Breaking the Nanometer Barrier: Advanced Strategies to Improve Detection Limits in Nanoplastic Analysis

The accurate detection and quantification of nanoplastics are paramount for assessing their environmental and human health impacts, yet current methods are hindered by significant analytical challenges, particularly regarding detection limits.

Breaking the Nanometer Barrier: Advanced Strategies to Improve Detection Limits in Nanoplastic Analysis

Abstract

The accurate detection and quantification of nanoplastics are paramount for assessing their environmental and human health impacts, yet current methods are hindered by significant analytical challenges, particularly regarding detection limits. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and scientists on the evolving landscape of nanoplastic analysis. We explore the foundational hurdles stemming from their minute size and environmental complexity, detail cutting-edge methodological advances in separation and detection technologies, offer practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for complex matrices, and present a critical comparative analysis of emerging high-resolution techniques. The synthesis of this information aims to equip the research community with the knowledge to push the boundaries of sensitivity and accuracy in nanoplastic research, thereby informing robust toxicological and biomedical studies.

The Nanoplastic Detection Challenge: Why Size and Complexity Limit Our View

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental size distinction between microplastics and nanoplastics, and why does it matter for analysis?

Microplastics (MPs) are typically defined as plastic fragments with dimensions less than 5 mm. [1] There is ongoing debate about the lower size limit, but it is often set at 1 µm based on the detection limits of common equipment like micro-spectroscopy. [1] Nanoplastics (NPs) are smaller, with size definitions still under discussion; they are often considered to be particles below 1 µm or 100 nm. [1] [2] This size distinction is critical because smaller particles like NPs have different physical and chemical properties. They interact with light differently, diffuse more readily in the environment, and can penetrate biological barriers (like the blood-brain barrier) more effectively than MPs, which directly impacts their environmental fate, toxicity, and the techniques required for their detection. [2] [3]

Q2: Why are techniques commonly used for microplastic analysis often ineffective for nanoplastics?

Established techniques for MPs, such as Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), lose sensitivity when analyzing NPs or complex plastic mixtures due to overlapping absorption signals. [4] [5] Furthermore, the small size of NPs (often below the diffraction limit of light) and their tendency to form heteroaggregates with natural organic matter or minerals make them difficult to visualize, separate, and quantify using standard optical microscopy and filtration methods. [6] [7] Their high reactivity and the need for extreme sensitivity require specialized and often more complex analytical approaches.

Q3: What are the biggest challenges in isolating and detecting nanoplastics in environmental samples?

The analysis of nanoplastics presents a multi-faceted challenge [6]:

- Lack of Standardized Methods: There is a significant lack of harmonized protocols for sampling, preparation, and analysis, making it difficult to compare results between studies. [1] [6]

- Complex Matrices: Environmental samples (water, soil, biological tissue) contain many other natural particles that can obscure or be mistaken for nanoplastics. Efficient separation is a major hurdle. [6]

- Contamination Control: The ubiquity of plastic in labs and the environment makes cross-contamination a significant issue during sample collection and processing. Using plastic-based gloves or equipment can introduce NPs into the sample. [1] [6]

- Low Environmental Concentrations: Detecting trace levels of NPs in real-world samples requires methods with very low detection limits, which many conventional instruments lack. [1]

Q4: What advancements are being made to improve the detection limits for nanoplastic analysis?

Researchers are developing several innovative approaches to overcome sensitivity barriers:

- Novel Optical Techniques: Methods like the "optical sieve" leverage Mie void resonances to sort and filter NPs by size, allowing for their detection using a standard light microscope. [3] Hyperspectral dark-field microscopy is also being used to visualize and quantify NPs within biological tissues. [4]

- Advanced Mass Spectrometry: New mass spectrometry methods, such as Flame Ionization Mass Spectrometry (FI-MS), are being developed to directly analyze plastics in seconds with minimal sample preparation, offering a fast and sensitive alternative to more complex techniques like Pyrolysis-GC/MS. [4]

- Enhanced Spectroscopy: Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) is being explored to boost the weak scattering signals from nanoplastics, improving their identification and characterization. [6]

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Recovery of Nanoplastics During Sample Preparation

Problem: Low or inconsistent recovery rates when spiking known amounts of nanoplastics into complex samples like soil, water, or tissue.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inefficient Digestion of Organic Matter | Check if biological debris remains on the filter after digestion, which could trap NPs. | Optimize digestion protocols. Microwave-assisted acid digestion (e.g., using HNO₃ at <200°C) has been shown to effectively digest organic tissue like fish without significantly degrading some common polymers. [8] |

| Formation of Heteroaggregates | Use dynamic light scattering or electron microscopy to check for aggregation in your sample suspension. | Implement a density separation step or use surfactants to disperse aggregates. Note that the right sample pre-treatment depends on the polymer type being studied, as some conditions can degrade specific plastics like polyamides. [8] [6] |

| Adsorption to Labware | Conduct a blank test by running solvents through your entire workflow and analyzing them. | Use glass or metal labware whenever possible instead of plastic. Use high-purity solvents and thoroughly rinse all equipment to minimize loss from adsorption. [6] |

Issue 2: Inability to Distinguish Nanoplastics from Natural Particles

Problem: Difficulty in confidently identifying synthetic polymers against a background of organic and inorganic colloids.

Solution: Employ a coupled technique that combines particle visualization with chemical identification.

- Filtration onto Silicon Filters: Filter the sample onto a smooth, reflective silicon filter. Silicon provides a Raman spectrum that does not overlap with most polymers, making it ideal for subsequent analysis. [5]

- Automated Particle Location: Use software tools (e.g., ParticleFinder) to automatically locate all particles on the filter based on size and shape under microscopy. [5]

- Chemical Identification: Perform Raman micro-spectroscopy on each located particle. Compare the acquired spectra against a dedicated polymer spectral library (e.g., using IDFinder software) for definitive identification. [5] This workflow moves beyond simple counting to provide chemical confirmation.

Issue 3: Low Sensitivity and High Detection Limits in Direct Analysis

Problem: Existing instruments cannot detect nanoplastics at the trace concentrations expected in real-world environmental or biological samples.

Solution: Implement emerging analytical techniques designed for high sensitivity.

- Protocol: Rapid Analysis via Flame Ionization Mass Spectrometry (FI-MS) [4]

- Principle: This method directly burns a sample in a flame, which simultaneously decomposes and ionizes plastic polymers. The resulting characteristic ions are detected by a mass spectrometer.

- Procedure:

- Minimal Sample Prep: Adsorb the sample (e.g., a liquid concentrate or a piece of filter paper containing the particles) onto a metal rod.

- Direct Introduction: Place the rod near the inlet of the mass spectrometer.

- Ignition and Data Acquisition: Apply a flame to the sample. Characteristic degradation products from polymers like PET (e.g., terephthalic acid, C₈H₆O₄) and PS are detected almost instantly.

- Advantages: This method requires minimal sample preparation, takes only seconds per analysis, and has been successfully demonstrated for detecting NPs in complex matrices like soil and mouse placenta tissue without extensive extraction. [4]

Methodologies & Workflows

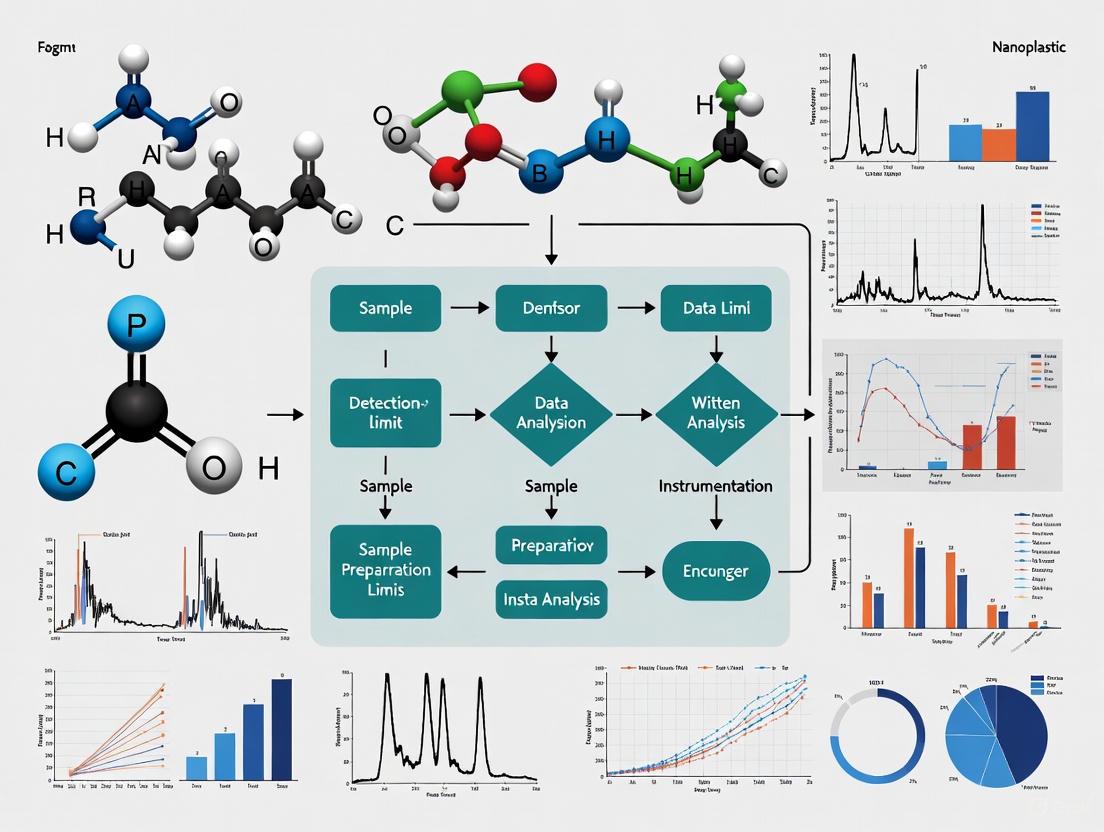

The following diagram illustrates a generalized, multi-technique workflow for the analysis of nanoplastics in complex environmental samples, highlighting the path from raw sample to validated data.

General Workflow for Nanoplastic Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Material Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for conducting robust nanoplastic research, particularly for sample preparation and analysis.

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Silicon Filters | Provides a smooth, reflective substrate for filtering samples for Raman microscopy. [5] | Its distinct Raman spectrum does not interfere with common polymer signals, allowing for clear particle identification. [5] |

| Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Used in diluted (< 3 mol/L) microwave-assisted digestion to remove organic biological tissue from samples without significantly degrading certain common polymers. [8] | Concentration, temperature, and reaction time must be optimized to avoid depolymerization of target analytes like polyamides. [8] |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Tablet or suspension formats containing a defined number and size of polymer particles, used to validate the entire analytical workflow. [5] | Essential for method validation and interlaboratory comparison; should mimic the irregular shapes of environmental microplastics. [5] |

| Model Nanoplastic Particles | Well-characterized, often spherical particles (e.g., Polystyrene latex beads) used in toxicity assays and method development. [4] | While valuable, their uniformity may not fully represent the heterogeneity of environmental nanoplastics, a limitation that should be acknowledged. [2] |

| Mie Void Resonator Array ("Optical Sieve") | A test strip made of high-refractive-index material (e.g., GaAs) with cylindrical holes that sort and trap NPs by size, enabling detection via color shift under a light microscope. [3] | Allows for rapid, on-site detection without extensive sample pre-cleaning, potentially overcoming a major bottleneck. [3] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why can't I directly use standard microplastic analysis methods for nanoplastics? Standard methods for microplastics often fail for nanoplastics due to fundamental physical differences. Techniques like visual counting or Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy lose effectiveness because the particles are smaller than the wavelength of light, making them invisible to conventional optical microscopy and leading to weak or undetectable spectroscopic signals. [9] [6] Furthermore, their small size and high reactivity cause nanoplastics to form heteroaggregates with natural organic matter, minerals, and other environmental components, which masks their identity and complicates isolation. [10] [6]

Q2: My sample has a lot of organic material. How does this interfere with nanoplastic detection? Complex organic matrices, such as proteins, fats, and biological tissues, create significant background interference. This interference obscures the faint signals from nanoplastic particles in spectroscopic techniques like Raman spectroscopy. [8] [11] For methods like Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC/MS), incomplete removal of this organic matter can lead to the generation of overlapping chemical markers during analysis, resulting in false positives or an overestimation of plastic concentration. [8]

Q3: What is the current lowest detectable concentration for nanoplastics in environmental samples, and how can I achieve it? Achieving low detection limits often requires a combination of advanced concentration techniques and sensitive detection technologies. For example, a novel approach combining Raman spectroscopy with machine learning has demonstrated detection sensitivity as low as 100,000 particles per liter (1E5 particles/L) in water samples. [11] Another method using an "optical sieve" can detect nanoplastics down to 300 nm in size within complex lake water samples without pre-cleaning. [3] The table below summarizes detection limits for several advanced techniques.

| Technique | Reported Detection Limit | Key Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectroscopy + Machine Learning [11] | 1E5 particles/L | Training ML models with known NP spectra. |

| Optical Sieve (Mie void resonators) [3] | 300 nm particle size | Sieve test strips with specific hole diameters. |

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) [6] | High sensitivity for single particles | Proximity to a metal surface for signal enhancement. |

Q4: I'm getting low recovery rates. What are the critical steps to improve nanoplastic yield during sample prep? Low recovery is frequently caused by particle loss during multiple transfer steps, adsorption to container walls, and incomplete separation from the matrix. [6] To improve yield:

- Optimized Digestion: Use controlled microwave-assisted acid digestion with diluted acids (< 3 mol/L HNO₃) and temperatures below 200°C to remove organic matter without degrading common polymers like PET, PE, and PP. [8]

- Minimize Transfers: Employ integrated workflows that reduce the number of sample handling steps.

- Quality Control: Implement rigorous lab practices, as standard disposable gloves can be a source of contamination. Use cotton gloves where possible and include procedural blanks. [6]

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Background Noise in Spectroscopic Detection

Issue: Raman or IR signals from nanoplastics are drowned out by interference from the sample matrix.

Solution: Combine physical separation with advanced data processing.

- Sample Pre-treatment: Apply a mild oxidative digestion to break down biological material. Validate that the digestion conditions (acid concentration, temperature, time) do not degrade the target nanoplastics. [8]

- Leverage Machine Learning: Train a Support Vector Machine (SVM) or other ML models on a library of pure nanoplastic Raman spectra. These models can then accurately identify nanoplastics even within noisy environmental data, achieving over 99% accuracy in controlled conditions. [11]

Problem: Inability to Detect and Size Nanoplastics in Complex Liquids

Issue: Traditional light scattering methods fail in "dirty" environmental water samples due to interference from natural colloids and organic matter.

Solution: Use an optical sieve based on Mie void resonance.

- Sample Processing: Pass the liquid sample (e.g., lake water) through a specialized test strip containing an array of cylindrical holes of precise diameters (e.g., 300, 350, 400, 450 nm). [3]

- Detection Principle: Nanoplastics are trapped in holes matching their size, causing a shift in the localized Mie resonance. This shift is observed as a bright color change under an ordinary light microscope. [3]

- Analysis: The color pattern across different hole-size arrays allows for simultaneous sizing and detection without complex sample pre-cleaning.

Problem: Overcoming the Limits of Single-Technique Analysis

Issue: Relying on a single analytical method provides an incomplete picture (e.g., concentration without polymer type, or identity without quantity).

Solution: Adopt a multimodal workflow that combines complementary techniques.

- Separation & Concentration: Use techniques like Field-Flow Fractionation (FFF) or ultracentrifugation to isolate and concentrate nanoplastics from a bulk sample. [6]

- Characterization & Identification: Analyze the concentrated fraction using a combination of methods.

- Py-GC-MS: Provides quantitative data on polymer mass and type by analyzing thermal degradation products. [9] [8]

- Raman Microscopy: Offers identification of individual particles based on their molecular fingerprint. [9] [11]

- SEM/TEM: Delivers high-resolution images for precise morphological analysis (size, shape). [9]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key materials used in advanced nanoplastic detection research.

| Item | Function in Nanoplastic Research |

|---|---|

| Gallium Arsenide (GaAs) / Silicon Wafer | Substrate material for fabricating "optical sieve" test strips with high-refractive-index Mie void resonators. [3] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Advanced adsorbents with high surface area and tunable porosity for concentrating and removing nanoplastics from water. [10] |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) Model | A machine learning algorithm trained on Raman spectral libraries to accurately identify nanoplastic polymers in complex, noisy data. [11] |

| Diluted Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | A reagent for microwave-assisted digestion to remove organic biological material from samples without significantly degrading most common nanoplastics. [8] |

| Magnetic Carbon Nanotubes | Functionalized adsorbents that can be easily separated using a magnet after binding to nanoplastics, aiding in concentration and purification. [10] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection & Preparation | High background contamination in blanks | Laboratory air, reagents, or plastic consumables introducing external nanoplastics [6] | Implement rigorous quality control: wear cotton lab coats, use non-plastic gloves, and process in HEPA-filtered environments [6]. | Dedicate equipment for NP analysis; use glass/metal materials; include procedural blanks in every batch [6]. |

| Unintentional formation of heteroaggregates | NPs forming complexes with minerals or natural organic matter in the sample matrix [6] | Apply separation techniques like field-flow fractionation (FFF) or ultracentrifugation to isolate individual NPs [6]. | Understand that heteroaggregates can alter NP transport and cellular interactions [6]. | |

| Method Selection & Validation | Technique fails to detect or characterize NPs | Method adapted from microplastic workflows is ineffective at the nanoscale [9] [6] | Employ a multimodal approach; no single technique provides complete information on identity, morphology, and concentration [9]. | Select methods based on physical principles suited for nanoscale analysis (e.g., TEM, Pyrolysis-GC-MS) during development [9]. |

| Poor method precision and accuracy | Uncontrolled critical process parameters in the analytical method [12] | Apply Design of Experiments (DOE) to characterize the method's design space and identify optimal factor settings [12]. | Define the method's purpose and concentration range early; perform a risk assessment of all method components [12]. | |

| Data Quality & Comparability | Inconsistent results between laboratories | Lack of harmonized methods and standardized protocols for NP analysis [9] | Follow a standards-oriented roadmap to connect current microplastic frameworks to future nanoplastic research needs [9]. | Report detailed methodologies, including quality control steps and instrument settings, to enable cross-lab comparisons. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why can't I simply use the same analytical methods for nanoplastics that I use for microplastics? Techniques commonly used for analyzing microplastics often prove ineffective for nanoplastics due to their vastly smaller size (1-100 nm), diverse polymeric compositions, and unique surface properties that facilitate strong interactions with complex environmental matrices. Adapting microplastic workflows frequently fails, necessitating the development of new, nanoscale-specific methods [9] [6].

Q2: What is the most significant source of contamination in nanoplastic analysis, and how can I control it? A primary source of contamination is the laboratory environment itself, including plastic-based consumables and reagents. A critical step is ensuring rigorous quality control to prevent unintentional sample contamination. This involves wearing cotton lab coats, using non-plastic gloves (e.g., cotton), and working in a controlled, low-particle environment. Plastic-based disposable gloves, while protecting the researcher, can themselves be a significant source of contamination [6].

Q3: My method works perfectly in clean water, but fails in complex matrices like wastewater or soil. What should I do? This is a common challenge. Nanoplastics in environmental samples rarely occur in isolation and tend to form heteroaggregates with various natural and anthropogenic substances, such as minerals and organic matter. This complexity directly affects analytical outcomes. You must incorporate a robust separation or cleanup stage into your protocol, such as chemical digestion, magnetic extraction, or field-flow fractionation (FFF), to isolate the nanoplastics from the interfering matrix before analysis [6].

Q4: How can I make my analytical method more robust and reliable? Utilize a systematic approach like Design of Experiments (DOE) during method development. DOE helps you move away from a one-factor-at-a-time approach to a more efficient process. It involves identifying the purpose of your method, defining the concentration range, performing a risk assessment to pinpoint factors that influence results (like pH, temperature, or analyst), and then designing experiments to quantify and minimize their influence on precision and accuracy. This creates a characterized "design space" for your method, ensuring it remains valid even with minor, expected variations [12].

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Detailed Methodology: Pyrolysis-GC-MS for Nanoplastic Identification and Quantification

This protocol is adapted for the analysis of polymer composition and mass-based quantification of nanoplastics isolated from water samples [9] [6].

- 1. Principle: The sample is thermally decomposed at high temperatures in an inert atmosphere (pyrolysis), and the resulting polymer-specific fragments are separated by gas chromatography and identified by mass spectrometry [9].

- 2. Key Equipment & Reagents:

- Pyrolysis unit (e.g., microfurnace or filament-type)

- Gas Chromatograph coupled with a Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS)

- High-purity helium or nitrogen carrier gas

- Certified reference materials of target polymers (e.g., polystyrene, polyethylene)

- Internal standards (e.g., deuterated compounds)

- 3. Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Sample Pre-concentration: Isolate and concentrate nanoplastics from the water sample via ultrafiltration or ultracentrifugation. Transfer the concentrate to a pyrolysis cup.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the GC-MS system using a series of known concentrations of polymer-specific reference materials and internal standards.

- Pyrolysis: Place the sample cup into the pyrolysis unit. The typical pyrolysis temperature range is 500-800°C, depending on the target polymer.

- Chromatographic Separation: The pyrolyzates are carried into the GC column, where they are separated based on their volatility and interaction with the column stationary phase.

- Mass Spectrometric Detection: Eluting compounds are ionized and fragmented in the MS ion source. The mass analyzer detects the resulting ions, creating a mass spectrum for each compound.

- Data Analysis: Identify polymers by comparing the resulting pyrograms and mass spectra to those of known reference materials. Quantify based on characteristic fragment ions.

- 4. Critical Parameters for Fidelity:

- Pyrolysis Temperature: Must be optimized for each polymer type to ensure complete decomposition without secondary reactions.

- Transfer Line Temperature: Must be high enough to prevent condensation of pyrolyzates.

- Quality Control: Include procedural blanks, replicates, and spikes with reference materials in every batch to monitor contamination and recovery.

Detailed Methodology: Design of Experiments (DOE) for Analytical Method Validation

This protocol provides a systematic framework for validating an analytical method, ensuring it is fit for purpose and robust [12].

- 1. Principle: DOE uses structured experiments to simultaneously evaluate the influence of multiple method parameters on key outputs (responses), quantifying relationships and optimizing conditions more efficiently than one-factor-at-a-time studies [12].

- 2. Key Steps:

- Define Purpose: Clearly state the method's goal (e.g., determine repeatability, intermediate precision, accuracy, LOD/LOQ).

- Define Range: Establish the range of concentrations and solution matrices the method will cover.

- Identify Factors & Responses: Via risk assessment, identify 3-8 critical factors (e.g., pH, temperature, analyst) and the responses to measure (e.g., peak area, retention time, % recovery).

- Design Experiment: Create an experimental matrix (e.g., full factorial or D-optimal design) and a sampling plan that includes replicates for precision estimation.

- Run Study & Analyze Data: Execute the experiments and use multiple regression/ANCOVA to model the effect of factors on responses.

- Verify & Document: Run confirmation tests at the optimal settings and document the method's design space—the allowable ranges for key factors where the method performs acceptably [12].

- 3. Critical Parameters for Fidelity:

- Risk Assessment: A thorough initial risk assessment is crucial to focus resources on the factors that truly matter.

- Error Control: Plan for and measure uncontrolled factors (e.g., ambient temperature, analyst) during the study.

- Replication: Include sufficient replicates and duplicates to properly quantify method variation (precision).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Nanoplastic Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Polymer Reference Materials | Calibration and quantification in mass-based techniques (e.g., Pyrolysis-GC-MS) [9]. | Select polymers relevant to your study (e.g., PE, PP, PS); ensure stability and proper storage to prevent degradation [12]. |

| Internal Standards (Deuterated) | Correct for analyte loss during sample preparation and instrument variability [12]. | Should be similar in chemical behavior to the target analytes but not present in the original sample. |

| HEPA-Filtered Laminar Flow Hood | Provides a clean air workspace to minimize atmospheric contamination of samples by background particulates [6]. | Critical for sample preparation steps prior to analysis. |

| Non-Plastic Consumables (Glass, Metal) | Used for sample storage, transfer, and processing to avoid leaching of plasticizers or introduction of micro/nanoplastic contamination [6]. | Prefer glass fiber filters over plastic membranes; use metal spatulas. |

| Ultrapure Water & High-Purity Solvents | Preparation of blanks, standards, and mobile phases for chromatography to minimize interference from impurities. | A key part of quality control; should be tested for background signals. |

| Field-Flow Fractionation (FFF) System | Separates nanoplastics based on diffusion coefficient (size) in complex environmental matrices, overcoming challenges from heteroaggregates [6]. | Can be coupled inline with detection techniques like MALS or DLS. |

In the field of nanoplastic analysis, simply confirming the presence of particles is no longer sufficient for meaningful risk assessment. While detecting nanoplastics in environmental and biological samples represents a significant technical achievement, it provides limited insight into the actual ecological and health threats posed by these pollutants. Quantification—determining the exact concentration, size distribution, and polymer composition—is the critical next step that transforms observational data into actionable risk intelligence.

The transition from qualitative detection to quantitative analysis presents substantial technical challenges. Current methodologies struggle with the inherent difficulties of measuring particles at the nanoscale, particularly in complex environmental matrices where organic and inorganic interferents abound. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guidance and experimental protocols designed to help researchers overcome these quantification barriers, thereby advancing beyond mere presence-absence studies toward robust, data-driven risk assessment.

Technical Challenges in Nanoplastic Quantification

Fundamental Obstacles

Researchers face multiple interconnected challenges when attempting to quantify nanoplastics:

Size-based detection limitations: As particle size decreases below 1μm, detection becomes increasingly difficult using conventional microscopy techniques, which may produce incomplete results for small particles [7]. This creates a significant quantification gap precisely where potential biological impacts may be greatest due to increased membrane penetration capability [13].

Matrix interference effects: Environmental samples (water, soil, biological tissues) contain numerous organic and inorganic substances that obscure nanoplastic signals. Without effective separation, quantification results may represent significant overestimates or underestimates of true nanoplastic loads [13].

Absence of standardized protocols: The field currently lacks universally accepted protocols for sampling, pretreatment, quantification, and classification [13]. This methodological variability makes cross-study comparisons unreliable and hampers the development of standardized risk assessment frameworks.

Instrumentation limitations: Even advanced spectro-microscopic techniques face diminishing efficiency for smaller contaminations, often becoming more expensive and less reliable at the nanoscale [13].

Troubleshooting Common Quantification Problems

Table: Common Quantification Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High background noise interfering with particle counts | Organic matter residue, inorganic sediments | Implement enzymatic digestion or use Fenton's reagent with caution [13] |

| Inconsistent results between replicate samples | Inadequate sample homogenization, particle loss during processing | Standardize separation protocols; use density separation with high-density salts (NaI, ZnCl₂) [13] |

| Underestimation of particle concentrations | Filtration methods missing nanoparticles, insufficient sample volume | Employ sequential filtration; increase sampling volume with low-flow pumping systems for groundwater [13] |

| False positive identification | Natural particles misidentified as plastics | Include natural particle controls (e.g., kaolin) to distinguish plastic-specific effects [14] |

| Particle aggregation affecting size distribution | Surface properties promoting clumping | Use surfactants cautiously; consider surface weathering effects in experimental design [14] |

Advanced Methodologies for Quantitative Analysis

Sample Preparation and Separation Techniques

Proper sample preparation is foundational to accurate quantification. The following workflow represents current best practices for processing environmental samples for nanoplastic analysis:

Detailed Protocols:

Density Separation for Complex Matrices

- Prepare high-density salt solutions (NaI, ZnCl₂, or Na₆(H₂W₁₂O₄₀)) with densities ranging from 1.6 to 1.8 g/cm³ to suspend a broader range of plastics, including PVC and PET [13]

- Centrifuge samples at 3000-5000 rpm for 15-30 minutes to facilitate separation

- Carefully collect the floating fraction containing plastic particles

- Note: Buoyant forces are minimal at the nanoscale, and particle density can be altered by surface fouling [13]

Organic Matter Digestion

- Wet Peroxidase Method: Effective for most organic matter without affecting most plastics, though some studies show potential alteration of nylon (PA) and LDPE [13]

- Fenton's Reagent: Provides intense oxidative reaction but may alter or destroy some nanoplastics; use with caution and validate for your specific polymer types [13]

- Enzymatic Digestion: Cheaper but time-consuming; enzymes may interact with other impurities present in sample, limiting efficacy [13]

Detection and Quantification Technologies

Advanced detection technologies have evolved significantly to address quantification challenges in nanoplastic research:

Table: Quantitative Analysis of Particle Effects on Microalgal Growth Inhibition

| Particle Type | Concentration (particles/ml) | Maximum Growth Inhibition (%) | Time to Significant Inhibition (days) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weathered PET (wPET) | 10,000 | 59.23 ± 5.73 | 4 [14] |

| Kaolin (natural particle control) | 10 | 67.05 ± 7.25 | 4 [14] |

| Virgin PET (vPET) | 10,000 | 53.32 ± 8.58 | 7 [14] |

Integrated Detection Protocol:

Sample Pre-screening with Fluorescence Microscopy

- Use Nile Red staining for rapid preliminary quantification

- Identify areas of interest for further analysis

- Document particle distribution and approximate concentrations

Targeted Analysis with Raman Spectroscopy

- Focus on specific particles identified during pre-screening

- Obtain polymer-specific spectral signatures for identification

- Generate quantitative data on particle composition distribution

Morphological Characterization with SEM

- Apply gold or carbon coating to non-conductive samples

- Image at various magnifications (5,000-50,000X) for detailed topography

- Measure particle sizes across multiple fields for statistical validity

Data Integration and AI-Assisted Classification

- Combine spectral and morphological data

- Apply machine learning algorithms for pattern recognition

- Generate quantitative reports on particle size distribution, concentration, and polymer type

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Nanoplastic Quantification

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Density Separation Salts (NaI, ZnCl₂, Na₆(H₂W₁₂O₄₀)) | Isolate plastics from environmental matrices based on density differences | Higher density salts (1.6-1.8 g/cm³) required for suspending PVC and PET [13] |

| Fenton's Reagent (H₂O₂ + Fe²⁺ catalyst) | Digest organic matter through intense oxidative reaction | May alter or destroy some nanoplastics; requires careful optimization [13] |

| Enzymatic Digestion Cocktails | Gently remove organic matter without damaging plastics | Time-consuming but preserves plastic integrity; may interact with impurities [13] |

| Nile Red Stain | Fluorescent dye for preliminary identification and quantification | Effective for rapid screening but may produce false positives with certain lipids [7] |

| Filter Membranes (polycarbonate, aluminum oxide) | Capture nanoplastics from liquid samples for analysis | Pore size selection critical (0.1-0.45 μm for NPs); sequential filtration recommended [13] |

| Reference Nanoplastic Materials | Positive controls for method validation | Include weathered particles to reflect environmentally relevant conditions [14] |

Frequently Asked Questions: Troubleshooting Experimental Challenges

Sample Collection and Preparation

Q: What is the minimum sample volume required for statistically reliable nanoplastic quantification in groundwater studies? A: For aquifers with very low contamination levels, use low-flow pumping systems connected to in situ filtration to collect hundreds of liters of groundwater. In more contaminated sites, a few liters collected using volumetric samplers may suffice. The key is conducting pilot studies to establish appropriate volumes for your specific environment [13].

Q: How can I prevent nanoplastic loss during sample purification? A: Implement sequential filtration rather than single-stage filtration. Avoid froth flotation techniques, which cause significant particle loss through bubble interactions. When using density separation, remember that buoyant forces are minimal at the nanoscale, and consider that particle density can be altered by surface fouling [13].

Detection and Analysis

Q: What approaches can minimize false positives in nanoplastic identification? A: (1) Include natural particle controls (e.g., kaolin) in your experiments to distinguish plastic-specific effects [14]. (2) Use complementary analytical techniques (e.g., combining microscopy with spectroscopy). (3) Employ AI-driven classification algorithms that can learn to distinguish plastics from natural particles based on multiple parameters [13].

Q: How can I improve detection limits for particles below 1μm? A: Current innovations include: (1) Holographic imaging in microscope configuration, which can image microplastics directly in unfiltered water and discriminate plastics from diatoms while differentiating sizes, shapes, and plastic types [7]. (2) Combining Raman spectroscopy with advanced microscopy techniques. (3) Using nanotechnology-based approaches with functionalized nanoparticles for enhanced detection [13].

Data Interpretation and Validation

Q: How can I determine if observed biological effects are specific to plastics rather than general particle effects? A: Always include natural particle controls (such as kaolin) in your experimental design. Research has shown that weathered PET and kaolin can cause similar inhibition patterns in microalgae, suggesting that particle properties rather than material identity may predominantly drive algal stress responses [14]. This experimental approach allows for disentanglement of plastic-specific effects from general particle effects.

Q: What metrics are most meaningful for reporting nanoplastic quantification results? A: Report multiple complementary metrics: (1) Particle number concentration (particles/volume), (2) Mass concentration where feasible, (3) Size distribution across relevant size classes, (4) Polymer composition distribution, and (5) Morphological characteristics. Always include measures of uncertainty and method detection limits for proper interpretation of your results.

The methodologies and troubleshooting guidance presented in this technical support center enable researchers to overcome critical barriers in nanoplastic quantification. By implementing these advanced protocols—from standardized sample preparation to integrated detection technologies and appropriate controls—the research community can generate the high-quality quantitative data essential for accurate risk assessment. This evolution from presence-absence studies to concentration-dependent effects analysis represents the foundation for developing evidence-based environmental regulations and protection strategies that effectively address the potential threats posed by nanoplastic pollution.

Next-Generation Instruments and Workflows for Enhanced Sensitivity

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the core principle behind AF4-MALS separation? Asymmetrical Flow Field-Flow Fractionation (AF4) separates particles in a thin, open channel. A laminar flow carries the sample forward, while a perpendicular crossflow pushes particles toward an accumulation wall (a semi-permeable membrane). Smaller particles, with higher diffusion coefficients, move further from the membrane into faster-flowing streamlines and elute first. Larger particles, which stay closer to the membrane, elute later. This provides a size-based separation from approximately 1 nm to over 1 μm [15] [16]. Multi-Angle Light Scattering (MALS) is then used as an online detector to independently measure the radius of gyration (Rg) of the separated particles, providing accurate size information regardless of their elution time [15] [17].

2. My sample recovery is low. What could be the cause? Low recovery is a common challenge, often caused by sample-membrane interactions or issues between analytical steps in a workflow [15] [18].

- Membrane Interactions: The membrane's chemical composition may not be compatible with your sample. Conditioning a new membrane with a sacrificial protein like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) can help saturate active binding sites and improve recovery [16].

- Carrier Liquid: The ionic strength and pH of the carrier liquid can affect particle-membrane interactions and sample stability. Optimizing these parameters, and using volatile salts like ammonium bicarbonate or ammonium carbonate when coupling to Py-GC-MS, can mitigate this issue [19] [18].

- Sample Loss Between Steps: In offline workflows (e.g., collecting AF4 fractions for further analysis), steps like freeze-drying and resuspension can introduce significant losses. Optimizing resuspension protocols (e.g., vortexing and sonication in an organic solvent like THF) is crucial [18].

3. How can I improve the detection limits for trace-level analytes like nanoplastics? The low concentrations of nanoplastics in environmental samples present a significant challenge [15].

- Large-Volume Injection (LVI): This technique allows for the injection of large sample volumes (e.g., 10 mL) directly into the AF4 channel. The particles are preconcentrated in-line at the channel head, significantly boosting the mass of analyte delivered to the detectors without requiring a separate, loss-prone preconcentration step [15] [18].

- Signal Enhancement: Technologies like Smart Stream Splitting (S3) can be used to increase the concentration of the sample eluting from the AF4 channel before it reaches the detectors, thereby improving signal intensity [20].

4. Why are my fractograms showing poor resolution or broad peaks? Poor resolution can stem from several method parameters:

- Suboptimal Crossflow: The crossflow rate is critical for separation. A gradient elution profile (starting with a higher crossflow and gradually reducing it) often provides better resolution for polydisperse samples than a constant crossflow [16].

- Inadequate Focusing Step: An improperly optimized focusing step can lead to band broadening. Ensure the focus flow rate and duration are sufficient to concentrate the sample into a sharp band at the channel head before elution begins [17] [16].

- Sample Overloading: Injecting too much sample can overwhelm the separation mechanism, leading to poor resolution and broad peaks [16].

5. My MALS data seems inconsistent. What should I check?

- System Calibration: Regularly calibrate the MALS detector according to the manufacturer's guidelines using an appropriate standard [16].

- Carrier Liquid Clarity: Ensure the carrier liquid is free of dust and particulates by using high-purity solvents and filtering the mobile phase.

- Complex Matrices: Be aware that in complex samples like wastewater, the environmental matrix itself can bias MALS measurements [15].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Suggested Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Backpressure | Membrane blockage, too high crossflow, channel obstruction [16]. | Filter samples and solvents; flush/clean the channel and membrane; replace the membrane if needed [16]. |

| Poor Separation Resolution | Incorrect crossflow rate, insufficient focusing, sample overloading, inappropriate membrane [16]. | Optimize crossflow gradient; ensure proper focus flow/duration; reduce injection mass; select correct membrane type/cut-off [16]. |

| Low Recovery/Adsorption | Sample-membrane interactions, unsuitable carrier liquid pH/ionic strength [15] [18]. | Condition membrane with BSA; optimize carrier liquid composition; use volatile salts for hyphenation with Py-GC-MS [18] [16]. |

| Irreproducible Retention Times | Inconsistent flow rates, air bubbles in the system, crossflow instability [16]. | Calibrate pumps; thoroughly degas solvents; ensure system is free of air bubbles; check for leaks. |

| Noisy MALS/UV Baseline | Dirty flow cell, contaminated carrier liquid, air bubbles in detectors [16]. | Clean detectors per manufacturer protocol; use fresh, filtered solvents; purge detectors to remove bubbles. |

Experimental Protocols for Nanoplastic Analysis

Protocol 1: Basic AF4-MALS Method for Polystyrene Nanoplastics in Freshwater

This protocol is adapted from an open-access study that successfully separated 50 nm and 100 nm PS NPs in freshwater [19].

1. Materials and Reagents

- AF4 System coupled with MALS and UV-Vis detectors.

- Carrier Liquid: 0.25 mM Ammonium carbonate or 1 mM Sodium dodecyl sulfate in ultrapure water [19] [18].

- Membrane: Polyethersulfone or Regenerated Cellulose, 10 kDa molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) [19] [16].

- Spacer: 350 μm thickness [19] [16].

- Standards: Monodisperse Polystyrene Nanoplastics (e.g., 50 nm, 100 nm).

2. Method Parameters

- Injection Volume: 1-100 μL (standard), or up to 10 mL using Large-Volume Injection (LVI) [19] [18].

- Focusing Step: 3-5 minutes with a focus flow rate of 1.5-3 mL/min [19] [16].

- Elution Program:

3. Data Analysis

- Use the MALS detector (e.g., 21-angle) to determine the radius of gyration (Rg) for each slice of the fractogram [15] [17].

- The UV signal (e.g., at 254 nm or 280 nm) provides a concentration profile [18].

Protocol 2: Offline AF4-MALS-Py-GC-MS Workflow for Polymer Identification

This advanced protocol details the steps for combining size-based separation with chemical identification, crucial for complex environmental nanoplastic analysis [18].

Workflow Overview

1. Sample Preparation (Pre-AF4)

- Sonication: Sonicate water samples for 10 minutes, three times, with 10-minute breaks to disperse aggregates [18].

- Filtration: Filter the sample through a 1 μm polyethersulfone (PES) syringe filter to remove large particles and debris [18].

2. AF4-MALS Separation and Fraction Collection

- AF4 Method: Follow a method similar to Protocol 1, using a volatile carrier liquid (e.g., 0.25 mM ammonium carbonate) to ensure compatibility with subsequent Py-GC-MS [18].

- Fraction Collection: After the void peak, manually or automatically collect 6-8 fractions (e.g., 7-minute intervals) into glass vials based on the MALS/UV fractogram [18].

3. Sample Handling Between AF4 and Py-GC-MS This is a critical step to minimize losses [15] [18].

- Freeze-Drying: Cap the collected fraction vials with a gas-permeable cloth (e.g., Miracloth), freeze them, and lyophilize to complete dryness to remove the aqueous carrier liquid.

- Resuspension: Carefully add 500 μL of THF to each dried fraction. Vortex for 20 seconds and sonicate for 10 minutes to resuspend the nanoplastic residues. Transfer the suspension to a Py-GC-MS vial.

4. Py-GC-MS Analysis

- Injection: Inject 55 μL of the resuspended sample into the Pyrolysis-GC-MS [18].

- Pyrolysis: Pyrolyze at 550°C to break down polymers into characteristic fragments [18].

- GC-MS Conditions:

- GC Oven: Ramp from 50°C to 320°C.

- MS: Operate in scan mode (e.g., m/z 60-300) to detect polymer-specific pyrolysis products [18].

- Identification: Identify and quantify polymers by comparing the target pyrolysis products and their masses with standards [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential materials and their functions for setting up an AF4-MALS experiment for nanoplastic analysis.

| Item | Function / Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| AF4 Channel Spacer | Defines the height and volume of the separation channel, impacting resolution and capacity [16]. | 350 μm thickness (common) [19] [16]. |

| Semi-Permeable Membrane | Forms the accumulation wall; allows solvent and small molecules to pass while retaining analytes. Critical for separation and recovery [16]. | Regenerated Cellulose or Polyethersulfone; 10 kDa MWCO [19] [16]. |

| Volatile Salt Buffer | Serves as a carrier liquid compatible with offline hyphenation to Py-GC-MS, as it can be evaporated cleanly [18]. | 0.25 - 1.0 mM Ammonium Carbonate or Ammonium Bicarbonate [19] [18]. |

| Surfactant | Added to the carrier liquid to reduce sample-membrane interactions and prevent aggregation of nanoparticles [19]. | 1 mM Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) [19]. |

| Size Standards | Used for system calibration and method validation [16]. | Monodisperse Polystyrene Nanoparticles (e.g., 50 nm, 100 nm) [19]. |

| Membrane Conditioner | Saturates active sites on a new membrane to minimize analyte adsorption and improve recovery [16]. | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), 5 mg/mL in carrier liquid [16]. |

AF4 System Setup and Flow Path Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the key components and flow paths of a typical AF4-MALS system, showing how the sample is focused, separated, and detected.

Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC-MS) is an advanced hyphenated technique that has become indispensable for polymer identification and quantification, particularly in the evolving field of nanoplastic research. This method combines thermal decomposition of samples with high-resolution separation and detection, enabling analysis of solid or insoluble polymeric materials that are unsuitable for traditional GC-MS. For researchers focused on pushing detection limits for nanoplastics, Py-GC-MS offers exceptional sensitivity, with detection capabilities reaching nanogram levels for many polymer types [21] [22].

The fundamental principle involves thermal fragmentation of analytical samples at high temperatures (500-1400°C) in an inert atmosphere, producing reproducible decomposition products characteristic of the original polymer. These pyrolyzates are then separated chromatographically and identified using mass spectrometry [23] [24]. This technique has proven particularly valuable for microplastic analysis in complex environmental matrices, where it can identify polymer types and quantify levels down to microgram concentrations while requiring minimal sample preparation [21] [22].

Technical Specifications and Method Optimization

Instrument Configuration and Parameters

Optimal Py-GC-MS performance requires careful configuration of multiple instrument parameters. Research indicates that a pyrolysis temperature of 700°C, a split ratio of 5:1, and an injector temperature of 300°C provide effective analysis conditions for most polymers [21]. The table below summarizes optimized parameters for polymer analysis based on published methodologies:

Table 1: Optimized Py-GC-MS Parameters for Polymer Analysis

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Alternative Settings | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrolysis Temperature | 700°C | 500-900°C range | 700°C optimal for most polymers [21] |

| Split Ratio | 5:1 | 10:1 to 50:1 | Lower ratios improve sensitivity [21] |

| Injector Temperature | 300°C | 250-300°C | Higher temperature reduces condensation [21] |

| Column Temperature | 60°C (1min) to 280°C at 10°C/min | Various gradients possible | Program depends on polymer complexity [24] |

| Carrier Gas | Helium | Nitrogen | Helium provides better separation efficiency [24] |

| Sample Size | 5-200 μg | Up to 500 μg | Minimal sample required [23] [25] |

Advanced Operational Modes

Py-GC-MS offers several operational modes that enhance its analytical capabilities:

- Single Shot Pyrolysis: Conducted at a single temperature (>500°C) to characterize the original sample through bond breaking [23]

- Double Shot Pyrolysis: Performed at both low (80-350°C) and high temperatures (500-800°C), with the lower temperature step examining thermal desorption of monomers, oligomers, and additives [23]

- Evolved Gas Analysis (EGA): The furnace temperature is increased at a set ramp rate to examine components that off-gas from the sample, helping identify optimal temperature ranges for specific compounds [23]

- Reactive Pyrolysis: Employs derivatization techniques for complex mixtures like polyesters, making data interpretation more manageable [23]

Experimental Protocols for Polymer Analysis

Standard Analytical Procedure

For reliable polymer identification and quantification, follow this standardized protocol:

Sample Preparation: Cut approximately 100-200 μg of solid sample with a scalpel and insert without further preparation into the pyrolysis solids-injector [24]. Place the sample with a plunger on the quartz wool of the quartz tube in the furnace pyrolyzer. Analyze three spots on each sample in duplicate to ensure reproducibility.

Instrument Setup: Configure the pyrolyzer to operate at a constant temperature of 700°C [21]. Set the helium carrier gas pressure to 95 kPa at the inlet to the furnace [24]. For the GC separation, use a 60 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25-μm df Elite-5ms fused-silica GC capillary column or equivalent [24].

Chromatographic Conditions: Program the column temperature as follows: 60°C for 1 minute, then increase to 100°C at 2.5°C/min, followed by a ramp to 280°C at 10°C/min with a 20-minute hold at the final temperature [24]. Maintain the split–splitless injector at 250°C with a split flow of 50 cm³/min.

Mass Spectrometry Detection: Operate the mass spectrometer in electron ionization (EI) mode with 70 eV kinetic energy. Set the ion source temperature to 250°C and scan in the mass range m/z 35-750 u [24]. Use NIST or Wiley mass spectral libraries for compound identification.

Quantitative Analysis Methodology

For quantification of specific polymers:

Indicator Compound Selection: Identify characteristic pyrolysis products for each polymer type (e.g., cyclopentanone for nylon 6-6, styrene for polystyrene) [24] [26]

Calibration Curve Development: Prepare external standards of target polymers at concentrations ranging from 0.1-100 μg. Process through the same Py-GC-MS method as unknown samples [26]

Tandem MS Enhancement: Implement Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) for improved sensitivity and selectivity, particularly for complex matrices. This approach can lower detection limits to the ng/L range for environmental samples [26]

Data Analysis: Use integrated peak areas of characteristic pyrolysis products for quantification, applying appropriate internal standards when available to correct for instrumental variations

Figure 1: Py-GC-MS Analytical Workflow

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Chromatographic and Detection Problems

Table 2: Common Py-GC-MS Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline instability or drift | Column bleed, contamination, detector instability | Bake-out column at higher temperature, replace if necessary, clean detector | Use high-quality columns, proper conditioning, stable carrier gas [27] |

| Peak tailing or fronting | Column overloading, active sites, improper vaporization | Reduce sample concentration, use split injection, condition column | Optimize injection technique, proper sample preparation [27] |

| Ghost peaks or carryover | Contaminated syringe/injection port, column bleed | Clean/replace syringe and injection port, column bake-out | Implement proper rinsing/purging between injections [27] |

| Poor resolution or peak overlap | Inadequate column selectivity, incorrect temperature program | Optimize column selection, adjust mobile phase, modify temperature program | Method development with standard mixtures [27] |

| Irreproducible results | Inconsistent sample prep, column contamination, unstable parameters | Standardize sample preparation, maintain column, consistent injection technique | Regular instrument calibration, stable operating conditions [27] |

| Decreasing signal over time | System contamination, detector aging | Systematic cleaning, component replacement | Regular maintenance, use of quality materials [21] |

Method-Specific Challenges

Polymer Mixture Complexity: When analyzing complex polymer blends, interpretation difficulties may arise due to overlapping pyrolysis products. In such cases, employ Heart Cut-EGA GC-MS (HC-EGA-GC-MS) to isolate desired elution zones for individual analysis [23].

Low Concentration Samples: For trace analysis of nanoplastics, implement cryotrapping capabilities using liquid nitrogen to narrow chromatographic bands and improve detection limits [23]. Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) has been shown to enhance sensitivity and selectivity, achieving detection limits in the ng/L range for bottled water analysis [26].

Non-Homogeneous Samples: Variable results from non-uniform samples can be mitigated by increasing replicate analyses and ensuring representative sampling. For surface analysis (e.g., fouling on failed parts), sample by rubbing the affected surface with quartz glass wool followed by Py-GC-MS of the enriched wool [25].

Advanced Applications in Nanoplastic Research

Enhancing Detection Limits for Nanoplastics

Improving detection limits for nanoplastic analysis represents a critical frontier in environmental analytics. Recent advancements in Py-GC-MS methodology have demonstrated promising approaches:

Tandem Mass Spectrometry: The use of MS/MS with Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) has shown significant improvements in sensitivity and selectivity for trace polymer analysis. This approach reduces chemical noise and enhances signal-to-noise ratios, enabling quantification of plastics at nanogram levels [26].

Integrated Hyphenated Techniques: Combining Py-GC-MS with additional analytical methods provides comprehensive characterization. For instance, hyphenated TGA-FTIR-GC/MS enables simultaneous thermal, spectroscopic, and chromatographic analysis, creating detailed polymer databases for more accurate identification [28].

Minimizing Background Contamination: At low detection levels, contamination control becomes paramount. Implement rigorous quality assurance protocols including procedural blanks, clean room conditions, and minimal plastic contact during sample preparation and analysis [26].

Quantitative Analysis of Environmental Samples

For nanoplastic quantification in environmental matrices:

Matrix-Specific Calibration: Develop calibration curves in matrix-matched standards to account for potential interference effects

Indicator Compound Validation: Confirm the specificity of selected indicator compounds through MRM experiments, particularly for similar polymers like PP and PE [26]

Standard Addition Methods: Employ standard addition quantification when matrix effects are significant, adding known amounts of target polymers to aliquots of the sample

Quality Control Measures: Include continuous quality control samples such as blanks, replicates, and reference materials to ensure method validity throughout analysis

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Py-GC-MS Analysis

| Item | Specifications | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrolysis tubes | Quartz wool packed | Sample holder in pyrolyzer | Ensure quartz wool is fresh to prevent contamination [24] |

| Reference polymers | PE, PP, PS, PET, PMMA, PC, Nylon | Calibration and method development | Use high-purity standards for accurate quantification [26] |

| GC capillary columns | 5% phenyl polysiloxane (60m, 0.25mm, 0.25μm) | Separation of pyrolysis products | DB-5ms, Elite-5ms, or equivalent recommended [24] |

| Helium carrier gas | Grade 5.0 or higher (99.999% purity) | Carrier gas for GC separation | High purity reduces background noise [24] |

| Mass spectral libraries | NIST, Wiley, MPW, Norman Mass Bank | Compound identification | Essential for polymer pyrolysis product identification [25] |

| Cryotrapping accessory | Liquid nitrogen cooling | Band focusing for trace analysis | Improves detection limits for nanoplastic research [23] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: What is the minimum sample size required for Py-GC-MS analysis? A: Py-GC-MS requires only microgram quantities of sample (typically 5-200 μg), making it ideal for limited or precious samples. The small sample size also facilitates analysis of discrete particles isolated from environmental matrices [23] [25].

Q: How does Py-GC-MS compare to spectroscopic techniques like FTIR or Raman for microplastic analysis? A: Py-GC-MS provides complementary information to spectroscopic techniques. While FTIR and Raman offer spatial information about individual particles, Py-GC-MS enables chemical identification of complex mixtures and particles containing pigments that may interfere with spectroscopic analysis [21]. Additionally, Py-GC-MS can analyze particles below the size limitations of spectroscopic methods.

Q: Can Py-GC-MS quantify polymer additives as well as the main polymer? A: Yes, specific Py-GC-MS operational modes like double-shot pyrolysis enable identification and quantification of additives. The initial lower temperature step (80-350°C) performs thermal desorption of additives, residual solvents, and other low molecular weight components before the high-temperature step fragments the polymer backbone [23].

Q: What are the key limitations of Py-GC-MS for nanoplastic research? A: The main limitations include: the destructive nature of analysis, difficulty with non-homogeneous samples, limited detection of inorganic components, potential for complex data interpretation with polymer mixtures, and the need for careful contamination control at ultra-trace levels [23] [26].

Q: How can I improve detection limits for nanoplastic analysis using Py-GC-MS? A: Implement tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) with MRM for enhanced selectivity and sensitivity, utilize cryotrapping to focus chromatographic bands, optimize pyrolysis temperature for specific polymers, minimize background contamination through rigorous controls, and employ heart-cutting techniques for complex matrices [23] [26].

Technical FAQ: Troubleshooting Common FI-MS Issues

Q1: The flame will not ignite or keeps going out. What should I check? This is often related to gas flows, temperature, or the igniter. Please check the following:

- Detector Temperature: Ensure the FID temperature is at least >150 °C. For more robust operation and to prevent water condensation, a temperature ≥300 °C is recommended [29].

- Gas Flows & Ratios: Verify that the actual gas flows meet the setpoints. The hydrogen-to-air ratio should be between 8-12%. Typical default flows are 30 mL/min for hydrogen, 400 mL/min for air, and 25 mL/min for makeup gas (nitrogen or helium) [29]. A higher hydrogen flow can sometimes aid ignition.

- Gas Quality: Use high-purity gases (99.9995% or better). Synthetic air with low oxygen content or gases contaminated with water or hydrocarbons can prevent ignition [29] [30].

- The Igniter: Visually inspect the igniter through the FID chimney during the ignition sequence. It should glow brightly. If it is corroded, broken, or glowing weakly, it must be replaced [29].

- Jet Blockage: A partially or fully plugged FID jet will restrict gas flow. Perform a "Jet Restriction Test" or remove the jet to inspect for blockages [29].

Q2: My baseline is noisy, or I am seeing random spikes in the signal. This typically indicates contamination.

- Source: The contamination likely originates from the fuel/makeup gases, a dirty FID jet, or over-tightened graphite ferrules that have shed particles into the jet [30].

- Solution:

Q3: The signal sensitivity is lower than expected. This can be caused by suboptimal gas flows or a dirty system.

- Gas Flow Optimization: Sensitivity peaks within a narrow hydrogen flow window (e.g., 30–45 mL/min). Maintain a 10:1 ratio of air to hydrogen for optimal performance [31].

- Reducing Noise: To achieve the lowest detection limits, lower the fuel gas flows to reduce background chemical noise, but ensure the flows are still high enough to prevent the flame from being blown out by solvent or high-concentration analytes [30].

- System Cleanliness: A contaminated jet or gas lines will increase noise and reduce the signal-to-noise ratio, directly impacting sensitivity [30].

Q4: Can FI-MS be used for quantitative analysis of nanoplastics? Yes. The FI-MS method has been successfully used for the quantitative analysis of nanoplastics like polystyrene in complex matrices, including soil and mouse placental tissue, achieving sub-microgram levels of detection [4] [32] [33]. Its minimal sample preparation reduces opportunities for sample loss, improving quantitative accuracy.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Core Protocol: Direct FI-MS Analysis of Nanoplastics

This protocol is adapted from the method developed for detecting polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polystyrene (PS) in environmental and biological samples [4].

Principle: A small open flame (using n-butane fuel) is applied to a sample, which simultaneously thermally decomposes and ionizes the plastic polymers. The resulting gaseous ions are then detected by a high-resolution mass spectrometer [4] [34].

Sample Preparation:

- Liquid Samples (e.g., Bottled Water, Juice): A known volume of liquid is passed through a cellulose membrane filter (e.g., 0.7 μm pore size) to capture plastic particles. The filter paper is then dried [4].

- Solid Samples (e.g., Soil, Biological Tissue): A small amount (e.g., 1 mg) of soil or tissue is placed directly on a sample rod or a piece of filter paper without any digestion or extraction [4] [32].

FI-MS Analysis:

- Instrument Setup: The mass spectrometer inlet is positioned approximately 1 cm from the center of the n-butane flame. The flame temperature is approximately 500 °C [34].

- Introduction of Sample: The sample (filter paper, soil, or tissue on a metal rod) is directly introduced into the outer flame region.

- Ignition and Data Acquisition: The sample is burned for a short duration (as little as 10 seconds). The resulting ions are monitored in real-time by the mass spectrometer [4] [33].

- Identification: Identify the plastic polymer by its characteristic decomposition product ions. For example:

Workflow Diagram: FI-MS Analysis for Nanoplastics

The following diagram illustrates the streamlined workflow for detecting nanoplastics using Flame Ionization Mass Spectrometry.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials required for FI-MS analysis of nanoplastics based on the cited research [4].

| Item | Function / Role in FI-MS Analysis |

|---|---|

| n-Butane Fuel | Serves as the fuel for the open flame, providing the thermal energy for desorption and ionization. It is optimal due to its gas state (easy flow control) and performance [34]. |

| Cellulose Membrane Filter Paper (0.7 μm) | Used to concentrate and capture micro- and nanoplastic particles from liquid samples like water or juice for direct introduction into the flame [4]. |

| Metal Sample Rods | Provides a platform for mounting solid samples (e.g., soil, biological tissue) for direct insertion into the flame [4] [34]. |

| High-Purity Gases | Zero-grade air and high-purity hydrogen (>99.9995%) are critical for stable flame operation and minimizing background signal noise [29] [30]. |

| Polymer Standards | PET microplastics, Polystyrene (PS) latex nanospheres, and PVC microspheres are used for instrument calibration, method development, and identification of characteristic ions [4]. |

Performance Data & Detection Limits

The quantitative performance of FI-MS for detecting various plastics across different sample matrices is summarized below [4] [33].

| Plastic Polymer | Sample Matrix | Characteristic Ion(s) (m/z) | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) | Bottled Water, Apple Juice | 149, 167, 191, 221 | Detected in seconds from filtered samples [4]. |

| Polystyrene (PS) | Mouse Placental Tissue | 104 ([C8H8]+) | Identified and quantified in 1 mg of tissue without digestion [4] [32]. |

| PET & PS | Agricultural Soil | Polymer-specific ions | Quantitative analysis achieved without extraction/isolation [4] [33]. |

| General Method | Various | Varies by polymer | Analysis speed: ~10 seconds/sample. Sensitivity: Sub-microgram levels [32] [33]. |

Ionization Pathway Diagram

The diagram below outlines the proposed ionization pathway when a plastic polymer is introduced into the n-butane flame, leading to the detection of characteristic ions.

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Common SERS Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: My SERS signals are inconsistent, even when using the same sample and substrate. What could be causing this?

Answer: Signal inconsistency in SERS is a common challenge, primarily caused by variations in substrate fabrication and the presence of electromagnetic "hotspots."

- Substrate Reproducibility: Small changes in nanofabrication conditions can lead to significant variations in enhancement factors. This is particularly problematic with colloidal nanoparticles where it's challenging to aggregate nanoparticles reproducibly [35] [36].

- Hotspot Dominance: The majority of SERS signal originates from nanoscale gaps and crevices with extremely high electric field enhancements. Small changes in the number of molecules occupying these regions create large intensity variations [36].

- Solution: Implement internal standardization using co-adsorbed molecules or stable isotope variants of your target analyte to correct for this variance. For quantitative work, measure multiple spots (one study suggested >100 spots may be necessary to properly capture variance) [36]. Consider using paper-based SERS platforms which have demonstrated relative standard deviations below 11.6% [37].

FAQ 2: The vibrational frequencies I observe in SERS don't match my reference Raman spectra. Is this normal?

Answer: Yes, this is a recognized phenomenon in SERS. Several factors can cause spectral changes:

- Surface Interactions: Molecules adsorbed on metal surfaces may experience changes in their geometric and electronic structure, modifying their vibrational frequencies [35].

- Surface Reactions: Electrons in plasmonic metals can drive chemistry on adsorbed analytes. A classic example is para-aminothiophenol, where new frequencies arise from the formation of dimercaptoazobenzene on the surface [36].

- Polarization Dependence: SERS selectively enhances modes aligned with the enhanced electric field, changing relative peak intensities [36].

- Solution: Generate calibration curves with known concentrations of your specific analyte using the same SERS substrate and low laser powers (<1 mW) to minimize photoreactions [36].

FAQ 3: My target molecule doesn't seem to enhance well, even though it works in spontaneous Raman. What could be wrong?

Answer: Not all molecules enhance equally in SERS due to differences in surface affinity and electronic properties:

- Surface Affinity: SERS is a short-range enhancement that decays within a few nanometers. Molecules must adsorb to or be very close to the metal surface [36].

- Chemical Structure: Molecules with aromatic rings, thiols, or pyridines often show better enhancement due to stronger surface interactions and potential charge-transfer contributions [36].

- Resonance Effects: Molecules with electronic resonances in the visible region (like rhodamine) show significantly better enhancement (SERRS) [36].

- Solution: For difficult molecules like glucose, consider surface functionalization with capture agents (e.g., boronic acid) that bring the analyte closer to the surface [36].

FAQ 4: I'm getting strong fluorescence background that's overwhelming my SERS signals. How can I reduce this?

Answer: Fluorescence interference is a common challenge, particularly with biological samples:

- NIR Excitation: Switch to near-infrared lasers (e.g., 785 nm) which typically reduce fluorescence as most fluorophores have electronic transitions in the visible spectrum [38] [39].

- Paper-based Platforms: Cellulose fiber-based SERS substrates have demonstrated strong tolerance to fluorescence interference from dye residues [37].

- SERS Continuum: Recognize that a fluorescence-like background (SERS continuum) is often present in biological SERS spectra due to analyte distance from the surface and sample complexity [39].

FAQ 5: My machine learning models show excellent performance during training but fail with new data. What am I doing wrong?

Answer: This typically indicates overfitting or data preprocessing errors:

- Independent Samples: Ensure you have sufficient independent replicates (at least 3-5 for cell studies, 20-100 patients for diagnostic studies) [40].

- Data Splitting: Implement "replicate-out" cross-validation where biological replicates or patients are kept entirely within training, validation, or test subsets. Normal cross-validation can overestimate performance by 40% or more [40].

- Preprocessing Order: Always perform baseline correction before spectral normalization. Normalizing before background correction encodes fluorescence intensity in the normalization constant, biasing your models [40].

- Model Complexity: Match model complexity to your dataset size. For small datasets, use low-parameterized linear models rather than deep learning architectures [40].

Quantitative SERS Performance Data

Table 1: SERS Enhancement Capabilities for Different Analytics

| Analyte | Particle Size | Enhancement Factor | Limit of Detection | Key Substrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene Nanoplastics | 20 nm | 10¹⁰ | 1 ppt | Paper-based Au substrate [37] |

| Polystyrene Nanoplastics | 50 nm | Not specified | 0.1 ppb | Silver nanowire membranes [37] |

| Pesticides (malathion, chlorpyrifos, imidacloprid) | Varies | Varies by substrate | Ultralow concentrations | Various plasmonic nanostructures [41] |

| Cocaine in blood plasma | Not applicable | Enables trace detection | Not specified | Metal nanoclusters on polymer nanofibers [35] |

Table 2: Machine Learning Algorithm Performance in SERS Analysis

| Application | Best Performing Algorithm | Reported Accuracy | Sample Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial identification | Random Forest | 99% | Pure bacterial samples [35] |

| Clinical sample analysis | SVM and CNN-LSTM-Attention | 92-96% | Clinical bacterial samples [35] |

| Food contaminant detection | Artificial Neural Networks | Strong R² values vs traditional methods | Food samples [35] |

| Soil dye degradation | Not specified | 97.9% | Environmental samples [35] |

| Exosome classification | Bagging algorithms (Extra Trees) | Highest accuracy | Commercial and clinical exosomes [42] |

Experimental Protocols for Nanoplastic Analysis

Protocol 1: Paper-based SERS Platform for Single-Nanoplastic Particle Detection

This protocol enables detection of nanoplastics down to 20 nm with 1 ppt sensitivity [37]:

Substrate Fabrication:

- Use cellulose filter paper as base substrate

- Perform vapor-phase modification with perfluorooctyltrichlorosilane (FOS) to reduce surface energy

- Thermally evaporate Au onto modified paper to form dense nanoparticle assemblies with narrow spacings (1-5 nm gaps)

- The surface energy difference promotes formation of plasmonic hotspots

Sample Preparation:

- Obtain nanoplastic standards (e.g., PS, nylon, PVC, PMMA) as 1 wt% suspensions in deionized water

- Dilute to appropriate concentrations (e.g., 1 ppt for LOD determination)

- For real samples (EPS containers, plastic teabags), appropriate extraction is required

SERS Measurement:

- Integrate with portable 785 nm Raman spectrometer

- Measure multiple spots to account for heterogeneity (recommended: >100 spots)

- Use low laser power (<1 mW) to avoid photodamage

- Acquisition parameters: 1-10 s integration time typically sufficient

Data Analysis:

- Employ machine learning algorithms (PCA, RF, SVM) for classification

- Use internal standards for quantification

- Implement appropriate preprocessing (background correction before normalization)

Protocol 2: Reliable SERS-ML Integration Workflow

This protocol ensures robust machine learning analysis of SERS data [40]:

Data Acquisition:

- Collect sufficient independent replicates (minimum 3-5 for cell studies)

- Include quality control measurements using wavenumber standards (e.g., 4-acetamidophenol)

- Perform weekly white light measurements for system calibration

Spectral Preprocessing Pipeline:

- Remove cosmic rays using automated algorithms

- Apply wavenumber calibration using standard reference

- Perform baseline correction using optimized parameters (grid search recommended)

- Apply spectral normalization (after baseline correction)

- Implement denoising appropriate for mixed Poisson-Gaussian noise

Machine Learning Implementation:

- For small datasets: Use linear models, PCA, or PLS

- For large datasets: Consider deep learning architectures

- Implement replicate-out cross-validation to prevent overfitting