Missing Peaks in Raman Spectroscopy: A Troubleshooting Guide for Researchers and Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing the challenge of missing or suppressed peaks in Raman spectroscopy.

Missing Peaks in Raman Spectroscopy: A Troubleshooting Guide for Researchers and Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing the challenge of missing or suppressed peaks in Raman spectroscopy. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it explores the root causes of signal loss—from instrumental issues and sample preparation errors to fluorescence interference and low analyte concentration. The content delivers a systematic, step-by-step troubleshooting framework, compares Raman with complementary techniques like IR spectroscopy, and highlights the impact of emerging technologies such as AI integration and portable SERS devices for improving detection sensitivity and reliability in biomedical and pharmaceutical research.

Understanding Raman Spectroscopy and Why Peaks Go Missing

Core Principles and Scattering Mechanisms

Raman spectroscopy is based on the interaction between light and matter, specifically the inelastic scattering of photons by molecules. When light hits a sample, most photons are elastically scattered (Rayleigh scattering), but a tiny fraction undergoes inelastic scattering (Raman scattering), providing a unique molecular fingerprint [1] [2].

Table 1: Fundamental Scattering Processes in Raman Spectroscopy

| Scattering Type | Energy Change | Process Description | Relative Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rayleigh Scattering | ΔE = 0 | Photon is scattered elastically with no energy change; the most common scattering process [3]. | Very High [2] |

| Stokes Raman Scattering | ΔE < 0 | Photon transfers energy to the molecule, exciting it to a higher vibrational state; scattered photon has lower energy [1]. | High (Most common for measurements) [1] |

| Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering | ΔE > 0 | Molecule in an excited vibrational state transfers energy to the photon; scattered photon has higher energy [1]. | Low (Requires pre-existing excited state) [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for a Raman Spectroscopy Experiment

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Monochromatic Laser | Excitation source to interact with the sample [1]. | Wavelength (e.g., 785 nm) balances performance and cost; choice affects fluorescence and resolution [1]. |

| High-Performance Detector | Collects the weak Raman scattered light [1]. | Type depends on laser: CCD for visible light, InGaAs for NIR [1]. Back-thinned CCDs offer high quantum efficiency [1]. |

| Bandpass Filter | Cleans the laser beam before it hits the sample [1]. | Ensures only the desired laser line reaches the sample, eliminating noise [1]. |

| Longpass Filter (Edge Filter) | Isolves the Raman signal after sample interaction [1]. | Blocks the intense Rayleigh scatter and allows longer wavelength Stokes Raman light to pass to the detector [1]. |

| Wavenumber Standard | Calibrates the spectrometer's wavenumber axis [4]. | Critical for accurate peak assignment; 4-acetamidophenol is an example [4]. |

| Anthopleurin-A | Anthopleurin-A, CAS:60880-63-9, MF:C215H326N62O67S6, MW:5044 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Tricyclo[2.2.1.02,6]heptan-3-one | Tricyclo[2.2.1.02,6]heptan-3-one, CAS:695-05-6, MF:C7H8O, MW:108.14 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Missing Peaks: FAQs and Experimental Protocols

FAQ 1: My Raman spectrum has a high fluorescence background that is drowning out the peaks. What should I do?

Fluorescence is a common issue that can obscure the much weaker Raman signal [1].

Primary Protocol: Change Excitation Wavelength

- Methodology: Use a laser with a longer wavelength, typically in the Near-Infrared (NIR) region, such as 785 nm or 1064 nm [1]. The energy of NIR photons is often insufficient to excite electronic transitions responsible for fluorescence, thereby suppressing the fluorescent background.

- Considerations: While NIR lasers reduce fluorescence, they can lead to lower signal intensity and higher instrument cost. A 785 nm laser is often a good compromise [1].

Alternative Approach: Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS)

- Methodology: Amplify the Raman signal itself. Adsorb the analyte onto specially prepared rough metallic surfaces (e.g., gold or silver nanoparticles) [1] [5]. This leverages localized surface plasmon resonance to enhance the electric field, dramatically boosting the Raman signal intensity, which can overcome a moderate fluorescence background [1].

FAQ 2: I am not detecting any Raman signal, or the signal is extremely weak. How can I enhance it?

The inherent inefficiency of the Raman effect means signal enhancement is a key area of research.

Protocol: Signal Enhancement Techniques

- Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS): As above, using metallic nanostructures provides a massive signal boost via the electromagnetic enhancement mechanism [1] [5].

- Resonance Raman Spectroscopy (RRS): Tune the laser wavelength to be close to an electronic absorption band of the molecule. This resonance condition can increase the intensity of specific Raman bands by several orders of magnitude [1].

Protocol: Optimize Detector and Optical Setup

FAQ 3: My Raman peaks are shifting between measurements, making identification unreliable. How do I fix this?

This is typically an instrument calibration issue.

- Protocol: Perform Regular Wavenumber Calibration

- Methodology: Frequently measure a standard reference material with known, sharp Raman peaks across your spectral range of interest (e.g., 4-acetamidophenol) [4].

- Procedure: Use the measured spectrum of the standard to construct a new, accurate wavenumber axis for your instrument. Interpolate all sample spectra to this common, fixed axis to correct for systematic drifts [4]. This step is crucial for reproducible results.

FAQ 4: My peaks are broad and poorly resolved. Is this a problem with my sample or my instrument?

Broadening and poor resolution can stem from both sample properties and instrument function.

Protocol: Analyze Peak Shape and Convolution

- Interpretation: Understand that peaks have inherent shapes (Gaussian/Lorentzian mixtures). Solids tend toward Gaussian shapes, while gases are more Lorentzian; liquids are a mix [6]. Overly broad peaks might be a convolution of two or more closely spaced, unresolved peaks [6].

- Action: Use peak-fitting software to deconvolve complex spectral features. Be cautious with automated routines and ensure the fitted peaks have a physical/chemical basis [6].

Protocol: Verify Spectrometer Resolution

- Check the specifications of your spectrometer's grating and slit width. A narrower slit and a grating with higher grooves/mm will provide better spectral resolution, allowing you to distinguish closely spaced peaks.

FAQ 5: My multivariate model for classifying samples seems too good to be true. What common mistake might I be making?

A very high model performance is often a result of incorrect validation, leading to over-optimistic results [4].

- Protocol: Ensure Proper Model Validation and Avoid Information Leakage

- Critical Mistake: Using the same sample (or replicates from the same biological subject) in both the training and test sets of a model [4]. This "information leakage" invalidates the test, as the model has already seen a highly similar data point.

- Correct Methodology: Always ensure that the training, validation, and test data subsets contain completely independent biological replicates or patients [4]. A method like "replicate-out" cross-validation should be used. This reliably estimates how the model will perform on new, unseen data [4].

FAQ: Fundamental Principles

Q1: What is the fundamental physical difference between an IR-active and a Raman-active vibration?

The core difference lies in the underlying physical mechanism that governs each technique:

- Infrared (IR) Absorption: A vibration is IR-active if it results in a change in the dipole moment of the molecule. IR spectroscopy measures the direct absorption of infrared light that excites the molecule to a higher vibrational energy level. [7]

- Raman Scattering: A vibration is Raman-active if it results in a change in the polarizability of the molecule's electron cloud. Raman spectroscopy measures the inelastic scattering of light, where the energy of the scattered photon is shifted due to interaction with the molecule. [8] [7]

Table: Comparison of Fundamental Selection Rules

| Feature | Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Process | Absorption of light | Inelastic scattering of light |

| Selection Rule | Change in dipole moment | Change in polarizability |

| Molecular Property | Asymmetric charge distribution | Distortability of electron cloud |

Q2: Can the same molecular vibration be active in both IR and Raman spectroscopy?

Yes, but this is not common for molecules with a center of symmetry. The Rule of Mutual Exclusion states that for centrosymmetric molecules (those possessing an inversion center), no vibrational modes can be both IR and Raman active. A mode that is symmetric about the center of inversion (gerade) is Raman active, while a mode that is antisymmetric (ungerade) is IR active. For non-centrosymmetric molecules, some vibrations can be active in both. [8]

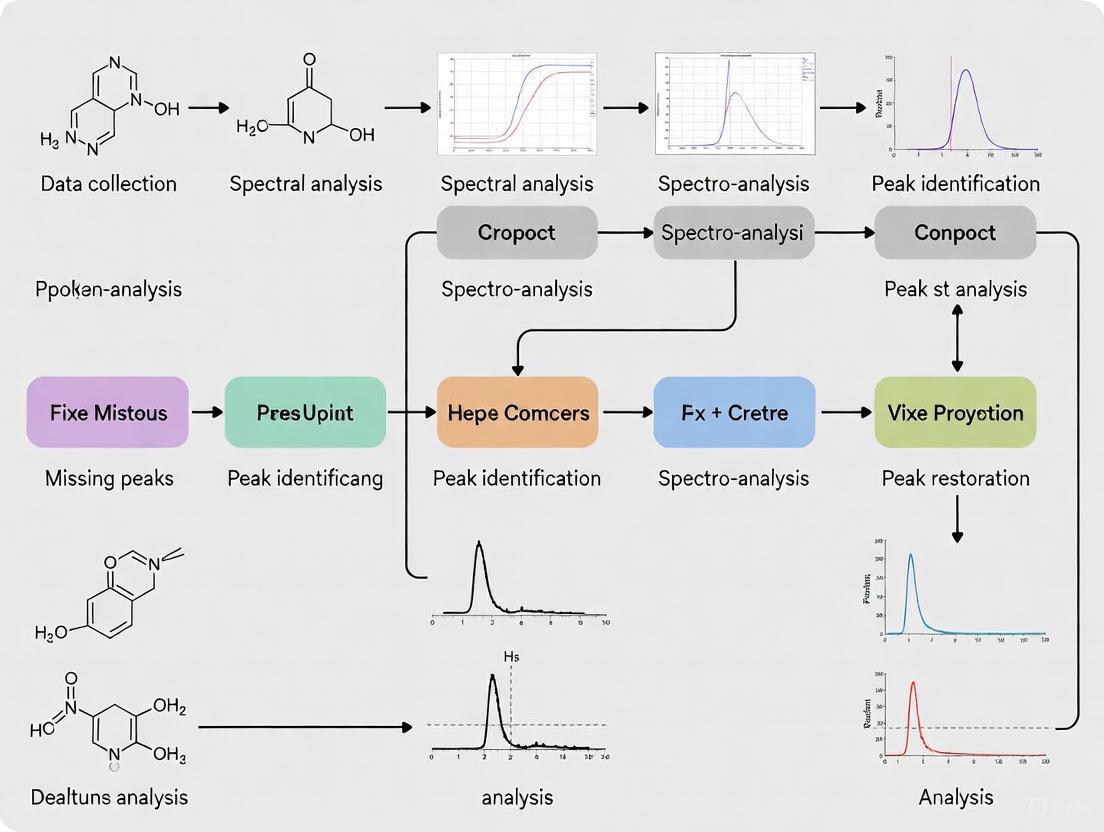

Diagram: Decision flow for IR and Raman activity of a molecular vibration.

Troubleshooting Guide: Fixing Missing Peaks in Raman Spectroscopy

Missing or weak peaks in Raman spectra can stem from various experimental and theoretical factors. This guide helps diagnose and resolve these issues.

Problem 1: The molecule is present, but no Raman peaks are observed.

- Possible Cause 1: Fluorescence Interference. Fluorescence is orders of magnitude stronger than Raman scattering and can completely swamp the weaker Raman signal, presenting as a large, broad background that obscures peaks. [7]

- Solution:

- Use a laser with a longer wavelength (e.g., 785 nm or 1064 nm instead of 532 nm) to reduce the energy that can excite electronic transitions. [9]

- Employ fluorescence quenching techniques or photobleaching the sample with the laser prior to measurement.

- Use advanced data processing algorithms like shifted-excitation Raman difference spectroscopy (SERDS) or built-in software functions (e.g., CleanPeaks) to separate the Raman signal from the fluorescent background. [10] [11]

- Possible Cause 2: The vibration is not Raman-active. The vibration does not induce a change in the polarizability of the molecule. [8]

- Solution:

- Check the selection rules. Perform a group theory analysis for your molecule's point group. A vibration is Raman active if it transforms like the direct products of the coordinates (e.g., xy, xz, yz, x², y², z²). If it does not, the peak will be absent. [8]

- Use a complementary technique. If a peak is expected but missing, collect an IR spectrum. If the peak appears in the IR spectrum, it is likely IR-active but not Raman-active due to the molecule's symmetry, confirming the theoretical prediction. [7]

Problem 2: Raman peaks are present but are much weaker than expected.

- Possible Cause: Poor instrument alignment or calibration. Misalignment of the laser path, confocal pinhole, or spectrometer can drastically reduce signal intensity. Incorrect calibration can make peaks appear at the wrong Raman shifts. [12] [13]

- Solution:

- Perform regular instrument alignment. Follow the manufacturer's automated or manual alignment procedures to ensure the laser focus and spectrometer collection volume coincide perfectly. [12]

- Calibrate the instrument. Perform both wavenumber and intensity calibration using standard materials. Wavenumber calibration ensures peak positions are accurate, while intensity correction ensures relative peak heights are reliable. [10] [13]

Problem 3: Peaks are broad, shifted, or the spectral background is high.

- Possible Cause: Sample-related issues or improper data preprocessing. This can include sample degradation, fluorescence, or a strong background from the substrate or buffer.

- Solution:

- Apply rigorous data preprocessing. [10] [9]

- Spike Removal: Identify and remove sharp, intense spikes caused by cosmic rays using interpolation or comparison with successive measurements. [10]

- Baseline Correction: Subtract the fluorescent background using algorithms like asymmetric least squares, polynomial fitting, or SNIP clipping. [10]

- Normalization: Scale the spectrum (e.g., by the area under the curve or a vector norm) to correct for intensity fluctuations due to focusing or laser power. [10]

- Apply rigorous data preprocessing. [10] [9]

Table: Troubleshooting Missing or Weak Raman Peaks

| Symptom | Most Likely Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No peaks, large background | Fluorescence | Use longer wavelength laser (785 nm), apply SERDS, use CleanPeaks algorithm [11] [7] |

| Specific expected peak is missing | Vibration is not Raman-active | Verify selection rules via group theory; check with IR spectroscopy [8] [7] |

| All peaks are weak | Instrument misalignment, wrong objective, low laser power | Realign instrument; use high-N.A. objective; optimize laser power (avoid damage) [12] |

| Peaks at wrong positions | Improper wavenumber calibration | Calibrate spectrometer with a standard (e.g., silicon peak at 520.7 cmâ»Â¹) [10] [13] |

Diagram: Systematic troubleshooting workflow for missing Raman peaks.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Raman Activity through Group Theory (Using BF₃ as an Example)

Boron trifluoride (BF₃) is a planar molecule with D₃h symmetry, making it an excellent example for applying the Rule of Mutual Exclusion. [8]

- Assign the Point Group: Determine the molecule's point group (for BF₃, it is D₃h). [8]

- Perform a Vibrational Analysis: Calculate the number of vibrational degrees of freedom (3N-6 for non-linear molecules). For BF₃ (N=4), there are 3(4)-6 = 6 normal modes.

- Generate the Reducible Representation (Γᵥᵢᵦ): Determine how the atomic displacements transform under each symmetry operation of the D₃h point group.

- Reduce Γᵥᵢᵦ to Irreducible Representations: For BF₃, this reduces to: Γᵥᵢᵦ = Aâ‚' (Raman) + Aâ‚‚' (IR) + 2E' (IR & Raman). The bending vibrations are also active.

- Consult the Character Table:

- The character table shows that Aâ‚' transforms like the binary products (e.g., x²+y², z²), indicating it is Raman-active only.

- Aâ‚‚' transforms like the z-axis (Rz), indicating it is IR-active only.

- E' transforms like the (x,y) coordinates and the direct products (x²-y², xy), indicating it is active in both IR and Raman. [8]

- Conclusion: This analysis predicts that the Raman spectrum of BF₃ will show peaks for the Aâ‚' and E' vibrations, but not for the Aâ‚‚'' vibration, which will only appear in the IR spectrum.

Protocol 2: Systematic Workflow for Raman Spectral Acquisition and Analysis

To ensure high-quality, reproducible Raman data and robust models, follow this structured workflow, which is critical for applications in drug development and diagnostics. [10] [9]

Experimental Design

- Sample Size Planning (SSP): Estimate the minimum number of samples (e.g., patients, batches) required to build a statistically meaningful model. This can be done by analyzing learning curves to find the sample size where model performance plateaus. [10]

- Design of Experiments (DOE): For quantitative analysis (e.g., monitoring bioreactor analytes), use DOE to intentionally vary Critical Process Parameters (CPPs). This creates a robust design space for calibration models. [14]

- Analyte Spiking: In cell culture processes, spike analytes like glucose or lactate to break natural correlations between components and extend the concentration range of the calibration model. This prevents cross-sensitivity and builds more robust models. [14]

Data Preprocessing

- Quality Control & Spike Removal: Inspect spectra for cosmic spikes (sharp, intense bands) and remove them via interpolation or by replacing them with intensities from a successive measurement. [10]

- Calibration: Ensure the spectrometer is calibrated for both wavenumber (using a standard like silicon) and intensity response. [10]

- Baseline Correction: Apply algorithms (e.g., asymmetric least squares, polynomial fitting) to remove fluorescent backgrounds. [10]

- Normalization: Scale spectral intensities to a standard (e.g., total area under the curve) to correct for intensity fluctuations. [10] [11]

Data Modeling & Model Transfer

- Dimension Reduction: Use techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Partial Least Squares (PLS) to extract the most meaningful features from the preprocessed spectra. [10] [9]

- Model Construction & Evaluation: Build classification or regression models (e.g., using machine learning) with a training dataset. Evaluate performance rigorously using an independent test set and cross-validation to avoid overestimation. [10]

- Model Transfer: If a model performs poorly on new data (e.g., from a different instrument), apply model transfer techniques to remove inter-instrument spectral variations or adjust model parameters. [10]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Raman Spectroscopy

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Silicon Wafer | Standard for wavenumber calibration. Its sharp peak at 520.7 cmâ»Â¹ provides a precise reference for ensuring Raman shifts are reported accurately. [10] |

| Intensity Standard | A material with a known, stable Raman cross-section (e.g., a certified polymer) used for intensity calibration. This corrects for the system's intensity response function, allowing for quantitative comparison between instruments. [10] |

| Immersion Oil | Used with oil-immersion objectives for depth profiling in transparent samples. It minimizes spherical aberration and refraction artifacts, preventing Z-scale compression and distortion in 3D Raman images. [12] |

| Spiked Analytic Solutions | Solutions of known concentration (e.g., glucose, lactate, glutamate) used to break correlations in complex mixtures like cell culture media. This is crucial for building robust multivariate calibration models that are specific to a single analyte. [14] |

| Cosmic Ray Removal Software | Algorithmic tools (e.g., joint inspection of successive spectra) that identify and remove spikes caused by high-energy particles striking the detector, preventing these artifacts from being misinterpreted as real Raman bands. [10] |

| 5-(Morpholinomethyl)-2-thiouracil | 5-(Morpholinomethyl)-2-thiouracil|CAS 89665-74-7 |

| N-Methyl-N-phenylnaphthalen-2-amine | N-Methyl-N-phenylnaphthalen-2-amine, CAS:6364-05-2, MF:C17H15N, MW:233.31 g/mol |

In Raman spectroscopy, peak suppression refers to the reduction in intensity or complete disappearance of expected Raman bands. This phenomenon compromises data quality and can lead to incorrect chemical identification or quantification. The inherently weak Raman signal, typically only one in a million scattered photons, is highly susceptible to various instrumental, sample-related, and environmental factors that can obscure or diminish the characteristic spectral features [15] [16]. Understanding these culprits is fundamental for researchers aiming to obtain reliable, reproducible spectra, particularly in critical fields like pharmaceutical development where material characterization is paramount.

Instrumental Causes of Peak Suppression

Instrumental factors are often the first place to investigate when troubleshooting missing or suppressed peaks. The components of the Raman system itself can significantly impact signal quality.

Laser Source Issues

The laser is a critical component, and its properties directly influence the Raman signal. The table below summarizes key laser-related parameters and their effects.

Table 1: Laser-Related Causes of Peak Suppression

| Factor | Effect on Raman Signal | Practical Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Laser Power [17] | Weak or missing vibrational signals; intensity drops below detection threshold. | Adjust power to balance signal intensity and avoid sample damage. |

| Laser Wavelength [18] [19] | Shorter wavelengths increase fluorescence, which can swamp the Raman signal. | Use longer wavelengths (e.g., 785 nm, 1064 nm) to minimize fluorescence. |

| Laser Instability [15] | Variations in output cause noise and baseline fluctuations, obscuring peaks. | Ensure laser is warmed up and stable; check for non-lasing lines requiring optical filtering. |

Spectral Resolution and Throughput

The ability of the spectrometer to resolve adjacent peaks is crucial. Poor spectral resolution can lead to broad, merged peaks that appear suppressed. Key factors include the spectrometer's focal length, grating groove density, and the entrance slit or pinhole size [19]. A low-throughput system, caused by factors like low-quality objectives, mirror-based beam guidance, or inefficient detectors, can also reduce the collected signal to a level where peaks are lost in noise [19].

Spatial Resolution Control

In hyperspectral imaging, improper control of spatial resolution can lead to impure spectra. If the measurement volume includes material from the substrate or surrounding matrix, the resulting spectrum will be a mixture, potentially diluting or suppressing the target analyte's peaks. This is especially critical for small particles like microfibers, where high spatial discrimination is needed [20]. Spatial resolution is primarily determined by the laser wavelength and the numerical aperture (NA) of the objective [19].

Sample-Related Causes of Peak Suppression

The sample itself is a frequent source of peak suppression, often introducing overwhelming background or altering the scattering efficiency.

Fluorescence Interference

Fluorescence is traditionally the biggest limitation in Raman spectroscopy. It is a much more efficient process than Raman scattering and can generate a broad, intense background that completely obscures weaker Raman peaks [18] [15]. This is particularly common in biological samples, colored materials, and organics.

Experimental Protocol for Mitigating Fluorescence:

- Use Near-Infrared (NIR) Excitation: Switch to a longer laser wavelength (e.g., 785 nm or 1064 nm) which has lower energy and is less likely to excite electronic transitions responsible for fluorescence [18] [20].

- Photobleaching: Expose the sample to the laser for an extended period before data acquisition to reduce fluorescent components [17].

- Time-Gated Raman Spectroscopy: For samples with fast Raman and slower fluorescence decay, this technique uses a pulsed laser and gated detector to temporally separate the Raman signal from the fluorescence [21].

- Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS): SERS can be used to detect specific components in mixtures or identify strongly colored dyes and materials, as it is not susceptible to fluorescence [18].

Sample Damage and Degradation

High laser power density, especially when tightly focused through a microscope objective, can cause thermal or photochemical degradation of the sample. This can alter the chemical structure, leading to changes in the spectrum, including the suppression of original peaks and the appearance of new ones from degradation products [21]. The risk is higher for sensitive samples and when using UV or visible laser wavelengths due to their higher photon energy [19].

Sample Composition and Morphology

The physical and chemical state of the sample affects its Raman signal. For instance:

- Additives and Dyes: Pigments and other additives in polymers can cause fluorescence or mask the polymer's Raman signal, complicating identification [20].

- Optical Properties: Strongly absorbing or reflecting samples may not efficiently generate or return the Raman signal to the detector.

- Sample Form: Differences in crystallinity can affect peak widths and intensities, which might be misinterpreted as suppression [19].

Environmental and Data Processing Causes

Background and Contamination

Stray light from the environment or a contaminated optical path can contribute to a background signal that reduces the signal-to-noise ratio. Similarly, fluorescence from the substrate used to immobilize the sample (e.g., certain filters or glass slides) can interfere with the measurement. It is recommended to use non-fluorescent substrates such as aluminum or calcium fluoride [20].

Data Preprocessing Errors

Improper data handling during analysis can artificially suppress peaks.

- Over-Optimized Preprocessing: Aggressive baseline correction or denoising algorithms can distort data, leading to reduced peak intensities and altered peak shapes [4] [16]. Parameters for these algorithms should be optimized using spectral markers as a merit, not the final model performance, to avoid overfitting [4].

- Incorrect Processing Order: Performing spectral normalization before background correction is a common mistake. The fluorescence background becomes encoded in the normalization constant, biasing the model and potentially suppressing peaks [4]. The correct workflow is to perform baseline correction before normalization [4].

Integrated Troubleshooting Workflow

A systematic approach is essential for efficient diagnosis and resolution of peak suppression issues. The following workflow synthesizes the key checks and actions.

Diagram 1: Peak suppression troubleshooting workflow.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My sample is highly fluorescent, completely burying the Raman signal. What are my options? You have several options to tackle fluorescence. The most common is to use a longer excitation wavelength (e.g., 785 nm or 1064 nm) to avoid exciting electronic transitions. Other methods include photobleaching the sample with the laser prior to measurement or employing advanced techniques like time-gated Raman spectroscopy, which separates the instantaneous Raman signal from the longer-lived fluorescence [18] [21] [17].

Q2: I am worried about damaging my precious sample with the laser. How can I prevent this? To minimize damage, use the lowest laser power that still provides a measurable signal. Begin with very low power and gradually increase it. Ensure the laser is defocused if possible, and use a shorter integration time rather than higher power. Techniques like time-gated Raman can also help by providing superior signal clarity without the need for excessive laser power [21].

Q3: My Raman peaks are very broad and poorly defined, making it hard to distinguish them. What could be the cause? This is often related to the spectral resolution of your instrument. Check if your spectrometer is properly calibrated and if the entrance slit, grating, and detector are suitable for the required resolution. Furthermore, ensure your laser source has a narrow line shape (well below 1 cmâ»Â¹) to avoid broadening the Raman lines [19].

Q4: After preprocessing my data, my peak intensities seem lower. Is this normal? Some baseline correction algorithms can reduce Raman peak intensity, particularly with complex baselines and broad peaks [16]. This is a known issue with classical algorithms. It is crucial to avoid over-optimizing preprocessing parameters. Newer deep learning-based preprocessing methods are being developed to better preserve peak intensities while performing denoising and baseline correction [16].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials and their functions for effective Raman spectroscopy, particularly in challenging applications like microplastics research [20].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Raman Analysis

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Fluorescent Substrates (e.g., Aluminum foil, CaFâ‚‚ slides) | To immobilize samples without adding background fluorescence. | Critical for measuring microplastics/fibers isolated from environmental samples. Avoid common glass slides which can be fluorescent [20]. |

| Wavenumber Standard (e.g., 4-acetamidophenol) | To calibrate the wavenumber axis of the spectrometer. | Ensures spectral stability and comparability between different measurement days [4]. |

| Intensity Standard | To calibrate the intensity response of the spectrometer. | Corrects for the spectral transfer function of optical components, generating setup-independent spectra [4]. |

| Long Wavelength Lasers (785 nm, 1064 nm) | To minimize fluorescence interference from samples. | A primary strategy for dealing with fluorescent biological or environmental samples [18] [20]. |

| High-NA Objectives | To maximize light collection efficiency and spatial resolution. | Improves signal strength and allows for analysis of smaller particles [19]. |

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is Single-Cell Raman Spectroscopy (SCRS) and why is it used for probiotics? Single-Cell Raman Spectroscopy (SCRS) is a label-free, culture-independent technique that provides a molecular "fingerprint" of a single cell based on its inherent vibrational properties. For probiotics, it enables species-level identification, quantification of cell viability, and measurement of metabolic vitality, all at the single-cell level and without the need for lengthy culture steps [22]. This is crucial for accurate quality assessment of live probiotic products.

2. My spectrum shows no peaks, only noise. What could be wrong? A flat or noisy spectrum typically indicates a fundamental setup issue. The most common causes and solutions are:

- Laser is off: Ensure the laser light on the spectrometer is ON and the interlock key is correctly positioned. Caution: Do not look directly into the probe to check [23].

- Low laser power: Verify the power at the probe tip. For a 785 nm system, it should be close to 200 mW [23].

- Communication error: Confirm that the computer and spectrometer are communicating properly [23].

3. The peaks in my spectrum are in the wrong locations. How do I fix this? Peaks appearing at incorrect locations usually indicate that the system requires calibration.

- For a 785 nm system, place the verification cap on the probe and perform a "Verification" procedure.

- For a 532 nm system, use isopropyl alcohol as a standard for calibration [23].

4. Some peaks in my spectrum are cut off at the top. What does this mean? Peaks that are cut off or flattened at the top indicate that the CCD detector is saturating. To resolve this:

- Reduce integration time to shorten the signal collection period.

- Defocus the laser beam by moving the probe slightly away from the sample, instead of holding it flush against the vial [23].

5. My spectrum has a very broad background that obscures the Raman peaks. How can I reduce this? A broad background is often caused by fluorescence from the sample or the substrate [23].

- Ensure you are using the appropriate excitation wavelength for your sample.

- The SCIVVS strategy uses Deuterium Oxide (Dâ‚‚O) to probe metabolic activity, which creates a distinct C-D band in the "silent region" (2040-2300 cmâ»Â¹) that is largely free from fluorescent background interference, providing a clearer signal for vitality assessment [22].

Troubleshooting Common SCRS Experimental Issues

The table below summarizes specific problems, their possible explanations, and recommended actions.

| Problem | Spectrum/ Error Message | Possible Explanation | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Communication Error | "Unable To Find Device With Serial:" or "Error Opening USB Device" | Software cannot find the device due to incorrect settings [23]. | Restart the software. If the error persists, contact technical support [23]. |

| Flat Spectrum | Spectrum is absolutely flat; all Y-values are zero [23]. | Computer and spectrometer are not communicating [23]. | Check USB connections and software settings. |

| Saturated Signal | Peaks are cut off at the top [23]. | CCD detector is saturating [23]. | Decrease integration time or defocus the laser beam by moving the probe backward [23]. |

| Fluorescence Background | Spectrum shows a very broad, sloping background under the peaks [23]. | Fluorescence from the sample is overwhelming the Raman signal [23]. | Consider using a different laser wavelength or leveraging the silent region (C-D band) for analysis [22]. |

| Incorrect Peak Locations | Peaks are present but their locations (Raman shift) do not match known references [23]. | The spectrometer is not properly calibrated [23]. | Perform system calibration using the verification cap (785 nm system) or isopropyl alcohol (532 nm system) [23]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: SCRS for Probiotics

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are essential for conducting SCRS analysis on probiotic bacteria, particularly when applying the advanced SCIVVS framework.

| Reagent/Material | Function in SCRS Experiment |

|---|---|

| Deuterium Oxide (Dâ‚‚O) | A key reagent for probing metabolic vitality. When incorporated by active cells, it generates a C-D band in the Raman spectrum, which is used to quantify metabolic activity levels and their heterogeneity [22]. |

| Reference Probiotic Strains | High-purity strains from statutory species (e.g., Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium) are used to build a reference SCRS database, enabling accurate species-level identification of unknown samples [22]. |

| Propidium Monoazide (PMA) / Ethidium Monoazide (EMA) | These DNA-binding dyes are used in some viability assays to selectively suppress signals from dead cells, though they can be invasive and less accurate than SCRS-based vitality assessment [22]. |

| Isopropyl Alcohol | Serves as a standard sample for calibrating Raman systems, particularly those with 532 nm lasers, to ensure peak positions are reported accurately [23]. |

| 1-naphthyl phosphate potassium salt | 1-naphthyl phosphate potassium salt, CAS:100929-85-9, MF:C10H7K2O4P, MW:300.33 g/mol |

| 2-Methoxy-2'-thiomethylbenzophenone | 2-Methoxy-2'-thiomethylbenzophenone, CAS:746652-03-9, MF:C15H14O2S, MW:258.3 g/mol |

SCRS Experimental Workflow for Probiotic Analysis

The diagram below outlines the core workflow for using SCRS to assess probiotic quality, from sample preparation to data analysis.

Decision Framework for Spectral Troubleshooting

This flowchart provides a logical pathway to diagnose and resolve the most common spectral issues encountered during SCRS experiments.

Technical Specifications of the SCIVVS Method

The table below quantifies the performance metrics of the SCIVVS strategy, a comprehensive framework that integrates SCRS for probiotic analysis.

| Performance Parameter | Metric Achieved by SCIVVS | Significance for Probiotic Research |

|---|---|---|

| Identification Accuracy | 93% accuracy at the species level [22] | Enables reliable verification of probiotic product ingredients against a reference database [22]. |

| Analysis Speed | >20-fold faster than traditional culture-based methods [22] | Whole process (excluding sequencing) can be completed in approximately 5 hours, enabling rapid quality assessment [22]. |

| Vitality Quantification | Measures Metabolic Activity Level (MAL) and its Heterogeneity Index (MAL-HI) [22] | Moves beyond simple viability to assess metabolic robustness, which is directly correlated with probiotic function [22]. |

| Genome Coverage | ~99.40% genome-wide coverage for source-tracking [22] | Provides high-quality single-cell assembled genomes for intellectual property protection and safety monitoring [22]. |

| Cost Efficiency | >10-times cheaper than conventional methods [22] | Makes comprehensive quality control more accessible and scalable for the industry [22]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Baseline and Fluorescence Issues

Q1: Why does my spectrum have a high, sloping background that obscures Raman peaks?

A: A sloping or curved baseline is most frequently caused by sample fluorescence, which can be orders of magnitude more intense than Raman signals [4]. Other causes include baseline drift from instrumental instability over long periods [24] or contributions from substrate/container materials [25].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Switch Excitation Wavelength: Use a near-infrared (785 nm) laser instead of a visible laser to significantly reduce fluorescence excitation [25].

- Apply Computational Baseline Correction:

- Verify Preprocessing Order: Always perform baseline correction before spectral normalization. Normalizing first encodes the fluorescence intensity into the normalization constant, biasing all subsequent models [4].

- Check Substrate: For biological samples on slides, replace standard glass with stainless steel, CaFâ‚‚, or MgFâ‚‚ slides to minimize background [25].

Q2: Why are my Raman peaks shifting between measurement days?

A: Wavenumber shifts are typically due to instrumental drift over time, often caused by changes in temperature or laser tuning. Systematic investigation has shown that device variability can reduce the reliability of results, especially in diagnostic applications [24].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Regular Calibration: Do not skip wavenumber calibration. Measure a wavenumber standard (e.g., 4-acetamidophenol, cyclohexane, polystyrene) with well-defined peaks weekly or whenever the setup is modified [4] [24].

- Construct New Axis: Use the standard's measurement to construct a new, stable wavenumber axis for each day and interpolate all spectra to a common, fixed axis [4].

Q3: Why do my peaks appear very broad or misshapen, making it hard to distinguish closely spaced peaks?

A: Peak broadening and convolution can arise from a mismatch between the true peak shape and the fitting model. The physical state of the sample (solid, liquid, gas) determines the Gaussian/Lorentzian character of the peaks [6]. Furthermore, two closely spaced, unresolved peaks can convolve into a single, asymmetric peak whose maximum position is not intuitive [6].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Understand Peak Shape: Recognize that solids tend toward Gaussian profiles, gases toward Lorentzian, and liquids are a mix. Use peak-fitting software that allows you to specify the percent Gaussian/Lorentzian contribution [6].

- Use Advanced Fitting Algorithms: Employ novel algorithms designed for rapid peak fitting and resolution enhancement of hyperspectral data. These can iteratively resolve overlapped peaks and even construct high-resolution spectra to enhance analysis [29].

Q4: Why is my signal completely lost or extremely weak?

A: Complete signal loss can result from several factors:

- Sample Damage: The laser power is too high, causing photodecomposition [25].

- Focus Issues: The sample is not in focus, especially problematic on uneven surfaces [25].

- Substrate Interference: A glass container or slide is masking the signal [25].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Reduce Laser Power: Lower the incident laser power density to below the sample's damage threshold [25].

- Use Line Focus: Spread the laser power over a larger area using a line focus mode to prevent localized damage [25].

- Employ Focus Tracking: For uneven samples, use automated focus-tracking technology (e.g., LiveTrack) to maintain optimal focus during data collection [25].

- Change Substrate: Replace glass containers with quartz and glass slides with stainless steel or low-background materials like CaFâ‚‚ [25].

Advanced Problem: Model Performance Degradation Over Time

Q5: Why does my machine learning model, trained on data from last month, perform poorly on new data from the same instrument?

A: This indicates long-term device instability. Spectral variations (both random and systematic) accumulate over time, causing the new data to deviate from the data distribution on which the model was trained. This drastically reduces model reliability [24].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Implement Weekly Quality Control (QC): Establish a protocol to measure stable quality control references (e.g., solvents, lipids, carbohydrates) weekly. This monitors instrumental drift [24].

- Suppress Variations Computationally: Use advanced data processing techniques to estimate and remove technical variations. Studies have successfully used a variational autoencoder (VAE) to estimate spectral variations and the extensive multiplicative scattering correction (EMSC) method to suppress them, improving prediction accuracy on independent measurement days [24].

- Re-evaluate Data Splits: Ensure your model evaluation does not leak information. For validation, entire biological replicates or patients must be placed in either the training or test set, not individual spectra from the same sample. Violating this leads to a significant overestimation of model performance [4].

Experimental Protocols for Systematic Anomaly Diagnosis

Protocol: Long-Term Device Stability Assessment

Objective: To systematically investigate and quantify the variability of a Raman setup over an extended period (e.g., 10 months) [24].

Materials:

- Raman spectrometer (e.g., HTS-RS system with a 785 nm laser) [24].

- Quality Control (QC) references: 13 stable substances covering standards, solvents, lipids, and carbohydrates (e.g., cyclohexane, DMSO, benzonitrile, isopropanol, ethanol, fructose, glucose, sucrose, squalene, squalane) [24].

- Sample holders: Quartz cuvettes for liquids and custom aluminum holders for powders [24].

Methodology:

- Weekly Measurement: Acquire approximately 50 Raman spectra for each of the 13 QC substances every week [24].

- Control Measurements: On each measurement day, also record the dark current and Raman spectra of water [24].

- Data Preprocessing: Follow a standard pipeline: despiking, wavenumber calibration, baseline correction, and L2 normalization [24].

- Stability Benchmarking: Analyze the collected data from multiple perspectives:

- Correlation Analysis: Calculate Pearson's correlation coefficient between mean spectra of different days [24].

- Clustering Analysis: Use a k-means-based pipeline to check if spectra cluster by measurement day instead of by substance [24].

- Classification: Test how well a classifier can identify the measurement day based on the spectral data [24].

Protocol: Baseline Correction Using Deep Learning

Objective: To correct complex fluorescence backgrounds and instrumentation-related distortions using a triangular deep convolutional network [28].

Materials:

- Raw Raman spectral data with fluorescence backgrounds.

- Computational resources (e.g., GPU) for deep learning model training/inference.

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Compile a dataset of raw, uncorrected Raman spectra.

- Model Selection/Training: Implement or use a pre-trained triangular deep convolutional network architecture. This network is specifically designed to outperform traditional mathematical methods by achieving superior correction accuracy, reducing computation time, and better preserving peak intensity and shape [28].

- Application: Feed raw spectra through the trained network to obtain baseline-corrected spectra.

Data Presentation

Common Spectral Anomalies and Solutions

The table below summarizes frequent problems and their verified solutions from current literature.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Guide for Common Raman Spectral Anomalies

| Anomaly Pattern | Primary Cause(s) | Recommended Solutions | Key Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High, Sloping Baseline | Sample fluorescence; Instrumental drift | Use NIR (785 nm) laser; Apply deep learning baseline correction (e.g., triangular CNN); Correct baseline before normalization. | [25] [28] [4] |

| Wavenumber Shift | Long-term instrumental drift; Lack of calibration | Perform weekly wavenumber calibration with standards (e.g., cyclohexane, polystyrene); Interpolate to a fixed common axis. | [24] [4] |

| Broad/Misshapen Peaks | Incorrect peak shape model; Convolution of closely spaced peaks | Use fitting software with adjustable Gaussian/Lorentzian %; Apply advanced resolution-enhancement algorithms. | [6] [29] |

| Complete Signal Loss | Sample damage; Defocusing; Substrate interference | Reduce laser power; Use line focus; Employ focus tracking; Change to low-background substrates (e.g., CaFâ‚‚). | [25] |

| Model Performance Drop | Long-term device instability; Data leakage in validation | Implement weekly QC with stable references; Use VAE+EMSC to suppress variations; Ensure independent sample splits for validation. | [24] [4] |

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials used in the featured experiments for anomaly diagnosis and correction.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Raman Spectroscopy QC

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Wavenumber Standards | Calibrating the wavenumber axis for stability over time. | Cyclohexane, Paracetamol, Polystyrene, Silicon [24]. |

| Quality Control References | Monitoring long-term intensity and spectral shape stability of the device. | Solvents (DMSO, benzonitrile), Carbohydrates (fructose, sucrose), Lipids (squalene) [24]. |

| Low-Background Substrates | Minimizing fluorescent or Raman background from slides/containers. | Calcium Fluoride (CaFâ‚‚), Magnesium Fluoride (MgFâ‚‚), mirror-polished stainless steel slides [25] [27]. |

| Non-Glass Containers | Reducing container-derived spectral contributions during measurement. | Quartz cuvettes [25]. |

Diagnostic Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for diagnosing the root cause of missing or anomalous peaks in Raman spectroscopy, based on the troubleshooting guides above.

Advanced Techniques and Applications for Enhanced Peak Detection

Raman spectroscopy is a powerful, non-destructive analytical technique that provides a molecular "fingerprint" for chemical identification [18]. However, a primary limitation is the inherent weakness of the Raman effect, with Raman scattering accounting for only approximately 0.0000001% of the scattered light [30]. This inherent low sensitivity can result in weak or missing peaks, particularly when analyzing trace amounts of material or molecules with low scattering cross-sections [31]. To overcome this challenge, enhancement techniques have been developed that amplify the Raman signal by many orders of magnitude. The two most prominent methods are Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) and Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (TERS). SERS can increase the intensity of Raman scattering from molecules adsorbed on metallic nanostructures by factors up to a billion times in some cases, enabling detection at very low concentrations [32]. TERS, a variant of SERS, combines Raman spectroscopy with scanning probe microscopy to provide both high chemical sensitivity and nanoscale spatial resolution below 50 nm [33]. This technical guide provides troubleshooting and FAQs to help researchers effectively implement these advanced techniques to resolve the common problem of missing peaks in their spectroscopic research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on SERS and TERS

1. What are SERS and TERS, and how do they enhance Raman signals?

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) is a specialized technique that increases Raman signal intensity by adsorbing analyte molecules onto specially prepared metal surfaces, typically gold or silver nanoparticles or nanostructures [32]. The enhancement originates primarily from two mechanisms: an electromagnetic effect, where localized surface plasmons in the metal nanostructures amplify the electric fields of both the incoming laser light and the outgoing Raman scattered light, and a chemical effect involving charge-transfer between the metal and adsorbed molecules that alters the molecular polarizability [32] [34]. This combination can yield signal enhancements from 10ⴠto over 10¹¹, enabling single-molecule detection in some cases [33].

Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (TERS) is a more advanced technique that combines SERS with scanning probe microscopy [32]. In TERS, a metallic-coated tip (typically AFM or STM) acts as the enhancing nanostructure. When the tip is brought within nanometers of the sample surface, the localized plasmonic field at the tip apex creates a highly confined enhancement region, leading to Raman signals with spatial resolution far beyond the optical diffraction limit [33]. TERS can resolve nanometre-sized particles compared to the >0.2 μm resolution limit of conventional far-field Raman scattering [32].

2. Why are my SERS/TERS signals inconsistent or missing entirely?

Inconsistent or missing signals are common frustrations in enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Based on experimental pitfalls documented in the literature, the main causes include:

Improper Nanostructure-Analyte Interaction: The SERS effect is a very short-range enhancement, typically effective only within a few nanometers of the metal surface [31]. If your molecules are not properly adsorbed or are too distant from the enhancing surface, signals will be weak or absent. This is particularly problematic for molecules with low affinity for metal surfaces, such as glucose, which often require surface functionalization (e.g., with boronic acid) for effective detection [31].

Irreproducible "Hotspot" Formation: The majority of the SERS signal originates from nanoscale gaps and crevices known as "hotspots" where electromagnetic enhancement is maximal [31]. In colloidal nanoparticle systems, it is challenging to aggregate nanoparticles reproducibly to form these hotspots. Even on patterned substrates, intensity variations of around 10% are common, requiring measurement of multiple spots (sometimes >100) to properly capture representative data [31].

Fluorescence Interference: While SERS can sometimes quench fluorescence, strongly fluorescent samples can still overwhelm the Raman signal [18]. Traditional solutions include switching to longer excitation wavelengths (e.g., from 532 nm to 785 nm or 1064 nm) where fluorescence is less likely to be excited [18] [30].

Sample Damage: Using excessive laser power can damage or alter samples, particularly biological specimens or delicate chemicals. Recommendations include using laser powers below 1 mW in a diffraction-limited focus and employing defocusing techniques (like line focus mode) to distribute power over a larger area [32] [31].

3. Can SERS and TERS be used for quantitative analysis?

Yes, but with important considerations. SERS has historically been perceived as poorly reproducible for quantitative work, though recent advances are addressing this challenge [35]. The key to quantitative SERS is implementing strategies to control the variability in enhancement:

Internal Standards: Using a co-adsorbed molecule with a known, stable Raman signal as an internal reference can correct for variations in enhancement and laser intensity [31]. For the highest accuracy, a stable isotope variant of the target molecule itself is preferable as it experiences nearly identical chemical environments and enhancement factors [31].

Standardized Protocols: Recent interlaboratory studies have demonstrated that reproducible quantitative SERS is achievable when laboratories follow the same standard operating procedures (SOPs) using the same materials [35]. Method validation according to international guidelines is essential for applications in regulated environments like pharmaceutical development [35].

4. What types of molecules are most suitable for SERS detection?

Not all molecules are enhanced equally in SERS. The technique is most effective for:

- Molecules with high affinity for metal surfaces, particularly aromatic thiols and pyridines that form stable bonds with gold and silver surfaces [31].

- Molecules with electronic resonances in the visible region (enabling Surface-Enhanced Resonance Raman Spectroscopy, SERRS), which provides an additional enhancement mechanism [31].

- Molecules capable of forming charge-transfer complexes with the metal surface, contributing to chemical enhancement [31].

Challenging molecules include those with low surface affinity (like glucose), ions, salts, and metals, which may require derivatization or specialized capture agents for effective detection [18] [31].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

SERS Troubleshooting

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common SERS Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak or No Signal | - Molecules not adsorbing to surface- Insufficient enhancement- Laser wavelength inappropriate- Low analyte concentration | - Functionalize surface to improve adsorption- Optimize nanoparticle aggregation- Switch laser wavelength (try 785 nm or 1064 nm)- Confirm concentration is above detection limit |

| High Background/Fluorescence | - Sample fluorescing- Substrate autofluorescence- Organic contamination | - Use longer excitation wavelength (785 nm, 1064 nm)- Employ SERS substrates with fluorescence rejection- Ensure proper substrate cleaning |

| Irreproducible Signals | - Inconsistent hotspot formation- Variable nanoparticle aggregation- Non-uniform sample preparation | - Use internal standards for normalization- Standardize aggregation protocol- Measure multiple spots (>100 recommended)- Use engineered substrates rather than colloids |

| Unexpected Spectral Peaks | - Surface chemistry or photoreactions- Contaminants- Molecular changes from laser heating | - Verify with control measurements- Use lower laser power (<1 mW)- Analyze surface reaction products |

TERS Troubleshooting

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common TERS Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Weak Enhancement | - Tip damage or contamination- Poor tip-sample alignment- Excessive tip-sample distance | - Inspect and replace damaged tips- Optimize alignment procedure- Ensure proper feedback control for stable tip positioning |

| Inconsistent Imaging | - Tip instability during scanning- Sample roughness- Laser instability | - Use more stable tip designs- Employ smoother substrates- Ensure laser power stability |

| Spatial Resolution Below Expectations | - Tip apex not sharp enough- Large tip-sample distance- Vibration interference | - Use tips with well-defined nanoscale apex- Improve feedback to maintain small distance- Enhance vibration isolation |

| Sample Damage | - Excessive laser power- Force from tip too high | - Reduce laser power to minimum required- Optimize set-point for lighter tip contact |

Experimental Protocols for Reliable Enhancement

Standard SERS Protocol Using Colloidal Nanoparticles

This protocol provides a methodology for detecting trace analytes using colloidal silver nanoparticles with 785 nm excitation, suitable for most routine SERS analyses [35].

Materials Required:

- Silver or gold colloidal nanoparticles (typically 40-60 nm diameter)

- Analyte solution in appropriate solvent

- Internal standard solution (e.g., 4-acetamidophenol for wavenumber calibration)

- Salt solution (e.g., KCl or MgSOâ‚„) for aggregation control

- Microcentrifuge tubes

- Raman spectrometer with 785 nm laser

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Sample Preparation:

- Mix 10 μL of nanoparticle colloid with 1 μL of analyte solution in a microcentrifuge tube.

- Add 1 μL of aggregation agent (e.g., 0.1 M KCl) and vortex gently for 5 seconds.

- Allow the mixture to incubate for 2-5 minutes to form stable aggregates with embedded "hotspots."

Deposition:

- Deposit 2-3 μL of the aggregated mixture onto a clean aluminum or glass substrate.

- Allow to air dry or use gentle nitrogen flow for controlled drying.

Spectral Acquisition:

- Focus laser beam on the sample with appropriate power (typically 0.1-5 mW at sample).

- Acquire spectra with 1-10 second integration time.

- Collect multiple spectra (minimum 10-20) from different spots to account for heterogeneity.

Data Processing:

TERS Protocol for Nanoscale Mapping

This protocol describes the procedure for obtaining nanoscale chemical maps using Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy, adapted from published methodologies for imaging antibody-conjugated nanoparticles on cellular membranes [33].

Materials Required:

- AFM-based TERS system with radial polarization capability

- Gold or silver-coated TERS tips (apex radius < 25 nm)

- Sample appropriately prepared on reflective substrate

- 632.8 nm or 532 nm laser source

Step-by-Step Procedure:

System Alignment:

- Engage the TERS tip over a clean, reflective area of the substrate.

- Optimize the tip position to maximize the enhanced Raman signal from a test sample (e.g., carbon nanotube or self-assembled monolayer).

- Align the radial polarization to ensure optimal plasmonic excitation at the tip apex.

Sample Approach:

- Navigate to the region of interest on the sample using optical microscopy or AFM topography.

- Approach the tip to the surface using standard AFM engagement procedures.

- Set the feedback parameters to maintain constant tip-sample distance during scanning (typically 1-2 nm for gap-mode TERS).

TERS Mapping:

- Set scan parameters (area, resolution, scan rate) based on desired spatial resolution.

- Acquire Raman spectra at each pixel with integration times of 10-100 ms.

- Monitor signal quality during acquisition to ensure stable enhancement.

Data Analysis:

- Construct chemical maps by integrating intensity of characteristic Raman bands.

- Correlate TERS maps with simultaneously acquired topographic images.

- Identify nanoscale chemical features based on spectral signatures.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SERS and TERS Experiments

| Category | Specific Items | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SERS Substrates | Silver colloidal nanoparticles (40-60 nm) | General purpose SERS, balance between enhancement and stability |

| Gold colloidal nanoparticles (50-80 nm) | Improved chemical stability, better for biological applications | |

| Patterned nanostructures (e.g., nanopyramids, nanoantennas) | Improved reproducibility, lower enhancement variance | |

| Commercial SERS substrates (Klarite, SERSitive) | Standardized performance, good for quantitative work | |

| TERS Components | Gold-coated AFM tips (radius < 25 nm) | Standard TERS probes, good enhancement at 633 nm excitation |

| Silver-coated STM tips | Higher enhancement factors, requires conductive substrates | |

| Radial polarization optics | Creates optimal field enhancement at tip apex | |

| Calibration Standards | 4-Acetamidophenol | Wavenumber calibration with multiple peaks across spectrum |

| Silicon wafer | Standard 520 cmâ»Â¹ peak for routine calibration | |

| Polystyrene beads | Intensity calibration and system performance validation | |

| Chemical Reagents | Aggregation agents (KCl, MgSOâ‚„) | Controlled nanoparticle aggregation for colloidal SERS |

| Alkanethiols | Surface functionalization for improved molecule adsorption | |

| Internal standards (e.g., deuterated compounds) | Signal normalization for quantitative measurements |

Advanced Enhancement Techniques

Fluorescence is traditionally the biggest limitation for Raman spectroscopy, as it is a much more efficient process that can overwhelm the Raman signal with background noise [18]. A common solution is to move the excitation wavelength away from the absorbance band of the fluorescent material. While 532 nm is a common Raman excitation wavelength, shifting to 638 nm or 785 nm often reduces fluorescence effects. The most effective reduction is typically achieved at 1064 nm excitation, where most molecules do not absorb and therefore do not fluoresce [18]. Modern Raman systems designed for 1064 nm excitation with FT-Raman detection provide the best solution for highly fluorescent samples [30].

Quantitative SERS Methodology

For quantitative applications, recent interlaboratory studies have established standardized approaches to improve reproducibility [35]. Key recommendations include:

- Centralized Material Preparation: All calibration standards and substrates should be prepared in a centralized location and distributed to ensure consistency across experiments [35].

- Strict SOP Adherence: Following detailed standard operating procedures for sample preparation, measurement, and data processing significantly improves interlaboratory reproducibility [35].

- Proper Data Processing Pipeline: Implement a consistent data analysis pipeline including cosmic spike removal, wavenumber calibration, intensity calibration, baseline correction, denoising, and normalization [4]. Critical mistakes to avoid include performing spectral normalization before background correction and using over-optimized preprocessing parameters [4].

Future Directions: SHINERS and Single-Molecule SERS

The SERS family of techniques continues to evolve with new methodologies that address previous limitations. Shell-Isolated Nanoparticle-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SHINERS) uses nanoparticles coated with an ultrathin, chemically inert shell (typically 2-4 nm of silica or alumina) that prevents direct contact between the metal core and the analyte while maintaining strong electromagnetic enhancement [34]. This approach expands the range of analyzable molecules and surfaces, particularly for corrosive environments or where metal-analyte interactions are undesirable.

Single-molecule SERS remains an active research frontier, achieving the ultimate sensitivity by exploiting the extremely high enhancement factors (up to 10¹¹) possible in precisely engineered plasmonic nanostructures [33] [34]. Successful implementation requires careful control of nanoparticle geometry, surface chemistry, and laser excitation conditions to create reproducible single-molecule detection events.

Single-Cell Raman Spectroscopy (SCRS) for Probing Cellular Heterogeneity

FAQs: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: Why are the characteristic Raman peaks from my cellular samples weak or missing?

Weak or missing peaks in SCRS can arise from several factors related to instrumental setup, sample preparation, and data processing. The most common causes and their solutions are:

- Insufficient Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N): The spontaneous Raman signal from a single cell is inherently weak [36]. This can be exacerbated by:

- Low Laser Power or Short Integration Time: Increasing laser power (while ensuring the cell is not damaged or burned, especially with a 532 nm laser [37]) or lengthening the spectrum acquisition time can improve signal.

- Suboptimal Excitation Wavelength: A 785 nm laser is often preferable to a 532 nm laser for eukaryotic cells, as it reduces autofluorescence and minimizes the risk of cellular damage or sample burning [37].

- Detector Quality: The use of a deep-depletion charge-coupled device (CCD) detector is crucial for suppressing etaloning and achieving satisfactory S/N with a 785 nm excitation [37].

- Fluorescence Background: A strong fluorescent background, which can be 2-3 orders of magnitude more intense than Raman bands, can obscure vibrational peaks [4]. This requires a dedicated baseline correction step in data preprocessing [4] [37]. It is critical that this step is performed before spectral normalization to avoid bias [4].

- Lack of Proper Calibration: Systematic drifts in the measurement system can cause peak shifts. Regularly measuring a wavenumber standard (e.g., 4-acetamidophenol or polystyrene) and a white light source for intensity calibration is essential to generate stable, setup-independent spectra [4] [37].

- Cosmic Ray Spikes: High-energy cosmic rays can create sharp, intense spikes in the spectrum that may be mistaken for peaks. A dedicated cosmic spike removal algorithm must be applied during preprocessing [4] [37].

Q2: How can I distinguish true biological differences from experimental artifacts in my SCRS data?

Robust experimental design and data processing are key to avoiding over-interpretation.

- Independent Replicates: Ensure you have a sufficient number of independent biological replicates (e.g., at least 3-5 independent cell cultures) rather than just multiple measurements from the same sample. This prevents overestimating model performance and ensures findings are generalizable [4].

- Avoid Information Leakage: During machine learning model evaluation, ensure that all spectra from a single biological replicate are placed entirely within either the training or test set. Violating this independence, for example by randomly splitting all spectra, causes information leakage and leads to a significant overestimation of model accuracy [4].

- Conservative Statistical Testing: When comparing multiple Raman band intensities, correct for multiple comparisons (e.g., using a Bonferroni correction) to avoid false positives from chance alone [4].

Q3: What are the advantages of using SCRS over fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) for studying cellular heterogeneity?

SCRS offers several distinct advantages as a label-free technique:

- No Labeling Required: SCRS provides an intrinsic molecular fingerprint without the need for fluorescent tags or labels. This avoids issues of cytotoxicity, non-specific binding, and interference with natural cellular functions that can occur with fluorescent probes [36].

- Broad Molecular Information: A single SCRS spectrum contains information on the vibrational modes of almost all intracellular macromolecules (proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, carbohydrates) simultaneously, providing a holistic phenotypic snapshot [36].

- Viability and Downstream Analysis: The technique is non-destructive and non-invasive, allowing sorted cells to remain alive and be used for subsequent genomic analysis, such as single-cell genomics or gene sequencing, thereby linking cell phenotype to genotype [36].

Troubleshooting Guide: Missing or Altered Peaks

This guide systematically addresses the issue of missing, shifted, or altered peaks in SCRS data.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Missing or Altered Peaks

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak or missing Raman signals across all samples | Inherently weak spontaneous Raman signal [36] | Check signal-to-noise ratio in raw spectra. | Optimize instrument: Increase laser power (avoid damage), use longer acquisition times, ensure use of a high-quality, deep-depletion CCD detector [37]. |

| Strong fluorescence background obscuring Raman bands [4] | Visually inspect raw spectra for a large, sloping fluorescence background. | Use a longer excitation wavelength (e.g., 785 nm). Apply a robust baseline correction algorithm (e.g., asymmetric least squares, extended multiplicative scattering correction) [4] [37]. | |

| Peaks are present but shifted in wavenumber | Lack of or incorrect wavenumber calibration [4] | Measure a known standard (e.g., polystyrene). Compare peak positions to reference values. | Perform regular wavenumber calibration using a standard with multiple peaks in the region of interest (e.g., 4-acetamidophenol). Interpolate all data to a common, fixed wavenumber axis [4] [37]. |

| Unexpectedly large variance or inconsistent peaks between replicates | Incorrect preprocessing order [4] [37] | Review the order of operations in your preprocessing pipeline. | Adhere to the established preprocessing order: 1) Wavenumber calibration, 2) Dark current correction, 3) Cosmic spike removal, 4) Intensity calibration, 5) Background correction, 6) Denoising [37]. Never normalize before background correction [4]. |

| Over-optimized preprocessing parameters [4] | Check if baseline correction parameters are too aggressive, potentially removing real Raman bands. | Optimize preprocessing parameters using spectral markers as a merit, not the final performance of a machine learning model, to prevent overfitting [4]. | |

| Specific biomolecular peaks (e.g., lipids, proteins) are absent or altered | Biological heterogeneity or cell damage | Ensure measurements are targeting the correct cellular region. Verify cell viability. | For consistent single-cell readings, acquire integrated Raman spectra by either expanding the beam diameter or rapidly scanning a diffraction-limited spot across the entire cell to average out intracellular variation [37]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol 1: Reliable Single-Cell Raman Measurement for Heterogeneity Studies

Objective: To acquire high-quality, reproducible single-cell Raman spectra that accurately reflect the biochemical composition of individual eukaryotic cells, minimizing artifacts and enabling the study of cellular heterogeneity.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- 4-Acetamidophenol or Polystyrene: A wavenumber standard for daily calibration [4] [37].

- NIST-traceable White Light Source: For intensity calibration of the spectrometer [37].

- Helix NP Blue or similar DNA dye: For locating cells/NETs when brightfield contrast is low, with confirmed non-interference with Raman signal [38].

- Appropriate Cell Culture Media: To maintain cell viability during measurement.

Methodology:

- Instrument Calibration:

- Prior to cell measurements, perform a wavenumber calibration by measuring the standard (e.g., 4-acetamidophenol) and fitting the measured peak positions to a reference spectrum.

- Perform an intensity calibration using the white light source to correct for the spectral transfer function of the optical system [37].

- Experimental Design & Measurement:

- To achieve statistically meaningful results for heterogeneity studies, plan to measure a large number of individual cells. If spatial distribution information is not required, acquire integrated Raman spectra for each cell by rapidly scanning the laser spot across the entire cell. This averages out intracellular variation and is faster than full hyperspectral imaging, allowing for higher throughput [37].

- For a 785 nm excitation, use moderate laser power and acquisition times of 1-2 seconds per spectrum to ensure a good S/N while avoiding cell damage [37].

- Data Preprocessing (Critical Order):

- Apply the following steps in sequence to all spectra [37]: a. Wavenumber Calibration b. Dark Current Correction c. Cosmic Spike Removal d. Intensity Calibration (using the system response function) e. Background Correction (e.g., using asymmetric least squares or EMSC) f. Denoising (e.g., Savitzky-Golay filter) g. Normalization (e.g., to the total spectrum intensity)

Workflow Diagram: SCRS Experimental and Analysis Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SCRS

| Item | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 4-Acetamidophenol | Wavenumber calibration standard with a high number of peaks in the biological spectral region of interest [4]. | Measure daily to construct a stable, common wavenumber axis and correct for systematic drifts [4]. |

| NIST-traceable White Light Source | Enables intensity calibration to correct for the spectral transfer function of the optical setup (lenses, filters, detector) [37]. | Generates setup-independent Raman spectra, making data comparable across different days and instruments [37]. |

| Silicon Wafer | Often used for intensity calibration and checking spectrometer performance. | Has a single, sharp Raman peak at ~520 cmâ»Â¹. |

| Helix NP Blue / Sytox Green | Fluorescent DNA dyes for locating cells or NET structures when brightfield contrast is insufficient [38]. | Must be validated to ensure they do not interfere with the Raman signal of interest [38]. |

| Deep-Depletion CCD Detector | The crucial component for detecting Raman signal, especially with 785 nm excitation [37]. | Essential for suppressing etaloning effects and achieving a high signal-to-noise ratio [37]. |

| Tetrachloroveratrole | Tetrachloroveratrole, CAS:944-61-6, MF:C8H6Cl4O2, MW:275.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Epitalon | Epitalon Peptide / Ala-Glu-Asp-Gly for Research | High-purity Epitalon (AEDG), a synthetic tetrapeptide for aging, telomere, and circadian rhythm research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Raman Mapping and Imaging for Spatial Distribution Analysis in Pharmaceuticals

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: Why am I missing peaks in my Raman map of a pharmaceutical tablet, and how can I fix it?

Issue: Missing or weak spectral peaks during Raman mapping can be caused by several factors, including instrumental setup, sample preparation, or the properties of the sample itself.

Troubleshooting Steps:

Verify Instrument Calibration and Configuration:

- Ensure the spectrometer is properly calibrated using a standard reference material [39]. New instrument lines often feature NIST-traceable calibration for this purpose.

- Confirm that the laser wavelength and power are appropriate for your sample. Excessive laser power can cause photobleaching or degradation of sensitive active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), especially in confocal setups [40].

- Check the objective lens and ensure it is clean and correctly aligned for the measurement.

Optimize Sample Preparation:

- For skin permeation studies or soft materials, improper preparation like the use of certain mounting media (e.g., Optimal Cutting Temperature compound (OCT)) can interfere with the signal. Freeze-drying is sometimes recommended as an improved protocol to preserve sample integrity and reduce fluorescence [40].

- Ensure the tablet surface or sample cross-section is flat and smooth. For 3D Raman imaging, creating optically flat surfaces via techniques like manual milling is essential to overcome depth penetration limitations and obtain accurate spatial information [41].

Review Data Acquisition Parameters:

- Increase the integration time or number of accumulations to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), particularly for weak scatterers or low-concentration components [42].

- For heterogeneous samples, ensure the spatial step size is small enough to resolve the features of interest. A step size larger than the particle size can cause small domains to be missed [41].

Check for Signal Interference:

- A high fluorescence background can obscure weaker Raman peaks. Techniques like photobleaching the area with extended laser exposure before data acquisition can help mitigate this, but this must be balanced against potential sample damage [40].

- If the API has a low Raman cross-section, consider using advanced techniques like Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) or Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering (CARS), which offer orders of magnitude higher sensitivity and faster imaging speeds than spontaneous Raman scattering [43].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the poor spatial resolution of my 3D chemical maps?

Issue: The reconstructed 3D distribution of components lacks detail or is inaccurate.

Solution:

- The most common limitation in 3D Raman imaging is the depth penetration and spatial resolution, typically limited to about 50µm from the surface with standard techniques [41].

- To overcome this, use serial section Raman tomography. This method involves:

- Physically sectioning the sample (e.g., a tablet) at regular intervals.

- Creating an optically flat surface at each new depth via milling or polishing.

- Collecting a 2D Raman chemical map from each newly exposed surface.

- Reconstructing the 2D maps into a 3D volume [41].

- This technique has been validated for quantifying the size, shape, and distribution of spherical API domains within a tablet matrix, providing qualitative and quantitative data with acceptable error [41].

FAQ 3: My multivariate model for concentration prediction is not robust. How can I improve it?

Issue: A calibration model built using Raman spectra and reference data fails to accurately predict analyte concentrations in new batches.

Solution:

- A key problem is often correlated analyte trends in the training data, which can lead to a model that is not specific to the target analyte.

- Implement a Design of Experiments (DOE) approach and an analyte spiking regimen during model development [14].

- DOE helps you plan experiments that systematically vary process parameters (e.g., CPPs) to create widespread process trajectories, making the model more robust to natural variations.

- Analyte Spiking involves adding known concentrations of the target analytes (like glucose or lactate) to the cell culture or sample during data collection. This:

- Breaks the natural correlations between analytes, reducing cross-sensitivity in the model.

- Extends the concentration range of the calibration model, as multivariate models cannot reliably extrapolate beyond the range they were calibrated on [14].