Advanced Sample Preparation Strategies for Robust HPLC Analysis of Drugs in Human Plasma

This article provides a comprehensive guide to sample preparation techniques for the HPLC analysis of drugs in human plasma, a critical step for therapeutic drug monitoring, pharmacokinetic studies, and clinical...

Advanced Sample Preparation Strategies for Robust HPLC Analysis of Drugs in Human Plasma

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to sample preparation techniques for the HPLC analysis of drugs in human plasma, a critical step for therapeutic drug monitoring, pharmacokinetic studies, and clinical research. It covers foundational principles, including the challenges posed by biological matrices like phospholipids and proteins. The content explores established and emerging methodological approaches such as protein precipitation, liquid-liquid extraction, and solid-phase extraction, with a focus on modern phospholipid removal protocols. It also delves into troubleshooting common issues like ion suppression, method optimization using Quality-by-Design principles, and the rigorous validation required for bioanalytical methods. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current best practices to ensure sensitive, specific, and reproducible results.

Foundational Principles: Understanding Plasma Matrix and Cleanup Goals

The Critical Role of Sample Preparation in Bioanalytical HPLC

Sample preparation is a critical pre-requisite for accurate and reliable bioanalytical High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) analysis, particularly when quantifying drugs and metabolites in complex biological matrices like human plasma. This step is indispensable for removing interfering matrix components, preconcentrating analytes, and protecting the analytical instrumentation, thereby ensuring the validity of results in therapeutic drug monitoring, pharmacokinetic studies, and bioequivalence research [1]. The complexity of plasma, which contains proteins, lipids, salts, and other endogenous compounds that can cause significant ion suppression or enhancement, necessitates robust and efficient sample clean-up protocols to achieve the required sensitivity and specificity [1]. This application note delineates fundamental sample preparation principles and provides detailed protocols for analyzing small-molecule drugs in plasma, framed within the context of a broader thesis on optimizing bioanalytical workflows.

Fundamental Principles and Considerations

Effective sample preparation strategy selection hinges on a deep understanding of both the biological matrix and the physicochemical properties of the target analytes.

- Matrix Composition: Human plasma is approximately 50% water, with the remainder consisting of proteins (such as albumin and globulins), lipids, phospholipids, and other components. These constituents can foul the HPLC column, reduce its lifetime, and cause significant matrix effects, leading to ion suppression or enhancement during detection [1]. The primary goals of sample preparation are to remove these interferents and isolate the analytes of interest.

- Analyte Properties: Key physicochemical properties of the drug molecule must guide the choice of extraction technique.

- Hydrophobicity: The log P (partition coefficient) value indicates whether an analyte is more hydrophilic (negative log P) or hydrophobic (positive log P), informing the choice of organic solvents for extraction [1].

- Ionization State: The pKa (acid dissociation constant) of a compound determines its charge state at a given pH. For extraction techniques like Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) that rely on the analyte being in a neutral form, the pH of the sample must be adjusted to at least two units away from the pKa to ensure the compound is fully uncharged [1]. For a basic drug, this typically means using a basic pH, and for an acidic drug, an acidic pH.

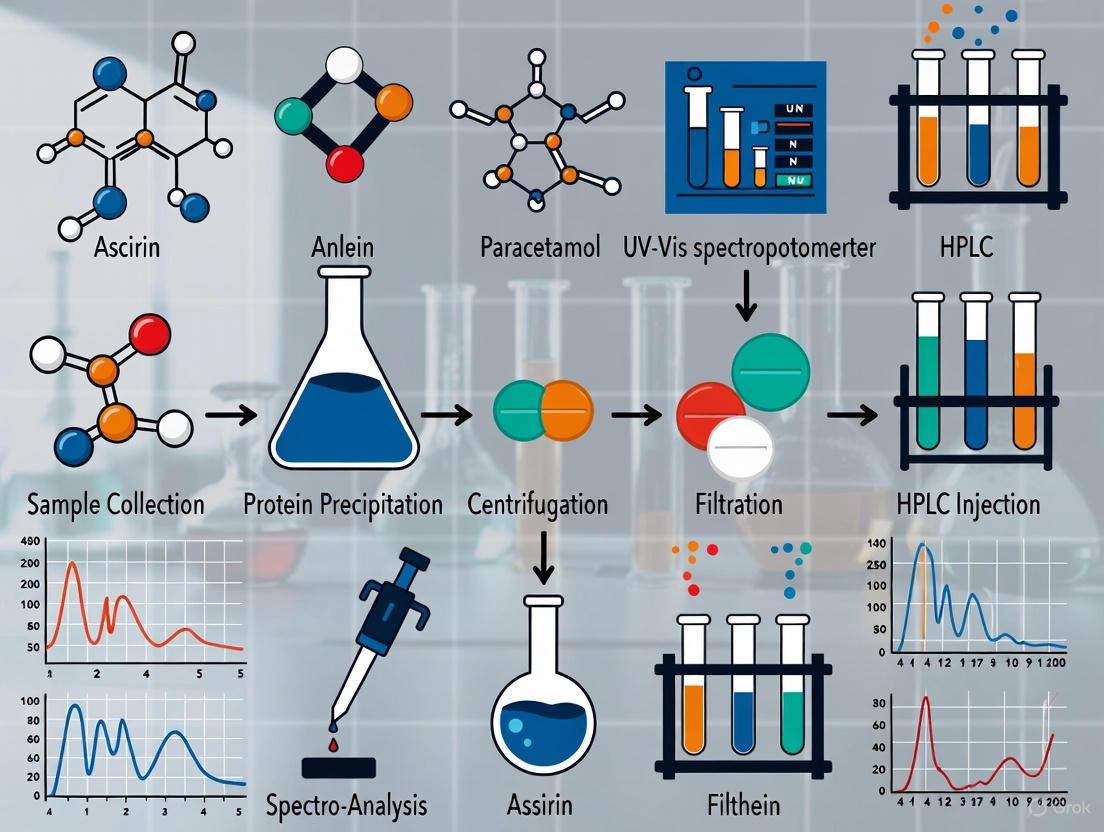

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting an appropriate sample preparation technique based on these factors:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Below are two standardized protocols for sample preparation, adapted and consolidated from recent research for the analysis of cardiovascular drugs in human plasma.

Protocol 1: Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) for Multiple Cardiovascular Drugs

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully extracted bisoprolol, amlodipine, telmisartan, and atorvastatin from human plasma using a two-step LLE procedure [2].

3.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Human Plasma Sample | Biological matrix containing analytes of interest |

| Absolute Ethanol | Protein precipitation and denaturation |

| Diethyl Ether | First organic solvent for liquid-liquid extraction |

| Dichloromethane | Second organic solvent for enhanced analyte recovery |

| Potassium Dihydrogen Phosphate | Buffer component for pH control |

| Nitrogen Gas Stream (40°C) | Gentle evaporation of combined organic extracts |

3.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Protein Precipitation: To a 200 µL aliquot of human plasma in a microcentrifuge tube, add 600 µL of absolute ethanol and 50 µL of the working standard solution. Vortex the mixture thoroughly for 30-60 seconds, then centrifuge at high speed (e.g., 10,000-14,000 rpm) for 2 minutes. This step precipitates and pellets the plasma proteins.

- First Liquid-Liquid Extraction: Carefully transfer the supernatant to a new clean glass tube. Add 1.0 mL of diethyl ether (the first extraction solvent). Vortex the mixture vigorously for 5 minutes to ensure partitioning of analytes into the organic phase. Centrifuge the tube at 3500 rpm for 5 minutes at 0°C to separate the phases clearly.

- Second Liquid-Liquid Extraction: Transfer the upper organic layer (diethyl ether phase) to another clean tube. To the remaining aqueous layer, add 0.5 mL of dichloromethane (the second extraction solvent). Vortex for 5 minutes and centrifuge again at 3500 rpm for 5 minutes at 0°C.

- Combine and Evaporate: Carefully collect the organic layer from this second extraction and combine it with the previously collected diethyl ether extract. Evaporate the combined organic extracts to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas in a water bath set at 40°C.

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the dried residue in 500 µL of ethanol by vortexing for 2 minutes to ensure complete dissolution.

- HPLC Analysis: The sample is now ready for injection into the HPLC system. A volume of 20 µL is typically injected for analysis [2].

Protocol 2: Protein Precipitation for Vancomycin

This protocol outlines a simpler, single-step protein precipitation method developed for the quantification of vancomycin in human plasma, suitable for therapeutic drug monitoring [3].

3.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Human Plasma Sample | Biological matrix containing the drug vancomycin |

| 10% Perchloric Acid | Protein precipitation agent and deproteination solvent |

| Caffeine (Internal Standard) | Internal Standard for HPLC analysis |

| HPLC Mobile Phase | Reconstitution solvent and chromatographic eluent |

3.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Deproteination: To a 300 µL aliquot of human plasma, add an appropriate volume of 10% perchloric acid. The exact volume should be optimized but is typically in a 1:1 or similar ratio. Vortex the mixture vigorously for 1 minute.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the mixture at high speed (e.g., 10,000-14,000 rpm) for 10 minutes. This will pellet the precipitated proteins.

- Collection: Carefully collect the clear supernatant, which contains the analyte of interest.

- HPLC Analysis: The supernatant can be directly injected into the HPLC system, or optionally filtered through a 0.2 µm membrane filter prior to injection [3].

The workflow for the LLE protocol (Protocol 1) is visualized below, highlighting its multi-step nature:

Method Validation and Performance Data

Robust sample preparation methods must be validated to ensure they produce reliable, accurate, and reproducible results. The following tables summarize key validation parameters for the described protocols, based on ICH and FDA guidelines [2] [4] [3].

Table 1: Linearity and Sensitivity of HPLC Methods Using Different Sample Prep Techniques

| Sample Preparation Method | Analytes (Matrix) | Linear Range | Correlation Coefficient (r²) | Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLE (Dual Solvent) | Bisoprolol, Amlodipine (Plasma) | 5–100 ng/mL | >0.99 | 5 ng/mL | [2] |

| LLE (Dual Solvent) | Telmisartan (Plasma) | 0.1–5 ng/mL | >0.99 | 0.1 ng/mL | [2] |

| LLE (Dual Solvent) | Atorvastatin (Plasma) | 10–200 ng/mL | >0.99 | 10 ng/mL | [2] |

| LLE | Felodipine (Plasma) | 0.01–1.00 µg/mL | 0.9998 | 0.01 µg/mL | [4] |

| LLE | Metoprolol (Plasma) | 0.003–1.00 µg/mL | 0.9999 | 0.003 µg/mL | [4] |

| Protein Precipitation | Vancomycin (Plasma) | 4.5–80 mg/L | >0.99 | 4.5 mg/L | [3] |

Table 2: Precision and Accuracy of Sample Preparation and HPLC Methods

| Analytes (Matrix) | Sample Prep Method | Precision (RSD%) | Accuracy (% of Nominal) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Felodipine & Metoprolol (Plasma) | LLE | Intra-day & Inter-day ≤ 2% | Within ± 10% | [4] |

| Vancomycin (Plasma) | Protein Precipitation | Intra-day CV%: 2.99–8.39% Inter-day CV%: 2.71–6.06% | Intra-day Error%: 0.36–6.02% Inter-day Error%: 3.71–7.36% | [3] |

| Four Cardiovascular Drugs (Plasma) | LLE (Dual Solvent) | Meets ICH criteria | Meets ICH criteria | [2] |

The meticulously optimized sample preparation protocols described herein are directly applicable in critical areas of pharmaceutical research and clinical chemistry.

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM): The vancomycin method enables precise monitoring of plasma concentrations in critically ill patients to ensure efficacy and avoid nephrotoxicity, directly impacting patient care [3].

- Pharmacokinetic and Bioequivalence Studies: The high-sensitivity LLE method for cardiovascular drugs allows for the accurate construction of concentration-time profiles, which is essential for determining key parameters like C~max~ and AUC in studies for new drug applications or generic drug approvals [2] [5].

- Fixed-Dose Combination Analysis: The ability to simultaneously extract and analyze multiple drugs from different classes from a single plasma sample is invaluable for studying the increasingly prevalent fixed-dose combination therapies, such as those for hypertension and hyperlipidemia [2] [4].

In conclusion, sample preparation is not merely a preliminary step but the foundation of successful bioanalytical HPLC. The choice between techniques like LLE and protein precipitation involves a trade-off between clean-up efficiency, operational simplicity, and recovery. As demonstrated, a well-designed and validated sample preparation protocol, tailored to the specific analyte and matrix properties, is non-negotiable for generating high-quality, reliable data in drug development and clinical monitoring. Integrating these robust sample preparation strategies into a broader HPLC workflow is paramount for achieving the sensitivity, accuracy, and precision demanded by modern bioanalysis.

Human plasma represents one of the most complex biological matrices in analytical science, presenting significant challenges for researchers conducting HPLC analysis of drugs. Its composition encompasses a vast dynamic range of proteins, diverse phospholipid classes, and numerous endogenous small molecules that can interfere with accurate drug quantification [6] [7]. Understanding these components is crucial for developing robust analytical methods that overcome matrix effects, achieve required sensitivity, and generate reliable data for pharmacokinetic and bioequivalence studies. This application note details the specific challenges posed by plasma constituents and provides validated protocols to address them, framed within the broader context of sample preparation strategy for drug development.

The fundamental challenge in plasma analysis lies in its extreme complexity and dynamic concentration range. Proteins span over 10 orders of magnitude in abundance, with albumin alone constituting approximately 50 mg/mL [8]. Phospholipids, particularly choline and ethanolamine ether phospholipids, exist at relatively low concentrations compared to other tissues but significantly contribute to matrix effects in mass spectrometry [7]. Simultaneously, endogenous compounds like amino acids and related metabolites present additional analytical hurdles due to their structural diversity and lack of UV chromophores [9]. These components collectively necessitate sophisticated sample preparation and chromatographic strategies to achieve accurate drug quantification.

The Plasma Proteome: Complexity and Abundance Challenges

Composition and Dynamic Range

The human plasma proteome exhibits extraordinary complexity, with comprehensive profiling identifying thousands of unique proteins. Table 1 summarizes key characteristics of the plasma proteome and the challenges they present for drug analysis.

Table 1: Human Plasma Proteome Characteristics and Analytical Challenges

| Characteristic | Scale/Magnitude | Impact on Drug Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Total Protein Diversity | 517+ unique proteins [10] | Non-specific binding, variable recovery |

| Dynamic Concentration Range | 10+ orders of magnitude [8] | Masking of low-abundance drug signals |

| High-Abundance Proteins | 14 proteins constitute ~99% of mass [10] | Ion suppression, column fouling |

| Immunoglobulin Diversity | Multiple classes and isoforms [6] | Interference with immunodepletion methods |

Depletion Strategies for Proteomic Interference

Abundant plasma proteins necessitate depletion strategies prior to HPLC analysis of small molecule drugs. Immunoaffinity depletion targeting the top 14 abundant proteins (including albumin, IgG, transferrin, and haptoglobin) significantly reduces matrix complexity [10]. This process typically utilizes commercially available columns such as the Multiple Affinity Removal System (MARS), with the following protocol:

Protocol: Immunodepletion of High-Abundance Plasma Proteins

- Sample Preparation: Dilute plasma sample 1:5 with provided buffer solution.

- Column Equilibration: Condition MARS column (4.6 × 100 mm) with equilibration buffer at flow rate of 1 mL/min for 10 minutes.

- Sample Loading: Inject diluted plasma sample (up to 20 μL) onto column.

- Fraction Collection: Collect flow-through fraction containing low-abundance proteins and small molecules.

- Column Regeneration: Elute bound abundant proteins with stripping buffer.

- Desalting: Process flow-through fraction using 5 kDa molecular weight cut-off filters or C18 solid-phase extraction.

- Quality Control: Verify depletion efficiency by SDS-PAGE analysis [10].

Phospholipid Interference in HPLC Analysis

Diversity and Analytical Behavior

Plasma phospholipids represent a major source of matrix effects in LC-MS/MS bioanalysis, particularly in electrospray ionization. Table 2 outlines the primary phospholipid classes and their specific challenges.

Table 2: Major Phospholipid Classes in Human Plasma and Their Impact on Bioanalysis

| Phospholipid Class | Abbreviation | Relative Abundance | Retention Behavior | Analytical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylcholine | PC | High | Mid-polar | Significant ion suppression |

| Lysophosphatidylcholine | LPC | Medium | Hydrophilic | Interface with early-eluting compounds |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine | PE | Medium | Mid-polar | Source of matrix effects |

| Ether Phospholipids | eEtnGpl, eChoGpl | Low [7] | Variable | Potential isobaric interference |

Phospholipid Removal and Analysis Techniques

Phospholipids can be addressed through both sample preparation and chromatographic strategies. A novel approach leverages enzymatic treatment with phospholipase A1 (PLA1), which hydrolyzes ester bonds at the sn-1 position of diacyl glycerophospholipids while leaving ether phospholipids intact [7].

Protocol: Phospholipase A1 Treatment for Phospholipid Management

- Reagent Preparation: Dilute PLA1 enzyme (from Thermomyces lanuginosus) with equal volume of 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 4.5).

- Sample Treatment: Add 20 μL of diluted PLA1 to 80 μL of plasma.

- Incubation: Incubate mixture at 45°C for 60 minutes.

- Lipid Extraction: Add 800 μL of n-hexane/isopropanol (3:2, v/v) to PLA1-treated plasma.

- Extraction: Vortex vigorously, place in ultrasound bath for 5 minutes.

- Phase Separation: Add 400 μL of Na2SO4 solution (6.7% w/v in water), let stand for 5 minutes.

- Collection: Recover hexane layer containing intact ether phospholipids and drug analytes [7].

For direct phospholipid profiling, an HPLC-ELSD method provides effective separation:

- Column: LiChrosphere 100 Diol (250 × 2 mm, 5 μm)

- Mobile Phase A: n-hexane/2-propanol/acetic acid (82:17:1, v/v/v) with 0.08% triethylamine

- Mobile Phase B: 2-propanol/water/acetic acid (85:14:1, v/v/v) with 0.08% triethylamine

- Gradient: 4% B to 37% B in 21 min, then to 85% B in 4 min

- Detection: Evaporative Light Scattering Detector (60°C evaporation, 1 L/min N2) [7]

Endogenous Compounds: Amino Acids and Metabolites

Analytical Challenges and Solutions

Endogenous amino acids and related compounds present unique challenges due to their hydrophilic nature, structural similarity, and lack of UV chromophores. A recently developed method for 48 endogenous amino acids employs hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) with tandem mass spectrometry [9].

Protocol: HILIC-MS/MS Analysis of Endogenous Amino Acids

- Sample Preparation: Precipitate plasma proteins with ice-cold methanol (1:3 ratio).

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 14,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- Surrogate Matrix Approach: Use dialyzed plasma or synthetic surrogate for calibration standards [9].

- Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: HILIC stationary phase (e.g., BEH Amide)

- Mobile Phase A: 10 mM ammonium formate in water (pH 3.0)

- Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid

- Gradient: High organic to aqueous transition

- Mass Spectrometry: Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) in positive ionization mode.

This method achieves excellent performance characteristics, with linearity (R² ≥ 0.99), precision (intra-day RSD 3.2-14.2%), and quantification limits ranging from 0.65 to 173.44 μM across the 48 analytes [9].

Integrated Workflow for Comprehensive Plasma Analysis

The following workflow diagram illustrates an integrated approach to addressing plasma challenges in drug analysis:

Case Study: Multi-Drug Analysis in Plasma

A recently developed method for simultaneous quantification of cardiovascular drugs (bisoprolol, amlodipine, telmisartan, and atorvastatin) demonstrates effective management of plasma challenges [11]. The method employs a dual detection approach with UV confirmation and fluorescence for enhanced specificity.

Protocol: HPLC Analysis of Cardiovascular Drugs in Plasma

- Sample Extraction:

- Protein precipitation with 600 μL absolute ethanol added to 200 μL plasma

- Centrifugation at 3500 rpm for 2 minutes

- Liquid-liquid extraction with 1.0 mL diethyl ether

- Second extraction with 0.5 mL dichloromethane

- Combined organic layers evaporated under nitrogen at 40°C

- Reconstitution in 500 μL ethanol [11]

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: Thermo Hypersil BDS C18 (150 × 4.6 mm, 5.0 μm)

- Mobile Phase: Ethanol and 0.03 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 5.2) (40:60)

- Flow Rate: 0.6 mL/min

- Temperature: 25-35°C

- Injection Volume: 20 μL

Detection Parameters:

- UV Detection: 210-260 nm for separation confirmation

- Fluorescence: Compound-specific excitation/emission wavelengths

- Bisoprolol: 227/298 nm

- Telmisartan: 294/365 nm

- Atorvastatin: 274/378 nm

- Amlodipine: 361/442 nm [11]

This method demonstrates excellent performance with linear ranges of 5-100 ng/mL for bisoprolol and amlodipine, 0.1-5 ng/mL for telmisartan, and 10-200 ng/mL for atorvastatin, achieving a rapid analysis time of under 10 minutes [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Plasma Sample Preparation

| Reagent/Technique | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Immunoaffinity Depletion Columns | Removal of abundant proteins | MARS Hu-14 column removes 14 top proteins [10] |

| Phospholipase Enzymes | Hydrolysis of phospholipids | PLA1 treatment preserves ether phospholipids [7] |

| Solid-Phase Extraction | Cleanup and concentration | C18 cartridges for peptide desalting [6] |

| Tandem Mass Tags | Multiplexed quantification | 11-plex TMT for comparative proteomics [8] |

| Surrogate Matrices | Calibration for endogenous analytes | Dialyzed plasma for amino acid quantification [9] |

| Stable Isotope Standards | Internal standardization | Deuterated analogs for drug quantification [11] |

The challenges presented by human plasma components—proteins, phospholipids, and endogenous compounds—require integrated strategies that combine sample preparation and advanced chromatographic techniques. The protocols presented here provide effective approaches for managing this complex matrix, enabling reliable drug quantification in research and development settings. As analytical technologies continue to advance, particularly in mass spectrometry detection and chromatography resolution, our ability to overcome plasma matrix effects will further improve, supporting more sensitive and accurate bioanalytical methods for drug development.

Matrix effects represent a significant challenge in the bioanalysis of drugs in plasma using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). These phenomena are defined as the alteration of analyte detection due to the influence of co-eluting compounds present in the sample matrix, leading to either ion suppression or ion enhancement [12]. In the context of a broader thesis on sample preparation for HPLC analysis of drugs in plasma, understanding and mitigating matrix effects is paramount, as they directly impact key analytical figures of merit including detection capability, precision, accuracy, and sensitivity [13] [14]. The fundamental problem stems from the fact that components in the sample matrix, which can include phospholipids, salts, metabolites, and proteins, can either enhance or suppress the detector response for the target analyte [15]. This is particularly problematic in clinical research and drug development, where accurate quantification is essential for therapeutic drug monitoring and pharmacokinetic studies [16] [17].

The mechanisms underlying matrix effects differ between detection techniques. In mass spectrometry, particularly with electrospray ionization (ESI), ion suppression occurs when matrix components compete with the analyte for available charge during the ionization process or alter droplet formation and evaporation efficiency [12] [14]. In contrast, for ultraviolet/visible (UV/Vis) absorbance detection, solvatochromism—where the absorptivity of analytes is affected by mobile phase solvents—can lead to similar matrix-related quantification errors [15]. The complexity of plasma as a matrix, with its diverse endogenous components and the potential for exogenous contaminants from sample collection and processing, makes it particularly susceptible to these effects [17]. Therefore, a systematic approach to assessing, understanding, and mitigating matrix effects is a critical component of robust bioanalytical method development and validation for plasma drug analysis.

Assessment and Quantification of Matrix Effects

Experimental Protocols for Evaluation

A comprehensive assessment of matrix effects is mandatory during bioanalytical method validation. The following protocols, which can be integrated into a single experiment, provide complementary information on the presence and magnitude of matrix effects [18].

Protocol 1: Post-Extraction Spiking Method This approach evaluates the relative matrix effect by comparing analyte response in matrix to that in a clean solution [18].

- Prepare three sets of samples using multiple lots of blank plasma (at least 6 lots are recommended by regulatory guidelines) [18].

- Set A (Neat Solution): Spike the analyte and internal standard (IS) directly into the mobile phase or a neat solvent.

- Set B (Post-Extraction Spiked): Extract blank plasma samples, then spike the analyte and IS into the extracted matrix.

- Set C (Pre-Extraction Spiked): Spike the analyte and IS into blank plasma before performing the extraction procedure.

- Analyze all sets using the developed LC-MS/MS method and calculate the matrix effect (ME), recovery (RE), and process efficiency (PE) using the formulas:

ME (%) = (B/A) × 100RE (%) = (C/B) × 100PE (%) = (C/A) × 100 = (ME × RE)/100

- Interpret results: An ME of 100% indicates no matrix effect; <100% indicates ion suppression; >100% indicates ion enhancement. High variability in ME between different plasma lots indicates a significant relative matrix effect that can impact method precision [18].

Protocol 2: Post-Column Infusion Experiment This qualitative approach identifies chromatographic regions affected by matrix effects [14].

- Prepare a solution containing the analyte of interest at a consistent concentration.

- Set up a post-column infusion system using a syringe pump to continuously introduce the analyte solution into the column effluent directed to the mass spectrometer.

- Inject a blank plasma extract onto the LC column while the post-column infusion is active.

- Monitor the analyte signal: A constant signal should be observed in the absence of matrix effects. Dips or peaks in this signal indicate regions of ion suppression or enhancement, respectively, caused by co-eluting matrix components [14].

- Use the results to optimize chromatographic separation to move the analyte away from regions of significant matrix interference.

Quantitative Data from Validation Studies

The following table summarizes typical acceptance criteria and results from validation studies assessing matrix effects, recovery, and process efficiency:

Table 1: Acceptance Criteria and Typical Results for Matrix Effect, Recovery, and Process Efficiency Assessment

| Parameter | Calculation | Acceptance Criteria | Typical Results in Optimized Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matrix Effect (ME) | (B/A) × 100 |

CV < 15% for IS-normalized MF [18] | 85-115% with minimal lot-to-lot variation |

| Recovery (RE) | (C/B) × 100 |

Consistent and reproducible [18] | >70% often achievable with efficient extraction [11] |

| Process Efficiency (PE) | (C/A) × 100 |

Meets accuracy and precision requirements [18] | Combines effects of ME and RE on overall method performance |

| IS-Normalized Matrix Factor | MF(analyte)/MF(IS) |

CV < 15% [18] | Close to 1.0, indicating effective compensation by IS |

The data and protocols above facilitate a systematic evaluation of matrix effects, which is crucial for validating reliable bioanalytical methods. The consistency of these parameters across different lots of plasma provides confidence in the method's robustness when applied to real patient samples [18].

Strategies for Mitigation of Matrix Effects

Sample Preparation Techniques

Effective sample preparation is the first line of defense against matrix effects. The goal is to remove interfering compounds while maintaining high recovery of the analyte.

- Protein Precipitation with Phospholipid Removal (PPR): While simple protein precipitation is a minimal cleanup technique, it leaves behind phospholipids that are major contributors to ion suppression in LC-MS/MS. Specialized products like Phree plates combine protein precipitation with a sorbent that retains phospholipids, significantly reducing this source of matrix effects [17].

- Solid Phase Extraction (SPE): SPE provides superior sample cleanliness compared to protein precipitation. Mixed-mode SPE sorbents (e.g., Strata-X), which utilize both hydrophobic and ionic interactions, offer selective retention of analytes and effective removal of polar and non-polar matrix interferences. The use of an SPE method development plate can efficiently identify the optimal sorbent chemistry for a specific application [17].

- Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE): LLE leverages the differential solubility of analytes and matrix components between immiscible solvents. A well-optimized LLE protocol, such as the two-step extraction using diethyl ether and dichloromethane described for cardiovascular drugs, can effectively remove proteins and phospholipids while achieving high analyte recovery [11].

Chromatographic and Instrumental Strategies

- Chromatographic Optimization: Improving the separation of the analyte from co-eluting matrix components is a highly effective strategy. This can be achieved by optimizing the mobile phase composition, gradient profile, and column temperature. The use of alternative stationary phases, such as phenyl-hexyl or biphenyl columns instead of traditional C18, can provide different selectivity that resolves analytes from interferences [17].

- Selection of Ionization Source: The choice between Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) can significantly influence susceptibility to matrix effects. APCI is generally less prone to ion suppression than ESI because the analyte is vaporized before ionization, reducing competition for charge in the droplet phase [12] [14]. Switching from ESI to APCI can sometimes dramatically reduce matrix effects.

- Use of Internal Standards: The internal standard method is one of the most potent tools for compensating for matrix effects, provided the correct IS is selected [15].

- Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards (SIL-IS): These are the ideal choice because they have nearly identical chemical and chromatographic properties to the analyte, ensuring they experience the same matrix effects. The IS-normalized matrix factor corrects for variability in ionization efficiency [18].

- Structural Analogues: If a SIL-IS is not available, a compound with a very similar structure and retention time to the analyte can be used, though compensation may be less perfect.

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for selecting the most appropriate mitigation strategy based on initial assessment results:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues key materials and reagents referenced in the search results that are essential for developing robust bioanalytical methods resistant to matrix effects.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating Matrix Effects in Plasma Drug Analysis

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application | Specific Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Mixed-Mode SPE Sorbents | Selective retention of analytes via reversed-phase and ion-exchange mechanisms; removes a wide range of interferences. | Strata-X (Polymeric reversed-phase with ion-exchange capacity) [17] |

| Phospholipid Removal Plates | Integrated protein precipitation and phospholipid removal for cleaner extracts than standard precipitation. | Phree PLC Cartridges [17] |

| Specialized LC Columns | Alternative selectivity to C18 for resolving analytes from matrix interferences. | Kinetex Biphenyl, Phenyl-Hexyl columns [17] |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled IS | Gold-standard internal standard for compensating matrix effects; behaves identically to analyte. | GluCer C22:0-d4 for glucosylceramide analysis [18] |

| Microelution SPE Plates | Low sorbent mass and elution volume; ideal for low sample volumes, eliminates evaporation step. | Various manufacturers (e.g., Phenomenex) [17] |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents/Additives | High-purity solvents and volatile additives minimize background noise and source contamination. | Ammonium formate, formic acid, LC-MS grade MeCN/MeOH [18] |

Matrix effects, manifesting as ion suppression or enhancement, are an inherent challenge in HPLC and LC-MS/MS analysis of drugs in plasma. Their impact on the accuracy, precision, and sensitivity of bioanalytical methods necessitates a systematic and multi-faceted approach. This involves rigorous assessment using standardized protocols, such as the post-extraction spiking and post-column infusion experiments. Effective mitigation hinges on strategic sample preparation designed to remove interfering phospholipids and other endogenous components, optimized chromatographic separation to resolve analytes from matrix interferences, and the use of appropriate internal standards—particularly stable isotope-labeled compounds—to normalize for variability in ionization efficiency. By integrating these strategies into method development and validation workflows, researchers and drug development professionals can ensure the generation of reliable, high-quality data that is critical for therapeutic drug monitoring and pharmacokinetic studies.

In the realm of bioanalytical chemistry, sample preparation is a critical prelude to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis, particularly for quantifying drugs in complex biological matrices like human plasma. The process of cleaning up a sample—removing unwanted matrix components while efficiently extracting target analytes—directly determines the success of the subsequent chromatographic separation and detection. This application note delineates the core objectives of sample cleanup for HPLC-based drug analysis in plasma: maximizing analyte recovery, ensuring sample cleanliness, and optimizing process throughput. These three pillars are deeply interconnected; focusing on one to the exclusion of others can compromise the entire analytical method. Herein, we explore this balance through the lens of contemporary techniques and provide a validated experimental protocol for the simultaneous determination of cardiovascular drugs in human plasma, a common challenge in pharmaceutical research and development.

The Core Trinity of Cleanup Objectives

The development of any sample preparation protocol revolves around three fundamental, and often competing, objectives:

- Analyte Recovery: This refers to the proportion of the target analyte successfully extracted from the plasma matrix and presented for HPLC analysis. High recovery is crucial for achieving the sensitivity and accuracy required for therapeutic drug monitoring and pharmacokinetic studies. Low recovery can lead to an underestimation of drug concentration and increased quantification uncertainty.

- Sample Cleanliness: The effectiveness of removing matrix interferences—such as proteins, lipids, and salts—from the final extract. A cleaner sample minimizes matrix effects in HPLC detection (e.g., ion suppression or enhancement in mass spectrometry), protects the analytical column from degradation, and enhances the specificity and reliability of the method.

- Throughput: The number of samples that can be processed reliably per unit of time. In drug development, where hundreds or thousands of samples may need analysis, high throughput is essential for rapid decision-making. Throughput is influenced by the number of steps, the potential for automation, and the total processing time per sample.

Striking an optimal balance among these objectives requires a deliberate choice of sample preparation technique and a deep understanding of the chemical properties of both the analyte and the plasma matrix.

Contemporary Sample Preparation Techniques and Trends

The field of sample preparation is evolving to meet the demands for higher efficiency and sustainability. Two prominent trends are the adoption of Green Sample Preparation (GSP) principles and the push toward full laboratory automation.

Green Sample Preparation (GSP) and Miniaturization

The transition from traditional, wasteful methods to greener practices is a key initiative in modern analytical chemistry. As highlighted by Psillakis, GSP principles focus on reducing energy consumption, minimizing solvent and reagent use, and minimizing waste generation [19]. Several strategies align perfectly with the cleanup objectives:

- Accelerating Sample Preparation: Applying assisted fields like vortex mixing, ultrasound, and microwaves can enhance extraction efficiency and speed up mass transfer, consuming less energy than traditional heating methods [19].

- Parallel Processing: Using miniaturized systems that handle multiple samples simultaneously increases overall throughput and reduces the energy consumed per sample, even if the preparation time for a single batch is long [19].

- Automation: Automated systems save time, lower the consumption of reagents and solvents, and reduce waste generation. They also minimize human intervention, thereby lowering the risks of handling errors and operator exposure to hazardous chemicals [19].

- Process Integration: Streamlining multi-step preparation into a single, continuous workflow simplifies operations, cuts down on resource use, and reduces the potential for sample loss or contamination [19].

Automation and the "Dark Lab" Concept

Automation is becoming indispensable for laboratories facing demands for higher throughput, improved accuracy, and cost efficiency. The global laboratory automation market, valued at $5.2 billion in 2022, is expected to grow to $8.4 billion by 2027 [20]. This trend is exemplified by new instrumentation and ambitious concepts:

- Automated Sampling Systems: Instruments like the Samplify automated sampling system from Sielc Technologies are designed for unattended, routine sampling. They improve reproducibility, minimize cross-contamination through thorough probe cleaning, and can be integrated with liquid handling systems for quenching and dilution [21].

- Multi-functional Instruments: The Alltesta Mini-Autosampler can operate not only as an autosampler but also as a fraction collector or a reactor sampling probe, enabling in-vial extraction and precise reagent additions [21].

- The Fully Autonomous "Dark Lab": Inspired by fully autonomous "dark factories" in China, initiatives like the FutureLab.NRW in Europe aim to digitize, automate, and miniaturize all laboratory processes and workflows, running 24/7 with minimal human intervention [20].

Experimental Protocol: Balanced Cleanup for Cardiovascular Drugs in Plasma

The following detailed protocol for the extraction and analysis of four cardiovascular drugs from human plasma exemplifies a practical balance of recovery, cleanliness, and throughput, adapting a method published in Scientific Reports [11].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential materials and reagents for sample preparation.

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Thermo Hypersil BDS C18 Column (150 x 4.6 mm, 5 µm) | Stationary phase for chromatographic separation. |

| Human Plasma | Biological matrix for the analysis. |

| Absolute Ethanol | Protein precipitation agent and solvent for reconstitution. |

| Diethyl Ether | First organic solvent for liquid-liquid extraction (LLE). |

| Dichloromethane | Second organic solvent for LLE to broaden analyte recovery. |

| Potassium Dihydrogen Phosphate | Buffer component for mobile phase. |

| Nitrogen Evaporation System | For gentle, concentrated sample reconstitution. |

| Refrigerated Centrifuge | For rapid phase separation at controlled temperatures (e.g., 0°C). |

Sample Preparation Workflow: Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE)

This protocol uses a two-step LLE, a classic technique that offers a good compromise between efficiency, cost, and simplicity.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Protein Precipitation: To 200 µL of plasma in a microcentrifuge tube, add 600 µL of absolute ethanol and 50 µL of the working standard solution of the analytes. Vortex the mixture vigorously for 1 minute and centrifuge at 6000 rpm for 2 minutes. This step precipitates and removes the majority of proteins, enhancing sample cleanliness.

- First Extraction (Diethyl Ether): Transfer the supernatant to a new clean test tube. Add 1.0 mL of diethyl ether (first extraction solvent). Vortex the mixture for 5 minutes to ensure thorough partitioning of analytes into the organic phase. Centrifuge at 3500 rpm for 5 minutes at 0°C. The low temperature aids in sharp phase separation. Carefully transfer the upper organic layer to a new, clean test tube.

- Second Extraction (Dichloromethane): To the remaining aqueous layer, add 0.5 mL of dichloromethane (second extraction solvent). Vortex for 5 minutes and centrifuge again at 3500 rpm for 5 minutes at 0°C. Collect the lower organic layer and combine it with the diethyl ether fraction from the previous step. This two-solvent system is designed to maximize the recovery of analytes with differing polarities.

- Evaporation and Reconstitution: Evaporate the combined organic extracts to dryness under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas at 40°C. Reconstitute the dry residue in 500 µL of ethanol, vortex for 2 minutes to ensure complete dissolution, and transfer to an HPLC vial. The injection volume is 20 µL.

Method Performance and Balance Assessment

The described LLE method was rigorously validated. The quantitative data below demonstrates how it successfully balances the three cleanup objectives.

Table 2: Validation data for the HPLC analysis of four cardiovascular drugs in plasma [11].

| Analyte | Linear Range (ng/mL) | Extraction Recovery (%) | Intra-day Precision (% RSD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bisoprolol (BIS) | 5 - 100 | >85% | <2% |

| Amlodipine (AML) | 5 - 100 | >87% | <2% |

| Telmisartan (TEL) | 0.1 - 5 | >90% | <2% |

| Atorvastatin (ATV) | 10 - 200 | >82% | <2% |

- Analyte Recovery: As shown in Table 2, the recovery for all four drugs exceeded 82%, with some achieving over 90%. This high recovery is critical for the accurate quantification of low-concentration analytes in plasma.

- Sample Cleanliness: The two-step LLE process effectively removed proteinaceous and other hydrophilic interferences from the plasma. This was evidenced by clean chromatographic baselines and the absence of significant matrix effects, allowing for precise integration of analyte peaks.

- Throughput: The total sample preparation time is approximately 25-30 minutes per sample. While not as fast as some modern solid-phase extraction (SPE) methods that can be automated, the protocol is straightforward and uses inexpensive solvents. The subsequent chromatographic run is completed in less than 10 minutes, contributing to an overall efficient workflow suitable for batch processing [11].

Figure 1: A strategic workflow for selecting a sample cleanup technique based on the primary analytical objective. The final balanced strategy often involves integrating aspects from multiple recommended paths.

Achieving an optimal balance between analyte recovery, sample cleanliness, and throughput is the cornerstone of robust and efficient bioanalytical method development for HPLC. As demonstrated, techniques like LLE can provide an excellent balance, but the landscape of sample preparation is rapidly advancing. The integration of Green Chemistry principles and full laboratory automation represents the future, promising methods that are not only analytically superior but also more sustainable and scalable. By carefully defining cleanup objectives at the outset and leveraging both established and emerging technologies, researchers can develop HPLC methods for plasma analysis that deliver reliable, high-quality data to accelerate drug development.

Methodologies in Practice: From Classic to Advanced Extraction Techniques

Within the framework of sample preparation for the HPLC analysis of drugs in plasma, protein precipitation (PPT) stands as a fundamental and widely employed technique. Bioanalysis often requires the precise quantification of small-molecule drugs in biological matrices such as plasma, which are rich in endogenous proteins that can interfere with chromatographic separation and detection. Protein precipitation addresses this by removing these interfering proteins, thereby protecting the analytical column and reducing background noise. The process involves the addition of a precipitating agent to the sample, which alters the solvent conditions and causes proteins to denature and aggregate, forming an insoluble pellet upon centrifugation. The resulting supernatant, now largely free of proteins, can then be injected directly or with further processing into an HPLC system [22] [23]. This application note details the core protocols, advantages, limitations, and necessary cleanup steps associated with PPT, providing a structured guide for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Principles and Mechanisms of Protein Precipitation

Protein precipitation is a controlled destabilization of proteins in solution, primarily driven by the disruption of their solvation layer. Understanding the underlying mechanisms is crucial for selecting and optimizing a precipitation protocol.

Solvation Layer Disruption

Proteins in an aqueous solution are stabilized by a solvation shell—a layer of water molecules that surrounds the protein and creates a protective barrier. Precipitating agents, such as organic solvents or salts, displace these water molecules from the protein surface. This removal from their solvation layer exposes hydrophobic regions of the protein, forcing them to precipitate out of solution [22].

Hydrophobic Interactions

The cooperative nature of hydrophobic interactions is a key driver in protein aggregation. The addition of precipitating agents increases the hydrophobicity of the water molecules towards the proteins. This disrupts the bonds between water and the proteins, leading to precipitation. The exposed hydrophobic patches on different protein molecules then interact with each other, forming large, insoluble aggregates [22].

Charge Neutralization (Isoelectric Point Precipitation)

Proteins carry a net charge that depends on the pH of their environment. At a specific pH, known as the isoelectric point (pI), the net charge of the protein is zero. This charge neutrality minimizes electrostatic repulsion between protein molecules, leading to aggregation and precipitation. The solubility of proteins is, therefore, at its minimum near their pI [22].

Common Protein Precipitation Methods: Protocols and Comparisons

Several chemical approaches are routinely used to induce protein precipitation in plasma samples. The following section outlines detailed protocols for the three most common methods and presents a comparative analysis.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Organic Solvent Precipitation

Principle: Organic solvents like acetonitrile reduce the dielectric constant of the aqueous medium, disrupting the solvation shell around proteins and causing dehydration and precipitation [23]. Workflow:

- Sample Volume: Use 100 µL of plasma.

- Precipitant Addition: Add 300 µL of ice-cold acetonitrile (a 1:3 sample-to-precipitant ratio).

- Vortex Mixing: Vortex the mixture vigorously for 30-60 seconds to ensure complete mixing.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C to form a compact protein pellet.

- Supernatant Collection: Carefully collect the supernatant for direct HPLC injection or further processing. Note: Acetonitrile is often preferred over methanol or acetone due to its superior protein removal efficiency and cleaner background [23].

Acidic Precipitation

Principle: Acids like trichloroacetic acid (TCA) or perchloric acid (PCA) cause protein denaturation and precipitation by both altering the pH towards the protein's pI and introducing anions that can disrupt the hydration sphere [22] [23]. Workflow:

- Sample Volume: Use 100 µL of plasma.

- Precipitant Addition: Add 100 µL of a 10-20% (w/v) TCA solution.

- Vortex Mixing: Vortex thoroughly for 30 seconds.

- Incubation: Allow the sample to stand on ice for 5-10 minutes to complete precipitation.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes.

- Supernatant Collection: Collect the supernatant. Due to its low pH, it may require neutralization or dilution with a buffer before HPLC analysis to ensure compatibility with the column [23].

Salt-Induced Precipitation (Salting Out)

Principle: High concentrations of salts, such as ammonium sulfate, compete with proteins for water molecules. This "preferential solvation" removes the hydration shell, leading to protein aggregation and precipitation [22]. Workflow:

- Sample Volume: Use 100 µL of plasma.

- Precipitant Addition: Add a saturated aqueous solution of ammonium sulfate to achieve the desired saturation level (e.g., 70-80%).

- Vortex Mixing: Vortex the mixture.

- Incubation: Let the sample stand on ice for 15-30 minutes.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes.

- Supernatant Collection: Collect the supernatant. The high salt content typically necessitates a desalting step (e.g., dialysis, solid-phase extraction) before HPLC analysis [22].

The following diagram illustrates the general decision-making workflow for selecting and implementing a protein precipitation method.

Comparative Analysis of Precipitation Methods

The choice of precipitating agent involves trade-offs between efficiency, simplicity, and compatibility with downstream analysis. The table below provides a structured comparison.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Common Protein Precipitation Methods

| Precipitation Method | Typical Sample-to-Reagent Ratio | Protein Removal Efficiency | Sample Dilution Factor | Compatibility with RPLC-MS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Solvent (ACN) | 1:2 to 1:4 | High (e.g., ~98% [23]) | High | Good, but can cause ion suppression [23] |

| Acidic Agent (TCA) | 1:1 | High (e.g., ~98% [23]) | Low | Poor; low pH may degrade analytes/column [23] |

| Ammonium Sulfate | Varies (to achieve saturation) | Moderate to High | Low | Poor; high salt causes ionization suppression [22] [23] |

| Zinc Hydroxide (Alternative) | ~1:1 (with salts) | Good (~91% [23]) | Low | Good; aqueous, near-neutral pH [23] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

A successful protein precipitation experiment relies on the appropriate selection of reagents and equipment. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Protein Precipitation

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile (HPLC Grade) | Organic precipitant; excellent for general use and RPLC-MS. | Superior protein removal and cleaner background compared to methanol [23]. |

| Ammonium Sulfate | Salt for "salting out"; often used for protein enrichment or fractionation. | High solubility; low toxicity; corrosive to stainless steel; requires desalting post-PPT [22]. |

| Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) | Strong acidic precipitant; minimal sample dilution. | Extreme low pH can hydrolyze labile analytes and damage HPLC columns [23]. |

| Zinc Sulfate / Sodium Hydroxide | Generates zinc hydroxide in situ for a mild, aqueous PPT. | Near-neutral pH supernatant; minimal dilution; good for polar compounds [23]. |

| Microcentrifuge | Pellet precipitated proteins after reagent addition. | Requires capability for ≥10,000 × g and temperature control (4°C) [11]. |

| Vortex Mixer | Ensure complete and homogenous mixing of sample and precipitant. | Critical for consistent precipitation yields and efficient contact [22] [24]. |

Pros, Cons, and the Imperative for Further Cleanup

While protein precipitation is a straightforward and rapid technique, its limitations often necessitate additional sample cleanup, especially for sensitive LC-MS assays in complex matrices like plasma.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Pros:

- Simplicity and Speed: The protocol is straightforward, involving few steps and can be performed quickly [22].

- Cost-Effectiveness: Requires only basic laboratory equipment and inexpensive reagents [22].

- High Sample Throughput: Easily automated and scaled for processing many samples in parallel.

- Broad Applicability: Effective for a wide range of small-molecule analytes and sample types.

Cons:

- Limited Cleanup: Only effectively removes proteins. The supernatant still contains phospholipids, salts, and other endogenous components that can cause matrix effects in LC-MS [23].

- Significant Sample Dilution: Particularly with organic solvents, leading to reduced sensitivity [23].

- Potential for Analyte Loss: Hydrophobic analytes can co-precipitate with proteins or adsorb to the protein pellet [23].

- Matrix Effects: Ion suppression or enhancement in mass spectrometry is a major concern due to remaining matrix components [23].

The Need for Further Cleanup

The "dilute-and-shoot" approach after PPT is often insufficient for demanding bioanalytical applications. The following diagram outlines scenarios and common subsequent cleanup paths.

- Evaporation and Reconstitution: This process involves evaporating the supernatant under a gentle stream of nitrogen at a controlled temperature (e.g., 40°C) and reconstituting the dry residue in a mobile phase-compatible solvent [11] [23]. This serves to concentrate the analytes, increasing sensitivity, and allows for transferring the sample into a solvent optimal for chromatographic separation [23]. It is particularly useful after organic solvent precipitation.

- Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE): SPE provides a selective and efficient cleanup by leveraging specific interactions (e.g., reversed-phase, ion-exchange) between the analyte, the sorbent, and the matrix. It effectively removes phospholipids and other interferences that cause matrix effects, making it the gold standard for robust LC-MS bioanalysis [24].

- Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE): LLE partitions analytes between an aqueous phase (the supernatant) and a water-immiscible organic solvent based on hydrophobicity. It is highly effective for extracting non-polar to moderately polar analytes, providing a clean extract and significant enrichment [11]. As demonstrated in one study, a two-step LLE using diethyl ether and dichloromethane was successfully employed to extract cardiovascular drugs from plasma after a preliminary protein denaturation step with ethanol [11].

Protein precipitation remains a cornerstone technique in the sample preparation workflow for HPLC analysis of drugs in plasma, valued for its simplicity and rapidity. However, researchers must be cognizant of its inherent limitations, particularly the potential for matrix effects and insufficient cleanup for sensitive applications. The choice of precipitating agent—organic solvent, acid, or salt—involves a direct trade-off between protein removal efficiency, sample dilution, and compatibility with the subsequent chromatographic system. For many modern bioanalytical methods, protein precipitation should be viewed not as a final cleanup step, but as an initial sample workup that may need to be coupled with a more selective technique like SPE or LLE. This hybrid approach ensures the production of a clean, concentrated sample extract, enabling reliable, accurate, and sensitive quantification of target analytes in complex biological matrices.

Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) remains a cornerstone technique in the bioanalytical scientist's toolkit, particularly in the preparation of complex biological samples for High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) analysis. In the context of therapeutic drug monitoring, pharmacokinetic studies, and bioequivalence assessments, the extraction of drugs and metabolites from plasma represents a critical step to ensure analytical accuracy, sensitivity, and reproducibility. This sample preparation technique leverages the differential solubility of analytes between two immiscible liquids—typically an aqueous biological matrix and a water-immiscible organic solvent—to isolate, concentrate, and purify target compounds while removing interfering matrix components such as proteins, lipids, and salts [25].

The fundamental importance of LLE in pharmaceutical research stems from its ability to handle the complex nature of plasma samples. Without effective sample cleanup, plasma matrix effects can severely compromise HPLC analysis through ion suppression, elevated background noise, column fouling, and unreliable quantification [26]. While alternative techniques exist—including protein precipitation (PPT), solid-phase extraction (SPE), and more recent methodologies like salting-out assisted liquid-liquid extraction (SALLE)—traditional LLE maintains widespread adoption due to its proven effectiveness, relatively low cost, and operational simplicity [27] [25].

This article provides a contemporary examination of LLE principles, systematic solvent selection strategies, and detailed application examples specifically tailored for HPLC analysis of drugs in plasma, thereby supporting the rigorous demands of modern drug development pipelines.

Theoretical Principles of LLE

The mechanistic foundation of LLE rests on the Nernst distribution law, which states that at equilibrium, a solute will distribute itself between two immiscible liquids in a constant ratio, independent of the total solute concentration [25]. This ratio is quantified as the partition coefficient (Kd), defined as:

Kd = Cₒᵣ𝑔 / Cₐ𝑞

Where Cₒᵣ𝑔 is the concentration of the solute in the organic phase and Cₐ𝑞 is its concentration in the aqueous phase at equilibrium [25].

A high Kd value (>10) indicates favorable partitioning into the organic phase, which is typically targeted for efficient extraction of non-polar analytes from aqueous plasma. In practice, the distribution ratio (D) provides a more practical measure as it accounts all chemical forms of the solute in each phase, making it pH-dependent for ionizable compounds [25]. The extraction efficiency (E), representing the percentage of analyte transferred to the organic phase, is directly related to D and the phase volume ratio (Vₒᵣ𝑔/Vₐ𝑞) [25].

For ionizable drugs, the pH of the aqueous phase becomes a critical parameter. The Henderson-Hasselbalch relationship dictates that successful extraction requires pH adjustment to suppress ionization, thereby increasing the lipophilicity of the analyte. Specifically, basic compounds are best extracted at pH values at least 2 units above their pKa, while acidic compounds require pH values at least 2 units below their pKa to remain in their non-ionized, extractable form [25].

The LLE process involves several key stages: first, the plasma sample is mixed with a buffer to control pH and an internal standard; next, an immiscible organic solvent is added, and the mixture is vigorously agitated to maximize the surface area for solute partitioning; after centrifugation, the phases separate based on density differences; finally, the organic layer containing the extracted analytes is collected, often evaporated to dryness, and reconstituted in a solvent compatible with the HPLC mobile phase [25].

Solvent Selection Strategy

Choosing an appropriate extraction solvent is paramount to achieving high recovery and selective isolation of target analytes from plasma matrix. The ideal solvent should possess high solubility for the analyte, immiscibility with water, low toxicity, favorable density for phase separation, and chemical compatibility with subsequent HPLC analysis [25].

Table 1: Common LLE Solvents and Their Properties

| Solvent | Polarity Index | Density (g/mL) | Water Miscibility | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diethyl Ether | 2.8 | 0.71 | Partial | Extraction of non-polar compounds; often used in combination [11] |

| Ethyl Acetate | 4.4 | 0.90 | Partial | Broad-spectrum extraction of medium polarity drugs [28] |

| Chloroform | 4.1 | 1.48 | Immiscible | Ion-pair extraction of basic compounds; often used in mixtures [29] |

| Dichloromethane | 3.1 | 1.33 | Immiscible | Efficient for non-polar to moderately polar compounds [11] |

| Hexane | 0.1 | 0.66 | Immiscible | Cleanup of very non-polar interferences; not for polar drugs |

The polarity of the extraction solvent should be matched to the hydrophobicity of the target analyte, which can be estimated from its octanol-water partition coefficient (Log P). Solvents with higher polarity indexes (e.g., ethyl acetate) are more effective for moderately polar drugs, while non-polar solvents (e.g., hexane) are suitable only for highly lipophilic compounds [25].

In many cases, binary solvent mixtures offer superior extraction profiles compared to single solvents. For instance, a combination of diethyl ether and dichloromethane (as utilized in the extraction of cardiovascular drugs) can balance extraction efficiency with selectivity, while chloroform-isopropanol mixtures have been successfully employed for the extraction of polar compounds like theophylline [11] [29]. The addition of a small percentage of alcohol (e.g., isoamyl alcohol) can prevent emulsion formation and improve recovery of certain analytes [25].

Advanced LLE Modifications

Salting-Out Assisted Liquid-Liquid Extraction (SALLE)

SALLE has emerged as a powerful hybrid technique that addresses key limitations of traditional LLE, particularly for polar analytes. This method involves the addition of a high concentration of salt to a mixture of plasma and a water-miscible organic solvent (typically acetonitrile), inducing phase separation through the "salting-out" effect [27] [26].

The salt ions preferentially hydrate, reducing the water molecules available to solvate the organic solvent and consequently expelling it to form a distinct phase. This process simultaneously accomplishes protein precipitation and analyte extraction in a single step [26]. Commonly employed salts include magnesium sulfate (MgSO₄), ammonium sulfate ((NH₄)₂SO₄), and sodium chloride (NaCl), with their selection and concentration requiring optimization for specific applications [27] [26].

SALLE offers distinct advantages: it eliminates the vigorous mixing steps required in conventional LLE, reduces solvent consumption, and provides cleaner extracts than protein precipitation alone. Furthermore, the technique is easily automated and avoids the use of expensive SPE cartridges, making it cost-effective for high-throughput laboratories [27] [26].

Supported Liquid Extraction (SLE)

SLE represents a modern adaptation of LLE principles to a solid support format. In SLE, the aqueous plasma sample is immobilized on an inert diatomaceous earth sorbent, after which an immiscible organic solvent is passed through the support, facilitating analyte partitioning without emulsion formation [25]. This technique offers improved reproducibility, easier automation, and reduced solvent volumes compared to traditional LLE, making it particularly suitable for high-throughput laboratory environments [25].

Application Examples in Plasma Drug Analysis

Recent research publications demonstrate the continued relevance and optimization of LLE techniques for diverse pharmaceutical compounds in plasma.

Table 2: Recent LLE Applications in Plasma Drug Analysis

| Drug/Analyte Class | Extraction Method | Solvent System | HPLC Analysis | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular Drugs (Bisoprolol, Amlodipine, Telmisartan, Atorvastatin) | Two-step LLE | 1. Diethyl Ether2. Dichloromethane | HPLC-FLD | Linear range: 0.1-200 ng/mLRecovery: Not specified | [11] |

| Antiepileptic Drug (Lamotrigine) | LLE | Ethyl Acetate with carbonate buffer (pH 10) | HPLC-UV | LLOQ: 0.1 µg/mLRecovery: ≥98.9%Precision: RSD <9% | [28] |

| Diterpene Lactones (Andrographolide, DDAG) | SALLE | Acetonitrile with MgSO₄ | HPLC-DAD | Linear range: 125-2000 ng/mLRecovery: >90%LLOQ: 70 ng/mL (AG), 234 ng/mL (DDAG) | [26] |

| Xanthones (Mangiferin, α-Mangostin) | LLE/SALLE | Solvent optimization required | HPLC-MS | Addressed poor bioavailabilitychallenges | [30] |

| Bronchodilator (Theophylline) | LLE | Chloroform:Isopropanol (20:1, v/v) with (NH₄)₂SO₄ | HPLC-UV | LLOQ: ~1 µg/mLEffective for plasma, saliva, urine | [29] |

Detailed Protocol: SALLE for Cardiovascular Drugs in Human Plasma

The following optimized protocol demonstrates the simultaneous extraction of multiple cardiovascular drugs from human plasma, adapted from a recent HPLC-FLD method [11]:

5.1.1 Reagents and Materials

- Drug standards: Bisoprolol fumarate, Amlodipine besylate, Telmisartan, Atorvastatin

- Internal standard: Appropriate deuterated analogs

- Solvents: HPLC-grade diethyl ether, dichloromethane, ethanol

- Salts: Analytical-grade sodium chloride or magnesium sulfate

- Buffer: 0.03 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 5.2)

- Equipment: Vortex mixer, refrigerated centrifuge, nitrogen evaporator, HPLC system with fluorescence detector

5.1.2 Extraction Procedure

- Protein Precipitation: To 200 µL of plasma sample in a screw-cap tube, add 50 µL of working standard solution and 600 µL of absolute ethanol. Vortex for 30 seconds and centrifuge at 3500 rpm for 2 minutes.

- First Extraction: Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and add 1.0 mL of diethyl ether. Vortex mix for 5 minutes, then centrifuge at 3500 rpm for 5 minutes at 0°C. Collect and transfer the organic layer to a clean tube.

- Second Extraction: To the remaining aqueous layer, add 0.5 mL of dichloromethane. Vortex for 5 minutes and centrifuge under the same conditions. Combine this organic layer with the first extract.

- Concentration: Evaporate the combined organic extracts to dryness under a gentle nitrogen stream at 40°C.

- Reconstitution: Reconstitute the residue in 500 µL of ethanol, vortex for 2 minutes, and inject 20 µL into the HPLC system.

5.1.3 HPLC Conditions

- Column: Thermo Hypersil BDS C18 (150 × 4.6 mm, 5.0 µm)

- Mobile Phase: Ethanol:0.03 M potassium phosphate buffer, pH 5.2 (40:60, v/v)

- Flow Rate: 0.6 mL/min

- Detection: FLD with programmed wavelength switching:

- Bisoprolol: λex/λem = 227/298 nm

- Amlodipine: λex/λem = 361/442 nm

- Telmisartan: λex/λem = 294/365 nm

- Atorvastatin: λex/λem = 274/378 nm

Detailed Protocol: LLE for Lamotrigine in Plasma for Forensic Toxicology

This validated method for antiepileptic drug monitoring in plasma exemplifies efficient extraction with minimal solvent volumes [28]:

5.2.1 Reagents and Materials

- Internal standard: Chloramphenicol

- Extraction solvent: Ethyl acetate

- Buffer: Carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 10)

- Equipment: Vortex mixer, centrifuge, nitrogen evaporator, HPLC-PDA system

5.2.2 Extraction Procedure

- To 250 µL of plasma in a conical tube, add 25 µL of internal standard working solution (chloramphenicol).

- Add 250 µL of carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 10) to adjust pH and inhibit ionization.

- Add 2 mL of ethyl acetate, vortex mix vigorously for 10 minutes.

- Centrifuge at 3500 rpm for 5 minutes to achieve phase separation.

- Transfer the organic (upper) layer to a clean tube and evaporate to dryness under nitrogen at 40°C.

- Reconstitute the residue in 100 µL of mobile phase, vortex, and inject 20 µL into the HPLC system.

5.2.3 HPLC Conditions

- Column: XBridge Shield RP18 (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 µm)

- Mobile Phase: Acetonitrile-phosphate buffer (pH 6.5; 1 mM) (30:70, v/v)

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Detection: PDA at 305.7 nm (lamotrigine) and 276.0 nm (internal standard)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for LLE in Plasma Sample Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile (ACN) | Water-miscible organic solvent for SALLE | Often combined with salts like MgSO₄; effective for polar analytes [26] |

| Ethyl Acetate | Medium-polarity extraction solvent | Broad applicability; suitable for drugs with moderate Log P values [28] |

| Diethyl Ether | Low-polarity extraction solvent | Volatile; often used in combination with other solvents [11] |

| Dichloromethane | Dense, non-polar solvent | Effective for non-polar compounds; sinks below aqueous phase [11] |

| Ammonium Sulfate | Salting-out agent | Promotes phase separation in SALLE; also aids in protein denaturation [29] |

| Carbonate/Bicarbonate Buffer | pH Control | Maintains alkaline conditions for extraction of basic compounds [28] |

| Phosphate Buffer | pH Control | Maintains slight acidity for extraction of acidic compounds [11] |

| MgSO₄ | Water-removing salt | Highly efficient in SALLE protocols; enhances partitioning to organic phase [26] |

Liquid-Liquid Extraction maintains its vital position in the bioanalytical workflow for plasma sample preparation, offering a robust, cost-effective means of extracting a wide spectrum of drug compounds from complex biological matrices. The continued evolution of LLE methodologies—particularly the development of SALLE and SLE—addresses contemporary challenges in pharmaceutical analysis, including the need for high-throughput processing, reduced solvent consumption, and improved extraction efficiency for polar analytes.

The selection of appropriate extraction conditions—including solvent system, pH adjustment, and potential implementation of salting-out strategies—remains fundamental to method success. When properly optimized, LLE provides excellent sample cleanup, effectively minimizes matrix effects, and delivers the sensitivity, precision, and accuracy required for reliable HPLC quantification of drugs in plasma. As pharmaceutical research advances toward increasingly complex molecules and lower therapeutic concentrations, the adaptability and effectiveness of LLE ensure its ongoing relevance in supporting drug development and therapeutic monitoring applications.

Solid-phase extraction (SPE) serves as a fundamental sample preparation technique in the analysis of drugs in biological matrices, particularly in plasma research. As a sample preparation technique based on principles similar to high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), SPE enables the selective sorption of analytes or interferences from simple to complex matrices [31]. For researchers quantifying pharmaceutical compounds in plasma, SPE provides critical advantages over traditional liquid-liquid extraction (LLE), including reduced solvent consumption, improved sample throughput, more tunable selectivity through appropriate stationary phase selection, easier automation, and avoidance of emulsion formation [31]. In the context of a broader thesis on sample preparation for HPLC analysis of drugs in plasma, understanding SPE is paramount, as it directly impacts method sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility.

The fundamental process of SPE operation involves four key steps: conditioning, sample addition, washing, and elution [31]. During conditioning, the bonded phase is solvated to readily accept the liquid sample load. The washing step removes interferences, while the elution step employs a strong solvent to recover the analyte of interest in a small volume suitable for direct injection into chromatographic systems [31]. The selection of appropriate SPE sorbents and protocols depends primarily on three factors: the chemical properties of the target analyte, the composition of the sample matrix, and the sample volume to be processed [32]. For bioanalytical methods supporting drug development, SPE has proven indispensable for achieving the low limits of quantification required for pharmacokinetic studies while effectively removing matrix components that could interfere with detection.

SPE Mechanisms: Reversed-Phase vs. Mixed-Mode

Reversed-Phase SPE

Reversed-phase SPE represents one of the most widely used mechanisms for extracting drugs from biological fluids. This approach utilizes nonpolar functional groups such as C18, C8, C6, C4, C2, phenyl, cyclohexyl, and cyanopropyl bonded to silica or polymer supports [32]. The primary retention mechanism involves van der Waals (dispersive) forces between the analyte and these nonpolar sorbent surfaces [32]. Reversed-phase sorbents are particularly effective for extracting molecules containing nonpolar functional groups from predominantly polar matrices like plasma, serum, or urine [32]. The interaction between analyte and sorbent is facilitated by polar solvents, which repel the analyte from the solution phase onto the sorbent surface. Elution typically requires solvents with nonpolar character (less polar than water) such as methanol, acetonitrile, isopropanol, or tetrahydrofuran to disrupt these hydrophobic interactions [32].

Mixed-Mode SPE

Mixed-mode SPE represents a more advanced approach that combines two or more primary retention mechanisms, most commonly hydrophobic and ion-exchange interactions [33] [32]. This dual-mechanism design provides enhanced selectivity for isolating analytes from complex biological matrices like plasma. In mixed-mode SPE, analytes with appropriate charge characteristics interact with ion-exchange functional groups, effectively "locking" them in place during the extraction process [33]. While securely retained by ionic interactions, the SPE cartridge can be washed with strong solvents to thoroughly remove impurities without risking analyte loss. Subsequently, the pH of the eluant is adjusted to neutralize the charge on either the analyte or the sorbent, releasing the compounds from the ion-exchange groups [33]. Since mixed-mode systems also retain analytes through reversed-phase mechanisms, the organic component percentage of the eluant can be simultaneously adjusted to achieve selective elution [33].

Mixed-mode sorbents can be manufactured through two primary methods: bonding the sorbent concurrently with different functional group chemistries or blending discrete sorbents in appropriate ratios [32]. The blending approach is often preferred due to the easier reproducibility of bonding a single functional group to the silica surface [32]. The development of protocols using mixed-mode sorbents typically requires more optimization than single-mechanism sorbents; however, the reward is significantly cleaner extracts from highly complex matrices like plasma [32]. For bioanalytical applications, this translates to reduced matrix effects in subsequent LC-MS/MS analysis and improved assay sensitivity.

Table 1: Comparison of Reversed-Phase and Mixed-Mode SPE Mechanisms

| Characteristic | Reversed-Phase SPE | Mixed-Mode SPE |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Retention Mechanisms | Hydrophobic interactions (van der Waals forces) | Combination of hydrophobic and ion-exchange interactions |

| Sorbent Functional Groups | C18, C8, phenyl, cyano | C8/SCX (benzenesulphonic acid), C18/SAX, etc. |

| Ideal Application | Nonpolar analytes from polar matrices | Ionizable compounds from complex biological matrices |

| Elution Requirements | Organic solvent (MeOH, ACN) to disrupt hydrophobic interactions | pH adjustment + organic solvent to disrupt both mechanisms |

| Selectivity | Moderate | High |

| Method Development Complexity | Low to moderate | Moderate to high |

| Matrix Removal Efficiency | Moderate | High |

Comparative Performance in Bioanalysis

The critical advantage of mixed-mode SPE over reversed-phase SPE becomes evident when examining their performance in extracting analytes from biological matrices. A direct comparison study investigating the enrichment and clean-up of surrogate peptides for Cystatin C (CysC) quantification in serum revealed significantly higher recoveries with mixed-mode SPE compared to reversed-phase SPE in serum matrix, attributed to differential matrix effects [34]. While both SPE approaches showed similar high recoveries in neat solution, the mixed-mode SPE demonstrated superior capability in reducing matrix interferences in biological samples [34].

Similarly, research examining the extraction of free arachidonic acid from plasma demonstrated that mixed-mode SPE provided more effective removal of phospholipids and proteins compared to protein precipitation, liquid-liquid extraction, or single-mode reversed-phase SPE [35]. Phospholipids represent particularly problematic matrix components in LC-MS/MS analysis as they can cause significant ion suppression or enhancement. The combination of ionic interaction and reversed-phase interaction in mixed-mode SPE was shown to remove these interferents more sufficiently than single-mechanism approaches [35]. This enhanced clean-up capability directly translates to improved analytical performance, with the mixed-mode method demonstrating recoveries of 99.38% to 103.21% with RSD less than 6% for arachidonic acid in plasma [35].

For basic pharmaceutical compounds and their metabolites extracted from biological fluids, mixed-mode SPE utilizing sorbents containing both C8 and strong cation-exchange (SCX) functional groups yielded recoveries greater than 90% across all compounds tested with relative standard deviations consistently less than 5% [33]. This performance level is particularly impressive given the trace level (10 ng/mL) concentrations targeted, demonstrating the effectiveness of mixed-mode SPE for bioanalytical applications requiring high sensitivity.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of SPE Techniques for Biological Samples