Precision at the Limit: A Strategic Guide to Method Validation for Low-Concentration Analytes

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating the precision of analytical methods at low concentration levels, a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals.

Precision at the Limit: A Strategic Guide to Method Validation for Low-Concentration Analytes

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating the precision of analytical methods at low concentration levels, a critical challenge for researchers and drug development professionals. Aligned with modern ICH Q2(R2) and FDA guidelines, the content explores foundational principles, methodological applications for HPLC and immunoassays, troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls, and a complete validation protocol. By synthesizing regulatory standards with practical case studies, this guide empowers scientists to generate reliable, high-quality data for pharmacokinetic studies, biomarker quantification, and impurity profiling, ensuring both regulatory compliance and scientific rigor.

The Critical Challenge: Understanding Precision and Accuracy at Low Concentrations

In the field of analytical method validation, precision is a fundamental parameter that confirms the reliability and consistency of measurement results. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with low concentration levels, a nuanced understanding of precision is not merely beneficial—it is critical for generating defensible data. Precision is quantitatively expressed as the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under prescribed conditions [1] [2]. It is typically measured as a standard deviation, variance, or coefficient of variation (relative standard deviation) [3].

This parameter is systematically evaluated under three distinct tiers of conditions, each providing a different level of stringency and accounting for different sources of variability: Repeatability, Intermediate Precision, and Reproducibility [4] [3].

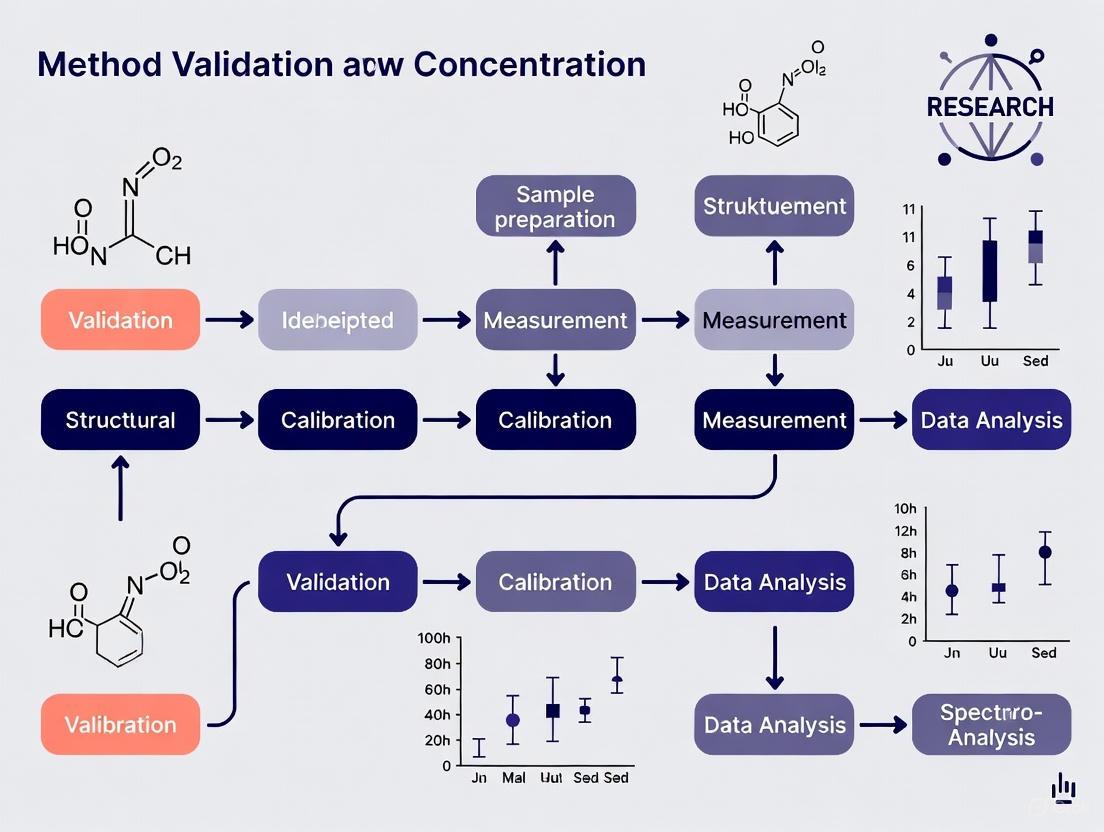

The logical relationship between these three tiers of precision can be visualized as a hierarchy of increasing variability and scope.

Detailed Definitions and Comparison

The following table provides a structured comparison of the three precision parameters, detailing the conditions and scope of each.

| Precision Parameter | Conditions | Scope of Variability Assessed | Typical Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeatability [4] [3] | Same procedure, operators, measuring system, operating conditions, location, and short period of time (e.g., one day or one analytical run). | The smallest possible variation; accounts for random noise under ideal, identical conditions. | Smallest |

| Intermediate Precision [4] [2] | Same laboratory and procedure over an extended period (e.g., several months) with deliberate changes such as different analysts, different equipment, different calibrants, different batches of reagents, and different columns. | Within-laboratory variability; accounts for random effects from factors that are constant within a day but change over time. | Larger than repeatability |

| Reproducibility [4] [2] [3] | Different laboratories, different operators, different measuring systems (possibly using different procedures), and an extended period of time. | Between-laboratory variability; provides the most realistic estimate of method performance in a multi-laboratory setting. | Largest |

Experimental Protocols for Determining Precision

For a method to be considered precise, its precision must be validated through controlled experiments. The protocols below outline the standard methodologies for assessing each tier of precision, with particular attention to the challenges of low-concentration analysis.

Protocol for Assessing Repeatability

Repeatability, or intra-assay precision, represents the best-case scenario for a method's performance and is expected to show the smallest possible variation [4] [3].

- Experimental Design: Analyze a minimum of nine determinations covering the specified range of the procedure. This is typically executed as three concentrations (low, mid, and high), each analyzed in triplicate, all within a single analytical run or day [2] [5].

- Sample Requirements: The sample must be homogeneous. For drug product assays, this involves multiple samplings from a single, well-mixed batch.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the mean, standard deviation, and relative standard deviation (%RSD) for the results at each concentration level. The %RSD is the primary metric for repeatability [2] [5].

- Low-Concentration Considerations: At the low end of the range, such as near the Limit of Quantitation (LOQ), the acceptance criteria for %RSD may be justifiably widened. A signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio of 10:1 is often used to define the LOQ, and the precision at this level should still be acceptable [2] [5].

Protocol for Assessing Intermediate Precision

Intermediate precision quantifies the "within-lab reproducibility" and is crucial for understanding the long-term robustness of a method in a single laboratory [4] [2].

- Experimental Design: Use an experimental design that incorporates the expected sources of laboratory variability. A common approach is to have two different analysts prepare and analyze replicate sample preparations over multiple days or weeks. Each analyst should use their own standards, solutions, and, if possible, different HPLC systems or key instruments [2].

- Variables Tested: The study should deliberately vary factors like the analyst, the instrument, the day, and batches of critical reagents [4].

- Data Analysis: The results are typically reported as %RSD, which now encompasses the variability from all the introduced factors. Some protocols also compare the mean values obtained by the two analysts using a statistical test (e.g., Student's t-test) to check for a significant difference [2].

Protocol for Assessing Reproducibility

Reproducibility is assessed through inter-laboratory collaborative studies and is generally required for method standardization or when a method will be used across multiple sites [4] [2].

- Experimental Design: A group of laboratories (e.g., 5-10) follows the same written analytical procedure. Each laboratory analyzes the same homogeneous test samples using its own analysts, equipment, and reagents.

- Sample and Standard Preparation: Each participating laboratory prepares its own standards and solutions independently.

- Data Analysis: The combined data from all laboratories is analyzed to determine the overall standard deviation, %RSD, and confidence intervals. The results provide a measure of the method's performance in a "real-world" multi-laboratory environment [2].

Experimental Data and Acceptance Criteria

Precision acceptance criteria are often concentration-dependent, which is especially critical for low-concentration studies. The following table summarizes typical data and criteria based on regulatory guidance and industry practices.

| Precision Level | Concentration Level | Typical Experimental Output | Common Acceptance Criteria (Chromatographic Assays) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeatability (n=6-9) [2] [5] | High (e.g., 100% of test concentration) | %RSD of multiple measurements | %RSD ≤ 1.0 - 2.0% |

| Low (e.g., near LOQ) | %RSD of multiple measurements | %RSD ≤ 5.0 - 20.0% [5] | |

| Intermediate Precision (Multi-day, multi-analyst) [2] | Overall (across all data) | Combined %RSD from all valid experiments | Overall %RSD ≤ 2.0 - 2.5% |

| Comparison of Means | Statistical test (e.g., t-test) p-value | p-value > 0.05 (no significant difference) | |

| Reproducibility (Multi-laboratory) [2] | Overall | Reproducibility Standard Deviation and %RSD | Criteria set by the collaborative study, generally wider than intermediate precision. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and instruments are fundamental for conducting precision studies, particularly in a chromatographic context for pharmaceutical analysis.

| Tool / Reagent | Critical Function in Precision Assessment |

|---|---|

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC/UHPLC) System [6] [7] | The primary instrument for separation, identification, and quantification of analytes. System suitability tests are run to ensure precision before a validation study. |

| Certified Reference Material (CRM) [3] | Provides an "accepted reference value" with established purity, essential for preparing known concentration samples to test accuracy and precision. |

| Chromatography Column [4] [2] | The stationary phase for separation. Using columns from different batches is a key variable in intermediate precision testing. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) Detector (e.g., LC-MS/MS) [2] [6] [7] | Provides superior specificity and sensitivity, crucial for confirming peak purity and accurately quantifying analytes at low concentrations. |

| Photodiode Array (PDA) Detector [2] | Used for peak purity assessment by comparing spectra across a peak, helping to demonstrate method specificity—a prerequisite for a precise assay. |

| High-Purity Solvents and Mobile Phase Additives | Consistent quality is vital for robust chromatographic performance and low background noise, directly impacting precision, especially at low concentrations. |

| CREBBP-IN-9 | CREBBP-IN-9, MF:C16H15N5O2S, MW:341.4 g/mol |

| Ivacaftor-d9 | Deutivacaftor (VX-561) |

A rigorous, tiered approach to precision—encompassing repeatability, intermediate precision, and reproducibility—is non-negotiable for building confidence in an analytical method. For researchers focused on low concentration levels, understanding the specific conditions and acceptance criteria for each parameter is paramount. A method that demonstrates tight repeatability but fails during intermediate precision testing is not robust and poses a significant risk to data integrity and regulatory submissions. Therefore, a well-designed validation strategy must proactively account for all expected sources of variability within the method's intended use environment, ensuring the generation of reliable and high-quality data throughout the drug development lifecycle.

In the field of analytical chemistry and bioanalysis, the reliable detection and quantification of substances at low concentrations is paramount for method validation, particularly in pharmaceutical development, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring. The limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantitation (LOQ) are two fundamental parameters that characterize the sensitivity and utility of an analytical procedure at its lower performance limits [8] [9]. These concepts are complemented by the quantification range (also known as the analytical measurement range), which defines the interval over which the method provides results with acceptable accuracy and precision [10].

Understanding the distinctions and relationships between these parameters is essential for researchers and scientists who develop, validate, and implement analytical methods. Proper characterization ensures that methods are "fit for purpose," providing reliable data that supports critical decisions in drug development, patient care, and regulatory submissions [8] [11]. This guide examines the regulatory definitions, calculation methodologies, and practical implications of LOD, LOQ, and the quantification range within the broader context of method validation for precision at low concentration levels.

Defining the Fundamental Parameters

Conceptual Definitions and Distinctions

The following table summarizes the core definitions and purposes of each key parameter:

| Parameter | Definition | Primary Purpose | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit of Blank (LOB) | The highest apparent analyte concentration expected when replicates of a blank sample (containing no analyte) are tested [8]. | Distinguishes the signal produced by a blank sample from that containing a very low analyte concentration [8]. | - Estimates the background noise of the method- Calculated as: Mean~blank~ + 1.645(SD~blank~) [8] |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest analyte concentration likely to be reliably distinguished from the LOB and at which detection is feasible [8]. | Confirms the presence of an analyte, but not necessarily its exact amount [9]. | - Greater than LOB [8]- Distinguishes presence from absence- Typically has a higher uncertainty than LOQ [9] |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | The lowest concentration at which the analyte can be reliably detected and quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy [8] [10]. | Provides precise and accurate quantitative measurements at low concentrations [9]. | - Cannot be lower than the LOD [8]- Predefined goals for bias and imprecision must be met [8]- Sometimes called the Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) [10] |

| Quantification Range | The interval between the LOQ and the Upper Limit of Quantification (ULOQ) within which the analytical method demonstrates acceptable linearity, accuracy, and precision [10]. | Defines the working range of the method for producing reliable quantitative results. | - LOQ is the lower boundary [10]- Samples with concentrations >ULOQ require dilution [10]- Samples with concentrations |

Regulatory Context and Importance

Regulatory guidelines such as the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R1) and various Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) documents provide frameworks for determining these parameters [8] [11]. Proper establishment of LOD and LOQ is crucial for methods used in detecting impurities, degradation products, and in supporting pharmacokinetic studies where low analyte concentrations are expected [12] [10]. For potency assays, however, LOD and LOQ are generally not required, as these typically operate at much higher concentration levels [11].

The relationship between LOB, LOD, and LOQ can be visualized through their statistical definitions and their position on the concentration scale, as shown in the following conceptual diagram:

Methodologies for Determining LOD and LOQ

Various methodologies exist for determining LOD and LOQ, each with specific applications depending on the nature of the analytical method, the presence of background noise, and regulatory requirements [11]. The ICH Q2(R1) guideline suggests several acceptable approaches [11] [13]:

- Visual Evaluation: Direct assessment by analyzing samples with known concentrations and establishing the minimum level at which the analyte can be reliably detected or quantified [12] [11].

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N): Applicable to methods with a measurable baseline noise (e.g., chromatographic methods) [12] [11].

- Standard Deviation of the Blank and Slope of the Calibration Curve: A statistical approach utilizing the variability of the blank response and the sensitivity of the analytical method [12] [13].

Detailed Calculation Methods

Signal-to-Noise Ratio Approach

This approach is commonly used in chromatographic methods (HPLC, GC) where instrumental background noise is measurable [12] [11].

- LOD: Generally accepted signal-to-noise ratio of 2:1 or 3:1 [12] [9].

- LOQ: Generally accepted signal-to-noise ratio of 10:1 [12] [10].

The signal-to-noise ratio is calculated by comparing measured signals from samples containing low concentrations of analyte against the signal of a blank sample [12]. The LOD and LOQ are the concentrations that yield the stipulated S/N ratios.

Standard Deviation and Slope of the Calibration Curve

This is a widely used statistical method, defined in ICH Q2(R1), that can be applied to instrumental techniques [13] [14]. The formulas are:

Where:

- σ = the standard deviation of the response

- S = the slope of the calibration curve

The standard deviation (σ) can be estimated in different ways, leading to subtle variations in the method [13]:

- Standard deviation of the blank: Measuring replicates of a blank sample and calculating the standard deviation of the obtained responses [12].

- Standard error of the regression (residual standard deviation): The standard deviation of the y-residuals of the calibration curve, often considered the simplest and most practical approach as it is readily obtained from regression analysis [13] [14].

- Standard deviation of the y-intercept: Using the standard deviation of the y-intercept of regression lines [12].

The EP17 Protocol: LOB, LOD, and LOQ

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) EP17 protocol provides a rigorous statistical framework, particularly relevant in clinical biochemistry [8]. This method explicitly incorporates the Limit of Blank (LOB) and uses distinct formulas:

- LOB = mean~blank~ + 1.645(SD~blank~) (assuming a Gaussian distribution) [8]

- LOD = LOB + 1.645(SD~low concentration sample~) [8]

The LOQ in this protocol is determined as the lowest concentration at which predefined goals for bias and imprecision (total error) are met, and it cannot be lower than the LOD [8]. A recommended number of replicates (e.g., 60 for establishment by a manufacturer, 20 for verification by a laboratory) is specified to ensure reliability [8].

Comparison of LOD/LOQ Determination Methods

The table below compares the performance of different methodological approaches as evidenced in recent scientific studies:

| Methodological Approach | Reported Performance Characteristics | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Strategy (Based on statistical concepts like SD/Slope or S/N) | Can provide underestimated values of LOD and LOQ; may lack the rigor of graphical tools [15]. | Initial estimates; methods where high precision at the very lowest limits is not critical. |

| Accuracy Profile (Graphical tool based on tolerance intervals) | Provides a relevant and realistic assessment of LOD and LOQ by considering the total error (bias + precision) over a concentration range [15]. | Bioanalytical method validation where a visual and integrated assessment of method validity is required. |

| Uncertainty Profile (Graphical tool based on β-content tolerance intervals and measurement uncertainty) | Considered a reliable alternative; provides precise estimate of measurement uncertainty. Values for LOD/LOQ are in the same order of magnitude as the Accuracy Profile [15]. | High-stakes validation requiring precise uncertainty quantification; decision-making on method validity based on inclusion within acceptability limits. |

A 2025 comparative study of these approaches for an HPLC method analyzing sotalol in plasma concluded that the graphical strategies (uncertainty and accuracy profiles) provide a more relevant and realistic assessment compared to the classical statistical strategy, which tended to underestimate the values [15].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Standard Protocol for LOD/LOQ Determination via Calibration Curve

This protocol outlines the steps to determine LOD and LOQ using the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve, in accordance with ICH Q2(R1) [13] [14].

Step 1: Prepare Calibration Standards Prepare a series of standard solutions at concentrations expected to be in the range of the LOD and LOQ. It is crucial that the calibration curve is constructed using samples within this range and not by extrapolation from higher concentrations [11] [13].

Step 2: Analyze Standards and Plot Calibration Curve Analyze the standards using the analytical method (e.g., HPLC, GC). Plot a standard curve with the analyte concentration on the X-axis and the instrumental response (e.g., peak area, absorbance) on the Y-axis [14].

Step 3: Perform Regression Analysis Use statistical software (e.g., Microsoft Excel's Data Analysis Toolpak) to perform a linear regression on the calibration data [14]. The key outputs required are:

- Slope (S) of the calibration curve.

- Standard Error (SE) or Residual Standard Deviation, which is used as the estimate for the standard deviation of the response (σ) [13] [14].

Step 4: Calculate LOD and LOQ Apply the regression outputs to the standard formulas:

Step 5: Experimental Verification The calculated LOD and LOQ values are estimates and must be experimentally confirmed [8] [13]. This involves:

- Preparing and analyzing a suitable number of replicates (e.g., n=5-6) at the calculated LOD and LOQ concentrations.

- For LOD: The analyte should be detected in the majority of these replicates, confirming reliable detection.

- For LOQ: The measurements must demonstrate acceptable precision and accuracy (e.g., ±20% CV and bias for bioanalytical methods at the LOQ level) [10]. If the results do not meet the predefined criteria, the LOQ must be re-estimated at a slightly higher concentration [8].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following materials are critical for experiments aimed at determining LOD and LOQ, particularly in a bioanalytical context:

| Material / Solution | Function in LOD/LOQ Experiments |

|---|---|

| Blank Matrix (e.g., drug-free plasma, buffer) | Serves as the analyte-free sample for determining the baseline response, LOB, and for preparing calibration standards [8] [10]. |

| Primary Analyte Standard (High Purity) | Used to prepare accurate stock and working solutions for spiking into the blank matrix to create calibration curves [10]. |

| Internal Standard (e.g., stable isotope-labeled analog) | Added equally to all samples and standards to correct for variations in sample preparation and instrument response, improving precision [15]. |

| Calibration Standards (Series in blank matrix) | A sequence of samples with known concentrations, typically in the low range of interest, used to construct the calibration curve and calculate the slope (S) [10] [13]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples (at LOD/LOQ levels) | Independent samples used to verify that the calculated LOD and LOQ meet the required performance characteristics for detection, precision, and accuracy [8] [10]. |

The Quantification Range in Method Validation

Defining the Upper and Lower Limits

The quantification range, or analytical measurement range, is bounded by the Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) and the Upper Limit of Quantification (ULOQ) [10]. While this guide focuses on precision at low levels, a complete method validation must also establish the ULOQ.

- LLOQ: As defined previously, it is the lowest concentration on the calibration curve that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy (e.g., CV and bias ≤20%) and an analyte response typically at least 5 times that of a blank [10].

- ULOQ: The highest calibration standard where the analyte response is reproducible, and the precision and accuracy are within acceptable limits (e.g., ≤15% for bioanalytical methods) [10].

A critical rule in bioanalysis is that the calibration curve should not be extrapolated below the LLOQ or above the ULOQ. Samples with concentrations exceeding the ULOQ must be diluted, while those below the LLOQ are reported as such [10].

Establishing the Working Range

The process of establishing the full quantification range involves analyzing calibration standards across a wide concentration span and verifying the performance with QC samples at the low, middle, and high ends of the range. The "accuracy profile" is a modern graphical tool that combines bias and precision data to visually define the valid quantification range as the interval where the total error remains within pre-defined acceptability limits [15] [10].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for establishing and validating the complete quantification range of an analytical method:

The precise determination of the Limit of Detection (LOD), Limit of Quantitation (LOQ), and the Quantification Range is a critical component of analytical method validation, especially for methods requiring precision at low concentration levels. While classical approaches based on signal-to-noise or standard deviation and slope provide a foundation, newer graphical tools like the uncertainty and accuracy profiles offer more realistic and integrated assessments by incorporating total error and tolerance intervals [15].

Researchers and drug development professionals must select the appropriate methodology based on the intended use of the method, regulatory requirements, and the necessary level of confidence. Ultimately, a well-validated method, with clearly defined and experimentally verified LOD, LOQ, and quantification range, is essential for generating reliable, high-quality data that supports scientific research and regulatory decision-making.

The Impact of Imprecision on Data Integrity in Pharmacokinetics and Biomarker Studies

In the rigorous world of drug development, data integrity serves as the foundational pillar for reliable scientific decision-making. Regulatory authorities like the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) define data integrity as encompassing the accuracy, completeness, and reliability of data, which must be attributable, legible, contemporaneous, original, and accurate (ALCOA) throughout its lifecycle [16]. Within this framework, imprecision—the inherent variability in analytical measurements—poses a persistent challenge to data quality. In pharmacokinetic (PK) and biomarker studies, where critical decisions about drug safety and efficacy hinge on precise quantitative data, uncontrolled imprecision can compromise study outcomes, leading to incorrect dosage recommendations, misguided efficacy conclusions, and ultimately, threats to patient safety.

The regulatory landscape is increasingly focused on these issues. Recent FDA draft guidance emphasizes that data integrity concerns can significantly impact "application acceptance for filing, assessment, regulatory actions, and approval as well as post-approval actions" [16]. This guide systematically compares how imprecision manifests and impacts data integrity across pharmacokinetic and biomarker studies, providing researchers with experimental approaches for its quantification and control.

Quantifying Imprecision: Analytical Perspectives

Key Validation Parameters for Assessing Imprecision

Analytical method validation provides the primary defense against imprecision. According to established guidelines, six key criteria ensure methods are "fit-for-purpose," encapsulated by the mnemonic Silly - Analysts - Produce - Simply - Lame - Results, which corresponds to Specificity, Accuracy, Precision, Sensitivity, Linearity, and Robustness [1]. Among these, precision (the closeness of agreement between multiple measurements) directly quantifies random error, while accuracy (closeness to the true value) detects systematic error. Robustness measures the method's capacity to remain unaffected by small variations in parameters, acting as a proxy for its susceptibility to imprecision under normal operational variations [1].

The Concept of Experimental Resolution

A crucial but often overlooked metric is experimental resolution, defined as the minimum concentration gradient an assay can reliably detect within a specific range [17]. Unlike the Limit of Detection (LoD), which only identifies the lowest detectable concentration, experimental resolution specifies the minimum change in concentration that can be measured, making it a more dynamic indicator of an assay's discriminatory power. Research has demonstrated significant variations in experimental resolution across common laboratory methods:

- Biochemical tests and automatic hematology analyzers: Typically achieve a resolution of 10% (with some reaching 1%) [17].

- Classical chemical assays (e.g., gas chromatography): Can achieve a resolution as low as 1% [17].

- Immunoassays (manual ELISA): Show a surprisingly lower resolution of only 25% [17].

- qPCR assays: Demonstrate a resolution of 10% [17].

This variation highlights that assays traditionally considered "sensitive" may lack the resolution needed for fine discrimination between closely spaced concentrations, a critical factor in PK and biomarker analysis.

Comparative Analysis: PK vs. Biomarker Studies

The impact and implications of imprecision differ notably between pharmacokinetic and biomarker studies, as detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Comparative Impact of Imprecision in PK and Biomarker Studies

| Aspect | Pharmacokinetic (PK) Studies | Biomarker Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Drug concentration (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion) [18] | Biological response indicators (e.g., PD-L1, TMB) [19] |

| Consequence of Imprecision | Incorrect half-life, clearance, and bioavailability estimates; flawed dosing regimens [20] | Misclassification of patient responders; incorrect predictive accuracy [19] [21] |

| Typical Analytical Techniques | LC-MS/MS, HPLC-UV, ELISA [18] [20] | Immunohistochemistry, sequencing, gene expression profiling, immunoassays [19] |

| Data Integrity Risk | Undermines bioequivalence and safety assessments; regulatory rejection [22] [16] | Compromised patient stratification; failed personalized medicine approaches [19] |

| Empirical Evidence | Formulation analysis methods require rigorous validation of precision for GLP compliance [20] | Combined biomarkers show superior predictive power (AUC: 0.75) over single biomarkers (AUC: 0.64-0.68) [19] |

Case Study: Imprecision in Biomarker Combinations

The superior performance of combined biomarkers underscores the additive effect of imprecision. A 2024 comparative study on NSCLC (Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer) demonstrated that while single biomarkers like PD-L1 IHC and tTMB had Area Under the Curve (AUC) values of 0.64 in predicting response to immunotherapy, a combination of biomarkers achieved a significantly higher AUC of 0.75 [19]. This enhancement results from the combination mitigating the individual imprecision of each standalone biomarker, leading to improved specificity, positive likelihood ratio, and positive predictive value [19].

Case Study: Imprecision in Exposure Biomarkers

A seminal study on prenatal methylmercury exposure revealed that the total imprecision of exposure biomarkers (25-30% for cord-blood mercury and nearly 50% for maternal hair mercury) was substantially higher than normal laboratory variability [21]. This miscalibration led to a significant underestimation of the true toxicity, causing derived exposure limits to be 50% higher than appropriate. After adjusting for this imprecision, the recommended exposure limit was set 50% lower than the prior standard [21]. This case powerfully demonstrates how unaccounted-for imprecision can directly impact public health guidelines.

Methodologies for Measuring and Controlling Imprecision

Experimental Protocol for Determining Experimental Resolution

The following workflow, adapted from published research, provides a robust method for quantifying the experimental resolution of an analytical assay [17].

The protocol involves creating a series of samples diluted in equal proportions (e.g., 10%, 25%, 50%) and measuring a target analyte (like Albumin initially) across the series [17]. A correlation analysis between the relative concentration and the measured value is performed. The dilution series is only accepted if the correlation shows a statistically significant linear relationship (p ≤ 0.01) [17]. The smallest concentration gradient that maintains this linearity is then defined as the experimental resolution for that assay [17].

Method Validation for Controlling Imprecision

For nonclinical dose formulation analysis—a critical component of PK studies—a full method validation is required. This process involves assessing several parameters to control imprecision [20]:

- Accuracy and Precision: Multiple sets of data are required, often using Quality Control (QC) samples at low, mid, and high concentrations to validate the method's reliability across the dynamic range [20].

- System Suitability Test (SST): Performed before each analytical run to ensure the instrument system is sufficiently sensitive, specific, and reproducible. Parameters include injection precision, theoretical plates, and tailing factor [20].

- Robustness Testing: Deliberately varying method parameters (e.g., pH, mobile phase composition) to ensure the method's performance remains unaffected by small, normal fluctuations [1].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Method Validation

| Reagent / Solution | Critical Function | Role in Mitigating Imprecision |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Provides analyte of known purity and concentration [20] | Serves as the benchmark for accuracy; establishes the conventional true value. |

| Matrix-Matched Quality Control (QC) Samples | QC samples prepared in the study vehicle/biological matrix [20] | Assesses accuracy and precision in the presence of matrix components, detecting interference. |

| Appropriate Formulation Vehicle | The excipient (e.g., methylcellulose, saline) used to deliver the test article [20] | Validated to ensure it does not interfere with the analysis, safeguarding specificity. |

| Stability Testing Solutions | Samples prepared and stored under defined conditions [20] | Evaluates the analyte's stability in solution, ensuring imprecision is not driven by analyte degradation. |

Regulatory Implications and Data Integrity Framework

The regulatory framework for data integrity explicitly compels sponsors and testing sites to create a culture of quality and implement risk-based controls to prevent and detect data integrity issues, including those stemming from undetected analytical imprecision [16]. Key requirements include:

- Comprehensive Data Governance: Managing data throughout its entire lifecycle to ensure it remains ALCOA-compliant [16] [23].

- Robust Quality Management Systems (QMS): Incorporating quality assurance (independent verification) and quality control (processes to identify issues) programs [16].

- Rigorous Audit Trails: For electronic data, audit trails must document who made changes, when, and why, providing transparency into data handling [16].

- Thorough Personnel Training: Ensuring all personnel interacting with data are trained on data integrity principles and their specific roles in upholding it [16].

Failure to address imprecision and maintain data integrity can lead to severe regulatory consequences, including refusal to file applications, withdrawal of approvals, and changes to product ratings [16].

Imprecision is an inherent part of any analytical measurement, but its impact on data integrity in pharmacokinetic and biomarker studies is too significant to be overlooked. As evidenced by the comparative data, unmitigated imprecision can distort critical study endpoints, from PK parameters like bioavailability to the predictive accuracy of biomarkers for cancer immunotherapy.

Proactive management through rigorous method validation, including the assessment of novel metrics like experimental resolution, is paramount. Furthermore, adopting a systematic data integrity framework aligned with regulatory guidance creates the necessary quality culture to detect and correct for imprecision early. By implementing the experimental protocols and validation strategies outlined in this guide, researchers and drug development professionals can significantly enhance the reliability of their data, ensuring that critical decisions on drug safety and efficacy are built upon a foundation of uncompromised integrity.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Ultraviolet detection (HPLC-UV) remains a cornerstone technique in pharmaceutical analysis due to its robustness, reliability, and cost-effectiveness. The validation of these methods is paramount to ensure the accuracy, precision, and reproducibility of data, particularly when quantifying drugs in complex matrices like human plasma. This case study examines precision data from a validated HPLC-UV method for the determination of Cinitapride, a gastroenteric prokinetic agent, in human plasma [24]. The research is situated within a broader thesis on method validation, with a specific focus on the challenges and considerations for proving precision at low concentration levels, a common scenario in pharmacokinetic studies.

Cinitapride is a substituted benzamide that acts synergistically on serotonergic (5-HT2 and 5-HT4) and dopaminergic (D2) receptors within the neuronal synapses of the myenteric plexi [24]. The analyzed method employed a reversed-phase (RP) separation on a Nucleosil C18 (25 cm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) column. The isocratic mobile phase consisted of 10 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.2), methanol, and acetonitrile (40:50:10, v/v/v), with a flow rate of 1 mL/min and UV detection at 260 nm [24]. Sample preparation was achieved via liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) using tert-butyl methyl ether.

Comparative Analysis with Other HPLC Methods

To contextualize the performance of the Cinitapride method, it is instructive to compare its key validation parameters with those of a separate, recent HPLC-UV method developed for a Glycosaminoglycan (GAG) API in topical formulations, validated per ICH Q2(R2) guidelines [25].

Table 1: Comparison of HPLC-UV Method Validation Parameters

| Validation Parameter | Cinitapride in Human Plasma [24] | GAG API in Topical Formulations [25] |

|---|---|---|

| Linearity Range | 1 – 35 ng/mL | Not Specified (r = 0.9997) |

| Correlation Coefficient (r²/r) | r² = 0.999 | r = 0.9997 |

| Precision (Repeatability) | Intraday & Interday %CV ≤ 7.1% | %RSD < 2% for assay |

| Accuracy (% Recovery) | Extraction Recovery > 86.6% | Recovery range: 98–102% |

| Sample Preparation | Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) | Direct dissolution / Extraction with organic solvent |

| Key Matrix | Human Plasma | Pharmaceutical Gel and Cream |

| Validation Guideline | US FDA | ICH Q2(R2) |

This comparison highlights several key differences dictated by the analytical challenge. The Cinitapride method deals with a much lower concentration range (ng/mL) in a complex biological matrix, which is reflected in its slightly higher, yet still acceptable, precision %CV (≤7.1%) and lower extraction recovery compared to the GAG method for formulated products. The GAG method, analyzing an API in a more controlled matrix, demonstrates the tighter precision (%RSD < 2%) and accuracy typically expected for drug substance and product testing [25].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology for the Cinitapride HPLC-UV Assay

The following protocols are reconstructed from the referenced study to provide a clear experimental workflow [24].

3.1.1 Materials and Reagents:

- Cinitapride reference standard (provided by Zydus Research Laboratories).

- Human plasma (obtained from Lion's Blood Bank, Guntur, India).

- HPLC-grade solvents: Methanol and Acetonitrile (Merck, Mumbai).

- Reagents: Analytical grade Ammonium Acetate and Triethyl amine (Merck, Mumbai).

- Water: Purified using a Milli-Q water purification system.

3.1.2 Instrumentation and Chromatographic Conditions:

- HPLC System: Shimadzu system equipped with an SPD-20A UV-Visible detector.

- Column: Nucleosil C18 (25 cm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm particle size).

- Mobile Phase: 10 mM Ammonium Acetate Buffer (pH 5.2) - Methanol - Acetonitrile (40:50:10, v/v/v).

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min.

- Detection Wavelength: 260 nm.

- Injection Volume: 20 µL.

- Sample Temperature: Maintained at 10°C during extraction.

3.1.3 Sample Preparation Protocol (Liquid-Liquid Extraction):

- Spiking: Pipette 500 µL of drug-spiked human plasma into a polypropylene tube.

- Extraction: Add 3 mL of tert-butyl methyl ether to the tube, cap it, and vortex mix for 10 minutes.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the samples at 4000 rpm for 5 minutes at 10°C to separate the layers.

- Evaporation: Transfer the standard supernatant (organic layer) to a clean tube and evaporate to dryness at 40°C under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas.

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the dried extract in 500 µL of the mobile phase.

- Injection: Inject a 20 µL aliquot into the HPLC system using a Hamilton syringe.

3.1.4 Precision and Accuracy Protocol:

- Quality Control (QC) Samples: Prepare low (LQC), medium (MQC), and high (HQC) quality control samples in plasma at concentrations of 3, 15, and 35 ng/mL, respectively, with six replicates each.

- Intraday Precision: Analyze all six replicates of each QC level on the same day.

- Interday Precision: Analyze all six replicates of each QC level on three different days.

- Calculation: For both intraday and interday studies, calculate the % Coefficient of Variation (%CV) for precision and the % Recovery of the nominal concentration for accuracy.

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of the experimental and validation process for the Cinitapride method.

Interpretation of Precision Data at Low Concentrations

Precision, which measures the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements, is critically tested at the lower limits of the analytical method. The data from the Cinitapride method reveals key insights for low-level quantification.

Precision Data Analysis

The precision was validated at three QC levels: LQC (3 ng/mL), MQC (15 ng/mL), and HQC (35 ng/mL). The results showed that the percent coefficient of variation (%CV) for both intraday and interday precision was ≤7.1% across all levels [24]. This demonstrates a consistent and reproducible performance.

Table 2: Precision and Recovery Data for Cinitapride HPLC-UV Method

| Quality Control Level | Concentration (ng/mL) | Intraday Precision (%CV) | Interday Precision (%CV) | Extraction Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LQC | 3.0 | ≤ 7.1% | ≤ 7.1% | > 86.6% |

| MQC | 15.0 | ≤ 7.1% | ≤ 7.1% | > 86.6% |

| HQC | 35.0 | ≤ 7.1% | ≤ 7.1% | > 86.6% |

Critical Considerations for Low-Concentration Precision

- Acceptance Criteria Context: While guidelines for assay of drug products often demand %RSD < 2.0% [26], a broader acceptance criterion is common for bioanalytical methods due to the complexity of the biological matrix and the very low analyte concentrations. A %CV of ≤7.1% at the LQC level, which is just three times the LOQ, is considered acceptable in many bioanalytical method validations and reflects the practical challenges of working at the method's lower limits [24].

- Impact of Sample Preparation: The liquid-liquid extraction recovery of >86.6% is a crucial factor contributing to the overall precision. High recovery indicates a clean and efficient extraction process, which minimizes analyte loss and reduces variability. Inefficient recovery can introduce significant error, especially at low concentrations where the absolute amount of analyte is small.

- System Suitability as a Foundation: The precision of the entire method is underpinned by the performance of the chromatographic system. The cited method reported a system suitability with a USP plate count of ≥5600 and a tailing factor of 1.05, indicating a highly efficient and symmetric peak [24]. This robustness is essential for obtaining reliable and precise data, particularly for low-concentration peaks where integration can be more challenging.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for developing and validating an HPLC-UV method like the one described for Cinitapride.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for HPLC-UV Method Validation

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example from Case Study |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Reference Standard | Serves as the benchmark for identifying the analyte and constructing calibration curves. | Cinitapride working standard [24]. |

| Chromatography Column | The heart of the separation; its chemistry dictates selectivity, efficiency, and retention. | Nucleosil C18 column [24]. |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Used in mobile phase and sample preparation to minimize UV background noise and prevent system damage. | Methanol and Acetonitrile from Merck [24]. |

| Buffer Salts & pH Adjusters | Control the pH and ionic strength of the mobile phase, critical for reproducible retention of ionizable analytes. | 10 mM Ammonium Acetate, pH adjusted with Triethylamine [24]. |

| Sample Preparation Solvents | For extracting, precipitating, or diluting the analyte from the sample matrix. | Tert-butyl methyl ether for liquid-liquid extraction [24]. |

| Matrix Source | The blank biological or formulation matrix used for preparing calibration standards and validation samples. | Human plasma from a blood bank [24]. |

| D159687 | D159687, CAS:1155877-97-6, MF:C21H19ClN2O2, MW:366.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| dBET57 | dBET57, CAS:1883863-52-2, MF:C34H31ClN8O5S, MW:699.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

This case study on the validated HPLC-UV method for Cinitapride provides a clear framework for interpreting precision data, with a special emphasis on low-concentration applications. The method demonstrates that with a robust chromatographic system (evidenced by high plate counts and low tailing) and an efficient sample preparation technique (LLE with >86% recovery), it is possible to achieve satisfactory precision (%CV ≤7.1%) even at concentrations as low as 3 ng/mL in a complex matrix like human plasma. This level of performance, when contextualized with appropriate acceptance criteria, meets the rigorous demands of bioanalytical method validation. The insights gained underscore the importance of a holistic validation approach where system suitability, sample preparation, and precision are intrinsically linked, providing a reliable foundation for quantitative analysis in pharmaceutical research and development.

Proven Methodologies: Designing and Executing Precision Studies for Sensitive Assays

Adhering to ICH Q2(R2) and FDA Guidelines for Analytical Method Validation

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R2) guideline, along with its companion ICH Q14 on analytical procedure development, represents a fundamental modernization of analytical method validation requirements for the pharmaceutical industry [27]. Simultaneously, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has adopted these harmonized guidelines, making compliance with ICH standards essential for regulatory submissions in the United States [27] [28]. This updated framework shifts the paradigm from a prescriptive, "check-the-box" approach to a scientific, risk-based lifecycle model that begins with method development and continues throughout the method's entire operational lifespan [27] [29].

For researchers focused on precision at low concentration levels, this modernized approach provides a structured framework for demonstrating method reliability, particularly through enhanced attention to quantitation limits, sensitivity, and robustness [2] [1]. The guidelines emphasize building quality into methods from the outset rather than attempting to validate them after development, ensuring that analytical procedures remain fit-for-purpose in an era of advancing analytical technologies [27].

Core Validation Parameters: From Traditional to Updated Requirements

Fundamental Validation Characteristics

The validation parameters required under ICH Q2(R2) establish the performance characteristics that demonstrate a method is fit for its intended purpose [27]. While the core parameters remain consistent with previous guidelines, their application and interpretation have been refined to accommodate modern analytical techniques [30].

Table 1: Core Analytical Method Validation Parameters and Requirements

| Parameter | Definition | Typical Acceptance Criteria | Importance for Low Concentration Precision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness of agreement between the true value and the value found [2] | 98-102% recovery for drug substances; 95-105% for drug products [30] | Ensures reliability of measurements at trace levels |

| Precision | Closeness of agreement between a series of measurements [2] | RSD ≤2.0% for assays; ≤5.0% for impurities [30] | Critical for demonstrating reproducibility at low concentrations |

| Specificity | Ability to assess unequivocally the analyte in the presence of interfering components [27] [2] | No interference from impurities, degradants, or matrix components [2] | Ensures target analyte response is distinguished from background noise |

| Linearity | Ability to obtain results directly proportional to analyte concentration [2] | Correlation coefficient (r²) with predefined acceptance criteria [31] | Establishes proportional response at low concentration ranges |

| Range | Interval between upper and lower concentrations with suitable precision, accuracy, and linearity [27] | Varies by application (e.g., 80-120% for assay; reporting threshold-120% for impurities) [28] | Defines the operational boundaries where method performance is validated |

| LOD/LOQ | Lowest concentration that can be detected (LOD) or quantified (LOQ) with acceptable accuracy and precision [2] | Signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1 for LOD; 10:1 for LOQ [2] | Fundamental for establishing method capability at trace levels |

Enhanced Approaches for Modern Analytical Techniques

The updated guidelines explicitly address modern analytical technologies that have emerged since the original Q2(R1) guideline was published [30]. This includes:

Multivariate analytical methods that employ complex calibration models, requiring validation approaches such as root mean square error of prediction (RMSEP) to demonstrate accuracy [28].

Non-linear calibration models commonly encountered in techniques like immunoassays, where traditional linearity assessments may not apply [28].

Advanced detection techniques including mass spectrometry and NMR, which may require modified validation approaches for specificity demonstration [28].

For researchers working with low concentration analyses, these expanded provisions allow for the application of highly sensitive techniques while maintaining regulatory compliance through appropriate validation strategies [30].

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Parameters

Establishing Accuracy and Precision at Low Concentrations

Protocol for Accuracy Determination:

- Prepare a minimum of nine determinations across at least three concentration levels covering the specified range [2]

- For drug products, prepare synthetic mixtures spiked with known quantities of components [2]

- Compare results to a reference value or well-characterized alternative method [2]

- Report as percent recovery of the known, added amount, or as the difference between the mean and true value with confidence intervals [2]

Protocol for Precision Assessment:

- Repeatability (Intra-assay Precision): Analyze a minimum of nine determinations covering the specified range (three concentrations, three repetitions each) or a minimum of six determinations at 100% of the test concentration [2]

- Intermediate Precision: Establish through experimental design incorporating variations such as different days, analysts, or equipment [2] [32]

- Reproducibility: Conduct collaborative studies between different laboratories, particularly important for methods intended for regulatory submission [2]

Table 2: Experimental Design for Precision Studies at Low Concentrations

| Precision Type | Minimum Experimental Design | Statistical Reporting | Acceptance Criteria for Trace Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeatability | 6 determinations at LOQ concentration | % RSD with confidence intervals | RSD ≤15% for trace analysis [31] |

| Intermediate Precision | 2 analysts preparing and analyzing replicate samples using different systems and reagents | % difference in mean values with Student's t-test | No statistically significant difference between analysts |

| Reproducibility | Collaborative testing between at least 2 laboratories | Standard deviation, RSD, confidence interval | Agreed upon between laboratories based on intended use |

Demonstrating Specificity and Robustness

Specificity Protocol:

- For chromatographic methods, demonstrate peak purity using photodiode-array detection or mass spectrometry [2]

- Conduct stress studies on samples (heat, light, pH, oxidation) to demonstrate separation of degradants from the analyte of interest [2]

- For impurity methods, spike drug substance or product with appropriate levels of impurities and demonstrate separation from main component and from each other [2]

Robustness Protocol:

- Identify critical method parameters (e.g., mobile phase pH, column temperature, flow rate) through risk assessment [27]

- Deliberately vary parameters within a predetermined range and monitor effects on method performance [1]

- Establish system suitability criteria based on robustness testing to ensure method reliability during routine use [28]

Determining Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) for Low Concentration Analysis

For researchers focused on precision at low concentrations, establishing a reliable LOQ is particularly critical. ICH Q2(R2) recognizes multiple approaches:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Typically 10:1, appropriate for chromatographic methods where noise can be measured [2]

- Standard Deviation of Response and Slope: LOQ = 10(SD/S), where SD is the standard deviation of response and S is the slope of the calibration curve [2]

- Visual Evaluation: May be used for non-instrumental methods or when the previous approaches cannot be applied [31]

Once the LOQ is determined, analysis of an appropriate number of samples at this limit must be performed to fully validate method performance [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Method Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Critical Quality Attributes | Application in Low Concentration Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Provides known purity material for accuracy and linearity studies | Certified purity, stability, appropriate documentation | Essential for preparing known concentration samples for recovery studies |

| Chromatographic Columns | Stationary phase for separation | Lot-to-lot reproducibility, stability under method conditions | Critical for achieving sufficient resolution at low concentrations |

| MS-Grade Solvents | Mobile phase components for LC-MS methods | Low background, minimal ion suppression | Reduces chemical noise for improved signal-to-noise at trace levels |

| Sample Preparation Materials | Extraction, purification, and concentration of analytes | Selective extraction, minimal analyte adsorption, clean background | Enables pre-concentration of dilute samples and matrix interference removal |

| System Suitability Standards | Verifies system performance before validation runs | Stability, representative of method challenges | Confirms instrument sensitivity and resolution are adequate for validation |

| DBPR108 | DBPR108, CAS:1186426-66-3, MF:C16H25FN4O2, MW:324.39 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| ABCB1-IN-1 | ABCB1-IN-1, CAS:1429239-98-4, MF:C33H31Cl2F3N6O3S2, MW:751.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Implementing the Analytical Method Lifecycle Approach

The integration of ICH Q14 on analytical procedure development with ICH Q2(R2) validation creates a comprehensive lifecycle management framework [27] [29]. This approach consists of several key elements:

Analytical Target Profile (ATP)

The ATP is a prospective summary of the method's intended purpose and desired performance criteria, defined before method development begins [27]. For low concentration applications, the ATP should explicitly define:

- Required detection and quantitation limits based on the analytical need

- Acceptable precision at the low end of the measuring range

- Specificity requirements considering potential matrix interferences

Risk-Based Validation Strategy

A risk assessment approach helps identify potential method vulnerabilities and focus validation efforts on high-risk areas [30]. This is particularly important for low concentration methods where small variations can significantly impact results. The risk assessment should consider:

- Sample preparation variability at low concentrations

- Instrument sensitivity and detection capabilities

- Matrix effects that may disproportionately affect low concentration measurements

Continuous Performance Verification

The lifecycle approach continues after initial validation with ongoing monitoring of method performance during routine use [29]. This includes:

- Trend analysis of system suitability data

- Regular assessment of quality control sample results

- Periodic review to determine if revalidation is necessary

For low concentration methods, this continuous verification is essential to detect subtle changes in method performance that might affect data reliability [29].

Comparison of Traditional vs. Modernized Validation Approaches

Table 4: Evolution from Q2(R1) to Q2(R2) Validation Requirements

| Aspect | Traditional Approach (Q2(R1)) | Modernized Approach (Q2(R2)) | Impact on Low Concentration Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validation Scope | Primarily focused on chromatographic methods | Expanded to include modern techniques (multivariate, spectroscopic) | Enables use of more sensitive techniques with appropriate validation |

| Development Linkage | Validation separate from development | Integrated with development through ATP and enhanced approach | Builds quality in rather than testing it out |

| Linearity Assessment | Focus on linear responses only | Includes non-linear response models | Accommodates realistic response behavior at concentration extremes |

| Robustness Evaluation | Often performed after validation | Incorporated early in development with risk assessment | Identifies sensitivity issues before validation |

| Lifecycle Management | Limited post-approval change management | Continuous verification and knowledge management | Allows for method improvements based on performance monitoring |

Adherence to ICH Q2(R2) and FDA guidelines requires a fundamental shift from treating method validation as a one-time event to managing it as a continuous lifecycle process [27] [29]. For researchers focused on precision at low concentration levels, this modernized framework provides the structure to develop and validate robust, reliable methods while maintaining regulatory compliance.

Successful implementation requires:

- Early definition of the Analytical Target Profile with specific attention to low concentration requirements [27]

- Science- and risk-based approaches to validation study design [30]

- Thorough understanding of method capabilities and limitations, particularly at the lower end of the measuring range [2]

- Comprehensive documentation of validation experiments and results [32]

By embracing these principles, researchers can ensure their analytical methods not only meet regulatory expectations but also generate reliable, high-quality data—particularly critical when working at the challenging limits of detection and quantitation.

Method validation provides documented evidence that an analytical procedure is suitable for its intended purpose, ensuring the reliability of data during normal use [2]. For research focusing on precision at low concentration levels, a meticulously planned experimental design is not merely a regulatory formality but the cornerstone of scientific integrity. It guarantees that the method can consistently reproduce results with acceptable accuracy and precision, even near the limits of quantitation. This guide objectively compares experimental design parameters by examining data from validation studies conducted according to established guidelines, such as those from the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) and the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) [2].

Comparative Experimental Data for Precision

The following tables summarize the experimental design requirements and typical performance outcomes for precision studies as per regulatory guidelines. These parameters are critical for assessing method performance at low concentration levels.

Table 1: Experimental Design Requirements for Precision Validation

| Precision Type | Minimum Number of Replicates | Minimum Concentration Levels | Key Statistical Reporting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Repeatability (Intra-assay) | 9 determinations total (e.g., 3 concentrations x 3 replicates each) or 6 determinations at 100% concentration [2] | 3 levels covering the specified range [2] | Percent Relative Standard Deviation (% RSD) [2] |

| Intermediate Precision | Replicate sample preparations by two different analysts using different equipment and days [2] | Typically at 100% of test concentration | % RSD and statistical comparison (e.g., Student's t-test) of results between analysts [2] |

Table 2: Example Acceptance Criteria for Precision

| Analytical Method Type | Target Precision (Repeatability) | Target Precision (Intermediate Precision) |

|---|---|---|

| Assay of Drug Substance | % RSD ≤ 1.0% - 2.0% | % RSD and mean difference between analysts within specified limits [2] |

| Impurity Quantification (at LOQ) | % RSD ≤ 5.0% - 10.0% | % RSD and mean difference between analysts within specified limits [2] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Establishing Accuracy and Precision

Objective: To demonstrate the closeness of agreement between the measured value and an accepted reference value (accuracy) and the agreement between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling (precision) [2].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a minimum of nine samples over a minimum of three concentration levels (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120% of the target concentration) covering the specified range of the procedure. This results in three concentrations with three replicates each [2].

- Analysis: Analyze all samples using the validated method.

- Data Analysis:

- Accuracy: Calculate the percent recovery of the known, added amount for each sample. Report the mean recovery and confidence intervals (e.g., ±1 standard deviation) for each concentration level [2].

- Precision (Repeatability): Calculate the % RSD for the results at each concentration level and across the entire study to demonstrate repeatability [2].

Protocol for Determining Limits of Detection and Quantitation

Objective: To determine the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be detected (LOD) and reliably quantified (LOQ) with acceptable precision and accuracy [2].

Methodology:

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio Approach:

- Prepare and analyze samples with known low concentrations of the analyte.

- LOD: The concentration at which the signal-to-noise ratio is approximately 3:1.

- LOQ: The concentration at which the signal-to-noise ratio is approximately 10:1 [2].

- Standard Deviation and Slope Method:

- Based on the formula:

LOD = 3.3(SD/S)andLOQ = 10(SD/S), where SD is the standard deviation of the response and S is the slope of the calibration curve [2]. - Regardless of the method used, the determined limits must be validated by analyzing an appropriate number of samples at the LOD and LOQ to confirm performance [2].

- Based on the formula:

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision-making process in a robust analytical method validation workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Method Validation Experiments

| Item | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Standard Reference Material | A substance with a known purity and composition, used as the primary standard to establish accuracy and prepare calibration curves [2]. |

| Drug Substance/Product | The actual sample matrix (e.g., active pharmaceutical ingredient, formulated product) used to test the method's specificity and accuracy in a relevant background [2]. |

| Known Impurities | Isolated impurities used to spike samples, allowing for the validation of the method's accuracy, precision, and specificity for impurity detection and quantification [2]. |

| Appropriate Chromatographic Column | The specific stationary phase (e.g., C18, phenyl) selected to achieve the required separation of analytes from each other and from matrix components, which is critical for demonstrating specificity [2]. |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents and Reagents | High-purity mobile phase components and buffers that ensure system suitability, reduce background noise, and provide reproducible chromatographic conditions essential for precision and robust results [2]. |

| DD-03-171 | DD-03-171, CAS:2366132-45-6, MF:C55H62N10O8, MW:991.1 g/mol |

| Desmethyl-VS-5584 | Desmethyl-VS-5584, MF:C16H20N8O, MW:340.38 g/mol |

In the pursuit of reliable analytical data, particularly for method validation focused on precision at low concentration levels, sample preparation is a critical first step. It aims to isolate analytes from complex matrices, reduce interference, and concentrate targets to detectable amounts, directly impacting a method's accuracy, sensitivity, and reproducibility. Among the various techniques available, Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) and Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) are two foundational approaches. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, supported by experimental data, to help researchers and drug development professionals select the appropriate technique for their specific application needs, especially when working with trace-level concentrations.

Fundamental Principles and Comparison

Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) separates compounds based on their relative solubility in two immiscible liquids, typically an organic solvent and an aqueous phase. The core mechanism relies on partitioning, where the analyte distributes itself between the two phases based on its chemical potential, aiming for a state of lower free energy [33]. The efficiency is measured by the distribution ratio (D) and the partition coefficient (Kd), which are influenced by temperature, solute concentration, and the presence of different chemical species [33]. LLE is versatile and can handle compounds with different volatilities and polarities.

Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) utilizes a solid sorbent material to selectively retain analytes from a liquid sample. After retention, interfering compounds are washed away, and the target analytes are eluted with a stronger solvent. SPE formats include cartridges, disks, and 96-well plates, and a wide variety of sorbent chemistries (e.g., C18, ion-exchange, mixed-mode) are available to cater to different analytes [34].

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of each technique:

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of LLE and SPE

| Characteristic | Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) | Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Partitioning between two immiscible liquid phases based on solubility [33] | Selective adsorption onto a solid sorbent, followed by washing and elution [34] |

| Primary Mechanism | Solubility and partitioning | Adsorption, chemical affinity (e.g., reversed-phase, ion-exchange) |

| Typical Throughput | Lower, manual process | Higher, potential for automation and 96-well plate formats [34] |

| Solvent Consumption | High | Lower, especially in micro-SPE formats [35] |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity, effective cleanup of complex matrices [33] | Selective, can be automated, lower solvent consumption [35] |

| Key Disadvantage | High solvent use, time-consuming, emulsion formation [35] | Can be prone to clogging, requires method development for sorbent selection |

Performance Data and Experimental Comparison

Quantitative Performance in Bioanalysis

A study comparing an optimized LLE method with a cumbersome combined LLE/SPE method for extracting D-series resolvins from cell culture medium demonstrated the potential of a well-designed LLE protocol. The results are summarized below:

Table 2: Performance Data for Resolvin Analysis using LLE [36]

| Performance Parameter | Optimized LLE Method | Combined LLE/µ-SPE Method |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Range | 0.1–50 ng mLâ»Â¹ | Not specified |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 0.05 ng mLâ»Â¹ | Not specified |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | 0.1 ng mLâ»Â¹ | Not specified |

| Recovery (%) | 96.9 – 99.8% | ~42 – 64% |

The data shows that the optimized LLE method provided excellent recovery and sensitivity, outperforming the more complex combined method [36]. This highlights that for specific applications, a straightforward LLE can be superior to more complicated multi-step procedures.

Comparison of SPE Formats and LLE for a Cyanide Metabolite

A study on extracting the polar cyanide metabolite 2-aminothiazoline-4-carboxylic acid (ATCA) from biological samples compared a conventional SPE method with two magnetic carbon nanotube-assisted dispersive-micro-SPE (Mag-CNTs/d-µSPE) methods.

Table 3: Performance Data for ATCA Analysis using Different Methods [35]

| Extraction Method | Matrix | LOD (ng/mL) | LOQ (ng/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mag-CNTs/d-µSPE | Synthetic Urine | 5 | 10 |

| Mag-CNTs/d-µSPE | Bovine Blood | 10 | 60 |

| Conventional SPE | Bovine Blood | 1 | 25 |

The conventional SPE method showed a slightly better LOD in blood, but the Mag-CNTs/d-µSPE methods demonstrated great potential for extracting polar and ionic metabolites with the advantage of being less labor-intensive and consuming less solvent [35]. This illustrates how modern SPE formats can address some limitations of traditional methods.

Application in Environmental and Proteomic Analysis

A comparative study of LLE, SPE, and solid-phase microextraction (SPME) for multi-class organic contaminants in wastewater found that both LLE and SPE provided satisfactory and comparable performance for most compounds [37].

In proteomics, a comparison of two SPE-based sample preparation protocols (SOLAµ HRP SPE spin plates and ZIPTIP C18 pipette tips) for porcine retinal tissue analysis found no significant differences in protein identification numbers or the quantitative recovery of 25 glaucoma-related protein markers [34]. The key difference was in analysis speed and convenience, with the SOLAµ spin plate workflow being more amenable to semi-automation [34].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol is for the extraction of D-series resolvins (RvD1, RvD2, etc.) from Leibovitz’s L-15 complete medium.

- Step 1: Internal Standard Addition. Add a mixture of deuterated internal standards (e.g., RvD1-d5, RvD2-d5, RvD3-d5) to the sample. A factorial design can be used to optimize the internal standard concentration.

- Step 2: Extraction. Use a suitable organic solvent pair. The specific solvent was not detailed in the abstract, but common choices for LLE include chloroform/methanol or ethyl acetate.

- Step 3: Mixing and Centrifugation. Vigorously mix the sample and organic solvent, then centrifuge to achieve complete phase separation.

- Step 4: Collection and Evaporation. Collect the organic layer (extract) and evaporate to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas.

- Step 5: Reconstitution. Reconstitute the dried extract in a small volume of solvent compatible with the LC-MS/MS mobile phase.

- Step 6: Analysis. Analyze using Liquid Chromatography triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

This protocol uses magnetic carbon nanotubes for dispersive micro-SPE.

- Step 1: Sample Pretreatment. Prepare the biological sample (e.g., blood) likely involving protein precipitation and centrifugation to obtain a clear supernatant.

- Step 2: Sorbent Addition. Add the magnetic carbon nanotubes (Mag-CNTs-COOH or Mag-CNTs-SO3H) to the sample supernatant.

- Step 3: Binding. Mix thoroughly to allow the analyte (ATCA) to adsorb onto the Mag-CNTs.

- Step 4: Separation. Use an external magnet to separate the Mag-CNTs (with bound analyte) from the sample solution. Discard the supernatant.

- Step 5: Washing. Wash the Mag-CNTs with a suitable solvent to remove weakly adsorbed interferents.

- Step 6: Desorption/Derivatization. For Mag-CNTs-COOH, a one-step desorption/derivatization is performed directly with a derivatization reagent. This step elutes the analyte and prepares it for GC-MS analysis in a single step.

- Step 7: Analysis. Analyze the derivatized eluate using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS).

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the general decision-making and procedural workflow when choosing and applying LLE or SPE.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials and reagents used in the featured experiments.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sample Preparation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Internal Standards | Correct for analyte loss during preparation; improve quantification accuracy. | RvD1-d5, RvD2-d5 used in LLE of resolvins for precise LC-MS/MS quantification [36]. |

| Magnetic Carbon Nanotubes (Mag-CNTs) | Dispersive micro-SPE sorbent; enables easy magnetic separation, high surface area for adsorption. | Mag-CNTs-COOH used for d-µSPE of ATCA from blood, enabling one-step derivatization/desorption [35]. |

| C18 Sorbent | Reversed-phase SPE sorbent; retains mid- to non-polar analytes from aqueous matrices. | ZIPTIP C18 pipette tips and SOLAµ HRP spin plates used for peptide desalting and purification in proteomics [34]. |

| Organic Solvents (e.g., Chloroform, Ethyl Acetate) | Extraction phase in LLE; dissolves and carries non-polar target analytes. | Used in LLE methods for resolvins and wastewater contaminants [36] [37]. |

| Buffers (e.g., Ammonium Acetate, Phosphate) | Control pH and ionic strength; critical for optimizing retention/elution in SPE and partitioning in LLE. | Phosphate buffer (5 µM) added to mobile phase in HILIC-MS to improve peak shape for polar metabolites [38]. |

| dMCL1-2 | dMCL1-2, MF:C61H66N10O12S, MW:1163.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| EF24 | EF24, CAS:342808-40-6, MF:C19H16ClF2NO, MW:347.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Both LLE and SPE are powerful techniques for obtaining clean samples. The choice between them is not a matter of which is universally better, but which is more suitable for the specific analytical challenge. LLE offers simplicity, low equipment costs, and highly effective cleanup for many applications, as demonstrated by its excellent performance in resolvin extraction [36]. SPE provides advantages in throughput, potential for automation, and lower solvent consumption, especially in modern formats like d-µSPE and 96-well plates [35] [34]. For methods requiring high precision at low concentrations, the decision should be guided by the nature of the analyte, the sample matrix, and the required throughput, with the understanding that both techniques, when properly optimized and validated, can deliver the rigorous performance demanded in research and drug development.

Chromatographic method development is a critical process in pharmaceutical analysis, requiring careful optimization of column chemistry, mobile phase composition, and detector parameters to achieve precise and accurate results, particularly at low analyte concentrations. Within the framework of method validation for precision at low concentration levels, each component of the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system contributes significantly to the overall method performance, sensitivity, and reliability.

This guide provides an objective comparison of available technologies and approaches for chromatographic optimization, supported by experimental data and structured within the rigorous requirements of analytical method validation. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these interrelationships is essential for developing robust methods that meet regulatory standards set forth by ICH Q2(R2) and FDA guidelines [27].

Column Chemistry Selection and Comparison

The stationary phase is the foundational element of chromatographic separation, directly influencing selectivity, efficiency, and resolution. Recent innovations in column technology have focused on improving peak shape, enhancing chemical stability, and reducing undesirable secondary interactions.

Table 1: Comparison of Modern HPLC Column Chemistries

| Column Type | Stationary Phase Chemistry | Key Characteristics | Optimal Application Areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| C18 | Octadecyl silane | High hydrophobicity; wide pH range (1-12 for modern phases); general-purpose workhorse | Pharmaceutical APIs, metabolites, environmental pollutants |

| Phenyl-Hexyl | Phenyl-hexyl functional groups | π-π interactions with aromatic compounds; enhanced polar selectivity | Metabolomics, isomer separations, hydrophilic aromatics |

| Biphenyl | Biphenyl functional groups | Combined hydrophobic, π-π, dipole, and steric interactions | Polar and non-polar compound analysis, complex mixtures |

| HILIC | Silica, amino, cyano, or diol | Hydrophilic interactions; retains polar compounds | Polar metabolites, carbohydrates, nucleotides |