Solvent Selection Guide for UV-Vis and FT-IR Spectroscopy: Principles, Applications, and Troubleshooting for Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical principles and practical methodologies for solvent selection in UV-Vis and FT-IR spectroscopy.

Solvent Selection Guide for UV-Vis and FT-IR Spectroscopy: Principles, Applications, and Troubleshooting for Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical principles and practical methodologies for solvent selection in UV-Vis and FT-IR spectroscopy. It covers the foundational science behind how solvents interact with electromagnetic radiation, details best practices for method development and sample preparation across various applications, and offers advanced troubleshooting techniques to optimize spectral quality. By presenting a direct comparative analysis of solvent requirements for both techniques and validating choices with real-world case studies, this guide serves as an essential resource for ensuring analytical accuracy, reproducibility, and efficiency in pharmaceutical and biomedical research.

The Science of Light-Matter Interactions: How Solvents Influence UV-Vis and FT-IR Spectra

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is an analytical technique that measures the amount of discrete wavelengths of UV or visible light absorbed by a sample in comparison to a reference or blank sample [1]. This property is influenced by the sample composition, providing information about what is in the sample and at what concentration [1]. The technique is widely used in diverse applied and fundamental applications, with the only requirement being that the sample absorbs in the UV-Vis region, meaning it must contain a chromophore [2].

Chromophores are molecules in a given material that absorb particular wavelengths of visible light, and in doing so confer color on the material [3]. In organic compounds, chromophores are typically pi-electron functions and hetero atoms having non-bonding valence-shell electron pairs [4]. The energy associated with the UV-Vis spectrum is sufficient to promote or excite a molecular electron to a higher energy orbital, which is why absorption spectroscopy carried out in this region is sometimes called "electronic spectroscopy" [4].

Table: The Electromagnetic Spectrum Relevant to UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Region | Wavelength Range | Energy Transitions |

|---|---|---|

| Ultraviolet (UV) | 200 - 400 nm | Electronic transitions (σ-σ, n-σ, π-π, n-π) |

| Visible | 400 - 780 nm | Electronic transitions (primarily π-π* and n-π*) |

| Near Infrared (NIR) | 780 - 3000 nm | Molecular overtones and combination bands |

Electronic Transitions in Molecular Orbitals

When a molecule absorbs UV or visible light, one of its electrons jumps from a lower energy to a higher energy molecular orbital [5]. The specific amount of energy needed is determined by the electronic structure of the molecule, with different bonding environments requiring different energy inputs [1].

The most common electronic transitions in organic chromophores can be understood through the molecular orbital model. When a molecule absorbs light with energy equal to the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) to Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO) energy gap, this energy is used to promote an electron from the HOMO to the LUMO [5].

Types of Electronic Transitions

For organic chromophores, four possible types of transitions are recognized [2]:

σ-σ* transitions: These require the most energy and occur at very short wavelengths (below 150 nm). An example is molecular hydrogen (H₂), which undergoes a σ-σ* transition at 111 nm [5].

n-σ* transitions: These involve the promotion of a non-bonding electron to an antibonding σ* orbital and typically occur in the 150-250 nm range.

π-π* transitions: These are the most common transitions observed in UV-Vis spectroscopy of conjugated systems. They involve the promotion of an electron from a π bonding orbital to a π* antibonding orbital. In ethene, this transition occurs at 165 nm, but with conjugation, the energy gap decreases, shifting the absorption to longer wavelengths [5].

n-Ï€* transitions: These involve the promotion of a non-bonding electron (often on oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur atoms) to a Ï€* antibonding orbital. These transitions are forbidden by selection rules, resulting in lower intensity absorption (ε typically 10-100 L molâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â¹) [4] [5].

Diagram: Electronic transitions in UV-Vis spectroscopy. The arrows show the four primary transition types with their relative energy requirements.

Transition Probabilities and Molar Absorptivity

The probability that light of a given wavelength will be absorbed when it strikes a chromophore is expressed through the molar absorptivity (ε) [4]. Molar absorptivities may be very large for strongly absorbing chromophores (>10,000 L molâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â¹) and very small if absorption is weak (10 to 100 L molâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â¹) [4]. The magnitude of ε reflects both the size of the chromophore and the probability of absorption [4].

The general relationship is expressed as: ε = 0.87 × 10²Ⱐ× P × a, where P is the transition probability (0 to 1) and a is the chromophore area in cm² [4]. For example, the n→π* transition of an isolated carbonyl group is lower in energy (λmax = 290 nm) than the π→π* transition (λmax = 180 nm), but the ε of the former is a thousand times smaller than the latter due to poor orbital overlap [4].

The Chromophore Concept and Conjugation

A chromophore is the part of a molecule responsible for its color, consisting of molecular components that absorb specific wavelengths of light [3] [2]. The presence of chromophores in a molecule is best documented by UV-Vis spectroscopy [4]. In organic compounds, the most significant chromophores are those with conjugated π-electron systems [4].

The Effect of Conjugation

Conjugation has a profound effect on the absorption characteristics of chromophores. As conjugated pi systems become larger, the energy gap for a π-π* transition becomes increasingly narrow, and the wavelength of light absorbed correspondingly becomes longer [5]. This bathochromic shift (red shift) moves absorption maxima toward longer wavelengths.

Table: Effect of Conjugation on Absorption Maxima

| Compound | Number of Conjugated Double Bonds | λmax (nm) | ε (L molâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethene | 1 | 165 | - |

| 1,3-Butadiene | 2 | 217 | 20,000 |

| 1,3,5-Hexatriene | 3 | 258 | - |

| β-Carotene | 11 | 470 | 15,000 |

In molecules with extended pi systems, the HOMO-LUMO energy gap becomes so small that absorption occurs in the visible rather than the UV region of the electromagnetic spectrum [5]. Beta-carotene, with its system of 11 conjugated double bonds, absorbs light with wavelengths in the blue region of the visible spectrum while allowing other visible wavelengths – mainly those in the red-yellow region – to be transmitted, which is why carrots are orange [5].

Instrumentation and Measurement Principles

UV-Vis Spectrophotometer Components

A UV-Vis spectrophotometer consists of several key components [1]:

Light Source: Commonly a xenon lamp for both UV and visible ranges, or two lamps (tungsten/halogen for visible and deuterium for UV) [1].

Wavelength Selector: Monochromators containing diffraction gratings (typically 1200-2000 grooves per mm) are most common, though absorption and interference filters are also used [1].

Sample Holder: Quartz cuvettes are required for UV examination because quartz is transparent to most UV light, while glass and plastic absorb UV radiation [1].

Detector: Photomultiplier tubes (PMT), photodiodes, or charge-coupled devices (CCDs) convert transmitted light into an electronic signal [1].

Diagram: Schematic workflow of a UV-Vis spectrophotometer showing key components and their sequence in the measurement process.

The Beer-Lambert Law

UV-Vis spectroscopy is routinely used for quantitative determination of diverse analytes using the Beer-Lambert law [2]. This law states that the absorbance of a solution is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species in the solution and the path length [2]. The mathematical relationship is expressed as:

A = ε × c × L

Where:

- A is the measured absorbance (dimensionless)

- ε is the molar absorptivity or extinction coefficient (L molâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â¹)

- c is the concentration of the absorbing species (mol Lâ»Â¹)

- L is the path length of light through the sample (cm)

The Beer-Lambert law is useful for characterizing many compounds but does not hold as a universal relationship for all substances [2]. Deviations can occur at high concentrations due to saturation and absorption flattening, or due to chemical changes in the sample [2].

Experimental Protocols for UV-Vis Spectroscopy

Sample Preparation Protocol

Materials Required:

- UV-transparent solvent (spectroscopic grade)

- Quartz cuvettes (for UV measurements) or glass/plastic cuvettes (visible only)

- Analytical balance

- Volumetric flasks

- Pipettes and micropipettes

Procedure:

Solvent Selection: Choose an appropriate solvent that does not absorb significantly in the spectral region of interest. Common solvents for UV-Vis include water, ethanol, hexane, and dichloromethane [2]. Ensure the solvent is spectroscopic grade to minimize impurities.

Sample Solution Preparation:

- Weigh an appropriate amount of analyte to achieve the desired concentration.

- Dissolve the analyte in the selected solvent using a volumetric flask.

- Typical concentrations should yield absorbance values between 0.1 and 1.0 AU for reliable measurements [1].

Reference Solution Preparation: Prepare a blank solution containing only the solvent used for sample preparation.

Cuvette Handling:

- Use quartz cuvettes for measurements below 350 nm [1].

- Ensure cuvettes are clean and free of scratches.

- Fill cuvettes appropriately, avoiding bubbles.

- Wipe the transparent surfaces with lint-free tissue before placement in the sample compartment.

Instrument Operation and Data Collection Protocol

Materials Required:

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Matched quartz cuvettes

- Computer with spectrometer control software

Procedure:

Instrument Initialization:

- Turn on the spectrophotometer and allow the lamp to warm up for 15-30 minutes.

- Initialize the control software and select appropriate parameters:

- Wavelength range (typically 200-800 nm for full UV-Vis scan)

- Scan speed

- Spectral bandwidth (typically 1-2 nm for most applications)

- Data interval

Baseline Correction:

- Place the reference solution in the light path.

- Run a baseline correction to account for solvent absorption and instrumental characteristics.

Sample Measurement:

- Replace the reference with the sample solution.

- Run the spectral scan according to instrument instructions.

- For quantitative analysis, measure at the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax).

Data Analysis:

- Identify λmax from the absorption spectrum.

- Calculate molar absorptivity using the Beer-Lambert law if concentration is known.

- For quantitative analysis, prepare a calibration curve using standard solutions of known concentrations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Reagents and Materials for UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Item | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample holder for UV measurements | Transparent down to 200 nm; more expensive than glass/plastic |

| Spectroscopic Grade Solvents | Dissolve samples without interfering absorbance | Low UV cutoff essential; common choices: water, acetonitrile, hexane |

| Deuterium Lamp | UV light source for spectrophotometer | Typical lifespan 1000 hours; requires replacement when output declines |

| Tungsten/Halogen Lamp | Visible light source | Complements deuterium lamp in many instruments |

| NIST-Traceable Standards | Instrument calibration and validation | Verify wavelength and photometric accuracy periodically |

| Diffraction Gratings | Wavelength selection in monochromator | Ruled vs. holographic; groove density affects resolution |

| Arecaidine hydrobromide | Arecaidine hydrobromide, CAS:6013-57-6, MF:C7H12BrNO2, MW:222.08 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Meclofenamic Acid | Meclofenamic Acid, CAS:644-62-2, MF:C14H11Cl2NO2, MW:296.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Solvent Effects in UV-Vis Spectroscopy

The choice of solvent significantly influences UV-Vis absorption spectra through solvatochromism - the shift in absorption maxima due to solvent-solute interactions [6]. These effects must be carefully considered in experimental design and data interpretation.

Solvent Polarity Effects on Different Transitions

The direction and magnitude of solvent-induced shifts depend on the type of electronic transition [6]:

π-π* Transitions: Generally exhibit a bathochromic shift (red shift) with increasing solvent polarity. For example, the peaks in the UV spectrum of benzene shift slightly toward the red portion of the spectrum when changing the solvent from hexane to methanol [6]. This occurs because the drop in energy of the π*-orbital is more than that of the π-orbital in polar solvents [6].

n-π* Transitions: Typically show a hypsochromic shift (blue shift) with increasing solvent polarity. For instance, the peaks in the 320-380 nm portion of the UV absorption spectrum of pyridine shift noticeably toward the blue portion of the spectrum when changing the solvent from hexane to methanol [6]. This occurs because the non-bonding electrons form hydrogen bonds with polar protic solvents, stabilizing the n-orbital more than the π*-orbital [6].

Practical Solvent Selection Guidelines

When selecting solvents for UV-Vis spectroscopy:

- Choose solvents with low UV cutoff values to minimize interference in the spectral region of interest

- Consider solvent polarity matching the chemical nature of the analyte

- Use the same solvent for all comparative studies

- Document solvent identity, purity, and preparation methods thoroughly

- For temperature-dependent studies, select solvents with appropriate freezing/boiling points

Recent advances in computational methods, including machine learning approaches, have shown promise in predicting UV-Vis absorption maxima of organic compounds in different solvents like dichloromethane, aiding in solvent selection for specific applications [7].

Advanced Applications and Data Interpretation

Spectral Fitting and Analysis

Advanced analysis of UV-Vis spectra may involve fitting procedures to extract quantitative information. The Pekarian function (PF) has been modified for fitting UV-Vis absorption and fluorescence spectra of organic conjugated compounds in solution with high accuracy and reproducibility [8]. This approach optimizes five parameters that define band shape for both vibronically resolved and unresolved bands [8].

For complex spectra with overlapping bands, multiple PF components may be required, each with its own set of fitting parameters [8]. The results of such fitting procedures can be compared with theoretical excitation energies calculated using time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) for comprehensive interpretation [8].

Method Validation and Quality Control

To ensure reliable UV-Vis results:

- Verify instrument performance using certified reference materials

- Control stray light levels, as it can cause significant errors in absorbance measurements, especially at high absorbances [2]

- Maintain proper spectral bandwidth settings based on application requirements

- Regularly calibrate wavelength and photometric accuracy

- Document all instrumental parameters and sample preparation details

Understanding these core principles of electronic transitions and the chromophore concept provides the foundation for effective application of UV-Vis spectroscopy across chemical, biological, and materials science research, particularly in the context of solvent selection for method development.

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy is a powerful, non-destructive analytical technique used to characterize molecular structures by measuring the absorption of infrared light. When IR radiation interacts with a sample, specific frequencies are absorbed, corresponding to the vibrational energies of chemical bonds within the molecules. This produces a unique spectral pattern that serves as a chemical fingerprint for substance identification and characterization. The foundational principle of infrared spectroscopy dates back to the discovery of IR light by Sir William Herschel in the 1800s, who found that invisible light beyond the red portion of the spectrum produced more heat than visible colors. The technique was later developed for chemical analysis by William Weber Coblentz in the early 1900s, who created the first IR spectra and characterized various compounds [9].

The significant advancement in this field came with the development of FT-IR spectroscopy, which superseded the original, time-consuming dispersive IR method. Unlike earlier techniques that checked each frequency individually, FT-IR uses an interferometer to examine all wavelengths simultaneously. This approach, followed by a mathematical Fourier transform to convert raw data into recognizable spectra, provides superior speed, accuracy, and signal-to-noise ratio compared to traditional IR spectroscopy [9] [10]. Today, FT-IR serves as an indispensable tool across numerous fields, including pharmaceutical development, environmental monitoring, materials science, and biomedical research, enabling both qualitative identification and quantitative analysis of complex chemical mixtures [9] [10].

Theoretical Foundations: Molecular Vibrations

The Nature of Infrared Light and Molecular Interactions

Infrared light occupies the electromagnetic spectrum between visible light and microwaves, with wavelengths ranging from 780 nm to 1 mm. In spectroscopic practice, IR light is categorized into near-infrared (NIR), mid-infrared (MIR), and far-infrared (FIR), with MIR being most commonly used for chemical analysis because its energy corresponds precisely with molecular vibrational frequencies [9]. Rather than using wavelength, IR spectroscopy typically employs wavenumbers (cmâ»Â¹), which indicate the number of wavelengths per unit distance and are directly proportional to energy [9].

The absorption of IR radiation occurs due to the interaction between the alternating electric field of IR light and molecular dipoles. For a molecule to be IR-active, it must undergo a net change in dipole moment during vibration or rotation. When the frequency of IR radiation matches the natural vibrational frequency of a molecular bond, energy is absorbed, altering the amplitude of molecular vibration [11]. This quantized energy absorption promotes molecules to higher vibrational energy states, creating characteristic absorption patterns that form the basis of spectral analysis [11].

Molecular Vibrations and Chemical Fingerprints

Atoms in chemical compounds are in constant motion, vibrating through various modes. Even simple molecules exhibit complex vibrational patterns. For example, a water molecule has six distinct vibrations: symmetric stretching, antisymmetric stretching, deformation (bending), rocking, twisting, and wagging [9]. Each vibration occurs at a frequency unique to the specific chemical bond and molecular structure, coinciding with frequencies in the MIR region (approximately 4000-400 cmâ»Â¹) [9].

When IR light passes through a sample, molecules absorb specific frequencies that excite their vibrational modes. A detector then identifies which frequencies were absorbed, and this information is plotted as an IR spectrum [9]. Since each chemical compound possesses a unique combination of bonds and functional groups, each produces a distinct spectral pattern—a chemical fingerprint that enables identification even in complex mixtures [9] [11]. Over decades, spectral libraries containing thousands of chemical fingerprints have been compiled, making IR spectroscopy particularly accessible for researchers who may not be experts in spectroscopic theory [9].

Table: Fundamental Molecular Vibrations in IR Spectroscopy

| Vibration Type | Description | Characteristic Frequencies (cmâ»Â¹) | Example Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-H Stretching | Strong, broad band due to hydrogen bonding | 3200-3600 | Water, Alcohols |

| N-H Stretching | Sharper than O-H, medium intensity | 3300-3500 | Amines, Amides |

| C-H Stretching | Multiple sharp bands | 2850-3000 | Hydrocarbons |

| C=O Stretching | Strong, sharp band | 1650-1750 | Aldehydes, Ketones |

| C-O Stretching | Strong, broad band | 1000-1300 | Alcohols, Esters |

Solvent Effects in Spectroscopic Analysis

Fundamental Solvent-Solute Interactions

In both UV-Vis and FT-IR spectroscopy, the choice of solvent profoundly influences spectral properties through specific interactions (such as hydrogen bonding) and non-specific effects (including dipole-dipole and polarization interactions) [12] [13]. These solvent-solute interactions can alter electronic transitions in UV-Vis spectroscopy and vibrational frequencies in FT-IR spectroscopy, making solvent selection a critical methodological consideration [6] [12].

For UV-Vis spectroscopy, solvent polarity significantly affects the position and intensity of absorption maxima, particularly for n→π* and π→π* transitions [6] [14]. In FT-IR spectroscopy, solvents can cause frequency shifts and intensity changes by modifying the electronic environment and vibrational coupling within molecules [12] [13]. Recent studies on benzaldehyde and metronidazole demonstrate how solvent effects can be systematically investigated using FT-IR spectroscopy combined with computational methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) [12] [13].

Characteristic Spectral Shifts

The direction and magnitude of solvent-induced spectral changes follow predictable patterns based on the nature of the electronic transition or vibrational mode:

n→π* transitions: These typically exhibit hypsochromic (blue) shifts in polar solvents because the ground state (with two non-bonding electrons) is stabilized more effectively through hydrogen bonding than the excited state (with one n electron) [6] [14]. For example, pyridine shows a blue shift in the 320-380 nm range when changing solvent from hexane to methanol [6].

π→π* transitions: These generally display bathochromic (red) shifts in polar solvents because the more polar excited state experiences greater stabilization than the ground state [6] [14]. Benzene demonstrates this effect with a slight red shift when moving from hexane to methanol [6].

Carbonyl stretching vibrations: The C=O stretching frequency is particularly sensitive to solvent effects. In benzaldehyde, the carbonyl stretching frequency decreases in polar solvents due to enhanced dipole-dipole interactions and possible hydrogen bonding [12].

Table: Solvent Effects on Spectral Transitions and Vibrations

| Transition/Vibration | Solvent Change | Observed Shift | Physical Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| n→π* (UV-Vis) | Non-polar → Polar | Hypsochromic (Blue) | Greater stabilization of ground state via H-bonding |

| π→π* (UV-Vis) | Non-polar → Polar | Bathochromic (Red) | Greater stabilization of excited state |

| C=O Stretch (FT-IR) | Non-polar → Polar | Frequency Decrease | Dipole-dipole interactions and H-bonding |

| O-H Stretch (FT-IR) | Non-polar → Polar | Broadening & Shift | Intermolecular H-bonding |

Experimental Protocols for Studying Solvent Effects

Protocol 1: Investigating Solvent Effects on Carbonyl Stretching Frequencies

Objective: To characterize the effect of solvent polarity on the carbonyl stretching frequency of benzaldehyde using FT-IR spectroscopy [12].

Materials and Reagents:

- Benzaldehyde (analytical grade)

- Spectroscopic-grade solvents: n-hexane, carbon tetrachloride, dichloromethane, methanol

- FT-IR spectrometer with liquid cell (KRS-5 windows, 0.5 mm pathlength)

- Volumetric flasks (10 mL)

- Micropipettes

Procedure:

- Prepare benzaldehyde solutions (4.0-5.0 × 10â»Â³ mol Lâ»Â¹) in each solvent using volumetric flasks.

- Record background spectrum for each pure solvent using the liquid cell.

- Load each benzaldehyde solution into the liquid cell and acquire FT-IR spectra (100 scans at 2 cmâ»Â¹ resolution).

- Identify the carbonyl stretching band in each spectrum (approximately 1700 cmâ»Â¹ region).

- Record the exact peak maximum for each solvent.

- Plot carbonyl frequency versus solvent polarity parameter (e.g., dielectric constant).

Data Analysis:

- The carbonyl stretching frequency typically decreases with increasing solvent polarity.

- In benzaldehyde, the frequency shifts from approximately 1706 cmâ»Â¹ in hexane to 1693 cmâ»Â¹ in methanol [12].

- Compare experimental results with theoretical predictions from DFT calculations using appropriate solvation models.

Protocol 2: Monitoring Hydrogen Bonding Effects in Drug Molecules

Objective: To evaluate solvent-induced hydrogen bonding in metronidazole using FT-IR spectroscopy [13].

Materials and Reagents:

- Metronidazole reference standard

- Deuterated water (Dâ‚‚O) and deuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO-d6)

- FT-IR spectrometer with ATR accessory (diamond crystal)

- Mortar and pestle for solid sample preparation

Procedure:

- Acquire background spectrum of clean ATR crystal.

- Place solid metronidazole directly on ATR crystal and acquire spectrum (4 cmâ»Â¹ resolution, 32 scans).

- Prepare saturated solutions of metronidazole in Dâ‚‚O and DMSO-d6.

- Apply each solution to ATR crystal and acquire solution spectra.

- Identify key functional groups (O-H, N-H, C=O, C-N stretches) in each spectrum.

- Note frequency shifts and bandwidth changes between solid and solution states.

Data Analysis:

- Compare vibrational frequencies in different environments.

- Broader O-H and N-H bands in Dâ‚‚O indicate stronger hydrogen bonding.

- Increased dipole moment in polar solvents correlates with enhanced solubility and reactivity [13].

FT-IR Measurement Techniques and Applications

Sampling Techniques in FT-IR Spectroscopy

Modern FT-IR instruments support multiple sampling geometries, each with distinct advantages for specific sample types:

Transmission: The original IR technique where light passes directly through the sample. It requires careful sample preparation, such as diluting solids with KBr or using thin slices, to avoid total absorbance. While it provides high-quality spectra, the extensive preparation is time-consuming and often destructive, making it suitable primarily for specific applications like polymer films or FT-IR microscopy [9].

Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR): Now the most popular technique, ATR requires minimal sample preparation. The sample is placed on a crystal (diamond, ZnSe, or Ge), and IR light undergoes internal reflection, interacting only with the first few microns of the sample. This non-destructive method produces high-quality spectra for solids, liquids, and gels without extensive preparation [9] [10].

Reflection Techniques: These methods detect IR light reflected from sample surfaces. Diffuse Reflectance (DRIFTS) collects scattered light from powders; Specular Reflection examines light bounced off reflective surfaces; and Reflection-Absorption analyzes thin samples on reflective substrates. These are particularly valuable for analyzing catalysts, soils, coatings, and large solid samples [9].

Table: Comparison of FT-IR Sampling Techniques

| Technique | Sample Preparation | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission | Extensive (KBr pellets, thin films) | Polymer films, proteins, forensic analysis | High-quality spectra, quantitative accuracy | Time-consuming, often destructive |

| ATR | Minimal (direct placement) | Pharmaceuticals, biological samples, liquids | Rapid analysis, non-destructive, minimal preparation | Spectral differences vs. transmission |

| DRIFTS | Moderate (dilution with KBr) | Powders, soils, catalysts | Effective for scattering samples | Requires careful sample preparation |

| Specular Reflection | Minimal | Surface layers, gemstones, art restoration | Non-contact, suitable for large samples | Limited to reflective surfaces |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Reagents for FT-IR Spectroscopy Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | IR-transparent matrix for solid samples | Used for transmission measurements; must be dry and spectroscopic grade [9] |

| Diamond ATR Crystal | Internal reflection element | Robust, chemical-resistant surface for ATR measurements [9] [10] |

| Deuterated Solvents (CDCl₃, D₂O) | Solvents for NMR and IR | Minimize interfering absorption bands in regions of interest |

| Carbon Tetrachloride (CClâ‚„) | Non-polar solvent for dilution | Transparent above 1600 cmâ»Â¹; useful for non-polar samples [9] |

| Spectroscopic-grade Methanol | Polar protic solvent | Studies hydrogen bonding effects; transparent above 210 nm [6] |

| n-Hexane | Non-polar solvent | Reference solvent for studying polarity effects; transparent in UV and IR regions [6] [12] |

| Clavamycin A | Clavamycin A|C16H22N4O9|CAS 103059-93-4 | Clavamycin A is a clavam antibiotic with strong anti-candida activity for microbiology research. This product is For Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human use. |

| Dehydropipernonaline | Dehydropipernonaline|CAS 107584-38-3|For Research |

Advanced Applications in Drug Development and Research

FT-IR spectroscopy provides valuable insights throughout the drug development pipeline, from initial compound characterization to formulation optimization and quality control.

In preformulation studies, FT-IR helps identify potential interactions between drug candidates and excipients by monitoring shifts in characteristic functional group vibrations [10]. For protein therapeutics, FT-IR quantifies secondary structure elements (α-helix, β-sheet) through analysis of the amide I and II bands (approximately 1600-1700 cmâ»Â¹), with reproducibility exceeding 90% in replicate spectra [10]. The technique also monitors conformational changes induced by environmental factors like pH, temperature, or denaturants [10].

Recent advances combine experimental FT-IR with computational chemistry. Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations predict vibrational frequencies and model solvent effects using approaches like the Conductor-like Polarizable Continuum Model (CPCM) [12] [15] [13]. This combined approach provides deeper insight into molecular interactions and reaction mechanisms in solution environments [12].

In drug delivery systems, FT-IR-ATR verifies the successful immobilization of active molecules in polymer matrices, detecting functional groups indicative of both covalent and non-covalent interactions [10]. This application supports the development of advanced biomaterials and implant coatings with controlled release properties [10].

FT-IR spectroscopy provides an indispensable platform for molecular characterization across the drug development continuum. The technique's foundation in molecular vibration analysis yields unique chemical fingerprints that enable precise compound identification, quantification, and interaction assessment. Understanding solvent effects is paramount, as solvent-solute interactions significantly influence spectral properties through hydrogen bonding, dipole-dipole interactions, and polarity effects.

The integration of FT-IR with computational methods like Density Functional Theory represents a powerful approach for deconvoluting complex solvent effects and predicting molecular behavior in different environments. For research and development scientists, mastery of FT-IR principles, sampling techniques, and solvent considerations provides a critical analytical capability for addressing challenges in pharmaceutical development, materials science, and biomedical research. As spectroscopic technologies continue to advance, FT-IR remains a cornerstone technique for molecular analysis with expanding applications in emerging scientific fields.

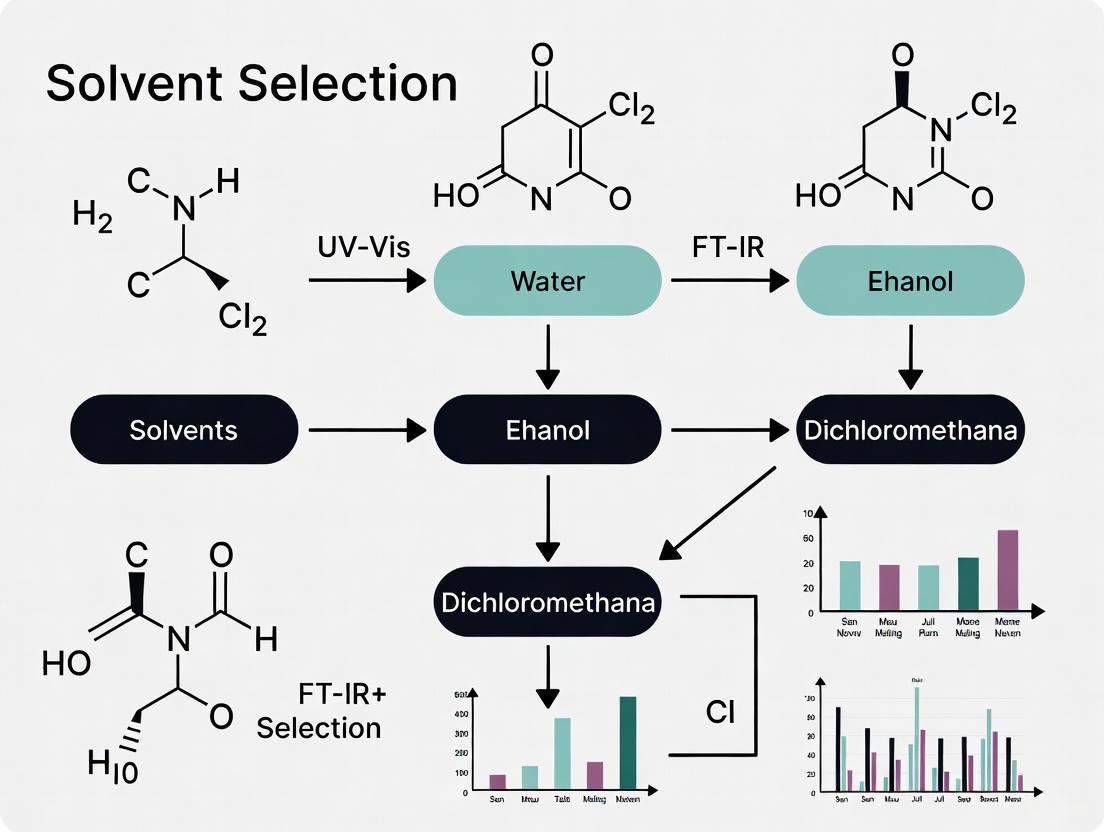

The selection of an appropriate solvent is a critical, yet often overlooked, foundational step in UV-Vis and FT-IR spectroscopic analysis. The choice of solvent directly influences the quality of the acquired data, the accuracy of quantitative results, and the feasibility of the experimental method itself. An ideal solvent must successfully balance three key properties: transparency within the spectral range of interest, sufficient solubility for the analyte, and chemical inertness to prevent reaction with the sample.

This application note provides a structured framework for solvent selection, detailing the fundamental principles, presenting comparative data on common solvents, and outlining validated experimental protocols tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. The guidance herein is framed within the broader context of method development, ensuring that spectroscopic data is reliable, reproducible, and fit for purpose.

Fundamental Principles of Solvent Selection

In spectroscopic analysis, the solvent acts as more than a mere diluent; it is an integral part of the analytical system. Its properties can significantly affect the energy of electronic and vibrational transitions in the analyte.

The Role of Transparency

A solvent must be sufficiently transparent to allow the relevant wavelengths of light to pass through to the detector.

- For UV-Vis Spectroscopy, this involves having a high UV cutoff wavelength below which the solvent itself absorbs too strongly to be useful. Operating at wavelengths below this cutoff results in excessive noise and renders data meaningless [16].

- For FT-IR Spectroscopy, the solvent should have minimal absorption bands that overlap with the characteristic vibrational frequencies of the analyte. Key functional group regions, such as O-H stretches (~3600-3200 cmâ»Â¹), C-H stretches (~3000-2850 cmâ»Â¹), and C=O stretches (~1800-1650 cmâ»Â¹), must be accessible [17] [18]. Solvents like water are strong IR absorbers and are rarely used in transmission IR unless dealing with aqueous samples specifically [19].

Solubility and Solvent-Solute Interactions

The solvent must completely dissolve the analyte at the desired concentration. Incomplete dissolution leads to light scattering and erroneous absorbance readings. The general principle of "like dissolves like" applies; polar analytes require polar solvents, and non-polar analytes require non-polar solvents. Furthermore, specific solute-solvent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, can cause shifts in absorption bands. For instance, hydrogen bonding can lead to a red-shift (bathochromic shift) and broadening of the O-H stretching band [20].

Chemical Inertness

The solvent must not react chemically with the analyte. Even weak interactions can alter the molecular structure of the analyte, thereby changing its spectroscopic signature and leading to incorrect identification or quantification.

Essential Data for Solvent Selection

The following tables summarize the key characteristics of common solvents used in UV-Vis and FT-IR spectroscopy, providing a quick reference for initial screening.

Table 1: UV-Vis Solvent Transparency (UV Cutoff)

| Solvent | UV Cutoff (nm) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | 190 | Polar aprotic; excellent for UV work below 220 nm. |

| Water | 190 | Inexpensive and safe; can form bubbles; may dissolve salts from atmosphere. |

| n-Hexane | 200 | Non-polar; suitable for many organic compounds. |

| Cyclohexane | 200 | Non-polar; often preferred over hexane due to lower toxicity. |

| Ethanol | 205 | Polar protic; can hydrogen bond with analytes. |

| Methanol | 205 | Similar to ethanol; common for HPLC with UV detection. |

| Chloroform | 245 | Contains stabilizers (e.g., ethanol) which affect cutoff; can dissolve many organics. |

| Carbon Tetrachloride | 265 | Non-polar; useful for IR (see Table 2); toxic. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | 270 | Excellent solubilizing power; high boiling point makes it difficult to remove. |

| Acetone | 330 | Strong UV absorber; generally avoided in UV-Vis. |

| Toluene | 285 | Aromatic; strong UV absorption; not suitable for low-UV work. |

Table 2: FT-IR Solvent Transparency and Properties

| Solvent | Key IR Transmission Windows (cmâ»Â¹) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Tetrachloride (CClâ‚„) | Above 800 cmâ»Â¹ [20] | Non-polar, relatively inert, transparent in MIR and NIR ranges [20]. Classic choice for IR studies of hydrocarbons and chlorinated compounds. |

| Chloroform (CHCl₃) | ~1200-800 cmâ»Â¹ (region between C-Cl and C-H absorptions) | Dissolves a wide range of organics. Its C-H stretch (~3020 cmâ»Â¹) can obscure analyte C-H regions. |

| Dichloromethane (CHâ‚‚Clâ‚‚) | Similar to chloroform | Common solvent for sample preparation. |

| Water (Dâ‚‚O, Heavy Water) | Varies, but transmits better than Hâ‚‚O in some regions | Used for biological molecules. Avoid Hâ‚‚O when possible due to strong, broad O-H absorption. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Multiple transmission windows between 4000-1000 cmâ»Â¹ | Excellent solubilizing power, but has strong S=O absorption ~1050 cmâ»Â¹. |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Material | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | IR-transparent salt used for preparing solid sample pellets in transmission FT-IR [17] [9]. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Common material for IR cell windows; suitable for most organic compounds but hygroscopic [17] [18]. |

| Calcium Fluoride (CaFâ‚‚) | IR window material; insoluble in water; useful for aqueous samples; attacked by acids [18]. |

| Barium Fluoride (BaFâ‚‚) | IR window material; wide transmission range; should not be used with ammonium salts [18]. |

| Zinc Selenide (ZnSe) | Common material for ATR crystals; insoluble in water but attacked by acids and strong alkalis [18]. |

| Diamond ATR Crystal | Virtually indestructible ATR crystal material; inert, suitable for a vast range of samples, including harsh chemicals [19] [9]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Sample Preparation for UV-Vis Spectroscopy in Solution

This protocol describes the standard procedure for analyzing a liquid sample using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

Workflow Overview

Materials

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer (single or double-beam)

- High-purity spectroscopic solvent

- Matched quartz cuvettes (e.g., 1 cm pathlength)

- Volumetric flasks and precision pipettes

- Analyte of interest

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Solvent Selection: Consult reference tables (e.g., Table 1) to select a solvent that is transparent across your wavelength range of interest. For example, use acetonitrile or water for measurements down to 190 nm.

- Blank Preparation: Fill a quartz cuvette with the pure, selected solvent. This is your blank solution, used to correct for solvent and cuvette absorbance.

- Instrument Calibration:

- Place the blank cuvette in the sample holder.

- On the instrument, perform a baseline correction or set 100% transmittance (0 absorbance) using the blank. Modern double-beam instruments automate this process by alternating the beam path between the blank and the sample [16].

- Sample Solution Preparation: Dissolve a precisely weighed amount of the solid analyte in the solvent using a volumetric flask to achieve the desired concentration. For liquid analytes, use precise volumetric dilution. The target absorbance should ideally be between 0.2 and 1.0 AU for optimal signal-to-noise ratio (following the Beer-Lambert law).

- Measurement:

- Transfer the sample solution into a clean quartz cuvette.

- Place the cuvette in the sample holder.

- Initiate the spectral scan across the predefined wavelength range.

- Data Analysis: Identify the wavelength of maximum absorption (λ_max). For quantification, use a calibration curve of standard solutions at known concentrations.

Protocol 2: Solid Sample Analysis via FT-IR Spectroscopy Using ATR

Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) is the most common sampling technique in modern FT-IR due to its minimal sample preparation.

Workflow Overview

Materials

- FT-IR spectrometer equipped with an ATR accessory (e.g., diamond crystal)

- High-purity solvent for cleaning (e.g., methanol, acetone)

- Laboratory wipes

- Solid or liquid sample

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Crystal Cleaning:

- Apply a few drops of a volatile, high-purity solvent (e.g., methanol) to the ATR crystal.

- Gently wipe the crystal clean with a lint-free laboratory wipe. Ensure the crystal is completely dry and free of residue before proceeding.

- Background Acquisition:

- With a clean, empty crystal, initiate the collection of a background spectrum. The instrument records the infrared profile of the environment, which is automatically subtracted from the sample spectrum.

- Sample Application:

- For solids: Place a small amount of the powdered or granular solid directly onto the crystal surface.

- For liquids: Apply a few drops directly onto the crystal.

- Clamping: Lower the pressure clamp onto the sample to ensure intimate contact between the sample and the crystal. Good contact is crucial for the evanescent wave to interact effectively with the sample [9].

- Sample Measurement:

- Initiate the collection of the sample spectrum. The instrument's interferometer collects all wavelengths simultaneously, and the Fourier Transform algorithm converts the raw interferogram into a recognizable IR spectrum [19].

- Data Processing and Interpretation:

- The software will display the absorbance spectrum. Compare the obtained spectrum to library databases for identification or analyze the characteristic absorption bands for functional group confirmation.

Protocol 3: Traditional KBr Pellet Method for FT-IR Transmission

This protocol is used when ATR is unsuitable or for direct comparison to historical transmission data.

Materials

- FT-IR spectrometer

- Potassium bromide (KBr), FT-IR grade

- Hydraulic pellet press die set

- Mortar and pestle (preferably agate)

- Vacuum line

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Grinding: Thoroughly grind approximately 0.5-1 mg of the solid analyte with 100-200 mg of dry KBr powder until a fine, homogeneous mixture is achieved.

- Die Loading: Transfer the mixture into a pellet press die.

- Pelleting: Place the die under a vacuum (to remove air and moisture) and apply high pressure (typically ~8-10 tons) for 1-2 minutes to form a transparent pellet.

- Measurement: Place the KBr pellet directly into a pellet holder in the FT-IR spectrometer and acquire the transmission spectrum. A pure KBr pellet is used to acquire the background spectrum.

Safety and Considerations: KBr is hygroscopic. All operations should be performed as quickly as possible to minimize water absorption, which results in a broad O-H stretch band ~3400 cmâ»Â¹ that can interfere with the analysis [17] [18].

The systematic selection of a solvent based on its transparency, solubility power, and chemical inertness is a non-negotiable aspect of robust spectroscopic method development. While ATR-FT-IR has simplified sample preparation immensely, understanding the principles behind solvent selection remains vital for both UV-Vis and FT-IR spectroscopy, especially when developing quantitative methods or analyzing novel compounds. By leveraging the data and protocols provided in this application note, researchers can make informed decisions that enhance data quality and drive efficient research and development processes.

UV-Vis Wavelength Range (190-800 nm) and Solvent Cutoff Criticality

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is a fundamental analytical technique employed across chemistry, biochemistry, and pharmaceutical development for the identification and quantification of analytes. The technique operates on the principle of measuring the absorption of light in the 190 to 800 nanometer (nm) range as electrons in molecular orbitals are promoted to higher energy states [2]. These electronic transitions—typically π–π, n–π, σ–σ, and n–σ—provide characteristic spectra that serve as molecular fingerprints [2].

A critical, yet sometimes overlooked, factor in obtaining accurate and reliable UV-Vis data is the selection of an appropriate solvent. The solvent is not merely a passive medium; it actively participates in the analysis. Every solvent possesses a UV cutoff, defined as the wavelength below which the solvent itself absorbs significantly, typically exceeding 1 Absorbance Unit (AU) in a 1 cm pathlength cell [21]. Using a solvent at wavelengths below its cutoff leads to excessive background absorption, obscuring the analyte's signal and compromising the validity of the results. This application note details the criticality of solvent cutoff within the standard UV-Vis range and provides structured protocols for optimal solvent selection.

The Interaction of Solvent Cutoff and Analytical Range

The standard UV-Vis range of 190-800 nm encompasses high-energy UV and lower-energy visible light. The low-wavelength end of this range is particularly susceptible to solvent interference.

- Far-UV Region (190-250 nm): This region is rich in information for many analytes with π-systems or non-bonding electrons. However, it is also where most solvents begin to absorb strongly. Selecting a solvent with a sufficiently low cutoff is paramount for measurements in this region [21].

- Mid-UV to Visible Region (250-800 nm): As wavelength increases, the number of suitable solvents expands. While solvent cutoff is less restrictive here, other solvent effects, such as polarity-induced spectral shifts (solvatochromism), can significantly influence the recorded spectrum [22] [23].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting a solvent based on the target analyte's expected absorption and the instrument's operational range.

Quantitative Solvent Cutoff Data

The provided table categorizes common laboratory solvents by their UV cutoff values, serving as an essential reference for method development. A general rule of thumb is to select a solvent whose cutoff is at least 20-30 nm below the wavelength of interest to ensure minimal background interference.

Table 1: UV Cutoff Wavelengths of Common Laboratory Solvents (Data adapted from Burdick & Jackson solvents list, presented in order of increasing cutoff) [21].

| Solvent | UV Cutoff (nm) | Solvent | UV Cutoff (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | 190 | n-Butyl Chloride | 220 |

| Pentane | 190 | Glyme | 220 |

| Water | 190 | Propylene Carbonate | 220 |

| Hexane | 195 | Ethylene Dichloride | 228 |

| Cyclopentane | 198 | Dichloromethane | 233 |

| Cyclohexane | 200 | Chloroform | 245 |

| Heptane | 200 | n-Butyl Acetate | 254 |

| Isopropyl Alcohol | 205 | Ethyl Acetate | 256 |

| Methanol | 205 | Dimethyl Sulfoxide | 268 |

| Ethyl Alcohol | 210 | Toluene | 284 |

| Tetrahydrofuran | 212 | Chlorobenzene | 287 |

| 1,4-Dioxane | 215 | o-Xylene | 288 |

| Ethyl Ether | 215 | Methyl Ethyl Ketone | 329 |

| Iso-Octane | 215 | Acetone | 330 |

Advanced Considerations: Solvent Polarity and Spectral Shifts

Beyond the cutoff, solvent polarity significantly influences UV-Vis spectra through a phenomenon known as solvatochromism. This occurs due to differential stabilization of the analyte's ground and excited states by the solvent [22] [23].

- Positive Solvatochromism (Red Shift): An absorption band shifts to a longer wavelength (bathochromic shift) with increasing solvent polarity. This indicates the excited state is more polar and stabilized more effectively by polar solvents than the ground state.

- Negative Solvatochromism (Blue Shift): An absorption band shifts to a shorter wavelength (hypsochromic shift) with increasing solvent polarity. This indicates the ground state is more polar and is stabilized more than the excited state [22].

For instance, studies on 1-iodoadamantane demonstrate that both σ→σ* and n→σ* electronic transitions exhibit blue shifts in polar solvents like DMSO compared to non-polar solvents like hexane, underscoring the profound effect of the solvent environment [23]. This effect must be accounted for when comparing spectra obtained in different solvents or when developing standardized methods.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determination of a Solvent's Practical UV Cutoff

This protocol verifies a solvent's suitability for a specific analytical method.

I. Research Reagent Solutions Table 2: Essential materials for solvent validation.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvent | The solvent under investigation. Must be "spectroscopic," "HPLC," or "UV" grade. |

| Spectrophotometer | Instrument capable of scanning the 190-800 nm range. |

| Matched Quartz Cuvettes | Quartz is transparent down to ~190 nm; ensure a matched pair for blank and sample. |

| Syringe Filters (0.45 μm, Nylon) | For removing particulate matter from the solvent. |

II. Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Filter the high-purity solvent using a syringe filter to remove any particulates that could cause light scattering.

- Instrument Initialization: Power on the UV-Vis spectrophotometer and allow it to warm up for the time specified by the manufacturer. Initiate the spectrum acquisition software.

- Baseline Correction: Fill a quartz cuvette with the solvent of interest and seal it. Place it in the sample compartment. Place an identical, empty cuvette in the reference compartment, or use an air reference as per instrument instructions. Perform a baseline correction (or 100% T adjustment) over the desired wavelength range (e.g., 190-400 nm).

- Spectral Acquisition: Without altering the setup, run a spectrum of the solvent versus air from 190 nm (or the instrument's lower limit) to 800 nm.

- Data Analysis: Identify the wavelength at which the solvent's absorbance reaches 1.0 AU. This is the practical UV cutoff for your instrument and cell pathlength [21]. The solvent should not be used for quantitative measurements at or below this wavelength.

Protocol: Investigating Solvatochromic Effects on an Analytic

This protocol demonstrates the tangible effect of solvent polarity on a chromophore's absorption spectrum.

I. Research Reagent Solutions Table 3: Key reagents for solvatochromism studies.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Analytic (e.g., 4-Pentylphenyl 4-n-benzoate derivative) | A model chromophore with a conjugated system [24]. |

| Series of Solvents | A range of solvents with different polarities (e.g., hexane, diethyl ether, ethyl acetate, ethanol, water). |

| Volumetric Flasks | For accurate solution preparation. |

| Analytical Balance | For precise weighing of the analytic. |

II. Procedure

- Solution Preparation: Prepare stock solutions of the analytic at an approximate concentration of 4 × 10â»âµ M in a series of solvents spanning a range of polarities (e.g., hexane, 1,4-dioxane, dichloromethane, ethanol) [24]. Ensure the analytic is fully dissolved.

- Spectrum Collection: Using a quartz cuvette, collect the UV-Vis absorption spectrum for each solution across the 200-800 nm range. Remember to use a pure solvent blank for each measurement.

- Data Analysis and Modeling:

- For each solvent, record the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) for a chosen absorption band.

- Plot the λmax values against a solvent polarity parameter, such as the empirical ET(30) parameter or the solvent dielectric constant.

- A positive correlation indicates positive solvatochromism, while a negative correlation indicates negative solvatochromism [22]. Statistical models like Linear Solvation Energy Relationships (LSERs) can be derived to quantitatively describe the solvent effect [24].

The following workflow visualizes the procedural steps for conducting a solvatochromism study.

Successful UV-Vis spectroscopic analysis hinges on a thorough understanding and careful consideration of the solvent's role. The two most critical solvent-related parameters are its UV cutoff and its polarity. Ignoring the solvent cutoff can lead to erroneous data and instrument damage from over-absorption of light, while neglecting solvent polarity effects can result in misinterpretation of spectral data. By adhering to the principles and protocols outlined in this document—consulting solvent cutoff tables, validating solvent transparency, and accounting for solvatochromic shifts—researchers and drug development professionals can ensure the generation of robust, reliable, and interpretable analytical data.

FT-IR Wavelength Range (2,500-16,000 nm) and Key Functional Group Regions

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy is a powerful analytical technique used to identify and quantify molecular components based on their interaction with infrared light. The technique provides a unique "chemical fingerprint" that is indispensable for molecular structural analysis across diverse fields including pharmaceutical development, materials science, and chemical research [25] [10]. The infrared region most useful for analyzing organic compounds spans wavelengths from 2,500 to 16,000 nanometers (nm), corresponding to the mid-infrared region with wavenumbers of 4,000 to 400 cmâ»Â¹ [25] [26]. This region is particularly valuable because the energies in this spectral range induce vibrational excitations in covalently bonded atoms, providing detailed information about functional groups and molecular structure [25].

The fundamental principle underlying FT-IR spectroscopy involves the absorption of specific frequencies of infrared light by chemical bonds as they undergo vibrational motions. When IR radiation interacts with a sample, photons are absorbed when their energy matches the energy difference between vibrational ground and excited states [10]. These vibrational modes include various stretching, bending, scissoring, rocking, and twisting motions [9]. For a vibration to be IR-active, it must result in a change in the dipole moment of the molecule [11]. This requirement makes FT-IR particularly sensitive to polar bonds while homonuclear diatomic molecules like Nâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚ do not absorb IR radiation [10] [11].

FT-IR spectrometers employ an interferometer rather than a dispersive element, providing significant advantages over traditional IR instruments. The core of the system uses a Michelson interferometer with a moving mirror that generates an interferogram containing encoded spectral information across all wavelengths [25] [10]. This interferogram is then subjected to a Fourier transform mathematical function to produce the familiar intensity-versus-wavenumber spectrum [25]. This approach provides three key advantages known as Fellgett's (multiplex) advantage, Jacquinot's (throughput) advantage, and Connes' (precision) advantage, resulting in spectra with superior signal-to-noise ratios, higher energy throughput, and better wavelength accuracy compared to dispersive instruments [10].

The FT-IR Spectral Range and Functional Group Correlation

Wavelength and Wavenumber Relationship

In FT-IR spectroscopy, the infrared spectrum is typically described using two complementary units: wavelength and wavenumber. Wavelength (λ) is measured in micrometers (μm or microns) or nanometers (nm), while wavenumber (ν̃) is expressed in reciprocal centimeters (cmâ»Â¹) [25] [26]. The relationship between these units is inverse: wavenumber = 10,000 / wavelength (in micrometers) [26]. The conventional 2,500-16,000 nm range corresponds to 4,000-625 cmâ»Â¹ in wavenumber units, which encompasses the mid-infrared region where most fundamental molecular vibrations occur [25] [9]. Most modern FT-IR instruments display spectra with wavenumber on the horizontal axis, as this scale is linear with energy and provides more convenient numbers for interpretation [26].

The mid-IR region is particularly valuable for organic compound analysis because the photon energies in this range (approximately 1-15 kcal/mole) are sufficient to excite molecular vibrations but not electronic transitions [26]. This region is commonly divided into two main areas: the group frequency region (4,000-1,450 cmâ»Â¹) where stretching vibrations of functional groups appear, and the fingerprint region (1,450-600 cmâ»Â¹) which contains complex patterns resulting from bending vibrations and single-bond stretches that are unique to each molecule [27] [26].

Key Functional Group Regions

Table 1: Characteristic IR Absorption Frequencies of Major Organic Functional Groups

| Functional Class | Bond/Vibration Type | Wavenumber Range (cmâ»Â¹) | Wavelength Range (nm) | Intensity & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkanes | C-H stretch | 2850-3000 | 3333-3509 | Strong |

| CH₂ & CH₃ deformation | 1350-1470 | 6802-7407 | Medium | |

| CHâ‚‚ rocking | 720-725 | 13793-13889 | Weak | |

| Alkenes | =C-H stretch | 3020-3100 | 3226-3311 | Medium |

| C=C stretch | 1630-1680 | 5952-6135 | Variable | |

| =C-H bend | 880-995 | 10050-11364 | Strong | |

| Alkynes | ≡C-H stretch | ~3300 | ~3030 | Strong, sharp |

| C≡C stretch | 2100-2250 | 4444-4762 | Variable | |

| Arenes | C-H stretch | ~3030 | ~3300 | Variable |

| C=C ring stretch | 1600 & 1500 | 6667 & 6667 | Medium-weak | |

| Alcohols & Phenols | O-H stretch (free) | 3580-3650 | 2739-2793 | Variable, sharp |

| O-H stretch (H-bonded) | 3200-3550 | 2817-3125 | Strong, broad | |

| C-O stretch | 970-1250 | 8000-10309 | Strong | |

| Amines | N-H stretch (1°) | 3400-3500 | 2857-2941 | Weak, 2 bands |

| N-H stretch (2°) | 3300-3400 | 2941-3030 | Weak | |

| C-N stretch | 1000-1250 | 8000-10000 | Medium | |

| Carbonyls | C=O stretch (aldehydes) | 1720-1740 | 5747-5814 | Strong |

| C=O stretch (ketones) | 1710-1720 | 5814-5848 | Strong | |

| C=O stretch (acids) | 1705-1720 | 5814-5865 | Strong | |

| C=O stretch (esters) | 1735-1750 | 5714-5763 | Strong | |

| Carboxylic Acids | O-H stretch | 2500-3300 | 3030-4000 | Very broad |

The information in Table 1 demonstrates that specific functional groups absorb IR radiation in characteristic regions, allowing for their identification in unknown samples [27] [26]. For example, the carbonyl (C=O) stretching vibration appears as a strong, sharp band between 1705-1750 cmâ»Â¹, making it one of the most recognizable features in IR spectra [26]. Similarly, hydroxyl (O-H) groups show a broad absorption in the 3200-3550 cmâ»Â¹ range when hydrogen-bonded, while free O-H groups produce a sharper band at higher frequencies (3580-3650 cmâ»Â¹) [27].

The region above 3000 cmâ»Â¹ provides immediate information about carbon hybridization: absorption above 3000 cmâ»Â¹ typically indicates sp² or sp C-H bonds (alkenes, arenes, alkynes), while absorption between 2850-3000 cmâ»Â¹ suggests sp³ C-H bonds (alkanes) [27] [26]. The distinctive C-H stretch of terminal alkynes appears as a sharp band near 3300 cmâ»Â¹, while the C≡C stretch of internal alkynes appears as a weaker band between 2100-2250 cmâ»Â¹ [27].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

FT-IR Instrumentation and Sampling Techniques

Modern FT-IR instruments can be configured with various sampling accessories to accommodate different sample types. The most common measurement techniques include transmission, attenuated total reflectance (ATR), diffuse reflectance, and specular reflectance [9] [28]. Each technique has specific advantages and sample preparation requirements, making them suitable for different applications.

Transmission FT-IR is the original and most straightforward technique where IR light passes directly through the sample [9] [28]. For solid samples, this typically requires grinding the sample with potassium bromide (KBr) and pressing into a pellet under high pressure [25] [28]. Liquid samples can be analyzed as thin films between two KBr plates or in sealed liquid cells with controlled pathlengths [28]. Gases require specialized gas cells with long pathlengths (typically 10 cm or more) to compensate for low sample density [28]. While transmission provides excellent quality spectra, the sample preparation can be time-consuming and may alter or destroy the sample [9].

Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) has become the primary sampling method for most applications due to minimal sample preparation requirements [9] [28]. In ATR, the sample is placed in direct contact with a high-refractive-index crystal (typically diamond, ZnSe, or Ge), and the IR beam undergoes total internal reflection within the crystal [28]. During each reflection, an evanescent wave penetrates a short distance (0.5-5 μm) into the sample, where absorption occurs [9] [28]. The major advantage of ATR is that solid and liquid samples can be analyzed directly without extensive preparation—solids are simply pressed against the crystal, while liquids are pipetted onto the crystal surface [25] [9]. Different crystal materials offer various properties: diamond is extremely durable and chemically resistant, ZnSe provides excellent throughput but is more fragile, and germanium offers a small penetration depth suitable for highly absorbing samples [28].

Reflectance techniques include several specialized approaches. Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (DRIFTS) is used for powder samples and involves measuring the scattered radiation from rough surfaces [10] [28]. Samples are typically diluted with KBr to reduce specular reflection and improve data quality [28]. Specular reflectance measures the direct reflection from smooth, mirror-like surfaces and is useful for analyzing thin films on reflective substrates [28]. Infrared Reflection-Absorption Spectroscopy (IRRAS) and its more sensitive variant Polarization Modulation-IRRAS (PM-IRRAS) are specialized for studying thin films on metal surfaces with monolayer sensitivity [28].

Table 2: Comparison of Major FT-IR Sampling Techniques

| Technique | Sample Types | Preparation Requirements | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission | Solids, liquids, gases | Extensive (grinding, pelleting, cell assembly) | Quantitative analysis, gas phase studies, reference methods | Excellent signal-to-noise, linear Beer-Lambert response | Time-consuming preparation, can destroy sample |

| ATR | Solids, liquids, pastes | Minimal (direct placement on crystal) | Routine analysis, quality control, heterogeneous samples | Rapid analysis, minimal preparation, non-destructive | Penetration depth varies with wavelength, intensity differences vs. transmission |

| DRIFTS | Powders, rough solids | Moderate (grinding, dilution with KBr) | Catalysts, soils, powders, solid state reactions | Minimal sample preparation for powders | Particle size and packing affect intensity, quantitative challenges |

| Specular Reflectance | Smooth surfaces, thin films on reflective substrates | Minimal (placement in beam) | Polymer coatings, surface layers on metals | Non-destructive, surface-sensitive | Spectral distortions may require Kramers-Kronig correction |

Standard Operating Procedure: ATR-FTIR Analysis

The following protocol details the steps for analyzing solid and liquid samples using ATR-FTIR, which has become the most common technique in modern laboratories [9].

Materials and Equipment:

- FT-IR spectrometer with ATR accessory

- ATR crystal (diamond, ZnSe, or Ge)

- High-purity solvent (methanol, acetone, or isopropanol) for cleaning

- Lint-free wipes

- Solid samples or liquid samples in appropriate containers

- Pressure device (for solid samples to ensure good crystal contact)

Procedure:

Instrument Preparation and Background Collection

- Power on the FT-IR spectrometer and allow it to warm up for at least 15 minutes to stabilize.

- Clean the ATR crystal thoroughly with appropriate solvent and lint-free wipes. Inspect the crystal to ensure it is free of residue.

- Open the instrument control software and create a new experiment with appropriate parameters (typically 4 cmâ»Â¹ resolution, 16-64 scans).

- Collect a background spectrum with no sample present on the crystal. This measures signal from the environment and crystal, which will be subtracted from sample spectra.

Sample Analysis

- For solid samples: Place a representative portion of the solid directly on the ATR crystal. Use the pressure device to apply firm, even pressure to ensure good contact between the sample and crystal.

- For liquid samples: Pipette a small volume (typically 20-100 μL) directly onto the ATR crystal, ensuring complete coverage of the crystal surface.

- Initiate data collection according to instrument protocols. The software will automatically subtract the background and display the resulting spectrum.

Data Collection Parameters

- Set the spectral range to 4000-400 cmâ»Â¹ (mid-IR region).

- Use 4 cmâ»Â¹ resolution for most applications; higher resolution (1-2 cmâ»Â¹) may be needed for gas phase samples or detailed analysis.

- Collect 16-64 scans and co-add to improve signal-to-noise ratio.

- Apply apodization function (typically Happ-Genzel) to reduce sidelobes in the transformed spectrum.

Post-Collection Processing

- Examine the spectrum for quality indicators: baseline stability, adequate signal-to-noise, and absence of saturation (absorbance < 1.5 AU).

- Apply atmospheric suppression if COâ‚‚ (2350 cmâ»Â¹) or water vapor (1650 cmâ»Â¹) bands are present.

- Perform baseline correction to remove scattering effects, particularly for uneven solid samples.

- For ATR spectra, apply the ATR correction algorithm to compensate for wavelength-dependent penetration depth, enabling comparison with transmission spectral libraries.

Instrument Shutdown and Cleaning

- Remove sample from the ATR crystal and clean thoroughly with appropriate solvent.

- Verify crystal cleanliness by collecting a background spectrum and comparing to the original.

- Power down the spectrometer according to manufacturer recommendations.

Quality Control Considerations:

- Regularly verify instrument performance using polystyrene reference standards with known absorption frequencies.

- Monitor ATR crystal for scratches or damage that could affect spectral quality.

- Maintain consistent pressure application for solid samples to ensure reproducible contact with the crystal.

- For quantitative analysis, develop calibration curves using standards of known concentration.

Visualization of FT-IR Experimental Workflows

FT-IR Instrumentation and Interferometer Operation

The following diagram illustrates the core components and operation of an FT-IR spectrometer with a Michelson interferometer, which is the fundamental design used in most modern instruments [25] [10].

FT-IR Instrument Optical Path and Signal Processing

Sample Analysis Workflow

This workflow diagram outlines the complete process for FT-IR sample analysis, from preparation to data interpretation, highlighting key decision points and procedures [25] [28].

FT-IR Sample Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for FT-IR Spectroscopy

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specifications | Handling Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | IR-transparent matrix for solid samples in transmission measurements; also used in DRIFTS as dilution medium | Optical grade, 99.9% purity, hygroscopic | Must be stored in desiccator; grind and press pellets in low-humidity environment; compatible with most organic compounds |

| Alkali Halide Plates (NaCl, KBr, KCl) | Windows for transmission measurements of liquids, gases, and solid thin films | Polished surfaces, specific IR transmission ranges (KBr: 400-4000 cmâ»Â¹) | Fragile and hygroscopic; clean with dry solvent; store in desiccator; not suitable for aqueous samples |

| ATR Crystals (Diamond, ZnSe, Ge) | Internal reflection elements for ATR measurements | Various hardness and refractive indices; diamond: most durable; ZnSe: best throughput; Ge: low penetration | Clean with appropriate solvents; avoid scratching surfaces; diamond crystal suitable for hard materials |

| Nujol (Mineral Oil) | Mulling agent for solid samples in transmission measurements | Hydrocarbon mixture, transparent in IR except C-H regions | Avoid for samples with C-H groups of interest; non-volatile, requires solvent cleaning |

| IR-transparent Solvents (CCl₄, CS₂, CHCl₃) | Solvents for sample preparation and liquid cell measurements | Anhydrous, IR grade with specified transmission windows | Handle in fume hood due to toxicity; use appropriate window materials (NaCl, KBr) for cells |

| Polystyrene Reference Standard | Instrument validation and wavelength calibration | Certified with specific absorption bands (e.g., 1601 cmâ»Â¹) | Use for routine performance verification; store protected from light and dust |

| Background Reference Materials | For background spectrum collection in different sampling modes | Matches sampling technique: clean ATR crystal for ATR, pure KBr pellet for transmission | Must be free of contaminants; collect fresh background frequently |

| Calceolarioside B | Calceolarioside B, CAS:105471-98-5, MF:C23H26O11, MW:478.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 7-Epi-Taxol | 7-Epi-Taxol, CAS:105454-04-4, MF:C47H51NO14, MW:853.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Solvent Selection Considerations for FT-IR and UV-Vis Spectroscopy

The selection of appropriate solvents is critical for both FT-IR and UV-Vis spectroscopy, though the considerations differ significantly between these techniques due to their different measurement principles and spectral regions of interest.

FT-IR Solvent Selection

For FT-IR spectroscopy, the primary consideration is that the solvent should not absorb strongly in spectral regions of interest for the analyte [26] [28]. Traditional IR-transparent solvents include carbon tetrachloride (CClâ‚„) and carbon disulfide (CSâ‚‚), which have relatively few IR absorption bands [26]. However, due to toxicity concerns, these have been largely replaced by alternative approaches, particularly ATR which requires minimal or no solvent [9]. When solvents must be used in FT-IR, the following guidelines apply:

- Avoid solvents with strong absorption in analyte regions: For example, avoid water when studying O-H or N-H stretches, as it has a broad O-H absorption that obscures these regions [25].

- Match solvent to spectral window of interest: Different solvents have "transmission windows" where they absorb minimally. Chloroform-d (CDCl₃) is often used in the fingerprint region (1500-900 cmâ»Â¹) while having strong absorptions in the C-H and C-D regions [28].

- Consider sample preparation technique: For transmission measurements, solvents must fully transmit IR radiation, while for ATR, solvent absorption is less critical but may still interfere with analyte signals [9] [28].

- Account for solvent-solute interactions: Hydrogen bonding solvents can shift absorption frequencies of functional groups like carbonyl and hydroxyl, potentially complicating interpretation [26].

UV-Vis Solvent Selection

UV-Vis spectroscopy operates in the ultraviolet and visible regions (200-800 nm), with different solvent requirements [29]. The key consideration is the UV cutoff - the wavelength below which the solvent absorbs strongly [29]. Common solvents and their approximate UV cutoffs include:

- Water (~190 nm)

- Acetonitrile (~190 nm)

- Cyclohexane (~200 nm)

- Methanol (~205 nm)

- Chloroform (~240 nm)

- Acetone (~330 nm)

For UV-Vis measurements, solvents must be "UV grade" with low absorbance in the spectral region of interest [29]. The solvent must also not react with the analyte or exhibit significant temperature-dependent absorption changes [29].

Comparative Considerations

When designing experiments that may incorporate both FT-IR and UV-Vis techniques, solvent selection requires careful compromise. No single solvent is ideal for both techniques across all applications. Key strategic considerations include:

- Technique priority: Determine which technique provides the critical information and optimize solvent choice accordingly.

- Sample compatibility: Ensure the solvent doesn't degrade or react with the analyte in ways that would affect both measurements.

- Pathlength considerations: FT-IR typically uses shorter pathlengths (0.1-1 mm) for liquids due to strong absorptions, while UV-Vis often uses standard 1 cm pathlengths [29] [28].

- Quantitative applications: For quantitative work, both techniques require solvents that don't interfere with analyte peaks of interest, with UV-Vis additionally requiring adherence to Beer-Lambert law conditions [29].

The development of ATR-FTIR has significantly simplified solvent selection for IR spectroscopy, as it enables analysis of aqueous solutions and other challenging samples that were difficult to measure by transmission [9]. This advancement has made FT-IR much more compatible with samples typically analyzed by UV-Vis, particularly in biological and pharmaceutical applications.

The Critical Impact of Solvent Polarity on Spectral Shifts and Band Resolution

Within the framework of a broader thesis on solvent selection for spectroscopic analysis, this document delineates the critical influence of solvent polarity on the spectral characteristics of analytes in UV-Vis and FT-IR spectroscopy. The solvation environment is a paramount consideration for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, as it directly governs the energy of electronic and vibrational transitions, thereby affecting spectral shifts (bathochromic or hypsochromic) and band resolution. Solvent polarity encompasses the overall solvation capability, which includes both nonspecific interactions (for example, dipole-dipole and dispersion forces) and specific interactions (such as hydrogen bonding) [30]. A profound understanding of these effects is indispensable for accurate material characterization, method validation in pharmaceutical analysis, and the rational design of molecular probes.

The following sections provide a detailed examination of the theoretical underpinnings of solvatochromism, supported by curated experimental data and structured protocols. The objective is to equip practitioners with the knowledge and methodologies necessary to make informed solvent selections, anticipate spectral alterations, and correctly interpret spectroscopic data within their research context.

Theoretical Foundations of Solvent Effects

Electronic (UV-Vis) and Vibrational (FT-IR) Transitions

Solvent-solute interactions manifest differently in UV-Vis and FT-IR spectroscopy due to the distinct nature of the transitions being probed. In UV-Vis spectroscopy, the focus is on electronic transitions, such as π→π and n→π. The differential stabilization of the ground versus the excited state dipole moment by the solvent cage gives rise to solvatochromism [22].

- π→π* Transitions: Typically, the excited state possesses a larger dipole moment than the ground state. Polar solvents stabilize the excited state more effectively, lowering its energy and resulting in a bathochromic (red) shift with increasing solvent polarity [6].

- n→π* Transitions: The non-bonding (n) electrons are strongly stabilized by hydrogen-bonding or polar solvents in the ground state. Upon excitation, this stabilization is lost, leading to a higher energy requirement for the transition and a hypsochromic (blue) shift in polar solvents [6]. For instance, the n→σ* transition in 1-iodoadamantane exhibits a blue shift in polar solvents [31].

In FT-IR spectroscopy, the transitions are vibrational, and the associated change in dipole moment is considerably smaller. Shifts arise from the solvent's electric field altering the bond force constants. Strong hydrogen-bonding solvents, for example, can weaken the bond strength of groups like C=O or O-H, leading to a redshift in their stretching frequencies [32] [30]. It is critical to note that not all IR peak shifts indicate a chemical change; some may arise from physical effects like the refractive index of the embedding matrix or anisotropy [33].

Key Solvent Parameters and Scales

The solvent influence can be quantified using empirical parameters, allowing for predictive correlations. The most prevalent scales include:

- ET(30): This is a comprehensive scale based on the molar transition energy of Reichardt's dye, capturing both nonspecific dielectric and specific hydrogen-bonding interactions [30] [22].

- Kamlet-Taft Parameters: This multi-parameter approach dissects solvent effects into π* (dipolarity/polarizability), α (hydrogen-bond donor acidity), and β (hydrogen-bond acceptor basicity) [31] [22].