The Unseen Error: How Dirty Spectrometer Windows Compromise Data Accuracy and Derail Scientific Research

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how contamination on spectrometer windows and optical components directly leads to data inaccuracy, instrument drift, and costly analytical errors.

The Unseen Error: How Dirty Spectrometer Windows Compromise Data Accuracy and Derail Scientific Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of how contamination on spectrometer windows and optical components directly leads to data inaccuracy, instrument drift, and costly analytical errors. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details the underlying mechanisms of signal degradation, offers proven methodologies for cleaning and maintenance, outlines systematic troubleshooting protocols, and establishes validation techniques to ensure data integrity. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with practical application, this guide serves as an essential resource for maintaining optimal spectrometer performance and safeguarding research outcomes in demanding biomedical and clinical environments.

The Silent Saboteur: Understanding How Contamination Distorts Optical Signals

The Fundamental Role of Optical Windows in Signal Fidelity

In spectroscopic analysis, the integrity of the optical window is a critical yet frequently overlooked factor that directly determines the accuracy and reliability of experimental data. Acting as the primary interface between a sample and the detector, an optical window is a flat, parallel, and optically transparent component designed to separate two environments while maximizing light transmission in a specified wavelength range [1] [2]. Its fundamental role is to protect sensitive internal optical systems and electronic sensors from the external environment without introducing optical power into the system [1].

Within the context of high-precision fields such as drug development and material science, even minor contamination—including dust, fingerprints, or chemical films—on a spectrometer window can introduce significant errors. This contamination acts as an uncontrolled variable, causing signal attenuation, increased scattering, and wavelength-dependent absorption, ultimately corrupting the spectral fingerprint [3] [4]. This article details how meticulous selection, maintenance, and analysis of optical windows are non-negotiable practices for ensuring signal fidelity and, by extension, the validity of scientific research.

Optical Window Fundamentals and Material Selection

Key Properties and Performance Parameters

The performance of an optical window is governed by a set of intrinsic material properties that dictate its interaction with light.

- Transmission Wavelength Range: This is the most critical property, defining the span of wavelengths for which the material transmits at least 80% of incident light [2]. Selecting a window with an inappropriate range leads to catastrophic signal loss.

- Refractive Index (nd): This measures how much a light beam bends when passing from air into the window material. A higher index, such as that of Germanium (n~4.0), results in more significant reflection losses at the surfaces unless mitigated by anti-reflective coatings [1] [2].

- Dispersion (Abbe Number, vd): The Abbe number quantifies how much the refractive index changes with wavelength. A low Abbe number indicates high dispersion, which can cause chromatic aberrations in broadband applications [1].

- Mechanical and Thermal Properties: For real-world applications, properties like Knoop Hardness (resistance to scratching), Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (dimensional stability with temperature change), and softening temperature are vital for durability in harsh environments [1].

A Guide to Optical Window Materials

The choice of material is application-dependent, primarily determined by the operational wavelength of the instrument. The table below summarizes key materials for different spectral regions.

Table 1: Properties of Common Optical Window Materials

| Material | Wavelength Range | Refractive Index (nd) | Knoop Hardness (kg/mm²) | Primary Application & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV Fused Silica | 180 nm - 2.5 µm [2] | 1.458 [1] | 500 [1] | UV Spectroscopy: High transmission deep into the UV; excellent laser damage threshold. |

| N-BK7 (Optical Glass) | 350 nm - 2.0 µm [2] | 1.517 [1] | 610 [1] | Visible (VIS) Spectroscopy: A cost-effective, general-purpose choice for the visible range. |

| Sapphire (Al₂O₃) | 150 nm - 4.5 µm [2] | 1.768 [1] | 2200 [1] | Harsh Environments: Extremely hard, chemically inert, and thermally robust. Ideal for process analytical technology (PAT). |

| Calcium Fluoride (CaF₂) | 130 nm - 9.5 µm [2] | 1.434 [1] | 158 [1] | UV/IR Laser Systems: Broad transmission from deep UV to mid-IR; relatively soft and susceptible to water. |

| Zinc Selenide (ZnSe) | 1 µm - 14 µm [2] | 2.403 [2] | 120 [1] | IR Spectroscopy & High-Power CO₂ Lasers: Low absorption and dispersion in the IR; soft and requires protective coatings. |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | 250 nm - 26 µm [2] | 1.527 [1] | 7 [1] | FTIR Spectroscopy: Extremely broad IR transmission; highly hygroscopic (water-soluble)—requires controlled, dry environments. |

The Impact of Window Contamination on Data Accuracy

A contaminated optical window functions as a faulty and uncalibrated optical component, systematically distorting the signal that reaches the detector. The mechanisms of this distortion are physical and predictable.

Physical Mechanisms of Signal Degradation

- Absorption: Contaminants such as organic films or chemical residues can absorb specific wavelengths of light. This creates a false absorption signal that is superimposed on the sample's authentic spectrum, leading to incorrect conclusions about chemical composition [3].

- Scattering: Particulate matter like dust or lint on the window surface scatters incident light. This scattering reduces the overall signal intensity (throughput) and increases the background noise level, thereby degrading the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and the detection limit of the instrument [1] [3].

- Interference Effects: Thin, uniform films of contamination can create parasitic interference fringes. These fringes manifest as a sinusoidal pattern on the measured spectrum, obscuring genuine spectral features and complicating data interpretation [4].

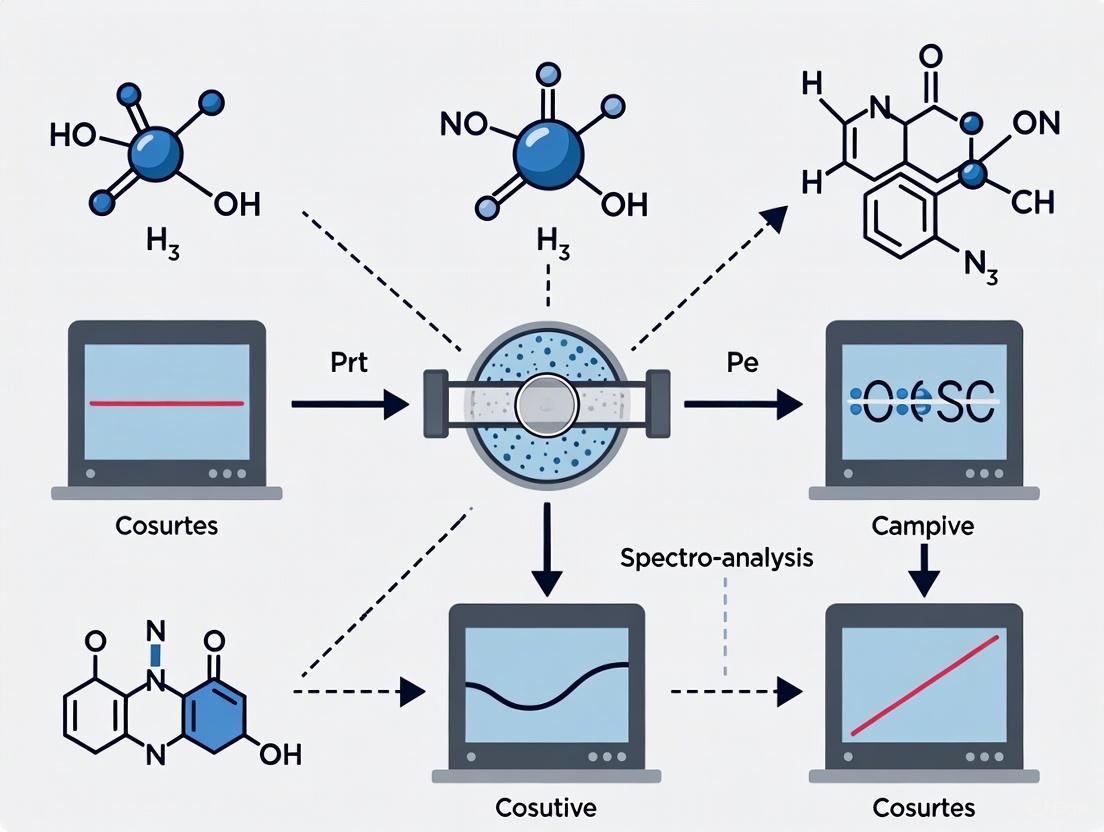

The following diagram illustrates how contamination alters the intended light path and introduces errors.

Quantifying Contamination: An Experimental Protocol

Research by Zhang and Green on cosmic dust provides a powerful analogy for understanding the quantitative impact of particulate matter on optical signals [5]. While their study focused on interstellar dust, the core principle of "extinction"—the combined effect of absorption and scattering—directly applies to contamination on optical windows. Their methodology involved using millions of stellar spectra to reconstruct the properties of intervening dust, demonstrating that particulate matter causes wavelength-dependent dimming and reddening [5].

In a laboratory setting, the effect of surface contaminants on optical components can be rigorously analyzed. A study employing Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) demonstrated a direct correlation between surface contamination and changes in the optical properties of glass, evidenced by ellipsometric measurements [4]. The experimental workflow for such an analysis is detailed below.

Experimental Protocol: Surface Contamination Analysis via LIBS [4]

- Objective: To perform a depth-resolved quantitative analysis of manufacturing-induced trace contaminants on optical glass surfaces and correlate them with changes in optical properties.

- Methodology: Calibration-free Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS).

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: The optical glass sample is mounted in the LIBS apparatus. The surface is not pre-cleaned to preserve the native contamination layer.

- Depth-Profiling: Spectra are recorded for successive laser pulses applied to the same irradiation site. Each pulse ablates a nanoscale layer of material, allowing for depth-resolved measurement.

- Spectral Analysis: The emitted spectra are analyzed using a calibration-free approach based on calculating the spectral radiance of a plasma in local thermodynamic equilibrium. This allows for the quantification of trace elements without standard reference samples.

- Ellipsometric Validation: The same contaminated surface undergoes ellipsometric measurements to detect changes in the refractive index and other optical properties caused by the contaminants.

- Reference Validation: The quantitative results from LIBS are validated against inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) for the bulk glass composition to confirm accuracy.

- Key Findings: The protocol successfully evidenced a surface contamination originating from polishing during manufacturing and established a correlation between the presence of these contaminants and measurable changes in the optical properties of the surface [4].

Best Practices for Maintaining Signal Fidelity

Cleaning and Maintenance Protocols

Regular and correct maintenance of optical windows is not merely good practice; it is essential for data integrity. The following protocol synthesizes general guidelines for cleaning instrumentation, drawing from rigorous standard operating procedures [3] [6].

Table 2: Optical Window Cleaning and Handling Protocol

| Step | Action | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Inspection & Frequency | Regularly inspect windows under bright light. Clean when visible contaminants are present or when a gradual loss of signal baseline is observed [3]. | The cleaning frequency depends on the operating environment. Dusty or high-traffic labs require more frequent checks [3]. |

| 2. Initial Dry Clean | Use a dry, low-pressure stream of ultra-clean, oil-free air or nitrogen to dislodge loose particulate matter. | Never wipe a dry, dirty surface, as this can grind particles into the optical surface, causing permanent scratches [6]. |

| 3. Solvent Cleaning | Apply high-purity solvents (e.g., spectroscopic-grade methanol, acetone, or isopropanol) to dissolve organic films. | - Do not use abrasive or harsh chemicals [3]. - Moisten a lint-free swab or wipe; do not pour solvent directly onto the window. |

| 4. Wiping Technique | Gently wipe the surface using a moistened lint-free swab (e.g., cellulose, microfiber). Use a circular motion from the center outwards. | - Wear lint-free nylon gloves to prevent fingerprints [6]. - Use minimal pressure. For small windows, a single pass may be sufficient. |

| 5. Final Rinse & Dry | For stubborn residues, a final rinse with a clean solvent may be needed. Allow the window to air dry completely in a clean, covered environment. | Ensure no solvent residue remains, as this can create a thin film that causes interference [6]. |

The Researcher's Toolkit for Optical Integrity

A systematic approach to optical window management is fundamental to a reliable color or spectral measurement program. The following tools and practices are considered essential.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit for Ensuring Optical Fidelity

| Tool or Practice | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Lint-Free Gloves & Swabs | Prevents the introduction of fingerprints and fibers during handling and cleaning, which are common sources of organic contamination [6]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Effectively dissolves and removes organic contaminants without leaving residual films that can distort spectral measurements. |

| Pressurized Air/Nitrogen Canister | Allows for non-contact removal of abrasive dust and particles as a first cleaning step, minimizing the risk of scratching [6]. |

| Light Booth / Controlled Lighting | Provides a standardized, consistent lighting environment (e.g., D65 daylight) for visual inspection of windows and samples, ensuring what you see matches the spectrophotometer's illuminant setting [7]. |

| Calibrated Spectrophotometer | The primary instrument for objective measurement. It provides a spectral "fingerprint" that is unaffected by subjective human vision or ambient light, crucial for identifying subtle signal drift caused by contamination [3] [7]. |

| Synchronized Illuminant Settings | Ensures correlation between instrumental data and visual inspection by setting the spectrophotometer and light booth to the same illuminant (e.g., D65), preventing mismatches in color or intensity assessment [7]. |

| Saccharin | Saccharin, CAS:128-44-9; 81-07-2, MF:C7H5NO3S, MW:183.19 g/mol |

| Glysperin C | Glysperin C, MF:C44H77N7O19, MW:1008.1 g/mol |

The synergistic use of a light booth for controlled visual evaluation and a spectrophotometer for objective numerical data creates a robust system for quality control. As one industry expert noted, "A spectrophotometer never has a bad day," highlighting its objectivity, while the light booth allows researchers to predict how a sample will look under real-world conditions [7].

The optical window is a guardian of signal fidelity. Its proper selection based on stringent material properties, and its meticulous maintenance through validated cleaning protocols, are foundational to the integrity of spectroscopic data. In research domains where conclusions hinge on the precise interpretation of a spectral signature, such as drug development and material characterization, compromising on optical window integrity is not an option. A disciplined, proactive approach to managing this critical component is therefore a direct investment in the accuracy, reliability, and ultimate success of scientific research.

In spectroscopic analysis, the integrity of optical components, particularly spectrometer windows, is paramount for data accuracy. Contamination on these windows introduces three primary mechanisms of interference—scattering, absorption, and reduced light throughput—that systematically distort spectral measurements. These effects are not merely experimental nuisances; they represent significant sources of error that can compromise quantitative analysis, bias machine learning algorithms, and lead to erroneous scientific conclusions in fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to environmental monitoring [8]. This technical guide examines the physical principles underlying these interference mechanisms, provides experimental evidence of their effects, and outlines methodologies for their detection and mitigation, framed within the critical context of ensuring data fidelity in research environments.

Fundamental Interference Mechanisms

Physical Principles of Interference

Spectroscopic measurements rely on the precise detection of light-matter interactions. Contamination on spectrometer windows disrupts this process through distinct physical phenomena:

Scattering: Particulate or film contamination causes incident light to deviate from its original path through two primary mechanisms. Elastic scattering (e.g., Mie, Rayleigh) redirects light without altering its wavelength, effectively stealing photons from the primary beam and reducing signal intensity. Inelastic scattering processes produce light at different wavelengths than the incident beam, generating background interference that obscures genuine spectral features [8]. The magnitude of scattering depends on the size, morphology, and refractive index contrast of the contaminant particles relative to the window material.

Absorption: Contaminant layers containing chromophores (light-absorbing molecules) remove specific wavelengths from the transmitted beam according to the Beer-Lambert law. This creates wavelength-dependent attenuation that distorts the spectral shape, mimicking genuine absorption features of the sample under investigation [8]. The resulting spectral distortions are particularly problematic for quantitative analysis, as they introduce non-linear baseline effects and reduce the linear dynamic range of measurements.

Reduced Light Throughput: The combined effects of scattering and absorption diminish the total photon flux reaching the detector. This reduction in signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is especially detrimental for weak signals, such as those encountered in Raman spectroscopy or fluorescence measurements, where the signal of interest may be only marginally stronger than the instrumental noise floor [8] [9]. In severe cases, contamination can effectively obscure faint spectral features entirely, rendering measurements useless for analytical purposes.

Mathematical Formalization of Interference Effects

The collective impact of contaminated windows on spectral measurements can be mathematically described as:

Imeasured(λ) = Isample(λ) × Twindow(λ) + Sadd(λ) + N

Where:

- Imeasured(λ) is the detected spectral intensity

- Isample(λ) is the true sample spectrum

- Twindow(λ) is the wavelength-dependent transmission coefficient of the contaminated window (incorporating both absorption and scattering losses)

- Sadd(λ) is added spectral structure from contaminant fluorescence or Raman scattering

- N is additive noise amplified by reduced light throughput

This equation demonstrates how contamination systematically alters both the amplitude and shape of measured spectra, creating a complex distortion that cannot be easily corrected without understanding the specific properties of the contaminant layer [8].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Contamination on Spectroscopic Measurements

| Interference Mechanism | Effect on Spectral Data | Impact on Quantitative Analysis | Typical Magnitude of Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scattering | Increased baseline offset and slope | Reduced calibration model accuracy | Can exceed 50% baseline elevation |

| Absorption | Artificial absorption features | False positive in compound identification | 5-30% signal attenuation at specific wavelengths |

| Reduced Light Throughput | Decreased signal-to-noise ratio | Increased limit of detection | 10-100x reduction in SNR for weak signals |

| Fluorescence Background | Broad spectral background | Obscures Raman features | Can completely overwhelm target signal |

Case Study: Contamination in Rubidium Vapor Cells

Experimental Context and Observations

A compelling example of window contamination comes from a rubidium vapor cell used in laser-induced plasma generation experiments. Researchers observed that the optical window "had gradually lost transparency due to the development of an opaque layer of unknown composition at the inner side during the normal operation of the cell" [10]. The contamination presented as "a matte black region with a grey halo" in the central part of the window, directly in the path of the laser beam. This contamination significantly compromised experimental integrity by reducing transmitted light intensity and potentially modifying the laser wavefront.

Contaminant Analysis Protocol

To characterize the contamination, researchers employed Raman spectroscopy following this analytical protocol:

- Sample Positioning: The contaminated vapor cell was placed under a Raman microscope with the laser beam focused on the affected region of the window.

- Spectral Acquisition: Raman spectra were collected from both contaminated and clean reference areas of the same window.

- Spectral Comparison: The contaminant spectrum was compared against reference spectra of potential materials, including rubidium compounds and window material alterations.

- Material Identification: The unknown peaks in the Raman spectrum "strongly suggested that the unknown material was Rubidium silicate," formed through interaction between the rubidium vapor and the quartz window under intense laser irradiation [10].

This case demonstrates how chemical interactions between the sample environment and optical components can generate persistent contamination that directly interferes with optical measurements.

Laser Cleaning Methodology

The research team successfully addressed the contamination using a targeted laser cleaning approach with the following parameters:

Table 2: Laser Cleaning Parameters for Rubidium Vapor Cell Window

| Parameter | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Laser System | Q-switched Nd:YAG | Provides high peak power for contaminant removal |

| Wavelength | 1064 nm | Selected for differential absorption between contaminant and substrate |

| Pulse Width | 3.2 ns (FWHM) | Short enough to avoid thermal damage to quartz |

| Pulse Energy | 50-360 mJ | Adjustable based on contamination level |

| Focusing | 1 mm behind inner window surface | Minimizes thermal stress on quartz substrate |

| Fluence | 400 J/cm² to 3 kJ/cm² | Sufficient to remove contamination without damaging window |

| Operation Mode | Single pulse | Prevents cumulative thermal effects |

The cleaning process resulted in complete removal of "the black discoloration at the focal spot and locally restored the transparency of the window" with a single laser pulse, demonstrating the efficacy of this approach for specialized contamination scenarios [10].

Detection and Diagnostic Methodologies

Spectral Artifact Recognition

Recognizing contamination-induced artifacts in spectral data is the first step in diagnosing window-related issues. Key indicators include:

Non-physical Baseline Shapes: Sudden changes in baseline slope or irregular baseline features that cannot be explained by sample properties may indicate contamination. As noted in spectroscopic reviews, "extrinsic perturbations (e.g., environmental fluctuations inducing baseline drifts or tilts)" commonly undermine quantification accuracy [8].

Spectral Distortion Patterns: The presence of broad absorption features that don't correspond to known sample components, particularly in regions where the sample is expected to be transparent, suggests window contamination.

Irreproducible Signals: Measurements that vary unpredictably between experiments without changes to the sample may indicate contamination that is interacting differently with the light source under varying conditions.

Systematic Diagnostic Protocol

A structured approach to diagnosing window contamination includes:

Baseline Validation: Measure a known reference standard (e.g., empty sample holder, solvent blank, or certified reference material) and compare against historical data from the same standard. Significant deviations in baseline shape or intensity indicate potential window issues.

Spatial Mapping: For inhomogeneous contamination, translate the sample or window while measuring a uniform standard. Variations in signal intensity or shape across different positions reveal localized contamination.

Polarization Analysis: Some contamination effects are polarization-dependent. Measuring the same sample with different polarization states can help distinguish contamination artifacts from genuine sample signals.

Comparative Measurements: Using multiple instruments or carefully cleaned duplicate windows provides a reference for identifying contamination-induced distortions.

Mitigation Strategies and Preprocessing Techniques

Preventive Maintenance Protocols

Preventing window contamination requires systematic maintenance approaches:

Regular Cleaning Schedules: Establish periodic cleaning protocols using appropriate solvents and techniques compatible with the window material. For mass spectrometer sources (with analogous contamination issues), "there is no regular schedule for cleaning... The source should be cleaned when the mass spectrometer symptoms indicate that the source is contaminated," including "poor sensitivity, loss of sensitivity at high masses, or high multiplier gain" [11].

Controlled Environment Operation: Minimize exposure to atmospheric contaminants by using sealed enclosures or purge systems when possible. This is particularly important for hyperspectral imaging systems, where "data quality is primarily affected by local weather conditions" and atmospheric constituents [12].

Handling Procedures: Implement strict handling protocols using lint-free gloves and proper storage to prevent fingerprint oils and particulate deposition on optical surfaces.

Computational Correction Methods

When contamination cannot be immediately removed, computational approaches can partially mitigate its effects:

Baseline Correction Algorithms: Advanced preprocessing techniques can help remove contamination-induced baselines. Methods include:

- Morphological Operations (MOM): Uses erosion/dilation with structural elements to maintain spectral peaks/troughs while correcting baselines [8].

- Piecewise Polynomial Fitting (PPF): Implements segmented polynomial fitting with adaptive order optimization for complex baselines [8].

- B-Spline Fitting (BSF): Employs local polynomial control via knots and recursive basis functions to handle irregular baselines without overfitting [8].

Scattering Correction: For specific scattering types, algorithms can estimate and subtract scattering contributions. These methods typically require knowledge of the scattering characteristics or reference measurements from clean systems.

Multivariate Correction: Techniques such as multiplicative scatter correction (MSC) and extended multiplicative signal correction (EMSC) can address certain types of contamination effects, particularly when applied to data from multiple samples with varying contamination levels.

Table 3: Computational Methods for Correcting Contamination Effects

| Algorithm Category | Core Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Correction | Models and subtracts low-frequency spectral distortions | Handles various baseline shapes; no physical model required | May accidentally remove broad sample features |

| Scattering Correction | Separates absorption and scattering contributions | Physics-based; preserves chemical information | Requires specific scattering model or reference |

| Normalization | Scales spectra to reference point or area | Compensates for uniform transmission losses | Does not correct spectral shape distortions |

| Digital Filtering | Applies noise-reduction filters | Improves apparent signal-to-noise ratio | May introduce artifacts; does not address signal loss |

Experimental and Quality Control Framework

Validation Protocols for Data Integrity

Ensuring data accuracy despite potential window contamination requires systematic validation:

Reference Standard Measurements: Regularly measure certified reference materials with known spectral features. Document signal intensity and line shapes to track window performance over time. The NEON imaging spectrometer program, for example, conducts "vicarious calibration flights... over known, well-characterized calibration tarps" to validate instrument performance [12].

System Suitability Tests: Implement daily or pre-measurement checks using stable internal standards. Establish acceptance criteria for signal intensity, noise levels, and spectral resolution that must be met before sample analysis.

Control Charting: Maintain statistical process control charts for key parameters such as baseline offset, reference peak intensity, and signal-to-noise ratio. Trend analysis can provide early warning of developing contamination issues before they critically impact data quality.

Quality Assurance Indicators

Develop specific metrics for assessing window-related degradation:

Throughput Efficiency: Monitor the total light transmission through the system using a stable light source. A decline of more than 10-15% typically indicates significant contamination requiring intervention.

Spectral Resolution Assessment: Track the width of sharp spectral features from reference materials. Broadening may indicate scattering from contaminated windows.

Stray Light Performance: Measure the signal response in spectral regions where no light is expected. Increased signal in these regions suggests significant scattering contamination.

Contamination on spectrometer windows introduces complex interference through scattering, absorption, and reduced light throughput mechanisms that systematically compromise data accuracy. These effects are particularly problematic in quantitative analysis and machine learning applications, where spectral distortions can lead to erroneous conclusions. The rubidium vapor cell case study demonstrates that both chemical analysis of contaminants and targeted cleaning methodologies can effectively address these issues. A comprehensive approach combining preventive maintenance, computational correction, and rigorous quality control provides the foundation for reliable spectroscopic measurements in research and development environments. As spectroscopic techniques continue to advance in sensitivity and resolution, maintaining optical component integrity becomes increasingly critical for realizing their full analytical potential across pharmaceutical, environmental, and materials science applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Contamination Management

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lint-free Gloves | Prevent fingerprint contamination during handling | Essential for all optical component manipulation [11] |

| High-Purity Solvents | Remove organic and particulate contaminants | Selection based on window material compatibility |

| Certified Reference Materials | Validate system performance | Establish baseline for detection of contamination effects |

| Raman Spectrometer | Analyze chemical composition of contaminants | Identifies unknown deposits on window surfaces [10] |

| Q-switched Nd:YAG Laser | Laser cleaning of specialized contaminants | Effective for rubidium silicate deposits; parameters require optimization [10] |

| Motorized Buffing Tools | Polishing metal spectrometer components | Dremel Moto-Tool with felt buffing wheels for stainless steel parts [11] |

| Micro Mesh Abrasive Sheets | Fine polishing of optical components | Produces finer finishes on stainless steel parts [11] |

| Volume Phase Holographic Gratings | High-efficiency dispersion elements | Less susceptible to contamination effects due to sealed design [13] |

| Pcsk9-IN-31 | Pcsk9-IN-31, MF:C23H26N4O3, MW:406.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 1,3-Diolein-d66 | 1,3-Diolein-d66, MF:C39H72O5, MW:687.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Appendix: Diagnostic Diagrams

In analytical research, the integrity of data generated by instruments like mass spectrometers is paramount. The optical surfaces and critical components of these systems, particularly spectrometer windows and sources, are highly susceptible to contamination. The presence of common contaminants such as fingerprints, dust, solvent residues, and pump oil can significantly degrade instrument performance, leading to compromised data, reduced sensitivity, and erroneous results. This guide details the mechanisms of contamination, provides protocols for identification and remediation, and establishes best practices for maintaining component cleanliness, thereby safeguarding the accuracy and reliability of scientific research.

Contaminant Mechanisms and Impacts on Data Fidelity

Different contaminants interfere with instrument operation through distinct physical and chemical mechanisms. Understanding these pathways is the first step in diagnosing and mitigating their effects.

Fingerprints primarily consist of skin oils and salts. When deposited on optical surfaces, they cause increased light scattering and absorption, reducing optical throughput and creating localized hot spots that can permanently damage coatings under high-intensity light sources [14]. In mass spectrometer ion sources, these non-volatile residues contribute to increased background noise and can create false peaks or suppress the ionization of target analytes.

Dust and Particulates scatter incident light, which is particularly detrimental to optical systems like spectrophotometers and the sensitive detectors of mass spectrometers. This scattering leads to elevated baseline noise, reduced signal-to-noise ratios, and can obscure low-abundance signals [15] [14]. In high-vacuum environments, particulates can also act as sites for outgassing, slowly releasing volatile compounds that further contaminate the system.

Solvent Residues often arise from improper cleaning or the use of low-purity solvents. They can leave behind thin films on surfaces, which may absorb light or interact with sample analytes. In liquid chromatography systems coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS), solvent residues are a common cause of ghost peaks in chromatograms, complicating data interpretation and quantitation [16].

Pump Oil can backstream into vacuum systems from roughing pumps or leak from hydraulic lines. It presents a severe contamination problem as it is typically composed of high molecular weight hydrocarbons and additives. In a mass spectrometer, pump oil vapor can be ionized in the source, producing a characteristic background spectrum that interferes with analyte detection and reduces sensitivity, particularly at lower masses [6].

The logical flow of how these contaminants lead to data inaccuracy is summarized in the following diagram:

Figure 1: Contamination Impact Pathway. This diagram illustrates the causal pathways through which common contaminants lead to data inaccuracy in spectroscopic systems.

Quantitative Impact of Contaminants

The following table summarizes the specific effects of each contaminant and the resulting symptoms observed in instrumental data.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Common Contaminants on Spectrometer Performance

| Contaminant | Primary Mechanism of Interference | Observed Impact on Data | Typical Symptom Severity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fingerprints | Light scattering & absorption on optics [14] | Up to 10% transmission loss; increased baseline offset | High |

| Dust & Particulates | Mie scattering of incident light; outgassing [15] [14] | Elevated baseline noise; reduced signal-to-noise ratio by >50% | Moderate to High |

| Solvent Residues | Formation of thin films; chemical interaction with analytes [16] | Ghost peaks in chromatograms; retention time shift | Moderate |

| Pump Oil | Ionization in source; hydrocarbon background spectrum [6] | High background in low mass range; signal suppression; sensitivity loss >80% | Critical |

Detection and Monitoring of Contamination

Early detection of contamination is crucial for preventative maintenance. A systematic inspection protocol should be established.

Visual Inspection: Optics should be inspected in a bright light source, held to reflect light off the surface. For transmissive optics, hold the component perpendicular to the line of sight and look through it. Use of a magnifier or microscope is often necessary to identify small particles or thin films [14].

Performance Monitoring: Instrument performance metrics are the most sensitive indicators of contamination. Key signs include:

- A consistent loss of sensitivity or requirement for higher multiplier gain during auto-tuning of a mass spectrometer [6].

- A rising baseline in optical spectra or chromatograms [16].

- The appearance of ghost peaks in HPLC or LC-MS analyses, indicating the gradual elution of accumulated contaminants [16].

- In ion mobility spectrometry (IMS), contamination can alter drift times and reduce sensitivity, requiring method-specific vigilance [17].

Advanced Monitoring Techniques: For critical applications, non-contact spectrophotometric techniques, including hyperspectral imaging, are emerging as powerful tools for monitoring surface contamination without risking damage through physical contact [18].

Experimental Protocols for Cleaning and Verification

General Cleaning Workflow for Optical Components

The following workflow is adapted from standard optical cleaning procedures [14]. Always handle optics with gloves or tweezers, holding only by the edges.

Inspection: Before cleaning, inspect the optic to determine the type and extent of contamination. Never skip this step.

Dry Gas Blowing: Use a blower bulb or canister of inert dusting gas (held upright 6-8 inches away) to remove loose dust. Do not use breath from your mouth, as it will deposit saliva [14].

Solvent Cleaning (If needed):

- For fingerprints and oils: Use a solvent rinse or the "Drop and Drag" method for flat surfaces. Place a drop of high-purity acetone or methanol on a clean lens tissue and drag it slowly across the surface in a single, continuous motion [14].

- For mounted or curved optics: Use the "Lens Tissue with Forceps" method. Fold a clean lens tissue, clamp it with forceps, moisten with solvent, and wipe the surface in a smooth motion while continuously rotating the tissue to present a clean surface [14].

- Washing: For heavily soiled, robust optics, washing with a mild solution of distilled water and optical soap may be approved by the manufacturer. Always follow with rinsing in clean distilled water and a quick-drying solvent dip to prevent water spots [14].

Final Inspection: Re-inspect the optic to ensure contaminants are removed and no new streaks or damage have been introduced.

Detailed Protocol: Cleaning a Mass Spectrometer Source

This protocol is a synthesis of established procedures for cleaning mass spectrometer ion sources, which are highly susceptible to pump oil and sample residues [6].

I. Disassembly

- Safety First: Shut down the mass spectrometer, turn off all power and vacuum pumps. Allow the source to cool completely before removal.

- Vent the System: Carefully vent the vacuum chamber to atmospheric pressure.

- Remove the Source: Following the manufacturer's manual, disconnect electrical leads and plumbing. Take digital photographs before and during disassembly to aid reassembly. Handle all parts with lint-free gloves.

- Disassemble Source: Place the source on a clean, lint-free cloth. Methodically disassemble, placing metal parts for abrasive cleaning in one beaker and delicate parts (ceramics, polymers, gold-plated components) in another.

II. Cleaning of Metal Parts

- Polishing: For stainless steel parts, use a motorized tool (e.g., Dremel) with a felt buffing wheel and a fine abrasive rouge to polish surfaces to a mirror finish. This removes residues and minimizes future contamination adherence.

- Abrasive Cloths/Powders: Alternatively, hand-polish with fine-grit abrasive sheets (e.g., Micro Mesh).

- Sandblasting: For stubborn deposits, a gentle sandblast with fine glass beads can be used, though this is often not necessary.

- Solvent Washing: After abrasive cleaning, wash all metal parts in an appropriate, high-purity solvent (e.g., methanol, isopropanol, acetone) to remove polishing residues.

III. Cleaning of Non-Metal Parts

- Ceramic Insulators: Clean with solvent; avoid abrasive methods which can damage conductive coatings.

- Vespel/Polymer Insulators & O-Rings: Clean only with solvent; do not bake at high temperatures.

- Gold-Plated Parts: Clean only with solvent; abrasive cleaning will remove the plating.

IV. Reassembly, Testing, and Baking

- Reassemble: Refer to pre-disassembly photos and manufacturer manuals. Reinstall all components and electrical connections correctly.

- Reinstall Source: Carefully reinstall the source into the vacuum housing.

- Pump Down and Bake-Out: Pump the system back to high vacuum. Perform a gentle bake-out if the instrument is equipped for it, to drive off any residual solvent or water vapor.

- Performance Test: Once operational, run standard tuning and calibration samples to verify that sensitivity and performance have been restored.

Cleaning Verification Protocol

Verifying the effectiveness of cleaning is as critical as the cleaning itself. Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS) offers a rapid, highly sensitive alternative to HPLC for cleaning verification [17].

Method Development:

- Selectivity: Determine the optimal ionization mode (positive/negative) for the target contaminant.

- Parameter Optimization: Optimize desorber temperature, injection volume, and drift flow velocity to maximize signal without causing thermal degradation.

- Calibration: Establish a second-order polynomial calibration curve relating IMS response to the amount of contaminant.

- Action Level: Determine a pass/fail "action level" by adjusting the target level for instrument variability.

Validation:

- Recovery Test: Spike a known amount of contaminant onto a representative surface (e.g., a 10 in.² stainless-steel coupon). Swab the surface using a standardized technique (e.g., horizontal strokes with one side of the swab, vertical with the other), extract the swab, and analyze. Calculate the recovery percentage [17].

- Solution Stability: Confirm the stability of standard and sample solutions over a typical holding time (e.g., 24 hours).

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Cleaning and Verification

| Item Name | Function / Application | Technical Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lens Tissue | Wiping optical surfaces without scratching | Low-lint, high-strength paper; used with solvents [14] |

| Webril Wipes | Soft, pure-cotton wipers for optics | Hold solvent well; less abrasive than other wipes [14] |

| Acetone, Methanol, Isopropanol | High-purity solvents for dissolving oils & residues | HPLC or optical grade; quick-drying; avoid impurities [14] |

| Alconox / Liquinox | Detergent for removing stubborn contaminants | 1-2% solution for HPLC system flushing & glassware [16] |

| Polyester Swab (Texwipe Alpha) | Standardized surface sampling for verification | Low-lint; used for recovery studies in validation [17] |

| Abrasive Rouge/Polishing Compound | Polishing metal source parts to a mirror finish | Used with felt buffing wheels on motorized tools [6] |

| Micro Mesh Abrasive Sheets | Hand-polishing of intricate metal components | Finer grit than standard sandpaper for a smooth finish [6] |

Contamination Control and Preventive Maintenance

A proactive approach to contamination control is more effective and cost-efficient than reactive cleaning.

Handling and Storage: Always wear appropriate gloves and use vacuum tweezers for small components. Store optics in a clean, dry environment, wrapped in lens tissue and placed in a dedicated storage box [14].

System Flushing and Maintenance: For HPLC and LC-MS systems, implement a regular flushing protocol. After running buffers, flush with water to remove salts, followed by a strong solvent (e.g., acetonitrile or methanol) to remove organic residues. Avoid storing systems in pure water to prevent microbial growth and "dewetting" of reversed-phase columns [19] [16].

Environmental Control: Maintain a clean laboratory environment. Use covers on instruments when not in use to minimize dust accumulation. Ensure proper maintenance of vacuum pumps to prevent oil backstreaming.

The fidelity of spectroscopic and chromatographic data is intrinsically linked to the cleanliness of the instrument's critical components. Contaminants like fingerprints, dust, solvent residues, and pump oil directly induce artifacts including increased noise, signal suppression, and ghost peaks, thereby compromising research conclusions. By implementing the rigorous cleaning protocols, verification methods, and preventative maintenance strategies outlined in this guide, researchers and drug development professionals can proactively mitigate these risks. A disciplined approach to contamination control is not merely a maintenance task, but a fundamental scientific practice essential for ensuring data accuracy, instrument longevity, and the overall integrity of the research process.

The presence of visible residue on instrument components represents a significant yet often underestimated challenge in mass spectrometry (MS), directly impacting the accuracy and reliability of data critical to fields like pharmaceutical development and food safety analysis [20] [21]. This contamination, which can arise from sample carryover, vacuum pump oils, or outgassed compounds from internal components, frequently accumulates on key surfaces such as ion source apertures, lenses, and, critically, the viewing windows of the vacuum chamber [22]. While a dirty viewport may seem like a mere cosmetic issue, it is often a visible indicator of a broader contamination problem that can severely degrade instrumental performance. This case study examines the direct correlation between such observable residue and specific performance degradation in mass spectrometers, framing the issue within the essential context of maintaining data integrity for research and quality control.

Mechanisms of Performance Degradation

Contamination-induced performance loss in mass spectrometers occurs through several interconnected physical mechanisms, primarily affecting the ion path and the detection system.

Ion Optical Fouling and Signal Suppression

The most direct impact occurs when residues accumulate on ion optics—including sampling cones, skimmers, and ion guides—leading to gradual signal suppression. These conductive deposits create unstable electrical fields on the surfaces responsible for focusing and transmitting the ion beam [23]. This instability manifests as a loss of ion transmission efficiency, requiring increased voltage on the affected lenses to maintain signal, which in turn accelerates the accumulation of further contamination. In liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), a prevalent technique in pharmaceutical analysis, co-eluting matrix components can cause ion suppression or enhancement, a phenomenon where the ionization efficiency of the analyte is altered by other compounds entering the ion source simultaneously [23] [24]. This effect compromises quantitative accuracy, as the measured signal no longer directly correlates to the analyte concentration.

Vacuum System Compromise and Increased Chemical Noise

Mass spectrometers require a high vacuum to operate correctly; contamination can compromise this in two ways. First, volatile or semi-volatile compounds condensed on surfaces in the vacuum chamber can act as a continuous source of outgassing, elevating the system pressure and increasing the frequency of collisions between ions and neutral molecules. These collisions scatter the ion beam, reducing sensitivity and mass resolution [22]. Second, these outgassed compounds can be ionized themselves, generating a persistent, high chemical background noise across a wide mass range. This elevated baseline reduces the signal-to-noise ratio for low-abundance analytes, impairing the detection limits essential for trace analysis in applications like drug metabolite profiling or contaminant screening [20] [25].

Quantitative Analysis of Contamination Impact

The correlation between residue accumulation and instrument performance can be quantified through specific analytical benchmarks. The following table summarizes key performance metrics and their degradation patterns observed in contaminated systems.

Table 1: Performance Metrics Affected by System Contamination

| Performance Metric | Impact of Contamination | Typical Observation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Signal Intensity | Progressive signal suppression over time; may require increasing source voltages to compensate [23]. | Trend analysis of system suitability check standards. |

| Signal-to-Noise (S/N) Ratio | Significant decrease due to increased chemical noise from outgassed contaminants [22]. | Comparison of peak height to baseline noise in MRM or full-scan chromatograms. |

| Mass Accuracy | Drift in high-resolution mass measurements due to unstable ion flight paths from charged deposits [23]. | Analysis of standard reference compounds with known exact mass. |

| Chromatographic Peak Shape | Peak tailing or broadening in LC-MS due to secondary interactions at a contaminated source [24]. | Evaluation of peak width and symmetry in analytical runs. |

The sensitivity of modern MS systems exacerbates these issues. Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) coupled with MS uses sub-2-μm particles, producing very narrow chromatographic peaks (1-3 seconds wide) [24]. Any contamination-induced instability or noise can severely impact the ability to integrate these sharp peaks accurately, directly compromising the high-throughput advantages of the technology.

Experimental Protocols for Assessment and Correlation

To systematically establish the correlation between visible residue and performance degradation, a structured experimental approach is required.

Protocol for Controlled Contamination Study

This protocol outlines a method for simulating and evaluating the effects of a common contaminant on MS performance.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a concentrated stock solution (e.g., 1 mg/mL) of a non-volatile, high-surface-tension compound like polyethylene glycol (PEG) 600 or a common phospholipid from biological matrices [20] [26].

- Contamination Simulation: Introduce a precise, small volume (e.g., 1-5 μL) of the stock solution into the ion source region via a direct infusion pump or by applying it to a dummy probe inserted into the sample stream. For viewport studies, a calibrated amount of residue can be applied to a viewport sample to simulate haze.

- Performance Monitoring: Throughout and after contamination, continuously infuse a standard solution containing a panel of analytes with known ionization efficiencies and masses (e.g., caffeine, reserpine, Ultramark). Monitor in real-time:

- Signal intensity for each analyte.

- Background noise levels in blank injections.

- Mass accuracy and resolution in full-scan mode.

- Vacuum gauge readings and ion source voltages.

- Data Correlation: Plot the degradation of each performance metric (e.g., S/N ratio) against the estimated amount of contaminant introduced or against the measured decrease in viewport transmission.

Protocol for System Suitability and Cleaning Validation

This method leverages LC-MS/MS techniques, commonly used for detecting drug residues on manufacturing equipment [21], to validate instrument cleanliness.

- Swabbing and Extraction: Use a solvent-moistened polyester swab to wipe critical surfaces in the ion source region and the interior of the viewport. Extract the residues from the swab tip with a suitable solvent (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile) [21].

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Analyze the extract using a validated LC-MS/MS method. A triple quadrupole mass spectrometer operating in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode is ideal for its high sensitivity and selectivity [21] [24].

- Quantification: Use a standard curve of a known compound (e.g., a previous API analyzed on the system) to quantify the level of residue recovered from the swab.

- Correlation Analysis: Correlate the quantified residue levels with the performance data collected from system suitability tests performed before cleaning. This provides a direct, quantitative link between the mass of residue present and the observed performance metrics.

Diagram 1: Contamination impact pathway on MS data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Maintaining spectrometer performance requires specific tools for monitoring, cleaning, and validation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Contamination Control

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Polyester Swabs | Non-abrasive physical collection of residues from instrument surfaces [21]. | Swabbing ion source components, extraction plates, and viewports for cleaning validation. |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents for extracting residues from swabs and for flushing/fl cleaning ion pathways without introducing new contaminants. | Methanol, acetonitrile, and water are used for final rinses in source cleaning protocols. |

| System Suitability Standard Mix | A solution of known compounds to benchmark instrument performance, including sensitivity, chromatographic integrity, and mass accuracy. | Used daily or before critical analyses to track performance degradation and trigger maintenance. |

| Isotopically Labelled Internal Standards | Compounds used to correct for variable ion suppression/enhancement effects in quantitative LC-MS/MS [23]. | Added to every sample and calibration standard to normalize the analytical signal and improve data accuracy. |

| sEH inhibitor-17 | sEH inhibitor-17, MF:C18H21F3N2O4S, MW:418.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Antitumor agent-80 | Antitumor agent-80, MF:C24H20ClNO2, MW:389.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Mitigation and Preventive Strategies

A proactive approach is crucial to minimize the impact of residue accumulation. Implementing a rigorous and scheduled preventive maintenance protocol for the ion source and vacuum system is the most effective strategy [21] [25]. This includes regular cleaning or replacement of consumable parts like sampling cones and ion transfer tubes. Furthermore, employing high-quality sample preparation techniques, such as Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE), can significantly reduce the introduction of non-volatile matrix components into the MS system [23]. For the viewport specifically, establishing a cleaning schedule using appropriate solvents and lint-free wipes is essential. Monitoring the baseline transmission of the viewport or simply documenting its visual clarity can serve as an early warning indicator of the internal state of the vacuum chamber [22].

Diagram 2: Contamination response workflow.

Visible residue on a mass spectrometer is far more than a cleanliness oversight; it is a clear visual proxy for internal contamination that directly and measurably degrades instrument performance. This degradation manifests as suppressed signal, elevated noise, and compromised quantitative accuracy, ultimately undermining the integrity of research and analytical data. By understanding the underlying mechanisms, implementing quantitative assessment protocols, and adhering to a disciplined preventive maintenance regimen, scientists and drug development professionals can safeguard their instruments. This proactive approach ensures the generation of reliable, high-quality data that is crucial for scientific discovery and product quality assurance.

Within the sensitive ecosystem of a spectrometer, optical windows serve as critical interfaces between the internal components and the external environment. Contamination on these windows is not merely a superficial issue; it is a primary catalyst for a chain of detrimental effects, culminating in analytical drift and outright failure. This whitepaper delineates the causal pathway linking dirty windows to data inaccuracy, supported by quantitative data on material properties and detailed protocols for experimental validation. Framed within broader research on data integrity in drug development, this guide provides researchers and scientists with the knowledge to diagnose, prevent, and correct errors stemming from this overlooked variable.

The Critical Role of Optical Windows in Spectrometry

Optical windows in spectrometers are designed to protect sensitive internal components, such as the optic chamber and detectors, from environmental contaminants while allowing light to pass through with minimal distortion. Their primary function is to separate the internal vacuum or controlled atmosphere from the external environment without compromising the optical path [27] [28].

Two windows are particularly vital for analytical integrity:

- The Fiber Optic Window: Located in front of the fiber optic cable, this window transmits light from the excitation source to the sample.

- The Direct Light Pipe Window: This window allows light from the sample to enter the detection system.

When these windows are contaminated, the instrument's analytical performance degrades directly. A dirty window acts as an unplanned optical filter, scattering and absorbing photons, which leads to instrument drift and a heightened need for frequent recalibration [27]. In the worst cases, it can cause a complete failure to obtain a viable reading, jeopardizing research integrity and development timelines.

Quantifying the Impact: From Signal Degradation to Analytical Failure

The consequences of window contamination are measurable and severe. The table below summarizes the primary failure modes and their direct impact on analytical results.

Table 1: Effects of Dirty Spectrometer Windows on Analytical Data

| Failure Mode | Impact on Signal | Result on Analytical Output |

|---|---|---|

| Light Scattering | Reduced light intensity; increased noise. | Inaccurate element concentrations; high detection limits. |

| Unwanted Absorption | Selective attenuation of specific wavelengths. | Incorrect values for elements in lower wavelengths (e.g., C, P, S) [27]. |

| Increased Background Noise | Elevated baseline signal. | Poor signal-to-noise ratio; reduced measurement precision. |

| Calibration Instability | Inconsistent response from the instrument over time. | Frequent recalibration required; poor reproducibility [27]. |

The degradation is especially critical for elements analyzed at lower wavelengths, such as carbon (C), phosphorus (P), and sulfur (S). These wavelengths, particularly in the ultraviolet spectrum, cannot effectively pass through a normal atmosphere, let than a contaminated window, leading to a loss of intensity or complete disappearance of the spectral line [27].

Material Science: Selecting Optical Windows for Research

The selection of window material is a critical design choice that dictates performance, durability, and susceptibility to contamination. Different materials offer unique transmission properties and physical characteristics suitable for specific spectral ranges and operational environments.

Table 2: Characteristics of Common Optical Window Materials

| Material | Primary Spectral Range | Key Characteristics | Knoop Hardness (Typical) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-BK7 | UV to Shortwave IR | High homogeneity, low dispersion, sensitive to acids [29]. | ~600 [29] |

| Fused Silica | UV to IR | Wide transmission, high thermal stability, resistant to many chemicals [29]. | ~500 [29] |

| Sapphire | Visible to NIR | Extremely hard, high thermal & chemical resistance, scratch-resistant [29]. | ~2,000 [29] |

| Calcium Fluoride (CaFâ‚‚) | UV to LWIR | Low dispersion, sensitive to thermal shock and scratches [29]. | ~200 [29] |

| Zinc Selenide (ZnSe) | Mid-IR to LWIR | High performance for IR lasers, soft and easily damaged, sensitive to moisture [29]. | ~150 [29] |

Harder materials like sapphire offer superior resistance to scratches and wear, reducing one potential source of contamination and signal scatter. The refractive index of these materials further determines how light is bent as it passes through, a factor that must be accounted for in the instrument's optical design [29].

Experimental Protocols for Validating Window-Induced Error

To systematically study the impact of window contamination, researchers can employ the following experimental protocols. These methodologies allow for the quantification of signal drift and the establishment of cleaning schedules based on empirical data.

Protocol for Monitoring Calibration Drift

Objective: To quantify the rate of calibration drift induced by controlled window contamination. Materials: Spectrometer, certified calibration standards, contamination simulants (e.g., fine particulate matter, fingerprint oils, vacuum pump oil).

- Baseline Establishment: Ensure windows are perfectly clean. Analyze a calibration standard 10 times consecutively to establish a baseline mean and standard deviation for key elements [27].

- Controlled Contamination: Apply a quantified amount of contaminant (e.g., a microliter of specified oil) to the external surface of the critical window.

- Drift Monitoring: Analyze the same calibration standard at defined time intervals (e.g., every 10 analyses). Record the measured values for carbon, phosphorus, and sulfur.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the relative standard deviation (RSD) and trend the values over time. An RSD exceeding 5% is a strong indicator of instability potentially linked to window contamination [27].

Protocol for Evaluating Cleaning Efficacy

Objective: To compare the effectiveness of different cleaning methods for restoring optical performance. Materials: Contaminated windows, various cleaning solvents (isopropanol, acetone), lint-free wipes, laser cleaning system (if available) [30] [31].

- Pre-Cleaning Measurement: Measure the transmittance of the contaminated window across the relevant spectral range using a spectrophotometer.

- Cleaning Procedure: Apply the cleaning method according to a strict, standardized procedure (e.g., wipe in a single direction with a solvent-soaked cloth).

- Post-Cleaning Measurement: Re-measure the transmittance of the window under identical conditions.

- Efficiency Calculation: Calculate the cleaning efficiency as the percentage of transmittance restored. Laser cleaning, for instance, has been shown to achieve cleanliness levels of over 99.9% on glass substrates [30].

The causal pathway from a contaminated window to analytical failure can be visualized as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A proactive maintenance regimen is essential for data integrity. The following table outlines key materials for the upkeep and validation of spectrometer windows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Window Maintenance

| Item | Function / Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Lint-Free Wipes | Low-particulate cloths for applying solvents and mechanically removing contaminants. | Prevents scratching and avoids adding new contaminants during cleaning [27]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Reagent-grade isopropanol or acetone for dissolving organic residues. | Must be residue-free; apply sparingly to avoid seepage into window seals. |

| Certified Calibration Standards | Stable reference materials with known concentrations of key elements. | Used for periodic verification of instrument performance and detecting drift [27]. |

| Laser Cleaning System | Non-contact cleaning using laser energy to ablate contaminants without damaging the substrate [30] [31]. | Ideal for delicate or hard-to-clean windows; parameters must be optimized to avoid substrate damage. |

| Contamination Seals | Custom seals for probe heads. | Prevents argon leakage and protects the window when analyzing convex or irregular surfaces [27]. |

| Z-Atad-fmk | Z-Atad-fmk, MF:C23H31FN4O9, MW:526.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pelirine | Pelirine, MF:C21H26N2O3, MW:354.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrating Prevention into a Broader Data Integrity Framework

The issue of window contamination is a microcosm of the larger challenge of ensuring data accuracy in research. Spectral data are inherently prone to interference from instrumental artifacts and environmental noise, which can bias feature extraction and machine learning-based analysis [32]. Therefore, preventative maintenance of hardware, like optical windows, must be integrated with robust data preprocessing routines.

Advanced techniques like context-aware adaptive processing and physics-constrained data fusion are transforming the field, enabling unprecedented detection sensitivity while maintaining high classification accuracy [32]. A holistic approach that combines impeccable instrument care with sophisticated data validation is the ultimate defense against analytical drift and failure, ensuring the reliability of results in critical drug development applications.

A Researcher's Guide to Effective Spectrometer Cleaning and Preventive Maintenance

Standard Operating Procedures for Safe Window and Component Cleaning

Contamination on optical components, particularly spectrometer windows, represents a critical and often underestimated variable in analytical research. The presence of residues, including active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), dust, and molecular films, can significantly compromise data accuracy by altering transmission characteristics, causing light scattering, and introducing erroneous absorption bands. This whitepaper establishes a standardized, validated framework for cleaning optical windows and components, with a specific focus on applications within pharmaceutical development and research. The procedures outlined are designed to ensure measurement integrity, instrument longevity, and regulatory compliance, directly supporting the reliability of spectroscopic data in drug development.

In the realm of spectroscopic analysis, the integrity of optical components is non-negotiable. The optical window of a spectrometer serves as a fundamental gateway for light, and its cleanliness is paramount for ensuring the accuracy of the resulting data. Contaminants on these surfaces, which can range from particulate matter to thin films of organic residues, directly interfere with the light path. This interference manifests in several detrimental ways:

- Altered Transmission and Absorption: Residual layers can absorb specific wavelengths, creating spurious peaks or depressing legitimate signals in UV-VIS-NIR spectra, which are critical for identifying electronic transitions in molecules [33].

- Increased Scatter and Stray Light: Particulate contamination scatters light, elevating baseline noise and reducing the signal-to-noise ratio, thereby obscuring weak spectral features [15].

- Irreproducible Results: Inconsistent contamination levels lead to variable performance, making it impossible to replicate experimental conditions or compare data over time.

The consequences are particularly acute in pharmaceutical quality control and research, where the accurate characterization of materials, such as tracking the oxidation states of catalysts or quantifying API concentrations, depends on precise spectrophotometric measurements [33] [34]. Furthermore, the trend towards in-situ spectroscopy places additional demands on the cleanliness of reactor cells and probe windows, as any fouling directly convolutes the data intended to monitor reaction mechanisms and kinetics [33]. This guide provides a systematic approach to mitigating these risks through robust cleaning and validation protocols.

Understanding Contaminants and Their Analytical Impact

A targeted cleaning strategy requires an understanding of potential contaminants. In a research and development setting, these can be broadly categorized.

Table 1: Common Contaminants in Laboratory Settings and Their Effects

| Contaminant Type | Example Sources | Primary Impact on Spectroscopic Data |

|---|---|---|

| Particulate Matter | Dust, lint, dried salts, micro-crystals of APIs [34] | Increased light scattering, elevated baseline noise/offset, reduced overall transmission [15]. |

| Molecular Films (Organic) | Oil vapors, silicone outgassing, residual solvents, plasticizers | Unwanted UV-Vis absorption bands, altered transmission profiles, especially in the UV range [33] [15]. |

| Metallic Stains/Droplets | Rubidium from vapor cells, other metal vapors [35] | Strong, broad-band absorption, complete blockage of light transmission. |

| Water Spots | Improper drying, use of non-deionized water | Mineral deposits cause light scattering; water films can produce IR absorption artifacts. |

The case of a contaminated rubidium vapor cell illustrates the severity of this issue. The inner optical window developed an opaque black layer of rubidium silicate, which severely compromised the cell's transparency and functionality for plasma generation experiments. This underscores how chemical interactions between the environment and the window material itself can form tenacious, optically destructive contaminants [35].

Standard Operating Procedures for Cleaning

General Principles and Safety

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Always wear appropriate PPE, including nitrile gloves and safety glasses, to protect both the analyst and the component from skin oils and accidental exposure to solvents.

- Environment: Perform cleaning in a clean, low-traffic area, ideally under a laminar flow hood to prevent recontamination by airborne particles.

- Material Compatibility: Confirm the chemical compatibility of all cleaning agents (solvents, detergents) with the optical substrate (e.g., quartz, fused silica, borosilicate glass) and any coatings.

- "Gentlest First" Approach: Always begin with the least aggressive method (e.g., dry gas, then aqueous solutions, then mild solvents) and proceed to more aggressive techniques only if necessary.

Manual Cleaning Protocol for Optical Windows

This protocol is adapted from established pharmaceutical cleaning validation principles for direct application to laboratory optics [36] [34].

Step 1: Dry Particle Removal

- Use a dedicated, clean, dry, oil-free air or inert gas (e.g., nitrogen) duster to blow off loose particulate matter. Hold the canister upright and use short, directed bursts.

- Alternatively, use a soft-bristled brush made of natural hair or specialized optics-cleaning microfiber.

Step 2: Solenoid Syringe Rinse

- Flush the surface with a stream of high-purity solvent. Reagent-grade acetonitrile or acetone are often effective for dissolving organic residues [34].

- Do not let the solvent bottle nozzle touch the surface. Use a solenoid syringe for controlled dispensing.

Step 3: Swab Cleaning (For Tenacious Residues)

- Moisten a polyester or microfiber swab with the selected solvent.

- Wipe the surface using a linear, overlapping stroke pattern. Turn the swab to use a clean area with each pass.

- Use minimal pressure to avoid generating static electricity or micro-scratches.

Step 4: Final Rinse and Drying

- Perform a final solvent rinse to remove any dislodged particles or residual film.

- Allow the surface to air-dry in a clean environment or use a gentle stream of dry, oil-free gas to accelerate drying.

Advanced Cleaning: Laser Ablation

For highly robust substrates with contaminants that cannot be removed chemically (e.g., the rubidium silicate layer), laser cleaning presents a non-contact, precise alternative [31] [35].

Experimental Protocol (Adapted from Laser Cleaning of a Rubidium Vapor Cell [35])

- Laser System: Q-switched Nd:YAG laser.

- Wavelength: 1064 nm (Infrared).

- Pulse Parameters: 3.2 ns pulse width, single-pulse mode to minimize thermal stress.

- Beam Delivery: The laser beam is passed through the uncontaminated side of the window and focused approximately 1 mm in front of the contaminated inner surface. This defocusing strategy is critical to avoid damaging the glass substrate itself.

- Mechanism: The high-intensity pulse creates a micro-plasma on the contaminant layer, generating a shockwave that ablates the material without transferring significant heat to the underlying quartz window. A single pulse is often sufficient to restore transparency at the focal spot.

Warning: Laser cleaning is a highly specialized technique. Parameters must be meticulously calibrated for the specific contaminant-substrate system to avoid permanent damage, such as micro-cracks or melting [31].

Verification of Cleanliness

Verifying cleanliness is as critical as the cleaning process itself. This aligns with the pharmaceutical industry's principle of cleaning verification [36].

- Visual Inspection: Examine the surface against a dark background using a bright, diffuse light source. Look for visible streaks, spots, or film.

- Solvent Rinse Test (Indirect Method): Rinse the cleaned surface with a known volume of high-purity solvent (e.g., 10 mL) and collect the rinseate. Analyze the rinseate using a sensitive technique like HPLC or Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS) to detect and quantify any residual API or contaminant [17] [34].

- Swab Test (Direct Method): Swab a defined area (e.g., 100 cm²) of the cleaned surface with a solvent-wetted polyester swab. Extract the residue from the swab and analyze the extract. This method is suitable for flat, accessible surfaces [34].

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Cleaning and Validation

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Protocol | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | Solvent for rinsing and swab extraction. | Effective for a wide range of organic residues and many APIs [34]. Use high-purity grade. |

| Acetone | Solvent for rinsing and swab extraction. | Slightly higher volatility and solubility for some compounds compared to acetonitrile [34]. |

| Polyester Swab | Direct mechanical removal of residues from surfaces. | Low-lint, chemically resistant. Preferred for reproducible sampling [34]. |

| Phosphate-Free Alkaline Detergent | Aqueous cleaning agent for manual or automated washing. | Breaks down organic residues; phosphate-free to avoid environmental and interference issues [34]. |

| High-Purity Water | Final rinse to remove ionic residues and detergents. | Must be at least Type II (deionized) grade to prevent water spots. |

Workflow and Contamination Control Strategy

A systematic approach from assessment to verification ensures consistent results and data integrity. The following workflow diagrams the core process and the logic for selecting the appropriate cleaning intensity.

The reliability of spectroscopic data in pharmaceutical research is fundamentally linked to the pristine condition of optical components. Dirty or contaminated spectrometer windows are not a minor nuisance but a significant source of analytical error that can invalidate experimental results and compromise scientific conclusions. The implementation of the Standard Operating Procedures outlined in this document—encompassing risk assessment, graded cleaning methodologies, and rigorous validation—provides a scientifically-grounded framework to control this critical variable. By adopting these practices, researchers and drug development professionals can safeguard data accuracy, ensure regulatory compliance, and uphold the integrity of their research outcomes.

The integrity of spectroscopic data is fundamentally dependent on the cleanliness of optical components. Contamination from particulates, fingerprints, or chemical residues on spectrometer windows and cuvettes can introduce significant errors, compromising research accuracy and reproducibility, particularly in sensitive fields like drug development. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide for researchers on establishing a rigorous cleaning protocol. We detail the selection and use of approved materials—lint-free cloths, canned air, and high-purity solvents—based on manufacturer guidelines and recent scientific findings. Supported by quantitative data and detailed methodologies, this guide aims to standardize cleaning procedures to ensure the highest data fidelity.

The Critical Impact of a Dirty Optic on Data Accuracy

In spectroscopic analysis, any contamination on the light path—be it the spectrometer's internal calibration disk, the external measurement window, or a quartz cuvette—acts as an uncontrolled variable. The consequences for data quality are severe and multifaceted:

- Signal Attenuation: Dust, lint, and dried residues scatter and absorb light, leading to a false reduction in measured absorbance or transmission. This is particularly critical at shorter wavelengths, such as those used for DNA quantification at 260 nm.

- Increased Noise and Baseline Drift: Particulates and smudges can cause light scattering, elevating the baseline noise and distorting the spectral background. This reduces the signal-to-noise ratio and can obscure weak peaks from low-concentration analytes.

- Introduction of Chemical Artifacts: Residues from improper cleaning solvents or contaminants can leach into samples or themselves absorb light, leading to false peaks or shifted baselines in sensitive assays like fluorescence spectroscopy, where low background signals are paramount.

The use of substandard or incorrect cleaning tools exacerbates these problems. A common lint-laden cloth can deposit more contamination than it removes, while solvents exposed to certain plastics can leave a persistent, data-altering film [37].

Essential Cleaning Tools and Their Specifications

A controlled cleaning regimen requires the correct materials to effectively remove contamination without damaging sensitive optical surfaces. The following tools form the cornerstone of an effective cleaning protocol.

Lint-Free Cloths

The primary tool for wiping optical surfaces must be meticulously selected to prevent scratching and fiber deposition.

Table 1: Specifications for Lint-Free Cloths

| Feature | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Material | 100% continuous filament knit polyester or microfiber [38] [39] | No loose fibers to detach and contaminate the optic. |

| Construction | Knitted with a knife-cut edge [39] | Reduces the potential for scratching compared to a frayed, woven edge. |

| Packaging | Laundered and packaged in an ISO Class 4 (Class 10) cleanroom [39] | Guarantees the cloth is delivered with minimal particulate burden. |

| Application | Used with a gentle, circular motion [40] | Effectively lifts contamination without grinding particles into the surface. |

Approved Gas Dusters

For removing loose, dry particulates from apertures and hard-to-reach surfaces, the type of gas duster is critical.