The Beer-Lambert Law in Drug Analysis: A Foundational Guide from Theory to Quality Control

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the Beer-Lambert Law, a cornerstone principle in spectroscopic drug analysis.

The Beer-Lambert Law in Drug Analysis: A Foundational Guide from Theory to Quality Control

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the Beer-Lambert Law, a cornerstone principle in spectroscopic drug analysis. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the fundamental theory, practical methodological applications for concentration determination, and advanced troubleshooting of limitations and deviations. It further explores validation protocols, comparative analysis with other techniques, and the integration of modern approaches like machine learning to ensure accurate, reliable, and compliant results in pharmaceutical quality assurance and development.

Understanding the Beer-Lambert Law: The Core Principle of Light Absorption

The Beer-Lambert law is a fundamental principle in optical spectroscopy that forms the quantitative backbone for analyzing light absorption in materials. In the specialized field of drug analysis research, this law provides the essential theoretical framework for determining the concentration of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), ensuring dosage uniformity, and monitoring impurity profiles [1]. The modern formulation of this law is the product of distinct discoveries made over more than a century, culminating in a unified relationship that connects a measurable optical property—absorbance—to both a physical dimension and a chemical property [2]. This article traces the historical development of the law from its origins with Pierre Bouguer and Johann Heinrich Lambert to its final form with August Beer, framing this progression within the context of modern pharmaceutical analysis. Understanding this historical context and the law's underlying assumptions is critical for research scientists and drug development professionals who rely on its application for precise, reliable quantitative results.

The Historical Progression of the Law

The development of the Beer-Lambert law was not a single event but a gradual process of scientific accretion, with each contributor building upon the work of his predecessors to expand the law's applicability from a broad physical observation to a precise chemical tool [2].

Pierre Bouguer (1729) – The Initial Observation

The foundation of the law began with French mathematician and astronomer Pierre Bouguer. In his 1729 work, Essai d'Optique, he studied the attenuation of starlight as it passed through the Earth's atmosphere [3] [4]. Through careful astronomical observation and calibration, Bouguer discovered that the intensity of light decreases in a geometric progression (i.e., exponentially) as it travels through successive layers of a homogeneous, absorbing medium [3] [2]. He recognized that this exponential decay was a fundamental property of light propagation in such media. However, while he correctly described the relationship, he did not formalize it into the precise mathematical equation used today [2]. His work identified the core natural phenomenon but remained within the context of atmospheric optics.

Johann Heinrich Lambert (1760) – Mathematical Formalization

Approximately three decades later, German physicist and mathematician Johann Heinrich Lambert cited Bouguer's findings in his own seminal treatise, Photometria (1760) [3] [2]. Lambert formalized Bouguer's observation into a rigorous mathematical expression. He postulated that the loss of light intensity when propagating through an absorbing medium is directly proportional to both the intensity of the light itself and the path length traveled [3]. This led to a differential equation whose solution yielded the exponential decay relationship [5]. Lambert is credited with isolating the physical parameter of path length and giving the law its mathematical form, establishing that absorbance (A) is directly proportional to the path length (l) of the light through the sample, or A ∠l [2]. His work generalized the finding beyond the atmosphere, establishing it as a fundamental principle of photometry.

August Beer (1852) – The Chemical Dimension

Nearly a century after Lambert, German chemist August Beer introduced the crucial chemical dimension to the law. In 1852, he published findings on the absorption of light by colored solutions [3] [2]. Through his experiments, Beer discovered that the absorbance of a solution is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing substance (the solute) [6] [2]. He conceptualized his result in terms of a given thickness's opacity, noting that for a double thickness, the coefficient of diminution would be squared [3]. His contribution, establishing that A ∠c, connected the physical law of light absorption directly to the field of analytical chemistry, enabling the quantification of substances in solution [2]. Beer's work was particularly notable for correcting for reflection losses at the interfaces of cuvettes before concluding on the constancy of transmittance [5].

Unification into the Modern Beer-Lambert Law

The modern Beer-Lambert law is a synthesis of these distinct discoveries. The first unified formulation, combining the contributions of Bouguer, Lambert, and Beer into the familiar logarithmic expression using molar concentration, did not appear until the early 20th century [3] [5]. An early, possibly the first, modern formulation was given by Robert Luther and Andreas Nikolopulos in 1913 [3] [5]. This merged the Bouguer-Lambert law, which describes attenuation through a medium, with Beer's law, which links this attenuation to solute concentration, creating the powerful quantitative tool indispensable to modern chemists and pharmaceutical scientists [5].

Table: Historical Contributors to the Beer-Lambert Law

| Scientist | Year | Key Contribution | Context of Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pierre Bouguer | 1729 | Discovered exponential decay of light intensity in a medium [3] [2]. | Astronomical studies of the Earth's atmosphere [3]. |

| Johann Heinrich Lambert | 1760 | Formalized the exponential relationship mathematically; established proportionality to path length (A ∠l) [3] [2]. | Fundamental photometry and the physics of light propagation [3]. |

| August Beer | 1852 | Established proportionality to the concentration of the solute (A ∠c) [3] [6] [2]. | Analysis of colored chemical solutions [3]. |

| Modern Synthesis (e.g., Luther & Nikolopulos) | ~1913 | Combined the laws into the modern form: A = εlc [3] [5]. | Quantitative chemical spectroscopy [3] [5]. |

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Formulation

The Beer-Lambert law provides a simple linear relationship that connects the attenuation of light to the properties of a solution. Its derivation and components are essential for a deep understanding.

Core Definitions: Transmittance and Absorbance

When monochromatic light passes through a solution, its intensity decreases. This interaction is quantified by two key parameters [7] [2]:

Transmittance (T): This is the fraction of incident light that passes through the sample. It is defined as the ratio of the transmitted intensity (I) to the incident intensity (Iâ‚€). Transmittance is often expressed as a percentage (%T) [7] [8].

( T = \frac{I}{I0} \quad \text{or} \quad \%T = \frac{I}{I0} \times 100\% )

Absorbance (A): Also known historically as optical density (OD), absorbance is a logarithmic measure of the amount of light absorbed by the sample [7] [2]. It is defined as the negative base-10 logarithm of transmittance [8] [2].

( A = -\log{10}(T) = \log{10} \left( \frac{I_0}{I} \right) )

The choice of a logarithmic scale for absorbance is deliberate. It transforms the exponential nature of light attenuation into a linear relationship, which is far more convenient for quantitative chemical analysis [2].

Table: Relationship between Transmittance and Absorbance

| Percent Transmittance (%T) | Transmittance (T) | Absorbance (A) |

|---|---|---|

| 100% | 1.0 | 0.0 |

| 50% | 0.5 | 0.301 |

| 10% | 0.1 | 1.0 |

| 1% | 0.01 | 2.0 |

| 0.1% | 0.001 | 3.0 |

The Beer-Lambert Equation

The modern Beer-Lambert law is expressed by the equation:

( A = \epsilon \, l \, c )

Where:

- A is the Absorbance, a dimensionless quantity [7] [8] [9].

- ε is the Molar Absorptivity (or molar extinction coefficient), with typical units of L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹ [8] [9]. This is a substance-specific constant that indicates how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at a particular wavelength [7] [9].

- l is the Path Length, the distance the light travels through the solution, usually measured in centimeters (cm) [8] [9]. In standard spectrophotometry, this is the width of the cuvette.

- c is the Concentration of the absorbing species in the solution, measured in moles per liter (mol/L) [8] [9].

The law states that the absorbance of a solution is directly proportional to both the concentration of the absorbing species and the path length of the light through the solution [9].

Derivation from First Principles

The law can be derived by considering the attenuation of light through an infinitesimally thin layer of a solution [3]. Imagine a beam of light with power P entering a thin slice of solution of thickness dx. The decrease in power, -dP, is proportional to the incident power P, the concentration of the absorber c, and the thickness dx [3]. This leads to the differential equation:

( -\frac{dP}{P} = k c \, dx )

Integrating this equation over the entire path length l from the initial power P₀ to the transmitted power P yields the logarithmic relationship. The proportionality constant k is incorporated into the molar absorptivity, ε, giving the familiar form of the Beer-Lambert law [3]. This derivation underscores that the linear relationship between A and c is a consequence of the fundamental, exponential nature of light absorption.

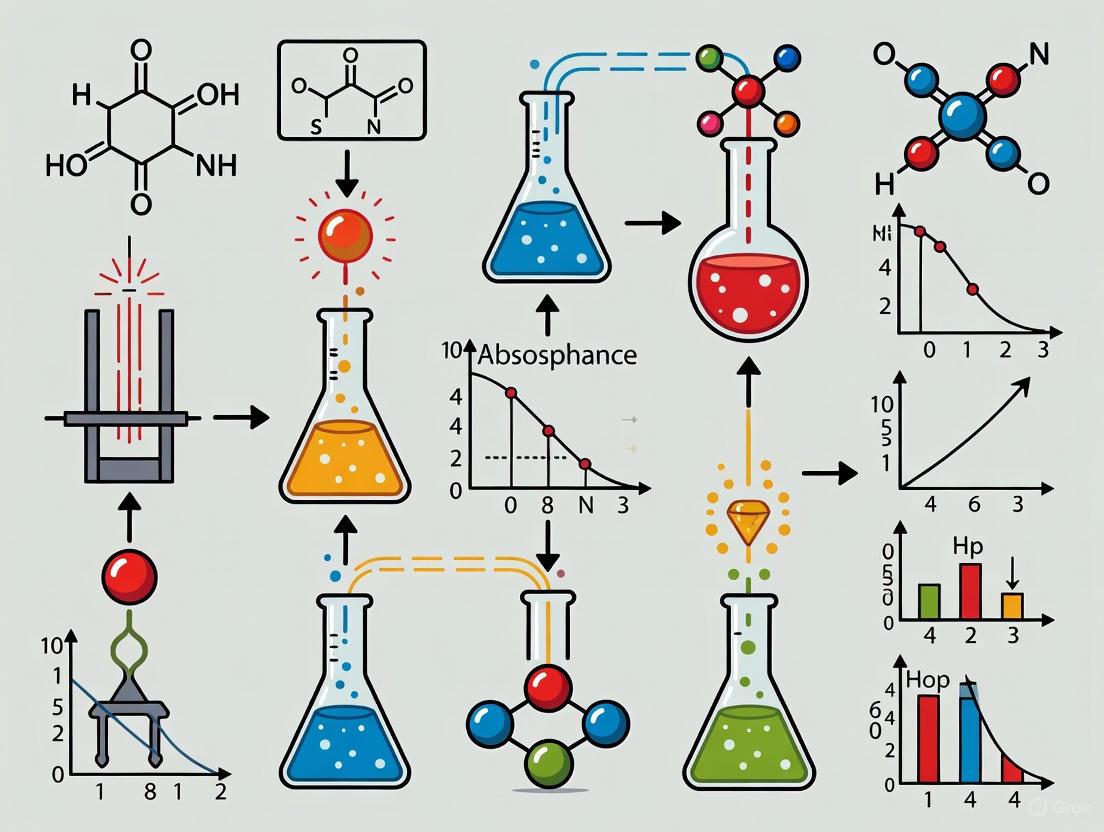

Diagram: The logical workflow from light transmission measurement to the application of the Beer-Lambert Law.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The practical application of the Beer-Lambert law in a pharmaceutical or research setting requires specific materials and instruments. The following table details essential items for conducting spectrophotometric analysis.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectrophotometric Analysis

| Item | Function & Importance in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Spectrophotometer | The core instrument that emits monochromatic light and measures the intensity of light before (Iâ‚€) and after (I) it passes through the sample to calculate absorbance [7] [2]. |

| Cuvette | A container, typically with a standard path length (e.g., 1 cm), that holds the sample solution. It must be made of a material transparent to the wavelength of light used (e.g., quartz for UV, glass/plastic for visible) [7] [9]. |

| Standard Reference Material | A high-purity chemical of known concentration and identity (e.g., a reference standard of an API) used to create a calibration curve and determine the molar absorptivity (ε) [7]. |

| Appropriate Solvent | A solvent that dissolves the analyte and is itself transparent (non-absorbing) at the wavelength of analysis to ensure that measured absorbance originates only from the solute [4]. |

| Buffer Solutions | Used to maintain a constant pH, which is critical as the absorption spectrum and ε of many pharmaceutical compounds (e.g., ionizable drugs) can be highly pH-dependent [10]. |

| GDC-0575 | GDC-0575, MF:C16H20BrN5O, MW:378.27 g/mol |

| Aminobenzenesulfonic auristatin E-d8 | Aminobenzenesulfonic auristatin E-d8, MF:C37H64N6O8S, MW:761.1 g/mol |

Experimental Protocol for Drug Quantification

The following detailed methodology outlines how the Beer-Lambert law is applied in a pharmaceutical research context to determine the concentration of an unknown sample, such as an active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) [7] [1].

Wavelength Selection: The first step is to identify the wavelength of maximum absorbance (λmax) for the analyte. This is done by scanning a standard solution of the analyte across a range of wavelengths and plotting the resulting absorption spectrum. Performing the measurement at λmax provides the greatest sensitivity and minimizes the relative error in concentration determination [7] [9].

Preparation of Standard Solutions: A series of standard solutions with known, precise concentrations of the API are prepared via serial dilution. The concentration range should bracket the expected concentration of the unknown sample. All solutions are prepared using the same solvent and, if necessary, buffered to a controlled pH [7].

Measurement of Absorbance: The absorbance of each standard solution is measured using the spectrophotometer at the predetermined λ_max. A blank (solvent-only) cuvette is used to zero the instrument, defining the incident intensity I₀ and accounting for any solvent or cuvette background absorption [7] [8].

Construction of Calibration Curve: A calibration curve (or standard curve) is created by plotting the measured absorbance (y-axis) against the known concentration (x-axis) for each standard solution. According to the Beer-Lambert law, this should yield a straight line that passes through the origin [7]. The slope of this line is equal to the product εl.

Analysis of Unknown Sample: The unknown sample (e.g., a dissolved tablet extract) is prepared and its absorbance is measured under identical conditions (same wavelength, path length, and solvent). The concentration of the unknown is then determined by locating its absorbance on the calibration curve and reading the corresponding concentration value [7] [9].

Worked Example

Scenario: A researcher needs to determine the concentration of a paracetamol solution extracted from a tablet. The molar absorptivity (ε) of paracetamol at 243 nm is known to be 6.50 × 10³ L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹. The sample is placed in a 1.00 cm cuvette, and the measured absorbance is 0.325 [1].

Calculation: Using the Beer-Lambert law: ( A = \epsilon l c ) ( 0.325 = (6.50 \times 10^3 \, \text{L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹}) \times (1.00 \, \text{cm}) \times c ) Solving for concentration, c: ( c = \frac{0.325}{(6.50 \times 10^3)} = 5.00 \times 10^{-5} \, \text{mol·Lâ»Â¹} )

This demonstrates a direct application for quantifying API concentration, a routine task in pharmaceutical quality control [1] [9].

Critical Limitations and Modern Considerations in Drug Analysis

While the Beer-Lambert law is foundational, its application in rigorous pharmaceutical research requires a clear understanding of its limitations. Deviations from the ideal linear behavior can lead to significant analytical errors [5] [4].

Fundamental and Chemical Limitations

High Concentrations: The law assumes that absorbance is linearly proportional to concentration. However, at high concentrations (typically >0.01 M), solute molecules can interact with one another (e.g., via dimerization or aggregation), altering their absorption properties and causing deviations from linearity [4] [10]. Furthermore, the refractive index of the solution changes with concentration, which can violate an underlying assumption of the derivation [5] [4]. To mitigate this, samples are often diluted to a range where linearity holds.

Electromagnetic Effects and Scattering: The classical derivation of the Beer-Lambert law neglects the wave nature of light and its consequences, such as reflection at cuvette interfaces and interference effects within thin samples [5] [4]. These optical effects can cause fluctuations in measured intensity that are unrelated to absorption, leading to inaccurate absorbance readings. For heterogeneous samples like suspensions or emulsions, light scattering can cause significant deviations, making the sample appear to have a higher absorbance than it truly does [3] [4].

Chemical Changes: Changes in the chemical environment, such as pH shifts or the presence of other reactive species, can alter the molecular structure of the analyte, thereby changing its molar absorptivity (ε) [10]. Since ε is supposed to be constant for a given substance and wavelength, this leads to a breakdown of the law. Stabilizing the chemical environment, for example by using buffer solutions, is therefore critical [10].

Instrumental and Methodological Limitations

Polychromatic Light: The law strictly holds only for monochromatic light. Real spectrophotometers use a band of wavelengths. If the molar absorptivity (ε) changes significantly across this wavelength band, the relationship between absorbance and concentration will deviate from linearity, especially at high absorbances [4]. Modern high-quality instruments with narrow bandwidths minimize this effect.

Stray Light: Any light that reaches the detector at wavelengths outside the intended band is termed stray light. At high sample absorbances, stray light becomes a significant fraction of the total signal reaching the detector, leading to a lower-than-expected measured absorbance and a negative deviation from the Beer-Lambert law [4].

For drug development professionals, recognizing these limitations is not an academic exercise but a practical necessity. It informs method development and validation, ensuring that spectrophotometric assays used for determining drug potency, monitoring dissolution profiles, and detecting impurities are robust, accurate, and reliable [1]. Advanced techniques, such as derivative spectroscopy or the integration of machine learning with spectroscopic data, are being explored to model and correct for some of these non-linearities and interactions, pushing the boundaries of quantitative analysis beyond the classical limits of the Beer-Lambert law [10].

The Beer-Lambert Law, formally expressed as A = εlc, serves as a foundational principle in quantitative chemical analysis, particularly in pharmaceutical research and drug development. This in-depth technical guide deconstructs this fundamental equation, examining its theoretical underpinnings, practical applications in drug analysis, and critical limitations. Within the context of modern drug development, understanding the precise relationship between absorbance (A), molar absorptivity (ε), path length (l), and concentration (c) is paramount for accurate dosage determination, quality control, and regulatory compliance. This whitepaper provides researchers and scientists with a comprehensive framework for applying this principle with scientific rigor, addressing both its powerful utility and important constraints in professional laboratory settings.

Theoretical Foundation of the Beer-Lambert Law

Historical Context and Fundamental Principle

The Beer-Lambert Law, also referred to as the Beer-Lambert-Bouguer Law, is an empirical relationship that describes the attenuation of light as it passes through a material [3] [11]. Its development spans centuries, beginning with Pierre Bouguer's 1729 work on atmospheric light attenuation [4] [11]. Johann Heinrich Lambert later provided the mathematical formulation in 1760, establishing the relationship between absorbance and path length [12] [13]. Finally, August Beer extended the law in 1852 to incorporate the concentration of solutions, completing the formulation essential to modern analytical chemistry [11] [14].

The fundamental principle states that the absorbance of light by a substance dissolved in a non-absorbing solvent is directly proportional to both the concentration of the substance and the path length of the light through the solution [12] [14]. This relationship is expressed mathematically as:

A = εlc

Where:

- A is Absorbance (unitless)

- ε is the Molar Absorptivity (Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹)

- l is the Path Length (cm)

- c is the Concentration (M)

This linear relationship forms the basis for quantitative analysis across pharmaceutical, environmental, and clinical laboratories worldwide [7] [13].

Component Deconstruction and Mathematical Derivation

Absorbance (A)

Absorbance is defined as the logarithm of the ratio of incident to transmitted light intensity [8] [7]:

A = logâ‚â‚€(Iâ‚€/I)

Where Iâ‚€ is the intensity of incident light and I is the intensity of transmitted light. Absorbance is a dimensionless quantity, though it is sometimes incorrectly reported in "Absorbance Units (AU)" [7]. The relationship between absorbance and transmittance (T = I/Iâ‚€) is logarithmic, meaning absorbance increases linearly with concentration while transmittance decreases exponentially [7].

Table 1: Relationship Between Absorbance and Transmittance

| Absorbance (A) | Transmittance (T%) | Light Transmitted |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100% | 100% |

| 1 | 10% | 10% |

| 2 | 1% | 1% |

| 3 | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| 4 | 0.01% | 0.01% |

Molar Absorptivity (ε)

The molar absorptivity coefficient (also molar extinction coefficient) is a substance-specific constant that measures how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at a particular wavelength [8] [15]. Its value depends on both the substance and the solvent used, with typical units of Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹ [15]. This coefficient represents the apparent cross-sectional area of absorption per mole of analyte and is influenced by the electronic structure of the molecule [13]. Higher values indicate greater absorption capability at a specific wavelength [8].

Path Length (l)

Path length represents the distance light travels through the sample solution, typically determined by the width of the cuvette or sample container [12] [7]. Standard cuvettes have a path length of 1 cm, though various specialized cells offer different path lengths for specific applications [7]. According to Lambert's Law, absorbance is directly proportional to path length when concentration remains constant [12] [14].

Concentration (c)

Concentration represents the molarity of the absorbing species in the solution (moles per liter) [8] [15]. Beer's Law establishes that absorbance is directly proportional to concentration when path length remains constant [12] [14]. This linear relationship enables quantitative analysis of unknown samples through calibration curves [7] [15].

Applications in Drug Analysis Research

Quantitative Analysis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients

The primary application of the Beer-Lambert Law in pharmaceutical research involves determining concentrations of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and their metabolites [13]. By measuring absorbance at specific wavelengths and applying the equation A = εlc, researchers can accurately quantify drug concentrations in various matrices including bulk materials, formulations, and biological fluids [7] [13]. This application is particularly valuable during drug development stages where precise concentration measurements are critical for dosage determination, stability testing, and bioavailability studies [13].

The standard methodology involves creating a calibration curve using samples of known concentration, then using this curve to determine unknown concentrations [7] [15]. The linear relationship between absorbance and concentration allows for both simple calculations and sophisticated statistical analysis of results, providing the precision required for regulatory submissions and quality control in Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) and Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) environments [7].

Specific Pharmaceutical Applications

Quality Control and Assay Development

In pharmaceutical manufacturing, the Beer-Lambert Law underpins numerous quality control procedures [13]. UV-Vis spectrophotometry based on this principle is used for identity testing, assay content uniformity, and dissolution testing of drug products [7]. The ability to quickly and accurately verify concentrations during production ensures batch-to-batch consistency and compliance with pharmacopeial standards [13].

Biological Fluid Analysis

The modified Beer-Lambert law (MBLL) finds application in measuring physiological parameters relevant to drug action, such as blood oxygen saturation in pulse oximeters [11] [13]. This application analyzes absorption of red and infrared light by hemoglobin, enabling non-invasive monitoring of drug effects on oxygenation [11]. Researchers have extended this principle to measure concentrations of bilirubin in blood plasma and hemoglobin components, providing critical data for pharmacokinetic studies [11].

High-Throughput Screening

In modern drug discovery, the Beer-Lambert Law facilitates high-throughput screening of compound libraries [16]. Automated spectrophotometric systems utilize this principle to rapidly quantify reaction yields and compound concentrations, significantly accelerating the lead identification and optimization processes [16]. Recent advances combine this traditional approach with machine learning techniques to further enhance throughput and accuracy [16].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Spectrophotometric Drug Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cuvettes | Contains sample solution with precise path length | All spectrophotometric measurements; typically 1 cm path length [7] |

| Reference Solvent | Dissolves analyte without interfering absorption | Blank measurement; establishes baseline Iâ‚€ [7] |

| Standard Solutions | Known concentrations for calibration curve | Quantification of unknown samples [7] [15] |

| Buffers | Maintains constant pH environment | Prevents spectral shifts due to pH changes [11] |

| K₂Cr₂O₇/KMnO₄ Solutions | Model compounds for method validation | Verification of instrument performance and linearity range [16] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Spectrophotometric Protocol for Drug Quantification

The following detailed protocol ensures accurate application of the Beer-Lambert Law for drug concentration determination in research settings:

Instrument Calibration

Standard Solution Preparation

Absorbance Measurement

Calibration Curve Construction

Sample Analysis

Method Validation Parameters

For regulatory compliance in pharmaceutical analysis, the following validation parameters must be established:

- Linearity: Demonstrated through calibration curves across the specified range [7] [15]

- Accuracy: Determined by recovery studies of spiked samples [15]

- Precision: Evaluated through repeatability (intra-day) and intermediate precision (inter-day) [15]

- Limit of Detection (LOD) and Quantification (LOQ): Calculated based on signal-to-noise ratios [15]

- Robustness: Assessed by evaluating the effect of small variations in experimental conditions [4]

Limitations and Advanced Modifications

Fundamental Limitations of the Beer-Lambert Law

Despite its widespread utility, the Beer-Lambert Law has several significant limitations that researchers must acknowledge:

Concentration Limitations

The law becomes inaccurate at high concentrations (typically >10 mM) due to several factors [12] [4]. Electrostatic interactions between solute molecules at close proximity alter their absorptivity [12] [13]. Changes in refractive index at high concentrations further contribute to nonlinearity [4] [13]. Additionally, molecular interactions such as dimerization or aggregation can change absorption characteristics [4] [15].

Chemical and Instrumental Limitations

Chemical equilibria between different molecular forms can cause deviations from Beer-Lambert behavior [14]. Fluorescence or phosphorescence in samples leads to measured absorbance values lower than true absorption [14]. Stray light in spectrophotometers, particularly at high absorbance values (>2), causes significant deviations from linearity [4]. Non-monochromatic light sources also violate a fundamental assumption of the law [12] [4].

Scattering and Turbidity Effects

The classical Beer-Lambert Law assumes no light scattering, making it inadequate for turbid or colloidal solutions without modification [4] [11]. In biological tissues, scattering effects dominate absorption, requiring significant modifications to the basic law [11].

Modified Beer-Lambert Law (MBLL) for Complex Matrices

For scattering media like biological tissues, the Modified Beer-Lambert Law incorporates additional factors:

OD = -log(I/Iâ‚€) = DPF · μâ‚d + G

Where:

- OD is optical density (accounting for both absorption and scattering)

- DPF is differential pathlength factor (typically 3-6 for biological tissues)

- μ₠is absorption coefficient

- d is inter-optode distance

- G is geometry-dependent factor [11]

This modification has proven essential for biomedical applications such as pulse oximetry and near-infrared spectroscopy of tissues [11]. For blood measurements, Twersky further extended the model to account for scattering from red blood cells [11].

Emerging Approaches and Machine Learning Integration

Recent research has explored machine learning approaches to surpass the limitations of the Beer-Lambert Law [16]. Ridge regression models trained on solution images can accurately predict concentrations beyond the linear range of traditional spectrophotometry [16]. These approaches analyze color intensity and pattern changes without relying solely on absorbance measurements, potentially revolutionizing high-concentration analysis in pharmaceutical applications [16].

The Beer-Lambert Law, deconstructed as A = εlc, remains a cornerstone of pharmaceutical analysis despite its simplicity. Understanding each component—absorbance (A), molar absorptivity (ε), path length (l), and concentration (c)—enables researchers to properly apply this principle while recognizing its limitations. In drug development research, this equation facilitates critical analyses from API quantification to formulation optimization. However, professionals must remain cognizant of its constraints at high concentrations, in scattering media, and with complex chemical systems. Contemporary modifications and emerging technologies like machine learning integration continue to extend the utility of this fundamental principle, ensuring its continued relevance in advancing pharmaceutical sciences and improving therapeutic outcomes through precise analytical measurements.

The Beer-Lambert law serves as a fundamental cornerstone in quantitative drug analysis research, providing the theoretical basis for determining solute concentrations in solution. This scientific principle establishes a direct, linear relationship between the absorbance of light by a solution and the concentration of the absorbing species within it [6]. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering the core parameters of this law—absorbance, molar absorptivity, path length, and concentration—is essential for applications ranging from determining protein concentrations and assessing nucleic acid purity to monitoring reaction kinetics and ensuring quality control in pharmaceutical formulations. This technical guide examines these critical parameters, their mathematical interrelationships, practical measurement methodologies, and their collective significance in ensuring accurate and reproducible analytical results within the framework of modern drug research and development.

Theoretical Foundations of the Beer-Lambert Law

The Beer-Lambert Law, also referred to as the Bouguer-Beer-Lambert Law, is a linear relationship between the absorbance and the concentration of an absorbing species [4]. The modern mathematical formulation of the law is expressed as:

A = ε * c * p

Where:

- A is the measured Absorbance (dimensionless)

- ε is the Molar Absorptivity (L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹)

- c is the Concentration of the absorbing substance (mol/L)

- p is the Path Length of light through the solution (cm) [17] [18] [19]

This equation synthesizes the contributions of Bouguer and Lambert, who established the dependence of attenuation on path length, and Beer, who related it to concentration [17] [4]. The law fundamentally states that the quantity of light absorbed by a solution is directly proportional to both the number of absorbing molecules (concentration) and the distance the light travels through those molecules (path length) [6]. The molar absorptivity (ε) serves as the proportionality constant that is intrinsic to the specific chemical substance and the wavelength of light used [18].

It is critical to recognize the assumptions and limitations of this law for its proper application in drug analysis. The Beer-Lambert law assumes a monochromatic light source, a homogeneous solution, non-interacting absorbing species, and the absence of phenomena such as fluorescence, scattering, or chemical equilibria that could alter the absorption characteristics [4]. Deviations from these ideal conditions, such as the use of insufficiently monochromatic light or high concentrations where molecular interactions become significant, can lead to non-linearity between absorbance and concentration, thus limiting the law's accuracy [4] [20]. Furthermore, in contexts involving thin films or high-precision reflectance measurements, interference effects due to the wave nature of light can necessitate more complex, wave-optics-based approaches [4].

Table 1: Fundamental Parameters of the Beer-Lambert Law

| Parameter | Symbol | Standard Units | Definition | Role in Beer-Lambert Law |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorbance | A | Dimensionless (Absorbance Units - AU) | Logarithm of the ratio of incident to transmitted radiant power [17] [19]. | The dependent variable; the measured quantity of light absorbed. |

| Molar Absorptivity | ε | L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹ | A constant representing a substance's ability to absorb light at a specific wavelength per unit concentration [18] [20]. | The proportionality constant; intrinsic property of the analyte. |

| Concentration | c | mol/L (Molarity) | Amount of the absorbing solute dissolved in a given volume of solvent. | An independent variable; directly proportional to absorbance. |

| Path Length | p | cm | The distance light travels through the sample solution [21]. | An independent variable; directly proportional to absorbance. |

Deep Dive into Core Parameters

Absorbance

Absorbance (A), also historically termed optical density (OD), is a dimensionless quantitative measure of the amount of light a sample absorbs at a particular wavelength [17] [19]. It is defined mathematically as the negative logarithm (base 10) of transmittance (T):

A = -logâ‚â‚€(T) = logâ‚â‚€(Iâ‚€/I)

Here, Iâ‚€ is the intensity of the incident light, and I is the intensity of the light after it has passed through the sample [17] [19]. Transmittance (T) is defined as I/Iâ‚€, representing the fraction of incident light that passes through the sample [19]. This logarithmic relationship is crucial because it transforms the exponential attenuation of light as it passes through a medium into a linear function that is directly related to concentration and path length, as described by the Beer-Lambert law [17].

In practical terms, for non-scattering solutions, absorbance measures the attenuation of the light beam primarily caused by absorption. However, it is important to note that in real-world measurements, other phenomena like reflection and scattering can also contribute to the reduction of the transmitted beam. To emphasize this, the term "attenuance" or "experimental absorbance" is sometimes used [17]. For optimal analytical performance, instrument detectors are designed to operate within a specific dynamic range. A target absorbance of 1 to 1.5 AU for key peaks provides an excellent signal-to-noise ratio, while the acceptable range is generally between 0.5 and 2.5 AU [21]. Measurements falling outside this range may suffer from poor precision.

Molar Absorptivity

Molar absorptivity (ε), also known as the molar extinction coefficient, is a fundamental physical constant that expresses the probability of a photon being absorbed by a specific chemical species at a given wavelength [18] [20]. It is defined as the absorbance of a 1 molar solution measured with a 1 cm path length. The value of ε is a direct reflection of the absorbing power of a molecule; a compound with a high molar absorptivity is exceptionally effective at absorbing light, which allows for the detection of that compound at very low concentrations [18]. This makes it a critical parameter for developing highly sensitive assays in drug analysis.

The magnitude of molar absorptivity is governed by the cross-sectional area of the absorbing species and the intrinsic probability that a photon passing through that area will be absorbed [20]. Maximum values for simple molecules can be on the order of 10âµ L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹ [20]. It is crucial to understand that ε is not an absolute constant for a substance under all conditions. Its value can be influenced by the solvent, temperature, and pH of the solution, as these factors can alter the chemical environment and electronic state of the molecule [4] [20]. Furthermore, at high concentrations, solute-solute interactions can cause deviations from the expected absorbance, leading to a breakdown of the Beer-Lambert law [4]. Consequently, while molar absorptivity values are often reported in the literature, they can vary significantly between studies due to differences in experimental conditions, reagent purity, and instrument precision [20].

Table 2: Typical Molar Absorptivity Values for Common Biomolecules

| Analyte | Wavelength (nm) | Typical Molar Absorptivity (L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹) | Analytical Application in Drug Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins | 280 | Varies (e.g., ~50,000 for BSA) | Quantification of protein therapeutics and enzymes. |

| DNA | 260 | ~50,000 (per nucleotide) | Determination of nucleic acid concentration and purity (A260/A280 ratio). |

| RNA | 260 | ~40,000 (per nucleotide) | Quality control for mRNA vaccines and RNA-based therapeutics. |

Path Length

Path length (p) is the distance, typically measured in centimeters (cm), that light travels through the sample solution [21]. According to the Beer-Lambert law, absorbance is directly proportional to path length; doubling the path length will double the measured absorbance for a given concentration [17] [21]. This principle is visually intuitive: a longer path through the sample provides more opportunities for photons to interact with and be absorbed by the analyte molecules.

In traditional cuvette-based spectrophotometry, the path length is fixed by the dimensions of the cuvette (e.g., 1 cm). In modern microplate readers, the path length can be more variable, but the principle remains the same [21]. Selecting the correct path length is a critical step in method development. The goal is to ensure that the measured absorbance for the analyte of interest falls within the ideal dynamic range of the detector (0.5 to 2.5 AU) [21]. For highly concentrated samples, a short path length (e.g., 1-2 mm) is necessary to prevent the signal from exceeding the detector's上é™. Conversely, for very dilute samples, a longer path length (e.g., 10 mm or more) is required to generate a measurable absorbance signal [21]. It is also important to distinguish between geometric path length (the physical distance) and optical path length, which is the product of the geometric path length and the refractive index of the medium [22]. For most liquid solutions in analytical chemistry, this distinction is minor, but it becomes critical in systems involving different media or high-precision interferometry.

Concentration

Concentration (c) represents the quantity of the absorbing solute present in a given volume of solvent, most commonly expressed in molarity (mol/L) for the Beer-Lambert law [17] [18]. It is the primary independent variable that researchers aim to determine through absorbance measurements. The linear relationship A ∠c is the foundation of quantitative analysis, allowing for the construction of a calibration curve from standards of known concentration, which is then used to determine the concentration of unknown samples [18] [19].

In the specific context of pharmacology and drug development, the accurate measurement of drug concentration is paramount. These measurements are performed in various matrices, including plasma, urine, and tissue biopsies, to understand a drug's pharmacokinetic profile—its absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) [23]. A key concept here is the steady-state concentration (SSC), which is the dynamic equilibrium achieved when the rate of drug administration equals the rate of drug elimination, resulting in a consistent plasma concentration over time [24]. Therapeutic drug monitoring aims to maintain drug levels within a therapeutic window, and spectrophotometric methods based on the Beer-Lambert law are often employed for such analyses [24]. It is critical that concentration values used in the Beer-Lambert equation are based on the number of molecules per unit volume (e.g., molarity), as mass or weight fractions are not inherently proportional to the number of absorbing entities and can lead to inaccuracies [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Protocol for Concentration Determination via UV-Vis Spectrophotometry

The following detailed methodology is standard for determining the concentration of an analyte, such as a protein or nucleic acid, using a UV-Visible spectrophotometer.

1. Instrument Calibration and Blank Measurement:

- Power on the UV-Vis spectrophotometer and allow the lamp to warm up for the time specified by the manufacturer (typically 15-30 minutes).

- Select the appropriate wavelength for your analyte (e.g., 280 nm for proteins, 260 nm for DNA/RNA).

- Prepare a blank solution containing all the components of your sample except the analyte (e.g., the buffer solvent).

- Place the blank in a clean, matched cuvette with the desired path length (e.g., 1 cm) and insert it into the sample holder.

- Perform the blank measurement to set the 0% transmittance (infinite absorbance) and 100% transmittance (zero absorbance) baseline for the instrument [4].

2. Preparation of Standard Solutions:

- Prepare a stock solution of the analyte of known, accurately determined concentration.

- Using serial dilution, create a series of standard solutions that cover a concentration range expected to produce absorbances between approximately 0.05 and 1.5 AU. A minimum of five standard concentrations is recommended for a reliable calibration curve.

3. Measurement of Standards and Unknowns:

- For each standard solution, measure the absorbance at the target wavelength. Ensure that the cuvette is properly oriented and clean. Repeat each measurement in triplicate to ensure reproducibility.

- Rinse the cuvette thoroughly with the next solution or use a new disposable cuvette to prevent cross-contamination.

- Follow the same procedure to measure the absorbance of the unknown sample(s).

4. Data Analysis and Calculation:

- Calculate the average absorbance for each standard concentration.

- Plot the average absorbance (y-axis) against the known concentration (x-axis) to create a calibration curve.

- Perform linear regression analysis on the data points to obtain the equation of the line (y = mx + b), which, in the context of Beer's law, becomes A = (εp)c + b, where the slope (m) is equal to εp.

- Determine the concentration of the unknown sample by substituting its measured absorbance into the linear equation and solving for c.

Protocol for Path Length Optimization

Selecting the correct path length is vital for obtaining data within the optimal absorbance range [21].

1. Initial Estimate:

- Based on the expected concentration of the analyte and its approximate molar absorptivity, use the Beer-Lambert law to estimate the required path length. For example, if a high concentration is expected, a short path length (e.g., 2 mm) should be selected.

2. Empirical Verification:

- If the estimated path length is adjustable (e.g., via a variable path length cell or different cuvettes), measure a representative sample.

- If the measured absorbance is too high (>2.5 AU), select a shorter path length. If it is too low (<0.1 AU), select a longer path length.

- For fixed path length systems, the sample may need to be diluted (for high absorbance) or concentrated (for low absorbance) to bring it into the optimal range.

3. Final Selection:

- The ideal target absorbance for the peak of interest is between 1 and 1.5 AU, as this provides the best signal-to-noise ratio. A compromise may be necessary when multiple analytes with different absorptivities are present [21].

Visualization of Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical and mathematical relationships between the core parameters of the Beer-Lambert Law and the process of concentration determination.

Diagram 1: Logical Flow of Quantitative Analysis Using the Beer-Lambert Law. This diagram shows how intrinsic chemical properties and experimental parameters feed into the Beer-Lambert law to calculate absorbance, which is used to determine unknown concentrations via a calibration curve.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for conducting accurate spectrophotometric analyses based on the Beer-Lambert law.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectrophotometric Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Critical Considerations for Drug Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| UV-Transparent Cuvettes/Plates | Containers for holding liquid samples during measurement. | Must be made of materials (e.g., quartz, UV-transparent plastic) that do not absorb significantly in the UV range (e.g., 220-320 nm) for protein/nucleic acid work. Path length must be known and consistent [21]. |

| High-Purity Analytical Standards | Pure compounds of known concentration and identity used to create the calibration curve. | Purity is paramount, as contaminants can lead to inaccurate molar absorptivity values and erroneous calibration [20]. Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) are ideal. |

| Spectrophotometric Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (e.g., water, buffers, ethanol) used to prepare sample and standard solutions. | Must have low absorbance in the spectral region of interest to minimize background signal and maximize the available dynamic range for the analyte. |

| Buffers and pH Adjusters | Solutions to maintain a constant and appropriate pH for the analyte. | pH can significantly affect the molar absorptivity and stability of many drug compounds and biomolecules (proteins, nucleic acids). Consistent buffer composition is critical [4]. |

| Serial Dilution Equipment | Precision pipettes, volumetric flasks, and pipette tips for accurate solution preparation. | Accurate and precise dilution is non-negotiable for creating a reliable calibration curve and for preparing samples within the linear range of the assay. |

| BMS-986449 | BMS-986449, MF:C21H21FN4O3, MW:396.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| DOTA-bombesin (1-14) | DOTA-bombesin (1-14), MF:C90H136N28O25S, MW:2042.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The parameters of absorbance, molar absorptivity, path length, and concentration form an interdependent framework that is fundamental to quantitative spectroscopic analysis in drug research. A deep and practical understanding of the Beer-Lambert law, including its mathematical formulation, its assumptions, and its limitations, is indispensable for researchers. By meticulously controlling experimental conditions, selecting appropriate path lengths, using high-purity standards, and recognizing the influence of the chemical environment on molar absorptivity, scientists can generate robust, reproducible, and meaningful concentration data. This rigorous application of foundational principles ensures the accuracy and reliability of data that underpins critical decisions in drug development, from initial discovery and formulation through to quality control and therapeutic monitoring.

Within the framework of drug analysis research, the Beer-Lambert law stands as a fundamental principle for quantifying analyte concentration. This technical guide delineates the core relationship between transmittance and absorbance, the foundational mathematical inverse upon which spectrophotometric analysis is built. A thorough comprehension of this critical link is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals to accurately design assays, interpret spectroscopic data, and determine the concentration of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and excipients, thereby ensuring drug efficacy and safety.

Fundamental Definitions and Mathematical Relationship

In spectrophotometric analysis, the interaction of light with a sample is quantified through two primary, inversely related concepts: transmittance and absorbance.

Transmittance (T) is defined as the ratio of the intensity of light transmitted through a sample (I) to the intensity of the incident light (Iâ‚€) [7] [25]. It is a dimensionless quantity often expressed as a percentage:

%T = (I / I₀) × 100 [7] [26].

Absorbance (A), conversely, is a logarithmic measure of the amount of light absorbed by the sample [7]. It is mathematically defined through the relationship with transmittance:

A = logâ‚â‚€(1/T) = logâ‚â‚€(Iâ‚€ / I) [7] [25] [8].

This logarithmic relationship means that absorbance increases as transmittance decreases. The following table illustrates this inverse correlation with key values, demonstrating how minute amounts of transmitted light correspond to very high absorbance values, which are critical for detecting low-concentration analytes in drug formulations.

Table 1: The Inverse Relationship Between Absorbance and Percent Transmittance

| Absorbance (A) | Percent Transmittance (%T) |

|---|---|

| 0 | 100% |

| 0.3 | 50% |

| 0.7 | 20% |

| 1 | 10% |

| 2 | 1% |

| 3 | 0.1% |

| 4 | 0.01% |

| 5 | 0.001% |

Figure 1: The Logical Pathway from Light Measurement to Absorbance. The diagram illustrates the process of measuring incident (Iâ‚€) and transmitted (I) light to first calculate transmittance (T), which is then used to compute absorbance (A) logarithmically.

The Beer-Lambert Law in Drug Analysis

The Beer-Lambert law formalizes the relationship between absorbance and the properties of the absorbing species in a solution [7] [6]. It states that absorbance is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species and the path length the light travels through [8]. The law is expressed as:

A = εlc

Where:

- A is the absorbance (dimensionless).

- ε is the molar absorptivity coefficient (Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹), a substance-specific constant that indicates how strongly a chemical species absorbs light at a particular wavelength [8].

- l is the path length (cm), typically the internal width of the cuvette used for measurement (often 1 cm) [7].

- c is the concentration of the absorbing substance (M, moles per liter) [7] [8].

In drug analysis research, this linear relationship between absorbance and concentration is the cornerstone for quantifying concentrations. Researchers prepare a series of standard solutions with known concentrations, measure their absorbances, and plot a calibration curve [7]. The concentration of an unknown sample can then be accurately determined from its measured absorbance using this calibration plot [7] [27]. This principle is routinely applied in the analysis of drugs such as tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, dolutegravir sodium, and emtricitabine, where the law is obeyed over specific, validated concentration ranges, typically between 10-100 µg/ml [27].

Experimental Protocols for Spectrophotometric Analysis

Accurate measurement of absorbance requires meticulous experimental procedure to minimize errors from instrumental noise, light loss, and other factors [28].

Instrument Calibration and Measurement Protocol

A proper absorbance measurement requires three sequential spectral measurements to account for instrumental effects [28]:

- Background Spectrum (Dark Measurement): Turn off the illumination source and record a spectrum. This measures the detector's signal due to thermal noise and electronic offset, which must be subtracted from all subsequent measurements [28].

- Reference Spectrum (Iâ‚€): With the illumination source on, record a spectrum without the sample. If measuring a solution in a cuvette, the reference should be an identical cuvette containing only the solvent (e.g., water, buffer). This accounts for light absorption and reflection by the solvent and cuvette walls, establishing the 100% transmittance (or 0 absorbance) baseline [28].

- Sample Spectrum (I): Place the sample of interest (e.g., the drug solution in the cuvette) in the light path and record the measurement spectrum. The background spectrum must be subtracted from this measurement [28].

Modern spectrophotometers often automate these steps, but understanding the underlying process is critical for troubleshooting.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Accurate Absorbance Measurement. The flowchart details the critical three-step measurement process required to obtain a reliable absorbance spectrum, highlighting the role of background and reference corrections.

Optimization and Best Practices

- Minimizing Light Loss: The Beer-Lambert law assumes light loss is due solely to absorption. However, light can also be lost through scattering (by particulates or turbid solutions) and reflection at cuvette interfaces [25] [28]. For accurate results, samples should be clear and free of bubbles. Techniques such as filtration or centrifugation may be necessary for turbid samples [28].

- Reducing Noise: To achieve a clean, low-noise absorbance spectrum [28]:

- Light Source Intensity: Use a source with high intensity over the measured wavelength range.

- Integration Time: Optimize the detector's integration time so the reference signal is near 90% of the spectrometer's saturation value.

- Spectral Averaging: Record and average multiple spectra to reduce random noise.

- Absorbance Range: The ideal absorbance range for accurate measurement is typically below 1.3 (transmittance >5%) [28]. For highly concentrated drug solutions, this can be achieved by diluting the sample or using a cuvette with a shorter path length to bring the measurement back into the linear range [25] [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for conducting valid spectrophotometric analysis in a drug research context.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Spectrophotometric Drug Analysis

| Item | Function & Importance in Analysis |

|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Instrument that emits specific wavelengths of light (typically 185-700nm) and measures the intensity of light transmitted through a sample. It is the core tool for acquiring absorbance/transmittance data [26]. |

| Cuvette | A container, typically with a standard path length of 1 cm, that holds the sample solution. It must be made of material transparent to the wavelengths being used (e.g., quartz for UV, glass/plastic for visible light) [7]. |

| Standard Reference Materials | High-purity samples of the drug compound of known concentration. These are used to create the calibration curve, establishing the linear relationship between absorbance and concentration as per Beer-Lambert law [7] [27]. |

| High-Purity Solvent | The liquid in which the drug is dissolved (e.g., water, buffered solutions). It serves as the blank in the reference measurement to isolate the absorbance signal originating solely from the analyte of interest [28]. |

| SL 0101-1 | SL 0101-1, MF:C25H24O12, MW:516.4 g/mol |

| Syntelin | Syntelin, MF:C21H20N6O2S3, MW:484.6 g/mol |

Limitations and Practical Considerations

While the Beer-Lambert law is foundational, its limitations must be respected to avoid analytical inaccuracies.

- Linearity Limits: The law assumes a linear relationship between absorbance and concentration. However, at high concentrations, electrostatic interactions between molecules can alter the absorption characteristics, leading to deviations from linearity [25]. It is crucial to validate the linear range for each specific drug compound during method development [27].

- Chemical Deviations: Apparent deviations can occur if the analyte undergoes chemical changes such as association, dissociation, or reaction with the solvent, which alter the nature of the absorbing species.

- Stray Light and Instrumental Errors: Imperfections in the spectrophotometer, such as stray light reaching the detector, can cause significant deviations, particularly at high absorbance values where the transmitted light signal is very weak.

Table 3: Summary of Beer-Lambert Law Applicability and Deviations

| Factor | Requirement for Beer-Lambert Validity | Common Cause of Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Concentration | Low to moderate concentrations. | High concentrations cause molecular interactions and non-linear absorbance [25]. |

| Optical Path | Fixed, known path length (e.g., 1 cm cuvette). | Use of mismatched or damaged cuvettes. |

| Sample Nature | Homogeneous, non-scattering, clear solution. | Turbid or particulate-containing samples scatter light [25] [28]. |

| Wavelength | Monochromatic light (single wavelength). | Use of insufficiently narrow bandwidths or polychromatic light. |

| Chemical Form | Single, stable absorbing species. | Acid-base equilibria, complex formation, or polymerization. |

The critical link between transmittance and absorbance, formalized by the Beer-Lambert law, is an indispensable principle in the toolbox of the drug development researcher. The logarithmic relationship A = logâ‚â‚€(Iâ‚€/I) transforms a simple light intensity measurement into a quantitative metric for determining concentration. By adhering to rigorous experimental protocols—meticulous background correction, using appropriate blanks, and operating within the validated linear range—scientists can leverage this fundamental relationship to ensure accurate, reliable, and reproducible quantification of pharmaceutical compounds, thereby upholding the stringent demands of drug analysis research.

Fundamental Assumptions for Linear Beer-Lambert Behavior

The Beer-Lambert law establishes a linear relationship between the absorbance of light and the concentration of an analyte, serving as a foundational principle for quantitative drug analysis. This whitepaper delineates the fundamental assumptions underpinning this linear behavior, examining theoretical frameworks, common deviation sources, and advanced methodological adaptations. Within drug development contexts, adherence to these assumptions ensures accurate concentration measurements for active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), excipient compatibility studies, and dissolution testing. Recent electromagnetic theory extensions and machine learning integrations demonstrate promising pathways for overcoming inherent limitations at high concentrations and in complex biological matrices, ultimately enhancing predictive accuracy in pharmaceutical research.

The Beer-Lambert law (BLL) provides the fundamental relationship for quantitative optical spectroscopy, mathematically expressed as ( A = \epsilon c l ), where ( A ) represents absorbance (a dimensionless quantity), ( \epsilon ) is the molar absorptivity (L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹), ( c ) is the concentration of the absorbing species (mol/L), and ( l ) is the optical path length (cm) [10] [29]. This formulation synthesizes Beer's concentration dependence with Lambert's path length dependence, creating an indispensable tool for analytical chemists and pharmaceutical scientists.

In drug analysis research, this linear relationship enables the quantification of API concentration in formulations, assessment of drug purity, and monitoring of reaction kinetics without complex separation procedures. The law's elegance lies in its straightforward application: by measuring absorbance at a specific wavelength and applying a pre-established calibration curve, researchers can accurately determine unknown concentrations in test samples [7] [29]. The generation of a standard curve using samples of known concentration represents the primary experimental implementation of this principle, providing the linear regression model ( A = mc + b ), where the slope ( m ) corresponds to ( \epsilon l ) and the ideal y-intercept ( b ) equals zero [29].

Fundamental Assumptions and Experimental Conditions

The linear relationship postulated by the Beer-Lambert law holds strictly only under specific experimental and physicochemical conditions. Deviations from these assumptions result in nonlinear calibration curves, compromised accuracy, and erroneous concentration estimates in pharmaceutical analysis.

Core Theoretical Assumptions

- Monochromatic Radiation: The law assumes incident light comprises a single wavelength [30] [4]. In practice, spectrophotometers isolate narrow bands, but residual polychromaticity causes deviations, especially with non-linear molar absorptivity across the bandwidth.

- Independent Absorbing Species: Each molecule should absorb light independently without molecular interactions [31] [4]. This condition frequently breaks down in drug solutions at high concentrations where solute-solute interactions (e.g., dimerization, aggregation) alter absorption characteristics.

- Non-Scattering Medium: The sample must be homogeneous and not scatter significant radiation [4] [32]. Scattering effects, prevalent in colloidal suspensions or particulate-containing formulations, artificially elevate measured absorbance.

- Uniform Path Length: The light path through the sample must be well-defined and constant [30] [7]. Irregular cuvettes or improper alignment introduce path length variations, causing deviations.

- No Chemical Changes: The absorbing species should not undergo concentration-dependent chemical transformations (e.g., association, dissociation, protonation) that alter its absorptivity [30]. Changes in pH, temperature, or solvent composition can induce such shifts.

Quantitative Manifestations of Deviations

Deviations manifest as non-linearity in absorbance-concentration plots. Positive deviations occur when measured absorbance exceeds theoretical predictions, while negative deviations present as lower-than-expected absorbance values [30]. The critical concentration threshold where linearity fails varies significantly between analytes; for instance, methylene blue exhibits deviations at concentrations as low as 10 µM, while many pharmaceuticals maintain linearity up to 10 mM [30].

Figure 1: Logical framework mapping Beer-Lambert law assumptions to ideal and deviation regions based on analyte concentration and experimental conditions.

Experimental Protocols for Verification

Validating Beer-Lambert linearity constitutes a critical step in developing analytical methods for pharmaceutical compounds. The following protocols ensure robust experimental verification.

Wavelength Accuracy Verification

Purpose: Confirm spectrophotometer wavelength calibration to prevent instrumental deviations.

- Materials: Holmium oxide or holmium glass filter with certified absorption peaks.

- Procedure:

- Place holmium filter in sample compartment.

- Scan absorption across 200-700 nm range with 0.5 nm spectral bandwidth.

- Record measured peak wavelengths (e.g., 241 nm, 361 nm, 445 nm, 536 nm, 641 nm).

- Compare measured peaks against certified values; tolerance should be ≤1 nm.

- Acceptance Criteria: All measured peaks within ±1 nm of certified values [31].

Absorbance-Concentration Linear Range Determination

Purpose: Establish the concentration range over which a pharmaceutical compound exhibits linear Beer-Lambert behavior.

- Materials: Analytical standard of API (e.g., paracetamol, ibuprofen), appropriate solvent, matched quartz cuvettes (typically 1 cm path length), calibrated UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

- Procedure:

- Prepare stock solution of accurately known concentration (e.g., 1000 μg/mL).

- Serially dilute stock to create 6-8 standard solutions spanning expected concentration range (e.g., 1-100 μg/mL).

- Measure blank (solvent) absorbance at λmax (determined from preliminary scan).

- Measure absorbance of each standard solution at identical λmax.

- Plot absorbance versus concentration, perform linear regression analysis.

- Analysis: Calculate correlation coefficient (R²), y-intercept, and residual sum of squares. The range demonstrating R² > 0.995, y-intercept approximating zero, and random residual distribution constitutes the linear range [29] [33].

Table 1: Experimental parameters for absorbance-concentration verification in pharmaceutical compounds

| Parameter | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Standards | 6-8 minimum | Ensures sufficient statistical power for regression analysis |

| Concentration Range | Should bracket expected sample concentrations | Verifies linearity across relevant analytical range |

| Path Length | Typically 1.0 cm (must be constant) | Maintains proportionality between A and c |

| λmax Determination | From preliminary spectral scan | Ensances measurement at maximum absorptivity |

| R² Acceptance | ≥0.995 | Confirms adequate linear correlation |

| Y-Intercept | Should not significantly differ from zero | Validates adherence to theoretical form of law |

Advanced Theoretical Framework: Electromagnetic Extensions

Traditional Beer-Lambert limitations have prompted theoretical refinements, particularly for high-concentration scenarios common in pharmaceutical formulations.

Electromagnetic Theory Modification

The classical Beer-Lambert law assumes constant refractive index, valid only at low concentrations. At high concentrations, the higher-order terms of refractive index become significant, leading to fundamental deviations [31]. The complex refractive index ( \hat{n} ) incorporates both scattering and absorption: [ \hat{n} = n + ik ] where ( n ) is the real refractive index and ( k ) is the imaginary component (extinction coefficient) related to the absorption coefficient ( \alpha ) by ( k = \frac{\alpha}{4\pi \nu} ), with ( \nu ) representing wavenumber [31].

From electromagnetic theory, the refractive index relates to concentration and polarizability (( \alpha' )) by: [ n \approx 1 + c\frac{NA \alpha'}{2 \in0} ] where ( NA ) is Avogadro's constant and ( \in0 ) is vacuum permittivity. At high concentrations, the polynomial expansion becomes: [ k \approx \beta c + \gamma c^2 + \delta c^3 ] where ( \beta ), ( \gamma ), and ( \delta ) are refractive index coefficients [31]. Incorporating this relationship yields the modified Beer-Lambert equation: [ A = \frac{4\pi \nu}{\ln 10 }(\beta c + \gamma c^2 + \delta c^3)l ] This model demonstrated exceptional performance with root mean square error (RMSE) <0.06 for organic and inorganic solutions including potassium permanganate, potassium dichromate, and copper(II) sulfate, significantly outperforming the classical model at high concentrations [31].

Figure 2: Progression from classical Beer-Lambert model to electromagnetic theory-based modification incorporating refractive index and extinction coefficient dependencies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful application of the Beer-Lambert law in pharmaceutical research requires specific materials and reagents to maintain optimal analytical conditions.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for Beer-Lambert compliant spectroscopy

| Item | Specification | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Matched Cuvettes | Spectrosil quartz or equivalent; pair-matched with <1% transmission difference | Maintains constant, reproducible path length; minimizes reflection and scattering losses |

| Holmium Oxide Filters | NIST-traceable certified wavelengths | Verifies spectrophotometer wavelength accuracy; identifies instrumental deviations |

| Buffer Systems | Pharmaceutical-grade (e.g., phosphate buffer); appropriate ionic strength and pH control | Maintains chemical stability of analyte; prevents pH-induced spectral shifts |

| Reference Standards | USP/EP-certified API analytical standards | Provides accurate calibration standards for quantitative analysis |

| Spectrophotometric Solvents | HPLC-grade solvents; UV-transparent at analytical wavelengths | Provides transparent medium; minimizes solvent background absorption |

| (R)-(4-NH2)-Exatecan | (R)-(4-NH2)-Exatecan, MF:C23H21N3O4, MW:403.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ZN148 | ZN148, MF:C26H33N5O6, MW:511.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The fundamental assumptions enabling linear Beer-Lambert behavior constitute critical considerations in pharmaceutical analysis research. While the classical law provides satisfactory performance in dilute solutions under controlled conditions, modern drug development increasingly encounters scenarios demanding advanced approaches—high-concentration formulations, complex biological matrices, and sophisticated quality-by-design paradigms. The integration of electromagnetic theory refinements, coupled with machine learning applications, presents a promising trajectory for overcoming classical limitations. As spectroscopic technologies evolve, maintaining rigorous adherence to these fundamental principles while embracing methodological innovations will ensure continued accuracy in drug quantification, ultimately enhancing pharmaceutical product quality and patient safety.

Practical Application: Implementing Beer's Law for Drug Quantification

Step-by-Step Guide to UV-Vis Spectrophotometry in Drug Analysis

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometry stands as a cornerstone analytical technique in pharmaceutical sciences, enabling both qualitative and quantitative assessment of drug compounds and their related substances. The principle is based on measuring the intensity of light absorbed by a compound at a specific wavelength, which is proportional to the concentration of the analyte in the sample [34]. This relationship is quantitatively described by the Beer-Lambert Law (also referred to as the Bouguer-Beer-Lambert Law), which forms the fundamental theoretical basis for most spectrophotometric analyses in drug development and quality control [4] [35].

The Beer-Lambert Law states that the absorbance (A) of a substance is directly proportional to its concentration (c), the path length of the sample cell (l), and the molar absorptivity (ε) [36] [34]. This relationship is mathematically expressed as:

A = εcl

Where:

- A is the measured absorbance (unitless)

- ε is the molar absorptivity or absorption coefficient (L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹)

- c is the concentration of the absorbing species (mol/L)

- l is the path length of the light through the sample (cm)

However, modern pharmaceutical researchers must recognize that this "law" operates more accurately as an approximation with specific limitations [4]. Critical limitations include the necessity for low analyte concentrations to minimize molecular interactions, the potential for interference effects in non-homogeneous samples, and the requirement that the solvent and measurement conditions do not significantly alter the absorbing species [4]. For precise quantitative work in drug analysis, understanding these constraints is essential for generating reliable, reproducible data that meets regulatory standards.

Instrumentation and Measurement Principles

Fundamental Relationships

Spectrophotometric analysis relies on two key optical measurements:

- Transmittance (T): The ratio of light intensity passing through a sample (I) to the initial intensity (Iâ‚€), often expressed as a percentage [35] [37]

- Absorbance (A): The negative logarithm of transmittance, calculated as A = -logâ‚â‚€T [37]

This relationship means that as absorbance increases, transmittance decreases exponentially. For accurate quantitative analysis, absorbance measurements should ideally fall between 0.1 and 1.0 (equivalent to 10-90% transmittance), with values exceeding 3.0 becoming increasingly unreliable for concentration determination [35].

The Critical Role of Wavelength Selection

The wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) is characteristic of the substance being analyzed and provides the highest sensitivity for detection [34]. Different drug compounds exhibit distinct absorbance spectra based on their molecular structure and chromophores (light-absorbing groups). For instance:

- Proteins and peptides are often quantified at 280 nm due to aromatic amino acid absorption

- Nucleic acids (DNA/RNA) display strong absorbance at 260 nm [35]

- NADH/NAD+ cofactors are monitored at 340 nm to follow enzymatic reactions [35]

Proper wavelength selection is crucial for method specificity, particularly when analyzing drug combinations where spectral overlap may occur [38].

Experimental Workflow and Procedures

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for spectrophotometric drug analysis:

Step-by-Step Analytical Procedure

Sample Preparation

Dissolve the pharmaceutical compound in an appropriate solvent based on solubility and compatibility with the spectrophotometric method [34]. Common solvents include ethanol, methanol, water, or buffer solutions, depending on the drug's properties [38].

Add specific reagents to induce color changes or enhance detection. The choice of reagent depends on the chemical nature of the drug and the desired reaction [34]:

- Complexing agents (e.g., ferric chloride for phenolic drugs like paracetamol)

- Oxidizing/reducing agents (e.g., ceric ammonium sulfate for ascorbic acid)

- pH indicators (e.g., bromocresol green for weak acids)

- Diazotization reagents (e.g., sodium nitrite/HCl for primary amines)

Optimize reaction conditions including time, temperature, and pH to ensure complete complex formation or reaction development [34].

Instrument Calibration and Operation

Turn on the spectrophotometer and allow it to warm up for at least 15 minutes to ensure stable operation [37].

Prepare the blank solution containing only the chemical solvent in which the analyte is dissolved. The blank must be in the same type of container and same volume as the experimental samples [37].

Clean cuvettes thoroughly with deionized water. Handle carefully, avoiding touching the clear sides where light passes through. Wipe the outside with a lint-free cloth before placement [37].

Set the appropriate wavelength based on the λmax of the target compound or complex [37].

Calibrate with the blank by placing it in the cuvette holder and setting the instrument to zero absorbance [37].

Absorbance Measurement

Load the experimental sample into the cuvette, ensuring the laser path passes through the liquid, not air [37].

Measure the absorbance,

Repeat readings at least three times for each sample and average the results to improve accuracy [37].

Calibration and Quantitative Analysis

Prepare standard solutions of known concentrations covering the expected range of the unknown samples [34].

Measure absorbance of each standard following the same procedure used for samples.

Construct a calibration curve by plotting absorbance values against corresponding concentrations [34].

Determine unknown concentrations by comparing sample absorbance to the calibration curve [34].

Advanced Methodologies for Complex Analyses

Analysis of Drug Combinations

For pharmaceutical formulations containing multiple active compounds, specialized spectrophotometric methods enable quantification without prior separation:

Zero-order method: Used when one drug exhibits significant absorption at a wavelength where other components show zero absorbance. For example, simeprevir can be quantified at 333 nm in combination with sofosbuvir, which has no absorption at this wavelength [38].

Dual-wavelength method: Employed for overlapping spectra by measuring the difference in absorbance at two wavelengths where the interferent shows equal absorption. Sofosbuvir can be measured using the difference in absorbance values at 259.40 and 276 nm, where simeprevir shows no net absorbance difference [38].

Method Validation Parameters

For pharmaceutical applications, spectrophotometric methods must be validated according to ICH guidelines [38]:

Table 1: Validation Parameters for Spectrophotometric Methods in Drug Analysis

| Parameter | Definition | Acceptance Criteria | Example Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linearity Range | Concentration interval where Beer-Lambert Law holds | r² ≥ 0.999 | 3-45 μg/mL for simeprevir [38] |

| LOD (Limit of Detection) | Lowest detectable concentration | Signal-to-noise ≥ 3:1 | 0.888 μg/mL for simeprevir [38] |

| LOQ (Limit of Quantification) | Lowest quantifiable concentration | Signal-to-noise ≥ 10:1 | 2.692 μg/mL for simeprevir [38] |

| Accuracy | Closeness to true value | % Recovery = 98-102% | 100.25% for simeprevir [38] |

| Precision | Repeatability of measurements | RSD ≤ 1% | 0.768% RSD for simeprevir [38] |

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful spectrophotometric analysis requires appropriate selection of reagents and materials based on the specific drug properties and analytical goals:

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spectrophotometric Drug Analysis

| Reagent Type | Function | Example Applications | Specific Examples |