Mastering XRF Sample Grinding: Techniques for High-Quality Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide to grinding techniques for X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) sample preparation, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and clinical research.

Mastering XRF Sample Grinding: Techniques for High-Quality Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to grinding techniques for X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) sample preparation, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and clinical research. It covers the foundational principles of how particle size affects analytical accuracy, details step-by-step methodological protocols for powdered and fusion-based preparation, offers solutions for common troubleshooting scenarios, and presents validation frameworks for comparing technique effectiveness. The content synthesizes current best practices to enable reliable, reproducible elemental analysis critical for biomedical applications, from raw material verification to the analysis of clinical biomarkers.

The Critical Link Between Grinding Fineness and XRF Analytical Accuracy

Why Particle Size is a Primary Source of Analytical Error in XRF

In X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy, the accuracy of quantitative elemental analysis is heavily influenced by sample characteristics, with particle size standing as a primary source of analytical error [1]. This technical note examines the fundamental mechanisms of particle size effects, presents quantitative data on their impact, and outlines standardized protocols to mitigate these errors for research scientists and drug development professionals.

The particle size effect introduces significant error because XRF is a surface-sensitive technique where the analyzed mass is confined to a shallow penetration depth. When particle dimensions approach or exceed the effective analysis layer thickness, it creates heterogeneity in the analyzed volume, leading to inaccurate intensity measurements of characteristic radiation [1] [2]. For light elements (Na-Ca) with low-energy emission lines, this effect is particularly pronounced due to their minimal penetration depths, sometimes as shallow as 10-20μm [2].

Fundamental Mechanisms of Particle Size Effects

Physical Principles

The interaction between X-rays and sample particles follows fundamental physical principles that explain the observed size effects:

Infinite Thickness and Effective Layer Thickness: For accurate analysis, a specimen should ideally have "infinite thickness" – sufficient depth that further increases do not affect measured intensities. The "effective layer thickness" represents the depth providing 99% of the analytical signal, which varies significantly by element and matrix [1]. For example, the effective layer thickness for sodium is approximately 4μm, while for aluminum and silicon it is about 10μm [1].

Penetration Depth Limitations: The penetration depth of X-ray radiation can be calculated using the equation:

d_pd = 4.61/μ, where μ is the linear attenuation coefficient [2]. When particle sizes approach or exceed this penetration depth, the analysis becomes highly sensitive to surface heterogeneity.Mineralogical Effects: Different minerals with identical chemical compositions can yield varying fluorescence intensities due to their crystalline structures and absorption characteristics [1]. This effect is particularly problematic in natural materials where mineralogy varies between standards and unknowns.

Table 1: Effective Analysis Layer Thickness for Selected Elements [1]

| Element | Approximate Effective Layer Thickness | Key Spectral Line |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium (Na) | 4 μm | Kα |

| Aluminum (Al) | 10 μm | Kα |

| Silicon (Si) | 10 μm | Kα |

| Iron (Fe) in carbon matrix | 3000 μm (3 mm) | Kα |

| Iron (Fe) in lead matrix | 11 μm | Kα |

Primary Error Mechanisms

Particle size influences XRF measurements through several interconnected mechanisms:

X-ray Scattering: Larger particles increase scattering of incident X-rays, heightening background signals and potentially obscuring weaker fluorescence emissions from trace elements [3].

Absorption Effects: The intensity of characteristic X-rays is affected by the absorption properties of both the emitting particles and the surrounding matrix. This creates a complex relationship where increased particle size can either increase or decrease measured intensity depending on relative absorption coefficients [4].

Surface Heterogeneity: Larger particles create irregular distribution of elements across the analysis surface, causing variations in X-ray path lengths and fluorescence signal intensities [3].

Granular Segregation: In powder mixtures, particles of different sizes and densities may segregate during handling, leading to non-representative sampling, particularly when small sample masses are analyzed [2].

Quantitative Evidence of Particle Size Effects

Experimental Data from Various Matrices

Recent studies across different materials provide quantitative evidence of how particle size impacts analytical accuracy:

Table 2: Particle Size Impact on Relative Error in Phosphate Slurry Analysis [5]

| Compound | Relative Error Ratio (Max vs. Min Size) | Particle Size Trend |

|---|---|---|

| Pâ‚‚Oâ‚… | 1.50 | Increases with larger size |

| Al₂O₃ | 4.01 | Increases with larger size |

| Kâ‚‚O | 15.58 | Increases with larger size |

| Cr₂O₃ | 1.22 | Increases with larger size |

| Fe₂O₃ | 1.51 | Increases with larger size |

| Sr | 1.11 | Increases with larger size |

| CaO | N/S | Decreases with larger size |

| SiOâ‚‚ | N/S | Decreases with larger size |

Research on copper-nickel powder mixtures demonstrates that calibration curves differ significantly between micro- and nano-sized powders, confirming that particle size effects must be accounted for in quantitative methods [4]. In extreme cases, analyzing samples with different particle size distributions can cause intensity variations exceeding 30% for light elements or analytes with long-wave characteristic lines [4].

Sample Mass and Representativeness

The relationship between particle size and representative sampling follows Poisson statistics, where the relative standard deviation (CV) of the sampling error can be estimated as CV = 1/√N, with N being the average number of particles in the sample portion [2]. This relationship highlights the critical connection between particle size reduction and improved sampling representativeness.

For a zirconium-containing sample with 100 ppm concentration and 30μm particle size, approximately 5g of material is required to achieve 1% sampling error [2]. This requirement becomes increasingly difficult to meet with larger particle sizes or limited sample availability.

Methodologies for Particle Size Effect Correction

Conventional Correction Approaches

Several established methodologies exist for addressing particle size effects:

Fundamental Parameters (FP) Method: Uses theoretical calculations based on the physics of X-ray matter interactions to correct for particle size impacts [3].

Compton Scatter Normalization: Normalizes fluorescence intensities using the Compton scattering peak as an internal reference, as it is less influenced by particle size effects [3].

Empirical Calibration: Develops matrix-matched calibration standards with particle size distributions closely matching unknown samples [1] [4].

Fusion Techniques: Creates homogeneous glass disks through high-temperature fusion with borate fluxes, effectively eliminating particle size effects and mineralogical influences [1] [6].

Advanced Correction Methods

Recent research has introduced innovative approaches leveraging computer vision and machine learning:

Imaging-Based Segmentation: The Segment Anything Model (SAM) enables high-precision particle size segmentation from microscopic images of coal samples, providing detailed morphological data for correction algorithms [7] [8].

Deep Learning Integration: Combining Spatial Transformer Networks (STN) with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) establishes robust correlations between particle size distribution and measurement error, enabling precise compensation for particle size effects [8].

Multimodal Data Fusion: Integrates image-based particle size parameters with spectral data from combined NIRS-XRF systems to correct ash prediction errors in coal analysis [7].

These advanced methods have demonstrated significant improvements, with one study reporting corrected results closely matching reference values and achieving near-laboratory accuracy for coarse coal samples [8].

Experimental Protocols for Particle Size Management

Standardized Grinding and Pelletization Protocol

Objective: Prepare representative powder samples with consistent particle size distribution for accurate XRF analysis.

Materials:

- Jaw crusher (e.g., BOYD Elite) for initial coarse crushing [6]

- Fine grinding mill (vibratory cup mill, planetary ball mill, or swing mill)

- Sieve set (100 μm/150 mesh or 75 μm/200 mesh)

- Hydraulic press (15-40 ton capacity) [9]

- XRF pellet dies (standard or ring-type, 32 mm or 40 mm diameter) [9]

- Binders (wax powder, cellulose, or lithium tetraborate flux)

Procedure:

- Coarse Crushing: For samples with grain size >12 mm, begin with jaw crusher, minimizing processing time to reduce contamination [6].

- Sample Division: Use rotating sample divider (RSD) for representative splitting; avoid cone-and-quartering or scoop sampling which introduce higher variability [6].

- Fine Grinding: Pulverize 250 g subsample to fine powder passing through 100 μm sieve; tungsten carbide grinding vessels recommended unless analyzing for W or Co [6].

- Contamination Control: Clean grinding equipment between samples using portion of next sample for cleaning (discarded after use) or pure silica cleaning run [6].

- Binder Addition: Mix powdered sample with binder (if required) at minimum necessary concentration to ensure pellet cohesion [9].

- Pellet Formation: Transfer mixture to die and compress at 15-40 tons pressure depending on material characteristics [9].

- Quality Assessment: Visually inspect pellet for surface smoothness and homogeneity; document pressing parameters for reproducibility.

Fusion Method for Highest Accuracy

Objective: Eliminate particle size and mineralogical effects through complete sample homogenization.

Materials:

- Fusion furnace (gas or electric, e.g., Phoenix or xrFuse series) [6]

- Platinum-gold crucibles (95% Pt-5% Au)

- Flux (lithium tetraborate/tetrametaborate mixtures, e.g., LT66:LM34)

- Non-wetting agent (lithium bromide or iodide solutions)

- Molds for glass disk formation

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Calcine samples at 950°C for 2 hours if necessary to determine loss on ignition [6].

- Weighing: Accurately weigh 1.250 g sample and 10.000 g flux (1:8 ratio) [6].

- Fusion Program:

- Melting: 200-250 seconds at 1100°C

- Mixing: 250-350 seconds swirling/rocking at 1100°C [6]

- Pouring and Cooling: Pour molten mixture into pre-heated mold, cool to form homogeneous glass disk.

- Quality Control: Inspect glass disk for completeness of fusion, bubbles, and surface imperfections.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for XRF Sample Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lithium Tetraborate | Flux for fusion method | Creates homogeneous glass disks; eliminates mineralogical effects [6] |

| Lithium Metaborate | Flux for fusion method | Combined with tetraborate for complete silicate dissolution [6] |

| Lithium Bromide | Non-wetting agent | Prevents melt adhesion to platinumware; typically 0.2% in flux mixture [6] |

| Wax Binders (Microcrystalline) | Binder for pressed powders | Enhances pellet cohesion; minimal addition recommended [9] |

| Cellulose | Binder for pressed powders | Provides structural integrity for fragile samples [10] |

| Tungsten Carbide | Grinding media | High hardness; avoid when analyzing for W or Co [6] |

Particle size remains a fundamental source of analytical error in XRF spectroscopy due to the shallow penetration depths of characteristic X-rays and the resulting representativeness challenges. Effective management requires either reducing particle size through mechanical processing to below critical thresholds (typically <75 μm) or eliminating granular structure through fusion techniques. Advanced approaches incorporating imaging and machine learning show promise for correcting particle effects in situations where standard preparation methods are impractical. For highest accuracy, researchers should implement standardized preparation protocols with careful attention to grinding consistency, particle size verification, and matrix-matched calibration strategies.

In X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) analysis, sample preparation is the foundational step governing data accuracy and precision. Inadequate preparation accounts for approximately 60% of all spectroscopic analytical errors [11]. This application note establishes definitive optimal particle size ranges and detailed protocols for various sample matrices, providing researchers with a standardized framework to minimize particle effects and enhance analytical reproducibility in XRF spectroscopy.

The accuracy of XRF analysis is intrinsically linked to sample preparation quality. The particle size effect introduces significant analytical errors, as larger particles can increase X-ray scattering, elevate background signals, and compromise the uniformity of the analyzed surface [3]. The effective analysis in XRF occurs only within a thin surface layer, with the effective layer thickness varying by element and matrix—for instance, the analytical depth for sodium is merely ~4 µm, while for aluminum and silicon it is ~10 µm [1]. When particle sizes approach or exceed these critical dimensions, the analyzed volume may fail to represent the bulk sample, leading to erroneous intensity measurements and flawed quantitative results [1]. Consequently, controlling particle size and distribution is not merely beneficial but essential for achieving homogenous specimens that yield reliable, reproducible data.

Optimal Particle Size Ranges for Different Sample Matrices

The target particle size is matrix-dependent, balancing analytical precision with practical preparation constraints. The following table summarizes the optimal particle size specifications for common material types analyzed via XRF.

Table 1: Optimal Particle Size Ranges for Different Sample Matrices in XRF Analysis

| Sample Matrix | Recommended Particle Size (µm) | Key Preparation Considerations | Primary Reference Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Powders (Soils, Ores, Minerals) | < 75 µm [12] | Grinding to fine, homogeneous powder; particle size < 100 µm is vital for refining powder uniformity [13]. | Pressed Pellet [13] |

| Coal & Solid Biofuels | < 200 µm (0.2 mm) for high accuracy; < 1 mm acceptable with correction [8] [14] | Particle size < 1 mm and water content ≤10% benefit measurement; larger sizes (e.g., 1 mm) require advanced correction algorithms [8]. | Pressed Powder or NIRS-XRF Coupled Analysis [8] |

| Cements, Slags, & Refractory Materials | < 75 µm for pressing; < 50 µm for high-precision fusion [11] | Fusion is the benchmark technique, eliminating mineralogical effects by creating a homogenous glass disk [13]. | Fusion [11] [13] |

| Metallic Alloys (Post-Milling/Linishing) | Surface finish of 20 - 50 µm smoothness for light elements [15] | A smooth, flat, and clean surface is critical. Milling produces a fine surface finish suitable for both hard and soft metals [16]. | Solid Surface (Milled/Linished) [16] [15] |

Experimental Protocols for Particle Size Reduction and Verification

Standard Grinding Protocol for Powdered Samples

This procedure is designed to achieve a homogenous powder with a target particle size of <75 µm for pressed pellet analysis.

- Objective: To reduce a representative bulk sample to a fine, homogeneous powder suitable for XRF pelletizing or fusion.

Materials & Equipment:

- Jaw Crusher: For initial size reduction of bulk materials to 2-12 mm fragments [13].

- Rotary Sample Divider (RSD): For obtaining a representative subsample [13].

- Swing Mill or Ball Mill: Equipped with appropriate grinding containers and media (e.g., agate, tungsten carbide, hardened steel) to minimize contamination [11] [13].

- Sieving Set: Including a 75 µm (200 mesh) sieve.

- Balance, Scoopula, and Sample Bags.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Crushing: Process the bulk sample using a clean jaw crusher to reduce it to fragments between 2 mm and 12 mm [13].

- Subsampling: Use an automated rotary sample divider to obtain a representative portion of the crushed material for grinding [13].

- Grinding: a. Transfer the subsample into the grinding mill. The choice of grinding media (e.g., agate for hard, contamination-sensitive materials; tungsten carbide for general use) should be based on sample hardness and composition [13]. b. Grind the sample for a predetermined time (established via a grinding curve analysis) to achieve the target fineness [1]. c. Clean the mill thoroughly between samples to prevent cross-contamination [11].

- Sieving (Verification): Pass the ground powder through a 75 µm sieve. If a significant fraction is retained, return the oversize material to the mill for further grinding.

- Homogenization: Gently mix the final powder to ensure uniformity before proceeding to pelletizing.

The following workflow outlines the particle size management process for solid and powdered samples.

Protocol for Managing Particle Size Effects in Coal Analysis

This protocol is adapted from recent research utilizing NIRS-XRF coupled technology, which is highly sensitive to particle variations [8].

- Objective: To achieve accurate coal quality analysis with particle sizes up to 1 mm by implementing a particle size distribution correction method.

Materials & Equipment:

- Grinder with adjustable gap setting (e.g., 1 mm).

- Microscope Camera for image acquisition of the sample surface.

- NIRS-XRF Combined Analyzer.

- Software with integrated Segment Anything Model (SAM), Spatial Transformer Network (STN), and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for image processing and correction [8].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Grind the coal sample using a grinder with a disc gap set to 1 mm to prevent blockages [8].

- Surface Leveling: Level the powder surface in the sample cup. Note that each re-leveling alters the particle size distribution on the surface, increasing measurement uncertainty [8].

- Image Acquisition: Before each measurement, use a microscope camera to capture an image of the coal sample surface to record the particle size distribution.

- Image Processing and Correction: a. Segmentation: Use the Segment Anything Model (SAM) to perform high-precision segmentation of coal particles in the microscopic images, generating binary images for particle size analysis [8]. b. Spatial Transformation: Apply a Spatial Transformer Network (STN) to correct geometric distortions in the images, enhancing the model's handling of spatial variations [8]. c. Feature Extraction and Prediction: Utilize a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to extract deep features from the optimized images, establishing a robust correlation between particle size distribution and measurement error [8].

- Measurement and Data Reporting: Perform the NIRS-XRF analysis and apply the model's correction to the raw results, thereby accounting for the particle size effect and reporting the final, accurate coal quality parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for XRF Sample Preparation

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Grinding Media (Agate, Tungsten Carbide, Hardened Steel) | Used in mills to comminute samples. Selection is based on sample hardness and the need to avoid contamination of critical analytes [13]. |

| Binder (Cellulose, Wax, Boric Acid) | Mixed with powdered samples to provide cohesion during pelletizing in a hydraulic press, forming stable pellets for analysis [11] [13]. |

| Flux (Lithium Tetraborate, Lithium Metaborate) | Used in fusion techniques to dissolve refractory samples at high temperatures (950-1200°C), creating a homogenous glass disk that eliminates mineralogical effects [11] [13]. |

| Hydraulic Press (15-30 Ton capacity) | Equipment used to compress powdered samples with or without a binder into solid, dense pellets (briquettes) for analysis [11] [13] [17]. |

| Fusion Furnace | High-temperature furnace designed to melt mixtures of sample and flux in platinum crucibles to produce homogeneous glass beads for the highest analytical accuracy [13] [16]. |

| Platinum Crucibles and Ware | Essential for fusion preparation due to platinum's high melting point and chemical inertness, withstanding aggressive fluxes and molten samples [13]. |

| XRF Sample Cups and Films | Hold loose powders or liquids. The film (e.g., polypropylene, polyester) must be selected for integrity and low impurity levels to prevent interference [12]. |

| Nolatrexed Dihydrochloride | Nolatrexed Dihydrochloride|AG-337|CAS 152946-68-4 |

| Carebastine | Carebastine |

Achieving the optimal particle size for a specific sample matrix is a critical determinant of success in XRF analysis. Adherence to the defined particle size targets—whether <75 µm for general powders, <200 µm for coal, or a 20-50 µm surface finish for metals—directly addresses the primary source of analytical error. By implementing the detailed experimental protocols and utilizing the appropriate tools outlined in this application note, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability and accuracy of their spectroscopic data, thereby strengthening the conclusions drawn from their research.

In the realm of X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy, sample preparation is the paramount source of error in quantitative analysis [1]. The physical state of the sample, particularly its particle size and homogeneity, directly influences the interaction between X-rays and matter, affecting the accuracy and precision of elemental determinations [1] [11]. The primary goal of an effective grinding workflow is to produce a homogeneous, representative sample with a consistently fine particle size, thereby minimizing analytical errors such as matrix effects, mineralogical interference, and particle heterogeneity [13]. This Application Note delineates a structured protocol for sample comminution, from coarse crushing of bulk materials to fine pulverization, ensuring reproducible and reliable XRF results.

The Comminution Workflow: A Stepwise Protocol

The following workflow outlines the sequential stages for transforming a raw, bulk sample into a fine, homogeneous powder ready for XRF analysis via pressed pellet or fusion.

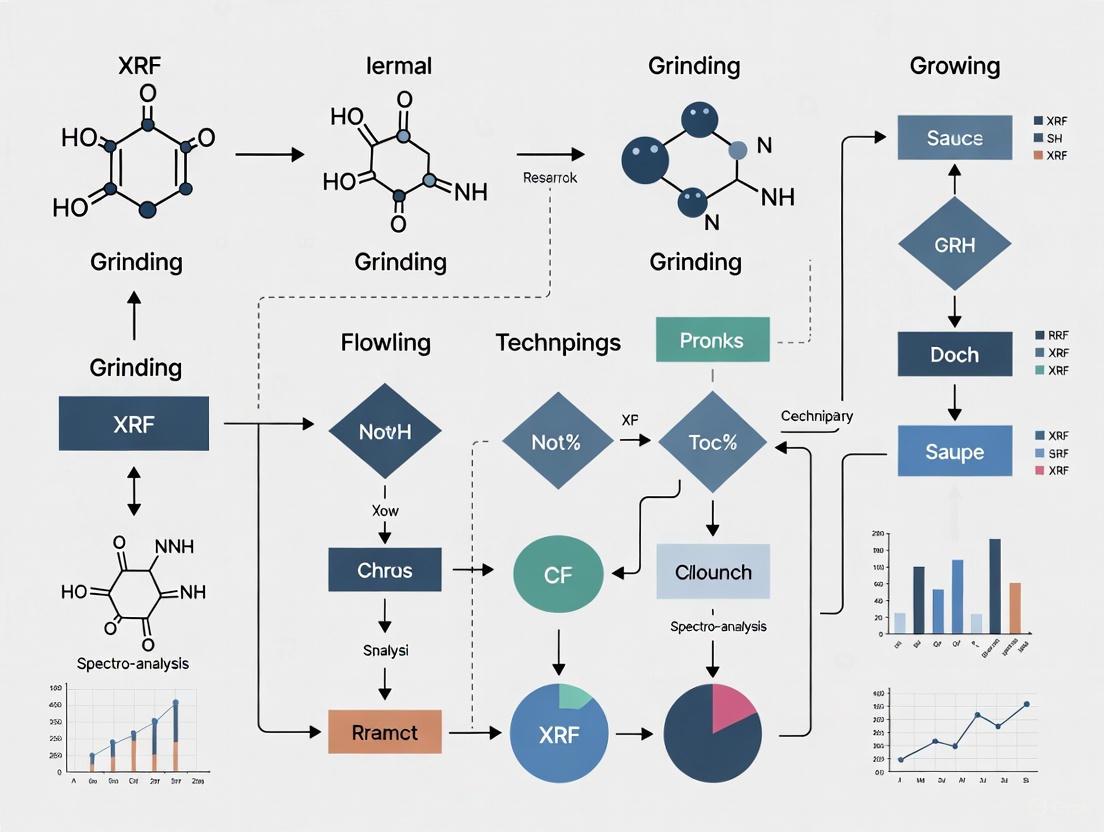

Workflow Diagram

The diagram below illustrates the complete grinding workflow for XRF sample preparation.

Detailed Procedural Steps

Step 1: Coarse Crushing The initial size reduction of bulk materials is crucial for subsequent homogenization. Jaw crushers are the preferred apparatus for this stage, capable of reducing sample volume by up to 35 times in a single pass [6] [18]. The objective is to achieve a nominal particle size range of 2 to 12 mm [13] [6]. To minimize cross-contamination, crusher jaws should be thoroughly cleaned between samples, ideally using a portion of the subsequent sample that is subsequently discarded ("contamination flushing") [6]. The crushing process should generate minimal heat to avoid altering the sample's chemical composition [13].

Step 2: Subsampling Following coarse crushing, a representative subset of the material must be selected for fine grinding, as processing the entire sample is often impractical [13]. A Rotary Sample Divider (RSD) is highly recommended for this step, as it provides superior representativeness with a standard deviation as low as 0.125% compared to traditional methods like cone and quartering (6.810%) or riffle splitting (1.010%) [6]. The target for this subsample is typically ~250 g [6], ensuring it accurately reflects the composition of the original bulk material.

Step 3: Fine Grinding/Pulverizing This is the most critical step for achieving analytical accuracy. The subsample is ground to a fine powder to ensure homogeneity and mitigate particle size effects during XRF measurement [1] [13]. The universally accepted target particle size for XRF analysis is <75 µm [6] [19]. Grinding equipment must be selected based on sample hardness and potential for contamination:

- Swing grinding mills are ideal for tough samples like ceramics and ferrous metals, using an oscillating motion that minimizes heat buildup [11].

- Cryogenic grinding is essential for polymers, elastomers, or other heat-sensitive materials, allowing particle sizes below 200 µm to be achieved [20].

Step 4: Quality Control Verification The success of the grinding protocol must be verified. This is typically done by passing the ground powder through a 75 µm sieve to confirm the particle size distribution [6]. If a significant portion of the sample does not pass the sieve, the material must be returned to the grinder for further processing. All samples and calibration standards must be prepared identically to maintain consistent systematic error, making results reproducible and comparable [6].

Equipment and Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate tools and materials is fundamental to the success of the grinding workflow. The table below catalogs essential equipment and their specific functions in the sample preparation process.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for XRF Sample Preparation

| Item Name | Function/Application | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Jaw Crusher | Primary sample crushing for bulk solid reduction [6] [18]. | Crushing capacity; reversible/interchangeable jaws for cleaning & maintenance [18]. |

| Rotary Sample Divider (RSD) | Representative subsampling of crushed material [13] [6]. | Precision in sample division (standard deviation ~0.125%) [6]. |

| Swing Grinding Mill | Fine grinding of hard, brittle materials (e.g., ores, ceramics) [16] [11]. | Programmable grinding time; swing motion to minimize heat. |

| CryoMill | Fine grinding of heat-sensitive materials (e.g., polymers, elastomers) [20]. | Liquid nitrogen cooling cycle; ability to achieve particles ≤ 200 µm [20]. |

| Tungsten Carbue Grinding Set | Grinding medium for hard, abrasive materials. | High wear resistance. Avoid if analyzing for W or Co [6]. |

| Agate Grinding Set | Grinding medium for applications where trace metal contamination must be avoided. | Low contamination potential for most elements; lower hardness [13]. |

| Cellulose Wax Binder | Binding agent for forming stable pressed pellets [19]. | Typical binder-to-sample ratio of 20-30% [19]. |

| Lithium Borate Flux | Fluxing agent for fusion technique to create homogeneous glass disks [13] [6]. | Common flux-to-sample ratios from 5:1 to 10:1 [6] [19]. |

Experimental Protocol: Grinding Curve Analysis for Pressed Powders

For the pressed powder technique, establishing a "grinding curve" is essential for method development and optimization. This experiment determines the optimal grinding time required to achieve satisfactory homogeneity and particle size for a specific sample type [1].

4.1 Objective To determine the relationship between grinding time and the precision of elemental intensities from pressed pellets, thereby identifying the most effective and efficient grinding duration.

4.2 Materials and Equipment

- Representative sample (e.g., soil, ore, cement)

- Laboratory pulverizer (e.g., swing mill)

- Grinding containers and media (e.g., tungsten carbide, agate)

- Hydraulic press and pellet die

- XRF spectrometer

4.3 Methodology

- Sample Preparation: Take a single, coarsely crushed sample and split it into several identical subsamples of ~10 g each using a rotary divider [6].

- Grinding Time Series: Grind each subsample for a different duration (e.g., 30 s, 1 min, 2 min, 5 min, 10 min). Ensure all other grinding parameters (e.g., mill oscillation frequency, sample mass) remain constant [1].

- Pelletizing: Precisely press each ground powder into pellets using a hydraulic press at a fixed pressure (e.g., 20-25 tons) for a consistent time [19].

- Intensity Measurement: Analyze each pellet using the XRF spectrometer. Measure the net intensity (counts per second) for major, minor, and trace elements of interest. Perform multiple measurements on each pellet if possible to assess short-term precision [1].

4.4 Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Plot the net intensity (and/or the relative standard deviation of intensity) for key elements against the grinding time.

- The optimal grinding time is identified as the point where intensity values plateau and the relative standard deviation is minimized, indicating that further grinding no longer improves homogeneity [1].

- This validated grinding time should then be applied consistently to all future samples of the same type.

Critical Considerations for XRF Analysis

Contamination Control: Contamination during grinding arises from two primary sources: cross-contamination from previous samples and wear from the grinding equipment itself [6]. Rigorous cleaning protocols, such as using pure silica or a disposable portion of the next sample to flush the system, are mandatory [6]. The selection of grinding media (e.g., tungsten carbide, chromium steel, or agate) must be made with the target analytes in mind to avoid introducing interfering elements [13] [6].

The Fusion Alternative: While pressing pellets is a common and cost-effective endpoint for ground powders, the fusion technique represents the gold standard for accuracy, particularly for complex mineralogical samples [6] [19]. Fusion involves mixing the ground sample with a borate flux (e.g., lithium tetraborate) and heating to 1000-1200 °C to form a homogeneous glass disk [13] [6]. This process completely eliminates mineralogical and particle size effects, providing superior accuracy for major element analysis, albeit with higher cost and sample dilution that can impact trace element detection [19]. For applications requiring the highest data quality, such as cement analysis, fusion is the prescribed reference method [6].

Understanding the Impact of Mineralogy and Heterogeneity

In X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis, the precision and accuracy of elemental composition data are fundamentally governed by the principles of specimen preparation. A poorly prepared sample is the primary barrier to obtaining trustworthy results, potentially leading to analytical errors exceeding 60% [13] [11]. For researchers engaged in method development, the most significant source of error in quantitative analysis no longer stems from modern instrumentation but from standard selection, sampling, and specimen preparation [1]. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on grinding techniques, details the profound influence of mineralogical and heterogeneity challenges and provides optimized protocols to mitigate them.

The "mineralogical effect" describes how identical elemental concentrations in different mineral phases can yield varying XRF intensities due to differences in mass attenuation coefficients [1]. Concurrently, particle size effects and heterogeneity can lead to non-representative sampling and stratification during analysis, severely compromising data integrity [13] [21]. Overcoming these effects is not merely a procedural step but a critical determinant for achieving analytical validity in research and quality control.

The Scientific Basis: Mineralogical and Particle Size Effects

The fundamental challenge in XRF analysis arises from its limited analytical depth. The characteristic X-rays of elements are generated from a shallow effective layer thickness, which can be as little as 4 µm for light elements like sodium and only 10 µm for aluminum and silicon [1]. When a sample is heterogeneous, the small portion analyzed in a single scan may not represent the whole sample, leading to non-reproducible results [11].

- The Mineralogical Effect: This matrix effect occurs because the X-ray fluorescence of an element is influenced by its chemical bonding and the surrounding mineral structure. Figure 6 illustrates how different iron-bearing minerals (pyrite, hematite, andradite), even when prepared as pressed pellets with the same particle size and iron concentration, yield different XRF intensities [1]. This makes accurate quantitative analysis impossible without perfectly matrix-matched standards unless the mineralogical effect is eliminated.

- The Particle Size Effect: As shown in Figure 5, if the particle size within a sample is larger than the analytical depth for a given wavelength, the analyzed surface layer will not be representative [1]. Larger particles can also cause uneven packing and stratification, leading to inconsistent X-ray penetration and fluorescence emission [22]. The optimal particle size to minimize these effects is typically below 75 µm [12], with some applications requiring a fineness of 80 µm or less for accurate analysis of light elements [21].

Quantitative Impact of Sample Preparation Methods

The choice of sample preparation method directly controls the extent to which mineralogical and heterogeneity effects can be minimized. The following table summarizes the performance of common preparation techniques against these challenges.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of XRF Sample Preparation Methods

| Preparation Method | Key Description | Impact on Mineralogical Effects | Impact on Heterogeneity | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loose Powder (LP) | Finely ground sample placed in a cup with an X-ray film window [23] [12]. | Does not mitigate effects. | Prone to segregation; requires fine grinding (<75 µm) for minimal homogeneity [12]. | Rapid screening, qualitative analysis. |

| Pressed Pellet (PP) | Powder is pressed at high pressure (15-20 tonnes) into a solid disk, often with a binder [13]. | Does not eliminate mineral effects [22] [1]. | Reduces surface effects but particle size variations remain a source of error [22]. | Production control, semi-quantitative analysis where speed is prioritized [13] [22]. |

| Pressed Pellet with Binder (PPB) | Powder is mixed with a binder (e.g., wax, cellulose) before pressing [23]. | Does not eliminate mineral effects. | Improves homogeneity and stability of the pellet compared to PP. | Provides better precision than PP; suitable for a wider range of quantitative analyses [23]. |

| Fusion | Sample is mixed with a borate flux (e.g., Lithium tetraborate) and melted at 1000-1200°C to form a homogeneous glass disk [13] [22]. | Eliminates mineralogical and matrix effects by destroying the original crystal structures [13] [1]. | Eliminates particle size effects and creates a perfectly homogeneous specimen [13] [22]. | High-precision quantitative analysis, regulatory testing, analysis of complex or variable minerals [13]. |

Empirical data underscores the performance differences between these methods. A study optimizing Energy-Dispersive XRF (EDXRF) for soils found that the pressed pellet with binder (PPB) method yielded the most element recoveries within the acceptable range of 80-120%, while pressed pellets (PP) without binder yielded the poorest recoveries [23]. Furthermore, research on ex-situ portable XRF (pXRF) demonstrated that grinding samples significantly enhanced accuracy, increasing the average coefficient of determination (r²) by 0.10, and also improved precision by reducing the average relative standard deviation (RSD) by 8.37% [24].

Experimental Protocols for Minimizing Effects

Protocol 1: The Pressed Pellet with Binder (PPB) Method

This protocol offers a balance between efficiency and analytical performance for quantitative analysis where fusion is not feasible.

- Application: Suitable for producing samples with improved homogeneity for quantitative analysis of soils, ores, and other powders [23].

- Experimental Workflow:

Diagram 1: Pressed pellet preparation workflow.

- Detailed Methodology:

- Crushing: Use a jaw crusher with abrasion-resistant jaws (e.g., tungsten carbide or zirconium oxide) to reduce bulk sample to fragments of 2-12 mm [13] [21]. This initial step improves material uniformity and prepares the sample for homogenization.

- Subsampling: Employ an automated rotary sample divider (RSD) to obtain a smaller, representative portion of the crushed material for further processing, minimizing the introduction of bias [13].

- Fine Grinding: Transfer the subsample to a vibratory disc mill or similar grinder. Grind to achieve a consistent particle size of <75 µm [12]. The grinding container and media (e.g., agate, tungsten carbide) should be selected based on sample hardness to prevent contamination [13]. The use of a combination unit that integrates a jaw crusher and disc mill can save time and prevent dust-related sample loss [21].

- Mixing with Binder: Weigh approximately 5 g of the ground powder and mix thoroughly with 1 g of a binder, such as cellulose or Licowax [23] [21]. The binder acts as a binding agent and helps produce a stable, cohesive pellet.

- Pressing: Load the mixture into an aluminum cap or die and press using a hydraulic or pneumatic press at a pressure of 15-20 tonnes for 30-60 seconds to form a solid, stable pellet [13] [1].

Protocol 2: The Fusion Method

This protocol is the benchmark for achieving the highest analytical accuracy by completely eliminating mineralogical and particle size effects.

- Application: Essential for high-precision quantitative analysis, certification of reference materials, and analysis of heterogeneous or difficult-to-dissolve samples like silicates, cements, and ceramics [13] [11].

- Experimental Workflow:

Diagram 2: Fusion method preparation workflow.

- Detailed Methodology:

- Weighing: Accurately weigh a portion of the finely ground sample (from Protocol 1, Step 3) into a platinum or platinum-gold alloy crucible.

- Mixing with Flux: Add a flux, typically lithium tetraborate or lithium metaborate, to the sample. Use a flux-to-sample ratio between 5:1 and 10:1 [13]. For sulfide ores or metals, a pre-oxidation step may be necessary before fusion [22].

- High-Temperature Melting: Place the crucible in a high-temperature fusion machine or muffle furnace. Heat to between 1000°C and 1200°C until the mixture is fully molten and appears as a homogeneous liquid [13] [11].

- Agitation and Pouring: Swirl the crucible or use an automated agitator to ensure complete homogenization. Pour the molten mixture into a preheated platinum-gold alloy mold.

- Cooling: Allow the melt to cool, forming a clear, homogeneous glass disk (bead) that is free of crystalline structure and ready for analysis [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials and Equipment for XRF Sample Preparation

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Jaw Crusher | Primary crushing of bulk samples to 2-12 mm fragments [13] [21]. | Use jaws of tungsten carbide or zirconium oxide to minimize contamination from abrasion [21]. |

| Vibratory Disc Mill | Fine grinding of subsamples to <75 µm for homogeneity [21]. | Grinding sets should be chosen based on sample hardness (e.g., agate for hard, contamination-sensitive samples; tungsten carbide for high-throughput milling of abrasive materials) [13] [11]. |

| Hydraulic Press | Pressing powdered samples into solid pellets at pressures of 10-30 tonnes [13] [22]. | Consistent pressure and holding time are critical for producing pellets of uniform density [22]. |

| Fusion Machine | High-temperature furnace for melting sample-flux mixtures to create homogeneous glass disks [13]. | Enables precise temperature control up to 1200°C for reproducible fusion. |

| Lithium Tetraborate Flux | A common borate flux used in fusion to dissolve silicate structures and form a homogeneous glass [13] [11]. | Purity is critical to prevent introduction of elemental contaminants. |

| Cellulose / Wax Binder | Binding agent added to powdered samples to improve cohesion and stability during pellet pressing [13] [23]. | Must be spectroscopically pure; requires accounting for dilution factors during quantitative calibration [11]. |

| Platinum Crucible & Mold | Labware for containing samples during high-temperature fusion [13]. | Platinum alloys (e.g., with 5% gold) are inert and withstand repeated heating/cooling cycles without reacting with the melt. |

| (R)-2-Acetylthio-3-phenylpropionic Acid | (R)-2-Acetylthio-3-phenylpropionic Acid|CAS 57359-76-9 | Explore (R)-2-Acetylthio-3-phenylpropionic Acid, an IMP-1 metallo-β-lactamase inhibitor. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Tosufloxacin Tosylate | Tosufloxacin Tosylate, CAS:100490-94-6, MF:C26H23F3N4O6S, MW:576.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The path to definitive XRF analysis is unequivocally determined by rigorous sample preparation. The inherent mineralogy and heterogeneity of a material are not merely obstacles but fundamental characteristics that must be actively managed through the selection and execution of appropriate protocols. While the pressed pellet with binder method offers a practical balance for many quantitative applications, the fusion method remains the undisputed benchmark for achieving the highest accuracy by eradicating mineralogical and particle size effects. By integrating the principles and detailed protocols outlined in this application note, researchers can establish a robust foundation for their analytical data, ensuring that results are not only precise but truly accurate and representative of the source material.

The Role of Grinding in Eliminating Matrix and Particle Size Effects

In X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy, the accuracy of analytical results is profoundly influenced by sample characteristics, with matrix and particle size effects representing two fundamental sources of potential error. Matrix effects refer to the phenomenon where the presence of certain elements influences the detection and quantification of other elements through absorption or enhancement of X-ray signals. Particle size effects arise when variations in particle dimensions and distributions cause inconsistent X-ray interactions, leading to signal instability and quantification inaccuracies [1].

Grinding serves as a critical sample preparation step to mitigate these effects by creating a homogeneous, fine-powdered sample with consistent particle size distribution. The importance of this preparation cannot be overstated, as inadequate sample preparation accounts for approximately 60% of all spectroscopic analytical errors [11]. This application note details the scientific basis, experimental protocols, and practical implementation of grinding techniques to eliminate matrix and particle size effects in XRF analysis, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for optimizing analytical accuracy.

Scientific Basis and Quantitative Evidence

The Fundamental Physics of Particle Size Effects in XRF

The effectiveness of grinding stems from its ability to control the effective layer thickness from which fluorescent X-rays emanate. In XRF analysis, characteristic X-rays are generated from a finite depth within the sample, with lower-energy signals (lighter elements) originating from more shallow depths than higher-energy signals (heavier elements). For instance, the effective analysis layer for sodium is approximately 4 µm, while for aluminum and silicon it is about 10 µm, with complete signal representation typically achieved within 200 µm—roughly twice the thickness of a human hair [1].

When particle sizes approach or exceed these critical depth dimensions, several problematic phenomena occur:

- Heterogeneous excitation: Irregular particle surfaces create varying paths for both incident and fluorescent X-rays [1]

- Incomplete representation: Individual particles may not represent the overall sample composition [1]

- Enhanced mineralogical effects: Differing mineral structures within larger particles yield variable fluorescence responses even at identical elemental concentrations [1]

Quantitative Impact of Grinding on Analytical Performance

Recent studies provide compelling quantitative evidence supporting the critical role of grinding in XRF analysis. The table below summarizes key findings from controlled experiments evaluating grinding's impact on analytical precision and accuracy.

Table 1: Quantitative Improvements in XRF Analysis through Grinding

| Study Context | Particle Size Reduction | Key Improvement Metrics | Elements Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic Waste Analysis [25] | <200 µm essential | Reliable determination of Al, Ti, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Nb, Pd, Au | 11 critical raw materials |

| Ex-situ pXRF for Post-Metallurgical Sites [24] | <125 µm (from <2 mm) | Average RSD improved by 8.37%; Accuracy (r²) enhanced by 0.10 | Pb, Cr, Mn, Ca, Fe, Sr |

| Coal Quality Analysis [8] | 0.2 mm optimal | Significant improvement in repeatability and accuracy of calorific value, ash, volatile, and sulfur content | C, H, O, N, S, inorganic elements |

The relationship between particle size and analytical performance follows a non-linear trend, with diminishing returns beyond certain thresholds. Research on electronic waste matrices established that particle sizes below 200 µm are "essential for reliable determinations" of critical raw materials [25]. Similarly, a comprehensive study on heterogeneous post-metallurgical samples demonstrated that grinding to <125 µm improved precision (as measured by Relative Standard Deviation) by an average of 8.37% and enhanced accuracy (quantified by r² values against reference ICP-MS measurements) by 0.10 on average [24].

Experimental Protocols for Optimal Grinding

Standardized Grinding Protocol for Geological and Environmental Samples

The following step-by-step protocol is adapted from validated methodologies for ex-situ portable XRF analysis of heterogeneous materials [24], with applications across geological, environmental, and industrial sample types.

Table 2: Essential Equipment for Grinding Protocol

| Equipment/Reagent | Specifications | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Disk Mill Grinder | Sieve mesh ≤125 µm, stainless steel construction | Primary particle size reduction |

| Laboratory Sieve | 2 mm aperture | Initial size classification |

| Drying Oven | Temperature range to 105°C ±5°C | Moisture removal |

| Analytical Balance | Precision ±0.01 g | Sample weighing |

| Hydraulic Press | 10-30 ton capacity | Pellet preparation (if required) |

| XRF Binding Agent | Boric acid, cellulose, or wax | Pellet formation and stability |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Initial Sample Preparation:

Grinding Operation:

- Transfer 30 g of sieved sample to disk mill grinder

- Process for 18 seconds to achieve target particle size of <125 µm [24]

- For more refractory materials, extend grinding time incrementally (5-second intervals) with cooling periods to prevent heat-induced alteration

Post-Grinding Processing:

Quality Control:

- Verify particle size distribution using laser diffraction or microscopic image analysis [8]

- Document sample mass pre- and post-grinding to identify potential cross-contamination or loss

Advanced Grinding Optimization Using Image Analysis

Recent methodological advances incorporate machine learning and image processing to optimize grinding parameters. This approach, validated for coal quality analysis, provides quantitative feedback on grinding effectiveness [8]:

Figure 1: This workflow implements the Segment Anything Model (SAM) for high-precision particle size segmentation, Spatial Transformer Network (STN) for correcting geometric distortions in images, and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) for establishing robust correlations between particle size distribution and measurement error [8].

Comparative Analysis of Grinding Applications

The specific approach to grinding must be tailored to material properties and analytical requirements. The table below compares grinding strategies across different sample types and analytical scenarios.

Table 3: Grinding Strategy Selection Guide

| Sample Type | Target Particle Size | Grinding Equipment | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metallic Alloys | Surface homogenization | Milling machine with cutting head | Avoid cross-contamination; surface renewal for each analysis [16] |

| Geological Materials | <75 µm [11] | Swing grinding mill | Address mineralogical effects; fusion may be required for refractory minerals [1] |

| Electronic Waste | <200 µm [25] | High-energy planetary mill | Heterogeneous composition demands extended grinding time |

| Coal & Organic-rich | 0.2 mm [8] | Ring-and-puck mill | Control for moisture content; avoid temperature-induced volatility |

| Soil & Sediment | <125 µm [24] | Disk mill | Remove organic matter if necessary (ignition at 450°C) |

Integration with Complementary Preparation Methods

Grinding represents one component in a comprehensive sample preparation workflow. The decision tree below illustrates how grinding integrates with other preparation methods based on analytical objectives and sample characteristics.

Figure 2: Method selection workflow for XRF sample preparation. The fusion method generally provides superior accuracy and precision by creating a homogeneous glass disk that eliminates mineralogical effects, but requires more time and skill than pressed powder techniques [1] [22].

Grinding serves as a fundamental preparation step in XRF analysis to eliminate matrix and particle size effects that would otherwise compromise analytical accuracy. Through controlled reduction of particle sizes to specific thresholds (typically <75µm to <200µm, depending on application), grinding enhances sample homogeneity, minimizes mineralogical interference, and ensures consistent X-ray interactions. The protocols and data presented herein provide researchers with evidence-based methodologies to optimize grinding parameters for specific sample types, ultimately supporting the generation of reliable, reproducible analytical data across diverse applications from mineral exploration to environmental monitoring and industrial quality control.

The integration of traditional grinding techniques with emerging technologies such as digital image analysis and machine learning represents the future of optimized sample preparation, enabling real-time monitoring and adjustment of grinding parameters to achieve optimal particle size distributions for specific analytical requirements [8].

Step-by-Step Grinding Protocols for Pressed Pellet and Fusion Bead Preparation

In X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis of pharmaceutical samples, the selection of appropriate grinding media is a critical parameter that directly influences analytical accuracy, sample integrity, and regulatory compliance. The grinding process must reduce particle size to enhance homogeneity while avoiding contamination that could compromise elemental analysis results. Pharmaceutical materials present unique challenges due to their often complex organic matrices, potential for heat degradation, and stringent purity requirements. The grinding media—agate, tungsten carbide, and hardened steel—each offer distinct advantages and limitations that must be carefully balanced against specific analytical requirements. This application note provides detailed protocols and comparative data to guide researchers in selecting optimal grinding media for pharmaceutical XRF sample preparation, ensuring reproducible results while maintaining sample integrity throughout the analytical workflow.

Comparative Analysis of Grinding Media Properties

Technical Specifications and Performance Characteristics

The selection of grinding media requires careful consideration of physical properties, contamination potential, and compatibility with pharmaceutical matrices. The table below summarizes key technical specifications for the three primary grinding media types:

Table 1: Technical Specifications of Grinding Media for Pharmaceutical Applications

| Property | Agate | Tungsten Carbide | Hardened Steel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composition | >99.9% SiOâ‚‚ [26] | Tungsten Carbide with Cobalt binder [26] | Typically 440C or 304/316 Stainless Steel [26] |

| Density (g/cm³) | 2.65 [26] | 14.95 [26] | 7.8 (440C) - 8.0 (304) [26] |

| Hardness | Mohs 7.2-7.5 [26] | 92.1 HRA [26] | 97 HRB (440C) [26] |

| Contamination Risk | Very low; introduces Si [26] | High for Co, W; introduces Co, W at ppm levels [27] | Moderate; introduces Fe, Cr, Ni [26] |

| Acid/Chemical Resistance | Excellent (except HF acid) [26] | Resistant to acidic and basic solutions [26] | Prone to corrosion; varies by grade [26] |

| Relative Cost | Moderate to High | High | Low to Moderate |

| Best Suited For | Trace element analysis, sensitive APIs | Hard, abrasive materials | General purpose, limited budget |

Pharmaceutical Contamination Profiles and Risk Assessment

Contamination from grinding media represents a significant concern in pharmaceutical analysis, particularly for elements monitored for toxicity or included in regulatory specifications. The following table details potential contaminant introduction and associated risk levels:

Table 2: Contamination Risk Assessment for Pharmaceutical Samples

| Grinding Media | Elements Introduced | Typical Contamination Levels | Risk Assessment for Pharmaceuticals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agate | Silicon (Si) [26] | Minimal; inherent to media composition | Low Risk: Si generally not a regulated element in pharmaceuticals |

| Tungsten Carbide | Tungsten (W), Cobalt (Co) [27] | Significant; ~5 ppm Co introduced in 7g silicate sample after 4 min grinding [27] | High Risk: Co is a potential genotoxic impurity; W may require monitoring |

| Hardened Steel | Iron (Fe), Chromium (Cr), Nickel (Ni) [26] | Variable; depends on sample hardness and grinding duration | Medium Risk: Elements not typically classified as genotoxic but may require justification |

Experimental Protocols for Media Evaluation and Implementation

Protocol 1: Contamination Profiling and Suitability Assessment

Objective: To quantify and compare elemental contamination introduced by different grinding media during pharmaceutical sample preparation.

Materials and Reagents:

- Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) or placebo material

- Grinding mills with agate, tungsten carbide, and hardened steel vessels/media

- XRF spectrometer with calibration for expected contaminants

- Microbalance (0.1 mg sensitivity)

- Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) for validation [28]

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Weigh three 10g aliquots of the selected API or placebo material.

- Process each aliquot using identical grinding parameters (time, speed) in the three different grinding media.

- Prepare pressed pellets using a consistent method with 20-30% binder ratio [29].

Contamination Analysis:

- Analyze all pellets by XRF spectroscopy with extended counting times for improved detection limits.

- Perform triplicate measurements on each pellet to assess variability.

- Compare results against unground control material and CRM data.

Data Interpretation:

- Calculate mean contamination levels for elements of concern (Co, W, Fe, Cr, Ni).

- Determine if contamination levels exceed internal specifications or regulatory thresholds (e.g., ICH Q3D elemental impurities).

- Assess homogeneity through relative standard deviation (RSD) measurements, targeting ≤5% [28].

Acceptance Criteria: Selected media must demonstrate contamination levels below 30% of the permitted daily exposure for any element as defined in ICH Q3D.

Protocol 2: Optimization of Grinding Parameters

Objective: To establish optimal grinding conditions for each media type that achieves target particle size without excessive heat generation or contamination.

Materials and Reagents:

- Thermolabile pharmaceutical excipient (e.g., lactose, microcrystalline cellulose)

- Laser diffraction particle size analyzer

- Infrared thermometer or thermal imaging camera

- Grinding aids (if applicable) [30]

Procedure:

- Grinding Time Optimization:

- Process identical samples of a representative pharmaceutical material with increasing grinding intervals (30s, 60s, 90s, 120s).

- After each interval, determine particle size distribution using laser diffraction.

- Plot particle size (D90) versus grinding time to identify the point of diminishing returns.

Thermal Profile Assessment:

- Monitor temperature changes during grinding using non-contact measurement methods.

- Establish maximum safe operating temperatures for heat-sensitive compounds.

Binding Efficiency Evaluation:

- For pellet preparation, assess binding efficiency using the two-step grinding method: initial grinding without binder followed by secondary grinding with 5-10% binder [27].

- Evaluate pellet integrity and resistance to fracturing.

Acceptance Criteria: Target particle size of <50µm for high-precision XRF analysis [28] with temperature increase not exceeding 10°C above ambient for heat-sensitive compounds.

Decision Framework and Implementation Workflow

The selection of appropriate grinding media requires systematic evaluation of multiple factors specific to the pharmaceutical application. The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision process:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Pharmaceutical XRF Sample Preparation

| Item | Function/Application | Selection Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Vibratory Disc Mill | Efficient grinding of hard, brittle pharmaceutical materials [31] | Suitable for sample volumes up to 250ml; multiple speed settings |

| Ring & Puck Mill | Effective pulverization of fibrous plant-based pharmaceuticals [28] | Available in various media materials; rapid particle size reduction |

| Hydraulic Pellet Press | Production of stable pressed pellets for XRF analysis [29] | Capability of 15-35T pressure; uniform pressure distribution |

| Cellulose Binders | Binding agent for powder consolidation [29] [30] | High purity; free of elemental contaminants; 20-30% sample dilution [29] |

| Microcrystalline Cellulose | Grinding aid and binding agent [30] | Improves flow properties; reduces caking during grinding |

| Certified Reference Materials | Method validation and quality control [28] | Matrix-matched to pharmaceutical samples; certified elemental concentrations |

| Aluminum Caps/Cups | Pellet support and stability during analysis [31] | High purity aluminum; consistent dimensions |

| Kibdelin B | Kibdelin B, CAS:103528-49-0, MF:C82H86Cl4N8O29, MW:1789.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Caffeic acid phenethyl ester | Caffeic acid phenethyl ester, CAS:100981-80-4, MF:C17H16O4, MW:284.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The selection of grinding media for pharmaceutical XRF sample preparation requires careful consideration of analytical requirements, regulatory constraints, and material properties. Agate emerges as the preferred choice for trace element analysis and situations where contamination from heavy metals must be avoided, particularly given the concerns around cobalt introduction from tungsten carbide media. Tungsten carbide offers superior performance for hard, abrasive materials but should be avoided when analyzing for tungsten or cobalt. Hardened steel represents a cost-effective alternative for general purpose grinding where iron, chromium, and nickel contamination does not interfere with analytical targets. Implementation of the provided experimental protocols enables science-based media selection, ensuring both analytical quality and regulatory compliance in pharmaceutical development. Through systematic evaluation and validation, researchers can establish robust sample preparation methods that generate reliable XRF data while maintaining the integrity of pharmaceutical materials.

Optimizing Grinding Duration and Intensity to Prevent Contamination and Heat Damage

In X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis, the sample preparation stage is paramount, with grinding being a critical step that directly influences the accuracy and precision of elemental composition data. Inadequate sample preparation accounts for approximately 60% of all spectroscopic analytical errors [11]. The processes of grinding and pulverization transform solid samples into fine, homogeneous powders, mitigating particle size effects and matrix inconsistencies that distort analytical signals [28]. The primary challenge lies in optimizing grinding parameters to achieve the requisite fineness and homogeneity while avoiding two major pitfalls: contamination from grinding media and heat-induced sample alteration [6]. This document establishes detailed protocols to balance these competing demands, ensuring reproducible and reliable XRF results within a rigorous research framework focused on grinding techniques.

The Impact of Grinding on XRF Analytical Data

The Necessity of Particle Size Reduction

The fundamental goal of grinding in XRF preparation is to create a homogeneous specimen where each particle contributes equally to the XRF signal. X-ray fluorescence is a surface-sensitive technique, with the effective layer thickness for analysis being remarkably shallow—often as little as 10 µm for light elements like aluminum and silicon [1]. In a heterogeneous sample with large particles, the analyzed micro-volume may not represent the bulk composition, leading to significant errors. This is known as the mineralogical or particle size effect [1]. Grinding to a consistent, fine particle size ensures that the analyzed surface is representative of the entire sample.

Quantitative Evidence of Grinding Efficacy

Recent research provides quantitative evidence of how grinding improves XRF data. A 2025 study on ex-situ portable XRF (pXRF) analysis of post-metallurgical soils and slags systematically evaluated pre-processing methods. The findings demonstrated that grinding enhanced the accuracy of measurements, with the average coefficient of determination (r²) increasing by 0.10 against reference ICP-MS methods. Furthermore, grinding improved precision, reducing the average relative standard deviation (RSD) by 8.37% [32]. The study concluded that for several elements, grinding was a necessary step to achieve quantitative or qualitative data quality [32].

Table 1: Impact of Sample Pre-Processing on pXRF Data Quality (Adapted from [32])

| Pre-Processing Step | Effect on Accuracy (Average r² change) | Effect on Precision (Average RSD change) |

|---|---|---|

| Sieving | Not Quantified | -7.17% |

| Drying | +0.03 | Not Quantified |

| Grinding | +0.10 | -8.37% |

| Ignition (Organic Matter Removal) | No Change | -0.32% |

Optimizing Grinding Parameters: A Balanced Approach

Defining the Target: Particle Size

The optimal particle size for XRF analysis depends on the specific application and required precision. General guidelines suggest grinding to below 75 µm [28] [6]. For high-precision analysis, a finer grind of below 50 µm is recommended [28]. The particle size distribution should be as narrow as possible to ensure uniformity [6].

Selecting Grinding Equipment

The choice of mill must be matched to the material's hardness and composition to ensure efficient grinding and minimize contamination [28].

Table 2: Grinding Mill Selection Guide for Different Sample Types

| Mill Type | Ideal Sample Materials | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Vibratory Disc Mill | Hard, brittle materials (e.g., ores, silicates) | Rapid, uniform grinding; good for general purposes [28]. |

| Planetary Ball Mill | Very hard materials (e.g., ceramics, cement) | Capable of achieving ultra-fine particle sizes [28]. |

| Ring and Puck Mill | Geological and mineral samples | Excellent reproducibility; suitable for a wide range of minerals [28]. |

Calibration and Standardization of Grinding Mills

To ensure long-term reproducibility, grinding mills must be properly calibrated and maintained. A Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) should define and record the following parameters [28]:

- Grinding time and rotational speed

- Sample load and vessel type

- Media size and composition

- Target particle size (e.g., D90 < 50 µm)

Performance should be regularly evaluated using certified reference materials (CRMs). Acceptance criteria can include a relative standard deviation (RSD) of ≤ 5% for replicate preparations and contamination levels below defined thresholds [28].

Critical Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining the Optimal Grinding Duration

This protocol establishes a method to determine the minimum grinding time required to achieve the target particle size without excessive heat generation or contamination.

1. Objective: To create a "grinding curve" that correlates grinding time with particle size and temperature for a specific sample type and mill.

2. Materials:

- Representative sample material (≥ 50 g)

- Calibrated grinding mill (e.g., ring and puck mill)

- Laser diffraction particle size analyzer or a set of analytical sieves

- Infrared thermometer or thermal probe

- Balance

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Pre-crush the sample to ~2 mm using a jaw crusher [6].

- Step 2: Split the crushed sample into 5 x 5 g aliquots using a rotating sample divider for representativeness [6].

- Step 3: Grind each aliquot for a different duration (e.g., 30 s, 60 s, 90 s, 120 s, 180 s) while keeping all other mill parameters constant.

- Step 4: For each aliquot, immediately measure the final temperature.

- Step 5: Determine the particle size distribution (PSD) of each ground powder.

4. Data Analysis:

- Plot a grinding curve with particle size (D90) on the Y-axis and grinding time on the X-axis.

- The optimal grinding time is identified as the point on the curve where the slope levels off (diminishing returns), and the recorded temperature remains below a critical threshold (e.g., 50°C).

The following workflow outlines this experimental protocol:

Protocol: Assessing and Mitigating Contamination

This protocol assesses contamination introduced by the grinding vessel and media, a major source of analytical error [6].

1. Objective: To quantify contamination from grinding media and establish a cleaning procedure to minimize cross-contamination.

2. Materials:

- High-purity silica or a sample blank with known low background elemental concentrations

- Grinding mill with vessels/media of different materials (e.g., zirconia, hardened steel, tungsten carbide)

- pXRF analyzer or ICP-MS

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Analyze the high-purity silica blank to establish baseline elemental concentrations.

- Step 2: Grind the blank following the standard protocol (e.g., 60 s).

- Step 3: Analyze the ground blank using a sensitive technique like ICP-MS.

- Step 4: Compare post-grinding concentrations with the baseline. Significant increases indicate contamination from the grinding media.

- Step 5 (Cleaning Validation): After cleaning the mill according to lab SOP, process a second blank. Analysis should show contamination levels below the method's detection limit or an acceptable threshold.

4. Data Analysis and Mitigation:

- Select grinding media materials that do not contain the target analytes (e.g., avoid tungsten carbide when analyzing for W or Co) [28].

- Dedicate specific grinding sets to particular sample types (e.g., one for geological samples, another for metals) [28].

- Implement a rigorous cleaning procedure between samples, which may involve using a portion of the next sample to be ground (which is then discarded) or milling pure silica as a cleaning agent [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Grinding Experiments

| Item | Function / Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Silica Blank | Used to quantify background contamination from grinding media and vessels. | The ideal material has a known, minimal elemental signature against which contamination is measured [6]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Validates the entire preparation and analytical process. Verifies that grinding achieves accurate and precise results. | Should be matrix-matched to the samples of interest (e.g., soil CRM for soil samples) [28]. |

| Zirconia Grinding Vessel & Media | Provides a hard, contamination-resistant grinding surface for a wide range of elements. | A versatile choice; avoids introducing Cr, Co, W, etc. Check for Zr and Hf interference on analytes [28]. |

| Agate Grinding Vessel & Media | Offers high purity for trace element analysis where Zr is an analyte of interest. | Softer than zirconia; may be less durable for very hard materials [28]. |

| Lithium Tetraborate / Metaborate Flux | Used in the fusion technique post-grinding to create homogeneous glass disks. | Fusion is the "gold standard" for eliminating mineralogical effects, providing the highest accuracy [1] [6]. |

| Rotating Sample Divider (RSD) | Ensures representative splitting of coarse or crushed samples before grinding. | Critical for obtaining a representative sub-sample; superior to cone and quartering or riffle splitting [6]. |

| 4-Vinylsyringol | 4-Vinylsyringol, CAS:28343-22-8, MF:C10H12O3, MW:180.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Chavicol | Chavicol, CAS:501-92-8, MF:C9H10O, MW:134.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Optimizing grinding duration and intensity is a fundamental requirement for generating high-quality XRF data. The protocols outlined herein provide a systematic approach to achieving a fine, homogeneous powder while proactively managing the risks of contamination and heat damage. The cornerstone of success is a balanced, calibrated process that is thoroughly documented and regularly validated against certified reference materials. By integrating these practices, researchers can ensure that the sample preparation phase supports, rather than compromises, the analytical integrity of their XRF-based research.

In the context of X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis, sample preparation is the paramount step for achieving high-quality quantitative results. Advances in XRF instrumentation hardware and software have shifted the largest potential source of error away from the spectrometer itself to the procedures used to prepare the specimen [1]. Among these procedures, grinding is a critical unit operation that directly addresses fundamental issues of representativity and particle heterogeneity, which can severely compromise analytical accuracy if not properly controlled. This protocol establishes a standardized, evidence-based method for grinding powdered samples to ensure the production of homogenous pressed pellets suitable for quality control screening. The objective is to mitigate analytical errors arising from particle size and mineralogical effects, thereby providing a reliable foundation for subsequent elemental quantification.

Key Grinding Parameters and Their Impact on Analytical Quality

The efficacy of the grinding process is quantified by its ability to produce a consistent fine powder, which directly correlates with the repeatability of the XRF analysis. The table below summarizes the key parameters and their validated impact on the analytical procedure.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Grinding in XRF Sample Preparation

| Parameter | Target Specification | Impact on Analysis if Not Controlled |

|---|---|---|

| Final Particle Size | < 50 µm (optimal); < 75 µm (acceptable) [29] [12] | Introduces particle size effects, leading to non-representative analysis and poor precision [1]. |

| Grinding Time | Determined empirically; e.g., 2-5 minutes, validated by a grinding curve [27]. | Incomplete homogenization and unstable results; excessive time may cause contamination [27]. |

| Grinding Vessel Material | Hardened steel, agate, or tungsten carbide, selected to avoid contamination [27]. | Introduction of contaminant elements (e.g., Co from WC mills) that can be detected and skew results [27]. |

| Sample Mass | Sufficient to be representative of the bulk; typically ~5 g for a 30-40 mm pellet [1]. | The analyzed specimen may not accurately reflect the original bulk sample. |

| Improvement in Repeatability | ~25% reduction in standard deviation post-grinding (as demonstrated in fertilizer analysis) [27]. | Higher variance between replicate measurements, reducing the reliability of the quality control screen. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Materials and Equipment

- Ring and Puck Mill Pulverizer or similar grinding device [1].

- Grinding Vessels: Select a vessel and grinding elements made from hardened steel, agate, or tungsten carbide. The choice must be justified based on the sample's hardness and the potential for introducing contaminant elements of interest [27].

- Laboratory Balance, accurate to at least 0.01 g.

- Sample Source: Bulk powder for analysis.

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Lab coat, safety glasses, and gloves.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Representative Sampling: Obtain a representative sub-sample from the bulk material using appropriate sample splitting techniques (e.g., cone and quartering). Weigh a mass sufficient for pellet formation, typically around 5-7 g [27] [1].

Load the Grinding Mill: Transfer the weighed sample into the clean grinding vessel. Ensure the grinding elements (ring and puck) are correctly seated.

Execute Grinding: Secure the vessel in the mill and grind for a pre-determined time. A typical starting point is 2 minutes for relatively soft materials, which may be extended to 4-5 minutes for harder samples [27].

Determine Optimal Grinding Time (Grinding Curve Analysis): For method development, the optimal grinding time must be determined empirically [1].

- Prepare multiple identical sub-samples.

- Grind them for progressively longer intervals (e.g., 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 minutes).

- Prepare pressed pellets from each and analyze via XRF.

- The optimal time is identified when the analytical results for key elements no longer change significantly with additional grinding [27].

Unload and Collect: Carefully open the vessel and transfer the ground powder to a suitable container for the next stage of pellet preparation, ensuring no cross-contamination occurs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the key materials required for the grinding and subsequent pelletization process.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Grinding and Pellet Preparation

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Ring & Puck Mill | A type of grinder that uses intense impact and friction to rapidly reduce particle size to the required <75 µm specification [1]. |

| Tungsten Carbide Grinding Set | Provides high hardness for efficient grinding of tough samples. Users must be aware of potential cobalt contamination from the binder [27]. |

| Cellulose/Wax Binder | A binding agent mixed with the ground powder (at 20-30% dilution) to ensure the pressed pellet coheres, reducing the risk of loose powder contaminating the spectrometer [29]. |

| Hydraulic Pellet Press | A press capable of applying 15-35 tonnes of pressure to form a robust, flat, and dense pellet from the powder-binder mixture [29]. |

| Pellet Die Set | A mold, typically made of steel, that defines the final diameter and shape of the pressed pellet during the application of pressure [27]. |

| Bromochloroacetonitrile | Bromochloroacetonitrile CAS 83463-62-1 |

| Valnemulin | Valnemulin |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for establishing and executing the grinding protocol, incorporating the critical feedback loop for optimization.

Data Interpretation and Technical Notes

- Rationale for Grinding: The primary goal of grinding is to mitigate the particle size effect and mineralogical effect [1]. XRF analysis occurs within a very shallow effective layer thickness (e.g., 10 µm for Al and Si), meaning a coarse, heterogeneous particle will not provide a representative analysis volume [1]. Grinding ensures homogeneity at this scale.

- Evidence of Efficacy: Data from the analysis of 12 fertilizer samples showed that grinding loose powder reduced the average standard deviation from 0.228% to 0.171%, a 25% improvement in repeatability [27]. This quantitative improvement directly validates the critical role of grinding in quality control.

- Contamination Control: Meticulous cleaning of the grinding vessel between samples is non-negotiable to prevent cross-contamination. The use of separate files or mills for different sample types is a recommended best practice extended from metal preparation to powders [12].