Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy for Trace Metal Analysis in Pharmaceutical Research: Techniques, Applications, and Best Practices

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) and related atomic spectrometry techniques for trace metal analysis in pharmaceutical research and drug development.

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy for Trace Metal Analysis in Pharmaceutical Research: Techniques, Applications, and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) and related atomic spectrometry techniques for trace metal analysis in pharmaceutical research and drug development. Covering fundamental principles to advanced applications, it explores how these technologies ensure drug safety and regulatory compliance by detecting elemental impurities. The content addresses methodological approaches, troubleshooting common issues, and comparative analysis with other techniques like ICP-MS and ICP-OES. With the atomic spectrometer market for pharmaceutical analysis projected to grow at 6.9% CAGR, reaching $502 million by 2032, this resource offers timely insights for researchers and scientists navigating stringent quality control requirements and advancing analytical capabilities in biomedical research.

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy Fundamentals: Core Principles for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Basic Principles of Atomic Absorption and Atomic Emission

Atomic spectroscopy is a cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, enabling the precise detection and quantification of elemental composition. Two of its most fundamental techniques are Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) and Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (AES). Both methods play a critical role in trace metal analysis across diverse fields, including pharmaceutical development, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics [1] [2]. This article details the core principles, instrumental setups, and standard protocols for AAS and AES, providing a structured guide for researchers and scientists engaged in trace metal analysis.

Fundamental Principles

Principle of Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS)

The underlying principle of AAS is that free, ground-state atoms in the gaseous state can absorb light at specific, characteristic wavelengths [1]. When a sample containing metallic elements is exposed to a light source emitting the unique wavelength of a particular element, the atoms of that element will absorb a fraction of this light. The amount of light absorbed is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing atoms in the sample, as described by the Beer-Lambert law [3].

The process involves electrons within the atoms being promoted from a lower energy level (ground state) to a higher energy level (excited state) by absorbing photons of specific energy [1]. Since the electronic configuration of every element is unique, the radiation absorbed represents a unique property of each individual element, allowing for selective quantification [1].

Principle of Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (AES)

In contrast, AES operates on the principle of measuring the light emitted by excited atoms or ions as they return to a lower energy state [2]. The sample is first atomized and excited using a high-energy source such as a flame, arc, spark, or plasma. The excited atoms have a finite lifetime and subsequently decay back to lower energy levels, emitting photons of light with wavelengths characteristic of the element [2]. The intensity of the emitted light at a specific wavelength is proportional to the concentration of that element in the sample.

Instrumentation and Workflows

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy Instrumentation

A typical atomic absorption spectrometer consists of four main components: the light source, the atomization system, a monochromator, and a detection system [1].

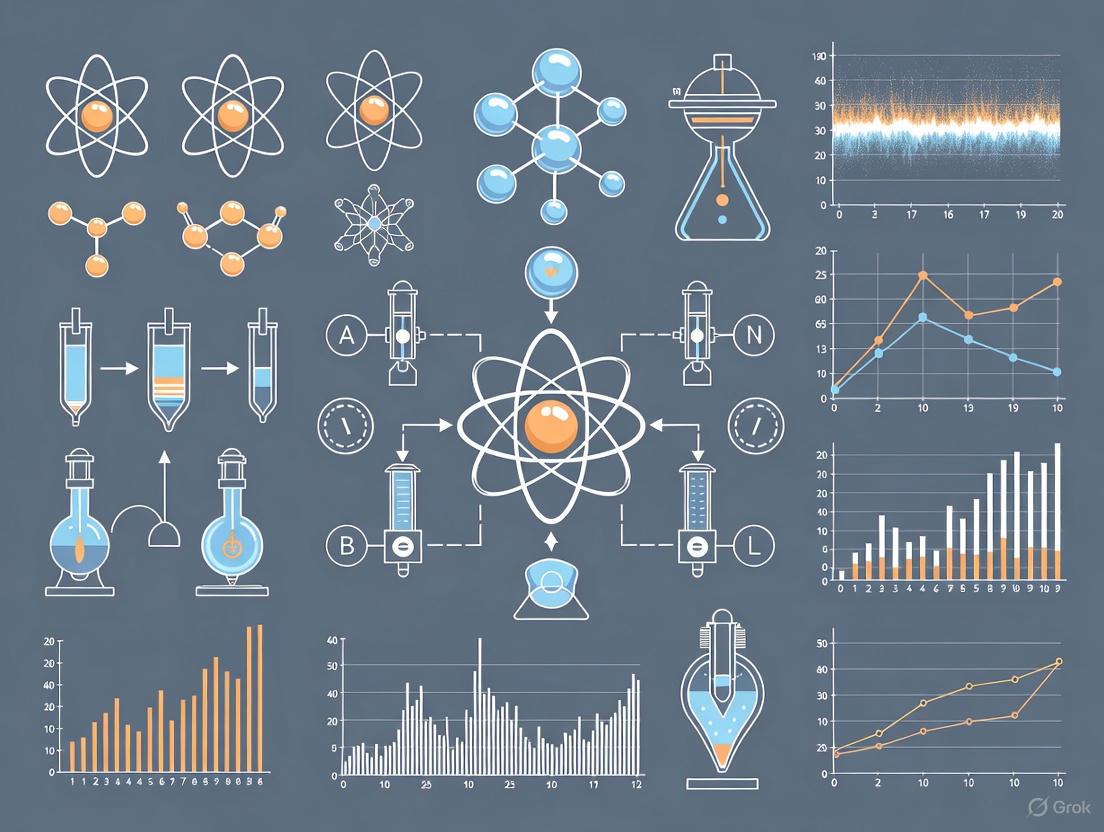

Diagram 1: Instrumental workflow of a typical Atomic Absorption Spectrometer.

Atomic Emission Spectroscopy Instrumentation

An atomic emission spectrometer typically features an excitation source, an optical system for wavelength separation (monochromator or polychromator), and a detector [2].

Diagram 2: Instrumental workflow of a typical Atomic Emission Spectrometer.

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

The choice between AAS, AES, and related techniques depends on the specific analytical requirements. Key performance metrics are compared in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Elemental Analysis Techniques

| Feature | Flame AAS (FAAS) | Graphite Furnace AAS (GFAAS) | ICP-OES (AES) | ICP-MS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Detection Limits | Low ppm to ppb range [4] | Low ppb to ppt range [1] [3] | Low ppb range [4] | Parts per trillion (ppt) range [4] |

| Multi-Element Capability | Single element [1] [4] | Single element | Simultaneous [4] | Simultaneous [4] |

| Sample Throughput | High (for single element) [3] | Low (slow heating cycle) [1] | Very High [4] | Very High [4] |

| Sample Volume | mL | µL (5-50 µL) [3] | mL | mL |

| Analytical Range | Narrow linear range [4] | Narrow linear range | Several orders of magnitude [4] | Several orders of magnitude [4] |

| Instrument & Operational Cost | Low [4] | Moderate | High [4] | Very High [4] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determination of Cadmium in Seawater by GFAAS

This protocol outlines a sensitive method for determining trace levels of Cadmium (Cd) in a complex seawater matrix using Graphite Furnace AAS, incorporating pre-concentration and matrix modification [5].

5.1.1. Principle Seawater samples are pre-concentrated via Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) to isolate and enrich Cadmium ions, mitigating matrix effects and improving the limit of detection. The concentrated analyte is then introduced into a graphite tube for electrothermal atomization and measurement [5].

5.1.2. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for GFAAS Cadmium Analysis

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Silica-based SPE Cartridge | Solid-phase extraction sorbent functionalized with chelating groups (e.g., iminodiacetate) to selectively bind Cd²⁺ ions from the seawater matrix [5]. |

| Nitric Acid (HNO₃), Ultrapure | For sample acidification (preservation) and elution of Cd from the SPE cartridge; also used for cleaning and as a component of matrix modifiers. |

| Matrix Modifier (e.g., Pd/Mg(NO₃)₂) | Added to the sample in the graphite tube to stabilize the analyte (Cd) to higher pyrolysis temperatures, allowing for the volatilization of the salt matrix (e.g., NaCl) before atomization [5]. |

| Cadmium Standard Solutions | Certified reference materials for instrument calibration and quality control, prepared in a matrix similar to the processed sample. |

| High-Purity Argon Gas | Inert gas used to purge the graphite furnace, preventing oxidation of the tube and removing vapors during the drying and pyrolysis stages. |

5.1.3. Procedure

- Sample Pre-treatment: Acidify the seawater sample to pH ~2 with ultrapure nitric acid.

- SPE Pre-concentration:

- Condition the silica-based SPE cartridge with 5 mL of methanol and 5 mL of high-purity water at a flow rate of 2-3 mL/min.

- Load the acidified seawater sample (e.g., 100 mL) onto the cartridge.

- Wash the cartridge with 10 mL of a weak ammonium acetate buffer (pH ~5.5) to remove interfering alkali and alkaline earth metals [5].

- Elute the captured Cadmium ions with 2-5 mL of 1.0 M nitric acid into a clean vial.

- GFAAS Analysis:

- Instrument Setup: Set the hollow cathode lamp wavelength to 228.8 nm. Implement a temperature program for the graphite furnace (see table below).

- Calibration: Prepare a calibration curve using Cd standards in the same nitric acid concentration as the eluent.

- Sample Introduction: Mix a 20 µL aliquot of the sample eluent with 5 µL of the Pd/Mg(NO₃)₂ matrix modifier and inject into the graphite tube.

- Measurement: Run the temperature program and record the integrated absorbance.

Table 3: Exemplary Graphite Furnace Temperature Program for Cd

| Step | Temperature (°C) | Ramp Time (s) | Hold Time (s) | Argon Flow (mL/min) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drying | 110 | 10 | 20 | 250 | Remove solvent |

| Pyrolysis | 500 | 15 | 10 | 250 | Remove matrix components |

| Atomization | 1500 | 0 | 5 | 0 | Measure atomic absorption |

| Cleaning | 2400 | 1 | 3 | 250 | Remove residue |

Protocol: Multi-Element Analysis via ICP-OES

This protocol describes the simultaneous determination of multiple metals (e.g., Mn, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Cd, Pb) in a digested water sample using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry [6] [4].

5.2.1. Principle A liquid sample is nebulized into a fine aerosol and transported into the high-temperature argon plasma (~6000-10000 K) [4]. The plasma efficiently atomizes and excites the elements present. The excited atoms emit light at characteristic wavelengths as they return to lower energy states. The emitted light is dispersed by a spectrometer, and its intensity is measured simultaneously for each target element [2].

5.2.2. Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Digest the water sample, if necessary, with nitric acid to break down organic complexes and ensure metals are in solution. Filter the sample through a 0.45 µm membrane filter.

- Instrument Setup:

- Plasma Ignition: Ensure stable plasma operation with adequate coolant, auxiliary, and nebulizer argon gas flows.

- Wavelength Selection: Program the spectrometer with the specific emission wavelengths for each analyte (e.g., Cd II 214.44 nm, Mn II 257.61 nm, Pb II 220.35 nm).

- Calibration: Prepare a multi-element calibration standard series covering the expected concentration range of the analytes.

- Analysis:

- Introduce the calibration standards, quality control samples, and unknown samples via the autosampler.

- The nebulizer converts the liquid into an aerosol, which is carried into the plasma.

- The spectrometer simultaneously measures the intensity at all selected wavelengths.

- Data Analysis: The software constructs a calibration curve for each element and calculates the concentration in the unknown samples based on the measured emission intensities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Beyond the specific reagents listed in the protocol above, several core components are essential for atomic spectroscopy.

Table 4: Core Components of an Atomic Spectroscopy Laboratory

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Hollow Cathode Lamps (HCLs) / Electrodeless Discharge Lamps (EDLs) | Element-specific light sources for AAS that emit sharp, characteristic line spectra [1]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Standards with certified analyte concentrations for instrument calibration, method validation, and quality assurance. |

| High-Purity Gases (Acetylene, Nitrous Oxide, Argon) | Acetylene (with air or nitrous oxide) is a common fuel for FAAS flames [1]. Argon is used as the plasma gas for ICP and the purge gas for GFAAS [1]. |

| Matrix Modifiers (e.g., Pd, Mg, NH₄⁺ salts) | Chemical modifiers used primarily in GFAAS to stabilize the analyte or modify the matrix, allowing for higher pyrolysis temperatures and reduced background interference [5]. |

| Autosampler | Automated system for precise introduction of samples and standards into the spectrometer, improving reproducibility and throughput [3]. |

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) stands as a cornerstone technique for quantitative trace metal analysis across diverse fields, including clinical research, pharmaceuticals, environmental monitoring, and forensic toxicology [1] [7]. Its principle is based on the phenomenon that free ground-state atoms of a specific element absorb light at characteristic wavelengths [8] [1]. The degree of absorption is directly proportional to the concentration of the element in the sample, as described by the Beer-Lambert law [8]. This application note details three core atomization techniques—Flame AA (FAAS), Graphite Furnace AA (GFAAS), and Vapor Generation (VGAA)—providing structured protocols and comparative data to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the optimal method for their trace metal analysis requirements.

The core difference between these AAS techniques lies in the method of atomization—the process of converting the sample into a cloud of free atoms [9].

Flame AA (FAAS) uses a continuous flame, typically air-acetylene or nitrous oxide-acetylene, to atomize a nebulized sample [8] [10]. It is a robust, high-throughput technique ideal for analyzing metal concentrations at parts-per-million (ppm) levels [11] [9].

Graphite Furnace AA (GFAAS), also known as Electrothermal AAS (ETAAS), employs a programmable graphite tube that is electrically heated through a series of temperature stages to dry, ash, and atomize a discrete micro-volume sample [8] [12]. This process concentrates the analyte within the tube, granting GFAAS superior sensitivity, with detection limits typically 100 to 1000 times lower than FAAS, reaching parts-per-billion (ppb) to parts-per-trillion (ppt) levels [8] [11].

Vapor Generation AA (VGAA) encompasses techniques where the element of interest is chemically converted into a vapor before being transported to the measurement cell. This includes Cold Vapor AAS (CVAAS) specifically for mercury [8] [11] and Hydride Generation AAS (HGAAS) for hydride-forming elements such as arsenic (As), selenium (Se), antimony (Sb), and bismuth (Bi) [8] [1]. VGAA offers exceptional sensitivity and selectivity for these specific elements.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key AAS Techniques

| Parameter | Flame AAS (FAAS) | Graphite Furnace AAS (GFAAS) | Vapor Generation AAS (VGAA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomization Method | Continuous flame (e.g., air-acetylene) [8] | Electrically heated graphite tube [8] | Chemical reduction to vapor (Hg or hydrides) [8] |

| Typical Sample Volume | 1 – 5 mL [8] | 5 – 50 µL [8] | 1 – 10 mL (for reaction) |

| Detection Limits | ppm to ppb range [8] [9] | ppb to ppt range (≈100-1000x better than FAAS) [8] [11] | ppb to ppt for target elements [8] |

| Analysis Speed | Very fast (seconds per sample) [13] [9] | Slow (several minutes per sample) [11] [9] | Moderate (requires offline chemistry) [8] |

| Precision | High (RSD 1-2%) [8] [9] | Good (slightly lower than FAAS due to discrete dosing) [9] | Good |

| Best For | High-throughput analysis of higher-concentration analytes [9] | Trace and ultra-trace analysis of small-volume samples [9] [12] | Specific, high-sensitivity analysis of Hg, As, Se, Sb, etc. [8] [11] |

| Key Limitation | Lower sensitivity, larger sample volume required [10] [9] | Higher cost, slower, more complex method development [9] [12] | Limited to specific elements; requires off-line chemistry [8] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determination of Essential Metals in Plant Extracts using Flame AA

This protocol is adapted from a study analyzing manganese, zinc, iron, calcium, and magnesium in medicinal plant extracts using a fully automated Flame AAS system [10].

3.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Plant Metal Analysis via FAAS

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specification/Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Sample digestion and extraction | Trace metal grade to prevent contamination |

| Deionized Water | Diluent and rinsing | ≥18 MΩ·cm resistivity |

| Element-Specific Hollow Cathode Lamps | Radiation source | One for each analyte (e.g., Mn, Zn, Fe, Ca, Mg) [8] [10] |

| Certified Single-Element Stock Standards | Calibration | 1000 mg/L in dilute acid |

| Air and Acetylene Gases | Oxidant and fuel for flame | High-purity; nitrous oxide-acetylene may be required for refractory elements [8] |

3.1.2 Method Workflow

3.1.3 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Oven-dry plant material at 70°C to constant weight. Grind to a fine, homogeneous powder using a ceramic or titanium mill to avoid metallic contamination.

- Acid Digestion: Accurately weigh ~0.5 g of powdered sample into a digestion tube. Add 10 mL of concentrated HNO₃. Digest using a block digester or microwave digestion system, ramping to 150°C for 30 minutes. Allow to cool completely.

- Solution Preparation: Filter the digested solution through a 0.45 µm membrane filter into a 50 mL volumetric flask. Dilute to the mark with deionized water. Prepare a reagent blank simultaneously.

- Calibration: Prepare a series of calibration standards (e.g., 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 5.0 ppm) for each element by diluting certified stock standards in a matrix of 2% HNO₃.

- Instrumental Analysis:

- Install the appropriate Hollow Cathode Lamp (HCL) and set the instrument to the recommended wavelength for the analyte.

- Optimize the flame composition (fuel-to-oxidant ratio) and burner height for maximum absorbance.

- Aspirate the calibration standards, blank, and samples. Measure the absorbance for each.

- Quantification: Construct a calibration curve (Absorbance vs. Concentration) for each element. The concentration of the analytes in the plant sample is calculated automatically by the instrument software based on the calibration curve after blank subtraction.

Protocol: Ultra-Trace Analysis of Lead in Drinking Water using Graphite Furnace AA

This protocol outlines the determination of lead at parts-per-billion levels, relevant for regulatory compliance testing [9].

3.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Water Pb Analysis via GFAAS

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specification/Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Sample preservation and acidification | Ultrapure grade (e.g., OPTIMA) |

| Deionized Water | Diluent and rinsing | ≥18 MΩ·cm resistivity |

| Lead Hollow Cathode Lamp | Radiation source | - |

| Certified Lead Stock Standard | Calibration | 1000 mg/L |

| Matrix Modifier (e.g., Pd/Mg) | Chemical modifier to stabilize volatile analytes during ashing [8] | - |

| High-Purity Argon Gas | Inert purging gas for graphite tube | - |

3.2.2 Method Workflow

3.2.3 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Preservation: Collect water samples in pre-cleaned polyethylene bottles and acidify to 0.2% (v/v) with high-purity nitric acid.

- Calibration Standards: Prepare lead standards in the range of 1 to 20 ppb in a 0.2% HNO₃ matrix.

- Instrument Setup:

- Install the lead HCL and set the wavelength (e.g., 283.3 nm).

- Optimize the graphite furnace temperature program. A typical program is:

- Drying: Ramp to 110°C to gently evaporate the solvent.

- Ashing: Ramp to 500°C (or optimized temperature) to remove organic matrix without losing volatile lead.

- Atomization: Rapidly heat to 1800°C; atomize the analyte and record the transient absorption signal.

- Clean-out: Heat to 2500°C to remove any residual material.

- Analysis: The auto-sampler injects a precise volume (e.g., 15 µL) of the sample and a matrix modifier (e.g., 5 µL of Pd/Mg) into the graphite tube. The furnace program runs automatically.

- Quantification: Use the method of standard addition or external calibration with a matrix-matched blank to quantify lead, reporting results in µg/L (ppb).

Protocol: Determination of Arsenic via Hydride Generation AA

This protocol is specific for hydride-forming elements like arsenic, enhancing sensitivity and separating the analyte from complex matrices [8] [1].

3.3.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for As Analysis via HGAAS

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specification/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Borohydride (NaBH₄) | Reducing agent | Prepared fresh in NaOH stabilizer [8] |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) | Reaction medium | Concentrated, trace metal grade |

| Potassium Iodide (KI) | Prereductant (for As(V) to As(III)) | - |

| Ascorbic Acid | Prereductant | - |

| Arsenic Hollow Cathode Lamp | Radiation source | - |

| Certified Arsenic Stock Standard | Calibration | 1000 mg/L |

| Inert Gas (Argon or Nitrogen) | Carrier gas | - |

3.3.2 Method Workflow

3.3.3 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Pretreatment: Digest solid or complex liquid samples with nitric acid to ensure all arsenic is in an inorganic form. For liquid samples like water, filtration and acidification may suffice.

- Prereduction: Convert all arsenic species to As(III), as this is the form that efficiently generates arsine. Add concentrated HCl to the sample to achieve a 5-10% (v/v) final concentration. Add KI (1-2% w/v) and ascorbic acid (0.1-0.2% w/v) and let stand for 30-60 minutes.

- Hydride Generation: Use a flow injection or continuous hydride generation system. Merge the acidified sample stream with a stream of sodium borohydride solution (e.g., 0.5-1.0% in 0.1% NaOH).

- Reaction and Transfer: The reaction (NaBH₄ + 3H₂O + H⁺ → H₃BO₃ + Na⁺ + 8H⁻; 8H⁻ + As³⁺ → AsH₃ + H₂) occurs in a gas-liquid separator. The generated arsine gas (AsH₃) is swept by an inert carrier gas (Ar) into a heated quartz cell positioned in the AAS light path.

- Atomization and Detection: The quartz cell is heated (typically 800-1000°C), decomposing AsH₃ into free arsenic atoms, which then absorb light from the arsenic HCL. The transient peak absorbance is measured.

- Quantification: Prepare calibration standards of As(III) treated identically to the samples. Construct a calibration curve to determine the arsenic concentration in the unknown samples.

Applications in Research

The techniques described are pivotal in modern trace metal research. FAAS is widely used for routine analysis of essential minerals in food products, agricultural materials, and clinical samples (e.g., Ca, Mg in serum) [11] [10]. GFAAS is indispensable for quantifying toxic metals like lead and cadmium in biological and environmental matrices at regulatory levels, and for analyzing precious or limited-volume samples [11] [14]. Vapor generation techniques are the method of choice for specific, high-sensitivity applications, such as measuring mercury in fish tissue (CVAAS) or arsenic in drinking water and hair samples (HGAAS) [8] [11]. In forensic and post-mortem toxicology, GFAAS and ICP-MS are applied to determine heavy metal concentrations in tissues like kidney, liver, and brain to investigate potential poisoning or chronic exposure, highlighting the critical need for sensitive and reliable trace metal analysis [14].

Atomic spectrometry techniques are indispensable tools for determining the elemental composition of samples at trace and ultra-trace levels. These techniques share a common principle of converting a sample into free atoms or ions, which are then quantified based on their interaction with energy. For researchers in drug development and trace metal analysis, understanding the capabilities, limitations, and appropriate applications of Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS), Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES), and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) is critical for ensuring data quality, regulatory compliance, and patient safety. The global trace metal analysis market, valued at USD 6.14 billion in 2025, reflects the growing importance of these techniques across pharmaceuticals, environmental monitoring, and food safety [15].

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, performance metrics, and relative costs of AAS, ICP-OES, and ICP-MS, providing a high-level comparison for technique selection.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major Atomic Spectrometry Techniques [16] [17]

| Feature | Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) | Inductively Coupled Plasma OES (ICP-OES) | Inductively Coupled Plasma MS (ICP-MS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Absorption of light by ground-state atoms in a flame or furnace | Emission of light by excited atoms/ions in a plasma | Ionization of atoms in a plasma followed by mass separation |

| Typical Detection Limits | Flame: ~hundreds of ppbGraphite Furnace: ~mid-ppt | ~High ppt to ppb | ~few ppq (parts per quadrillion) to ppt |

| Working Range | Flame: few hundred ppb to ppmFurnace: ppt to ppb | High ppt to mid % (parts per hundred) | few ppq to few hundred ppm |

| Sample Throughput | Sequential single-element analysis; slower | Fast multi-element analysis | Very fast multi-element analysis |

| Element Coverage | Good for many metals | Excellent for metals and some non-metals | Excellent for most elements, isotopic information |

| Capital & Operational Cost | Lower | Medium | High |

Detailed Technique Breakdown

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS)

AAS operates on the principle that free, ground-state atoms can absorb light at specific wavelengths. The amount of light absorbed is proportional to the concentration of the element in the sample.

- Instrumentation and Workflow: The core components include a primary light source (Hollow Cathode Lamp or Electrodeless Discharge Lamp), an atomizer (flame or graphite furnace), a monochromator, and a detector [17]. The liquid sample is introduced into the atomizer, where it is desolvated, vaporized, and atomized. Light from the source passes through the cloud of atoms, and the specific wavelength is absorbed and measured [17].

- AAS Variants: Flame AAS uses a nebulizer to create an aerosol introduced into a flame. It is robust and cost-effective for higher concentration analyses. Graphite Furnace AAS (GFAA) introduces the sample directly into a small graphite tube, which is electrically heated in a programmed sequence to dry, ash, and atomize the sample. GFAA offers superior sensitivity and requires smaller sample volumes but has slower analysis times [17].

Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES)

ICP-OES uses a high-temperature argon plasma (6000–8000 K) to atomize and excite sample elements. As excited electrons return to lower energy states, they emit light at characteristic wavelengths, the intensity of which is measured [17].

- Plasma Source and Detection: The sample is nebulized and injected into the plasma, where it is completely atomized and excited. The emitted light is separated by a spectrometer and detected [17].

- Radial vs. Axial Viewing: Instruments can view the plasma radially (side-on) or axially (end-on). Radial viewing is more robust for complex matrices with high dissolved solids, while axial viewing provides better detection limits for cleaner samples [16].

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS)

ICP-MS also uses an argon plasma for atomization and ionization. The resulting ions are then separated and quantified based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) by a mass spectrometer [17].

- Ionization and Mass Analysis: Ioles generated in the plasma are extracted through a series of cones into a high-vacuum mass spectrometer. The mass spectrometer filters ions by m/z, which are then counted by a detector [17].

- Performance Advantages: ICP-MS provides the lowest detection limits, a wide dynamic range, and the capability for isotopic analysis. It is the preferred technique for ultra-trace analysis and meeting stringent regulatory limits, such as those for heavy metals in pharmaceuticals [16] [17].

Technique Selection Workflow

The choice of analytical technique depends on the specific requirements of the analysis, including detection limits, sample matrix, and regulatory methods. The following diagram outlines a logical decision pathway for selecting the most appropriate atomic spectrometry technique.

Figure 1: Decision workflow for selecting an atomic spectrometry technique based on analytical requirements [16] [17].

Application-Specific Analysis Protocols

Pharmaceutical Trace Elemental Impurity Testing (via ICP-MS)

This protocol is designed for compliance with regulatory guidelines like ICH Q3D and USP <232>/<233>, which mandate monitoring of toxic elemental impurities in drug products and ingredients [17].

- Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh ~0.1–0.5 g of homogenized sample into a clean digestion vessel. Add 5–10 mL of high-purity nitric acid. Allow pre-digestion at room temperature for 15 minutes. Perform microwave-assisted digestion using a controlled temperature ramp (e.g., to 180°C over 20 minutes and hold for 15 minutes). After cooling, dilute the digestate with high-purity water (e.g., 18.2 MΩ·cm) to a final volume of 50 mL. Include method blanks, continuing calibration verification (CCV), and internal standard spikes in all batches [17].

- ICP-MS Instrumental Parameters:

- Plasma & Sample Introduction: RF power: 1550 W; Nebulizer Gas Flow: ~1.0 L/min; Auxiliary Gas Flow: ~0.8 L/min; Plasma Gas Flow: 15 L/min; Sample Uptake Rate: ~0.4 mL/min.

- Data Acquisition: Dwell Time: 50–100 ms per mass; Sweeps: 100; Replicates: 3; Measurement Mode: Spectrum hopping or single.

- Internal Standardization: Use a cocktail of internal standards (e.g., Sc, Ge, In, Bi) added online to all samples and standards to correct for signal drift and matrix suppression [17].

- Quality Control: Analyze a calibration blank, initial calibration verification (ICV), and continuing calibration verification (CCV) every 10–20 samples. Recovery for ICV/CCV should be within 85–115%.

Environmental Water Analysis (via ICP-OES/ICP-MS)

This protocol outlines the analysis of trace metals in water samples, compliant with EPA Methods 200.7 (ICP-OES) and 200.8 (ICP-MS) [16].

- Sample Preparation: Collect water samples in pre-cleaned polyethylene bottles and acidify to pH < 2 with high-purity nitric acid. For ICP-OES, samples with high total dissolved solids (TDS) may be analyzed directly or with a minimal dilution. For ICP-MS, samples often require dilution (e.g., 1:10 or 1:50) to keep TDS below ~0.2% and minimize polyatomic interferences [16].

- ICP-OES Instrumental Parameters:

- Plasma Viewing: Use radial view for wastewater and groundwaters; use axial view for cleaner waters (e.g., drinking water) for better detection limits.

- Wavelength Selection: Choose analyte-specific wavelengths free of known spectral interferences (e.g., Cd II 214.440 nm, Pb II 220.353 nm).

- ICP-MS Interference Management: For drinking water analysis per EPA 200.8 v5.4, collision cell technology is not permitted. Use mathematical correction equations or high-resolution instruments to manage polyatomic interferences [16].

Analysis of Biological Tissues (via GFAA)

This protocol is adapted from a research study analyzing trace elements in human intervertebral disc tissue, demonstrating the application of GFAA for small, complex biological matrices [18].

- Sample Preparation (Freeze-Drying & Digestion): Freeze the tissue sample immediately after collection. Lyophilize (freeze-dry) the sample for 24 hours until completely dry. Accurately weigh 0.2–0.6 g of the freeze-dried tissue into a digestion vessel. Add 2.0–6.0 mL of 65% nitric acid (Merck, Germany) to achieve a 10x dilution factor. Allow the mixture to stand overnight for slow, cold mineralization. The following day, complete the digestion in a closed-vessel microwave system (e.g., Mars Xpress) using a controlled temperature program [18].

- GFAA Instrumental Parameters (Example for Pb): The following table provides optimized GFAA conditions based on the research. Ramp programs are critical for removing the matrix without losing the volatile analyte.

Table 2: Example GFAA Operating Parameters for Lead (Pb) Analysis [18]

Parameter Setting for Pb Wavelength 283.3 nm Slit Width 0.7 nm Lamp Current 10 mA Lamp Mode D2 (Deuterium Background Correction) Drying 150°C for 30 s Ashing 800°C for 20 s Atomization 2400°C for 5 s Cleaning 2600°C for 2 s - Quantification & QC: Prepare calibration standards in the same acid matrix. Run all analyses in triplicate. The percent Relative Standard Deviation (%RSD) should not exceed 5% for GFAA analysis [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists critical reagents, standards, and consumables required for precise and contamination-free trace metal analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Trace Metal Analysis [18] [17]

| Item | Specification / Purpose | Key Function |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Acids | Trace metal grade nitric acid, hydrochloric acid. | Sample digestion and dilution; purity is critical to minimize blank levels. |

| Elemental Stock Standards | Single- or multi-element certified reference solutions (e.g., 1000 ppm). | For preparation of calibration standards and quality control materials. |

| Internal Standards | Certified solution of non-analyte elements (e.g., Sc, Y, In, Bi, Ge). | Added to all samples and standards in ICP-MS and ICP-OES to correct for signal drift and matrix effects. |

| High-Purity Water | Type I (18.2 MΩ·cm) water, purified via systems like Milli-Q. | Primary diluent for all solutions to prevent contamination. |

| Argon Gas | High-purity (≥99.995%) argon gas. | Plasma generation gas for ICP-OES and ICP-MS; also used as a purge gas in GFAA. |

| Hollow Cathode Lamps (HCLs) or Electrodeless Discharge Lamps (EDLs) | Element-specific light sources. | Required for AAS to provide the characteristic wavelength for atomic absorption. |

| Graphite Tubes & Cones | Standard or platform tubes for GFAA; sampler/skimmer cones for ICP-MS. | Consumable components in contact with the sample or plasma; their condition affects sensitivity and stability. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Matrix-matched reference materials (e.g., water, tissue, soil). | Used for method validation and verifying analytical accuracy. |

Workflow for Sample Analysis

The entire process, from sample collection to data reporting, must be carefully controlled to ensure the accuracy and reliability of trace metal results. The following diagram maps this comprehensive workflow.

Figure 2: End-to-end workflow for trace metal analysis, highlighting the critical quality control feedback loop.

The Role of Trace Metal Analysis in Pharmaceutical Quality Control

The presence of trace elemental impurities in pharmaceutical products presents a significant risk to patient safety, potentially causing toxicological harm without providing any therapeutic benefit. These impurities can originate from various sources, including catalysts used in synthetic processes, raw materials, manufacturing equipment, or environmental contamination during production [19] [20]. The regulatory landscape has evolved substantially, moving from non-specific, limit-based tests toward quantitative, element-specific methodologies that provide accurate data for risk assessment [19]. Modern pharmacopeial standards, including the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) chapters <232>/<233> and the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q3D guideline, now mandate strict Permitted Daily Exposure (PDE) limits for elements of toxicological concern, classified based on their toxicity and likelihood of occurrence in drug products [20]. This application note details the critical role of atomic spectroscopy techniques, specifically Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS), in achieving the stringent requirements of modern pharmaceutical quality control, ensuring product safety and regulatory compliance.

Analytical Techniques for Trace Metal Analysis

Several atomic spectroscopy techniques are employed for trace metal analysis in pharmaceuticals, each offering distinct advantages, limitations, and suitable application ranges. The selection of an appropriate technique depends on factors such as required detection limits, number of elements to be analyzed, sample throughput, and cost considerations.

Table 1: Comparison of Atomic Spectroscopy Techniques in Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Technique | Acronym | Typical Detection Limits | Key Advantages | Common Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrometry | FAAS | Low parts per million (ppm) [19] | Cost-effective, simple operation, high sample throughput [19] | Analysis of alkali/alkaline earth elements [21] |

| Graphite Furnace AAS | GFAAS | Low parts per billion (ppb) [19] | High sensitivity, small sample volume requirement [22] [19] | Determination of Cd, Pb, Cr in feed/fish [22] [23] |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry | ICP-OES / ICP-AES | Parts per million to parts per billion [19] | Multi-element capability, wide linear dynamic range [19] | Multi-element analysis per USP/ICH guidelines [19] |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry | ICP-MS | Parts per trillion (ppt) [19] | Exceptional sensitivity, multi-element capability, isotopic analysis [22] [19] | Ultra-trace analysis of As, Cd, Pb, Hg [20] |

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) Techniques

AAS techniques are well-established for single-element quantification. In Flame AAS (FAAS), a liquid sample is aspirated and atomized in a flame (e.g., air-acetylene). Light from an element-specific hollow cathode lamp passes through the flame, and the amount of light absorbed at a characteristic wavelength is measured, proportional to the element's concentration [19]. While robust and straightforward, FAAS sensitivity is sufficient for elements like potassium and sodium but often inadequate for toxic impurities with low PDEs.

Graphite Furnace AAS (GFAAS), also known as Electrothermal AAS, offers significantly higher sensitivity. The sample is deposited in a graphite tube, which is then heated electrically through a temperature program to dry, char (pyrolyze), and finally atomize the sample. The transient signal produced allows for detection limits 10 to 1000 times lower than FAAS, making it suitable for determining highly toxic elements like cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb) at regulated levels [22] [23]. GFAAS can eliminate the sample matrix prior to atomization, providing greater flexibility for complex organic matrices like pharmaceuticals [22].

Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Techniques

ICP-OES and ICP-MS represent more advanced, multi-element techniques. In both, a sample aerosol is injected into a high-temperature argon plasma (~10,000 K), which efficiently atomizes and ionizes the elements. ICP-OES measures the characteristic light emitted by excited atoms or ions, while ICP-MS separates and detects ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio [19]. ICP-MS is the most sensitive technique, and its use is central to complying with the low PDEs set by ICH Q3D for elements like arsenic and mercury [20]. Although ICP techniques require greater operational expertise and are more costly, their multi-element nature and high throughput make them ideal for comprehensive screening of elemental impurities [19].

Method Validation

To ensure that any analytical method is fit for its intended purpose, rigorous validation is required as per international standards such as ISO/IEC 17025:2017 [22]. The validation process confirms the reliability, accuracy, and robustness of the method for the quantitative determination of trace metals.

Table 2: Key Validation Parameters and Typical Acceptance Criteria

| Validation Parameter | Description & Protocol | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Linearity | The ability to obtain test results directly proportional to analyte concentration. Assessed by analyzing a series of standard solutions across a defined range. | Coefficient of determination (R²) ≥ 0.995 [23] [22] |

| Accuracy (Trueness) | The closeness of agreement between the accepted reference value and the value found. Evaluated via spike recovery experiments using a Certified Reference Material (CRM) or spiked samples. | Recovery of 90-104% for spiked samples [23] |

| Precision | The closeness of agreement between independent test results under stipulated conditions. Includes repeatability (same day, same operator) and reproducibility (different days, different operators). | Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) < 10% [23] |

| Limit of Detection (LoD) | The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be detected. Calculated as 3 times the standard deviation of the blank signal (or the response) divided by the slope of the calibration curve. | Element-specific; e.g., for GFAAS: Cd: 0.010 μg/g, Pb: 0.078 μg/g [23] |

| Limit of Quantification (LoQ) | The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision. Calculated as 10 times the standard deviation of the blank signal divided by the slope of the calibration curve. | Element-specific; e.g., for GFAAS: Cd: 0.021 μg/g, Pb: 0.156 μg/g [23] |

| Selectivity/Specificity | The ability to measure the analyte accurately in the presence of other components, such as matrix interferences. Verified by comparing calibration slopes of aqueous standards versus matrix-matched standards or standard additions [23]. | No significant difference between slopes (e.g., via Student's t-test) [23] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: GFAAS Analysis of Trace Metals

The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for the determination of trace levels of Lead (Pb) and Cadmium (Cd) in a typical pharmaceutical matrix (e.g., a powdered excipient or active pharmaceutical ingredient) using Graphite Furnace AAS, based on validated approaches [22] [23].

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow from sample preparation to data analysis.

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Specification / Function | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hollow Cathode Lamps (HCLs) or Electrodeless Discharge Lamps (EDLs) | Element-specific light source for AAS. | Required for each analyte (e.g., Pb, Cd) [19]. |

| Suprapur or Trace Metal Grade Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Primary digestion acid; minimizes introduction of elemental impurities. | Essential for low procedural blanks [23]. |

| High-Purity Deionized Water | >18 MΩ·cm resistivity; used for all dilutions and rinsing. | Prevents contamination from water impurities [24]. |

| Single-Element Standard Stock Solutions | 1000 mg/L; used for preparation of calibration standards. | Certified reference materials from accredited suppliers (e.g., Merck) [23]. |

| Chemical Modifiers | e.g., NH₄H₂PO₄ for Cd, Pd-based modifiers for Pb. | Stabilize volatile analytes during pyrolysis step, allowing higher charring temperatures to remove matrix [23]. |

| Certified Reference Material (CRM) | e.g., CRM 142Q (sewage sludge amended soil) or similar matrix-matched CRM. | Crucial for verifying method accuracy (trueness) [24]. |

| Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) Vessels | For microwave-assisted acid digestion. | Must be meticulously cleaned with 20% HNO₃ to avoid cross-contamination [23]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Preparation (Microwave Digestion):

- Accurately weigh approximately 0.5 g of the homogenized powdered sample into a clean PTFE digestion vessel.

- Add 6 - 8 mL of concentrated nitric acid (HNO₃) to the vessel [23]. For more complex matrices, a mixture of HNO₃ and HCl (aqua regia) may be used [24].

- Carry out digestion using a controlled microwave program. A typical two-step program involves:

- Ramp Step: Linearly increase temperature to 180°C over 10-15 minutes.

- Hold Step: Maintain the temperature at 180°C for 15 minutes [23].

- After cooling, carefully transfer the digestate to a volumetric flask (e.g., 25 mL or 50 mL) and dilute to volume with deionized water. A clear, particulate-free solution indicates complete digestion.

Calibration Standard Preparation:

- Prepare a series of working standards by appropriate dilution of the single-element stock solutions (1000 mg/L) in 1% (v/v) HNO₃.

- A typical calibration range for Pb in GFAAS might be 5 - 75 µg/L, and for Cd, 1 - 6 µg/L, covering the expected concentrations in the digested samples [23].

- Include a procedural blank (all reagents, no sample) throughout the entire process.

GFAAS Instrumental Setup and Analysis:

- Install and align the HCL for the target element (e.g., Pb at 283.3 nm, Cd at 228.8 nm) according to the manufacturer's instructions [23].

- Program the graphite furnace temperature protocol. A generalized method is outlined below. Note: Optimal temperatures must be determined experimentally for each matrix and instrument.

Table 4: Exemplary GFAAS Temperature Program [23]

Step Temperature (°C) Ramp (s) Hold (s) Gas Flow Purpose Drying 1 85-95 5-10 10-20 Max Remove solvent (water) Drying 2 95-120 5-10 10-20 Max Complete drying Pyrolysis 400-700 (Pb), 200-400 (Cd) 5-10 10-20 Max Remove organic matrix without analyte loss Atomization 1500-2000 (Pb), 1200-1600 (Cd) 0 (Max Power) 3-5 Stop Produce free atoms for measurement Clean-out 2400-2600 1-2 2-3 Max Remove residual matrix from tube - Inject a known volume (e.g., 10-20 µL) of the sample digest, blank, or standard into the graphite tube, typically with an autosampler.

- Run the analysis sequence, ensuring that the calibration curve yields an R² value of at least 0.995.

Data Processing and Quality Control:

- The instrument software will calculate analyte concentrations in the samples based on the calibration curve.

- Subtract the value of the procedural blank from all sample results.

- Verify analytical accuracy and precision within the batch by analyzing a CRM and spiked samples. Recovery should be within 90-104% [23].

- Report the final concentration in the original sample (e.g., µg/g or ng/mg), taking into account the sample weight and dilution factor.

Applications in Pharmaceutical Analysis

The application of trace metal analysis is critical throughout the pharmaceutical product lifecycle. Adherence to ICH Q3D and USP 〈232〉/〈233〉 guidelines is mandatory, classifying elements based on toxicity and setting PDEs for different routes of administration (oral, parenteral, inhalation) [20]. For example, the PDEs for oral products for Class 1 elements are As (15 µg/day), Cd (5 µg/day), Pb (5 µg/day), and Hg (30 µg/day) [20].

Recent studies analyzing over-the-counter (OTC) medicines from various global markets have demonstrated the practical importance of this testing. While many products show acceptable levels of As, Cd, and Hg, some have been found to contain lead (Pb) at levels where common non-compliance with recommended dosages could lead to exposures reaching up to 50% of the Pb PDE [20]. This highlights a potential health risk, particularly for vulnerable populations like children, and underscores the necessity of rigorous quality control.

Beyond monitoring toxic impurities, atomic spectroscopy is also used to quantify essential elements (e.g., alkali and alkaline earth metals) in formulations where they play a specific role and to monitor catalyst residues (e.g., Pd, Pt) from the synthesis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) [21] [19] [25].

Trace metal analysis is an indispensable pillar of modern pharmaceutical quality control, directly impacting patient safety. The transition from classical wet chemistry to sophisticated atomic spectroscopy techniques like GFAAS and ICP-MS enables precise, accurate, and compliant quantification of elemental impurities as required by global regulatory standards. The successful implementation of these methods hinges on robust sample preparation, meticulous method validation, and strict adherence to a quality control protocol. As the pharmaceutical industry continues to globalize and supply chains become more complex, the role of reliable trace metal analysis in ensuring the quality and safety of all drug products, from prescription to over-the-counter medicines, remains paramount.

Regulatory Landscape and Compliance Requirements for Elemental Impurities

Elemental impurities in pharmaceutical products represent a significant area of regulatory concern due to their potential toxicological effects on patients. These impurities are inorganic contaminants that may be present in drug products, active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), excipients, or may be introduced from manufacturing equipment or container closure systems [26]. Unlike organic impurities, elemental impurities cannot be eliminated or reduced through synthesis pathway optimization, making their control through analytical testing and risk assessment paramount. The regulatory landscape has evolved substantially from traditional wet chemistry methods to modern instrument-based approaches that provide greater accuracy, specificity, and sensitivity.

The fundamental framework for controlling elemental impurities is established through collaborative efforts between international regulatory bodies and pharmacopeias. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q3D Guideline serves as the foundational document, which has been adopted by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and integrated into the United States Pharmacopeia (USP) general chapters <232> and <233> [26] [27]. This harmonized approach provides a consistent methodology for the classification of elemental impurities based on their toxicity and likelihood of occurrence, establishment of permitted daily exposure (PDE) limits, and validation of analytical procedures to ensure accurate quantification.

Regulatory Framework and Guidelines

ICH Q3D Guideline Framework

The ICH Q3D Guideline establishes a systematic, risk-based approach to controlling elemental impurities in drug products. This framework classifies elements into three categories based on their toxicity and probability of occurrence in drug products. Class 1 elements include arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), and lead (Pb), which are known human toxins with limited or no use in pharmaceutical manufacturing. Class 2 elements are divided into 2A (e.g., cobalt, nickel, vanadium) and 2B (e.g., silver, gold, iridium), with Class 2A having relatively high probability of occurrence. Class 3 elements (e.g., barium, chromium, copper) typically have lower toxicity profiles but require assessment when administered parenterally or inhaled [26].

The guideline establishes Permitted Daily Exposure (PDE) limits for each element, representing the maximum acceptable intake per day without significant risk to patient health. These limits vary according to the route of administration (oral, parenteral, inhalation), reflecting differences in bioavailability and potential toxicity. The PDE values are derived from comprehensive toxicological assessments and form the basis for establishing appropriate control strategies throughout the product lifecycle.

FDA Implementation and USP Harmonization

The U.S. FDA formally adopted the ICH Q3D Guideline in August 2018 through its guidance "Elemental Impurities in Drug Products," effectively making elemental impurity control mandatory for all prescription and over-the-counter drug products marketed in the United States [26]. While FDA guidance documents represent non-binding recommendations, they encapsulate the agency's current thinking on this topic and establish expectations for compliance.

Concurrently, the United States Pharmacopeia has harmonized its general chapters with these international standards. USP Chapter <232> defines the PDE limits for elemental impurities, while USP Chapter <233> establishes validated analytical procedures for their detection and quantification [26]. Recent updates to these chapters have achieved greater harmonization with the European Pharmacopoeia and Japanese Pharmacopoeia, facilitating global drug development and manufacturing. The official date for the harmonized USP <233> chapter is May 1, 2026 [27].

Table 1: PDE Limits (μg/day) for Selected Elemental Impurities by Route of Administration Based on USP <232> and ICH Q3D

| Element | Oral PDE | Parenteral PDE | Inhalation PDE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cadmium (Cd) | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Lead (Pb) | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Arsenic (As) | 15 | 15 | 2 |

| Mercury (Hg) | 30 | 3 | 1 |

| Cobalt (Co) | 50 | 5 | 3 |

| Vanadium (V) | 100 | 10 | 1 |

| Nickel (Ni) | 200 | 20 | 5 |

Documentation Requirements

The regulatory framework mandates specific documentation to demonstrate compliance. For new drug applications (NDAs and ANDAs), manufacturers must include a comprehensive risk assessment that identifies potential elemental impurities, determines their likely concentrations, and compares these levels to established PDEs [26]. For already-approved products, this documentation must be submitted via supplemental applications or annual reports. Similarly, for over-the-counter drugs, manufacturers must maintain complete documentation on-site for FDA review during inspections [26].

The risk assessment process follows a structured three-step approach: First, identification of all known and potential sources of elemental impurities in the drug product; second, determination of the concentration of each impurity through testing or scientific justification; and third, comparison of calculated daily exposure to the PDE [26]. If the risk assessment indicates that impurity levels may exceed 30% of the PDE, additional controls must be implemented and documented.

Analytical Techniques for Elemental Impurities

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS)

Atomic absorption spectroscopy operates on the principle that free atoms in their ground state can absorb light at specific characteristic wavelengths. When a sample containing metal atoms is exposed to light at these wavelengths, the amount of absorption is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing atoms [1]. The fundamental components of an AAS system include a light source (typically a hollow-cathode lamp), an atomization system (flame or graphite furnace), a monochromator to select the specific wavelength, and a detection system [1].

AAS offers several advantages for pharmaceutical analysis, including high specificity, relatively low operational costs, and well-established methodology. However, traditional AAS is limited to single-element analysis, requiring lamp changes and separate method setups for different elements. This limitation has reduced its application for comprehensive elemental impurity screening, though it remains valuable for targeted analysis of specific elements known to be potential impurities in a given drug product [1].

Inductively Coupled Plasma-Based Techniques

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) has emerged as the premier technique for elemental impurity analysis due to its exceptional sensitivity, wide linear dynamic range, and multi-element capability. ICP-MS can detect most elements at concentrations ranging from parts per billion (ppb) to parts per trillion (ppt), comfortably below the required PDE levels for pharmaceutical products [28]. The technique involves the ionization of sample atoms in a high-temperature argon plasma, followed by separation and detection based on mass-to-charge ratios.

Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) provides an alternative with somewhat higher detection limits but excellent precision and stability. ICP-OES measures the characteristic emission spectra of excited atoms in the plasma, allowing simultaneous multi-element analysis [26] [28]. Both ICP techniques require sample digestion to create aqueous solutions for analysis, typically employing microwave-assisted digestion to ensure complete dissolution of organic matrices and recovery of target elements [28].

Table 2: Comparison of Analytical Techniques for Elemental Impurity Analysis

| Technique | Detection Limits | Multi-element Capability | Sample Throughput | Key Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flame AAS (FAAS) | ppm to ppb | Single element | Moderate | Limited use for high-concentration elements |

| Graphite Furnace AAS (GFAAS) | ppb to ppt | Single element | Low | Specific, sensitive determination of Class 1 elements |

| ICP-OES | ppb | Simultaneous | High | Routine analysis of multiple elements |

| ICP-MS | ppt to ppq | Simultaneous | High | Comprehensive screening and ultra-trace analysis |

Specialized Sampling Techniques

Certain elements require specialized sampling approaches due to their unique chemical properties. Hydride generation techniques are employed for elements such as arsenic, selenium, and bismuth, improving detection limits by converting the analytes to volatile hydrides that can be efficiently transported to the detection system [1]. Cold vapor atomization is specifically used for mercury analysis, taking advantage of mercury's volatility at room temperature to achieve detection limits appropriate for its stringent PDE limits [1].

For direct solid sampling, electrothermal vaporization (ETV) systems can be coupled with ICP-OES or ICP-MS, eliminating the need for sample digestion and reducing contamination risks [28]. Laser ablation techniques offer another solid sampling approach, particularly useful for localized analysis and mapping elemental distribution in heterogeneous samples.

Experimental Protocols

Risk Assessment Protocol

The initial risk assessment represents the foundation of the control strategy for elemental impurities. The protocol involves three systematic steps [26]:

Step 1: Identification of Potential Elemental Impurities

- Compile complete list of drug product components: APIs, excipients, packaging materials

- Identify potential elemental sources: catalysts, natural contaminants, manufacturing equipment

- Consider processing steps that may introduce or concentrate impurities

- Document all known and theoretically possible elemental impurities

Step 2: Concentration Determination

- Select appropriate analytical methods based on required detection limits

- Analyze representative batches of all components and final drug product

- Alternatively, use scientifically justified predictions based on supplier data

- Calculate potential daily intake for each identified element

Step 3: PDE Comparison and Control Strategy

- Compare calculated daily exposure to established PDE limits

- Implement additional controls for elements approaching 30% of PDE

- Establish routine testing protocols for critical elements

- Document complete assessment with scientific justification

ICP-MS Method Protocol for Comprehensive Screening

Sample Preparation:

- Accurately weigh approximately 0.5 g of homogenized drug product into microwave digestion vessels

- Add 5 mL concentrated nitric acid (trace metal grade) and 2 mL hydrogen peroxide (30%)

- Perform microwave digestion using a validated temperature program (typically ramping to 180°C over 20 minutes, holding for 15 minutes)

- Cool samples, transfer to volumetric flasks, and dilute to 50 mL with high-purity deionized water (18 MΩ·cm)

- Prepare reagent blanks and quality control samples identically

Instrumental Conditions:

- ICP-MS system with collision/reaction cell technology

- RF power: 1550 W

- Plasma gas flow: 15 L/min argon

- Auxiliary gas flow: 0.9 L/min argon

- Nebulizer gas flow: 1.05 L/min argon

- Sample introduction: perfluoroalkoxy (PFA) microflow nebulizer with cyclonic spray chamber

- Data acquisition: 3 points per peak, 3 replicates per sample

- Dwell time: 100 ms per isotope

Internal Standardization and Calibration:

- Use yttrium (89Y) and bismuth (209Bi) as internal standards [28]

- Prepare calibration standards in the range of 0.1-100 μg/L in 2% nitric acid

- Include quality control samples at low, medium, and high concentrations

- Verify instrument performance with system suitability standards before analysis

Validation Parameters:

- Specificity: No interference from matrix components

- Accuracy: 85-115% recovery for all target elements

- Precision: ≤15% RSD for repeatability and intermediate precision

- Linearity: r² ≥ 0.995 for all calibration curves

- Limit of Quantitation: Sufficiently low to detect elements at 30% of PDE

GFAAS Protocol for Specific Element Determination

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare sample solutions as described for ICP-MS analysis

- Further dilute samples if necessary to remain within linear range

- Add matrix modifiers as required (e.g., palladium for lead determination) [28]

Instrumental Conditions (Exemplary for Lead Determination):

- Wavelength: 283.3 nm

- Lamp current: 75% of maximum

- Spectral bandwidth: 0.7 nm

- Graphite furnace temperature program:

- Injection volume: 20 μL

- Use peak area for quantification

Method Validation:

- Characteristic mass: 24.4 pg for lead [28]

- Limit of detection: 31.4 pg/kg for lead [28]

- Recovery: 98.0-105.0% across validated concentration range [28]

- Within-batch precision: ≤6.4% RSD [28]

Workflow Visualization

Elemental Impurity Risk Assessment Workflow

Analytical Method Selection Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Elemental Impurity Analysis

| Item | Function | Quality Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Nitric Acid | Primary digestion acid for sample preparation | Trace metal grade (<5 ppt total impurities) |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Oxidizing agent for complete digestion of organic matrices | Semiconductor grade, stabilized |

| Multi-Element Calibration Standards | Instrument calibration and quantification | Certified reference materials with NIST traceability |

| Internal Standard Solutions | Correction for instrument drift and matrix effects | High-purity mixed element solutions (e.g., Sc, Y, Bi, Rh) |

| Tune Solutions | ICP-MS instrument optimization | Contains elements covering full mass range (Li, Y, Ce, Tl) |

| Matrix Modifiers (GFAAS) | Thermal stabilization of volatile analytes | High-purity palladium, magnesium, or ammonium phosphate |

| Certified Reference Materials | Method validation and quality control | Pharmaceutical matrices with certified elemental concentrations |

| High-Purity Water | Sample dilution and preparation | 18 MΩ·cm resistivity, <5 ppt total organic carbon |

The regulatory landscape for elemental impurities in pharmaceuticals has matured into a harmonized, science-based framework that prioritizes patient safety while enabling efficient compliance strategies. The successful implementation of this framework requires a comprehensive understanding of both regulatory expectations and analytical capabilities. Atomic absorption spectroscopy continues to play a role in targeted analysis, while ICP-MS has emerged as the predominant technique for comprehensive screening due to its sensitivity, multi-element capability, and efficiency.

The critical success factors for compliance include: conducting thorough, science-based risk assessments; selecting appropriate analytical methodologies validated according to USP <233> requirements; implementing robust quality control measures throughout the product lifecycle; and maintaining complete documentation ready for regulatory inspection. As the regulatory requirements continue to evolve globally, particularly with the extension of similar principles to cosmetic products under MoCRA, the established approaches for pharmaceutical elemental impurity control provide a valuable foundation for related product categories [26].

In the modern pharmaceutical industry, ensuring product safety and efficacy is paramount. Trace metal analysis, particularly via Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS), is a critical quality control step for detecting and quantifying elemental impurities in drug substances, products, and excipients. This application note examines the growing market for these analytical techniques and provides detailed protocols to support researchers in maintaining rigorous compliance and scientific standards. The global trace metal analysis market, valued at USD 6.14 billion in 2025, is projected to expand to USD 13.80 billion by 2034, demonstrating a robust compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.42% [15]. This growth is heavily driven by stringent global regulatory requirements and the expanding analytical needs of the pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors [15].

The pharmaceutical industry's reliance on precise trace metal analysis is intensifying due to several convergent trends: an increase in stringent safety and quality regulations, rising R&D spending in life sciences, and the growing need to ensure the purity of complex biologics and personalized medicines [15]. Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy remains a cornerstone technology in this landscape due to its reliability, high throughput, and cost-effectiveness for analyzing elements in solution [7].

Key Market Drivers and Quantitative Outlook

The following table summarizes the core market drivers and key growth projections for the trace metal analysis market within the pharmaceutical sector.

Table 1: Market Drivers and Growth Projections for Pharmaceutical Trace Metal Analysis

| Aspect | Detail | Source/Projection |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Market Driver | Stringent regulatory mandates (e.g., FDA, EMA, ICH Q3D) for quality control and patient safety. | [15] |

| Key Growth Segment | Pharmaceutical & biotechnology products testing; anticipated to witness the fastest growth. | [15] |

| Global Market Size (2025) | USD 6.14 billion | [15] |

| Projected Market Size (2034) | USD 13.80 billion | [15] |

| Projected CAGR (2025-2034) | 9.42% | [15] |

Technology Trends: The Impact of AI and Automation

The field is being transformed by technological advancements, notably the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and automation. AI algorithms are revolutionizing trace metal analysis by enhancing data analytics, predictive modeling, and real-time monitoring, which in turn improves efficiency, accuracy, and decision-making [15]. Furthermore, the market is witnessing a growing demand for outsourcing analytical services to specialized contract research organizations (CROs), creating opportunities for laboratories to leverage advanced external expertise [15].

Experimental Protocol: Determining Heavy Metals in Pharmaceutical Materials by GFAAS

This protocol outlines a validated method for determining trace levels of heavy metals, such as Chromium (Cr), Cadmium (Cd), and Lead (Pb), in pharmaceutical feed materials using Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (GFAAS), based on established guidelines and validation parameters [29]. GFAAS is preferred for its high sensitivity and ability to handle small sample volumes.

Principle

The sample is digested and introduced into a graphite tube. Under controlled, stepwise heating, the sample is dried, ashed (to remove organic matrix), and atomized. The free atoms of the target element absorb light from a hollow-cathode lamp at a characteristic wavelength. The amount of absorbed light is proportional to the concentration of the element in the sample [1] [7].

Equipment and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Graphite Furnace AAS | Instrument platform (e.g., Model AA-7000). Must include a temperature-programmable graphite furnace and auto-sampler. |

| Hollow-Cathode Lamps | Element-specific light source for Cr, Cd, and Pb. |

| High-Purity Argon Gas | Inert gas used to purge the graphite tube and prevent oxidation of the sample and tube during atomization. |

| High-Purity Nitric Acid | For sample digestion and preparation of standards. |

| Deionized Water | (>18 MΩ·cm) For all dilutions and reagent preparation. |

| Standard Stock Solutions | Certified single-element solutions (1000 mg/L) for calibration. |

Sample Preparation

- Digestion: Accurately weigh approximately 0.5 g of the homogenized solid sample (e.g., poultry feed as a model for pharmaceutical materials) into a digestion tube. Add 10 mL of concentrated nitric acid.

- Heating: Heat the mixture on a block digester or hotplate at 95°C for 10-15 minutes, or until the production of brown fumes ceases and a clear digestate is obtained.

- Cooling and Dilution: Allow the tube to cool. Carefully transfer the digestate to a 50 mL volumetric flask and make up to the volume with deionized water. This yields a 10-fold dilution.

- Blank Preparation: Prepare a method blank by processing the same volume of nitric acid through the entire digestion and dilution procedure without the sample.

Instrumental Analysis and GFAAS Conditions

The GFAAS program involves a series of temperature-controlled steps to prepare and analyze the sample.

Table 3: Exemplary GFAAS Operating Parameters for Heavy Metal Analysis

| Parameter | Chromium (Cr) | Cadmium (Cd) | Lead (Pb) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength (nm) | 357.9 | 228.8 | 283.0 |

| Drying | 110°C, 20s | 110°C, 20s | 110°C, 20s |

| Ashing | 700°C, 10s | 400°C, 10s | 500°C, 10s |

| Atomization | 2200°C, 3s | 1500°C, 3s | 1800°C, 3s |

| Cleaning | 2400°C, 2s | 2400°C, 2s | 2400°C, 2s |

| Inert Gas | Argon | Argon | Argon |

Calibration and Quantification

- Prepare a blank and at least three standard calibration solutions by serial dilution of stock solutions in a matrix of 2% nitric acid. The calibration range should be appropriate for the expected concentrations in the samples.

- Run the calibration standards, blank, and samples following the temperature program in Table 3.

- Construct a calibration curve by plotting absorbance against concentration. The curve should be linear with a coefficient of determination (r²) > 0.999 [29].

- The concentration of the analyte in the sample is calculated automatically by the instrument software based on the calibration curve.

Method Validation Parameters

For regulatory compliance, the method must be validated. The following table summarizes the typical acceptance criteria for key validation parameters based on the referenced study [29].

Table 4: Method Validation Criteria and Acceptance Parameters

| Validation Parameter | Result for Cr, Cd, Pb | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Linearity (r²) | > 0.999 | > 0.995 |

| Recovery (%) | 93.97 - 101.63 | 80 - 110% |

| Repeatability (CV%) | 8.70 - 8.76% | < 10% |

| Reproducibility (CV%) | 8.65 - 9.96% | < 10% |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 0.01 - 0.11 mg/kg | Based on signal-to-noise |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | 0.03 - 0.38 mg/kg | Based on signal-to-noise |

The trace metal analysis market is on a strong growth trajectory, firmly anchored by the non-negotiable demand for drug safety and quality in the pharmaceutical industry. Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy, especially the highly sensitive GFAAS, remains a vital tool for complying with stringent global regulations like ICH Q3D. The integration of AI and automation is set to further enhance the accuracy, efficiency, and predictive capabilities of these analytical techniques. The detailed protocol provided herein offers a validated and reliable roadmap for researchers and quality control professionals to perform essential trace metal analysis, thereby contributing to the delivery of safe and effective pharmaceutical products to the market.

Practical Applications and Method Development for Drug Analysis

Sample Preparation Strategies for Pharmaceutical Matrices

Sample preparation is a critical preliminary step in the analysis of pharmaceutical matrices for trace metal content using atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) and other elemental techniques. Its primary purpose is to extract the target analytes and remove redundant matrix components that could interfere with analytical accuracy [30]. The complexity of biological and drug matrices necessitates robust sample preparation methods to mitigate matrix effects, which remain a significant challenge in bioanalytical sample preparation [30]. Competent sample preparation ensures the reliability of data supporting regulatory filings such as investigational new drug applications and new drug applications [30]. This application note details current methodologies and protocols for preparing various pharmaceutical samples, framed within the context of AAS for trace metal analysis.

Understanding Pharmaceutical Matrices

Pharmaceutical analysis encompasses a diverse range of biological and drug product matrices, each presenting unique challenges for sample preparation and trace metal analysis.

Biological Matrices

Biological fluids are complex and require specific handling to accurately determine their trace metal content [30].

- Blood, Plasma, and Serum: These matrices contain various proteins, glucose, hormones, and minerals. Plasma constitutes approximately 55% of blood fluid in humans, while serum is the fluid component without fibrinogens [30].

- Urine: Composed of approximately 95% water, with inorganic salts (sodium, phosphate, sulfate, ammonia), urea, creatinine, and proteins [30].

- Hair: A stable, strong matrix that is non-invasively collected and easy to handle. Hair analysis is used to provide evidence of drug exposure and heavy metal accumulation [30].

- Human Breast Milk: Contains fats, proteins, lactose, and minerals. It serves as an excellent biomarker for detecting drugs and environmental pollutants, with lipophilic compounds having higher excretion tendencies [30].

- Tissues: Can be categorized into soft tissues (e.g., liver, kidney), tough tissues (e.g., stomach, intestine, muscle), and hard tissues (e.g., bone, nail). Each type requires specific preparation methods, with quantification in tissues like skin being particularly challenging due to low analyte concentrations and sample rigidity [30].

Drug Substances and Products

Drug substances (DS) are typically free-flowing solid powders with high chemical purity, while drug products (DP) such as tablets and capsules include excipients that form solid matrices from which the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) must be extracted [31].

Table 1: Common Pharmaceutical Matrices and Their Characteristics

| Matrix Type | Key Characteristics | Primary Challenges for Metal Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Blood/Plasma/Serum | High protein content, various metabolites and minerals [30] | Matrix effects, protein binding, low metal concentrations |

| Urine | High water and salt content [30] | Salt precipitation, variable viscosity |

| Hair | Stable, tough matrix [30] | External contamination, digestion difficulty |

| Tablets/Capsules | Composite solid forms with API and excipients [31] | Complete extraction from insoluble excipients |

| Tissue Samples | Heterogeneous cellular structures [30] | Homogenization, complete digestion of organic matter |

Sample Preparation Techniques

The fundamental goal of sample preparation for AAS is to present the analyte in a suitable liquid form, free from interferences that could affect atomization [32].

Digestion Techniques

Digestion is essential for solid samples and complex matrices to break down organic matter and release bound metals into solution for AAS analysis.

- Acid Digestion: Involves reacting the sample with mineral acids such as HNO₃, HCl, or H₂SO₄, often with heating to speed up the reaction [32] [33]. This can be performed in open vessels or closed systems.

- Microwave Digestion: A pressurized digestion method that uses microwave energy to directly heat the sample-acid mixture, significantly reducing total digestion time compared to traditional hotplate methods [33]. Modern systems feature rotor inserts with digestion vessels made of PTFE or quartz, with optical pressure control and temperature monitoring for safety and process control [33].

- High-Pressure Digestion: Systems like the High Pressure Asher (HPA) provide ultimate performance in wet chemical high-pressure digestion sample preparation for AAS, ICP, and voltammetry [34].

Extraction Techniques

For drug products, extraction techniques are employed to separate the analyte from the formulation matrix.

- Dilute-and-Shoot: A straightforward approach for drug substances where the sample is dissolved in an appropriate diluent [31]. The nature and composition of the diluent depend on the API's aqueous solubility and physicochemical properties [31].

- Grind, Extract, and Filter: A more elaborate process for drug products where tablets are crushed, the API is extracted into solution, and the extract is filtered to remove particulate matter [31].

- Solid-Liquid Extraction (SLE): Used for comprehensive extraction of analytes from solid samples [30].

Microextraction Techniques

Novel sample preparation techniques have gained popularity over the past decade due to advantages in automation, ease of use, and reduced solvent consumption [30].

- Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME): A non-exhaustive method that integrates sampling, preconcentration, and extraction into a single step [30].

- Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (DLLME): Has become more acceptable in clinical investigations due to its advantages in minimal solvent use and high preconcentration factors [30].

- Electromembrane Extraction (EME): Gaining acceptance for its selectivity and clean-up capabilities [30].

Experimental Protocols

Microwave Digestion Protocol for Biological Tissues

This protocol is designed for preparing tissue samples (e.g., liver, kidney) for trace metal analysis by Graphite Furnace AAS [30] [33].

Table 2: Reagent Solutions for Microwave Digestion

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Primary digesting agent for organic matrices [33] | Trace metal grade, 65-70% concentration |