Strategies to Identify, Troubleshoot, and Overcome Non-Specific Binding in SPR Experiments

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling non-specific binding (NSB) in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments.

Strategies to Identify, Troubleshoot, and Overcome Non-Specific Binding in SPR Experiments

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling non-specific binding (NSB) in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments. It covers the foundational principles of NSB, explores advanced methodological and immobilization strategies to minimize its occurrence, details systematic troubleshooting and optimization protocols, and discusses validation techniques to ensure data integrity. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this resource aims to empower scientists to produce highly reliable, publication-quality kinetic and affinity data, thereby accelerating discoveries in biomolecular interaction analysis and therapeutic development.

Understanding Non-Specific Binding: From Core Concepts to Impact on Data Quality

Defining Non-Specific vs. Specific Binding in SPR

FAQs on Non-Specific Binding

1. What is the fundamental difference between specific and non-specific binding in SPR?

Specific binding refers to the desired, specific molecular interaction between the immobilized ligand and the analyte in solution. This interaction is typically characterized by defined kinetics (association and dissociation phases) and saturability [1] [2]. Non-specific binding (NSB) occurs when the analyte interacts with the sensor surface or the immobilized ligand at unintended, non-target sites. These interactions are often driven by non-specific molecular forces such as hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, or electrostatic (charge-based) attractions, rather than a specific biological recognition event [1] [2]. NSB can inflate the measured response units (RU), leading to erroneous kinetic data and incorrect conclusions about the interaction [1].

2. How can I quickly test if my experiment has significant non-specific binding?

A simple preliminary test is to run your analyte over a bare sensor surface without any immobilized ligand [1] [3]. If you observe a significant binding response, non-specific binding is present. Another method is to use the reference channel on your SPR instrument. The response on the sample channel contains signal from specific binding, non-specific binding, and bulk refractive index shift. In contrast, the response on the reference channel (which should be coated with an irrelevant molecule or a blank surface) contains only non-specific binding and bulk shift [4]. If the response on the reference channel is greater than about a third of the sample channel response, you should take steps to reduce the NSB [4].

3. What are the most common causes of non-specific binding?

The primary causes can be categorized as follows:

- Charge-Based Interactions: A positively charged analyte will often bind non-specifically to a negatively charged sensor surface (e.g., a carboxylated dextran chip) [1] [3].

- Hydrophobic Interactions: Hydrophobic patches on your analyte can interact with the sensor surface [1].

- Surface and Immobilization Issues: The nature of the sensor surface itself or the chemistry used to immobilize the ligand can expose sites prone to non-specific adsorption [1] [2].

- Sample Impurities: Contaminants or aggregates in your sample can adhere to the sensor surface [2].

4. My regeneration step isn't working. Could non-specific binding be the cause?

Yes, they are often related. If your regeneration step does not completely remove bound analyte, it can cause carryover effects and baseline drift, which may be due to very strong non-specific binding [5]. Successful regeneration requires a solution that disrupts the specific ligand-analyte interaction without damaging the ligand. However, the same solution might be ineffective against strongly adhered non-specifically bound analyte. Optimizing your regeneration conditions (e.g., using acidic, basic, or high-salt solutions) is crucial, and reducing NSB at the source will make regeneration more effective [6] [3].

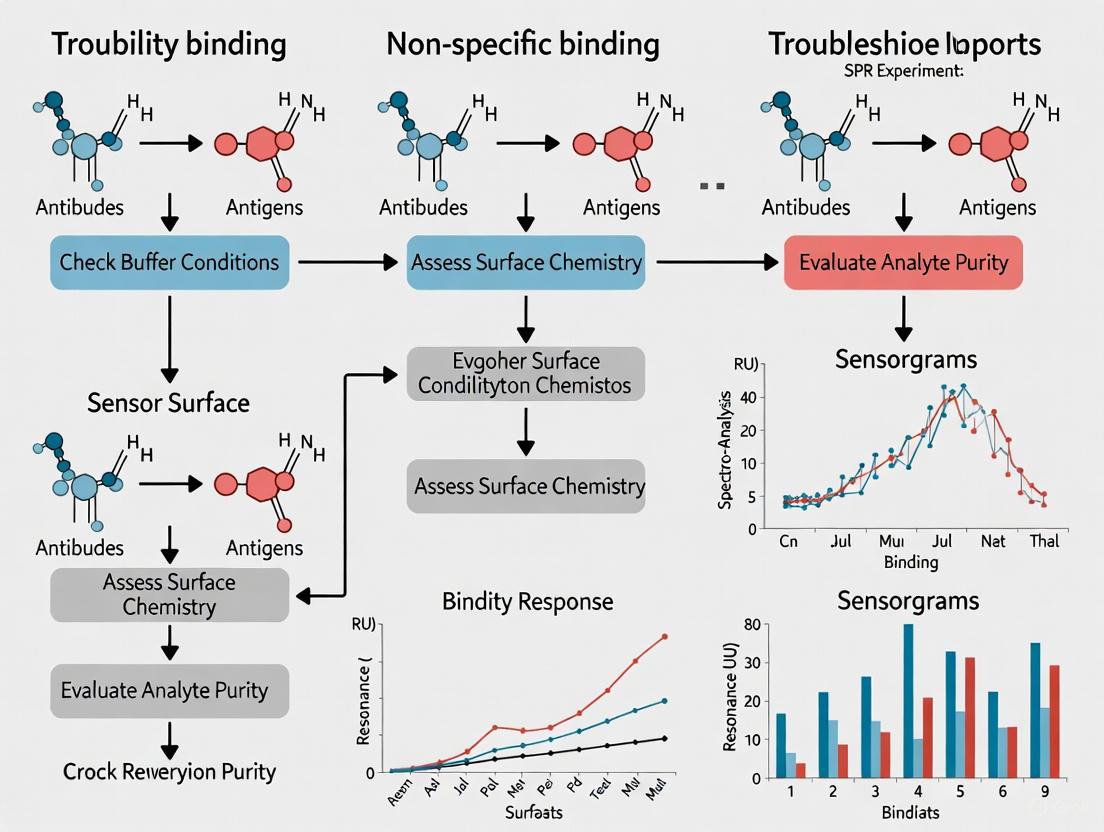

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Non-Specific Binding

Follow the systematic workflow below to identify and mitigate non-specific binding in your SPR experiments.

Quantitative Solutions for Non-Specific Binding

The table below summarizes key buffer additives and their typical working concentrations to combat different types of NSB.

Table 1: Common Reagents to Reduce Non-Specific Binding

| Reagent / Strategy | Typical Working Concentration / Range | Primary Function & Mechanism | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [1] [3] [4] | 0.5 - 2 mg/mL [4] (often 1% [1]) | Protein blocker; shields molecules from non-specific interactions by occupying charged/hydrophobic sites on surfaces and tubing [1]. | Use during analyte runs only, not during ligand immobilization, to avoid coating the sensor chip [3]. |

| Tween 20 (surfactant) [1] [3] [4] | 0.005% - 0.1% [4] | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions; mild non-ionic detergent reduces adsorption [1] [3]. | Low concentrations are effective; higher concentrations may interfere with some protein functions. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) [1] [3] [4] | Up to 500 mM [4] (e.g., 200 mM [1]) | Reduces charge-based interactions; high ionic strength shields charged groups on the analyte and surface [1]. | Can affect the stability of some electrostatic-dependent specific interactions. |

| Ethylenediamine (post-coupling) [4] | As a blocking agent after amine coupling | Blocks negative charge on carboxylated sensor chips; alternative to ethanolamine for reducing charge-based NSB with positive analytes [4]. | Specifically useful for positively charged analytes on standard carboxymethyl dextran chips. |

| Sensor Chip Dextran [4] | 1 mg/mL added to running buffer | For dextran chips; saturates the dextran matrix to prevent analyte from getting stuck non-specifically [4]. | Chip-specific strategy. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Diagnostic Test for Non-Specific Binding

This protocol helps you determine the level of NSB in your system before running a full binding experiment [1] [3].

- Prepare Surfaces: Use a sensor chip with at least two flow cells. Leave one flow cell bare (underivatized) or deactivated. A second flow cell can be immobilized with your ligand as per your standard procedure.

- Prepare Analyte: Use the highest concentration of your analyte from your planned dilution series.

- Run the Experiment: Inject the high-concentration analyte over both the bare surface and the ligand-immobilized surface using your standard running buffer.

- Analyze the Data:

- Interpretation: If the NSB response is more than ~30% of the specific signal, you should implement the strategies listed in Table 1 and the workflow above before proceeding [4].

Protocol 2: Scouting for Optimal Regeneration Conditions

Incomplete regeneration can lead to carryover of both specific and non-specifically bound analyte, corrupting subsequent data points [5]. This protocol helps find a solution that fully cleans the surface.

- Immobilize Ligand: Immobilize your ligand on the sensor chip.

- Bind Analyte: Inject a single, medium concentration of analyte to achieve a robust binding level.

- Scout Regenerants: After the dissociation phase, inject a short pulse (e.g., 15-60 seconds) of a candidate regeneration solution. Start with mild conditions and progress to harsher ones if needed [3]. Common solutions include:

- Assess Regeneration: The goal is to return the signal to the baseline level before analyte injection. Monitor the stability of the baseline after regeneration; a drifting baseline can indicate incomplete regeneration or surface damage [5].

- Check Ligand Activity: Inject a known positive control analyte to ensure the regeneration step did not denature or strip the ligand from the surface. A stable binding response over multiple cycles confirms successful regeneration [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for SPR Experiments Focused on Minimizing NSB

| Item | Function in SPR | Key Consideration for NSB |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 / Carboxyl Sensor Chip | Standard chip for covalent amine coupling of proteins/ligands. | The negatively charged dextran matrix can cause NSB with positively charged analytes [3] [4]. |

| NTA Sensor Chip | Captures His-tagged proteins via nickel chelation, allowing for oriented immobilization. | Can reduce NSB by improving ligand orientation, but the metal chelate itself can sometimes cause NSB. |

| Planar / C1 Sensor Chip | Sensor with a flat, low-swelling hydrogel surface. | Can reduce NSB from analytes that penetrate the 3D matrix of dextran chips [4]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Versatile blocking agent for proteins. | Use as a buffer additive after ligand immobilization to block NSB sites in the system [3]. |

| Tween 20 | Non-ionic surfactant to disrupt hydrophobic NSB. | Effective at very low concentrations; also prevents analyte loss to tubing and vials [1]. |

| Ethylenediamine | Blocking agent for carboxyl chips. | Provides a more neutral charge than the standard ethanolamine, better reducing NSB for positive analytes [4]. |

| Glycine-HCl (pH 2.0-3.0) | Common acidic regeneration solution. | Effective for disrupting antibody-antigen interactions; harsh conditions may inactivate some ligands [6]. |

| (R)-MDL-101146 | (R)-MDL-101146, CAS:163660-53-5, MF:C29H37F5N4O6, MW:632.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SAR405838 | SAR405838, CAS:1303607-60-4, MF:C29H34Cl2FN3O3, MW:562.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary molecular forces responsible for Non-Specific Binding (NSB) in SPR experiments? NSB is primarily driven by three fundamental molecular forces: hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic (charge-based) interactions, and Van der Waals forces [1]. These forces cause the analyte to interact with non-target sites on the sensor surface or the immobilized ligand itself, rather than with the specific binding pocket, which can inflate the response signal and lead to erroneous kinetic data [1].

Q2: How can I experimentally determine which force is causing NSB in my assay? You can identify the dominant force by conducting a series of preliminary tests. A simple test involves running your analyte over a bare sensor surface without any immobilized ligand to confirm the presence of NSB [1] [3]. Based on the results, you can hypothesize the cause and test specific additives:

- If you suspect electrostatic interactions, try increasing the salt concentration (e.g., NaCl) to shield the charges [1] [3].

- If you suspect hydrophobic interactions, add a non-ionic surfactant like Tween 20 to disrupt them [1] [3].

- Using a protein blocker like BSA can help shield the analyte from various non-specific interactions with the surface and tubing [1] [3]. Observing which additive reduces the NSB signal can pinpoint the main contributing force.

Q3: My protein has a high isoelectric point (pI). How can I reduce charge-based NSB? For a positively charged analyte (high pI), it will readily interact with a negatively charged sensor surface [1]. To mitigate this:

- Adjust your buffer pH: Set the pH of your running buffer to the isoelectric point (pI) of your protein, where it has a neutral overall charge, or to a pH that neutralizes the surface charge [1] [3].

- Block the surface charge: If using amine coupling, block the sensor chip with ethylenediamine instead of ethanolamine after immobilization. Ethylenediamine provides a primary amine that leaves a less negative surface, reducing attraction to your positively charged analyte [7].

- Increase salt concentration: Adding salts like NaCl to your buffer can produce a shielding effect, reducing charge-based interactions [1].

Q4: Can changing my sensor chip chemistry help with NSB? Yes, selecting an appropriate sensor chip is a fundamental strategy. If you are experiencing significant NSB, consider switching to a sensor chip with a different surface chemistry [8] [6]. For instance, if you are using a negatively charged carboxyl or NTA sensor and your analyte is also negatively charged, you may see repulsion instead of binding. Conversely, a positively charged analyte will have strong NSB on this surface. In such cases, switching to a neutral or positively charged surface, or using a planar chip instead of a dextran-based chip, can significantly reduce NSB [3] [7].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving NSB

Step 1: Confirm the Presence of NSB

Before troubleshooting, confirm that NSB is affecting your data.

- Method: Immobilize your ligand on one flow cell. Use a second flow cell as a reference, which should be activated and blocked but without ligand immobilized [6]. Inject a high concentration of your analyte and observe the binding response on both the ligand and reference surfaces.

- Interpretation: A significant binding response on the reference surface indicates NSB [3]. If the NSB signal is less than 10% of your specific binding signal, you may be able to correct your data by subtracting the reference signal. If it is higher, you need to mitigate it [3].

Step 2: Identify the Dominant Molecular Force

The table below summarizes the characteristics and initial tests for different NSB types.

Table 1: Identifying the Molecular Forces Behind Non-Specific Binding

| Molecular Force | Common Manifestation | Preliminary Diagnostic Test |

|---|---|---|

| Electrostatic Interactions | Strong NSB with oppositely charged surfaces or molecules [1]. | Add 150-200 mM NaCl to the running buffer. A reduction in NSB confirms charge involvement [1]. |

| Hydrophobic Interactions | NSB due to non-polar regions on the analyte or surface [1]. | Add a non-ionic surfactant (e.g., 0.005%-0.1% Tween 20) to disrupt hydrophobic forces [1] [7]. |

| Van der Waals / General Adsorption | General, non-specific adhesion to the sensor surface or tubing. | Add a blocking agent like 0.5-1 mg/mL BSA to surround and shield the analyte [1] [7]. |

Step 3: Apply Targeted Solutions

Once you have identified the likely cause, apply the solutions detailed in the table below.

Table 2: Targeted Solutions for Different Types of Non-Specific Binding

| Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Example & Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Electrostatic Interactions | - Adjust buffer pH to protein's pI [1] [3].- Increase ionic strength with salts [1] [3].- Use ethylenediamine for blocking [7]. | Example: Addition of 200 mM NaCl to running buffer significantly reduced NSB of rabbit IgG on a negatively charged surface [1].Mechanism: The ions in the salt shield the charged groups on the analyte and sensor surface, preventing their attraction. |

| Hydrophobic Interactions | - Add non-ionic surfactants [1] [3].- Change to a more hydrophilic sensor chip [7]. | Example: Using Tween 20 at concentrations as low as 0.005% [7].Mechanism: Surfactants coat hydrophobic patches, making them less available for non-specific interactions. |

| General Adsorption & Surface Effects | - Add protein blockers (BSA, casein) [8] [3].- Use additives like carboxymethyl dextran or PEG [7]. | Example: Using 1% BSA in the buffer and sample solution [1] [3].Mechanism: These agents adsorb to non-specific sites on the surface and tubing, preventing your analyte from doing so. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Workflow to Mitigate NSB

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing NSB in an SPR experiment.

Title: NSB Troubleshooting Workflow

Detailed Protocol Steps:

- Preliminary NSB Test: Prepare a sensor chip where at least one flow cell has no ligand immobilized (a bare surface). Inject your highest analyte concentration over this surface. The observed binding response is your baseline NSB level [1] [3].

- Assessment: Compare the NSB response to the specific binding response on your ligand-immobilized surface. If NSB is less than 10%, you can subtract it during data processing. If it is higher, proceed to mitigation [3].

- Diagnose the Force: Systematically test different buffer additives to diagnose the dominant force.

- Begin by supplementing your running buffer with 150-200 mM NaCl. If NSB decreases, electrostatic forces are a key contributor [1].

- If salt has little effect, try adding 0.005% Tween 20. An improvement indicates significant hydrophobic interactions [1] [7].

- As a broad-spectrum initial approach, 1% BSA can be added to shield the analyte from various surface interactions [1].

- Re-test and Iterate: After applying a solution, repeat the preliminary NSB test to check for improvement. You may need to combine strategies (e.g., a slightly higher salt concentration with a low amount of surfactant) for optimal results.

- Final Validation: Once NSB is minimized, run a full analyte concentration series over your specific ligand surface to collect kinetic data.

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key reagents used to combat NSB, along with their functions and typical working concentrations.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Mitigating Non-Specific Binding

| Reagent | Function & Mechanism | Typical Working Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Reduces charge-based NSB by shielding electrostatic interactions between charged residues on the analyte and the sensor surface [1] [3]. | 150 - 500 mM [1] [7]. |

| Tween 20 | A non-ionic surfactant that disrupts hydrophobic interactions by coating hydrophobic patches on the analyte or surface [1] [3]. | 0.005% - 0.1% [1] [7]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A protein blocking agent that adsorbs to non-specific sites on the sensor surface and tubing, shielding the analyte from non-target interactions [1] [3]. | 0.5 - 2 mg/mL (or ~0.05% - 0.2%) [1] [7]. |

| Ethylenediamine | An alternative to ethanolamine for blocking after amine coupling. It leaves a less negative (more neutral) surface charge, reducing NSB with positively charged analytes [7]. | Used as a 1 M solution, pH 8.5 [7]. |

| Carboxymethyl Dextran | When added to the buffer, it can saturate dextran-based sensor surfaces, preventing analyte adsorption through competitive occupation of non-specific sites [7]. | 1 mg/mL [7]. |

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a powerful, label-free technique for studying biomolecular interactions, but its performance is often compromised by non-specific binding (NSB), a long-standing challenge that can lead to erroneous data and false conclusions [9] [10]. This guide helps you identify and troubleshoot the common sources of NSB in your experiments.

FAQ: The Top Questions on Non-Specific Binding

What is non-specific binding (NSB) in SPR? NSB occurs when molecules in your sample (the analyte) interact with the sensor surface or non-target molecules without any specific recognition, leading to a false signal that inflates the response units (RU) and compromises kinetic data [9] [1].

How can I quickly check if my experiment has NSB? A simple preliminary test is to run your analyte over a bare sensor surface or a reference channel that lacks the immobilized ligand. A significant response on this surface indicates NSB that needs to be addressed [1] [4].

My sensorgram is noisy and the baseline is drifting. Is this NSB? Not necessarily. Noisy signals and baseline drift can have other causes, such as sample impurities (e.g., protein aggregates) or buffer incompatibility [11] [8]. However, these factors can also contribute to or exacerbate NSB, so a thorough investigation is recommended.

The Core Culprits of NSB and Their Solutions

The table below summarizes the primary causes of NSB and the corresponding strategies to mitigate them.

Table 1: Common Culprits of Non-Specific Binding and Mitigation Strategies

| Culprit Category | Specific Cause | Mechanism | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensor Surface Chemistry | Hydrophilic -OH terminated surfaces | Significant NSB signal observed with liposomes [12] | Use -CH₃ or -COOH terminated surfaces [12] |

| Negatively charged carboxymethyl dextran | Attracts positively charged analytes [13] | Switch to short-chain thiols or planar surfaces [4] [13] | |

| Sample Composition | Impurities (aggregates, denatured proteins) | Cause noisy signals and curious sensorgrams [11] | Purify sample to >95% purity; use SEC-MALS for QC [11] |

| Inactive or denatured protein | Loss of specific binding function [11] | Source proteins with verified bioactivity [11] | |

| Buffer Conditions | Incorrect pH | Analyte carries a net positive charge, interacting with a negative surface [1] | Adjust buffer pH to the isoelectric point of the analyte [1] |

| Low ionic strength | Insufficient shielding of charged molecules [1] | Increase salt concentration (e.g., up to 200-500 mM NaCl) [1] [4] | |

| Hydrophobic interactions | Non-polar interactions with the surface [1] | Add non-ionic surfactants (e.g., Tween-20 at 0.005%-0.1%) [1] [4] |

Quantitative Impact of Surface Chemistry

The choice of sensor surface chemistry has a direct and quantifiable impact on the level of NSB. The following table summarizes experimental data from a study using liposomes, showing how different surface terminations affect the SPR signal.

Table 2: Quantifying NSB: SPR Signal Change vs. Sensor Surface Chemistry

| Sensor Surface Termination | SPR Signal Change at 100 μM Phospholipid (mRIU) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| -COOH (on sensor) paired with -COOH (on liposome) | ~1 mRIU | NSB almost completely eliminated [12] |

| -CH₃ | Minimal (performance similar to -COOH) | NSB significantly minimized [12] |

| -OH | ~4 mRIU | Significant NSB observed [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Minimizing NSB

Protocol 1: Systematic Optimization of Buffer Conditions

This protocol is a first-line strategy for reducing NSB caused by electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions [1].

- Prepare Stock Solutions: Prepare a 1M NaCl stock solution for ionic strength adjustment, a 10% (v/v) stock of a non-ionic surfactant like Tween 20, and a 1-10% (w/v) stock of a blocking agent like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA).

- Baseline Test: Run your analyte over a bare sensor surface or reference channel to establish the baseline NSB level.

- Adjust Ionic Strength: If NSB is suspected to be charge-based, add NaCl to the running buffer and sample, testing a range from 50 mM up to 500 mM [1] [4]. Monitor for a reduction in the reference channel signal.

- Add Surfactant: If hydrophobic interactions are suspected, introduce Tween 20 to a final concentration between 0.005% and 0.1% to both the running buffer and sample [1] [4].

- Use a Blocking Agent: Add BSA at a concentration of 0.5 to 2 mg/ml to block remaining non-specific sites on the sensor surface [9] [4]. Note that this is added to the buffer, not the sample.

- Iterate and Combine: You may need to combine strategies (e.g., a moderate salt concentration with a low level of surfactant) for optimal results. Always verify that your specific binding signal remains strong.

Protocol 2: Advanced Surface Selection and Control Experiments

This protocol uses strategic surface selection and experimental design to account for NSB, which is particularly useful in complex media like serum [14].

- Select the Right Surface: Based on the data in Table 2, choose a sensor chip with a surface chemistry that minimizes NSB for your system, such as a planar COOH or CH₃ terminated chip over an OH-terminated one [12] [4].

- Employ a Multi-Channel Strategy:

- Channel 1 (Ligand Channel): Immobilize your target ligand.

- Channel 2 (Reference Channel): Prepare a surface that mimics the ligand channel but lacks specific activity. This can be achieved by immobilizing an irrelevant protein, using a chemical block (e.g., ethanolamine), or, for capture assays, capturing a non-cognate target structurally similar to your ligand [14].

- Run Simultaneous Measurements: Inject your sample over both channels simultaneously.

- Subtract the Signal: During data analysis, subtract the response from the reference channel (non-specific signal) from the response in the ligand channel (specific + non-specific signal) to obtain the true specific binding signal [4].

This workflow for advanced surface selection and control experiments ensures that non-specific signals are effectively identified and accounted for.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Troubleshooting NSB in SPR

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Protein-based blocking agent that covers non-specific binding sites on the sensor surface [9] [4]. | Typically used at 0.5-2 mg/ml. Ensure it does not interfere with the specific interaction [1] [4]. |

| Tween 20 | Non-ionic surfactant that disrupts hydrophobic interactions [1]. | Use at low concentrations (0.005%-0.1%). Higher concentrations may denature proteins [1] [4]. |

| NaCl | Salt used to shield electrostatic interactions by increasing ionic strength [1]. | Test a range from 50 mM to 500 mM. Can be combined with other additives [1] [4]. |

| Carboxyl-terminated (-COOH) Sensor Chip | Sensor surface chemistry that minimizes NSB, especially when paired with negatively charged analytes [12]. | A planar COOH chip is an alternative to dextran-based chips if NSB is high [4]. |

| Ethanolamine | Small molecule used to deactivate and block remaining active ester groups after amine coupling [8]. | A standard step in immobilization protocols that also reduces charge-based NSB [8]. |

| NHS ester of 16-mercaptohexadecanoic acid | Short-chain thiol for creating self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) that drastically reduce NSB from complex media [13]. | Offers lower NSB compared to traditional carboxymethyl dextran surfaces [13]. |

| Wf-516 | Wf-516, CAS:310392-93-9, MF:C25H26Cl3N3O4, MW:538.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MIR96-IN-1 | MIR96-IN-1, MF:C33H48N8O2, MW:588.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Non-Specific Binding (NSB) in SPR? In SPR experiments, non-specific binding (NSB) occurs when the analyte interacts with the sensor surface or other non-target sites, rather than specifically with the immobilized ligand [1]. These unintended interactions are typically driven by non-covalent molecular forces such as hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, or ionic (charge-based) attractions [1] [15].

Why is NSB a critical problem for data interpretation? NSB is not just a minor nuisance; it directly compromises the integrity of your kinetic data. It inflates the measured response units (RU), leading to an overestimation of binding levels [1]. This results in erroneous calculations of affinity (KD) and kinetic rate constants (ka and kd) [3]. Essentially, the reported parameters reflect a combination of specific and non-specific events, making them unreliable.

What are the real-world consequences of NSB? In practical terms, NSB can cause:

- Low recovery of your analyte, making it seem like your sample has disappeared [16].

- High variability between sample replicates, ruining the reproducibility of your assay [16].

- Poor sensitivity, which can mask weak but biologically important interactions and limit the dynamic range of your assay [16].

How can I quickly test if my experiment has NSB? A simple preliminary test is to run a high concentration of your analyte over a bare sensor surface (a flow cell with no immobilized ligand) [3] [1]. Any significant response change indicates that NSB is present and must be addressed before collecting final data.

Can't I just subtract the NSB signal during data analysis? While reference channel subtraction can correct for some NSB, this is not always perfect [3]. If the NSB signal accounts for less than 10% of your total signal, subtraction can be a valid correction [3] [1]. However, for higher levels of NSB, the underlying kinetic constants are often already skewed. The best practice is to actively minimize NSB through experimental optimization rather than relying solely on data correction [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Solving NSB

Step 1: Diagnose the Type of NSB

The most effective mitigation strategy depends on the primary cause of your non-specific binding. The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing NSB based on experimental observations.

Step 2: Apply Targeted Solutions

Once you have a hypothesis for the type of NSB, employ the specific strategies detailed in the table below. These methods work by altering the chemical environment to disrupt the forces causing non-specific interactions.

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Example Protocol | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjust Buffer pH [1] [15] | Alters the net charge of proteins to reduce charge-based attraction to the sensor surface. | Prepare running buffer with a pH closer to the isoelectric point (pI) of your analyte, where its net charge is neutral. | Extreme pH may denature your biomolecule. Test a range of ±1 pH unit from the initial condition. |

| Increase Salt Concentration [1] [15] | Shields charged groups on both the analyte and sensor surface, disrupting ionic interactions. | Add 150-200 mM NaCl to both the running buffer and analyte samples [15]. | Very high salt concentrations may cause protein precipitation or salting-out effects. |

| Add Non-Ionic Surfactants [3] [1] | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions by coating hydrophobic surfaces and analyte regions. | Add Tween 20 to buffers at a low concentration (e.g., 0.05% v/v). | Surfactants can be difficult to flush from the system and may interfere with some detection methods. |

| Use Protein Blocking Additives [3] [1] | Coats the sensor surface and tubing with an inert protein (e.g., BSA) to block adsorption sites. | Add 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) to your buffer and sample solutions. | Adds complexity to the sample and may not be compatible with all downstream analyses, like LC-MS [17]. |

Experimental Protocol: Systematic NSB Testing and Optimization

This protocol provides a detailed methodology to diagnose NSB and test the effectiveness of mitigation strategies.

Objective: To confirm the presence of NSB and identify the optimal buffer condition to minimize it.

Materials:

- SPR instrument.

- Bare sensor chip (e.g., carboxymethyl dextran chip without immobilized ligand).

- Purified analyte at a high concentration (e.g., 10x expected KD).

- Running buffer.

- Test buffers with different additives (see table above).

Procedure:

- Establish a Baseline: Prime the SPR system with your standard running buffer.

- Initial NSB Test: Inject your analyte at a high concentration over the bare sensor surface using the standard running buffer. Observe the response.

- Result: A significant response (RU) indicates NSB is present.

- Test Mitigation Buffers: Repeat the injection with the same analyte concentration, but now using a series of running buffers that contain different additives.

- Example series: Standard buffer, buffer + 200 mM NaCl, buffer + 0.05% Tween 20, buffer + 1% BSA.

- Analyze Results: Compare the response levels from each injection. The condition that yields the lowest response on the bare sensor chip is the most effective at reducing NSB.

- Validate on Ligand Surface: Once an optimal buffer is identified, immobilize your ligand and run a full analyte concentration series. The sensorgrams should show cleaner association and dissociation phases, and the resulting data should fit better to a 1:1 binding model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Having the right reagents is crucial for designing a robust SPR experiment and combating NSB. The following table lists essential materials and their functions.

| Item | Function in SPR Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip [18] | A versatile chip with a carboxymethylated dextran matrix for covalent immobilization of ligands via amine coupling. | The standard choice for many applications, but the negatively charged dextran can contribute to charge-based NSB. |

| NTA Sensor Chip [3] [18] | For capturing His-tagged ligands, providing a uniform orientation. | Requires a ligand with a 6x-His tag. The surface may need stabilization after capture. |

| SA Sensor Chip [8] | For capturing biotinylated ligands with high affinity and defined orientation. | Requires a biotinylated ligand. |

| HEPES Buffered Saline (HBS) [18] | A common running buffer that provides physiological pH and ionic strength. | A good starting point for many protein interaction studies. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [3] [1] | A blocking agent used to coat surfaces and prevent NSB of proteinaceous analytes. | Can complicate data if it binds to the ligand; not suitable for all detection methods [17]. |

| Tween 20 [3] [1] | A non-ionic detergent used to reduce hydrophobic interactions and prevent analyte loss to tubing and containers. | Use at low concentrations (0.01-0.05%) to avoid damaging proteins or creating bubbles. |

| EDC/NHS Chemistry [8] [18] | The standard crosslinking chemistry for covalent immobilization of ligands on carboxylated surfaces (e.g., CM5). | Can lead to heterogeneous ligand orientation if the protein has multiple lysine residues. |

| ML204 hydrochloride | ML204 hydrochloride, CAS:2070015-10-8, MF:C15H19ClN2, MW:262.78 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SR9186 | SR9186, CAS:1361414-26-7, MF:C28H19F3N6O3, MW:544.49 | Chemical Reagent |

Proactive Design: Methodological Choices to Suppress Non-Specific Binding

FAQs: Core Principles and Selection

Q1: What is the primary function of a sensor chip in an SPR experiment? The sensor chip is the core of the SPR system. It provides a stable, functionalized surface to immobilize a ligand (e.g., a protein, antibody, or nucleic acid). When an analyte in solution binds to this ligand, it causes a change in the refractive index on the sensor surface, which is detected in real-time as a shift in the resonance angle. The chip's surface chemistry is designed to facilitate this immobilization while minimizing non-specific binding (NSB) to ensure accurate data [19] [20].

Q2: How does the choice of sensor chip directly impact non-specific binding? Non-specific binding occurs when analytes interact with the sensor surface itself rather than the target ligand, leading to false-positive signals and skewed data. The immobilization matrix on the sensor chip (e.g., dextran, SAM, or lipid layer) is designed to be hydrophilic and bio-inert, which reduces these unwanted hydrophobic or electrostatic interactions. Selecting a chip with the appropriate surface chemistry for your specific ligand and analyte is the first and most critical step in mitigating NSB [19] [20] [5].

Q3: When should I use a dextran-based sensor chip? Dextran-based chips (e.g., CM5) are versatile and widely used. Their 3D hydrogel structure provides a high surface area for ligand immobilization, making them ideal for studying interactions involving small molecules and proteins. However, this 3D structure can sometimes lead to steric hindrance for very large analytes, such as viruses or whole cells, potentially trapping analytes and contributing to NSB [21] [19].

Q4: What are the advantages of a Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) chip? SAMs, typically formed from alkanethiols on a gold surface, create a flat, two-dimensional (2D) surface. This planar geometry is better suited for studying interactions between large molecules, such as large proteins, virus particles, or whole cells, as it minimizes steric crowding. Mixed SAMs can be engineered with specific terminal groups (e.g., carboxyl, hydroxyl) to optimize ligand attachment and reduce NSB [21] [22].

Q5: For which applications are lipid-based sensor chips essential? Lipid-based chips (e.g., L1 and HPA) are designed to mimic biological membranes. The L1 chip captures intact liposomes or membrane vesicles within a dextran matrix, while the HPA chip supports the formation of a single lipid monolayer on a hydrophobic surface. These are indispensable for studying membrane-protein interactions, lipid-protein binding, and the function of membrane-embedded receptors in a near-physiological environment [20] [23] [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Non-Specific Binding (NSB)

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High binding signal in the reference channel or on a bare surface. | Analyte is interacting non-specifically with the sensor chip surface. | - Add blocking agents like BSA (0.1-1%) to the running buffer [6] [3] [5].- Supplement buffer with non-ionic surfactants (e.g., Tween 20) to disrupt hydrophobic interactions [3].- Increase salt concentration (e.g., NaCl) to shield charge-based interactions [3]. |

| Signal increases linearly during association without curvature. | Mass transport limitation; analyte diffusion to the surface is slower than its binding rate. | - Increase the flow rate during analyte injection [3] [5].- Reduce the ligand density on the sensor chip to slow the capture rate [3]. |

| Inconsistent binding responses and high background. | The surface charge of the chip is attracting the analyte oppositely. | - Adjust the buffer pH to match the isoelectric point (pI) of your protein analyte to neutralize its charge [3].- Switch to a sensor chip with a lower charge density (e.g., from CM5 to CM4) [24]. |

| NSB persists despite buffer optimization. | Incompatible sensor chip chemistry for the ligand-analyte pair. | - Switch the immobilization chemistry. If using covalent amine coupling, try a capture method (e.g., NTA for His-tagged proteins) to improve orientation and reduce denaturation [6] [19]. |

Troubleshooting Sensor Chip Regeneration

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete dissociation; baseline does not return to original level. | The regeneration solution is too mild or the contact time is too short. | - Optimize regeneration scouting: Start with mild conditions (e.g., low salt, mild pH) and progressively increase strength [3].- Use short, high-flow rate pulses (e.g., 100 µL/min) of regeneration buffer [3].- Test alternative solutions: 10 mM glycine pH 2.0, 10 mM NaOH, or 2 M NaCl [6]. |

| Ligand activity drops after regeneration. | The regeneration solution is too harsh and damages the immobilized ligand. | - Use a milder regeneration buffer. Adding 10% glycerol can help stabilize the ligand [6].- For capture chips, be prepared to re-immobilize the ligand after each regeneration cycle [3]. |

| Gradual decay of binding capacity over multiple cycles. | Cumulative damage to the sensor chip surface or ligand. | - Ensure the regeneration solution is compatible with the sensor chip surface chemistry (e.g., avoid detergents on L1 or HPA chips) [23].- Follow manufacturer guidelines for surface maintenance and storage [5]. |

Comparative Data and Experimental Protocols

Sensor Chip Comparison Table

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the three main sensor chip types to guide your selection.

| Feature | Dextran Polymer (e.g., CM5) | Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) | Lipid Structures (e.g., L1, HPA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Geometry | 3D hydrogel matrix (~100-200 nm thick) [19] | Flat, 2D monolayer [22] | L1: 3D dextran with lipophilic groups; HPA: 2D lipid monolayer [23] [24] |

| Ideal For | Small molecules, protein-protein interactions, high ligand density [19] [20] | Large analytes (viruses, cells), reduced steric hindrance [21] [22] | Membrane proteins, lipid-protein interactions, mimicking cell membranes [20] [23] |

| Common Immobilization | Covalent coupling (amine, thiol) [19] | Covalent coupling to terminal groups [21] | Hydrophobic capture of liposomes (L1) or lipid monolayer fusion (HPA) [23] [24] |

| NSB Considerations | Hydrophilic matrix reduces NSB; can trap large molecules [19] [20] | Can be engineered with mixed SAMs to minimize NSB [21] | Full lipid coverage is critical to block the hydrophobic surface and prevent NSB [23] |

| Key Advantage | High binding capacity due to 3D structure. | Planar surface ideal for large binding partners. | Provides a native-like membrane environment. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function in SPR Experiments |

|---|---|

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | A common blocking agent added to running buffers (typically at 1%) to coat the sensor surface and minimize non-specific protein adsorption [6] [3]. |

| Tween 20 | A non-ionic surfactant used at low concentrations in buffers to disrupt hydrophobic interactions that cause NSB [3]. |

| EDC/NHS | Cross-linking reagents used for covalent amine coupling on carboxylated surfaces (e.g., CM5 chips) to activate the surface for ligand attachment [21]. |

| Octyl-glucoside | A detergent used to prepare and clean hydrophobic HPA sensor chips before lipid monolayer formation [23]. |

| NaOH (e.g., 10-100 mM) | A common, harsh regeneration solution used to strip bound analyte from the ligand surface. Concentration must be optimized to avoid ligand denaturation [6] [23]. |

| Glycine-HCl (e.g., 10 mM, pH 2.0) | A common, mild acidic regeneration solution used to disrupt protein-protein interactions without permanently damaging the ligand [6]. |

Workflow Diagram: Strategic Chip Selection

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting the appropriate sensor chip based on your experimental goals.

Experimental Protocol: Coating an HPA Chip with a Lipid Monolayer

This protocol details the steps for creating a lipid monolayer on an HPA sensor chip, a critical process for membrane interaction studies [23].

The choice of immobilization technique in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) is a critical foundational step that directly influences the reliability and interpretability of your binding data. The primary challenge in many SPR experiments is non-specific binding (NSB), which can artificially inflate response signals and lead to erroneous kinetic calculations [1]. A significant contributor to NSB is suboptimal ligand orientation on the sensor surface.

When a ligand is immobilized randomly, its active binding site may become obstructed or altered. This not only reduces the specific signal from your target interaction but can also increase the relative contribution of non-specific interactions with other parts of the sensor surface or the ligand itself [25] [6]. Therefore, selecting an immobilization strategy that promotes correct orientation is not merely a matter of efficiency—it is a primary strategy for troubleshooting and mitigating NSB.

This guide compares two principal immobilization philosophies—Direct Covalent Coupling and Affinity Capture—focusing on their practical implementation, their inherent advantages and limitations for controlling orientation, and their direct impact on the success of your experiments within a broader research context focused on minimizing NSB.

Technical Deep Dive: Method Comparison and Selection Criteria

The following table provides a comparative overview of the two major immobilization techniques to guide your initial selection.

Table 1: Comparison of Immobilization Techniques for Optimal Orientation

| Feature | Direct Covalent Coupling | Affinity Capture |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Irreversible, covalent attachment of the ligand to the sensor surface via chemical reactions [26]. | Non-covalent, reversible attachment using a high-affinity intermediate molecule [25] [26]. |

| Typical Methods | Amine, Thiol, and Aldehyde coupling chemistries [25]. | Streptavidin-Biotin, His-Tag-NTA, Antibody-Antigen (e.g., Protein A for IgG) [25] [26]. |

| Control over Orientation | Low to None. Coupling occurs randomly via common functional groups (e.g., lysine amines), which can block active sites [25] [6]. | High. The capture mechanism directs a specific, uniform orientation, presenting the ligand optimally [25] [26]. |

| Impact on Ligand Activity | Risk of activity loss due to random coupling, harsh pH during immobilization (e.g., low pH for amine coupling), or the blocking step [25] [6]. | Generally preserves activity as the ligand is not chemically modified and is often captured in its native conformation [25]. |

| Surface Stability | High. Covalent bonds create a stable surface that can withstand stringent regeneration conditions [26]. | Moderate. Stability depends on the affinity of the capture pair; ligands can dissociate over time or during regeneration [25] [26]. |

| Best Suited For | Robust ligands without sensitive orientation requirements; when maximum surface stability is critical [25]. | Ligands with specific tags (His, biotin); antibodies (via Protein A); when orientation is crucial to preserve function [25] [26]. |

Workflow Visualization of Immobilization Techniques

The following diagrams illustrate the key procedural and logical steps involved in each method.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs and Solutions

Q1: My data shows a high response signal, but my negative controls are also high, suggesting significant non-specific binding. Could my immobilization method be the cause?

Yes, this is a classic symptom. Random orientation from direct covalent coupling can be a primary contributor. When ligands are immobilized haphazardly, hydrophobic or charged regions that are normally buried can become exposed to the solution, promoting non-specific interactions with the analyte or other components [1] [6].

- Solution A (Switch Technique): Transition from amine coupling to an affinity capture method. For instance, if your ligand is an antibody, using a Protein A sensor kit ensures it is captured via its Fc region, presenting the antigen-binding domains uniformly away from the surface and reducing non-productive interactions [26].

- Solution B (Optimize Covalent Coupling): If you must use covalent coupling, consider targeted chemistry. For antibodies, digest them to generate Fab' fragments with free thiol groups, which can then be directionally immobilized using thiol coupling chemistry [25].

- Solution C (Buffer Additives): As an adjunct to changing immobilization, incorporate buffer additives to mitigate existing NSB. This includes using non-ionic surfactants like Tween 20 (e.g., 0.05%) to disrupt hydrophobic interactions, or adding BSA (e.g., 1%) to block non-specific sites [1] [8].

Q2: I am using an NTA sensor chip to capture his-tagged ligand, but my baseline drifts downward during analyte injection, suggesting my ligand is dissociating. How can I improve stability?

This indicates that the affinity of the NTA-His-tag interaction is not sufficient to withstand the flow conditions or the interaction with the analyte, a known limitation of this method [25] [26].

- Solution A (Increase Stability): Supplement your running buffer with a low concentration of a non-chelating metal ion like NiCl₂ (e.g., 1-10 µM). This can help stabilize the NTA-metal-His-tag complex without promoting non-specific binding.

- Solution B (Control Density): Ensure you have not overloaded the surface with the his-tagged ligand. A very high density can lead to steric crowding, weakening the individual capture bonds and making them more prone to dissociation.

- Solution C (Alternative Method): If stability cannot be achieved, consider a more stable capture system. For his-tagged proteins, a capture antibody specific to the tag can be covalently immobilized, providing a stronger hold. Alternatively, if feasible, biotinylate the ligand and use a streptavidin-biotin system, which has one of the highest known affinities [25] [26].

Q3: After covalent immobilization, I suspect my ligand has lost its biological activity. How can I confirm this and prevent it in the future?

Loss of activity can occur if the coupling process targets amino acids critical for the binding function or if the low pH incubation during amine coupling denatures the ligand [25] [6].

- Confirmation Test: Perform an activity assay in solution if possible. Alternatively, inject a known binding partner at a high concentration over the immobilized surface. A complete lack of binding, combined with a successful immobilization (high RU), strongly suggests deactivation.

- Prevention Strategy: Shift to an affinity capture system that does not require harsh chemical treatment or pH shifts. If covalent coupling is necessary, use a method that targets a specific site on the ligand away from the active site, such as thiol coupling after introducing a unique cysteine residue [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Immobilization

| Item | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Carboxyl Sensor Chip (CM5) | The standard surface for covalent amine coupling via EDC/NHS chemistry [26]. | A versatile first choice for many ligands. Be mindful of random orientation. |

| NTA Sensor Chip | Captures ligands featuring a polyhistidine tag (His-tag) [26]. | Excellent for purified his-tagged proteins. Allows surface regeneration with EDTA. Ligand leaching can be an issue. |

| Protein A Sensor Kit | Directionally captures antibodies via their Fc region [26]. | The preferred method for IgG-based antibodies to ensure optimal antigen binding site presentation. |

| Biotin-Streptavidin Sensor | Captures any biotinylated ligand with very high affinity [25] [26]. | Requires ligand biotinylation but offers extremely stable immobilization and controlled orientation. |

| EDC/NHS Activation Kit | Activates carboxyl groups on the sensor surface for covalent coupling to ligand amines [26]. | Essential for standard covalent immobilization on carboxyl chips. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | A blocking agent used to coat unused reactive sites on the sensor surface after immobilization [1]. | Critical for reducing NSB. Typically used at 0.1-1% concentration. |

| Tween 20 | A non-ionic surfactant added to running buffers to minimize hydrophobic interactions [1] [8]. | Very effective at reducing NSB. Common working concentration is 0.05% (v/v). |

| ML399 | ML399, MF:C27H28FN3O2, MW:445.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MT 63-78 | MT 63-78, MF:C21H14N2O2, MW:326.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Decision Pathway for Technique Selection

Use this logical flowchart to determine the most appropriate immobilization strategy for your specific ligand and experimental goals.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is non-specific binding (NSB) in SPR, and why is it a particular concern for cell-based assays? In SPR, non-specific binding (NSB) occurs when the analyte interacts with the sensor surface or other non-target molecules, not through the specific, biologically relevant interaction you are trying to study [1]. This produces a false signal that inflates the response units (RU), leading to inaccurate kinetic data [1]. In cell-based SPR, where the ligand is a membrane protein in its native lipid environment, the risk of NSB is heightened. The complex cellular surface presents a multitude of potential non-specific interaction sites, and the detergents or lipids necessary to keep membrane proteins stable can further promote NSB [27] [28].

2. My baseline is unstable and drifting. What could be the cause? Baseline drift can stem from several sources [5]. A common cause is improper buffer preparation; ensure your buffer is freshly prepared, properly degassed to eliminate bubbles, and filtered [27] [5]. Other causes include leaks in the fluidic system, a contaminated sensor surface, or buffer mismatches between your sample and running buffer [8] [5]. Always ensure your analyte is in the same buffer as your running buffer (e.g., through dialysis) to minimize bulk refractive index shifts [27].

3. I see no signal change when I inject my analyte. What should I check? A lack of signal can be frustrating. Please investigate the following areas [5]:

- Ligand Activity: Confirm that your immobilized membrane protein is still active and properly folded. Inactivity can occur if the binding pocket is blocked due to the orientation during immobilization [6].

- Ligand Density: Check the immobilization level; it may be too low to produce a detectable signal [5].

- Analyte Concentration: Verify that your analyte concentration is sufficient for detection [8] [5].

- Flow Rate: Adjust the flow rate, as a rate that is too high might not allow sufficient time for binding [8].

4. How can I effectively regenerate my sensor chip when working with delicate membrane proteins? Successful regeneration removes the bound analyte while keeping the ligand (your membrane protein) intact and active. Because the optimal conditions are highly system-dependent, you must test different solutions [6]. Common regeneration agents include:

- Acidic solutions: 10 mM glycine (pH 2.0) or 10 mM phosphoric acid [6].

- Basic solutions: 10 mM sodium hydroxide (NaOH) [6].

- High salt solutions: 2 M sodium chloride (NaCl) [6]. To help stabilize delicate targets during regeneration, you can add 10% glycerol to the solution [6].

Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: High Non-Specific Binding

NSB occurs when your analyte binds to the sensor surface itself rather than specifically to your target ligand. This is a primary source of error in SPR data [1] [4].

Solutions:

- Optimize Buffer Composition: The simplest and most effective first step is to modify your running buffer with additives that shield or block non-specific interactions. The table below summarizes common solutions.

- Adjust Buffer pH: The pH dictates the charge of your biomolecules. If your analyte is positively charged and NSB is occurring, it may be interacting with a negatively charged sensor surface. Adjusting the pH to the isoelectric point (pI) of your analyte can neutralize it and reduce these interactions [1].

- Use a Different Sensor Chip: If you are using a dextran-based chip (e.g., CM5) and see high NSB, switching to a planar chip (e.g., C1) can help. Conversely, the dextran matrix of a CM5 chip can itself help passivate the surface against some forms of NSB, which might be preferable for nanoparticle analytes [29].

- Include a Proper Reference Channel: Always use a reference cell that is similarly treated but lacks your specific ligand. The response from this channel, which contains only NSB and bulk shift, can be subtracted from your sample channel data [27] [4].

Problem: Low Signal Intensity

A weak binding signal makes it difficult to obtain reliable kinetic data.

Solutions:

- Optimize Ligand Immobilization Density: A density that is too low will produce a weak signal, while one that is too high can cause steric hindrance. Perform immobilization level tests to find the optimal density for your system [8].

- Improve Immobilization Efficiency: Ensure your ligand is properly oriented and active. For his-tagged membrane proteins, using an NTA chip provides a standardized capture method. For other proteins, consider different coupling chemistries (e.g., thiol coupling) if amine coupling obstructs the active site [6].

- Increase Analyte Concentration: If feasible, increase the concentration of your analyte. Be mindful that too high a concentration can lead to other issues, like mass transport limitation [8].

- Use High-Sensitivity Chips: Consider using sensor chips designed for enhanced sensitivity, especially if you are working with low-abundance membrane protein targets [8].

Problem: Poor Reproducibility

Inconsistent data between replicate experiments undermines the reliability of your results.

Solutions:

- Standardize Immobilization: Ensure your ligand immobilization procedure is highly consistent in terms of time, temperature, and pH [8].

- Use Control Samples: Always include negative controls (e.g., an irrelevant ligand or a non-binding analyte) to validate the specificity of your interaction and control for variability [8].

- Ensure Sample Quality: Protein aggregates or impurities are a major source of inconsistency. Always purify your proteins and remove aggregates immediately before the experiment, using methods like gel filtration or ultracentrifugation [27] [8] [5].

- Monitor Environmental Factors: Perform experiments in a controlled environment, as temperature fluctuations can impact both the instrument and the biomolecular interactions [8].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps in troubleshooting an SPR experiment, from identifying the symptom to applying targeted solutions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful cell-based SPR experiments require careful selection of reagents and materials. The following table details essential items for immobilizing membrane proteins and optimizing assays to minimize non-specific binding.

Table: Essential Reagents for Membrane Protein SPR Assays

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| NTA Sensor Chip [27] | A sensor chip functionalized with nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) is ideal for capturing his-tagged membrane proteins, a common purification strategy. This allows for a standardized and oriented immobilization [27]. |

| Mild Detergents (e.g., DDM) [27] | Detergents like n-Dodecyl β-D-maltoside (DDM) are essential for extracting and solubilizing membrane proteins from the lipid bilayer while keeping them stable and functional in solution [27]. |

| BSA [1] [4] | Used as a blocking agent in the buffer (0.5-2 mg/mL) to occupy non-specific binding sites on the sensor chip surface and fluidics, effectively reducing background noise [1] [4]. |

| Tween 20 [1] [4] | A non-ionic surfactant added to the running buffer (0.005%-0.1%) to disrupt hydrophobic interactions that are a major cause of NSB [1] [4]. |

| Nickel Solution (e.g., NiClâ‚‚) [27] | Required to charge the NTA chip before his-tagged protein capture. A typical concentration is 0.5 mM in running buffer [27]. |

| Regeneration Solutions [6] | Solutions like 350 mM EDTA (to strip his-tagged proteins and Ni²⺠from the NTA chip), 10-100 mM HCl, or 0.25% SDS are used to clean the sensor surface between binding cycles or for final stripping [27] [6]. |

| Mutant IDH1-IN-1 | Mutant IDH1-IN-1, MF:C30H31FN4O2, MW:498.6 g/mol |

The Role of Surface Pre-Conditioning and Ligand Density Control in Minimizing NSB

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Surface Pre-Conditioning and Ligand Density

1. What is baseline drift and how can surface pre-conditioning help?

Baseline drift, where the sensor's baseline signal gradually shifts over time, is often a sign of a not optimally equilibrated sensor surface [30]. Pre-conditioning the chip with several cycles of buffer flow stabilizes the surface and removes any contaminants [8]. It is sometimes necessary to run the flow buffer overnight to achieve full equilibration [30].

2. How does ligand density affect non-specific binding (NSB)?

Using a lower ligand density is generally recommended to avoid analyte depletion and can help minimize mass transport effects [3]. Furthermore, a surface that is too densely packed with ligand can increase the potential for non-specific interactions. If NSB is observed and you are using a negatively charged sensor, one strategy is to immobilize the more negatively charged molecule as the ligand to reduce charge-based NSB [3].

3. My analyte is positively charged and attracted to the dextran surface. How can I pre-condition the surface to prevent this?

For a positively charged analyte, you can modify the standard amine-coupling protocol. After ligand immobilization, instead of using ethanolamine for deactivation, block the sensor chip with ethylenediamine [4]. This compound adds a primary amine group, reducing the negative charge of the sensor surface and thus decreasing the potential for electrostatic, non-specific binding.

4. What are the signs of an inadequately pre-conditioned surface?

Signs include significant baseline drift at the start of your experiment and sudden spikes or shifts at the beginning of an analyte injection, which can also point to carry-over from a poorly washed system [30]. A well-conditioned surface should exhibit a stable baseline with minimal drift.

5. How can I experimentally determine the optimal ligand density for my experiment?

Aim for a lower ligand density initially to avoid mass transport limitations and potential steric hindrance [3]. For preliminary experiments, you can immobilize the ligand at a higher density if low surface activity is suspected and readjust later. The optimal density is one that provides a strong specific signal while minimizing NSB and mass transport effects. You can perform a ligand dilution series to find a density that gives a good signal-to-noise ratio for your analyte [8].

Research Reagent Solutions for Surface Pre-Conditioning and NSB Control

The following table details key reagents used to prepare sensor surfaces and manage ligand immobilization to minimize Non-Specific Binding.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Pre-Conditioning/NSB Control | Typical Usage/Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Running Buffer | Equilibrates the sensor surface and hydrodynamics; its composition (pH, salts) is critical for stabilizing the baseline and minimizing charge-based NSB [30] [8]. | Varies by system; often HBS-EP or PBS. Must be matched with analyte buffer to avoid bulk shift [3]. |

| Regeneration Buffers | Strips bound analyte from the immobilized ligand between analysis cycles, restoring the surface for the next injection without damaging ligand activity [3]. | Acidic (e.g., 10 mM glycine pH 2.0), basic (e.g., 10 mM NaOH), high salt (e.g., 2 M NaCl). Must be optimized for each interaction [6] [3]. |

| Ethylenediamine | A blocking agent used after amine coupling to neutralize negative surface charges, thereby reducing NSB from positively charged analytes [4]. | Used as an alternative to the standard ethanolamine deactivation solution [4]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A protein additive used to block remaining active sites on the sensor surface, shielding the analyte from non-specific interactions [1] [3]. | 0.5 - 2 mg/ml (or ~0.1%) added to running buffer and sample solution during analyte runs [1] [4] [3]. |

| Non-Ionic Surfactants (e.g., Tween 20) | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions between the analyte and the sensor surface or immobilized ligand, a common cause of NSB [1] [3]. | 0.005% - 0.1% in running buffer [1] [4]. |

| NaCl | Shields charged molecules via its ions, reducing electrostatic-based NSB between the analyte and the sensor surface [1] [3]. | Up to 500 mM in running buffer; concentration requires optimization [1] [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Surface Preparation

Protocol 1: Standard Surface Pre-Conditioning and Equilibration

This protocol aims to stabilize the sensor chip surface and fluidics to achieve a stable baseline before ligand immobilization or sample injection.

- Install Sensor Chip: Place the chosen sensor chip into the instrument according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Initial Prime: Prime the entire microfluidic system with your chosen, filtered, and degassed running buffer.

- Surface Pre-Conditioning: Initiate a flow of running buffer over the sensor surface. For a new or stored chip, perform several injections of a mild regeneration solution (e.g., a short pulse of 10 mM glycine, pH 2.0, or 10 mM NaOH) to clean and condition the surface [8].

- Baseline Equilibration: Continue flowing running buffer over the surface until a stable baseline is achieved. This may require running the buffer for an extended period, sometimes even overnight, to fully equilibrate the system [30].

- Baseline Stability Check: Monitor the baseline signal for drift. A stable baseline (drift of < 1-2 RU per minute) indicates a well-conditioned system ready for ligand immobilization.

Protocol 2: Optimizing Ligand Immobilization Density

This protocol provides a method to find an appropriate ligand density that provides a strong signal while minimizing artifacts.

- Select Immobilization Method: Choose a suitable covalent (e.g., amine coupling) or capture (e.g., His-NTA, antibody capture) method based on your ligand's properties [3].

- Prepare Ligand Dilutions: Prepare a series of ligand solutions at different concentrations. For amine coupling, use a low-pH immobilization buffer (e.g., pH 4.0-5.5) if the ligand is a protein.

- Scouting Immobilization Levels: For each ligand concentration, perform a short injection (1-5 minutes) over an activated surface (for covalent coupling) or a capture surface.

- Measure Response: Record the final immobilization level in Response Units (RU). Aim for a range of densities. A lower density is generally preferred to avoid mass transport limitations [3].

- Test with Analyte: Test each immobilized surface with a mid-range concentration of your analyte. Evaluate the binding response for characteristics of mass transport (a linear association phase) [3] and check a reference surface for NSB.

- Select Optimal Density: Choose the ligand density that yields a strong, specific binding signal with a curved association phase, minimal NSB, and good reproducibility.

Surface Pre-Conditioning and Ligand Density Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points for using surface pre-conditioning and ligand density control to minimize Non-Specific Binding (NSB) in SPR experiments.

A Step-by-Step Troubleshooting Playbook for Non-Specific Binding

This technical support guide focuses on the critical role of buffer optimization in troubleshooting non-specific binding (NSB) in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments. Non-specific binding, where analytes interact with the sensor surface or ligand through unintended forces, is a major challenge that can skew kinetic data and lead to erroneous conclusions in biomolecular interaction studies [1] [31]. Properly optimized buffer conditions are among the most effective strategies to minimize these artifacts, ensuring the collection of reliable, high-quality data for researchers and drug development professionals [8] [3]. The following FAQs and guides address the most common buffer-related issues encountered during SPR experiments.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ: What is non-specific binding and how does it affect my SPR data?

Non-specific binding (NSB) occurs when your analyte interacts with the sensor chip surface or the immobilized ligand through means other than the specific, biologically relevant interaction you intend to study [1] [31]. This can include hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, or electrostatic (charge-based) attractions [1]. The consequence is an inflated response signal (RU), which leads to inaccurate calculations of affinity (KD) and kinetic rate constants (ka and kd) [1] [3]. Effectively managing NSB is therefore essential for data integrity.

FAQ: How can I quickly test if my experiment has non-specific binding?

A simple preliminary test is to inject your highest concentration of analyte over a bare sensor surface (a channel with no immobilized ligand) or over a surface coated with an irrelevant protein, such as BSA [6] [3]. A significant binding response on this reference surface indicates that NSB is present and must be addressed before proceeding with your main experiment [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: My SPR data shows significant non-specific binding. How can I optimize my buffer to fix this?

The table below summarizes the core buffer parameters you can adjust to mitigate non-specific binding.

Table 1: Buffer Optimization Strategies to Combat Non-Specific Binding

| Buffer Parameter | Mechanism of Action | Recommended Starting Points | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjust Buffer pH | Modifies the net charge of proteins to reduce electrostatic interactions with the charged sensor surface [1] [3]. | Adjust pH to the isoelectric point (pI) of your analyte to neutralize its charge [1]. | Know the pI of your ligand and analyte. A positively charged analyte will bind to a negatively charged dextran surface [1]. |

| Increase Ionic Strength | High salt concentrations shield charged groups on proteins and the surface, disrupting charge-based interactions [1] [3]. | Supplement running buffer with 150-500 mM NaCl [1] [4]. | Very high salt may destabilize some proteins or even promote hydrophobic binding [8]. |

| Add Non-Ionic Surfactants | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions by acting as a mild detergent [1] [3]. | Add Tween-20 to running buffer at a concentration of 0.005% - 0.1% [4]. | Also prevents analyte loss to tubing and vials [1]. |

| Use Protein Blocking Additives | Acts as a sacrificial protein to occupy non-specific binding sites on the surface and in the flow system [1] [4]. | Add BSA to running buffer and sample solution at 0.1 - 2 mg/mL [1] [4]. | Do not use during ligand immobilization, as it will coat the sensor chip [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Buffer Scouting for NSB Reduction

The following workflow provides a methodology for empirically determining the optimal buffer conditions to minimize NSB for your specific experimental system.

- Baseline Establishment: Begin by running your analyte over a bare sensor surface (or your actual ligand surface) using your standard running buffer. This establishes your baseline level of NSB [3].

- Systematic Additive Screening: Prepare a series of running buffers, each incorporating one of the additives from Table 1 (e.g., Buffer A + 0.05% Tween-20, Buffer B + 1 mg/mL BSA, Buffer C + 200 mM NaCl).

- Test and Compare: Inject the same high concentration of analyte over the test surface using each of the new buffers. Monitor the response level on a reference surface (without ligand).

- Evaluate and Combine: Identify the buffer condition that yields the greatest reduction in NSB signal without affecting the specific binding signal. If NSB persists, consider combining additives (e.g., 0.01% Tween-20 + 100 mM NaCl).

- Validate Specific Binding: Once a condition is found that minimizes the reference signal, perform a full concentration series of the analyte over the ligand surface to confirm that the specific binding signal and expected kinetics are preserved.

This systematic approach to buffer scouting is summarized in the following workflow diagram:

FAQ: My sensorgram has a large, square-shaped signal that appears immediately at injection. Is this non-specific binding?

This "square" shape is typically a bulk shift (or solvent effect), not non-specific binding [3]. It is caused by a difference in refractive index between your running buffer and the buffer in your analyte sample. While reference subtraction can help, the best solution is to precisely match the composition of your running buffer and analyte buffer, or to dialyze your analyte into the running buffer [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential reagents used in SPR buffer optimization to reduce non-specific binding.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for SPR Buffer Optimization

| Reagent | Primary Function in SPR | Key Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | Protein blocking additive; occupies non-specific sites on the sensor surface and fluidics [1] [4]. | Use at 0.1-2 mg/mL in running and sample buffers during analyte runs only [1] [4]. |

| Tween-20 | Non-ionic surfactant; disrupts hydrophobic interactions [1] [3]. | Effective at very low concentrations (0.005%-0.1%). Mild and generally does not denature proteins [4]. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Salt used to increase ionic strength; shields charged groups to reduce electrostatic NSB [1] [3]. | Commonly used from 150 mM up to 500 mM. Titrate to find a level that reduces NSB without impacting specific binding [1] [4]. |

| Carboxymethyl Dextran | Polymer additive; can be used to block specific surfaces by occupying the dextran matrix [4]. | Add at 1 mg/mL to running buffer when using carboxymethyl dextran chips (e.g., CM5) [4]. |

| Ethylenediamine | Blocking agent; used after amine coupling to cap the sensor surface. Reduces negative charge more effectively than ethanolamine [4]. | Particularly useful when analyzing a positively charged analyte to reduce electrostatic attraction to the surface [4]. |

FAQs: Addressing Common Challenges with Blocking Agents

Q1: What is the primary cause of non-specific binding (NSB) in SPR experiments, and how do blocking agents help? Non-specific binding is caused by undesirable molecular forces—such as hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, and Van der Waals interactions—between the analyte and the sensor surface. These interactions can inflate response units (RU), leading to erroneous kinetic data [1]. Blocking agents work by occupying these non-specific sites on the sensor surface. Proteins like BSA and casein create a protective shield around the analyte, while surfactants like Tween 20 disrupt hydrophobic interactions [1] [32].

Q2: My data shows high NSB even after using Tween 20. What alternatives can I try? While Tween 20 is a common surfactant, some experimental systems, particularly ELISA, have documented high NSB when using it as a primary blocking agent [32] [33]. In these cases, replacing Tween 20 with a non-reactive protein like casein in the antibody diluent and wash buffers can be more effective. One study found that casein outperformed both BSA and gelatin in reducing high NSB encountered with low-titre antisera [32] [33].

Q3: How can I reduce charge-based non-specific interactions for a positively charged analyte? For a positively charged analyte, NSB often occurs with negatively charged sensor surfaces [1] [4]. You can:

- Adjust buffer pH: Modify your running buffer to a pH near the isoelectric point (pI) of your analyte, where it carries a neutral net charge [1].

- Increase ionic strength: Add salts like NaCl (commonly up to 500 mM) to your buffer. The ions produce a shielding effect, reducing charge-based interactions [1] [4] [34].

- Modify the sensor surface: After amine coupling, block the sensor chip with ethylenediamine instead of ethanolamine. This leaves a less negatively charged surface, reducing electrostatic attraction to a positive analyte [4].

Q4: Are there any stability or compatibility concerns when using Tween 20? Yes, Tween 20 is not stable to autoclaving. Autoclaving can cause it to precipitate, forming yellow-orange clumps, which renders the solution ineffective and potentially introduces contaminants [35]. Tween 20 solutions should be filter-sterilized instead of autoclaved.

Troubleshooting Guide: Optimizing Your Blocking Strategy

This guide outlines a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving NSB issues related to blocking agents and surfactants.

Problem: Persistent High Non-Specific Binding After Initial Blocking

Issue Identified: Your initial attempts to reduce NSB, perhaps with a standard concentration of a blocking agent, have been insufficient. The sensorgram shows a high response on the reference channel.

Step 1: Verify and Characterize NSB Confirm that the response on your reference channel is more than about a third of the response on your sample channel [4]. Inject your analyte over a bare or deactivated (e.g., ethanolamine-blocked) sensor surface to quantify the level of NSB [1] [34].

Step 2: Select and Apply an Advanced Strategy Based on the characterization in the flowchart above, proceed with one or more of the following strategies:

For Suspected Hydrophobic Interactions: Introduce a non-ionic surfactant like Tween 20 to your running buffer. Effective concentrations typically range from 0.005% to 0.1% [4] [34]. This mild detergent disrupts hydrophobic interactions without denaturing most proteins.

For Suspected Charge-Based Interactions:

- Increase Shielding: Supplement your buffer with NaCl. Concentrations from 150 mM up to 500 mM can effectively shield charges and reduce electrostatic NSB [1] [4] [34].

- Neutralize Surface: If your analyte is positively charged, block the sensor chip with ethylenediamine instead of ethanolamine after amine coupling. This provides a less negatively charged surface [4].

For Complex or Persistent NSB:

- Use a High-Efficiency Protein Block: Add Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) at 0.5 to 2 mg/mL to occupy remaining hydrophobic and charged sites on the surface [4].

- Substitute with Casein: If Tween 20 and BSA are ineffective, replace them with casein as your primary blocking agent. Historical data shows casein can be more effective than BSA or gelatin in certain solid-phase assays [32] [33].

Step 3: Evaluate and Iterate Re-test your analyte over the reference surface after implementing the new strategy. If NSB is still unacceptably high, consider combining strategies (e.g., using a protein blocker and a surfactant simultaneously) or exploring alternative sensor chips with different surface chemistries (e.g., planar instead of dextran) [4] [6].

Experimental Protocols: Detailed Methodologies

Protocol 1: Systematic Optimization of Buffer Additives to Minimize NSB

This protocol provides a step-by-step method for empirically determining the optimal buffer conditions to suppress NSB.