UV-Vis Spectroscopy for Raw Material Identification: Principles, Applications, and Advanced Methodologies for Pharmaceutical Research

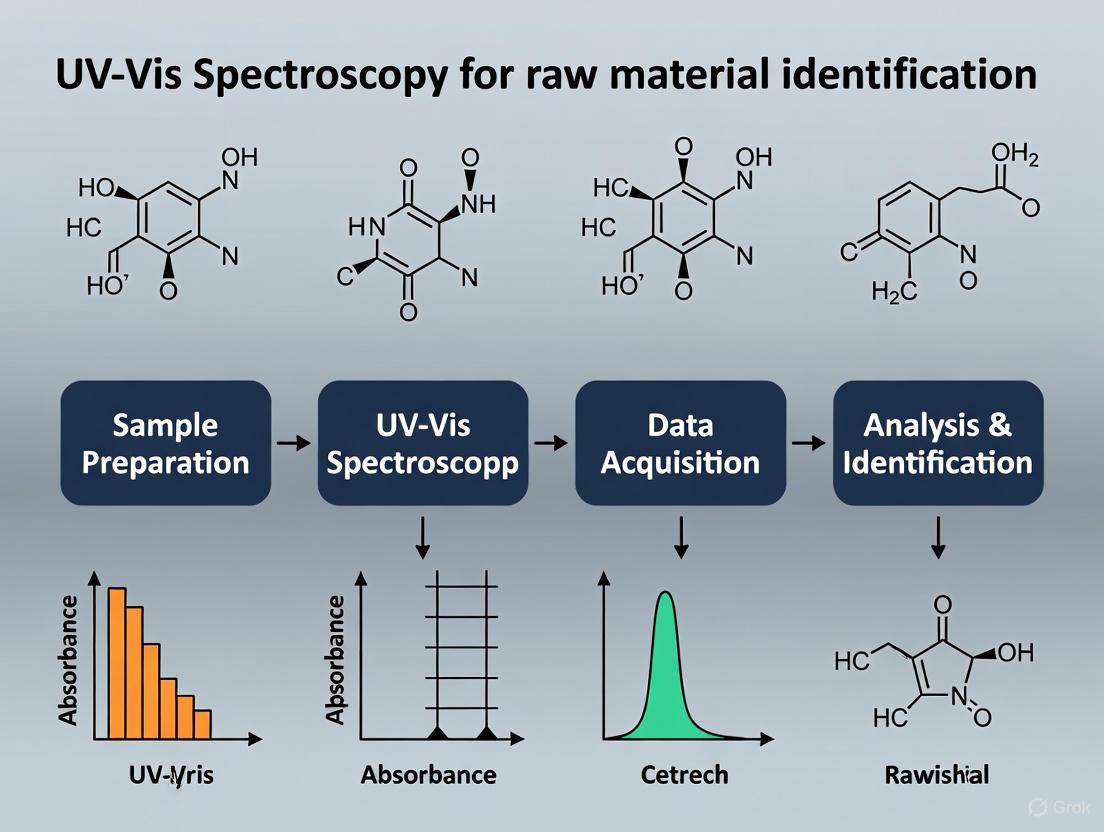

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy as a critical tool for raw material identification in pharmaceutical development and quality control.

UV-Vis Spectroscopy for Raw Material Identification: Principles, Applications, and Advanced Methodologies for Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy as a critical tool for raw material identification in pharmaceutical development and quality control. It explores foundational principles, including the Beer-Lambert law and instrumental configurations like single-beam and double-beam systems. The content details methodological applications from traditional solution analysis to advanced solid-formulate techniques like Diffuse Reflectance Spectroscopy, alongside emerging trends such as machine learning integration for complex sample analysis. Practical guidance on troubleshooting common instrumental and sample-related challenges is included, along with validation frameworks and comparative analyses with other spectroscopic techniques. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current practices and future directions to ensure efficacy, safety, and compliance in raw material verification.

UV-Vis Spectroscopy Fundamentals: Core Principles for Pharmaceutical Raw Material Analysis

The Beer-Lambert Law (also referred to as Beer's Law) is an empirical relationship that forms the quantitative cornerstone of absorption spectroscopy, including Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy. It defines the attenuation of light as it passes through a material, establishing a direct relationship between the light absorbed by a substance and its concentration within a solution [1] [2]. This principle is indispensable for raw material identification in pharmaceutical development, enabling researchers to accurately determine the concentration of an absorbing species in a solution through straightforward absorbance measurements [3].

The law is a combination of the findings of two scientists: August Beer, who described the relationship between absorbance and concentration, and Johann Heinrich Lambert, who related absorbance to the path length light travels through a material [4] [5]. The modern formulation of the law states that the absorbance of a light beam by a solution is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing substance and the length of the path the light takes through the solution [1] [4].

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Formulation

Core Components and Equation

The Beer-Lambert Law is mathematically expressed by the fundamental equation:

A = εlc

- A is the Absorbance (also called optical density), a dimensionless quantity.

- ε is the Molar Absorptivity (or molar extinction coefficient), with units of L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹.

- l is the Path Length, the distance the light travels through the solution, typically measured in centimeters (cm).

- c is the Concentration of the absorbing species in the solution, expressed in moles per liter (mol/L).

This formula is derived from the logarithmic relationship between the incident and transmitted light intensities [1] [5]. Absorbance is defined as the logarithm (base 10) of the ratio of the incident light intensity ((I_0)) to the transmitted light intensity ((I)):

Relationship between Absorbance and Transmittance

Transmittance (T) is a directly measurable quantity representing the fraction of incident light that passes through a sample [3]. It is defined as:

T = I / Iâ‚€

Transmittance is often expressed as a percentage (%T). Absorbance and transmittance have an inverse logarithmic relationship, meaning that as absorbance increases, transmittance decreases [3] [2]. This relationship can be expressed as:

A = -logâ‚â‚€T

The following table provides a comparison of key terms and their relationships within the Beer-Lambert Law framework.

Table 1: Core Components of the Beer-Lambert Law

| Term | Symbol | Definition | Role in Beer-Lambert Law | Common Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorbance | A | Measure of light absorbed by the sample | The calculated dependent variable | Dimensionless |

| Molar Absorptivity | ε | Constant indicating how strongly a species absorbs light at a specific wavelength | A proportionality constant unique to each substance | L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹ |

| Path Length | l | Distance light travels through the solution | An independent variable, typically fixed by the cuvette | Centimeters (cm) |

| Concentration | c | Amount of absorbing solute in the solution | The primary independent variable to be determined | mol/L (M) |

| Transmittance | T | Fraction of incident light that passes through the sample | The directly measured quantity from which A is derived | Dimensionless or % |

Conceptual Workflow

The logical flow from measurement to quantitative analysis using the Beer-Lambert Law is summarized in the following diagram.

Experimental Validation and Quantitative Analysis

For drug development professionals, the practical application of the Beer-Lambert Law for quantifying analytes relies on robust and reproducible experimental protocols.

Standard Operating Protocol for UV-Vis Quantification

The following workflow outlines the key steps for a standard quantitative analysis using UV-Vis spectroscopy.

Step 1: Instrument Calibration. Prior to analysis, a wavelength accuracy test should be performed using a standard reference material, such as a holmium oxide or holmium glass filter, which has known, sharp absorption peaks at specific wavelengths (e.g., 361 nm, 445 nm, 460 nm) [6]. This verifies that the spectrophotometer is free from significant instrumental errors [6].

Step 2: Preparation of Standard Solutions. A stock solution of the analyte of known, high concentration is prepared. This stock is then serially diluted with an appropriate solvent to create a set of standard solutions covering a range of concentrations from very dilute to relatively high, ensuring the expected absorbances fall within a reliable range (typically 0.1 to 1.0 AU) [6] [3]. For example, a 2 M stock solution of potassium permanganate (KMnOâ‚„) can be diluted to concentrations ranging from 0.0001 M to 0.1 M [6].

Step 3: Spectrum Acquisition. The absorbance of each standard solution is measured at a fixed wavelength, typically the absorption maximum (λₘâ‚â‚“) for the analyte, using a cuvette with a constant path length (e.g., 1 cm) [3]. The solvent (blank) is measured first to establish a baseline of 0 absorbance.

Step 4: Calibration Curve Construction. A graph is plotted with absorbance on the y-axis and the known concentration of each standard solution on the x-axis [3]. The data should form a straight line. Linear regression is performed to obtain the equation of the line (y = mx + b), where the slope (m) is equal to the product of the molar absorptivity and the path length (εl) [3].

Step 5: Analysis of Unknown Sample. The absorbance of the prepared unknown sample is measured under identical instrumental conditions (same wavelength, same cuvette).

Step 6: Concentration Calculation. The measured absorbance of the unknown is substituted into the linear equation of the calibration curve to calculate its concentration [3].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, materials, and equipment required for conducting UV-Vis analysis in a research setting for raw material identification.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for UV-Vis Analysis

| Item | Function / Role | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Grade Analyte | The pure substance to be identified or quantified; used to prepare a standard. | e.g., Pure caffeine, potassium permanganate [6] [2] |

| Spectrophotometric Grade Solvent | A solvent that does not absorb significantly in the spectral region of interest; used to dissolve the analyte and for blank measurement. | e.g., Distilled water, HPLC-grade methanol, hexane [6] |

| Volumetric Glassware | For precise preparation and dilution of standard and sample solutions. | Class A volumetric flasks and pipettes |

| Cuvette | A container of fixed path length that holds the sample solution in the light path. | 1 cm path length; material compatible with wavelength range (e.g., quartz for UV, glass/plastic for Vis) |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | The instrument that generates light and measures the intensity of light transmitted through the sample. | Should include a monochromator to select specific wavelengths and a suitable detector [3] |

| Wavelength Standard | Used to verify the accuracy of the spectrophotometer's wavelength scale. | Holmium glass filter [6] |

Limitations and Advanced Considerations

Despite its widespread utility, the Beer-Lambert Law is an idealization and is subject to several significant limitations that researchers must recognize to avoid analytical errors.

Fundamental Limitations

Concentration Limitations: The law assumes a linear relationship between absorbance and concentration. However, at high concentrations (typically >0.01 M), electrostatic interactions between analyte molecules can alter the analyte's ability to absorb radiation, leading to negative deviations from linearity [6] [7] [8]. This is considered a fundamental or real deviation [6].

Chemical Deviations: Changes in the chemical environment of the analyte, such as shifts in pH, temperature, or solvent composition, can cause association, dissociation, or solvation, which may change the absorption spectrum (e.g., shift the λₘâ‚â‚“ or alter ε) [6] [8].

Instrumental Deviations: The law assumes the use of monochromatic light. In practice, spectrophotometers use a band of wavelengths, which can lead to inaccuracies, especially where the molar absorptivity changes rapidly with wavelength [6] [7]. Stray light reaching the detector is another common source of error, particularly at high absorbances [7] [2].

Optical and Scattering Effects: The derivation of the law neglects reflection losses at cuvette surfaces and light scattering due to particulates or turbidity in the sample [7] [8] [2]. For samples on reflective substrates (e.g., thin films on metals), interference effects from the wave nature of light can drastically alter band shapes and intensities [7] [8].

Beyond the Classical Law: Electromagnetic and Machine Learning Extensions

Recent research has focused on developing models that surpass the limitations of the classical Beer-Lambert Law.

Electromagnetic Theory Extensions: A unified electromagnetic framework has been proposed to address fundamental deviations at high concentrations [6]. This model incorporates the complex refractive index, accounting for effects of polarizability and electric displacement. It extends the classical law from a linear to a polynomial form to account for the non-linear effects of refractive index changes at high concentrations [6] [7]:

A = (4πν / ln10) * (βc + γc² + δc³) * l

Where β, γ, and δ are refractive index coefficients. This modified model has demonstrated superior performance with very low error (RMSE < 0.06) in both organic and inorganic solutions like KMnO₄ and methyl orange [6].

Machine Learning Approaches: Innovative methods are being developed that integrate image analysis with machine learning (ML) to estimate chemical concentrations [9]. For instance, a ridge regression ML model trained on images of K₂Cr₂O₇ and KMnO₄ solutions can predict concentrations with high precision based solely on color intensity, effectively bypassing limitations related to molecular interactions and offering a calibration-free approach for certain applications [9].

The Beer-Lambert Law remains the fundamental quantitative principle underpinning UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy. Its straightforward equation, A = εlc, provides drug development researchers with a powerful tool for the identification and quantification of raw materials. A thorough understanding of its principles, coupled with rigorous experimental protocols for creating calibration curves, is essential for generating reliable analytical data. However, an awareness of the law's limitations—including deviations at high concentrations, chemical changes, and instrumental factors—is critical for its correct application. Emerging advancements, particularly those rooted in electromagnetic theory and machine learning, promise to extend the capabilities of quantitative absorption spectroscopy beyond the constraints of the classical law, paving the way for even more accurate and robust analytical methods in pharmaceutical research and development.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy stands as a cornerstone analytical technique in pharmaceutical research, particularly for the identification and verification of raw materials. The reliability of these analyses is fundamentally governed by the instrumental design employed. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the three principal UV-Vis spectrophotometer architectures—single-beam, double-beam, and array-based systems. It delineates their operational principles, comparative performance characteristics, and specific applicability within a pharmaceutical raw material identification framework. By integrating detailed experimental protocols and data analysis workflows, this whitepaper serves as a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists tasked with selecting and implementing the optimal spectroscopic system to ensure regulatory compliance and analytical integrity in drug development.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is an analytical technique that measures the amount of discrete wavelengths of UV or visible light that are absorbed by or transmitted through a sample in comparison to a reference or blank sample [10]. The underlying principle involves the promotion of electrons in a substance to a higher energy state upon absorbing a specific amount of energy, which is inversely proportional to the light's wavelength [10]. In the context of pharmaceutical raw material identification, this technique is indispensable for qualitative verification, quantitative assay, and the detection of impurities based on characteristic absorption profiles.

The fundamental components of a UV-Vis spectrophotometer include a light source, a wavelength selection device, a sample holder, and a detector [10] [11]. A steady source capable of emitting light across a wide range of wavelengths is essential, with common configurations utilizing a deuterium lamp for the UV region and a tungsten or halogen lamp for the visible range [10]. The wavelength selector, typically a monochromator containing a diffraction grating, is used to isolate a narrow band of light to probe the sample [10] [11]. Finally, the transmitted light is measured by a detector, such as a photomultiplier tube (PMT) or a silicon photodiode, which converts the light intensity into an electronic signal [10] [11]. The configuration and quality of these components, especially the optical path, critically determine the instrument's performance, leading to the development of single-beam, double-beam, and array-based systems.

Core Instrumentation Architectures

Single-Beam Spectrophotometers

A single-beam instrument employs the most straightforward optical arrangement. In this configuration, light from the source passes through a monochromator, then through the sample, and finally to the detector [12] [11]. The absorbance measurement is performed by first measuring the intensity of the incident light (Iâ‚€) with a blank reference placed in the sample holder, followed by measuring the transmitted light (I) with the sample in place. The absorbance is calculated as A = logâ‚â‚€(Iâ‚€/I) [12] [10].

The primary advantage of this system is its simpler mechanical and optical design, which translates to a lower initial cost [12]. However, a significant limitation is its susceptibility to fluctuations in the light source intensity and baseline drift over time, as these factors directly impact the measured absorbance value [12] [11]. Consequently, single-beam instruments require frequent recalibration with a blank and are generally considered less stable than double-beam systems, making them best suited for routine quantitative analyses in educational or quality control settings where high precision is not the paramount requirement [12].

Double-Beam Spectrophotometers

Double-beam instruments are designed to compensate for the inherent instabilities of single-beam systems. In this architecture, the light beam from the monochromator is split into two separate paths: one beam passes through the sample, and the other, the reference beam, passes through a blank solvent [12] [11]. A beamsplitter, which can be static or dynamic, facilitates this division. The intensities of both beams are then measured simultaneously or in rapid alternation by a single detector or a pair of matched detectors, and the instrument's electronics calculate the absorbance based on the ratio of the two signals (A = logâ‚â‚€(Iáµ£/Iâ‚›)) [12].

This ratiometric measurement is the key to its performance. Any fluctuation in the light source intensity or drift in the detector electronics affects both the sample and reference beams equally, thereby canceling out the effect on the final absorbance reading [12] [11]. This provides superior accuracy and precision, excellent baseline stability, and a wider dynamic range. While these instruments are more complex and expensive, they are the preferred choice for research applications, detailed spectral scanning, and any scenario demanding highly reliable quantitative data [12].

Array-Based (Diode Array) Spectrophotometers

Array-based systems, often referred to as Diode Array Detector (DAD) systems, represent a significant paradigm shift in optical design. Unlike conventional systems that use a monochromator before the sample to select a single wavelength at a time, a DAD uses a polychromatic light source that irradiates the sample with the full spectrum of light simultaneously [10]. The transmitted light is then dispersed onto a fixed array of hundreds of individual silicon photodiode detectors, each corresponding to a specific nanometer wavelength [10].

The most profound advantage of this "reverse optics" design is speed, as the entire spectrum can be captured in less than a second. This makes it ideal for kinetic studies, monitoring chromatographic eluents in HPLC, and analyzing unstable compounds. Furthermore, because the entire optical path after the sample is static, with no moving gratings, these systems often demonstrate enhanced mechanical reliability and photometric accuracy [10]. The primary trade-off can be a slightly lower resolution compared to high-end double-beam scanning instruments, though this is sufficient for the vast majority of pharmaceutical applications.

Performance Comparison and Selection Criteria

Selecting the appropriate instrument requires a careful balance between performance needs, application requirements, and budgetary constraints. The table below provides a direct comparison of the key characteristics of the three systems.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of UV-Vis Spectrophotometer Architectures

| Feature | Single-Beam | Double-Beam | Array-Based (DAD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optical Path | Single path through sample [12] | Split into sample and reference beams [12] | Polychromatic light through sample; dispersion after sample [10] |

| Measurement Speed | Good for single wavelengths | Slower for full spectrum scanning | Very fast; full spectrum capture in milliseconds [10] |

| Accuracy & Precision | Lower; susceptible to source drift [12] | High; compensates for source drift [12] | High; no moving parts during acquisition [10] |

| Baseline Stability | Subject to drift over time [12] | Excellent stability; drift affects both beams equally [12] | Very good; minimal drift due to fixed optics |

| Wavelength Resolution | Determined by monochromator slit width [11] | Determined by monochromator slit width [11] | Fixed by diode spacing and optical design |

| Dynamic Range | Limited, especially at high/low absorbance [12] | Wider dynamic range [12] | Wide dynamic range |

| Cost | Lower initial cost [12] | Higher initial cost [12] | Higher initial cost |

| Ideal Applications | Routine QC, educational labs, fixed-wavelength quantitation [12] | Research, method development, high-precision quantitation, spectral scanning [12] | HPLC detection, kinetic studies, rapid-scan spectroscopy, process analysis [10] |

For raw material identification (ID), the choice often hinges on the required level of confidence and workflow integration. A double-beam system is ideal for creating highly reproducible reference spectral libraries and for verifying materials with subtle spectral differences. Its stability ensures that the recorded spectrum is a true representation of the material, which is critical for regulatory filings. An array-based system, on the other hand, offers unparalleled efficiency for high-throughput environments, allowing for near-instantaneous ID checks against a library. The single-beam system can be considered for less critical, high-volume ID tests where cost is a primary driver.

Experimental Protocol for Raw Material Identification

This section outlines a detailed methodology for identifying a pharmaceutical raw material using a double-beam UV-Vis spectrophotometer, a common scenario in a GMP-compliant research laboratory.

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Critical Specification/Note |

|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Analytical instrument for measuring light absorption. | Double-beam or array-based system, validated and qualified. |

| Quartz Cuvettes | Holder for sample and reference solutions. | Must be paired, with a defined path length (e.g., 1 cm); quartz is transparent to UV light [10]. |

| High-Purity Solvent | Dissolves the analyte to form a homogeneous solution. | Spectroscopic grade (e.g., HPLC grade methanol, water); must be transparent in the measured range. |

| Reference Standard | Authentic, certified material for comparison. | Pharmacopoeial standard (e.g., USP, Ph. Eur.) of the target raw material. |

| Volumetric Flasks | For precise preparation of sample and standard solutions. | Class A glassware. |

| Micropipettes | For accurate and precise transfer of liquid volumes. | Calibrated regularly. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Instrument Preparation: Power on the spectrophotometer and the computer. Allow the instrument to initialize and the lamp to warm up for the time specified by the manufacturer (typically 30 minutes). Open the associated software and select the spectral acquisition mode.

- Baseline Correction: Using a pair of matched quartz cuvettes, fill both with the pure solvent. Place them in the sample and reference compartments. Execute a "baseline correction" or "auto-zero" function across the desired wavelength range (e.g., 200-400 nm for UV analysis). This step records the solvent's absorption profile and stores it for automatic subtraction from subsequent sample measurements.

- Sample Preparation:

- Test Sample: Accurately weigh a quantity of the unknown raw material. Dissolve and dilute it with the solvent to a target concentration expected to yield an absorbance within the ideal range of 0.2 to 1.0 AU [10].

- Reference Standard Solution: Prepare a solution of the authentic reference standard at a concentration similar to the test sample.

- Spectral Acquisition:

- Replace the solvent in the sample cuvette with the test sample solution. Ensure the cuvette's optical faces are clean and properly aligned in the beam path.

- In the software, initiate a full spectrum scan. The instrument will automatically measure the sample and reference beams, calculate the absorbance at each wavelength, and generate a spectrum.

- Repeat the process for the reference standard solution.

- Data Analysis and Identification:

- Overlay Spectra: Overlay the spectrum of the test sample with that of the reference standard within the software.

- Compare Key Features: Identify and compare the λ_max (wavelength of maximum absorption) for all significant peaks. The presence and relative positions of these peaks are a primary identifier.

- Calculate Similarity: Use the software's spectral comparison algorithm (e.g., correlation coefficient, spectral contrast angle) to obtain a quantitative measure of the match between the two spectra. A match score above a pre-defined threshold (e.g., >0.995) confirms the identity of the raw material.

The workflow for this identification process is summarized in the following diagram:

Advanced Considerations for Pharmaceutical Applications

Impact of Instrument Parameters

The fidelity of a UV-Vis spectrum is critically dependent on several instrumental parameters:

- Spectral Bandwidth (SBW): This is the width of the wavelength window selected by the monochromator, expressed as Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) [11]. A narrower SBW provides better spectral resolution, allowing closely spaced peaks to be distinguished. However, it also reduces the light energy reaching the detector, which can worsen the signal-to-noise ratio. A broader SBW improves light throughput but can cause peaks to broaden and fine structure to be lost [11]. The bandwidth should typically be set to 1/10 of the natural width of the sample's absorption peak [11].

- Stray Light: This is any light that reaches the detector at wavelengths outside the selected SBW [11]. It becomes a significant problem at high sample absorbances, as it causes a deviation from the Beer-Lambert law, resulting in falsely low absorbance readings [11]. This directly impacts the photometric linearity of the instrument. Double-monochromator designs are specifically used to minimize stray light for demanding applications involving highly absorbing samples [11].

Data Analysis and Validation

For robust raw material identification, simple visual comparison of spectra is insufficient. Modern software employs sophisticated algorithms:

- Chemometrics and Machine Learning: Techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) can be used to differentiate between raw materials from different suppliers based on subtle spectral variations that may be imperceptible to the eye. The field of chemometrics is increasingly falling under the broader umbrella of data science and machine learning, with tools allowing for the incorporation of domain knowledge for interpretable results [13].

- Method Validation: Even for qualitative ID tests, the analytical procedure must be validated. This includes demonstrating specificity (the method can distinguish the target compound from others), robustness (to minor changes in instrument parameters), and repeatability.

The selection of a UV-Vis spectrophotometer—whether single-beam, double-beam, or array-based—is a critical decision that directly influences the accuracy, efficiency, and regulatory standing of pharmaceutical raw material identification research. Single-beam systems offer a cost-effective solution for routine tasks but lack the stability for high-precision work. Double-beam instruments remain the gold standard for research and method development due to their superior stability and accuracy, making them ideal for building definitive spectral libraries. Array-based systems provide unmatched speed and reliability for high-throughput and hyphenated techniques like HPLC.

A deep understanding of the principles, performance trade-offs, and advanced operational parameters of these systems empowers scientists and drug development professionals to make informed decisions. This ensures that the chosen instrumentation not only meets the immediate need for material identification but also supports the broader goals of product quality, patient safety, and regulatory compliance throughout the drug development lifecycle.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is a foundational analytical technique in material identification research that measures the absorption of ultraviolet and visible light by molecules. This absorption occurs when electrons in molecular orbitals are promoted to higher energy states through the excitation by specific wavelengths of light [14]. The technique covers wavelengths from approximately 200 to 800 nanometers, bridging the high-energy ultraviolet region (200-400 nm) and the visible spectrum (400-800 nm) that human eyes can perceive [15] [10]. The visible spectrum itself encompasses violet (400-420 nm) through red (620-780 nm) light [15]. Molecules that absorb this light contain functional groups known as chromophores, characterized by their ability to capture photons of specific energies, leading to electronic transitions [14].

The principle underlying this technique is quantized energy absorption. When a photon carries energy exactly matching the energy difference (ΔE) between a ground state and an excited state molecular orbital, it can be absorbed, promoting an electron to a higher energy level [16]. This relationship is described by the equation E = hν, where E is energy, h is Planck's constant, and ν is the frequency of light [16]. The resulting absorption spectrum, a plot of absorbance versus wavelength, provides a characteristic fingerprint that researchers use to identify substances, quantify concentrations, and investigate molecular properties [10].

The Electronic Structure of Chromophores and Light Absorption

Molecular Orbitals and Electronic Transitions

Chromophores typically feature systems with delocalized π electrons [14]. In molecular orbital theory, electrons occupy discrete energy levels. The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) are central to UV-Vis absorption [17] [16]. The energy gap between these orbitals determines the wavelength of light a chromophore will absorb. A smaller HOMO-LUMO gap corresponds to absorption at longer wavelengths [16].

When light of sufficient energy strikes a chromophore, an electron undergoes an electronic transition from the HOMO to the LUMO. The probability of this transition depends significantly on the spatial overlap of the orbitals involved [15]. Transitions between orbitals with good overlap, such as π to π, have high probabilities and intense absorptions, while transitions between orbitals with poor overlap, such as n to π, have low probabilities and weak absorptions [15].

Types of Electronic Transitions

Chromophores can undergo several types of electronic transitions, each with characteristic energy requirements and absorption intensities. The most common transitions in organic molecules involve σ, π, and n (non-bonding) electrons.

Table 1: Characteristics of Electronic Transitions in Organic Chromophores

| Transition Type | Typical λmax Range | Molar Absorptivity (ε) | Chromophore Example | Molecular Orbital Overlap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ → σ* | < 200 nm [16] | High | C-C, C-H [17] | Good |

| n → Ï€* | 150 - 250 nm [17] | Low (10-3000 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹) [17] | Carbonyl compounds [17] | Poor [15] |

| Ï€ → Ï€* | ~170 nm and higher [16] | Very High (>10,000 Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹) [15] | Alkenes, conjugated systems [17] | Excellent [15] |

| n → σ* | ~150-250 nm | Moderate | Alcohols, amines [17] | Moderate |

The π → π* transition is particularly important in conjugated systems. In isolated alkenes like ethene, this transition occurs at approximately 170 nm [16]. However, conjugation—the alternation of single and double bonds—shifts this absorption to longer wavelengths (lower energies), a phenomenon known as a bathochromic shift [15] [16]. This occurs because conjugation lowers the HOMO energy and raises the LUMO energy, effectively reducing the energy gap (ΔE) between them [16].

Diagram 1: Electronic transition from HOMO to LUMO

Factors Influencing Chromophore Absorption Properties

Conjugation and Delocalization

Conjugation represents the most significant factor affecting chromophore absorption. As the extent of conjugation increases, the λmax value shifts to longer wavelengths and the intensity of absorption often increases [16]. This systematic bathochromic and hyperchromic shift with increasing conjugation provides researchers with a predictable relationship for designing molecules with specific absorption properties.

Table 2: Effect of Conjugation on Absorption Maxima in Polyenes

| Compound | Number of Conjugated Double Bonds | λmax (nm) | Observed Color |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethene | 1 | ~174 [16] | Colorless |

| 1,3-Butadiene | 2 | ~217 [16] | Colorless |

| 1,3,5-Hexatriene | 3 | ~258 [16] | Colorless |

| Lycopene | 11 | ~472 | Red |

| β-Carotene | 11 | ~454 | Orange |

This relationship between conjugation length and absorption wavelength enables researchers to tailor organic chromophores for specific applications, including extended shortwave infrared (ESWIR) absorption by designing systems with extremely narrow optical gaps through sophisticated donor-acceptor architectures incorporating antiaromatic cores [18].

Solvent Effects

The polarity of the solvent significantly influences absorption spectra, particularly for transitions involving non-bonding electrons [19]. Polar solvents can stabilize n and π orbitals to different degrees through hydrogen bonding and dipole-dipole interactions, causing shifts in λmax. For n→π* transitions, increasing solvent polarity typically causes a hypsochromic shift (blue shift) to shorter wavelengths, as polar solvents more effectively stabilize the n electrons in their ground state relative to the excited state [17]. Conversely, π→π* transitions often experience bathochromic shifts in polar solvents due to better stabilization of the more polar excited state.

pH and Molecular Environment

Changes in pH can dramatically alter chromophore absorption by affecting the ionization state of functional groups [19]. For example, the amino acid tyrosine absorbs at 274 nm at pH 6 but shifts to 295 nm under alkaline conditions (pH 13) due to ionization of the phenolic hydroxyl group [19]. This property is exploited in pH indicators, where protonation/deprotonation changes the conjugation system or electron distribution, resulting in visible color changes [14]. In material identification, these pH-dependent shifts can help characterize functional groups in unknown compounds.

Instrumentation and Measurement for Material Identification

UV-Vis Spectrophotometer Components

A UV-Vis spectrophotometer consists of several key components that work together to measure light absorption accurately [17] [10]:

- Light Source: Produces broad-spectrum radiation. Instruments typically use both UV (deuterium lamp) and visible (tungsten or halogen lamp) sources to cover the full wavelength range, with an automatic switcharound 300-350 nm [17] [10].

- Wavelength Selector: Isolates specific wavelengths from the broad-source spectrum. Monochromators containing diffraction gratings (typically with 1200-2000 grooves/mm) provide the highest resolution and flexibility [10].

- Sample Container: Holds the solution being analyzed. For UV studies, quartz or fused silica cuvettes are essential as they are transparent to UV light, while glass cuvettes can be used for visible-only measurements [17] [10].

- Detector: Converts transmitted light intensity into an electrical signal. Photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) offer high sensitivity for low-light detection, while photodiodes and charge-coupled devices (CCDs) provide robust alternatives [17] [10].

- Signal Processor and Readout: Converts the detector signal into absorbance values and displays the resulting spectrum [17].

Diagram 2: UV-Vis spectrophotometer components

Single Beam vs. Double Beam Instruments

Two principal instrument designs are employed in UV-Vis spectroscopy:

- Single Beam Spectrophotometers: Measure reference and sample spectra sequentially. While simpler and more cost-effective, they are susceptible to source fluctuation errors and require manual blank correction between measurements [17].

- Double Beam Spectrophotometers: Split the light beam into reference and sample paths, allowing simultaneous measurement. This design automatically compensates for source drift, solvent absorption, and other fluctuations, enabling continuous spectral recording with higher accuracy [17].

Quantitative Analysis and the Beer-Lambert Law

UV-Vis spectroscopy provides quantitative data through the Beer-Lambert Law, which relates light absorption to sample concentration [10] [14]. The fundamental relationship is expressed as:

A = εbc

Where:

- A is the measured absorbance (unitless)

- ε is the molar absorptivity coefficient (L·molâ»Â¹Â·cmâ»Â¹)

- b is the path length through the sample (cm)

- c is the concentration of the absorbing species (mol·Lâ»Â¹)

The molar absorptivity (ε) is a characteristic of each chromophore at a specific wavelength, indicating how strongly it absorbs light [15]. Values can range from below 100 for weak absorbers to over 100,000 for highly absorbing chromophores [15]. For accurate quantification, absorbance values should generally be maintained below 1.0 (within the instrument's dynamic range), which can be achieved by sample dilution or using shorter path length cuvettes [10].

Experimental Protocols for Material Characterization

Sample Preparation and Measurement Protocol

- Solvent Selection: Choose a solvent transparent in the spectral region of interest. Common choices include water, hexane, methanol, and acetonitrile. For UV measurements below 300 nm, high-purity solvents are essential [10].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare sample solutions at appropriate concentrations (typically 10â»âµ to 10â»Â² M) to ensure absorbance readings fall within the instrument's ideal range (0.1-1.0 AU) [10].

- Reference Measurement: Fill a matched cuvette with pure solvent and collect a baseline spectrum to account for solvent absorption and instrument characteristics [10].

- Sample Measurement: Replace the reference cuvette with the sample solution and acquire the absorption spectrum across the desired wavelength range (e.g., 200-800 nm).

- Data Analysis: Identify λmax values and corresponding molar absorptivities. For quantitative analysis, prepare a calibration curve using standard solutions of known concentration.

Protocol for Studying Solvent Effects on Chromophores

- Prepare identical concentrations of the chromophore in a series of solvents with varying polarity (e.g., hexane, diethyl ether, ethanol, water).

- Record full UV-Vis spectra for each solution using matched cuvettes or a cuvette-free system.

- Note the shifts in λmax and changes in absorption intensity for different transitions.

- Correlate the direction and magnitude of observed shifts with solvent polarity and the specific electronic transition type (n→π* vs. π→π*).

Protocol for Studying pH Effects on Chromophores

- Prepare buffer solutions covering a wide pH range (e.g., pH 2-12).

- Add equal amounts of chromophore to each buffer solution, ensuring identical final concentrations.

- Measure absorption spectra for each pH solution.

- Plot λmax and/or absorbance versus pH to identify pKa values and protonation-dependent spectral changes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Item | Function/Purpose | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample holder for UV-Vis measurements | 1 cm path length standard; transparent down to 200 nm [17] [10] |

| Deuterium Lamp | UV light source | Covers 200-400 nm range; typically paired with visible source [17] [10] |

| Tungsten/Halogen Lamp | Visible light source | Covers 350-800 nm range; stable, long-life output [17] [10] |

| Diffraction Grating | Wavelength selection in monochromators | 1200-2000 grooves/mm; blazed holographic for better resolution [10] |

| Photomultiplier Tube (PMT) | High-sensitivity light detection | Amplifies electron emission; essential for low-light applications [17] [10] |

| Solvent Grade Acetonitrile | Common UV-transparent solvent | UV cutoff ~190 nm; suitable for low-wavelength studies [15] |

| Buffer Salts (e.g., Phosphate) | pH control for aqueous studies | Maintains constant pH; minimal UV absorption above 220 nm |

| MPT0B392 | MPT0B392, MF:C19H20N2O6S, MW:404.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Oxomemazine | Oxomemazine, CAS:174508-13-5, MF:C18H22N2O2S, MW:330.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Applications in Research and Development

Material Identification and Characterization

UV-Vis spectroscopy provides rapid identification of unknown compounds through their characteristic absorption profiles. By comparing λmax values and spectral shapes with databases, researchers can identify chromophores present in complex samples. In pharmaceutical research, this technique verifies raw material identity and detects impurities through deviation from reference spectra [20] [10]. The combination of UV-Vis with chemometric tools like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) enables classification of complex pigment mixtures, extracting characteristic molecular benchmarks from spectral data [21].

Concentration Determination in Biological Systems

The technique is indispensable for quantifying biomolecules without extensive purification. Nucleic acid purity and concentration are routinely assessed using absorbance at 260 nm, with the A260/A280 ratio indicating protein contamination [20] [10]. Similarly, protein concentration can be determined using specific chromophores like peptide bonds (~200 nm) or aromatic side chains (280 nm) [20].

Molecular Interaction Studies

Researchers employ UV-Vis spectroscopy to monitor molecular interactions in real-time. Changes in absorption spectra during binding events can reveal stoichiometry, binding constants, and reaction kinetics. This is particularly valuable in drug development for studying ligand-receptor interactions and enzyme kinetics [20]. Charge-transfer complexes often exhibit distinctive, intense absorption bands that provide insight into electron donor-acceptor relationships in material science [17].

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy has re-emerged as a powerful analytical sensor for raw material identification (ID), driven by technological advancements and sophisticated chemometric data analysis. This technique provides a unique spectralprint for materials, enabling rapid, cost-effective, and simple verification essential for industries like pharmaceuticals and food and beverages. This whitepaper details the core advantages of UV-Vis spectroscopy for raw material ID, supported by quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and visual workflows. By integrating modern chemometrics, UV-Vis spectroscopy transforms from a simple spectrophotometric tool into a robust, non-destructive analytical sensor, ensuring quality control and compliance with regulatory standards.

In the context of raw material identification, the fundamental challenge lies in rapidly and accurately verifying the identity and quality of incoming materials to ensure they meet strict specifications. Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy analyzes the interaction of light in the 200-800 nm range with matter, providing a distinct absorption profile or spectralprint unique to a material's chemical composition [22] [23]. Historically used for quantifying single analytes in solution, UV-Vis was considered limited for complex mixtures due to its broad, overlapping absorption bands. However, the paradigm has shifted. The advent of sensitive array detectors and, crucially, the integration of chemometrics (multivariate statistical analysis of chemical data), have endowed UV-Vis with new vitality [23]. It is no longer merely a data provider but a solver of complex analytical problems, capable of distinguishing between raw materials from different geographical origins or with subtle structural differences through non-targeted, spectralprint analysis [22] [23]. This guide explores how this combination delivers unparalleled speed, cost-effectiveness, and simplicity for raw material ID.

Core Advantages in Raw Material Identification

The selection of UV-Vis spectroscopy for raw material ID is driven by three compelling advantages that address critical operational needs in research and quality control environments.

Speed and High-Throughput Capability

The rapid analysis time of UV-Vis spectroscopy significantly accelerates raw material screening and release processes.

- Rapid Analysis: Modern photodiode array detectors can acquire a full UV-Vis spectrum almost instantaneously, providing results in a matter of seconds [24]. This eliminates the bottleneck of lengthy analytical procedures.

- Minimal Sample Preparation: Unlike chromatographic methods which often require complex sample derivatization or separation, many UV-Vis ID methods need only a simple hydroalcoholic extraction, dramatically reducing pre-analysis workload [22].

- Real-Time and Inline Potential: With accessories like flow cells and fiber-optic probes, UV-Vis can be integrated into process analytical technology (PAT) frameworks for real-time monitoring of raw material streams, moving quality control from a lab-based to an inline activity [23].

Cost-Effectiveness and Economic Value

UV-Vis spectroscopy offers a superior return on investment, making it accessible for both large corporations and smaller laboratories.

- Low Initial Investment and Operational Costs: The equipment is relatively affordable, with a lower initial investment compared to techniques like HPLC, GC-MS, or ICP-MS [24]. Operational expenses are further minimized by low maintenance requirements and durability of the instruments [24].

- Reduced Consumable Expense: The technique typically uses inexpensive quartz cuvettes, avoiding the high recurring costs of chromatography columns and specialty solvents [24].

- Economic Lifetime: The robustness and durability of UV-Vis spectrophotometers contribute to a long operational lifetime, enhancing their long-term cost-effectiveness [24].

Table 1: Cost and Performance Comparison of Analytical Techniques for Raw Material ID

| Technique | Estimated Instrument Cost | Analysis Speed | Sample Preparation Complexity | Operational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | $10,000 - $100,000+ [25] | Seconds to minutes [24] | Low [22] | Low [24] |

| HPLC | >$50,000 | Minutes to hours | High | High |

| GC-MS | >$80,000 | Minutes to hours | High | High |

| ICP-MS | >$150,000 | Minutes | Medium | High |

Operational and Technical Simplicity

Ease of use reduces training time and minimizes operational errors, ensuring reliable results.

- User-Friendly Operation: Modern UV-Vis spectrophotometers are engineered with intuitive software interfaces, making them accessible to personnel with minimal specialized training [24].

- Non-Destructive Analysis: The technique allows for the sample to be recovered after analysis, which is valuable for investigating rare or expensive raw materials [23].

- Straightforward Data Interpretation with Chemometrics: While the underlying chemometrics are complex, the output for the operator is simplified. Classification models built using pattern recognition provide clear, actionable results (e.g., "Pass/Fail" or "Material A/Material B") based on the spectralprint, rather than requiring deep interpretation of complex chromatograms or spectra [22] [23].

Quantitative Data and Market Validation

The widespread adoption and growth of UV-Vis spectroscopy are reflected in robust market data. The global UV-Vis spectroscopy market was valued at $1.57 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow to $2.12 billion by 2029, at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 6.7% [26]. This growth is fueled by its application across key industries, demonstrating its relevance and economic impact.

Table 2: UV-Vis Spectroscopy Market Segmentation by End-User Industry

| End-User Industry | Approximate Market Share | Primary Applications in Raw Material ID |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical & Biotechnology | ~35% [25] | Identity testing of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), excipients, and raw material quality control [27]. |

| Food & Beverage | ~15% [25] | Authentication of medicinal plants, verification of ingredient purity, detection of adulteration [28] [22]. |

| Environmental Testing | ~20% [25] | Analysis of water and soil samples, though less directly for raw material ID. |

| Academic & Research | ~10% [25] | Fundamental research, method development, and educational use. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Authentication of Medicinal Plant Raw Materials

The following protocol, adapted from a 2024 study, demonstrates a practical application of UV-Vis spectroscopy and chemometrics for authenticating plant material from different geographical origins [22].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for the Experimental Protocol

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Certified Plant Materials | Reference standards for model building (e.g., from specialized producers or pharmacopeias). |

| Test Plant Materials | Unknown or unverified samples for authentication. |

| Ethanol-Water Mixture (70:30 v/v) | Hydroalcoholic extraction solvent for polyphenols and other chromophores. |

| Ball Mill | For crushing and homogenizing plant material into a fine powder. |

| Centrifuge | To clarify extracts by removing particulate matter. |

| Double-Beam UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Instrument for acquiring spectral data; equipped with 10 mm quartz cells. |

| Chemometrics Software | Software package (e.g., Statistica, Python with scikit-learn, MATLAB) for multivariate data analysis. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh 2.0 g of crushed plant powder. Subject it to maceration with 20 mL of 70:30 (v/v) ethanol-water solvent for 10 days at room temperature. Separate the extract by decantation, wash the residue, and centrifuge. Combine the extracts and dilute to a final volume of 25 mL with the extraction solvent. Prior to analysis, centrifuge the samples again at 4000 rpm for 15 minutes and perform a 1:100 dilution with the ethanol-water solvent [22].

- Spectral Acquisition: Using a double-beam spectrophotometer (e.g., Jasco V-550), acquire the UV-Vis spectra in the range of 200-800 nm. Use a 0.5 nm slit width, a 10 mm pathlength quartz cell, and a scanning speed of 400 nm/min. Use the ethanol-water mixture as a blank reference. Collect all spectra in duplicate at room temperature and average them to ensure reproducibility [22].

- Data Pre-processing: Apply a Savitzky-Golay smoothing filter (e.g., 23-point quadratic polynomial) to the raw spectral data to reduce high-frequency noise. Subsequently, compute the first-, second-, third-, and fourth-order derivatives of the spectra. Derivativization is a critical step as it helps resolve overlapping absorption bands and enhances minor spectral features that are significant for discrimination [22].

- Chemometric Analysis for ID:

- Unsupervised Pattern Recognition (Hierarchical Clustering Analysis - HCA): Use HCA with Ward's method and 1-Pearson r distance measurement to observe natural groupings in the data without prior classification of samples. This provides an initial visual assessment of whether samples from the same origin cluster together [22].

- Dimensionality Reduction (Principal Component Analysis - PCA): Apply PCA with varimax rotation to the original and derivative spectral data. This technique reduces the hundreds of wavelength variables into a few key Principal Components (PCs) that capture the majority of the variance in the data set. The varimax rotation simplifies the interpretation by maximizing the variation of loadings, making it easier to identify the specific spectral regions (wavelengths) that contribute most to sample classification [22].

- Supervised Classification (Linear Discriminant Analysis - LDA): Use the scores from the significant PCs as input variables for LDA. This model learns to maximize the separation between pre-defined classes (e.g., country of origin) and builds a mathematical function to classify new, unknown samples. The model's performance is validated using techniques like leave-one-out cross-validation, which in the referenced study achieved a 98.04% correct classification rate [22].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of the experimental protocol from sample preparation to final identification.

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for UV-Vis Raw Material Authentication

The Critical Role of Chemometrics

Chemometrics is the cornerstone that revives UV-Vis spectroscopy for complex raw material ID. It transforms broad, non-specific spectra into powerful classification tools.

- From Data to Information: A UV-Vis spectrum of a complex plant extract is a vector of hundreds of absorbance values. Chemometric techniques like PCA compress this data, identifying the underlying latent variables that truly differentiate, for instance, Romanian from Italian lavender [22] [23].

- Handling Complex Matrices: In raw materials, the analyte of interest is often in a matrix of other chromophores. Multivariate calibration techniques allow the quantitative determination of a component of interest without prior physical separation, by extracting its specific spectral information from the complex background [23].

- Building Predictive Models: Supervised methods like LDA use a training set of known samples to create a model that can predict the identity of unknown samples with high accuracy, providing a direct and automated ID tool for quality control laboratories [22].

UV-Vis spectroscopy, supercharged by modern instrumentation and chemometrics, presents a compelling solution for raw material identification. Its core advantages of speed, cost-effectiveness, and simplicity are not merely theoretical but are demonstrated in practical, published methodologies for authenticating complex materials like medicinal plants. By providing a unique spectralprint and leveraging powerful pattern recognition techniques, it offers a robust, non-destructive, and efficient platform for ensuring the integrity of raw materials within the pharmaceutical, food, and botanical industries. As innovations in portability, data fusion, and artificial intelligence continue, the role of UV-Vis spectroscopy as a primary analytical sensor for raw material ID is poised for further significant growth.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy is a foundational analytical technique in modern laboratories, particularly for raw material identification in pharmaceutical and biotechnology research. The global UV-Vis spectroscopy market, valued at $1.57 billion in 2024 and projected to reach $2.12 billion by 2029, demonstrates the technique's critical importance across industries [26]. This growth is fueled largely by increased pharmaceutical production and vaccine development, where UV-Vis spectroscopy provides rapid, quantitative determination of analytes including transition metal ions, highly conjugated organic compounds, and biological macromolecules [26].

Despite its widespread adoption and utility, UV-Vis spectroscopy possesses inherent technical limitations that researchers must acknowledge and address in method development and validation. This technical guide examines three core limitations—sensitivity constraints, specificity challenges, and spectral overlap phenomena—within the context of raw material identification research for drug development. By understanding these limitations and implementing the complementary experimental approaches outlined herein, scientists can enhance the reliability of their analytical results while leveraging the technique's advantages of speed, simplicity, and cost-effectiveness.

Core Limitations of UV-Vis Spectroscopy

Sensitivity Limitations

UV-Vis spectroscopy exhibits fundamental sensitivity constraints that can impact its applicability for trace analysis in raw material identification. The technique typically operates effectively in the concentration range of 10^-5 to 10^-2 M, making it less suitable for detecting low-abundance impurities or contaminants without pre-concentration steps. This limited sensitivity stems from the relatively low molar absorptivity coefficients (ε) of many compounds, which generally fall between 1,000 and 100,000 L·mol^-1·cm^-1 for electronic transitions.

Several technical factors contribute to these sensitivity constraints. The reliance on Beer-Lambert law applicability means measurements become non-linear at high concentrations due to electrostatic interactions between molecules, while at low concentrations, the signal-to-noise ratio diminishes significantly. Stray light effects in spectrometer optics further limit the maximum measurable absorbance to approximately 2-3 AU, establishing practical detection boundaries. Additionally, the presence of spectral noise from various sources—including detector shot noise, flicker noise from source instability, and thermal noise—establishes a floor below which detection becomes unreliable.

Table 1: Sensitivity Comparison with Complementary Techniques

| Technique | Typical Detection Limit | Applicability to Trace Analysis | Sample Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | 10^-5 - 10^-2 M | Limited without pre-concentration | Minimal preparation |

| ICP-MS | 0.10 - 0.85 ng/mL [28] | Excellent for elemental analysis | Acid digestion often required |

| ICP-OES | 0.06 μg/g (Sr) to 400 μg/g (S) [28] | Good for multiple elements | Solid or liquid samples |

| SERS | Single molecule detection possible [28] | Excellent for molecular specific detection | Often requires nanoparticle substrates |

Specificity Challenges

The specificity of UV-Vis spectroscopy is fundamentally constrained by its basis on electronic transitions in molecules, which typically produce broad absorption bands spanning 20-100 nm. These broad features make discrimination between structurally similar compounds particularly challenging—a significant limitation in pharmaceutical raw material identification where isomeric impurities or closely related compounds must be distinguished.

Specificity issues manifest primarily through two mechanisms. Chromophore dependency means only compounds with appropriate chromophores (typically involving π→π, n→π transitions) absorb in the UV-Vis range, leaving many substances undetectable without derivatization. Matrix effects further complicate specificity as sample matrices can alter absorption characteristics through solvent polarity effects, pH-induced spectral shifts, or formation of charge-transfer complexes that modify the observed spectrum.

For raw material identification, these specificity limitations present substantial risks. False positives may occur when different compounds exhibit nearly identical absorption maxima, while false negatives can result from impurities with similar chromophores to the primary compound but different toxicological profiles. Without orthogonal verification, these limitations can compromise material quality assessment and potentially impact drug safety.

Spectral Overlap

Spectral overlap represents one of the most practically significant limitations in UV-Vis spectroscopy, particularly for complex mixtures commonly encountered in raw material analysis. This phenomenon occurs when multiple components in a sample absorb at similar wavelengths, creating composite spectra where individual contributions become indistinguishable.

The mathematical foundation for spectral overlap is rooted in the additive property of absorbance, where for a multi-component system, the total absorbance at any wavelength (Atotal(λ)) equals the sum of individual component absorbances: Atotal(λ) = Σεi(λ)cil. This additive relationship creates analytical challenges when component spectra exhibit significant overlap, as deconvolution becomes increasingly difficult with more components and greater spectral similarity.

Table 2: Quantitative Measures of UV-Vis Limitations in Raw Material Identification

| Limitation Category | Quantitative Metric | Impact on Raw Material Identification |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Detection Limit: ~10^-6 M for strong chromophores | May miss low-concentration impurities in APIs |

| Quantitation Limit: ~10^-5 M for strong chromophores | Limited accuracy for impurity profiling | |

| Specificity | Spectral Bandwidth: 20-100 nm | Difficulty distinguishing structural analogs |

| Chromophore Requirement: π→π, n→π transitions | Limited to conjugated systems or charge-transfer complexes | |

| Spectral Overlap | Resolution: 0.5-5 nm (conventional instruments) | Co-eluting compounds in HPLC-UV appear as single peak |

| Similarity Index: >0.85 between compounds | High risk of misidentification without orthogonal methods |

In pharmaceutical raw material identification, spectral overlap becomes particularly problematic when analyzing natural product extracts, process intermediates containing multiple related compounds, or excipient blends where multiple components contain similar chromophores. The overlap effectively masks the presence of individual components, potentially allowing contaminants or impurities to remain undetected.

Experimental Protocols for Mitigation

Protocol for Standard Addition Method

The standard addition method effectively addresses matrix effects that compromise sensitivity and specificity in UV-Vis analysis of complex samples.

Materials and Reagents:

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer with matched quartz cuvettes (1 cm pathlength)

- Stock standard solution of analyte (certified reference material)

- Test sample solution

- Appropriate solvent (HPLC grade)

- Volumetric flasks (10 mL, Class A)

- Precision micropipettes (100-1000 μL, calibrated)

Procedure:

- Prepare a blank solution containing all matrix components except the analyte.

- Pipette identical aliquots (e.g., 5.0 mL) of the sample solution into five 10-mL volumetric flasks.

- Add increasing volumes (0, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0 mL) of standard stock solution to the flasks.

- Dilute each flask to volume with the appropriate solvent and mix thoroughly.

- Measure the absorbance of each solution at the predetermined λ_max.

- Plot absorbance versus concentration of added standard and extrapolate the line to the x-intercept to determine the original sample concentration.

Validation Parameters:

- Linearity: R^2 > 0.995 for standard addition curve

- Precision: %RSD < 2% for replicate measurements (n=6)

- Recovery: 98-102% for spiked samples

Protocol for Derivative Spectroscopy

Derivative spectroscopy enhances specificity by resolving overlapping spectral features and eliminating baseline offsets.

Materials and Reagents:

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer with derivative capability (or software processing)

- Standard solutions of pure components (for validation)

- Sample solution

- Appropriate solvent

Procedure:

- Acquire the normal absorption spectrum of the sample from 200-800 nm with high resolution (≤1 nm interval).

- Apply the derivative function (typically second or fourth derivative) using the instrument software or external processing.

- Optimize derivative parameters: Δλ = 3-10 nm for smoothing balance between noise reduction and feature preservation.

- Identify zero-crossing points in the derivative spectrum where interfering compounds contribute minimally.

- Construct calibration curves using derivative amplitude at selected wavelengths rather than raw absorbance.

- Quantify analytes using the derivative calibration model.

Applications for Specificity Enhancement:

- Binary mixture analysis by selecting zero-crossing wavelengths

- Elimination of background scattering interference in turbid samples

- Resolution of shoulder peaks into distinct, quantifiable features

Protocol for Chemometric Analysis

Multivariate calibration methods, particularly Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, effectively address spectral overlap through mathematical resolution of multi-component systems.

Materials and Reagents:

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer with digital spectral output

- Chemometric software (e.g., MATLAB with PLS Toolbox, R, or Python with scikit-learn)

- Calibration set of standards with known composition

- Validation set of independent samples

Procedure:

- Design a calibration set that spans the expected concentration ranges and component ratios using a factorial design or similar approach.

- Acquire full UV-Vis spectra (200-800 nm) for all calibration standards.

- Preprocess spectra using appropriate methods: Savitzky-Golay smoothing, standard normal variate (SNV) correction, or multiplicative scatter correction (MSC).

- Develop PLS regression models using leave-one-out cross-validation to determine the optimal number of latent variables.

- Validate the model using an independent set of samples not included in calibration.

- Apply the validated model to unknown samples for quantitative prediction of multiple components simultaneously.

Model Validation Metrics:

- Root Mean Square Error of Calibration (RMSEC)

- Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP)

- Ratio of Performance to Deviation (RPD)

- Coefficient of Determination (R^2) for predicted vs. actual values

Complementary Techniques and Advanced Approaches

Orthogonal Analytical Techniques

When UV-Vis limitations preclude definitive raw material identification, orthogonal techniques provide the necessary verification and enhanced capabilities.

Vibrational Spectroscopy:

- FT-IR Spectroscopy: Identifies functional groups and molecular structures through fundamental vibrational transitions, providing complementary information to electronic transitions observed in UV-Vis [28]. Particularly valuable for distinguishing structural isomers with identical chromophores.

- Raman Spectroscopy: Offers molecular fingerprinting capabilities with minimal sample preparation, especially when enhanced through Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) for trace detection [28]. Effective for analyzing aqueous solutions where IR suffers from strong water absorption.

Elemental and Structural Techniques:

- ICP-MS and ICP-OES: Provide exceptional sensitivity for trace elemental analysis with detection limits ranging from 0.10 to 0.85 ng/mL for ICP-MS and 0.06 μg/g to 400 μg/g for ICP-OES [28]. Essential for quantifying catalyst residues or elemental impurities in pharmaceutical raw materials.

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Delivers comprehensive molecular structural information, resolving isomeric compounds that challenge UV-Vis discrimination. Particularly effective for authenticity assessment of complex natural product-derived materials [28].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Enhanced UV-Vis Analysis

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in UV-Vis Analysis | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Derivatizing Agents (e.g., dansyl chloride, DNPH) | Introduce chromophores into non-absorbing compounds | Enabling detection of aliphatic amines, carbonyl compounds |

| Charge-Transfer Complexing Agents (e.g., π-acceptors) | Enhance molar absorptivity through complex formation | Increasing sensitivity for specific compound classes |

| pH Buffer Solutions | Control ionization state of analytes | Shifting λ_max for improved specificity in mixture analysis |

| Surfactant Solutions (e.g., CTAB, SDS) | Enable micellar stabilization of hydrophobic compounds | Allowing analysis of water-insoluble compounds |

| Metal Chelators (e.g., 1,10-phenanthroline) | Form colored complexes with metal ions | Quantitative metal impurity analysis in raw materials |

Instrumentation Advancements

Recent technological developments have partially addressed traditional UV-Vis limitations through improved instrument design and detection capabilities.

Array-Based Systems: Modern array-based UV-Vis systems utilize CCD or CMOS detectors to simultaneously acquire entire spectral regions, enabling rapid spectral acquisition and enhanced signal-to-noise ratios through averaging [26]. These systems facilitate real-time monitoring of reaction kinetics and improved resolution of transient species.

High-Speed Detection Systems: Innovative systems like the Tm Analysis System integrate UV-Vis spectrometry with temperature control for biomolecular analysis, enabling determination of melting temperatures (T_m) for nucleic acids through thermal denaturation profiling [26]. This approach demonstrates how hybrid methodologies expand UV-Vis applications despite inherent limitations.

Microspectrophotometry: Advanced instruments such as the 2030PV PRO UV-visible-NIR microspectrophotometer enable non-destructive analysis across broad spectral ranges (UV to NIR), facilitating spatially resolved measurements of microscopic samples [26]. This capability is particularly valuable for heterogeneous raw material characterization.

Visualization of Method Selection and Workflows

Decision Framework for Addressing UV-Vis Limitations

UV-Vis Method Validation Workflow for Raw Material ID

The inherent limitations of UV-Vis spectroscopy—sensitivity constraints, specificity challenges, and spectral overlap—represent significant considerations in pharmaceutical raw material identification research. Rather than precluding its use, these limitations define the technique's appropriate application boundaries and necessary complementary approaches. Through implementation of the experimental protocols, orthogonal verification methods, and decision frameworks outlined in this technical guide, researchers can leverage UV-Vis spectroscopy effectively while ensuring analytical reliability. The continuing evolution of UV-Vis instrumentation, particularly through integration with advanced detection systems and hybrid analytical approaches, promises enhanced capability to address these fundamental limitations while maintaining the technique's essential advantages of operational simplicity, rapid analysis, and cost-effectiveness in pharmaceutical research and quality control environments.

From Theory to Practice: Methodological Applications in Raw Material Identification

Within the framework of research on raw material identification, Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy stands as a fundamental analytical technique for the qualitative and quantitative analysis of pharmaceutical compounds. The reliability of the data generated, however, is profoundly dependent on two critical, and often overlooked, foundational choices: solvent selection and cuvette use. The solvent must provide a transparent window for the analyte's absorbance, while the cuvette must serve as an inert, optically precise container. Errors in either selection can lead to inaccurate absorbance measurements, compromised spectral data, and ultimately, faulty material identification. This guide details the standard procedures for optimizing these key parameters to ensure data integrity in pharmaceutical research and development.

Fundamental Principles of UV-Vis Spectroscopy

UV-Vis spectroscopy measures the amount of ultraviolet or visible light absorbed by a sample. The core principle is governed by the Beer-Lambert Law (Equation 1), which states a linear relationship between absorbance (A) and the concentration (c) of the absorbing species [29].

Equation 1: Beer-Lambert Law

A = εbc

Where:

- A is the measured absorbance (unitless)

- ε is the molar absorptivity coefficient (Mâ»Â¹cmâ»Â¹)

- b is the path length of the cuvette (cm)

- c is the concentration of the solution (M)

In a spectrophotometer, light from a source (e.g., deuterium or tungsten lamp) passes through a monochromator to select a specific wavelength, travels through the sample held in a cuvette, and is measured by a detector (e.g., photomultiplier tube) [10]. The instrument is zeroed using a blank solution containing only the solvent, which allows the measurement to isolate the absorbance of the analyte of interest [10] [29]. For raw material identification, this facilitates the creation of a unique absorbance spectrum, serving as a fingerprint for the compound, provided the solvent and cuvette do not introduce interference.

Solvent Selection Guidelines

The choice of solvent is paramount, as it must be transparent in the spectral region where the analyte absorbs and must not chemically interact with the sample in a way that alters its absorbance profile.

Key Selection Criteria

- UV Cutoff Wavelength: The most critical property is the solvent's "UV cutoff," the wavelength below which the solvent itself absorbs significantly, creating a high background absorbance. Measurements must be performed at wavelengths longer than the solvent's cutoff. Table 1 provides the UV cutoff for common solvents used in pharmaceutical analysis [10].

- Polarity and Solvent-Analyte Interactions: The solvent's polarity can shift the absorbance spectrum of the analyte. Polar solvents can stabilize n→π* transitions, causing a blue shift (hypsochromic shift), and stabilize π→π* transitions, causing a red shift (bathochromic shift). The solvent should be chosen to ensure complete dissolution and spectral stability.

- Purity: Spectroscopic-grade solvents are essential to avoid interference from fluorescent or absorbing impurities, which is especially crucial for sensitive photoluminescence measurements [30].

Table 1: UV Cutoff Wavelengths of Common HPLC/Spectroscopic Solvents

| Solvent | UV Cutoff (nm) | Common Applications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Water (HPLC Grade) | ~190 nm | Ideal for aqueous-soluble biomolecules (proteins, nucleic acids). |

| Acetonitrile | 190 nm | Common mobile phase in HPLC; excellent UV transparency. |

| n-Hexane | 200 nm | For non-polar compounds; useful for lipid-soluble analytes. |

| Methanol | 205 nm | Versatile for a wide range of organic compounds. |

| Ethanol | 210 nm | Similar applications to methanol. |

| Diethyl Ether | 215 nm | Suitable for some non-polar applications. |

| Dichloromethane | 235 nm | Useful for water-insoluble compounds. |

| Chloroform | 245 nm | Use with caution due to toxicity; ensure cuvette compatibility. |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | 245 nm | Good solvent for polymers and various organics. |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | 270 nm | High boiling point solvent for challenging solubilities. |

| Acetone | 330 nm | Limited UV range; useful primarily for visible spectroscopy. |

| Benzene | 280 nm | Avoid due to carcinogenicity. |

Experimental Protocol: Solvent Suitability Verification

Before analyzing any analyte, the suitability of the solvent must be confirmed.

- Procedure:

- Fill a matched quartz cuvette with the proposed solvent.

- Place the cuvette in the sample holder and run a baseline or blank correction scan across the entire intended wavelength range (e.g., 190-800 nm).

- Examine the resulting spectrum. The absorbance should be low and flat (typically <1.0 Absorbance Unit) across the entire range of interest. A significant upward slope or peak indicates the solvent is absorbing too much light and is unsuitable for use in that region.

- Common Pitfall: Attempting to measure a protein sample at 280 nm using a solvent with a cutoff of 240 nm. The solvent absorbance will be high, leading to signal saturation and inaccurate quantitation.

Cuvette Selection and Handling

The cuvette is the container that holds the sample in the light path. Its material and design directly impact the types of experiments that can be performed and the quality of the resulting data [31].

Material Composition and Wavelength Range

The primary differentiating factor between cuvette types is the material's transparency to different wavelengths of light.

Table 2: Comparison of Common Cuvette Materials

| Feature | Quartz (Fused Silica) | Optical Glass | Plastic (PS/PMMA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission Range | Excellent (190–2500 nm) | Limited (>320 nm) | Not supported |

| UV Transparency | Excellent (down to 190 nm) | Poor (blocks UV below ~350 nm) | Poor (blocks UV below ~400 nm) |

| Autofluorescence | Very Low | Moderate | High |

| Chemical Resistance | High (except HF, hot strong bases) [31] | Moderate | Low |

| Max Temperature | 150–1200 °C | ~90 °C | ~60 °C |

| Relative Cost | Higher | Mid | Low (Disposable) |

| Best Use | UV-Vis, Fluorescence, harsh solvents | Visible-only assays, teaching labs | Teaching, visible colorimetric assays, disposable QC. |

Selection Guide:

- For UV-Vis spectroscopy below 350 nm (e.g., DNA/RNA at 260 nm, proteins at 280 nm, or drug compounds with UV chromophores), a quartz cuvette is essential [31]. Plastic and glass cuvettes are unsuitable as they absorb UV light [10].

- For fluorescence spectroscopy, a quartz cuvette with four polished windows is required because light is detected at a 90° angle to the excitation source, and very low autofluorescence is critical for detecting weak signals [31].

- For visible-light-only measurements (>350 nm), optical glass or disposable plastic cuvettes may be sufficient and more cost-effective.

Cuvette Handling and Cleaning Protocols