Mastering Baseline Drift: A Scientist's Guide to Stable Measurements in Sensitive Instruments

This comprehensive guide addresses the pervasive challenge of baseline drift in sensitive analytical instruments, a critical issue for researchers and drug development professionals seeking reliable data.

Mastering Baseline Drift: A Scientist's Guide to Stable Measurements in Sensitive Instruments

Abstract

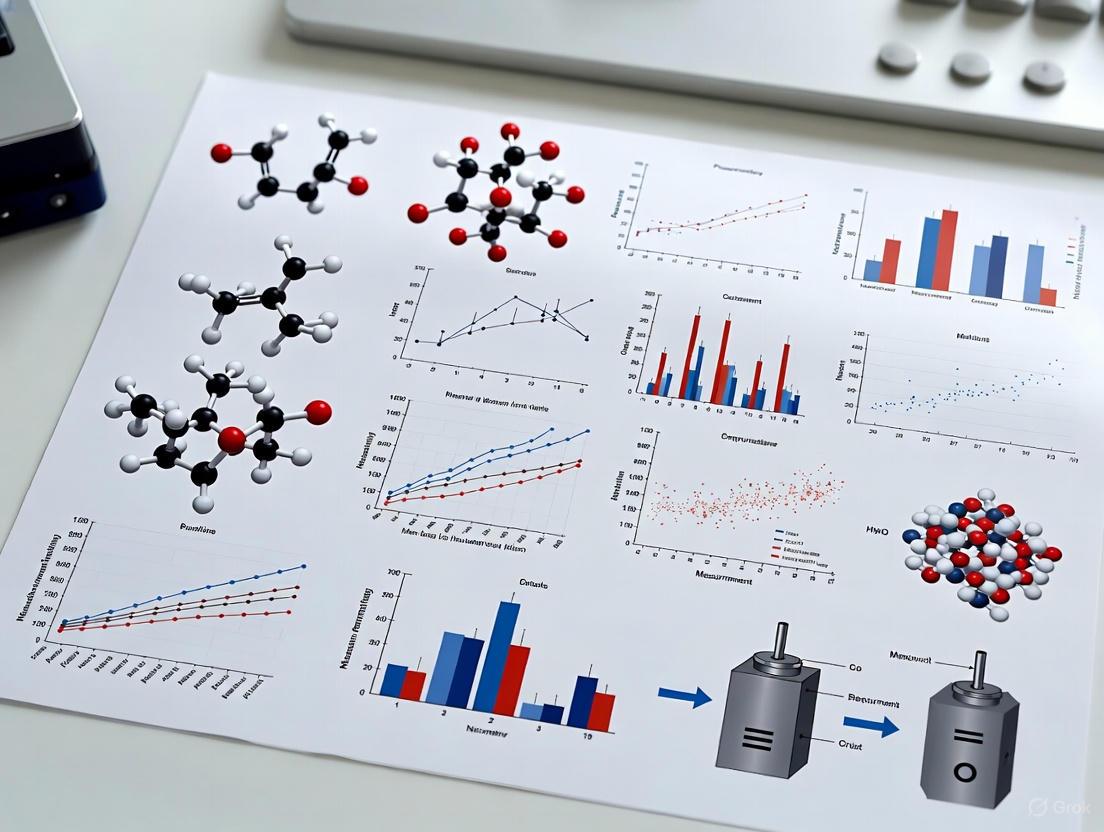

This comprehensive guide addresses the pervasive challenge of baseline drift in sensitive analytical instruments, a critical issue for researchers and drug development professionals seeking reliable data. The article provides a foundational understanding of drift types—including zero, span, and zonal drift—and their root causes across systems like HPLC, SPR, and HPLC-ECD. It details proven methodological approaches for correction, from algorithmic post-processing to optimized experimental setup. A systematic troubleshooting framework, supported by real-world case studies, empowers scientists to diagnose and resolve drift issues efficiently. Finally, the guide covers validation strategies and comparative analyses of correction techniques, ensuring data integrity and enhancing research outcomes in biomedical and clinical applications.

What is Baseline Drift? Understanding the Fundamentals of Measurement Instability

What are the fundamental types of measurement drift?

In sensitive instrumentation, measurement drift is a gradual shift in an instrument's measured values over time, leading to errors if uncorrected [1]. Nearly all measuring instruments experience drift during their lifetime, which can compromise data quality and cause safety hazards [1]. The primary types of drift are categorized based on how they affect the measurement range [1] [2].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each drift type.

| Type of Drift | Alternate Name | Description of Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Zero Drift | Offset Drift | A consistent, uniform shift across all measured values in the range [1]. |

| Span Drift | Sensitivity Drift | A proportional increase or decrease in measured values that grows as the measured value moves away from the calibrated baseline [1]. |

| Zonal Drift | - | A shift away from calibrated values that occurs only within a specific range of measured values, while other ranges remain accurate [1]. |

| Combined Drift | - | The simultaneous occurrence of multiple types of drift (e.g., both Zero and Span Drift) in a single instrument [1]. |

What causes drift in sensitive instruments, and how can I manage it?

Drift arises from multiple factors. Understanding these causes is the first step in managing them effectively [1] [2].

Causes of Measurement Drift

- Environmental Changes: Fluctuations in temperature and humidity are common causes [1] [2].

- Instrument Aging: Normal wear and tear or aging of electronic components lead to long-term drift [1] [3].

- Physical Stress: Sudden shock, vibrations, or improper handling can accelerate drift [1].

- Electrical Interference: Electromagnetic fields or variations in power supply can affect readings [2].

- Chemical Contamination: Debris buildup or sensor poisoning, particularly in gas sensors and chromatography systems, alters performance [1] [3].

Proactive Drift Management Strategies

Managing drift requires a systematic approach combining preventive maintenance, continuous monitoring, and process control.

- Regular Calibration: Perform periodic calibration against traceable standards, adjusting zero before span [4] [2].

- Environmental Control: Maintain stable temperature and humidity in the laboratory environment [1] [2].

- Use Reference Standards: Use in-house reference tools with known values for regular cross-checking [1].

- Proper Handling: Treat instruments as delicate equipment, avoiding drops, bumps, and misuse [1].

- Preventive Maintenance: Implement scheduled cleaning, lubrication, and component replacement [1] [2].

- Statistical Process Control: Track reference values on control charts to reveal trends and identify root causes [1].

How do I troubleshoot a drifting baseline in my chromatogram?

Baseline drift in analytical techniques like Gas Chromatography (GC) is a common but solvable problem. The underlying causes fall into distinct categories, allowing for efficient diagnosis [5].

The workflow above provides a systematic troubleshooting path. Key experimental protocols for resolving common issues include:

- Diagnosing Detector Gas Flow Issues: Use a digital gas flow meter to independently measure each detector gas flow (e.g., FID fuel, air, and makeup gas). Compare measured values against the instrument's set points to identify inconsistencies, often caused by faulty gas generators or regulator failures [5].

- Proper Column Equilibration (Conditioning): Flawed conditioning accelerates column bleed. To properly purge and equilibrate a new GC column [5]:

- Connect the column with carrier gas flowing.

- Purge at room temperature for at least 6 column volumes to remove dissolved oxygen from the stationary phase. Calculate time using:

Column Volume (min) = [L(mm) x π x (id/2)²] / Flow Rate (mL/min). - After purging, begin a slow temperature ramp to the method's maximum temperature.

How can I detect and correct for drift in high-throughput screening (HTS) data?

Traditional quality control (QC) metrics in drug screening (like Z-prime) often fail to detect systematic spatial artifacts on assay plates because they rely solely on control wells [6]. A control-independent approach is needed.

Advanced QC Metric: Normalized Residual Fit Error (NRFE)

The Normalized Residual Fit Error (NRFE) metric evaluates plate quality directly from drug-treated wells by analyzing deviations between observed and fitted dose-response values [6]. This method can identify systematic spatial errors (e.g., edge effects, pipetting stripes) that traditional metrics miss.

- Experimental Protocol for NRFE Analysis: Researchers can implement NRFE using the

plateQCR package available athttps://github.com/IanevskiAleksandr/plateQC[6]. The workflow involves:- Inputting raw dose-response data with plate location information.

- Fitting a model to the dose-response curves for each compound.

- Calculating the NRFE based on the residual errors between the observed data and the model fit.

- Flagging plates with an NRFE value above a predetermined threshold (e.g., >15 indicates low quality, 10-15 requires scrutiny, and <10 is acceptable) [6].

- Validation: Analysis of over 100,000 duplicate measurements showed that NRFE-flagged experiments had a 3-fold lower reproducibility among technical replicates. Integrating NRFE with existing QC methods improved cross-dataset correlation in the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) project from 0.66 to 0.76 [6].

What are the essential tools and reagents for researching drift?

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential materials used in experiments focused on understanding and compensating for drift, as derived from cited research.

| Item | Function / Relevance in Drift Research |

|---|---|

| Stable Reference Standards | Known-value substances for regular instrument calibration and accuracy verification [2]. |

| Calibrated Source/Signal Generator | Provides a highly accurate simulated input (e.g., pressure, electrical signal) for zero and span adjustments [4]. |

| Digital Gas Flow Meter | Critical for diagnosing and verifying detector gas flows in GC, a common source of baseline drift and noise [5]. |

| Controlled Analytic Samples (e.g., Diacetyl, Ethanol) | Well-characterized volatile compounds for generating long-term drift datasets in gas sensor and E-nose studies [3]. |

| Electronic Nose (E-nose) System | A multi-sensor array platform for studying first-order (sensor aging) and second-order (environmental) drift effects [3]. |

plateQC R Package |

Software tool for implementing the NRFE metric to detect spatial artifacts in high-throughput drug screening plates [6]. |

| L-366682 | L-366682, CAS:127819-96-9, MF:C40H53N9O6, MW:755.9 g/mol |

| LY3200882 | LY3200882|ALK5 Inhibitor|For Research Use |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the critical rule for the order of adjustments during calibration?

Always perform zero adjustment before span adjustment. Adjusting the span can affect the zero point, so a final re-check of the zero is also recommended [4].

Q2: What is the difference between short-term and long-term drift?

Short-term drift is temporary, often caused by factors like thermal expansion or vibrations; values often return to normal once the influence is removed. Long-term drift is typically permanent and caused by regular wear and tear or component aging, usually requiring a physical adjustment or calibration to correct [1] [2].

Q3: My instrument has automatic zeroing. Is that sufficient to control drift?

Automatic zeroing is helpful for compensating for zero drift but does not address span drift or zonal drift. A full calibration cycle that includes both zero and span checks is necessary for comprehensive drift management [2].

Q4: In chromatography, what is the visual difference between column bleed and contamination?

True column bleed typically manifests as a smooth, rising baseline. Discrete peaks or a noisy, erratic baseline are more likely caused by contamination from late-eluting compounds or a dirty detector [5].

The Impact of Drift on Data Quality and Research Outcomes

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide: HPLC Baseline Drift

Q: What is baseline drift and how does it affect my research data? A: Baseline drift refers to a gradual, one-directional change in the background signal of sensitive measurement instruments over time, such as in High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) [7]. In an ideal system, the baseline should remain stable when no sample is being analyzed. Drift obscures low-intensity peaks, compromises quantification accuracy, and can lead to incorrect interpretations of research outcomes, ultimately reducing data reliability and reproducibility [8] [9].

Q: What are the most common causes of baseline drift in sensitive instruments? A: Causes can be chemical or physical. Common sources include [7] [8] [9]:

- Temperature Fluctuations: Changes in laboratory or detector temperature.

- Mobile Phase Issues: Contaminated solvents, degassing problems, or impurities.

- Column-Related Problems: Elution of residual components or leaching from packing materials.

- Equipment Malfunction: Inconsistent pump flow or stuck check valves.

Q: My HPLC-ECD baseline is drifting. What should I check first? A: For HPLC with Electrochemical Detection (ECD), follow this systematic approach [7]:

- Stabilize Temperature: Ensure the laboratory temperature has been stable for at least two hours. Place mobile phase bottles in a water bath to buffer against room temperature changes.

- Diagnose the Source: Temporarily remove the analytical column and replace it with a zero-dead-volume union connector.

- If the drift disappears, the issue is likely with the column or pre-column.

- If the drift persists or worsens, the problem originates from the mobile phase or the instrument itself.

- Inspect Mobile Phase: Prepare a fresh batch of high-quality mobile phase, using different solvent bottles or a different brand to rule out contamination.

Q: How can I prevent mobile phase impurities from causing drift? A: Mobile phase impurities are a leading cause of drift [7] [9].

- Use High-Purity Reagents: Always use HPLC-grade or higher solvents and additives.

- Prepare Fresh Solutions: Make up new mobile phase solutions daily if possible.

- Choose Materials Wisely: Use PEEK tubing instead of stainless steel to prevent metal ion leaching.

- Check for "Ghost Peaks": Run a blank gradient (injecting no sample) to see if impurity peaks appear, which indicates a contaminated mobile phase or system [9].

Q: My gradient HPLC method has a rising and falling baseline. Is this normal? A: A baseline that shifts predictably with the solvent gradient is often normal due to the changing absorbance of the mobile phase components. However, it should be relatively smooth. To minimize this [8]:

- Balance Absorbance: Fine-tune the aqueous and organic mobile phases to have matched absorbance at your detection wavelength.

- Add a Static Mixer: Install a mixer between the pump and column to ensure a homogenous mobile phase.

- Additive Balance: Add the same concentration of buffer or additive to both the aqueous and organic solvent reservoirs.

Troubleshooting Guide: Data Pipeline Drift

Q: What is "data drift" in analytical research pipelines? A: In the context of data quality, "drift" refers to the gradual degradation of data quality over time. This is distinct from, but analogous to, instrumental baseline drift. It manifests as issues like decreasing data completeness, increasing errors, or schema changes that break data pipelines [10] [11]. This type of drift makes analytical results and research outcomes unreliable.

Q: What are the key metrics to track for data quality? A: Consistently monitoring core dimensions of data quality is essential for identifying drift. The following table summarizes the key metrics [12]:

| Metric | Description | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Completeness | The amount of usable or complete data in a sample. | Incomplete data skews analysis and leads to biased results. |

| Accuracy | How well data reflects the real-world values it represents. | Inaccurate data directly causes erroneous conclusions. |

| Consistency | Uniformity of data across different systems or datasets. | Inconsistent data creates contradictions and confuses analysis. |

| Validity | How much data conforms to a specified format or business rule. | Invalid data formats can break pipelines and computations. |

| Timeliness | The readiness of data within a required time frame. | Stale data results in missed opportunities and outdated insights. |

| Uniqueness | The volume of non-duplicate records in a dataset. | Duplicate records inflate counts and corrupt statistical analysis. |

Q: What tools can help automatically detect and alert data quality drift? A: Several open-source and commercial tools can automate data quality monitoring. These tools use machine learning to establish normal data patterns and alert you to anomalies [10] [13] [11].

| Tool | Type | Key Capabilities for Drift Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Monte Carlo | Commercial | ML-powered anomaly detection for data volume, freshness, and schema; automated root cause analysis [10] [11]. |

| Great Expectations | Open-Source | Library for defining "expectations" (tests) for your data; integrates with pipelines for validation [10] [13]. |

| Anomalo | Commercial | Automatically monitors data warehouses and detects issues without requiring pre-set rules or thresholds [10]. |

| Soda Core | Open-Source | Uses a simple YAML syntax to define data quality checks and scans datasets for violations [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Why is a systematic, one-change-at-a-time approach critical in troubleshooting drift? A: Changing multiple variables simultaneously makes it impossible to identify the true root cause. If the problem recurs, you gain no new knowledge. A careful, stepwise approach of forming a hypothesis, testing it, and observing the result is the essence of scientific troubleshooting. Always change one factor, observe the outcome, and only then proceed to the next candidate [7].

Q: How can negative research outcomes related to drift be valuable? A: Documenting and sharing failed troubleshooting attempts or experimental runs ruined by drift prevents other researchers from wasting time and resources duplicating the same costly mistakes. Creating a knowledge base of "negative outcomes" helps de-risk and accelerate research for the entire community [14].

Q: Beyond the instrument itself, what environmental factors should I control? A: The laboratory environment is a significant contributor to drift [7] [8]:

- Temperature: Stabilize room temperature and avoid placing instruments directly under air conditioning vents.

- Drafts: Shield the instrument from direct airflow from doors, windows, or vents.

- Power Supply: Ensure a stable power source free from fluctuations; use line conditioners if necessary.

- Vibration: Place instruments on stable, vibration-damping tables.

Q: What is the recommended protocol for systematic instrument equilibration? A: After mobile phase preparation, system priming, or column replacement [7] [8]:

- Start the flow at the method's standard rate.

- Allow the system to equilibrate for a minimum of 30 minutes, or until the baseline is stable.

- For coulometric detectors or after major changes, full stabilization may take several hours or even days.

- Run a blank injection to confirm system cleanliness and baseline stability before analyzing actual samples.

Experimental Protocols and Visualizations

Detailed Methodology: Diagnosing HPLC Baseline Drift

Objective: To systematically identify the root cause of baseline drift in an HPLC system.

Materials:

- HPLC system with appropriate detector (e.g., UV-Vis, ECD)

- Fresh, HPLC-grade mobile phase components (aqueous and organic)

- Zero-dead-volume union connector

- Instrument documentation and schematics

Procedure:

- Initial Assessment: Observe the drift pattern (e.g., steady rise/fall, noisy, saw-tooth) to form an initial hypothesis [9].

- Temperature Stabilization: Ensure the laboratory and detector temperatures have been stable for at least two hours. Record the temperature [7].

- Mobile Phase Replacement: Replace all mobile phases with fresh, freshly prepared solvents from different lots or brands if possible. Degas thoroughly [8].

- Bypass Column Diagnosis:

- Carefully remove the analytical column.

- Install a zero-dead-volume union in its place.

- Start the mobile phase flow and observe the baseline.

- Interpretation: If the drift disappears, the column is the source. If it persists, the issue is in the mobile phase or the instrument hardware [7].

- Pump and Check Valve Inspection: If the drift persists after Step 4, inspect pump check valves for stickiness and ensure all pump seals are functioning correctly. A saw-tooth baseline pattern often indicates a pump issue [9].

- Final Verification: Once a potential fix is applied, reassemble the system and allow for full re-equilibration. Run a blank to confirm the resolution.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical process for diagnosing drift:

Data Quality Monitoring Framework

Objective: To establish a continuous monitoring protocol for data quality dimensions, preventing "data drift" in research outcomes.

Materials:

- Data pipeline (e.g., ETL/ELT process)

- Data storage (e.g., data warehouse, database)

- Data quality tool (e.g., Great Expectations, Soda Core) or custom validation scripts

Procedure:

- Define Metrics: For critical datasets, define the specific data quality dimensions to monitor (see Table: Data Quality Metrics) [12].

- Establish Benchmarks: Use historical data to establish normal baselines for metrics like data volume, freshness, and value distributions.

- Implement Checks: Using your chosen tool, implement automated checks. Examples include:

- Configure Alerting: Set up alerts to notify data stewards via Slack, email, or other channels when a data quality check fails.

- Create Documentation: Maintain a data catalog that documents the lineage of data assets, making root cause analysis faster when issues are detected [13].

The relationship between core data quality concepts is shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and their functions for preventing drift in sensitive measurements.

| Item | Function | Critical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Low UV absorbance; minimal organic and ionic impurities to reduce baseline noise and "ghost peaks". [8] [9] | >99.9% purity; packaged in amber glass to prevent degradation. |

| High-Purity Water | A common source of hydrophobic organic contaminants; using low-quality water can cause severe long-term drift. [7] | 18.2 MΩ·cm resistivity (from Milli-Q or equivalent). |

| PEEK Tubing | Replaces stainless steel tubing to prevent leaching of metal ions into the mobile phase, which can catalyze degradation or react with analytes. [7] | 1/16" outer diameter; various inner diameters. |

| In-Line Degasser | Removes dissolved air from the mobile phase to prevent bubble formation in the detector flow cell, which causes sudden spikes and noisy baselines. [8] | Compatible with your HPLC system's pressure limits. |

| Static Mixer | Ensures complete and homogeneous mixing of miscible solvents before the column, crucial for stable baselines in gradient methods. [8] | Low dead volume; compatible with mobile phase solvents. |

| Check Valves | Prevents backflow and ensures consistent pump operation; a malfunctioning valve causes compositional inaccuracy and saw-tooth baseline noise. [8] [9] | Ceramic or ruby ball for durability, especially with ion-pairing reagents. |

| LY-402913 | LY-402913, CAS:334970-65-9, MF:C28H24ClN3O6, MW:534.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| LY900009 | LY900009, CAS:209984-68-9, MF:C23H27N3O4, MW:409.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Baseline Drift

Baseline drift is a common challenge that can compromise data quality across various sensitive instruments. The table below summarizes the common culprits and solutions for each technology.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Baseline Drift and Instability Across Instruments

| Instrument | Common Culprits for Drift/Instability | Proven Solutions & Correction Methods |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC (Amperometric Detection) | - Temperature Fluctuations: Room temperature changes affecting detector and mobile phase. [15]- Mobile Phase Issues: Contaminated solvents or degassing problems causing bubbles. [8] [15]- Column Issues: Elution of residual components or leaching from packing materials. [15] | - Stabilize Temperature: Control lab temperature; use a column oven; place solvent bottles in a water bath. [8] [15]- Use Fresh Mobile Phase: Prepare daily; use high-quality, fresh solvents. [8]- System Maintenance: Degas mobile phase thoroughly; clean or replace check valves; purge system to remove bubbles. [8] [16] |

| SPR Microscopy (SPRM) | - Focus Drift: Tiny drifts cause significant image quality loss and reduced signal-to-noise ratio. [17] | - Focus Drift Correction (FDC): Use a reflection-based method to prefocus and monitor drift without extra hardware. [17] |

| Electrochemical Air Sensors (e.g., for NO₂, O₃) | - Coefficient Drift: Long-term drift of baseline and sensitivity coefficients. [18] | - In-situ Baseline Calibration (b-SBS): Apply a universal sensitivity value and remotely calibrate the baseline using statistical characteristics of sensor batches. [18] |

| Low-Cost Particulate Matter (PM) Sensors | - Environmental Factors: Humidity and temperature affecting readings. [19] [20]- Algorithmic Limitations: Built-in functions for particle number-to-mass conversion lack transparency. [19] | - Machine Learning Calibration: Use models (Log-Linear, Random Forest) or ANN surrogates with environmental data to correct readings. [19] [20] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

HPLC

Q: My HPLC baseline drifts upward continuously. I've changed the mobile phase, and the problem persists. What should I check next?

- A: Temperature instability is a very likely culprit. Ensure the laboratory room temperature is stable for at least two hours before starting measurements and that air conditioning vents are not blowing directly on the detector. Placing your mobile phase bottles in a water bath can act as a temperature buffer and significantly reduce drift. [15]

Q: After switching to a different brand of HPLC-grade methanol, my baseline is noisy, and I have lost sensitivity. What could be wrong?

- A: The new methanol brand may contain trace hydrophobic organic impurities. These impurities are first adsorbed by the column, saturate it over time, and then migrate to the working electrode, coating it and causing noise and sensitivity loss. Revert to the original methanol brand to confirm. This problem can be persistent and may require replacing the column and electrode after switching back to a pure solvent. [15]

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

- Q: Why is focus stability so critical in SPR Microscopy (SPRM), and how can it be maintained during long-term observations?

- A: SPRM systems use high-magnification objectives with a very short depth of field (often < 1 μm). Any tiny focus drift, caused by optical components or environmental factors, can introduce abnormal interference fringes, reduce image contrast, and lower the signal-to-noise ratio. This is particularly detrimental for quantitative analysis and dynamic process monitoring. A focus drift correction (FDC) method that uses the relationship between defocus displacement and the position of a reflected laser spot can be used to prefocus the system and continuously monitor drift without complex algorithms or extra hardware. [17]

Electrochemical & Particulate Sensors

Q: I manage a large network of electrochemical air quality sensors. Recalibrating each one side-by-side with a reference instrument is impractical. Is there a scalable solution?

- A: Yes, an in-situ baseline calibration (b-SBS) method is designed for this purpose. It relies on the finding that the sensitivity coefficients for a batch of similar sensors are often clustered within a 20% variation. This allows for applying a universal, pre-determined median sensitivity value to all sensors in the network. Only the baseline needs to be calibrated remotely, which can be done using data from a reference station without physical co-location, dramatically reducing operational costs. [18]

Q: My low-cost particulate matter sensor works well indoors but becomes inaccurate when deployed outside. How can I improve its field reliability?

- A: Environmental variables like humidity and temperature significantly impact the accuracy of optical PM sensors. Simple linear regression is often insufficient to correct for these non-linear effects. Machine learning calibration models that use the sensor's raw readings along with local temperature, humidity, and atmospheric pressure data as inputs can dramatically improve performance. Techniques include multivariate linear regression, random forest, and artificial neural networks (ANNs), which can correct for both additive and multiplicative biases. [19] [20]

Experimental Protocols for Drift Mitigation & Correction

Protocol: In-situ Baseline Calibration (b-SBS) for Electrochemical Sensor Networks

This protocol enables remote calibration of distributed electrochemical (EC) sensors without direct co-location with a reference monitor, based on validated field trials. [18]

- Preliminary Coefficient Characterization:

- Co-locate a large batch of identical EC sensors (e.g., 75+ units) with a reference-grade monitor (RGM) for multiple 5-10 day trials.

- For each sensor and trial, calculate its unique sensitivity (a, in ppb/mV) and baseline (b, in ppb) coefficients using traditional linear regression on the RGM data.

- Statistically analyze the distribution of all calculated sensitivity coefficients. The study on NO₂, NO, CO, and O³ sensors found coefficients clustered with a Coefficient of Variation (CV) of 15-22%.

- Establish Universal Calibration Parameters:

- Select the median sensitivity value from the population distribution for each gas type as the universal sensitivity (

a_universal).

- Select the median sensitivity value from the population distribution for each gas type as the universal sensitivity (

- Remote Baseline Calibration:

- For a deployed sensor in the network, collect its raw output signal (mV).

- Obtain concentration data from a nearby RGM or use the 1st percentile method to estimate the baseline.

- Calculate the calibrated concentration using:

Concentration = (Raw Signal × a_universal) + b_remote, whereb_remoteis determined remotely based on reference data.

Protocol: Focus Drift Correction (FDC) in SPR Microscopy

This protocol details the reflection-based method to correct for focus drift in SPRM, enhancing image quality for static and dynamic nanoparticle observations. [17]

- System Setup:

- Ensure the SPRM system is configured to allow for the capture of the reflected laser spot on an imaging camera.

- Prefocusing Step (Before Imaging):

- Use an image processing program to retrieve the displacement of the reflected spot (ΔX) on the camera plane from its position at perfect focus.

- Using a pre-derived auxiliary focus function (FDC-F1), calculate the corresponding defocus displacement (ΔZ).

- Adjust the system's focus mechanism by ΔZ to return to the optimally focused state.

- Focus Monitoring Step (During Imaging):

- Continuously track the position of the reflected spot during the experimental time series.

- Use a second auxiliary function (FDC-F2) to relate spot displacement to focus drift in real-time.

- Apply corrective adjustments to the focus mechanism to compensate for any observed drift.

Workflow Visualization: Systematic Troubleshooting for Baseline Issues

The following diagram outlines a general, systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving baseline instability across instrument types, incorporating principles from the specific protocols.

Diagram 1: A generalized troubleshooting workflow for addressing baseline issues across different instruments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Featured Experiments

| Item | Function / Application | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) | Common ion-pairing agent and mobile phase additive in reversed-phase HPLC. [8] | A known source of UV absorbance and baseline noise, especially at low wavelengths. Use fresh and handle carefully; 214 nm is often an ideal detection wavelength to minimize interference. [8] |

| Stabilized Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Organic solvent for HPLC mobile phases. [8] | Prone to degradation causing baseline noise. Using a stabilized grade can reduce baseline drift in gradient methods. [8] |

| Phosphate Buffer Salts | For preparing buffered aqueous mobile phases in HPLC. [8] | At high organic concentrations in gradients, phosphate buffers can precipitate, leading to noisy baselines and column blockages. [8] |

| PEEK Tubing | Replacement for stainless-steel tubing in HPLC-ECD systems. [15] | Prevents leaching of trace metal ions from stainless steel into the mobile phase, which can contribute to baseline drift and noise. [15] |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Electrode modification in electrochemical aptasensors to enhance surface area and electron transfer. [21] | Used in screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs) for sensitive detection of pathogens like S. aureus. [21] |

| Silicon Nitride (Si₃N₄) Spacer | A thin dielectric layer in enhanced SPR sensor architectures. [22] | Acts as an impedance-matching layer, reduces radiation damping, and concentrates the evanescent field closer to the analyte, boosting sensitivity. [22] |

| Tungsten Disulfide (WSâ‚‚) | A 2D material used as an ultra-thin capping layer in SPR sensors. [22] | Provides a high refractive index at atomic thickness, further concentrating the evanescent field at the sensing interface and enhancing signal for biomolecular interactions like DNA hybridization. [22] |

| M2698 | M2698, CAS:1379545-95-5, MF:C21H19ClF3N5O, MW:449.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Raf inhibitor 1 | B-Raf Inhibitor 1|Potent Raf Kinase Antagonist | B-Raf Inhibitor 1 is a potent, selective Raf kinase antagonist for cancer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Technical Diagrams: Advanced SPR Sensor Configuration

The following diagram illustrates the multilayer architecture of a high-sensitivity SPR biosensor, which is designed to minimize drift and improve detection limits for label-free DNA hybridization. [22]

Diagram 2: A multilayer SPR biosensor stack using Ag, Si₃N₄, and WS₂ to enhance performance and stability.

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the most common root causes of baseline drift in my sensitive analytical instruments?

Baseline drift is a common symptom with multiple potential origins. A systematic root cause analysis (RCA) is the most effective way to move beyond treating symptoms to eliminating the underlying problem. The causes can be categorized as follows [23]:

- Environmental Causes: Fluctuations in ambient temperature and humidity are frequent culprits. Temperature-sensitive detectors, like Refractive Index (RI) detectors, are particularly susceptible. Drafts from air conditioning units or heating vents can also introduce noise or oscillations [8].

- Chemical Causes: The quality and composition of your mobile phases and solvents are paramount. Degraded or contaminated solvents, buffers at the precipitatio [8]n limit, and UV-absorbing additives like trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) can all cause a rising or falling baseline [8].

- Mechanical Causes: This category includes subtle equipment failures. Worn pump seals, malfunctioning check valves, and the formation of air bubbles in the system tubing or detector flow cell can all lead to drift. In other process equipment, issues like pump cavitation or bearing wear due to misalignment are common mechanical triggers for drift and failure [24] [8].

To diagnose the issue, start by using a simple RCA technique like the 5 Whys to drill down from the symptom to the root cause [24] [23]. For example:

- Why is the baseline drifting? Because the detector signal is unstable.

- Why is the detector signal unstable? Because the temperature of the mobile phase entering the flow cell is fluctuating.

- Why is the temperature fluctuating? Because the laboratory's ambient temperature is not controlled, and the instrument is in the path of a cold air draft.

FAQ 2: How can I distinguish between instrument drift and a true sample signal?

Differentiating between drift and signal is critical for data accuracy. The table below summarizes key characteristics for comparison:

| Feature | Baseline Drift | True Sample Signal |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Pattern | A slow, continuous, and monotonic trend (upward or downward) over the entire run [8]. | A sharp, peak-shaped deviation that returns to the original baseline [8]. |

| Reproducibility | Pattern may change daily or with environmental conditions; not consistently linked to sample injection. | Consistently appears at the same retention time when the same sample is injected. |

| Response to Test Conditions | May be eliminated by running a blank gradient or after system maintenance [8]. | Only appears when the sample is present. |

| Root Cause | Linked to systemic issues like temperature, mobile phase degradation, or equipment wear [8]. | Linked to the physicochemical properties of the analytes in the sample. |

Experimental Protocol for Identification:

- Run a Blank: Perform a "blank" injection (e.g., pure solvent) using the same method. If the drift pattern persists without any sample, the issue is instrumental, not from your sample.

- Change the Method: Alter the method parameters, such as using an isocratic hold instead of a gradient. If the drift disappears, the cause is likely related to the gradient composition or a refractive index effect [8].

- Systematic Isolation: Isolate parts of the system. For example, disconnect the column and replace it with a restriction capillary. If drift continues, the issue is in the pump or detector. If it stops, the issue may be related to the column or contaminants accumulating on it.

FAQ 3: A key sensor in my setup is showing a slow, consistent drift. How can I determine if the cause is environmental or a sensor fault?

Sensor drift can stem from the sensor itself or its environment. A Fishbone (Ishikawa) Diagram is an excellent tool to brainstorm all potential causes before investing in costly replacements [24] [25]. The main categories to investigate are Methods, Machines, Materials, People, and Environment.

Diagnostic Protocol:

- Environmental Logging: Correlate the sensor's output with high-resolution logs of ambient temperature and humidity. A strong correlation points to an environmental cause.

- Calibration Check: Perform a full calibration of the sensor using certified standards. A consistent offset might suggest a calibration issue, while an inability to hold calibration suggests a failing sensor.

- Substitution Test: If possible, replace the sensor with a known-good unit. If the drift disappears, the original sensor is faulty. If the drift continues, the issue is elsewhere in the system or environment.

- Signal Analysis: Use advanced process control (APC) principles to analyze the sensor's signal. Low-frequency, time-correlated drift often indicates an environmental influence, which can be separated from the true signal through path-optimized scanning and filtering techniques [26].

Advanced Drift Suppression Methodologies

FAQ 4: What are the latest computational or methodological approaches for suppressing low-frequency drift?

Traditional methods like forward-backward sequential scanning rely on averaging and have limited effectiveness against nonlinear drift [26]. Inspired by the principles of a lock-in amplifier (LIA), a novel approach shifts the suppression strategy from simple cancellation to altering the frequency-domain characteristics of the drift itself [26].

Core Principle: Instead of trying to average out drift, the measurement strategy is designed to convert time-domain, low-frequency drift into spatially high-frequency artifacts. These high-frequency components can then be effectively suppressed using low-pass filtering, isolating the true signal [26].

Experimental Protocol: Path-Optimized Scanning This protocol is based on research in long-range surface profilers and can be adapted for other scanning instruments [26].

- Define Measurement Points: Identify the

mspatial points (xâ‚€, xâ‚, xâ‚‚, ..., x_{m-1}) you need to measure on your sample. - Implement Scan Path: Instead of sequential scanning (

0, 1, 2, ...), use an optimized path that disrupts the temporal-spatial correspondence. The forward-backward downsampling path is highly effective [26]:0, 2, 4, ..., m, m-1, m-3, ..., 1This means scan every other point going forward, then return backward to get the points you skipped. - Data Collection & Reorganization: Collect the measurement data

M(xâ‚›)which contains the true signals(xâ‚›)and the time-dependent driftD(tâ‚›). Reorganize the collected data back into the correct spatial order. - Filtering: Apply a low-pass filter to the reorganized data. The drift, now transformed into a high-frequency component, will be attenuated, leaving behind the true surface profile or signal

s(xâ‚›).

Research has shown this method can control drift errors significantly while also reducing single-measurement cycle times by nearly 50% compared to traditional sequential scanning [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents critical for preventing and troubleshooting drift in sensitive measurements, particularly in liquid chromatography.

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents minimize UV-absorbing contaminants that cause baseline rise and noise. Using fresh, small-quantity bottles is essential [8]. |

| Inline Degasser | Removes dissolved gases from the mobile phase to prevent bubble formation in the detector flow cell, a common cause of sudden baseline spikes and drift [8]. |

| Static Mixer | Placed between the gradient pump and column, it ensures a homogenous mobile phase blend, reducing refractive index noise and baseline shifts during gradient runs [8]. |

| Certified Calibration Weights/Masses | Regular calibration checking with certified standards is the first line of defense against instrument drift, ensuring the accuracy of force, pressure, or mass measurements [27]. |

| Stable Buffers & Additives | Using stable, UV-transparent buffers at appropriate concentrations prevents precipitation at high organic concentrations, which can cause noisy, drifting baselines and system damage [8]. |

| Temperature & Humidity Logger | Essential for correlating instrument output with environmental fluctuations. This data is critical for RCA when drift is suspected to be environmentally caused [8]. |

| PF-06815345 | PF-06815345 PCSK9 Inhibitor|For Research Use |

| MDVN1003 | MDVN1003, MF:C22H20FN7O, MW:417.4 g/mol |

Proactive Strategies and Correction Methods for Stable Baselines

In sensitive analytical techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), the quality and management of your solvents and mobile phases are foundational to success. Proper management is the most effective proactive strategy for reducing baseline drift and ensuring data integrity. Dissolved gases in the mobile phase can form bubbles, which disrupt pump operation, cause detector noise, and lead to erratic retention times [28]. Furthermore, contaminated or degraded solvents introduce impurities that slowly elute from the column, causing a gradual rise or fall in the baseline signal [29] [8]. Using fresh, properly degassed buffers is therefore not just a recommendation—it is a critical requirement for obtaining stable, reproducible, and reliable results in sensitive instrument research.

The Critical Role of Degassing in Mobile Phase Management

Why Degassing is Necessary

When solvents are exposed to the atmosphere, gases like oxygen and nitrogen dissolve into them. When these solvents are mixed, particularly in the case of aqueous and organic blends, the combined gas content can exceed the mixture's solubility limit, creating a supersaturated condition [28]. This leads to outgassing and bubble formation within the HPLC system. The consequences are severe and multifaceted [28] [30]:

- Pump Cavitation and Unstable Flow: Bubbles in the pump can cause cavitation, leading to unstable flow rates and erratic retention times.

- Baseline Noise and Spikes: Bubbles passing through the optical flow cell of a UV-Vis or other detector scatter light, generating significant noise, spikes, or a drifting baseline.

- Reduced Sensitivity and Accuracy: These disruptions obscure analyte peaks, compromising the quality of your quantitative data.

Comparison of Common Degassing Techniques

Understanding the different degassing methods allows you to choose the right one for your application. The two main categories are inline (continuous) and offline (batch) degassing.

Table 1: Side-by-Side Comparison of HPLC Degassing Techniques [28]

| Aspect | Offline Degassing | Inline Degassing |

|---|---|---|

| Timing | Performed as a batch process before the HPLC run. | A continuous process occurring during the HPLC run. |

| Common Methods | Helium sparging, vacuum filtration, sonication. | Vacuum or membrane degasser built into the HPLC system. |

| Degassing Efficiency | Variable: Helium sparging (~80%), vacuum (~60%), sonication alone (~30%). | Removes the majority of dissolved gas, though not 100%. Prevents bubble formation effectively. |

| Risk of Gas Re-dissolving | High, as degassed solvents are exposed to the atmosphere. | Low, as the mobile phase is isolated in a closed system. |

| Impact on Composition | Possible loss of volatile components during sparging or vacuum. | Solvent composition remains unchanged. |

| Maintenance | Low; involves clean glassware and filters. | Low; membrane degassers are durable but can clog. |

| Cost | Low initial investment (excluding helium). | Higher initial cost for the dedicated degasser unit. |

| Best For | Occasional use, setups without inline degassers, or large batch preparation. | Routine analyses, high-sensitivity methods, and long runs requiring maximum stability. |

For applications highly sensitive to oxygen, such as those using electrochemical detection (ECD) or low-wavelength UV, a combination of offline helium sparging followed by inline degassing provides the highest level of protection against dissolved oxygen interference [28].

Troubleshooting Guide: Solvent-Related Baseline Issues

This guide helps you diagnose and resolve common problems stemming from solvent and mobile phase management.

Table 2: Troubleshooting FAQ for Solvent and Mobile Phase Issues

| Question & Symptom | Likely Causes | Solutions & Experimental Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| My HPLC baseline is drifting upwards or downwards over time. What should I check? | - Mobile phase contamination or degradation [29] [8].- Column leaching from packing materials [29].- Temperature fluctuations affecting the detector or mobile phase [29]. | 1. Prepare Fresh Mobile Phase: Always use fresh buffers daily and high-purity solvents. Check water quality [8].2. Diagnose the Column: Replace the column with a zero-dead-volume union. If the drift disappears, the column is the source. Flush or replace it [29].3. Stabilize Temperature: Ensure room temperature is stable. Place mobile phase bottles in a water bath to buffer against temperature shifts [29]. |

| I observe rapid baseline noise and spikes in my chromatogram. | - Air bubbles in the pump or detector flow cell [28] [31].- Inefficient degassing leading to micro-bubble formation [28]. | 1. Purge the System: Thoroughly purge the pump and all lines with fresh, degassed mobile phase [31].2. Verify Degasser Function: Ensure the inline degasser is operational. For offline degassing, use helium sparging for at least 5-10 minutes.3. Apply Backpressure: Add a backpressure regulator after the detector, especially with UV detectors, to suppress bubble formation [8]. |

| After a buffer change or system startup, my baseline is unstable and wavy. | - The system is not adequately equilibrated with the new buffer [32].- The previous buffer is mixing with the new one in the pump and tubing. | 1. Prime and Flush: Prime the system thoroughly after every buffer change [33].2. Equilibrate with Flow: Flow the new running buffer through the system at the experimental flow rate until the baseline stabilizes. This can take 30 minutes to several hours for full equilibration [32]. |

| My baseline is stable without the column, but drifts when the column is installed. | - The column is contaminated with residual sample components or impurities from previous runs [29] [31].- The column packing is leaching into the mobile phase. | 1. Clean the Column: Flush the analytical column according to the manufacturer's recommended cleaning procedure [31].2. Use a Guard Column: Always use a guard column matched to your analytical column phase to capture contaminants [31].3. Replace the Column: If cleaning fails, the column may be degraded and need replacement [31]. |

Best Practices for Mobile Phase Preparation and System Hygiene

Adhering to strict protocols for mobile phase preparation and system care is the best defense against baseline problems.

- Use Fresh Buffers Daily: Buffer solutions are susceptible to microbial growth and chemical degradation. Prepare new mobile phases daily and do not add fresh buffer to old stocks [32] [8].

- Employ High-Purity Water: Impurities in water are a common source of contamination and baseline drift. Use LC-MS grade water or similarly high purity for sensitive applications [29].

- Filter and Degas Consistently: Filter all aqueous and buffer mobile phases through a 0.22 µm or 0.45 µm membrane filter to remove particulates. This should be followed by a consistent and effective degassing method [32].

- Prime All Solvent Lines: After preparing fresh mobile phases, prime all solvent lines—not just the ones in use—to ensure the system is completely flushed with fresh, clean solvent. This prevents the growth of algae or bacteria in old solvent lines and ensures optimal degasser performance [33].

- Implement System Flushing for Storage: Never store the system in buffer. After completion of work, flush the entire system (pump, column, and detector) with a storage solvent compatible with your column, such as 15/85 methanol/water for reverse-phase systems, to prevent buffer crystallization and microbial growth [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials for Optimal Solvent Management

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | Minimize UV-absorbing impurities and ionic contaminants that cause baseline drift and noise, especially in sensitive detection modes [29] [31]. |

| High-Purity Water | A common source of hydrophobic organic contaminants that adsorb to the column and slowly elute, causing drift. Using LC-MS grade water is critical [29]. |

| In-line Degasser | A standard component of modern HPLC systems; continuously removes dissolved gases during operation to prevent bubble formation and ensure pump and detector stability [28] [30]. |

| Guard Column | A small, disposable cartridge placed before the analytical column. It traps contaminants and particulates, protecting the more expensive analytical column and preserving peak shape and baseline stability [31]. |

| 0.22 µm Membrane Filters | Used for filtering mobile phases to remove particulates that could clog frits, columns, or tubing, causing high backpressure and pressure fluctuations [32]. |

| Helium Gas Cylinder | Used for helium sparging, an effective offline degassing method that removes up to 80% of dissolved air, ideal for oxygen-sensitive applications like ECD [28]. |

| Sealed/Schott Bottles | Using amber or sealed bottles for mobile phase storage limits solvent evaporation and degradation from exposure to light and atmospheric CO2, preserving composition and stability [8]. |

| ME1111 | ME1111|Antifungal Agent|Succinate Dehydrogenase Inhibitor |

| MI-2-2 | MI-2-2, MF:C17H20F3N5S2, MW:415.5 g/mol |

Workflow Diagram: Proactive Management for Stable Baselines

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for managing solvents and mobile phases to prevent baseline drift, from preparation through to analysis and storage.

Troubleshooting Guides

Why is my HPLC baseline drifting upwards or downwards during analysis?

Baseline drift is a steady upward or downward trend in the background signal that can obscure important peaks and compromise data quality. The following table outlines the common causes and their respective solutions. [8]

| Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Temperature Fluctuations | Stabilize laboratory room temperature; allow system to stabilize for at least two hours before use; insulate exposed tubing; use a water bath for mobile phase bottles. [8] [34] |

| Mobile Phase Issues | Prepare fresh mobile phases daily; use high-quality, fresh solvents; ensure thorough degassing (e.g., with inline degassers); balance the UV absorbance of aqueous and organic phases in gradient methods. [8] [32] |

| Bubbles in the System | Degas solvents thoroughly; add a flow restrictor at the detector outlet to increase backpressure and prevent bubble formation in the flow cell. [8] |

| System Contamination | Perform regular system cleaning; check mobile phase containers, tubing, and filters for contamination; ensure mobile phase bottles are dedicated to specific solvents to avoid cross-contamination. [8] |

| Column-Related Issues | Equilibrate the column sufficiently with the mobile phase before analysis; for suspected column contamination, replace the column with a union; if drift disappears, the column is the source. [34] [32] |

How do I resolve unstable temperature or humidity in an environmental chamber?

Instabilities in environmental chambers are often mechanical and can be diagnosed systematically. Begin by confirming that all appropriate functions (humidity, refrigeration, etc.) are activated. [35]

Humidity Exceeding Set Point This is often caused by delivering too much heat to the steam generator or a restriction in water flow. [35]

- Check water flow: Inspect the solenoid valve, float switch, or other mechanical device controlling water entry into the steam generator. An obstruction or failure can reduce water flow, causing the heater to overheat and generate excess steam. [35]

- Check control relays: A failed mechanical relay can cut off the signal from the controller that directs the unit to reduce humidity. [35]

Humidity Below Set Point This is typically caused by a mechanical failure or issues with the source water. [35]

- Check the steam generator heater: Verify the thermal fuse associated with the heater. If the fuse is intact, check the heater's resistivity against the manufacturer's specifications. [35]

- Inspect the float switch: A faulty float switch that is constantly calling for water can cool the steam generator, preventing it from producing enough steam. [35]

- Look for leaks: Check for loose fittings or unsealed ports along the humidity pathway where steam may be escaping. [35]

Temperature Above Set Point

- Check control relays: A failed relay may be blocking the "decrease temperature" signal from the controller. [35]

- Check the refrigeration unit: A failure in the refrigeration system will prevent heat from being removed from the chamber. [35]

Temperature Below Set Point

- Check the air heaters: Verify the voltage and resistivity of the air heaters. Check for and replace any blown thermal fuses associated with the heaters. [35]

- Check control relays: A failed relay may be blocking the "increase temperature" signal. [35]

What are the best practices for laboratory temperature monitoring to ensure data integrity?

Effective temperature monitoring protects valuable samples, ensures replicability, and maintains compliance.

| Practice | Description |

|---|---|

| Precise Instrument Calibration | Schedule routine calibration of all monitoring equipment to a known standard of accuracy to ensure data reliability. [36] |

| Automated Data Logging | Use systems that automatically log data to reduce the risk of human error from manual recording and to enable more frequent data collection. [36] [37] |

| Comprehensive Alarm Protocols | Set customizable alarm limits for temperature excursions. Define escalation paths to ensure the right personnel are notified and can respond promptly. [38] [39] |

| Secure Data Storage | Use systems with robust data storage (internal memory, local PC, or secure cloud) to maintain logs for the entire product shelf life plus one year for audits. [36] [37] |

| Remote Monitoring | Implement cloud-based platforms for 24/7 remote access to temperature data and alarms from any location, facilitating quick intervention. [37] [39] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How long should I equilibrate my HPLC system to minimize baseline drift?

Equilibration time can vary. For HPLC systems, particularly after a buffer change or column swap, flow the running buffer at the experimental flow rate until a stable baseline is achieved. This may take 30 minutes to several hours. Some systems, like coulometric electrochemical detectors, may require days to stabilize fully. Incorporating several "dummy" injections of running buffer at the start of an experiment can help stabilize the system. [34] [32]

My laboratory temperature is stable, but my HPLC-ECD baseline is still drifting. What should I check next?

Temperature stability is crucial, but other factors can cause drift. A systematic troubleshooting approach is key. [34]

- Isolate the column: Replace the column with a zero-volume union. If the drift disappears, the issue is related to the column (e.g., leaching of packing materials or elution of residual sample components). [34]

- Check the mobile phase: If drift persists without the column, or suddenly increases when the column is removed, the mobile phase is likely contaminated. Trace hydrophobic organic impurities in solvents can be adsorbed by the column and then slowly leach out, causing drift and sensitivity loss. Always use high-quality solvents and water. [34]

- Change one factor at a time to accurately identify the root cause. [34]

What type of water should I use for the humidification system in my environmental chamber?

Always use the water quality specified by the equipment manufacturer. Using water with incorrect purity can lead to mineral scaling, contamination, and eventual mechanical failure of the steam generator or other components. [35]

We use a manual temperature monitoring system. How can we improve our compliance with Good Laboratory Practices (GLP)?

While manual monitoring is sometimes acceptable, electronic systems offer significant advantages for GLP compliance. Automated monitoring systems provide 24/7 real-time data, eliminate human error and bias from manual recording, and generate tamper-evident, auditable trails. These systems also offer automated reporting, making it straightforward to demonstrate compliance during audits. [37]

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Establishing a Stable HPLC Baseline for Sensitive Analysis

This protocol is designed to minimize baseline drift in HPLC methods, especially for gradient runs and sensitive detection.

Materials:

- HPLC system with inline degasser

- HPLC column

- High-purity solvents and additives

- 0.22 µm membrane filters

- Clean, dedicated mobile phase bottles

Procedure:

- Mobile Phase Preparation: Prepare fresh mobile phases daily. Use high-purity solvents and water. Filter and degas all phases thoroughly using a 0.22 µm membrane filter and an inline degasser or helium sparging. [8] [32]

- System Preparation: Prime the system thoroughly with the fresh mobile phase to remove any residual solvent from the previous experiment. Ensure all tubing is clean and there are no leaks. [8] [32]

- Column Equilibration: Install the column and set the flow rate to the method's specified value. Allow the mobile phase to flow through the column until the baseline is stable. Monitor the baseline signal; equilibration is sufficient when the drift is minimal and the baseline noise is low. [32]

- Blank Run Execution: For gradient methods, perform a blank gradient run (injecting only the sample solvent) to characterize the baseline profile. This blank run can be subtracted from sample runs during data processing to correct for inherent mobile phase-induced drift. [8]

- System Stabilization Cycle: Before sample analysis, run 3-5 start-up cycles. These cycles should mimic the analytical method but inject only running buffer (blank). This "primes" the system and column, stabilizing them before actual sample analysis. Do not use these start-up cycles for calibration or blank subtraction. [32]

Workflow: Systematic Troubleshooting of Environmental Chamber Failures

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing an environmental chamber that is not maintaining its set points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This table details key materials and solutions critical for maintaining environmental stability and instrument performance.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents | Minimize UV-absorbing contaminants that cause baseline noise and drift in chromatographic systems. Essential for preparing mobile phases. [8] [34] |

| Static Mixer | Placed between the gradient pump and the column, it evens out small inconsistencies in the mobile phase blend, leading to a smoother baseline in gradient methods. [8] |

| Inline Degasser | Removes dissolved gases from the mobile phase to prevent bubble formation in the detector flow cell, which is a common cause of baseline spikes and drift. [8] |

| Thermal Buffer (e.g., Glycol Bottle) | Used with temperature probes in refrigerators and incubators, it buffers brief temperature fluctuations from door openings, providing a more accurate reading of the sample's temperature. [36] |

| PEEK Tubing | An alternative to stainless steel tubing in HPLC systems, it prevents metal ion leaching into the mobile phase, which can contribute to baseline noise and drift, especially with electrochemical detection. [34] |

| Certified Reference Materials | Used for the calibration of temperature probes and sensors to ensure measurement accuracy and traceability to international standards, a core requirement for GLP compliance. [36] |

| Mitochonic acid 35 | Mitochonic acid 35, MF:C19H19NO5, MW:341.4 g/mol |

| MK-2048 | MK-2048, CAS:869901-69-9, MF:C21H21ClFN5O4, MW:461.9 g/mol |

HPLC Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Why does my HPLC baseline drift during a gradient run, and how can I fix it?

Baseline drift during gradient runs is primarily caused by the different UV absorbance profiles of your mobile phase solvents. As the proportion of solvents changes during the gradient, the overall UV absorption changes, creating a sloped baseline [40]. Additional causes include mobile phase impurities, dissolved air, temperature fluctuations, and system contamination [8] [9].

Solutions:

- Mobile Phase Matching: Check the UV absorbance of each pure mobile phase at your detection wavelength. Fine-tune their composition to better match absorbance, which will minimize drift during the gradient [8].

- Static Mixer: Install a static mixer between the gradient pump and the column to eliminate small inconsistencies in the mobile phase blend [8].

- Blank Gradient Run: Perform a blank gradient (injecting no sample) to characterize the baseline drift. This baseline can often be subtracted during data processing [8].

- Fresh Mobile Phases: Prepare fresh mobile phase daily using high-quality solvents to prevent drift caused by degraded or contaminated solvents [8].

- Proper Degassing: Use an inline degasser or helium sparging to remove dissolved air, which can form bubbles and cause baseline drift [8].

My HPLC baseline is noisy and unstable. What are the common culprits?

Noise and instability are often related to physical issues within the HPLC system, such as air bubbles, contamination, or component failure [8] [16].

Solutions:

- Check for Leaks: Inspect all fittings for leaks and tighten gently if loose. Also, check pump seals and replace them if worn out [16].

- Remove Bubbles: Thoroughly degas your mobile phase and purge the system to remove air bubbles [16].

- Clean the System: Flush the detector flow cell with a strong organic solvent. If the problem persists, the flow cell may need replacement. Also, replace a contaminated guard column or analytical column [16].

- Replace UV Lamp: A UV lamp with low energy can cause significant noise; replace it if it's near the end of its lifespan [16].

How can I minimize baseline drift when using buffers or ion-pairing reagents like TFA?

- Use Ceramic Check Valves: Switching to ceramic check valves can reduce noise, particularly in methods using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) [8].

- Optimal Wavelength: For UV-absorbing additives like TFA, find a detection wavelength with minimal interference. For TFA, 214 nm is often ideal [8].

- Fresh Reagents: Ion-pairing reagents can degrade over time. Use fresh reagents and prepare mobile phases frequently [8].

HPLC Baseline Drift: Common Causes and Solutions

The table below summarizes additional frequent issues and their fixes for HPLC baseline drift.

| Cause | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature Fluctuation [8] [16] | Gradual baseline drift. | Use a thermostat-controlled column oven. Insulate exposed tubing to prevent drafts from air conditioning [8]. |

| Poor Column Equilibration [16] | Drift at the beginning of a run or after a mobile phase change. | Increase column equilibration time. Purge the system and pump with 20 column volumes of the new mobile phase [16]. |

| Mobile Phase Impurities [9] [41] | High or changing baseline; "ghost peaks." | Prepare a fresh mobile phase from high-quality solvents. Use different suppliers or LC-MS grade solvents if needed [9] [41]. |

| Inconsistent Pump Flow [9] | A saw-tooth or periodic pattern in the baseline. | Clean or replace sticking check valves. Purge the system to remove trapped air bubbles [9]. |

SPR Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

How do I properly equilibrate an SPR sensor surface to minimize baseline drift?

Surface equilibration is critical for a stable baseline. Drift is often a sign of a non-optimally equilibrated sensor surface, frequently seen after docking a new chip or after immobilization [32].

Protocol:

- Post-Immobilization Wash: After immobilizing the ligand, wash the sensor surface extensively with your running buffer to rehydrate the surface and wash out all chemicals from the immobilization process [32] [42].

- Extended Equilibration: Flow the running buffer over the surface until the baseline is stable. This can take 5–30 minutes, and in some cases, it may be necessary to flow buffer overnight to achieve perfect stability [32].

- Start-Up Cycles: Before analyte injection, run at least three "start-up cycles" that mimic your experimental method but inject only running buffer (and a regeneration solution if used). This primes the surface and stabilizes the system. Do not use these cycles in your final analysis [32].

My SPR baseline is drifting. What steps should I take to stabilize it?

Solutions:

- Fresh Buffers: Prepare fresh running buffer daily, filter it through a 0.22 µM filter, and degas it before use. Never add fresh buffer to old buffer, as contaminants can grow [32].

- System Priming: After changing the running buffer, always prime the system several times to ensure complete replacement of the old buffer [32].

- Check for Bubbles: Ensure the buffer is properly degassed and check the fluidic system for leaks that could introduce air bubbles [43].

- Control Environment: Place the instrument in a stable environment with minimal temperature fluctuations and vibrations [43].

What does a good SPR baseline look like, and when is it safe to start my experiment?

Before starting any experiment, the baseline should be practically flat [42]. After equilibration:

- Drift should be minimal: Ideally less than ± 0.3 RU/minute [42].

- Noise should be low: The overall noise level should be very low (e.g., < 1 RU) [32].

- Stable after injection: Inject running buffer to test the system. The response should be low (< 5 RU), and the baseline should quickly stabilize after any injection-related spikes [42]. Only begin your analyte injections once these criteria are met.

SPR Baseline Issues: Troubleshooting Guide

| Cause | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Surface Regeneration [44] | Drift after analyte injection cycles. | Optimize regeneration conditions (e.g., buffer pH, ionic strength) to completely remove bound analyte without damaging the ligand [44]. |

| Buffer Incompatibility [44] | Drift after a buffer change. | Check that buffer components (salts, detergents) are compatible with the sensor chip. Prime the system thoroughly after a buffer change [32] [44]. |

| Start-Up Drift [32] | Drift immediately after initiating flow. | Some sensor surfaces are flow-sensitive. Wait 5–30 minutes for the baseline to stabilize before injecting your first sample [32]. |

| Reference Channel Mismatch [32] | Apparent drift after reference subtraction. | Use double referencing: subtract both a reference flow cell and blank (buffer) injections to compensate for drift and bulk effects [32]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key reagents and materials crucial for successful and stable HPLC and SPR experiments.

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents minimize UV-absorbing impurities that cause baseline drift and noise [8] [41]. | Purchase in small quantities to ensure freshness. Use stabilizer-free THF for UV detection [8]. |

| 0.22 µm Solvent Filters | Removes particulate matter that can clog lines, frits, and columns, causing pressure fluctuations and noise [32] [16]. | Always filter mobile phases and samples before use. |

| In-line Degasser / Helium Sparging | Removes dissolved air from the mobile phase to prevent bubble formation in the detector flow cell, a major cause of baseline noise and drift [8] [43]. | Essential for both HPLC and SPR systems. |

| SPR Sensor Chips (e.g., CM5, NTA, SA) | Gold surfaces functionalized with specific chemistries for immobilizing ligands (proteins, DNA, etc.) [44]. | Select a chip type that matches your immobilization strategy (e.g., amine coupling, His-tag capture) to minimize non-specific binding [44]. |

| High-Purity Buffer Additives (e.g., TFA) | Provides ion-pairing and pH control in HPLC. In SPR, used in immobilization and regeneration [8] [42]. | Use fresh additives; degradation products can cause drift. For SPR, choose the mildest effective regeneration buffer [8] [42]. |

| MK-3328 | MK-3328|CAS 1201323-97-8|Research Chemical | MK-3328 is a chemical reagent for pharmaceutical research use only. Explore its potential in novel therapeutic agent development. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| MK-4409 | MK-4409|FAAH Inhibitor|For Research Use |

Experimental Workflow for Baseline Stabilization

HPLC Gradient Optimization Protocol

SPR Surface Equilibration Protocol

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Baseline Drift Concepts

1. What is baseline drift and why is it a problem in sensitive measurements? Baseline drift is a low-frequency, wandering change in the baseline signal of an instrument over time. It is classified as a type of long-term noise and is often caused by temperature fluctuations, solvent programming effects on detectors, or environmental factors during prolonged operation [45]. This drift introduces errors in the determination of critical parameters like peak height and area in chromatographic analysis, compromising the accuracy and reliability of quantitative data [45]. In engineering trials using strain gauges, for instance, baseline drift can reduce data stability and validity [46].

2. What are the most common sources of baseline drift? The common sources vary by instrument but often include:

- Temperature Instability: Slight changes in the lab environment or between the column and detector [8] [45].

- Mobile Phase Composition: Differences in the UV absorbance of the aqueous and organic solvents used in gradient HPLC methods [47].

- System Equilibration: Sensor surfaces or columns that are not fully equilibrated with the running buffer or mobile phase [32].

- Contamination or Bubbles: Contaminants in the system or air bubbles forming in the detector flow cell [8].

- Electronic Noise: Inherent detector electronic noise or from an aging light source [48].

Algorithmic and Filtering Solutions

3. How does a High-Pass Filter (HPF) work to correct baseline drift? A high-pass filter is a circuit or algorithm that attenuates low-frequency signal components (which constitute the slow-moving baseline drift) while allowing high-frequency components (which often contain the analytical signal of interest) to pass through [49]. In electronic circuits, this is achieved with resistors and capacitors (passive HPF) or with operational amplifiers for signal gain (active HPF) [49]. Digitally, HPFs can be implemented using algorithms like Finite Impulse Response (FIR) or Infinite Impulse Response (IIR) filters [50].

4. What are the key differences between passive and active high-pass filters? The table below summarizes the core differences:

| Feature | Passive High-Pass Filter | Active High-Pass Filter |

|---|---|---|

| Power Requirement | No external power needed [49]. | Requires an external power source [49]. |

| Core Components | Resistors and capacitors only [49]. | Operational amplifiers, resistors, and capacitors [49]. |

| Signal Gain | Does not provide gain; may incur signal loss [49]. | Provides signal gain and can boost output strength [49]. |

| Design Complexity & Cost | Simple design and low cost [49]. | More complex design and higher cost [49]. |

| Performance | Moderate cutoff frequency accuracy; performance can be affected by the load [49]. | High cutoff frequency accuracy and stable performance [49]. |

| Best Suited For | Simple, low-cost applications where signal gain is not required [49]. | Complex applications requiring signal strength, precise control, and high performance [49]. |

5. Beyond hardware filters, what algorithmic methods exist for baseline correction? Several software-based algorithms are highly effective, particularly for post-acquisition data processing. The table below compares key methods:

| Algorithm | Principle | Key Parameters | Pros & Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penalized Least Squares (PLS) | Balances fidelity (fit to original data) and smoothness of the fitted baseline [51]. | Smoothness (λ), Asymmetry (p) [51]. | Pro: Fast, avoids peak detection [51].Con: Parameters often require manual optimization [51]. |

| Wavelet Transform | Decomposes the signal into different frequency components to isolate and remove the baseline [46] [45]. | Wavelet basis, Decomposition level [45]. | Pro: Effective for non-stationary signals [46].Con: Difficult to select optimum parameters [45]. |

| Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) | Adaptively decomposes a signal into intrinsic mode functions, separating noise, baseline, and signal [46]. | Number of intrinsic mode functions. | Pro: Highly adaptive to signal nature [46].Con: Poor performance with highly randomized drift [46]. |

| Transformer Model (Deep Learning) | Uses a self-attention mechanism to learn global dependencies in the input signal and generate a corrected output [46]. | Network architecture, Learning rate. | Pro: Excels at capturing complex, long-term dependencies; suitable for real-time systems [46].Con: Requires substantial data for training [46]. |

Implementation and Troubleshooting

6. My baseline is still drifting after applying a standard HPF. What could be wrong? This is a common challenge in dynamic data streaming environments. Potential issues include:

- Incorrect Cut-off Frequency: The filter's cut-off frequency may be set too low, allowing low-frequency drift to pass, or too high, distorting your analytical signal.

- Non-Stationary Drift: The characteristics of the drift may be changing over time, requiring an adaptive filter that can automatically adjust its parameters [50].

- Computational Limitations: Implementing complex filters on high-volume, high-velocity data streams can introduce latency if the algorithm is not optimized for computational efficiency [50].

7. How can I automatically select parameters for a baseline correction algorithm? Recent research has focused on automating parameter selection. One method for Penalized Least Squares, called erPLS, automates the smoothness parameter (λ) selection by:

- Linearly expanding the ends of the spectrum and adding a known Gaussian peak.

- Processing the expanded signal with different λ values.

- Selecting the optimal λ that results in the minimal root-mean-square error (RMSE) in the predicted baseline of the expanded region [51]. This approach turns a subjective manual optimization into a reproducible, automated process.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Baseline Drift in HPLC

Problem: A steady upward or downward trend in absorbance obscures peaks during an HPLC gradient run.

Investigation and Resolution Flowchart The following workflow visualizes a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving HPLC baseline drift.

Step-by-Step Instructions:

Verify Mobile Phase and Wavelength:

- Action: At low UV wavelengths (<220 nm), the absorbance of your mobile phase components (especially methanol) can cause significant drift [47] [48].

- Solution: Switch to acetonitrile, which has lower UV absorbance at low wavelengths. Alternatively, add a UV-absorbing buffer like phosphate to the aqueous solvent (A) to match the absorbance of the organic solvent (B) [47]. Increasing the detection wavelength can also mitigate drift [47].

Check for Bubbles and Contamination:

- Action: Inspect the system for air bubbles or contamination in the mobile phase, tubing, or detector flow cell [8] [48].

- Solution: Thoroughly degas all mobile phases using an inline degasser or helium sparging. Perform regular system cleaning, checking mobile phase filters and containers for contamination [8].

Assess Pump and Mixing Performance:

- Action: If the baseline shows regular oscillations or noise on top of the drift, improper solvent mixing or a failing pump component could be the cause [48].

- Solution: Ensure the system's mixer is appropriate for the method. Consider adding a post-market static mixer. Inspect and clean or replace pump check valves and proportioning valves if necessary [48].

Guide 2: Implementing a Modern Algorithmic Correction