Troubleshooting High Background Noise in Spectroscopic Analysis: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This comprehensive guide addresses the critical challenge of background noise in spectroscopic analysis, a key limitation in biomedical research and drug development.

Troubleshooting High Background Noise in Spectroscopic Analysis: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This comprehensive guide addresses the critical challenge of background noise in spectroscopic analysis, a key limitation in biomedical research and drug development. Covering both foundational principles and advanced applications, we explore the origins of noise from instrumental and sample sources, evaluate traditional and cutting-edge noise reduction methodologies including wavelet transforms and AI-based approaches, provide systematic troubleshooting protocols for common laboratory scenarios, and establish rigorous validation frameworks for detection limit determination and method comparison. Designed for researchers and analytical scientists, this resource provides practical strategies to enhance signal fidelity, improve detection capabilities, and generate more reliable spectroscopic data in complex biological matrices.

Understanding Spectroscopic Noise: Sources, Types, and Impact on Data Quality

In analytical spectroscopy, "noise" refers to any unwanted signal fluctuation that obscures the true analytical data. It is a critical concept that extends far beyond simple background interference, fundamentally determining the sensitivity, accuracy, and detection limits of your measurements. Understanding its sources and characteristics is the first step in effective troubleshooting.

Noise originates from various sources within the instrument, the sample, and the external environment [1]. It primarily reduces the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), which is a key metric for data quality [2]. A low SNR makes it difficult to distinguish the true signal from random fluctuations, compromising the reliability of your results [1].

The table below categorizes common types of noise encountered in spectroscopic systems, their origins, and their impact on your data [1].

Table 1: Common Types of Noise in Spectroscopy

| Noise Type | Primary Origin | Key Characteristics & Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Shot Noise | Detector & electronics; uneven electron emission [1]. | Related to current/light intensity; fundamental limit for strong signals [2] [1]. |

| Readout Noise | Readout circuit instability & quantization errors [1]. | Fixed, signal-independent noise; limits performance at very low signals [2]. |

| Dark Noise | Stray light & thermal excitation in detector [2] [1]. | Measurable signal without light; increases with integration time & temperature [2]. |

| Electronic Noise | Amplifiers, A/D converters, electronic components [1]. | Generated by instrument electronics; can be reduced with low-noise components [1]. |

| Fixed Pattern Noise (FPN) | Pixel-to-pixel variation in detector [1]. | Consistent spatial pattern; corrected via calibration with reference images [1]. |

| Baseline Noise/Drift | Instrument instability & environmental factors [1]. | Baseline fluctuations; affects accuracy, especially for low-concentration samples [1]. |

Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and Detection Limits

The Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) quantifies data quality. A higher SNR indicates a clearer, more reliable signal [2]. The total measured signal includes contributions from the light (signal), dark current, and a baseline offset [2]. Therefore, the extracted signal is calculated as: ( s = m{\text{light}} - m{\text{dark}} ) [2].

The overall noise is a combination of all noise sources [2]: ( n{\text{total}} = \sqrt{n{\text{phot}}^2 + n{\text{dark}}^2 + n{\text{base}}^2 + n_{\text{read}}^2} )

The SNR determines the effectiveness of your measurements and is defined differently depending on which noise source is dominant [2]:

- Shot-Noise Limited Regime (High Signal): ( \text{SNR} = \sqrt{QN} ). This is the ideal scenario, where SNR increases with the square root of the number of photons.

- Read-Noise Limited Regime (Very Low Signal): ( \text{SNR} = \frac{\alpha QN}{n_{\text{read}}} ). Here, SNR increases linearly with signal, and read noise is the limiting factor.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Common Spectroscopic Detectors [2]

| Detector | Technology | Pixel Size (µm) | Full Well Depth (ke-) | Read Noise (counts) | Maximum SNR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hamamatsu S10420 | CCD | 14 x 896 | 300 | 16 | 475 |

| Hamamatsu S11156-01 | CCD | 14 x 1000 | 200 | 21 | 390 |

| Hamamatsu S11639 | CMOS | 14 x 200 | 80 | 26 | 360 |

| Sony ILX511B | CCD | 14 x 200 | 63 | 53 | 215 |

Troubleshooting FAQs: Resolving High Background Noise

Q1: My baseline is noisy and unstable. What are the first things I should check? A1: Begin with these fundamental checks:

- Control the Environment: Ensure ambient temperature and humidity are stable, as fluctuations can cause significant baseline drift [1].

- Check Gas Purity: For techniques like GC-MS, use high-quality, pure carrier gases to minimize background contamination [1].

- Inspect Sample Introduction: For ICP-MS, ensure sample introduction components (e.g., nebulizers) are clean and not clogged, and consider matrix composition effects [3].

- Subtract a Dark Spectrum: Always acquire and subtract a "dark" reference spectrum (measured without illumination) to account for dark current and electronic offset [2].

Q2: My signal is weak, and the data is very noisy, even with long integration times. How can I improve this? A2: This is typical of read-noise-limited conditions.

- Optimize Detector Gain: Use the detector's highest gain setting (highest sensitivity) to maximize the signal for weak light conditions [2].

- Reduce Readout Speed: If your instrument allows, a slower readout speed typically lowers readout noise [2].

- Consider Signal Averaging: Acquire and average multiple spectra. While this increases measurement time, it can improve SNR by reducing random noise [4].

- Cool Your Detector: Cooling the detector (e.g., using a Peltier cooler or liquid nitrogen) dramatically reduces dark current, which is crucial for long integration times [2].

Q3: I work with mass spectrometry (e.g., Orbitrap), and noise is biasing my multivariate analysis. What can I do? A3: Noise in MS is often heteroscedastic (varying with signal intensity), which biases statistical models.

- Apply Advanced Scaling: Use specialized scaling methods like the Weighted Sum of Rician (WSoR) distributions, designed for Orbitrap data, to reduce the undue influence of noise in techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [5].

- Understand Noise Structure: Recognize that at low signals, detector noise and data censoring dominate; at intermediate signals, ion counting (Poisson) noise is key [5].

Q4: The noise calculation methods in my protocol seem subjective and inconsistent. Is there a more robust approach? A4: Yes, traditional SNR-based detection limits can be problematic, especially in ultra-low-noise systems like modern MS where background noise can be nearly zero [6].

- Use Statistical Methods: For a more rigorous estimate of Instrument Detection Limits (IDL), perform replicate injections (n≥7) of a standard near the expected detection limit. Calculate the standard deviation (STD) and use the formula: ( \text{IDL} = (t{\alpha}) \times (\text{STD}) ), where ( t{\alpha} ) is the one-sided Student's t-value for n-1 degrees of freedom at a 99% confidence level [6].

Experimental Protocol: Characterizing and Minimizing Noise

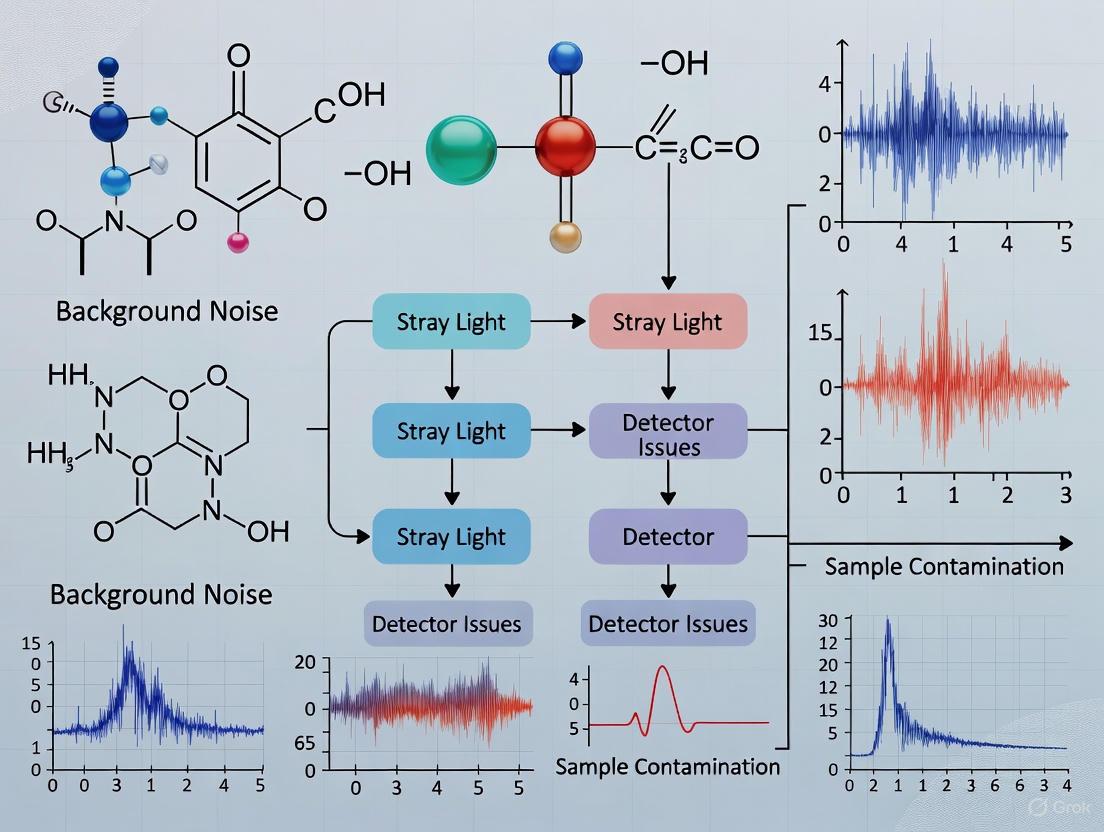

This workflow provides a systematic approach to diagnose and mitigate noise issues in spectroscopic experiments. The process is summarized in the diagram below.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Acquire a Dark Reference Spectrum:

- Procedure: Block the light path to the detector or use a blank sample. Acquire a spectrum using the same integration time and instrument settings as your sample measurement.

- Purpose: This measures the combined contribution of the baseline offset and dark current. Subtract this spectrum from all subsequent sample measurements to isolate the light-derived signal [2].

Characterize SNR vs. Signal Intensity:

- Procedure: Measure a series of spectra from a stable light source at varying intensity levels (e.g., using neutral density filters). For each intensity, calculate the mean signal and the standard deviation (noise) for a specific wavelength. Plot SNR versus signal on a double-logarithmic plot [2].

- Purpose: The slope of the curve identifies the dominant noise regime. A slope of ~0.5 indicates shot-noise limitation, while a slope of ~1 indicates read-noise limitation [2].

Implement Noise-Specific Mitigation Strategies:

- Based on your diagnosis from Step 2, apply the targeted strategies outlined in the workflow diagram and detailed in the Troubleshooting FAQs section.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Noise Troubleshooting

| Item / Reagent | Function in Noise Management |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Carrier Gases | Minimizes background chemical noise in GC-MS and ICP-MS by reducing impurities [1]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Acts as an internal standard in MS to correct for signal drift and matrix-induced noise [6]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Validates method accuracy and helps distinguish between analyte signal and background interference [3]. |

| Optical Filters & Beam Dumps | Reduces stray light and scattered light noise within the spectrometer optical path [1]. |

| Cooling Systems for Detectors | Significantly reduces dark current and its associated shot noise, crucial for long exposures [2]. |

| Low-Noise Electronic Components | Found in high-quality spectrometers to minimize inherent electronic and readout noise [1]. |

| Aurachin C | Aurachin C | Cytochrome bd Oxidase Inhibitor | RUO |

| Glidobactin B | Glidobactin B | Potent Proteasome Inhibitor | RUO |

What is the impact of noise on my spectroscopic data? Noise directly compromises the accuracy, precision, and detection limits of your analytical measurements. In spectroscopic analysis, it manifests as a fluctuating baseline (instability) or an elevated background signal, which can obscure weak analyte signals and lead to inaccurate quantification [7]. Effectively troubleshooting these issues requires a systematic approach to classify and identify the source of the noise.

This guide classifies noise sources into three primary categories to streamline your troubleshooting process:

- Instrumental Noise: Originates from the analytical instrument's components and physics.

- Environmental Noise: Arises from external electrical or acoustic interference.

- Sample-Derived Noise: Caused by the sample's properties or its preparation.

The following sections provide detailed FAQs and troubleshooting guides for each category.

Instrumental Noise

My Flame Ionization Detector (FID) shows high background and noise. What should I do? High background or noise in an FID is a common issue often linked to gas purity, contamination, or component failure. A logical troubleshooting procedure is recommended [8]:

- Eliminate the Column: Disconnect and cap the column from the FID. If the noise subsides, the issue is likely contaminated carrier gas or excessive column bleed [8].

- Check Gas Flows: Use a flow meter to verify hydrogen, air, and makeup gas flows are set correctly. Optimal signal-to-noise is often achieved at a ~1:1 ratio of Hâ‚‚ to the combined column and makeup gas flow [8].

- Measure Leakage Current: With the flame off and the detector at operating temperature, the background signal should be low (e.g., 2-3 pA) and stable. A higher or unstable signal suggests a contaminated, loose, or deformed interconnect spring or contaminated PTFE insulators [8].

- Clean the FID: Perform maintenance by cleaning or replacing the FID jet, collector, and inspect for corrosion [8].

- Bake Out the Detector: Bake the detector at a high temperature (e.g., 350 °C) to remove condensed sample contaminants [8].

Table 1: Troubleshooting High Background in FID Detectors

| Observation | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| High background (>20 pA) | Contaminated gas supplies (carrier, Hâ‚‚, air) | Check gas purity; install or replace gas traps [8]. |

| Noisy, unstable baseline | Partially plugged FID jet; contaminated detector interior | Clean or replace the FID jet assembly; perform full FID cleaning [8]. |

| Extremely high signal output (>500,000 pA) | Short circuit from a bent/damaged FID interconnect spring | Cool and power off the GC; inspect and replace the spring [8]. |

| Periodic cycling baseline | Defective gas compressor or regulator; faulty electronics | Check gas supply regulation; contact technical support [8]. |

How can I diagnose electrical noise in my instrument? Electrical noise can often be identified using spectrum analysis. This process plots the frequency components of a signal, where noise appears as distinct spikes within the instrument's operational bandwidth [9]. To diagnose:

- Use built-in or external software to generate a spectrum plot.

- Identify any sharp peaks or an elevated noise floor within the operational frequency range.

- Common sources include switching power supplies, improper grounding, or electromagnetic interference from nearby equipment [9].

A modern approach to instrumental noise uses "Noise Learning." How does it work? Noise Learning (NL) is a deep learning method that statistically learns the intrinsic noise pattern of a specific instrument. Unlike conventional methods, it does not require large, pre-existing datasets of sample data. Instead, it uses a physics-based model to generate clean spectra and trains a neural network to recognize and subtract the instrument's unique noise signature from measured data. This instrument-dependent approach has been shown to improve the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) of Raman spectra by approximately 10-fold [10].

Diagram: Noise Learning (NL) Workflow for Instrumental Denoising

Environmental Noise

What are the common sources of environmental noise in a laboratory? Environmental noise primarily includes acoustic noise from equipment and people, and electrical noise from power lines and other devices. In urban areas, common external sources are road, rail, and air traffic, which generate broadband noise [11]. Inside the lab, noise can come from engines, pumps, compressors, and HVAC systems, which introduce vibrations and broad-spectrum interference [9].

How can I identify and reduce electrical noise affecting my instrumentation? Identifying the source is key, as electrical noise cannot be filtered out during post-processing [9].

- Check Power Supplies: Switching power supplies are common culprits. Look for periodic spikes in a spectrum analysis that align with switching activity [9].

- Verify Grounding: Ensure the instrument is properly grounded. In some cases, a grounding plate must be in direct contact with a conducting medium like seawater [9].

- Locate Electromagnetic Interference: Nearby radios, sonar, acoustic modems, or other transmitting devices can emit interfering signals. Physically relocate or shield your instrument from these sources [9].

- Inspect Cabling: Ensure all cables and connectors are properly shielded and grounded [9].

Sample-Derived Noise

My sample preparation is causing high background. How can I fix this? Inadequate sample preparation is a leading cause of analytical errors [12]. The solution depends on your technique:

- For XRF: Ensure samples have a flat, homogeneous surface. Grind particles to the appropriate size (typically <75 μm) and create pressed pellets or fused beads to ensure uniform density and minimize scattering [12].

- For ICP-MS: Solid samples must be completely dissolved. Use accurate dilutions and filter samples (e.g., 0.45 μm or 0.2 μm) to remove particles that could clog the nebulizer. Use high-purity acids to prevent contamination [12].

- For FT-IR & UV-Vis: Select a solvent that does not absorb strongly in the analytical region of interest. For FT-IR, deuterated solvents are often used. Ensure sample concentration is optimized to avoid detector saturation or poor SNR [12].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Sample-Derived Noise in Spectroscopic Techniques

| Technique | Common Sample Issues | Preparation Solution |

|---|---|---|

| XRF | Rough surface; heterogeneous particle size; mineralogical effects | Grind to <75 μm; create uniform pellets; use fusion for refractory materials [12]. |

| ICP-MS | Incomplete dissolution; high solid content; contamination | Use total digestion; perform accurate dilution; filter; use high-purity reagents [12]. |

| FT-IR | Solvent absorption bands; scattering from rough surfaces | Use deuterated or IR-transparent solvents; grind with KBr for pellet formation [12]. |

| HPLC/FLD | High background from mobile phase; sample solvent too strong | Use high-purity solvents; degas mobile phase; dissolve sample in starting mobile phase [13]. |

I see unexpected peaks and broadening in my HPLC analysis. Could this be sample-derived? Yes. Several symptoms in HPLC chromatograms can be traced back to the sample:

- Peak Tailing: Can be caused by basic compounds interacting with silanol groups on the stationary phase. Use high-purity silica columns or competing bases like triethylamine in the mobile phase [13].

- Peak Fronting: Often due to a blocked frit or channels in the column. Replace the pre-column frit or the analytical column. Can also be caused by column overload—reduce the amount of sample injected [13].

- Unexpected Broad Peaks: Can result from the sample being dissolved in a solvent stronger than the mobile phase. Always try to dissolve samples in the starting mobile phase composition [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Noise Reduction

| Item | Function in Noise Troubleshooting |

|---|---|

| Gas Purification Traps | Removes moisture, oxygen, and hydrocarbons from carrier and detector gases, minimizing high FID background and contamination [8]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Reduces high background signal in HPLC/UV-Vis by minimizing interfering UV-absorbing impurities [13] [12]. |

| Bonders (e.g., KBr, Cellulose) | Creates homogeneous, transparent pellets for XRF and FT-IR, minimizing light scattering and ensuring representative analysis [12]. |

| Lithium Tetraborate Flux | Used in fusion techniques for XRF to fully dissolve refractory samples, eliminating particle size and mineralogical effects for accurate quantitative analysis [12]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃) | Provides minimal interfering absorption bands in FT-IR analysis, allowing for clear observation of analyte signals [12]. |

| Internal Standards | Added to samples in ICP-MS to compensate for matrix effects and instrument drift, improving quantitative accuracy and precision [12]. |

| 5-Bromo-6-chloro-1H-indol-3-yl acetate | 5-Bromo-6-chloro-1H-indol-3-yl acetate | RUO |

| Orysastrobin | Orysastrobin | Fungicide for Plant Pathology Research |

Advanced Protocols & Data Analysis

Detailed Protocol: Cleaning an FID to Reduce High Background and Noise Tools Required: Torx T20 screwdriver, new septum, ferrule, and column nut [8].

- Safety First: Allow the FID to cool to at least 50°C before starting [8].

- Disassemble: Remove the detector cap and the collector assembly. Take care not to touch the interconnect spring with bare hands, as oils can cause current leakage [8].

- Clean Components: Remove the jet and clean it with a suitable solvent (e.g., methanol). Soak and sonicate the collector and the insulator. Inspect the brass castle nut for rust or corrosion and replace if dirty [8].

- Reassemble: Reinstall all components, ensuring the interconnect spring is correctly seated in its channel and is not deformed. Ensure all fittings are tight to prevent mechanical noise [8].

- Bake Out: Reconnect gas lines, set the detector temperature to 350°C (with no gas flows), and bake out for 1-2 hours to remove residual contaminants [8].

- Re-establish Flows & Ignite: Set gas flows to recommended levels (e.g., Hâ‚‚: 30-40 mL/min, Air: 300-400 mL/min) and reignite the flame [8].

Detailed Protocol: Automated Noise Source Identification using Acoustic Array Purpose: To automatically identify and assess the contribution of individual environmental noise sources to the total sound pressure level [11].

- Setup: Deploy a 4-channel microphone array (or acoustic camera) coupled with a Class 1 sound level meter at the measurement point [11].

- Data Acquisition: Simultaneously capture sound signals from all microphones at a high sampling rate (e.g., 192 kHz) over a representative time period [11].

- Source Localization: Process the signals using a beamforming algorithm like Delay-and-Sum (DAS) or Average Square Difference Function (ASDF). This calculates the Direction of Arrival (DOA) of sound events [11].

- Spatial Filtering: Combine the DOA data with the instantaneous sound pressure level to create an "immission directivity" plot, which shows the direction and strength of noise sources over time [11].

- Classification: Apply unsupervised machine learning algorithms to the spatial and acoustic features (e.g., psychoacoustic parameters) to automatically classify and quantify the contribution of different noise sources (e.g., traffic, machinery) to the total measured level [11].

Diagram: Automated Environmental Noise Assessment Workflow

FAQs: Understanding Core Noise Concepts

What is the fundamental difference between shot noise and read noise? Shot noise originates from the inherent, random fluctuation in the arrival rate of photons at the detector. Even a perfectly stable light source will exhibit this variability, and it follows a Poisson distribution where the noise equals the square root of the signal. In contrast, read noise is produced by the camera's own electronics during the process of converting the accumulated charge in each pixel into a digital number. The key distinction is that shot noise depends on the signal level, while read noise is a fixed value, independent of both the signal strength and exposure time [14] [15].

Why is my spectroscopic data noisy even with very short exposure times or in complete darkness? In low-signal or very short-exposure scenarios, read noise is often the dominant factor. Since it is a fixed amount of noise added during the readout of each pixel, its impact is most pronounced when the photo-generated signal is weak. Furthermore, even in darkness, a small electric current known as dark current flows through the detector. The random generation of electrons that constitute this current also produces shot noise, contributing to the overall noise floor of your measurement [14] [16].

How does fixed-pattern noise differ from other temporal noise sources? Shot, read, and dark current noise are temporal, meaning they vary randomly from one readout to the next. Fixed-pattern noise (FPN) is a spatial noise; it is a static, repeatable pattern across the sensor. FPN has two main components: Photo Response Non-Uniformity (PRNU), which is the variation in how different pixels respond to the same amount of light, and Dark Signal Non-Uniformity (DSNU), which is the variation in the dark current output of individual pixels [14] [17].

When is my measurement considered "shot-noise limited," and why is this desirable? A measurement is shot-noise limited when the photon shot noise is the largest contributor to the total noise. This typically occurs when you have a strong, clean signal. This is considered the ideal regime because it represents the fundamental physical limit of detection. In this state, the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) increases with the square root of the signal. Achieving this involves using high-quality detectors and ensuring your signal is sufficiently strong to dwarf the read noise and dark current [2] [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing High Background Noise

Problem: Consistently high background noise is obscuring weak spectral features. Step-by-Step Investigation:

- Perform a Dark Measurement: Acquire a spectrum with the light source blocked or the shutter closed, using your standard integration time. A high signal in this dark measurement indicates significant dark current.

- Check for Fixed Patterns: If the dark measurement shows a structured pattern (e.g., stripes, columns) rather than random noise, your system is affected by fixed-pattern noise [17] [18].

- Analyze Signal Dependence: Collect data at different illumination levels. If the noise increases proportionally with the square root of the signal, your system is likely shot-noise limited, and you need a stronger signal. If the noise level remains fairly constant across signal levels, read noise is the dominant source [2].

- Verify Calibration Protocols: Ensure that standard calibration procedures, such as regular dark frame and flat field acquisitions, are being performed correctly. In Raman spectroscopy, skipping wavelength calibration can cause systematic drifts to be misinterpreted as sample-related changes [19].

Guide 2: Mitigating Fixed-Pattern Noise (FPN) in Imaging Spectrometry

Fixed-pattern noise can be particularly stubborn as it requires processing to remove. The following workflow outlines several algorithmic correction methods.

Detailed Correction Methods:

- Median Projection FPN Correction (mFPNc): This is a simple and fast method where the median value of each column (or row) is calculated and then subtracted from every pixel in that corresponding column. This effectively removes a common offset but may not handle more complex patterns [17].

- Column Projection FPN Correction (cpFPNc): A more advanced heuristic method. It creates a binary mask to exclude pixels containing actual sample signal (e.g., from particles) before calculating the column-wise mean. This produces a cleaner FPN signature for subtraction, preserving sample data [17].

- FFT Fixed Pattern Noise Correction (fFPNc): This technique separates image structures from column-wise patterns in the frequency domain. By using iterative filtering in both spectral and spatial domains, it can effectively remove stripe non-uniformity while preserving image information [17].

Guide 3: Optimizing Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in Detector-Limited Experiments

The total noise in a measurement is the combination of all independent noise sources. The goal is to maximize the signal relative to this total noise.

Total Noise Calculation:

Total Noise = √(Shot Noise² + Read Noise² + Dark Current Noise²) [2]

Optimization Strategy:

- Maximize Signal: Increase integration time or illumination intensity until just below the sensor's saturation point. This helps enter the shot-noise limited regime [2] [15].

- Minimize Read Noise: Use a camera with low read noise and, if available, select a slower readout speed on the camera, which often reduces read noise [20] [2].

- Suppress Dark Current: Cool the detector. For every 6-7°C reduction in temperature, dark current is typically halved. Use short integration times if cooling is not an option [2].

- Leverage Calibration: Faithfully subtract dark frames to remove the mean dark current offset and use flat-field correction to account for PRNU [14] [17].

Quantitative Data & Detector Comparison

The performance of different detector technologies can be directly compared using their key parameters. The following table summarizes specifications and measured performance for several common detectors used in spectroscopy.

Table 1: Technical Specifications and Measured SNR of Common Spectroscopic Detectors [2]

| Detector | Technology | Pixel Size (µm) | Full Well Capacity (k e-) | Read Noise (counts) | Maximum SNR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S10420 | CCD | 14 x 896 | 300 | 16 | 475 |

| S11156-01 | CCD | 14 x 1000 | 200 | 21 | 390 |

| S11639 | CMOS | 14 x 200 | 80 | 26 | 360 |

| Sony ILX511B | CCD | 14 x 200 | 63 | 53 | 215 |

The relationship between signal level and SNR for any detector follows a predictable pattern, which can be visualized on a log-log scale. The following diagram illustrates this universal SNR curve, showing the transition from read-noise dominance at low signals to shot-noise dominance at high signals.

Table 2: Dominant Noise Source and Mitigation Strategies

| Dominant Noise Source | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Read Noise | SNR ∠Signal | Use a lower-read-noise camera; slow down readout speed; bin pixels; increase signal to become shot-noise limited [20] [2]. |

| Shot Noise | SNR ∠√(Signal) | Increase integration time or light intensity; this is the ideal regime and represents the fundamental detection limit [2] [15]. |

| Dark Current | SNR ∠Signal / √(Dark Current) | Cool the detector; use shorter integration times; subtract dark frames [2] [16]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Measuring Camera Read Noise

Objective: To determine the read noise of a camera system in electrons. Background: Read noise is a fixed value added by the camera's electronics during readout. This protocol uses the standard deviation of a series of bias frames to calculate it.

Materials:

- Camera under test

- Stable power supply

- Light-tight enclosure

Procedure:

- Ensure the camera is in a light-tight environment.

- Set the integration time to the shortest possible value (effectively zero).

- Capture a series of at least 50 consecutive bias frames.

- Select a region of interest (ROI) away from obvious defects.

- For one of the frames in the series, calculate the standard deviation of the pixel values in the ROI. This value, in Analog-to-Digital Units (ADUs), is the temporal read noise.

- To convert this to electrons, divide the standard deviation in ADU by the system's conversion gain (in e-/ADU). The conversion gain can often be found in the camera's specification sheet or measured via the photon transfer technique [2] [15].

Protocol: Establishing a Routine for Fixed-Pattern Noise Correction

Objective: To acquire the necessary calibration frames to remove fixed-pattern noise from scientific images. Background: FPN correction requires a reference pattern that is subtracted from your data. This is achieved through dark and flat-field frames.

Materials:

- Scientific camera

- Uniform, stable light source (for flat fields)

Procedure:

- Acquire Dark Frames:

- Block all light to the camera sensor.

- Use the same exposure time and temperature as your scientific experiments.

- Capture a master dark frame by taking the median of 10-50 individual dark frames. This master dark contains the combined DSNU and the average dark current.

- Acquire Flat Fields:

- Illuminate the sensor with a uniform light source. A defocused screen or an integrating sphere is ideal.

- Adjust the exposure time so the average signal level is between 30% and 70% of the full well capacity (avoid saturation).

- Capture a master flat field by taking the median of 10-50 individual flat frames.

- Apply Correction:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Noise Troubleshooting

| Item | Function in Noise Management |

|---|---|

| Cooled CCD/CMOS Detector | Integrated thermoelectric cooling dramatically reduces dark current, a critical step for long-exposure measurements [2]. |

| Uniform Light Source / Integrating Sphere | Provides even illumination essential for acquiring high-quality flat fields to correct for Photo Response Non-Uniformity (PRNU) [17]. |

| Wavenumber Standard (e.g., 4-acetamidophenol) | A reference material with known, sharp peaks used to calibrate the wavenumber axis of a Raman spectrometer, preventing systematic drift from being misinterpreted as noise [19]. |

| Light-Tight Enclosure | A simple but vital tool for accurately characterizing camera-specific noise sources like dark current and read noise without contamination from stray light [2]. |

| Jietacin A | Jietacin A | Anticancer Natural Product | RUO |

| Chamigrenol | Chamigrenol | Natural Sesquiterpenoid | For Research |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary sources of sample-induced noise in fluorescence spectroscopy? Sample-induced noise primarily arises from three sources: fluorescence background from native fluorophores or impurities in the sample buffer; scattering effects (Rayleigh and Raman scattering) caused by the interaction of light with the sample matrix; and matrix interferences where components of the sample matrix alter the detector's response to the target analyte, leading to signal suppression or enhancement [21] [22] [23].

2. How does light scattering affect a fluorescence measurement? Light scattering can significantly increase the background noise, reducing the signal-to-noise ratio. Rayleigh scattering occurs at the same wavelength as the excitation light and can overwhelm the detector if not properly filtered. Raman scattering occurs at a shifted wavelength and can be mistaken for or overlap with the desired fluorescence signal, leading to inaccurate readings [21] [23].

3. What is meant by 'matrix effect' in quantitative analysis? The matrix effect refers to the phenomenon where components of the sample, other than the analyte, alter the detector's response. In liquid chromatography, this can cause ionization suppression or enhancement in mass spectrometric detection, fluorescence quenching, or effects on aerosol-based detectors. This compromises quantitative accuracy because the same analyte concentration yields different signals in different matrices [22].

4. What are some practical strategies to mitigate matrix interference? Effective strategies include:

- Sample Preparation: Techniques like dilution, filtration, centrifugation, and buffer exchange can reduce the concentration of interfering components [24].

- Internal Standard Method: Using a known amount of a structurally similar internal standard (e.g., a stable isotope-labeled compound) can correct for variations in detector response and sample preparation [22].

- Matrix-Matched Calibration: Creating standard curves using standards diluted in the same matrix as the experimental samples accounts for matrix effects during calibration [24].

5. Can these noise issues be overcome with instrumentation alone? While instrumental features like dual monochromators and optical filters are crucial for suppressing stray light and scattered excitation light [21] [23], instrumentation alone is often insufficient. Computational and algorithmic approaches are increasingly important. For example, the RNP (robust non-negative principal matrix factorization) algorithm integrates robust feature extraction to separate meaningful fluorescence signals from noisy speckles and background interference in scattering tissue environments [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Correcting High Fluorescence Background

A high background signal can obscure the target fluorescence, reducing sensitivity and quantitative accuracy.

Symptoms:

- Elevated signal in blank or control samples.

- Poor signal-to-noise ratio.

- Unstable or drifting baseline.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Description | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Impure Solvents/Buffers | Fluorescent impurities in reagents. | Use high-purity solvents (e.g., HPLC grade) and check blanks [21]. |

| Dirty Cuvettes | Contaminants on the surface of the sample holder. | Thoroughly clean cuvettes with appropriate solvents. |

| Sample Autofluorescence | Native fluorophores in the sample (e.g., proteins with tryptophan). | Use optical filters to isolate target emission; consider a red-shifted fluorescent dye [21] [23]. |

| Scattered Excitation Light | Rayleigh scatter entering the detector. | Ensure proper alignment and use high-quality emission filters or a double monochromator [23]. |

Experimental Protocol: Blank Subtraction and System Validation

- Prepare a Blank: Create a sample containing all components except the target fluorophore.

- Acquire Blank Spectrum: Measure the fluorescence emission spectrum of the blank under the exact same conditions (excitation wavelength, slit widths, etc.) as your experimental samples.

- Subtract the Spectrum: Use software to subtract the blank spectrum from the sample spectrum.

- Validate: Regularly run blanks to ensure the background level has not changed due to reagent lot variations or cuvette contamination.

Guide 2: Managing Scattering Effects in Dense or Turbid Samples

Samples like biological tissues or colloidal suspensions scatter light, degrading image quality and spectral fidelity.

Symptoms:

- Broadened or distorted peaks.

- Significant signal loss with increasing sample depth or concentration.

- The appearance of peaks at unexpected wavelengths (Raman scatter).

Quantitative Comparison of Scattering Mitigation Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Best for | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time-Gating [26] | Separates single-scattered signal from multiple-scattering noise based on flight time. | Label-free reflectance imaging; obtaining high resolution in thick samples. | Requires pulsed laser and fast detection; complex instrumentation. |

| Computational Correction (e.g., RNP) [25] | Algorithmically decomposes speckled images to extract sparse features from a noisy, low-rank background. | Fluorescence microscopy in scattering tissues; large field of view imaging. | Requires capturing multiple speckle images; computational processing time. |

| Optical Sectioning (Confocal) [26] | Uses a pinhole to reject out-of-focus light. | Rejecting scattered light from outside the focal plane. | Signal loss; aberrations can spread signals away from the pinhole. |

| Polarization Discrimination | Uses a polarizer in the detection path to reject depolarized scattered light. | Differentiating between single and multiple scattering events. | Less effective for highly scattering media. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing RNP for Scattering Imaging The RNP framework enables fluorescence imaging through scattering media on a standard epi-fluorescence microscope [25].

- Setup: Incorporate a motorized rotating diffuser into the excitation path of a wide-field fluorescence microscope to produce random speckle illumination.

- Data Acquisition: Capture a sequence of raw fluorescence images through the scattering medium under different random speckle illuminations.

- Algorithmic Processing: Process the image stack through the RNP algorithm:

- Preprocessing: Apply Fourier domain filtering to enhance contrast and remove noise.

- Decomposition: Use robust principal-component analysis (RPCA) to decompose each image (Ik) into a sparse feature component (Sk) and a low-rank background component (Lk), such that Ik = Sk + Lk. This enhances speckle contrast.

- Dimension Reduction: Apply non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) to the sparse features to assign speckle patterns to their corresponding emitters and reconstruct the final image.

Guide 3: Overcoming Matrix Interferences in Quantitative Assays

Matrix effects can lead to inaccurate quantification, particularly in complex samples like serum or tissue homogenates.

Symptoms:

- Inconsistent calibration curves when using different sample matrices.

- Low spike recovery rates.

- Signal suppression or enhancement observed in post-column infusion experiments [22].

Practical Solutions for Mitigating Matrix Effects

| Solution | Approach | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Dilution | Diluting the sample with a compatible buffer to reduce interference concentration [24]. | Must not dilute analyte below the limit of quantification (LOQ). |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) | Selectively extracting the analyte from the interfering matrix. | Adds time and cost; requires method development. |

| Internal Standard (IS) | Adding a known quantity of a similar, but distinguishable, compound to correct for variable detector response [22]. | Ideal IS is a stable isotope-labeled version of the analyte. |

| Matrix-Matched Calibration | Preparing standards in a matrix similar to the sample [24]. | Can be difficult to obtain a true "blank" matrix. |

| Standard Addition | Adding known amounts of analyte directly to the sample. | Labor-intensive; best suited for a small number of samples. |

Experimental Protocol: Post-Column Infusion for Diagnosing Matrix Effects This experiment helps visualize where in the chromatogram matrix suppression or enhancement occurs [22].

- Setup: Connect an infusion pump containing a dilute solution of your analyte to a T-union between the LC column outlet and the mass spectrometer inlet. The analyte is thus continuously introduced into the effluent.

- Run a Blank Matrix Injection: Inject a sample of the blank matrix (e.g., stripped serum, buffer) onto the LC column and start the gradient method.

- Observe the Signal: Monitor the signal of the infused analyte. A constant signal indicates no matrix effect. A dip or rise in the signal indicates regions where co-eluting matrix components are causing ion suppression or enhancement, respectively.

- Interpretation: The resulting chromatogram pinpoints retention times where method development should focus to improve separation and mitigate the interference.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential materials and reagents used to combat sample-induced noise.

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents | Minimize fluorescent background from impurities in blanks and samples [21]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standard | Corrects for analyte loss during preparation and matrix effects during detection, ensuring quantitative accuracy [22]. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., BSA) | In immunoassays, these proteins reduce nonspecific binding of antibodies to surfaces or sample components, mitigating one form of matrix interference [24]. |

| Buffer Exchange Columns | Rapidly desalt samples or transfer them into an assay-compatible buffer, removing interfering salts or small molecules [24]. |

| Optical Filters & Monochromators | Isolate the fluorescence emission light from the much stronger excitation light, critical for suppressing Rayleigh scatter [21] [23]. |

| Utibapril | Utibapril | ACE Inhibitor | Research Chemical |

| Carbazomycin D | Carbazomycin D | Antibacterial Agent | For Research |

Experimental Workflow and Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing the three main types of sample-induced noise.

The Critical Relationship Between Signal-to-Noise Ratio and Detection Limits

FAQs: Understanding Signal-to-Noise Ratio and Detection Limits

What are the official definitions for LOD and LOQ based on Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N)?

According to the ICH Q2(R1) guideline, the Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ) can be determined directly from the signal-to-noise ratio [27]. The following table summarizes these definitions, noting that an upcoming revision (Q2(R2)) will formalize the LOD requirement to a 3:1 ratio.

| Term | Definition | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N) | Regulatory Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The minimum concentration at which an analyte can be reliably detected. | 2:1 to 3:1 (3:1 will be mandatory per ICH Q2(R2)) | ICH Q2(R1) |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | The minimum concentration at which an analyte can be reliably quantified. | 10:1 | ICH Q2(R1) |

In practice, for challenging real-life samples and analytical conditions, scientists often employ stricter S/N ratios: 3:1 to 10:1 for LOD and 10:1 to 20:1 for LOQ [27].

How is the Signal-to-Noise Ratio calculated, and why are there different values reported?

There are two common methods for calculating the S/N, which leads to reported values differing by a factor of two [28].

- Standard Calculation:

S/N = Signal (S) / Noise (N)- The signal (S) is measured from the middle of the baseline noise to the top of the peak.

- The noise (N) is the peak-to-peak baseline noise measured over a representative section of the baseline [28].

- Pharmacopoeia (USP/EP) Calculation:

S/N = 2H / h- Here,

His the signal height, andhis the peak-to-peak noise. This method considers only half the noise band, resulting in an S/N value that is twice that of the standard calculation [28].

- Here,

It is critical to know which calculation your data system employs and to maintain consistency when comparing results or validating methods against regulatory standards.

What is the practical impact of a low Signal-to-Noise Ratio on my data?

A low S/N ratio directly compromises data quality and can lead to two significant problems [27]:

- Failure to Detect Analytes: If the analyte signal is not sufficiently distinguishable from the baseline noise, the substance may not be detected at all, leading to false negatives [27].

- Inaccurate Quantification: Even if a peak is detected, a low S/N makes it difficult for the data system to accurately integrate the peak's area and height, resulting in imprecise and unreliable quantitative results [29].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Excessive Background Noise

Excessive background noise reduces the S/N ratio, thereby raising your practical detection limits. The following workflow provides a systematic approach to isolate and resolve the source of contamination.

Step 1: Run a Blank and Isolate the Problem

Begin by injecting a pure solvent or mobile phase blank. Observe the baseline noise and any ghost peaks. This helps determine if the noise originates from the analytical system itself or is introduced by the sample preparation process [29] [30]. Consistently high background across the run or varying noise after the instrument sits idle often points to system contamination [29].

Step 2: Isolate the LC Flow Path (Liquid Chromatography)

To determine if the noise source is before or after the column, replace the analytical column with a zero-dead-volume union and run the method again [30]. If the high noise persists, the problem is in the LC system (injector, pump, detector). If the noise is significantly reduced, the column is likely contaminated or degraded.

Step 3: Inspect and Replace Consumables

Many common noise issues are resolved by replacing consumables that have reached the end of their lifespan.

| Component | Potential Issue | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile Phase/Solvents | Contaminants, microbial growth, or dissolved air [30]. | Use fresh, high-quality HPLC-grade solvents. Filter water. Ensure the degasser is functioning. |

| Inlet Septum (GC) | Septum bleed or degradation at high inlet temperatures [29] [31]. | Replace with a high-quality, low-bleed septum appropriate for your temperature. |

| Inlet Liner (GC) / Guard Column (HPLC) | Active sites accumulating non-volatile residues or sample decomposition products [29] [31]. | Clean or replace the liner/guard column. |

| Gas Filters (GC) | Contaminated filter introducing impurities into the carrier gas [29]. | Check the indicator (if available) and replace the filter according to the maintenance schedule. |

Step 4: Perform Active Cleaning

If contamination is suspected in the inlet or column, active cleaning procedures are necessary.

- For GC Inlets: A rigorous cleaning technique involves flushing the injection port with high volumes of pre-heated carrier gas (up to 350°C), purging contaminants out through the septum purge and split vent lines. This method has been shown to reduce GC background by over 99% [31].

- For GC Columns: If the column is contaminated, a controlled bake-out (1-2 hours) at the maximum allowable isothermal temperature can help. Caution: Do not exceed the manufacturer's recommended maximum temperature limit, as this will permanently damage the column [29].

- For HPLC Systems: Flush the entire system thoroughly with strong solvents (e.g., high percentage of acetonitrile or methanol) without the column attached to remove accumulated contaminants from the flow path.

Step 5: Verify Detector and Electronics

If the previous steps do not resolve the issue, the detector itself may be the source.

- Detector Lamps (HPLC/UV): A deteriorating UV lamp will show reduced intensity and increased electronic noise. Review the lamp's usage hours and replace it if necessary [30].

- Detector Flow Cell (HPLC/UV): A contaminated flow cell can cause noise and spurious peaks. Follow manufacturer guidelines for cleaning.

- Detector Parameters: Incorrect detector gas flow rates (in GC) can contribute to noise. Verify that all flow rates are within the manufacturer's recommended specifications [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent and Material Solutions

Using high-purity reagents and appropriate consumables is fundamental to minimizing background noise.

| Item | Function | Considerations for Noise Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Mobile phase components. | Use high-purity grades to minimize UV-absorbing contaminants, especially at low wavelengths [30]. |

| High-Purity Gases (GC) | Carrier, detector, and purge gases. | Use high-purity grades (e.g., 99.999%) and ensure gas filters/traps are fresh to prevent introduction of hydrocarbons, water, and oxygen [29]. |

| Low-Bleed Septa (GC) | Seals the inlet. | "Thermogreen" or similar low-bleed septa significantly reduce siloxane background peaks [31]. |

| Deactivated Inlet Liners (GC) | Vaporization chamber for samples. | Choose a liner design appropriate for your injection mode and volume to minimize sample contact with active sites [31]. |

| In-line Solvent Filters | Placed in solvent reservoirs. | Prevent particulates from the solvent bottles from entering the HPLC pump and check valves [30]. |

| Guard Column | Protects the analytical column. | Traps contaminants and particulate matter that would otherwise foul the more expensive analytical column, preserving peak shape and reducing background [30]. |

| Elbanizine | Elbanizine | High-Purity Research Compound | Supplier | Elbanizine for research. Explore its applications in neuroscience. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

| Rubitecan | Rubitecan, CAS:104195-61-1, MF:C20H15N3O6, MW:393.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Strategies: Optimizing Signal-to-Noise in Data Acquisition and Processing

Beyond instrumental troubleshooting, S/N can be enhanced through method optimization and intelligent data processing.

Data Smoothing and Filtering

Mathematical filters can be applied to reduce baseline noise, but they must be used judiciously to avoid distorting the data.

- Time Constant (Electronic Filter): Many detectors use an electronic time constant (or response time) to smooth the signal. While a higher value reduces noise, it can also over-smooth the data, broadening peaks and potentially smoothing small analyte peaks into the baseline until they are no longer detectable [27].

- Post-Acquisition Processing: Applying filters like Gaussian convolution, Savitsky-Golay smoothing, or Fourier transform after data acquisition is often safer. Since the raw data is preserved, you can adjust parameters or revert changes without permanent data loss [27]. The Wavelet transform is a powerful advanced technique that can both reduce noise and help resolve smaller peaks from the shoulders of larger ones [27].

Optimizing Spectral Data Collection

In techniques that collect spectra across a chromatographic peak (e.g., LC-MS), summing all spectra across the entire peak duration is not ideal for maximizing S/N. Research shows that to achieve the best S/N in the summed spectrum, you should only include spectra whose relative abundance is above 38% of the peak maximum. Including weaker signals from the peak's leading and trailing edges often decreases the overall S/N [32].

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the common types of noise in spectroscopic measurements? Several types of noise can affect spectral data, including:

- Baseline Noise (Drift): Fluctuations in the baseline when no sample is present, caused by the instrument or method, affecting accuracy and stability, especially for low-concentration samples [1].

- Dark Noise: Stray light from the spectrometer's internal optical system and detector, which reduces the signal-to-noise ratio [1].

- Electronic Noise: Generated by electronic components like amplifiers and A/D converters [1].

- Shot Noise: Caused by the uneven emission of electrons from detectors [1].

- Chemical Noise: Background signals from residual chemicals, such as inorganic salts in the sample matrix [33].

2. How does noise specifically impact quantitative analysis? Noise degrades analytical accuracy in several key ways [1]:

- It reduces the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), making it difficult to distinguish the true analyte signal from background noise.

- It leads to poor baseline stability, complicating the accurate integration and quantification of spectral peaks.

- It can decrease the effective resolution of the spectrum, causing blurring in the frequency domain and reducing the accuracy of results.

3. What is the relationship between spectral resolution and noise? The optimal spectral resolution for quantitative analysis can depend on the characteristics of the target analyte. Research on Open-Path FTIR has shown that [34]:

- Gases with narrow spectral features (narrow Full Width at Half Maximum, or FWHM), like ethylene (Câ‚‚Hâ‚„), are often quantified more effectively at higher spectral resolutions (e.g., 1 cmâ»Â¹).

- Gases with broad spectral features (broad FWHM), like propane (C₃H₈), can be quantified effectively at lower resolutions (e.g., 16 cmâ»Â¹), where the standard deviation of concentration results is lower.

Troubleshooting Guides

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| General baseline drift & instability [1] | Fluctuations in ambient temperature/humidity; unstable instrument electronics. | Optimize laboratory environmental controls; allow sufficient instrument warm-up time; use high-quality, stable carrier gases [1]. |

| Elevated baseline across the entire spectrum [33] [1] | High chemical noise from sample matrix (e.g., salts); scattered light noise from optical components. | Purify the sample to remove interferents; ensure optical components are clean and properly aligned [1]. |

| Consistent spurious peaks at fixed positions [1] | Fixed Pattern Noise (FPN) from the detector. | Perform a dark noise measurement and subtract it from subsequent sample measurements during data processing [1]. |

Guide 2: Methodologies for Noise Reduction and Baseline Correction

Protocol A: Sequential Layer Deduction for Baseline Determination (Mass Spectrometry) This practical approach separates baseline drift from the chemical noise level [33].

Determine Baseline Drift:

- Obtain a mass spectrum in profile mode and generate a full list of spectral data points [33].

- Calculate the number of peaks (N) in the spectrum. For a unit resolution spectrum with a peak width of 0.7 Th, N = total data points × 0.07 [33].

- Sort all intensity data in ascending order and average the N lowest intensities. This average is the baseline drift [33].

- Subtract this value from every raw data point to create a baseline drift-deducted dataset (Data Set 0) [33].

Determine Noise Level via Transition Layer:

- Iteratively deduct "layers" from Data Set 0. For each iteration (M), average the N lowest intensities from Data Set M-1 and deduct this value to create Data Set M [33].

- The thickness of these deducted layers will initially be small but will show an accelerated increase at a specific iteration. This is the transition layer, which marks the boundary between noise and signal [33].

- The noise level is the sum of the thicknesses of all layers deducted from the first layer up to and including the transition layer [33].

- Deduct the total noise level from Data Set 0 to obtain a spectrum corrected for both baseline drift and noise [33].

Protocol B: Convolutional Denoising Autoencoder (CDAE) for Raman Spectroscopy This deep learning approach effectively reduces noise while preserving Raman peak integrity [35].

- Model Architecture: The CDAE uses convolutional and pooling layers in the encoder to extract features and eliminate noise. The decoder uses convolutional and upsampling layers to reconstruct the denoised output. A key feature is the addition of two extra convolutional layers at the bottleneck to enhance feature learning without excessive compression [35].

- Training: The model is trained using corrupted spectral data (input) and the original clean data (target output). A Mean Square Error (MSE) loss function is used to minimize the difference between the predicted and original spectra [35].

- Application: The trained model can take a noisy Raman spectrum as input and output a denoised spectrum, successfully retrieving Raman signals free from noise while maintaining peak shapes and intensities [35].

Quantitative Data on Noise and Resolution Impact

The table below summarizes experimental data on how spectral resolution affects quantification precision for gases with different spectral profiles, using a Nonlinear Least Squares (NLLS) method [34].

| Gas Analyte | Spectral FWHM Characteristic | Optimal Spectral Resolution | Standard Deviation of Concentration | Allan Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethylene (Câ‚‚Hâ‚„) | Narrow | 1 cmâ»Â¹ | 0.492 | 0.256 |

| Propane (C₃H₈) | Broad | 16 cmâ»Â¹ | 0.661 | 0.015 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Inert Gases (e.g., Nâ‚‚) | Used to obtain ideal background/reference spectra by creating an environment free of the target analyte [34]. |

| Internal Standards (for Mass Spectrometry) | Known compounds added to the sample for accurate quantification through direct comparison of ion intensities, which requires proper baseline correction [33]. |

| High-Quality Solvents & Salts | To prepare purified samples and calibrants, minimizing chemical noise introduced by the sample matrix [33] [1]. |

| 2-Methylestra-4,9-dien-3-one-17-ol | 2-Methylestra-4,9-dien-3-one-17-ol | High Purity RUO |

| Kibdelin C2 | Kibdelin C2, CAS:105997-85-1, MF:C83H88Cl4N8O29, MW:1803.4 g/mol |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and mitigating high background noise, incorporating both traditional and machine-learning approaches.

Key Experimental Protocols Cited

1. Protocol for Synthetic Background Spectrum in OP-FTIR [34]

- Purpose: To generate a reliable background spectrum for quantitative analysis when directly measuring a background without the target gas is impossible.

- Method:

- Perform moving average filtering on the measured spectral data (S) to create a smoothed spectrum (S1).

- Construct a new spectrum (S0) by replacing all values in S that are less than their corresponding values in S1 with the values from S1.

- Repeat this process iteratively on S0 until a pre-set number of iterations is completed. The final S1 is the synthetic background spectrum.

2. Protocol for Convolutional Autoencoder for Baseline Correction (CAE+ Model) [35]

- Purpose: To perform baseline correction without the parameter dependence of traditional algorithms.

- Method:

- The model is based on a convolutional autoencoder but uses the original spectral data as input, not corrupted data.

- The encoder compresses the input spectrum to extract its features.

- A key component is a comparison function applied after the decoder, which is specifically designed for effective baseline correction.

- The model is trained to capture and remove the baseline features from the input spectrum.

Advanced Noise Reduction Techniques: From Traditional Methods to AI-Driven Solutions

FAQs on Signal Averaging and Noise Reduction

What is signal averaging and how does it improve my data? Signal averaging is a method used to increase the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) by combining multiple repetitions of a periodic signal that are in phase. The signal, being coherent, adds constructively, while random noise tends to cancel out. Theoretically, this provides a SNR improvement proportional to the square root of the number of repetitions (N). For example, averaging 100 signal repetitions improves the SNR by a factor of 10 [36] [37].

What are the fundamental assumptions for successful signal averaging? The technique typically relies on four key assumptions [36]:

- The signal and noise are uncorrelated.

- The timing of the signal is known.

- A consistent signal component exists across repeated measurements.

- The noise is random with a mean of zero. Violations of these assumptions can reduce the effectiveness of the averaging process.

Why is my averaged signal distorted or attenuated? Distortion often stems from trigger jitter, which is the instability in the timing signal used to align each repetition. When waveforms are not perfectly aligned, the averaging process blurs the signal, particularly affecting high-frequency components [38]. The impact of trigger jitter is a frequency-dependent roll-off in the amplitude of your averaged signal [38].

Is there a limit to how much I can average? Yes, the effectiveness of signal averaging is finite. Instrumental instabilities, such as thermal drift or source power fluctuations, eventually prevent further noise reduction. The Allan variance is a metric used to analyze instrument stability and determine the optimal averaging time for a given setup. Beyond this time, further averaging does not improve the SNR [39].

My signal is very weak and gets lost even after averaging. What are my options? For signals with very low initial SNR (around 1), advanced post-processing techniques like wavelet denoising can be highly effective. Methods such as Noise Elimination and Reduction via Denoising (NERD) can separate noise from the signal in the wavelet domain and have been shown to improve SNR by up to three orders of magnitude, successfully retrieving weak spectroscopic signals that averaging alone cannot resolve [40].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Signal Averaging Problems

| Problem & Symptoms | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Background/Noise in Averaged Signal | Insufficient number of averages (N). | Check SNR improvement against the √N rule. | Increase the number of signal repetitions averaged [36]. |

| Non-random, structured noise (e.g., 50/60 Hz interference). | Visually inspect individual traces for repeating noise patterns. | Use a notch filter to remove AC power line interference [37]. | |

| Distorted or Attenuated Signal After Averaging | Excessive trigger jitter causing misalignment. | Measure the standard deviation of your trigger timing. | Use a high-stability, low-jitter trigger source [38]. |

| Improper signal alignment during averaging. | Check the alignment fiducial point (e.g., the point of maximum correlation). | Implement sub-sample alignment algorithms or cross-correlation for precise alignment [37] [38]. | |

| No Further SNR Improvement Despite Averaging | Instrumental drift (thermal, mechanical, or source power). | Perform an Allan variance analysis to find the optimal averaging time [39]. | Reduce drift sources; limit averaging time to the stability-determined optimum [39]. |

| Signal morphology changes over time. | Compare the waveform of the first and last acquisitions in the average. | Reduce the number of averages or use a classifying marker to average only similar signal classes [37] [38]. |

Advanced Methodologies and Protocols

1. Protocol: Determining the Limits of Signal Averaging Using Allan Variance This protocol helps you find the maximum useful averaging time for your experimental setup, preventing wasted time and helping you understand the fundamental limits of your instrument [39].

- Principle: The Allan variance measures the stability of a signal over different time scales. It identifies the point at which the instrument's own drift starts to dominate over random noise.

- Procedure:

- With no target sample, collect a long, continuous data stream from your detector (e.g., spectrometer).

- Calculate the Allan variance (σ²(τ)) for the dataset over a range of averaging times (τ). Many scientific computing libraries (e.g., Python's

allantools) can perform this calculation. - Plot the Allan deviation (σ(τ)) against the averaging time on a log-log plot.

- Interpretation: The curve will typically decrease initially (showing noise reduction) and then reach a minimum before increasing (showing the influence of drift). The averaging time (Ï„) at the minimum of the Allan deviation curve is your optimal averaging time.

2. Protocol: Signal Averaging Test for Spectrometer Validation This test verifies that your signal averaging system is functioning correctly and quantifies its performance [36].

- Procedure:

- Obtain a series of replicate scan-to-scan spectra.

- Average different numbers of scans (e.g., 1, 4, 16, 64, 256).

- For each averaged spectrum, calculate the photometric noise level (e.g., the standard deviation in a flat region of the spectrum).

- Expected Result: The noise level should be reduced by a factor of approximately 1/√N. For instance, averaging 16 scans should reduce the noise to about one-quarter of the single-scan noise level. A failure occurs when the measured noise is more than twice the expected value [36].

3. Methodology: Wavelet Denoising for Weak Signal Extraction When signal averaging is insufficient, wavelet denoising can recover very weak signals.

- Workflow: The NERD method follows a structured process [40]:

- Transform: The noisy signal is transformed into the discrete wavelet domain, decomposing it into different frequency sub-bands (detail components).

- Noise Thresholding: Wavelet coefficients with magnitudes below a statistically determined threshold are eliminated, as they are considered noise.

- Signal Identification & Windowing: To recover weak signal coefficients that were eliminated in the previous step, "windows" in the signal domain are identified from the low-frequency components. Within these windows, coefficients in higher frequency bands are restored.

- Inverse Transform: The processed wavelet coefficients are transformed back to the signal domain, yielding the denoised signal.

The following diagram illustrates this workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key parameters, their functions, and strategic considerations for optimizing signal averaging experiments.

| Item/Parameter | Primary Function | Strategic Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Averages (N) | Directly controls theoretical SNR improvement (√N). | Balance the law of diminishing returns with total acquisition time and system stability. |

| Trigger Source | Provides the timing reference for aligning repetitive signals. | A low-jitter, dedicated external trigger is superior to software-based triggers from the signal itself [38]. |

| Allan Variance | A diagnostic metric to determine the stability-limited optimal averaging time. | Use it to characterize your instrument and avoid futile averaging beyond the system's intrinsic stability [39]. |

| Alignment Fiducial | The specific point in each signal repetition used for alignment. | The point of maximum cross-correlation is more robust against noise than a simple threshold-based peak detection [37]. |

| Wavelet Denoising | A post-processing technique to extract signals from noise when averaging is insufficient. | Particularly powerful for recovering very weak signals (SNR ~1) and preserving sharp, localized features [40]. |

| Classifying Marker | An external signal that categorizes data segments for conditional averaging. | Enables separate averaging of different signal types (e.g., "good" vs. "bad" events), preventing morphological blurring [38]. |

| Glidobactin A | Glidobactin A | Potent Proteasome Inhibitor | RUO | Glidobactin A is a potent natural proteasome inhibitor for cancer & cell biology research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Cefuroxime | Cefuroxime | Second-Generation Cephalosporin | RUO | High-purity Cefuroxime for antibiotic resistance research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My spectroscopic signal is still noisy after applying a Fourier filter. Why is a Wavelet transform potentially a better method?

The key difference lies in how the two methods localize information. The Fourier Transform is excellent for identifying frequencies but loses all time information; a small frequency change affects the entire Fourier domain, making it impossible to know where a particular signal occurred. In contrast, wavelet functions are localized both in frequency (or scale) and in time. This means that after a Wavelet Transform, you retain both time and frequency information, allowing you to remove noise from specific regions of your signal without affecting the entire dataset [41] [42]. This makes wavelets particularly superior for processing non-stationary signals or signals with abrupt changes, which are common in spectroscopic analysis [43].

Q2: How do I choose the right wavelet function (e.g., Daubechies, Symlet) for my spectroscopic data?

There is no single "best" wavelet for all scenarios, but the choice is critical. The general principle is to select a wavelet whose shape closely resembles the features you wish to preserve in your signal [42].

The table below summarizes common wavelet families and their typical applications in spectroscopy:

| Wavelet Family | Key Characteristics | Common Use Cases in Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Daubechies (dbN) | Orthogonal, compact support, asymmetric [41] [44] | A widely used default choice; effective for denoising a broad range of spectral signals [45] [46] |

| Symlets (symN) | Nearly symmetric, orthogonal [44] | Designed to have higher symmetry than Daubechies, which can be beneficial for reducing signal distortion [42] |

| Coiflets (coifN) | More symmetric than Daubechies, with scaling functions that also have vanishing moments [44] | Useful when improved symmetry is desired for feature preservation [41] |

| Biorthogonal Spline (biorNr.Nd) | Symmetric, linear phase, offers perfect reconstruction [44] | Excellent for tasks requiring precise signal reconstruction; used in medical imaging and JPEG2000 [44] |

A practical approach is to test a few (e.g., db4, db8, sym8) and evaluate the output based on the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) improvement and the preservation of critical peaks [42].

Q3: What is the difference between hard, soft, and improved thresholding, and which should I use?

The threshold function determines how the wavelet coefficients are modified to suppress noise.

| Threshold Type | Function Principle | Pros & Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Hard Threshold | Sets all coefficients with an absolute value below the threshold (λ) to zero; leaves others unchanged [44] | Pro: Better preservation of sharp features like peaks [47]. Con: Can cause artificial "jitter" or discontinuities in the reconstructed signal [43] [47] |

| Soft Threshold | Sets coefficients below λ to zero and shrinks other coefficients towards zero by λ [44] | Pro: Yields a smoother output [47]. Con: Can lead to an oversmoothing effect and loss of peak amplitude [48] [47] |

| Improved Threshold | A dynamic function that aims to combine the advantages of hard and soft thresholding, often by introducing a variable correction factor [48] [47] | Pro: Adapts to the noise level and signal structure, offering a better balance between noise removal and signal preservation [48] [47]. Con: More complex to implement. |

For spectroscopic signals where preserving the amplitude and shape of peaks is critical, an improved adaptive threshold strategy is often recommended over traditional hard or soft thresholding [48].

Q4: How do I determine the optimal decomposition level and threshold value for my experiment?

Selecting these parameters is a crucial step for effective denoising.

- Decomposition Level: If the level is too low, noise will not be separated effectively. If it is too high, the useful signal will be compressed and distorted, leading to information loss [43]. A method based on entropy analysis of the wavelet coefficients has been proposed to select the optimal level objectively [43]. A practical rule of thumb is that the maximum useful level can be calculated as ( \log_2(N) ), where ( N ) is the number of data points in your signal [46].

- Threshold Value: The universal threshold, often called the VisuShrink method, is a common starting point and is defined as ( \lambda = \sigma \sqrt{2 \log(N)} ), where ( \sigma ) is the noise standard deviation and ( N ) is the signal length [43] [47]. The noise standard deviation ( \sigma ) can be robustly estimated from the median of the absolute deviation of the finest detail coefficients: ( \sigma = \frac{{\text{median}(|Cd_{j,k}|)}}{0.6745} ) [47]. For better results, use level-dependent thresholds [43].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Basic Wavelet Denoising of a Spectrum using Python

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for denoising a one-dimensional spectral signal using the PyWavelets library.

Import Libraries.

Decompose the Signal. Perform a multilevel wavelet decomposition on your input spectrum

X.The

coeffsvariable is a list containing the approximation coefficients at the highest level followed by the detail coefficients from the finest to the coarsest level [45].Apply Thresholding. Create a copy of the coefficients and apply a threshold. A simple soft threshold can be implemented as follows:

Reconstruct the Signal. Use the thresholded coefficients to reconstruct the denoised signal.

Protocol 2: Advanced Denoising with an Improved Threshold Strategy

For applications requiring higher precision, such as Tunable Diode Laser Absorption Spectroscopy (TDLAS) or Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS), an improved threshold strategy can be implemented [48] [43].

- Follow Steps 1 and 2 from the basic protocol.

- Implement an Improved Threshold Function. This function creates a smoother transition between the hard and soft threshold behaviors [48].

- Apply the Improved Threshold. Use the function from the previous step on the detail coefficients. The parameter

alphacan be tuned, wherealpha=0gives a soft threshold and a largeralphamakes it harder [48]. - Reconstruct the Signal as in Step 4 of the basic protocol.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a standard wavelet denoising process.

Wavelet Denoising Logical Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

The following table details key computational "reagents" and tools essential for implementing wavelet denoising in spectroscopic research.

| Item / Software | Function / Purpose | Example / Note | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PyWavelets (Python) | A comprehensive open-source library for Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT), Stationary Wavelet Transform (SWT), and more [45] | The primary library used in the experimental protocols above. | ||

| SciKit-Image (Python) | Image processing library that includes a ready-to-use denoise_wavelet function for 1D signals and 2D images [45] |

Useful for quick implementation without manually handling coefficients. | ||

| MATLAB Wavelet Toolbox | A commercial toolbox with GUI apps and command-line functions for wavelet analysis and denoising [42] | Includes the Wavelet Signal Denoiser app for interactive analysis. | ||

| Daubechies Wavelets (dbN) | A family of orthogonal wavelets with compact support; a common default choice [41] [45] | db4, db8 are frequently used; higher 'N' implies smoother wavelets. |

||

| Symlets (symN) | Nearly symmetric wavelets from the Daubechies family, designed for higher symmetry [42] [44] | sym8 is a popular alternative to db8 to reduce signal distortion. |

||

| Universal Threshold | A standard global threshold rule for initial experiments [43] [47] | ( \lambda = \hat{\sigma} \sqrt{2 \log(N)} ) | ||

| Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) | A robust method for estimating the noise standard deviation (σ) from the data itself [47] | ( \hat{\sigma} = \frac{{\text{median}( | Cd_{j,k} | )}}{0.6745} ) |

| Mifepristone methochloride | Mifepristone methochloride | High Purity | RUO | Mifepristone methochloride: a potent steroid antagonist for biochemical research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | ||