Accuracy and Precision in Spectroscopic Measurements: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive framework for understanding, achieving, and validating accuracy and precision in spectroscopic measurements, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Accuracy and Precision in Spectroscopic Measurements: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for understanding, achieving, and validating accuracy and precision in spectroscopic measurements, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers foundational concepts of measurement quality, practical methodologies for enhancing data reliability, systematic troubleshooting of common spectral anomalies, and robust protocols for method validation and comparative analysis. By integrating current best practices, advanced techniques like AI-driven analysis, and proactive maintenance strategies, this guide aims to empower scientists to generate trustworthy spectroscopic data that meets the rigorous demands of biomedical and clinical research.

Accuracy vs. Precision: Foundational Concepts for Reliable Spectral Data

Defining Accuracy and Precision in the Spectroscopic Context

In spectroscopic research, accuracy and precision represent two distinct yet equally crucial aspects of data quality. Accuracy is defined as the closeness of agreement between a test result and the true value, incorporating both random error components and a common systematic error or bias component [1]. In practical terms, accuracy measures the deviation between what is measured and what should have been, or what is expected to be found [1]. Precision, conversely, refers to the consistency or reproducibility of measurements under unchanged conditions, indicating how closely multiple measurements of the same quantity agree with each other [2]. High precision implies that repeated measurements yield similar results, whereas low precision indicates significant variability among measurements [2].

The distinction between these concepts can be visualized through a classic target analogy: high precision with low accuracy results in tightly clustered hits away from the bullseye; high accuracy with low precision produces scattered hits centered on the bullseye; and high accuracy with high precision yields tightly clustered hits centered perfectly on the bullseye. Understanding this distinction is fundamental for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on spectroscopic data for critical decisions in method development, validation, and regulatory submission.

Quantitative Assessment: Metrics and Mathematical Formulations

Accuracy Metrics and Calculations

Accuracy in spectroscopic analysis is quantitatively assessed through several established metrics. Percent error is commonly used, calculated as: [ \text{Percent Error} = \left( \frac{|\text{Experimental Value} - \text{True Value}|}{\text{True Value}} \right) \times 100\% ] where a lower percent error indicates higher accuracy [2]. Alternative expressions include weight percent deviation (Deviation = %Measured – %Certified) and relative percent difference [1]. For spectroscopic measurements, accuracy is often determined through comparative replicate measurements of Certified Reference Materials (CRMs), where the mean value of replicates must fall within a specified range of the certified value [3].

Precision Metrics and Calculations

Precision is mathematically assessed using the standard deviation (σ) of a set of measurements: [ \sigma = \sqrt{\frac{\sum{i=1}^{n}(xi - \overline{x})^2}{n-1}} ] where (x_i) represents each individual measurement, and (\overline{x}) is the mean of the measurements [2]. Precision can be categorized as repeatability (ability to obtain the same measurement under identical conditions over a short period) and reproducibility (ability to obtain consistent measurements under varying conditions, such as different laboratories or analysts) [2]. In practical spectroscopic applications, precision may be specified as a standard deviation not exceeding a certain percentage (e.g., 0.5%) or as a range of deviations from the mean [3].

Table 1: Decision Rules for Assessing Spectrophotometer Performance

| Decision Rule Number | Criteria | Acceptance Limits |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | Mean absorbance | ± 0.005 A from certified standard |

| #2 | SD of individual absorbances | Not greater than 0.5% |

| #3 | Range of individual absorbances | ± 0.010 A |

| #4 | Range of individual deviations from observed mean absorbance | ± 0.010 A |

Source: Adapted from Spectroscopy Europe/World [3]

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Accuracy and Precision

Certified Reference Materials and Calibration

The assessment of spectroscopic accuracy fundamentally relies on Certified Reference Materials (CRMs). These materials have certified values along with their uncertainties, typically established through multiple independent analytical methods [1]. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) provides Standard Reference Materials for this purpose, with certified values representing the average of two or more independent analytical methods, and uncertainties listed as 95% prediction intervals [1]. For very high accuracy work, the absorbance, index of refraction, thickness, and scattering properties of a filter should be supplied by the standards laboratory instead of just a single transmittance value [4].

A typical experimental protocol for determining absorbance accuracy involves making six replicate measurements of a CRM. The accuracy requirement may specify that "the absorbance accuracy of the mean must be ± 0.005 from the certified value (for absorbance values below 1.0 A) or ± 0.005 multiplied by A (for absorbance values above 1.0 A) and that the range of individual values must not exceed ± 0.010 from the certified value" [3]. This approach ensures both accuracy and precision are assessed simultaneously.

Correlation Curves and Statistical Validation

Perhaps the most robust way of assessing the accuracy of an analytical method is through correlation curves for various elements or compounds of interest. Such curves plot certified or nominal values along the x-axis versus measured values along the y-axis [1]. This visualization provides immediate assessment of analytical technique accuracy. To quantify accuracy in correlation curves, two criteria are applied: (1) a correlation coefficient (R²) must be calculated, with values greater than 0.9 indicating good agreement and values of 0.98 or higher indicating excellent accuracy; and (2) the slope of the regression line through the data must approximate 1.0 with a y-intercept near 0 [1]. Deviations from this 45° straight line through the origin indicate bias in the analytical method.

Advanced Spectroscopic Techniques and Applications

Precision-Enhancement Methodologies

Recent advances in spectroscopic techniques have dramatically improved both precision and accuracy in molecular spectroscopy. Doppler-free cavity-enhanced saturation spectroscopy referenced to optical frequency combs has pushed accuracy into the kHz (10⁻⁷ cm⁻¹) regime, improving the accuracy of many lines and energy levels of molecular databases by orders of magnitude [5]. Techniques such as noise-immune cavity-enhanced optical heterodyne molecular spectroscopy (NICE-OHMS) allow recording saturated Doppler-free lines with ultrahigh precision, typically resulting in linewidths on the order of 100 kHz (half width at half maximum) [5].

Frequency combs represent another powerful tool for precision measurement, enabling researchers to generate a spectrum of evenly spaced frequencies that can be used to probe the properties of atoms and molecules with high accuracy [6]. The frequency comb can be described by the equation: [ fn = f0 + n fr ] where (fn) is the frequency of the (n^{th}) mode, (f0) is the offset frequency, and (fr) is the repetition rate [6]. These advances have been particularly beneficial for studying benchmark systems like water, where precise measurements of 156 carefully-selected near-infrared transitions for H₂¹⁶O have been detected at kHz accuracy [5].

Network Theory and Spectroscopic Validation

The Spectroscopic-Network-Assisted Precision Spectroscopy (SNAPS) approach offers a universal, versatile, and flexible algorithm designed for all measurement techniques and molecules where rovibrational lines are resolved individually [5]. This methodology strongly relies on network theory and the generalized Ritz principle, providing sophisticated tools to exploit all the spectroscopic information coded in the connections of rovibronic lines [5]. The SNAPS procedure: (a) starts with the selection of the most useful set of target transitions allowed by the range of primary line parameters, (b) continues with the measurement of the target lines, (c) supports cycle-based validation of the accuracy of a large number of detected lines, and (d) allows the transfer of the high experimental accuracy to the derived energy values and predicted line positions [5].

Research Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Specification Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Accuracy verification and instrument calibration | NIST Standard Reference Materials or ISO/IEC 17025 certified materials with documented uncertainty budgets |

| Spectrophotometric Standards | Establishing measurement traceability | Materials with certified absorbance, index of refraction, thickness, and scattering properties |

| Calibration Solutions | Quantitative analysis calibration | Solutions with known concentrations of analytes of interest in appropriate solvent matrices |

| Wavelength Standards | Verification of spectrometer wavelength accuracy | Holmium oxide solutions or didymium filters with characteristic absorption peaks |

| Stray Light Reference Materials | Assessment of instrumental stray light | Solutions with sharp cut-off characteristics (e.g., potassium iodide, sodium nitrite) |

| Neutral Density Filters | Linearity verification and photometric accuracy | Filters with certified transmittance values at specified wavelengths |

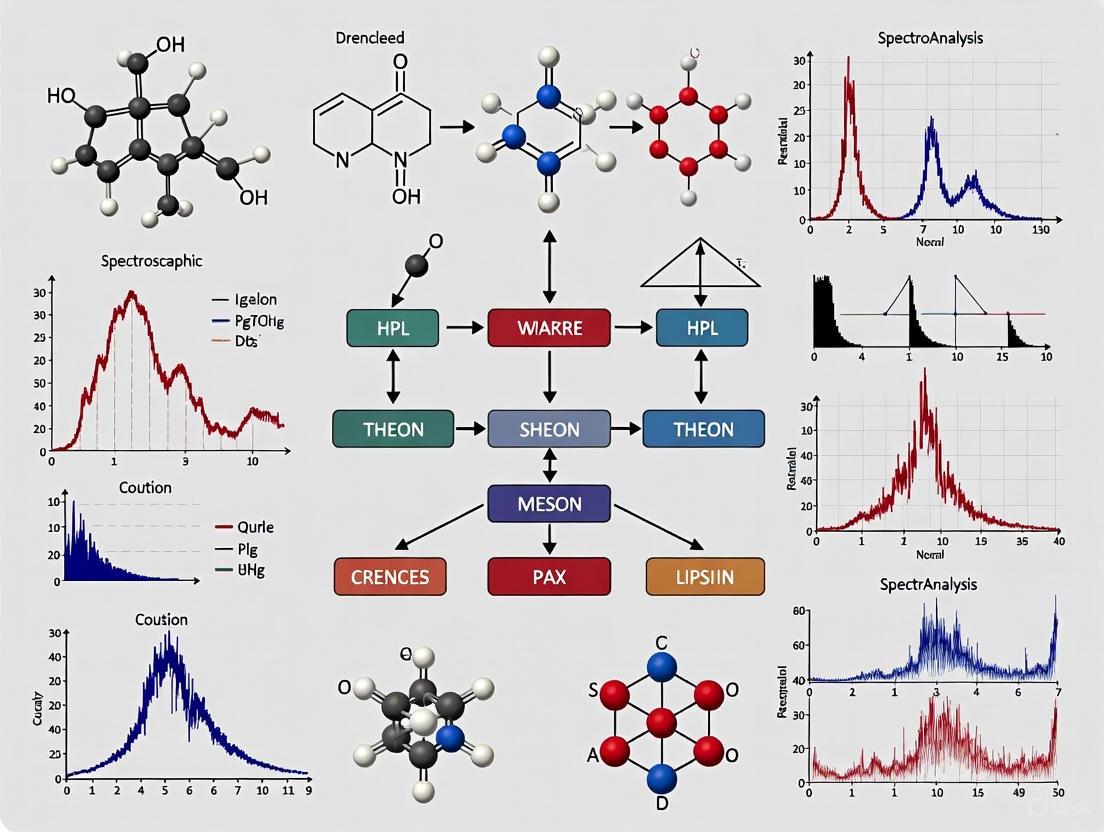

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Spectroscopic Method Validation Workflow

Accuracy and Precision Relationship Diagram

Comparative Experimental Data Across Techniques

Table 3: Accuracy and Precision Levels Across Spectroscopic Techniques

| Technique | Typical Accuracy Level | Typical Precision Level | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional UV-Vis Spectrophotometry | ± 0.005 A (visible range) [4] | SD ≤ 0.5% [3] | Concentration determination, quality control |

| High-Accuracy Spectrophotometry | < 0.001 transmittance (visible) [4] | Not specified | Reference method development, fundamental studies |

| NICE-OHMS Spectroscopy | kHz (10⁻⁷ cm⁻¹) accuracy [5] | Linewidths ~100 kHz HWHM [5] | Fundamental molecular spectroscopy, database refinement |

| Frequency Comb Spectroscopy | High accuracy for atomic transitions [6] | High precision for frequency standards [6] | Optical frequency metrology, fundamental constant measurement |

| WL-SERS for Food Analysis | Tenfold sensitivity increase [7] | High precision for contaminant detection [7] | Trace contaminant detection in complex matrices |

| AI-Enhanced Spectroscopy | Accuracy validated against CRMs | Up to 99.85% identification accuracy [7] | Pattern recognition, complex mixture analysis |

The rigorous definition and assessment of accuracy and precision in spectroscopic measurements form the foundation of reliable analytical data across research and industrial applications. For drug development professionals specifically, understanding these concepts directly impacts method validation, quality control protocols, and regulatory compliance. The continuing advancement of spectroscopic techniques, including Doppler-free methods, frequency combs, and AI-enhanced analysis, continues to push the boundaries of both accuracy and precision. By implementing robust experimental protocols using Certified Reference Materials, statistical validation methods, and advanced spectroscopic networks, researchers can ensure the generation of trustworthy, reproducible data that advances scientific understanding and technological innovation.

In spectroscopic measurements, the pursuit of truth is a delicate balance between accuracy and precision, each governed by distinct types of measurement errors. For researchers in drug development and analytical science, understanding the fundamental distinction between systematic errors (which affect accuracy) and random errors (which affect precision) is not merely academic—it is a critical prerequisite for generating reliable, trustworthy data [8] [1]. This guide provides a structured comparison of these errors, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to spectroscopic research.

Defining the Core Concepts: Accuracy, Precision, and Error

The validity of any spectroscopic measurement is assessed through the lenses of accuracy and precision, concepts that are often conflated but have distinct meanings [8] [9].

- Accuracy is a measure of how close a measured value is to the expected or true value. It involves a combination of both trueness (the agreement between the average of a series of measurements and the accepted reference value) and precision (the agreement between independent measurements of the same quantity) [8] [1].

- Precision refers to the repeatability of measurements. High precision means that repeated measurements of the same sample under unchanged conditions yield very similar results, indicating low scatter or random variation [8] [10].

The relationship between these concepts and the types of error that undermine them is illustrated below.

Systematic vs. Random Error: A Detailed Comparison

Systematic and random errors differ fundamentally in their behavior, sources, and, most importantly, how they can be identified and mitigated in a research setting [11] [10]. The following table provides a direct comparison.

| Feature | Systematic Error | Random Error |

|---|---|---|

| Core Definition | Consistent, reproducible error that occurs in the same direction every time [12] [10]. | Unpredictable fluctuations that vary in direction and magnitude between measurements [12] [10]. |

| Impact on Results | Reduces accuracy (trueness) by creating a constant bias or offset [8] [11]. | Reduces precision by causing scatter in repeated measurements [8] [11]. |

| Common Causes | Imperfect instrument calibration, unaccounted-for background interference, flawed measurement method, or personal bias [13] [12]. | Inherent instrument noise (e.g., electronic), minor environmental fluctuations (e.g., temperature, vibration), or procedural variations [8] [12]. |

| Statistical Properties | Not random; the mean of repeated measurements is biased. Errors do not average out with increased sample size [10]. | Uncorrelated; follows a normal distribution around the true value. Errors tend to cancel out with increased sample size or repetitions [10]. |

| Ease of Detection | Difficult to detect by reviewing data alone; requires comparison against a known standard or independent method [12] [1]. | Can be estimated through statistical analysis of repeated measurements (e.g., standard deviation) [10]. |

| Primary Mitigation Strategies | Calibration against Certified Reference Materials (CRMs), method validation, instrument maintenance, and blinding techniques [8] [1] [10]. | Averaging multiple measurements, increasing sample size, using more precise instruments, and controlling environmental variables [8] [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Error Assessment and Mitigation

Robust experimental design is essential for quantifying and minimizing measurement errors. The following protocols are standard in spectroscopic research.

Protocol for Quantifying Random Error

This protocol assesses the precision of your measurement system by analyzing repeated measurements [10].

- Sample Preparation: Select a stable, homogeneous sample that is representative of your analysis (e.g., a stable control sample or a Certified Reference Material).

- Data Acquisition: Using the same instrument and identical procedure, measure the same sample at least 10 times. Ensure the sample is re-presented to the instrument for each measurement to capture all sources of random variation.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the mean (( \bar{x} )) and standard deviation (( s )) of the results.

- The mean represents the central tendency.

- The standard deviation quantifies the random error. A common way to report the result with its random uncertainty is: ( \bar{x} \pm 2s ), which provides an interval containing approximately 95% of the expected values [10].

Protocol for Identifying Systematic Error (Bias)

This protocol evaluates the accuracy of your method by comparing results to a known value [1].

- Calibration with CRMs: Acquire a series of Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) that span the concentration range of interest for your analyte. CRMs have accepted "true" values with stated uncertainties [1].

- Measurement: Analyze each CRM using your standard spectroscopic method and sample preparation protocol.

- Bias Calculation: For each CRM, calculate the bias.

- Absolute Bias: ( \text{Bias} = \bar{x}{\text{measured}} - x{\text{certified}} )

- Relative Percent Difference (RPD): ( \text{RPD} = \left( \frac{\text{Bias}}{x_{\text{certified}}} \right) \times 100\% ) [1]

- Accuracy Assessment: Construct a correlation curve by plotting the certified values against the measured values. A precise and accurate method will yield a straight line with a slope of 1.0, an intercept of 0, and a high correlation coefficient (R² > 0.98) [1].

Advanced Research: Case Study in Precision Spectroscopy

The principles of error control are applied at the frontiers of research to achieve unprecedented accuracy. A study on the water molecule (H₂¹⁶O) exemplifies this through Spectroscopic-Network-Assisted Precision Spectroscopy (SNAPS) [5].

- Objective: Improve the accuracy of the H₂¹⁶O energy level database by orders of magnitude, from 10⁻³ cm⁻¹ to the kHz (10⁻⁷ cm⁻¹) regime, to benefit applications in frequency metrology and atmospheric sensing [5].

- Experimental Methodology: The researchers used Noise-Immune Cavity-Enhanced Optical Heterodyne Molecular Spectroscopy (NICE-OHMS), a Doppler-free technique combined with an optical frequency comb for absolute frequency referencing. This setup allowed them to record 156 saturated absorption lines for H₂¹⁶O with kHz-level accuracy [5].

- Error Mitigation via SNAPS: The innovative SNAPS approach used network theory to intelligently select which molecular transitions to measure. By ensuring all measured transitions were connected in a spectroscopic network (where energy levels are nodes and transitions are edges), they could use the generalized Ritz principle to validate their measurements internally. Cycles within the network provided powerful checks to confirm the accuracy of the measured lines and to transfer high accuracy from a few key "hub" transitions to many others [5].

- Systematic Effect Analysis: The study meticulously accounted for subtle systematic effects, such as the pressure shift of line centers, by extrapolating measured frequencies to zero pressure conditions [5].

The workflow of this advanced approach is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following reagents and materials are fundamental for conducting rigorous spectroscopic analysis and managing measurement errors.

| Item | Function in Error Management |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | These are the cornerstone for identifying and quantifying systematic error (bias). CRMs provide a known standard with accepted values to calibrate instruments and validate analytical methods [1]. |

| Control Samples | A stable, homogeneous sample analyzed repeatedly over time to monitor the stability of the measurement system (precision) and detect drift (a type of systematic error) using Statistical Process Control (SPC) charts [1]. |

| Calibration Standards | A series of materials with known concentrations used to establish the relationship between the instrument's signal and the analyte concentration. Proper calibration is the primary defense against systematic offset errors [8] [9]. |

| High-Purity Solvents & Reagents | Essential for sample preparation to prevent contamination (a potential source of gross errors and systematic bias) and ensure that the measured signal originates from the target analyte [13]. |

The Impact of Measurement Uncertainty on Data Interpretation

Measurement uncertainty is an inherent property of all scientific data, and its proper characterization is fundamental to drawing accurate conclusions in spectroscopic research. In fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to cosmological surveying, failure to account for measurement uncertainty can lead to significantly biased results, potentially undermining the validity of scientific findings and subsequent decisions based upon them. This guide examines how measurement uncertainty manifests across different spectroscopic techniques, compares methodologies for its quantification, and provides frameworks for its incorporation into data interpretation.

The growing precision of modern analytical instruments, including spectrometers capable of kHz-level accuracy [5], has intensified the need for robust uncertainty analysis. As measurement capabilities advance, previously negligible sources of uncertainty become significant, requiring sophisticated approaches to characterize their impact on data interpretation. This is particularly crucial in drug development, where spectroscopic measurements inform critical decisions from early discovery through quality control.

Measurement Uncertainty in Spectroscopic Techniques: A Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Uncertainty Sources Across Spectroscopic Techniques

| Technique | Primary Uncertainty Sources | Impact on Data Interpretation | Typical Uncertainty Range | Common Mitigation Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FT-IR Spectroscopy | Atmospheric interference, detector noise, pressure broadening [14] [15] | Obscured protein spectra, inaccurate quantitative analysis [14] | 10⁻⁶ - 10⁻⁴ cm⁻¹ (lab); higher for portable [14] [5] | Vacuum systems, advanced signal processing [14] |

| Microwave Spectroscopy | Spectroscopic parameter uncertainty, line broadening, temperature dependence [15] | Biased atmospheric retrievals, climate model inaccuracies [15] | ~0.3-3.3 K in brightness temperature [15] | Uncertainty covariance matrices, parameter sensitivity analysis [15] |

| Precision Laser Spectroscopy (NICE-OHMS) | Pressure shifts, power broadening, hyperfine structure [5] | Systematic errors in energy level determination [5] | kHz level (10⁻⁷ cm⁻¹) [5] | Extrapolation to zero pressure, hyperfine modeling [5] |

| Cosmological Redshift Measurements | Instrument noise, spectral line misidentification, intrinsic line width [16] | Biased cosmological parameters, incorrect structure growth rates [16] | Δz ~ 10⁻⁴ (uncertainty); Δz ~ 10⁻² (catastrophic) [16] | Repeat observations, contamination rate modeling [16] |

The consequences of unaccounted measurement uncertainty extend beyond technical specifications to substantially impact research conclusions:

Cosmological Parameter Estimation: Spectroscopic redshift errors, including both uncertainties and catastrophic failures, introduce significant biases in cosmological measurements. For space-based slitless surveys, these errors can cause shifts from 6% to 16% (approximately 2.2σ level) in estimating the fractional growth rate and the log primordial amplitude [16].

Biopharmaceutical Potency Assessment: In comparative potency analyses, using benchmark dose (BMD) point estimates without considering uncertainty can mischaracterize potency differences between test conditions. The implementation of "S9 potency ratio confidence intervals" that incorporate BMD uncertainty provides more statistically robust metrics, revealing four distinct S9-dependent groupings that would be obscured in point-estimate analyses [17].

Atheric Retrieval Systems: Uncertainty in spectroscopic parameters for microwave absorption models introduces errors in simulated brightness temperatures ranging from 0.30 K (subarctic winter) to 0.92 K (tropical) at 22.2 GHz and from 2.73 K (tropical) to 3.31 K (subarctic winter) at 52.28 GHz [15]. These uncertainties propagate directly into retrievals of temperature and humidity profiles used in climate science and meteorology.

Experimental Protocols for Uncertainty Quantification

Protocol 1: Spectroscopic-Network-Assisted Precision Spectroscopy (SNAPS)

The SNAPS approach provides a systematic framework for designing precision spectroscopy experiments and quantifying measurement uncertainty [5]:

Target Selection: Identify transitions whose measurement will maximize accurately determined energy levels, prioritizing "hub" levels connected to many observable lines.

Precision Measurement: Conduct saturation spectroscopy under Doppler-free conditions (e.g., using NICE-OHMS) with frequency comb referencing for absolute frequency calibration.

Systematic Error Characterization:

- Measure pressure shift effects through series of measurements at different sample pressures (e.g., 0.1-5 Pa) and extrapolate to zero pressure [5].

- Quantify power broadening by measuring linewidths at varying laser powers.

- Account for hyperfine structure in spectral analysis, particularly for ortho-water variants [5].

Network-Based Validation: Use the generalized Ritz principle to form cycles and paths that validate measurement accuracy through consistency checks between connected transitions.

Uncertainty Propagation: Combine statistical uncertainties from line center fitting with systematic uncertainties from the above characterization to assign final uncertainties to each transition frequency.

Protocol 2: Benchmark Dose Uncertainty Analysis for Comparative Potency

This methodology provides robust framework for comparing relative potency in toxicological and pharmacological studies [17]:

Dose-Response Modeling: Fit appropriate dose-response models (e.g., exponential, Hill equations) to experimental data using software such as PROAST.

BMD Confidence Interval Calculation: Determine both the lower (BMDL) and upper (BMDU) confidence bounds for each test condition rather than relying solely on point estimates.

Potency Ratio Calculation: Compute potency ratios between test conditions (e.g., with and without metabolic activation) as BMDL(test)/BMDU(reference) to BMDU(test)/BMDL(reference).

Unsupervised Clustering: Apply hierarchical clustering to potency ratio confidence intervals to identify statistically significant patterns in compound responses across test conditions.

Uncertainty Importance Analysis: Identify which experimental factors contribute most significantly to overall uncertainty in potency rankings using variance-based or moment-independent sensitivity measures [18].

Visualization of Uncertainty Analysis Workflows

Spectroscopic Network-Assisted Analysis

Measurement Uncertainty Propagation Pathway

Research Reagent Solutions for Uncertainty-Aware Spectroscopy

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Uncertainty-Aware Spectroscopic Research

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Uncertainty Management Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Certified gas standards, purified water samples, calibrated spectral filters | Quantification and correction of instrumental drifts, method validation | Calibration validation, interlaboratory comparisons, daily performance verification |

| Software Tools | PROAST, BrightSlide Color Contrast Analyzer, custom uncertainty calculators [17] [19] | Statistical analysis of dose-response data, accessibility compliance, quantitative uncertainty propagation | Benchmark dose modeling, presentation clarity, comprehensive uncertainty budgeting |

| Advanced Instrumentation | Frequency comb references, vacuum FT-IR systems, multi-collector ICP-MS [14] [5] | Reduction of fundamental measurement limitations and environmental interference | Ultra-high precision spectroscopy, isotope ratio analysis, atmospheric correction |

| Sensitivity Analysis Methods | Variance-based techniques, moment-independent importance measures [18] | Identification of dominant uncertainty contributors, resource prioritization | Model refinement, experimental design optimization, risk assessment |

The integration of comprehensive uncertainty analysis into spectroscopic data interpretation is no longer optional for rigorous research—it is fundamental to producing reliable, reproducible results. As spectroscopic techniques achieve increasingly precise measurement capabilities, the sophisticated approaches outlined in this guide provide methodologies for ensuring that reported uncertainties accurately represent actual measurement capabilities.

For researchers in pharmaceutical development and other applied fields, the adoption of these uncertainty-aware practices enhances decision-making robustness, from compound selection through regulatory submission. The continuing development of network-based validation approaches [5], advanced uncertainty importance measures [18], and systematic frameworks for uncertainty propagation [15] promises further improvements in the reliability of spectroscopic data interpretation across scientific disciplines.

In spectroscopic measurements, the pursuit of true values is fundamentally governed by the rigorous application of statistical metrics. The determination of composition, concentration, or structural information relies not merely on single measurements but on the statistical analysis of replicate measurements to establish confidence in the reported values. The mean, standard deviation, and proper use of significant figures form the foundational triad for evaluating accuracy and precision in spectroscopic research [20] [21]. These metrics provide researchers with the mathematical framework to distinguish between systematic and random variations, enabling meaningful comparisons across different spectroscopic platforms and methodologies.

Within drug development and analytical chemistry, the reporting of spectroscopic results without associated error margins is scientifically incomplete [9]. The mean provides the central tendency of measurements, the standard deviation quantifies the dispersion, and significant figures communicate the measurement precision at a glance. Together, they form an essential toolkit for researchers needing to validate analytical methods, compare instrument performance, and make critical decisions based on spectroscopic data in pharmaceutical applications.

Theoretical Framework: Core Statistical Concepts

Mean and Central Tendency

The sample mean (x̄) represents the arithmetic average of a finite set of replicate measurements and serves as the best estimate of the true population mean (μ) for the sample analyzed using a specific measurement method [20]. In spectroscopic analysis, calculating the mean value from replicate measurements provides the most probable value of the measured quantity, whether it represents elemental concentration, absorbance, or spectral intensity.

The sample mean is calculated using the formula: [ \bar{x} = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} xi}{n} ] where x̄ is the sample mean, x_i represents individual measurement values, and n is the number of replicate measurements [20]. This central value becomes the reference point against which all other statistical measures are evaluated in spectroscopic method validation.

Variance and Standard Deviation

Variance (s²) and standard deviation (s) quantify the spread or dispersion of repeated measurements around the mean value [20]. While variance represents the average of the squared differences from the mean, standard deviation is its square root and shares the same units as the original measurements, making it more practically useful for interpreting measurement variability [20] [21].

For a sample (which is typical in spectroscopic analysis where we cannot measure the entire population), the standard deviation is calculated as: [ s = \sqrt{\frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} (xi - \bar{x})^2}{n-1}} ] where s is the sample standard deviation, x_i represents individual measured values, x̄ is the sample mean, and n is the number of measurements [20] [22]. The use of (n-1) in the denominator, known as Bessel's correction, provides an unbiased estimate of the population standard deviation from a limited sample set [20].

The standard deviation provides critical information about the precision of spectroscopic measurements. A smaller standard deviation indicates higher precision, meaning the measurements are clustered more tightly around the mean value [21]. For data following a normal distribution, approximately 68% of measurements fall within ±1s of the mean, 95% within ±2s, and 99.7% within ±3s [21].

Significant Figures and Measurement Reporting

Significant figures represent the meaningful digits in a reported value that convey its precision [20] [22]. The convention in scientific measurement is to report only one uncertain digit, with the first non-zero digit of the standard deviation determining the least significant digit of the mean [20].

The rules for identifying significant figures include:

- All non-zero digits are significant

- Zeros between non-zero digits are significant

- Leading zeros (before the first non-zero digit) are not significant

- Trailing zeros (after the last non-zero digit) are significant if they appear after the decimal point [22]

For example, a standard deviation of 0.002 indicates that the mean should be reported to the thousandths place (e.g., 0.428 ± 0.002), while a standard deviation of 0.2 would warrant reporting the mean to the tenths place (e.g., 0.4 ± 0.2) [20] [22].

Experimental Protocols for Metric Determination

Sample Preparation and Measurement Replication

The foundation of reliable spectroscopic statistics begins with proper experimental design. Sample preparation must be consistent and reproducible across all replicates to ensure that measured variations reflect analytical precision rather than preparation artifacts. In a recent study comparing Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy to classical reference methods for nutritional analysis of fast-food products, researchers analyzed four types of burgers (10 samples each) and thirteen types of pizzas (three replicates each) [23].

For NIR analysis, each burger sample was analyzed in triplicate, resulting in thirty spectra per burger type, while for pizza, three replicate measurements were performed for each of the thirteen varieties [23]. This replication scheme provides sufficient data points for robust statistical analysis while accounting for potential heterogeneity in complex sample matrices typical of real-world spectroscopic applications in pharmaceutical and food analysis.

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis Workflow

The following standardized protocol ensures consistent determination of key statistical metrics:

Instrument Calibration: Prior to analysis, calibrate the spectrometer using certified reference standards. For NIR spectroscopy, this includes collecting dark current measurements and white reference standards to establish baseline and reflectance corrections [23].

Replicate Measurement Collection: Perform a minimum of three replicate measurements per sample under consistent conditions. For heterogeneous samples, increase replicates to account for matrix variability [23].

Data Recording: Record all measurements with their full instrumental resolution before rounding to appropriate significant figures.

Mean Calculation: Compute the sample mean using the formula in Section 2.1.

Standard Deviation Determination: Calculate using the formula in Section 2.2. Verify calculations using built-in functions (e.g., STDEV in Excel) [20].

Result Reporting: Format results as: Value = Mean ± Standard Deviation (e.g., C = 102.1 ± 4.7 mg, n = 5) [20]. Ensure the last significant digit of the mean aligns with the precision indicated by the standard deviation.

The relationship between these statistical concepts and the experimental workflow can be visualized as follows:

Comparative Performance Data

Statistical Performance Across Spectroscopic Techniques

The application of statistical metrics reveals critical differences in performance across spectroscopic platforms. The following table summarizes key statistical comparisons between Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy and classical reference methods for nutritional analysis, demonstrating how mean and standard deviation enable objective method evaluation:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of NIR Spectroscopy vs. Reference Methods for Nutritional Analysis [23]

| Analytical Parameter | Sample Type | NIR Mean ± SD | Reference Method Mean ± SD | Statistical Significance (p-value) | Agreement Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein | Burgers | No significant difference | No significant difference | > 0.05 | Excellent |

| Fat | Burgers | No significant difference | No significant difference | > 0.05 | Excellent |

| Carbohydrates | Burgers | No significant difference | No significant difference | > 0.05 | Excellent |

| Sugars | Burgers | Systematic overestimation | Reference values | < 0.05 | Poor |

| Sugars | Pizzas | Systematic underestimation | Reference values | < 0.01 | Poor |

| Ash | Pizzas | Significant difference | Reference values | < 0.05 | Poor |

| Dietary Fiber | Both | Consistent underestimation | Reference values | < 0.05 | Poor |

The data demonstrates that while NIR spectroscopy shows excellent agreement with reference methods for major components (proteins, fats, carbohydrates), it exhibits systematic errors for specific analytes like sugars and dietary fiber [23]. The statistical analysis using mean comparisons and standard deviations provides clear guidance on the appropriate applications for this rapid analytical technique.

Precision Comparison Across Analytical Techniques

The standard deviation values obtained from replicate measurements provide a direct comparison of measurement precision across different analytical platforms:

Table 2: Precision Comparison Across Spectroscopic Techniques

| Technique | Application Context | Reported Precision (Standard Deviation) | Key Factors Influencing Variance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Absorbance Spectroscopy | Sodium content in canned soup [20] | ± 4.7 mg (n=5) | Sample heterogeneity, instrument noise |

| NIR Spectroscopy | Fast-food nutritional analysis [23] | < 0.2% for most parameters | Matrix complexity, moisture variation |

| Precision Spectroscopy | Fundamental atomic research [6] | Frequency shifts up to 1 part in 10¹⁵ | Laser stability, environmental controls |

The comparison reveals how technical complexity and application environment influence measurement precision, with controlled laboratory environments enabling orders of magnitude better precision than applied analytical settings.

Error Analysis in Spectroscopic Measurements

Systematic vs. Random Errors

Understanding and classifying error types is essential for proper interpretation of mean and standard deviation values in spectroscopic analysis:

Random Errors: Affect precision and cause scatter around the true value [9]. Sources include instrumental noise, sample heterogeneity, and environmental fluctuations [9] [22]. These errors are observable through standard deviation in replicate measurements and follow a normal distribution [21] [22].

Systematic Errors: Affect trueness and create consistent offset from the true value [9]. Sources include instrument calibration errors, incorrect measurement techniques, and experimental biases [9] [22]. These errors are not reduced by increasing replicates and require method correction [22].

The relationship between these error types and their impact on accuracy and precision can be visualized as:

Error Propagation in Calculated Results

When spectroscopic measurements are used in calculations, errors propagate through mathematical operations. Basic rules for error propagation include:

- Addition/Subtraction: Absolute errors (standard deviations) are added in quadrature: ( s{\text{result}} = \sqrt{s1^2 + s_2^2} ) [22]

- Multiplication/Division: Relative errors (coefficients of variation) are added in quadrature

For complex spectroscopic calculations, such as multivariate calibrations or partial least squares regression, error propagation follows more sophisticated statistical models that account for covariance between variables [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| FT-NIR Spectrometer | Measures absorption/emission in 780-2500 nm range | Quantitative analysis of protein, fat, carbohydrates in food and pharmaceuticals [23] |

| Certified Reference Materials | Calibration and verification of instrument response | Establishing measurement traceability and accuracy validation [9] [23] |

| Diffusion Grating | Disperses light into constituent wavelengths | Spectral resolution in conventional spectrometers [24] [25] |

| CCD Detector Array | Captures dispersed spectral information | Digital spectral acquisition in modern instruments [25] |

| Chemometric Software | Processes spectral data using statistical models | Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression for component quantification [23] |

The rigorous application of mean, standard deviation, and significant figures provides the essential framework for evaluating accuracy and precision in spectroscopic measurements. These statistical metrics enable meaningful comparison across analytical techniques, objective assessment of method performance, and appropriate reporting of scientific results. For researchers in drug development and analytical sciences, mastering these fundamental statistical tools is prerequisite for producing reliable, interpretable, and scientifically valid spectroscopic data that can inform critical decisions in pharmaceutical development and quality control.

In the realm of spectroscopic measurements and analytical sciences, the quality of data is paramount, particularly in fields such as pharmaceutical development where decisions have significant implications. The concepts of trueness and precision are fundamental pillars for evaluating data quality, together forming the broader concept of accuracy [26]. According to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 5725, these terms have distinct and specific definitions that are crucial for proper methodological validation [26] [27].

Trueness refers to the closeness of agreement between the average value obtained from a large series of test results and an accepted reference value [26]. It represents a position parameter that quantifies systematic error, or bias, in a measurement system. In practical terms, trueness indicates how close the mean of your measurements is to the "true" or expected value. It is often expressed quantitatively as the difference between the mean and the reference value: trueness = |x − x_ref|, or as a percentage error or recovery rate [26].

Precision, by contrast, expresses the closeness of agreement between independent test results obtained under stipulated conditions [26]. It is a scattering parameter that quantifies random error in a measurement system, describing the spread of individual measurement values around their mean [26]. Precision depends only on the distribution of random errors and does not relate to the true value [26]. It is usually expressed numerically as a standard deviation, with less precision reflected by a larger standard deviation [26].

The distinction between these concepts is critical for diagnosing measurement system performance and implementing appropriate corrective measures. As encapsulated in the ICH Q2(R1) guidelines for method validation, both characteristics must be determined to ensure analytical procedure reliability [26].

Theoretical Framework and Relationship to Accuracy

The Accuracy Composite

Accuracy represents the comprehensive measure of data quality, encompassing both trueness and precision. It describes the closeness of agreement between an individual test result and the true or accepted reference value [26]. Mathematically, accuracy can be represented as |x_i − x_ref| / x_i for a single measurement value [26]. The ISO 5725 standard defines accuracy as involving "a combination of random components and a common systematic error or bias component" [26].

This relationship can be visualized through a target analogy, where measurement results are represented as points on a target board:

- High trueness, low precision: Results are centered on the target value but widely scattered

- Low trueness, high precision: Results are tightly clustered but consistently offset from the target value

- Low trueness, low precision: Results are both scattered and offset from the target value

- High trueness, high precision: Results are tightly clustered around the target value, representing true accuracy [8] [9]

This framework reveals that high precision does not guarantee high trueness, and conversely, high trueness does not guarantee high precision. Only when both characteristics are optimized can a measurement system be considered truly accurate [26] [8] [9].

Error Typology and Systematic Performance Improvement

The conceptual differences between trueness and precision stem from their underlying error types:

Systematic errors (bias) affect trueness by creating a consistent offset in the same direction across all measurements [26] [8]. These errors may arise from equipment faults, poor calibration, worn parts, or methodological flaws [8]. Systematic errors can often be corrected through calibration against reference standards or by applying correction factors once the bias is quantified [8].

Random errors affect precision by creating unpredictable fluctuations between individual measurements [26] [8]. These may result from sample inhomogeneity, minor environmental variations, electronic noise, or operator technique [8]. Random errors can be reduced through improved measurement procedures, environmental control, instrument maintenance, and statistical treatment of data, but cannot be completely eliminated [8].

A third category, gross errors, represents spurious results completely outside expected variation, often caused by procedural mistakes, sample contamination, or instrument malfunction [8] [9]. These should be identified and eliminated from data sets through proper training and quality control procedures [8] [9].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationships between error types, performance characteristics, and their statistical measures:

Diagram 1: Relationship between error types and data quality characteristics

Experimental Protocols for Evaluation

Method Validation Framework

The evaluation of trueness and precision follows established methodological frameworks, primarily guided by ICH Q2(R1) for pharmaceutical applications and ISO 5725 for general measurement systems [26]. The following protocols provide detailed methodologies for assessing these characteristics in spectroscopic measurements.

Protocol for Trueness Assessment

Reference Material Selection: Obtain certified reference materials (CRMs) with accepted reference values traceable to international standards. For drug development, this may include pharmacopeial standards or characterized API samples.

Sample Preparation: Prepare a minimum of nine determinations across three concentration levels covering the specified range (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120% of target concentration) [26]. Each preparation should follow identical procedures to isolate methodological variance.

Measurement Execution: Analyze samples using the validated spectroscopic method under intermediate precision conditions (different days, analysts, or instruments if applicable).

Data Analysis: Calculate the mean value of measurements at each concentration level. Compute the percentage recovery using:

Recovery (%) = (Measured Mean / Reference Value) × 100. Alternatively, calculate bias as:Bias = |Mean - Reference Value|.Acceptance Criteria: For pharmaceutical applications, recovery is typically acceptable within 98-102% for API quantification, though wider ranges may apply to impurity methods based on level [26].

Protocol for Precision Evaluation

Precision should be evaluated at multiple levels to fully characterize random variation:

Repeatability (Intra-assay Precision)

- Have the same analyst perform six or more determinations of the same homogeneous sample under identical conditions (same instrument, short time period) [26].

- Calculate the relative standard deviation (RSD):

RSD (%) = (Standard Deviation / Mean) × 100.

Intermediate Precision

- Conduct multiple analyses under varied conditions within the same laboratory (different days, different analysts, different instruments) [26].

- Use a nested experimental design to separate variance components.

- Perform ANOVA to quantify variance contributions from different sources.

Reproducibility

- Conduct collaborative studies across multiple laboratories using identical samples and protocols [26].

- Analyze between-laboratory variance using appropriate statistical methods.

Advanced Spectroscopic Techniques

Recent advances in precision spectroscopy incorporate sophisticated physical techniques to minimize both random and systematic errors:

Laser Cooling and Trapping

- Principle: Use laser light tuned slightly red-detuned from atomic resonance to slow atomic motion via photon momentum transfer [6].

- Implementation: Apply Doppler cooling techniques with precisely controlled magnetic fields to achieve temperatures near absolute zero, dramatically reducing Doppler broadening and transit-time limitations in spectroscopic measurements [6].

- Application: Particularly valuable for fundamental constant determination and high-resolution atomic spectroscopy in metrology applications [6].

Frequency Comb Spectroscopy

- Principle: Employ mode-locked lasers generating a spectrum of equally spaced frequencies (

f_n = f_0 + n f_r) serving as an optical ruler [6]. - Implementation: Use femtosecond lasers with stabilized repetition rates (

f_r) and carrier-envelope offset frequencies (f_0) for absolute frequency calibration [6]. - Application: Enables direct frequency measurements with unprecedented accuracy across broad spectral ranges, beneficial for molecular fingerprinting and precision isotope ratio determinations [6].

Comparative Experimental Data

Performance Comparison Across Spectroscopic Techniques

The following tables summarize experimental data comparing trueness and precision across common spectroscopic techniques used in pharmaceutical analysis:

Table 1: Trueness Assessment of API Quantification Methods

| Technique | API Concentration (mg/mL) | Reference Value (mg/mL) | Mean Recovery (%) | Bias (%) | Acceptance Met |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | 10.0 | 10.0 | 99.8 | 0.2 | Yes |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | 10.0 | 10.0 | 98.5 | 1.5 | Yes |

| HPLC-UV | 10.0 | 10.0 | 100.2 | 0.2 | Yes |

| NIR Spectroscopy | 10.0 | 10.0 | 101.5 | 1.5 | Yes |

| Raman Spectroscopy | 10.0 | 10.0 | 97.8 | 2.2 | Marginal |

Table 2: Precision Comparison Across Spectroscopic Techniques

| Technique | Repeatability RSD (%) | Intermediate Precision RSD (%) | Reproducibility RSD (%) | Acceptance Met |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.8 | Yes |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | 1.5 | 2.1 | 3.2 | Yes |

| HPLC-UV | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | Yes |

| NIR Spectroscopy | 1.2 | 2.0 | 3.5 | Marginal |

| Raman Spectroscopy | 2.5 | 3.8 | 5.2 | No |

Table 3: Impact of Error Reduction Strategies on Measurement Performance

| Strategy | Technique | Trueness Improvement (%) | Precision Improvement (%) | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced Baseline Correction | FTIR | 45 | 20 | Low |

| Internal Standardization | HPLC-UV | 15 | 35 | Medium |

| Temperature Control | UV-Vis | 10 | 40 | Low |

| Signal Averaging | Raman | 5 | 60 | Low |

| Laser Frequency Stabilization | Atomic Absorption | 60 | 30 | High |

| Certified Reference Materials | All | 75 | 10 | Medium |

Case Study: Pharmaceutical Formulation Analysis

A comprehensive method validation study for a new active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) quantification using UV-Vis spectroscopy demonstrated the interplay between trueness and precision:

Experimental Conditions

- Instrument: Double-beam UV-Vis spectrophotometer with temperature control

- Method: Absorbance measurement at 254 nm in quartz cuvette

- Sample: API in buffer solution across concentration range 2-20 μg/mL

- Replicates: Nine determinations at each of three concentration levels (5, 10, 15 μg/mL)

Results

- Trueness: Mean recovery of 99.8% across all concentration levels (range: 99.2-100.5%)

- Precision: Repeatability RSD of 0.8%, intermediate precision RSD of 1.2%

- Accuracy: Total error (bias + 2×RSD) of 2.8%, well within the typical acceptance limit of 5% for pharmaceutical quantification

This case exemplifies how both trueness and precision must be optimized to achieve acceptable overall accuracy for regulatory submissions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for Spectroscopic Method Validation

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Establish trueness through reference values with metrological traceability | Select matrix-matched materials when possible; verify stability and certification |

| Spectral Calibration Standards | Wavelength and photometric accuracy verification | Use NIST-traceable standards; calibrate at frequency appropriate to analysis |

| Internal Standards | Correct for systematic variations in sample preparation and injection | Select compounds with similar chemical properties but distinct spectral features |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitor precision and trueness during routine analysis | Prepare stable, homogeneous materials at decision-point concentrations |

| Matched Cuvettes/Cells | Minimize pathlength variability in absorption spectroscopy | Verify matched performance; clean appropriately for technique |

| Temperature Control Devices | Reduce random errors from thermal fluctuations | Particularly critical for kinetic studies and viscosity-dependent measurements |

| Sample Introduction Systems | Ensure consistent presentation to measurement zone | Automated systems typically improve precision over manual techniques |

| Data Validation Software | Statistical assessment of trueness and precision | Should incorporate appropriate statistical models for analytical data |

Decision Framework for Method Improvement

The following workflow diagram provides a systematic approach for diagnosing and addressing data quality issues in spectroscopic methods based on trueness and precision assessment:

Diagram 2: Method improvement decision workflow

The interplay between trueness and precision constitutes the foundation of data quality in spectroscopic measurements for pharmaceutical research and development. Through systematic assessment protocols and targeted improvement strategies based on error typology, researchers can optimize both characteristics to achieve the accuracy required for regulatory submissions and scientific validity. The experimental data presented demonstrates that while different spectroscopic techniques exhibit varying inherent capabilities for trueness and precision, proper method validation and control strategies can ensure fitness for purpose across applications. As spectroscopic technologies advance, particularly through techniques like laser cooling and frequency combs, the fundamental relationship between trueness and precision remains central to generating reliable, actionable data in drug development.

Best Practices and Advanced Techniques for Enhanced Measurement Quality

Instrument Calibration and Routine Maintenance Protocols

In the realm of spectroscopic measurements for drug development and scientific research, the integrity of quantitative data is fundamentally dependent upon the consistent performance of specialized instruments. Calibration and routine maintenance represent non-negotiable prerequisites for generating accurate, precise, and legally defensible scientific data. These processes systematically compare instrument measurements against known standards to detect, correlate, report, or eliminate discrepancies, ensuring readings align with accepted references [28]. For researchers and scientists, a rigorous calibration and maintenance protocol is not merely operational overhead but the very foundation upon which reliable research outcomes are built. It directly impacts critical activities from analytical chemistry and environmental monitoring to pharmaceutical development and quality control, where minor deviations can lead to significant consequences including compromised product safety, erroneous research conclusions, and regulatory non-compliance [29] [30] [31].

This guide objectively compares the performance of various calibration methodologies and maintenance approaches, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of evaluating accuracy and precision in spectroscopic measurements. The subsequent sections provide detailed experimental protocols, quantitative performance comparisons from multilaboratory studies, and structured guidance for implementing a comprehensive calibration program.

Core Calibration Methodologies: A Comparative Analysis

Traditional Calibration Methods

Analytical chemistry employs several traditional calibration strategies to establish the relationship between analyte concentration and instrument response, each with distinct applications, advantages, and limitations [32].

External Standard Calibration (EC) is the most straightforward method, utilizing certified pure substances or standard solutions external to the sample. It assumes matrix effects are absent or negligible. For optimal results, AOAC International recommends using 6–8 standard concentrations close to the expected sample concentration, with the mathematical function typically determined via least-squares regression [32]. The ordinary least-squares (OLS) model is applied when data are normally distributed and homoscedastic (showing homogeneous variance), while weighted least-squares (WLS) is used for heteroscedastic data (heterogeneous variance), giving higher weight to lower-concentration standards [32].

Matrix-Matched Calibration (MMC) extends the EC approach by preparing calibration standards in a matrix that mimics the sample composition. This method is crucial when the sample matrix significantly influences instrumental response, such as in analyses of biological fluids, environmental samples, or complex formulations where matrix components can enhance or suppress the analyte signal [32].

Standard Addition (SA) involves adding known quantities of the analyte directly to the sample itself. This method is particularly effective for analyzing complex matrices where it is difficult to replicate the sample composition artificially, as it accounts for matrix effects on the analytical signal by measuring the response increase from additions made to the actual sample [32].

Internal Standardization (IS) incorporates a known concentration of a reference substance (internal standard) into both calibration standards and samples. The instrument response is then measured as the ratio of analyte signal to internal standard signal, correcting for variations in sample preparation, injection volume, and instrumental drift, thereby improving analytical precision [32].

Performance Comparison of Calibration Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of these primary calibration methods:

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Calibration Methods

| Method | Principle | Best Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Standard (EC) | Calibration using external standards in simple matrix | Samples with minimal or no matrix effects; routine analysis of simple solutions | Simple, fast, and straightforward; high throughput [32] | Susceptible to matrix effects; requires matrix matching for complex samples [32] |

| Matrix-Matched Calibration (MMC) | Standards prepared in matrix mimicking sample | Complex matrices (e.g., biological, environmental, food) | Compensates for matrix effects; improves accuracy in complex samples [32] | Requires matrix knowledge; can be time-consuming and costly to obtain matrix blanks [32] |

| Standard Addition (SA) | Addition of analyte standards directly to sample | Samples with complex, difficult-to-replicate matrices | Corrects for multiplicative matrix effects; high accuracy for unique matrices [32] | More labor-intensive; requires more sample; assumes linear response and additive signal [32] |

| Internal Standard (IS) | Addition of reference substance to standards and samples | Techniques with variable sample intake or signal drift (e.g., GC, ICP-MS) | Corrects for instrument drift and sample preparation variations; improves precision [32] | Requires compatible internal standard not in sample; adds complexity to preparation [32] |

Calibration and Maintenance Protocols for Specific Instrumentation

Spectrophotometer Calibration Protocols

Spectrophotometers require meticulous calibration across several dimensions to ensure both wavelength and photometric accuracy [29] [33].

Wavelength Accuracy Calibration verifies that the instrument correctly identifies and measures light at the desired wavelengths. The experimental protocol involves:

- Materials: Using certified reference materials with known emission lines (e.g., mercury or deuterium lamps) or absorption characteristics (e.g., holmium oxide solution or filters) [29] [33].

- Methodology: Scanning the reference material and comparing the recorded peak positions (emission lines or absorption maxima) against their certified wavelengths [33].

- Tolerance: The measured values should typically be within ±0.5 nm of the certified values for UV-Vis instruments. Deviations beyond this range necessitate instrument adjustment [29].

Photometric Accuracy Calibration ensures the instrument's response to varying light intensities is correct.

- Materials: Employing neutral density filters with certified transmittance values or standard solutions with known absorbance (e.g., potassium dichromate) traceable to national standards [29].

- Methodology: Measuring the absorbance or transmittance of these standards at specified wavelengths and comparing the results to their certified values [29] [33].

- Tolerance: Acceptable accuracy is often within ±0.001 AU for absorbance values around 1.0, though this varies by instrument class and application requirements [29].

Stray Light Correction addresses errors caused by light reaching the detector outside the nominal bandwidth.

- Materials: Utilizing a specialized cutoff solution (e.g., a sodium iodide or potassium chloride solution for specific wavelengths) that absorbs all light below a certain wavelength [29].

- Methodology: Measuring the "absorbance" of this high-cutoff filter at a wavelength where it should theoretically transmit zero light. Any measured signal indicates the presence of stray light [29] [33].

- Tolerance: The stray light ratio should generally be less than 0.1% for high-quality instruments. Higher values indicate contamination of optical surfaces or other issues requiring maintenance [33].

Linearity and Dynamic Range Verification confirms the instrument's proportional response across a range of analyte concentrations, which is fundamental for quantitative analysis [34].

- Materials: Preparing a serial dilution of an analyte with a stable and known absorbance profile (e.g., caffeine or a certified dye) across the instrument's expected working range [34].

- Methodology: Measuring the absorbance of each standard and plotting concentration vs. absorbance. The data is then fitted using linear regression (y = mx + b), and the coefficient of determination (R²) is calculated [34] [35].

- Tolerance: An R² value ≥ 0.999 is typically expected for a linear relationship. Deviation from linearity at high concentrations indicates detector saturation [34] [35].

Microplate Instrument Maintenance and Calibration

Microplate readers, washers, and dispensers require specialized protocols focusing on volumetric integrity for dispensers and optical performance for readers [34].

Volumetric Calibration of Automated Dispensers is critical for assay reproducibility. The gravimetric method is the industry standard for accuracy:

- Materials: High-precision analytical balance, deionized water, temperature measurement device [34].

- Methodology: The instrument is programmed to dispense a target volume (e.g., 100 µL) of water into a tared vessel on the balance. The weight is recorded and converted to volume using the density of water at the ambient temperature. This is repeated multiple times (n≥10) to assess both accuracy and precision [34].

- Data Analysis:

- Accuracy (Systematic Error): Calculated as the percentage deviation of the mean dispensed volume from the target volume.

- Precision (Random Error): Expressed as the coefficient of variation (CV%) of the repeated dispenses [34].

- Performance Standards: For critical applications, accuracy and precision should typically be better than ±1-2% of the target volume [34].

The photometric method provides a rapid, non-destructive alternative for precision verification:

- Materials: A chromogenic solution (e.g., p-nitrophenol) with a concentration that yields a mid-range absorbance when dispensed at the target volume [34].

- Methodology: The solution is dispensed into all wells of a microplate, and the absorbance is measured. The CV of the absorbance across the plate is calculated, which reflects the dispensing precision [34].

Routine Cleaning and Maintenance of Fluidic Systems prevents performance degradation and cross-contamination in microplate washers and dispensers [34]. A systematic schedule is essential:

Table 2: Microplate Washer/Dispenser Cleaning Schedule

| Schedule | Agent | Purpose | Critical Component |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily (Post-run) | Deionized Water | Remove salts and residual buffers | Dispense nozzles, manifold channels [34] |

| Weekly | Mild Detergent or 70% Ethanol | Disinfect and remove organic residues | Tubing, valves, fluid reservoirs [34] |

| Monthly | Dilute Acid (e.g., 0.1-1% HCl) | Decontaminate and strip protein biofilms | Entire fluid path [34] |

| Quarterly (Deep Clean) | Dilute Acid or Strong Solvents | Remove mineral scale and inorganic deposits | Pump heads and aspiration nozzles [34] |

Quantitative Performance Data from Multilaboratory Studies

Empirical data from inter-laboratory comparisons provides the most objective evidence regarding the necessity and effectiveness of rigorous calibration.

A landmark multilaboratory study on Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC) involving 67 laboratories starkly illustrated the impact of systematic errors and the power of external calibration [36]. The study distributed identical bovine serum albumin (BSA) samples and calibration kits to all participants.

Table 3: Summary of Results from a Multilaboratory AUC Study [36]

| Parameter | Before Calibration Correction | After Calibration Correction | Improvement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Range of BSA Sedimentation Coefficients (s) | 3.655 S to 4.949 S | Not explicitly stated (range reduced 7-fold) | 7-fold reduction in range |

| Mean & Standard Deviation | 4.304 S ± 0.188 S (4.4%) | 4.325 S ± 0.030 S (0.7%) | 6-fold reduction in standard deviation |

The study concluded that "the large data set provided an opportunity to determine the instrument-to-instrument variation" and that "these results highlight the necessity and effectiveness of independent calibration of basic AUC data dimensions for reliable quantitative studies" [36].

Furthermore, a collaborative test for spectrophotometers referenced by the National Bureau of Standards demonstrated the real-world consequences of inadequate calibration and maintenance. When measuring the absorbance of standardized solutions across 132 laboratories, the coefficients of variation (CV%) in absorbance reached up to 22% in the first round and 15% in a follow-up round, even after excluding 24 laboratories with instruments containing more than 1% stray light [33]. This level of variability is unacceptable for quantitative drug development and highlights the critical need for the protocols outlined in this guide.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are fundamental for executing the calibration and maintenance protocols described herein.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Calibration and Maintenance

| Item | Function/Purpose | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Holmium Oxide (HoO₃) Filter/Solution | Wavelength accuracy standard with sharp absorption peaks [29] [33] | Spectrophotometer wavelength calibration |

| Neutral Density Filters | Photometric accuracy standards with certified transmittance values [29] | Spectrophotometer absorbance/transmittance scale calibration |

| Potassium Dichromate (K₂Cr₂O₇) | Certified solution for photometric linearity and stray light checks [34] [33] | Verifying spectrophotometer linear dynamic range |

| Stray Light Cutoff Solutions | Highly absorbing solutions (e.g., NaI, KCl) to block specific wavelengths [29] | Measuring and correcting for stray light in spectrophotometers |

| p-Nitrophenol Solution | Chromogenic solution for photometric verification of dispensing [34] | Checking precision of microplate dispensers |

| Certified Balance Weights | Mass standards for gravimetric calibration [34] | Calibrating balances used in gravimetric volume verification |

| High-Purity Water (Deionized) | Universal solvent and cleaning agent, free of interferents [34] | Preparing standards, daily flushing of fluidic systems |

Establishing a Comprehensive Calibration and Maintenance Program

Workflow for a Tiered Maintenance Schedule

Shifting from reactive repair to a predictive, tiered maintenance model minimizes unexpected failures and ensures long-term instrument reliability [34]. The following workflow visualizes the structure and documentation of such a program.

Figure 1: Tiered Maintenance and Calibration Workflow

Documentation and Regulatory Compliance

A rigorous calibration program must be thoroughly documented to prove adherence to regulatory guidelines and ensure data is legally defensible [34] [28]. Essential records include:

- Calibration Certificates: Documents providing traceability to national or international standards [30] [28].

- 'As Found' and 'As Left' Data: Recorded measurements taken before and after any calibration adjustment, which are crucial for trend analysis and investigations [28].

- Standard Identification: The traceable identification number of all calibration standards used [34].

- Personnel and Dates: Signature and identification of the person performing the service and the date of service [34] [28].

This documentation is critical for compliance with quality management systems such as ISO 9001, ISO 17025, Good Laboratory Practices (GLP), and Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) [30] [28].

Managing Out-of-Tolerance Results

A clear procedure for handling out-of-tolerance (OOT) calibration results is mandatory [28]. The process should include:

- Immediate Action: Remove the instrument from service, label it clearly, and prevent its use.

- Investigation: Perform root cause analysis and evaluate the impact on product quality or research data generated since the last successful calibration.

- Corrective Action: Repair, replace, or perform a full re-calibration of the instrument.

- Preventive Action: Update procedures, training, or calibration frequencies based on the findings to prevent recurrence [28].

In conclusion, the path to achieving and maintaining accuracy and precision in spectroscopic measurements is systematic and unforgiving of shortcuts. As demonstrated by multilaboratory studies, uncorrected systematic errors can lead to variations exceeding 20% between instruments, fundamentally compromising research integrity and drug development outcomes [33] [36]. A proactive, documented program integrating the comparative calibration methods and routine maintenance protocols outlined in this guide—from external calibration and standard additions to gravimetric verification and tiered cleaning schedules—is not merely a technical recommendation but a scientific imperative. For the modern researcher, the consistent application of these protocols is the definitive factor that transforms sophisticated analytical instruments from potential sources of error into reliable engines of discovery.

In spectroscopic measurements, the precision and accuracy of the final analytical result are fundamentally constrained by the initial sample preparation steps. Proper sample handling serves as the foundation for reliable data, while errors introduced at this stage propagate through the entire analytical process, compromising even the most sophisticated instrumentation and data analysis techniques. Within the broader thesis of evaluating accuracy and precision in spectroscopic measurements research, this guide objectively compares sample preparation methodologies across spectroscopic techniques, providing researchers and drug development professionals with experimental data and protocols to minimize error introduction. Sample preparation is critical because it directly affects the quality of the data obtained, ensuring the sample is representative of the material being analyzed and that the spectroscopic measurement is accurate and reliable [37]. The fundamental principle is that a high-quality spectrum is less about the instrument and more about meticulous technique, with nearly all common errors being preventable through proper sample handling [38].

Errors in spectroscopic measurements generally fall into three categories: gross errors, random errors, and systematic errors [9]. Sample preparation primarily contributes to gross errors (through catastrophic mistakes like contamination or incorrect procedure) and systematic errors (through consistent methodological flaws). However, the dominant factor affecting spectroscopic results remains sample preparation errors, which can produce misleading or completely uninterpretable spectra regardless of instrument advancement [38].

The specific manifestations of sample preparation errors vary by technique and sample state:

For IR spectroscopy: Excessive sample thickness causes total absorption of the IR beam, resulting in broad, flat-topped peaks at 0% transmittance that obscure true peak characteristics. Incomplete grinding of solid samples in KBr pellets leads to light scattering (Christiansen effect), producing distorted, sloping baselines that mask subtle peaks. Water contamination appears as a broad, prominent peak around 3200-3500 cm⁻¹, potentially obscuring actual O-H or N-H stretching signals [38].

For liquid and solid samples generally: Incorrect sample concentration (either too much or too little) creates spectral issues ranging from signal saturation to poor signal-to-noise ratios. Residual solvent peaks can overwhelm sample signals, leading to misinterpretation [38].

For all sample types: Sample inhomogeneity creates representativeness errors where the analyzed portion does not reflect the bulk material, while improper storage leads to degradation that alters chemical composition [39] [37].

Comparative Analysis of Sample Preparation Methods

Solid Sample Preparation Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Solid Sample Preparation Methods for Spectroscopy

| Method | Optimal Application | Key Error Sources | Error Minimization Strategies | Reported Impact on Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grinding & Sieving | IR spectroscopy, XRF spectroscopy [37] | Incomplete grinding causing light scattering; particle size inconsistency [38] | Grind to flour-like consistency; use standardized sieve sizes; ensure complete dryness | Distorted baselines reduced by ~80% with proper grinding [38] |

| KBr Pellet Preparation | IR spectroscopy of solids [38] | Moisture absorption; inhomogeneous mixing; incorrect sample/KBr ratio [38] | Use anhydrous KBr; grind until homogeneous mixture; ensure pellet transparency | 95% reduction in water peak interference with dry materials [38] |

| Pellet Preparation (XRF) | XRF spectroscopy [37] | Inhomogeneous distribution; incorrect pressure application; particle segregation | Use binding agents; apply consistent pressure; verify homogeneity | Not quantified in results |