Advanced Strategies for Calibration Drift Correction in Field Spectrometers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing calibration drift in field spectrometers.

Advanced Strategies for Calibration Drift Correction in Field Spectrometers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing calibration drift in field spectrometers. It covers the fundamental causes of drift, including environmental factors and instrumental aging, and explores a range of correction methodologies from traditional standardization to advanced machine learning algorithms. The content offers practical troubleshooting advice, compares the performance of different correction techniques through real-world case studies, and delivers actionable validation protocols to ensure data integrity in long-term biomedical and clinical research studies.

Understanding Calibration Drift: Sources and Impacts on Data Integrity

Defining Calibration Drift and Its Critical Importance in Field Spectroscopy

Definition and Causes of Calibration Drift

What is calibration drift? Calibration drift is the slow, often monotonic change in the response of a measurement instrument over time, leading to a gradual loss of measurement accuracy. It is a key concern in field spectroscopy, where it can cause skewed readings and increase measurement uncertainty, potentially compromising data integrity and research outcomes [1].

What are the primary causes of calibration drift? The causes are multifaceted and can include:

- Environmental Factors: Sudden changes in temperature or humidity are common causes of drift [1]. Deep-sea environments, combining low temperatures and high pressure, present particular challenges [2].

- Instrument Aging and Use: The natural aging of electronic or mechanical components, along with frequent use, accelerates the need for recalibration [1].

- Physical Stress: Exposure to harsh conditions, mechanical shock, or vibration can induce calibration errors [1].

- Optical Component Issues: Dirty windows or lenses in front of fiber optics or light pipes can cause analysis to drift [3].

- Component Degradation: Aging light sources (e.g., calibration lamp bulb degradation) and detectors can alter the system's response [4].

Quantitative Data on Calibration Drift

The following table summarizes documented drift rates and impacts from various spectroscopic and sensor applications.

Table 1: Documented Calibration Drift Rates and Impacts

| Instrument/Sensor Type | Observed Drift Rate / Magnitude | Primary Cause / Context | Impact on Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iridium-192 Brachytherapy Source | +0.15% per year (post-2018) [5] | Update of primary metrology standards [5] | Dosimetric discrepancies in medical radiotherapy [5] |

| Quartz Resonance Pressure Sensor | Increased drift with deployment depth [2] | Deep-sea environment (low temperature, high pressure) [2] | Accumulated depth and positioning errors [2] |

| Optical π-FBG Pressure Sensor | Annual drift reduced to < ±0.002 MPa after correction [2] | Sensor aging in deep-sea conditions [2] | High-precision depth measurement for underwater navigation [2] |

| Calibration Light Source | Output change: ~0.1%/hr at 350 nm; ~0.02%/hr at 900 nm [4] | Natural bulb degradation over time [4] | Introduces uncertainty in radiometric calibration [4] |

Troubleshooting FAQs for Field Spectrometers

Q1: My spectral analysis results are inconsistent between measurements of the same sample. What should I check?

- Step 1: Clean optical windows. Dirty windows on the fiber optic or direct light pipe are a common cause of drift and poor results [3]. Clean them according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

- Step 2: Verify calibration. Recalibrate your spectrometer. It is recommended to calibrate before starting a job and at least once daily [6].

- Step 3: Check the vacuum pump (if applicable). In optical emission spectrometers, a malfunctioning vacuum pump can cause low-intensity loss for elements like Carbon, Phosphorus, and Sulfur, leading to incorrect values [3]. Listen for unusual pump noises and check for oil leaks [3].

- Step 4: Ensure proper sample preparation. Ensure samples are not contaminated during handling (e.g., by skin oils) and are properly prepared (e.g., reground) before analysis [3].

Q2: How can I tell if my spectrophotometer's color measurements are drifting?

- Symptom: Customers may reject shipments due to color inaccuracies, or you may identify color issues during quality control checks [6].

- Prevention: Regular calibration and maintenance are critical. A device should be calibrated each time you start a job and at least once a day. The longer you go without calibration, the harder it is for the device to correct itself [6].

- Verification: For fleets of instruments, use a tool like NetProfiler to check wavelength errors and validate that all devices are measuring consistently on a monthly basis [6].

Q3: What is the recommended long-term maintenance schedule for a field spectrometer?

- Daily/Per Job: Perform a full instrument calibration [6].

- Weekly/Monthly: Clean the instrument's optical components, such as the aperture and white reference tile, following the user manual. Frequency depends on the operating environment (e.g., daily in a factory, monthly in a clean lab) [6].

- Annually: Seek factory ISO certification. Annual certification verifies measurement accuracy, provides NIST traceability, and is often required for regulatory compliance [6].

Advanced Drift Correction Methodologies

For long-term research projects, advanced correction methods are essential for data integrity. These often involve algorithmic correction and specialized experimental design.

Algorithmic Correction for Long-Term Studies

In techniques like Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), signal drift over extended periods (e.g., 155 days) can be corrected using quality control (QC) samples and machine learning [7].

- Workflow: A virtual QC sample is established from all QC measurements. Correction factors for each chemical component are calculated based on its peak area and a function of batch number and injection order. Algorithms like Random Forest (RF) are then used to model and correct the drift in sample data [7].

- Performance: Research shows that the Random Forest algorithm provides the most stable and reliable correction for long-term, highly variable data, outperforming Spline Interpolation and Support Vector Regression [7].

In-Situ Drift Correction with Reference Probes

A powerful hardware-based method for field sensors involves using a reference probe deployed alongside the primary sensor [2].

- Principle: The reference probe is designed to be insensitive to the primary analyte (e.g., pressure) but remains exposed to the same environmental conditions (e.g., temperature) that cause drift. The drift coefficients are extracted from the reference probe and used to correct the primary sensor's output [2].

- Experimental Validation: This method has been validated in simulated deep-sea environments, where it reduced the annual drift of an optical pressure sensor to less than ±0.002 MPa. Time-series forecasting with an ARIMA model suggested a calibration period not exceeding six months for long-term deployment [2].

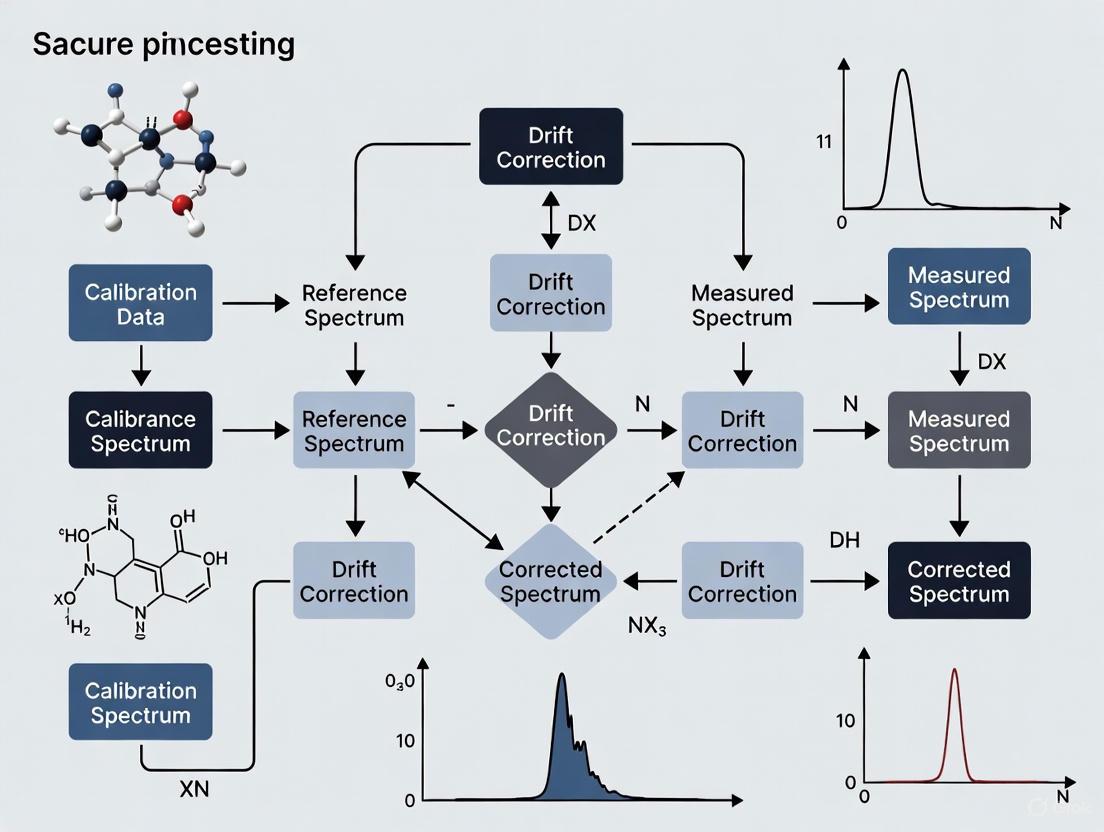

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow and relationship between components in a reference probe correction system.

In-Situ Drift Correction with a Reference Probe

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Drift Monitoring and Correction

| Item Name | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| NIST-Traceable Calibration Light Source | Provides a known spectral output to calibrate the spectrometer's radiometric response. Requires periodic recalibration due to inherent output degradation (e.g., ~0.1%/hr at 350 nm) [4]. |

| Emission Line Sources (Hg, Ar, Xe, etc.) | Used for precise wavelength calibration. The distinct atomic emission lines allow for accurate characterization and correction of the wavelength axis across the spectrometer's range [4]. |

| Non-Absorbing Reference Matrix (KBr, KCl) | Essential in techniques like DRIFTS for diluting powdered samples to minimize spectral artefacts and provide a consistent scattering environment for quantitative analysis [8]. |

| Stray Light Filters (e.g., Holmium Oxide) | Used to measure and characterize stray light within the spectrometer, which is critical for manufacturing quality control and long-term performance tracking [4]. |

| Virtual QC Sample | A computational construct in chromatographic analysis, created from pooled Quality Control sample data. Serves as a meta-reference for normalizing test samples and correcting for long-term signal drift using algorithms [7]. |

Instrumental drift is a pervasive challenge in analytical measurements, undermining the long-term reliability and accuracy of field spectrometers and other chemical sensors. It refers to the gradual, undesired change in a sensor's quantitative response over time, even when measuring a constant standard. For researchers and scientists, effectively troubleshooting drift is paramount for ensuring data integrity. This guide provides a structured framework to diagnose and address the primary sources of instrumental drift, categorized into environmental influences and internal hardware factors.

The first step in diagnosis is to identify the likely source of the drift. The table below contrasts common symptoms and examples of these two primary drift types.

| Characteristic | Environmental Variation Drift | Hardware/Instrumental Drift |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cause | Changes in the external measurement environment or sample matrix [9] [10] | Physical aging and changes within the instrument itself [9] [10] |

| Example Factors | Ambient temperature, humidity, pressure, and interfering chemical species [10] | Sensor aging (e.g., catalyst degradation, membrane fouling), component wear, and source intensity decay [11] [10] [12] |

| Typical Signal Behavior | Often correlated with measured environmental parameters; can be reversible or cyclical [9] | Generally exhibits a monotonic trend (e.g., constant shift or gradual slope) over time [11] |

Troubleshooting FAQs and Guides

How can I determine if drift is due to environmental changes or the instrument itself?

Objective: To isolate the root cause of observed drift in sensor measurements.

Experimental Protocol:

- Step 1: Collect Concurrent Data: During your measurements, systematically record not only the sensor's output but also relevant environmental variables such as ambient temperature, humidity, and atmospheric pressure [9].

- Step 2: Analyze with Reference Data: Compare your sensor's readings to those from a co-located, high-accuracy reference instrument, if available [9].

- Step 3: Apply Probabilistic Modeling: Use statistical techniques to decouple the influences. Importance sampling can be employed to re-weight data and isolate the instrumental drift component from the environmental variation [9]. Plot your sensor error against the logged environmental variables to identify correlations.

- Interpretation: A strong correlation between the sensor error and an environmental parameter (like temperature) points to environmental variation as a primary cause. A steady, uncorrelated change in the signal suggests inherent instrumental drift [9].

What are the established methods for correcting instrumental drift?

Objective: To apply mathematical or procedural corrections to compensate for instrumental drift.

Experimental Protocol:

- Step 1: Regular Drift Monitoring: Use a stable, known reference material (a "drift monitor") not used in the original calibration. Measure this monitor at regular intervals throughout an analytical run [12].

- Step 2: Calculate a Correction Factor: For each monitoring session, calculate a drift correction factor, ( R(t) ). This can be based on a known isotope ratio in mass spectrometry or a standard signal intensity in spectroscopy [11] [12]. ( R(t) = \frac{I!R(t)}{I!RT} ) Where ( I!R(t) ) is the measured ratio at time ( t ), and ( I!RT ) is the known true value.

- Step 3: Apply the Correction: Use the calculated ( R(t) ) to correct your sample measurements. This can be done via an interpolating polynomial fitted to the monitor's drift over time or by using the monitor as an internal standard for ratio-based correction [11].

Our calibration model has become unstable. How can we update it without a full recalibration?

Objective: To update a multivariate calibration model using a minimal set of new standard samples.

Experimental Protocol:

- Step 1: Standardization Subset Selection: Identify a small, representative set of standard samples (the "standardization subset") [10].

- Step 2: Measure Under New Conditions: Measure this subset under the new conditions where the model is failing (e.g., on a new instrument, or after significant drift has occurred).

- Step 3: Model Transfer: Establish a mathematical relationship (e.g., using Piecewise Direct Standardization (PDS)) between the responses of the original (master) instrument and the drifted (child) instrument using the standardization subset data [13] [10].

- Step 4: Apply Transformation: Use this relationship to transform new measurements from the child instrument to the scale of the master instrument, allowing the original calibration model to be applied accurately [13].

Instrumental Drift Detection and Correction Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a generalizable workflow for detecting and responding to calibration drift, adaptable to various instrumental platforms.

Research Reagent Solutions for Drift Management

The following table details key materials and their functions in monitoring and correcting for instrumental drift.

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Field of Application |

|---|---|---|

| Drift Monitors (e.g., fused glass discs) | Stable reference materials for regular instrument monitoring to quantify and correct for intensity drift of the X-ray tube [12]. | X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) Spectrometry |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | High-accuracy standards used for initial calibration and periodic validation of instrument performance. | All Spectroscopic Methods |

| Internal Standard Solution | A known compound added to all samples and standards to correct for signal fluctuations and instrument drift [10]. | Chromatography, Mass Spectrometry |

| Isotopically Labeled Standards | The most accurate internal standard for isotope dilution methods, correcting for sample preparation losses and instrument drift [10]. | Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry |

| Standardization Subset | A small set of stable standards used to transfer a calibration model from a master to a child instrument without full recalibration [13] [10]. | Multivariate Calibration (e.g., NIR, E-nose) |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary sources of spectral variability between instruments? The main sources of inter-instrument variability are wavelength alignment errors, spectral resolution and bandwidth differences, and detector and noise variability. These hardware-induced spectral variations cause models developed on one instrument to fail when applied to data from other spectrometers [14].

Q2: How does environmental humidity affect spectrometer measurements? Water vapor causes substantial spectral interference, leading to significant biases in measurements. For methane isotopic composition (δ¹³CH₄) measurements, humidity-induced biases can be corrected using empirical correction functions (quadratic for ¹²CH₄ and ¹³CH₄, linear for δ¹³CH₄) established over a water vapor range of 0.15–4.0% [15].

Q3: What is long-term instrumental drift and how can it be corrected? Long-term drift refers to gradual changes in instrument response over extended periods. In GC-MS instruments over 155 days, effective correction uses quality control (QC) samples and algorithms like Random Forest, which provided the most stable and reliable correction model for highly variable data [7]. For CO₂ sensors, drifts producing biases up to 27.9 ppm over 2 years can be corrected via linear interpolation [16].

Q4: Can calibration models be transferred between different instruments? Yes, but this requires specific standardization techniques. Methods like Direct Standardization (DS), Piecewise Direct Standardization (PDS), and External Parameter Orthogonalization (EPO) can map spectral domains between master and slave instruments, though each method has limitations regarding linearity assumptions and computational requirements [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Inaccurate Analysis Results

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Significant variation between tests on same sample | Improper calibration | Recalibrate using proper sequence; analyze standard sample 5x consecutively; RSD should not exceed 5% [3] |

| Consistent low readings for carbon, phosphorus, sulfur | Vacuum pump malfunction | Check pump for noise, overheating, or oil leaks; service or replace pump [3] |

| Drifting results or frequent need for recalibration | Dirty optical windows | Clean windows in front of fiber optic and in direct light pipe [3] |

| Inconsistent readings between replicates | Sample degradation or improper handling | Ensure sample is light-stable; minimize time between measurements; use same cuvette orientation [17] |

Signal and Noise Issues

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable or drifting readings | Insufficient instrument warm-up | Allow spectrophotometer to warm up for 15-30 minutes before use [17] |

| Low light intensity or signal error | Dirty optics or misaligned cuvette | Clean sample cuvette; check for debris in light path; ensure proper cuvette alignment [18] |

| High noise rate and dark current | Spacer design in MRPC detectors | Pad spacers outperform fishline spacers by reducing electrical creepage effects in high-rate conditions [19] |

| Negative absorbance readings | Blank solution dirtier than sample | Use exact same cuvette for blank and sample measurements; ensure proper blank solution [17] |

Environmental Impact on Sensor Accuracy

| Sensor Type | Environmental Factor | Impact on Accuracy | Correction Method | Post-Correction Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cavity Ring-Down Spectrometer [15] | Water vapor (0.15-4.0%) | Substantial biases in δ¹³CH₄ | Empirical humidity correction | Stable & accurate across conditions |

| NDIR CO₂ Sensor (SENSE-IAP) [16] | Temperature, humidity | RMSE: 5.9 ± 1.2 ppm | Multivariate linear regression | RMSE: 1.6 ± 0.5 ppm |

| SenseAir K30 CO₂ Sensor [16] | Environmental factors | ±30 ppm ±3% of reading | Environmental correction | RMSE: 1.7-4.3 ppm |

Long-Term Drift Performance and Correction

| Instrument Type | Drift Magnitude | Time Period | Correction Algorithm | Performance After Correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC-MS [7] | Large fluctuations | 155 days | Random Forest (RF) | Most stable and reliable correction |

| GC-MS [7] | Large fluctuations | 155 days | Support Vector Regression (SVR) | Tendency to over-fit and over-correct |

| GC-MS [7] | Large fluctuations | 155 days | Spline Interpolation (SC) | Least stable performance |

| NDIR CO₂ Sensor [16] | Up to 27.9 ppm bias | 2 years | Linear interpolation | RMSE reduced to 2.4 ± 0.2 ppm |

Calibration Transfer Technique Comparison

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Standardization (DS) [14] | Linear transformation between instruments | Simple, efficient with paired samples | Vulnerable to local nonlinear distortions |

| Piecewise Direct Standardization (PDS) [14] | Localized linear transformations | Handles local nonlinearities better than DS | Computationally intensive; can overfit noise |

| External Parameter Orthogonalization (EPO) [14] | Removes non-chemical variability | Works without paired sample sets | Requires proper estimation of orthogonal subspace |

Experimental Protocols

Humidity-Induced Bias Correction for Methane Isotopic Measurements

Purpose: To establish and apply correction functions for accurate δ¹³CH₄ measurements in both dry and humid air [15].

Materials:

- Cavity ring-down spectrometer

- Nafion dryer for dry air measurements

- Humidity control system

- Reference gas standards

Procedure:

- Perform laboratory experiments across water vapor range of 0.15–4.0%

- Establish empirical correction functions:

- Quadratic corrections for ¹²CH₄ and ¹³CH₄ concentrations

- Linear correction for δ¹³CH₄ values

- Apply correction functions to field measurements in both dried air (SORPES site) and humid air (Jurong site)

- Compare performance of delta-based calibration versus isotopologue-specific calibration

- Validate with reference measurements

Key Findings: Isotopologue-specific calibration coupled with explicit water vapor correction delivered stable and accurate δ¹³CH₄ measurements across all conditions, while delta-based calibration showed significant biases in humid air correlated with 1/CH₄ [15].

Long-Term Drift Correction Using Quality Control Samples

Purpose: To correct instrumental data drift in GC-MS measurements over 155 days using quality control samples and multiple algorithms [7].

Materials:

- GC-MS instrument

- Quality control samples (pooled)

- Reference standards

- Computational resources for algorithm implementation

Procedure:

- Conduct 20 repeated tests on six commercial tobacco products over 155 days

- Establish "virtual QC sample" by incorporating chromatographic peaks from all 20 QC results

- Classify sample components into three categories:

- Category 1: Present in both QC and sample

- Category 2: In sample only but within retention time tolerance

- Category 3: In sample only, outside retention time tolerance

- Calculate correction factors for component k in i-th measurement: yᵢ,ₖ = Xᵢ,ₖ/XT,ₖ where Xᵢ,ₖ is peak area, XT,ₖ is median peak area across all measurements

- Apply three correction algorithms:

- Spline Interpolation Correction (SC)

- Support Vector Regression (SVR)

- Random Forest (RF)

- Evaluate performance using principal component analysis and standard deviation analysis

Key Findings: Random Forest algorithm provided the most stable and reliable correction model for long-term, highly variable data, while SC showed the least stability and SVR tended to over-fit [7].

Low-Cost Sensor Drift Evaluation and Correction

Purpose: To evaluate and correct long-term drifts in low-cost CO₂ sensors over 30 months of field deployment [16].

Materials:

- SENSE-IAP sensor units (SenseAir K30)

- Picarro reference analyzer (G2401)

- Environmental monitoring equipment

- Calibration gases

Procedure:

- Perform co-located observations using LCS units alongside Picarro reference analyzer

- Develop environmental correction system using multivariate linear regression

- Monitor long-term drifts and seasonal drift cycles

- Apply linear interpolation for drift correction

- Evaluate correction effectiveness by comparing with reference measurements

- Determine optimal calibration frequency

Key Findings: Environmental correction reduced RMSE from 5.9 ± 1.2 to 1.6 ± 0.5 ppm. Long-term drifts produced biases up to 27.9 ppm over 2 years, but linear interpolation reduced 30-month RMSE to 2.4 ± 0.2 ppm. Recommended calibration frequency: within 3 months, not exceeding 6 months [16].

Workflow Visualization

Instrument Calibration Transfer Workflow

Long-Term Drift Correction Process

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Pooled Quality Control (QC) Samples [7] | Establish correction dataset for long-term drift | GC-MS measurements over extended periods |

| Nafion Dryer [15] | Remove water vapor from air samples | Humidity control for spectral measurements |

| Certified Reference Standards [18] | Instrument calibration and validation | Spectrophotometer accuracy verification |

| Low-Resistive Glass [19] | Improve rate capability in MRPC detectors | High-rate timing detectors for physics experiments |

| Virtual QC Sample [7] | Meta-reference for normalization | Long-term GC-MS studies with changing components |

| SenseAir K30 Sensor [16] | Low-cost CO₂ monitoring | Urban emission network deployment |

The Real-world Impact of Uncorrected Drift on Long-term Study Reliability

Your Troubleshooting Guide to Instrument Drift

Instrument drift is a gradual change in an instrument's measurement output over time, even when measuring the same sample. In long-term studies, uncorrected drift can compromise data integrity, leading to inaccurate results and unreliable conclusions [20] [21]. This guide helps you identify, correct, and prevent drift in your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the real-world consequences of uncorrected drift in my research? Uncorrected drift can severely impact your study's reliability. In a clinical study using an electronic nose for disease detection, sensor drift had a more profound effect on the results than the actual clinical disease state, threatening the diagnostic algorithm's validity [21]. In reading research, drift can move eye fixations from one word or line to another, leading to the misidentification of eye-movement effects and incorrect research findings [22]. In spectroscopy, drift directly reduces the accuracy and repeatability of your elemental analysis [20] [12].

2. I use an XRF Spectrometer. How can I check for drift? The standard method is to use a dedicated drift monitor [20] [12]. These are stable, glass-fused discs with a known elemental composition.

- Procedure: Regularly measure the drift monitor using your standard method. A change in the measured count rate compared to its established reference value indicates instrument drift.

- Key Point: Drift monitors are for monitoring instrument stability and performing drift correction; they are not Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) for calibration [20] [12].

3. My spectrophotometer's color measurements are inconsistent. Is this drift? Yes, spectrophotometers are susceptible to color drift due to factors like temperature changes, aging light sources, and photo detector degradation [6]. To confirm and correct:

- Daily Calibration: Calibrate your instrument at the start of every job and at least once daily [6].

- Regular Cleaning: Clean the aperture and white tile regularly according to the manufacturer's guidelines to prevent contaminants from causing errors [6].

- Annual Certification: For absolute confidence, have your device factory-certified annually to ensure it meets original performance specifications [6].

4. How can I correct for drift in my datasets after collection? Post-acquisition software correction is a powerful approach. Methods vary by field:

- Eye-Tracking: Expert manual correction is considered highly accurate. Automated algorithms also exist and are improving, with novices performing on par with the best algorithms [22].

- Biomolecular NMR Spectroscopy: The SAFR (Simultaneous Acquisition of a Frequency Reference) method can be used. An auxiliary 1D spectrum is acquired with each scan to monitor and correct for magnetic field drift during the experiment [23].

- Electronic Nose Data: Machine learning techniques like Kernel Transformation (DCKT) and Deep-learning Neural Networks can be employed to correct for sensor drift [21].

Quantitative Impact of Drift

The tables below summarize data on drift magnitude and correction effectiveness across different instruments.

Table 1: Documented Drift Magnitude in Various Instruments

| Instrument Type | Observed Drift | Impact & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Hydraulic Pressure Gauge [24] | ~0.02% of output (after 140 days at 100 MPa) | Significant for long-term monitoring of stable pressures, such as in seafloor crustal movement detection. |

| Electronic Nose (Cyranose 320) [21] | Sensor response drift over 4 days | Drift effect was more profound than clinical features, directly impacting diagnostic algorithm accuracy. |

| XRF Spectrometer [20] | Range of inconsistent results for the same substance | Compromises reliability and accuracy of elemental composition data. |

Table 2: Effectiveness of Different Drift Correction Methods

| Correction Method | Field of Application | Reported Outcome / Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Drift Monitor Use [20] [12] | XRF Spectrometry | Ensures long-term stability and optimal performance; reduces need for frequent full recalibrations. |

| Manual Correction [22] | Eye-Tracking (Reading) | Expert correction is significantly more accurate than automated algorithms. |

| SAFR Method [23] | Biomolecular Solid-State NMR | Corrects non-linear field drifts, allowing high-quality spectra recording even during field changes of ~0.1 ppm/h. |

| Logistic Regression Correction [21] | Electronic Nose Diagnostics | Improved accuracy for differentiating patient groups (Accuracy: 0.68). |

Experimental Protocols for Drift Assessment & Correction

Protocol 1: Routine Drift Monitoring for an XRF Spectrometer This protocol uses a drift monitor to correct instrument readings [20] [12].

- Acquire a Drift Monitor: Obtain a drift monitor disc (e.g., Ausmon) with a composition similar to your samples (e.g., cement, nickel, silicates).

- Establish a Baseline: When the instrument is known to be well-calibrated, measure the drift monitor multiple times to establish a stable, reference count rate.

- Implement Routine Checks: Before each measurement session or at regular intervals, measure the same drift monitor under identical conditions.

- Calculate and Apply Correction: Compute a correction factor based on the ratio of the current reading to the reference reading. Apply this factor to subsequent sample measurements to correct for the instrument's drift.

Protocol 2: The SAFR Method for NMR Spectrometry This protocol corrects for magnetic field drift during long NMR experiments [23].

- Modify Pulse Sequence: Add a small-flip-angle reference pulse (e.g., 1°) at the beginning of each scan in your multi-dimensional experiment.

- Simultaneous Acquisition: Acquire the auxiliary 1D reference spectrum immediately after the reference pulse. This spectrum, typically of a solvent signal, acts as a navigator for the magnetic field's state.

- Reconstruct Field Evolution: Process the raw data to track the frequency of the solvent signal's maximum across all scans. This reconstructs the temporal evolution of the magnetic field drift.

- Apply Data Correction: Use the reconstructed field drift data to apply a phase correction to the raw FID (Free Induction Decay) data of the main experiment in both the direct and indirect dimensions.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Drift Management

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Drift Control

| Item | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Drift Monitors [20] [12] | Stable reference materials to monitor and correct for instrument drift in spectrometers. | XRF Scientific Ausmon discs (e.g., for cement, iron ore). Note: These are not Certified Reference Materials (CRMs). |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | To verify instrument accuracy and perform full calibration. | NIST-traceable standards. Used for initial calibration and periodic validation. |

| Non-Absorbing Matrix [8] | A spectral reference material for DRIFTS to enhance signal quality and minimize artefacts. | KBr (Potassium Bromide) or KCl for mid-IR measurements; diamond powder for robust applications. |

| Stable Polystyrene Standard [13] | A reference standard for verifying wavelength/wavenumber accuracy in spectrophotometers. | Highly crystalline polystyrene filter (e.g., 1mm thickness). |

Workflow Diagram for Managing Instrument Drift

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing instrument drift in your experiments.

Correction Methodologies: From Traditional Standardization to Machine Learning

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the primary goal of Direct Standardization (DS) and External Parameter Orthogonalization (EPO) in field spectroscopy?

The main objective of both DS and EPO is to remove the interfering effects of external parameters, such as variable soil moisture content, from vis–NIR spectra. This correction is necessary to enable accurate predictions of soil properties, like Soil Organic Carbon (SOC), using calibration models developed on air-dried spectral libraries [25].

2. When should I consider using these techniques?

These techniques are particularly valuable when you aim to use a spectral library built under controlled, lab-based conditions (e.g., on air-dried soils) to predict properties from spectra collected in the field, where variable conditions like moisture content can severely degrade prediction accuracy [25].

3. How do I know if moisture is affecting my spectral data?

A clear indicator is a decrease in the accuracy of your SOC prediction models. If predictions become less reliable when using field-moist spectra compared to air-dried spectra, moisture is likely a contributing factor [25].

4. Can these techniques be applied to instruments other than vis–NIR spectrometers?

Yes, the principle of correcting for external parameters is universal. For instance, the EPO method was originally derived from a technique called EPO-PLS, which was developed for temperature-independent measurement of sugar content in intact fruits [25].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Issue: Corrected spectra do not improve prediction model accuracy.

- Potential Cause 1: The calibration set used for the standardization does not adequately represent the moisture variations encountered in your field samples.

- Solution: Ensure the calibration samples used to develop the DS or EPO transformation cover a wide and representative range of moisture conditions [25].

- Potential Cause 2: The model drift may be too severe or non-linear for a linear correction method to handle effectively.

- Solution: Investigate more advanced non-linear calibration techniques or ensure that the pre-launch or pre-deployment calibration of the instrument is robust, as initial calibration stability is critical for long-term data accuracy [26] [27].

Issue: Results are inconsistent after applying correction techniques.

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent sample preparation can introduce new variations that the model cannot separate from the target signal.

- Solution: Standardize sample handling protocols meticulously. For soil samples, ensure consistent grinding and avoid contaminants like oils from skin or quenching media, as these can lead to unstable and inconsistent results [3].

Quantitative Comparison of Techniques

The following table summarizes the performance of two moisture correction methods based on an experimental study aiming to predict Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) [25].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Soil Moisture Correction Methods for SOC Prediction

| Method | Key Principle | Required Calibration Set | Reported R² | Reported RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Standardization (DS) | Transforms spectra from moist conditions to match their appearance under dry conditions. | A set of samples scanned under both moist and dry conditions. | 0.84 | 0.45% |

| External Parameter Orthogonalization (EPO) | Projects spectra into a space orthogonal to the directions of variation caused by moisture. | A set of samples scanned under both moist and dry conditions. | 0.87 | 0.41% |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Applying External Parameter Orthogonalization (EPO)

This protocol outlines the steps to remove the effect of water from vis–NIR spectra using the EPO method [25].

- Calibration Set Preparation: Collect a subset of soil samples (

n=50in the cited study) that represent the expected range of soil types and moisture contents. - Spectral Acquisition under Different Conditions: Scan each sample in the calibration set twice:

- Condition A (Field-Moist): Scan the samples at their natural, field-moist state.

- Condition B (Oven-Dried): Oven-dry the same samples at 105°C for 24 hours and then scan them again. These spectra represent the "reference" or target state.

- Calculate Spectral Difference Matrix: For each sample, compute a difference spectrum:

Difference = Spectrum_moist - Spectrum_dry. - Perform Decomposition: Apply a principal component analysis (PCA) to the matrix containing all the difference spectra.

- Develop EPO Transformation: Use the first few principal components (which represent the main directions of moisture-induced variation) to create a projection matrix

P. - Apply Correction: Transform all future field-moist spectra (

X_moist) to their corrected, dry-like form using the equation:X_corrected = X_moist * P.

Protocol 2: Applying Direct Standardization (DS)

This protocol describes the process for correcting spectra using the DS method [25].

- Calibration Set Preparation: Follow the same steps 1 and 2 as in the EPO protocol to obtain paired spectral data from moist and dry conditions.

- Establish Transformation Matrix: Instead of using a difference matrix, the DS algorithm calculates a transformation matrix

Fthat directly maps the entire moist spectrum to its corresponding dry spectrum. - Apply Transformation: For any new field-moist spectrum, the corrected spectrum is calculated as:

X_corrected = X_moist * F.

Method Workflow and Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and relationship between the different standardization techniques and their application.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Spectroscopic Calibration and Drift Correction Experiments

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Calibration Samples | A set of well-characterized samples (e.g., various soil types, alloy standards) used to develop the transformation between different instrument states or environmental conditions [25] [26]. |

| NIST-Traceable Standards | Reference materials with known, certified properties used for primary instrument calibration to ensure data accuracy and traceability to international standards [27]. |

| High-Purity Argon Gas | In Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS), argon is used to create a controlled atmosphere for the plasma. Contaminated argon leads to inconsistent and unstable analytical results [3]. |

| Certified Wavelength Calibration Source | A source containing known emission lines (e.g., from elements like Ti, Fe) used to calibrate the wavelength axis of a spectrometer, which is critical for correct peak assignment, especially when dealing with instrumental drift [26]. |

Leveraging Quality Control Samples for Long-term Drift Correction

This technical support guide provides researchers and scientists with practical methodologies for detecting and correcting long-term instrumental drift in field spectrometers and analytical instruments using Quality Control (QC) samples.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is long-term instrumental drift, and why is it a problem? Long-term drift is a gradual change in an instrument's measurement signal over extended periods. It is caused by factors such as component aging (e.g., light source degradation in spectrometers), environmental changes, and routine maintenance operations like column replacement or ion source cleaning [16] [28]. This drift introduces bias and reduces the reliability of quantitative data, making it difficult to compare results from experiments conducted over weeks or months, which is critical for long-term studies and ensuring product stability [28] [29].

2. How can Quality Control (QC) samples correct for this drift? QC samples, typically a pooled mixture representative of your test samples, are measured at regular intervals throughout an experimental timeline. The variation in the measured response of the QC components over time is used to model the instrumental drift. This model generates correction factors that can be applied to your actual experimental data, normalizing them to a stable baseline and compensating for the drift [28] [29].

3. What is the recommended frequency for running QC samples? The optimal frequency depends on the instrument's stability and the required data precision. Research in gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) has successfully used 20 QC measurements over a 155-day period to model drift [28] [29]. For CO2 sensors, maintaining calibration (a form of QC) every 3 months, and not exceeding 6 months, is recommended to ensure accuracy within 5 ppm [16]. A good practice is to analyze a QC sample at the beginning of each batch and after every few experimental samples.

4. My sample contains compounds not present in the QC pool. Can they still be corrected? Yes, strategies exist for this scenario. Components can be categorized based on their presence in the QC, and different correction approaches are used [28]:

- Category 1: Components present in both QC and sample are directly corrected using their own drift model.

- Category 2: Components in the sample not matched in the QC, but with a similar retention time (in chromatography), can be corrected using the model from the adjacent QC peak.

- Category 3: Components in the sample completely absent from the QC can be normalized using an average correction coefficient derived from all QC components [28].

Troubleshooting Guide: QC-Based Drift Correction

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Drift Correction | QC samples not representative of test samples; incorrect correction algorithm [28]. | Ensure the pooled QC contains all (or most) chemicals found in your test samples. For complex data, use robust algorithms like Random Forest instead of simpler interpolation [28]. |

| High Variation in Corrected Data | QC measurements are too infrequent to capture drift pattern; instrument has high short-term noise [28] [17]. | Increase the frequency of QC sample analysis. Ensure the instrument is properly warmed up (15-30 mins) and maintained (clean optics, stable environment) before analysis [17]. |

| Drift Model Fails After Maintenance | Major hardware changes (e.g., new lamp, column) alter the instrument's response, resetting the drift curve [28]. | Consider the post-maintenance data as a new "batch." Re-establish the baseline by running a series of QC samples to build a new drift model for the new batch [28]. |

| Inconsistent Correction Across Components | Different chemical components or sensor responses drift at different rates and are influenced by different factors [16] [28]. | Build a separate correction model, f(p, t), for each key component or response, rather than using a global model for all data [28]. |

Experimental Protocol: Establishing a QC-Based Drift Correction System

The following workflow details the steps for implementing a drift correction procedure, based on methodologies successfully applied in GC-MS studies [28] [29].

Step-by-Step Methodology

Step 1: Preparation of Pooled Quality Control (QC) Sample

- Procedure: Combine equal aliquots from all test samples to be analyzed over the long-term study to create a homogeneous pooled QC sample. This ensures the QC contains a representative profile of all target analytes [28].

- Storage: Divide the pooled QC into single-use aliquots and store under conditions that preserve stability (e.g., -80 °C) to prevent composition changes from affecting the drift model.

Step 2: Establishing the Analysis Schedule

- Procedure: At the start of the experiment, analyze the QC sample 5-10 times to establish a robust baseline and estimate initial variability. Thereafter, analyze a single QC sample at regular intervals interspersed with the test samples. A practical approach is to run a QC after every 4-10 test samples or at the start and end of each analytical batch [28] [30].

- Documentation: Record two key parameters for every analysis (QC and test samples):

- Batch Number (

p): An integer incremented each time the instrument is shut down and restarted or undergoes major tuning. - Injection Order Number (

t): An integer representing the sequence of analysis within a batch [28].

- Batch Number (

Step 3: Data Collection and Calculation of Correction Factors

- Procedure: Collect all data, including the peak areas or instrument responses for each component in the QC samples over time.

- Calculation: For each component

kin thenQC samples, calculate its true value (X_T,k) as the median of all its measured peak areas. Then, compute the correction factor (y_i,k) for that component in thei-thQC measurement using the formula [28]:- Formula:

y_i,k = X_T,k / X_i,k - Where

X_i,kis the raw peak area for componentkin thei-thQC measurement.

- Formula:

Step 4: Modeling Drift and Correcting Data

- Procedure: Use the calculated correction factors

{y_i,k}as the target variable and the batch (p) and injection order (t) numbers as input features to train a drift correction model,f_k(p, t) - Algorithm Selection: The following table compares algorithms evaluated for this purpose in a 155-day GC-MS study [28]:

| Algorithm | Description | Pros / Cons | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spline Interpolation (SC) | Uses segmented polynomials for interpolation. | Simpler approach, but showed the least stability with sparse data [28]. | Preliminary analysis. |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | A variant of SVM for continuous function prediction. | Can over-fit and over-correct with highly variable data [28]. | Datasets with low noise. |

| Random Forest (RF) | An ensemble learning method using multiple decision trees. | Most stable and reliable for long-term, highly variable data [28]. | Complex, long-term datasets. |

- Application: For a given test sample analyzed at batch

pand injection ordert, the corrected valuex'_s,kfor componentkis calculated as [28]:- Formula:

x'_s,k = x_s,k * f_k(p, t) - Where

x_s,kis the raw measurement in the test sample.

- Formula:

Step 5: Validation of the Correction Procedure

- Procedure: Validate the effectiveness of the drift correction by performing Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the QC data before and after correction. Successful correction will show tight clustering of all QC samples in the PCA scores plot, indicating reduced variance over time [28]. Additionally, the standard deviation of each component across the corrected QC samples should be significantly reduced.

Quantitative Data from Research Studies

The following tables summarize empirical findings on drift magnitude and correction efficacy from published research.

Table 1: Drift Magnitude and Correction in CO2 Sensor Networks

This data is from a 30-month field evaluation of low-cost CO2 sensors [16].

| Metric | Value Before Correction | Value After Correction |

|---|---|---|

| Daily RMSE | 5.9 ± 1.2 ppm | 1.6 ± 0.5 ppm |

| Long-term Drift Bias | Up to 27.9 ppm over 2 years | 2.4 ± 0.2 ppm (with interpolation) |

| Seasonal Drift RMSE | Up to 25 ppm after 6 months | Maintained within 1-3 ppm daily |

Table 2: Performance of Correction Algorithms in GC-MS

This data is from a study comparing three algorithms over 155 days and 20 QC runs [28].

| Algorithm | Stability & Reliability | Suitability |

|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | Most stable and reliable | Highly variable, long-term data |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | Less stable, tends to over-fit | Datasets with lower variation |

| Spline Interpolation (SC) | Least stable with sparse data | -- |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Drift Correction |

|---|---|

| Pooled QC Sample | A composite of all test samples; serves as the stable, representative material used to model instrumental drift over time [28]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Materials with certified stability and traceable values; can be used as a superior QC sample or to validate the accuracy of the correction method [31]. |

| Internal Standards | Compounds added to both QC and test samples; correct for variations during sample preparation and analysis, complementing the inter-sample drift correction [28]. |

| Particle Size Standards | Suspensions of monodisperse particles; used for the calibration and validation of particle sizing/counting instruments, ensuring that part of the measurement system is standardized [32]. |

| Stable Control Samples | For non-chromatographic instruments like field spectrometers, a stable, homogeneous physical standard (e.g., a colored tile or sealed gas cell) acts as the QC sample to track instrument drift [16] [33]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is calibration drift and why is it a problem for field spectrometers? Calibration drift refers to the gradual change in an instrument's measurement accuracy over time. For field spectrometers, this is a critical problem because it compromises the reliability and portability of data. Inter-instrument variability, caused by factors like wavelength alignment errors, spectral resolution differences, and detector noise variability, means a model developed on one spectrometer often fails on another, even of the same model. This drift can lead to inaccurate chemical quantification and requires correction for trustworthy analytical results [14].

Q2: When should I choose SVR over Random Forest for drift correction, and vice versa? The choice depends on your data's characteristics and the desired outcome. Support Vector Regression (SVR) is particularly powerful for capturing complex, non-linear relationships, especially when you have a clear theoretical margin of tolerance (epsilon) for errors [34] [35]. Random Forest often demonstrates superior stability with highly variable data and can better maintain calibration across different probability ranges, making it less prone to overfitting in these scenarios [36] [7]. For long-term, highly variable datasets, one study found Random Forest to provide the most stable correction [7].

Q3: My SVR model is overfitting the drift in my training data. How can I improve it? Overfitting in SVR is often a result of hyperparameter misconfiguration. You can address it by:

- Reducing the model complexity: Decrease the value of the

Cparameter. A lowerCvalue creates a softer margin, allowing for more errors and a simpler model [37] [35]. - Adjusting the kernel: If using an RBF kernel, increase the

gammaparameter. A highergammamakes the model more sensitive to individual data points, so reducing it can help smooth the decision boundary [35]. - Increasing epsilon: A larger

epsilonvalue widens the tolerance margin, making the model less sensitive to small fluctuations and noise in the training data [35].

Q4: How can I preprocess my spectral data for effective drift correction with these algorithms? Proper preprocessing is vital. Key steps include:

- Feature Scaling: Always normalize or standardize your features before using SVR, as it is sensitive to the scale of data [34] [35]. Algorithms like

StandardScalerin Python are commonly used. - Quality Control (QC) Samples: Regularly measure pooled QC samples throughout your data acquisition period. These samples serve as a reference to model and correct for instrumental drift over time [7].

- Parameterizing Drift: Represent the drift by incorporating parameters like batch number (to mark instrument power cycles or maintenance) and injection order number (to track sequence within a batch) as input features for your correction model [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Performance After Transferring Model to a New Spectrometer

Description: A calibration model that performs well on the original ("master") instrument produces inaccurate predictions when applied to a new ("slave") spectrometer or the same instrument after a period of time [14].

Diagnosis: This is a classic symptom of inter-instrument variability or calibration drift. The source of the spectral distortion must be identified.

Solution:

- Diagnose the Source of Variability:

- Wavelength Misalignment: Check for small shifts in the wavelength axis. This can distort the alignment of absorbance bands with the original model's regression vector [14].

- Resolution Differences: Differences in spectral resolution or bandwidth can broaden or narrow spectral peaks, altering their shape [14].

- Detector Noise: Changes in signal-to-noise ratio between instruments can introduce systematic errors [14].

- Apply Calibration Transfer Techniques:

- Direct Standardization (DS): Assumes a global linear transformation between the slave and master spectra. It is simple but may not handle local non-linearities well [14].

- Piecewise Direct Standardization (PDS): An improvement over DS that applies localized linear transformations across the spectrum, offering better handling of local distortions [14].

Issue: Random Forest Model Fails to Correct Drift for Low-Abundance Compounds

Description: The drift correction model works for major constituents but fails for trace-level components in the sample.

Diagnosis: The pooled Quality Control (QC) sample may not adequately represent low-abundance compounds, or the signal for these compounds is too weak for the model to learn a reliable correction function [7].

Solution:

- Enhance QC Samples: Ensure your pooled QC sample contains a representative amount of the low-abundance compounds. This may require spiking the QC with these analytes.

- Implement Advanced Correction Strategies: For components not present in the QC samples, use alternative normalization methods. One approach is to use the average correction factor derived from all reliable QC components. Another is to use the correction factor from a chromatographic peak adjacent to the target compound, assuming the drift behavior is similar [7].

- Data Filtering: As a last resort, consider filtering out highly unstable spectral features that cannot be reliably corrected, as this can improve the overall statistical power for the remaining, stable features [38].

Experimental Protocol: Correcting GC-MS Long-Term Drift

The following table summarizes a published methodology for correcting long-term instrumental drift in Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) data, which is directly applicable to spectrometer data [7].

- Objective: To establish a reliable protocol for correcting long-term signal drift in GC-MS data using machine learning algorithms.

- Summary: The study involved repeated tests on smoke from six commercial tobacco products over 155 days using a GC-MS instrument. Twenty pooled QC samples were measured throughout this period to model the drift.

| Protocol Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Experimental Duration | 155 days [7] |

| Quality Control (QC) | 20 pooled QC samples were analyzed periodically [7] |

| Data Parameters | Batch number (to mark instrument power cycles) and injection order number (sequence within a batch) were recorded for each measurement [7] |

| Algorithms Tested | Spline Interpolation (SC), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Random Forest (RF) [7] |

| Key Innovation | Creation of a "virtual QC sample" from all QC results for normalization and accounting for batch/injection order effects [7] |

| Performance Outcome | Random Forest provided the most stable and reliable correction for long-term, highly variable data [7] |

The workflow for this experiment is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key materials and computational tools required for establishing a drift correction protocol for field spectrometers, based on the cited research.

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Pooled Quality Control (QC) Sample | A composite sample containing aliquots from all samples to be analyzed. It serves as a reference for modeling instrumental drift over time [7]. |

| Internal Standards (IS) | A set of known compounds added to samples to correct for variations in sample preparation and instrument response. Useful when QC samples lack some sample components [7]. |

| StandardScaler (or similar) | A software tool for feature scaling. It is critical for SVR performance to normalize all input features to the same scale [34] [35]. |

| scikit-learn Library (Python) | A machine learning library that provides implementations for both Support Vector Regression (SVR) and Random Forest algorithms [37] [39]. |

| R-based Scripts | Custom scripts, such as those used for nonlinear retention time correction and peak alignment in metabolomics data, can be adapted for spectral drift correction [38]. |

Hyperparameter Tuning for Optimal Performance

The performance of SVR and Random Forest is highly dependent on their hyperparameters. The table below provides a guide for tuning them in the context of drift correction.

| Algorithm | Key Hyperparameters | Function & Tuning Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | Kernel (e.g., rbf, linear) [37] [39] |

Determines the model's ability to capture non-linearity. RBF is a good default for complex drift patterns [37] [35]. |

| C (Regularization) [37] [35] | Controls the trade-off between a smooth model and fitting the training data perfectly. A lower C can prevent overfitting to noisy drift data. |

|

| Gamma (for RBF kernel) [35] | Defines the influence of a single training example. Lower values create a smoother model, which can be more robust. | |

| Epsilon (ε) [35] | Defines the margin of error within which no penalty is given. A larger epsilon creates a wider, more tolerant margin. | |

| Random Forest | n_estimators [36] | The number of trees in the forest. A higher number generally improves performance but increases computational cost. |

| max_features [36] | The number of features to consider for the best split. It controls the randomness and strength of the trees. | |

| max_depth [36] | The maximum depth of the trees. Limiting depth helps prevent overfitting. |

The process of building and applying a drift correction model can be visualized as follows.

Implementing Real-time Drift Monitoring with Probability Distribution Functions (PDFs)

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Particle Filter Estimator Divergence

Problem: The state estimates from your Particle Filter (PF) become inaccurate and do not converge, even with a sufficient number of particles.

| Symptoms | Potential Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Rapidly decreasing effective particle count [40] | Excessive process noise; model mismatch with true system dynamics. | Tune the process noise covariance matrix (Q); validate and refine your system model f(x(t-1), u(t-1), v(t-1)) [40]. |

| High variance in particle weights, with most weights near zero [40] | Severe sensor fault or drift distorting the measurement update. | Implement sensor fault detection; inspect the consistency between model predictions and observations [40]. |

| State distribution becomes overly dispersed and fails to track the true state [40] | Insufficient particle diversity leading to sample impoverishment. | Increase the number of particles; consider implementing a more advanced resampling algorithm [40]. |

Guide 2: Resolving Inadequate Drift Correction Performance

Problem: The drift correction algorithm is running, but the corrected data still shows significant residual drift or introduces new artifacts.

| Symptoms | Potential Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Corrected signal shows high-frequency noise or distortions. | The drift model is overfitting to short-term variations in the signal rather than the long-term drift. | Apply a smoothing constraint or reduce the complexity of the drift model. For PDF-based methods, analyze the correlation structure of states for inconsistencies [40]. |

| The calibration model becomes invalid after sensor replacement. | The calibration was not successfully transferred to the new sensor set. | Apply calibration transfer techniques like Direct Standardization (DS) or Piecewise Direct Standardization (PDS) using a small set of standardization samples [41]. |

| Corrected data violates fundamental physical or chemical relationships (e.g., Kramers-Kronig relations in EIS) [42]. | The drift correction method is applied to a system with a fundamentally changing impedance, which it cannot correct. | Do not rely on drift correction. Re-evaluate measurement stability; shorten measurement time or investigate system non-stationarity [42]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between implicit and explicit drift correction methods?

- Implicit Correction Methods (ICM): These methods expand the calibration model by incorporating new data collected under drifting conditions. They add drift as a new source of variance in the model itself. This requires periodic reference measurements to update the model [43].

- Explicit Correction Methods (ECM): These methods explicitly model the drift component, often as a direction or a subspace in the data. The calibration model is then made orthogonal or invariant to this estimated drift space. ECM can be more efficient as it directly targets and removes the identified drift [43].

FAQ 2: When is it inappropriate to use algorithmic drift correction?

Algorithmic drift correction is not a universal solution. It is typically inappropriate when:

- The underlying system impedance or properties are fundamentally changing during the measurement (non-stationary behavior) [42].

- The drift is highly non-linear and abrupt, and your model (e.g., a simple polynomial) cannot capture its dynamics [44].

- There is a physical sensor failure or a major change in the sensor array that requires hardware intervention or full recalibration [41].

FAQ 3: How can I monitor the health and performance of my Particle Filter in real-time?

You can monitor several key indicators derived from the estimated state PDF [40]:

- Distribution Heterogeneity: Use entropy or the ratio of effective-to-total particles to ensure the particle set does not collapse.

- Correlation Structure: Track the correlation coefficients between state variables over time. A sudden breakdown in the expected correlation pattern can indicate a fault or model mismatch.

- Prediction-Observation Consistency: Continuously check if the actual measurements are consistent with the distribution of predictions made by your model particles.

FAQ 4: What are the main strategies for maintaining a calibration model over time?

The three primary strategies are [41]:

- Drift Correction: Modeling the sensor drift directly and applying a corrective transform to new data.

- Calibration Standardization: Correcting new data to make it appear as if it was generated under the original calibration conditions, using a small set of standard samples.

- Calibration Update: Incorporating new data from the drifting conditions into the original calibration model to expand its validity.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing Particle Filter-Based Drift Monitoring

This protocol outlines the steps for setting up a real-time drift monitor using Particle Filters, as derived from fault diagnostics research [40].

Objective: To detect and diagnose sensor drift by analyzing the probability distribution of system states estimated by a Particle Filter.

Materials:

- A defined state-space model of your system (Eq. 1 and 2 in [40]).

- A stream of real-time sensor data.

- Computing environment capable of running Particle Filter algorithms.

Methodology:

- Initialization: Define your state-transition function

fand measurement functionh. Initialize the PF withN_sparticles, drawing from your initial state distribution. - State Estimation Loop: For each new time step

t:- Prediction: Propagate each particle forward using the state-transition function

f, adding process noisev(t-1). - Update: Upon receiving a new measurement

y(t), calculate the likelihood for each particle and update its weight accordingly. - Resampling: If the effective number of particles falls below a threshold, perform resampling to avoid weight degeneracy.

- Output: Obtain the estimated state PDF from the weighted particles.

- Prediction: Propagate each particle forward using the state-transition function

- Drift Monitoring: Calculate the following metrics from the estimated PDF in real-time:

- Entropy: Monitor the dispersion of the state distribution.

- Effective Particle Ratio:

N_eff = 1 / sum(w_i^2), wherew_iare the particle weights. A low ratio indicates potential problems. - Residuals: Analyze the difference between the actual measurement and the weighted mean of the predicted measurements from the particles.

Diagram: Particle Filter Monitoring Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Drift Monitoring |

|---|---|

| Particle Filter (PF) | A Monte Carlo-based state estimator that approximates the posterior Probability Distribution Function (PDF) of system states, which is essential for tracking non-linear and non-Gaussian processes [40]. |

| Standardization Samples | A small, stable set of physical samples with known properties. Used to establish a relationship between instrument responses under different conditions (e.g., before and after drift) for calibration transfer [41]. |

| State-Space Model | A mathematical model consisting of state-transition and measurement equations. It defines the expected system dynamics and is the core model used by the Particle Filter for prediction [40]. |

| Orthogonal Signal Correction (OSC) | A data pre-processing technique that filters out variation in the sensor data that is orthogonal (unrelated) to the target analyte, often used to remove structured noise like drift [41]. |

| Temporal Convolutional Neural Network (TCNN) | A lightweight deep learning model suitable for embedded deployment. It can learn to model and correct for complex drift patterns directly from temporal sensor data [44]. |

Key Metrics for PDF Analysis

The following table summarizes quantitative metrics for monitoring the health of your PDF-based drift monitor, derived from particle filter diagnostics [40].

| Metric | Formula/Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Effective Sample Size ((N_{eff})) | ( N{eff} = \frac{1}{\sum{i=1}^{Ns} (wi^{(t)})^2} ) | A low ( N_{eff} ) indicates weight degeneracy and a loss of particle diversity. |

| Shannon Entropy ((H)) | ( H(X) = - \sum{i=1}^{Ns} wi \log(wi) ) (for discrete weights) | Measures the uncertainty or dispersion of the state distribution. A sudden change can signal a fault. |

| State Correlation ((\rho)) | Pearson correlation coefficient between different state variables, calculated from the particle cloud. | A breakdown in the expected correlation structure can reveal sensor faults or actuator failures. |

Optimizing Performance: Best Practices and Proactive Maintenance

Establishing Optimal Calibration Frequency and Schedules

FAQs on Calibration Frequency and Scheduling

1. What factors determine the optimal calibration frequency for a field spectrometer? The optimal frequency is not a fixed interval but is determined by several factors, including the instrument's inherent stability, the criticality of the measurements, and the operating environment. Instruments in harsh conditions with fluctuating temperatures or humidity, or those used for compliance-critical measurements, require more frequent calibration. A key strategy is to analyze historical calibration drift trends; consistent deviation in analyzer readings over time is a primary indicator that the current schedule is insufficient [45] [46].

2. How can I extend the time between calibrations? Proactive maintenance and advanced data processing can help extend calibration validity. This includes ensuring stable operating conditions (e.g., using temperature control), performing regular instrument health checks (e.g., inspecting light sources and optics), and employing mathematical drift correction or calibration update techniques. These methods use a small set of standard samples to model and correct for drift, reducing the need for full recalibration [41].

3. Our lab has multiple spectrometers. How can we manage calibration efficiently? Implementing a strategic calibration transfer framework can significantly reduce the experimental burden. This involves building a robust calibration model on a primary instrument and then transferring it to other similar instruments using a minimal set of standardization samples. Research shows that methods like ridge regression with Orthogonal Signal Correction (OSC) preprocessing are particularly effective for this, maintaining accuracy while reducing calibration runs by 30-50% [47].

4. What are the immediate signs that my spectrometer needs recalibration? The most common signs include inconsistent readings or drift (where results change systematically over time without a change in the sample), unexpected baseline shifts, and failed calibration gas checks. For quantitative analysis, a growing bias in prediction errors is a clear red flag [48] [49] [45].

Troubleshooting Common Calibration Drift Issues

| Issue | Possible Cause | Corrective Action | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Readings/Drift | [48] [45] | Aging light source (e.g., deuterium lamp), temperature fluctuations, sensor aging, dirty optics. | Replace lamps per manufacturer's schedule; allow instrument warm-up; track drift trends; clean sample cuvettes and optics with lint-free cloth. |

| Failed Calibration Gas Checks | [45] | Expired or contaminated calibration gas; leaks in gas delivery lines; incorrect gas flow rates. | Use NIST-traceable, in-date gases; perform leak checks on all connections; verify gas flow rates (e.g., 1-2 L/min) with a calibrated flow meter. |

| Low Signal Intensity | [49] | Scratched or dirty sample cuvette; misaligned cuvette; debris in the light path. | Inspect and clean the cuvette; ensure proper alignment in the sample holder; check for obstructions in the optical path. |

| Unexpected Baseline Shifts | [49] | Residual sample contamination in the flow cell; electronic drift; need for baseline correction. | Perform a full baseline correction or recalibration; thoroughly clean the flow cell between samples. |

| Software/Data Handling Errors | [45] | Miscommunication between analyzer and data system; unsynchronized system clocks; misconfigured calibration logic. | Audit Data Acquisition System (DAHS) programming; synchronize clocks between all devices; review and test alarm thresholds. |

Experimental Protocol: Automated Calibration and Drift Monitoring

This protocol, inspired by automated systems like ATLAS (Automated Transient Learning for Applied Sensors), outlines a method for efficient calibration model building and continuous drift assessment [50].

Objective: To rapidly develop a multivariate calibration model (e.g., PLS or Ridge Regression) for a field spectrometer and establish a framework for ongoing drift monitoring with minimal manual intervention.

Materials and Reagents:

- Stock Solutions: Certified standard solutions for all analytes of interest.

- Automated Fluid Handling System: A system with pneumatic or syringe pumps and in-line flow meters for precise control.

- Flow Cell: A suitable flow cell compatible with your spectrometer.

- Data Analysis Software: Software capable of multivariate modeling (e.g., Python with SciKit Learn, Unscrambler).

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Generate an optimal experimental design (e.g., D- or I-optimal) to define the combination of analytes and concentrations for the calibration set. This minimizes the number of required samples while maximizing information [50] [47].

- System Setup: Connect stock solutions to the automated fluid handling system. Program the system to deliver the specified concentrations from the experimental design to the flow cell positioned in the spectrometer.

- Data Acquisition: The automated system cycles through the calibration concentrations. The spectrometer collects spectral data continuously. Flow rates and spectral data are logged simultaneously.

- Model Building: Post-run, extract spectral data from stable periods at each concentration level. Use these spectra and the known concentrations to build a multivariate calibration model (e.g., PLSR or Ridge Regression).

- Drift Monitoring Implementation: Program the system to periodically run a small set of validation standards (e.g., daily or weekly). Use the predictions for these standards to monitor for drift. Establish control limits; if predictions exceed these limits, it triggers a calibration review or update.

Advanced Drift Correction Methodologies

For integration into a research thesis, the following advanced concepts are key. The table below summarizes computational and mathematical approaches to drift correction beyond simple recalibration.

| Method | Principle | Application Context | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal Signal Correction (OSC) | [47] [41] | Removes signal components orthogonal to the analyte concentration that are often associated with drift. | Used as a preprocessing step before PLS or Ridge Regression to enhance model robustness against drift. |

| Differentiable Programming | [51] | Uses automatic differentiation to optimize calibration parameters by minimizing the difference between measured data and a target probability distribution. | High-precision X-ray spectroscopy; can be adapted to improve energy scale calibration and reduce systematic uncertainty. |

| Component Correction (e.g., PCA, CCA) | [41] | Models the direction of drift in the sensor response space using a series of measurements, then corrects new data by projecting out this direction. | Electronic noses/tongues; used for classification tasks when sensor drift is the main concern. |

| Calibration Transfer (DS, PDS) | [47] [41] | Standardizes signals between a master and slave instrument (or across time on the same instrument) using a small set of standard samples, enabling model sharing. | Pharmaceutical PAT, multisensor systems; allows calibration models to remain valid when instruments are replaced or drift. |

Workflow for Differentiable Programming Calibration

The following diagram illustrates the advanced calibration method that uses differentiable programming to enhance precision, which is particularly relevant for managing drift in complex spectroscopic data [51].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in Calibration Research |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provide a traceable, accurate standard for establishing the fundamental calibration curve and validating instrument accuracy [45] [46]. |

| NIST-Traceable Calibration Gases | Essential for gas-phase spectroscopy and CEM systems to ensure the known concentration of analytes delivered during calibration [45]. |

| Drift Monitors / Stable Solid Standards | Specialized, stable materials (e.g., Ausmon drift monitors) used to track instrument stability over time and trigger corrective actions before significant drift occurs [46]. |

| Optical Alignment Sets | Tools for maintaining optimal light path configuration, as misalignment is a common source of signal degradation and drift [48]. |

| Automated Fluidics System | Enables rapid, precise, and reproducible delivery of liquid standards for high-throughput calibration model development and validation [50]. |

Environmental Control and Sample Preparation to Minimize Drift

FAQs on Drift Causes and Prevention

What is calibration drift and why is it a problem? Calibration drift is the slow, unwanted change in the response of a measurement instrument over time, leading to a gradual loss of accuracy. This can result in skewed readings, increased measurement risk, and can compromise the longevity of your equipment. In research, unaddressed drift directly compromises data integrity and the reliability of scientific conclusions [1].

What are the most common causes of drift in field spectrometers? The primary causes can be categorized as follows:

- Environmental Factors: Sudden changes in ambient temperature or humidity are major contributors. Temperature fluctuations can cause materials in the instrument to expand or contract, leading to mechanical drift [1] [52] [17].

- Instrument Handling: Mechanical shock from dropping the device or exposure to vibrations can misalign sensitive optical components [1] [52].

- Sample Preparation Issues: Using dirty or scratched cuvettes, improper blanking, or having air bubbles in your sample can cause significant light scattering and unstable readings [17].