Analytical Sensitivity vs. Functional Sensitivity: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomarker and Diagnostic Assay Development

This article provides a critical examination of analytical and functional sensitivity, two pivotal performance metrics in the development and validation of diagnostic assays and biomarkers.

Analytical Sensitivity vs. Functional Sensitivity: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomarker and Diagnostic Assay Development

Abstract

This article provides a critical examination of analytical and functional sensitivity, two pivotal performance metrics in the development and validation of diagnostic assays and biomarkers. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational definitions, distinctions, and regulatory frameworks governing these parameters. The scope extends to methodological approaches for their assessment across various technology platforms—including immunoassays, molecular diagnostics, and novel biosensors—addressed through intent-focused sections on troubleshooting, optimization, and rigorous validation. By synthesizing current standards with emerging trends such as AI-driven optimization and dual-modality biosensors, this guide aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to enhance assay robustness, ensure regulatory compliance, and successfully translate biomarkers from research to clinical application.

Demystifying Sensitivity: Core Concepts and Regulatory Foundations for Robust Assay Design

In the field of bioanalysis, accurately measuring substances at very low concentrations is crucial for drug development, clinical diagnostics, and regulatory decision-making. The terms Limit of Blank (LoB), Limit of Detection (LoD), and Limit of Quantitation (LoQ) are used to describe the smallest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably measured by an analytical procedure [1]. These parameters form a critical foundation for characterizing the analytical sensitivity of an assay and are essential for understanding its capabilities and limitations to ensure it is "fit for purpose" [1]. Within the broader context of analytical versus functional sensitivity performance research, clearly distinguishing between these related but distinct concepts enables researchers to properly validate methods, compare assay performance, and make informed decisions based on reliable data, particularly at the lower limits of detection.

Core Definitions and Statistical Foundations

LoB, LoD, and LoQ represent progressively higher concentration levels that define an assay's detection capabilities, each with specific statistical definitions and practical implications [1].

| Parameter | Definition | Sample Characteristics | Statistical Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit of Blank (LoB) | The highest apparent analyte concentration expected when replicates of a blank sample (containing no analyte) are tested [1]. | Sample containing no analyte (e.g., zero-level calibrator), commutable with patient specimens [1]. | LoB = mean~blank~ + 1.645(SD~blank~) [1] |

| Limit of Detection (LoD) | The lowest analyte concentration likely to be reliably distinguished from the LoB and at which detection is feasible [1]. | Low concentration sample, commutable with patient specimens [1]. | LoD = LoB + 1.645(SD~low concentration sample~) [1] |

| Limit of Quantitation (LoQ) | The lowest concentration at which the analyte can be reliably detected and measured with predefined goals for bias and imprecision [1]. | Low concentration sample at or above the LoD [1]. | LoQ ≥ LoD; concentration where predefined bias/imprecision goals are met [1] |

The relationships and progression from LoB to LoD and LoQ can be visualized as a continuum of detectability and reliability.

The diagram above illustrates the hierarchical relationship where each limit builds upon the previous one. The LoB establishes the baseline noise level of the assay. The LoD represents a concentration that produces a signal strong enough to be distinguished from this noise with high statistical confidence (typically 95% that the signal is not from a blank) [1]. The LoQ is the level at which not only can the analyte be detected, but it can also be measured with specified accuracy and precision, often defined by a target coefficient of variation (CV%), such as 10% or 20% [2] [3].

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Standardized Protocols for Determination

The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guideline EP17 provides a standardized method for determining LoB, LoD, and LoQ [1]. The experimental process involves specific sample types and replication strategies to ensure statistical reliability.

Recommended Experimental Replication:

- Manufacturer Establishment: 60 replicates for both LoB and LoD [1]

- Laboratory Verification: 20 replicates for LoB and LoD verification [1]

LoB Determination Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Multiple replicates of a blank sample containing no analyte are tested [1].

- Data Analysis: The mean and standard deviation (SD) of the blank sample results are calculated [1].

- Calculation: LoB = mean~blank~ + 1.645(SD~blank~) (assuming a Gaussian distribution) [1]. This formula ensures that only 5% of blank sample measurements would exceed the LoB due to random variation, representing a false positive rate (Type I error) of 5% [1].

LoD Determination Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Test replicates of a sample containing a low concentration of analyte [1].

- Data Analysis: Calculate the mean and SD of the low concentration sample [1].

- Calculation: LoD = LoB + 1.645(SD~low concentration sample~) [1]. This ensures that 95% of measurements at the LoD concentration will exceed the LoB, with only 5% falling below (Type II error) [1].

LoQ Determination Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Test samples containing low concentrations of analyte at or above the LoD [1].

- Data Analysis: Determine the concentration at which predefined goals for bias and imprecision (e.g., CV ≤ 20% or ≤ 10%) are met [1] [3].

- Validation: The LoQ is confirmed when the measurement uncertainty at that concentration falls within acceptable limits [2].

Comparison of Calculation Approaches

Researchers have developed multiple approaches for calculating these limits, which can yield different results and require careful interpretation.

Statistical vs. Empirical Approaches:

- Statistical Approach: Based on measuring replicate blank and low-concentration samples per CLSI guidelines [1]. A traditional approach calculates LoD as the mean of blank samples + 2 SD, though this may underestimate the true LoD [1] [4].

- Empirical Approach: Involves measuring progressively more dilute concentrations of analyte [4]. This method often provides more realistic LoD values, with studies showing empirical LoDs can be 0.5-0.03 times the magnitude of statistically determined LoDs [4].

Graphical Validation Approaches:

- Uncertainty Profile: A modern graphical tool that combines uncertainty intervals with acceptability limits, based on β-content tolerance intervals [2]. A method is considered valid when uncertainty limits are fully included within acceptability limits [2].

- Accuracy Profile: Another graphical method using tolerance intervals for method validation [2].

Comparative studies have shown that while the classical statistical strategy often provides underestimated values of LoD and LoQ, graphical tools like uncertainty and accuracy profiles offer more relevant and realistic assessments [2].

Comparative Performance Data in Analytical Applications

Case Study: High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T (hs-cTnT) Assays

A 2025 study evaluating the analytical performance of the new Sysmex HISCL hs-cTnT assay provides illustrative data on how these parameters are determined and compared in practice [3].

| Assay Parameter | Sysmex HISCL hs-cTnT | Roche Elecsys hs-cTnT |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Blank (LoB) | 1.3 ng/L | Not specified in study |

| Limit of Detection (LoD) | 1.9 ng/L | Established reference method |

| Functional Sensitivity (CV 20%) | 1.8 ng/L | Not specified in study |

| Functional Sensitivity (CV 10%) | 3.3 ng/L | Not specified in study |

| Assay Precision | 2.2% at 3253 ng/L, 2.5% at 106 ng/L | Not specified in study |

| Method Comparison | r = 0.95 with Roche hs-cTnT | Reference method |

This verification followed CLSI EP17-A2 guidelines for LoB and LoD determination [3]. The functional sensitivity (a term often used interchangeably with LoQ) was determined by testing serial dilutions and identifying concentrations corresponding to CVs of 20% and 10% [3]. The study concluded that the Sysmex HISCL hs-cTnT fulfills the criteria for a high-sensitivity assay, demonstrating the practical application of these performance metrics in assay validation [3].

Ultrasensitive vs. Highly Sensitive Thyroglobulin Assays

A 2025 comparison of thyroglobulin (Tg) assays for monitoring differentiated thyroid cancer patients demonstrates how different generations of assays vary in their detection capabilities [5].

| Assay Generation | Representative Assay | Limit of Detection | Functional Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-Generation | Initial Tg tests | 0.2 ng/mL | 0.9 ng/mL |

| Second-Generation (Highly Sensitive) | BRAHMS Dynotest Tg-plus | 0.035-0.1 ng/mL | 0.15-0.2 ng/mL |

| Third-Generation (Ultrasensitive) | RIAKEY Tg IRMA | 0.01 ng/mL | 0.06 ng/mL |

This study found that the ultrasensitive Tg assay demonstrated higher sensitivity in predicting positive stimulated Tg levels and potential recurrence compared with the highly sensitive assay, though with lower specificity [5]. The clinical performance differences between these assay generations highlight the importance of understanding LoD and LoQ characteristics when selecting analytical methods for specific clinical applications.

Advanced Considerations and Research Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions for Sensitivity Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Sensitivity Determination |

|---|---|

| Blank Matrix | Sample containing all matrix constituents except the analyte of interest; essential for LoB determination [6]. |

| Zero-Level Calibrator | Calibrator with no analyte; used for LoB studies and establishing baseline signals [1]. |

| Low-Concentration Quality Controls | Samples with analyte concentrations near the expected LoD; used for LoD and LoQ determination [1]. |

| Calibration Curve Standards | Series of standards spanning from blank to above expected LoQ; essential for linearity assessment and LoQ confirmation [2]. |

| Tolerance Interval Calculators | Statistical tools for computing β-content tolerance intervals used in uncertainty profile validation [2]. |

Critical Methodological Considerations

Matrix Effects: The sample matrix significantly impacts LoB, LoD, and LoQ determinations. For complex matrices, generating a proper blank can be challenging, particularly for endogenous analytes that are constituent parts of the matrix [6].

Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Some approaches use signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) for estimating detection limits, typically requiring a ratio of 3:1 for LoD and 10:1 for LoQ [6] [7]. This method allows for initial estimation of the concentration range to be tested.

Uncertainty Profile Validation: This approach involves calculating β-content tolerance intervals and comparing them to acceptance limits [2]. The LoQ is determined by finding the intersection point of the uncertainty profile with the acceptability limit, providing a statistically robust method validation approach [2].

The precise determination and distinction of LoB, LoD, and LoQ are fundamental to characterizing analytical sensitivity and ensuring the reliability of bioanalytical methods. While standardized protocols like CLSI EP17 provide statistical frameworks for these determinations, comparative studies show that empirical and graphical approaches may offer more realistic assessments of assay capabilities, particularly for complex matrices. As assay technology advances toward increasingly sensitive detection, exemplified by the evolution from highly sensitive to ultrasensitive thyroglobulin and cardiac troponin assays, understanding these fundamental performance parameters becomes increasingly critical for researchers, method developers, and clinicians relying on accurate low-end measurement capabilities. The appropriate application of these concepts enables meaningful comparison of analytical methods and ensures that data generated at the limits of detection can be interpreted with appropriate scientific confidence.

In the realm of bioanalytical science, accurately quantifying the lowest concentration of an analyte is paramount for reliable data in drug development and clinical diagnostics. While terms like analytical sensitivity and Limit of Detection (LOD) describe an assay's ability to detect an analyte, they do not guarantee that the measurement is quantitatively precise. Functional Sensitivity, or the Lower Limit of Quantitation (LLOQ), addresses this critical distinction by defining the lowest analyte concentration that can be measured with stated acceptable precision and accuracy, making it the true benchmark for practical, clinically useful results. This guide objectively compares these performance characteristics, providing researchers with the experimental protocols and data needed to evaluate and implement functional sensitivity in their analytical workflows.

Understanding the Key Performance Parameters

Before comparing performance, it is essential to define the distinct parameters that describe an assay's capabilities at low analyte concentrations.

Limit of Blank (LoB) is the highest apparent analyte concentration expected to be found when replicates of a blank sample containing no analyte are tested. It describes the background noise of the assay. Statistically, it is calculated as

Mean_blank + 1.645(SD_blank), assuming a Gaussian distribution where 95% of blank measurements will fall below this value [1] [8].Limit of Detection (LOD), sometimes referred to as Analytical Sensitivity, is the lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably distinguished from the LoB. It is a measure of detection, not quantification, and does not guarantee accurate concentration measurement. Its calculation incorporates the LoB:

LOD = LoB + 1.645(SD_low concentration sample), ensuring that 95% of measurements at the LOD exceed the LoB [1] [9] [10].Limit of Quantitation (LoQ) or Lower Limit of Quantitation (LLOQ), also known as Functional Sensitivity, is the lowest concentration at which the analyte can not only be reliably detected but also measured with acceptable precision and accuracy. The LLOQ is the practical lower limit for reporting quantitative results [1] [11]. It is defined by meeting predefined performance goals for bias and imprecision, most commonly a coefficient of variation (CV) of 20% [9] [10].

Table 1: Core Definitions and Distinctions

| Parameter | Core Question | Definition | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit of Blank (LoB) | What is the background noise? | Highest concentration expected from a blank sample [1]. | Describes assay background; not for sample measurement. |

| Analytical Sensitivity (LOD) | Can the analyte be detected? | Lowest concentration distinguished from the LoB [1] [10]. | Confers presence/absence; results are not quantitatively reliable. |

| Functional Sensitivity (LLOQ) | Can the analyte be measured reliably? | Lowest concentration measured with acceptable precision and accuracy [1] [10]. | Defines the practical reporting limit; results are quantitatively valid. |

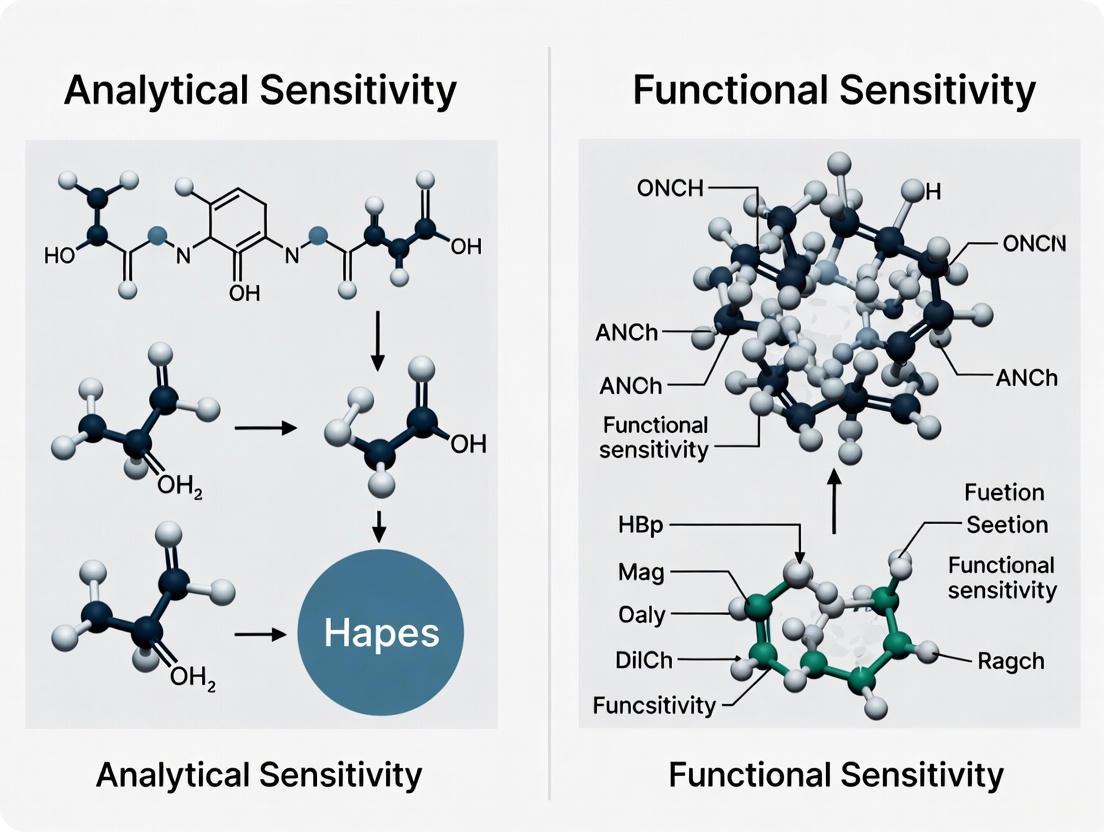

Analytical Sensitivity vs. Functional Sensitivity: A Performance Comparison

The conflation of analytical sensitivity (LOD) and functional sensitivity (LLOQ) is a common source of confusion. The critical difference lies in their clinical utility and reliability.

Analytical sensitivity, or LOD, has limited practical value because imprecision increases rapidly as analyte concentration decreases. At the LOD, the imprecision (CV) is so great that results are not reproducible enough for clinical decision-making [10]. Consequently, the LOD does not represent the lowest measurable concentration that is clinically useful.

Functional sensitivity was developed to address this limitation. Originally defined for Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH) assays, it is "the lowest concentration at which an assay can report clinically useful results," with "useful results" defined by good accuracy and a maximum CV of 20% [10]. This concept ensures that reported results are sufficiently precise to be actionable.

Table 2: Performance Characteristic Comparison

| Feature | Analytical Sensitivity (LOD) | Functional Sensitivity (LLOQ) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Detection | Quantification |

| Defining Criterion | Distinguishes signal from LoB [1] | Meets predefined precision/accuracy goals (e.g., ≤20% CV) [10] |

| Clinical Utility | Low | High |

| Result Reliability | Qualitative (detected/not detected) | Quantitative (precise concentration) |

| Typical Position | Below the LLOQ | At or above the LOD [1] |

| Impact on Reporting | Results at or near LOD should not be reported as numerical values [10] | Defines the lowest concentration that can be reported as a precise numerical value |

The relationship between these parameters can be visualized as a continuum of confidence at low concentrations.

Experimental Protocols for Determining Functional Sensitivity

Determining the functional sensitivity (LLOQ) of an assay is an empirical process that requires testing samples with low concentrations of the analyte and evaluating their precision and accuracy.

- Define Performance Goals: Establish the precision goal (e.g., CV ≤ 20%) that represents the limit of clinical usefulness for the specific assay and its intended application.

- Source Low-Concentration Samples: Ideally, use several undiluted patient samples or pools of patient samples with concentrations spanning the target range (bracketing the expected LLOQ). If such samples are unavailable, reasonable alternatives include:

- Patient samples diluted to concentrations in the target range.

- Control materials with concentrations in or near the target range.

- Note: Use an appropriate diluent to avoid biasing the results.

- Execute Longitudinal Testing: Analyze the selected samples repeatedly over multiple independent runs (e.g., across different days or weeks, using different reagent lots) to capture day-to-day (inter-assay) precision.

- Calculate Imprecision and Determine LLOQ: For each sample, calculate the mean concentration and the CV. The functional sensitivity is the lowest concentration at which the CV meets the predefined goal (e.g., 20%). This can be determined directly if a tested sample meets the criterion or by interpolation between the CVs of two samples that bracket the goal.

- Source Blank Sample: Use a true zero-concentration sample with an appropriate sample matrix (e.g., a zero calibrator or processed matrix without the analyte).

- Replicate Testing: Assay a minimum of 20 replicates of the blank sample.

- Calculate Mean and Standard Deviation (SD): Determine the mean and SD of the analytical signals (e.g., counts, absorbance) from the blank replicates.

- Compute LOD: The LOD is the concentration equivalent to the mean of the blank plus 2 or 3 times the SD. For immunometric assays, it is typically

Mean_blank + 2(SD_blank)[10] [8].

Data Presentation: Comparative Experimental Results

The following table summarizes hypothetical experimental data from a validation study for a cardiac biomarker assay, illustrating how LOD and LLOQ are determined and why the LLOQ is the critical parameter for reporting.

Table 3: Hypothetical Experimental Data from a Cardiac Biomarker Assay Validation

| Sample Type | Nominal Concentration (pg/mL) | Mean Measured Concentration (pg/mL) | Standard Deviation (SD) | Coefficient of Variation (CV%) | Meets 20% CV Goal? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blank | 0 | 0.5 | 0.2 | N/A | No |

| LoB (Calculated) | 0.8 | - | - | - | - |

| Low Sample A | 2.0 | 2.1 | 0.5 | 23.8% | No |

| Low Sample B | 3.0 | 3.2 | 0.6 | 18.8% | Yes |

| Low Sample C | 5.0 | 5.1 | 0.8 | 15.7% | Yes |

| Resulting Metrics | |||||

| LOD (Calculated) | ~1.6 pg/mL | ||||

| LLOQ (Functional Sensitivity) | 3.0 pg/mL |

Interpretation: While the assay can detect the analyte at concentrations as low as 1.6 pg/mL (LOD), the CV at this level is unacceptably high. The data shows that 3.0 pg/mL is the lowest concentration (LLOQ) where the CV falls below the 20% threshold, making it the lowest reportable and clinically usable value.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful determination of functional sensitivity requires careful selection of critical materials.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Validation | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Blank Matrix | Used to determine LoB and background signal. | Must be commutable with patient specimens and truly analyte-free [1]. |

| Low-Level QC Materials / Patient Pools | Used to determine LOD and LLOQ by testing precision at low concentrations. | Pools of actual patient samples are ideal. If using spiked samples, the matrix should match the blank [1] [10]. |

| Appropriate Diluent | For preparing sample dilutions for the LLOQ study. | The diluent must not contain the analyte or interfere with the assay; routine sample diluents may bias results [10]. |

| Calibrators | Establish the standard curve for converting signal to concentration. | The lowest calibrator should be near the expected LLOQ. The curve should not be extrapolated below the LLOQ [11]. |

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the distinction between analytical sensitivity (LOD) and functional sensitivity (LLOQ) is critical for generating reliable and actionable data. While the LOD indicates the theoretical detection capability of an assay, the LLOQ defines its practical, quantitative utility. By adopting the experimental protocols outlined here and focusing validation efforts on establishing a robust LLOQ, scientists can ensure their analytical methods are truly "fit-for-purpose," providing the precision and accuracy necessary to drive confident decision-making in both drug development and clinical diagnostics.

In the development of diagnostic tests and therapeutic agents, a fundamental gap often exists between a technology's theoretical capability and its practical, clinical utility. Theoretical capability, often represented by metrics like analytical sensitivity, describes the optimum performance of a technology under ideal, controlled conditions. Clinical utility, in contrast, is measured by a test's or intervention's ability to positively influence real-world health outcomes by informing clinical decision-making, streamlining workflows, and ultimately improving patient care [12]. This guide objectively compares these concepts, focusing on the specific context of analytical sensitivity versus functional sensitivity, to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a framework for evaluating performance in biologically relevant matrices.

Defining the Concepts: Analytical vs. Functional Sensitivity

The distinction between analytical and functional sensitivity provides a foundational model for understanding the broader divide between theoretical capability and clinical utility in diagnostic testing.

Analytical Sensitivity, often termed the "detection limit," is a measure of theoretical capability. It describes the lowest concentration of an analyte that an assay can reliably distinguish from a blank sample with no analyte [10] [9]. It answers the question, "How low can you detect?" This metric is typically determined by measuring replicates of a zero-concentration sample and calculating the concentration equivalent to the mean signal plus a specific multiple (e.g., 2 or 3) of the standard deviation [10]. While crucial for understanding an assay's fundamental detection strength, its primary limitation is that it does not account for the precision or reproducibility of the measurement at these low levels. Consequently, a result at or near the analytical sensitivity may be detectable but not reproducible enough for clinical interpretation [10].

Functional Sensitivity is a key indicator of clinical utility. It is defined as the lowest analyte concentration that can be measured with a specific, clinically acceptable level of precision, often expressed as a coefficient of variation (CV) of 10% or 20% [10] [3] [9]. This concept was developed specifically to address the limitations of analytical sensitivity by answering the question, "How low can you report a clinically useful result?" [10]. It is determined by repeatedly testing patient samples or pools over multiple days and identifying the concentration at which the inter-assay CV meets the predefined precision goal [10] [3]. This metric ensures that results at the low end of the measuring range are not only detectable but also sufficiently reproducible to support reliable clinical decision-making.

Table 1: Core Conceptual Distinctions Between Analytical and Functional Sensitivity

| Feature | Analytical Sensitivity (Theoretical Capability) | Functional Sensitivity (Clinical Utility) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Lowest concentration distinguishable from background noise [10] [9] | Lowest concentration measurable with a defined, clinically acceptable precision [10] [3] |

| Primary Question | "Can the analyte be detected?" | "Is the result reproducible enough for clinical use?" |

| Key Determining Factor | Signal-to-noise ratio | Assay imprecision (CV%) |

| Typical Metric | Meanblank + 2SD [10] | Concentration at a CV of 10% or 20% [3] |

| Clinical Relevance | Limited; indicates detectability only | High; defines the lower limit of clinically reportable range [10] |

Performance Data and Experimental Comparison

The performance gap between theoretical and functional limits is consistently demonstrated in assay validation studies. The following data, drawn from recent research, quantifies this disparity.

A recent evaluation of the Sysmex HISCL hs-cTnT assay provides clear quantitative data on these performance characteristics [3]. The study followed rigorous protocols to establish the assay's limits and its functional performance at the 99th-percentile upper reference limit (URL), a critical clinical decision point for diagnosing myocardial infarction.

Table 2: Performance Data for the Sysmex HISCL hs-cTnT Assay [3]

| Performance Characteristic | Value | Protocol Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Blank (LOB) | 1.3 ng/L | Determined according to CLSI EP17-A2 guidelines using assay diluent [3]. |

| Limit of Detection (Analytical Sensitivity) | 1.9 ng/L | Determined according to CLSI EP17-A2 guidelines. Distinguishable from LOB with high probability [3]. |

| Functional Sensitivity (at 20% CV) | 1.8 ng/L | Determined by serial dilution of control reagents; 20 replicates tested to establish mean and CV%; value found by curve-fitting [3]. |

| Functional Sensitivity (at 10% CV) | 3.3 ng/L | Protocol as above, with a more stringent precision requirement [3]. |

| 99th Percentile URL (Overall) | 14.4 ng/L | Established using 1004 cardio-renal healthy individuals. Assay CV was below 10% at this level, confirming high-sensitivity status [3]. |

The data shows that while the assay can theoretically detect concentrations as low as 1.9 ng/L, its precision at that level is poor. For clinical use where a 10% CV is required, the reliably reportable limit is nearly 74% higher (3.3 ng/L). Furthermore, the clinical decision point (14.4 ng/L) is significantly higher, situated well within the assay's precise measurement range. This demonstrates that the clinically useful range is substantially narrower than the theoretically detectable range.

Experimental Protocol for Determination

The following workflow details the standard methodology for establishing these key metrics, as applied in the Sysmex study and other validation workflows [10] [3].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful validation of assay sensitivity requires specific, high-quality materials. The table below details key reagents and their functions based on the cited experimental protocols.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sensitivity Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Validation | Example from Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| Blank Matrix / Diluent | Serves as the analyte-free sample for determining the Limit of Blank (LOB) and background signal [10]. | HISCL diluent used in determining LOB and for serial dilution in LoQ studies [3]. |

| Control Materials | Characterized samples with known, low analyte concentrations used for precision profiling and determining functional sensitivity [10]. | HISCL control reagents serially diluted to establish the precision profile and functional sensitivity [3]. |

| Calibrators | Solutions with precisely defined analyte concentrations used to establish the instrument's calibration curve [3]. | Sysmex HISCL uses a 6-point calibration curve (C0-C5) with human serum, stable for 30 days [3]. |

| Patient-Derived Samples/Pools | Undiluted or pooled serum from patients provides a biologically relevant matrix for assessing real-world performance and establishing reference limits [10]. | Used in the Sysmex study to establish the 99th percentile URL in a cohort of 1004 healthy individuals [3]. |

Implications for Drug Development and Clinical Research

The analytical/functional sensitivity paradigm extends to broader concepts in pharmaceutical development. Clinical Utility Assessments and Multi-Attribute Utility (MAU) analysis are formal frameworks used to weigh multiple factors—including efficacy, safety, biomarker data, and patient quality of life—into a single quantitative metric for decision-making on compound selection and dose/regimen optimization [13]. This moves beyond the theoretical "can it work?" to the practical "should it be advanced?" based on a holistic view of risk and benefit.

Similarly, the growing use of Real-World Evidence (RWE) underscores the importance of performance in real-world matrices. While Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) establish efficacy under ideal conditions (theoretical capability), RWE studies how interventions perform in routine clinical practice with heterogeneous patients, comorbidities, and variable adherence—directly assessing clinical utility [14] [15]. For diagnostic tests, a result must not only be accurate (clinical validity) but must also lead to an intervention that improves patient outcomes to possess true clinical utility [12].

The distinction between theoretical capability and clinical utility is critical for effective research and development. As demonstrated by the comparison between analytical and functional sensitivity, an assay's pure detection power is a poor predictor of its real-world value. True utility is defined by reproducible, reliable performance at clinically relevant decision thresholds within complex biological matrices. For researchers and drug developers, prioritizing functional performance and clinical utility from the early stages of design and validation is essential for creating diagnostic tests and therapies that deliver meaningful improvements to patient care.

In Vitro Diagnostics (IVDs) are critical medical devices used to perform tests on samples derived from the human body, providing essential information for disease diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment decisions [16]. The global regulatory landscape for IVDs is primarily governed by three distinct frameworks: the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations, the European Union's In Vitro Diagnostic Regulation (IVDR), and the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) in the United States. Each framework approaches performance evaluation with different requirements, oversight mechanisms, and philosophical underpinnings, creating a complex environment for manufacturers and researchers.

Performance evaluation serves as the cornerstone of all three regulatory systems, ensuring that IVD devices are safe, effective, and clinically valid. However, the specific requirements, terminology, and evidentiary standards vary significantly between these frameworks. Understanding these differences is particularly crucial when conducting research on performance metrics such as analytical sensitivity and functional sensitivity, as regulatory expectations directly influence study design, data collection, and validation methodologies. This guide provides a detailed comparison of how FDA, IVDR, and CLIA approaches performance evaluation, with special emphasis on sensitivity requirements to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Regulatory Frameworks

The FDA, IVDR, and CLIA represent fundamentally different approaches to ensuring IVD quality and performance. The FDA employs a comprehensive premarket review process, the IVDR establishes a risk-based classification system with ongoing surveillance, and CLIA focuses primarily on laboratory operations and quality control rather than device-specific approval.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of IVD Regulatory Frameworks

| Characteristic | FDA (U.S.) | IVDR (EU) | CLIA (U.S.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Focus | Device safety and effectiveness [16] | Device performance and clinical benefit [17] [18] | Laboratory testing quality and accuracy [16] [19] |

| Primary Authority | U.S. Food and Drug Administration | Notified Bodies (designated by EU member states) | Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) [20] |

| Applicable Products | Commercially distributed IVD kits [19] | Commercially distributed IVDs and laboratory-developed tests [17] | Laboratory-developed tests (LDTs) and laboratory testing procedures [20] |

| Basis for Oversight | Risk-based classification (Class I, II, III) [16] | Risk-based classification (Class A, B, C, D) [21] | Test complexity (waived, moderate, high) [16] |

| Premarket Review | Required (510(k), PMA, or De Novo) [22] [16] | Required for most devices (Technical Documentation review) [21] | Not required for LDTs; laboratory accreditation required [20] |

| Clinical Evidence Requirements | Required for all IVDs; extent varies by classification [22] [21] | Performance Evaluation Report required for all classes [17] [18] | Not required for LDTs; analytical validation required [20] |

Table 2: Performance Evaluation Requirements Across Frameworks

| Requirement | FDA | IVDR | CLIA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Performance Studies | Comprehensive testing required [22] | Comprehensive testing required [18] | Internal validation required [19] |

| Clinical Performance Studies | Required; comparative studies with predicate device [22] | Required; clinical performance report mandatory [17] | Not formally required; clinical validity often not assessed [20] |

| Scientific Validity | Implicit in substantial equivalence determination [22] | Explicitly required and documented [18] | Not assessed [20] |

| Post-Market Surveillance | Adverse event reporting required [19] | Formal Post-Market Performance Follow-up (PMPF) required [17] [21] | Proficiency testing and quality control required [16] |

| Key Documentation | 510(k), PMA submission [16] | Performance Evaluation Plan, Performance Evaluation Report, Clinical Performance Report [17] | Validation records, quality control data, proficiency testing results [20] |

Regulatory Pathways for IVD Devices: This diagram illustrates the distinct classification and regulatory pathways under FDA, IVDR, and CLIA frameworks, highlighting their different risk-based approaches.

Performance Evaluation: Core Concepts and Methodologies

Analytical vs. Functional Sensitivity in Performance Evaluation

Understanding the distinction between analytical and functional sensitivity is fundamental to designing appropriate performance evaluation studies across regulatory frameworks. These related but distinct metrics serve different purposes in assessing device performance and clinical utility.

Analytical Sensitivity, often referred to as the limit of detection (LOD), represents the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be distinguished from background noise [10] [9]. This parameter establishes the fundamental detection capability of an assay under controlled conditions. The standard methodology for determining analytical sensitivity involves testing multiple replicates of a blank sample (containing no analyte) to establish the mean background signal and standard deviation. The analytical sensitivity is typically calculated as the concentration equivalent to the mean blank value plus two standard deviations for immunometric assays [10].

Functional Sensitivity represents the lowest concentration at which an assay can report clinically useful results with acceptable precision [10] [9]. Unlike analytical sensitivity, functional sensitivity incorporates precision requirements, typically defined as the concentration at which the assay achieves a coefficient of variation (CV) of ≤20% [10]. This metric better reflects real-world performance where precision limitations may render results clinically unreliable even at concentrations above the theoretical detection limit.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Sensitivity Metrics

| Characteristic | Analytical Sensitivity | Functional Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Lowest concentration distinguishable from background [10] [9] | Lowest concentration measurable with ≤20% CV [10] |

| Primary Focus | Detection capability | Clinical utility and precision |

| Typical Methodology | Measurement of blank replicates to establish mean + 2SD [10] | Testing patient samples at multiple concentrations over time to establish precision profile [10] |

| Regulatory Emphasis | FDA and IVDR require demonstration [22] [18] | Often required for assays where low-end precision impacts clinical decisions [10] |

| Clinical Relevance | Limited - indicates detection potential but not necessarily reliable measurement [10] | High - indicates concentration range for clinically reportable results [10] |

| Common Applications | All quantitative IVDs [22] | Hormone assays, tumor markers, cardiac markers [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Sensitivity Determination

Protocol for Determining Analytical Sensitivity

Purpose: To establish the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from a blank sample with no analyte [10].

Materials and Reagents:

- Matrix-appropriate blank sample (true zero concentration)

- Calibrators with known analyte concentrations

- Assay reagents and controls

- Appropriate instrumentation

Procedure:

- Prepare a minimum of 20 replicates of the blank sample [10]

- Analyze all replicates in the same run under identical conditions

- Record measurement signals for each replicate (e.g., counts, optical density)

- Calculate mean signal and standard deviation of the blank measurements

- Compute analytical sensitivity as mean blank signal + 2 standard deviations [10]

- Convert signal to concentration using the assay calibration curve

Acceptance Criteria: The determined analytical sensitivity should meet or exceed manufacturer claims and be comparable to predicate devices for FDA submissions [22].

Protocol for Determining Functional Sensitivity

Purpose: To establish the lowest analyte concentration that can be measured with acceptable precision (typically ≤20% CV) for clinical use [10].

Materials and Reagents:

- Patient samples or pools with concentrations near expected functional sensitivity

- Matrix-appropriate diluent if sample dilution is required

- Assay reagents, calibrators, and controls

- Appropriate instrumentation

Procedure:

- Identify target concentration range based on preliminary data or package insert

- Obtain 3-5 patient samples or pools spanning the target concentration range [10]

- Analyze each sample in duplicate or triplicate over multiple runs (minimum 10-20 runs)

- Space analyses over different days (minimum 5-10 days) to capture inter-assay precision [10]

- Calculate mean, standard deviation, and coefficient of variation for each concentration level

- Plot CV versus concentration and determine the concentration where CV crosses 20%

- Verify with additional testing if necessary

Acceptance Criteria: Functional sensitivity should demonstrate ≤20% CV or a pre-specified precision goal appropriate for the assay's clinical application [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful performance evaluation requires carefully selected reagents and materials that meet regulatory standards and ensure experimental integrity.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Performance Evaluation Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Samples | Validation with real-world matrices | Must reflect intended use population; fresh specimens preferred over stored samples [22] |

| Interferent Panels | Specificity testing | Should include structurally similar compounds, common medications, endogenous substances [22] |

| Calibrators | Establishing measurement scale | Traceable to reference materials; matrix-matched to patient samples [10] |

| Quality Controls | Monitoring assay performance | Multiple concentration levels (low, medium, high); stable and well-characterized [10] |

| Matrix Components | Equivalence studies | Critical when comparing different sample types (serum vs. plasma); demonstrate minimal matrix effects [22] |

| Stability Materials | Establishing shelf life | Used in real-time and accelerated stability studies; support expiration dating claims [22] |

Regulatory Pathways and Their Impact on Performance Evaluation

FDA 510(k) Substantial Equivalence Pathway

The FDA 510(k) pathway requires manufacturers to demonstrate substantial equivalence to a legally marketed predicate device [22] [16]. This comparative approach heavily influences performance evaluation design, requiring head-to-head studies against the predicate device across multiple performance characteristics.

Performance Evaluation Emphasis:

- Analytical Performance: Comprehensive testing including precision, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and interference [22]

- Clinical Performance: Focus on positive percent agreement (PPA) and negative percent agreement (NPA) compared to predicate [22]

- Statistical Requirements: Adequate sample sizes to demonstrate non-inferiority with pre-specified confidence intervals [22]

Common Pitfalls: Underpowered studies, inadequate statistical justification, and unrepresentative clinical populations are frequent causes of FDA requests for additional information [22].

IVDR Performance Evaluation Process

The IVDR introduces a systematic, ongoing performance evaluation process consisting of three key elements: scientific validity, analytical performance, and clinical performance [18]. Unlike the FDA's predicate-based approach, IVDR requires direct demonstration of performance relative to the device's intended purpose.

Performance Evaluation Structure:

- Performance Evaluation Plan (PEP): Prospective plan outlining the approach to generating necessary evidence [17]

- Performance Evaluation Report (PER): Comprehensive report integrating all performance data [17]

- Clinical Performance Report (CPR): Detailed documentation of clinical performance evidence [17]

Ongoing Requirements: IVDR mandates continuous performance evaluation through Post-Market Performance Follow-up (PMPF), requiring regular updates to performance documentation [17].

CLIA Laboratory Validation Approach

CLIA takes a fundamentally different approach by regulating laboratory testing quality rather than device performance [16] [20]. Laboratories developing LDTs must establish assay performance characteristics but without the comprehensive premarket review required by FDA or IVDR.

Validation Requirements:

- Analytical Validation: Demonstration of precision, accuracy, reportable range, reference range, and sensitivity [19]

- Verification of FDA-Cleared Tests: Establishment of performance specifications for modified FDA-cleared assays [20]

- Quality Control: Ongoing monitoring through internal quality control and external proficiency testing [16]

Regulatory Developments: Recent FDA initiatives aim to increase oversight of LDTs, potentially aligning CLIA requirements more closely with traditional IVD regulations [20].

Sensitivity Concepts and Methodologies: This diagram illustrates the relationship between analytical and functional sensitivity, their distinct methodologies, and different regulatory applications.

The regulatory frameworks governing IVD performance evaluation continue to evolve, with increasing convergence on the need for robust clinical evidence while maintaining distinct philosophical approaches. Researchers and manufacturers should consider several strategic implications:

For Global Market Access:

- FDA submissions require rigorous comparative studies against predicate devices [22]

- IVDR mandates direct demonstration of clinical performance and scientific validity [18]

- CLIA focuses on laboratory process quality rather than device-specific claims [20]

For Sensitivity Studies:

- Analytical sensitivity establishes fundamental detection capability required by all frameworks [22] [18]

- Functional sensitivity demonstrates clinical utility, particularly important for assays with critical low-end performance requirements [10]

- Study designs must accommodate framework-specific statistical and methodological requirements

For Future Development: The increasing regulatory scrutiny of LDTs [20] and the emphasis on real-world evidence across all frameworks suggest continued evolution toward more standardized, evidence-based approaches to performance evaluation. Researchers should design studies with sufficient rigor to satisfy multiple regulatory requirements while generating scientifically valid data on device performance.

The Critical Role in Diagnostic Accuracy and Early Biomarker Detection

The accurate detection of protein biomarkers is a cornerstone of modern in vitro diagnostics (IVD), providing dynamic readouts of physiological states that are critical for monitoring diseases ranging from cancer to neurological disorders [23]. In clinical practice, the sensitivity of an immunoassay—its ability to detect minute quantities of an analyte—directly influences diagnostic accuracy and the potential for early disease detection. Substantial advancements in assay technology have led to the development of increasingly sensitive tests, broadly categorized into generations based on their detection capabilities [24]. First-generation assays provided initial testing capabilities but with limited sensitivity. Second-generation, or highly sensitive (hs) assays, offered improved sensitivity with functional sensitivity values between 0.15 and 0.2 ng/mL, making them the current most widely used tests in clinical practice. The latest development, third-generation ultrasensitive (ultra) assays, can detect proteins at extremely low levels, with a functional sensitivity of 0.06 ng/mL [24]. This evolution is particularly impactful in monitoring differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC), where thyroglobulin (Tg) measurement serves as the gold standard for detecting residual or recurrent disease [24]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these assay generations, focusing on their performance characteristics and clinical implications to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Analytical Comparison: Ultrasensitive vs. Highly Sensitive Assays

Performance Characteristics and Metrics

The critical difference between highly sensitive (hs) and ultrasensitive (ultra) assays lies in their detection limits. Functional sensitivity, defined as the lowest concentration measurable with acceptable precision (typically with a coefficient of variation <20%), represents the assay's clinical reliability in real-world settings [24]. In contrast, analytical sensitivity denotes the minimum detectable concentration under optimal conditions, reflecting the assay's technical detection limits [24].

Table 1: Direct Comparison of Highly Sensitive vs. Ultrasensitive Tg Assays

| Performance Parameter | Highly Sensitive (hsTg) Assay | Ultrasensitive (ultraTg) Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Representative Platform | BRAHMS Dynotest Tg-plus IRMA | RIAKEY Tg Immunoradiometric Assay |

| Analytical Sensitivity | 0.1 ng/mL | 0.01 ng/mL |

| Functional Sensitivity | 0.2 ng/mL | 0.06 ng/mL |

| Correlation with Stimulated Tg (R value) | 0.79 (overall) | 0.79 (overall) |

| Correlation in TgAb-Positive Patients (R value) | 0.52 | 0.52 |

| Optimal Cut-off for Predicting Stimulated Tg ≥1 ng/mL | 0.105 ng/mL | 0.12 ng/mL |

| Sensitivity at Optimal Cut-off | 39.8% | 72.0% |

| Specificity at Optimal Cut-off | 91.5% | 67.2% |

| Key Clinical Advantage | Higher specificity reduces false positives | Higher sensitivity enables earlier recurrence detection |

Clinical Performance Data

A 2025 study directly comparing these technologies demonstrated that while both assays show a strong correlation (R=0.79, P<0.01) with stimulated Tg levels, their clinical performance differs significantly [24]. The correlation was notably weaker in Tg antibody-positive patients (R=0.52) for both platforms, highlighting a shared limitation in the presence of interfering antibodies [24]. The ultrasensitive Tg assay demonstrated superior sensitivity (72.0% vs. 39.8%) in predicting stimulated Tg levels ≥1 ng/mL, but this came at the cost of reduced specificity (67.2% vs. 91.5%) compared to the highly sensitive assay [24]. This trade-off has direct clinical implications: the higher sensitivity of ultraTg may lead to earlier detection of potential recurrence, while its lower specificity may result in more frequent classifications of biochemical incomplete response [24].

Table 2: Clinical Outcomes Comparison Based on Assay Type

| Clinical Scenario | Highly Sensitive (hsTg) Assay Interpretation | Ultrasensitive (ultraTg) Assay Interpretation | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 Discordant Cases (hsTg <0.2 ng/mL but ultraTg >0.23 ng/mL) | Suggests negative/low risk | Suggests elevated risk | 3 patients developed structural recurrence within 3.4-5.8 years |

| Response Classification in 2 Patients | Excellent response | Indeterminate or biochemical incomplete response | Altered follow-up strategy and patient management |

Technological Foundations and Methodologies

Experimental Protocols for Tg Assay Comparison

The comparative data presented in this guide primarily derives from a rigorous 2025 study conducted at Seoul National University Hospital [24]. The experimental methodology is outlined below:

Subject Population: The study included 268 individuals who underwent total thyroidectomy for differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) and either radioiodine treatment or I-123 diagnostic scanning. Patients were enrolled when planning to undergo radioiodine treatment or an I-123 diagnostic scan between November 2013 and December 2018 [24].

Sample Collection: After patients provided informed consent, blood samples were collected for measurement of TSH, Tg, and TgAb levels using two different immunoradiometric assay (IRMA) kits. Unstimulated serum samples were collected after total thyroidectomy. Stimulated samples were obtained after TSH stimulation, performed either through levothyroxine withdrawal or intramuscular injection of recombinant human TSH (rhTSH) [24].

Assay Methods: For Tg measurement, two IRMA kits representing different generations of Tg assays were utilized:

- Second-generation Tg IRMA (hsTg): Dynotest Tg-plus kit (BRAHMS Diagnostic GmbH) with functional sensitivity of 0.2 ng/mL and analytical sensitivity of 0.1 ng/mL

- Third-generation Tg IRMA (ultraTg): RIAKEY Tg IRMA kit (Shinjin Medics) with functional sensitivity of 0.06 ng/mL and analytical sensitivity of 0.01 ng/mL [24]

Statistical Analysis: Reliability between hsTg and ultraTg assays was assessed using Pearson correlation coefficient. The diagnostic performance of unstimulated Tg levels in predicting positive stimulated Tg values was evaluated using functional and analytical sensitivities as cut-off thresholds. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated. Optimal cut-off values were determined using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis [24].

Sensitivity Enhancement Techniques in Immunoassays

Efforts to enhance ELISA sensitivity have primarily focused on two key areas: optimizing capture antibody immobilization to improve biomarker retention and developing efficient signal amplification strategies to boost detection sensitivity [23]. Unlike nucleic acids, which can be amplified using PCR or isothermal amplification techniques, proteins lack an intrinsic amplification mechanism, making these optimization strategies crucial [23].

Surface Modification Strategies: Traditional passive adsorption of capture antibodies onto polystyrene microplates often results in random antibody orientation and partial denaturation, reducing the number of functionally active capture antibodies. To address this, several advanced strategies have been developed:

- Nonfouling surface modifications using synthetic polymers like polyethylene glycol (PEG) or polysaccharides such as dextran, chitosan, and hyaluronic acid can prevent non-specific protein adsorption [23].

- Antibody orientation strategies using Protein A, Protein G, or the biotin-streptavidin system ensure proper orientation of capture antibodies, significantly enhancing antigen accessibility and assay sensitivity [23].

- Covalent crosslinking provides permanent and stable attachment of antibodies to solid surfaces, preventing antibody loss during wash steps [23].

Signal Amplification Approaches: Digital ELISA represents a revolutionary advancement in ultrasensitive immunoassays, detecting proteins at ultra-low concentrations in the femtomolar range (fM; 10⁻¹⁵M) compared to nanomolar (nM; 10⁻⁹M) to picomolar (pM; 10⁻¹²M) levels in conventional ELISA [25]. This technology uses beads to isolate and detect single enzyme molecules in femtoliter-sized wells, allowing for orders of magnitude greater sensitivity than standard sandwich-based immunoassay techniques [25].

Figure 1: Enhanced Immunoassay Workflow with Sensitivity Optimization Strategies. This diagram illustrates the sequential steps in a sensitive immunoassay workflow, highlighting key technological enhancement strategies (red boxes) that improve detection capabilities at each stage.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Ultrasensitive Immunoassays

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Paramagnetic Beads | Solid support for antibody immobilization | Enable digital counting in single molecule arrays; higher surface area-to-volume ratio than traditional plates [25] |

| Protein A/Protein G | Antibody orientation | Binds Fc region of antibodies, ensuring uniform orientation and enhanced antigen accessibility [23] |

| Biotin-Streptavidin System | Antibody immobilization | Strong interaction ensures uniform, functional antibody state; requires biotinylation of capture antibody [23] |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Nonfouling surface modification | Prevents non-specific protein adsorption; improves signal-to-noise ratio [23] |

| Polymer-Based Detection Systems | Signal amplification | Multiple peroxidase molecules and secondary antibodies attached to dextran polymer backbone increase sensitivity [23] |

| Chromogenic Substrates (DAB, NovaRed) | Signal generation | Produce colored product after incubation with enzyme labels; compatible with light microscopy [26] |

| Antigen Retrieval Buffers (e.g., citrate buffer) | Epitope unmasking | Breaks protein cross-links caused by fixation; essential for FFPE tissue analysis [26] |

| Blocking Reagents (BSA, casein, skim milk) | Reduce nonspecific binding | Occupies uncoated surface areas to minimize false-positive signals [23] |

Clinical Decision Pathway and Research Implications

Figure 2: Clinical Decision Pathway for Thyroid Cancer Monitoring. This diagram outlines the decision-making process for selecting and interpreting thyroglobulin assays in differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) monitoring, highlighting the different performance characteristics and clinical implications of highly sensitive versus ultrasensitive testing approaches.

The choice between highly sensitive and ultrasensitive assays should be guided by specific clinical and research objectives. For routine monitoring of differentiated thyroid cancer patients with low to intermediate risk, highly sensitive assays provide sufficient sensitivity with excellent specificity, reducing the likelihood of false positives and unnecessary additional testing [24]. For high-risk patients or those with clinically suspicious cases where highly sensitive Tg falls below the cut-off but clinical suspicion remains, ultrasensitive assays may provide additional diagnostic value by detecting minimal residual disease earlier [24]. In research settings focused on biomarker discovery or early detection, ultrasensitive technologies offer the potential to identify novel low-abundance biomarkers and establish earlier disease detection windows [23] [25].

The emerging field of cell-free synthetic biology promises to further bridge the sensitivity gap between protein and nucleic acid detection. Recent developments such as expression immunoassays, CRISPR-linked immunoassays (CLISA), and T7 RNA polymerase-linked immunosensing assays (TLISA) demonstrate how programmable nucleic acid and protein synthesis systems can be integrated into ELISA workflows to surpass current sensitivity limitations [23]. By combining synthetic biology-driven amplification with traditional immunoassay formats, researchers are developing increasingly modular and adaptable diagnostic platforms capable of detecting protein biomarkers at concentrations previously undetectable in peripheral biofluids [25].

The evolution from highly sensitive to ultrasensitive immunoassays represents a significant advancement in diagnostic accuracy and early biomarker detection. While highly sensitive assays remain the standard in many clinical applications due to their robust performance and higher specificity, ultrasensitive technologies offer unprecedented detection capabilities that are reshaping diagnostic paradigms, particularly in neurology, oncology, and endocrinology. The trade-off between sensitivity and specificity must be carefully considered in both clinical practice and research applications. As synthetic biology and digital detection technologies continue to mature, the next generation of immunoassays promises to further dissolve the sensitivity barriers between protein and nucleic acid detection, potentially enabling earlier diagnosis and more precise monitoring across a spectrum of diseases.

From Theory to Practice: Methodologies for Assessing Sensitivity Across Assay Platforms

Standardized Protocols for Establishing LoD and LLOQ

In analytical science, the Limit of Detection (LoD) and Lower Limit of Quantitation (LLOQ or LoQ) are fundamental performance characteristics that define the capabilities of an analytical procedure. The LoD represents the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from zero, while the LLOQ is the lowest concentration that can be measured with acceptable precision and accuracy [1]. These parameters are essential for method validation across diverse fields including clinical diagnostics, pharmaceutical development, and environmental testing, providing critical information about the dynamic range and sensitivity of analytical methods [27].

Understanding the distinction between these parameters is crucial for proper method characterization. The LoD represents a detection capability, whereas the LLOQ represents a quantitation capability where predefined goals for bias and imprecision are met [1]. The LLOQ may be equivalent to the LoD or exist at a much higher concentration, but it can never be lower than the LoD [1]. This relationship becomes particularly important when establishing the reportable range of an assay, as results below the LLOQ but above the LoD may be detected but not quantified with sufficient reliability for analytical purposes [10].

Standardized Frameworks and Guidelines

Key Regulatory Guidelines

Two primary standardized frameworks govern the establishment of LoD and LLOQ: the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) EP17 guideline and the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R2) guideline [1] [28]. The CLSI EP17 guideline, titled "Evaluation of Detection Capability for Clinical Laboratory Measurement Procedures," provides a comprehensive approach specifically tailored for clinical laboratory measurements [28]. This protocol defines three critical parameters: Limit of Blank (LoB), LoD, and LLOQ, each with distinct definitions and statistical approaches for determination [1].

The ICH Q2(R2) guideline, "Validation of Analytical Procedures," offers a broader framework applicable to various analytical methods, particularly in pharmaceutical quality control [27] [28]. This guideline describes multiple approaches for determining detection and quantitation limits, including methods based on visual evaluation, signal-to-noise ratio, standard deviation of the blank, and standard deviation of the response relative to the slope of the calibration curve [27]. The choice between these frameworks depends on the intended application of the analytical method and regulatory requirements.

Table 1: Comparison of CLSI EP17 and ICH Q2(R2) Approaches for LoD and LLOQ Determination

| Characteristic | CLSI EP17 Protocol | ICH Q2(R2) Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Clinical laboratory measurements | Pharmaceutical analysis |

| Key Parameters | LoB, LoD, LLOQ | LoD, LLOQ |

| Statistical Basis | Defined formulas based on blank and low-concentration sample distributions | Multiple approaches: visual evaluation, signal-to-noise, standard deviation of blank/response |

| Sample Requirements | 60 replicates for establishment, 20 for verification [1] | Varies by approach; typically 5-7 concentrations with 6+ replicates [27] |

| LoD Definition | Lowest concentration reliably distinguished from LoB [1] | Lowest amount detectable but not necessarily quantifiable as exact value [27] |

| LLOQ Definition | Lowest concentration meeting predefined bias and imprecision goals [1] | Lowest concentration quantifiable with acceptable precision and accuracy [27] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

CLSI EP17 Protocol

The CLSI EP17 protocol employs a three-tiered approach involving the determination of LoB, LoD, and finally LLOQ [1]. This method requires testing blank samples (containing no analyte) and low-concentration samples (containing known low concentrations of analyte) in sufficient replication to capture expected performance variability.

Limit of Blank (LoB) Determination: The LoB is defined as the highest apparent analyte concentration expected to be found when replicates of a blank sample are tested [1]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Testing approximately 60 replicates of a blank sample using at least two different instruments and reagent lots

- Calculating the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the blank measurements

- Applying the formula: LoB = meanblank + 1.645(SDblank) [1]

- This establishes a one-sided 95% confidence limit, assuming a Gaussian distribution where 95% of blank measurements fall below this value

Limit of Detection (LoD) Determination: The LoD represents the lowest analyte concentration likely to be reliably distinguished from the LoB [1]. The experimental approach includes:

- Testing approximately 60 replicates of a sample with low analyte concentration

- Calculating the mean and standard deviation of these low-concentration measurements

- Applying the formula: LoD = LoB + 1.645(SD_low concentration sample) [1]

- This ensures that 95% of measurements at the LoD concentration exceed the previously established LoB

Limit of Quantitation (LLOQ) Determination: The LLOQ is established as the lowest concentration at which the analyte can be quantified with predefined levels of bias and imprecision [1]. Unlike LoD, LLOQ requires meeting specific performance goals for total error. If these goals are met at the LoD concentration, then LLOQ equals LoD; if not, higher concentrations must be tested until the goals are achieved [1].

The following diagram illustrates the complete CLSI EP17 workflow for establishing these fundamental parameters:

ICH Q2(R2) Approaches

The ICH Q2(R2) guideline provides four distinct approaches for determining LoD and LLOQ, offering flexibility based on methodological characteristics [27].

Visual Evaluation Approach: This subjective method involves analyzing samples with known concentrations of analyte and determining the minimum level at which the analyte can be reliably detected [27]. The experimental protocol typically employs:

- Five to seven concentration levels prepared from a known reference material

- Six to ten replicate determinations at each concentration level

- Binary scoring (detected/not detected) by analysts or instruments

- Statistical analysis using logistic regression to determine the concentration corresponding to 99% detection probability for LoD

Signal-to-Noise Ratio Approach: This method is applicable only when the analytical method exhibits measurable background noise [27]. The experimental design includes:

- Five to seven concentration levels with six or more replicates each

- Calculation of signal-to-noise ratio at each concentration (signal = measurement, noise = blank control)

- Establishment of LoD at a signal-to-noise ratio of 2:1 or 3:1

- Establishment of LLOQ at a signal-to-noise ratio of 10:1 or based on precision profiles

- Nonlinear modeling using four-parameter logistic curves for interpolation

Standard Deviation of the Blank Approach: This method utilizes the mean and standard deviation of blank samples to establish limits [27]. The protocol involves:

- Minimum of ten blank sample determinations in appropriate matrix

- Calculation of LoD and LLOQ using defined formulas:

- LoD = meanblank + 3.3(SDblank)

- LLOQ = meanblank + 10(SDblank)

Standard Deviation of Response and Slope Approach: This approach is particularly suitable for methods with calibration curves and minimal background noise [27]. The methodology includes:

- Analysis of samples at five concentrations in the expected LoD/LLOQ range

- Minimum of six determinations at each concentration level

- Calculation of LoD and LLOQ using the formulas:

- LoD = 3.3σ/slope

- LLOQ = 10σ/slope

- Where σ represents the standard deviation of the response and slope is the slope of the calibration curve

Table 2: Comparative Experimental Requirements for Different ICH Q2(R2) Approaches

| ICH Q2(R2) Approach | Minimum Sample Types | Replicates per Level | Statistical Method | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Evaluation | 5-7 concentration levels | 6-10 | Logistic regression | Qualitative and semi-quantitative methods |

| Signal-to-Noise | 5-7 concentration levels + blanks | 6+ | Nonlinear modeling (4PL) | Methods with measurable background noise |

| SD of Blank | Blank samples | 10+ | Direct calculation | Methods with clean background |

| SD of Response/Slope | 5 concentration levels in low range | 6+ | Linear regression | Methods with calibration curves |

Comparative Experimental Data

Application in Molecular Diagnostics

In molecular diagnostics, particularly for pathogen detection, the empirical determination of LoD using probit analysis represents a robust approach [29]. This method involves testing multiple replicates across a dilution series of the target analyte and applying statistical analysis to determine the concentration at which 95% of samples test positive.

A recent study on human cytomegalovirus (hCMV) DNA detection using loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) technology demonstrated this approach [29]:

- Eight different hCMV DNA concentrations were tested with at least 24 replicates per concentration

- Results were scored as detected or not detected for each replicate

- Probit analysis was applied to determine the LoD as the concentration yielding 95% detection (C95)

- This empirical approach provides a statistically robust LoD estimate that accounts for methodological variability

Similar approaches have been applied to compare the analytical sensitivity of seven commercial SARS-CoV-2 automated molecular assays, highlighting how LoD values can vary significantly between different methodological platforms [30].

Case Study: Ultrasensitive PCR Assay

Research on JC virus (JCV) DNA detection in cerebrospinal fluid for diagnosing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) demonstrates the application of these principles in clinical validation [31]. An ultrasensitive multiplex quantitative PCR assay was developed with both LoD and LLOQ established at 10 copies per milliliter [31]. This validation included:

- Comprehensive determination of both LoD and LLOQ at the same concentration level

- Implementation as a reference method for clinical sample testing

- Application in longitudinal monitoring of virological burden in clinical trials

- Demonstration that meeting precision requirements at the detection limit allows LoD and LLOQ to coincide

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental protocols for establishing LoD and LLOQ require specific research reagents and materials tailored to the analytical method. The following table outlines essential solutions across different methodological approaches:

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for LoD/LLOQ Determination

| Reagent/Material | Function in LoD/LLOQ Studies | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Blank Matrix | Provides analyte-free background for LoB determination and background noise assessment | All methods; must be commutable with patient specimens [1] |

| Low-Concentration Calibrators | Used for testing samples near the expected LoD and LLOQ | CLSI EP17 protocol; should mimic actual sample matrix [1] |

| Reference Standards | Provide known analyte concentrations for preparing dilution series | All quantitative approaches; certified reference materials preferred |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitor assay performance during validation studies | All protocols; should span critical concentrations including LoD/LLOQ |

| Sample Diluents | Prepare dilution series for empirical determination | Critical selection; inappropriate diluents may bias results [10] |

Critical Considerations in Protocol Implementation

Method Selection and Fit-for-Purpose Validation

Selecting the appropriate protocol for establishing LoD and LLOQ requires careful consideration of the analytical method's characteristics and intended application [27]. The "fit-for-purpose" principle dictates that the validation approach should match the eventual use of the method, with more rigorous requirements for clinical decision-making compared to research applications [1].

Key considerations include:

- Matrix effects: Blank and low-concentration samples should be commutable with actual patient specimens to ensure realistic performance assessment [1]

- Instrumentation variability: LoD and LLOQ determination should incorporate multiple instruments and reagent lots when establishing performance characteristics [1]

- Total error requirements: LLOQ establishment must consider the total allowable error (bias + imprecision) required for clinical or regulatory purposes [10]

- Practical limitations: While CLSI EP17 recommends 60 replicates for establishment, practical constraints may require verification with fewer replicates (e.g., 20) [1]

Troubleshooting Common Challenges

Several common challenges arise during LoD and LLOQ determination that require methodological adjustments:

- High background noise: When blank samples produce significant signal, the signal-to-noise approach may be most appropriate [27]

- Non-Gaussian distributions: For methods where blank results don't follow normal distribution, non-parametric statistical methods should be employed [1]

- Limited sample availability: For methods with scarce matrices, creative approaches using diluted samples may be necessary while recognizing potential limitations [10]

- Discrepancies between approaches: When different methodologies yield substantially different LoD/LLOQ values, empirical testing with clinical samples may be needed to determine the clinically relevant limit

The relationship between different performance characteristics and their application to real-world analytical challenges can be visualized as follows:

Standardized protocols for establishing LoD and LLOQ provide essential frameworks for characterizing analytical method performance. The CLSI EP17 and ICH Q2(R2) guidelines offer complementary approaches with varying levels of rigor and applicability to different methodological challenges. Proper selection and implementation of these protocols require understanding both statistical principles and practical experimental considerations to ensure methods are fit for their intended purpose. As analytical technologies continue to evolve with increasing sensitivity demands, these standardized approaches provide the foundation for reliable method validation across diverse scientific disciplines.

In biomedical research and drug development, the accurate detection and quantification of biomarkers are paramount. The core challenge lies in measuring increasingly low-abundance targets—from rare genetic variants to single protein molecules—within complex biological matrices. This comprehensive guide objectively compares three foundational technology classes: Immunoassays, including ultra-sensitive platforms like Single Molecule Array (Simoa); the Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) and its digital derivatives; and Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS). The analysis is framed within the critical context of analytical sensitivity (the lowest concentration an assay can reliably detect) versus functional sensitivity (the lowest concentration an assay can measure with acceptable precision, often defined as ≤20% coefficient of variation) [32]. Understanding this distinction and the performance boundaries of each technology is essential for selecting the optimal tool for diagnosing diseases, monitoring treatment efficacy, and advancing precision medicine.

Immunoassays: Antibody-Based Protein Detection

Immunoassays are designed for the detection of proteins and other antigens. Their fundamental principle relies on the specific binding of an antibody to a target antigen. The most common format, the sandwich ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay), immobilizes a capture antibody on a solid substrate, which binds the target protein from a sample. A detection antibody, conjugated to an enzyme like Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP), then binds to the captured protein. The enzyme catalyzes a colorimetric, fluorescent, or chemiluminescent reaction, generating a signal proportional to the target concentration [33]. The sensitivity of standard immunoassays typically ranges from 1 pg/mL to 10 ng/mL [33].

Recent advancements have pushed these limits. Single Molecule Array (Simoa) technology represents a revolutionary ultra-sensitive immunoassay. It uses antibody-coated beads to capture single protein molecules, which are then labeled with an enzymatic detection antibody. The beads are isolated in femtoliter-sized wells, creating a confined space where the enzyme converts a substrate into a highly concentrated fluorescent product that is easily imaged. This single-molecule counting enables detection in the femtomolar (fg/mL) range, offering a sensitivity up to 1,000 times greater than conventional ELISA [33] [32].

PCR and Digital PCR: Nucleic Acid Amplification

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is a cornerstone of molecular biology for detecting nucleic acids (DNA and RNA). It enables the in vitro enzymatic amplification of a specific DNA sequence, exponentially copying it through repeated heating and cooling cycles. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) allows for the real-time monitoring of this amplification using fluorescent probes, providing quantitative data on the initial amount of the target sequence [34] [35].