Mastering XRF Pelletizing: A Complete Guide to Methods, Optimization, and Pharmaceutical Applications

This comprehensive guide details the critical pelletizing methods for preparing samples for X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) analysis, a cornerstone technique for elemental analysis in pharmaceutical development and research.

Mastering XRF Pelletizing: A Complete Guide to Methods, Optimization, and Pharmaceutical Applications

Abstract

This comprehensive guide details the critical pelletizing methods for preparing samples for X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) analysis, a cornerstone technique for elemental analysis in pharmaceutical development and research. It covers the foundational principles of creating high-quality pressed pellets, step-by-step methodological protocols, advanced troubleshooting for common pitfalls, and a comparative validation against other elemental analysis techniques. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this article provides the practical knowledge needed to ensure accurate, reliable, and regulatory-compliant results in biomedical and clinical research settings.

The Science of XRF Pelletizing: Building a Solid Foundation for Accurate Analysis

Why Sample Preparation is the Most Common Source of Error in Modern XRF

In modern X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) analysis, technological advancements have significantly improved instrument stability, detector sensitivity, and correction algorithms. Despite these improvements, sample preparation remains the most prevalent source of analytical error [1]. Contemporary XRF spectrometers feature highly stable generators, tubes, and electronics, with sophisticated empirical and theoretical correction algorithms integrated into software [1]. Consequently, the largest error in the most exacting quantitative analyses now originates from standard selection, sampling, and, most critically, specimen preparation [1].

The process of transforming a bulk material into an analysis-ready specimen introduces numerous potential variations that can compromise the representativeness of the final data. This application note examines the fundamental reasons why sample preparation is the dominant error source, provides quantitative evidence from comparative studies, and outlines detailed protocols to mitigate these errors, with a specific focus on pelletizing methods for research applications.

The Dominance of Sample Preparation Error

The Hierarchy of Analytical Errors

In XRF spectroscopy, the total error is the square root of the sum of the squares of errors from individual components of the system, as expressed in the analysis of variance [1]:

Total Error = √(Error₲ + Error₂² + ... + Errorₙ²)

The major contributors include:

- Counting Statistics

- Power Source Stability

- Spectrometer Performance

- Macro Sampling Process

- Specimen Preparation Process

- Reference Standards

- Correction Algorithms

Due to engineering improvements, errors from the instrument hardware and counting statistics have been minimized, making the specimen preparation process the largest remaining variable in most analytical scenarios [1]. This is particularly true for powder analysis, where preparation techniques such as loose powder, pressed pellets, and fused beads introduce distinct analytical challenges.

Fundamental Physical Principles

The extreme surface sensitivity of XRF analysis makes proper specimen preparation non-negotiable. The effective layer thickness—the depth from which most of the analytical signal originates—is remarkably shallow, varying with both the element of interest and the sample matrix [1].

Table 1: Effective Layer Thickness for Selected Elements

| Element | Effective Layer Thickness (µm) | Matrix Dependency |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium (Na) | 4 | Highly matrix-dependent |

| Aluminum (Al) | ~10 | Highly matrix-dependent |

| Silicon (Si) | ~10 | Highly matrix-dependent |

| Iron (Fe) | 3000 in Carbon, 11 in Lead | Extremely matrix-dependent |

For context, the average human hair is approximately 100 µm thick, meaning the analytical signal for light elements like sodium originates from a layer 25 times thinner than a single hair [1]. Any surface imperfection, contamination, or inhomogeneity within this critical layer will directly and significantly impact the analytical results.

Quantitative Evidence from Comparative Studies

Performance of Different Preparation Techniques

Research directly comparing preparation methods demonstrates clear performance differences. A study on raw clay analysis evaluated three preparation techniques for eleven elements and found substantial variation in method accuracy across different element types [2].

Table 2: Method Performance in Clay Analysis (Recovery %)

| Element Group | Loose Powder (LP) | Pressed Pellet (PP) | Pressed Pellet with Binder (PPB) | Fired Pressed Pellet (FPP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light Elements | Variable recovery (89-238%) | Poorest recoveries | Most recoveries within 80-120% | Improved homogeneity |

| Heavy Elements | Less preparation-dependent | Better than for light elements | Consistent performance | Good performance |

| Overall Suitability | Limited for quantitation | Not recommended for light elements | Recommended for most applications | Excellent for challenging materials |

A separate soil analysis study confirmed these findings, reporting that pressed pellets with wax binder (PPB) yielded the highest number of element recoveries within the acceptable 80-120% range compared to loose powder and pressed pellets without binder [3]. The pressed pellet with binder method provided superior homogeneity and surface integrity, directly translating to improved analytical accuracy.

Impact of Particle Size and Homogeneity

The relationship between particle size and analytical error is well established. Grinding curve analysis—plotting X-ray intensity against grinding time—provides a method to determine the optimal particle size for specific applications [1]. Generally, samples must be ground until particles are smaller than the analytical depth for all wavelengths of interest [2].

When samples are not sufficiently ground, the mineralogical effect or inter-mineral effect occurs, where the analyzed surface layer is neither homogeneous nor representative of the bulk material [1]. This effect is vividly demonstrated by the analysis of kyanite, sillimanite, and andalusite (three polymorphs of Al₂O₃·SiO₂). Despite identical chemical composition, using one as a standard to analyze another can yield analysis totals ranging from 75% to 125% due to differential absorption and enhancement effects between the crystal structures [1].

Detailed Pellet Preparation Protocols

Pressed Pellet Workflow for Powders

The following workflow details the optimal procedure for creating pressed pellets for XRF analysis:

Critical Parameters for High-Quality Pellets

Grinding and Particle Size Control

- Equipment Selection: Use vibratory mills, planetary ball mills, or swing mills appropriate to sample hardness and required final particle size.

- Particle Size Target: Grind until 95% of particles pass through a 75 µm (200 mesh) sieve [1].

- Cross-Contamination Prevention: Use mill materials and grinding media that won't contaminate samples with elements of interest. For example, avoid tungsten carbide mills when analyzing tungsten or cobalt.

- Grinding Curve Development: For new materials, create a grinding curve by plotting X-ray intensity of key elements against grinding time to identify the point of diminishing returns.

Binder Selection and Mixing

- Binder Types: Common binders include cellulose-based materials (Whatman cellulose, Microcrystalline Cellulose), waxes (Cereox, Hoechst Wax), and chemical binders (lithium tetraborate for fusion) [2] [3].

- Mixing Ratios: Typical sample-to-binder ratios range from 5:1 to 10:1 depending on sample cohesion characteristics [3].

- Mixing Methodology: Use mechanical mixers for consistency. For manual mixing, employ geometric dilution techniques to ensure homogeneous distribution.

- Binder Function: Binders reduce particle segregation, improve cohesion during pressing, and enhance mechanical stability of the final pellet.

Pressing Conditions

- Pressure Range: Apply 15-35 tons for a standard 40 mm diameter pellet, depending on sample compressibility [4].

- Dwell Time: Maintain pressure for 30-60 seconds to allow particle rearrangement and stress relaxation.

- Pressure Application: Apply pressure gradually to avoid entrapped air and laminate formation.

- Decompression: Use programmable decompression when available to minimize pellet fracture from rapid pressure release [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for XRF Pellet Preparation

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Equipment for XRF Pellet Preparation

| Item | Function | Specifications | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vibratory Mill | Particle size reduction | Capable of achieving <75 µm | Contamination-free grinding chambers |

| Hydraulic Pellet Press | Pellet formation | 20-40 ton capacity, programmable decompression | Carver AutoPellet presses recommended [4] |

| Pellet Dies | Mold for pellet formation | 32-40 mm diameter, stainless steel | Vacuum-compatible dies reduce entrapped air |

| Cellulose Binder | Matrix for powder cohesion | Microcrystalline, purity >99% | Suitable for most applications; ashless |

| Wax Binder (Cereox) | Binder for difficult materials | Fluxana Cereox wax [2] | Improved recovery for light elements [3] |

| XRF Sample Cups | Holder for loose powders | 32 mm with 4 µm propylene film [3] | For loose powder method comparison |

| Dasotraline hydrochloride | Dasotraline Hydrochloride|SNDRI Inhibitor|Research Chemical | Bench Chemicals | |

| 8-Deoxygartanin | 8-Deoxygartanin, CAS:33390-41-9, MF:C23H24O5, MW:380.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Advanced Strategies for Error Reduction

Fusion Technique for Challenging Materials

For materials exhibiting significant mineralogical effects or extreme heterogeneity, the fusion method using lithium tetraborate or similar fluxes creates a homogeneous glass bead that eliminates particle size and mineralogical effects [1]. Although more time-consuming and requiring specialized equipment, fusion provides the highest accuracy for complex natural materials and is recommended when analyzing unfamiliar samples or developing reference methods.

Binder-Free Fired Pellets for Specialized Applications

Recent research has explored fired pressed pellets (FPP) for analyzing raw clays and other mineralogical samples [2]. This technique involves pressing samples without binder followed by controlled heating to induce slight sintering, creating a cohesive pellet without dilution effects. While not universally applicable, FPP shows promise for specific material classes where traditional binders may interfere with light element analysis.

Calibration Standard Preparation

The "Golden Rule for Accuracy in XRF Analysis" states that the closer the standards match the unknowns in mineralogy, particle homogeneity, particle size, and matrix characteristics, the more accurate the analysis will be [1]. Therefore, calibration standards must undergo identical preparation procedures as unknown samples to avoid systematic errors from differential absorption or enhancement effects.

Sample preparation remains the most common source of error in modern XRF analysis due to the fundamental physics of the X-ray fluorescence process and the extreme surface sensitivity of the technique. While modern instrumentation has minimized hardware-related errors, the preparation of a representative, homogeneous specimen with appropriate particle size and surface characteristics continues to challenge analysts.

The evidence from comparative studies clearly demonstrates that pressed pellets with appropriate binders generally provide superior accuracy compared to loose powder or binder-free pressed pellets, particularly for light elements. Through adherence to the detailed protocols outlined in this application note—with particular attention to particle size reduction, binder selection, and pressing parameters—researchers can significantly reduce analytical errors and produce reliable, reproducible data for their research and development needs.

X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy is a widely used analytical technique for determining the elemental composition of materials across various scientific and industrial fields. The accuracy and precision of XRF analysis are highly dependent on the quality of sample preparation, with pressed pellet formation being a cornerstone method for creating homogeneous, representative specimens. This technique transforms powdered samples into solid pellets, mitigating matrix effects and physical inconsistencies that otherwise compromise analytical results. The principles of creating an effective pressed pellet involve a comprehensive understanding of the interactions between X-rays and matter, the systematic preparation of powdered samples, and the application of controlled pressure to yield a uniform analytical surface. This application note details the fundamental principles and standardized protocols for producing high-quality pressed pellets, enabling researchers to achieve superior accuracy in quantitative XRF analysis.

The Science of XRF and the Imperative for Homogeneous Samples

The XRF process begins when a primary X-ray beam excites atoms in a sample, causing the ejection of inner-shell electrons. As outer-shell electrons fill these vacancies, they emit characteristic secondary (fluorescent) X-rays with energies specific to each element [5]. The intensity of these emissions allows for quantitative analysis. However, the effective layer thickness—the depth from which most characteristic X-rays escape the sample—is remarkably shallow, often just a few micrometers for light elements and up to several millimeters for heavy elements in a light matrix [1]. This underscores the critical need for a perfectly flat and homogeneous surface at the microscopic level.

Analytical errors arise from several sample-related factors:

- Particle Size Effects: Variations in particle size and packing density lead to inconsistent X-ray absorption and scattering, distorting emission intensities.

- Mineralogical Effects: Even with uniform particle size, different mineral forms of the same element can yield varying fluorescence intensities due to differences in crystal structure and density [1].

- Surface Irregularities: Rough or uneven surfaces alter the geometry between the sample, X-ray source, and detector, introducing significant signal noise and error.

Pressed pellets address these issues by grinding the sample to a fine, consistent particle size and compressing it into a dense, flat disk. This process homogenizes the sample, reduces background scattering, and creates a uniform analytical surface, leading to a higher signal-to-noise ratio and more reliable quantification [6]. The following workflow outlines the complete pellet preparation process.

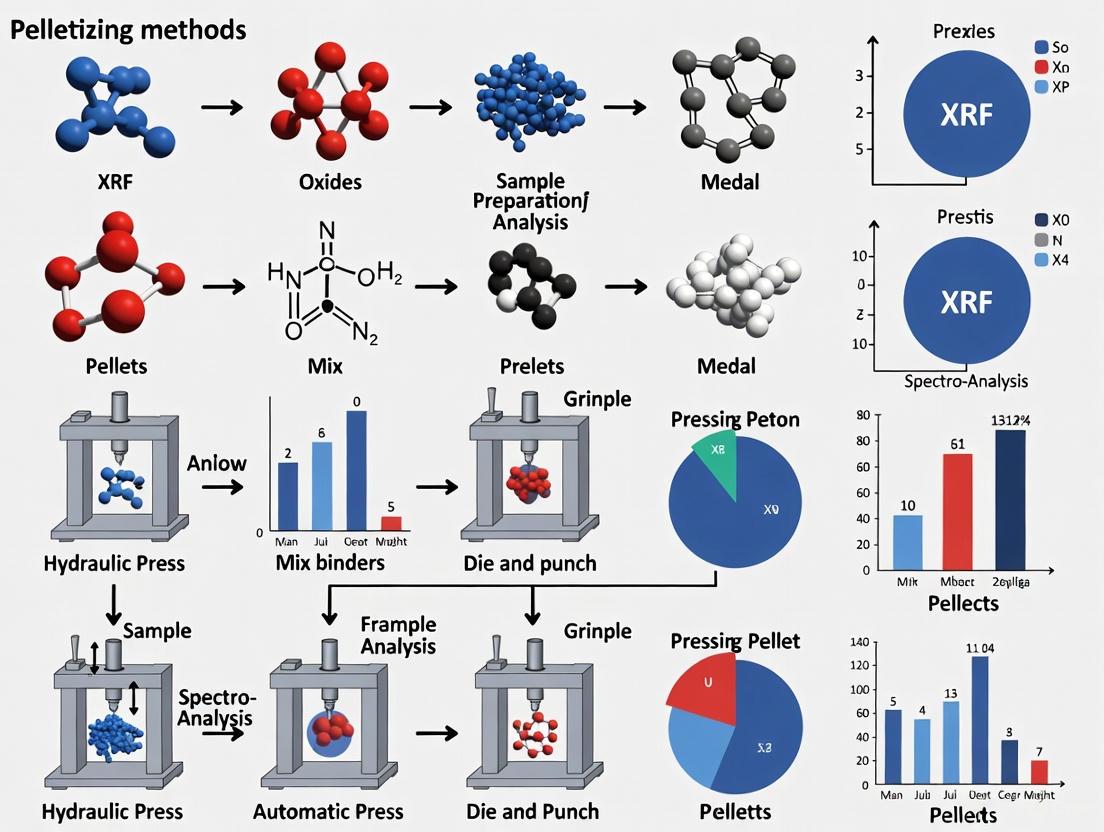

Diagram 1: The Pressed Pellet Preparation Workflow.

Quantitative Advantages of the Pressed Pellet Method

The superiority of the pressed pellet technique over the analysis of loose powders is demonstrated by quantitative data. A comparative study on Portland cement revealed significant discrepancies when using loose powder, whereas pressed pellets provided results closely aligned with expected values [6].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Cement Analysis: Pressed Pellets vs. Loose Powder

| Compound | Loose Powder (%) | Pressed Pellet (%) | Expected Range (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SiOâ‚‚ | 7.75 | 18.90 | 19.0 - 21.8 |

| Al₂O₃ | 1.16 | 4.35 | 3.9 - 6.1 |

| Fe₂O₃ | 5.70 | 2.32 | 2.0 - 3.6 |

| MgO | 0.12 | 1.06 | 0.8 - 4.5 |

| CaO | 78.57 | 65.60 | 61.5 - 65.2 |

| Naâ‚‚O | Not detected | 0.25 | 0.2 - 1.2 |

Source: Specac Ltd. (2023) [6]

The data shows that loose powder analysis leads to a severe underestimation of lighter elements (Si, Al, Mg, Na) and a consequent overestimation of heavier elements (Fe, Ca). This is because loose powders have void spaces and greater heterogeneity, which disproportionately affect the detection of lower-energy X-rays from light elements. The pressed pellet method eliminates these voids, creating a denser, more homogeneous matrix that allows for the accurate detection of all elements, from sodium to heavy metals [6] [7].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Pressed Pellet Preparation

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for XRF Pellet Preparation

| Item | Function & Specification |

|---|---|

| Planetary Ball Mill | For fine grinding and homogenization of samples to achieve consistent particle size (e.g., Retsch PM 200) [8]. |

| Hydraulic Pellet Press | Applies controlled, high pressure (e.g., 20-40 tons) to form pellets. Automated presses ensure consistency [6] [9]. |

| XRF Pellet Die Set | High-quality stainless steel die and pellets (pressing anvils) to form the sample. A mirror-finish on the pressing faces is critical for a smooth pellet surface [9]. |

| Binder (Cellulose Wax) | Aids in particle cohesion and pellet stability. Common binders include microcrystalline cellulose (e.g., SpectroBlend) typically added at 10-30% w/w [6] [8] [7]. |

| Aluminium Support Cups / Rings | Thin, low-cost cups that are crushed during pressing to provide a supportive backing for the pellet, or metal rings that hold the pellet for automated loading systems [9]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Sample Drying and Grinding

- Air-dry the sample thoroughly. For complete moisture removal, oven-dry at 105°C for 24 hours [8].

- Use a planetary ball mill to grind the sample to a fine, consistent powder. A grinding time of 10-20 minutes is typical to achieve sufficient fineness [6] [8].

Step 2: Blending with Binder

- Weigh out the ground sample.

- Add a binding agent, such as microcrystalline cellulose, at a concentration of 10-20% by weight [6] [8].

- Homogenize the mixture thoroughly in the ball mill for an additional 10-20 minutes to ensure an even distribution of the binder. This step is crucial for the mechanical stability of the final pellet.

Step 3: Loading the Die Set

- Select the appropriate die set (standard or ring-type) based on spectrometer requirements [9].

- If using an aluminium cup, place it securely within the die barrel.

- Transfer the homogenized sample-binder mixture into the die assembly, ensuring an even distribution.

Step 4: Pressing the Pellet

- Place the assembled die into the hydraulic press.

- Apply pressure gradually. A step-wise pressure increase is beneficial for allowing air to escape, minimizing voids and potential pellet cracking [9].

- Apply the final load. The required pressure is sample-dependent but typically ranges from 15 to 40 tons for industrial minerals and ores. For example, cement is often pressed at 20 tonnes [6] [9] [1].

- Maintain the pressure for 1-3 minutes to allow for plastic deformation and bonding of particles [8].

Step 5: Pellet Ejection and Storage

- Carefully release the pressure and eject the pellet from the die set.

- Visually inspect the pellet for surface smoothness, cracks, and homogeneity.

- Store the pellet in a dry environment to prevent moisture absorption, which can alter the sample matrix and affect analytical results.

Critical Parameters for Optimal Pellet Quality

The relationship between process parameters and pellet quality is complex. The diagram below illustrates the primary factors and their interconnected effects on the final analytical outcome.

Diagram 2: Key Parameters Influencing Pellet Quality.

- Particle Size and Homogeneity: The sample must be ground to a fine and consistent particle size. This is the most critical factor in reducing mineralogical and grain size effects, which are major sources of error in quantitative analysis [1].

- Binder Selection and Concentration: The binder must be free of the target analytes. The optimal concentration is a balance; too little binder results in a friable pellet, while too much dilutes the sample and can weaken X-ray signals [8].

- Applied Pressure: Pressure must be sufficient to form a cohesive pellet but not so high as to induce strain or damage the press tools. The optimal pressure is material-specific and should be determined empirically. For many geological and cementitious materials, pressures of 20-25 tonnes are standard [6] [10].

The pressed pellet method is an indispensable sample preparation technique for achieving high-quality quantitative analysis in XRF spectroscopy. By systematically controlling the factors of particle size, binder concentration, and applied pressure, researchers can produce homogeneous, stable pellets that minimize matrix effects and background noise. This protocol provides a reliable foundation for generating analytically precise data, forming a critical step in any rigorous research involving the elemental characterization of solid materials. Mastery of this fundamental technique ensures the integrity and reliability of data in both academic research and industrial quality control.

X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) analysis is a widely employed analytical technique for determining the elemental composition of materials across diverse sectors including pharmaceuticals, geology, and materials science [11]. The accuracy and precision of XRF results are heavily dependent on sample preparation, with pressed pellets being one of the most common and effective methods [12] [13]. The quality of these pellets is paramount, as inconsistencies can introduce errors that outweigh the limitations of modern spectrometer technology [12]. This application note delineates the three core components—binder, particle size, and pressure—that are critical for formulating successful XRF pellets, providing researchers and scientists with detailed protocols and data to ensure reliable and reproducible analytical outcomes.

Core Component Analysis

Binder Selection and Function

Binders are agents used to cohesively bind powdered samples together, forming a stable pellet that can withstand handling and analysis without disintegrating. Their primary function is to ensure pellet integrity, thereby preventing loose powder from contaminating the spectrometer and skewing results [12]. The choice of binder is vital, as it can influence the XRF background and must be free of elements that could interfere with the analysis of the sample.

Table 1: Common XRF Binders and Their Properties

| Binder Name | Chemical Composition | Key Characteristics & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulose-based (e.g., XR-tab) | >90% Cellulose + lubricant [14] | Ideal for intense grinding; acts as both grinding aid and binder; provides high stability and moisture resistance [14]. |

| Wax-based (e.g., CEREOX) | Wax [15] | Forms perfect, clean pellets with high stability under X-rays; suitable for a wide range of materials [15]. |

| Boric Acid (BOREOX) | H₃BO₃ [15] [16] | Harmless organic material; excellent as a backing material; ideal if measuring oxygen (O) due to its high oxygen content [15] [16]. |

| SpectroBlend | C: 81.0%; H: 13.5%; N: 2.6%; O: 2.9% [16] | Pre-mixed binder; trace elements like N must be considered for potential spectral interference [16]. |

| X-Ray Mix | C: 48.7%; H: 8.1%; B: 0.6%; O: 42.6% [16] | Pre-mixed binder; composition should be checked for interference with target analytes [16]. |

Dilution Ratio: A consistent binder-to-sample dilution ratio is critical for analytical accuracy. A ratio of 20-30% binder is commonly recommended to ensure pellet strength without excessive dilution of the sample [12]. Other sources suggest a lower ratio of 1:5 (binder to sample), equating to approximately 20%, is sufficient for a strong pellet [16]. The minimum effective amount should always be used to avoid increasing background scattering, which can reduce sensitivity for light elements [17].

Particle Size Optimization

Particle size directly influences the homogeneity and surface smoothness of the pellet, which in turn affects the intensity and accuracy of the X-ray signal. Fine, consistent particle sizes minimize void spaces and reduce background scattering, leading to more reliable quantification [13].

Optimal Range: For pressed pellets, a particle size of <50 µm is recommended for optimal results, although <75 µm is generally acceptable [12] [13]. Achieving a fine powder is typically accomplished using ring and puck pulverizers, with grinding materials (e.g., hardened steel, agate, tungsten carbide) selected to minimize sample contamination [17].

Experimental Evidence: A study on phosphate slurry demonstrated the significant effect of particle size on analytical error. The relative error for various compounds increased as the particle size coarsened, underscoring the necessity of fine grinding for accurate analysis [18].

Table 2: Effect of Particle Size on XRF Measurement Relative Error [18]

| Compound | Relative Error at 106 µm | Relative Error at 425 µm | Ratio of Error (Max/Min Size) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pâ‚‚Oâ‚… | Baseline | Increased | 1.50 |

| Al₂O₃ | Baseline | Increased | 4.01 |

| Kâ‚‚O | Baseline | Increased | 15.58 |

| CaO | Baseline | Decreased | Inverse relationship |

| SiOâ‚‚ | Baseline | Decreased | Inverse relationship |

Pressure Application

Pressure is the factor that consolidates the powdered mixture into a solid, dense pellet. The correct pressure ensures the binder recrystallizes effectively and eliminates void spaces, creating a homogenous sample with optimal integrity for analysis [12] [13].

Optimal Pressure Ranges: The required pressure varies depending on the sample material. A general starting condition is 15-35 tons for 1-2 minutes [12] [13]. However, the specific optimal range must be determined empirically based on the sample's characteristics.

Table 3: Recommended Pressure Ranges by Sample Type

| Sample Type | Recommended Pressure Range (Tons) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| General / Most Samples | 15 - 25 [13] | A good starting point for method development. |

| Complex Materials (e.g., Ores, Slag) | 25 - 40 [12] [9] [13] | Higher pressures may be needed for complete compression. |

| Pharmaceuticals | ~20 [9] | Requires higher binding than foodstuffs. |

| Foodstuffs | As low as 2 [9] | Very low loads may be sufficient. |

Consequences of Inadequate Pressure:

- Insufficient Pressure: Results in low-density pellets that are crumbly, prone to disintegration, and have increased porosity. This leads to inaccurate results and potential instrument contamination [13].

- Excessive Pressure: Can cause sample deformation, cracking, or poor spectral quality [13]. It is crucial to experiment with increasing pressure until the intensity for light elements stabilizes [13].

Integrated Experimental Protocol for XRF Pellet Preparation

The following workflow outlines the comprehensive procedure for preparing high-quality pressed pellets, integrating the three core components.

Materials and Equipment

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item Category | Specific Examples / Types | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Binders | Cellulose (XR-tab [14]), Wax (CEREOX [15]), Boric Acid (BOREOX [15]) | Binds powder particles into a coherent pellet. |

| Grinding Mill | Ring & Puck Pulverizer [17] | Reduces sample particle size to the optimal fineness. |

| Grinding Media | Hardened steel, Tungsten Carbide, Agate [17] | Material of the grinding set; chosen to avoid contaminating the sample. |

| Pellet Die | Standard Die (32mm or 40mm), Ring Die (35mm inside dia.) [9] [16] | Acts as a mold to form the pellet under pressure. |

| Hydraulic Press | Manual, Automatic (e.g., Autotouch [16]), Programmable [9] | Applies the required tonnage (2-40T) to compress the powder. |

| Support Cups/Rings | Crushable aluminium cups, Metal rings (e.g., 51.5mm dia.) [9] | Provides structural support for the pellet during and after pressing. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Grinding: Weigh approximately 10-15g of the sample. Using a ring and puck mill, grind the sample to a fine powder with a target particle size of <50 µm [12] [17]. The grinding time should be optimized (e.g., 2-5 minutes) until further grinding does not significantly change the analytical results [17].

- Mixing with Binder: Weigh the ground sample and add the selected binder at a consistent 20-30% by weight ratio [12] [16]. For a two-step method that improves pellet resilience, add the binder after the initial grinding and grind for an additional 30 seconds to ensure a homogeneous mixture and prevent agglomeration [17].

- Pressing:

- Assemble the clean die. If using a support cup or ring, place it in the die first [9].

- Transfer the mixture into the die, ensuring an even distribution.

- Place the die in the hydraulic press. For a typical sample, apply a load of 25-35 tons for 1-2 minutes [12] [13]. For compressible samples, use a press with an auto top-up function to maintain the load [16].

- Critical Step: Release the pressure slowly to prevent cracking of the pellet surface [13].

- Pellet Ejection and Handling: Carefully eject the pellet from the die. Inspect the pellet for any visible cracks, voids, or surface imperfections. A properly prepared pellet should be smooth, dense, and resilient.

The synergy between a correctly chosen binder, an optimally fine particle size, and appropriately applied pressure forms the foundation of successful XRF pellet preparation. By meticulously controlling these three core components as outlined in this application note, researchers can consistently produce high-quality pellets that minimize analytical errors, enhance detection limits, and ensure the reliability of their XRF data. This rigorous approach to sample preparation is indispensable for advancing research in drug development, material science, and any field requiring precise elemental analysis.

The Critical Role of Pelletizing in Pharmaceutical Impurity Testing (ICH Q3D)

The control of elemental impurities in pharmaceutical products is a critical safety requirement, governed globally by the ICH Q3D guideline [19]. This guideline presents a process to assess and control these impurities using the principles of risk management, providing a platform for developing a risk-based control strategy to limit elemental impurities in the drug product [19]. Elemental analysis techniques must therefore be capable of reliable detection and quantification to ensure compliance. Among the available analytical techniques, X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for pharmaceutical elemental analysis, offering several strategic advantages including minimal sample preparation, no requirement for hazardous chemicals, and the ability to provide rapid results suitable for high-throughput quality control environments [20] [21].

The reliability of any analytical technique, however, is fundamentally dependent on proper sample preparation. For XRF analysis, sample presentation significantly affects the accuracy and precision of results, particularly for light elements which are notoriously difficult to detect [6] [22]. This application note examines the critical role of pelletizing as a sample preparation method for XRF analysis within the framework of ICH Q3D compliance, providing detailed protocols and data-driven comparisons to guide pharmaceutical scientists in implementing robust impurity testing methodologies.

The Scientific Basis: Why Sample Preparation Matters in XRF

Fundamental Principles of XRF Analysis

XRF spectroscopy functions by irradiating a sample with high-energy X-rays, causing elements within the sample to emit characteristic secondary (fluorescent) X-rays that are detected and quantified [22] [21]. The intensity of these characteristic X-rays is directly related to the concentration of the element present [22]. However, the measured signal is profoundly influenced by physical matrix effects, including particle size, mineral composition, particle density, and surface homogeneity [6]. These factors affect the background scattering and intensity of the emission peaks, ultimately impacting analytical accuracy [6].

The penetration and escape depths of X-rays within a sample present particular analytical challenges. Primary X-rays penetrate the sample, and the resulting fluorescent X-rays must escape to be detected. The energy of these X-rays determines their behavior; heavy elements (e.g., Cu, Ag, Au) produce high-energy fluorescent X-rays that can travel through significant sample depths, while light elements (e.g., Na, Mg, Al, Si) produce low-energy fluorescent X-rays that can only be detected from very near the surface [22]. This makes preparation of a uniform, flat surface critical, especially for detecting lighter elements.

Comparative Advantages of Pelletizing Over Loose Powder

The preparation of samples as pressed pellets addresses key physical matrix effects by creating a homogeneous, uniform-density sample with a smooth, flat surface. Grinding samples to a very fine particle size and then compressing them into smooth, flat XRF pellets significantly reduces background scattering and improves the detection of emissions [6]. This process enhances the signal-to-noise ratio, which is particularly crucial for detecting light elements that are often superimposed on a continuous X-ray background [6].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of XRF Sample Preparation Methods

| Characteristic | Loose Powder | Pressed Pellets |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation Time | Minimal (quick and convenient) [6] | Longer (involves grinding and pressing) [6] [8] |

| Homogeneity | Low; heterogeneous particle distribution [8] | High; homogeneous distribution achieved through grinding and pressing [8] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Lower, increasing detection limits [6] | Higher, allowing detection of lightest elements [6] |

| Physical Matrix Effects | Significant; affects accuracy [6] [8] | Minimized through controlled density and surface [8] |

| Quantitative Accuracy for Light Elements | Poor; often leads to underestimation [6] | Excellent; provides accurate quantification [6] |

| Analytical Precision | Lower due to heterogeneity and particle effects | Higher due to improved homogeneity and surface uniformity |

| Suitability for Regulatory Testing | Limited for quantitative analysis of light elements | Recommended for accurate quantification [6] [23] |

The data clearly demonstrates that while loose powder analysis offers speed and convenience, it comes with significant analytical compromises. For example, in cement analysis, loose powder samples resulted in substantial underestimation of lighter elements (Al, Mg, Na), which subsequently led to overestimation of heavier elements like Fe and Ca [6]. In contrast, pressed pellets provided quantification in line with established reference ranges [6]. Similar findings were reported in soil fertility analysis, where pellet preparation, while more time-consuming, yielded superior predictive performance for exchangeable nutrients compared to loose powder [8].

Experimental Protocols for Pharmaceutical Sample Preparation

Standard Protocol for Preparing Pharmaceutical Pellets for XRF Analysis

This protocol is designed for the analysis of elemental impurities in active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), excipients, and finished drug products in compliance with ICH Q3D.

Materials and Equipment:

- Analytical balance (0.1 mg sensitivity)

- Planetary ball mill (e.g., Retsch PM 200) with grinding jars and balls (tungsten carbide or zirconia recommended)

- Hydraulic pellet press (capable of applying 15-25 tonnes, e.g., SPEX 3624B X-Press or similar)

- Pellet dies (stainless steel, typically 15-40 mm diameter depending on sample holder)

- High-purity cellulose or wax binder (e.g., Microcrystalline Cellulose, SpectroBlend)

- Mortar and pestle (if preliminary grinding is required)

Procedure:

- Pre-drying: Dry the pharmaceutical sample at 105°C for 2 hours to remove absorbed moisture, which can affect grinding efficiency and pellet integrity.

- Binder Addition: Weigh 0.9 g of the dried sample and mix with 0.1 g of cellulose binder (10% w/w ratio) using a mortar and pestle. The binder improves pellet cohesion and reduces friability, especially for powdery samples [8].

- Grinding and Homogenization: Transfer the mixture to a planetary ball mill. Grind at 400 rpm for 20 minutes using a cycle of 5 minutes clockwise followed by 5 minutes counter-clockwise, with a 10-second pause between direction changes [8]. This ensures thorough homogenization and particle size reduction.

- Pellet Pressing:

- Assemble the clean pellet die.

- Transfer the entire ground mixture (1.0 g) into the die cavity.

- Place the die in the hydraulic press and apply a force of 15-20 tonnes (e.g., 8.0 t cmâ»Â²) for 3 minutes [8].

- Slowly release the pressure and carefully eject the pellet.

- Quality Inspection: Visually inspect the pellet for a smooth, uniform surface without cracks or imperfections. The pellet should be structurally stable.

Protocol for Loose Powder Preparation

For scenarios where rapid screening is prioritized over maximum accuracy.

Procedure:

- Ensure the sample is air-dried.

- Sieve the sample through a 2 mm sieve to remove large, heterogeneous particles [8].

- Fill an open-ended XRF sample cup with approximately 10 g of the prepared powder [6].

- Secure the powder in the cup by covering the open end with a 6 µm Mylar film [6].

Calibration and Quality Control

For quantitative analysis, calibration is paramount. Two primary methods are used:

- Fundamental Parameters (FP) Method: Software algorithms based on theoretical X-ray physics correct for matrix effects, band overlaps, and spectral backgrounds. This method is robust and works well for various matrices without the need for extensive standards [22].

- Calibration with Standards: For highest accuracy, calibrate using certified reference materials (CRMs) with matrices similar to the analyzed pharmaceutical samples [22]. The ideal solid calibration standards are pressed pellets of matrix-matched CRMs [23].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for XRF Pellet Preparation

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Cellulose Binder | Binding agent to provide pellet cohesion and mechanical stability. | Low elemental background; recommended at 10% w/w ratio [8]. |

| Planetary Ball Mill | Efficient grinding and homogenization of sample-binder mixture. | Ensures particle size reduction and homogeneity; tungsten carbide jars minimize contamination [8]. |

| Hydraulic Pellet Press | Application of high pressure to form stable pellets. | Must be capable of applying 15-25 tonnes of force [6] [8]. |

| Pellet Dies | Molds for forming pellets of specific diameters. | Stainless steel construction; size compatible with XRF spectrometer sample chamber. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Calibration and method validation. | Matrix-matched to pharmaceutical samples for highest accuracy [23]. |

Data Analysis and Workflow Integration

The following workflow diagrams illustrate the comparative analytical processes and the decision-making pathway for implementing pelletizing in a pharmaceutical context.

Within the stringent framework of ICH Q3D, where accurate identification and quantification of elemental impurities are non-negotiable for drug safety and regulatory compliance, the choice of analytical methodology is critical. While loose powder XRF analysis offers a rapid approach for screening heavy elements, its limitations in homogeneity, signal quality, and accuracy for light elements make it unsuitable for definitive compliance testing [6].

The pelletizing method, despite requiring more initial preparation time, establishes the foundation for a robust, reliable XRF analysis by effectively mitigating physical matrix effects. It provides the high signal-to-noise ratio, improved homogeneity, and surface uniformity necessary for accurate quantitative analysis across a broad elemental range [6] [8]. For pharmaceutical development and quality control professionals, investing in proper pellet preparation protocols is not merely a technical optimization—it is a critical component in building a risk-based control strategy that ensures patient safety and regulatory adherence as mandated by ICH Q3D [19].

Step-by-Step Protocols: Optimized Pelletizing Methods for Pharmaceutical Samples

A Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for Creating Pressed Pellets

Within the broader context of pelletizing methods for X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) analysis research, the preparation of pressed pellets constitutes a fundamental sample preparation technique. XRF is a widely used non-destructive analytical method for determining the elemental composition of materials [7]. The accuracy and reliability of XRF analysis are highly dependent on sample preparation, with pressed pellets representing a critical middle ground between the simplicity of loose powders and the high accuracy of fused beads [24]. This Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) outlines a detailed protocol for creating homogeneous and analytically representative pressed pellets, thereby minimizing common errors and ensuring data integrity in research and quality control environments [12] [25].

Principles and Importance of Pressed Pellet Preparation

The primary goal of pressing samples into pellets is to create a homogeneous, flat, and dense surface for XRF analysis. This process enhances analytical accuracy by eliminating void spaces and minimizing sample dilution, which leads to higher signal intensities for most elements and improved detection limits for trace components [7]. The technique mitigates the effects of sample heterogeneity and particle size, which are significant sources of error, by providing a uniform matrix from which characteristic X-rays can be emitted with minimal scatter and absorption variations [26] [27]. Compared to the analysis of loose powders, pressed pellets reduce variations in distance to the detector, decrease scattered background radiation, and improve the detection sensitivity for low atomic weight elements [24].

Materials and Equipment

The following materials and equipment are essential for the pressed pellet preparation process.

Table 1: Essential Reagents and Materials for Pressed Pellet Preparation

| Item | Function and Specification |

|---|---|

| Sample Powder | Finely ground material representative of the bulk sample. Particle size should ideally be <50µm, and certainly <75µm, to ensure proper binding and a smooth surface [12] [28]. |

| Binder / Wax | A binding agent (e.g., cellulose, Cereox wax) used to hold powder particles together, improve pellet stability, and prevent contamination of the XRF spectrometer. Typical dilution ratios are 20-30% binder to sample [7] [2] [12]. |

| Aluminum Cups (Optional) | Provide structural support for pellets that are prone to breaking, facilitating handling, storage, and transport [7]. |

| Grinding Aid | A liquid such as ethanol or iso-propanol used during the milling process to reduce heat and prevent volatile loss [25]. |

Table 2: Essential Equipment for Pressed Pellet Preparation

| Equipment | Function and Specification |

|---|---|

| Grinding/Milling Machine | Apparatus used to reduce the particle size of the sample to the required fineness. Agate or tungsten carbide grinding vessels are recommended to minimize contamination [28] [25]. |

| Pellet Die Set | A precision-machined block comprising a die barrel and plungers. Standard diameters are 32 mm or 40 mm, determining the final pellet size [7] [28]. |

| Hydraulic Pellet Press | A press capable of applying sufficient uniaxial pressure (typically 15-40 tons, depending on the sample) to form a stable, dense pellet [12] [26]. |

| Analytical Balance | For accurately weighing the sample and binder to ensure consistent dilution ratios. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete pressed pellet preparation process.

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Sample Preparation and Grinding

- Drying: If the sample is moist, dry it in an oven at a suitable temperature (e.g., 105°C) to remove adsorbed water, which can affect analysis and pellet integrity.

- Grinding/Milling:

- Transfer a representative portion of the sample (at least 10g is recommended for a 40mm pellet) into a grinding or milling vessel [28].

- Use a spectroscopic grinding or milling machine to reduce the particle size. The final powder must be fine and homogeneous; powders that feel "gritty" are unsuitable and must be reground [28] [25].

- Target Particle Size: Grind to a particle size of <50µm (optimal) or at least <75µm (acceptable) [12].

Binder Addition and Mixing

- Weighing: Accurately weigh the ground sample powder.

- Binder Addition: Add a binding agent (e.g., cellulose wax, boric acid) at a proportion of 20% to 30% of the sample mass [7] [12].

- Mixing: Blend the sample and binder thoroughly in a mixing vessel for at least 2-3 minutes to ensure a homogeneous distribution of the binder throughout the sample. Inadequate mixing can lead to localized compositional changes and poor pellet homogeneity [12] [27].

Pellet Pressing

- Die Assembly: Assemble the clean pellet die. If using aluminum cups for support, place a cup into the die barrel.

- Loading: Transfer the sample-binder mixture into the die barrel. For even settling, gentle vibration or tapping of the die during filling is recommended to optimize packing density and prevent particle segregation [27].

- Pressing:

- Place the die in a hydraulic press.

- Apply pressure gradually. A stepwise compaction with brief holds between pressure increments is an advanced technique that allows particles to rearrange, collapse trapped voids, and promotes even stress distribution [27].

- Final Pressure: Apply a final pressure of 25-35 tons for a standard 40mm die. Harder mineral ores may require up to 40 tons of pressure [12] [26].

- Dwell Time: Maintain the maximum pressure for 1 to 2 minutes to ensure complete compression and binder recrystallization [12].

Pellet Ejection and Inspection

- Decompression: Release the pressure slowly using a controlled decompression sequence. This prevents microcracks or localized elastic rebound that can create density gradients within the pellet [27].

- Ejection: Carefully eject the pressed pellet from the die.

- Quality Control Inspection: Visually inspect the pellet for surface smoothness, cracks, or other defects. The pellet should be mechanically stable, with a flat, uniform surface. A defective pellet must be discarded, and the process repeated.

Data Presentation and Analysis

The following table summarizes key parameters for successful pellet preparation and their impact on the final analysis, synthesizing data from multiple sources [7] [2] [12].

Table 3: Quantitative Parameters and Their Impact on Pressed Pellet Quality

| Parameter | Optimal Specification | Effect of Deviation | Research Context / Comparative Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size | < 50 µm (optimal) < 75 µm (acceptable) | Gritty powders produce unstable pellets, poor homogeneity, and scattered X-rays, leading to inaccurate results [12] [28]. | Finer particles pack more densely, reducing void spaces and matrix effects for more accurate quantification [27]. |

| Binder Ratio | 20% - 30% by mass | Too little: fragile pellet, risk of breakage. Too much: over-dilution of sample, reduced signal intensity [7] [12]. | Binders not detected by XRF (e.g., cellulose/wax) ensure analysis focuses on sample elements [7]. |

| Pressing Pressure | 25 - 35 Tons (up to 40T for minerals) | Insufficient pressure: porous pellet, poor homogeneity. Excessive pressure: may damage die or induce stress fractures [12] [26]. | Higher pressure ensures no void spaces are present, creating a dense, representative sample [12]. |

| Pellet Thickness | Infinitely thick to X-rays | If too thin, X-rays penetrate completely, leading to inaccurate readings as the signal is not solely from the sample [12]. | For a 40mm pellet, ~8g of powder is typically required to achieve sufficient thickness [28]. |

| Technique Comparison | Pressed Pellet (PPB) vs. Fired Pressed Pellet (FPP) | PPB is faster but may retain some mineralogical effects. FPP can improve recoveries for light elements [2]. | A 2023 study on raw clays showed FPP (no binder) provided superior recoveries for light elements (e.g., Na, Mg) compared to PPB with wax binder [2]. |

Advanced Techniques and Methodologies

For research requiring the highest level of analytical precision, several advanced pelletizing techniques can be employed to further enhance sample homogeneity.

- Cold Isostatic Pressing (CIP): This technique applies uniform hydrostatic pressure from all directions as a secondary densification step. It eliminates the directional stress gradients typical of standard uniaxial pressing, resulting in a compact with exceptional internal uniformity, which is advantageous for trace-element determination [27].

- Creep Annealing or Hot Pressing: This involves maintaining a moderate temperature while the sample remains under pressure. This enables slow plastic deformation of particles, promoting stress relaxation, binder redistribution, and microvoid healing. The result is a denser, more coherent structure without altering the elemental composition [27].

- Vibration-Assisted Filling: Applying gentle vibration or tapping during die filling helps powders settle evenly, prevents arching or segregation, and allows smaller particles to fill gaps between larger ones. This optimizes packing density before pressing, leading to a smoother surface and a more isotropic structure [27].

Troubleshooting and Quality Assurance

- Contamination: This is one of the biggest problems in XRF sample preparation. It can originate from the grinding process or cross-contamination between samples. Meticulous cleaning of all equipment between samples is mandatory. Using grinding vessels made of materials that will not interfere with the analysis (e.g., agate for trace element work) is crucial [12] [25].

- Unstable or Crumbling Pellets: If pellets lack mechanical integrity, consider increasing the binder percentage, ensuring the powder is finely ground, increasing the pressing dwell time, or using aluminum cups for structural support [7] [12].

- Poor Analytical Reproducibility: Inconsistent results between pellets from the same sample batch are often due to variations in particle size, binder ratio, applied pressure, or mixing time. Strict adherence to this SOP and the use of automated equipment where possible can significantly improve reproducibility [27] [25].

The preparation of high-quality pressed pellets is a critical step in ensuring the accuracy and precision of XRF analysis. This SOP provides a standardized, detailed protocol covering the entire process from sample grinding to final pellet inspection. By rigorously controlling parameters such as particle size, binder concentration, and pressing force, researchers can produce homogeneous pellets that faithfully represent the bulk sample's composition. The implementation of this protocol, along with the consideration of advanced techniques for demanding applications, forms a solid foundation for reliable elemental analysis within a thesis on pelletizing methods, contributing to robust and defensible research outcomes.

In X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis, sample preparation is the most significant source of potential error, with binder selection playing a pivotal role in achieving accurate and reproducible results [12] [1]. Pressed pellets are a standard preparation method because they create a homogeneous, flat, and dense sample surface ideal for X-ray interaction [29]. The fundamental purpose of a binder is to act as a "glue" that holds powdered sample particles together, forming a cohesive pellet that remains intact during handling and analysis, thereby preventing loose powder from contaminating the XRF spectrometer [12] [30].

The selection of an appropriate binder is critical to the "Golden Rule for Accuracy in XRF Analysis," which states that the highest accuracy is achieved when standards and unknowns are nearly identical in characteristics such as particle homogeneity, particle size, and matrix effects [1]. An unsuitable binder can lead to pellet failure, sample heterogeneity, and spectral interference, ultimately compromising the analytical integrity of the data, which is particularly critical in pharmaceutical development and geological research where precise elemental quantification is required.

Binder Types and Properties

Various binders are commercially available, each with distinct chemical compositions and physical properties that make them suitable for specific analytical scenarios. The optimal choice depends on the sample's nature and the elements of interest.

Table 1: Common XRF Binders and Their Elemental Composition (mass %)

| Binder | Chemical Composition | Key Characteristics | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose/Wax Mixture [12] [16] [30] | C: ~48-81%; H: ~8-14%; O: ~3-43%; B: ~0.6%; N: ~2.6% [16] | Excellent homogenization; easy mixing; good general-purpose binding [12] [30]. | General analysis excluding low-Z elements like Boron (B) or Nitrogen (N). |

| Boric Acid [16] [29] | O: 77.6%; H: 4.9%; B: 17.5% [16] | High oxygen content; forms a protective crust [16] [29]. | Analysis focused on oxygen; backing for weak pellets. |

| Acrylic Binders [30] | Not specified in search results | Can be challenging to homogenize; may require manual mixing [30]. | Specific applications where cellulose is unsuitable. |

| Pre-Mixed Pellets [30] | Varies by product (e.g., SpectroBlend) [16] | Ensures consistent binder distribution; convenient and saves time [30]. | High-throughput laboratories prioritizing reproducibility and efficiency. |

The elemental makeup of the binder is a primary consideration. Cellulose/wax mixtures are the most widely used general-purpose binders due to their effective homogenization and binding capabilities during the mixing and pressing stages [12] [30]. However, their composition includes elements like carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and sometimes boron and nitrogen, which can cause spectral interference if these elements are analytes in the sample [16]. For instance, analyzing for nitrogen would preclude the use of a binder like SpectroBlend [16]. Conversely, boric acid, with its high oxygen content, is an excellent choice for protocols involving oxygen analysis but would be entirely unsuitable if boron is the target element [16].

Pre-mixed binder pellets offer a significant operational advantage by automating the addition of binder during milling, ensuring a consistent and homogeneous mixture with the sample powder [30]. This consistency enhances the reproducibility of pellet quality and analytical results, making them ideal for high-throughput laboratory environments.

Selection Criteria and Experimental Protocol

Selecting the optimal binder requires a systematic approach that aligns with the sample's physical characteristics and the analytical goals of the XRF measurement.

A Framework for Binder Selection

The following workflow outlines the key decision points for choosing the most appropriate binder for a given sample and analysis.

Detailed Pellet Preparation Protocol

The following step-by-step protocol details the standard method for preparing pressed pellets using a binder, ensuring results suitable for rigorous quantitative analysis.

Step 1: Sample Grinding

- Objective: Achieve a fine and uniform particle size to minimize heterogeneity and particle size effects [12] [30] [29].

- Procedure: Grind the representative sample using a crusher, grinder, or mill to a particle size of < 50 μm (acceptable up to <75 μm) [12] [31]. This fine consistency is critical as it ensures efficient compaction and a homogeneous distribution of elements, preventing "shadowing" effects from larger particles that skew analytical data [30] [29].

Step 2: Powder-Binder Mixing

- Objective: Create a homogeneous mixture of the sample and binder to ensure uniform binding strength and consistent X-ray interaction [30].

- Procedure:

- Weigh the ground sample powder.

- Add the selected binder at a 20-30% sample dilution ratio (a 1:5 binder-to-sample ratio is often sufficient) [12] [16].

- Mix thoroughly. For cellulose/wax mixtures and pre-mixed pellets, this can often be done in the grinding vessel. Acrylic binders may require careful manual mixing to ensure homogeneity [30].

Step 3: Pellet Pressing

- Objective: Transform the powder-binder mixture into a dense, stable pellet with a perfectly flat surface.

- Procedure:

- Transfer the mixture into a clean die, typically 32 mm or 40 mm in diameter [31] [16].

- Press the powder in a hydraulic press. Apply a load of 15-35 tons (a good starting condition is 25 tons) for a duration of 1-2 minutes [12] [16]. This high pressure is necessary to recrystallize the binder and completely compress the sample, eliminating void spaces that could scatter X-rays and weaken the signal [12].

- For compressible samples, use a press with a top-up function to reapply pressure and ensure optimal density [16].

Step 4: Quality Control and Storage

- Objective: Verify pellet integrity and ensure stability for analysis and potential re-analysis.

- Procedure: Visually inspect the pellet for a smooth, crack-free surface without air inclusions [31]. A durable pellet should not flake or break easily. Label and store the pellets in a dry environment to prevent moisture absorption or physical damage, as their stability allows for archiving and re-analysis [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for XRF Pellet Preparation

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Cellulose/Wax Binder | A general-purpose binding agent that homogenizes with the sample powder to create a strong, cohesive pellet [12] [30]. |

| Boric Acid (H₃BO₃) | A binding and backing material, particularly useful for its high oxygen content and ability to form a protective crust for fragile pellets [16] [29]. |

| Hydraulic Pellet Press | A press capable of applying 10-40 tons of pressure to compress the powder-binder mixture into a dense, flat pellet [12] [16]. |

| Grinding Mill | Equipment to reduce sample particle size to the required <50 μm fineness, ensuring sample homogeneity [31] [25]. |

| XRF Die Set (e.g., 32 mm) | The mold that defines the pellet's size and shape during the pressing process, often used with an aluminum cap or ring for stability [16] [1]. |

| Pre-Mixed Binder Pellets | Pre-weighed binder tablets that ensure consistent concentration and homogeneous distribution with the sample, optimizing for reproducibility and throughput [30]. |

| 1,3,7-Trihydroxy-2-prenylxanthone | 1,3,7-Trihydroxy-2-prenylxanthone, CAS:20245-39-0, MF:C18H16O5, MW:312.3 g/mol |

| Walsuronoid B | Walsuronoid B | High-Purity Research Compound |

Troubleshooting Common Pelletization Issues

Even with a robust protocol, challenges can arise. Identifying and rectifying these common issues is key to maintaining high-quality analysis.

Problem: Weak or Crumbling Pellets

Problem: Contamination

- Cause: External contaminants introduced during grinding or from improperly cleaned dies and equipment; cross-contamination from previous samples [12] [30].

- Solution: Implement rigorous cleaning procedures for all equipment between samples using appropriate solvents. Use grinding tools made of inert materials like boron carbide or stainless steel to minimize contamination from the equipment itself [30] [25].

Problem: Inaccurate Analytical Results (Heterogeneity)

- Cause: Inadequate grinding leading to large particle sizes (>75 μm) or poor homogenization of the sample and binder [12] [30].

- Solution: Strictly control the grinding process to achieve a particle size of <50 μm. For difficult samples, ensure the binder is mixed thoroughly, considering automated milling with pre-mixed pellets for superior homogeneity [30].

Problem: Spectral Interference

In X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) analysis, the accuracy of quantitative elemental determination is profoundly influenced by the quality of the prepared sample. Among the various sample preparation techniques, the pressed pellet method stands out for its excellent balance of analytical quality, speed, and cost-effectiveness [32] [24]. This method enhances results by compressing powdered materials into a dense, solid form that is free of voids and possesses a smooth, flat analytical surface, thereby reducing variations in the distance to the detector and lowering scattered background levels [32]. The overarching goal of this preparation is to create a homogeneous specimen that is representative of the bulk material, thereby minimizing errors introduced by particle size and mineralogical effects [1]. This application note delineates a detailed protocol for the creation of high-quality pressed pellets, focusing on the three pivotal parameters identified as most critical for success: grinding the sample to a particle size of <50µm, employing a binder at a ratio of 20-30% by weight, and applying an optimal pressing force of 25-35 tonnes [33] [34].

The Critical Role of Sample Preparation in XRF Analysis

Sample preparation is a cornerstone of accurate XRF analysis, often constituting the most significant source of error in quantitative results [1]. The fundamental physics of XRF dictates that the characteristic X-rays of lighter elements (such as sodium) originate from a very shallow depth—sometimes as little as 4-10 micrometers [1]. This makes the analysis exceptionally susceptible to surface imperfections and heterogeneity. Inadequate preparation leads to a host of issues, including the "shadow effect" where larger grains obscure the X-ray signal from smaller ones, and the "mineralogical effect," where the same element in different crystal structures emits slightly different X-ray intensities [32] [17]. The pressed pellet method directly addresses these challenges by creating a homogeneous, flat, and infinitely thick specimen, which ensures consistent and reliable analysis across all elements of interest [32] [7].

Table 1: Key Physical Effects Mitigated by Proper Pellet Preparation

| Effect | Description | Consequence of Neglect | How Pressed Pellets Help |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size Effect [17] | Inhomogeneous analyzed volume due to variable particle sizes. | Inaccurate concentrations, poor precision. | Grinding to a fine, consistent size creates a uniform analyzed volume. |

| Mineralogical Effect [32] [17] | Same element in different crystal configurations emits different X-ray intensities. | Systematic error in quantitative analysis. | Grinding reduces, but does not eliminate, this effect. Fusion is the only complete solution. |

| Surface Irregularity [32] | Variations in the distance from the sample surface to the XRF detector. | Increased background scatter, reduced signal, especially for light elements. | Creates a smooth, flat surface that minimizes distance variation. |

| Low Density & Porosity [33] [7] | Void spaces and low density in loose powders scatter X-rays. | Reduced XRF signal intensity, lower sensitivity for trace elements. | Compression creates a void-free, dense pellet that improves signal-to-noise. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Pressed Pellet Preparation

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for preparing a pressed pellet for XRF analysis, from the raw sample to the final product.

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for XRF Pellet Preparation

| Item | Function/Description | Critical Parameters & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Pulverizing Mill [17] [34] | Reduces sample particle size to the required <50µm for homogeneity. | Ring and puck mills are common; materials include hardened steel, agate, or tungsten carbide to avoid sample contamination. |

| Binder / Grinding Aid [34] [7] | Holds the sample together, providing structure and support for a resilient pellet. | Cellulose/wax mixtures are common. Must be free of contaminating elements and stable under radiation. |

| Hydraulic Pellet Press [33] [24] | Applies the high, controlled force necessary to compress the powder into a solid pellet. | Capable of applying 25-40 tonnes of force. Can be manual or semi-automatic (e.g., Specac APEX 400). |

| Pellet Die Set [33] [7] | Acts as the mold that defines the shape and size of the pellet. | Must withstand high loads and be the correct size for the spectrometer. Can include aluminum caps for pellet support. |

| Analytical Balance | Precisely weighs the sample and binder to maintain the critical 20-30% ratio. | Precision of 0.001g is typically sufficient for this application. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Grinding (<50µm Particle Size)

- Weigh out a representative portion of the bulk sample (typically 5-10g) [17] [1].

- Transfer the sample to a pulverizing mill (e.g., a ring and puck mill). The choice of mill material (tungsten carbide, agate, etc.) should be based on the sample hardness and potential for contamination [17].

- Grind the sample until it achieves a fine, consistent powder. A particle size of <50µm is ideal, as this ensures better compression and minimizes analytical heterogeneity [34]. A grinding time of 2-5 minutes is often a good starting point, but this should be optimized for each sample type [17].

Mixing with Binder (20-30% Ratio)

- Weigh the ground sample. Accurately add a binder at 20-30% of the sample's weight [34]. This ratio is crucial, as it ensures a robust pellet that can withstand handling without excessively diluting the sample.

- For cellulose/wax binders, add the binder to the ground sample in the grinding or mixing vessel and mix for an additional 30 seconds to ensure complete homogenization [17] [34]. Adding the binder after the initial grinding step helps prevent agglomeration.

Pressing the Pellet (25-35T Pressure)

- Assemble the clean pellet die. Transfer the sample-binder mixture into the die bore, ensuring an even distribution.

- Carefully place the plunger on top. Insert the entire assembly into the hydraulic press.

- Apply a force of 25-35 tonnes [33] [34]. This is the critical range where most samples achieve maximum compression, and the intensity for light elements stabilizes.

- Hold the pressure for 1-2 minutes to allow for binder recrystallization and complete compression, eliminating void spaces [33] [34].

Pellet Ejection and Finishing

- After the hold time, slowly release the pressure over a period of 10-20 seconds. A rapid release can create internal stresses and cause the pellet to crack [33].

- Carefully disassemble the die and extract the finished pellet. The pellet should be dense, smooth, and approximately 3mm thick [17]. Handle the pellet by its edges to avoid contaminating the analytical surface.

Optimization and Troubleshooting

Parameter Interdependence and Optimization

The three core parameters are not independent; they work synergistically to produce a high-quality pellet. Fine grinding (<50µm) enables effective binding and uniform compression. The correct amount of binder (20-30%) ensures the finely ground particles cohere into a solid form under high pressure (25-35T). Applying this optimal pressure is the final step that densifies the mixture, eliminates voids, and creates a smooth surface. To empirically determine the ideal pressure for a new sample type, one should prepare pellets using increasing pressures and measure the XRF intensity of light elements (e.g., Na, Mg); the optimal pressure is reached when this intensity reaches a maximum and stabilizes [34].

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Pressed Pellet Issues

| Problem | Probable Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Pellet crumbles easily [33] | Insufficient pressure or insufficient binder. | Increase pressure within the 25-35T range. Ensure binder is at 20-30% and is thoroughly homogenized. |

| Cracks in the pellet [33] [34] | Pressure released too quickly. | Always release pressure slowly after the hold time. |

| Poor analytical precision [33] [17] | Inhomogeneous sample (inadequate grinding) or variable pellet density. | Ensure grinding to <50µm. Maintain consistent pressure and binder ratio for all samples and standards. |

| Weak signal for light elements [33] [34] | Voids or porosity in the pellet (incomplete compression). | Ensure pressure is sufficient and held for 1-2 minutes. Verify particle size is fine enough for effective compression. |

The rigorous application of the parameters detailed in this protocol—grinding to a particle size of <50µm, using a 20-30% binder ratio, and applying 25-35T of pressure—is fundamental to producing high-quality pressed pellets for XRF analysis. This methodology directly addresses the primary physical and mineralogical challenges inherent in the technique, resulting in a homogeneous, dense, and stable specimen. By standardizing this sample preparation process, researchers and scientists can minimize a major source of analytical error, thereby achieving the high levels of accuracy and precision required for advanced research and development across diverse scientific fields.

Within the broader thesis on pelletizing methods for X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) analysis research, this document provides specific application notes and protocols for using hydraulic pellet presses and dies. Consistent and reliable sample preparation is a foundational step in analytical research, directly influencing the accuracy, repeatability, and consistency of XRF results [9]. The process of transforming powdered samples into solid pellets involves compacting them under high pressure with a binding agent, creating a homogeneous solid sample with a uniform surface ideal for X-ray irradiation [9]. This guide details the practical steps and critical parameters for researchers and drug development professionals to achieve optimal pellets, thereby supporting the integrity of subsequent elemental analysis data.

The Pellet Press and Die System: Components and Principles

A thorough understanding of the equipment is essential for effective operation. A standard powder pelleting die set consists of several precision components designed to work together seamlessly [35].

- Die Sleeve: A hollow cylindrical body that forms a blind tube into which the powder sample is poured. It acts as the main structure of the pellet die [35].

- Plunger Rod: This component is inserted into the die sleeve and is used to apply pressure to the powder sample during the pelletizing process [35].

- Base Plate: This forms the bottom of the die assembly and provides crucial support for the powder sample during compression [35].

- Spacers: These are removable components used to adjust the final thickness of the pellets being formed. They also help reduce cross-contamination between different samples [35].

- Release Ring: This part, often equipped with a viewing slot, is used to separate the base from the body of the die and to push the finished pellet out after pressing [35].

The fundamental principle of operation involves compressing a powder sample against the base and walls of the die using a hydraulic press. The applied load causes individual powder grains to bind together, forming a solid pellet [35]. For consistent performance, these dies are machined to high tolerances to prevent powder escape and jamming, and the interior pressing surface is typically polished to a mirror finish to reduce friction and improve pellet surface quality [35] [9].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents required for the pelletizing process in XRF research.

Table 1: Essential Materials for XRF Pellet Preparation

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| High-Quality Pellet Die | Constructed from hardened tool steel or stainless steel with a mirror-finished pressing surface to ensure precise pellet formation and prevent contamination [35] [9]. |

| Hydraulic Pellet Press | Equipment that generates the required pressure (typically 15-40 tons for XRF) to compact the powder. Can be manual or automatic [9] [36]. |

| Binding Agent | A material mixed with the sample powder to promote cohesion during and after pressing. Common examples include paraffin wax, stearic acid, and cellulose-based binders [9] [37]. |

| Lubricant | Applied to the die walls to reduce friction during the pressing and ejection phases, minimizing the risk of pellet cracking. Examples include WD-40, stearates, and boron nitride [37]. |

| XRF Support Cup/Ring | Thin aluminium cups that act as a support for fragile pellets, or metal rings into which samples are pressed for use with automated loading systems [9]. |

| FlexHone Tool | A specialized honing tool used for minor restoration of the die sleeve's interior surface in case of scratching [37]. |

Experimental Protocol: Standardized XRF Pellet Preparation

This protocol outlines a detailed methodology for preparing pellets suitable for XRF analysis, incorporating best practices for consistent results.

Sample Preparation and Die Setup

- Sample Milling: Begin by milling or grinding the sample to a fine, consistent particle size. This ensures optimal distribution and evenness, which is critical for accurate and repeatable XRF results [9].

- Mixing with Binder: Mix the powdered sample with a suitable binder/grinding aid. The choice and quantity of binder depend on the sample material, but the general rule is to use the minimum amount required to safely bind the sample when pressed [9].

- Die Cleaning: Before use, thoroughly clean the die set with a detergent and dry it completely. Any residual material from previous use can lead to cross-contamination [37].

- Die Assembly: Assemble the die set by placing the base plate on a stable surface. Insert the die sleeve over the base plate. If using an aluminium support cup or a metal ring, place it inside the die sleeve at this stage [9].

Powder Loading and Pressing Procedure

- Loading Powder: Pour the prepared powder mixture into the die sleeve. Crucially, do not overfill the die sleeve, as this can prevent the plunger from seating properly and may lead to excessive force on the die components [37].

- Inserting the Plunger: Carefully insert the plunger rod into the die sleeve.

- Pressing Force Application:

- Place the assembled die set centrally on the lower platen of the hydraulic press.

- Activate the press to bring the upper platen into contact with the plunger.

- Gradually increase the pressure to the desired load. A step-wise increase in load is beneficial for allowing air or gases to escape from the sample, preventing air pockets that can cause analysis errors [9].

- Maintain the load for a dwell time (e.g., 1-2 minutes) to allow for plastic deformation and bonding.

Pellet Ejection and Post-Processing

- Pressure Release: Slowly release the pressure from the hydraulic press.

- Pellet Ejection: Transfer the die set to a bench. Use the release ring to separate the base plate from the die sleeve. Gently apply pressure to the plunger to push the finished pellet out of the die sleeve [35].

- Inspection: Visually inspect the pellet for defects such as cracks, chips, or surface irregularities. A well-pressed pellet should be solid and have a smooth, uniform surface.

- Storage: If not analyzed immediately, store the pellet in a desiccator to protect it from moisture and contamination.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence of the XRF pellet preparation protocol.

Critical Parameters for Consistent Results

Achieving high-quality, consistent pellets requires careful control of several operational parameters. The data below should be used as a guideline; optimal conditions may vary by specific sample type.

Pressing Force and Die Specifications

Table 2: Pressing Force Guidelines and Die Specifications

| Parameter | Typical Range / Specification | Notes and Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| General Pressing Force | 5,000 - 10,000 psi | This range is often sufficient for good pellets. Excessively high forces can cause pellet cracking or "capping" [37]. |

| XRF-Specific Load | 15 - 40 tons | Required load depends on material; foodstuffs may need as low as 2 tons, while mineral ores may require 25+ tons [9]. |

| Maximum Pellet Height | Should not greatly exceed pellet diameter | Tall pellets risk non-uniform compaction, with more stress concentration at the top [37]. |

| Die Material Hardness | >80,000 psi yield strength | High-strength steel is standard. A 50% safety margin on the recommended load is advised [37]. |

| Minimum Particle Size | ~10-20 microns | Nano-powders can be used but may cause jamming due to escape around the plunger [37]. |

Troubleshooting Common Pelletizing Issues

Even with a standardized protocol, issues can arise. The following table addresses common problems and their solutions.