Sample Integrity: A Scientist's Complete Guide to Preventing Contamination During Sample Preparation

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for safeguarding sample integrity from collection to analysis.

Sample Integrity: A Scientist's Complete Guide to Preventing Contamination During Sample Preparation

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for safeguarding sample integrity from collection to analysis. Covering foundational principles, practical methodologies, advanced troubleshooting, and validation techniques, it addresses critical contamination risks in sensitive workflows like qPCR, cell culture, and low-biomass microbiome studies. By synthesizing current best practices and preventative strategies, the article empowers professionals to generate reproducible, reliable data and avoid the costly consequences of compromised samples.

Understanding the Enemy: Defining Contamination Sources and Impacts on Data Integrity

Contamination represents a critical and pervasive risk in scientific research and drug development, capable of compromising data integrity, invalidating experimental results, and derailing research projects. In pharmaceutical manufacturing alone, contamination issues have led to significant regulatory actions, including a documented case where 20% of bioreactor runs at a major facility were rejected over a 30-month period due to contamination concerns [1]. The challenges are particularly acute in low-biomass microbiome studies and biologics manufacturing, where even minimal contaminant introduction can disproportionately impact results. This technical guide examines the contamination landscape across research domains, provides detailed methodologies for contamination prevention and detection, and presents a comprehensive framework for safeguarding research integrity from sample preparation through data analysis. By implementing robust contamination control strategies, researchers can ensure data reliability and accelerate the development of safe, effective therapeutics.

The Contamination Landscape: Quantifying the Problem

Contamination manifests in multiple forms across research environments, each with distinct characteristics and impacts on data integrity.

Table 1: Types of Research Contamination and Their Impacts

| Contamination Type | Primary Sources | Key Impact on Research | Common Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial [1] | Raw materials, human operators, environment, process additives | Compromises cell cultures, alters biochemical assays, affects product safety and efficacy | Rapid microbiological methods, PCR, sterility testing [1] |

| Chemical [2] [3] | Residual solvents, heavy metals, extractables from materials | Causes chemical poisoning, alters reaction kinetics, introduces impurities | Spectroscopy, chromatography [2] |

| Cross-Contamination [4] | Well-to-well leakage, improper sample handling, equipment reuse | False positives/negatives, incorrect sample attribution, skewed population data | Sample tracking controls, unique tracers, historical data comparison [5] [4] |

| Data Contamination [6] | Evaluation data leakage into training sets for LLMs | Inflated performance metrics, unreliable capability assessment, inaccurate benchmarking | String matching, n-gram analysis, behavioral analysis [6] |

The market data for contamination detection reflects growing recognition of these challenges. The contamination detection in pharma products market is experiencing robust growth, with North America holding a dominant 45.2% market share in 2024 [3]. Segment analysis reveals that:

- By contamination type, chemical contamination detection held the largest revenue share (36.5%) in 2024, while microbial contamination detection is projected to be the fastest-growing segment from 2025 to 2035 [2].

- By technology, spectroscopy-based detection dominated (34.2% share) in 2024, with PCR and molecular diagnostics expected to register the fastest growth [3].

- By sample type, finished pharmaceutical products testing led (52.8% share) in 2024, while biologics & cell culture samples represent the fastest-growing segment [3].

Table 2: Contamination Detection Market Segmentation (2024)

| Segmentation Category | Dominant Segment (2024) | Market Share | Fastest-Growing Segment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contamination Type | Chemical Contamination | 36.5% | Microbial Contamination |

| Detection Technology | Spectroscopy-Based | 34.2% | PCR & Molecular Diagnostics |

| Product & Service Type | Instruments | 49.6% | Consumables & Reagents |

| Sample Type | Finished Pharmaceutical Products | 52.8% | Biologics & Cell Culture Samples |

| End User | Pharmaceutical Companies | 63.4% | Biotechnology Companies |

Contamination Detection Methodologies

Advanced Detection Technologies

Modern contamination detection leverages multiple technological approaches, each with specific applications and limitations:

Molecular Detection Methods: PCR and molecular diagnostics represent the fastest-growing detection technology segment [3]. These methods enable highly sensitive identification of specific organisms and genetic markers through targeted amplification. For microbial detection, PCR assays can identify low levels of bacterial and mold contamination in therapeutic samples, comprising less than 10 CFU (colony-forming units) [2]. The methodology involves:

- Sample Preparation: DNA extraction using validated kits free of contaminating DNA [1]

- Amplification: Target-specific primer binding and thermal cycling

- Detection: Fluorescence measurement or gel electrophoresis for amplicon visualization

- Validation: Comparison with authenticated microbial cultures and USP standards [1]

Spectroscopy-Based Techniques: Spectroscopy dominates the detection technology landscape with a 34.2% market share [2]. Machine-learning aided UV absorbance spectroscopy has emerged as an advanced approach for identifying contamination during cell therapy product manufacture [2]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Sample Introduction: Minimal preparation with negligible sample volume requirements

- Spectral Analysis: Absorbance measurement across wavelength ranges

- Pattern Recognition: Machine learning algorithms to classify contamination signatures

- Validation: Cross-referencing with established contamination markers

Rapid Microbiological Methods: These innovative approaches reduce traditional culture times from days to hours through:

- ATP bioluminescence for viable organism detection

- Flow cytometry for cellular contamination identification

- Microscopy with advanced imaging for particulate contamination [1]

Historical Data Review for Anomaly Detection

Beyond technological detection methods, historical data review provides a powerful statistical approach for identifying contamination events. This methodology involves comparing reported data to previous analytical results for specific sampling locations [5]. The process requires a robust dataset (at least 4-5 previous results) and consistent sampling locations [5]. Implementation involves three primary approaches:

- Tabular Review: Direct numerical comparison of current results to historical data

- Historical Time Series: Graphical representation of data trends over time

- Statistical Approach: Establishing upper and lower control limits to flag outliers [5]

When historical review identifies anomalies, a thorough investigation includes examining laboratory data packages, evaluating seasonal trends, reviewing field measurements (pH, ORP, specific conductance), and assessing weather conditions [5]. Case studies demonstrate effectiveness, with one example identifying sample switch events during metals analysis that weren't apparent through standard quality control measures [5].

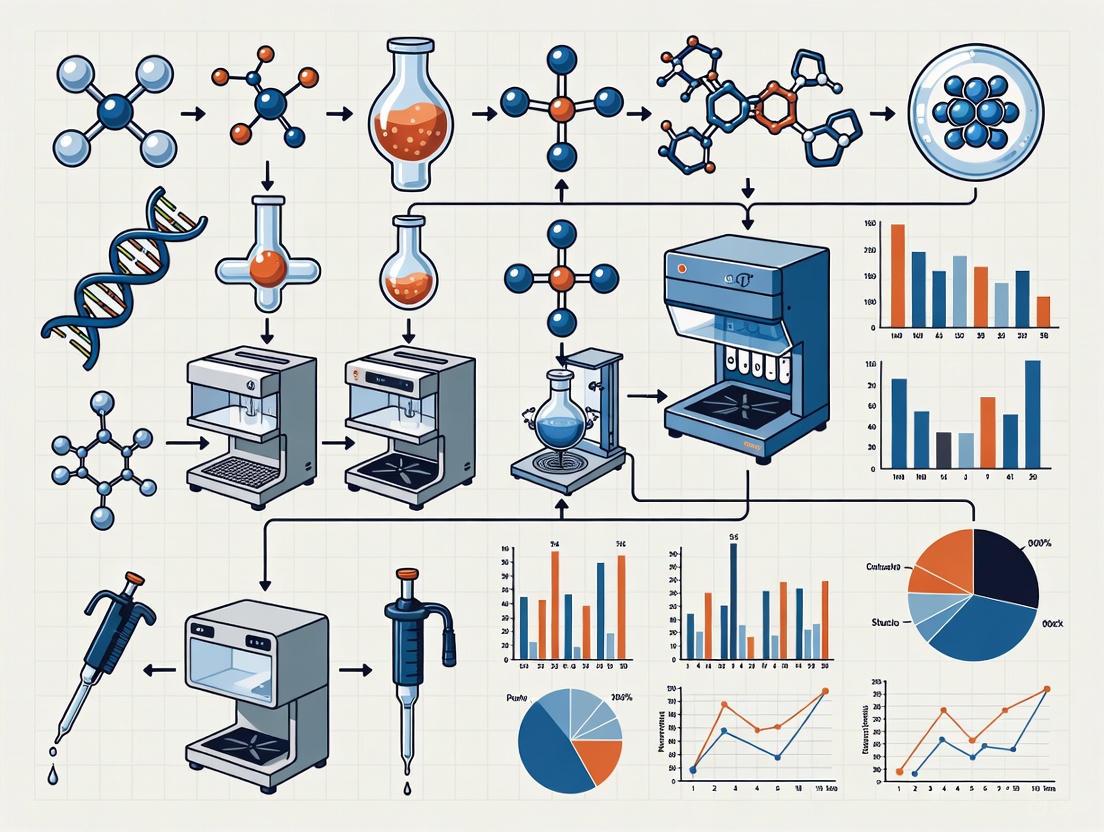

Diagram 1: Historical data review workflow for contamination detection.

Contamination Prevention Protocols

Sample Handling and Processing Guidelines

Effective contamination prevention begins with rigorous sample handling protocols, particularly critical in low-biomass research where contaminants can constitute most of the detected signal [4].

Sample Collection Protocols:

- Equipment Decontamination: Sequential treatment with 80% ethanol (to kill contaminating organisms) followed by nucleic acid degrading solution (to remove residual DNA) [4]

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Utilization of gloves, goggles, coveralls, and shoe covers appropriate for the sampling environment to minimize human-derived contamination [4]

- Single-Use Materials: Implementation of DNA-free swabs and collection vessels when possible

- Pre-treatment of Storage Materials: Autoclaving or UV-C light sterilization of plasticware/glassware, maintained sealed until sample collection [4]

Laboratory Processing Controls:

- Environmental Monitoring: Risk-based monitoring programs with trending of data to identify potential contamination concerns before impacting processes [1]

- Control Samples: Inclusion of empty collection vessels, air-exposed swabs, and preservation solution aliquots processed alongside experimental samples [4]

- Process Validation: Regular validation of disinfection protocols using authenticated reference materials [1]

Decontamination Methodologies

Both manual and automated decontamination approaches play roles in contamination prevention, with selection dependent on application requirements.

Table 3: Automated Decontamination Method Comparison

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Peroxide Vapor [7] | Excellent distribution, material compatibility, quick cycle times with active aeration, low-level safety sensors | Higher initial capital investment | Isolators, cleanrooms, regular production campaigns |

| UV Irradiation [7] | Speed, no requirement to seal enclosure | Prone to shadowing, may not kill spores, efficacy decreases with distance | Surface decontamination, supplemental cleaning |

| Chlorine Dioxide [7] | Highly effective microbe killing, quick with high concentrations | Highly corrosive, toxic (OEL <0.1 ppm), high consumables cost | Emergency decontamination, sealed environments |

| Aerosolized Hydrogen Peroxide [7] | Good material compatibility, effective microbe killing | Liquid droplets prone to gravity, relies on direct line of sight, longer cycle times | Small isolators, limited applications |

Manual Decontamination Protocols:

- Surface Disinfection: Application of validated disinfectants using spraying, mopping, and wiping techniques [7]

- Validation Requirements: Proof that selected disinfectant kills expected microbes after specified contact time [7]

- Limitations: Human variability in application, difficult validation, inconsistent coverage [7]

Automated Decontamination Advantages:

- Consistency and Repeatability: Same conditions replicated exactly in every cycle [7]

- Reduced Downtime: Faster cycle times compared to manual approaches [7]

- Enhanced Traceability: Monitoring and documentation of decontamination parameters [7]

- Operator Safety: Reduced chemical exposure and health risks [7]

Diagram 2: Comprehensive contamination prevention framework.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Implementing effective contamination control requires specific reagents and materials validated for research use.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Protocol | Validation Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Degrading Solutions [4] | Removal of contaminating DNA from surfaces and equipment | Apply after ethanol decontamination, followed by rinsing with DNA-free water | Demonstration of DNA removal without residual inhibitory effects on downstream applications |

| Authenticated Microbial Cultures [1] | Reference materials for method validation and quality control | Use as positive controls in detection assays following USP standards | Verification against USP microbiological standards for regulatory filings |

| DNA-Free Collection Vessels [4] | Prevention of sample contamination during collection and storage | Pre-treat with UV-C light or autoclaving, maintain sealed until use | Testing for nucleic acid contamination and microbial growth |

| Rapid Microbiology Test Kits [1] | Detection of microbial contamination in raw materials and process samples | Follow manufacturer protocols for sample processing and incubation | Comparison with traditional culture methods for sensitivity and specificity |

| Process Analytical Technology (PAT) Sensors [3] | Real-time monitoring of critical process parameters for contamination | Integration into manufacturing processes for continuous monitoring | Calibration against reference methods and demonstration of robustness |

| Cyclopropyl(phenyl)methanethiol | Cyclopropyl(phenyl)methanethiol|CAS 151153-46-7 | Bench Chemicals | |

| Methyl 3-fluoro-2-vinylisonicotinat | Methyl 3-fluoro-2-vinylisonicotinate|CAS 1379375-19-5 | Methyl 3-fluoro-2-vinylisonicotinate (CAS 1379375-19-5) is a versatile fluorinated building block for pharmaceutical and material science research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or animal use. | Bench Chemicals |

Case Studies: Contamination Consequences and Resolutions

Laboratory Sample Contamination

An environmental laboratory case study demonstrates how historical data review identified chromium data significantly higher than previously reported levels [5]. The investigation revealed:

- Anomaly Detection: Statistical outlier identification through comparison with historical trends

- Evidence Gathering: Parent sample results provided strong evidence of potential laboratory issues

- Corrective Action: Laboratory reanalysis confirmed contamination, leading to improved cleaning procedures and process updates [5]

- Systemic Resolution: Implementation of formal corrective action to address recurring contamination incidents

Sample Switch Incident

Historical data review identified a sample switch during metals analysis where results for "Well A" and "Well B" were swapped [5]. Key findings included:

- Pattern Recognition: Discrepancy identified through deviation from historical well-specific profiles

- Targeted Investigation: Issue confined to metals analysis, not observed in other analytical fractions

- Laboratory Confirmation: Reanalysis confirmed sample switch in metals laboratory

- Process Improvement: Formal corrective action implemented due to recurrence in the same department [5]

Contamination presents substantial risks to research integrity across scientific disciplines, with potential impacts ranging from data distortion to complete study invalidation. The increasing complexity of biological therapeutics and sensitivity of analytical methods heightens vulnerability to contamination effects. Effective contamination control requires a comprehensive, proactive strategy integrating prevention, monitoring, and detection components. By implementing robust sampling protocols, validated decontamination methodologies, systematic control measures, and advanced detection technologies, researchers can safeguard data integrity throughout the research lifecycle. As technological advancements continue to improve detection capabilities and prevention strategies, maintaining vigilance against contamination remains fundamental to producing reliable, reproducible research outcomes and ensuring the development of safe, effective pharmaceutical products.

Contamination represents a pervasive and critical challenge in scientific research, with the potential to compromise experimental integrity, skew analytical results, and generate misleading data. In the specific context of sample preparation—a foundational step across numerous scientific disciplines—contamination control transcends mere best practice to become an essential requirement for producing valid, reproducible science. This technical guide provides a comprehensive examination of contamination vectors within research environments, focusing particularly on three primary domains: environmental contaminants from pharmaceutical sources, analytical reagents and consumables, and physical cross-contamination between samples. The guide is structured within the broader thesis that proactive contamination prevention during sample preparation is not merely a technical consideration but a fundamental prerequisite for research quality and reliability. Through detailed analysis of contamination mechanisms, standardized protocols for detection and prevention, and curated toolkits of mitigation reagents, this document aims to equip researchers with the practical knowledge necessary to safeguard their experimental processes against increasingly complex contamination threats. By adopting the systematic framework presented herein, research professionals and drug development specialists can significantly enhance the validity of their analytical outcomes while contributing to the broader scientific goal of methodological rigor and reproducibility across experimental domains.

The environmental compartment represents a significant and often underestimated vector for contamination in analytical science, particularly concerning the pervasive presence of pharmaceuticals and their metabolites. Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), along with their transformation products, enter environmental matrices through multiple pathways including industrial and hospital effluent, domestic wastewater treatment plant discharges, and agricultural runoff from treated animals [8]. These residues constitute a prominent group of contaminants contributing to the global chemical pollution crisis, with nearly 1,000 APIs or their transformation products already detected in natural environments globally, including over 700 within the European Union alone [9].

The concerning property of pharmaceutical contaminants lies in their intentional design to elicit specific biological responses by interacting with evolutionarily conserved molecular targets across diverse taxa [8]. The degree of interspecies conservation directly correlates with the risk of eliciting unintended pharmacological effects in non-target organisms, with documented effects occurring even at environmentally relevant concentrations (ng/L to μg/L range) [8]. Notable case examples illustrate the severe ecological consequences of such contamination events:

- Diclofenac: Off-label use of this non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug caused catastrophic population declines (>99%) in Gyps vulture species across India and Pakistan due to renal failure following consumption of contaminated cattle carcasses [8] [9].

- Ivermectin: Detection in soil and water environments has raised concerns about its potential role as a source of single- or multi-drug resistance, in addition to its insecticidal effects on ecologically important species [8] [9].

- Amitriptyline: This antidepressant affects feeding behavior and reproduction in freshwater mollusks at low concentrations due to its action on highly conserved serotonin and norepinephrine transporters [9].

Table 1: Documented Ecological Impacts of Pharmaceutical Contaminants

| Pharmaceutical | Ecological Impact | Mechanism | Affected Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diclofenac | Population decline >99% | Renal failure | Gyps vulture species |

| Ivermectin | Ecosystem disruption, potential resistance development | Insecticidal activity | Dung beetles, aquatic organisms |

| Amitriptyline | Altered feeding/reproduction | Serotonin/norepinephrine transport disruption | Freshwater mollusks |

| Estrogenic APIs | Feminization | Vitellogenin upregulation | Male fish species |

The regulatory framework for managing environmental pharmaceutical contamination remains inconsistent. The European Union introduced mandatory chronic ecotoxicity testing for human medicines only in 2006, meaning most legacy drugs registered before this date lack comprehensive ecotoxicity data [8]. Consequently, only approximately 12% of all pharmaceuticals have a complete set of ecotoxicity data, with environmental risk assessment (ERA) data absent for 281 out of 404 APIs used in human medicines on the German market alone [8]. This significant knowledge gap underscores the critical importance of integrating One Health principles—recognizing the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental health—throughout drug development and environmental monitoring workflows.

Analytical Contamination Vectors in Sample Preparation

Within the laboratory environment, sample preparation represents a critical vulnerability point for contamination introduction, particularly through consumables, reagents, and procedural artifacts. Modern sample preparation workflows utilize increasingly sophisticated products that themselves present potential contamination vectors if not properly qualified and controlled. Solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges, QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe) kits, and automated sample preparation instrumentation each present distinct contamination risks that must be systematically managed.

Recent market introductions specifically target the analysis of persistent environmental contaminants like per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), which themselves represent significant analytical contaminants due to their pervasive presence in manufacturing materials and laboratory environments [10]. Key products introduced between 2024-2025 include:

- Captiva EMR-PFAS Food Cartridges: Designed for PFAS analysis in food matrices, these 6-mL cartridges utilize Enhanced Matrix Removal technology but risk introducing PFAS contamination from the cartridge materials if not properly quality-controlled [10].

- Resprep PFAS SPE: Dual-bed SPE cartridges containing weak anion exchange media and graphitized carbon black that may leach fluoropolymer contaminants during extraction [10].

- InertSep WAX FF/GCB and GCB/Wax FF: Featuring alternating bed configurations to provide different selectivity, these cartridges require verification of their "high purity sorbents" to ensure they do not contribute to the analytical background [10].

The increasing automation of sample preparation introduces additional contamination vector considerations. Instruments like the Sielc Samplify automated sampling system and Alltesta Mini-Autosampler, while improving reproducibility, present potential cross-contamination risks through shared fluidic paths, probe surfaces, and vial positioning systems [10]. These systems must incorporate rigorous cleaning protocols and contamination monitoring to prevent sample-to-sample carryover, particularly when handling high-concentration samples preceding low-concentration analyses.

Table 2: Recent Sample Preparation Products and Contamination Considerations

| Product | Type | Application | Potential Contamination Vectors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Captiva EMR-PFAS | SPE cartridge | PFAS in food | Leaching from cartridge materials |

| Resprep PFAS SPE | Dual-bed SPE | Aqueous/solid samples | Fluoropolymer components |

| InertSep WAX/GCB | SPE cartridge | EPA Method 1633 | Sorbent impurities |

| Q-Sep QuEChERS | Extraction salts | PFAS in food/feed | Salt purity, background contamination |

| Samplify | Automated sampler | Liquid sampling | Probe carryover, vial cross-contamination |

| Alltesta Mini-Autosampler | Multi-function autosampler | Fraction collection, reactor sampling | Fluid path memory effects |

Detection and Computational Assessment of Contamination

Robust contamination detection represents a critical component of comprehensive contamination control strategies. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis, particularly in cancer research, has driven the development of sophisticated computational methods for identifying and quantifying sample cross-contamination [11]. These methods primarily leverage genetic data to detect anomalies indicative of contamination events, providing researchers with objective metrics for quality control.

The fundamental principle underlying computational contamination detection involves identifying deviations from expected genetic patterns. In NGS analysis, cross-contamination detection methods utilize variant allele frequency (VAF) distributions, single nucleotide variant (SNV) profiles, and population genetics statistics to identify admixed samples [11]. Key methodologies include:

- ConSPr (Contamination Source Predictor): Identifies potential contamination sources by analyzing shared genetic variants between samples.

- VAF-based methods: Detect contamination through shifts in variant allele frequency distributions that deviate from expected heterozygous or homozygous patterns.

- Population genetics approaches: Utilize deviations from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium or anomalous linkage disequilibrium to identify contaminated samples.

- Similarity-based methods: Identify unexpectedly high genetic similarity between purportedly unrelated samples.

Different computational methods offer complementary strengths, with performance varying based on contamination level, sequencing depth, and the genetic characteristics of the samples involved. Integration of multiple approaches typically provides the most robust contamination detection, particularly for low-level contamination events that might evade detection by individual methods.

Beyond genetic analysis, analytical chemistry approaches employ blank samples, standard reference materials, and matrix spike recoveries to monitor for contamination throughout sample preparation workflows. For environmental pharmaceutical analysis, method blanks are essential for identifying contamination introduced during sample preparation, particularly when analyzing trace-level APIs. The implementation of quality control samples at frequencies recommended by regulatory methods (typically 5-10% of analytical batch size) provides statistical power to identify contamination events and maintain analytical integrity.

Experimental Protocols for Contamination Control

Standardized Environmental Risk Assessment Protocol

The European Medicines Agency's (EMA) guidelines advocate a tiered approach to Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA) for veterinary medicinal products, providing a structured framework for evaluating potential environmental contamination [8]. This protocol can be adapted more broadly for assessing contamination risks in research settings:

Phase I: Initial Exposure Assessment

- Evaluate the environmental exposure potential based on physiochemical characteristics, usage patterns, and disposal pathways

- Calculate Predicted Environmental Concentration (PEC) using standardized models

- Determine if PEC exceeds established thresholds (e.g., PECsoil ≥ 100 μg/kg)

- Products with limited environmental exposure conclude at Phase I

Phase II Tier A: Preliminary Hazard Assessment

- Generate ecotoxicity data using standard model organisms (e.g., Daphnia, algae, fish)

- Calculate Predicted No-Effect Concentration (PNEC)

- Compute PEC/PNEC ratio; proceed to Tier B if ratio >1

Phase II Tier B: Refined Assessment

- Conduct environmental fate studies (hydrolysis, photolysis, biodegradation)

- Perform prolonged ecotoxicity tests with more sensitive endpoints

- Refine PEC and PNEC values based on experimental data

Phase II Tier C: Field Validation

- Execute simulated field studies or mesocosm experiments

- Implement risk mitigation measures if unacceptable risks identified

- Weigh environmental risks against product benefits for approval decisions

Sample Preparation Contamination Control Protocol

Implementing rigorous contamination controls during sample preparation requires standardized procedures for reagent qualification, equipment maintenance, and process verification:

Reagent and Consumable Qualification

- Pre-screen all SPE cartridges and QuEChERS kits using method blanks

- Certify solvent purity through concentrated extracts analyzed by LC-MS/MS

- Establish vendor qualification protocols with acceptance criteria for background contamination

- Implement lot-testing requirements for critical consumables

Instrument Decontamination Procedure

- Execute between-sample needle washes with staggered solvent polarity (water → acetonitrile → methanol → isopropanol)

- Perform weekly system decontamination with 1% Contrad 70 or equivalent detergent

- Validate autosampler carryover using high-low concentration sequences

- Document decontamination efficacy in instrument logs

Process Blank Implementation

- Incorporate method blanks at frequency of 1 per 20 samples minimum

- Include extraction blanks, instrument blanks, and field blanks where applicable

- Establish investigation and corrective action procedures for blank contamination

- Track blank performance metrics for trend analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Prevention

Implementing effective contamination control requires strategic selection and application of specialized reagents and materials. The following toolkit catalogs essential solutions for preventing, detecting, and mitigating contamination across sample preparation workflows.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Prevention

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context | Contamination Control Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Captiva EMR-Lipid HF | Lipid removal cartridge | Fatty sample matrices | Size exclusion with hydrophobic interaction reduces co-extractives |

| Resprep FL+CarboPrep Plus | Dual-bed SPE cartridge | Organochlorine pesticides | Florisil + GCB combination enhances selectivity |

| InertSep QuEChERS kit | Multi-residue extraction | Pesticides, veterinary drugs, mycotoxins | Validated sorbent blends minimize interference |

| Q-Sep QuEChERS salts | Extraction salts | PFAS in food/feed | Certified PFAS-free composition |

| Samplify System | Automated sampling | Unattended liquid sampling | Probe cleaning protocol prevents carryover |

| Alltesta Mini-Autosampler | Multi-function autosampler | Microscale sample handling | Dedicated fluidic paths for different sample types |

| PFAS-free vials and caps | Sample containers | Trace-level PFAS analysis | Certified materials prevent background introduction |

| High-purity solvents | Extraction media | All sensitive applications | LC-MS grade with verified contamination profiles |

| Silanized glassware | Laboratory containers | Trace analysis | Prevents analyte adsorption to surfaces |

| Process blanks | Quality control | All analytical methods | Monitors systemic contamination |

| 1-Benzyl-n-methylcyclopentanamine | 1-Benzyl-N-methylcyclopentanamine|CAS 19166-01-9|RUO | Research-use 1-Benzyl-N-methylcyclopentanamine (CAS 19166-01-9). Explore its potential in scientific studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. | Bench Chemicals |

| (2S)-3-(bromomethyl)but-3-en-2-ol | (2S)-3-(bromomethyl)but-3-en-2-ol|High-Purity | Bench Chemicals |

The selection of appropriate contamination control reagents must be guided by the specific analytical context and potential contamination vectors. For PFAS analysis, this necessitates PFAS-free certified materials throughout the workflow, from SPE cartridges to collection vials [10]. For multi-residue methods targeting diverse analyte classes, balanced sorbent combinations like those in QuEChERS kits provide effective matrix cleanup while minimizing analyte loss [10]. The implementation of automated systems like the Samplify and Alltesta requires validation of cleaning protocols specific to the target analytes and matrices, with particular attention to carryover prevention in high-throughput environments where concentration ranges may vary significantly between samples.

Contamination control in sample preparation represents a multidimensional challenge requiring integrated strategies across environmental, analytical, and procedural domains. The contamination landscape is continuously evolving, driven by increasingly sensitive analytical techniques, expanding regulatory requirements, and growing recognition of the interconnectedness between research quality and environmental impact. Successful navigation of this landscape demands researcher vigilance, methodological rigor, and systematic implementation of the contamination prevention frameworks outlined in this guide. By adopting proactive contamination assessment protocols, leveraging appropriate reagent solutions, validating automated systems, and implementing robust quality control measures, research professionals can significantly enhance data reliability while contributing to the broader scientific goals of reproducibility and environmental stewardship. The principles articulated herein provide a foundational framework for developing contamination-resistant workflows capable of supporting the exacting requirements of modern analytical science across diverse application domains.

In clinical diagnostics and research, the integrity of laboratory results is paramount. The total testing process is a complex pathway that can be segmented into pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical phases. Among these, the pre-analytical phase—encompassing everything from test ordering and patient preparation to sample collection, handling, and transport—has been consistently identified as the most error-prone. A contemporary large-scale study analyzing over 11 million specimens found that a striking 98.4% of all laboratory errors occurred in the pre-analytical phase, impacting approximately 0.79% of all specimens [12]. This phase constitutes the fragile foundation upon which all subsequent analytical processes are built; when compromised, it undermines the entire diagnostic enterprise.

The significance of these errors extends beyond statistical concern—they directly threaten patient safety, research validity, and healthcare economics. With an estimated 60-70% of clinical decisions relying on laboratory results, pre-analytical errors can lead to misdiagnosis, inappropriate treatment, and compromised patient safety [13] [14]. This technical guide examines the mechanisms behind pre-analytical vulnerability, details evidence-based prevention strategies, and provides a contamination-focused framework for researchers and drug development professionals dedicated to sample integrity.

Quantitative Analysis of Pre-analytical Errors

Understanding the distribution and frequency of pre-analytical errors is essential for targeted quality improvement. The following table synthesizes data from recent studies on error rates across the testing continuum:

Table 1: Distribution of Errors in the Laboratory Testing Process

| Testing Phase | Error Rate (% of total errors) | Error Rate (Parts Per Million) | Most Common Error Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-analytical | 46-98.4% | 984,000 PPM | Hemolysis (69.6%), incorrect sample type, collection container errors, insufficient volume [12] [13] |

| Analytical | 0.5-13% | 5,000 PPM | Equipment malfunction, calibration issues, reagent problems [12] [14] |

| Post-analytical | 1.1-19% | 11,000 PPM | Transcription errors, delayed reporting, incorrect interpretation [12] [14] |

When examining specific pre-analytical error types, hemolysis emerges as the dominant concern. One comprehensive study documented 87,317 total errors, of which 60,748 (69.6%) were attributed to hemolysis impacting specimen integrity [12]. The high prevalence of hemolysis underscores the critical importance of proper phlebotomy technique and sample handling procedures. Excluding hemolysis, the remaining pre-analytical errors still account for 94.6% of non-hemolysis related errors, emphasizing that multiple failure points exist throughout the initial testing stages [12].

Table 2: Frequency of Specific Pre-analytical Error Types

| Error Category | Specific Error Types | Relative Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Incorrect patient identification, wrong collection tube, improper order of draw, hemolysis | High |

| Sample Handling | Improper mixing, incorrect storage temperature, prolonged transit time | Medium-High |

| Patient Preparation | Non-fasting, medication interference, improper posture | Medium |

| Sample Transport | Tube breakage, exposure to extreme temperatures, delayed delivery | Medium |

| Pre-labeling | Misidentification, wrong tube pre-labeling | Low-Medium |

The Contamination Pathway in Pre-analytical Processes

Contamination represents a particularly insidious category of pre-analytical error, with the potential to completely invalidate test results and derail research outcomes. In low-biomass microbiome studies, for instance, contaminants can disproportionately influence results, potentially leading to false conclusions about microbial presence [4]. The vulnerability of different sample types to contamination varies significantly, with some materials being exceptionally prone to interference.

Contamination can infiltrate samples at multiple points along the pre-analytical pathway, with different mechanisms operating at each stage:

- Sample Collection: Contamination from skin flora, improper sterilization of collection sites, or non-sterile collection devices [14]

- Sample Processing: Cross-contamination between samples during aliquoting, improper homogenization techniques, or use of contaminated tools [15]

- Reagents and Consumables: Impurities in chemicals, kit contaminants, or DNA/RNA contamination in supposedly sterile disposables [4] [16]

- Environmental Exposure: Airborne particles, contaminated work surfaces, or improper storage conditions [4]

The impact of these contaminants is magnified in molecular techniques like qPCR, where the extreme sensitivity of the method can amplify minuscule contaminating DNA fragments, generating false positives and compromising experimental validity [16]. For low-biomass samples, the contaminant "noise" can easily overwhelm the true biological "signal," leading to fundamentally flawed data interpretation [4].

The Pre-pre-analytical Concept

Recognizing that many errors occur before samples even reach the laboratory, experts have further divided the pre-analytical phase to highlight the "pre-pre-analytical" stage [17]. This sub-phase encompasses initial steps including test requesting, patient preparation, sample labeling, and primary collection. Errors introduced at this stage are particularly problematic as they often escape early detection and propagate through subsequent processes.

Professor Mario Plebani's concept of the "Five Rights" in the pre-pre-analytical phase emphasizes: right patient, right test, right time, right sample collection method, and right transportation [17]. Adherence to these principles establishes a foundation for quality that protects subsequent analytical processes.

Evidence-Based Strategies for Error Reduction

Structural and Process Interventions

Implementing a systematic framework for pre-analytical quality control can yield dramatic improvements in error rates. One recent study applied the Structure-Process-Outcome (SPO) model to pre-analytical quality management with significant success [13]. The intervention included:

- Structural Components: Formation of a multidisciplinary team, establishment of a grid management system with laboratory staff assigned to specific hospital areas, implementation of a non-punitive reporting system for non-compliant specimens, and creation of a dedicated specimen transport team [13]

- Process Components: Diverse training programs aligned with established guidelines, development of comprehensive standard operating procedures (SOPs), optimization of information processes with automated error interception, and introduction of barcode technology for patient and specimen identification [13]

This systematic intervention resulted in significantly lower rates of non-compliance across all measured parameters: sample type, collection container, volume, contaminated blood cultures, and coagulated samples (all p < 0.01) [13]. Additionally, the study documented improved nurse knowledge (Cohen's d = 0.44) and behaviors (Cohen's d = 1.56), along with enhanced operational standardization (92.5 ± 3.2 vs 85.7 ± 4.1), patient satisfaction (93.8% vs 87.2%), and clinical doctor trust (91.2% vs 84.5%) [13].

Diagram 1: SPO Model for Quality Management

Practical Contamination Control Protocols

Sample Collection and Handling

Proper blood collection techniques are fundamental to preventing common pre-analytical errors:

- Minimize Hemolysis: Limit tourniquet time, use appropriately sized needles, allow alcohol disinfectant to fully dry before venipuncture, avoid transferring blood from syringe to tube through a needle, and mix tubes by gentle inversion rather than shaking [14]

- Prevent Cross-Contamination: Adhere to correct order of draw (blood cultures → sodium citrate → gel → lithium heparin → EDTA), avoid collecting blood from intravenous lines or the same arm receiving IV fluids, and never transfer blood between tubes [14]

- Ensure Proper Timing: Collect time-sensitive tests (e.g., cortisol, therapeutic drug monitoring) at appropriate intervals, document drug administration times, and note patient position for affected tests [14]

Laboratory Processing Controls

For sample processing, particularly in sensitive molecular applications, implementing strict contamination control protocols is essential:

- Physical Separation: Establish dedicated pre- and post-amplification areas with separate equipment, supplies, and protective gear [16]. Maintain unidirectional workflow from clean to potentially contaminated areas [4] [16]

- Decontamination Procedures: Regularly clean work surfaces and equipment with 70% ethanol, followed by 10-15% fresh bleach solution for DNA removal, allowing 10-15 minutes contact time before wiping with deionized water [4] [16]

- Personal Protective Equipment: Use appropriate PPE including gloves, lab coats, and in some cases face masks or cleanroom suits to minimize human-derived contamination [4]

- Molecular Safeguards: Incorporate uracil-N-glycosylase (UNG) in qPCR master mixes to prevent carryover contamination from previous amplifications [16]

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Contamination Prevention

| Reagent/Material | Function in Contamination Control | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Hypochlorite (Bleach) | DNA degradation and surface decontamination | Use 10-15% solution, prepare fresh regularly, 10-15 minute contact time [4] [16] |

| 70% Ethanol | Surface disinfection and microbial reduction | Effective for general lab cleaning; does not remove DNA [4] |

| UNG Enzyme | Degrades uracil-containing DNA from previous amplifications | Incorporated into qPCR master mixes; effective against carryover contamination [16] |

| DNA Removal Solutions | Eliminates contaminating DNA from surfaces | Commercial products like DNA Away; critical for DNA-free environments [15] |

| Aerosol-Resistant Filter Tips | Prevents aerosol contamination during pipetting | Essential for sensitive molecular workflows and sample preparation [16] |

Special Considerations for Research Settings

Low-Biomass Microbiome Studies

Research involving low-biomass samples presents unique pre-analytical challenges, as the contaminant signal can easily overwhelm the true biological signal. Consensus guidelines recommend:

- Comprehensive Controls: Include extraction controls, sampling controls (empty collection vessels, air swabs), and PCR controls to identify contamination sources [4]

- Rigorous Decontamination: Beyond standard sterilization, implement DNA removal protocols for all equipment and surfaces [4]

- Environmental Monitoring: Sample the laboratory environment and reagents to establish a contaminant profile [4]

Sample Homogenization Practices

The choice of homogenization method significantly impacts contamination risk:

- Stainless Steel Probes: Durable but require meticulous cleaning between samples, creating potential for cross-contamination and workflow bottlenecks [15]

- Disposable Plastic Probes: Eliminate cross-contamination risk but may lack durability for tough samples [15]

- Hybrid Probes: Combine stainless steel outer shafts with disposable plastic inner rotors, balancing durability and contamination control [15]

Validating cleaning procedures for reusable equipment is essential, including running blank solutions after cleaning to verify absence of residual analytes [15].

The predominance of pre-analytical errors in laboratory testing represents both a formidable challenge and a significant opportunity for quality improvement. The evidence is clear: approximately 75% of laboratory errors originate in the pre-analytical phase, with contamination constituting a major contributor to unreliable results [15]. Addressing this vulnerability requires a systematic approach that integrates structural organization, standardized processes, and continuous quality monitoring.

Successful pre-analytical quality management demands collaboration across disciplines—engaging clinicians, phlebotomists, laboratory scientists, and researchers in a unified system focused on specimen integrity [13] [17]. By adopting evidence-based frameworks like the SPO model, implementing rigorous contamination control protocols, and maintaining vigilance through comprehensive quality indicators, laboratories and research facilities can significantly reduce pre-analytical errors.

The journey toward pre-analytical excellence begins with recognition of a fundamental principle: no degree of analytical sophistication can compensate for a compromised sample. As Professor Plebani aptly observed, "good samples make good assays" [17]. In an era of increasingly sensitive analytical technologies and growing dependence on laboratory data for critical decisions, ensuring the integrity of the pre-analytical phase has never been more essential.

Diagram 2: Laboratory Testing Workflow Phases

Special Considerations for Low-Biomass and High-Sensitivity Applications

Low-biomass environments, which contain minimal native microbial content, present unique challenges for molecular analysis. These include certain human tissues (respiratory tract, placenta, blood), processed pharmaceuticals, drinking water, hyper-arid soils, and the deep subsurface [4] [18]. In these contexts, the DNA from contaminants originating from reagents, laboratory environments, or researchers can equal or exceed the target signal, fundamentally compromising data integrity and biological conclusions [4] [18]. The inherent sensitivity of next-generation sequencing, while powerful, becomes a double-edged sword, efficiently detecting both target sequences and contaminating DNA [19]. This technical guide outlines a systematic framework for preventing, identifying, and mitigating contamination throughout the experimental workflow, from sample collection to data analysis, ensuring the validity of results in low-biomass and high-sensitivity applications.

The table below summarizes the primary contamination types and their impacts:

Table 1: Contamination Types and Their Impacts in Low-Biomass Studies

| Contamination Type | Description | Primary Sources | Impact on Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| External Contaminant DNA | DNA introduced from sources other than the sample [18]. | Reagents, kits, laboratory environment, researchers [4] [18]. | Can be misinterpreted as a genuine signal, leading to false positives and skewed community profiles [18] [20]. |

| Cross-Contamination (Well-to-Well Leakage) | Transfer of DNA or sequence reads between samples processed concurrently [4] [20]. | Adjacent wells on sample plates, aerosol generation during liquid handling [4] [20]. | Creates artificial similarity between samples, obscuring true biological patterns and relationships [20]. |

| Host DNA Misclassification | Predominantly a concern in metagenomics; host DNA is misidentified as microbial [20]. | High abundance of host DNA in samples like human tissue or blood [20]. | Generates noise and can produce artifactual signals if confounded with a phenotype, impeding true signal detection [20]. |

A Proactive Framework for Contamination Prevention

A successful low-biomass study requires a proactive, preventative approach integrated into every stage of experimental design. Relying solely on post-hoc computational correction is insufficient.

Strategic Experimental Design

The single most important step is to avoid batch confounding, where the variable of interest (e.g., case vs. control status) is processed in separate batches [20]. When batches are confounded with the study groups, technical artifacts like varying contamination profiles or processing biases can create false associations [20]. Active randomization or tools like BalanceIT should be used to ensure that batches contain a similar ratio of all sample types and controls [20]. Furthermore, the analysis should assess the generalizability of results across batches to confirm findings are not batch-specific artifacts [20].

Rigorous Pre-Analytical and Laboratory Practices

Contamination control begins before a sample enters the laboratory. During sample collection, all equipment, tools, and vessels should be single-use and DNA-free where possible [4]. When reusables are necessary, thorough decontamination is critical. A two-step process of 80% ethanol (to kill organisms) followed by a nucleic acid degrading solution like sodium hypochlorite (bleach) or commercially available DNA removal products is recommended, as sterility alone does not guarantee the absence of cell-free DNA [4]. Personnel should use appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) including gloves, cleansuits, and masks to act as a barrier against human-derived contamination from skin, hair, or aerosols generated by breathing [4].

Within the lab, meticulous practices continue. The use of disposable plastic consumables, such as homogenizer probes, can virtually eliminate the risk of cross-contamination between samples [15]. For reusable tools, validating cleaning procedures is essential. This can involve running a blank solution through the equipment after cleaning to check for residual analytes [15]. Laboratory surfaces should be routinely decontaminated with solutions like 70% ethanol or 10% bleach, with specialized products like DNA Away used to eliminate persistent nucleic acids [15]. When handling samples in multi-well plates, spinning down plates before seal removal and removing seals slowly and carefully can reduce the risk of well-to-well leakage [15].

Essential Validation and Control Methodologies

Implementing a Comprehensive Control Strategy

The use of process controls is non-negotiable for identifying the nature and extent of contamination [4] [20]. These controls should be included in every processing batch and carried through the entire experimental workflow alongside actual samples.

Table 2: Essential Process Controls for Low-Biomass Studies

| Control Type | Composition & Purpose | When to Collect/Use |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Blank Control | An empty tube that undergoes the full DNA/RNA extraction process [18] [20]. | With every batch of extractions; identifies contaminants from reagents and the extraction process itself [21]. |

| No-Template Control (NTC) | A water sample included during the PCR amplification or library preparation step [20]. | With every amplification batch; identifies contaminants present in polymerase mixes and other amplification reagents [20]. |

| Sampling/Kit Control | An empty collection vessel or a swab exposed to the air in the sampling environment [4]. | During sample collection; identifies contaminants from collection kits and the sampling environment [4]. |

| Positive Control | A known, low-biomass mock community. Validates that the entire workflow can detect expected signals at relevant concentrations. | With each processing batch; assesses sensitivity and detects inhibition. |

It is crucial to collect multiple types of controls and to include them in every batch, as contamination profiles can vary over time and by location [20] [21]. The optimal number of controls is study-dependent, but at least two controls per type per batch are recommended to account for variability [20].

Cleaning Validation Protocol for Laboratory Equipment

For reusable laboratory equipment, a formal cleaning validation protocol ensures effective decontamination. The following methodology, adapted from pharmaceutical quality control, provides a structured approach [22].

- Identify a Worst-Case Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) or Analytic: Select a molecule that is difficult to remove due to low water solubility and/or high potency. The rationale is that a protocol effective for the worst-case analyte will be effective for others [22]. For example, Oxcarbazepine, an anticonvulsant with very low water solubility (0.07 mg/mL), is often used as a benchmark [22].

- Establish Residue Acceptable Limits (RALs): Define a scientifically justified threshold for residual contamination. A common industry standard is 10 ppm of a substance, though study-specific limits based on toxicity or analytical sensitivity may be applied [22] [23].

- Select Solvents for Residue Recovery: Choose solvents that effectively solubilize the target analyte. For Oxcarbazepine, acetonitrile and acetone are suitable due to their high solubility for this compound and common availability [22].

- Perform Recovery Studies Using Swab and Rinse Methods:

- Swab Method: For flat or irregular surfaces (e.g., Petri dishes, spatulas). A polyester swab is pre-wetted with solvent, used to scrub a defined surface area (e.g., 100 cm²) with horizontal and vertical strokes, and then placed in a test tube for extraction before analysis [22].

- Rinse Method: For equipment with internal geometries (e.g., pipes, tubes). A defined volume of solvent (e.g., 10 mL) is agitated within the equipment to ensure contact with all surfaces, and the resulting solution is collected for analysis [22].

- Analyze and Document: Use sensitive analytical techniques (e.g., HPLC) to quantify residue levels. The protocol is validated if results are consistently below the established RAL. This process must be thoroughly documented [22] [23].

The workflow for this validation process is systematic and iterative.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Polyester Swabs | Surface sampling for cleaning validation; chosen for strength and consistency in residue recovery [22]. | Swabbing a 100 cm² area of a glass mortar after cleaning to validate Oxcarbazepine removal [22]. |

| DNA Degrading Solution | Chemically destroys contaminating DNA on surfaces and equipment, going beyond microbial killing [4]. | Decontaminating laboratory benches, pipettors, and reusable tools before setting up PCR reactions [4] [15]. |

| Ultra-Pure Solvents | High-purity acetonitrile and acetone used to dissolve and recover residual analytes during cleaning validation [22]. | Extracting API residues from a swab or as a rinse solvent for laboratory glassware [22]. |

| Disposable Homogenizer Probes | Single-use probes for sample homogenization that eliminate the risk of carryover contamination between samples [15]. | Processing multiple low-biomass tissue samples sequentially without a cleaning step [15]. |

| Phosphate-Free Detergent | Used in manual or automated cleaning of labware; phosphate-free formulations are more environmentally friendly [22]. | Cleaning glassware and stainless-steel equipment in an industrial laboratory washer [22]. |

| Spiro[3.5]nonane-9-carboxylic acid | Spiro[3.5]nonane-9-carboxylic Acid|CAS 1558342-25-8 | Buy Spiro[3.5]nonane-9-carboxylic acid (CAS 1558342-25-8), a C10H16O2 building block for research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| 2,3,3-Trimethyl-5-phenyl-3H-indole | 2,3,3-Trimethyl-5-phenyl-3H-indole|CAS 294655-87-1 |

Data Analysis and Interpretation in a Contamination-Aware Context

Once data is generated, a contamination-aware analytical approach is vital. Data from all process controls must be integrated into the bioinformatic pipeline. Several computational tools can help statistically identify and subtract contaminant sequences based on their prevalence and abundance in controls compared to real samples [4] [20]. However, these methods have limitations, particularly when well-to-well leakage contaminates the negative controls themselves, violating their core assumptions [20]. Therefore, the most robust results are achieved when these tools are used to support conclusions based on a well-designed experiment with extensive controls, rather than to salvage a poorly controlled one.

Finally, reporting standards must be elevated. The research community is moving toward minimal reporting criteria, such as the "RIDE" checklist (Reporting of Ix-D-E), to ensure transparency [18] [19]. Authors should explicitly detail all controls used, the bioinformatic decontamination steps applied, and acknowledge the limitations of their study in the context of potential residual contamination. This level of transparency allows reviewers, editors, and the broader scientific community to accurately assess the validity of the findings.

Building Your Defenses: Practical Protocols for a Contamination-Free Workflow

In molecular biology and diagnostic laboratories, the exquisite sensitivity of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and other amplification techniques makes them vulnerable to contamination from previously amplified products, known as amplicons. A typical PCR reaction can generate as many as 10^9 copies of a target sequence, and if aerosolized, even the smallest droplet can contain up to 10^6 amplification products [24]. Without proper controls, this buildup of aerosolized amplification products will contaminate laboratory reagents, equipment, and ventilation systems, ultimately leading to false-positive results that compromise research integrity and diagnostic accuracy [24].

Documented cases exist where false-positive PCR findings have led to serious consequences, including misdiagnosed cases of Lyme disease (one with fatal outcome) and formal retraction of published manuscripts [24]. Within the broader context of preventing contamination during sample preparation research, the strategic separation of pre- and post-amplification areas represents the most fundamental defense against amplicon carryover contamination. This whitepaper outlines an evidence-based, practical framework for implementing this critical separation, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the knowledge to design laboratories that ensure data reliability and reproducibility.

Understanding Amplification Product Contamination

Amplicon carryover contamination represents the most significant challenge in laboratories performing nucleic acid amplification. The primary sources of contamination include:

- Previously amplified products: The vast quantity of amplicons generated in prior amplification reactions accumulates in the laboratory environment over time [24].

- Plasmid clones: Recombinant plasmids derived from previously analyzed organisms may be present in large numbers in the laboratory environment [24].

- Cross-contamination between samples: High concentrations of target organisms in clinical specimens can lead to contamination between samples during processing [24].

The vulnerability of amplification techniques stems from their designed sensitivity. When working with low-biomass samples, the contaminant "noise" can easily overwhelm the target "signal," leading to spurious results and incorrect conclusions [4]. This is particularly problematic in applications such as pathogen detection, microbial microbiome studies in low-biomass environments, and clinical diagnostics where results directly impact patient care [4].

Consequences of Contamination

The implications of amplification product contamination extend beyond wasted reagents and time:

- Compromised Research Integrity: Contamination can distort ecological patterns and evolutionary signatures, potentially misleading entire research fields [4].

- Diagnostic Errors: In clinical settings, false-positive results can lead to misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment selection, with documented cases of patient harm [24].

- Reproducibility Crisis: Contamination contributes to the broader scientific reproducibility crisis, where published results cannot be replicated by other laboratories [4].

Core Principles of Laboratory Zoning

The Unidirectional Workflow

The foundational principle for preventing amplicon carryover contamination is implementing a strict unidirectional workflow. This means physically separating the laboratory into distinct areas and ensuring that personnel, samples, reagents, and equipment move in a single direction—from clean pre-amplification areas to contaminated post-amplification areas, with no backtracking [24].

All traffic must flow unidirectionally from reagent preparation to sample preparation, to amplification, and finally to amplification product analysis [24]. These areas should be optimally physically separated and preferably situated at a substantial distance from each other [24].

Detailed Zone Specifications

A properly designed amplification laboratory should include at a minimum four distinct physical areas:

1. Reagent Preparation Area (Clean Zone)

- Function: Preparation of master mixes, aliquoting of reagents, and storage of clean materials.

- Features: Positive air pressure relative to other areas, dedicated equipment, UV light source for decontaminating surfaces and equipment [24].

- Critical controls: Access restricted to personnel performing reagent preparation, dedicated laboratory coats and supplies.

2. Sample Preparation Area

- Function: Nucleic acid extraction from clinical or research specimens.

- Features: Physically separated from reagent preparation and amplification areas, dedicated equipment for extraction, biosafety cabinets for processing potentially infectious samples [24].

- Critical controls: Unidirectional movement of samples into this area only, no amplified products permitted.

3. Amplification Area

- Function: Setup of amplification reactions and running of thermal cyclers.

- Features: Restricted access, dedicated equipment, negative air pressure relative to cleaner areas.

- Critical controls: No sample extraction or reagent preparation permitted, physical separation from post-amplification areas.

4. Post-Amplification Analysis Area (Contaminated Zone)

- Function: Analysis of amplification products (e.g., gel electrophoresis, fragment analysis).

- Features: Physically isolated from all pre-amplification areas, dedicated equipment and supplies.

- Critical controls: No movement of materials or personnel back toward cleaner areas, distinct laboratory coats and equipment.

The following diagram illustrates the proper unidirectional workflow and critical control points in a separated lab design:

Laboratory Equipment and Environmental Controls

Specialized Containment Equipment

Proper selection of containment equipment is essential for protecting both samples and personnel. The table below compares the primary types of containment devices used in molecular biology laboratories:

Table 1: Comparison of Laboratory Containment Equipment

| Feature | Biological Safety Cabinet (Class II) | Laminar Flow Cabinet | Chemical Fume Hood |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Protection | Personnel, product, and environment [25] [26] | Product only [27] [25] | Personnel only [26] [28] |

| Air Filtration | HEPA-filtered intake and/or exhaust [25] [26] | HEPA-filtered supply air [27] | No filtration; direct exhaust [26] |

| Airflow Pattern | Laminar, sterile downflow [26] | Laminar flow (horizontal or vertical) [27] | Inward flow of unfiltered lab air [28] |

| Recirculation | Can recirculate HEPA-filtered air (Class II A) [26] | 100% recirculation within workspace [27] | No recirculation; 100% exhaust [28] |

| Ideal Use Case | Sample preparation for nucleic acid extraction [24] | Reagent preparation and master mix aliquoting [27] | Handling volatile chemicals during nucleic acid extraction [26] |

Environmental Monitoring and Decontamination

Rigorous environmental controls are essential for maintaining contamination-free pre-amplification areas:

- Surface Decontamination: Work stations should be cleaned with 10% sodium hypochlorite solution (bleach), which causes oxidative damage to nucleic acids, followed by ethanol removal of the bleach [24]. Note that bleach treatment renders specimens unsuitable for amplification, so it should only be used for surface decontamination [24].

- UV Irradiation: After packages have been opened, all pipettes and disposable devices should be stored in a UV light box. Preparation of amplification master mix and specimen processing should also be carried out in a UV light box [24]. UV light induces thymidine dimers and other covalent modifications in DNA that render contaminating nucleic acid inactive as a template for amplification [24].

- Air Quality Management: Proper ventilation with controlled air pressure differentials (positive pressure in clean areas, negative pressure in contaminated areas) helps prevent aerosolized amplicons from entering clean areas [24].

Procedural Controls and Best Practices

Personnel Management and Training

Human factors represent both the greatest contamination risk and the most powerful control point. Laboratory personnel must receive comprehensive training regarding:

- Awareness of Contamination Sources: Technologists must be alert to the possibility of transferring amplification products on their hair, glasses, jewelry, and clothing from contaminated rooms to clean rooms [24].

- Strict Adherence to Unidirectional Flow: Personnel should complete all tasks in one area before moving to the next, with no backtracking between areas [24].

- Proper Use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Dedicated lab coats, gloves, and other PPE for each area, with color-coding to prevent accidental transfer between areas [4].

Mechanical and Chemical Barriers

Implementation of both mechanical and chemical barriers provides redundant protection against contamination:

- Physical Barriers: Strict separation of laboratory areas with necessary instruments, disposable devices, laboratory coats, gloves, aerosol-free pipettes, and ventilation systems dedicated to each area [24].

- Chemical Barriers: In addition to surface decontamination with bleach, incorporation of enzymatic inactivation methods such as uracil-N-glycosylase (UNG) provides pre-amplification sterilization of potential contaminants [24].

Practical Workflow Implementation

The following workflow diagram details the specific procedures and contamination controls for each laboratory zone:

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The following toolkit details essential materials and reagents for implementing effective contamination control in amplification laboratories:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Uracil-N-Glycosylase (UNG) | Enzymatic degradation of carryover amplicons [24] | Incorporated into PCR mix; hydrolyzes uracil-containing contaminants from previous reactions [24] |

| dUTP | Substitute for dTTP in PCR reactions [24] | Allows incorporation of uracil into amplicons, making them susceptible to UNG degradation [24] |

| Sodium Hypochlorite (Bleach) | Surface decontamination [24] | 10% solution causes oxidative damage to nucleic acids; surfaces must be rinsed with ethanol after use [24] |

| HEPA Filters | Airborne particulate removal [27] [25] | Essential for BSCs and laminar flow cabinets; removes 99.97% of particles ≥0.3μm [27] |

| UV Light Source | Nucleic acid decontamination [24] | Induces thymidine dimers; used to sterilize surfaces and equipment in pre-amplification areas [24] |

| DNA-Decontaminating Solutions | Surface sterilization [4] | Commercial formulations or 80% ethanol followed by DNA removal solutions for sampling equipment [4] |

Validation and Quality Control Measures

Monitoring Contamination

Regular monitoring is essential for detecting contamination events before they compromise experimental results:

- Negative Controls: Multiple negative controls should be included in every amplification run, including no-template controls (NTC) that contain all reaction components except the target nucleic acid [24] [4].

- Environmental Monitoring: Regular swabbing of work surfaces and equipment in pre-amplification areas followed by amplification to detect amplicon contamination [24].

- Reagent Testing: Periodic testing of critical reagents (especially water and master mix components) for the presence of amplifiable nucleic acids [4].

Procedural Audits

Systematic reviews of laboratory procedures help maintain contamination control standards:

- Workflow Audits: Regular assessment of personnel movement and material transfer between areas to ensure compliance with unidirectional workflow [24].

- Equipment Calibration: Annual certification of biological safety cabinets and laminar flow cabinets to ensure proper airflow and filtration [25].

- Documentation Review: Maintenance of detailed records for reagent preparation, lot numbers, and quality control results to facilitate troubleshooting of contamination events [4].

Strategic laboratory design with strict physical separation of pre- and post-amplification areas represents the cornerstone of effective contamination prevention in molecular biology research and diagnostics. When implemented as part of a comprehensive approach that includes appropriate equipment selection, procedural controls, and rigorous quality monitoring, this separation provides the foundation for reliable, reproducible amplification results.

The unidirectional workflow principle, coupled with mechanical barriers, chemical decontamination, and enzymatic sterilization methods, creates a multi-layered defense against amplicon carryover contamination. As amplification technologies continue to evolve toward greater sensitivity and throughput, maintaining these fundamental contamination control practices becomes increasingly critical for research integrity and diagnostic accuracy.

By adopting the evidence-based strategies outlined in this whitepaper, researchers and laboratory managers can create environments that support robust molecular analysis while minimizing the risk of false-positive results due to amplification product contamination.

In sample preparation research, the integrity of scientific findings depends fundamentally on the effectiveness of decontamination protocols. Contaminating biological molecules, particularly DNA, can compromise experiments, lead to erroneous conclusions, and set back drug development timelines. Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) remain a significant patient safety risk, with approximately 1.7 million cases reported annually in the United States alone, highlighting the critical importance of stringent environmental cleaning protocols [29]. The enduring challenge of infections caused by surface-surviving pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridioides difficile demands a comprehensive approach to environmental design that supports optimal cleaning and disinfection protocols [29].

Within research laboratories, the challenge extends to invisible contaminants that can jeopardize months of careful work. DNA contamination presents particular difficulties for sensitive techniques like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and next-generation sequencing. Recent studies have confirmed that bacterial DNA contamination is present in seven of nine commercially available PCR enzyme products, originating from a variety of bacterial species [30]. This contamination can lead to the false detection of bacterial communities in samples that should be sterile, potentially invalidating critical research findings in microbiome studies and drug development [30].

The interaction between surface materials and cleaning efficacy further complicates decontamination strategies. Research demonstrates that material characteristics such as porosity, texture, and chemical composition significantly affect pathogen survival and the success of disinfection efforts [29]. Nonporous, smooth materials in high-touch areas have been shown to support more effective infection prevention due to their compatibility with both chemical and non-chemical disinfection methods [29]. This technical guide provides researchers with evidence-based strategies for selecting and implementing decontamination protocols that protect sample integrity throughout the research workflow.

Decontamination Fundamentals: Principles and Definitions

Key Terminology and Mechanisms

Establishing effective decontamination protocols begins with understanding the precise terminology and mechanisms involved. According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines adopted in recent scientific reviews, the following definitions are essential [29]:

- Cleaning refers to the physical removal of soil, dust, and organic matter from surfaces, typically using water, detergents, and mechanical action. This process does not necessarily destroy microorganisms but reduces their numbers and removes organic material that might protect them.

- Disinfection refers to the use of chemical or physical agents (e.g., disinfectant wipes, sprays, or UV light) to kill or inactivate pathogenic microorganisms on surfaces. Unlike sterilization, disinfection does not eliminate all microorganisms but reduces them to a level safe for public health.

- Decontamination is a broader term that includes both cleaning and disinfection steps to render a surface safe for use.

- Sanitation is generally defined as reducing microbial contamination to a level considered safe by public health standards, often without specifying the methods used.

The efficacy of decontamination agents depends on their mechanism of action. Chemical disinfectants like sodium hypochlorite (bleach) exert their effects through protein denaturation and irreversible oxidation of organic compounds [31]. Alcohols, most effective at 60-90% concentration, cause membrane damage and protein denaturation, relying on water molecules for optimal virucidal activity [31]. Physical methods like UV radiation damage DNA through oxidation of bases, introducing single- and double-strand breaks in DNA molecules [32].

The Research Context: Special Considerations for Sample Preparation

In research environments, particularly those involving molecular techniques, decontamination requirements extend beyond pathogen control to include the elimination of trace nucleic acids that could contaminate sensitive experiments. The consequences of contamination are particularly severe in fields like microbiome research, forensic analysis, and drug development, where minute quantities of contaminating DNA can generate false results.

The stability and ubiquity of DNA in the environment make nucleic acid contamination of laboratory consumables and reagents nearly inevitable [30]. This has led to the coining of the term "kitome" – contaminating bacterial sequences that result from laboratory consumables and nucleic acid isolation kits [30]. Despite widespread knowledge of this issue, only a minority of microbiome papers report using methodology to control for contamination, and most studies lack specific negative controls [30].

The sensitivity of modern analytical techniques exacerbates these challenges. Improved typing kits for forensic analysis may allow STR profiling on DNA extracted from only a few cells, while mitochondrial DNA analysis permits testing of even lower DNA input amounts due to the high copy number of mtDNA in each cell [32]. At these sensitivity levels, eliminating potential sources of contamination through rigorous decontamination protocols becomes essential for research validity.

Quantitative Comparison of Decontamination Strategies

Chemical Agent Efficacy on Different Surface Types

The efficiency of decontamination strategies varies significantly based on the cleaning agent, application method, and surface material. A 2022 study systematically evaluated ten different cleaning strategies for their ability to remove contaminating DNA molecules from plastic, metal, and wood surfaces [32]. The results demonstrated substantial differences in DNA removal efficiencies between cleaning strategies and across different surfaces.

Table 1: Efficiency of Cleaning Strategies for Cell-Free DNA Removal Across Surfaces [32]

| Cleaning Agent | Plastic (% DNA Recovered) | Metal (% DNA Recovered) | Wood (% DNA Recovered) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No treatment (Control) | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| 70% Ethanol | 19.8% | 3.3% | 4.3% |

| UV Radiation (20 min) | 2.9% | 0.6% | 0.3% |

| Ethanol + UV | 0.9% | 0.2% | 0.1% |

| Fresh Bleach (0.54%) | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Stored Bleach (0.4%) | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| 1% Virkon | 0.004% | 0.002% | 0.001% |

| 10% Trigene | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.3% |