Verifying Functional Sensitivity: A Practical Guide to Establishing Interassay Precision Profiles for Robust Bioanalytical Methods

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on verifying functional sensitivity through interassay precision profiles.

Verifying Functional Sensitivity: A Practical Guide to Establishing Interassay Precision Profiles for Robust Bioanalytical Methods

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on verifying functional sensitivity through interassay precision profiles. It covers foundational principles distinguishing functional sensitivity from analytical sensitivity, details CLSI-aligned methodologies for precision testing, strategies for troubleshooting poor precision, and frameworks for statistical validation and comparison against manufacturer claims. The content synthesizes current guidelines, practical protocols, and emerging trends to equip scientists with the knowledge to reliably determine the lower limits of clinically reportable results for immunoassays and other bioanalytical methods, thereby ensuring data integrity and regulatory compliance in preclinical and clinical studies.

Functional Sensitivity vs. Analytical Sensitivity: Defining the Clinically Relevant Detection Limit

For researchers and drug development professionals, the journey from theoretical detection to clinically useful results is paved with critical performance verification. The terms "analytical sensitivity" and "functional sensitivity" represent fundamentally different concepts in assay validation, with the former describing pure detection capability and the latter defining practical utility in real-world settings. Analytical sensitivity, formally defined as the lowest concentration that can be distinguished from background noise, represents the assay's detection limit and is typically established by assaying replicates of a sample with no analyte present, then calculating the concentration equivalent to the mean counts of the zero sample plus 2 standard deviations for immunometric assays [1]. While this parameter provides fundamental characterization, its practical value is limited because imprecision increases dramatically as analyte concentration decreases, often making results unreliable even at concentrations significantly above the detection limit [1].

The critical limitation of analytical sensitivity led to the development of functional sensitivity, which addresses the essential question: "What is the lowest concentration at which an assay can report clinically useful results?" [1] Functional sensitivity represents the lowest analyte concentration that can be measured with acceptable precision and accuracy during routine operating conditions, typically defined by interassay precision profiles with a coefficient of variation (CV) not exceeding 20% for many clinical applications [1]. This distinction is not merely academic—it directly impacts clinical decision-making, therapeutic monitoring, and diagnostic accuracy across diverse applications from cardiac troponin testing to cancer biomarker detection and infectious disease diagnostics.

Key Concepts: Analytical vs. Functional Sensitivity

Fundamental Definitions and Distinctions

The transition from theoretical detection to clinical usefulness requires understanding both the capabilities and limitations of analytical methods. The following table summarizes the core differences between these two critical performance parameters:

| Parameter | Analytical Sensitivity | Functional Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Lowest concentration distinguishable from background noise [1] | Lowest concentration for clinically useful results with acceptable precision [1] |

| Common Terminology | Detection limit, limit of detection (LOD) [1] [2] | Lower limit of quantitation (LLOQ) [3] |

| Calculation Method | Mean of zero sample ± 2 SD (depending on assay type) [1] | Concentration where CV reaches predetermined limit (typically 20%) [1] |

| Primary Focus | Signal differentiation from background [1] | Result reproducibility and reliability [1] |

| Clinical Utility | Limited - indicates detection capability only [1] | High - defines clinically reportable range [1] |

| Relationship to Precision | Not directly considered [1] | Defined by precision profile [1] |

| Typical Value Relative to Detection Limit | Lower concentration [1] | Higher concentration (often significantly above detection limit) [1] |

The Precision Profile: Connecting Imprecision to Clinical Usefulness

The precision profile provides the crucial link between theoretical detection and clinical usefulness by graphically representing how assay imprecision changes with analyte concentration [1]. As concentration decreases toward the detection limit, imprecision increases rapidly, creating a zone where detection is theoretically possible but clinically unreliable. Functional sensitivity establishes the boundary of this zone by defining the concentration at which imprecision exceeds a predetermined acceptability threshold [1].

The selection of an appropriate CV threshold (commonly 20% for TSH assays) determines where functional sensitivity is established along the precision profile [1]. This threshold represents the maximum imprecision tolerable for clinical purposes, balancing analytical capabilities with medical decision requirements. For a sample with a concentration at the functional sensitivity limit, a 20% CV implies that 95% of expected results from repeat analyses would fall within ±40% of the mean value (±2 SD) [1]. This degree of variation has significant implications for interpreting serial measurements and detecting clinically meaningful changes in analyte concentration.

Experimental Approaches for Verification

Protocol for Determining Functional Sensitivity

Establishing functional sensitivity requires a methodical approach focusing on interassay precision across the measuring range. The following workflow outlines the key steps:

Step 1: Define Performance Goal - Establish the maximum acceptable interassay CV representing the limit of clinical usefulness for the specific assay and its intended application. While a 20% CV has been widely used since the concept's origin in TSH testing, this threshold should be determined based on clinical requirements for each specific assay [1]. Some applications may tolerate higher imprecision while others require more stringent limits.

Step 2: Identify Target Concentration Range - Based on prior studies, package insert data, and estimates from the assay's precision profile, identify a concentration range bracketing the predetermined CV limit [1]. Technical services can often assist in identifying this target range.

Step 3: Prepare Test Samples - Ideally, use several undiluted patient samples or pools of patient samples with concentrations spanning the target range. If these are unavailable, reasonable alternatives include patient samples diluted to appropriate concentrations or control materials within the target range [1]. If dilution is necessary, select diluents carefully as routine sample diluents may have measurable apparent concentrations that could bias results.

Step 4: Execute Interassay Precision Testing - Analyze samples repeatedly over multiple different runs, ideally over a period of days or weeks to properly assess day-to-day precision [1]. A single run with multiple replicates does not provide a valid assessment of functional sensitivity, as it fails to capture the interassay variability encountered in routine use.

Step 5: Calculate CV at Each Concentration - For each sample tested, calculate the CV as (standard deviation/mean) × 100%. This quantifies the interassay precision at each concentration level across the evaluated range.

Step 6: Determine Functional Sensitivity - Identify the concentration at which the CV reaches the predetermined performance goal. If this concentration doesn't coincide exactly with one of the tested levels, it can be estimated by interpolation from the study results [1].

Comparison of Verification Protocols

Different assay performance characteristics require distinct verification approaches, as summarized in the following table:

| Verification Type | Protocol Focus | Sample Requirements | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Sensitivity | Distinguishing signal from background [1] | 20 replicates of true zero concentration sample [1] | Concentration equivalent to mean zero ± 2 SD [1] |

| Functional Sensitivity | Interassay precision at low concentrations [1] | Multiple samples across target range, analyzed over different runs [1] | Lowest concentration with acceptable CV [1] |

| Lower Limit of Reportable Range | Performance across reportable range [1] | 3-5 samples spanning entire reportable range [1] | Verified concentration range with clinically useful performance [1] |

| Spike Recovery | Accuracy in sample matrix [3] [2] | Samples spiked with known analyte concentrations [2] | Percent recovery (target: 80-120%) [3] |

| Dilutional Linearity | Sample dilution integrity [3] | Spiked samples diluted through ≥3 dilutions [3] | Recovery across dilutions (target: 80-120%) [3] |

Advanced Verification Techniques

Modern verification approaches incorporate sophisticated methodologies to ensure assay reliability:

LLOQ Verification - The Lower Limit of Quantification represents the lowest point on the standard curve where CV <20% and accuracy is within 20% of expected values [3]. This parameter aligns closely with functional sensitivity and is verified through precision and accuracy profiles.

Inter- and Intra-Assay Precision - Inter-assay precision involves analyzing the same samples on multiple plates over multiple days to ensure reproducibility, with acceptable values typically within 20% across experiments [3]. Intra-assay precision tests multiple samples in replicate on the same plate, with %CV ideally less than 10% [2].

Specificity Testing - For high-sensitivity applications, specificity is demonstrated through spike recovery experiments where the analyte is added at the lower end of the standard curve to ensure accurate measurements in real sample matrices [3] [2]. A minimum of 10 samples are typically spiked with acceptable recovery between 80-120% [3].

Case Studies & Applications

High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin Testing

Recent verification studies demonstrate the critical importance of functional sensitivity in cardiac biomarker testing. A 2025 study of the novel Quidel TriageTrue hs-cTnI assay for implementation in rural clinical laboratories exemplifies rigorous verification in practice [4]. The precision study was performed over 5-6 days with 5 replicates daily using quality control materials and patient plasma pools corresponding to clinical decision thresholds. The assay demonstrated a coefficient of variation (CV) <10% near the overall 99th percentile upper reference limit (URL), confirming its functional sensitivity meets the requirements for high-sensitivity troponin testing [4]. The study further established >90% analytical concordance at the 99th percentile URL and <10% risk reclassification compared to established hs-cTnI assays, validating its clinical utility [4].

Emerging Technologies and Applications

CRISPR-Based Detection Systems - Advanced molecular diagnostics now incorporate functional sensitivity principles through innovative designs. A programmable AND-logic-gated CRISPR-Cas12 system for SARS-CoV-2 detection achieves exceptional sensitivity (limit of detection: 4.3 aM, ~3 copies/μL) while maintaining 100% specificity through dual-target collaborative recognition [5]. This approach significantly enhances detection specificity and anti-interference capability through target cross-validation, demonstrating how functional reliability can be engineered into diagnostic systems.

Dual-Functional Probes for Cancer Detection - Novel detection platforms integrate multiple technologies to enhance sensitivity and specificity. A dual-functional aptamer sensor based on Au NPs/CDs for detecting MCF-7 breast cancer cells achieves sensitive detection by recognizing MUC1 protein on cell surfaces while integrating inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and fluorescence imaging technology [6]. This combination enhances sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy for breast cancer cell detection, with Mendelian randomization analysis further verifying MUC1's potential as a biomarker for multiple cancers [6].

AI-Enhanced Drug Response Prediction - The PharmaFormer model demonstrates how advanced computational approaches can predict clinical drug responses through transfer learning guided by patient-derived organoids [7]. This clinical drug response prediction model, based on custom Transformer architecture, was initially pre-trained with abundant gene expression and drug sensitivity data from 2D cell lines, then fine-tuned with limited organoid pharmacogenomic data [7]. The integration of both pan-cancer cell lines and organoids of a specific tumor type provides dramatically improved accurate prediction of clinical drug response, highlighting how data integration enhances functional prediction capabilities [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful verification of functional sensitivity requires specific reagents and materials designed to challenge assay performance under realistic conditions:

| Tool/Reagent | Function in Verification | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| True Zero Concentration Sample | Establishing analytical sensitivity [1] | Appropriate sample matrix is essential; any deviation biases results [1] |

| Patient-Derived Sample Pools | Assessing functional sensitivity [1] | Multiple individual samples spanning target concentration range [1] |

| Quality Control Materials | Precision verification [4] | Concentrations near clinical decision points [4] |

| Sample Diluents | Preparing concentration gradients [1] | Routine diluents may have measurable apparent concentration; select carefully [1] |

| Reference Standards | Accuracy determination [8] | Characterized materials for spike recovery studies [2] |

| Matrix-Matched Materials | Specificity assessment [2] | Evaluate interference from sample components [2] |

| GDC-0349 | GDC-0349, CAS:1207360-89-1, MF:C24H32N6O3, MW:452.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Setanaxib | Setanaxib, CAS:1218942-37-0, MF:C21H19ClN4O2, MW:394.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The distinction between analytical and functional sensitivity represents more than technical semantics—it embodies the essential transition from theoretical detection capability to clinically useful measurement. While analytical sensitivity defines the fundamental detection limits of an assay, functional sensitivity establishes the practical boundaries of clinical usefulness based on reproducibility requirements. This distinction becomes particularly critical at low analyte concentrations where imprecision increases rapidly, potentially compromising clinical interpretation even when detection remains technically possible.

For researchers and drug development professionals, rigorous verification of functional sensitivity through interassay precision profiles provides the evidence base needed to establish clinically reportable ranges. The continuing evolution of detection technologies—from high-sensitivity immunoassays to CRISPR-based molecular diagnostics and AI-enhanced prediction models—further emphasizes the importance of defining and verifying functional performance characteristics. By implementing systematic verification protocols that challenge assays under conditions mimicking routine use, the field advances toward more reliable, reproducible, and clinically meaningful measurement systems that ultimately support improved diagnostic and therapeutic decisions.

For researchers and scientists in drug development and clinical diagnostics, understanding the lower limits of an assay's performance is critical for generating reliable data. The terms analytical sensitivity, functional sensitivity, and interassay precision are fundamental performance metrics, yet they are often confused or used interchangeably. This guide clarifies these core definitions, compares their performance characteristics, and provides the experimental protocols required for their verification. Framed within the broader thesis of verifying functional sensitivity with interassay precision profiles, this article serves as a practical resource for validating assay performance.

Core Definitions and Comparative Analysis

The table below provides a concise comparison of these three critical performance metrics.

Table 1: Core Performance Metrics Comparison

| Metric | Definition | Primary Focus | Typical Determination | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Sensitivity [1] [9] | The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be distinguished from background noise (a blank sample). | Detection Limit | Mean signal of zero sample ± 2 SD (for immunometric/competitive assays); also known as the Limit of Detection (LoD) [1]. | Limited; indicates presence/absence but does not guarantee clinically reproducible results [1]. |

| Functional Sensitivity [1] [9] | The lowest concentration at which an assay can report clinically useful results, defined by an acceptable level of imprecision (e.g., CV ≤ 20%). | Clinical Reportability | The concentration at which the interassay CV meets a predefined precision goal (often 20%) [1] [9]. | High; defines the lower limit of the reportable range for clinically reliable results [1]. |

| Interassay Precision [10] | The reproducibility of results when the same sample is analyzed in multiple separate runs, over days, and often by different technicians. | Run-to-Run Reproducibility | Coefficient of variation (CV%) calculated from results of a sample tested across multiple independent assays [10]. | High; ensures consistency and reliability of results over time in a clinical or research setting [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Determination

Accurate determination of each metric requires specific experimental designs and statistical analysis.

Determining Analytical Sensitivity (Limit of Detection)

Objective: To verify the lowest concentration distinguishable from a zero calibrator (blank) [1].

Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Use a true zero concentration sample with an appropriate sample matrix. Any other type of sample may bias the results [1].

- Replication: Assay 20 replicates of the zero sample in a single run [1].

- Calculation:

- Calculate the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the measured counts (or signals) from the replicates.

- For immunometric ("sandwich") assays, the Analytical Sensitivity is the concentration equivalent to the mean signal of the zero sample + 2 SD.

- For competitive assays, it is the concentration equivalent to the mean signal - 2 SD [1].

This protocol provides an initial estimate for comparison with manufacturer claims. A robust assessment requires multiple experiments across several kit lots [1].

Determining Functional Sensitivity

Objective: To establish the lowest analyte concentration that can be measured with a defined interassay precision (e.g., CV ≤ 20%) [1] [9].

Protocol:

- Set Precision Goal: Define the maximum acceptable interassay CV (e.g., 20%) based on the assay's intended clinical application [1].

- Sample Selection: Ideally, use several undiluted patient samples or pools with concentrations spanning the expected target range near the limit. If unavailable, patient samples diluted to these concentrations or control materials are alternatives [1].

- Longitudinal Testing: Analyze these samples repeatedly over multiple different runs (e.g., over days or weeks). A single run of replicates is insufficient, as it does not capture day-to-day variability [1].

- Data Analysis:

- For each sample, calculate the mean, standard deviation, and CV% of the results from all runs.

- Plot the CV% against the mean concentration for each sample to create a precision profile.

- The Functional Sensitivity is the lowest concentration at which the CV meets the predefined goal (e.g., 20%), which can be estimated by interpolation [1].

Determining Interassay Precision

Objective: To measure the total variability of an assay across separate runs under normal operating conditions [10].

Protocol:

- Sample Selection: Use at least two levels of quality control materials or patient samples (e.g., low, medium, and high concentrations) [11].

- Testing Schedule: Include the samples in multiple independent assay runs. This should involve different calibrations, different days, and ideally different operators [11] [10].

- Replication: A common design is to test each sample in duplicate or triplicate over five consecutive days [11].

- Calculation:

- Pool all results for a given sample from all runs.

- Calculate the overall mean and standard deviation.

- The Interassay CV% is calculated as: (Overall Standard Deviation / Overall Mean) × 100 [10].

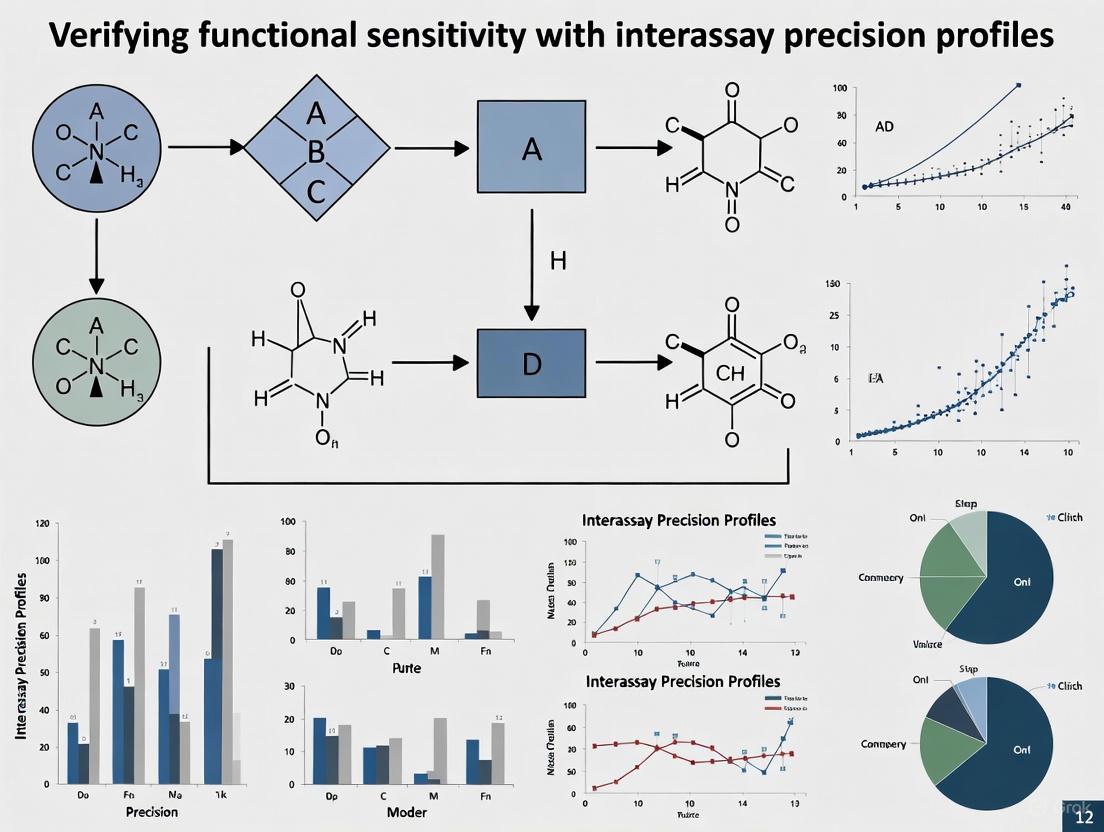

Diagram 1: Experimental protocol workflows for determining key assay performance metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials required for the experiments described above.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Critical Note |

|---|---|

| True Zero Calibrator | A sample with an appropriate matrix confirmed to contain no analyte. Crucial for a valid Analytical Sensitivity (LoD) study [1]. |

| Patient-Derived Sample Pools | Undiluted patient samples or pools with analyte concentrations in the low range are the ideal material for Functional Sensitivity studies [1]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Materials | Commercially available or internally prepared controls at low, medium, and high concentrations are essential for assessing Interassay Precision [11]. |

| Appropriate Diluent | If sample dilution is necessary, the choice of diluent is critical to avoid bias; routine sample diluents may have low apparent analyte levels [1]. |

| Precision Profiling Software | Software capable of calculating CV%, generating precision profiles, and performing interpolation is needed for data analysis [1]. |

| GNF-5837 | GNF-5837, CAS:1033769-28-6, MF:C28H21F4N5O2, MW:535.5 g/mol |

| LolCDE-IN-3 | LolCDE-IN-3, MF:C20H21N3O2, MW:335.4 g/mol |

Current Data and Application in High-Sensitivity Assays

The concepts of functional sensitivity and interassay precision are actively applied in cutting-edge research, particularly in the validation of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) assays. A 2025 study on hs-cTnI assays provides a relevant example of performance verification in a clinical context [11].

Table 3: Performance Data from a 2025 hs-cTnI Assay Study

| Performance Metric | Verified Value | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Blank (LoB) | Determined statistically | Two blank samples measured 30 times over 3 days [11]. |

| Limit of Detection (LoD) | 2.5 ng/L | Two samples near the estimated LoD measured 30 times over 3 days [11]. |

| Functional Sensitivity (LoQ at CV=20%) | Interpolated from precision profile | Samples at multiple low concentrations (2.5-17.5 ng/L) analyzed over 3 days; CV calculated for each [11]. |

| Interassay Precision | CV% reported for three levels | Three concentration levels analyzed in triplicate over five consecutive days [11]. |

This study underscores the hierarchy of these metrics: the LoD (Analytical Sensitivity) is the bare minimum for detection, while the Functional Sensitivity (the concentration at a CV of 20%) defines the practical lowest limit for precise quantification, directly informed by Interassay Precision data [11]. This relationship is foundational to verifying functional sensitivity with interassay precision profiles.

The Critical Role of the Precision Profile in Functional Sensitivity Determination

In the field of clinical laboratory science and biotherapeutic drug monitoring, functional sensitivity represents a critical performance parameter defined as the lowest analyte concentration that an assay can measure with an interassay precision of ≤20% coefficient of variation (CV) [12]. This parameter stands distinct from the lower limit of detection (LoD), which is typically determined by measuring a zero calibrator and represents the smallest concentration statistically different from zero. Unlike LoD, functional sensitivity reflects practical usability under routine laboratory conditions, making it fundamentally more relevant for clinical applications where reliable quantification at low concentrations directly impacts therapeutic decisions [12].

The precision profile, also known as an imprecision profile, serves as the primary graphical tool for determining functional sensitivity. Originally conceived by Professor R.P. Ekins in an immunoassay context, this profile expresses the precision characteristics of an assay across its entire measurement range [13]. By converting complex replication data into an easily interpreted graphical summary, precision profiles enable scientists to identify the precise concentration at which an assay transitions from reliable to unreliable measurement. For researchers and drug development professionals, this tool is indispensable for validating assay performance, particularly when monitoring biologic drugs like adalimumab and infliximab, where precise quantification of drug levels and anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) directly informs treatment optimization [14].

Experimental Protocols for Precision Profiling

Foundational Methodological Approach

The determination of functional sensitivity through precision profiling follows established clinical laboratory guidelines with specific modifications for comprehensive profile generation. The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) EP5-A guideline provides the foundational experimental design, recommending the analysis of replicated specimens over 20 days with two runs per day and two replicates per run [12] [13]. This structured approach yields robust estimates of both within-run (repeatability) and total (interassay) CVs, with the latter being most relevant for functional sensitivity determination.

The experimental workflow begins with preparation of multiple serum pools or control materials spanning the assay's anticipated measuring range, with particular emphasis on concentrations near the expected lower limit. These materials are typically analyzed in singleton or duplicate across multiple batches, incorporating multiple calibration events and reagent lot changes to capture real-world variability [13]. The resulting CV values are plotted against mean concentration values, generating the precision profile curve. The functional sensitivity is then determined by identifying the concentration where this curve intersects the 20% CV threshold [12].

Direct Variance Function Estimation

Modern implementations often employ direct variance function estimation to construct precision profiles. This approach fits a mathematical model to replicated results without requiring precisely structured data, allowing laboratories to merge method evaluation data with routine internal quality control (QC) data [13]. A commonly used three-parameter variance function is:

σ²(U) = (β₠+ β₂U)ᴶ [13]

Where U represents concentration, βâ‚, β₂, and J are fitted parameters, and σ²(U) is the predicted variance. This model offers sufficient curvature to describe variance relationships for both competitive and immunometric immunoassays. Once fitted, the model generates a smooth precision profile across the entire assay range, from which functional sensitivity is easily determined [13].

Comparative Analysis of Assay Performance

Case Study: Third Generation Allergen-Specific IgE Assay

The development of a third generation chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay for allergen-specific IgE (sIgE) on the IMMULITE 2000 system demonstrates the critical importance of precision profiling in functional sensitivity determination. This assay incorporated a true zero calibrator, enabling reliable quantification at concentrations previously inaccessible to earlier assay generations [12].

Table 1: Functional Sensitivity Comparison - IgE Assays

| Assay Generation | Detection Limit (kU/L) | Functional Sensitivity (kU/L) | Measuring Range (kU/L) | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Generation (mRAST) | ~0.35 | Not determined | 0.35-100 | Radioisotopic detection, single calibrator |

| Second Generation (CAP System) | 0.35 | ~0.35 (extrapolated) | 0.35-100 | Enzyme immunoassay, WHO standardization |

| Third Generation (IMMULITE 2000) | <0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1-100 | True zero calibrator, liquid allergens, automated washing |

As illustrated in Table 1, the third generation assay demonstrated a functional sensitivity of 0.2 kU/L, a significant improvement over second generation assays that treated their lowest calibrator (0.35 kU/L) as both the detection limit and functional sensitivity [12]. The precision profile for this assay (Figure 2 in the original study) showed total CVs meeting NCCLS I/LA20-A performance targets, with ≤20% at low concentrations (near 0.35 kU/L) and ≤15% at medium and high concentrations [12].

Case Study: i-Tracker Drug & Anti-Drug Antibody Assays

A 2025 validation study of the i-Tracker chemiluminescent immunoassays (CLIA) for adalimumab, infliximab, and associated anti-drug antibodies further exemplifies the application of precision profiling in biotherapeutic monitoring. This automated, cartridge-based system demonstrated up to 8% imprecision across clinically relevant analyte ranges [14].

Table 2: Precision Profiles - i-Tracker Assays on IDS-iSYS Platform

| Analyte | Within-Run Precision (% CV) | Total Precision (% CV) | Functional Sensitivity | Drug Tolerance of Total ADA Assay |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adalimumab | ≤5% (across range) | ≤8% (across range) | Established per CLSI guidelines | Detected ADAs in supratherapeutic drug concentrations |

| Infliximab | ≤5% (across range) | ≤8% (across range) | Established per CLSI guidelines | Demonstrated higher ADA detection rate vs. reference method |

| Total Anti-Adalimumab | Data included in total precision | Similar profile to drug assays | Determined from precision profile | >85% qualitative agreement with reference method |

| Total Anti-Infliximab | Data included in total precision | Similar profile to drug assays | Determined from precision profile | <60% negative agreement with reference method |

The i-Tracker validation emphasized that robust analytical performance, including functional sensitivity determination via precision profiling, suggests "potential for clinical application" for monitoring adalimumab- and infliximab-treated patients [14]. The study also highlighted how method comparisons reveal functional differences between assay formats, an essential consideration when transitioning between platforms for therapeutic drug monitoring [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Precision Profiling Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Allergens | Maintain natural protein conformations for optimal antibody binding in IgE assays | IMMULITE 2000 sIgE assay [12] |

| Biotinylated Allergens | Enable immobilization on streptavidin-coated solid phases | IMMULITE 2000 sIgE assay [12] |

| ADA Reference Materials | Polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies for spiking experiments | i-Tracker validation using polyclonal anti-adalimumab [14] |

| Drug Biosimilars | Enable preparation of calibrators and spiked samples at known concentrations | i-Tracker validation using adalimumab/ infliximab biosimilars [14] |

| Zero Calibrator | Establishes true baseline for curve fitting and low-end quantification | Third generation IgE assay with true zero calibrator [12] |

| Stable Serum Pools | Multiple concentrations for precision profiling across measuring range | CLSI EP5-A guideline implementation [13] |

| Chemiluminescent Substrate | Signal generation with broad dynamic range | Acridinium ester in i-Tracker; adamantyl dioxetane in IMMULITE [14] [12] |

| Monoclonal Anti-IgE Antibody | Specific detection of bound IgE in sandwich assays | Alkaline phosphatase-labeled anti-IgE in IMMULITE 2000 [12] |

| GS-441524 | GS-441524, CAS:1191237-69-0, MF:C12H13N5O4, MW:291.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lenacapavir | Lenacapavir, CAS:2189684-45-3, MF:C39H32ClF10N7O5S2, MW:968.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Visualization of Precision Profile Concepts

Experimental Workflow for Precision Profiling

Precision Profile Interpretation

Implications for Clinical Application & Drug Development

The strategic application of precision profiling extends beyond analytical validation to directly impact patient care in biotherapeutic monitoring. For drugs like adalimumab and infliximab, where therapeutic trough levels correlate with clinical efficacy and anti-drug antibodies cause secondary treatment failure, establishing reliable functional sensitivity enables clinicians to make informed dosage adjustments and treatment strategy pivots [14]. The i-Tracker validation study exemplifies this principle, demonstrating how robust precision profiles support the clinical application of automated monitoring systems [14].

Furthermore, precision profiling reveals critical differences between assay methodologies that directly impact clinical interpretation. The observed discrepancy between i-Tracker and reference methods for anti-infliximab antibody detection (<60% negative agreement) underscores how functional sensitivity differences can significantly alter patient classification [14]. This highlights the essential role of precision profiling in method comparison and selection for therapeutic drug monitoring programs, particularly as laboratories transition to increasingly automated platforms promising improved operational efficiency [14].

In the pharmaceutical and drug development industries, the reliability of analytical data is the foundation of quality control, regulatory submissions, and ultimately, patient safety. Researchers and scientists navigating this landscape must adhere to a harmonized yet complex framework of regulatory guidelines. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) provide the primary guidance for assay validation, ensuring that analytical procedures are fit for their intended purpose [15].

A modern understanding of assay validation has evolved from a one-time event to a continuous lifecycle management process, a concept reinforced by the simultaneous release of the updated ICH Q2(R2) and the new ICH Q14 guidelines [15]. This shift emphasizes a more scientific, risk-based approach, encouraging the use of an Analytical Target Profile (ATP)—a prospective summary of the method's intended purpose and desired performance characteristics [15]. For studies focused on verifying functional sensitivity with interassay precision profiles, these guidelines provide the structure for designing robust experiments and demonstrating the requisite analytical performance for regulatory acceptance.

Comparative Analysis of Key Guidelines

The following table summarizes the scope and primary focus of the major regulatory guidelines relevant to assay validation.

Table 1: Key Regulatory Guidelines for Assay Validation

| Guideline | Issuing Body | Primary Focus and Scope |

|---|---|---|

| ICH Q2(R2): Validation of Analytical Procedures [16] | International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) | Provides a global framework for validating analytical procedures; covers fundamental performance characteristics for methods used in pharmaceutical drug development [15] [16]. |

| ICH M10: Bioanalytical Method Validation and Study Sample Analysis [17] | ICH (adopted by FDA) | Describes recommendations for method validation of bioanalytical assays (chromatographic & ligand-binding) for nonclinical and clinical studies supporting regulatory submissions [17]. |

| CLSI EP15: User Verification of Precision and Estimation of Bias [18] | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) | Provides a protocol for laboratories to verify a manufacturer's claims for precision and estimate bias; designed for use in clinical laboratories [18]. |

| FDA Guidance on Bioanalytical Method Validation for Biomarkers [19] | U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | Provides recommendations for biomarker bioanalysis; directs use of ICH M10 as a starting point, while acknowledging its limitations for biomarkers [19]. |

Detailed Comparison of Validation Parameters

While all guidelines aim to ensure data reliability, the specific parameters and acceptance criteria can vary based on the assay's intended use. The table below delineates the core validation parameters as described in these documents.

Table 2: Core Validation Parameters Across Guidelines

| Validation Parameter | ICH Q2(R2) Context [15] | ICH M10 Context [17] | CLSI EP15 Context [18] | Relevance to Functional Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Closeness between test result and true value. | Recommended for bioanalytical assays. | Estimated as "bias" against materials with known concentrations. | Confirms measured concentration reflects true level at low concentrations. |

| Precision | Degree of agreement among repeated measurements. Includes repeatability, intermediate precision. | Required, with specific focus on incurred sample reanalysis for some studies. | Verified through a multi-day experiment to estimate imprecision. | Directly measured via interassay precision profiles to determine functional sensitivity. |

| Specificity | Ability to assess analyte unequivocally in presence of potential interferents. | Assessed for bioanalytical assays. | Not a primary focus of the EP15 verification protocol. | Ensures precision profile is not affected by matrix interferences at low analyte levels. |

| Linearity & Range | Interval where linearity, accuracy, and precision are demonstrated. | The working range must be validated. | Range verification is implied through the use of multiple samples. | Defines the assay's quantitative scope and the lower limit of quantitation. |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | Lowest amount quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision. | Established during method validation. | Not directly established; protocol verifies performance near claims. | Functional sensitivity is the practical LOQ based on interassay precision (e.g., ≤20% CV). |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Functional Sensitivity

Protocol 1: Establishing the Interassay Precision Profile

The interassay precision profile is a critical tool for determining the functional sensitivity of an assay, which is defined as the lowest analyte concentration that can be measured with a specified precision (e.g., a coefficient of variation (CV) of 20%) across multiple independent runs [20].

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a minimum of 8-10 samples of the analyte spanning the expected low end of the working range, including concentrations below the anticipated functional sensitivity. A pool of the authentic biological matrix is strongly recommended to reflect true assay conditions [20].

- Experimental Design: Analyze each sample in duplicate or triplicate in at least 5-6 independent analytical runs conducted by different analysts over different days. This design captures between-run variance, a key component of interassay precision [18] [20].

- Data Analysis:

- For each concentration level, calculate the mean, standard deviation (SD), and CV%.

- Plot the CV% (y-axis) against the mean concentration (x-axis) to generate the precision profile.

- The functional sensitivity is the concentration at which the precision profile intersects the pre-defined CV acceptability criterion (e.g., 20% CV).

Protocol 2: Comparison of Methods for Systematic Error

This protocol estimates the systematic error (bias) of a new test method against a comparative method, which is essential for contextualizing functional sensitivity data [20].

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Selection: Analyze a minimum of 40 different patient specimens to cover the entire working range of the method, with a focus on the medically relevant decision levels [20].

- Experimental Execution: Analyze each specimen by both the test and comparative methods within a short time frame (ideally within 2 hours) to maintain specimen stability. The experiment should be conducted over multiple days (minimum of 5) to incorporate routine source of variation [20].

- Statistical Analysis:

- For a wide analytical range: Use linear regression analysis (

Y_test = a + b * X_comparative) to estimate the slope (b) and y-intercept (a). The systematic error (SE) at a critical medical decision concentration (Xc) is calculated asSE = (a + b*Xc) - Xc[20]. - For a narrow analytical range: Calculate the average difference (bias) between the test and comparative methods using a paired t-test [20].

- For a wide analytical range: Use linear regression analysis (

The workflow below illustrates the key stages of this comparative method validation.

Figure 1: Method Comparison Experiment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting robust assay validation studies, particularly those focused on precision and sensitivity.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Validation Studies

| Item | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Authentic Biological Matrix | Serves as the sample matrix for preparing calibration standards and quality controls; critical for accurately assessing matrix effects, specificity, and functional sensitivity [20]. |

| Reference Standard | A well-characterized analyte of known purity and concentration used to prepare calibration curves; its quality is fundamental for establishing accuracy and linearity [15]. |

| Stable, Pooled Patient Samples | Used in interassay precision profiles to measure total assay variance over time; the foundation for determining functional sensitivity [20]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Materials | Samples with known (or assigned) analyte concentrations analyzed in each run to monitor the stability and consistency of the assay's performance over time [18]. |

| Surrogate Matrix | Used when the authentic matrix is difficult to obtain or manipulate; allows for the preparation of calibration standards, though parallelism must be demonstrated to ensure accuracy [19]. |

| GS-6620 | GS-6620, CAS:1350735-70-4, MF:C29H37N6O9P, MW:644.6 g/mol |

| GS-9191 | GS-9191, CAS:859209-84-0, MF:C37H51N8O6P, MW:734.8 g/mol |

Navigating the regulatory context of ICH, CLSI, and FDA guidelines is paramount for successful drug development. ICH Q2(R2) and M10 provide the comprehensive, foundational framework for validating new methods, while CLSI EP15 offers an efficient pathway for verifying performance in a local laboratory [18] [15] [21]. For the specific thesis context of verifying functional sensitivity, the interassay precision profile is the cornerstone experiment. It directly measures the assay's reliability at low analyte concentrations and provides concrete data on its practical limits of quantitation. By designing studies that align with these harmonized guidelines and incorporating a rigorous, statistically sound assessment of precision, researchers can generate defensible data that withstands regulatory scrutiny and advances the development of safe and effective therapies.

A Step-by-Step Protocol for Generating Interassay Precision Profiles and Calculating Functional Sensitivity

The accuracy and reliability of bioanalytical data in drug development hinge on the rigorous selection and characterization of patient samples, controls, and matrices. Within the critical context of verifying functional sensitivity—the lowest analyte concentration that can be measured with acceptable precision, often defined by an interassay precision profile (e.g., CV ≤20%)—the choice of materials directly impacts the robustness of this determination. This guide objectively compares the performance of various sample types and analytical platforms, providing a framework for selecting the right materials to ensure data integrity across different stages of method validation and application.

Experimental Protocols for Performance Comparison

To ensure a fair and objective comparison of analytical performance, standardized experimental designs are crucial. The following protocols, drawn from recent studies, provide a framework for generating comparable data on sensitivity, precision, and accuracy.

Protocol for High-Throughput Molecular Detection System Validation

This protocol, based on a study evaluating an automated system for pathogen nucleic acid detection, outlines a comprehensive validation strategy [22].

- Sample Types: Use a panel of clinically characterized residual patient samples (e.g., plasma, oropharyngeal swabs) and internationally recognized reference standards (e.g., WHO International Standards) [22].

- Experimental Design:

- Concordance & Accuracy: Analyze a minimum of 40 patient specimens covering the assay's working range, comparing results to a validated reference method. For quantitative assays, test samples at multiple concentrations (e.g., five gradients) in replicate [22] [20].

- Precision Profile: Perform both intra-assay (within-run) and interassay (between-run, over ≥5 days) precision testing. Calculate the coefficient of variation (CV) for each concentration level to establish the functional sensitivity (the concentration at which CV reaches 20%) [22].

- Linearity: Serially dilute reference materials in a negative matrix to create a concentration series. Assess the linear correlation coefficient (|r|) to confirm the assay's quantitative range [22].

- Carryover & Interference: Test samples in a high-low sequence to detect carryover contamination and spike potential interferents to assess specificity [22].

Protocol for Targeted Mass Spectrometry Assay Development

This protocol, derived from a study on hemoglobinopathy screening, details the creation of a multiplexed targeted assay [23].

- Sample Preparation: Punch discs from dried blood spots (DBS) or extract from liquid matrices. Denature proteins, then reduce and alkylate disulfide bonds. Digest proteins with trypsin and desalt the resulting peptides [23].

- Selection of Internal Standards: Synthesize stable isotope-labeled versions of target peptides (e.g., for wild-type and mutant globin chains) to use as internal standards for precise quantification [23].

- Mass Spectrometry Optimization:

- Method Development: By direct infusion, optimize precursor and product ion transitions (quantifier and qualifier), collision energy, and other MS parameters for each peptide.

- Scheduled SRM: Use a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer coupled to UHPLC. Develop a scheduled Selected Reaction Monitoring (SRM) method based on the optimized retention time of each peptide [23].

- Data Analysis: Calculate ratios of endogenous to internal standard peptide peaks. Determine globin chain ratios (e.g., α:β) to identify thalassemias and confirm the presence of variant-specific mutant peptides [23].

Comparative Performance Data

The selection of biological matrices and analytical platforms significantly influences key performance metrics. The following tables summarize experimental data comparing these variables across different applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Biological Matrices for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM)

Data synthesized from a systematic review of UHPLC-MS/MS methods for antipsychotic drug monitoring [24].

| Matrix | Recovery (%) | Matrix Effects | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma/Serum | >90% (High) | Minimal | High analytical reliability, standard for pharmacokinetic studies | Invasive collection, requires clinical setting |

| Dried Blood Spots (DBS) | Variable | Moderate | Less invasive, stable for transport, low storage volume | Hematocrit effect, variable recovery, requires validation |

| Whole Blood | Variable | Significant | Reflects intracellular drug concentrations | Complex matrix, requires extensive sample cleanup |

| Oral Fluid | Variable | Moderate | Non-invasive collection, correlates with free drug levels | Contamination risk, variable pH and composition |

Table 2: Analytical Performance of Different Platform Types

Data compiled from evaluations of molecular detection and MS-based systems [22] [23] [24].

| Performance Metric | High-Throughput Automated PCR [22] | LC-MS/MS for Hemoglobinopathies [23] | UHPLC-MS/MS for Antipsychotics (Plasma) [24] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytes | EBV DNA, HCMV DNA, RSV RNA | Hemoglobin variants (HbS, HbC, etc.), α:β globin ratios | Typical & Atypical Antipsychotics and Metabolites |

| Interassay Precision (CV) | <5% | <20% | Typically <15% |

| Limit of Detection (LoD) | 10 IU/mL for DNA targets | Not specified | Compound-specific, generally in ng/mL range |

| Throughput | High (~2000 samples/day) | Medium (Multiplexed in single run) | Medium to High |

| Key Strength | Full automation, minimized contamination | Multiplexing, high specificity for variants | Gold standard for specificity and metabolite detection |

Visualizing Experimental Workflows

The diagrams below illustrate the logical flow of key experimental protocols described in this guide.

Diagram 1: Molecular System Validation Workflow

Diagram 2: Targeted MS Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

A successful experiment depends on the quality and appropriateness of its core components. This toolkit details essential materials for the featured methodologies.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Role in Experimental Integrity |

|---|---|

| International Reference Standards (WHO IS) [22] | Provide a universally accepted benchmark for quantifying analyte concentration, ensuring accuracy and enabling cross-laboratory and cross-study comparability. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (SIS) [23] | Account for variability during sample preparation and MS analysis by behaving identically to the native analyte, thereby improving quantification accuracy and precision. |

| Characterized Patient Samples [22] [25] | Serve as the ground truth for validating assay concordance and specificity. A well-characterized panel covering the pathological range is crucial for a realistic performance assessment. |

| Negative Matrix (e.g., Normal Plasma) [22] | Used as a diluent for preparing calibration curves and for assessing assay specificity and potential background signal, establishing the baseline "noise" of the assay. |

| Certified Detection Kits & Reagents [22] | Assay-specific reagents (e.g., primers, probes, antibodies) whose lot-to-lot consistency is critical for maintaining the validated performance of the method over time. |

| GS-9901 | GS-9901, CAS:1640247-87-5, MF:C22H17ClFN9O, MW:477.9 g/mol |

| GSK2236805 | GSK2236805, CAS:1256390-53-0, MF:C42H52N8O8, MW:796.9 g/mol |

In the field of clinical laboratory science, the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) provides critical guidance for evaluating the performance of quantitative measurement procedures. For researchers conducting functional sensitivity with interassay precision profiles research, understanding the distinction between two key documents—EP05-A2 and EP15-A2—is fundamental to proper experimental design. These protocols establish standardized approaches for precision assessment, yet they serve distinctly different purposes within the method validation and verification workflow. EP05-A2, titled "Evaluation of Precision Performance of Quantitative Measurement Methods," is intended primarily for manufacturers and developers seeking to establish comprehensive precision claims for their diagnostic devices [26]. In contrast, EP15-A2, "User Verification of Performance for Precision and Trueness," provides a streamlined protocol for clinical laboratories to verify that a method's precision performance aligns with manufacturer claims before implementation in patient testing [18] [27].

The evolution of these guidelines reflects an ongoing effort to balance scientific rigor with practical implementation. Earlier editions of EP05 served both manufacturers and laboratory users, but the current scope has narrowed to focus primarily on manufacturers establishing performance claims [28] [29]. This change clarified the distinct needs of manufacturers creating claims versus laboratories verifying them, with EP15-A2 now positioned as the primary tool for end-user laboratories [28]. For research on functional sensitivity, which requires precise understanding of assay variation at low analyte concentrations, selecting the appropriate protocol is essential for generating reliable, defensible data.

Key Comparisons Between EP05-A2 and EP15-A2

The following table summarizes the fundamental differences between these two precision evaluation protocols:

| Feature | EP05-A2 | EP15-A2 |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Establish precision performance claims [28] | Verify manufacturer's precision claims [18] |

| Intended Users | Manufacturers, developers [28] | Clinical laboratory users [18] |

| Experimental Duration | 20 days [30] | 5 days [30] [18] |

| Experimental Design | Duplicate analyses, two runs per day for 20 days [30] | Three replicates per day for 5 days [30] |

| Levels Tested | At least two concentrations [30] | At least two concentrations [30] |

| Statistical Power | Higher power to characterize precision [30] | Lower power, suited for verification [18] |

| Regulatory Status | FDA-recognized for establishing performance [28] | FDA-recognized for verification [18] [27] |

Beyond these operational differences, the conceptual framework of each protocol aligns with its distinct purpose. EP05-A2 employs a more comprehensive experimental design that captures more sources of variation over a longer period, resulting in robust precision estimates suitable for product labeling [30]. EP15-A2 utilizes a pragmatic verification approach that efficiently confirms the method operates as claimed without the resource investment of a full precision establishment [30] [18]. For researchers investigating functional sensitivity, this distinction is crucial—EP05-A2 would be appropriate when developing new assays or establishing performance at low concentrations, while EP15-A2 would suffice when verifying that an implemented method meets sensitivity requirements for clinical use.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

EP05-A2 Experimental Methodology

The EP05-A2 protocol employs a rigorous experimental design intended to comprehensively capture all potential sources of variation in a measurement procedure. The recommended approach requires testing at minimum two concentrations across the assay's measuring range, as precision often differs at various analytical levels [30]. The core design follows a "20 × 2 × 2" model: duplicate analyses in two separate runs per day over 20 days [30]. This extended timeframe is deliberate, allowing the experiment to incorporate typical operational variations encountered in routine practice, including different calibration events, reagent lots, operators, and environmental fluctuations.

Critical implementation requirements include maintaining at least a two-hour interval between runs within the same day to ensure distinct operating conditions [30]. Each run should include quality control materials different from those used for routine quality monitoring, and the test materials should be analyzed in a randomized order alongside at least ten patient samples to simulate realistic testing conditions [30]. This comprehensive approach generates approximately 80 data points per concentration level (20 days × 2 runs × 2 replicates), providing substantial statistical power for reliable precision estimation across multiple components of variation.

EP15-A2 Experimental Methodology

The EP15-A2 protocol employs a streamlined experimental design focused on practical verification rather than comprehensive characterization. The protocol requires testing at two concentration levels with three replicates per level over five days [30] [18]. This condensed timeframe makes the protocol feasible for clinical laboratories to implement while still capturing essential within-laboratory variation. The experiment generates 15 data points per concentration level (5 days × 3 replicates), sufficient for verifying manufacturer claims without the resource investment of a full EP05-A2 study.

A key feature of EP15-A2 is its statistical verification process. If the calculated repeatability and within-laboratory standard deviations are lower than the manufacturer's claims, verification is successfully demonstrated [30]. However, if the laboratory's estimates exceed the manufacturer's claims, additional statistical testing is required to determine whether the difference is statistically significant [30]. This approach acknowledges that limited verification studies have reduced power to definitively reject claims, protecting against false rejections of adequately performing methods while still identifying substantially deviant performance.

Statistical Analysis and Data Interpretation

Precision Component Calculations

Both EP05-A2 and EP15-A2 employ analysis of variance (ANOVA) techniques to partition total variation into its components, though the specific calculations differ slightly due to their different experimental designs. For EP15-A2, the key precision components are calculated as follows:

Repeatability (within-run precision) is estimated using the formula: [ sr = \sqrt{\frac{\sum{d=1}^D \sum{r=1}^n (x{dr} - \bar{x}d)^2}{D \cdot (n - 1)}} ] Where D is the total number of days, n is the number of replicates per day, (x{dr}) is the result for replicate r on day d, and (\bar{x}_d) is the average of all replicates on day d [30].

Within-laboratory precision (total precision) incorporates both within-run and between-day variation and is calculated as: [ sl = \sqrt{sr^2 + \frac{n \cdot sb^2}{n}} ] Where (sb^2) is the variance of the daily means [30].

For functional sensitivity research, typically defined as the analyte concentration at which the coefficient of variation (CV) reaches 20%, these precision components are particularly valuable. The CV, calculated as (CV = \frac{s}{\bar{x}} \times 100\%) where s is the standard deviation and (\bar{x}) is the mean, allows comparison of precision across concentration levels [30]. By establishing precision profiles across multiple concentrations, researchers can identify the functional sensitivity limit where imprecision becomes unacceptable for clinical use.

Data Evaluation and Acceptance Criteria

The evaluation approach differs significantly between the two protocols based on their distinct purposes. For EP05-A2, the resulting precision estimates are typically compared to internally defined quality goals or regulatory requirements appropriate for the intended use of the assay [28]. Since EP05-A2 is used to establish performance claims, the results directly inform product specifications and labeling.

For EP15-A2, verification is achieved through a two-tiered approach: if the laboratory's calculated repeatability and within-laboratory standard deviations are less than the manufacturer's claims, performance is considered verified [30]. If the laboratory's estimates exceed the manufacturer's claims, a statistical verification value is calculated using the formula: [ Verification\ Value = \sigmar \cdot \sqrt{\frac{C}{\nu}} ] Where (\sigmar) is the claimed repeatability, C is the 1-α/q percentage point of the Chi-square distribution, and ν is the degrees of freedom [30]. This approach provides statistical protection against incorrectly rejecting properly performing methods when using the less powerful verification protocol.

Experimental Workflow and Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting and implementing the appropriate CLSI precision protocol:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials required for implementing CLSI precision protocols:

| Reagent/Material | Function in Precision Studies | Protocol Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Pooled Patient Samples | Matrix-matched materials for biologically relevant precision assessment [30] | Preferred material for both EP05-A2 and EP15-A2 [30] |

| Quality Control Materials | Stable materials for monitoring assay performance over time [30] | Should be different from routine QC materials used for instrument monitoring [30] |

| Commercial Standard Materials | Materials with assigned values for trueness assessment [30] | Used when pooled patient samples are unavailable [30] |

| Calibrators | Materials used to establish the analytical measurement curve [30] | Should remain constant throughout the study when possible [30] |

| Patient Samples | Native specimens included to simulate routine testing conditions [30] | EP05-A2 recommends at least 10 patient samples per run [30] |

Application to Functional Sensitivity Research

For researchers investigating functional sensitivity with interassay precision profiles, both EP05-A2 and EP15-A2 provide methodological frameworks, though for different phases of assay development and implementation. Functional sensitivity, typically defined as the lowest analyte concentration at which an assay demonstrates a CV of 20% or less, requires precise characterization of assay imprecision across the measuring range, particularly at low concentrations.

The EP05-A2 protocol is ideally suited for establishing functional sensitivity during assay development or when validating completely new methods [28]. Its extended 20-day design comprehensively captures long-term sources of variation that significantly impact precision at low analyte concentrations. The robust dataset generated enables construction of precise interassay precision profiles that reliably demonstrate how CV changes with concentration, allowing accurate determination of the functional sensitivity limit.

The EP15-A2 protocol serves well for verifying that functional sensitivity claims provided by manufacturers are maintained in the user's laboratory setting [18]. While less powerful than EP05-A2 for establishing performance, its condensed 5-day design provides sufficient data to confirm that claimed sensitivity thresholds are met under local conditions. This verification is particularly important for assays measuring low-abundance analytes like hormones or tumor markers, where maintaining functional sensitivity is critical for clinical utility.

When designing functional sensitivity studies, researchers should consider that precision estimates from short-term EP15-A2 verification should not typically be used to set acceptability limits for internal quality control, for which longer-term assessment is recommended [30]. Additionally, materials selected for precision studies should ideally be pooled patient samples rather than commercial controls alone, as they better reflect the matrix effects encountered with clinical specimens [30].

In the context of verifying functional sensitivity with interassay precision profiles, assessing the precision of an analytical method is a fundamental step to confirm its suitability for use. Precision refers to the closeness of agreement between independent measurement results obtained under stipulated conditions and is solely related to random error, not to trueness or accuracy. A robust precision assessment is critical in fields like drug development and functional drug sensitivity testing (f-DST), where it helps personalize the choice among cytotoxic drugs and drug combinations for cancer patients by ensuring the reliability of the in-vitro diagnostic test methods [31].

A trivial approach to estimating repeatability (within-run precision) involves performing multiple replicate analyses in a single run. However, this method is insufficient as the operating conditions at that specific time may not reflect usual operating parameters, potentially leading to an underestimation of repeatability. Therefore, structured protocols that span multiple days and runs are essential for a realistic and accurate estimation of both repeatability and total within-laboratory precision [30].

Comparison of Experimental Protocols for Precision Verification

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) provides two primary protocols for determining precision: EP05-A2 for validating a method against user requirements, and EP15-A2 for verifying that a laboratory's performance matches manufacturers' claims. The table below summarizes the core requirements of each protocol.

Table 1: Comparison of CLSI Precision Evaluation Protocols

| Feature | EP05-A2 Protocol (Method Validation) | EP15-A2 Protocol (Performance Verification) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Validate a method against user-defined requirements; often used by reagent/instrument suppliers [30]. | Verify that a laboratory's performance is consistent with manufacturer claims [30]. |

| Recommended Use | For in-house developed methods requiring a higher level of proof [30]. | For verifying methods on automated platforms using manufacturer's reagents [30]. |

| Testing Levels | At least two levels, as precision can differ over the analytical range [30]. | At least two levels [30]. |

| Experimental Design | Each level run in duplicate, with two runs per day over 20 days (minimum 2 hours between runs) [30]. | Each level run with three replicates over five days [30]. |

| Additional Samples | Include at least ten patient samples in each run to simulate actual operation [30]. | Not specified in the provided results. |

| Data Review | Data must be assessed for outliers [30]. | Data must be assessed for outliers [30]. |

Detailed Experimental Methodology

Core Protocol for Multi-Day, Multi-Run Replicates

The following workflow details the general procedure for conducting a multi-day precision study, which forms the basis for both EP05-A2 and EP15-A2 protocols.

Data Analysis and Calculation Procedures

After data collection, the following statistical calculations are performed to derive estimates of precision. The formulas for calculating repeatability (Sr) and within-laboratory precision (Sl) are based on analysis of variance (ANOVA) components [30].

Table 2: Formulas for Calculating Precision Metrics

| Metric | Formula | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Repeatability (Sr) | ( sr = \sqrt{\frac{\sum{d=1}^{D} \sum{r=1}^{n} (x{dr} - \bar{x}_d)^2}{D(n-1)}} ) | Estimates the within-run standard deviation. Here, (D) is the total days, (n) is replicates per day, (x{dr}) is result for replicate (r) on day (d), and (\bar{x}d) is the average for day (d) [30]. |

| Variance of Daily Means (s₆²) | ( sb^2 = \frac{\sum{d=1}^{D} (\bar{x}_d - \bar{\bar{x}})^2}{D-1} ) | Estimates the between-run variance. Here, (\bar{\bar{x}}) is the overall average of all results [30]. |

| Within-Lab Precision (Sl) | ( sl = \sqrt{sr^2 + s_b^2} ) | Estimates the total standard deviation within the laboratory, combining within-run and between-run components [30]. |

The data analysis process, from raw data to final verification, can be visualized as the following logical pathway:

Quantitative Data and Results Comparison

The application of these protocols and calculations yields concrete data for comparing performance. The following table presents a summary of hypothetical experimental data collected for calcium according to an EP15-A2-like protocol, showing the results from three replicates over five days for a single level [30].

Table 3: Example Experimental Data and Precision Calculations for Calcium

| Day | Replicate 1 (mmol/L) | Replicate 2 (mmol/L) | Replicate 3 (mmol/L) | Daily Mean (x̄d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.015 | 2.013 | 1.963 | 1.997 |

| 2 | 2.019 | 2.002 | 1.979 | 2.000 |

| 3 | 2.025 | 1.959 | 2.000 | 1.995 |

| 4 | 1.972 | 1.950 | 1.973 | 1.965 |

| 5 | 1.981 | 1.956 | 1.957 | 1.965 |

| Overall Mean (x̿) | 1.984 |

Calculated Precision Metrics from this Dataset [30]:

- Repeatability (Sr): 0.023 mmol/L

- Within-Laboratory Precision (Sl): 0.027 mmol/L

When the estimated repeatability (e.g., 0.023 mmol/L) is greater than the manufacturer's claimed value, a statistical test is required to determine if the difference is significant. This involves calculating a verification value. If the estimated repeatability is less than the claimed value, precision is considered consistent with the claim [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The successful execution of precision studies, particularly in advanced fields like functional drug sensitivity testing (f-DST), relies on specific materials and reagents.

Table 4: Essential Materials for Precision Studies and Functional Testing

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Pooled Patient Samples | Serves as a test material with a matrix closely resembling real patient specimens; used to assess precision under realistic conditions [30]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Materials | Used to monitor the stability and performance of the assay during the precision study; should be different from the routine QC used for instrument control [30]. |

| Cytotoxic Agents | Drugs like 5-FU, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan; used in f-DST to expose patient-derived cancer tissue to measure individual vulnerability and therapy response [31]. |

| Stem Cell Media | Used in f-DST to culture and expand processed cancer specimens (e.g., organoids, tumoroids) into a sufficient number of testable cell aggregates [31]. |

| Commercial Standard Material | Provides a known value for validation and calibration, helping to ensure the accuracy of measurements throughout the precision assessment [30]. |

| GSK5852 | GSK5852, CAS:1331942-30-3, MF:C27H25BF2N2O6S, MW:554.4 g/mol |

| GSK2838232 | GSK2838232, CAS:1443460-91-0, MF:C48H73ClN2O6, MW:809.6 g/mol |

Calculating Interassay Precision (%CV) and Plotting the Precision Profile

In the rigorous field of analytical method validation, demonstrating that an assay is reproducible over time is paramount. Interassay precision, also referred to as intermediate precision, quantifies the variation in results when an assay is performed under conditions that change within a laboratory, such as different days, different analysts, or different equipment [8]. It is a critical component for verifying the functional sensitivity and reliability of an assay throughout its lifecycle.

The most common statistical measure for expressing this precision is the percent coefficient of variation (%CV), a dimensionless ratio that standardizes variability relative to the mean, allowing for comparison across different assays and concentration levels [32]. It is calculated as:

%CV = (Standard Deviation / Mean) × 100% [32] [33]

The precision profile is a powerful graphical representation that plots the %CV of an assay against the analyte concentration. This visual tool is fundamental to research on functional sensitivity, as it helps identify the concentration range over which an assay delivers acceptable, reliable precision, thereby defining its practical limits of quantification [8].

This guide will objectively compare the performance of different analytical platforms by providing standardized protocols and presenting experimental data for calculating interassay %CV and constructing precision profiles.

Experimental Protocols for Determining Interassay Precision

A standardized methodology is essential for generating robust and comparable interassay precision data. The following protocol outlines the key steps.

Core Experimental Workflow

The general process for evaluating interassay precision involves repeated testing of samples across multiple independent assay runs.

Detailed Methodology

The workflow above is implemented through the following specific procedures:

Experimental Design: Prepare a set of samples spanning the expected concentration range of the assay, including quality control (QC) samples at low, medium, and high concentrations. The experiment should be designed to include a minimum of three independent assay runs conducted by two different analysts over several days [8] [34]. Each sample should be tested in replicates (e.g., n=3) within each run.

Assay Execution: For each independent run (representing one assay event), process all samples and QCs according to the standard operating procedure. Adherence to consistent technique is critical to minimize introduced variability. Key considerations include:

- Pipetting: Use calibrated pipettes and proper technique (e.g., pre-wetting tips, holding pipettes vertically) to ensure accuracy [32].

- Washing: Optimize and maintain a consistent wash protocol. Overly aggressive or inconsistent washing is a common source of high %CV [33].

- Incubation: Keep plates covered and in a stable environment away from drafts to prevent well drying and ensure even temperature distribution [32].

- Instrumentation: Use calibrated plate readers and ensure appropriate software settings. Checking instrument performance with empty wells or a non-adsorbing liquid can diagnose background noise issues [33].

Data Collection and Analysis: For each sample across the multiple assay runs, collect the raw measurement data (e.g., Optical Density for ELISA) or the calculated concentration.

- Calculate the Mean (µ) and Standard Deviation (σ): Compute these values for each sample using the results gathered from all independent runs.

- Compute %CV: For each sample, apply the formula: %CV = (σ / µ) × 100% [32].

Comparative Performance Data

Presenting data in a clear, structured format is key for objective comparison. The following tables summarize typical acceptance criteria and example experimental data from different assay platforms.

Interassay Precision Acceptance Criteria

Table 1: General guidelines for acceptable %CV levels in bioanalytical assays.

| Assay Type | Target Interassay %CV | Regulatory Context |

|---|---|---|

| Immunoassays (e.g., ELISA) | < 15% | Common benchmark for plate-to-plate consistency [32] [33] |

| Cell-Based Potency Assays | ≤ 20% | Demonstrates minimal variability in complex biological systems [34] |

| Chromatographic Methods (HPLC) | Varies by level | Based on validation guidelines; typically stricter for active ingredients [8] |

Example Experimental Data

Table 2: Example interassay precision data from an impedance-based cytotoxicity assay (Maestro Z platform) measuring % cytolysis at different Effector to Target (E:T) ratios. Data adapted from a validation study [34].

| E:T Ratio | Mean % Cytolysis | Standard Deviation | %CV |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10:1 | ~80% | To be calculated | < 20% |

| 5:1 | To be reported | To be calculated | < 20% |

| 5:2 | To be reported | To be calculated | < 20% |

| 5:4 | To be reported | To be calculated | < 20% |

Table 3: Simulated interassay precision data for a quantitative ELISA measuring a protein analyte, demonstrating the dependence of %CV on concentration.

| Sample / QC Level | Mean Concentration (ng/mL) | Standard Deviation (ng/mL) | %CV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low QC | 5.0 | 0.8 | 16.0% |

| Mid QC | 50.0 | 4.0 | 8.0% |

| High QC | 150.0 | 10.5 | 7.0% |

| Calibrator A | 2.0 | 0.5 | 25.0% |

Constructing and Interpreting the Precision Profile

The precision profile transforms the tabulated %CV data into a visual tool that defines the usable range of an assay.

Workflow for Precision Profile

The process of building the profile involves specific data transformation and visualization steps.

Interpretation for Functional Sensitivity

The precision profile visually demonstrates a key principle: %CV is often concentration-dependent. As shown in the simulated ELISA data (Table 3), variability is typically higher at lower concentrations, where the signal-to-noise ratio is less favorable [8].

- Defining the Working Range: The profile plots the calculated %CV for each sample against its mean concentration. A regression curve is often fitted to these points. The functional sensitivity of the assay is frequently defined as the lowest concentration at which the curve intersects a predefined %CV acceptance threshold (e.g., 20%) [34]. Concentrations above this point are considered to be within the reliable quantitative range of the assay.

- Comparative Tool: When comparing assay platforms, a precision profile that maintains a lower %CV across a wider concentration range indicates a more robust and sensitive method. For instance, a well-validated impedance-based assay can show %CVs below 20% across all tested conditions, confirming its suitability for potency assessment [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key research reagent solutions and materials essential for conducting interassay precision studies.

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|