Absorption and Emission Spectroscopy: Principles, Methods, and Breakthrough Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles and cutting-edge applications of absorption and emission spectroscopy, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Absorption and Emission Spectroscopy: Principles, Methods, and Breakthrough Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles and cutting-edge applications of absorption and emission spectroscopy, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores the core physics of light-matter interactions, details advanced methodologies from laser-based techniques to X-ray spectroscopy, and addresses key challenges in complex sample analysis. A comparative analysis of spectroscopic techniques highlights their unique strengths for specific pharmaceutical applications, from characterizing metal complexes in proteins to real-time monitoring of chemical processes. The content synthesizes foundational knowledge with the latest methodological advances to serve as a practical guide for leveraging spectroscopy in biomedical innovation.

The Physics of Light-Matter Interactions: Core Principles of Absorption and Emission

Spectroscopy is a suite of analytical techniques that deduces the composition and structure of matter by analyzing its interaction with electromagnetic radiation [1] [2]. This whitepaper delineates the core principles of absorption and emission spectroscopy, establishing how the interplay between light energy and atomic or molecular energy levels generates unique spectral fingerprints [2] [3]. Within the context of basic spectroscopic research, we detail the instrumentation, methodologies, and data interpretation frameworks that underpin these techniques. Furthermore, we explore the integration of advanced data preprocessing and machine learning, which is revolutionizing quantitative analysis and predictive modeling in fields such as pharmaceutical development [4] [5] [6].

Spectroscopy is founded on the study of interactions between electromagnetic radiation (light) and matter [1] [2]. The fundamental principle is that atoms and molecules can exist only in specific, discrete energy states. The transition between these states involves the absorption or emission of a photon of light, whose energy is precisely equal to the difference between the two states [3].

This energy relationship is governed by the equation E = hν, where E is energy, h is Planck's constant, and ν is the frequency of the light [3]. Since the speed of light c is constant, frequency ν is inversely related to wavelength λ (c = λν), making wavelength and energy effectively equivalent concepts in spectroscopy [2] [3]. Shorter wavelengths correspond to higher energy, and longer wavelengths to lower energy. When light passes through or interacts with a sample, matter can absorb specific wavelengths, promoting electrons, atoms, or molecules to higher energy states. The resulting pattern of absorbed or emitted wavelengths—the spectrum—serves as a characteristic fingerprint, revealing the material's identity, composition, and environment [7] [1] [2].

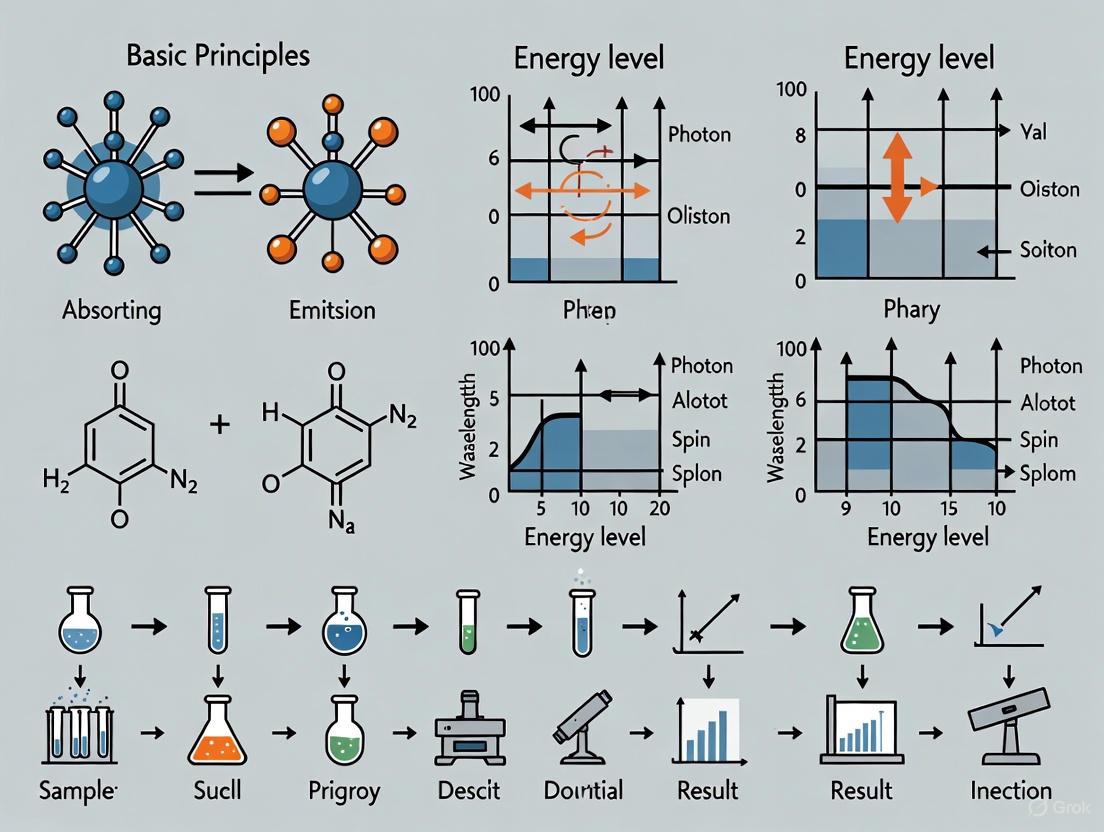

The following diagram illustrates the core logical workflow of spectroscopic analysis, from the initial light-matter interaction to the final analytical result.

The Electromagnetic Spectrum and Spectroscopic Techniques

The electromagnetic spectrum encompasses all possible wavelengths of light, from high-energy gamma rays to low-energy radio waves [2] [3]. The specific type of energy transition a photon can induce—whether in the nucleus, an electron, or the entire molecule—depends on its energy, and thus, its wavelength. Consequently, different spectroscopic techniques, operating in distinct spectral regions, probe different aspects of a material's structure [7] [3].

Table 1: Spectral Regions and Corresponding Spectroscopic Techniques

| Spectral Region | Wavelength Range | Energy Transition Probed | Common Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray | 0.01 nm – 10 nm | Core electron transitions | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) [3] |

| Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) | 200 nm – 800 nm | Electronic transitions (valence electrons) | UV-Vis Spectroscopy [7] [8] |

| Infrared (IR) | 700 nm – 1 mm | Molecular vibrations and rotations | Fourier Transform IR (FTIR) [1] [3] |

| Microwave | 1 mm – 1 m | Molecular rotations | Microwave Spectroscopy [1] |

| Radio Wave | 1 m and above | Nuclear spin transitions | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) [7] [1] |

Absorption and Emission: Two Fundamental Processes

The two primary processes for generating a spectrum are absorption and emission, which form the basis for a wide range of analytical techniques.

Absorption Spectroscopy: This technique measures the specific wavelengths of light a sample absorbs. When the energy of an incident photon matches the energy required for a quantum-level transition (electronic, vibrational, etc.), the photon is absorbed [3] [8]. The resulting absorption spectrum plots absorbance versus wavelength, showing characteristic "peaks" where absorption occurs. Quantitative analysis is governed by the Beer-Lambert Law: (A = \epsilon l c), where (A) is absorbance, (\epsilon) is the molar absorptivity, (l) is the path length, and (c) is the concentration of the absorbing species [8]. Common absorption techniques include UV-Vis, IR, and NMR spectroscopy [7] [1].

Emission Spectroscopy: This technique analyzes the light emitted by a sample when excited atoms or molecules return from a higher-energy state to a lower-energy state [1] [9]. The sample must first be excited, typically by thermal energy (e.g., in a flame or plasma), electrical energy, or a laser. The emitted photons produce a spectrum with characteristic lines or bands that identify the elements or molecules present. The intensity of the emission is proportional to the concentration of the emitting species. Key emission techniques include Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (AES) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) [9].

Instrumentation and Experimental Protocol

The precise configuration of a spectrometer varies by technique, but the core components follow a similar logical flow to measure absorption or emission.

Core Instrumental Workflow

The following diagram details the generic workflow and components of a spectroscopic instrument, applicable to many absorption and emission techniques.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS)

The following protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for quantifying trace metal content using Flame Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (FAAS), a standard technique in analytical chemistry [9].

Objective: To determine the concentration of a specific metal (e.g., sodium) in a prepared liquid sample.

Principle: Free atoms in the gaseous state, produced in a flame, absorb light from a hollow cathode lamp (HCL) at a characteristic wavelength. The amount of light absorbed is proportional to the concentration of the metal in the sample [9].

Materials and Reagents:

- Atomic Absorption Spectrometer (with hollow cathode lamp for the target metal)

- High-purity nitric acid

- Deionized water

- Certified single-element standard solution (e.g., 1000 ppm Na stock)

- Laboratory glassware (volumetric flasks, pipettes)

- Sample filtration apparatus (if needed)

Procedure:

Sample Preparation:

- If the sample is solid, perform an acid digestion. Accurately weigh a representative portion and digest with high-purity nitric acid using appropriate heating to dissolve the analyte and destroy organic matter [9].

- For liquid samples, acidify with 1% (v/v) nitric acid to keep metals in solution.

- Filter the prepared sample if particulate matter is present.

- Dilute the sample to bring the expected analyte concentration within the linear range of the calibration curve.

Preparation of Calibration Standards:

- Perform a serial dilution from the 1000 ppm stock standard to prepare at least four calibration standards (e.g., 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 ppm) in a matrix matching the sample (e.g., 1% nitric acid) [9].

- Include a blank (1% nitric acid).

Instrument Setup and Calibration:

- Install the appropriate hollow cathode lamp and allow it to warm up for 15-20 minutes.

- Set the instrument to the recommended wavelength for the analyte (e.g., 589.0 nm for sodium).

- Optimize other instrument parameters (slit width, lamp current) as per manufacturer guidelines.

- Align the burner head and ignite the flame (typically an air-acetylene mixture).

- Aspirate the blank and set the instrument to zero absorbance.

- Aspirate the calibration standards in order of increasing concentration and record the absorbance for each.

- Generate a calibration curve by plotting absorbance versus concentration. The instrument software typically performs a linear regression. The correlation coefficient (R²) should be ≥ 0.995.

Sample Analysis and Quantification:

- Aspirate the prepared sample solution and record the absorbance.

- If the absorbance falls outside the calibration range, dilute the sample and re-analyze.

- The instrument software interpolates the sample absorbance against the calibration curve to calculate the concentration in the analyzed solution.

- Apply the appropriate dilution factor from the sample preparation step to report the original concentration in the solid or liquid sample.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for AAS Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Hollow Cathode Lamp (HCL) | Provides the narrow, element-specific spectral line required for high-selectivity absorption measurements [9]. |

| Certified Standard Solutions | High-purity reference materials used to create the calibration curve, ensuring quantitative accuracy [9]. |

| High-Purity Nitric Acid | Used for sample digestion and acidification to dissolve analytes, prevent precipitation, and minimize matrix interference [9]. |

| Flame or Graphite Furnace Atomizer | Converts the liquid sample into a cloud of free, gaseous atoms, which is essential for atomic absorption to occur [9]. |

Data Analysis, Preprocessing, and the Role of AI

A raw spectral measurement is often corrupted by noise and artifacts, making preprocessing a critical step before quantitative or qualitative analysis [6] [10].

Essential Spectral Preprocessing Techniques

Preprocessing aims to remove unwanted signal components while preserving the chemically relevant information.

Table 3: Common Spectral Preprocessing Methods

| Preprocessing Category | Specific Methods | Purpose & Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Artifact Removal | Cosmic Ray Removal, Spike Filtering [6] | Identifies and removes sharp, spurious spikes caused by high-energy particles, crucial for Raman and IR spectra. |

| Baseline Correction | Piecewise Polynomial Fitting, Morphological Operations [6] | Corrects for low-frequency background drift caused by instrumental effects or sample scattering (e.g., fluorescence). |

| Scattering Correction | Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) [6] | Compensates for light scattering effects in powdered or particulate samples, common in NIR spectroscopy. |

| Normalization | Standard Normal Variate (SNV) [6] | Removes path-length effects and offsets to allow for direct comparison between samples. |

| Feature Enhancement | Spectral Derivatives (Savitzky-Golay) [6] | Enhances the resolution of overlapping peaks and suppresses baseline offsets. |

Machine Learning and Chemometrics in Spectroscopy

Machine learning (ML) has revolutionized the analysis of complex spectral data. Classical chemometric methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression are now complemented by advanced AI frameworks [5].

- Supervised Learning: Models are trained on labeled spectral data to perform regression (predicting concentration) or classification (e.g., authentic vs. adulterated) [4] [5]. Common algorithms include Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and deep neural networks (DNNs). These can model complex, non-linear relationships that traditional methods cannot [5].

- Unsupervised Learning: Algorithms like PCA discover latent structures in unlabeled data, useful for exploratory analysis, clustering similar samples, and detecting outliers [4] [5].

- Generative AI: Can create synthetic spectral data to balance datasets, augment training libraries, and enhance the robustness of calibration models, especially when experimental data is limited [5].

The integration of ML enables high-throughput screening, achieves sub-ppm detection sensitivity, and maintains >99% classification accuracy in applications like pharmaceutical quality control [6].

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Spectroscopy is a cornerstone technique across scientific disciplines, with particular importance in pharmaceutical research and development.

- Pharmaceutical Quality Control: UV-Vis spectroscopy is routinely used for quantitative analysis of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and for checking purity (e.g., by measuring absorbance ratios) [8]. IR and NIR spectroscopy are employed for raw material identification, monitoring blend homogeneity in solid dosages, and detecting counterfeit drugs [3].

- Biomolecular Analysis: UV-Vis spectroscopy quantifies nucleic acids (absorption at 260 nm) and proteins (absorption at 280 nm) [3]. NMR spectroscopy is indispensable for determining the 3D structure of complex molecules, including small-molecule drugs and proteins, in solution [1] [3].

- Environmental and Food Monitoring: Atomic absorption and emission spectroscopy are standard for trace metal analysis in water, soil, and food products to ensure safety and compliance with regulatory limits [9] [8].

Table 4: Comparison of Atomic Absorption and Emission Spectroscopy

| Feature | Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) | Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (AES) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Measures absorption of light by ground-state atoms [9]. | Measures light emitted by excited atoms [9]. |

| Selectivity | Highly selective for individual elements [9]. | Can suffer from spectral interferences due to overlapping lines [9]. |

| Multi-element Capability | Generally limited to single-element analysis [9]. | Capable of simultaneous multi-element analysis (e.g., via ICP-AES) [9]. |

| Linear Dynamic Range | Narrower (typically 2-3 orders of magnitude) [9]. | Wider (up to 5-6 orders of magnitude) [9]. |

| Instrument Cost & Operation | Relatively inexpensive and simple to operate [9]. | Requires more advanced instrumentation and skilled operators [9]. |

Absorption and emission spectroscopy are foundational techniques in analytical science that exploit the interaction of electromagnetic radiation with matter. When molecules or atoms are exposed to specific wavelengths of light, they can absorb energy, promoting electrons to higher energy states or increasing molecular vibrations. The subsequent measurement of this absorption, or the emission of radiation as the species returns to its ground state, provides a powerful means for identification and quantification [11]. The electromagnetic spectrum encompasses a broad range of wavelengths and energies, each interacting with matter in distinct ways that can be harnessed for analytical purposes. This guide focuses on the specific regions from infrared to X-rays, detailing their unique properties and the analytical roles they play in modern research, particularly in pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical development [12].

The fundamental principle governing these interactions is expressed by the equation c = fλ, where the speed of light (c) is constant, meaning frequency (f) and wavelength (λ) are inversely proportional [13]. Higher-frequency electromagnetic waves are generally more energetic and possess greater penetrating power, enabling techniques that probe molecular and atomic structures with remarkable precision [13]. The careful interpretation of spectra yields a wealth of information about the structure, dynamics, and local environments of molecular systems under study, making spectroscopy a versatile complement to other analytical techniques [14].

The Infrared Region: Molecular Fingerprinting

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

The infrared (IR) region of the electromagnetic spectrum lies beyond the red color of visible light, with wavelengths ranging from approximately 0.7 to 500 microns (wavenumbers of about 14,000 to 10 cm⁻¹) [11] [14]. This radiation is emitted by all bodies with a temperature above absolute zero and interacts with matter primarily through excitation of molecular vibrations and rotations [11]. For a molecule to absorb IR radiation, it must undergo a change in its dipole moment—the product of the distance and the magnitude of equal but opposite charges [11]. The resonant frequencies at which absorption occurs are characteristic of specific molecular bonds and functional groups, creating a unique "fingerprint" for chemical identification [15].

Infrared spectrometers consist of several key components: a source of IR radiation, a system for focusing energy onto the sample, a monochromator to isolate narrow spectral ranges, a detector, and an output recorder [11]. Modern Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometers have largely replaced dispersive instruments, offering higher sensitivity, faster acquisition times (modern instruments can measure up to 32 times per second), and better wavelength accuracy [15]. The infrared spectrum is typically divided into three regions: near-infrared (NIR: 14,000-4,000 cm⁻¹), mid-infrared (MIR: 4,000-400 cm⁻¹), and far-infrared (FIR: 400-10 cm⁻¹), each with distinct applications [14].

Table 1: Infrared Spectral Regions and Their Applications

| Spectral Region | Wavelength Range | Wavenumber Range (cm⁻¹) | Primary Transitions | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Near-IR (NIR) | 0.78-2.5 µm | 14,000-4,000 | Overtone and combination vibrations of C-H, O-H, N-H | Quality control of food and dairy products [14] |

| Mid-IR (MIR) | 2.5-25 µm | 4,000-400 | Fundamental molecular vibrations | Chemical structure elucidation, protein secondary structure analysis [14] [15] |

| Far-IR (FIR) | 25-500 µm | 400-10 | Skeletal vibrations, lattice modes | Inorganic compound analysis, geological studies [14] |

Analytical Applications and Experimental Protocols

Infrared spectroscopy provides unique information on features of molecular structure, including the family of minerals to which a specimen belongs, the mixture of isomorphic substituents, the distinction of molecular water from constitutional hydroxyl, the degree of structural regularity, and the presence of both crystalline and noncrystalline impurities [11]. In geochemical research, for example, IR spectroscopy has revealed that chalcedony contains hydroxyl in structural sites as well as several types of nonstructural water held by internal surfaces and pores [11].

Experimental Protocol: Protein Secondary Structure Analysis via FT-IR

- Sample Preparation: Prepare protein solution in appropriate buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl, pH 7.4). For solid samples, create KBr pellets or use attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessories that require minimal sample preparation [14].

- Instrument Calibration: Verify wavelength accuracy using polystyrene film standards. Purge instrument with dry air or nitrogen to minimize atmospheric CO₂ and water vapor interference [14].

- Data Collection: Acquire spectrum in the mid-IR region (4000-400 cm⁻¹) with sufficient scans (typically 32-64) to achieve adequate signal-to-noise ratio. For solution studies, use sealed demountable cells with appropriate pathlengths [14].

- Spectral Processing: Subtract buffer or background spectrum. Apply smoothing functions if necessary and perform baseline correction [14].

- Analysis: Focus on the amide I band (1600-1700 cm⁻¹), primarily associated with C=O stretching vibrations, which is sensitive to protein secondary structure. Use second derivative analysis or Fourier self-deconvolution to resolve overlapping components. Alternatively, apply hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) in Python to assess similarity of secondary structures under different conditions [12].

In enzymology, IR spectroscopy stands out by virtue of its complementarity to other key experimental techniques. While X-ray crystallography offers molecular structures of unmatched detail, it is limited to static, solid-phase crystal samples. IR spectroscopy cannot offer the same structural resolution, but its fast inherent timescale, structural sensitivity, and applicability to aqueous samples make it a versatile complement to X-ray or cryo-EM techniques [14].

Diagram 1: IR Spectroscopy Analytical Workflow

The Visible and Ultraviolet Region: Electronic Transitions

Fundamental Principles

The ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) region encompasses wavelengths from approximately 190 nm to 800 nm, covering both ultraviolet and visible light. This region probes electronic transitions in molecules, where photons promote electrons from ground states to excited states [16]. The energy required for these transitions corresponds to the energy difference between molecular orbitals, particularly involving π→π, n→π, and charge-transfer transitions [17]. The most common measurement in UV-Vis spectroscopy is absorbance (A), which follows the Beer-Lambert Law (A = εbc), relating absorbance to molar absorptivity (ε), path length (b), and concentration (c) [17].

UV-Vis spectrophotometers typically consist of a light source (deuterium lamp for UV, tungsten lamp for visible), a monochromator to select specific wavelengths, sample and reference cells, a detector, and data processing electronics [16]. Instruments may be single-beam, double-beam, or array-based systems, with each configuration offering distinct advantages for specific applications [18]. The market for UV-Vis instrumentation continues to grow, projected to reach $2.19 billion by 2029, with a compound annual growth rate of 7.2%, driven by pharmaceutical development, environmental analysis, and quality assurance in food and beverages [18].

Analytical Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

UV-Vis spectroscopy is a well-established analytical technique in the pharmaceutical industry for testing in both research and quality control stages of drug development [16]. It provides highly accurate measurements that meet United States Pharmacopeia (USP), European Pharmacopoeia (EP), and Japanese Pharmacopoeia (JP) performance characteristics, enabling 21 CFR Part 11 compliance with appropriate security software [16].

Experimental Protocol: Drug Analysis According to Pharmacopeia Monographs

- Standard Solution Preparation: Precisely weigh 10 mg of drug reference standard and dissolve in 15 mL methanol. Add 85 mL water to adjust volume to 100 mL (100 ppm stock solution). Transfer 5 mL of stock to a 50 mL volumetric flask and dilute to volume with methanol-water (15:85 v/v) diluent [17].

- Test Solution Preparation: Weigh and powder 20 tablets. Transfer powder equivalent to 100 mg of active ingredient to a 100 mL volumetric flask. Add 15 mL methanol and shake vigorously to dissolve. Add 85 mL water to adjust volume to 100 mL. Withdraw 1 mL of this solution and transfer to a 100 mL volumetric flask, diluting to volume with diluent [17].

- Spectrophotometric Analysis: Using a double-beam UV-Vis spectrophotometer with matched quartz cells (1 cm pathlength), scan the standard solution between 200-400 nm using diluent as blank. Identify λmax (e.g., 243 nm for paracetamol) [17].

- Quantification: Measure absorbance of both standard and test solutions at λmax. Calculate drug content using the formula: Concentration(test) = [Absorbance(test) × Concentration(standard)] / Absorbance(standard) [17].

- Method Validation: Establish specificity, precision, linearity, accuracy, and robustness according to regulatory guidelines. For dissolution testing, use UV-Vis to analyze results of dissolution testing of solid oral dosage forms like tablets [16].

Table 2: Key UV-Vis Applications in Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Application Area | Specific Use | Experimental Details | Regulatory Compliance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Discovery | Development of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) | From scans to stop-flow kinetics | USP, EP, JP [16] |

| Quality Control | Quantification of impurities | Pharmaceutical monographs for quantifying impurities in drug ingredients | 21 CFR Part 11 with Insight Pro Security Software [16] |

| Dissolution Testing | Analysis of solid oral dosage forms | Method for analyzing dissolution testing of tablets | USP performance characteristics [16] |

| Chemical Identification | Confirm chemical identity and purity | Identification tests for quality confirmation of samples (e.g., ibuprofen) | USP and EP monographs [16] |

UV-Vis spectroscopy also plays crucial roles in life science applications, enabling quantification of biomolecules including nucleic acids, proteins, and bacterial cultures [16]. In bacterial culturing, spectrophotometers monitor growth by measuring optical density (OD) at 600 nm, helping simplify the management of this central technique of microbiology [16]. Recent advances include the development of UV-Vis imaging to mimic transport within human tissue, such as subcutaneous tissue, where introducing high-molecular-weight dextrans enhances optical clearing, improving transmittance and resolution [12].

The X-ray Region: Probing Atomic Structure

Fundamental Principles

X-rays represent the high-energy portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, with extremely short wavelengths of approximately 1 Ångstrom (10⁻¹⁰ meters) [13]. These high-energy photons are generated by either inner electronic transitions or fast collisions involving accelerated electrons [13]. The interaction of X-rays with matter provides information about atomic and molecular structures, unlike IR and UV-Vis spectroscopies, which provide information about molecular vibrations and electronic transitions, respectively [13].

The fundamental technique in this region for analytical applications is X-ray diffraction (XRD), particularly powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) for pharmaceutical analysis. When X-rays interact with a crystalline material, they are scattered by the electrons of the atoms in the crystal, producing a diffraction pattern that can be interpreted to determine the atomic arrangement within the crystal [12]. The shorter wavelength of X-rays enables the resolution of much smaller structural details compared to other spectroscopic techniques [13].

Analytical Applications in Material Science and Pharmaceuticals

X-ray techniques provide critical information about the crystalline identity and structure of active pharmaceutical compounds, which is essential for ensuring drug efficacy, stability, and reproducibility [12]. Different polymorphs of the same drug compound can have significantly different bioavailability, dissolution rates, and stability profiles, making PXRD an indispensable tool in pharmaceutical development.

Experimental Protocol: Co-crystal Characterization via PXRD

- Sample Preparation: Prepare co-crystals using methods such as liquid-assisted grinding with appropriate co-formers (e.g., nicotinamide, cinnamic acid, sorbic acid). For norfloxacin co-crystals, use approximately 1:1 molar ratios of drug to co-former with minimal solvent [12].

- Instrument Setup: Configure PXRD instrument with Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5418 Å), typically operating at 40 kV and 40 mA. Set scanning range from 5° to 40° 2θ with step size of 0.02° and counting time of 1-2 seconds per step [12].

- Data Collection: Mount sample on zero-background holder, ensuring uniform surface. Acquire diffraction pattern under ambient conditions. For temperature-dependent studies, use specialized sample chambers with controlled atmosphere [12].

- Structure Determination: Use Material Studio Software or similar computational packages to determine crystal structures. Index diffraction peaks and determine unit cell parameters. Refine structures using Rietveld method [12].

- Property Characterization: Evaluate improvements in solubility, dissolution profiles, and pharmacokinetic parameters. For norfloxacin co-crystals, researchers observed significant improvements: 8 to 3-fold solubility enhancement, 6 to 2-fold dissolution improvement, and 2 to 1.5-fold higher peak plasma concentration compared to norfloxacin alone [12].

The ability of X-rays to penetrate materials also makes them valuable for medical diagnostics and security applications, though these uses fall somewhat outside the scope of analytical spectroscopy as applied to chemical analysis [13].

Diagram 2: X-ray Diffraction Analytical Workflow

Comparative Analysis and Complementary Techniques

Integrated Spectroscopic Approaches

Modern analytical challenges often require the integration of multiple spectroscopic techniques to fully characterize complex systems, particularly in pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical research. Each region of the electromagnetic spectrum provides complementary information, and together they offer a more complete picture of molecular structure and behavior.

Fluorescence spectroscopy detects the emission of light by substances after excitation, often used for tracking molecular interactions, kinetics, and dynamics [12]. A recent study explored non-invasive in-vial fluorescence analysis to monitor heat- and surfactant-induced denaturation of bovine serum albumin (BSA), eliminating the need for sample removal and offering a cost-effective, portable solution for assessing biopharmaceutical stability from production to patient administration [12].

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, while not technically part of the electromagnetic spectrum discussed here, provides detailed information about molecular structure and conformational subtleties through the interaction of nuclear spin properties with an external magnetic field [12]. Solution NMR can monitor monoclonal antibody (mAb) structural changes and interactions, while 2D NMR methods can detect higher-order structural changes and interactions in biopharmaceutical formulations [12].

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques

| Technique | Spectral Region | Energy Transitions | Information Obtained | Detection Limits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infrared Spectroscopy | 0.7-500 µm | Molecular vibrations | Functional groups, molecular fingerprint | Nanogram to microgram |

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | 190-800 nm | Electronic transitions | Concentration, conjugation, chromophores | Picomole to nanomole |

| X-ray Diffraction | ~1 Å | Electron scattering | Crystal structure, polymorphism | Milligram quantities |

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy | UV-Vis range | Electronic emission | Molecular interactions, environment | Femtomole to picomole |

Emerging Trends and Instrumentation

The field of analytical spectroscopy continues to evolve with emerging trends and technological advancements. According to the 2025 Review of Spectroscopic Instrumentation, several key developments are shaping the future of the field [19]:

Portable and Handheld Devices: There is increasing demand for compact, portable instruments that can be taken directly to the sample rather than requiring samples to be brought to the laboratory. Companies like Metrohm and SciAps have introduced field-portable NIR and vis-NIR instruments with performance characteristics approaching laboratory-quality instruments [19].

Advanced Microscopy Integration: Microspectroscopy has become increasingly important as application areas deal with smaller and smaller samples. New products like the Bruker LUMOS II ILIM (a Quantum Cascade Laser-based microscope) and Protein Mentor (designed specifically for protein analysis in biopharmaceuticals) provide enhanced capabilities for analyzing minute samples [19].

Process Analytical Technology (PAT): Raman spectroscopy is being increasingly implemented for inline product quality monitoring in biopharmaceutical manufacturing. A 2023 study showcased real-time measurement of product aggregation and fragmentation during clinical bioprocessing using hardware automation and machine learning, accurately measuring product quality every 38 seconds [12].

Specialized Software Solutions: Software is becoming as important as hardware in the modern analytical laboratory. Instrument control, data processing, and specialized analysis packages are being developed for specific applications, such as BeerCraft Software for beer analysis or Visionlite Wine Analysis Software for wine and juice analysis [16].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Technical Specification | Application Context | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tris-HCl Buffer | 0.1 M, pH 7.4, with 0.1 M NaCl | Protein-ligand interaction studies | Simulates physiological conditions for protein binding experiments [17] |

| Methanol-Water Diluent | 15:85 (v/v) ratio | Pharmaceutical dissolution testing | Dissolves drug compounds while maintaining solubility for UV-Vis analysis [17] |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | FT-IR grade, 99+% purity | IR sample preparation | Matrix for preparing solid pellets for transmission FT-IR measurements [14] |

| Deuterium Oxide (D₂O) | 99.9% isotopic purity | Protein amide H-D exchange in FT-IR | Solvent for monitoring protein structural changes via amide I band shifts [14] |

| Nicotinamide Co-former | Pharmaceutical grade, >98% purity | Pharmaceutical co-crystal development | Forms hydrogen-bonded complexes with APIs to enhance solubility [12] |

| Ultrapure Water | 18.2 MΩ·cm resistivity | Mobile phase and sample preparation | Minimizes spectral interference in UV-Vis and FT-IR analyses [19] |

The electromagnetic spectrum, from infrared to X-rays, provides an extraordinary array of tools for analytical science, each with unique capabilities for probing different aspects of molecular and atomic structure. Infrared spectroscopy reveals detailed information about molecular vibrations and functional groups, UV-Vis spectroscopy enables quantification and electronic structure characterization, and X-ray techniques illuminate atomic-level structural arrangements. Together, these methods form a complementary toolkit that continues to evolve through technological advancements in portability, sensitivity, and integration with computational methods.

For researchers in pharmaceutical development and other analytical fields, understanding the fundamental principles, applications, and experimental protocols associated with each spectral region is essential for selecting the appropriate technique for specific analytical challenges. The continuing growth of the spectroscopy market, particularly in UV-Vis and portable IR instruments, reflects the enduring importance of these techniques in addressing the complex analytical needs of modern science and industry. As spectroscopic technologies continue to advance, they will undoubtedly unlock new capabilities for understanding and manipulating matter at the molecular level.

The interaction of light with matter is a cornerstone of modern analytical science, forming the basis of techniques indispensable to researchers and drug development professionals. When atoms or molecules absorb light, they undergo a precise transition from a lower energy state to a higher one. This process is not continuous but quantized, governed by the fundamental principle that an atom or molecule can absorb a photon only if the photon's energy exactly matches the difference between two of its permitted energy states [20] [21]. This selective absorption, and the subsequent emission of radiation as the excited species relaxes, provides a unique fingerprint for identifying substances and quantifying their concentration. Understanding these core principles is essential for leveraging spectroscopic methods in research, from elucidating molecular structures in drug discovery to conducting ultra-trace elemental analysis.

Core Principles of Light-Matter Interaction

The Quantum Nature of Absorption

At the heart of absorption spectroscopy lies the quantum nature of both matter and energy. Atoms and molecules can exist only in a series of discrete states of electronic energy, often referred to as energy levels [20].

- Quantized Energy Levels: The lowest energy level is the ground state, which is the most stable configuration for the atom or molecule. Higher energy levels are termed excited states [20].

- The Photon and Energy Matching: Light energy is delivered in discrete packets called photons. The energy of a single photon is given by the Einstein-Planck relation: ( E = h\nu ) where ( h ) is Planck's constant and ( \nu ) is the frequency of the light [21]. For absorption to occur, the condition ( \Delta E = h\nu ) must be satisfied, meaning the energy of the incoming photon must precisely equal the difference in energy between a lower and a higher quantum state [21] [22].

- The Absorption Act: When this condition is met, the atom or molecule absorbs the photon, and an electron is promoted from its ground state to a higher-energy excited state. The atom or molecule is then said to be "excited" [20] [21].

From Atoms to Molecules: Complexity in Spectra

While the basic principle of quantized energy levels applies to both atoms and molecules, the resulting spectra differ significantly due to the increased complexity of molecular structure.

- Atomic Spectra: Atoms possess only electronic energy levels. Therefore, their absorption and emission spectra consist of a series of sharp, well-defined lines [22]. Each element has a unique spectral pattern, acting as a fingerprint that allows for precise identification [9] [22].

- Molecular Spectra: Molecules have three types of quantized energy levels: electronic, vibrational, and rotational. When a molecule undergoes an electronic transition, it is simultaneously excited to a higher vibrational and rotational state. The close spacing of these vibrational and rotational levels causes the sharp lines seen in atomic spectra to broaden into continuous bands [20]. This makes molecular spectra more complex but also information-rich, containing data about bond strengths and molecular geometry [22].

Table 1: Fundamental Energy Transitions and Their Spectral Regions

| Transition Type | Energy Region | Spectroscopic Technique | Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic | Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) | UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Electron orbital energies, chromophore concentration |

| Vibrational | Infrared (IR) | Infrared Spectroscopy (IR) | Bond strengths, functional groups, molecular identity |

| Rotational | Microwave | Microwave Spectroscopy | Bond lengths, molecular geometry |

The Franck-Condon Principle and Stokes Shift

The transition between electronic states in a molecule occurs so rapidly (in femtoseconds) that the much heavier atomic nuclei do not have time to move during the absorption act. This is the essence of the Franck-Condon Principle [20].

- Vertical Transitions: On a potential energy diagram, which plots a molecule's energy against the interatomic distance, electronic transitions are represented by vertical arrows. Because the nuclei are stationary during the transition, the molecule is promoted from the lowest vibrational level of the ground electronic state to a higher vibrational level of the excited electronic state [20].

- Vibrational Relaxation: The molecule finds itself in a non-equilibrium, vibrating state in the excited electronic state. It rapidly loses this excess vibrational energy to the surrounding medium (as heat) in a process called vibrational relaxation, settling at the lowest vibrational level of the excited state [20].

- Fluorescence and Stokes Shift: When the molecule returns to the ground state, it often emits light, a phenomenon known as fluorescence. The fluorescence transition is also vertical. Since some energy was lost as heat after absorption, the emitted photon has lower energy (longer wavelength) than the absorbed photon. This displacement of the fluorescence band to longer wavelengths compared to the absorption band is known as the Stokes' shift [20].

Diagram 1: Franck-Condon Principle and Stokes Shift

Quantitative Absorption: Beer-Lambert Law

At the macroscopic level, the absorption of light by a solution is quantitatively described by the Beer-Lambert Law (often simply called Beer's Law). This law relates the attenuation of light to the properties of the material through which the light is traveling [21].

The Beer-Lambert Law is expressed as: ( A = \epsilon b c ) where:

- ( A ) is the Absorbance (a dimensionless quantity).

- ( \epsilon ) is the Molar Absorptivity or extinction coefficient (typically in L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹).

- ( b ) is the Path Length of the light through the solution (in cm).

- ( c ) is the Concentration of the absorbing species (in mol·L⁻¹) [21].

Absorbance is defined in terms of transmittance. Transmittance (( T )) is the ratio of the intensity of transmitted light (( I )) to the intensity of incident light (( I0 )), so ( T = I / I0 ). Absorbance is then defined as ( A = - \log_{10} T ) [21].

This linear relationship between absorbance and concentration is the foundation for quantitative analysis in UV-Vis spectroscopy. A chromophore is a chemical species that strongly absorbs light, typically in the visible region, and its concentration can be determined directly from a measured absorbance value using a pre-established calibration curve [21].

Table 2: Beer-Lambert Law Parameters and Their Significance in Quantitative Analysis

| Parameter | Symbol | Units | Role in Quantitative Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorbance | ( A ) | Dimensionless | The measured quantity, proportional to the amount of light absorbed by the sample. |

| Molar Absorptivity | ( \epsilon ) | L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹ | A constant for a given chromophore at a specific wavelength; indicates how strongly it absorbs. |

| Path Length | ( b ) | cm | The distance light travels through the sample; fixed by the cuvette design (e.g., 1 cm). |

| Concentration | ( c ) | mol·L⁻¹ | The target variable for quantification, determined from ( A ), ( \epsilon ), and ( b ). |

Experimental Methodologies in Absorption Spectroscopy

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS)

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy is a powerful technique for determining the concentration of specific metal elements in a sample.

- Principle: AAS is based on the principle that ground state free atoms in the gas phase can absorb light of a characteristic wavelength. The amount of light absorbed is proportional to the concentration of the element in the sample [23] [9].

- Instrumentation and Protocol:

- Atomization: The liquid sample is converted into a fine aerosol (nebulization) and then introduced into a high-temperature flame or graphite furnace. This heat breaks down the sample into free, ground state atoms [23] [9].

- Irradiation: A hollow cathode lamp (HCL), which emits light of a wavelength peculiar to the target element, is used as the light source. This beam is passed through the cloud of atoms [23].

- Measurement: The atoms absorb a fraction of the light at their characteristic wavelength. A monochromator selects the specific wavelength, and a detector measures its intensity after passing through the atom cloud [23] [9].

- Quantification: The degree of absorption is measured and compared to calibrations standards to determine the unknown concentration in the sample [23].

Diagram 2: Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy Instrumental Workflow

Molecular UV-Visible Absorption Spectroscopy

This technique is used to study molecules that contain chromophores, allowing for both qualitative identification and, most importantly, quantitative determination of concentration.

- Principle: Molecules in a solution absorb ultraviolet or visible light, promoting electrons from the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). The resulting absorption spectrum provides information about the molecular structure, and the absorbance follows the Beer-Lambert law for quantification [21].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: The analyte is dissolved in a suitable solvent that does not absorb significantly in the spectral region of interest. The solution is placed in a transparent cuvette (e.g., quartz for UV, glass for Vis) [21].

- Baseline Correction: A blank containing only the solvent is placed in the spectrometer, and a baseline measurement is taken to account for any absorption from the cuvette or solvent.

- Spectral Scan: The sample is placed in the beam, and the absorbance is measured across a range of wavelengths to obtain the absorption spectrum and identify the wavelength of maximum absorption (( \lambda{max} )) [21].

- Quantitative Measurement: At the predetermined ( \lambda{max} ), the absorbance of the sample and a series of standard solutions of known concentration is measured. A calibration curve of absorbance versus concentration is plotted, and the concentration of the unknown sample is determined from this curve [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, materials, and instruments essential for conducting absorption spectroscopy experiments in a research and development context.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Absorption Spectroscopy

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Hollow Cathode Lamps (HCLs) | Light source for Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS). Each lamp is specific to a single element, emitting sharp, characteristic spectral lines for high selectivity [23] [9]. |

| Graphite Furnace/Tubes | Electrothermal atomizer for flameless AAS. Provides higher sensitivity than flame AAS by confining the sample in a small volume and allowing for longer atom residence times, suitable for ultra-trace metal analysis [23] [9]. |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Source | A high-temperature plasma source (~6000-10,000 K) used primarily in emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES). It efficiently atomizes and excites a wide range of elements simultaneously, enabling high-sensitivity multi-element analysis [9]. |

| Spectrophotometric Cuvettes | Transparent containers for holding liquid samples during UV-Vis spectroscopy. Quartz is used for UV light, while glass or plastic can be used for the visible range only [21]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Solvents such as water, hexane, or methanol that are transparent in the spectral region of interest. They are used to dissolve samples without contributing interfering background absorption [21]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Standards with known, certified concentrations of specific elements or compounds. These are critical for calibrating instruments and validating analytical methods to ensure accuracy and precision [9]. |

| Nitric Acid & Other Digestion Acids | High-purity acids used in sample preparation to digest solid samples (e.g., tissues, alloys) into a liquid form, extracting the target analytes for subsequent analysis by AAS or ICP techniques [9]. |

The process of photon release during electron relaxation is a fundamental phenomenon underpinning the field of emission spectroscopy. When an atom or molecule absorbs energy, its electrons are promoted to higher, unstable energy states. The subsequent return of these electrons to lower energy states—a process termed relaxation or decay—results in the emission of electromagnetic radiation, often in the form of visible light or other spectral regions [24]. This emission spectrum serves as a unique fingerprint for elements and compounds, forming the analytical basis for techniques widely used in chemical analysis, pharmaceutical development, and materials science [25] [9]. Understanding the kinetics and mechanisms of these relaxation processes is therefore critical for advancing spectroscopic research and its applications.

Quantum Mechanical Principles of Electron Relaxation

Atomic Energy Levels and Electron Transitions

At the core of emission phenomena lies the quantum mechanical principle that electrons within an atom can only occupy discrete energy levels or orbitals. An electron cannot exist between these defined states. When an electron occupies a higher energy orbital, the atom is in an excited state, which is inherently unstable [25]. The energy difference between these quantized states is precise and element-specific.

When an electron transitions from a higher energy state ((E2)) to a lower one ((E1)), the excess energy, ( \Delta E = E2 - E1 ), is emitted as a photon. The energy of this emitted photon dictates its wavelength (( \lambda )) according to the formula: [ E_{\text{photon}} = h\nu = \frac{hc}{\lambda} ] where (h) is Planck's constant, (\nu) is the frequency of the light, and (c) is the speed of light [24]. This direct relationship between energy levels and emitted wavelength is why each element possesses a unique emission spectrum, analogous to a barcode [25].

Table 1: Characteristic Visible Emission Lines of Hydrogen

| Element | Wavelength (nm) | Color | Electron Transition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen | 410 | Violet | Jump down to level 2 (4→2) [25] |

| Hydrogen | 434 | Blue | Jump down to level 2 (3→2) [25] |

| Hydrogen | 486 | Blue-green | Jump down to level 2 (4→2) [25] |

| Hydrogen | 656 | Red | Jump down to level 2 (3→2) [25] |

Relaxation Pathways

The journey of an excited electron back to the ground state can occur through several distinct relaxation pathways, each with different kinetics and spectroscopic signatures:

- Nonradiative Relaxation: This process involves the dissipation of energy through molecular or atomic collisions, resulting in the generation of heat without photon emission. While not directly useful for emission spectroscopy, it is a common competing pathway [26].

- Radiationless transitions occur very rapidly, on the order of (10^{-15}) to (10^{-12}) seconds [26].

- Emission / Resonance Fluorescence: This is the direct emission of a photon with energy equal to that of the absorbed photon, corresponding to the electron falling directly back to its original ground state. This is the primary process observed in atomic emission spectroscopy [24] [26].

- Fluorescence: In molecular systems, an excited electron may first undergo a nonradiative vibrational relaxation to the lowest vibrational level of the excited electronic state. It then emits a photon as it returns to the ground electronic state. Because some energy was lost as heat, the emitted photon has lower energy (longer wavelength) than the absorbed photon. Fluorescence occurs on a time scale of about (10^{-8}) seconds [26].

- Phosphorescence: This involves a "forbidden" intersystem crossing between states of different spin multiplicity (e.g., from a singlet to a triplet excited state). The subsequent transition back to the singlet ground state is also spin-forbidden, causing a significant delay. Phosphorescence can persist from minutes to hours after the initial excitation source is removed [26].

Experimental Methodologies in Emission Spectroscopy

The fundamental principles of electron relaxation are harnessed in various spectroscopic techniques to determine elemental composition and concentration.

Flame Emission Spectroscopy Protocol

A classical method for observing atomic emission, particularly for alkali and alkaline earth metals, is flame emission spectroscopy [24].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Introduction: A solution containing the analyte is drawn into a nebulizer and dispersed into the flame as a fine spray or aerosol [24].

- Desolvation: The heat of the flame first causes the solvent to evaporate, leaving finely divided solid particles of the analyte [24].

- Atomization: These solid particles move to the hottest region of the flame, where they are vaporized and dissociated into free, gaseous ground-state atoms [24].

- Excitation: Collisions with thermal energy in the flame promote a fraction of these ground-state atoms to excited electronic states [24].

- Eission and Detection: The excited atoms spontaneously relax to lower energy states, emitting photons at characteristic wavelengths. A monochromator is used to select a specific wavelength, and a detector measures the intensity of the emitted light [24]. This intensity is proportional to the concentration of the element in the sample, enabling quantitative analysis [9].

This simple flame test is a direct application; for example, sodium salts produce an amber-yellow flame, while strontium salts produce a red flame [24].

Advanced Instrumentation for Atomic Emission

For more sensitive and multi-element analysis, advanced techniques like Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES) are employed.

Instrumentation and Workflow:

- Excitation Source: An inductively coupled plasma (ICP) torch generates an argon plasma at extremely high temperatures (6,000–10,000 K). This efficiently atomizes the sample and excites a wide range of elements simultaneously [9].

- Optical System: The emitted light is collected and directed into a wavelength selector, such as a monochromator or polychromator, which separates the light into its constituent wavelengths [9].

- Detection and Data Acquisition: A detector (e.g., a photomultiplier tube or CCD) measures the intensity of light at each specific wavelength. A data system processes these signals, identifying elements based on their characteristic wavelengths and quantifying them based on emission intensity [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of emission spectroscopy requires specific instrumentation and chemical reagents to ensure accurate and sensitive elemental analysis.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Instrumentation for Atomic Emission Spectroscopy

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Hollow Cathode Lamp (HCL) | An element-specific light source used in Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS). It emits narrow, characteristic spectral lines of the target element for absorption measurements [9]. |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Source | A high-temperature plasma source (6,000-10,000 K) used in ICP-AES to efficiently atomize and excite a wide range of elements simultaneously, enabling high-sensitivity, multi-element analysis [9]. |

| Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | A high-purity acid used in the sample preparation step of acid digestion to dissolve solid samples and extract metallic analytes into a solution suitable for introduction into the spectrometer [9]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Standards with known, certified concentrations of elements. Used to create calibration curves for the accurate quantification of analytes in unknown samples [9]. |

| Argon Gas | Used to generate and sustain the inductively coupled plasma in ICP-AES and as a nebulizer gas to transport the sample aerosol into the plasma torch [9]. |

| Internal Standard Solution | A known concentration of an element not present in the sample, added to all samples and standards. Its signal is used to correct for instrument drift and matrix effects, improving analytical precision [9]. |

Data Analysis and Kinetic Models

Quantitative Analysis

The relationship between emitted light intensity and analyte concentration is fundamental for quantification. For atomic emission, the intensity of an emission line is directly proportional to the concentration of the emitting atoms, allowing for the construction of calibration curves [9]. For molecular fluorescence and phosphorescence, the relationship is described by a modified form of Beer's Law: [ F \text{ or } P = I \Phi \varepsilon b C ] where (F) or (P) is the fluorescence or phosphorescence intensity, (I) is the intensity of the excitation source, (\Phi) is the quantum yield of the process, (\varepsilon) is the molar absorptivity, (b) is the path length, and (C) is the molar concentration [26]. The high sensitivity of fluorescence techniques stems from the ability to measure the emitted light against a dark background, leading to detection limits that can be 1-3 orders of magnitude lower than absorption-based methods [26].

Challenges in Kinetic Modeling

Modeling the kinetics of electron-hole recombination and relaxation in solids, such as in X-irradiated alkali halide crystals, presents significant challenges. Early kinetic theories based on simple mono- and bi-molecular reaction models and the statistical thermodynamic theory of absolute reaction rates have proven inadequate for satisfactorily fitting or explaining experimentally observed decay curves [27]. A primary difficulty lies in the need for an a priori assumption of the order of the kinetics parameter, which often leads to a lack of correlation between theory and experiment [27]. Even non-isothermal relaxation methods like thermally stimulated luminescence can only provide estimates of activation energies or trap depths if the kinetic order is known from other measurements [27]. More recent research continues to develop models for complex relaxation phenomena, including Auger-recombination and radical-recombination electron emission, to better explain the energy transfer processes involved [28].

The release of photons during electron relaxation is a fundamental process governed by the quantum mechanical structure of matter. The ability to measure and analyze these emitted photons through techniques like flame emission, ICP-AES, and fluorescence spectroscopy provides researchers and drug development professionals with a powerful toolkit for elemental identification and quantification. While the core principle—that electrons emitting photons of specific wavelengths when falling to lower energy levels—is elegantly simple, the practical application and full theoretical understanding of the kinetics involved remain a rich area of scientific inquiry. Continued refinement of experimental protocols and kinetic models will further enhance the sensitivity, accuracy, and scope of emission-based analytical methods.

The concept of a "spectral fingerprint" is fundamental to analytical spectroscopy, providing a unique identifier for elements and molecules based on their interaction with light. Just as human fingerprints are unique to each individual, spectral fingerprints are unique to each chemical species, arising from the quantized energy levels within their atomic and molecular structures. These fingerprints form the theoretical foundation for a wide array of analytical techniques that identify substances by measuring their absorption or emission of electromagnetic radiation.

The principle operates on both atomic and molecular scales. For elements, atomic spectroscopy techniques like Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) and Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (AES) exploit the fact that the electronic transitions of atoms occur at precise, element-specific wavelengths [9] [29]. For molecules, vibrational spectroscopy techniques like Infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopy utilize the unique patterns generated by molecular vibrations and rotations, which are influenced by the entire molecular structure, including bond types, strengths, and atomic masses [30] [31] [32]. This technical guide explores the quantum mechanical origins of these unique signatures, the analytical techniques that leverage them, and their critical applications in modern scientific research, particularly in pharmaceutical development and environmental monitoring.

Theoretical Foundations: The Origin of Unique Spectral Signatures

Atomic Spectra and Electronic Transitions

The uniqueness of atomic spectra stems from the discrete, quantized nature of electronic energy levels in an atom. Each element possesses a unique configuration of electrons occupying specific orbitals around the nucleus. The energy difference between these orbitals is characteristic of the element.

When an atom absorbs a photon whose energy exactly matches the difference between a ground state and an excited state energy level, an electron is promoted to a higher orbital. Conversely, when an excited electron returns to a lower energy level, a photon is emitted with an energy corresponding to that specific difference [29]. These transitions result in sharp, narrow absorption and emission lines at wavelengths unique to each element. For example, the simple hydrogen atom, with its multiple possible electronic transitions, produces a spectrum with several lines, while more complex multi-electron elements produce even richer spectra [29]. Because no two elements share the exact same arrangement of electronic energy levels, no two elements produce identical atomic spectra, making these lines a definitive fingerprint for elemental identification [9].

Molecular Spectra and Vibrational Modes

Molecular spectra are significantly more complex than atomic spectra due to the additional degrees of freedom in a molecule. While electronic transitions still occur, the unique "fingerprint" for molecules primarily arises from vibrational and rotational transitions.

In molecules, atoms are connected by chemical bonds that behave like springs, constantly vibrating. These vibrations—such as stretching, bending, and wagging—occur at specific, quantized frequencies that depend on the bond strength and the masses of the atoms involved [32]. When exposed to infrared radiation, a molecule will absorb photons whose energies correspond exactly to the energy difference between its vibrational ground state and an excited vibrational state. This absorption creates the characteristic pattern of an IR spectrum.

The fingerprint region in IR spectroscopy (approximately 1450 to 500 cm⁻¹) is where complex, molecule-specific patterns appear due to the coupling of multiple vibrational modes [30] [32]. These patterns are highly sensitive to the overall molecular structure, making them unique to each compound and nearly impossible to replicate exactly in another molecule. Similarly, Raman spectroscopy, which measures inelastic scattering of light rather than direct absorption, provides a complementary fingerprint based on changes in molecular polarizability during vibration [31] [33]. The combination of all possible vibrational modes, influenced by the entire molecular architecture, ensures that every molecule has a distinctive spectral signature.

Key Analytical Techniques and Their Fingerprinting Capabilities

Atomic Spectroscopy Techniques

Atomic spectroscopy techniques are designed specifically for elemental analysis by exploiting unique atomic fingerprints.

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS): AAS measures the absorption of light by free, ground-state atoms in the gas phase. The sample is atomized using a flame or graphite furnace, and a hollow cathode lamp emits light of a characteristic wavelength specific to the target element. The amount of light absorbed is proportional to the concentration of that element in the sample [23] [9]. Its high selectivity makes it ideal for targeted analysis.

Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (AES): AES measures the intensity of light emitted by excited atoms as they return to the ground state. High-temperature sources like an inductively coupled plasma (ICP) simultaneously atomize and excite the elements in a sample. Each element emits light at its characteristic wavelengths, which can be used for both identification and quantification [9] [29]. ICP-AES is renowned for its ability to perform rapid multi-element analysis.

Table 1: Comparison of Atomic Spectroscopy Techniques

| Feature | Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) | Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (AES) |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Phenomenon | Absorption of light | Emission of light |

| Atomization Source | Flame or Graphite Furnace | Flame, Arc, Spark, or ICP |

| Excitation Source | Hollow Cathode Lamp | High-temperature source (e.g., Plasma) |

| Primary Strength | High selectivity and sensitivity for specific elements | Simultaneous multi-element analysis |

| Spectral Interferences | Generally low | More common, requires background correction |

| Sample Throughput | Lower (sequential element analysis) | Higher (simultaneous analysis) |

Molecular Spectroscopy Techniques

Molecular techniques identify compounds based on the unique vibrational fingerprints of their molecular structure.

Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy: IR spectroscopy is a cornerstone technique for molecular identification. A molecule absorbs IR radiation at frequencies that match its natural vibrational frequencies. The resulting spectrum is divided into two main regions: the functional group region (~4000-1450 cm⁻¹), which provides clues about specific bond types (e.g., O-H, C=O), and the fingerprint region (~1450-500 cm⁻¹), which provides a unique pattern for definitive compound confirmation [30] [32].

Raman Spectroscopy: Raman spectroscopy complements IR spectroscopy. It relies on the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser. The measured "Raman shift" corresponds to the vibrational energy levels of the molecule. A specific sub-region from 1550 to 1900 cm⁻¹ is sometimes called the "fingerprint in the fingerprint" region, as it is particularly rich in vibrations from functional groups like C=N, C=O, and N=N, which are common in active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and often free from interference from common excipients [31].

Table 2: Comparison of Molecular Vibrational Spectroscopy Techniques

| Feature | Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Phenomenon | Absorption of light | Inelastic scattering of light |

| Governed by | Change in dipole moment | Change in polarizability |

| Key Spectral Region | 1450 - 500 cm⁻¹ (Fingerprint Region) | 1550 - 1900 cm⁻¹ ("Fingerprint in Fingerprint") |

| Sample Preparation | Can be minimal, but may require milling with KBr | Often minimal; can analyze solids, liquids, and gases directly |

| Water Compatibility | Strong water absorption can interfere | Weak water signal; suitable for aqueous solutions |

| Primary Use in Pharma | General molecular identity testing | API-specific identity testing, even in formulated products |

Advanced Applications and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Rapid Pathogen Screening via Raman Spectral Fingerprinting

Recent research demonstrates a powerful application of spectral fingerprinting for public health. The following protocol, based on current research, outlines a method for rapid screening of food and waterborne pathogens using a combination of bead-based capture and Raman spectroscopy [34].

- 1. Research Objective: To capture and identify bacterial pathogens like Salmonella and E. coli directly from liquid samples in hours instead of the days required by traditional culture methods.

- 2. Sample Preparation & Pathogen Capture:

- Immunomagnetic silica beads, decorated with pathogen-specific antibodies, are introduced to the liquid sample (e.g., water, food slurry).

- The beads selectively bind to target pathogens, concentrating them from the sample matrix.

- Signal-enhancing gold particles may be added to amplify the subsequent Raman signal.

- 3. Spectral Fingerprint Acquisition:

- The bead-bound pathogens are analyzed using a compact, low-cost Raman spectrometer.

- The laser illuminates the sample, and the inelastically scattered light (the Raman signal) is collected.

- This results in a unique Raman spectral signature for the captured microbe.

- 4. Data Analysis and Identification:

- The resulting spectra are fed into an on-device machine learning pipeline.

- The algorithm compares the unknown spectrum to a library of known pathogen fingerprints to accurately identify the species and even assess antibiotic resistance.

- 5. Impact: This technology has the potential to revolutionize food and water safety by reducing costs, preventing outbreaks, and protecting public health [34].

Protocol 2: API Identity Testing via the Raman "Fingerprint-in-Fingerprint" Region

In pharmaceutical development, ensuring the identity of the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) is a critical quality control step. The following methodology leverages a specific Raman spectral region for unambiguous identification [31].

- 1. Research Objective: To confirm the identity of an API in a solid dosage form (tablet or capsule) without interference from excipients (inactive ingredients).

- 2. Instrumentation and Calibration:

- A Fourier-Transform (FT) Raman spectrometer with a 1064 nm laser is used to minimize fluorescence.

- The instrument is calibrated for wavelength and intensity using a standard reference material.

- 3. Data Acquisition:

- A sample of the drug product (or a pure API reference standard) is placed under the laser.

- Raman spectra are collected at a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹ over a range of 150–3700 cm⁻¹.

- 4. Targeted Spectral Analysis:

- The acquired spectrum is analyzed, with a specific focus on the 1550–1900 cm⁻¹ region ("fingerprint-in-fingerprint").

- This region is ideal because common excipients (e.g., magnesium stearate, lactose, titanium dioxide) show no Raman signals here, while APIs display strong, unique peaks due to C=O, C=N, and N=N vibrations [31].

- 5. Identity Confirmation:

- The spectrum of the unknown is compared to a reference spectrum of the authentic API material.

- A match within this specific region provides a high level of confidence in the API's identity.

The diagram below illustrates the core workflow common to spectral fingerprinting experiments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful spectral fingerprinting relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components used in the featured experiments and broader field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Spectral Fingerprinting

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Hollow Cathode Lamp (HCL) | Light source for AAS; contains the element of interest and emits its characteristic narrow-line spectrum for absorption measurements [9]. |

| Immunomagnetic Beads | Silica beads functionalized with specific antibodies; used to selectively capture and concentrate target pathogens from complex liquid samples for Raman analysis [34]. |

| Matrix Materials (e.g., CHCA, DHB) | Organic compounds used in MALDI mass spectrometry to assist in the desorption and ionization of analyte molecules for mass spectrometry imaging [35]. |

| Metal Nanoparticles (Au, Ag) | Used as matrix-free substrates in MS or as signal-enhancing particles in Raman spectroscopy (e.g., Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy) [35]. |

| ICP Torch & Argon Gas | The core component of ICP-AES/MS; the argon-supported plasma torch atomizes and ionizes the sample at extremely high temperatures (~6000-10,000 K) for excitation [9] [29]. |

| Pharmaceutical Excipients | Inactive ingredients (e.g., lactose, magnesium stearate) used as a matrix for drug products; their spectral silence in key regions (e.g., 1550-1900 cm⁻¹ Raman) is crucial for API identity testing [31]. |

| Reference Spectral Databases | Curated libraries of known spectra (e.g., open-source Raman data [33], commercial IR libraries); essential for automated matching and identification of unknown compounds. |

Spectral fingerprints are a direct consequence of the quantum mechanical laws governing atoms and molecules. The unique arrangement of energy levels in each element and the specific vibrational modes of each molecule create an immutable identity card that can be read through techniques like AAS, AES, IR, and Raman spectroscopy. The ongoing development of these techniques—such as the integration of machine learning for pathogen identification [34] and the refinement of targeted spectral regions for pharmaceutical testing [31]—continues to expand the power and applicability of spectral fingerprinting. As a fundamental principle in analytical science, it remains an indispensable tool for researchers and professionals dedicated to ensuring public safety, drug quality, and scientific discovery.

Spectroscopy, a fundamental tool in analytical science, operates on the principle that atoms and molecules interact with electromagnetic radiation in unique, quantized patterns. These patterns—manifested as line spectra and band spectra—serve as distinctive "fingerprints" for identifying substances from distant stars to complex pharmaceutical compounds [25]. The core thesis of this research establishes that the fundamental differences between atomic and molecular energy structures produce these divergent spectral patterns, providing critical insights for research applications ranging from astronomical discovery to drug development.

When light from a source is dispersed through a prism or diffraction grating, it separates into its constituent wavelengths, producing a spectrum that reveals the electronic structure of the emitting or absorbing material [36]. Line spectra appear as discrete, sharp lines at specific wavelengths and are the signature of individual atoms [36] [37]. In contrast, band spectra present as broad regions of closely-spaced lines that often appear continuous to basic detectors and are characteristic of molecular structures [38] [39]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these spectral patterns, their quantum mechanical origins, and their critical applications in scientific research and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations: Quantum Origins of Spectral Lines

Atomic Energy Levels and Line Spectra

The quantum behavior of electrons within atoms directly produces the observed phenomenon of line spectra. According to quantum theory, electrons occupy discrete energy levels around the atomic nucleus. When an electron transitions between these fixed levels, it must absorb or emit a photon with energy exactly equal to the difference between the two states [25]. This quantized energy exchange follows the principle:

Ephoton = Efinal - E_initial = hc/λ

where h is Planck's constant, c is the speed of light, and λ is the wavelength of the absorbed or emitted photon [25]. The hydrogen atom demonstrates this principle clearly—its electron transitions between specific energy levels produce absorption and emission lines at precisely 410 nm (violet), 434 nm (blue), 486 nm (blue-green), and 656 nm (red) in the visible spectrum [25]. Because these energy levels are unique to each element, the resulting line spectrum serves as an unambiguous identifier, much like a barcode or atomic fingerprint [36] [25].

Molecular Energy Levels and Band Spectra

Molecules exhibit more complex quantum behavior than individual atoms due to additional degrees of freedom. While atoms possess only electronic energy levels, molecules feature three types of quantized states: electronic, vibrational, and rotational [40] [41]. Each electronic energy level contains multiple vibrational sublevels, and each vibrational sublevel contains numerous rotational sublevels [40]. This hierarchical energy structure means molecules can undergo transitions that combine changes in electronic, vibrational, and rotational states simultaneously [41].

The combined effect of these closely-spaced rotational-vibrational transitions produces the characteristic band structure observed in molecular spectra [40] [39]. As molecules become more complex and are crowded together (as in solids or dense gases), the individual lines broaden and blend into what appears as a continuous band [42]. This phenomenon explains why molecular spectra typically manifest as bands rather than discrete lines, with each band comprising numerous barely-resolved transitions between rotational-vibrational states [40] [38].

Diagram: Quantum transitions creating line spectra (left) with discrete wavelengths versus band spectra (right) with multiple closely-spaced transitions.

Comparative Analysis: Line Spectra versus Band Spectra

Fundamental Characteristics and Differences

The distinction between line and band spectra stems directly from their different quantum origins. The table below summarizes their key characteristics:

| Characteristic | Line Spectrum | Band Spectrum |

|---|---|---|

| Origin Source | Individual atoms or ions [36] | Molecules [38] [39] |

| Appearance | Discrete, sharp lines at specific wavelengths [37] | Closely-spaced lines forming continuous bands [39] |

| Spectral Composition | Isolated wavelengths with dark spaces between [36] | Numerous unresolved lines across limited frequency ranges [39] |

| Energy Transitions | Electronic transitions between atomic energy levels [25] | Combined rotational, vibrational, and electronic transitions [40] [41] |

| Complexity Factors | Determined by atomic number and electron configuration [42] | Influenced by molecular structure, bonds, and atomic masses [39] |

| Typical Applications | Elemental identification, stellar composition analysis [36] [42] | Molecular identification, compound characterization [41] [39] |

Formation Mechanisms and Spectral Interpretation