Assessing Laser-Induced Damage Threshold After Optical Cleaning: Protocols, Impacts, and Validation for High-Power Systems

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and engineers on the critical relationship between optical cleaning processes and the Laser-Induced Damage Threshold (LIDT) of components.

Assessing Laser-Induced Damage Threshold After Optical Cleaning: Protocols, Impacts, and Validation for High-Power Systems

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and engineers on the critical relationship between optical cleaning processes and the Laser-Induced Damage Threshold (LIDT) of components. It covers the foundational science of laser damage, details established and emerging cleaning methodologies—from chemical and ultrasonic to advanced laser-based techniques—and analyzes their direct impact on LIDT. The content further addresses troubleshooting for common post-cleaning defects, outlines the latest international standards for damage testing and validation (including the updated ISO 21254-1:2025), and offers comparative insights to guide the selection of optimal cleaning protocols for enhancing optical component longevity and performance in high-power laser systems, from industrial applications to scientific facilities.

The Science of Cleanliness: How Contamination and Defects Govern Laser-Induced Damage

The Laser-Induced Damage Threshold (LIDT) is formally defined by the ISO 21254 standard as the highest quantity of laser radiation incident upon an optical component for which the extrapolated probability of damage is zero [1]. In practical terms, it specifies the maximum laser fluence (for pulsed lasers, typically in J/cm²) or intensity (for continuous wave lasers, in W/cm²) that an optical component can withstand before damage occurs [1]. This parameter represents a critical bottleneck in developing high-power laser systems for scientific, industrial, and medical applications, where optical components must maintain integrity under extreme photon fluxes.

Within the context of optical cleaning research, understanding LIDT is paramount. Cleaning procedures aim to remove contaminants and subsurface damage that can act as initiation sites for laser damage. However, these very processes may also introduce new surface defects or modify material properties in ways that affect damage resistance. This guide systematically compares damage mechanisms, measurement methodologies, and material performance to establish a foundational framework for assessing how cleaning protocols influence the ultimate durability of optical components.

Fundamental Damage Mechanisms

Laser-induced damage mechanisms are predominantly dictated by the temporal characteristics of the laser irradiation, shifting from thermally-dominated processes to field-induced effects as pulse durations decrease.

Thermal Overheating (Continuous Wave and Long-Pulse Lasers)

- Primary Mechanism: Damage from continuous-wave (CW) lasers and long pulses primarily results from thermal effects caused by absorption in the optic's coating or substrate. Energy from absorbed laser radiation converts to heat, causing temperature rise within the material [1]. When the resulting thermal stress exceeds the material's strength or when temperatures reach melting, boiling, or decomposition points, irreversible damage occurs [2].

- Material Vulnerabilities: Components with inherent absorption issues, such as metal-coated mirrors and absorbing filters, are particularly susceptible. Cemented optical components (e.g., achromats, polarizers) also exhibit lower CW damage thresholds due to absorption or scattering in the cement layer [1] [2].

- Process Dynamics: The damage is governed by the balance between the rate of heat deposition from the laser and the rate of heat dissipation through thermal conduction. This makes it dependent on both the absorption coefficient and the thermal conductivity of the material [2].

Dielectric Breakdown and Nonlinear Effects (Short and Ultrashort Pulses)

As pulse durations shorten to the nanosecond regime and below, the damage mechanism transitions from purely thermal to dielectric breakdown [1]. This occurs when the high electric fields in the laser beam exceed the material's intrinsic breakdown threshold, liberating electrons and creating a micro-plasma [2].

For ultrashort pulses (femtoseconds to picoseconds), thermal processes become negligible because the pulse duration is shorter than the electron-lattice interaction time [1]. Damage results from nonlinear excitation of electrons through a sequence of processes:

- Seed Electron Generation: Initial free electrons are generated via multiphoton absorption, multiphoton ionization, or tunnel ionization [1] [2].

- Avalanche Ionization: These seed electrons are accelerated by the laser's electric field, colliding with bound electrons and ionizing them in an avalanche process that exponentially increases the free electron density [1].

- Material Modification: Once the free electron density reaches a critical value (often referred to as the plasma critical density), the material becomes strongly absorbing, leading to energy deposition and permanent damage through ablation or melting [1] [2].

Table 1: Dominant Laser-Induced Damage Mechanisms by Pulse Duration

| Pulse Duration Regime | Dominant Damage Mechanism | Governing Physical Principles | Typical Damage Morphology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous Wave (CW) | Thermal Overheating | Linear absorption, heat diffusion, thermal stress | Melting, burning, cracking, delamination [2] |

| Long-Pulse (μs-ms) | Thermal Overheating | Linear absorption, heat diffusion | Large-scale fractures, discoloration, burning |

| Short-Pulse (ns) | Dielectric Breakdown & Thermal | Avalanche ionization, plasma formation, combined thermal effects | Isolated pits, cracks, coating removal [2] |

| Ultrashort (fs-ps) | Nonlinear Ionization | Multiphoton absorption, avalanche ionization, cold ablation [2] | Precise ablation, minimal heat-affected zone, pinpoint defects [2] |

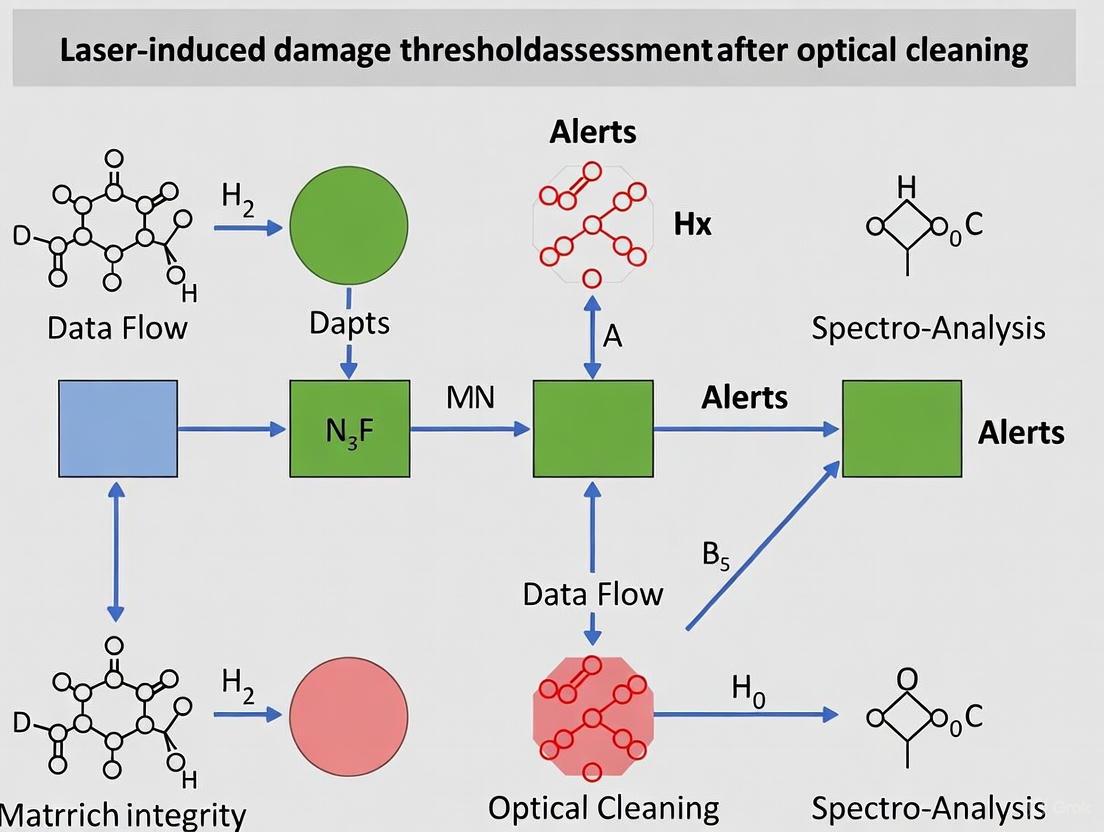

Figure 1: Laser-induced damage mechanisms bifurcate based on pulse duration, leading to either thermal or dielectric breakdown pathways.

Experimental Protocols for LIDT Measurement

Standardized measurement of LIDT is governed by ISO 21254, which provides methodologies for deterministic and probabilistic damage testing. The fundamental principle involves irradiating multiple test sites on a sample with different fluence levels and determining the damage probability at each fluence [1].

Test Setup and Damage Detection

A standard LIDT test configuration requires:

- Laser Source: A laser with parameters (wavelength, pulse duration, repetition rate) relevant to the intended application.

- Beam Conditioning Optics: Lenses and apertures to control spot size, shape, and uniformity.

- Energy/Power Measurement: Calibrated sensors to measure incident pulse energy or average power.

- Sample Positioning System: A motorized stage for precise site-to-site movement.

- Online Damage Detection: Typically achieved by monitoring scattered light from the sample surface, transmission changes, or plasma emission [2].

According to ISO 21254, any detectable change in the optic after laser exposure constitutes damage [1]. This can be assessed through:

- Optical Microscopy: Identifying visible pits, cracks, or discoloration.

- Scatter Measurement: Monitoring increased levels of stray light (Total Integrated Scattering).

- Functional Testing: Detecting changes in performance (e.g., reflectivity of a mirror) [2].

Data Analysis and LIDT Determination

The raw data consists of damage probability (number of damaged sites divided by total tested sites) versus incident fluence. The LIDT is statistically defined as the fluence at which the damage probability extrapolates to zero [1]. For Gaussian beams, special consideration is needed as the effective beam diameter scales with fluence, increasing the probability of encountering a defect [1].

Figure 2: Standardized workflow for LIDT measurement according to ISO 21254, integrating both in-situ and post-mortem damage analysis.

Material Performance Comparison

The resistance of optical components to laser damage is highly dependent on both the base material and the fabrication process. Research continuously seeks materials with higher bandgaps and improved coating technologies to push LIDT limits.

Bulk Material and Coating Performance

- Bulk vs. Surface Damage: Surfaces typically have substantially lower damage thresholds than bulk material due to a higher density of microscopic defects from polishing and potential contamination [2]. Subsurface damage left from grinding and polishing can create localized stress points with enhanced absorption [1].

- Coating Challenges: Thin films are generally the weakest part of optical systems [3]. The LIDT of coatings depends on material properties, deposition technology, and the electric field distribution within the multilayer structure [3]. For instance, complex designs like dispersive mirrors for ultrafast lasers often exhibit lower damage thresholds due to high internal field intensities [2].

Advanced Coating Materials

Recent research focuses on mixture coatings to achieve better comprehensive performance. A 2023 study compared Ta₂O₅-based mixture coatings deposited via plasma-ion-assisted e-beam co-evaporation [4]:

Table 2: Performance of Ta₂O₅-Based Mixture Coatings for Femtosecond Lasers

| Coating Material | Refractive Index (at 800 nm) | Optical Bandgap (eV) | Relative Femtosecond LIDT | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ta₂O₅ (Pure) | 2.08 | 4.02 | 1.00 (Reference) | High refractive index but relatively narrow bandgap [4] |

| Ta₂O₅-TiO₂ | 2.18 | 3.76 | ~0.85 | Increased index but reduced bandgap and LIDT [4] |

| Ta₂O₅-HfO₂ | 2.02 | 4.41 | ~1.35 | Larger bandgap, significantly improved LIDT [4] |

| Ta₂O₅-Al₂O₃ | 1.94 | 4.83 | ~1.55 | Largest bandgap, highest LIDT enhancement [4] |

| Ta₂O₅-SiO₂ | 1.89 | 5.26 | ~1.25 | Very large bandgap, high LIDT [4] |

The data demonstrates a clear trend: when refractive indices are similar, the femtosecond LIDT of mixture coatings primarily depends on their optical bandgap [4]. Doping Ta₂O₅ with wide-bandgap materials like Al₂O₃, HfO₂, and SiO₂ effectively enhances damage resistance by reducing linear and nonlinear absorption.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Methods in LIDT and Optical Coating Research

| Category/Reagent | Function/Application | Performance Significance |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Coating Materials | ||

| Ta₂O₅ (Tantalum Pentoxide) | High-refractive-index coating material | Common high-n material with relatively narrow bandgap limits LIDT [4] |

| HfO₂ (Hafnium Dioxide) | High-index, wide-bandgap coating material | Large bandgap (∼5.5 eV) contributes to high LIDT; used in mixtures [4] |

| SiO₂ (Silicon Dioxide) | Low-index coating material | Wide bandgap, used in multilayer coatings and mixtures to enhance LIDT [4] |

| Al₂O₃ (Aluminum Oxide) | Wide-bandgap doping material | Largest bandgap enhancement in Ta₂O₅ mixtures, yields highest LIDT [4] |

| Substrate Processing | ||

| Fused Silica Substrates | Common substrate for high-power optics | High purity and low absorption are critical for bulk LIDT [4] |

| Magnetorheological Finishing | Advanced surface polishing technique | Reduces subsurface damage, improving surface LIDT [2] |

| Ion Beam Etching | Pre-coating substrate preparation | Removes contaminated surface layers, enhancing adhesion and LIDT [2] |

| Deposition Technologies | ||

| Ion-Beam Sputtering (IBS) | High-quality coating deposition | Produces dense, low-absorption coatings with high LIDT [3] |

| Plasma-Ion-Assisted E-beam Evaporation | Coating deposition for complex mixtures | Enables co-evaporation of multiple materials for tailored properties [4] |

Implications for Optical Cleaning Research

The relationship between LIDT and optical cleaning is multifaceted. Cleaning aims to remove extrinsic contaminants that act as absorption sites and damage initiators [3] [1]. However, cleaning processes themselves must be evaluated for their potential to introduce or modify surface and subsurface defects.

- Contamination Control: Proper surface preparation, contamination control, and environmental degradation prevention are recognized methods for improving the performance of optical surfaces [3]. Contaminants like machine oils can outgas and deposit on optics, leading to gradual degradation and reduced LIDT [2].

- Cleaning Technique Efficacy: Techniques such as wet chemical etching, ion beam etching, and UV laser conditioning have been developed to improve surface damage thresholds by removing or passivating defects [2]. The effectiveness of these methods is highly material-dependent.

- Assessment Protocol: Validating cleaning methods requires rigorous LIDT testing following the experimental protocols outlined in Section 3. The focus should be on the statistical nature of damage initiation, as improved cleaning should reduce the density of damage-initiating defects, thereby increasing the measured LIDT, particularly for large-area beams [1] [2].

Laser-Induced Damage Threshold is a complex, multifaceted property determined by the interplay of laser parameters, material properties, and manufacturing processes. The fundamental damage mechanisms transition from thermal overheating to nonlinear dielectric breakdown as pulse durations decrease from continuous wave to the femtosecond regime. Accurate measurement requires standardized methodologies like ISO 21254 to ensure reliable, comparable data.

Current research on advanced materials, particularly oxide mixture coatings, demonstrates that engineering optical properties like the optical bandgap is a promising path to higher LIDT. For optical cleaning research, the imperative is to develop and validate processes that effectively remove extrinsic contaminants without introducing new defects, thereby pushing the damage threshold closer to the intrinsic limit of the base material. This comprehensive understanding of LIDT provides the critical foundation for advancing high-power laser applications across scientific and industrial fields.

In high-power laser systems, the ultimate performance and longevity of optical components are not solely determined by their design or base material, but critically by the presence of microscopic "enemies within"—collectively known as damage precursors. These precursors are localized imperfections that serve as initiation points for laser-induced damage, a phenomenon that limits system performance and reliability in applications from inertial confinement fusion to advanced manufacturing [5] [6]. Laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) is formally defined by ISO 21254 as the "highest quantity of laser radiation incident upon the optical component for which the extrapolated probability of damage is zero" [7]. However, this theoretical threshold is profoundly influenced by the population of damage precursors introduced during manufacturing, handling, or cleaning processes.

The relationship between precursors and laser damage follows a deterministic pathway: precursors absorb laser energy more efficiently than the surrounding bulk material, leading to localized heating, plasma formation, and ultimately, permanent damage to the optical surface [5] [7]. For researchers assessing laser-induced damage threshold after optical cleaning, understanding these precursor classes is paramount, as cleaning processes can either mitigate or inadvertently introduce these critical defects. This guide provides a systematic comparison of damage precursor classes, their characteristics, and the experimental methods used to detect and quantify them, framing this within the critical context of optical cleaning research.

Classification and Comparison of Damage Precursors

Damage precursors in optical components can be systematically categorized into four distinct classes based on their origin, physical characteristics, and interaction with laser radiation. The following sections provide a detailed comparison of particulates, residues, subsurface defects, and impurities.

Particulates

Particulate contaminants represent a pervasive class of damage precursors involving foreign material deposition on optical surfaces. These include abrasive particles from polishing compounds (e.g., cerium oxide, zirconia), dust from the manufacturing environment, or other microscopic debris that adheres to the surface during handling or cleaning. The damage mechanism for particulates is primarily thermal: metallic particles, for instance, exhibit strong absorption at laser wavelengths, leading to rapid heating, melting, and potential plasma formation that catastrophically damages the underlying substrate [5] [8]. Even dielectric particles can cause damage through field enhancement or by acting as thermal conduits. The susceptibility of particulate-induced damage depends critically on the material's absorption properties, size, and distribution density across the optical surface.

Residues

Residues encompass a range of surface-bound contaminants with varying chemical compositions and origins. This class includes cleaning agent remnants (surfactants, solvents), water spots, fingerprints, organic films, and redeposited material from polishing processes [5] [8]. Unlike particulates, residues typically form continuous or semi-continuous films that can significantly increase surface absorption, particularly in the ultraviolet spectrum. The damage mechanism often involves thermochemical degradation, where the residue film absorbs laser energy, undergoes chemical breakdown, and transfers thermal energy to the substrate or creates localized stress points. The Beilby layer—a redeposited, amorphous material layer formed during polishing—represents a particularly problematic type of residue that is challenging to detect and remove completely [8].

Subsurface Defects (SSD)

Subsurface damage constitutes perhaps the most structurally significant category of damage precursors, consisting of micro-fractures and cracks embedded beneath the optically polished surface. These defects are systematically introduced during mechanical processes like grinding, lapping, and polishing, where brittle fracture occurs below the material removal zone [6] [8]. The fundamental damage mechanism for SSD involves field intensification at crack tips, where the electric field of incident laser light can be significantly enhanced, promoting dielectric breakdown. Additionally, these cracks may contain trapped polishing compounds or other absorptive materials, creating a combined thermal and mechanical vulnerability [8]. The depth and density of subsurface damage are directly correlated with processing parameters, particularly abrasive size and applied pressure during grinding operations.

Impurities

Impurity-type precursors involve atomic or molecular-scale contaminants either embedded within the optical material's matrix or concentrated at the surface. These include metallic impurities (e.g., iron, copper, cerium) from polishing tools or abrasives, as well as intrinsic point defects in the material structure such as oxygen-deficient centers (ODCs) and non-bridging oxygen hole centers (NBOHCs) in fused silica [5] [8]. The damage mechanism for impurities is primarily through linear and nonlinear absorption processes. Metallic impurities create electronic energy states within the material's bandgap, enabling enhanced absorption at laser wavelengths. Under high fluence, these sites can initiate multi-photon absorption, avalanche ionization, and ultimately plasma formation [7] [8]. Unlike other precursor classes, some impurity defects can be generated or transformed by the laser radiation itself through a process known as laser darkening.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Damage Precursor Classes

| Precursor Class | Physical Scale | Origin | Primary Damage Mechanism | Influence of Cleaning Processes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particulates | Micron to sub-micron | Foreign material deposition, environment | Thermal absorption and plasma formation | Can be removed by proper cleaning; improper cleaning can redeposit or embed particles |

| Residues | Molecular to nano-scale | Cleaning agents, polishing fluids, fingerprints | Thermochemical degradation, increased surface absorption | Directly introduced or removed by cleaning; residue-free drying is critical |

| Subsurface Defects | Nano to micron scale | Mechanical processing (grinding, polishing) | Field enhancement at crack tips, trapped absorbers | Generally unaffected by cleaning; may be exposed by etching processes |

| Impurities | Atomic to molecular scale | Raw material, processing tools, abrasives | Linear/non-linear absorption, electron excitation | Metallic impurities may be redistributed by certain cleaning methods |

Experimental Detection and Characterization Methods

A diverse array of experimental techniques has been developed to detect and characterize damage precursors, each with specific capabilities, limitations, and detection sensitivities. The following section details the primary methodologies employed in precursor analysis.

Photothermal Weak Absorption Measurements

The photothermal common-path interferometry (PCI) method has emerged as a powerful non-contact technique for quantitatively mapping absorptive defects on optical surfaces. This method operates by focusing a pump laser beam (typically at 355 nm for UV optics) onto the test location, where localized heating from absorbing defects causes a minute change in the refractive index. A probe laser (e.g., He-Ne at 632.8 nm) then detects this change through interferometry, allowing for precise measurement of absorption levels with sensitivity approaching 0.4 ppm [5].

In practice, PCI systems perform two-dimensional scanning across the sample surface, generating statistical distributions of absorbing defects at various absorption levels. This capability proved crucial in a recent study that established a strong correlation between the density of defects with absorption over 2 ppm and the damage initiation threshold of fused silica optics [5]. The methodology enables researchers to distinguish between surface and bulk absorption, making it particularly valuable for evaluating the effectiveness of different post-treatment processes, including those aimed at cleaning and surface purification.

Laser-Induced Damage Threshold (LIDT) Testing

LIDT testing serves as the fundamental performance validation method for optical components in high-power laser applications. According to ISO standards 21254, this destructive testing involves exposing multiple sites on an optical component to progressively higher laser fluence until damage is detected [7] [9]. Two primary testing protocols are employed:

- Single-shot (1-on-1) tests administer one laser pulse per test site across at least 10 different sites with varying fluence levels. The damage probability is plotted against fluence and extrapolated to find the zero-probability damage threshold [9].

- Multi-shot (S-on-1) tests expose each site to a series of laser pulses (typically 10-1000 shots) to better predict real-world performance and avoid the statistical uncertainty of the "infant mortality" region observed with low shot counts [9].

Damage detection employs several complementary methods. Nomarski-type differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy enhances contrast for transparent samples, allowing visual identification of surface modifications. Scattered light diagnostics uses a probe beam to detect increased scattering from damage sites, while plasma spark monitoring detects the plasma generated during optical breakdown [9]. The choice of detection method significantly influences the measured LIDT value, as different techniques have varying sensitivities to different damage morphologies.

Material-Specific Characterization Techniques

Beyond the primary methods above, several specialized techniques provide unique insights into specific precursor types:

Coda Wave Interferometry (CWI): This ultrasonic method analyzes the later-arriving "coda" portion of guided waves, which is highly sensitive to distributed precursor damages like matrix microcracking, fiber breakages, and local fiber-matrix debonding in composite materials. The technique employs a modified stretching algorithm to quantify phase shifts in the coda wave, detecting damage long before macroscopic signs appear [10].

Destructive Subsurface Analysis: Traditional methods for characterizing subsurface damage include taper polishing, which involves cutting a sample at a shallow angle and polishing to expose the subsurface for direct microscopic observation. The SSD depth (d) is calculated using the formula d = x · sinα, where x is the observed distance of the defect from the surface along the wedge and α is the wedge angle [8].

Multi-sensor Image Fusion: Recent advances in defect detection combine visible and infrared imaging through sophisticated fusion algorithms. One approach, termed NPP, integrates non-subsampled contourlet transform, principal component analysis, and pulse-coupled neural network frameworks to enhance detection capability for damage precursors in complex environments [11].

Table 2: Detection Methods for Different Precursor Classes

| Detection Method | Principle of Operation | Precursor Types Detected | Sensitivity/Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Photothermal PCI | Measures refractive index change from local heating | Absorbing impurities, residues, metallic particulates | ~0.4 ppm sensitivity; requires scanning |

| Scattered Light Diagnostics | Detects increased light scattering from surface defects | Particulates, subsurface defects breaking surface | Background noise dependent |

| Coda Wave Interferometry | Analyzes ultrasonic wave scattering from distributed defects | Subsurface microcracks, material heterogeneity | Specialized for composite materials |

| DIC Microscopy | Optical interference contrast enhancement | Surface-breaking defects, residues, particulates | Limited to surface and near-surface defects |

| Taper Polishing | Direct visual observation of cross-sectioned material | Subsurface cracks, fractured layer depth | Destructive; requires sample sacrifice |

Experimental Protocols for Precursor Analysis

Sample Preparation and Post-Treatment Methodologies

Standardized sample preparation is essential for meaningful comparison of damage precursors across different processing conditions. For fused silica optics studies, high-purity substrates (e.g., Corning 7980) are typically prepared using conventional polishing processes with CeO₂ as the abrasive [5]. To evaluate the effectiveness of cleaning and post-processing methods, samples are subjected to different treatments:

- Dynamic Chemical Etching (DCE): This process submerges samples in an HF-based etchant (e.g., 49 wt.% HF and 30 wt.% NH₄F with volume ratio 1:4) under multi-frequency ultrasonic transducers. The etching rate is typically calibrated to ~0.1 μm/min, with material removal precisely controlled [5].

- Magnetorheological Finishing (MRF): This post-treatment utilizes a magnetorheological fluid with CeO₂ polishing particles (~0.2 μm size) at controlled removal rates (e.g., 1.8 × 10⁷ μm³/min) to redefine the surface layer without introducing significant new damage [5].

- Laser-Based Processing: Advanced CO₂ laser ablation techniques enable uniform layer-by-layer material removal with longitudinal resolution <5 nm, serving as both a characterization tool for subsurface damage and a mitigation strategy [6].

Following post-treatment, samples undergo rigorous cleaning in Micro90 solution or similar cleaners, followed by rinsing with deionized water and air-drying [5]. Surface roughness is quantitatively measured using white light interferometry to track changes induced by processing.

Correlation Analysis Protocol

Establishing quantitative relationships between precursor populations and damage performance requires systematic correlation analysis. The experimental protocol involves:

- Precursor Mapping: Using PCI or other mapping techniques to generate statistical distributions of absorbing defects across multiple 3 mm × 3 mm regions with a step size of 50 μm [5].

- Damage Testing: Conducting LIDT testing on corresponding sample areas using standardized single-shot or multi-shot protocols.

- Statistical Correlation: Analyzing the relationship between defect density at various absorption levels and the resulting damage thresholds.

This approach has revealed that defects with absorption exceeding 2 ppm show particularly strong correlation with damage initiation thresholds, with high-density defects at this level enabling accurate prediction of damage density [5].

Signaling Pathways and Damage Initiation Workflows

The progression from pristine optic to laser-induced damage follows a deterministic pathway involving specific physical processes. The diagram below illustrates the conceptual signaling pathway of damage initiation from precursors.

Diagram 1: Damage initiation pathway from precursors to system failure

The experimental workflow for precursor characterization and LIDT assessment follows a systematic process as illustrated below.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for precursor-LIDT correlation studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Precursor Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Corning 7980 Fused Silica | Standard substrate material with well-characterized properties | Fundamental LIDT and precursor studies [5] |

| Cerium Oxide (CeO₂) Abrasive | Standard polishing compound for optical finishing | Introduces specific particulate and impurity precursors [5] [8] |

| HF-based Etchants | Chemical removal of damaged surface layers | Dynamic Chemical Etching post-processing [5] |

| Magnetorheological Fluids | Precision surface finishing with minimal new damage | MRF post-treatment process [5] |

| Micro90 Cleaning Solution | Standardized cleaning for particulate and residue removal | Sample preparation and cleaning effectiveness studies [5] |

| Photothermal PCI Calibration Standards | Quantitative calibration of absorption measurements | Metal-coated fused silica references for system calibration [5] |

The systematic classification of damage precursors into particulates, residues, subsurface defects, and impurities provides a critical framework for understanding laser-induced damage in optical components. Through advanced characterization techniques including photothermal absorption mapping, LIDT testing, and specialized methods like coda wave interferometry, researchers can quantitatively correlate precursor populations with damage performance. For studies focused on optical cleaning effectiveness, this classification system enables precise evaluation of which precursor types are mitigated by specific cleaning protocols and which persist to limit ultimate laser damage resistance. The experimental methodologies and comparative data presented here provide a foundation for ongoing research aimed at extending the performance boundaries of high-power laser systems through precursor-informed manufacturing and cleaning processes.

In high-power laser systems, from industrial cutters to scientific instruments like the National Ignition Facility, optical components are the linchpin of performance and reliability. The laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) defines the maximum energy density an optical surface can withstand before failure, and extrinsic contaminants represent the primary factor limiting this threshold [2] [12]. These surface impurities—ranging from metallic ions to organic residues—act as preferential sites for energy absorption, initiating a cascade of physical events that frequently culminate in catastrophic component failure [2] [13]. The imperative for effective optical cleaning is therefore not merely about cleanliness, but about preserving the fundamental integrity of the entire laser system. This article examines the mechanisms by which contaminants compromise performance and objectively compares post-cleaning LIDT outcomes for prevalent mitigation techniques, providing a scientific framework for assessing optical cleaning efficacy.

The Physics of Failure: How Contaminants Initiate Damage

Laser-induced damage begins at the microscopic level, where contaminants fundamentally alter the interaction between light and matter. The following diagram illustrates the primary failure pathways initiated by extrinsic contaminants on optical surfaces.

Key Damage Mechanisms

Photon Absorption and Thermal Stress: While bulk optical materials like fused silica are highly transparent, metallic contaminants (e.g., Fe, Cu, Ni) and organic residues are strong absorbers. They convert photonic energy into heat, creating localized hot spots that generate immense thermal stress as they expand against the cooler bulk material. When this stress exceeds the material's elastic limit, microfractures occur [2] [12].

Dielectric Breakdown: The intense electric field of a focused laser beam becomes concentrated at contaminant sites, particularly metallic particles. This field enhancement can trigger avalanche ionization, essentially a microscopic lightning bolt that blasts material from the surface, creating permanent damage pits [2] [12].

Coating Adhesion Failure: Contaminants act as a release layer, preventing proper bonding between the optical substrate and thin-film coatings. This leads to delamination under thermal or mechanical stress and creates nodular defects that propagate through the coating stack, becoming points of mechanical weakness and light scattering [2] [12].

Methodologies for Laser Damage Threshold Assessment

Standardized testing protocols are essential for meaningful comparison of cleaning technique efficacy. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 21254 provides the definitive framework.

Core Experimental Protocols

1-on-1 Test Protocol: This method involves irradiating multiple fresh sites on a sample with a single laser pulse per site. The fluence is increased incrementally until damage occurs. The Laser-Induced Damage Threshold (LIDT) is calculated as the average of the lowest fluence causing damage and the highest fluence not causing damage [14].

S-on-1 Test Protocol: This approach tests the component's resistance to laser fatigue. A single site is irradiated by multiple laser pulses (often S=1000 or S=10,000) at a fixed fluence level. This method reveals cumulative damage effects and is crucial for applications involving high-repetition-rate lasers [14].

Critical Measurement Parameters

For valid, reproducible LIDT data, these parameters must be meticulously controlled and reported:

- Beam Characterization: Precise measurement of beam diameter and spatial profile (typically Gaussian) is required to accurately calculate fluence (for pulses) or intensity (for continuous-wave lasers) [2].

- Damage Detection: Damage inception is typically identified through in situ microscopy to observe visible changes, or by monitoring a sudden increase in scattering losses [2].

- Pulse Duration Regime: The dominant damage mechanism shifts with pulse duration. Ultrashort pulses (femtosecond to picosecond) cause deterministic, ablation-dominated damage, while long pulses (nanosecond) and continuous-wave irradiation produce probabilistic, thermally-dominated damage [2] [14].

Quantitative Comparison of Optical Cleaning Techniques

Different cleaning methodologies offer distinct mechanisms for contaminant and defect removal, with corresponding variations in post-processing LIDT performance.

Table 1: Post-Cleaning LIDT Performance of Fused Silica Optics

| Cleaning Technique | Key Mechanism | Reported LIDT Increase | Introduced Defects/Issues | Primary Contaminant/Defect Targeted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microsecond-pulsed CO₂ Laser Cleaning [13] | Thermal evaporation/removal of contaminants and defect layer | 0% probability LIDT: ~150% of baseline100% probability LIDT: ~160% of baseline | Minimal thermal stress; no redeposition | Subsurface defects, elemental impurities (Ce, Fe), chemical structural defects |

| HF Etching [13] | Isotropic chemical dissolution of surface layer | LIDT improvement noted, but specific % not quantified | Redeposition of reaction products; increased surface roughness | Surface/subsurface defects, some impurities |

| HF Etching + CO₂ Laser Polishing [13] | Combines chemical removal with thermal smoothing | LIDT improvement noted, but specific % not quantified | Process complexity; potential thermal stress | Surface/subsurface defects, impurities |

| Ion Beam Etching [13] | Physical sputtering at atomic scale | LIDT improvement noted, but specific % not quantified | Time-consuming; expensive; ion implantation defects | Surface/subsurface defects |

| Magnetorheological Finishing (MRF) [13] | Shear-stress-based material removal | LIDT improvement noted, but specific % not quantified | New polishing layer with embedded MR fluid components | Surface/subsurface defects |

Table 2: Scaling of LIDT with Laser Pulse Duration for Metallic Coatings [14]

| Pulse Duration Regime | Dominant Damage Mechanism | LIDT Scaling Law | Critical Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Femtosecond (fs) to Picosecond (ps) | Avalanche ionization, Coulomb explosion | Nearly constant or weak dependence on τ | Electronic band structure, film morphology |

| Picosecond (ps) to Nanosecond (ns) | Electron-phonon coupling, rapid melting | Scaling with τ^0.25 to τ^0.5 | Absorption, thermal conductivity of metal |

| Nanosecond (ns) to Continuous Wave (CW) | Thermal diffusion, melting, boiling | Scaling with τ^0.5 in pulsed regime; linear with power in CW | Absorption, coating thickness, substrate thermal properties |

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Contaminant-Free Optics

Achieving high LIDT requires not only selecting the right cleaning process but also using research-grade materials to prevent introducing new contaminants.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Precision Optical Cleaning

| Reagent/Material | Purity Grade Required | Primary Function | Critical Impurity Limits | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) [12] | ACS Reagent Grade (Minimum) | Saponification of organic films; controlled etching | Fe ≤ 10 ppm; Ni ≤ 10 ppm; Heavy Metals (as Pb) ≤ 20 ppm | Technical grade introduces catastrophic metallic contamination |

| Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) [13] | High Purity (Electronic Grade) | Isotropic etching of fused silica to remove subsurface damage | Sub-ppm levels for metallic ions | Reacts with silica; redeposition of products is a key limitation |

| Deionized (DI) Water [12] | >18 MΩ·cm Resistivity | Final rinsing to remove all chemical traces | Low Total Organic Carbon (TOC) | Multi-stage cascade rinsing is essential to prevent spotting |

| Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) [12] | High Purity Semiconductor Grade | Final vapor drying for spot-free surface | Low non-volatile residue | Used in IPA vapor dryer or Marangoni dryer |

The experimental data confirms that the choice of optical cleaning methodology has a direct and measurable impact on the Laser-Induced Damage Threshold. Microsecond-pulsed CO₂ laser cleaning demonstrates superior performance in systematically removing diverse defect types without introducing new damage precursors, yielding the highest reported LIDT values [13]. In contrast, traditional wet-chemical methods like HF etching, while effective, often introduce new failure points through redeposition or surface roughening [13]. The selection criteria must extend beyond ultimate LIDT, encompassing the specific contaminant profile, required surface quality, and process scalability. For mission-critical applications in high-power laser systems, an integrated approach that combines the contaminant-removal capability of laser cleaning with the surface-smoothing action of subsequent processes may offer the most reliable path to maximizing optical component lifetime and system performance.

In the field of high-power laser systems, the longevity and reliability of optical components are paramount. The performance of these components is critically dependent on a complex interplay between their inherent material properties, the cleaning strategies employed to maintain them, and their resulting susceptibility to laser-induced damage. Laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) serves as a key metric for evaluating optical component performance, representing the maximum laser fluence an optical material can withstand without sustaining damage [15]. Recent revisions to international standards, including the technically updated ISO 21254-1:2025, introduce new testing methodologies such as the "Functional raster scan test" specifically designed for large optics where sparse defects dominate damage mechanisms [15]. This guide systematically compares how different substrate and coating properties influence cleaning protocol effectiveness and subsequent damage susceptibility, providing researchers with evidence-based selection criteria for optical components in laser systems.

Fundamental Material Properties and Laser Damage Mechanisms

Substrate Materials: Composition and Susceptibility

Optical substrates form the foundation upon which functional coatings are deposited, and their material properties significantly influence cleaning compatibility and laser damage resistance.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Common Optical Substrate Materials

| Material Type | Chemical Resistance | Thermal Stability | Mechanical Hardness | Primary Damage Mechanisms | Cleaning Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fused Silica | High resistance to acids; vulnerable to HF etching | Excellent thermal shock resistance | Moderate hardness (∼550 HK) | Subsurface damage, color center formation, cracking | Compatible with most solvents; avoid strong bases |

| Optical Glasses | Variable by composition; generally good | Moderate; prone to thermal stress | Variable (400-650 HK) | Inclusion-initiated damage, thermal cracking | Dependent on chemical composition; pH-neutral cleaners recommended |

| Crystals (e.g., CaF₂) | Vulnerable to thermal shock, soluble in water | Poor thermal shock resistance | Relatively soft (∼150-200 HK) | Cleavage along crystal planes, thermal lensing | Avoid water-based cleaners; use dry techniques |

| Stainless Steel | Prone to pitting from acids/oxidizers [16] | High thermal conductivity | High hardness | Metal corrosion, particle generation [16] | Require protective coatings; avoid chloride-containing cleaners |

Coating Materials: Design and Vulnerability

Thin-film coatings represent the most vulnerable element in high-power optical systems, with their layered structures creating complex interfaces where damage initiates [17].

Table 2: Laser Damage Performance of Common Coating Materials at 351 nm

| Coating Material | Damage Initiation Threshold | Damage Growth Threshold | Dominant Failure Mechanisms | Recommended Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HfO₂/SiO₂ Multilayers | Moderate | Low [18] | Defect-initiated absorption, thermal runaway | High-power mirrors where damage growth is monitored |

| Al₂O₃/SiO₂ Multilayers | Moderate | ∼2× higher than HfO₂ [18] | Interface imperfections, stress-induced delamination | High-repetition-rate systems requiring damage growth resistance |

| Dielectric Stacks | Varies with design/processing [17] | Design-dependent | Electric field enhancement, nano-scale defects [17] | Mirrors, polarizers, filters where electric field management is critical |

| Metasurfaces | Emerging technology | Not fully characterized | Nanostructure deformation, resonance shifting | Beam shaping, wavefront control where conventional optics fail |

Cleaning Methodologies and Material Compatibility

Experimental Protocols for Cleaning Assessment

Standardized methodologies are essential for evaluating cleaning efficacy and its impact on damage susceptibility:

Accelerated Aging Protocol [19]:

- Sample Preparation: Material coupons (1 ft. × 2 in.) exposed to control and disinfectant solutions

- Exposure Conditions:

- Wiping tests: 200 cycles with Kimtech wipes wetted with test solutions at ∼0.04 MPa pressure

- Immersion tests: 4 weeks continuous exposure at room temperature

- Post-Treatment: Rinsing with deionized water followed by characterization

Surface Characterization Suite:

- Profilometry/AFM: Quantitative surface roughness (Rq) measurements [19] [20]

- Contact Angle Goniometry: Wettability changes indicating surface chemistry modification [19]

- FTIR/XPS: Chemical bonding changes and surface composition analysis [19]

- Optical Microscopy: Macroscopic defect identification and mapping [19]

Material-Cleaning Compatibility Matrix

Different material classes exhibit varying susceptibility to cleaning-induced damage, which directly impacts their laser damage resistance.

Table 3: Material Responses to Cleaning Protocols

| Material Category | Chemical Exposure Effects | Mechanical Cleaning Effects | Laser Damage Susceptibility Post-Cleaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymers (HDPE, PC) | Stress whitening, chemical etching [19] | Increased roughness (ΔSa = 10.55-37.45 nm) [20] | Significant increase due to surface defects and subsurface fractures |

| Metals (Stainless Steel) | Pitting corrosion, particularly with acids/oxidizers [16] | Minor scratching; potential for particle generation | Moderate increase primarily through defect initiation sites |

| Ceramics & Glasses | Etching, pitting, and micro-cracking [16] | Brittle fracture, sub-surface damage | Substantial increase due to light-scattering centers and absorption sites |

| Dielectric Coatings | Contamination embedding, interfacial degradation | Coating delamination, edge chipping | Extreme sensitivity; LIDT reduction up to 50% observed with improper cleaning |

Advanced Testing and Standardization

Laser Damage Testing Methodologies

The recently updated ISO 21254-1:2025 standard introduces critical testing methodologies for evaluating laser damage threshold [15]:

1-on-1 Test: Traditional method where each site receives a single laser pulse to determine damage probability S-on-1 Test: Multiple pulses delivered to same site to evaluate cumulative damage effects Functional Raster Scan Test: New method recommended for large optics with sparse defects [15] Damage Growth Threshold Quantification: Specialized method to determine fluence required for existing damage sites to propagate [18]

Laser Damage Testing Workflow: ISO 21254-1:2025 introduces functional raster scanning for large optics [15].

Damage Mechanisms and Material Response Pathways

The interaction between cleaning-induced surface modifications and laser-induced damage follows predictable pathways dependent on material properties.

Damage Mechanism Pathways: Surface modifications from cleaning create initiation sites for laser damage.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Laser Damage and Cleaning Compatibility Research

| Category | Specific Materials | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coating Materials | HfO₂, Al₂O₃, SiO₂ [18] | Multilayer dielectric mirrors | Al₂O₃/SiO₂ shows ∼2× higher damage growth threshold than HfO₂/SiO₂ [18] |

| Substrate Materials | Fused silica, optical glasses, crystals | Base optical components | Chemical compatibility with coatings and cleaning methods critical |

| Cleaning Reagents | Isopropyl alcohol, neutral cleaners [16] [19] | Contaminant removal | Avoid ammonium hydroxide, strong oxidizers with polymers/elastomers [16] |

| Characterization Tools | AFM, profilometry, optical microscopy [19] [20] | Surface topography quantification | AFM essential for nanoscale damage detection [19] |

| Laser Testing | Functional raster scan systems [15] | LIDT determination according to ISO 21254-1:2025 | Essential for large optics with sparse defects [15] |

| Chemical Analysis | XPS, FTIR spectroscopy [19] | Surface chemistry characterization | Identifies chemical changes from cleaning agents |

The interplay between substrate and coating properties, cleaning methodologies, and laser damage susceptibility presents a complex optimization challenge for optical researchers and engineers. Experimental evidence demonstrates that Al₂O₃/SiO₂ multilayer coatings offer approximately double the damage-growth threshold compared to HfO₂/SiO₂ alternatives at 351 nm [18], while proper cleaning protocols must be carefully matched to material compatibility requirements. The adoption of standardized testing methodologies, particularly the functional raster scan test introduced in ISO 21254-1:2025 [15], provides essential tools for statistically representative evaluation of large optics. As laser systems continue to advance in both power and repetition rate, the strategic selection of material-cleaning combinations will remain critical for maximizing component lifetime and system reliability. Future research directions should focus on nanoscale defect engineering, advanced cleaning techniques that minimize surface modification, and the development of comprehensive models predicting long-term damage progression under operational conditions.

A Practical Guide to Optical Cleaning Methods and Their Direct Impact on LIDT

In the field of optical research, particularly for studies assessing the laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT), the cleanliness of optical components is a critical factor. Contaminants such as dust, oils, and residual chemicals can significantly lower the LIDT, leading to compromised experimental results and component failure. This guide objectively compares three conventional cleaning protocols—solvent wiping, ultrasonic baths, and neutral detergents—within the context of LIDT research.

Each method is evaluated based on its cleaning efficacy, potential for surface damage, residue formation, and impact on the optical surface. The following sections provide detailed experimental methodologies, quantitative comparisons, and analytical frameworks to help researchers select appropriate cleaning protocols for sensitive optical applications.

Methodology for Comparison

To ensure an objective comparison, the assessment of cleaning protocols is structured around standardized experimental procedures and evaluation criteria relevant to high-precision optical applications.

Experimental Design and Evaluation Metrics

The cleaning efficacy is primarily evaluated through controlled laboratory contamination and cleaning cycles. Standard contaminants, including fingerprint oils, diamond turning fluid, dust particles, and buffing compounds, are applied to substrate surfaces such as BK7, fused silica, and coated optics before subjecting them to each cleaning protocol [21].

Post-cleaning evaluation involves:

- Visual Inspection: Under bright light and dark-field illumination to identify residual contaminants and streaks [21].

- Microscopic Analysis: Using magnification devices to detect surface defects, scratches, or residual sub-micron particles [21].

- LIDT Testing: Measuring the laser-induced damage threshold using standardized S-on-1 test methods to quantify the impact of cleaning residues or surface alterations on laser durability [22].

- Surface Analysis: Employing techniques like white-light interferometry to assess surface roughness and optical scatter.

Detailed Cleaning Protocols

Solvent Wiping Methods

Solvent wiping is a precise, manual cleaning process ideal for spot cleaning and flat surfaces.

- Materials: Optical-grade solvents (acetone, methanol, or isopropanol), pure cotton wipes (Webril Wipes), lens tissue, or cotton-tipped applicators [21].

- Procedure: The "Drop and Drag" method is recommended for flat surfaces. A lens tissue is held above the optic, and one or two drops of solvent are placed on it. The tissue is dragged across the surface in a single, steady motion without lifting, ensuring contaminants are lifted off rather than spread [21]. For curved or mounted optics, the "Lens Tissue with Forceps" method is used, where a solvent-dampened tissue is wiped across the surface with continuous rotation to present a clean surface area throughout the wipe [21].

- Critical Considerations: Wipes must be used damp, never dry, to prevent scratching. Isopropyl alcohol is preferred for coated optics, as eyeglass cleaning cloths can contain anti-fogging substances that damage coatings and lower LIDT [22].

Ultrasonic Bath Cleaning

Ultrasonic cleaning uses high-frequency sound waves (typically 20–80 kHz) in a liquid medium to create cavitation bubbles that implode, dislodging contaminants from even internal geometries and blind holes [23] [24].

- Materials: Ultrasonic cleaning system (generator, transducers, tank), appropriate cleaning solution, and distilled or deionized water [25].

- Procedure: Components are fully immersed in a tank filled with a cleaning solution—often a neutral-pH, biodegradable detergent diluted in distilled water. The system is activated for a cycle of 5–20 minutes, often at elevated temperatures (40–60°C) to enhance chemical activity [26] [25]. A degassing step (running the cleaner empty for 5–10 minutes) before introducing components is crucial for peak performance [25].

- Critical Considerations: Ultrasonic cleaning is not recommended for delicate coatings, soft materials, or metal coatings, which can be damaged by cavitation forces [22] [24]. Post-cleaning rinsing with distilled water and drying are essential to prevent residue deposition [25].

Neutral Detergent Cleaning

This method uses mild, neutral-pH enzymatic detergents for cleaning, often followed by rinsing.

- Materials: Neutral enzymatic detergent (e.g., Liquiclean, EndoPreZyme), distilled water, lint-free wipes or sponges [27] [28].

- Procedure: The optic is first rinsed with water, then cleaned with a detergent solution using a sterile cotton swab or lint-free wipe. It is subsequently rinsed with clean water to remove detergent residues and dried with a lint-free tissue [27]. Recent studies indicate that with certain specialized detergents and validated subsequent processing, the final rinse step can be omitted, reducing water use and processing time [28].

- Critical Considerations: This method is particularly suitable for surfaces incompatible with harsh chemicals. The detergent must be fully rinsed to avoid residue that could absorb laser energy and reduce LIDT.

Comparative Analysis

The table below summarizes the key performance characteristics of the three cleaning protocols, with a specific focus on factors influencing laser-induced damage threshold.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Optical Cleaning Protocols

| Feature | Solvent Wiping | Ultrasonic Bath | Neutral Detergent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cleaning Mechanism | Mechanical dissolution and lift-off [21] | Acoustic cavitation in liquid medium [23] | Chemical dissolution and emulsification [27] |

| Efficacy on Oils/Grease | High (with appropriate solvent) [21] | High [24] | High [27] |

| Efficacy on Particles | Moderate (risk of dragging) [21] | Very High (even in crevices) [23] | Moderate (requires mechanical action) [27] |

| Risk of Surface Damage | Moderate (if done incorrectly) [21] | Low to Moderate (cavitation corrosion on soft coatings) [24] | Very Low [27] |

| Risk of Residual Contamination | Low (with fast-drying solvents) [21] | Moderate (requires post-rinse) [25] | Moderate (requires thorough rinsing) [27] |

| Impact on LIDT | Low risk if solvent-grade and lint-free wipes are used [22] | Potential risk for soft coatings; low risk for robust substrates [24] | Low risk if thoroughly rinsed [27] |

| Best For | Flat surfaces, spot cleaning, coated optics [21] | Complex geometries, internal channels, bulk cleaning [23] | Sensitive surfaces, preliminary cleaning, medical optics [27] |

Experimental Data and Efficacy

Quantitative studies provide insight into the efficacy of these methods. Research on ophthalmic lenses contaminated with common ocular pathogens, including MRSA and adenovirus, demonstrated that cleaning with a neutral detergent and water effectively eliminated all microorganisms from the lens surface without the need for a subsequent high-level disinfectant like bleach [27].

Furthermore, operational studies on detergent use show that optimizing the rinsing protocol can reduce cleaning time by approximately 15% and significantly cut water consumption [28]. While ultrasonic cleaning drastically reduces manual labor and processes items in 5-20 minutes, its effectiveness is highly dependent on solution chemistry and temperature [26] [25].

Table 2: Experimental Results from Cleaning Studies

| Study Parameter | Neutral Detergent (with rinse) | Ultrasonic Cleaning |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial Reduction | Eliminated S. epidermidis, C. straitum, MRSA, Adenovirus, and HSV-1 [27] | Not specifically tested for microbes in sources |

| Average Cleaning Time | 11-13 minutes per item [28] | 5-20 minutes per cycle [26] |

| Process Efficiency | 15% reduction in manual cleaning time with optimized protocol [28] | 60-85% reduction in operating time vs. manual methods [23] |

| Resource Consumption | 25L water savings per item by omitting final rinse [28] | Up to 70% reduction in water use vs. traditional methods [23] |

Selection Workflow and Decision Framework

Choosing the correct cleaning protocol depends on the substrate material, the nature of the contaminant, and the required precision. The following workflow diagram outlines the logical decision process.

Diagram 1: Optical Cleaning Protocol Selection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of these cleaning protocols requires the use of specific, high-purity materials. The following table details essential items for a laboratory engaged in optical cleaning research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Optical Cleaning

| Item | Specification / Grade | Primary Function in Cleaning |

|---|---|---|

| Isopropyl Alcohol (IPA) | Optical Grade / High Purity [22] | Dissolves organic contaminants; fast-drying with minimal residue. |

| Acetone | Optical Grade / High Purity [21] | Powerful solvent for organics and oils; used in drop-and-drag method. |

| Neutral Enzymatic Detergent | e.g., Liquiclean, EndoPreZyme [27] [28] | Breaks down organic residues and bio-contaminants without damaging surfaces. |

| Ultrasonic Cleaning Solution | Neutral pH, low-foaming, for precision optics [25] | Enhances cavitation effect and dissolves specific contaminants in the bath. |

| Distilled / Deionized Water | ASTM Type II or better [25] | Primary diluent and rinsing agent; prevents mineral deposits. |

| Pure Cotton Wipes | Lint-free (e.g., Webril Wipes) [21] | Application of solvents and detergents without scratching or leaving fibers. |

| Lens Tissue | High-quality, acid-free [21] | For gentle wiping of optical surfaces, particularly in drop-and-drag method. |

| Inert Gas Duster | Moisture-free [21] | Initial removal of loose abrasive particles before wet cleaning. |

| Nitrile or Powder-Free Gloves | Cleanroom compatible [22] | Prevents fingerprint oils and skin residues from contaminating optics. |

The assessment of solvent wiping, ultrasonic baths, and neutral detergents reveals that no single cleaning protocol is universally superior for all optical components in LIDT research. The optimal choice is a function of the contaminant type, substrate sensitivity, and component geometry.

For highest-precision LIDT work on coated or flat optics, solvent wiping with high-purity reagents offers control and minimal residue. For components with complex geometries, ultrasonic baths provide unparalleled thoroughness, provided the substrate can withstand cavitation forces. Neutral detergents offer a safe, effective alternative for sensitive surfaces and biological contaminants. A rigorous, multi-step approach—often combining these methods—followed by mandatory LIDT verification, is essential for ensuring the performance and longevity of critical optical components in scientific research.

In high-power laser systems, such as those used in inertial confinement fusion and advanced lithography, fused silica optics are subjected to extreme fluences. The laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) of these components often determines the entire system's performance and operational lifespan. Post-polishing, these optics typically exhibit substantial subsurface damage (SSD), including cracks, scratches, and embedded impurities that severely limit their damage resistance [29] [30]. Chemical etching, particularly using hydrofluoric acid (HF)-based solutions, has emerged as a critical post-processing technique to eliminate these damage precursors and enhance optical performance [29] [31] [13]. This review comprehensively evaluates HF-based etching techniques for fused silica, comparing processing methodologies, performance outcomes, and inherent challenges, with a specific focus on implications for LIDT enhancement.

HF-Based Etching: Fundamental Mechanisms and Methodologies

Chemical Reaction Principles

The dissolution of fused silica in HF-based solutions is a complex chemical process governed by the breakdown of the robust siloxane (Si-O-Si) network. The overall reaction can be summarized as:

SiO₂ + 6HF → H₂SiF₆ + 2H₂O

This simplified equation represents a multi-stage process involving surface protonation, nucleophilic attack on electrophilic silicon atoms, and subsequent Si-F bond formation [29] [32]. The etching efficacy heavily depends on the specific fluoride species present in the solution. Notably, the HF₂⁻ ion is a particularly reactive species, exhibiting an etching rate 2000-3000 times faster than neutral (HF)₂ dimers, while free F⁻ ions contribute minimally to the reaction [32]. The distribution of these active species is influenced by the solution pH and the NH₄F:HF ratio, making etchant composition a critical processing parameter [31] [32].

Primary Etching Methodologies

Two primary HF-based etching methodologies are employed in optical fabrication:

- Concentrated HF Etching: Utilizes high-concentration HF solutions for rapid material removal. This approach effectively exposes and eliminates subsurface cracks through chemical undercutting, significantly reducing the time required to remove SSD from grinding processes [29].

- Buffered Oxide Etchant (BOE): Combines HF with ammonium fluoride (NH₄F) to stabilize the etching rate and improve process control. BOE solutions offer enhanced protective mask resistance and produce superior surface quality, which is crucial for high-LIDT applications [31] [33] [32].

Comparative Performance of Etching Techniques

Etching Solutions and Parameters

Table 1: Comparison of HF-based etching solutions and their characteristics

| Etchant Type | Typical Composition | Etching Rate | Surface Roughness | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentrated HF | 49% HF [31] | ~100 nm/min [31] | Increased due to isotropic attack [29] | High removal efficiency; Effective crack removal [29] | Poor mask resistance; Roughness degradation [29] |

| Standard BOE | HF (5-10% wt), NH₄F (10% wt), H₂O (80-85% wt) [33] | Varies with ratio | Superior smoothness | Stable etching rate; Better surface quality [31] [33] | Chemical deposit formation [33] |

| Optimized BOE | HF:NH₄F:H₂O (1:4:10 vol%) [31] | ~100 nm/min (matched to HF) | < 1 nm RMS achievable | High LIDT; Low fluorescence defect density [31] | Requires precise control of parameters [31] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 2: Laser-induced damage threshold performance across different etching conditions

| Treatment Method | Material Removal | LIDT Performance | Surface Quality (Roughness) | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF Only Etching | 3 µm | Lower LIDT | Higher roughness | Etching-related precursors reappear [31] |

| HF/NH₄F Etching | 3 µm | Higher LIDT | Lower roughness | Improved fluorescence characteristics [31] |

| RIE + HF/NH₄F | 1-3 µm | Optimal LIDT | Superior smoothness | Damage resistance depends on etching depth [31] |

| Reference (Polished) | N/A | Baseline | ~1 nm RMS | Limited by scratches and impurities [30] |

Experimental Protocols for HF-Based Etching

Standard BOE Etching Procedure

Materials and Reagents:

- Substrate: Corning 7980 fused silica samples (typically 50 mm diameter × 5 mm thickness) [31]

- Etchant: Buffered Oxide Etchant (BOE) with composition 5-10% wt HF, 10% wt NH₄F, 80-85% wt H₂O [33]

- Cleaning solutions: Absolute ethyl alcohol, ultra-pure water [34]

- Protective masking: Molybdenum, chromium, or gold/chromium layers [32]

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Clean substrates ultrasonically in ethyl alcohol at 40°C for 10 minutes to remove organic contaminants and polishing residues [34]

- Mask Patterning: Apply and pattern protective metal masks using standard photolithography and etching techniques [32]

- Etching Process: Immerse samples in BOE solution at controlled temperature (typically 20-25°C) with mild agitation [32]

- Post-Processing: Remove masks using appropriate solvents and thoroughly rinse with deionized water [33]

- LIDT Testing: Evaluate using Nd:YAG laser (355 nm, 8 ns pulse duration) with raster scanning methodology per ISO 21254 standard [31] [30]

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for HF-based etching of fused silica optics

Advanced Combined RIE and HF Etching Protocol

Materials and Reagents:

- Reactive Ion Etching (RIE) system with CHF₃/Ar gas mixture [31]

- HF/NH₄F solution (1:4:10 volume ratio of 49% HF:30% NH₄F: H₂O) [31]

- Identical fused silica substrates as in standard protocol [31]

Experimental Workflow:

- RIE Pretreatment: Etch fused silica surfaces using CHF₃/Ar plasma with approximately 35 nm/min etch rate to remove 1 µm of material [31]

- Dynamic Cleaning: Apply dynamic cleaning process to remove residual contaminants [31]

- HF-based Etching: Employ HF/NH₄F solution with controlled etch depth (1-3 µm) at rate of ~100 nm/min [31]

- Characterization: Analyze surface roughness, fluorescence spectra, light scattering, and weak absorption [31]

Challenges and Limitations in HF Etching

Key Technical Challenges

Despite its effectiveness, HF-based etching faces several significant challenges that impact its implementation for high-LIDT optics:

Chemical Deposit Formation: Reaction products, particularly (NH₄)₂SiF₆, redeposit on etched surfaces, creating new laser damage precursors. The affected surface area increases with material removal amount and is highly sensitive to cleaning procedures [33]. These deposits can reach several micrometers in height and reduce LIDT to 41.62% of reference samples [33].

Surface Roughness Degradation: The isotropic nature of chemical etching can accentuate surface and subsurface defects, increasing surface roughness and light scattering [29] [13]. This effect is particularly pronounced with concentrated HF solutions without buffering agents [29].

Masking Limitations: Achieving high-resolution features is challenging due to mask undercutting from isotropic etching. Photoresist masks exhibit limited adhesion and resistance to HF solutions, while metal masks (Cr, Au/Cr, Mo) can develop microcracks from stress or poor adhesion, causing pinhole defects [32].

Figure 2: Challenges in HF-based etching and their impact on laser damage performance

Alternative and Complementary Techniques

Non-Chemical Processing Methods

Table 3: Comparison of alternative processing techniques for fused silica optics

| Technique | Mechanism | Material Removal | LIDT Improvement | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactive Ion Etching (RIE) | Plasma-based anisotropic removal | ~35 nm/min [31] | Significant when combined with wet etching [31] | Anisotropic; Nanoscale precision | Ion bombardment induces structural defects [31] |

| Microsecond-pulsed CO₂ Laser Cleaning | Thermal evaporation and structural modification | Non-ablative [13] | Substantial improvement demonstrated [13] | Non-contact; No chemical waste | Thermal stress management; Process complexity [13] |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Polishing | Plasma-surface interaction for atom migration | Variable rate [34] | Improved surface quality | Environmentally friendly; High efficiency | Limited shape correction capability [34] |

| Magnetorheological Finishing (MRF) | Shear-based mechanical removal | Variable [13] | Moderate | No introduction of new SSD | MR fluid contamination; High cost [13] [34] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key research reagents and materials for fused silica etching experiments

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrofluoric Acid (HF) | 49% concentration, electronic grade [31] | Primary etching agent for SiO₂ dissolution | Handling requires specialized PPE and fume hood |

| Ammonium Fluoride (NH₄F) | 30% wt solution, high purity [31] | Buffer agent to stabilize etch rate and improve surface quality | Enables more controllable process than pure HF |

| Buffered Oxide Etchant (BOE) | Various NH₄F:HF ratios (1:1 to 14:1) [32] | Controlled etching with balanced rate and surface quality | Optimal composition depends on specific application requirements |

| Molybdenum Mask | High-purity sputtered films (200-500 nm) [32] | Protective masking for pattern definition | Superior adhesion to fused silica; low dissolution rate (~19 Å/min) |

| Fused Silica Substrates | Corning 7980, typical dimensions 50mm×5mm [31] | Base material for optics manufacturing | Consistent material properties essential for reproducible results |

| Ultrasonic Cleaning Solution | Absolute ethyl alcohol, analytical grade [34] | Pre-etching surface preparation | Effective removal of organic contaminants and polishing residues |

HF-based chemical etching remains a vital processing technique for enhancing the laser damage resistance of fused silica optics. The comparative analysis presented demonstrates that buffered etchants (BOE) generally provide superior LIDT performance and surface quality compared to concentrated HF solutions, particularly when combined with preliminary RIE treatment. However, challenges such as chemical deposit formation and surface roughness degradation necessitate careful process optimization. The development of hybrid approaches that combine HF etching with alternative techniques like laser cleaning or plasma processing represents the most promising direction for achieving fused silica optics with exceptional laser damage resistance suitable for next-generation high-power laser systems.

In the fabrication of high-performance optics, the processes designed to perfect a surface can also be the very source of its degradation. Abrasive and mechanical methods, including grinding, polishing, and ultrasonic cleaning, are fundamental for achieving the surface quality and cleanliness required for demanding applications, from high-energy laser systems to precision analytical instruments. However, these same techniques inherently risk introducing surface and subsurface damage, such as scratches, micro-cracks, and a structurally altered "Beilby" layer, which can act as precursors to laser-induced damage [35] [36]. This creates a critical paradox for researchers and engineers: how to aggressively remove contaminants and shape the substrate without introducing new defects that compromise optical performance and longevity. The laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) is a key metric of optical quality, and its maximization is often directly at odds with the potential side effects of traditional cleaning and finishing protocols. This guide objectively compares the performance of common abrasive and mechanical methods, weighing their contaminant removal efficacy against their propensity for scratch introduction. By synthesizing current research and experimental data, it aims to provide a framework for selecting and optimizing processes that protect the delicate surface integrity of optical components.

Comparative Analysis of Cleaning and Finishing Methods

The quest for an optimal surface finish involves a trade-off between the thoroughness of contaminant removal and the preservation of the original substrate. The table below provides a high-level comparison of key methods, summarizing their core mechanisms and primary trade-offs.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Abrasive and Mechanical Methods

| Method | Cleaning/Finishing Mechanism | Contaminant Removal Efficacy | Risk of Introducing Scratches/Defects | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical-Mechanical Polishing (CMP) | Chemical corrosion and mechanical micro-abrasion in synergy [37] | High (achieved nanoscale smoothness on InF₃ glass) [37] | Moderate to High (risk of scratches from hard abrasives like Al₂O₃; requires precise slurry/pad selection) [37] | Slurry chemistry is material-specific; requires careful control of pH and load pressure to avoid corrosion or scratches [37]. |

| Ultrasonic Cleaning | Cavitation-induced micro-jets in a liquid medium [38] [39] | High for loose contaminants and complex geometries [38] | Low to Moderate (risk of cavitation erosion on delicate surfaces and soft materials) [38] [39] | Line-of-sight limitation; cannot selectively clean areas; produces contaminated liquid waste [38]. |

| Traditional Grinding & Polishing | Mechanical abrasion using rigid or semi-rigid tools with abrasives [35] | High for macroscopic shape correction and material removal | High (generates subsurface mechanical damage (SSD), micro-cracks, and a damaged "Beilby" layer) [35] [36] | A confining layer often hides subsurface damage, which can be exposed during subsequent processes or under laser irradiation [35]. |

| Laser Cleaning | Ablation via photothermal, photomechanical, or photochemical effects [40] [36] | Selective and high for specific contaminants (rust, coatings, sub-surface damage) [40] [36] | Very Low when parameters are optimized (non-contact; can achieve damage-free ablation) [40] [36] | High initial investment; requires parameter tuning to avoid thermal damage (melting, discoloration); line-of-sight process [38] [41] [40]. |

The data indicates that no single method is universally superior. CMP excels at achieving ultra-smooth surfaces but is a delicate process where abrasive choice and pH are critical to avoid damage [37]. Ultrasonic cleaning is unparalleled for cleaning intricate geometries but poses a non-selective erosion risk [38]. In contrast, laser-based methods offer a non-contact alternative with minimal mechanical damage risk, though they carry their own thermal damage risks if parameters are misconfigured [41] [40].

Quantitative Data from Experimental Studies

Controlled studies provide quantitative insights into the performance and outcomes of these methods. The following table summarizes key experimental findings from recent research, highlighting measurable results on surface quality and damage.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Surface Finishing and Cleaning Studies

| Study Material | Method | Key Parameters | Before Treatment (Roughness) | After Treatment (Roughness) | Reported Defects/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| InF₃ Glass [37] | Chemical-Mechanical Polishing (CMP) | Damping cloth pad, CeO₂ slurry, pH=11, optimized load | ~200 nm (Rq) | Ultra-smooth, damage-free surface (nanoscale) | Achieved with alkaline slurry; acidic environments or hard abrasives caused corrosion and scratches. |

| Fused Silica [36] | CO₂ Laser Ablation & Polishing | Layer-by-layer uniform ablation | N/A (Sub-surface damage removal) | Micro-crack-free surface | LIDT increased by 41-65.7% compared to conventional processing; effective SSD removal. |

| ZnSe Crystal [37] | Chemical-Mechanical Polishing (CMP) | Al₂O₃ powder, pH=11 (NH₃) | N/A | 0.578 nm (Ra) | Demonstrated efficacy of alkaline slurry for mid-infrared materials. |

| 4H-SiC Wafer [42] | Picosecond Laser Polishing | 1064 nm laser, optimized power and speed | 2265 nm | 207.33 nm (90.85% reduction) | Ultrafast laser minimized subsurface damage compared to mechanical polishing. |

| Pliocene Sandstone [41] | Nd:YAG Laser Cleaning | Short free-running regime, 20 μs pulse, fluence control | N/A | N/A | Surface darkening and melting observed when fluence exceeded damage threshold. |

The experimental data underscores the capability of advanced methods to significantly improve surface quality. The 90.85% roughness reduction on a 4H-SiC wafer with a picosecond laser [42] and the achievement of a nanoscale smooth, damage-free surface on InF₃ glass via CMP [37] exemplify successful outcomes. Critically, these results are contingent on precise parameter control, as evidenced by the damage observed in sandstone cleaning when laser fluence exceeded the safe threshold [41].

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Damage Assessment