Advanced Spectroscopic Techniques in Material Science: A Comprehensive Guide for Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced spectroscopic techniques essential for modern material science and pharmaceutical development.

Advanced Spectroscopic Techniques in Material Science: A Comprehensive Guide for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of advanced spectroscopic techniques essential for modern material science and pharmaceutical development. It explores foundational principles of FT-IR, NMR, Raman, and UV-Vis spectroscopy, detailing their specific applications in characterizing polymers, batteries, and biopharmaceuticals. The content offers practical methodological guides for real-world analysis, a systematic framework for troubleshooting spectral anomalies, and a comparative analysis of technique selection for validation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide integrates the latest instrument advancements and data analysis strategies to enhance material characterization, process optimization, and quality control.

Core Spectroscopic Principles and Techniques for Material Characterization

Spectroscopic techniques form the cornerstone of modern material science research, providing indispensable tools for characterizing molecular structures, identifying chemical compositions, and understanding material properties. This article details the fundamental principles, applications, and standardized protocols for four pivotal spectroscopic methods—Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR), Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), Raman, and Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy. Within the context of drug development and advanced material research, these techniques enable scientists to probe everything from protein structures and polymer crystallinity to inorganic nanomaterial surfaces and pharmaceutical formulations. The following sections provide a comprehensive technical resource, including comparative analysis tables, detailed experimental methodologies, and visual workflows to support researchers in selecting and implementing the appropriate spectroscopic characterization strategies for their specific research challenges.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Operating Principles

Each spectroscopic technique operates on distinct physical principles, probing different aspects of molecular and material interactions with electromagnetic radiation.

FT-IR Spectroscopy measures the absorption of infrared light by molecules undergoing vibrational transitions. When IR radiation interacts with a sample, specific frequencies are absorbed that correspond to molecular bond vibrations, such as stretching and bending. The resulting absorption spectrum provides a molecular "fingerprint" based on the energy required to change these vibrational states [1]. The Fourier transform algorithm converts raw interferogram data into an interpretable spectrum, offering significant advantages through multiplex, throughput, and precision benefits over dispersive instruments [1].

NMR Spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei (e.g., ( ^1H ), ( ^13C )) when placed in a strong external magnetic field. Nuclei with non-zero spin absorb electromagnetic radiation in the radiofrequency range and undergo transitions between spin states. The resulting NMR spectrum reveals detailed information about the chemical environment, connectivity, and dynamics of molecules [2]. For solid-state materials, techniques like magic-angle spinning (MAS) and cross-polarization (CP) enhance resolution and sensitivity [3].

Raman Spectroscopy is based on the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser source. When photons interact with molecular vibrations, a tiny fraction (approximately 1 in ( 10^7 ) photons) undergoes a shift in energy corresponding to the vibrational modes of the chemical bonds. Stokes Raman scattering occurs when the scattered photon has less energy than the incident photon, while anti-Stokes Raman has higher energy [4]. This technique complements FT-IR by probing vibrational modes that involve a change in polarizability rather than dipole moment.

UV-Vis Spectroscopy measures the absorption of ultraviolet or visible light by molecules, which causes electronic transitions from ground states to excited states. The amount of light absorbed at specific wavelengths follows the Beer-Lambert law, enabling quantitative analysis of analyte concentrations [5]. The technique probes electronic structure, particularly in molecules with conjugated systems or transition metal complexes.

Comparative Technical Specifications

Table 1: Comparative analysis of key spectroscopic techniques for material science applications

| Technique | Spectral Range | Primary Information | Key Applications in Material Science | Detection Limits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FT-IR | 4000 - 400 cm( ^{-1} ) | Molecular vibrations, functional groups | Polymer degradation, surface chemistry, protein secondary structure [1] | ~1% for most functional groups |

| NMR | 300 - 1000 MHz (for ( ^1H )) | Chemical environment, molecular structure, dynamics | Molecular dynamics in polymers, surface functionalization of nanoparticles [3] [2] | mM range for ( ^1H ) (high-field) |

| Raman | 50 - 4000 cm( ^{-1} ) shift | Molecular vibrations, crystal structure, stress | Carbon allotrope characterization, pharmaceutical polymorphism [6] [4] | ~0.1 M for organics (conventional) |

| UV-Vis | 190 - 800 nm | Electronic transitions, chromophore concentration | Nanoparticle size quantification, protein concentration, reaction kinetics [5] | ~µM for strong chromophores |

Table 2: Sample requirements and preparation considerations

| Technique | Sample Form | Preparation Methods | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| FT-IR | Solids, liquids, gases | ATR (minimal prep), KBr pellets, thin films | Water interference, limited depth profiling (conventional) |

| NMR | Liquids, solids (MAS) | Dissolution in deuterated solvents, packing rotors | Requires isotopic labeling for low-sensitivity nuclei |

| Raman | Solids, liquids, gases | Minimal – often no preparation needed | Fluorescence interference, thermal degradation with lasers |

| UV-Vis | Liquids, transparent solids | Dilution to optimal absorbance range, cuvette selection | Requires chromophores, scattering interference in turbid samples |

Experimental Protocols

FT-IR Spectroscopy Protocol for Polymer Characterization

Objective: To identify functional groups and monitor oxidation in polymer materials using FT-IR spectroscopy.

Materials and Equipment:

- FT-IR spectrometer with ATR accessory (diamond or ZnSe crystal)

- Polymer samples (pristine and aged)

- Forceps and cleaning supplies (methanol, lint-free wipes)

- Hydraulic press for film preparation (optional)

Procedure:

- Instrument Preparation: Power on the spectrometer and purge with dry nitrogen for 30 minutes to reduce atmospheric water vapor and CO( _2 ) interference [1].

- Background Collection: Clean the ATR crystal thoroughly with methanol and lint-free wipes. Collect a background spectrum with no sample present (64 scans, 4 cm( ^{-1} ) resolution).

- Sample Loading: Place the polymer sample directly on the ATR crystal. Apply consistent pressure using the instrument's anvil to ensure good contact.

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect sample spectrum (64 scans, 4 cm( ^{-1} ) resolution) across the 4000-650 cm( ^{-1} ) range.

- Data Processing: Subtract background spectrum. Apply atmospheric compensation and baseline correction algorithms. For oxidation monitoring, integrate the carbonyl stretch region (1650-1800 cm( ^{-1} )) and normalize to a reference peak (e.g., C-H stretch at 2900 cm( ^{-1} )) [1].

Data Interpretation: Key spectral regions for polymer analysis include: O-H/N-H stretch (3200-3600 cm( ^{-1} )), C-H stretch (2800-3000 cm( ^{-1} )), carbonyl region (1650-1800 cm( ^{-1} )), and fingerprint region (1500-500 cm( ^{-1} )) for material identification.

Solid-State NMR Protocol for Material Surface Analysis

Objective: To characterize surface functional groups on inorganic nanoparticles using dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) enhanced NMR.

Materials and Equipment:

- DNP-NMR spectrometer (e.g., Bruker system with gyrotron) [3]

- Nanoparticle sample (e.g., silicon nanopowder)

- Biradical polarizing agent (e.g., TOTAPOL)

- 3.2 mm MAS rotor

- Deuterated solvent for radical dissolution

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Impregnate nanoparticles with polarizing agent solution (e.g., 15 mM TOTAPOL in appropriate solvent) [3]. Remove excess solvent under reduced pressure.

- Rotor Packing: Carefully pack the prepared sample into a MAS rotor under inert atmosphere if sensitive to moisture.

- Instrument Setup: Set MAS rate to 8-12 kHz. Optimize microwave frequency and power for DNP enhancement. Set temperature to ~100 K for optimal DNP performance.

- Spectral Acquisition: Acquire ( ^29Si ) CP-MAS spectra with DNP enhancement using typical parameters: 2 ms contact time, 3 s recycle delay, 1024 scans. Compare with non-DNP enhanced spectrum for sensitivity assessment.

- Data Processing: Apply Fourier transformation with appropriate line broadening. Reference chemical shifts to external standard (e.g., TMS at 0 ppm).

Data Interpretation: Analyze chemical shift regions for specific surface functionalities. For silicon nanoparticles, Q-species (Si-O-( _n )) appear between -80 to -120 ppm, while surface hydrides (Si-H) typically resonate at -40 to -60 ppm [3].

Raman Spectroscopy Protocol for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Objective: To identify polymorphic forms in active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) using Raman spectroscopy.

Materials and Equipment:

- Raman spectrometer with 785 nm laser source

- Microscope attachment for small particle analysis

- Glass slide or aluminum substrate

- Standard reference materials (known polymorphs)

Procedure:

- Laser Optimization: Set laser power to 50-100 mW at sample to prevent polymorphic transition [4]. Use 785 nm laser to minimize fluorescence.

- Sample Preparation: Place small amount of API powder on substrate. For confocal measurements, ensure flat surface for optimal focus.

- Spectral Acquisition: Focus laser on representative particles. Collect spectra with 4 cm( ^{-1} ) resolution, 10 s integration time, 3 accumulations. Ensure signal-to-noise ratio >20:1 for key peaks.

- Calibration: Perform wavelength calibration using silicon standard (peak at 520.7 cm( ^{-1} )).

- Data Processing: Apply cosmic ray removal, vector normalization, and baseline correction between 1800-200 cm( ^{-1} ).

Data Interpretation: Identify characteristic low-wavenumber lattice modes (<200 cm( ^{-1} )) that are sensitive to crystal packing. Compare fingerprint region (1500-500 cm( ^{-1} )) with reference spectra for polymorph identification.

UV-Vis Spectroscopy Protocol for Nanoparticle Characterization

Objective: To determine concentration and monitor surface plasmon resonance (SPR) of gold nanoparticles.

Materials and Equipment:

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer with 1 cm pathlength quartz cuvettes

- Gold nanoparticle suspension

- Reference solvent (e.g., deionized water)

- Serial dilution materials

Procedure:

- Instrument Initialization: Power on instrument and allow lamp to warm up for 30 minutes. Set scanning parameters: 300-800 nm range, 1 nm data interval, medium scan speed.

- Blank Measurement: Fill quartz cuvette with reference solvent and place in sample holder. Collect baseline spectrum.

- Sample Preparation: Dilute nanoparticle suspension to achieve absorbance <1.0 at SPR maximum (typically ~520 nm for spherical Au NPs) [5].

- Spectral Acquisition: Place diluted sample in cuvette and acquire spectrum using same parameters as blank.

- Data Processing: Subtract blank spectrum. Identify SPR maximum wavelength and measure absorbance. Calculate concentration using Beer-Lambert law with known extinction coefficient.

Data Interpretation: SPR position indicates nanoparticle size and shape, while absorption intensity provides quantitative concentration data. Aggregation state is reflected in broadening or red-shifting of SPR band.

Experimental Workflows

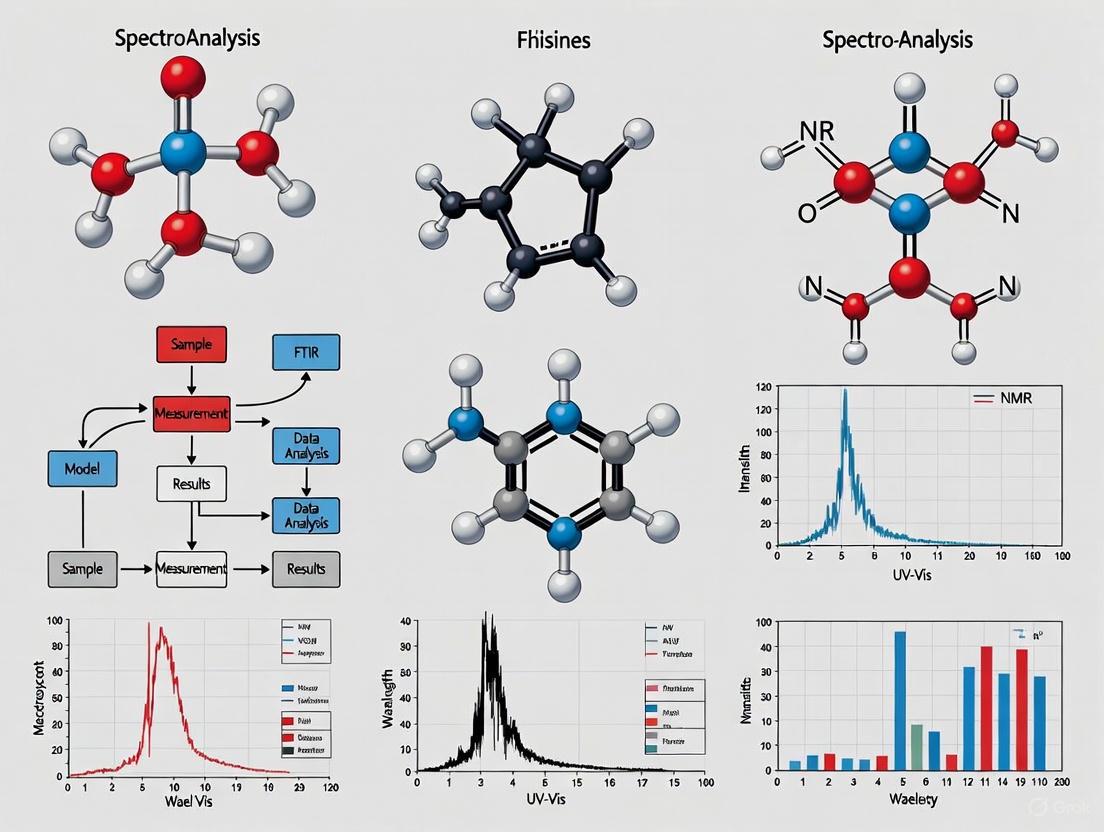

The following diagrams illustrate standardized workflows for the spectroscopic techniques discussed, providing visual guidance for experimental execution.

Diagram 1: FT-IR experimental workflow from sample preparation to data analysis.

Diagram 2: Solid-state NMR workflow with DNP enhancement for material characterization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for spectroscopic analysis

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ATR Crystals (Diamond, ZnSe) | Internal reflection element for FT-IR | Diamond: durable, wide range; ZnSe: higher sensitivity but soluble in water [1] |

| Deuterated Solvents (DMSO-d6, CDCl3) | NMR solvent with minimal interference | Provides lock signal, minimizes solvent peaks in ( ^1H ) NMR |

| MAS Rotors (3.2 mm, 1.3 mm) | Sample containment for solid-state NMR | Zirconia rotors withstand high spinning speeds (up to 60+ kHz) |

| Raman Lasers (785 nm, 532 nm) | Excitation source for Raman scattering | 785 nm reduces fluorescence; 532 nm provides higher Raman efficiency [4] |

| Quartz Cuvettes (1 cm pathlength) | UV-Vis sample containment | Transparent down to 190 nm; required for UV measurements [5] |

| Polarizing Agents (TOTAPOL, AMUPol) | DNP enhancement for NMR | Biradicals for cross-effect DNP; improve sensitivity by 10-200x [3] |

| KBr Powder | IR-transparent matrix | For transmission FT-IR pellet preparation; must be dry and spectroscopic grade |

| NMR Reference Standards (TMS, DSS) | Chemical shift calibration | Tetramethylsilane (0 ppm for ( ^1H ), ( ^13C )); internal or external referencing |

The sophisticated application of FT-IR, NMR, Raman, and UV-Vis spectroscopic techniques provides an indispensable analytical foundation for material science research and drug development. Each method offers unique capabilities for probing molecular structure, composition, and interactions at various scales. FT-IR excels in functional group identification and polymer characterization, while NMR provides atomic-level structural details, particularly with DNP enhancement for surface analysis. Raman spectroscopy offers complementary vibrational information with minimal sample preparation, and UV-Vis enables quantitative electronic transition studies for nanomaterials and biomolecules. By implementing the standardized protocols, workflows, and technical comparisons outlined in this article, researchers can effectively leverage these powerful analytical tools to advance their material characterization capabilities and accelerate discovery in pharmaceutical and material science applications.

Molecular fingerprinting via spectroscopic techniques is a foundational methodology in material science research, providing a non-destructive means to decode the intricate chemical details of a sample. These techniques generate unique spectral "fingerprints" that reveal molecular structure, composition, and interactions by measuring the absorption, emission, or scattering of light. The resulting spectra serve as characteristic patterns, identifying specific functional groups, bond types, and molecular conformations. This Application Note details the principles and protocols of key spectroscopic methods for molecular fingerprinting, framed within contemporary research applications from drug development to inorganic material analysis. It provides a structured guide to the experimental workflows, data interpretation, and advanced machine-learning integration that underpin modern spectroscopic analysis.

Principles of Spectroscopic Molecular Fingerprinting

Molecular fingerprinting spectra arise from the interaction of electromagnetic radiation with matter, which causes transitions between molecular energy levels. The specific frequencies at which a molecule absorbs or scatters light are dictated by its chemical structure and composition.

- Infrared Spectroscopy: Probes vibrational transitions of molecular bonds. When the frequency of infrared light matches the natural vibrational frequency of a chemical bond, absorption occurs, producing characteristic peaks. The mid-IR region (4000-400 cm⁻¹) is particularly rich in information, often called the "fingerprint region," as it provides a unique pattern for each compound [7] [8].

- Raman Spectroscopy: Measures inelastic scattering of light, providing complementary information to IR. It is highly sensitive to symmetrical covalent bonds and is less affected by aqueous solvents, making it ideal for biological samples [9] [10].

- Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy: Detects electronic transitions in molecules, particularly those with conjugated systems. The absorption maxima and spectral shape provide insights into chromophore presence and concentration [9].

The resulting fingerprint is a plot of the intensity of interaction versus wavelength or wavenumber, which can be deconvoluted to extract detailed molecular information.

Application-Specific Workflows and Protocols

Protocol: FTIR-based Diagnosis of Arboviral Infections from Serum

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, utilizes FTIR spectroscopy to detect host biomolecular changes in serum for distinguishing dengue and chikungunya infections with machine learning [10].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Collect human serum samples from confirmed dengue (N=142), chikungunya (N=120), and healthy controls (N=40).

- Store samples at -80°C until analysis. Avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

- Thaw samples at room temperature and vortex gently before analysis.

2. Spectral Acquisition:

- Instrument: FTIR Spectrometer with ATR accessory.

- Parameters: Acquire spectra in the mid-IR range (4000-400 cm⁻¹). Accumulate 64 scans per spectrum at a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹.

- Background: Collect a background spectrum with a clean ATR crystal before each sample measurement.

- Replicates: Perform triplicate measurements for each sample to ensure reproducibility.

3. Data Preprocessing:

- Perform atmospheric compensation to remove contributions from CO₂ and water vapor.

- Apply vector normalization to the entire spectral dataset.

- Use first- or second-derivative Savitzky–Golay filtering (e.g., 9-point window, 2nd-order polynomial) to enhance spectral resolution and minimize baseline drift [10] [8].

4. Machine Learning and Analysis:

- Extract specific wavenumber regions of interest (e.g., Amide I ~1650 cm⁻¹, Amide III ~1240-1300 cm⁻¹).

- Input preprocessed spectral data into machine learning models: Support Vector Machine (SVM), Neural Network (NN), and Random Forest (RF).

- Employ a 70:15:15 split for training, validation, and test sets. Validate model performance using k-fold cross-validation.

Table 1: Key Spectral Biomarkers for Arboviral Infection Detection [10]

| Spectral Region (cm⁻¹) | Biomolecular Assignment | Observed Spectral Change in Infection |

|---|---|---|

| 1650 (Amide I) | Protein C=O stretching | Increase in β-sheet content, loss of α-helical structures |

| 1240-1300 (Amide III) | Protein N-H bending, C-N stretching | Distinctive patterns for dengue vs. chikungunya |

| 1080-1100 | Nucleic acid backbone vibrations | Observable differences in infected sera |

| 2950-2850 | Lipid CH₂/CH₃ stretching | Alterations indicative of host response |

Protocol: Gastric Cancer Screening from Biofluids using Mid-IR Spectroscopy

This protocol outlines the use of mid-IR spectroscopy for the molecular diagnosis of gastric cancer (GC) from diverse biofluids, including blood serum, plasma, and saliva [8].

1. Sample Collection and Processing:

- Collect biofluid specimens (blood serum, plasma, saliva, endoscopy wash/disinfection fluid) from clinically confirmed GC cases and healthy controls.

- Centrifuge blood samples at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes to separate serum/plasma.

- Use a freeze-dryer system to remove water/moisture from all biofluid specimens.

2. Mid-IR Spectroscopy with ATR:

- Instrument: FTIR Spectrometer equipped with a diamond/ZnSe ATR crystal.

- Data Collection: Record spectra from 4000 to 650 cm⁻¹. Accumulate 3351 scans per spectrum under a nitrogen gas flux to minimize atmospheric interference.

- Cleaning: Clean the ATR crystal with a solvent mixture of acetone and ethanol after each measurement.

3. Chemometric Analysis:

- Preprocess spectra using smoothing (first-derivative Savitzky–Golay) and normalization.

- Apply unsupervised methods (Principal Component Analysis - PCA, Hierarchical Cluster Analysis - HCA) for exploratory data analysis and to identify natural clustering.

- Apply supervised methods (Linear Discriminant Analysis - LDA, Soft Independent Modelling of Class Analogy - SIMCA) to build classification models discriminating GC from control cases.

- Validate models using cross-validation and report performance metrics (sensitivity, specificity).

Table 2: Key Mid-IR Spectral Signatures for Gastric Cancer Detection in Biofluids [8]

| Wavenumber (cm⁻¹) | Vibrational Mode Assignment | Biomolecule Correlation | Remarks in GC Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~1648 | C=O stretching (Amide I) | Proteins | Altered intensity, indicating protein conformational changes |

| ~1534 | N–H bending, C–N stretching (Amide II) | Proteins | Significant changes observed |

| ~1450 | CH₂/CH₃ bending | Lipids, Fatty Acids | Decreased intensity, suggesting lipid metabolism alterations |

| ~1243 | P=O stretching (asymmetric) | Nucleic Acids (RNA/DNA) | Indicative of changes in nucleic acid content |

| ~1081 | P=O stretching (symmetric) | Phospholipids, Nucleic Acids | Observable changes in carbohydrate and phospholipid metabolism |

| ~927, 969 | C–C stretching, Ring vibrations | DNA/RNA, Carbohydrates | Associated with cancer-related energy necessities |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the generalized end-to-end workflow for molecular fingerprinting, from sample preparation to final interpretation, integrating the protocols above.

Diagram 1: Generalized workflow for molecular fingerprinting analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Fingerprinting

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| FTIR Spectrometer with ATR | Core instrument for acquiring IR absorption spectra from solid/liquid samples. | Bruker Vertex NEO platform features vacuum optics to remove atmospheric interference [9]. |

| Diamond/ZnSe ATR Crystal | Sampling accessory enabling direct measurement of samples with minimal preparation. | Provides high durability and a wide spectral range; requires cleaning with ethanol/acetone [8]. |

| Ultrapure Water System | Provides water for sample preparation, buffer making, and instrument cleaning. | Milli-Q SQ2 series water purification system ensures solvent purity [9]. |

| Nitrogen Purge Gas | Inert atmosphere for optical paths to minimize spectral interference from atmospheric CO₂ and H₂O. | Essential for high-sensitivity measurements in the mid- and far-IR regions [9] [8]. |

| Standard Reference Materials | Used for instrument calibration and spectral validation. | Polystyrene films for IR wavenumber calibration. |

| Chemometrics Software | For multivariate analysis, machine learning, and classification of spectral data. | CAMO Unscrambler, Octave, Python (scikit-learn) for PCA, LDA, SVM, Neural Networks [10] [8]. |

Data Interpretation and Integration with Machine Learning

The power of modern molecular fingerprinting is unlocked by coupling spectral data with machine learning (ML). This synergy allows researchers to move beyond simple identification to complex pattern recognition, prediction, and classification.

- Feature Representation: Spectral data can be treated as its own fingerprint, where each wavenumber is a feature. Alternatively, molecular fingerprints derived from structure (e.g., Morgan fingerprints, Extended Connectivity Fingerprints - ECFP) can be used in tandem with spectral data for enhanced predictive modeling of properties like taste or odor [11] [12] [13].

- Model Performance: In a study on arboviral infection, ML models (SVM, NN, RF) trained on FTIR data achieved near-perfect classification (AUC = 1.000; CA-score ≥0.989) [10]. For odor prediction, models using Morgan fingerprints with XGBoost achieved an AUROC of 0.828, outperforming other feature representations [12].

- Model Interpretation: Techniques like t-SNE and Silhouette analysis help visualize how well different sample classes (e.g., healthy vs. diseased) cluster in the reduced-dimensionality space defined by their spectral fingerprints, providing insight into the robustness of the classification [10].

Molecular fingerprinting through spectroscopic techniques provides an unparalleled window into the structural and compositional essence of materials. The protocols and data presented herein demonstrate its versatility, from diagnosing diseases with high precision via biofluid analysis to characterizing novel inorganic materials. The integration of these techniques with robust chemometric and machine learning methods transforms complex spectral data into actionable, predictive knowledge. As instrumentation advances—becoming more portable, sensitive, and automated—and as machine learning algorithms grow more sophisticated, the application of molecular fingerprinting is poised to expand further, solidifying its role as an indispensable tool in material science and drug development research.

The field of materials characterization is undergoing a significant transformation, driven by advancements in spectroscopic instrumentation. A clear trend is emerging, bridging the gap between high-performance, centralized benchtop systems and portable, on-site handheld analyzers, while simultaneously witnessing the rise of powerful new techniques like Quantum Cascade Laser (QCL)-based microscopy. This evolution is fundamentally changing how researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals approach material analysis, enabling deeper insights and greater operational flexibility. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning is further augmenting these capabilities, creating intelligent systems that enhance productivity and decision-making [14]. These developments provide a more comprehensive toolkit for elucidating the structure, composition, and dynamics of materials, from battery components to biopharmaceuticals.

This application note details these key advancements, providing a structured comparison of new instrumentation, detailed experimental protocols for emerging techniques, and a curated list of essential research tools. Framed within the broader context of spectroscopic techniques for material science research, the information herein is designed to help scientists select the appropriate methodology and implement it effectively in their R&D and quality control workflows.

Advances in Spectroscopic Instrumentation

The instrumentation landscape is diversifying, with innovations aimed at enhancing sensitivity, resolution, and accessibility. The following tables summarize key recent product introductions and their specifications, highlighting the parallel development of sophisticated laboratory systems and capable field-portable devices.

Table 1: Recent Advances in Benchtop and Laboratory Instrumentation

| Technique | Instrument/Platform | Key Advancements | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| FT-IR Spectrometry | Bruker Vertex NEO [9] | Vacuum optical path to remove atmospheric interference; multiple detector positions; interleaved time-resolved spectra. | Protein studies, far-IR research, analysis requiring high spectral fidelity. |

| Multi-collector ICP-MS | Thermo Fisher Scientific Neoma [14] | New detector array for a broad range of isotopic applications; Qtegra Intelligent Scientific Data Solution software. | High-precision ultratrace elemental and isotopic analysis. |

| NMR Spectrometry | Benchtop NMR (e.g., Oxford Instruments) [15] | Cryogen-free operation using permanent magnets; small footprint (0.5-2.5 T, 20-100 MHz); enables in-line reaction monitoring. | Structural and compositional analysis of chemicals and polymers in lab or near-line manufacturing. |

| UV/vis Spectrometry | Shimadzu Lab UV/vis [9] | New software functions to ensure properly collected data. | Reliable and consistent ultraviolet and visible light absorption/reflectance measurements. |

| Fluorescence Spectrometry | Horiba Veloci A-TEEM [9] | Simultaneous collection of Absorbance, Transmittance, and Excitation-Emission Matrix (A-TEEM). | Biopharmaceutical analysis (monoclonal antibodies, vaccine characterization, protein stability). |

Table 2: Recent Advances in Portable, Handheld, and Specialized Systems

| Technique | Instrument/Platform | Key Advancements | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Handheld NIR | Various (e.g., Metrohm, SciAps) [9] [16] | Miniaturization down to ~100g; use of MEMS and linear-variable filters; simplified sample presentation. | Agricultural product quality control, pharmaceutical raw material verification, polymer identification. |

| Handheld Raman | Metrohm TaticID-1064ST [9] | 1064 nm laser; on-board camera and note-taking capability; analysis guidance for users. | Hazardous material identification for emergency response teams. |

| QCL Microscopy | Bruker LUMOS II ILIM [9] | QCL source (1800-950 cm⁻¹); room-temperature focal plane array; fast imaging (4.5 mm²/s). | High-resolution chemical imaging for contaminants and material defects. |

| Super-Resolution MIP Microscopy | SIMIP [17] | Combines structured illumination with mid-infrared photothermal detection; ~60 nm resolution. | Nanoscale chemical and biological analysis beyond the diffraction limit. |

| Microwave Spectrometry | BrightSpec Broadband CP-MS [9] | First commercial broadband chirped pulse microwave spectrometer. | Unambiguous determination of gas-phase molecular structure and configuration. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Nanoscale Chemical Imaging with SIMIP Microscopy

Principle: Structured Illumination Mid-Infrared Photothermal (SIMIP) microscopy breaks the optical diffraction limit in chemical imaging by integrating structured illumination microscopy (SIM) with mid-infrared photothermal (MIP) detection. A quantum cascade laser (QCL) excites molecular vibrations, causing localized heating that modulates the fluorescence of adjacent thermosensitive dyes. A separate SIM system projects patterned light to resolve high-frequency spatial details normally unresolvable [17].

Figure 1: SIMIP Microscopy Experimental Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps for achieving super-resolution chemical imaging, from sample preparation to final image reconstruction.

Materials:

- SIMIP Microscope System: Equipped with a tunable QCL, a spatial light modulator (SLM), a 488 nm continuous-wave laser, and a scientific CMOS (sCMOS) camera [17].

- Sample Substrate: Glass coverslip suitable for high-resolution microscopy.

- Fluorescent Beads: 200 nm polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) or polystyrene beads embedded with thermosensitive fluorescent dyes for system validation [17].

- Biological or Material Sample: e.g., fixed cells or polymer blend thin sections.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: [17]

- Embed your sample with a thermosensitive fluorescent dye if it does not possess intrinsic autofluorescence.

- For validation, prepare a sample with 200-nm PMMA beads as a reference standard.

- Mount the sample on the microscope stage.

System Setup and Alignment:

- Synchronize the QCL and the SIM illumination system. Precise temporal synchronization is critical for imaging speed and accuracy [17].

- Set the QCL to the desired wavenumber range (e.g., 1420–1778 cm⁻¹) corresponding to the molecular vibration of interest (e.g., C=O stretch at ~1720 cm⁻¹).

Data Acquisition: [17]

- Project multiple striped light patterns onto the sample at different angles and phases using the SLM.

- For each pattern, the sCMOS camera acquires two images: one with the QCL on ("hot" image) and one with the QCL off ("cold" image).

- The QCL-induced heating reduces the fluorescence brightness in the "hot" image, creating a subtle photothermal signal.

Image Reconstruction and Analysis: [17]

- Process the acquired image stack using dedicated algorithms (e.g., Hessian SIM and sparse deconvolution) to extract the high-resolution MIP signal and reconstruct the final chemical image.

- The result is a chemical map with a spatial resolution of approximately 60 nm, which is about 1.5 times better than conventional MIR photothermal imaging.

Protocol: Cross-Modal Spectral Data Generation with SpectroGen AI

Principle: SpectroGen is a generative AI tool that acts as a virtual spectrometer. It is trained on a large dataset of materials with known spectra across multiple modalities (e.g., IR, X-ray, Raman). It learns the mathematical correlations between these modalities, allowing it to take an input spectrum (e.g., IR) and generate a predicted spectrum for a different modality (e.g., X-ray) with high accuracy, saving time and equipment costs [18].

Figure 2: SpectroGen AI Spectral Generation Workflow. This diagram illustrates the process of using AI to generate spectral data in a different modality from a single physical measurement, enabling rapid material quality assessment.

Materials:

- SpectroGen AI Platform: The generative AI tool, typically accessed via specialized software [18].

- Input Spectrometer: A physical spectrometer for the initial measurement (e.g., a low-cost infrared instrument).

- Sample: The material to be analyzed (e.g., a newly synthesized solid-state electrolyte).

Procedure:

- Data Collection and Preparation: [18]

- Scan your material sample using a single, accessible spectroscopic modality (e.g., Infrared).

- Ensure the spectral data is of high quality. Preprocess the data as needed (e.g., normalization, baseline correction) to match the input requirements of the SpectroGen model.

AI Model Execution: [18]

- Input the preprocessed spectral data into the SpectroGen AI tool.

- Specify the desired output modality (e.g., X-ray diffraction).

Output and Validation: [18]

- SpectroGen will generate the predicted spectrum in the target modality in less than one minute.

- The AI-generated spectra have been shown to have a 99% correlation with spectra obtained from physical instruments. For critical applications, spot-checking results with physical measurements is recommended.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The successful implementation of advanced spectroscopic methods relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components for the experiments and techniques described in this note.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Spectroscopy

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Thermosensitive Fluorescent Dyes | Dyes whose fluorescence intensity is modulated by local temperature changes induced by MIR absorption. | Acts as the reporter signal in MIP and SIMIP microscopy [17]. |

| Ultrapure Water (e.g., Milli-Q SQ2) | Provides water free of ionic and organic contaminants for sample preparation and buffer formulation. | Critical for preparing samples for FT-IR and NMR analysis to avoid interference [9]. |

| Deuterated Solvents | Solvents where hydrogen is replaced by deuterium, creating an NMR-silent background for 1H NMR analysis. | Essential for dissolving samples for NMR spectroscopy to avoid solvent signal overwhelming analyte signals [15]. |

| ATR Crystals (Diamond, ZnSe) | Crystals used in Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) accessories for FT-IR that enable direct measurement of solids and liquids without preparation. | Standard sampling accessory for modern FT-IR spectrometers for rapid material identification [9] [14]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Materials with a certified composition or spectral profile traceable to a national standard. | Used for calibration and validation of spectroscopic instruments, including handheld devices [16]. |

The ongoing advancements in spectroscopic instrumentation, from the miniaturization of handheld devices to the sophistication of QCL-based microscopy and AI-powered data generation, are profoundly enhancing the capabilities of materials science research. These developments provide researchers and drug development professionals with an unprecedented suite of tools that offer both high performance and remarkable flexibility. By enabling detailed analysis from the benchtop to the production line and down to the nanoscale, these techniques accelerate innovation, improve quality control, and open new avenues for discovery. The integration of these technologies promises to further streamline workflows and unlock deeper insights into the chemical and structural properties of next-generation materials.

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) is an advanced analytical technique that merges spectroscopy and digital imaging to provide detailed spatial and chemical information about a sample. Unlike standard imaging that captures only three broad color bands (red, green, and blue), HSI collects the full spectrum of light at each pixel in an image [19]. This data is structured as a three-dimensional array known as a hyperspectral data cube [20] [21].

The data cube consists of two spatial dimensions (x, y) and one spectral dimension (λ) [19] [21]. Each "slice" of the cube is a monochromatic image captured at a specific, narrow wavelength band. Conversely, for every single pixel in the image, a complete spectrum is obtained, which serves as a unique chemical spectral fingerprint for the material at that location [22] [19]. This capability to map chemical composition directly onto visual structure makes HSI a powerful tool for non-destructive analysis in material science.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of a Hyperspectral Data Cube

| Characteristic | Description | Typical Values/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Dimensions (x, y) | The number of pixels defining the image's length and width. | Varies with sensor resolution (e.g., 1024 x 1024 pixels) |

| Spectral Dimension (λ) | The number of contiguous wavelength bands measured. | Hundreds of bands [23] |

| Spectral Range | The portion of the electromagnetic spectrum covered. | Visible to Near-Infrared (Vis-NIR), e.g., 400–2500 nm [22] [24] |

| Spectral Resolution | The width of each individual wavelength band. | Can be ≤10 nm [24] |

| Data per Pixel | A full spectrum, acting as a unique material signature. | Spectral fingerprint [22] |

Figure 1: Hyperspectral Data Cube Structure. The cube is formed from two spatial (X, Y) and one spectral (λ) dimension. Each pixel in the spatial plane contains a full spectrum.

Core Principles and Data Acquisition Methodologies

The fundamental principle of HSI is that different materials interact with light in unique ways due to their specific chemical composition and physical structure. These interactions—including absorption, reflection, and emission—create a characteristic spectral signature [19]. HSI sensors detect these subtle variations across a wide, contiguous range of wavelengths, far beyond human vision [22] [23].

Several scanning techniques exist for acquiring the hyperspectral datacube, each with distinct advantages for material science applications [19].

- Spatial Scanning (Push Broom): A line-scanning sensor captures the full spectrum for each pixel in a line simultaneously. The datacube is built up as the sensor moves relative to the sample [19]. This is common for remote sensing and conveyor belt systems.

- Spectral Scanning (Tunable Filter): The entire scene is imaged at one specific wavelength at a time. A complete datacube is generated by sequentially scanning through each wavelength band using tunable filters [19]. This method is suitable for static laboratory analysis.

- Snapshot HSI: Emerging technologies capture the entire spatial and spectral information in a single exposure [19] [25]. Systems like Coded Aperture Snapshot Spectral Imagers (CASSI) enable real-time video-rate HSI, which is crucial for monitoring dynamic processes [25].

Table 2: Hyperspectral Data Acquisition Techniques

| Technique | Acquisition Method | Best Suited For | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Scanning (Push Broom) | Line-by-line, each with full spectral data [19] | Remote sensing, conveyor belt analysis, quality control | High spectral fidelity | Requires stable, relative movement |

| Spectral Scanning (Tunable Filter) | Wavelength-by-wavelength, full scene per wavelength [19] | Laboratory analysis, static samples | High spatial resolution; flexible band selection | Slower acquisition; potential for spectral smearing with moving samples |

| Snapshot HSI | Single exposure captures full datacube [19] [25] | Real-time monitoring, dynamic processes | No scanning artifacts; very fast acquisition | Higher cost; complex data reconstruction [25] |

Experimental Protocols for Material Analysis

Protocol 3.1: Hyperspectral Imaging for Material Identification and Classification

This protocol outlines the steps for using HSI to identify and classify different materials within a solid sample, such as in waste streams for recycling [22].

- 1. Sample Preparation: Present the sample in a stable manner. For mixed material streams (e.g., plastics, paper, composites), ensure the surface is accessible to the imager and free from obstructions that create shadows.

- 2. System Setup and Calibration:

- Instrumentation: Use a hyperspectral imager (push-broom or snapshot system) covering the Visible to Near-Infrared (Vis-NIR) or Short-Wave Infrared (SWIR) range (e.g., 400–2500 nm) [22].

- Spatial Resolution: Set the resolution so the pixel size is smaller than the features of interest to avoid mixed pixels.

- Calibration: Perform white and dark reference calibration to correct for sensor noise and uneven illumination.

- 3. Data Acquisition: Acquire the hyperspectral datacube. For push-broom systems, ensure a constant speed between the sensor and the sample. For snapshot or tunable filter systems, ensure the sample is static during capture.

- 4. Data Preprocessing:

- Radiometric Correction: Convert raw digital numbers to reflectance or absorbance values using the calibration data.

- Denoising: Apply algorithms (e.g., non-local meets global approach) to reduce sensor noise [20].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Use techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Maximum Noise Fraction (MNF) to reduce data volume and highlight meaningful variance [20].

- 5. Spectral Unmixing and Analysis:

- Endmember Extraction: Identify the pure spectral signatures of constituent materials using algorithms like Pixel Purity Index (PPI) or N-FINDR [20]. These are the "endmembers."

- Abundance Estimation: For each pixel in the image, estimate the fractional abundance of each endmember present using linear spectral unmixing (e.g., with

estimateAbundanceLSfunction) [20].

- 6. Validation: Validate the identified materials and their distributions by comparing with results from a complementary technique, such as Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, on selected points.

Figure 2: HSI Material Analysis Workflow. Key steps from sample preparation to validation, highlighting preprocessing and spectral analysis phases.

Protocol 3.2: Real-time Snapshot HSI for Dynamic Process Monitoring

This protocol is designed for monitoring dynamic processes or reactions in real-time, leveraging snapshot HSI technology [25].

- 1. System Configuration:

- Instrumentation: Employ a snapshot hyperspectral imaging system (e.g., CASSI-based) capable of video-rate acquisition [25].

- Lighting: Ensure consistent, high-intensity illumination to compensate for the low light throughput of some snapshot systems and maintain a good signal-to-noise ratio.

- 2. Onboard Processing Setup:

- Hardware: Integrate a compact, powerful processing unit like an NVIDIA Jetson platform for edge computing [26].

- Reconstruction Algorithm: Implement a pre-trained deep learning model (e.g., a lightweight Convolutional Neural Network or a deep unfolding network) on the hardware to rapidly reconstruct the hyperspectral datacube from the compressed 2D measurement [24] [25].

- 3. Real-time Data Acquisition and Processing: Initiate the process and begin continuous imaging. The system captures snapshot measurements and the onboard AI reconstructs the datacubes in real-time.

- 4. Target Detection and Monitoring: Program the system to analyze each reconstructed datacube for specific spectral signatures of interest. This could involve:

- 5. Data Logging and Output: Log the results, which could be the abundance of a key component over time, a chemical map of the reaction surface for each frame, or an alert when a specific spectral signature is detected.

Application in Material Science: Waste Material Characterization

A pivotal application of HSI in material science is the characterization and sorting of complex waste streams to enhance recycling efficiency. A study demonstrated this using HSI to identify material components in municipal solid waste [22].

- Objective: To rapidly identify and quantify materials in mixed waste (like paper, plastic, and composites) for separation and recycling.

- Methodology: Researchers used HSI in the short-wave infrared range to capture unique spectral fingerprints of materials. They applied the Pixel Purity Index (PPI) and the sequential maximum angle convex cone algorithms to extract the spectral signatures of pure components (endmembers) like cellulose, lignin, and polypropylene from the complex dataset [22].

- Results and Efficacy: The methodology was successfully applied to a disposable coffee cup, accurately detecting and quantifying the mixed materials. The area estimation for different materials had an error of less than 1% [22]. This high precision allows for the creation of abundance maps that show the location and concentration of each material type, enabling automated sorting systems to efficiently separate recyclables.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Hyperspectral Imaging

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role in HSI | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Imager | Core sensor for capturing spatial-spectral datacacubes. | Types: Push-broom, snapshot (CASSI), tunable filter. Selection depends on required speed, resolution, and sample type [19] [25]. |

| Spectral Calibration Lamps | Provides known emission lines for accurate wavelength calibration of the HSI system. | Essential for quantitative analysis; ensures spectral signatures are measured at correct wavelengths. |

| White Reference Standard | A material with near-perfect, flat reflectance across the spectral range of interest. | Used for radiometric calibration to convert raw sensor data to reflectance/absorbance values [20]. |

| Dark Reference Standard | A material with near-zero reflectance (e.g., a closed lens cap). | Captures system noise and dark current, which is subtracted during calibration. |

| Spectral Library | A database of pure spectral signatures from known materials. | Serves as a reference for spectral matching and material identification (e.g., ECOSTRESS library) [20]. |

| AI/ML Processing Software | Tools for denoising, unmixing, and classifying large HSI datasets. | Algorithms like CNN, PPI, and N-FINDR are critical for interpreting complex hyperspectral data [22] [20] [24]. |

Practical Applications in Material Science and Pharmaceutical Development

The advancement of lithium-ion battery (LIB) technology is intrinsically linked to the deep characterization of its core components: electrodes and electrolytes. Within the broader context of material science research, spectroscopic techniques provide the essential toolkit for elucidating the chemical and structural properties that govern battery performance, safety, and longevity [27]. Among these, Fourier Transform-Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy stand out as pivotal, complementary methods for probing molecular structures, interfacial processes, and dynamic behaviors [28]. This application note details the protocols and applications of these techniques, providing a framework for researchers to investigate and optimize battery materials from fundamental research to failure analysis.

FT-IR spectroscopy functions on the principle that chemical bonds within a molecule vibrate at specific frequencies when exposed to infrared light, creating a unique absorption spectrum that serves as a molecular fingerprint [29] [30]. This makes it exceptionally capable of identifying functional groups and molecular structures. NMR spectroscopy, conversely, provides insights into the local chemical environment, dynamics, and mobility of specific nuclei, such as lithium-7, offering an unparalleled view of ion transport and coordination in electrolytes [27].

The synergy of these techniques is particularly powerful. While FT-IR excels at identifying molecular bonding and degradation products, NMR is uniquely suited to study ion mobility and structural changes within electrodes during cycling [27] [31]. This combination is instrumental in solving complex challenges in battery science, from optimizing the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) to understanding calendar aging.

Theoretical Background & Application Scope

Fundamentals of FT-IR and NMR for Battery Analysis

In FT-IR spectroscopy, the interaction between infrared radiation and molecular vibrations that create a dipole moment produces an absorption spectrum. Different vibrational modes, such as stretching and bending, appear as characteristic peaks, allowing for the identification of functional groups in electrode coatings, binder polymers, and electrolyte species [29]. For instance, the formation of a carbonyl group (C=O) from electrolyte degradation can be readily identified by a sharp peak around 1700 cm⁻¹ [29].

NMR spectroscopy leverages the magnetic properties of certain nuclei. When placed in a strong magnetic field, these nuclei absorb and re-emit electromagnetic radiation at frequencies characteristic of their chemical environment. For LIBs, this is crucial for studying lithium-ion dynamics, quantifying ion concentrations in electrolytes, and detecting the formation of metallic lithium deposits on anodes, which is a critical safety concern [31].

Application Across the Battery Lifecycle

The integration of FT-IR and NMR provides comprehensive insights across the entire battery development and lifecycle management chain [27].

- Research & Development (R&D): FT-IR is used to analyze the molecular structure of novel electrolyte additives and binder systems, while NMR studies the local chemical environments and ion mobility in new electrolyte formulations to improve conductivity and thermal stability [27].

- Manufacturing & Quality Control: FT-IR monitors the composition of binders and electrolytes during production and assesses the purity of electrolytes to ensure no organic impurities are present [27].

- Performance Testing: Both techniques track degradation processes. FT-IR identifies organic components and decomposition products within the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) on electrodes, and NMR analyzes the mobility of lithium ions within the electrolyte during battery cycling to evaluate ion diffusion performance [27] [31].

- Failure & Safety Analysis: FT-IR gas analyzers can rapidly identify and quantify toxic and hazardous gases released during thermal runaway events [31]. Ex-situ NMR can investigate degradation mechanisms of electrode materials over time [31].

Table 1: Key Applications of FT-IR and NMR in LIB Analysis

| Battery Component | FT-IR Applications | NMR Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Electrolyte | Identify Li salts (e.g., LiPF₆); Detect solvent degradation (e.g., formation of esters, ethers, carbonates); Characterize polymer electrolytes [27] [32] | Quantify Li⁺ concentration & coordination; Measure ion mobility & diffusion coefficients; Study transport mechanisms [27] [31] |

| Cathode & Anode | Analyze binder composition (e.g., PVDF); Characterize functional groups in novel materials (e.g., metal oxides); Study surface chemistry & SEI layer composition [27] [33] | Probe local structure of Li in electrode hosts; Identify Li metal plating; Characterize structural changes during cycling [27] [31] |

| Interphases | Molecular identification of SEI components (e.g., Li₂CO₃, P-O, C-O species) [27] | Study the structure, dynamics, and electrochemical properties at interfaces [31] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: FT-IR Analysis of Electrolyte Degradation

This protocol outlines the procedure for characterizing the molecular composition of a liquid electrolyte and identifying its degradation products after cycling using the Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) technique.

1. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials Table 2: Essential Materials for FT-IR Analysis of Electrolytes

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| FT-IR Spectrometer | Must be equipped with an ATR accessory (e.g., diamond crystal). |

| Argon-filled Glovebox | For safe handling of air- and moisture-sensitive electrolytes (< 1 ppm H₂O/O₂). |

| Anhydrous Solvents | e.g., Dimethyl Carbonate (DMC), for cleaning the ATR crystal. |

| Syringe & Pipettes | For transferring small volumes of electrolyte. |

| Kimwipes or Lint-free Cloth | For cleaning. |

2. Sample Preparation

- Environment: All sample preparation must be performed in an argon-filled glovebox to prevent contamination by air and moisture.

- Crystal Cleaning:

- Apply a few drops of anhydrous DMC to the diamond ATR crystal.

- Gently wipe clean with a lint-free cloth. Repeat until no residue from previous measurements is detected.

- Background Measurement:

- Ensure the crystal is perfectly clean and dry.

- Collect a background spectrum with 32 scans at 4 cm⁻¹ resolution.

- Sample Loading:

- For pristine electrolyte: Carefully place a single drop of the electrolyte onto the center of the ATR crystal.

- For cycled electrolyte: Extract electrolyte from a disassembled cell in the glovebox and place a drop on the crystal.

3. Data Acquisition

- Parameters:

- Spectral Range: 4000 - 650 cm⁻¹

- Resolution: 4 cm⁻¹

- Number of Scans: 64-128 (to ensure a good signal-to-noise ratio)

- Measurement: Initiate data collection. The instrument will record the infrared absorption spectrum.

4. Data Analysis

- Process spectra by applying atmospheric suppression and baseline correction algorithms.

- Identify characteristic peaks by comparing the pristine and cycled electrolyte spectra. Key regions to monitor include:

- ~1750-1700 cm⁻¹: Possible formation of carbonyl-containing degradation products (e.g., esters).

- ~1500-1300 cm⁻¹: Changes in C-H bending regions.

- ~1100-1000 cm⁻¹: Changes in P-F and P-O-C vibrations from LiPF₆ salt decomposition.

- Use difference spectroscopy (subtracting the pristine spectrum from the cycled spectrum) to highlight the formation of new species.

The following workflow summarizes the FT-IR analysis protocol:

FT-IR Analysis Workflow

Protocol 2: NMR Investigation of Li-Ion Mobility in Electrolytes

This protocol describes the use of solution-state NMR to study the local environment and mobility of lithium ions in a liquid electrolyte system.

1. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials Table 3: Essential Materials for NMR Analysis of Electrolytes

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| High-Field NMR Spectrometer | Preferably with a dedicated broadband probe. |

| NMR Tubes | Standard 5 mm OD, with PTFE caps. |

| Argon-filled Glovebox | For sample preparation. |

| Deuterated Solvent | e.g., Deuterated Acetonitrile (CD₃CN), to provide a lock signal. |

| Capillary Tube | Containing a reference compound (e.g., TMS). |

2. Sample Preparation

- Environment: Prepare the sample in an argon-filled glovebox.

- NMR Tube Preparation:

- In a vial, mix the electrolyte with ~10% v/v of a deuterated solvent (e.g., CD₃CN) to provide the instrument lock signal.

- Using a Pasteur pipette, transfer approximately 500-600 µL of the mixture into a 5 mm NMR tube.

- Seal the tube tightly with a PTFE cap to prevent solvent evaporation and contamination.

3. Data Acquisition

- Insert Sample: Place the NMR tube into the spectrometer magnet.

- Tune, Match, and Lock: Automatically tune the probe to the ⁷Li frequency, and lock the signal to the deuterated solvent.

- Shim the Magnet: Optimize the magnetic field homogeneity for the sample.

- Acquire ⁷Li Spectrum:

- Set the number of scans (e.g., 16-64).

- Set a pulse width corresponding to a 30-45° flip angle.

- Use a sufficient relaxation delay (D1 > 5 * T1, typically 10-30 seconds for ⁷Li).

- Run the experiment to obtain a 1D ⁷Li NMR spectrum.

- (Optional) Diffusion-Ordered Spectroscopy (DOSY): To measure Li⁺ diffusion coefficients, a DOSY pulse sequence can be run.

4. Data Analysis

- Analyze the chemical shift (δ, ppm) of the ⁷Li signal, which provides information on the Li⁺ coordination environment.

- Measure the signal linewidth, which can be related to ion mobility and exchange dynamics.

- If DOSY was performed, process the data to extract the diffusion coefficient, which can be used to calculate ionic conductivity.

The following workflow summarizes the NMR analysis protocol:

NMR Analysis Workflow

Advanced and Integrated Methodologies

In-situ and Operando Techniques

Moving beyond ex-situ analysis, in-situ and operando methodologies allow for the real-time monitoring of battery processes under operating conditions, providing a direct correlation between electrochemical performance and molecular/structural changes [31] [34].

- In-situ FT-IR: Researchers can synchronize FT-IR spectroscopy with electrochemical reactions to monitor molecular changes during voltage cycling in a lab-level battery model system [31]. This provides insight into the reaction process of the molecules in addition to the electrochemical response.

- In-situ Solid-State NMR: This technique allows for the investigation of the behavior of electrolyte and electrode materials during battery charging and discharging cycles [31]. For example, it can be used to detect the formation of metallic lithium species on hard carbon anodes, providing critical information on degradation and failure mechanisms [31].

Infrared Nanospectroscopy (nano-FTIR)

A groundbreaking advancement in the field is infrared nanospectroscopy (nano-FTIR), which combines FT-IR with atomic force microscopy to achieve nanoscale spatial resolution [35]. This technique overcomes the diffraction limit of conventional FT-IR, enabling the characterization of battery material interfaces in their native environment at a resolution of one-billionth of a meter [35]. This is particularly valuable for studying hidden interfacial processes at the nanoscale that are critical to the operation and safety of Li-ion batteries, such as the formation and evolution of the SEI layer [35].

FT-IR and NMR spectroscopy are indispensable tools in the modern battery researcher's arsenal, providing deep, complementary insights into the molecular and ionic world of lithium-ion batteries. From routine quality control to cutting-edge operando and nanoscale analysis, these techniques empower scientists to decipher complex degradation pathways, optimize material properties, and engineer safer, more efficient energy storage systems. The detailed protocols and applications outlined in this document provide a foundational guide for leveraging these powerful spectroscopic methods within the broader context of material science research, ultimately contributing to the accelerated development of next-generation battery technologies.

The adoption of Process Analytical Technology (PAT) frameworks, encouraged by regulatory agencies worldwide, is transforming pharmaceutical manufacturing by enabling real-time quality assurance [36] [37]. Raman spectroscopy has emerged as a premier PAT tool for both bioprocessing monitoring and active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) quantification due to its molecular specificity, minimal sample preparation requirements, and compatibility with aqueous environments [36] [37]. This application note details standardized protocols for implementing inline Raman spectroscopy to monitor bioreactor processes and quantify API content in solid dosage forms, supporting the broader thesis that advanced spectroscopic techniques are essential for modern material science research in pharmaceuticals.

Application Principles and Techniques

Raman spectroscopy is based on the inelastic scattering of light from molecular vibrations, providing a unique "molecular fingerprint" for chemical compounds [38]. Unlike infrared spectroscopy, Raman is particularly effective for aqueous systems because water produces a weak Raman signal, minimizing interference when analyzing dissolved analytes in bioreactors [37]. For solid dosage forms, Transmission Raman Spectroscopy (TRS) has gained prominence as it probes the entire volume of a tablet, providing more representative API content measurements compared to surface-based techniques [39].

Table 1: Raman Spectroscopy Techniques for Pharmaceutical Applications

| Technique | Application Scope | Key Advantage | Typical Configuration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inline Bioprocess Monitoring | Real-time monitoring of nutrients, metabolites, and products in bioreactors [40] [41] | Non-invasive measurement through view ports or immersion probes without breaking sterility [40] | 785 nm laser, immersion probe with sapphire tip, fingerprint region (270-2000 cm⁻¹) [40] |

| Transmission Raman Spectroscopy (TRS) | Bulk quantification of APIs in solid dosage forms [42] [39] | Measures Raman photons transmitted through entire sample, providing superior bulk content representation [39] | Tablets compressed at 150-300 N, laser penetration through full thickness [42] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Inline Monitoring of a Fed-Batch Bioreactor

This protocol details the implementation of Raman spectroscopy for real-time monitoring of nutrients, metabolites, and products in a lab-scale E. coli bioprocess, based on a recently published study [40].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Bioprocess Raman Monitoring

| Material/Equipment | Specification | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectrometer | Portable, 785 nm laser, 450 mW power, f/1.3 optical bench, TEC-cooled detector [40] | Provides excitation source and detects inelastically scattered photons with high sensitivity |

| Immersion Raman Probe | Sapphire ball lens, 100 µm working distance, high temperature/pressure rated [40] | Enables non-invasive measurements in optically dense bioreactor media |

| Bioreactor System | 50 L capacity, glycerol-fed, with E. coli strain producing pharmaceutical compounds [40] | Provides controlled environment for bioprocess with relevant analytes |

| HPLC System | With appropriate columns and detectors | Provides reference "ground truth" measurements for chemometric model calibration [40] |

| RamanMetrix Software | Web-based interface with preprocessing and modeling capabilities [40] | Simplifies chemometric analysis for users without specialized expertise |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Bioprocess Operation: Conduct the glycerol-fed E. coli bioprocess according to established protocols. Extract samples hourly from the bioreactor for reference analysis [40].

Reference Analytics: Analyze all extracted samples using HPLC to determine reference concentrations for feedstock (glycerol), active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), and side products. These values serve as ground truth for model calibration [40].

Raman Spectral Collection: For each extracted sample, collect approximately 20 Raman spectra using the immersion probe. Use full laser power (450 mW) with 1500 ms acquisition time per spectrum. Ensure the probe is properly immersed in the sample [40].

Spectral Preprocessing: Import Raman spectra into analysis software (e.g., RamanMetrix). Apply baseline correction to remove fluorescence background and normalize spectra to correct for variations in laser power and acquisition time [40].

Chemometric Modeling: Associate preprocessed spectra with HPLC reference data. Develop a Support Vector Machine (SVM) model based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA) scores with six components for predicting concentrations of key analytes (glycerol, Product 1, Acid 3) [40].

Model Validation: Validate model performance using cross-validation techniques and independent test sets. A successfully calibrated model should accurately predict analyte concentrations from Raman spectra alone, enabling real-time monitoring [40].

The workflow below illustrates the complete process from data acquisition to real-time monitoring.

Protocol 2: Transmission Raman Spectroscopy for API Quantification in Tablets

This protocol describes the use of TRS for non-destructive quantification of API content in orally disintegrating tablets (ODTs), based on studies of acetaminophen in D-mannitol matrices [42] and ondansetron tablets [43].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for TRS API Quantification

| Material/Equipment | Specification | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Transmission Raman Spectrometer | With transmission geometry, 785 nm excitation [42] | Enables measurement of Raman signals transmitted through entire tablet |

| Pharmaceutical Materials | Acetaminophen (API) and D-mannitol (excipient) [42] | Model system for method development and validation |

| Tablet Compression System | Capable of applying controlled forces (150-300 N) [42] | Produces tablets with consistent physical properties |

| HPLC System | Validated method for API quantification [43] | Provides reference measurements for model calibration |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Tablet Preparation: Prepare tablets with varying API concentrations (e.g., 2-10 mg for ondansetron) using compression forces of 150 N and 300 N. For method development, ensure API content spans the expected range [42] [43].

Reference Analysis: Quantify actual API content in all calibration tablets using established HPLC methods. This provides reference values for model development [43].

TRS Spectral Acquisition: Position each tablet in the transmission Raman spectrometer. Collect spectra using appropriate laser power and integration times to achieve sufficient signal-to-noise ratio without damaging the sample [42].

Spectral Correction: Apply correction techniques to mitigate spectral distortions caused by tablet thickness, porosity, and compaction force. Recent studies have developed specialized standardization methods that significantly improve model accuracy [39].

Multivariate Modeling: Develop Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression models to correlate spectral features with API content. Use a minimum of three latent variables for optimal performance [43].

Model Validation: Validate models using independent test sets not included in model calibration. For the ondansetron model, well-validated PLS showed strong correlation with HPLC results (R²CV = 0.95, RMSECV = 0.68; R²Pred = 0.96, RMSEP = 0.57) [43].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Performance Metrics for Raman Applications

Table 4: Quantitative Performance of Raman Spectroscopy in Pharmaceutical Applications

| Application | Analytes | Model Performance | Key Validation Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli Bioprocess Monitoring [40] | Glycerol, Pharmaceutical Products, Acidic Byproducts | Accurate concentration prediction demonstrated via cross-validation | Comparison with HPLC reference methods |

| Perfusion Bioreactor Control [41] | Glucose, Lactate | Glucose control at 1.5-4 g/L with ±0.4 g/L variability | RMSEP ~0.2 g/L for glucose |

| Tablet API Quantification [42] | Acetaminophen in D-mannitol | High linear correlation (R² = 0.98) | RMSEP: 1.22-1.59% |

| Personalized Medicine Tablets [43] | Ondansetron (2-10 mg) | R² = 0.95-0.96 with HPLC | Prediction error: 2-3% (excluding 10 mg samples) |

Advanced Implementation: Automated Control Systems

For advanced applications, Raman systems can be integrated into automated control loops. In perfusion cell cultures, integrating a Raman flow cell in the cell-free harvest stream enables real-time glucose control without interference from high cell densities [41]. Implementation involves:

Robust Model Development: Creating quantitative models for glucose based on multiple cultivations across different bioreactor scales [41].

Control Loop Integration: Using model predictions to automatically adjust external glucose feed rates, maintaining concentrations at desired setpoints (e.g., 1.5 g/L or 4 g/L) [41].

System Validation: Demonstrating control stability over several days with minimal variability (±0.4 g/L) [41].

The diagram below illustrates this automated control implementation.

Inline Raman spectroscopy represents a powerful PAT tool that aligns with Quality by Design principles and regulatory guidance for pharmaceutical manufacturing [36]. The protocols detailed in this application note demonstrate robust methodologies for implementing Raman spectroscopy across diverse pharmaceutical applications, from monitoring complex bioprocesses to quantifying API content in solid dosage forms. As the technology continues to advance with improved instrumentation, standardized data analysis techniques, and open-source spectral databases [38], Raman spectroscopy is positioned to become an increasingly accessible and vital tool for pharmaceutical scientists committed to ensuring product quality through advanced material characterization techniques.

Within the broader context of a thesis on spectroscopic techniques for material science research, the precise characterization of polymers and nanomaterials is paramount for understanding the fundamental structure-property relationships that govern their performance. These relationships are heavily influenced by molecular-level interactions, particularly at the polymer-filler interface in nanocomposites [44]. The dispersion of filler particles, the extent of interfacial bonding, and the dynamics of polymer chains at the interface are critical factors that determine the macroscopic properties of the material, such as its mechanical, electrical, and thermal characteristics [44]. This application note provides detailed protocols and a toolkit for researchers and drug development professionals to effectively characterize these relationships using a suite of complementary spectroscopic techniques.

Experimental Protocols for Spectroscopic Characterization

Protocol: Characterizing Polymer-Nanofiller Interfaces using Solid-State NMR and FT-IR

This protocol details a combined approach to analyze the interfacial region in a polymer nanocomposite, using a mixed-matrix membrane (MMM) for CO₂ capture as a model system [45].

1. Hypothesis: The incorporation of a metal-organic framework (MOF) nanofiller into a polymer matrix preserves the filler's adsorption mechanism and enhances the composite's selectivity and permeability through specific interfacial interactions.

2. Materials:

- Polymer matrix (e.g., a suitable polyimide or polyetherimide).

- Nanofiller (e.g., a metal-organic framework such as ZIF-8).

- Solvent for polymer dissolution (e.g., dichloromethane or N,N-Dimethylformamide).

- Laboratory mixer (e.g., an overhead stirrer or centrifugal mixer).

3. Equipment:

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectrometer equipped with an Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) accessory.

- Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectrometer.

4. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare the MMM by dispersing the MOF filler at a specific loading (e.g., 10-20 wt%) into the polymer solution. Cast the mixture into a film and allow the solvent to evaporate fully. Prepare a pure polymer film for control analysis.

- FT-IR Analysis:

- Collect a background spectrum using the clean ATR crystal.

- Place a small section of the MMM film on the ATR crystal and ensure good contact.

- Acquire the FT-IR spectrum in the range of 4000-600 cm⁻¹ with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹ and 32 scans.

- Repeat for the pure polymer film and the pure MOF filler.

- Data Analysis: Identify shifts in characteristic absorption bands (e.g., C=O stretching, C-N stretching) in the composite spectrum compared to the pure components. A shift may indicate hydrogen bonding or other interactions between the polymer chains and the filler surface [45].

- Solid-State NMR Analysis:

- Pack the finely ground MMM film into a magic-angle spinning (MAS) NMR rotor.

- Acquire ¹³C cross-polarization magic-angle spinning (CP/MAS) NMR spectra.

- Data Analysis: Compare the chemical shifts of the polymer's carbon atoms in the composite with those in the pure polymer spectrum. Changes in chemical shift or signal broadening can reveal the restricted mobility of polymer chains at the filler interface and confirm the nature of the interactions [44] [45].

5. Interpretation: The combination of FT-IR and solid-state NMR provides a comprehensive picture. FT-IR identifies the chemical groups involved in bonding, while solid-state NMR confirms the molecular-level constraints and interactions, validating that the MOF's adsorption sites remain accessible and functional within the polymer matrix [45].

Protocol: Microplastic Identification and Characterization via Integrated IR and Raman Spectroscopy

This protocol, adapted from the work of Ramos and Dias, uses a dual-technique approach to accurately identify and characterize microplastics from complex environmental samples [46].

1. Hypothesis: Integrating the complementary strengths of infrared and Raman spectroscopy will overcome the limitations of either technique used alone, enabling accurate identification of mixed and weathered polymer types.

2. Materials:

- Environmental sample (e.g., filtered water or sediment).

- Analytical filters.

- Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) for organic matter removal.

3. Equipment:

- FT-IR Microscope.

- Raman Microscope with appropriate laser wavelengths (e.g., 785 nm to reduce fluorescence).

4. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Sieve and filter the environmental sample to isolate particles below 5 mm. Treat with H₂O₂ if necessary to degrade organic matter. Deposit the particles on an analytical filter suitable for transmission IR or on a glass slide for Raman analysis.

- FT-IR Analysis:

- Locate individual particles using the microscope's visible light.

- Acquire IR spectra in transmission or reflection mode.

- Compare the acquired spectrum to a library of polymer reference spectra (e.g., polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE), polystyrene (PS)).

- Raman Analysis:

- Locate the same or similar particles.

- Acquire Raman spectra, ensuring the laser power does not degrade the sample.

- Compare the fingerprint region (e.g., 500-1500 cm⁻¹) to reference libraries.

- Data Integration:

- For complex particles, use the IR data for robust functional group identification (e.g., C-Cl bond for PVC) and the Raman data for detailed structural fingerprints (e.g., backbone conformation of PS) [46].

- Apply multivariate curve resolution (MCR) or similar deconvolution algorithms to separate overlapping signals from polymer mixtures or additives [46].

5. Interpretation: The synergy between the two techniques allows for confident polymer identification. Infrared spectroscopy efficiently screens for chemical bonds, while Raman spectroscopy provides complementary structural details, which is particularly useful for weathered samples where spectra can be altered [46].

Table 1: Summary of Spectroscopic Techniques for Polymer and Nanomaterial Characterization

| Technique | Key Measurable Parameters | Typical Data Output | Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid-State NMR [44] [45] | Chemical shift, signal intensity, relaxation times | ¹³C CP/MAS spectrum | Molecular structure, polymer-chain dynamics at interface, degree of cross-linking. |

| FT-IR / ATR-FTIR [44] [45] [47] | Wavenumber (cm⁻¹), absorbance/transmittance | Infrared absorption spectrum | Chemical bonding, functional groups, surface chemistry, polymer-filler interactions. |

| Raman Spectroscopy [44] [46] | Raman shift (cm⁻¹), intensity | Raman scattering spectrum | Molecular vibrations, crystal structure, chemical structure of fillers (e.g., graphene defects). |