Validating Specificity and Sensitivity in Handheld Spectrometers: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of specificity and sensitivity in handheld spectrometers, critical for their reliable application in drug development and clinical diagnostics.

Validating Specificity and Sensitivity in Handheld Spectrometers: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of specificity and sensitivity in handheld spectrometers, critical for their reliable application in drug development and clinical diagnostics. It explores the foundational principles of these performance metrics, details methodological approaches for application across pharmaceutical workflows, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and presents rigorous procedures for instrument validation against established laboratory techniques. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current advancements, including the role of AI and portable technologies, to ensure data integrity and regulatory compliance in fast-paced and resource-limited settings.

Core Principles: Defining Specificity and Sensitivity for Handheld Spectrometers

For researchers and professionals in drug development and environmental monitoring, the analytical performance of a spectrometer is paramount. Two of the most critical metrics defining this performance are the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and the Detection Limit. SNR quantifies the clarity of a target signal against background interference, while the detection limit defines the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably detected. For handheld spectrometers, these metrics determine the boundary between a usable field measurement and an undetectable trace amount. This guide objectively compares the sensitivity of different spectrometer technologies and configurations, providing a foundation for informed instrument selection based on empirical data.

Defining Key Metrics of Sensitivity

In analytical spectroscopy, sensitivity is quantitatively assessed through several standardized parameters.

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): This is a measure of the strength of a desired signal relative to the background noise. A higher SNR allows for more confident identification and quantification of an analyte. In practice, the noise is often estimated from the standard deviation of the background signal [1].

- Limit of Detection (LOD): The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from a blank sample. It is typically calculated using the formula LOD = 3.3 × σ / S, where 'σ' is the standard deviation of the blank response, and 'S' is the slope of the analytical calibration curve [1].

- Limit of Quantification (LOQ): The lowest concentration that can be quantitatively determined with acceptable precision and accuracy. It is calculated as LOQ = 10 × σ / S [1].

Comparative Performance Data

The following table summarizes experimental detection data for various spectrometer types and analytes, illustrating how performance varies with technology and application.

| Spectrometer Type / Technology | Analyte | Detection Limit | Key Experimental Conditions | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handheld Raman (Enhanced) | Nitrate in water | 2.89 mg/L (as N) | 785 nm laser; optical feedback mechanism; analysis time <1 min [2]. | Environmental water screening |

| Handheld Raman (Rigaku ResQ-CQL) | Diphenylamine (DPA) | 10.87 mM (in acetone) | 1064 nm laser; higher laser power; reduced fluorescence [3]. | Intact explosives detection |

| Handheld Raman (B&W Tek HandyRam) | Diphenylamine (DPA) | 30.25 mM (in acetone) | 785 nm laser; lower signal; observed fluorescence [3]. | Intact explosives detection |

| UV-Spectrophotometry | Terbinafine HCl | 1.30 μg/mL | Analysis at λmax 283 nm; validated per ICH guidelines [1]. | Pharmaceutical analysis |

| UV-Spectrophotometry | Amoxicillin (AMX) | 0.32 mg/L | Azo dye coupling reaction measured at λmax 425 nm [4]. | Pharmaceutical analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Sensitivity Assessment

Protocol 1: Establishing Detection Limits for a Handheld Raman Spectrometer

This methodology is adapted from studies on nitrate and explosives detection [2] [3].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a series of standard solutions with concentrations spanning the expected detection limit. For solid analytes like explosives stabilizers, dissolve them in an appropriate solvent such as acetone, which has been shown to produce low detection limits and high reproducibility [3].

- Data Acquisition: Using the handheld Raman spectrometer, collect multiple spectra for each standard concentration and for a blank solvent. Key parameters include:

- Laser Wavelength: 785 nm is common, but 1064 nm can significantly reduce fluorescence for some samples [3].

- Laser Power: Use the maximum power that does not damage the sample.

- Integration Time: Optimize for sufficient signal intensity without saturating the detector.

- Data Analysis:

- Calibration Curve: Plot the intensity of a characteristic Raman peak against the known concentration for each standard. Perform linear regression to obtain the slope (S) of the curve.

- Noise Calculation: Calculate the standard deviation (σ) of the Raman signal from multiple measurements of the blank sample.

- LOD/LOQ Calculation: Calculate the LOD and LOQ using the formulas LOD = 3.3 * σ / S and LOQ = 10 * σ / S [1].

Protocol 2: Theoretical Sensitivity Analysis for Spectral Imaging

This standardized methodology, adapted from biomedical spectral imaging research, allows for the objective comparison of different hardware and algorithms without a perfect ground truth [5].

- Control Sample Acquisition: Collect spectral image data from control samples that are known to contain (positive control) and not contain (negative control) the target signature (e.g., a specific fluorescent label).

- Algorithm Application: Apply various spectral analysis algorithms (e.g., Linear Unmixing, Spectral Angle Mapper) to the control data. The target signature to be detected is defined as a spectrum from the positive control.

- Performance Evaluation: For each algorithm, the ability to correctly identify the target in positive controls (sensitivity) and reject false positives in negative controls (specificity) is quantitatively evaluated. This process can be repeated to compare different imaging platforms or acquisition settings [5].

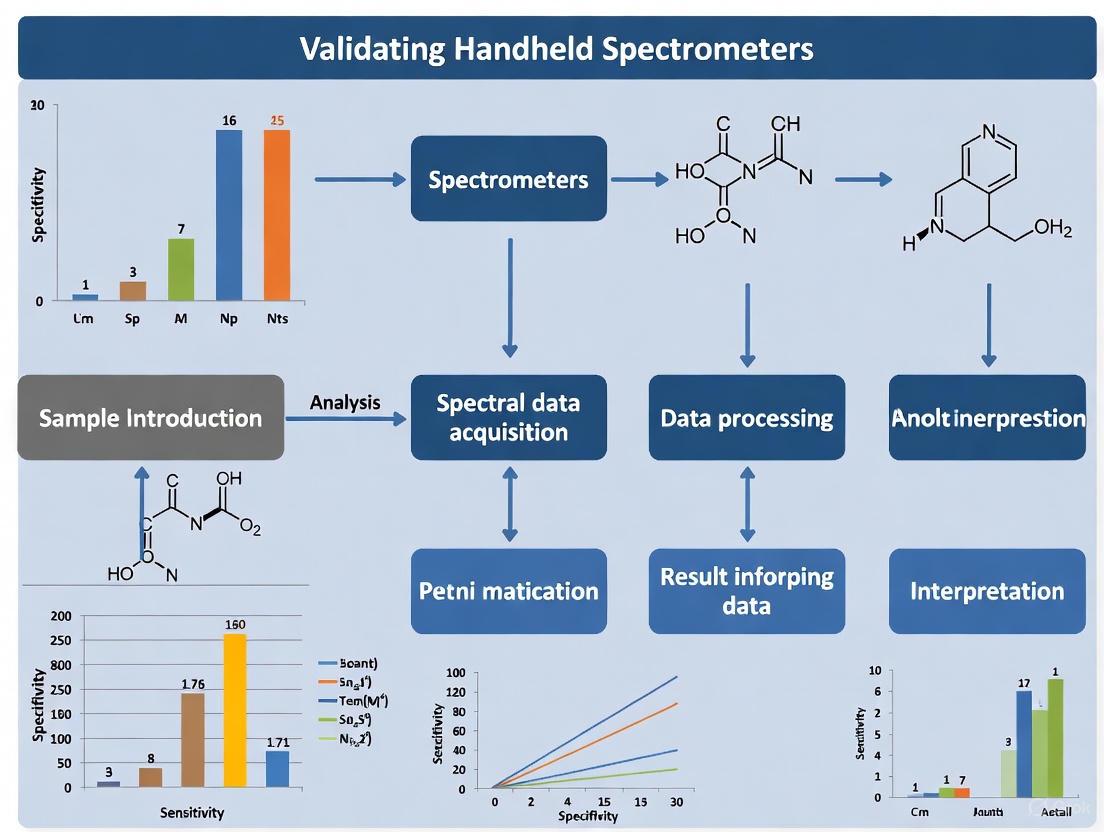

The workflow for this methodology is systematic and can be visualized as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential materials and their functions in spectrometer sensitivity experiments.

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Analytical Grade Reagents (e.g., KNO₃, DPA) | High-purity materials for preparing standard solutions with known concentrations, ensuring calibration accuracy [2] [3]. |

| Standard Solvents (e.g., Acetone, Deionized Water) | Matrix for dissolving analytes; choice of solvent can critically impact signal intensity and detection limits [3]. |

| Cuvette / Sample Vial | Holds liquid sample for analysis; material (e.g., glass, quartz) must be compatible with the excitation laser and not produce interfering signals [2]. |

| Optical Feedback Device | A component, such as a concave reflector, used to enhance Raman signal intensity by facilitating multiple reflections of incident light [2]. |

| Spectral Library | A collection of known reference spectra for target analytes, enabling identification and algorithms like linear unmixing [5]. |

| 2-Methylcyclopropane-1-carbaldehyde | 2-Methylcyclopropane-1-carbaldehyde, CAS:39547-01-8, MF:C5H8O, MW:84.12 g/mol |

| ER-076349 | ER-076349, CAS:253128-15-3, MF:C40H58O12, MW:730.9 g/mol |

The choice of spectrometer involves a careful balance of sensitivity, portability, and application-specific requirements. The data demonstrates that enhanced handheld Raman spectrometers are a powerful tool for rapid, on-site detection, achieving limits suitable for environmental monitoring of nitrates [2]. However, their performance can be influenced by laser wavelength, with 1064 nm systems offering advantages in reducing fluorescence for certain explosives analysis compared to 785 nm systems [3]. For pure quantitative analysis of pharmaceuticals, UV-spectrophotometry remains a highly sensitive, simple, and cost-effective validated method [1] [4]. Ultimately, validating sensitivity through established protocols, such as constructing calibration curves and theoretically assessing detection capabilities, is essential for generating reliable, reproducible data in both laboratory and field settings.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the central challenge in analytical chemistry is not merely detecting a substance, but definitively identifying it within a complex and interfering background. This capability, known as specificity, is paramount in applications ranging from identifying drug metabolites in biological fluids to detecting synthetic drug analogues in forensic samples. While lab-scale instruments like liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) have long been the gold standard, recent advances are pushing high-performance analysis into the field through handheld spectrometry.

Handheld spectrometers offer the promise of rapid, on-site analysis, but their ability to deliver the requisite specificity for critical applications is a key focus of validation research. This guide objectively compares the performance of three advanced handheld technologies—Mass Spectrometry (MS), High-Field Asymmetric waveform Ion Mobility Spectrometry (FAIMS), and Raman spectroscopy—in achieving selective identification. We will summarize quantitative performance data, detail the experimental protocols that generate this data, and provide a curated list of research reagent solutions essential for method development.

Technology Comparison: Performance Metrics and Mechanisms

The following table compares the core operational principles and documented performance of three leading handheld spectrometer technologies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Handheld Spectrometry Technologies

| Technology | Core Principle | Best For Specificity In Mixtures | Reported Performance (Specific Mixtures) | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handheld Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Separates ions by their mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio [6]. | Differentiating molecules with distinct molecular weights and fragmentation patterns. | Identification of drugs of abuse (cocaine, morphine) and chemical warfare agents in complex samples [6]. | Requires vacuum systems; can struggle with isobaric compounds (same m/z). |

| High-Field Asymmetric Ion Mobility Spectrometry (FAIMS) | Separates ions based on differences in ion mobility under high vs. low electric fields [7]. | Distinguishing isomers and conformers with subtle structural differences. | Deep learning model identified ethanol, ethyl acetate, and acetone in a 5-chemical mixture with 96.7-100% accuracy [7]. | Spectrum interpretation is complex; ion-molecule reactions can cause nonlinear effects. |

| Handheld Raman Spectroscopy | Detects inelastic scattering of light, revealing molecular vibrational fingerprints [8]. | Identification through unique spectral libraries, especially for inorganic pigments and crystals. | Identification of narcotics and raw materials using libraries of >20,000 reference spectra [8]. | Fluorescence from impurities or the sample itself can swamp the Raman signal. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

To objectively assess specificity, rigorous and standardized experimental protocols are essential. The methodologies below are adapted from recent research publications.

Handheld MS for Drug Detection

Protocol Aim: To validate a handheld ion trap mass spectrometer for the detection of specific drugs of abuse in complex mixtures [6].

- Sample Preparation: Drug standards (e.g., cocaine, morphine) are obtained and dissolved in appropriate solvents. For analysis of complex mixtures, samples can be coupled with ambient ionization sources (e.g., paper spray) requiring minimal pre-treatment [6] [9].

- Instrument Parameters: The instrument utilizes a Discontinuous Atmospheric Pressure Interface (DAPI) and a sinusoidal frequency scanning technique to drive the ion trap. The RF voltage is scanned to eject ions of specific m/z ratios for detection [6].

- Data Analysis: Specificity is confirmed by the accurate detection of the parent ion's m/z value for each target compound. Further confirmation can be achieved by observing characteristic fragment ions, a process boosted by techniques like grid-SWIFT which enables a pseudo-Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode on miniature instruments [6].

FAIMS with Deep Learning for VOC Identification

Protocol Aim: To identify specific volatile organic compounds (VOCs) within a complex mixture using a FAIMS system coupled with a deep learning model [7].

- Sample Preparation: Pure compounds (ethanol, ethyl acetate, acetone, etc.) and an equal-volume mixture of all five are prepared in brown glassware. The headspace vapor is introduced into the FAIMS system using high-purity nitrogen as a carrier gas [7].

- Instrument Parameters: A "homemade" FAIMS system is used. The RF voltage is ramped from 180 V to 280 V in 10 V steps, while the compensation voltage (CV) is scanned across a range of -13 V to +13 V. This generates a two-dimensional spectrum (RF vs. CV) with ion intensity represented in color [7].

- Data Analysis: Instead of traditional feature extraction, the entire 2D FAIMS spectral image is fed into a pre-trained EfficientNetV2 deep learning model. The model is trained to recognize the unique "fingerprint" of each specific substance, even within the mixed ion signals, and output an identification [7].

Handheld Raman for Raw Material Verification

Protocol Aim: To verify the identity of a specific raw material, such as a pharmaceutical active ingredient, through transparent packaging [8].

- Sample Preparation: Minimal preparation is required. The sample can be analyzed in its original container, such as a glass vial or a plastic bag, using the appropriate measurement tip.

- Instrument Parameters: The BRAVO handheld Raman spectrometer utilizes DuoLaser excitation (785 nm and 852 nm) and a patented Sequentially Shifted Excitation (SSE) method to mitigate fluorescence. The instrument is equipped with an IntelliTip system that automatically recognizes the measuring tip being used [8].

- Data Analysis: The measured Raman spectrum of the unknown material is automatically compared against a custom or commercial library containing over 20,000 reference spectra. A verification result is generated based on spectral matching algorithms, confirming the identity of the material [8].

The experimental workflow for FAIMS, which demonstrates a modern approach to tackling mixture analysis, is visualized below.

Figure 1: FAIMS Deep Learning Workflow. This diagram illustrates the process of using a FAIMS system coupled with a deep learning model to identify specific compounds in a complex gas mixture, achieving high accuracy as demonstrated in recent research [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following reagents and materials are fundamental for developing and validating assays for specific detection in complex mixtures, as cited in the research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimentation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Standards (e.g., Cocaine, Morphine) [6] | Serve as authentic references to validate instrument response and confirm specificity. | Method development for forensic detection of drugs of abuse using handheld MS [6]. |

| Volatile Organic Compounds (e.g., Ethanol, Acetone) [7] | Used to create complex mixtures for challenging sensor and spectrometer specificity. | Testing FAIMS sensor array performance and training deep learning models [7]. |

| Chemical Mixtures (e.g., Equal-volume blends of 5+ VOCs) [7] | Simulate real-world complex samples to test selectivity and identify signal interference. | Evaluating the ability of a platform to identify a specific analyte amidst interferents [7]. |

| High-Purity Carrier Gas (e.g., Nitrogen, 99.999%) [7] | Transports vapor samples to the detector without introducing contaminants. | Essential for gas-phase analysis in FAIMS and membrane-inlet MS [6] [7]. |

| Spectral Library (e.g., >20,000 reference spectra) [8] | Provides the fingerprint database against which unknown samples are matched for identification. | Raw material verification and narcotic identification with handheld Raman [8]. |

| 1-Methylcyclohexene | 1-Methylcyclohexene, CAS:1335-86-0, MF:C7H12, MW:96.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (-)-Enitociclib |

The pursuit of definitive specificity in complex mixtures is driving innovation in handheld spectrometry. Each technology offers a distinct path: handheld MS provides direct structural information via mass analysis; FAIMS leverages ion mobility and AI to deconvolve overlapping signals with remarkable accuracy; and handheld Raman relies on extensive spectral libraries for rapid identification. The choice of technology is not a matter of which is universally "best," but which is most fit-for-purpose. Researchers must align the instrument's core principle—whether it is mass, ion mobility, or vibrational fingerprint—with the specific analytical question, particularly the nature of the target analyte and its potential interferents. As experimental protocols become more robust and integrated with advanced data analysis like deep learning, the confidence in on-site, specific identification will only grow, further blurring the lines between the field laboratory and the central analytical facility.

Handheld spectrometers are revolutionizing fields from pharmaceuticals to food safety by moving analytical capabilities from the lab directly into the field. However, their adoption hinges on a critical, often difficult, balance between analytical performance and practical deployment needs. Sensitivity (correctly identifying true positives) and specificity (correctly identifying true negatives) are the bedrock of reliable results, while selectivity (the ability to distinguish the target analyte from interferences) becomes paramount in complex real-world samples. This guide provides an objective comparison of leading handheld spectroscopy technologies, supported by recent experimental data and validation protocols, to inform researchers and professionals in drug development and other applied sciences.

Technology Comparison: NIR, Raman, and Deep-UV Raman Spectrometry

The following table summarizes the key performance characteristics of three prominent portable technologies, based on independent and comparative studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Handheld Spectrometry Technologies

| Technology | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity | Key Strengths | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handheld NIR Spectrometry [10] | 11% (all drug types); 37% (analgesics) | 74% (all drug types); 47% (analgesics) | Non-destructive; rapid analysis (~20 sec); requires minimal sample prep; cloud-based AI libraries [10]. | Low sensitivity for substandard/falsified drug detection; performance varies significantly by drug formulation [10]. |

| Handheld Raman Spectrometry [11] | Not explicitly quantified in results | Courts accept data as legally prosecutable [11] | High molecular specificity; effective for counterfeit drug verification and forensic analysis [11]. | Fluorescence interference from colored or impure samples can limit use [12]. |

| Deep-UV Raman Spectrometry [12] | Detects MDMA at 1% w/w in tablets | Can distinguish MDMA from analogues and isomers [12] | Operates in fluorescence-free region; resonance enhancement provides high selectivity for specific compounds [12]. | Semi-portable; less suited for quantitative analysis; challenges with multiple absorbing substances [12]. |

The data reveals a clear performance trade-off. While standard NIR offers operational simplicity, its sensitivity can be critically low for many applications. Conventional Raman improves specificity but is vulnerable to fluorescence. Deep-UV Raman addresses the fluorescence limitation and offers high selectivity but currently faces portability and quantification challenges.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Robust validation is essential to quantify the trade-offs in any spectrometer. Below are detailed methodologies from recent studies.

This protocol was designed to test a handheld NIR device's ability to detect substandard and falsified (SF) medicines against the gold standard of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

- Objective: To measure the sensitivity and specificity of a proprietary AI-powered handheld NIR spectrometer in detecting SF medicines in a real-world setting.

- Sample Collection: 246 drug samples (analgesics, antimalarials, antibiotics, and antihypertensives) were purchased from randomly selected pharmacies across six geopolitical regions of Nigeria.

- NIR Analysis: Samples were tested using the handheld NIR spectrometer. The device compared the spectral signature (750-1500 nm) of each sample to a cloud-based AI reference library of authentic products. A "non-match" result indicated a poor-quality medicine. The process took approximately 20 seconds per sample.

- Reference Method Analysis: All samples underwent compositional quality analysis using HPLC in a controlled laboratory setting to definitively determine API content.

- Data Analysis: HPLC results were used as the ground truth to calculate the sensitivity (ability to correctly identify SF medicines) and specificity (ability to correctly identify authentic medicines) of the NIR device.

This protocol highlights how a different wavelength can be leveraged to overcome the limitations of conventional Raman.

- Objective: To explore the use of deep-ultraviolet resonance Raman spectroscopy (DUV-RRS) for detecting MDMA in ecstasy tablets and compare its performance to commercial handheld and benchtop systems.

- Instrument Setup: An in-house DUV-RRS system was built using a commercial 248.6 nm NeCu laser.

- Sample Preparation: Ecstasy tablets of varying colors and compositions were used. Low-dose samples were created by diluting MDMA with common excipients to concentrations as low as 1% w/w.

- Analysis: Transmission spectra of the samples were acquired and compared against those obtained from two commercial handheld Raman systems and a benchtop instrument.

- Performance Metrics: The study assessed the limit of detection (LOD), ability to overcome fluorescence from colored samples, and capability to distinguish MDMA from its chemical analogues and isomers.

Experimental Workflow and Validation Pathway

The following diagrams map the logical progression from technology selection to full system validation, illustrating the critical decision points and processes.

Field Deployment Spectrometer Workflow

Integrated Validation Protocol

For regulated environments like pharmaceuticals, a rigorous and integrated validation protocol is mandatory. The following diagram outlines a streamlined approach that combines Analytical Instrument Qualification (AIQ) and Computerized System Validation (CSV) into a single, efficient process [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful development and validation of handheld spectrometer methods rely on a set of essential materials and reagents.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectrometer Validation

| Item | Function in Development & Validation |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Provides a ground truth with known purity and composition for calibrating instruments, building spectral libraries, and verifying method accuracy [13] [14]. |

| Representative Field Samples | Collected from the actual environment where the device will be used, these samples are critical for testing performance under real-world conditions and ensuring method robustness [10]. |

| Chemometric Software & Tools | Enables the application of multivariate statistical analyses (e.g., PCA, PLS regression) to complex spectral data for both qualitative identification and quantitative measurement [14]. |

| Spectral Library | A curated database of authentic product signatures used as a baseline for comparative analysis; its quality and comprehensiveness directly impact the specificity of the method [10]. |

| Validation Protocol Kits | Commercially available kits that provide a comprehensive set of integrated documents to guide end-users through the system validation process, including IQ/OQ/PQ procedures [15]. |

| AZD-5991 | AZD-5991, CAS:2143010-83-5, MF:C35H34ClN5O3S2, MW:672.3 g/mol |

| Erucic acid | Erucic acid, CAS:63541-50-4, MF:C22H42O2, MW:338.6 g/mol |

The choice of a handheld spectrometer for field deployment is a strategic decision that involves navigating a landscape of critical trade-offs. Technologies like NIR offer speed and operational simplicity but may sacrifice critical sensitivity. Raman methods provide high specificity but can be foiled by fluorescent samples, a limitation addressed by emerging Deep-UV Raman systems. The path to successful deployment is anchored in a rigorous, integrated validation process that objectively quantifies these parameters against a gold standard using real-world samples. For researchers and drug development professionals, prioritizing independent performance evaluation and a robust validation framework is not just best practice—it is essential for ensuring that field-based results are reliable, actionable, and trustworthy.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Spectrometers in Pharmaceutical Workflows

Application in Raw Material Identification and Verification

The verification of raw materials is a critical quality control (QC) checkpoint in pharmaceutical manufacturing and other regulated industries. Traditionally, this process relies on compendial methods that often require sample preparation and time-consuming laboratory analysis, leading to significant delays in material release. Handheld Raman spectrometers have emerged as a powerful alternative, enabling rapid, non-destructive identification of materials directly in warehouse environments. These portable analytical instruments deliver laboratory-quality chemical identification in seconds without sample preparation, using laser-based Raman spectroscopy to provide a unique molecular "fingerprint" of the substance being analyzed [16].

The adoption of this technology aligns with a broader thesis in analytical science: that with proper validation of specificity and sensitivity, handheld spectrometers can provide legally defensible and regulatory-compliant results. This shift is part of the move towards Pharma 4.0 principles, which emphasize highly automated processes with continuous verification and a holistic control strategy [17]. The core advantage of handheld Raman systems lies in their ability to analyze materials through transparent packaging such as glass and plastic, protecting sample integrity and vastly reducing analysis time from weeks to minutes [16] [18]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of handheld Raman spectrometer performance against traditional and alternative analytical techniques, supported by experimental data and validation protocols.

Performance Comparison: Handheld Raman vs. Alternative Techniques

Key Performance Metrics and Experimental Data

The evaluation of any analytical technique for identity testing requires assessment of several key performance parameters, including specificity, sensitivity, limit of detection, and operational robustness. The following tables summarize comparative experimental data for handheld Raman spectrometers against other common techniques.

Table 1: Technique Comparison for Raw Material Identification

| Parameter | Handheld Raman | Benchtop Raman | Colorimetric Tests | HPLC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Time | 10-30 seconds [16] | 1-5 minutes [16] | 1-2 minutes [19] | 30+ minutes [17] |

| Sample Prep | None; through packaging [16] | May require mounting [16] | Required; destructive [19] | Extensive; destructive [17] |

| Specificity | High (Category A technique) [19] | Very High | Low to Moderate [19] | Very High |

| Portability | Excellent (<2 kg) [16] | Poor (lab-bound) | Good | Poor |

| Sensitivity (LOD) | 10-40 wt% for cocaine [19] | <5 wt% | Variable | <0.1 wt% |

| Regulatory Acceptance | 21 CFR Part 11 compliant [16] | Well-established | Presumptive only [19] | Gold standard |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance in Pharmaceutical Mixtures

| Analytical Technique | API Compound | Concentration Range | Prediction Error (RMSECV) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handheld NIR | Ibuprofen | Not specified | 1.118 [20] | [20] |

| Handheld NIR | Paracetamol | Not specified | 0.558 [20] | [20] |

| Handheld NIR | Caffeine | Not specified | 0.319 [20] | [20] |

| Benchtop NIR | Various APIs | Not specified | Lower than portable [20] | [20] |

| Handheld Raman | Cocaine HCl | 0-100 wt% | LOD: 10-40 wt% [19] | [19] |

Operational and Economic Considerations

Beyond technical performance, operational factors significantly influence technique selection for raw material verification. A study evaluating the implementation of a handheld Raman Rapid ID method for 46 common raw materials demonstrated a significant reduction in quality release time from weeks to minutes [17]. The economic impact of this acceleration is substantial, reducing working capital requirements and warehouse quarantine space. Furthermore, the non-destructive nature of Raman analysis preserves material integrity and eliminates costs associated with sample consumption [16] [17].

Handheld Raman systems consistently demonstrate high specificity across various material types, including amino acids, polyatomic salts, polymers, emulsifiers, peptides, and organic chemicals (both solid and liquid) [17]. This performance stems from Raman spectroscopy's fundamental principle of detecting characteristic molecular vibrations, which provide distinctive spectral fingerprints for different chemical structures [16]. However, the technique does face limitations with highly fluorescent materials, though this can be mitigated by using instruments with 1064 nm excitation lasers instead of the more common 785 nm systems [16] [19].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Development and Validation of Raman Spectral Libraries

The foundation of reliable raw material identification using handheld Raman spectrometers is a comprehensively validated spectral library. The development process follows a rigorous protocol to ensure accurate identification under real-world conditions [21] [17].

Diagram 1: Spectral Library Development and Validation Workflow

The validation process must establish specificity, robustness, and reproducibility under various operational conditions [17]. Specificity testing involves challenging the method with materials that are chemically similar or commonly used as excipients to ensure accurate discrimination. Robustness testing evaluates performance against environmental and operational variables such as temperature fluctuations, different operators, and instrument variations. Reproducibility assessment confirms consistent results across multiple instruments, lots, and testing conditions [21].

For raw material verification, the hit quality index (HQI) threshold is statistically determined using tolerance limits based on authentic reference materials. One validation study established a lower HQI threshold of 0.996 using a 95% confidence limit from 150 scans of authentic samples [21]. This threshold must be set to minimize both false positives and false negatives, ensuring that authentic materials are correctly identified while rejecting non-conforming materials.

Impact of Packaging Materials on Verification

A critical advantage of handheld Raman spectrometers is their ability to analyze materials through packaging, but container composition can impact spectral quality and identification reliability. Experimental studies have systematically evaluated this effect by testing various container types.

Table 3: Container Interference in Raman Spectroscopy [18]

| Container Type | Material Tested | Result | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene Bags | Titanium Dioxide | PASS through 35 layers | Strong Raman scatterer |

| Polyethylene Bags | Weak Raman scatterers | PASS through fewer layers | Material dependent |

| Amber Glass Bottles | Acetaminophen | PASS (p≥0.1) | Reliable identification |

| Clear Glass Bottles | Alcohols | PASS (p≥0.1) | Strong solvent response |

| Polystyrene | Various powders | FAIL initially | Required container-specific reference |

| Thick-walled Glass | Weak scatterers | FAIL | Luminescence interference |

Experimental protocols for addressing container interference include acquiring reference spectra through specific packaging materials when necessary. For challenging containers like polystyrene, creating container-specific references effectively compensates for packaging-induced spectral effects [18]. The most significant interference occurs with thick-walled glass containers due to variations in luminescence profiles between different glass thicknesses and suppliers [18].

Essential Research Toolkit for Method Validation

Implementing handheld Raman spectroscopy for raw material verification requires specific materials and protocols to ensure robust performance. The following research reagents and materials are essential for proper method development and validation.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Studies

| Item | Function in Validation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Authentic Reference Standards | Spectral library development | Pharmaceutical raw materials (APIs, excipients) [17] |

| Placebo/Blanks | Specificity testing | Distinguish API from excipient signals [21] |

| Common Cutting Agents | Specificity & interference studies | Lactose, cellulose, magnesium stearate [19] |

| Stressed Samples | Robustness assessment | Heat/humidity exposed materials [21] |

| Container Variants | Packaging interference studies | Different glass/plastic types and thicknesses [18] |

| Chemometric Software | Data analysis & modeling | PLS-DA, PCA, spectral matching algorithms [19] [20] |

| INCB9471 | INCB9471 | Potent, selective CCR5 antagonist for HIV entry inhibitor research. INCB9471 is For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| ZCL279 | ZCL279, MF:C24H18N2O7S2, MW:510.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The validation process must also include instruments from multiple production lots to establish method ruggedness. One study demonstrated this by testing spectral signatures across five different lots of a tablet product using two different portable spectrometers, establishing consistent performance with average match values of 0.998 and 0.997 respectively [21]. This instrument-to-instrument consistency is critical for methods deployed across multiple locations or by different operators.

Handheld Raman spectrometers represent a transformative technology for raw material identification and verification when implemented with rigorous validation protocols. The experimental data and performance comparisons presented in this guide demonstrate that these portable instruments provide an optimal balance of speed, specificity, and operational flexibility for warehouse and receiving dock environments. While traditional laboratory methods like HPLC offer superior sensitivity for trace analysis, and benchtop Raman systems provide higher spectral resolution, handheld Raman spectrometers deliver adequate performance for identity testing with unprecedented efficiency gains.

The validation framework outlined—encompassing comprehensive spectral library development, container compatibility testing, and rigorous assessment of specificity and robustness—provides a roadmap for researchers and quality professionals to implement these technologies with confidence. As the global handheld spectrometer market continues to grow at a CAGR of 8.3%, projected to reach USD 2.5 billion by 2032 [22], these validation protocols will become increasingly important for ensuring data integrity and regulatory compliance across pharmaceutical, chemical, and other material-dependent industries.

In-Process Quality Control and Blend Homogeneity Monitoring

In the pharmaceutical industry, ensuring blend homogeneity is a critical quality attribute for solid dosage forms. A non-homogeneous blend can result in tablets with incorrect dosages, compromising patient safety and therapeutic efficacy. Traditional methods for assessing blend uniformity involve stopping the manufacturing process, collecting powder samples from multiple locations within a blender, and analyzing them using chromatographic techniques. This approach is time-consuming, labor-intensive, and poses a risk of powder segregation during sampling [23].

Over the past two decades, significant technological advancements have been made in low-cost, portable screening devices for quality control [10]. Process Analytical Technology (PAT) frameworks, encouraged by regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA, advocate for real-time monitoring to ensure final product quality [23]. Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for real-time, non-destructive analysis of powder blends, capable of detecting both the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) and excipients without sample preparation [23] [24]. This guide objectively compares the performance of handheld and benchtop spectrometers, with a specific focus on their sensitivity and specificity in validating blend homogeneity.

Performance Comparison of Spectroscopic Tools

The choice between handheld and benchtop spectrometers involves a trade-off between analytical performance and operational flexibility. The following table summarizes a direct comparison based on recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Handheld NIR vs. Benchtop HPLC for Medicine Analysis

| Performance Metric | Handheld NIR Spectrometer | Benchtop HPLC (Reference Method) |

|---|---|---|

| Study Context | Analysis of 246 drug samples from Nigerian pharmacies [10] | Analysis of 246 drug samples from Nigerian pharmacies [10] |

| Overall Sensitivity | 11% | 100% (by definition) |

| Overall Specificity | 74% | 100% (by definition) |

| Analgesics Sensitivity | 37% | 100% (by definition) |

| Analgesics Specificity | 47% | 100% (by definition) |

| Prevalence of SF Medicines Detected | Lower subset (analgesics only) | 25% of all samples |

| Analysis Time | ~20 seconds [10] | Lengthy (hours, including preparation) |

| Analysis Nature | Non-destructive, real-time [10] | Destructive, laboratory-based |

While benchtop instruments like HPLC are reference standards, the comparison between different types of spectrometers is also crucial. A study on maritime pine resin demonstrated that a handheld NIR spectrometer (SCiO) could perform comparably to a benchtop NIR spectrometer (MPA I) for quantifying chemical components, provided robust chemometric models are used [25].

Table 2: Comparison of Spectrometer Technologies for On-Scene Analysis

| Feature | Portable IR Spectrometer | Portable Raman Spectrometer | Color-Based Field Tests |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 25% for cocaine HCl with adulterants [26] | Higher LOD than IR [26] | 10% for cocaine HCl [26] |

| False Positives | Minimal with a well-built library [26] | Minimal with a well-built library [26] | High (e.g., lidocaine tests positive for cocaine) [26] |

| Analysis Speed | Rapid (minutes) [26] | Rapid (minutes) [26] | Fast (minutes) [26] |

| Destructive to Sample | No [26] | No [26] | Yes [26] |

| Key Challenge | Library-dependent, lower sensitivity for low-dose APIs [10] [26] | Fluorescence interference from impurities [26] | Poor specificity, subjective interpretation [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

To ensure the reliable deployment of spectroscopic methods, particularly handheld devices, rigorous experimental protocols must be followed to validate their sensitivity and specificity against reference methods.

Protocol 1: Field Validation of Handheld NIR for Substandard and Falsified Medicines

This protocol is based on a 2025 study comparing a handheld AI-powered NIR spectrometer to HPLC in Nigeria [10].

- Sample Collection: Purchase medicine samples from randomly selected pharmacies in both urban and rural areas. The study used 12 enumerators as "mystery shoppers" across six geopolitical zones [10].

- Sample Size: A total of 246 drug samples were purchased, covering analgesics, antimalarials, antibiotics, and antihypertensives [10].

- NIR Analysis: Test all drug samples using the handheld NIR spectrometer. The device compares the spectral signature of the sample to a cloud-based AI reference library of authentic products. A "non-match" result indicates a failed product. The process takes approximately 20 seconds per sample [10].

- Reference Method Analysis: A weighted sub-sample of the purchased medicines is selected and analyzed using HPLC for compositional quality. This serves as the gold standard [10].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the sensitivity and specificity of the handheld NIR device using the HPLC results as the ground truth. The study calculated these values overall and for specific drug categories [10].

Protocol 2: In-Line NIR Monitoring for Continuous Manufacturing

This protocol, derived from Rangel-Gil et al. (2024), details the use of in-line NIR for monitoring a low-dose formulation in a continuous manufacturing process [24].

- Formulation: Use a low-drug load formulation (e.g., 2.5–7.5% w/w Ibuprofen DC 85 W) with excipients like microcrystalline cellulose and croscarmellose sodium [24].

- Equipment Setup: Integrate a continuous direct compression (CDC) line with Loss-in-Weight (LIW) feeders and a continuous powder mixer. Install a stream sampler at the mixer outlet, which presents the powder to an in-line NIR probe in a reproducible manner, minimizing errors from air gaps or powder heterogeneity [24].

- PLS Calibration Model Development: Collect NIR spectra from powder blends of known API concentration during preliminary runs. Use Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to build a quantitative model that correlates spectral data to the API concentration [24].

- Real-Time Monitoring & Variographic Analysis: During continuous production, use the PLS model to predict API concentration in real-time. Perform variographic analysis on the stream of NIR predictions to quantify total sampling and analytical errors, providing a rigorous statistical assessment of blend uniformity [24].

The workflow for validating and deploying a handheld spectrometer for quality control involves a structured process from initial setup to final decision-making, as outlined below:

Diagram 1: Handheld Spectrometer Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successfully implementing a spectroscopic blend monitoring program requires more than just a spectrometer. The following table details key materials and their functions based on the cited experimental protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Blend Monitoring

| Material/Reagent | Function in Experimentation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Authentic Drug Samples | To build and validate the spectral reference library; serves as the ground truth for calibration. | Sourced from manufacturers for the NIR library [10]. |

| Ibuprofen DC 85 W | A model Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) for low-dose formulation studies. | Used as API in 2.5–7.5% w/w concentration [24]. |

| Prosolv SMCC HD90 | A commonly used excipient (silicified microcrystalline cellulose) that aids in flow and compression. | Main excipient in continuous manufacturing study [24]. |

| Croscarmellose Sodium | A super-disintegrant excipient used in tablet formulations. | Used in the continuous manufacturing formulation [24]. |

| Magnesium Stearate | A lubricant excipient to prevent powder from sticking to equipment. | Used in the continuous manufacturing formulation [24]. |

| Stream Sampler | A specialized interface that presents flowing powder reproducibly to an in-line NIR probe, reducing measurement error. | Implemented at the outlet of a continuous mixer for accurate NIR reading [24]. |

| PLS Chemometric Model | A multivariate calibration model that correlates spectral data to API concentration; essential for quantitative analysis. | Developed to monitor 2.5–7.5% w/w Ibuprofen concentration in real-time [24]. |

| SIC-19 | SIC-19, MF:C29H26N4O5S2, MW:574.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| FPMINT | FPMINT, MF:C24H24FN7, MW:429.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The drive towards real-time quality control and continuous manufacturing in the pharmaceutical industry is accelerating the adoption of spectroscopic methods like NIR. While handheld NIR spectrometers offer unparalleled advantages in portability, speed, and non-destructive analysis, current independent evaluations indicate that their sensitivity, particularly for low-dose APIs, may not yet meet the stringent requirements for detecting substandard and falsified medicines in all contexts [10]. The performance is highly dependent on a well-constructed spectral library and robust chemometric models.

In contrast, in-line NIR systems, especially when coupled with advanced sampling interfaces like the stream sampler and validated using PLS regression and variographic analysis, demonstrate high accuracy and precision for monitoring blend homogeneity in a continuous manufacturing setting [24]. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice of technology must be guided by the specific application: handheld devices show promise for rapid, on-site screening, whereas in-line benchtop-grade systems are currently more reliable for quantitative, real-time control of critical process parameters. Future developments should focus on improving the sensitivity of handheld devices and expanding their spectral libraries for a wider range of drug formulations.

Detecting Substandard and Falsified (SF) Medicines in Supply Chains

The proliferation of substandard and falsified (SF) medical products represents a critical global public health challenge, compromising patient safety and undermining health systems worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 1 in 10 medicines in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are substandard or falsified, leading to significant health and economic consequences [27]. Substandard products fail to meet quality standards specifications, while falsified products deliberately misrepresent their identity, composition, or source [27].

In response to this complex challenge, handheld spectroscopic devices have emerged as promising tools for rapid, on-site screening of medicine quality within supply chains. This guide provides an objective comparison of the leading technologies—Raman and Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy—framed within the context of validating their specificity and sensitivity for detecting SF medicines. We present experimental data, detailed methodologies, and analytical frameworks to support researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in evaluating and implementing these technologies.

Technology Comparison: Raman vs. NIR Spectroscopy

Performance Metrics and Experimental Findings

Handheld spectrometers identify medicines by analyzing their unique spectral fingerprints and comparing them against verified reference libraries. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from controlled studies:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Handheld Spectrometers for SF Medicine Detection

| Technology | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity | Analysis Time | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectrometry [28] [29] | 98-100% | 96-100% | 15-60 seconds | Limited penetration through packaging; variable performance with fluorescent compounds |

| NIR Spectrometry [10] | 11-37%* | 47-74%* | ~20 seconds | Lower sensitivity in field conditions; requires extensive chemometric modeling |

| Laboratory Reference (HPLC) [10] | N/A (Gold standard) | N/A (Gold standard) | 45 minutes - hours | Requires laboratory setting, trained personnel, and sample preparation |

*Varies significantly by drug formulation; higher value specific to analgesics

Technical Principles and Analytical Approaches

Both Raman and NIR spectroscopy probe molecular vibrations but utilize different physical mechanisms with distinct implications for medicine verification:

Raman Spectroscopy: Measures inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser. It provides sharp spectral features that are highly specific to molecular structure, particularly effective for identifying active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) through glass or plastic packaging [28] [29].

Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy: Utilizes absorption of light in the NIR region (750-1500 nm). Spectra contain information on both chemical composition and physical properties, but require sophisticated chemometric algorithms for interpretation [10] [30].

The selection of analytical algorithms significantly impacts performance. Common approaches include:

- Spectral correlation methods (e.g., Hit Quality Index): Simple, computationally efficient, but may lack robustness against variations in measurement conditions [30].

- Class modeling techniques (e.g., SIMCA): Statistically characterizes target drugs and tests compatibility of new samples, particularly effective for specific brand identification [30].

- Machine learning algorithms: Emerging approaches using proprietary algorithms to enhance detection accuracy, particularly for substandard medicines with incorrect API concentrations [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Testing Protocol for Handheld Spectrometers

To ensure reproducible validation of handheld spectrometers, researchers should implement the following standardized protocol adapted from multiple studies:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Authentic Medicine Standards | Reference materials for spectral library development | Must be obtained directly from manufacturers with verified chain of custody |

| Handheld Spectrometer | Field-deployable analysis device | Requires regular calibration according to manufacturer specifications |

| Chemical Reference Standards | HPLC method validation | Certified reference materials for API quantification |

| Portable Environmental Chamber | Control temperature and humidity during analysis | Critical for ensuring measurement consistency in field conditions |

Sample Collection and Preparation:

- Randomized Sampling: Collect medicine samples from various supply chain points (wholesalers, pharmacies, hospitals) using random walk methods to avoid bias [10].

- Blinded Analysis: Code samples to ensure analysts are blinded to origin and expected composition during testing.

- Environmental Control: Maintain consistent temperature (20-25°C) and humidity (40-60% RH) during analysis to minimize spectral variations.

Instrument Operation and Data Collection:

- Library Development: Create reference spectral libraries using authenticated drug samples from legitimate manufacturers, covering multiple production batches where possible [28].

- Validation Set Testing: Analyze samples of known quality (both authentic and confirmed SF) to establish sensitivity and specificity thresholds.

- Field Simulation: Test a subset of samples through original packaging to evaluate real-world performance [29].

Reference Methodologies: HPLC Analysis

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) serves as the gold standard for validating handheld spectrometer results:

Sample Preparation:

- Precisely weigh and dissolve tablet/powder samples in appropriate solvents

- Use serial dilution to achieve concentrations within analytical method range

- Filter solutions through 0.45μm or 0.22μm membranes before injection

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: C18 reverse phase (e.g., 250mm × 4.6mm, 5μm)

- Mobile phase: Optimized for specific APIs (e.g., acetonitrile-phosphate buffer mixtures)

- Flow rate: 1.0 mL/min with UV detection at API-specific wavelengths

- Injection volume: 10-20μL

- Analysis temperature: 25°C [10]

Validation Parameters:

- Specificity: No interference from excipients or degradation products

- Linearity: R² > 0.999 over specified concentration range

- Precision: RSD < 2% for repeatability

- Accuracy: 98-102% recovery of spiked samples

Detection Workflows and Decision Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for validating handheld spectrometers, integrating both field screening and laboratory confirmation:

Diagram 1: SF Medicine Detection Workflow (Width: 760px)

The decision pathway for spectral analysis involves multiple algorithmic approaches, each with distinct advantages for specific detection scenarios:

Diagram 2: Spectral Analysis Decision Pathway (Width: 760px)

Discussion and Research Implications

Contextualizing Performance Metrics

The substantial disparity in sensitivity between Raman and NIR spectrometers observed in recent field studies [10] highlights the critical importance of context in technology validation. While Raman demonstrated excellent performance in controlled studies of specific drug classes like anti-malarials [29], the generalized application of both technologies across diverse pharmaceutical formulations requires more extensive validation.

The analytical approach employed appears to be as significant as the instrumental technology itself. As noted in comparative studies, "there is no ideal vibrational spectrophotometer" [30], indicating that optimal detection strategies must match the technology and analytical method to specific verification scenarios. Factors including packaging material, drug formulation characteristics, and environmental conditions all substantially influence performance.

Advancing Specificity and Sensitivity Validation

Future research should prioritize several key areas to enhance validation protocols:

Standardized Reference Materials: Develop and characterize well-defined SF medicine simulants that represent realistic falsification scenarios across multiple drug classes.

Multi-site Validation Studies: Coordinate testing across multiple geographic regions with varying environmental conditions to establish instrument robustness.

Algorithm Improvement: Enhance machine learning approaches, particularly for NIR technology, to improve sensitivity in detecting substandard medicines with incorrect API concentrations.

Integrated Supply Chain Solutions: Combine spectroscopic screening with track-and-trace technologies and supply chain security frameworks [31] to create comprehensive protection systems.

The validation of handheld spectrometers represents a crucial component in the global effort to secure medical supply chains against substandard and falsified products. By implementing rigorous, standardized testing protocols and understanding the performance characteristics of each technology, researchers and regulators can make informed decisions about technology deployment that ultimately protects patient safety worldwide.

Leveraging AI and Deep Learning for Automated Spectral Analysis

Automated spectral analysis, powered by artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning, is transforming analytical chemistry. This guide compares the performance of AI-enhanced spectroscopic techniques, focusing on their validation for specificity and sensitivity in critical applications like pharmaceutical analysis.

Comparative Performance of AI-Enhanced Spectral Techniques

The table below summarizes experimental data for different spectroscopic techniques integrated with AI, highlighting their performance in specific applications.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI-Enhanced Spectroscopic Techniques

| Technique | AI Model | Application | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy | Transformer-based (Patch-based) | Molecular Structure Elucidation | Top-1 Accuracy: 63.79%; Top-10 Accuracy: 83.95% | [32] |

| Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) | Deep Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Geochemical Classification (Multi-distance) | Maximum Testing Accuracy: 92.06% (Precision, Recall, F1-score also improved) | [33] |

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) | Random Forest (RF), SVM, CNN-LSTM | Bacterial Detection | Accuracy: 99% (pure samples), 92-96% (clinical samples) | [34] |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy | Proprietary Machine Learning Algorithm | Detection of Substandard/Falsified Medicines | Overall Sensitivity: 11%; Specificity: 74% (Varied significantly by drug type) | [10] |

Analysis of Comparative Performance

IR Spectroscopy for Structure Elucidation: The transformer-based model represents a state-of-the-art benchmark, demonstrating that AI can directly predict molecular structures from IR spectra with high accuracy, a problem traditionally considered unsolved [32].

LIBS for Ruggedized Classification: The deep CNN model excels in a challenging real-world scenario with varying detection distances, a common issue in planetary exploration. Its high accuracy without needing pre-processing "distance correction" showcases the robustness AI can bring to field-deployed instruments [33].

SERS for High-Sensitivity Detection: The combination of SERS and ML consistently achieves high accuracy (>95%) across diverse fields. The technique is particularly powerful for identifying trace molecules, with AI overcoming traditional limitations like overlapping peaks and complex spectral data [34].

NIR for Field-Based Pharmaceutical Screening: This case study provides a crucial counterpoint, highlighting the validation challenges for handheld AI-spectrometers in complex real-world tasks. The low overall sensitivity indicates a high risk of false negatives, which is unacceptable for public health protection. This underscores that potential does not always equate to immediate readiness [10].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

AI-Driven Infrared Structure Elucidation

This protocol is based on the state-of-the-art model that set new benchmarks for predicting molecular structures from IR spectra [32].

Objective: To predict the molecular structure (as a SMILES string) directly from an infrared (IR) spectrum and the compound's chemical formula.

AI Model & Architecture: A patch-based Transformer architecture was used, inspired by Vision Transformers. Key refinements included:

- Post-layer normalization for improved gradient flow during training.

- Gated Linear Units (GLUs) as activation functions for enhanced model expressivity.

- Learned positional embeddings instead of fixed sinusoidal encodings.

- An optimal patch size of 75 data points was determined for experimental spectra.

Training Data & Strategy:

- Pretraining: The model was first trained on a large dataset of ~1.4 million simulated IR spectra.

- Fine-tuning: The model was then fine-tuned on 3,453 experimental spectra from the NIST database using 5-fold cross-validation.

- Data Augmentation: Strategies like horizontal shifting of spectra and using non-canonical SMILES representations were critical for improving model generalization.

Performance Validation: Model performance was validated by its Top-1 and Top-10 accuracy in predicting the correct molecular structure from an experimental IR spectrum.

Handheld NIR Spectrometer for Medicine Screening

This protocol outlines the independent validation of a commercial AI-powered handheld NIR device for detecting substandard and falsified (SF) medicines in Nigeria [10].

Objective: To evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of a handheld NIR spectrometer against the reference method of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

Device & AI Model: A patented, handheld NIR spectrometer (750-1500 nm) using a proprietary, cloud-based machine learning algorithm. The device compares a drug's spectral signature to a library of authentic products.

Sample Collection:

- Location: 246 drug samples were purchased from randomly selected pharmacies across six geopolitical zones of Nigeria.

- Drug Categories: Analgesics, antibiotics, antimalarials, and antihypertensives.

Experimental Method:

- NIR Screening: All purchased samples were tested on-site with the handheld NIR device. The result is a binary "match" or "non-match" with the authentic spectral signature.

- HPLC Reference Analysis: The same drug samples were sent to a licensed laboratory (Hydrochrom Analytical Services Limited, Lagos) for quantitative composition analysis via HPLC, which is a standard method for assessing drug quality.

Data Analysis: The results from the NIR device were compared to the HPLC results to calculate:

- Sensitivity: The ability of the NIR device to correctly identify SF medicines (true positive rate).

- Specificity: The ability of the NIR device to correctly identify authentic medicines (true negative rate).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key materials and computational resources used in the advanced spectroscopic experiments cited in this guide.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for AI-Enhanced Spectroscopy

| Item Name | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| ZrC (Zirconium Carbide) Discs | High-temperature material used as a standardized target for LIBS calibration and method development. | LIBS for surface temperature estimation [35] |

| SERS Substrates (e.g., Au/Ag Nanoparticles) | Nanostructured metal surfaces that dramatically enhance Raman signals for sensitive detection. | SERS for pathogen, cocaine, and food contaminant detection [34] |

| Certified Reference Materials (GBW Series) | Geochemical samples with certified composition, used for model training and validation. | LIBS classification of geological samples [33] |

| NIST Spectral Database | A large, curated database of experimental IR spectra, used as a benchmark for training and testing AI models. | AI-driven IR structure elucidation [32] |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) / GPU Clusters | Computational resources necessary for training large deep learning models, such as Transformers and CNNs. | Training patch-based Transformer models [32] |

| E6-272 | E6-272, MF:C26H28N2O, MW:384.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| EGFR-IN-121 | EGFR-IN-121, MF:C23H26N2O5, MW:410.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Diagram: AI-Driven Spectral Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for developing and deploying an AI model for automated spectral analysis, integrating common steps from the cited research.

AI-Driven Spectral Analysis Workflow

Key Technological Advancements

The performance gains shown in this guide are driven by several key technological advancements:

Explainable AI (XAI): Techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) are increasingly integrated to reveal which spectral features drive AI predictions. This is vital for regulatory acceptance and scientific trust, moving beyond "black box" models [36].

Generative AI for Data Augmentation: Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and diffusion models are used to create synthetic spectral data. This helps mitigate the challenge of small or biased experimental datasets, improving the robustness of calibration models [36].

Multimodal and Foundation Models: Emerging platforms like SpectrumLab and SpectraML aim to create foundation models trained on millions of spectra. The integration of multiple data types (e.g., IR with mass spectrometry) is a powerful trend for improving elucidation power [36].

Non-Destructive Analysis for Clinical Diagnostics and Biomarker Detection

The integration of handheld spectrometers into clinical diagnostics represents a paradigm shift toward decentralized, rapid, and non-destructive analysis. Traditional methods for biomarker detection, such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or mass spectrometry, often require centralized laboratories, trained personnel, and are time-consuming [37]. In contrast, handheld spectroscopic devices offer the potential for on-site, real-time analysis with minimal sample preparation, enabling faster decision-making in point-of-care settings, environmental monitoring, and pharmaceutical development [38]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance of various handheld spectroscopy technologies, focusing on their validated specificity and sensitivity for clinical biomarker detection, to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

The core advantage of these portable systems lies in their ability to provide a rapid molecular "fingerprint" without consuming or altering the sample. This is particularly valuable for screening applications, intraoperative diagnosis, and monitoring dynamic biological processes [39] [40]. The following sections compare the technical capabilities of prevalent handheld spectroscopy platforms, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols from recent research.

Technology Performance Comparison

The selection of an appropriate handheld spectrometer depends heavily on the application's specific requirements for sensitivity, specificity, and operational convenience. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the most prominent technologies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Handheld Spectroscopic Technologies

| Technology | Key Principles | Best For | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handheld Raman Spectroscopy | Inelastic scattering of light providing molecular vibrational fingerprints [39]. | Intraoperative diagnosis, pharmaceutical authentication, and cancer biomarker detection [40]. | High chemical specificity; minimal sample preparation; can be enhanced with SERS for extreme sensitivity [39] [40]. | Inherently weak signal; can be masked by sample fluorescence; lower sensitivity for trace analytes without SERS [39] [41]. |

| Handheld NIR Spectroscopy | Absorption of near-infrared light by overtone and combination molecular vibrations [38]. | Quality control of pharmaceuticals, agricultural product analysis, and food safety screening [38]. | Deep penetration; rapid analysis; robust and easy to use. | Complex data interpretation often requiring multivariate calibration; less specific than Raman or mid-IR. |

| Handheld XRF Spectrometry | Emission of characteristic secondary X-rays from a material excited by a primary X-ray source [38]. | Elemental analysis, detecting heavy metals and hazardous substances [38]. | Excellent for elemental and isotopic composition; quantitative analysis. | Generally not suitable for organic molecule or biomarker detection. |

| Handheld FTIR Spectroscopy | Absorption of infrared light corresponding to molecular bond vibrations [42]. | Serum metabolome analysis for predicting patient outcomes, protein stability studies [42] [43]. | Fast, cost-effective, and high-throughput operation; suitable for complex biological populations [43]. | Water interference can be challenging for aqueous biological samples. |

Quantitative Data from Clinical and Experimental Studies

Recent studies have rigorously benchmarked these technologies against gold-standard methods, generating critical performance data for researchers.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics in Clinical and Pharmaceutical Applications

| Application Context | Technology | Key Experimental Findings | Reported Metrics | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ovarian Cancer Biomarker (Haptoglobin) Detection | Portable Single-Peak Raman Reader | Detection of Hp in ovarian cyst fluid via a TMB-based enzymatic assay. | Sensitivity: 100.0%Specificity: 85.0%Negative Predictive Value: 100.0% | [40] |

| Alzheimer's Disease Plasma Biomarker (Aβ42/40) Detection | Immunoprecipitation-Mass Spectrometry (IP-MS) | Discrimination of AD patients from other neurological groups using a composite biomarker. | AUC: 0.91 (vs. SCI), 0.89 (vs. OND), 0.81 (vs. NDD) | [44] |

| Predicting ICU Patient Outcomes (Invasive Ventilation/Death) | FTIR Spectroscopy | Classification of patient outcomes based on serum metabolome analysis, outperforming UHPLC-HRMS in unbalanced groups. | Model Accuracy: 83% | [43] |

| Identification of Counterfeit Medicines | Laboratory vs. Handheld Raman | Handheld Raman successfully identified counterfeit drugs but was more susceptible to fluorescence interference from coatings. | Identification success was highly dependent on API concentration and sample form (intact vs. powdered). | [45] |

Experimental Protocol: Raman-Based Biomarker Detection

The high-performance results for ovarian cancer diagnosis, as shown in Table 2, were achieved through a carefully designed experimental protocol.

Objective: To detect and quantify the cancer biomarker Haptoglobin (Hp) in ovarian cyst fluid (OCF) using a portable Raman system [40].

Materials & Reagents:

- Biomarker: Haptoglobin (Hp) of human origin.

- Assay Reagents: Hemoglobin (Hb), 3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate, citrate buffer solution, and a reaction stop solution.

- Samples: Clinical OCF samples, centrifuged and stored at -80°C until analysis.

- Equipment: Portable single-peak Raman reader (785 nm laser) or commercial Raman microscope for validation.

Procedure:

- Complex Formation: Mix purified Hp standard or clinical OCF with a fixed concentration of Hb. Incubate for 10 minutes to form an irreversible [Hb-Hp] complex.

- Enzymatic Reaction: Add TMB reagent to the [Hb-Hp] complex. The complex catalyzes the oxidation of TMB to TMB²âº, which is strongly Raman active. Allow the reaction to proceed at room temperature for a few minutes.

- Reaction Quenching: Add a stop solution to quench the reaction.

- Raman Measurement: Pipette 10-20 µL of the final reaction mixture onto a glass slide with a microwell. Measure the Raman intensity in the wavenumber region of 1500–1700 cmâ»Â¹, which corresponds to the characteristic peak of TMB²âº.

- Quantification: Generate a calibration curve using Hp standards of known concentration. Use this curve to determine Hp concentration in unknown OCF samples based on the measured Raman intensity [40].

This protocol highlights how a biochemical assay can be coupled with a simplified, portable reader to achieve high diagnostic performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of spectroscopic methods in research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Spectroscopic Clinical Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| SERS Substrates | Nano-roughened metal surfaces or colloidal nanoparticles (e.g., gold, silver) that enhance weak Raman signals by several orders of magnitude [39]. | Detection of trace biomarkers, contaminants, or pharmaceuticals at ultra-low concentrations [39] [41]. |

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) | A technique that uses SERS substrates to drastically increase Raman signal intensity, enabling single-molecule detection in some cases [39]. | |

| TMB (3,3',5,5'-Tetramethylbenzidine) | A chromogenic and Raman-inactive substrate that, when oxidized by a target enzyme or complex (e.g., Hp-Hb), becomes a Raman-active product (TMB²âº) [40]. | Creating a Raman-detectable signal for biomarker detection assays, as used in ovarian cancer diagnosis [40]. |

| Linear Variable Filters (LVFs) | Optical filters used in miniaturized spectrometers where the wavelength transmitted varies linearly along the length of the filter, enabling compact design [46]. | Key components in portable spectrometer designs for space exploration (e.g., ExoMars) and field-deployable instruments [46]. |

| Ultrapure Water Purification System | Provides water free of contaminants and particles that could interfere with sensitive spectroscopic measurements. | Critical for sample preparation, dilution, and mobile phase preparation in supporting analytical techniques [42]. |

| DB28 | DB28, CAS:16296-42-7, MF:C8H9N3O5, MW:227.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| KH-3 | (2E)-3-[5-(4-tert-butylbenzenesulfonamido)-1-benzothiophen-2-yl]-N-hydroxyprop-2-enamide | High-purity (2E)-3-[5-(4-tert-butylbenzenesulfonamido)-1-benzothiophen-2-yl]-N-hydroxyprop-2-enamide for research use only (RUO). Not for human or veterinary use. CAS 1215115-03-9. |

Logical Workflow for Handheld Spectrometer Validation

The transition from a laboratory technique to a validated field-deployable method follows a structured pathway. The diagram below illustrates this key logical progression.

Diagram 1: The pathway from laboratory validation to field-deployed decision-making, highlighting the iterative cycle of data acquisition and model refinement.

Handheld Raman, NIR, and FTIR spectrometers have matured into powerful tools for non-destructive clinical analysis. The experimental data demonstrates that their performance can meet, and in some cases surpass, the requirements for specific diagnostic applications such as cancer biomarker detection and patient stratification. The choice of technology involves a careful balance between the required sensitivity, specificity, and operational pragmatism. As innovations in machine learning, reagent science, and hardware miniaturization continue, the specificity and sensitivity of these portable platforms are expected to expand their role in clinical diagnostics and drug development further, enabling a future of truly decentralized, data-driven precision medicine.

Overcoming Limitations: Strategies for Enhanced Performance and Reliability

Mitigating Fluorescence in Raman Spectroscopy with Novel Hardware and Algorithms

Raman spectroscopy is a powerful, non-destructive analytical technique used for molecular identification across pharmaceutical, clinical, and materials sciences. However, its widespread adoption, particularly for emerging handheld devices, is constrained by a significant challenge: fluorescence interference. This unwanted signal, often several orders of magnitude more intense than the inherently weak Raman scattering, can obscure the characteristic vibrational fingerprints, reducing analytical sensitivity and specificity [47] [48].

The mitigation of fluorescence is thus a critical focus in the validation of handheld spectrometers. This guide objectively compares the performance of contemporary hardware and algorithmic strategies designed to suppress fluorescence, providing researchers with a structured analysis of their operational principles, experimental protocols, and comparative efficacy to inform development and application decisions.

Hardware-Based Mitigation Approaches

Hardware approaches aim to physically prevent fluorescence from reaching the detector or to separate it from the Raman signal based on its temporal or spectral properties.

A fundamental hardware strategy involves selecting a laser excitation wavelength that minimizes the excitation of electronic transitions responsible for fluorescence.

- Near-Infrared (NIR) Excitation: Using longer wavelength lasers (e.g., 785 nm or 830 nm) reduces the energy of incident photons, making it less likely to excite fluorescent states in many samples. A comparison of 532 nm and 785 nm excitation on a gemstone showed a broad fluorescence band at 532 nm was entirely removed at 785 nm, yielding a clean Raman spectrum [47].

- Shifted Excitation Raman Difference Spectroscopy (SERDS): This advanced technique uses two slightly shifted excitation wavelengths (e.g., at 830 nm and 832.4 nm). The Raman peaks shift correspondingly, while the broad fluorescence background remains static. Subtracting the two spectra cancels the fluorescence, and the resulting difference spectrum is reconstructed into a fluorescence-free Raman spectrum [48]. SERDS is particularly effective in highly fluorescent biological samples and can also remove interference from optical fibres and etaloning effects in the CCD detector [48].

Table 1: Comparison of Laser Wavelength Strategies

| Technique | Typical Laser Wavelength(s) | Mechanism of Action | Key Applications | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIR Excitation | 785 nm, 830 nm, 1064 nm | Avoids electronic excitation to prevent fluorescence [47]. | General-purpose analysis of fluorescent solids, pharmaceuticals. | Effective fluorescence removal in gemstones and pharmaceuticals; 1064 nm is superior for colored/fluorescent samples [16]. |