring the best possible configuration for a given sample's turbidity [43]. |

| Specialized Advanced Techniques [44] | Uses two independent laser beams detecting the same scattering volume and cross-correlates the signals. | Physically suppresses the contribution of multiple scattering to the correlation function, as these events are uncorrelated between the two beams [44]. |

Sample Preparation and Measurement Protocol

Proper sample handling is crucial for obtaining meaningful data from turbid samples.

- Sample Viscosity: Ensure the sample viscosity does not exceed 10 cP for reliable analysis [46].

- System Suitability: Use a monodisperse, standard reference material (e.g., 200 nm polystyrene latex spheres) at a comparable concentration to your sample to verify instrument performance under turbid conditions [44].

- Data Quality Verification: Before starting the actual measurement, use the instrument's live view to check the intensity trace and correlation function.

- The intensity trace should show regular fluctuations. Sharp spikes may indicate dust, while a steady ramp up or down can signal aggregation or sedimentation [45].

- The correlation function should be smooth with a single exponential decay. A non-linear baseline or "bumps" suggest the presence of large contaminants or aggregates [45].

The following workflow summarizes the key decision points for analyzing a turbid sample via DLS:

Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key materials required for DLS analysis of turbid samples.

| Item | Function | Specification Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Cuvettes | Holds the liquid sample for measurement. | Standard square or cylindrical cells for clear to moderately turbid samples. |

| High-Concentration Cuvettes | Holds the liquid sample for measurement. | Specialized cells (e.g., ultra-thin flat cells) with reduced path lengths (e.g., 10 µm to 1 mm) to minimize multiple scattering [44]. |

| Size Reference Standards | Validates instrument performance and method accuracy under turbid conditions. | Monodisperse polystyrene latex spheres (e.g., 200 nm nominal diameter) [44]. |

| Filtration/Syringe Filters | Removes dust and large aggregates from solvents and samples. | Use appropriate pore sizes (e.g., 0.1 µm or 0.22 µm) before loading samples into cuvettes [47]. |

| Viscosity Standard | Verifies accurate viscosity input for the Stokes-Einstein equation. | Certified oil or solvent with known viscosity at the measurement temperature. |

| Methylcobalamin hydrate | Methylcobalamin hydrate, MF:C63H93CoN13O15P, MW:1362.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 5-Methyl-2-thiouridine | 5-Methyl-2-thiouridine, CAS:32738-09-3, MF:C10H14N2O5S, MW:274.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can DLS be used for turbid samples at all? Yes, this is a common misconception. While standard DLS setups may struggle, modern instruments with backscattering detection (175°), adjustable laser focus, and automatic angle selection are specifically designed to provide reliable data for turbid samples [45] [43].

Q2: My DLS results for a turbid sample show a smaller size than expected. What is the likely cause? This is a classic signature of multiple scattering. When photons are scattered multiple times, the detected motion appears slower, and the correlation function decays faster, leading to an underestimation of the true particle size [44]. Switching to a backscattering geometry is the primary solution.

Q3: How does sample concentration affect my DLS measurement? Finding the right concentration is critical. Excessively high concentrations cause multiple scattering, distorting results [47]. Conversely, overly dilute samples may not scatter enough light, leading to a poor signal-to-noise ratio [45] [47]. The optimal concentration provides a strong signal without causing multiple scattering.

Q4: What are the key indicators of good data quality in a DLS measurement for a turbid sample? Monitor the correlation function: it should be smooth with a single exponential decay and a stable, linear baseline. Also, observe the intensity trace: it should show regular fluctuations without sharp spikes (dust) or steady ramping (sedimentation/aggregation) [45]. A high intercept value in the correlation function also indicates good signal quality [48].

Q5: Are there alternatives to standard DLS for highly turbid samples? Yes, advanced techniques exist. 3D Dynamic Light Scattering (3D-DLS) uses cross-correlation of two laser beams to suppress signals from multiple scattering physically [44]. Diffusing Wave Spectroscopy (DWS) leverages multiple scattering but requires a different theoretical model and is less sensitive to particle size distribution [44].

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) is a cornerstone technique for determining the size distribution of nanoparticles in suspension. For researchers in drug development, analyzing turbid or highly concentrated samples—common in lipid nanoparticle or protein formulation workflows—presents a significant challenge due to the phenomenon of multiple scattering, where photons are scattered by more than one particle before detection. This scrambles the signal and makes accurate size determination difficult. Utilizing a back-scattering detection angle, typically at 175°, provides an effective solution to this problem by minimizing the path length of the laser light within the sample, thereby substantially reducing multiple scattering events. This configuration is indispensable for obtaining reliable data from challenging, yet industrially relevant, biopharmaceutical samples.

Core Principles and Advantages of the 175° Angle

How Back-Scattering Minimizes Multiple Scattering

In a standard DLS setup, a laser is directed into a sample, and the scattered light is detected at a specific angle. The core principle of back-scattering detection lies in the strategic placement of the scattering volume. When the detector is positioned at 175°, the overlap between the incident laser beam and the detected scattered light occurs very close to the front wall of the cuvette. This configuration results in a very short path length for the laser light within the sample [45].

This short path is crucial because it drastically reduces the probability that a single photon will be scattered by multiple particles on its journey. In highly turbid samples, a longer path length (as encountered in a 90° side-scattering geometry) makes multiple scattering inevitable. By minimizing these events, back-scattering ensures that the detected fluctuations in light intensity are predominantly caused by Brownian motion of single particles, leading to a more accurate autocorrelation function and, consequently, a more reliable particle size distribution [45] [33]. For larger particles and those with a high refractive index contrast, this limits the technique to very low particle concentrations without a cross-correlation or back-scattering approach [33].

Operational Advantages for Drug Solution Research

The primary advantage of this configuration is the ability to analyze samples that would otherwise be inaccessible to conventional DLS. This directly enhances efficiency in drug development pipelines by minimizing the need for sample dilution, which can alter the state of the particles and provide unrepresentative results [49].

Key benefits include:

- Measurement of Concentrated Formulations: Enables direct sizing in liposomal, polymeric nanoparticle, and protein suspension formulations at their processing concentrations [49].

- Improved Data Quality: Provides a cleaner signal from turbid samples by suppressing the noise introduced by multiple scattering [45] [33].