Spectroscopy in Chemistry Careers: From Techniques to Drug Development Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of spectroscopic careers in chemistry, focusing on the pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical sectors.

Spectroscopy in Chemistry Careers: From Techniques to Drug Development Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of spectroscopic careers in chemistry, focusing on the pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical sectors. It explores the foundational techniques—including NMR, ICP-MS, Raman, and FT-IR—and their critical applications in drug discovery, development, and quality control. Readers will gain insights into methodological best practices, strategies for troubleshooting and optimization, and the importance of method validation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content also addresses the skills gap between academia and industry and highlights resources for continuous career development.

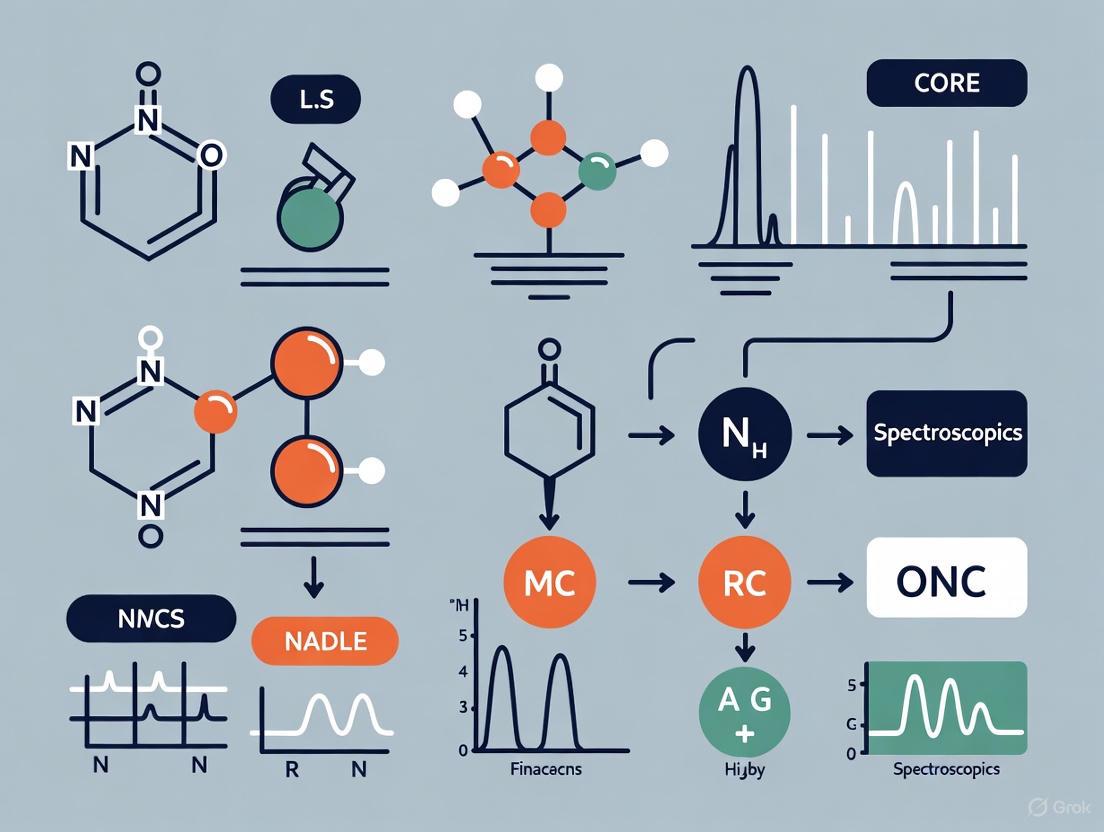

Core Spectroscopic Techniques and the Chemistry Career Landscape

In the modern pharmaceutical landscape, where the cost of developing a new drug is estimated to be approximately $2 billion and only about 12% of candidates entering clinical trials ultimately gain FDA approval, the role of advanced analytical techniques has become increasingly critical for derisking development and ensuring product quality, safety, and efficacy [1]. Spectroscopic methods form the foundational toolkit for molecular analysis throughout the drug development lifecycle, from initial discovery through manufacturing and quality control. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of four core spectroscopic techniques—Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS), Raman spectroscopy, and Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy—framing their applications, methodologies, and complementary strengths within contemporary pharmaceutical analysis. These techniques enable researchers to address diverse challenges including structural elucidation, trace element detection, molecular fingerprinting, and real-time process monitoring, collectively supporting the industry's alignment with Quality by Design (QbD) principles and Process Analytical Technology (PAT) initiatives [2].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

Fundamental Principles and Pharmaceutical Applications

NMR spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei to provide detailed information about molecular structure, conformation, and dynamics. When placed in a strong magnetic field and exposed to radiofrequency pulses, nuclei such as ¹H (proton) and ¹³C (carbon-13) resonate at characteristic frequencies, producing chemical shifts that reveal the electronic environment around atoms [3]. NMR serves as a powerful tool for structural elucidation, providing atom-level mapping of molecular frameworks, stereochemistry, and conformational details through one-dimensional (¹H, ¹³C) and two-dimensional (COSY, HSQC, HMBC, NOESY/ROESY) experiments [3] [4].

Key pharmaceutical applications include identification and confirmation of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) and impurities, characterization of protein-protein and protein-excipient interactions in biologics formulation development, monitoring of monoclonal antibody (mAb) structural changes, and quantitative monitoring of isometric and dehalogenated impurities in pharmaceutical raw materials [3] [5]. NMR is particularly valuable for studying dynamic systems in real time, identifying and validating small molecule ligands binding to biomolecular targets such as G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), and metabolomic profiling to track drug response in patients [4] [6].

Experimental Protocol: Structure Elucidation of a Novel Small Molecule API

Objective: Structural confirmation and chiral center assignment of a novel small molecule API, specifically an antihypertensive compound [3].

Sample Preparation:

- Sample Purity: Purify the compound to >95% homogeneity using preparatory HPLC.

- Solvent Selection: Dissolve 5-10 mg of sample in 0.6 mL of deuterated solvent (e.g., DMSO-d6 or CDCl3) based on solubility.

- Reference Standard: Add 0.1% tetramethylsilane (TMS) as internal chemical shift reference.

Instrument Parameters:

- Instrument: High-field NMR spectrometer (600 MHz or higher)

- Temperature: 298 K

- Probe: Triple-resonance cryoprobe for enhanced sensitivity

Data Acquisition Sequence:

- ¹H NMR: Single pulse experiment, 64 scans, spectral width 12 ppm, relaxation delay 2 seconds

- ¹³C NMR: Proton-decoupled experiment, 512 scans, spectral width 220 ppm, relaxation delay 2 seconds

- 2D COSY: Correlates proton-proton couplings through three bonds

- 2D HSQC: Detects direct ¹H-¹³C correlations (1-bond couplings)

- 2D HMBC: Detects long-range ¹H-¹³C correlations (2-3 bond couplings)

- NOESY/ROESY: For stereochemical assignment through spatial proximities

Data Interpretation Workflow:

- Analyze ¹H NMR for chemical shifts, integration (number of protons), and splitting patterns (J-coupling)

- Examine ¹³C NMR for carbon environments and functional groups

- Utilize COSY to establish proton connectivity networks

- Construct carbon skeleton using HSQC and HMBC correlations

- Determine relative stereochemistry and 3D configuration through NOESY/ROESY cross-peaks

- Compare experimental chemical shifts with predicted values or known analogues

A case study demonstrated that this comprehensive NMR approach identified a critical stereochemical inversion at the 4th carbon of a cardiovascular drug candidate, enabling correction prior to IND application and resulting in a 30% reduction in development time [3].

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS)

Technical Fundamentals and Regulatory Significance

ICP-MS combines an inductively coupled plasma source (operating at >6,000°C) with mass spectrometry to detect and quantify elemental impurities at ultra-trace levels, achieving parts-per-trillion (ppt) sensitivity [7]. The technique enables simultaneous multi-element analysis (up to 70 elements in a single run), isotopic analysis, and boasts a broad dynamic range, making it the gold standard for elemental impurity testing in pharmaceuticals as mandated by regulatory frameworks including USP Chapters <232> and <233>, and ICH Q3D [7].

Primary pharmaceutical applications include testing for toxic elemental impurities (e.g., arsenic, cadmium, lead, mercury) in APIs and finished products, analyzing excipient purity, monitoring residual metal catalysts (e.g., platinum, palladium, rhodium) used in drug synthesis, and conducting stability studies to track metal leaching throughout a drug's shelf life [7]. The technique is particularly valuable for speciation analysis, as demonstrated by hyphenated techniques such as size exclusion chromatography coupled with ICP-MS (SEC-ICP-MS), which differentiates between metals interacting with proteins and free metals in solution—critical for understanding metal-protein interactions in biologic therapeutics [5].

Experimental Protocol: Elemental Impurity Testing per ICH Q3D

Objective: Quantification of Class 1 (As, Cd, Hg, Pb) and Class 2A (Co, Ni, V) elemental impurities in a finished drug product per ICH Q3D guidelines [7].

Sample Preparation:

- Digestion: Accurately weigh ~100 mg of homogenized tablet powder into microwave digestion vessels

- Acid Addition: Add 5 mL of high-purity nitric acid (69% HNO₃) and 1 mL of hydrogen peroxide (30% H₂O₂)

- Microwave Digestion: Digest using a stepped temperature program (ramp to 180°C over 20 minutes, hold for 15 minutes)

- Dilution: Cool and quantitatively transfer to 50 mL volumetric flask, dilute to volume with ultra-pure water (18.2 MΩ·cm)

- Blank Preparation: Prepare method blanks following identical procedures without sample

Instrument Parameters:

- Instrument: Quadrupole ICP-MS with collision/reaction cell

- Nebulizer: Micro-flow concentric nebulizer

- Spray Chamber: Scott-type double-pass cooled spray chamber (2-4°C)

- RF Power: 1550 W

- Carrier Gas: Argon, 1.0 L/min

- Cell Gas: Helium (4.5 mL/min) for kinetic energy discrimination to remove polyatomic interferences

- Internal Standards: Add Sc, Ge, In, Bi (10 ppb final concentration) to all samples, blanks, and standards

Data Acquisition:

- Calibration Standards: Prepare in 2% HNO₃ at 0.1, 0.5, 1, 10, 50, and 100 ppb for each analyte

- Quality Controls: Include continuing calibration verification (CCV) and duplicate samples

- Acquisition Mode: No gas (He) mode for all elements

- Integration Time: 1 second per mass, 3 replicates per sample

- Mass Monitoring:

- â·âµAs (interference: â´â°Ar³âµCl → monitored in He mode)

- ¹¹¹Cd, ¹¹â´Cd

- ²â°Â²Hg

- ²â°â¸Pb

- âµâ¹Co

- â¶â°Ni

- âµÂ¹V

Data Analysis and Validation:

- Quantitation: Use internal standard method with linear calibration curves (r² > 0.999)

- Detection Limits: Calculate method detection limits (3× standard deviation of blanks)

- Recovery Studies: Spike samples with known concentrations of analytes (70-150% acceptance)

- System Suitability: Verify sensitivity (response for 1 ppb tuning solution), stability (RSD < 5% for internal standards), and resolution (peak width at 10% height < 0.8 amu)

Raman Spectroscopy

Principles and Emerging Applications in Pharma

Raman spectroscopy is a molecular analysis technique based on inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser source. The resulting spectrum provides a vibrational fingerprint of the sample, offering high sensitivity for molecular structure analysis, component identification, and real-time monitoring [8]. Recent advancements, particularly the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning algorithms, have significantly expanded Raman's analytical power by overcoming traditional challenges like background noise and complex data interpretation [8].

Pharmaceutical applications span drug development and manufacturing, including drug structure characterization, impurity detection, monitoring of drug-biomolecule interactions, real-time monitoring of product aggregation and fragmentation during clinical bioprocessing, and optimization of cell culture processes through inline monitoring of 27 critical components [8] [5]. Emerging clinical applications include early disease detection through high-resolution component mapping and personalized treatment planning [8]. A notable 2025 study demonstrated Raman's utility in quantifying the spatiotemporal disposition of metronidazole within the skin to establish bioequivalence for complex generic topical products, potentially reducing the need for prolonged clinical trials [9].

Experimental Protocol: Inline Bioprocess Monitoring Using AI-Enhanced Raman

Objective: Real-time monitoring of product aggregation and fragmentation during clinical bioprocessing to ensure consistent product quality [5].

Sample Presentation:

- Configuration: Immersion probe directly inserted into bioreactor

- Probe Specifications: Stainless steel housing with quartz window, compatible with steam-in-place sterilization

- Laser Source: 785 nm diode laser (500 mW power) to minimize fluorescence

- Spectral Range: 200-2000 cmâ»Â¹

- Laser Filter: Notch filter for Rayleigh rejection >8 OD

Instrument Parameters:

- Spectrometer: High-throughput f/1.8 imaging spectrometer

- Detector: Deep-cooled CCD (-60°C)

- Resolution: 4 cmâ»Â¹

- Acquisition Time: 10 seconds per spectrum, 3 accumulations

- Total Measurement Frequency: Every 38 seconds

AI-Enhanced Data Processing Workflow:

- Spectral Pre-processing:

- Background Correction: Automated fluorescence background subtraction using modified polynomial fitting algorithm

- Normalization: Vector normalization on entire spectral range

- Smoothing: Savitzky-Golay filter (2nd polynomial, 9 points)

Anomaly Detection:

- Algorithm: Isolation Forest unsupervised learning

- Input Features: First derivatives of pre-processed spectra

- Output: Automatic identification and elimination of anomalous spectra

Multivariate Modeling:

- Algorithm: Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression

- Training Set: 150 reference samples with known aggregation levels via SEC-HPLC

- Validation: 7-fold cross-validation

- Performance Metrics: Q² (predictive R-squared) >0.8, RPD (relative percent difference) >2.0 for all components except glucose

Real-Time Prediction:

- Deployment: Trained model deployed in production environment

- Output: Real-time predictions of critical quality attributes every 38 seconds

- Control Integration: Data fed to process control system for automated adjustment

Model Maintenance:

- Recalibration: Monthly model performance assessment with independent test set

- Drift Monitoring: Control charts tracking model prediction stability

- Update Protocol: Model retraining when process changes implemented

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

Core Principles and Formulation Applications

FT-IR spectroscopy characterizes molecules based on their absorption of infrared light, producing a spectral fingerprint that reflects the vibrational modes of chemical bonds in the sample [2]. The technique is particularly valuable for its sensitivity to molecular environment, making it ideal for monitoring polymorphic forms, drug-excipient interactions, and subtle chemical changes during formulation development and manufacturing [2]. FT-IR operates across mid-IR (4,000-400 cmâ»Â¹) and near-IR (12,800-4,000 cmâ»Â¹) ranges, with sampling modes including transmission/absorbance, attenuated total reflectance (ATR), and diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) to accommodate diverse sample types from powders and tablets to gels and suspensions [2].

Key pharmaceutical applications encompass drug-excipient compatibility studies, polymorph monitoring and screening, quality control of blend uniformity in solid oral formulations, moisture content analysis, API identity and concentration assessment, and detection of counterfeit medicinal products [2]. FT-IR has proven particularly valuable for stability testing of protein drugs, where it can track changes in secondary structure under varying storage conditions [5]. The technique aligns well with PAT frameworks and continuous manufacturing strategies, providing rapid data acquisition that supports real-time monitoring of critical quality attributes (CQAs) and immediate feedback to manufacturing systems [2].

Experimental Protocol: Polymorph Screening and Drug-Excipient Compatibility

Objective: Identification of optimal API polymorph and screening for incompatibilities with proposed excipients [2].

Sample Preparation Methods:

- API Polymorph Generation:

- Solvent Evaporation: Prepare saturated solutions of API in 5 different solvents, evaporate slowly at controlled temperature

- Precipitation: Rapidly add anti-solvent to API solution with stirring

- Thermal Treatment: Heat API to melting point, then cool at controlled rates (0.5, 5, 50°C/min)

- Drug-Excipient Compatibility Blends:

- Physical Mixtures: Blend API with individual excipients (1:1 ratio) using mortar and pestle

- Stressed Samples: Expose blends to 40°C/75% RH for 4 weeks in stability chambers

- Controls: Include pure API and pure excipients stored under identical conditions

Instrumental Parameters:

- Spectrometer: FT-IR with DTGS detector

- Accessory: Diamond ATR (Golden Gate) with temperature controller

- Resolution: 4 cmâ»Â¹

- Scan Number: 32 scans per spectrum

- Spectral Range: 4000-400 cmâ»Â¹

Data Acquisition Protocol:

- Background Scan: Collect background spectrum before each sample or when changing temperature

- Polymorph Screening:

- Analyze all polymorph samples at 25°C

- Select promising forms for variable temperature studies (25-300°C, 5°C/min)

- Compatibility Study:

- Analyze initial physical mixtures

- Analyze stressed samples after 1, 2, 3, 4 weeks

- Compare with pure API and excipient controls

Data Analysis:

- Spectral Interpretation:

- Identify key functional group regions: O-H (3200-3600 cmâ»Â¹), C=O (1650-1800 cmâ»Â¹), C-H (2800-3000 cmâ»Â¹)

- Note shifts >5 cmâ»Â¹ in key API peaks indicating interactions

- Monitor appearance/disappearance of characteristic polymorph peaks

Multivariate Analysis:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): For clustering of similar spectra

- Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA): In Python to assess similarity of secondary structures in protein drugs [5]

Compatibility Assessment:

- Major Incompatibility: Significant peak shifts (>10 cmâ»Â¹), appearance of new peaks, disappearance of API peaks

- Minor Interaction: Peak shifts 5-10 cmâ»Â¹, peak broadening

- Compatible: Spectrum matches superposition of API and excipient spectra

Comparative Analysis and Technique Selection

Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Spectroscopic Techniques in Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Parameter | NMR | ICP-MS | Raman | FT-IR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Detail | Full molecular framework, stereochemistry, dynamics [3] | Elemental composition only [7] | Molecular fingerprint, functional groups [8] | Molecular fingerprint, functional groups [2] |

| Sensitivity | Moderate (μM-mM) [3] | Excellent (ppt levels) [7] | Moderate (μM) [8] | Moderate (μM) [2] |

| Quantitative Ability | Accurate without external standards [3] | Excellent with internal standards [7] | Good with calibration models [8] | Good with calibration models [2] |

| Sample Throughput | Low to moderate (minutes to hours) [3] | High (minutes per multi-element run) [7] | High (seconds with automation) [5] | High (seconds to minutes) [2] |

| Sample Requirements | mg quantities, deuterated solvents [3] | Digested solutions, ppb-ppm concentrations [7] | Minimal preparation, solids/liquids in situ [8] | Minimal preparation, solids/liquids [2] |

| Key Strengths | Atomic-level structural information, stereochemistry [3] | Ultra-trace multi-element detection, isotopic analysis [7] | Non-destructive, in-situ monitoring, AI-compatible [8] | Rapid polymorph identification, compatibility screening [2] |

| Primary Limitations | Low sensitivity, requires expert interpretation [1] [3] | Sample digestion required, matrix effects [7] | Fluorescence interference, weak signal for some compounds [8] | Water interference, overlapping peaks in mixtures [2] |

Integrated Workflows and Complementary Applications

Modern pharmaceutical analysis increasingly leverages the complementary strengths of multiple spectroscopic techniques through integrated workflows. The combination of Raman and IR spectroscopy provides complete vibrational characterization, with Raman sensitive to non-polar symmetric bonds and IR detecting dipole moment changes [10]. Similarly, Raman-NMR integration enables correlation of functional group vibrations with atomic structure, particularly valuable for organic synthesis and polymer characterization [10]. The emerging trend of hybrid instrumentation and unified software platforms facilitates such multi-technique approaches, enabling comprehensive material characterization that informs critical development decisions [10].

Table 2: Strategic Technique Selection for Common Pharmaceutical Analysis Scenarios

| Analysis Scenario | Primary Technique | Complementary Techniques | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| API Structure Elucidation | NMR (1D/2D) [3] | MS, FT-IR [10] | NMR provides complete structural and stereochemical assignment; MS confirms molecular weight; FT-IR confirms functional groups |

| Elemental Impurities | ICP-MS [7] | ICP-OES | ICP-MS delivers required sensitivity for regulatory compliance; ICP-OES may supplement for higher concentration elements |

| Polymorph Screening | FT-IR [2] | Raman, PXRD [10] | FT-IR sensitive to subtle molecular environment changes; Raman provides complementary vibrational data; PXRD confirms crystal structure |

| Biologic Higher Order Structure | NMR [4] | Raman, FT-IR [5] | NMR detects higher-order structural changes; Raman and FT-IR monitor secondary structure in formulations |

| Process Monitoring | Raman [5] | NIR, FT-IR [10] | Raman enables non-invasive in-situ monitoring; NIR and FT-IR provide alternative PAT approaches for different process stages |

| Raw Material Purity | FT-IR [2] | NMR, MS [1] | FT-IR offers rapid identity confirmation; NMR and MS identify and quantify isomeric impurities |

Method Visualization and Workflow Integration

Pharmaceutical Analysis Technique Selection

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmaceutical Spectroscopy

| Reagent/Material | Technical Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (DMSO-d6, CDCl3, D2O) | Provides NMR-inert solvent matrix without interfering proton signals [3] | Sample preparation for ¹H and ¹³C NMR analysis of small molecules and APIs |

| High-Purity Acids (HNO₃, HCl) | Sample digestion for elemental analysis without introducing contaminants [7] | Microwave-assisted digestion of pharmaceutical tablets for ICP-MS analysis |

| ATR Crystals (Diamond, ZnSe) | Enables minimal sample preparation for FT-IR analysis through attenuated total reflectance [2] | Direct analysis of solid dosage forms, polymorph screening, compatibility studies |

| Chiral Tag Molecules | Forms diastereomeric complexes for chiral distinction in MRR/NMR [1] | Enantiomeric excess determination of chiral pharmaceuticals like pantolactone |

| Internal Standards (Sc, Ge, In, Bi for ICP-MS) | Corrects for instrument drift and matrix effects during quantitative analysis [7] | Multi-element quantification in ICP-MS to ensure analytical accuracy |

| SERS Substrates (Au/Ag nanoparticles) | Enhances Raman signal intensity through plasmonic surface enhancement [5] | Detection of low-concentration analytes, protein aggregation studies |

| Certified Reference Materials | Provides traceable quantification standards for method validation [7] | Calibration and quality control for regulatory-compliant testing |

| Stable Isotope Labels (¹³C, ¹âµN, ²H) | Enables tracking of specific atoms in metabolic and mechanistic studies [4] | Metabolic pathway identification, protein-ligand interaction studies |

The four spectroscopic techniques detailed in this guide—NMR, ICP-MS, Raman, and FT-IR—represent essential, complementary tools in the modern pharmaceutical analytical toolkit. Their strategic implementation across the drug development lifecycle enables comprehensive characterization of drug substances and products, ensures regulatory compliance, and supports the industry's progression toward more efficient, quality-focused manufacturing paradigms. NMR provides unparalleled structural insights for candidate identification and validation; ICP-MS delivers the extreme sensitivity required for safety-critical impurity detection; Raman spectroscopy enables real-time process monitoring and control; while FT-IR offers rapid, versatile molecular fingerprinting for formulation development and quality assessment.

The ongoing evolution of these techniques, including the integration of artificial intelligence with Raman spectroscopy [8], advancements in NMR for studying dynamic biological systems [4] [6], and the development of hybrid instrumental approaches [10], promises to further expand their capabilities and applications. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastery of these spectroscopic methods and their appropriate implementation within integrated analytical workflows remains crucial for accelerating the development of safe, effective, and high-quality pharmaceutical products in an increasingly complex regulatory and technological landscape.

This technical guide delineates the strategic career progression from a Quality Control (QC) Analytical Chemist to a Senior Research Scientist within the pharmaceutical and drug development sectors. Framed within the context of career applications for spectroscopic analysis, this document provides a detailed examination of the requisite skill evolution, core responsibilities, and advanced methodological expertise required for this transition. The guide incorporates detailed experimental protocols for forced degradation studies, visualizes career and technical workflows, and catalogs essential research reagents, serving as a comprehensive roadmap for professionals aiming to advance into research-oriented roles.

Spectroscopic analysis stands as a foundational pillar in both quality control and innovative research within drug development. As a nondestructive technique, it allows for the qualitative and quantitative measurement of a substance's composition, concentration, and structural characteristics through its interaction with electromagnetic radiation [11]. In QC environments, the focus is primarily on adherence to standardized methods for the precise determination of known compounds and impurities. In contrast, research and development (R&D) leverages these techniques for molecular characterization, structural elucidation, and the investigation of new chemical entities. The journey from a QC Analytical Chemist to a Senior Research Scientist is, in essence, a path from mastering the application of established spectroscopic methods to pioneering their use in solving novel analytical problems and driving scientific innovation [12].

Career Pathway Analysis

The progression from a QC-focused role to a senior research position involves a defined expansion of technical responsibilities, strategic influence, and scientific leadership.

Phase Comparison: Core Responsibilities and Skill Evolution

Table 1: Comparison of Role Phases from QC Analytical Chemist to Senior Research Scientist

| Career Phase | Primary Focus & Responsibilities | Key Spectroscopic & Analytical Skills |

|---|---|---|

| QC Analytical Chemist (Entry-Level) | - Routine testing of raw materials, intermediates, and finished products [12]- Operation and maintenance of analytical instruments (HPLC, GC, UV-Vis) [12]- Strict adherence to SOPs and cGMP/GLP guidelines [12]- Data documentation and reporting for quality release | - Mastery of routine operation of HPLC/UHPLC, GC, UV-Vis spectrophotometers [12]- Sample preparation: weighing, dissolving, extracting, diluting [12]- Understanding of method validation parameters (accuracy, precision, LOD/LOQ) [12] |

| Senior Analytical Chemist (Mid-Level) | - Method development and validation for new assays [12]- Troubleshooting complex instrument and methodology issues [12]- Mentoring junior staff and ensuring data integrity [12]- Interfacing with quality, production, and R&D teams | - Development and optimization of chromatographic (HPLC/UHPLC) and spectroscopic methods [12]- Advanced mass spectrometry interpretation (LC-MS/MS) [12]- Structural elucidation using techniques like FTIR and NMR [11] |

| Senior Research Scientist (Advanced) | - Leading research initiatives for new drug candidate characterization- Designing and executing forced degradation studies to understand stability profiles- Integrating advanced spectroscopic data for mechanistic studies- Publishing findings and contributing to regulatory submissions | - Advanced spectroscopic hyphenation (e.g., LC-MS-NMR, LC-DAD-MS)- Chemometrics and multivariate data analysis for complex datasets [12]- Designing and validating stress-testing protocols |

Visualization of the Career Progression Pathway

The following diagram summarizes the typical progression and key transition requirements.

Core Spectroscopic Techniques in Drug Development

The application of spectroscopy spans the entire drug development lifecycle. The transition to a Senior Research Scientist requires a deep, practical understanding of these techniques beyond routine operation.

- Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy: In QC, used for quantitative analysis of drugs in formulations. In research, it is crucial for determining extinction coefficients, monitoring reaction kinetics, and studying protein-ligand binding interactions [13].

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: A vital tool for qualitative analysis and structural fingerprinting. It provides information on vibrational states of molecular bonds, enabling the identification of functional groups and changes in molecular structure, such as those occurring in polymorphs or degradation products [11] [13].

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): The cornerstone of modern analytical research. Coupled with separation techniques like Liquid Chromatography (LC-MS) or Gas Chromatography (GC-MS), it provides high sensitivity and selectivity for identifying and quantifying compounds. A Senior Research Scientist must be proficient in interpreting mass spectral data to elucidate structures of impurities, metabolites, and degradation products [12].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Considered the gold standard for definitive structural elucidation. It is used to determine the precise structure of complex molecules, including stereochemistry, and to confirm the identity of new chemical entities [11].

Experimental Protocol: Forced Degradation Study for Drug Substance

Forced degradation studies (stress testing) are a critical research activity that bridges analytical chemistry and pharmaceutical development, providing data on the intrinsic stability of a drug molecule.

Objective

To subject a new drug substance to various stress conditions (hydrolytic, oxidative, photolytic, thermal) to identify potential degradation products, elucidate their structures, and infer degradation pathways, thereby supporting the development of stable formulations and analytical methods.

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for Forced Degradation

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Drug Substance | The active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) under investigation. |

| 0.1 M HCl and 0.1 M NaOH | To create acidic and basic hydrolytic stress conditions, revealing susceptibility to hydrolysis. |

| 3% Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) | To induce oxidative stress, identifying functional groups prone to oxidation. |

| Inert Solvent (e.g., Acetonitrile, Methanol) | For preparing drug stock solutions where solubility in aqueous stresses is limited. |

| High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | The primary tool for separating and quantifying the drug substance from its degradation products [12]. |

| Photostability Chamber | Provides controlled exposure to visible and UV light as per ICH Q1B guidelines for photolytic stress testing. |

| Stability Oven | Provides controlled thermal stress conditions (e.g., 50°C, 75°C). |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | The key hyphenated system for obtaining separation (HPLC) paired with mass-based identification (MS) of degradation products [12]. |

Methodology

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a stock solution of the drug substance (~1 mg/mL) in an appropriate solvent.

- For hydrolytic stress, aliquot the stock solution and dilute with 0.1 M HCl, 0.1 M NaOH, and neutral water. Heat at 70°C for 24-72 hours.

- For oxidative stress, add 3% H₂O₂ to an aliquot of the drug solution. Keep at room temperature or mildly elevated temperature (e.g., 40°C) for 24 hours.

- For thermal solid-state stress, expose the solid drug substance to 70°C in a stability oven for 1-2 weeks.

- For photolytic stress, expose solid drug and drug solutions to specified light conditions in a photostability chamber as per ICH guidelines.

- Include a protected control sample for all conditions.

Analysis:

- Analyze all stressed samples and controls using an optimized HPLC method with Diode Array Detection (DAD). This provides a purity chromatogram and spectral data for each peak [13].

- Inject the same samples into an LC-MS system. Compare the mass chromatograms of stressed samples to the control to identify new peaks corresponding to degradation products.

Data Interpretation and Reporting:

- For each degradation peak observed in the HPLC-UV chromatogram, use the corresponding MS data to determine its molecular weight.

- Use MS/MS fragmentation patterns to propose structures for the major degradation products.

- For critical impurities, advanced techniques like NMR spectroscopy may be employed for definitive structural confirmation.

- Compile a report detailing the conditions, the structures of identified degradation products, and proposed degradation pathways.

Visualization of the Forced Degradation Workflow

The experimental process is logically structured as follows.

Essential Technical Skills for Career Advancement

Beyond technical knowledge, advancing to a senior research role requires cultivating a specific set of competencies.

- Advanced Data Analysis and Chemometrics: Moving from univariate calibration to multivariate analysis is critical. Proficiency with software tools (e.g., R, Python, JMP) for analyzing complex datasets from hyphenated instruments allows for pattern recognition in stability data, biomarker discovery, and robust method development [12].

- Regulatory Knowledge and Quality by Design (QbD): A deep understanding of ICH guidelines (e.g., Q1 Stability, Q2 Validation, Q3 Impurities) is non-negotiable. Implementing QbD principles in analytical method development—defining an Analytical Target Profile (ATP) and understanding method robustness through deliberate experimentation—is a key differentiator for research scientists [12].

- Automation and Emerging Technologies: Familiarity with Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS), automated sample preparation (robotics), and the fundamentals of data science is increasingly important. The ability to work with IoT-connected instruments and handle large datasets efficiently is a sought-after skill in modern research environments [12] [14].

The career pathway from a QC Analytical Chemist to a Senior Research Scientist is a transformative journey of expanding one's scientific impact. It necessitates a strategic shift from applying established methods to innovating new ones, from ensuring product quality to driving fundamental drug development science. Mastery of spectroscopic techniques forms the backbone of this transition, providing the tools necessary to solve complex research problems. By deliberately cultivating expertise in advanced methodology, structural elucidation, data science, and regulatory science, motivated analytical chemists can successfully navigate this path and assume leadership roles at the forefront of pharmaceutical research and development.

The Role of Professional Societies and Mentorship in Career Advancement

For researchers and scientists in spectroscopic analysis, navigating the transition from academic theory to industrial application presents a significant challenge. This whitepaper details how professional societies and structured mentorship programs serve as critical conduits for career advancement, skill development, and successful application of spectroscopic techniques in chemistry research and drug development. Within the context of spectroscopic applications, we examine the synergistic relationship between societies that provide essential technical education and mentors who offer practical wisdom, thereby bridging the industry-academia gap and fostering robust career trajectories.

A stark disconnect often exists between the spectroscopic techniques taught in academic curricula and the practical skills demanded by industrial positions in research and drug development [15]. While academia focuses on theory and independent research, industry requires scientists to apply techniques like infrared (IR), Raman, and near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy proficiently and without error [15]. For instance, IR spectroscopy is frequently listed among the top five skills required for industrial scientists, yet it is often inadequately covered in university courses [15]. This gap can hinder the productivity of early-career spectroscopists, underscoring the necessity for external frameworks of support and education provided by professional societies and mentors.

The Critical Role of Professional Societies

Professional societies, such as the Coblentz Society and the Society for Applied Spectroscopy, are invaluable resources that directly address the skills gap through curated education, networking, and mentorship opportunities.

Access to Continuing and Practical Education

Societies provide targeted continuing education that translates theoretical knowledge into applicable industrial skills. These offerings are designed by experienced instructors to address specific, observed gaps in knowledge [15]. The table below summarizes key types of educational programs and their career applications.

Table 1: Professional Society Educational Programs for Spectroscopists

| Program Type | Example Topics | Career Application |

|---|---|---|

| In-Person Short Courses (e.g., at Pittcon, SciX) | "Introduction to Infrared, Raman, and Near-infrared Spectroscopy"; "Collecting Infrared Spectra and Avoiding the Pitfalls" [15] | Provides foundational, practical knowledge on instrument use and data collection critical for daily lab work. |

| Virtual Learning | "Spectral Interpretation of Vibrational Spectra"; "Introduction to Data Analytics for the Analytical Chemist" [15] | Offers accessible, on-demand upskilling in data analysis and interpretation, enabling remote continuous learning. |

| Advanced Topic Courses | "Two-Dimensional Correlation Spectroscopy (2D-COS)"; technologies for miniature spectrometers [15] | Keeps senior scientists and researchers at the forefront of technological and methodological innovations. |

Networking and Discreet Mentorship

Conferences and events organized by professional societies serve as vital networking hubs. They facilitate connections with seasoned colleagues and potential mentors who can offer advice that is aligned with the scientist's career, rather than their immediate employer's interests [15]. These interactions can extend to in-depth discussions about specific data or problems in a confidential setting, providing guidance that might not be available internally due to proprietary or competitive concerns [15].

The Multifaceted Impact of Mentorship

Mentorship is a powerful catalyst for professional growth, combining experienced-based guidance with psychological support. Quantitative evidence demonstrates its profound impact on career outcomes.

Quantitative Evidence of Mentorship Benefits

Mentorship significantly influences career progression, job satisfaction, and retention for both mentors and mentees. The following table synthesizes key statistics from corporate and academic settings.

Table 2: Impact of Mentorship on Career Development and Retention

| Metric | Impact of Mentorship | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Career Progression | Mentees are promoted 5x more often; Mentors are promoted 6x more often than those not in a program. | [16] |

| Salary Grade Change | 25% of mentees had a salary grade change, compared to only 5% in a control group. | [16] |

| Employee Retention | Retention rates were 72% for mentees and 69% for mentors, versus 49% for non-participants. | [16] |

| Job Satisfaction | Over 90% of workers with a mentor report being happy in their job. | [17] |

| Diversity & Inclusion | Mentoring programs boosted minority representation in management by 9% to 24%. | [16] |

Functional Roles of a Mentor in Spectroscopy

Within the technical field of spectroscopy, mentors provide several critical functions:

- Wisdom and Network Sharing: Mentors share hard-won experiential knowledge, technical expertise, and their professional networks to help mentees solve problems and identify opportunities [18] [19].

- Career Decision-Making Assistance: They assist in evaluating complex personal and professional factors when considering career paths or job options, helping to balance objective analytics with emotional priorities [18].

- Mistake Avoidance: Mentors help mentees avoid common pitfalls, such as focusing on short-term benefits over long-term career fit or not rigorously evaluating the merits of a current position against a new one [18].

Integrated Workflow: Leveraging Societies and Mentorship

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic, cyclical relationship between engagement with professional societies and mentorship in building a successful spectroscopy career.

Experimental Protocols for Career Development

Implementing a structured approach to mentorship and society engagement is akin to following a rigorous experimental protocol. The following methodologies are essential for success.

Protocol 1: Establishing a Mentor-Mentee Relationship

Objective: To form a productive, goal-oriented mentorship relationship.

- Identification: Identify potential mentors through professional society directories, conference presentations, or publications in your specific area of spectroscopic research (e.g., pharmaceutical analysis using NIR).

- Initial Contact: Reach out via professional channels, referencing a specific technical talk or paper of theirs. Propose an initial, low-commitment meeting (e.g., a 20-minute virtual coffee).

- Goal Setting: In the first meeting, clearly articulate your career objectives and specific areas where you seek guidance (e.g., "I aim to lead a spectroscopy team in drug development and need to improve my skills in quantitative spectral data analysis").

- Structure Formation: Establish a rough schedule for meetings (e.g., bi-monthly) and preferred communication channels.

- Action and Review: Prepare for each meeting with updates and specific questions. Regularly review progress toward the defined goals and adjust the relationship as needed.

Protocol 2: A Decision-Matrix for Career Choices

Objective: To objectively evaluate career options (e.g., job offers, project directions) by weighing personal and professional factors [18]. Methodology:

- List Factors: List all relevant professional (e.g., boss, job responsibilities, colleagues, advancement opportunities) and personal (e.g., family, location, salary) factors as rows in a matrix [18].

- Assign Importance: Score each factor's importance (f) from 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest) [18].

- Score Options: List potential options as columns. Score the relative benefit (a, b) of each option for every factor, also on a scale of 1 to 5 [18].

- Calculate Totals: Multiply the importance score (f) by the benefit score (a, b) for each cell. Sum the totals for each option column [18].

- Compare and Integrate: Compare the analytical priority derived from the scores with your "gut feeling." If they differ, review scores or add "gut feeling" as a new factor with an importance weight to reconcile the analytical and emotional perspectives [18].

The Scientist's Career Toolkit

Beyond laboratory reagents, a successful spectroscopist's toolkit includes key resources provided by societies and mentors.

Table 3: Essential "Research Reagent Solutions" for Career Advancement

| Toolkit Item | Function in Career Development | Example in Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Structured Short Courses | Fills specific, practical knowledge gaps not covered in academic curricula. | A half-day course on "Searching Infrared and Raman Spectra" to effectively use commercial spectral libraries. |

| Conference Networking | Facilitates formation of peer groups and access to informal mentors. | Discussing a challenging FT-IR accessory problem with a course instructor after a session at SciX. |

| Mentor's Decision Matrix | Provides an objective framework for making high-stakes career decisions. | Using the matrix [18] to decide between a postdoc offer and an industrial scientist position. |

| Affinity/Groups | Offers support and shared experience, particularly for underrepresented groups. | A society's women in spectroscopy group or a dependent care award to offset childcare costs at conferences [15]. |

| (Rac)-Carbidopa-13C,d3 | (Rac)-Carbidopa-13C,d3, MF:C10H14N2O4, MW:230.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mao-B-IN-9 | Mao-B-IN-9 is a potent MAO-B inhibitor for neurodegenerative disease research. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

For professionals engaged in the career applications of spectroscopic analysis, passive career management is insufficient. The combination of proactive engagement with professional societies and the cultivation of dedicated mentor-mentee relationships creates a powerful framework for continuous learning and career advancement. These interconnected elements effectively bridge the theory-practice divide, accelerate professional growth, and enhance job satisfaction. By systematically utilizing the education, networks, and guidance these resources provide, spectroscopists can navigate the complexities of the modern research and drug development landscape and achieve long-term, fulfilling careers.

Applied Spectroscopy: Driving Drug Discovery and Biopharmaceutical Development

Structural Elucidation and Purity Analysis with NMR and FT-IR

Structural elucidation and purity analysis represent fundamental pillars of modern chemical research, particularly in pharmaceutical development and materials science. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy stand as complementary analytical techniques that provide critical insights into molecular identity, structure, and purity. Within the context of career applications in chemistry research, proficiency in these techniques enables scientists to address challenges spanning from drug discovery to the development of advanced materials. This technical guide examines the integrated analytical workflows combining NMR and FT-IR, detailing their theoretical foundations, methodological applications, and implementation in contemporary research environments.

The evolving landscape of analytical chemistry continues to emphasize these techniques, as evidenced by current research trends. For 2025, pharmaceutical companies are significantly increasing investment in NMR-based structure elucidation services to address the growing complexity of drug molecules and meet stringent regulatory requirements [3]. Simultaneously, technological advancements in FT-IR, including integration with machine learning algorithms, are revitalizing its application for automated structure elucidation [20]. For chemistry professionals, expertise in these methodologies represents a valuable career specialization with applications across research, quality control, and regulatory affairs.

Theoretical Foundations

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei to determine physical and chemical properties of atoms/molecules. When placed in a strong magnetic field, nuclei such as ¹H and ¹³C absorb electromagnetic radiation at characteristic frequencies, providing detailed information about molecular structure, dynamics, and environment.

Fundamental Principles: NMR operates on the principle that many atomic nuclei possess spin, creating a magnetic moment. When exposed to an external magnetic field, these nuclei align with or against the field, creating distinct energy states. Transitions between these states are stimulated by radiofrequency pulses, generating detectable signals. The resulting chemical shifts (measured in parts per million, ppm) provide information about electronic environment, while J-coupling constants reveal connectivity through bonds [3].

Information Content: NMR spectra yield multidimensional structural data:

- Chemical shift: Indicates electronic environment of nuclei

- Integration: Quantifies number of equivalent nuclei

- Multiplicity: Reveals number of neighboring nuclei (J-coupling)

- Relaxation times: Provide dynamic information [3]

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

FT-IR spectroscopy measures the absorption of infrared light by chemical bonds, which corresponds to vibrational transitions. The technique provides information about functional groups and molecular conformation through characteristic absorption frequencies.

Fundamental Principles: Chemical bonds vibrate at specific frequencies corresponding to discrete energy levels. When irradiated with infrared light, bonds absorb energy at frequencies matching their vibrational modes, creating an absorption spectrum. Fourier transformation of the interferogram generates the familiar IR spectrum with wavenumber (cmâ»Â¹) on the x-axis and percent transmittance or absorbance on the y-axis [20].

Information Content: IR spectra reveal:

- Functional group identification through characteristic absorption regions

- Molecular fingerprint in the 400-1500 cmâ»Â¹ region

- Quantitative analysis through Beer-Lambert law applications

- Molecular conformation and intermolecular interactions [21]

Technical Approaches and Methodologies

NMR Techniques for Structural Elucidation

Modern NMR utilizes diverse experiment types to extract comprehensive structural information:

Table 1: NMR Experiment Types and Applications

| Experiment Type | Information Gained | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| ¹H NMR | Chemical environment, integration, coupling constants | Proton counting, substitution patterns |

| ¹³C NMR | Carbon skeleton, chemical environment | Carbon counting, functional group identification |

| DEPT | Carbon multiplicity (CH, CH₂, CH₃) | Carbon type determination |

| COSY | Proton-proton through-bond correlations | Proton connectivity mapping |

| HSQC/HMQC | Direct proton-carbon correlations | Direct C-H bond connectivity |

| HMBC | Long-range proton-carbon correlations (2-3 bonds) | Carbon skeleton assembly |

| NOESY/ROESY | Through-space interactions | Stereochemistry, conformational analysis [3] [22] |

Advanced NMR Applications:

- Chiral Analysis: NMR can distinguish enantiomers using chiral solvating agents, providing critical stereochemical information for pharmaceutical compounds [3].

- Quantitative NMR (qNMR): Enables purity determination without reference standards by comparing integral values of target compound against internal standard [3].

- Dynamic Nuclear Polarization (DNP): Enhances sensitivity by transferring electron polarization to nuclei, particularly valuable for natural abundance samples or insensitive nuclei [23].

FT-IR Methodologies

FT-IR analysis employs specific spectral regions for functional group identification:

Table 2: Characteristic FT-IR Absorption Frequencies

| Functional Group | Absorption Range (cmâ»Â¹) | Intensity | Molecular Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|

| O-H stretching | 3200-3600 | Broad, strong | Alcohols, carboxylic acids |

| N-H stretching | 3300-3500 | Medium, sharp | Amines, amides |

| C-H stretching | 2850-3000 | Medium | Alkanes |

| C=O stretching | 1650-1750 | Strong | Carbonyl compounds |

| C=C stretching | 1600-1680 | Variable | Alkenes, aromatics |

| C-O stretching | 1000-1300 | Strong | Alcohols, esters, ethers |

| C-N stretching | 1080-1360 | Medium | Amines [21] [20] |

Advanced FT-IR Applications:

- Machine Learning Integration: Transformer models can predict molecular structures directly from IR spectra, achieving 44.4% top-1 accuracy for compounds containing 6-13 heavy atoms [20].

- Hydrogen Bonding Analysis: FT-IR identifies hydrogen bonding in Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) through frequency shifts and band broadening [21].

- Quality Control: Automated spectral matching for impurity detection in pharmaceutical compounds [20].

Integrated Experimental Workflows

Complementary Technique Integration

NMR and FT-IR provide orthogonal data that, when combined, offer comprehensive structural information. The following workflow diagram illustrates their synergistic application:

Purity Assessment Protocol

Simultaneous Purity Analysis:

- FT-IR Purity Indicators:

- Absence of unexpected absorption bands

- Sharp, well-defined O-H and N-H stretches (indicating absence of moisture)

- Consistent fingerprint region with reference standard [21]

- NMR Purity Assessment:

- Integration ratios matching expected proton counts

- Absence of extraneous signals in ¹H NMR

- Consistent ¹³C NMR signal count matching proposed structure

- Detection and quantification of isomeric impurities undetectable by LC-MS [3]

Quantitative Impurity Detection: NMR excels at identifying impurities that chromatographic methods may miss, including:

- Isomeric impurities (positional isomers, tautomers)

- Non-ionizable compounds undetectable by MS

- Residual solvents and excipients

- Structurally similar degradation products [3]

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents for implementing these analytical techniques:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents | NMR sample preparation | DMSO-d6, CDCl3, D2O (99.8% deuterium) |

| Internal Standards | Chemical shift referencing | TMS (tetramethylsilane) for ¹H/¹³C NMR |

| qNMR Standards | Quantitative NMR | Maleic acid, dimethyl sulfone (high purity) |

| ATR Crystals | FT-IR sample analysis | Diamond, ZnSe, or Ge crystal materials |

| Chiral Solvating Agents | Stereochemical analysis | Tris(3-heptafluorobutyryl-d-camphorato)europium(III) |

| NADES Components | Green solvent preparation | Betaine, amino acids, sugars, polyalcohols [21] [23] |

Applications in Pharmaceutical Development

Drug Discovery and Development

NMR and FT-IR play critical roles throughout pharmaceutical development:

Early Discovery:

- Structure Validation: Confirm identity of novel chemical entities

- Hit Validation: Verify compound identity following high-throughput screening

- Medicinal Chemistry: Monitor reaction progress and intermediate characterization [3]

Development Phase:

- Polymorph Screening: Identify crystalline forms through characteristic IR patterns

- Stability Studies: Detect degradation products through spectral changes

- Formulation Analysis: Characterize API-excipient interactions [3] [22]

Regulatory Submissions:

- ICH Compliance: Support impurity profiling per ICH Q3A/B guidelines

- Forced Degradation Studies: Identify and characterize degradation pathways

- Comparative Analyses: Demonstrate equivalence for generic APIs [3]

Case Study: Cardiovascular Drug Development

A mid-sized pharmaceutical company utilized comprehensive NMR analysis to resolve a critical development challenge with a novel antihypertensive small molecule. Their internal analytical team struggled to identify the stereochemical integrity of a chiral center critical to drug efficacy.

Solution: ResolveMass Laboratories employed advanced 2D-NMR techniques including COSY, HSQC, and HMBC, complemented by chiral NMR methodologies. The analysis revealed a stereochemical inversion at the 4th carbon that was negatively impacting therapeutic activity.

Results:

- 30% reduction in development timeline

- Successful Investigational New Drug (IND) application

- Significant cost savings through early-stage correction [3]

Emerging Methodologies and Future Directions

Technological Advancements

NMR Innovations:

- High-Field Instruments: 600-800 MHz systems providing enhanced resolution and sensitivity [3]

- Cryoprobes: Significantly improved sensitivity for mass-limited samples

- Solid-State NMR: Advanced techniques including magic-angle spinning (MAS) for insoluble compounds [22]

- Hyperpolarization: Dynamic Nuclear Polarization (DNP) dramatically enhancing signal intensity [23]

FT-IR Advancements:

- Optical Photothermal IR (O-PTIR): Submicron spatial resolution for microscopic analysis [24]

- Machine Learning Integration: Transformer models predicting molecular structures directly from spectra [20]

- Portable Instruments: Field-deployable systems for point-of-need analysis

Computational Integration

The intersection of spectroscopy and computational chemistry represents a rapidly evolving frontier:

Spectral Prediction:

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Generate realistic IR spectra incorporating anharmonic effects [20]

- Quantum Mechanical Calculations: Predict NMR chemical shifts and coupling constants

- Database Mining: Leverage large spectral libraries (NIST) for pattern recognition [20]

Machine Learning Applications:

- Structural Elucidation: Transformer models achieving 69.8% top-10 accuracy for structure prediction from IR spectra [20]

- Spectral Interpretation: Convolutional neural networks identifying functional groups with high accuracy

- Automated Analysis: Streamlined workflows reducing analyst dependency [20]

Career Context in Analytical Chemistry

Proficiency in NMR and FT-IR represents a valuable skillset with diverse career applications:

Industry Positions:

- Pharmaceutical Analysis: Structure elucidation and impurity profiling roles [3]

- Method Development: Creating standardized protocols for quality control

- Regulatory Science: Preparing analytical sections for regulatory submissions [3]

Academic Research:

- Natural Products Chemistry: Structural characterization of bioactive compounds [22]

- Materials Science: Polymer characterization and functional material development [25]

- Metabolomics: Compound identification in complex biological mixtures [26]

Emerging Specializations:

- AI-Enhanced Spectroscopy: Developing machine learning tools for spectral analysis [20] [26]

- Green Chemistry: Applying NADES and sustainable solvents [21]

- Forensic Science: Drug identification and evidence characterization [26]

The integration of NMR and FT-IR continues to evolve, with career opportunities expanding into computational chemistry, method development, and cross-disciplinary applications. For chemistry professionals, maintaining expertise in these foundational techniques while adapting to technological innovations ensures continued relevance in the changing landscape of chemical analysis.

Trace Elemental Impurity Analysis with ICP-MS for Drug Safety

Elemental impurities (EIs) in pharmaceutical products pose significant patient health risks, including organ damage, cancer, and neurological issues due to their toxicity [27]. These impurities do not provide any therapeutic benefit and must be strictly controlled to ensure drug safety and efficacy [27]. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q3D guideline provides a globally harmonized framework for classifying elemental impurities and establishing Permitted Daily Exposure (PDE) limits based on robust medical data that consider element toxicity and route of administration [28] [29].

Elemental impurities can originate from various sources throughout the pharmaceutical manufacturing process, including residual catalysts added intentionally to materials, impurities present in drug substances or excipients, interactions with processing equipment, and leachables from container closure systems [27]. They can also affect the stability and shelf life of drugs due to their catalytic activities [30]. The ICH Q3D guideline categorizes elemental impurities into three classes based on their toxicity and probability of occurrence in drug products, with Class 1 and Class 2A elements being of primary concern for risk assessment [27].

ICP-MS Fundamentals and Advantages

Technical Principle

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) is an advanced analytical technique that combines two powerful technologies: an Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) source that generates a plasma torch at temperatures exceeding 6,000°C to ionize the sample, and a Mass Spectrometry (MS) system that separates and quantifies ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) [7] [31]. This combination enables the technique to detect elements at parts-per-trillion (ppt) levels and analyze up to 70 elements simultaneously in a single run [7].

When a sample is introduced into the plasma, it undergoes desolvation, vaporization, atomization, and ionization before the resulting ions are extracted into the mass spectrometer at low pressure via sampling and skimmer cones [31]. The ions then travel through a series of ion lenses toward the mass analyzer (typically a quadrupole), where they are separated according to their mass-to-charge ratio before being detected by an electron multiplier and amplified [31].

Comparative Advantages

ICP-MS has emerged as the gold standard technique for elemental impurity testing in pharmaceuticals due to several compelling advantages over other analytical techniques [7]. The following table compares ICP-MS with other common elemental analysis techniques:

Table 1: Comparison of Elemental Analysis Techniques

| Technique | Sensitivity | Multi-Element Detection | Speed | Regulatory Acceptance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICP-MS | Excellent (ppt) | Yes | High | Global Standard |

| ICP-OES | Moderate (ppb) | Yes | High | Limited |

| AAS | Low | No | Slow | Less Preferred |

ICP-MS provides unmatched sensitivity with detection capabilities at ppt levels, simultaneous multi-element detection, a wide dynamic range, and high throughput suitable for laboratories handling large sample volumes [32] [7]. Additionally, it is globally recognized by regulatory bodies like the FDA, EMA, USP, and ICH as a standard method for elemental impurity testing [32] [7].

Analytical Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Risk Assessment Approaches

The ICH Q3D guideline outlines two primary approaches for assessing elemental impurities in drug products [28]:

Component Approach (Option 2b): This method involves a risk-based analysis of elemental impurity levels in each component of the finished product, using supplier data to predict impurity levels in the final product [28]. This approach is cost-effective and can demonstrate compliance if data reliability is ensured.

Finished Product Approach (Option 3): This method entails direct analytical testing of the finished drug product to quantify elemental impurities, typically using ICP-MS [28]. This approach provides precise impurity quantification and is often used to validate the component approach.

A study comparing both methods for an oral effervescent tablet found that both approaches demonstrated compliance with ICH Q3D limits, with actual EI concentrations measured by ICP-MS consistently lower than those predicted by the component approach [28]. The risk assessment results showed that all estimated EI levels were well below 30% of PDE, suggesting no need for additional controls [28].

Sample Preparation Protocols

Proper sample preparation is critical for accurate ICP-MS analysis. The Product Quality Research Institute (PQRI) interlaboratory study established two primary digestion methods for pharmaceutical samples [27]:

Table 2: Sample Preparation Methods for ICP-MS Analysis

| Method Type | Reagents Used | Microwave Parameters | Final Acid Concentration | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exhaustive Extraction | Concentrated nitric acid with 1000 μg/mL gold inorganic standard | Temperature ramp to 175°C over 10 minutes, hold at 175°C for 10 minutes, cool to <60°C | 2% nitric acid, 2% hydrochloric acid | Routine analysis of organic materials |

| Total Digestion | Concentrated HCl, HNO₃, H₃PO₄, and fluoroboric acid (from HF + boric acid) | Temperature ramp to maximum safe temperature over 25 minutes, hold for 20 minutes, cool to <60°C | 2% HNO₃, 2% HCl, 0.2% HF | Difficult-to-digest inorganic samples |

For solid samples, laser ablation techniques can be used directly, while liquid samples are typically introduced using pneumatic nebulization [31]. Microwave-assisted digestion is generally preferred over traditional acid digestion for better reproducibility of volatile, low-concentration, and low-volume elements [31].

ICP-MS Analysis Workflow

The general workflow for ICP-MS analysis of pharmaceutical products involves multiple critical steps from sample preparation to final reporting, with specific considerations at each stage to ensure accurate quantification of elemental impurities as visualized below:

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful ICP-MS analysis requires high-purity reagents and specialized materials to prevent contamination and ensure accurate results:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ICP-MS Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Specification Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Nitric Acid | Primary digestion acid for organic matrices | Trace metal grade, preferably sub-boiling distilled |

| Internal Standard Mixture | Correction for matrix effects and instrument drift | Elements not present in samples (e.g., Sc, Ge, Rh, In, Bi) |

| Certified Reference Materials | Calibration and method validation | NIST-traceable multi-element standards |

| Collision/Reaction Gases | Interference reduction in collision cell | High-purity helium, hydrogen, or ammonia |

| Quality Control Materials | Verification of method accuracy and precision | Matrix-matched control materials with certified values |

Applications in Pharmaceutical Development and Quality Control

Drug Product Testing

ICP-MS plays a critical role throughout the pharmaceutical development lifecycle with several key applications:

Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) Testing: ICP-MS ensures ultra-trace detection of toxic metals such as arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), and mercury (Hg) in active pharmaceutical ingredients, helping products meet strict regulatory standards [32] [7].

Excipients Testing: Even inactive excipients can introduce impurities during manufacturing. ICP-MS provides precise analysis to confirm excipient purity and safety, as excipients are often derived from natural sources or synthesized using various reagents [32].

Finished Product Testing: Quality control of the final pharmaceutical product is vital for regulatory compliance. ICP-MS analyzes finished products for metal contaminants from manufacturing processes, equipment, or packaging [32].

Monitoring Metal Catalysts: Many drugs are synthesized using metal-based catalysts like platinum, palladium, or rhodium. ICP-MS verifies that residual metals remain below regulatory thresholds [7].

Stability Studies and Leachables Testing

Beyond initial quality control, ICP-MS has important applications in ongoing product assessment:

Stability Studies: During stability studies, ICP-MS tracks product degradation over time. Some pharmaceutical products may degrade into new compounds containing elemental impurities. Manufacturers use ICP-MS to monitor these changes and assess whether products remain within acceptable limits throughout their shelf life [32] [7].

Leachables Testing: ICP-MS is employed to detect elements that may leach from container closure systems into drug products over time, in accordance with USP <1664> guidelines [27]. This is particularly important for injectable and ophthalmic products where container interactions pose significant risks.

Challenges and Solutions in ICP-MS Analysis

Despite its significant advantages, ICP-MS analysis presents several challenges that require specific approaches to mitigate:

Table 4: Common ICP-MS Challenges and Recommended Solutions

| Challenge | Impact on Analysis | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Matrix Interference | Signal suppression/enhancement from complex samples | Use collision/reaction cells; internal standards; standard addition method [32] [7] |

| Sample Preparation Complexity | Incomplete digestion leading to inaccurate results | Implement microwave-assisted digestion; automated preparation systems [32] [7] |

| Contamination Risks | False positives from environmental contamination | Use cleanrooms, high-purity reagents, dedicated labware, and blank testing [32] [7] |

| Specialized Handling Needs | Loss of volatile elements like mercury | Use chemical stabilizers (gold salts); closed-vessel digestion [27] |

| Regulatory Compliance | Meeting validation requirements | Thorough method validation per ICH Q2; complete documentation [32] [7] |

The PQRI interlaboratory study highlighted that mercury and vanadium present particular analytical challenges, with these elements showing the most variable results and lowest recoveries across laboratories [27]. Mercury's volatility can lead to losses during sample preparation, while vanadium analysis can suffer from false positives due to chlorine-based interferences (ClOâº) [27]. These challenges can be addressed through optimized collision cell parameters and specialized sample preparation techniques that stabilize volatile elements [27].

Career Applications in Spectroscopic Analysis

The field of spectroscopic analysis, particularly ICP-MS specialization, offers diverse career opportunities for chemistry researchers in the pharmaceutical industry. Spectroscopists specializing in analytical techniques like ICP-MS work in various settings, including universities, government laboratories, and private industry, conducting both basic research and applied projects [33].

For early-career scientists, transitioning from academic to industrial environments can be challenging. Professional societies such as the Coblentz Society and Society for Applied Spectroscopy offer valuable resources including continuing education, mentorship programs, and networking opportunities that can accelerate career success [15]. These organizations provide practical short courses on topics such as "Introduction to Infrared, Raman, and Near-infrared Spectroscopy" and "Spectral Interpretation of Vibrational Spectra" that bridge the gap between academic theory and industrial application [15].

The analytical skills developed through ICP-MS work are highly transferable, with applications in pharmaceutical research, environmental testing, clinical diagnostics, and material science [33]. As regulatory requirements for elemental impurity testing continue to evolve, expertise in ICP-MS remains in high demand within the pharmaceutical industry, particularly for professionals who can develop validated methods, troubleshoot analytical challenges, and interpret complex data within regulatory frameworks [29] [27].

ICP-MS has established itself as an indispensable technique for trace elemental analysis in pharmaceutical quality control, offering unmatched sensitivity, multi-element capability, and regulatory compliance. As drug formulations become increasingly complex and global regulations tighten, the role of ICP-MS in ensuring drug safety continues to expand. The technique's applications span the entire drug development lifecycle, from API and excipient testing to finished product analysis and stability studies.

For chemistry researchers and drug development professionals, expertise in ICP-MS and related spectroscopic techniques provides valuable career opportunities in the pharmaceutical industry. The continuous evolution of regulatory standards, coupled with advances in ICP-MS instrumentation and methodology, ensures that specialized knowledge in this field will remain in high demand. Through proper method development, validation, and application of robust quality control measures, ICP-MS serves as a critical tool for protecting patient safety by ensuring that pharmaceutical products meet stringent global standards for elemental impurity control.

Real-Time Process Monitoring with Raman and UV-Vis Spectroscopy

In the demanding fields of pharmaceutical development and industrial bioprocessing, real-time monitoring is crucial for ensuring product quality, optimizing yields, and meeting regulatory standards. Optical spectroscopy techniques, particularly Raman and UV-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy, have emerged as powerful tools for non-invasive analysis of chemical and biological processes. These techniques align with the Process Analytical Technology (PAT) framework, encouraging innovation in manufacturing through better process understanding and control [34]. For scientists and researchers, proficiency in these methods is not just a technical skill but a significant career asset, opening doors in sectors ranging from pharmaceuticals to environmental science.

This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison of Raman and UV-Vis spectroscopy, detailing their principles, implementation protocols, and applications. It is designed to equip professionals with the knowledge to select, develop, and apply these techniques effectively for real-time monitoring challenges.

Technical Foundations and Comparative Analysis

Principles of UV-Vis Spectroscopy

UV-Vis spectroscopy measures the absorption of ultraviolet and visible light by molecules. When a molecule absorbs this light, electrons are promoted from a ground state to an excited state. The primary electronic transitions involved are σ → σ*, n → σ*, π → π*, and n → π* [35]. Quantitative analysis is governed by the Beer-Lambert Law (A = εbc), which states that the absorbance (A) of a solution is directly proportional to the concentration (c) of the absorbing species, its molar absorptivity (ε), and the path length (b) of the light through the sample [35]. This direct relationship makes UV-Vis a robust and straightforward method for concentration determination, widely used for tracking compounds like proteins in bioreactors [36] or pollutants in environmental water samples [35].

Principles of Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy is a vibrational technique that relies on the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, usually from a laser. Most scattered light is at the same wavelength as the laser source (Rayleigh scattering), but a tiny fraction undergoes a shift in wavelength due to interactions with molecular vibrational modes [37]. This shift provides a unique "fingerprint" of the molecule, offering detailed information on chemical structure, crystal form, and molecular interactions [37] [38]. Unlike UV-Vis, it does not require the analyte to possess a chromophore and is particularly valuable for studying complex mixtures and aqueous systems.

Side-by-Side Technical Comparison

The choice between Raman and UV-Vis spectroscopy depends on the specific application requirements, including the nature of the analyte, required sensitivity, and operational constraints. The table below summarizes their key characteristics for easy comparison.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Raman and UV-Vis Spectroscopy for Process Monitoring

| Feature | UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Principle | Absorption of light | Inelastic scattering of light |

| Information Provided | Concentration of chromophores | Molecular fingerprint; chemical structure |

| Primary Applications | Protein concentration [36], pollutant detection [35] | Cell culture monitoring [39], polymer curing [37], material characterization |

| Sensitivity & Selectivity | Less sensitive and selective; suitable for main component analysis [34] | Highly selective; sensitive to subtle structural changes [37] |

| Sample Considerations | Requires UV-absorbing chromophores | Effective for non-chromophoric analytes; suitable for aqueous solutions |

| Complexity & Cost | Technically simpler; generally lower cost [36] | Higher complexity and traditionally higher cost, though becoming more affordable [36] |

| Key Limitation | Limited to chromophores; interference from other absorbing species | Weak signal; susceptible to fluorescence interference [38] |

Implementation and Integration in Bioprocessing

Modes of Real-Time Monitoring

In an industrial context, real-time monitoring can be implemented in several configurations, each with distinct advantages:

- In-line monitoring: A non-invasive optical probe is inserted directly into the bioreactor. This provides a continuous, real-time measurement without removing samples or compromising sterility [34].

- On-line monitoring: A sample is automatically withdrawn from the bioreactor and diverted through a flow cell for analysis before being returned to the vessel or discarded. This protects the instrument from harsh process conditions [34].

- At-line monitoring: A sample is manually or automatically withdrawn and analyzed near the process line using dedicated instrumentation. This is faster than off-line analysis but not truly continuous [34] [39].

Experimental Protocol: Monitoring Protein Concentration in a Bioreactor

The following protocol outlines a typical workflow for implementing combined UV-Vis and Raman spectroscopy for monitoring a mammalian cell culture process, a common application in biopharmaceutical development.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Bioreactor System | Controlled environment (pH, temperature, dOâ‚‚) for cell culture. Can be lab-scale or miniature (ambr) systems [39]. |