Real-Time Reaction Monitoring: Advanced Spectroscopic Methods for Pharmaceutical Research and Development

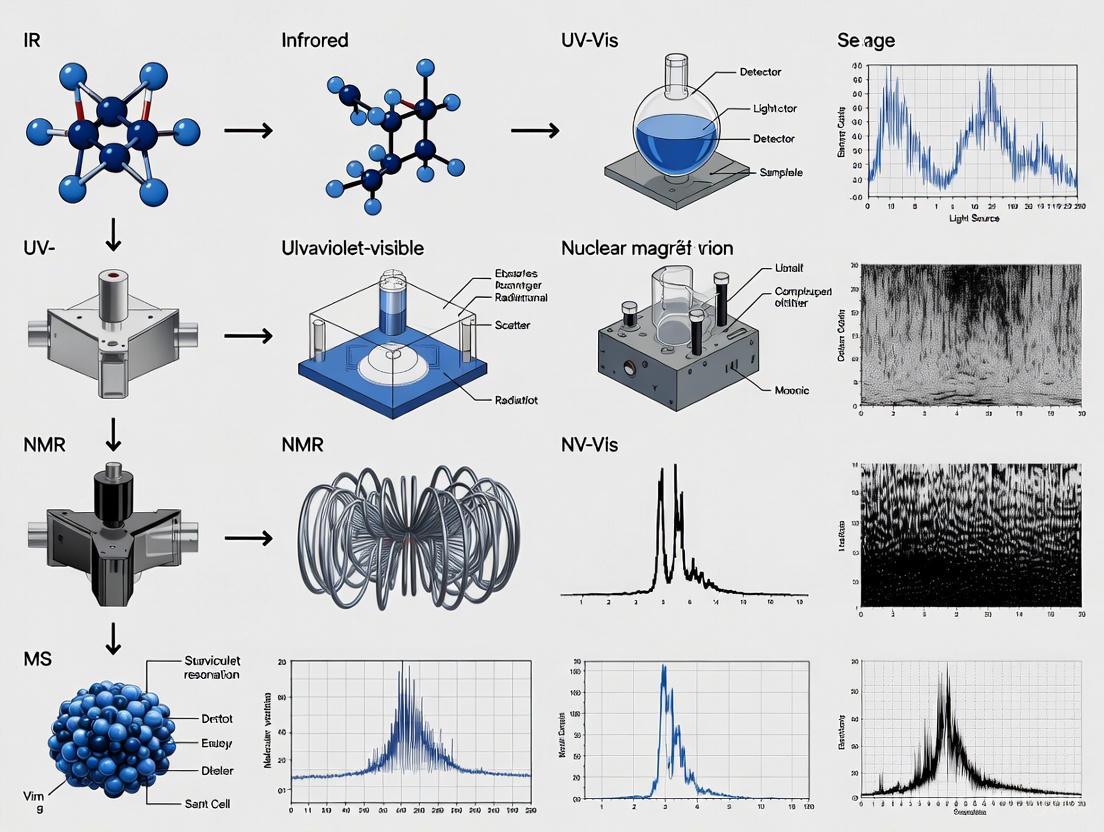

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern spectroscopic techniques for real-time chemical reaction monitoring, a critical capability for accelerating drug development and process optimization.

Real-Time Reaction Monitoring: Advanced Spectroscopic Methods for Pharmaceutical Research and Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern spectroscopic techniques for real-time chemical reaction monitoring, a critical capability for accelerating drug development and process optimization. It explores the foundational principles of in situ spectroscopy, detailing specific applications of NMR, FTIR, Raman, and Mass Spectrometry in tracking reaction kinetics and intermediates. The content delivers practical methodological guidance, addresses common troubleshooting challenges, and presents a comparative analysis of technique validation. Aimed at researchers and development professionals, this resource bridges theoretical knowledge with industrial application to enhance efficiency and reliability in pharmaceutical R&D.

The Core Principles of In Situ Spectroscopy for Reaction Monitoring

In situ reaction monitoring, derived from the Latin for "on site," refers to the analysis of chemical processes within their native environment, such as directly in a reactor vessel, without the need for sample removal [1]. This approach stands in direct contrast to ex situ or off-line analysis, where samples are physically extracted for study elsewhere, a process that can perturb the system being observed [1] [2]. Within the framework of spectroscopic methods for chemical reaction monitoring research, in situ techniques provide real-time, dynamic data that are crucial for developing a fundamental understanding of reaction mechanisms, kinetics, and pathways.

The essential value of in situ monitoring lies in its ability to capture the true nature of a chemical process as it unfolds. By preserving the original reaction context—including temperature, pressure, and compositional equilibrium—these methods provide insights that are simply unattainable through conventional off-line analysis [2]. This application note details the specific scenarios that necessitate in situ monitoring, provides validated experimental protocols, and presents the key tools required for implementation, with a particular focus on vibrational spectroscopy and related techniques.

When is In Situ Reaction Monitoring Essential?

In situ spectroscopy is not always the required tool for every reaction monitoring task. A decision-making process, in consultation with the process owner and project team, is critical for determining its appropriateness [2]. The following scenarios represent conditions where in situ monitoring transitions from being a useful option to an essential methodology.

Critical Scenarios Requiring In Situ Monitoring

- Transient and Labile Intermediates: When reaction mechanisms involve short-lived intermediate species whose concentration would change significantly between sample withdrawal and off-line analysis [2]. In situ monitoring captures these fleeting species in real-time.

- Perturbation-Sensitive Equilibria: For reactions involving a chemical (e.g., esterification, hydrolysis) or physical (e.g., vapor-liquid) equilibrium that is substantially disturbed by sampling. Changes in temperature and pressure upon sampling can cause the system composition to re-adjust, giving an inaccurate picture of the true reaction state [2].

- Rapid Reaction Kinetics: When reactions occur too quickly to make sample withdrawal and traditional analysis practical [2]. In situ methods can collect data on the scale of seconds, capturing the full kinetic profile.

- Air- and Moisture-Sensitive Reactions: When the reaction is highly sensitive to atmospheric components, and minimizing exposure by avoiding sampling is necessary to maintain system integrity [2].

- Limited or Expensive Reagents: When reagent cost or availability severely limits the number of samples that can be affordably taken. With proper probe design, in situ monitoring can be performed with just a few milliliters of sample [2].

- Process Understanding and Optimization: When the goal is to know reaction progress in real-time, determine when a steady state has been reached, or optimize a process in the shortest time possible [3] [4]. Real-time data helps identify the ideal timing for grabbing samples for other, more specific off-line analyses.

Decision Framework for Technique Selection

Once a project is deemed suitable for in situ monitoring, selecting the appropriate spectroscopic technique is the next critical step. This decision should be driven by the specific chemical and physical properties of the reaction system. Key considerations and questions are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Considerations for Selecting an In Situ Spectroscopic Technique

| Consideration | Guiding Questions | Technique Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Concentration & Species of Interest | What are the typical concentration ranges? What species (reactants, products, intermediates) need tracking? | Mid-IR is sensitive to functional groups; Raman is better for symmetric bonds and can avoid water interference; NIR is suitable for bulk analysis but requires chemometrics for complex spectra [2] [5]. |

| Reaction Matrix | Is the reaction neat, in solution (organic/aqueous), or a slurry? | ATR probes handle most liquid phases; transmission flow cells are used for homogeneous solutions; reflectance probes may be needed for highly scattering media [2]. |

| Physical Conditions | What is the operational temperature and pressure range? | Probe material and construction must withstand process conditions (e.g., diamond ATR crystals for high pressure, specific alloys for corrosive environments) [2] [3]. |

| Homogeneity | Is the reaction mixture homogeneous or heterogeneous? | Heterogeneous systems (slurries, gases) can cause light scattering; Raman may suffer from fluorescence; probe positioning in a high-shear zone is critical to avoid fouling and ensure representative sampling [2]. |

| Accuracy Requirements | What level of quantitative accuracy and precision is needed? | Techniques like FT-IR can be quantitative with robust calibration, while others like NIR almost always require multivariate calibration (e.g., PLS) for quantitative results [2] [5]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for deciding when and how to implement in situ reaction monitoring, from project scoping to technique selection.

Essential Protocols for In Situ Reaction Monitoring

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for implementing in situ reaction monitoring, using a combination of vibrational spectroscopy techniques as a model.

Protocol: Multi-Technique In Situ Monitoring of a Model Schiff Base Formation

This protocol is adapted from a recent study that integrated NIR, Raman, and online NMR for monitoring a condensation reaction, showcasing how data from multiple techniques can be fused for a comprehensive process understanding [5].

1. Reaction Setup and Probe Configuration

- Apparatus Assembly: Use a three-necked round-bottom flask equipped with a spherical condenser and a magnetic stirrer set to a constant, vigorous speed (e.g., 700 rpm) [5].

- Probe Integration:

- NIR: Position an immersion transflection probe (e.g., 1 mm pathlength) directly in the reactor, above the stirrer to ensure representative sampling [5].

- Raman: Configure a flow system using an inert tubing (e.g., PFA) and a pump to circulate the reaction mixture from the flask through a Raman flow cell and back to the reactor. This ensures the analyzed sample is representative and allows for temperature control at the flow cell [5] [6].

- Online NMR: Integrate an automated liquid handler to periodically withdraw a small aliquot (e.g., 400 µL) from the recirculating Raman stream and inject it into the flow cell of a dedicated online NMR spectrometer [5].

2. Spectral Acquisition Parameters

- NIR Spectroscopy:

- Raman Spectroscopy:

- Online NMR Spectroscopy:

3. Data Acquisition and Pre-processing

- Background Collection: Acquire a background spectrum for each technique before reactants are introduced (e.g., for NIR and Raman, collect a spectrum of the solvent system; for NMR, a solvent reference) [5] [6].

- Initiate Reaction: Add the catalyst to the reaction mixture to start the process.

- Continuous Monitoring: Allow the software to automatically collect spectra at the defined intervals for the entire reaction duration (e.g., 310 minutes) [5].

- Pre-processing: Perform baseline correction, normalization, and, for NMR, phase correction and referencing on all acquired spectra using standard algorithms [5].

4. Data Analysis and Model Building

- Identify Relevant Spectral Regions: Use two-dimensional heterocorrelation spectroscopy (2D-COS) on the spectral series from different techniques to identify and select spectral regions that show the highest sensitivity to reaction changes [5].

- Qualitative Analysis: Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the pre-processed spectral data to visualize the general trajectory and state changes of the reaction over time [5].

- Quantitative Modeling: Develop quantitative prediction models (e.g., for reactant consumption or product formation) using chemometric methods. Common approaches include:

- Multivariate Curve Resolution-Alternating Least Squares (MCR-ALS): Useful for resolving pure component spectra and concentration profiles without prior calibration [5].

- Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression: A standard method for building robust quantitative models from complex spectral data. Data fusion (low-level or mid-level) of spectral regions from NIR, Raman, and NMR can significantly enhance the predictive accuracy of the PLS model [5].

5. Validation

- Validate the results and concentration profiles obtained from the in situ spectroscopy against a primary analytical technique, such as offline High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or Gas Chromatography (GC), especially if the model is to be used for rigorous kinetic analysis or process control [2] [4].

The workflow for this integrated protocol is visualized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of in situ monitoring relies on both the spectroscopic instrumentation and the consumables and software that interface with the reaction environment. The following table details essential components.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Software for In Situ Reaction Monitoring

| Item | Function & Application | Example Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ATR Probe (ZnSe) | For Mid-IR monitoring; excellent for organic solvents and general purpose use. | Spectral Range: 600-3300 cmâ»Â¹ [3]. Note: Susceptible to damage in strongly basic or acidic aqueous solutions. |

| ATR Probe (Diamond) | Rugged probe for Mid-IR; resistant to scratches and harsh chemical environments. | Spectral Range: 600-1900 cmâ»Â¹ & 2300-3300 cmâ»Â¹ (due to diamond absorption) [3]. |

| ATR Probe (ZrOâ‚‚) | For NIR monitoring; robust material for process environments. | Spectral Range: 1550-8000 cmâ»Â¹ [3]. |

| Silver Halide Fibres | Transmit Mid-IR light from spectrometer to immersion probe. | Compatible with ZnSe and diamond ATR probes [3]. |

| Chalcogenide Fibres | Transmit NIR light from spectrometer to immersion probe. | Compatible with ZrOâ‚‚ ATR probes [3]. |

| Raman Flow Cell | Provides a fixed, reproducible sampling volume for Raman analysis in flow systems. | Standard material is quartz (e.g., QS 10.00 mm flow cell) [5]. |

| Back-Pressure Regulator | Maintains system pressure in flow chemistry setups, preventing degassing and ensuring consistent flow through the cell. | Typically set to ~7 bar for organic solvents [6]. |

| Chemometrics Software | Essential for data analysis, from pre-processing to advanced multivariate modeling. | Key functions: Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Partial Least Squares (PLS), Multivariate Curve Resolution (MCR) [2] [5]. |

| Rutin-d3 | Rutin-d3, MF:C27H30O16, MW:613.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Efavirenz-13C6 | (S)-Efavirenz-13C6 Stable Isotope | (S)-Efavirenz-13C6 is a CAS 1261394-62-0 labeled internal standard for accurate LC-MS/MS bioanalysis in HIV research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Quantitative Data and Technical Specifications

To facilitate the selection and implementation of in situ analyzers, the following table summarizes the performance specifications of a commercially available, dedicated reaction monitoring system.

Table 3: Technical Specifications of a Representative In Situ Reaction Monitor (ABB MB-Rx)

| Parameter | Specification | Notes / Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Technique | Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy | [3] |

| Spectral Ranges | ZnSe ATR: 600-3300 cmâ»Â¹Diamond ATR: 600-1900 & 2300-3300 cmâ»Â¹ZrOâ‚‚ ATR (NIR): 1550-8000 cmâ»Â¹ | Depends on probe and fiber type selected [3] |

| Apodized Resolution | Adjustable from 1 cmâ»Â¹ to 64 cmâ»Â¹ | Adjustable in 2 cmâ»Â¹ increments [3] |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 0.1% w/w for acetone in toluene | Acquisition: 60s, Resolution: 4 cmâ»Â¹ [3] |

| Signal Sampling | 24-bit ADC | [3] |

| Key Software Modules | Horizon MB RX (real-time monitoring)Horizon MB FTIR (basic ops)Horizon MB Quantify (chemometrics) | [3] |

In situ reaction monitoring is an indispensable methodology in modern chemical research and development, essential for scenarios where capturing the true, unperturbed nature of a chemical process is paramount. Its application is critical for understanding reactions involving transient intermediates, sensitive equilibria, and rapid kinetics, and is a cornerstone of the Quality by Design (QbD) and Process Analytical Technology (PAT) initiatives in the pharmaceutical industry [4] [5]. By following structured protocols that leverage the complementary strengths of spectroscopic techniques like Mid-IR, Raman, NIR, and NMR, and by employing advanced data analysis such as heterocorrelation spectroscopy and data fusion, researchers can achieve an unprecedented level of process understanding and control.

The real-time monitoring of chemical reactions provides invaluable insights for researchers in drug development and materials science. However, many critical reactions involve highly reactive, short-lived intermediates or exist in a delicate equilibrium that traditional off-line analysis methods can disturb. In situ spectroscopic techniques offer a powerful solution, enabling scientists to track reaction progress directly within the reaction vessel without the need for sampling. This application note details the specific advantages of these methods for tracking labile intermediates and maintaining chemical equilibrium, providing validated protocols for their implementation. By preserving the intrinsic reaction conditions, these techniques yield more accurate mechanistic understanding and support robust reaction optimization [2].

Core Advantages for Critical Analytical Challenges

In situ spectroscopy addresses two fundamental challenges in reaction monitoring that are often insurmountable with ex situ methods.

Tracking Labile Intermediates

Labile or transient intermediates are often present at low concentrations and possess short lifetimes. Removing a sample for off-line analysis can allow these species to react or degrade before measurement, rendering them undetectable.

- Real-Time Observation: In situ techniques capture spectral data continuously throughout the reaction, providing a direct window into the formation and consumption of transient species. This is often the only viable option for observing intermediates in fast reactions or those involving unstable species [2].

- Structural Insight: While optical spectroscopy like IR or Raman provides information on functional groups and molecular vibrations, advanced mass spectrometry techniques offer deeper structural characterization. Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry (IM-MS), for instance, can separate and analyze the structures of intermediates based on their size, shape, and charge, providing insight into previously inaccessible complex species such as those formed in coordination-driven self-assembly [7]. Furthermore, tandem mass spectrometry (MS²) with collision-induced dissociation (CID) can be used to probe the structure of mass-selected intermediates by analyzing their fragmentation patterns, helping to distinguish between isobaric species [8].

Maintaining Chemical Equilibrium

Many chemical processes, such as esterifications, hydrolyses, or metal-ligand exchanges in self-assembling systems, exist in a dynamic equilibrium. Sampling disturbs this balance by changing temperature, pressure, or concentration, causing the equilibrium to shift and providing an inaccurate picture of the true reaction state [2] [7].

- Non-Invasive Monitoring: In situ probes measure the reaction mixture directly in the reactor, leaving the equilibrium unperturbed. This provides a true representation of species concentrations under actual process conditions [2].

- Studying Dynamic Systems: This capability is essential for understanding and optimizing reversible reactions and self-assembly processes, which proceed through repeated association and dissociation events. Monitoring these systems in situ allows researchers to understand the pathway to the final thermodynamic product, including the role of "off-cycle" pathways and erroneous intermediates [7].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of In Situ Spectroscopic Techniques for Monitoring Challenging Reactions.

| Analytical Challenge | Recommended In Situ Techniques | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tracking Labile Intermediates | Mid-IR, Raman, Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry (IM-MS) | Detects short-lived species in real-time; Provides structural information on intermediates; High sensitivity for low-abundance species [2] [7] [8]. | C-H activation catalysis; Photocatalysis; Coordination-driven self-assembly [7] [8]. |

| Maintaining Chemical Equilibrium | Mid-IR, NIR, Raman | Non-invasive measurement prevents perturbation; Monitors equilibrium concentrations directly; Tracks reactions sensitive to Oâ‚‚/moisture [2]. | Esterification/hydrolysis; Studying self-assembly pathways; Biopharmaceutical process development [2] [7]. |

| Analyzing Complex Mixtures with Isomeric Species | Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry (IM-MS) | Separates ions based on size and shape; Resolves isomeric intermediates with identical mass [7]. | Characterization of self-sorting systems; Analysis of supramolecular complexes [7]. |

| Reactions with Minimal Sampling Volume | Mid-IR (ATR), Raman | Requires only a few mL of sample; Can be implemented with microreactors [2]. | Reactions with expensive reagents; High-throughput screening; Milligram-scale synthesis [2]. |

Experimental Protocols

The following protocols provide a framework for implementing in situ spectroscopy, focusing on the use of vibrational spectroscopy and mass spectrometry.

Protocol 1: In Situ Reaction Monitoring with Vibrational Spectroscopy (ATR-FT-IR)

This protocol outlines the key steps for monitoring a reaction in situ using Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier-Transform Infrared (ATR-FT-IR) spectroscopy [2].

1. Feasibility Assessment and Technique Selection:

- Discuss with the project team whether in situ monitoring is the right tool. Key indicators include: presence of transient intermediates, a sensitive equilibrium, fast kinetics, or air/moisture-sensitive chemistry [2].

- Select the appropriate technique (Mid-IR, NIR, Raman) by considering the reaction matrix, concentrations, and the molecular vibrations of interest. For example, avoid Raman if the mixture has strong fluorescence [2].

2. Proof-of-Concept and Calibration:

- Collect reference spectra of neat starting materials, expected products, and any known intermediates using benchtop instruments.

- Perform a calibration run with solutions of known concentration to establish a quantitative relationship between spectral response and concentration. For simple systems, single-point calibration may suffice; for complex systems, use multiple calibration points [2].

3. In Situ Data Acquisition:

- Position the probe in a high-shear zone of the reactor to minimize fouling and ensure representative sampling.

- Collect a background spectrum (e.g., with a clean ATR crystal in air or under nitrogen).

- Initiate the reaction and begin continuous spectral collection. Set the data acquisition frequency based on reaction kinetics (e.g., every few seconds for fast reactions, every few minutes for slow reactions) [2].

4. Data Analysis and Validation:

- Analyze spectral data using methods ranging from simple peak height/area analysis to multivariate techniques like Partial Least Squares (PLS) for heavily overlapping bands [2].

- Validate in situ results against a primary analytical technique (e.g., GC, LC, NMR) if quantitative kinetics or endpoint determination is critical [2].

Protocol 2: Investigating Intermediates via Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry

This protocol is adapted for studying reactive intermediates, particularly in metal-catalyzed or self-assembly reactions [7] [8].

1. Sample Preparation and Ionization:

- Direct Infusion: Introduce the reaction mixture directly via syringe pump or from a quenched/aliquoted sample.

- Liquid Chromatography Coupling: Use LC-IM-MS for complex mixtures to separate species before ionization.

- Ionization: Typically use Electrospray Ionization (ESI). For neutral organometallic complexes, employ charge-tagging by incorporating a permanently charged group on a ligand or substrate that does not interfere with the reaction [8].

2. Mass Spectrometry and Ion Mobility Analysis:

- Mass Analysis: Use a high-resolution mass spectrometer to accurately determine the elemental composition of potential intermediates.

- Ion Mobility Separation: Direct the mass-selected ions into the ion mobility drift tube. Ions are separated based on their collision cross-section (size and shape) as they drift through an inert gas under the influence of an electric field. This separates isomeric species that have the same mass-to-charge ratio [7] [8].

3. Structural Elucidation:

- Tandem MS (MS/MS): Subject mobility-separated ions to collision-induced dissociation (CID) to study their fragmentation pathways and confirm structural assignments.

- Data Interpretation: Correlate measured collision cross-sections with computational models and use fragmentation patterns to validate the structure of intermediates, distinguishing them from isobaric side-products [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents, materials, and instrumentation critical for successful in situ reaction monitoring experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for In Situ Monitoring.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| ATR Flow Cell Probe | A probe with a diamond or ZnSe crystal that is inserted directly into a reactor; enables in situ ATR-FT-IR measurements by providing a robust, chemically resistant surface for internal reflection spectroscopy [2]. |

| Charge-Tagging Reagents | Ligands or reactants functionalized with a permanent charged group (e.g., quaternary ammonium); allows for efficient detection of neutral organometallic intermediates by ESI-MS [8]. |

| Robust Raman Probes | Immersion probes with sapphire or quartz tips and laser-focusing optics; used for in situ Raman measurements. Sapphire tips provide durability but have characteristic Raman peaks that must be accounted for [2]. |

| Stable Isotope Labels | Non-radioactive isotopes (e.g., ²H, ¹³C, ¹âµN); used as tracers to follow the fate of specific atoms or molecules in a reaction, enabling detailed metabolic and mechanistic studies when detected by techniques like CRIMS or NMR [9]. |

| Ultrapure Water System | (e.g., Milli-Q series); provides ultrapure water for sample and buffer preparation, critical for ensuring no background interference in sensitive spectroscopic analyses, especially in biopharmaceutical applications [10]. |

| Reaction Analysis Software | Software packages with chemometric capabilities (e.g., for PLS, MCR); essential for processing and interpreting the large, complex spectral data sets generated by in situ monitoring, particularly for quantitative analysis [2]. |

| Meldonium-d3 | Mildronate-d3 HCl |

| Semax acetate | Semax acetate, MF:C39H55N9O12S, MW:874.0 g/mol |

Workflow and Advantage Conceptualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting and applying in situ monitoring techniques based on the specific analytical challenge, culminating in the key advantages gained.

Monitoring chemical reactions in real time is a critical capability in research and industrial laboratories, enabling scientists to understand reaction kinetics, identify transient intermediates, and determine optimal endpoints. Among the most powerful techniques for this purpose are Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), Infrared (IR), and Raman spectroscopy, each providing unique molecular-level insights through distinct physical principles. These vibrational spectroscopic methods are particularly valued for being non-destructive and providing direct, quantitative information about molecular structure and concentration changes during chemical processes.

The integration of these techniques with flow chemistry and automation has created transformative opportunities for reaction optimization. Benchtop NMR systems can now be installed directly in fume hoods, while fiber-optic probes for IR and Raman allow remote, in-line monitoring in reactors [11] [12]. This evolution from off-line to in-line analysis represents a significant advancement, providing real-time feedback for process control without the need for manual sampling. Mass spectrometry (MS), while not covered in detail here, complements these techniques by providing precise molecular weight and structural information.

Technique Comparison and Selection Guide

Table 1: Comparison of Key Spectroscopic Techniques for Reaction Monitoring

| Technique | Principle | Key Applications | Quantitative | In-line Capability | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMR | Measures absorption of radiofrequency radiation by atomic nuclei in a magnetic field | Reaction kinetics, endpoint determination, intermediate detection, deuterium labeling studies | Excellent (linear signal concentration dependence) | Yes (flow systems with PTFE tubing or glass flow cells) | Non-destructive; insensitive to sample matrix; provides detailed structural information | Lower sensitivity than other techniques; requires specialized flow equipment |

| IR | Measures absorption of IR light by molecular vibrations | Organic synthesis, enzymatic reactions, polymerization, reaction mechanism studies | Good (follows Beer-Lambert law) | Yes (fiber probes with ATR, transmission, or reflectance) | Rapid measurement (as fast as 25 msec); multiple probe types for different applications; well-established for quantitative analysis | Challenging for aqueous solutions (strong water absorption); pathlength adjustment needed for transmission |

| Raman | Measures inelastic scattering of monochromatic light | Polymerization (e.g., epoxy curing), polymorph transformation, blend uniformity, reactive extrusion | Good with proper calibration | Yes (fiber-optic immersion or non-contact probes) | Minimal sample preparation; suitable for aqueous solutions; measures through packaging; provides specific molecular fingerprints | Weak signal; susceptible to fluorescence interference; can cause sample heating with dark materials |

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

Application Notes

NMR spectroscopy excels in reaction monitoring due to its quantitative nature and detailed structural elucidation capabilities. NMR signals change linearly with concentration variations, allowing precise kinetic studies without being affected by the sample matrix [11]. The technique is particularly valuable for detecting short-lived intermediates and determining reaction endpoints with high reliability.

Recent technological advances have made NMR more accessible for routine reaction monitoring. Benchtop NMR spectrometers like the Spinsolve systems can be installed directly in fume hoods and connected to reactors using continuous flow systems with PTFE tubing or specialized glass flow cells [11]. This configuration enables real-time monitoring of reactions as they proceed, with samples continuously pumped from the reactor through the NMR flow cell and back to the reaction vessel. The non-destructive nature of NMR analysis makes this closed-loop sampling particularly advantageous for precious or hazardous materials.

NMR has demonstrated particular utility in specialized applications including phosphine ligand identification and oxidation reaction monitoring using ³¹P NMR, deuteration reaction optimization by replacing H₂O with D₂O in flow hydrogenation systems, and complex multi-step hydrogenation reactions where real-time feedback enables parameter optimization [11]. The technique also provides exceptional value in studying imine formation (Schiff base reactions), where it can distinguish between monoimine and diimine products and track their formation kinetics simultaneously [11].

Experimental Protocol

Reaction Monitoring via Time-Arrayed ¹H NMR Spectroscopy

This protocol describes the setup for in-situ reaction monitoring using a kinetics experiment array in NMR spectroscopy, adapted from established procedures [13].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NMR Reaction Monitoring

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| PTFE Tubing or Glass Flow Cell | Forms closed-loop between reactor and NMR magnet for continuous monitoring [11] |

| Deuterated Solvent | Provides field frequency lock signal for stable NMR measurements |

| Spinsolve Benchtop NMR | Compact spectrometer for installation in fume hoods [11] |

| Reaction Monitoring Software | Enables easy setup of reaction loops and data processing [11] |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Initial Setup: Prepare the reaction mixture in an appropriate deuterated solvent. For rapid reactions, preliminary setup may be performed on a "dummy" sample without catalyst or initiator to minimize delay.

Experiment Configuration: Set up the first ¹H NMR experiment with optimized parameters: minimal scans (ns=1-4), no dummy scans (ds=0), appropriate spectral width (sw), and recycle delay (d1). The goal is to achieve sufficient signal-to-noise while capturing rapid reaction changes.

Temperature Equilibrium: For elevated temperature studies, pre-heat the NMR probe to the desired temperature using either the dummy sample or the actual reaction mixture. For temperatures above 80°C, use a ceramic spinner instead of standard glass NMR tubes.

Array Design: Create a variable delay list (vdlist) specifying time intervals between successive spectra. Structure the intervals based on expected reaction kinetics (e.g., shorter intervals initially: 300, 300, 600, 600, 1800 seconds).

Queue Implementation: After acquiring the first spectrum, use the

iexpnocommand to create a duplicate experiment file, then executemulti_zgvdto initiate the kinetic series. Select variable delay mode and specify the created vdlist when prompted.Data Collection: The system will automatically acquire spectra according to the predefined time intervals. Monitor progress and use

killcommand only if essential to terminate the entire series, ashaltstops only the current acquisition.

Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy

Application Notes

IR spectroscopy provides powerful capabilities for monitoring chemical reactions through the detection of functional group transformations in real time. The technique measures the absorption of infrared radiation by molecular vibrations, creating characteristic spectral fingerprints that change as reactants convert to products.

Modern IR systems enable exceptional flexibility in reaction monitoring configurations. Fiber-optic probes can be selected in transmission, reflectance, or ATR (Attenuated Total Reflection) geometries according to the specific application requirements [12]. The VIR series spectrometers can control up to six separate fibers simultaneously, allowing a single instrument to monitor multiple reactors [12]. This multi-reactor capability significantly enhances throughput in screening and optimization campaigns.

ATR sampling provides particular advantages for reaction monitoring by analyzing the interface between an ATR prism and the solution, eliminating the need for optical pathlength adjustment typically required in transmission measurements [12]. This configuration was successfully employed to study the interaction between oil and surfactant, where rapid-scan measurements at 80 msec intervals captured the biphasic solubilization process [12]. The observed spectral changes revealed that the emulsification occurred in two distinct steps: rapid initial contact followed by slower dispersion.

Advanced IR techniques continue to emerge, including MIR dispersion spectroscopy that utilizes quantum cascade lasers and Mach-Zehnder interferometry to detect refractive index changes rather than conventional absorption [14]. This approach achieves sensitivity to 6.1×10â»â· refractive index units and offers 1.5 times better sensitivity than FT-IR with sevenfold longer analytical path lengths, significantly enhancing robustness for liquid-phase analysis [14]. This methodology has been successfully applied to monitor invertase enzyme activity with sucrose, tracking the formation of resultant monosaccharides and their progression toward thermodynamic equilibrium.

Experimental Protocol

Reaction Monitoring Using ATR Fiber Probe with Rapid-Scan FTIR

This protocol describes the setup for monitoring chemical reactions using an ATR fiber probe with rapid-scan capability, based on established methodologies [12].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for IR Reaction Monitoring

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| ATR Fiber Probe | Enables in-situ measurement without pathlength adjustment; available with ZnSe, diamond, or other crystal materials [12] |

| Chalcogenide Fiber | Mid-IR transparent fiber material for transmitting IR signal to remote samples |

| VIR-200/300 Spectrometer | FTIR systems with rapid scan capability (up to 25 msec intervals) [12] |

| Temperature-Controlled Reaction Cell | Maintains consistent reaction temperature for kinetic studies |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

System Configuration: Connect the ATR fiber probe to the VIR series spectrometer via the fiber interface unit. Select appropriate measurement parameters: 4 cmâ»Â¹ resolution, MCT detector, and rapid-scan interferometer drive system.

Background Collection: Acquire a background spectrum with the ATR prism immersed in the pure solvent or one reaction component under identical conditions to the planned reaction.

Probe Positioning: Immerse the ATR probe tip directly into the reaction mixture, ensuring proper contact between the prism surface and the solution. For heterogeneous reactions, position the probe to maintain consistent contact with the liquid phase.

Rapid-Scan Setup: Configure the rapid-scan method with appropriate measurement intervals (e.g., 80 msec for very fast reactions) and maximum measurement time based on expected reaction duration.

Reaction Initiation: Start spectral acquisition followed immediately by reaction initiation through addition of catalyst, heating, or mixing of components. Precise timing is critical for capturing initial kinetics.

Spectral Monitoring: Continuously collect spectra throughout the reaction progression. For the oil-surfactant interaction study, characteristic spectral changes included decrease in -CH peak (2925 cmâ»Â¹, from oil) and increase in -OH peak (1639 cmâ»Â¹, from surfactant) [12].

Data Analysis: Process 3D spectral data to extract kinetic information. For the surfactant system, time-dependent intensity changes revealed biphasic behavior: rapid initial changes followed by slower progression [12].

Raman Spectroscopy

Application Notes

Raman spectroscopy has emerged as a particularly valuable technique for in-line reaction monitoring due to its minimal sample preparation requirements and ability to measure through packaging or reactor walls [15]. The technique analyzes inelastically scattered light, providing molecular fingerprints specific to the chemical bonds and symmetry of molecules in the sample.

A significant advantage of Raman spectroscopy for industrial applications is its suitability for aqueous solutions, as water exhibits weak Raman scattering, unlike its strong absorption in IR spectroscopy [15]. This makes Raman ideal for monitoring biological reactions, enzymatic processes, and aqueous-phase synthesis. Additionally, the non-destructive nature and capability for remote measurement through fiber-optic probes enable safe monitoring of hazardous reactions [15].

Raman spectroscopy has proven exceptionally valuable in polymerization monitoring, particularly for tracking epoxy curing reactions [16]. The technique can follow the disappearance of the epoxy ring breathing mode near 1275 cmâ»Â¹ as the ring opens during cross-linking [16] [15]. For the fast-curing Gorilla brand epoxy, measurements over a 4-hour period captured not only the epoxy consumption but also the disappearance of sulfhydryl groups above 2500 cmâ»Â¹, revealing their role as cross-linking agents [16].

In industrial extrusion processes, Process Raman spectroscopy serves as an essential tool for real-time monitoring of polymer blending, reactive extrusion, and composite production [17]. For PP/EVA blends, Raman probes integrated into die ports monitor blend uniformity in real time, enabling immediate adjustments to maintain product quality [17]. Similarly, for reactive extrusion of PLA, Raman spectroscopy tracks chemical modifications as they occur, ensuring desired molecular changes are achieved [17].

Experimental Protocol

In-line Reaction Monitoring Using Raman Spectroscopy

This protocol describes the setup for monitoring chemical reactions using in-line Raman spectroscopy, based on established applications in polymerization and chemical synthesis [16] [15] [17].

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Raman Reaction Monitoring

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Fiber-Optic Raman Probe | Enables remote, in-situ measurements; chemically and thermally resistant for reactor integration [17] |

| 785 nm Diode Laser | Standard excitation wavelength providing high sensitivity and reduced fluorescence [17] |

| Benchtop Raman Spectrometer | Compact instruments with CCD or InGaAs detectors for spectral acquisition [15] |

| Process Raman Analyzer | Industrial systems for continuous monitoring in manufacturing environments [17] |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

System Configuration: Connect the Raman probe to the spectrometer and initialize the laser. For epoxy curing monitoring, a 785 nm diode laser with a benchtop spectrometer like the MacroRAM provides optimal performance [16].

Probe Installation: Position the probe for optimal measurement. For extrusion processes, integrate the probe into die ports or mid-barrel ports [17]. For laboratory reactions, immerse the probe directly or use a flow-through cell.

Spectral Acquisition Parameters: Set acquisition parameters based on reaction kinetics: integration time (seconds to minutes), number of accumulations, and time intervals between measurements. For fast reactions, use continuous monitoring with short integration times.

Reaction Initialization: Begin spectral acquisition to establish a baseline, then initiate the reaction through catalyst addition, temperature change, or reactant mixing.

Real-time Monitoring: Collect spectra continuously throughout the reaction. For epoxy curing, monitor specific bands including the epoxy ring breathing mode (~1275 cmâ»Â¹), aromatic ring doublet (~1600 cmâ»Â¹), and SH stretch (>2500 cmâ»Â¹) [16].

Data Analysis: Employ multivariate methods such as Classical Least Squares (CLS) to analyze spectral changes and quantify component concentrations. Generate scores plots to visualize reaction progression.

Endpoint Determination: Identify reaction completion through stabilization of key spectral features. For epoxy systems, the disappearance of the 1275 cmâ»Â¹ epoxy ring signal indicates full conversion [16] [15].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of spectroscopic reaction monitoring is rapidly evolving with several emerging trends enhancing capabilities. Machine learning and artificial intelligence are transforming spectral analysis through automated interpretation, pattern recognition, and predictive modeling [18]. Spectroscopy Machine Learning (SpectraML) now enables both forward problems (predicting spectra from molecular structures) and inverse problems (deducing molecular structures from spectra) with increasing accuracy [18].

The integration of multiple spectroscopic techniques provides complementary information for complex reaction systems. Combined Raman and NMR setups have been used for quantifying hydrogen in natural gas, demonstrating the power of multimodal analysis [19]. Similarly, large-scale computational datasets containing both Raman and IR spectra for thousands of molecules are enabling new machine learning approaches for spectral interpretation and prediction [20].

Miniaturization and field-deployable instruments represent another significant trend, with benchtop NMR [11] and compact Raman spectrometers [15] bringing advanced analytical capabilities directly to process lines. These developments, coupled with real-time data analytics, are paving the way for fully autonomous self-optimizing reaction systems that can continuously adjust parameters to maximize yield and selectivity without human intervention [11].

The Role of Real-Time Data in Accelerating Reaction Optimization

The optimization of chemical reactions is a fundamental yet resource-intensive process in research and industrial chemistry. Traditional methods, which often rely on one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approaches and offline analysis, are slow, inefficient, and can miss optimal conditions. The integration of real-time analytical data is transforming this paradigm, enabling rapid, data-driven decision-making. Framed within spectroscopic methods for chemical reaction monitoring, this application note details how real-time spectroscopic data, particularly from Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), accelerates reaction optimization. This approach provides researchers and drug development professionals with unprecedented insights into reaction kinetics, mechanisms, and pathways, significantly shortening development timelines for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) and other complex molecules [11] [21].

The synergy between continuous flow chemistry, benchtop NMR spectroscopy, and machine intelligence creates a powerful framework for autonomous experimentation. This closed-loop system allows for real-time adjustment of reaction parameters, moving beyond simple endpoint analysis to active process control [11] [21]. This document provides detailed protocols and application examples to implement these advanced techniques in the laboratory.

Technologies for Real-Time Reaction Monitoring

Spectroscopic Techniques and Applications

Various spectroscopic techniques can be deployed for real-time monitoring, each with unique strengths and applications. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the most prominent methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Spectroscopic Techniques for Reaction Monitoring

| Technique | Spectral Region | Key Measurable Parameters | Primary Applications in Reaction Monitoring | Advantages for Real-Time Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMR Spectroscopy [22] [11] | Radiofrequency | Concentration, conversion yield, kinetic profiles, mechanistic intermediates | Tracking reactants, products, and intermediates; determining kinetics and end points; structural elucidation | Inherently quantitative; non-destructive; provides rich structural information; insensitive to sample matrix |

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy [23] | Ultraviolet to Visible (190–780 nm) | Concentration of chromophores, reaction progress based on absorbance changes | Monitoring reactions involving chromophores; HPLC detection; color measurement | High sensitivity; fast data acquisition; compatible with fiber optics |

| IR & NIR Spectroscopy [23] | Infrared | Functional group presence and concentration; molecular vibrations | Tracking specific functional group transformations (e.g., carbonyls, amines); process control in industry | Fast; can probe through glass and some polymers; suitable for aqueous solutions |

| Raman Spectroscopy [23] | Visible (for laser excitation) | Molecular vibrations, functional groups, crystal forms | Monitoring heterogeneous reactions; aqueous systems; reactions in glass vessels | Minimal sample preparation; weak interference from water and glass; complementary to IR |

Enabling Hardware and Software Platforms

The practical implementation of real-time monitoring relies on integrated hardware and software solutions.

- InsightMR: A combined hardware and software solution from Bruker, designed for online monitoring of chemical reactions under real process conditions. Its flow tube enables continuous transfer of the reaction mixture to the NMR probe, while the dedicated software allows for on-the-fly adjustment of acquisition parameters based on real-time kinetic data [22].

- Benchtop NMR Systems: Instruments like Magritek's Spinsolve can be installed directly in a laboratory fume hood. This facilitates online monitoring by pumping reactants from the reactor to the magnet and back using standard PTFE tubing or a glass flow cell, making NMR more accessible and integrable into reaction setups [11].

- Mnova Suite: Software solutions that enhance reaction monitoring by integrating and analyzing data from multiple techniques like NMR and LC-MS. It automates the extraction of spectroscopic and kinetic concentration data, enabling real-time tracking and optimization across multiple parallel reactions [24].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Real-Time NMR Monitoring of a Schiff Base Formation

Principle: This protocol monitors the condensation of an amine and an aldehyde to form an imine (Schiff base), a reaction crucial in coordination chemistry and pharmaceutical applications [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Schiff Base Formation Monitoring

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Benchtop NMR Spectrometer (e.g., Spinsolve) | Enables online, non-destructive analysis of the reaction mixture directly from the flow reactor. |

| Peristaltic or HPLC Pump | Controls the continuous flow of the reaction mixture between the reactor vessel and the NMR flow cell. |

| PTFE Tubing or Glass Flow Cell | Provides an inert and pressure-resistant conduit for the reaction mixture. |

| Deuterated Solvent (e.g., CD₃CN) | Provides a locking signal for the NMR spectrometer; the reaction can also be run in non-deuterated solvents with specialized systems [22]. |

| Software with Kinetics Module (e.g., Mnova, InsightMR) | Automates data acquisition, processing, and visualization of kinetic profiles from stacked NMR spectra. |

Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: Charge a solution of phenylenediamine and isobutyraldehyde in acetonitrile into a stirred reaction vessel. Maintain at a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C).

- Flow System Configuration: Connect the reaction vessel to the benchtop NMR spectrometer using PTFE tubing and a pump, creating a closed loop.

- NMR Data Acquisition:

- Initiate continuous pumping to circulate the reaction mixture through the NMR flow cell.

- Configure the NMR software to automatically acquire successive ¹H NMR spectra (e.g., 2 scans per spectrum with a 30-second repetition time).

- Set the total acquisition time to cover the complete reaction (e.g., 160 minutes).

- Data Analysis:

- Process the arrayed NMR spectra to identify signals for the diamine starting material, the monoimine intermediate, and the diimine product.

- Integrate the characteristic peaks for each species in every spectrum.

- Plot the integral values against time to generate concentration-time profiles, revealing the sequential formation of the mono- and diimine products [11].

Protocol 2: Automated Multi-Objective Reaction Optimization with Machine Learning

Principle: This protocol combines High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) with a Machine Learning (ML) framework (e.g., Minerva) for highly parallel optimization of challenging reactions, such as nickel-catalyzed Suzuki couplings, balancing multiple objectives like yield and selectivity [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Driven Optimization

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| HTE Robotic Platform | Enables automated, miniaturized preparation of numerous (e.g., 96) parallel reactions in a plate-based format. |

| Online or At-Line Analyzer (e.g., UPLC, NMR) | Provides quantitative data on reaction outcomes (e.g., yield, selectivity) for the ML algorithm. |

| Machine Learning Software (e.g., Minerva) | Uses Bayesian optimization to select the most informative next batch of experiments based on previous results. |

| Chemical Descriptors | Numerical representations of categorical variables (e.g., solvents, ligands) that allow the ML model to navigate the chemical space. |

Methodology:

- Define Search Space: Specify the reaction parameters to be optimized (e.g., ligand, solvent, base, temperature, catalyst loading). The space of all plausible combinations can be vast (e.g., 88,000 conditions).

- Initial Experimentation: Use algorithmic quasi-random Sobol sampling to select an initial batch of diverse experiments (e.g., a 96-well plate) that broadly cover the defined search space.

- Analysis and ML Iteration:

- Execute the batch of experiments using the HTE platform.

- Analyze the outcomes (e.g., yield and selectivity) using an online/at-line analytical technique.

- Feed the results into the ML framework. The algorithm (e.g., using a Gaussian Process regressor) models the reaction landscape and uses an acquisition function (e.g., q-NParEgo) to select the next batch of experiments that best balance exploration of new regions and exploitation of promising conditions.

- Convergence: Repeat step 3 for several iterations. The process is terminated when performance converges, optimal conditions are identified, or the experimental budget is exhausted. This approach has been shown to identify conditions with >95% yield and selectivity for API syntheses in a fraction of the time required by traditional methods [21].

Data Visualization and Workflow Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate the core logical relationships and experimental workflows described in the protocols.

Diagram 1: NMR Kinetic Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: ML-Driven Optimization Loop

The integration of real-time data, particularly from spectroscopic methods like NMR, is no longer a niche advantage but a core component of modern, efficient reaction optimization. The protocols outlined demonstrate a clear evolution from passive observation to active, intelligent experimentation. By implementing these application notes, researchers can achieve deeper mechanistic understanding, rapidly identify optimal reaction conditions, and significantly accelerate the development of chemical processes, from fundamental organic synthesis to industrial-scale API production. The future of reaction optimization lies in the continued fusion of robust analytical hardware, intelligent software, and automated platforms, creating a seamless, data-rich research environment.

Implementing Spectroscopic Techniques: From Benchtop to Flow Reactor

Benchtop NMR for Quantitative Kinetics and Automated Reaction Endpoint Determination

The integration of benchtop Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy into chemical reaction monitoring represents a significant advancement in process analytical technology. Unlike traditional high-field NMR spectrometers, which require dedicated facilities and cryogenic cooling, modern benchtop systems provide compact, cryogen-free operation with minimal maintenance requirements, enabling deployment in standard laboratory fume hoods and production environments [11] [25]. This accessibility, combined with the quantitative, non-destructive nature of NMR measurements, makes benchtop NMR particularly valuable for determining reaction kinetics and endpoints in both academic research and industrial drug development [11].

The fundamental principle underlying NMR reaction monitoring is the linear relationship between NMR signal intensity and analyte concentration, which allows for direct quantification without extensive calibration curves [11]. Furthermore, NMR is matrix-insensitive, meaning measurements remain reliable despite changes in reaction composition, and the technique provides structural insight simultaneously with quantification, enabling identification of intermediates and side products [11]. Recent technological advances, particularly in magnetic field homogeneity and solvent suppression techniques, have expanded applications to include samples in protonated solvents, eliminating the previous requirement for deuterated solvents and enabling direct analysis from reactors [26].

Technical Specifications and Quantitative Performance

Sensitivity and Resolution Specifications

The analytical performance of benchtop NMR systems for quantitative applications depends critically on magnetic field homogeneity, which directly influences both spectral resolution and sensitivity [27]. Sensitivity, defined as the ability to detect low concentrations of analytes, is formally measured as the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for a standardized reference sample [27]. The standard test for 1H sensitivity in benchtop NMR utilizes 1% ethylbenzene in CDCl3, with measurement of the SNR for the methylene quartet at approximately 2.65 ppm under specific acquisition parameters [27].

Table 1: Performance Specifications of Commercial Benchtop NMR Systems

| Instrument | 1H Frequency (MHz) | Line Width 50% (Hz) | 1H Sensitivity | Lock System | Solvent Suppression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bruker Fourier 80 | 80 | 0.3 (HD option) | ≥220 (with PFG) | External | Yes |

| Magritek Spinsolve 80 Ultra | 80 | <0.25 | 280 (single channel) | External | Yes |

| Magritek Spinsolve 90 | 90 | <0.4 | >240 (dual channel) | External | Yes |

| Nanalysis 100PRO | 100 | <1 | 220 | Internal | Yes |

| Oxford Instruments X-Pulse | 60 | <0.35 | 130 | Internal | Yes |

Signal Averaging and Detection Limits

A fundamental aspect of NMR quantification is the relationship between measurement time and signal-to-noise ratio through signal averaging. The SNR improves proportionally to the square root of the number of scans according to the equation:

SNRN = SNR1 × N¹/²

where N is the number of scans, SNR1 is the signal-to-noise from a single scan, and SNRN is the cumulative signal-to-noise after N scans [27]. This relationship has practical implications for reaction monitoring: an instrument with four times lower sensitivity would require sixteen times longer measurement time to achieve equivalent SNR, potentially limiting temporal resolution for fast kinetic processes [27].

Experimental Protocols for Reaction Monitoring

System Configuration and Hardware Integration

Successful implementation of benchtop NMR for reaction monitoring requires appropriate flow system integration to transport reaction mixtures between the reactor and NMR flow cell. Two primary configurations have been established:

Continuous-flow systems: Reaction mixture is continuously pumped through the NMR flow cell, enabling real-time monitoring with minimal delay [11] [28]. This approach provides high data density but may require correction for shorter spin-lattice relaxation times (T1) due to flow effects [28].

Stopped-flow systems: Discrete aliquots are transferred to the NMR flow cell and measurement occurs while flow is stopped [28]. This approach ensures complete spin-lattice relaxation between acquisitions, providing more quantitatively reliable data for nuclei with longer T1 values, at the cost of temporal resolution [28].

Table 2: Comparison of Benchtop NMR Sampling Methods for Reaction Monitoring

| Parameter | Continuous-Flow | Stopped-Flow |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Resolution | High (seconds to minutes) | Moderate (minutes) |

| Data Density | High | Moderate |

| Quantitative Reliability | May require T1 correction for long T1 nuclei | High (no T1 correction needed) |

| Sample Consumption | Continuous | Discrete aliquots |

| Hardware Complexity | Moderate | Moderate |

| Representative Applications | Fast kinetics, process optimization | Accurate quantification, reactions with long T1 nuclei |

Magritek offers specialized kits for both approaches, including a glass flow tube with an expanded 4 mm internal diameter section in the measurement zone, and a cost-effective alternative using PTFE tubing with a glass guide tube [11]. For automated systems, daisy-chained valve configurations have been implemented to maximize port availability for reagents and modules while maintaining efficient fluidic paths [29].

Practical Implementation Workflow

Automated Reaction Optimization Systems

Advanced implementations integrate benchtop NMR with laboratory automation systems to create self-optimizing reactor platforms. These systems combine automated synthesis workstations with benchtop NMR spectrometers and intelligent control software that uses real-time NMR data to adjust reaction parameters [30] [29]. For example, the integration of Chemspeed automation workstations with Bruker's Fourier 80 benchtop NMR and Advanced Chemical Profiling software enables fully automated Design of Experiments (DoE) optimization without human intervention [30].

In one documented application, this approach was used to optimize a transesterification reaction, where the automated platform prepared aliquots at designated intervals, acquired NMR data, processed it automatically, and used the results to adjust reaction parameters [30]. Similarly, the "Chemputer" system has demonstrated autonomous multi-step synthesis of molecular machines, utilizing online 1H NMR for yield determination and reaction control throughout a complex synthetic sequence [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Benchtop NMR Reaction Monitoring

| Item | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Benchtop NMR Spectrometer | 60-100 MHz 1H frequency with external lock capability | Quantitative spectral acquisition directly in fume hood |

| Flow System | Peristaltic or syringe pumps with PTFE tubing (0.5-1 mm ID) | Transport of reaction mixture between reactor and NMR |

| NMR Flow Cell | Glass construction with 4 mm ID expanded measurement zone | Houses sample during NMR measurement in flow mode |

| Reference Standard | 1% ethylbenzene in CDCl3 + 0.1% TMS | Sensitivity verification and system performance validation |

| Deuterated Solvent | CDCl3, DMSO-d6, etc. (for reference measurements) | Lock signal for high-resolution experiments |

| Protonated Solvents | Standard laboratory solvents with suppression | Routine reaction monitoring without deuterated solvents |

| Automation Software | Reaction monitoring module with automated processing | Data acquisition, processing, and integration with robot control |

| Inert Gas Manifold | Nitrogen or argon supply | Handling air-sensitive reactions and reagents |

| Ciwujianoside D2 | Ciwujianoside D2, MF:C54H84O22, MW:1085.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| HCV-IN-7 | HCV-IN-7, MF:C40H48N8O6S, MW:768.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Applications in Chemical Synthesis and Optimization

Reaction Kinetics and Mechanistic Studies

Benchtop NMR has proven particularly valuable for monitoring reaction kinetics in homogeneous systems, where the quantitative nature of NMR enables precise determination of rate constants and reaction orders. For example, in the synthesis of a diimine from phenylenediamine and isobutyraldehyde, stacked 1H NMR spectra clearly showed the decrease of phenylene diamine and the sequential growth of mono- and diimine intermediates, providing direct insight into the reaction mechanism [11]. Similarly, the technique has been applied to study imine formation (Schiff base reactions), which are important intermediates in coordination chemistry, pharmaceuticals, and biochemistry [11].

Process Optimization and Endpoint Determination

The combination of benchtop NMR with flow reactors has created powerful platforms for rapid process optimization. In one application, researchers optimized a two-step hydrogenation reaction of ethyl nicotinate by monitoring the effect of temperature, pressure, hydrogen equivalents, and flow rate on conversion and selectivity [11]. The real-time feedback enabled identification of optimal conditions with minimal manual intervention.

For endpoint determination, the quantitative nature of NMR allows precise detection of reaction completion, minimizing both incomplete reactions and product degradation from extended reaction times. This is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical development, where reaction consistency directly impacts product quality and yield [11].

Specialized Applications with Heteronuclei

While 1H NMR is most commonly used for reaction monitoring, benchtop systems also support studies of other nuclei relevant to chemical synthesis:

19F NMR: Excellent sensitivity and wide chemical shift range make 19F NMR valuable for monitoring reactions involving fluorinated compounds, which are prevalent in pharmaceutical research [25] [28]. Studies have compared 19F NMR reaction profiles using both continuous-flow and stopped-flow methods [28].

31P NMR: Used to identify phosphine ligands and monitor their oxidation reactions in real time, important for homogeneous catalysis development [11].

13C NMR: Despite lower sensitivity, 13C NMR provides complementary structural information through 1H-13C correlation experiments, though typically requiring higher concentrations or longer acquisition times [25].

Data Processing and Analysis Protocols

Quantitative Analysis Methods

Accurate quantification in benchtop NMR requires careful data processing to extract meaningful concentration data from spectral time courses. The standard approach involves:

- Phasing and baseline correction of all spectra in the time series

- Application of consistent 1 Hz exponential line broadening to improve signal-to-noise without excessive line broadening [27]

- Integration of characteristic peaks for starting materials, intermediates, and products

- Normalization of integrals to account for variations in sample volume or concentration

- Conversion to concentration using internal or external standards

For automated systems, software such as Bruker's Advanced Chemical Profiling can perform these steps automatically, providing machine-readable outputs for feedback control [30].

Solvent Suppression Techniques

The ability to analyze samples in protonated solvents significantly enhances the practicality of benchtop NMR for reaction monitoring. Modern systems achieve effective solvent suppression through highly selective techniques such as PRESAT or WET, which require exceptional magnetic field stability and homogeneity [26]. With proper implementation, these methods can attenuate solvent peaks by two to three orders of magnitude, reducing interference with analyte signals [26].

Benchtop NMR spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for quantitative reaction monitoring, combining the structural elucidation capabilities of traditional NMR with the practical accessibility required for routine laboratory use. The integration of these systems with flow chemistry platforms and automation robotics enables unprecedented capabilities in reaction optimization and kinetic studies. As technological advances continue to improve sensitivity, resolution, and solvent suppression capabilities, benchtop NMR is poised to become an indispensable technique for chemical research and development, particularly in pharmaceutical applications where understanding reaction kinetics and endpoints directly impacts process efficiency and product quality.

FT-IR and ATR Probes for Functional Group Tracking in Heterogeneous Mixtures

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, particularly when coupled with Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) probes, has become a cornerstone technique for the real-time monitoring of chemical reactions in complex, heterogeneous mixtures. This capability is paramount in the broader context of spectroscopic methods for chemical reaction monitoring research, where understanding molecular-level interactions is key to optimizing processes in pharmaceutical development, biofuel production, and material science [31] [32]. The ATR-FTIR technique is label-free, non-destructive, and requires minimal to no sample preparation, allowing for the direct observation of functional group dynamics in situ [32] [33]. Its integration into reaction systems provides a powerful feedback mechanism for process control, enabling researchers and drug development professionals to track reaction progress, identify intermediates, and verify endpoints with high specificity, thereby ensuring product quality and process efficiency [31].

Key Applications and Quantitative Tracking

The application of ATR-FTIR probes for functional group tracking spans diverse fields, from biofuel synthesis to biopharmaceutical production. The following table summarizes key quantitative data from recent research, demonstrating the technique's versatility in monitoring specific functional groups and reaction components.

Table 1: Quantitative Functional Group Tracking in Heterogeneous Mixtures via ATR-FTIR

| Application Domain | Reaction / Process Monitored | Key Functional Groups / Components Tracked | Characteristic IR Wavenumbers (cmâ»Â¹) | Quantitative Correlation & Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofuel Production [31] | Ethanolysis of vegetable oils to biodiesel (Fatty Acid Ethyl Esters, FAEE) | Triglycerides (TG), Fatty Acid Ethyl Esters (FAEE), Glycerol | Specific regions identified via correlation analysis (e.g., -C-O- stretch in esters; -C=O stretch) | Simple Linear Regression (SLR) model performance: RMSEP = 2.11, comparable to complex PLS models and reference Gas Chromatography. |

| Biopharmaceuticals [32] | Protein aggregation, denaturation, and secondary structure changes | Amide I band (C=O stretch), Amide II band (N-H bend) | Amide I: ~1600-1700; Amide II: ~1480-1575 | Used to identify impurities, compare biosimilars, and monitor aggregation prone to stress conditions (thermal, mechanical). |

| Toxic Metal Profiling in Food [34] | Metal-binding interactions in food matrices | Functional groups involved in metal complexation (e.g., -OH, -COOH, -NHâ‚‚) | Varies by specific metal and ligand (e.g., -OH stretch: 3200-3600; -COOâ» asym/sym stretch: ~1550-1650 & ~1400) | Identifies functional groups participating in metal binding; requires complementary techniques (e.g., AAS, ICP-MS) for direct quantification. |

| Polymer & Microplastics Analysis [33] | Identification and classification of environmental microplastics | Polymer-specific functional groups (e.g., -CHâ‚‚-, -C=O in polyesters, -C-H in polyolefins) | Varies by polymer (e.g., polyethylene: ~2915, 2848, 1465; polystyrene: ~3025, 1601, 1493) | Enables precise identification and classification of polymer types in complex environmental samples. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Real-Time Monitoring of Biodiesel Ethanolysis

This protocol details the online monitoring of fatty acid ethyl ester (FAEE) formation during the ethanolysis of vegetable oils, adapted from a 2025 study [31].

- Objective: To track the conversion of triglycerides (TG) to FAEE in real-time using an ATR-FTIR flow cell, providing a feedback tool for process control.

- Materials:

- Reaction Materials: Vegetable oil, anhydrous ethanol, sodium hydroxide (NaOH) catalyst.

- Instrumentation: FTIR spectrometer equipped with an ATR accessory and a continuous flow cell.

- Reference Analysis: Gas Chromatography (GC) system for validation.

- Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: Perform ethanolysis reactions in a reactor under varying conditions (e.g., temperature: 40–60 °C; catalyst concentration: 0.25–1.0% w/w NaOH) to build a comprehensive dataset.

- Online FTIR Monitoring: Direct the reaction mixture through the ATR flow cell continuously. Collect infrared spectra at regular intervals (e.g., every minute) without any sample pre-treatment.

- Reference Data Acquisition: Simultaneously, draw samples from the reactor at specific time points for offline analysis using the validated GC method. Interpolate the GC data using a reaction kinetics model to estimate FAEE content corresponding to each FTIR spectrum.

- Data Analysis:

- Perform a correlation analysis between the interpolated FAEE content and all wavenumbers in the FTIR spectra to identify spectral regions most sensitive to reaction progress.

- Using these identified regions, develop a simple linear regression (SLR) or multiple linear regression (MLR) calibration model to predict FAEE content from the FTIR spectra.

- Validation: Validate the model's performance by comparing its predictions against the GC reference data, calculating metrics like the Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP).

Protocol 2: Assessing Protein Aggregation in Biopharmaceuticals

This protocol describes the use of ATR-FTIR to monitor protein secondary structure and aggregation, a critical quality attribute in biopharmaceutical production [32].

- Objective: To detect and characterize protein aggregation or unfolding under various stress conditions relevant to bioprocessing.

- Materials:

- Sample: Protein solution (e.g., monoclonal antibody).

- Instrumentation: FTIR spectrometer with a diamond or ZnSe ATR crystal.

- Methodology:

- Sample Application: Apply a small volume (e.g., 10-50 µL) of the protein solution directly onto the ATR crystal.

- Spectra Acquisition: Collect spectra in the mid-IR region (e.g., 4000-1000 cmâ»Â¹). For aqueous solutions, collect a background spectrum of the buffer and subtract it from the sample spectrum to correct for water vapor and buffer contributions.

- Spectral Analysis:

- Focus on the Amide I (≈1600-1700 cmâ»Â¹) and Amide II (≈1480-1575 cmâ»Â¹) regions, which are sensitive to protein secondary structure.

- Use techniques like second derivative analysis and curve-fitting to deconvolute the overlapping bands in the Amide I region to quantify different structural elements (α-helix, β-sheet, random coil).

- Monitor spectral shifts, changes in band intensity, or the appearance of new bands (e.g., a sharp band at ≈1615 cmâ»Â¹ often indicates intermolecular β-sheets characteristic of aggregates).

- Application: Subject the protein to stress conditions (thermal, mechanical agitation, pH shift) and use ATR-FTIR to track structural changes in real-time.

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for real-time reaction monitoring using an ATR-FTIR probe, as applied in biodiesel production monitoring [31].

Figure 1: Real-Time ATR-FTIR Reaction Monitoring Workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table lists essential reagents, materials, and equipment for setting up ATR-FTIR for functional group tracking in heterogeneous mixtures, based on the cited applications.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ATR-FTIR Spectrometer | Core instrument for acquiring infrared spectra. | Should be equipped with a robust interferometer and a sensitive detector [35]. |

| Flow Cell ATR Accessory | Enables continuous, online monitoring of liquid reaction mixtures. | Critical for real-time process monitoring in applications like biodiesel ethanolysis [31]. |

| Diamond ATR Crystal | Internal Reflection Element (IRE) for measuring a wide range of samples, including abrasive solids. | Offers durability and chemical resistance; common for general purpose and heterogeneous sample analysis [32]. |

| ZnSe or Ge ATR Crystal | IRE for specialized applications, particularly with aqueous solutions or requiring high sensitivity. | ZnSe is suitable for studying proteins in aqueous environments [32]. Ge has a high refractive index for high spatial resolution [35]. |

| Chemometric Software | For data processing, multivariate calibration, and pattern recognition. | Used for techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Partial Least Squares (PLS), and Simple Linear Regression (SLR) to extract quantitative information from complex spectra [31] [33]. |

| Reference Analytical Instrument | For validating and calibrating the FTIR method. | Gas Chromatography (GC) for biodiesel [31]; Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) or ICP-MS for metal profiling [34]. |

| Enpp-1-IN-15 | Enpp-1-IN-15, MF:C16H20N6O2S, MW:360.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| GPS491 | GPS491, MF:C13H5F6N3OS2, MW:397.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (EC-MS) for Capturing Fleeting Intermediates

Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (EC-MS) is a powerful analytical technique that combines the controlled electron transfer of electrochemistry with the molecular specificity of mass spectrometry. This synergy allows researchers to directly detect and identify short-lived reactive intermediates and products formed during electrochemical reactions, providing unparalleled insights into reaction mechanisms [36] [37]. Traditional methods for studying electrochemical reactions, such as cyclic voltammetry and spectroelectrochemistry, often lack the specificity to provide direct molecular information about transient species, particularly those with lifetimes of milliseconds or less [37]. EC-MS bridges this gap by enabling real-time, in-situ monitoring of electrochemical processes, making it indispensable for advancing fields such as organic electrosynthesis, electrocatalysis, and energy conversion research [36].

The core challenge in monitoring electrochemical reactions lies in the rapid shuttling of reactive intermediates (e.g., cationic species) between the electrode-electrolyte interface and the bulk solution, where they undergo multi-step electron transfers and reactions with other species [38]. EC-MS addresses this by coupling an electrochemical cell directly to a mass spectrometer, often via soft ionization techniques like electrospray ionization (ESI), allowing for the continuous sampling and analysis of the reaction mixture [37]. This capability is crucial for deciphering complex reaction networks and has become a robust methodology for mechanistic investigation [36].

The DEC-FMR-MS Platform: Design and Capabilities

A significant recent advancement in this field is the development of the Decoupled Electrochemical Flow Microreactor hyphenated with Mass Spectrometry (DEC-FMR-MS) platform [38]. This platform is specifically designed to spatially decouple interfacial electrochemical events from subsequent homogeneous chemical processes, enabling segmented dissection of reaction pathways that are traditionally interwoven in complex reaction networks.

Platform Configuration and Workflow

The DEC-FMR-MS platform integrates two primary electrochemical flow microreactors (EC-FMRs) whose outlets merge at a T-junction, with the combined flow directed to a Venturi-sonic spray ion source for MS detection [38]. This design allows independent electrochemical activation of two different substrates—one in each EC-FMR—before they mix and react homogeneously in a capillary leading to the ion source. The "dip-and-run" sampling mode, facilitated by a motorized XY-stage, enables rapid injection and switching of samples in an electrochemical microplate (ECMP), achieving a throughput of approximately 4 seconds per sample [38]. The use of a Venturi-sonic spray ion source eliminates the need for high ionization voltages, which can interfere with the intrinsic electrochemistry, thereby allowing flexible tuning of experimental variables such as potential, catalyst, and substrate during screening [38].

Table 1: Key Design Features of the DEC-FMR-MS Platform and Their Functions

| Design Feature | Function |

|---|---|

| Two EC-FMRs | Enables independent electrochemical activation of two different substrates [38] |

| Spatial Decoupling | Isolates interfacial electrochemistry from homogeneous follow-up reactions [38] |

| Venturi-Sonic Spray Ion Source | Allows high-voltage-free ionization, preventing interference with electrochemistry [38] |

| "Dip-and-run" Sampling | Permits high-throughput screening from an electrochemical microplate [38] |

| T-junction Mixer | Initiates homogeneous chemical reactions between intermediates from separate reactors [38] |