Beyond the Spectrum: Advanced AI and Machine Learning for Complex Spectral Data Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive overview of cutting-edge data analysis techniques transforming the interpretation of complex spectral data.

Beyond the Spectrum: Advanced AI and Machine Learning for Complex Spectral Data Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of cutting-edge data analysis techniques transforming the interpretation of complex spectral data. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the evolution from classical chemometrics to modern artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML). We cover foundational concepts, delve into specific methodological applications—including real-world case studies in pharmaceutical analysis and remote sensing—and address critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. The content also provides a comparative analysis of model validation techniques, offering a practical guide for selecting the right tools to enhance accuracy, efficiency, and reliability in biomedical and clinical research.

The New Landscape of Spectral Analysis: From Classical Chemometrics to Modern AI

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Correcting Spillover and Unmixing Errors in Spectral Flow Cytometry

Problem: Incorrect spillover identification in spectral flow cytometry leads to skewed data and artificial correlations or anti-correlations between channels [1].

Diagnostic Symptoms:

- Skewed Signals: Populations appear to "lean" into an adjacent channel [1].

- Hyper-negative Events: Events appear below zero on the axis, which is biologically impossible and indicates an artifact [1] [2].

- Correlation/Anti-correlation: An unexpected strong correlation between two channels, especially those with overlapping emission spectra [1].

Protocol for Resolution:

- Inspect Single-Color Controls: Verify that the controls are correctly compensated or unmixed. Check for automated gating errors that may have misidentified positive and negative populations [1] [2].

- Compare Brightness: Ensure the fluorescence intensity in your single-color control is as bright or brighter than in your fully stained experimental samples [2].

- Validate Reagents and Treatment: Confirm that the exact same fluorophore was used in controls and samples, and that both were treated identically (e.g., same fixation protocol) [2].

- Check for Tandem Dye Breakdown: If a tandem dye (e.g., PE-Cy7) breaks down, its emission spectrum can shift, causing spillover errors not present in the control. This requires new staining with fresh reagents [1].

- Re-make Controls if Necessary: If controls are flawed (e.g., made with beads instead of cells, or are contaminated), new controls must be prepared that perfectly match the experimental samples [1] [2].

Guide: Avoiding Common Errors in Raman Spectral Analysis

Problem: A flawed data analysis pipeline leads to an overestimated and unreliable model performance [3].

Diagnostic Symptoms:

- Model performance is perfect or near-perfect on a small dataset.

- Fluorescence background dominates the Raman signal.

- The model fails when applied to new data from a different day.

Protocol for Resolution:

- Wavenumber Calibration: Regularly measure a wavenumber standard (e.g., 4-acetamidophenol) to create a stable, common wavenumber axis for all measurements. Skipping this causes systematic drifts [3].

- Correct Preprocessing Order: Always perform baseline correction to remove fluorescence background before applying spectral normalization. Reversing this order biases the data [3].

- Prevent Over-fitting: Use a grid search to optimize preprocessing parameters (e.g., for baseline correction) based on spectral markers, not the final model performance [3].

- Ensure Independent Validation: During model evaluation, ensure that all replicates from a single biological sample or patient are placed in the same training or test subset. Splitting them causes information leakage and severely inflates performance estimates [3].

- Select Appropriate Models: Use low-parameterized models (e.g., linear models) for small datasets and reserve complex models (e.g., deep learning) for large, independent datasets [3].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is there a strong negative correlation between my material-specific images in spectral CT? In two-material decomposition (2-MD) spectral CT, the noise correlation coefficient between the two material-specific images approaches -1. This is a fundamental property of the decomposition mathematics. In more complex multi-material decomposition (m-MD, with m ≥ 3), the noise correlation between different material pairs can alternate between positive and negative values [4].

Q2: How can I fix a spillover error that is only present in my fully stained samples but not in the single-color controls? This indicates that your single-color controls did not accurately represent your experimental samples. The most common reasons are [2]:

- The control was less bright than the sample.

- A different reagent was used in the control (e.g., FITC control for a GFP sample, or compensation beads instead of cells).

- The sample and control were treated differently (e.g., one was fixed and the other was not). The solution is to create new, properly matched controls.

Q3: What is the most critical mistake to avoid in Raman spectral preprocessing? The most critical mistake is performing spectral normalization before baseline correction. The intense fluorescence background becomes encoded in the normalization constant, creating a significant bias in all subsequent analysis. Always correct the baseline first [3].

Q4: Can I manually edit a compensation matrix to fix spillover errors? Manually editing a compensation matrix is generally not recommended. While it might make one plot look better, spillover errors propagate through multiple data dimensions. A manual adjustment in one channel can introduce unseen errors in other channels. It is safer to recalculate the matrix using improved controls or a specialized algorithm [1].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Spectral Artifacts and Their Signatures

| Artifact Type | Field | Key Diagnostic Signature | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noise Correlation | Spectral CT | Correlation coefficient of ~ -1 in 2-MD images [4] | Fundamental property of material decomposition algorithms [4]. |

| Spillover/Unmixing Error | Flow Cytometry | Skewed populations & hyper-negative events [1] [2] | Incorrect control samples or spectral reference [1] [2]. |

| Fluorescence Background | Raman Spectroscopy | Intense, broad background underlying sharper Raman peaks [3] | Natural overlap of Raman effect with sample fluorescence [3]. |

| Wavenumber Drift | Raman Spectroscopy | Systematic shift in peak positions across measurements [3] | Lack of or improper wavelength/wavenumber calibration [3]. |

| Cosmic Spike | Spectroscopy | Sharp, single-pixel spike in intensity [3] | High-energy cosmic particles striking the detector [3]. |

| Tandem Dye Breakdown | Flow Cytometry | Spillover error in full stain but not control [1] | Degradation of the tandem dye conjugate in the sample [1]. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Spectral Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Single-Color Control Samples | Used to generate the spectral library or compensation matrix for unmixing; must be biologically and chemically identical to test samples [1] [2]. |

| Wavenumber Standard (e.g., 4-acetamidophenol) | Provides known reference peaks for calibrating the wavenumber axis of a spectrometer, ensuring consistency across measurements [3]. |

| Polymer Stain Buffer | Prevents fluorophore aggregation and sticking when multiple polymer dyes (e.g., Brilliant Violet dyes) are used in a single panel [2]. |

| FMO (Fluorescence Minus One) Control | Helps distinguish true positive signals from spillover spread and aids in setting positive gates, especially for problematic markers [1]. |

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Protocol: Investigating Noise Correlation in Photon-Counting CT

This protocol is derived from simulation studies on the performance of spectral imaging based on multi-material decomposition (m-MD) [4].

1. System Configuration:

- X-ray Technique: Set to 140 keV tube voltage and 1000 mA tube current.

- Gantry Rotation: 1 rotation per second.

- Spectral Channelization: Define energy thresholds based on the number of materials (m) to be decomposed.

- For 2-MD: Use two bins, [1–58, 59–140] keV.

- For 3-MD: Use three bins, [1–51, 52–68, 69–140] keV.

- For 4-MD: Use four bins, [1–43, 44–58, 59–72, 73–140] keV [4].

2. Data Acquisition Modeling:

- Model the detected signals in each spectral channel ( k ) using the equation: ( Ik(L) = Poisson \left( \int{E{min}}^{E{max}} Dk(E) N0(E) \exp\left( -\sum{p=1}^P Ap(L) \mup(E) \right) dE \right) ) where ( Dk(E) ) is the spectral response, ( N0(E) ) is the source spectrum, ( Ap(L) ) is the line integral of basis material ( p ), and ( \mu_p(E) ) is its attenuation coefficient [4].

3. Material Decomposition:

- Solve the set of integral equations for ( A_p(L) ) using an iterative numerical method like the Newton-Raphson algorithm. Initial conditions are obtained through system calibration [4].

4. Noise Correlation Analysis:

- Calculate the noise correlation coefficients between all pairs of the resulting material-specific (basis) images.

- The expected result is a correlation coefficient approaching -1 for 2-MD. For m-MD (m ≥ 3), coefficients will alternate between +1 and -1 for different material pairs [4].

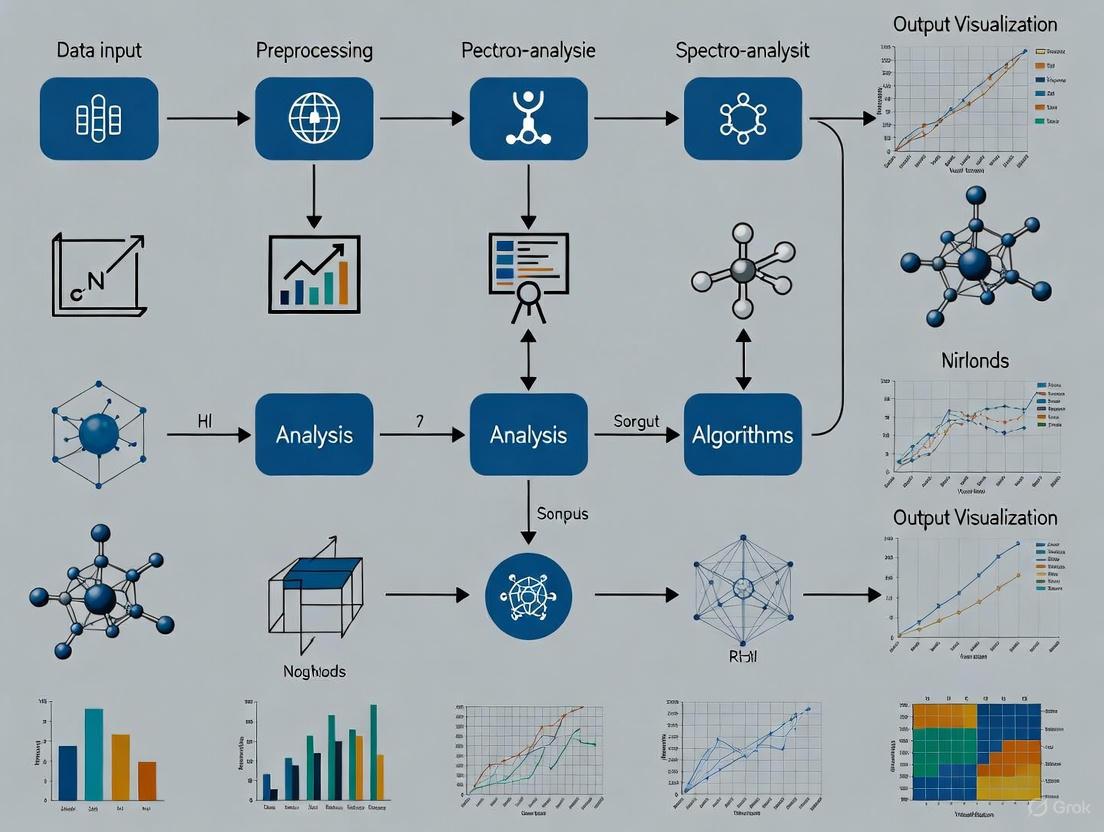

Workflow Visualization

Diagram: Spectral Data Analysis Pipeline

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Classical Chemometrics. This resource is designed for researchers and scientists working with complex spectral data, providing foundational troubleshooting guides and FAQs. While modern artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) frameworks offer advanced capabilities, classical chemometric methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, and Soft Independent Modeling of Class Analogy (SIMCA) remain vital for multivariate data analysis [5] [6]. This guide helps you navigate common challenges in applying these robust, interpretable techniques, ensuring reliable data analysis and a solid foundation for exploring advanced AI integrations.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between PCA and PLS? A1: PCA is an unsupervised technique primarily used for exploratory data analysis, dimensionality reduction, and outlier detection. It finds combinations of variables (principal components) that describe the greatest variance in your X-data (e.g., spectral intensities) without using prior knowledge of sample classes [6] [7]. In contrast, PLS is a supervised technique used for regression or classification. It finds components in the X-data that are most predictive of the Y-variables (e.g., analyte concentrations or class labels), maximizing the covariance between X and Y [5] [6].

Q2: My PCA model is unstable, and the scores plot changes dramatically with small changes in my data. What could be wrong? A2: This often indicates that your model is highly sensitive to noise and outliers. Classical methods can be susceptible to these issues [5].

- Solution: Ensure your data is properly pre-processed (e.g., scaling, normalization). Use the outlier detection capabilities inherent in PCA and other chemometric methods. Techniques like SIMCA are specifically designed to assess the analogy of a sample to a class model, which includes checking for outliers [5].

Q3: When should I use SIMCA over other classification methods? A3: SIMCA is particularly useful when you have well-defined classes and want to build a separate PCA model for each class. It is ideal for class modeling problems, where the question is "Does this sample belong to this specific class?" rather than "Which of these classes does this sample belong to?" [5] [7]. It allows a sample to be assigned to one, multiple, or no classes.

Common Experimental Issues & Solutions

The table below outlines specific problems you might encounter during chemometric analysis of spectral data, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Problem Description | Root Cause | Solution & Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Noisy or Unreliable PCA/SIMCA Model | High influence of noise and undetected outliers in the spectral data [5]. | Leverage the built-in noise and outlier reduction features of your chemometric software. Re-scan samples if necessary to ensure data quality [5]. |

| Poor PLS Regression Predictions | Model is overfit or built on irrelevant spectral regions; non-linear relationships not captured by classical PLS [6]. | Ensure proper variable selection and model validation (e.g., cross-validation). For complex non-linearities, consider complementing your work with AI techniques like Support Vector Machines (SVM) or Random Forest [6]. |

| Incorrect Classification in SIMCA | Poorly defined class boundaries or samples that are not well-represented by the training set [7]. | Review the quality and representativeness of your training set for each class. Validate the model with a robust test set and adjust the confidence level for class assignment [7]. |

| Strange or Negative Peaks in Spectral Baseline | Underlying spectral issues from the instrument, such as a dirty ATR crystal or instrument vibrations [8]. | Perform routine instrument maintenance. Clean the ATR crystal and take a fresh background scan. Ensure the spectrometer is on a stable, vibration-free surface [8]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Developing a PCA Model for Spectral Data Exploration

Objective: To explore a spectral dataset, identify natural groupings, and detect outliers.

Materials:

- Spectral data (e.g., NIR, IR, Raman)

- Software with PCA capability (e.g., Mnova Advanced Chemometrics plugin) [5]

Methodology:

- Data Pre-processing: Load your spectral matrix. Apply necessary pre-processing steps such as Standard Normal Variate (SNV), detrending, or derivatives to minimize scattering effects and baseline shifts.

- Model Building: Execute PCA. The software will calculate the principal components (PCs) that capture the maximum variance.

- Visualization & Interpretation:

- Examine the Scores Plot (e.g., PC1 vs. PC2) to visualize sample clustering and identify potential outliers.

- Examine the Loadings Plot to interpret which spectral variables (wavelengths) are responsible for the patterns seen in the scores plot.

- Validation: Use statistical metrics like Q-residuals and Hotelling's T² to quantitatively identify outliers that do not fit the model well [5].

Protocol 2: Building a PLS Regression Model for Quantification

Objective: To develop a predictive model that correlates spectral data (X-matrix) with a quantitative property, such as analyte concentration (Y-matrix).

Materials:

- Spectral data with known reference values for the property of interest

- Software with PLS regression capability [5]

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Split your data into a calibration (training) set and a validation (test) set.

- Model Training: Build the PLS model on the calibration set. The algorithm will find latent variables in X that best predict Y.

- Model Diagnostics: Evaluate the model performance using the Root Mean Square Error of Calibration (RMSEC) and the coefficient of determination (R²) for the calibration set.

- Model Validation: Apply the model to the independent validation set. Use Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP) and R² for prediction to assess the model's predictive accuracy and avoid overfitting.

- Prediction: Use the validated model to predict the property Y in new, unknown samples.

Workflow Visualization: Chemometric Analysis Pathway

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for applying classical chemometrics to spectral data, from data acquisition to model deployment and the potential transition to advanced AI techniques.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key software tools and algorithmic approaches that form the essential "research reagents" in the field of classical chemometrics.

| Item Name | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | An unsupervised algorithm for exploratory data analysis, dimensionality reduction, and outlier detection. It is fundamental for visualizing inherent data structure [5] [6] [7]. |

| Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression | A supervised algorithm for building predictive models. It correlates spectral data (X) with quantitative properties (Y), such as analyte concentration, and is a cornerstone of multivariate calibration [5] [6]. |

| Soft Independent Modeling of Class Analogy (SIMCA) | A supervised classification method that builds a separate PCA model for each class. It is used for sample classification and authenticity testing [5] [7]. |

| Multivariate Curve Resolution (MCR) | An algorithm used for peak purity assessment in complex data like LC-MS, helping to resolve the contribution of individual components in a mixture [5]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How do I correct for baseline drift and scattering effects in my spectroscopic data?

Issue: Spectroscopic data (e.g., from NIR, IR, Raman) often contain non-chemical artifacts from baseline drifts and multiplicative scatter, which obscure the true analyte signal and hinder accurate quantitative analysis [9]. These distortions arise from physical phenomena like particle size variation, sample packing, instrumental drift, or, in Raman spectroscopy, fluorescence [9] [10] [11].

Solution: Apply established correction methods designed to isolate and remove these physical effects.

- For Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC): This method assumes the measured spectrum is a linear transformation of an ideal reference spectrum (often the mean spectrum of the dataset). It corrects for both additive and multiplicative effects commonly found in diffuse reflectance spectra [9] [12].

- For Standard Normal Variate (SNV): This is a spectrum-specific transformation. It centers and scales each spectrum individually, making it particularly useful for heterogeneous samples where a common reference spectrum is not appropriate [9] [12].

- For Extended Multiplicative Scatter Correction (EMSC): This is a more powerful extension of MSC. It can model and remove not only scatter effects but also polynomial baseline trends and other known spectral interferents simultaneously [9] [13]. Recent studies have successfully used EMSC to suppress instrumental variations in long-term Raman measurement data [13].

Experimental Protocol: Applying MSC

- Calculate the mean spectrum from your entire calibration dataset to use as the reference spectrum.

- For each individual spectrum, perform a linear regression (e.g., using least squares) of the sample spectrum against the reference spectrum.

- The corrected spectrum is obtained by subtracting the estimated additive effect and then dividing by the estimated multiplicative coefficient [9].

FAQ 2: What are the modern approaches for complex, nonlinear baseline problems?

Issue: Traditional polynomial fitting methods may fail or require extensive manual parameter tuning for complex, nonlinear baselines, especially in techniques like Raman spectroscopy where fluorescence can create a strong, varying background [10] [11].

Solution: Implement advanced baseline estimation techniques or leverage deep learning.

- Asymmetric Least Squares (AsLS): This method estimates the baseline by solving an optimization problem that penalizes positive residuals (the peaks) more heavily than negative residuals (the baseline), resulting in a smooth function that fits the baseline without fitting the analyte peaks [9].

- Deep Learning-Based Correction: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can be trained to learn the complex patterns of baseline distortions directly from data. For example, a Triangular Deep Convolutional Network has been shown to outperform traditional methods by achieving superior correction accuracy, reducing computation time, and better preserving peak intensity and shape [10]. These methods offer greater adaptability and enhance automation by eliminating manual parameter tuning for different datasets [10].

Experimental Protocol: AsLS Baseline Correction

- Define the asymmetry parameter (e.g., 0.001-0.1 for most spectra) and the smoothness parameter.

- Solve the optimization problem to estimate the baseline, which is a smooth curve that lies below the spectral peaks.

- Subtract the estimated baseline from the original spectrum to obtain the baseline-corrected spectrum [9].

FAQ 3: How should I normalize my multi-omics data for a time-course study?

Issue: In mass spectrometry-based multi-omics (e.g., metabolomics, lipidomics, proteomics), data normalization is crucial to remove systematic errors without masking true biological variation, which is especially critical in time-course experiments where temporal differentiation must be preserved [14].

Solution: Select a normalization method that is robust and preserves the biological variance of interest.

- Probabilistic Quotient Normalization (PQN): This method has been identified as optimal for metabolomics and lipidomics data in temporal multi-omics studies. It works by assuming that the majority of peaks have a constant ratio between samples. It calculates a most probable dilution factor by comparing the quotients of all variables to a reference spectrum (often the median spectrum) [14].

- LOESS Normalization: Locally Estimated Scatterplot Smoothing (LOESS) is another top-performing method for metabolomics, lipidomics, and proteomics. It fits a smooth curve to the data points in a scatterplot, which is effective for correcting intensity-dependent biases [14].

- Median Normalization: For proteomics data, median normalization is a robust and simple method. It scales the data so that the median intensity is the same across all samples [14].

Important Consideration: A study evaluating normalization for multi-omics datasets from the same cell lysate found that while machine learning methods like SERRF can outperform others in some cases, they can also inadvertently mask treatment-related variance in others. Therefore, the choice of method should be validated for your specific dataset [14].

Performance Comparison of Key Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Scattering and Baseline Correction Methods

| Method | Core Mechanism | Primary Application Context | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) [9] | Linear transformation relative to a reference spectrum. | Diffuse reflectance spectra (NIR) with additive/multiplicative effects. | Interpretable, computationally efficient. | Requires a representative reference spectrum. |

| Standard Normal Variate (SNV) [9] | Centers and scales each spectrum individually. | Heterogeneous samples without a common reference. | No reference needed; useful for particle size effects. | Assumes scatter effect is constant across the spectrum. |

| Extended MSC (EMSC) [9] [13] | Models scatter, polynomial baselines, and interferents. | Complex distortions in multi-center or long-term studies. | Handles multiple interference types simultaneously. | More complex model requiring more parameters. |

| Asymmetric Least Squares (AsLS) [9] | Optimization with asymmetric penalties on residuals. | Nonlinear baseline drift in various spectroscopies. | Flexible adaptation to nonlinear baselines. | Requires tuning of asymmetry and smoothness parameters. |

| Deep Learning (CNN) [10] | Trained convolutional filters learn to remove baselines. | Complex baselines (e.g., Raman fluorescence) requiring automation. | High accuracy, fast computation, preserves peak shape. | Requires a large, diverse training dataset. |

Table 2: Evaluation of Normalization Methods for Multi-Omics Datasets [14]

| Normalization Method | Metabolomics | Lipidomics | Proteomics | Considerations for Time-Course Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probabilistic Quotient (PQN) | Optimal | Optimal | Excellent | Preserves time-related variance; robust. |

| LOESS | Optimal | Optimal | Excellent | Effective for intensity-dependent bias. |

| Median | Good | Good | Excellent | Simple and robust for proteomics. |

| SERRF (Machine Learning) | Variable Performance | Not Assessed | Not Assessed | Can outperform but may mask biological variance. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Quality Control Standards for Raman Spectroscopy [13]

| Reagent / Material | Function in Spectral Preprocessing & Analysis |

|---|---|

| Cyclohexane | A standard reference material used for precise wavenumber calibration of the spectrometer. |

| Paracetamol | A stable solid substance used for wavenumber calibration and stability benchmarking. |

| Polystyrene | A polymer with well-defined Raman bands, used as a standard for wavenumber calibration. |

| Silicon | Used to calibrate the exposure time and ensure consistent intensity of its characteristic 520 cm⁻¹ Raman band. |

| Squalene | A stable lipid used to evaluate instrumental performance and stability over time. |

Technical Support Center: AI for Spectral Data Analysis

This support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals integrating AI and Machine Learning into their work with complex spectral data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How is AI transforming the analysis of spectral data in research? AI and machine learning are revolutionizing spectral analysis by enabling the detection of subtle, complex patterns that are often imperceptible to the human eye. Spectroscopy techniques are prone to interference from environmental noise, instrumental artifacts, and sample impurities. Machine learning algorithms can overcome these challenges by learning to identify and correct for these perturbations, significantly enhancing measurement accuracy and feature extraction. This allows for unprecedented detection sensitivity, achieving sub-ppm levels while maintaining >99% classification accuracy in applications like pharmaceutical quality control and environmental monitoring [15].

2. What is data-centric AI and why is it important for spectral analysis? Data-centric AI is a paradigm that shifts the focus from solely refining models to systematically improving the quality of the datasets used for training. This is crucial for spectral data because even the most advanced model will underperform if trained on poor-quality data. The core idea is that increasing dataset quality—by correcting mislabeled entries, removing anomalous inputs, or increasing dataset size—is often far more effective at improving a model's final output than increasing model complexity or training time. Initiatives like DataPerf provide benchmarks for this data-centric approach [16].

3. My AI model performs well on training data but poorly on new spectral data. What is wrong? This is a classic sign of data leakage or overfitting [17]. It means your model has memorized patterns from your training set that do not generalize to new data.

- Solution: Ensure there is absolutely no overlap between the data used for training and the data used for testing or validation. All data preprocessing steps (like normalization) should be fit on the training data and then applied to the test data, preventing the model from gaining any unfair knowledge about the test set beforehand [17].

4. What are the common machine learning mistakes to avoid with spectral data? The table below summarizes key pitfalls and their solutions.

| Mistake | Consequence | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Data Preprocessing [17] | Model captures noise and artifacts instead of real spectral signatures, leading to inaccurate predictions. | Implement a robust preprocessing pipeline: handle missing values, perform baseline correction, apply scattering correction, and use spectral derivatives [15]. |

| Ignoring Data Analysis [17] | Biases in raw data lead to biased models, undermining prediction accuracy and causing unfair outcomes. | Perform thorough Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA). Use visualization and statistical techniques to understand data distribution, detect anomalies, and audit for biases before training [17]. |

| Choosing the Wrong Algorithm [17] | Poor model performance and an inability to capture the relevant patterns in the spectral data. | Start with simpler, interpretable models (e.g., PCA-LDA) [18]. Understand your data and problem; not every task requires a complex neural network [17]. |

| Insufficient Model Evaluation [17] | Poor generalization to new data, wasted resources, and false confidence in the model's capabilities. | Go beyond a single accuracy score. Use rigorous evaluation practices like cross-validation and multiple metrics. Regularly update and re-evaluate models post-deployment [17]. |

| Lack of Domain Knowledge [17] | Models may use irrelevant features or make predictions that are chemically or biologically implausible. | Collaborate closely with domain experts (e.g., spectroscopists, biologists) to identify meaningful features and validate model findings [17] [18]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Classification Accuracy with Raman Spectroscopy Data

This guide addresses low accuracy when classifying spectral data, such as exosomes from different cancer cell lines.

Experimental Protocol & Methodology

The following workflow, based on a study achieving 93.3% classification accuracy, outlines a proven methodology for analyzing Raman spectral data [18].

- Step 1: Data Acquisition. Collect Raman spectra from your samples. In the referenced study, exosomes were isolated from colon (COLO205), skin (A375), and prostate (LNCaP) cancer cell lines [18].

- Step 2: Spectral Preprocessing. Process raw spectra to remove noise and artifacts. Key steps include:

- Step 3: Feature Extraction. Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimensionality of the spectral data. PCA identifies the most significant wavenumber regions that contribute to variance (e.g., 700–900 cm⁻¹ for lipids, 2800–3000 cm⁻¹ for CH-stretching modes), transforming the data into a set of principal components (PCs) that are easier for classifiers to process [18].

- Step 4: Model Training and Classification. Train a classifier, such as Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), on the extracted principal components. LDA finds a linear combination of features that best separates the different classes (e.g., cancer types) [18].

- Step 5: Validation. Evaluate model performance using a separate, held-out test dataset. Report overall accuracy and per-class metrics like F1 scores to ensure balanced performance across all categories [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details essential components for a spectral data analysis project.

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Cancer Cell Lines (e.g., COLO205, A375, LNCaP) [18] | Serve as the biological source of exosomes; different lines provide distinct spectral signatures for model training and classification. |

| Raman Spectrometer [18] | The core instrument for generating label-free, chemically specific vibrational spectra from samples. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [18] | A dimensionality reduction algorithm critical for extracting chemically significant features from complex, high-dimensional spectral data. |

| Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) [18] | A classification algorithm that models differences between classes based on the extracted features, enabling categorical prediction. |

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) Substrates [18] | Nanostructured metallic surfaces that can be used to significantly amplify weak Raman signals, improving detection sensitivity for low-concentration analytes. |

Problem: AI Model Fails to Generalize from Preclinical Data

Challenge: An AI model trained on preclinical data (e.g., from cell lines or animal models) performs poorly when applied to human clinical data due to differences in data distribution and complexity.

Solution Guide:

- Leverage Digital Twins: Create computational models of a biological system (e.g., an organ) trained on multi-modal data. These "digital twins" can act as personalized control arms, providing a more robust basis for predicting human response and reducing the translatability gap seen in conventional models [19].

- Use Context-Aware and Physics-Constrained Models: Move beyond generic models. Employ adaptive processing techniques that account for specific experimental conditions and incorporate known physical laws or biological constraints into the AI model. This improves the realism and generalizability of predictions [15].

- Ensure Regulatory Preparedness: For drug development, be aware of the evolving regulatory landscape. The FDA advocates for a risk-based framework. Prepare for scrutiny on how the AI model’s behavior impacts the final drug product's quality, safety, and efficacy. Maintain rigorous audit trails and controls to prevent issues like data hallucination [20].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is preprocessing raw spectral data so critical for machine learning and multivariate analysis? Raw spectral signals are weak and inherently contaminated by noise from various sources, including the instrument, environment, and sample itself. These perturbations—such as baseline drift, cosmic rays, and scattering effects—degrade measurement accuracy and can severely bias the feature extraction process of machine learning models like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and convolutional neural networks. Proper preprocessing is essential to remove these artifacts, thereby ensuring the analytical robustness and reliability of subsequent models [ [15] [11]].

Q2: What are the common signs of a poorly corrected baseline, and how can it affect my quantification? A poorly corrected baseline is often visually identifiable as a persistent low-frequency drift or tilt underlying the true spectral peaks. This can manifest as a non-zero baseline in peak-free regions or an uneven baseline that distorts the true shape and intensity of peaks. Quantitatively, this leads to systematic errors in concentration estimates, as the baseline contributes inaccurately to the measured peak intensities, violating the assumptions of techniques like the Beer-Lambert law [ [21] [11]].

Q3: My extracted spectrum has unexpected spikes. What is the most likely cause, and how can I remove them? Sharp, narrow spikes in a spectrum are typically caused by cosmic rays striking the detector. This is a common issue in techniques like Raman and gamma-ray spectroscopy. Several removal techniques exist, ranging from simple moving average filters that detect and replace outliers to more advanced methods like the Multistage Spike Recognition (MSR) algorithm, which uses forward differences and dynamic thresholds to identify and correct these artifacts, especially in time-resolved data comprising multiple scans [ [11]].

Q4: How does the choice of normalization technique impact the interpretation of my spectral data? Normalization controls for unwanted systematic variations in absolute signal intensity, which may arise from factors like sample thickness or instrument responsivity, and not the underlying chemistry. The choice of technique is crucial:

- Misapplied Normalization: Can suppress real, meaningful biological or chemical variance, rendering important differences undetectable.

- Appropriate Normalization: Allows for valid comparisons between samples by preserving the relative shapes of the spectra and the chemically relevant variance [ [21]].

Q5: What should I do if my pipeline fails to extract a spectrum for a faint source? Automatic spectral extraction pipelines can fail for faint sources, particularly when they are near much brighter objects, as the software may only detect and extract the bright source. In such cases, manual intervention is required. This typically involves reprocessing the data and manually defining the extraction parameters, such as the position and width of the extraction window, to ensure the faint source is included [ [22]].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Noise Levels Obscuring Spectral Features

Problem: The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in your spectra is too low, making it difficult to distinguish genuine peaks from background noise.

Diagnosis and Solution Protocol: This issue requires a multi-step approach to isolate and reduce noise. The following workflow outlines a systematic protocol for diagnosis and resolution.

Inspect Raw Data and Acquisition Parameters:

- Examine the raw, unprocessed signal to confirm the noise is not an artifact of incorrect processing.

- Verify that fundamental acquisition parameters are optimal. For NMR, this includes ensuring an adequate number of transients (scans) and proper receiver gain. Increasing the acquisition time or scan count is the most direct way to improve SNR [ [21]].

Apply Digital Filtering and Smoothing:

- Use algorithms like the Savitzky-Golay filter to smooth the data. This filter preserves the shape and width of spectral peaks better than a simple moving average [ [11]].

Utilize Spectral Derivatives:

- Calculate the first or second derivative of your spectrum. This advanced technique can help resolve overlapping peaks and suppress broad, low-frequency baseline contributions, thereby enhancing the visibility of sharp, informative features [ [11]].

Issue 2: Persistent Baseline Drift or Tilt

Problem: The spectrum exhibits a significant low-frequency curvature, making accurate peak integration and quantification difficult.

Diagnosis and Solution Protocol: Baseline correction is a critical step. The choice of algorithm depends on the nature of the drift and the spectral features.

Table 1: Common Baseline Correction Methods

| Method | Core Mechanism | Best For | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Piecewise Polynomial Fitting (PPF) [ [11]] | Fits a low-order polynomial (e.g., cubic) to user-selected, peak-free regions of the spectrum. | Spectra with complex, non-linear baselines. | Intuitive and offers user control. | Sensitive to the manual selection of baseline points. |

| Morphological Operations (MOM) [ [11]] | Uses erosion/dilation operations (like image processing) with a structural element to estimate the baseline. | Spectra with many narrow peaks, common in pharmaceutical analysis. | Automatic and preserves peak shapes well. | Requires tuning the width of the structural element. |

| Two-Side Exponential (ATEB) [ [11]] | Applies bidirectional exponential smoothing with adaptive weights. | High-throughput data with smooth to moderate baselines. | Fast, automatic, and requires no manual peak tuning. | Less effective for spectra with sharp baseline fluctuations. |

Issue 3: Inconsistent Compound Identification Across Samples

Problem: The same compound appears at slightly different wavelengths or chemical shifts in different samples, leading to misidentification.

Diagnosis and Solution Protocol: This is typically a problem of spectral alignment (warping) and referencing.

Chemical Shift Referencing:

- For NMR spectra, always use an internal chemical shift standard. We strongly recommend DSS over TSP, as TSP is pH-sensitive and can lead to referencing errors, especially in poorly buffered samples like urine [ [21]].

Spectral Alignment (Warping):

- Apply alignment algorithms to correct for small, non-linear shifts between spectra. These algorithms stretch and compress spectral segments to match a reference spectrum, ensuring peaks from the same compound align perfectly across all samples [ [21]].

Statistical Validation:

- After alignment, use multivariate tools like Principal Components Analysis (PCA). Successful alignment will result in tighter clustering of replicate samples in the PCA scores plot, indicating reduced technical variance [ [23]].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Preprocessing Techniques & Materials

Table 2: Key Spectral Preprocessing Techniques and Their Functions

| Technique | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Cosmic Ray Removal [ [11]] | Identifies and removes sharp, spurious spikes caused by high-energy particles. | Choose an algorithm (e.g., Moving Average, Nearest Neighbor Comparison) suited to your data's SNR and whether you have replicate scans. |

| Scattering Correction [ [15]] | Compensates for light scattering effects in turbid or powdered samples (e.g., Extended Multiplicative Signal Correction). | Critical for recovering pure absorbance/reflectance information in NIR analysis of biological powders or mixtures. |

| Normalization [ [21]] | Removes unwanted variations in absolute intensity to enable sample comparison. | Choose a method (e.g., Total Area, Probabilistic Quotient) based on what source of variance you wish to correct. Misapplication can remove biological signal. |

| Spectral Binning [ [21]] | Reduces data dimensionality and improves SNR by integrating intensities over small spectral regions (bins). | Increases SNR at the cost of spectral resolution. Optimal bin size depends on the information density of your spectrum. |

Advanced Workflow: From Raw Data to Multivariate Model

For researchers aiming to build predictive models from spectral data, the pipeline extends beyond basic preprocessing. The following diagram and protocol detail the steps for a robust multivariate analysis workflow, such as developing a calibration model to predict constituent concentrations.

Experimental Protocol for Multivariate Calibration:

Preprocessing Pipeline: Apply the necessary preprocessing steps (baseline correction, normalization, etc.) determined through the troubleshooting guides above. Consistency across all training and future prediction samples is paramount [ [15] [11]].

Outlier Detection:

- Use the Model Driven Multivariate Control Chart (MDMCC) or similar tools to identify spectral outliers.

- Charts for T² (distance from data center in model plane) and SPE (distance from model plane) are used to flag spectra that are atypical or poor fits to the initial model. These outliers should be investigated and potentially excluded before model building [ [23]].

Exploratory Analysis:

Multivariate Calibration:

- For functional data like spectra, use specialized tools like the Functional Data Explorer (FDE) in JMP Pro. FDE performs a functional PCA, which can lead to more efficient models [ [23]].

- The Functional DOE Profiler can then be used to build a calibration model that predicts the spectral shape or the concentration of constituents (inverse calibration) at combinations not explicitly measured in the original experiment [ [23]].

Model Validation:

- Never rely solely on model performance from the training data. Always validate the final model using a completely independent set of samples that was not used in any step of the training or preprocessing optimization process. This provides an unbiased estimate of the model's predictive performance on new data.

Advanced Methods in Action: Machine Learning and Deep Learning Applications

In the analysis of complex spectral data, selecting and correctly applying the appropriate machine learning algorithm is paramount to the success of a research project. Techniques like Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS), Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, and Raman spectroscopy generate high-dimensional datasets where the differences between classes can be exceptionally subtle. Within this domain, three methods have established themselves as foundational tools: Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), and Random Forest (RF). This guide addresses the most common challenges researchers face when implementing these algorithms, providing targeted troubleshooting advice and experimental protocols to ensure robust and interpretable results in applications ranging from drug discovery to food authentication and biomedical diagnostics.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Q: Under what conditions should I choose PLS-DA over LDA for my spectral data?

- A: Your choice should be guided by the specific characteristics of your dataset. Opt for PLS-DA when your data has a high number of features (e.g., thousands of spectral wavelengths) and a relatively small sample size. PLS-DA is explicitly designed to handle multicollinearity, which is common in spectral data, by projecting the variables into a latent space that maximizes covariance with the class labels [24] [25]. In contrast, LDA requires the within-class scatter matrix to be invertible, a condition that fails when the number of features exceeds the number of samples or when features are perfectly correlated [25]. Therefore, for high-dimensional spectral data, PLS-DA is generally the more robust and applicable choice.

2. Q: How can I improve the performance of LDA on my high-dimensional spectral dataset?

- A: A common and effective strategy is to combine LDA with a prior dimensionality reduction step. You can apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to your spectral data first and then perform LDA on the PCA scores. This PCA-LDA hybrid approach overcomes the mathematical limitations of standard LDA by working in a reduced, orthogonal feature space [24]. Studies have successfully used this method to classify FTIR spectra of cancer cells and vibrational spectra of biological materials with accuracies exceeding 90% [24].

3. Q: Random Forest is often called a "black box." How can I interpret which spectral regions are most important for the classification?

- A: Random Forest provides an inherent feature importance metric, which is a key to its interpretability. The algorithm calculates the mean decrease in Gini impurity or the mean increase in accuracy for each feature (e.g., wavenumber or wavelength) when it is used to split nodes across all the trees in the forest. By examining these importance scores, you can identify the specific spectral regions or peaks that are the most discriminative for your classification task [26] [27]. For instance, this approach has been used to pinpoint spectral biomarkers in blood plasma for multiple sclerosis diagnosis [27].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 1: Common Algorithm Issues and Proposed Solutions

| Problem | Likely Cause | Solution | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poor LDA performance on spectral data | High dimensionality and multicollinearity causing singular within-class scatter matrix [25]. | Use PCA-LDA or switch to PLS-DA [24] [25]. | A study on apple origin authentication found PLS-DA more suitable than LDA for ICP-MS data with strong multicollinearity [25]. |

| PLS-DA model is overfitting | Too many Latent Variables (LVs) are used, modeling noise instead of signal. | Optimize the number of LVs using cross-validation. Use a separate test set for final validation [25]. | Research classifying nephrites achieved a testing accuracy of 95.9% with RF, demonstrating generalizability by validating on a hold-out set [28]. |

| Random Forest has high accuracy but low interpretability | The model is complex, and key features are not being communicated. | Extract and plot feature importance scores. Relate important features back to known biochemical compounds [26] [27]. | In a food study, RF's feature importance was used to identify key wavenumbers for discriminating gluten-free and gluten-containing bread, adding chemical validity [26]. |

| Class imbalance leading to biased models | One class has many more samples than another, skewing the classifier. | Apply algorithmic adjustment like balanced sub-sampling in RF, adjust class weights in PLS-DA and LDA, or use SMOTE [29]. | A voting ensemble classifier was designed with specific weights to mitigate misclassification and achieve balanced accuracy for nephrite origins [28]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comparing Classifier Performance for Spectral Discrimination

This protocol outlines a standardized workflow for evaluating and comparing PLS-DA, LDA, and Random Forest on vibrational spectral data, based on established methodologies [28] [24] [26].

1. Sample Preparation and Spectral Acquisition:

- Samples: Use a well-defined set of samples with confirmed class labels (e.g., healthy vs. diseased tissue, authentic vs. adulterated food).

- Spectroscopy: Acquire vibrational spectra (e.g., FTIR, Raman, NIR) using standardized instrumental parameters.

- Replicates: Collect multiple technical replicates per sample to account for instrumental noise.

2. Data Preprocessing:

- Perform preprocessing to remove artifacts and enhance spectral features. Common steps include:

3. Data Splitting:

- Split the dataset into a training/calibration set (typically 70-80%) and a test set (20-30%). Use algorithms like Kennard-Stone to ensure the test set is representative of the spectral space [26].

4. Model Training and Optimization:

- PLS-DA: Use the training set to build a PLS-DA model. Determine the optimal number of Latent Variables (LVs) through k-fold cross-validation to avoid overfitting.

- LDA/PCA-LDA: First, apply PCA to the training spectra to obtain scores. Then, use these scores to build an LDA model. Select the number of Principal Components (PCs) that capture the majority of the variance.

- Random Forest: Train a forest of decision trees. Use cross-validation to optimize key hyperparameters such as the number of trees, the maximum depth of trees, and the number of features to consider at each split.

5. Model Evaluation:

- Apply the trained models to the held-out test set.

- Evaluate performance using metrics such as Accuracy, Sensitivity, Specificity, and Balanced Accuracy.

- For RF, additionally generate and analyze feature importance plots to identify discriminative spectral regions.

Protocol 2: Developing a Diagnostic Model with ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy of Blood Plasma

This protocol is adapted from a study that successfully discriminated between Multiple Sclerosis (MS) patients and healthy controls using ATR-FTIR and a linear predictor [27].

1. Biological Sample Collection and Ethical Approval:

- Obtain ethical approval and informed consent from all participants.

- Collect blood plasma from confirmed patient and healthy control groups. Ensure groups are matched for age and gender where possible.

2. Spectral Acquisition:

- Acquire ATR-FTIR spectra from dried plasma samples.

- Focus on key spectral regions: the high-frequency region (3050–2800 cm⁻¹) for lipid and fatty acid C-H stretches, and the fingerprint region (1800–900 cm⁻¹) for proteins, nucleic acids, and carbohydrates.

- Collect and average multiple replicates per sample.

3. Extraction of Spectral Biomarkers:

- Instead of using full spectra, calculate specific spectral biomarkers (absorbance ratios) based on biological relevance. Examples include:

A_{HR} / A_{amide I + amide II}(Lipid-to-Protein ratio)A_{C=O} / A_{HR}(Ester carbonyl band relative to lipids)A_{CH2 asym} / A_{CH2 sym + CH2 asym}(Lipid acyl chain packing order) [27].

4. Construction of a Linear Predictor:

- Use logistic regression (a generalized linear model) to construct a predictive model.

- The model combines the selected spectral biomarkers into a single score that predicts the probability of a sample belonging to the patient group.

- The equation takes the form:

Logit(Probability) = β₀ + β₁*Biomarker₁ + β₂*Biomarker₂ + ...[27].

5. Model Validation:

- Validate the model using a separate cohort of samples not used in the model building.

- Report Sensitivity and Specificity to demonstrate clinical utility.

Essential Workflow Visualizations

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Spectral Data Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Purpose | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| LIBS (Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy) | Provides elemental composition data by analyzing plasma emission from laser-ablated material. | Discrimination of nephrite jade geographical origins [28]. |

| ATR-FTIR Spectrometer | Measures infrared absorption to provide a biochemical "fingerprint" of a sample with minimal preparation. | Diagnosing Multiple Sclerosis from blood plasma [27]. |

| Raman Spectrometer | Measures inelastic scattering of light to provide information on molecular vibrations, effective in aqueous solutions. | Differentiating malignant and non-malignant breast cancer cells [24]. |

| NIR Spectrometer | Measures overtones and combinations of molecular vibrations; rapid and non-invasive. | Analyzing protein and moisture content in bread samples [26]. |

| ICP-MS (Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry) | Provides ultra-trace elemental and isotopic quantification. | Authenticating the geographical origin of apples [25]. |

| Python with Scikit-learn & XGBoost | Open-source libraries providing implementations of PLS-DA, LDA, Random Forest, and hyperparameter optimization tools. | Building and comparing classification models for food discrimination [26]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: Core Concepts and Architecture

Q1: Why is a specialized CNN architecture necessary for hyperspectral data, as opposed to standard 2D CNNs used for RGB images?

Hyperspectral images (HSIs) contain rich information in both the spatial domain (like a traditional image) and the spectral domain (dozens or hundreds of contiguous narrow wavelength bands) [30]. Standard 2D CNNs are primarily designed to extract spatial features and do not fully leverage the unique, information-rich spectral signature of each pixel. Specialized architectures are required to effectively fuse these spectral and spatial features [31] [32]. For instance, a two-branch CNN (2B-CNN) uses a 1D convolutional branch to extract spectral features and a 2D convolutional branch to extract spatial features, subsequently combining them for a more powerful representation [31] [33].

Q2: What are the primary causes of overfitting when working with limited hyperspectral data, and how can it be mitigated?

Overfitting is a significant challenge in HSI analysis due to the high dimensionality of the data and often limited labeled training samples (the p ≫ n problem, where variables exceed samples) [31]. Key strategies to mitigate this include:

- Network Design: Employing a fully convolutional structure without fully-connected layers, using dropout layers, and incorporating batch normalization [31].

- Data Augmentation: Artificially expanding the training set through techniques like rotation, mirroring, and scaling [34].

- Regularization: Using methods like L2 regularization (weight decay) but ensuring the regularization strength is not overwhelming other components of the loss function [34].

- Simpler Models: Starting with a simpler, shallower network architecture can be beneficial when training data is scarce [35].

Q3: How can I identify which spectral wavelengths are most important for my classification task using a CNN?

A key advantage of some CNN architectures is their ability to assist in effective wavelengths selection without additional re-training. In a two-branch CNN (2B-CNN), the weights learned by the first convolutional layer of the 2D spatial branch can be used as an indicator of important wavelengths [31] [33]. These weights comprehensively consider the discriminative power in both the spectral and spatial domains, providing a data-driven way to identify spectral regions that are critical for the classification task, which can help in reducing equipment cost and computational load [31].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q1: My model's training loss is not decreasing. What could be wrong?

This issue often stems from an incorrectly configured training process or model architecture. Follow this systematic approach:

- Verify Input Data: Ensure your data is correctly normalized (e.g., subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation) and that pre-processing steps like image correction have been applied properly [35]. Incorrect input is a common source of bugs.

- Inspect the Loss Function: Confirm that the loss function matches the network's output. For example, using a loss function that expects logits (raw outputs) with a softmax output layer will lead to incorrect gradients [35].

- Check Learning Rate: An excessively high learning rate can cause gradient oscillations, while a very low one leads to slow progress. The optimal learning rate is close to the maximum rate before the training error increases [34]. Try a learning rate schedule that starts with a larger value and decreases over time [30].

- Overfit a Single Batch: A highly effective debugging heuristic is to try and overfit a single, small batch of data (e.g., as few as 5-10 samples). If the model cannot drive the training loss on this batch close to zero, it indicates a likely implementation bug, such as an incorrect loss function or gradient computation [35].

Q2: The model trains but performance is significantly lower than reported in literature. How should I proceed?

Discrepancies in performance can arise from multiple factors. A structured debugging strategy is crucial [35].

- Start Simple: Begin with a simple architecture, such as a LeNet-like model for spatial data or a shallow 1D CNN for spectral data, to establish a baseline [35]. Use sensible defaults: ReLU activation, normalized inputs, and no regularization initially [35].

- Compare to a Known Result: Reproduce the results of a reference paper on the same dataset, if possible. Line-by-line comparison of your code with an official implementation can help identify subtle bugs in data pipeline, model architecture, or training recipe [35].

- Evaluate Data and Model Fit: Ensure your dataset construction is correct. Check for issues like noisy labels, imbalanced classes, or a mismatch between the training and test set distributions [35]. Your dataset may simply be more varied or smaller than the one used in the reference paper, leading to different results [36].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Perform a thorough search of hyperparameters such as learning rate, batch size, and network depth [34]. Deep learning models are often very sensitive to these choices [35].

Q3: I am encountering "NaN" or "inf" values during training. How can I resolve this?

Numerical instability, leading to NaN (Not a Number) or inf (infinity) values, is a common bug [35].

- Gradient Explosion: This is a frequent cause. Implement gradient clipping to limit the size of the gradients during backpropagation [30].

- Custom Operations: If you are using custom layers or operations, perform gradient checks to ensure the forward and backward passes are implemented correctly [34].

- Activation Functions: Check for operations that can produce large or undefined values, such as exponents, logarithms, or divisions, especially in relation to the activation functions used [35].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

The table below summarizes several advanced CNN architectures for HSI classification, highlighting their core approaches and relative robustness as evaluated in a recent critical study.

Table 1: Comparison of CNN Architectures for Hyperspectral Image Classification

| Model Name | Core Architectural Idea | Reported Strengths | Relative Robustness Score* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2B-CNN [31] [33] | Two-branch network for separate spectral (1D-CNN) and spatial (2D-CNN) feature extraction and fusion. | Effective spectral-spatial fusion; enables wavelength selection. | Information not provided in search results. |

| FDSSC [32] | Fast Dense Spectral-Spatial Convolution using dense connections. | High robustness; stable performance with few training samples. | High |

| Tri-CNN [32] | Uses different scales of 3D-CNN to extract and fuse features, leveraging inter-band correlations. | High robustness against distortions. | High |

| HybridSN [32] | Hybrid 2D and 3D convolutional network. | Good performance on standard benchmarks. | Medium |

| MCNN [32] | Integrates mixed convolutions with covariance pooling. | Enhanced discriminative features with limited samples. | Medium |

| 3D-CNN [32] | Uses 3D convolutions to jointly process spatial and spectral dimensions. | Fundamental approach for joint spectral-spatial learning. | Low to Medium |

| FC3DCNN [32] | A compact and computationally efficient fully convolutional 3D CNN. | Suitable for real-time applications. | Low to Medium |

Robustness scores (High, Medium, Low) are based on mutation testing results from a 2024 study that evaluated model performance in the presence of various input and model distortions [32].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following table provides example performance metrics for various models on different HSI classification tasks, illustrating the performance gains of spectral-spatial methods.

Table 2: Example Classification Accuracies (%) of Different Models on Hyperspectral Datasets

| Model | Herbal Medicine Dataset [31] | Coffee Bean Dataset [31] | Strawberry Dataset [31] | Indian Pines Dataset [30] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 92.60% (average) | 92.60% (average) | 92.60% (average) | - |

| 1D-CNN | 92.58% (average) | 92.58% (average) | 92.58% (average) | - |

| GLCM-SVM | 93.83% (average) | 93.83% (average) | 93.83% (average) | - |

| 2B-CNN | 96.72% (average) | 96.72% (average) | 96.72% (average) | - |

| CSCNN (Custom Spectral CNN) | - | - | - | 99.8% |

Workflow Diagram: Spectral-Spatial HSI Classification with 2B-CNN

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end workflow for hyperspectral image classification using a two-branch CNN architecture.

Troubleshooting Workflow for Low Performance

Adopt a systematic approach when your model underperforms, as outlined in the decision tree below.

Table 3: Key Resources for Developing CNN-based HSI Classifiers

| Item / Resource | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Datasets | Benchmark data for training and evaluating models. | Indian Pines, Herbal Medicine, Coffee Bean, Strawberry datasets [31] [30]. |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Provides environment for model definition, training, and evaluation. | PyTorch, TensorFlow [30] [37]. |

| Hardware Accelerators | Dedicated processors to drastically speed up CNN inference. | AI microcontrollers (e.g., MAX78000) for low-power edge deployment [37]. |

| Data Augmentation Tools | Functions to artificially expand training datasets and reduce overfitting. | Built-in functions in frameworks for mirroring, rotation, cropping, random scaling [34]. |

| Architecture Modules | Pre-defined, tested components for building complex networks. | PyTorch modules (e.g., nn.Conv1d, nn.Conv2d, nn.BatchNorm2d, nn.Dropout) [36]. |

| Sensitivity Analysis Frameworks | Tools to evaluate model robustness against distortions and mutations. | Mutation testing frameworks like MuDL for HSI classifiers [32]. |

FAQs: Addressing Common Experimental Challenges

1. My multimodal model performs worse than my unimodal one. What is the root cause?

This is often caused by using an inappropriate fusion strategy that fails to effectively capture complementary information. The performance of different fusion techniques is highly dependent on your data characteristics and task.

- Solution: Systematically evaluate early, intermediate, and late fusion strategies. If your modalities are well-aligned and you have a robust dataset, early fusion (concatenating raw features) allows the model to learn complex cross-modal interactions. If modalities are asynchronous or have different sampling rates, late fusion (combining model decisions) is more flexible. Intermediate fusion often provides a good balance, using joint representations learned in middle layers of a neural network [38] [39].

2. How can I handle missing data for one modality in my multimodal pipeline?

This is a common challenge in real-world experiments. Advanced techniques can impute the missing information rather than discarding the entire sample.

- Solution: Consider algorithms like Full Information Linked ICA (FI-LICA), which is designed to recover missing latent information during fusion by utilizing all available data from complete cases [40]. Another approach is to use model architectures trained with modality dropout, which learn to make robust predictions even when one data stream is unavailable [38] [41].

3. My spectral and spatial data are difficult to align. What preprocessing is essential?

Effective fusion requires meticulous synchronization. The core issues are often temporal and spatial misalignment.

- Solution: Implement a preprocessing pipeline with two key steps:

- Temporal Alignment: Use timestamp matching or interpolation techniques to synchronize data streams collected at different frequencies [38] [41].

- Spatial Registration: For imaging data, employ keypoint detection and scene segmentation algorithms to ensure pixels across modalities correspond to the same physical location [38]. For spectral-spatial cubes, ensure precise pixel-level registration [42].

4. How can I interpret which features from each modality are driving my model's predictions?

Model interpretability is critical for scientific validation. Use post-hoc analysis tools designed for complex models.

- Solution: Integrate SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis into your workflow. This technique pinpoints the contribution of individual input features (e.g., specific wavelengths in a spectrum) to the final prediction, providing both global and local interpretability. This has been successfully used, for instance, to identify that wavelengths in the 2000–2500 nm region were critical for predicting resistant starch content in rice [43].

5. I have limited labeled samples for a complex multimodal task. How can I improve accuracy?

With limited samples, the focus should be on extracting the most informative features from your data.

- Solution: Explore frequency-domain enhancement techniques. Methods like the Spatial-Spectral-Frequency interaction network (S2Fin) use high-frequency sparse enhancement to amplify critical details such as edges and textures in images, which are essential for discrimination. This reduces reliance on massive labeled datasets by creating more discriminative features [42].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Model Generalization and Overfitting

Symptoms: High accuracy on training data but poor performance on validation/test sets.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Training Data | - Check dataset size vs. model complexity (e.g., number of parameters).- Perform learning curve analysis. | - Apply data augmentation (e.g., spectral noise injection, image transformations) [43].- Use generative AI to create synthetic spectral or image data [6]. |

| Modality Noise | - Evaluate the performance of each modality independently.- Analyze the signal-to-noise ratio of raw data streams. | - Apply modality-specific filtering and preprocessing.- Implement fusion strategies (e.g., late fusion) that are more robust to noisy modalities [38] [39]. |

| High Model Complexity | - Compare training vs. validation loss over epochs. | - Increase regularization (e.g., L1/L2, dropout).- Simplify the model architecture.- Use Random Forest or XGBoost, which are less prone to overfitting with tabular features [6]. |

Issue: Suboptimal Fusion Strategy Selection

Symptoms: Fusion does not yield expected performance gains, or model is unstable.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Mismatched Fusion Strategy | - Train and evaluate unimodal baselines.- Test all three fusion types on a validation set. | Follow the decision criteria in the diagram below to select the optimal technique [38] [39]. |

| Poor Cross-Modal Interaction | - Visualize attention maps or intermediate features.- Check if model uses information from all inputs. | - Implement attention mechanisms or transformer architectures to dynamically weight the importance of features from different modalities [38] [42].- Use intermediate fusion with dedicated cross-talk layers. |

Decision Framework for Fusion Strategy Selection

Issue: Computational Bottlenecks in Processing

Symptoms: Extremely long training times, inability to load large datasets into memory.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| High-Dimensional Data | - Profile memory usage by data type.- Check dimensions of input tensors. | - Apply dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA on spectral data) [44] [6].- Use model quantization or mixed-precision training.- Process data in smaller batches. |

| Inefficient Architecture | - Monitor GPU/CPU utilization during training. | - For spectral sequences, use RNNs or Mamba architectures, which are efficient for long sequences [42] [45].- For images, use optimized CNN backbones like ResNet or SqueezeNet [46]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Building a Baseline Multimodal Classification Pipeline

This protocol outlines the steps to construct and evaluate a core multimodal model, suitable for tasks like material classification using spectral and spatial data.

1. Data Preprocessing & Alignment

- Spectral Data (e.g., NIR, HSI): Apply Savitzky-Golay smoothing and Standard Normal Variate (SNV) normalization to reduce scatter effects [43]. Mean-center the data.

- Spatial Data (e.g., RGB, LiDAR): Resize images to a uniform resolution. Normalize pixel values. For LiDAR point clouds, voxelize or create height maps.

- Alignment: Spatially co-register spectral and image data to a common grid. Use timestamp alignment for temporal data [41].

2. Unimodal Feature Extraction

- Spectral: Extract features using a 1D Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) or simply use the preprocessed spectra.

- Spatial/Image: Extract features using a pre-trained 2D CNN (e.g., ResNet).

- Tabular/Other: Pass through a fully connected neural network layer.

3. Fusion & Model Training

- Implement the three primary fusion strategies in separate experiments:

- Early Fusion: Concatenate the feature vectors from step 2 and feed into a final classifier.

- Intermediate Fusion: Combine features from intermediate layers of the unimodal networks, then classify.

- Late Fusion: Train separate classifiers on each unimodal feature set, then average or weight their prediction scores.

- Use a consistent validation strategy (e.g., 5-fold cross-validation) to fairly compare performance.

4. Evaluation & Interpretation

- Compare the accuracy, F1-score, and other relevant metrics of all fusion methods against unimodal baselines.

- Apply SHAP analysis to the best-performing model to identify which spectral bands and image regions were most influential [43].

Protocol 2: Integrating Frequency-Domain Features for Enhanced Detail

This advanced protocol is for scenarios with limited labeled data or where fine-grained details (edges, textures) are critical for discrimination [42].

1. Frequency Domain Transformation

- For Spectral Data: Apply a 1D Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to each spectral signature to decompose it into its frequency components.

- For Spatial Data: Apply a 2D FFT to image patches to obtain frequency representations.

2. High-Frequency Enhancement

- Design a filter to amplify the high-frequency components of the signal, which correspond to sharp edges, textures, and fine details in the data.

- Techniques like the High-Frequency Sparse Enhancement Transformer (HFSET) can be used to optimize filter parameters and focus on the most discriminative spectral-spatial features [42].

3. Feature Fusion and Classification

- Fuse the enhanced frequency-domain features with the original spatial-spectral features.

- Use an adaptive fusion module to balance the contribution of low-frequency (global structure) and high-frequency (local details) information.

- Train a final classifier on the combined feature set.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Multimodal Data Fusion

| Tool / Technique | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Extracts spatial and spectral features from images and spectral data cubes [43] [46]. | Ideal for grid-like data; requires significant data for training; pre-trained models available. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Provides model interpretability by quantifying feature contribution to predictions [43]. | Critical for validating models; computationally expensive for large datasets. |

| SpecimINSIGHT Software | A commercial tool for hyperspectral data analysis and classification model building without coding [44]. | Reduces need for programming expertise; specific to hyperspectral imaging applications. |

| Linked ICA & FI-LICA | Statistical methods for fusing multimodal datasets and handling missing data [40]. | Particularly useful for neuroimaging and other data with natural group structure. |

| Spatial-Spectral-Frequency Network (S2Fin) | A specialized architecture for fusing remote sensing data by interacting spatial, spectral, and frequency domains [42]. | State-of-the-art for limited labeled data; enhances high-frequency details. |

| Random Forest / XGBoost | Traditional machine learning models robust to overfitting, effective for tabular-like feature sets [6]. | Good performance with smaller datasets; provides native feature importance scores. |

This technical support center is established as a resource for researchers and scientists working at the intersection of Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) and machine learning for analytical applications, particularly in the domain of rapid drug abuse detection. The guidance provided herein is framed within a broader thesis on advanced data analysis techniques for complex spectral data research, focusing on the practical experimental challenges encountered when translating theoretical models into reliable laboratory results. The following sections provide detailed troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions (FAQs) to address specific issues you might encounter during experimental workflows.

Troubleshooting Guides for SERS Experiments

Guide: Addressing Low or Irreproducible SERS Signal

A lack of consistent and strong SERS signal is one of the most frequently reported issues. The following workflow provides a systematic approach for diagnosing and resolving this problem.

Step-by-Step Instructions:

Check Analyte-Surface Interaction: The SERS effect is a short-range enhancement that decays within a few nanometers. If your molecule is not adsorbing to the metal surface, the enhancement will be weak or non-existent [47].

- Action: Modify the chemical environment to promote adsorption. For example, adjust the pH of the solution to change the surface charge of the nanoparticles and the protonation state of your analyte. A molecule and surface with opposite charges will have stronger affinity [48].

- Verification: A successful interaction can sometimes be inferred from a color change in the colloidal solution or by observing new peaks in the SERS spectrum that indicate surface binding.

Verify Nanoparticle Aggregation: The largest SERS enhancements originate from "hotspots"—nanometer-scale gaps between metal nanoparticles [47]. Controlling the creation of these hotspots is critical.

- Action: Systematically optimize the concentration of an aggregating agent (e.g., NaCl, KNO3, or HCl). Use a design of experiments (DoE) approach to find the optimal balance, as too little agent provides no hotspots, and too much causes full precipitation and signal loss [48] [49].

- Verification: Monitor the UV-Vis absorption spectrum; successful aggregation for spherical nanoparticles often shifts the plasmon band to longer wavelengths and broadens it.

Confirm Hotspot Formation: Small changes in the number of molecules in hotspots cause large intensity variations, leading to perceived irreproducibility [47].

- Action: Ensure your substrate fabrication or colloidal aggregation protocol is consistent. For quantitative work, consider using internal standards (e.g., a co-adsorbed molecule or a deuterated variant of your analyte) to correct for variance in hotspot occupancy [47].

- Verification: Use techniques like scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to visualize the nanostructures and confirm the presence of nanogaps.

Optimize Laser Wavelength: The SERS enhancement is strongest when the laser excitation is in resonance with the localized surface plasmon of the metallic nanostructure [50] [51].