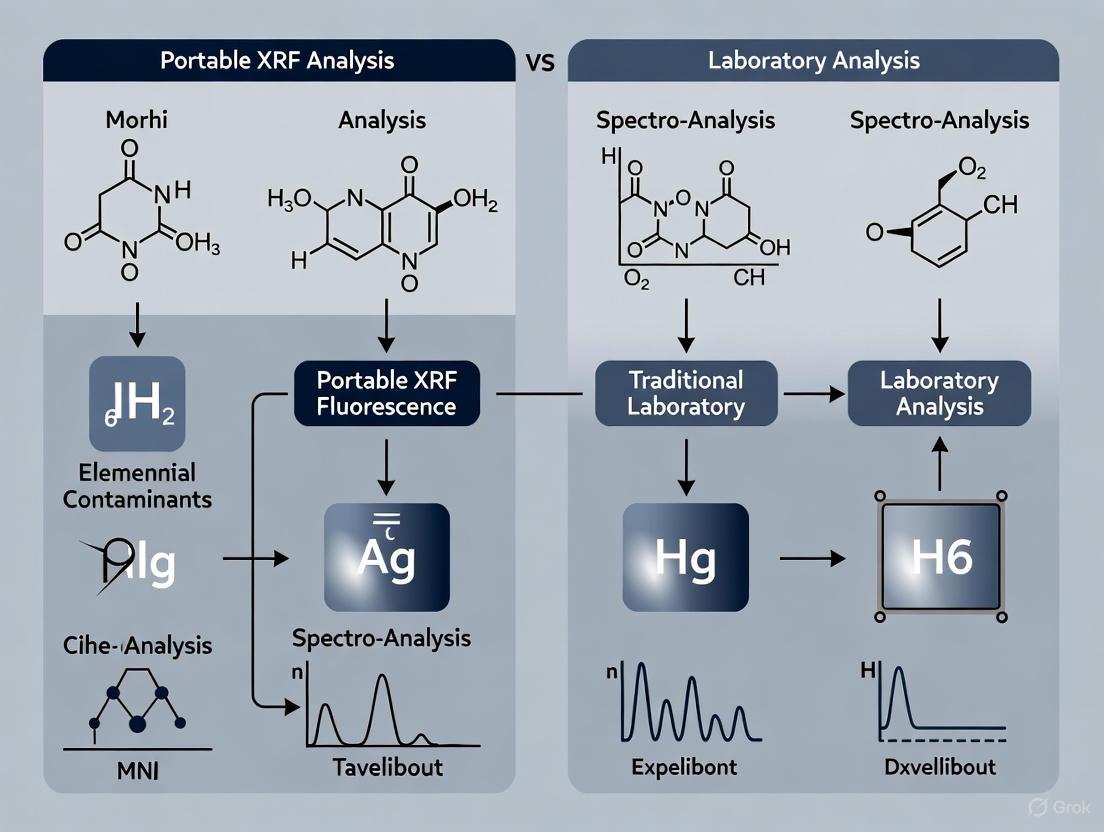

Portable XRF vs. Laboratory Analysis for Elemental Contaminants: A Strategic Guide for Pharmaceutical Professionals

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive analysis of portable XRF and laboratory-based techniques for elemental impurity testing.

Portable XRF vs. Laboratory Analysis for Elemental Contaminants: A Strategic Guide for Pharmaceutical Professionals

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive analysis of portable XRF and laboratory-based techniques for elemental impurity testing. Covering foundational principles, regulatory applications, method optimization, and a direct performance comparison, it offers actionable insights for selecting the right technology to ensure compliance with ICH Q3D and other global guidelines, enhance efficiency, and safeguard product quality.

Understanding Elemental Analysis: Core Technologies and Regulatory Drivers

X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) is an analytical technique used to determine the elemental composition of materials. It is non-destructive, reliable, and requires minimal sample preparation, making it suitable for analyzing solids, liquids, and powdered samples [1]. XRF operates on the principle that when a material is exposed to high-energy X-rays, its atoms emit secondary (or fluorescent) X-rays with characteristic energies unique to each element. This elemental "fingerprint" enables both qualitative and quantitative analysis, capable of detecting elements from fluorine (9) to americium (95) with detection limits at the sub-parts per million (ppm) level and concentrations up to 100% [1] [2].

The technique is widely utilized across numerous fields, including geology, metallurgy, environmental science, archaeology, pharmaceuticals, and mining [1] [2]. A key context for its application is the comparison between portable (field) and laboratory XRF systems for researching elemental contaminants. This guide will objectively compare the performance of these systems, supported by experimental data and protocols, to aid researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate analytical tool.

The Fundamental Working Principle of XRF

The effect of X-ray fluorescence is based on the excitation of atoms in a sample, specifically through interaction with their inner shell electrons [1].

The process begins when a sample is irradiated with high-energy primary X-rays, typically generated by an X-ray tube [1] [2]. When an incident X-ray collides with an atom in the sample, if its energy is greater than the binding energy of an electron in one of the atom's inner orbital shells (e.g., the K or L shell), it can eject that electron from the atom [2]. This creates an unstable atom with a vacancy in its inner shell.

To regain stability, an electron from a higher-energy outer shell drops down to fill the vacancy. As this electron moves to the lower energy state, it releases a fluorescent X-ray photon [2]. The energy of this emitted photon is precisely equal to the difference in energy between the two quantum states of the electron. This energy is characteristic of the specific element and the particular electron transitions involved, thereby identifying the element present [1] [2].

Signal Detection and Spectrum Interpretation

In a sample containing multiple elements, X-rays with different characteristic energies are emitted simultaneously [1]. In an energy-dispersive XRF (EDXRF) instrument, this fluorescence radiation is collected by a semiconductor detector. The incoming X-rays create electrical signals in the detector proportional to their energy. These signals are processed by a multi-channel analyzer, which sorts them by energy level and converts them into a spectrum [1].

The resulting spectrum is a graph of X-ray intensity (typically in counts per second) against emission energy [1]. The position of a peak on the energy axis (x-axis) identifies the element present, while the height or intensity of the peak is generally indicative of its concentration in the sample [2]. Modern detectors can handle millions of counts per second, allowing spectra to be recorded quasi-simultaneously and providing sufficient information for composition analysis even with short measurement times [1].

The following diagram illustrates the core process of XRF analysis, from excitation to spectrum generation.

Key Instrumentation Types: Portable vs. Laboratory XRF

XRF instrumentation is primarily categorized into portable (handheld) and laboratory (benchtop) systems, each with distinct advantages and limitations. Furthermore, laboratory systems can be subdivided based on their detection technology.

Handheld XRF Analyzers

Handheld XRF (hhXRF) analyzers are portable, battery-operated devices designed for on-the-go elemental analysis [3]. They are engineered to provide instant elemental analysis in situations where immediate feedback is needed to determine the next course of action [4].

- Advantages: Their primary advantages are portability, speed (results within seconds), and minimal sample preparation requirements, making them ideal for fieldwork [3].

- Limitations: They generally offer moderate accuracy and are less sensitive, particularly for light elements and trace-level analysis. They are typically limited to surface-level analysis [3].

Benchtop XRF Analyzers

Benchtop XRF analyzers are stationary devices designed for more detailed, high-accuracy analysis in controlled laboratory settings [3]. They are the standard for analytical laboratories serving diverse applications like cement manufacturing, metallurgy, mining, and pharmaceuticals [4].

- Energy Dispersive XRF (EDXRF): EDXRF instruments are a convenient technology to screen all kinds of materials for quick identification and quantification with little sample preparation. They are characterized by their lower cost of ownership and rapid analysis [4].

- Wavelength Dispersive XRF (WDXRF): WDXRF technology is well-established for high sensitivity (including for low atomic number elements), high repeatability, and excellent element selectivity. It offers a wide dynamic range and is considered the performance leader for routine industrial applications requiring the highest data quality [4] [5].

The table below provides a structured comparison of handheld and benchtop XRF analyzers.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Handheld vs. Benchtop XRF Analyzers

| Feature | Handheld XRF | Benchtop XRF |

|---|---|---|

| Portability | Highly portable, ideal for field use [3] | Stationary, requires a laboratory setup [3] |

| Analysis Speed | Fast, provides results in seconds for rapid screening [3] | Slower, requires more preparation and analysis time [3] |

| Accuracy & Precision | Moderate, suitable for screening and semi-quantitative analysis [3] | High, ideal for precise quantitative analysis [4] [3] |

| Sensitivity (Trace Elements) | Lower, detection limits are typically higher [3] | Higher, superior for detecting trace elements [3] |

| Light Element Analysis | Less reliable for elements like Na, Mg, Al [3] | Excellent, WDXRF is superior for low Z elements (B to Na) [5] |

| Sample Throughput | Lower, suited for individual spot checks | Higher, automated for processing many samples [4] |

| Sample Types | Best for solid, surface-level samples [3] | Versatile; handles solids, liquids, powders, fused beads [4] [3] |

| Operational Cost | More affordable initial investment [3] | Higher initial cost and maintenance [3] |

| Typical Applications | Field exploration, scrap metal sorting, on-site PMI [2] [3] | Quality control, regulatory compliance, research & development [4] [3] |

Experimental Data: Comparing Portable XRF and Laboratory Methods

To objectively assess performance, it is critical to compare data from handheld XRF against laboratory reference methods like Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). The following experimental protocol and data are drawn from a study conducted in a U.S. Superfund community, focusing on environmental contaminants.

Experimental Protocol: Environmental Soil and Air Analysis

- Objective: To evaluate the level of agreement between metal concentrations in environmental samples analyzed via field portable XRF (FP XRF) versus laboratory ICP-MS analysis [6].

- Sample Collection:

- Sample Preparation:

- Soils were analyzed by FP XRF following the manufacturer's method for soils (80 source seconds). The other half was analyzed by an independent lab using ICP-MS following EPA method 6020A [6].

- Air filters were analyzed directly by FP XRF (80 source seconds) and then digested and analyzed via ICP-MS (EPA method 6020A) [6].

- Data Analysis: A split-half design was used. Half the samples created correction factors for the FP XRF, and the other half evaluated the agreement between the corrected FP XRF and ICP-MS results using paired t-tests, linear regression, and Bland-Altman plots [6].

Key Findings and Comparative Data

The study demonstrated that while FP XRF provides rapid, on-site results, its accuracy can be improved using correction factors derived from a subset of samples analyzed by ICP-MS. The ratio correction factor method was found to provide the best fit for the FP XRF device, enhancing the prediction of ICP-MS concentrations for elements like arsenic and lead [6].

The workflow below summarizes the experimental process used to validate portable XRF data against a laboratory reference method.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for XRF Analysis

Successful XRF analysis, whether with portable or laboratory systems, relies on several key reagents and materials. The following table details essential items for sample preparation and calibration, which are critical for achieving accurate and reliable results.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for XRF Analysis

| Item | Function in XRF Analysis | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| XRF Sample Cups | Holds loose powders, granules, or liquids for analysis without leakage [1]. | Universal for solid and liquid sample presentation in benchtop systems. |

| Binding Agents / Binders | Mixed with powdered samples to provide cohesion for pressed pellet formation [1]. | Creating stable, homogeneous pressed pellets from powders for robust analysis. |

| Flux (e.g., Lithium Tetraborate) | Mixed with powdered samples at high temperatures to create homogeneous fused beads, eliminating mineralogical and particle size effects [1]. | Essential for accurate major element analysis in geological and complex materials [5]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Calibrates the XRF instrument and validates analytical methods against a known standard [6]. | Crucial for both initial calibration and ongoing quality control for quantitative work. |

| Collimators | Physically defines the size of the X-ray beam that strikes the sample, controlling the analysis area [7]. | Key for micro-XRF and mapping applications to achieve high spatial resolution. |

| Primary Beam Filters | Selectively attenuate certain energies from the X-ray tube, reducing background and spectral overlaps [1]. | Used to optimize excitation conditions for specific element groups and improve detection limits. |

| Doryx | Doryx (Doxycycline Hyclate) | Doryx (doxycycline hyclate) is a tetracycline-class antibiotic for research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human consumption. |

| Cbdha | Cbdha, MF:C23H32O4, MW:372.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Application Spotlight: XRF in Cultural Heritage and Pharmaceuticals

The non-destructive nature of XRF makes it invaluable in fields where sample preservation is paramount.

In cultural heritage, handheld XRF scanners have been adapted for real-time elemental mapping of artifacts. A study using a Bruker Tracer 5i spectrometer coupled with an automated stage successfully scanned a 19th-century religious icon. The resulting elemental maps identified pigments (e.g., Hg in vermilion red, Cu in azurite blue) and revealed an underlying painting, providing insights into the artist's technique and the object's history without any physical damage [7].

In the pharmaceutical industry, XRF analyzers are used for quality control and assurance. A key application is screening for the presence of harmful heavy metal contaminants (e.g., As, Pb, Cd, Hg) in active pharmaceutical ingredients and final drug products. This ensures compliance with stringent pharmacopeial standards, such as USP chapters <232> and <2232>. Benchtop XRF systems are particularly suited for this quantitative analysis due to their high sensitivity and precision [8] [5].

XRF spectroscopy is a powerful and versatile technique for non-destructive elemental analysis. Its core principle—the measurement of characteristic secondary X-rays emitted from excited atoms—provides a robust foundation for both qualitative and quantitative material characterization.

The choice between portable and laboratory XRF systems is not a matter of superiority but of application-specific suitability. Portable XRF offers unmatched speed and convenience for on-site screening, field exploration, and rapid decision-making. Laboratory XRF, particularly WDXRF, delivers the high precision, sensitivity, and robust quantification required for quality control, regulatory compliance, and advanced research. For researchers investigating elemental contaminants, a hybrid approach often proves most effective: using portable XRF for initial field screening and mapping to guide sampling strategy, followed by confirmatory analysis of critical samples using laboratory-based ICP-MS or high-performance WDXRF. This workflow balances efficiency with the uncompromising data quality demanded by scientific and regulatory standards.

For researchers and scientists investigating elemental contaminants, selecting the appropriate analytical tool is a critical first step. X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry has become a cornerstone technique for qualitative and quantitative elemental analysis across diverse fields, from environmental science to pharmaceutical development. This guide provides an objective comparison between the two primary implementations of this technology: portable handheld XRF analyzers and laboratory-based benchtop systems, with a specific focus on their application in research settings.

XRF is a non-destructive analytical technique that determines the elemental composition of materials. When a sample is exposed to high-energy X-rays, atoms become excited and emit secondary (or fluorescent) X-rays at energies characteristic of each element, providing a unique elemental "fingerprint" [4] [9].

The two main technological implementations are:

- Portable/Handheld XRF (pXRF): Typically use Energy Dispersive XRF (EDXRF) technology. These battery-operated devices are designed for field use with minimal sample preparation, providing instant elemental analysis to guide immediate action [4] [3].

- Laboratory Benchtop XRF: Includes both EDXRF and Wavelength Dispersive XRF (WDXRF) systems. WDXRF instruments provide superior sensitivity and precision by using crystals to physically separate fluorescent X-rays by wavelength, making them the standard for high-performance laboratory applications [4] [9].

The table below summarizes the fundamental differences between these systems.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Portable and Laboratory XRF Systems

| Feature | Portable/Handheld XRF (pXRF) | Laboratory Benchtop XRF |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Technology | Energy Dispersive XRF (EDXRF) | Wavelength Dispersive XRF (WDXRF) or high-performance EDXRF |

| Operation Principle | Detects and measures energy of fluorescent X-rays | Uses crystals to diffract and separate X-rays by wavelength [4] |

| Portability | Highly portable; designed for field use [3] | Stationary; requires laboratory setup [3] |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal to none [4] [3] | Often extensive (e.g., grinding, pressing pellets, fusion beads) [4] [9] |

| Analysis Speed | Seconds to a few minutes for rapid results [3] | Longer measurement times, from minutes to tens of minutes [3] |

| Primary Use Case | On-site screening, rapid identification, field survey | Confirmatory analysis, high-precision quantification, regulatory compliance [4] |

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data

For research purposes, understanding the performance boundaries of each system is essential for experimental design and data interpretation. The following tables consolidate key quantitative metrics for easy comparison.

Table 2: Analytical Performance and Detection Capabilities

| Performance Metric | Portable/Handheld XRF (pXRF) | Laboratory Benchtop XRF |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Detection Limits | ~10-150 ppm for mid-Z elements in light matrices [10]; µg/g range for toxic elements (As, Cd, Pb, Hg) [11] | Parts-per-million (ppm) to sub-ppm (hundreds of ppb) levels [9] [12] |

| Elemental Range | Typically sodium (11Na) to uranium (92U); best for mid- to high-Z elements [9] [13] | Often beryllium (4Be) to uranium (96Cm) [9] [13] |

| Accuracy & Precision | Moderate; suited for screening. Bias for key toxic elements can range from -14% to 16% in controlled conditions [11] | High repeatability and precision; essential for process and quality control [4] |

| Light Element Analysis | Limited reliability for elements lighter than sodium (e.g., Mg, Al, P) [3] [13] | Excellent sensitivity for low atomic number elements (e.g., Be, B, C, N, O) [9] |

Table 3: Practical Considerations for Research Deployment

| Practical Consideration | Portable/Handheld XRF (pXRF) | Laboratory Benchtop XRF |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Versatility | Solids, powders (with caution); limited for liquids, uneven surfaces [9] [3] | All kinds of materials: solids, liquids, loose powders, pressed pellets, fusion beads, coatings [4] |

| Cost | Lower initial investment and ongoing costs [3] [11] | Higher initial cost and maintenance [3] |

| Throughput | High for field screening; rapid on-site decision-making [4] [3] | High for prepared samples in a lab; suited for batch analysis [4] |

| Data Complexity | Proprietary software with pre-set modes; requires spectral interpretation skills for complex samples [11] | Advanced software for detailed data analysis, custom calibrations, and complex matrix correction [4] [3] |

| Ideal Application | Field surveys, rapid screening, sample triage, in-situ measurement [4] [14] [6] | Quantitative analysis, research and development, regulatory compliance, analysis of complex/heterogeneous samples [4] [9] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The validity of research data hinges on rigorous methodology. The protocols for using portable and laboratory XRF differ significantly, reflecting their distinct purposes and operating environments.

Typical Protocol for Portable XRF Analysis

Portable XRF is often deployed for rapid screening of contaminants like heavy metals in environmental media. The following workflow, adaptable for field-based research on soil or air filters, outlines a common approach [6].

Figure 1: Portable XRF Field Screening Workflow

Key Steps Explained:

- Sample Preparation: Minimal preparation is a key advantage. Soil is typically air-dried and sieved to homogenize the sample and ensure a consistent, flat analysis surface [6]. Air filter samples can be analyzed directly.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibration is crucial. This involves analyzing Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) with known concentrations that are matrix-matched to the samples (e.g., NIST soil standards) to create instrument-specific calibration factors [6] [11].

- Measurement & Validation: Samples are analyzed using manufacturer-recommended modes (e.g., "Soil Mode"). A common practice to ensure data quality is a split-sample design, where one portion is analyzed by pXRF and another is sent for confirmatory analysis using a reference method like ICP-MS [6].

- Data Correction: Empirical correction factors (e.g., ratio correction factors) can be developed from the split-sample data to improve the agreement between pXRF results and laboratory data, thereby maximizing the field data's reliability for research purposes [6].

Typical Protocol for Laboratory WDXRF Analysis

Laboratory WDXRF is employed when high-precision, quantitative results are required. The methodology involves more extensive sample preparation to control for matrix effects.

Figure 2: Laboratory WDXRF Quantitative Analysis Workflow

Key Steps Explained:

- Robust Homogenization: Samples are ground to a fine, consistent powder (often to particle sizes below 50-75 µm) to ensure homogeneity and minimize particle size effects, which is critical for analytical precision [9] [12].

- Precise Sample Formatting: Two common methods are used:

- Pressed Pellets: The powdered sample is mixed with a binding agent and pressed under high pressure into a solid, flat pellet [9].

- Fusion Beads: The sample is dissolved in a flux (e.g., lithium tetraborate) at high temperatures to create a homogeneous glass bead. This method effectively destroys the original mineral structure, eliminating mineralogical and particle size effects, and is considered the gold standard for achieving the highest accuracy [9].

- Measurement & Data Processing: Analysis is performed under optimized conditions (e.g., vacuum/helium flush for light elements). Quantification relies on sophisticated algorithms, such as the Fundamental Parameters (FP) method, which models the physics of X-ray interactions to correct for complex matrix effects, thereby providing highly accurate results without the need for an exhaustive set of calibration standards [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Materials for XRF Analysis

Successful XRF analysis, whether in the field or the lab, depends on the use of appropriate consumables and reference materials.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for XRF Analysis

| Item | Function | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Instrument calibration and validation of analytical accuracy. | NIST soil standards (e.g., 2709, 2710), USGS rock standards, custom matrix-matched CRMs [6] [15]. |

| XRF Flux | Acts as a solvent and binder during fusion bead preparation to create a homogeneous glass disk. | Lithium tetraborate (Li₂B₄O₇), often with oxidizing agents like Lithium nitrate (LiNO₃) [9]. |

| Binding Agent | Holds powdered samples together in pressed pellets to ensure structural integrity during analysis. | Cellulose wax, boric acid, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) [9]. |

| Internal Standard Solutions | Added to liquid or suspension samples in methods like TXRF to correct for variations in sample presentation and instrument response. | Aqueous solutions of Gallium (Ga), Cobalt (Co), or Yttrium (Y) at known concentrations [15]. |

| Sample Cups & Support Films | Hold loose powders or liquids for analysis in benchtop systems. | Plastic cups with polypropylene or Mylar film bottoms that are X-ray transparent [9]. |

| Edtah | Edtah, CAS:38932-78-4, MF:C10H20N6O8, MW:352.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Yrgds | Yrgds, MF:C24H36N8O10, MW:596.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Portable handheld XRF and laboratory benchtop WDXRF systems serve complementary roles in the researcher's toolkit. Portable XRF excels as a rapid, on-site screening tool for high-throughput field surveys and initial sample triage, offering unparalleled speed and convenience at the cost of ultimate precision and sensitivity. Laboratory WDXRF is the definitive choice for high-precision quantitative analysis, providing superior accuracy, lower detection limits, and robust data for regulatory compliance and fundamental research. The choice between them should be guided by a clear understanding of research objectives, required data quality, and operational constraints. A synergistic approach, using portable XRF for field screening and laboratory systems for confirmatory analysis, often provides the most powerful and efficient strategy for comprehensive elemental contaminants research.

Elemental impurities (EIs), such as arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury, in drug products pose significant patient risks including organ damage, cancer, and neurological issues due to their toxicity. These metallic contaminants can arise from multiple sources including residual catalysts intentionally added during synthesis, impurities in raw materials, interactions with manufacturing equipment, and leachables from container closure systems. Because elemental impurities provide no therapeutic benefit and can adversely impact drug stability and efficacy, global regulatory bodies have established stringent guidelines for their control using modern risk-based approaches and analytical methodologies.

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q3D guideline provides the foundational global framework for classifying elemental impurities and setting permitted daily exposure (PDE) limits based on rigorous toxicological assessment. This guideline has been adopted and implemented regionally through various pharmacopeial standards: the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) chapters <232> (Limits) and <233> (Procedures), the European Pharmacopoeia (Ph. Eur.) chapters 5.20 (Limits) and 2.4.20 (Procedures), and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) regulatory framework. These harmonized standards represent a significant advancement over traditional heavy metals testing (e.g., USP <231>), which relied on colorimetric methods and has now been largely replaced by more specific, sensitive instrumental techniques [16] [17].

Core Regulatory Framework Comparison

ICH Q3D Guideline: The Global Standard

The ICH Q3D guideline, currently in its second revision (R2) effective September 2022, establishes a comprehensive risk-based process for assessing and controlling elemental impurities in drug products. The guideline categorizes elemental impurities into three classes based on their toxicity and likelihood of occurrence:

- Class 1: Elements of significant toxicity (As, Cd, Hg, Pb) that require evaluation across all potential sources and administration routes

- Class 2: Route-dependent human toxicants divided into:

- Class 2A: Elements with high probability of occurrence (Co, Ni, V) requiring risk assessment

- Class 2B: Elements with low probability of occurrence (Ag, Au, Ir, Os, Pd, Pt, Rh, Ru, Se, Tl) that may be excluded unless intentionally added

- Class 3: Elements with relatively low toxicity by oral administration (Ba, Cr, Cu, Li, Mo, Sb, Sn) that may require assessment for inhalation or parenteral routes [16]

ICH Q3D(R2) introduced corrected PDEs for Gold, Silver, and Nickel, and added limits for cutaneous and transcutaneous routes of administration. The guideline promotes a risk-based control strategy aligned with ICH Q9 Quality Risk Management principles, where manufacturers must conduct a comprehensive risk assessment considering all potential sources of elemental impurities and establish appropriate controls to ensure drug product safety [18] [16].

USP Chapters <232> and <233>: Implementation in the United States

The United States Pharmacopeia implements the ICH Q3D framework through two primary general chapters:

USP <232> Elemental Impurities—Limits: Establishes PDEs for elemental impurities in drug products aligned with ICH Q3D, with updates to incorporate Q3D(R2) revisions including new cutaneous/transcutaneous PDEs and corrected values for nickel, gold, and silver [19].

USP <233> Elemental Impurities—Procedures: Specifies analytical procedures for testing elemental impurities, recently harmonized with European and Japanese Pharmacopoeia texts. The updated chapter, official May 1, 2026, permits use of any procedure meeting specified validation criteria and incorporates application of ICH Q3D concepts [20].

USP has established a graduated implementation timeline, with full applicability of <232> and <233> to drug product monographs effective January 1, 2018, replacing the outdated <231> Heavy Metals test [19].

EMA and Ph. Eur.: Implementation in Europe

The European Medicines Agency and European Pharmacopoeia have similarly implemented ICH Q3D:

Ph. Eur. 5.20 (Limits) and 2.4.20 (Procedures) provide requirements aligned with ICH Q3D, replacing traditional heavy metals testing methods [16].

EMA implementation began in June 2016 for products with new marketing authorization containing new active substances, with full compliance required for all marketed products from December 2017 [16].

The Ph. Eur. Commission specifically recommends maintaining tests for "other elements" without established PDEs in individual monographs, particularly for substances of natural origin which represent major potential sources of elemental contamination [16].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Elemental Impurities Regulatory Frameworks

| Aspect | ICH Q3D | USP | EMA/Ph. Eur. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foundation | Global harmonization initiative | USP General Chapters <232> & <233> |

Ph. Eur. 5.20 & 2.4.20 |

| Classification | Class 1, 2A, 2B, 3 | Class 1, 2A, 2B, 3 | Class 1, 2A, 2B, 3 |

| PDE Limits | Based on route of administration | Aligned with ICH Q3D | Aligned with ICH Q3D |

| Analytical Procedures | No specific method prescribed | USP <233> procedures |

Ph. Eur. 2.4.20 procedures |

| Implementation Date | Effective September 2022 (R2) | <232>/<233> applicable from Jan 1, 2018 |

New products: June 2016; All products: Dec 2017 |

| Current Status | Q3D(R2) in implementation | Harmonized <233> official May 2026 |

Ph. Eur. 9.3 (Jan 1, 2018) |

Permitted Daily Exposure Limits

The cornerstone of elemental impurities control is the establishment of Permitted Daily Exposure (PDE) limits, which represent the maximum acceptable intake of a specific element per day without significant patient risk. These limits are established based on comprehensive toxicological evaluation and vary according to the route of administration due to differences in bioavailability and toxicity across exposure pathways [17].

Table 2: Permitted Daily Exposures (PDEs) for Elemental Impurities by Route of Administration (μg/day) [21] [22]

| Element | Class | Oral PDE | Parenteral PDE | Inhalation PDE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cadmium | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Lead | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Arsenic | 1 | 15 | 15 | 2 |

| Mercury | 1 | 30 | 3 | 1 |

| Cobalt | 2A | 50 | 5 | 3 |

| Vanadium | 2A | 100 | 10 | 1 |

| Nickel | 2A | 200 | 20 | 6 |

| Thallium | 2B | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Gold | 2B | 300 | 300 | 1 |

| Palladium | 2B | 100 | 10 | 1 |

| Iridium | 2B | 100 | 10 | 1 |

| Osmium | 2B | 100 | 10 | 1 |

| Rhodium | 2B | 100 | 10 | 1 |

| Ruthenium | 2B | 100 | 10 | 1 |

| Selenium | 2B | 150 | 80 | 130 |

| Silver | 2B | 150 | 15 | 7 |

| Platinum | 2B | 100 | 10 | 1 |

| Lithium | 3 | 550 | 250 | 25 |

| Antimony | 3 | 1,200 | 90 | 20 |

| Barium | 3 | 1,400 | 700 | 300 |

| Molybdenum | 3 | 3,000 | 1,500 | 10 |

| Copper | 3 | 3,000 | 300 | 30 |

| Tin | 3 | 6,000 | 600 | 60 |

| Chromium | 3 | 11,000 | 1,100 | 3 |

The PDE values reflect significant toxicological differences across administration routes. For example, mercury's inhalation PDE (1 μg/day) is substantially lower than its oral PDE (30 μg/day), reflecting enhanced pulmonary absorption and toxicity. Similarly, elements like silver exhibit markedly different PDEs across routes (oral: 150 μg/day; parenteral: 15 μg/day; inhalation: 7 μg/day) [21]. ICH Q3D(R2) has introduced corrections to PDEs for nickel (inhalation), gold (all routes), and silver (parenteral) to address calculation errors identified during implementation [19].

Analytical Procedures and Methodologies

Approved Analytical Techniques

Modern elemental impurities analysis has transitioned from traditional wet chemistry methods to advanced instrumental techniques capable of detecting impurities at parts-per-billion (ppb) concentrations required by regulatory PDEs:

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS): Preferred for ultratrace analysis at ppb levels, offering exceptional sensitivity, wide dynamic range, and multi-element capability [16] [17].

Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES): Suitable for higher concentration ranges (ppm levels), with robust performance for less challenging matrices [16].

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS): Still employed for specific applications but largely superseded by plasma-based techniques for multi-element analysis [21].

USP <233> and Ph. Eur. 2.4.20 provide validation criteria for analytical procedures but do not mandate specific methodologies, allowing flexibility in technique selection provided validation requirements are met. The updated USP <233> chapter removes the distinction between "alternative" and "compendial" procedures, emphasizing performance-based validation rather than prescriptive methodologies [20].

Sample Preparation Workflows

Proper sample preparation is critical for accurate elemental impurities analysis. Recent interlaboratory studies have standardized two primary approaches:

Sample Preparation Workflow for Elemental Impurities Analysis

Exhaustive Extraction: Utilizes concentrated nitric acid with gold standard addition (for mercury stabilization), followed by microwave-assisted digestion at 175°C for 20 minutes and dilution to final acid concentration of 2% HNO₃ and 2% HCl. This approach is suitable for most organic matrices and provides sufficient extraction for compliance assessment [17].

Total Digestion: Employs a mixed acid system (HCl, HNO₃, H₃PO₄, and HBF₄ from HF and boric acid) with more aggressive microwave parameters (maximum safe temperature for 45 minutes), resulting in final solutions containing 2% HNO₃, 2% HCl, and 0.2% HF. This method is essential for complete dissolution of challenging inorganic materials like silicon dioxide, titanium dioxide, and talc [17].

Analytical Instrumentation and Optimization

ICP-MS analysis requires careful optimization to achieve required detection limits while minimizing interferences:

Collision/Reaction Cells: Utilization of helium or hydrogen gas to reduce polyatomic interferences through kinetic energy discrimination or chemical reactions [17].

Interference Management: Specific attention to chlorine-based interferences (e.g., ClO⺠on vanadium detection) requiring optimized cell parameters [17].

Mercury Stabilization: Addition of gold to analytical solutions to prevent mercury adsorption and volatility losses during analysis [17].

Quality Control: Implementation of system suitability testing with matrix-matched calibration standards prepared from NIST-traceable reference materials [17].

Experimental Data and Recent Study Findings

PQRI Interlaboratory Study Methodology

The Product Quality Research Institute (PQRI) conducted a comprehensive interlaboratory study published in 2025 to evaluate variability in elemental impurities testing across 21 participating ICP-MS laboratories. The study focused specifically on ICH Q3D Class 1 and Class 2A elements (As, Cd, Pb, Hg, Co, Ni, V) due to their significant toxicity and high probability of occurrence in drug products [17].

Standardized test samples included pharmaceutical tablets and raw materials (lactose, magnesium aluminum silicate, microcrystalline cellulose, red ferric oxide, silicon dioxide standards, starch, and stearic acid) fortified with target elements at three concentration levels:

- 30% PDE (control threshold)

- 100% PDE (maximum permitted level)

- 300% PDE (exceedance level)

All participating laboratories performed both exhaustive extraction and total digestion sample preparation followed by ICP-MS analysis using standardized isotopes, calibration approaches, and quality control measures while allowing laboratory-specific selection of internal standards and collision cell gases [17].

Key Findings and Implications

The PQRI study revealed several critical insights for elemental impurities analysis:

Overall Performance: Favorable accuracy and reproducibility for most target elements across participating laboratories, demonstrating the robustness of modern ICP-MS methodologies for regulatory compliance [17].

Element-Specific Challenges: Mercury and vanadium exhibited the highest variability and lowest recoveries in tablet samples. Mercury losses were attributed to volatility issues, while vanadium inaccuracies resulted primarily from ClO⺠polyatomic interferences [17].

Sample Preparation Impact: Total digestion provided superior recovery for challenging matrices like silicon dioxide compared to exhaustive extraction, particularly for elements tightly bound within mineral structures [17].

Variability Assessment: Intralaboratory (within-lab) variability was significantly lower than interlaboratory (between-lab) variability, highlighting the importance of method harmonization and standardized protocols for cross-laboratory comparisons [17].

Matrix Considerations: Raw material samples generally showed less variability and more accurate recoveries compared to tablet formulations, suggesting additional complexity introduced by drug product manufacturing processes [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Elemental Impurities Analysis

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Calibration and quality control | NIST-traceable multi-element standards for ICP-MS calibration [16] |

| High-Purity Acids | Sample digestion and dilution | HNO₃, HCl, HF, H₃PO₄ of ultrapure grade to minimize background contamination [17] |

| Internal Standards | Correction for instrument drift | Elements not present in samples (e.g., Sc, Ge, Rh, Ir) to normalize analytical response [17] |

| Collision/Reaction Gases | Interference reduction | High-purity He, Hâ‚‚ for ICP-MS collision cells to minimize polyatomic interferences [17] |

| Mercury Stabilizer | Prevention of Hg loss | Gold-containing standards added to samples and calibration standards to stabilize mercury [17] |

| Microwave Digestion System | Sample preparation | Closed-vessel microwave systems with temperature/pressure control for reproducible digestion [17] |

| Silicon Dioxide Standards | Method validation | Challenging matrix for verifying complete extraction of tightly bound elements [17] |

| Quality Control Materials | Method verification | Certified reference materials with known element concentrations to validate analytical accuracy [17] |

| Dmbap | Dmbap, MF:C19H28N2O5, MW:364.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| CoPoP | CoPoP Liposome|Cobalt Porphyrin-Phospholipid|RUO | CoPoP (Cobalt Porphyrin-Phospholipid) for his-tagged antigen display in vaccine research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary diagnostic use. |

Regulatory Assessment and Control Workflow

Implementation of elemental impurities control requires a systematic approach to risk assessment and analytical verification as outlined in ICH Q3D:

Elemental Impurities Control Workflow

This workflow emphasizes the iterative nature of elemental impurities control, beginning with identification of administration route-specific PDEs, comprehensive assessment of all potential contamination sources, analytical verification, and establishment of ongoing control strategies with periodic re-assessment based on process changes or supplier modifications [18] [17].

The harmonized framework established by ICH Q3D and implemented through USP, Ph. Eur., and EMA guidelines represents a significant advancement in elemental impurities control, transitioning from prescriptive testing requirements to risk-based strategies grounded in modern toxicological science. Successful implementation requires careful consideration of administration route-specific PDEs, comprehensive risk assessment across all potential contamination sources, selection of appropriate analytical methodologies capable of detecting impurities at required levels, and establishment of robust control strategies.

Recent interlaboratory studies demonstrate that while modern ICP-MS methodologies generally provide accurate and reproducible results for regulatory compliance, specific challenges remain for volatile elements like mercury and interference-prone elements like vanadium, requiring specialized analytical approaches. The continued harmonization of analytical procedures across pharmacopeias and incorporation of ICH Q3D(R2) updates further strengthen this global framework, ultimately enhancing drug product quality and patient safety through science-based regulation of elemental impurities.

In the critical field of elemental contaminants research, from Superfund sites to pharmaceutical raw material verification, researchers face a fundamental choice between analytical methods: the traditional accuracy of laboratory-based analysis or the rapid, on-site capabilities of portable X-ray Fluorescence (pXRF). Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) represents the gold standard for laboratory analysis, capable of detecting a multitude of elements simultaneously with low limits of detection and quantification [6]. In recent years, pXRF has emerged as a powerful alternative, offering real-time results and significantly lower ongoing costs, though not without analytical trade-offs [6] [23]. The core challenge, and the central thesis of this guide, is that the performance of pXRF is not uniform across the periodic table. Its efficacy is strongly dependent on atomic number, creating a clear divide between the reliable detection of heavy elements and the problematic analysis of light elements—a divide that directly influences method selection for research on environmental, clinical, and pharmaceutical contaminants.

This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of pXRF and laboratory-based ICP-MS for researchers and drug development professionals. We will dissect the elemental range of pXRF from sodium to uranium, quantify its performance through experimental data, detail standardized protocols, and provide a toolkit for making informed analytical decisions in contaminants research.

The Elemental Range of Portable XRF

Portable XRF technology operates on the principle of exciting atoms in a sample with X-rays, causing them to emit characteristic fluorescent X-rays that are detected and quantified [24]. The energy of these fluorescent X-rays is directly proportional to the atomic number of the element. This relationship fundamentally dictates which elements can be measured effectively.

The Detectable Spectrum and Its Limits

Theoretically, pXRF can measure elements from magnesium (Mg, atomic number 12) to bismuth (Bi, atomic number 83) and beyond [25]. In practice, the technique's performance creates three distinct zones of analytical capability:

- Light Elements (Approx. Magnesium - Calcium, Z=12-20): This region is analytically challenging. Elements like sodium (Na, Z=11) are nearly impossible to analyze with standard pXRF, and those up to sulfur (S, Z=16) present significant difficulties [26]. Performance for elements like potassium (K, Z=19) and calcium (Ca, Z=20) is more variable and highly dependent on instrumentation and sample conditions [27].

- Mid-Range Elements (Approx. Manganese - Molybdenum, Z=25-42): This is the sweet spot for pXRF analysis. The sensitivity reaches its maximum values for these elements, allowing for excellent detection limits and analytical precision [7].

- Heavy Elements (Beyond Z=42): pXRF performs very well for heavy metals, including environmentally relevant contaminants like lead (Pb), arsenic (As), and cadmium (Cd) [6] [27]. The primary limitation for these elements is not the physics of detection, but the achievable detection limit relative to the required concentration, especially for trace-level analysis [24].

Table 1: Summary of pXRF Performance Across the Elemental Range

| Elemental Group | Atomic Number Range | Example Elements | pXRF Performance | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light Elements | ~12-20 | Mg, Al, P, S, K, Ca | Poor to Variable | Low fluorescence yield, strong absorption by air/sample, high background noise [24] [26] [27] |

| Mid-Range Elements | ~25-42 | Mn, Fe, Cu, Zn, As, Mo | Excellent | High sensitivity and best detection limits [7] |

| Heavy Elements | >42 | Cd, Pb, Bi | Very Good | Detection limits may not suffice for ultra-trace analysis [6] [24] |

The Fundamental Challenge of Light Elements

The difficulties with light elements are rooted in the physics of the X-ray fluorescence process and are characterized by three primary factors:

- Low Fluorescence Yield: The probability that an excited atom will emit a characteristic X-ray, rather than an Auger electron, decreases sharply as atomic number decreases. Light elements simply produce fewer fluorescent X-rays for the same incoming X-ray dose, resulting in a weaker signal [26].

- Absorption of Low-Energy X-rays: The characteristic X-rays from light elements are very low in energy (1–2 keV). These soft X-rays are easily absorbed by the sample itself (self-absorption), the air gap between the sample and detector, and even the thin protective window (often made of beryllium) on the detector [24] [26].

- High Background Noise: The low-energy fluorescent signal must be distinguishable from the background noise generated by scattered X-rays (Rayleigh and Compton scattering). This can mask the already weak signal, leading to poor detection limits, often in the 0.5-1% (5000-10,000 ppm) range for the lightest measurable elements [24].

The following diagram illustrates the cascade of physical effects that hinder light element analysis.

Technological Advances and Methodological Workarounds

To overcome these inherent challenges, instrument manufacturers and researchers have developed several key technological and methodological strategies.

Instrumental Improvements

Modern pXRF systems incorporate specific features to enhance light element performance:

- High-Power X-Ray Tubes: Increasing the tube current (e.g., to 1000 µA instead of a standard 200 µA) boosts the excitation energy, quintupling sensitivity for light elements by generating a stronger initial signal [26].

- Advanced Detectors: Silicon Drift Detectors (SDDs) with large areas allow more energy to be received and measured. Coupling these with ultra-thin graphene or polymer entrance windows (as thin as 0.9 µm) instead of standard beryllium windows drastically reduces the absorption of low-energy X-rays before they reach the detector [24] [26].

- Vacuum and Helium Purge: Removing the absorbing air between the sample and detector is critical. This is achieved either by creating a vacuum or, more conveniently in the field, by purging the path with helium gas, which has very low absorption for low-energy X-rays [26].

Methodological and Data Processing Approaches

Beyond hardware, methodological adjustments are essential for reliable data:

- Empirical Recalibration: Even with built-in soil calibrations, elements like P, S, and Mg can be significantly overestimated (e.g., 5 to 13 times) [27]. Using matrix-matched calibration standards or developing site-specific correction factors is often necessary. One study on arsenic and lead in soils found that applying a ratio correction factor method significantly improved the agreement between pXRF and ICP-MS results [6].

- Dilution to Mitigate Matrix Effects: For trace analysis in a heavy matrix (e.g., trace metals in uranium), a simple dilution of the sample can reduce the absorption and enhancement effects caused by the dominant matrix elements, allowing for more accurate trace element determination without complex sample preparation [28].

Experimental Comparison: pXRF vs. Laboratory-Based ICP-MS

To objectively compare these techniques, we turn to experimental data from controlled studies. The following table synthesizes findings from multiple research efforts, focusing on elements relevant to contaminants research.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of pXRF vs. ICP-MS/OES

| Element | Sample Matrix | Laboratory Method | Key Finding | Correlation/Agreement | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic (As) | Residential Soil & Air Filters | ICP-MS | pXRF results were not as accurate as ICP-MS, but agreement was improved using a ratio correction factor. | High agreement post-correction; precise level dependent on correction method. | [6] |

| Lead (Pb) | Residential Soil & Air Filters | ICP-MS | pXRF results were not as accurate as ICP-MS, but agreement was improved using a ratio correction factor. | High agreement post-correction; precise level dependent on correction method. | [6] |

| Lead (Pb) | Wetland Soils | Aqua Regia Digestion + AAS | A straight 1:1 correlation was observed between the lab method and pXRF. | Strong correlation. | [29] |

| Copper (Cu), Zinc (Zn) | Wetland Soils | Aqua Regia Digestion + AAS | pXRF reported higher concentrations (as it measures total content) but with a consistent, strong correlation. | Strong correlation, but with a proportional bias. | [29] |

| Magnesium (Mg), Phosphorus (P), Sulfur (S) | Diverse European/African Soils | Various Lab Methods (ICP-AES, etc.) | Concentrations were significantly overestimated by pXRF (up to 5x for Mg, 13x for P). | Poor without empirical recalibration. | [27] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

To contextualize the data in Table 2, the following workflow outlines a standard experimental design for a method comparison study, as seen in the Superfund community research [6] and the comprehensive multi-scanner evaluation [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for pXRF Analysis

For researchers embarking on pXRF analysis, particularly for environmental contaminants, the following tools and materials are essential.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for pXRF Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Portable XRF Spectrometer | The core analytical device for on-site, non-destructive elemental analysis. | Bruker S1 Titan, Olympus Vanta, Oxford Instruments XMET 8000 [27]. |

| Silicon Drift Detector (SDD) | Key component for high-resolution energy detection, especially for light elements. | Large-area SDD (30-40 mm²) with graphene window [26] [7]. |

| Helium Purge System / Vacuum Pump | Reduces absorption of low-energy X-rays from light elements in the air path. | Integrated system for purging the analysis chamber [26]. |

| XRF Sample Cups & Prolene Film | Holds powdered samples; the thin (4µm) film minimizes X-ray absorption. | 30mm cups sealed with 4.0µm prolene film [27]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Critical for instrument calibration and validation of analytical results. | NIST soil standards (e.g., 2709, 2710) [6]. |

| Sample Preparation Tools | For homogenizing samples to ensure analytical representativeness. | Stainless steel sieves (2mm, 250µm), grinder, press for pelletizing [6] [27]. |

| bPiDI | bPiDI, MF:C22H34I2N2, MW:580.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Citfa | Citfa, MF:C25H35NO2, MW:381.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between portable XRF and laboratory-based ICP-MS is not a simple binary but a strategic decision based on research objectives, required data quality, and constraints.

pXRF is the superior choice for rapid screening, high-throughput mapping, and situations where on-site, immediate results drive decision-making. Its performance is excellent for heavy metal contaminants like lead and arsenic (post-calibration) and very good for many mid-range elements. It excels in providing semi-quantitative data and identifying contamination hotspots quickly and cost-effectively.

ICP-MS remains indispensable for applications requiring definitive, high-precision quantitative data, especially for trace-level contaminants and light elements. It is the required method for regulatory compliance, definitive risk assessments, and research where the highest level of accuracy and the lowest detection limits are non-negotiable.

For a comprehensive research strategy, the two methods are complementary. pXRF can be used for extensive initial site characterization to identify areas of interest, which are then targeted for limited, but definitive, laboratory analysis via ICP-MS. This hybrid approach leverages the strengths of both techniques, providing both breadth of coverage and depth of certainty—a rational and efficient path forward for modern elemental contaminants research.

Elemental analysis has become a cornerstone of pharmaceutical development and manufacturing, essential for ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of drug substances and products [30]. By detecting contaminants and verifying purity, elemental analysis supports regulatory compliance and helps to safeguard public health. The growing adoption of guidelines like ICH Q3D, which categorizes elemental impurities based on their toxicity and likelihood of occurrence, has intensified the focus on robust testing protocols. This landscape drives the continuous evaluation of analytical techniques, balancing the need for precision, throughput, and operational efficiency. Within this context, the comparison between portable techniques like X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) and traditional laboratory methods forms a critical area of research for modern pharmaceutical scientists.

Analytical Techniques Face-Off: Portable XRF vs. Laboratory-based Analysis

The choice of analytical technique is pivotal. While Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) spectrometry is the traditional laboratory method, portable XRF presents a modern, complementary alternative.

Portable X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF)

Principle of Operation: XRF is an atomic emission method. A handheld or portable XRF analyzer uses an X-ray tube to emit primary X-rays onto a sample [31]. This excites the atoms in the sample, causing them to emit fluorescent X-rays with discrete energies characteristic of the elements present [30]. The instrument detects these secondary X-rays to provide a qualitative and quantitative elemental analysis [32].

Key Advantages:

- Speed and Non-Destructive Analysis: XRF delivers results rapidly, with minimal sample preparation, and without altering or destroying the sample [30] [33]. This allows the same sample to be used for further testing.

- On-Site Capability: Handheld XRF analyzers are designed for use in the field, on the production floor, or in the lab, providing immediate feedback [4] [31].

- Ease of Use: Operators can obtain robust results with minimal training, and the technique does not require hazardous chemicals for sample preparation [33].

Limitations:

- Sensitivity: While its sensitivity has improved, XRF is generally less sensitive than ICP-MS, typically operating in the parts-per-million (ppm) range rather than parts-per-billion (ppb) or lower [33].

- Surface Analysis: It is primarily a surface-level technique and may be less effective for analyzing heterogeneous samples without proper preparation [3].

Laboratory-Based Analysis: ICP Spectrometry and Benchtop XRF

Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometry: ICP-OES and ICP-MS are the established go-to solutions for elemental analysis in pharmaceutical laboratories [30].

- Principle of Operation: These techniques involve digesting the sample into a liquid solution, which is then vaporized and passed through argon plasma. The high-temperature plasma atomizes and ionizes the elements. In ICP-OES, the emitted light is measured, while ICP-MS separates and counts the ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio [34].

- Key Advantages: The primary advantage is exceptional sensitivity and low detection limits, with ICP-MS capable of detecting trace levels down to parts-per-trillion [34] [33].

- Limitations: ICP techniques require extensive, hazardous sample preparation (using strong acids and microwaves), are labor-intensive, require highly skilled operators, and involve longer lead times from sample to result [30] [33].

Benchtop XRF Systems: These laboratory instruments use the same fundamental physics as portable XRF but are larger, more powerful, and offer higher sensitivity and precision [4] [3]. They are versatile and can analyze a wide range of sample types, including liquids, powders, and solid materials, often with automated features for higher throughput [4] [30].

Direct Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes key differences between portable XRF and laboratory-based ICP techniques.

Table 1: Analytical Technique Performance Comparison for Pharmaceutical Applications

| Feature | Portable XRF | Benchtop XRF (e.g., Epsilon 4, Revontium) | ICP-MS (Laboratory) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Sensitivity | Parts-per-million (ppm) | Parts-per-million (ppm) to parts-per-billion (ppb) [30] | Parts-per-trillion (ppt) [33] |

| Sample Throughput | Very High (seconds to minutes) [31] | High (10-45 minutes for full analysis) [30] | Moderate to Low (includes lengthy preparation) [30] |

| Sample State | Solid, powder (minimal prep) | Solids, powders, liquids, fused beads [4] [30] | Liquid (requires digestion) [30] |

| Analysis Type | Non-destructive [30] | Non-destructive [30] | Destructive [30] |

| Operational Cost | Low (no consumables) [33] | Low (no consumables) [33] | High (gases, acids, maintenance) [33] |

| Technician Skill | Low | Moderate | High [33] |

| Regulatory Compliance | Complies with USP <735>, EP 2.2.37, ICH Q3D [33] | Complies with USP <735>, EP 2.2.37, ICH Q3D [33] | Industry standard for compliance |

Supporting Experimental Data: XRF in Action

Independent studies and application notes provide evidence for the capabilities of XRF in elemental analysis.

Comparative Analysis of Household Alloys

A 2024 study directly compared a handheld XRF analyzer to Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive X-ray (SEM-EDX) for analyzing household alloy materials [32].

- Experimental Protocol: Fifteen common alloy samples (coins, screws, wires) were analyzed by both handheld XRF and SEM-EDX. The instruments were calibrated according to manufacturers' specifications, and performance tests were conducted prior to analysis.

- Key Findings: The study reported that "XRF detected a broader range of elements, particularly trace metals such as Pb, Sn, and Mo, whereas SEM-EDX was more sensitive to lighter elements like aluminum and silicon." The total number of metal detections across all samples was 110 for XRF versus 43 for SEM-EDX, highlighting XRF's proficiency in bulk material analysis and trace element detection [32].

- Statistical Analysis: A paired t-test confirmed a statistically significant difference in the detection capabilities of the two techniques, reinforcing their complementary nature. XRF was superior for bulk composition, while SEM-EDX excelled at surface-specific, high-resolution characterization [32].

Environmental Analysis and Correlation with ICP-MS

Research in a U.S. Superfund community explored the correlation between Field Portable (FP) XRF and ICP-MS for analyzing metals in soil and air filters [6].

- Experimental Protocol: Ninety-one soil samples and 42 air filter samples were collected. A split-half design was used, where half the samples were used to create correction factors for the XRF, and the other half were used to evaluate the level of agreement between the corrected XRF results and ICP-MS results.

- Key Findings: The study concluded that with appropriate correction factors, FP XRF could achieve a high level of agreement with ICP-MS for elements like arsenic and lead. This demonstrates that for screening and monitoring purposes, portable XRF can provide sufficiently accurate data with much faster turnaround times [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Solutions for Elemental Analysis

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Elemental Analysis

| Item | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| XRF Sample Cups & Films | Hold powdered or liquid samples during analysis. The film provides a vacuum-seal and contamination-free window for X-ray transmission. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Used for instrument calibration and validation to ensure analytical accuracy and traceability to international standards. |

| Fusion Fluxes | High-purity chemicals (e.g., lithium tetraborate) used to create homogeneous glass beads from powdered samples for more accurate benchtop XRF analysis [4]. |

| Microwave Digestion Acids | High-purity nitric, hydrochloric, and hydrofluoric acids used in closed-vessel microwave digestion to dissolve solid samples for ICP analysis [30]. |

| Internal Standards (for ICP) | Elemental solutions added to samples and calibrants in ICP-MS to correct for instrument drift and matrix effects. |

| C-Gem | C-Gem Prodrug|Thioredoxin Reductase-Actated |

| Cnbca | Cnbca, MF:C26H34O5, MW:426.5 g/mol |

Workflow and Decision-Making in Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the typical analytical workflow and the decision points for selecting a technique.

Diagram: Elemental Analysis Technique Selection Workflow

The growing demand for elemental testing in the pharmaceutical industry is being met by a suite of complementary analytical techniques. While traditional laboratory methods like ICP-MS remain the gold standard for ultra-trace analysis, portable and benchtop XRF technologies are proving to be powerful tools for accelerating development workflows. The strategic adoption of XRF offers significant operational advantages, including faster analysis times, reduced costs, improved safety, and non-destructive testing. For researchers and drug development professionals, the optimal approach often involves leveraging the strengths of both portable XRF for rapid screening and high-throughput analysis and laboratory-based ICP for confirmatory, ultra-trace level quantification. This synergistic use of technologies ensures both efficiency and compliance in the modern pharmaceutical landscape.

Implementing XRF in Pharmaceutical Workflows: From Raw Materials to Finished Products

For researchers and drug development professionals, the decision between on-site rapid screening and laboratory analysis directly impacts project timelines, costs, and data quality. Portable X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) analyzers have emerged as powerful tools for rapid elemental screening across diverse fields including environmental science, pharmaceutical development, and mining.

This technology provides the distinct advantage of delivering non-destructive analysis in the field or on the production floor, generating results in seconds to minutes rather than days [35]. However, strategic deployment requires a clear understanding of its performance boundaries, particularly when analyzing elemental contaminants in complex matrices. Portable XRF serves as a complementary technique to laboratory methods like ICP-MS, offering a balance between speed and precision that is revolutionizing screening protocols [6] [30].

Technology Comparison: Portable XRF vs. Laboratory Analysis

Understanding the fundamental differences between portable XRF and laboratory techniques is crucial for appropriate method selection.

How Portable XRF Works

XRF analyzers determine elemental composition by measuring the characteristic fluorescent X-rays emitted from a sample when irradiated by a primary X-ray beam [9] [35]. The process involves:

- X-ray Emission: The analyzer directs an X-ray beam at the sample surface [35].

- Electron Displacement: High-energy X-rays displace inner-shell electrons from atoms in the sample [35].

- Fluorescence: As outer-shell electrons fill the vacancies, they emit secondary (fluorescent) X-rays with element-specific energy levels [9] [35].

- Detection and Analysis: A detector captures these fluorescent X-rays, and a processor converts the data into elemental composition information [35].

Comparative Performance Metrics

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics of portable XRF compared to standard laboratory techniques.

Table 1: Performance Comparison: Portable XRF vs. Laboratory Techniques

| Parameter | Portable XRF | Laboratory ICP-MS | Laboratory WDXRF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Detection Limits | ppm to % range [9] [13] | ppb to ppt levels [6] | ppm to ppb levels [9] |

| Elemental Range | Typically magnesium (12Mg) to uranium (92U); sodium (11Na) with optimized systems [9] [36] [13] | Virtually all metals and some non-metals | Beryllium (4Be) to uranium (92U) [9] |

| Analysis Time | Seconds to minutes [35] | Hours to days (including sample preparation) [30] | Minutes to hours |

| Sample Throughput | High (immediate on-site results) [35] | Moderate to low (requires transport and queuing) | Moderate |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal to none [35] [13] | Extensive (digestion with strong acids, dilution) [30] | Moderate (often requires pelletizing or fused beads) [9] |

| Destructive to Sample? | No [9] [35] | Yes (sample digested) [30] | No [9] |

Operational and Economic Considerations

Beyond technical specifications, operational factors significantly impact deployment strategy:

- Speed and Efficiency: Portable XRF eliminates sample transport and laboratory queuing. One pharmaceutical study noted that ICP analysis could take "days or even weeks" from sample preparation to result, while XRF preparation takes minutes and analysis under 30 minutes [30].

- Cost Structure: Portable XRF requires a significant initial investment (

$15,000to over$60,000for handheld models) but has low operational costs [37] [35]. Laboratory ICP-MS involves lower initial equipment costs but higher recurring expenses for labor, gases, and consumables [30]. - Workflow Integration: Portable XRF enables real-time decision-making during field surveys or production line checks, allowing for immediate investigation of anomalies [36].

Experimental Validation: Protocols and Data Correction

To ensure reliable data, researchers must follow standardized protocols and understand methods for improving accuracy.

Typical Experimental Protocol for Soil Contaminant Screening

The following methodology, adapted from a Superfund site investigation, outlines a rigorous approach for environmental screening [6]:

- Site Reconnaissance and Sampling: Establish a sampling grid based on preliminary site assessment.

- Sample Collection: Using a sanitized hand trowel, collect soil from 0-6 inches depth after removing surface vegetation. Combine sub-samples from each location into a composite sample [6].

- Sample Preparation:

- XRF Analysis:

- Place the sample cup in the instrument's test stand for stability.

- Analyze for a minimum of 80 source seconds to ensure adequate precision [6].

- Run in triplicate and average results to account for micro-heterogeneity.

- ICP-MS Validation:

- Data Analysis:

- Apply matrix-specific correction factors to XRF data.

- Perform statistical comparison (paired t-tests, linear regression) between XRF and ICP-MS results.

Improving Data Accuracy: Correction Methodologies

A key study in a U.S. Superfund community demonstrated that applying correction factors can significantly improve agreement between portable XRF and ICP-MS [6]. Researchers developed a ratio correction factor method which provided the best fit for their analytical device:

- Calibration: Analyze certified reference materials (CRMs) covering expected concentration ranges.

- Factor Calculation: For each element of concern, calculate a ratio correction factor based on the CRM data.

- Application: Apply these factors to field measurements to predict ICP-MS equivalent concentrations.

This approach is particularly valuable for specific contaminants like arsenic and lead in soil, enhancing data reliability for decision-making [6].

Essential Research Toolkit for Portable XRF Analysis

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Portable XRF Analyzer | Core analytical instrument for on-site elemental determination | Choose model based on target elements (e.g., capability for light elements); typical detection limits 2-20 ng/cm² for micro samples [13]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Calibration validation and quality control | Select CRMs with matrix similar to samples (e.g., soil, sediment, pharmaceutical powder). |

| Sample Preparation Kit | Ensuring representative and consistent analysis | Includes sieves (250 μm), sample cups, non-contaminating grinding equipment, and pellet dies if required [6]. |

| Field Documentation System | Maintaining chain of custody and sample integrity | GPS unit, camera, and field notebooks for precise sample location and condition recording. |

| Tbtdc | Tbtdc, MF:C36H22N6S3, MW:634.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Kirel | Kirel, MF:C20H34O4, MW:338.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Strategic Application Guidelines

When Portable XRF is Ideal

- Rapid Site Characterization: Initial screening of metal contaminants in soil, sediment, or air filters at Superfund sites, industrial facilities, or agricultural land [6] [36].

- Large-Scale Mapping Projects: Geochemical surveys in mining and mineral exploration where high-density sampling is required [9] [35].

- Material Identification and Sorting: Verification of alloy composition in scrap metal recycling or identification of RoHS-regulated elements in electronic waste [35].

- At-Line Quality Control | Monitoring raw materials in pharmaceutical production or cement manufacturing, reducing transport time to central labs [30] [36].

When to Choose Laboratory Analysis

- Regulatory Compliance Testing: When data must meet specific regulatory criteria that currently mandate ICP-MS or other reference methods [6].

- Analysis of Light Elements: For elements lighter than sodium (e.g., carbon, boron, lithium), where XRF has limited capability [9] [35].

- Ultra-Trace Level Detection: When required detection limits are below 10 ppb, which is beyond the capability of most portable XRF units [9].

- Complex Matrices with Severe Interferences: Samples where spectral overlaps cannot be adequately resolved by the XRF instrument's software [9] [13].

Portable XRF analyzers represent a transformative technology for rapid, on-site elemental screening when deployed strategically. Their greatest value lies in providing immediate data for time-sensitive decisions, conducting high-density spatial mapping, and serving as a cost-effective screening tool before committing samples to more expensive laboratory analyses.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the most effective approach often involves a tiered analytical strategy—using portable XRF for rapid initial assessment and spatial guidance, followed by targeted laboratory analysis of critical samples where ultra-trace detection, regulatory compliance, or light element quantification is required. This hybrid methodology maximizes both efficiency and data quality, accelerating research timelines while maintaining scientific rigor.

For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate elemental analysis technique is a critical decision that impacts data integrity, regulatory submission robustness, and quality control efficiency. This guide provides a detailed, data-driven comparison between portable X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and traditional laboratory analysis, specifically framing their performance within the context of Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) environments. The evolution of handheld XRF technology has narrowed the performance gap with laboratory systems, making it a viable technique for specific applications where immediate, on-site results are required for rapid decision-making [38]. However, fundamental differences in precision, sensitivity, and operational parameters dictate that the choice between these techniques is not one of replacement, but of strategic application. We objectively compare their capabilities using published experimental data and technical specifications, providing a scientific basis for method selection in pharmaceutical development and compliance testing.

Handheld XRF Spectrometry

Handheld XRF analyzers function by directing an X-ray beam at a sample, causing atoms to fluoresce and emit secondary X-rays characteristic of their elemental identity [39]. The instrument's detector measures the energy and intensity of these fluorescent X-rays, enabling simultaneous qualitative and quantitative analysis of elements from magnesium to uranium, directly on-site without destroying the sample [40] [39]. Modern handheld models have largely transitioned to miniaturized X-ray tubes, enhancing safety and performance, and can now detect some light elements, a capability once limited to laboratory systems [38].

Laboratory-Based XRF Analysis

Laboratory-based XRF encompasses two primary technologies, each with distinct advantages:

- Energy Dispersive XRF (EDXRF): Often available in benchtop configurations, EDXRF measures the energy and intensity of fluorescent X-rays simultaneously for multiple elements. It offers operational simplicity and is suitable for routine screening and quality control [4] [37].

- Wavelength Dispersive XRF (WDXRF): This high-performance laboratory standard uses analyzing crystals to diffract fluorescent X-rays at specific wavelengths. WDXRF is characterized by superior spectral resolution, high sensitivity for light elements (down to beryllium), and exceptional repeatability, making it the preferred technology for demanding quantitative analysis and regulatory compliance [4] [37].

The following workflow illustrates the typical analytical journey from sample to result for both techniques, highlighting key divergences in their application:

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data

The following tables consolidate key performance metrics and cost considerations, critical for laboratory selection and budgeting.

Table 1: Technical Performance and Operational Comparison

| Feature | Handheld XRF (EDXRF) | Benchtop EDXRF | Lab WDXRF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Analytical Range | Magnesium (12Mg) to Uranium (92U) [39] | Sodium (11Na) to Uranium (92U) [37] | Beryllium (4Be) to Uranium (92U) [37] |

| Limit of Quantification | Parts per million (ppm) to % [13] | Low ppm to % [37] | Parts per billion (ppb) to % [37] |

| Light Element Analysis | Limited reliability [3] | Good for Na and heavier [37] | Excellent, down to Be [4] [37] |

| Precision & Accuracy | Moderate; suited for screening [3] | High for most industrial needs [37] | Very high; industry standard for precision [4] |

| Sample Throughput | Very high (seconds per analysis) [3] | Moderate to High [3] | Moderate (requires more preparation) [3] |

| Sample Types | Solids, surfaces, limited powders [40] | Solids, powders, liquids [3] | All types: solids, powders, liquids, fused beads [4] |

| Operational Environment | Field and on-site [40] [3] | Laboratory or production at-line [37] | Controlled laboratory [4] [37] |

Table 2: Investment and Operational Cost Analysis

| Cost Factor | Handheld XRF | Benchtop XRF | Lab WDXRF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Investment | \$15,000 - \$60,000+ [37] | \$25,000 - \$150,000+ [37] | \$180,000 - \$500,000+ [37] |

| Typical X-ray Tube Power | 1W - 5W [37] | 4W - 200W [37] | 200W - 4000W [37] |

| Operational Costs | Low | Low to Moderate | Higher (may require consumables, P10 gas) [37] |

| Regulatory Compliance | Screening and spot-checking | Suitable for many QC protocols | Ideal for rigorous regulatory testing |

Experimental Data: Method Agreement in Environmental Analysis

A 2024 preprint study provides a rigorous, real-world comparison of a Field Portable (FP) XRF analyzer against the laboratory benchmark method, Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) [6]. This methodology and its findings are highly relevant for assessing the suitability of techniques for contaminant analysis.

Experimental Protocol

- Objective: To evaluate the level of agreement between FP XRF and ICP-MS for metals in environmental samples and establish optimal correction factors [6].

- Sample Collection: 91 residential soil samples (0-6 inch depth) and 42 weekly ambient air particulate filters were collected [6].

- Sample Preparation: Soil samples were air-dried, sieved to <250 μm, and split for parallel analysis. Air filters were analyzed directly after gravimetric measurement [6].

- Instrumental Analysis:

- Statistical Analysis: A split-half design was used. Correction factors were developed from one half of the dataset and validated on the other half. Agreement was assessed using paired t-tests, linear regression, and Bland-Altman plots [6].

Key Findings

The study concluded that while FP XRF could not perfectly replicate ICP-MS results, its performance was significantly improved by applying a ratio correction factor, making it a viable tool for screening purposes [6]. This underscores that with proper method development and calibration, portable techniques can be integrated into a broader analytical framework.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions in elemental analysis, particularly for laboratory-based methods.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Elemental Analysis